Final Evaluation of the UNDP/GEF

Lake Manzala Engineered Wetlands Project

EGY/93/G31

Final Report

24, October 2007

PREFACE

This evaluation report provides findings, lessons learned and recommendations for the

UNDP/GEF Lake Manzala Engineered Wetlands Project (LMEWP). The report conforms to the

Terms of Reference developed by UNDP-Cairo for this assignment. The evaluation has been

developed based on a review of project reports and reference materials coupled with interviews

and site visits, carried out during May June 2007. The conclusions and recommendations

provided are solely those of the evaluator and are not binding upon the project management &

sponsors.

Contact:

Alan Fox

Transboundary Consulting

i

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Preface

i

Table of Contents

ii

Executive Summary

iii

Glossary

vi

1 Introduction

1

2 The project and its development context

2

2.1

Problems that the project sought to address

3

2.2

Project start and duration

4

2.3

Immediate and development objectives of the project

5

2.3.1

Overall Objectives

5

2.4

Main stakeholders

5

2.5

Expected Results

6

3 Findings and Conclusions

8

3.1

Project Formulation

8

3.1.1

Conceptualization/Design (R)

8

3.1.2

Country-ownership/Driveness

9

3.1.3

Replication approach

11

3.1.4

Linkages to Other Projects

11

3.2

Project Implementation

12

3.2.1

Implementation Approach (R)

13

3.2.2

Monitoring and Evaluation (R)

14

3.2.3

Stakeholder participation / Public Involvement (R)

17

3.2.4

Financial Planning

18

3.2.5

CoSt-effectiveness of Achievements

19

3.2.6

Financial Management and Co-financing

19

3.2.7

Leveraged resources

20

3.2.8

Execution and implementation modalities

21

3.3

Project Results

22

3.3.1

Attainment of Outcomes/Achievement of objectives (R)

22

3.3.2

Sustainability

30

3.4

Contribution to upgrading skills of the national staff/experts

31

3.4.1

Comparative Analysis engineered wetlands vs. other treatment systems

32

4 Recommendations

34

4.1

Future directions for Lake Manzala and Egypt

34

4.2

Considerations for UNDP/GEF and other Funders

36

ii

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Brief description of the project

The Lake Manzala Engineered Wetland Project (LMEWP) demonstrates low-cost innovative water

treatment solutions in the Nile Delta of Egypt. The project is managed by the Egyptian Environmental

Affairs Agency (EEAA), implemented by UNDP and funded through the GEF International Waters

focal area. The project commenced in 1999 and has recently concluded (July 2007).

The main aim of the project was to construct and operate an engineered wetland facility to treat 25,000

50,000 m3 per day of wastewater from the Bahr El Baqar Drain (Bashtir Canal), flowing into Lake

Manzala. In addition to the construction of a treatment facility, the project evolved to include a

commercial scale 60 feddans (= acres) fish farm, designed to utilise the treated water and help offset

plant operational costs. The fish farm is still under development.

Through the construction and testing of the LMEWP, project sponsors hoped to stimulate an increased

use of innovative, low cost wastewater treatment technologies in the region, to improve water quality

and fisheries production in Lake Manzala and to enhance economic opportunities in the local area

where the facility was constructed.

The poor quality of north-flowing drainage waters in Egypt is a major environmental and economic

concern. Much of the heavily polluted drain water crossing the Nile Delta enters large coastal lakes,

such as Lake Manzala, before flowing into the Mediterranean Sea. The resulting pollution of the

Mediterranean Sea violates international agreements, including the Barcelona Convention, signed by

Egypt.

Lake Manzala is located on the north-eastern edge of the Nile Delta, between the two port cities of

Dormietta and Port Said. The area is one of the most poorly served in Egypt. Local residents do not

have access to potable water, sanitation, electricity and other basic services. Contaminated water and

tainted fish stocks bring human and ecosystem health risks. Many people live as squatters on

government land and lack the security of land ownership and economic stability.

Concise summary of the findings and conclusions

Working under challenging site conditions, the project team has constructed a functioning wastewater

treatment facility and has demonstrated that engineered wetlands are an appropriate and cost-effective

treatment technology for agriculture drainage water. Egypt and nations with similar economic and

climactic conditions can benefit from the adoption of this technology, especially in rural areas where

land availability is not a major constraint. The project has demonstrated that treatment levels can be

attained that enable a wide range of (non-potable) reuse options, in particular for fish farming.

The project has expanded national expertise on engineered wetlands. The Egyptian consulting and

engineering teams who worked on the project, the six PhD and Masters degree students who conducted

research at the site, and the many water hydrology and water pollution control experts who are now

familiar with the technology as a result of the LMEWP are helping to make Egypt self-sufficient in

engineered wetlands and a regional leader in the use of innovative waste water treatment technologies.

In addition to constructing an innovative treatment facility, the project set ambitious ,,ancillary

expectations with respect to wetlands research, local economic development and improvements to the

iii

Lake Manzala ecosystem. Many of these broader expectations remain still to be achieved at the end of

GEF funding.

The Project was to test various methodologies at the site in order to optimise treatment

effectiveness, including trials with various wetland species and different types and strength of

wastewater.

While some demonstrations to determine optimal treatment efficiencies were carried out, more trials

will be required to consider treatment effectiveness at higher flow rates, with stronger effluent

types, and with the higher pollutant loadings from the fish farm effluent. Work is still needed to

determine optimal use of a TVA proprietary Reciprocating Gravelbed System (RGS) that has yet

to become fully operable. More work is needed to consider what wetland plant species can be used

effectively in the highly saline soils of the region.

The LMEWP design included expectations for follow-on plans and feasibility studies to utilise

engineered wetlands to improve Lake Manzala water quality and replicate the treatment technology

elsewhere

These expectations were not met. A draft Test Plan developed by consultants late in the project

provides recommendations on future planning and research, however these recommendations come

too late for the project team to implement and should be taken up by the government as the project

is mainstreamed within national institutions.

The project was expected to support the local community through training and the marketing of

bio-products

Training of local residents included a workshop on engineered wetlands and fish farming attended

by 25 persons. Beyond this, local support was limited. There was no marketing of bio-products,

although local farmers were given permission to harvest the reeds as animal fodder.

Intentions were for the project to broaden government, scientific and public support for the use of

engineered wetlands

Some progress was made in building government and scientific support, especially through the

Technical Advisory Committee (TAC). Some public support was raised, with good media interest

for the facility start up and closing ceremonies. Promotion of the project through scientific papers

and the public media was limited.

Further studies were expected on utilising the LMEWP technology to improve Lake Manzala water

quality and to support fisheries research and production to help restore and strengthen Lake Manzala

fisheries

No water quality studies were initiated through the LMEWP for Lake Manzala and the project

made no significant contribution to the restoration and strengthening of Lake Manzala fisheries

At the end of the GEF contribution, the project has succeeded to develop and operate an engineered

wetland treatment system, yet has been unable to accomplish broader environmental and economic

goals. Achievement of these broader goals has been stymied by a number of constraints on project

design and implementation:

Unresolved land ownership issues in the Delta region remain a key constraint on government efforts

to improve environmental and economic conditions.

iv

Multiple agencies at the national and governorate level have overlapping authority over water

pollution, agriculture drainage, and fisheries. To make a substantive contribution to Lake Manzala

environmental quality, all of the key government actors need to be involved.

The LMEWP was designed to achieve policy and public awareness outcomes as well as technical /

engineering outcomes, yet only a two person, technically-focused team arrangement was proposed

and implemented. Policy and legal development, communications and stakeholder outreach, and

community development are all areas where special expertise is needed if broader social and

economic outcomes are to be achieved.

The natural tendency in demonstration projects is to focus attention on near term practical matters,

such as managing construction and handling operations. It is up to the advisory committees and

implementing agencies such as UNDP, to keep broader project goals in focus.

