E1288

v 6

Public Disclosure Authorized

Regional Environmental

Assessment (REA)

for

Public Disclosure Authorized

Manila Third Sewerage Project

February 11, 2005

(Revised Draft)

Public Disclosure Authorized

Public Disclosure Authorized

Manila Water Company, Inc.

Manila, Philippines

Regional Environmental Assessment

1

Introduction.......................................................................................... 1-1

1.1 Background ................................................................................................. 1-1

1.2 Environment ................................................................................................ 1-1

1.3 Public Health ............................................................................................... 1-2

1.4 Fisheries and Ecosystems........................................................................... 1-2

1.5 Tourism ....................................................................................................... 1-2

1.6 Economic Impacts ....................................................................................... 1-3

1.7 Moving Forward........................................................................................... 1-3

2

Background to the Regional Environmental Assessment ............... 2-1

2.1 Objectives of the REA ................................................................................. 2-1

2.1.1 Steps in the Conduct of a REA............................................................. 2-1

2.2 Scope of the REA........................................................................................ 2-2

2.2.1 Wastewater Management Component ................................................. 2-2

2.2.2 Sludge and Septage Management ....................................................... 2-3

2.3 Regional Planning Integration ..................................................................... 2-4

3

Overview of the Adopted Region ....................................................... 3-1

3.1 Regional Sub-Basins................................................................................... 3-1

3.2 Topography ................................................................................................. 3-2

3.3 Vulnerability to Flooding .............................................................................. 3-2

3.4 Land Use..................................................................................................... 3-3

3.5 Regional Flow Regimes............................................................................... 3-3

3.5.1 Wet and Dry Season Flow Variation..................................................... 3-3

3.5.2 Tidal Influence on Laguna Lake ........................................................... 3-4

3.6 Groundwater ............................................................................................... 3-4

3.6.1 Confined Aquifers................................................................................. 3-4

3.6.2 Unconfined Aquifers............................................................................. 3-5

3.7 Sources of Water Pollution.......................................................................... 3-5

3.7.1 BOD5.................................................................................................... 3-5

3.7.2 Suspended Solids ................................................................................ 3-6

3.7.3 Pathogens and Indicators..................................................................... 3-7

3.7.4 Nutrients............................................................................................... 3-7

3.7.5 Persistent Pollutants............................................................................. 3-8

3.7.6 Solid Waste.......................................................................................... 3-8

3.8 Population ................................................................................................... 3-8

4

Baseline Conditions ............................................................................ 4-1

4.1 Terrestrial Environment ............................................................................... 4-1

4.1.1 Terrestrial Flora.................................................................................... 4-1

4.1.2 Terrestrial Fauna.................................................................................. 4-3

4.1.3 Air Quality............................................................................................. 4-3

4.1.4 Noise.................................................................................................... 4-3

4.2 Water Quality .............................................................................................. 4-3

4.2.1 Background.......................................................................................... 4-4

4.2.2 Existing Monitoring Programs............................................................... 4-4

4.3 Review of Water Quality Monitoring Datasets ............................................. 4-6

4.3.1 Possible Testing Anomalies ................................................................. 4-7

4.3.2 Possible Data Anomalies...................................................................... 4-7

4.4 Interpretation of Water Quality Data............................................................ 4-8

4.4.1 Seasonality and Correlation ................................................................. 4-8

4.4.2 Sampling Frequency ............................................................................ 4-8

4.4.3 Sampling Time and Tidal State ............................................................ 4-8

4.4.4 River Flow Data.................................................................................... 4-9

4.4.5 Replication ........................................................................................... 4-9

4.5 Summary of Water Quality Data.................................................................. 4-9

4.5.1 Overview .............................................................................................. 4-9

Draft

i

9:41 AM 02/09/05

Regional Environmental Assessment

4.5.2 Utility as a Baseline .............................................................................. 4-9

4.6 Aquatic Ecology......................................................................................... 4-10

4.6.1 Plankton ............................................................................................. 4-10

4.6.2 Soft-Bottom Benthos .......................................................................... 4-10

4.6.3 Fisheries, Types of Aquatic Life and Other Uses................................ 4-12

4.7 Socio-Economics....................................................................................... 4-13

4.7.1 Population, Density, and Land Area ................................................... 4-13

4.7.2 Income ............................................................................................... 4-13

4.7.3 Health................................................................................................. 4-15

4.7.4 Economy ............................................................................................ 4-16

5

Existing Water, Sewerage and Septage Management Facilities ..... 5-1

5.1 Water Supply............................................................................................... 5-1

5.2 Sewerage .................................................................................................... 5-1

5.2.1 Other Systems ..................................................................................... 5-5

5.2.2 Private Sewerage System in the MWCI Concession Area.................... 5-5

5.3 Sanitation Facilities ..................................................................................... 5-6

5.4 Regional Issues in Relation to Sewage Management.................................. 5-7

5.5 Historical Infrastructure Investment Pattern................................................. 5-8

6

Policy and Institutional Framework ................................................... 6-1

6.1 Overview ..................................................................................................... 6-1

6.2 Land Use Planning and Zoning ................................................................... 6-1

6.3 Sewerage and Sanitation ............................................................................ 6-2

6.3.1 Sanitation Code.................................................................................... 6-3

6.3.2 Clean Water Act ................................................................................... 6-3

6.3.3 Other Legislation .................................................................................. 6-4

6.4 Mandates in Sewerage Management .......................................................... 6-4

6.5 Institutional Recommendations.................................................................... 6-5

6.5.1 Relative Priority of Wastewater Services.............................................. 6-5

6.5.2 Connection to Public Sewerage Systems ............................................. 6-6

6.5.3 Project Financing ................................................................................. 6-6

6.5.4 Low Willingness to Pay and the Lack of Sanctions............................... 6-7

6.5.5 Monitoring of Compliance to Existing Laws .......................................... 6-7

6.5.6 MTSP Impacts on Existing Private Septage Haulers ............................ 6-8

6.5.7 IEC on Health Impacts of Wastewater.................................................. 6-8

6.6 Summary..................................................................................................... 6-9

7

Generic Wastewater Management Alternatives ................................ 7-1

7.1 Background ................................................................................................. 7-1

7.1.1 Total Wastewater Management Schemes............................................ 7-1

7.1.2 Supplementary Wastewater Management Strategies........................... 7-1

7.2 Disposal to Water........................................................................................ 7-1

7.2.1 Discharge to Freshwater or Lakes........................................................ 7-1

7.2.2 Discharge Treated Effluent to Estuaries............................................... 7-2

7.2.3 Piped Ocean Discharge ....................................................................... 7-3

7.3 Application to Land Options......................................................................... 7-3

7.3.1 Irrigate Lahar Affected Areas ............................................................... 7-3

7.3.2 Hinterland Irrigation .............................................................................. 7-4

7.4 Recycling Options ....................................................................................... 7-4

7.4.1 Indirect Potable Reuse ......................................................................... 7-4

7.4.2 Direct Potable Reuse ........................................................................... 7-4

7.5 Supplementary Options ............................................................................... 7-4

7.5.1 Dual Reticulation .................................................................................. 7-5

7.5.2 Irrigate Parks and Sports Fields with Treated Effluent.......................... 7-5

7.5.3 Industrial Re-use .................................................................................. 7-5

7.5.4 Special Uses and Commercial.............................................................. 7-6

Draft

ii

9:41 AM 02/09/05

Regional Environmental Assessment

7.5.5 Ground Water Recharge ...................................................................... 7-6

7.6 On-Site Systems ......................................................................................... 7-6

7.6.1 Treatment Upgrades ............................................................................ 7-6

7.6.2 On-Site Disposal................................................................................... 7-7

7.7 Collection System Options ........................................................................... 7-8

7.7.1 Common Effluent Drainage Systems.................................................... 7-8

7.7.2 Modified Common Effluent Drainage ..................................................... 7-8

7.7.3 Conventional versus Combined Sewers ................................................ 7-9

7.7.4 Reticulation Summary ........................................................................... 7-9

7.8 Waste Minimisation Options ........................................................................ 7-9

7.9 Flood Flow Manipulation............................................................................ 7-10

7.10 No Project Option ................................................................................. 7-10

7.11 Comparison of Options .......................................................................... 7-11

8

MTSP Framework ................................................................................ 8-1

8.1 Introduction ................................................................................................. 8-1

8.2 Background Summary................................................................................. 8-3

8.3 Concessionaire Sewerage and Sanitation Obligations ................................ 8-3

8.3.1 JICA Master Plan Study ....................................................................... 8-5

8.3.2 MWCI First Wastewater Strategy Plan, 2000 ....................................... 8-5

8.4 Experience from Ongoing Projects.............................................................. 8-6

8.4.1 MSSP Community Sanitation Project (MCSP)...................................... 8-6

8.4.2 MSSP-4................................................................................................ 8-6

8.4.3 Pateros Sewer System ......................................................................... 8-6

8.5 Specific Implementation Difficulties ............................................................. 8-6

8.5.1 Land Availability and Cost .................................................................... 8-7

8.5.2 Community and Traffic Disruptions ...................................................... 8-7

8.5.3 Enforcing Sewerage Connections ........................................................ 8-7

8.5.4 Tariffs................................................................................................... 8-7

8.5.5 External Factors ................................................................................... 8-8

8.6 Rate Rebasing ............................................................................................ 8-8

8.7 Project Development ................................................................................... 8-9

8.7.1 Land Availability ................................................................................. 8-10

8.7.2 Applicable Concepts........................................................................... 8-10

8.7.3 Social Acceptability ............................................................................ 8-10

8.8 Selection Criteria and Methodology........................................................... 8-10

8.8.1 Availability and Land Criteria .............................................................. 8-10

8.8.2 Catchment Area Selection.................................................................. 8-11

8.8.3 Health/Environmental Impact ............................................................. 8-11

8.8.4 Financial and Economic Considerations............................................. 8-11

8.9 Overview of the Manila Third Sewerage Project ....................................... 8-12

Draft

iii

9:41 AM 02/09/05

Regional Environmental Assessment

9

MTSP Integration into Other Regional Projects................................ 9-1

9.1 Existing Projects.......................................................................................... 9-1

9.1.1 Manila Second Sewerage Project (MSSP) ........................................... 9-1

9.1.2 Pasig River Rehabilitation Project Sanitation Component ................. 9-1

9.2 MWCI Master Plan ...................................................................................... 9-2

9.2.1 Reasons for Selection of Alternatives................................................... 9-2

9.2.2 Description of Variations Between Alternatives .................................... 9-3

9.2.3 Comparisons Between Specific Alternatives ........................................ 9-3

9.2.4 Summary of Alternatives Evaluation..................................................... 9-4

10 The Project Components .................................................................. 10-1

10.1 Component 1: Taguig Sewerage System................................................10-1

10.1.1

Options Background ........................................................................10-1

10.1.2

Component Summary......................................................................10-1

10.2 Component 2: Riverbanks Sewage Treatment Plants.............................10-3

10.2.1

Options Background ........................................................................10-3

10.2.2

Component Summary......................................................................10-4

10.3 Component 3: Septage Treatment Plants...............................................10-4

10.3.1

Options Background ........................................................................10-4

10.3.2

Component Summary......................................................................10-5

10.4 Component 4: Low Income Sewerage System .......................................10-6

10.4.1

Options Background ........................................................................10-6

10.4.2

Component Summary......................................................................10-7

