Report No. ORASECOM/005/2009

ORASECOM

GROUNDWATER REVIEW OF THE MOLOPO-NOSSOB

BASIN FOR RURAL COMMUNITIES INCLUDING

ASSESSMENT OF NATIONAL DATABASES AT THE SUB-

BASIN LEVEL FOR POSSIBLE FUTURE INTEGRATION

FINAL REPORT

July 2009

In association with

GEOTECHNICAL CONSULTING SERVICES (PTY) LTD

CONTINENTAL CONSULTANTS (PTY) LTD

Plot No. 61687, Unit 2, Broadhurst Industrial,

Plot No. 20630, Broadhurst Industrial,

P.O.Box:201675, Gaborone, Botswana

P.O.Box:45560, Gaborone, Botswana

Te

Tel: 00267 316 5820

l/Fax: 00267 313 2967; email gcs@info.bw

Report No. ORASECOM/005/2009

Title:

Final Report

Authors:

Dr Leif Carlsson with inputs from, Mrs Constance Masalila-

Dodo, Dr R Bejugam, Mr L Sola, Dr B F Alemaw, Mr

I.Mahomed, and Mr G.Madec

Project Name:

Groundwater Review of the Molopo-Nossob Basin for Rural

Communities including Assessment of National Databases at

the Sub-basin Level for Possible Future Integration

Status of report:

Final

Date:

July 2009

Keywords:

Molopo River, Nossob River, Groundwater Resources

______________________________________________________________________

Geotechnical Consulting Services (Pty) Ltd

Approved for and on behalf of Geotechnical Consulting Services (Pty) Ltd

by

...............................................

.......................................

Dr Ravinder Bejugam

Date

Director: Geotechnical Consulting Services (Pty) Ltd

ORANGE SENQU RIVER COMMISSION

Approved on behalf of ORESECOM by

...............................................

......................................................

Mr Lenka Thamae

Date

Executive Secretary ORASECOM

Groundwater Review of the Molopo-Nossob Basin

Report No. ORASECOM/005/2009

Groundwater Review of the Molopo-Nossob Basin for Rural Communities

including Assessment of National Databases at the Sub-basin Level for

Possible Future Integration

Executive Summary

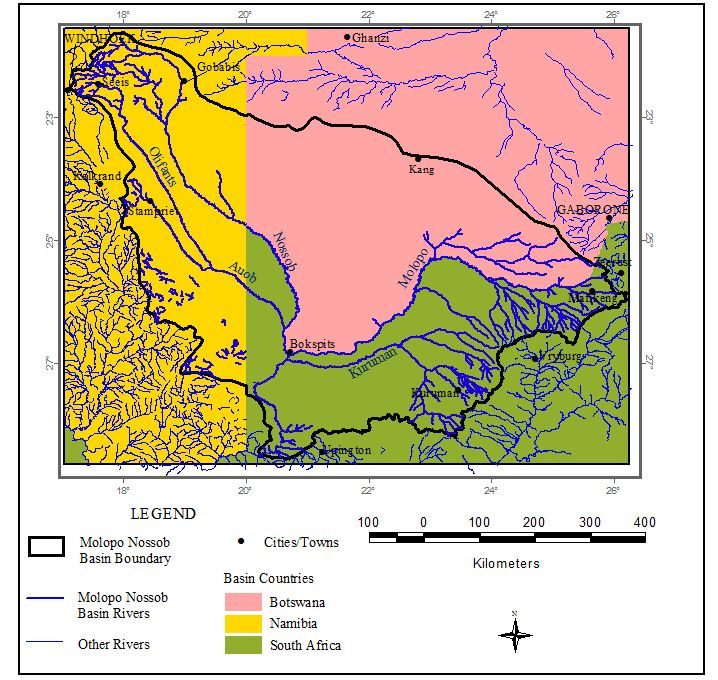

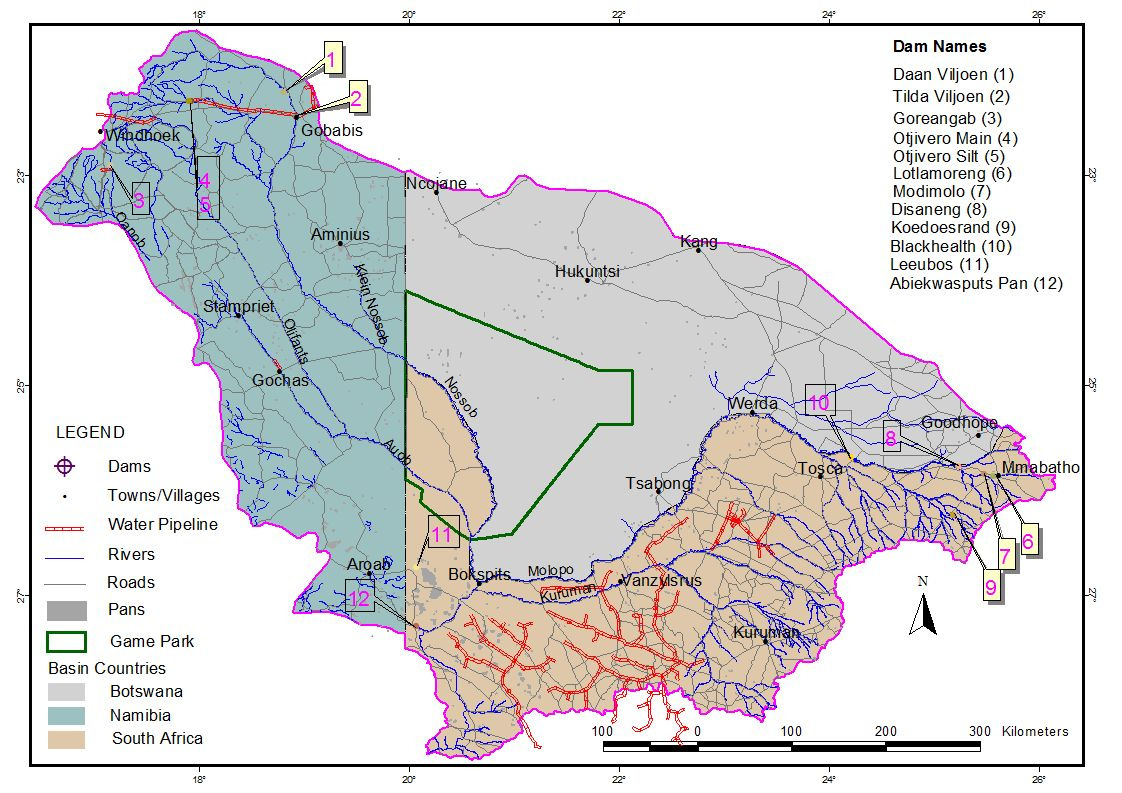

The Molopo River is an ephemeral tributary of the Orange Senqu River system, an

international river basin shared by Lesotho, Namibia, Botswana and South Africa. The

Orange-Senqu River Commission (ORASECOM) is established to advise the parties on water

related issues. The size of the Molopo-Nossob Basin is approximately one and a half times

the size of Great Britain, 12 times the size of Lesotho or almost equal to the size of Japan.

The main objective of the project was to evaluate the groundwater resources of the Molopo-

Nossob Basin based on an exhaustive analysis of the available data and information. This

included a thorough analysis of the data/databases in each of the basin states in order to

make recommendations on how data can best be shared between the basin states and

integrated in a common database.

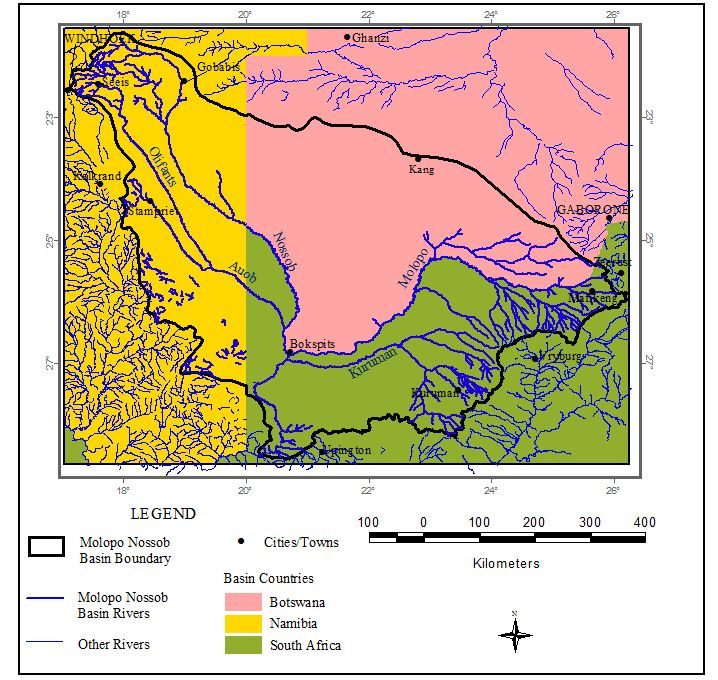

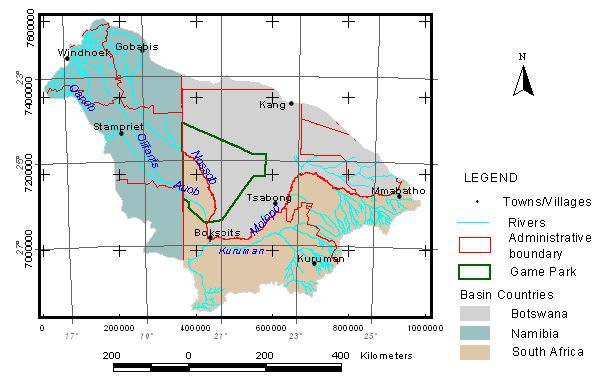

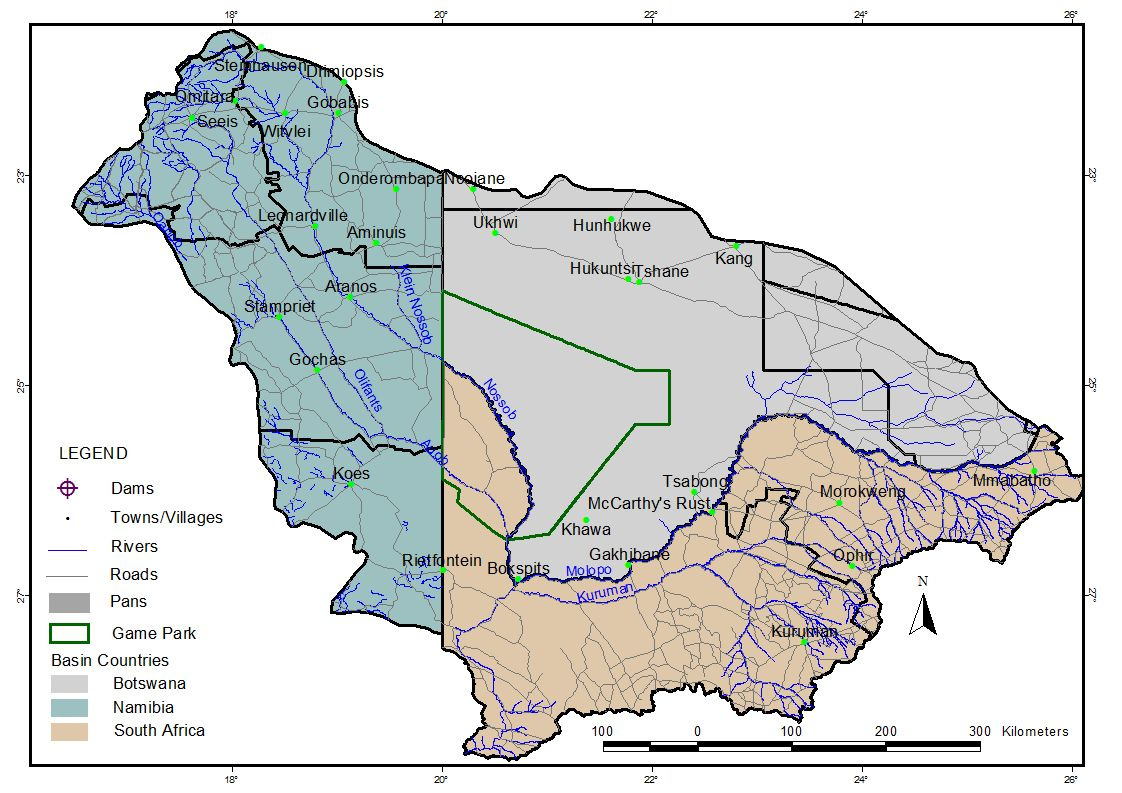

The Molopo-Nossob Basin covers an area of 367,201 km2delineated from the surface water

catchment. Of the basin, Botswana covers 37%, Namibia 33% and South Africa 30%. The

basin contains the catchment areas of four main rivers; Molopo, Kuruman, Nossob and Auob

Rivers.

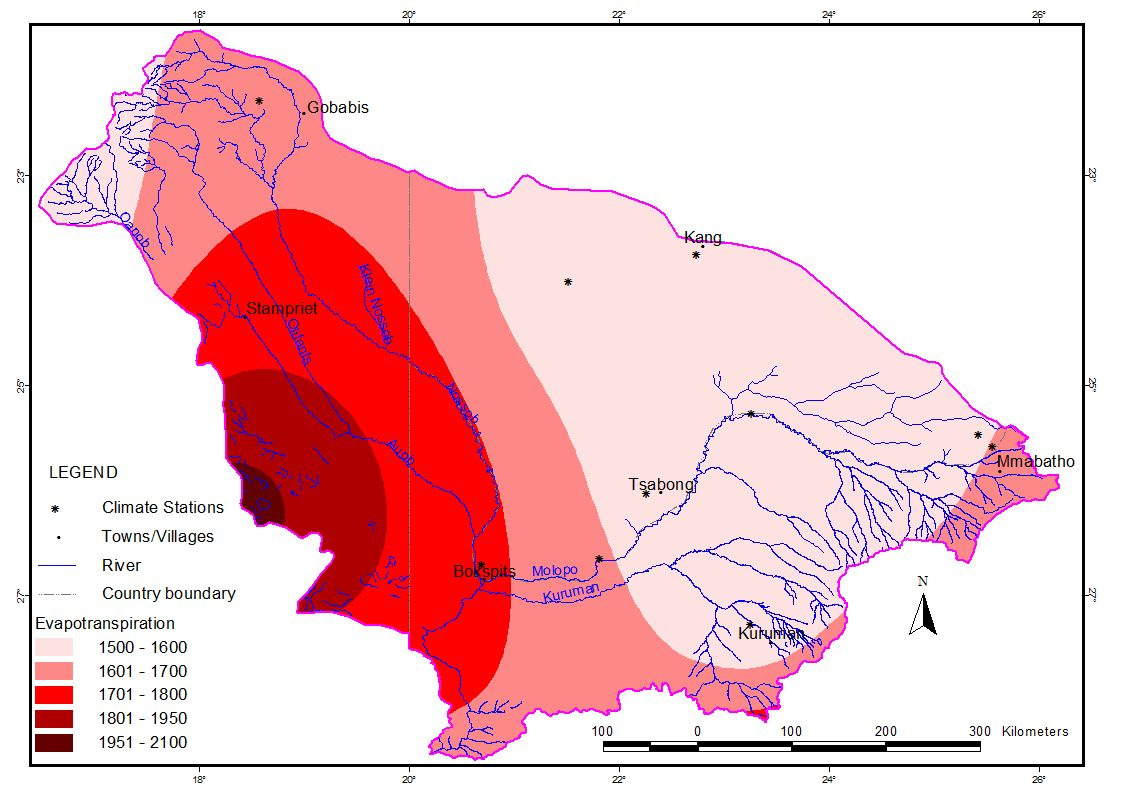

The long term average annual precipitation varies from 100 mm/a in the south-western part

of the basin to over 500 mm/a in the eastern part in South Africa, and 400 mm/a in the

northern part in Namibia. Evaporation and potential evapotranspiration highly exceed the

average rainfall. According to UNEP classification, the whole basin is arid to semi-arid.

The population in the Molopo-Nossob Basin is about one million, and the livestock units

(ELSU) are about 1.6 million including wildlife. The population per km2 varies from 0.2 in

Kgalagadi North District in Botswana to 62 for the Upper Molopo catchment area

(Mmabatho area in South Africa) and an average for the basin the population density is 2.7

persons per km2. The ELSU density is almost similar in the three countries (4.2 to 4.6 ELSU

per km2).

The water requirement in the Molopo-Nossob Basin is referred to domestic, livestock,

irrigation and mining users. The total requirement is 128 Mm3/a (2000). Of this 69% is

required in South Africa, 18% in Namibia and 13% in Botswana. About 37% of the water

requirement goes to livestock watering, 27% to domestic purposes, 27% to irrigation and 9%

to industry (mining). Only 0.1% is for tourism.

Development which requires a major quantity of water is foreseen in the Botswana part of

the Basin where plans for irrigation developments will require about 6.2 Mm3/a of water

from the year 2015. Other major water consuming developments are for the mining industry

in South Africa together with plans for increased irrigation. The future water requirements

for the three countries will increase by the year 2015 to about 160 Mm3/a. On the average

an annual increase in the water requirement for the Molopo-Nossob Basin is about 1.5%.

Geotechnical Consulting Services

I

Groundwater Review of the Molopo-Nossob Basin

Report No. ORASECOM/005/2009

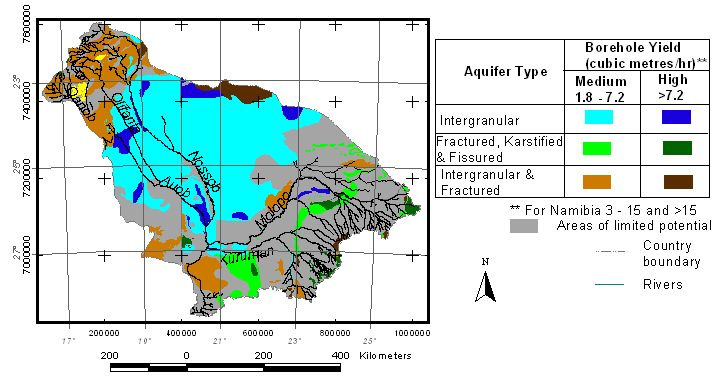

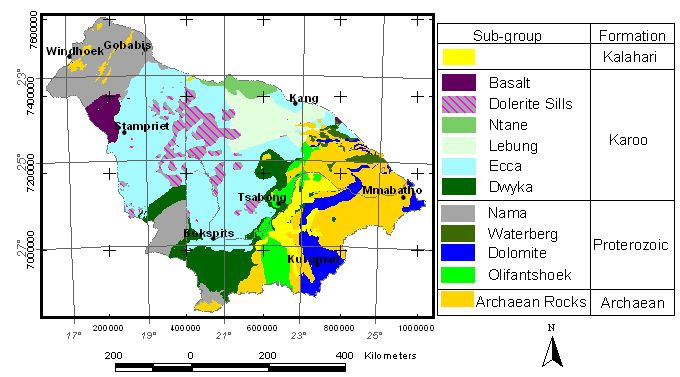

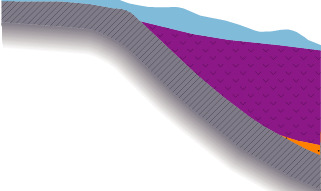

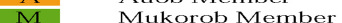

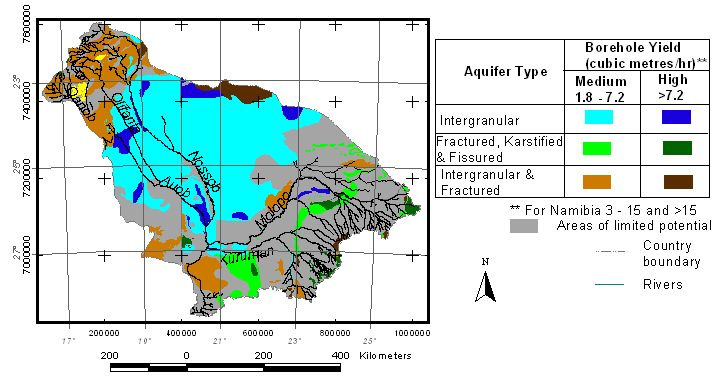

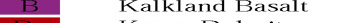

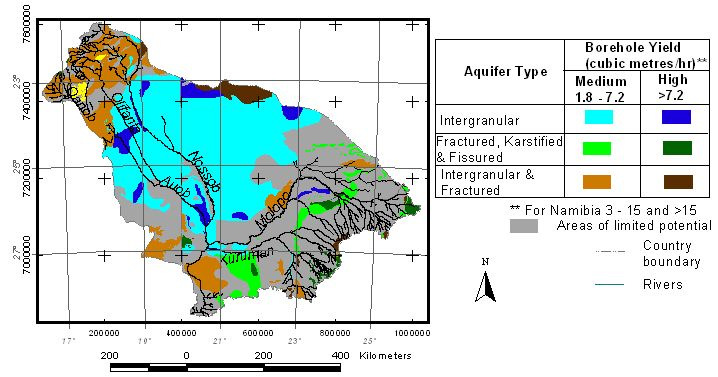

The geology of the basin covers geological formations from the Archean to Recent, a time

span of more than 2,500 million years. The formations host a variety of aquifers;

intergranular, fractured intergranular, fractured and karstic aquifers.

The potential of the aquifer is assessed from the mean borehole yields displayed on

hydrogeological maps over the Namibian and the South African part of the basin. Three

classes of potential are recognized; high, medium and low potential. For Botswana the

potential is based on regional groundwater maps combined with results from groundwater

investigation in local areas in the basin.

