The Regional Organization for the

Conservation of the Environment of

the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden

(PERSGA)

Standard Survey Methods

for Key Habitats and Key Species

in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden

PERSGA Technical Series No. 10

June 2004

PERSGA is an intergovernmental organisation dedicated to the conservation of coastal and marine

environments and the wise use of the natural resources in the region.

The Regional Convention for the Conservation of the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden Environment (Jeddah

Convention) 1982 provides the legal foundation for PERSGA. The Secretariat of the Organization was formally

established in Jeddah following the Cairo Declaration of September 1995. The PERSGA member states are

Djibouti, Egypt, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, and Yemen.

PERSGA, P.O. Box 53662, Jeddah 21583, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

Tel.: +966-2-657-3224. Fax: +966-2-652-1901. Email: persga@persga.org

Website: http://www.persga.org

'The Standard Survey Methods for Key Habitats and Key Species in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden' was prepared

cooperatively by a number of authors with specialised knowledge of the region. The work was carried out

through the Habitat and Biodiversity Conservation Component of the Strategic Action Programme for the Red

Sea and Gulf of Aden, a Global Environment Facility (GEF) project implemented by the United Nations

Development Programme (UNDP), the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the World Bank

with supplementary funding provided by the Islamic Development Bank.

© 2004 PERSGA

All rights reserved. This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or

non-profit purposes without the permission of the copyright holders provided that acknowledgement of the

source is given. PERSGA would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this material as a

source. This publication may not be copied, or distributed electronically, for resale or other commercial purposes

without prior permission, in writing, from PERSGA.

Photographs: Abdullah Alsuhaibany, Birgit Eichenseher, Gregory Fernette, Fareed Krupp, Hunting Aquatic

Resources, Hagen Schmid, Mohammed Younis

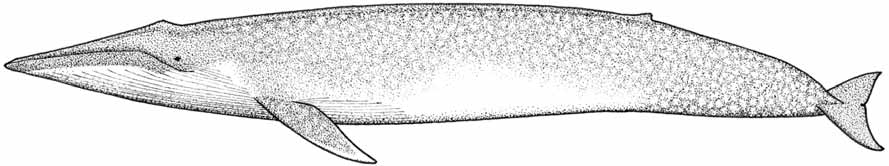

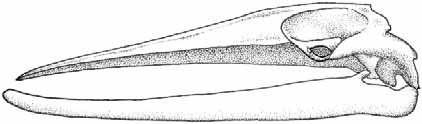

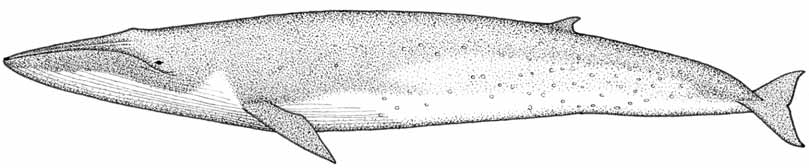

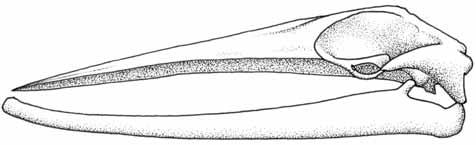

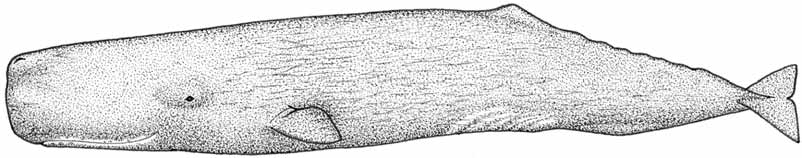

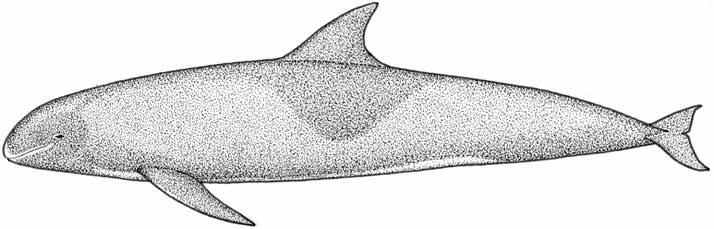

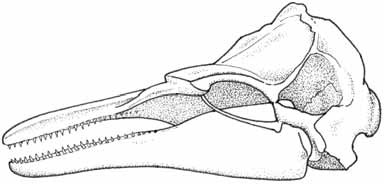

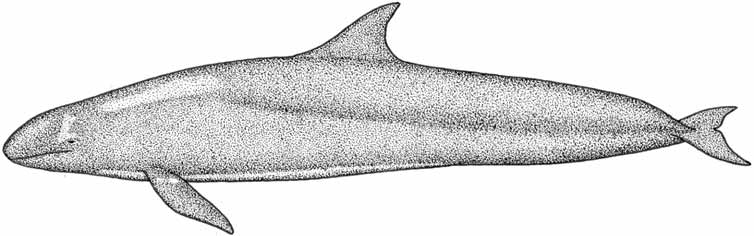

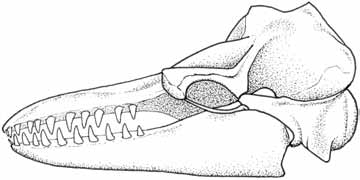

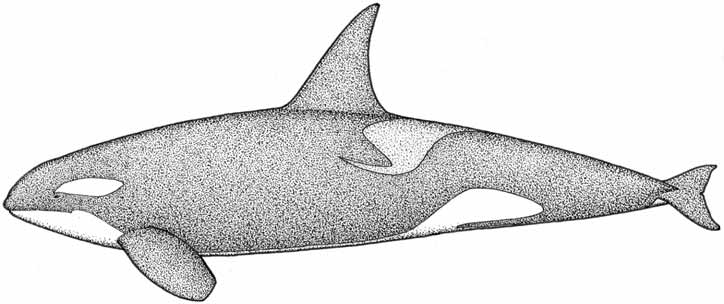

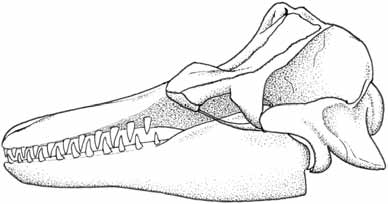

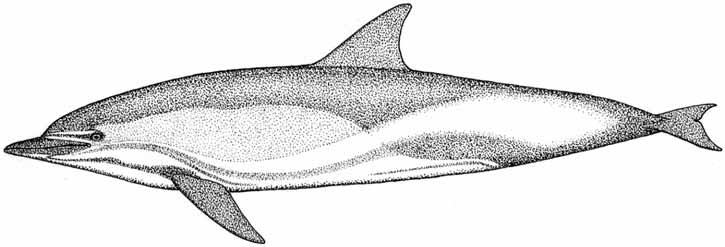

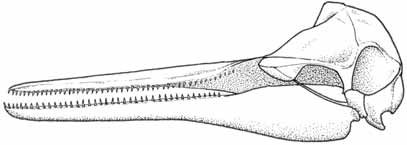

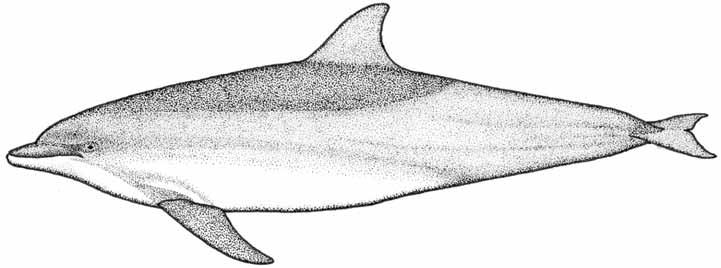

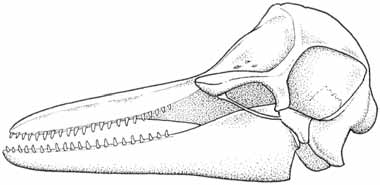

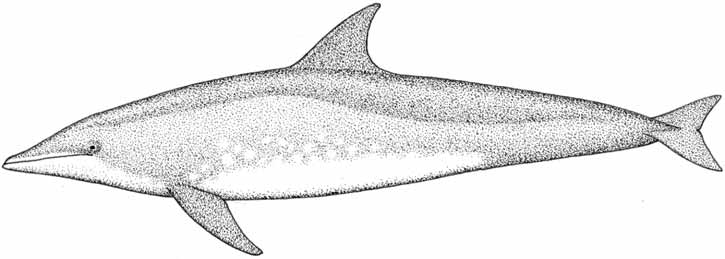

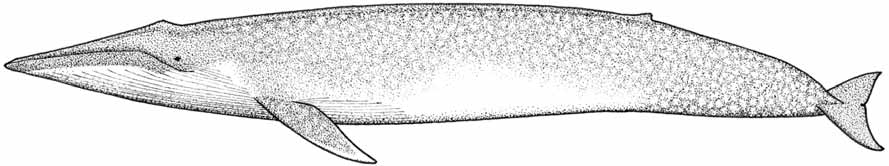

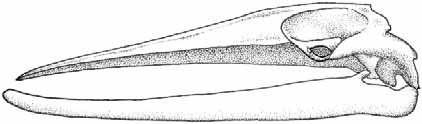

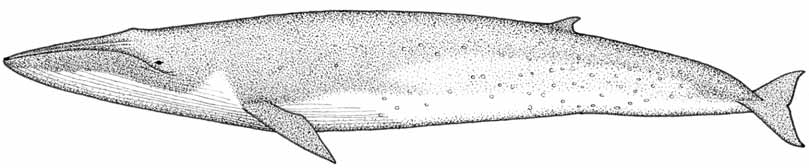

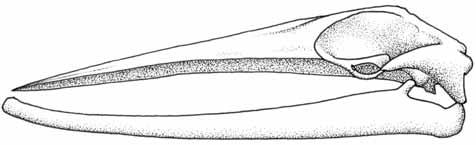

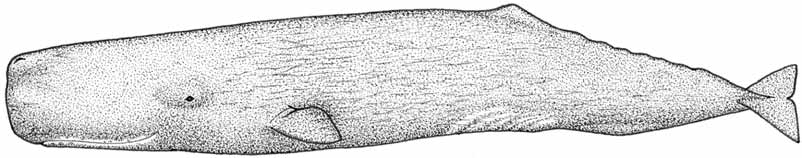

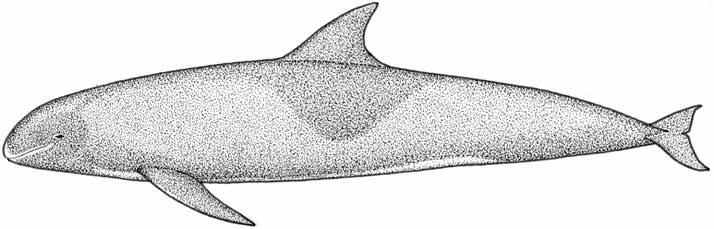

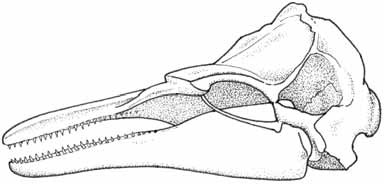

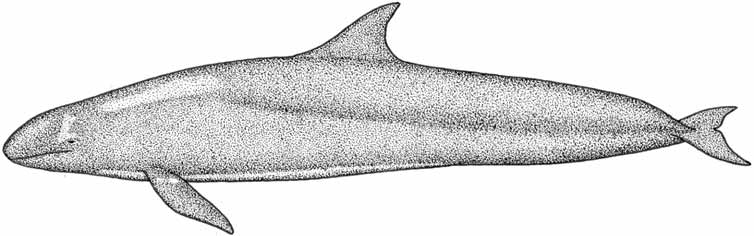

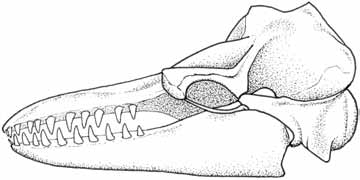

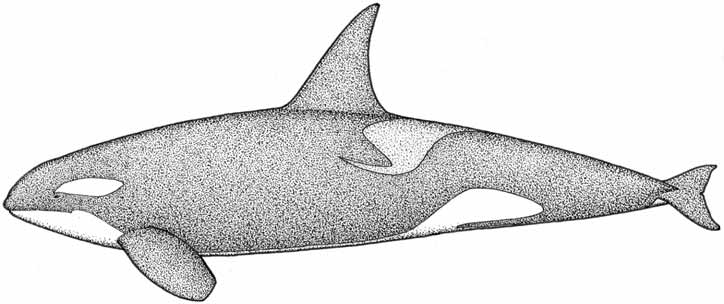

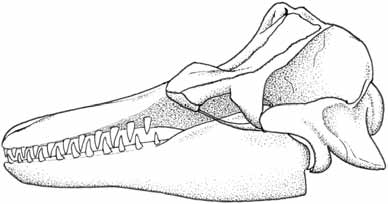

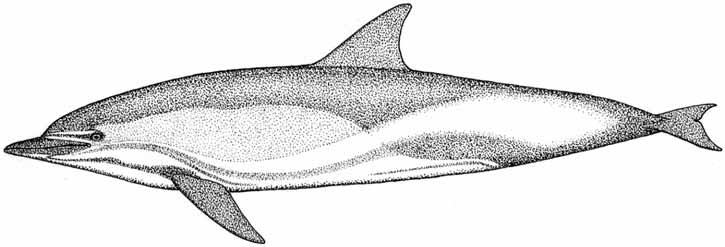

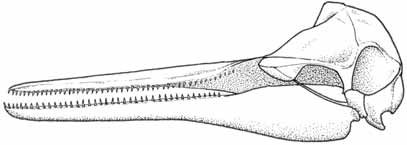

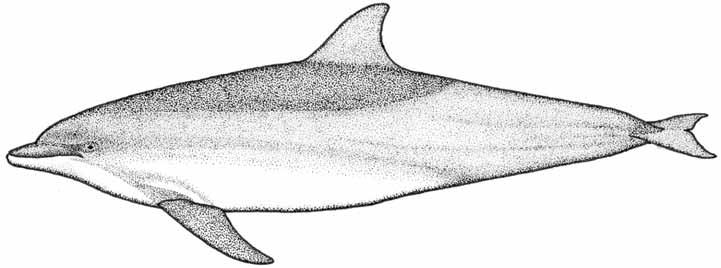

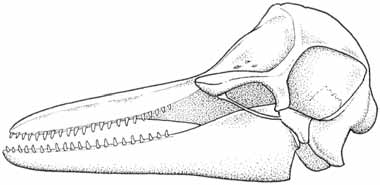

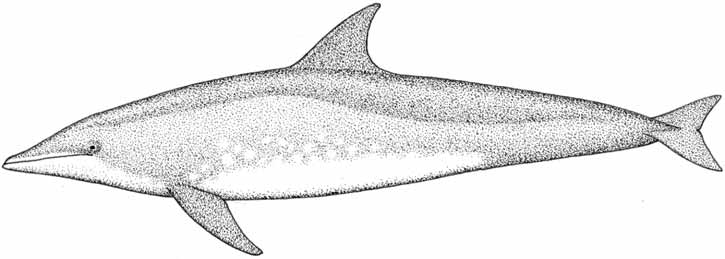

Cetacean illustrations: Alessandro de Maddalena

This publication may be cited as:

PERSGA/GEF 2004. Standard Survey Methods for Key Habitats and Key Species in the Red Sea and Gulf of

Aden. PERSGA Technical Series No. 10. PERSGA, Jeddah.

