Lake Tanganyika Biodiversity Project

Projet sur la Biodiversité du Lac Tanganyika

Lake Tanganyika:

Results and Experiences of

the UNDP/GEF Conservation

Initiative (RAF/92/G32) in

Burundi, D.R. Congo,

Tanzania, and Zambia

prepared by

Kelly West

28 February 2001

TABLE of CONTENTS

ACRONYMS

08

CHAPTER 1.

INTRODUCTION to LAKE TANGANYIKA

11

1.1 Why is Lake Tanganyika Special?

11

1.1.1 Physiographic Considerations

11

1.1.2 Biological Considerations

12

1.1.3 Socio-Political Considerations

17

1.2 Threats to this Resource

19

1.2.1 Pollution

19

1.2.2 Sedimentation

20

1.2.3 Overfishing

21

1.2.4 People

22

CHAPTER 2.

ORIGIN, STRUCTURE and EVOLUTION of LTBP

23

2.1 History

23

2.2 Project Objectives

25

2.3 Project Structure

25

2.4 Chronology of LTBP

28

CHAPTER 3.

IMPLEMENTATION and OUTPUTS of LTBP

31

3.1 Capacity-Building and Training

31

3.1.1 Material Capacity Building

31

3.1.2 Human Capacity Building and Training

32

3.2 Technical Programmes

35

3.2.1 Biodiversity Special Study

35

3.2.1.1 Objectives and Strategy

35

3.2.1.2 Products

36

3.2.1.2.1 Methodology

37

3.2.1.2.2 Human Capacity

38

3.2.1.2.3 Databases

38

3.2.1.2.4 Biodiversity in Lake Tanganyika

39

Habitats

39

Lakewide Biodiversity Patterns

41

Biodiversity Patterns near PAs

41

3.2.2 Pollution Special Study

45

3.2.2.1

Objectives and Strategy

45

3.2.2.2

Products

46

3.2.2.2.1 Water Quality Studies

46

3.2.2.2.2 Industrial Pollution Inventory

47

Bujumbura, Burundi

48

2

Uvira, D.R. Congo

4 8

Kigoma, Tanzania

48

Mpulungu, Zambia

48

3.2.2.2.3 Pesticide and Heavy Metals Studies

49

3.2.3 Sedimentation Special Study

49

3.2.3.1 Objectives and Strategy

49

3.2.3.2 Products

50

3.2.3.2.1 River Gauging Studies

50

Burundi

51

D.R. Congo

51

Tanzania

51

Zambia

52

3.2.3.2.2 Coring Studies

52

3.2.3.2.3 Erosion Modelling

53

3.2.3.2.4 Sediment Transport Studies

54

3.2.3.2.5 Nutrient Dynamics

55

3.2.3.2.6 Biological Impact of Sediments

55

3.2.4 Fishing Practices Special Study

56

3.2.4.1 Objectives and Strategy

57

3.2.4.2 Products

57

3.2.4.2.1 Fishing Gears of Lake Tanganyika

57

3.2.4.2.2 Fishing Threats to Protected Areas

58

Gombe Stream National Park, Tanzania

58

Mahale Mountains National Park, Tanzania

58

Nsumbu National Park, Zambia

59

Rusizi Nature Reserve

59

3.2.4.2.3 Capacity of National Institutions to Monitor Fishing

59

3.2.5 Socio-Economic Special Study

60

3.2.5.1 Objectives and Strategy:

60

3.2.5.2 Products:

60

3.2.5.2.1 Overview

60

Fisheries livelihoods

61

Agricultural land use and livestock

62

Deforestation, energy needs and woodland management

62

Population growth and movements

62

3.2.5.2.2 Burundi Surveys

63

3.2.5.2.3 DR Congo Surveys

64

3.2.5.2.4 Tanzania Surveys

64

3.2.5.2.5 Zambia Surveys

66

3.2.6 Environmental Education Programme

66

3.2.6.1 Objectives and Strategy

67

3.2.6.2 Products

67

3.2.6.2.1 EE activities in Burundi

67

3.2.6.2.2 EE activities in D.R. Congo

68

3.2.6.2.3 EE activities in Tanzania

68

3.2.6.2.4 EE activities in Zambia

69

3

3.2.7 Other Studies

69

3.2.7.1 LARST Station

69

3.2.7.2 Geographic Information Systems

70

3.3 The Strategic Action Programme

70

3.3.1 Process: Special Studies Contributions to the SAP

70

3.3.1.1 Biodiversity Special Study Recommendations

72

3.3.1.1.1 Coastal Zone Management

72

3.3.1.1.2 Protected Areas

73

3.3.1.2 Pollution Special Study Recommendations

74

3.3.1.3 Sedimentation Special Study Recommendations

75

3.3.1.4 Fishing Practices Special Study Recommendations

76

3.3.1.4.1 Pelagic Zone Fisheries

76

3.3.1.4.2 Littoral Zone Fisheries

76

3.3.1.4.3 Monitoring the Effect of Fishing Practices

77

3.3.1.5 Socio-economic Special Study Recommendations

77

3.3.1.5.1 Alternative livelihoods

78

3.3.1.5.2 Poverty alleviation and development

78

3.3.1.5.3 Sustainable fisheries

78

3.3.1.5.4 Sustainable agriculture

79

3.3.1.5.5 Sustainable woodland management

79

3.3.1.5.6 Institutional factors

79

3.3.2 Process

79

3.3.2.1 Principles and Analytical Framework

7 9

3.3.2.2 National Consultation

81

3.3.2.3 Regional Consultation

82

3.3.2.4 Interim Lake Tanganyika Management Body

83

3.3.3 Products

84

3.3.3.1 Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis

84

3.3.3.2 The Strategic Action Programme

87

3.4 The Legal Convention

102

3.4.1 Process: Creating the Convention

102

3.4.1.1 The Process

102

3.4.1.2 The Next Steps

103

3.4.2 Product: The draft Legal Convention

103

3.4.2.1 Preamble

104

3.4.2.2 Articles 1-3: Introductory Provisions

104

3.4.2.3 Articles 4-12: Principle Obligations

104

3.4.2.4 Articles 13-22: Mechanisms for Implementation

104

3.4.2.5 Articles 23-28: Institutional Arrangements

105

3.4.2.6 Articles 29-32: Liability and Settlement of Disputes

105

3.4.2.7 Articles 33-44: Miscellaneous Procedural Matters

106

3.4.2.8 Annexes

106

3.4.3 Anticipated Benefits of the Convention

106

4

3.5 Dissemination of LTBP Results

106

3.5.1 Project Document Database

106

3.5.2 Website

107

3.5.3 CD-ROM

107

CHAPTER 4.

