FINAL

IC/093

01-Dec-2004

Policy and legal reforms and

implementation of investment projects

related to the

ICPDR Joint Action Programme

2001 2005

Implementation Report

Reporting Period 2001 2003

G:\danube\DOCUMENTS of the ICPDR\IC 1-\IC 093 JAP - Interim Implementation Report\ORD-07 - Interim Implementation Report of JAP.doc

G:\danube\DOCUMENTS of the ICPDR\IC 1-\IC 093 JAP - Interim Implementation Report\ORD-07 - Interim Implementation Report of JAP.doc

DRAFT

INTERIM IMPLEMENTATION REPORT

Policy and legal reforms and implementation

of investment projects related to the

ICPDR Joint Action Program

2001-2005

REPORTING PERIOD 2001-2003

International Commission for

the Protection of the Danube River

NOVEMBER 2004

G:\danube\DOCUMENTS of the ICPDR\IC 1-\IC 093 JAP - Interim Implementation Report\ORD-07 - Interim Implementation Report of JAP.doc

2

This report has been prepared by Dr. Mihaela Popovici, using information from the results of the

ICPDR Expert Groups, DABLAS report 2002 and reporting results of the Danube countries (apart of

Austria and Germany) on the ICPDR Joint Action Program within the frame of EU DABLAS project,

2004. Austria and Germany have separately provided their respective reports on the JAP implementa-

tion.

Overall supervision: Philip Weller, Executive Secretary of the ICPDR

ICPDR Document IC/093

International Commission for the Protection of the Danube River

Vienna International Centre D0412

P.O. Box 500

A-1400 Vienna, Austria

Phone: +(43 1) 26060 5738

Fax: +(43 1) 26060 5895

e-mail: icpdr@unvienna.org

web: http://www.icpdr.org/DANUBIS

Date: November 2004

G:\danube\DOCUMENTS of the ICPDR\IC 1-\IC 093 JAP - Interim Implementation Report\ORD-07 - Interim Implementation Report of JAP.doc

3

Acknowledgements

In preparation of this report, the efforts of the following individuals should be

acknowledged:

DRB Countries

Richard Stadler for Austrian contribution on the implementation of JAP

Jens Jedlitscka and Irena Burchardt for German contribution on the implementation of JAP

DABLAS II project team:

Diana Celac · Gheorghe Constantin · Alexander Hoebart · Viktor Karamushka · David

Kersch · Tarik Kuposovic · James Lenoci · Mojca Luksic · Zoran Marjanovic · Ladislav

Pavlovsky · Ildikó Pek · Mihaela Popovici · Elena Rajczykova · Stefan Speck · Ulrich

Schwarz · Marietta Stoimenova · Oana Tortolea · Kranic Uros · Alexander Zinke.

Technical Experts of the ICPDR Secretariat: Ursula Schmedtje and Igor Liska

This report was coordinated and edited by Mihaela Popovici.

G:\danube\DOCUMENTS of the ICPDR\IC 1-\IC 093 JAP - Interim Implementation Report\ORD-07 - Interim Implementation Report of JAP.doc

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1

INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................... 4

2

JOINT ACTION PROGRAM ................................................................................................. 6

2.1 Background ............................................................................................................................... 6

3

ASSESSMENT OF RESULTS................................................................................................. 9

3.1 Policy

Objectives....................................................................................................................... 9

3.2 Status of Legislation Dealing with Water Management ..................................................... 11

3.3 Main Barriers to Policy and Legal Reforms in implementing JAP ................................... 15

3.4 Proposed actions and measures in response to JAP............................................................ 18

3.5 Estimated cost for reforms concerning institutional and legal measures to

respond to JAP and new water related regulations............................................................. 18

4

TASKS OF THE JOINT ACTION PROGRAM.................................................................. 22

4.1 Reduction of Pollution from Point Sources.......................................................................... 23

4.1.1

Issues in need of special attention................................................................................ 23

4.1.2 Municipal

Discharges .................................................................................................. 26

4.1.3 Industrial

Discharges.................................................................................................... 35

4.1.4

Point Discharges from Agriculture .............................................................................. 39

4.2 Reduction of Pollution from Non-Point Sources ................................................................. 40

4.2.1

Inventory of Diffuse Sources of Nitrogen and Phosphorus and propose

further measures for their reduction ........................................................................................... 40

4.2.2

Set up an Inventory of the programmes of measures undertaken in the States

of the Danube River Basin.......................................................................................................... 43

4.2.3

Implementation of JAP national investment programs: land use sector ...................... 46

4.3 Wetland and floodplain restoration...................................................................................... 46

4.3.1

Addressing the nutrient retention................................................................................. 46

4.3.2

Implementation of JAP national Investments program: wetlands ............................... 50

4.4 Improving the scope of the TNMN, in order to get it in line with the EC

Water Frame Directive and to enable its timely operation ................................................ 50

4.4.1 Upgrading

TNMN........................................................................................................ 50

4.4.2

Joint Danube Survey .................................................................................................... 55

4.4.3 Introduction of quality control procedures: Analytical Quality Control

(AQC) in the DRB ...................................................................................................................... 55

4.4.4 Load

assessment

program ............................................................................................ 55

4.5 List of Priority Substances..................................................................................................... 56

4.6 Water Quality Standards....................................................................................................... 58

4.7 Prevention of accidental pollution events and maintenance of the accident

emergency warning system .................................................................................................... 60

4.7.1

Inventory of accident risk spots in the Danube River Basin........................................ 60

4.7.2

Operation and upgrade of the Danube Accident Emergency Warning System............ 61

4.7.3

Inventory of contaminated sites in flood-risk areas ..................................................... 62

4.8 Reduction of pollution from inland navigation.................................................................... 62

4.9 Product

controls...................................................................................................................... 64

4.10 Minimizing the impacts of floods .......................................................................................... 65

G:\danube\DOCUMENTS of the ICPDR\IC 1-\IC 093 JAP - Interim Implementation Report\ORD-07 - Interim Implementation Report of JAP.doc

2

4.11 Water Balance......................................................................................................................... 67

4.12 River Basin Management....................................................................................................... 68

4.12.1 Progress in developing the Danube River Basin Management Plan in line

with the WFD ............................................................................................................................. 69

4.12.2 Characterization of surface waters types and harmonized system for

reference conditions.................................................................................................................... 70

4.12.3 Identification of significant pressures .......................................................................... 71

4.12.4 Development of DRBD Overview map and preparation of thematic maps ................ 75

4.12.5 Development of public participation strategy.............................................................. 75

4.12.6 Development of economic indicators .......................................................................... 75

4.13 Reporting JAP......................................................................................................................... 76

5

INVESTMENTS, FINANCING AND POLLUTION REDUCTION ................................ 77

5.1 Overview of environmental projects in the DRB................................................................. 77

5.1.1

Overview of Results..................................................................................................... 77

5.1.2

Overview of Project Realisation by the end of 2003 ................................................... 80

5.1.3 Pollution

Reduction...................................................................................................... 81

5.1.4 Nutrient

Reduction....................................................................................................... 82

5.2 Financing ................................................................................................................................. 84

5.2.1 Project

Development.................................................................................................... 84

5.2.2

Funding Sources and Project Realisation..................................................................... 85

6

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................................ 88

7

COUNTRY REPORTS........................................................................................................... 90

7.1 Germany .................................................................................................................................. 93

7.2 Austria ..................................................................................................................................... 94

7.3 Czech

Republic ....................................................................................................................... 95

7.4 Slovakia.................................................................................................................................... 96

7.5 Hungary................................................................................................................................... 97

7.6 Slovenia.................................................................................................................................... 98

7.7 Croatia ..................................................................................................................................... 99

7.8 Bosnia-HerZegovina............................................................................................................. 100

7.9 Serbia and Montenegro........................................................................................................ 101

7.10 Bulgaria ................................................................................................................................. 102

7.11 Romania................................................................................................................................. 103

7.12 Moldova ................................................................................................................................. 104

7.13 Ukraine .................................................................................................................................. 105

