Sharing

g the Water Resources

Of the Orange

g -Senqu River Basin

Report No: 007/2009

Feasibility Study of the Potential for

Sustainable Water Resources

Development in the Molopo-Nossob

Watercourse

Main Report

Final

Submitted by:

PO Box 68735

Highveld

0169

Tel: (012) 695 0900

Fax: (012) 665 1886

Contact: Dr M van Veelen

July 2009

Molopo Nossob Feasibility Study Main Report

Title:

Main Report

Authors:

Dr M van Veelen and T Baker with input from K Mulale,

A Bron, Dr A Fanta, Dr V Jonker, W Mullins, H Schoeman

Project Name:

Feasibility Study of the Potential for Sustainable Water

Resources

Development

in

the

Molopo-Nossob

Watercourse

Status of report:

Final

ILISO Project No:

700192

Date:

July 2009

Keywords:

Molopo River, Nossob River, Water Resources

______________________________________________________________________

ILISO Consulting (PTY) LTD

Approved for and on behalf of ILISO Consulting (Pty) Ltd, Ninham Shand

Incorporated, Schoeman and Partners and Conningarth Economists by

ORANGE SENQU RIVER COMMISSION

Approved on behalf of ORESECOM by

23 July 2009

i

Molopo Nossob Feasibility Study Main Report

LIST OF STUDY REPORTS IN FEASIBILITY STUDY OF THE POTENTIAL FOR

SUSTAINABLE WATER RESOURCES DEVELOPMENT IN THE MOLOPO-NOSSOB

WATERCOURSE PROJECT:

This report forms part of a series of reports done for the Molopo-Nossob Feasibility Study, all

reports are listed below:

Report Number

Name of Report

002/2008

Hydrology Report

003/2008

Catchment Status Inventory Report

006/2009

Ground water Study

007/2009

Main Report

23 July 2009

ii

Molopo Nossob Feasibility Study Main Report

FEASIBILITY STUDY OF THE POTENTIAL FOR SUSTAINABLE

WATER RESOURCES DEVELOPMENT IN THE MOLOPO NOSSOB

WATERCOURSE: MAIN REPORT

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The Molopo River receives most of its flow from tributaries in the Republic of South

Africa, most of which have now been dammed for irrigation in agriculture. As a

result, inflow from these sources to the Molopo River, which forms the boundary

between Botswana and South Africa, has become reduced and even non-existent in

some years. The Nossob River originates in Namibia and some dams have been

constructed in the upper reaches. It later forms the south-western boundary between

Botswana and South Africa down to its confluence with the Molopo River. There is

no record of the Molopo River surface flows ever reaching the main stem of the

Orange River. The reduction of flows in these sub-basins has placed a strain on the

sustainability of rural activities in the south-western corner of Botswana and some

parts of South Africa along the Molopo and Nossob Rivers.

As an attempt to remedy the situation, the ORASECOM countries has appointed

ILISO Consulting, in association with Ninham Shand Incorporated, Schoeman and

Partners and Conningarth Economists to study the feasibility of the potential for the

sustainable water resources development in the Molopo Nossob Sub River Basin.

The objective of the project was to assess and evaluate the water resources of the

Molopo-Nossob catchment to formulate a method to improve the management of the

area that will be environmentally sound, economically viable and financially

achievable. The possibility of restoring flows to the river system was also

investigated, as well as the identification and assessment of sustainable surface

water development options. In doing so the catchment was studied as an interrelated

system, even though it falls within the political area of three different countries

(Namibia, Botswana and South Africa).

Hydrological modelling has been undertaken to provide first order estimates of typical

surface water runoff volumes in the main rivers in the Molopo-Nossob catchment.

The modelling was done by means of the Pitman rainfall-runoff model, local observed

rainfall records and current land use information. Estimates of natural and present

day surface water runoff have been calibrated based on observed flow records where

available as well as on historical records of floods in the Molopo-Nossob catchment.

23 July 2009

iii

Molopo Nossob Feasibility Study Main Report

The modelling results have shown that the total natural runoff from the Molopo-

Nossob catchment, without any channel losses, equals 164 Mm3/a. However, once

losses are taken into account, the total cumulative runoff for each of the main

subcatchments reduces to zero, except in the case of the Kuruman catchment where

the average net outflow equals 4.1 Mm3/a under natural conditions and 4.0 Mm3/a

under present day conditions

First order estimates of typical gross storage-yield characteristics for the upper parts

of the Molopo, Kuruman and Nossob catchments have shown that significant storage

is required to provide yield at an acceptable level of assurance. An assessment of

the central parts of the Molopo-Nossob catchment, situated within the drier, central

Kalahari Desert, has indicated that it is not feasible for dams to be constructed in this

area due to the lack of reliable runoff.

The Molopo-Nossob system does not function in the same way as more conventional

rivers, where groundwater discharge provides a baseflow during dry conditions. In

the case of the Molopo-Nossob system, the occasional floods are totally absorbed

along the river bed and recharge the ground water aquifers along the course of the

river. From the investigation it is clear that surplus water is only generated at a

recurrence interval of less than 20 years. For the rest of the time, floods are entirely

absorbed as ground water recharge along the course of the river.

As the water along the course of the river is needed for small communities and stock

watering, there is little sense in building storage dams. It is far more financially and

economically viable to abstract the water from boreholes and wells at the point of

use, as this will not only cut out the evaporation losses from the surface of a

reservoir, but also the necessity of an expensive distribution network.

The study has conclusively shown that there is no surplus water in the Molopo-

Nossob catchment that can be economically exploited. It was also shown that the

occasional floods serve to recharge the ground water aquifers along the river course,

and that any storage that is created will therefore reduce the availability of ground

water along the course of the river.

23 July 2009

iv

Molopo Nossob Feasibility Study Main Report

It is therefore recommended that no further surface water development in the form of

dams is considered in the study area, and that the development of ground water

sources is investigated in more detail.

However, the development of ground water should be undertaken with some caution,

as making more water available may lead to overgrazing and the destruction of the

natural vegetation, especially where subsistence farming is practised.

23 July 2009

v

Molopo Nossob Feasibility Study Main Report

FEASIBILITY STUDY OF THE POTENTIAL FOR SUSTAINABLE

WATER RESOURCES DEVELOPMENT IN MOLOPO-NOSSOB

WATERCOURSE : MAIN REPORT

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1.

INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1-1

1.1

BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................................ 1-1

1.2

PURPOSE OF STUDY ............................................................................................................... 1-1

1.3

PURPOSE OF REPORT ............................................................................................................. 1-2

1.4

REPORT STRUCTURE .............................................................................................................. 1-2

2.

DESCRIPTION OF STUDY AREA .............................................................................................. 2-1

2.1

LOCATION .............................................................................................................................. 2-1

2.2

TOPOGRAPHY ......................................................................................................................... 2-1

2.3

DRAINAGE .............................................................................................................................. 2-1

2.3.1 Nossob River .................................................................................................................... 2-2

2.3.2 Aoub River ........................................................................................................................ 2-2

2.3.3 Kuruman River ................................................................................................................. 2-2

2.3.4 Molopo River .................................................................................................................... 2-3

2.4

LANDUSE ............................................................................................................................... 2-3

2.5

GEOLOGY AND SOIL ................................................................................................................ 2-4

2.5.1 Namibia ............................................................................................................................ 2-4

2.5.2 South Africa ...................................................................................................................... 2-4

2.5.3 Botswana .......................................................................................................................... 2-6

2.6

VEGETATION .......................................................................................................................... 2-6

2.6.1 Namibia ............................................................................................................................ 2-6

2.6.2 South Africa ...................................................................................................................... 2-6

2.6.3 Botswana .......................................................................................................................... 2-7

2.7

CLIMATE ................................................................................................................................ 2-8

2.7.1 Rainfall ............................................................................................................................. 2-8

2.7.2 Evaporation .................................................................................................................... 2-10

3.

SOCIO-ECONOMICS ................................................................................................................ 3-12

3.1

CATCHMENT ADMINISTRATIVE DISTRICTS ................................................................................ 3-12

3.1.1 Botswana ........................................................................................................................ 3-12

3.1.2 Namibia .......................................................................................................................... 3-12

3.1.3 South Africa ...................................................................................................................... 3-1

3.2

LANDUSE ............................................................................................................................... 3-1

3.2.1 Botswana .......................................................................................................................... 3-1

3.2.2 Namibia ............................................................................................................................ 3-2

3.2.3 South Africa ...................................................................................................................... 3-3

3.3

POPULATION .......................................................................................................................... 3-4

3.3.1 Botswana .......................................................................................................................... 3-4

3.3.2 Namibia ............................................................................................................................ 3-8

3.3.3 South Africa .................................................................................................................... 3-11

3.4

ECONOMY ............................................................................................................................ 3-14

23 July 2009

vi

Molopo Nossob Feasibility Study Main Report

3.4.1 Botswana ........................................................................................................................ 3-14

3.4.1.1

Kgalagadi District ................................................................................................................. 3-14

3.4.1.2

Southern District .................................................................................................................. 3-15

3.4.2 Namibia .......................................................................................................................... 3-17

3.4.3 South Africa .................................................................................................................... 3-18

3.5

TOURISM .............................................................................................................................. 3-20

3.5.1 Botswana ........................................................................................................................ 3-20

3.5.2 Namibia .......................................................................................................................... 3-20

3.5.3 South Africa .................................................................................................................... 3-21

3.6

WATER AND SANITATION ....................................................................................................... 3-22

3.6.1 Botswana ........................................................................................................................ 3-22

3.6.1.1

Kgalagadi District ................................................................................................................. 3-22

3.6.1.2

Southern District .................................................................................................................. 3-24

3.6.2 Namibia .......................................................................................................................... 3-25

3.6.3 South Africa .................................................................................................................... 3-27

3.7

ECONOMIC ACTIVITIES .......................................................................................................... 3-29

3.7.1 Irrigation agriculture ....................................................................................................... 3-29

3.7.2 Livestock farming ........................................................................................................... 3-29

3.7.3 Mining ............................................................................................................................. 3-30

3.7.4 Tourism .......................................................................................................................... 3-30

3.8

IRRIGATION AGRICULTURE .................................................................................................... 3-30

3.8.1 Methodology ................................................................................................................... 3-30

3.8.2 Country Discussion: - Irrigation Farming ........................................................................ 3-31

3.9

LIVESTOCK FARMING ............................................................................................................ 3-31

3.9.1 Methodology ................................................................................................................... 3-31

3.9.2 Country Discussion: - Livestock Farming ....................................................................... 3-32

3.9.3 Conclusion ...................................................................................................................... 3-33

3.10

MINING ................................................................................................................................ 3-33

3.10.1

Methodology ............................................................................................................... 3-33

3.10.2

Country Discussion: - Mining ..................................................................................... 3-34

3.10.3

Conclusion .................................................................................................................. 3-34

3.11

TOURISM .............................................................................................................................. 3-35

3.11.1

Botswana .................................................................................................................... 3-35

3.11.2

Conclusion .................................................................................................................. 3-35

3.12

MACRO ECONOMIC IMPACTS ................................................................................................. 3-36

4.

AVAILABILITY OF WATER ........................................................................................................ 4-1

4.1

SURFACE WATER ................................................................................................................... 4-1

4.1.1 Quantity ............................................................................................................................ 4-1

4.1.2 Assurance of Supply ........................................................................................................ 4-3

4.1.3 Water Quality .................................................................................................................... 4-4

4.2

GROUND WATER ..................................................................................................................... 4-5

4.2.1 Aquifers ............................................................................................................................ 4-5

4.2.2 Basement Aquifers ........................................................................................................... 4-5

4.2.3 Karst Aquifers ................................................................................................................... 4-7

4.2.4 Karoo Aquifers .................................................................................................................. 4-8

4.2.4.1

Dwyka Formation Aquifers .................................................................................................... 4-8

4.2.4.2

Ecca Group Aquifers ............................................................................................................. 4-8

4.2.5 Kalahari Group Aquifers ................................................................................................. 4-10

23 July 2009

vii

Molopo Nossob Feasibility Study Main Report

4.2.5.1

Recharge in the Molopo and Kuruman catchments ............................................................. 4-11

4.3

DAMS ................................................................................................................................... 4-12

4.3.1 Main Dams ..................................................................................................................... 4-12

4.3.2 Farm Dams ..................................................................................................................... 4-17

4.3.3 Pans ............................................................................................................................... 4-17

5.

WATER REQUIREMENTS .......................................................................................................... 5-1

5.1

SURFACE WATER .................................................................................................................... 5-1

5.1.1 Urban and Rural Water Requirements ............................................................................. 5-1

5.1.2 Mining Water Requirements ............................................................................................. 5-1

5.1.3 Return Flows .................................................................................................................... 5-1

5.1.4 Water Transfers ................................................................................................................ 5-2

5.1.5 Ecological Reserve Requirements ................................................................................... 5-3

5.2

GROUND WATER ..................................................................................................................... 5-3

5.2.1 Available Water ................................................................................................................ 5-5

5.2.2 Water Quality .................................................................................................................... 5-7

6.

