ENVIRONMENTALLY SOUND TECHNOLOGIES

FOR WASTEWATER AND STORMWATER

MANAGEMENT IN SMALL ISLAND DEVELOPING

STATES IN THE PACIFIC

Ed Burke

Consultant

SOPAC Technical Report 321

(Pacific contribution to the International Source Book on Environmentally

Sound Technologies for Waterwater and Stormwater Management)

Responsible Agency : South Pacific Applied Geoscience Commission (SOPAC)

[2]

This report is Chapter 8 of the International Source Book on Environmentally Sound

Technologies for Wastewater and Stormwater Management published under the

auspices of the International Environmental Technology Centre. Within-chapter

numbering of the Pacific Islands Developing States (Pacific) contribution is retained.

Attached to this report is a draft of the Source Book useful for viewing the scope of the

book and the areas of the world covered for each topic.

The International Source Book is to be formally published in the Technical Publication

series of the International Environmental Technology Centre.

[SOPAC Technical Report 321 Burke]

[3]

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CHAPTER 8 of the International Source Book on Environmentally Sound Technologies for Wastewater and

Stormwater Management

REGIONAL OVERVIEWS AND INFORMATION SOURCES

8. SMALL ISLAND DEVELOPING STATES (PACIFIC)

8.0

Introduction

8.0.1

Background ................................................................................................................ 5

8.0.2

Overview Compiling Method........................................................................................ 5

8.1

Wastewater Characteristics

8.1.1

Domestic Wastewater ................................................................................................. 6

8.1.2

Industrial Wastewater.................................................................................................. 6

8.1.3

Stormwater Disposal ................................................................................................... 8

8.1.4

Cultural Influences ...................................................................................................... 9

8.1.5

Environment and Public Health ................................................................................... 9

8.2 Collection and Transfer (Topic b) ............................................................................................... 9

8.3 Treatment (Topic c)................................................................................................................. 10

8.3.1

Small-scale and Community Technologies ................................................................. 11

8.3.2

Large-scale Technologies ......................................................................................... 11

8.3.3

Traditional Waste Disposal Technologies ................................................................... 12

8.3.4

Regional Technologies ............................................................................................. 12

8.4 Reuse (Topic d) ...................................................................................................................... 13

8.5 Disposal (Topic e) ................................................................................................................... 13

8.5.1

Ocean and River Outfalls .......................................................................................... 13

8.5.2

Land based .............................................................................................................. 14

8.6 Policy and Institutional Framework (Topic f).............................................................................. 14

8.6.1

Regulatory Framework .............................................................................................. 15

8.6.2

Institutional Framework ............................................................................................. 15

8.6.3

Policy Framework ..................................................................................................... 16

8.7 Training (Topic g).................................................................................................................... 16

8.8 Public Education (Topic h) ....................................................................................................... 17

8.9 Financing (Topic i) .................................................................................................................. 17

8.10 Information Sources (Topic j) ................................................................................................... 18

8.11 Case Studies (Topic k) ............................................................................................................ 32

8.11.1 Case Study 1: Sanitation in the Federated States of Micronesia................................... 32

8.11.2 Case Study 2: Composting Toilet Trial on Kirimati....................................................... 37

[SOPAC Technical Report 321 Burke]

[4]

APPENDIX

1

Regional Wastewater Agencies Data Sheets .............................................................. 45

2

Regional Wastewater Systems plus Constraints and Advantages ................................ 51

3

Draft Copy of Source Book for scope of study ............................................................. 54

