Report nr.

ORASECOM 002/2009

ORANGE-SENQU RIVER COMMISSION

(ORASECOM)

ASSESSMENT OF POTENTIAL FOR THE

DEVELOPMENT AND USE OF MARGINAL

WATERS

Final Report

Version 2.0

July 2009

SUBMITTED BY

Ninham Shand (Pty) Ltd

Acting as Agent for Aurecon SA (Pty) Ltd

In association with:

Golder Associates Africa (Pty) Ltd,

And

Sechaba Consultants (Pty) Ltd

Address:

Aurecon South Africa (Pty) Ltd

1st Floor, Outspan House

1006 Lenchen Ave North

Centurion

0046

Tel: +27 12 643 9000

Fax: +27 12 663 3257

Email: Aurecon@af.aurecongroup.com

i

Final Report

Assessment and Potential for the Development

July 2009

and Use of Marginal Waters

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

INTRODUCTION

Scarcity of water in semi-arid regions of the world, similar to the Orange-Senqu River Basin, has

necessitated the development of strategies to optimise the use of available water resources. One of

the most widely adopted measures is the augmentation of the water supply through the use of

unconventional or marginal water sources. Marginal water can be used to supplement intensively

exploited conventional sources.

For the purpose of this study, Marginal Waters will be defined as:

Water that can be recycled, reused or reclaimed, including naturally occurring non-potable water,

such as sea water, brackish water, saline and sodic water, unpotable groundwater, rainwater and fog

harvesting.

The following definitions for recycle, reuse and reclaim have been adopted for the purposes of this

report:

Re-cycle When water is used in a process and then reused in the same process with or without any

purification / treatment or improvement of the water quality.

Reuse When water is used and is then used again for another purpose with or without purification

to some acceptable level (not yet potable).

Reclaim Water that was previously used for potable or any other purposes is treated up to potable

quality standards so that it can again be used for potable purposes.

SUMMARY OF THE STATUS QUO

Examples of the different types of marginal water have been obtained from within the Orange-Senqu

River Basin. An indication of the different types of marginal water is shown in Table E1.

i

ii

Final Report

Assessment and Potential for the Development

July 2009

and Use of Marginal Waters

Table E1: Different types of marginal waters within the Orange-Senqu Basin

Namibia

Botswana

Lesotho

South

Africa

1. Reclamation of waste water for potable use

2. Reuse for irrigation after treatment

3. Reuse and recycling of industrial water

4. Reuse of water in mining sector

5. Rainwater & fog harvesting

6. Fog harvesting

6. Rainfal Enhancement

7. Use of brackish groundwater

8. Sea water and desalinisation

9. Use of dual systems

Examples from within the basin countries that are worth mentioning are:

· Botswana: Debswana mine. This mine is a good example in the sense that four types of marginal

water are being exploited, i.e.:

o Rainwater harvesting

o Irrigation with treated effluent

o Recycling of process water

o Use of brackish water

· Namibia: Windhoek reclaiming water from sewage water to potable standards.

· Lesotho: Rainwater harvesting

· South Africa: Emalahleni plant in Witbank, where heavy metals are removed from acid mine water

and where the water is treated to potable standards.

Two distinct examples in other countries of the world are:

· Australia: Irrigation of open spaces with water from package treatment plants plugged into sewers.

· Japan: Best example of dual systems for large scale buildings.

ii

ii

Final Report

Assessment and Potential for the Development

July 2009

and Use of Marginal Waters

IMPORTANT ISSUES RELATING TO MARGINAL WATER USE

The following implications have been identified for marginal water use:

· Institutional: Different tiers of institutional structures do not cooperate to promote marginal water

use to its optimum.

· Legislation: Regulation needed on water quality standards.

· Environment: Marginal water use can have both positive and negative impacts on the environment

e.g. positive when water is released into the environment with improved water quality and

negative when e.g. lime precipitates and blocks boreholes in limestone areas.

· Health: Faecal coliform guidelines must be met when irrigating with treated waste water in order to

avoid helminth and bacterial infections.

· Cost trends of marginal water use are shown in Figure E1.

Comparative Cost of Marginal Water Approaches

20

tank

³

/month)

15

kl

30

/month)

kl

Sea water desalination

45

10

Household with 5 m

Rand per kilolitre

Bloemfontein (7

Water

Namibian Towns (average)

Botswana mines (average)

5

Dam & Tunnels

Windhoek (7

Desalination of acid mine drainage

Bloem

TCTA Vaal River

Polihali

0

Raw

Bulk

Retail

Reverse

Rainwater

Water

Water

Water

Osmosis

Harvesting

Potable

Potable

Figure E1: Comparative cost of Marginal Water Approaches

TRENDS AND FUTURE POTENTIAL OF MARGINAL WATER

Trends in marginal water use and future potential are shown in Table E2.

ii

iv

Final Report

Assessment and Potential for the Development

July 2009

and Use of Marginal Waters

Table E2: Marginal Water Use Trends and Potential within the Orange-Senqu Basin

Type of Marginal

Namibia

Botswana

Lesotho

South Africa

Water use

Current

Future Potential

Current

Future Potential

Current

Future Potential

Current

Future Potential

Reuse water for irrigation of

Mines within basin use

Apart from current use by

Treated effluent sold for

Sway public perception

No information found.

Treated waste water could General practice in SA.

Current practice to be

recreational facilities and

effluent for irrigation of

mines, + 2 mill m³

use in gardens. Sport field and use treated effluent

be used for irrigation of

Treated waste water is

continued, however

agricultural crops with

sport fields and golf

domestic sewage effluent

irrigation e.g. by

water from Gabarone

Maseru s sport fields and

discharged in river and

discharging institutions

treated waste water.

courses. So does

in the larger towns can

Debswana mine and

works for irrigation of food

golf course.

abstracted downstream by

must ensure that they

Windhoek (outside basin)

become available for

Maru-A-Pula school.

crops.

irrigators. Some industries

comply to quality

reuse.

reuse process water for

standards.

irrigation, including crop

irrigation.

Recycle and/or reuse for

Rössing Uranium Mine

Continuation of present

Localised examples, e.g.

Continuation of present

Recycling of water e.g. in

Continuation of present

Some industries reuse

More industries could be

industrial and mining

recycles + 62% of their

use.

Debswana mines.

use.

textile industry and

use.

their water e.g. SAB Mil er. encouraged. There should

purposes with treated or

water purchased from

reusing process water by

be a financial incentive.

untreated water.

NamWater.

e.g. SAB Miller in Maseru.

Recycling at diamond

mines.

Reclamation of waste water

24% of total water

+ 2 mill m³ sewage

Not practised in Botswana

If public perception can be

Not practised in Lesotho

Maseru has limited water

Not practised in South

Limited potential in basin.

for potable use

consumption of Windhoek

effluent available from

as yet.

swayed, waste water of

as yet.

source and should look at

Africa as yet. (Direct

Other water users

is reclaimed water from

larger towns but reusing

Gaborone could possibly

this option.

reclamation).

currently dependent on

sewage effluent (outside

rather than reclaiming is

be reclaimed for potable

the discharged treated

basin).

more attractive.

purposes.

waste water.

Aquifer recharge

Aquifer recharge/banking

Localised / limited

Localised examples.

There is potential to

Not practised in Lesotho

Localised / limited

Not practised within the

Localised / limited

successfully applied

opportunities.

recharge aquifers with

as yet.

opportunities.

basin in South Africa as

opportunities.

outside basin (Omaruru

surface water to reduce

yet.