RIVER FLOWS ............................................................................................................................ 6-1

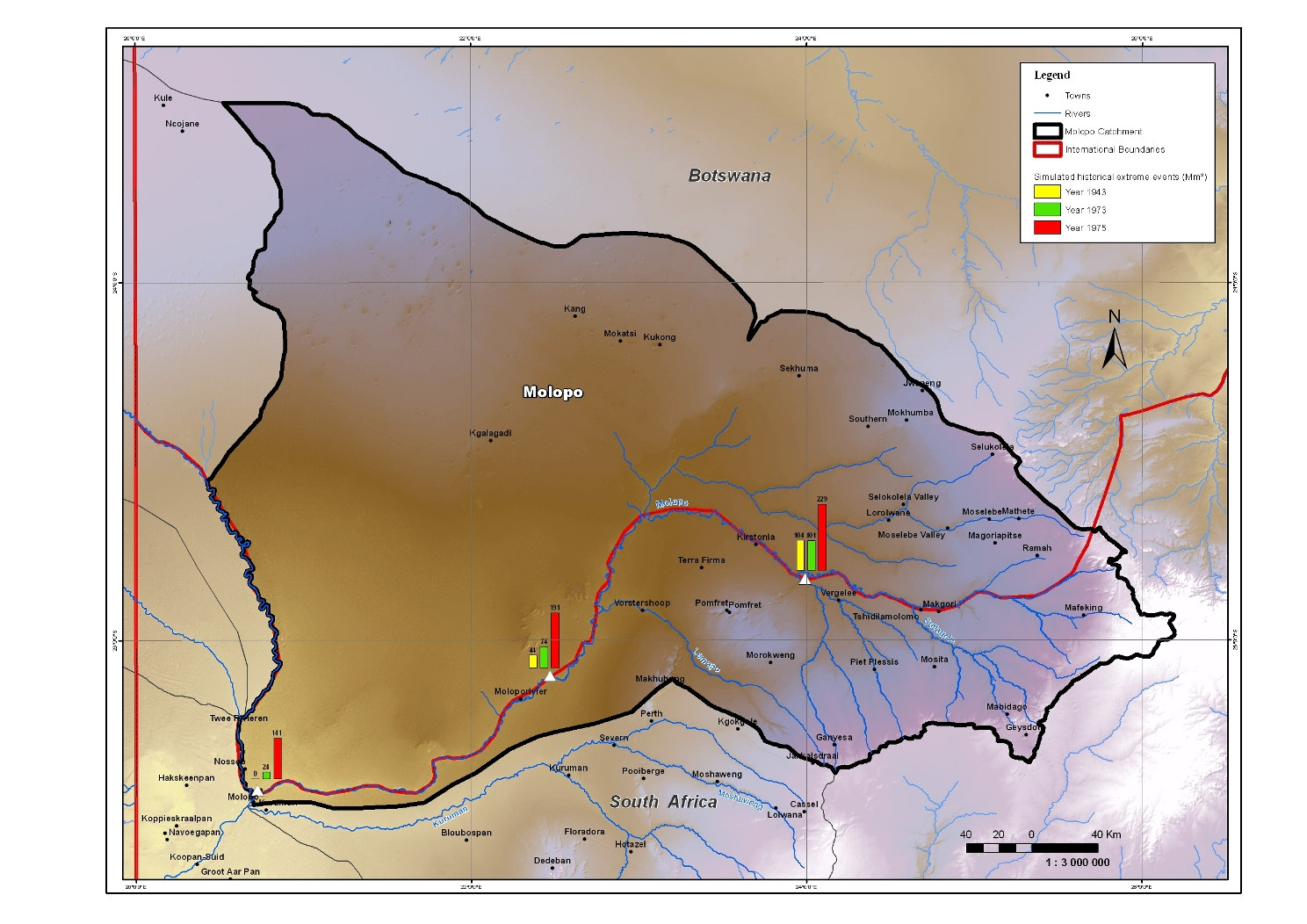

6.1

HISTORICAL EXTREME EVENTS ................................................................................................ 6-1

6.2

DESIGN FLOOD VOLUMES ........................................................................................................ 6-1

7.

DISCUSSION ............................................................................................................................... 7-1

8.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ........................................................................... 8-1

9.

LITERATURE CONSULTED ....................................................................................................... 9-1

LIST OF TABLES

TABLE 2.1: MAIN SUBCATCHMENTS WITHIN THE MOLOPO-NOSSOB SYSTEM .............................................. 2-1

TABLE 2.2: DETAILS OF PANS IN THE STUDY CATCHMENT .......................................................................... 2-2

TABLE 3.1: NAMIBIAN REGIONS AND CONSTITUENCIES ........................................................................... 3-12

TABLE 3.2: POPULATION BY DISTRICT ...................................................................................................... 3-4

TABLE 3.3: POPULATION OF TOWNS IN DISTRICT ...................................................................................... 3-4

TABLE 3.4: KGALAGADI DISTRICT POPULATION BY VILLAGE/LOCALITY ....................................................... 3-5

TABLE 3.5: NGWAKETSE AND NGWAKETSE WEST POPULATION BY VILLAGE/LOCALITY................................ 3-6

TABLE 3.6: BAROLONG POPULATION BY VILLAGE/LOCALITY ....................................................................... 3-7

TABLE 3.7: NAMIBIAN POPULATION GROWTH ........................................................................................... 3-9

TABLE 3.8: DIFFERENCES IN URBAN AND RURAL POPULATIONS .............................................................. 3-11

TABLE 3.9: SOUTH AFRICAN POPULATION GROWTH ............................................................................... 3-13

TABLE 3.10: WATER SUPPLY DATA FOR SETTLEMENTS UNDER DEPARTMENT OF WATER AFFAIRS IN

KGALAGADI DISTRICT .................................................................................................................... 3-24

TABLE 3.11: NAMIBIA NUMBER OF ACTIVE WATER POINTS ..................................................................... 3-26

TABLE 3.12: NORTHWEST AND NORTHERN CAPE PROVINCES WATER AND SANITATION (2001 CENSUS) ... 3-28

TABLE 3.13: CROPS ANALYZED ............................................................................................................. 3-30

TABLE 3.14: IRRIGATED CROPS, HECTARES AND WATER USE (2007) ..................................................... 3-31

TABLE 3.15: LIVESTOCK CALCULATIONS ................................................................................................ 3-32

TABLE 3.16: MINING IN THE MOLOPO NOSSOB CATCHMENT (2007 PRICES) .......................................... 3-34

TABLE 3.17: TOURISM ACTIVITY IN THE MOLOPO NOSSOB CATCHMENT (2007 ESTIMATES) ................... 3-35

23 July 2009

viii

Molopo Nossob Feasibility Study Main Report

TABLE 3.18: - DIRECT AND TOTAL MACRO ECONOMIC INDICATORS OF THE DIFFERENT ACTIVITIES FOR THE

MOLOPO NOSSOB CATCHMENT (2007 PRICES) ........................................................................... 3-36

TABLE 3.19: - WATER BASED MACRO ECONOMIC MULTIPLIERS APPLICABLE IN THE MOLOPO- NOSSOB

CATCHMENT (2007 PRICES) ......................................................................................................... 3-37

TABLE 4.1: TOTAL INCREMENTAL MAR PER MAIN SUBCATCHMENT ............................................................ 4-2

TABLE 4.2: TYPICAL YIELD-RELIABILITY CHARACTERISTICS (UPPER MOLOPO/KURUMAN) ............................ 4-4

TABLE 4.3: TYPICAL YIELD-RELIABILITY CHARACTERISTICS (UPPER NOSSOB) ............................................. 4-4

TABLE 4.4: FEATURES OF THE MAIN DAMS IN THE MOLOPO-NOSSOB CATCHMENT .................................. 4-15

TABLE 4.5: FEATURES OF THE FARM DAMS IN THE MOLOPO-NOSSOB CATCHMENT.................................. 4-17

TABLE 4.6: FEATURES OF THE PANS IN THE MOLOPO-NOSSOB CATCHMENT............................................ 4-17

TABLE 4.7: SUMMARY OF RUN-OFF, STORAGE AND YIELD ........................................................................ 4-18

T

3

ABLE 5.1: LOCALITY AND AMOUNT OF LARGE SCALE GROUND WATER ABSTRACTION (MILLION M /A) ........... 5-4

TABLE 5.2: ESTIMATES OF WATER USAGE IN THE STAMPRIET ARTESIAN BASIN AREA ................................ 5-5

TABLE 5.3: GROUND WATER STORAGE OF EACH AQUIFER ......................................................................... 5-7

T

3

ABLE 6.1: DESIGN STORM RUNOFF VOLUMES IN THE MOLOPO RIVER (MM ) ............................................. 6-1

T

3

ABLE 6.2: DESIGN STORM RUNOFF VOLUMES IN THE MOLOPO RIVER (MM ): NATURAL CONDITIONS .......... 6-1

T

3

ABLE 6.3: PRESENT DAY CONDITIONS (MM ) (ASSUMING MAXIMUM INTERCEPTION OF FLOODS BY MAJOR AND

FARM DAMS) ................................................................................................................................... 6-1

LIST OF FIGURES

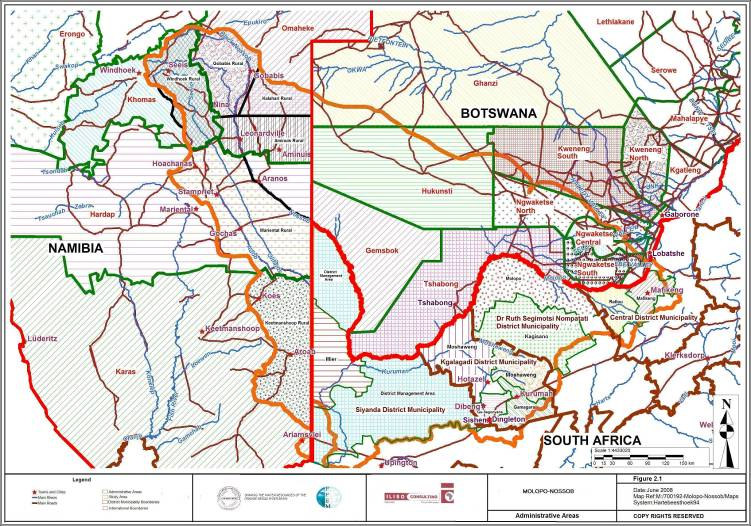

FIGURE 2.1: STUDY CATCHMENT ............................................................................................................. 2-1

FIGURE 2.2: CATCHMENT TOPOGRAPHY .................................................................................................. 2-1

FIGURE 2.3: TYPICAL SEASONAL RAINFALL DISTRIBUTION IN STUDY CATCHMENT ...................................... 2-8

FIGURE 2-4: MAJOR SOIL TYPES ............................................................................................................. 2-9

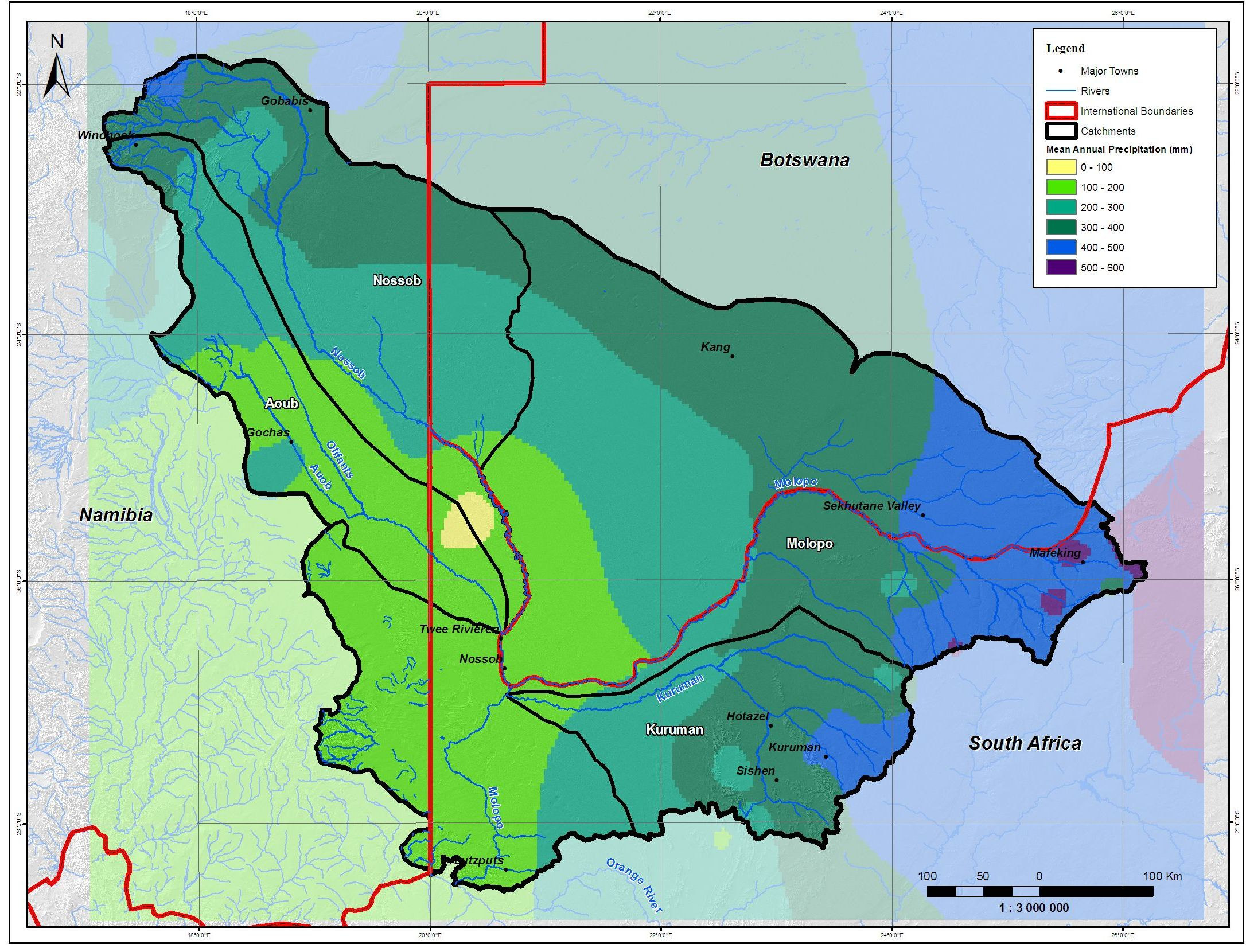

FIGURE 2-5: MEAN ANNUAL PRECIPITATION ........................................................................................... 2-11

