United Nations Environment Programme

IIIIi

A Directory of Environmentally

Sound Technologies for the

Integrated Management of Solid,

Liquid and Hazardous Waste for

Small Island Developing States

(SIDS) in the Pacific Region

Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) 2002. A directory of environmentally sound technologies

for the integrated management of solid, liquid and hazardous waste for Small Island Developing States

(SIDS) in the Pacific.

Note: Compiled by OPUS International in conjunction with SPREP & SOPAC

vi, 124 p.

ISBN: 92-807-2226-3.

1. Directories

2. Hazardous materials

3. Waste disposal

4. Wastewater treatment

I.

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP)

II.

South Pacific Regional Environment Programme (SPREP)

III.

South Pacific Applied Geoscience Commission (SOPAC)

IV.

Title

V.

Series

United Nations Environment Programme

IIIIi

A Directory of Environmentally

Sound Technologies for the

Integrated Management of Solid,

Liquid and Hazardous Waste for

Small Island Developing States

(SIDS) in the Pacific Region

Compiled by OPUS International

in conjunction with the

South Pacific Regional Environment Programme (SPREP)

and the

South Pacific Applied Geoscience Commission (SOPAC)

July 2002

Prepared for printing by the

South Pacific Applied Geoscience Commission (SOPAC)

Suva, Fiji Islands

UNEP : Directory of Environmentally Sound Technologies for Waste Management in Pacific SIDS

CONTENTS

PREFACE............................................................................................................................................................................................. iii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.................................................................................................................................................................v

1

Introduction...............................................................................................................................................................................1

1.1

Background...................................................................................................................................................................1

1.2

Purpose of the Directory...........................................................................................................................................2

1.3

Structure of the Directory.........................................................................................................................................3

2

Solid Waste Technologies.......................................................................................................................................................5

2.1

Introduction..................................................................................................................................................................5

2.1.1

What is a Sound Practice?........................................................................................................................6

2.1.2

Criteria for Evaluating Alternatives......................................................................................................7

2.1.3

Background Conditions that affect the selection of an EST in the Pacific Region..................7

2.2

Waste Reduction .........................................................................................................................................................9

2.2.1

The key concepts of waste reduction are:............................................................................................9

2.2.2

Tools for Environmentally Sound Technologies for Waste Reduction....................................10

2.3

Collection and Transfer...........................................................................................................................................13

2.3.1

Environmentally Sound Technology for Collection and Transfer of Waste...........................13

2.3.2

Principles for Selection of Collection Vehicles.................................................................................13

2.3.3

Sound Principles for Selection of Set-out Containers ....................................................................16

2.3.4

Sound Practice for Route Design and Operation ............................................................................16

2.3.5

Sound Practice for Transfer of Waste.................................................................................................18

2.3.6

Sound Practice in Keeping Streets Clean...........................................................................................19

2.4

Composting ................................................................................................................................................................21

2.4.1

Critical Lessons in Sound Composting Practice..............................................................................21

2.4.2

Sound Technologies for Composting..................................................................................................23

2.4.3

Sound Marketing Approaches for Composting ..............................................................................33

2.4.4

Environmental Impacts of Composting Technology.....................................................................33

2.4.5

Conclusions.................................................................................................................................................34

2.5

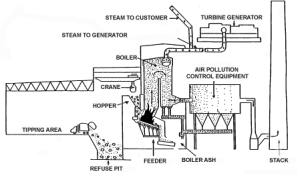

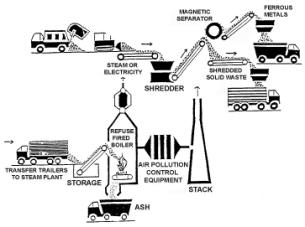

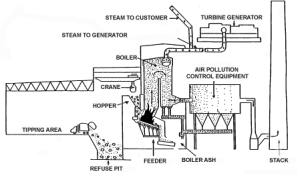

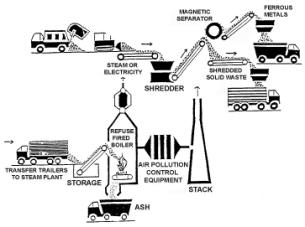

Incineration of Municipal Solid Waste...............................................................................................................34

2.5.1

Practice for Choosing Incineration Technology..............................................................................34

2.5.2

Environmental Impacts from Incineration Technology................................................................40

2.5.3

Conclusion...................................................................................................................................................40

2.6

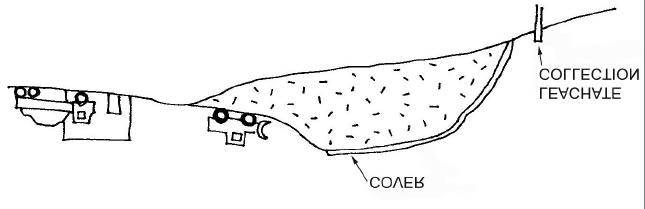

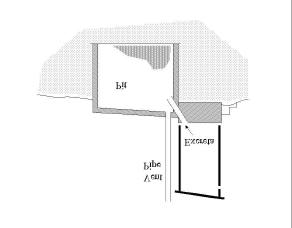

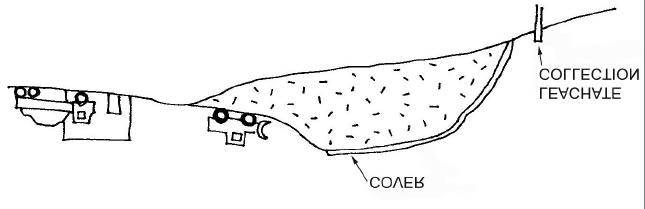

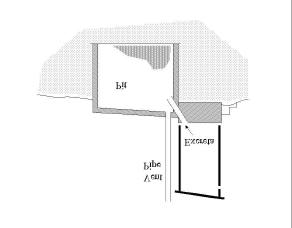

Landfills and Other Methods of Disposal on Land........................................................................................41

2.6.1

Open Dumps..............................................................................................................................................41

2.6.2

Land Reclamation Using Solid Waste................................................................................................43

2.6.3

Landfill Technology Summaries..........................................................................................................44

2.6.4

Sound Practices for Landfill Technology...........................................................................................47

2.7

Special Wastes............................................................................................................................................................52

2.7.1

Tires...............................................................................................................................................................52

2.7.2

Construction and demolition debris ...................................................................................................52

2.8

Information Sources for the Pacific Region ......................................................................................................53

3

Hazardous Waste Technologies..........................................................................................................................................54

UNEP July 2002

UNEP : Directory of Environmentally Sound Technologies for Waste Management in Pacific SIDS

3.1

Introduction................................................................................................................................................................54

3.1.1

Export of hazardous Waste....................................................................................................................55

3.2

Medical Waste............................................................................................................................................................55

3.3

Household and Agricultural Hazardous Waste .............................................................................................58

3.4

Used Oils.....................................................................................................................................................................59

3.5

Batteries........................................................................................................................................................................59

3.6

Asbestos.......................................................................................................................................................................60

3.7

Human excreta, sewage sludge, septage, and slaughterhouse waste......................................................60

3.8

Industrial waste.........................................................................................................................................................61

3.9

Information Sources for the Pacific Region ......................................................................................................61

4

Wastewater Technologies.....................................................................................................................................................64

4.1

Introduction................................................................................................................................................................64

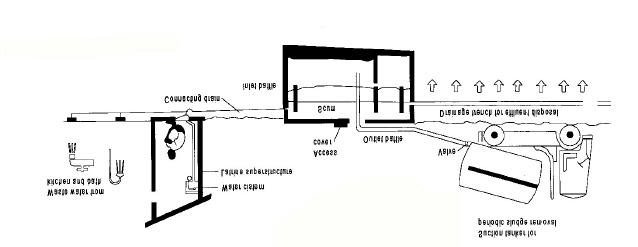

4.2

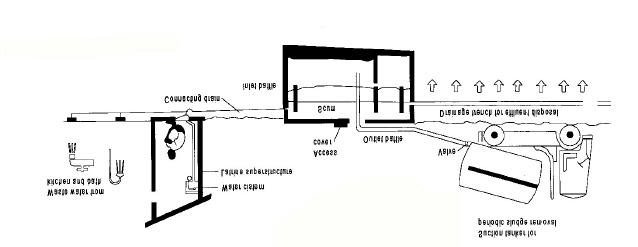

Wastewater Collection and Transfer ..................................................................................................................64

4.2.1

Sewerage Systems.....................................................................................................................................66

