Strategic Planning Workshop on Global Oceans Issues in

Marine Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction in

the Context of Climate Change

Briefing Volume on Key Sources

of Information

January 23-25, 2008

Nice, France

CANADA

SINGAPORE

Note from the Workshop Secretariat: Key sources of information may be accessed through links to their

original publication source as well as through links to copies on the Global Forum website as indicated on

pages 23-24 in this volume.

Briefing Volume on Key Sources of Information

Table of Contents

1. The status of scientific knowledge regarding marine areas beyond

national jurisdiction

Overview...1

Key source(s) attached to this document...6

Other important documents...6

2. Human uses of marine areas beyond national jurisdiction

Overview...8

Key source(s) attached to this document...9

Other important documents...9

3. Climate change and marine areas beyond national jurisdiction

Overview...15

Key source(s) attached to this document...16

Other important documents...17

4. Policy and legal issues related to marine areas beyond national

jurisdiction

Overview...19

Key source(s) attached to this document...20

Other important documents...21

5. Information on progress achieved in meeting the international goals on

oceans, coasts, and small island developing states from the 2002 World

Summit on Sustainable Development

Report on Meeting the Commitments on Oceans, Coasts, and Small Island

Developing States Made at the 2002 World Summit on Sustainable Development:

How Well Are We Doing? Global Forum on Oceans, Coasts, and Islands

(2006)...23

6. Sources attached to this volume...23

1. The status of scientific knowledge regarding marine areas beyond

national jurisdiction

Overview Scientific understanding of ecosystems in marine areas beyond the

limits of national jurisdiction

The current debate on the high seas within the United Nations has focused on the

following specific ecosystems: seamounts, cold water coral reefs, hydrothermal vents and

other ecosystems. This background document provides information about knowledge of

these ecosystems, including their distribution, ecology, and the threats they are facing.

Seamounts

Seamounts are isolated mountains or mountain chains beneath the surface of the sea.

They are generally formed over upwelling plumes (hotspots) and in island arc convergent

settings. Hotspots are points of frequent volcanic activity in the earth's crust persisting

over millions of years.

Because seamounts do not break the sea surface, knowledge of their distribution comes

primarily from remote sensing, which is unlikely to be able to comprehensively map all

seamounts in the world. According to the Census of Marine Life project on seamounts

(CenSeam), there are potentially up to 100,000 seamounts over 1 km high and many

more of smaller elevation. They are found in every ocean basin and most latitudes,

although nearly half of the world's known or inferred seamounts are found in the Pacific

Ocean.

Relatively few seamounts have been studied, with only about 350 having been sampled.

Of these, fewer than 200 have been studied in any detail, many in waters within national

jurisdiction. Although seamount biodiversity is still poorly understood on a global scale

due to lack of sampling and exploration, available research results suggest that seamounts

are often highly productive ecosystems that can support high biodiversity and special

biological communities, including cold water coral reefs, as well as abundant fisheries

resources. Some evidence suggests high levels of endemic species on seamounts,

although these levels may vary between individual seamounts, regions and taxa.

According to the Census of Marine Life, "seamounts represent important ecosystems for

study that have not, to date, received scientific attention consistent with their biological

and ecological value."

Seamount ecosystems may be vulnerable because of their geographical isolation, which

for some species may indicate genetic isolation. They are also vulnerable because of the

characteristics of their associated species, which include cold water coral reefs that are

fragile to physical disturbances from destructive practices such as bottom trawling, and

long-lived, slow-growing fish species that are intrinsically vulnerable to fishing.

Consequently, the biggest current threat to seamounts comes from fishing activities.

Other threats include the mining of deep water corals associated with seamounts for the

jewellery trade, bioprospecting, potential future seabed mining related to mineral

resources of ferromanganese crusts and polymetallic sulphides (from vents, which may

1

occur at some younger seamounts). Climate change may also present a future threat as

seamount community structure may change because of differences in species' thermal

preference and changes in ocean current patterns.

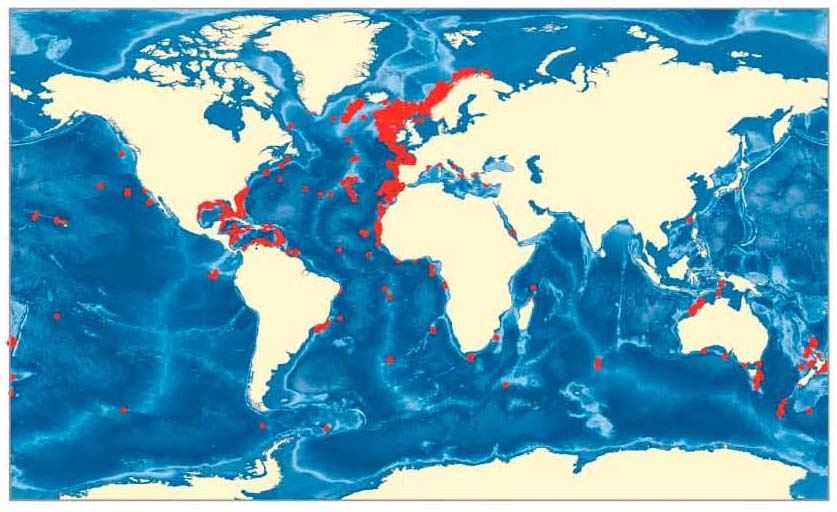

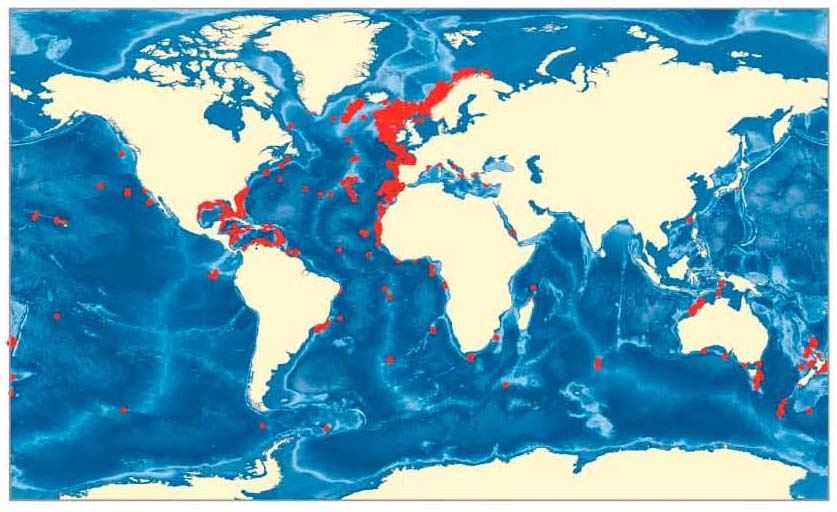

Figure 1. Current global distribution of reef frameworkforming cold-water corals [modified from

