Global Conference on

Oceans, Coasts, and Islands

Mobilizing for Implementation of the

Commitments Made at the

2002 World Summit on Sustainable Development

PRE-CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS VOLUME

Global Conference, UNESCO, Paris, November 12-14, 2003

WORLD

BANK

INSTITUTE

NATIONAL

Fisheries and

International

O C E A N S

Oceans, Canada

U N E S C O

Ocean Institute

OFFICE

Australia

Table of Contents

Foreword.......................................................................................................................................................5

CHINA'S ACTION FOR MARINE SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT

Sun Zhihui, State Oceanic Administration, China..............................................................................................7

PROBLEMS AND OPPORTUNITIES IN THE IMPLEMENTATION

OF WSSD COMMITMENTS: THE INDIAN PERSPECTIVE

Harsh K. Gupta, Secretary to the Government of India....................................................................................11

WSSD IMPLEMENTATION IN EAST ASIA

Chua Thia-Eng, PEMSEA..............................................................................................................................15

CHALLENGES AND POTENTIAL SOLUTIONS FOR ACHIEVING SYNERGIES

AT THE REGIONAL LEVEL ON OCEAN AND COASTAL GOVERNANCE

Gunnar Kullenberg, International Ocean Institute............................................................................................25

TOWARDS A REGIONAL LEGAL FRAMEWORK FOR INTEGRATED

COASTAL AREA MANAGEMENT IN THE MEDITERRANEAN

Harry Coccosis, University of Thessaly...........................................................................................................31

VOLGA/CASPIAN BASIN. REGIONAL CO-OPERATION BENEFITS

AND PROBLEMS

I. Oliounine, International Ocean Institute .......................................................................................................35

MANAGING THE MANAGERS: IMPROVING THE STRUCTURE AND

OPERATION OF FISHERIES DEPARTMENTS IN SIDS

Robin Mahon and Patrick McConney, University of the West Indies.................................................................39

ENVIRONMENT OUTLOOK OF SMALL ISLAND DEVELOPING STATES

Sherry Heileman and Marion Cheatle, United Nations Environment Programme................................................43

BEYOND THE LAW OF THE SEA CONVENTION? STATUS AND PROSPECTS

OF THE LAW OF THE SEA CONVENTION AT THE 20TH ANNIVERSARY

Tullio Treves, International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, and University of Milano........................................45

A SUGGESTED CALL TO ACTION BY THE OCEANS FORUM ON

CARRYING OUT THE WSSD PLAN OF IMPLEMENTATION

Xavier Pastor, I. L. Pep. Fuller, Jorge Varela, Oceana......................................................................................49

SHIP & OCEAN FOUNDATION'S PERSPECTIVES ON WSSD IMPLEMENTATION

Hiroshi Terashima, Ship & Ocean Foundation..................................................................................................53

CAPACITY BUILDING IN SUPPORT OF WSSD IMPLEMENTATION

Francois Bailet, International Ocean Institute...................................................................................................57

3

GLOBAL CONFERENCE ON OCEANS, COASTS, AND ISLANDS

SUSTAINABILITY AND VIABILITY: REINFORCING THE

CONCEPTS OF THE JOHANNESBURG DECLARATION ON

SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT

Eduardo Marone, International Ocean Institute, and

Paulo da Cunha Lana, Federal University of Parana.......................................................................................63

OBSTACLES TO ECOSYSTEM-BASED MANAGEMENT

Lawrence Juda, University of Rhode Island...................................................................................................67

WHEN CAN MARINE PROTECTED AREAS IMPROVE

FISHERIES MANAGEMENT?

Serge Garcia et al., United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization............................................................73

THE REGIONAL MANAGEMENT OF FISHERIES

Hance D Smith, Cardiff University................................................................................................................77

DEVELOPING A CAPABLE, RELEVANT NETWORK TO ADDRESS

MARINE AND COASTAL ENVIRONMENTAL CONCERNS AND

FOOD SECURITY IN AFRICA AND NEIGHBOURING

SMALL ISLAND DEVELOPING STATES (SIDS)

Grant Trebble, AMCROPS...........................................................................................................................81

TARGETING DEVELOPMENT ASSISTANCE TO MEET WSSD GOALS

RELATED TO MARINE ECOSYSTEMS

Alfred Duda, Global Environment Facility.......................................................................................................85

A FISHERMAN'S PERSPECTIVE ON SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT

AND THE GLOBAL OCEANS AGENDA

Pietro Parravano, World Forum of Fish Harvesters & Fishworkers..................................................................89

PERSPECTIVES ON GLOBAL FUNDING MECHANISMS FOR

OCEANS, COASTS AND ISLANDS

Scott Smith, The Nature Conservancy............................................................................................................93

THE WORLD OCEAN OBSERVATORY A FORUM FOR OCEAN AFFAIRS

Peter Neill, South Street Seaport Museum..................................................................................................... 97

BUILDING A CONSERVATION VISION FOR THE

GRAND BANKS OF NEWFOUNDLAND, CANADA

Charlotte Breide and Robert Rangely, World Wildlife Fund International...........................................................99

PROGRESS TOWARDS A TEN-YEAR HIGH SEAS MARINE

PROTECTED AREA STRATEGY

Kristina M. Gjerde, International Union for Conservation of Nature.................................................................103

4

November 12-14, 2003 UNESCO, Paris

Foreword

This Pre-Conference Volume contains the papers prepared for the Global Conference on Oceans, Coasts, and

Islands: Mobilizing for Implementation of the Commitments Made at the 2002 World Summit on Sustainable

Development, held on 12-14 November 2003 at UNESCO Headquarters in Paris.

The major purposes of the Conference are to review what has been done to date in implementing the WSSD

commitments, and to catalyze action on WSSD implementation through collaboration among governments, interna-

tional organizations, nongovernmental organizations, and the private sector. The conference focuses, as well, on

approaches to mobilizing public and private sector support for the global oceans agenda, and on the identification of

emerging ocean issues. More specifically, the Conference aims to:

1) Focus on useful strategies for and experiences in implementing the commitments made at the World Summit on

Sustainable Development at global, regional, and national levels, through discussions among experts from govern-

ments, international organizations, nongovernmental organizations, and the private sector.

2) Discuss emerging issues on oceans, coasts, and islands for which international consensus is still to be reached.

3) Develop strategies for mobilizing private sector involvement and increased public awareness on oceans, coasts,

and islands, to insure continued support for the

global oceans agenda.

The Global Conference is organized by the Global Forum on Oceans, Coasts, and Islands, comprised of individuals

from governments, intergovernmental and international organizations (IOs), and nongovernmental organizations

(NGOs), with the common goals of advancing the interest of oceans-- incorporating 72% of the Earth; coasts--

the home of 50% of the world's population, and islands--43 of the world's nations are small island developing

states, which are especially dependent on the oceans. The Forum was created at the World Summit on Sustainable

Development in Johannesburg in September 2002 by the WSSD Informal Coordinating Group on Oceans, Coasts

and Islands.

Many thanks are due to the Secretariat staff of the Global Forum for their tireless work in the Conference preparations,

especially to Jorge Gutierrez and Kevin Goldstein for their work on this volume. We would also like to thank all of the

Conference participants for their contributions in this important step toward implementation of the WSSD

Commitments.