LIST OF ACRONYMS

REGIONAL MAP

PHOTOS

1. Stormwater disposal well in Guam

2. Community toilet in Tarawa, Kiribati that lacks daily maintenance

3. Disposal of septic tank solids into clarigester in American Samoa

4. Typical ocean outfall in Honiara, Solomon Islands

5. Septic tank discharge problems into unsuitable soil conditions

6. Construction of compost toilet in Fiji

DIAGRAMS

1. Open defecation

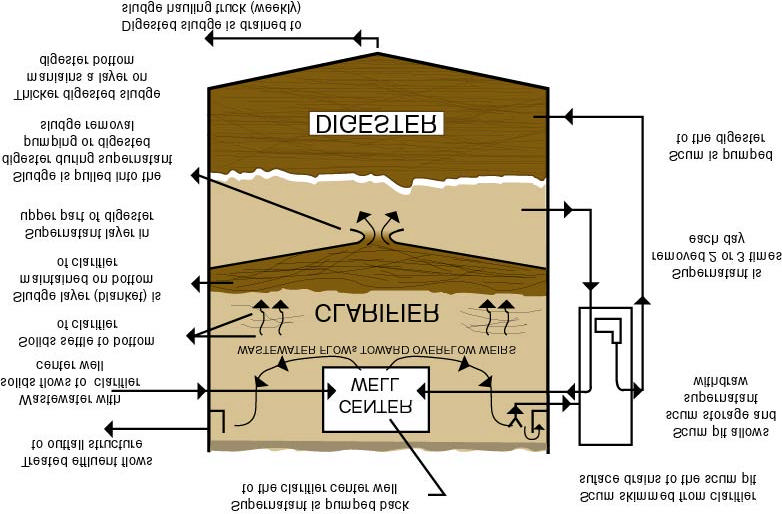

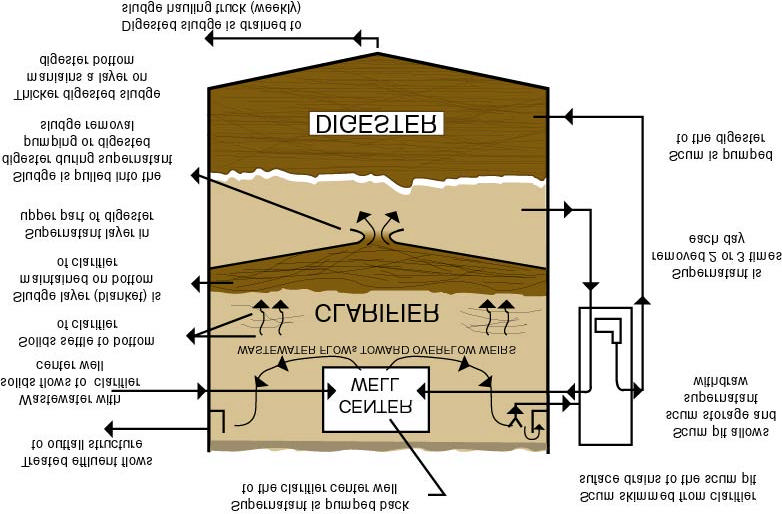

2. Clanigester operation

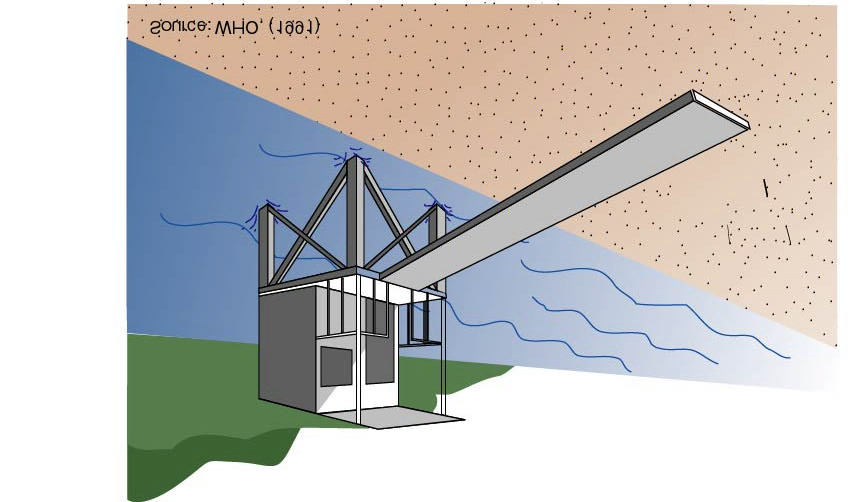

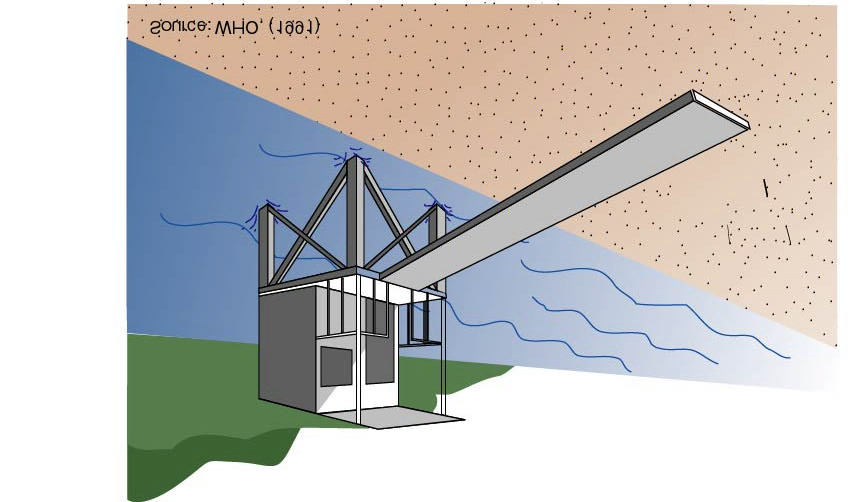

3. Overhang Latrine

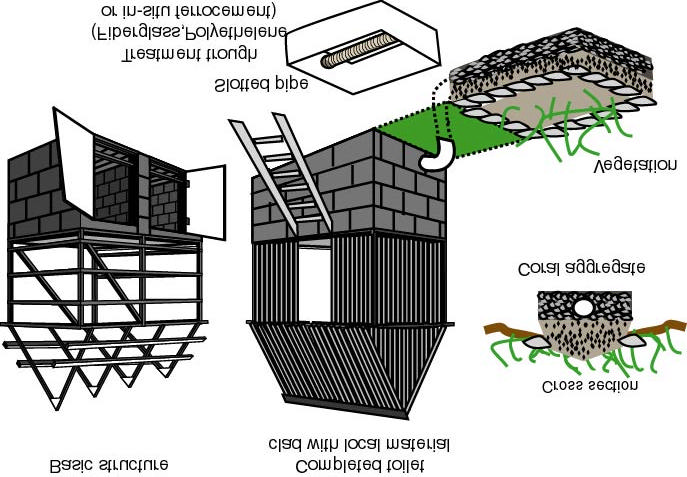

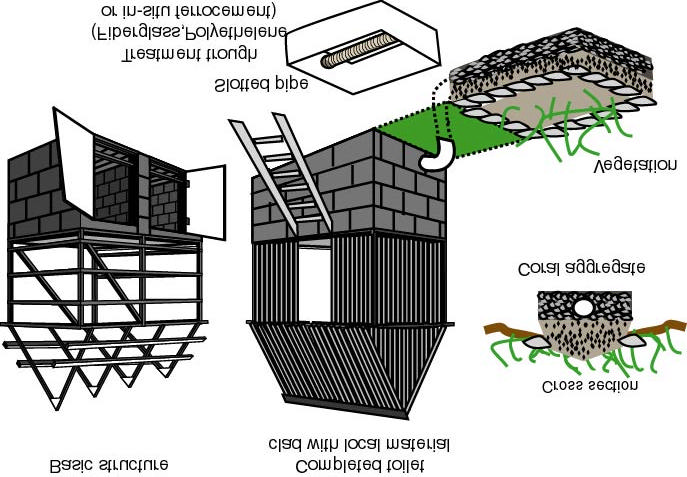

4. Composting toilet sketch used in Kiritimati

5. Evapotranspiration trench sketch

[SOPAC Technical Report 321 Burke]

[5]

8. Small Island Developing States (Pacific)

8.0 Introduction

8.0.1 Background

The Pacific Ocean covers some 18 million km2 or about 36% of the Earth's surface. Scattered

throughout the Pacific are over 30 000 small islands and a number of larger islands (each over

2000 km2 in area) which emerge from the sea floor. Of these about 1000 are inhabited. The

attached Map shows the Pacific Region covered in this report.

Small Island Developing States (SIDS) are unique. They consist of relatively small landmasses

completely surrounded by the sea. The ocean isolates SIDS from one another so they have no

shared borders with other countries. Travel between islands may be difficult and expensive.

The natural environment throughout the Pacific SIDS is extremely fragile and is highly vulnerable

to both natural and human impacts. Natural hazards like cyclones, droughts, earthquakes and

tsunamis may strike at anytime and in most places within the Pacific Region. In the past decade,

changing climate patterns, rapidly growing populations and increasing pressures on limited

natural resources in many countries have produced a crisis of damage to, and depletion of, these

resources most necessary for basic life support, especially freshwater supply. The economic and

public health implications of the crisis have provoked an urgent need for greatly improved

management, planning, operation, and maintenance of the water supply and sanitation sector,

associated environmental protection, and conservation of both surface and groundwater

resources.

Traditionally and culturally people living on SIDS have strong ties with their coastal marine areas.

The disposal of wastewater and stormwater definitely has negative impacts on both freshwater

and coastal marine environments affecting public health, ecosystems and the economy of SIDS.

Greater efforts and resources are required regionally, nationally and individually to help minimise

these impacts of land-based waste disposal on the fragile environment.

8.0.2 Overview Compiling Method

Information presented in this overview was obtained by:

· Abstraction from existing reports and studies

· Contact with individual agencies responsible for wastewater and stormwater management

(see Appendix 1 for responses)

· Personal knowledge of waste disposal methods within the Region

Appendix 1 presents the information collected for this regional overview on a series of data

sheets.

While compiling this overview it became obvious that there is a lack of comprehensive and on-

going data collection for all wastewater parameters. Very few utilities monitor wastewater

influence and/or effluence. Neither are receiving bodies of water (rivers, streams, groundwater or

seawater) monitored for quality. Thus there is little hard data available for use in this overview.

The general lack of water sector monitoring and data collection is a major problem in the Region.

[SOPAC Technical Report 321 Burke]

[6]

8.1 Wastewater Characteristics (Topic a)

Unfortunately there is lack of sufficient data available to assess typical characteristics of

wastewater produced in the Region. However the following information has been obtained.

8.1.1 Domestic Wastewater

The Kinoya wastewater treatment plant in Suva, Fiji, caters for a population of 85,000. Incoming

BOD and suspended solids (SS) are approximately 450mg/L and 290mg/L with final effluent at

20-45mg/L and 30-60mg/L respectively. Average dry weather flows are in the order of 270 litres

per person per day (l/p/d) while peak wet weather flows are 550 l/p/d.

In American Samoa two primary treatment plants treat domestic sewage only, and have a

combined average daily discharge of 8160m3 with 2600 house and business connections.

Average influent for the two plants (in October 1998) shows that BOD and SS were 70 mg/L and

50 mg/L respectively. Average effluent quality from the two plants, during the same period, was

BOD at 30mg/L and SS at 17mg/L. The sewage has been descried as "weak" due to leaking

faucets and running toilets. This is reflected in an estimated average flow of 520 l/p/d, which is

similar to the peak wet weather flow of the Kinoya treatment plant in Fiji.

No specific information could be found on other wastewater characteristics such as nitrogen and

phosphorus concentrations. However a South Pacific Regional Environment Programme

(SPREP) publication Land-Based Pollutants Inventory for the South Pacific Region, (see

Reference 2) has estimated waste loads from domestic wastewater per year that enters the

environment as shown in Table 1 below. These were based on each country's estimated

population, using various methods of treatment and an estimated concentration for each

characteristic (ie BOD, SS, N, and P)

8.1.2 Industrial Wastewater

Most operators of regional wastewater treatment plants indicated that industrial wastes were not

allowed into their collection systems. It would be naive to think that illegal connections did not

exist. Major industries in the region include edible oils, sugar refining, fish canning and beer

brewing. Most industrial operations provide some sort of treatment and disposal systems, but

again there is little information available plus a lack of discharge monitoring. Potential economic

opportunities exist with expanding industry growth along with increased industrial waste types

and volumes that will have to be dealt with to protect the environment. More control over

discharges will need to be exercised by government authorities to minimise adverse effects to the

environment.

[SOPAC Technical Report 321 Burke]

[7]

Table 1. Summary for waste loads from domestic wastewater.