At the conclusion of the GEF project, there is reason for optimism concerning sustainability. During

the final months of the project, the Egyptian government finalised its future management expectations

for the facility, with responsibility now under the National Water Research Centre (NWRC) and its

Drainage Research Institute (DRI). The NWRC has committed financing to operate the facility and to

continue research efforts. The NWRC have received a series of reports from LMEWP consultants

giving detailed recommendations on facility operations and maintenance, monitoring, business planning

and suggested further research efforts. These recommendations constitute a solid basis for future facility

planning, however additional work will be needed to streamline and integrate the recommendations.

In the future, the Egyptian government will need to decide whether and how to pursue some of the

broader LMEWP objectives. With donor assistance, the government of Egypt has been making major

improvements in sewerage and treatment upstream along the Nile, with attendant positive effects on the

drainage canals flowing into Lake Manzala. Nevertheless, the drainage of pollutants into Lake Manzala

still exceeds national limits and fisheries production remains imperilled.

The LMEWP offers a useful model to study and learn from for future projects involving the

construction of innovative low cost wastewater technologies. A multitude of issues for the LMEWP

will surely arise elsewhere, including:

coping with land ownership controversies,

overcoming site complexities,

identifying cost recovery options including profitable reuse,

effectively using international consultants and their proprietary techniques,

the appropriate size and scope of management teams,

the extent of monitoring needed and its cost implications,

the scope for private sector involvement, and

how to build public support.

Taking into account the many project achievements and lessons learned, on balance the Lake Manzala

effort represents a successful demonstration of engineered wetlands technology, which should provide

important knowledge sharing on low-cost wastewater treatment systems options.

v

GLOSSARY

APP

Advisory Panel Project on Water Management

APR

Annual Project/Programme Report

BAT

Best Available Technology

BOD

Biological Oxygen Demand

CIDA

Canadian International Development Agency

COD

Chemical Oxygen Demand

DRI

Drainage Research Institute (Egypt)

EC

European Commission

EEAA

Egyptian Environmental Affairs Agency

EIA

Environmental Impact Assessment

EPADP

Egyptian Public Authority for Drainage Projects

EU

European Union

EUR

Euro

GDP

Gross Domestic Product

GEF

Global Environment Facility

GIS

Geographical Information System

ICLARM

International Centre for Living Aquatic Resources Management (Egypt)

IW

International Waters

LE

Egyptian Pound (currency)

LFA

Logical Framework Approach

LMEW

Lake Manzala Engineered Wetlands

M&E

Monitoring and Evaluation

MOU

Memorandum of Understanding

MSEA

Ministry of State for Environmental Affairs (Egypt)

MTE

Mid-Term Evaluation Report

MWRI

Ministry of Water Resources and Irrigation (Egypt)

NAWQAM

National Water Quality and Availability Management Project

NGOs

Non Government Organisations

NWRC

National Water Research Centre (Egypt)

OP8

Operational Programme 8

PCU

Project Coordination Unit

PIR

Project Implementation Review

ProDoc

Project Document

RGS

Reciprocating gravel system (TVA proprietary design)

SAP

Strategic Action Plan

TAC

Technical Advisory Committee

TDA

Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis

TOR

Terms of Reference

TRC

Tripartite Review Committee

TRR

Tripartite Review Reports

TSS

Total Suspended Solids

TVA

Tennessee Valley Authority (USA)

UNDP

United Nations Development Program

UNOPS

United Nations Office for Project Services

USD

United States Dollar

vi

1

INTRODUCTION

Purpose of the Evaluation

This report provides an assessment of the relevance, performance and success of the UNDP/GEF

Lake Manzala Engineered Wetlands project (LMEWP) in conformance with evaluation guidelines

and Terms of Reference set by the UN Development Programme (UNDP) and the Global

Environmental Facility (GEF).

Key issues addressed

The evaluation considers potential impacts and sustainability of results, including the contribution to

capacity development and the achievement of global environmental goals. As a demonstration

project, it is important to capture key parameters (technical, economic and social) which have

facilitated or constrained replication of the prototype. The evaluation includes recommendations for

Egypt and other countries as they consider using innovative wastewater treatment technologies.

The project has faced many constraints, including unresolved land tenure issues and difficult site

conditions. These and other challenges are discussed within the evaluation, highlighting where

progress has been achieved, and where adaptive management approaches have been taken.

Methodology and structure of the evaluation

The report is based from a document review, field visit to the LMEWP and interviews with key

stakeholders, including Egyptian government officials, local and international consultants and other

involved persons. The mission itinerary and a list of reviewed documents are included as annexes to

the report.

1

2

THE PROJECT AND ITS DEVELOPMENT CONTEXT

The Lake Manzala Engineered Wetland Project (LMEWP) has been funded by the Global

Environmental Facility (GEF) and implemented through the Cairo office of the UN Development

Programme (UNDP). The executing agency was the Ministry of State for Environmental Affairs

(MSEA) through the Egyptian Environmental Affairs Agency (EEAA). A closely associated

government partner has been the Ministry for Water Resources and Irrigation (MWRI), and its

affiliated agency the National Water Research Centre (NWRC). In the final stages of the LMEWP,

ownership and responsibility of the facility passed to the MWRI.

The objectives of the Lake Manzala Wetland Project were to (1) promote sustainable development

by enhancing environmental and economic opportunities at the local and national level and (2)

construct and operate a demonstration engineered wetland facility that will treat 25,000 50,000 m3

per day of wastewater from the Bahr El Baqar Drain (Bashtir Canal), which flows into Lake

Manzala.

The wetland facility was designed to demonstrate innovative, low-cost approaches for improving

water quality and to promote Egyptian self-sufficiency in engineered wetlands technology. The

project also sought to enhance sustainable development by involving local residents and

organisations in the design, construction, and operation of the facility, and by engaging local

residents and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) in research, training and other national

capacity building activities.

The facility plan evolved to include a 60 feddans (= acres) fish farm, still under development, which

will utilise the wetlands-treated effluent. The expected income from fish production will be used to

offset plant operational costs.

