SIS

Y

TITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK ANAL

3.0 LEGAL AND INS

3

The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this document do not imply the expression of any

IMPRINT

opinion whatsoever on the part of UNEP/MAP concerning the legal status of any State, Territory, city or area, or of its

authorities, or concerning the delimitation of their frontiers or boundaries.

This TDA was prepared within the GEF Project "Determination of priority actions for the further elaboration and

implementation of the Strategic Action Programme for the Mediterranean Sea", under the coordination of Mr Ante

Baric, PhD, Project Manager.

Responsibility for the concept and the preparation of this document was entrusted to MED POL (Mr Fouad

Abousamra, PhD, MED POL Programme Officer).

© 2005 United Nations Environment Programme / Mediterranean Action Plan (UNEP/MAP), P.O. Box 18019, GRAthens

This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes with-

out special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. UNEP/MAP

would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source.

This publication cannot be used for resale or for any other commercial purpose whatsoever without permission in

writing from UNEP/MAP.

ISBN: 92 807 2578 5

Job Nr.: MAP/0676/AT

For bibliographic purposes this publication may be cited as:

UNEP/MAP/MED POL: Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis (TDA) for the Mediterranean Sea, UNEP/MAP, Athens, 2005.

*

Graphic Design & Infographics: /fad.hatz@november

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

-10

List of Tables

-7

List of Figures

-6

Acronyms & Abbreviations

-4

FOREWORD

0

i. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

i

i.1 TDA Content and Process

i

i.2 Mediterranean Sea Environmental Status and its Major Transboundary Issues

iii

i.3 Environmental Quality Objectives

xiv

i.4 Priority Actions and Interventions for NAPs / SAP

xiv

able of Contents

T

INTRODUCTION

1

1.0 THE MEDITERRANEAN REGION

3

1.1 Environmental Characteristics

4

1.1.1 Geographic setting and climate

4

1.1.2 The hydrological system

6

1.1.3 Biological diversity

9

1.1.4 Natural resources

11

1.2 Socio-economic Aspects

11

1.2.1 Demography and human settlements

11

1.2.2 Industrial activity and trade

13

1.2.3 Agriculture and Fisheries

13

1.2.4 Tourism

14

2.0 MAJOR ENVIRONMENTAL CONCERNS

17

2.1 Decline of Biodiversity

17

2.1.1 Transboundary elements

18

2.1.2 Environmental impacts

18

2.1.3 Socio-economic impacts

19

2.1.4 Causal Chain Analysis

19

-10

»

»

2.1.5 Supporting data

19

2.1.5.1 Exploitation of living marine resources

21

2.1.5.2 Degradation and conversion of critical habitats

21

2.1.5.3 Pollution

26

2.1.5.4 Introduction and invasion of alien species

39

2.1.5.5 Destruction of habitats by fishing pressure

41

2.2 Decline in Fisheries

41

2.2.1 Transboundary aspects

42

2.2.2 Environmental impacts

43

2.2.3 Socio-economic impacts

43

2.2.4 Causal Chain Analysis

44

2.2.5 Supporting data

46

2.2.5.1 State of the resources

46

2.2.5.2 Interactions of fishing with non-commercial resources

47

2.2.5.3 Eutrophication

47

2.2.5.4 Interaction of mariculture with fisheries

47

2.2.5.5 Overall characteristics of the Mediterranean fishing sector

49

2.3 Decline of Seawater Quality

51

2.3.1 Transboundary elements

51

2.3.2 Transboundary source-receptor relationships in PAHs deposition

52

2.3.3 Environmental impacts

53

2.3.4 Socio-economic impacts

53

2.3.5 Causal Chain Analysis

54

2.3.6 Supporting data

56

2.3.6.1 Eutrophication

56

able of Contents

T

2.3.6.2 Heavy metals

62

2.3.6.3 Persistent toxic substances (PTSs)

71

2.3.6.4 Pollution Hot Spots

80

2.4 Human Health Risks

82

2.4.1 Transboundary elements

82

2.4.2 Environmental impacts

83

2.4.3 Socio-economic impacts

83

2.4.4 Causal Chain Analysis

83

2.4.5 Supporting data

85

2.4.5.1 Chemical contamination

85

2.4.5.2 Microbiological pollution

93

3.0 LEGAL AND INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK ANALYSIS

101

3.1 Major problems identified with legal and institutional frameworks in the Mediterranean

101

3.1.1 Major problems identified with legal arrangements

for addressing transboundary environemental issues

101

3.1.1.1 Issues at the national level

102

3.1.1.2 Issues at the regional level

102

3.1.2 Major problems identified with institutional arrangements and capacity

for addressing transboundary environmental issues

103

3.2 Existing Legal and Policy Frameworks in the Mediterranean

103

3.2.1 The Barcelona System

103

-9

»

»

3.2.2 Regional Protocol and Policy Instruments related to the Barcelona Convention

105

3.2.2.1 Pollution

105

3.2.2.2 Conservation of Biodiversity

111

3.2.2.3 Fisheries

115

4.0 STAKEHOLDER ANALYSIS

121

4.1 Mediterranean Stakeholders

121

4.2 MAP Civil Society Partners

122

4.3 Suggestions for Improving Cooperation with MAP Civil Society Partners

122

5.0 ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY OBJECTIVES (EQOs)

125

5.1 Objective 1: Reduce the Impacts of LBS on Mediterranean Marine Environment

and Human Health

125

5.1.1 The Strategic Action Programme to address pollution from LBS

125

5.2 Objective 2: Sustainable Productivity from Fisheries

127

5.2.1 Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries

128

5.2.2 Objectives of the Code

128

5.2.3 Relationship with other International Instruments

128

5.2.4 Implementation, monitoring and updating

129

5.2.5 Special requirements of developing countries

129

5.2.6 General principles

129

able of Contents

T

5.2.7 Fisheries management

131

5.2.8 Fishing operations

133

5.2.9 Aquaculture development

136

5.2.10 Integration of fisheries into coastal area management

137

5.2.11 Post-harvest practices and trade

138

5.2.12 Fisheries Research

139

5.3 Objective 3: Conserve the Marine Biodiversity and Ecosystem

139

5.3.1 SAP BIO objectives and targets

139

5.3.2 SAP BIO Portfolio

152

6.0 REFERENCES & SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

155

Annex I

Contributors to the TDA

165

Annex II

Threatened Species in the Mediterranean

168

Annex III

List of Regional Pollution Hot Spots

181

Annex IV

List of Regional Pollution Sensitive Areas

186

Annex V

Signatories to the Barcelona Convention and its Protocols

188

Annex VI

National Action Plans for the Conservation of Biodiversity

190

-8

List of Tables

Table i.1

Transboundary sites at risk related to Mediterranean marine biodiversity

vi

Table i.2

Marine and coastal sites of particular interest identified by country,

with relevant actions listed

vii

Table i.3

Locations where sensitive ecosystems are threatened by eutrophication

ix

Table i.4

The 20 urban centres discharging the most BOD

xi

Table i.5

Some of the main sources of TPBs to the Mediterranean

xii

Table i.6

Locations where major industrial waste problems exist

xiii

Table i.7

Targets categorized according to Environmental Quality Objective

xv

Table i.8

Areas and activities for priority interventions

xvi

Table 1.1

Variation of species according to depth zones

10

ables

Table 2.1

Serious eutrophication incidents in the Mediterranean

28

List of T

Table 2.2

Algal species reported to cause algal blooms in Mediterranean Waters

29

Table 2.3

Differences in mean density (S.D.), mean biomass and mean individual fish weight

for seagrass fish bed assemblages in marine reserves and in areas open to fishing