10.5 Component 5: Quezon City Marikina Sewerage System......................10-8

10.5.1

Options Background ........................................................................10-8

10.5.2

Component Summary......................................................................10-8

10.6 Component 6: Upgrade of Existing Sanitation System............................10-9

10.6.1

Options Background ........................................................................10-9

10.6.2

Component Summary....................................................................10-10

10.7 Sludge/Septage Re-use........................................................................10-10

10.7.1

Options Background ......................................................................10-10

10.7.2

Septage Characteristics.................................................................10-11

10.7.3

Sludge Characteristics...................................................................10-12

10.7.4

MTSP Septage/Sludge Quantities and Sources.............................10-13

10.8 MTSP Summary and Issues .................................................................10-15

11 Public Consultation ........................................................................... 11-1

11.1 Introduction.............................................................................................11-1

11.2 First Level Consultations.........................................................................11-1

11.2.1

Scoping Workshop ..........................................................................11-1

11.2.2

Focused Group Discussions ............................................................11-2

11.3 Second Level Consultations....................................................................11-3

11.4 Public Consultation .................................................................................11-4

11.4.1

Scoping Workshop ..........................................................................11-4

11.4.2

Focused Group Discussions (FGDs) ...............................................11-4

11.4.3

Summary of Public Consultation ......................................................11-8

12 Cumulative Impact Assessment....................................................... 12-1

12.1 Introduction.............................................................................................12-1

12.1.1

No Project Options...........................................................................12-1

12.1.2

MTSP Option ...................................................................................12-1

12.2 General Benefits.....................................................................................12-2

12.2.1

Water Quality Improvement .............................................................12-2

12.2.2

Better Health....................................................................................12-2

12.2.3

Greater Tourism ..............................................................................12-2

12.2.4

Greater Fishery Production..............................................................12-2

12.2.5

Property Values ...............................................................................12-2

DRAFT

iv

9:42 AM 02/09/05

Regional Environmental Assessment

12.2.6

General Aesthetic improvements .....................................................12-3

12.2.7

Improved Institutional Implementation .............................................12-3

12.2.8

Septage/Sludge Management .........................................................12-3

12.3 MTSP General Impacts...........................................................................12-3

12.4 Flow-on Affects.......................................................................................12-4

12.5 Typical Impacts.......................................................................................12-4

12.5.1

Noise ...............................................................................................12-4

12.5.2

Air Pollution .....................................................................................12-5

12.5.3

Water Pollution ................................................................................12-5

12.5.4

Aesthetics ........................................................................................12-5

12.5.5

Flora and Fauna ..............................................................................12-5

12.6 Economic Analysis..................................................................................12-6

12.6.1

Introduction......................................................................................12-6

12.6.2

Project Economic Cost ....................................................................12-6

12.6.3

Health Benefits ................................................................................12-6

12.6.4

Determination of Environmental Benefit...........................................12-7

12.6.5

Water Quality Improvement .............................................................12-7

12.6.6

Consumer Surplus ...........................................................................12-7

12.6.7

Septage/Sludge Application to Land ................................................12-7

12.6.8

Environmental fee and sewerage charges .......................................12-8

12.6.9

Summary of Economic Benefits.......................................................12-8

13 Regional Environmental Management System ............................... 13-1

13.1 Introduction.............................................................................................13-1

13.2 Institutional Aspects................................................................................13-1

13.2.1

Relative Priority of Wastewater Services .........................................13-2

13.2.2

Connection to Public Sewerage Systems ........................................13-3

13.2.3

Project Financing .............................................................................13-3

13.2.4

Low Willingness to Pay and the Lack of Sanctions ..........................13-3

13.2.5

Monitoring of Compliance to Existing Laws......................................13-4

13.2.6

MTSP Impacts on Existing Private Septage Haulers .......................13-4

13.2.7

IEC on Health Impacts of Wastewater .............................................13-5

13.3 Project Specific Enhancement/ Mitigation Strategies ..............................13-5

13.4 Air Sector Enhancement/ Mitigation Strategies.......................................13-5

13.5 Water Enhancement/ Mitigation Strategies.............................................13-6

13.6 Monitoring Strategies..............................................................................13-6

13.6.1

Environmental Monitoring Plan ........................................................13-6

13.6.2

Air/Noise Monitoring ........................................................................13-7

13.6.3

Effluent and Water Quality Monitoring Strategy ...............................13-7

13.6.4

Groundwater Monitoring ..................................................................13-8

13.6.5

Surface Water Ambient Monitoring ..................................................13-8

13.6.6

Socio-Economic Monitoring .............................................................13-8

13.6.7

Financial Guarantee Mechanisms....................................................13-9

13.7 REMS Summary .....................................................................................13-9

13.7.1

Components ....................................................................................13-9

13.7.2

Costs ...............................................................................................13-9

13.8 Background to Water Quality and Ecosystem Monitoring .....................13-14

13.8.1

Background ...................................................................................13-14

13.8.2

Monitoring Program Aims ..............................................................13-14

13.8.3

Level of Acceptable Change ..........................................................13-14

13.8.4

Statistical Level Of Confidence ......................................................13-14

13.8.5

Adopted Values for Base Monitoring Program ...............................13-15

13.8.6

Water Quality and Ecosystem Pilot Monitoring Program................13-15

13.8.7

Types of Monitoring Program.........................................................13-15

13.8.8

Data Review - Power Analysis .......................................................13-16

DRAFT

v

9:42 AM 02/09/05

Regional Environmental Assessment

13.8.9

Geographical Extent of Survey ......................................................13-17

13.8.10 Sampling Frequency......................................................................13-17

13.8.11 Ambient Water Quality Data Quality Assurance.............................13-17

13.8.12 Control Sites or River System ........................................................13-18

13.9 Recommended Water Quality and Ecological Monitoring Program.......13-18

13.9.1

Water Quality and Ecological Monitoring Priorities.........................13-18

13.9.2

Water Quality and Ecological Pilot Program Year one ................13-19

13.9.3

Statistical Review...........................................................................13-20

13.9.4

Water Quality Pilot Program If required to extend beyond Year 113-

21

13.9.5

Water Quality and Ecological Base Monitoring Program................13-22

13.9.6

Criteria Review ..............................................................................13-23

13.9.7

Costs .............................................................................................13-24

13.9.8

Community Water Quality Monitoring Programs ............................13-24

14 Conclusions and Recommendations............................................... 14-1

14.1 Conclusions ............................................................................................14-1

14.2 Recommendations..................................................................................14-6

Appendix A - Baseline Data.......................................................................A-1

A.1

Physical Environment .............................................................................. A-1

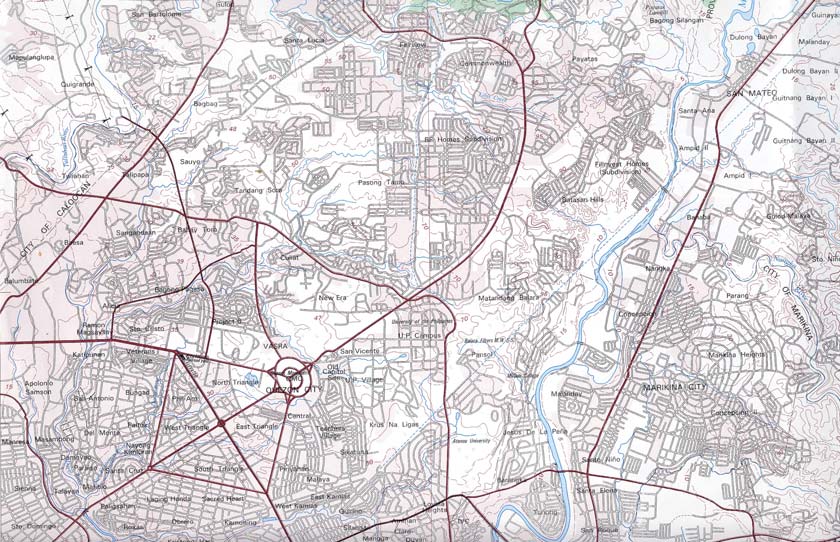

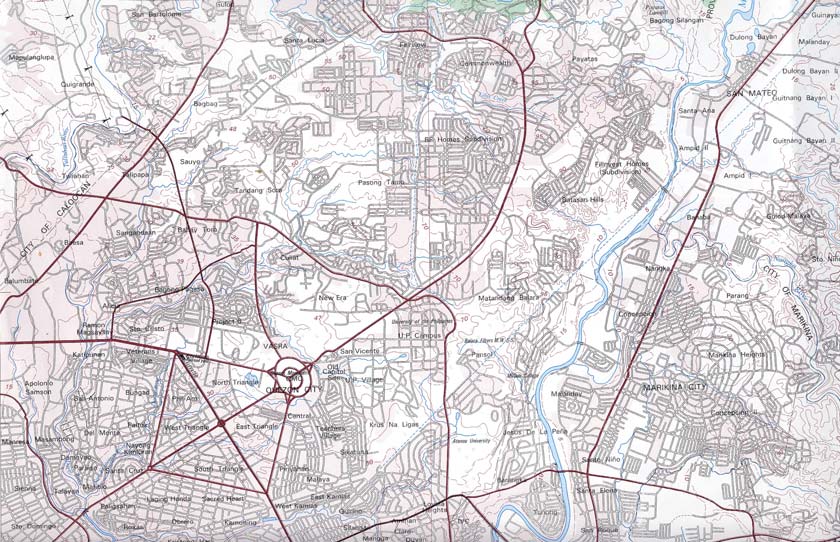

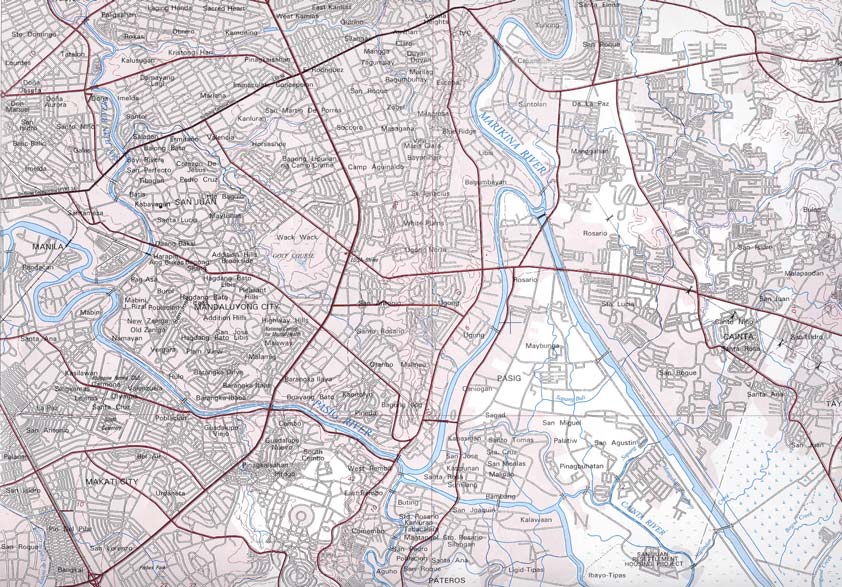

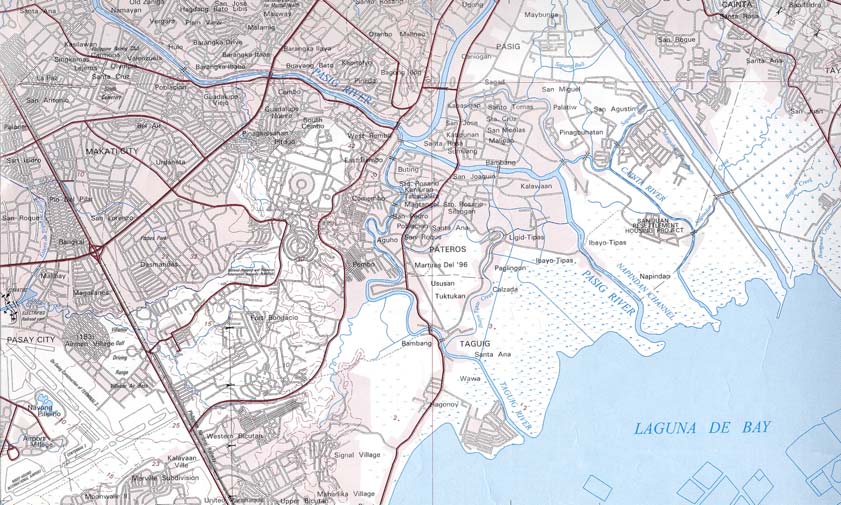

A.1.2 Topography.......................................................................................... A-1