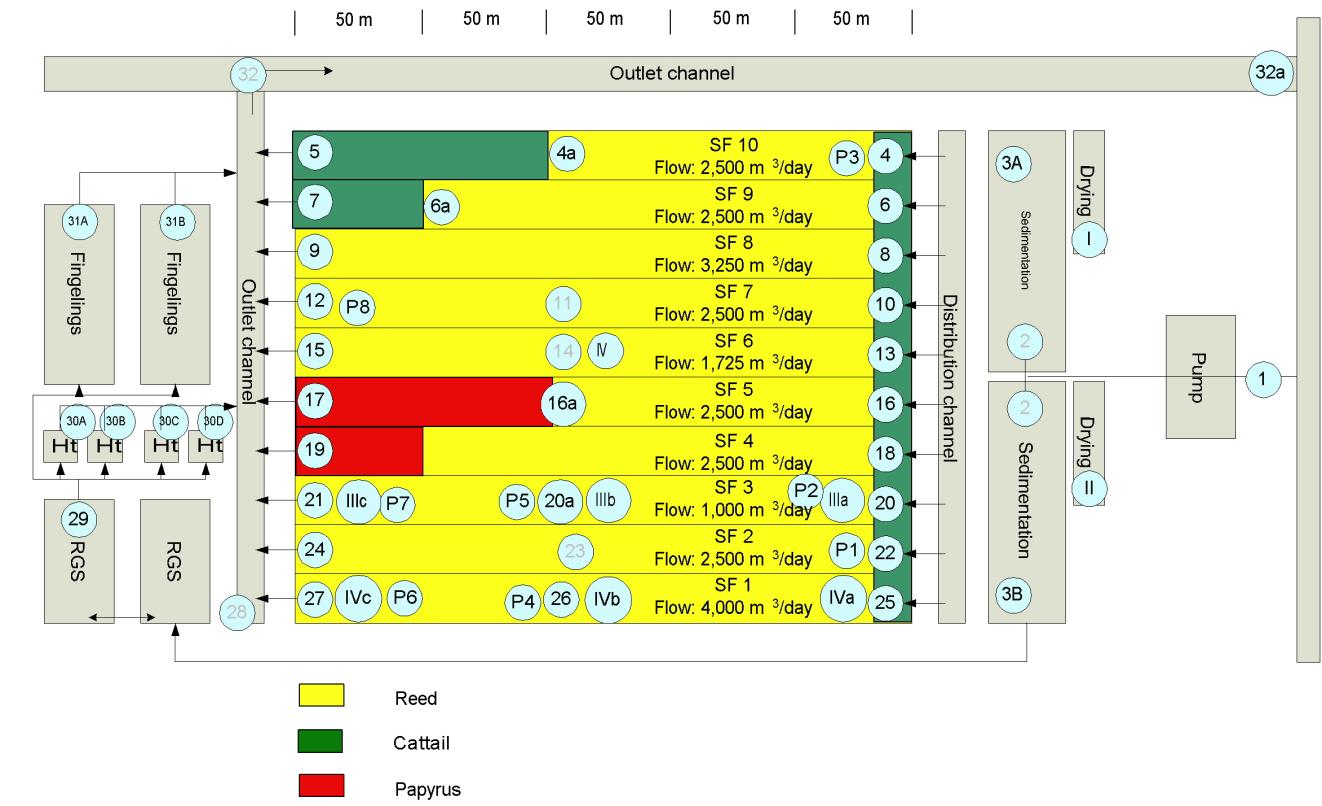

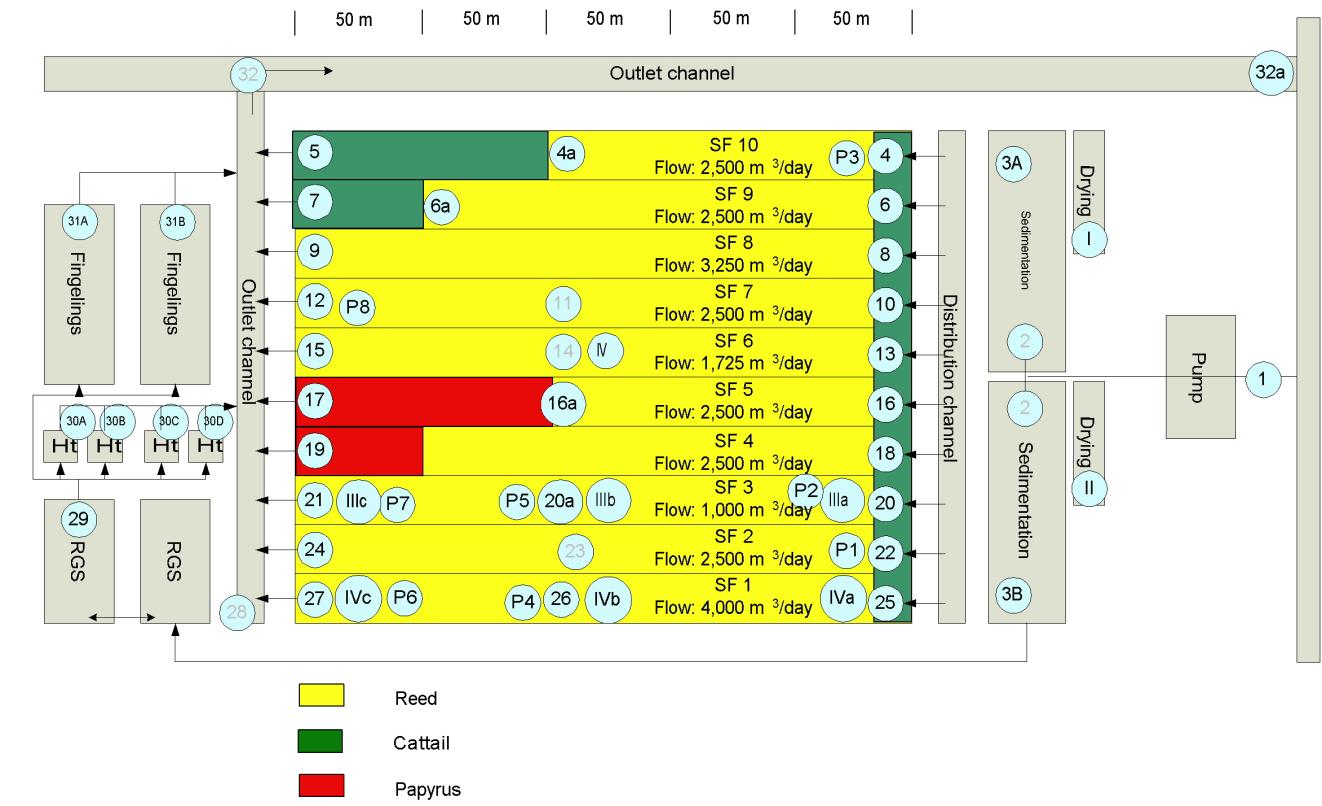

The entire facility includes:

Administration building, laboratory & equipment shed

Intake and pumping facilities

Two sedimentation basins

Ten surface flow wetland treatment cells

Two reciprocating flow gravel beds

6 small ponds (4 hatchery, 2 fingerlings)

Water distribution and outflow channels

Weather and climate monitoring station

Fish ponds (10 cells, 5 acres each)

The following is a flow diagram of the treatment facility and includes sample points and

anticipated flows. This diagram does not include the new fish farm.

2

2.1 PROBLEMS THAT THE PROJECT SOUGHT TO ADDRESS

As noted in the LMEWP Project Document (ProDoc), Egypt faces development and population

pressures contributing to the deterioration of Nile River water quality, with ramifications for

human and ecological health. While the Government of Egypt has over the past 20 years initiated a

large number of sanitation projects designed to significantly reduce the discharge of untreated or

partially treated sewage water, the extent of the treatment needs in Egypt remain substantially in

excess of available local, national and international funding, especially if Egypt continues to opt

for high-cost conventional treatment methods.

The poor quality of north-flowing drainage waters is a major environmental and economic

concern. In this arid country, heavily dependent on agricultural production, the Nile is a vital

resource. It is estimated that each m3 of Nile water gets used and returned two to three times. Much

of the heavily polluted drain water crossing the Nile Delta flows through a complex network of

irrigation canals, including the Bahr El Baqar drain. These canals empty into coastal lakes,

including Lake Manzala, before flowing into the Mediterranean Sea. The resulting pollution of the

Mediterranean Sea violates international agreements that Egypt is party to, in particular the

Barcelona Convention.

Lake Manzala is located on the north-eastern edge of the Nile Delta, between the two port cities of

Dormietta and Port Said. The area is one of the most poorly served in Egypt. Local residents do

not have access to potable water, sanitation, electricity and other basic services. Contaminated

water and tainted fish stocks bring human and ecosystem health risks. Many people live as

squatters on Government land and lack the security of land ownership and economic stability.

As noted in the LMEWP Project Document, Lake Manzala is highly eutrophic with both

macrophytes and planktonic algae contributing to extensive carbon fixation. The nutrient input

3

comes from fresh water inflows, and productivity decreases as salinity increases nearer the

Mediterranean Sea. The nutrient input, particularly through the Bahr El Baqar drain, has a relative

excess of phosphorous compared to nitrogen.

At the end of the 1990s approximately 90 percent of the total catch in Lake Manzala consisted of

four species of tilapia with the majority of individual fish less than ten centimetres in length.

Catches in this lake, which once provided 30 percent of all Egypt's fish, are dominated by the

smallest and hardiest of the tilapia species, T. zilli. This species has shown a high frequency (85

percent) of organ malformation and discoloration, caused by environmental and contaminant

stress. Among the Port Said inhabitants, Lake Manzala fish now have a reputation for

contamination (chemical and microbial) and are avoided by those who can afford to. The resulting

reduction in economic benefit from Lake Manzala fishing has had a severe social and economic

impact on lake area residents as well as local and national political repercussions.

2.2 PROJECT START AND DURATION

The LMEWP builds upon a project concept developed in the early 1990s to significantly reduce

the levels of pollution flowing into Lake Manzala from the Bahr El Baqar drain. The initial project

idea was to construct a large scale facility capable of treating as much as 50% of the Bahr El Baqar

flow. The concept received interest from the Danish government to provide financial support, but

the Danes eventually withdrew. One reason for the failure of the initial project idea had to do with

land tenure. The complexities of developing a large scale engineered wetland facility, requiring

the use of hundreds of acres of land, in an area inhabited by ,,squatters without land title, proved

too contentious. Denmark was not willing to proceed unless the land tenure issues were first

resolved.