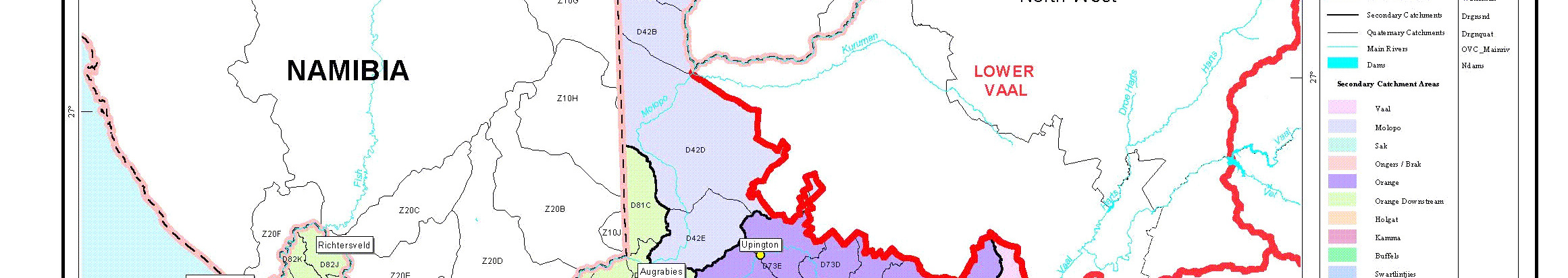

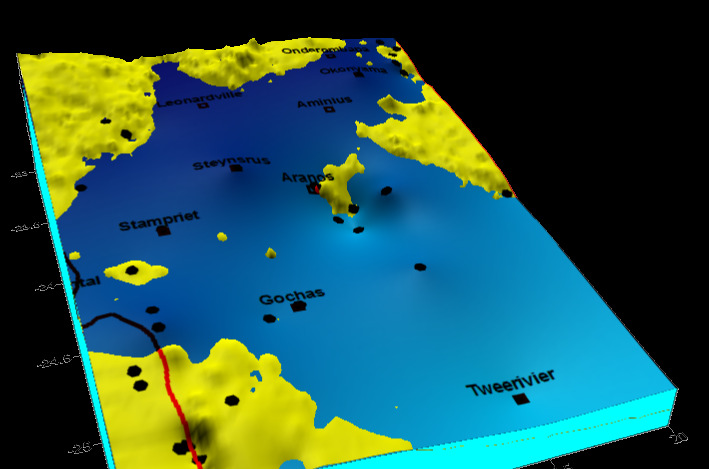

The Kalahari Beds contains locally groundwater. "Saturated" Kalahari Beds are found in

the Gemsbok National park and the continuation into the Namibian part of the basin

following the river Nossob and Auob up to Stampriet and Aminuis. Large areas are also

found along the Upper Molopo River Course, in Gordonia and in the central part of

Botswana. Beside these larger areas, "perched aquifers" occur locally in the Kalahari Beds.

-22°S

Saturated Kalahari Beds

-23°S

Aminuis

Kang

-24°S

Stampriet

200

Gochas

-25°S

180

160

140

-26°S

120

100

Bokspits

-27°S

80

60

40

Saturated

-28°S

thickness

20

m

0

Kalahari Beds limit

17°E

18°E

19°E

20°E

21°E

22°E

23°E

24°E

25°E

26°E

Geotechnical Consulting Services

II

Groundwater Review of the Molopo-Nossob Basin

Report No. ORASECOM/005/2009

The largest aquifers in the basin are the fractured intergranular Ecca aquifer (the Auob

aquifer) and the intergranular Kalahari Bed aquifer. These two aquifers interact in areas

where they are in contact with each other. Multiple aquifers occur in areas in Namibia and

Botswana where a deep layer of sandstone (Nossob sandstone) is found below the Ecca

aquifer and interlayered low permeable formations. The extensive Ecca aquifer of Karoo

Supergroup (combined with the Kalahari Bed) is classified as a medium potential aquifer, but

it includes many areas assessed as high potential aquifers. In the Karoo Supergroup a high

potential Ntane Sandstone aquifer is also found above the Ecca aquifer in the northern

Botswana.

The aquifers with the highest potential in karst environment are found in the dolomitic

formations in South Africa and Botswana. These formations are also host areas currently

classified as medium potential aquifers.

The crystalline bedrock is classified as low potential aquifers. These formations are found in

the northern part of Namibia and in eastern Botswana and large part of South Africa.

Groundwater is available but limited to the occurrence in fractures and fissures. Where

fractures form pronounced and extensive zones, good yielding local aquifers are

encountered.

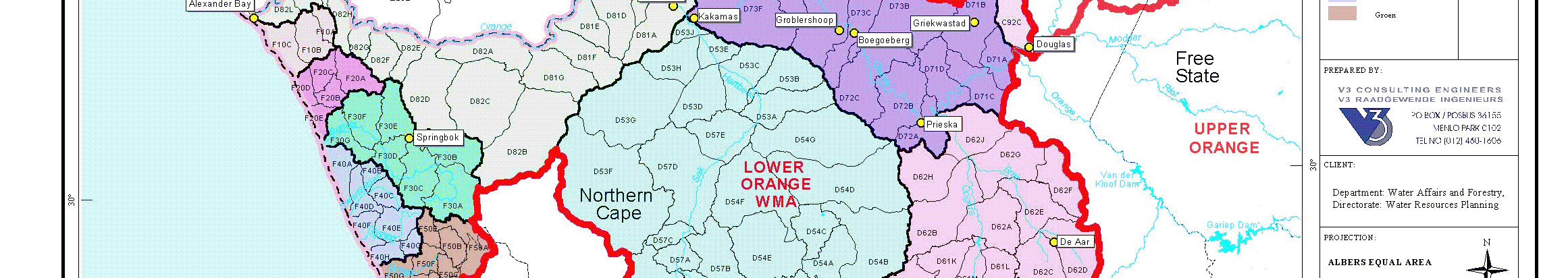

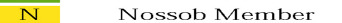

The quality of the groundwater varies within the basin. Guidelines for domestic use and for

livestock watering regarding the content of Total Dissolved Solids (TDS), nitrate (NO3) and

fluoride (F) are similar in the three countries. Maps are constructed to show the areas in

which the guideline values are met or exceed.

-22°S

Areas with water exceeding

-22°S

Areas with water exceeding

quality guidelines

Gobabis

Windhoek

quality guidelines

for human consumption

for livestock watering

-23°S

-23°S

Ncojane

Aminuis

Kang

Hukuntsi

-24°S

-24°S

Stampriet

Gochas

Gochas

-25°S

-25°S

Salt-

Werda

Goodhope

Block

Tosca

Mmabatho

area

Tsabong

-26°S

-26°S

Aroab Bokspits Vanzylsrus

-27°S

-27°S

Kuruman

-28°S

-28°S

17°E

18°E

19°E

20°E

21°E

22°E

23°E

24°E

25°E

26°E

17°E

18°E

19°E

20°E

21°E

22°E

23°E

24°E

25°E

26°E

NO3 > 45 mg/l

F >1,5 mg/l

TDS > 2,000 mg/l

NO3 > 180 mg/l

F >4 mg/l

TDS > 10,000 mg/l

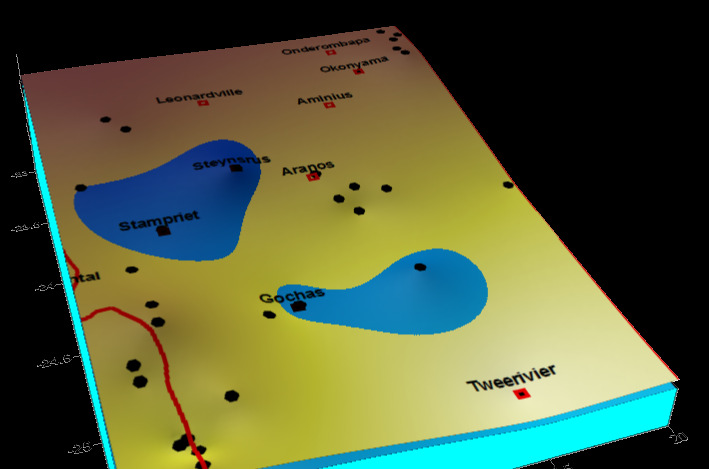

The larger part of Botswana has groundwater quality exceeding the guidelines for human

consumption. In Namibia, the groundwater quality is poor along the Auob River downstream

Gochas (the Salt-Block area). The area of poor water quality continues into South Africa

where almost the whole Gordonia experience water quality exceeding the guideline limits for

TDS and F. Areas of good water quality are found in the middle and northern part on

Namibia, central and eastern part of South Africa and easternmost and north-western part of

Botswana. Limited minor areas of high NO3 are found referring to local groundwater

pollution.

Geotechnical Consulting Services

III

Groundwater Review of the Molopo-Nossob Basin

Report No. ORASECOM/005/2009

For livestock watering the areas of unfit groundwater are limited to central and southern

parts of Botswana, the Salt-Block area in Namibia and a minor part in the Gordonia area.

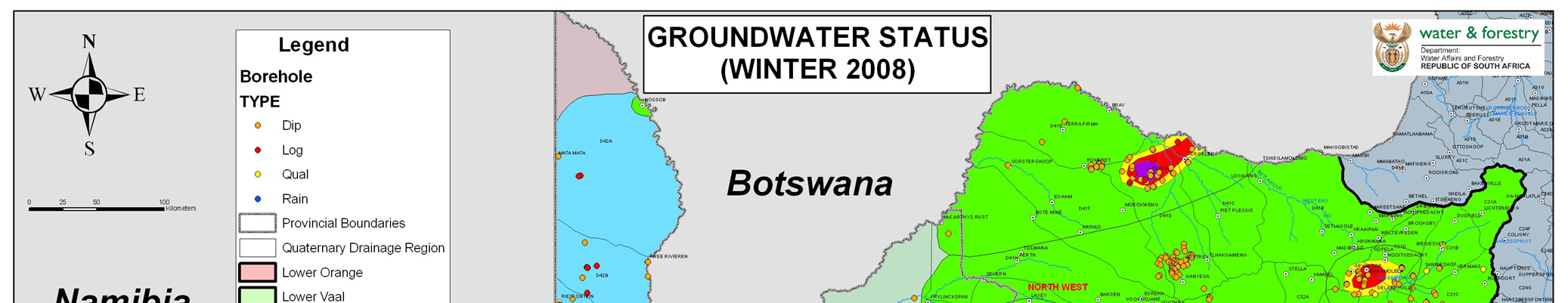

Monitoring of the groundwater level is done in more than 600 boreholes in the Molopo-

Nossob Basin. The majority of monitoring boreholes are close to abstraction boreholes or in

wellfield areas. Monitoring is done on various time intervals and using different methods.

The use of automatic monitoring devices has increased which has resulted in improved

continuity of the records.

-22°S

Regional groundwater level map

-23°S

Kang

-24°S

1850

Stampriet

1800

1750

-25°S

1700

1650

1600

1550

1500

1450

-26°S

1400

1350

1300

1250

1200

1150

-27°S

1100

1050

Bokspits

1000

950

900

Groundwater

850

-28°S

800

level

750

700

m.a.m.s.l.

650

17°E

18°E

19°E

20°E

21°E

22°E

23°E

24°E

25°E

26°E

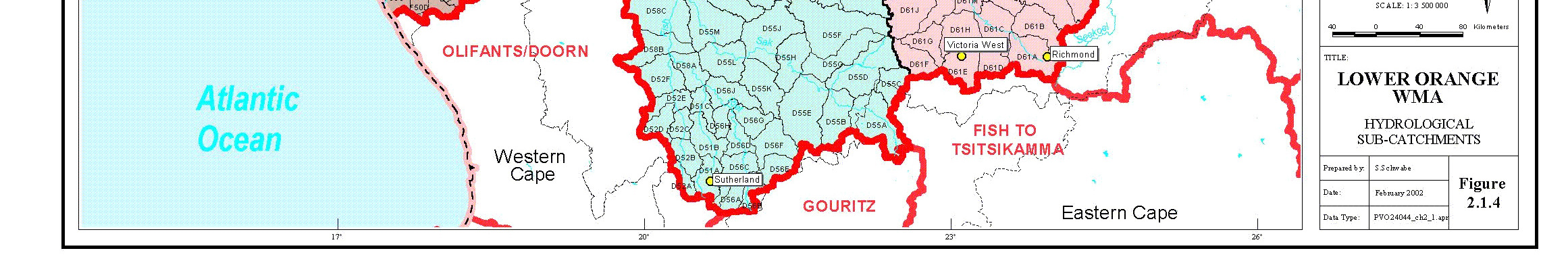

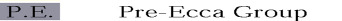

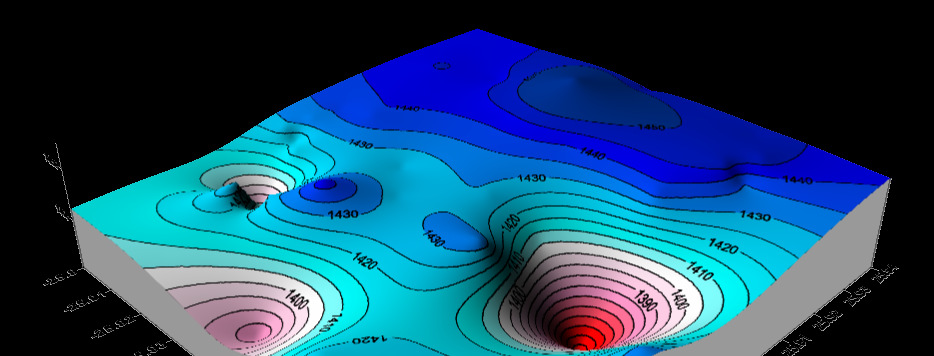

Groundwater level data stored in the borehole archives in all the three countries, together

over 34,000 boreholes, forms the background information for a regional groundwater level

map over the Molopo-Nossob Basin. The map shows that the highest groundwater levels

(1,750 mamsl) are in the northern Namibian part of the basin. From there the groundwater

flow is directed southeast into Botswana and South Africa and from there towards the south

and out from the basin through the area along the southern part of the Molopo River (750

mamsl). High groundwater level is also encountered in the south-eastern South African part

of the basin (1,450 mamsl).

The groundwater divide in northern Botswana does not follow the surface water divide as it

is illustrated on Botswana water maps. That makes in fact the Molopo-Nossob Basin smaller

than derived from the surface water divide.

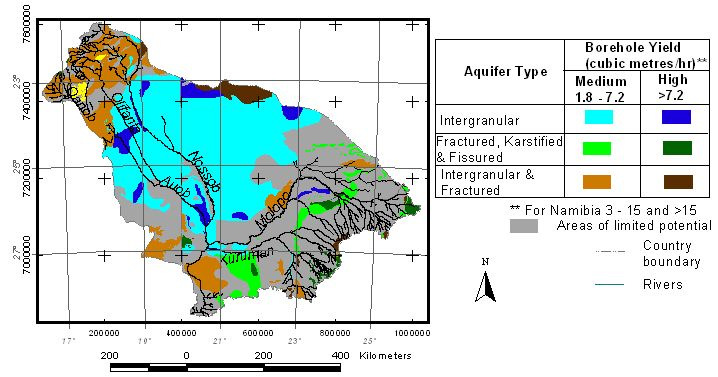

The Chloride Mass Balance method was used to assess the groundwater recharge from the

rainfall. This method shows that large areas of the basin receive less than 1 mm/a recharge

as a long term average. Recharge of more than 10 mm/a is assessed for the northern part and

for the area northwest of Stampriet and Aminuis in Namibia and south-eastern part

(Mmabatho) and the Kuruman area in South Africa.

Extreme low recharge (< 0.1 mm/a as an average annual value) is assessed for the central

part of Botswana close to the Gemsbok National park, an area northeast of Bokspits and for

the central part of Gordonia in South Africa. In Botswana recharge of more than 2 mm/a is

found for the north-western and the south-eastern parts.

Geotechnical Consulting Services

IV

Groundwater Review of the Molopo-Nossob Basin

Report No. ORASECOM/005/2009

-22°S

Groundwater Recharge in mm/a

assessed using

the Chloride Mass Balance Method

-23°S

Aminuis

Kang

-24°S

Stampriet

Gochas

20

-25°S

10

-26°S

5

2

Bokspits

-27°S

1

0.5

Recharge

-28°S

mm/a

0.1

17°E

18°E

19°E

20°E

21°E

22°E

23°E

24°E

25°E

26°E

The hydrogeological regime of the Molopo-Nossob Basin is complex with many types of

geological formation and hence of groundwater resources (aquifers). A qualitative indicative

assessment approach was taken by combining various data sets and knowledge collected to

delimit areas where the already described water quality guidelines are not satisfied together

with recharge estimated at a minimum 0.2 mm/a to produce two new set of maps as part of

the groundwater resource evaluation..

-22°S

Human Consumption

-22°S

Gobabis

Gobabis

Livestock Watering

Windhoek

Windhoek

-23°S

Ncojane

-23°S

Ncojane

Aminuis

Kang

Aminuis

Kang

Hukuntsi

Hukuntsi

-24°S

-24°S

Stampriet

Stampriet

Gochas

Gochas

-25°S

Werda

-25°S

Werda

4

Goodhope

Goodhope

Tosca

Mmabatho

Tosca

Mmabatho

Tsabong

3

Tsabong

-26°S

-26°S

3

Aroab

Bokspits

Vanzylsrus

Aroab

Bokspits

Vanzylsrus

-27°S

-27°S

2

2

Kuruman

Kuruman

-28°S

-28°S

1

1

17°E

18°E

19°E

20°E

21°E

22°E

23°E

24°E

25°E

26°E

17°E

18°E

19°E

20°E

21°E

22°E

23°E

24°E

25°E

26°E

Integrated GIS based Basin Information System is based on the availability and level of

information differs between the countries. There is a need to share data between countries in

order to best understand the groundwater situation and for optimum planning, resource

development and sustainable management. The integration of both databases and the

exchange facilities requires that information systems within the countries are compatible.

A proposal to facilitate the exchange of data as well as possible integration will be a GIS

data storage and management system. The system should have capabilities to be used as an

information centre for the basin in order to provide rapid responses to groundwater

evaluation and modeling of the sub-basin and facility for dissemination and exchange of data

within the states.

Geotechnical Consulting Services

V

Groundwater Review of the Molopo-Nossob Basin

Report No. ORASECOM/005/2009

It is recommended that the database be developed in Microsoft SQL Server technology.

It is recommended that monitoring of groundwater; both quality and level should be

continued and extended to include areas which are remote and not affected by human

development.

It is further recommended that more than the currently used chloride mass method for

recharge assessment should be applied in the basin. The current assessment of recharge

should also be assessed in comparison with the general flow of groundwater in the basin

through mathematical modeling.

The use of the concept of Groundwater Harvest Potential introduced in South Africa should

be extended and map produced also for Namibia and Botswana, especially for areas of low

groundwater recharge.

Large parts of the basin has water unfit for human consumption and for livestock watering.

Water treatment options exist and could be applied for private and communal use. The

current and future use of such treatment option should be addressed.

Geotechnical Consulting Services

VI

Groundwater Review of the Molopo-Nossob Basin

Report No. ORASECOM/005/2009

Groundwater Review of the Molopo-Nossob Basin for Rural Communities

including Assessment of National Databases at the Sub-basin Level for

Possible Future Integration

FINAL REPORT

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1

INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1

1.1

Background ............................................................................................................................. 1

1.2

Purpose of the Study ............................................................................................................... 2

1.3

Purpose of this Report ............................................................................................................. 2

1.4

Structure of this Report ........................................................................................................... 2

2

DESCRIPTION OF THE MOLOPO-NOSSOB BASIN ................................................................ 3

2.1

Main Catchment areas ............................................................................................................. 3

2.2

Relief and drainage ................................................................................................................. 5

2.3

Administrative Units ............................................................................................................... 5

2.4

Climate .................................................................................................................................... 7

2.4.1

Climate data considered .................................................................................................. 7

2.4.2

Precipitation .................................................................................................................... 8

2.4.3

Temperature .................................................................................................................. 10

2.4.4

Humidity ....................................................................................................................... 11

2.4.5

Solar radiation and sunshine hours ............................................................................... 13

2.4.6

Evaporation and Evapotranspiration ............................................................................. 14

2.4.7

Rainfall and ETo at selected stations ............................................................................ 16

2.4.8

Aridity Index ................................................................................................................. 16

2.4.9

Droughts ........................................................................................................................ 18

2.5

Main Rivers ........................................................................................................................... 21

2.5.1

Auob River .................................................................................................................... 21

2.5.2

Nossob River ................................................................................................................. 24

2.5.3

Molopo River ................................................................................................................ 25

2.5.4

Kuruman River .............................................................................................................. 26