LESSONS LEARNED FROM LTBP

109

4.1Introduction

109

4.2 Civil Wars and Insecurity

109

4.2.1 Remain flexible and seek creative solutions

110

4.2.2 Maintain a presence

111

4.2.3 Facilitate regional collaboration

112

4.2.4 Remain neutral

112

4.2.5 Do not underestimate people's good will during difficult times

112

4.2.6 Be briefed on security and have contingency plans

113

4.3 Project Ownership and Partnerships

113

4.3.1 National and Regional Ownership

113

4.3.2 Need to implicate highest levels of government

113

4.4. National Ownership

114

4.4.1 Lead institutions and their relationship to the lake

114

4.4.2 Assessment of institutional mandates and capacity

115

4.4.3 National Coordinators and National Directors

115

4.4.4 Financial Control

115

4.4.5 Stakeholder Participation

116

4.5 Execution and Implementation

116

4.5.1 Cultivating a shared vision

116

4.5.2 Establishing a coordianted project mission

117

4.5.3 Linking the social sciences and the natural sciences

117

4.5.4 Financial incentives are necessary

117

4.5.5 Be sensitive to language considerations and budget time and

118

money for translation

4.5.6 Do not underestimate staffing needs

119

4.5.7 Recruitment

119

4.5.8 It takes time

119

4.5.9 Email links and websites facilitate communications

119

4.5.10 Planning for the post-project phase

120

4.5.11 Use Appropriate Technologies

120

4.5.12 The countries in a multi-country project are different

121

4.6 Other Considerations: Conservation and Development at

121

Lake Tanganyika

5

EPILOGUE LOOKING TOWARD THE FUTURE

125

REFERENCES

127

Figures

Figure 1.1 Lake Tanganyika and its riparian nations

10

Figure 2.1 Organogram for the Lake Tanganyika Biodiversity Project

26

Figure 3.1 Relationships between the various technical components of LTBP

36

Figure 3.2 Sample littoral zone substrate map derived from manta survey of

39

Nsumbu NP

Figure 3.3 Habitat profile map from BIOSS surveys using SCUBA

40

Figure 3.4 Sediment Source and Erosion Hazard Zones

53

Figure 3.5 Analytical Framework for the SAP

80

Tables

Table 1.1 Physiographic statistics for Lake Tanganyika

12

Table 1.2 Inventory of species in Lake Tanganyika

13

Table 1.3 Socio-economic statistics for Tanganyika's riparian nations

16

Table 1.4 Sources of Pollution in the Tanganyika Catchment

20

Table 2.1 Lead Agencies and National Coordinators for LTBP

27

Table 2.2 Chronology of key LTBP activities

29

Table 3.1 Material resources and infrastructure provided by LTBP

31

Table 3.2 LTBP Training Activities

33

Table 3.3 The proportion of each major substrate-type recorded by Manta-board

40

surveys

Table 3.4 Number of species found exclusively in each basin of Lake Tanganyika

42

Table 3.5 Number of species per family recorded in each riparian country

42

Table 3.6 Number of fish species recorded in the waters adjacent each NP

42

Table 3.7 Complementarity analysis, fish species richness

44

Table 3.8 Complementarity analysis, mollusc species richness

45

Table 3.9 Basic Limnological Parameters for Lake Tanganyika

46

Table 3.10 Some Water and Sediment Discharge Rates

50

Table 3.11 The 12 most important fishing gears in Lake Tanganyika

56

Table 3.12 Summary of Capacity to Monitor Fisheries in Each Country

59

Table 3.13 Data collected at the LARST Station in Kigoma

70

Table 3.14 National Consultation Meetings for the SAP

81

Table 3.15 Regional Consultation Meetings for the SAP

82

Table 3.16 Main Threats and General Action Areas

84

Table 3.17 Prioritization of Problems - Reduction of Fishing Pressure

85

Table 3.18 Prioritization of Problems - Control of Pollution

85

Table 3.19 Prioritization of Problems - Control of Sedimentation

85

Table 3.20 Prioritization of Problems - Habitat Conservation

85

Table 3.21 National Actions in Response to Excessive Fishing Pressure in the

88

Littoral Zone

6

Table 3.22 National Actions in Response to Excessive Fishing Pressure in the

89

Pelagic Zone

Table 3.23 National Actions to Control the Ornamental Fish Trade

90

Table 3.24 Burundi: National Actions to Control Urban and Industrial Pollution

91

Table 3.25 D.R. Congo: National Actions to Control Urban and Industrial Pollution

92

Table 3.26 Tanzania: National Actions to Control Urban and Industrial Pollution

93

Table 3.27 Zambia: National Actions to Control Urban and Industrial Pollution

94

Table 3.28 National Actions to Control Harbor Pollution

95

Table 3.29 National Actions to Manage Future Mining Operations

96

Table 3.30 National Actions in Response to Major Marine Accidents

97

Table 3.31 National Actions to Promote Sustainable Agriculture

98

Table 3.32 National Actions to Counteract Deforestation

99

Table 3.33 National Actions to Support Parks Management 100

Table 3.34 National Actions to Conserve Sensitive Coastal Habitats 101

7

ACRONYMS

AfDB

African Development Bank

BIOSS

Biodiversity Special Study

CBD

Convention on Biological Diversity

CRH

Centre de Recherche en Hydrobiologie (Uvira, D.R. Congo)

DOF

Department of Fisheries

D.R. Congo

Democratic Republic of Congo

ECZ

Environmental Council of Zambia

EE

Environmental Education

EIA

Environmental Impact Assessment

FAO

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

FINNIDA

Finnish Development Agency

FPSS

Fishing Practices Special Study

GDP

Gross Domestic Product

GEF

Global Environmental Facility

GIS

Geographic Information System

GNP

Gross National Product

HDI

Human Development Index

ICAD

Integrated Conservation and Development

IFE

Institute of Freshwater Ecology

ILMB

Interim Lake Management Body

ILMC

Interim Lake Management Committee

ILMS

Interim Lake Management Secretariat

INECN

Institut National pour l'Environnement et la Conservation de la Nature

IZCN

Institut Zairois pour la Conservation de la Nature

LARST

Local Application of Remote Sensing Techniques

LTA

Lake Tanganyika Authority

LTBP

Lake Tanganyika Biodiversity Project

LTR

Lake Tanganyika Research project

MRAG

Marine Resources Assessment Group

NGO

Non Governmental Organization

NOAA

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

NP

National Park

NRI

Natural Resources Institute

NWG

National Working Group

OAU

Organization of African Unity

PA

Protected Area

PC

Project Coordinator

PCU

Project Coordination Unit

PDF

Project Development Fund

POLSS

Pollution Special Study

PRA

Participatory Rural Appraisal

RVC

Rapid Visual Census

SAP

Strategic Action Programme (sometimes called Plan, but should be Programme)

SC

Steering Committee

SCM

Steering Committee Meeting

SCUBA

Self contained underwater breathing apparatus

SLO

Scientific Liaison Officer

SEDS

Sedimentation Special Study

SESS

Socio-Economic Special Study

SVC

Stationary Visual Census

TAC

Technical Advisory Committee

TAFIRI

Tanzania Fisheries Research Institute

TANAPA

Tanzanian National Parks Authority

TANGIS

Geographic Information System created by LTBP for Lake Tanganyika

8

TDA

Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis

TEEC

Training Education and Communications Coordinators

TNA

Training Needs Assessment

TOT

Training of Trainers

UK

United Kingdom

UN

United Nations

UNCED

United Nations Conference on the Environment and Development

UNDP

United Nations Development Programme

UNEP

United Nations Environment Programme

UNHCR

United Nations High Comission for Refugees

UNOPS

United Nations Office for Project Services

VC

Village Council

VCDC

Village Conservation and Development Committee

9

Figure 1.1 Lake Tanganyika and its riparian nations:

Burundi, Democratic Republic of Congo, Tanzania and Zambia.

10

CHAPTER 1.

INTRODUCTION to LAKE TANGANYIKA

1.1 Why is Lake Tanganyika

Major border faults have further delineated

Special?

these two major basins into several sub-

basins (Tiercelin and Mondeguer 1991).

A variety of factors, in concert, make Seismic reflection data suggest that Lake

Lake Tanganyika an exceptionally rich

Tanganyika was divided into three

and interesting ecosystem. The

hydrologically, chemically and biologically

following sections detail the geological,

distinct paleolakes during lake low stands

physiographical, biological and socio-political

between 150,000 and 50,000 years ago

settings and context of Lake Tanganyika.

(Scholz and Rosendahl 1988). However, for

the past 2,800 years, lake levels have been

relatively stable, fluctuating between 765-775

1.1.1 Physiographic Considerations

meters above sea level for most of this time

(Cohen et al. 1997). Modern annual lake level

Rifting is separating the African

variation is about one meter (Edmond et al.

continent into two blocks, the African block to

1993).

the west and the Somalian block to the east.

Situated between the latitudes of

Lakes Turkana, Albert, Edward, Kivu,

03º20' and 08º48' South and the longitudes

Tanganyika, Rukwa and Malawi/Nyasa

of 29º03' and 31º12' East, Lake Tanganyika

1 mark

the scars of this NW-SE trending rift (see Fig.

is an elongate lake. At 673 km along its major

1).

axis, Tanganyika is the longest lake in the

These African lakes have persisted

world and ranges from 12 to 90 km in width

for long periods, which is unusual among lake

with a shoreline perimeter of 1,838 km

ecosystems. Whereas most modern lakes

(statistics from Hanek et al. 1993). Geologic

were formed by glaciation within the last

processes have, to a great extent, determined

12,000 years and have a history of frequent

the shoreline substrates around the lake. Of

water chemistry fluctuations and/or

the 1,838 km shoreline perimeter, 43 percent

desiccation (Wetzel 1983), the African Great

is rocky substrate, 21 percent is mixed rock

Lakes are geologically long-lived. Based on

and sand substrate, 31 percent is sand

sediment accumulation rates in the basin,

substrate and 10 percent is marshy substrate

geologists estimate that Lake Tanganyika has

(Coenen et al. 1993).

existed for approximately 12 million years

A catchment area of 220,000 km2

(Scholz and Rosendahl 1988; Cohen et al.

feeds Lake Tanganyika. The lake's average

1993). Lake Tanganyika is the oldest of the

depth is 572 meters, with a maximum depth

African Lakes, and after Lake Baikal in

of 1,310 meters in the northern basin and

Russia, it is the second oldest lake in the

1,470 meters in the southern basin, making it

world.

the world's second deepest lake, after Lake

However, this long history has not

Baikal. Lake Tanganyika is fed by numerous

been geologically static. Lake Tanganyika

small rivers and two major influent rivers, the

consists of two major basins, northern and

Rusizi draining Lake Kivu to the north, and

southern, separated by a complex, block-

the Malagarasi, draining Western Tanzania

faulted structure known as the Kalemie shoal.

south of the Victoria Basin. Only a single

outlet, the Lukuga River, drains Lake

1 Lake Victoria, also in this region, is not a rift lake per se, rather it fills a depression on the platform between the eastern and western

branches of the African Rift. Victoria, Tanganyika and Malawi/Nyasa are often collectively referred to as the `African Great Lakes.'