Country

Pollutant Constituent (tonnes/yr)

BOD

SS

N

P

American Samoa

217.41

259.47

89.48

7.99

Cook Islands

831.02

15.28

53.27

6.46

Fed. States of Micronesia

1010.93

1314.26

53.27

6.46

Fiji

3270.31

1390.78

2043.26

240.98

French Polynesia

1251.51

0.00

812.32

98.46

Guam

2565.44

1013.54

781.70

80.27

Kiribati

409.07

406.96

174.57

21.16

Nauru

102.13

160.84

26.54

3.22

New Caledonia

948.27

1344.30

410.17

49.10

Niue

9.78

0.00

6.35

0.77

North Mariana Islands

99.36

155.07

110.60

6.27

Palau

73.29

73.33

38.63

3.78

Papa New Guinea

5665.54

2424.70

3106.91

374.49

Pitcairn

0.24

0.00

0.61

0.02

Rep. of Marshall Islands

419.05

579.70

150.54

18.11

Solomon Islands

2136.96

1762.56

979.15

139.21

Tokelau

12.42

28.80

55.94

0.72

Tonga

563.82

161.62

344.72

43.28

Tuvalu

36.48

16.92

23.00

2.79

Vanuatu

817.74

560.04

457.01

58.35

Wallis and Futuna

64.57

0.00

41.91

5.08

Western Samoa

1170.04

584.53

739.50

83.04

TOTAL

21 675.38

12 252.70

10 499.45

1250.01

Source: SPREP Land-Based Pollutants Inventory for the South Pacific Region

Mining activities exist in PNG, New Caledonia, Nauru, Fiji, Solomon Islands and Vanuatu all

produce wastewater that requires treatment and are potentially dangerous to the environment.

Each mining operation would have its own treatment facilities. The disposal of mining wastewater

has not been considered in this report.

The SPREP publication also provides estimated waste loads from industrial wastewater within

the Region as shown in Table 2.

[SOPAC Technical Report 321 Burke]

[8]

Table 2. Summary table for waste loads from industrial wastewater.

Pollutant Constituent (tonnes/yr)

BOD

SS

N

P

American Samoa

4.53

179.18

255

167.30

Cook Islands

ND

ND

ND

ND

Fed. States of Micronesia

ND

ND

ND

ND

Fiji

510.63

431.92

25.63

0.91

French Polynesia

ND

ND

ND

ND

Guam

ND

ND

ND

ND

Kiribati

ND

ND

ND

ND

Nauru

ND

ND

ND

ND

New Caledonia

37.4

6.1

ND

ND

Niue

ND

ND

ND

ND

North Mariana Islands

ND

ND

ND

ND

Palau

ND

ND

ND

ND

Papa New Guinea

508.94

1,083.40

ND

ND

Pitcairn

ND

ND

ND

ND

Rep. of Marshall Islands

ND

ND

ND

ND

Solomon Islands

513.60

494.81

18.7

0.1

Tokelau

ND

ND

ND

ND

Tonga

ND

ND

ND

ND

Tuvalu

ND

ND

ND

ND

Vanuatu

548.09

241.42

117.21

42.72

Wallis and Futuna

ND

ND

ND

ND

Western Samoa

63.7

10.42

ND

ND

TOTAL

2186.89

2447.25

416.54

211.03

Source: SPREP Land-Based Pollutants Inventory for the South Pacific Region

Note: ND = No data

8.1.3 Stormwater disposal

There does not appear to be any combined wastewater and stormwater collection systems in the

Region. Apart from the larger urban centres in the region, stormwater collection and disposals

systems do not exist. Normally stormwater would follow natural or man-made surface water

channels to the sea or just left to seep into the surrounding ground. Stormwater that falls on roofs

could be used for domestic water supplies in many SIDS or discharged into the surrounding

ground. Potential exists to use stormwater to recharge groundwater aquifers or freshwater lenses

that are used for water supply purposes. Instead of directing stormwater to the nearest outlet, the

rainwater could be infiltrated into the ground by soakage wells or ponds. Photo 1 shows a

stormwater disposal well use in Guam.

However, it is expected that some stormwater would enter wastewater sewer systems through

old and poorly constructed pipes, and through illegal connections. An example of this would be

the difference in the dry (270 l/p/d) and wet (550 l/p/d) weather flows for Fiji's Kinoya treatment

plant as noted in section 8.1.1 above.

[SOPAC Technical Report 321 Burke]

[9]

8.1.4 Cultural influences

The most drastic influence on wastewater disposal methods would have been that imposed by

Western society on the indigenous people by those countries that colonised the Pacific Region.

Prior to this intervention I would have imagined that waste disposal was a simple matter managed

by families and villages. It was Western society that introduced systems that collected and

concentrated large volumes of waste to be discharged at point sources, into the sea or rivers

causing pollution of marine and freshwater resources. Many of these systems failed to be

sustainable due to lack of resources and local inputs into operation, maintenance and

understanding of the systems. (See Case Study 1) Photo 2 shows a community toilet in Tarawa,

Kiribati that has not been maintained.

8.1.5 Environment and public health

Tables 1 and 2 indicate the order of pollutants that are discharged into Pacific SIDS environment

each year. Approximately 80% of the pollutants enters the coastal marine zone. This very

important zone that provides food and recreation for both SIDS residents and tourists is under

attack from both land-based and on-the-water pollution. The attributes that attract tourists (sandy

beaches, excellent diving and fishing) are being threatened by increasing algal blooms, dying

coral and decreasing numbers of marine life. Bathing and eating seafood from polluted coastal

waters puts public health at risk as well.

In many atolls freshwater lenses, that have traditionally been used as a source of water, are now

being polluted by poor wastewater disposal practices and by increasing population densities of

both people and animals. At times people are forced to use polluted water sources thus

increasing the risk of poor public health. In many SIDS, local health centres consistently treat a

large number of water borne related diseases.

Improved wastewater disposal planning, management and systems would definitely have a

positive impact on the environment and improve the general health of SIDS residents.

8.2 Collection and Transfer (Topic b)

Approximately 6.1 million people live in the Pacific SIDS of which 3.7 million people (or about

60 %) live in Papua New Guinea alone. Of the total population approximately 694 200 (or 11 %)

are serviced by a reticulated wastewater system. If PNG was excluded from the calculation then

approximately 546 000 people out of 2.4 million (or 23 %) have access to reticulated wastewater

systems. Note that of those people serviced by collection systems (694 200), wastewater from

over 100 000 people is discharges direct into the coastal environment without treatment. Also

many of the existing treatment plants do not preform as designed. Table 3 shows SIDS

populations, the number of people served by wastewater reticulation systems and where the

effluence is discharged.

The balance (or majority) of the people would dispose their waste through septic tanks, various

types of latrines and over water latrines. In some SIDS composting toilets have been introduced

as an alternative method of disposal. The bush and beach are still used for defecation, especially

by children, in many countries.

[SOPAC Technical Report 321 Burke]

[10]

Table 3. Estimate of regional population and population sewered.

Country

Population

Population

Outfall

Sewered

Discharge

American Samoa

35 000

15 500

Ocean

Cook Islands

18 000

None

None

Kosrae, FSM

7700

1000

Ocean

Pohnpei, FSM

35 200

14 100*

Ocean

Chuuk, FSM

52 000

9000*

Ocean

Yap, FSM

11 300

1100

Ocean

Palau

15 000

5500

Ocean

Fiji

760 000

110 000

Ocean/River

French Polynesia

196 000

ND

ND

Guam

139 000

151 000***

Ocean

Kiribati

72 000

20 000*

Ocean

Nauru

8500

3000*

Ocean

New Caledonia

165 000

92 700

Ocean

Niue

2500

None

None

Mariana Islands

59 000

39 000

Ocean

Papua New Guinea

3 700 000

138 300**

Ocean/River

Rep. of Marshall Islands

46 200

28 500*

Ocean

Solomon Islands

333 000

25 000*

Ocean/River

Tokelau

1200

None

None

Tonga

100 000

None

None

Tuvalu

9000

None

None

Vanuatu

160 000

None

None

Western Samoa

165 000

None

None

TOTAL

6 105 600

694 200

Note: * = Sewered but not treated **=some not treated ***=includes military population

ND = No Data

It appears that combined wastewater and stormwater collection sewers are not used in the

Region. However as mentioned in Section 8.1.3, stormwater does find its way into wastewater

systems during periods of rainfall.