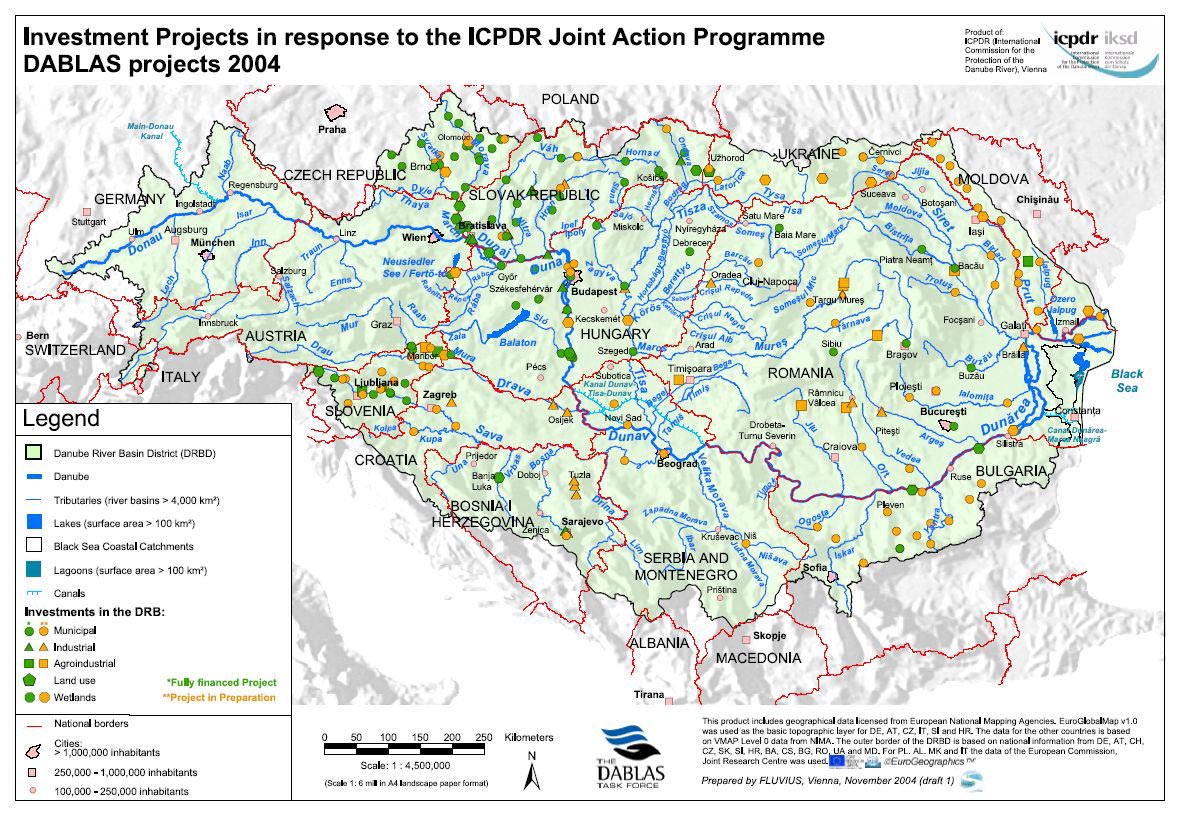

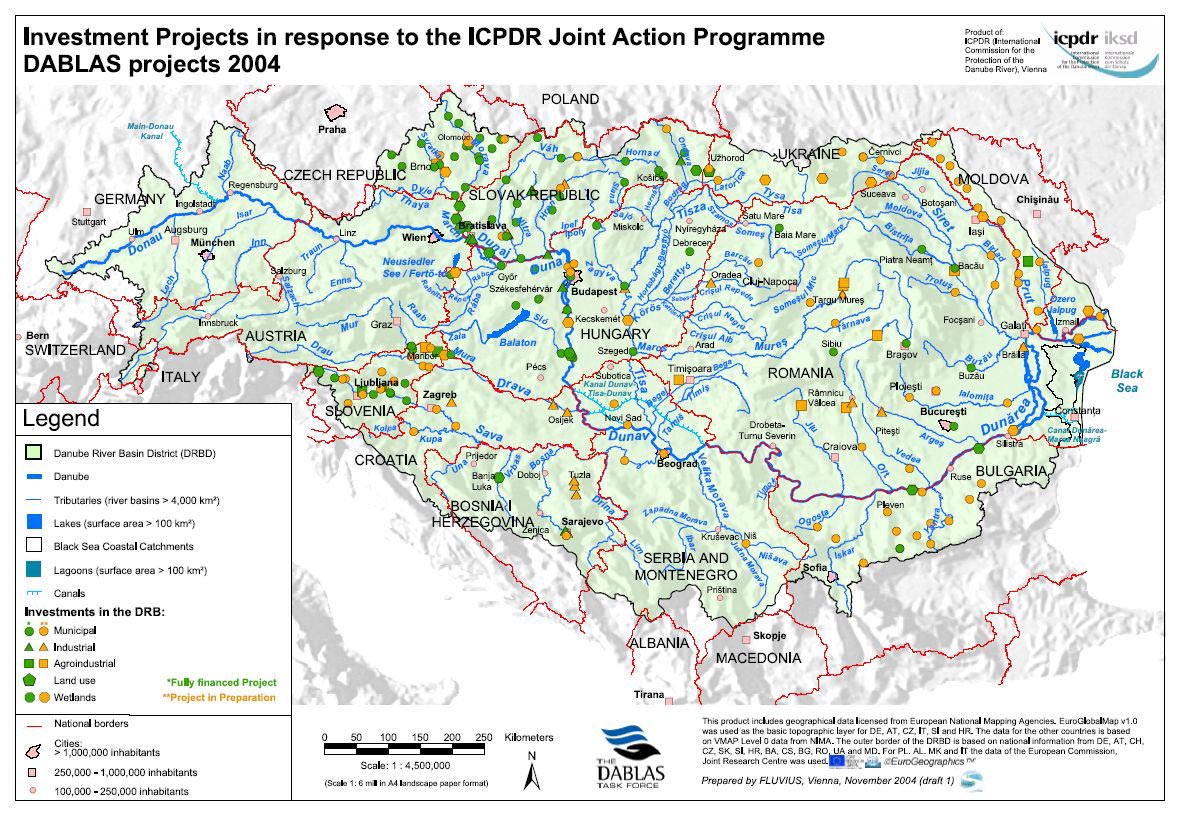

8

MAP ....................................................................................................................................... 106

9

DABLAS DATABASE FORM............................................................................................. 107

G:\danube\DOCUMENTS of the ICPDR\IC 1-\IC 093 JAP - Interim Implementation Report\ORD-07 - Interim Implementation Report of JAP.doc

3

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

EG Expert

Group

B&H Bosnia-Herzegovina

BOD5

Biochemical Oxygen Demand in 5 days

CNC

Czech National Council

COD

Chemical Oxygen Demand

CPC

Country Program Coordinator

DRPC

Danube River Protection Convention

DPRP

Danube Pollution Reduction Programme

DRB

Danube River Basin

DRBPRP

Danube River Basin Pollution Reduction Programme

WFD

Water Framework Directive

DWQM

Danube Water-Quality Model

EC European

Commission

EIA

Environmental Impact Assessment

EMIS/EG

Emission Expert Group

EPA Environmental

Protection

Agency

EU European

Union

GEF

Global Environment Facility

ICPDR

International Commission for the Protection of the Danube River

IPPC

Integrated Pollution Prevention and Control

ISPA

Instrument for Structural Policies for Pre-Accession

JAP

Joint Action Program of the ICPDR, 2001- 2005

MAFF

Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Food

ME

Ministry of the Environment

MESP

Ministry of Environment and Spatial Planning

MI

Ministry of the Interior

MOE

Ministry of Environment

MOEW

Ministry of Environment and Waters

N

Nitrogen (all forms)

N/A

Not Available (i.e. missing data)

NEAP

National Environmental Action Programme

NEPP

National Environmental Protection Program

P

Phosphorus (all forms)

PE

Population Equivalent = load of one person into waste water

PHARE

European Union Programme for Development

RBM

River Basin Management

SIA

Significant Impact Areas

UNDP

United Nations Development Programme

UWWTD

Urban Waste Water Treatment Directive

WWTP

Waste Water Treatment Plant

G:\danube\DOCUMENTS of the ICPDR\IC 1-\IC 093 JAP - Interim Implementation Report\ORD-07 - Interim Implementation Report of JAP.doc

4

1 INTRODUCTION

This Report addresses the status of implementation of the ICPDR Joint Action Programme (JAP), with

particular attention to the introduction of policy and legal reforms and implementation of investment projects

in the municipal, industrial and agricultural sectors for pollution control and nutrient reduction in the Danube

basin.