Delta Aquifer and

evaporation losses.

Windhoek Aquifer).

Infiltration dams needed.

Dual systems

Dual systems used at the

Separate networks for

Car washing stations in

Continuation of present

Not practised in Lesotho

Could possibly be

Not practised within the

Use of dual systems

mines and in Windhoek

irrigation of parks and

Gaborone use treated

use.

as yet.

considered for Maseru.

basin in South Africa as

including Japanese hand

(outside basin), i.e.

sport fields of towns.

effluent water.

yet.

washing/ flushing system

separate pipe systems for

for toilet flushing could be

drinking and gardening.

introduced for Gauteng

Region.

Use of brackish Ground

Brackish water from Kahn

Continuation of present

Used for stock drinking

Continuation and new

Not practised in Lesotho

Localised / limited

Private boreholes used for Current practice to be

water

River used for dust

use.

and wild life drinking.

copper mines at Ghanzi

as yet.

opportunities.

stock drinking.

continued. Limited

suppression at Rössing

could use saline ground

potential for expansion.

Uranium Mine.

water as process water.

Seawater and Groundwater

Two farms use

Seawater: Only coastal

Locked in land no

Continuation and possible

Not applicable for

Not applicable for

Only coastal town is

Limited scope within the

desalinisation

desalinated water.

town gets water from

access to sea. Several

expansion of desalination

Lesotho.

Lesotho.

Alexander Bay which does basin for major GW

Thermal distillation plant

Orange. Brackish GW: Not GW desalination plants in

plants for utilising saline

not need seawater

desalinisation project.

at Lüderitz (outside basin)

regarded attractive

operation in Botswana.

ground water.

desalinisation. No info on

today redundant.

enough.

E.g. Debswana mines.

GW desalinisation.

Rainwater & Fog harvesting

Schools harvest rainwater

Annual rainfall very low

Harvested rainwater used

Continuation and possible

Harvested rainwater used

Option for Maseru from

Individual household

Better utilisation of

from roofs for drinking

(250 mm/a). Not seen as

for gardening and car

expansion.

for gardening.

rooftops of public

rainwater tanks for

DWAF s subsidy scheme

purposes. Some house-

viable option, in many

washing e.g. at Maru-A-

buildings.

gardening purposes.

for resource poor farmers.

holds harvest rainwater for places for crop production

Pula school. 3.5 mill m³/a

Rainwater tanks are being

swimming pools. Fog

but good for drinking

harvested by Debswana.

subsidised.

harvesting unfeasible.

where other water is too

saline or has a bad taste.

Reclaim mine drainage

Localised / limited mine

Localised / limited

Localised / limited mine

Localised / limited

Localised / limited mine

Localised / limited

Some mine GW water is

Huge potential. + 150 mill

water

drainage.

opportunities.

drainage.

opportunities.

drainage.

opportunities.

currently used for mining.

m³/a available. Currently

being investigated by

W.U.C. (see para.4.1.5)

iv

v

Final Report

Assessment and Potential for the Development

July 2009

and Use of Marginal Waters

ASSESSMENT OF KEY PROJECTS

The following projects have been identified in the four basin countries.

Lesotho

· Irrigation of sport fields, the golf courses and suitable food crops in Maseru with treated sewage

effluent.

· Reclamation of Maseru s sewage water for potable use.

· Rainwater harvesting from rooftops of large buildings in Maseru.

Botswana

· Irrigation of food crops with treated sewage effluent.

· Reclaiming Botswana s treated sewage effluent to potable standards.

· Recharge aquifers with treated sewage effluent.

· Better utilisation of Botswana s saline groundwater.

· Public awareness strategy for reclaiming sewage water to potable standards (directly or by means

of aquifer recharge) and irrigating food crops with treated waste water.

Namibia

· Irrigation of sport fields and suitable food crops with treated sewage effluent.

South Africa

· Installation of dual systems for new developments in Gauteng

· Rainwater harvesting for food security.

· Reclaiming mine water to potabl e standards in Gauteng.

· Developing guidelines for the installation of dual reticulation systems in Gauteng.

Transboundary

· Review of institution, policy, legislation, and guidelines in the four countries.

· Development of guidelines for marginal water use by the industry sector.

SELECTION CRITERIA

The following eleven criteria were used for selecting between the list of projects.

i. The extent to which the project will combat poverty, the greater the better.

i . Water stressed areas should receive preference.

i i. Does it provide an opportunity to test new technology?

iv. Wil the public perception towards the possible project be positive?

v

vi

Final Report

Assessment and Potential for the Development

July 2009

and Use of Marginal Waters

v. The beneficial impact of the project on the basin as a whole.

vi. The extent to which the project will alleviate environmental problems.

vii. The management intensity of the project, the lower the better.

vii . The ability to duplicate (i.e. ease of adding modules and in so doing, expanding the project) or to

copy project in other areas, the easier the better.

ix. Wil the project leave other water users downstream in a weaker position? E.g. Water quality in

the Orange River to the detriment of export grape farmers.

x. To what extent wil the project lead to institutional growth?

xi. Wil the project defer other projects (e.g. future augmentation projects which will be more

expensive) in the basin state (locally or regionally)?

A condition with which it was recommended, all projects should be in place where a marginal waters

project is to be implemented was that all possible water conservation and water demand management

(WC/WDM) measures should already be being implemented. Normally WC/WDM is the cheapest and

most efficient way of making the most use of the available water. However in cases where the usage

of any marginal water option would be cheaper, the latter could be pursued as long as the WC/WDM

had been con sidered.

Apart from the above 11 criteria, a separate objective was set, namely to get an even spread of

projects in the four basin countries.

SELECTED PROJECTS

Six projects have been selected for further study, i.e.:

i. Botswana: Awareness campaign to promote indirect potable water reuse and irrigation of food

crops with treated sewage effluent.

i . South Africa: Dual reticulation system guidelines for Gauteng

i i. Lesotho: Irrigation of sport fields, the golf course and suitable food crops in Maseru with treated

wastewater

iv. Namibia: Irrigation of sport fields and suitable food crops in larger Namibian towns

v. Transboundary: Institutional, Policy, Legislative and Guidelines Review

vi. Transboundary: Guidelines for marginal water use for the industrial sector

Scopes of Works have been drafted for each of the above six projects and are bound in this report as

Appendix C.

COLOUR BROCHURE

A colour brochure has been prepared to promote the use of marginal waters and is included in this

report in Appendix B.

vi

vii

Final Report

Assessment and Potential for the Development

July 2009

and Use of Marginal Waters

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1.

INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................ 1

1.1 Background To This Project............................................................................................... 1

1.2 Definition Of Marginal Waters ............................................................................................ 2

1.3 The Systems Perspective Of Marginal Water Use ............................................................. 3

1.4 Project Phases And Purpose Of This Report ..................................................................... 3

2.