There are all types and sizes of pipes used in the Region to reticulate wastewater. Generally it is

current practice in the Region to use plastic pipes, however other pipe materials that best suit the

situation are used.

In Kiribati, Marshall Islands and Nauru, seawater is used to flush toilets and convey sewage to

discharge outfalls. Seawater, used to conserve limited freshwater resources, is pumped to

household toilet tanks and collected again for disposal in separate reticulation systems or to

septic tanks.

8.3 Treatment (Topic c)

The Pacific has been described as a "junk yard" of water sector technologies with failed systems

spread throughout the region. Developed country technologies have been superimposed on the

Region with less then successful results mainly due to the lack of sustainable resources for on

going operation and maintenance. A SOPAC organised Regional workshop on Appropriate and

Affordable Sanitation for Small Islands was held in Kiribati in 1996. It became clear from the

workshop that sanitation involves more than just physical structures for excreta disposal. Health

and hygiene education is also regarded as important aspects for any proposed sanitation project.

Also community involvement and participation is most important to have a successful project.

[SOPAC Technical Report 321 Burke]

[11]

The production of the SOPAC publication Guidelines for Selection and Development for Small

Islands (see reference 3) was a result of the Kiribati workshop.

Previous American influenced countries in the Region (American Samoa, FSM, Guam, Mariana

Islands, Marshall Islands and Palau) have some sort of wastewater reticulation system and

primary to secondary treatment for their main urban centres. However the standard of effluent

produced ranges from raw sewage from Marshall Islands to good quality from Guam and

American Samoa. All these countries discharge their wastewater into coastal areas.

Apart from the major urban centres in Fiji, PNG, Kiribati, New Caledonia and the Solomon

Islands, plus the above mentioned American influenced countries, the balance of the Region's

communities use septic tanks, various types of latrines and over water latrines. Composting

toilets have been introduced and trialed in some SIDS including Kiribati, FSM, Fiji and Samoa

(see Case study 2). The bush, beach and the sea are still used for defecation in many places

(see Diagram 1).

8.3.1 Small-scale and Community Technologies

Septic tanks and various types of latrines are exclusively used in the Cook Islands, Niue,

Tokelau, Tonga, Tuvalu, Vanuatu and Samoa but are used throughout the Region as well. These

methods are mainly for individual family and household use. Some communities (in PNG and

Kosrae) use large septic tanks along with some schools and hospitals for wastewater treatment

and disposal. Appendix 2 shows various types sanitation systems plus constraints and

advantages used in the Region.

UNESCO/SOPAC trials were carried in Tonga to assess what the safe distance between shallow

wells and household "toilet" discharges. The study found that most wells used for the study were

already polluted. The results were inconclusive suggesting that the minimum distance should be

as far apart as possible.

In Yap (FSM) an Imhoff tank is use to treat wastewater. The utility reports that there is a big

demand for the dried sludge taken from the Imhoff tank.

Section 8.5.2 discusses land base wastewater disposal in more detail.

Oxidation ponds only appear to be used in Fiji, PNG and Kosrae. Pond treatment methods

generally do suit atoll conditions where land is very limited and ground conditions very permeable

results in expansive implementation.

8.3.2 Large-scale Technologies

Again large treatment plants service the large urban centres such as in Fiji and Guam.

Treatment methods include sedimentation, trickling filters, and anaerobic and aerobic lagoons.

Currently the Kinoya treatment plant, that service about 85,000 people in the Suva area, is being

upgraded using extended aeration and will eventually be able service 360,000 people. Raw

sludge is digested and put into drying beds. The circular digester produces about 63m3 of sludge

per day. Some of the dried sludge is used as soil conditioner and that not used is dumped into a

landfill. In Guam belt presses are used to mechanically dry sludge.

In American Samoa two separate treatment plants use clarigesters for the primary treatment of

wastewater. A clarigester is a clarifier that sits on top of a digester constructed as one unit. (See

Diagram 2) The clarigesters separate settleable solids and floating debris from the inflow of

wastewater. Settleable solids sink to the digester compartment where they undergo digestion and

eventually removed as sludge. Sludge is removed from the clarigesters and dewatered in

[SOPAC Technical Report 321 Burke]

[12]

covered drying beds. Supernatant from the digester compartment and drainage from the drying

beds is pumped back into the plant headworks. Clarigester treated wastewater is than disinfected

using chlorine and discharged into two ocean outfalls (30 m and 45 m deep). As shown in Photo

3, the plant also has the facility to except and treat septage, trucked in from septic tanks through

the island.

American Samoa and Guam are the only countries in the Region where treated wastewater is

disinfected before discharging into the sea.

It should be noted that raw sewage which has been collected through sewer systems in Kiribati

(Tarawa), Nauru, Marshall Islands (Majuro), Solomon Islands (Honiara) and PNG (parts of Port

Moresby) is discharge into ocean outfalls with out treatment. Also some of the older treatment

plants (Pohnpei and Chuuk) do not operate properly thus not improving influence quality much.

8.3.3 Traditional Waste Disposal Technologies

Before the arrival of missionaries, Western ways and densely populated areas, going to the bush,

the beach or the sea was the normal methods to relieve one's self within the region. Water was

not required for flushing, paper was not required and a disposal system was not required. All that

was required was a private place and that was not too hard to find. It was the outside world that

introduced toilets, collection systems and treatment plants to the Region.

The closest to a regional "small scale" traditional disposal technology would be the over water

(overhung) latrines (also as known as "benjos" in FSM as described in Case Study 1). These are

"latrines" that are constructed over a body of water into which excreta drops directly as shown in

Diagram 3. They are cheap and easy to construct no water or paper was required, easy to clean

and maintain and some had a great view. Also they were communal in nature (ie several people

could use them at same time) and thus presented the opportunity to catch up on the latest

gossip. What else could you ask for? However with growing populations resulting in larger

discharges and pressure on marine food resources, the risk of pollution and disease also

increased. The tourist industry also frowned on them lining the beaches. Over water latrines are

now history however that are still use in some parts of the region.

In rural coastal areas throughout the region the over water latrine still has potential to provide an

important service to the community. Under favourable conditions and good management

practices the over water latrines will still be part of the region's waste disposal seen.

8.3.4 Regional Technologies

As seen from above the current wastewater treatment technologies used in the Region range

from none to secondary treatment with no one method standing out as the one to use. Without

performance monitoring data available, it would still be fair to conclude that many of the existing

treatment plants and methods are not working, as they should. The problem may be that the

systems are old, expensive to maintain, operate and to replace. The utilities do not have the

resources to adequately provide an environmentally friendly service to its customers and the

customers cannot afford to pay for an adequate service. Therefore service deteriorates and the

environment suffers.

As concluded from the SOPAC workshop on Appropriate and Affordable Sanitation for Small

Islands, for a sanitation project to be understood, accepted and used, the community must

support and be involved with the project's development. Public education and awareness is

needed so that the community can see the benefits of both improved health and environment

brought about through improved wastewater disposal facilities.

[SOPAC Technical Report 321 Burke]

[13]

8.4 Reuse (Topic d)

The reuse of wastewater in agriculture and aquaculture has much potential and is used in many

other regions. It can replace the use of limited freshwater for the irrigation of crops or be used as

an additional source to increase production of crops and in the forestry industry. Aquaculture is

becoming popular and may provide additional economic opportunities in developing countries.

Nutrients found in wastewater discharges, that normally pollute the environment, are beneficial

when used with irrigation and aquaculture applications. However the reuse of wastewater is

currently not practiced in the Pacific Region. With many SIDS experiencing limited water

resources the reuse of wastewater would be attractive by conserving water and reducing pollution

potential to marine and surface water resources.

There is potential in Fiji to use wastewater to irrigate sugarcane and/or for fish farming that has

been recently established there. However these rural activities are generally remote from urban

centres where treated wastewater is available. SIDS priorities to provide appropriate and

affordable sanitation facilities should explore all possibilities to reuse wastewater where ever

possible.

In many SIDS and in especially in Papua New Guinea there are strong traditional feelings against

the reuse of wastewater. Much talking and convincing would be required to introduce this

concept. The issue of `most appropriate' technology needs to be explored and thoroughly

discussed with potential users before proceeding with any new development. Also irrigation is not

practice extensively in the Pacific thus water for irrigation use is not a high priority in most SIDS.