4.3

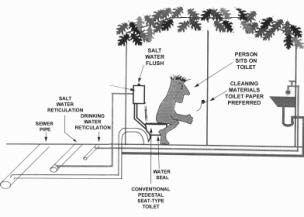

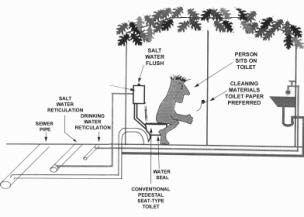

Wastewater Treatment (Onsite) ...........................................................................................................................72

4.4

Septic Tank Systems.................................................................................................................................................78

4.5

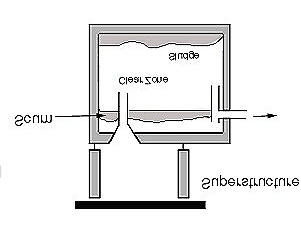

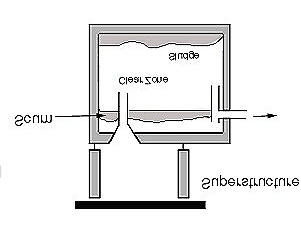

Wastewater Treatment (Centralised and Decentralised) .............................................................................84

4.5.1

Preliminary Treatment ............................................................................................................................84

4.5.2

Primary Treatment....................................................................................................................................84

4.5.3

Secondary Treatment...............................................................................................................................84

4.5.4

Tertiary Treatment....................................................................................................................................85

4.6

Waterless toilets......................................................................................................................................................101

4.6.1

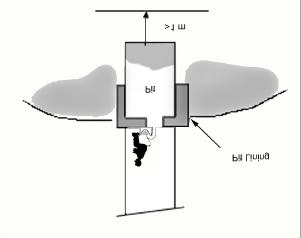

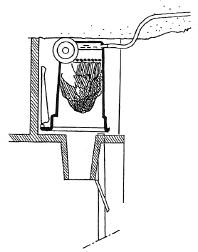

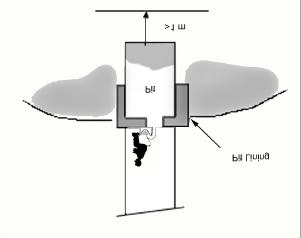

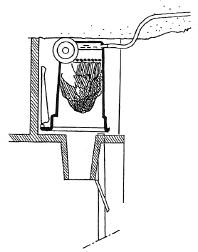

Continuous Composting Toilets.........................................................................................................101

4.6.2

Batch Compostimg Toilets ...................................................................................................................103

4.6.3

Maintenance of CTs................................................................................................................................103

4.6.4

Choosing a CT..........................................................................................................................................104

4.6.5

Acceptance ................................................................................................................................................104

4.7

Wastewater Reuse..................................................................................................................................................105

4.8

Wastewater Disposal Systems ............................................................................................................................108

4.8.1

Outfalls.......................................................................................................................................................108

4.9

"Zero" Discharge....................................................................................................................................................114

5

Bibliography..........................................................................................................................................................................120

6

Contact Persons ....................................................................................................................................................................122

7

Glossary..................................................................................................................................................................................124

UNEP July 2002

UNEP : Directory of Environmentally Sound Technologies for Waste Management in Pacific SIDS

PREFACE

As highlighted in the 1994 Barbados Programme of Action, waste management is a major

area of concern for Small Island Developing States (SIDS). SIDS, like other developing

countries, have problems with the management of waste. However, SIDS experience

additional constraints arising from small land areas, high dependence on imports and high

population densities exacerbated by high tourist inflows. Because of limited access to

appropriate technologies, on many occasions waste management technologies are

transferred from larger and more developed countries, and as such are not always suitable

for SIDS. Some SIDS have developed appropriate technologies which, with or without

adaptation, could be applied in similar situations. Unfortunately, the information has not

been shared with other SIDS in the same regions or in other regions. Hence the need for the

directory which compiles a list of practical technologies applicable to SIDS.

UNEP, in partnership with SIDS regional institutions, embarked on a programme to

improve the access of SIDS to appropriate technology. A draft directory containing

technologies found to be appropriate for SIDS from practical experience as well as literature

review was compiled. It was subjected to peer review at a global level by experts from

regional SIDS institutions (Caribbean, Indian, Mediterranean and Atlantic Ocean SIDS

(IMA/SIDS) and Pacific), UN agencies, the Commonwealth Secretariat as well as

universities. The review was made at the UNEP Meeting of Experts on Waste Management

in Small Island Developing States Waste Management in SIDS, held in London from 2 and

5 November 1999. The experts found the technologies to be appropriate to SIDS and

recommended that each SIDS region further reviews and adapts the technologies according

to their conditions.

The IMA/SIDS region adapted the technologies to suit their conditions and published the

A Directory of Environmentally Sound Technologies for the Integrated Management of Solid,

Liquid, and Hazardous Waste for Small Island Developing States (SIDS) in the Indian,

Mediterranean and Atlantic Region. This document `A Directory of Environmentally Sound

Technologies for the Integrated Management of Solid, Liquid, and Hazardous Waste for Small Island

Developing States (SIDS) in the Pacific Region' is the result of a review of the original

directory by national experts from the Pacific Island Countries in Majuro, in October 2001.

This publication is part of UNEP collaboration with SIDS on the implementation of the

Waste Management chapter of the Barbados Programme of Action. Through this initiative a

series of publications have been made. The first publication in 1998 was the Guidelines for

Solid Waste Management in the Pacific developed in collaboration with the South Pacific

Regional Environment Programme (SPREP). The second was in 1999, The Strategic

Guidelines for Integrated Waste Management in SIDS. These are planning guidelines

developed with input from all SIDS regions and subjected to intensive peer review. The

guidelines are based on the premise that, if systematic improvements are introduced at the

various stages of the waste cycle, the quantity of waste to be managed at each of the

subsequent stages would be reduced considerably.

UNEP July 2002

UNEP : Directory of Environmentally Sound Technologies for Waste Management in Pacific SIDS

The third document included in the UNEP waste management series is the IMA-SIDS Waste

Management Strategy with special emphasis on Minimisation and Resource Recovery. These were

developed with input from national experts in the region and adopted by the governments

in the region.

It is hoped that these publications will make a useful contribution to the promotion of

integrated waste management in SIDS, in particular those in the Pacific region, and will

foster an increased awareness about the special circumstances of SIDS, especially the fact

that these states face special constraints in their options for sustainable development.

Donald Kaniaru

Director

Division of Environmental Policy Implementation

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP)

Nairobi, Kenya

UNEP July 2002

UNEP : Directory of Environmentally Sound Technologies for Waste Management in Pacific SIDS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This document represents the combined efforts and achievement of numerous people over the last

3 years in the Pacific, Caribbean and the Indian, Atlantic and Mediterranean SIDS regions. In

particular, UNEP and SOPAC, recognise the contributions made by Ed Burke and Jonathan

Thorpe, Opus International Consultants Ltd, New Zealand for compiling the document. We are

grateful to the following individuals who have contributed to this project: Vincente Santiago

(UNEP), Elizabeth Khaka (UNEP), Rhonda Bower (SOPAC), Leonie Crennan (Resource Strategist),

Mike Dworsky (ASPA) and Bruce Graham (SPREP).

We also acknowledge the contribution made by the Commonwealth Secretariat and

representatives from the Indian, Mediterranean, Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean regions during the

review of the technologies in London, from 2 to 5 November 1999. Our appreciation is also

extended to the national representatives from American Samoa, Cook Islands, Federated States of

Micronesia, Fiji Islands, Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Nauru, Niue, Palau, Papua New Guinea,

Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tonga, Tuvalu and Vanuatu for reviewing the Directory in Majuro,

Marshall Islands, October 2001.

UNEP July 2002

UNEP : Directory of Environmentally Sound Technologies for Waste Management in Pacific SIDS

ACRONYMS

ACP countries

: African, Caribbean and Pacific countries

ADB

: Asian Development Bank

ASPA

: American Samoa Power Authority

BOD

: Biological Oxygen Demand

COD

: Chemical Oxygen Demand

CT

: Composting Toilet

DVC

: Double Vault Composting.

EST's

: Environmentally Sound Technologies

FSM

: Federated States of Micronesia

GCL

: Geosynthetic Clay Liner

GW

: Groundwater

HRT

: Hydraulic Retention Time

MSWM

: Municipal Solid Waste Management

MSW

: Municipal Solid Waste

NZODA

: New Zealand Official Development Assistance

PCB's

: Polychlorobiphenyls

PIC's

: Pacific Island Countries

POPs

: Persistent Organic Pollutants

PVC

: Polyvinyl Chloride

RDF

: Refuse Derived Fuel

ROEC

: Reed Odourless Earth Closet

SANEX

: Sanitation Expert Systems.

SIDS

: Small Island Developing States

SOPAC

: South Pacific Applied Geoscience Commission

SPREP

: South Pacific Regional Environmental Programme.