Freiwald et al. 2004]. Source: Roberts et al. (2006).1

Cold water coral reefs

Cold-water corals include stony corals (Scleractinia), soft corals (Octocorallia), black

corals (Antipatharia), and hydrocorals (Stylasteridae). They are widely distributed and

have thus far been found in the Atlantic, Mediterranean, Indian, Pacific and Southern

oceans see Figure 1). Most of the cold water corals discovered to date appear to be on the

edges of the continental shelf or on seamounts. The total area covered by cold water coral

reefs globally is still unknown, although studies indicate that coverage could equal, or

exceed, that of warm-water reefs. A conservative estimate of cold water coral reef

coverage is 284,300 km2.

There are still large gaps in our understanding of the distribution of cold water coral reefs,

their biology and ecology. These gaps are mainly due to the difficulty of researching

these environments, where observation and sampling often require expensive ship time

and sophisticated equipment. Our current knowledge consists of a series of snapshots of

well-studied reefs, most of which are located in the higher latitudes, including the

intensively mapped and studied Lophelia reefs in Norway. We do know that cold water

corals grow slowly, at only a tenth of the growth rate of warm-water tropical corals.

1 Roberts, J.M., A.J. Wheeler and A. Freiwald. 2006. Reefs of the Deep: The Biology and Geology of Cold-

Water Coral Ecosystems. Science 312:543-547.

2

Many of them produce fragile calcium carbonate skeletons that resemble bushes or trees

and provide habitat for associated animal communities.

There is no doubt that cold-water coral reefs support diverse communities of unique

species. These species include invertebrates and economically important fisheries species.

Thus, cold-water coral reefs may be considered biodiversity hotspots in the open ocean.

Major threats to cold-water corals include destructive fishing practices, such as bottom

trawling, other bottom-contact fishing (e.g. mid-water trawls may drag the bottom, long

lines may snag on corals), hydrocarbon drilling, seabed mining, ocean acidification and

direct exploitation. Of these, ocean acidification presents a potentially serious future

threat.

The overall ecological health status of cold water coral reefs is unknown. Most of the

reefs studied thus far show physical damage from trawling activities. Only in a few cases

has this damage been quantified. The rate of regeneration and recovery of once-damaged

cold water coral reefs is unknown, but is estimated to be on the scale of decades to

centuries for a reef to regain ecological function owing to the very slow growth rate of

cold water coral reefs.

Hydrothermal vents

The discovery of hydrothermal vents along the Galapagos Rift in the eastern Pacific in

1977 arguably represented one of the most important findings in biological science in the

latter quarter of the twentieth century. Hydrothermal vents were the first ecosystem on

Earth found to be independent from the sun as an original source of energy, relying

instead on chemosynthesis. Hydrothermal vents are now known to occur along all active

mid ocean ridges and back-arc spreading centres. The InterRidge Hydrothermal Vent

Database currently lists 212 separate vent sites, though more are likely to exist.

Our knowledge about where hydrothermal vents occur, and how extensive they are, is far

from complete. Hydrothermal activity does not take place everywhere along mid-ocean

ridge systems. Since the 1990s, there have been large-scale, systematic searches for

undiscovered vent sites. Many of these searches rely on inferring the presence of vents

from water column observations by measuring optical properties, temperature and

particle anomalies, as well as chemical tracers that distinguish hydrothermal plumes from

the surrounding seawater.

There are also knowledge gaps in regards to the biodiversity and ecology of hydrothermal

vent ecosystems, and their interactions with surrounding communities. Generally,

biomass of hydrothermal vent communities is high but biodiversity is low. Endemism is

high, with 91% of species that have been discovered from hydrothermal vents to date

being endemic. Vent sites support exceptionally productive biological communities in the

deep sea, and vent fauna range from tiny chemosynthetic bacteria to tube worms, giant

clams, and ghostly white crabs. Many species are exclusive to these ecosystems and

would be unable to exist outside them.

3

The only currently documented anthropogenic impacts to hydrothermal vent ecosystems

in areas beyond the limits of national jurisdiction result from marine scientific research.

However, the mining of polymetallic sulphide deposits associated with hydrothermal

vents presents a potentially much more serious and urgent threat to vent ecosystems, and

is moving closer to becoming a reality, at least within national EEZs. Bioprospecting of

hydrothermal vent organisms is already taking place, and some have been used for the

purposes of biotechnology. High-end tourism presents another potential future threat to

vent ecosystems.

Other ecosystems

Other ecosystems include pelagic habitats, as well as benthic sponge reefs and fields,

cold seeps and abyssal plains.

Pelagic habitats

Species diversity in the pelagic environment is generally lower than in the benthic

environment despite the far greater volume of the pelagic environment. The lower

diversity in pelagic systems may be a result of their openness, which allows for rapid and

widespread gene flow through pelagic communities. However, the pelagic ecosystem is

far from uniform in terms of productivity, and distinct hot spots exist in the world's

oceans. The pelagic ecosystem is fuelled by phytoplankton primary production.

Herbivorous zooplankton graze on phytoplankton, and in turn support predators including

fish. Many pelagic species, ranging from krill to tunas and marine mammals, migrate

during different stages of their different life history.

Many pelagic species are threatened directly or indirectly by commercial fishing. Pelagic

fishes are caught as target species and as by-catch. Following a long history of intensive

exploitation of large pelagic fish, and the global expansion of longline fisheries since the

1950s, predators such as sharks and tunas have declined drastically (one study indicates a

90% decline over 50 years), although the magnitude of the decline is still being debated.

Bycatch by pelagic gillnet and longline fishing continues to kill marine mammals,

seabirds and sea turtles. Bioaccumulation of chemical contaminants poses threats to the

health of pelagic animals, particularly top predators.

Climate change may have a potentially large impact on pelagic systems in the high seas.