In 1994, GEF support was sought for the project idea, and the concept was reduced in scope to a

demonstration project, which would treat approximately 1% of the Bahr El Baqar drain flow. With

this change, the project became an opportunity to demonstrate the effectiveness of engineered

wetlands, yet ceased to be an instrument to significantly improve Lake Manzala water quality. The

project shifted from direct environmental impact brought about by extensive treatment, to a more

indirect impact built on applied research, training, public awareness raising and replication.

GEF support was provided for project planning in 1996, and a project document for the LMEWP

was prepared for UNDP by the Tennessee Valley Authority1 (TVA) in March, 1997. After

development of the Project Document, several years were required to finalise the project

particulars and begin implementation. GEF funding and Egyptian co-financing commitments were

secured in late 1999, and the project timeline was expected to last 5 years, through the end of 2004.

The project duration was subsequently extended twice, and finally concluded in June 2007. The

1 The TVA is a US Government Agency, established in 1933 to improve the navigability of the Tennessee

River, provide flood control and also to boost agricultural and industrial development and reforestation in the

Tennessee Valley. The TVA has evolved into a wide-ranging parastatal agency, and is the US largest public

power company. TVA also operates the US largest research and development facility dedicated to the

science and engineering of constructed wetland treatment systems.

4

extended project implementation period did not require additional GEF financial support.

Extensions were requested and approved to account for delays in project construction and

treatment monitoring.

2.3 IMMEDIATE AND DEVELOPMENT OBJECTIVES OF THE PROJECT

2.3.1 OVERALL OBJECTIVES

The project was expected to demonstrate cost effective methods for improving water quality

entering Lake Manzala and the Mediterranean Sea and to facilitate the transfer of a low cost

biotechnology (engineered wetlands) to Egypt. A local hiring policy and a technical assistance

program were to be established to facilitate successful operation of the wetlands and transfer of the

technology to other parts of the country.

The cleaner water made possible through the engineered wetlands system should help to "increase

job opportunities for local residents, small scale industries that utilise biomass by-products;

opportunities for the women in the local community; support and reinforcement of regional efforts

to manage the resources of Lake Manzala and the coastal Mediterranean area; an improved fishery

in Lake Manzala; decreased health risk associated with consumption of Lake Manzala fish; and

decreased health risk associated with contact with the water from Lake Manzala." (LMEWP

ProDoc)

2.4 MAIN STAKEHOLDERS

The Project Document utilises the term ,,beneficiaries rather than ,,stakeholders to define those

persons and organisations likely to benefit from successful implementation of the LMEWP. These

include:

Local residents and in particular, those that are involved in operating the wetland for biomass

products and aquaculture.

Local residents who will be employees in the construction and operation of the wetland.

Local fishermen who adopt improved fish farming techniques demonstrated by the aquaculture

facility.

NGOs that participate in the wetland demonstration and focus on the project area and its

development.

All residents regardless of economic category because of the enhanced environmental

awareness and emphasis on the health risk associated with water pollution.

Regional scientific institutions and individual scientists that use the wetland facility for

research studies and training.

The Governorate of Port Said.

National governmental bodies, and in particular, the EEAA.

It should also be recognised that successful implementation of this engineered wetlands

demonstration may benefit local communities in other countries where low-cost innovative

technologies can help address pollution problems.

5

2.5 EXPECTED RESULTS

The ProDoc includes a list of expected benefits (emphasis added):

At the end of the five year project, there will be a fully operational, engineered wetland

treating 25,000 to 50,000 m3 per day of highly-polluted drain water. There will be a biomass

harvesting and aquaculture facility operated by local employees and assisted by NGOs.

The project will provide an example of sustainable development in practice, with

improvements in both the local economy and the environment

By the end of the project, there will be a wetland authority that will be responsible for the

facility. The institutional arrangements for long-term operation of the facility will be

determined before the project ends. At the end of the project, much of the routine operations

and maintenance will be conducted by the local employees who are selling biomass and fish

products. There will be a continuing need for the Government of Egypt to provide the

electricity to the facility and oversight management and monitoring.

The wetland will demonstrate a sustainable low cost alternative to conventional waste

treatment in Egypt and a national self-sufficiency to implement this technology throughout

the country.

The project team, governmental technical focal points, and selected graduate students will be

familiar with the biotechnology and will be able to lead Egypt's efforts in wetland

self-sufficiency. The project team will compile economic and monitoring data on the

effectiveness of the wetland and aquaculture systems over a range of conditions. Information

will be obtained concerning wetland function, operation, and transferability to other sites in

Egypt

Institutional strengthening will occur at the local and national level through the cooperative

efforts required to plan and manage the wetland, and to market wetland by-products.

EEAA will have an enhanced role and reputation as a leader in the provision and protection of

environmental quality in Egypt. EEAA will gain institutional strength in project delivery

and implementation that can be transferred to other Egyptian problem areas.

The quality of life for the local participants will improve as the wetland generates

employment, reduces the risk of disease from contaminated water and fish, and improves local

fisheries.

The local participants will be assisted in operating the aquaculture facility, and in harvesting

and marketing biomass products, such as fuel pellets and animal feed.

An integrated environmental monitoring and information program will be implemented to

record, compile, and assess the wetland operating efficiency, including pollution reduction,

biophysical changes, and socioeconomic improvements.

The level of pollutants flowing into Lake Manzala and the Mediterranean Sea will decrease.

The improved quality of water entering the Lake through the Bahr El Baqar drain will promote

biodiversity and enhance habitats for fish and bird species that are unable to survive in the

present aquatic ecosystem.

6

The production of greenhouse gases from the polluted Bahr El Baqar drain flowing into Lake

Manzala will be reduced and the generation of oxygen will increase.

With extrapolation and wider use of this technology by local residents, both Lake Manzala and

the Mediterranean Sea will have improved water and sediment quality as inflow

contaminants are reduced. There will be enhanced fish habitats, healthier fish, more fish

and bird biodiversity, and a reduction in climate gases of the anoxic drain water. The

health of the local population will be improved with the enhanced environmental quality.

7

3

FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS2

3.1 PROJECT FORMULATION

The findings on project formulation include consideration of the project design, the extent to which

the project feeds into Egyptian government priorities, the planned involvement of stakeholders,

and ,,other aspects, including the projects connection to related projects and the role of UNDP as

the implementing agency.

3.1.1 CONCEPTUALIZATION/DESIGN (R)

The project included expectations for tendering and awarding of an international contract for

consulting assistance. The expectation was for a five year contract, to include an International

Coordinator, International Wetland Designer, International Wetland Advisor, and International

Field Manager. The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) was awarded the contract in 1999. The

chief deliverable from TVA was the Conceptual plan, submitted in November 1999. TVA

provided design assistance until March of 2003 and was compensated $272,000. Unfortunately,

they were restricted from travelling to Egypt for consultations on final construction and start up,

due to US government security concerns, and withdrew from the project.

Achievement of the project conceptualisation and design has been satisfactory. The LMEWP

Project Document and annexes set out plans for a treatment system that is based on proven

concepts and designs from the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), who have decades of

experience in running such systems in the US. Whats more, the concept of utilising engineered

wetlands to treat agriculture drain water is highly relevant for Egypt. The decision to scale down

the project to demonstration level made sense as it was clear during the planning stages there was

a lack of financing, available land and political will to construct a large scale wetland treatment

facility.

The LMEWP ProDoc retained some grand objectives relating to the improvement of Lake Manzala

water quality and fisheries. As a small scale demonstration project, substantial environmental

improvement would require considerable attention to replication and policy reform. While the

ProDoc sets transformational objectives, it does not identify and then allocate funding for the kinds

of activities and mechanisms that would be needed to accomplish significant environmental

improvements.