SS

: Suspended Solids

UNEP-IETC

: United Nations Environment ProgramInternational Environmental Technology

Centre

UNESCO

: United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organisation.

UNHCS Habitat

: United Nations Centre for Human Settlements

VIP

: Ventilated Improved Pit

WHO

: World Health Organisation

WM

: Waste Management

UNEP July 2002

UNEP : Directory of Environmentally Sound Technologies for Waste Management in Pacific SIDS

1

Introduction

1.1

Background

Small Islands have special physical, demographic and economic features. Their much

reduced areas, shortage of natural resources (arable land, freshwater, minerals and

conventional energy sources), geological complexity, isolation and widespread nature of

their territories, exposure to natural disasters (typhoons, hurricanes, cyclones, earthquakes,

volcanic eruptions and tsunamis) sometimes make the water resources, solid waste and

wastewater problems of these islands very serious (UNESCO, 1991).

The need for waste management in the Pacific Island Countries (PICs) was small for most

part of the last centuries as most waste products were biodegradable and populations were

dispersed. Commonly, wastes were disposed of through individual dumping in lagoon and

rivers or on unused land close to villages. Over the last decade, the region urbanized at a

very fast rate that the governments could not keep pace with facilities and services making

the disposal of wastes, both solid and liquid difficult. Urban population rose from 20.4 %

to 24.9 % in 1995 (United Nations Populations Division, 1996) and the trend is continuing.

The result of this rapid expansion is the pollution of water resources, difficulty in disposing

of solid and human wastes, increasing diseases related to poor and unsanitary living

conditions such as respiratory and gastro-intestinal complaints. Diseases related to water

supply and sanitation are prevalent especially in the informal settlements where dwellers

are living in marginal areas with inadequate waste disposal, potable water and sanitation

systems (Pacific Environment Outlook 1999).

The rapid urban population and increasing imports of non-biodegradable material and

chemicals related to agriculture and manufacturing have rapidly brought about a

confrontation with the realities of management of toxic and hazardous substances. All

PICs now share the problem of disposal of waste and the prevention of pollution. In major

towns, the search for environmentally safe and socially acceptable sites for waste disposal

has become a perennial concern that needs a sustainable solution. Inadequate sanitation for

the disposal or treatment of liquid wastes have resulted in high coliform contamination in

surface waters and in groundwater in urban areas. Pollution by toxins from industrial

wastes, effluent from abattoirs or food processing plants, biocides and effluent from

sawmills has also been reported.

According to the Pacific Environment Outlook (1999), the areas of concern in the Pacific

region until 2010 include the environmentally sound management of solid and liquid

wastes, toxic chemicals and hazardous wastes. Particular effort is required at the national

level to strengthen the capacity of island countries to minimize and prevent pollution. In

the long term because of the land constraints of islands, cost- effective disposal options are

limited. Pacific island countries will need to focus on reusing, recycling and minimizing

wastes and the use of technology appropriate to islands in order to manage the waste

generated.

UNEP July 2002

UNEP : Directory of Environmentally Sound Technologies for Waste Management in Pacific SIDS

Most SIDS do not have access to appropriate waste management technologies. Because of

this constraint, on many occasions, waste management technologies are transferred from

larger and more developed countries, and as such are not always suitable for SIDS. Some

SIDS have developed appropriate technologies which, with or without adaptation, could be

applied in similar situations. There are numerous waste management technologies used

throughout the world. Many of these technologies have been used in the Pacific, but have

failed for a range of different reasons. Some of the reasons for failure include being an

inappropriate technology, having insufficient operation and maintenance input, and a lack

of funding and/or skilled personnel. Unfortunately, the information has not been shared

with other SIDS in the same region or in other regions. Hence the need for this directory

which compiles a list of practical technologies applicable to the Pacific SIDS.

Waste management has been identified as a high priority area by PICs (Pacific

Environment Outlook 1999). It is also one of the 14 priority areas of the Barbados

Programme of Action. The Waste Management chapter of the Programme of Action urges

SIDS to `introduce clean technologies and treatment of wastes at the source and appropriate

technology for solid waste treatment' and the international community to `support the

strengthening of national and regional capabilities to carry out pollution monitoring and

research and to formulate and apply pollution control and abatement measures'. The need

to transfer environmentally sound technologies (EST) and improve co-operation and

building capacity within developing countries was underscored in Chapter 34 of Agenda

21. Improved access to information on environmentally sound technologies has been

identified as a key factor in transferring technologies to developing countries.

In response to the Barbados Programme of Action, the Twentieth Session of the United

Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) Governing Council adopted decision GC20/19

which invited the UNEP Executive Director to `prepare guidelines and programmes for

waste minimization, reduction treatment and disposal applicable under the constraints of

small island developing States'. This directory is part of UNEP's efforts to assist SIDS in the

management of wastes.

1.2

Purpose of the Directory

This Directory on Environmentally Sound Technologies for Waste Management in the

Pacific Small Island Developing States (SIDS) focuses primarily on proven sound

environmental technologies for waste management plus those currently successfully being

used in SIDS within the Pacific Region.

In addressing each broad waste management topic, sound practices are also provided,

based on lessons learnt from the past. These sound practices give guidelines for selection of

the most appropriate of the technologies listed for a given application. These sound

practices can also be used to evaluate any existing or new technologies that arise in the

future that are not listed in this directory.

UNEP July 2002

UNEP : Directory of Environmentally Sound Technologies for Waste Management in Pacific SIDS

Note that the technologies presented in this Directory are also applicable to Small Island

Developing States in other Regions.

1.3

Structure of the Directory

The Directory is divided into 3 major parts, which include

§

Solid Waste Technologies

Discusses information on different Municipal Solid Waste Management (MSWM)

technologies that are currently used in different regions of the world, and gives a

guide as to which of these are economically feasible, and Environmentally Sound

Technologies (ESTs).

§

Hazardous Waste Technologies

Addresses the proper management of various types of hazardous wastes, as they

require special handling, treatment and disposal due to their hazardous potential.

§

Liquid Waste or Wastewater Technologies

In SIDS wastewater disposal systems are just as important for public health as a

water supply distribution system. This section discusses various wastewater

treatment and disposal technologies from on-site systems to centralised and

decentralised systems.

The Directory is a simple guide, which tries to convey technical issues in an easy and

understandable manner and is a UNEP initiative to assist SIDS in addressing waste

management issues

UNEP July 2002

UNEP : Directory of Environmentally Sound Technologies for Waste Management in Pacific SIDS

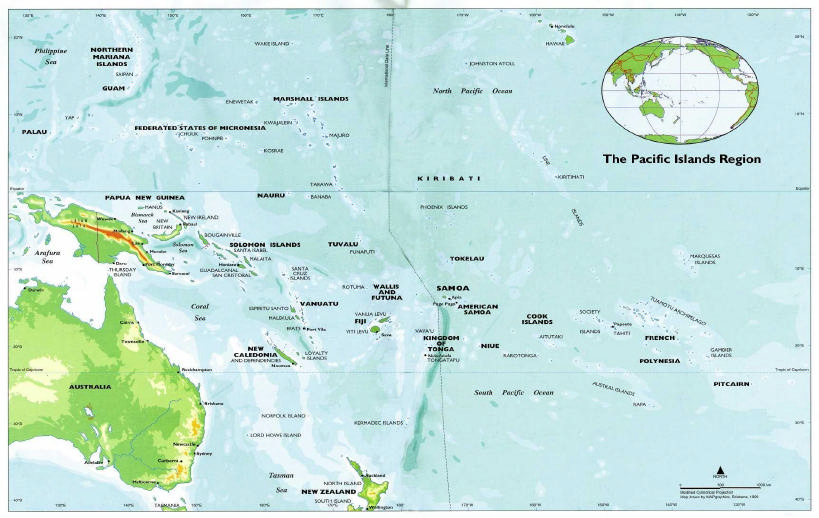

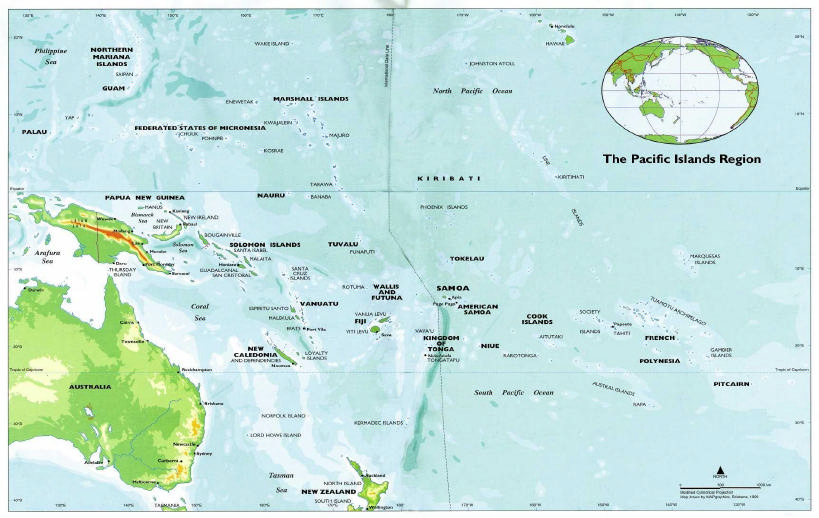

Source: Map Graphics, Brisbane, 1996.