FIGURE 3-1: LOCALITY OF THE MOLOPO NOSSOB RIVER CATCHMENT ..................................................... 3-13

FIGURE 3.2: LANDUSE IN THE CATCHMENT ............................................................................................... 3-1

FIGURE 3.3: POPULATION DISTRIBUTION IN THE CATCHMENT AREA .......................................................... 3-10

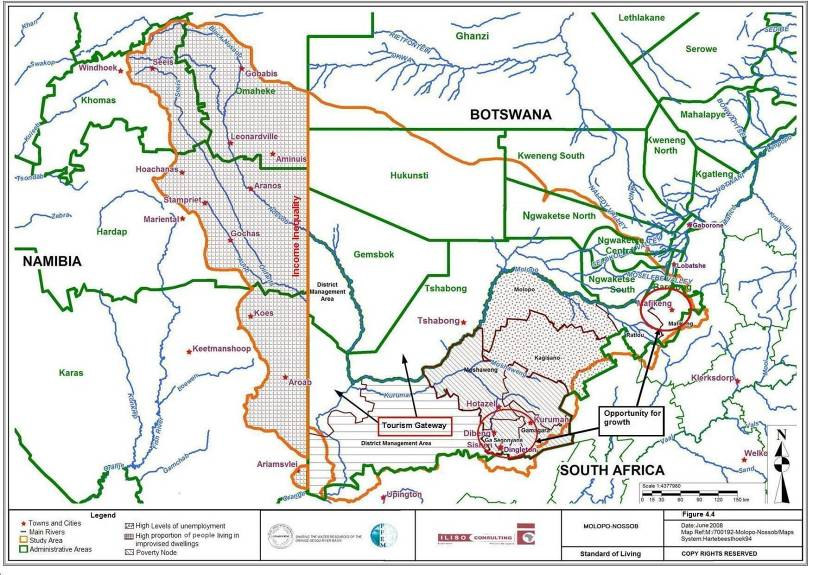

FIGURE 3.4: MAP REPRESENTING THE STANDARD OF LIVING IN THE CATCHMENT AREA ............................. 3-16

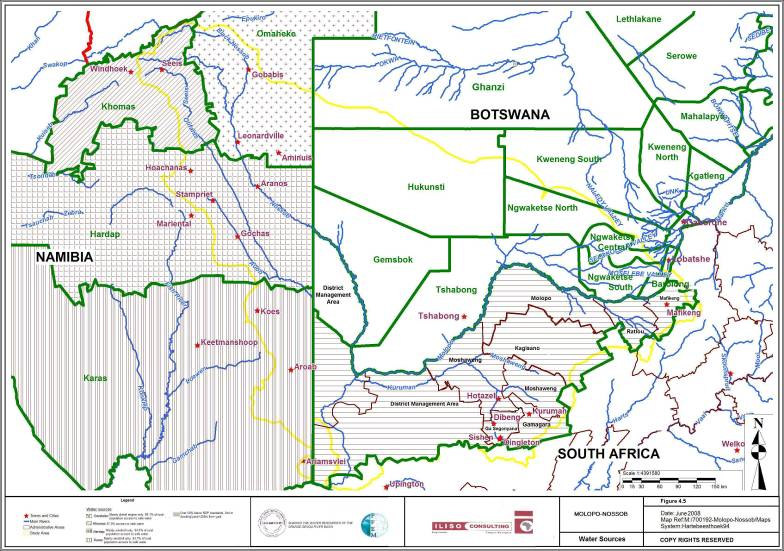

FIGURE 3-5: WATER SOURCES .............................................................................................................. 3-23

FIGURE 4.1: LOCATION OF MAIN DAMS IN THE MOLOPO-NOSSOB CATCHMENT AREA ............................... 4-16

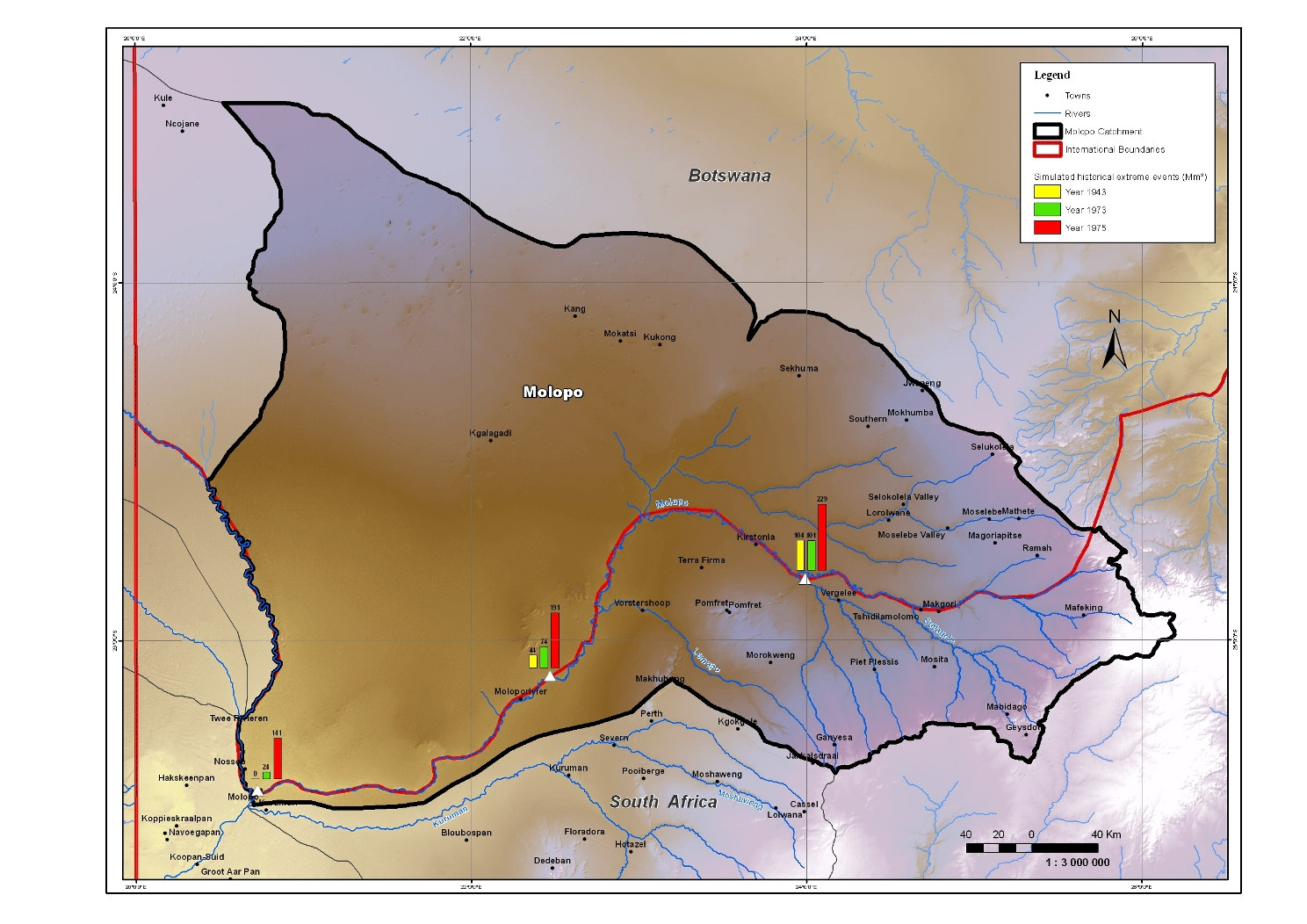

FIGURE 6.1: SIMULATED EXTREME HISTORICAL RUNOFF EVENTS ............................................................... 6-1

23 July 2009

ix

Molopo Nossob Feasibility Study Main Report

ACRONYMS

BEE

Black Economic Empowerment

CASP

Comprehensive Agricultural Support

CBNRM

Community Based Natural Resource Management

CHA

Controlled Hunting Areas

DM

District Municipality

DWA

Department of Water Affairs

DWAF

Department of Water Affairs and Forestry

DWNP

Department of Wildlife National Parks

IDP

Integrated Development Plan

ISARM

Internationally Shared Aquifer Resources Management

ISRDS

Integrated Sustainable Rural Development Strategy

LM

Local Municipality

LSU

Large Stock Units

MAE

Mean Annual Evaporation

MDG

Millennium Development Goal

ORASECOM

Orange-Senqu River Commission

RADP

Remote Area Development Policy

RADS

Remote Area Dwellers

RDP

Reconstruction and Development Programme

RSA

Republic of South Africa

SES

Socio-Economic Status

TDS

Total Dissolved Solids

TGLP

Tribal Grazing Land Policy

UMK

United Manganese of Kalahari

WARD

Women in Agriculture and Rural Development

WMA

Wildlife Management Area

23 July 2009

x

Molopo Nossob Feasibility Study - Main Report

FEASIBILITY STUDY OF THE POTENTIAL FOR SUSTAINABLE

WATER RESOURCES DEVELOPMENT IN MOLOPO NOSSOB

WATERCOURSE:

MAIN REPORT

1.

INTRODUCTION

1.1

BACKGROUND

The Molopo River is an ephemeral tributary of the Orange Senqu system which is

an international river basin shared by the Kingdom of Lesotho, the Republic of

Namibia, the Republic of Botswana and the Republic of South Africa. The Orange-

Senqu River Agreement signed by the governments of the four countries established

the Orange-Senqu River Commission (ORASECOM) to advise the parties on water

related issues.

The Molopo River receives most of its flow from tributaries in the Republic of South

Africa, most of which have now been dammed for irrigation and urban water supply.

As a result, inflow from these sources to the Molopo River, which forms the boundary

between Botswana and South Africa, has become reduced and even non-existent in

some years. The Nossob River originates in Namibia and some dams have been

constructed in the upper reaches. It later forms the south-western boundary between

Botswana and South Africa down to its confluence with the Molopo River. There is

no record of the Molopo River surface flows ever reaching the main stem of the

Orange River. The reduction of flows in these sub-basins has placed a strain on the

sustainability of rural activities in the south-western corner of Botswana and some

parts of South Africa along the Molopo and Nossob Rivers.

1.2

PURPOSE OF STUDY

As an attempt to remedy the situation, ORASECOM has appointed ILISO Consulting,

in association with Ninham Shand Incorporated, Schoeman and Partners and

Conningarth Economists, to study the feasibility of the potential for the sustainable

water resources development in the Molopo-Nossob Sub River Basin.

The objective of the project was to assess and evaluate the water resources of the

Molopo-Nossob catchment to formulate a method to improve the management of the

area that will be environmentally sound, economically viable and financially

achievable. The possibility of restoring flows to the river system was also

investigated, as well as the identification and assessment of sustainable surface

23 July 2009

1- 1

Molopo Nossob Feasibility Study Main Report

water development options. In doing so the catchment was studied as an interrelated

system, even though it falls within the political area of three different countries

(Namibia, Botswana and South Africa).

The Terms of Reference originally included the identification, feasibility and

prioritisation of possible surface water development schemes. The surface water

investigations undertaken in the second stage of the study (the catchment status

inventory) revealed that the surface water resources of the study area have largely

been developed and there is very little scope for further development. At the same

time the catchment seems to have reached a saturation point as far as development

is concerned. The real need for water that was identified lies in providing water at the

household level and as the population lives dispersed and in small communities,

ground water offers the only viable source of water.

The exploitation of the dolomitic aquifer in South Africa has had a significant

influence on ground water levels, and thereby affected the flow in the upper reaches

of the Molopo River. It was therefore agreed that the third stage of the study would

consider the availability of ground water in more detail, and focus on the

development of this resource, rather than surface water.

1.3

PURPOSE OF REPORT

The purpose of this report is to present the findings and recommendations of the

study.