PROJECT SUMMARY............................................................................................................... 4

2.1 Summary Of Status Quo.................................................................................................... 4

2.1.1 Lesotho .................................................................................................................. 4

2.1.2 Botswana ............................................................................................................... 4

2.1.3 Namibia.................................................................................................................. 4

2.1.4 South Africa ........................................................................................................... 5

2.1.5 In the rest of the world............................................................................................ 6

2.2 Summary Of Important Issues ........................................................................................... 7

2.2.1 Institutional............................................................................................................. 7

2.2.2 Legislation.............................................................................................................. 7

2.2.3 Environment........................................................................................................... 8

2.2.4 Health .................................................................................................................... 9

2.2.5 Costs ..................................................................................................................... 9

2.3 Trends And Future Potential Of Marginal Waters............................................................. 11

2.3.1 Trends and future potential in relation to the sources ........................................... 13

2.3.2 Trends and future potential in relation to the uses................................................ 13

2.3.3 Trends and future potential in relation of mechanisms (Dual systems) ................. 15

3.

ASSESSMENT OF K EY PROJECTS ...................................................................................... 15

3.1 Possible Future Projects.................................................................................................. 15

3.2 Selection Criteria ............................................................................................................. 18

3.3 Evaluation Matrix ............................................................................................................. 19

4.

POTENTIAL PROJECTS SELECTED FOR FURTHER STUDy .............................................. 21

4.1 Introduction...................................................................................................................... 21

4.2 Awareness Campaign For The Reuse Of Treated Effluent In Botswana.......................... 22

4.3 Guidelines For The Implementation Of Dual Reticulation Systems In New Developments In

Gauteng, South Africa ..................................................................................................... 22

4.4 Irrigation Of Sports Fields, The Golf Course And Suitable Crops With Treated Effluent, In

Maseru Lesotho............................................................................................................... 23

vii

viii

Final Report

Assessment and Potential for the Development

July 2009

and Use of Marginal Waters

4.5 Irrigation of sports fields and suitable crops with treated effluent, in larger towns in

Namibia .......................................................................................................................... 23

4.6 Legislative, Policy, Institutional and guideline review of Basin States Arrangement with

regards to the use of Marginal Waters ............................................................................. 24

4.7 Best practice guidelines for industry for the recycling, reuse and reclamation of industrial

effluent .......................................................................................................................... 24

5.

COLOUR BROCHURE ............................................................................................................ 25

6.

WAY FORWARD ..................................................................................................................... 25

6.1 General .......................................................................................................................... 25

6.2 Scopes Of Work .............................................................................................................. 26

APPENDIX A: BIBLIOGRAPHY....................................................................................................... 27

A.1 Ful Reference In Endnote Format................................................................................... 27

A.2 Bibliography List .............................................................................................................. 28

APPENDIX B: COLOUR BROCHURE ............................................................................................. 40

APPENDIX C: SCOPES OF WORK ................................................................................................. 41

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1.1

Map of Orange-Senqu River Basin ............................................................................1

Figure 1.2

The role of engineered treatment, reclamation, and reuse facilities............................3

Figure 2.1

Portable Waste Water Treatment Works , Melbourne Australia ..................................6

Figure 2.2

Comparative cost of water .......................................................................................10

LIST OF TABLES

Table 2.3

Marginal Water Use Trends and Potential within the Orange-Senqu Basin..............12

Table 3.3

Assessment of Potential at workshop on 11 March 2009 .........................................20

viii

ix

Final Report

Assessment and Potential for the Development

July 2009

and Use of Marginal Waters

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

CSIR

-

Council for Scientific and Industrial Research

DEAT

-

Department of Environmental Affairs & Tourism

DME

-

Department of Mineral & Energy

DWAF

-

Department of Water Affairs and Forestry (South Africa)

EWR

-

Environmental Water Requirement

GAC

-

Granular Activated Carbon

Ha

-

Hectares

HDI

-

Historically Disadvantaged Individuals

IDP

-

Integrated Development Plan (South Africa)

IWRM

-

Integrated Water Resources Management

IWRMS

-

Integrated Water Resources Management Scenarios

NAFU

-

National African Farmers Union

LNDC

-

Lesotho National Development Corporation

NDA

-

National Department of Agriculture

MSF

-

Multi-Stage Filtration

NWMPR

-

National Water Master Plan Review

NAMPAAD

-

National Master Plan for Agricultural Development

PDO

-

Petroleum Development Oman

PIT

-

Project Implementation Team

PIU

-

Project Implementation Unit

PSC

-

Project Steering Committee

RSA

-

Republic of South Africa

SAAWU

-

South African Association of Water Utilities

SALGA

-

South African Local Government Association

SAR

-

Sodium Absorption Ratio

SoW

-

Scope of Works

STP

-

Sewage Treatment Plants

SWRO

-

Salt Water Reverse Osmosis

TDS

-

Total Dissolved Solids

ZSW

-

Centre for Solar Energy and Hydrogen Research (Namibia)

[Zentrum für Sonneregie und Wasserstoff Forschung

USEPA

-

United States Environmental Protection Association

WC&DM

-

Water Conservation and Demand Manageme nt

WRC

-

Water Research Council

WRM

-

Water Resource Management

WRMD

-

Water Resource Management and Development

WWTWs

-

Waste Water Treatment Works

ix

1

Final Report

Assessment and Potential for the Development

July 2009

and Use of Marginal Waters

1.

INTRODUCTION

1.1

BACKGROUND TO THIS PROJECT

Scarcity of water in semi-arid regions of the world, similar to the Orange-Senqu River Basin

shown in Figure 1.1, has necessitated the development of strategies to optimise the use of

available water resources. One of the widely adopted measures is the augmentation of the

water supply through the use of unconventional or marginal water sources. Marginal water

can be used to improve the efficiency of water use and supplement intensively exploited

conventional sources.

Figure 1.1 Map of Orange-Senqu River Basin

The foremost objective of this project was to determine the status quo of the use of marginal

waters within the Orange-Senqu River Basin, before identifying opportunities and key projects

or areas to improve or increase the use of marginal waters , resulting in the ful er use of the

existing supplied and otherwise available water.

2

Final Report

Assessment and Potential for the Development

July 2009

and Use of Marginal Waters

In order to achieve the objectives, the Orange Senqu River Commission (ORASECOM)

(Client) implemented this project for Consultancy Services for the Assessment of Potential for

the Development and Use of Marginal Waters .

1.2

DEFINITION OF MARGINAL WATERS

For the purpose of this study, Marginal Waters were defined as:

Water that can be recycled, reused or reclaimed, including naturally occurring non-potable

water, such as sea water, brackish water, saline and sodic water, unpotable groundwater,

rainwater and fog harvesting.

The following definitions for recycle, reuse and reclaim have been adopted for the purposes of

this study:

Re-cycle When water is used in a process and then reused in the same process with or

without any purification / treatment or improvement of the wate r quality.

Reuse When water is used and is then used again for another purpose with or without

purification to some acceptable level (not yet potable).

Reclaim Water that was previously used for potable or any other purposes is treated up to

potable quality standards so that it can again be used for potable purposes.

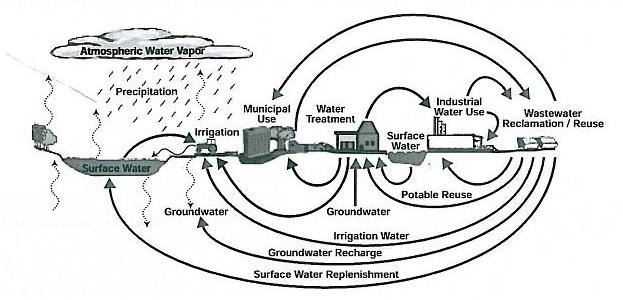

Figure 1.2 illustrates the role of marginal waters in the hydrological cycle.