Thus, the report summarizes the achievements that have been realized through the work of the countries

under the JAP for the first period of reporting to JAP implementation - until 31 December 2003. This report

is also presenting estimates of projects under implementation, in pipeline, or in preparation, for the whole

period of JAP, reporting period until December 2005.

In assessing the implementation of JAP tasks, the report considers the transfer of EU water related directives

(Nitrates Directive, Urban Waste Water Directive, IPPC Directive, Water Framework Directive, etc) into

national policies, regulations, and compliance mechanisms. The estimated cost for reforms concerning

institutional and legal measures and direct investments that have been carried out to respond to JAP tasks, is

also diiscussed. If the national commitments do not yet include obligations towards EU directives, the

assessment of JAP implementation is based on the National Environmental Action Plan of the respective

country.

The implementation of investment projects, taking into account municipal, industrial and agro-industrial

projects, measures for wetland restoration, agricultural reforms and land use planning is analysed.

Thisincludes:

· project implemented in the past five years taking into account type of project (technical description),

investment cost, financing modalities and achieved results in terms of compliance with EU directives

and pollution reduction (BOD, COD, N and P)

· projects under implementation or in pipeline, which are well prepared and do not need any further

technical or financial support, taking into account same description as above, indicating expected results

· projects in preparation, which need further technical and financial support; these projects shall be

described as above, indicating the needs for technical and financial support for project preparation

and/or project implementation and the expected results (for municipal projects, the results of the before-

going "Development of an Operational Framework for the Prioritisation of Projects" will be taken into

account and updated).

The compiled information provide a clear picture of the results achieved by the individual Danube countries,

the policy and legal reforms under preparation, the gaps to be filled and the investment projects, which need

further technical and financial support. The results may also be used as a baseline for evaluating subsequent

progress at the national and regional levels.

The JAP 2001-2005 reflects the general strategy for the implementation of the DRPC for the respective

period. It deals i.a. with pollution from point and diffuse sources, wetland and floodplain restoration, priority

substances, water quality standards, prevention of accidental pollution, floods prevention and control and

river basin management. Important successes of Danube countries in implementing the JAP include: Trans-

national Monitoring Network (TNMN) operational with 79 sampling stations, Analytical Quality Control

(AQC) programme to ensure quality and comparability of data, Emissions Inventories updated for point and

diffuse sources of pollution, AEWS operational and upgraded, Action Plan for Sustainable Flood Protection

in the Danube River Basin developed, Accident prevention system in place, Habitat and species protection

areas defined and measures to restore and protect wetlands and floodplains under implementation.

The Report is based on the compilation of national contributions submitted by national experts, appointed by

the Heads of Delegations in the DRB countries. It includes a thorough revision and assessment of policy

objectives, priorities and strategies as well as water related legislation and practices in line with the ICPDR

JAP; the identification of main deficiencies and necessary steps to be taken regarding policy, legal and

regulatory reform, and finally the estimates on the cost for reforms concerning institutional and legal

measures and direct investments that have been carried out to respond to new water related regulations

linked with JAP tasks.

G:\danube\DOCUMENTS of the ICPDR\IC 1-\IC 093 JAP - Interim Implementation Report\ORD-07 - Interim Implementation Report of JAP.doc

5

The DABLAS database developed in 2002 was expanded to include projects from sectors other than

municipal. Data submission on the investments projects was made on the Internet and the database was

automatically updated; the further development of the database was intended to allow more flexible and

interactive updating and tracking.

The structure of the Country Report follows the structure of the national reports, which are structured as

follows:

(1)

Policy objectives

(2)

Status of legislation dealing with water management (in force, in progress, main deficiencies)

(3) Main barriers to policy and legal reforms to water-related policy and legal reform and JAP

implementation

(4)

Proposed actions and measures in relation to JP

(5) Estimated cost for reforms concerning institutional and legal measures to respond to JAP and new

water related regulations.

G:\danube\DOCUMENTS of the ICPDR\IC 1-\IC 093 JAP - Interim Implementation Report\ORD-07 - Interim Implementation Report of JAP.doc

6

2 JOINT

ACTION

PROGRAM

2.1 Background

Since 1992 the European Community (PHARE and TACIS programs) and the UNDP/GEF (Danube

Pollution Reduction Program-1997 to 1999) have supported the efforts of the Danube countries to develop

the necessary mechanisms for effective implementation of the DRPC. The Danube Environmental Program

Investments 1992 2000 has included 27 million USD from the EU Phare/Tacis, and 12.4 million USD were

provided by the UNDP/GEF.

This support has enabled the elaboration of a regional Strategic Action Plan (SAP) based on national

contributions and the development of a Transboundary Analysis Report (TAR) to define causes and effects

of transboundary pollution within the DRB and on the Black Sea.

The Strategic Action Plan provides guidance concerning policies and strategies in developing and supporting

the implementation measures for pollution reduction and sustainable management of water resources

enhancing the enforcement of the DRPC.

According to the Strategic Action Plan, the main problems in the Danube River Basin that affect water

quality use are: (i) high loads of nutrients and eutrophication, (ii) contamination with hazardous substances,

including oils, (iii) microbiological contamination, (iv) contamination with substances causing heterotrophic

growth and oxygen-depletion; and (v) competition for available water.

The SAP outlined regional policies and strategies for pollution reduction and environmental protection in

response to the Danube River Protection

The objectives and target of the SAP considered (i) the development of national policies, regulations and

actions, (ii) the development of coherent approaches to pollution reduction and transboundary cooperation,

(iii) reinforcing of coordination of interventions in relation to sub basin area, (iv) encouraging transboundary

cooperation for pollution reduction in Significant Impact Areas.

The Transboundary Analysis Report (TAR) provide a scientific analysis of the root causes of environmental

pollution in the DRB, identifying causes and effects of pollution with particular attention to transboundary

issues and nutrient transport to the Black Sea. TAR defined priorities for control and management strategies

at the regional and national levels. Based on the National Review Reports more than 500 hot spots, in three

sectors (municipal, industrial and agricultural) have been identified and ranked.

In the frame of the Danube Pollution Reduction Program 1999 (DPRP), based on the results of the

Transboundary Analysis, an investment portfolio has been developed with particular attention to nutrient

reduction. All the measures, projects and programs proposed to reduce emissions from both point and non-

point sources of pollution will improve water quality, considering a reduction of 50 % in Chemical Oxygen

Demand (COD) emissions and 70 % in Biological Oxygen Demand (BOD) emissions and other toxic

elements, and thus reduce transboundary effects within the Danube River Basin. Once implemented, these

measures would further substantially contribute to reducing nutrient transport (Phosphorus by 27 % and

Nitrogen by 14 %) to the Black Sea to further improve, over time, environmental status indicators of Black

Sea ecosystems of the western shelf. A total of 421 projects for 5.66 billion USD, primarily addressing hot

spots have been identified for municipal, industrial and agricultural projects.

Responding to the DRPC requirements, and based on the DPRP results, the ICPDR developed a first Joint

Action Programme (JAP) for the years 2001 - 2005, which was adopted at the ICPDR Plenary Session in

November 2000. The ICPDR Joint Action Programme 2001-2005 reflects the general strategy for the

implementation of the DRPC for the respective period. The general objectives of the ICPDR Joint Action

Program 2001-2005 are harmonized with the three main objectives of the Contracting Parties, laid down in

Article 2 of the DRPC:

· shall strive at achieving the goals of a sustainable and equitable water management, ...