1.4

REPORT STRUCTURE

The physical aspects of the study area are described in Chapter 2 and the social and

economic in Chapter 3. The availability of water is presented in Chapter 4 and the

water requirements in the study area in Chapter 5. The impact of groundwater use

on river flows in presented in Chapter 6. Chapter 7 is a discussion of the findings

and Chapter 8 presents the conclusion and recommendations.

23 July 2009

1-2

Molopo Nossob Feasibility Study Main Report

2.

DESCRIPTION OF STUDY AREA

2.1

LOCATION

The Molopo-Nossob system forms part of the Orange-Senqu system and is

shared by the countries of Namibia, the Republic of Botswana and the

Republic of South Africa (RSA). A significant portion of the catchment falls

within the Kalahari Desert. The system is an ephemeral system and consists

of four main subcatchments viz. the Molopo, Kuruman, Nossob and Aoub

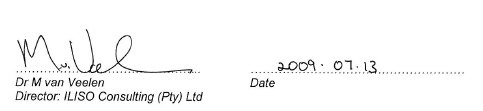

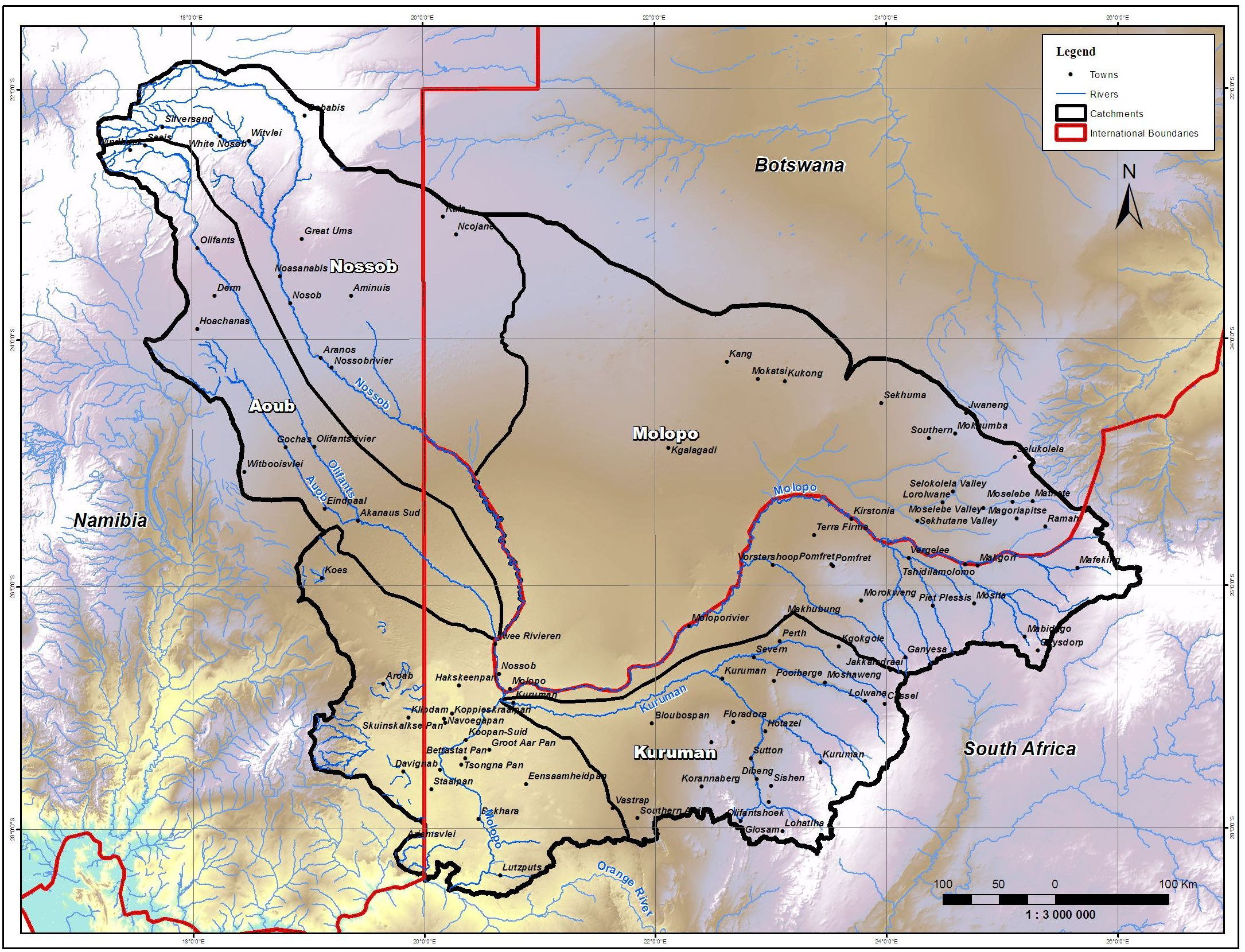

catchments. The locations of these catchments are shown in, Figure 2-1

while the catchment areas per country are presented in Table 2-1.

Table 2-1: Main Subcatchments within the Molopo-Nossob System

Catchment Area (km2)

RSA

Namibia

Botswana

Total

Molopo

61 882

18 120

112 583

192 585

Kuruman

41 194

0

0

41 194

Nossob

4 704

46 928

17 426

69 058

Aoub

5 589

34 601

0

40 190

Total

113 369

99 649

130 009

343 027

2.2

TOPOGRAPHY

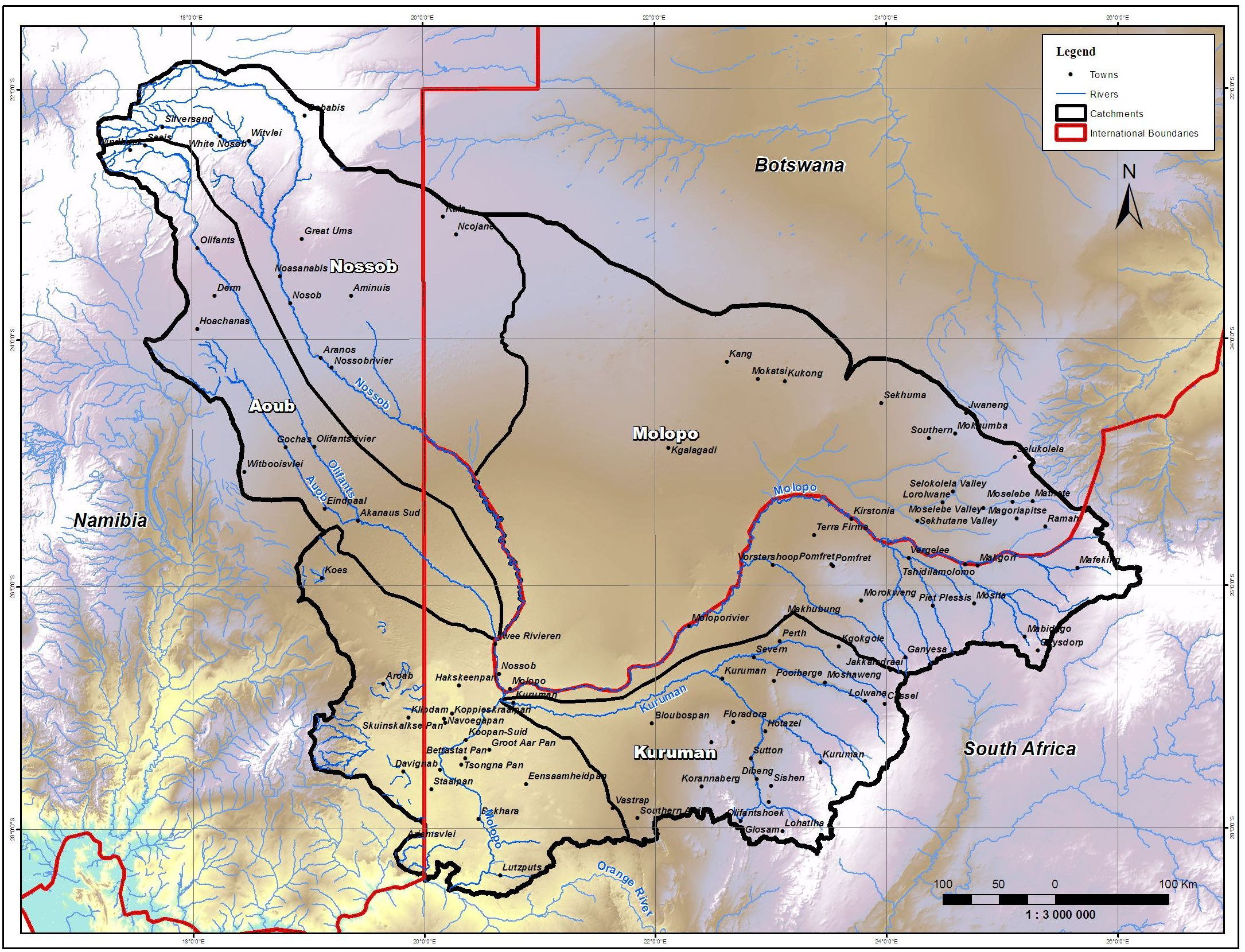

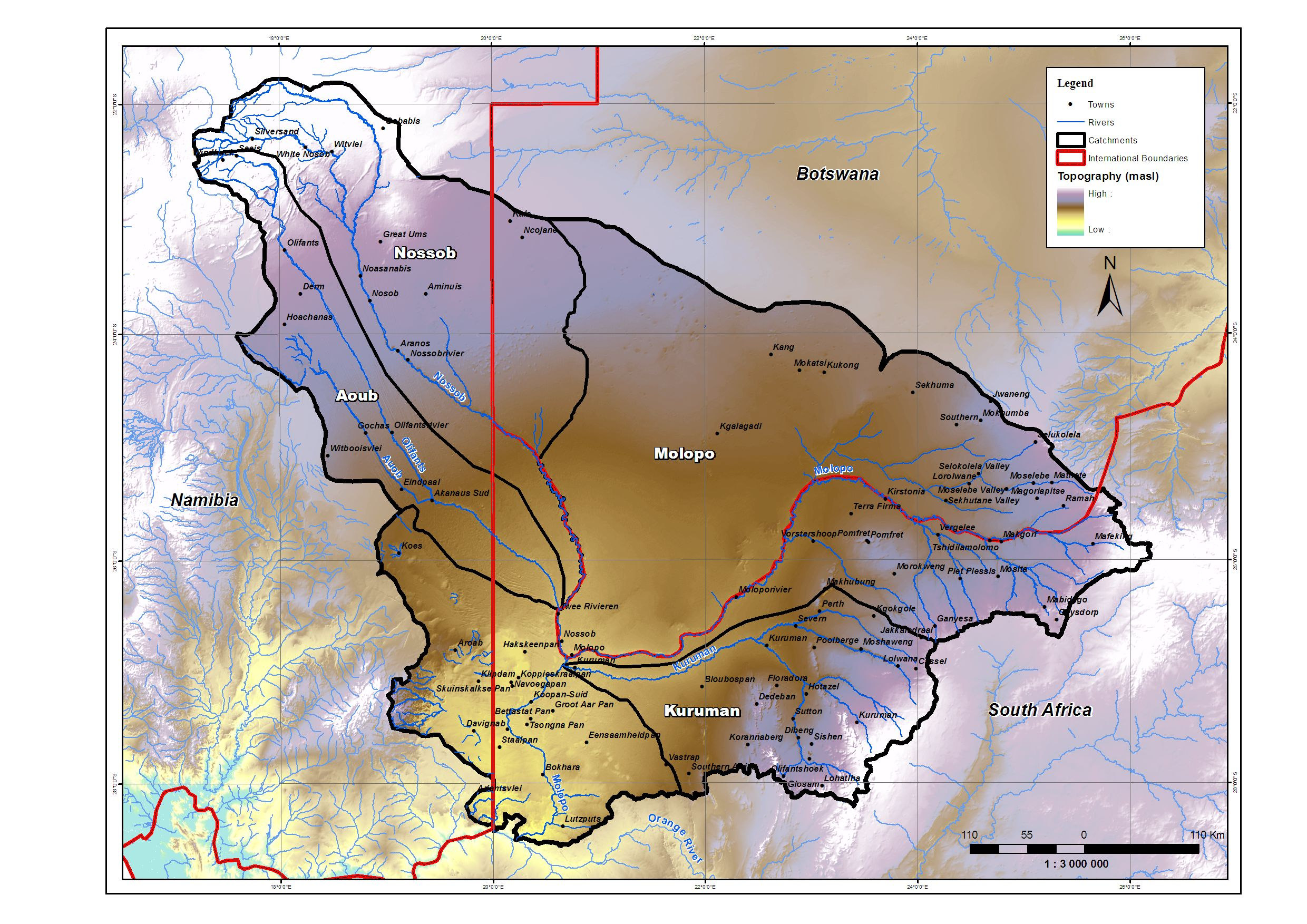

There are no distinct topographic features in the study area, with the

majority of the area being relatively flat with no climatic barriers. The upper

tributaries of the Nossob and Aoub rivers, in the mountainous areas

surrounding Windhoek, are characterised by higher elevations (1 700 to

2 000 masl), while high-lying areas to the east and south of Mafikeng

(1 500 masl) and Kuruman (1 336 masl) form the watershed divide between

the Molopo-Kuruman system to the north and the Vaal-Orange system to the

south.