Dynamics of pelagic systems depend largely on sea water temperature and current flow

patterns, which affect the magnitude and temporal and spatial distribution of primary

productivity. These factors, in turn, affect the distribution of zooplankton, pelagic fishes

and other pelagic megafauna. Carbon sequestration, a proposed strategy to combat

climate change, may also present a threat.

Sponge reefs

Sponge reefs, which are formed by glass sponges with three-dimensional silica skeletons,

are built in a manner similar to coral reefs, by new generations growing on previous ones.

Sponge stalk communities can be found on the soft mud bottom of the deep sea

throughout the world's oceans between the depths of 500 and 3,000m. Despite their

worldwide distribution, the main occurrences of sponge reefs are in cold waters

4

associated with bathymetric and topographic structures, such as seamounts, continental

slopes and underwater canyons, where fast-flowing, nutrient-rich deepwater currents can

be found. However, our current knowledge of the global distribution of sponge reefs is

incomplete and biased by insufficient sampling.

Similar to cold water coral reefs, sponge reefs are slow-growing and long-lived. Their

growth rate is generally two to seven cm per year and they can live to be up to 6,000

years old. Sponges provide habitat for many species, including invertebrates and

commercially important fish. The invertebrate diversity associated with sponges is high.

The threats facing sponge reefs are similar to those facing cold-water coral reefs, and

include destructive fishing practices such as bottom trawling, other bottom-contact

fishing (e.g., mid-water trawls, long lines), hydrocarbon drilling, seabed mining and

direct exploitation. Many sponge reefs show impact of bottom fishing activities, and

sponges are common as bycatch from fishing operations. Sponge reefs may also be of

future interest for bioprospectors.

Cold seeps

Cold seeps are deep soft-bottom areas where oil or gases seep out of the sediments.

"Seepage" encompasses everything from vigorous bubbling of gas from the seabed to the

small-scale emanation of microscopic bubbles or hydrocarbon compounds in solution.

Seep fluids contain a high concentration of methane. Cold seeps are found along the

world's passive and active continental margins at depths extending from 400 m to over

7000 m.

There are still knowledge gaps relating to the distribution, biodiversity and ecology of

cold seeps. Cold seeps are known to support relatively high diversity. Over 210 species

have been reported from cold seeps. This is very likely an under-estimate because of

insufficient samples and poor taxonomic identification of cold-seep assemblages. The

rate of endemism is high.

Threats to cold seeps include bottom fishing activities. Recent research reports from New

Zealand record evidence of trawl damage, including extensive areas of coral rubble, as

well as lost fishing gear on cold seeps. Oil, gas and mineral exploration are potential

threats to cold seep biodiversity. At the present time, such exploration occurs mainly on

the continental shelf. However, the rich oil, gas and mineral reserves at or near cold seeps

beyond national jurisdiction may attract exploration in the future, thus threatening their

associated communities.

Abyssal plains

Abyssal plains cover almost 50% of the deep seabed, and are comprised mainly of mud

flats. There is a relatively high diversity of animals living in and on deep-sea sediments,

including bottom-dwelling fishes, sea cucumbers, star fishes, brittle stars, anemones,

glass sponges, sea pens, stalked barnacles, mollusks, worms and small crustaceans.

However, despite the large number of rare animals, a few species make up the individuals

5

in deep-sea samples. The most diverse species are macrofauna, small animals of up to

1mm in size.

Key source attached to this document2

Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). 2006. Scientific Information on

Status and Trends of, and Threats to, Deep Seabed Genetic Resources beyond

National Jurisdiction. Note by the Executive Secretary pursuant to SBSTTA

recommendation XI/8. 10 February 2006. Available:

http://www.biodiv.org/doc/programmes/areas/marine/marine-status-en.doc

Other important documents

Clark M.R., Tittensor D., Rogers A.D., Brewin P., Schlacher T., Rowden A., Stocks K.,

Consalvey M. (2006). Seamounts, deep-sea corals and fisheries: vulnerability of

deep-sea corals to fishing on seamounts beyond areas of national jurisdiction.

UNEP-WCMC, Cambridge, UK. Available:

http://www.cbd.int/doc/meetings/mar/ewsebm-01/other/ewsebm-01-clark-en.pdf

Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) (2005) Status and trends of, and threats to,

deep seabed genetic resources beyond national jurisdiction, and identification of

technical options for their conservation and sustainable use

(UNEP/CBD/SBSTTA/11/11). See:

http://www.biodiv.org/doc/meetings/sbstta/sbstta-11/official/sbstta-11-11-en.doc

CBD. 2006. Global Coastal and Marine Biogeographic Regionalization as a Support tool

for Implementation of CBD Programmes of Work. Note from the Executive

Secretary. 21 February 2006. UNEP/CBD/COP/8/INF/34. 21 February 2006.

Available: http://www.biodiv.org/doc/meetings/cop/cop-08/information/cop-08-inf-

34-en.pdf

CBD.2007. synthesis and review of the best available scientific studies on priority areas

for biodiversity conservation in marine areas beyond the limits of national

jurisdiction. An information document for SBSTTA 13.

Freiwald, A., J.H Fossċ, A. Grehan, T. Koslow and J. M. Roberts. 2004. Cold-water

Coral Reefs. UNEP-WCMC, Cambridge, UK.

Freiwald, A. and Roberts, J.M. (eds.) 2005. Cold-water Corals and Ecosystems. Springer-

Verlag Berlin Heidelberg

2 The sources noted as "attached to this volume" are on the Global Forum website and maybe downloaded

by participants through links on pages 23-24.

6

Pitcher, T.J., Morato, T., Hart, P.J.B., Clark, M.R., Haggan, N. and Santos, R.S. (eds)

2007. Seamounts: Ecology, Conservation and Management. Fish and Aquatic

Resources Series, Blackwell, Oxford, UK. (in press).

Roberts JM, Wheeler AJ, Freiwald A. 2006. Reefs of the deep: the biology and geology

of cold-water coral ecosystems. Science 312:543-547

Rogers, A.D. 2004. The Biology, Ecology and Vulnerability of Deep-Water Coral Reefs.

Report for the World Conservation Union for the 7th Convention of Parties,

Convention for Biodiversity, Kuala Lumpur, February 8th 19th. 8pp. Available

at Available at http://www.iucn.org/themes/marine/pubs/pubs.htm

Van Dover, C. 2000. The Ecology of Deep-Sea Hydrothermal Vents (Princeton

University Press).