Figure 1.2 The role of engineered treatment, reclamation, and reuse facilities in the multiple

uses of water through the hydrological cycle. (Source: adapted from Asano, 1995).

3

Final Report

Assessment and Potential for the Development

July 2009

and Use of Marginal Waters

1.3

THE SYSTEMS PERSPECTIVE OF MARGINAL WATER USE

When a catchment is viewed holistically, as a system, and acknowledging that all forms of

water are part of the hydrological cycle, then water recycling, reuse and reclamation as well as

rainwater and fog harvesting cannot create more water.

The objective of promoting use of marginal waters through this project is to use water more

efficiently, to minimise water losses and wastage and to ensure that water, particularly potable

water, is used for the most beneficial purposes.

The situation in a catchment might be that waste water discharges are already being used

downstream (e.g. by irrigators) and that the resource is fully allocated or utilised and that no

water is flowing out at the downstream end of the catchment. A decision by any up-stream

water user to reuse/recycle/reclaim water or to intercept water by harvesting rainwater might

therefore have a negative impact on downstream water users that rely on the discharges. This

must always be taken into consideration when planning to use marginal waters.

However it may be that the recycling/reuse/reclaiming of water upstream is a more efficient or

beneficial use and a country s best interest compared with the downstream use. These

aspects must be factored into any decision making.

1.4

PROJECT PHASES AND PURPOSE OF THIS REPORT

The study was sub-divided into three phases, i.e. Inception Phase, Assessment Phase and

Proposal Phase. The Inception Phase was completed and an Inception Report finalised and

issued to the client. A comprehensive Bibliography was compiled using EndNote software

which was delivered to the client and presented in Appendix A. The Assessment Phase

comprised mainly an assessment of current marginal water use in the Orange-Senqu River

Basin and of the future potential for use of marginal waters. That phase was completed in

March 2009 and the Mid-Term report finalised and issued to the client. The third phase

identified potential marginal water projects and Scopes of Work were drafted for them. This

Final Report documents the findings of the Assessment Phase and presents the Scopes of

Work for the selected priority projects. This report also displays the colour brochure which has

been prepared about the project.

4

Final Report

Assessment and Potential for the Development

July 2009

and Use of Marginal Waters

2.

PROJECT SUMMARY

2.1

SUMMARY OF STATUS QUO

2.1.1 Lesotho

Extensive rain water harvesting projects funded through various donor agencies are currently

in place in Lesotho. The harvested water is mainly used for watering private and community

gardens. The mines in Lesotho also recycle water within their processes, for example the

diamond mines and quarries. Within Maseru, the textile industry reuses their process water.

The SAB Mil er brewery in Maseru also reuses their industrial effluent for crate washing among

other things.

2.1.2 Botswana

The Debswana mines in Botswana have set a precedent for mine water management. The

mines are involved in rain water harvesting, approximately 3.5 million m3 per annum (rainwater

harvesting is also carried out in other locations such as at schools and government buildings).

The rain water is used to water gardens. The process water from mining activities is reused

within the processes. The sewage effluent gathered at the mines and mine villages is also

treated and used to irrigate the sports fields and landscaped gardens at the mines. Botswana

has also been busy with investigating the possibility of aquifer re-charge using treated effluent.

However, the negative public perceptions have slowed progress on the reuse of treated

sewage effluent. Car wash stations in Gabarone use treated effluent as their water supply.

Another source of widely used marginal water in Botswana is saline groundwater. The saline

groundwater is used extensively for stock drinking. Similarly, several desalination plants or in

operation through out Botswana, utilising the widely available saline groundwater and further

plants are being proposed.

2.1.3 Namibia

In Windhoek Namibia, 24% of the total water consumption is from reclaimed sewage effluent.

Although this example falls outside the Orange-Senqu basin, it is an important example for this

project. The reclaimed water is also used for irrigation purposes. The mines in Namibia

provide good examples of using marginal waters both in the basin, and in the country as a

whole. Many of the mines in Namibia reuse effluent for irrigation of their facilities and golf

courses. Rössing Uranium Mine recycles approximately 62% of their water purchased from

NamWater. Rössing also use brackish water from the Kahn River for dust suppression. Some

of the mines make use of dual reticulation systems. Within Windhoek, the industrial area also

has a dual reticulation system installed and operating. Many schools in Namibia conduct

rainwater harvesting projects. The water collected is then used for drinking purposes. Most of

5

Final Report

Assessment and Potential for the Development

July 2009

and Use of Marginal Waters

the rainwater harvesting projects are individual initiatives, for example, using harvesting

rainwater for swimming pools. Although not in the basin, but still in Namibia, Omaruru Delta

Aquifer and Windhoek Aquifer have been successfully recharged through water banking

projects. A thermal distillation plant was installed at Lüderitz, however it is currently out of

action.

2.1.4 South Africa

In South Africa there are currently a few examples of marginal waters in use. Many of the

examples are by individual companies rather than sector driven, or government driven.

Treated effluent is indirectly used in the basin for potable purposes. Effluent released back into

the river is then later abstracted further down stream for purification for potable use. The

Northern Waste Water Treatment Works, in Johannesburg, pumps treated sewage effluent

directly to the Kelvin Power Station for cooling of the stacks. Within the Durban region, treated

effluent is used both in the Paper and Pulp industry, as well as Shell SAPREF Refinery. The

treated effluent, collected from households and treated, is then piped to the industries where it

is used for various industrial processes including cooling processes. SAB Miller plants

throughout the country also practice various techniques of water recycling and reusing,

including for crate washing.

In eMalahleni, in Witbank, Acid Mine Drainage is reclaimed to potable standards to augment

the local drinking water supplies. A similar project is currently being researched, within the

basin area, where acid mine drainage will be collected and treated and pumped to the drinking

water reservoirs. The treating of the acid mine drainage provides a positive environmental

impact, as better quality water is released to the rivers.

Brackish groundwater is used for stock drinking in water-scarce areas of the country. Similarly

in high rainfall areas, rain water harvesting is conducted on a small and private scale. The

water is then utilised for garden watering, dust suppression, and drinking purposes. Sea water

desalination is being done by the Albany Water Board in the Eastern Cape.

The responses received from the questionnaires indicated that so long as water was coming

from the tap, the majority of respondents weren t concerned about using marginal water, or

investigating alternative sources of water.

6

Final Report

Assessment and Potential for the Development

July 2009

and Use of Marginal Waters

2.1.5 In the rest of the world

Australia

Throughout Australia there are examples of reusing treated effluent as well as other marginal

water sources. One example is the latest water recycling development in Melbourne, of a

portable sewer mining plant, Figure 2.1. The plant uses membrane technologies (ultra

filtration and reverse osmosis) producing Class A reclaimed water from Melbourne s sewage

mains. The unit, is mounted in a 12 metre shipping container, and connects directly into the

sewage mains via available manholes. The treated water is used to irrigate Melbourne s

parklands and waste products are returned to the sewage mains.

Figure 2.1: Portable WWTW in 12 metre shipping container used for sewer-mining ,

Melbourne, Australia. (Mallia, 2003).

Japan

Approximately 150 million m3 of water is recycled annually. Since 1997, 163 publicly owned

Waste Water Treatment Works (WWTW) provide water recycling in 192 use areas, and 1475

on-site individual and block-wide water recycling systems provide toilet flushing water in

commercial buildings and apartments as well as water for landscaping. The Tokyo

Metropolitan Government produced a set of guidelines for the reuse of treated miscellaneous-

use water in 1984. Based on these guidelines, Tokyo directs the operators of large-scale

buildings with a floor area of more than 30 000m2 or that use a daily total volume of 100m3 of

water for non-drinking water purposes to reuse water.