41

Table 2.4

Age structures of Diplodus annularis taken from a protected area (Medias Islands)

and a non-protected area (Port da la Selva)

41

Table 2.5

Percentage contribution to the total biomass by different trophic groupings

in Mediterranean rocky zones, protected (Meded islands) and non-protected (Tossa)

41

Table 2.6

Some shared stocks and fisheries in the Mediterranean

50

Table 2.7

Documented rivers for dissolved nutrients

60

Table 2.8

Sector-based emissions of NOx in the Mediterranean region (kton N/yr)

61

Table 2.9

Atmospheric versus riverine inputs of Pb and Zn to the Mediterranean (tonnes/yr)

69

Table 2.10

Concentrations (in ng/g ww) of organochlorinated compounds in samples

of fish tissues collected in the NW Mediterranean

71

Table 2.11

PTS inputs (in kg/yr) of the Rhone and Seine Rivers into the sea

75

Table 2.12

Estimated distribution of TBTs in the Mediterranean Sea

77

Table 2.13

Intakes of persistent toxic substances and corresponding safety thresholds

85

Table 2.14

Pathogens and indicator organisms commonly found in raw sewage

95

Table 2.15

Cities (> 50,000 and < 900,000 inh.) without WWTP in the Mediterranean

98

Table 2.16

Bacteriological water quality in some Mediterranean rivers

99

Table 5.1

SAP Urban environment EQOs

125

Table 5.2

SAP Industrial development EQO's

126

Table 5.3

SAP Biodiversity EQOs

140

-7

List of Figures

Figure i.1

Flow Diagram for the TDA Process

ii

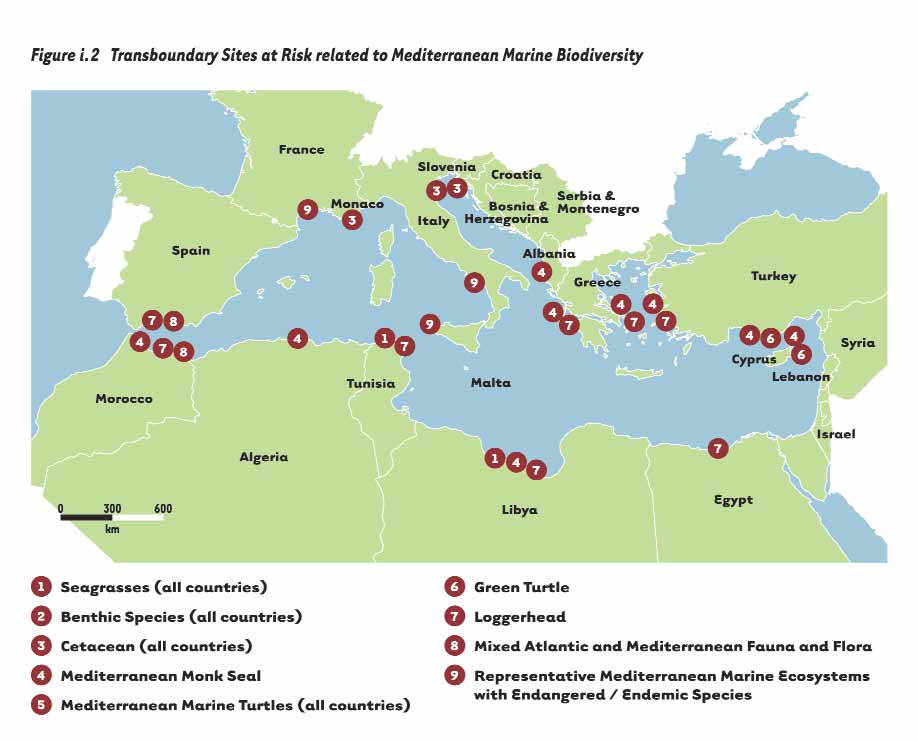

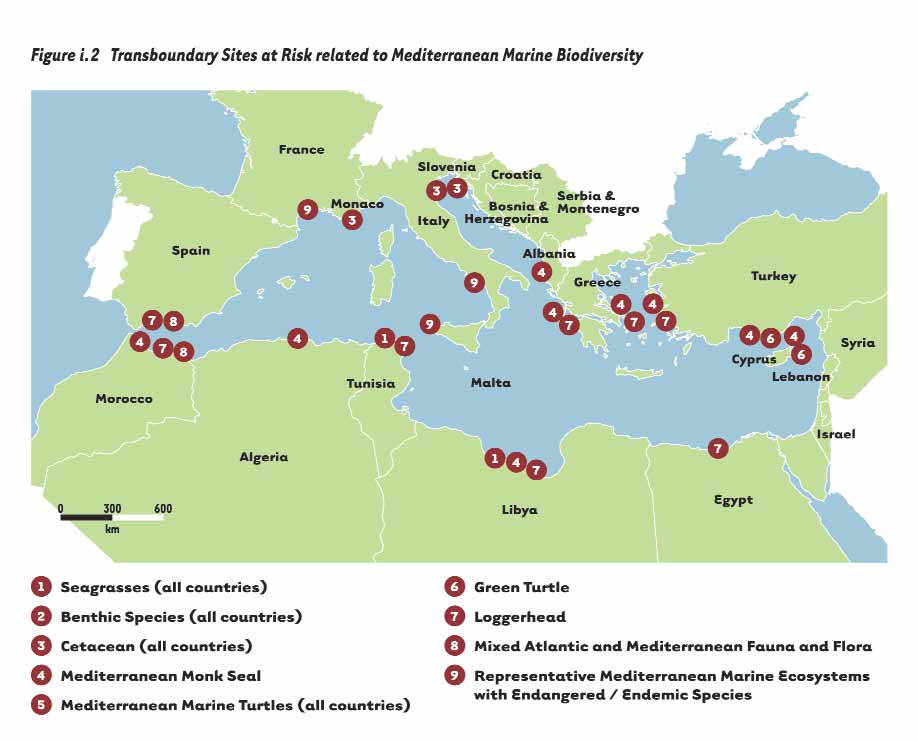

Figure i.2

Transboundary Sites at Risk related to Mediterranean Marine Biodiversity

vi

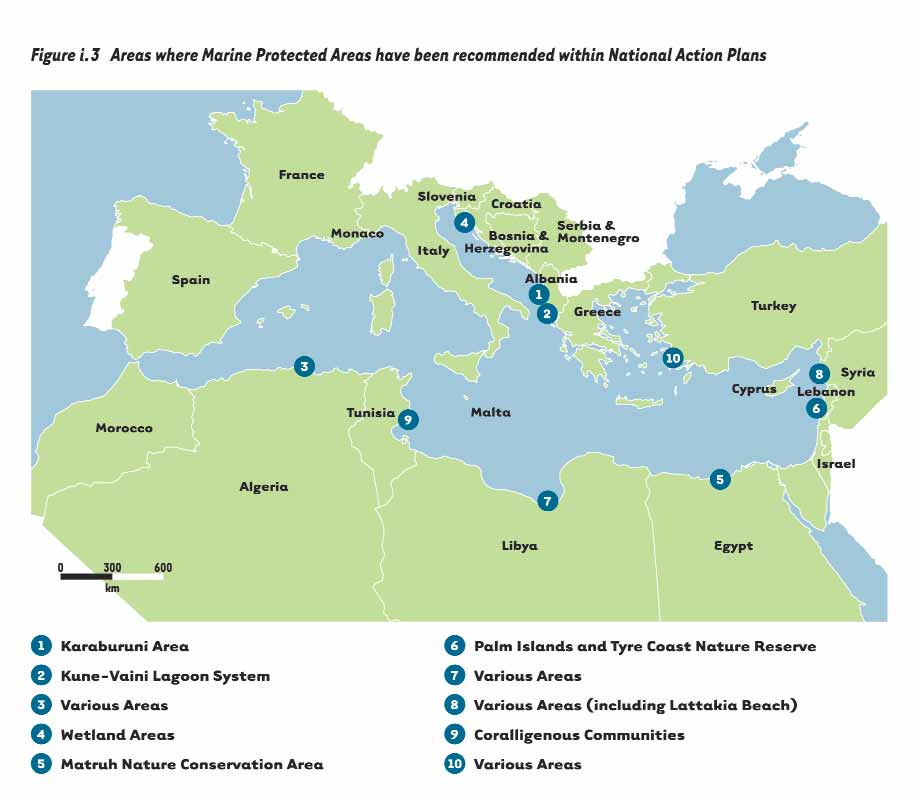

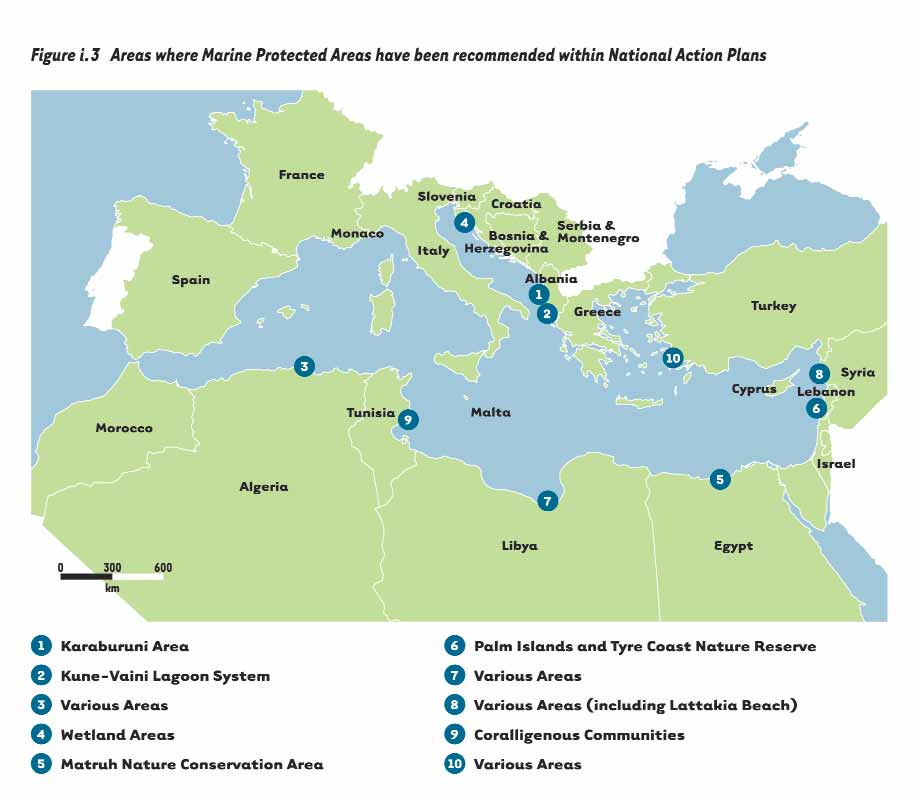

Figure i.3

Areas where Marine Protected Areas have been recommended within National Action Plans