The LMEWP Project Document was developed prior to the UNDP/GEF requirements to include

logical frameworks, and prior to the strengthening of requirements to elaborate verifiable

indicators. Accordingly, while the activities focused on facility construction are clear and

achievable, and the indicators are straightforward, the projects socio-economic objectives are less

clearly elaborated, and have proven difficult to implement.

2 Some of the subsections are denoted with (R), which indicates that a rating has been given,

based on a 4 point scale of project achievement: Highly Satisfactory, Satisfactory, Marginally

Satisfactory, and Unsatisfactory.

8

In hindsight, it is apparent that the timescales for facility completion were overly optimistic.

However, the delays were primarily due to the difficulties in utilising the chosen facility site.

Under less arduous and difficult conditions, the timescales, including a two year time horizon for

construction and facility start-up, would have been reasonable.

Site Selection

Site selection was a major issue both in the original (Danish-supported) concept and then during

the UNDP/GEF supported initiative. The Egyptian Government, together with the Governorate of

Port Said, selected a challenging site for the facility. The positives and negatives of the site

location can be considered as follows:

+ site positives

-- site negatives

close proximity to Lake Manzala, so

12 kilometres away from the nearest

positive, albeit minor, impact on lake water

electricity lines, no potable water or

quality

sanitation

Publicly owned land so minimal cost and

Difficult access due to unpaved road and

legal problems

structurally unsound bridges

Chance to improve the quality of life for

Poorly situated for extensive research: no

impoverished local residents

overnight facilities, no computer/internet

Chance to clean up social problems in the

access, and potentially unsafe area, distant

area, increasing safety for residents

from the cooperating universities.

Well-suited for aquaculture

Poorly suited for agriculture poor saline

soils

Facility Design:

The design for the engineered wetlands facility is appropriate and based on longstanding

experience with the technology by TVA. The project included initial construction of a small pilot

test site, and then development of the full scale facility.

The project included construction of a reciprocating gravel system (RGS), based from a TVA

proprietary design that has proven successful for TVA when applied in the US, including in hot,

arid climates not significantly different from the climate in the Delta area of Egypt. Unfortunately,

the withdrawal of TVA from the project prior to facility completion created difficulties for the

project team to effectively operate the RGS

The two sediment basins were scaled according to expected influent parameters analysed during

the project development stage. 7 years later, when the facility came on line, it was soon evident

that 50% smaller sediment basins would have been sufficient. The over-estimate was due in large

part to the improving water quality of the Bahr El Baqar Drain as a result of upstream water quality

treatment improvements in the Cairo metropolitan area.

3.1.2 COUNTRY-OWNERSHIP/DRIVENESS

The LMEWP is highly relevant to the Egyptian environment and economy and to human health.

The project was formulated in full realisation of the importance of finding low-cost solutions to

Egypts pressing wastewater treatment needs.

9

The Egyptian Environmental Affairs Agency has served as national executing agency, responsible

for overall project management. The rationale for EEAA supervision was sound, as it is the GEF

focal point and also has a cross-functional mandate; however a case could also have been made for

implementation through the Ministry for Water Resources and Irrigation (MWRI), which is

directly involved in the management of irrigation canals throughout Egypt. As it turns out, the

logic of MWRI responsibility grew as the project progressed. At the conclusion of the LMEWP,

responsibility for the facility has changed hands to the National Water Research Centre (NWRC)

of the MWRI.

The project was viewed by the Egyptian Government as an important aspect of its goal to focus

increased attention on ,,environmental black spots" such as Lake Manzala. The lake has been

prominently featured in Egypts National Environmental Action Plan and the LMEWP was

included as an important project for Egypts Supreme Committee for the Rehabilitation of Lake

Manzala.

The Government of Egypt, and Port Said, agreed to a set of financial commitments during project

formulation, to include covering basic municipal infrastructure (land, road access), offices and

equipment, and some manpower contributions, for steering committee meetings, etc. In the end,

the government has followed through, and its in-kind contributions have exceeded their initial

commitments.

While spurring local economic development was a key project objective, the facility was not part

of any comprehensive development plans by the Port Said Governorate to improve development

opportunities and quality of life in the area. The LMEWP was rather a ,,one-off project whose

economic benefit has so far been very limited.

There are other aspects of country ownership that blend project formulation and implementation

issues. For instance, there is the question of whether the government has approved policies and/or

modified regulatory frameworks in line with the projects objectives. In the case of the LMEWP,

the project formulation did not lay out expectations for changing national policies, and

implementation of the project did not deliver policy transformation.

Based on interviews with Egyptian officials and scientists, the project has increased interest in the

merits of engineered wetlands. The project has successfully added to earlier research and

investigations on gravel bed hydroponic systems, carried out in 1991 - 1995 in Ismalia, Egypt, by

the Suez Canal University with UK support.

While the LMEWP has been under development, the Government of Egypt has approved a new

Code on wastewater reuse. The new reuse code has been under development for 8 years and its

final approval is unrelated to the Manzala project, nevertheless the code is a welcome addition to

Egyptian law, and should spur increased interest in engineered wetland systems. Also of note, the

NWRC is expanding its engineered wetland research, with promising studies already undertaken

on in-situ wetland systems within the agricultural drains.

The Manzala project included private sector participation in the design, engineering and

construction of the facility. As a result of the project, Egyptian contractors now possess expertise

that can be put to use in future constructed wetlands projects in the region. The availability of local

expertise is critical to replication of the technology as it should allow for lower design and

construction costs.

10

There have been some small scale actions involving employment of local residents for security and

maintenance of the facility; however the extent of local economic development is below initial

expectations, given ProDoc indications that there would be substantial increased economic benefits

to the surrounding community. While it was the executing agency for the project, the EEAA

expressed interest for the planned aquaculture business to be opened to private investment and

management. The NWRC has not indicated whether it will consider using private concession

contracts.

The project was able to provide training for 25 local persons on engineered wetlands and water

quality for fish farming; however it is unclear whether this training has resulted in local economic

benefits, such as improvements in local fish farming practices or replication of the engineered

wetlands treatment process.

3.1.3 REPLICATION APPROACH

The LMEWP Project Document does not set out a replication approach. Instead, replication

opportunities are inferred on page 23 in the capacity building and dissemination outputs 1.2 & 1.3.

There are no specific outputs for scaling up the LMEWP, for reforming policies and remove

barriers to replication, or for applying lessons learned elsewhere in Egypt.

While the project developers did not articulate how replication should be fostered, it is important to

recognise there is real potential for Egypt to expand its use of constructed wetland systems. The

NWRC is considering these systems to extend treatment of the Bahr El Baqar Drain, and there is

interest to extend the technology for treatment of domestic sewage for villages on the fringes of the

delta where land is more readily available.

3.1.4 LINKAGES TO OTHER PROJECTS

The project was not developed with explicit linkages to other related projects. The Project

Document lists a series of related projects (see ProDoc pg 11) but makes no mention of synergies,

shared resources, shared information, etc.

A related pilot rock-reed wetland demonstration at Ismalia was operated by the Suez Canal

University in collaboration with Portsmouth Polytechnic in the UK. Project management was

aware of this effort, however no specific efforts were made to compare and contrast results.

The ProDoc indicates that the Water Hyacinth Institute was working to commercialize water

hyacinth products and the LMEWP provided an opportunity to turn benchmark results into

commercial opportunities. The LMEWP project team has indicated it did some research on water

hyacinths during the pilot phase and concluded that the saline groundwater and soils at the site

made it impossible to cultivate this wetland plant.

Where there were successful programme linkages were through the NWRC and its Drainage

Research Institute (DRI). For instance, the DRI has been studying various low-cost mechanisms to

improve water quality in the agricultural drains, and are considering lessons learned from the

LMEWP.

11

3.2 PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION

The selection process for facility design and construction supervision was carried out in an

appropriate manner and the contractors chosen were well qualified for the assignment. The

Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) was the original facility design engineers, supporting a local

engineering team, led by Ahmed Abdel Warith Consulting Engineers (AAW), together with

KOMEX Egypt. The construction contract was awarded to Misr Concrete Development Co. in

November 2000.