The Nossob and Aoub catchments gradually fall towards the south, while the

Molopo and Kuruman catchments display a gradual decline in elevation

towards the west.

23 July 2009

2-1

Molopo Nossob Feasibility Study Main Report

Figure 2.1: Study Catchment

23 July 2009

2-1

Molopo Nossob Feasibility Study Main Report

After the confluence of these rivers, to the south of the Kgalagadi

Transfrontier Park, the Molopo River continues southwards until its

confluence with the Orange River in the vicinity of the Augrabies Falls in the

RSA (Figure 2-2).

2.3

DRAINAGE

As a result of the low rainfall, flat topography and the occurrence of pans,

dunes and sandy soils over much of the study area, specifically where the

rivers flow through the Kgalagadi, little surface runoff is generated. Although

occasional runoff occurs in the upper parts of the various subcatchments,

evaporation and seepage losses, in conjunction with relatively large storage

dams, specifically in the upper Molopo and Nossob catchments, prevent this

runoff from reaching the lower reaches except during extreme events.

Although there is anecdotal evidence of occasional flow along the lower

Kuruman, Molopo, Nossob and Aoub rivers, linked to specific flood events,

there is no record of flows in the Molopo River ever having reached the

Orange River and the Molopo-Nossob catchment is therefore classified as an

endoreic area. Previous recordings of flow in the lower reaches of the Molopo

and/or Kuruman rivers were in 1933, 1974/5 and 1975/76. Flow along the

lower reaches of the Nossob and Aoub rivers has been recorded in 1934,

1963, 1974 and 1999/2000. A recent event of flow in the Aoub River in the

Kagalagadi Transfronteir Park was reported in the press

The occurrence of pans in the study area, which are common in the

Botswana and Namibian parts of the catchment, also has a significant impact

on local drainage patterns and further reduces runoff. Schoeman and

Partners, as part of the landuse task of this study, calculated that the water

retaining capacity of all 2 607 the pans in the study area equaled some 1

900 million m³. The number, area and volume of pans in the study area are

summarised in Table 2-2.

.

23 July 2009

2-1

Molopo Nossob Feasibility Study Main Report

Figure 2.2: Catchment Topography

23 July 2009

2-1

Molopo Nossob Feasibility Study Hydrology Report

Table 2-2: Details of Pans in the study catchment

Volume

Area

Subcatchment

No. Pans

(Mm3)

(km2)

Molopo

1 179

1 406

972

Kuruman

226

71

54

Nossob

676

279

167

Aoub

526

230

141

TOTAL

2 607

1 986

1 334

2.3.1

Nossob River

The Nossob River originates in the mountainous area to the north-east of

Windhoek and its upper reaches are characterised by two main tributaries viz.

the Black Nossob and the White Nossob. These tributaries originally drain in

an easterly direction towards Gobabis, where they turn south until their

confluence at the town of Hoaseb, approximately 70 km south of Gobabis.

From Hoaseb, the Nossob River flows in a south-easterly direction and

eventually constitutes the border between the Republic of Botswana and the

Republic of South Africa. The Nossob River has its confluence with the Aoub

River at Twee Rivieren in the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park and with the

Molopo River at the town of Bokspits, 60 km south of the Aoub confluence.

2.3.2

Aoub River

The Aoub River has its origin in the Karubeam Mountains in Namibia north

east of Mariental, from where it flows in a south-easterly direction towards the

Republic of South Africa. Approximately 80 km upstream of the

Namibian/South African border, the Aoub River is joined, from the north, by its

main tributary, the Olifants River. The Olifants River originates in the

mountainous areas surrounding Windhoek and flows parallel to the Aoub

River until their point of confluence. The Aoub River joins the Nossob River at

Twee Rivieren in the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park (Figure 2-1).

2.3.3

Kuruman River

The Kuruman River originates south east of Kuruman, where it is fed by

various springs, most notably the Great Koning Eye, Little Koning Eye and

the Kuruman Eye. Originally, the river flows in a north-westerly direction over

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

January 2009

2-2

Molopo Nossob Feasibility Study Hydrology Report

a distance of approximately 140 km, after which it turns west and flows

parallel to the Molopo River, until it has its confluence with the Molopo River

at Andriesvale, in close proximity to the Nossob/Molopo confluence. Various

tributaries join the Kuruman River along its upper reaches, including the Ga-

Mogara, Moshaweng, Mathlawareng and Kgokgole rivers. The Kuruman

catchment is the only subcatchment within the Molopo-Nossob system

which falls completely within the Republic of South Africa (RSA).

2.3.4

Molopo River

The Molopo River emanates from the area to the east of Mafikeng, where it

is fed by various springs, most notably the Molopo Eye and the Grootfontein

Eye. From here it flows in a westerly direction and essentially constitutes the

border between South Africa and Botswana until its confluence with the

Nossob. Several dry-bed, ephemeral streams join the Molopo stem along its

upper reaches. These include localised tributaries from the south (South

Africa) e.g. Setklagole, Phepane and Disipi rivers, which drain north-

westwards towards the Molopo River, and tributaries from Botswana e.g.

Ramatlabama and Melatswane, which drain westwards before joining the

main stem of the Molopo River. The Molopo River is joined by the Nossob

River at Bokspits and the Kuruman River at Andriesvale, immediately south

of the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park, from where it flows southwards before

joining the Orange River about 300 km downstream.

2.4

LANDUSE

Most of the land in the study catchment is under natural vegetation and a

large portion of the catchment falls within the Kagalagadi. Areas of

cultivation are found in the Upper Nossob and Olifants catchments, where

irrigation is predominantly from ground water sources, and the south-eastern

parts of the Molopo catchment near Mafikeng where the demand is satisfied

from farm dams. No afforestation or large-scale infestations of invasive alien

vegetation occur in the study area, although land-invasion by Prosopis

species is on the increase in Namibia. There is large-scale mining activity in

the vicinity of Sishen and Hotazel in the upper Kuruman catchment where

manganese ore, iron ore, tiger's eye and crocidolite (blue asbestos) are

mined. The towns of Mafikeng, Kuruman, Gobabis and part of Windhoek

represent the only significant urban areas in the study catchment, while

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

January 2009

2-3

Molopo Nossob Feasibility Study Hydrology Report

scattered rural settlements and small towns supporting mining activities

abound.

2.5

GEOLOGY AND SOIL

2.5.1 Namibia

At the Omaheke, the sandveld constitutes mainly an Aeolian sand mantle

about 50 m thick. It has a low relief of vegetated ancient longitudinal sand

dunes and windblown sand. Those sandy soils together with the flat

topography have produced the poorly developed drainage lines of the region

all of which rise in the west. The harder surfaces of the landscapes to the

west, together with the more gentle relief, result in better-defined drainage

lines.

The common base material of the Kalahari is remarkably uniform, relatively

unweathered medium-textured sand. The clay content is very low and the

soils are in general weakly developed, shallow and calcareous. Closer to the

drainage lines the soils contain deposits of limestone and quartzite while

sandstone and shale also occur. The sandy nature of the soil accounts for

the very low water-retaining capacity.

The high clay content of the soil in the Hardap Region limits water penetration

which results in a nearly total absence of vegetation. The western border of

the Kalk plateau is characterised by isolated drainage systems and many

pans. To the north the Kalk plateau changes gradually to the rocky

landscape surrounding Rehoboth.

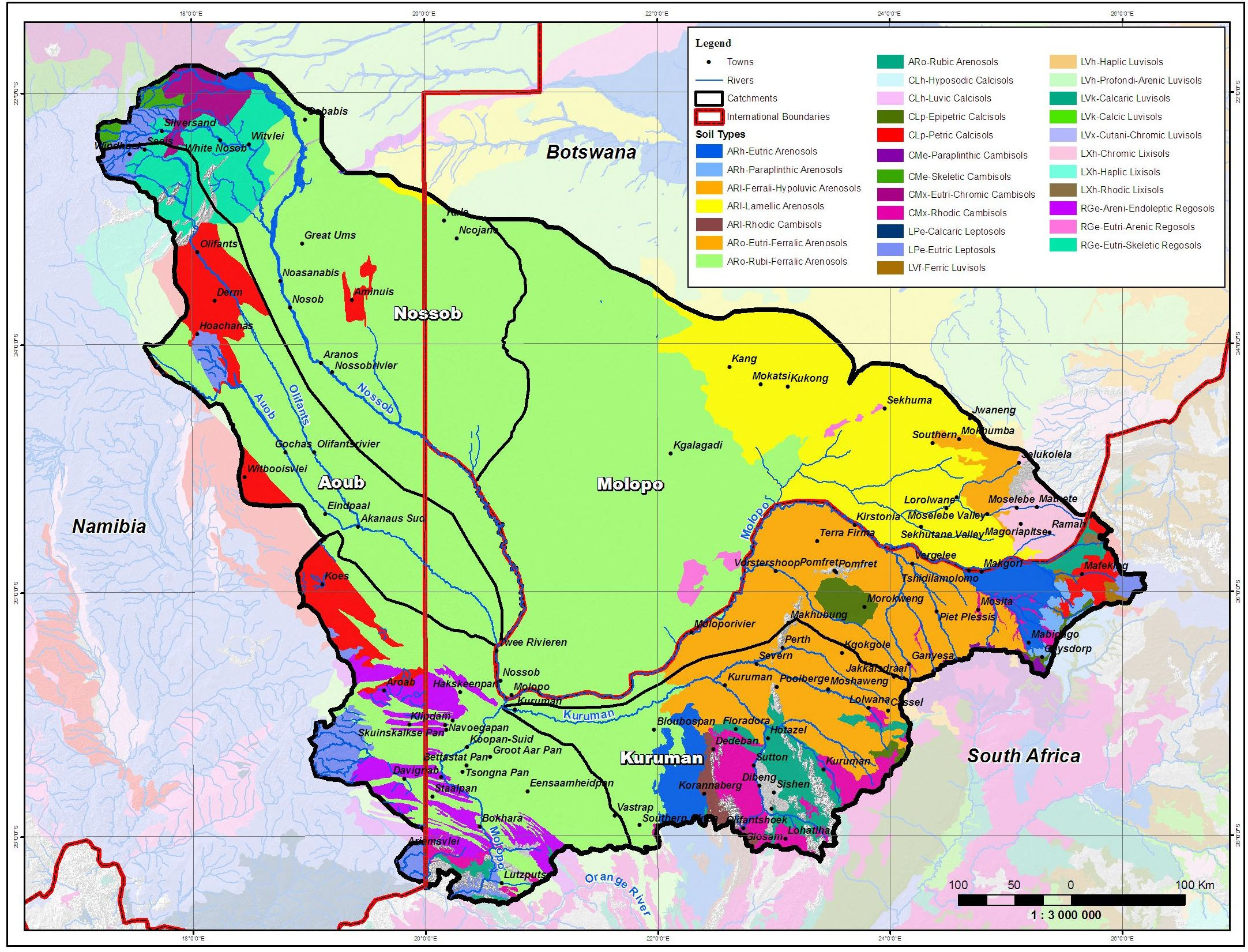

2.5.2 South Africa

Dunes are associated with the arid environment of the Kalahari occur in the

far western region. It also has an interesting and ancient geological heritage,

rich in minerals and palaeontological artefacts. The north-eastern and north-

central regions of the Province are largely dominated by igneous rock

formations, as a result of the intrusion of the Bushveld Complex. Ancient

igneous volcanic rocks dating back to the Ventersdorp age (more than 2 000

million years) appear to be the dominant formations in the western, eastern

and southern regions of the Province.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

January 2009

2-4

Molopo Nossob Feasibility Study Hydrology Report

The sub river basin area in the Northern Cape is considered to be of medium-

low ecological sensitivity.The Northern Cape's landscape is characterised by

the Kalahari Desert, wavy hills, sand plains, red sand dunes. The rocky soil

type of the Richtersveld are more suited to crop production than the soils of

the rest of the Namaqua District Municipality (DM), but their relatively shallow

depth and adverse climate conditions as well as the steep mountainous

topography makes crop production non-viable. The southern part of the

district has granite-derived loam soils in the valleys. Alluvial soils with high

loam contents result in relatively highly fertile soils.

Due to the dynamic nature of soils of the North West Province, they are

constantly evolving and degrading by means of natural and man-induced

processes. The weathering of rocks in deserts and semi-arid areas tends to

be superficial and hence these soils tend to be shallow and stony. Erosion

and deposition by the agents of wind and water are responsible for the

transportation of soils from one location to another.

Due to the low rainfall, soils only slightly leached over much of the western

region. With high evaporation rates, there is a predominance of upward

movement of moisture in the soils. This often leads to high concentrations of

salts such as calcium and silica in soils, which sometimes lead to the

formation of hard pans or surface duricusts. As a result, high levels of salinity

or alkalinity may develop in these areas. Levels of organic matter tend to be

low, governing the vegetation types which are able to grow there.