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). 2006. Ecosystems and biodiversity in

deep waters and high seas. UNEP Regional Seas Reports and Studies No. 178.

UNEP/IUCN Switzerland 2006.

United Nations General Assembly (UNGA). 2005. Oceans and the law of the sea Report

of the Secretary-General. Addendum. Document A/60/63/Add.1 presented to the

Ad Hoc Open-ended Informal Working Group to study issues relating to the

conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity beyond areas of

national jurisdiction. See: http://daccess-

ods.un.org/access.nsf/Get?Open&DS=A/60/63/Add.1 &Lang=E

7

2. Human uses of marine areas beyond national jurisdiction

Overview Human uses of marine areas beyond the limits of national jurisdiction

Current human uses of marine areas beyond the limits of national jurisdiction include

capture fisheries and aquaculture, shipping, marine scientific research, bioprospecting,

tourism, oil and gas extraction, mining, deep sea cable and pipeline industry, disposal of

nuclear waste or other substances, and military uses. New and emerging uses of marine

areas beyond national jurisdiction may present new opportunities in which to utilize

ocean resources, but also may have unknown impacts on these areas. Such uses include

carbon sequestration, ocean fertilization, and floating energy and mariculture facilities,

among others. Continued research on these new and emerging uses will provide essential

information on how to best reap the benefits, as well as mitigate any negative impacts.

Human uses of marine areas beyond national jurisdiction produce important benefits to

human economies and livelihoods.

The Workshop will consider the benefits and problems/opportunities related to three

industries operating in areas beyond national jurisdiction: fishing, submarine cables, and

maritime transportation.

In general, the economic and social values and perspectives on future problems/

opportunities of various ocean industries have not been well documented and aggregated.

To remedy this gap, the Global Forum on Oceans, Coasts, and Islands, together with

industry and UNIDO, will be developing a study on the economic and social values

associated with these industries and the outlooks of industry leaders on constraints,

challenges, and opportunities they will be facing in the next decade.

Human uses may also have impacts on the marine environment and biodiversity. The

following lists some of the key issues associated with various human uses. Table 1

provides some options and relevant actors for preventing and mitigating identified

threats:

the capture fisheries sector continues being affected by shortage of resources,

mainly due to unsustainable exploitation practices and underlying causes related

to fisheries governance;

illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing has adverse ecological impacts,

but also the economic and social costs of it are significant and result in increased

costs, lower employment, lower incomes and lower export revenues for legal

fishers and adverse effects on the livelihoods of developing country fishing

communities due to the reduction of the resources on which those livelihood

systems are based;

there are difficulties in keeping track of scientific research and monitoring

activities in the open ocean and deep sea environments;

8

there are issues related to cruise ship wastes, whose disposal is generally

unregulated, as well as to the adverse economic and social effects that cruise

tourism can entail;

in the marine environment, extractive activities for the purpose of energy

development remain a major economic industry. In marine areas afar from the

coastline, the main extractive activity related to energy production is offshore oil

and natural gas. The occupation of certain areas for the purpose of energy

production may conflict with other uses and also entail environmental effects in

those areas;

mining in the seabed, the ocean floor and subsoil beyond national jurisdiction

(`the Area') is organized and controlled by the International Seabed Authority

(ISA) according to relevant provisions under the United Nations Convention on

the Law of the Sea. The Authority coordinates expert work on environmental

effects of mining and on exploring linkages between non-living and living

resources in the Area, but its mandate relates to non-living resources solely;

despite their relatively limited direct uses of ocean's spaces and resources in areas

beyond national jurisdiction, indigenous and local communities seem to have

well-defined expectations as stakeholders (in the general sense of the term as

including rightholder) with regard to marine biodiversity in areas beyond national

jurisdiction.

An integrated approach to the study and management of the ocean's spaces and resources

would imply that all actual stakeholders, directly as well as indirectly involved, be

identified and consulted in an appropriate manner. Future work is needed in this regard.

Key source attached to this document3

UNU-IAS. 2006. Implementing the Ecosystem Approach in Open Ocean and

Deep Sea Environments - An Analysis of Stakeholders, their Interests and

Existing Approaches. UNU-IAS Report.

http://www.ias.unu.edu/binaries2/DeepSea_Stakeholders.pdf

Other important documents

CBD. 2005. The International Legal Regime of the High Seas and the Seabed Beyond

National Jurisdiction. CBD Technical Report No. 19.

http://www.cbd.int/doc/publications/cbd-ts-19.pdf

International Cable Protection Committee. About Submarine Telecommunications Cables.

3 The sources noted as "attached to this volume" are on the Global Forum website and maybe downloaded

by participants through links on pages 23-24.

9

An informative presentation on submarine cables, and their role in today's world.

Available:

http://www.iscpc.org/About_Cables_LowRes/About_SubTel_Cables_LowRes_R

ev7.pps.

10

Table 1. Summary of threats to selected seabed habitats, and options and relevant actors for

preventing and mitigating identified threats4

Existing and

Existing options

Options under

Relevant actors

potential threats

development

Hydrothermal vents

Existing

· 2006 InterRidge statement of

· Code of conduct for · Organizations

· Marine scientific

commitment to responsible research

marine protected

undertaking marine

research with

practices at deep sea hydrothermal

areas in the Azores

scientific research,

destructive

vents

Triple Junction

· Bioprospecting

impacts

· The Commitment to Responsible

· International Seabed

companies

· Bioprospecting

Marine Research of the Senate

Authority (ISA)

· High-end tourism

Commission on Oceanography of

draft regulations on

operators and tourists

Potential

the German Research Foundation

prospecting and

· Deep sea mining

· Mining of

(DFG) and the German Marine

exploration for

companies

polymetallic

Research Consortium (KDM)

polymetallic

· Energy development

sulphide deposits · CBD Voluntary guidelines on

sulphides and cobalt-

companies

associated with

biodiversity-inclusive

rich ferromanganese · Relevant UN

vent systems

environmental impact assessment

crusts in the Area 5/

organizations

· Submarine-based

· ISA exploration and · Regional

marine tourism

mine site model to

organizations

block selection for

including the regional

cobalt-rich

seas organizations

ferromanganese

and regional fishery

crusts and

management

polymetallic

organizations

sulphides 6/

(RFMOs)