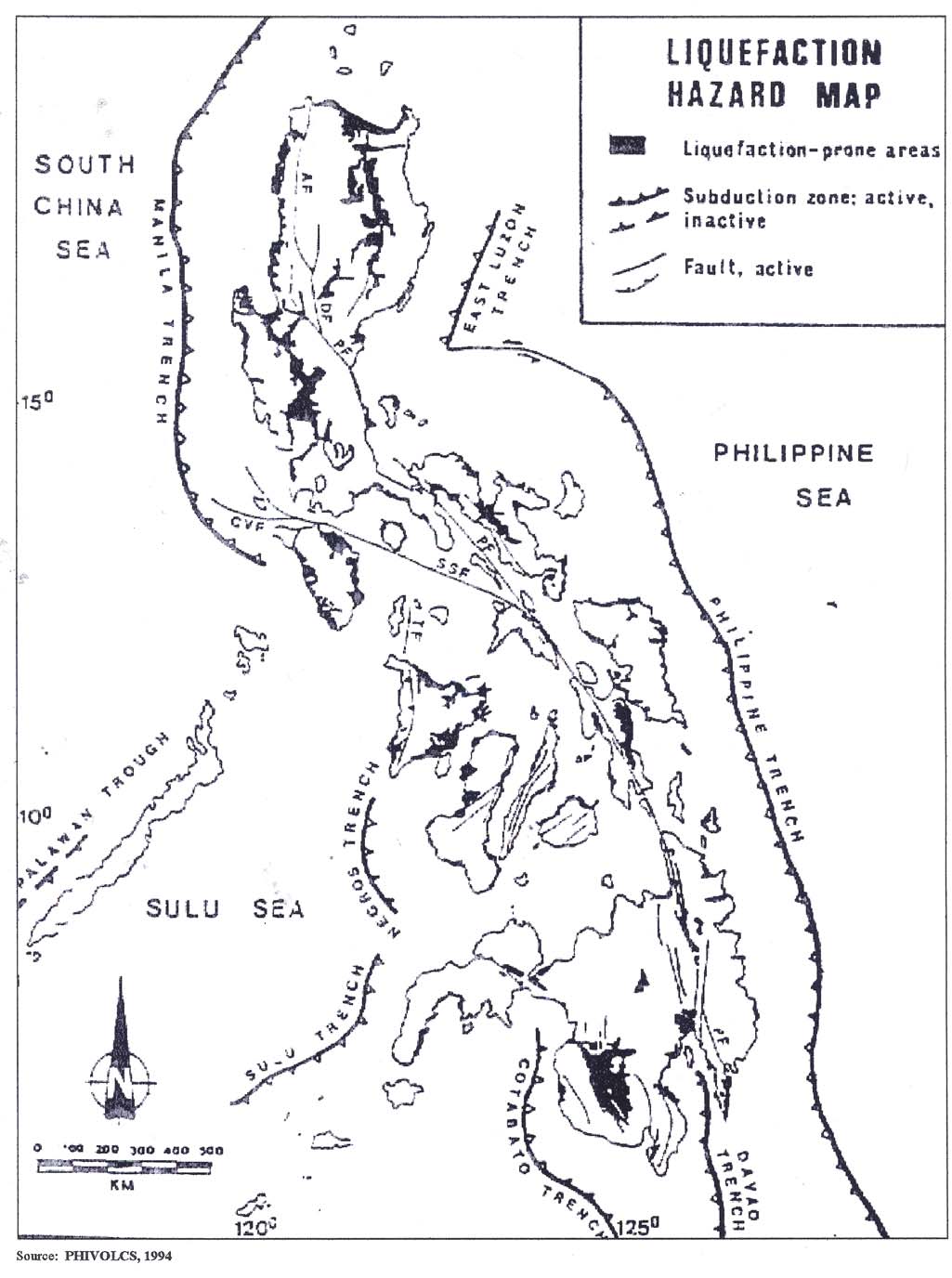

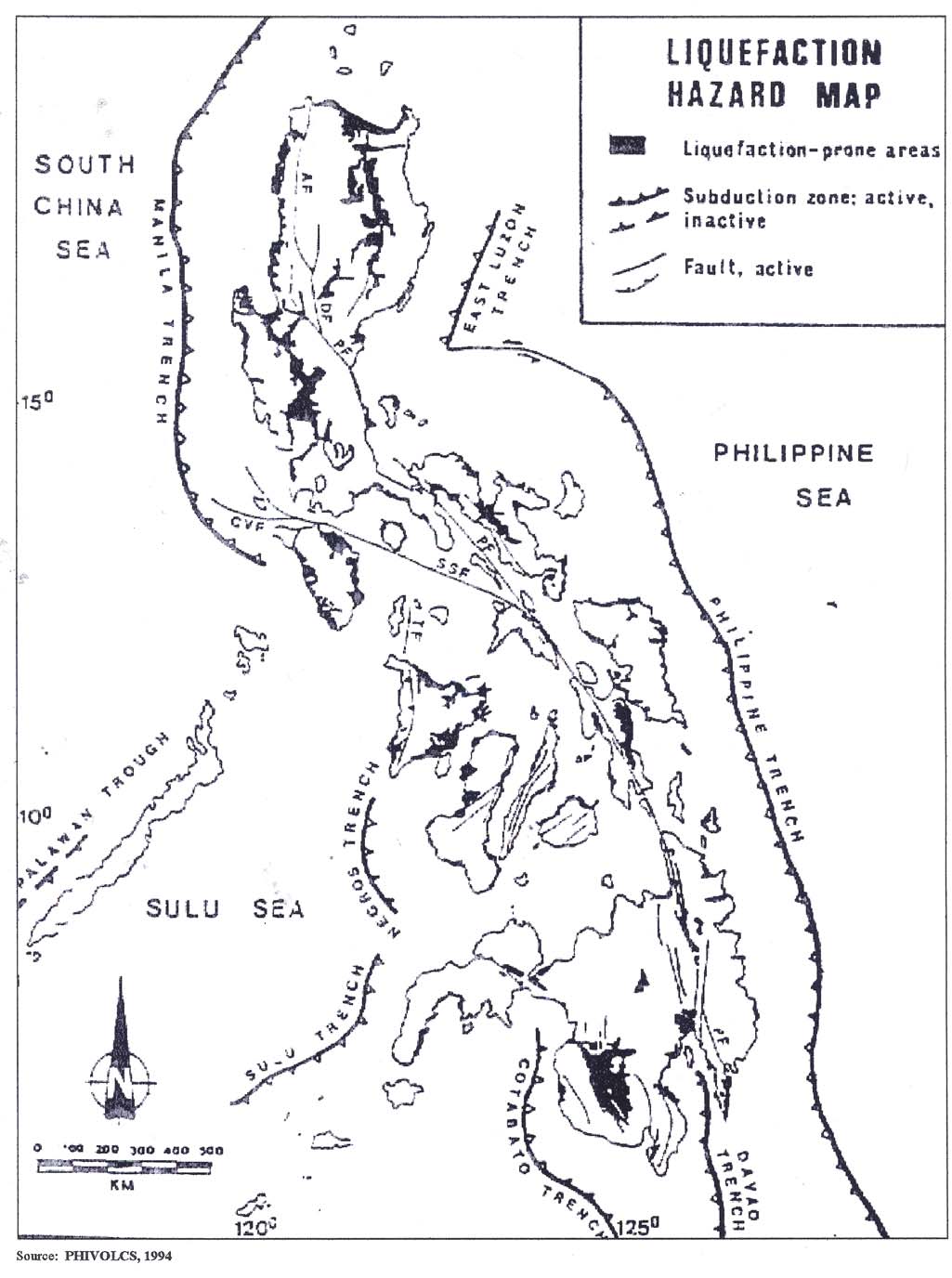

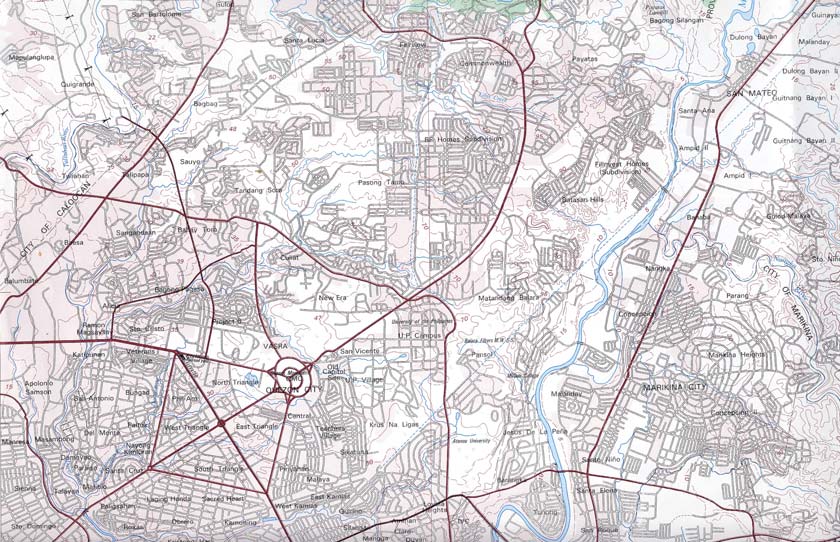

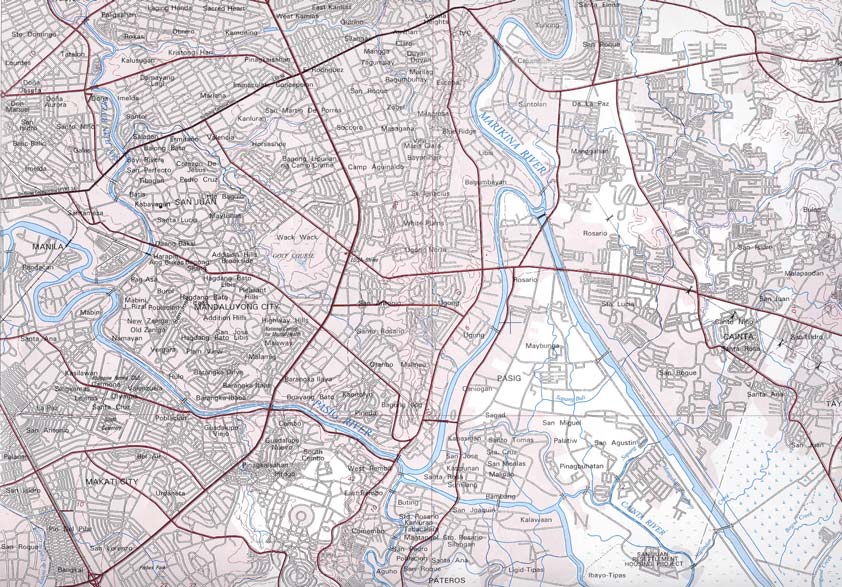

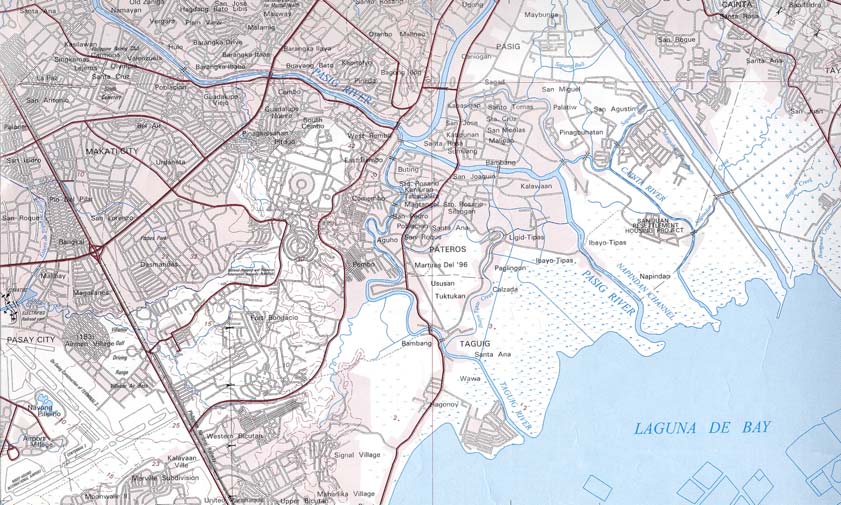

A.1.3 Geology and Natural Hazards .............................................................. A-1

A.1.3 Soils ................................................................................................... A-12

A.1.4 Land Use............................................................................................ A-13

A.1.5 Hydrology........................................................................................... A-17

A.1.7 Meteorology and Ambient Air Quality ................................................. A-31

A.1.8 Noise Level ........................................................................................ A-39

A.2

BIOLOGICAL ENVIRONMENT.............................................................. A-42

A.2.1 Terrestrial Ecology ............................................................................. A-42

A.2.2 Aquatic Ecology ................................................................................. A-46

A.3

Socio Economic and Cultural Environment ............................................ A-53

Appendix B Monitoring Sites and Programs .......................................B-1

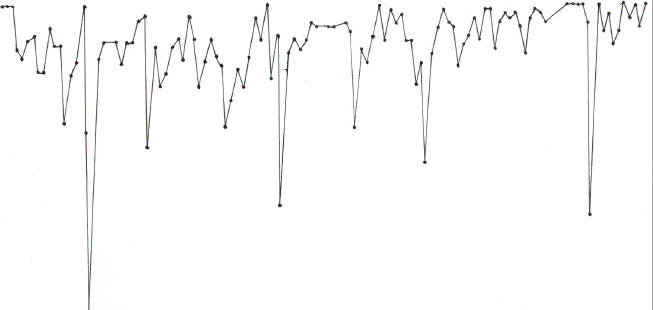

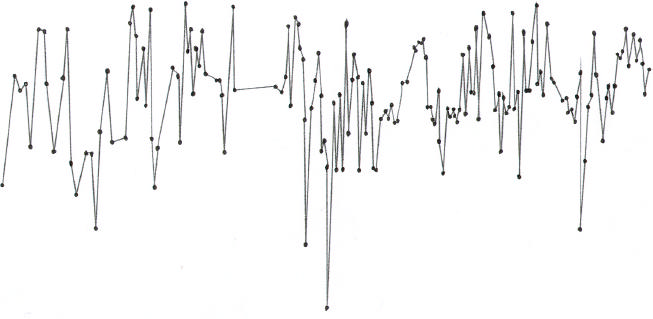

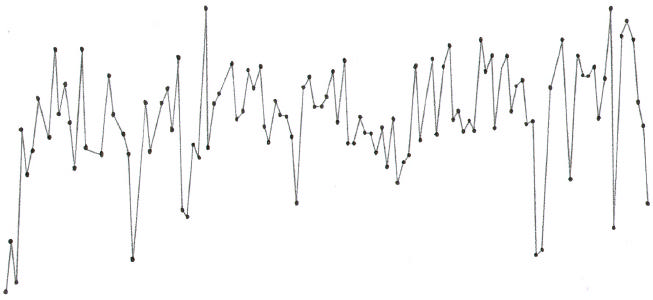

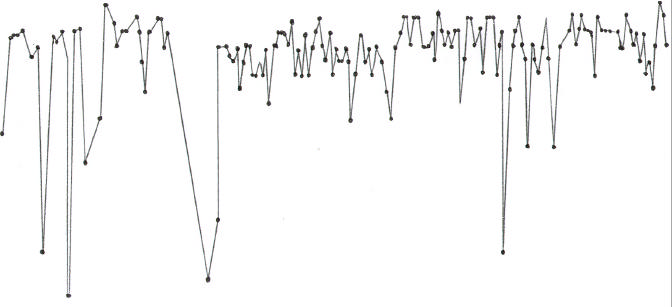

Appendix C Monitoring Data Graphs and Tables.................................C-1

Appendix D Institutional Framework Details ........................................D-1

D.1

Role of National Agencies in Sewerage Management ............................. D-1

D.1.2 Department of Health ........................................................................... D-1

D.1.3 Department of Environment and Natural Resources ............................ D-2

D.1.4 Department of Public Works and Highways ......................................... D-2

D.1.5 Metropolitan Waterworks and Sewerage System ................................. D-3

D.1.6 The Manila Water Company, Inc. and its Service Area ........................ D-4

D.1.7 Metro Manila Development Authority.................................................... D-5