Co-Chairs of the Global Forum on Oceans, Coasts and Islands

Dr. Biliana Cicin-Sain

Dr. Patricio Bernal

Dr. Veerle Vandeweerd

Director

Executive Secretary

Coordinator

Gerard J. Mangone Center

Intergovernmental Oceanographic

Global Programme of Action

for Marine Policy

Commission

for the Protection of the Marine Environment

University of Delaware

United Nations Educational,

from Land-based Activities

Scientific and Cultural Organization

United Nations Environment Programme

5

GLOBAL CONFERENCE ON OCEANS, COASTS, AND ISLANDS

6

November 12-14, 2003 UNESCO, Paris

CHINA'S ACTION FOR

MARINE SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT

Sun Zhihui

Deputy Administrator, State Oceanic Administration

1 Fuxingmenwai Ave, Beijing,

phone: 86-10-68019791

Email: zzh@soa.gov.cn

Ocean Agenda 21, providing the guidelines for marine sus-

rine industries referred to include marine fisheries, marine trans-

tainable development and utilization. In recent years, particularly

portation, oil and gas, tourism, ship, sea salt and chemical engi-

since WSSD in 2002, to implement the Johannesburg Declaration

neering, seawater desalination and comprehensive utilization,

on Sustainable Development and the Plan of Implementation, China

marine biological medicines. The programming period lasts 10

promulgated the National Marine Functional Zonation Scheme in

years from 2001 to 2010.

2002, and issued/approved the National Programming Compen-

dium on Marine Economic Development in May of this year. Be-

The principles of the Compendium is adhering to the principle

sides, China recently revised the Fishery Law and Law on Marine

of placing equal stress on economical development and protec-

Environment Protection, and put into force the law on Manage-

tion of resources and environment; intensifying the protection

ment of Sea Area Use and other marine-related laws and regula-

and construction of marine ecological environment; accommo-

tions. In this regard, I would like elaborate on some of the specific

dating the development scale and growth to the carrying capacity

and important actions China has taken to realize the marine sus-

of environment, etc.

tainable development.

The overall objective of marine economy, put forward in the

Compendium, is to increase the contribution of marine economy

PLANNING AND PROGRAMMING

in the National Economy, optimize the marine economy structure

and industry layout, rapidly develop backbone industries and

China Ocean Agenda 21

new-booming industries, apparently improved the quality of ma-

rine ecological environment. The GDP derived from the marine

China formulated the China Ocean agenda 21, which set forth

economy will amount to 4% of national total by 2005, and over 5%

the strategy, objectives, countermeasures and major action areas.

by 2010.

The overall objective is to restore healthy marine ecosystem,

The Compendium also puts forward the following objectives

develop rational marine development system, and promote the

of the protection of biological environment and resources: the

marine sustainable development.

amount of main pollutants into the sea in 2005 will be reduced by

The countermeasures include: guiding the establishment and

10% compared to 2000. Further improve the capability to monitor

expansion of marine industry on the principle of sustainable de-

red tide, make efforts to mitigate the loss by red tide, gradually

velopment; placing equal stress on development and social and

realize the conservation and sustainable utilization at key river

economic sustainable development; gradually solving the con-

mouth, wetlands and tidal flats.

straint problems such as freshwater and energy shortage in coastal

areas by means of well-planned marine development activities;

The National Marine Functional Zonation Scheme

sustainably utilizing the resources of islands and protecting its

To plan all relevant ocean-related use as a whole, protect and

ecologic balance and its biodiversity; setting up marine protected

ameliorate the ecological environment, promote the sustainable

areas such as coral reef, mangrove and sea grass bed, spawning

use of sea area; secure the safety at sea, the State Council ap-

grounds, protecting special species and ecosystem; promoting

proved the National Marine Functional Zonation Scheme in 2002,

the sustainable development by reliance of science and technol-

which provides a scientific basis for sea area use management

ogy; establishing ICM system; intensifying ocean observations,

and environmental protection, to ensure a sound development of

forecasting, disaster warning and mitigation; strengthening inter-

national economy.

national cooperation; enhancing public awareness.

In this scheme, in light of the requirement of location, natural

National Programming Compendium on Marine Economy

resources and utilization, all jurisdictional sea areas are divided

into ten types of functional areas for port and transportation,

To provide macro guidance, coordination and programming,

utilization and conservation of fisheries, tourism, and marine re-

the State Council approved and publicized the National Program-

serve, and so on.

ming Compendium on Marine Economy this year. The main ma-

7 |

GLOBAL CONFERENCE ON OCEANS, COASTS, AND ISLANDS

LEGISLATION

ronment by coastal construction projects, prevention the pollu-

tion damage to the marine environment by marine construction

Based on the United Nations Convention on the Law of the

projects, prevention of the pollution damage to the marine envi-

Sea, the Law on Territorial Sea and Contiguous Zone of the People's

ronment by dumping at sea, and prevention of the pollution dam-

Republic of China and the Law on Exclusive Economic Zone and

age to the marine environment by ships and other related opera-

Continental Shelf of the People's Republic of China , in recent

tion activities.

years China has stipulated or amended following laws:

The Fishery Law of the People's Republic of China

The Law on Management of Sea Area Use

In order to strengthen protection, propagation, development

In order to protect the ownership of the national sea area and

and utilization of the fishery resources, the National People's

the legitimate rights and interest of the users of the sea area,

Congress amended the Fishery Law of the People's Republic of

prevent exhaustive development and utilization of the marine re-

China recently.

sources, protect the marine ecological environment, ensure sci-

The amended Fishery Law provides that "the State shall de-

entific and rational use of the marine resources, and promote sus-

termine the total catch ability based on the principle that the catch

tainable development of the marine economy, the National

is lower than the increase of the fishery resources and practice

People's Congress promulgated the Law on Management of Sea

fishing quota system. The state shall practice fishing license sys-

Area Use and put it into effect as of 1 January 2002.

tem for the fish catching industry". Besides, the law also pro-

This law has established the following three basic systems:

vided the propagation and protection of the fishery.

the sea area entitlement system, the marine functional zoning sys-

tem and the sea area paid-use system. The sea area entitlement

Regulations on Management of Protection and Utilization of

system clearly defined that the sea area is owned by the State,

the Uninhabited Islands

and any organization or individual who intends to use the sea

Recently China has just promulgated the Regulations on

area, must apply in advance according to relevant regulations.

Management of Protection and Utilization of the Uninhabited Is-

They are entitled to use the sea area only after approval from the

lands for the purpose of strengthening the management of the

government. The marine functional zoning system is the founda-

uninhabited islands and protecting the island ecological environ-

tion for marine development and management, under which the

ment of the uninhabited islands. Although it is only a regulatory

sea area is divided into different types of functional zones ac-

document at present, it will play a positive role to a large extent in

cording to the standard of the functions of the sea area and the

the protection of the islands and their resources since there is no

optimum order of functions of the sea area use so as to control

formal legislation for the islands in China now.

and guide the direction of the sea area use and provide scientific

basis for rational use of the sea area. The sea area paid-use sys-

The regulations have clearly defined that "the State shall imple-

tem embodied that the sea area is the state-owned asset, and any

ment the system of functional zoning and protection and utiliza-

organization or individual who intends to use the sea area to carry

tion planning for the uninhabited islands, encourage rational de-

out production and business activities must pay for sea area use.

velopment and utilization of the uninhabited islands, strictly re-

According to the provisions, the fee of sea area use may be re-

strict such activities that cause damage to the uninhabited is-

duced or exempted based on the purpose of use.

lands and the marine environment and natural landscape around

them as explosion, excavation of the sand and gravels, construc-

The Marine Environment Protection Law of the People's

tion of dams to link the islands. The uninhabited islands that are

Republic of China

of special value for protection and the sea area around them will

be built into marine nature reserves or special marine protected

In order to protect and improve the marine environment more

areas, etc., according to law through application by the compe-

effectively, protect marine resources, prevent pollution damage,

tent oceanic administrative agencies above the county level.

ensure human health, and promote sustainable development of

the economy and society, the National People's Congress amended

In addition, according to the Law on Territorial Sea and Con-

the original Marine Environment Protection

tiguous Zone of the People's Republic of China and the Law on

Law of the People's Republic of China, and put it into effect as of

Exclusive Economic Zone and Continental Shelf of the People's

April 2000.