viii

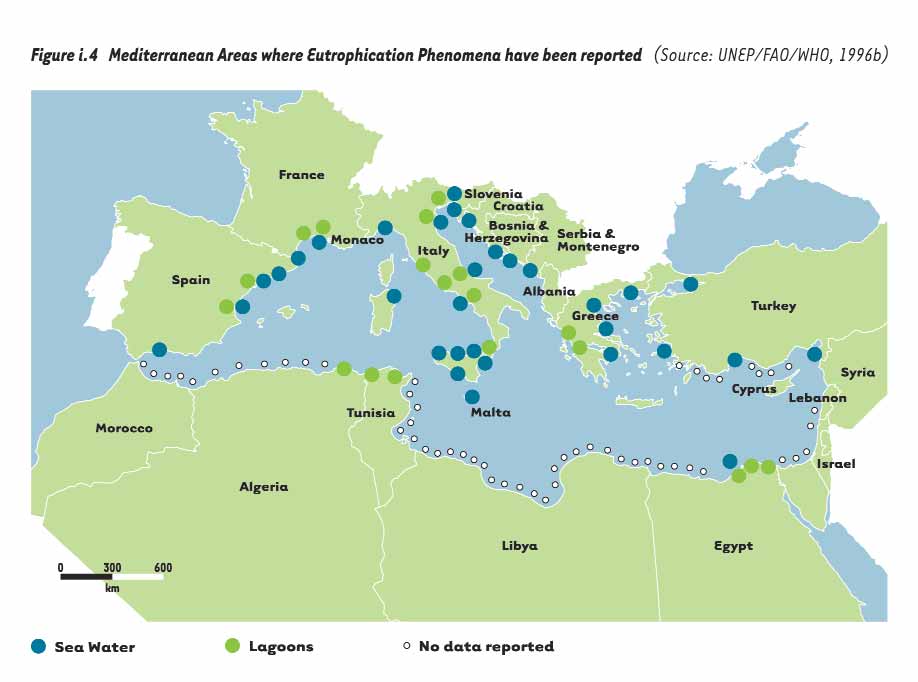

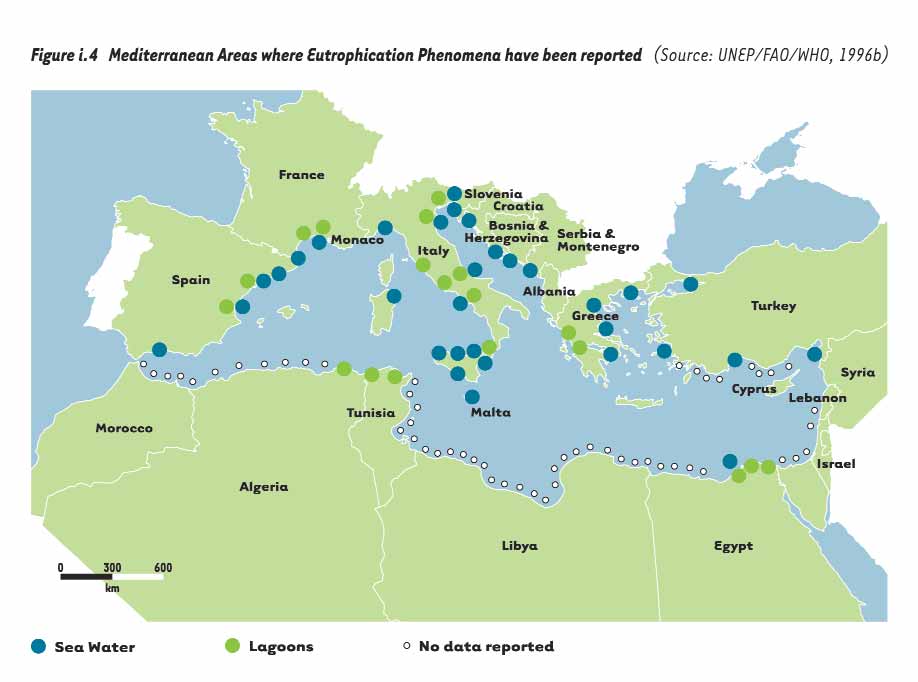

Figure i.4

Mediterranean Areas where Eutrophication Phenomena have been reported

viii

Figure i.5

Pollution Hot Spots in the Mediterranean Sea

x

Figure i.6

Ecosystems associated with Highest Pollutant-load Hot Spots

xi

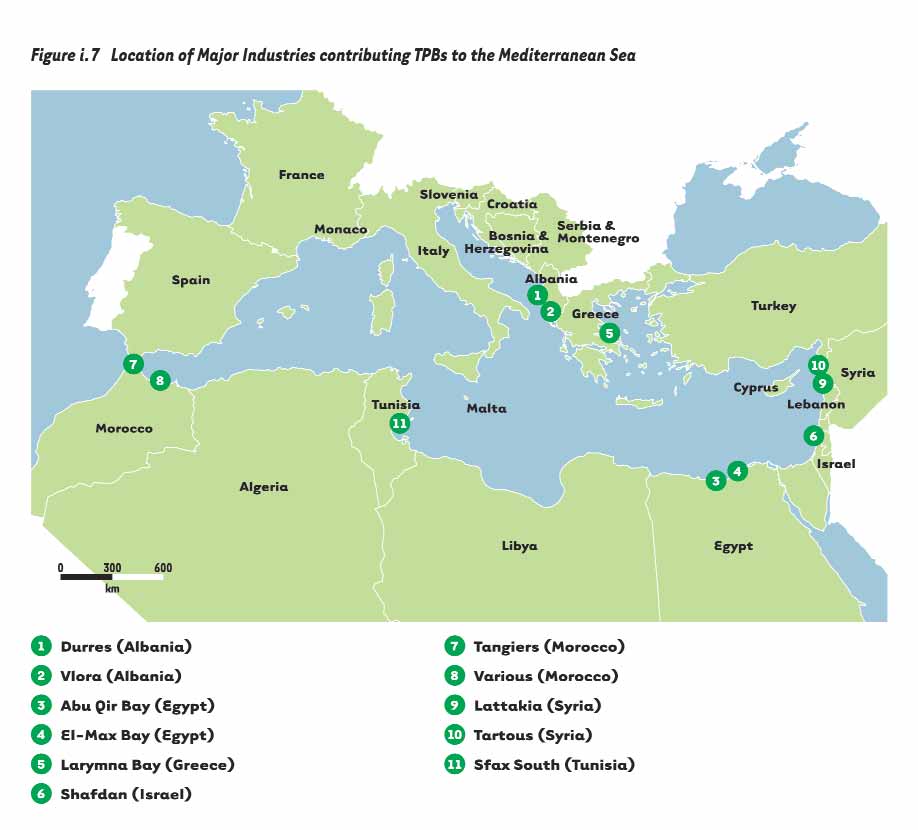