FOREWORD

PERSGA took the initiative during the execution of the Strategic Action Programme for the

Red Sea and Gulf of Aden (SAP) to consider the importance of conserving regional habitats and

biodiversity. The Habitats and Biodiversity Conservation (HBC) component of the SAP developed

a strategy that contained five clear steps: (i) develop a set of standard survey methods (SSMs) for

the region, (ii) train national specialists to use these methods, (iii) execute regional surveys, (iv)

prepare conservation plans, and (v) implement the plans.

In order to evaluate and monitor the status of marine habitats and biodiversity within the Red

Sea and Gulf of Aden, surveys must be undertaken that are comparable in extent, nature, detail and

output. Standardising survey methodology within the region is essential to allow valid comparison

of data, and for the formulation of conservation efforts that are regionally applicable.

The preparation of this guide to the Standard Survey Methods for Key Habitats and Key

Species in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden was initiated following a review of the methods currently

in use around the world. Contextual SSMs were then drafted for each of the relevant fields: sub-

tidal, coral reefs, seagrass beds, inter-tidal, mangroves, as well as for important groups such as reef

fish, marine mammals, marine turtles and seabirds. The SSM guide was discussed at a regional

workshop in September 2000 held in Sharm el-Sheikh where scientists from both inside and

outside the region reviewed the first drafts and provided the authors with useful comments.

During 2001 PERSGA conducted a series of training courses for regional specialists to teach

them some of these specific methods. The training courses were also used as tools to evaluate the

methods and to determine their applicability to our region. The results of the evaluations given by

the specialists recognized the suitability of these SSMs for our region due to a combination of

factors: their widespread use, their simplicity and the particular adaptations made to suit the region.

We are proud to provide our region with this SSM guide. It has been recognized by experts

from all over the world and tested by regional specialists. We hope this guide can be improved

upon in the future and will play its part in achieving the goal of sustainable development of marine

and coastal resourses in the region.

This guide will form an important tool to be used by management to help make decisions that

will prevent an otherwise irreversible decline in the status of our marine habitats and species.

Dr. Abdelelah A. Banajah

Secretary General PERSGA

i

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This document was prepared by PERSGA through the Habitat and Biodiversity Component of the Strategic

Action Programme for the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden (SAP). Due acknowledgement is accorded to the GEF

Implementing Agencies (UNEP, UNDP, the World Bank) and the Islamic Development Bank for financial and

administrative support. Our sincere thanks go to all the authors and illustrators who contributed to the preparation

of this document.

Several regional specialists are thanked for the significant contribution they made to the completion of this

document. They are: Dr. Nabil Mohamed (Djibouti), Dr. Mohamed Abou Zaid (Egypt), Dr. Salim Al-Moghrabi

(Jordan), Dr. Abdul Mohsen Al-Sofyani (Saudi Arabia), Mr. Salamudin Ali Ehgal (NE Somalia), Mr. Sam Omar

Gedi (NW Somalia), Dr. Ahmed Al-Wakeel (Sudan), Mr. Majed Sorimi (Yemen), and Mr. Abdullah Alsuhaibany

(PERSGA).

Our thanks are given to Dr. James Perran Ross, Dr. Fareed Krupp, Dr. Ahmed Khalil, Dr. John Turner, Dr.

Charles Sheppard, Dr. Salim Al-Moghrabi, and Dr. Robert Baldwin for reviewing the chapters. The regional

trainees and their trainers are thanked for their efforts in the evaluation of these methods during the regional

training courses.

LIST OF AUTHORS

Chapter 1. Rapid Coastal Environmental Assessment

Dr. A.R.G. Price, Ecology and Epidemiology Group, Department of Biological Sciences, University

of Warwick, Coventry CV4 7LA, England.

Chapter 2. Intertidal Biotopes

Dr. D. Jones, School of Ocean Sciences, University of Wales, Menai Bridge, Anglesey, Gwynedd

LL59 5EY, Wales.

Chapter 3. Corals and Coral Communities

Dr. L. DeVantier, Australian Institute of Marine Science, Townsville, Queensland, Australia.

Chapter 4. Seagrasses and Seaweeds

Dr. F. Leliaert and Prof. Dr. E. Coppejans, Ghent Univeristy, Department of Biology, Research

Group Phycology, Krijgslaan 281, S8, 9000 Ghent, Belgium.

Chapter 5. Subtidal Habitats

Dr. J. Kemp, Department of Biology, University of York, Heslington, York YO10 5DD, England.

Chapter 6. Reef Fish

Dr. W. Gladstone, Sustainable Resource Management and Coastal Ecology, Central Coast Campus,

University of Newcastle, PO Box 127, Ourimbah, NSW 2258, Australia.

Chapter 7. Marine Turtles

Dr. N. Pilcher, Marine Research Foundation, 1-3A-7 The Peak, Lorong Puncak 1, 88400 Kota

Kinabalu, Sabah, Malaysia.

Chapter 8. Breeding Seabirds

Dr. S.F. Newton, BirdWatch Ireland, Rockingham House, Newcastle, Co. Wicklow, Ireland.

Chapter 9. Marine Mammals

Dr. A. Preen, 'Oberon', Scott's Plain Road, Rollands Plains, 2441 NSW, Australia.

ii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

FOREWORD . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .i

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .ii

TABLES AND FIGURES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .v

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .vii

STANDARD SURVEY METHODS

INTRODUCTION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1

1. RAPID COASTAL ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .5

1.1 INTRODUCTION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .5

1.2 CHARACTERISTICS OF RAPID ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .6

1.3 METHODOLOGY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .8

1.4 DATA ANALYSIS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .14

1.5 REFERENCES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .25

1.6 APPENDICES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .28

2. INTERTIDAL AND MANGROVE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .31

2.1 INTRODUCTION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .31

2.2 AIMS OF SURVEYS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .32

2.3 SURVEY METHODS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .33

2.4 BIOTOPE SPECIFIC METHODOLOGY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .34

2.5 REFERENCES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .42

2.6 APPENDICES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .46

3. CORALS AND CORAL COMMUNITIES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .51

3.1 INTRODUCTION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .51

3.2 METHODOLOGY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .53

3.3 SELECTED METHODS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .58

3.4 DATA ANALYSIS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .71

3.5 DATA PRESENTATION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .76

3.6 REFERENCES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .80

3.7 APPENDICES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .91

4. SEAGRASSES AND SEAWEEDS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .101

4.1 INTRODUCTION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .101

4.2 METHODOLOGY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .104

4.3 DATA ANALYSIS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .115

4.4 REFERENCES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .122

iii

5. SUBTIDAL HABITATS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .125

5.1 INTRODUCTION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .125

5.2 GENERAL PRINCIPLES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .125

5.3 STANDARD METHODS FOR ALL SURVEY OR SAMPLING SITES . . . . . . . . . . . . . .127

5.4 SURVEY OF BENTHIC COMMUNITIES OF SOFT SEDIMENTS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .129

5.5 NONCORAL REEF HARD SUBSTRATE COMMUNITIES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .136

5.6 REFERENCES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .141

6. REEF FISH . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .143

6.1 INTRODUCTION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .143

6.2 METHODOLOGIES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .146

6.3 DATA ANALYSIS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .163

6.4 DATA PRESENTATION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .178

6.5 DECISION MAKING . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .183

6.6 REFERENCES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .187

6.7 APPENDICES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .194

7. MARINE TURTLES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .207

7.1 INTRODUCTION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .207

7.2 DESKTOP SURVEYS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .210

7.3 INTERVIEWS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .211

7.4 PRELIMINARY SURVEYS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .211

7.5 AERIAL SURVEYS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .215

7.6 NESTING SEASON SURVEYS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .217

7.7 GENETIC STUDIES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .228

7.8 FORAGING AREA SURVEYS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .229

7.9 REMOTE MONITORING . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .231

7.10 FISHERIES INTERACTION STUDIES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .232

7.11 REFERENCES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .234

7.12 APPENDICES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .236

8. SEABIRDS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .241

8.1 INTRODUCTION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .241

8.2 METHODS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .245

8.3 DATA ANALYSIS AND PRESENTATION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .260

8.4 REFERENCES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .261

8.5 APPENDICES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .265

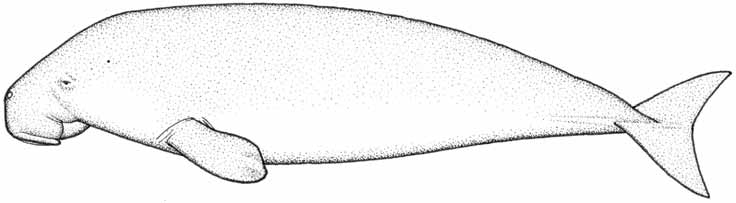

9. MARINE MAMMALS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .267

9.1 INTRODUCTION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .267

9.2 METHODOLOGY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .271

9.3 DATA ANALYSIS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .283

9.4 A PHASED APPROACH TO MARINE MAMMAL SURVEYS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .285

9.5 REFERENCES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .286

9.6 APPENDICES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .288

iv

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1.1

Features of rapid assessment vs. detailed methodologies . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .7

Table 1.2

Uses and value of rapid assessment . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .8

Table 1.3

Ecosystems, species groups, uses and impacts examined . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .9

Table 1.4

Logarithmic ranked/ordinal scale . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .11

Table 1.5

Correlations between latitude and abundance/magnitude . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .14

Table 1.6

Summary of environmental data for Chagos . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .16

Table 1.7

Illustration of use of the database . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .18

Table 1.8

Median values of biological data along the Red Sea coast of Saudi Arabia . . . . . . . . . .20

Table 1.9

Environmental diagnostics . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .20

Table 1.10 Summary statistics for abundance and use/impact data . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .21

Table 1.11 Key steps in coastal management, planning and decision making . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .24

Table 3.1

Attributes assessed during Site Description for coral reefs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .58

Table 3.2

A coral reef site description data sheet . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .60

Table 3.3

A reef check point-intercept line transect field data sheet . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .63

Table 3.4

Categories of sessile benthic lifeforms surveyed . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .64

Table 3.5

Example of data entry for benthic cover . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .65

Table 3.6

Example of partially completed field data sheet . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .67

Table 3.7

Example showing the top half of a coral bio-inventory data sheet . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .68

Table 3.8

Example of results of a lifeform line-intercept transect . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .73

Table 4.1

The Tansley scale . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .104

Table 4.2

The Braun-Blanquet's sociability scale . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .104

Table 4.3

Braun-Blanquet's combined estimation of species' abundance and cover . . . . . . . . . .109

Table 4.4

Example of a macroalgal vegetation sampling sheet . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .110