11

Table 1.1 Physiographic statistics for Lake Tanganyika (modified from Coulter 1994).

Latitude

03º20' - 08º48' South

Longitude

29º03' - 31º12' East

Age

about 12 million years

Altitude

773 m above sea level

Length

673 km

Width

12 90 km, average about 50 km

Surface Area

32,600 km2

Volume

18,880 km3

Shoreline Perimeter

1,838 km

Maximum Depth

1,320 m in north basin, 1,470 m in south basin

Mean Depth

570 m

Catchment

220,000 km2

Stratification

permanent, meromictic

Oxygenated Zone

- 70 m depth in north, - 200 m depth in south

Temperature

23-27 °C

pH

8.6 9.2

Salinity

approx. 460 mg/liter

Tanganyika, though the flow of this river has

mixing at the lake's southern end (Coulter and

changed directions in historical times (Beadle

Spigel 1991). The lake's morphology, a

1981). Most of Tanganyika's water loss is

steeply sided rift cradling a deep anoxic mass

through evaporation. Calculations from Lake

and capped by a thin oxygenated layer, has

Tanganyika's water budget suggest a water

profound implications for the distribution of

residence time of 440 years (lakevolume/

organisms in Lake Tanganyika. Most of Lake

[precipitation+inflow volume], roughly the time

Tanganyika's water mass is uninhabited.

it takes a given particle which has entered

Organisms are limited to the upper

the system to exit) and a flushing time of 7,000

oxygenated zone. Because of the steeply

years (lake volume/lake outflow volume,

sloping sides of the Tanganyika basin, benthic

roughly the time it takes to exchange all the

organisms (which rely on the substrate for at

water in the system) (Coulter 1991). Lake

least some aspect of their life cycle) are limited

Tanganyika, with an approximate surface area

to a thin habitable ring fringing the lake's

of 32,600 km2 and volume of 18,940 km3,

perimeter which extends sometimes only tens

contains 17 percent of the Earth's free fresh

of meters offshore. Coulter (1991) makes the

water (statistics from Hutchinson 1975,

following delineation: littoral zone from shore

Edmond et al. 1993, Coulter 1994).

to 10 m depth; sub-littoral zone from 10 m

Lake Tanganyika is stratified into an

to 40 m depth; benthic zone from 40 m to

oxygenated upper layer (penetrating to about

the end of the oxygenated zone. The

70 m depth at the north end and 200 m at the

temperature and pH of surface waters vary

south end) and an anoxic lower layer, which

between 23-28º C and 8.6-9.2, respectively

constitutes most of the lake's water volume

(Coulter 1994).

(Beauchamp 1939, Hutchinson 1975, Coulter

and Spigel 1991). Stratification is permanent

1.1.2 Biological Considerations

(meromictic), that is the oxygenated and

anoxic layers generally do not mix, though

Lakes Malawi/Nyasa, Victoria and Tanganyika

wind-induced upwelling results in some

are famous for their endemic species flocks2

2 The term `species flock' refers to a closely-related group of organisms, descended from a common ancestor, endemic to a geographically

circumscribed area and possessing unusual diversity or richness relative to other occurrences of this group.

12

of cichlid fishes. Lake Malawi hosts a large

leeches and sponges. Table 1.2 (modified

flock, estimated to include 700+ cichlid fish

from Coulter 1994) lists the number of species

species (Snoeks 2000). Before the

in Lake Tanganyika by taxonomic grouping.

introduction of the predatory Nile Perch, the

The invertebrate species numbers are

Lake Victoria cichlid fish species flock

probably significantly underestimated, as

included 500+ species (Seehausen 1996).

these groups in general have received

Lake Tanganyika hosts 250+ cichlid species

relatively little attention from taxonomists and

parsed between several subflocks (Snoeks

in addition, much of the Tanganyikan coast

et al. 1994). The African cichlid fish are the

has not been adequately explored.

largest and most diverse radiation of

Nonetheless, it is clear that invertebrates in

vertebrates on earth.

other lakes do not show nearly these levels

However, unlike the other African

of diversity. Lake Tanganyika, with more than

Great Lakes, Lake Tanganyika also hosts

2,000 species of plants and animals, is among

species flocks of non-cichlid fish and

the richest freshwater ecosystems in the

invertebrate organisms, including gastropods,

world.

bivalves, ostracodes, decapods, copepods,

Table 1.2 Inventory of species in Lake Tanganyika

(modified from Coulter 1994).

Taxon

# Species

% Endemic

Algae

759

Aquatic plants

81

Protozoans

71

Cnidarians

02

Sponges

09

78

Bryozoans

06

33

Flatworms

11

64

Roundworms

20

35

Segmented worms

28

61

Horsehair worms

09

Spiny head worms

01

Pentastomids (small group of parasites)

01

Rotifers

70

07

Snails

91

75

Clams

15

60

Arachnids (spiders, scorpions, mites, ticks)

46

37

Crustaceans

219

58

Insects

155

12

Fish (family Cichlidae)

250

98

Fish (non-cichlids)

75

59

Amphibians

34

Reptiles

29

07

Birds

171

Mammals

03

Total:

2,156

13

More than 600 of these species are

Limnocnida tanganyicae (Martens 1883).

endemic to the Tanganyika Basin, i.e. they

When it was discovered there were no other

are not found anywhere else. This includes

known occurrences of freshwater jellyfish.

a remarkable 98 percent of the cichlid fish

Today, we know of several other examples,

species, 59 percent of the noncichlid fish

but how jellyfish came to live in a virtually

species, 75 percent of the gastropod species,

closed lake, thousands of kilometers from the

60 percent of the bivalve species, 71 percent

nearest ocean, remains one of the lake's great

of the ostracod species, 93 percent of the

biological mysteries.

decapod species, 48 percent of the copepod

In contrast, the absence of cladoceran

species, 60 percent of the leech species, 78

arthropods (water fleas) from Lake

percent of the sponge species, and others

Tanganyika is equally puzzling (Sars 1909).

more than 600 species in all- are unique to

Given the great species flocks of other

the Tanganyika basin (Coulter 1994). It is

arthropods in Tanganyika, the presence of at

thought that the proto Lake Tanganyika was

least 20 cladoceran species in associated

colonized by organisms from the ancient Zaire

waters, and the ubiquity of Cladocera

River system (which pre-dates the lake), and

throughout inland African waters, the absence

these pioneer species evolved and radiated

of Cladocera in the lake proper is noteworthy.

within the lake basin, creating Tanganyika's

While several authors have speculated that

great diversity (Coulter 1994). In many cases

Tanganyika does not offer a suitable food

these taxa also represent endemic genera

source for Cladocera (Sars 1912; Leloup

and sometime endemic families. With its

1952), others propose that predation by the

great number of species, including endemic

sardine Limnothrissa miodon accounts for

species, genera and families, it is clear that

their absence (see Coulter 1991).

Lake Tanganyika makes an important

Lake Tanganyika's snails have also

contribution to global biodiversity.

created considerable debate. With their thick

An abundance of species in a large

and ornamented shells that resemble marine

and nearly closed system is bound to produce

species more closely than they resemble

interesting morphological, physiological,

other freshwater species, the first biologists

evolutionary, ecological and behavioral

that described these organisms did not

patterns. Most biological studies on Lake

hesitate to classify them in marine families,

Tanganyika's faunas fall within five major

genera and species. Early investigators

categories: taxonomy and systematics,

proposed that Lake Tanganyika was once

biological limnology, fisheries biology,

connected to the ocean due to the presence

evolutionary biology and behavioral ecology

of jellyfish and the marine-like appearance of

(refer to Coulter 1991 for a review of literature

Tanganyika's snails. This hypothesis was

on the Tanganyikan faunas). Below is a brief,

abandoned (Cunnington 1920) when

selective review of some aspects of Lake

geological evidence failed to support it and

Tanganyika's biology. These examples were

biological evidence suggested an association

chosen to illustrate interesting aspects of the

between the Tanganyikan snails and other

Tanganyika system and ways in which this

African freshwater snails which they did not

system may help us understand larger

closely resemble in shell form. More recently,

biological processes.

researchers (West et al. 1991, 1994, 1996)