D.1.8 Laguna Lake Development Authority.................................................... D-6

D.2

Role of Local Government Units (LGU) in Sewerage Management ......... D-7

D.3

Role of the Private Sector ...................................................................... D-10

D.4

National Sewerage Management Policies.............................................. D-13

D.4.1 Sanitation Code of the Philippines...................................................... D-13

D.4.2 Implementing Rules and Regulations (IRR) of the Code on Sanitation.......

........................................................................................................... D-14

D.4.3 The Local Government Code ............................................................. D-15

D.4.4 Provincial Water Utilities Act of 1973.................................................. D-16

D.4.5 The Plumbing Law and the National Plumbing Code of the Philippines......

........................................................................................................... D-16

D.4.6 Complementary Laws......................................................................... D-17

D.4.7 The Clean Water Act.......................................................................... D-18

Appendix E Community Consultation Record......................................E-1

DRAFT

vi

9:42 AM 02/09/05

Regional Environmental Assessment

Executive Summary

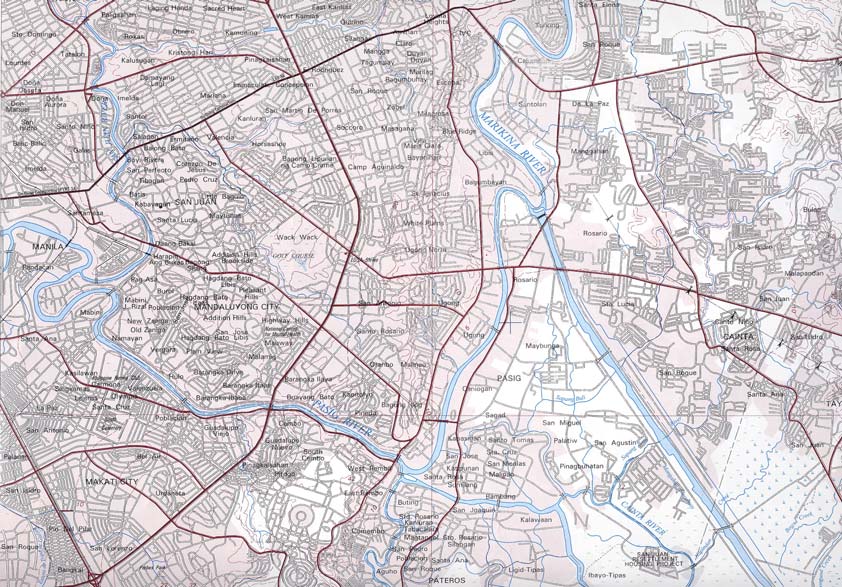

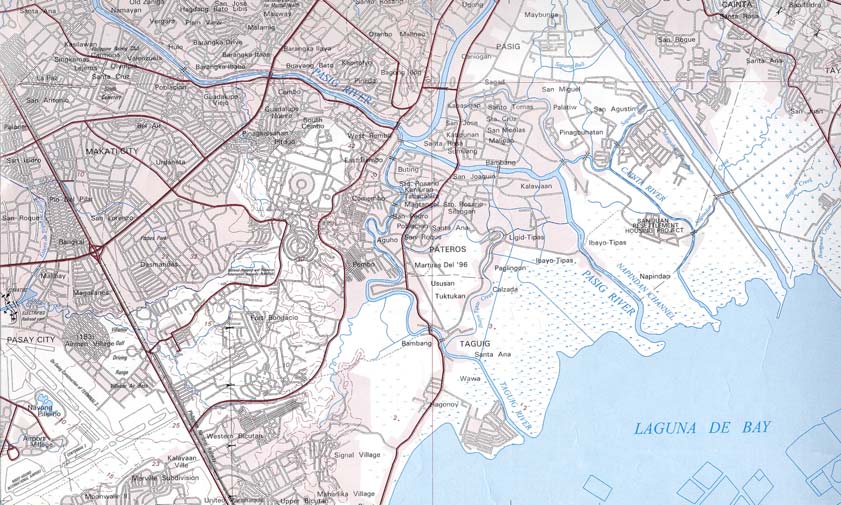

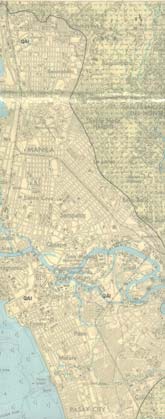

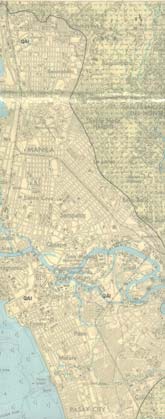

Metro Manila lies at the western part of the Philippine archipelago. It is the largest

among 16 regions of the country. It has a total land area of 636 square kilometres

and, as of year 2000, is home to 9.9 million people. Some other estimates suggest

the population is closer to 12 million people. It is composed of 17 cities and 5

municipalities subdivided into 1,692 barangays. Metro Manila is bounded by the

province of Bulacan in the north, the province of Rizal in the east, Manila Bay in the

west and Laguna Lake, and Cavite and Laguna in the south. The Pasig River

traverses through a significant area of the metropolis. It drains towards the Laguna

Lake in the south or the Manila Bay in the west, depending on base flow and tidal

state.

