PROJECT

Development Facility

Request

for Pipeline Entry Approval

Concept

paper

Agency’s Project ID:

3339

GEFSEC

Project ID:

Country:

Hungary, Slovakia, Romania, Ukraine, Serbia & Montenegro

Project

Title: : Reversal of land and water degradation in the Tisza basin ecosystem: Establishment of Mechanisms for Land and Water Management

GEF Agency:

UNDP

Other Executing Agency(ies):

UNOPS

Duration: 4 years

GEF Focal

Area: Pipeline EntryInternational Waters

GEF

Operational Program: OP 9 “Integrated Land and Water”

GEF Strategic Priority: IW 2

– Capacity building for IW

Estimated Starting Date:

Estimated

WP Entry Date: Pipeline Entry November 2006

Pipeline Entry Date: November

2004

|

Financing Plan

(US$)

|

|

GEF Allocation

|

|

Project (estimated)

|

5.0 mil.

|

|

Project Co-financing (estimated)

|

6.0 mil.

|

|

PDF A*

|

|

|

PDF B**

|

|

|

PDF C

|

|

Sub-Total

GEF PDF

|

|

PDF Co-financing (details provided

in Part II, Section E – Budget)GEF Agency National

Contribution Others Sub-Total

PDF Co-financing: Total PDF

Project Financing: *

Indicate approval date of PDFA

** If

supplemental, indicate amount and date of originally approved PDF

Record of endorsement on behalf

of the Government:

|

(Enter Name, Position, Ministry)

|

Date: (Month, day, year)

|

|

|

|

N/A

|

This

proposal has been prepared in accordance with GEF policies and

procedures and meets the standards of the GEF Project Review

Criteria for Pipeline Entry approval.

|

|

Mr.Yannick Glemarec

IA/ExA Coordinator

|

Mr. Nick Remple, GEF Regional

Coordinator

Project Contact Person

|

|

Date: 6 October 2004

|

Tel. and email:tel:+421 2 59 337

458, e-mail: nick.remple@undp.org

|

PART

I - Project Concept

A –

Summary

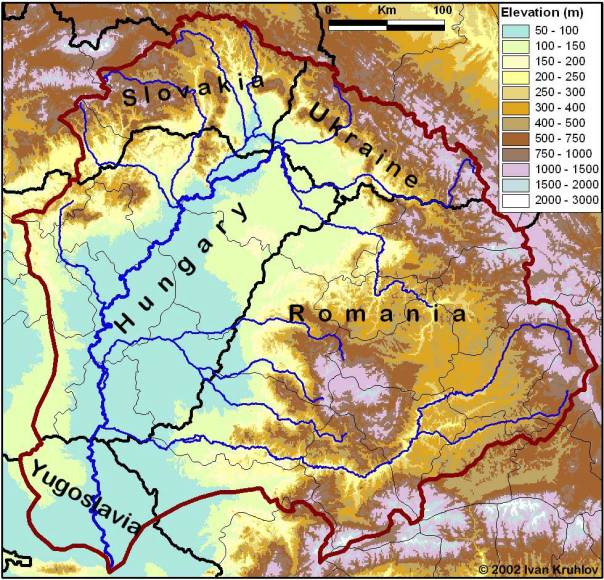

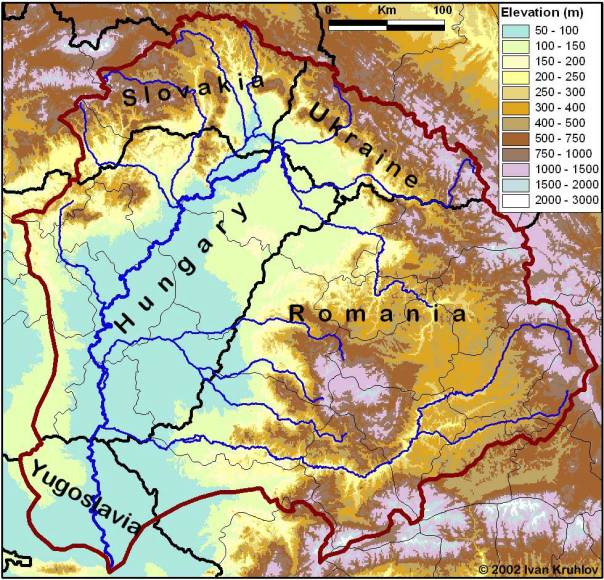

The Tisza river system

is an internationally significant river system, which is seriously

degraded and continues to be threatened. The river drains from the

Carpathian Mountains into a 157,200 square kilometer area, and is

home to some 14 million people. It begins in the territories of

Romania, Slovakia and Ukraine as a number of smaller tributaries fed

by mountain streams. It flows into the Pannonian flood plain of

eastern Hungary and then south into Serbia and Montenegro where it

joins the Danube. This river is the main water source for Hungary, a

significant source for Serbia and Montenegro and significant for

western Romania and southern Slovakia.

This project will build

on what has already been achieved through the EU accession process

and the EU and GEF support of the ICPDR in implementation of the

Water Framework Directive, and the UNDP sustainable development

initiatives in the basin. It will take the concept of Integrated

River Basin Management further by truly integrating the management of

land and water resources, embedding rather than retrofitting

conservation and environmental policy into the planning framework.

The product will be a

River Basin Plan which meets the requirements of the Water Framework

Directive while at the same time addressing wider sustainability

issues in the water, agriculture, energy, industry and navigation

sectors. In a single planning document the project will provide a

bridge between the two on-going initiatives, allowing for a deepening

and widening the planning scope.

Project Objectives

The intermediate

objectives are to:

stakeholders in the basin.

B - Country ownership

Country Eligibility

Only the

non-EU countries will receive GEF support all of which are eligible

for GEF support: Ukraine, Romania and Serbia and Montenegro. The EU

countries of Hungary and Slovakia will be either supported by the EU

through the ICPDR or will be self-supporting.

Country Drivenness

Generally the Tisza

Basin is well-persevered landscape with vast complexes of forested

areas, and viable populations of many species that are no longer

found in Western Europe. The river basin is characterized by

pollution hotspots, heavy industries in decline, poor economic

development, high levels of unemployment, emerging patterns of

regular flooding, and increasing levels of social and ethnic tensions

exacerbated by the countries widely varying courses of transition.

The condition of the waters is degraded by untreated waste waters

from municipal and mining wastes, emissions from declining heavy

industry, agricultural runoff, soil erosion, flooding, oil and

deforestation in critical riparian habitats. Additionally, the

canalization of tributaries, irrigation and draining of critical

wetlands has left the Tisza river basin in significantly diminished

conditions.

Where river floodplains

traditionally supported flood tolerant grasses, water meadows a nd

fishponds, modern agricultural production demands low and tightly

regulated water levels and protection from seasonal inundation. This

trend has been exacerbated by the availability of arable area, crop

intervention payments, and grant aid for drainage, including pumped

drainage within floodplains. This has led to the development of

arable agriculture that demands low water levels in associated

rivers. Flood risks and urban building have also increased within

drained floodplains.

nd

fishponds, modern agricultural production demands low and tightly

regulated water levels and protection from seasonal inundation. This

trend has been exacerbated by the availability of arable area, crop

intervention payments, and grant aid for drainage, including pumped

drainage within floodplains. This has led to the development of

arable agriculture that demands low water levels in associated

rivers. Flood risks and urban building have also increased within

drained floodplains.