Republic of China, etc., other laws and regulations concerning

ocean administrative management have been stipulated and pro-

The amended Marine Environment Protection Law provides

mulgated by the State Council such as the Regulations on Dump-

that "the State shall establish and implement the control system

ing of Wastes at Sea, Regulations of the People's Republic of

for gross pollutants discharged into the sea in the key areas,

China Concerning Environmental Protection in Offshore Oil Ex-

define the index of gross control of the major pollutants discharged

ploration and Exploitation, Regulations on Management of the

into the sea, and distribute the controlled discharge volume for

Fishing Permit, etc.

the major pollution sources".

Some new contents have been added in this amended Law,

mainly including: protection of marine ecology, prevention of the

pollution damage to the marine environment by land-sources pol-

lutants, prevention of the pollution damage to the marine envi-

| 8

November 12-14, 2003 UNESCO, Paris

MANAGEMENT

out fishery administration and effectively practicing the system

of fishing closed season in summer, for 2^3 months a year, involv-

Management of the sea area use

ing over a million of the fishermen. Positive progress has been

achieved in the protection and management of the ecological en-

The public awareness is increasing continuously, and the

vironment in fishing areas. Pilot projects on artificial fish reefs

supporting bylaw system has been gradually completed. The four-

have been carried out in provinces of Guangdong, Zhejiang and

level marine functional zoning system involving the central gov-

Fujian, etc. and they are actively exploring the measures to re-

ernment, provincial government, municipal government and the

cover the ecological environment in the near-shore areas.

county government has primarily taken shape. Above two thirds

of the cities and counties of the 11 coastal provinces and munici-

Marine public service

palities have completed the drafting of their functional zonation

Through decades of development, comparatively complete

scheme and most of them have been approved and implemented.

system for marine environmental monitoring and forecast service

The sea-area-use rights confirmation and certificates issuance

has been established to carry out real-time operational forecast

have been carried out steadily. The phenomena of irrational use

for storm surges, sea waves, sea ice and seawater temperature. At

of the sea area have been comprehensively straightened out. The

the same time, research on the phased forecast and pre-warning

management of collection of the fee for sea area use has been

of various kinds of marine hazards such as the phenomena of El

strengthened which has ensured maintenance and increase of the

Nino and La Nina, coastal erosion, the seawater flowing intru-

value of the national resources assets of the sea area. Boundary

sion, as well as sea level rise has been conducted. This work has

delimitation of the administrative divisions has been carried out

played an important role in prevention and mitigation of the ma-

in an all-round way. The construction of demonstration sites for

rine disaster as well as in the service to the sea-related trades.

management of sea area use at national level has gained promi-

Since last year, in particular, we have initiated the environmental

nent results and 30 national-level demonstration sites for man-

forecasting for the major bathing beach in the country. The fore-

agement of sea area use have been established.

casts are made public timely through China Central Television

Management of the marine environment

(CCTV) and other major news media. We have started the report

on environmental quality for aquaculture in the monitoring and

The supporting regulations and bylaw system have been per-

control areas of the red-tides, which provides good guidance in

fected. The Environmental Protection Program has been formulat-

the local fishery and aquaculture production.

ing. The national marine environmental monitoring and assess-

ment have been enhanced. The three-level marine monitoring

FUTURE EFFORTS TO TAKE

operational systems involving the central government, provincial

government and municipal government have preliminarily come

In response to the calls of the Summit Conference on Sustain-

into being. The red-tide monitoring has been intensified, and the

able Development and carry out well the plans of implementation

oceanic administrative agencies of the coastal local governments

of Agenda 21, China will put greater emphasis to push forward the

have put in place a monitoring system and an emergency response

work in the following fields:

system in the red-tide monitoring and control area. Protection of

marine ecology has also been consolidated, and 76 marine nature

a. Perfect the planning and programming system and work out

reserves, among which 21 are at the national level and 55 at the

the National Environmental Protection Program and integrated

local level, have been set up. Some representative marine ecosys-

management programs for key sea areas like the Bohai Sea.

tems of rare and endangered marine animals, mangroves and coral

b. Perfect the marine legal system and realize more effective

reefs have been brought under protection. In 2002, the national

marine/coastal integrated management;

marine ecological investigation was carried out, which lasted for 8

months. And strict supervision and management of dumping at

c. Perfect the marine environmental monitoring system and

sea and prevention of the pollution caused by marine construc-

assessment system, set up ecological monitoring and control ar-

tion projects has been strengthened.

eas, and continue to strengthen the construction and manage-

ment of marine protected areas;

Management of the marine fishery resources

d. Improve the capability to prevent and mitigate marine di-

In response to the significant impact of the new international

sasters, and complete marine service system;

marine legal regime brought forth by the UNCLOS, China is work-

ing out and implementing relevant policies and measures to guide

e. Consolidate development, utilization and protection of the

the fishermen to reduce the number of fishing boats and turn to

uninhabited islands;

other jobs. Some provincial governments allot financial subsidies

f. Promote international cooperation in the region, and further

for the fishermen and direct them to shift to non-catching indus-

push primarily such international programs as the Marine Sus-

tries.

tainable Development Strategy for the Seas of East Asia, as well

China is carrying out the general investigation of fishing

as such projects on the Protection of the Marine Biodiversity in

boatsexploring actively the system of quota management of the

the south China seas and Protection and on the Management of

fishery resources and the compulsory end-of-life system for fish-

the Large Marine Ecosystem in the Yellow Sea(YSLME) in coop-

ing boats, reducing gradually the number of fishing boats, and

eration with GEF and other related countries.

controlling fishing intensity. China is also continuously carrying

9 |

GLOBAL CONFERENCE ON OCEANS, COASTS, AND ISLANDS

| 10

November 12-14, 2003 UNESCO, Paris

PROBLEMS AND OPPORTUNITIES IN THE

IMPLEMENTATION OF WSSD COMMITMENTS:

THE INDIAN PERSPECTIVE

Dr. Harsh .K. Gupta

Secretary to Government of India, Department of Ocean Development,

CGO Complex, Lodhi Road, New Delhi 110 003

Tel: +91-11 24360874, Fax: +91-11-24362644

e-mail: dodsec@dod.delhi.nic.in

INTRODUCTION

cesses and their impact on the sustainable development globally

and within the region in particular.

The vital role of oceans in sustaining life on planet Earth has

been recognised in India from its ancient past. An integral part of

India has a coastline of about 7500 kilometres, and the seas

the global sustainable development process, oceans, coasts and

around India influence the life of about 370 million coastal popu-

islands support a diverse array of activities yielding enormous

lations and the living of 7 million fishing community. We have

economic and social benefits. The Earth Summit of 1992 and the

the two island systems viz, Andaman & Nicobar and Lakshadweep

World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD) of 2002

with their special geographical connection with the seas around

brought the global community to address holistically and collec-

them. Further, we have a fragile but precious coastal ecosystem

tively, among other issues, the ecological, economic, and social

that needs to be preserved for the posterity.

importance of oceans, coasts, and islands for the global well-be-

ing and to prepare a time-bound action plan that need to be imple-

THE VISION AND PERSPECTIVE PLAN 2015 FOR

mented with synergy of several actors. It is heartening to note that

OCEAN DEVELOPMENT IN INDIA

ocean, coasts and islands received the due importance in the

WSSD, as indicated in its major outcomes viz. (a) Plan of Imple-

Our recognition of the intricate and long-term role that the

mentation of the World Summit on Sustainable Development, (b)

ocean plays in determining our environment and the equally criti-

the Johannesburg Declaration on Sustainable Development and

cal role that we play in modifying its characteristics coupled with

(c) Partnership initiatives to strengthen the implementation of

our realisation of the incompleteness of the understanding that

Agenda 21.

we have on this complex process, have been the driving force for

setting out, in the year 2002, a Vision and Perspective Plan 2015

The WSSD has given us a time-bound action plan over a wide

for Ocean Development in India. The mission is to improve our

spectrum of areas covering fisheries, biodiversity and ecosystem

understanding of the ocean, especially the Indian Ocean, for sus-

functions, marine pollution, maritime transportation, marine sci-

tainable development of ocean resources, improving livelihood,

ence, small islands, developing States and several related cross-

and for timely warnings of coastal hazards. The Vision 2015 hinges

sectoral aspects. The Global Forum on Oceans, Coasts and Is-

around improving our understanding of ocean processes through

lands is indeed an important platform for ensuring this imple-

conceiving and implementing long-term observational

mentation process. India would be pleased to join this global ef-

programmes and incubating cutting edge marine technology so

fort, particularly by contributing to Indian Ocean region, and fo-

that we are able to (i) improve understanding of the Indian Ocean

cussing her national efforts in ocean development.

and its various inter-related processes, (ii) assess the living and

non-living resources of our seas and their sustainable level of

THE INDIAN OCEAN.-.A COMPLEX OCEANIC

utilization, (iii) contribute to the forecast of the course of the

REALM

monsoon and extreme events, (iv) model sustainable uses of the

coastal zone for decision-making, (v) forge partnerships with In-

The Indian Ocean, the third largest ocean in the world has a

dian Ocean neighbours through the awareness and concept of one

unique geographic setting with more than 1.5 billion population

ocean, (vi) secure recognition for the interests of India and the

around, who are predominantly agrarian and monsoon-dependant.