While the city has a sound economy, it faces a multitude of problems. Among its

pressing concerns are housing, employment, health, solid waste and wastewater

management, traffic, air and water pollution. The national and local governments

develop and implement programs to address these issues. However, bureaucracy

and politics often make it difficult to successfully implement programs as they are

conceived.

Presently, less than 8% of the Metro Manila population is served by sewerage

systems. These systems are localized in Makati, Quezon City and the Central

Manila area. Some 85% of the population relies on individual septic tanks, most of

which are improperly designed and ill maintained. The sullage usually flows directly

out of the IST into local drains. There is insufficient land to incorporate sullage

soakage trenches. At the moment, there is no facility for proper septage treatment

and disposal. The remainder of the population resorts to pits and latrines while a

significant number has no access to even basic sanitation facilities.

The two main rivers in the metropolis Marikina River and Pasig River, have been

pronounced biologically dead. The Pasig River, once renowned for its pristine

waters and aquatic resources, is now one of the world's most polluted river systems

with dissolved oxygen levels in the central reaches dropping to near zero for most of

the year. Faecal coliform levels exceed standards of the Department of Environment

and Natural Resources (DENR) and international standards by several orders of

magnitude.

The World Bank publication "Philippines Environment Monitor 2003" provides data

on sources of illness for 5 years up to year 2000. The data notes that 31% of all

illnesses are water related, or nearly 5 million of the reported illnesses were water

borne in the previous 5 year period throughout the country. These are due to a

mixture of non-potable standard water supply being ingested and contact with

polluted water in open drains.

The cost of these and other impacts or benefits can be determined by economic

assessment as follows:

Ø avoidable health costs due to losses in direct income and medical expenses for

both in and out patients are estimated at 3.3 billion pesos a year.

Ø the Philippine economy loses 17 billion pesos annually due to degradation of the

marine fishery environment.

Ø tourism losses are exceeding 47 billion pesos in 2004.

Draft

1

9:41 AM 02/09/05

Regional Environmental Assessment

This clearly demonstrates that the present socio-environmental status of pollution

has major negative economic impacts, to the extent of some P67 billion a year.

Given that the most polluted region of the country is the NCR, it may be expected

that a significant portion of the economic losses would impact upon the NCR.

To further increase the need for some interventions, the region's population is

increasing rapidly, and this will result in increasing pollution load, unless interventions

are initiated.

Specifically the population within the MWCI concession area (East zone) is predicted

to increase from 5.3 million persons in 2004 to 8.2 million in 2021. There are no

indications that the population growth will subside even after this period of sustained

growth.

As a result, the Manila Third Sewerage Project (MTSP) is being proposed by Manila

Water Company Inc. (MWCI) in response to a range of these forcing functions, such

as socio-environmental pressures and Concession Agreements specifying the

sewerage and sanitation targets required under the concession. The MWCI has the

concession for the eastern half on Metro Manila, and Maynilad Water (MWSI) the

western concession.

Because the MWCI concession area is only part of the Metro Manila area, a

Regional Environmental Assessment (REA) has been prepared to assess if the

investment proposed integrates with the MWCI/ MWSI overall investment strategy

and environmental management plans. The REA also facilities a strategic

assessment of the options available. The REA has been structured to;

Ø develop the REA details,

Ø lead into an options review,

Ø refine the options into a coordinated project (the MTSP),

Ø consider the institutional issues,

Ø assess the impacts, both negative and positive, of the adopted project, and

Ø develop an appropriate EMS and recommend institutional improvements.

The need for a REA is that the proposed project can have significant environmental

benefits and impacts that need to be addressed at the regional level. Although these

projects' impacts can be addressed through project-specific environmental

assessments, the REA will enable the Land Bank of the Philippines (LBP) as the

drawer of the loan, and the funding agency (World Bank) to assess the cumulative

and interactive impacts of these project components. This larger-scale appreciation

will allow the LBP and the World Bank to better evaluate the MTSP as an investment

and compare this with other alternatives.

In terms of baseline conditions, the key issue for which is there are large datasets

are water quality and ecosystems. The water quality data has been reviewed and

statistically analysed.

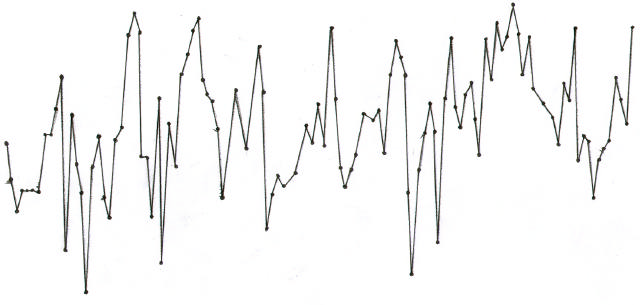

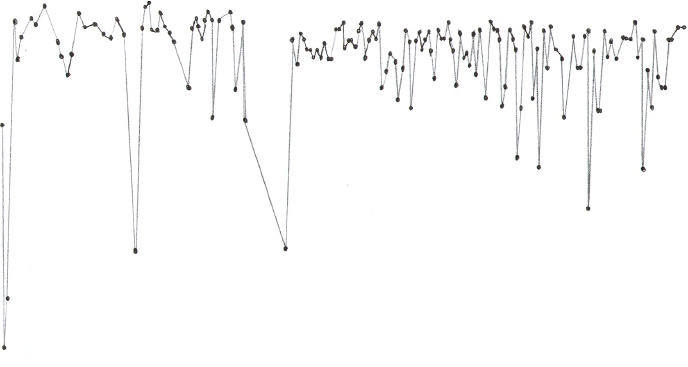

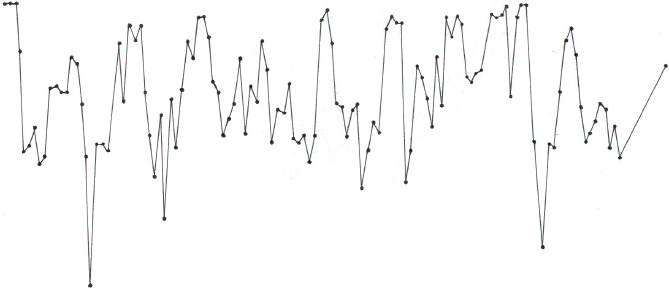

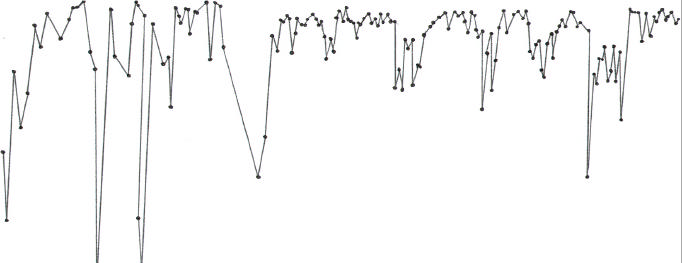

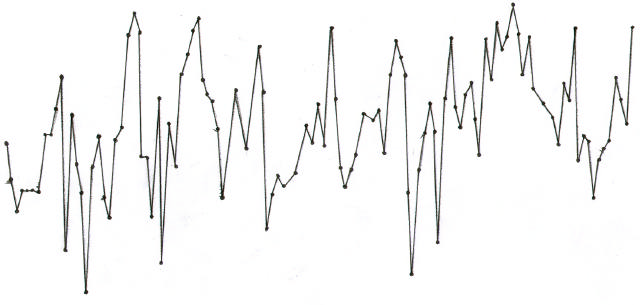

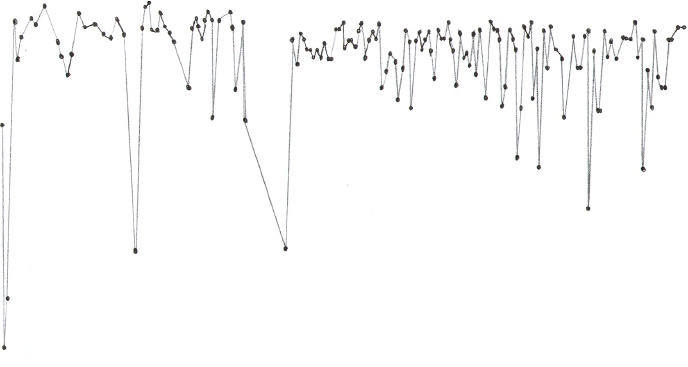

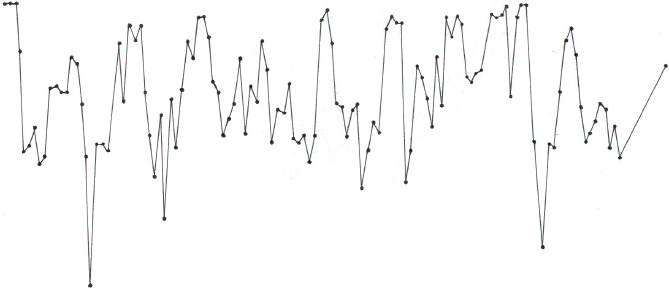

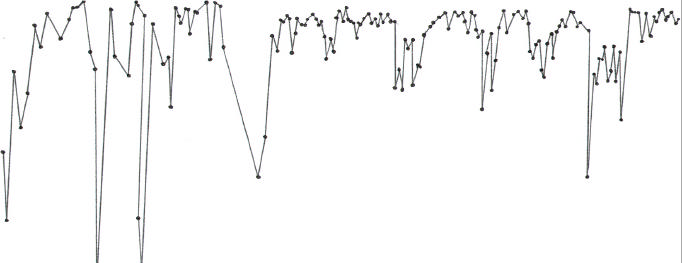

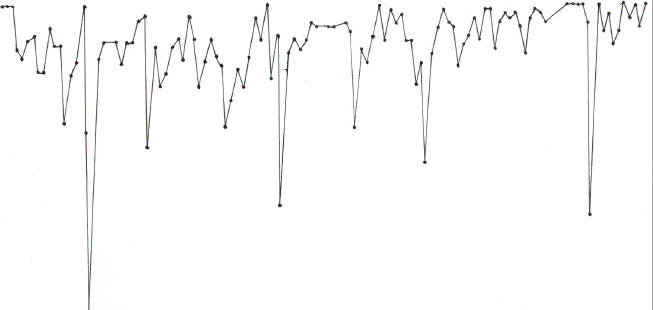

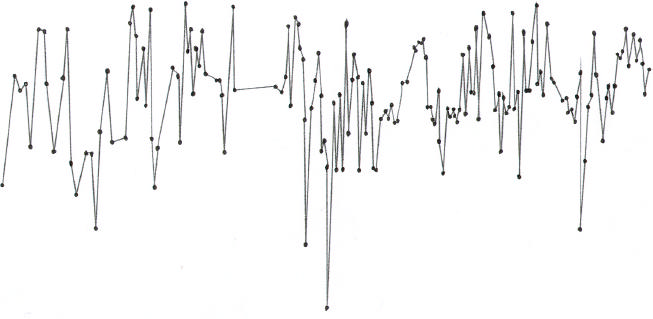

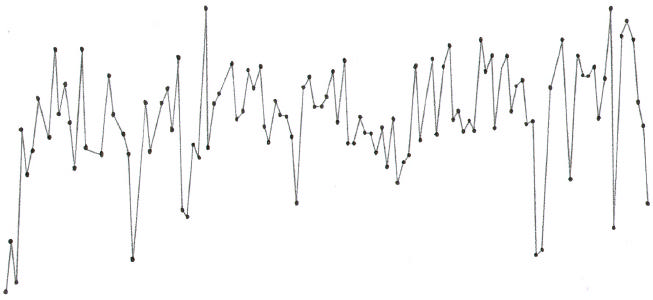

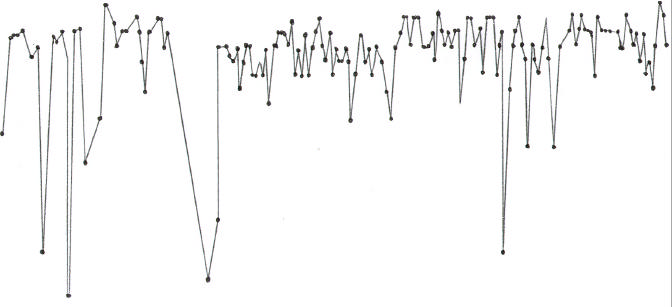

The data also demonstrates high levels of inter-annual variability. This means that

the present dataset cannot be used for trend interpretations based on just using one

years data. For example, the BOD levels at some sites decreased significantly from

1998 to 1999, but the previous 5 years show a very different trend. This indicates

that any formal trend conclusions should only be made if at least 5 years data is

reviewed. This also means that any proposed monitoring program must be run for a

number of years before making statistical interpretations of the possible trends.