· OSPAR 7/ code of

· Developed and

conduct for scientific

developing States

research

· Environmental non-

· FAO guidelines for

governmental

deep-sea fisheries in

organizations

the high seas

4 Source: CBD. 2007. Options for preventing and mitigating the impacts of some activities to selected

seabed habitats, and ecological criteria and biogeographic classification systems for marine areas in need of

protection. UNEP/CBD/SBSTTA/13/4. 13 November 2007. Available:

http://www.cbd.int/doc/meetings/sbstta/sbstta-13/official/sbstta-13-04-en.doc

5 ISBA/10/C/WP.1Rev.1; ISBA/13/LTC/WP.1

6 ISBA/12/C/3

7 The Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic (the OSPAR

Convention)

11

Existing and

Existing options

Options under

Relevant actors

potential threats

development

Cold Seeps

Existing

· Code of Conduct for Responsible

· ISA draft regulations · Oil and gas

· Prospecting by

Fisheries (FAO 1995) and its

on prospecting and

companies

the petroleum

relevant international plans of

exploration for

· Organizations

industry

action

polymetallic

undertaking marine

· Destructive

· General Assembly resolution

sulphides and cobalt-

scientific research

fishing practices

61/105, on sustainable fisheries,

rich ferromanganese · Biotechnology

· Scientific

paras. 83-91

crusts in the Area

companies

investigation with · Voluntary guidelines on

· Management

· Deep sea mining

destructive

biodiversity-inclusive

measures in line with

companies

impacts

environmental impact assessment

General Assembly

· Fishers

· Micro-organisms sustainable use

resolution 61/105, on · Relevant UN

Potential

and access regulation international

sustainable fisheries,

organization/s

· Direct harvest of

code of conduct (MOSAICC)

bottom fisheries

including the

seepage minerals · Code of practice for ocean mining

measures, paras.83-

International Seabed

(IMMS 2002)

86, to be developed

Authority,

· Management measures developed

by regional fisheries · Regional

by regional fisheries management

management

organizations

organizations or arrangements, e.g.

organizations or

including the regional

the South Pacific RFMO and the

arrangements and

seas organizations

Northwest Atlantic Fisheries

flag States

and RFMOs

Organizations

· OSPAR code of

· Flag States

· The Commitment to Responsible

conduct for scientific · Non-governmental

Marine Research of the Senate

research

environmental

Commission on Oceanography of

· FAO guidelines for

organizations

the German Research Foundation

deep-sea fisheries in · Developed and

(DFG) and the German Marine

the high seas

developing states

Research Consortium (KDM)

·

Seamounts

Existing

· Code of Conduct for Responsible

· ISA International

· Fishers

· Overexploitation

Fisheries (UN FAO 1995) and its

Seabed Authority

· Deep sea mining

of high seas

relevant international plans of

draft regulations on

companies

fishing on

action

prospecting and

· Relevant UN

seamounts

· General Assembly resolution

exploration for

organization/s

· Destructive

61/105, on sustainable fisheries,

polymetallic

· Regional

fishing practices

paras. 83-91

sulphides and cobalt-

organizations,

· Mining of deep-

· Management measures developed

rich ferromanganese

including the regional

water corals

by regional fisheries management

crusts in the Area

seas organizations

associated with

organizations and arrangements,

· Management

and RFMOs

seamounts for the

including pursuant to General

measures in line

· Flag States

jewellery trade

Assembly resolution 61/105, on

with General

· Non-governmental

sustainable fisheries, e.g. the South

Assembly

environmental

Potential

Pacific RFMO and the Northwest

resolution 61/105,

12

Existing and

Existing options

Options under

Relevant actors

potential threats

development

· Mining of

Atlantic Fisheries Organizations

on sustainable

organizations

ferromanganese

· Cooperative agreements or

fisheries, bottom

· Developed and

oxide and

arrangements of mutual assistance

fisheries measures,

developing countries

polymetallic

on a global, regional, sub-regional

paras.83-86, to be

sulphides

or bilateral basis

developed by

· Bioprospecting

· Code of practice for ocean mining

regional fisheries

· Possible

(International Marine Minerals

management

exploitation of

Society 2002) Voluntary guidelines

organizations or

methane gas

on biodiversity-inclusive

arrangements and

hydrates

environmental impact assessment

flag States

· Climate change

· The Commitment to Responsible

· OSPAR code of

Marine Research of the Senate

conduct for scientific

Commission on Oceanography of

research

the German Research Foundation

· FAO guidelines for

(DFG) and the German Marine

deep-sea fisheries in

Research Consortium (KDM)

the high seas

Cold- water coral and sponge reefs

Existing

· Code of conduct for responsible

· Management

· Fishers

· Destructive

fisheries (FAO 1995) and its

measures in line with · Scientific researchers

fishing practices

relevant international plans of

UNGA 61

and bioprospectors

action

sustainable fisheries

· Biotechnology

Potential

· General Assembly resolution

resolution and

companies

· Hydrocarbon

61/105, on sustainable fisheries,

bottom fisheries

· Oil and gas

drilling and

paragraphs 83-91

measures (OP83-86)

companies, and end

seabed mining

· Management measures developed

to be developed by

users of oil and gas

· Ocean

by regional fisheries management

regional fisheries

· Relevant UN

acidification

organizations and arrangements,

management

organization/s,

· Placement of

including pursuant to the

organizations or

· Regional

pipelines and

sustainable fisheries resolution

arrangements and

organizations,

cables

UNGA 61

Flag States

including the regional

· Pollution

· Cooperative agreements or

· Technical annex to

seas organizations

· Research

arrangements of mutual assistance

the draft OSPAR

and RFMOs

activities

on a global, regional, subregional or

code of conduct for

· Flag States

· Dumping

bilateral basis

scientific research

· Companies that use

· IMO Code for the Construction and · FAO guidelines for

cables and pipelines

Equipment of Mobile Offshore

deep-sea fisheries in · Environmental non-

Drilling Units, 1989 (MODU Code)

the high seas

governmental

· Environmental impact assessment

organizations

and mitigation measures adopted by

· Developed and

oil and gas companies as stated in

developing countries

8 Irish Department of the Environment, Heritage and Local Government 2006

9 Energy and Biodiversity Initiative 2003

13

Existing and

Existing options

Options under

Relevant actors

potential threats

development

environmental impact statements

· Code of practice for marine

scientific research in cold water

corals 8/

· Voluntary guidelines on

biodiversity-inclusive

environmental impact assessment

· Good and best practices for

offshore oil and gas operations 9/

· The Commitment to Responsible

Marine Research of the Senate

Commission on Oceanography of

the German Research Foundation

(DFG) and the German Marine

Research Consortium (KDM)

14

3. Climate change and marine areas beyond national jurisdiction

Overview Climate change

While climate change science has made considerable progress, large uncertainties still

continue to exist in regards to our understanding of the impacts of climate on change on

oceans, their biota and ecology. Much of the current scientific research has focused on

climate change impacts in coastal regions, particularly in regards to coral bleaching and

sea level rise. Less is known about potential impacts to open oceans and deep seas.