2.6

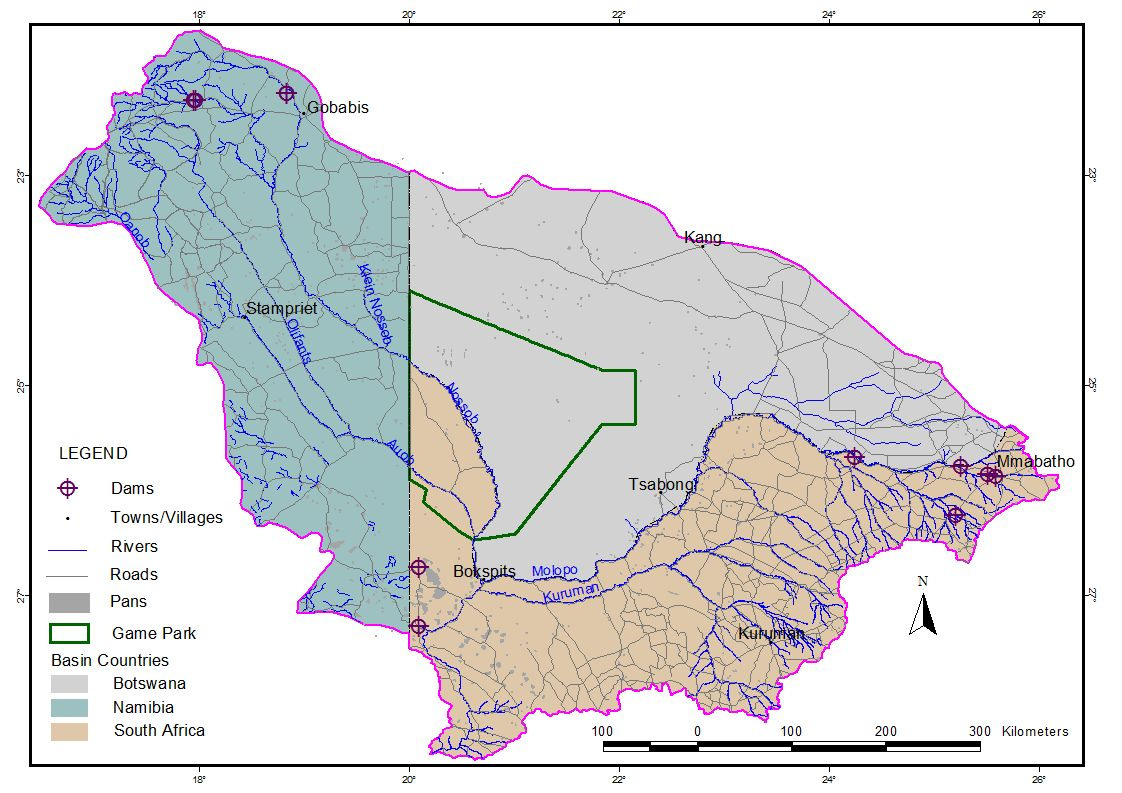

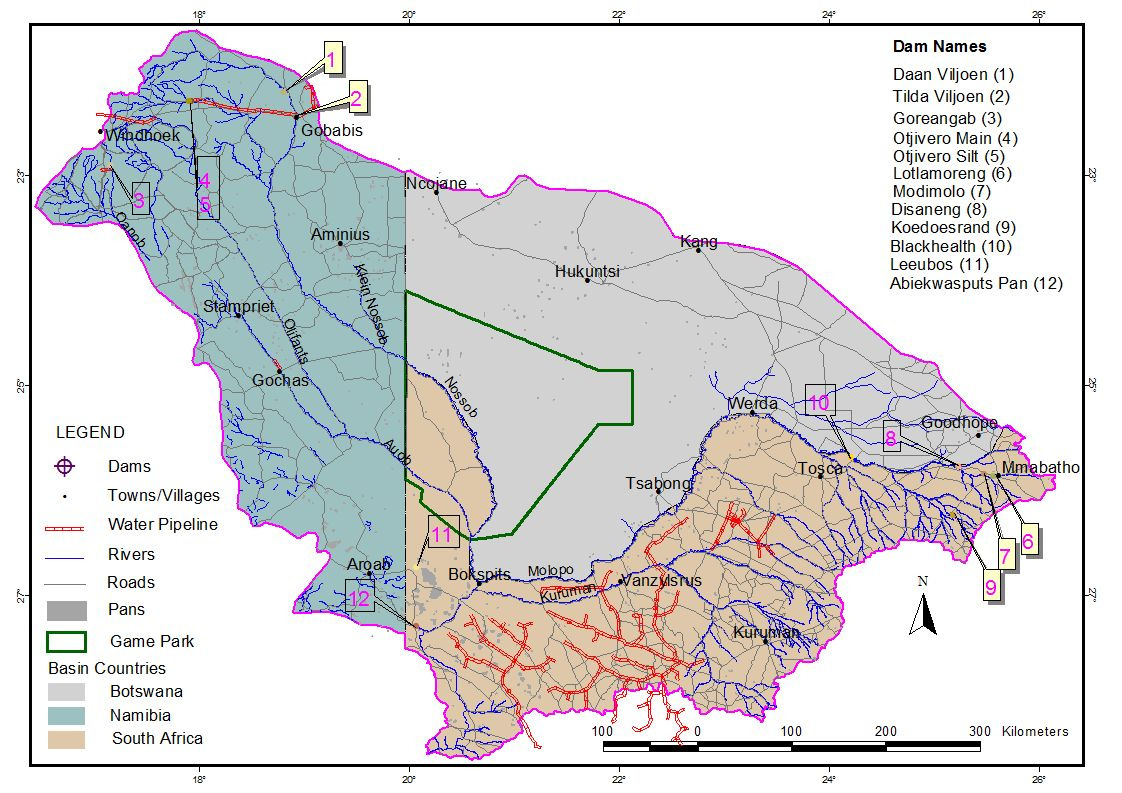

Dams ..................................................................................................................................... 26

2.7

Transfer Systems ................................................................................................................... 27

2.8

Pans ....................................................................................................................................... 28

3

WATER REQUIREMENT ........................................................................................................... 30

3.1

Users ..................................................................................................................................... 30

3.2

Botswana ............................................................................................................................... 30

3.3

Namibia ................................................................................................................................. 36

3.4

South Africa .......................................................................................................................... 45

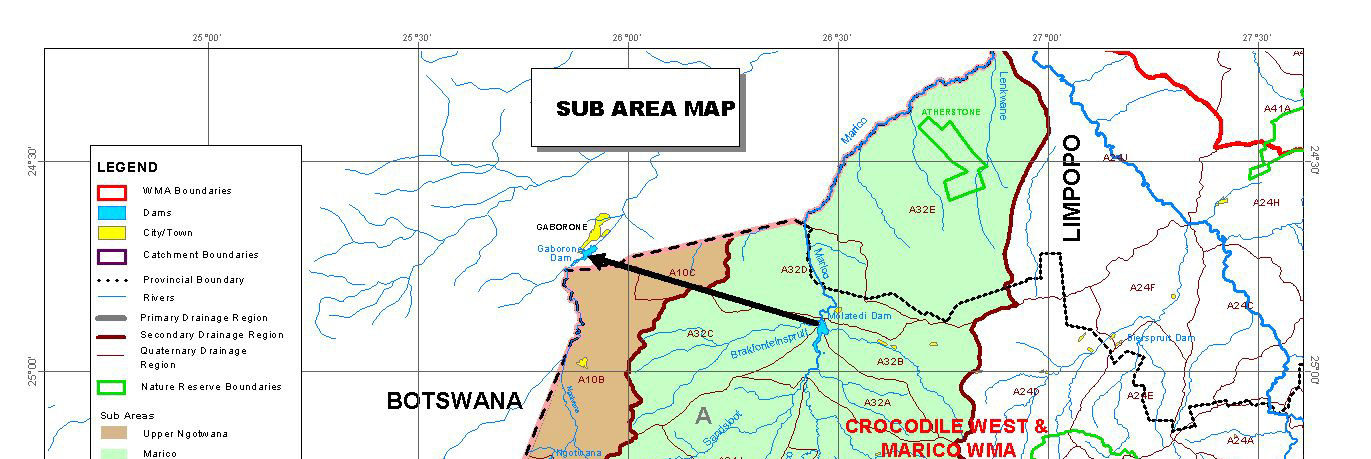

3.4.1

Water management Areas ............................................................................................. 45

3.4.2

Upper Molopo ............................................................................................................... 46

3.4.3

Middle Molopo ............................................................................................................. 47

3.4.4

Lower Molopo .............................................................................................................. 49

Geotechnical Consulting Services

i

Groundwater Review of the Molopo-Nossob Basin

Report No. ORASECOM/005/2009

3.4.5

Summary for Molopo-Nossob Basin in South Africa ................................................... 51

3.5

Summary for Molopo-Nossob Basin .................................................................................... 56

4

DEVELOPMENT ACTIVITIES .................................................................................................. 61

4.1

Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 61

4.2

Current Development Activities ........................................................................................... 61

4.2.1

Botswana ....................................................................................................................... 61

4.2.2

Namibia ......................................................................................................................... 62

4.2.3

South Africa .................................................................................................................. 64

4.3

Development Activities in the Districts ................................................................................ 64

4.3.1

Agriculture .................................................................................................................... 65

4.3.2

Mining ........................................................................................................................... 66

4.3.3

Tourism ......................................................................................................................... 67

4.4

Planned Development Activities ........................................................................................... 69

4.5

Future Water Requirement .................................................................................................... 70

5

GEOLOGY AND HYDROGEOLOGY ....................................................................................... 73

5.1

Geology ................................................................................................................................. 73

5.1.1

Background Information ............................................................................................... 73

5.1.2

Geological Map ............................................................................................................. 73

5.2

Hydrogeology ....................................................................................................................... 82

5.2.1

Aquifers ......................................................................................................................... 82

5.2.2

Groundwater Quality..................................................................................................... 90

5.2.3

Groundwater Monitoring and Flow ............................................................................ 111

5.2.4

Springs ........................................................................................................................ 134

5.2.5

Groundwater Replenishment ....................................................................................... 136

5.2.6

Groundwater Modeling ............................................................................................... 142

6

GROUNDWATER RESOURCES ............................................................................................. 158

6.1

Evaluation process .............................................................................................................. 158

6.2

Resources ............................................................................................................................ 161

7

INTEGRATED GIS BASED SUB-BASIN INFORMATION SYSTEM .................................. 165

7.1

Background ......................................................................................................................... 165

7.2

Elements in an integrated database system ......................................................................... 165

7.3

Existing databases ............................................................................................................... 166

7.3.1

Botswana ..................................................................................................................... 166

7.3.2

Namibia ....................................................................................................................... 167

7.3.3

South Africa ................................................................................................................ 170

7.4

Meta database ...................................................................................................................... 173

7.5

Proposal for storage and exchange of information ............................................................. 174

7.5.1

Separate databases....................................................................................................... 174

7.5.2

Data integration ........................................................................................................... 174

7.5.3

Requirements for developing basin information system ............................................. 176

8

LITERATURE REFERENCES .................................................................................................. 177

8.1

ENDNOTE Software .......................................................................................................... 177

8.2

Geographic and Administrative Description ....................................................................... 178

8.3

Climatic Information ........................................................................................................... 179

Geotechnical Consulting Services

ii

Groundwater Review of the Molopo-Nossob Basin

Report No. ORASECOM/005/2009

8.4

Hydrological Information ................................................................................................... 179

8.5

Groundwater Information ................................................................................................... 179

8.6

Water Requirements ............................................................................................................ 180

8.7

Future Plans and Developments .......................................................................................... 181

9

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ..................................................................... 182

9.1

Conclusions ......................................................................................................................... 182

9.2

Recommendations ............................................................................................................... 185

10

REFERENCES ....................................................................................................................... 187

Geotechnical Consulting Services

iii

Groundwater Review of the Molopo-Nossob Basin

Report No. ORASECOM/005/2009

LIST OF TABLES

Table 2-1 Main sub-catchment areas within the Molopo-Nossob River Basin ................................... 3

Table 2-2 Administrative districts within the three riparian countries of the Molopo-Nossob basin .. 6

Table 2-3 Major districts and settlements in Namibia and South Africa part of Molopo-Nossob ....... 7

Table 2-4 Selected rainfall stations in Molopo-Nossob basin ............................................................. 8

Table 2-5 UNEP classification of various degrees of aridity based on their index of aridity (UNEP,

1992) .................................................................................................................................. 18

Table 2-6 SPI and corresponding cumulative probability ................................................................. 20

Table 2-7 Interpretation of SPI classes .............................................................................................. 21

Table 2-8 Dams within the Molopo-Nossob Basin............................................................................ 26

Table 2-9 Major water transfer schemes into and within the Molopo-Nossob Basin ........................ 28

Table 2-10 Details of Pans in the Molopo-Nossob Sub-basin ............................................................. 29

Table 3-1 Major towns and villages in the Molopo-Nossob Basin.................................................... 31

Table 3-2 Districts and sub-districts covered by the Molopo-Nossob basin in Botswana ................. 32

Table 3-3 Water requirements for the village (domestic water requirement) within the district of

Botswana in the Molopo-Nossob basin (DWA, 2006) ...................................................... 33

Table 3-4 Livestock Population by district and region in the Molopo-Nossob Basin 2002.

Equivalent Large Stock Units (ELSU) .............................................................................. 34

Table 3-5 Water requirement in Mm3/a for various livestock in the Districts in Botswana within the

Molopo-Nossob Basin. The requirements include wastage of water with 50% ................ 34

Table 3-6 Potential and planned irrigation in the Molopo-Nossob Basin in Botswana (NAMPAD,

2000) .................................................................................................................................. 35

Table 3-7 Estimated water requirement for the Molopo-Nossob basin in Botswana ........................ 35

Table 3-8 Sizes of basins in the Namibian part of the Molopo-Nossob Basin (MAWRD, 2000) ..... 36

Table 3-9 Estimated Population in the Molopo-Nossob Basin in Namibia (MAWRD, 2000,

ORASECOM, 2007b) ....................................................................................................... 37

Table 3-10 Water use and requirement in Auob River and Nossob River Basin2 in Namibia 1999,

2005 and 2015 (MAWRD, 2000) ...................................................................................... 38

Table 3-11 Water user and requirement (Mm3/a) in Molopo-Nossob Basin in Namibia 1999, 2005

and 2015 (MAWRD, 2000) ............................................................................................... 38

Table 3-12 Veterinary area codes and sizes in the Molopo-Nossob basin. Calculated water

requirement for livestock, based on numbers from 1999 (MAWF, 2006) ......................... 40

Table 3-13 Daily assumed water consumption of various animals and percentage water wastage

assumed (MAWRD, 2000) ................................................................................................ 41

Table 3-14 Number of livestock and water requirement in Auob River and Nossob River basins

(source: MAWF, 2006) ...................................................................................................... 42

Table 3-15 Nam Water Groundwater Schemes in the Molopo-Nossob basin (Nam Water, 2008,

ORASECOM, 2007a) ........................................................................................................ 44

Table 3-16 Dams within the Molopo-Nossob basin included in the Nam Water schemes .................. 44

Table 3-17 Quaternary regions (WMA) in the Molopo-Nossob basin in South Africa ....................... 45

Table 3-18 The division in three zones for assessment of the water requirement in the Molopo basin

in South Africa................................................................................................................... 45

Geotechnical Consulting Services

iv

Groundwater Review of the Molopo-Nossob Basin

Report No. ORASECOM/005/2009

Table 3-19 Data on population, ESLU (1995) and size of the quaternary WMA in the Upper Molopo

defined area (DWAF 2002d) ............................................................................................. 47

Table 3-20 Water requirement (1995) in Mm3/a for the quaternary WMA in the defined Upper

Molopo area (DWAF, 2002d) ............................................................................................ 47

Table 3-21 Data on population, ESLU (1995) and size of the quaternary WMA in the Middle Molopo

defined area (DWAF 2002b and 2002c) ............................................................................ 48

Table 3-22 Water requirement in Mm3/a (1995) for the quaternary WMA in the defined Middle

Molopo area (DWAF, 2002b and 2002c)........................................................................... 48

Table 3-23 Data on population, ESLU (1995) and size of the quaternary WMA in the Lower Molopo

defined area (DWAF 2002b and 2002c) ............................................................................ 50

Table 3-24 Water requirement in Mm3/a (1995) for the defined Lower Molopo area (DWAF, 2002b

and 2002c) ......................................................................................................................... 51

Table 3-25 Water requirement in Mm3/a (1995) for the defined Lower Molopo area referred to the

major river catchment areas (DWAF, 2002b and 2002c) .................................................. 51

Table 3-26 Summary of sizes, population and ESLU in the Molopo-Nossob basin in South Africa .. 51

Table 3-27 Summary of water requirements (1995) for the Molopo-Nossob basin in South Africa ... 53

Table 3-28 Transfer of water into the Molopo-Nossob basin in South Africa ..................................... 55

Table 3-29 Water balance for the Molopo-Nossob basin in South Africa in the year 2000 (Mm3/a) .. 55

Table 3-30 Figures on area sizes, population and ESLU in the Molopo-Nossob Basin ...................... 56

Table 3-31 Figures on area sizes, population and ESLU in different regions in the Molopo-Nossob

Basin .................................................................................................................................. 56

Table 3-32 Water requirement for Botswana, Namibia and South Africa in the Molopo-Nossob Basin

57

Table 3-33 Water requirement for various uses in different regions in the Molopo-Nossob Basin ..... 58

Table 3-34 Water requirement for various uses in different regions in the Molopo-Nossob Basin ..... 59

Table 4-1 Population Botswana districts in the Molopo- Nossob Basin ........................................... 61

Table 4-2 Namibian Population Growth ............................................................................................ 63

Table 4-3 Summary of the Projected Effect of Aids on the Namibian Population ............................ 63

Table 4-4 Population of South Africa districts in the Molopo- Nossob Basin (CSO, 2001 and

ORASECOM, 2008b) ....................................................................................................... 64

Table 4-5 Tourism Activity in Molopo- Nossob catchment (2007estimates) .................................... 68

Table 4-6 Scenarios for Tourism Growth over a Period of 10 years ................................................. 69

Table 5-1 Geological and Hydrogeological maps used in collation of the simplified geological map

in Figure 5-1. ..................................................................................................................... 73

Table 5-2 Regional stratigraphy in the Molopo-Nossob Basin ......................................................... 75

Table 5-3 Karoo Supergroup Stratigraphy and nomenclature in Botswana, Namibia and South

Africa relevant to the Molopo-Nossob Basin .................................................................... 77

Table 5-4 Reports from groundwater investigations used in collecting information on borehole

yields and aquifer parameters ............................................................................................ 85

Table 5-5 Number of information used in the fitting the yields from various aquifers with normal

distribution and the coefficient of determination, r2 .......................................................... 86

Table 5-6 Borehole yield classes used in Botswana, Namibia and South Africa. (Taken from DWA,

1987, Christelis and Struckmeier, 2001, DWAF, 1995 ...................................................... 89

Geotechnical Consulting Services

v

Groundwater Review of the Molopo-Nossob Basin

Report No. ORASECOM/005/2009

Table 5-7 Databases from which information of groundwater chemistry are extracted to form the

base for construction of map over Molopo-Nossob basin ................................................. 90

Table 5-8 Guidelines and recommendations for domestic water supply regarding the components

TDS, NO3 and F ................................................................................................................ 91

Table 5-9 Guidelines on Total Dissolved Solids, TDS for water use for livestock from FAO (1976)

and proposal from DGS (1994) ......................................................................................... 91

Table 5-10 Livestock salinity tolerance (South Australia department of Agriculture, Livestock Water

Supplies facts sheet no 82/77, September 1982) (Source: DGS, 1994) ............................ 91

Table 5-11 Number of data used in the compilation of water chemistry maps over Molopo-Nossob

basin .................................................................................................................................. 92

Table 5-12 Effects of TDS and EC on Human Health, Aesthetics, Household Distribution Systems

and Water Heating Appliances (DWAF, 1996a) ................................................................ 94

Table 5-13 TDS concentration limits chosen for the construction of the TDS map (Figure 5-12) ..... 97

Table 5-14 Area sizes in the Molopo-Nossob Basin of unsuitable groundwater for human and

livestock consumption based on TDS limits of 2,000 and 5,000 mg/l respectively .......... 97

Table 5-15 Effects of Nitrate on Human Health (DWAF, 1996a) ...................................................... 101

Table 5-16 NO3 concentration limits chosen for the construction of the NO3 map (Figure 5-12) .... 102

Table 5-17 Effects of Fluoride on Aesthetics and Human Health (DWAF, 1996a) ........................... 105

Table 5-18 Effects of Fluoride on Livestock Health (DWAF, 1996b) ............................................... 106

Table 5-19 F concentration limits chosen for the construction of the Fluoride map (Figure 5-14) ... 108

Table 5-20 Number of sites and boreholes for groundwater monitoring in Molopo-Nossob Basin .. 113

Table 5-21 Basic information on the groundwater level monitoring in the Kanye area, Southern

District, presented in Figure 5-24 .................................................................................... 115

Table 5-22 Changes in groundwater level monitored in Bokspits-Khawa area................................. 117

Table 5-23 Data on monitoring sites presented in the current report ................................................. 122

Table 5-24 Data on monitoring sites presented in the current report ................................................. 127

Table 5-25 Groundwater level information sources in the Molopo-Nossob Basin ........................... 134

Table 5-26 Various practical methods to determine recharge (Bredenkamp et al, 1995, ORASECOM,

2009) ................................................................................................................................ 136

Table 5-27 Recharge rainfall relationship in the Molopo-Nossob Basin in South Arfica developed and

presented in ORASECOM report (2009) ........................................................................ 139

Table 5-28 Recharge methods and values obtained from investigation in the Molopo-Nossob Basin

140

Table 5-29 Modeling exercises conducted in the Molopo-Nossob Basin ......................................... 145

Table 5-30 Scenario cases in the JICA groundwater modeling of the SAB (JICA, 2002) ................ 155

Table 5-31 Results of the Groundwater Simulation of the SAB (JICA, 2002) ................................. 155

Table 5-32 Scenario modeled and results obtained in the Tosca Molopo investigation (van Dyk,

2005) ................................................................................................................................ 157

Table 6-1 Classes and values used in the assessing of groundwater potential in the Molopo-Nossob

Basin (human consumption) ............................................................................................ 159

Table 6-2 Classes and values used in the assessing of groundwater potential in the Molopo-Nossob

Basin (livestock watering) ............................................................................................... 159

Table 6-3 Characteristics from the borehole yield and Transmissivity distribution diagrams in

Chapter 5.2 ...................................................................................................................... 160

Geotechnical Consulting Services

vi

Groundwater Review of the Molopo-Nossob Basin

Report No. ORASECOM/005/2009

Table 7-1 Summary of Borehole data table ..................................................................................... 166

Table 7-2 Groundwater monitoring data table ................................................................................. 166

Table 7-3 Water quality data table ................................................................................................... 166

Table 7-4 Databases carrying groundwater information in Botswana ............................................. 167

Table 7-5 Basic site information/borehole data table ...................................................................... 171

Table 7-6 Other borehole identifier used ......................................................................................... 171

Table 7-7 Water level data table ...................................................................................................... 172

Table 7-8 Water quality table ........................................................................................................... 172

Table 7-9 Metadata elements ........................................................................................................... 173

Table 7-10 Integrated Water Levels Table Record Example ............................................................. 175

Geotechnical Consulting Services

vii

Groundwater Review of the Molopo-Nossob Basin

Report No. ORASECOM/005/2009

LIST OF FIGURES

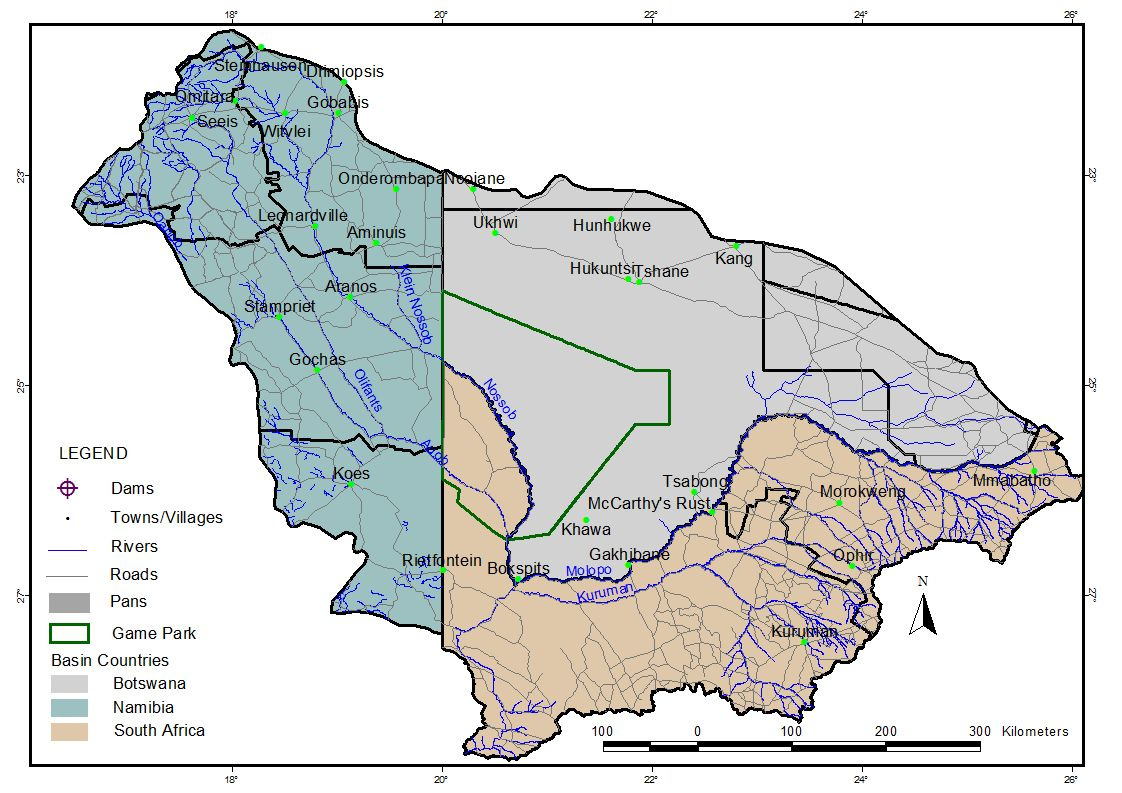

Figure 1-1

Molopo-Nossob Basin and major rivers within the basin ............................................... 1