It is not only the number of species

proposed that the marine-like appearance of

within the lake which is remarkable, but also

the Tanganyikan snail shells had evolved for

the composition and characteristics of this

the same reason biologists put forth to explain

diversity. For example, Lake Tanganyika

the morphologies of marine snail shells: i.e.

hosts a species of freshwater jellyfish

to protect the snails from shell-crushing

14

predators (Vermeij 1977). While this is

example the Perissodus species have

thought to be one of the major forces guiding

asymmetrical mouth openings, with some

the evolution of snail shells in marine systems,

individuals having mouths turned to their right

such a predator-prey coevolutionary

side and others having mouths turned to their

relationship between snails and shell-crushing

left. Fish with the right-sided asymmetry

crabs and fish had not been previously

attack the left side of their prey whereas

documented in freshwater systems.

individuals with the left-sided mouths attack

The Tanganyikan cichlid fish exhibit

their prey's right flank. These two different

a variety of unusual behaviors and

morphologies are not evenly represented in

evolutionary strategies. With so many

natural populations. Prey species apparently

species packed into a narrow habitat

become habituated to attacks from the

(requiring oxygenated waters and substrate,

dominant morphology, with the result that the

cichlids are confined to the upper 100 m [in

rare morphology is the more successful

the north] to 200 m [in the south] of water),

predator. The dominance of right versus left

cichlids have adapted to exploit seemingly

mouth asymmetry in Perissodus populations

any and every available niche. The term

oscillated every five years in this, the first field

`evolutionary plasticity' has been used to

study documenting frequency-dependent

describe cichlid jaws. Cichlid jaws have

natural selection (Hori 1993).

evolved into many diverse forms and feeding

The patterns of genetic evolution in

specializations (including: algal scrapers,

the African cichlids are equally compelling.

plankton feeders, deposit feeders, scale

Genetic variation in the Lake Victoria species

eaters, egg eaters, fish eaters, shrimp eaters,

flock is extremely low, as the 500+ species

and mollusc eaters) and are thought to be a

are genetically less variable than the human

mechanism promoting cichlid diversification

species (Meyer et al. 1990). However in Lake

(Fryer and Isles 1972; Liem 1974, 1979).

Tanganyika, the Tropheus lineage, comprised

The Tanganyika cichlids confer

of six species differentiated only by color

considerable parental care to their offspring,

patterns, shows six times as much genetic

brooding the fry in their mouths, guarding

variation as the entire Victoria flock

them in nests or a combination of both

(Sturmbauer and Meyer 1992). The Victoria

(Brichard 1989). Brood parasitism in the

flock shows significant morphological

endemic catfish Synodontis multipunctatus

evolution without much molecular evolution

offers a bizarre example of feeding and

whereas the Tropheus lineage shows

parental care specialization (Sato 1986). The

considerable molecular diversification without

catfish deposits its fertilized eggs at the same

much morphological differentiation. It appears

time and place as the cichlid host species.

that in the evolution of African cichlids,

The mouth-brooding cichlid species picks up

anything is possible.

the catfish eggs when she recovers her own

While Lake Tanganyika's cichlid

eggs and incubates both in her mouth.

species flocks are world famous, six non-

However, the catfish eggs develop faster and

cichlid species have drawn even more human

after they have absorbed their yolk sacs, the

interest. Two clupeid (sardine) species and

catfish fry proceed to feed upon the host's

four centropomid species from the genus

eggs and fry. The catfish thus exploit the

Lates dominate the lake's biomass and are

cichlid hosts for protection and food, and at

the target of the lake's artisanal and industrial

the same time, they may also destroy the

fisheries. The sardine species, like their

host's entire parental investment!

marine relatives, are small, numerous, short-

Predatory fish-feeding strategies have

lived and highly fecund. The Lates species

led to other unusual phenomena. For

are large predators. All are pelagic fish

15

(residing offshore), though some species may

subsequent to this time that promoted

spend a portion of their lifecycle in nearshore

dispersal and diversification (Verheyen et al.

regions. The potential yield of these fish

1996). Also, compared to other freshwater

stocks has been estimated at 380,000

ecosystems, Lake Tanganyika has offered a

460,000 tonnes per year, making them an

relatively stable environment, where selective

important part of the ecosystem and economy

pressures could perhaps advance beyond

(Coulter 1991).

strategies for survival and reproduction in a

With its significant fish stocks and its

fluctuating environment (Cohen and Johnston

species exhibiting complex, derived

1987, West 1997). Intrinsic biological factors,

evolutionary patterns and behaviors, Lake

such as reproductive mode, dispersal abilities

Tanganyika is a biologically fascinating and

and trophic specializations have also been

complex system. What factors have

implicated (Fryer and Isles 1972, Liem 1974,

promoted this? Many hypotheses have been

Cohen and Johnston 1997). While these

put forward over the years to explain the

hypotheses will continue to be debated, it is

extraordinary evolutionary patterns in Lake

certain that Lake Tanganyika is an

Tanganyika. For example, formation of the

extraordinary biological system and it

rift lakes created vacant ecological niches

provides a natural laboratory for investigating

(which are generally rare on the planet) and

a myriad of evolutionary and ecological

it was perhaps the rapid colonization of these

questions (e.g. Michel et al. 1992).

empty niches that encouraged the faunal

diversification (see West 1997). Or perhaps

it was the partitioning of the lake into three

basins and the lake level fluctuations prior and

Table 1.3 Socio-economic statistics for Tanganyika's riparian nations

(UNDP, World Bank 2000)

Burundi

D.R.Congo

Tanzania

Zambia

Population (in millions)

6.7

49.8

32.99.9

Population Growth Rate

2.0%

3.2%

2.4%

2.2%

Population per square km.

249.9

20.6

35.4

12.7%

Life Expectancy at Birth (years)

42

51

47

43

Adult Literacy (% > age 14)

45.8%

58.9%

73.6%

76.3%

School Enrollment (% of school age pop.)

51%

78%

67%

89%

Per Capita GNP (in US$)

$120

$110

$240

$320

Population < Natl. Poverty Line (%)

36.2%

-

51.1%

86%

Population Living on <$1/day (%)

-

-

19.9%

72.6%

Population without access to:

safe water (%)

48%

32%

34%

62%

health service

20%

-

7%

25%

sanitation

49%

-

14%

29%

Share of income or consumption:

poorest 20%

7.9%

-

6.8%

4.2%

richest 20%

41.6%

-

45.5%

54.8%

richest 20% - poorest 20%

5.3%

-

6.7%

13%

Human Development Index (of 174)

170

152

156

153

16

1.1.3 Socio-Political Considerations

transport and communications. Dating back

to their respective Belgian and British colonial

The countries of Burundi, Democratic

periods, Burundi and D.R. Congo both list

Republic of Congo, Tanzania and Zambia

French as an official language whereas

share Lake Tanganyika. Of the lake's

Tanzania and Zambia similarly list English.

shoreline perimeter, 9 percent is in Burundi,

Compared to other regions of these

43 percent is in D.R. Congo, 36 percent is in

four countries, the Tanganyika Basin is not

Tanzania, and 12 percent is in Zambia (Hanek

endowed with significant mineral resources

et al. 1993).

or especially fertile agricultural grounds. This,

These four countries are among the

coupled with its distance from seaports

poorest in the world. The Human

resulted in much of the region being

Development Index (HDI), ranked D.R. Congo

comparatively marginalized during colonial

at #152, Zambia at #153, Tanzania at #156

administrations. Except for Burundi which has

and Burundi at #170 from a total of 174

its capital on the lake, the lakeshore regions

countries (UNDP 2000). The HDI is an

of D.R. Congo, Tanzania and Zambia are

indexed measure of standard of living (per

remote, far from international airports,

capita GDP), longevity (life expectancy at

seaports and their countries' capital cities and

birth), and education (combination of adult

economic centers. Except for a few large

literacy rates with primary, secondary, and

towns and one city, the basin still lacks basic

tertiary school enrollment ratios). See Table

infrastructure (access, electricity, running

1.3 (extracted from World Bank 1999 and

water, communications) and little

UNDP 2000) for relevant indicator statistics

industrialization has taken place.

for these countries. Life expectancy in

Population growth rates range from

Tanganyika's riparian nations averages 42-

2.0-3.2 percent in Tanganyika's riparian

51 years. Literacy rates range from 45-76

nations, resulting in a rapid doubling time of

percent. Per capita income ranges from 110-

25-30 years (World Bank 1999). Population

320 US$ per year with significant proportions

densities vary considerably in the Tanganyika

of the population living below the national

Basin. In 1999 World Bank statistics,

poverty lines and at less than $1 US per day.