Draft

2

9:41 AM 02/09/05

Regional Environmental Assessment

The overall conclusion is that the existing monitoring programs have some utility but

are insufficient to be able to detect trends in water quality and ecosystem recovery at

a suitable level of confidence for the adopted level of acceptable change in the

future. Therefore a more comprehensive monitoring program is still required to

statistically determine present water quality conditions, and allow valid comparisons

with future monitoring to assess improvements or otherwise. This presented in the

Regional Environmental Management System.

Of the approximately 2.1 million households in the Region, representing 14% of the

country's total (2000), over 51% have their own faucet or community water supply,

which is almost double the national rate of 28%. If adding "own" and "shared

community" facilities, over 75% of the population of the Region have access to piped

treated water. However, less than 8% of the Region is sewered according to the

1996 Master Plan. This imbalance requires addressing to overcome the resulting

environmental impacts

Only some 30% of sewage generated in the region undergoes some form of

treatment. The rest is either directly discharged in drainage canals (combined

sewers), or simply have no sewers to convey untreated wastewater and it flows in

road table-drains or other common drains.

Further, the ADB (2000) estimated that in the Pasig River basin alone there are one

million Individual Septic Tanks (ISTs) of which only 15% are regularly de-sludged. It

is fair to assume that the majority of the rest are full of sludge. Inappropriately

maintained septic tanks provide no effective detention time and are therefore unable

to capture suspended solids leading to elevated levels of biochemical oxygen

demand, suspended solids, and faecal coliform in the sullage discharges.

The assessment of the policy, legal, and administrative framework of the sanitation

and sewerage management system in Metro Manila yields several issues which

need to be addressed. This portion of the review carries with it the key management

and policy concerns which have been identified and lists some recommended

actions.

Firstly, there is no umbrella agency trying to limit population growth in the Region,

either by imposing restrictions on rural migration into the Region or in terms of

generic and sustained family planning campaigns. Therefore substantially

increasing populations within the Region are a given.

The basic land use planning (CLUPs) and zoning controls (ZOs) are also not

effective. Therefore an approach of planning controls cannot be used to guide

development nor even control the location of ongoing development.

The existing wastewater, environment and health management legislation is too

complex, overlapping and unclear not just in terms of basic laws, but also in terms of

the devolution status. A number of obligations have been devolved from one agency

to another and eventually to the LGU in some cases, but without a clear mandate or

operational guidelines.

A series of recommendations have been made on how to improve some of these

issues. However it is critical that an action plan be developed to make these

changes, and this will require political commitment, community pressure following on

Draft

3

9:41 AM 02/09/05

Regional Environmental Assessment

from extensive environmental and health education, and of course funding and

adoption of a time-bound program for implementation.

Therefore, it was recommended that the present strategy on wastewater

development must take the pragmatic approach where clusters of

cities/municipalities will coalesce to plan, agree on and implement wastewater

projects for the protection of the health and environment of the areas under their

jurisdiction ("river basin approach"). Projects may not be designed on a per location

basis but would cover expansive catchment areas. Innovative solutions, such as

combined systems for highly urbanized cities should be seriously considered. Only

with this approach can the objectives of protecting the water environment be

achieved at the right economies of scale.

As a result, a range of generic wastewater collection and management options have

been reviewed.

It was confirmed that onsite treatment and disposal or reuse is unsustainable

because of small lot sizes and use of groundwater as a water supply. Similarly the

higher technology options of indirect and direct potable reuse are unaffordable at the

present time. Effluent irrigation was also dismissed because of cost reasons.

Given the very small percentage of sewerage coverage in Metro Manila, and the high

population density, the usual strategy in these circumstances would be to sewer all

of the Region as soon as possible. This would be practical in less densely

developed urban areas, but only where;

Ø a large sinking fund has historically been established to fund the large capital

expenditure required,

Ø the infrastructure can be installed with community support and forbearance

Ø the population will connect to the sewer system, and

Ø the households will consistently pay the tariff for wastewater management.

However in this case, the present low percentage of sewerage coverage in the

Eastern Concession Zone, together with the required capital and operating cost

requirements, and social issues such as lack of community support and household

affordability, precludes adoption of an immediate global sewerage and treatment

strategy. Some less densely populated areas in the Zone can be sewered and have

the wastewater directed to new sewage treatment plants in these catchments, but

this will only account for a small portion of the Zone's customers.

Therefore, in the medium term at least, ISTs will be part of the east zone's

wastewater management systems into the future. Septic systems only work

efficiently when the tanks are regularly desludged. This prevents excessive solids

carrying over with the sullage. These solids carry large quantities of pathogens

(disease causing organisms), have high organic loads and can cause downstream

pipework blockages. A priority must therefore be to maintain the operation of these

septic tanks to minimise both health and environmental impacts.

To improve septic tank efficiency, a fleet of tankers is required to allow desludging of

tanks approximately every 5 years. There are some other individual operators

providing a tank desludging service, but this is only upon request, and usually only

when tanks are completely blocked up with solids. There is no programmed

maintenance of the septic tanks that will minimize the present environmental

impacts.

Draft

4

9:41 AM 02/09/05

Regional Environmental Assessment

Once a fleet of collection vehicles is established, there will be a need for septage

treatment and/or disposal facilities. The present independent tanker operators are

most likely dumping their septage illegally, as no permits have been issued by the

DENR for a disposal facility in the Region. A network of septage treatment plants is

therefore required. The resulting dewatered or dried septage/sludge will then require

disposal either at an approved landfill or land applied. In addition, opportunities for

productive reuse of the septage/septage are available, such as applying the

organically rich septage/sludge to poor agricultural soils, especially the lahar affected

areas to the North of the Region.

Locally, sullage is usually simply discharged into stormwater drains. Some of these

are open drains, which allows physical contact by the community with the untreated

wastewater, and attendant health risks. Usually it is the children involved in this

contact and they represent some of the most susceptible members of the community

to such disease risks. This health risk is exacerbated if the septic tank has not been

maintained and biological solids are carrying over.

Morbidity data are presented elsewhere in this report indicating significant water

borne disease events are not uncommon in Manila. A further priority is therefore to

limit the contact possibilities between sullage and the community. This will require

some drainage repairs and covering of other drains.

The present sanitation system generally has septic tanks without the requisite

soakage tranches or evapotranspiration beds. Therefore the sullage (the ongoing

liquid outflow from septic tanks) is discharged to a stormwater drainage system

rather than disposed of on site or directed to a dedicated sewer. In most countries, a

septic system is environmentally sustainable only when there is sufficient land

associated with the system to allow either infiltration into the soil or

evapotranspiration of sullage. That is, there should be no uncontrolled liquid

discharge off the site into drainage systems to pollute the environment. There is no

opportunity locally to provide soakage trenches or evapotranspiration beds because

of a lack of land space in almost every existing site.

These septic tanks can serve either individual dwellings or commercial

establishments, or be a community-based tank system. One priority is therefore to

convert some of the community septic tanks into sewage treatment plants.

Even if the septic tanks are appropriately maintained, the sullage eventually reaches

local watercourses such as the Pasig River. These water bodies are highly polluted

as a result, and the pollution takes many forms, but especially;

Ø organics (which deplete the oxygen in the watercourse so higher aquatic life

forms cannot survive), and

Ø pathogens (disease causing organisms which concentrate in biological solids).

Therefore a program is required to either;

Ø sewer these areas and direct the sullage to a sewage treatment plant (or convey

raw sewage to a treatment plant if the septic tank is removed), or

Ø provide an interception system to collect the sullage and other wastewater from

the stormwater drains, and divert the dry weather flows to a sewage treatment

plant

Dedicated sewerage systems are expensive to install, cause disturbance to

roadways and access paths, and may not be used unless the community agrees to

connect to the sewer. Finally, the householders must be willing to continue to pay

Draft

5

9:41 AM 02/09/05

Regional Environmental Assessment

their tariffs to fund the operation of the sewerage system. Local experience

indicates that many of these items will not occur.

A second alternative is to install drainage modifications within catchments to divert

dry weather flows in stormwater drains and esteros into purpose-built sewage

treatment plants. This then limits the dry weather discharge of sullage into the local

major watercourses. This may apply for both small drainage systems and also larger

drains associated with flood control networks. These are termed combined sewers

and are now allowed under the revised Concession Agreement (CA), but were not

allowed under the original CA. Most environmental impact occurs in the dry season

when there is little diluting flow in the local water bodies, so treating the dry weather

flows of sewage/sullage is still very beneficial environmentally.

Septage/sludges from the septage treatment plants and also the sewage treatment

plants as well as some raw septage will require disposal. The ocean dumping trials

were curtailed and so a new disposal option is required. Appropriate application of

these sludges to poor agricultural soils would improve the soil organic content, water

holding capacity, general fertility and increase the Cation Exchange Capacity.

Suitable environmental studies would be required to demonstrate the sustainability of

such applications supported by management plans for ongoing applications.

In addition to the physical and financial aspects of the sewerage and sanitation

improvements, the up-grades will only be sustainable if the community is educated

about the benefits, and importantly, the requisite need to fund these benefits.

Therefore a project component providing an Information and Education Campaign is

a high priority.