· shall make all efforts to control the hazards originating from accidents ...and

G:\danube\DOCUMENTS of the ICPDR\IC 1-\IC 093 JAP - Interim Implementation Report\ORD-07 - Interim Implementation Report of JAP.doc

7

· shall endeavour to contribute to reducing the pollution loads of the Black Sea from sources in the

catchment area".

The JAP deals i.a. with pollution from point and non-point sources, wetland and floodplain restoration,

reduction and control of priority substances, water quality standards, prevention of accidental pollution,

floods prevention and control and river basin management. Particular attention is given to both

structural/investment and non structural/policy reforms measures that address nutrient reduction and

protection of transboundary waters and ecosystems:

· Coordinating and developing the River Basin Management Plan for the Danube River Basin in

implementing the EU Water Framework Directive;

· Maintaining and updating emission inventories and implementing proposed measures for pollution

reduction from point sources and non point sources;

· Restoring wetlands and floodplains to improve flood control, to increase nutrient absorption

capacities and to rehabilitate habitats and biodiversity;

· Operating and further developing the Transnational Monitoring Network (TNMN) to assess the

ecological and chemical quality status of rivers, including establishing respective water quality

standards;

· Developing and introducing recommendations on BAT and BEP to assure prevention and/or

reduction of hazardous and dangerous substances;

· Operating and upgrading the Accidental Emergency Warning System (AEWS), considering its use

also for flood warnings, establishing classified inventories of accidental risk spots and developing

preventive measures.

The Joint Action Program 2001 2005 is directed to

· the improvement of the water ecological and chemical status,

· the prevention of accidental pollution events and

· the minimization of the impacts of floods.

The implementation of the Joint Action Program will - in addition to the main objectives

· improve the standard of life,

· enhance economic development,

· contribute to the accession process to the European Union,

· restore the biodiversity, and

· strengthen the cooperation amongst the Contracting Parties.

In the frame of the ICPDR Joint Action Programme, 243 committed investment projects and strategic meas-

ures have been identified out of which 156 are in the municipal sector and only 44 in the industrial sector.

This reflects the situation in most transition countries where industries are not operational or using mostly

outdated technologies. Most of these projects, listed generally as "hot spots" or point sources of emission, are

representing national priorities and taking equally into account the obligation to mitigate transboundary ef-

fects. Particular attention was also given to the identification of sites for wetland restoration, which play an

important role not only as natural habitats but also for flood protection and as nutrient sinks.

The total investment foreseen in the JAP period 2001-2005 to respond to priority needs is estimated to be

about 4.404 billion , with 245 priority point source projects mainly being:

· Municipal waste water collection and treatment plants: 3.702 billion

· Industrial waste water treatment: 0.267 billion

· Agricultural projects and land use: 0.113 billion

· Rehabilitation of wetlands: 0.323 billion

G:\danube\DOCUMENTS of the ICPDR\IC 1-\IC 093 JAP - Interim Implementation Report\ORD-07 - Interim Implementation Report of JAP.doc

8

From the total amount of investment of 4.4 billion for point sources reduction, 3.54 billion are earmarked

as national contributions.

The structure of the identified investment requirements by sector is as follows:

Table 1. Investments per sectors, 2001-2005.

Municipal

Industrial

Agricultural

Wetlands

Total

No of Projects 157

44

21

23

245

MEUR

3,702

267

113

323

4,404

(%)-Structure

84% 6% 3% 7% 100

Table 2. Projects and investments per country in the DRB

DE AT CZ

SK

HU SI

HR BA

CS

BG RO MD UA TOT

No of

11 4 12 20 24 24 11 12 40 21 25 31 10 245

Proj.

MEUR

231 264 147

118 687 384

433 176 785 125 493 493 67

4,404

(%) 5 6 3 3 16 9 10

4 18 3 11 11 1 100

The ICPDR is asked to report on the implementation of the Joint Action Program for the period 2001 to 2003

in 2004, and for the period 2001 to 2005 in 2006.

G:\danube\DOCUMENTS of the ICPDR\IC 1-\IC 093 JAP - Interim Implementation Report\ORD-07 - Interim Implementation Report of JAP.doc

9

3 ASSESSMENT OF RESULTS

3.1

Policy Objectives

Danube countries face substantial challenges in establishing and strengthening the policy and institutional

framework required for functioning market-based and democratic societies. Today, progress can be reported

with all Danube countries in redesigning policies, programs and regulations, in establishing appropriate

incentive structures, redefining partnerships with stakeholders, and strengthening financial sustainability of

environmental services. Following a challenging and demanding period of transition, all DRB countries have

in the last years developed a comprehensive hierarchic system of short, medium and long-term

environmental policy objectives, strategies and principles which reflect the political context of each country,

key country-specific environmental problems and the sector priorities on national and regional levels.

Still the key challenge Danube countries face in the policy field is to identify the most effective ways of

transposing EU environmental directives. Country's choice on how to achieve compliance with EU

directives will have a significant influence on compliance costs.

In all DRB countries the legal framework for environmental management of water resources and ecosystems

consists of a hierarchic system of decrees, laws, directives, ordinances, regulations and standards on different

administrative levels. In addition to the WFD, there has been a high level of transposition of the EU

Directives into the national legislations of the DB countries. The Urban Wastewater Treatment and IPPC

Directives are considered as the most challenging areas for compliance. This is reflected in the negotiated

derogation periods and agreed long transition periods.

All DRB countries currently have a more or less comprehensive system of environmental and water sector-

related policies and strategies, which usually reflects:

· the capability of the country to contribute to the solution of transboundary problems;

· the significance and evidence of country-specific environmental problems;

· the significance and evidence of environment-related health hazards;

· the economic development and potential of the country.

Despite the diversity of problems, interests and priorities across the basin, the Danube countries share certain

values and principles relating to the environment and the conservation of natural resources.

The key principles for water management and water pollution that have formed the basis for the revision of

legal and institutional arrangements adopted by Danube countries include:

· Consider water as a finite and vulnerable resource, a social and economic good

· Use of the integrated river basin management approach

· Implement precautionary principle

· Introduction and use of BAT, BAP and BEP

· Control of pollution at the source and creation of cleaner production centres

· Apply polluter pays principle and the beneficiary pays principle

· Implement principle of shared responsibilities, respectively the principle of subsidiarity

· Use market based instruments

· Implement good international practices in managing environmental expenditures

· Strengthen international partnership and transboundary cooperation

G:\danube\DOCUMENTS of the ICPDR\IC 1-\IC 093 JAP - Interim Implementation Report\ORD-07 - Interim Implementation Report of JAP.doc

10

Long-term objectives of water policies in the DRB countries mainly focus on:

· Preservation of a sound environment for the future generations;

· Protection of biological diversity;

· Protection of drinking water resources.

The status of water-related policy and programmes in the DRB countries can be assessed in general terms as

follows:

Table 3. Status of water-related policy, programmes and National Environmental Action Plans in the

DRB countries

Country Explicitly formulated policy

Programmes especially dealing

Programmes especially

objectives for water management

with water management and

dealing with WFD

and pollution control

pollution control

implementation

DE

Appropriate system of policy objectives

Action Programs

Strategy for WFD

completely in line with the requirements

Environmental Statute Book

implementation

of the relevant EU Directives

AT

Appropriate system of policy objectives

Action Programme to control diffuse

Strategy for WFD

completely in line with the requirements

pollution

implementation

of the relevant EU Directives

Austrian Programme of

Austrian Water Protection Policy

Environmental Friendly Agriculture

Water Right Act

CZ

Appropriate system of policy objectives

Program for adequate implementation The State Environmental

of municipal WWTPs

Policy 2004 2010

Resolution 339, 2004

SK

Satisfactory system of policy objectives in National Environmental Action

Strategy for WFD

the Strategy for National Environmental

Program Codex of Good Agricultural implementation

Action Program, 1993; National Strategy Practices

Inter sectoral Strategic

for Sustainable Development, 2000 and

State Water Protection Plan

Group

Water Management policy

Action Plan for the protection of

Coordinating office

biological and landscape diversity

Working Groups

HU

Appropriate system of policy objectives

National Environmental Program

Strategy for WFD

National waste water collection and

implementation

treatment programs

National agro-environmental

protection program

Other programmes (lake, oxbow lake,

low land, etc.)