Figure 2-1

Molopo-Nossob Basin in Botswana, Namibia and South Africa .................................... 4

Figure 2-2

Oanob River sub-basin in the Molopo-Nossob Basin ..................................................... 4

Figure 2-3

Percentage of coverage of the Molopo-Nossob Basin by Botswana, Namibia and South

Africa .............................................................................................................................. 5

Figure 2-4

Percentage of coverage of the Molopo-Nossob Basin by the four major rivers, Molopo,

Kuruman, Nossob and Auob ........................................................................................... 5

Figure 2-5

Relief map of the Molopo-Nossob Basin ........................................................................ 6

Figure 2-6

Administrative units within the Molopo-Nossob Basin belonging to Botswana,

Namibia and South Africa .............................................................................................. 7

Figure 2-7

Distribution of rainfall stations in the Molopo-Nossob Basin ........................................ 8

Figure 2-8

Monthly mean rainfall at selected stations in the Molopo-Nossob Basin ....................... 9

Figure 2-9

Annual average rainfall over the Molopo-Nossob Basin .............................................. 10

Figure 2-10

Mean daily maximum and minimum temperatures and highest and lowest temperatures

for the Meteorological stations Ghanzi, Tshane and Tsabong in Botswana (source;

DWA, 2006) .................................................................................................................. 10

Figure 2-11

Monthly mean maximum temperature at selected sites in the project area................... 11

Figure 2-12

Monthly mean minimum temperature at selected sites in the project area ................... 11

Figure 2-13

Mean monthly Relative Humidity (%) for Tsabong, Tshane and Ghanzi meteorological

stations in Botswana. (Source: data DWA, 2006) ........................................................ 12

Figure 2-14

Mean monthly humidity at selected sites in the project area ........................................ 12

Figure 2-15

Monthly mean wind speed at selected sites in the project area ..................................... 12

Figure 2-16

Monthly mean Sunshine hours at selected sites in the project area .............................. 13

Figure 2-17

Monthly mean solar radiation at selected sites in the project area ................................ 13

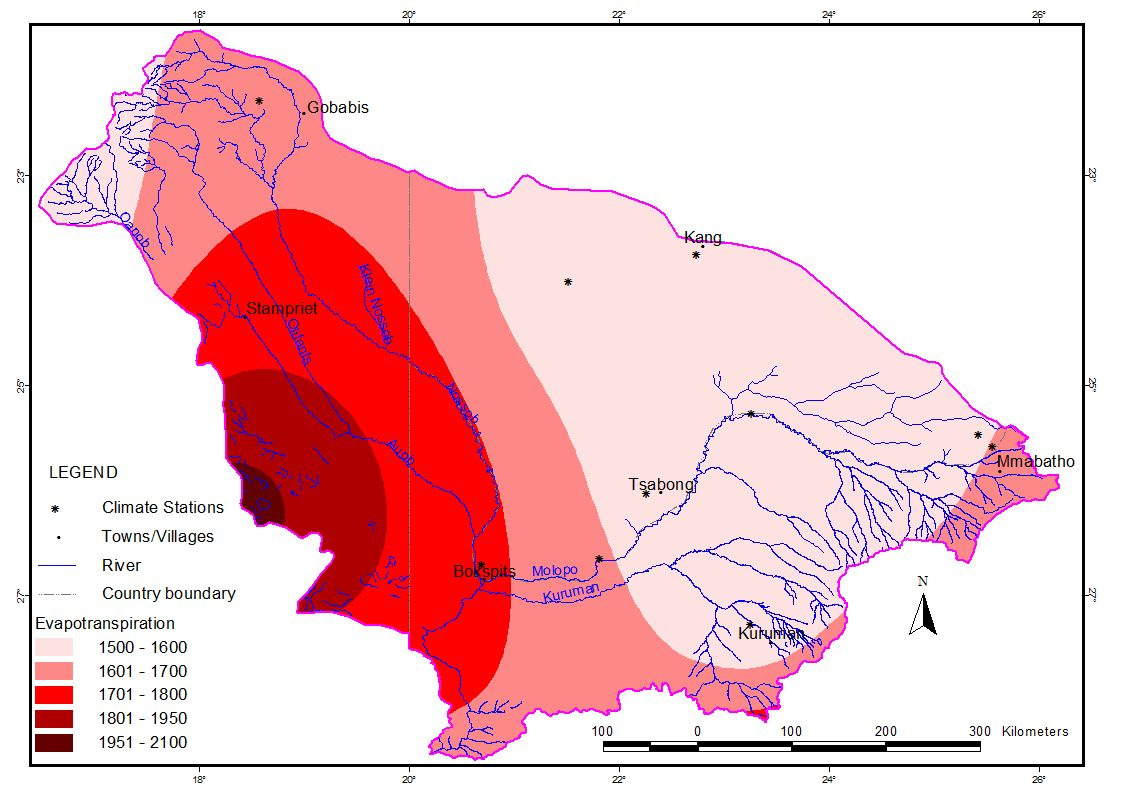

Figure 2-18

Monthly mean potential evapotranspiration at selected sites ........................................ 15

Figure 2-19

Monthly mean evaporation at selected stations in the project area ............................... 15

Figure 2-20

Mean annual reference evapotranspiration in the Molopo-Nossob sub-basin .............. 16

Figure 2-21

Mean monthly rainfall and potential evapotranspiration in the Molopo-Nossob Basin 17

Figure 2-22

Aridity Index Map of the Study area ............................................................................. 18

Figure 2-23

Monthly rainfall and SPI values for Tsabong ................................................................ 22

Figure 2-24

Annual rainfall and SPI values for Tsabong .................................................................. 22

Figure 2-25

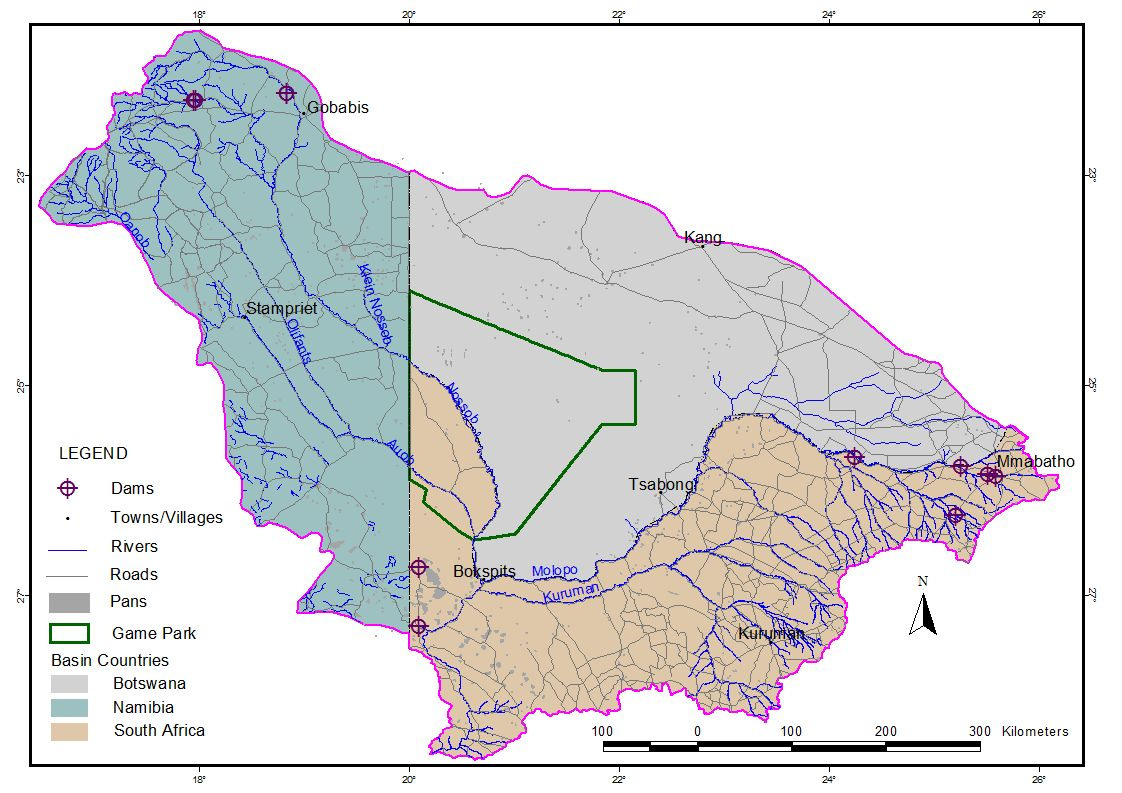

Annual rainfall and SPI values for Tsabong .................................................................. 23

Figure 2-26

Annual rainfall and SPI values for Kuruman ................................................................ 23

Figure 2-27

Dams in the Molopo-Nossob Basin .............................................................................. 27

Figure 2-28

Major waterworks and transfers in the Molopo-Nossob Basin ..................................... 28

Figure 2-29

Geographic distribution of pans in the Molopo-Nossob Basin ..................................... 29

Figure 3-1

Area of Botswana included in the Molopo-Nossob basin based on surface water divide

...................................................................................................................................... 32

Geotechnical Consulting Services

viii

Groundwater Review of the Molopo-Nossob Basin

Report No. ORASECOM/005/2009

Figure 3-2

(A) Number or various livestock and (B) Water requirement for various livestock and

wildlife in the Kgalagadi, Southern, Barolong and Ghanzi District within the Nossob

River basin (source: DWA, 2006) ................................................................................ 33

Figure 3-3

Predicted water requirements for Molopo-Nossob Basin in Botswana ........................ 36

Figure 3-4

(A). Water requirement in the Auob River and Nossob River Basins in Namibia ........ 39

Figure 3-5

Irrigation schemes in the Auob catchment area (blue) and Nossob catchment area (red)

(source: MAWRD, 2000) ............................................................................................. 39

Figure 3-6

Distribution of water requirements for the Irrigation schemes in the Molopo-Nossob

Basin (MAWRD, 2000) ................................................................................................ 40

Figure 3-7

Veterinary areas in Namibia in the Molopo-Nossob Basin ........................................... 41

Figure 3-8

(A) Number or various livestock and (B) Water requirement for various livestock in the

Auob River and Nossob River basins (MAWF, 2006) ................................................. 42

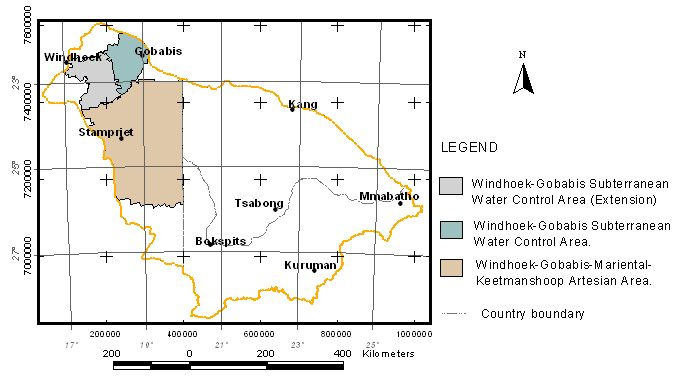

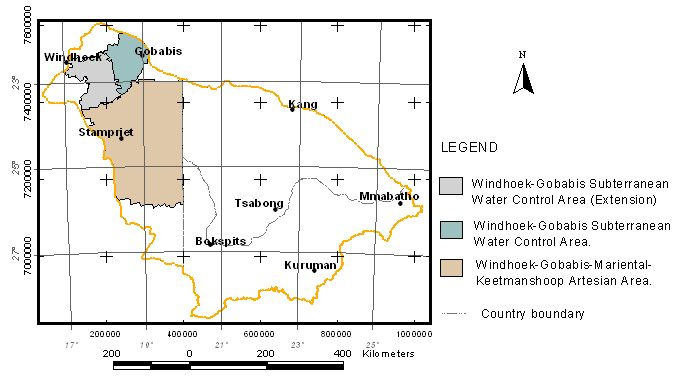

Figure 3-9

Groundwater Control Areas in the Molopo-Nossob Basin, Namibia ............................ 43

Figure 3-10

Villages supplied by Nam Water ("Bulk Consumers") in the Molopo-Nossob Basin .. 43

Figure 3-11

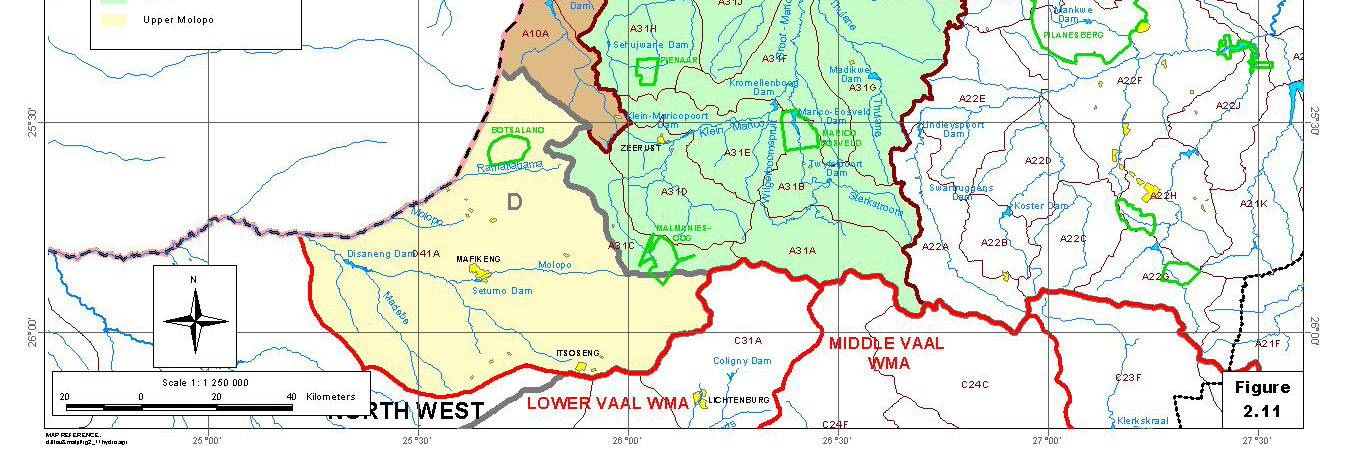

Upper Molopo WMA (the quaternary WMA D41A), marked D in the figure (DWAF,

2004c) ........................................................................................................................... 46

Figure 3-12

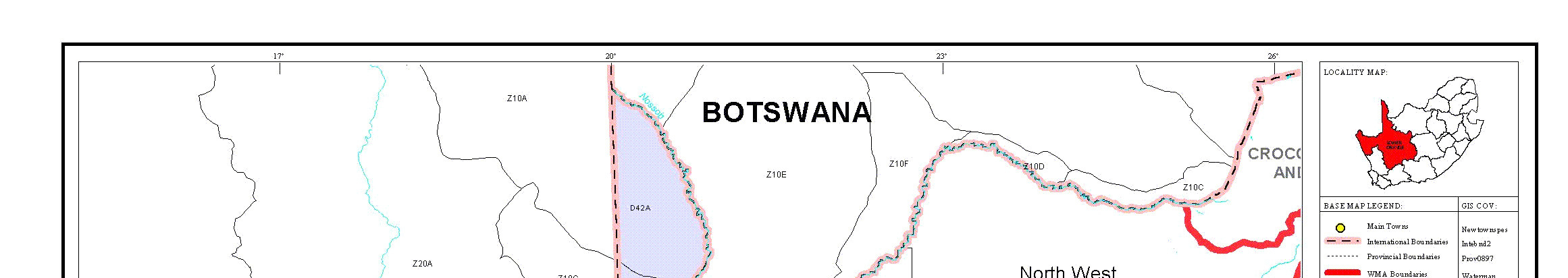

Lower Vaal WMA and its sub-areas Molopo, Harts and Vaal d/s Bloemhof Dam

(DWAF 2004) ............................................................................................................... 49

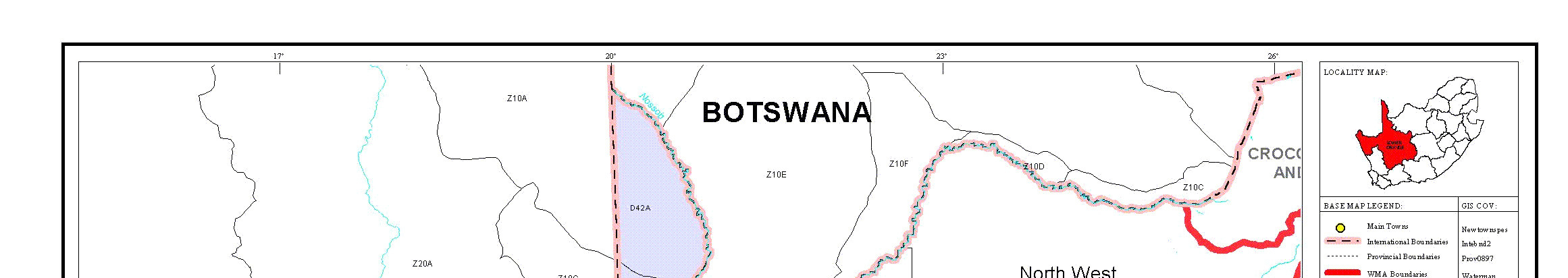

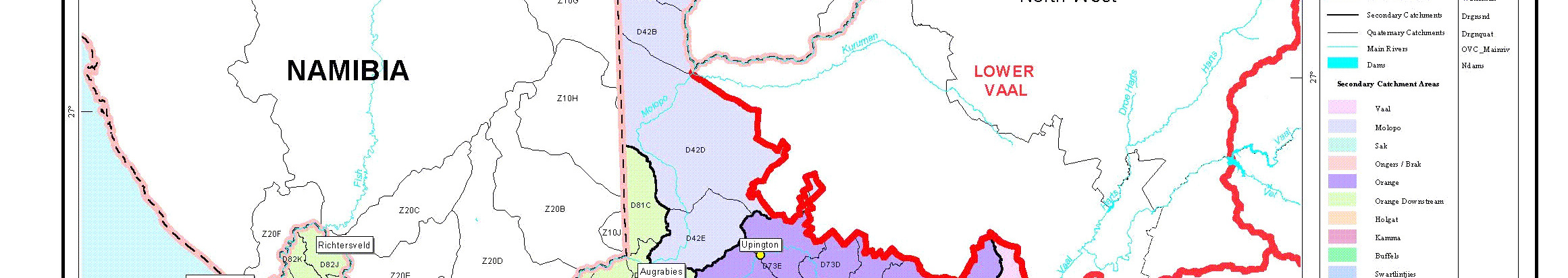

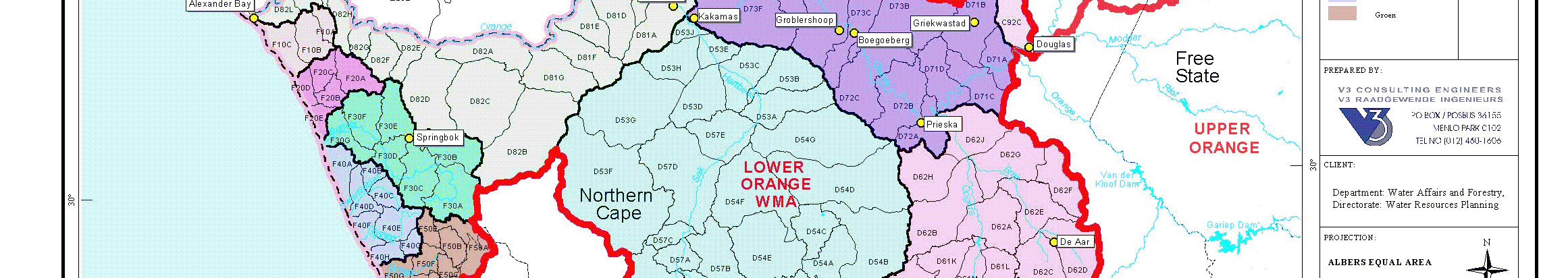

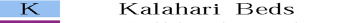

Figure 3-13

Lower Orange WMA and hydrological sub-catchments (DWAF, 2004b) .................... 50

Figure 3-14

A. Sizes of the quaternary WMA in the Molopo basin in South Africa ........................ 52

Figure 3-15

Number of livestock units (ESLU) and population in the quaternary WMA in the

Molopo River basin of South Africa............................................................................. 52

Figure 3-16

Number of livestock units (ESLU) and population in the Molopo River sub-areas of

South Africa .................................................................................................................. 53

Figure 3-17

Water requirements (1995) in the quaternary WMA in the Molopo River basin of South

Africa ............................................................................................................................ 53

Figure 3-18

Water requirement (1995) in the Molopo River sub-areas of South Africa .................. 54

Figure 3-19

Water requirement assessed as m3/km2 annually (1995 data) in the quaternary WMA in

the Molopo River basin of South Africa ....................................................................... 54

Figure 3-20

Water requirement assessed as m3/km2 annually (1995 data) in the Molopo River sub-

areas of South Africa .................................................................................................... 55