In addition to the

altered nature of floodplains, the land use of the upper catchment is

also crucial to the overall risk management situation. Loss of

uncultivated land, especially within the buffer zone of headwater

streams, is increasing the speed of runoff, suspended solid and

nutrient loads, and producing more unstable catchment behavior, where

the retention time of rainfall is reduced, leading to larger flood

pulses downstream. Cumulatively, the reduction in upper and

mid-catchment water retention leads to more flood events downstream

where river channels no longer contain peak water levels, even from

minor flood events. Within the Hungarian plain, disruptive downstream

flooding and consequent disruption of economic activity has been

frequent, and is driving the relevant authorities to greater

cooperative efforts to regulate the Tisza, primarily for

socio-economic reasons.

National Contexts

Hungary

The Tisza River feeds

into the Pannonian flood plain of eastern Hungary. In Hungary, the

waters of the Tisza are used for irrigation of agricultural crops

through a series degraded canals, and there is a desire to improve

conditions to reduce flooding, improve agricultural yields and

develop tourism. Agriculture is intensive in the Pannonian flood

plain. As a result, river and tributaries are heavily regulated. For

irrigation purposes, wetlands have been drained and rivers unbraided,

resulting in the Hungarian portion of the Tisza being subject to

severe flood damage. Though there have been efforts by

international NGOs to mitigate pollution by identifying specific hot

spots and lobbying the government, these efforts have not come to

fruition. In Hungary, as in many of the Tisza basin states,

environmental concerns are secondary to economic demands.

Immediate attention to

mitigating flood damages has drawn the focus away from a more

holistic and integrated water management strategy. As a result of

efforts to reduce flood impacts by building higher dykes and

continued regulation, there is a build up of silt within the canals,

which inadvertently increases flood risks. Draining of the Tisza

wetlands began in the 19th century and today some 500,000

people – 5% of Hungary's population - live on land reclaimed

from the Tisza. In towns and villages near the river, many are used

to seeing strong dykes as their only defense against inundation. A

new plan to allow floodwaters to flow into meadows planted with

indigenous species that have high absorptive capacities, mimicking

more natural flood conditions while reducing flood impacts on human

settlements is under consideration. Though there is an interest in

improving eco-tourism in Hungary, there is also the realization that

until water conditions are improved this will be difficult to

achieve.

Romania

The Romanian section of

the Tisza is probably the most closely studied because of the 2000

cyanide spill. Romania depends on the Tisza for agriculture,

industry, mining and domestic purposes. Flooding and pollution from

agricultural and industrial and municipal sewerage are recognized as

serious concerns. Basin runoff is highly variable and there are

periods of drought and flooding that are difficult to forecast and

manage effectively. The water pollution in the Tisza river basin is

mainly generated by economic activities and accidental wastewater

discharges: the Crisul Negru and Crisul Alb tributaries receiving

mining waste, Crisul Repede receiving wasterwaters from chemical

industries, the Barcau waste from oil drillings and refining industry

and the Mures river from municipal sources and mining activities.

Industry, specifically the mining for non-ferrous metals, generates

much needed income within Romania along the Somes and Mures Rivers

the major Romanian tributaries to the Tisza. However, the

environmental dangers involved in these activities continue to raise

concerns throughout the region as additional mining sites are

established. According to studies, 80% of wastewater discharges are

not adequately treated prior to discharge into natural receptors such

as rivers in the Romanian Tisza basin.

Above

the town of Borsa (Romania), whole hillsides of trees have collapsed

because of indiscriminate logging, yet the economic conditions in

Baia Borsa are so bleak that there are few other activities except

forestry to generate income for local residents. Further downstream,

the soils are lacking nutrients and therefore there are high levels

of nutrients used in the agricultural industry. The soils are also

polluted by heavy metals, and oil as a result of flooding incidents

in the lower basin areas. There is also salinzation of soils due to

poor irrigation practices. The agricultural production relies on

agrochemicals, which runoff into rivers, and ground waters.

Serbia and Montenegro

The Tisza flows through

Serbia and Montenegro for 164 kilometers through a catchment area of

8.000 square km. In Serbia and Montenegro, over 90% of all surface

waters are from transboundary sources. The use of the Tisza is for

waste disposal as for well as some agricultural uses, with high

concerns regarding flooding. There is a lack of capacity in water

management agencies and a strong need to develop environmental

legislation. Further it is in Serbia and Montenegro where the Tisza

meets the Danube and hence the risks of flooding are especially high

here. International conflict including bombing of industrial sites in

the 1990s has impacted the environment of the Tisza as well, though

addressing these concerns has not been a top priority for the

government. The low capacity in the country combined with the lack of

reliable scientific data at present signals the intensity of the need

for action in Serbia and Montenegro.

Slovakia

In Slovakia the Tisza

river is 18.000 km2, and the river basin makes up about

42% of the Slovak Danube basin. The northern part is hilly with high

mountains, which are mainly woodlands. Forestry is one of the main

economic activities and the intensity of forest management is having

negative impacts on the retention capacity of the landscape. In

Slovakia the desire for improved water management stems from the need

to reduce flooding threats and to improve economic development

through better agricultural practices. Additionally, in the lowlands,

most streams are canalized, which reduces the flood mitigation

efforts.

Ukraine

In Ukraine forestry

management is acknowledged to be closely linked to the health of the

Tisza river and therefore there has been a moratorium placed on

forestry activities in the oblast where the Tisza headwaters are

based. The Zakarptska oblast of western Ukraine has high levels of

unemployment and thus there has been difficulty enforcing forestry

regulations. Ukraine also has the legacy of unrealistically stringent

and therefore unenforceable environmental regulations. As a result,

the environmental conditions are historically degraded and there is a

lack of reliable scientific data on specific regions. There is a need

to support improved infrastructure, enforcement capacity and

technological developments in this oblast. The Ukrainian Carpathians

has been identified as potential area for tourist development,

particularly winter sports, and real estate values are increasing.

Ukraine faces

significant environmental challenges in water management in the Tisza

basin. For instance, it was reported that on 17 September 2003 that a

five-kilometer oil slick formed on the river Latorytsya in western

Ukraine's Trans-Carpathian region as a result of a Druzhba oil

pipeline incident. With no automatic shut off valves, a regional

official said the amount released was likely to have been huge given

the pumping rate and the pipe's diameter and reported that there was

a risk that oil might get into the river Latyrka, the only source of

drinking water for the city of Chop, on the Hungarian-Ukrainian

border, and 20 other settlements in the region. Though the spill was

largely contained, and downstream nations were less impacted, the

treatment of such accidents remains an ever-present concern.

Additional background

information on country driveness is provided in Annex 1.

C – Program and Policy Conformity

Program Designation and

Conformity

This project will build

on what has already been achieved through the EU accession process

and the EU and GEF support of the ICPDR in implementation of the

Water Framework Directive, and the UNDP sustainable development

initiatives in the basin. It will take the concept of Integrated

River Basin Management further by truly integrating the management of

land and water resources, embedding rather than retrofitting

conservation and environmental policy into the planning framework.