Burundi's population density was estimated

While these statistics are in many cases

at 250 persons per km2, Congo was 21

several years old, they provide a general idea

persons per km2, Tanzania 35 persons per

of the socio-economic situation faced by many

km2 and Zambia 13 persons per km2. In the

citizens of the Tanganyika Basin. With the

Tanganyika Basin, settlements are typically

exception of Bujumbura Marie, the lakeside

small and concentrated on areas of relatively

province hosting Burundi's capital, it is

flat topography. Relief is often steep between

frequently the poorest and least developed

them. The main lakeside urban settlements

regions of these poor countries which border

for the four countries are:

Lake Tanganyika.

An estimated 10 million people reside

· Bujumbura, Burundi (pop: 400,000), a

in the Tanganyika catchment (UNDP 1999)

capital city with an international airport

representing diverse ethnic groups of

and more than eighty industries (paint,

predominantly Bantu origins. Many Bantu

brewery, textile, soap, battery etc.);

languages are spoken in the Tanganyika

basin. Swahili, a national language of

· Kalemie (population unknown) and

Tanzania and D.R. Congo, but also common

Uvira, D.R. Congo (pop: 100,000),

in the lake regions of Burundi and Zambia, is

Kalemie has some industries and a rail

the lingua franca on the Lake for commerce,

link to other centers in D.R. Congo,

17

Uvira has cotton processing and sugar

afternoon and work all night. The catch is

production industries but depends

processed during the day.

heavily on nearby Bujumbura for

Flat, fertile land in the Tanganyika

goods and services;

Basin is extremely limited and most farming

occurs on steep slopes or narrow strips of land

· Kigoma, Tanzania (pop: 135,000) the

between the rift escarpment and the lake. The

largest transit point for goods and

principal crop is cassava, grown primarily for

people entering/exiting the lake region,

subsistence. Cash crops include oil palm and

with a rail link to other centers in

limited rice, beans, corn and banana

Tanzania;

production (Meadows and Zwick 2000).

Historically, cattle-herding has not been

· Mpulungu, Zambia (pop: 70,000) the

widespread in the basin due to tsetse flies

seat of the industrial fishing fleets.

(however, regional insecurities have caused

some cattle owners in Burundi and D.R.

These towns are all served by ports, which

Congo to move their cattle to nearby lakeside

link people and cargo between Tanganyika's

areas). As a result of clearing land for

riparian nations. Land-locked Burundi and

agriculture and fuel-wood demands, there are

Eastern Congo in particular, depend heavily

fuel-wood shortages in many lakeshore

on goods coming by rail from Dar es Salaam

villages (Meadows and Zwick 2000).

to Kigoma or by road from South Africa to

Riparian

governments

have

Mpulungu. Railways link Kalemie and Kigoma

designated `protected areas' (PAs) in several

to larger economic centers in D.R. Congo and

locations bordering the lake. Burundi has two

Tanzania, respectively. Mpulungu links to

PAs, the Rusizi Natural Reserve (recently

other economic centers in Zambia by a paved

downgraded from National Park) and

and maintained road. Burundi has a good

Kigwena Forest; Tanzania has two PAs,

road extending the length of its coastline.

Gombe Stream National Park and Mahale

Congo has a poor, unmaintained road

Mountains National Park; and Zambia has

extending from Uvira to Baraka. Most of the

one PA, Nsumbu National Park. Congo

other roads run tangential to the lake and are

currently has no protected areas along the

not well maintained.

lake. The Rusizi Natural Reserve is a site of

At population centers, people are

international ornithological interest as it hosts

often involved with administration and aspects

a diverse resident and migrant bird fauna.

of international trade between the four

Gombe Stream and Mahale Mountains

countries (e.g. buying/selling goods, providing

National Parks, hosting chimpanzees and

transport). Outside of these areas,

other primates, are the sites of the longest-

subsistence and small-scale commercial

running primate studies. Nsumbu National

fishing and farming dominate people's

Park harbors elephants, lions, leopards,

livelihoods (Quan 1996, Meadows and Zwick

gazelles and other game, but in low densities.

2000). Most households have diversified into

Both Mahale Mountains and Nsumbu National

both domains. Commercial fishing activities

Parks provide some protection to the lake as

are controlled by the phase of the moon and

their borders extend 1.6 km into the lake. To

the primary gears are lift nets used with

date, tourism remains relatively undeveloped

catamarans, beach seines, gill nets and lines,

in this region because of the remoteness, lack

though with more than 50 different fishing

of infrastructure, regional insecurities, and

gears identified in Lake Tanganyika, every

competition from other locales.

niche is exploited (Lindley 2000). Fishermen

Refugee movements and wars have

(women are not involved in harvesting fish)

ravaged the northern Tanganyika Basin during

typically begin their activities in the late

the last decade. Much of the Burundi and

18

Congolese coastlines have experienced

and over-fishing or fishing with destructive

recurrent fighting and instability, dating back

gears. These environmentally destructive

to October 1993 in Burundi and October 1995

activities are a function of the socio-economic

in D.R. Congo. Consequently, 100,000

conditions of the riparian citizens and

Burundians remain internally displaced while

countries. This section provides background

285,000 have sought refuge in Tanzania. In

information on each of these threats as we

Congo 700,000 people are internally

understood them at the beginning of the

displaced while 118,000 have sought refuge

project in 1995 (subsequent sections will

in Tanzania (UNHCR 2000). Most refugees

detail the findings of the project).

reach Tanzania via Lake Tanganyika. While

some refugees (not reflected in these figures)

1.2.1 Pollution

settle in relatively unpopulated areas along

the Tanzanian coast or in villages with family/

While the Tanganyika Basin is not nearly as

friends, many live in camps within the Kigoma

industrialized or populated as other parts of

region in order to benefit from international

sub-Saharan Africa, pollution is a threat to

assistance. While population movements are

Lake Tanganyika because the basin's popu-

concentrated in the Northern Basin, all of

lation is rapidly increasing and little legislation

Tanganyika's riparian nations have hosted

exists to protect the environment. Given the

refugees. These population movements have

lake's fluid medium for transport and that it is

had repercussions on society, the regional

a nearly-closed system, with long water

economy and the environment. Population

residence and flushing times (440 years and

movements and ongoing civil wars have also

7,000 years respectively), pollution is

effected the relationship between

potentially catastrophic to the lake's water

Tanganyika's riparian states.

quality, economically important fish stocks and

Lake Tanganyika is an important

overall biodiversity. Pollution abatement

resource for its riparian nations. It provides

facilities in the basin are extremely limited.

freshwater for drinking and domestic use.

Currently Burundi, with the largest

Between 165,000-200,000 tonnes of fish are

population density and the most industries in

harvested annually from Lake Tanganyika

the basin, poses the greatest pollution threat.

(Reynolds 1999). This represents a

Bujumbura hosts a variety of industries and

significant source of protein in the local diet.

potential pollution sources within several

Harvesting, processing, transporting and

kilometers of the lakeshore, including: a

marketing these fish some of which are sent

textile-dying plant, a brewery, paint factories,

to markets hundreds of kilometers away in

soap factories, battery factories, fuel transport

Lubumbashi, the Zambian Copper Belt and

and storage depots, a harbor and a

Dar es Salaam - provides jobs and livelihoods

slaughterhouse, among others. Fuel depots,

for more than 1 million people (Reynolds

Kigoma's harbor and electricity-generating

1999). Finally, the lake serves as an

facilities, industrialized fishing in Mpulungu,

`international highway' linking people and

and cotton and sugar processing plants in

cargo between the four riparian countries.