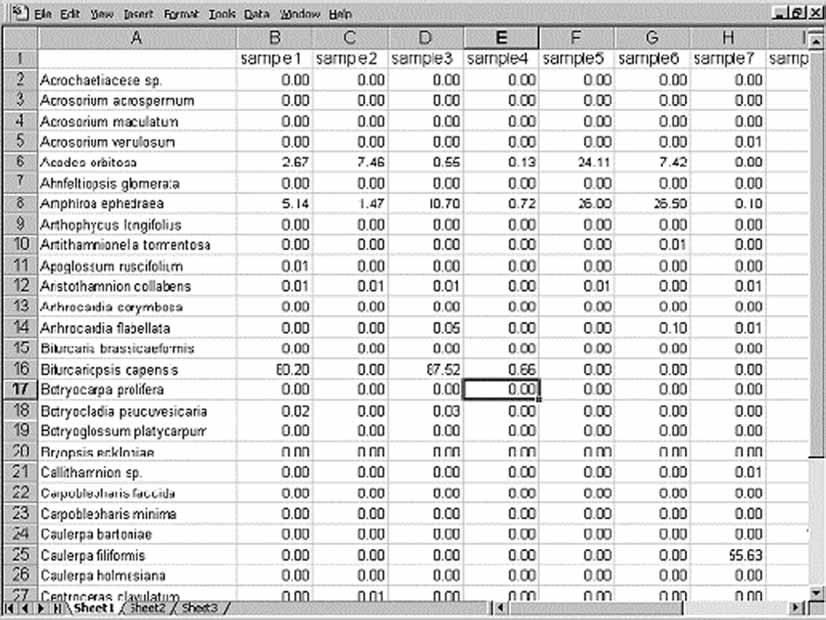

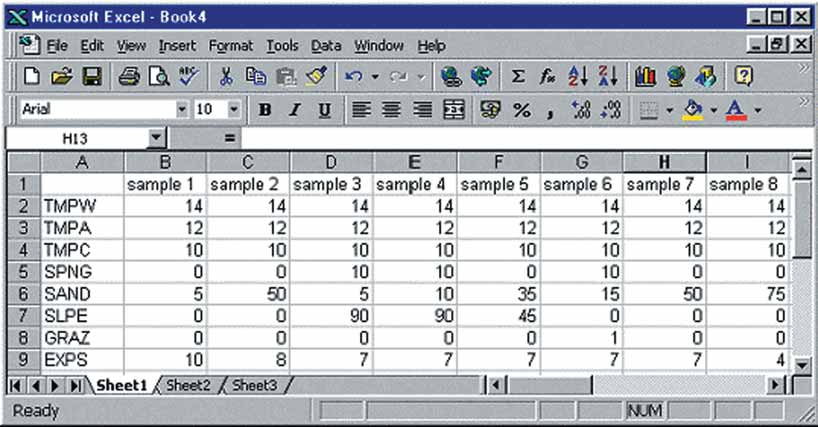

Table 4.5

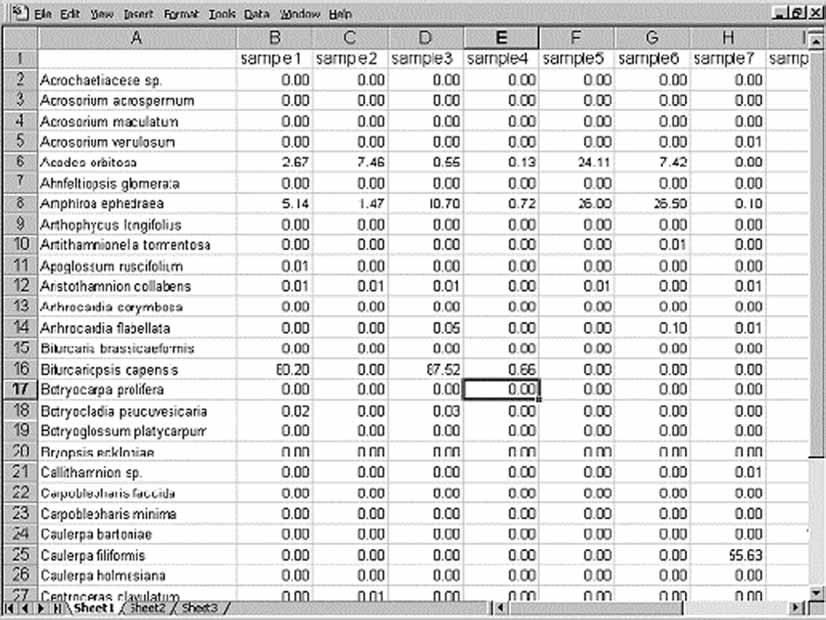

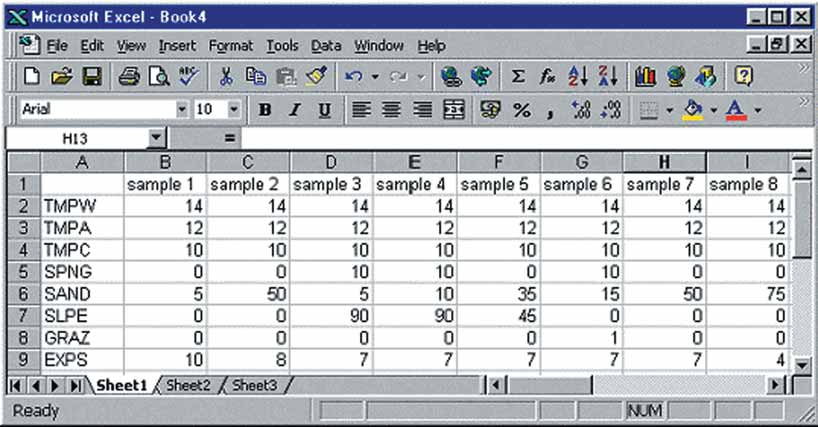

Example of a matrix with species data and environmental data . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .116

Table 5.1

Substrate categories for hard substrate surveys . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .139

Table 5.2

Percentage cover and abundance categories . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .139

Table 5.3

Taxonomic categories for hard substrate surveys . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .140

Table 6.1

Five years of Reef Check, 1997 to 2001 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .146

Table 6.2

Groups of reef fishes recommended for survey . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .148

Table 6.3

Reef types occurring in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .153

Table 6.4

Numbers of fishes within abundance categories . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .157

Table 6.5

An orthogonal sampling design for a survey . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .167

Table 6.6

An example of a nested sampling design . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .168

Table 6.7

Partially hierarchical sampling design . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .169

Table 6.8

An orthogonal sampling design . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .170

Table 6.9

Sampling design to test for the effects of an impact . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .171

Table 6.10 A Multiple BeforeAfter ControlImpact sampling design . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .172

Table 6.11 Asymmetrical sampling design . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .174

Table 6.12 Summary of asymmetrical ANOVA results . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .175

Table 6.13 The ability of surveys and monitoring . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .184

Table 7.1

Questions related to marine turtle populations in the RSGA region . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .209

Table 7.2

Morphometric summary of adult loggerhead turtles in Socotra. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .223

Table 7.3

Suggested layout of tagging records . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .224

Table 8.1

Seabird numbers and distribution in the RSGA region . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .242

Table 9.1

Marine mammals reported from the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .268

Table 9.2

The main survey methods for marine mammals . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .270

Table 9.3

Abbreviated Beaufort scale . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .276

v

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1.1 Schematic showing configuration and dimensions of the `site inspection quadrats' . . . .9

Figure 1.2 Cluster analysis of biological resource data . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .22

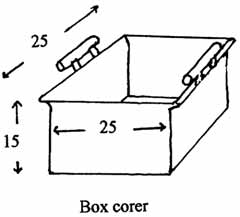

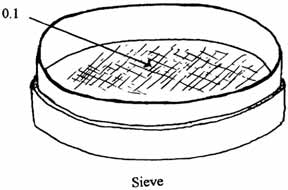

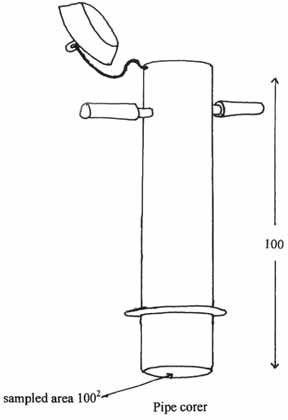

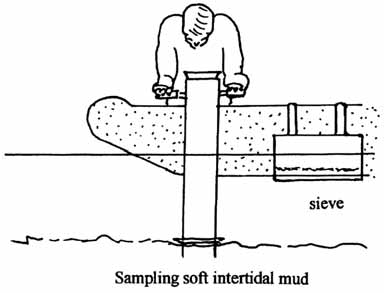

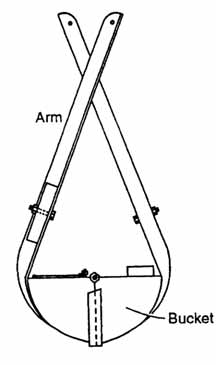

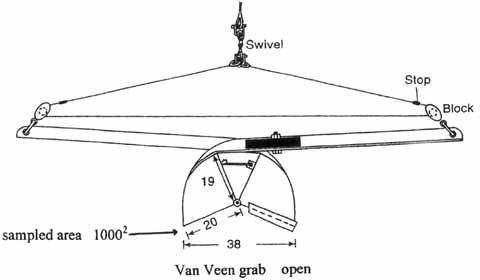

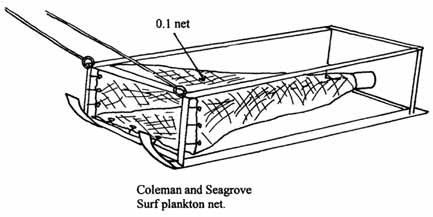

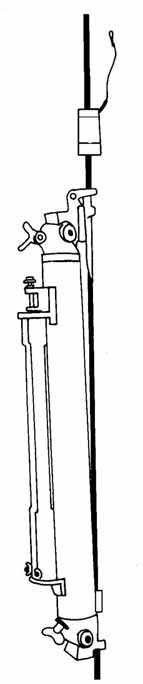

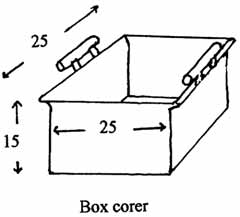

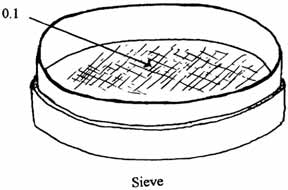

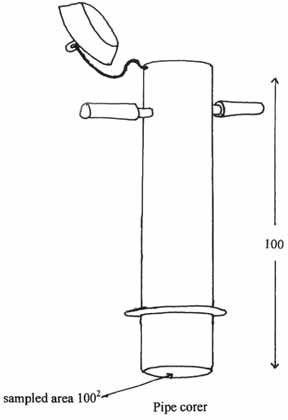

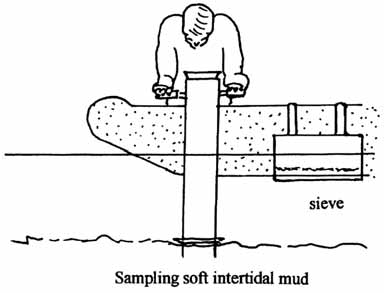

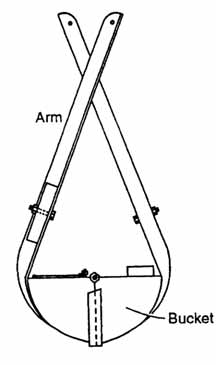

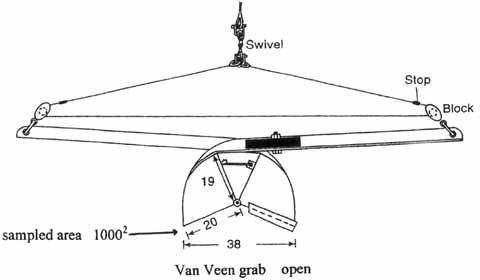

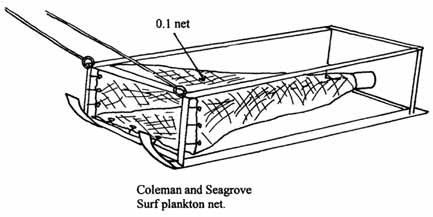

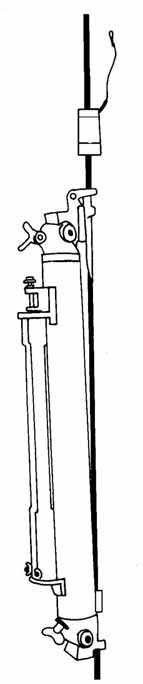

Figure 2.1 Intertidal sampling gear . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .39

Figure 3.1 Example of stratified sampling regime for coral reef monitoring . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .54

Figure 3.2 Example of results of Reef Check line-transect surveys . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .77

Figure 3.3 Bar graphs illustrating differences in various categories of benthic cover . . . . . . . . . . .77

Figure 3.4 Example of Principal Components Analysis bi-plot . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .78

Figure 3.5 Example of multivariate analysis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .79

Figure 3.6 Example of multivariate analysis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .79

Figure 4.1 A sample strategy to determine changes in species composition . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .108

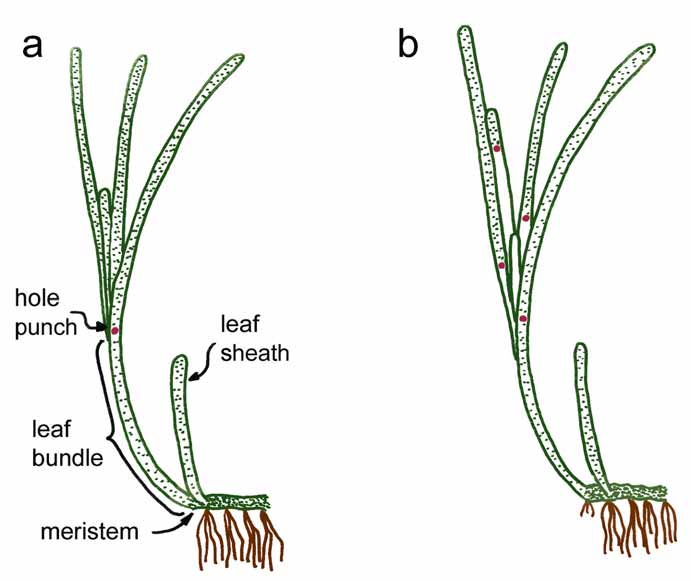

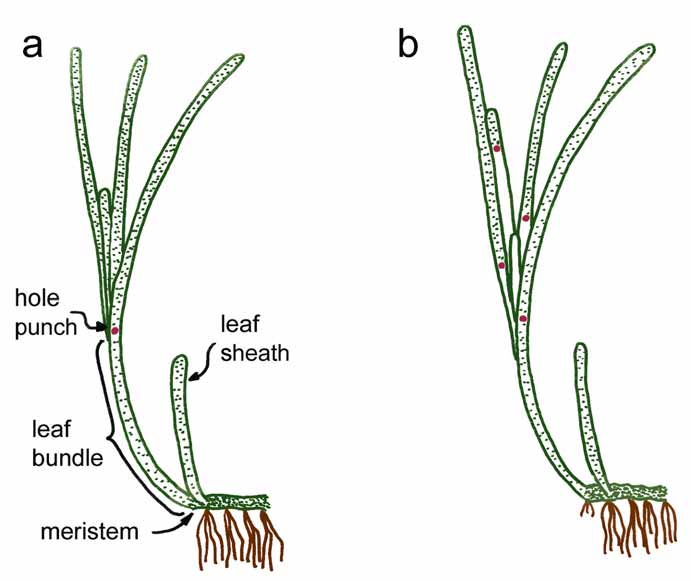

Figure 4.2 Hole-punch method of leaf marking . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .112

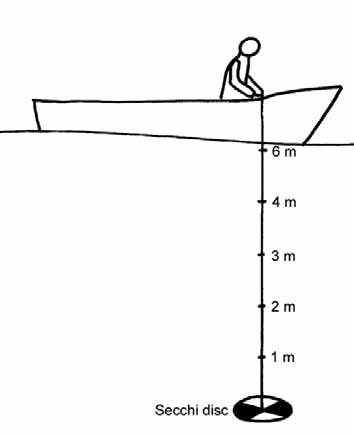

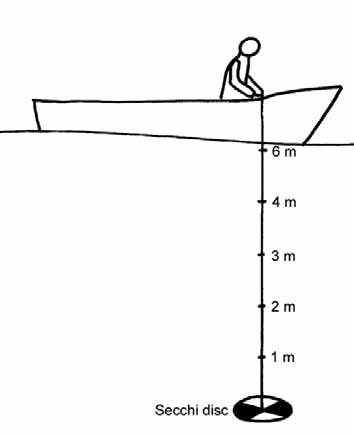

Figure 4.3 Use of a Secchi disc to measure water transparency . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .114

Figure 4.4 Use of a level meter and surveyor's rod . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .115