Figure 3-21

Population and ESLU per km2 in Botswana, Namibia and South Africa in the Molopo-

Nossob Basin ................................................................................................................ 56

Figure 3-22

Population and ESLU per km2 in Botswana, Namibia and South Africa within the

Molopo-Nossob Basin .................................................................................................. 57

Figure 3-23

Water requirements for Botswana, Namibia and South Africa in the Molopo-Nossob

Basin ............................................................................................................................. 58

Figure 3-24

Water requirements for various regions in the Molopo-Nossob Basin ......................... 59

Figure 3-25

Water requirements in m3/km2 per year for various regions in the Molopo-Nossob

Basin ............................................................................................................................. 60

Figure 4-1

Future predicted water requirement for the three sub-areas of the Molopo-Nossob basin

in South Africa .............................................................................................................. 71

Figure 4-2

Future predicted water requirements for the Molopo-Nossob River Basin .................. 72

Geotechnical Consulting Services

ix

Groundwater Review of the Molopo-Nossob Basin

Report No. ORASECOM/005/2009

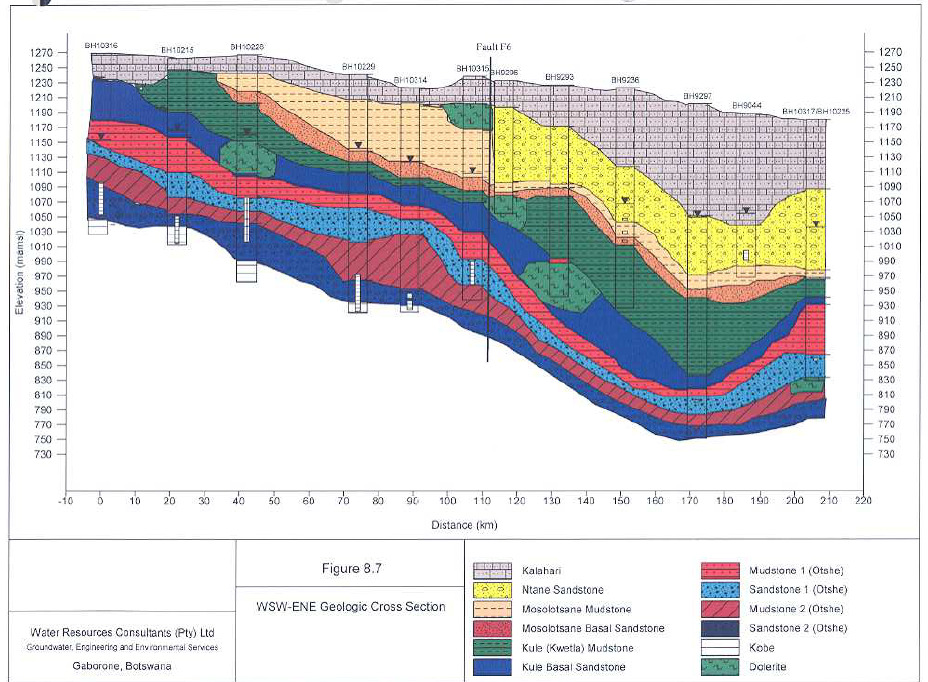

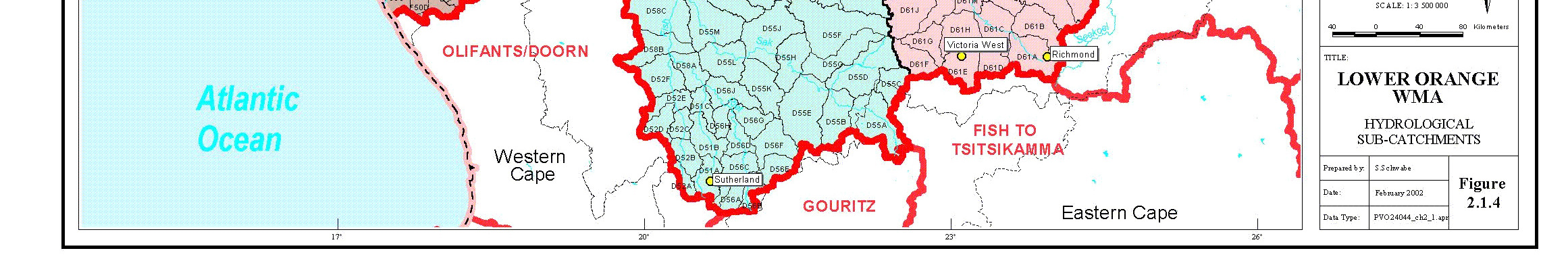

Figure 5-1

Simplified geology map over the Molopo-Nossob Basin. References given in Table 5-1

...................................................................................................................................... 74

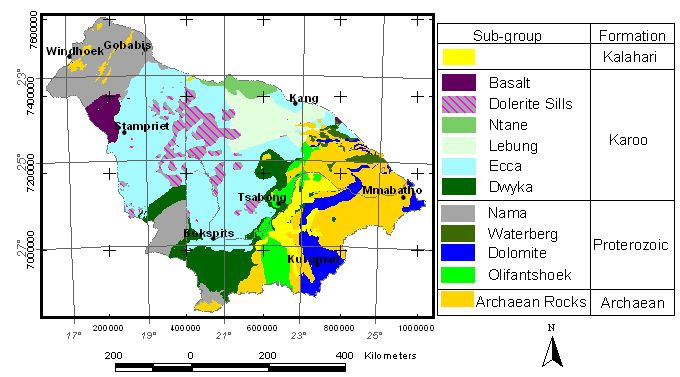

Figure 5-2

Geological cross-section through the Ecca sediments in the Stampriet Artesian Basin

from North-West to the border with South Africa in South-East (Gemsbok Park). The

Auob aquifer in orange, Nossob Aquifer in light yellow and the Kalahari beds in light

blue. (Copied from JICA, 2002) ................................................................................... 78

Figure 5-3

Kalahari Bed thickness .................................................................................................. 80

Figure 5-4

Pre-Kalahari surface ...................................................................................................... 81

Figure 5-5

Thickness of Kalahari Beds below the groundwater surface ........................................ 82

Figure 5-6

Borehole yield data from various aquifers and locations in Botswana and Namibia.

SAB (Stampriet Artesian Basin) ................................................................................... 86

Figure 5-7

Borehole yield data from various aquifers and locations in Botswana and Namibia.

SAB (Stampriet Artesian Basin) ................................................................................... 87

Figure 5-8

Borehole yields to be expected within the standard deviation limits of the log-normal

distribution of borehole yields from various aquifers in Botswana and Namibia.

=median value........................................................................................................... 87

Figure 5-9

Transmissivity data from Ecca aquifer at various locations in Botswana ..................... 88

Figure 5-10

Transmissivity data to be expected within the standard deviation limits of the log-

normal distribution of transmissivity from Ecca aquifer in Botswana.

=median value

...................................................................................................................................... 88

Figure 5-11

Groundwater Potential Map. Compiled from hydrogeological Maps over Botswana,

Namibia and South Africa ............................................................................................ 90

Figure 5-12

TDS concentration in the groundwater within the Molopo-Nossob Basin ................... 97

Figure 5-13

Areas of unsuitable groundwater quality of human consumption (TDS>2,000 mg/l) and

livestock watering (TDS>10,000 mg/l) ........................................................................ 98

Figure 5-14

TDS in the Nossob Aquifer in the Stampriet Artesian Aquifer in Molopo-Nossob Basin

in Namibia. Data source: JICA, 2002 ........................................................................... 99

Figure 5-15

NO3 concentration in the groundwater within the Molopo-Nossob Basin .................. 102

Figure 5-16

Relationship between Maximum Daily Air Temperature and Optimum Fluoride

Concentration (after DWAF, 1996a) ........................................................................... 105

Figure 5-17

Fluoride (F) concentration in the groundwater within the Molopo-Nossob Basin ..... 107

Figure 5-18

Groundwater Fluoride (F) content in the Nossob aquifer in the Stampriet Artesian

Basin in Namibia. Data source: JICA, 2002 ............................................................... 108

Figure 5-19

Areas exceeding guideline limits for human consumption ......................................... 109

Figure 5-20

Areas exceeding guidelines for livestock watering ..................................................... 110

Figure 5-21

Location of data (boreholes) from which information of TDS (upper left), NO3 (upper

right) and F (lower) are obtained ................................................................................ 111

Figure 5-22

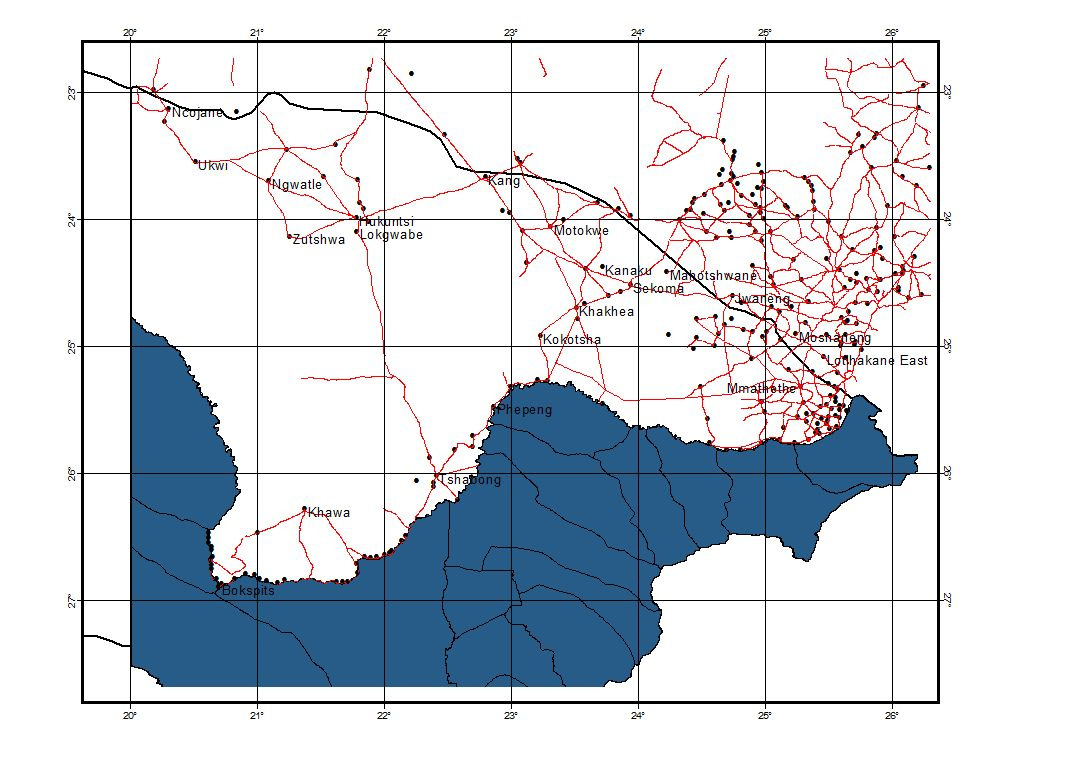

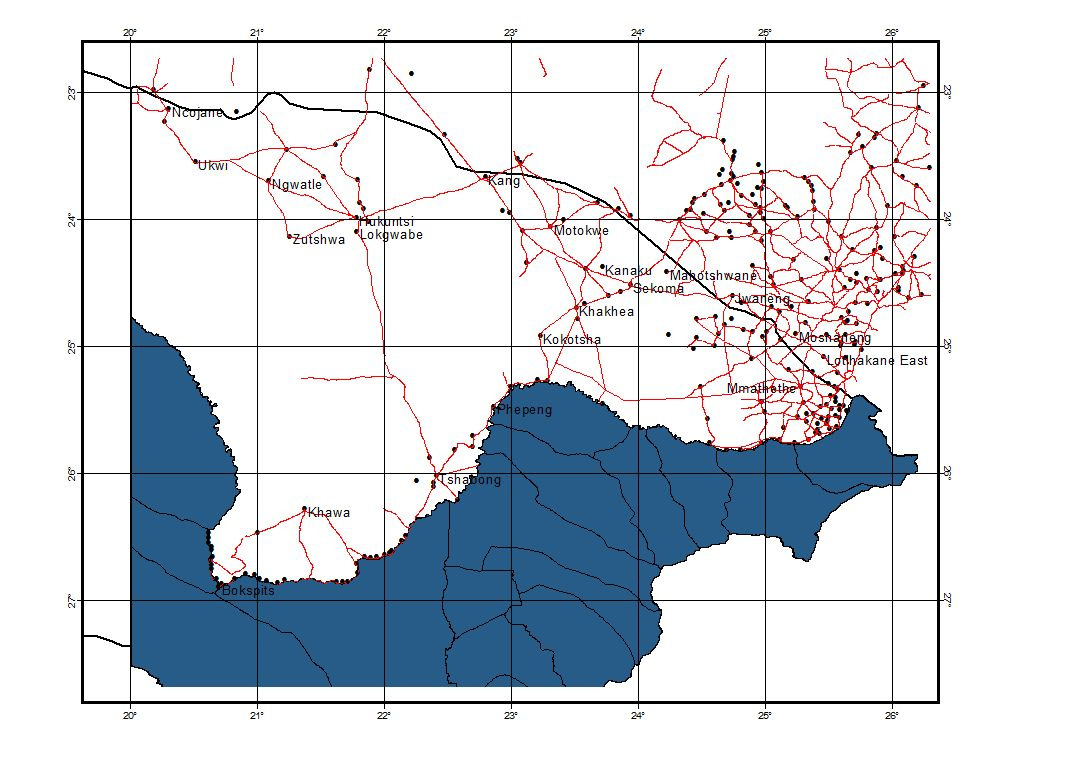

Monitoring boreholes in Botswana and boreholes presented in the current report ..... 114

Figure 5-23

Monitoring and abstraction boreholes in the Kanye wellfield area in Botswana ........ 114

Figure 5-24

Groundwater level in monitoring boreholes in the Kanye wellfield area, influenced and

not influenced by the abstraction from the wellfields ................................................ 115

Figure 5-25

Abstraction from the Kanye wellfields predicted from linear extrapolation of

monitored annual abstraction ..................................................................................... 115

Geotechnical Consulting Services

x

Groundwater Review of the Molopo-Nossob Basin

Report No. ORASECOM/005/2009

Figure 5-26

Groundwater level monitored in observation boreholes surrounding the Tsabong

wellfield in Botswana ................................................................................................. 116

Figure 5-27

Monitored and predicted abstraction from the Tsabong wellfield, Botswana ............. 116

Figure 5-28

Groundwater level in monitoring boreholes in Matsheng and Bokspits-Khawa ........ 117

Figure 5-29

Mean annual minimum temperature for January and July from the meteorological

station in Tsabong. Calculated difference between the January and July annual mean

minimum temperature. (Data source: Department of Meteorological Services,

Botswana) ................................................................................................................... 118

Figure 5-30

Groundwater level in monitoring boreholes in Makunda, Khakea-Sekoma and

Sedibeng ..................................................................................................................... 118

Figure 5-31

Brief overview of the geological and hydrogeological classification of the Stampriet

Artesian Basin (JICA, 2002) ...................................................................................... 120

Figure 5-32

Monitoring boreholes and boreholes presented in the current report .......................... 121

Figure 5-33

Groundwater level monitoring at Okonyama and Olifantswater in Namibia ............. 123

Figure 5-34

Groundwater level monitoring at Steinrus, Tugela, Jackalsdraai and Tweerivier in

Namibia ...................................................................................................................... 123

Figure 5-35

General groundwater contours in the Nossob aquifer from monitoring of water level in

boreholes penetrating the aquifer. (Data source: JICA, 2002) .................................... 124

Figure 5-36

Blue areas show the groundwater level in the Nossob aquifer being higher than the

general groundwater level (Auob and Kalahari aquifers). (Data source: JICA, 2002)

.................................................................................................................................... 125

Figure 5-37

Blue areas show the groundwater level (head) in the Nossob aquifer above the ground

surface level (artesian conditions). (Data source: JICA, 2002) .................................. 125

Figure 5-38

Monitoring boreholes in South Africa and monitoring results presented in the current

report .......................................................................................................................... 126

Figure 5-39

Monitored groundwater level in boreholes in the Grootfontein area, South Africa,

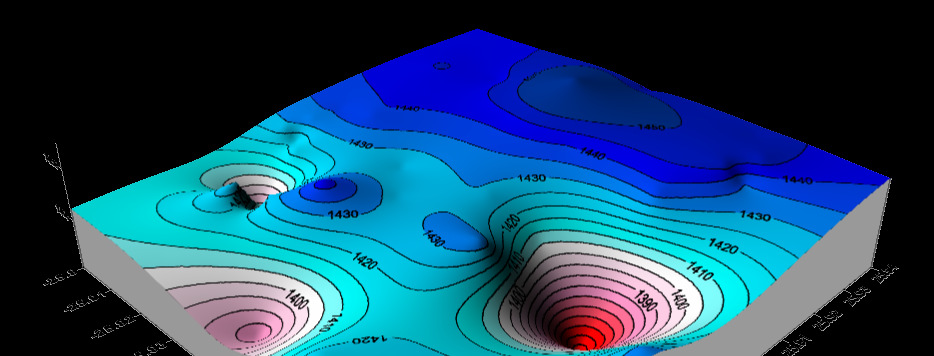

Water Management Area, WMA, D41A .................................................................... 128

Figure 5-40

Grootfontein, WMA D41A, South Africa, groundwater level counters early-mid 1980-

es (Left) and groundwater counters form recent time, 2000-2004, (Right). The counters

interpolated using Kriging application in the Surfer programme ............................... 128

Figure 5-41

3-D graph for the groundwater level from monitoring boreholes at Grootfontein, South

Africa, WMA D41A ................................................................................................... 129

Figure 5-42

Monitored groundwater level in boreholes in the South Africa, Water Management

Area D41G, H, J and M, see Table 5-24 ..................................................................... 129

Figure 5-43

Monitored groundwater level in boreholes in South Africa, Water Management area

D41H, see Table 5-24 ................................................................................................. 130

Figure 5-44

Monitored groundwater level in boreholes in South Africa, Water Management Area

D41a and C, see Table 5-24 ........................................................................................ 130