Background

Climate change may bring about large changes in ocean temperature and circulation. In

2006, the German Advisory Council on Global Change (WBGU) released a Special

Report, "The Future Oceans Warming up, Rising High, Turning Sour" which shows

that climate change is having severe impacts on the state of the oceans. Three critical

processes, ocean warming, ocean acidification and sea-level rise, are a direct outcome of

the atmospheric enrichment of pollution with greenhouse gases, especially carbon

dioxide. The report emphasizes the need for a rapid response - because of the major time

lags, human action now will determine the state of the oceans for many centuries to come.

According to the fourth IPCC report, observations since 1961 show that the average

temperature of the global ocean has increased to depths of at least 3000 m and that the

ocean has been taking up over 80% of the heat being added to the climate system. Most

coupled ocean-atmosphere models suggest a weakening of the convective overturning of

the ocean in the North Atlantic and around Antarctica, which would affect ocean

circulation and could have significant regional impacts on climate. Conditions setting up

such changes may be initiated in the 21st century, but the effects may not become evident

until centuries later.

Oceanographic changes caused by climate change may affect marine organisms in a

variety of ways including their abundance, distribution and breeding and migration

cycles. These changes may cause community-level shifts that will affect the functioning

of the oceanic ecosystem. In addition, international studies indicate that the productivity

of marine systems will be affected by climate change. These changes may also influence

the ability of the ocean ecosystems to produce food for human consumption.

This background note summarises some of the key concerns of climate change impacts

on ecosystems and species in marine areas beyond the limits of national jurisdiction.

Climate change and the pelagic environment

Climate change may have a potentially large impact on pelagic systems in the high seas.

Dynamics of pelagic systems depend largely on sea water temperature and current flow

patterns, which affect the magnitude and temporal and spatial distribution of primary

productivity. These factors, in turn, affect the distribution of zooplankton, pelagic fishes

and other pelagic megafauna. However, the extent to which climate change may threaten

species in the pelagic systems requires further research. For example, there is as yet

insufficient knowledge about impacts of climate change on regional ocean currents and

15

about physical-biological linkages to enable confident predictions of changes in fisheries

productivity.

Ocean acidification

According to the fourth IPCC report, the uptake of anthropogenic carbon since 1750 has

led to the ocean becoming more acidic with an average decrease in pH of 0.1 units.

Increasing atmospheric CO2 concentrations lead to further acidification. Projections

based on SRES scenarios give a reduction in average global surface ocean pH of between

0.14 and 0.35 units over the 21st century. While the effects of observed ocean

acidification on the marine biosphere are as yet undocumented, the progressive

acidification of oceans is expected to have negative impacts on marine shell-forming

organisms and their dependent species.

Consequently, ocean acidification presents a potentially serious future threat to cold

water coral reefs and plankton with calcareous shells (such as foraminifera). Increasing

acidification de-saturates aragonite in water, making conditions unfavourable for corals

to build their carbonate skeletons. Current research predicts that tropical coral

calcification would be reduced by up to 54% if atmospheric carbon dioxide doubled.

Because of the lowered carbonate saturation state at higher latitudes and in deeper waters,

cold water corals may be even more vulnerable to acidification than their tropical

counterparts. Also, the depth at which aragonite dissolves could become shallower by

several hundred meters, thereby raising the prospect that areas once suitable for cold-

water coral growth will become inhospitable in the future. It is predicted that 70% of the

410 known locations with deep-sea corals may be in aragonite-undersaturated waters by

2099.

Carbon sequestration

Carbon sequestration is a proposed method for mitigating the impacts of climate change,

which may present a threat to ocean habitats and species. It has been suggested that one

strategy for combating climate change is to enhance the ocean's natural capacity to absorb

and store atmospheric carbon dioxide, either by inducing and enhancing the growth of

carbon-fixing plants in the surface ocean, or by speeding up the natural, surface-to-deep

water transfer of dissolved carbon dioxide by directly injecting it into the deep ocean.

The environmental consequences of this activity are unknown, and the carbon dioxide

dumped in the oceans will eventually percolate to the surface and back into the

atmosphere.

Key sources attached to this document10

Observations, some current conditions and evaluations on climate change and marine

areas beyond national jurisdiction, Dr. Gunnar Kullenberg, former Executive

Secretary, Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission

10 The sources noted as "attached to this volume" are on the Global Forum website and maybe downloaded

by participants through links on pages 23-24.

16

German Advisory Council on Global Change. 2006. The Future Oceans Warming

Up, Rising High, Turning Sour. Special Report. Berlin.

http://www.wbgu.de/wbgu_sn2006_en.pdf

World Climate Research Programme Briefing to IOC 2007. Available:

http://wcrp.ipsl.jussieu.fr/SF_OceanClimate.html

Other important documents and sources of information

CBD. 2001. Interlinkages between climate change and biodiversity. CBD Technical

Report No. 10. http://www.cbd.int/doc/publications/cbd-ts-10.pdf

Gateway to the UN System's Work on Climate Change. Available:

http://www.un.org/climatechange/index.shtml

Guinotte, J.M., Orr, J., Cairns, S., Freiwald, A., Morgan, L. and George, R. 2006. Will

human-induced changes in seawater chemistry alter the distribution of deep-sea

scleractinian corals? Front. Ecol. Environ. 4(3): 141-146.

Hobday, Alistair J., Thomas A. Okey, Elvira S. Poloczanska, Thomas J. Kunz, Anthony J.

Richardson (Eds.) 2006. Impacts of climate change on Australian Marine Life.