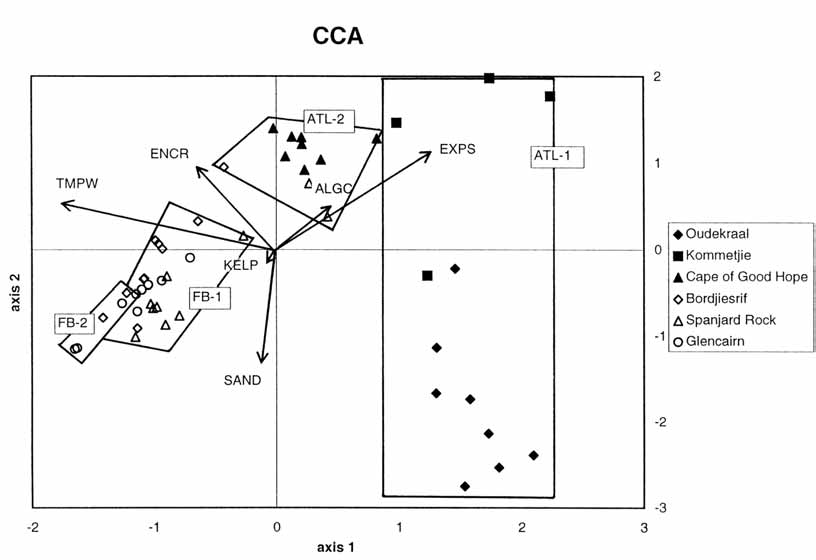

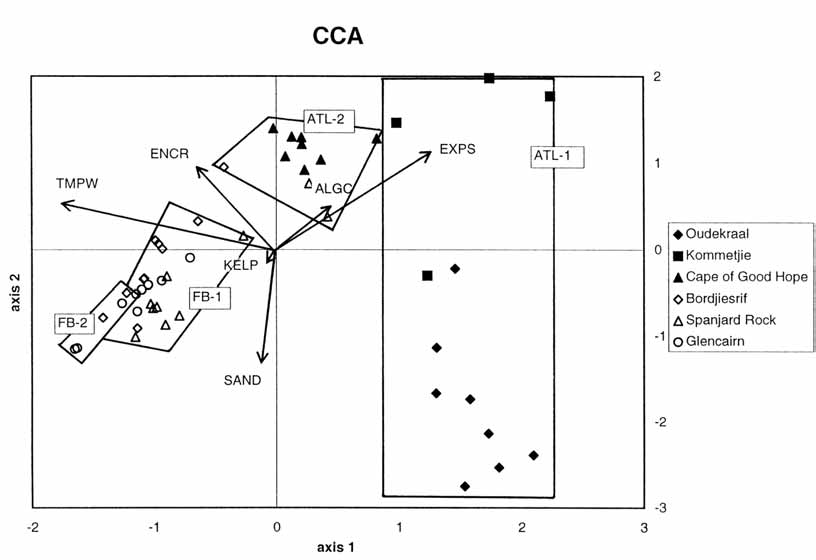

Figure 4.5 An example of an ordination diagram . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .118

Figure 4.6 An example of a TWINSPAN classification . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .119

Figure 5.1 Nansen bottle . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .133

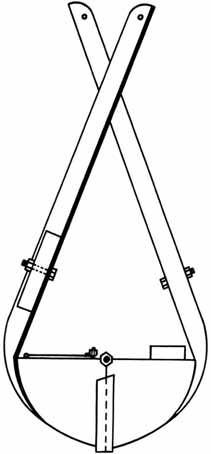

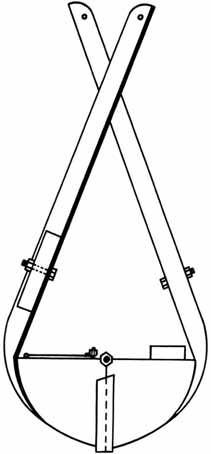

Figure 5.2 Van Veen grab, closed . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .133

Figure 5.3 Van Veen grab, open . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .133

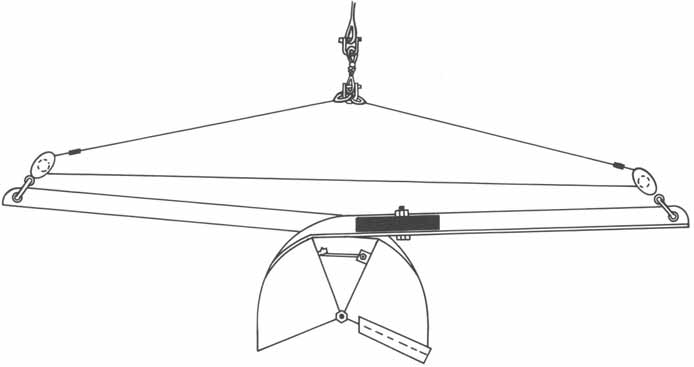

Figure 5.4 Ockelmann sledge . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .133

Figure 6.1 Non-metric multi-dimensional scaling ordination . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .177

Figure 6.2 Mean abundance of Parma alboscapularis and Girella tricuspidata . . . . . . . . . . . . . .180

Figure 6.3 Area of movement for four size classes of coral trout . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .181

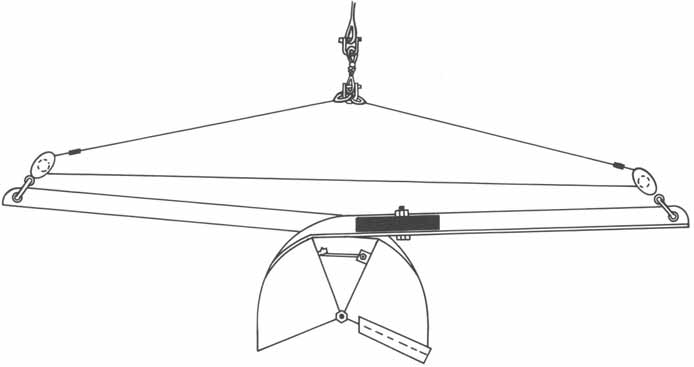

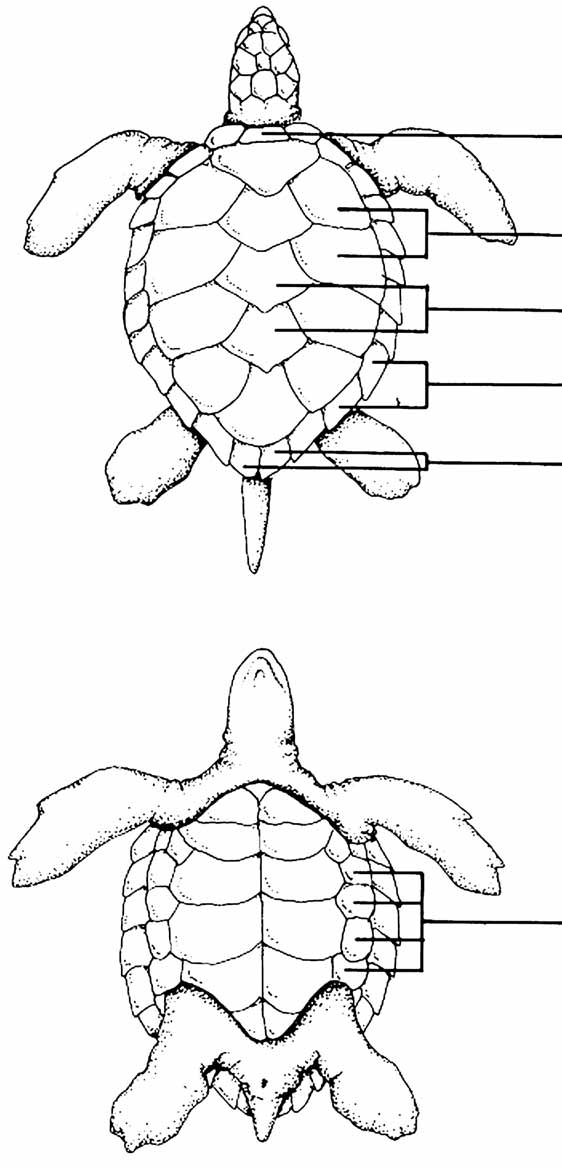

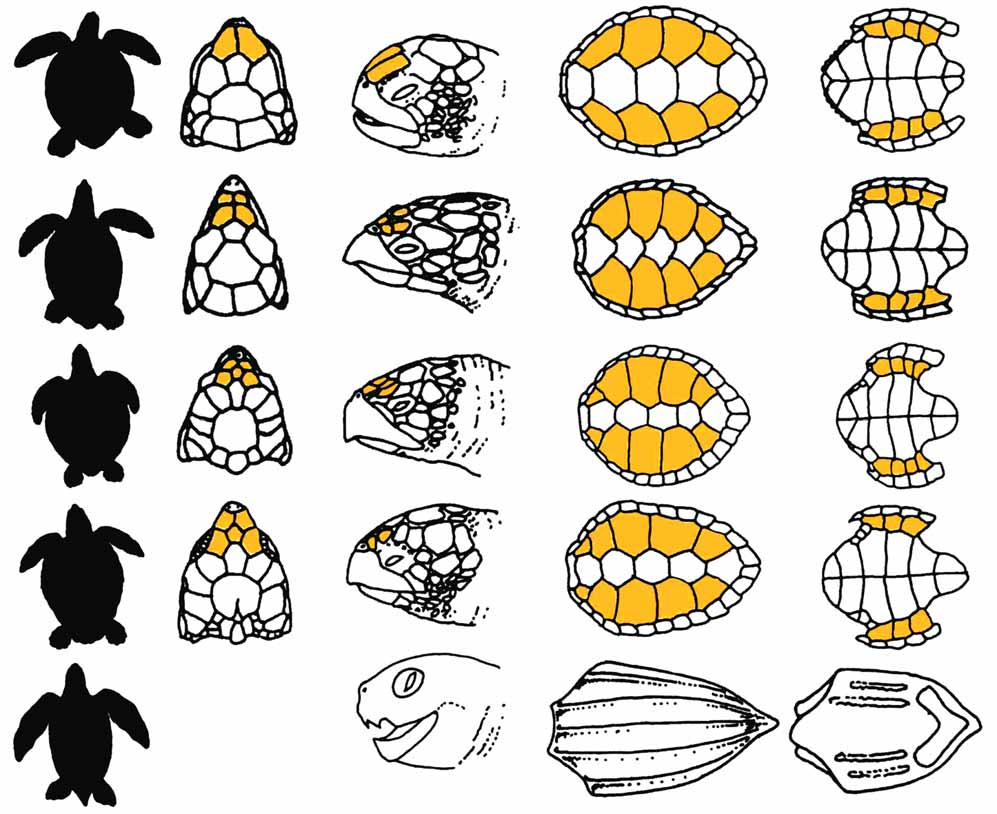

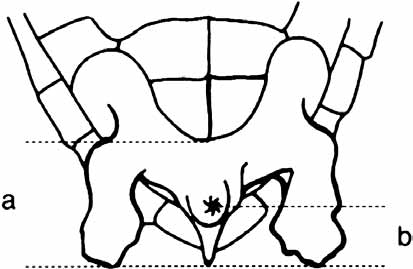

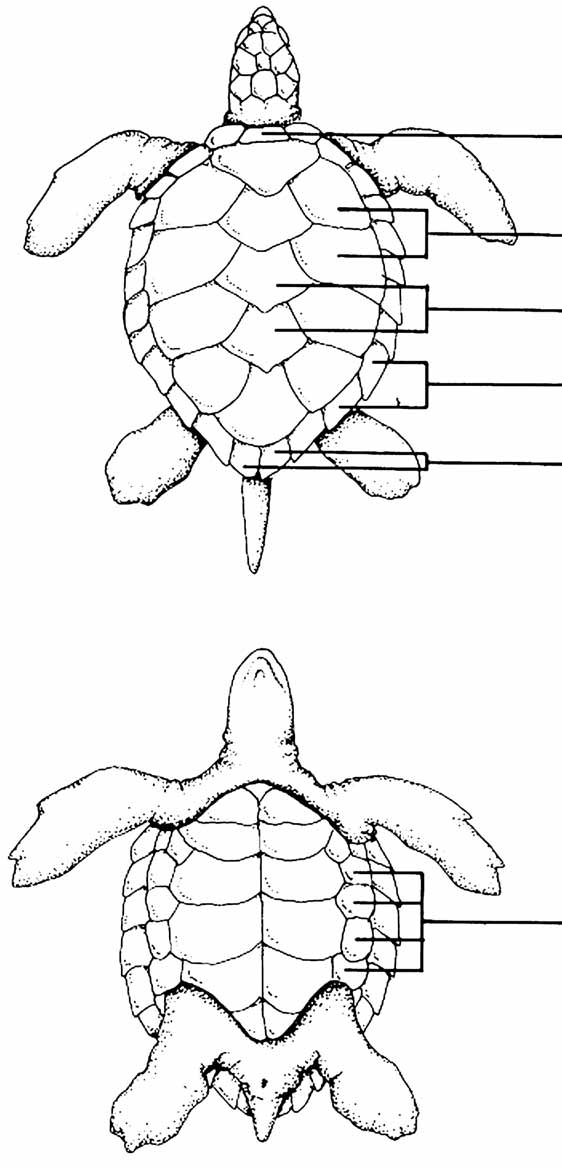

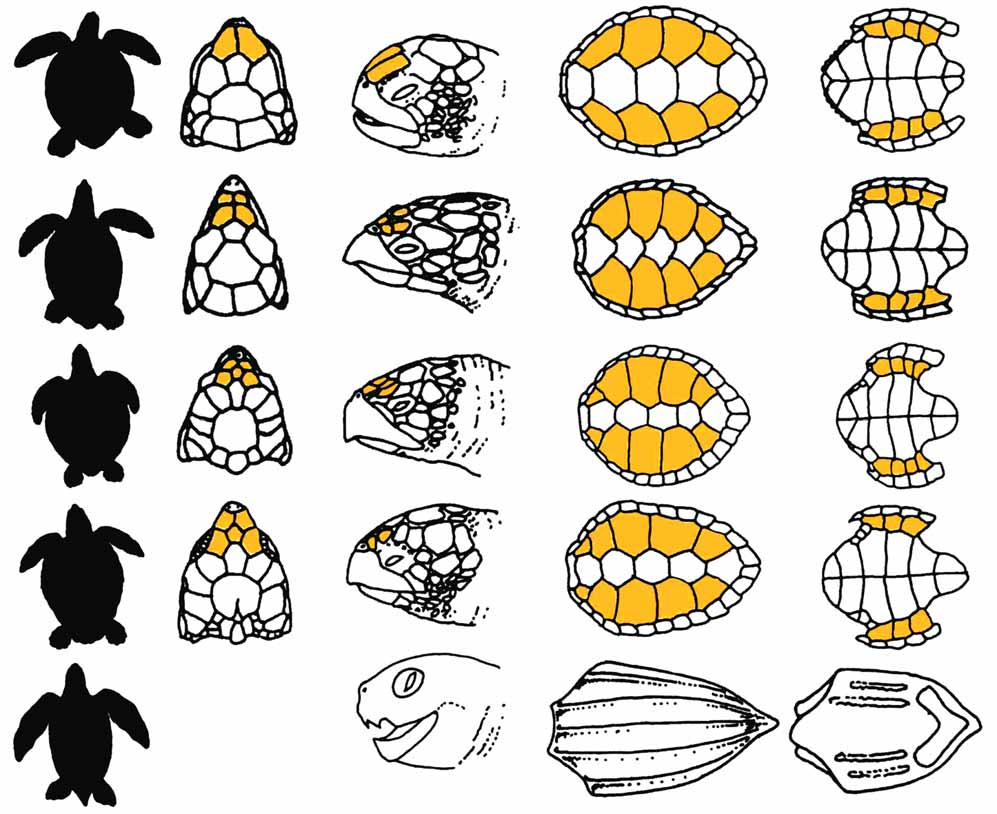

Figure 7.1 Aircraft setup . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .216