It is understood that design and construction complications created unanticipated costs, in

particular due to the difficult site location; however the original contracts and pricing were

honoured. The local team was very much on its own, with limited help from TVA. That the

facility is now operating at or above design criteria, (with the notable exception of the RGS), is a

testament to the capabilities of the local design and construction team.

After TVA withdrew in 2003, The PCU tendered for another external consultant to assist on

operations and maintenance issues and monitoring plans. After an open tendering process, the

Danish firm NIRAS, together with their local affiliates ECMA, were awarded the contract.

Unfortunately, two years passed before the NIRAS team was selected and started to work.

The initial concept was to utilise the LMEW treated effluent for small scale agriculture and

aquaculture research, including fish stocking for Lake Manzala. NIRAS recommended a shift to

commercial scale aquaculture. A decision was made for the project to develop a fish farming

enterprise at the site. The issue was taken up at the 2005 Tripartite Review Committee meeting

and received strong support. The UNDP Resident Representative strongly encouraged that the fish

farm be pursued as an important job creation component of the project.

The earthworks for the agreed upon 60 acre fish farm were completed in August, 2007, and by

October 2007 the ponds were flooded. Operations have yet to commence, and funding is needed to

get the facility into production, including for fish stock (fingerlings), fish food, aeration systems,

etc.

Developing the facility to include a commercial fish farm was a reasonable adaptation of the

project, especially if it enhances local job creation, ensures an ongoing source of revenues to

operate the treatment facility, and enables the NWRC to continue using the facility as a research

station.

It is evident that the LMEWP site was selected due to its proximity to Lake Manzala and the Bahr

El Baqar drain, and because it was a relatively large under-utilised site without private land title

issues. These factors allowed the site to come without land purchase costs, and the short distance to

the Bahr El Baqar drain ensured lower pumping costs. The selection of this particular site also had

negative consequences. There were construction delays, largely stemming from the facility

location, and the need for extensive road excavations and also significant earthworks on site. Also,

water and electricity services have yet to be extended to the area where the facility is located. In

addition, the isolated location of the site and lack of overnight accommodation created problems in

carrying out project management and research. Considering these various tradeoffs, the site was

not ideal, yet it was workable. There is little in the project background information to suggest that

a major effort was made to compare the pros and cons of possible sites.

It wasnt until August 2006 that the monitoring plan developed with the assistance of NIRAS was

implemented. While there are data available from analyses starting from sampling in 2004, the

12

inconsistent monitoring up until 2006 means that it is only in the final months of 2007 that annual

and seasonal comparisons of treatment effectiveness can start to be made. Plant operations and

monitoring were further impacted during the period April June 2007 while negotiations were

carried out concerning the transfer of plant supervision from EEAA to MWRI.

3.2.1 IMPLEMENTATION APPROACH (R)

The implementation approach taken in the LMEWP can be considered marginally satisfactory. A

review of the annual APR/PIR reports, coupled with the projects annual work plan spreadsheet and

notes from the tripartite review meetings, suggest that the project management focused mainly on

the practical matters of construction and operation. In this regard there is a good measure of

success.

The second level of planning and management concerns the applied research and monitoring at the

facility, as well as the development of training programmes and public awareness campaigns. Here

the project had marginal success but more was expected. .

On the positive side, there was a useful partnership put together with the MWRI/NWRC, which

operated linked research activities at the site. This partnership served to maintain NWRC interest

and create the opportunity for their assumption of project ownership and management in 2007.

Through the NWRC, a close cooperation was formed with the Dutch-Egyptian Advisory Panel

Project (APP) on Water Management, which carried out 2 training workshops for Egyptian experts

that also included several regional representatives from Uganda, Sudan and Ethiopia. In addition,

twenty five local residents received training in a workshop on engineered wetlands and fish

farming that ICLARM led on behalf of the project.

On the minus side, the project made little use of electronic information technologies to support

project implementation, participation and monitoring. In addition, it was not apparent that lessons

and practices from other engineered wetlands projects were taken into account for the LMEWP,

other than serving as the basis for TVAs initial conceptual design.

Adaptive management is an important aspect of project implementation, as circumstances change

teams must react and adapt. In the case of the LMEWP, the team had to handle land use and

squatter issues, site construction difficulties, a shifting currency exchange rate, and the withdrawal

of TVA, its key external consultant. The project also made a significant change in expected

outcomes with the decision to build a fish farm. Each of these constraints was handled, but with

varying methods and degrees of success.

The squatter issues were handled temporarily through equal parts diplomacy and increased

security, yet the fundamental land tenure issues in the region remain. The site construction issues

were handled through tough negotiations with contractors. Budgets were kept but schedules

slipped. The shifting currency rates enabled the project to be extended without additional funding,

yet project management decided to operate using a very thin project team and a number of the

broader research expectations were not achieved. The facility was completed without TVA

involvement; however TVAs proprietary RGS was a casualty as it has never worked properly.

In these adaptive management cases, the decision making process was led by the project team

leader, with recommendations from the TRC and TAC advisory committees, including UNDP. In

each case, while there appeared to be open discussions on the way forward, a detailed analysis of

risks and opportunities was not included. The decision to establish a 60 feddan fish pond was

13

supported through NIRAS recommendations including some basic financial analysis of costs and

benefits (see NIRAS Inspection Report, 09082005), and discussed in comments to the NIRAS

inspection report and at the 2005 TRC meeting. Nevertheless, there is no indication that the

project document or project implementation plan were revised to account for this change from a

small aquaculture facility raising juvenile fish for restocking of Lake Manzala to a fish farm. In

general, it can be seen that UNDPs risk management and monitoring system was not closely

followed as the project responded to changing circumstances.

The major TORs developed during the project were uneven. The ProDoc provides a rather

perfunctory TOR outline for the Project Manager and Senior Project Engineer, and outlines the

roles of four international consultants - an international coordinator, international wetland

designer, international wetland advisor and international field manager. In hindsight, the project

management ranks were far to thin, and the project would have benefited from the inclusion of

another expert to handle the significant public awareness, training, outreach and external linkage

expectations.

The ProDoc included a top-heavy team of four international consultants from TVA, who provided

the requisite design parameters but then were not available to offer first hand troubleshooting

assistance. It is exceedingly difficult to provide effective advice and guidance on an innovative

project with proprietary design systems, without periodically travelling to the site.

3.2.2 MONITORING AND EVALUATION (R)

The Lake Manzala project has included both a mid term and final evaluation, there have been

regularly scheduled annual Tripartite Review Meetings (Project Steering Committee), and the

project has been audited annually by an independent accounting firm. The M&R activities have

been carried out in a satisfactory manner.

The mid term evaluation for the Lake Manzala project was carried out in December and January

2004. The MTE included provided the following recommendations for the project:

Extend the project for 1 year (until 2007) to enable the monitoring and experimental

programme to be devised and implemented;

Undertake a detailed review of the facility design, in particular to consider issues such as

sediment pond desludging and the potential for short-circuiting within the wetland beds

Draw up an action plan for engaging the local community and disseminating information to

them.

Develop on-site laboratory facilities, have technically and scientifically qualified personnel on

site at all times, and utilise continuous flow measurements for the influent and effluent

streams, plus composite flow sampling for water quality parameters.

Develop an external peer review process during project inception to address facility problems

as they arise.

Formalise arrangements, including appropriate resources, with external consultants involved in

the feasibility and conceptual designs, to avoid risks of ,,weakening technology transfer

aspects of the project.

14

The recommendations were by and large accepted and utilised by the project management,

although an action plan for engagement of the local community and information dissemination was

not realised.

The project document did not include a logical framework (LFA) and none were subsequently

developed. There were a number of expected outcomes, in the areas of training, public awareness,

and for small business sideline ventures like the sludge bricks and papyrus cultivation concepts,

where the project might have been able achieve greater success if an LFA with verifiable indicators

were developed.

Tripartite Review Committee (TRC) meetings were conducted during the project on an annual

basis. The TRC included representatives from the project team, UNDP Cairo, EEAA, and the

Egyptian Ministry for Foreign Affairs. Tripartite Review Reports (TRR) were produced, and

include information on project status and decisions made.