Figure i.7

Location of Major Industries contributing TPBs to the Mediterranean Sea

xii

Figure i.8

Sources of Solid Waste to the Marine Environment

xiii

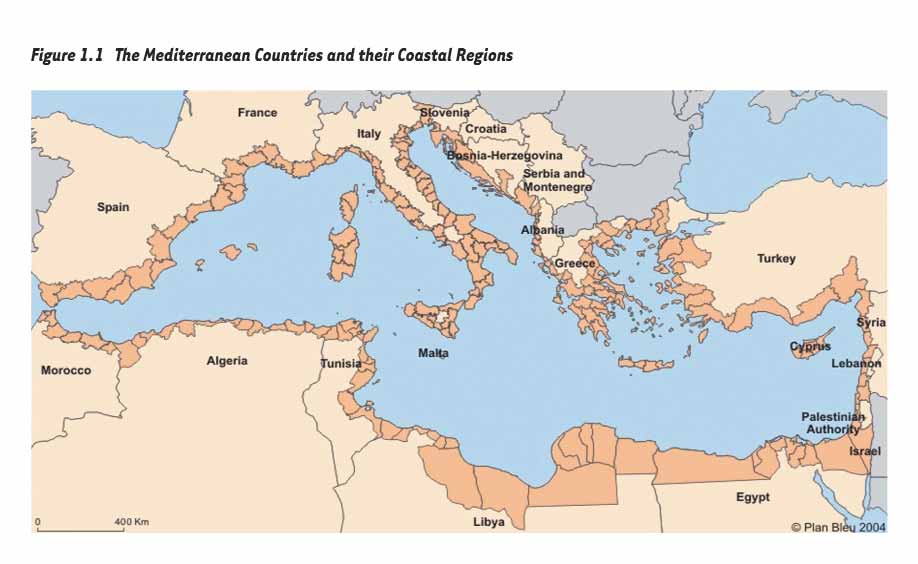

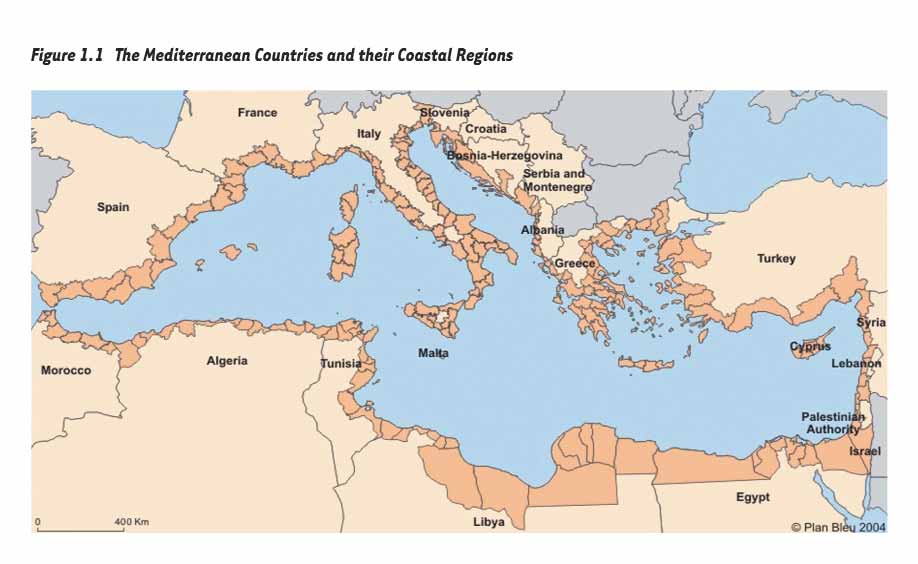

Figure 1.1

Mediterranean countries and their different watershed limits

3

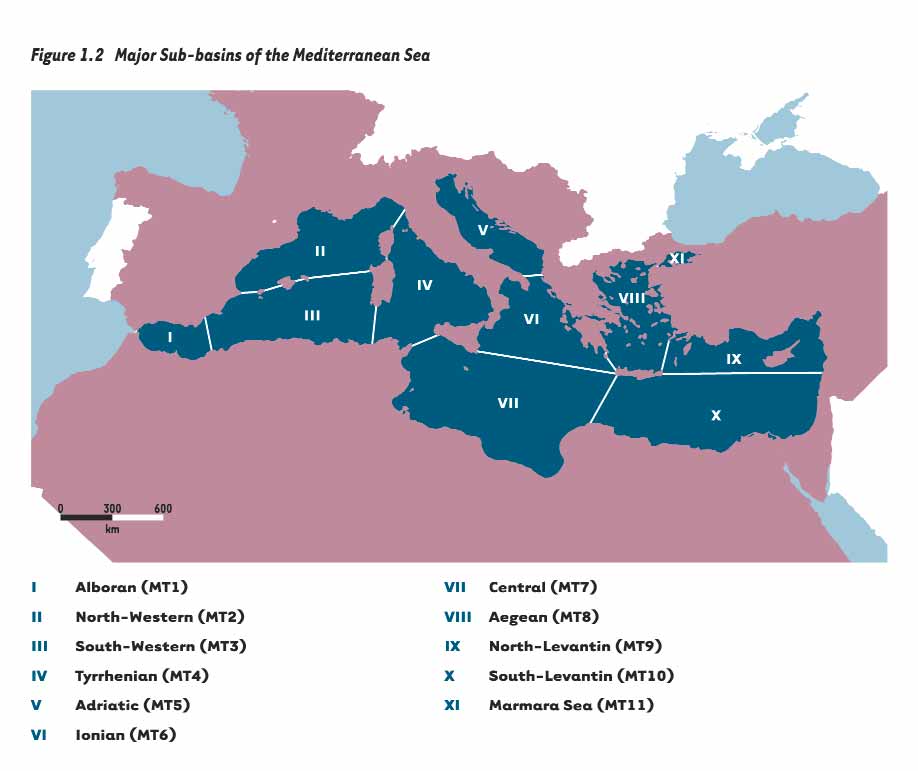