SI

Satisfactory system of policy objectives

National Environmental Action Plan,

Strategy for WFD

1999

implementation

New Environmental Action Plan in

preparation

Operative program for wastewater

collection and treatment

HR

Satisfactory system of policy objectives in State Water Protection Plan

Strategy for WFD

the current legislation:

Strategy and Action Plan

implementation

National Strategy for Environmental

Protection, 2002

State Water Protection Plan, 1999

Environmental protection Plan

Nature Protection Act, 1999

Water Act, 1995

BA

Limited number of policy objectives

EU CARDS Program

New Water Law in line

USAID, WB, GEF programmes

with WFD, expected 2005

National Environmental Action Plan,

2003

G:\danube\DOCUMENTS of the ICPDR\IC 1-\IC 093 JAP - Interim Implementation Report\ORD-07 - Interim Implementation Report of JAP.doc

11

Country Explicitly formulated policy

Programmes especially dealing

Programmes especially

objectives for water management

with water management and

dealing with WFD

and pollution control

pollution control

implementation

CS

Insufficient system of policy objectives

No explicit programmes

Harmonisation with EU

and focussed programs

legislation

BG

Satisfactory system of policy objectives

Environmental Strategy to implement Strategy for WFD

ISPA objectives

implementation

Program for UWWT Directive

implementation National Strategy for

Management and development of the

water sector until 2015 Programme for

construction of municipal WWTPs

RO

Satisfactory system of policy objectives

National Environmental Action Plan

Strategy for WFD

Strategy for environmental protection implementation

Strategy for water resources

management

Series of nutrient-related programmes

to be carried out during the

forthcoming period

Action program for reduction of

pollution due to dangerous substances

MD

Reduced policy objectives.

National Water resources management Strategy for WFD

National Strategy for sustainable

Strategy, 2003

implementation

development, 2000

Water Supply and Sewage program,

Concept of the Environmental Policy,

2002

2001

National Action Plan on Health and

Environment, 1995

UA

Under the revision system of policy

Program of the Development of Water Water Code of Ukraine

objectives within the frame of the update Economy

harmonized with EU

version of the Sustainable Development

Governmental Action Plan

Directives (expecting

Strategy

approval)

3.2

Status of Legislation Dealing with Water Management

Countries in the DRB have increasingly recognized that developing and implementing regulation (at the

national, regional and local level) is a precondition for effectively responding to a range of key challenges.

Further assistance and efforts are still needed to building institutional capacity at central and local

government level to address the broad challenges of legal reforms.

The water legislation was amended, or is under revision, according to the EU Directives in most of the

countries. The water sector-related policies and strategies reflect:

· country's commitment to respond to EU requirements and international agreements obligations

· the need to incorporate general principles for sustainable development, environmental, economic and

social concerns into the national development strategies

· capability of the country to contribute to the solution of transboundary problems

· the significance and evidence of country-specific environmental problems.

A fundamental objective of regulatory reforms in the Danube countries is to foster high quality regulation

that will improve the efficiency of national economies and environmental actions, and will eliminate the

substantial compliance costs generated by low quality regulations. By helping countries to revise their legal

and institutional arrangement, the ICPDR has contributed to long-term economic prosperity and increased

opportunities for investments to reduce pollution and protect natural resources.

The following section summarizes the policy and legislation achievements in the countries.

G:\danube\DOCUMENTS of the ICPDR\IC 1-\IC 093 JAP - Interim Implementation Report\ORD-07 - Interim Implementation Report of JAP.doc

12

In general terms, the 13 DRB countries can be categorized and characterized as follows: Germany and

Austria have substantially reformed their regulatory regimes to assure the functioning of their democracies

and market-based economies, with all legislation in compliance with the "highest environmental standards".

Significant efforts are also required for EU member states for reaching an acceptable level of

implementation.

The German water management and protection policy is in compliance with EU water policy, aiming at

achieving of good water status for all waters by 2015. With the elimination of biological and chemical

pollutions from municipal and industrial sources the most important conditions for further continuous

improvements of the water ecology are already met. The responsibilities for preparation and implementation

of the Flood Action Plans belong to the Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and

Nuclear Safety, Bavarian State Ministry of the Environment, Public Health and Consumer Protection, and

the Ministry of the Environment and Traffic Baden-Württemberg.

The core of water legislation in Austria is the Water Right Act, which was revised in 2003 to accommodate

the EU Directives principles. Austria is currently engaged in developing an Ordinance defining water quality

objectives for rivers as well as for lakes and an Ordinance for the management of the Austrian Water Data

Register. Primary goal of water policy is to ensure sustainable water management through a prudent human

interference into waters. Main principles are: (i) minimizing impacts on water quantity and quality via a

stringent system of permits and control, (ii) protection of population and its living pace and goods against

floods, and (iii) public awareness on the value of water and for it rational use. The WFD implementation is

regarded as an important supporting tool to achieve the primary goal of water policy in Austria. In response

to the disastrous floods 2002 activities for the protection against floods are intensified taking into account

developments on the international level. Federal Ministry of Agriculture & Forestry Environment and Water

Management is the competent authorities responsible for preparation and implementation of the Flood

Action Plans.

The experience of the new Member States having joined EU in May 2004 is an important information for

other Danube countries.

In March 2004, the Czech Ministry of Environment prepared the updated State Environmental Policy for

2004 2010. Considerable attention is paid to wetland ecosystems, to rehabilitation of aquatic biotopes, to

effective and sustainable protection of surface and ground water bodies, to harmful contaminants, to

integrated water protection and management. Through river basin management plans, measures to protect

wetlands and floodplains shall be implemented. The use of wetlands and water resources should be

sustainable in view of economic pressures and global changes, and this includes principles referring to

landscape and environmentally sound agricultural practice, wetland and floodplain uniqueness, restoration,

remediation and rehabilitation of damaged wetlands areas. Both the Ministry of Environment and Ministry of

Agriculture are the competent authorities responsible for preparation and implementation of the Flood Action

Plans.

Slovenia has developed appropriate legislative tools that outline the objectives and strategies for

environmental regulation and water management. The lately approved Environmental Protection Act (May

2004) primarily focuses on pollution from point sources and is consistent with EU environmental

requirements. The 1999 National Environmental Action Programme (NEAP) established a more balanced

relationship between the environment and economic sectors and introduced a system of economic incentives

to encourage manufacturers and consumers to use resources in a more "environmentally successful" manner.

The Water Act considers the whole water policy such as protection of water, water use, management of

water and protection of water depending ecosystems. The Ministry of Environment Spatial Planning and

Energy is the competent authorities responsible for preparation and implementation of the Flood Action

Plans.

The National Environmental Programme of Hungary includes substantial provisions and measures for the

conservation and management of surface and groundwater resources. Some of the key targets and approved

policy directions are: regulation development to encourage sustainable and economical water use;

improvement of water quality for the main water bodies (Danube and Tisza Rivers, Lake Balaton); gradual

increase (to a level of 65%) of the number of settlements with sewers; at least biological treatment of

wastewater from sewers; nitrate and phosphorous load reductions for highly protected and sensitive waters.

By 2003 the Hungarian legislation on water quality protection was fully harmonized with the EU regulations,

including the appropriate institutional set-up. The Ministry of Environment and Water and the National

G:\danube\DOCUMENTS of the ICPDR\IC 1-\IC 093 JAP - Interim Implementation Report\ORD-07 - Interim Implementation Report of JAP.doc

13

Directorate for Environment, Nature and Water are the competent authorities responsible for preparation and

implementation of the Flood Action Plans.