The project team met its expected obligations to UNDP/GEF with respect to the completion and

submission of annual progress implementation reports (PIRs) and Annual Progress Reports

(APRs).

Facility Monitoring

Consideration of project oversight and monitoring can also include the establishment of a

monitoring programme for the treatment facility. After TVA ceased its involvement, the LMEWP

Steering Committee agreed to tender for another international consultant to help with monitoring

systems development, operational planning and staff training.

The outcome of the tendering procedure was the awarding of a contract in May, 2005 to the Danish

company NIRAS (and its local partner ECMA). NIRAS together with ECMA were contracted to

do the following:

Coordinate with NWRC, through the Project Manager, to train staff, transfer technology and

raise NWRC competence to a level that it can operate the facility after GEF project

completion.

Produce an inspection report assessing how the project as built deviates from the original

project conceptual plan and rational for design set out in the project Document.

Develop a Monitoring and Experimental Program Plan, identifying additional facility

modifications deemed necessary to meet operational demonstration and research objectives.

This plan is to include also a communication strategy for promotion of the technology.

Develop Operating Procedures and Guidelines for the wetland facility, including technical

assistance and training in sampling techniques, water quality analysis, and plant harvesting and

data management.

The TOR developed for the monitoring consultancy covered some but not all of the essential

activities that the consultant ended up participating in. By project conclusion, the consultant had

done significantly more than was initially intended, including in particular the development of a

business plan for the facility.

As is common in many demonstration project TORs, the terms developed for the monitoring

consultancy focus directly on facility operations, and offer very little assistance on the broader

project aspects such as replication and local economic development. The TOR did include an

15

expectation that the consultant provide a communications strategy within the commissioned

Research Plan. The most significant missing aspect to the TOR was a clarification on the feedback

loop. There were no requirements indicated in terms of presenting findings and discussing

alternatives. The expectation was just for the consultants to present their draft plans, and then

await approval and then receive payment. This effectively placed the monitoring consultant as an

external provider of ideas rather than an integral part of the project team.

NIRAS conducted their facility inspection in May - June, 2005 and their inspection report noted a

number of key issues.

With respect to the RGS system, it was mentioned (pg 4) that "It is questionable whether RGS

systems normally would be used for treating irrigation drainage water. This system is first of all

designed for treating higher strength wastewater. Further, it is doubtful whether it would be

affordable for fish farmers to install such a cost-intensive system, both in establishment and

operation. However, this component is now in place, and should therefore be tested in order to

verify the expected performance, or if possible, adapt the technology to local conditions, which is

likely to be of benefit to other treatment situations in Egypt".

The Inspection report sets out a proposal for 5 testing objectives:

Overall objective: A focal centre for engineered wetlands capacity building, technology

transfer, adaptation and awareness creation established.

Immediate objective 1. Establish feasibility of improving the water quality of Lake Manzala

through engineered wetland technology.

Immediate objective 2. Potential for local economic activities enabled by engineered wetland

technology established.

Immediate objective 3. Low cost solutions for village level waste water treatment identified

and design foundation specified.

Immediate objective 4. Cost effective affordable, competitive means of water production for

economic activities developed.

Immediate objective 5. Steady state conditions, long term sustainability, lifespan forecasting

and life cycle economics established.

NIRAS recommended developing a floating pontoon system for continuous rather than batch

desludging of the sedimentation ponds. They also suggested options for revising the v-notch

system of weirs from the sedimentation ponds to the wetland cells. The facility should either revise

the weirs to provide a 6 cm fall, installing wheeled gates of the v-notch type for better accurate

hydraulic adjustment, or then dispensing with the v-notches and constructing valve chambers in the

inlet and outlet of each cell wetland, with electronic flow meters.

NIRAS provides a suggestion to undertake research in treating higher strength wastewater, from a

nearby village, or industrial facility, septic sludge, or from intensive agricultural production. The

proposal was to switch one of the surface flow wetland beds to a subsurface flow bed in the pilot

system. NIRAS also suggested developing a subsurface flow bed in the main wetland system next

to the RGS to better compare the performance of the RGS. They further suggested testing the

performance of the RGS at different pulse/pause schemes and load levels in order to set

management and operational parameters based on strength of the wastewater, size of the system

and degree of treatment desired.

16

NIRAS advocated expansion of the fish farming, utilising 60 feddans (+ acres) of land utilising

12,500 m3 /d of treated water. NIRAS further suggested that a closed circuit water supply for the

fish production be developed, which would circulate fish farm water back through the treatment

facility. NIRAS suggested franchising the fish farming activities out to local fishermen, and

establishing a quality control program for fish production.

The inception / inspection report is comprehensive and provides very good recommendations for

how to proceed in the completion of the LMEWP both in terms of facility operational fine

tuning, and also with respect to research and outreach activities. Some of the recommendations

were carried out for instance the major decision to develop a commercial fish farm. Other

aspects, in particular related to operating the RGS, were not achieved. Also, the suggested studies

of higher strength wastewater were not done. It is recognised that the remote position of the

facility made it somewhat difficult to bring wastewater to the site for testing.

At the time of the evaluation mission, NIRAS had drafted out reports covering the rest of their

expected outputs. These were:

Operations and Maintenance Manual (draft final, May 2007) \

Test Plan (draft final, May 2007)

Monitoring Plan (draft final May 2007)

Business Plan (draft final, June 2007)

In the following sections, each of these plans and manuals is discussed. In general, they provide

useful information and will contribute to the sustainability and replicability of the project. Yet

there are shortcomings, mostly relating to the fact that they are external consultant reports, not

facility plans. Released at the end of the project, they now require discussions, agreements and

major revisions to become documents that can be used as plans that can guide the future

activities at the Manzala facility. Some expected deliverables such as a communications strategy

for promoting engineered wetlands technology, were not well developed in the Business Plan, and

were delivered too late in the project to be implemented.

3.2.3 STAKEHOLDER PARTICIPATION / PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT (R)

Achievement in the area of stakeholder participation and public involvement was marginally

satisfactory. The project team was able to solve a crucial initial problem, regarding the suspicion

and mistrust of some members of the local population where the facility was to be constructed.

This issue not only imperilled the project, it also constituted a safety issue for facility personnel

and construction crews. The ability of the project team to win over the trust of local inhabitants,

and to complete the project without any major security incidences, was a significant achievement.

The project team employed persons from the local community for site construction, security and

maintenance. The project team also provided ad hoc opportunities for community members to

view the wetland and fish pond system, and to receive training and advice on how to use wetland

systems for improving fish pond water quality.

In terms of more general stakeholder involvement, the project was not very successful. In

particular, information dissemination, through the development and implementation of public

outreach and awareness campaigns, did not progress as expected. It is evident that for much of the

project, the small project team was consumed with day to day construction management and

17

facility operations, so communications and public relations received less attention. A

communications strategy was not developed by the team, and as noted above, the NIRAS

developed Business Plan included only a very brief consideration of communications aspects as

part of the recommended Action Plan, which was only delivered during the final several months of

the project. Nevertheless, some public information and dissemination activities were successfully

carried out. In 2004, a short documentary film was produced, including interviews with

participants and local residents. This was subsequently updated and utilised together with a case-

study note for the RBAS/RBEC Virtual Water Fair, November 15-17, 2006. Several project

brochures on the facility have been developed, the last in early 2006, and an explanatory note and

presentation were given at the GEF International Waters Conference in Cape Town, South Africa,

July, 2007. The project team participated and made presentations at a series of workshops

sponsored by APP and NAWQAM, and has participated in international processes through the

GEF IW:LEARN project (e.g. participation in Brazil international conference on nutrient reduction

and control).

The project manager maintained regular communications with key institutional managers and

technical experts. During evaluation interviews, the top management at both the Egyptian

Environmental Affairs Agency (EEAA) and the Ministry of Water Resources and Irrigation

(MWRI) expressed their satisfaction with the information flow from the project and expressed

interest in sustaining the facility.

Involvement with local and international NGOs during the project was minimal. In part, this can

be attributed to the isolated site, and the absence of NGO activity in this part of the Nile Delta.