The product will be a

River Basin Plan which meets the requirements of the Water Framework

Directive while at the same time addressing wider sustainability

issues in the water, agriculture, energy, industry and navigation

sectors. In a single planning document the project will provide a

bridge between the two on-going initiatives, allowing for a deepening

and widening the planning scope. However, in the design of this

comprehensive Strategic Action Programme (SAP), great care will be

taken in defining its bounds, as, if they are too wide, it could

undermine the practical implementation. The SAP should be supported

by national action plans, which in turn will take their clue from

existing national and sectoral development plans. It is anticipated

that the development of the SAP will provide the impetus needed to

tackle the key issues in the basin which have been not given the

regional priority they deserve, although they are acknowledged.

The Tisza basin has

been subject to many assessment studies, particularly following the

Baia Mare spill, but no concrete actions have resulted at yet from

this work. Information on flood risks and flood management and

pollution sources, two key issues, will be taken from the work of the

Tisza Environmental Forum and the ICPDR Danube Pollution Reduction

Programme/EU DABLAS working group respectively. The frustration in

the countries is clear and there is a wish to move on beyond the

assessment and early planning stages. The new GEF project will be

designed to build upon these previous efforts and not to duplicate

them. It is envisaged that the TDA stage will not be lengthy, though

a formal stakeholder analysis and causal chain analysis should be

undertaken. Similarly the SAP/NAP process can be accelerated,

building upon the EU roof and national reports to be delivered a part

of WFD compliance, utilizing the same technical planning bodies,

while extending and deepening stakeholder involvement. It is proposed

therefore that the development and promotion of the SAP and

accompanying national plans be undertaken during the PDF-B stage. The

focus in the PDF -B stage therefore will be the development of the

pilot projects and perhaps the trialing of a project, and the

formalization in each country of the inter-ministerial committee.

Decentralization of

government in many of the Tisza states on the one hand brings

fragmentation of the planning process but on the other hand provides

an opportunity to introduce the concept of Integrated River Basin

Management to a potentially more receptive planning authority, less

affected by institutional and sectoral structural constraints. Clear

terms of reference for the inter-ministerial committee, including its

composition, are required to ensure that it is fit for purpose. The

involvement of the Ministry of Finance as well as the other relevant

Ministries on the Committee is critical if its decisions and

endorsements are to hold and be confirmed at the highest Government

level. The current GEF Danube project is working with the basin

countries to establish the inter-ministerial committees under the

ICPDR, and the new project will work with these committees very

closely throughout, making every effort to strengthen them.

Project Design

Major

Threats

The Tisza River drew

international attention in 2000 when heavy rains and severe flooding

led to the overflow of a dam containing mine tailings laden with

cyanide and heavy metals. For days news broadcasts of the devastation

dominated the international airwaves as a horrified public looked on.

Questions of how could this happen, and who is at fault prevailed

while dead fish floated downstream towards the Danube. The shock of

this incident highlighted the lack of infrastructure support in

Eastern European countries since the collapse of the Soviet era. It

also increased the public and international awareness of the need for

coordinated efforts. Though this single incident fostered recognition

of the initial cause of the spill, there are other interrelated

challenges in the Tisza region that must be addressed by all

countries through regional prioritization and coordinated efforts.

These issues include: threats from flooding; pollution from industry,

[including accidental spills], agriculture and municipal wastes;

deforestation and associated environmental degradation and loss of

biodiversity. These integrated problems must be addressed at a

regional level in order to successfully mediate the threats to this

unique ecosystem and can be overcome most effectively through

integrated water and land use management strategies.

Flooding

Flooding is a

significant threat to the ecosystems of the Tisza River and to the

communities settled in this basin. The rainfall in the Carpathian

Mountains is substantial, as weather fronts crossing southern Europe

and the Mediterranean spill rains into the crescent shaped mountain

range. The sudden rains, combined with extensive drainage, floodplain

development, deforestation and canalization reduces the ability of

the catchment to attenuate the flood wave. When heavy rains occur,

the flooding threatens human lives as water levels rise quickly and

without sufficient warning. The lack of coordinated mechanisms for

mitigating flooding upstream leads to compounded impacts downstream.

When flooding occurs, industrial sites, mining areas and dams,

agricultural fields, and municipal waste facilities become inundated

and spill biohazards into the Tisza waters. The transboundary

impacts of flooding are cumulative, especially for those counties

further downstream and a coordinated flood mitigation strategy is

essential. In order to be effective these measures must be taken

throughout the entire river basin and not just on a country by

country basis.

Deforestation

Deforestation in the

Tisza basin, especially in the tributaries endangers the water

quality of the Tisza, impacts the diverse biodiversity of this region

and exacerbates and the flooding problem. The loss of forests

encourages soil erosion and loss of absorptive capacity during heavy

rains. Deforestation in mountainous areas increases the propensity

for landslides endangering human settlements. The traditional

approach to forestry management focuses on trees rather than

ecosystems and as a result the losses of biodiversity can be

considerable. The increased economic reliance on forestry has been

exacerbated by a decline in opportunities in transitional economic

systems. Forestry practices vary from country to country and are not

generally addressed in conjunction with water management issues,

despite the very close linkages within an integrated ecosystem

management framework.

Pollution

Pollution in the Tisza

originates from: agro chemicals, industrial effluents, untreated

municipal wastes and mining tailings. These pollutants have resulted

in portions of the Tisza River being considered unable to support

fish life. Low economic conditions, high unemployment, poor usage of

lands, ineffective monitoring and enforcement and the lack of

standardized regulations have significantly impacted the river basin

ecosystem.

The excessive use

of agrochemicals, including fertilizers, pesticides and herbicides

are symptomatic of cultivating inappropriate crops for the given

climate and soil conditions in several basin countries. This results

in higher nutrient loads washing into Tisza tributaries and

negatively affects the aquatic wildlife. Further, runoff from

agricultural lands increases the sediment loading of Tisza, reducing

the efficiency of downstream impoundments and damaging the

composition and productivity of the riverine ecosystem.

Industrial

effluents have actually diminished slightly in the past decade as

the economic transition has occurred in the Tisza region. However,

as economic conditions improve across the region there is concern

that effluents will again increase. Further there is a need for

improved and updated technologies to reduce discharges into the

Tisza and its tributaries. There is variation across the region in

the level of enforcement of discharge standards and investment in

updating technologies. The ability of governments to effectively

enforce the economic instruments aimed at emissions reduction also

varies widely. Further location of new industrial facilities should

be carefully considered for the ecological impacts, both in terms of

discharge and potential flooding scenarios.

Throughout the

Tisza basin there is a lack of municipal wastewater treatment

facilities. Though some cities and towns have more up-to-date

standards, the majority of inhabitants live where there is a lack of

wastewater treatment. As a result, raw and partially treated sewer

is dumped into the tributaries of the Tisza. In addition, runoff

from stockyards and animal wastes flow into the Tisza river

increasing the organic loading and bacterial levels of the waters.

While steps are being taking to improve these conditions under the

EU Urban Waste Water Directive and the GEF Danube intervention, in

some cases there are areas where more than 80% of municipal

wastewaters enter the Tisza and its tributaries untreated.

Mining wastes,

including cyanide from non-ferrous mining activities pose

significant threats to the Tisza river basin. Even after the Baia

Mare spill, mining activities continue and there is risk of further

incidents occurring under similar circumstances. Though the Baia

Mare spill drew focused international attention to this problem, the

challenge continues to be a basin wide issue that must be managed

collectively.