The implementation of the Slovak water management and protection policy is in compliance with EU water

policy, i.e the WFD, aiming at achieving of good water status for all waters by 2015. The legislative tools for

achieving policy objectives have been prepared. All EC directives have been transposed into the national law

system. The transposition was finished in 2004 through an updated version of the Water Act (no. 364/2004).

Main priority in relevant sectors (urban wastewater, industrial wastewater, land use, wetlands) is the

implementation of EC directives' requirements (urban and industrial wastewater during the transition

periods), namely reduction of nutrients and priority substances and creation of effective water management

that will be able to promote sustainable water use based on long - term protection of available resources.

The Ministry of Environment is the competent authority responsible for preparation and implementation of

the Flood Action Plans.

The need to implement a unified policy on the environment and the use of natural resources, which integrates

environmental requirements into the process of national economic reform, along with the political desire for

European integration, has resulted in the review of the existing environmental legislation in Moldova. The

current priorities for water management include the strengthening of institutional and management capability

through improvement of economic mechanisms for environmental protection and the use of natural

resources, setting internal environmental performance targets and controls, self-monitoring, review of current

legislation in line with European Union legislation, and the adjustment or elaboration on a case-by-case basis

of implementation mechanisms. The Ministry of Ecology and Natural Resources is the competent authority

responsible for preparation and implementation of the Flood Action Plans.

Bosnia and Herzegovina is faced with major challenges in the environmental and water management area.

Among specific objectives for environment is the development of an environmental framework in Bosnia

and Herzegovina based on the Acquis. The most important issues in the environment sector will be identified

in the Environmental Action Plan, which is being developed with World Bank support. The EU is supporting

a Water Institutional Strengthening Programme, which is complemented by two Memoranda of

Understanding (2000, 2004) between both Entities and the EC. The responsibility for preparation and

implementation of the Flood Action Plans is with Federal Ministry of Agriculture, Water Management and

Forestry Environment and the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry Environment and Water Management. The

proposed schedule for approximation with EU indicates a new Water Law and a Law on Environment,

compatible with the Acquis, to enter into force by January 2005.

Since the WFD was adopted, numerous and diverse activities were initiated in Serbia & Montenegro to

further implement the Directive. The water management is faced with serious tasks that require, above all: (i)

the creation of a system of stable financing for water management, (ii) the reorganization of water

management sector, and (iii) the revision of water legislation and related regulations, in compliance with

requirements of European legislation. In the Republic of Serbia, the responsibility for preparation and

implementation of the Flood Action Plans is with the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Water

Management and the Directorate for Water.

The remaining accession countries Romania, Bulgaria, Croatia as well as those non-accession countries are

experiencing the historic opportunity of European integration, which is the most important driver of reforms

but brings great challenges at the same time:

The adoption in 1999 of the Strategy for the Integrated Water Management marked the beginning of the

reforms in the water sector in Bulgaria in line with the WFD and assumed obligations under international

instruments. Several other programs such as Environmental Strategy to implement the ISPA objectives, the

Program for the UWWT Directive implementation or the National Strategy for Management and

Development of the Water Sector until 2015 complete the picture of on going efforts in Bulgaria towards

complying with EU legislation. The Ministry of Environment and Water is responsible for preparation and

implementation of the Flood Action Plans.

In Croatia, the current basic environmental and water legislation and regulations (such as the Water Act,

Water Management Financing Act, State Water Protection Plan) will be revised to meet the EU directives

requirements within the frame of two CARDS projects expected to start at the end of 2004. The Ministry of

Agriculture, Forestry and Water Management, Water Management Directorate is responsible for preparation

and implementation of the Flood Action Plans.

G:\danube\DOCUMENTS of the ICPDR\IC 1-\IC 093 JAP - Interim Implementation Report\ORD-07 - Interim Implementation Report of JAP.doc

14

Romania just closed Chapter 22 on harmonization of environmental legislation with EU requirements. Basic

water legislation (Water Law) and implementing regulations, standards and ordinances regulations have

already been fully harmonized with the EU directives. The Ministry of Environment and Water Management

is responsible for preparation and implementation of the Flood Action Plans.

Ukraine has not yet updated the environmental policy act (the Principal Direction, 1998). The update

version of the Sustainable Development Strategy, however, has been recently submitted for approval by the

Parliament. The Program of the Development of Water Economy is in force but still specific legislation on

water management is missing. The current Governmental Action Plan is a comprehensive document, which

integrates economic, social and environmental concerns. Efforts are currently undertaken to finalize in 2005

the revision of the Protocol on the Protection of the Black Sea Marine Environment against Pollution from

Land-Based Sources, in line with WFD principles. The Water Code of Ukraine harmonized with EU

Directives is submitted as well for approval. The Ministry for Environmental protection of Ukraine and the

Ukrainian State Committee of Water Management are responsible for preparation and implementation of the

Flood Action Plans.

The status of water-related legislation in the DRB countries is presented in the Table 4.

Table 4. Status of water related legislation in the DRB countries` and proposed measure

Country

Main existing legal provisions for water Proposed measures regarding water management

management and pollution control

and pollution control

DE

Fully appropriate legislation

Implementation and ordinances for enforcement

The Water Resources Policy Act, Fertilizer Act,

Fertilizer Ordinance, etc.

AT

Fully appropriate legislation

Implementation and ordinances for enforcement

Water act, and Acts on the adoption of EU

Directives UUWT, IPPC, etc.

CZ

Complete set of legislation, such as:

Remaining Directives to be implemented

State Environmental Policy, 2004

Enforcement of legislation

Act on Environmental Protection, 1992

Ownership transfer in agricultural sector

Water Act, 2002

Clarification of competencies among all parties

Act on Agriculture, etc.

SK

Appropriate legislation fully harmonized with EU Implementation of updated legislation

Water Act, 2004-

Finalize harmonization of legislation under the

Natura Protection Act, 2003

competencies of local authorities

Environmental Protection Act, 1999

Increase share of population connected to sewage

GD No 491/2002 Coll.

and wastewater treatment plants

MO 249/2003

Increase water quality for drinking water

Act No on IPPC No 245/2003 Coll.

Implement Program of measures against flooding

HU

Appropriate legislation fully harmonized with EU Improve the institutional structures and clarify

directives

responsibilities

Act LIII of 1995 on the General Rules of the Implement the adopted legislation

Protection of the Environment

Ministerial decree on the observation and

Act LVII of 1995 on Water Management

monitoring of ground waters

Nature Protection Act

Ministerial decree on the observation and

Government Decree No. 221/2004. (VII. 21.) on monitoring of surface waters

certain rules of river basin management

Government Decree No. 220/2004. (VII. 21.) on

the rules of the protection of the quality of surface

waters

Government Decree No. 219/2004. (VII. 21.) on

the protection of groundwater

SI

Environmental Law, 2004; Water Act, 2002; Regulations for enforcement and compliance

Nature Conservation Act, 2002; IPPC; UWWT

HR

Law on Environmental protection, 1999;

Compliance and enforcement plans

Nature Protection Act; Water Act; Water Water quality standards by water classes;

Management Financing Act

Standards on hazardous substances;

G:\danube\DOCUMENTS of the ICPDR\IC 1-\IC 093 JAP - Interim Implementation Report\ORD-07 - Interim Implementation Report of JAP.doc

15

Country

Main existing legal provisions for water Proposed measures regarding water management

management and pollution control

and pollution control

Effluent standards: maximum allowed concentration

of hazardous substances

BA

Explicit legal provisions in the Water Laws (RS, New Water Law, expected 2005

2002 and F BiH, 2003)

New Environmental Law, expected 2005

CS

Legislation not fully satisfactory.