Indian Ocean in regional and international bodies. This vision is

The frequent cyclones of the Bay of Bengal, the unique bio-

congruent with the WSSD outcome on oceans, coasts and islands.

geochemical processes of Arabian Sea as well as the bi-annual

The national agenda for ocean development in India during the

reversal of monsoon winds and currents make the Indian Ocean a

coming decades, as set out in the perspective plan are:

complex oceanic realm. The Indian Ocean has been a subject of

serious concern for the countries around this region as well as the

· Promoting ocean science, supporting technology

international community. It is also recognised that, as compared

development and strengthening observations, so as to

to the Atlantic and Pacific, the Indian Ocean still lacks systematic

continuously improve our understanding of local and

observations that are essential for understanding the oceanic pro-

remote processes,

11 |

GLOBAL CONFERENCE ON OCEANS, COASTS, AND ISLANDS

· Modelling sustainable uses of the coastal zone and

time-bound actions in the area of ocean & climate, coastal ocean,

reliably predicting extreme events,

data management and satellite applications, such as:

·

· IOGOOS Workshop on "Capacity Building and

Understanding the influence of the ocean on monsoons

Strategy for Data and Information Management" to be

and contributing to the capability to forecast it,

held in December 2003 at Colombo, as a prelude to the

·

establishment of ocean data and information network

Strengthening programmes in the southern ocean and

for the Indian Ocean,

Antarctica that offer unlimited opportunities to study

planet Earth in its pristine state,

· IOGOOS Workshop on "Marine Biodiversity" to be

·

held in December 2003 at Goa to evolve a strategy and

Mapping ocean resources and evolving guidelines for

action plan for long-term sustained monitoring of

proper stewardship so that they are sustainably utilized

coastal and ocean biodiversity in the region,

with minimal environmental impact,

·

·

Formulation of a "Strategy for Capacity Building in

Developing reliable and safe deep sea technology that

the Indian Ocean region on remote sensing applications

permits man to understand, quantify and harness ocean

for oceanographic and coastal studies",

resources,

·

·

Setting up of a "Joint CLIVAR/IOC-GOOS Indian

Partnering Indian Ocean neighbours in mutually

Ocean Panel on Climate" that would coordinate and

beneficial programmes,

plan a unified approach to all the basin-scale observa-

tions in the Indian Ocean for both research and

· Creating awareness in stakeholders about the complex

operational oceanography,

functioning of the ocean and the inherent limits to

predictability of ocean processes, and

· Pursuing a Project proposal on Marine Impacts on

Low lands Agriculture and Coastal (MILAC) resources

· Creating an Ocean Commission as a national frame-

jointly with JCOMM to contribute to natural disaster

work so that national efforts on ocean issues are

reduction in coastal lowland impacted by tropical

effectively coordinated.

cyclones,

GOOS REGIONAL ALLIANCE IN INDIAN OCEAN

· Formulation of a Pilot project on the Monitoring and

Management Systems for the Shallow Water Penaeid

The Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS) of the Inter-

Prawns for the Indian Ocean region, and

governmental Oceanographic Commission, evolved in 1992 and

co-sponsored by WMO, UNEP and ICSU, is an internationally

· Participation in the GOOS Regional Alliances

organized system for effective management of the marine envi-

Networking Development (GRAND) Project that

ronment and sustainable utilisation of its natural resources. Along

would facilitate knowledge networking among all

with the Global Climate Observing System and the Global terres-

regional GOOS alliances and also benefit from the

trial Observing System, GOOS would be playing a key role in the

advances made by EuroGOOS and MedGOOS over

observation of ocean, atmosphere and land. GOOS envisages (i)

the last decade.

an internationally accepted global design to address the broad

realms of ocean & climate and coastal ocean, (ii) a set of regional

INDIAN CONTRIBUTION TO OCEAN OBSERVING IN

alliances of countries that will focus on issues of common con-

THE INDIAN OCEAN

cerns and interests of the region and (iii) national contributions

for implementation of the observational systems.

India's plan for the near future is to establish a well-planned

India is playing an important role for ocean observations in

network of in-situ ocean observing system in the north Indian

the Indian Ocean by (i) leading the process of establishing of the

Ocean with 150 Argo profiling floats, 40 moored data buoys, 150

GOOS Regional Alliance - IOGOOS - for the Indian Ocean re-

drifting Buoys, 4 equatorial current meter moorings, expendable

gion in November 2002 (ii) being called upon to host IOGOOS

bathythermograph surveys along three major shipping routes and

Secretariat for the next 6 years as well as to lead IOGOOS in the

tide gauges, complemented by satellite observations through the

coming years to formulate and guide projects on Ocean observa-

Oceansat series of India. The progress of implementation has been

tions and applications of common concern in the region and (iii)

quite good.

taking decisive roles in IOC and other important international

India had the opportunity to host the Argo Implementation

forum pertaining to GOOS. Already 19 Institutions from Austra-

Planning Meeting in July 2001 and this marked the beginning of

lia, India, Iran, Kenya, Mauritius, Madagascar, Mozambique,

Argo float deployment in the Indian Ocean by several countries.

Reunion, South Africa and Sri Lanka have become Members of

India was then called upon to be the Regional Coordinator for the

IOGOOS and a few more are expected to join soon.

international Argo project in the Indian Ocean and also to be the

IOGOOS, along with a group of experts has initiated several

Regional Data Centre. It is satisfying to note that within a span of

| 12

November 12-14, 2003 UNESCO, Paris

two years, the Argo array in the Indian Ocean has reached 50 % of

timely potential fishing zone advisories using satellite data to the

its target (of 450 floats by 2006).

fishing community of the entire coastline of the country in a mis-

sion mode. Frequent and intense interactions between the scien-

India has already deployed 31 Argo floats and 20 more are

tists and fishing community at the fishing harbours, and use of a

scheduled to be deployed soon. The first results with Argo data

wide range of media such as fax, telephone, electronic display

are very encouraging. We have also mounted a national effort

boards, radio and internet have ensured that these advisories pro-

with the oceanographic and atmospheric community for assimi-

vided in the local languages becomes part of the value chain of

lation of Argo data with the end goal of improving the predict-

the fishing community. It has been validated that the search time

ability of the upper ocean and our climate. Capacity building in

has been reduced by 30 to 70 % due to the usage of these adviso-

this area is crucial if we need to harness the full benefit from this

ries. This is an excellent example of reaching the benefits of sci-

valuable stream of data.

ence to society. Experimental Ocean State forecast that is being

India has already established network of 20 Moored Data

provided on a daily basis is a typical example of multi-institu-

Buoys in both deep and shallow waters to measure a host of met-

tional endeavour to translate scientific knowledge into a service

ocean parameters. Surface Drifting Buoys (for measuring sea sur-

useful for safe operations in the sea. Setting up of an Ocean Infor-

face temperature and atmospheric pressure), Current Meter Ar-

mation Bank supported by a national chain of Marine Data cen-

rays (for time series profiles of current speed and direction at

tres and Observation systems as well as Web-based on-line ser-

fixed locations), Expendable Bathythermographs (for tempera-

vices with web computing capability are significant milestones

ture profiles) and Tide Gauges (for sea level) in the Arabian Sea,

towards the mission to provide the ocean information and advi-

Bay of Bengal and tropical Indian Ocean that have been provid-

sory services on a timely manner.

ing very valuable data for operational oceanography, weather fore-

casting and research. There is an active programme for ship ob-

INTEGRATED COASTAL AND MARINE AREA

servations using the four Research Vessels of the Department of

MANAGEMENT (ICMAM)

Ocean Development, in addition to ships of opportunity.