Underlying Cause

The above threats to

the Tisza environment have many underlying causes, including:

At a regional level:

Lack of

understanding of the importance of fully integrated land and water

resource management

Weakness in

understanding and policy recognition of the value of biodiversity

conservation for current and future generations

Weak public

(stakeholder) participation at levels of decision-making and weak

public awareness (under-developed civil society) of environmental

issues

Absence of

national budget allocated for the environment due to low priorities

Multiple

initiatives working at cross purposes

Lack of a

framework for a sub-basin cooperation framework for cooperation

At the national level:

Weaknesses in

existing policy, legal, and regulatory institutional frameworks to

address specific problems of the Tisza basin

Low enforcement of

existing laws and regulations

Low income levels

and poverty amongst some Tisza basin residents

General weakness

of Environmental Agencies/Ministries in the region

Absence of

government will and funding for environmental matters

Corruption in

natural resource management (use of resources, planning/management)

Lack of effective

buffer zone planning and management function in all five countries

Weak intersectoral

cooperation on environmental issues

The impact of pollution from both point and

non-point sources is significant. The socio-economic impacts are

serious, affecting human health, the availability of resources,

access to healthy fisheries, safety to human settlements, and

development of the tourism industry capable of competing with less

environmentally challenged regions.

Baseline Scenario

The

concerned countries recognize the problems regarding River

Basin Management in the Tisza. At this time their efforts tend to be

fragmented even though they have a guiding policy document in the EU

Water Framework Directive and strong institutional and legal

frameworks in the form of the Danube and Carpathian Conventions. The

Tisza countries need to make better use of these instruments to

address the sub-basin problems. The EU member states of Slovakia and

Hungary are required by to implement the WFD but cannot fully comply

unless the non-EU basin states also comply. The non EU-states include

Romania and Ukraine, which are upstream, and

Serbia-Montenegro, which is at the bottom of the basin at confluence

of the Tisza with the Danube. These non-EU states are committed to

implementation of the WFD, along with much of the EU environmental

acquis, but the implementation is likely to be slow. It is understood

that the EU is not considering including Serbia and Montenegro and

Ukraine in the EU enlargement process in the short or medium term.

Therefore it is expected that the implementation of the EU WFD will

be a long term processes in the Tisza basin. This delay is in part

due to the lack of institutional and economic capacities of the

non-EU countries to prioritise and address water management issues.

It should be noted that even in the EU countries the implementation

of the WFD focuses is on the water sector and Integrated River Basin

Management is not fully practiced. Also, the participatory approach

of multiple stakeholder groups is not practiced, except through the

consultation process required by the WFD.

The ICPDR

has thirteen member states and has made immense efforts in the last

ten years to tackle the major problems of pollution on the River

Danube; the organisation is now turning its efforts to implementation

of other aspects of the Joint Action Programme including integrated

river basin management planning. The Carpathian Convention has

specific articles addressing sustainable and integrated river basin

management and sustainable agriculture and forestry, which should be

called upon in support of implementation of the GEF project and

subsequent SAP.

International assistance

has not helped this situation. Though there are many initiatives they

have overlapping goals. These lack significant coordination with

different regional and national champions. This further complicates

efforts due to a myriad of projects that risk becoming competitive in

the region, which has a dire need for cooperation. The situation is

not intentional, and has developed largely out of a desire to assist

this region. There is an urgent need for an implementable action plan

to address key transboundary issues in the basin. This must be a

joint plan to which all countries are committed.

Alternative

Scenario

The UNDP, the EU, the

ICDPR and the Carpathian Convention recognize the impasse in the

Tisza basin and have observed the frustration in the countries and

the local communities that little is being done to address the key

transboundary issues. They also admit that this problem is in part of

their own making. This project will help build a common legal,

institutional and planning framework, capable of attracting the

national funding required to tackle the transboundary issues. It will

dispel the myth that the EU will and can fund all the improvements.

The project will enforce the need for proper regulation and

compliance with standing legislation. Building on the WFD the project

will encourage greater integration of inter-sectoral policy and

planning, and wider and deeper stakeholder participation. The project

will assist in implementation of the Tisza SAP and JAP that will then

continue to develop, supported by the ICPDR, to tackle transboundary

issues at the baseline and the regional level. Other international

assistance efforts can also be included in this coordination effort

and can develop more harmonious regional assistance.

The implementation of

an initial transboundary demonstration project at the PDF-B stage

will provide valuable information in the design of the full sized

project demonstration projects, in terms of what can and cannot be

done at the community level and, hopefully, begin to answer how basin

wide sustainability criteria can be interpreted at the local level.

It also should help answer whether sustainable development and

economic improvements can be achieved in parallel, without

accompanying relatively high levels of investment.

Why should GEF get involved at all?

This project will give

an opportunity to meld the outputs of five existing GEF projects to a

single land and water management use project platform. There will be

significant crossover between the GEF biodiversity and the

International Waters portfolios with the potential for significant

synergies and perhaps ideas for new, more effective project design.

The linkage to the UNDP Carpathian-region Umbrella programme

demonstrates the programmatic approach that is keenly advocated by

the GEF Council. The GEF have forged a long and successful

partnership with the European Union in the Danube basin. Together

they have supported the implementation of the Danube Convention,

established the ICPDR and addressed priority transboundary issues.

This project would be an extension of that partnership. The ICPDR has

13 member states and its approach cannot be as in depth as it would

like, because its members have different development paths and

speeds. In complex basins, such as the Tisza, a more integrated land

and water management approach is required to tackle the transboundary

problems. These are more complex than those currently being

implemented by the states under the EU Water Framework Directive. The

EU, which is a contracting party to the Convention, is keen to see

that its members comply with the WFD at the basin and sub-basin level

and link it to other initiatives such as their Flooding Communication

and their Water Initiative for the EECCA region. Other international

assistance efforts can gravitate to this effort as well, in order to

best invest their efforts without being redundant.

Sustainability (financial,

social, environmental) of the full project

The sustainability of

the project will be ensured with the adoption of the SAP and NAPs at

regional and national levels and the government commitment to

implement them. The establishment and continuation of the

inter-ministerial committees and allocation of government funds to

these plans will be clear signs of sustainability. The project must

work with the countries to implement the EU acquis and not sent up

competing planning frameworks. There is no specific sub-basin legal

and management framework for the Tisza at present and there is still

discussion between the countries as to the best approach. It is

envisaged that a final decision will be made on this matter at the

end of the two-year PDF-B stage and should be set as a pre-requisite

for endorsement of the full project.

Replicability

The Global

Environmental Facility (GEF) has funded 4 biodiversity projects in

the Tisza river basin at the country level. These are in Hungary,

Romania, Slovakia and Ukraine. Additionally, a Biodiversity Strategic

Action Programme in Serbia and Montenegro is supported by GEF.

The Hungarian

project focuses on conservation and restoration of the globally

significant biodiversity of the Tisza river floodplain through

integrated floodplain management.

The Romanian

project focuses on strengthening Romania’s protected area

system by demonstrating public-private partnership in Romania’s

Maramures Nature Park.

The Slovakian

project focuses on integration of ecosystems management principles

and practices into land and water management of Slovakia’s

Eastern lowlands.

The Ukrainian

project Conserving globally significant biodiversity and

mitigating/reducing environmental risk by integrating biodiversity

conservation principles and practices into forestry and watershed

management in Ukraine’s Trans Carpathian region.

These

national level GEF biodiversity projects each have a demonstration

component that links integrated land and water river basin management

with socio-economic realities within this region. These projects are

varied enough to serve as very important role model for other similar

projects in a transboundary setting. Through sustainable watershed

management these GEF Biodiversity projects address many of the

environmental challenges facing the broader Tisza river basin. These

will provide valuable lessons for the proposed project and have the

potential to be replicated not only in the Tisza but also in broader

Danube and other transboundary river basin management programmes.

The

project would develop a series of demonstration projects for

inclusion in the SAP implementation phase, aimed at improving water

and land resource management; looking for win-win situations, where

the principles of sustainable development can be applied to increase

productivity and increase environmental protection.

Stakeholder Involvement/Intended

Beneficiaries

Stakeholders involved

in this project include, inter alia:

Ministry officials

from:

Environmental

protection and management

Agriculture and

forestry

Transportation

Energy

Public health

Planning and land

use and urbanization

Soil management

Industry

Mining

Education

Tourism

Communication and

emergency services

Economic and or

finance

Foreign affairs

Defense

District, local

and municipal leaders

International and

bilateral assistance agencies

Local, national,

regional and international NGOs

Coastal residents

Community based

organizations

Construction

company owners and workers

Industry owners

and workers

Mine owners and

miners

Farmers

Fishermen

Forestry workers

Educators

Agricultural

support industry

Public healthcare

providers

Scientists and

researchers

Tourism industry

specialists

Media, including

print and broadcast

International

investors interested in the region

D – Financing

Financing Plan

The PDF-B stage would

be two years duration, followed by a four year SAP implementation

project.

In the PDF-B stage, EU

funding will be used to fund EU member states involvement and

specific basin wide elements relating to the implementation of WFD.

GEF and UNDP funds will be used to support the three non-EU states:

Romania, Serbia and Montenegro and Ukraine.

The UNDP Regional

Centre for Europe and the CIS was established expressly to manage

projects of a cross boarder nature, and is uniquely qualified to

implement the proposed project. The Regional Centre is prepared to

commit approximately $200,000 in cost-sharing to implement the PDF-B

stage of the project.

Only the

non-EU countries will receive GEF support all of which are eligible

for GEF support: Ukraine, Romania and Serbia and Montenegro. The EU

countries of Hungary and Slovakia will be either supported by the EU

through the ICPDR or will be self-supporting.

Estimated GEF

contribution for Full size project is USD 5.0mil, with co-financing

USD 6.0 million.

Co-Financing

The PDF-B would be

co-funded by the EU, UNDP and the Carpathian Convention through UNEP,

as well as the participating states. Approximately $2 million will be

requested from the international agencies and GEF for PBF-B

execution.

Co-financing for Full

size project is expected from EU funds, UNEP and national and local

governments of participating countries.

E - Institutional Coordination and

Support

Core Commitments and Linkages

The Tisza countries are

all signatories to the Danube River Protection Convention (DRPC),

which is a legally binding document and provides a framework for

cooperation between the parties. The Danube countries under the

obligations of the DRPC have established the International Commission

for the Protection of the Danube River (ICPDR) creating an

institutional framework not only for pollution control and protection

of water bodies in the Danube basin, but also the integrated

management and sustainable use of basin’s natural resources.

In November 2000 the ICPDR adopted its first Joint Action Programme

(JAP) for the Danube which addresses pollution from point and

non-point sources, wetland and floodplain restoration, priority

substances, water quality standards, prevention of accidental

pollution, flooding and river basin management. Any planning document

prepared for the Tisza basin must be consistent with the ICPDR’s

JAP.

There are significant

challenges in the management of the Tisza basin water resources, and

the five countries of the basin are well aware of these challenges.

The Tisza riparian countries are at different phases of development,

and have widely divergent capacities to address local, national and

regional river basin management issues. The combination of economic

readjustment and development, transitional political systems, and

expansion of the European Union has led to wide variation in capacity

throughout the region to address and mitigate environmental risks.

While some of these circumstances have resulted in advancements that

have been positive for the region as a whole, historically there has

been a lack of coordinated environmental management among the Tisza

states, even though management and institutional structures may exist

to do so. This lack of coordination has hampered efforts to

successfully manage flood and other crisis events.

Recent efforts of the

EU (EU is holding the rotating presidency of the ICDPR this year)

have taken steps to mitigate this situation (Annex 3). Yet, despite

major coordination attempts, there are still challenges, as each

country tends to focus primarily on the waters only within its own

borders without fully recognizing the impacts of its actions on

neighboring countries. This lack of coordination diminishes the

success of other national and local level projects because it creates

separate standards within each state for monitoring success and

managing crises. On the positive side, each of the Tisza riparian

countries has committed to implementing the EU Water Framework

Directive (EU WFD), including the requirements for management of

transboundary waters, but the capacity of each county to effectively

meet the WFD requirements varies widely. Two of the five countries

are not EU member or accession states, and therefore the high

standards set by the WFD

Consultation, Coordination and

Collaboration between and among Implementing Agencies, Executing

Agencies, and the GEF Secretariat, if appropriate.

Currently there are a number if existing

international assistance and regional initiatives aimed at various

components of water management. There is a lack of coordination

across these initiatives and often they have overlapping or redundant

efforts. The International Commission on Protection of the Danube

River (ICPDR) serves as an umbrella agency for the larger Danube

Basin, but there is not a similar organization functioning in the

Tisza basin.

The Project will be

managed under the umbrella of the Danube River Basin Convention and

coordinated by the ICPDR. Coordination with the GEF Danube Regional

Project is crucial to avoid duplication but more importantly to

benefit from wider basin activities under both the DRP itself and the

associated Danube - Black Sea partnership. A donor co-ordination

group will ensure good communication between the major environmental

projects within the Tisza basin.

The new project will

bring together and find common ground for the three major

initiatives, and working closely with the ICPDR, the project will

ensure maximum project synergy and minimum project overlap through

the establishment of a ‘Friends of the Project’ group.

The project will demonstrate flexibility and pragmatism in bringing

the partners together.

Implementation/Execution

Arrangements

UNDP Regional Centre in Bratislava

would focus its efforts on substantive implementation/monitoring and

supervision of the GEF project, and the execution work would be done

by UNOPS who has well developed structures/systems for project

execution.

The Project Steering

Committee would include the five basin countries, the EU and the

three GEF implementing agencies, UNDP, UNEP and the WB.

PART

II - Project Development Preparation

This part is an

additional information about PDF B stage, that will be submitted

later on in 2004.

A

- Description of Proposed PDF B activities

The project activities

during the PDF-B and full implementation stage will be:

PDF-B

A detailed basin

stakeholder analysis to identify the stakeholders and articulate

their concerns

Establishment of

stakeholder groups at regional, national and (where appropriate)

local levels

Establishment of a

‘Friends of the Project Group’

In each

participating state, establish/reinforce and support inter-ministry

committees that include the finance ministries, to direct the

planning process

Synthesis of the

available data and information on transboundary issues in a TDA and

Roof report.

Causal Chain

Analysis of transboundary issues

Identification of

priority transboundary issues and the drafting of Ecosystem Quality

Objectives, constituting a long-term vision for the basin

Development and

endorsement of national action plans (which will include approved

financial plans) to

Development and

regional endorsement of a Strategic Action Programme for the basin,

to include a realistic financial plan and an M&E framework

Production of

project documents for transboundary demonstration projects to be

implemented as part of the SAP, at least one project per country

Implementation of

a small-scale pilot project to demonstrate concrete advantages of

the Integrated River Basin Management

Two regional

workshops to discuss the legal and institutional framework for the

Basin Authority

Donor conference

to launch the SAP and lever funds for its implementation.

Preparation of the

full project document.

B

- PDF Block B Outputs

Agreement on the

legal and institutional framework for the Basin Authority (this will

be made a pre-requisite of the approval of the full project)

Provision of

technical assistance and training to the Basin Authority

Strategic studies

to fill information and data gaps

Revision of the

TDA

Implementation of

demonstration projects

Public

dissemination of results of pilot project through study tours,

conferences and published material, and the identification of

replicable sites

Monitoring and

Evaluation of the SAP and National Action Plans (NAP) in the basin

states.

Review SAP and

NAPs

C

- Justification

The ICPDR under EU

Presidency has this year prepared a discussion document (Annex 3) to

initiate a dialogue on the Tisza. The document called for dialogue to

concentrate, streamline and coordinate all the water resource

management initiatives towards a common vision and goal. ICPDR wish

to convert the pragmatic national approach to water resources

currently operating in the Tisza, to a sub-basin approach in order to

meet the demands of the EU Water Framework Directive (WFD). The WFD

planning process requires development of RBM plan based on sound

analysis of water bodies conditions, pressures and impact analysis,

setting environmental objectives and a development of program of

measures to achieve good ecological status of all waters in the

basin. The roof reporting methodology, established by ICPDR as

working method, is comparable to the GEF approach calling for TDA/SAP

and national action plans. The ICPDR discussion paper also calls for

further application of Integrated Water Resource Management, as

promoted by the EU Water Initiative launched at the Johannesburg

summit, and European Commission new Communication on ‘Flood

risk management, flood prevention, protection and mitigation’.

These proposals are closely compatible with the GEF TDA/SAP approach.

D

- Timetable

In consultation

with ICPDR and the Carpathian Convention interim secretariat, agree

and finalize concept paper (September 2004)

Have project

accepted into GEF IW pipeline (October 2004)

Hold regional

stakeholder meeting to discuss concept paper and elicit ideas for

PDF-B/full project stages (November 2004)

Develop PDF-B

document; this is a complex project and warrants execution of a

separate PDF-A stage (December 2004)

Hold second

regional stakeholder meeting to finalize concept paper (January

2005)

Meeting of the

donors to secure co-financing for PDF-B and full project co-funding

(January 2005)

Submission of

PDF-B to GEF secretariat for approval (March 2005)

Following country

approval execution of PDF-B (June 2005 – December 2006)

Submission of full

project document to GEF Council Spring 2007.

Following GEF

Council approval, CEO endorsement and country approval, full project

implementation June 2007 – June 2010.

Proposed

project development strategy

The UNDP/GEF

International Waters Projects (IWP) and the EU/WFD share similarities

stemming from concurrent objectives of improving overall water

quality though linked regional initiatives. They are highly

complementary, and the processes for reaching the same ends are

closely related.

The similarities

between IWP objectives and those of the EU/WFD can both apply to the

Tisza River Basin through integrated river basin management

strategies. Common broad objectives include: protection of fresh

water sources against pollution; use and conservation of wetlands;

sensitivity to environmental impacts of human development in coastal

areas; the recognition of multiple uses for water and the economic,

social and political sensitivity of shared water resources; the

ability for shared cooperation over natural resources to extend into

other spheres throughout the region.

TDA/SAP methodology and

WFD implementation commonalities include: the importance of

intersectoral cooperation; regionally linked national policies for

monitoring and prevention of degradation through natural or

anthropogenic causes; the need to include economic and environmental

needs in project development; importance of including all users

within the basin equally and working with multiple stakeholder groups

to develop processes; the need to coordinate national and basin wide

policies as much as possible; the importance of developing long term

regionally sustainable practices; setting commonly accepted

objectives for improvements; application of the polluter pays

principle and precautionary principle whenever achievable; use of

pilot projects; recognition and compliance with existing

environmental international agreements.

These similarities

enable these two approaches to work closely together, in a

complementary fashion. With regards to some environmental challenges,

the EU/WFD implementation strategy is more fully developed and quite

sophisticated, while with regards to other challenges, the IWP

TDA/SAP process can enhance the approach advocated by the EU/WFD

Implementation Strategy. Neither is necessarily better than the

other, and should not be thought of as such. Rather, at this juncture

these approaches have the ability to enable organizations to learn

from each other in a cooperative manner.

The Framework

Convention on the Protection and Sustainable Development of the

Carpathians provides for the development of River Basin Management

Plans, particularly in the upper catchment where forestry management,

nature conservation and downstream flood management are inter-linked.

The UNDP Tisza River

Basin Sustainable Development Programme (TRB SDP) has the following

broad objectives:

securing the

prosperity of the people living in the river basin;

making sustainable

use of the basin’s natural resources;

minimizing

environmental risks;

preserving natural

and cultural values; and

developing a

participatory framework for cooperation between countries, sectors,

communities and stakeholders.

Within UNDP the TRB SDP

has developed into a broader Carpathian -region development

programme, which will provide an umbrella not only for this project,

but also some 20 regional and local development projects, including

ethnic issues, and environmental governance initiatives (see concept

paper Annex 4). The GEF project will be one of two major regional

matrix projects under the - Carpathian region umbrella, to which the

smaller local development projects will be linked and into which

lessons learnt will be fed. The matrix projects will deal with the

twin issues of Environmental Sustainability and Sustainable Income

Generation, contributing to the UNDP objective of harmonious social,

economic and environmental development in the region’s

communities.

The new project will

bring to together and find common ground for these three major

initiatives, in addition to the European Council CEMAT initiative

(see section above). Working closely with the ICPDR, the project will

ensure maximum project synergy and minimum project overlap through

the establishment of a ‘Friends of the Project’ group.

The project will demonstrate flexibility and pragmatism in bringing

the partners together.

Part IV –

Response to Reviews

A -

Convention Secretariat

B - Other

IAs and relevant ExAs

ANNEXES:

Annex 1:

Additional Information on Country Driveness

Annex 2:

Map of Tisza

Annex

3: Towards a Sub-River Basin Management Plan for the Tisza River: A

Discussion document initiating a dialogue on the Tisza by the EU

Presidency and the Permanent Secretariat of the ICPDR

Annex

1: Additional Information on Country Drivenness

The Tisza River Basin

is the largest tributary to the Danube. The streams and rivers

feeding into the Tisza originate in the Carpathian Mountains and flow

through Hungary, Romania, Serbia and Montenegro, Slovakia, and

Ukraine (see map of Tisza basin, annex 2). These rivers pass through

areas significantly degraded by deforestation, industrial,

agricultural and municipal wastes, past deleterious mining sites and

through precariously protected wetlands. The waters of the basin

serve as a crucial means of irrigation for crops, for transportation,

for domestic and industrial use, as a waste disposal mechanism, to

sustain other human activities and to support the regional

ecosystems.

The Tisza River serves

a variety of purposes within the wider basin. The waters serve as a

crucial means of irrigation for crops, for transportation, for

domestic and industrial use, as a waste disposal mechanism, to

sustain other human activities and to support the regional

ecosystems. The countries of the Tisza river basin are aware of the

challenges before them in management of their collectively owned

water resources.

In 2000 the Tisza drew

international alarm due to a cyanide spill from the Romanian mine

tailings dam in Baia Mare during seasonal flooding. 100,000 tones of

cyanide laden sludge spilled into the Tisza leaving almost 1,000

kilometers of the river lifeless, including fish, invertebrates and

birds. The water became lethal, and though the cyanide decomposed

quickly, the heavy metals remained leaving legacy of the event,

including an increase in long-term ill health risk among residents in

the region. Though significant international attention has been paid

to the region in terms of studying the effects and taking steps to

minimize the impacts of Baia Mare, there has been a lack of

regionally coordinated mitigation efforts that focus on transboundary

remediation. Furthermore, there are a variety of international

initiatives within the region addressing different aspects of river

basin management; however there is lack of coordination of these

efforts and resources are being squandered. This project is designed

to address these shortfalls.

The Tisza riparian

countries are at different phases of development, and have wide

ranging capacities to address local, national and regional river

basin management issues. The combination of economic readjustment and

development, transitional political systems, and expansion of the

European Union has led to a wide variation in capacity throughout the

region to address and mitigate environmental risks. While some of

these circumstances advancements have been positive for the region as

a whole, historically there has been a lack of coordinated

environmental management among the Tisza states, even though

management and institutional structures may exist to do so. This lack

of coordination has hampered efforts to successfully manage flood

crisis events. The Tisza flood plain in Hungary has over time has

become drained and developed, the main channel has been canalized and

braiding removed. Upstream canalization has been particularly

critical. All of this has caused reduced flood attenuation and a

concentration of the flood wave in downstream countries in the Tisza

basin and beyond.

Recent efforts of the

EU ICDPR have taken steps to mitigate this situation. Yet, despite

major coordination attempts, there are still challenges, as each

country tends to focus primarily on the waters only within its own

borders without fully recognizing the impacts of its actions on

neighboring countries. This lack of coordination diminishes the

success of other national and local level projects because it creates

separate standards within each state for monitoring success and

managing crises. These efforts have been promising as each of the

Tisza riparian countries has committed to implementing the EU Water

Framework Directive (EU WFD), including the requirements for

management of transboundary waters, though the capacity of each

county to effectively meet the WFD requirements varies widely.

Further, two of the five countries are not EU member or accession

states, and therefore are distinctly disadvantaged by the high

standards set by the WFD.

National Policies

Hungary

In Hungary, the water

management has three basic functions that determine its objectives,

programmes and methods as well as its relation to and cooperation

with other sectors of society (National Strategy for Water

Management, 2000) These are: protection of the population against the

hazard of water; supply of the water needed by the citizens and their

activities; and, preservation of water resources, particularly

drinking water supply, in such as state as to remain in harmony with

the environment to ensure their long-term sustainable use. Hungarian

legislation has been changing with the aim of adoption of the

requirements of the EU. This legislation has been aligned with the

environmental acquis of the EU regarding the quality control

requirements, specifically pertaining to discharges of wastewaters

and sewerage. With regards to water quantity and water management in

general, new government decrees have been adopted in the field of

protection of water basins, water management authorities, utilization

and use of different water sections. Work is still being carried out

to meet the EU WFD, though the government has adopted a Strategic

Document defining the tasks and deadlines to be achieved. Other

legislative work remains in other related sectors.

In the past two years

there has been an effort to link water management institutions,

including those for water protection and environmental protection

authorities, inspectorates and various regional agencies. There is an

intergovernmental, multi-sectors national body dealing with

sustainable water management issues and coordination among the

different sectors including environment, agriculture, tourism,

transport, and nature conservation. This body coordinates the

implementation of the EU requirements and EU directives to specific

sectors.

Hungary is party to the

Helsinki Convention on the protection and use of transboundary water

courses and international lakes, the Sofia Convention on cooperation

for the protection and sustainable use of the Danube river, the New

York Convention on the law of the non-navigational use of

international water courses and the Tisza Convention on measures to

combat pollution of the Tisza river and its tributaries. Hungary also

has bilateral agreements with Romania, Slovakia, Serbia and

Montenegro, and Ukraine.

Romania

In Romania the water

bodies are state property and overseen by the Water Department of the

Ministry of Agriculture, Forests, Waters and Environment (MAFWE). As

Romania strives to accede to the European Union all the EU water

directives are being transposed into the Romanian legislation, by

amending the existing water laws. The transition period for

implementation is under negotiation, and heavy investment is needed.

Also a new Water Management Strategy based on the recommendations of

the Second Forum for Sustainable Water Management is under

preparation. Currently the main legal acts for sustainable water

management in Romania address: environmental permits and licensing

issued by water bodies; meeting the requirements for the EU WFD;

water management plans at the basin level; legislation to involve all

ministries dealing with water issues; and legislation on drinking

water quality and the expansion and rehabilitation of the water

supply system.

Romania is party to the

Helsinki Convention on the protection and use of transboundary water

courses and international lakes, the Sofia Convention on cooperation

for the protection and sustainable use of the Danube river, the ECE

Convention dealing with transboundary impacts of accidents, and the

Tisza Convention on measures to combat pollution of the Tisza river

and its tributaries. Romania also has bilateral agreements with

Hungary, Serbia and Montenegro, and Ukraine.

Serbia and Montenegro

The situation in

Serbia and Montenegro remains relatively fluid. The management of

water issues is based on the specific territory, and water management

is carried out separately. There is a Constitutional Charter in

progress in Serbia and Montenegro, though at this time the Water Law

of the Republic of Serbia is beginning enacted contrary to the

federal laws which have not been enforced until now. The Ministry of

Agriculture and Water Management is overseeing the Water Directorate,

procedures for new Water Law and Law on Financing of Water

Management. The largest problems currently are developing and

implementing water quality and wastewater treatment status because of

the lack of legislation and poor economic conditions.

The relatively unstable

situation has hampered water management at a priority. However as the

impetus to join the EU increases within Serbia and Montenegro it is

expected that water management will become more important. It is

acknowledged that water management based on sustainable development

will be critical to the integration and accession process. The

existing water management approach is still more traditional in

approach because of the remaining legal provisions that are still in

force. New laws on Natural Resource and Environmental Protection are

under going adoptions.

Though flood control is

most closely regulated based on existing laws, it is expected that

more coordination throughout the basin will assist these efforts.

Serbia and Montenegro (as the Former Yugoslavia) are party to the

Sofia Convention on cooperation for the protection and sustainable

use of the Danube River, and the Tisza Convention on measures to

combat pollution of the Tisza river and its tributaries. Serbia and

Montenegro also has bilateral agreements with Romania and Hungary.

Slovakia

Slovakia tends to have

a fairly sophisticated environmental policy status regarding water

management, with awareness that circumstances require improvement,

and what those specific improvements are. They have a National

Strategy for Sustainable Development, though there are difficulties

with enforcement at local levels. There is an acknowledgement of

general problems with enforcement of environmental laws, existing

corruption and low legislative and environmental awareness.

Nonetheless, the EU WFD has been transposed into the new draft law of

the Water Act, focusing on watershed management, protection of the

ecosystem and human health. It is anticipated that these will improve

enforcement of existing laws.

Within the Slovak

legislation is the Water Act, which specifies water management tools

and tools for protection of water quality. This includes obligations

for water withdrawals and wastewater discharge. Water management,

water quality, and quantity protection and its rationale utilization,

as well as river basin management, flood protection an control are

ensured though this law, through the River management plan and

hydro-ecological plans of the watersheds and based on the Generel of

water utilization and its protection.

Slovakia is party to

the Helsinki Convention on the protection and use of transboundary

water courses and international lakes, the Sofia Convention on

cooperation for the protection and sustainable use of the Danube

river, the Espoo Convention on Environmental Impact Assessment in the

transboundary context, Stockholm Convention on persistent organic

substances, The Bern Agreement- Convention on protection of European

wildlife and natural sites, Convention on transboundary transport of

dangerous wastes, the Ramsar Convention on wetlands protections and

the Tisa Convention on measures to combat pollution of the Tisa river

and its tributaries. Slovakia also has bilateral agreements with

Hungary and Ukraine.

Ukraine

The Ukrainian Water

Code is comprehensive and covers most issues of water quantity and

quality management groundwater protection and others. There is

division between the Ministry of Environmental Protection of Ukraine

and State Committee of Ukraine on Water Management share

responsibilities for water management. Other laws such as Law on

Environmental Protection also address water management issues and

there are multiple agencies charged with various aspects of water

related management. As a result the situation tends to be quite

complicated. All waters are owned by the state, and overseen by the

Parliament, elected councils of the oblasts and local level.

Ukraine as a former

Soviet state has the legacy of extremely stringent environmental

policies. The legislation is some of the most aggressive

environmental in history, however, enforcement during the Soviet era

left something to be desired. Nonetheless, there is an interest in

adjusting national policies to meet the EU WFD as part of an ambition

towards eventual accession to the EU. Within Ukraine there is an

interest in harmonizing water policy with the EU approach including

development of basin principles of water management and water

protection; developing improved tariff policy and water pricing;

developing of ecological standards of water quality; improving the

environmental situation in watersheds; increasing stakeholder and

public participation involvement in water management. These ideals

have yet to be reached in either the EU or Ukraine, though for

different reasons. The main challenge that will face Ukraine will be

enforcement, effective monitoring and compliance with the EU WFD over

time.

Ukraine is party to the

Helsinki Convention on the protection and use of transboundary water

courses and international lakes, the Sofia Convention on cooperation

for the protection and sustainable use of the Danube river, and the

Tisa Convention on measures to combat pollution of the Tisa river and

its tributaries. Ukraine also has bilateral agreements with Hungary,

Slovakia and Romania.

Sub-regional Policies

and Cooperation

Currently there are a

number if existing international assistance and regional initiatives

aimed at various components of water management. There is a lack of

coordination across these initiatives and often they have overlapping

or redundant efforts. The International Commission on Protection of

the Danube River (ICPDR) serves as an umbrella agency for the larger

Danube Basin, but there is not a similar organization functioning in

the Tisza basin. In some cases various Tisza initiatives have taken

similar parallel approaches to addressing components of water

management. Though each of these initiatives contributes to the over

progress being made there is a need to more formally link these

projects to avoid possible redundancy of efforts, and to develop a

strong transboundary approach to river basin management. Each of

these projects makes important contributions and should be

appreciated as such. These initiatives include: the Tisza Forum; and

the Tisza Environmental Forum; the Sustainable Spatial Development of

the Tisza River Basin; UNEP Feasibility Study : Integrated Management

of the Carpathian River Basins - Tools and Implementation, Framework

Convention on Protection and Sustainable Development of the

Carpathians; Tisza River Project – EU Research Project; Tisza

River Basin Sustainable Development Project; and several GEF

biodiversity projects focusing on water related habitat conservation

measures.

The Budapest

Declaration signed by the five Tisza basin countries in 2001 commits

them to co-operate and develop regional plans on flood protection

and control in the basin. There is no permanent secretariat instead

the Tisza Forum, as it is known meets twice a year, with the chair

rotating around the basin states. There are eight working groups at

the expert level that meet regularly dealing with all aspects of

flood protection and risk. The Tisza Forum is funded wholly by the

participating states and in March 2004 produced an Action Plan for

Sustainable Flood Protection of the Tisza Basin.

In September 2003

under the Council of Europe CEMAT programme the Tisza countries

signed a Declaration of Cooperation Concerning the Tisza basin and

an initiative on Sustainable Spatial Development of the Tisza River

Basin. The Council of Europe’s European Conference of

Ministers responsible for Regional/Spatial Planning (CEMAT) has

developed the “Initiative on the sustainable spatial

development of the Tisza/Tisa river basin” supported by the

ministries responsible for Regional/Spatial Planning of Hungary,

Romania, Serbia and Montenegro, Slovak Republic and Ukraine. Within

this programme they seek to implement planning strategies that will

improve socio-economic conditions while taking steps to improve

environmental management.

The Framework

Convention on Protection and Sustainable Development of the

Carpathians is an international agreement of the seven Central and

Eastern European States: the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland,

Romania, Serbia and Montenegro, the Slovak Republic and Ukraine.

Signed by the six basin states at the Fifth Ministerial Environment

for Europe Conference in Kiev 2003, the Convention provides a

framework for co-operation on:

integrated

approaches on land and water use management;

conservation and

sustainable use of biological and landscape diversity;

development of

sustainable agriculture, forestry, transport, industry and tourism;

preservation of

cultural heritage and traditional knowledge;

environmental

impact assessment; and

enhanced

awareness-raising, education and public participation

The

interim secretariat of the Convention is located in the UNEP Vienna

office that promotes its ratification, information exchange,

documentation, and acts as a liaison office with the Alpine

Convention and the ICPDR.

The Tisza River

Project – EU Research Project is part of

the European Super-project (cluster of projects) called CATCHMOD,

which combines and harmonizes similar catchment modeling projects on

European level. It was initiated in 2001 and is funded by the

European Union. This project draws on government and ministerial

support, organizations and universities. It includes the countries

of Slovakia, Romania and Hungary with an outlook to Ukraine

subcontracting partners. Serbia and Montenegro are not included in

this aspect of this project. This project will link closely with the

EU WFD as a means to build upon and compliment the advances made by

the countries in meeting the WFD objective, extended to all the

Tisza basin countries.

The UNDP Regional

Environmental Governance Programme in Bratislava with the Regional

Environmental Centre for Central and Eastern Europe have implemented

the first and second phases of the Tisza River Basin Sustainable

Development Project. Additional support for this project is from the

Carpathian Foundation, and the British Embassy in Budapest. This

project had the goals of: securing the prosperity of the people

living the Tisza river basin; making sustainable use of the basin’s

natural resources; preserving natural and cultural values; and

developing a participatory framework for cooperation between

countries, sectors, communities and stakeholders in the river basin.

In the first phase of this networking of individuals and

organizations from all five Tisza basin countries. Strong

stakeholder involvement was emphasized in this phase in order to

encourage national level ownership of the project and to encourage

intersectoral buy-in when needed. In the second phase a report was

produced through national and regional assessments of legal, policy

and institutional frameworks related to sustainable water management

issues in Tisza riparian countries. These phased efforts and reports

are a compilation of extensive research findings and lay a solid

framework in which to couch a regionally owned and managed

sustainable development project. In addition, UNDP through its

Bratislava office is developing the concept for Eco-region umbrella

programme to shelter the UNDP’s many social, poverty

alleviation and environmental projects in the basin.

Following the Baia Mare

spill, the Tisza Environmental Forum was formed to address regional