Harmonization with EU water and environmental

Law on water and Law on water management legislation

financing under preparation

Involvement in transboundary cooperation within

Law on Environmental Protection, 1991 (Serbia) the frame of international conventions

and 1996 (Montenegrin)

BG

Explicit policy objectives and appropriate Implementation rules for complying with EU

legislation in place

legislation

Environmental protection Act

Water Law, amended 2003

RO

Explicit policy objectives and appropriate Implementation rules for complying with EU

legislation in place

legislation

Environmental Protection Law

Ministerial Order concerning the National Water

Water Law

Monitoring System

Environmental protection strategy

Governmental Decision concerning the type and size

Law 645/2002 on IPPC

of the sanitary protected areas

Law 462/2001 on regime of natural protected areas Ministerial Order concerning the public participation

and conservation of habitats

in the water management decision making

Drinking Water Law 458/2002

Law 5/1991 wetlands and floodplain restoration

MD

Law on Biological Security

Revision of system of standards, including water

Law on Environmental Protection

quality standards, emission standards, and effluent

Law on payment for environmental pollution

standards

Water Code

Strengthening capacity building

Ecological Funds

Restructuring institutional arrangements

UA

The specific legislation on water management is Water Code, harmonized with EU Directives

under revision

expecting approval

The Law on the State Program of Protection and

Rehabilitation of the Environment of the Black and

Azov Seas

The Law on the State Program of the Development

of Water Industry

The Law on Fish, other Alive Water Resources

and Food Products from Them

The Law on Drinking Water and Drinking Water

Supply

3.3

Main Barriers to Policy and Legal Reforms in implementing JAP

Regulatory challenges facing Danube Countries are significant. Progress is slow in some countries but the

governments are gradually adopting modern regulatory and policies instruments to improve the quality of the

regulatory environment and management practices to send a clear signal to the foreign and national financing

institutions on their needs for investments.

Enforcement and compliance are considered as the main barriers to the effective implementation of the

ICPDR JAP. The difference between high regulatory standards and compliance capacity of the regulated

bodies, without having designed flexible compliance schedules prevent authorities from effectively enforcing

their regulatory instruments. Lack of a unifying concept on policies instruments choice and implementation

G:\danube\DOCUMENTS of the ICPDR\IC 1-\IC 093 JAP - Interim Implementation Report\ORD-07 - Interim Implementation Report of JAP.doc

16

across various levels of government still exist in some countries (e.g Moldova, Ukraine, Serbia &

Montenegro) where decentralization and democratisation of structures has not yet taken place. In some

countries, problems with decentralization are associated with absence of subsidiarity principle approach

(clarifying of competencies by all authorities in government, in regions, districts and municipalities).

Additionally, costs for fulfilment of EU directives requirements will increase of water services prices.

Implementation of Directive 76/464/EEC requires education of state water administration concerning new

permits for discharging of wastewaters. Sometimes, weak enforcement is associated with ineffective

penalties system or with inconsistencies between the current structure/content of the laws, and the conflicts

and overlapped provisions in various other laws.

Other barriers impeding the implementation are linked to the insufficient capacity building, lack of access to

water and environmental relevant information, absence of public participation mechanisms in the

environmental decision-making process. High investment needs, sometimes more demanding national

legislation than that at the EU, administrative burdens, and insufficient co-operation between governmental

institutions can complete the barriers picture.

Based on the information provided by the national contributions, the main barriers to policy and legal reform

can be categorized as outlined below.

The assessment for the particular DRB countries (*** = "high relevance"; * = "low relevance) has to be

considered as provisional and should in the first place serve for a formalized identification of country-

specific areas for improvement.

(1) Historical

issues

· Outdated legal and administrative structures

· Inappropriate business structures / methods

· Inappropriate industrial and agricultural structures and practices

· Unsolved ownership situation - public and private sectors

· Insufficient awareness of population (wastage of water, etc)

Provisional assessment of the relevance of historical issues for the particular DRB country:

AT

BA

BG

HR

CZ

DE

HU

MD

RO

CS

SK

SI

UA

***

*

**

*

*

*

***

*

*

***

(2) Economic

issues

· Deteriorated economic capacities

· Decreased industrial and agricultural production

· Decreased livestock farming

· Inadequate status of privatisation

· Inappropriate public infrastructure (waste water collection systems, WWTP)

Provisional assessment of the relevance of economic issues in the particular DRB country:

AT

BA

BG

HR

CZ

DE

HU

MD

RO

CS

SK

SI

UA

AT

***

**

**

*

***

**

***

*

*

***

(3) Financial

issues

· Lack of domestic public funds for environmental issues

· Lack of international funds at favourable terms

· Lack of adequate funding mechanisms

· Lack of adequate funding tools (incentives, charges)

G:\danube\DOCUMENTS of the ICPDR\IC 1-\IC 093 JAP - Interim Implementation Report\ORD-07 - Interim Implementation Report of JAP.doc

17

Provisional assessment of the relevance of financial issues in the particular DRB country:

AT

BA

BG

HR

CZ

DE

HU

MD

RO

CS

SK

SI

UA

AT

***

*

**

*

***

*

***

*

***

(4)

Institutional / administrative issues

· Inadequate personnel capability and qualification

· Inadequate technical equipment

· Inadequate structure of administration

· Inadequate allocation of responsibilities (gaps, overlaps, not defined)

· Lack of adequate vertical and horizontal coordination

· Lack of adequate cooperation within public administration

· Lack of adequate cooperation between public administration and private sector

· Lack of adequate tools for enforcement of legislation

· Lack of private sector participation (investment, management)

Provisional assessment of the relevance of institutional issues in the particular DRB country:

AT

BA

BG

HR

CZ

DE

HU

MD

RO

CS

SK

SI

UA

***

*

**

*

***

*

***

*

***

(5) Participatory

issues

· Lack of public awareness (regarding environmental issues)

· Lack of adequate awareness of decision makers (regarding environmental issues)

· Lack of public interest in solving environmental deficiencies / problems

· Lack of organizational capability (inadequate representation of NGOs)

· Lack of private sector participation (investment, management)

Provisional assessment of the relevance of participatory issues in the particular DRB country:

AT

BA

BG

HR

CZ

DE

HU

MD

RO

CS

SK

SI

UA

**

**

**

*

***

**

***

*

***

(6)

Natural / environmental issues

· Degradation of ecosystem

· Loss of adequate biodiversity

· Inadequately high concentration of nutrients in agricultural areas

· Uncontrolled flood risk

· Inadequate utilization of water resources

· Uncontrolled discharge of waste water (in the past / ongoing)

· Insufficient monitoring capacities

· Inadequate agricultural practices (in the past / ongoing)

· Inadequate utilization of fertilizers, pesticides, etc. (in the past / ongoing)

G:\danube\DOCUMENTS of the ICPDR\IC 1-\IC 093 JAP - Interim Implementation Report\ORD-07 - Interim Implementation Report of JAP.doc

18

Provisional assessment of the relevance of natural issues in the particular DRB country:

AT

BA

BG

HR

CZ

DE

HU

MD

RO

CS

SK

SI

UA

*

***

**

**

*

*

*

***

**

***

*

*

***

3.4

Proposed actions and measures in response to JAP

In a number of countries, numerous laws and regulations were adopted a long time ago, have been frequently

amended during the previous years of transition and need a fundamental revision. In others, the relevant

legislation is currently in the phase of substantial reform and modernization. Due to the complexity of this

task it can be anticipated that the completion of the ongoing reform process will take several years before the

relevant legislation has reached an acceptable level of compliance with international requirements.

Still, in some non-accession countries, the current environmental and water-related legislation cannot be

considered as adequate regarding sound and sustainable environmental management of water resources and

ecosystems. The current essential deficits and problems can be summarized as follows:

· the environmental and water-related legislation is still based to a certain extent on historical

structures, with the consequence that the various changes, adjustments and modifications have

led to critical inconsistencies;

· the practical applicability and effectiveness of the recent established new environmental and

water - related legislation is not yet been proven is some countries;

· the impossibility to enforce the relatively sophisticated systems of environmental and water-

related legislation, due to critical social and economic issues in some countries.