7

Final Report

Assessment and Potential for the Development

July 2009

and Use of Marginal Waters

California

In the United States, California residents reuse on average 656 million m3 of municipal waste

water annually, the majority of which is reused for irrigation (agriculture and landscape

irrigation) purposes, as well as meeting environmental flows, groundwater recharge and

recreational impoundment.

Oman

In Oman, Petroleum Development Oman (PDO) produces nearly five barrels of water for every

barrel of oil. The water is mixed with the oil and gas deposits and brought to the surface during

production. The water contains small amounts of salts and oil, and is often pumped back into

the well. PDO are in the process of researching reed fields to absorb the contaminants from

the water and making the water available to the local communities. During the reed-bed

process, the water becomes more saline due to evaporation. The water will also be used to

grow salt-resistant crops. The use of the reed-beds has reduced the costs to PDO of pumping

the water back into the wells, as well as reducing the CO2 emissions.

2.2

SUMMARY OF IMPORTANT ISSUES

2.2.1 Institutional

The main problem identified in the research relating to institutional structures and

arrangements was the separation of functions and responsibilities between agencies for water

management and sewage services functions. Water resource management issues is usually

the responsibility of a higher tier of government, whereas sewage services is usually a lower

order organisation or municipality and this resulted in a lack of coordination, differing goals

and standards, as well as conflicting developments or installations.

A second identified problem is the need for a paradigm shift, instead of first looking to potable

reclamation solutions, to rather begin with reuse or recycling in order to reduce the demand on

potable water for non-drinking purposes. Whilst this falls into Water Demand Management,

which is dealt with in another project, this problem was identified in this research and

questionnaire responses.

2.2.2 Legislation

In terms of the legislation in the basin, Botswana s National Wastewater and Sanitation

Planning and Design Manual (2003) provides some guidance towards the reuse of water. The

Manual highlights the difference between water quality standards and water quality guidelines.

8

Final Report

Assessment and Potential for the Development

July 2009

and Use of Marginal Waters

Water quality standards are legal impositions enacted by means of laws, regulations or

technical procedures, which are established in countries by adapting guidelines to their

national priorities and taking into account their technical, economic, social, cultural and

political characteristics and constraints. Water quality guidelines on/for the reuse of water

quality are mainly based on research and epidemiological findings, and as such provide

guidance for making risk management decisions related to the protection of public health and

the preservation of the environment. (Botswana).

In the rest of the world, there are more advanced pieces of legislation and guidelines for the

reuse of water. For example:

Europe The European Urban Waste Waster Treatment Directive (91/271/EEC) defines

standards for the collection, treatment and discharge of urban waste water and waste water

from some industrial sectors. The Directive states that (with a few exceptions) all urban waste

water discharges greater than 10,000 person equivalents to coastal waters and greater than

2,000 person equivalents to freshwater and estuaries will be subject to secondary treatment

by 2005. (Radcliffe, 2006)

Australia At a Federal level, the National Water Quality Strategy (NWQMS) National Water

Quality Managemen t Strategy Australian Guidelines for Water Recycling Management Health

and Environmental Risk (Phase 1) published in 2006, provides a national reference for the

supply, use and regulation for the reuse of water. The guidelines aim to provide a consistent

risk based approach to reusing water. The guidelines do not specify end uses for the water,

but rather provide a process to determine if the environmental and health risks are being

adequately managed. There are both health and environmental targets set for individual

hazards as well as a number of end uses.

United States California s Waste water Reclamation Criteria (Title 22) has been the basis for

many other sets of regulations. (Radcliffe, 2006).

Tunisia National Reuse Policy (Decree 89-1047). (Radcliffe, 2006).

2.2.3 Environment

Many of the environmental impacts identified through the research relate to desalination of sea

water plants. The intakes to the plants lead to marine life impingement. There is currently

research into better intake designs for the plants, so as to avoid the entrainment of the marine

life. In the Middle East, an outbreak of red tide has affected some of their desalination plants.

The intakes have to be shut down to avoid contamination. On a positive aspect, both the US

9

Final Report

Assessment and Potential for the Development

July 2009

and Use of Marginal Waters

and Australia are looking to implement requirements for desalination plants to be carbon

neutral, and research into wind and solar energy supplies is currently in process.

With regards to boreholes, in the karst (limestone) areas, excessive pumping from boreholes

can result in deeper lime-rich water being exposed to oxygen and thereby causing the lime to

precipitate and block the borehole. The borehole then has to be abandoned and re-drilled.

Recycling, reuse or reclamation of water will usually result in an environmental benefit, as the

water released into the environment will be of a better quality. One of the trends identified in

the international research, is that one of the main reuses of marginal waters was to meet

environmental flow requirements.

2.2.4 Health

The main health impact identified, related to water quality assurance, and therefore the

implementation of strict regulations. The reclamation of water for potable use, even for aquifer

recharge or dilution purposes was ranked fairly low among the examples researched.

The main use of marginal water, identified through the research, was for irrigation purposes.

Within this use, there is the need for strict regulation and enforcement, to prevent the

contamination of foodstuffs from the waste water.

Irrigation with untreated waste water is very hazardous to health, with both fieldworkers and

consumers being at high risk of helminth infections; consumers are also at a high risk of

bacterial infections such as cholera and typhoid fever. Treated effluent for irrigation must meet

the faecal coliform guidelines of less than 1 000 parts per 100ml to protect consumers from

these bacterial diseases.

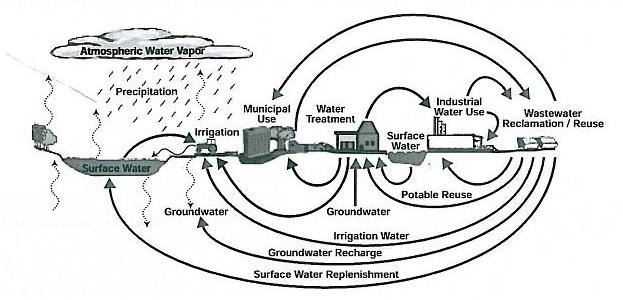

2.2.5 Costs

This financial comparison is an indication of the relative costs of implementing various

marginal water approaches in the basin. The operational, maintenance and capital costs were

obtained from actual projects in the basin. Where the capital costs were provided as a once off

fixed cost, it was first converted into an annual cost using an interest rate of 10% per annum,

capitalised 6 monthly over a 20 year period and then converted into a per cubic metre cost.

The cost of the rainwater tank assumes a life of 10 years and that the 5m3 tank can meet a

demand of 15 Kl per month for 6 months of the year. This might be a generous assumption in

the drier areas. Conventional surface water resource schemes and water supply were used as

benchmarks.

1 0

Final Report

Assessment and Potential for the Development

July 2009

and Use of Marginal Waters

Comparative Cost of Marginal Water Approaches

20

month)

³

tank

15

30 kl/

45 kl/month)

Sea water desalination

10

Rand per kilolitre

Household with 5 m

Bloemfontein (7

Namibian Towns (average)

Windhoek (7

Botswana mines (average)

5

Desalination of acid mine drainage

Bloem Water

TCTA Vaal River

Polihali Dam & Tunnels

0

Raw

Bulk

Retail

Reverse

Rainwater

Water

Water

Water

Osmosis

Harvesting

Potable

Potable

Figure 2.2 Comparative cost of water

The cost of the marginal water approaches indicated in Figure 2.2, are indicative and actual

costs will depend on a number of factors and especial y on the quality of the influent. The

poorer the influent the higher the cost of desalination. Desalination of sea water being on the

higher end of the cost spectrum. From the results it appears that the cost of marginal water is

not out of the ordinary, and while more expensive than the price of conventional water

supplies in South Africa, the cost of marginal water is competitive with the cost of water in the

drier Namibia.