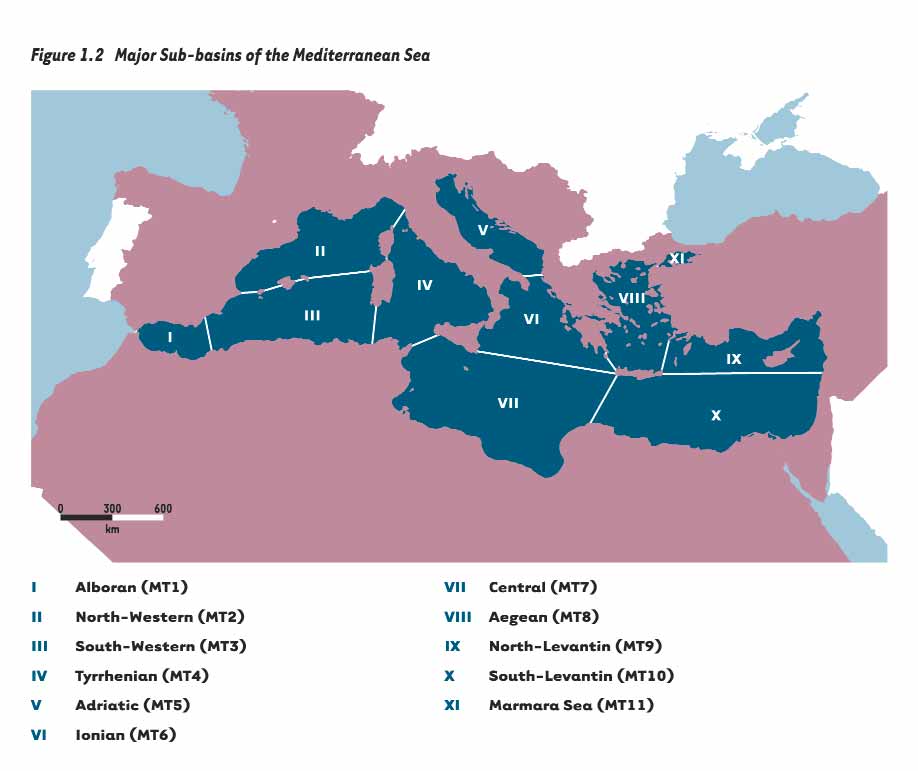

Figure 1.2

Major Sub-basins of the Mediterranean Sea

6

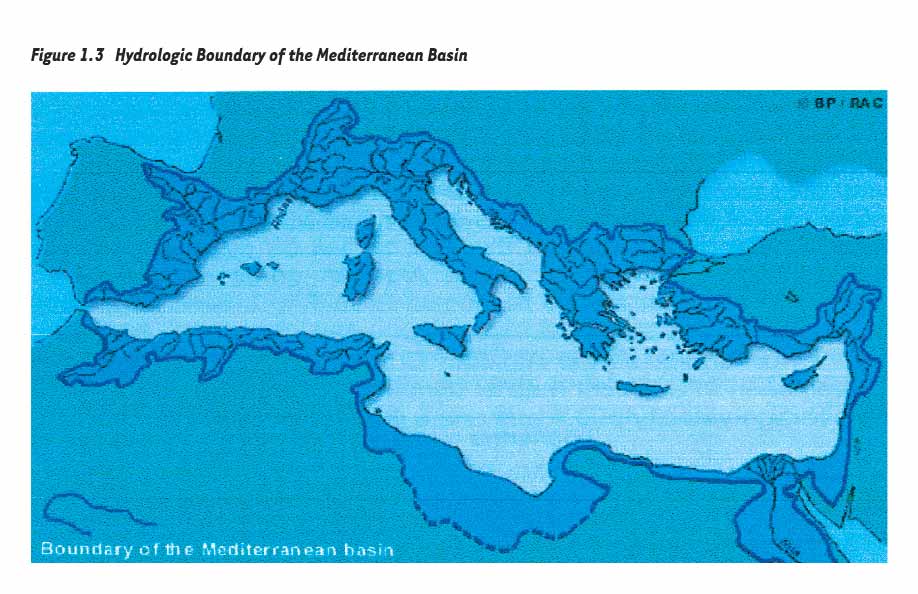

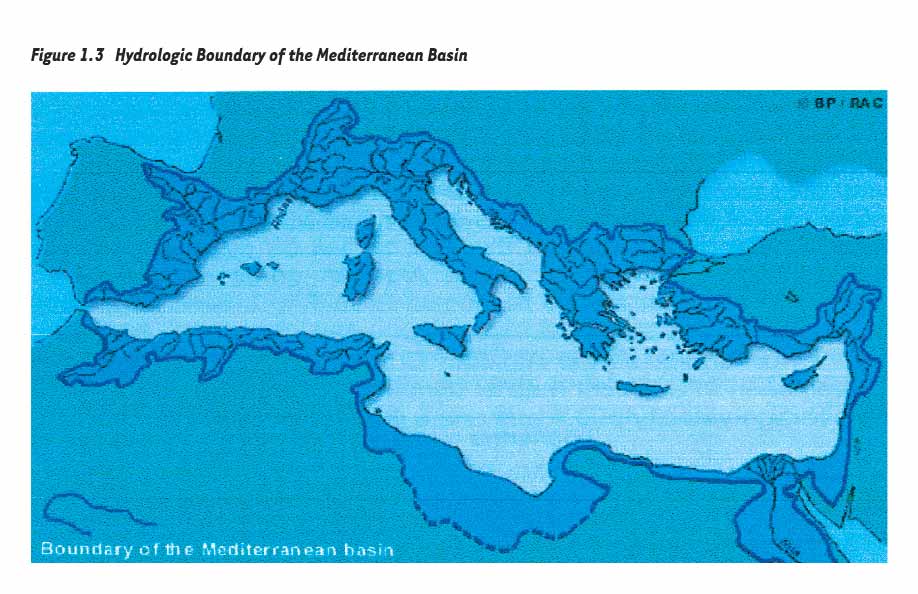

Figure 1.3

Hydrologic boundary of the Mediterranean basin

7

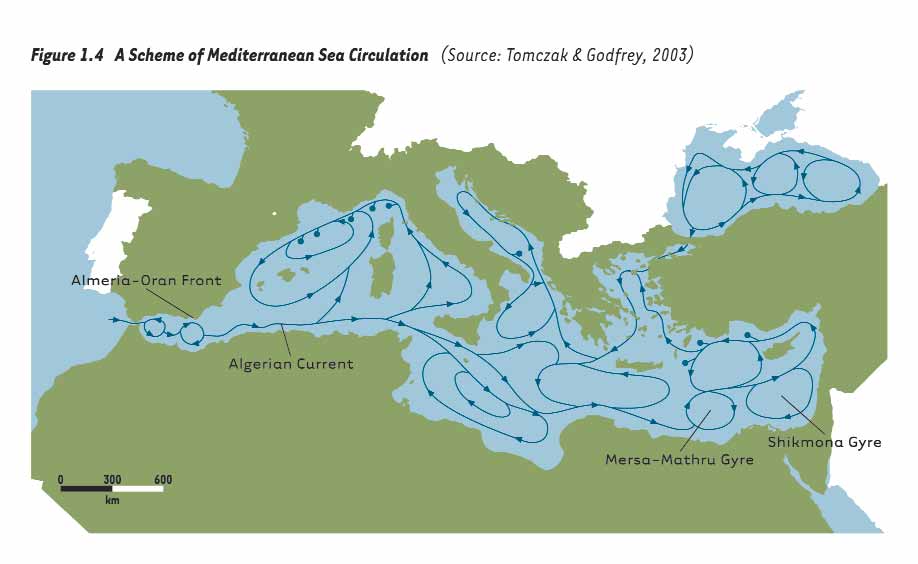

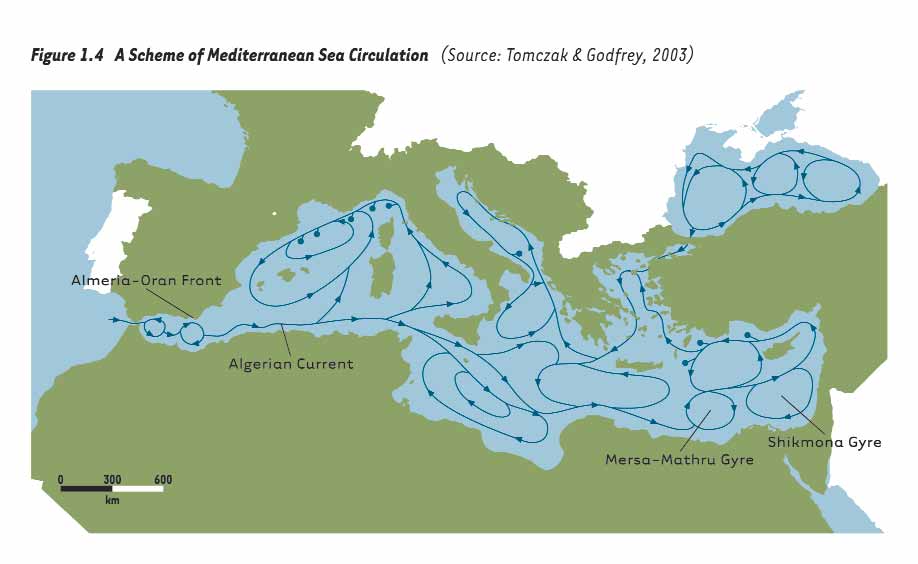