The central region has areas covered by red or brown non-shifting sands with

rock. This region also has weakly developed lime soils associated with the

dolomite limestone formations. The south-western region also has areas

characterised by undifferentiated rock and lithosols. Lithosols are shallow

soils containing coarse fragments and solid rock at depths less than 30 cm.

The southern and central regions have black and red clays as well as

ferrisiallitic soils of sands, loams and clays. The drier western region is

characterised by red and yellow arenosols while the south west has

calcareous sands and loams and arenaceous lithosols.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

January 2009

2-5

Molopo Nossob Feasibility Study Hydrology Report

2.5.3 Botswana

Botswana is characterised by the Kgalagadi (Kalahari) sanda, a mantle of

sand covering the Kalahari Basin, and vast flat, semi-arid and comparative

featureless landscape, except for occasional rocky outcrops. The mean

altitude above sea level is 1 000 m.

2.6

VEGETATION

2.6.1 Namibia

The vegetation can be classified as dry, medium tall savannah associated

areas with good edible grass cover, dominated by acacia thorn bush over the

western and central areas, but do not always form dense stands. To the east

it changes gradually to the Camelthorn (Acacia eroloba) savannah,

characterised by dense edible grass stands with lone standing trees and

mixed stands of shrubs. To the north east it changes to forest savannah and

dry woodland, becoming denser to the north as taller trees appear.

Tall trees and denser stands of the mixed shrubs are confined to

watercourses between the slopes. Over the extreme eastern and southern

part lone standing Camelthorn (Acacia erioloba) trees are more prominent.

Low shrub trees and bushes of varying density become sparser towards the

west and the vegetation changes to a semi-desert dwarf shrub savannah.

Desertification is an issue throughout the region, but especially in the western

areas due to human activity and the injudicious utilisation of the veld. Since

years of drought always predominate over wetter years in an arid

environment, the degeneration of vegetation cannot be stopped by a period of

high rainfall. In the delicately balanced ecosystem of the arid environment

over-utilisation of vegetation, particularly by feeders such as small stock,

could lead to total destruction of the habitat.

2.6.2 South Africa

Only savannah and grassland biomes occur in the North West Province. The

western part of the province falls within the Grassland Biome comprising a

wide variety of grasses typical of arid areas. Given the arid and semi-arid

conditions of the western half of the North West Province, the vegetation of

this region largely comprises plants that are adapted to these conditions

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

January 2009

2-6

Molopo Nossob Feasibility Study Hydrology Report

(known as xerophytes). As a result, low biomass, productivity and species

richness of plants tend to prevail in this region. With the east-west variation in

climate and rainfall, there is a corresponding gradation in the vegetation types

from xerophytic in the west to open grassland and savannah in the central

region.

There is a predominance of Kalahari deciduous Acacia thornveld (open

savannah of Acacia erioloba and A. haematoxylin as well as desert grasses)

and shrub bushveld in the dry western half of the province. The rocky soil is

conducive to Tarchonanthus veld on the dolomite Ghaap Plateau.

The northern and eastern regions reflect the greatest variability of vegetation

types in the province. Vegetation types include sourish mixed bushveld (open

savannah dominated by Acacia caffra and grasses of the Cymbopogon and

Themeda types), turf thornveld and isolated pockets of Kalahari thornveld and

shrub bushveld.

The Northern Cape has unique vegetation consisting of the orange scattered

field and the Kalahari-Dune field, with a large bio-diversity of plants and

animals' species, which are endemic to the respective field types.

The primary threats to biodiversity, ecosystem goods and services are habitat

transformation and degradation, and invasive alien species. Many invasive

species are well established and cause substantial damage, including:

Atriplex lindleyi (Sponge-fruit saltbush); Nummularia (old-man saltbush);

Nicotiana gluaca (wild tobacco); Opuntia ficus-indica (sweet prickly pear) and

torreyana/velutina (honey mesquite). These alien invasive species cause

threats of massive economic and social threats, in terms of our water security,

the productive use of land, intensity of fires and floods, and ultimately the

ecological integrity of the natural system.

2.6.3 Botswana

The vegetation of the south-western parts of Botswana is the Kalahari Acacia

wooded grassland and deciduous bushland, shrub savanna, dominated by

Acacia species (mainly A. haematoxylin, A. mellifera, and A. erioloba),

Terminalia sericea and same Bascia albitrunca.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

January 2009

2-7

Molopo Nossob Feasibility Study Hydrology Report

2.7

CLIMATE

2.7.1

Rainfall

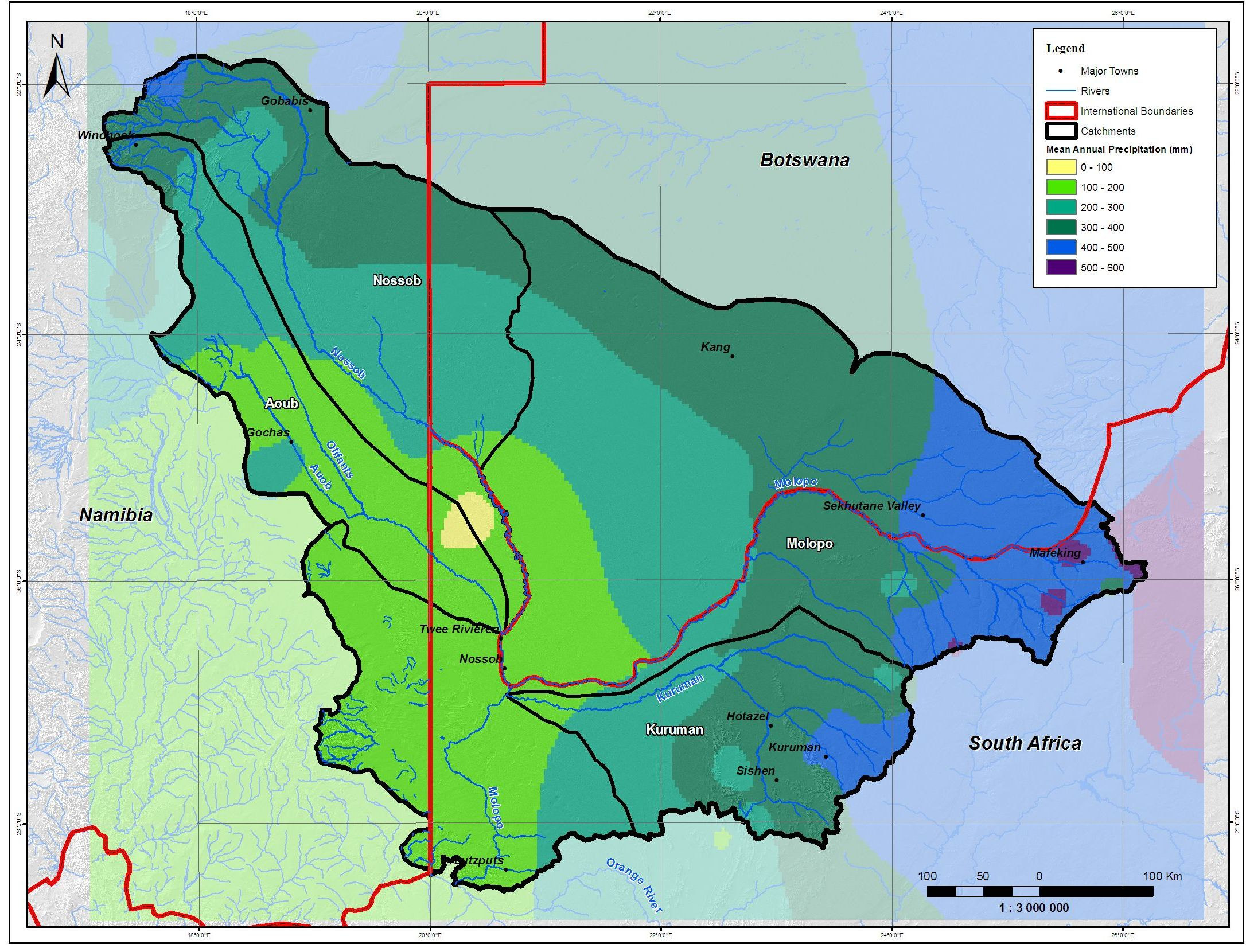

Rainfall within the study area is highly seasonal with most rain occurring

during the summer period (October to April). The peak rainfall months are

February and March. Rainfall generally occurs as convective thunderstorms

and is sometimes accompanied by hail. The mean annual rainfall over the

Molopo and Kuruman catchments decreases fairly uniformly from more than

500 mm in the east (upper Molopo catchment) to approximately 150 mm in

the vicinity of the Orange River confluence. In the Nossob and Aoub

catchments, mean annual rainfall decreases in a southerly direction and

varies from about 400 mm in the upper Nossob catchment to less than

200 mm at the confluence with the Molopo River.

Figure 2.3 shows the typical seasonal distribution of rainfall within the study

area, while Figure 2-4 depicts the variation in mean annual precipitation over

the study area.

Mariental

28 May 08, 17:08

Seasonal Distribution

30

20

]

P

A

M

%

[

l

l

a

f

n

i

a

R

10

0

Oct

Nov

Dec

Jan

Feb

Mar

Apr

May

Jun

Jul

Aug

Sep

Months, Oct-Sep 1917-1998

Legend:

marient.nsi

Figure 2.3: Typical Seasonal Rainfall Distribution in Study Catchment

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

January 2009

2-8

Molopo Nossob Feasibility Study Hydrology Report

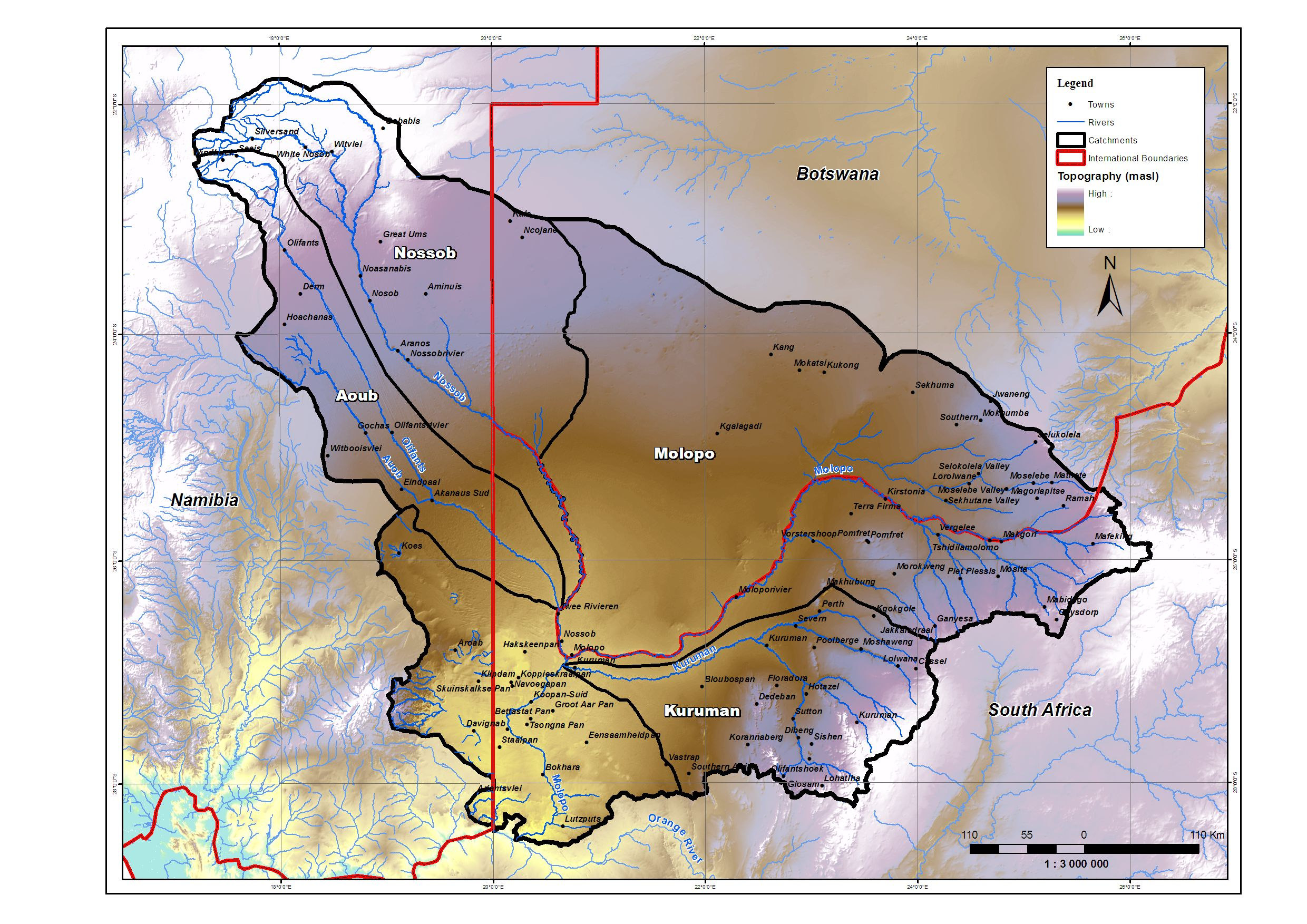

Figure 2-4: Major Soil Types

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

February 2009

2-9

Molopo Nossob Feasibility Study Hydrology Report

2.7.2

Evaporation

Evaporation in the Molopo-Nossob catchment is significant with Mean Annual

Evaporation (MAE) generally increasing in a north-westerly direction. MAE (S-

Pan) varies from about 1 900 mm in the upper Molopo catchment to more

than 2 600 mm in the Kalahari Desert. Similar to rainfall, evaporation in the

study area is highly seasonal, with evaporation in the summer months more

than twice as high as during the winter

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

January 2009

2-10

Molopo Nossob Feasibility Study Main Report

Figure 2-5: Mean Annual Precipitation

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

February 2009

2-11

Molopo Nossob Feasibility Study - Main Report

3.