The cost of marginal water should not be a deterrent to a more detailed preliminary design

level analysis which would result in more accurate costing and perhaps a more cost efficient

approach.

11

Final Report

Assessment and Potential for the Development

July 2009

and Use of Marginal Waters

2.3

TRENDS AND FUTURE POTENTIAL OF MARGINAL WATERS

Use of marginal water use has become common practice in many countries of the world. As

available conventional resources are taken up, water users are forced to make increasing use

of marginal waters. Factors, other than just the scarcity of water may force countries to opt for

reusing water.

· E.g. Japan, where topographical conditions are a constraint for impoundment

infrastructure.

· E.g. Oman, where water that is used in the treatment of oil, is reused for the irrigation of

salt tolerant crops.

Table 2.3 provides a summary of the status quo of marginal water use in the Basin and of the

future potential. From this table, three types of trends and future potential have been identified

i.e. in relation to the sources, in relation to the uses and in relation to the mechanisms. Each of

these is described below.

The areas of future potential where it was recommended that further work be undertaken and

which were considered for preparation of a scope of work under this project, are highlighted.

12

Final Report

Assessment and Potential for the Development

July 2009

and Use of Marginal Waters

Table 2.3 Marginal Water Use Trends and Potential within the Orange-Senqu Basin

Type of Marginal

Namibia

Botswana

Lesotho

South Africa

Water use

Current

Future Potential

Current

Future Potential

Current

Future Potential

Current

Future Potential

Reuse water for irrigation of

Mines within basin use

Apart from current use by

Treated effluent sold for

Sway public perception

No information found.

Treated waste water could General practice in SA.

Current practice to be

recreational facilities and

effluent for irrigation of

mines, + 2 mill m³

use in gardens. Sport field

and use treated effluent

be used for irrigation of

Treated waste water is

continued, however

agricultural crops with

sport fields and golf

domestic sewage effluent

irrigation e.g. by

water from Gabarone

Maseru s sport fields and

discharged in river and

discharging institutions

treated waste water.

courses. So does

in the larger towns can

Debswana mine and

works for irrigation of food

golf course.

abstracted downstream by must ensure that they

Windhoek (outside basin)

become available for

Maru-A-Pula school.

crops.

irrigators. Some industries

comply to quality

reuse.

reuse process water for

standards.

irrigation, including crop

irrigation.

Recycle and/or reuse for

Rössing Uranium Mine

Continuation of present

Localised examples, e.g.

Continuation of present

Recycling of water e.g. in

Continuation of present

Some industries reuse

More industries could be

industrial and mining

recycles + 62% of their

use.

Debswana mines.

use.

textile industry and

use.

their water e.g. SAB Mil er. encouraged. There should

purposes with treated or

water purchased from

reusing process water by

be a financial incentive.

untreated water.

NamWater.

e.g. SAB Miller in Maseru.

Recycling at diamond

mines.

Reclamation of waste water

24% of total water

+ 2 mil m³ sewage

Not practised in Botswana

If public perception can be Not practised in Lesotho

Maseru has limited water

Not practised in South

Limited potential in basin.

for potable use

consumption of Windhoek

effluent available from

as yet.

swayed, waste water of

as yet.

source and should look at

Africa as yet. (Direct

Other water users

is reclaimed water from

larger towns but reusing

Gaborone could possibly

this option.

reclamation).

currently dependent on

sewage effluent (outside

rather than reclaiming is

be reclaimed for potable

the discharged treated

basin).

more attractive.

purposes.

waste water.

Aquifer recharge

Aquifer recharge/banking

Localised / limited

Localised examples.

There is potential to

Not practised in Lesotho

Localised / limited

Not practised within the

Localised / limited

successfully applied

opportunities.

recharge aquifers with

as yet.

opportunities.

basin in South Africa as

opportunities.

outside basin (Omaruru

surface water to reduce

yet.

Delta Aquifer and

evaporation losses.

Windhoek Aquifer).

Infiltration dams needed.

Dual systems

Dual systems used at the

Separate networks for

Car washing stations in

Continuation of present

Not practised in Lesotho

Could possibly be

Not practised within the

Use of dual systems

mines and in Windhoek

irrigation of parks and

Gaborone use treated

use.

as yet.

considered for Maseru.

basin in South Africa as

including Japanese hand

(outside basin), i.e.

sport fields of towns.

effluent water.

yet.

washing/ flushing system

separate pipe systems for

for toilet flushing could be

drinking and gardening.

introduced for Gauteng

Region.

Use of brackish Ground

Brackish water from Kahn

Continuation of present

Used for stock drinking

Continuation and new

Not practised in Lesotho

Localised / limited

Private boreholes used for Current practice to be

water

River used for dust

use.

and wild life drinking.

copper mines at Ghanzi

as yet.

opportunities.

stock drinking.

continued. Limited

suppression at Rössing

could use saline ground

potential for expansion.

Uranium Mine.

water as process water.

Seawater and Groundwater

Two farms use

Seawater: Only coastal

Locked in land no

Continuation and possible

Not applicable for

Not applicable for

Only coastal town is

Limited scope within the

desalinisation

desalinated water.

town gets water from

access to sea. Several

expansion of desalination

Lesotho.

Lesotho.

Alexander Bay which does basin for major GW

Thermal distillation plant

Orange. Brackish GW: Not GW desalination plants in

plants for utilising saline

not need seawater

desalinisation project.

at Lüderitz (outside basin)

regarded attractive

operation in Botswana.

ground water.

desalinisation. No info on

today redundant.

enough.

E.g. Debswana mines.

GW desalinisation.

Rainwater & Fog harvesting

Schools harvest rainwater

Annual rainfall very low

Harvested rainwater used

Continuation and possible

Harvested rainwater used

Option for Maseru from

Individual household

Better utilisation of

from roofs for drinking

(250 mm/a). Not seen as

for gardening and car

expansion.

for gardening.

rooftops of public

rainwater tanks for

DWAF s subsidy scheme

purposes. Some house-

viable option, in many

washing e.g. at Maru-A-

buildings.

gardening purposes.

for resource poor farmers.

holds harvest rainwater for places for crop production

Pula school. 3.5 mill m³/a

Rainwater tanks are being

swimming pools.

but good for drinking

harvested by Debswana.

subsidised.

where other water is too

saline or has a bad taste.