It should be noted in Kiribati, Nauru and Majuro saltwater is reticulated to households for toilet

flushing to reduce the stress on limited freshwater resources. However the potential to reuse

human waste mixed with saltwater would be limited to non irrigation usage.

8.5 Disposal (Topic e)

Table 3 notes the Regional SIDS that discharge wastewater through ocean and river outfall

systems (see Photo 4 a typical ocean outfall in Honiara). Over water latrines also uses the ocean

and rivers to dispose of waste. All countries in the Region use land based disposal systems of

various types. With SIDS populations concentrated on coastal areas, much of the land based

wastewater discharges would eventually enter the ocean through groundwater and surface water

flows. Many coastal areas are being polluted by wastewater disposal resulting in large algae

blooms, dying corals (reefs) and the decline in marine life. This all impacts on traditional food

resources, public health and the tourism industry. With most SIDS relaying on tourism for

economic growth, pristine marine environments are essential to attract tourists and getting them

to come back. Thus the promotion of suitable wastewater disposal facilities should be encourage

by governments.

.

8.5.1 Ocean and River Outfalls

Detrimental effects to the environment from areas that are sewered, with various degrees of

treatment, can be minimised by using good effluent disposal practices. Locations of ocean

outfalls ideally should be beyond the reef, in high circulation areas and below the thermocline. No

outfall disposal system in the region meets all these criteria while a few systems do meet some of

the criteria. All too often the outfall locations are chosen by treatment plant or pump station siting

opposed to the best outfall locations. These basic design criteria should be investigated for the

construction of any new system or the upgrading of an existing system to avoid problems

currently experienced by many SIDS. The regional organisation, SOPAC, has both the expertise

and equipment to implement outfall location investigations.

[SOPAC Technical Report 321 Burke]

[14]

The use of wetlands for wastewater is not used much in the Region with only PNG indicating its

use. Overseas, wetlands have proved to be an acceptable alterative to discharge of treated

wastewater. Wetlands may be either natural or artificial. There is be potential in the Region to

develop wetlands for the disposal of treated effluent.

8.5.2 Land Based

In the Region the Cook Islands, Niue, Samoa, Tonga, Tokelau, Tuvalu and Vanuatu exclusively

used land-based disposal of wastewater. Note that groundwater is the main water source for Niue

and Tonga hence protection from wastewater pollution is most important. All other countries use

this method as well especially in rural areas and on remote islands.

In the urban areas septic tanks are normally use to treat wastewater. If properly designed,

constructed and maintained, septic tank systems can treat wastewater adequately. However it is

the author's observation that too much effort goes into the sizing and construction of the septic

tank itself and very little effort goes into the design and installation of disposal systems for the

septic tank effluent (see Photo 5 where septic tank effluent is discharge into unsuitable soils in

Suva). In most low island cases the effluent from the septic tanks is discharged into a "soakage"

pit giving more or less direct access to the groundwater instead of using the soil as a filter to

further improve effluent quality. Infiltration drains may over come this problem but generally are

not implemented for digging a soakage pit is less of a task and cheaper then laying a drain.

Often when located in urban communities there is insufficient area available to construct

adequate effluent disposal systems. In this case the groundwater should not be used for

domestic use unless it is treated in some way.

Pollution of groundwater is common in the Region especially on crowded atolls due to ineffective

land based disposal methods. On Funafuti, Tuvalu, the groundwater is not used for domestic use

due to land based pollution from wastewater disposal. Groundwater reserve areas have been

created in Tarawa, Kiribati to protect groundwater lens resources, used for suppling populated

areas with water, from pollution. Both Tonga and Niue use the unpopulated areas of the islands

to supply freshwater from groundwater lenes. Increasing population growth in the Region is

creating pressure on reserve areas to be used for settlement and this may adversely affect the

groundwater quality.

With populated areas located on coastal margins, poor land based disposal methods still have

impacts on reef and lagoon areas with pollutants being conveyed by groundwater and surface

water flows. Hence any improvement to land based treatment and disposal methods would

benefit the Regions residents in many ways.

The use of composting toilets, currently being trialed in the region, has much potential to reduce

groundwater pollution, eliminate the need for "flushing" water, and the compost material

generated can be use to improve soil conditions (see case study two). Photo 6 shows the

construction of a composting toilet in Fiji while Diagram 4 shown the type of composting toilet

used in Kiritimati, Kiribati.

8.6 Policy and Institutional Framework (Topic f)

There is a general lack of effective policy, regulation and institutional structure within the region's

water sector. Also more emphases is placed on providing safe water to households than the

disposal of wastewater, and the protection of the environment. Stormwater disposal is given even

less attention regarding policy and regulations.

[SOPAC Technical Report 321 Burke]

[15]

8.6.1 Regulatory Framework

In the old American associated SIDS, where wastewater disposal is generally regulated by the

Environmental Protection Agencies (EPA) established in each country or state. EPA standards

are normally very strict requiring resources that are not available in most SIDS to ensure

compliance. This works satisfactorily in Guam and American Samoa. In other countries/states

regulations exist, but there are little or no resources allocated to monitor and enforce regulation

compliance. Hence the environment continues to suffer at the expense of wastewater disposal.

Health Departments in some SIDS monitor groundwater and surface waters for pollution but

again they have little authority and resources to act accordingly. Many countries in the Region

have neither regulations nor standards regarding the discharge of wastes into the environment.

Building code standards for septic tank sizing and construction exist throughout the Region, but

this do not guarantee an adequate discharge quality. Little attention is given to the disposal of

septic tank effluent into the ground, which is a common source of groundwater pollution.

8.6.2 Institutional Arrangement

National management of water sector activities within the region is generally very fragmented

with many ministries, government departments, boards, authorities and utilities responsible for an

array of activities. Table 4 below indicates the responsible agencies for the disposal of

wastewater for urban areas in the Region. Note that rural areas and outer islands usually come

under national health departments for providing assistance in sanitation issues.

Table 4. Agencies responsible for wastewater disposal.

Country/State

Wastewater Discharges

Monitoring and Standards

American Samoa

American Samoa Power Authority

EPA monitoring and standards

Cook Islands

Individuals

No monitoring or standards

Kosrae, FSM

Dept. of Transportation & Utility

No monitoring; US EPA standards

Pohnpei, FSM

Pohnpei Utilities Corporation

EPA monitoring and standards

Chuuk, FSM

Chuuk Public Utilities Corporation

EPA monitoring and standards

Yap, FSM

Yap State Public Services Corp

EPA monitoring and standards

Palau

Ministry of Natural Resources &

Development

Fiji

Ministry of Communication, Works and

Ministry of Environment; no standards

Energy

Guam

Guam Water Works Authority

EPA monitoring and standards

Kiribati

Public Utilities Board

No monitoring or standards

Nauru

Nauru Phosphate Company

No monitoring or standards

New Caledonia

ND

ND

Niue

Individuals

No monitoring or standards

Mariana Islands

Commonwealth Utilities Corp.

EPA?

Papua New Guinea The Water Board plus private

Royal Commission Standards

companies

Marshall Islands

Majuro Water & Sewer Company

EPA monitoring and standards

Solomon Islands

Solomon Islands Water Board

No monitoring or standards

Tokelau

Individuals

No monitoring or standards

[SOPAC Technical Report 321 Burke]

[16]

Tonga

Individuals

Health Dept. monitors groundwater

Tvualu

Individuals

No monitoring or standards

Vanuatu

Individuals

Western Samoa

Samoa Water Board

No monitoring or standards

Schychells

Public Utilities Corporation

Ministry of Environment &

Transportation monitor pollution

Individuals = responsible for provide own disposals facilities ND = No Data

8.6.3 Policy Framework

Most government polices are general, stating that everyone should have access to safe water

and sanitation facilities plus the importance of a healthy environment. However with limited

monetary and human resources, most countries relay on bilateral support in the development of

national master plans. Often these master plans suggest policy and legislation changes and

additions to enable the implementation of sound wastewater disposal practices. Also loaning

agencies, like the Asian Development Bank, may put conditions on loans to encourage

sustainable sanitation development.

Governments must provide the framework, through policy and legislation, to allow its

implementing bodies (ie government departments, utilities, boards or authorities) to be able to

operate efficiently. The results would be better disposal systems, healthier people and a cleaner

environment. This can be difficult for promoting polices like "user pays", that would provide the

resources to improved wastewater disposal methods and the environment, would be very

unpopular with both the public and politicians.

8.7 Training (Topic g)

Regionally there is a lack of adequately trained national personnel within the water sector at all

levels. Many utilities still rely on expatriates to plan, operate and maintain water sector systems

and project developments.

Most utilities have some sort of in-house training for trades personnel. Treatment plant operators

are often trained overseas through both utility and bilateral funding. The American Samoan utility

provides training to other American associated SIDS using its own staff. Buddy systems have

been established where personnel are exchanged to learn from each other's utilities. This

system has appeared to work well.

Water sector engineers and planners are generally educated overseas on bilateral scholarships.

The University of Lae in PNG has a school of engineering and has produced water sector

engineers that currently still practice in the Region. However many trained national engineers and

planners have left the Region in pursuit of higher compensating employment in New Zealand,

Australia and the USA. Hence it is not only training but the retention of trained personnel that has

been an on going problem in the Region.

In past years PNG has had the facilities to provide water sector training. However these facilities

are now not Regionally utilisation to its potential.

The University of the South Pacific located in Fiji and the University of Guam contributes to the

Regions human resources development. Both universities run environment programs but neither

have specific water sector engineering programs. Guam University does have a Water &

Environment Research Institute.

[SOPAC Technical Report 321 Burke]

[17]

Often decision makers make discussions that are outside their field of expertise because they are

put in position as being the best person available.

Regional organisations like SOPAC, SPREP and SPC have provided water sector training

opportunities and short term expertise to the member countries. The Water Resources Unit at

SOPAC currently tries to coordinate Regional water sector activities and develop donor funded

programs and projects. SPREP also runs programs to assist in waste management. Regional

workshop like that ran by SOPAC on Appropriate and Affordable Sanitation for Small Islands

bring together and expose local practitioners to current sanitation ideas.

The newly formed Pacific Water and Wastewater Association (PWA) potentially will be able to

assist with training activities. It gives utilities an opportunity to discuss comment problems that

may have been solved by another utility in the Region.

UN originations like UNEP, UNDP, WHO, UNESCO and ESCAP are all potential sources for

Regional training opportunities and have already contributed much to human resources

development in the Region.

Not only is more and better training required in the region but better incentives by utilities and

governments to retain qualified personnel.

8.8 Public Education (Topic h)

Regionally very little effort is put into educating the public about the disposal of wastewater. It's

one of those subjects that Pacific residents do not like to hear about and utilities do not like to talk

about. Never the less public education and awareness is a very useful tool in promoting good

health and hygiene practices as well as the adverse impacts on the environment related to

wastewater disposal.

Utilities in Yap (FSM), American Samoa and in PNG have indicated that they undertake public

education through awareness campaigns, public meetings, printed materials and the radio. The

Solomon Island Water Authority (SIWA) has a very active Public Relations section but its main

focus is in providing freshwater to customers.

When trying to introduce a new technology like composting toilets or when promoting new or

upgraded projects, the public must be informed to gain their confidence and support.

8.9 Financing (Topic i)

Paying for the collection, treatment and disposal of wastewater is generally expensive in the

Region. None of the utilities in the region even recover their costs in providing a wastewater

disposal service. Hence this is a major problem in providing a service that protects public health

and is friendly to the environment.

Most utilities in the region, charge for wastewater services on the basis of the amount of

freshwater supplied to each connection. A few utilities do not specifically charge for wastewater

services. In all regional utilities the wastewater services are subsidised by either or their water

and electricity charges. No where in the region does wastewater charges cover the costs of

providing the service.

In Fiji and Kosrae (FSM), and maybe other SIDS, respective governments subsidise wastewater

disposal. The Nauru Phosphate Company pays for wastewater disposal costs in Nauru.

[SOPAC Technical Report 321 Burke]

[18]

At least six Pacific SIDS do not have any sanitation services provided, thus there are no charges.

Individual households and businesses are responsible for providing and maintaining their own

disposal systems in these countries.

In most countries where wastewater systems exist, governments initially were responsible for

providing the infrastructure and then turned them over to boards, authorities or companies to run.

Generally governments still maintain some control or interest in the utilities especially regarding

charging.

Finance for major projects and master plans are still normally channelled through governments to

either guarantee loans and/or negotiate bilateral funding. The Asian Development Bank has

prepared many Technical Assistance wastewater studies in the Region and has loaned money to

implement projects.

8.10 Information Sources (Topic j)

The following are contacts for various national, regional and UN agencies that are involved with

the water sector in the Pacific Region: (Note that some Indian Ocean SIDS are given as well)

American Samoa Power Authority (ASPA)

P O Box PPB

Pago Pago 96799

American Samoa

Telephone

: 684 644 2772

Fax

: 684 644 1337/5005

Email

: sewer@satala.aspower.com

Contact

: Chief Excitative Officer

Topics covered: a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i

Description

: A public utility that plans, develops and provides electricity,

water and wastewater services to the people American

Samoa.

Format of information

: Report, regulations, polices, guidelines, project funding, public

relations

Internet

: None

Language

: English

Consulting or support services : In house and regional training programs.

Appropriate Technology Enterprises, Inc.

PO Box 607

Chuuk

Federated States of Micronesia

Telephone

: 691 330 3000

Fax

: 691 330 2633

Email

: swinter@mail.fm

Contact

: Dr Stephen J Winter

Topics covered: c, d, e, g, h

Description

: Private consultant who has much practical experience (former

Director of WERI in Guam) in small island water issues and

[SOPAC Technical Report 321 Burke]

[19]

may provide information on the water sector within the

Federated States on Micronesia.

Format of information

: Reports

Internet

: NA

Language

: English

Consulting or support services : May provide technical advice.

Asian Development Bank (ADB)

P O Box 789

Manila

Phillippines

Telephone

: 632 632 6835

Fax

: 632 636 2445

Email

: NA

Contact

: Manager Pacific Region

Topics covered: a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i

Description

: Regional development bank that can provide information,

technical assistance and finance on the water sector activities

for Pacific SIDS

Format of information

: Reports

Internet

: www.asiandevbank.org.mainpage.asp

Language

: English

Consulting or support services : Regional data collection and technical assistance leading to

possible ADB finance of water sector projects.

Caledonienne Des Eaux

15 rue Jean Chalier P K 4 BP 812

98845 Noumea Cedex

Nouvelle

Caledonie

Telephone

: 687 282 040

Fax

: 687 278 128

Email

: NA

Contact

: Philippe de Greslan

Topics covered: a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i

Description

: A public utility that provides water supply services to the

people on the New Caledonia.

Format of information

: Reports, regulations

Internet

: None

Language

: French

Consulting or support services : In house training

Central Water Authority

Head Office

St. Paul

Mauritius

Telephone

: 230 686 5071

Fax

: 230 686 6264

Email

: NA

[SOPAC Technical Report 321 Burke]

[20]

Contact

: Director

Topics covered: a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i

Description

: A public utility that provides water and wastewater services to

the people on the Mauntius.

Format of information

: Reports, regulations, project funding

Internet

: http://nub.intnet.mu/mpu/wwa

Language

: English

Consulting or support services : In house training

Chuuk Public Utilities Corporation

Box 1507

Wono

Chuuk 96942

Telephone

: 691 330 2400

Fax

: 691 330 3259

Email

: NA

Contact

: General Manager

Topics covered: a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i

Description

: A public utility that plans, develops and provides electricity,

water and wastewater services to the people Chuuk.

Format of information

: Report, regulations, polices, guidelines

Internet

: None

Language

: English

Consulting or support services : In house training

Department of Resources & Development

PO Box 12

Palikir

Pohnpei

Federated States of Micronesia

Telephone

: 691 3202620

Fax

: 691 3205854

Email

: NA

Contact

: Director

Topics covered: a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i

Description

: Government department that can provide water sector

information for the Federated States of Micronesia

Format of information

: Report, regulations, polices, project funding

Internet

: None

Language

: English

Consulting or support services : Project funding through regional and international

organisations

Department of Water Works Ministry or Works, Environment & Physical Planning

P O Box 102

Rarotonga

[SOPAC Technical Report 321 Burke]

[21]

Telephone

: 682 20034

Fax

: 682 21134

Email

: nbp@oyster.net.ck

Contact

: Director

Topics covered: a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i

Description

: Government department that provides water sector services to

the people of Rarotonga

Format of information

: Report, regulations, polices, project funding

Internet

: None

Language

: English

Consulting or support services : In house training

Guam Environmental Protection Agency - Water Pollution Control Program

Post Office Box 22439

GMF

Barrigada

Guam 96921

Telephone

: 671 472 9505

Fax

: 671 477 9402

Email

: NA

Contact

: The Manager

Topics covered: a, c, e, h, i

Description

: Government agency that regulates, set standards, monitors,

collects and enforces water sector performance in Guam

Format of information

: Reports, regulations, standards, guidelines

Internet

: NA

Language

: English

Consulting or support services : Monitoring of water and wastewater quality standards.

Guam Water Works Authority

P O Box 3010

Agana 96932

Telephone

: 671 647 7606/7826

Fax

: 671 649 0369

Email

: NA

Contact

: General Manger

Topics covered: a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i

Description

: A public utility that plans, develops and provides water and

wastewater services to the people Guam.

Format of information

: Report, regulations, polices, guidelines

Internet

: None

Language

: English

Consulting or support services : In house training

Majuro Water & Sewer Company

P O Box 1751

Majuro

[SOPAC Technical Report 321 Burke]

[22]

Marshall Islands 96960

Telephone

: 692 625 8934

Fax

: 692 625 3837

Email

: NA

Contact

: The Manager

Topics covered: a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i

Description

: A public utility that plans, develops and provides water and

wastewater services to the people Majuro.

Format of information

: Report, regulations, polices, project funding

Internet

: None

Language

: English

Consulting or support services : In house training

Maldives Water & Sanitation Authority

Ameenee Magu,

Machchangolhi

Male 20-04

Republic of Maldives

Telephone

: 960 317 568

Fax

: 960 317 569

Email

: NA

Contact

: Director

Topics covered: a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i

Description

: A public utility that provides water and wastewater services to

the people on the Maldives.

Format of information

: Report, regulations, standards, funding

Internet

: None

Language

: English

Consulting or support services : In house training

Marshall Islands Environmental Protection Authority

PO Box 1322

Majuro

Marshall Islands

Telephone

: 692 6253035

Fax

: 692 6255202

Email

: NA

Contact

: Mr Abe Hicking

Topics covered: a, g, h

Description

: Monitor and water quality testing of water supplies in the

Marshall Islands

Format of information

: Reports, regulations, standards

Internet

: None

Language

: English

Consulting or support services : Monitoring and water quality analyses

[SOPAC Technical Report 321 Burke]

[23]

Ministry of Health and Medical Services, Rural Water Supply and Sanitation Section

Ministry and Health and Medical Services

Honiara

Solomon Islands

Telephone

: 677 20830

Fax

: 677 20085

Email

: n/a

Contact

: Mr Robinson Figue

Topics covered: a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i

Description

: This section provides assistance to the rural areas of the

Solomons in developing sustainable water, sanitation and

health facilities as well as training locals in these areas.

Format of information

: Reports, manuals, and guidelines

Internet

: None

Language

: English

Consulting or support services : Training is all aspects of rural water and waste

Ministry of Natural Resources & Development

Division of Utility, Water & Sewer Branch

P O Box 100

Koror

Palau 96940

Telephone

: 680 488 2438

Fax

: 680 488 3380

Email

: NA

Contact

: Chief

Topics covered: a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i

Description

: A public utility that plans, develops and provides water and

wastewater services to the people Palau.

Format of information

: Reports, regulations, project funding

Internet

: None

Language

: English

Consulting or support services : In house training.

Ministry of Outer Island Development

Rarotonga

Cook Islands

Telephone

: 682 20321

Fax

: 682 24321

Email

: NA

Contact

: Mr Tenga Mana

Topics covered: a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i

Description

: A government department that provides a water and sanitation

service for the people who live on the outer islands in the

Cook Islands.

[SOPAC Technical Report 321 Burke]

[24]

Format of information

: Reports, guidelines, funding

Internet

: None

Language

: English

Consulting or support services : Provides water sector assistance

Pacific Water Association (PWA)

Naibati House

Goodenough Street

Suva

Fiji

Telephone

: 679 306 022

Fax

: 679 302 038

Email

: Ppa@is.com.fj

Contact

: Executive Director

Topics covered: a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i

Description

: Regional organisation consisting of most Pacific water sector

utilities plus suppliers, consultants and other interested in

promoting safe water supply and wastewater disposal

Format of information

: Reports, guidelines, regional data and information on member

utilities

Internet

: www/sopac.org.fj/wru/#PWA

Language

: English

Consulting or support services : Provides technical support and training for water sector

utilities

Pohnpei Utilities Corporation

P O Box C

Kolonia

Pohnpei

FSM 96941

Telephone

: 691 320 2374

Fax

: 691 320 2422

Email

: Puc@mail.fm

Contact

: General Manager

Topics covered: a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i

Description

: A public utility that plans, develops and provides electricity,

water and wastewater services to the people Pohnpei.

Format of information

: Report, regulations, polices, guidelines

Internet

: None

Language

: English

Consulting or support services : In house training

Public Utilities Board

P O Box 443

Betio

Tarawa

Kiribati

Telephone

: 686 262 92

Fax

: 686 26106

[SOPAC Technical Report 321 Burke]

[25]

Email

: NA

Contact

: Chief Executive Officer

Topics covered: a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i

Description

: A public utility that plans, develops and provides electricity,

water and wastewater services to the people Kiribati.

Format of information

: Report, regulations, polices, guidelines, project funding

Internet

: None

Language

: English

Consulting or support services : In house and regional training

Public Utilities Corporation (Water & Sewerage Division)

P O Box 34

Unity House, Victoria

Seychelles

Telephone

: 248 322 444

Fax

: 248 321 020

Email

: NA

Contact

: General Manager

Topics covered: a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i

Description

: A public utility that provides water and wastewater services to

the people on the Seychelles Islands

Format of information

: Reports, guidelines, regulations

Internet

: None

Language

: English

Consulting or support services : In house training

Public Works Department

Private Mail Bag

Funafuti

Tuvalu

Telephone

: 688 203 00

Fax

: 688 203 01

Email

: NA

Contact

: Director

Topics covered: a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i

Description

: Government department that can provide water and

wastewater services.

Format of information

: Reports, regulations, and guidelines.

Internet

: None

Language

: English

Consulting or support services : In house training.

Rural Water Supply Department

Private Mail Bag 001

Port Vila

Vanuatu

[SOPAC Technical Report 321 Burke]

[26]

Telephone

: 678 23179

Fax

: 678 25639

Email

: NA

Contact

: Mr Roy Matariki

Topics covered: b, c, e, f, g, h, i

Description

: Government department that assists rural communities with

the planning and implementation of water sector services.

Format of information

: Reports, guidelines

Internet

: None

Language

: English

Consulting or support services : Training and public education

Samoa Water Authority

P O Box 245

Apia

Samoa

Telephone

: 685 204 09

Fax

: 685 212 98

Email

: swalatu@samoa.net

Contact

: General Manager

Topics covered: a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i

Description

: A state owned utility that provides water and wastewater

services to the people of Samoa.

Format of information

: Report, standards, regulations, guidelines, project funding,

public relations

Internet

: None

Language

: English

Consulting or support services : In house and regional training

School of Pure and Applied Science

The University of South Pacific

P O Box 1168

Suva

Fiji

Telephone

: 679 313 900

Fax

: 679 302 548

Email

: Isalat@usp.ac.fj

Contact

: The Director

Topics covered: g, h

Description

: Regional educational organisation that can provide water

sector information

Format of information

:

Internet

: www.usp.ac.fj

Language

: English

Consulting or support services : Education and training

[SOPAC Technical Report 321 Burke]

[27]

Solomon Islands Water Authority (SIWA)

P O Box 1407

Honiara

Solomon Islands

Telephone

: 677 239 85

Fax

: 677 207 23

Email

: Dmakini@welkam.solomon.com.sb

Contact

: General Manager

Topics covered: a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i

Description

: A public utility that provides water and wastewater services to

the people on the Solomon Islands

Format of information

: Reports, regulations, public relations, funding

Internet

: None

Language

: English

Consulting or support services : In house and regional training

SOPAC Secretariat

Private Mail Bag

GPO Suva

Fiji

Telephone

: 679 381377

Fax

:

679 370040

Email

: alf@SOPAC.org.fj

Contact

: Director

Topics covered: a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i

Description

: Regional organisation that can provide water sector

information for most Pacific SIDS. A Water Unit exists at

SOPCA to provide technical support, guidance, training plus

actively seeks donor funding for water sector projects.

Format of information

: Reports, guidelines, standards, newsletters, training reports,

educational materials

Internet

: www.sopac.org.fj

Language

: English

Consulting or support services : Has resources to provide water sector support for all member

SIDS including data collection, technical services, training and

project proposal preparation.

South Pacific Community (SPC)

B P D5 98848

Noumea Cedex

New Caledonia

Telephone

: 687 260 000

Fax

: 687 263 818

Email

:

Contact

: Director

Topics covered: a, b, c, d, e, g, h, i

[SOPAC Technical Report 321 Burke]

[28]

Description

: A regional organisation that in the past provided sanitation

resources for Pacific SIDS. However there are no current

sanitation programs in operation.

Format of information

: Reports, guidelines

Internet

: www.spc,org.fj

Language

: English/French

Consulting or support services : Training

South Pacific Regional Environment Programme (SPREP)

PO Box 240

Apia

Samoa

Telephone

: 685 21929

Fax

: 685 20231

Email

: Sprep@talofa.net

Contact

: The Director

Topics covered: a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i

Description

: A regional organisation that has the resources to implement

wastewater and environmental programs to enhance the SIDS

environment of member countries.

Format of information

: Reports, guidelines, and newsletters

Internet

: http://www.sidsnet.org/pacific/sprep/whatsprep_.htm

Language

: English

Consulting or support services : May seek funding and implement programs.

The Water Board

P O Box 2779

Boroko

Port Moresby

Papua New Guinea

Telephone: 675 323 5700

Fax:

675 323 1453

Email:

NA

Contact:

Managing Director

Topics covered: a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i

Description

: Public utility that provides water and wastewater services to

the people of Papua New Guinea.

Format of information

: Reports, standards, regulations, funding

Internet

: None

Language

: English

Consulting or support services : In house and regional training

Tonga Water Board

P O Box 92

Nuku'alofa

Tonga

Telephone

: 676 232 99

Fax

: 676 235 18

[SOPAC Technical Report 321 Burke]

[29]

Email

: twbhelu@candw.to

Contact

: General Manager

Topics covered: a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i

Description

: A state owned utility that provides water and wastewater

services to the people of Tonga.

Format of information

: Reports, regulations, funding

Internet

: None

Language

: English

Consulting or support services : In house and regional training

UNELCO

B.P. 26

Port Vila

Vanuatu

Telephone

: 678 222 11

Fax

: 678 250 11

Email

: uncelco@uneclo.co.va

Contact

: Water Supply Manager

Topics covered: a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i

Description

: A private utility that provides water supply services to the

people of Port Vila, Vanuatu.

Format of information

: Reports, regulations, and standards.

Internet

: None

Language

: French/English

Consulting or support services : In house training.

United Nations Development Program (UNDP)

Private Mail Bag

Suva

Fiji

Telephone

: 679 312500

Fax

: 679 301718

Email

: webweaver@undp.org.fj

Contact

: Resident Representative

Topics covered: a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i

Description

: UN organisation that can provide information on the water

sector

Format of information

: Reports, and educational materials

Internet

: www.undp.org.fj

Language

: English

Consulting or support services : Have the resources to arrange water sector country projects.

Water and Energy Research Institute of the Western Pacific (WERI)

UOG Station

Mangilao

Guam

Telephone

: 671 7343132

[SOPAC Technical Report 321 Burke]

[30]

Fax

: 671 734-8890

Email

: lheitz@uog.edu

Contact

: The Director

Topics covered: a, c, d, e, g, h, i

Description

: Regional educational organisation part of the University of

Guam that can provide water sector information.

Format of information

: Reports, guidelines, educational materials, newsletters

Internet

: http://uog2.uog.edu/weri/index.htm

Language

: English

Consulting or support services : Technical and educational assistance

Water and Sewerage Division

C/- Ministry of Communication, Works & Energy

Private Mail Bag

Suva

Fiji

Telephone

: 679 384 111

Fax

: 679 383 013

Email

: NA

Contact

: The Director

Topics covered: a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i

Description

: Government department that provides water and wastewater

services to the people of Fiji.

Format of information

: Report, standards, regulations, guidelines, project funding

Internet

: None

Language

: English

Consulting or support services : In house and regional training

Water for Survival

PO Box 6208

Wellesley Street

Auckland

New Zealand

Telephone

: 64 9 5289759

Fax

: 64 9 5289759

Email

: johnwfs@clear.net.nz

Contact

: Mr John La Roche

Topics covered: c, d, e, f, g, h, i

Description

: Volunteer organisation that can provide water sector

information

Format of information

: Reports, newsletters

Internet

: None

Language

: English

Consulting or support services : May provide information and funding for small projects.

[SOPAC Technical Report 321 Burke]

[31]

Water Supply and Sanitation, Department of Health

PO Box 807

Waigani

Port Moresby

Papua New Guinea

Telephone

: 675 3248698

Fax

: 675 3250826

Email

: NA

Contact

: Mr Joel Kolam

Topics covered: a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i

Description

: Government department that provides sanitation assistance to

the rural communities of Papua New Guinea.

Format of information

: Reports, guidelines, general data

Internet

: None

Language

: English

Consulting or support services : Reports, collection on data, guidelines

Water Supply & Sanitation Division, Public Works Department

PO Box 38

Alofi

Niue

Telephone

: 683 4297

Fax

: 683 4223

Email

: waterworks@mail.gov.nu

Contact

: The Director

Topics covered: a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i

Description

: A government department that provides water and wastewater

services to the people of Niue.

Format of information

: Report, standards, regulations, guidelines, project funding

Internet

: None

Language

: English

Consulting or support services : In house training

World Health Organisation

P O Box 5898

Boroko

N.C.D

Papua New Guinea

Telephone

: 675 324 8698

Fax

: 675 325 0568

Email

: info@who.ch

Contact

: Regional Representative

Topics covered: a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i

Description

: UN organisation that may provide resources on public health

and how it effects water and wastewater.

Format of information

: Reports, standards, and newsletters.

Internet

: http://www.oms.ch/aboutwho/

[SOPAC Technical Report 321 Burke]

[32]

Language

: English

Consulting or support services : May provide resources with public health issues.

Yap State Public Service Corporation

P O Box 667

Colonia

Yap 96943

Telephone

: 691 350 4427

Fax

: 691 350 4518

Email

: Robwesterfield@mail.fm

Contact

: General Manager

Topics covered: a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i

Description

: A public utility that plans, develops and provides electricity,

water and wastewater services to the people Yap.

Format of information

: Report, regulations, polices, guidelines

Internet

: None

Language

: English

Consulting or support services : In house training

8.11 Case Studies (Topic k)

The following two case studies demonstrate the use of on-site deposal methods that are most

commonly used in the region as well as composting toilets that are currently being trialed. Both

studies were commissioned by SOPAC.

8.11.1 Case Study 1: Sanitation in the Federated States of Micronesia

by Dr Stephen Winter

Appropriate Technology Enterprises, Inc.

Chuuk, FSM

Introduction

In the 1970's the "benjo" represented the state of the art in sanitary facilities in Micronesia. There

were two types: over-water and over-land. The over-water benjo was the most conspicuous and

often desecrated an otherwise pristine beach. It consisted of a small enclosure (a privy) with a

hole in the floor elevated on poles over the intertidal zone. One would get to this facility by

negotiating various types of cat-walks (not always an easy task for the new comer!). At low tide,

the mess below these facilities was in plain view. At high tide, one was lucky if it got washed

away. The bay in Colonia, Yap, was affectionately called "Benjo Bay" because of the prevalence

of these facilities. Similar facilities could be found over rivers (even up-stream of bathing areas)

and in mangroves (where there is little or no movement of the water). The over-land benjo was

essentially an unimproved pit latrine --- little more than a hole in the ground with a house over it.