In response to these common deficiencies, the needs for improvement regarding the water sector-related

legislation in the DRB countries can be summarized as follows:

· restructuring and adjustment of relevant legislation to the requirements of modern

environment-oriented market economy;

· streamlining, simplification and elimination of inconsistent components, basically resulting

from ad-hoc changes during the previous transition period;

· ensuring utmost compatibility of interacting legislation on the various administrative levels;

· specification of efficient implementing regulations and enforcement mechanisms; elimination

of all kinds of unjustified exemptions;

· further harmonization of national legislation with EU regulations and standards.

The need for improvement of water-related legislation in the particular DRB countries is assessed in Table 4.

3.5

Estimated cost for reforms concerning institutional and legal measures to

respond to JAP and new water related regulations.

All DRB countries consider the harmonization of national environment and water-related legislation with the

EU legislation as the most essential prerequisite for long-term sustainable water management in their

countries.

The 4 recent new Danube member states have fully transposed their regulatory frameworks in line with EU

environmental requirements, but realising actual compliance will require significant time and financial

resources. Among the Danube River Basin countries, the total environmental costs range from 2,723 MEUR

for Slovenia to 10,000 MEUR for Hungary and the Czech Republic. The second tier of accession countries,

Bulgaria and Romania, require even more to achieve compliance: 11,000 MEUR and 17,000 MEUR,

respectively.

G:\danube\DOCUMENTS of the ICPDR\IC 1-\IC 093 JAP - Interim Implementation Report\ORD-07 - Interim Implementation Report of JAP.doc

19

Table 5. Estimated total environmental costs to meet EU standards

Country

Population

Total environmental costs to meet EU standards (MEUR)

Bulgaria

8.2 million

11,000

Czech Republic

10.4 million

10,000

Hungary

10 million

10,000

Romania

22.4 million

17,700

Slovakia

5.4 million

4,005

Slovenia

1.99 million

2,723

The Urban Wastewater Treatment Directive is expected to be the most expensive water quality requirement

to implement, accounting for 8% (Slovenia) to over 45% (Romania) of the total estimated environmental

compliance investment. The new member states have been granted transitional periods for implementing the

UWWT, as much as 10 years beyond the 2005 deadline stipulated in the directive.

Shorter transition periods were reached for complying with the IPPC Directive, the most significant

challenge facing the industrial sector. Industrial restructuring has been underway in the region for several

years, but meeting the IPPC Directive requirements by the 2007 deadline will be a major challenge for many

Danube enterprises. Estimated costs complying with the IPPC Directive among the Danube River Basin

countries ranges from 50 MEUR for Slovenia to 3,725 MEUR in the Czech Republic:

In the agricultural sector, the Nitrates Directive is the most relevant EU environmental legislation.

Agricultural nitrate pollution is generally much lower in lower Danube countries than in intensely farmed

portions of western EU countries, primarily because the lower Danube countries agricultural sector is still

recovering from the break-up of former communal farms. However, many intensive animal husbandry

operations throughout these countries are faced with significant financial burdens for improving manure

storage and handling facilities.

The new member states did not receive transition periods for nature conservation compliance. The Birds and

Habitats directives are usually not considered as investment-heavy legislation, but balancing conservation

efforts with infrastructure improvements is paramount. For example, many transportation projects in the

region threaten potential Natura 2000 sites. There is an agreed need to accelerate the process of identifying

areas to be protected.

The high cost of achieving EU environmental compliance is a formidable challenge for the new member

states, Bulgaria and Romania, and several Balkan countries that have negotiated Stabilisation and

Association Agreements (SAAs) with the EU to bring their countries closer to EU standards.

Since the beginning of accession negotiations, the EU has stressed that at least 90% of the cost of

environmental compliance must be borne from countries' own sources, representing 2-3% of GDP for many

years to come.

The reforms should concern institutional and legal measures. For Czech Republic, for the water sector, it

will be required for 5 years period 1,130 1,500 MEUR, and for 10 years period 2,260 3,000 MEUR.

Values related to the direct investments within the Morava River, which have to be carried out, to respond to

new water related regulations are estimated to reach a total amount of 200 250 MEUR for period of 5

years. Cost assessment for implementation of the WFD is about 10 MEUR for years 2003 2015, of which

for years 2004 2006 is presupposed amount 2.6 MEUR. State budget is the main source of finance. No

additional institutions are requested. In the 19922002 period, the State Environmental Fund of the Czech

Republic spent 1.1 billion and supported the various environmental and water related investments, of

which construction or reconstruction of 1,115 waste water treatment plants and sewer systems and 1,295

projects to decrease the burden on nature and the landscape.

For some countries (Moldova, Croatia, B&H and Serbia and Montenegro), the time frame for the

approximation of national legislation to EU legislation is determined by the currently not fully satisfactory

status of water sector legislation and the economic capability and potential of the particular country. For

these countries the approximation process has to be considered as a medium to long-term task.

Moldova is committed to implement the WFD and the ICPDR JAP. A detailed revision of needs in terms of

legislation to respond to WFD is not yet done. The needed investment for JAP implementation is: 296.7

G:\danube\DOCUMENTS of the ICPDR\IC 1-\IC 093 JAP - Interim Implementation Report\ORD-07 - Interim Implementation Report of JAP.doc

20

MEUR for municipal wastewater treatment plants, including sewerage systems, 111.2 MEUR for industrial

wastewater treatment plants, and 85.0 MEUR for restoring and protecting the wetlands.

For Bosnia, the financial allocation for 2002-2004 is 25,6 MEUR. From Slovene EcoFund 0,211 MEUR

were spent on wastewater treatment and 1,875 MEUR for wastewater collection systems as part of the NEAP

priorities only in 2002.

Romania is the recipient of funding from the EU-ISPA Programme that provides support for the transport

and environment sectors, with an annual allocation of 208-270 MEUR for the period 2000-06.

The two first Danube EU member countries Germany and Austria have significantly achieved high

standards of emission reduction and water pollution control. In 1997 and 1998 Germany invested more then

2.88 billion for pollution reduction measures to respond to EU Water Directives and in particular the

Nitrate Directive. Current investment in the water sector in the German part of the Danube River Basin is at

the level of about 1.8 billion per year of which 1.5 billion is spent for communal wastewater treatment

facilities (including 3rd stage for nutrient removal). From 1993 to 1999 Austria invested about 936 MEUR

per year for municipal wastewater treatment including nutrient removal facilities. Concerning the ongoing

projects indicated in the ICPDR JAP, further investments of 234 MEUR for Germany and 264 MEUR for

Austria are foreseen for the period from 2001 to 2005.

As minimising floods impacts is one of the main tasks of the JAP, estimates of the financial resources for

implementation of the Action Programme for Sustainable Flood Protection in the Danube River Basin show

the following sources:

· National budgets and other national sources

· Stakeholders contribution

· EU funds, including new cohesion funds

Relevant projects on flood action planning and implementation could financially be supported from

programmes and funds of European Union, such as: Common Agriculture Policy, European Regional

Development Fund, INTERREG IIIB CADSES, Special Action Programme for Agriculture and Rural

Development (SAPARD), LIFE, PHARE Cross Border Co-operation (CBC), or TACIS. The European

Commission has made a proposal for European Regional Development Fund 2007-2013 (COM (2004) 495

final) and has proposed to simplify the funding of external assistance (COM (2004) 626 final).

Table 6 shows a schedule for the envisaged approximation of the national legislation to the EU legislation

(regarding selected EU Directives which are directly or indirectly related to the JAP tasks).

G:\danube\DOCUMENTS of the ICPDR\IC 1-\IC 093 JAP - Interim Implementation Report\ORD-07 - Interim Implementation Report of JAP.doc

21

Table 6: Planned Schedule for Approximation of National Legislation to EU Legislation

Country 2000/60 EC EC 91/271/EC EC 91/676/EC

EC 80/68/EC on the 96/61/EC

EC 98/83/EC

EC 76/464/EC

EC 73/404/EC

EC 78/659/EC

Water

on urban waste Nitrates Directive protection of ground IPPC Directive on the quality of

on dangerous

on

on the quality of

Framework water treatment, on the protection water

on integrated

water for human

substances

biodegradability fresh water

Directive

amended as

of waters against

consumption and

of detergents