Reclaim mine drainage

Localised / limited mine

Localised / limited

Localised / limited mine

Localised / limited

Localised / limited mine

Localised / limited

Some mine GW water is

Huge potential. + 150 mill

water

drainage.

opportunities.

drainage.

opportunities.

drainage.

opportunities.

currently used for mining.

m³/a available. Currently

being investigated by

W.U.C. (see para.4.1.5)

13

Final Report

Assessment and Potential for the Development

July 2009

and Use of Marginal Waters

2.3.1 Trends and future potential in relation to the sources

There are mainly four sources of marginal waters in the basin that have been utilised so

far, namely:

· Treated sewage effluent

· Brackish (Saline) groundwater

· Harvested rainwater

· Treated industrial effluent

It is foreseen that the basin countries wil continue to utilise these sources and there is

scope to expand the present use. A further source in South Africa which has not so far

been utilised to its full potential but is proposed to be utilised, is:

· Mine drainage

At the shaft openings of abandoned gold mines in the Upper Vaal River Catchment

the mine drainage water has become acidic and contains heavy metals. This poses

a threat to the receiving environment. Approximately 150 mil ion m3 / annum of Acid

Mine Drainage (AMD) is pumped or decanted from the mines. The AMD is

proposed to be treated by a private sector company, to supplement potable water

supplies in the Gauteng region.

2.3.2 Trends and future potential in relation to the uses

The main trends in relation to uses in the basin are:

· Rainwater harvesting for garden watering.

· Irrigation of sport fields, golf courses and suitable food crops with treated sewage

effluent.

· Recharging of aquifers (water storage)

· Mine / Industrial process water

· Treated sewage effluent for domestic drinking water

· Saline groundwater for stock drinking

The following potential water uses can be further investigated:

· In Lesotho, the sports fields, golf course and suitable food crops in Maseru could

be irrigated with treated sewage effluent instead of potable water.

14

Final Report

Assessment and Potential for the Development

July 2009

and Use of Marginal Waters

· Maseru could also look at the option to reclaim its sewage water for potable use.

Both these uses would defer the building a further expensive augmentation and

treatment scheme from a conventional water resource.

Botswana

· Irrigation of crops for food production in Gaborone. The public is currently opposed

to reclaiming water indirectly (through aquifer recharge) for potable uses and to

irrigation, particularly irrigation of crops for food production with treated sewage

water and it will be necessary to sway the public perception.

· The recharge of aquifers with treated sewage effluent in Botswana should be

continued and could be expanded.

· The use of saline groundwater for mine processes can be expanded. New copper

mines at Ghanzi, Botswana can be targeted for this.

· Debswana has already had success with rainwater harvesting. Additional rainwater

harvesting projects in Botswana could be investigated (e.g. col ecting water from

the roofs of large buildings and from paved areas).

Namibia

· Reuse of treated sewage water of the larger Namibian towns within the Orange

River Basin for irrigation of sport fields / golf courses or small scale production of

suitable crops. A volume of approximately 2 mil ion m3 per annum treated sewage

water is available for this purpose.

· Reclamation of treated sewage water of the larger Namibian towns in the Orange-

Senqu River Basin for potable use is a possibility that could be further investigated.

However without the benefit of scale, small reclamation plants might not be feasible.

South Africa

· In South Africa, the irrigation of vegetables by resource poor people with harvested

rainwater can be encouraged. The current subsidy scheme of DWAF for subsidies

on rainwater tanks can be better utilised.

· The Gauteng region has the highest rate of growth and development in the basin.

This puts much strain on the limited water sources which are augmented from

outside the region. The compulsory installation of dual reticulation systems for all

new housing, office parks, commercial and similar developments could assist to

alleviate the current water deficits in Gauteng.

15

Final Report

Assessment and Potential for the Development

July 2009

and Use of Marginal Waters

2.3.3 Trends and future potential in relation of mechanisms (Dual systems)

Dual systems are one of the mechanisms to enable us to make use of marginal waters.

The following are possibilities for future use of dual systems.

· Maseru should have a separate water distribution system for taking water to its

parks, sport fields and golf course(s).

· The rainwater harvested in Maseru from the roof tops of large buildings should have

a separate water distribution system for taking the water to areas of use e.g. toilet

flushing.

· The larger Namibian towns should have their own distribution works (pump, pipe

network, sprinklers etc.) to the sport fields and golf courses, if found to be feasible.

· The Japanese example of dual system in buildings and of hand washing basins

connecting to toilet cisterns for direct water reuse could possibly be promoted in

Gauteng where water deficits are expected until 2019 when the next phase of the

Lesotho Highlands transfer scheme comes into operation.

3.

ASSESSMENT OF KEY PROJECTS

3.1

POSSIBLE FUTURE PROJECTS

After having studied the status quo and trends of present marginal water use in and outside

the basin, possible future projects were identified from the interviews with the current water

users and from the workshop with stakeholders and steering committee members that

followed after the submission of the draft Mid-term report. The future potential projects can be

divided into two main groups, i.e.:

· Physical infrastructure projects.

· Enabling projects for future marginal water use.

The potential physical infrastructure projects in each country are as fol ows.

Lesotho:

i. Irrigation of sport fields, the golf course and suitable food crops in Maseru with treated

sewage effluent.

i . Reclamation of Maseru s sewage water for potable use in stead of building a further

expensive augmentation scheme from a conventional water resource.

16

Final Report

Assessment and Potential for the Development

July 2009

and Use of Marginal Waters

i i. Rainwater harvesting from rooftops of large buildings in Maseru. Although some rainwater

harvesting projects are already funded and being carried out in Lesotho there is more

scope for these kinds of projects where harvested rainwater is reused within the large

buildings and surrounds.

Botswana:

iv. Irrigation of food crops with treated sewage effluent of Botswana. This project referred to

the implementation of irrigating food crops throughout Botswana with treated sewage

effluent. The project would identify a pilot project.

v. Reclaiming Botswana s treated sewage effluent to potable standards. Currently

reclamation of sewage effluent to potable standards is not being done in Botswana. There

is some resistance from the public against such a solution.

vi. Recharge aquifers in Botswana with treated sewage effluent. Plans are already in place for

the implementation of this project. This project aims to recharge certain aquifers with

treated sewage effluent, within Botswana.

vii. Better utilisation of Botswana s saline groundwater. There are several plans in place

already for the utilisation of saline groundwater, especially at the Debswana mines. This

project is aimed at establishing the feasibility and implementation of utilising saline

groundwater for various uses, particularly industry and mining.

Namibia:

vii . Irrigation of the sport fields or suitable crops with treated sewage effluent of larger

Namibian towns. The project refers to the irrigation of sport fields and other open areas,

and potentially food crops, in the larger towns within the basin, with treated sewage

effluent.

South Africa:

ix. Installation of dual reticulation systems for new developments in Gauteng. This province is

the fastest growing and developing area within the basin. The installation of dual systems

for new developments (e.g. residential complexes, office parks, shopping centres) can

significantly reduce the potable water requirements as treated effluent is then provided for

certain secondary uses through a separate system.

17

Final Report

Assessment and Potential for the Development

July 2009

and Use of Marginal Waters

x. Rainwater harvesting for food security purposes in South Africa. This project is already

being carried out in some community gardening projects. The project objective is the

increased implementation of rain watering harvesting within the basin for smal scale

projects (both irrigation and domestic purpose).

xi. Reclaiming mine water to potable standards in Gauteng. Large volumes water are being

pumped from active gold mines or are decanting from abandoned mines. Some of the

water from active gold mines is recycled but large volumes are released in the water

courses of the basin. These volumes can be reclaimed to potable standards and

distributed to Gauteng users.

Of the above physical infrastructure projects, projects (v), (ix) and (xi) were removed from the

list for the following reasons:

Project (v), Botswana:

It was felt that the towns within the basin are not big enough to justify reclamation works.