The overall MTSP being proposed has four proposed components:

Ø Sewerage System and Treatment - Involved the expansion of sewer network and

treatment plants at strategic locations within the East-concession area

Ø Septage Management large scale septic tank de-sludging program on the

western section of the service area, namely: Mandaluyong, part of Makati and

Quezon City, Pasig, San Juan, Taguig, Marikina, and Pateros

Ø Technical Assistance will cater to the need for information and education on the

good practices, infrastructure, and benefits from proper sewage management

However this REA predominantly deals with the first two components of the MTSP;

sewerage systems and treatment, and septage management. These two

components will be implemented through six projects listed below:

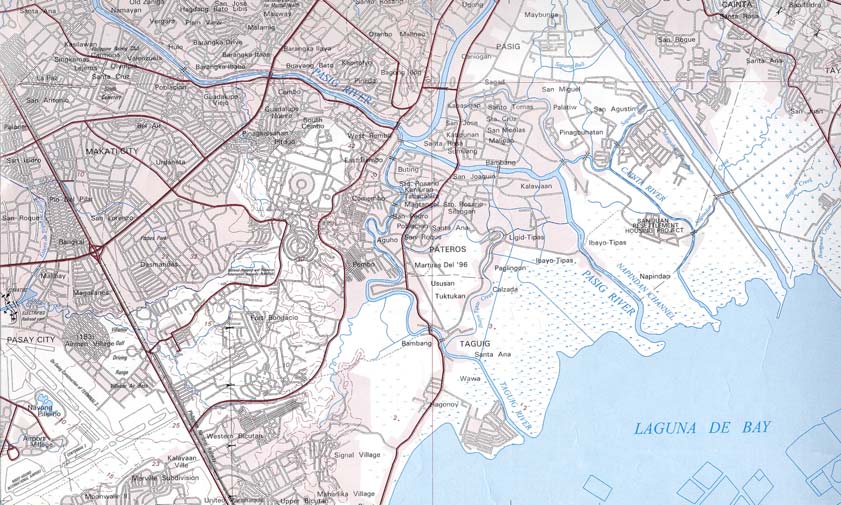

(1)

Taguig Sewerage System

This project is in line with the flood control project of the Department of Public Works

and Highways (DPWH) covering Taguig, Pateros and parts of Rizal. The DPWH will

construct four (4) drainage/flood retention ponds adjacent to the Laguna de Bay.

The proposed sewerage project will involve the development of the retention ponds

as part of a wastewater treatment system to treat the sewage before discharge to

Laguna de Bay during the dry season.

(2)

Riverbanks Sewage Treatment Plants

This project will involve the construction of at least three (3) underground STPs

along the riverbanks of Pasig River, located in Makati, Mandaluyong, and Pasig.

Draft

6

9:41 AM 02/09/05

Regional Environmental Assessment

Sewage will be intercepted and collected from existing drainage lines in these areas

for treatment before discharge to Pasig River. If necessary, rehabilitation of the

drainage outfalls and lines will be included in the project.

(3)

Septage Treatment Plants

This project is essential in providing sanitation services, septage treatment and

proper septage/sludge disposal. An initial plan is to construct SPTPs in the southern

and northern portion of the East Zone.

(4)

Sanitation for Low-Income Communities

This project will involve the construction of Communal Septic Tanks or STPs, as

appropriate, and shallow, small-diameter sewer lines to serve low-income

communities in the East Zone which have inadequate sanitation facilities.

(5)

Quezon City-Marikina Sewerage System

This project will utilize portions of the legal easement for Marikina River. Main

drainage collector pipes which collect combined sewage and drainage from

communities in Quezon City and Marikina will be connected to a STP to be

constructed to treat the dry weather drainage/sewage flow.

(6)

Upgrade of Existing Sanitation Systems

This project will involve the upgrade of existing Communal Septic Tanks (CSTs) in

Quezon City to STPs. This will ensure compliance with environmental standards for

wastewater effluent.

As part of all six components, a supporting Sludge/Septage Disposal and Reuse

program is proposed. In summary, the adopted system involves the trucking of

various sludges and septage solids wastes to the lahar-affected area some 60 km to

the north, as follows;

Ø Liquid sludge (biosolids) from the biological treatment process at sewage

treatment plants for the proposed MTSP, and also those plants under MSSP,

located at Pabahay Village, Valle Verde, Karangalan Village, general MTSP

plants (Road 5, Anonas Street, QC Barangays, Camp Atienza, Taguig,

Manggahan, Capitolyo, Ilaya, Poblacion in Pasig City, Labansan, Tapayan and

Hagonoy) giving a volume of 194 m3/day of liquid sludge. This is essentially a

liquid at 2 or 3 percent solids, and will be tankered to the septage treatment

plants for dewatering. Dewatered sludge will be 25% solids and is sufficiently dry

to shovel and treat as a solid, even though still very wet.

Ø Dewatered primary sludges from the primary treatment plants at the Taguig

ponds will yield another 48 m3/day. These will not be stabilised and could

possibly be odorous. In a traditional sewage treatment plant, the primary sludges

contain highly active organic material such as gross solids. These sludges are

very odorous. With the Taguig primary treatment plants, the inflow is sullage not

raw sewage, so gross solids and other highly organic materials will not be

present. It is expected that a large fraction of the primary sludge will be

inorganics resulting from street runoff and catchment erosion entering the

combined sewer flows. Therefore it is appropriate to operate the primary

Draft

7

9:41 AM 02/09/05

Regional Environmental Assessment

treatment facilities as proposed, and monitor the biological activity of the primary

sludge to assess if additional treatment is required such as lime stabilisation.

Ø Dewatered secondary (biological) sludges from the MSSP and MTSP STPs

totalling 127 m3/day. This sludge will be about 25% solids, and is sufficiently dry

to shovel and treat as a solid, even though still very wet. It is not stabilised and

as such can only be used under certain restrictions, such as burial within 8 hours

and not for certain food crops, such as those consumed raw unless there is

certain period between sludge application and harvesting the food.

Ø Dewatered unstabilised septage/sludge volume of 177 m3/day from the two

MTSP SPTPs, at 25% dry weight. This dewatered septage/sludge is actually a

mixture of the raw solids entering the SPTP which are settled and then

dewatered, and the biological secondary sludge from the liquid treatment plant

for the liquor following on from the septage solids removal. The septage/sludge

is therefore a mixture of septage solids and biosolids or biological sludge. It is

not going to be stabilised, but there will be some chemicals added to assist in the

dewatering process. These will be at very small doses, just sufficient to ensure

that the dewatering targets are achieved. The chemicals will be standard

polyelectrolytes used globally for such processes.

Ø Dewatered stabilised septage/sludge volume of 90 m3/day from the PRRC

SPTP at Antipolo, at 25% dry weight. This dewatered septage/sludge is also a

mixture of the raw solids entering the SPTP which are settled and then

dewatered, and the biological secondary sludge from the liquid treatment plant

for the liquor following on from the solids removal. The septage/sludge is

therefore a mixture of septage solids and biosolids or secondary sludge. It is

going to be stabilised by lime addition, at high dose rates of up to 0.5 kilograms

of lime per kilogram of solids. The lime increases the pH and also increases the

temperature to inactivate the pathogens. The resulting septage sludge will meet

the Class A requirements of the US EPA and as such is acceptable for almost

unrestricted reuse applications. The PRRC is investigating possible sludge

reuse locations on farms close to Antipolo, but the backstop will be blending the

PRRC material with the other sludges to transport to the Pampanga areas.

Ø Dried biological sludges (biosolids) amounting to approximately 5 m3/day

from the existing Magallanes STPs. These sludges have been dried on sludge

drying beds and can be even drier than the 25% dewatered solids achieved

mechanically. They are stabilised by virtue of the open exposure over a longer

term of weeks to months.

The total sludge volume to be managed locally every day is therefore 194 m3/day of

liquid sludge to be transported from the STPs to the SPTPs for dewatering. This is a

local transport issue only.

The septage/sludge quantity to be transported to the Pampanga region is

approximately 450 m3/day. Because it is a solid, the only option is trucking not

pumping. The septage/sludges will be combined apart from the PRRC

septage/sludge and dried sludges which are stabilised.

A comprehensive public consultation program has been undertaken.

A key issue to note is that only three families require resettlement in the entire MTSP

project. MWCI already has a standard resettlement framework, and a specific

resettlement action plan will be developed for the 3 families prior to resettlement

being required. The very small number of resettlement involved is a direct result of

the component sites being selected which minimise social dislocation. This number

may change if the mooted San Mateo SPTP site is adopted instead of the Payatas

Draft

8

9:41 AM 02/09/05

Regional Environmental Assessment

SPTP site. However negotiations are underway to assess the various

responsibilities for resettling the 11 families informally settling on the San Mateo site.

Consultation has been completed on all components with the exception of the two

sites for SPTP component. Consultation with the adjacent property owners and

residents for the proposed Payatas Septage Treatment is to be conducted after

agreement has been reached with the property owner on the sale of the land. This

may now not proceed if the site is abandoned in favour of the San Mateo SPTP site.

In the case of the FTI site, discussion has been had with the Management of the

Complex (FTI) on the use of a portion near the existing treatment facility of the

complex. Consultation is not deemed necessary in the case of the FTI site.

The key issues were typical for a wastewater management strategy relating to costs,

odour, lack of knowledge of the environmental and health impacts of poor sanitation

or sewerage, traffic impacts and disruption during construction, flooding impacts or

benefits and so on.

In assessing the cumulative impacts, the No Project option has been considered. In

this option, there would be no interventions in the present state of sanitation,

sewerage and wastewater management. However the present socio-environmental

conditions in the Region are already very poor, with demonstrated economic

impacts.

The population in the east zone Concession Area is predicted to increase from 5.3

million persons to 8.2 million in 2021. This 60% increase without any improvements

in the standard of sanitation, sewerage and wastewater management will result in

even greater socio-environmental impacts. The impact quantum cannot be predicted

but it would safe to project that, for example, the presently limited periods of

adequate DO in the major river systems would be even further reduced, perhaps

even eliminated. The ecological implications are that the present intermittent

biological activity and higher life forms residing or transitting through these

waterways would cease almost entirely.

The health impacts of greater population and population density can only exacerbate

the present health impacts in terms of water borne diseases and associated

environmental costs.

The No Project option cannot reasonably be considered any further as an option,

based on these expected consequences.

By comparison, the MTSP will have net benefits on the Region. Overall benefits

include the following;

Ø reducing the pollution of key Metro Manila waterways

Ø reducing the health hazards associated with human exposure to sewage by drain

covering and effluent disinfection

Ø improved property values along watercourses

Ø improved aesthetics as the water quality improves

Ø improved fish catches

Ø improved tourism

Ø improved soil condition and crop yields in lahar affected areas

Ø providing design and implementation feedback on the combined sewer systems

efficacy and the STP/SPTP designs, in effect a pilot scheme for the many

innovations proposed under MTSP

Draft

9

9:41 AM 02/09/05

Regional Environmental Assessment

Ø cessation of uncontrolled dumping of septage from privately owned and operated

tankers

Ø provides a viable alternative to sea dumping of septage/sludge

Ø cessation of the hauling of liquid septage to the lahar affected areas north of the

Region. It is environmentally and financially unsustainable to be hauling so much

water in the non-dewatered septage such a distance and with the attendant

environmental risks associated with accidents and attendant spillages of the

liquid septage

Ø improved institutional implementation of sanitation and sewerage services,

including more clearly defined roles and responsibilities and enforcement, and

Ø elevating the commitment and political will required to improving sanitation,

sewerage and wastewater treatment in the minds of politicians, government

agencies, NGOs, civil society and the general public.

As always there will be some short term localised construction impacts such noise,

dust and traffic interruptions, but these are short term and are very minor compared

with the longer-term benefits.

Essentially the Present Value of economic benefits over the life of MTSP until 2025

is estimated to be P2.7 billion, with Health Benefits and Environment Benefits each

providing some P1.2 billion of this total.

A Regional Environmental Management System has been prepared for the MTSP.