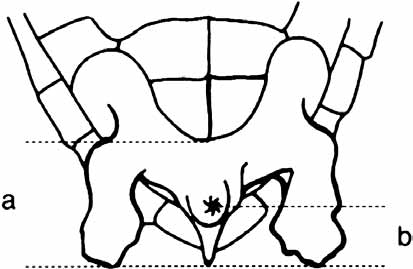

Figure 7.2 Nest relocation technique . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .220

Figure 7.3 Curved and straight carapace length measurements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .221

Figure 7.4 Curved and straight carapace width measurements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .221

Figure 7.5 Plastron length and width measurements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .222

Figure 7.6 Tail measurements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .222

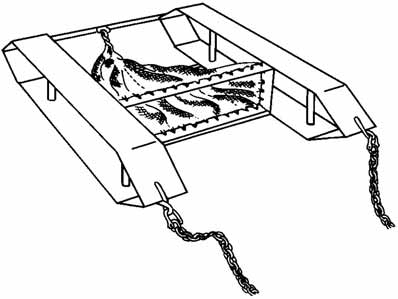

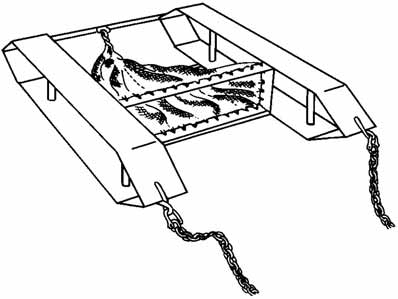

Figure 7.7 Weighing a turtle . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .222

Figure 7.8 Tag position . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .224

Figure 9.1 Calibrating transect markers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .279

Figure 9.2 Plane flying with transect widths of 200 m . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .280

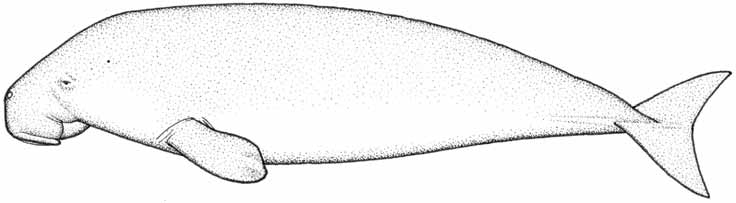

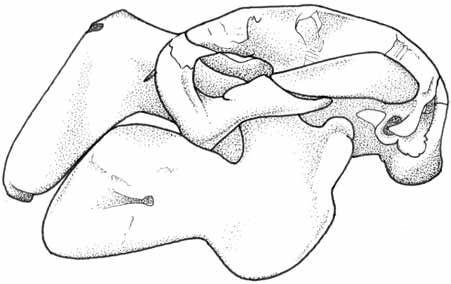

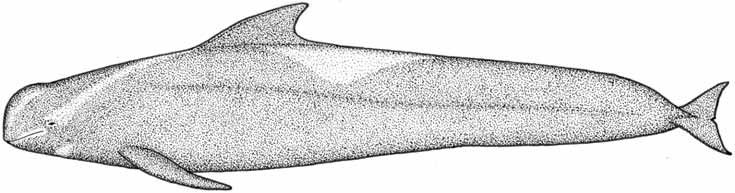

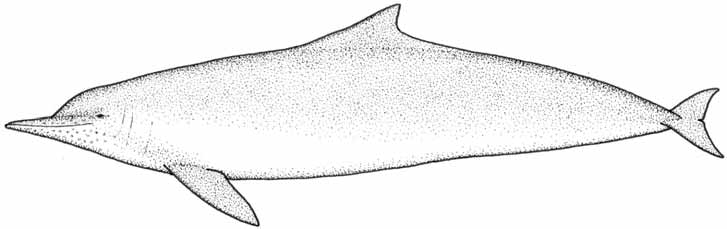

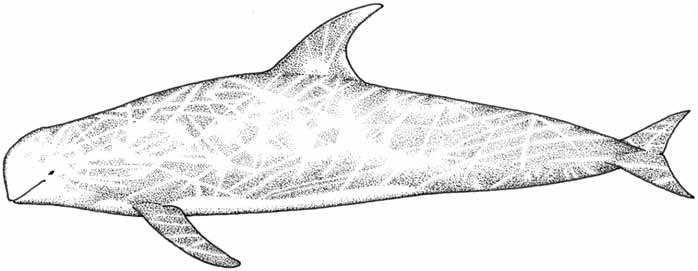

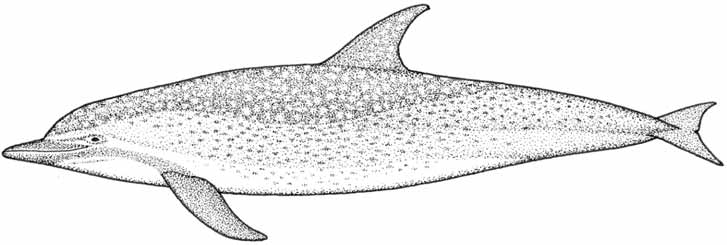

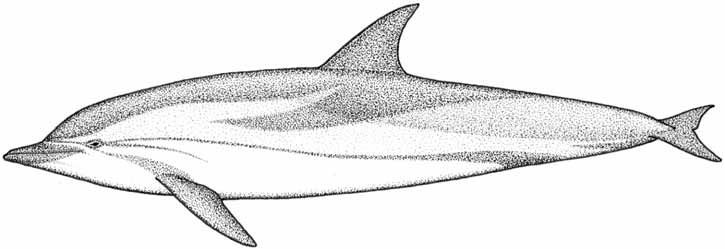

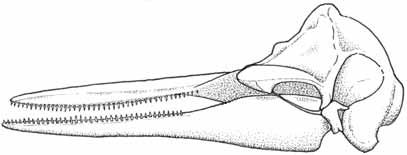

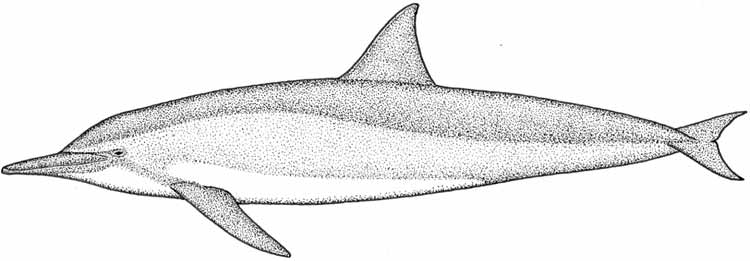

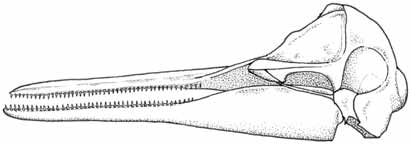

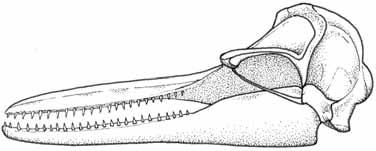

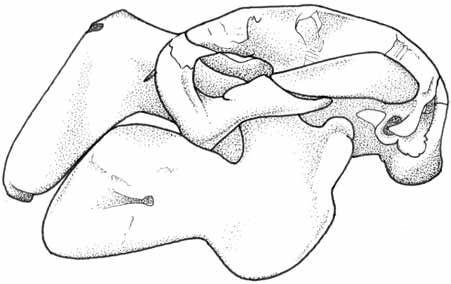

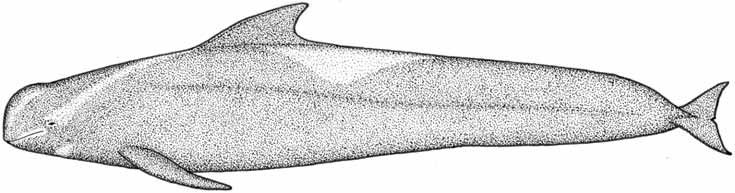

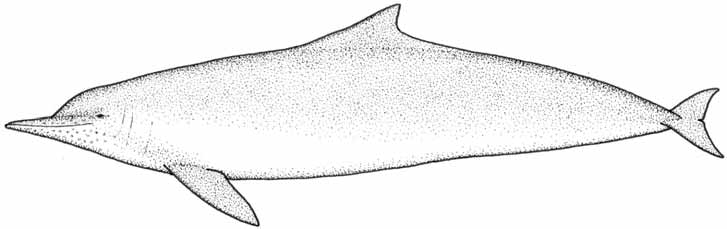

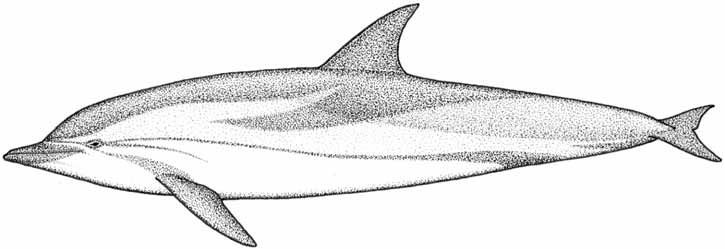

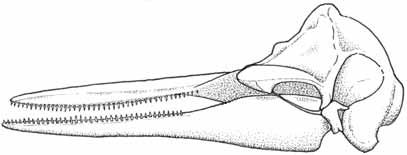

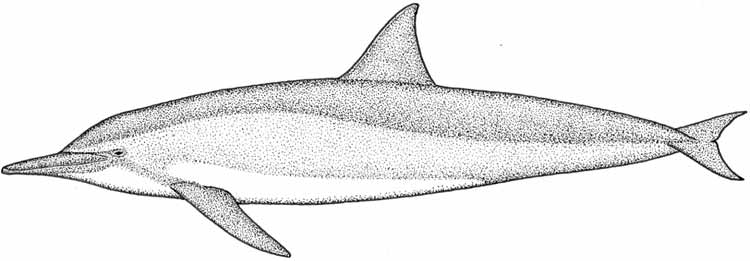

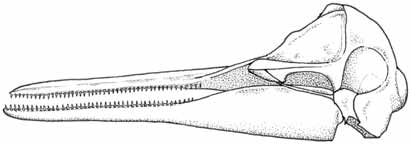

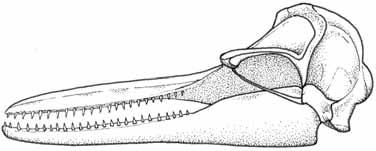

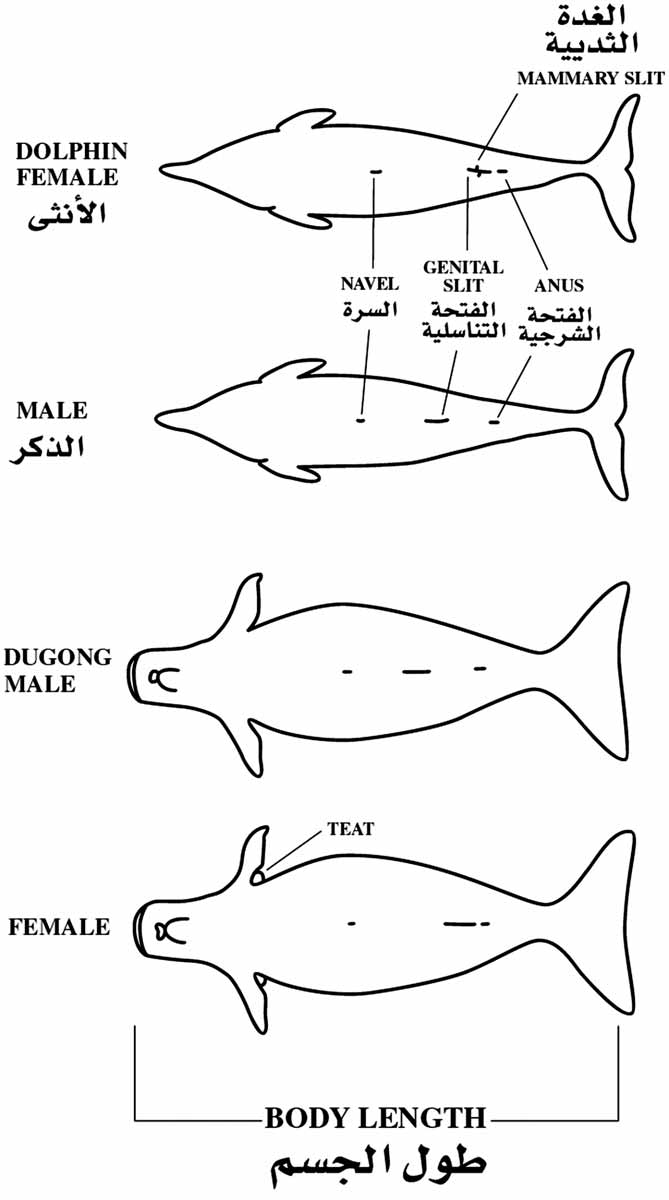

Figure 9.3 How to measure dolphin and dugong length and to determine sex . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .300