D.R. Congo present other cases of potential

industrial pollution. The wastes from these

1.2 Threats to this Resource

enterprises typically are not treated before

they are discharged and ultimately make their

In spite of its unique physiographic setting,

way to the lake. The same is true for domestic

contribution to global biodiversity, and its

waste. Even in highly populated areas, no

importance as a resource for its riparian

municipal or household wastewaters are

nations, Lake Tanganyika faces a variety of

treated before they are discharged. Run-off

threats, including: pollution, sedimentation

from agricultural pesticides may also be an

19

important source of pollution. Mercury and

1.2.2 Sedimentation

other chemicals used in small-scale gold and

diamond mining in the catchment represent

Another form of pollution affecting Lake

other potential lake pollutants. Leaks and

Tanganyika is sediment pollution. Increased

accidents in the lake's cargo/shipping

deforestation and consequently erosion in the

industry, executed by a fleet of ancient

catchment has caused an increase in

vessels, is another potential environmental

suspended sediment entering the lake

hazard. Finally, although no production is

through streams. Increased sedimentation

occurring yet, petroleum exploration has been

can have a profound negative effect upon

conducted on the Rusizi Plain and the

biodiversity by altering habitats (e.g. changing

Kalemie Trough while plans for nickel mining

rocky substrates to mixed or sandy

in Burundi are well underway. Table 1.4

substrates) and disrupting primary

(modified from Table 3.3, Patterson and Makin

productivity and food webs, thereby leading

1998) summarizes the various types and

to a reduction in species diversity.

sources of pollution identified in the

Cohen (1991) reports that Landsat

Tanganyika Catchment.

image analysis revealed that 40-60 percent

The impact of these various

of original forested land in the lake's central

discharges is poorly understood. While

basin, and almost 100 percent in the northern

Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs)

basin, had been cleared, as evidenced by

have not been conducted, some studies

headward erosion, stream incision and gully

suggest that pollution has altered, in some

formation, all features associated with

areas, the composition of phytoplankton

deforestation. Much of this land was probably

communities (Cocquyt et al. 1991). As the

cleared for fuel-wood, burned and converted

Tanganyika Basin's population continues to

for subsistence agriculture or grazing.

grow we can expect industrial and domestic

Analyses of sedimentation rates from 14C

pollution to grow accordingly.

dated cores (Tiercelin and Mondregeur 1991)

confirmed the high sediment impact in the

northern basin with the southern and central

basins receiving < 1,500 mm / 1,000 years

Table 1.4 Sources of Pollution in the Tanganyika Catchment

(modified from Patterson and Makin 1998)

Type of Pollution

Sources within the Catchment

Industrial wastewater

>80 industries in Bujumbura, Burundi

Urban domestic wastewater

Bujumbura, Uvira, Kalemie, Kigoma, Rumonge,

Mpulungu

Chlorinated hydrocarbons, pesticides

Rusizi Plain, Malagarasi Plain

Heavy metals

North Basin waters from industrial wastes

Mercury

Malagarasi River

Ash residues

Cement processing in Kalemie

Nutrients associated with fertilizers

Rusizi Plain, Malagarasi Plain and

other catchments

Organic wastes, sulphur dioxide

Sugarcane refining plant near Uvira

Fuel, oil

Ports, harbor and shipping and boats in all

four countries

20

and < 500 mm / 1,000 years respectively,

Tanganyika's biodiversity. Fishing activities

compared to the northern basin which

on Lake Tanganyika include: commercial

received about 4,700 mm / 1,000 years.

fishing by both industrial and artisanal

Bizimana and Duchafour (1991) have

fishermen, subsistence fishing, and

estimated soil erosion rates in the deforested

ornamental fish extraction for export.

and steep sloping Ntahangwa River

Each of Tanganyika's riparian nations

catchment in northern Burundi to be between

hosts one or more companies which export

20 and 100 tonnes/hectare/year. Increased

ornamental fish to markets in Europe, America

sedimentation rates are manifested in the lake

and Japan. A variety of fish, predominately

by sediment inundated rocky habitats,

cichlids, are targeted by divers and

common along the Burundi coast, and

snorkellers, captured alive and exported to

prograding river deltas, such as the Rusizi

aquarium enthusiasts abroad. Though the

River Delta. The Rusizi River Delta is the

impact of ornamental fishing has not been

major drainage in the northern basin and

studied, the effects on population and

appears to have increased its outbuilding by

community structure could be considerable

an order of magnitude during the past 20

by the very nature of the work, which is to

years (Cohen 1991).

target rare and exotic species and extract as

The dynamics and behavior of

many as possible because of the high

sediment entering the lake are complex and

mortality rates in shipping.

not well understood. It appears, however, that

Subsistence fishermen primarily

much sediment deposition occurs in the littoral

target the sardines and Lates species, though

zone, precisely where most of the lake's

in their efforts they catch and utilize many

biodiversity is concentrated. Increased water

other species. They operate close to shore,

turbidity as a function of sediment load and

from small canoes, using lusengas (large,

sediment deposition thwart algal growth,

conical scoop nets), bottom-set gill nets,

which may have profound effects upon other

beach seines, basket traps and handlines.

components of the foodweb. In studying

Oftentimes the lusengas and beach seines

ostracodes across a variety of habitats that

are outfitted with small mesh netting, even

were lightly, moderately or highly disturbed

mosquito netting, which is thought to be

by sediment, Cohen et al. (1993) found that

especially destructive to stocks, for it catches

ostracodes from highly disturbed

everything, including juveniles. In addition to

environments (both hard and soft substrate)

disrupting population structure in this way,

were significantly less diverse than those from

beach seines are additionally harmful

the less disturbed environments with

because they drag along the bottom, turning-

differences in species richness that ranged

over the substrate, and thus obliterating food

from 40-62 percent. Species richness for

sources and cichlid nests.

deepwater ostracodes followed the same

Commercial fishermen target the

general pattern, though the differences were

sardine and Lates species and work further

not as great. These data suggest that

offshore in the pelagic zone. Commercial

sediment input may have already had an

fishers, both artisanal and industrial, have

important role in altering ostracod community

usually made a significant financial

structure.

investment in gears and motors to access the

pelagic zone. Artisanal fishing relies on

1.2.3 Overfishing

canoe-catamarans that use lights to attract

fish and deploy lift-nets to collect them.

Overfishing and fishing with destructive

Industrial fishing typically employs 15 m purse

methods are another major threat to Lake

seiners and a number of smaller vessels to

21

attract the fish and deploy seines. Industrial

In addition to impacting biodiversity by altering

fishing has been limited to a few areas

population and community structures of fish

(Bujumbura, Uvira, Kigoma, Mpulungu) which

stocks and food webs, overfishing and fishing

have access to larger markets.

with destructive methods have negative

Several studies have suggested that

repercussions on the socio-economic

commercial fisheries have already drastically

circumstances of riparian communities

reduced the fish stocks. Burundi once hosted

through loss of jobs and livelihoods.

a large industrial fishing fleet, but by the early

1990s they could no longer make a living and

1.2.4 People

all the vessels were dormant or had been sold

to companies in Congo or Zambia (Petit and

Ultimately all of these threats to Tanganyika's

Kiyuku 1995). Pearce (1995) calculates that

biodiversity, i.e. pollution, sedimentation and

the fishing effort in Zambia had tripled by the

overfishing/destructive fishing practices, are

early 1990s and catches had been decreasing

human behaviors. More specifically, they are

since 1985. These efforts have apparently

the behaviors of people who either do not

effected the community structure of the stocks

understand the implications for the future of

in Zambia for initially the catch was 50 percent

the resource or who do not have any

sardines, 50 percent Lates (Coulter 1970)

alternatives. Poverty and overpopulation in

whereas since 1986 the catch has been 62-

some areas, combined with lack of

94 percent Lates stappersi. The fishery has

environmental education and regional

evolved from a six-species fishery (two

insecurities are the ultimate causes of

sardines, four Lates spp.) to a single species

environmentally damaging behaviors and

fishery (Lates stappersi).

habitat destruction in the Tanganyika Basin.

22

CHAPTER 2.

ORIGIN, STRUCTURE and EVOLUTION of LTBP

2.1 History

development, conservation research, and

industrial fisheries/conserving the fisheries

International Conference on the

resource base made a series of

Conservation and Biodiversity of Lake

recommendations for safe-guarding the

Tanganyika:

health of the ecosystem.

Based on their findings, the workshop

Following a 1989 International participants expressed grave concern for the

Limnological Society workshop on

future of Lake Tanganyika's unique

conservation

and

resource

biodiversity and economically important

management in the African Great Lakes, a

resources. The conference's proceedings

group of scientists concerned with

were published by the Biodiversity Support

conservation issues at Lake Tanganyika was

Program (Cohen 1991). Led by Dr. Andrew

organized. Their efforts led to the First

Cohen (University of Arizona), several

International Conference on the Conservation

conference participants used the ideas

and Biodiversity of Lake Tanganyika held at

expressed therein to form the basis of a

the University of Burundi in Bujumbura,

proposal for a large-scale regional

Burundi from 11-13 March 1991. This meeting

conservation initiative in Lake Tanganyika.

brought together key individuals from the

The team then sought to attract the interest

fields of research, resource management

of international funding agencies to support

(water, fisheries and agroforestry) and

this initiative.

conservation to discuss the current state and

the future of the Lake Tanganyika Basin. The

The Global Environmental Facility

65 participants included scientists, non-

governmental organizations (NGOs), natural

The Global Environmental Facility (GEF) was

resource managers and policy makers from

created in 1991 to promote cooperation and

Tanganyika's four riparian nations (Burundi,

provide financing for initiatives that address

Tanzania, Zaire [now D.R. Congo] and

critical threats to the global environment.