UNEP July 2002

4

UNEP : Directory of Environmentally Sound Technologies for Waste Management in Pacific SIDS

2

Solid Waste Technologies

2.1

Introduction

Prior to the introduction of imported goods, and packaging, the waste produced from a

typical Pacific Island was entirely organic in origin, and could be broken down or

composted without thought or problem. To varying degrees, the majority of Pacific Islands

have now moved from this lifestyle toward a cash based, consumer goods society. This

shift can be attributed to western influences, tourism, imported goods, and effects of

expatriate communities.

As a result, waste products which do not break down easily, and which are harmful to the

environment have increased to the point where significant problems are being experienced.

In the majority of cases, SIDS have not been aware of the need, or have not been able, to

developed suitable waste management systems to cope with these changes in waste

character.

ESTs are therefore needed for the Pacific Islands to help solve the problems that now exist,

and to ensure that further environmental, and health related problems do not occur as a

result of solid wastes.

In 1996, the United Nations Environment Programme's (UNEP) International

Environmental Technology Centre (IETC) published the "International Source Book on

Environmentally Sound Technologies for Municipal Solid Waste Management" (Technical

Publication Series No. 6). This book presented information about different MSWM

technologies that are currently used in different regions of the World, and gave a guide as

to which of these are economically feasible, and ESTs.

The task of identifying ESTs is complicated by the fact that what constitutes an EST is

highly dependent on the environmental, economic, climatic, cultural, and social context in

which the technology is set.

It is for this reason that this current directory has been prepared, to identify and describe

ESTs which are suited to the environmental, economic, climatic, cultural, and social context

of the Pacific Region. As was done in the International Source Book, this directory, focused

on the Pacific Region, is structured around 6 separate topics of waste management. These 6

topics relate directly to the physical materials, and processes of waste management. These

topics are:

1. Waste Reduction

2. Collection

3. Composting

4. Incineration

5. Landfills

6. Special wastes (These are covered in Section 3 Hazardous Wastes)

UNEP July 2002

UNEP : Directory of Environmentally Sound Technologies for Waste Management in Pacific SIDS

Other issues relating to overall waste management are waste characterisation, management

and planning, training, public education and financing. These issues are dealt with in the

guidelines section of this document.

It needs to be stressed at this point that the use of particular technologies such as are

discussed in the following pages must be integrated into an overall waste management

strategy to be effective.

2.1.1 What is a Sound Practice?

Before identifying (ESTs) for the Pacific Region, the question needs to be asked,

"What is a "sound" practice for Waste management?" The UNEP (1999)

International Source Book on Environmentally Sound Technologies for Wastewater and

Stormwater: Pacific Regional Overview of Small Island Developing States, defines a

"Sound Practice" as "a technically and politically feasible, cost effective, sustainable,

environmentally beneficial, and socially sensitive solution to an MSWM problem".

Extending this definition to the Pacific Region, a sound practice not only achieves

the management of municipal solid waste, but in the process, takes into account the

specific physical, environmental, social, and political background conditions of the

area. For the SIDS of the Pacific, these background conditions (which tend to make

solid waste management difficult) include:

·

high population density on some small islands accelerated by high growth

rates;

·

small population numbers spread over many small islands;

·

high tourist numbers;

·

lack of funding from within SIDS governments;

·

poor planning;

·

limited area to deal with waste absorption capacity;

·

low levels of training; and

·

fragile environments.

Alternative technologies and waste management strategies need to be evaluated to

identify whether they fit in with the background conditions of the Pacific Region,

and hence whether they are "sound". The following are criteria used by the UNEP

in their International Source Book for evaluating technologies and policy.

UNEP July 2002

UNEP : Directory of Environmentally Sound Technologies for Waste Management in Pacific SIDS

2.1.2 Criteria for Evaluating Alternatives

(a)

Is the option likely to accomplish its purpose in the circumstances where it

would be used?

(b)

Is the option technically feasible and appropriate given the financial and

human resources available?

(c)

Focusing on the financial aspects of the option, is it the most cost-effective

option available?

(d)

What are the environmental benefits, and costs of the option?

· Could the environmental soundness of the option be significantly

enhanced, given a small increase in cost?

· Conversely, would it be possible to significantly reduce the cost, with

only a small detriment to the environment?

(e)

Is the practice administratively feasible and sensible?

(f)

Is it practical in the given social and cultural environment?

(g)

How would specific sectors of society be affected by the adoption of this

option?

(h)

Do these effects promote or conflict with the overall social goals of the

society?

2.1.3 Background Conditions that affect the selection of an EST in the Pacific Region

As already discussed, there are many factors which help determine what should be

considered a sound practice within a particular situation. The following is a

summary of the background conditions typical in SIDS of the Pacific Region. For

this summary, information is based on background conditions of the following

Islands:

·

Rarotonga in the Cook Islands;

·

Funafuti in Tuvalu;

·

Tarawa in Kiribati;

·

Niue;

·

Pohnpei in Micronesia;

·

Port Vila in Vanuatu; and

UNEP July 2002

UNEP : Directory of Environmentally Sound Technologies for Waste Management in Pacific SIDS

·

Majuro in the Marshall Islands.

Information has also been drawn from reports on waste issues in the African,

Caribbean and Pacific (ACP) countries. These include:

·

Fiji;

·

Papua New Guinea;

·

Samoa;

·

Solomon Islands; and

·

Tonga.

However, generally, most of the technologies presented would be suitable for all

SIDS.

The following factors may be used in assessing the background conditions present

for individual situations:

Level of Development:

·

The economic development, including relative cost of capital, labour and

other resources.

·

The technological development.

·

The human resource development, in the municipal solid waste field and in

the society as a whole.

Natural Conditions:

·

The physical conditions, such as topography, soil characteristics, and type

and proximity of bodies of water.

·

The climate including temperature, rainfall, tendency for thermal inversions,

and winds.

·

The specific environmental sensitivities of a region.

Conditions due to human activities:

·

The waste characteristics including density, moisture content, combustibility,

recyclability, and presence of hazardous waste in Municipal Solid Waste

(MSW).

·

The population characteristics such as population size, density, and

infrastructure development.

UNEP July 2002

UNEP : Directory of Environmentally Sound Technologies for Waste Management in Pacific SIDS

Social and Political Considerations:

·

The degree to which decisions are constrained by political considerations,

and the nature of these constraints.

·

Degree of importance assigned to community involvement (including that of

women and the poor) in carrying out MSWM activities.

·

Social and cultural practices.

2.2

Waste Reduction

Currently, there is very limited waste reduction activity on Pacific SIDS. This is due to a

combination of factors including:

·

increased demand for imported packaged goods due to rapid urbanisation, with

related rise in standard of living expectations;

·

isolation of islands from potential markets for recycled materials;

·

lack of waste reduction legislation and policies;

·

lack of knowledge and therefore enforcement of waste related legislation; and

·

lack of education of the general public.

As a consequence, the quantity of waste generated through imported goods, and other

activities, is very similar to the quantity of waste disposed of by burning, dumping in the

sea, or landfilling.

2.2.1 The key concepts of waste reduction are:

·

Reducing waste at the source.

·

Source separation of waste.

·

Waste and materials recovery for re-use.

·

Re-cycling waste materials.

·

Reducing use of toxic or harmful materials.

Waste reduction is the first line of attack for solid waste management. Waste

reduction minimises the quantity of waste produced, thus reducing all other costs

down the line, such as collection, transporting, and disposal. Disposal sites last

longer, and costs are reduced by using resources more efficiently.

UNEP July 2002

UNEP : Directory of Environmentally Sound Technologies for Waste Management in Pacific SIDS

In the Pacific Region, almost all islands are small and remote, with limited or no

suitable area for disposal by landfilling. This makes waste reduction even more

crucial to ensure sound MSWM.

2.2.2 Tools for Environmentally Sound Technologies for Waste Reduction

The following "sound practice" tools for promoting waste reduction and materials

recovery were identified by the UNEP International Source Book. Each of these

tools are evaluated below in terms of sound practice against existing background

conditions in SIDS:

1.