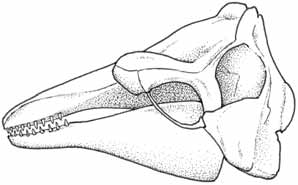

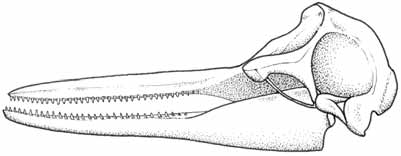

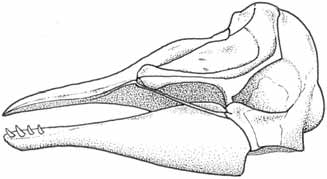

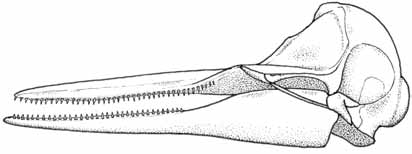

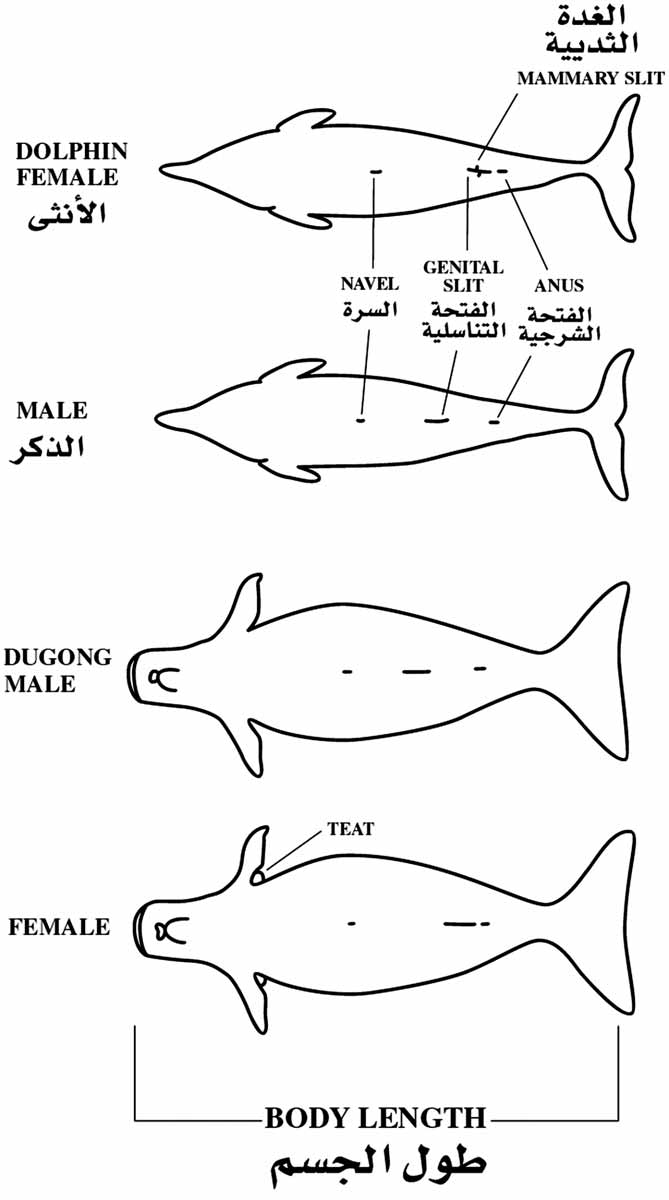

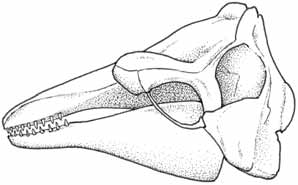

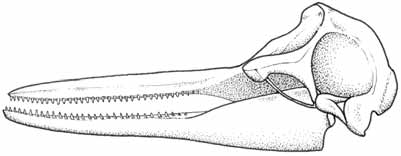

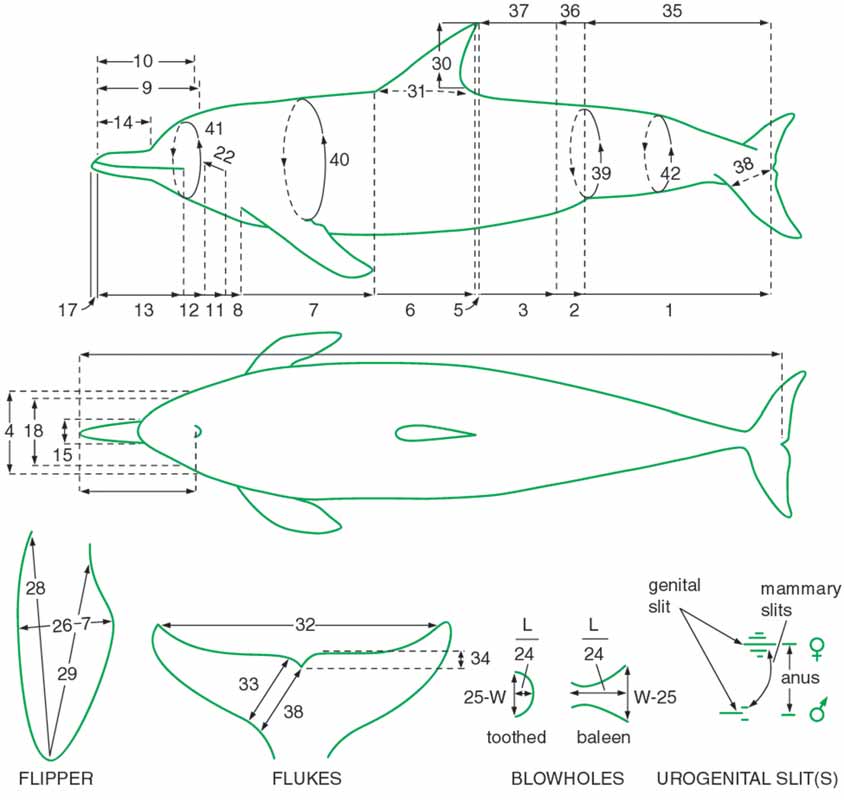

Figure 9.4 Schematic for collecting morphometric data from cetaceans . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .302

vi

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

ACCSTR

Archie Carr Centre for Sea Turtle Research

A-C-I

After-Control-Impact

AFDW

Ash-Free Dry Weight

AIMS

Australian Institute of Marine Science

ANOSIM

Analysis of Similarity

ANOVA

Analysis of Variance

ARMDES

AIMS Reef Monitoring Data Entry System

ATV

All Terrain Vehicle

BACI

Before-After Control-Impact

CA

Correspondence Analysis

CARICOMP

Caribbean Coastal Marine Productivity

CCA

Canonical Correspondence Analysis

CCL

Curved Carapace Length

CCW

Curved Carapace Width

CI

Coral Replenishment Index

CITES

Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora

CoT

Crown of Thorns (Starfish)

DAN

Diver Alert Network

DCA

Detrended Correspondence Analysis

df

Degrees of freedom

DIC

Dissolved Inorganic Carbon

EI

Exposure Index

EIA

Environmental Impact Assessment

EMR

Electro-Magnetic Radiation

FAO

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

GCRMN

Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network

GEF

Global Environment Facility

GIS

Geographical Information System

GPS

Global Positioning System

HW

Head Width

HWN

High Water Neap

HWS

High Water Spring

ICZM

Integrated Coastal Zone Management

IT

Information Technology

IUCN

World Conservation Union (formerly International Union for the Conservation of

Nature and Natural Resources)

JICA

Japanese International Co-operation Agency

KSA

Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

LE

Lower eulittoral

LF

Littoral fringe

LWN

Low water neap

LWS

Low water spring

MBACI

Multiple Before-After Control-Impact

MDS

Multi-dimensional scaling

vii

MEPA

Meteorology and Environmental Protection Administration (Saudi Arabia)

Mn

Median

MPA

Marine Protected Area

MS

Mean Squares

mtDNA

mitochondrial DNA

NCWCD

National Commission for Wildlife Conservation & Development (Saudi Arabia)

nDNA

nuclear DNA

NESDIS

National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service

NOAA

National Oceanographic and Aeronautical Administration

NPMANOVA

Non-Parametric Multivariate Analysis of Variance

ONC

Operational Navigation Charts

PC

Personal Computer

PCA

Principal Component Analysis

PERSGA

Regional Organization for the Conservation of the Environment of the Red Sea and

Gulf of Aden

PL

Plastron Length

PQ

Permanent Quadrat

PTL

Permanent Transect Line

PVC

Polyvinyl Chloride

PW

Plastron Width

R/S

Root/Shoot ratio

RAM

Rapid Assessment Methods

RDA

Redundancy Analysis

REA

Rapid Ecological Site Assessment

RI

Rarity Index

RSA

Rapid Site Assessment

RSGA

Red Sea and Gulf of Aden

S

Species

SAP

Strategic Action Programme for the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden

SCA

Seabird Colony Register

SCL

Straight Carapace Length

SCUBA

Self Contained Underwater Breathing Apparatus

SCW

Straight Carapace Width

SD

Standard Deviation

SF

Sublittoral Fringe

SMP

Seabird Monitoring Programme

SS

Sum of Squares

SSM

Standard Survey Methodology

SST

Sea Surface Temperature

TL

Tail Length

TMRU

Tropical Marine Research Unit

TPC

Tactical Pilotage Charts

TWINSPAN

Two-way Indicator Species Analysis

UE

Upper Eulittoral

UNDP

United Nations Development Programme

UNEP

United Nations Environment Programme

UNOPS

United Nations Office for Project Services

viii

INTRODUCTION

The Red Sea and Gulf of Aden (RSGA) represent a complex

and unique tropical marine ecosystem with an extraordinary

biological diversity and a remarkably high degree of endemism.

This narrow band of water is also an important shipping lane,

linking the world's major oceans. The natural coastal resources

have supported populations for thousands of years, and

nourished the development of a maritime and trading culture

linking Arabia and Africa with Europe and Asia. While large

parts of the region are still in a pristine state, environmental

threats notably from habitat destruction, over-exploitation and

pollution are increasing rapidly requiring immediate action to

conserve and protect the region's coastal and marine

environment.

During the implementation of the Strategic Action

Programme for the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden (SAP), PERSGA

focussed attention on the conservation of regional habitats and

biodiversity. A review of previous work in the region brought to

light two important points. Some areas had received

disproportionately more attention that others, and a variety of

different survey methods had been used rendering a comparable

analysis or synthesis of the data next to impossible. In order to

evaluate the current status of key habitats and species within the

region surveys had to be undertaken that were comparable in

extent, nature, detail and output. To achieve this goal PERSGA

initiated the preparation of a set of standard survey methods.

1

Standard Survey Methods

When used consistently over a period of

account for bias introduced when surveys are

time, the surveys will provide data that give

conducted by different people, with different

an accurate and objective assessment of the

capacities and levels of training. The SSMs

true status of the region's biodiversity, acting

also allow for integration between surveys

as a cornerstone in the implementation of

wherever possible (for instance the collection

long-term monitoring programmes. Several

of turtle and dugong data during the same

chapters provide a range of alternative

aerial survey).

methods designed to suit surveys of

increasing complexity when more detailed

information is required. As the data collected

A workshop was held in September 2000

using these methods will be comparable

in Sharm el-Sheikh to discuss progress with

across the region, they will allow

the SSMs. It provided an opportunity for

environmental changes to be detected and

participating experts from inside and outside

monitored at a regional level. Standardised

the region to discuss the development of the

data collection and analysis will also provide

methods. Following extensive discussions and

the necessary information from which similar,

refinement, teams of regional specialists were

consistent, regional legal and executive

trained and the methods were field tested.

frameworks can be developed for habitat and

biodiversity conservation.

There are a number of general but

important points that should be considered at

The key habitats and key species that are

the design stage before commencing any

covered in this guide include: coral reefs,

sampling programme. Variation is a

seagrass and seaweed beds, other subtidal

characteristic of all biological systems. It is a

communities, intertidal communities,

natural phenomenon. If one of the objectives

mangroves and their associated fauna, as well

of the sampling programme is to detect the

as faunal groups such as reef fish, marine

effect of human activities, then it will be

turtles, seabirds and marine mammals.

essential to be able to differentiate between

the natural or background variation, and any

change supposedly caused by human

The standard survey methods (SSMs)

interference in the ecosystem.

were prepared by respected international

experts with many years of experience in the

region. Initially a review was made of

It is important therefore to know the

methods currently in use in this region and

biology of key species, to understand the

elsewhere. Then the SSMs were drafted and

ecology of the community under study.

tailored to suit the particular conditions of the

Knowledge of the feeding and reproductive

region, taking into account the geographical

behaviour, diurnal rhythms, migratory

variation within the Red Sea's northern,

patterns, generation times, predator and prey

central, and southern sectors, and the Gulf of

relationships is essential to avoid making

Aden. They were designed to be simple and

inaccurate deductions and hence devaluing

straightforward, suitable for use in surveys,

the advice offered to environmental managers.

monitoring, and as a training guide. Though

the methods are user-friendly, they are of

sufficiently high accuracy to provide the

For example, a survey programme carried

minimum requirements needed to assess the

out over a number of years to assess

status and health of environments and their

populations of a small fish species in

constituent populations, and are able to

seagrasses beds, might suddenly show a

2

Introduction

collapse in numbers if the data collected in the

Each chapter in this volume follows a

first few years happened to be collected on a

broadly similar format: an introduction, a set

rising tide, whereas a later survey was

of survey methods often of increasing

conducted on a falling tide.

complexity to allow researchers to collect data

at different levels of precision,

recommendations for statistical analysis and

In northern or southern latitudes,

data presentation, a list of references and

reproductive cycles may be linked to seasonal

additional useful literature. The survey

changes. Closer to the tropics these

methods are complemented with line

environmental changes are less pronounced

drawings where necessary and with survey

and generation periods may be different.

sheets that can be readily photocopied for use

Small, mobile species may have several

in the field.

generations within one year. Sampling at

different times on an annual basis might strike

natural peaks or troughs in population

Data collected using the standard survey

numbers leading to erroneous conclusions on

methods will be fully geo-referenced, collated

the status of the population. Species with a

at PERSGA headquarters and stored in a

naturally high temporal variability will need

geographical information system (GIS)

more frequent sampling.

database. This will allow temporal and spatial

changes to be displayed graphically and in a

form suitable for a wide range of data users.

It will be important to differentiate

between natural disasters and anthropogenic

influences. For example, a cold wet winter

It is our hope that researchers in the region

may be as or more devastating to a breeding

using these standard survey methods will

seabird colony than a minor oil spill. It is

suggest modifications and improvements that

important to understand the reproductive

can be included in subsequent editions. All

potential of a species, its ability to respond to

comments can be sent to PERSGA at the

normal events and to re-establish its `average'

address given.

population density in order to be able to give

the appropriate weight to any

recommendations for extra conservation

measures.

3

Standard Survey Methods

4

1

RAPID COASTAL ENVIRONMENTAL

ASSESSMENT

1.1 INTRODUCTION

The Red Sea, together with the Gulf of Aden, constitutes the

Red Sea Large Marine Ecosystem (SHERMAN 1994) or PERSGA

region. Biological research in the region extends back to at least

the 1700s, with an early emphasis on taxonomy (VINE 1985;

SHEPPARD et al. 1992). Recent work has included ecological

surveys of various intertidal biotopes (e.g. JONES et al. 1987;

PRICE et al. 1987a; SHEPPARD et al. 1992; TURNER et al. 1999).

Subtidal surveys have focused on coral reefs, although other

hard substrata, seagrasses and sedimentary benthos have also

been examined (reviews by SHEPPARD et al. 1992; MEDIO et al.

2000; SHEPPARD et al. 2000).

Assessments of environmental pressures and coastal

management requirements have also been made (IUCN/MEPA

1987a,b). Of these, the recent Strategic Action Programme

(SAP) for the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden has been particularly

significant (PERSGA 1998). This sets out management

interventions, at regional and national levels, for biodiversity

conservation through marine protected areas and supporting

measures. Following these and other initiatives (see PRICE et al.

1998), integrated environmental understanding of the PERSGA

region has advanced considerably.

5

Standard Survey Methods

Site-specific data on resources, human

1.2 CHARACTERISTICS OF

uses and impacts represent a key input to

RAPID ENVIRONMENTAL

coastal planning and management (PRICE

ASSESSMENT

1990). However, this information is limited or

absent for some PERSGA member states.

Such information can be obtained more

1.2.1 High-resolution data versus low-

readily from broadscale, rapid environmental

resolution data

assessments than from focused disciplinary

research. For these and other reasons, the

Assessment of coastal systems in any

value of rapid assessment is becoming

region can be undertaken at a range of scales

increasingly recognised (reviews in PRICE et

and intensities depending on several factors.

al. 1988; DEVANTIER

et al. 1998).