The Agenda 21 adopted in UNCED (1992) emphasises the

STORM SURGE FORECAST FOR NORTH INDIAN

need to adopt the concept of Integrated Coastal and Marine Area

OCEAN

Management (ICMAM) for sustainable utilisation of coastal and

marine resources and prevention of degradation of marine envi-

The coastal regions bordering the Bay of Bengal are severely

ronment. ICMAM project is being implemented in India from

affected by the storm surges associated with tropical cyclones,

1997-98, with two major components viz. capacity building and

particularly for the East Coast of India and Bangladesh. Since

development of infrastructure for R&D and training. The capac-

the coastal regions are densely populated, it is important to make

ity building activities cover development of GIS-based informa-

realistic forecast of inundations caused by the storm for prepara-

tion system for 11 critical habitats, determination of waste as-

tion of contingency plan to prevent loss of life and property. A

similation capacity in estuaries and coastal waters, EIA studies

project entitled "Storm Surges Disaster Reduction in the North-

and, development of ICMAM plans for major cities. A world class

ern part of the Indian Ocean", aimed at development of capabil-

facility has been created for the development of human resources

ity and infrastructure to provide storm surge and disaster warning

in this important area.

to save lives, reduce damage and encourage sustainable develop-

ment in coastal regions had received much consideration by IOC,

COASTAL MONITORING AND PREDICTION SYSTEM

WMO and the International Hydrological Programme of

UNESCO in the recent past. However, this Project is yet to take

A national programme on Coastal Ocean Monitoring and Pre-

off. JCOMM and IOGOOS are pursuing this.

diction system (COMAPS) was launched in 1991 by in India to

constantly assess the health of our marine environment and to

Also, India has developed software for prediction of storm

indicate areas that need immediate and long-term remedial ac-

surges and estimation of coastal inundation due to surges, along

tion. Considering the levels and sources of pollutants, the data on

the East coast of India. Using this software and the available data

nearly 25 environmental parameters are being collected at 82 lo-

sets, the path and height of storm surges have been successfully

cations in the 0-25 km sector of the entire coastline of the country

hindcasted. It is pertinent to note that a bilateral proposal has

using two dedicated vessels. Mathematical models are also being

been prepared for implementation between India and Bangladesh

developed to predict diffusion and dispersion characteristics of

for operational oceanographic and hydrological storm surge pre-

pollutants in specific areas. The data and information are regu-

diction facility along with improvement of meteorological, ma-

larly disseminated to the State Pollution Control Boards for le-

rine and hydrological observing systems and data processing sys-

gal/remedial action.

tems. A key component of the proposal is capacity building and

human resources development in the region.

NATIONAL INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK

OCEAN INFORMATION AND ADVISORY SERVICES

Modern oceanographic research in the country has a heritage

IN INDIA

four decades. Over the years, India has set up the Department of

Ocean Development and a chain of leading national institutions

The concerted efforts of Indian scientific community Scien-

with primary focus on Ocean Sciences and Research, Ocean Tech-

tists have culminated in a unique service to provide reliable and

nology, Antarctic and Polar Sciences, Ocean Observation, Infor-

13 |

GLOBAL CONFERENCE ON OCEANS, COASTS, AND ISLANDS

mation and Services, Costal Area Management, Marine Liv-

ing Resources. These institutions are supported by a large net-

work of academia and industry. Close interaction at both research

and operational level between the scientific community from

Ocean, Atmosphere and Space has ensured that there is a seam-

less flow of data, information and knowledge that percolates down

to the end users, thereby getting integrated with the development

process in the country.

CONCLUSION

India has been pursuing its efforts in ocean development with

a missionary zeal, addressing not only the imperatives for sus-

tainable development of its coasts, islands and seas around it but

also contributing to the well-being of the entire Indian Ocean re-

gion. India would thus be an active contributor as well as a ben-

eficiary of the implementation of the action plan on Ocean, Coast

and Islands that were set out at the WSSD.

| 14

November 12-14, 2003 UNESCO, Paris

WSSD IMPLEMENTATION IN EAST ASIA

Chua Thia-Eng

Partnerships in Environmental Management for the Seas of East Asia

Tel: (632) 926-9712

Email: chuate@pemsea.org

ABSTRACT

·

Addressing poverty issues which might exacerbate

non-sustainable use of living resources.

For the last 10 years, countries around the Seas of East Asia

(SEA) collaborated through a regional partnership programme

The countries also collaborated in the development of a "Sus-

(PEMSEA) to address their environmental concerns which pose

tainable Development Strategy for the Seas of East Asia (SDS-

ecosystem and public health risks that undermine their food se-

SEA)". With 228 action programs, the SDS-SEA covers a wide

curity, safety at sea, and sustainable use of their coastal and ocean

area of concern including maritime transportation, marine pollu-

resources. Most of their activities are also in response to the

tion, biodiversity, ecosystem functions, fisheries, science, small

concerns and recommendations of UNCED and WSSD related

islands and cross-sectoral issues which are also major concerns

to the coasts and oceans.

of the WSSD. The implementation of the SDS-SEA represents

regional implementation of the Plan of Implementation of the

Major efforts focused on developing and demonstrating work-

WSSD for the SEA. It also provides a working platform for con-

ing models on integrated coastal management, developed and

cerned partners to work together in the implementation of the

tested management techniques, increased local and national ca-

WSSD. Fourteen UN, international and regional organizations,

pacity to plan and manage their coastal and ocean resources as

multi-lending institutions, international and regional NGOs and

well as developing management framework and platform for

national agencies have been enlisted as collaborators. They form

stakeholders collaboration. Specific focus included:

the key partners in the implementation of the Strategy particu-

·

Integrating environmental concerns into economic

larly when it will complete its final passage for government en-

development plans through the implementation of sea

dorsement at the forthcoming Ministerial Forum on December

use zoning schemes and integration of sector policies

2003 in Malaysia.

and functions of line agencies;

INTRODUCTION

·

Developing programmatic, ecosystem-based manage-

ment strategies and action plans for managing coastal

The main feature of the countries bordering the seas of East

resource systems, river basin-coastal seas and large

Asia (Fig. 1) is their close linkages in terms of political, cultural,

marine ecosystems and subsystems;

social, economic, and ecological relationships [1-2]. These link-

ages are transformed into regional and sub-regional political and

·

Building intergovernmental, interagency, multi-sector

economic structures such as the Association of the Southeast Asian

and inter-sector partnerships at the local, national,

Nations (ASEAN) or the wider grouping consisting of the ASEAN

and regional levels;

countries and their 3 northern neighbors, PR China, Japan and

RO Korea (ASEAN + 3). For the last several decades, these group-

·

Strengthening local governance by increasing local

ings promoted regional cooperation in various areas of common

capacity, involving stakeholders in planning and

concerns including security, economic, trade, tourism, culture, edu-

implementation, making information more readily

cation, environment, etc. The political and economic groupings

available to the public, bringing science closer to

also lay a strong foundation for regional cooperation in address-

policymakers and economic and environmental

ing many sustainable development issues of the SEA.

managers, and forming interagency, multi-sector

coordinating mechanism;

The SEA plays a pivotal role in the economic well being of

1.9 billion people, a majority of which resides close to the coast.