Promote educational campaigns

Education of both government authorities responsible for waste

management, and the general public is identified as one of the most critical

actions necessary in SIDS to help find solutions to the solid waste problem.

Government authorities should be seen to lead good waste management by

example. This education should inform people of the environmental, health,

and economic impacts of the current solid waste generation and disposal

habits. Such education will help give public ownership of the problem, and

should help promote involvement by the public by providing information on

methods of waste reduction, recycling, and materials reuse that they can

adopt at a household and village level.

With increased public awareness, pressure can be applied to importers by

the public, by using their purchasing power to avoid the purchase of high

waste, or non-biodegradable products.

There are many sources of information which can be used for educational

material namely posters, comic books, videos and internet sites. These can be

obtained from SPREP.

2.

Study waste streams (quantity and composition),

Very little information has been gathered regarding the quantity and

composition of the waste streams from SIDS. This information is crucial to

enable the set-up of recovery and recycling systems, markets for recyclables,

and to identify problems within existing Waste Management (WM)

practices. Where appropriate, the local municipal authority can then take a

facilitative/regulatory role.

3.

Support source separation, recovery, and trading networks

Apart from informal source separation, recovery and local recycling/reuse,

this is often not appropriate for the majority of SIDS, as the quantities of

waste is not large enough to support viable trading networks. In addition,

the isolation of the islands makes delivery of most recovered materials to

UNEP July 2002

UNEP : Directory of Environmentally Sound Technologies for Waste Management in Pacific SIDS

outside markets uneconomic. However, there is a strong case for separation

of items such as paper, cardboard, glass bottles, aluminium cans and steel for

reuse or recycling. Separation of the items are either carried out at `curb'

collection where items such as paper/cardboard, glass and metals are put in

small separate containers for collection. Where there is no "curb" side

collection, recoverable items may be put in to large collection containers

located at convenient areas for individuals to place items. This may be at a

school or shopping centre.

Materials Recycling Collection

Container (Credit Warmer Bulletin)

4.

Facilitate small enterprises and public-private partnerships by new or

amended regulations

This is already in place to a small extent. An example of this is the collection,

crushing and sale of aluminium cans, which is done in many of the different

SIDS including Tuvalu and the Cook Islands. This type of venture has often

met problems with can crushers becoming broken, and not being able to be

fixed, or other impurities, such as steel being mixed with the aluminium,

resulting in the reduction of value. Another small enterprise example is the

operation of a privately operated waste collection contractor in Rarotonga.

Given the small populations however, and isolation of most Islands,

opportunities for such enterprises would be limited.

5.

Assist waste pickers

As there is little if any waste picking done on SIDS, assistance in this is not

needed, however, where there is informal interest in waste picking, or small

enterprise this should be encouraged along with some general guidelines to

minimise health and safety problems relating to waste picking.

UNEP July 2002

UNEP : Directory of Environmentally Sound Technologies for Waste Management in Pacific SIDS

6.

Reduce waste via legislation and economic instruments

After consulting with major stakeholders, advocate, where advisable,

selective waste reduction legislation on packaging reduction, product

redesign, and coding of plastics.

The majority of non-biodegradable waste in SIDS waste streams is derived

from the importing of packaged goods. Packaging could be reduced

through selective waste reduction legislation, however, it is argued that the

Pacific Island markets are too small to impose special packaging

requirements on distant exporters. The region is at the end of the line for

many waste streams generated by manufacturing countries. Special

measures, for example surcharges, taxes, or deposits, may be justified for

plastics, cans or bottles. Funding thus obtained could be used to ensure

these materials can be sorted and backloaded to destinations where recycling

can be carried out.

7.

Export re-cyclables

For SIDS, export of re-cyclables is really only possible for materials that have

sufficient value, such as crushed aluminium cans. A number of SIDS export

used tires to Fiji for re-treading.

8.

Promote innovation

To create new uses for goods and materials that would otherwise be

discarded after initial use.

Given the relatively low labour cost in the SIDS, value could be added to

recovered waste materials by making the materials into new products. This

type of enterprise would require investigation of potential markets. These

could be to the local public, to tourists, or for export.

Reuse of items such as glass bottles, and containers for storing kaleke, other

foods, and bottling coconut oil (sinu) is already common in Tuvalu for

example. (AusAID 1998).

9.

Reducing use of substances which produce toxic, or hazard waste

This can be done through education of the public, providing information on

hazardous or toxic goods, alternative products that are not toxic or

hazardous, and implementing legislation which prevents the importation of

such products.

UNEP July 2002

UNEP : Directory of Environmentally Sound Technologies for Waste Management in Pacific SIDS

2.3

Collection and Transfer

Collection and transfer of waste on the smallest islands and some of the larger islands is

generally up to the public. In these cases, it is the public's responsibility to deliver waste to

the designated landfill. Often, waste is haphazardly landfilled, dumped in the mangroves,

or placed on the reef to be taken out to sea on the high tide.

In the more populated islands, collection is usually the responsibility of the municipality

within the urban areas. Waste is either left at the front gate, or deposited at central transfer

points, where it is then collected by the municipality. In Kiribati, waste is swept into piles

on the street, and collected by a small team of council workers using a shovel, broom, and

sheet, to throw the waste onto a trailer. There are also some instances where waste

collection has been contracted to private enterprises. In some larger islands such as

Pohnpei in the Federated States of Micronesia, rural inhabitants are expected to deliver

their own waste to the landfill, or burn as much of it as possible.

Typically, in SIDS, a large percentage of waste collection equipment does not operate

properly, or is out of service completely due to lack of maintenance, spare parts, or

necessary expertise. Any of the different collection technologies suggested will only be

sound practice, if the necessary preventative maintenance, is carried out. Such

maintenance includes replacement of worn parts, lubrication, top up of oil and brake fluid,

cleaning, and washing.

2.3.1 Environmentally Sound Technology for Collection and Transfer of Waste

The collection vehicle used must be appropriate to the terrain, the type and density

of waste generation points, the roads and ways it must travel, the kinds of materials

it will be used to collect, the strength, stature, and capability of the working crew,

and the point and manner of discharge of its load. The type of vehicle selected

should also be evaluated in terms of relative capital cost and labour inputs,

maintenance requirements, and local availability of technical repair expertise and

parts.

Given the isolation of most of the islands, it is recommended that a vehicle type be

chosen which is already in use on the island, or within the Country.

2.3.2 Principles for Selection of Collection Vehicles

The following principles outlined below represent sound practice, with reference to

Pacific SIDS:

·

Select vehicles that use the minimum amount of energy and technical complexity

necessary to collect the targeted materials efficiently. Given the high energy costs

and relative lack of technical backup on most SIDS, a trade off between

relative cost of capital and labour is needed.

UNEP July 2002

UNEP : Directory of Environmentally Sound Technologies for Waste Management in Pacific SIDS

·

Choose locally made equipment, traditional vehicle design, and local expertise

whenever possible. There is a long history of vehicles being provided by

international aid agencies which are not appropriate for their application,

rust in the harsh environment, and cannot be fixed when they break down

due to lack of parts or local expertise.

·

Select equipment that can be locally serviced and repaired, and for which parts are

available. This is critical in SIDS of the Pacific to ensure ongoing utilisation

from capital investment in the vehicles.

·

Choose muscle- and animal-powered or light mechanical vehicles in crowded or hilly

areas or informal settlements, where access by larger vehicles is not possible. These

types of vehicle are significantly less capital intensive, easy to maintain, and

have less impact on the environment, however use more labour, and may be

perceived as old fashioned.

·

Choose non-compactor trucks, wagons, tractors, dump trucks, or vans, where

population is dispersed, or waste is already dense. These vehicles are lighter,

easier to maintain, and offer lower capital costs but higher labour

requirements. Waste collected in the majority of Pacific SIDS is already at a

high density, with high proportions of organic waste, therefore compaction

in most cases is not necessary.

·

Consider the advantages of hybrid systems. Where there is a significant

difference between the urban and rural areas, or within a compact urban

area, a hybrid system with two or more types of collection vehicle could be

used. E.g. combining small muscle powered carts for collecting down

narrow side streets and alleyways which then deliver back to a larger truck

or wagon which moves slowly along the main street.

·

Consider compactor trucks in industrialised urban areas where roads are paved, and

waste is not too dense or wet. Compaction is often seen as more efficient,

however, due to the typically high organic content and therefore high

density of waste collected in SIDS, compaction does not significantly reduce

the volume of waste collected. These trucks require more maintenance, and

are not fuel efficient.

·

Select dual collection vehicles to enable simultaneous collection of both organics and

recyclables within separate compartments. Where waste separation is a priority,

this collection method avoids the need for duplicating the collection runs for

different separated materials.