Figure 5-45

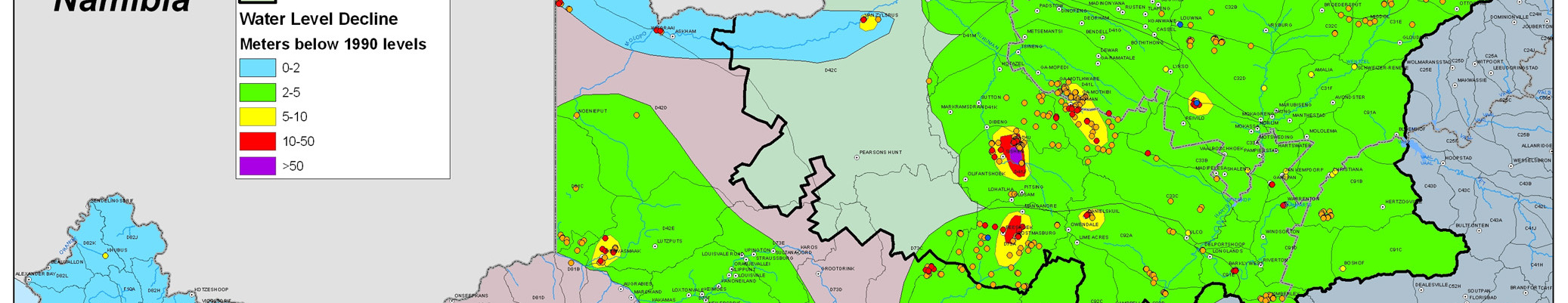

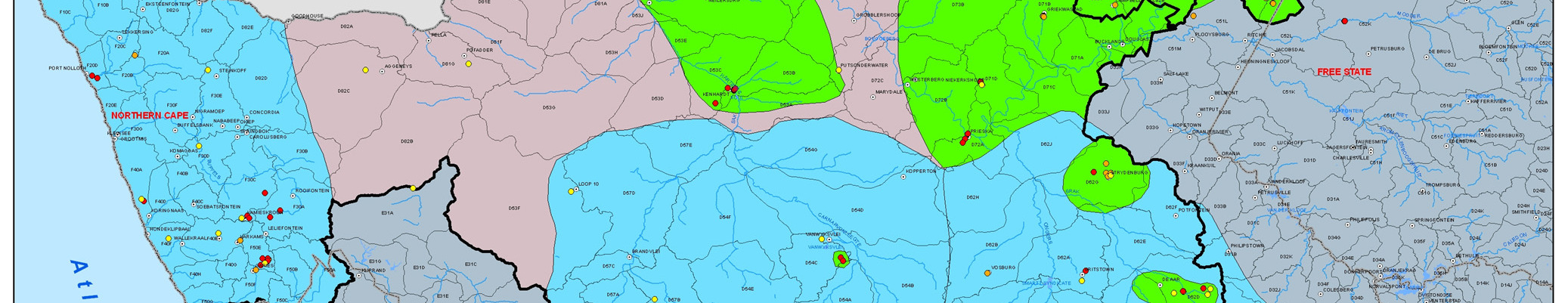

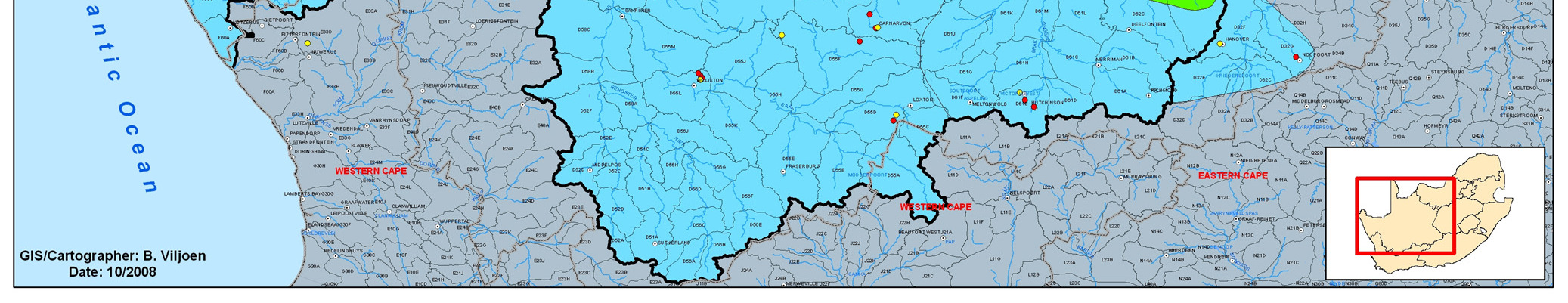

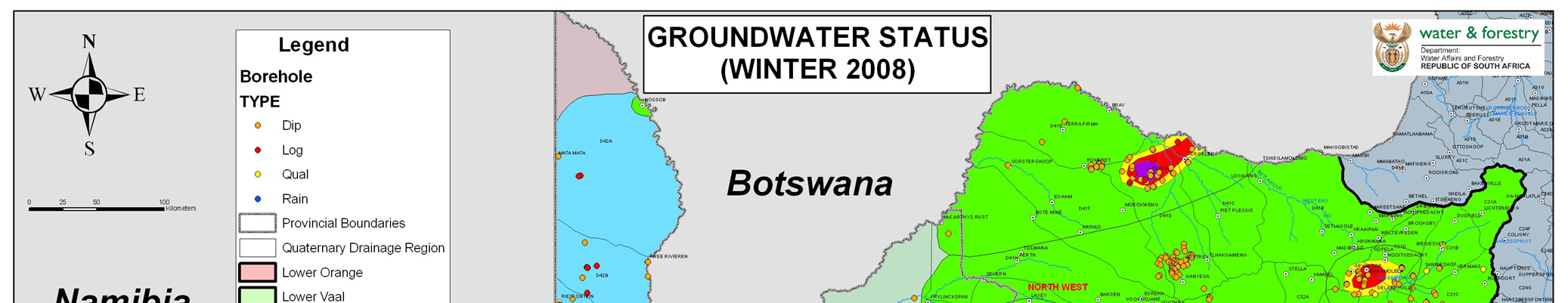

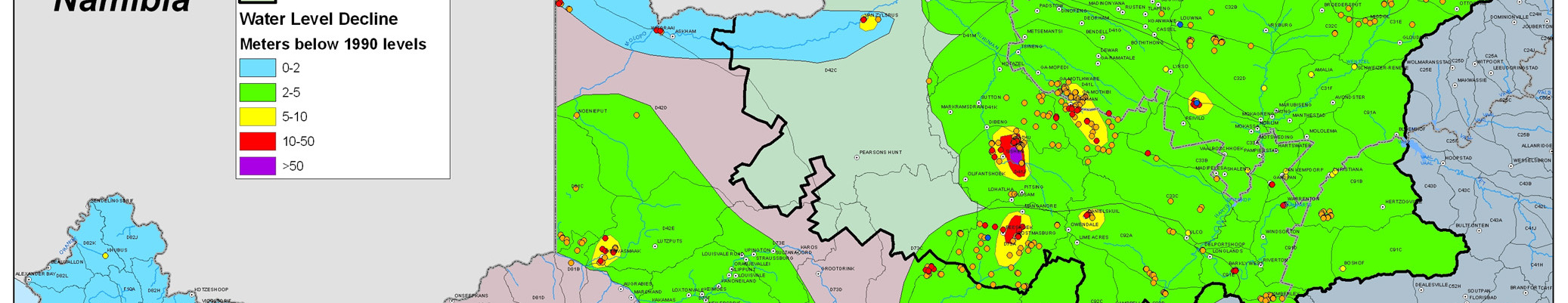

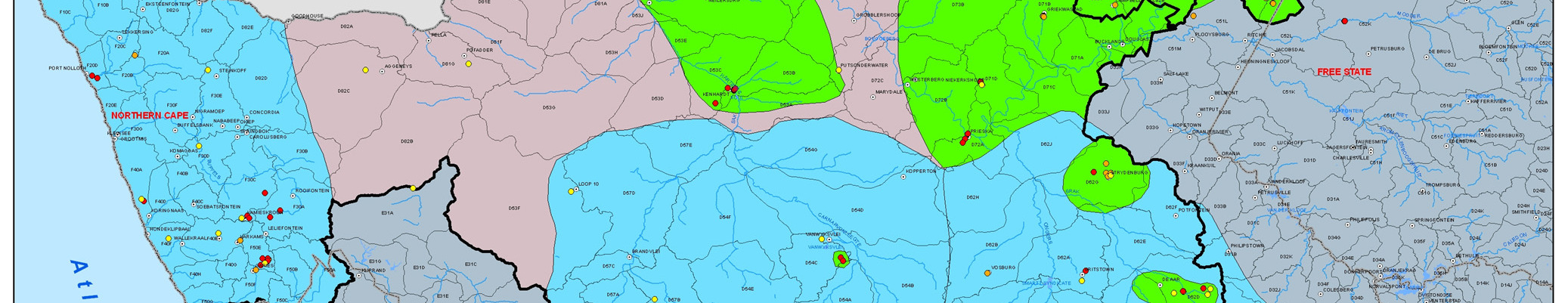

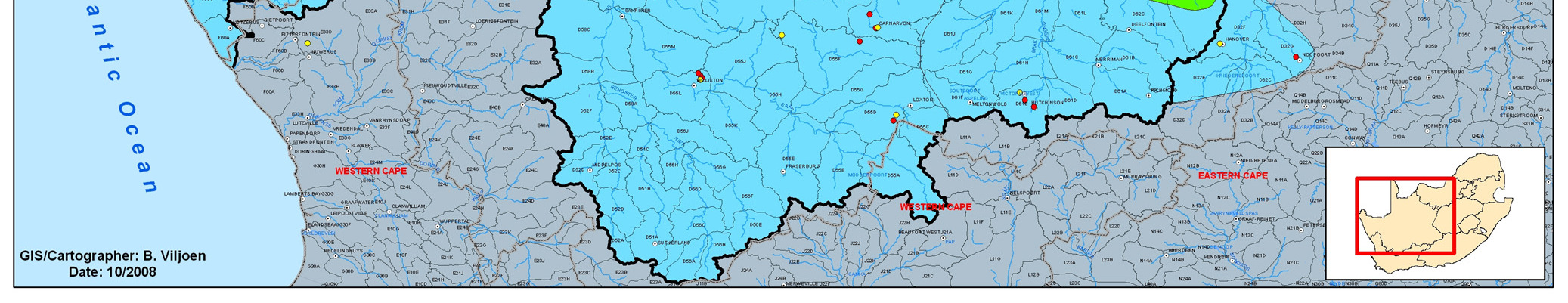

Groundwater Status in the Northern Cape, winter 2008, based on Groundwater level

Decline since 1990 (van Dyk et al, 2008) .................................................................. 132

Figure 5-46

Regional groundwater level map over Molopo-Nossob Basin ................................... 133

Figure 5-47

Location of boreholes used in the construction of the groundwater level map over

Molopo-Nossob Basin (Figure 5-46) .......................................................................... 135

Geotechnical Consulting Services

xi

Groundwater Review of the Molopo-Nossob Basin

Report No. ORASECOM/005/2009

Figure 5-48

Location of springs in Molopo-Nossob Basin (data source: Vegter, 1995 and DWA

Namibia) ..................................................................................................................... 135

Figure 5-49

Total chloride deposition (mg/a and m2) calculated for the Molopo-Nossob Basin

according to formula given by JICA (2002) and adjusted with a factor 0.75 ............. 141

Figure 5-50

Chloride concentration in the groundwater within Molopo-Nossob Basin ................. 141

Figure 5-51

Groundwater recharge in mm/a assessed using the Chloride Mass Balance method

(CMB) ........................................................................................................................ 142

Figure 5-52

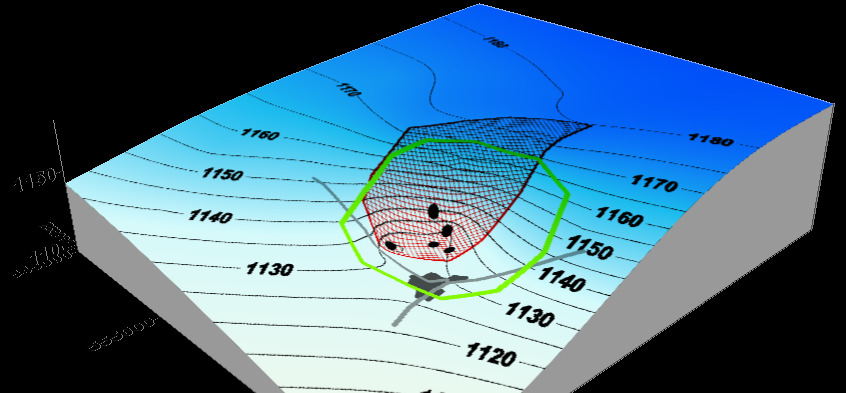

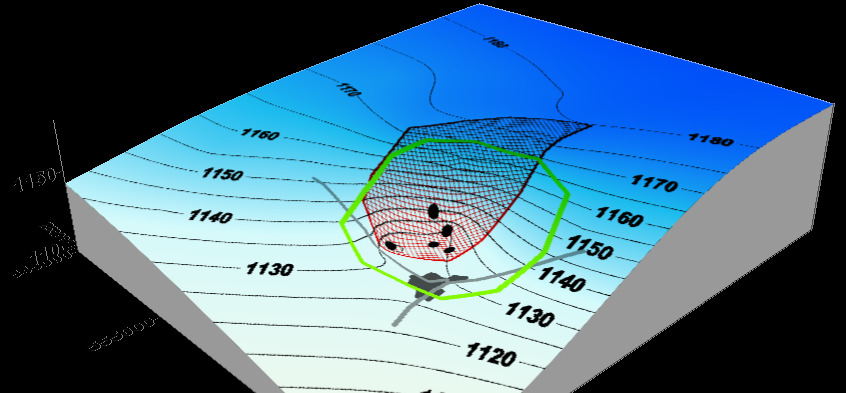

Example of a 3-dimensional grid for numerical modeling ......................................... 143

Figure 5-53

Location of areas where groundwater modeling is conducted. Numbers refer to Table

5-29 ............................................................................................................................. 145

Figure 5-54

Example of protection zone delineation (Ghanzi, Botswana) using results from

numerical modeling (Red zone for 100 years travelling time, green zone restricting for

drilling and abstraction of groundwater) .................................................................... 146

Figure 5-55

Grid lay-out for the Kang-Phuduhudu numerical model wit delineated wellfield areas

and simulated production wells (DWA, 2007) ........................................................... 148

Figure 5-56

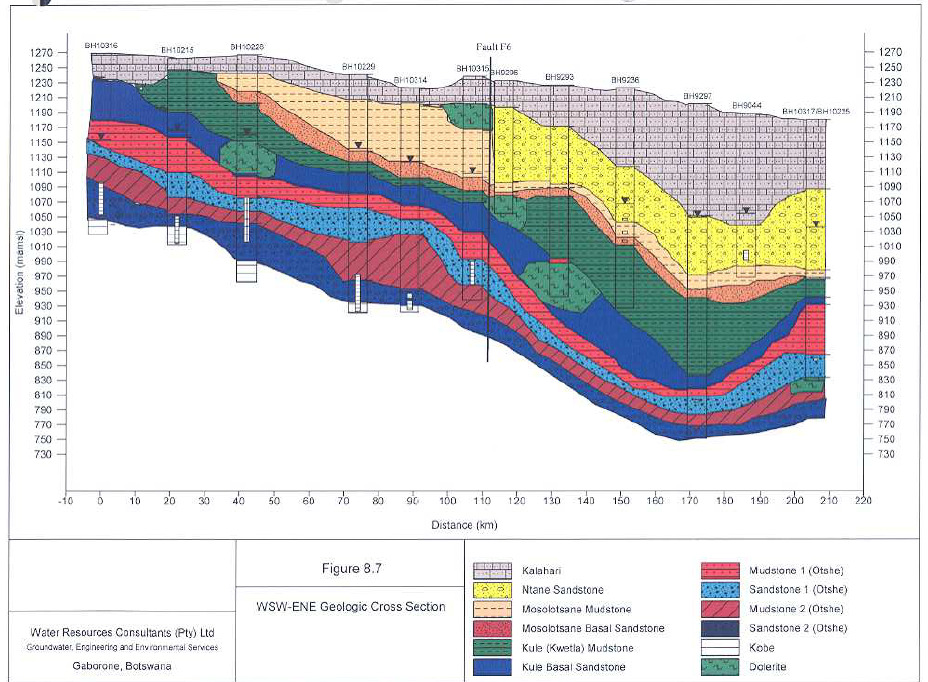

Geologic cross section WSW-ENE through the Ncojane area in Botswana (DWA,

2008). The three aquifers considered are Ntane, Otshe sandstone1 and Otshe sandstone

2. ................................................................................................................................. 150

Figure 5-57

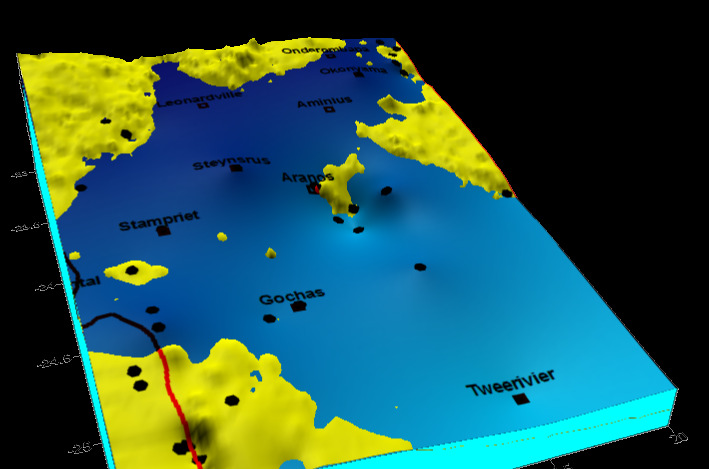

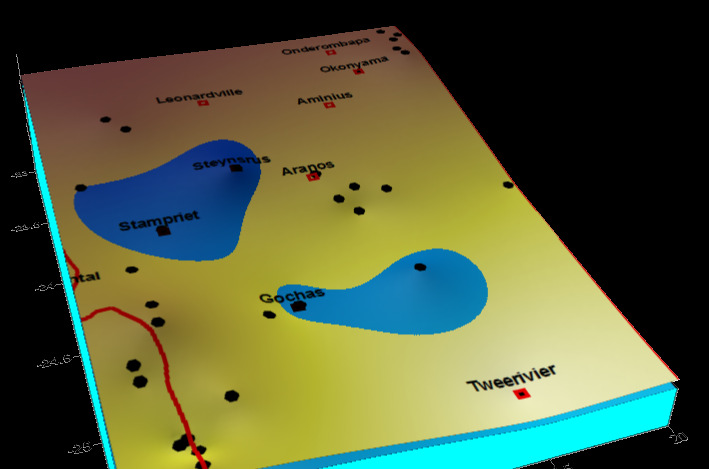

Three-dimensional image of the modeled aquifer system. (Note that the upper surface

is not the topographic surface, but extrapolated depth to first water strike. The system

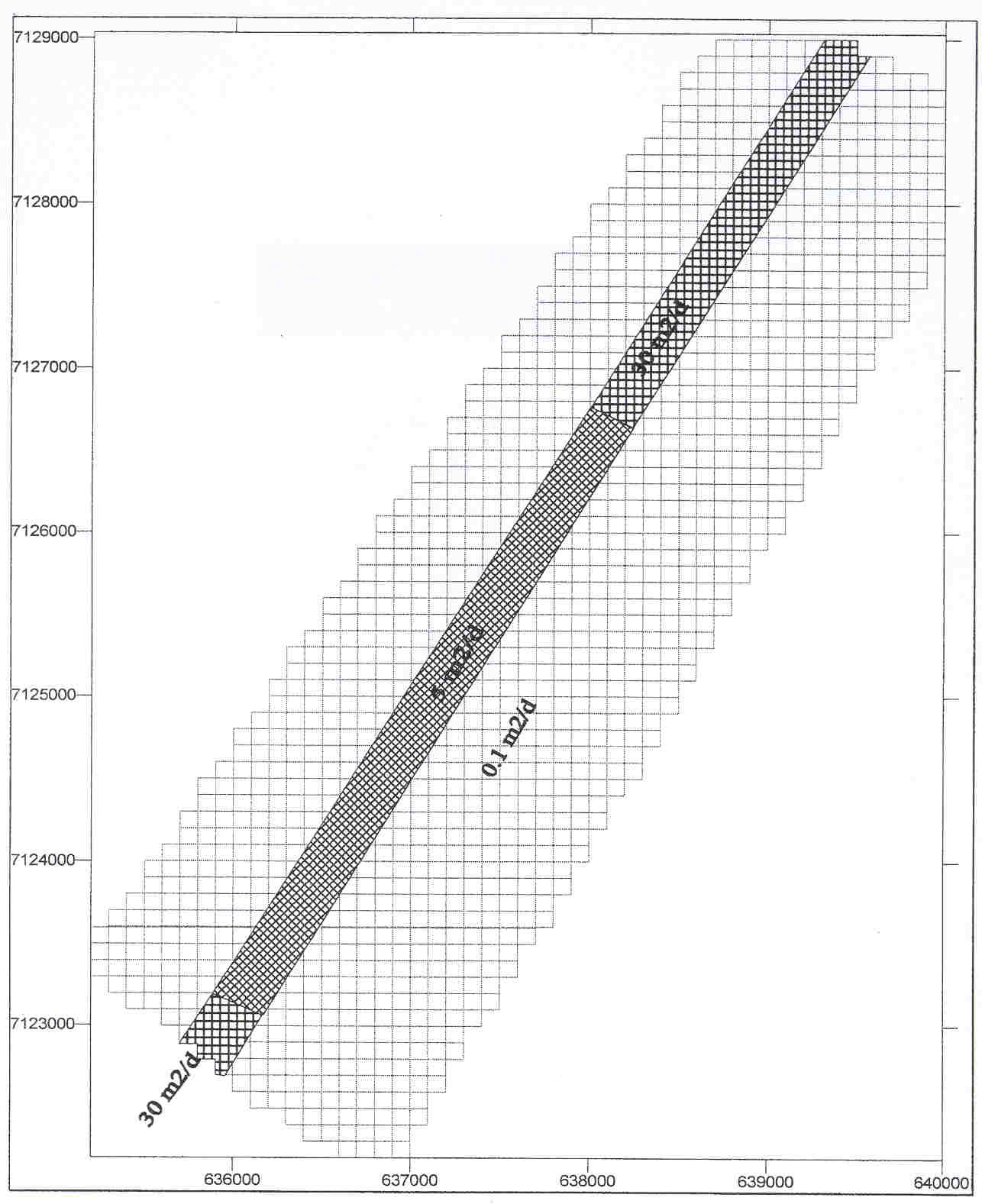

thus represents confined/unconfined structure) (DGS, 2003) .................................... 152

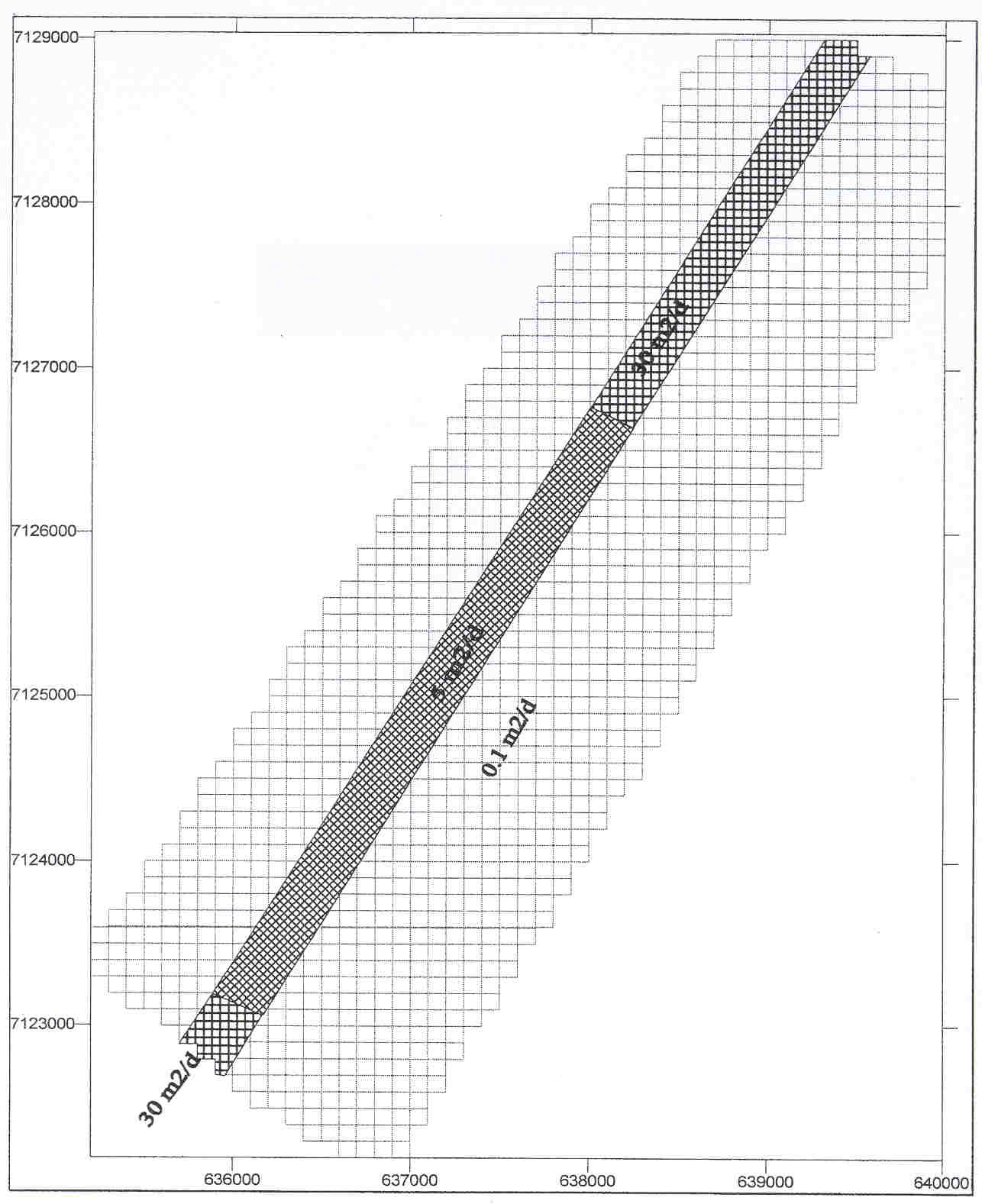

Figure 5-58

Grid net used and assigned Transmissivity values in modeling in Tsabong (DWA,

2002) ........................................................................................................................... 154