Stakeholder involvement was primarily achieved through the meetings of the TAC. For instance,

the World Fish Centre (ICLARM) served as a member of the TAC and was also contracted by the

project, in November 2005, to organise a training course on constructed wetlands and fish farming

for the local community in the Lake Manzala area. 25 local residents received this training.

To improve upon project effectiveness in the area of stakeholder outreach and public participation,

another project expert should have been added to the team, with communications and writing

expertise.

3.2.4 FINANCIAL PLANNING

The Lake Manzala project has utilised the UNDP Cairos OUDA financial management system,

tracking all receipts and expenditures carried out under the project. The system is easy to utilise

and appears to have functioned well. All project funds were expended by July 2007. Indications

are that the invoice and payment procedures with UNDP-Cairo were handled professionally, with a

minimum of delay.

The project team developed annual work plans, which provide a general expectation of funds to be

spent against objectives, outputs and activities. However, there is no evidence that these work

plans were closely matched against actual expenditures. Also there was no effort to develop a

shadow budget for keeping day to day accounts matched against outputs and activities. The

annual work plan budgets do not include an aggregate sum of the funds utilised previously for

particular outputs and activities.

18

3.2.5 COST-EFFECTIVENESS OF ACHIEVEMENTS

The cost effectiveness of achievements on the LMEW project can be considered based upon:

Completion of planned activities and meeting of objectives

Use of benchmarking or comparison approach to setting the cost structure

In terms of the timely achievement of objectives, and their relationship to cost effectiveness, it can

be seen that the difficulties of developing the chosen site led to significant project delays, which

were exacerbated by delays in switching international consultants. Some parts of the operation

have failed to work as intended, in particular the RGS, and can therefore be considered

uneconomical at this point.

No benchmarking was initiated at the project document stage, or subsequently, to consider the cost

of the facility against other facilities of its kind in similar developing regions. Partly this can be

attributed to the lack of available data from other treatment facilities treating agricultural drainage

water.

Some comparative cost calculations were done by the project staff to consider the LMEW against

more conventional technologies. Rough calculations suggest that engineered wetland systems can

be built and operated for 10% of the cost of an activated sludge wastewater treatment system in

Egypt however these comparisons are based against very general design estimates, not actual

expenditures, as follows:

Method of Treatment

Capital Cost (L.E/m3)

Running Cost (L.E/m3)

Extended Aeration

3500

140

Oxidation Ditch

1700

105

Aerated Lagoon

1800

70

Oxidation Pond

1300

20

Engineered Wetland

400

Less than 1

3.2.6 FINANCIAL MANAGEMENT AND CO-FINANCING

The project was originally planned to conclude at the end of 2003, and yet it lasted through mid-

2007. The plan was also altered to enable construction of a commercial fish farm. These changes

have been made without additional financing from GEF, and despite increased construction costs

for the facility, which grew from L.E. 6.7 million to L.E. 10.9 million. The budget was able to

stretch because of:

A rigid enforcement of contractually-agreed financial terms with contractors, regardless of cost overruns

and unforeseen facility construction complications.

An (overly) lean project staffing.

Cutbacks in some expected research efforts

Additional in-kind support from Egypt

The strengthening dollar against the Egyptian Pound (LE), led to an increased project budget in

Egyptian Pounds. In the January 2003 LE devaluation the $ value jumped from LE 3.30 to LE 5.75.

Since the project budget was in dollars, the amount in LE was increased. (It should be noted that while

this increased the project amount in LE, it also resulted in negative impacts on the project contractor, in

particular when buying foreign goods and services).

19

The LMEW has been audited on an annual basis. The 2006 audit, submitted by an independent

auditor in April, 2007, states that the project statements of assets and equipment, as well as its

stated cash position, present a fair and accurate indication of the projects financial condition. In

addition, the auditors indicate that appropriate steps were taken by project management in response

to (minor) recommendations from previous audits.

The LMEWP received financial and in-kind support from the GEF, and co-financing from the

Government of Egypt. No additional grants, loans, concessional credits or equity investments were

provided. Egypt has provided direct support matching its planned co-financing contribution of

$346,000, which was roughly 8% of the overall project budget. Based on the project team

estimates, the Egyptian contribution can be considered as high as $1.5 million - if the cost of land

is factored in.

The team has estimated the land value at LE 23,000 per feddan, which for 245 feddans

(including the treatment facility, fish ponds and unused space on the property) comes to just

more than $1 million.

The cost of the 12 km of road construction is estimated at $350,000 ,

Another $81,000 has been estimated for donated office space and utilities.

An additional in-kind contribution of $18,000 in time and expenses has been estimated for the

project technical committee.

The NWRC has also financed some facility O&M costs, including paying for diesel fuel to run

the plant.

With the Governments agreement to continue to operate the LMEW Facility, and its plans to

develop a commercial scale fish farm, there will be a significant continuing financial obligation by

the Egyptian Government, at least until such time as the fish farm is making a profit.

The draft Business Plan submitted by NIRAS in June 2007 includes cost / benefit analyses for the

treatment facility and fish farm operation. The Business Plan sets out expectations that the

operation can be self sustaining following its 3rd year of operation, but suggests that an additional 1

million LE ($200,000 US) will be needed in order to get the fish farm into full production while

continuing to operate the treatment works. The Business Plan further suggests a tripling of the fish

farm size, in order to make the operation fully self sustaining and capable of paying back the initial

NWRC/DRI investment.

3.2.7 LEVERAGED RESOURCES

Leveraged resources can include connected activities carried out by the Government of Egypt,

NGOs and private companies. The annual PIR/APR reports for the project include an assessment

of partnership strategies, including estimated financial contributions. The total leveraged amount,

$155,000, roughly 3% of the total project budget, includes:

$45,000 in parallel funding from the National Water Availability and Quality Monitoring

Project (NAWQAM) -- a Canadian supported (CIDA) project, for sampling and analyzing the

irrigation related parameters of the LMEWP facility influent and effluent, and testing the use

of water for irrigation.

$30,000 in direct costs absorbed by the Dutch-Egyptian Water Advisory Panel for two joint

workshop and training programme at the LMEWP facility,

20

$20,000 in-kind from the World Fish Centre (ICLARM), providing planning and advice for the

projects fish farming activities.

$60,000 provided in-kind from the German company Bona Nova to demonstrate/compare

biophysical wastewater treatment techniques vis-à-vis the engineered wetlands method.

Several Universities provided resources to enable their doctoral students to work at the site.

The Project team was not expected to develop a donor strategy or devote time to identifying

additional external sources of funding for post-GEF sustainability and replication; however donor

support will likely be needed, in particular for undertaking continued research programmes that

have been identified in the draft Test Plan. Canada has reportedly expressed some interest to

provide further funding support for wetlands research through its ongoing partnership with Egypt

in the NAWQAM programme.

3.2.8 EXECUTION AND IMPLEMENTATION MODALITIES

UNDP Implementation

The UNDP has been an appropriate implementing agency for the LMEWP, bringing several

comparative advantages. It is focused on capacity building and the application of new techniques

for environmental improvement and social development. While other UN agencies provide

important services in the areas of environmental protection (UNEP) and scientific research

(UNESCO), the UNDP has long played a pivotal role in supporting structural and policy changes

that improve environmental management, and in particular that foster sustainable development.

The UNDP office in Cairo has a good track record in working with Egyptian counterparts at

national and local levels. They played a significant backstopping role for the LMEWP in

particular through developing and disseminating public communications on the project. A close

UNDP-LMEWP connection was forged after the senior LMEWP project engineer joined UNDP

Cairo in 2002.

UNDP effectively played its traditional fiduciary role, overseeing payments and ensuring that

consulting assignments were carried out using proper UNDP procedures, (approved TORs, open

bidding procedures, etc.). UNDP also played a useful role helping to coordinate between the

national and governorate authorities during LMEWP facility construction, and assisted the project

team with prodding EEAA and MWRI to accelerate their handover negotiations prior to project

conclusion.

Greater UNDP support would have been useful during the critical transition period when the

facility was under construction and TVA announced it was unable to provide direct, on-site review