·

Building a regional network of local government

The SEA produces close to 40 per cent of the world's fish pro-

practicing integrated coastal management;

duction; sustains a third of the world's coral reefs, and mangrove

wetlands, and is considered as the world center of marine

·

Catalyzing public sector-private sector partnerships

biodiversity. The SEA is also the global center of maritime trade,

for environmental investments;

providing services in nine of the world's 20 mega-ports and a

network of terminals and sea-ports for passengers, cargoes, and

·

Increasing the effectiveness of international conven-

fish landings. Heavy shipping traffic of oil tankers and container

tions through regional and local implementation; and

vessels, to and from the region ply through the Straits of Malacca

and Singapore.

15 |

GLOBAL CONFERENCE ON OCEANS, COASTS, AND ISLANDS

The SEA has indeed contributed significantly to the food se-

disciplinary and management expertise, substantial financial re-

curity and livelihoods of millions of fishermen and coastal inhab-

sources, concerted stakeholders' support, and strong national and

itants.

regional political will [1].

With one-third of the world's population, coupled with diver-

INTEGRATING ENVIRONMENT CONCERNS

sified economic activities along the coasts and the adjacent seas,

INTO ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT PLANS

the sustainable use of coastal and marine resources present major

challenges to the economic and environmental managers of the

A major effort of PEMSEA is to promote the integration of

region. It certainly poses significant challenges to achieving the

environmental concerns into economic development plans at na-

goals of the recent World Summit for Sustainable Development

tional and local levels. This proactive approach is intended to

(WSSD) and that of Agenda 21 of the United Nations Confer-

prevent or reduce environmental degradation due to economic

ence on Environment and Development (UNCED) of 1992.

development caused by development projects. In many countries

From 1993 to 1999, 11 countries of the region participated in

of the region, government infrastructure projects are often the

a regional project designed to address marine pollution of the

major contributors to environmental degradation despite the ap-

SEA [3]. The project was financed by the Global Environment

plication of Environmental Impact Assessments.

Facility (GEF), implemented by the United Nations Development

Programme (UNDP), and executed by the International Maritime

Sea use zoning schemes

Organization (IMO). In late 1999 the same countries further col-

PEMSEA promotes the application of sea use zoning and in-

laborated in the implementation of a follow-on project, "Build-

tegrates it with the conventional land use plans at local or na-

ing Partnerships on Environmental Management for the Seas of

tional levels. The Xiamen Municipality of PR China developed

East Asia (PEMSEA)". With Japan joining PEMSEA two years

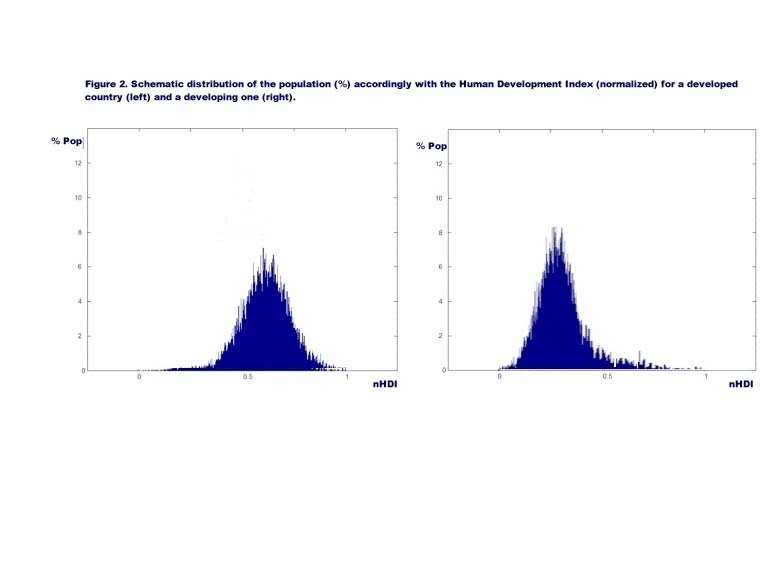

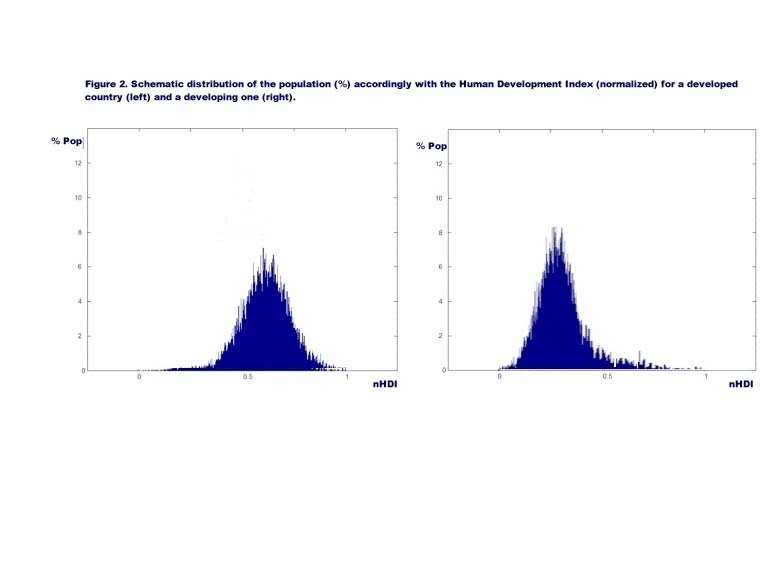

and implemented a sea use zoning scheme in mid 1990s (Fig. 2)

later, the regional project is now participated fully by all the coun-

by classifying the utilization of the municipal sea area according

tries around the SEA [1].

to its ecological and economic functions and traditional practices

A large part of PEMSEA's activities are in fact implementing

[4]. The zoning scheme delineates specific zones for navigation,

the recommendations of Chapter 17 of Agenda 21. Current and

port, tourism, fishing, mariculture, and conservation. A permit

other planned activities also complement the Plan of Implemen-

system was developed and is being implemented to regulate us-

tation of WSSD related to the coasts and oceans. PEMSEA's scope

ers according to the zoning criteria. The zoning scheme is well

of operation and the issues addressed present a working model

integrated into the land use plan of the municipality, thus effec-

for regional implementation of WSSD's Plan of Implementation.

tively regulating land development on the coast. Although this

process takes time and resources, it has proven to be effective not

PEMSEA'S APPROACH, STRATEGIES,

only in preventing pollution but has also effectively reduced the

AND ACTIVITIES

conflicts between shipping and the fishing sectors, and other

multiple use conflicts.

PEMSEA takes into consideration the following challenges

The success in Xiamen Municipality on sea use zoning has

to sustainable coastal development in designing its strategies and

significantly influenced the enactment of a sea space utilization

activities:

law by the People Assembly of PR China, requiring coastal prov-

·

Current management efforts are not adequate or

inces and municipalities to undertake sea use planning for the

inefficient in slowing down or reversing the rate of

entire coast of the country. To date, all Chinese coasts are being

environmental degradation;

zoned.

Based on the experience of Xiamen, several other PEMSEA

·

Poverty continues to exacerbate unsustainable

participating provinces and municipalities practicing integrated

development;

coastal management (ICM) have started developing similar sea

·

Adverse environmental impacts of globalization and

use zoning schemes at Batangas Bay [5-6], Bataan, Danang, Bali,

regionalization of the economy remain unabated;

and Port Klang.