These factors include:

Comprehensive manuals describing methods

and protocols have been developed (e.g.

The main purpose of the investigation

ENGLISH et al. 1997), ensuring comparability

(the principal consideration),

of approach so that regional comparisons are

valid. However, the focus of these and most

The type of coastal system being

other rapid assessment approaches is

assessed,

generally on particular ecosystems, such as

coral reefs, rather than on the coastal

Physical, human and economic

environment per se (i.e. mixed biotopes and

resources available, and related to this,

ecosystems, species groups and

The time available to undertake the

environmental impacts).

assessment.

Some of the characteristics of rapid

This chapter outlines a rapid assessment

environmental assessment compared to more

technique developed for a comprehensive

detailed, quantitative methodologies are

survey of the Red Sea and its natural systems

summarised in Table 1.1. Detailed

during the 1980s, in conjunction with other

methodologies are used more commonly

methodologies. Unlike many other

when the focus is on particular biotopes or

approaches, different resources (ecosystems

ecosystems. These are described in other

and species) and associated impacts (uses and

chapters. The `detailed' and the `rapid'

pressures) are examined concurrently, using

methodologies represent two extremes.

the same scale for assessment, and within the

Clearly observations can be made and data

same sample or observational unit. The same

collected using either approach, as well as a

technique, with minor modifications, has

range of `intermediate technologies'. A key

subsequently been applied to several other

concern for coastal management should not be

regions of the world (see section 1.3.2). The

whether detailed or rapid investigation is

merits and shortcomings of the technique are

appropriate, but what balance or combination

also described. The main emphasis of the

of methodologies best address the problems or

chapter is on the methodology used for

issues. There is an inevitable compromise

collecting and then analysing the data.

between low resolution data collected from

many sites using low-cost methodologies, and

higher resolution data from fewer sites using

generally more costly methodologies.

6

Rapid Coastal Environmental Assessment

It is also critical that social and political

1.2.2 Target and applications

factors are fully taken into account. For

example, while it might be considered

Rapid assessment methods (RAMs) are an

necessary, technically, to undertake detailed

appropriate approach for the effective survey

assessment at the site of a proposed new hotel

of relatively large areas of marine and coastal

development, the developer may only be able

environment to help with the development

or prepared to wait for a limited period before

and design of site-specific management plans

the survey results become available. Such

for proposed marine protected areas (MPAs).

urgency can be problematic unless rapid

Rapid assessment provides the first tier of

assessment is considered acceptable.

survey methods for MPA surveys, with a

subset of sites surveyed in more detail. RAMs

are more widely applicable to general habitat,

The overall benefits of rapid assessment

biodiversity, resource use and human impact

methodologies compared with more

surveys and assessments.

quantitative surveys include: the provision of

a thorough, integrated understanding of the

Further details of applications for which

coastal area, which is seldom possible through

rapid assessment may be used are summarised

a more disciplinary focus; the feasibility of

in Table 1.2. This follows on from the

surveying extensive tracts of coastline (e.g.

information in section 1.2.1. Cross-reference

> 1,000 km) over relatively short time scales;

is also made to the corresponding analytical

the limited resources required (human,

techniques appropriate for generating this

physical and economic). Set against these

information. Applications here are divided

advantages, rapid assessment data is

into those associated with ecology, coastal

necessarily of lower resolution and hence

planning or management and regional

more imprecise than more quantitative

comparison, although these divisions may not

approaches.

always be clear.

Feature Detailed

Rapid assessment

assessment/sampling

Number of sites examined

Few

Many

Coverage/representativeness of coast

Low

High

Range of factors examined

Limited

Considerable

Detail of information for each factor

High

Low

Precision of data collected

High

Low

Technology/cost Moderate/high

Low

Type of data generated

Parametric1 Non-parametric2

Statistical analysis possible

Parametric

Non-parametric

Types of statistical analysis possible

Univariate &

Univariate &

multivariate

multivariate

Table 1.1 Features of rapid assessment vs. detailed methodologies for coastal environmental assessment.

1 'Real' measurements, such as length of fish or actual number of birds, are examples of parametric data. For these

measurements, provided they follow certain distributions (usually the normal), parametric statistics/tests can be performed.

Examples include mean (average), Pearson's correlation coefficient (degree of association) and Student's t test (comparison).

2 Ranked or ordinal data, for example the 06 scale used in the present rapid assessment, are an example of non-parametric

data. For this type of data, corresponding non-parametric statistical tests must be used. For example median, Spearman's rank

correlation, and Mann-Whitney U test, rather than mean, Pearson's correlation coefficient and Student's t test, which are the

equivalent parametric tests. (Non-parametric tests should also be used when parametric data are not normally distributed).

7

Standard Survey Methods

Application or feature

Analytical/statistical

technique (section 1.4.2)

A. ECOLOGY

Community composition and biogeographic patterns/variability

a

Ground-truthing, e.g. of satellite imagery

b

B. COASTAL PLANNING, BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION AND

PROTECTED AREA MANAGEMENT

Overall state of coastal environment: data summary for whole coast or

c

particular region

Identification of resource-use conflicts

d

Selection of protected area sites using cluster analysis

e

Repeat surveys as part of monitoring programmes

f

C. REGIONAL COMPARISON AND GOVERNANCE

Environmental comparison with other regions

g

Compliance with environmental legislation

h

Table 1.2 Uses and value of rapid assessment also showing corresponding analytical techniques (section 1.4.2).

1.3 METHODOLOGY

coast. For example, if 90% of the coast is sand

beach and 10% mangrove, equidistant site

selection might result in no mangrove being

1.3.1 Survey design

sampled, especially if it occurs as small

stands. A random selection can still be

The choice of locations (sites) for rapid

achieved via a random stratified horizontal

assessment should be well integrated with the

distribution of sites, where a similar number

survey design planned for any parallel,

of sites are sampled within all features, thus

detailed or quantitative surveys. To minimise

ensuring that sites in mangrove are sampled as

bias, the coast may be divided up so that sites

well as beach. Equidistant sampling will

are more or less equidistant from each other.

probably suffice on long homogeneous coasts

This will help to avoid any temptation to

where many sites are sampled (e.g. the Red

sample `interesting' features (e.g. a large

Sea), but difficulties might be encountered on

mangrove stand), perhaps at the expense of

shorter heterogeneous ones (e.g. coast of

other less interesting areas, such as an open

Socotra).

sandy beach.

For any region, the minimum number of

An alternative view is that the coast

sites examined should not be less than about

should not be divided up equidistantly, but

30 for statistical reasons and, if possible,

rather, should take into account features of the

substantially more. In the rapid assessment of

8

Rapid Coastal Environmental Assessment

the entire Red Sea coast of Saudi Arabia and

Positioning System (GPS), recorded at a

islands (c. 2,000 km) conducted during the

suitable point such as the mid point of a

1980s approximately 1,400 sites were

survey quadrat. This also facilitates revisiting

surveyed (PRICE et al. 1998). The position of

sites during monitoring programmes.

each site should be determined by Global

500 m

Intertidal

Subtidal

SEA

5

00 m

Beach

Seagrass

(e.g. mud/sand)

Mangroves

Coral Reef

Figure 1.1 Schematic diagram showing configuration and dimensions of the `site inspection quadrats' used

in rapid environmental assessment. At each site, estimates are made of the abundance of key ecosystems and

species groups, and also of human uses/environmental pressures (impacts) within 250,000 m2 (i.e. 500 x 500 m).

ECOSYSTEMS/SPECIES

HUMAN USES / PRESSURES (IMPACTS)

Flora

Fauna

Seagrasses Reefs/corals

Oil

Algae

Birds

Human litter (plastics, metals, other solid waste)

Halophytes Turtles3

Driftwood and wood litter

Mangroves Mammals4 Construction/development

Freshwater

Fish Fishing

vegetation

Invertebrates

Table 1.3 Ecosystems, species groups, uses and impacts examined by rapid assessment. (Counts of empty

nesting pits included in estimates of turtles, since information on nesting locations is important for management.)

3Useful to separate nesting females, turtle pits on the intertidal/landward component of the quadrat (both within 500 x 250 m)

and swimming/feeding turtles in subtidal component of the quadrat (within 500 x 250 m).

4Useful to separate marine mammals (e.g. dugongs and dolphins) and terrestrial mammals (e.g. rats and mice, which can affect

turtle and bird breeding). In areas such as Somalia and Sudan, terrestrial mammals of conservation significance (e.g. antelope)

may be present and should be included in recordings. This provides a good example of how rapid environmental assessment

can consider both marine and terrestrial conservation.

9

Standard Survey Methods

1.3.2 Overview of methodology

assessment is also required. During the

planning of the survey it is important to allow

The use and application of a simple, well-

sufficient time for transport between sites.

proven yet robust technique for rapid

Often this can be more time-consuming than

environmental assessment is described below.

the actual observations or rapid assessment.

The methodology was originally developed

for the Red Sea (DAWSON SHEPHERD &

ORMOND 1987; JOBBINS 1996; PRICE et al.

Minor modifications to the methodology

1988, 1998). It has subsequently been utilised

are needed if sites do not conform with the

in other parts of the Arabian region (PRICE et

above configuration (i.e. 500 x 500 m). These

al. 1987b; PRICE 1990; PRICE & COLES 1992;

are considered in section 1.3.3 in Assessment

PRICE et al. 1993, 1994; HUNTINGTON &

of `non-standard' coastal sites.

WILSON 1995; WILSON et al. 2003), as well as

further afield in the Chagos archipelago,

Indian Ocean, (PRICE 1999) and Cameroon,

1.3.3 Survey methods

West Africa (PRICE et al. 2000).

Data sheets and recording

Each coastal site comprises an `inspection

Data are recorded on special proforma

quadrat' about 500 x 500 m bisecting the

data sheets, ideally of waterproof paper

beach, extending 250 m up the shore and

(Appendix 1.6.1). It may eventually be

250 m down into the subtidal zone (Figure

possible or desirable to record observations

1.1). The GPS position is recorded at the mid

using a hand-held computer and GPS. Use of

point of the survey quadrat. With experience,

a mobile phone would allow transmission of

dimensions of the quadrat can be determined

survey data, already in spreadsheet or

quite accurately, but initially use of GPS can

database format, back to `home base'. This

facilitate this. However, it is worth

would help minimise errors during

emphasising that demarcation of the quadrat

transcription of data from field notes, and also

only needs to be an estimate, not an accurate

allow immediate computer analysis.

measure. The intertidal/land component of the

quadrat (500 x 250 m) is determined from

observations while walking. The subtidal

Ecosystems and species groups

component (500 x 250 m) is examined

A logarithmic scale of 06 (Table 1.4) is

while snorkelling. In some instances (e.g.

used for field estimates of the abundance of

Chagos), scuba-diving may be necessary in

ecosystems and species groups. In the case of

order to survey steeper drop-offs within

flora, corals, and reefs, scores are based on

250 m from the shore. Within each quadrat,

estimates of areal extent (m2) within each

the abundance of biotopes (ecosystems) and

sample area of 250,000 m2 (500 x 500 m). In

species groups, and magnitude of uses and

practice, this is often best determined by

pressures (impacts) are estimated and

visual estimate of percentage cover from a

recorded (Table 1.3). Further details are

number of spot assessments while

given below.

snorkelling, then converting the results to the

log abundance scale. For example, the results

of estimation of seagrass cover during six

Observations at each site typically take

representative spot dives might be: 50, 75, 60,

about one hour. Clearly, a longer survey time

75, 20, and 90 per cent. The average value is

than one hour for both intertidal and subtidal

about 60 per cent seagrass cover. This is

areas should be included if diving subtidal

equivalent to 0.6 x 500 x 250 (assuming

10

Rapid Coastal Environmental Assessment

Ranked

Areal extent (m2): flora and reefs

abundance/magnitude

or

score

No. of individuals: other fauna

(log scale)

(equivalent arithmetic range)

0 0

1 1-9

2 10-99

3 100-999

45 1,000-9,999

56 10,000-99,999

6 100,000

+

Table 1.4 Logarithmic ranked/ordinal scale of 06 used for abundance estimates of coastal ecosystems

(flora and reefs) and species groups (fauna). The same scale is used to estimate the magnitude of uses/pressures

(impacts).

seagrass is confined to the subtidal), i.e.

abundance score as a population as high as

75,000 m2. The corresponding log abundance

9,999 (i.e. 4; see Table 1.4). In the Chagos,

value using the 06 scale would therefore be 5

validation of the technique was provided by

(see Table 1.4).

the highly significant correlation observed

between bird abundance values based on

scores (06) derived from rapid assessment

For fauna, except corals and reefs, the

and actual counts made by a professional

same 06 scale is used, but here it reflects the

ornithologist (Peter Symens; PRICE 1999).

estimated number of individuals (e.g. birds),

again within each sample area of 250,000 m2

(500 x 500 m). In some situations, the

Though abundance values may be used for

observer may consider it difficult to assign the

species groups of both flora and fauna, it is

correct abundance score in instances of very

also possible to collect data for individual

high faunal densities. For example, during a

species. This was done for seagrasses (PRICE

recent survey of the Chagos archipelago,

et al. 1988) as part of the rapid assessment of

seabirds were present in remarkably high

the Red Sea in the 1980s (PRICE et al. 1998).

numbers at some sites (thousands of

Clearly, the overall abundance value of a

individuals). Of significance, however, is that

species group (e.g. seagrasses) cannot simply

a log scale is used for rapid assessment. It

be obtained by adding abundance values for

therefore seems likely that visual estimation

individual species, because of the log scale.

of birds, or other attributes, would be

For example, species abundance values for

sufficiently accurate. For example, a bird

Halodule uninervis, Halophila stipulacea and

population of only 1,000 is assigned the same

Halophila ovalis might be 3, 2 and 3.

5 Abundance value of '4' initially based on (semi-log) scale of 1,00029,999, but later changed to fully log scale (1,0009,999;

see PRICE 1999).

6 Abundance value of semi-log scale 30,00099,999 initially adopted for abundance value of '5', but later changed to fully

log scale (10,00099,999; see PRICE 1999).

11

Standard Survey Methods

Summation of values would give 8 (The range

Human uses and environmental pressures

of the scale is 06). Hence, the abundance

A scale of 06 (Table 1.4) is also used to

value for each species must be first converted

assess the relative magnitude (0: nil,

to abundance/cover in m2, as indicated below.