·

If collection of waste will only take up one or two days per week, select a machine

that can be utilised for other activities during the remainder of the week such as a

tractor or tip truck.

UNEP July 2002

UNEP : Directory of Environmentally Sound Technologies for Waste Management in Pacific SIDS

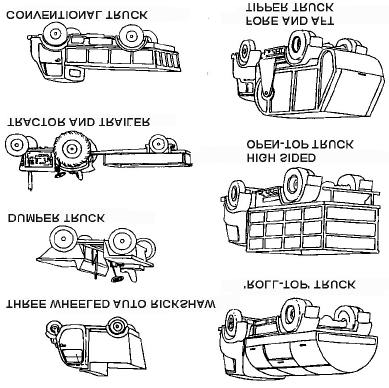

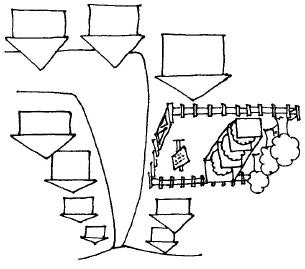

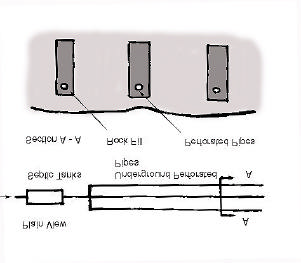

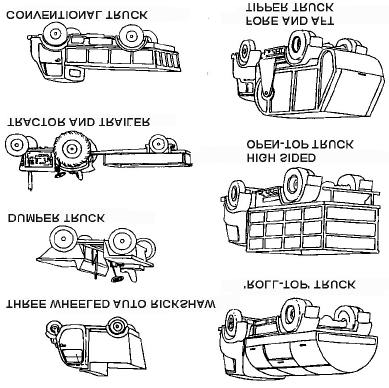

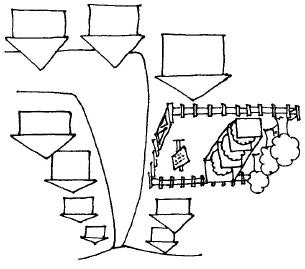

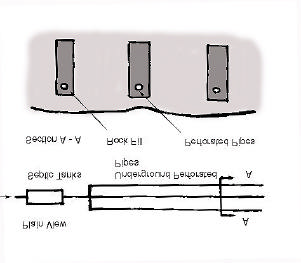

Table 1: Different collection vehicles available.

Type of

Extent/potential

Collection

Comment

Vehicle

use in SIDS

Small dumper

May be used

based on modified jeep or 4WD,

trucks

smaller capacity

Fore-and-aft

Known to be used

enables mechanical loading from transfer bins, and compaction

tipper/compaction

in Fiji

of waste. Not suitable in most SIDS

truck

Tractor and

Commonly used on

easily used for other work apart from waste collection

Trailer

SIDS

Conventional

Commonly used on

can be used for other work apart from waste collection

Truck

SIDS

Roll Top truck

Not likely to be used more difficult to utilise for other uses

can have compartments for keeping different wastes separate

for recycling or composting

Highside open-top

Is used in some

suitable for large loads. Could be used in combination with small

truck,

SIDs

collectors

Human drawn

Not likely to be used These types of micro-collection vehicles are inexpensive to build

handcart, Animal

and maintain, and therefore are often far more sound compared to

drawn cart, and

motorised vehicles.

human pedal cart.

likely to be hard to persuade locals to use these.

A large variety of vehicles can be chosen from for collection. (Credit: UNCHS (Habitat)).

UNEP July 2002

UNEP : Directory of Environmentally Sound Technologies for Waste Management in Pacific SIDS

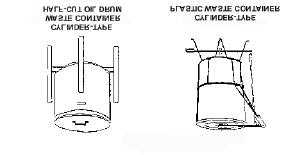

2.3.3 Sound Principles for Selection of Set-out Containers

The following principles are recommended when choosing or designing a new

system of set-out containers:

·

Choose containers made of

local, recycled, or readily

available materials. Examples

used within SIDS include 200

litre drums cut in half, or

recycled tyre rubber formed

into containers.

·

Choose containers which are

easy to identify, either due to Set out Containers can be made from a wide variety of

shape, colour or special materials (Credit: United Nations Centre for Human

markings.

Settlements (UNCHS Habitat)).

§

Choose containers which are sturdy and/or easy to repair or replace.

§

Consider identification of containers with the waste generators name or

address. This helps give more of a sense of ownership and participation in

the waste collection process.

§

Choose containers that suit the collection objectives. Easy to open and

empty, dog proof, and of sufficient size to hold the expected waste quantities

produced, but not larger than needed as this will promote increased waste

disposal rather than minimisation.

§

Where separation of organic waste and or recyclable waste is proposed,

more than one collection container will be necessary. These containers

should be clearly distinguishable, for example, different size or colour.

§

Choose containers that are appropriate for the terrain. On wheels where

there are regular paved streets, water proof in areas where rainfall is

significant, and heavy and squat where there are often strong winds.

2.3.4 Sound Practice for Route Design and Operation

Collection of waste or recyclables tends to be organised into areas or routes. A

service area is the region or area which falls under the responsibility of a local

government, public authority, or private company. The method, frequency, and

timing of waste collection can vary significantly, depending on each situation. The

most efficient system should be sought to meet the specific needs and conditions

that exist in each island, and within different areas of each island. An efficient

UNEP July 2002

UNEP : Directory of Environmentally Sound Technologies for Waste Management in Pacific SIDS

system should aim to cover the necessary service area while using the least amount

of capital, labour and time.

Sound principles in collection route design and operation include:

·

Timing of collection should coincide with times when other traffic on the

road is least, to avoid unnecessary delays in collection and for other road

users.

·

Sizing of collectors appropriately so that the time spent travelling between

the source and the disposal site is minimised.

·

Speed of vehicle: Where households are far apart (in rural areas), a faster

vehicle will be more efficient. Where households are close and compact (in

urban areas), a slower larger capacity vehicle may be better

·

Collection frequency should be set to match the expected volume of waste

produced, size of containers, and local preferences, and should keep in mind

the health risks that would arise from infrequent collection.

·

Kerbside collection of waste from containers set on the kerb or roadside is

common.

·

Central location: In some situations requiring households to take rubbish to

a central collection point (such as the end of a street) will increase the

efficiency of collection. It may also result in the reduction of waste quantities,

as households become more aware of the amount they need to cart to the

central collection point.

·

Competitions to encourage tidiness: In many areas of Indonesia, the

responsibility of waste collection and street sweeping is given to each village

or kampung. All waste from the village is taken by hand or cart to a central

point where it can be collected by the municipal authorities. Competitions

are then held between different kampung to encourage tidiness. A system

like this could easily operate within SIDS with divisions between villages, or

between streets, whichever is appropriate.

·

Communal collection points, where individuals bring their waste directly to

a central point (usually a container) is often used in developing countries.

This method of collection requires regular servicing by municipal authorities

to ensure the central collection site is emptied, cleaned to minimise odours,

vectors, animals, and flies. There is also more potential for hazardous wastes

to be left at the central site without knowing who left them. A series of

recycling containers could be used at these sites to encourage separation of

particular wastes such as glass, paper, aluminium, or organics for reuse. (See

also Transfer Below)

UNEP July 2002

UNEP : Directory of Environmentally Sound Technologies for Waste Management in Pacific SIDS

·

Special Collection runs for bulky, items such as old appliances, and

electronics, furniture, or construction materials.

·

Rules for collection of rubbish should be made clear to all residents and

businesses before the new collection system is introduced. These rules

should include the times of collection, frequency, and list of what wastes can

be disposed of, and what materials should be kept aside for recycling or

reuse.

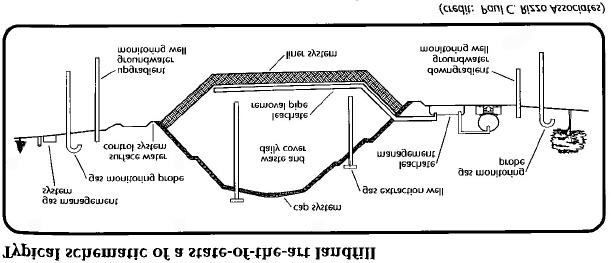

2.3.5 Sound Practice for Transfer of Waste

Transfer stations are centralised facilities where waste is unloaded from smaller

collection vehicles near to waste sources, and reloaded into larger vehicles

(including sea barges), for transport to the final disposal or processing site.

Transfer stations represent sound technology when:

·

there is considerable distance between the main waste source, and the final

waste disposal site;

·

they can double as a sorting, and separation point for recyclable, reusable,

hazardous, and compostable materials;

·

they can accommodate the full range of collection vehicles already in use or

planned, including private trailers;

·

sized to allow waste to be accumulated if necessary prior to long haul

transport;

·

operators respect and abide by agreements made with neighbours; and

·

locally made equipment, local designs, and local expertise are used where

possible.