Policy and functional integration

·

Difficulties in managing complexity;

The lack of integration and coordination of sector policies

·

Inadequacies in policy and institutional arrangements;

and functions of line agencies often result in policy, legislative,

and operational conflicts with potential serious environmental and

·

Inadequate local capacity in integrated planning and

economic consequences. PEMSEA promotes policy and functional

management;

integration of line agencies by forging a common vision and mis-

·

Resistance to change; and

sion of stakeholders at the national and local levels. In all of

PEMSEA's participating provinces and municipalities implement-

·

Inadequate public knowledge on the functions of the

ing ICM programs, coastal strategies are developed through the

ecosystems.

process of risk assessments, environmental profiling, and stake-

holders' consultations. The process enables the stakeholders to

Solutions to the above challenges require longer time, inter-

determine and prioritize management issues and collectively de-

| 16

November 12-14, 2003 UNESCO, Paris

termine solutions. The stakeholders will eventually agree to a

grams have already achieved significant results.

common vision pertaining to the use of their coastal and marine

resources. The involvement of various concerned line agencies is

In Xiamen, the endangered white dolphins are now frequently

very essential as the process forges better understanding amongst

sighted in the municipal coastal waters; the egrets have now re-

government agencies and other stakeholders for addressing is-

turned in large numbers while the prehistoric fish, the lancelets,

sues of common concerns, thereby enhancing synergies and co-

(Brachiostoma belcheri) are being effectively conserved. The once

ordination amongst various sector policies and the functions of

heavily polluted Yuandang Lagoon has been completely cleaned

line agencies.

and rehabilitated with significant socioeconomic impacts. Water

quality of Xiamen coastal waters did not deteriorate while the

A similar approach is being applied at the national level through

city still maintains an economic growth rate of 16-19 per cent

the formulation process of a national coastal policy, strategies

[10]. There was only one red tide outbreak since the implementa-

and other national maritime agenda.

tion of ICM program.

DEVELOPING PROGRAMMATIC, ECOSYSTEM-

In Bataan, a mangrove-replanting program is in place to re-

BASED MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES, AND ACTION

claim some of the lost mangrove wetlands. Shoreline improve-

PLANS

ments and landscaping along the coasts of Danang and Chonburi

have enormous socioeconomic impacts while in Sihanoukville,

the only natural marine reserve has been incorporated into the

PEMSEA adopts ecosystem-based management and program-

ICM management program so as to sustain and strengthen man-

matic approaches in addressing sustainable coastal and marine

agement measures. The ICM efforts in Batangas have regulated

area development of the SEA. PEMSEA's efforts are directed at

and prevented the establishment of pollutive industries and mo-

managing human activities on coastal resource systems, river ba-

bilized stakeholders in the protection of the remaining coral reefs

sin-coastal seas, and large marine ecosystems (LME) and sub-

in the bay.

systems.

Managing river-basin - coastal seas

Managing coastal resource systems

The Manila Bay Coastal Strategy, which was developed in

The coastal resource systems are natural systems influenced

close consultation with the coastal and inland provinces, central

by land-sea interactions and human activities. These include bays,

line agencies, and other stakeholders, takes into consideration the

coastal zones, estuaries, lagoons, and gulfs, where one or more

socioeconomic and ecosystem connectivity [11]. The Strategy

ecosystems or habitats such as coral reefs, mangroves, sea grass

covers the watershed areas and the rivers draining into the Ma-

beds, mudflats, and sandy and rocky shores are present. The coastal

nila Bay where the city of Manila is located. The Manila Bay

resource systems sustain a variety of economic activities and live-

Coastal Strategy is an example of river-basin-coastal sea ecosys-

lihoods of many coastal inhabitants. Human settlement centers

tem-based management approach with a management regime be-

such as urban cities are often located along the coast and they

ing developed for addressing management issues arising from the

strongly influence the functional integrity of these natural sys-

multiple use of the 90,000 hectare- Laguna De Bay, and the Ma-

tems.

nila Bay, which are physically connected by the Pasig River.

For the last 10 years, PEMSEA developed and tested working

Various subprojects are being undertaken to strengthen insti-

models on ICM as a viable mechanism for managing the use of

tutional coordination and capacity of concerned agencies to meet

the coastal resource systems in a sustainable manner [7]. The ICM

management challenges for the Manila Bay and the associated

program includes activities that analyze ecosystem and public

river basins. Special efforts are also directed at determining the

health risks caused by economic development and develop long-

severity of ecosystem degradation and impacts to public health,

term measures to prevent or reduce such risks through appropri-

and at developing appropriate management interventions. A vari-

ate management interventions. The ICM approach provides an

ety of management measures are being developed. They include

integrated management framework, planning, and implementing

amongst others the following:

processes, the application of which can address a variety of sus-

tainable development issues in accordance with local capacity

·

Develop action plans to address short and long term

[8-9].

environmental concerns;

Eleven coastal provinces and municipalities from nine

·

Strengthen the national capability of oil spill contin-

PEMSEA participating countries participated in the development

gency response and preparedness as well as on claims

and implementation of ICM programs. The ecosystem-based man-

on cost recovery of oil spill clean-up;

agement approach guided the preparation and implementation of

the various ICM program activities at Bali and Sukabumi (Indo-

·

Improve port safety and environmental management;

nesia), Bataan and Batangas (Philippines), Chonburi (Thailand),

Danang (Vietnam), Nampo (DPR Korea), Port Klang (Malay-

·

Strengthen integrated information management

sia), Shiwa (RO Korea), Sihanoukville (Cambodia), and Xiamen

system; and

Municipality (PR China).

·

Launch integrated education and public awareness

Although some ICM programs are more mature than others in

campaigns.

terms of the timeframe and investment of resources, several pro-

17 |

GLOBAL CONFERENCE ON OCEANS, COASTS, AND ISLANDS

The Bohai Sea, which is the only inland sea of PR China is

Managing multiple LMEs: the Seas of East Asia

drained by three major river systems, (Yellow, Hai and the Liao

River systems) with a watershed area of 1.4 million km2. A Bohai

The countries around the SEA semi-enclose the five LMEs

Sea Coastal Strategy is being developed with the cooperation and

making the region unique in terms of its socio-cultural, political,

collaboration of three coastal provinces (Liaoning, Shantung,

economic and ecological connectivity, which goes beyond na-

Hebei) and the two coastal cities of Tienjin and Dalian. Other

tional, political and ecological boundaries. The SEA in fact cre-

activities of the Bohai project include institutional coordinating

ates political, economic and ecological niches arising from the

arrangements, enactment of a regional law for the management

same geographical boundary. From the ecosystem standpoint, the

of the Bohai Sea, development of zoning scheme, risk assess-

region is one of the richest in terms of biodiversity, supporting a

ment and management, pollution load assessments, oil spill con-

number of habitats, fisheries and other marine resources. In terms

tingency plan and response, wetlands management, public edu-

of economic characteristics, countries in the region are interde-

cation and awareness, and environmental investments.

pendent and yet competitive with a vast disparity between the

haves and the have-nots. In terms of ecological features, the eco-

The regional management framework is useful to allow inter-

systems cuts across temperate and tropical zones with lush eco-

agency cooperation while fulfilling their sectoral responsibilities.

systems on land (tropical rainforests) and sea (coral reefs).