Figure 1.4

A scheme of Mediterranean Sea circulation

8

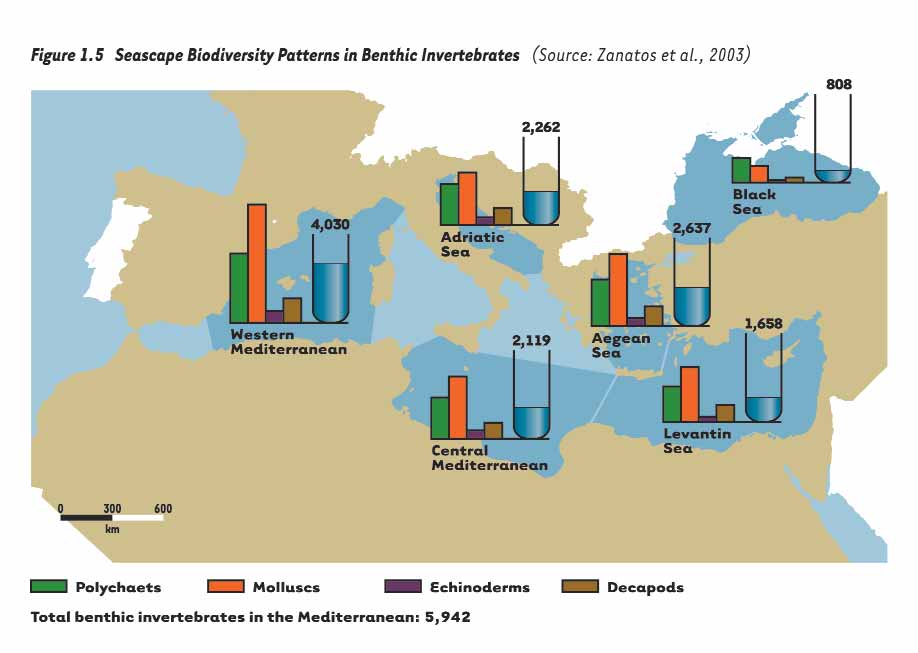

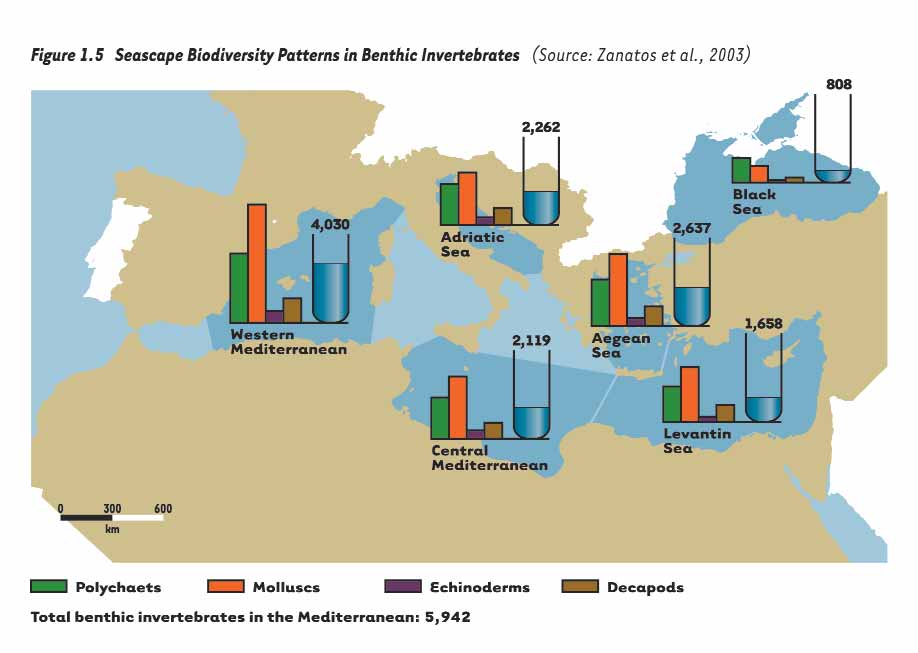

Figure 1.5

Seascape Biodiversity Patterns in Benthic Invertebrates

10

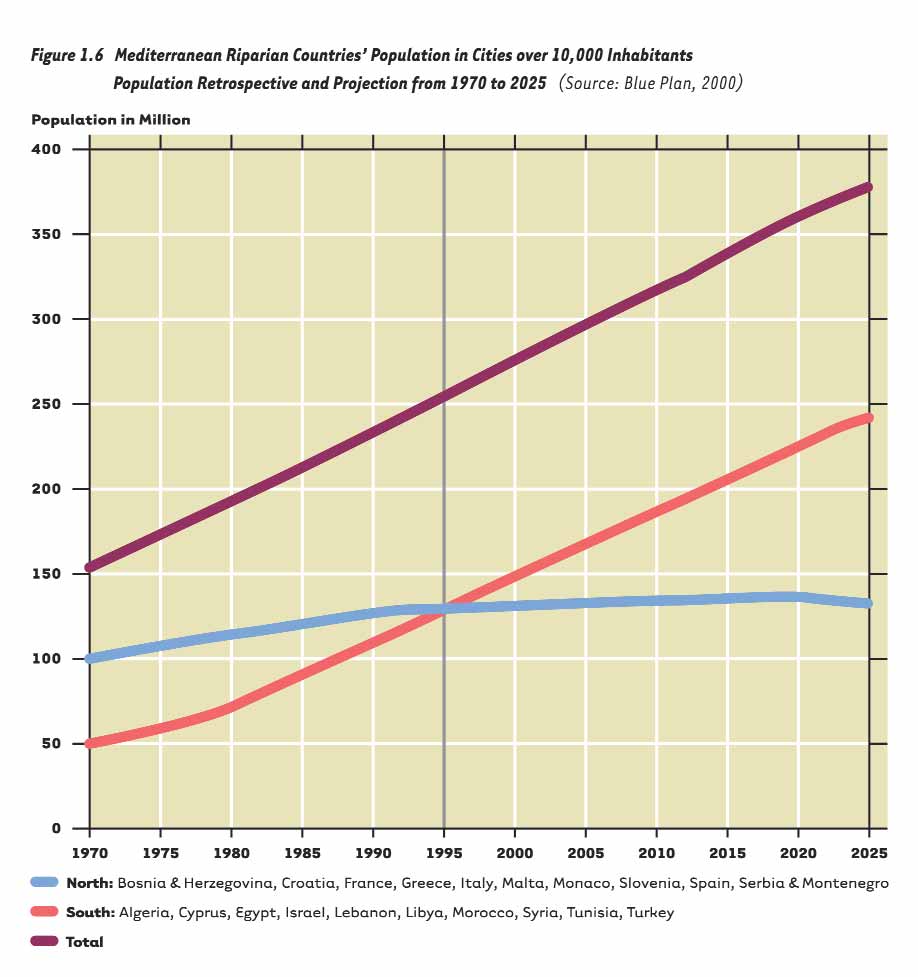

Figure 1.6

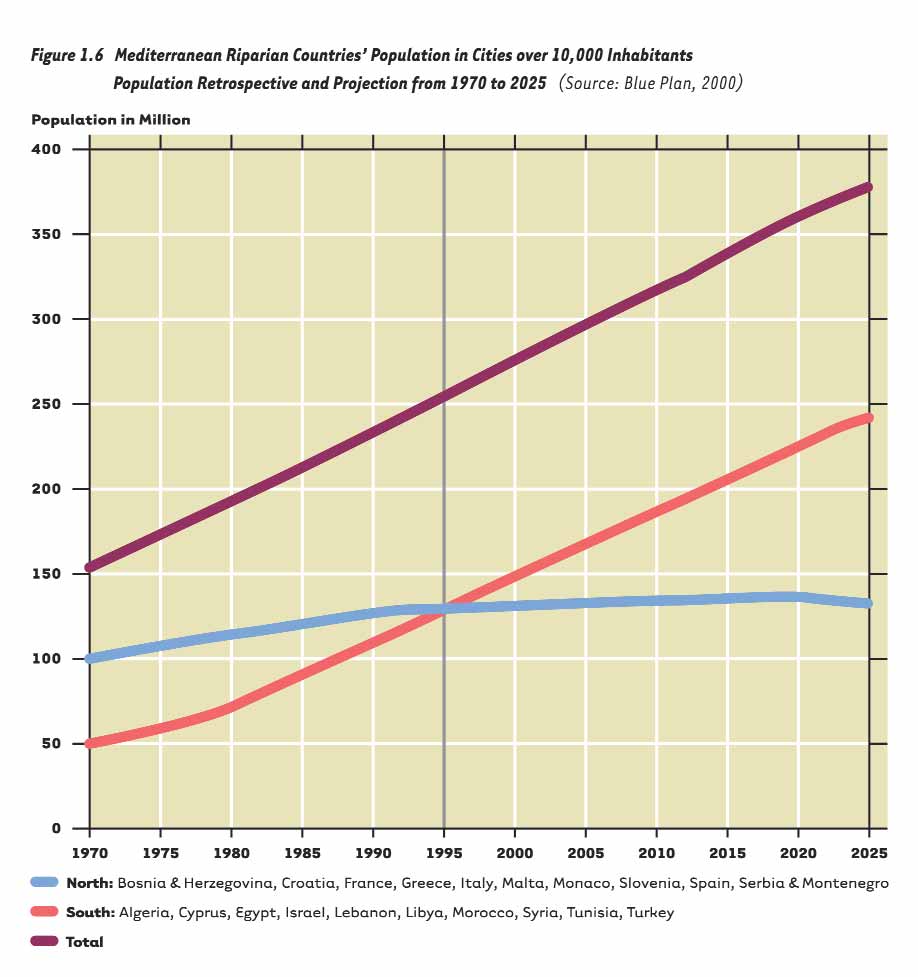

Mediterranean Riparian Countries' Population in Cities over 10,000 Inhabitants