Water reclamation could have been considered for Botswana s capital, Gabarone, but this city

falls outside the Orange-Senqu River Basin. Furthermore, in view of the fact that there is a

perceived public resistance against this type of project in Botswana it was decided at the

workshop of 11 March 2009 to rather focus on an awareness campaign that could remove any

possible negativism against reclaiming sewage effluent or reusing treated effluent water for

the irrigation of suitable food crops.

Project (ix), South Africa

Before the installation of dual systems in Gauteng can be enforced or encouraged, a set of

guidelines is firstly required. It was therefore decided that the installation of dual systems in

Gauteng is a bit premature and should rather follow a project that focuses on the preparation

of guidelines. It was therefore decided to remove the physical implementation of dual systems

as a possible project from the list and replace it with an enabling project, namely The

Preparation of Guidelines for Instal ing Dual Systems.

Project (xi), South Africa:

After identifying the better usage of mine water as a possible project, the PSP was made

aware of the fact that the Western Utility Corporation (WUC) is already planning a project for

the treatment of mine water. WUC is envisaging a water treatment plant that will remove all

heavy metals and other undesired constituents from the acidic mine water. WUC s first phase

would treat as much as 75 M /day which would then be sold as potable water to Rand Water.

18

Final Report

Assessment and Potential for the Development

July 2009

and Use of Marginal Waters

The inclusion of the mine water project would therefore have been a duplication of a project

that has already progressed far in terms of a feasibility study.

The remaining eight possible projects on the list were then accepted for evaluation by the PSC

Workshop on 11 March 2009 and, at the workshop, the following enabling projects for future

marginal water use were added to the l ist.

xii. The preparation of guidelines for dual systems in Gauteng where the second system will

supply treated wastewater for non-drinking purposes to large buildings, office blocks,

shopping centres, office parks etc.

xii . A review of the institutions, policy, legislation and guidelines in the four countries and the

addressing of gaps to enable easier implementation of the physical infrastructure projects

and to improve collaboration between the four basin countries.

xiv. Awareness campaign about the need and practice of reclaiming Botswana s treated

sewage effluent to potable standards and about the safety of irrigating food crops with

treated sewage effluent. Due to the negative public perception regarding the reuse and

reclamation of sewage effluent in Botswana, this project is aimed at addressing the public

perception. The outcome would be a greater public acceptance.

xv. The preparation of guidelines for use of treated waste water by the industry sector.

3.2

SELECTION CRITERIA

The following eleven criteria were used for prioritising the potential projects.

i. The extent to which the project will combat poverty, the greater the better.

i . Water stressed areas should receive preference.

i i. Does it provide an opportunity to test new technology?

iv. Wil the public perception towards the possible project be positive?

v. Wil the project have a beneficial impact on the basi n as a whole?

vi. The extent to which the project will alleviate environmental problems.

vii. The management intensity of the project, the lower the better.

vii . The ability to duplicate (i.e. ease of adding modules and in so doing, expanding the

project) or to copy project in other areas, the easier the better.

ix. Wil the project leave other water users downstream in a weaker position? E.g. Water

quality in the Orange River to the detriment of export grape farmers.

x. To what extent will the project lead to institutional growth?

19

Final Report

Assessment and Potential for the Development

July 2009

and Use of Marginal Waters

xi. Wil the project defer other projects (e.g. future augmentation projects which wil be more

expensive) in the basin state (locally or regionally)?

A condition with which it was recommended, all projects should be in place where a marginal

waters project is to be implemented was that al possible water conservation and water

demand management (WC/WDM) measures should already be being implemented. Normally

WC/WDM is the cheapest and most efficient way of making the most use of the available

water. However in cases where the usage of any marginal water option would be cheaper, the

latter could be pursued as long as the WC/WDM ha d been considered.

Apart from the above 11 criteria, a separate objective was to get a spread of projects in the

four basin countries.

In terms of the spread of projects, it would be ideal to have at least one project in each of the

basin countries.

3.3

EVALUATION MATRIX

An evaluation matrix was designed in which each project could be scored according to the

listed 11 criteria. Each of the 11 criteria had the same weight.

The evaluation matrix is shown in Table 3.3. All 11 potential projects are listed in the first

column of the matrix. In the second column (first grey column) it can be indicated whether

WC/WDM had been properly considered. The second grey column shows in which country the

project will be. The objective is to have an even spread of projects among the four basin

countries.

Since it is required that Scopes of Work for at least five projects are prepared, it meant that at

least one project should fall in each of the basin countries. The next 11 columns show11

criteria described in paragraph 3.2 above. The green colour represents the most favourable

evaluation with a score of 3, the blue represents a medium score of 2 and the yel ow the least

favourable with a score of 1.

The awareness strategy for Botswana was awarded the highest point of 29 out 33 while the

two rainwater harvesting projects (Lesotho and South Africa) were awarded the lowest score

(both 23 out of 33).

20

Final Report

Assessment and Potential for the Development

July 2009

and Use of Marginal Waters

Table 3.3 Assessment of Potential Projects at workshop on 11 March 2009

Potential Project Assessment

Criteria

WC&DM

Spread of

Poverty

Water

New

Public

Benefits to

Environmental Management

Duplicate or

Downstrea Institutional

Defer local

Total

Priority

projects

Alleviation

stressed

technology perception

the basin

impacts

intensity

Copy

m users

growth

projects

Projects

Potential Projects

Irrigation - Maseruand

lowland towns

Lesotho

2

3

1

3

1

2

2

3

3

3

2

25

Effluent reclaim - Maseru

Lesotho

3

2

2

1

1

2

1

3

3

3

3

24

Rainwater harvest - Maseru

Lesotho

3

2

1

3

1

2

3

2

2

2

2

23

Irrigation - Botswana

Botswana

2

3

1

3

1

2

2

3

3

3

2

25

Effluent reclaim (awareness) -

Botswana

n/a

Botswana

3

3

2

2

2

2

3

3

3

3

3

29

Aquifer recharge - Botswana

Botswana

3

3

3

3

2

2

1

3

2

2

3

27

Saline groundwater -

Botswana

Botswana

3

3

3

3

2

2

1

3

2

2

3

27

Irrigation - large basin towns

Namibia

2

3

1

3

1

2

2

3

3

3

2

25

Dual system guidelines -

Gauteng

n/a

South Africa

2

3

2

2

3

2

3

3

2

3

3

28

Rainwater harvest - SA

South Africa

3

2

1

3

1

2

3

2

2

2

2

23

Industrial use Guidelines

(Transboundary)

n/a

All

1

3

2

2

3

3

3

3

3

3

2

28

Institutional review

(Transboundary)

n/a

All

1

3

2

2

3

2

3

3

2

3

1

25

Other

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

Other

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

33

Key

3

High

2

Medium

1

Low

21

Final Report

Assessment and Potential for the Development

July 2009

and Use of Marginal Waters

In order to satisfy the objective to achieve an even spread of projects between the four

countries, it was not possible to simply choose the five projects with the highest scores. It was

therefore decided to select one country specific project for each of the four basin states and

then to select another two transboundary projects, with high scores that would be beneficial to

all four basin states. The Terms of Reference required the selection of at least five projects.

The six selected projects, as indicated in the last column of the evaluation matrix are the

following:

i. Botswana: Awareness campaign to promote indirect potable water reuse and irrigation of

food crops with treated sewage effluent.

i . South Africa: Dual reticulation system guidelines for Gauteng

i i. Lesotho: Irrigation of sport fields, the golf course and suitable food crops in Maseru with

treated wastewater