In the case of the Bohai Sea, a new but complementary GEF/WB

project is being developed for reducing nutrient pollution in the

Managing the SEA in a sustainable manner is a daunting task

Hai River Basin by improving sanitation facilities to reduce sew-

requiring strong management interventions, technical skills, in-

age discharge directly into the Bohai Sea.

terpersonal skills, foresight, and courage of the managers and

political leaders. It also requires time and resources for address-

Managing LMEs and subsystems

ing the enormous environmental and economic pressures arising

from the large and dense population along the coasts, the com-

The SEA covers five LMEs, viz: the Yellow Sea, East China

plex, diverse, and dynamic economic activities, as well as the

Sea, South China Sea, Sulu-Celebes Seas and the Indonesian Seas.

need to balance political and cultural differences. On the other

Currently there are two GEF funded projects focusing on South

hand, the need to manage this important water body is real and

China Sea and Yellow Sea [12]. The South China Sea project

urgent.

focuses on reversing the trends of environmental degradation and

is being implemented by UNEP. The Yellow Sea Project on the

Since 1999, PEMSEA embarked on an initiative to explore

other hand has yet to be operational. There is another regional

what can be done for the SEA. Through extensive discussion and

effort addressing marine biodiversity of the Sulu-Celebes Seas,

debates with experts and stakeholders from both the public and

which is a collaborative project between Malaysia, Philippines

the private sectors, it was apparent that some long-term strategy

and Indonesia [13].

is needed to guide the region towards sustainable use of its ocean

heritage. This effort culminated in the development of the "Sus-

The strategy of PEMSEA is to encourage a programmatic

tainable Development Strategy for the Seas of East Asia", which

approach in the management of each of the five LMEs based on

is discussed in the last section of this article.

its ecological boundary. Many transboundary environmental and

natural resource issues of the concerned LMEs should be ad-

BUILDING INTERGOVERNMENTAL, INTERAGENCY,

dressed by the concerned stakeholders taking note of the political

MULTI-SECTOR, AND INTER-SECTOR

and socioeconomic situations of the concerned countries and ur-

PARTNERSHIPS

gency of the environmental issues. Some of the transboundary

issues are politically sensitive such as the sea piracy issue in the

This approach is integrated into various levels of PEMSEA

Straits of Malacca and the South China Sea; the boundary dispute

activities especially in the development and implementation of

over the Spratly Islands and other areas of the region; the shared

coastal policies, strategies and action plans.

fish stocks; and the exportation of wastes and marine litters. Sci-

entific information on the LMEs is scant and needs to be grossly

Intergovernmental and interagency partnerships

strengthened to provide the scientific basis for management in-

terventions.

Efforts are made to forge stronger partnerships between local

and central governments towards harmonizing sector specific

On the other hand, regional or sub-regional management ef-

policies, legislation and management interventions. These efforts

forts could be focused on less contentious issues and in smaller

need to be further strengthened in light of the decentralization of

areas such as the Gulf of Thailand and the Tongkin Gulf. An ex-

authority to the local governments. A large number of local gov-

ample would be the collaborative project between Cambodia,

ernment units are not ready especially in harmonizing the above

Thailand and Vietnam in addressing oil and chemical spills in the

conflicts caused by the change of authority. These areas of con-

Gulf. It focuses on developing an oil spill response contingency

cern require partnerships between the central and local govern-

plan, strengthening capacity to combat oil spills on the ground,

ment to straighten out legislative and administrative disparities.

developing the necessary database to monitor changes in the event

of oil spills and making the necessary preparation for cost recov-

The risk assessment and risk management activities being

ery claims.

implemented in the ICM sites and large coastal seas (Bohai Sea,

Manila Bay, and the Gulf of Thailand) provide a working forum

for concerned line agencies (e.g., marine, fisheries, environment,

coast guard/navy, tourism, public health, etc.) to work together

| 18

November 12-14, 2003 UNESCO, Paris

(e.g., in combating oil spills) for achieving common objectives

plan and manage their coastal resources on a sustain-

(e.g., in seeking compensation for lost revenue and habitat resto-

able manner. This is done through involving local

ration) [14].

government units in the design and implementation of

the ICM program. They also undergo specialized

The coordinating mechanism, either in the form of a project

project development and management training and

coordinating committee, management council, or authority estab-

other technical training to increase their management

lished for an ICM program or for Manila Bay, Bohai Sea, and

skills and confidence in program implementation.

Gulf of Thailand, is a good vehicle for interagency partnerships.

It provides a regular forum where concerned agencies are involved

·

Involving multiple stakeholders in the planning and

in discussing site or issue specific management matters and often

implementation of projects thereby increasing program

promote collaborative activities jointly undertaken by the agen-

transparency and promoting participation. Concerned

cies concerned [15].

sectors and government line agencies are involved in

At the regional level, PEMSEA forges intergovernmental part-

the processes of coastal profiling, identification of

nerships through a variety of activities that are of transboundary

issues, setting of visions, missions and objectives of

in nature. Project activities include the oil spill contingency and

the management program, and designing of activities,

response project for the Gulf of Thailand which involves Cambo-

etc. This process strengthens ownership and buy-ins

dia, Thailand, and Vietnam and the implementation of the Marine

from all sectors.

Electronic Highway initiative for the Straits of Malacca and

Singapore, which involves Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore

·

Making information more readily available. This is

[16]. The most obvious one is the development of the regional

being undertaken through the development of

Sustainable Development Strategy for the Seas of East Asia, which

websites, the implementation of communication plans

involves the 12 concerned countries to collectively develop a stra-

to identify targets and the development of strategies

tegic framework acceptable for implementation by all concerned.

and action plans to promote dissemination of informa-

tion to the public and the policymakers.

Multi-sector and inter-sector partnerships

·

Bringing science closer to the policymakers and the

Multi-sector and inter-sector partnerships have been forged

economic and environmental managers. This is

in the development and implementation of ICM programs at

undertaken by involving experts from the universities

Bataan and Batangas Bay, Philippines, as well as the municipal-

or scientific institutions in the programs of the local

ity of Bali, and Sukabumi Regency in Indonesia [17]. In Bataan

governments so as to improve decision making with

Province, the private sector formed a Coastal Care Foundation to

sound scientific basis. This approach is especially

support the efforts of the provincial government in the manage-

successful in the Xiamen ICM program where a

ment of the coastal areas. Members of the Foundation are from

permanent interdisciplinary expert team forms part of

various sectors of the economy but work in close partnerships

the management decision-making process [15].

towards implementing activities identified through the ICM frame-

work. They were important partners in formulating the Bataan

·

Forming an interagency, multi-sector coordinating

Coastal Strategy, in implementing mangrove planting projects and

mechanism. This is to provide a regular forum for

educational and public awareness activities, and undertaking an-

mutual consultation and decision-making amongst

nual coastal clean-ups [18].

concerned line agencies and concerned stakeholders

Common solid waste disposal facilities in Bataan Province

so as to reduce interagency and multi-sectoral conflicts

and San Fernando City are being developed through the public-

while increasing partnerships at the operational level.

private sector partnerships (PPP) arrangement. Over the long pro-

cess of consultations, the public and the private sectors are able

·

Encouraging the involvement of women in the

to go through a negotiating process of identifying partners for

decision-making process. Of the 11 ICM programs,

joint development and operation of the above facilities.

five programs (Bataan, Batangas, Bali, Chonburi and

Danang) are headed by women. Most programs

In Sukabumi, various sectors of the tourism industry, the food

involved women in the decision making process.

industry and non-government organizations forged partnerships

in assisting the Sukabumi Regency in the implementation of ICM

The above efforts are part of the ICM approach designed to

activities, especially in the improvement of the shorefront and its

increase the capacity of the concerned local authority in

management.

environmental governance.

STRENGTHENING LOCAL GOVERNANCE

BUILDING A REGIONAL ICM NETWORK

OF LOCAL GOVERNMENTS

At each of the 11 PEMSEA participating provinces and mu-

nicipalities practicing ICM, efforts are made to strengthen local

When a local government embraces the concept and practice

governance by:

of ICM as a mechanism to achieve sustainable development, it

·

Increasing the capacity of local government units to

will integrate ICM practices into its regular program. Amongst

the 11 provinces and municipalities practicing ICM, some of them

19 |

GLOBAL CONFERENCE ON OCEANS, COASTS, AND ISLANDS

(i.e., Xiamen and Batangas) have already gone through 10

a joint venture between the public and private sector.

years of ICM practice; many with 3-4 years experience and a few

are just in the beginning stage.

The PPP approach provides another option to the conven-

tional Build, Operate and Transfer (BOT) or Build, Operate and

The 11 provinces and municipalities from nine countries of

Own (BOO) approaches. The advantage of the PPP process is the

the region comprising 64 local government units formed them-

reduction of political, social and investment risks that might not

selves into a regional ICM network. They take turns in organiz-

be available in other conventional approaches. PEMSEA's role

ing annual meetings to share experiences and lessons learned in

as honest broker helps to build confidence and trust amongst the