Zambia) as well as technical and scientific

In 1992 The Convention on Biological

experts and donor agencies from eight other

Diversity (CBD) was presented and opened

countries. The participants were charged with

for signature at the UN Conference on the

discussing research, immediate to long range

Environment and Development (UNCED) in

conservation goals and formulating specific

Rio de Janeiro (this meeting is also referred

recommendations and goals for the same.

to as the Earth Summit). The CBD promotes

Among its principal outputs, this

the conservation of global biodiversity through

meeting identified excess sedimentation,

the sustainable use of its components and

overfishing and pollution as the primary

the equitable sharing of benefits arising from

threats to Lake Tanganyika. Most of the 27

this use. It was also recognized at UNCED

presentations addressed the nature and

that while agreeing philosophically with the

severity of these threats and the state of the

CBD, many developing nations would have

system. Working groups on land-lake

difficulty putting the principles of the CBD into

interactions,

underwater

reserve

practice. At UNCED the World Bank

23

committed funds to GEF to assist developing

Pollution Control and Other Measures to

countries in meeting their obligations as

Protect Biodiversity in Lake Tanganyika:

signatories to international environmental

agreements, such as the CBD. The GEF is

In late 1991 UNDP/GEF mounted a project

the principal financing mechanism of the CBD.

appraisal mission to the countries bordering

Since 1991 GEF has invested almost

Lake Tanganyika. The mission assessed the

$3 billion US in more than 680 projects in 154

interest and canvassed the views of the four

countries. Public and private co-financing for

riparian governments and other key

GEF projects is almost $8 billion US, including

organizations for a project aimed at assessing

$2 billion US from developing countries

the threats to Lake Tanganyika and

themselves (GEF 2000). The UN

developing mechanisms to monitor and

Development Program (UNDP), the UN

ameliorate these threats.

Environment Program (UNEP) and the World

By February 1995, after some delay

Bank all implement projects on behalf of GEF.

in the approval process, the project document

GEF was a natural source of funding

"Pollution Control and Other Measures to

for a conservation/biodiversity initiative for

Protect Biodiversity in Lake Tanganyika" had

Lake Tanganyika and was one of the first

been signed by all four riparian countries as

projects to be approved during the GEF pilot

well as the funding agency (UNDP/GEF) and

phase. Following the three-year pilot phase,

the executing agency (UN Office for Project

GEF was restructured in 1994 into its current

Services [UNOPS]). With this document

form. GEF currently finances activities that

UNDP/GEF committed $10 million US to a

address at least one of four critical threats to

five-year project designed to "improve

the global environment: loss of biodiversity,

understanding of the ecosytems function of

climate change, degradation of international

Lake Tanganyika and the effects of stresses

waters and ozone depletion. Activities

on its lake system, take action to maintain the

addressing land degradation are also eligible

health and biodiversity of the ecosystem and

for GEF funding. Although originally

coordinate the efforts of the four countries to

conceived as a biodiversity initiative, under

control pollution and prevent the loss of the

the current system the Tanganyika initiative

exceptional diversity of Lake Tanganyika."

corresponded to both GEF's `Biodiversity' and

The governments of Burundi, Tanzania, Zaire

`International Waters' focal areas.

(now D.R. Congo) and Zambia are listed as

`Biodiversity of Coastal, Marine and

counterpart agencies and committed to in-

Freshwater Ecosystems' and `Waterbody-

kind contributions.

based Programme' were the relevant

In early 1995 the executing agency,

operational programmes within these focal

UNOPS, opened the "Pollution Control and

areas. The `Integrated Land and Water

Other Measures to Protect Biodiversity in

Multiple Focal Area' operational programme

Lake Tanganyika" project up for international

was also relevant. Following the GEF

tender. As a result of this process, a UK-

Council's adoption of the new GEF

based Consortium consisting of the Institute

Operational Strategy, an effort was made to

of Freshwater Ecology (IFE) (now called the

modify the Tanganyika project, making it more

Center for Ecology and Hydrology), the

consistent with the International Waters

Marine Resources Assessment Group

portion of the Operational Strategy. These

(MRAG) and the Natural Resources Institute

modifications included adopting the

(NRI) as lead agency was selected as the

Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis and

Implementing Subcontractor. Their contract

Strategic Action Programmes as principal

for $7.8 million US (subsequently amended

project activities (Section 3.3.3).

24

to $8.123 million US) to implement the project

· establish tested mechanisms for

took effect 7 August 1995. Early in the project,

regional coordination in conservation

the name Lake Tanganyika Biodiversity

management of the Lake Tanganyika

Project (LTBP) became a popular

basin;

abbreviation for the full project title, "Pollution

· produce a comprehensive strategic

Control and Other Measures to Protect

plan for long-term application to be

Biodiversity in Lake Tanganyika."

based upon the results of a series of

special studies aimed at improving the

2.2 Project Objectives

understanding of the lake as a whole.

Information derived from these studies

The project's ultimate objective, as stated in

is fundamental in the development of

the Project Document, was:

long-term management strategies and

will in some cases provide the baseline

and framework for long-term research

to demonstrate an effective regional approach

and monitoring programmes;

to control pollution and to prevent the loss of

· implement sustainable activities within

the exceptional diversity of Lake Tanganyika's

the Lake Tanganyika Strategic Plan

international waters. For this purpose, the

development objective, which has to be met, is

and incorporated environmental

the creation of the capacity in the four

management proposals.

participating countries to manage the lake on a

regional basis as a sound and sustainable

The Project Document also recognized that

environment.

successfully achieving these objectives

depended upon the participation of a wide

range of stakeholders.

In developing the project's logical framework

A Project Inception Workshop,

during the Inception Workshop, this objective

marking the end of the literature reviews and

was summarized into the definitive project

baseline studies and the beginning of regional

purpose: A Coordinated Approach to the

activities, occurred in March 1996. This

Sustainable Management of Lake

workshop brought together, for the first time,

Tanganyika.

members of the UK-based consortium and a

This larger development objective

variety of stakeholders from the four countries,

was broken down into six immediate

including scientists, NGOs and policy makers.

objectives, each with its own list of outputs

The Inception Workshop delegates

and activities (Project Document). The six

scrutinized the project's immediate objectives,

immediate objectives were to:

outputs, activities and framework. Preliminary

· establish a regional long term

workplans were also created.

management programme for pollution

control, conservation and maintenance

2.3 Project Structure

of biodiversity in Lake Tanganyika;

· formulate a regional legal framework

The project had a complex, multi-tiered

for cooperative management of the

structure, Figure 2.1. It should be noted that

lake environment;

the organogram depicted in Figure 2.1 was

· establish

a

programme

of

modified from earlier versions published in

environmental education and training

project documents. It was revised with

for Lake Tanganyika and its basin;

hindsight to reflect the organs, order and r

3 The difference, $1,319,068 (operational budget of $9,440,609 less the $8,121,541 contract to the NRI consortium), was used to finance the

interagency agreement with FAO for lake ciruculation studies, related vessel leasing expenses, mid-term and final evaluations, translation

and reporting, and monitoring expenses (UNDP and UNOPS participation atTripartite Reviews and Steering Committee meetings).

25

UNDP

Steering

GEF

Committee

UNOPS

Technical

Advisory Committee

NRI Consortium

& Project

Natl. Steering

Natl. Steering

Coordination Unit

Committee: Tanzania

Committee: Zambia

Natl. Coord.+

Natl. Coord.+

Natl. Coord.+

Natl. Coord.+

Natl. Working

Natl. Working

Natl. Working

Natl. Working

Group Burundi

Group DR Congo

Group Tanzania

Group Zambia

Natl.

Natl.

Natl.

Natl.

Institutions

Institutions

Institutions

Institutions

Burundi

D.R. Congo

Tanzania

Zambia

Training and Environmental Education

Special Studies

in:

Strategic

draft

Biodiversity

Action

Legal

Pollution

Programme

Convention

Sedimentation

ratification

Fishing Practices

Socio-Economics

Conservation and Sustainable Management

of Biodiversity in Lake Tanganyika

Figure 2.1 Organogram for the Lake Tanganyika Biodiversity Project.

Organs are listed in outlined shapes, those in bold type had a regional mandate. Grey shapes represent

components of LTBP, with the grey outlined shape representing the main LTBP objective.

relationships established during the project.