CSIRO Marine and Atmospheric Research report to the Australian Greenhouse

Office , Department of the Environment and Heritage. September 2006

http://www.greenhouse.gov.au/impacts/publications/marinelife.html

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 2007. Fourth Assessment Report

Climate Change 2007: Synthesis Report. http://www.ipcc.ch/ipccreports/ar4-

syr.htm

Ocean Observations Panel for Climate (OOPC). Available:

http://ioc3.unesco.org/oopc/about/index.php

Orr, J.C., Fabry, V.J., Aumont, O., Bopp, L., Doney, S.C., Feely, R.A., Gnanadesikan, A.,

Gruber, N., Ishida, A., Joos, F., Key, R.M., Lindsay, K., Maier-Reimer, E.,

Matear, R., Monfray, P., Mouchet, A., Najjar, R.G., Plattner, G., Rodgers, K.B.,

Sabine, C.L., Sarmiento, J.L., Schlitzer, R., Slater, R.D., Totterdell, I.J., Weirig,

M., Yamanaka, Y. and Yool, A. 2005. Anthropogenic ocean acidification over the

twenty-first century and its impact on calcifying organisms. Nature 437: 681-686.

Roberts JM, Wheeler AJ, Freiwald A (2006) Reefs of the deep: the biology and geology

of cold-water coral ecosystems. Science 312:543-547

The Bali Action Plan (Advance unedited version). Available:

http://unfccc.int/files/meetings/cop_13/application/pdf/cp_bali_action.pdf

17

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Fourth Assessment Report.

http://www.ipcc.ch/ipccreports/ar4-syr.htm

The Ocean Acidification Network. Available: http://www.ocean-acidification.net/

18

4. Policy and legal issues related to marine areas beyond national

jurisdiction

Overview

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) provides the legal

framework within which all activities in the oceans and seas must be carried out (see Part

VII of UNCLOS. UNCLOS, its Implementing Agreements (namely the Agreement

relating to the Implementation of Part XI of the United Nations Convention on the Law

of the Sea of 10 December 1982, the Agreement for the Implementation of the Provisions

of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea of 10 December 1982 relating to

the Conservation and Management of Straddling Fish Stocks and Highly Migratory Fish

Stocks), and the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) are the major legal

instruments governing marine areas beyond national jurisdiction, along with several other

international conventions, regional seas agreements, and regional fishery management

conventions as well as a number of non-binding global instruments (see the CBD report

on the International Legal Regime of the High Seas and the Seabed beyond the Limits of

National Jurisdiction and Options for Cooperation for the Establishment of Marine

Protected Areas (MPAs) in Marine Areas beyond the Limits of National Jurisdiction, and

the UN Secretary-General's reports on the website of the United Nations Division for

Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea, e.g., A/59/62, A/59/62/Add.1, A/60/63/Add.1,

A/62/66).

The United Nations, through its relevant organizations has undertaken various initiatives

to implement the provisions of UNCLOS and its Implementing Agreements related to the

governance of marine areas beyond national jurisdiction, recently through: 1) the

establishment of an Ad Hoc Open-ended Informal Working Group to study issues

relating to the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity beyond

areas of national jurisdiction; 2) UN Open-ended Informal Consultative Process on

Oceans and the Law of the Sea; 3) UN General Assembly (UNGA) resolutions.

The UNGA through resolution 59/24 on Oceans and the Law of the Sea (17 November

2004, paragraph 73), called for the establishment of an Ad Hoc Open-ended Informal

Working Group to study issues relating to the conservation and sustainable use of marine

biological diversity beyond areas of national jurisdiction. The UNGA in resolution

61/222 of 20 December, 2006, on Oceans and the Law of the Sea, requested the

Secretary-General to convene a second meeting of the UN Ad Hoc Open-ended Working

Group and also decided that the eighth meeting of the UN Open-Ended Informal

Consultative Process on the Law of the Sea (the Consultative Process) would focus its

discussions on "marine genetic resources."

In UNGA resolution (61/222, 2006), the UNGA identified five main areas for discussion

at the second meeting of the Ad Hoc Open-ended Informal Working Group (to be held on

April 28-May 2): 1) Environmental impacts of anthropogenic activities on marine

biological diversity beyond areas of national jurisdiction: overfishing, destructive fishing

practices, pollution from shipping and other sources, introduction of invasive alien

19

species, mineral exploration and exploitation, marine debris, marine scientific research,

anthropogenic underwater noise, climate change, including mitigation techniques such as

carbon sequestration and ocean fertilization; 2) cooperation and coordination among

States as well as relevant intergovernmental organizations and bodies for the

conservation and management of marine biological diversity beyond areas of national

jurisdiction; 3) the role of area-based management tools; 4) genetic resources beyond

areas of national jurisdiction; and 5) whether there is a governance or regulatory gap and

if so, how it should be addressed.

The ongoing debate on the governance of marine areas beyond national jurisdiction in

formal and informal fora has been contentious. The main divisive issue is the divergence

of views regarding whether marine genetic resources (MGRs) in areas beyond national

jurisdiction should be governed by the common heritage of mankind principle or high

seas freedom provisions. There is also conflict as to whether resources should be used

for the benefit of mankind as a whole or on a competitive basis (first come, first serve)

and whether the exploitation of marine genetic resources in marine areas beyond national

jurisdiction should be regulated. There is also the question of whether a new

implementation agreement to UNCLOS is needed or whether existing legal instruments

are sufficient. In a paper delivered to the International Tribunal on the Law of the Sea,

Ms. Lori Ridgeway, Co-Chair of the United Nations Informal Consultative Process (ICP)

on Oceans and the law of the Sea, describes some key aspects of the current policy debate

regarding MGRs, drawing from international discussions that have taken place in the

United Nations -- most recently in the 8th session of the Informal Consultative Process

(ICP) on Oceans and the Law of the Sea, held in New York, June 25-29, 2007.

More recently, through the initiative of IUCN and other NGOs, over 50 experts in

international marine policy, science, law and economics gathered to explore policy and

regulatory options to improve oceans governance beyond areas of national jurisdiction

with a focus on the protection and preservation of the marine environment and marine

biological diversity, in the IUCN Workshop on High Seas Governance for the 21st

Century held in New York City on October 17-19, 2007.