SOCIO-ECONOMICS

3.1

CATCHMENT ADMINISTRATIVE DISTRICTS

The Molopo River forms the border between South Africa and Botswana for most of

its length to the confluence of the Nossob River, while the Nossob River forms the

border between South Africa and Botswana from where it crosses the border

between Namibia and Botswana to the confluence with the Molopo River. The three

countries have a common border and the point where the Nossob River crosses the

Namibia/Botswana border.

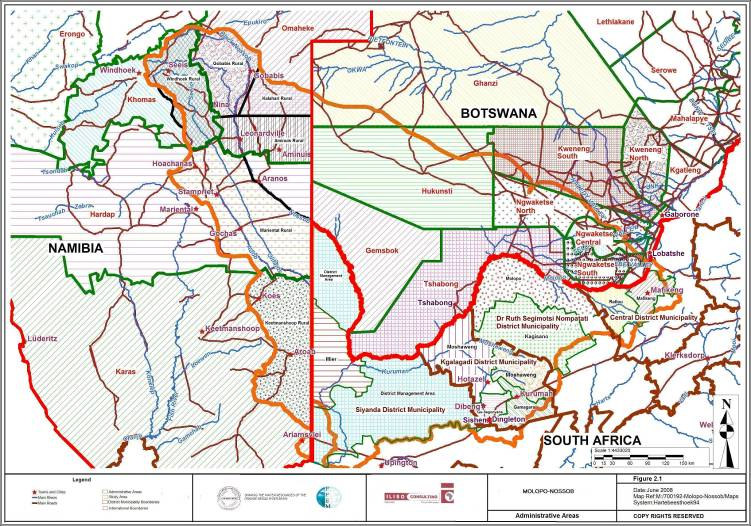

3.1.1 Botswana

The Molopo-Nossob catchment area in Botswana covers the Kgalagadi and

Southern Districts (Figure 3-1). The Kgalagadi District is sub-divided into Kgalagadi

North and South Sub-Districts. The Southern District is sub-divided into three Sub-

regional centers of Good hope, Mabutsane and Moshupa. The district headquarters

is Kanye Village. The Good hope sub-regional center represents the Barolong

region, the Mabutsane sub-regional center represents the Ngwaketse West region

and the Moshupa sub-regional and Kanye regional centers represent the Ngwaketse

region.

3.1.2 Namibia

The administrative regions in Namibia that fall in the Molopo-Nossob catchment are

Omaheke, Komas, Hardap and Karas. More specifically, for Karas, parts of

Keetmanshoop rural and Karasburg constituencies are included; for Hardap mainly

the Mariental rural constituency is included; for Khomas mainly the Windhoek rural

constituency is included; for Omaheke the Aminuis, Gobabis and Kalahari

constituencies are included (Figure 3-1 and Table 3-2).

Table 3-1: Namibian Regions and Constituencies

Region

Constituency

Some Villages in Region

Hardap

Mariental rural

Stampriet, Hoachanas, Bernafy,

Aranos, Gotchas

Karas

Keetmanshoop rural

Koes, Aroab

Karasburg

Ariamsvlei

Khomas

Windhoek rural

Seeis

Omaheke

Aminuis

Aminius, Leonardville

Gobabis

Gobabis

Kalahari

23 July 2009

3- 12

Molopo Nossob Feasibility Study - Main Report

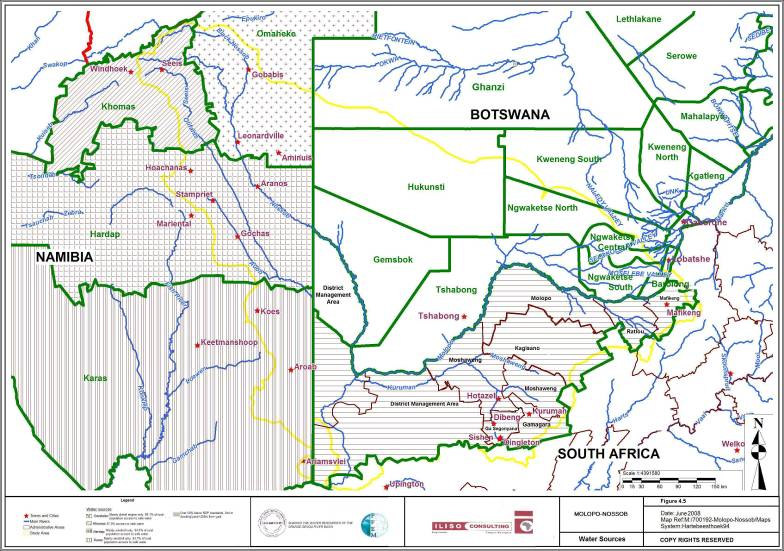

Figure 3-1: Locality of the Molopo Nossob River Catchment

23 July 2009

3- 13

Molopo Nossob Feasibility Study - Main Report

3.1.3 South Africa

In South Africa, the Molopo-Nossob sub river basin covers a northern section of the

Northern Cape Province and the north-western section of the North West Province.

It covers the area between Mafikeng and the South African-Namibian border, north of

the N14. Mafikeng and Kuruman are included in this catchment, and Upington is

excluded. The local municipalities of three district municipalities fall in the sub river

basin (Figure 3-1).

3.2

LANDUSE

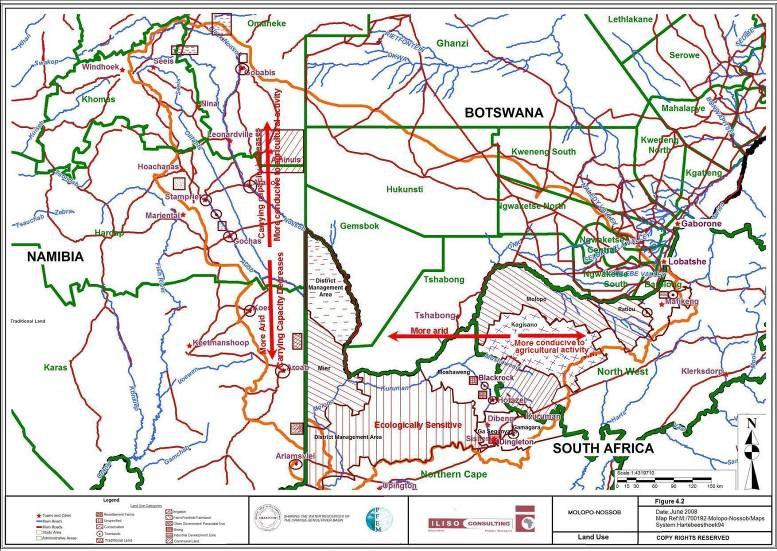

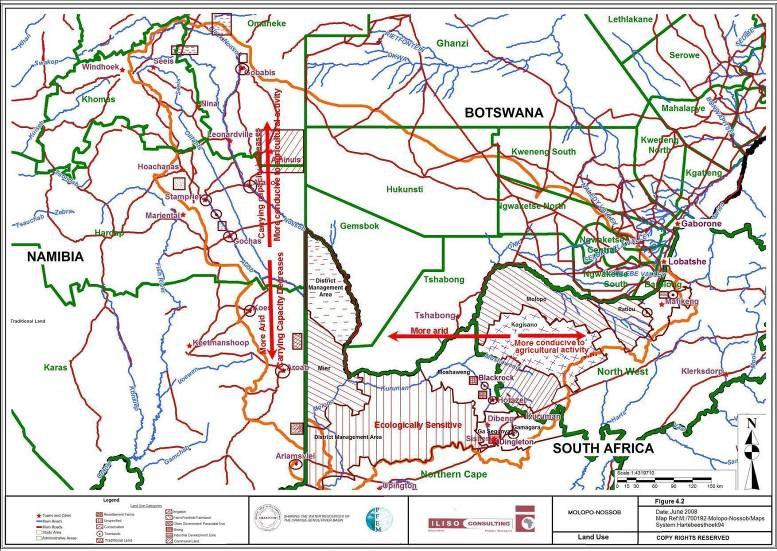

3.2.1 Botswana

There are four main types of land use in the Botswana part of the study area

(Figure 3-2) namely:

·

Communal Area - In this area all the major villages are situated and traditional

livestock rearing is the most important land use. Apart from livestock rearing a

number of arable fields, especially around the villages are found in this land use

zone.

·

Commercial grazing (tribal lease) - In accordance with the Tribal Grazing Land

Policy (TGLP), ranches have been established. TGLP ranches were created to

relieve grazing pressure on communal grazing land. In the Kgalagadi District

there are 6 blocks of TGLP ranches being, the Bokspits Block, the Middlepits

Block, Tsabong Block, Makopong Block, Werda Block and Hukuntsi Block.

·

Commercial grazing (freehold, state land leased) - this land use zone is entirely

taken by the freehold and leasehold farms of the Molopo Block. Since these

farms are not situated in the Kgalagadi Tribal Territory, they are administered by

the Department of Surveys and Lands. Generally these farms are developed, well

managed and commercially run.

·

Wildlife Management Area (WMAs) - the Wildlife Conservation Policy of 1986

converted stretches of land that were formerly designated as "reserved" under

the Tribal Grazing Land Policy of 1975 into WMAs. According to NDP 9 2003/04

to 2008/09 (MFDP, 2003, p. 246), WMAs were established by the Department of

Wildlife National Parks and Division of Land Use Planning to serve as migratory

corridors for wildlife between the protected areas as they allowed for movement

that is essential for the survival of Botswana's wildlife in the arid environment.

The WMAs were further sub-divided by DWNP and Division of Land Use

Planning into Controlled Hunting Areas (CHAs), and these CHAs were

subsequently earmarked for various kinds of management and utilization, and

23 July 2009

3- 1

Molopo Nossob Feasibility Study - Main Report

Figure 3.2: Landuse in the catchment

23 July 2009

3- 1

Molopo Nossob Feasibility Study - Main Report

3.2.2 Namibia

In Namibia, the area in the sub river basin consists of farms/freeholds farmlands on

which large scale commercial agriculture takes place (Figure 3-2).

Pockets of communal land on which subsistence agricultural activities take place

exist north of Aranos and Ariamsvlei. Where grazing for subsistence purposes occur

in this area, the carrying capacity of the land tends to be overloaded.

The carrying capacity of the land decreases from the northern part of the sub basin to

the southern part, from 30-39 kg/ha to 4-9 kg/ha. The cattle density reduces from 5-

12/ha to 0-4/ha (Atlas of Namibia Project, 2002).

Information about the suitability of soil in the affected area in Namibia for crop

production could not be sourced. However, the fact that mostly grazing occurs in this

area indicates that crop farming is not considered to be suitable.

In general, where crop farming occurs, dry land farming is practiced because of lack

of water which is required for effective irrigation. Crop farming and some irrigation

was observed between Gobabis and Windhoek. The Gobabis area where crop

farming with irrigation was observed was in close proximity to the Tilda and Daan

Viljoen Dams in Namibia. The water supply from the dams proved to be inadequate

to provide for the users, and the Gobabis Water Supply Scheme was implemented to

supplement water from the dams.

At Bernatey in the Mariental rural constituency, irrigation of crop fields, mainly

vegetables for subsistence and citrus for the commercial market, occurs. Bernatey is

on the southern end of the Stampriet artesan aquifer on the Auob River.

Mining is not a significant land use in the Namibian sub river basin. Planned mining

developments in the sub basin in Namibia could not be determined.

As far as could be established, no major industries operate in the Namibian sections

of the sub river basin.

23 July 2009

3- 2

Molopo Nossob Feasibility Study Main Report

3.2.3 South Africa

The land in the sub river basin is mainly private land, with some state/tribal land in

the North West Province and Moshaweng LM in the Northern Cape (Figure 3-2).

These are also the areas where most of the subsistence farming occurs.

Irrigation occurs along the Orange River, which does not fall in the sub-basin.

However, water usage along this river might affect the water availability in the sub

basin.

More than 80 % of the land in the Northern Cape is used for natural grazing to feed

an array of animal's mostly cattle, but also sheep, and goats, game and ostriches

(Northern Cape Provincial Government, 2007).

The eastern part is more conducive to agricultural activities. The land south of the

Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park is considered to be of high ecological sensitivity.

Mining does occur, mainly in Kgalagadi District Municipality. The active mining takes

place at Sishen (meaning "new place") and Hotazel. Sishen Iron Ore Mine, a

subsidiary of Kumba Resources, is located south of Kathu ("town under the trees") in

the Gamagara Local Municipality. This mine intends to further expand, which will

have implications for job creation, economic activity, and service delivery.