6: greatest impact) of fishing, construction or

developments (e.g. ports and jetties) as well as

oil, other impacts and driftwood, within the

Thus, the overall species abundance (all

sample area of 250,000 m2 (500 x 500 m).

species) is 642 m2, which on the (log) 06

The latter is included since driftwood can

scale is equivalent to 3 (Table 1.4).

discourage female turtles from crawling up

beaches to nest and can, together with other

solid waste, exacerbate problems of beach

As indicated earlier, rapid assessment of

contamination in the event of an oil spillage.

ecosystems and species groups may be

augmented by more detailed quantitative

surveys. Chapter 2 by Jones provides methods

Assessment of uses and pressures is

for sampling intertidal biotopes including

undertaken as follows:

mangroves and associated biota. In addition to

Construction and development (e.g.

detailed measurements, such as tree density,

jetties) and oil pollution according to

height, and girth at breast height, aerial

(log) areal extent (06 scale), as used

photography is suggested as a means of

in estimates of floral and coral reef

determining the extent of mangrove cover.

abundance (above) 7,

This supplements area estimates at sites

determined by rapid assessment. Chapter 3 by

Human litter (e.g. metal, plastics,

DeVantier gives detailed sampling procedures

other solid waste & pollution) and

for coral reefs, which includes percentage

driftwood according to (log) number

cover estimates at higher resolution than

items (06 scale), as used in estimates

undertaken by rapid assessment. Similarly,

of fauna, except corals (above) 7,

chapter 5 by Kemp outlines survey

approaches for hard and soft substrata and,

Fishing: qualitative assessment of

again, percentage cover estimates are among

relative magnitude (06 scale) 8,

the recommended procedures for hard

Other impacts: crown-of-thorns (CoT)

substratum categories such as macroalgae.

starfish and CoT scars both according

Sampling methods are also provided for

to (log) number (06 scale), as well as

unconsolidated sediments, devoid of marine

recent coral bleaching (white) and algal

flora. However, sediments and associated

turf on coral/reef 9 both according to

benthos are not among the attributes

(log) areal extent (06 scale); these are

examined by rapid assessment.

all coral/reef impacts.

Abundance value

Range

Geometric mean

(of upper & lower value)

3 100-999

316

2

10-99 31

3 100-999

316

Total

642

12

Rapid Coastal Environmental Assessment

In instances where attributes are not or

component 500 x 250 m and subtidal

cannot be quantified, a binary scale is utilised:

component 500 x 250 m). These situations

0 (absent) or + (present). The same scale is

are likely to include:

used for assessment of attributes outside the

site inspection quadrat (right hand box or

1. sites having only a subtidal component

column on proforma data sheet; Appendix

(e.g. a patch reef);

1.6.1). For example, mangroves might be

absent within the quadrat, but a large stand

2. sites having an intertidal/land

might occur one kilometre away, i.e. outside

component which is smaller than the

the quadrat. In such cases, it would be scored

standard size configuration of 500 x

in the right hand box or column as `+',

250 m, such as a small island, but

irrespective of its abundance.

having the normal subtidal component

(500 x 250 m);

Other recorded data

3. sites having a steep cliff on shore or a

Physical features recorded on the

steep drop off offshore but within the

proforma data sheets include details of the

250 m sections of intertidal and

shore profile, substratum type and surface

subtidal zone (e.g. Socotra). These

salinity; the latter measured with a hand-held

clearly have little area value

refractometer. In addition, qualitative notes on

horizontally, but both provide

the environment can be made. Photographs are

substantial habitat area vertically.

also valuable, and details of the film and frame

number should be included. Photographic

records were particularly valuable during

Notes to facilitate assessment of these

rapid assessment of the Gulf coast of Saudi

`non-standard' coastal sites are provided in

Arabia both before (PRICE 1990) and after the

Appendix 1.6.2. In both situations, it might be

1991 Gulf War (PRICE et al. 1993, 1994). This

appropriate to identify or highlight such sites

provided a useful, visual record of changes in

in the computer database (e.g. *, ** and ***

oil pollution along the shore.

for situations one, two and three respectively).

Assessment of `non-standard' coastal sites

1.3.4 Data storage

In some instances, coastal sites may be

encountered in the PERSGA region that do

Data recorded on the pro-forma recording

not fit the standard quadrat configuration of

sheets (Appendix 1.6.1) should be transferred

500 x 500 m (i.e. intertidal or land

to a computer database, preferably MICROSOFT

7 A modification of the qualitative assessment of relative magnitude of each impact to a semi-quantitative assessment is given

in PRICE (1999).

8 Fishing is perhaps the most difficult attribute to assess. A semi-quantitative index can be obtained by summing the lengths

of boats and nets recorded at a site to give a yardstick of fishing effort, and simply ranking the data uniformly into in a 06

scale (where 0 indicates no boats or nets, and 6 indicates the maximum value of lengths of boats + nets recorded during the

survey (PRICE et al. 1998). However, inter-regional comparison may be problematic using this approach, and a simple

qualitative assessment of the magnitude of fishing (06 scale), as originally devised, may prove to be more satisfactory. In

addition to direct fishing, it may be useful to assess indirect fishing, semi-quantitatively, for example as the number (converted

to 06 scale) of discarded nets and discarded pots ('ghost' gear). Besides accounting for 'size' of fishing unit as described, some

assessment is required of the number of vessels actually in use, rather than simply available, i.e. drawn up on shore. Many

boats spend much of their life on shore, and hence this affects real estimates of fishing effort.

9 Algal turf on reefs can be associated with a number of conditions, including colonisation of reef corals during a post-

bleaching period.

13

Standard Survey Methods

Mainland

sites

Mainland and offshore

(island) sites combined

Attribute

Rs

p

Rs

p

ECOSYSTEMS & SPECIES

Mangrove

- 0.44

< 0.001

- 0.26

< 0.001

Seagrasses

- 0.14

< 0.001

- 0.01

NS

Halophytes

-

0.03

NS

0.08

NS

Algae

- 0.53

< 0.001

- 0.46

< 0.001

Freshwater vegetation

0.01

NS

0.03

NS

Reef

0.41

< 0.001

0.29

< 0.001

Birds

- 0.58

< 0.001

- 0.48

< 0.001

Bird nesting

- 0.07

NS

- 0.13

< 0.001

Turtles

- 0.13

< 0.001

- 0.14

< 0.001

Turtle nesting

0.12

< 0.001

0.07

NS

Terrestrial mammals

- 0.27

< 0.001

- 0.2

< 0.001

Marine mammals

- 0.12

< 0.001

- 0.19

0.001

Fish

- 0.28

< 0.001

0.4

< 0.001

Invertebrates

- 0.74

< 0.001

- 0.74

< 0.001

USES/IMPACTS

Construction

0.02

0.04

NS

Fishing

- 0.07

NS

- 0.07

NS

Beach oil

0.28

< 0.001

0.24

< 0.001

Human litter

- 0.08

NS

- 0.05

NS

Wood litter

- 0.13

< 0.01

- 0.1

< 0.01

Table 1.5 Correlations between latitude and abundance/magnitude of ecosystems, species groups, uses and

impacts in the Saudi Arabian Red Sea using the Spearman's rank correlation coefficient (Rs)10; p = degree of

significance; NS = not significant (from PRICE et al. 1998).

EXCEL or ACCESS. This facilitates data storage,

problems and issues (see also Table 1.2).

access, manipulation and analysis. As on the

Software that may be useful include:

data sheet, rows represent different sites, and

MICROSOFT EXCEL or STATVIEW (univariate

columns different attributes (ecosystems,

statistics) and STATISTICS (multivariate

species groups, impacts).

statistics: cluster analysis and/or

multidimensional scaling); see SHEPPARD

(1994). However, in the absence of analytical

1.4 DATA ANALYSIS

software, simple and useful data manipulation

and analysis may still be performed manually.

This might be a significant issue for some

1.4.1 Statistical software

regional states where information technology

constraints prevail.

Many types of analysis can be performed

using rapid assessment data. Analyses are

shown below in relation to particular topics,

10 Since the data are non-parametric, Spearman's rank correlation coefficient (Rs), rather than Pearson's correlation coefficient

(parametric test) must be used to determine strength of correlation. As with other tests, significance is determined using

conventional statistical tables.

14

Rapid Coastal Environmental Assessment

1.4.2 Analyses in relation to particular

This will need to take into account the 500

issues or problems

x 500 m survey area in relation to the

resolution, and hence pixel size, of a satellite

a) Community composition and

image. When ground-truthing satellite

biogeographic patterns/variability

imagery, survey sites should endeavour to

Latitudinal or other trends in abundance of

cover a homogeneous area represented by a

ecosystems or species groups or magnitude of

central pixel identifiable in a habitat class in

use or pressures can be determined readily from

the image, surrounded on all sides by similar

rapid assessment data sets. This is illustrated by

pixels, i.e. a minimum area of 3 x 3 pixels.

analysis of Red Sea data (PRICE et al. 1998). The

Thus, when using LANDSAT imagery, where

abundance of most ecosystems and species

the resolution is 30 m (and hence pixel size is

groups increased significantly towards the

30 m x 30 m), the minimum area to survey

southern Red Sea, with only reefs and turtle

for one ground-truth observation is 90 x 90 m

nesting (coastal sites only) showing greater

which is well covered by the 500 x 250 m of

abundance to the north (Table 1.5). Fish were

the Rapid Site Assessment method explained

significantly more abundant towards the south

here. When using SPOT the pixel size is 20 x

at coastal sites, but the reverse pattern was

20 m. Thus an intertidal or subtidal part of the

evident for the offshore sites. Of the human uses

survey area covers around 8.3 x 16.6 pixels in

and impacts recorded, the magnitude of beach

LANDSAT, and 12.5 x 25 pixels in SPOT.

oil was greater in the north, whereas wood litter

Given that these areas are relatively large,

showed the opposite trend (Table 1.5).

they may represent heterogeneous rather than

Latitudinal correlations with other uses and

homogeneous parts of the satellite image, i.e.

impacts were not significant.

cover several different classes of pixels,

representing more than one habitat type. Thus

sub-sampling, to capture the second tier of

Similar analyses can be done for individual

data (above) would be required for ground-

species, such as seagrass. Using the same

truth work. This is more likely around smaller

dataset for the Red Sea (PRICE et al. 1988,

features, such as islands, rather than extensive

1998), overall seagrass abundance and

beach systems.

abundance of at least five taxa increased

significantly towards the south: Halophila

ovalis, Halodule uninervis, Thalassia

c) Overall state of coastal environment:

hemprichii, Cymodocea spp. and Enhalus

data summary for whole coast or region

acoroides. The reverse pattern was shown by

The status of the coastal and marine

three species: Halophila stipulacea,

environment can be determined simply from a

Syringodium isoetifolium and Thalassodendron

table showing the following for each

ciliatum.

ecosystem, species group and use or pressure

(impact):

b) Ground-truthing, e.g. of satellite imagery

Range of abundance or magnitude

Use of satellite imagery or other remotely

values (upper and lower value)

sensed data requires ground-truthing to verify

the occurrence of a particular intertidal or

Prevalence (%)

subtidal feature on the image (e.g. mangrove,

coral, causeway). An extra tier of detail in the

Median (Mn).

form of semi-quantitative information can be

usefully provided, with minimal time and effort,

by the collection of rapid assessment data.

15

Standard Survey Methods

3

(Mn)

Median

0

0

0

1.5

6

0

0

(0)

0

0

5

8

8

8

ence

(%)

< 1

< 1

58

58

(0)

11

Arabian Gulf pre 1991 Gulf

CAMEROON

0-6

0-2

0-1

0-5

0-6 94

0-3

0-2

(0)

0-2

0-4

(1996: 36 sites)

Range Preval-

0

3

3

3

0

2

0

0

0

1

5

(Mn)

Median

1

2

ence

(%)

1

29

52

73

75

11

53

49

11

7

8

3

14

84

85

1

1

2

assessed using the same methodology:

RED SEA

(1982-84: 1 400 sites)

Range Preval-

0-6

0-6

0-6

0-6

0-6

0-6

0-5

0-5

0-2

0-3

0-2

0-4

0-6

0-6

0

0

4

4

0

0

1

0

6

(Mn)

Median

6

4

ence

(%)

46

74

90

19

75

36

98

et al. 2000). Data shown are abundance of ecosystems and magnitude of human uses/impacts

and comparison with `sites'

RICE

0-6

0-6

0-6

0-6

0-3

0-3

0-3

(0) (0) (0)

(0) (0) (0)

0-4

0-6

1999)

ARABIAN GULF

Range Preval-

(1986: 53 sites)

RICE

c

(0)

(0)

(0)

4

6

5

2

0

0

5

6

Median

(Mn)

Chagos (P

b

1

2

ence

(0)

(0)

(0)

100

100

100

100

100

100

Preval-

(%)

19

38

et al. 1998) and Cameroon (P

1

2

a

(0)

(0)

(0)

2-6

4-6

1-5

1-4

-

1

0-1

4-6

4-6

RICE

CHAGOS

(1996: 21 sites)

onmental data for

tes

l

s

0

1990), Red Sea (P

a

mma

RICE

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Attribute Range

ECOSYSTEMS

AND SPECIES

Mangroves

Seagrasses

Halophy

Algae

Freshwater

vegetation

Reefs

Birds

Turtles

M

Fish

Invertebrates

able 1.6 Summary of envir

ar data (P

T

W

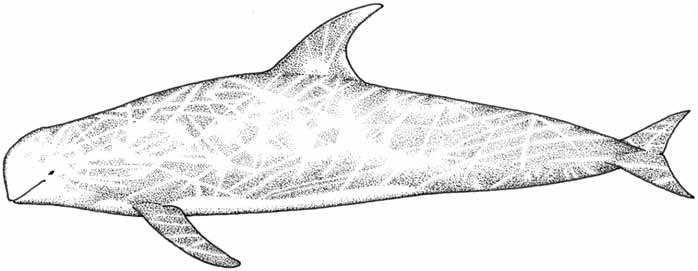

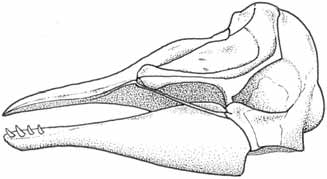

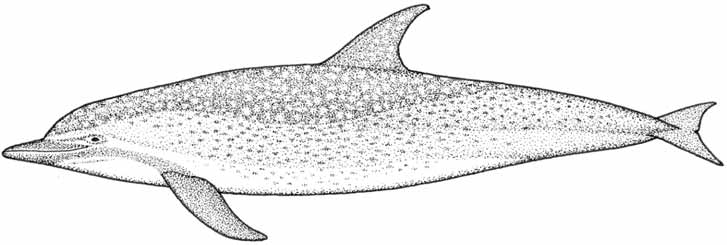

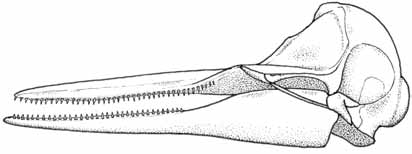

using ordinal data (06 scale) collected during rapid coastal assessments.