The actual management and monitoring required for the REMS is as follows;

Ø Primary ambient water quality and ecological monitoring. This is by far the

biggest component and is described in Attachment 4.

Ø Review and economic interpretation of secondary data on health, fisheries,

property valuation, etc. The actual monitoring is to be done by others as part of

their ongoing charter

Ø Driving the institutional structural and implementation changes required

There are no site-specific monitoring or management plans as these items are

presented in the EIS as component specific requirements, not Regional.

The pilot water quality and ecological monitoring study would cost approximately

P2.5M if undertaken by an agency such as DENR, and the ongoing baseline would

cost about P0.75M a year. This cost includes an allowance for hiring staff on a

monthly basis but not for a profit component if undertaken by a private consultant or

organisation.

The cost of the institutional management components is as follows;

Ø Relative Priority of Wastewater Services

- IEC costing P5M

Ø Connection to Public Sewerage Systems

- no direct cost

Ø Project Financing

- TA grant of P10M

Ø Low Willingness to Pay and the Lack of Sanctions

- no direct cost

Ø Monitoring of Compliance to Existing Laws

- Institutional study P10M

Ø MTSP Impacts on Existing Private Septage Haulers

- GEF funded

Ø IEC on Health Impacts of Wastewater

- IEC costing P5M

Draft

10

9:41 AM 02/09/05

Regional Environmental Assessment

1 Introduction

1.1 Background

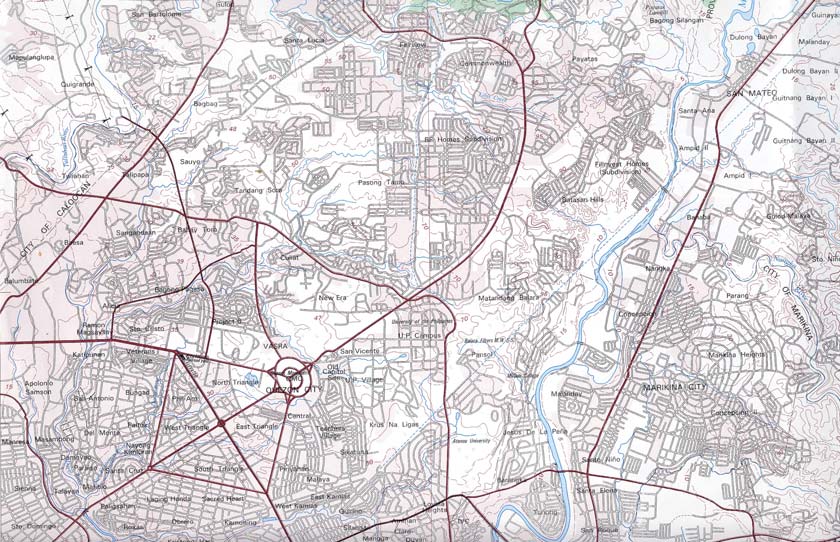

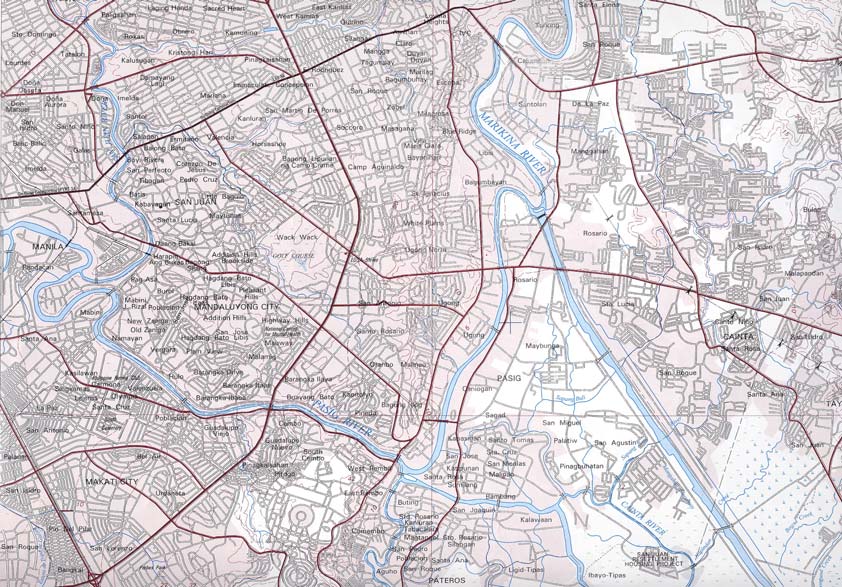

Metro Manila lies at the western part of the Philippine archipelago. It is the largest

among 16 regions of the country. It has a total land area of 636 square kilometres

and, as of year 2000, is home to 9.9 million people. Some other estimates suggest

the population is closer to 12 million people. It is composed of 17 cities and 5

municipalities subdivided into 1,692 barangays. Metro Manila is bounded by the

province of Bulacan in the north, the province of Rizal in the east, Manila Bay in the

west and Laguna Lake, and Cavite and Laguna in the south. The Pasig River

traverses through a significant area of the metropolis. It drains towards the Laguna

Lake in the south or the Manila Bay in the west, depending on base flow and tidal

state.

As the capital of the Philippines, Metro Manila is the centre of commerce, science,

technology and political governance. The city's economy is primarily commercial with

commercial establishments or services taking up 63% of the market. Industries

make up 37% of the local economy.

While the city has a sound economy, it faces a multitude of problems. Among its

pressing concerns are housing, employment, health, solid waste and wastewater

management, traffic, air and water pollution. The national and local governments

develop and implement programs to address these issues. However, bureaucracy

and politics often make it difficult to successfully implement programs as they are

conceived.

1.2 Environment

Presently, less than 8% of the Metro Manila population is served by sewerage

systems. These systems are localized in Makati, Quezon City and the Central

Manila area. Some 85% of the population relies on individual septic tanks, most of

which are improperly designed and ill maintained. The sullage usually flows directly

out of the IST into local drains. There is insufficient land to incorporate sullage

soakage trenches. At the moment, there is no facility for proper septage treatment

and disposal. The remainder of the population resorts to pits and latrines while a

significant number has no access to even basic sanitation facilities. (Feasibility Study

for the Manila Third Sewerage Project Final Report by Nippon Jogesuido Sekkei

Co., Ltd in association with CEST, INC. and Mott MacDonald Co., Ltd, 2004).

By contrast, of the approximately 2.1 million households in Metro Manila, over 51%

have their own faucet or community water supply, which is almost double the

national rate of 28%. If considering "shared community" facilities, over 75% of the

population of the Region have access to piped treated water. (NJS, 2004)

The two main rivers in the metropolis Marikina River and Pasig River, have been

pronounced biologically dead. The Pasig River, once renowned for its pristine

waters and aquatic resources, is now one of the world's most polluted river systems

with dissolved oxygen levels dropping to near zero for most of the year. Faecal

coliform levels exceed standards of the Department of Environment and Natural

Resources (DENR) and international standards by several orders of magnitude.

Findings of the DANIDA study confirm domestic wastewater as the primary source of

water pollution. (Pasig River BOD Load Assessment and Water Quality Projections

Draft

1-1

9:41 AM 02/09/05

Regional Environmental Assessment

Report, funded by DANIDA, by Carl Bro International, Danish Hydraulic Institute and

Institute for the Water Environment, 1999) According to the DENR, 75% of the

pollution loading into the Pasig River comes from domestic wastewater. Industrial

and commercial effluent contributes only 25% to the pollution of the Pasig River.

Given the amount of pollution contributed by domestic wastewater, the state of the

water resources in Metro Manila can be directly correlated to the dearth of

functioning sanitation systems and low sewerage coverage.

1.3 Public Health

The World Bank publication "Philippines Environment Monitor 2003" provides data

on sources of illness for 5 years up to year 2000. The data notes that 31% of all

illnesses are water related, or nearly 5million of the reported illnesses were water

borne in the previous 5 year period throughout the country. These are due to a

mixture of non-potable standard water supply being ingested and contact with

polluted water in open drains.

When combining the 1995 and 2000 data, it is obvious that water pollution is

resulting in major morbidity issues in the community. Given that the most polluted

waterways and densest population areas are within the National Capital Region

(NCR), then any improvements to water quality or isolation of the community from

polluted water by drain covering will have social and health benefits.

It is likely that the water borne disease impacts have been under-estimated in any

case. The most common waterborne disease is caused by the Norwalk Type A

virus. This usually results in a 24 hour GI infection (Diarrhoea). This morbidity is

often confused with minor food poisoning so the water borne health data is probably

understated, because it is interpreted as being derived from non-water related

sources. This would then underestimate the potential benefits of improving sewage

management by either installing sewerage systems or drain improvements, and

improving water quality and treated effluent disinfection.

1.4 Fisheries and Ecosystems

The paucity of commercial fish in the main rivers within the NCR is a direct result of

the level of pollution in these waterways. Most of the year there is insufficient

oxygen within the waterways to support anything but the coarsest fish species. In

the wet season, there is substantial diluting runoff which improves the river water

quality to such an extent that some fish can survive. The fish are not breeding in

commercial quantities in the river, but are just motile species moving from the

cleaner upper reaches of the Marikina River and Laguna Lake towards Manila Bay.

Residents living along the Pasig and Marikina Rivers catch some of these fish. The

health impacts of eating these fish has not been established by specific

epidemiological studies, but may be expected to have some chronic impacts given

the presence of persistent chemicals within the river systems.

1.5 Tourism

Tourists are obviously not attracted to polluted environments. This has the result of

reduced capital inflow, reduced income receipts, reduced job opportunities and other

negative impacts.

Draft

1-2

9:41 AM 02/09/05

Regional Environmental Assessment

1.6 Economic Impacts

The cost of these and other impacts or benefits can be determined by economic

assessment, and are taken from the World Bank Environment Monitor, 2003.

For example, avoidable health costs due to losses in direct income and medical

expenses for both in and out patients are estimated at 3.3 billion pesos a year.

Similarly the Philippine economy loses 17 billion pesos annually due to degradation

of the marine fishery environment.

Tourism losses are exceeding 47 billion pesos in 2004.

This clearly demonstrates that the present socio-environmental status of pollution

has major negative economic impacts, to the extent of some P67 billion a year.

Given that the most polluted region of the country is the NCR, it may be expected

that a significant portion of the economic losses would impact upon the NCR.

1.7 Moving Forward

The Manila Third Sewerage Project (MTSP) is being proposed by Manila Water

Company Inc. (MWCI) in response to a range of these forcing functions, such as

socio-environmental pressures and Concession Agreements specifying the

sewerage and sanitation targets required under the concession. The MWCI has the

concession for the eastern half on Metro Manila, and Maynilad Water (MWSI) the

western concession.

Because the MWCI concession area (the eastern part of Metro Manila) is only part

of the Metro Manila area, a Regional Environmental Assessment (REA) has been

prepared to assess if the investment proposed integrates with the MWCI/ MWSI

overall investment strategy and environmental management plans. The REA also

facilities a strategic assessment of the options available.

The above impacts clearly demonstrate that there is a raft of problems with the local

NCR environment, largely due to the paucity of wastewater management systems.

Prior to committing to a specific strategy to improve the problems, a Regional

Environmental Assessment (REA) has been requested by the World Bank.

Based on this,the REA has been structured to include;

Ø develop the REA details,

Ø lead into an options review,

Ø refine the options into a coordinated project (the MTSP),