Figure 5-59

Simulated drawdown in the Kalahari and Auob aquifers (Case 2) in the Stampriet

Artesian Basin, SAB (JICA, 2002). ............................................................................ 156

Figure 6-1

Grid-net of 0.2o distance over the Molopo-Nossob Basin to achieve values inn points of

chemical and recharge data ......................................................................................... 160

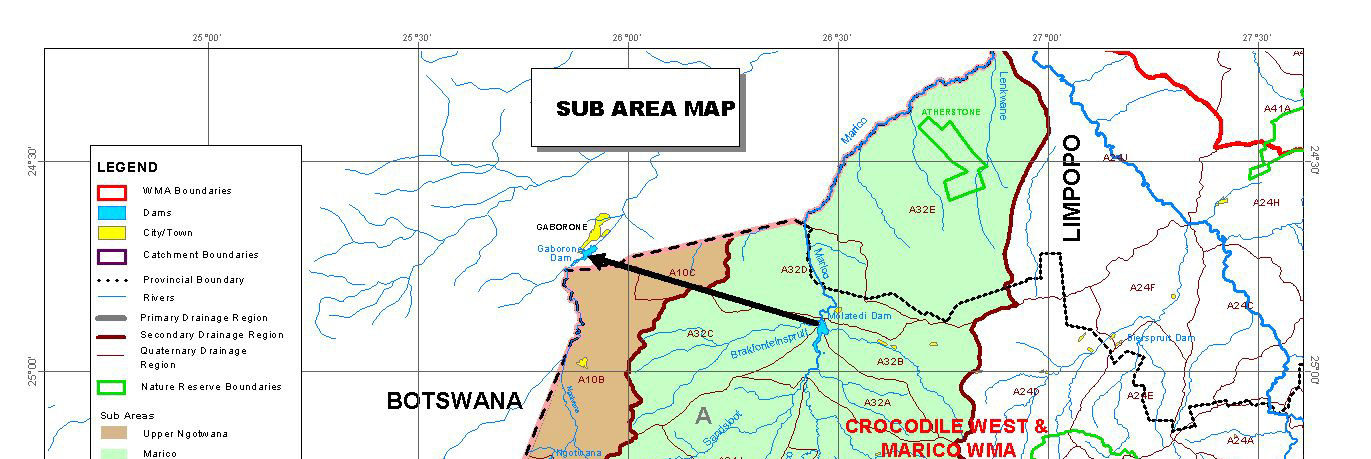

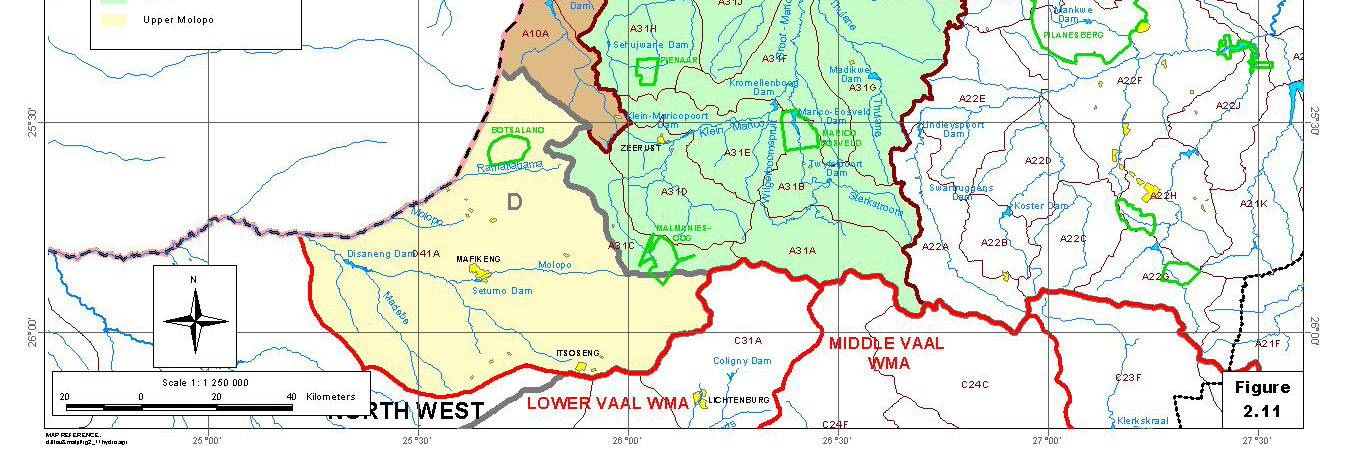

Figure 6-2

Number of chemical guideline for human consumption and for livestock watering

exceeded in the Molopo-Nossob Basin (indicator maps) ........................................... 161

Figure 6-3

Number of chemical guideline for human consumption and for livestock watering

exceeded and recharge of 0.2 mm/a not achieved in the Molopo-Nossob Basin

(indicator maps) .......................................................................................................... 161

Figure 6-4

Values for the groundwater chemistry in accordance with Table 6-1 ......................... 162

Figure 6-5

Values for the groundwater chemistry and recharge in accordance with Table 6-1 .... 162

Figure 6-6

Depth to the groundwater level. Map constructed from the ground surface map and the

groundwater level map given in this report ................................................................ 164

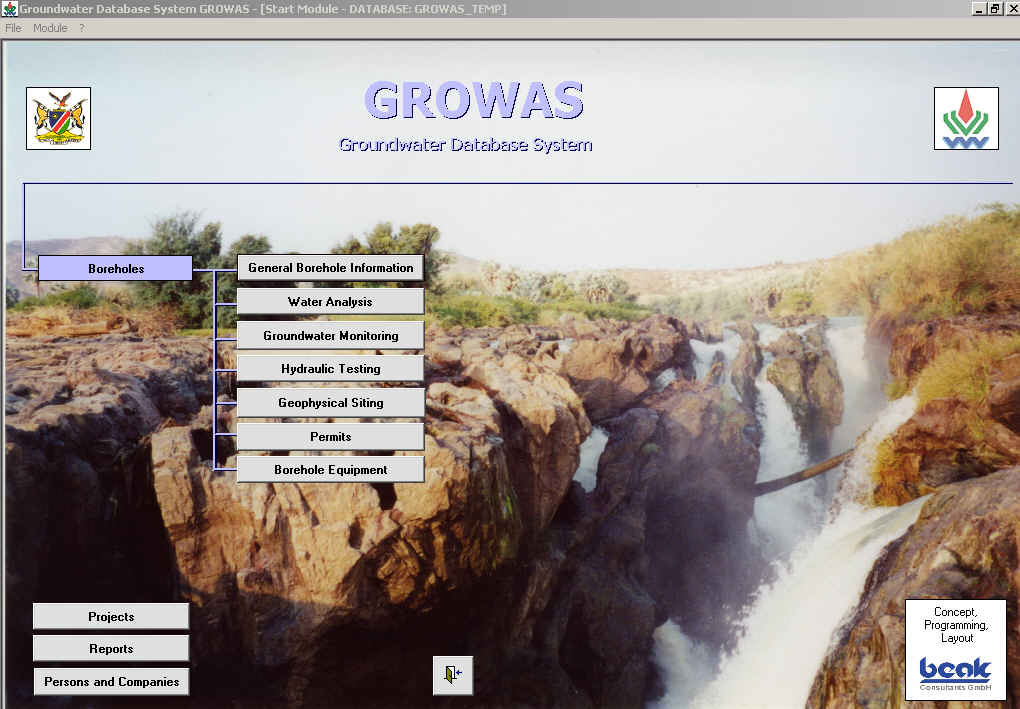

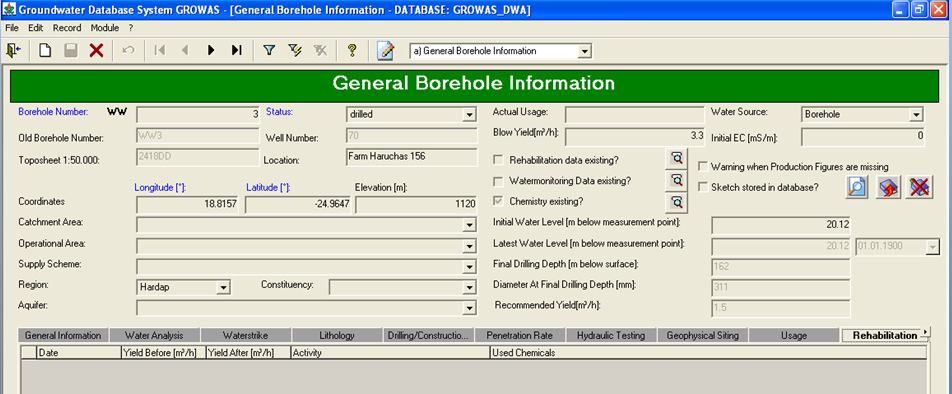

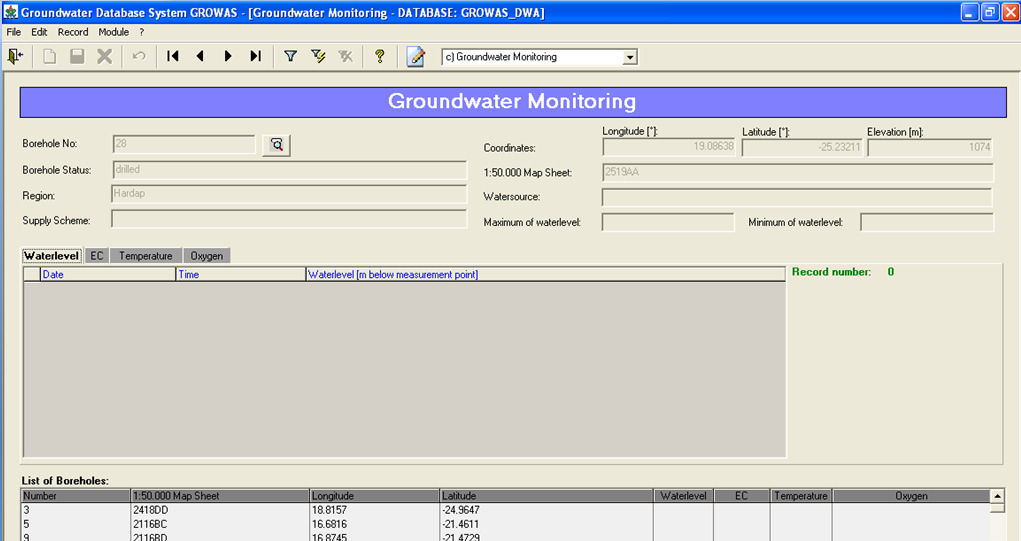

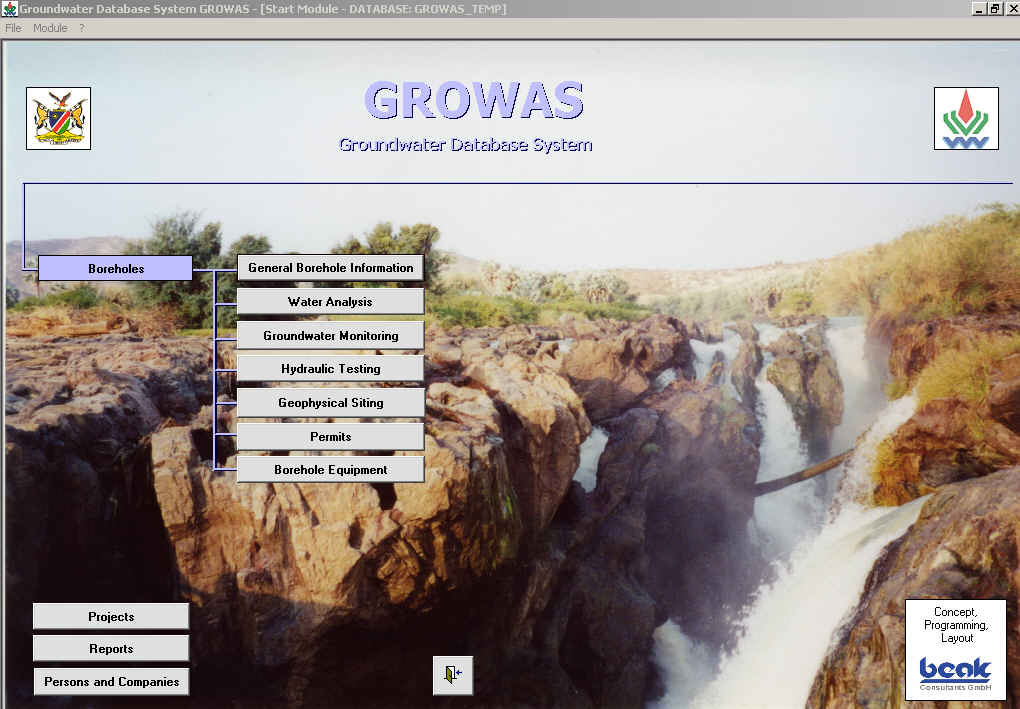

Figure 7-1

The GROWAS database front-end page ..................................................................... 168

Figure 7-2

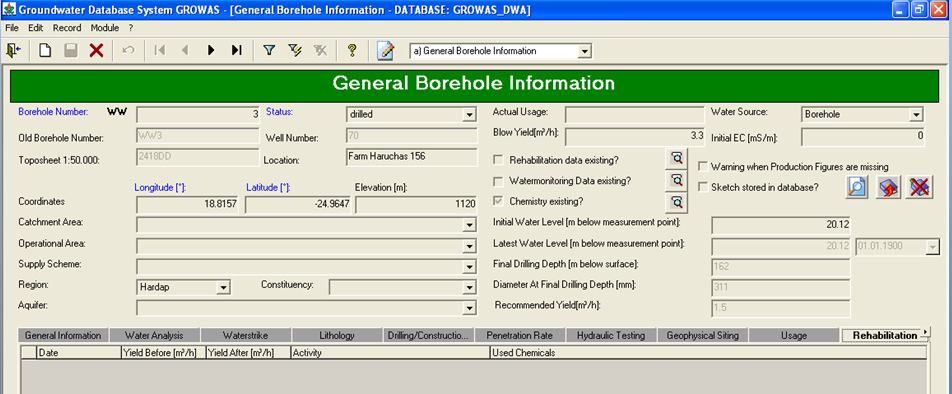

The GROWAS database - General Borehole Information form ................................. 169

Figure 7-3

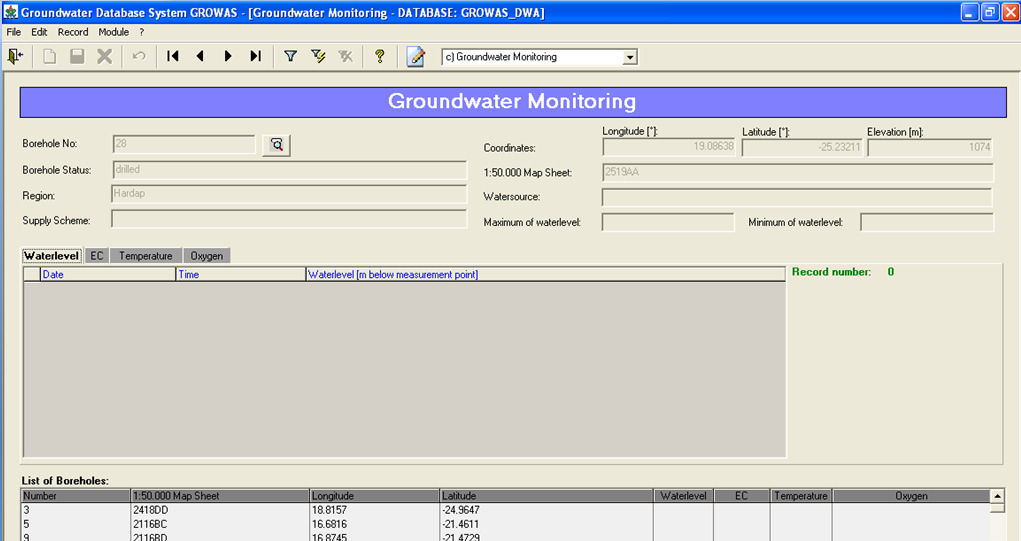

The GROWAS database - Groundwater Monitoring form .......................................... 169

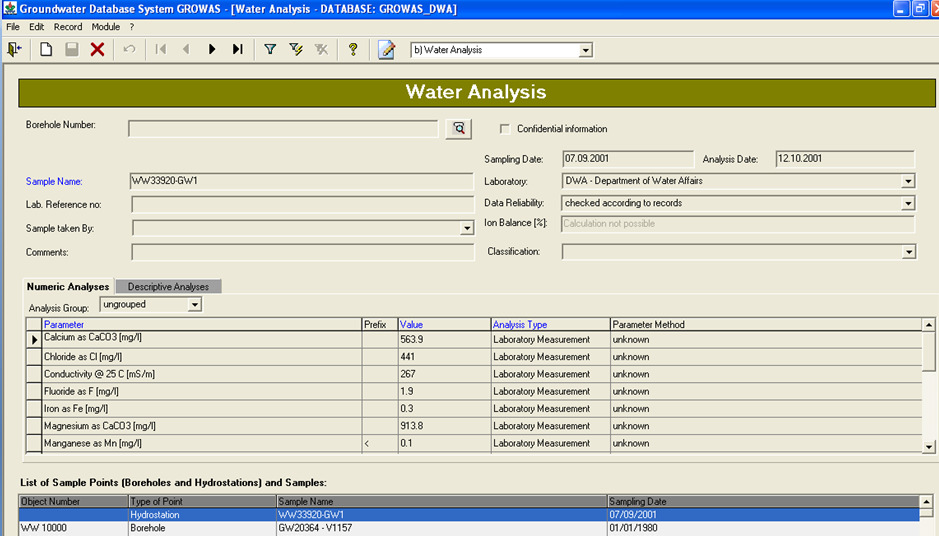

Figure 7-4

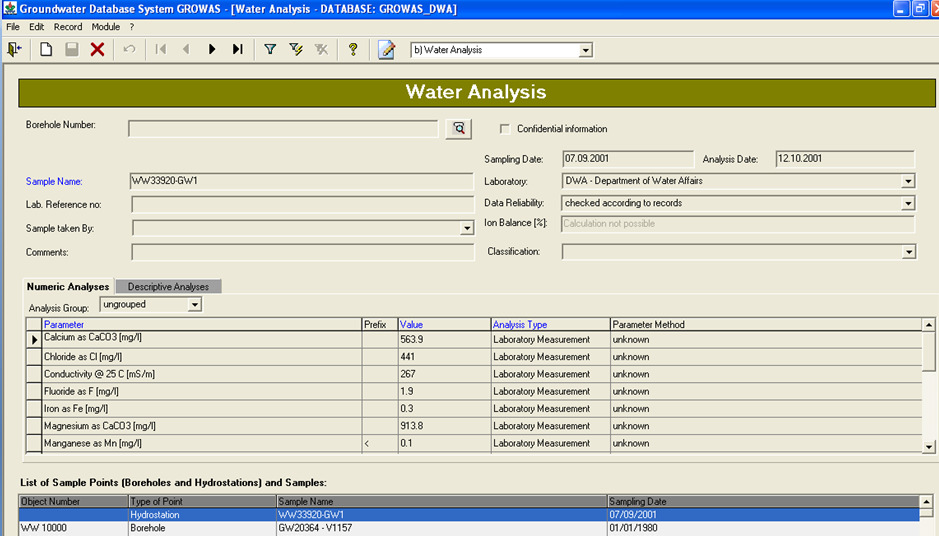

The GROWAS database Water Analysis form ......................................................... 170