Almost all of the estimated 12 billion tonnes of manganese in South Africa are

located in the Kalahari (Kgalagadi Nodal Economic Profiling Project, 2007).

Samancor Manganese at Hotazel also plans to expand.

Assmang is situated in Blackrock, and it is not expected to increase (Kgalagadi Nodal

Economic Profiling Project, 2007). Assmang operates three divisions: manganese

ore, iron ore, and chrome ore. The manganese and iron ore operations are in

Nchwaning and Beeshoek in the Northern Cape.

As far as could be established, no other economically viable mineral resources have

been found in the sub river basin, except for recent findings in the Rietfontein (Mier

Municipality) area. According to the Kgalagadi DM's Integrated Development Plan

(IDP) (2004) there are small pockets of various minerals. The largest are copper and

zinc of Areachap north of Upington. Various small concentrations of calcite, lead,

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

February 2009

3-3

Molopo Nossob Feasibility Study Main Report

fluorspar, barite, wolfram and amethyst have been mapped but not at a notable

scale.

Currently, salt is being mined at two pans, namely Groot Witpan, 95 km northwest of

Upington and at Witpan, 115 km northwest of Upington. If one takes into account

that there are 110 saltpans in the interior (69 coastal saltpans, as well as sea salt

plants where salt is produced), the importance of the two pans north of Upington is

clear. It might seem as if South Africa has inexhaustible reserves because of the

great number of pans, but available information indicates that the production at most

pans is small and uncertain. Rain is not conducive to salt production. Some pans

have to stop production for years after a good rainy season (Kgalagadi DM IDP,

2002).

As far as could be established, except for the Mafikeng area, no major industries

operate in the South African and Namibian sections of the sub river basin. An

Industrial Development Zone is planned for Mafikeng.

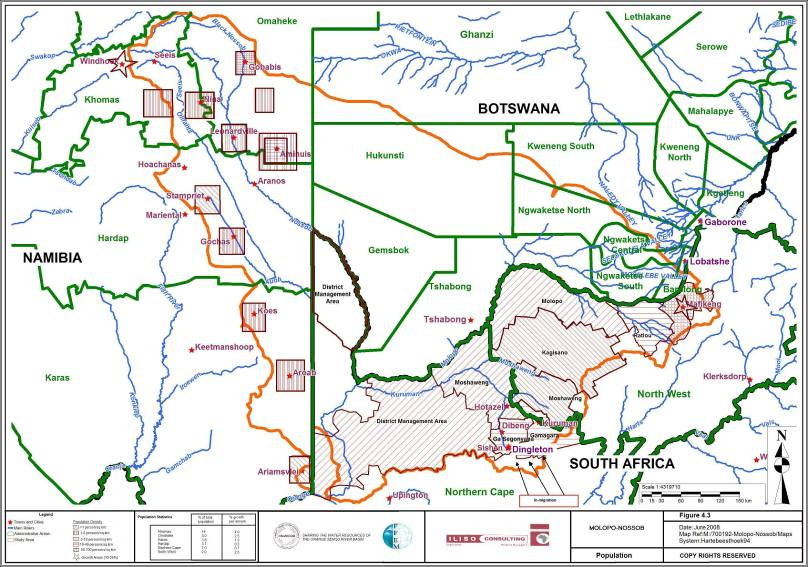

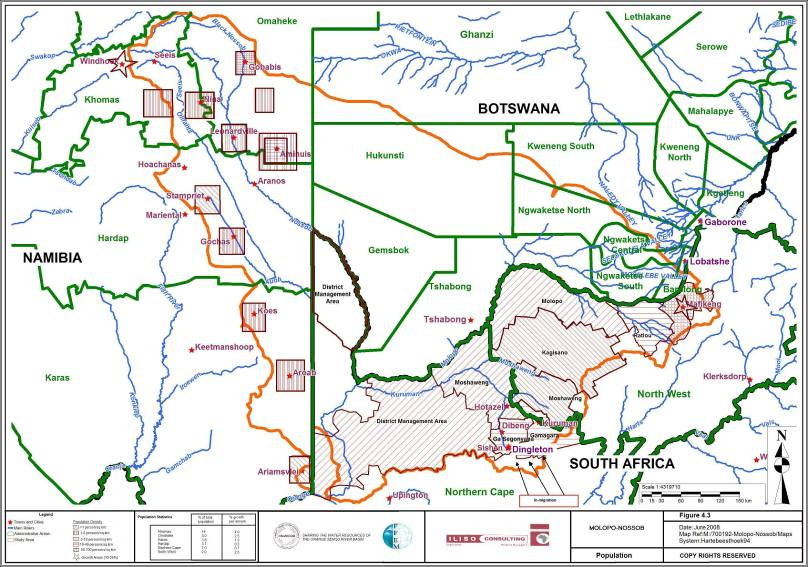

3.3

POPULATION

3.3.1 Botswana

The population figures for the census years 1971, 1981, 1991 and 2001 are

presented in Tables 3-2 to 3-6. The data on the tables also shows population

changes between the census years. Overall, there was a population increase.

Table 3-2: Population by District

District

1971

1981

% Change 1991

% Change 2001

% Change

1971-1981

1981 - 1991

1991-2001

Kgalagadi District

Kgalagadi North

3699

6707

81

11 340

69

16 111

42

Kgalagadi

15 137

24 059

59

19 794

-18

25 938

31

South

Southern District

Ngwaketse

70 558

104 182

48

128 989

24

124 175

-4

Barolong

10 973

15 471

41

18 400

19

47 477

158

Total

100 367

150 419

50

178 523

19

213 701

20

Table 3-3: Population of towns in District

Town

1971

1981

% Change 1991

% Change 2001

% Change

1971-1981

1981 - 1991

1991-2001

Towns

Lobatse

12 920

19 034

47

26 052

37

29 689

14

Jwaneng

-

5 567

-

11 188

101

15 179

36

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

February 2009

3-4

Molopo Nossob Feasibility Study Main Report

Table 3-4: Kgalagadi District Population by Village/Locality

Village/Locality

1971

1981

%

1991

%

2001

% Change

Change

Change

1991-2001

1971-

1981

-

1981

1991

Hukuntsi Sub District (Kgalagadi North)

Hukuntsi

1 116

2 009

73

2 562

28

3 807

49

Hukuntsi area

-

256

-

306

20

4 131

1 250

Kang

1 110

1 684

52

2 657

58

4 124

55

Phuduhudu

-

629

-

322

-49

621

93

Lokgwabe

300

866

189

1 037

20

1 304

26

Lokgwabe area

-

538

-

233

57

1 435

516

Lehututu

448

713

59

1 304

83

1 719

32

Lehututu area

-

753

-

231

-69

1 778

670

Tshane

604

637

5

706

11

858

22

Hunhukwe/Ohe

42

424

910

356

-16

579

63

Ohe

Same

Same

Same as

77

-

Part of

-

as

as

above

Hunhukwe

above

above

Manong (RAD)

4

100

2 400

232

132

172

26

Ukhwi (RAD)

31

274

784

313

14

454

45

Ngwatle (RAD)

-

-

-

92

-

206

124

Zutshwa (RAD)

-

-

-

203

-

525

159

Ncaang

-

-

-

-

-

175

-

Maake (RAD)

-

-

-

182

-

366

101

Lokgware (RAD)

-

-

-

307

-

-

-

Caa Cattle-post

-

-

-

100

-

(Part of

-

Zutshwa)

Cawane

-

-

-

34

-

(Part of

-

Kang)

Shobowe

-

-

-

340

-

-

-

Inalegolo

-

-

-

-

-

558

-

Other settlements

93

-

129

39

Totals

3 699

6 707

81

11 340

69

16 111

42

Kgalagadi South

Tsabong

647

1 732

168

4 585

165

7 228

58

Werda

706

1 109

57

1 974

78

2 237

13

Makopong

519

824

59

1 270

54

1 635

29

Phepheng/Draaihoek

337

569

69

826

45

998

21

Omaweneno

330

491

49

974

98

1 134

16

Khuis

213

490

130

696

42

851

22

Kolonkwane

240

415

73

751

81

762

2

Gakhibana

221

376

70

659

75

797

21

Middlepits

212

369

74

454

23

657

45

Bokspits

250

312

25

395

27

575

46

Maubelo

110

271

146

395

46

453

25

Bogogobo

191

225

18

368

64

341

-7

Kisa

352

197

44

1 021

418

545

-47

Kokotsha (RAD)

-

-

-

874

-

1 333

53

Vaal-hoek

-

185

-

224

21

346

55

Struizendum

136

182

34

289

59

313

8

Rappelspan

82

151

84

306

103

458

50

Bray

135

269

99

768

186

899

17

Maralaleng

164

186

13

Associated

-

487

-

with Kisa

Khawa

-

-

-

424

-

623

47

Maleshe

-

-

-

-

-

455

-

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

February 2009

3-5

Molopo Nossob Feasibility Study Main Report

Village/Locality

1971

1981

%

1991

%

2001

% Change

Change

Change

1991-2001

1971-

1981

-

1981

1991

Other

settlements

-

-

-

1 743

-

2 811

61

(RADs)

Totals

15

24

59

19 794

-18

25 938

31

137

059

Table 3-5: Ngwaketse and Ngwaketse West population by Village/Locality

Village/Locality

1971

1981

% Change 1991

%

2001

%

1971-1981

Change

Change

1981

-

1991-

1991

2001

Ngwaketse

Kanye

10 664

20 215

90

44 520

120

48 143

8

Ranaka

1 470

1 914

30

3 176

66

3 124

-2

Lotlhakane West

213

884

315

906

2.5

1 192

32

(Lotlhakane

(Lotlhakane

East & West) East & West)

Gasita

84

137

62

-

-

2 046

-

Lorolwana

60

115

30

574

399

1 090

90

Tsonyane

-

304

-

-

-

609

-

Kgomokasitwa

299

838

180

1 518

81

1 447

-5

Pitseng/Ralekgeth

149

226

-

-

-

850

-

o

Mokhoma

-

295

-

-

-

839

-

Lekgolobotlo

204

389

91

1 075

176

1 193

11

Seherelela

-

-

-

-

-

536

-

Lotlhakane

Considered

Considered

Considered

2 581

-

4 692

82

under

under

under

Lotlhakane

Lotlhakane

Lotlhakane

West

West

West

Sese

37

370

900

-

-

1 725

-

Sesung

181

695

284

-

-

440

-

Mogotlhwane

272

661

143

1 039

57

1 131

9

Segwagwa

32

278

760

-

-

1 062

-

Manyana

964

2 004

108

2 943

47

3 488

19

Maokane

140

653

366

1 344

106

1 629

21

Dipotsana

696

-

-

-

-

124

-

Diabo

65

283

337

-

-

272

-

Molapowabojang

346

778

125

4 371

462

7 499

72

Moshaneng

589

716

22

1 732

142

1 637

6

Moshupa

3 114

6 612

112

22 429

239

22 811

2

Ntlhantlhe

421

936

122

2 412

158

2 172

-10

Tshwaane

654

-

-

-

-

204

-

Samane

117

274

134

1 219

345

886

-27

Tlhankane

-

-

-

-

-

503

-

Selokolela

384

512

33

3 028

491

1 825

40

Mogonye

186

362

94

496

37

535

8

Totals

70 558 (for

104 182 (for

48

128 989

24

113

-

Ngwaketse

Ngwaketse

(for

704

and

and

Ngwake

Ngwaketse

Ngwaketse

tse and

West

West

Ngwake

combined)

combined)

tse

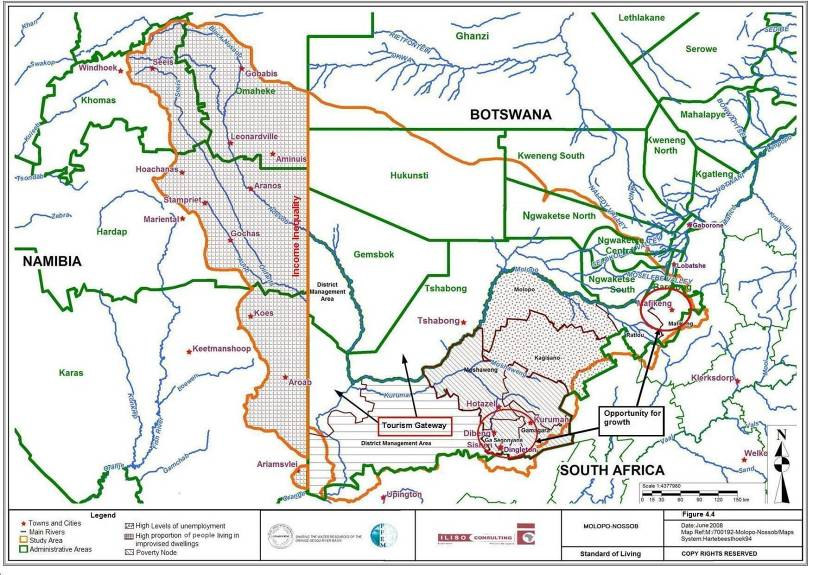

West