Key sources attached to this document11

Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). 2005. The International Legal

Regime of the High Seas and the Seabed beyond the Limits of National

Jurisdiction and Options for Cooperation for the Establishment of Marine

Protected Areas (MPAs) in Marine Areas beyond the Limits of National

Jurisdiction. Note by the Executive Secretary. Ad-Hoc Open-Ended Working

Group on Protected Areas. First Meeting, Montecatini, Italy, 13-17 June 2005. 28

April 2005. UNEP/CBD/WG-PA/1/INF/2. Available:

http://www.biodiv.org/doc/meetings/pa/pawg-01/information/pawg-01-inf-02-

en.doc

11 The sources noted as "attached to this volume" are on the Global Forum website and maybe downloaded

by participants through links on pages 23-24.

20

United Nations General Assembly (UNGA). 2006. Report of the Ad Hoc Open-

ended Informal Working Group to study issues relating to the conservation and

sustainable use of marine biological diversity beyond areas of national

jurisdiction. Transmittal letter dated 9 March 2006 from the Co-Chairpersons of

the Working Group to the President of the General Assembly. 20 March 2006.

Available: http://daccess-ods.un.org/access.nsf/Get?Open&DS=A/61/65&Lang=E

United Nations General Assembly (UNGA). 2007. Report on the work of the

United Nations Open-ended Informal Consultative Process on Oceans and the

Law of the Sea at its eighth meeting. Letter dated 30 July 2007 from the Co-

Chairpersons of the Consultative Process addressed to the President of the

General Assembly. A/62/169. Available:

http://daccessdds.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N07/443/75/PDF/N0744375.pdf?Ope

nElement.

Ridgeway, L. 2007. Marine Genetic Resources: Outcomes of the United Nations

Informal Consultation Process (ICP) and Policy Implications of the Debate.

ITLOS Symposium on Marine Genetic Resources, forthcoming publication, in

press.

IUCN Workshop on High Seas Governance for the 21st Century, New York,

October 17-19, 2007. Co-Chairs' Summary Report. December 2007. Available:

http://www.iucn.org/themes/marine/pubs/pubs.htm

· Burnett, Douglas R. Legal Jurisdiction over International Submarine Cables.

Other important documents

CBD. 2005. The International Legal Regime of the High Seas and the Seabed Beyond

National Jurisdiction. CBD Technical Report No. 19.

http://www.cbd.int/doc/publications/cbd-ts-19.pdf

United Nations General Assembly (UNGA). 2005. Report of the Secretary General.

Addendum. Oceans and the Law of the Sea. 15 July 2005. A/60/63Add1. Available:

http://daccessdds.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N05/425/11/PDF/N0542511.pdf?OpenE

lement.

United Nations General Assembly (UNGA). 2007. Brazil, Canada, Cape Verde, Fiji,

Finland, Guatemala, Iceland, Indonesia, Malaysia, Mexico, Monaco, Norway,

Philippines, Portugal, Slovenia, Sweden and United States of America: draft

resolution. 4 December 2007. A/62/L.27. Available:

http://daccessdds.un.org/doc/UNDOC/LTD/N07/625/18/PDF/N0762518.pdf?Open

Element.

United Nations General Assembly (UNGA). 2007. Resolution 62/215. 22 December

21

2007.

United Nations General Assembly (UNGA). 2007. Report of the Secretary General

Addendum. Oceans and the Law of the Sea. 10 September 2007. A/62/66Add.2.

Available:

http://daccessdds.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N07/500/06/PDF/N0750006.pdf?OpenE

lement

22

5. Information on progress achieved in meeting the international goals

on oceans, coasts, and small island developing states from the 2002 World

Summit on Sustainable Development

Report on Meeting the Commitments on Oceans, Coasts, and Small Island

Developing States Made at the 2002 World Summit on Sustainable Development:

How Well Are We Doing? Global Forum on Oceans, Coasts, and Islands (2006)

Global Forum Working Group Co-chairs Report from the Third Global

Conference

6. Sources attached to this volume

The sources noted as "attached to this volume" are on the Global Forum website and

maybe downloaded by participants through links on pages 23-24.

Burnett, Douglas R. Legal Jurisdiction over International Submarine Cables.

Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). 2005. The International Legal Regime of the

High Seas and the Seabed beyond the Limits of National Jurisdiction and Options for

Cooperation for the Establishment of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) in Marine Areas

beyond the Limits of National Jurisdiction. Note by the Executive Secretary. Ad-Hoc

Open-Ended Working Group on Protected Areas. First Meeting, Montecatini, Italy, 13-17

June 2005. 28 April 2005. UNEP/CBD/WG-PA/1/INF/2.

Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). 2006. Scientific Information on Status and

Trends of, and Threats to, Deep Seabed Genetic Resources beyond National Jurisdiction.

Note by the Executive Secretary pursuant to SBSTTA recommendation XI/8. 10

February 2006.

German Advisory Council on Global Change. 2006. The Future Oceans Warming Up,

Rising High, Turning Sour. Special Report. Berlin.

IUCN Workshop on High Seas Governance for the 21st Century, New York, October 17-

19, 2007. Co-Chairs' Summary Report. December 2007.

Observations, some current conditions and evaluations on climate change and marine

areas beyond national jurisdiction, Dr. Gunnar Kullenberg, former Executive Secretary,

Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission.

Ridgeway, L. 2007. Marine Genetic Resources: Outcomes of the United Nations

Informal Consultation Process (ICP) and Policy Implications of the Debate. IFLOS

Symposium on Marine Genetic Resources, Forthcoming publication, in press.

23

United Nations General Assembly (UNGA). 2006. Report of the Ad Hoc Open-ended

Informal Working Group to study issues relating to the conservation and sustainable use

of marine biological diversity beyond areas of national jurisdiction. Transmittal letter

dated 9 March 2006 from the Co-Chairpersons of the Working Group to the President of

the General Assembly. 20 March 2006.

United Nations General Assembly (UNGA). 2007. Report on the work of the United

Nations Open-ended Informal Consultative Process on Oceans and the Law of the Sea at

its eighth meeting. Letter dated 30 July 2007 from the Co-Chairpersons of the

Consultative Process addressed to the President of the General Assembly. A/62/169.

UNU-IAS. 2006. Implementing the Ecosystem Approach in Open Ocean and Deep Sea

Environments - An Analysis of Stakeholders, their Interests and Existing Approaches.

UNU-IAS Report.

World Climate Research Programme Briefing to IOC 2007.

24

Document Outline