Figure 7-5

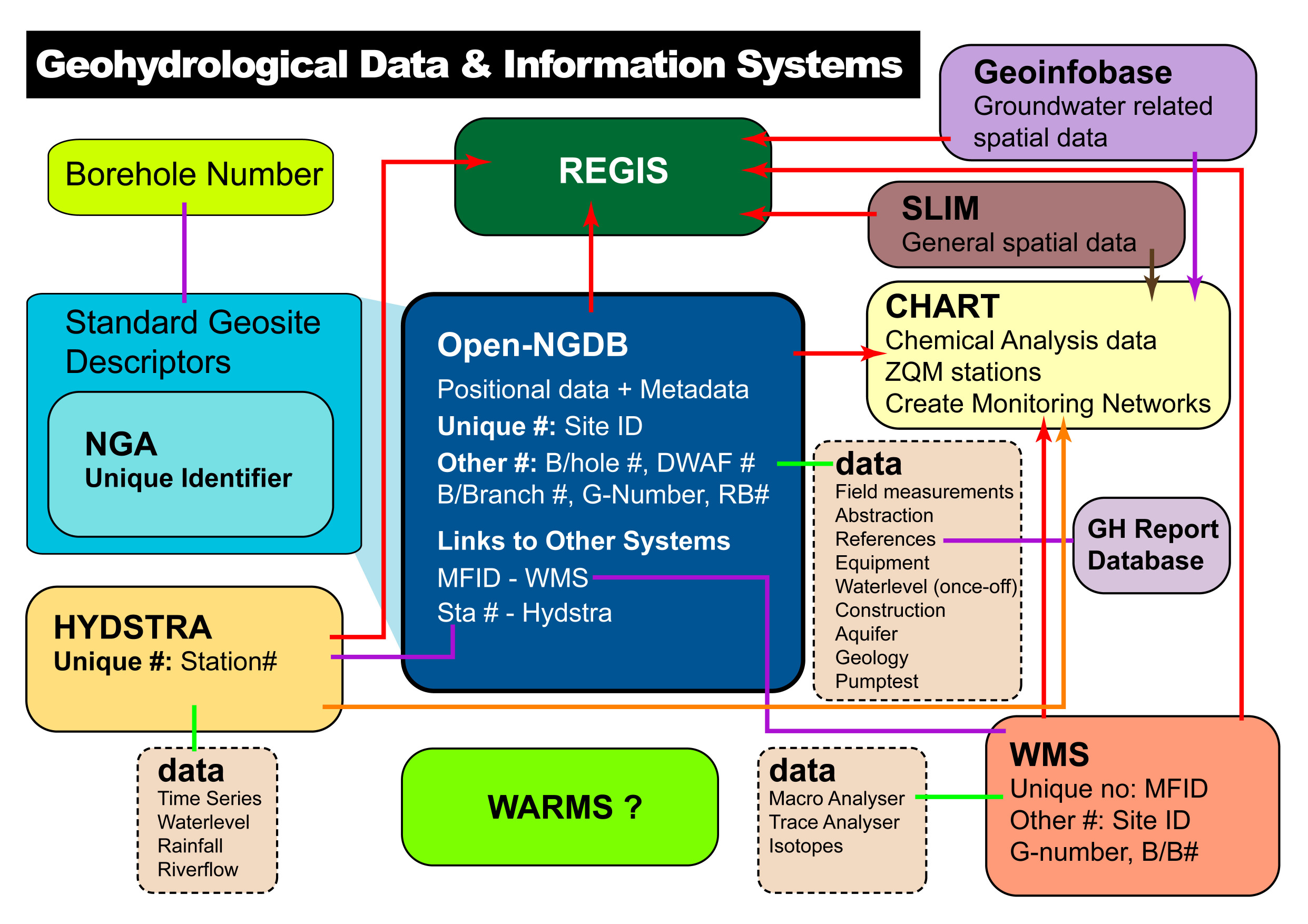

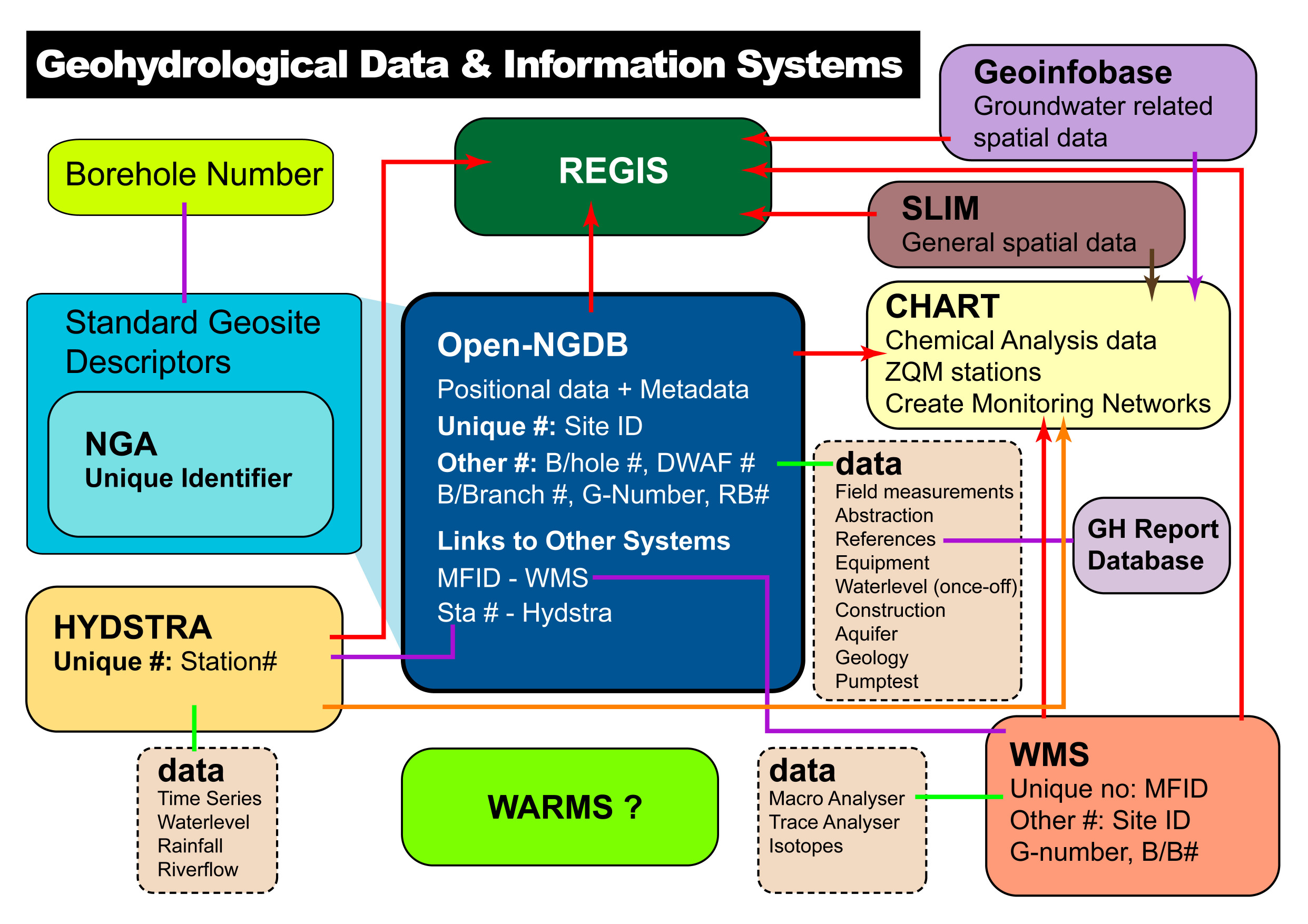

Model for the Databases in South Africa (E. Bertman, DWAF, 2007) ....................... 171

Figure 7-6

Integration of water level monitoring data .................................................................. 175

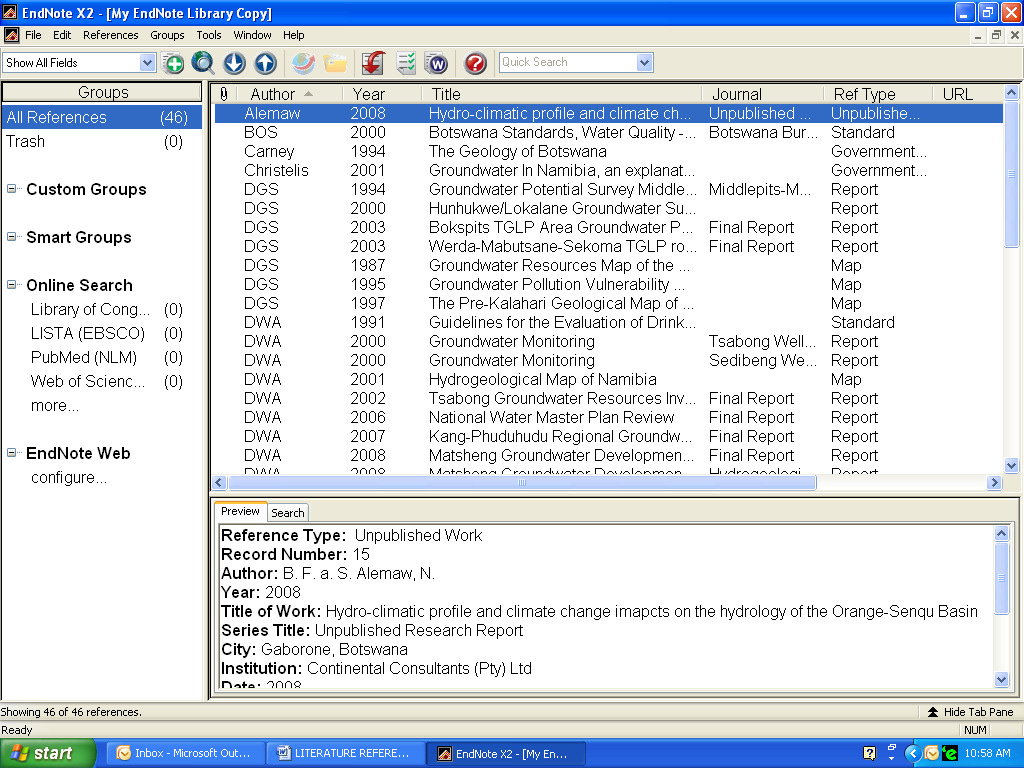

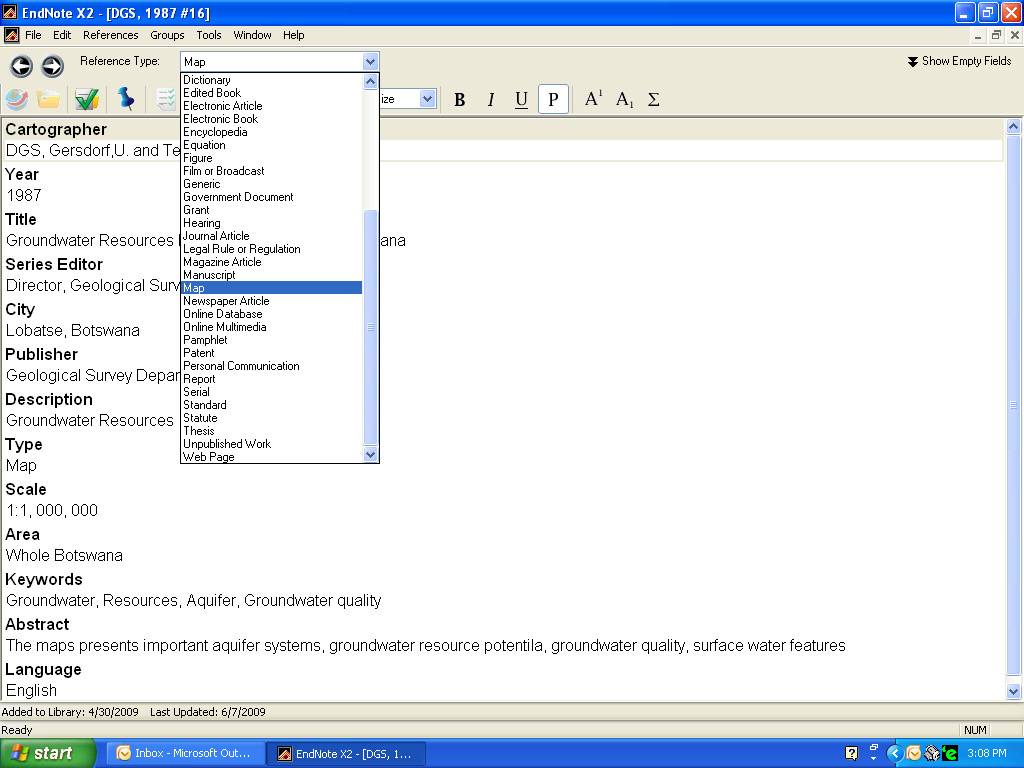

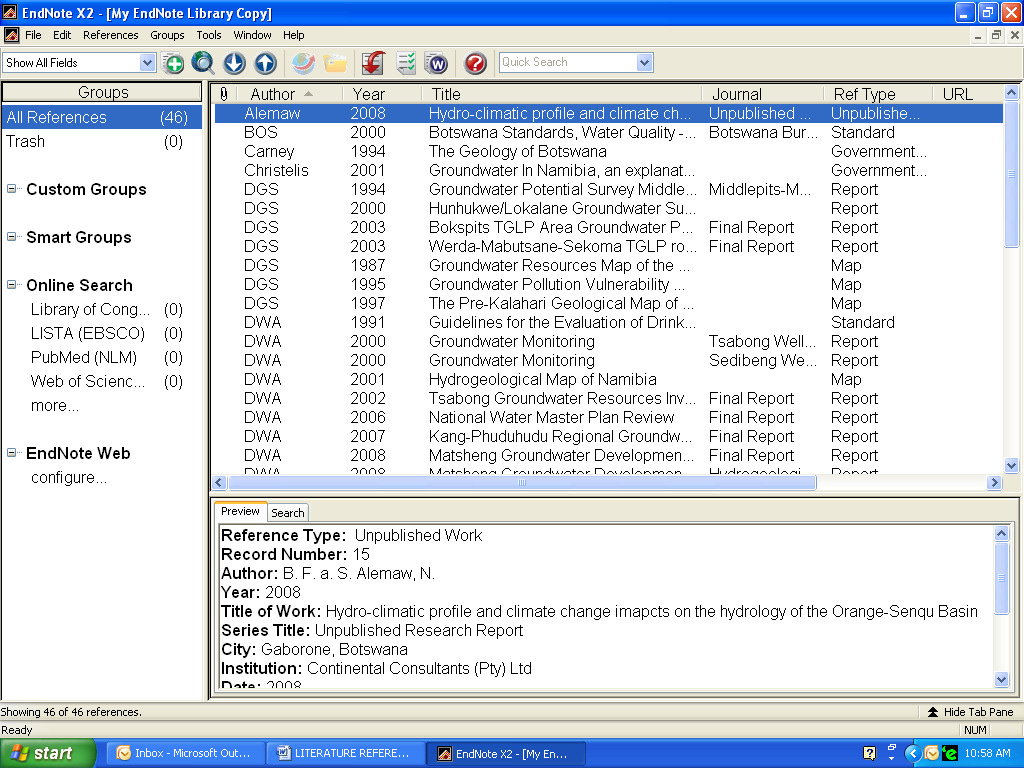

Figure 8-1

Overview of ENDNOTE software .............................................................................. 177

Geotechnical Consulting Services

xii

Groundwater Review of the Molopo-Nossob Basin

Report No. ORASECOM/005/2009

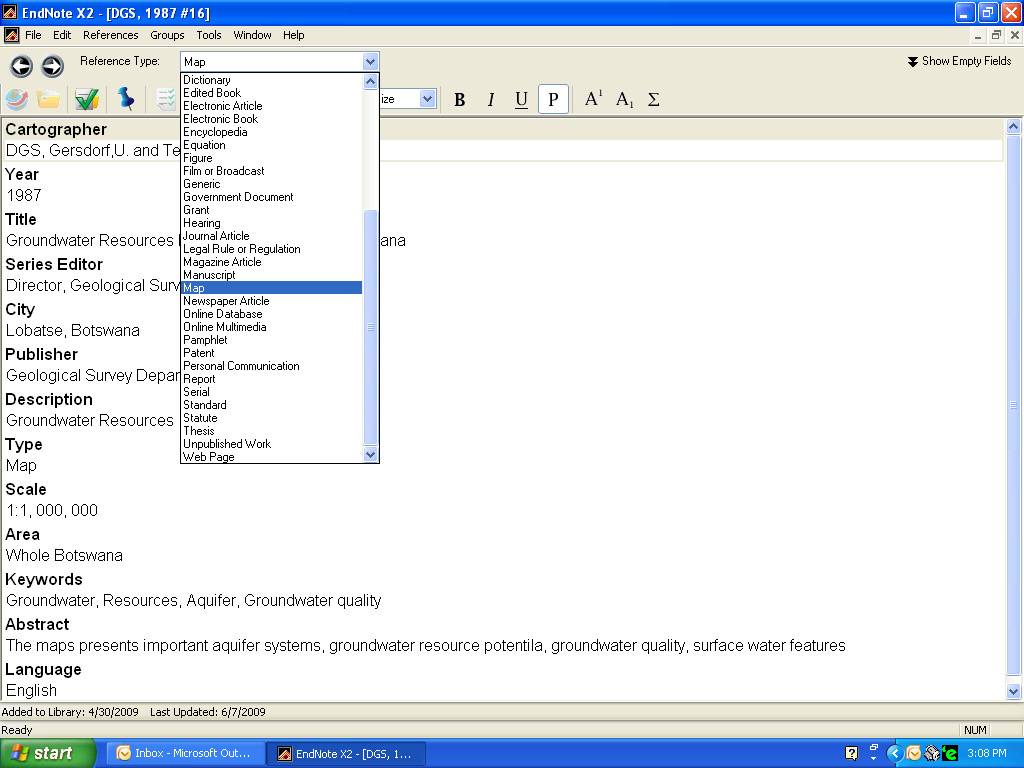

Figure 8-2

Reference types in the ENDNOTE Software .............................................................. 178

LIST OF APPENDICES

Appendix - I

Molopo-Nossob Basin metadata records

Geotechnical Consulting Services

xiii

Groundwater Review of the Molopo-Nossob Basin

Report No. ORASECOM/005/2009

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND SYMBOLS

ADG

Average Daily Gain

AEM

Analytical Element Method

AI

Aridity Index

AIDS

Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome

ARV

Anti Rretroviral (HIV/AIDS drug)

BH

Borehole

BDF

Botswana Defence Force

BEM

Boundary Element Method

BOBS

Botswana Bureau of Standards

CBNRM

Community based Natural Resource Management

CMA

Catchment Management Agencies

CMB

Chloride Mass Balance

CRD

Cumulative Rainfall Departures

CSO

Central Statistics Office

DEA

Department of Environmental Affairs

DGS

Department of Geological Survey

DWA

Department of Water Affairs

DWAF

Department of Water Affairs and Forestry

E

East

EC

Electrical conductivity

ELSU

Equivalent Livestock Unit

EOS

Economically Oriented Scenario

ET

Evapotranspiration

F

Fluoride

FAO

Food and Agriculture Organisation

FCR

Feed Conversion Ratio

FDM

Finite Difference Method

FEM

Finite Element Method

GDC

Ghanzi Dostrict Council

GIS

Geographic Information Systems

GOB

Government of Botswana

ha

Hectare

HIV

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

hr

Hour

JICA

Japan International Cooperating Agency

KDC

Kgalagadi District Council

Km

Kilometre

Geotechnical Consulting Services

xiv

Groundwater Review of the Molopo-Nossob Basin

Report No. ORASECOM/005/2009

Km2

Square Kilometre

l/s

Litre per Second

m

Meter

m3

Cubic Meter

MAWRD

Ministry of Agriculture, Water and Rural Development

mamsl

Meters above Mean Sea Level

mg/l

Milligrams per litre

m2/d

Square Meter per Day

m3/a

Cubic Meter Per Annum

m3/d

Cubic Meter per Day

m3/h

Cubic Meter Per Hour

mm

Millimeter

Mm3

Million Cubic Meter

Mm3/yr

Million Cubic Meter per year

mm/a

Milligrams Per Annum

mS/m

Millisimians per meter

N

North

NAMPAAD

National Master Plan for Agricultural Development

NC

Northern Cape

NDP

National Development Plan

NO3

Nitrate

NGIS

National Geological Information System

NWA

National Water Act

NWMPR

National Water Master Plan Review

NWRS

National Water Resource Strategy

ORASECOM

Orange-Senqu River Commission

PDE

Partial Differential Equation

PET

Potential Evapotranspiration

RAPS

Rescaled Adjusted Partial Sums

RDP

Regional Development Plan

oC

Degree Centigrade

S

South

SAB

Stampriet Artesian Basin

SADC

South African Development Community

SDC

Southern District Council

SOS

Socially Oriented Scenario

SPI

Standardized Precipitation Index

SVF

Saturated Volume Fluctuation

SWCA

Subterranean Water Control Area

T

Transmissivity

Geotechnical Consulting Services

xv

Groundwater Review of the Molopo-Nossob Basin

Report No. ORASECOM/005/2009

TDS

Total Dissolved Solids

TWQR

Target Water Quality Range

UNDP

United Nations Development Programme

UNICEF

United Nations International Children's Educational Fund

UNEP

United Nations Environment Programme

USGS

United States Geological Survey

W

West

WMA

Water Management Area

WTO

World Tourism Organization

WUA

Water Users Associations

WUC

Water Utilities Corporation

%

Percentage

Geotechnical Consulting Services

xvi

Groundwater Review of the Molopo-Nossob Basin

Report No. ORASECOM/005/2009

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1

Background

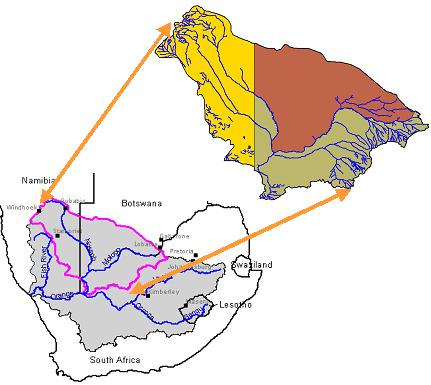

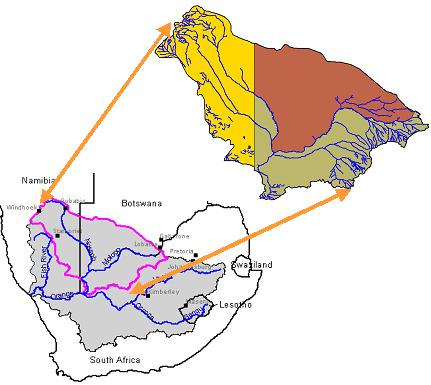

The Molopo River is an ephemeral tributary of the Orange Senqu River system which is an

international river basin shared by Lesotho, Namibia, Botswana and South Africa (Figure 1-

1). The Orange-Senqu River Agreement signed by the governments of the four countries

established the Orange-Senqu River Commission (ORASECOM) to advise the parties on

water related issues.

Orange Senqu River Commission (ORASECOM) has appointed Geotechnical Consulting

Services (Pty) Ltd, to evaluate the groundwater resources in the Molopo-Nossob basin based

on the analysis of available data and information basin-wide. The project commenced on

November 1, 2008.

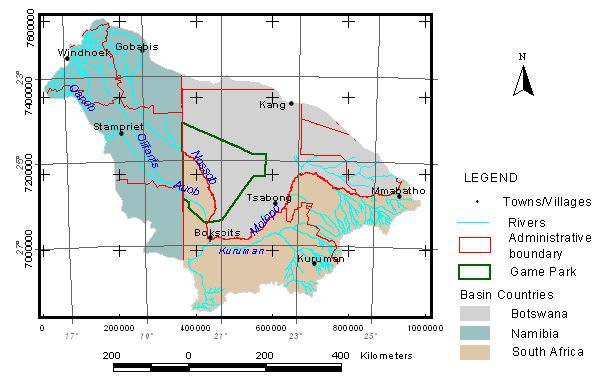

Figure 1-1

Molopo-Nossob Basin and major rivers within the basin

Geotechnical Consulting Services

1

Groundwater Review of the Molopo-Nossob Basin

Report No. ORASECOM/005/2009

1.2 Purpose of the Study

The main objective of the project is to evaluate the groundwater resources of the Molopo-

Nossob basin based on an exhaustive analysis of the available data and information on

boreholes and wells, groundwater monitoring, existing groundwater models, water supply

and demand, water uses, water rights, pollution sources, infrastructure and operating

procedures, environmental and socio-economic information etc. This is necessitated

accessing and analyzing the data/databases in each of the basin states for the whole project

area.

A major sub-objective of the project is the quality assessment, and integration of different

data sets as well as recommendations for how data can be shared between the basin states and

integrated in a common database.

The study, with the mission as stated by the main objective, is divided into three phases:

1. Inception Phase

2. Data Collection, Assessment and Preliminary Integration Phase

3. Groundwater Evaluation and Reporting Phase

The three phases form a logical sequence, in addition project management and reporting will

be a cross-cutting activity over the duration of the project.

1.3 Purpose of this Report

The purpose of this report is to present the results based on the exhaustive analysis of the

available data and information on the groundwater resources of the Molopo-Nossob and

recommendations of the study.

1.4 Structure of this Report