Transfer stations require additional capital costs to set up, additional handling of

waste, and need to have sufficient supervision and management to ensure the sites

operate efficiently, and do not degenerate into unregulated dumps.

Transfer station should be sited appropriately taking into account the location of the

final waste destination, source of the waste, and potential impacts on neighbouring

properties, remembering that transfer stations can produce significant noise, odour,

air emissions, and traffic. Where the waste disposal site is far from a village, city or

town a transfer station is often the best way to ensure users have easy access to

dispose of waste, and that the waste can be efficiently transported.

UNEP July 2002

UNEP : Directory of Environmentally Sound Technologies for Waste Management in Pacific SIDS

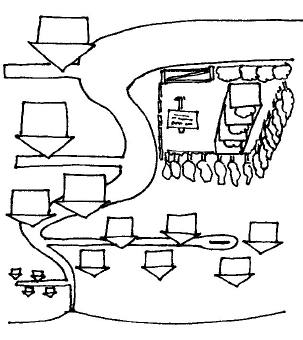

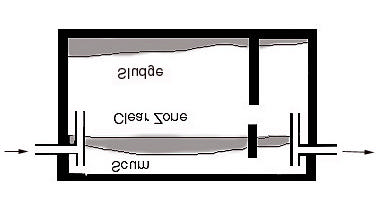

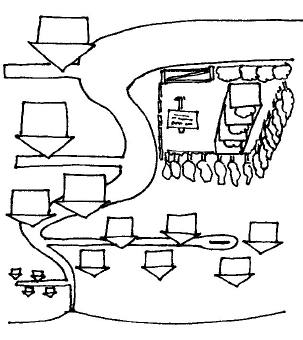

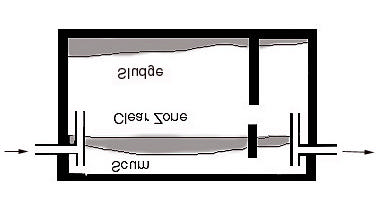

Table 2: Different transfer technologies.

Type of

Potential use in

Transfer

Comments

Technologies

SIDS

Large truck and

Not likely

Likely to be oversized for most SIDS applications.

trailer units

Single high sided trucks may be most appropriate.

Sea Barge

Good potential

Where waste is to be disposed of on another island.

Presents possible problems with loosing waste to sea during the

voyage, and when transferring on and off the barge.

Open tipping floor

Most suited to SIDS

More efficient for small volumes of waste.

Allows waste sorting, materials recovery, and transfer of

materials onto different vehicles for different destinations.

Open Pit

May be suited in

Similar to tipping floor but is not ideal for sorting and recovery of

some cases

materials.

Has higher capital and operating costs, and

Is more vulnerable to breakdown.

Direct dumping

Not recommended

Collection trucks unload through hoppers directly into larger

in SIDS

transfer trucks.

Does not permit sorting and recovery of materials.

Requires high equipment maintenance, repair, and replacement.

2.3.6 Sound Practice in Keeping Streets Clean

The majority of urban and semi-urban areas in the world have some form of system

in place for keeping streets clean. These include litter bins, mechanical sweepers,

and manual sweepers. The intensity of such cleaning activities, varies depending on

the level of use, and quantity of dust and other litter that is generated in a particular

area.

·

Provide litter bins in public areas such as central shopping areas, beaches,

and outside small food shops, and encourage their use through education,

and enforcement if necessary.

·

Clearly define responsibility for emptying litter bins so that they do not spill

onto the street.

·

Planning of sweeping routes needs to be done while taking account of the

length of route that can be completed in one day, the frequency of sweeping,

and where sweepings will be deposited.

·

Manual sweeping systems are the standard in sound practice for most

countries.

For a manual system, sweepers collect their own sweepings in a small cart

and meet a collection vehicle at a centralised point.

Alternatively the wastes could be placed in paper bag or litter basket or lined

up in piles on the kerb side to be collected by a separate truck.

UNEP July 2002

UNEP : Directory of Environmentally Sound Technologies for Waste Management in Pacific SIDS

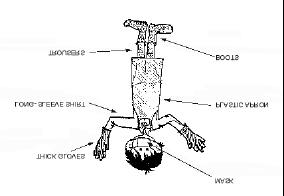

· Mechanical sweeping systems

include four and three-wheeled

sweepers, and vacuum trucks.

· Mechanical sweepers should only

be used where these can be matched

appropriately with the service

areas.

· In the majority of SIDS, it is likely

that manual sweeping will be

preferred over mechanical

sweeping as the mechanical

sweepers require high capital,

operation, and maintenance

expenditure.

· Optimise manual pickup efficiency

and health and safety, by providing

The status of waste workers can be

sweepers with better uniforms,

improved with uniforms and good

brooms, collector bins, and gloves.

equipment. (Credit: Chris Furedy).

·

Keeping streets clean should be the responsibility of the Municipality.

However, there may be a case in SIDS for a more decentralised system,

where the responsibility is placed on individual streets, or villages leaders to

delegate this work appropriately.

There are many possible variations in background conditions even within SIDS,

which affect the selection and design of a sound solid waste collection and transfer

system. These include terrain, settlement patterns, cultural preference and waste

composition. Designers of waste collection systems need to take these into account

and will often need to combine different technologies as they seek to account for the

background conditions of the particular location.

UNEP July 2002

UNEP : Directory of Environmentally Sound Technologies for Waste Management in Pacific SIDS

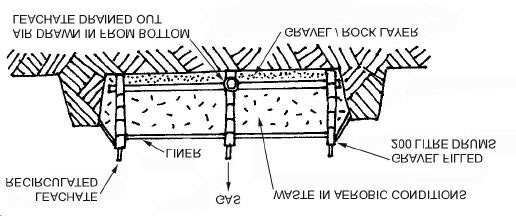

2.4

Composting

In many SIDS, where there is limited or no space for landfilling, and where the soils are

sandy, and poor in structure, the production of compost from organic waste would have a

two-fold benefit. Firstly, it reduces the volume of waste to be land filled, and secondly, it

provides a nutrient, and structural boost to the soils where it is applied.

Composting can be defined as the biological decomposition of complex animal, and

vegetable materials into their constituent components. Composting occurs best when the

ideal conditions are provided to enable bacteria and other organisms to break down the

waste materials. This process can either be aerobic (with oxygen) or anaerobic (without

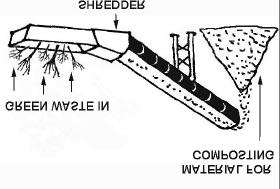

oxygen), however, aerobic composting is most common.

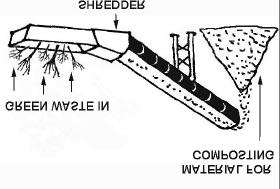

For aerobic composting, the ideal conditions are for the waste to be broken into small

particles. This is often done using a shredder. Aerobic bacteria require a mix of

approximately one part nitrogen, to 30-70 parts carbon food supply, and need 40-60% water

in their environment and plenty of oxygen.

Anaerobic processes, on the other hand, occur in the absence of oxygen. The by-products

include non-oxygenated compounds except for phosphates and water such as methane,

ammonia and hydrogen sulphide. These by-products are not plant food and instead serve

as a system contaminant.

Separation and composting of organic materials for use as a soil conditioner, fertiliser or

growth medium is common practice in many countries to a varying scale, and with varying

success. Apart from the success stories, there are an alarming number of cases where

composting systems have failed completely or operate at only 30% of their capacity. It is

often the case in these situations that the composting technologies and/or associated

management systems installed are inappropriate for the area of application. It is therefore

vital that the reasons for these failures are understood, and that sound practices are

followed for identifying suitable technologies and management systems for composting in

the Pacific region SIDS.

2.4.1 Critical Lessons in Sound Composting Practice

The following sound composting practice guidelines have been developed, based on

critical lessons learned from historical waste composting systems, which have

failed, either completely or in part.

(a)

The materials to be composted must be compostable in order to produce a marketable

product.

§

In most SIDS, the waste stream is already up to 50% organic, and

therefore is ideal for composting.

UNEP July 2002

UNEP : Directory of Environmentally Sound Technologies for Waste Management in Pacific SIDS

§

The compostable fraction of the waste stream can be enhanced by

setting in place the appropriate collection and transfer systems, to

ensure the compostable waste stream is kept separate.

(b)

Mechanical pre-processing of mixed solid waste does not work well enough in most

cases, therefore source separation or manual separation of inorganic materials should

be used.