The regional Steering Committee

Key organs of LTBP included: the regional

(SC) consisted of the National Coordinator

Steering Committee; the Technical Advisory

and three senior civil servants from each

Committee; National Steering Committees in

country representing ministries of the

some countries; National Coordinators and

environment, natural resources, development

National Working Groups; National

and other sectors. The Project Coordination

Institutions; Biodiversity, Pollution,

Unit (PCU) and UNDP were also represented

Sedimentation, Fishing Practices and Socio-

on the SC. The SC was responsible for:

Economic Special Studies teams in the four

providing overall direction to the project,

countries, Training and Environmental

reviewing project progress, directing and

Education Components, the Project

decision making on policy matters and

Coordination Unit, the Implementing

approving future planning. A regional

Subcontractor (NRI Consortium), the

Technical Advisory Committee (TAC),

executing agency (UNOPS) and the donor

consisting of technical experts from agencies

agency (UNDP/GEF).

actively involved in the project (e.g. fisheries,

26

parks, water, universities), supported the SC,

SAP. This programme consisted of scientific

providing guidance on implementing the

studies in biodiversity and the threats to it,

technical studies and drafting the Strategic

namely: pollution, sediments, fishing practices

Action Programme (SAP).

as well as socio-economic conditions around

Tanzania and Zambia elected to have

the lake. Training and environmental

formal National Steering Committees with

education programmes supported these

senior representatives from relevant

studies. These programmes will be

ministries directing project activities in their

developed in Section 3.2

countries. In Burundi and D.R. Congo, the

In addition, the NRI Consortium

National Working Groups (NWGs) fulfilled this

furnished the Project Coordination Unit (PCU)

role. In all four countries, the National

consisting of the Project Coordinator (PC),

Coordinator (NC), who in each case was a

Scientific Liaison Officer (SLO) and support

senior representative from the lead agency

staff. The PCU administered and facilitated

for conservation and the environment (Table

all regional activities, with the PC tending to

2.1), led the NWG. The NWG, consisting of

the management aspects and the SLO

8-12 members drawn from the participating

tending to the technical programme. The NRI

national institutions and stakeholder groups,

Consortium also provided technical expertise

guided the implementation of the technical

in the form of special study leaders and

programmes in each country and through a

facilitators in the areas of: biodiversity

consultation process established their

(MRAG), pollution (IFE), sedimentation (NRI),

national priorities for the SAP.

fishing practices (MRAG), socio-economics

The project included a large technical

(NRI), training and EE (NRI with subcontracts

programme to support the development of the

to consultants), strategic planning (NRI) and

Table 2.1 Lead Agencies and National Coordinators for LTBP

Lead Agencies and National Coordinators

Lead Agency in Burundi:

National Institute for the Environment and

Conservation of Nature

National Coordinator:

Dr. Gaspard Bikwemu (1995-1997)

Jean-Berchmans Manirakiza (1997-1999)

Boniface Nykageni (1999-2000)

Jérôme Karimumuryango (2000)

Assistant National Coordinator:

Gabriel Hakizimana

Lead Agency in D.R. Congo:

Dept. for Management of Renewable Natural

Resources

National Coordinator:

Mady Amule

Assistant National Coordinator:

Dr. Nshombo Muderhwa

Lead Agency in Tanzania:

Division of the Environment

National Coordinator:

Rawson Yonazi

Assistant National Coordinator:

Hawa Msham

Lead Agency for Zambia:

Environmental Council of Zambia

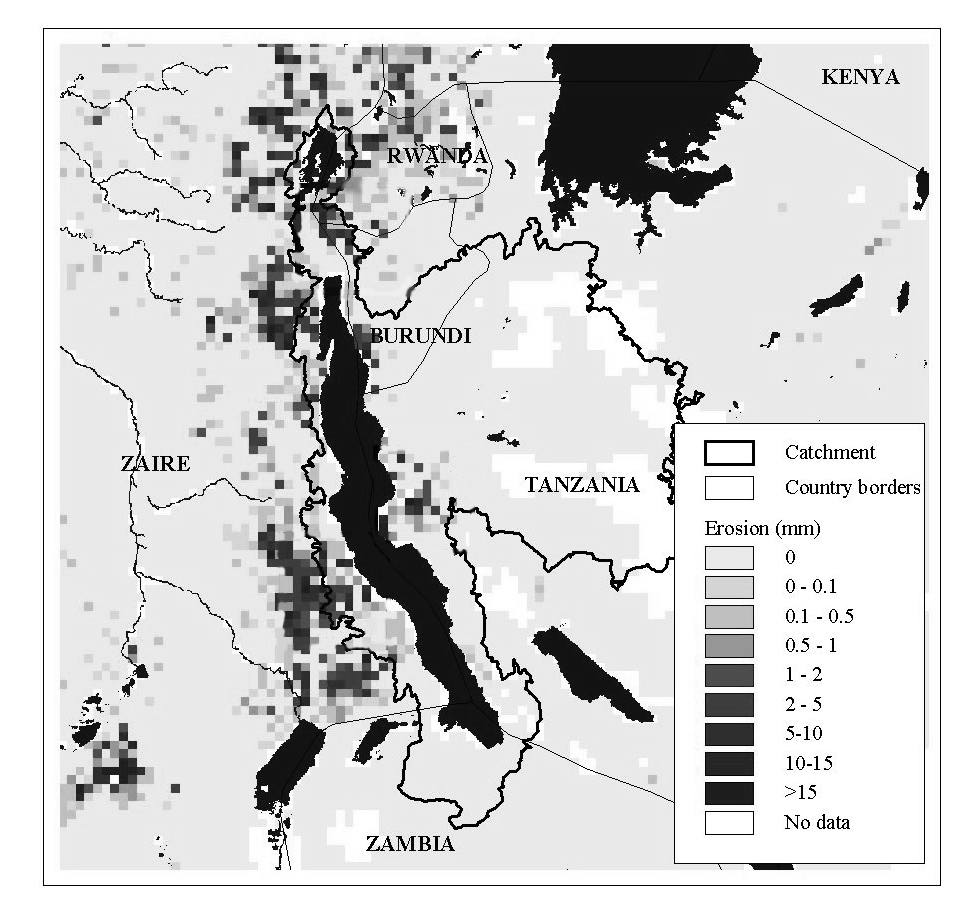

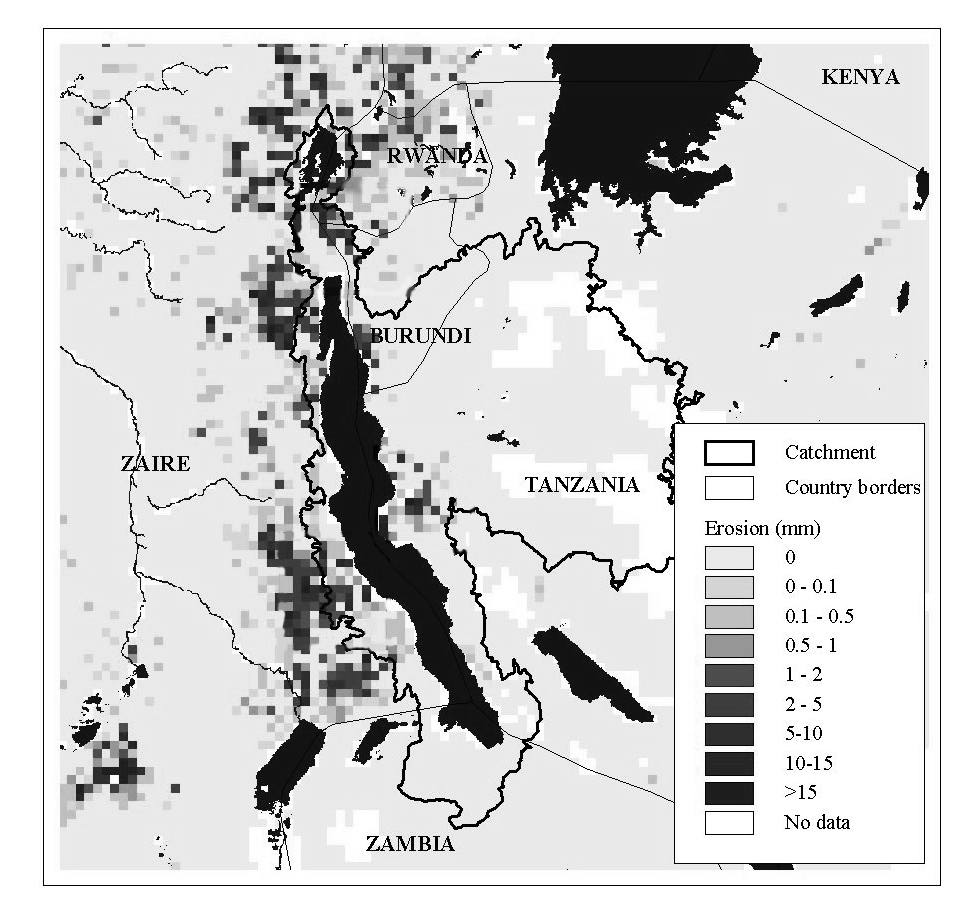

National Coordinator: