Water Pollution Control - A Guide to the Use of Water Quality Management

Principles

Edited by Richard Helmer and Ivanildo Hespanhol

Published on behalf of the United Nations Environment Programme, the Water Supply &

Sanitation Collaborative Council and the World Health Organization by E. & F. Spon

© 1997 WHO/UNEP

ISBN 0 419 22910 8

Chapter 3* - Technology Selection

* This chapter was prepared by S. Veenstra, G.J. Alaerts and M. Bijlsma

3.1 Integrating waste and water management

Economic growth in most of the world has been vigorous, especially in the so-called

newly industrialising countries. Nearly all new development activity creates stress on the

"pollution carrying capacity" of the environment. Many hydrological systems in

developing regions are, or are getting close to, being stressed beyond repair. Industrial

pollution, uncontrolled domestic discharges from urban areas, diffuse pollution from

agriculture and livestock rearing, and various alterations in land use or hydro-

infrastructure may all contribute to non-sustainable use of water resources, eventually

leading to negative impacts on the economic development of many countries or even

continents. Lowering of groundwater tables (e.g. Middle East, Mexico), irreversible

pollution of surface water and associated changes in public and environmental health

are typical manifestations of this kind of development.

Technology, particularly in terms of performance and available waste-water treatment

options, has developed in parallel with economic growth. However, technology cannot

be expected to solve each pollution problem. Typically, a wastewater treatment plant

transfers 1 m3 of wastewater into 1-2 litres of concentrated sludge. Wastewater treatment

systems are generally capital-intensive and require expensive, specialised operators.

Therefore, before selecting and investing in wastewater treatment technology it is always

preferable to investigate whether pollution can be minimised or prevented. For any

pollution control initiative an analysis of cost-effectiveness needs to be made and

compared with all conceivable alternatives. This chapter aims to provide guidance in the

technology selection process for urban planners and decision makers. From a planning

perspective, a number of questions need to be addressed before any choice is made:

· Is wastewater treatment a priority in protecting public or environmental health? Near

Wuhan, China, an activated sludge plant for municipal sewage was not financed by the

World Bank because the huge Yangtse River was able to absorb the present waste load.

The loan was used for energy conservation, air pollution mitigation measures (boilers,

furnaces) and for industrial waste(water) management. In Wakayama, Japan, drainage

was given a higher priority than sewerage because many urban areas were prone to

periodic flooding. The human waste is collected by vacuum trucks and processed into

dry fertiliser pellets. Public health is safeguarded just as effectively but the huge

investment that would have been required for sewerage (two to three times the cost of

the present approach) has been saved.

· Can pollution be minimised by recovery technologies or public awareness? South

Korea planned expansion of sewage treatment in Seoul and Pusan based on a linear

growth of present tap water consumption (from 120 l cap-1 d-1 to beyond 250 l cap-1 d-1).

Eventually, this extrapolation was found to be too costly. Funds were allocated for

promoting water saving within households; this allowed the eventual design of sewers

and treatment plants to be scaled down by half.

· Is treatment most feasible at centralised or decentralised facilities? Centralised

treatment is often devoted to the removal of common pollutants only and does not aim to

remove specific individual waste components. However, economies of scale render

centralised treatment cheap whereas decentralised treatment of separate waste streams

can be more specialised but economies of scale are lost. By enforcing land-use and

zoning regulations, or by separating or pre-treating industrial discharges before they

enter the municipal sewer, the overall treatment becomes substantially more effective.

· Can the intrinsic value of resources in domestic sewage be recovered by reuse?

Wastewater is a poorly valued resource. In many arid regions of the world, domestic and

industrial sewage only has to be "conditioned" and then it can be used in irrigation, in

industries as cooling and process water, or in aqua- or pisciculture (see Chapter 4).

Treatment costs are considerably reduced, pollution is minimised, and economic activity

and labour are generated. Unfortunately, many of these potential alternatives are still

poorly researched and insufficiently demonstrated as the most feasible.

Ultimately, for each pollution problem one strategy and technology are more appropriate

in terms of technical acceptability, economic affordability and social attractiveness. This

applies to developing, as well as to industrialising, countries. In developing countries,

where capital is scarce and poorly-skilled workers are abundant, solutions to wastewater

treatment should preferably be low-technology orientated. This commonly means that

the technology chosen is less mechanised and has a lower degree of automatic process

control, and that construction, operation and maintenance aim to involve locally available

personnel rather than imported mechanised components. Such technologies are rather

land and labour intensive, but capital and hardware extensive. However, the final

selection of treatment technology may be governed by the origin of the wastewater and

the treatment objectives (see Figure 3.2).

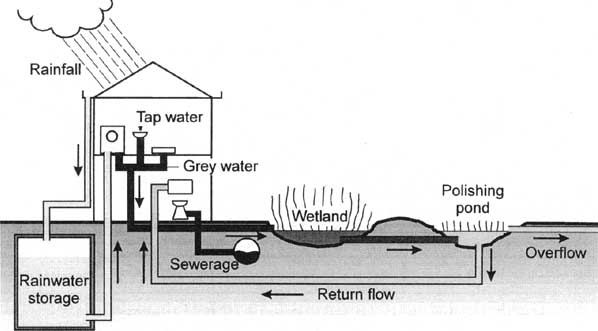

Figure 3.1 Origin and flows of wastewater in an urban environment

3.2 Wastewater origin, composition and significance

3.2.1 Wastewater flows

Municipal wastewater is typically generated from domestic and industrial sources and

may include urban run-off (Figure 3.1). Domestic wastewater is generated from

residential and commercial areas, including institutional and recreational facilities. In the

rural setting, industrial effluents and stormwater collection systems are less common

(although polluting industries sometimes find the rural environment attractive for

uncontrolled discharge of their wastes). In rural areas the wastewater problems are

usually associated with pathogen-carrying faecal matter. Industrial wastewater

commonly originates in designated development zones or, as in many developing

countries, from numerous small-scale industries within residential areas.

In combined sewerage, diffuse urban pollution arises primarily from street run-off and

from the overflow of "combined" sewers during heavy rainfall; in the rural context it

arises mainly from run-off from agricultural fields and carries pesticides, fertiliser and

suspended matter, as well as manure from livestock.

Table 3.1 Typical domestic water supply and wastewater production in industrial,

developing and (semi-) arid regions (l cap-1 d-1)

Water supply service

Industrial regions Developing regions (Semi-) arid regions

Handpump or well

na

<50

<25

Public standpost

na

50-80

20-40

House connection

100-150

50-125

40-80

Multiple connection

150-250

100-250

80-120

Average wastewater flow 85-200

65-125

35-75

na Not applicable

Within the household, tap water is used for a variety of purposes, such as washing,

bathing, cooking and the transport/flushing of wastes. Wastewater from the toilet is

termed "black" and the wastewater from the kitchen and bathroom is termed "grey".

They can be disposed of separately or they can be combined. Generally, the wealthier a

community, the more waste is disposed by water-flushing off-site. Such wastewater

disposal may become a public problem for downstream areas.

Domestic wastewater generation is commonly expressed in litres per capita per day (l

cap-1 d-1) or as a percentage of the specific water consumption rate. Domestic water

consumption, and hence wastewater production, typically depends on water supply

service level, climate and water availability (Table 3.1). In moderate climates and in

industrialising countries, 75 per cent of consumed tap water typically ends up as sewage.

In more arid regions this proportion may be less than 50 per cent due to high

evaporation and seepage losses and typical domestic water-use practices.

Industrial water demand and wastewater production are sector-specific. Industries may

require large volumes of water for cooling (power plants, steel mills, distillation

industries), processing (breweries, pulp and paper mills), cleaning (textile mills,

abattoirs), transporting products (beet and sugar mills) and flushing wastes. Depending

on the industrial process, the concentration and composition of the waste flows can vary

significantly. In particular, industrial wastewater may have a wide variety of micro-

contaminants which add to the complexity of wastewater treatment. The combined

treatment of many contaminants may result in reduced efficiency and high treatment unit

costs (US$ m-3).

Hourly, daily, weekly and seasonal flow and load fluctuations in industries (expressed as

m3 s-1 or m3 d-1 and as kg s-1 or kg d-1 of contaminant, respectively) can be quite

considerable, depending on in-plant procedures such as production shifts and workplace

cleaning. As a consequence, treatment plants are confronted with varying loading rates

which may reduce the removal efficiency of the processes. Removal of hazardous or

slowly-biodegradable contaminants requires a constant loading and operation of the

treatment plant in order to ensure process and performance stability. To accommodate

possible fluctuations, equalisation or buffer tanks are provided to even out peak flows.

Fluctuations in domestic sewage flow are usually repetitive, typically with two peak flows

(morning and evening), with the minimum flow at night.

Table 3.2 Major classes of municipal wastewater contaminants and their significance

and origin

Contaminant Significance

Origin

Settleable solids

Settleable solids may create sludge deposits and

Domestic, run-

(sand, grit)

anaerobic conditions in sewers, treatment facilities or

off

open water

Organic matter

Biological degradation consumes oxygen and may

Domestic,

(BOD); Kjeldahl-

disturb the oxygen balance of surface water; if the

industrial

nitrogen

oxygen in the water is exhausted anaerobic conditions,

odour formation, fish kills and ecological imbalance will

occur

Pathogenic

Severe public health risks through transmission of

Domestic

microorganisms

communicable water borne diseases such as cholera

Nutrients (N and P)

High levels of nitrogen and phosphorus in surface water Domestic, rural

will create excessive algal growth (eutrophication). Dying run-off,

algae contribute to organic matter (see above)

industrial

Micro-pollutants

Non-biodegradable compounds may be toxic,

Industrial, rural

(heavy metals,

carcinogenic or mutagenic at very low concentrations (to run-off

organic compounds) plants, animals, humans). Some may bioaccumulate in

(pesticides)

food chains, e.g. chromium (VI), cadmium, lead, most

pesticides and herbicides, and PCBs

Total dissolved solids High levels may restrict wastewater use for agricultural

Industrial, (salt

(salts)

irrigation or aquaculture

water intrusion)

Source: Metcalf and Eddy Inc., 1991

3.2.2 Wastewater composition

Wastewater can be characterised by its main contaminants (Table 3.2) which may have

negative impacts on the aqueous environment in which they are discharged. At the

same time, treatment systems are often specific, i.e. they are meant to remove one class

of contaminants and so their overall performance deteriorates in the presence of other

contaminants, such as from industrial effluents. In particular, oil, heavy metals, ammonia,

sulphide and toxic constituents may damage sewers (e.g. by corrosion) and reduce

treatment plant performance. Therefore, municipalities may set additional criteria for

accepting industrial waste flows into their sewers.

Table 3.3 Variation in the composition of domestic wastewater

Contaminant Specific

production Concentration1

(g cap-1 d-1)2

(mg l-1)2

Total dissolved solids

100-150

400-2,500

Total suspended solids

40-80

160-1,350

BOD 30-60

120-1,000

COD 70-150

280-2,500

Kjeldahl-nitrogen (as N)

8-12

30-200

Total phosphorus (as P)

1-3

4-50

Faecal coliform (No. per 100 ml) 106-109 4×106-1.7×107

BOD Biochemical oxygen demand

COD Chemical oxygen demand

1 Assuming water consumption rate of 60-250 l cap-1 d-1

2 Except for faecal coliforms

Contaminated sewage may be rendered unfit for any productive use. Several in-factory

treatment technologies allow selective removal of contaminants and their recovery to a

high degree and purity. Such recovery may cover part of the investment if it is applied to

concentrated waste streams. For example, in textile mills pigments and caustic solution

can be recovered by ultra-filtration and evaporation, while chromium (VI) can be

recovered by chemical precipitation in leather tanneries. In other situations, sewage can

be made suitable for irrigation or for reuse in industry.

Domestic waste production per capita is fairly constant but the concentration of the

contaminants varies with the amount of tap water consumed (Table 3.3). For example,

municipal sewage in Sana'a, Yemen (water consumption of 80 l cap-1 d-1), is four times

more concentrated in terms of chemical oxygen demand (COD) and total suspended

solids (TSS) than in Latin American cities (water consumption is around 300 l cap-1 d-1).

In addition, seepage or infiltration of groundwater may occur because the sewerage

system may not be watertight. Similarly, many sewers in urban areas collect overflows

from septic tanks which affects the sewage quality. Depending on local conditions and

habits (such as level of nutrition, staple food composition and kitchen habits) typical

waste parameters may need adjustment to these local conditions. Sewage composition

may also be fundamentally altered if industrial discharges are allowed into the municipal

sewerage system.

Figure 3.2 Treatment technology selection in relation to the origin of the

wastewater, its constituents and formulated treatment objectives as derived from

set discharge criteria

3.3 Wastewater management

3.3.1 Treatment objectives

Technology selection eventually depends upon wastewater characteristics and on the

treatment objectives as translated into desired effluent quality. The latter depends on the

expected use of the receiving waters. Effluent quality control is typically aimed at public

health protection (for recreation, irrigation, water supply), preservation of the oxygen

content in the water, prevention of eutrophication, prevention of sedimentation,

preventing toxic compounds from entering the water and food chains, and promotion of

water reuse (Figure 3.2). These water uses are translated into emission standards or, in

many countries, water quality "classes" which describe the desired quality of the

receiving water body (see also Chapter 2). Emission or effluent standards can be set

which may take into account the technical and financial feasibility of wastewater

treatment. In this way a treatment technology, or any other action, can be taken to

remove or prevent the discharge of the contaminants of concern. Standards or

guidelines may differ between countries. Table 3.4 gives some typical discharge

standards applied in many industrialised and developing countries, in relation to the

expected quality or use of the receiving waters.

3.3.2 Sanitation solutions for domestic sewage

The increasing world population tends to concentrate in urban communities. In densely

populated areas the sanitary collection, treatment and disposal of wastewater flows are

essential to control the transmission of waterborne diseases. They are also essential for

the prevention of non-reversible degradation of the urban environment itself and of the

aquatic systems that support the hydrological cycle, as well as for the protection of food

production and biodiversity in the region surrounding the urban area. For rural

populations, which still account for 75 per cent of the total population in developing

countries (WHO, 1992), concern for public health is the main justification for investing in

water and sanitation improvement. In both settings, the selected technologies should be

environmentally sustainable, appropriate to the local conditions, acceptable to the users,

and affordable to those who have to pay for them. Simple solutions that are easily

replicable, that allow further upgrading with subsequent development, and that can be

operated and maintained by the local community, are often considered the most

appropriate and cost-effective.

Table 3.4 Typical treated effluent standards as a function of the intended use of the

receiving waters

Variable

Discharge in

Discharge in water sensitive Effluent use in irrigation

surface water

to eutrophication

and aquaculture

High

Low

quality

quality

BOD (mg l-1) 20

50

10

1001

TSS (mg l-1) 20

50

10

<501

Kjeldahl-N (mg l-

10 -

5

-

1)

Total N (mg l-1) - -

10

-

Total P (mg l-1) 1 -

0.1

-

Faecal coliform

- -

-

<1,000

(No. per 100 ml)

Nematode eggs

- -

-

<1

per litre

SAR -

- -

<5

TDS (salts) (mg l-

- -

-

<5002

1)

- No standards set

BOD Biochemical oxygen demand

TSS Total suspended solids

SAR Sodium adsorption ratio

TDS Total dissolved solids

1 Agronomic norm

2 No restriction on crop selection

Sources: Ayers and Westcot, 1985; WHO, 1989

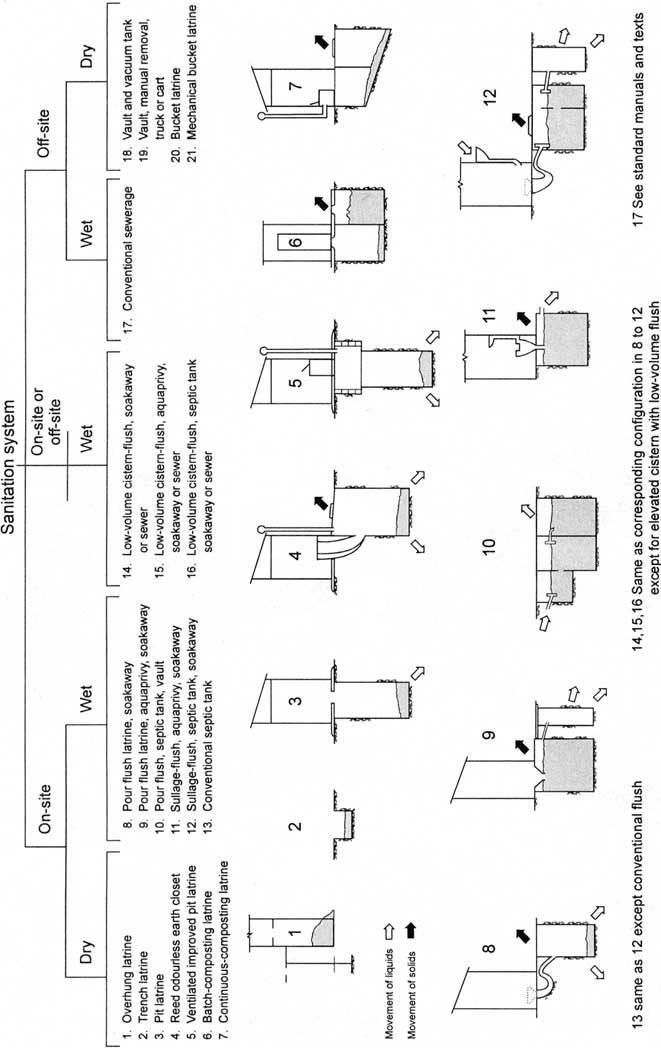

The first issue to be addressed is whether sanitary treatment and disposal should be

provided on-site (at the level of a household or apartment block) or whether collection

and centralised, off-site treatment is more appropriate. Irrespective of whether the

setting is urban or rural, the main deciding criteria are population density (people per

hectare) and generated wastewater flow (m3 ha-1 d-1) (Figure 3.3). Population density

determines the availability of land for on-site sanitation and strongly affects the unit cost

per household. Dry and wet sanitation systems can be distinguished by whether water is

required for flushing the solids and conveying them through a sewerage system. The

present trend for increasing tap water consumption (l cap-1 d-1) together with increasing

urban population densities, is creating a continuing interest in off-site sanitation as the

main future strategy for wastewater collection, treatment and disposal.

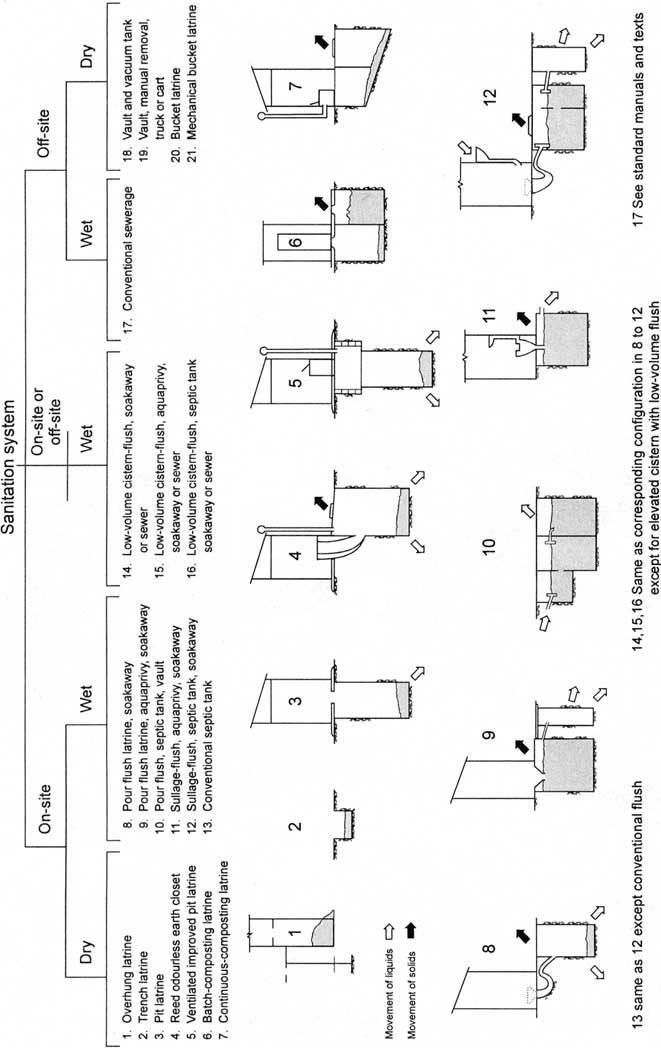

Figure 3.3 Classification of basic sanitation strategies. The trend of development

is from dry on-site to wet off-site sanitation (After Veenstra, 1996)

In wealthier urban situations, off-site solutions are often more appropriate because the

population density does not allow for percolation of large quantities of wastewater into

the soil. In addition, the associated risk of ground water pollution reported in many cities

in Africa and the Middle East is prohibitive for on-site sanitation. Frequently, towns and

city districts cannot afford such capital-intensive solutions due to the lower population

density per hectare and the resultant high unit costs involved. Depending on the local

physical and socio-economic circumstances, on-site sanitation may be feasible, although

if this is not satisfactory, intermediate technologies are available such as small bore

sewerage. The latter approach combines on-site collection of sewage in a septic tank

followed by off-site disposal of the settled effluent by small-bore sewers. The settled

solids accumulate in the septic tank and are periodically removed (desludged). The

advantage of this system is that the unit cost of small bore sewerage is much lower

(Sinnatamby et al., 1986).

3.3.3 Level of wastewater treatment

To achieve water quality targets an extensive infrastructure needs to be developed and

maintained. In order to get industries and domestic polluters to pay for the huge cost of

such infrastructure, legislation has to be set up based on the principle of "The Polluter

Pays". Treatment objectives and priorities in industrialised countries have been gradually

tightened over the past decades. This resulted in the so-called first, second and third

generation of treatment plants (Table 3.5). This step-by-step approach allowed for

determination of the "optimum" (desired) effluent quality and how it can be reached by

waste-water treatment, on the basis of full scale experience. As a consequence, existing

wastewater treatment plants have been continually expanding and upgrading; primary

treatment plants were extended with a secondary step, while secondary treatment plants

are now being completed with tertiary treatment phases.

Table 3.5 The phased expansion and upgrading of wastewater treatment plants in

industrialised countries to meet ever stricter effluent standards

Decade Treatment objective

Treatment Operations included

1950-

Suspended/coarse solids

Primary

Screening, removal of grit, sedimentation

60

removal

1970

Organic matter degradation

Secondary Biological oxidation of organic matter

1980 Nutrient

reduction

Tertiary

Reduction of total N and total P

(eutrophication)

1990

Micro-pollutant removal

Advanced Physicochemical removal of micro-

pollutants

In general, the number of available treatment technologies, and their combinations, is

nearly unlimited. Each pollution problem calls for its specific, optimal solution involving a

series of unit operations and processes (Table 3.6) put together in a flow diagram.

Primary treatment generally consists of physical processes involving mechanical

screening, grit removal and sedimentation which aim at removal of oil and fats,

settleable suspended and floating solids; simultaneously at least 30 per cent of

biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) and 25 per cent of Kjeldahl-N and total P are

removed. Faecal coliform numbers are reduced by one or two orders of magnitude only,

whereas five to six orders of magnitude are required to make it fit for agricultural reuse.

Secondary treatment mainly converts biodegradable organic matter (thereby reducing

BOD) and Kjeldahl-N to carbon dioxide, water and nitrates by means of microbiological

processes. These aerobic processes require oxygen which is usually supplied by

intensive mechanical aeration. For sewage with relatively elevated temperatures

anaerobic processes can also be applied. Here the organic matter is converted into a

mixture of methane and carbon dioxide (biogas).

Table 3.6 Classification of common wastewater treatment processes according to their

level of advancement

Primary Secondary Tertiary Advanced

Bar or bow screen

Activated sludge

Nitrification

Chemical treatment

Grit removal

Extended aeration

Denitrification

Reverse osmosis

Primary

Aerated lagoon

Chemical

Electrodialysis

sedimentation

precipitation

Comminution

Trickling filter

Disinfection

Carbon adsorption

Oil/fat removal

Rotating bio-discs

(Direct) filtration

Selective ion

exchange

Flow equalisation

Anaerobic

Chemical oxidation

Hyperfiltration

treatment/UASB

pH neutralisation

Anaerobic filter

Biological P removal Oxidation

Imhoff tank

Stabilisation ponds

Constructed wetlands Detoxification

Constructed

wetlands

Aquaculture

Aquaculture

UASB Upflow Anaerobic Sludge Blanket

In primary and secondary treatment, sludges are produced with a volume of less than

0.5 per cent of the wastewater flow. Heavy metals and other micro-pollutants tend to

accumulate in the sludge because they often adsorb onto suspended particles.

Nowadays, the problems associated with wastewater treatment in industrialised

countries have shifted gradually from the wastewater treatment itself towards treatment

and disposal of the generated sludges.

Non-mechanised wastewater treatment by stabilisation ponds, constructed wetlands or

aquaculture using macrophytes can, to a large extent, provide adequate secondary and

tertiary treatment. As the biological processes are not intensified by mechanical

equipment, large land areas are required to provide sufficient retention time to allow for a

high degree of contaminant removal.

Tertiary treatment is designed to remove the nutrients, total N (comprising Kjeldahl-N,

nitrate and nitrite) and total P (comprising particulate and soluble phosphorus) from the

secondary effluents. Additional suspended solids removal and BOD reduction is

achieved by these processes. The objective of tertiary treatment is mainly to reduce the

potential occurrence of eutrophication in sensitive, surface water bodies.

Advanced treatment processes are normally applied to industrial wastewater only, for

removal of specific contaminants. Advanced treatment is commonly preceded by

physicochemical coagulation and flocculation. Where a high quality effluent may be

required for reclamation of groundwater by recharge or for discharge to recreational

waters, advanced treatment steps may also be added to the conventional treatment

plant.

Table 3.7 reviews the degree to which contaminants are removed by treatment

processes or operations. Most treatment processes are only truly efficient in the removal

of a small number of pollutants.

3.3.4 Best available technology

In taking precautionary or preventive end-of-pipe treatment measures, authorities may

by statute require the polluter, notably industry, to rely on the best available technology

(BAT), the best available technology not entailing excessive costs (BATNEEC), the best

environmental practices (BEP) and the best practical environmental option (BPEO) (see

also Chapter 5).

The best available technology is generally accessible technology, which is the most

effective in preventing or minimising pollution emissions. It can also refer to the most

recent treatment technology available. Assessing whether a certain technology is the

best available requires comparative technical assessment of the different treatment

processes, their facilities and their methods of operation which have been recently and

successfully applied for a prolonged period of time, at full scale.

The BATNEEC adds an explicit cost/benefit analysis to the notion of best available

technology. "Not entailing excessive cost" implies that the financial cost should not be

excessive in relation to the financial capability of the industrial sector concerned, and to

the discharge reductions or environmental protection envisaged.

The best environmental practices and the best practicable environmental options have a

wider scope. The BPEO requires identification of the least environmentally damaging

method for the discharge of pollutants, whereas a requirement for the use of treatment

processes must be based upon BATNEEC. Best practical environmental option policies

also require that the treatment measures avoid transferring pollution or pollutants, from

one medium to another (from water into sludge for example). Thus BPEO takes into

account the cross-media impacts of the technology selected to control pollution.

3.3.5 Selection criteria

The general criteria for technology selection comprise:

· Average, or typical, efficiency and performance of the technology. This is usually the

criterion considered to be best in comparative studies. The possibility that the technology

might remove other contaminants than those which were the prime target should also be

considered an advantage. Similarly, the pathways and fate of the removed pollutants

after treatment should be analysed, especially with regard to the disposal options for the

sludges in which the micro-pollutants tend to concentrate.

· Reliability of the technology. The process should, preferably, be stable and resilient

against shock loading, i.e. it should be able to continue operation and to produce an

acceptable effluent under unusual conditions. Therefore, the system must accommodate

the normal inflow variations, as well as infrequent, yet expected, more extreme

conditions. This pertains to the wastewater characteristics (e.g. occasional illegal

discharges, variations in flow and concentrations, high or low temperatures) as well as to

the operational conditions (e.g. power failure, pump failure, poor maintenance). During

the design phase, "what if scenarios should be considered. Once disturbed, the process

should be fairly easy to repair and to restart.

· Institutional manageability. In developing countries few governmental agencies are

adequately equipped for wastewater management. In order to plan, design, construct,

operate and maintain treatment plants, appropriate technical and managerial expertise

must be present. This could require the availability of a substantial number of engineers

with postgraduate education in wastewater engineering, access to a local network of

research for scientific support and problem solving, access to good quality laboratories,

and experience in management and cost recovery. In addition, all technologies

(including those thought "simple") require devoted and experienced operators and

technicians who must be generated through extensive education and training.

· Financial sustainability. The lower the financial costs, the more attractive the

technology. However, even a low cost option may not be financially sustainable,

because this is determined by the true availability of funds provided by the polluter. In

the case of domestic sanitation, the people must be willing and able to cover at least the

operation and maintenance cost of the total expenses. The ultimate goal should be full

cost recovery although, initially, this may need special financing schemes, such as

cross-subsidisation, revolving funds, and phased investment programmes.

· Application in reuse schemes. Resource recovery contributes to environmental as well

as to financial sustainability. It can include agricultural irrigation, aqua- and pisciculture,

industrial cooling and process water re-use, or low-quality applications such as toilet

flushing. The use of generated sludges can only be considered as crop fertilisers or for

reclamation if the micro-pollutant concentration is not prohibitive, or the health risks are

not acceptable.

· Regulatory determinants. Increasingly, regulations with respect to the desired water

quality of the receiving water are determined by what is considered to be technically and

financially feasible. The regulatory agency then imposes the use of specified, up-to-date

technology (BAT or BATNEEC) upon domestic or industrial dischargers, rather than

prescribing the required discharge standards.

Table 3.7 Percentage efficiency for potential contaminant removal of different processes

and operations used in wastewater treatment and reclamation

Varia Pri Acti Nitrif Denit Tri R Co Filt Car Am Sel Brea Re Ov Irri Infilt Chlo Oz

ble

mar vat icati rificati cki B ag. rati bon mo ecti k

ver erla gati ratio rinati on

or

y

ed on

on

ng C -

on ads nia ve point se nd on n-

on

e

cont trea slu

filt

Flo aft orpti stri ion chlor os flo

perc

amin tme dge

er

c.- er on ppi exc inati mo w

olati

ant

nt

(AS

Se AS

ng han on

sis

on

)

di

ge

m.1

BOD 25- >50 >50 25

>5 > >5 25- >50 25- >5 >50 >5 >50

25

50

0

5 0 50

50

0

0

0

COD 25- >50 >50 25

>5 >5 25- 25- 25 25- >5 >50 >5 >50

>5

50

0

0 50 50

50

0

0

0

TSS >50 >50 >50 25 >5 > >5 >5 >50

>50

>5 >50 >5 >50

0 5 0 0

0

0

0

NH3- 25 >50

>50 25-50

> 25 25- 25- >50 >50 >50 >5 >50 >5 >50

N

5

50 50

0

0

0

NO3- >50

25- 25

25-

N

50

50

Phos 25 25- >50 >50 >5 >5 >50 >5 >50 >5 >50

phor

50

0 0

0

0

us

Alkal 25-

25- >5 25-

inity

50

50 0

50

Oil

>50 >50 >50

25- 25- >50

>5 >50

arid

50

50

0

grea

se

Total >50

>50

25

>5 >50 >50

>50

>5 >50 >50 >5

colifo

0

0

0

rm

TDS

>5

0

Arse 25- 25- 25-

25- >5 25

nic

50 50 50

50 0

Bariu 25- 25

25- 25

m

50

50

Cad 25- >50 >50

25 2 >5 25- 25

25

miu

50

5- 0 50

m

5

0

Chro 25- >50 >50

25 > >5 25- 25-

miu

50

5 0 50 50

m

0

Cop 25- >50 >50

>5 > >5 25 25- >50

per 50

0

5 0

50

0

Fluor

25- 25

25-

ide

50

50

Iron 25- >50 >50

25- > >5 >5 >50

50

50 5 0 0

0

Lead >50 >50 >50

25- > >5 25 25- 25-

50 5 0

50

50

0

Man 25 25- 25-

25

25- >5 25- >5

gane

50 50

50 0

50

0

se

Merc 25 25 25

25 > 25 25- 25

ury

5

50

0

Sele 25 25 25

25 >5 25

nium

0

Silve >50 >50 >50

25- >5 25-

r

50

0

50

Zinc 25- 25- >50

>5 > >5 >50 >50

50 50

0

5 0

0

Colo 25 25- 25-

25

>5 25- >50 >5 >50 >5 >50

>5

ur

50 50

0 50

0

0

0

Foa 25- >50 >50

>5 25- >50 >5 >50 >5 >50

25

ming 50

0

50

0

0

agen

ts

Turbi 25- >50 >50 25

25- >5 >5 >50 >5 >50 >5 >50

dity 50

50

0 0

0

0

TOC 25- >50 >50 25

25- >5 25- >50 25 25

>5 >50 >5 >50

>5

50

50

0 50

0

0

0

The percentage relates to the influent concentration. Where no percentage efficiency is

indicated no data are available, the results are inconclusive or there is an increase.

1 Coagulation-Floculation-Sedimentation

RBC Rotating Biological Contactor (bio-disc)

BOD Biochemical oxygen demand

COD Chemical oxygen demand

TSS Total suspended solids

TDS Total dissolved solids

TOC Total organic carbon

Source: Metcalf and Eddy, 1991

3.4 Pollution prevention and minimisation

Although end-of-pipe approaches have reduced the direct release of some pollutants

into surface water, limitations have been encountered. For example, end-of-pipe

treatment transfers contaminants from the water phase into a sludge or gaseous phase.

After disposal of the sludge, migration from the disposed sludge into the soil and

groundwater may occur. Over the past years, there has been growing awareness that

many end-of-pipe solutions have not been as effective in improving the aquatic

environment as was expected. As a result, the approach is now shifting from "waste

management" to "pollution prevention and waste minimisation", which is also referred to

as "cleaner production".

Pollution prevention and waste minimisation covers an array of technical and non-

technical measures aiming at the prevention of the generation of waste and pollutants. It

is the conceptual approach to industrial production that demands that all phases of the

product life cycle should be addressed with the objective of preventing or minimising

short- and long-term risks to humans and the environment. This includes the product

design phase, the selection, production and preparation of raw materials, the production

and assembly of final products, and the management of all used products at the end of

their useful life. This approach will result in the generation of smaller quantities of waste

reducing end-of-pipe treatment and emission control technologies. Losses of material

and resources with the sewage are minimised and, therefore, the raw material is used

efficiently in the production process, generally resulting in substantial financial savings to

the factory.

In the past, pollution prevention and minimisation were an indirect, although beneficial,

result of the implementation of water conservation measures. Water demand

management aimed to conserve scarce water by reducing its consumption rates. This

was an important and relevant issue in the industrial, domestic and agricultural sector

because of the rapid growth in water demand in densely populated regions of the world.

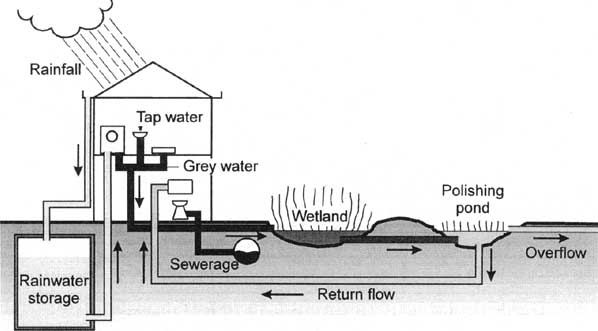

With regard to the generation of wastewater, pollution prevention and minimisation

technologies are mainly implemented in the industrial sector (Box 3.1). Minimisation of

wastewater from domestic sources is possible to a limited extent only and is mainly

achieved by the introduction of water-saving equipment for showers, toilet flushing and

gardening. In the Netherlands a new concept has been developed for residential areas

where the grey water fraction is used for toilet flushing after treatment by a constructed

wetland (Figure 3.4). In the agricultural sector, measures are directed primarily at water

conservation through the application of, for example, water-saving irrigation techniques.

Box 3.1 Examples of successful waste minimisation in industry

Example 1

Tanning is a chemical process which converts putrescible hides and skins into stable leather.

Vegetable, mineral and other tanning agents may be used (either separately or in combination) to

produce leather with different qualities and quantities. Trivalent chromium is the major tanning

agent, producing a modern, thin, light leather. Limits have been set for the discharge of the

chromium. Cleaner production technology was used to recover the trivalent chromium ion from

the spent liquors and to reuse it in the tanning process, thereby reducing the necessary end-of-

pipe treatment cost to remove chromium from the wastewater.

Tanning of hides is carried out with basic chromium sulphate, Cr(OH)SO4. The chromium

recovery process consists of collecting and treating the spent tanning solution after its use,

instead of simply wasting it. The spent liquor is sieved to remove particles and fibres. Through the

addition of magnesium oxide, the valuable chromium precipitates as a hydroxide sludge. By the

addition of concentrated sulphuric acid, this sludge dissolves and yields the chromium salt

(Cr(OH)SO4) solution that can be reused. Whereas in a conventional tanning process 20-40 per

cent of the used chrome is lost in the wastewater, in this waste minimisation process 95-98 per

cent of the waste chromium can be recycled.

This recovery technique was first developed and applied in a Greek tannery. The increased

yearly operating costs of about US$ 30,000 were more then compensated for by the yearly

chromium savings of about US$ 74,000. The capital investment of US$ 40,000 was returned in

only 11 months.

Example 2

Sulphur dyes are a preferred range of dyes in the textile industry, but cause a significant

wastewater problem. Sulphur dyes are water-insoluble compounds that first have to be converted

into a water-soluble form and then into a reduced form having an affinity for the fibre to be dyed.

The traditional method of converting the original dye to the affinity form is treatment with an

aqueous solution of sodium sulphide. The use of sodium sulphide results in high sulphide levels

in the textile plant wastewater which exceed the discharge criteria. Therefore, end-of-pipe

treatment technology is necessary.

To avoid capital expenditure for wastewater treatment, a study was undertaken in India of

available methods of sulphur black colour dyeing and into alternatives for sodium sulphide. An

alternative chemical for sodium sulphide was found in the form of hydrol, a by-product of the

maize starch industry. Only minor adaptations in the textile dyeing process were necessary. The

introduction of hydrol did not involve any capital expenditure and sulphide levels in the mill's

wastewater were reduced from 30 ppm to less than 2 ppm. The savings resulting from not having

to install additional end-of-pipe treatment to reduce sulphide level in the wastewater were about

US$ 20,000 in investment and US$ 3,000 a year in running costs.

Waste minimisation involves not only technology but also planning, good housekeeping,

and implementation of environmentally sound management practices. Many obstacles

prevent the introduction of these new concepts in existing or even in new facilities, such

as insufficient awareness of the environmental effects of the production process, lack of

understanding of the true costs of waste management, no access to technical advice,

insufficient knowledge of the implementation of new technologies, lack of financial

resources and, last but not least, social resistance to change.

Figure 3.4 Potential reuse of grey water for toilet flushing after treatment by a

constructed wetland (Based on van Dinther, 1995)

In the past, the requirements of most regulatory agencies have centred on treatment and

control of industrial liquid wastes prior to discharge into municipal sewers or surface

waters. As a result, over the last 20 years the number of industries emitting pollutants

directly into aquatic environments reduced substantially. However, most of the

implemented environmental protection measures consisted of end-of-pipe treatment

technologies, with the "end" located either inside the factory or industrial zone, or at the

entry of the municipal sewage treatment plant. As a consequence the industry pays for

its share in the cost of sewer maintenance and treatment operation. In both cases, the

industry should be charged for the treatment and management effort that has to take

place outside the factory, in particular in the municipal treatment works. This charge

should be made up of the true, overall treatment cost. By this principle, industries are

specifically encouraged:

· To prevent waste production by Interfering in the production process.

· To reduce the occurrence of hydraulic or organic peak loads that may render a

municipal treatment system more expensive or vulnerable.

· To treat their waste flows to meet discharge requirements, to prevent damage to the

municipal sewer or to realise cost savings for municipal treatment.

Table 3.8 Typical regulations for industrial wastewater discharge into a public sewer

system in the United Kingdom, Hungary and The Netherlands

Variable UK

Hungary Netherlands

pH 6-10

6.5-10

6.5-10

Temperature (°C)

<40

nrs

<30

Suspended solids (mg l-1) <400 nrs

_1

Heavy metals (mg l-1) <10 specific

_1

Cadmium (mg l-1) <100

<10,000 _1

Total cyanide (mg l-1) <2 <1 _1

Sulphate (mg l-1) <1,000

<400

<300

Oil and grease (mg l-1) <100 <60 _1

nrs No regulations set

1 No coarse, explosive or inflammable solids are allowed. Contaminants that might

interfere with biological treatment should be in concentrations that do not differ from

domestic sewage

Sources: UN ECE, 1984; Appleyard, 1992

Table 3.8 provides examples of discharge criteria into municipal sewers. A method to

calculate pollution charges into sewers or the environment is provided in Box 3.2.

3.5 Sewage conveyance

3.5.1 Storm water drainage

In many developing countries, stormwater drainage should be part of wastewater

management because large sewage flows are carried into open storm water drains or

because stormwater may enter treatment works with combined sewerage. In

industrialised countries, stormwater drainage receives great attention because it may be

polluted by sediments, oils and heavy metals which may upset the subsequent

secondary and tertiary treatment steps.

In urbanised areas, the local infiltration capacity of the soil is not sufficient usually to

absorb peak discharges of storm water. Large flows often have to be transported in short

periods (20-100 minutes) over long distances (500-5,000 m). Drainage cost is

determined, to a large extent, by the actual flow rate of the moment and, therefore,

retention in reservoirs to dampen peak flows allows the use of smaller conduits, thereby

reducing drainage cost per surface area. In tropical countries, peak flow reduction by

infiltration may not be feasible because the peak flows can by far exceed the local

infiltration capacities.

Box 3.2 Calculation of pollution charges based on "population equivalents"

Calculation of the financial charges for industrial pollution in the Netherlands is based on standard

population equivalents (pe):

where Q

= wastewater flow rate (m3 d-1)

COD = 24 h-flow proportional COD concentration (mg COD l-1)

TKN = 24 h-flow proportional Kjeldahl-N concentration (mg N l-1)

136 = waste load of one domestic polluter (136 g O2-consuming substances per day)

and by definition set at one population equivalent.

Heavy metal discharges are charged separately:

· Each 100 g Hg or Cd per day are equivalent to l pe.

· Each 1 kg of total other metal per day (As, Cr, Cu, Pb, Ni, Ag, Zn) is equivalent to 1 pe.

An annual charge of US$ 25-50 (1994) is levied per population equivalent by the local Water

Pollution Control Board; the charge is region specific and relates to the Board's overall annual

expenses.

3.5.2 Separate and combined sewerage

In separate conveyance systems, storm water and sewage are conveyed in separate

drains and sanitary sewers, respectively. Combined sewerage systems carry sewage

and storm water in the same conduit. Sanitary and combined sewers are closed in order

to reduce public health risks. Separate systems require investment in, and operation and

maintenance of, two networks. However, they allow the design of the sanitary sewer and

the treatment plant to account for low peak flows. In addition, a more constant and

concentrated sewage is fed to the treatment plant which favours reliable and consistent

process performance. Therefore, even in countries with moderate climate where the

rainfall pattern would favour combined sewerage (rainfall well distributed over the year

and with limited peak flows) newly developed residential areas are provided, increasingly,

with separate sewerage. Combined sewerage is generally less suitable for developing

countries because:

· Sewerage and treatment are comparatively expensive, especially in regions with high

rain intensity during short periods of the year.

· It requires simultaneous investment for drainage, sewerage and treatment.

· There is commonly a lack of erosion control in unpaved areas.

Combined sewerage is most appropriate for more industrialised regions with a phased

urban development, with an even rainfall distribution pattern over the year and with soil

erosion control by road surface paving. The advantage of combined sewerage is that the

first part of the run-off surge, which tends to be heavily polluted, is treated along with the

sewage. The sewage treatment plants have to be designed to accommodate, typically,

two to five times the average dry weather flow rate, which raises the cost and adds to

the complexity of process control. The disadvantage of the combined sewer is that

extreme peak flows cannot be handled and overflows are discharged to surface water,

which gets contaminated with diluted sewage. These overflows can create serious local

water quality problems.

Sanitary sewers are feasible only in densely populated areas because the unit cost per

household decreases. Although most street sewers carry only small amounts of sewage,

the construction cost is high because they require a minimum depth in order to protect

them against traffic loads (minimum soil cover of 1 m), a minimum slope to ensure

resuspension and hydraulic flushing of sediment to the end of the sewer, and a minimum

diameter to prevent blockage by faecal matter and other solids (preferably 25 cm

diameter). The required flushing velocity (a minimum of 0.6 m s-1 at least once a day)

occurs when tap water consumption rates in the drainage area are in excess of 60 l cap-1

d-1.

To reduce costs, sewers may use smaller diameters, may be installed at less depth and

may apply a milder gradient. However, these measures require entrapment of settleable

solids in a septic tank prior to discharge into the sewer. Such small-bore sewers are only

cost-effective if they are maintained by the local community. This demands a high level

of sustained community participation. Small-bore sewers may, ultimately, discharge into

a municipal sanitary sewer or a treatment plant. Alternatively, in flat areas with unstable

soils and low population density, small-bore pressure or vacuum sewers can be applied,

but these are not considered a "low-cost" option.

Successful examples of low-cost small-bore sewerage are reported from Brazil,

Colombia, Egypt, Pakistan and Australia. At population densities in excess of 200

persons per hectare, these small-bore sewer systems tend to become more cost

effective than on-site sanitation. Companhia de Saneamento Basico do Estado de São

Paulo (SABESP, São Paulo, Brazil) estimates the average construction cost (1988) for

small towns to be US$ 150-300 per capita for conventional sewerage and US$ 80-150

per capita for simplified, small-bore sewerage (Bakalian, 1994). It is common in

developing countries for most plot owners not to desludge their septic tank or cess pit

regularly or adequately. Examples from Indonesia and India show that overflowing septic

tanks are sometimes illegally connected to public open drains or sewers, and that during

desludging operations often only the liquid is removed leaving the solids in the septic

tank. Therefore, the implementation of small-bore sewerage requires substantial

investment in community involvement to avoid the major failure of this technology.

3.6 Costs, operation and maintenance

Investment costs notably cover the cost of the land, groundwork, electromechanical

equipment and construction. Recurring costs relate mainly to the paying back of loans

(interest and principal), and to the costs for personnel, energy and other utilities, stores,

laboratories, repair and sludge disposal. Both types of cost may vary considerably from

country to country, as well as in time. Any financial feasibility analysis requires the use of

a discount factor. This factor depends on inflation and interest rates and is also subject

to substantial fluctuations. Therefore, comparing different technologies is always difficult

and requires extensive expert analysis. Nevertheless, Figure 3.5 offers typical

comparative cost levels (for industrialised countries) for primary, secondary and tertiary

treatment of domestic wastewater. Table 3.9 provides a comparison of the unit

construction costs for on-site and off-site sanitation for different world regions.

Operation and maintenance (O&M) is an essential part of wastewater management and

affects technology selection. Many wastewater treatment projects fail or perform poorly

after construction because of inadequate O&M. On an annual basis, the O&M

expenditures of treatment and sewage collection are typically in the same order of

magnitude as the depreciation on the capital investment. Operation and maintenance

requires:

· Careful exhaustive planning.

· Qualified and trained staff devoted to its assignment.

· An extensive and operational system providing spare parts and O&M utilities.

· A maintenance and repair schedule, crew and facility.

· A management atmosphere that aims at ensuring a reliable service with a minimum of

interruptions.

· A substantial annual budget that is uniquely devoted to O&M and service improvement.

Maintenance policy can be corrective, i.e. repair or action is undertaken when

breakdown is noticed, but this leads to service interruption and hence dissatisfied

customers. Ideally, maintenance is preventive, i.e. replacement of mechanical parts is

carried out at the end of their expected life time. This allows optimal budgeting and

maintenance schedules that have minimal impact on service quality. Clearly, O&M

requirements are important factors when selecting a technology; process design should

provide for optimal, but low cost, O&M.

Figure 3.5 Typical total unit costs for wastewater treatment based on experience

gained in Western Europe and the USA (After Somlyody, 1993)

Table 3.9 Typical unit construction cost (US$ cap-1) for domestic wastewater disposal in

different world regions (median values of national averages)

Region

Urban sewer connection Rural on-site sanitation

Africa 120

22

Americas 120

25

South-East Asia

152

11

Eastern Mediterranean

360

73

Western Pacific

600

39

Source: WHO, 1992

The most common reasons for O&M failure are inadequate budgets due to poor cost

recovery, poor planning of servicing and repair activities and weak spare parts

management, and inadequately trained operational staff.

3.7 Selection of technology

The technology selection process results from a multi-criteria optimisation considering

technological, logistic, environmental, financial and institutional factors within a planning

horizon of 10-20 years. Key factors are:

· The size of the community to be served (including the industrial equivalents).

· The characteristics of the sewer system (combined, separate, small-bore).

· The sources of wastewater (domestic, industrial, stormwater, infiltration).

· The future opportunities to minimise pollution loads.

· The discharge standards for treated effluents.

· The availability of local skills for design, construction and O&M.

· Environmental conditions such as land availability, geography and climate.

Considerations for industrial technology selection tend to be relatively straightforward

because the factors interfering in selection are primarily related to anticipated

performance and extension potential. Both of these are associated directly with cost.

3.7.1 On-site sanitation technologies

For domestic wastewater the suitability of various sanitation technologies must be

related appropriately to the type of community, i.e. rural, small town or urban (Table

3.10). Typically, in low-income rural and (peri-)urban areas, on-site sanitation systems

are most appropriate because:

· They are low-cost (due to the absence of sewerage requirements).

· They allow construction, repair and operation by the local community or plot owner.

· They reduce, effectively, the most pressing public health problems.

Moreover, water consumption levels often are too low to justify conventional sewerage.

With on-site sanitation, black toilet water is disposed in pit latrines, soak-aways or septic

tanks (Figure 3.6) and the effluent infiltrates into the soil or overflows into a drainage

system. Grey water can infiltrate directly, or can flow into drainage channels or gullies,

because its suspended solids and pathogen contents are low. The solids that

accumulate in the pit or tank (approximately 40 l cap-1 a-1) have to be removed

periodically or a new pit has to be dug (dual-pit latrine). Depending on the system, the

sludge may or may not be well stabilised. At the minimum solids retention time of six

months the sludge may be considered to be pathogen-free and it can be used in

agriculture as fertiliser or as a soil conditioner. Digestion of the full sludge content for

several months can be carried out if a second, parallel pit is used while the first is

digesting.

Table 3.10 Typical sanitation options for rural areas, small townships and urban

residential areas

Rural area

Township

Urban area

Community

<10,000 pe

10,000-50,000 pe

>50,000 pe

size

Density

<100 >100-<200

>200

(persons per

hectare)

Water supply

Well, handpump

Public standpost

House connection

service

Water

<50 l cap-1 d-1

50-100 l cap-1 d-1

>100 l cap-1 d-1

consumption

Sewage

<5 m3 ha-1 d-1 5-20

m3 ha-1 d-1 >20

m3 ha-1 d-1

production

Treatment

Dry on-site

Dry and wet on-site

Centre: Sewerage plus off-site

options

sanitation by VIP sanitation; small-bore

treatment. Peri-urban: wet on-

or composting

sewerage may be feasible

site sanitation with small-bore

latrines

depending on population

sewerage and septage

density and soil conditions

handling

VIP Ventilated Improved Pit latrine

The accumulating waste (septage) in septic tanks must be regularly collected and

disposed of. After drying and dewatering in lagoons or on drying beds it can be disposed

at a landfill site, or it can be co-composted with domestic refuse. Reuse in agriculture is

only feasible following adequate pathogen removal and provided the septage is not

contaminated with heavy metals. Alternatively, the septage can be disposed of in a

sewage treatment plant, or it can be stabilised and rendered pathogen-free by adding

lime (until the pH>10) or by extended aeration. The latter two methods, however, are

expensive.

3.7.2 On-site versus off-site options

In densely populated urban areas the generation of wastewater may exceed the local

infiltration capacity. In addition, the risk of groundwater pollution and soil destabilisation

often necessitates off-site sewerage. At hydraulic loading rates greater than 50 mm d-1

and less than 2 m unsaturated ground-water flow, nitrate and, in a later stage, faecal

coliform contamination may occur (Lewis et al., 1980).

The unit cost for off-site sanitation decreases significantly with increasing population

density, but sewering an entire city often proves to be very expensive. In cities where

urban planning is uncoordinated, implementation of a balanced mix of on-site and off-

site sanitation is most cost-effective. For example, in Latin America the population

density at which small-bore sewerage becomes competitive with on-site sanitation is

approximately 200 persons per hectare (Sinnatamby et al., 1986). The deciding factor in

these cost calculations is the cost of the collection and conveyance system.

Figure 3.6 Classification of sanitation systems as on-site and off-site (based on

population density) and as dry and wet sanitation (based on water supply) (After

Kalbermatten et al., 1980)

Box 3.3 provides guidance for preliminary decision-making with respect to on- or off-site

sanitation. In situations where there is a high wastewater production per hectare per day,

sewerage is needed to transport either the liquids alone (in the case of small-bore

sewerage) or the liquid plus suspended solids (in the case of conventional sewerage).

Additional decisive parameters are whether shallow wells used for water supplies need

to be protected, the population density, the soil permeability and the unit cost. To

minimise groundwater contamination, a typical surface loading rate of 10 m3 ha-1 d-1 is

recommended (Lewis et al., 1980), provided that prevailing groundwater tables ensure at

least 2 m unsaturated flow in a vertical direction.

When the wastewater production rate is in excess of 10 m3 ha-1 d-1, conventional sanitary

sewerage may be feasible for managing municipal sewage, with or without the inclusion

of storm water. Studies indicate that at 200-300 persons per hectare, gravity sewerage

becomes economically feasible in developing countries; in industrialised countries the

equivalent population density is about 50 persons per hectare.

If groundwater protection is not required, the infiltration rate may exceed 10 m3 ha-1 d-1,

provided the soil permeability and stability allow it. If soil permeability is low, off-site

sanitation needs consideration. Depending on the socio-economic environment and the

degree of community involvement that can be generated, small-bore sewerage may be

feasible. In such cases additional stormwater drainage facilities must be provided.

In addition to technical, logistic and financial criteria, reliable management by a local

village-based entity or local government is essential for sustainable functioning of the

system. Most off-site treatment technologies benefit from economies of scale although

anaerobic technologies tend to scale down easily to township or local level without the

unit cost rising seriously. This makes anaerobic technologies suitable for inclusion in

urban sanitation at community level (Alaerts et al., 1990). This "community on-site"

option can stimulate more disciplined operation and desludging when compared with the

often poor performance of individual units. At the same time, it retains the advantage

that it can be managed by a local committee and semi-skilled caretakers.

3.7.3 Off-site centralised treatment technologies

There is a large variety of off-site treatment technologies. The selection of the most

appropriate technology is determined, first of all, by the composition of the wastewater

flow arriving at the treatment plant and also by the discharge requirements. Questions

for assessing the expected composition and behaviour of the sewage to be treated

include:

· To what extent is industrial wastewater included?

· Will sewerage be separate, combined or small-bore?

· Is groundwater expected to infiltrate into the sewer?

· Are septic tanks removing settleable solids prior to discharge into the conveyance

system?

· What is the specific water and food consumption pattern?

· What is the quality of the drinking water?

Box 3.3 Preliminary assessment for on-site sanitation, intermediate small-bore sewerage or

conventional off-site sewerage for domestic or municipal wastewater disposal

- Not valid

+ Valid

DWF Dry weather flow (m3 d-1)

Wastewater production

population density (pe ha-1) × specific wastewater

production (WPR) (l pe-1 d-1)

Local infiltration

infiltration area available (m2 ha-1) × long-term applicable

potential (LIP): infiltration rate (m3 m-2 d-1); LIP at least equal

to WPR

Groundwater at risk

This may occur if: depth of unsaturated zone is less than 2

m, the hydraulic load exceeds 50 mm d-1, or shallow wells

for potable supplies exist within a distance (in metres) of 10

times the horizontal groundwater flow velocity (m d-1)

Each off-site treatment plant is composed of unit processes and operations that enable

the effluent quality to meet the criteria set by the regulatory agency. Therefore, when

selecting a technology the first step is to develop a complete flow diagram where all unit

processes and operations are put together in a logical fashion. Off-site treatment

systems are generally composed of primary treatment, usually followed by a secondary

stage and, in some instances, a tertiary or advanced treatment stage. Table 3.7

summarises the potential performance of common technologies that can be applied in

wastewater treatment.

Primary treatment

In most treatment plants mechanical primary treatment precedes biological and/or

physicochemical treatment and is used to remove sand, grit, fibres, floating objects and

other coarse objects before they can obstruct subsequent treatment stages. In particular,

the grit and sand conveyed through combined sewers may settle out, block channels

and occupy reactor space. Additional facilities may be designed to equalise peak flows.

Approximately 50-75 per cent of suspended matter, 30-50 per cent of BOD and 15-25

per cent of Kjeldahl-N and total P are removed at moderate cost by means of settling.

Settling tanks that include facilities for extended sludge or solids retention may facilitate

the stabilisation of sludge and are, therefore, convenient for small communities.

Physicochemical processes may be incorporated in the primary treatment stage in order

to further enhance removal efficiencies, to adjust (neutralise) the pH, or to remove any

toxic or inhibitory compounds that may affect the functioning of the subsequent

treatment steps. Flocculation with aluminium or iron salts is often used. Such enhanced

primary treatment is comparatively cheap in terms of capital investment but the running

costs are high due to the chemicals that are required and the additional sludge produced.

This approach is attractive when it is necessary to expand the plant capacity due to a

temporary (e.g. seasonal) overload.

Secondary treatment

The most common technology used for secondary treatment of wastewater relies on

(micro)biological conversion of oxygen consuming substances such as organic matter,

represented as BOD or COD, and Kjeldahl-N. The technologies can be classified mainly

as aerobic or anaerobic depending on whether oxygen is required for their performance,

or as mechanised or non-mechanised depending on the intensity of the mechanised

input required. Table 3.11 provides a matrix classification of available (micro)biological

treatment technologies. Further detailed information is available in Metcalf and Eddy

(1991) and Arceivala (1986).

The choice between aerobic and anaerobic technologies has to consider mainly the

added complexity of the oxygen supply that is need for aerobic technologies. The supply

of large amounts of oxygen by a surface aeration or bubble dispersion system adds to

the capital cost of the aeration equipment substantially, as well as to the running cost

because the annual energy consumption is rather high (it can reach 30 kWh per

population equivalent (pe)).

The choice between mechanised or non-mechanised technologies centres on the locally

or nationally available technology infrastructure which may ensure a regular supply of

skilled labour, local manufacturing, operational and repair potential for used equipment,

and the reliability of supplies (e.g. power, chemicals, spare parts). Additional key

considerations are land requirements and the potential for biomass resource recovery. In

general, non-mechanised technologies rely on substantially longer retention time to

achieve a high degree of contaminant removal whereas mechanised systems use

equipment to accelerate the conversion process. If land costs are in excess of US$ 20

per square metre, non-mechanised systems lose their competitive cost advantage over

mechanised systems. Resource recovery may be possible if, for example, the algal or

macrophyte biomass generated is marketable, generating revenue and employment

opportunities. For example, constructed wetlands using Cyperus papyrus may generate

about 40-50 tonnes of standing biomass per hectare a year which can be used in

handicraft or other artisanal activities.

For non-biodegradable (mainly industrial) wastewaters physicochemical alternatives

have been developed that rely on the physicochemical removal of contaminants by

chemical coagulation and flocculation. The generated sludges are typically heavily

contaminated and have no potential for reuse other than for landfill.

Overall, the selection process for the most appropriate secondary technology may have

to be decided using multi-criteria analysis. In addition to the overall unit costs, the

environmental, aesthetic and health risks involved, the quality standards to be met, the

skilled staff and land requirements, and the reliability of the potential for recovery by the

technology, all have to be evaluated to give a total score that indicates the feasibility of

each technology for a particular country or location (Handa et al., 1990).

Table 3.11 Classification of secondary treatment technology

Conversion

Mechanised technology

Non-mechanised technology

method

Aerobic

Activated sludge

Facultative stabilisation ponds

Trickling filter

Maturation ponds

Rotating bio-contactor

Aquaculture (e.g. algal, duck weed or fish

ponds)

Constructed

wetlands

Anaerobic

Upflow anaerobic sludge bed

Anaerobic ponds

(UASB)

Anaerobic (upflow) filter

Physicochemical treatment. Physicochemical technologies can achieve significant BOD,

P and suspended solids reduction, although it is generally not the preferred option for

domestic sewage because removal rates for organic matter are rather poor (Table 3.12).

It is often used for industrial wastewater treatment to remove specific contaminants or to

reduce the bulk pollutant load to the municipal sewer. Physicochemical treatment can

also be combined with primary treatment to enhance removal processes and to reduce

the load on the subsequent secondary treatment stage. For wastewater with a high

organic matter content, like domestic sewage, (micro)biological methods are commonly

preferred because they have lower operational costs and achieve a higher reduction of

BOD.

The skills required to operate chemical dosing equipment, and the difficulty in ensuring a

reliable supply of chemicals are often prohibitive for the selection of physicochemical

technologies in developing countries where systems are more prone to malfunctioning.

In particular, the fluctuating flow and composition of the incoming sewage makes

frequent adjustments of the chemical dosing necessary. Biological treatment systems

are more sturdy and ensure a constant effluent quality because they have a high internal

buffering capacity for peak flows and loads.

Examples of physicochemical processes used in industrial applications include:

· Chemical oxidation with, for example, O2, O3 or Cl2 (cyanide removal and oxidation of

refractory organic compounds).

· Chemical reduction (for example, H2S assisted conversion of Cr (VI) into Cr (III)).

· Desorption (stripping) (NH3 and odorous gas removal).

· Adsorption on activated carbon (removal of refractory organics and heavy metals).

· Ultra- and micro-filtration (separation of colloidal and dissolved compounds).

Table 3.12 Advantages and disadvantages of physicochemical treatment of domestic or

municipal wastewater

Advantages Disadvantages

Compact technology with low

Chemical dosing is labour intensive due to fluctuating sewage

area needs

load and composition

Good removal of micro-

Generation of chemical sludges

pollutants and P

Fast start-up

High unit cost per m3 of water treated

Insensitivity to toxic compounds

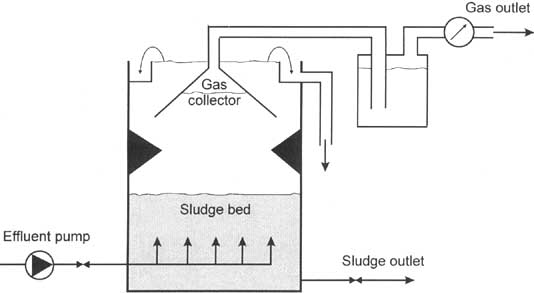

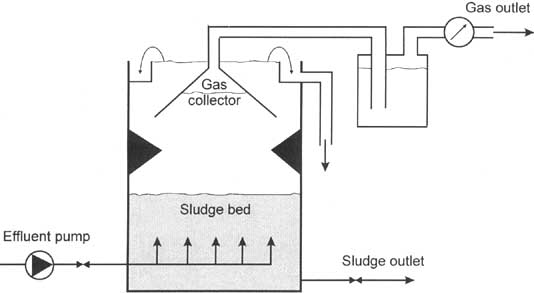

Anaerobic treatment. Aerobic treatment methods have traditionally dominated treatment

of domestic and industrial wastewater. Since the 1970s, however, anaerobic treatment

has become the preferred technology for concentrated organic wastewater from, for

example, breweries, alcohol distilleries, fermentation industries, canning factories, pulp

and paper mills (Hulshoff Pol and Lettinga, 1986). The principal characteristic of

anaerobic processes is that degradation of the organic pollutants takes place in the

absence of oxygen. The bacteria produce considerable quantities of methane gas. In

addition, the process can proceed at exceptionally high hydraulic loading rates. Of the

many process design alternatives, the Upflow Anaerobic Sludge Blanket (UASB)

process is the most cost-effective in most types of industrial wastewater treatment

(Figure 3.7). The reactor consists of an empty volume covered with a plate settler zone

to catch and to recycle suspended matter escaping from the sludge blanket below. The

water flows upwards through a blanket of suspended granules or floes containing the

active biomass. The methane and CO2 bubbles are caught below the plate settlers and

taken out of the reactor separately.

World-wide, over 400 anaerobic plants treat industrial wastewater, whereas operational

experience on domestic sewage derives from approximately 10 full-scale UASB plants

(size 20,000-200,000 pe) in Colombia, Brazil and India (Alaerts et al., 1990; Draaijer et

al., 1992; Schellinkhout and Collazos, 1992; van Haandel and Lettinga, 1994). Whereas

the aerobic process achieves 90-95 per cent removal of BOD, the anaerobic process

achieves only 75-85 per cent necessitating, in most cases, post-treatment to meet

effluent standards. Anaerobic treatment also provides minimal N and P removal but

generates much less, and a better stabilised, sludge. Biogas recovery is only feasible on

a large scale or in an industrial context. Many tropical developing countries would

probably prefer anaerobic processes because of the numerous agro-industries and the

(often) high domestic sewage temperatures.

Figure 3.7 Schematic representation of the Upflow Anaerobic Sludge Blanket

(UASB) reactor

The choice between aerobic and anaerobic treatment depends primarily on the

wastewater characteristics (Box 3.4). If the average sewage temperature is above 20 °C

(with a minimum of 18 °C over a maximum period of 2 months) and is highly

biodegradable (COD:BOD ratio below 2.5) and concentrated (typically BOD > 1,000 mg

l-1), anaerobic treatment has clear economic advantages. If neither condition can be met,

aerobic treatment is the only feasible option. If only one condition is met the choice is

determined by additional considerations such as:

· Desired effluent quality: anaerobic technologies yield lower removal efficiencies. The

presence of residual BOD, ammonium and, occasionally, sulphide in the effluent may

require post-treatment.

· Sludge handling and disposal: anaerobic sludge production is less than half of that in

aerobic treatment plants, and the sludge is already stabilised which facilitates further

processing.

· Effluent use: anaerobic treatment retains more nutrients (N, P, K) and thus effluent

have higher potentials for use in irrigation.

· Reliability of power supply: aerobic treatment performance is highly dependent on

power input for aeration and mixing. Power failure may create rapid malfunctioning of