§

In a technical sense, manual pre-processing of mixed waste, works

best on small to medium scale systems for highly compostable waste

streams.

§

A disadvantage of manual processing is that it may not be either

pleasant or safe for workers.

(c)

Economic viability depends on three factors. Failure of any of these three can cause

the system to fail.

1.

Unless composting has traditionally been performed, landfilling or

dumping must be controlled and sufficiently expensive to make the

moderate cost of composting (US $20-40/tonne) competitive with the

cost of dumping. For many SIDS, the cost of land area, shipping of

waste to centralised landfills, and environmental degradation due to

landfilling should also be included in this assessment. Until these

costs are fully recognised, it is unlikely that composting will be more

cost effective than landfilling.

2.

There must be a market or use for the compost, at the quality that it is

produced. If this market or use does not produce a net income, the

Government or Municipality should be prepared to cover the

difference.

3.

The waste stream composition has a large effect on the quality and

marketability of the end product. Enhancement of the compostable

waste stream by support of source separation, and materials recovery

of non-compostables, is therefore needed.

(d)

Technical viability depends on three factors:

1.

There should not be dependence on mechanical pre-processing. This

often breaks down.

2.

The scale of the composting operation should not be too large.

3.

The entire system from source separation to final screening must be

designed as an integrated system, to deliver the appropriate inputs,

and a high quality product output.

UNEP July 2002

UNEP : Directory of Environmentally Sound Technologies for Waste Management in Pacific SIDS

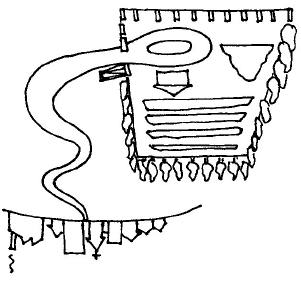

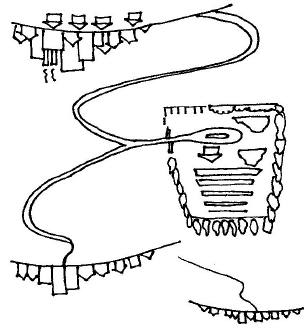

2.4.2 Sound Technologies for Composting

The following tables provide a range of technologies available for composting, from

small backyard to large scale regional systems. In evaluating composting as a

technology, the character and type of waste stream to be composted needs to be

determined. In this respect, the following points should be noted and investigated

further if relevant:

§

Waste may need shredding or chipping to reduce size and speed up

composting

§

Kitchen waste can be high in protein from meats, dairy products and some

vegetables, leading to unpleasant odours. In this case, combination with

high carbon wastes such as yard leaves, and lawn clippings, improves

compostability

§

The extent of animal feeding using kitchen waste should be accounted for.

In many SIDS, pigs are kept to consume kitchen wastes, and provide meat,

resulting in reduced quantities of waste being available for composting.

Feeding waste to animals achieves a higher level of nutrient utilisation than

composting, however, has associated health risks with animals transferring

pathogens or diseases directly or via the water supply.

§

Wastewater sludge, and human faecal matter can be composted, however,

they are high in nitrogen and moisture. They must therefore be composted in

combination with carbon sources such as wood chip, paper, and bulking

agents to allow oxygen into the compost piles. Such practice requires health

and safety precautions to avoid pathogen hazards.

§

Manure and animal waste is generally composted in farm applications, and

is an important aspect of sustainable farming. Such wastes can easily be

incorporated into community or larger scale composting systems.

UNEP July 2002

UNEP : Directory of Environmentally Sound Technologies for Waste Management in Pacific SIDS

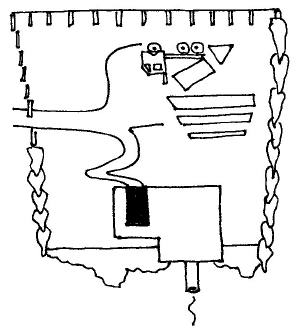

Composting system:

Technology Description:

This is the smallest scale of composting. Composting in the

Backyard Composting on Household

back yard can be done informally, simply by creating a heap

Scale

of compostable waste, or can be held using bricks, timber or

an old drum.

Compostable waste such as kitchen scraps, paper, lawn

clippings, and garden waste are all placed within the

composting container. Once the container is full, a second

is used or the first is shifted leaving the waste to break down

over time to form compost. While the first pile breaks down,

fresh waste is placed in the second container. The compost

needs to be aerated by turning with a fork, and water added

if necessary to maintain the correct moisture content.

If encouraged on a regional scale, a municipality may issue

standard compost bins and educational information which

encourage backyard composting, make it tidier, and

minimise the potential for problems to occur

Extent of Use:

· only on an informal basis in a few areas

· encouraged in some SIDS but not common in others

Operation and Maintenance:

· relies only on some input by householders to monitor, water, and turn the compost to ensure good compost is made

Advantages:

Disadvantages/constraints:

· no collection, transfer and final marketing costs

· can cause significant problems with high vermin

· low cost

populations

· encourages public involvement

· relies on public participation

· less controlled

Relative Cost:

Cultural Acceptability:

· very low

· no known cultural unacceptability

· costs for bins, and for training

Suitability:

· Yes, where houses have sufficient yard space

· Yes, where organic wastes are not otherwise fed to animals

· Yes, where the waste stream contains primarily vegetable matter rather than animal matter

· Yes, because they are appropriate technology, and can be developed locally

UNEP July 2002

UNEP : Directory of Environmentally Sound Technologies for Waste Management in Pacific SIDS

Composting system:

Technology Description:

Neighbourhood, Block, or Business Scale Decentralised composting where quantities of less than 5

Composting

tons per day of waste are collected to a central composting

point within a neighbourhood, block, or number of

businesses.

The site would include a series of concrete or timber bins

which could be alternately filled, composted, and emptied.

Support from the Municipality with technical advice, turning

of compost, and emptying would likely be necessary.

The site would need good signs and fencing instructing of

acceptable wastes, current dumping area, and to keep

unwanted animals out.

This Technology is a Sound approach when:

· within close proximity of the waste source,

· sited beside community gardens, or park reserve,

· has approval from all neighbours,

· the waste stream contains primarily vegetable matter

rather than animal matter,

· clearly designated with signs,

· have adequate fencing, and

· good soil for leachate adsorption.

Extent of Use: Encouraged on some SIDS but not generally

common

Operation and Maintenance:

· on this scale of operation, collection would typically be up to individual households, with responsibility for co-

ordinating, cleaning and maintaining order given to a neighbourhood supervisor, with backup from the municipality

to provide technical advice, support for removal of undesired items, or turning of the piles.

Advantages:

Disadvantages/constraints:

· minimal collection, transfer and final marketing costs

· can cause significant problems with high vermin

· low cost

populations, animals, insects, and odours from site

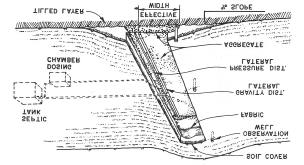

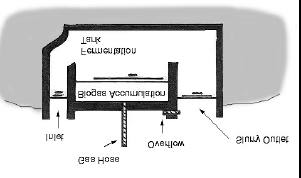

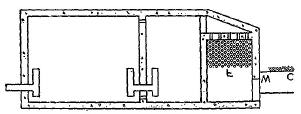

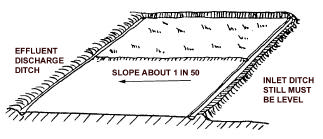

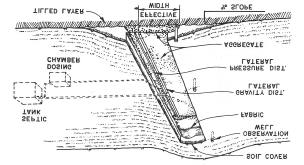

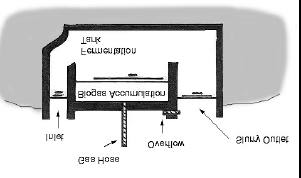

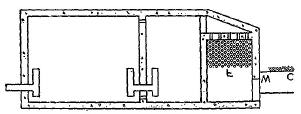

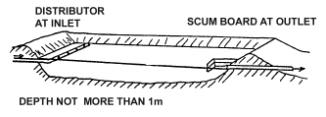

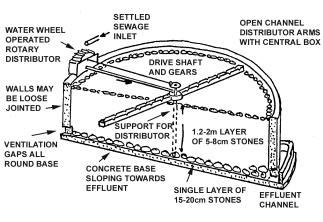

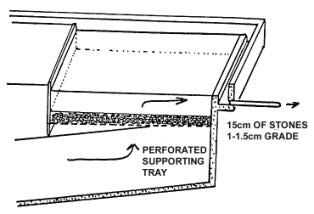

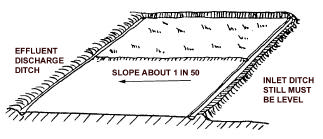

· encourages public involvement