Population Retrospective and Projection from 1970 to 2025

12

List of Figures

Figure 2.1.1

Causal Chain Analysis

20

Figure 2.1

SPAMI in the Mediterranean

24

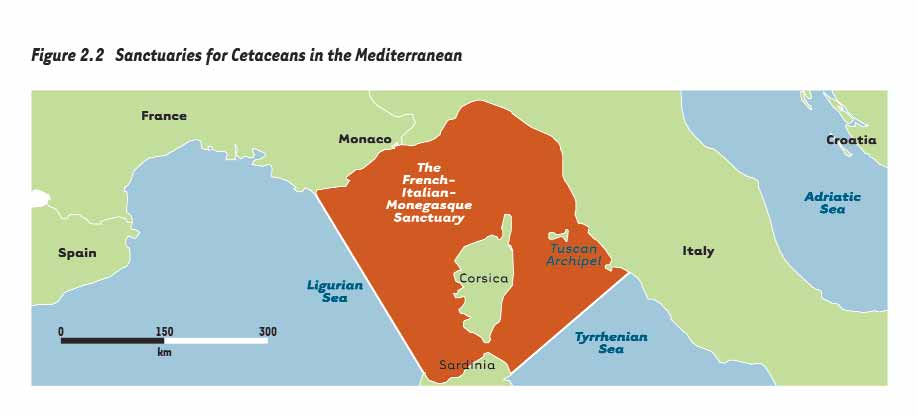

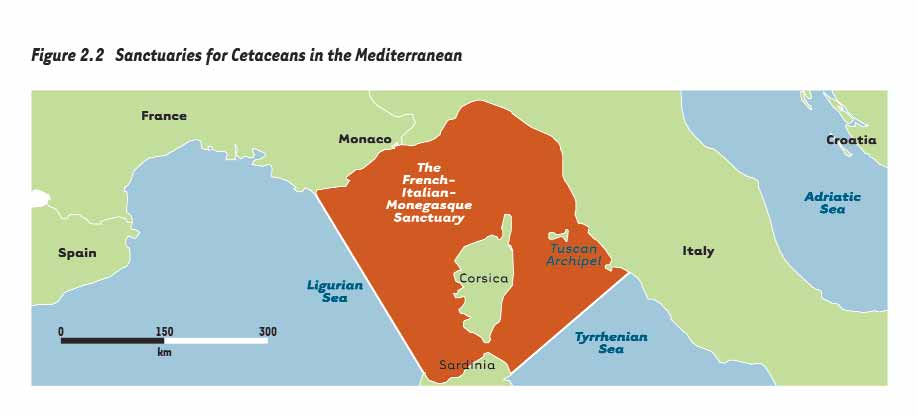

Figure 2.2

Sanctuaries for Cetaceans in the Mediterranean

25

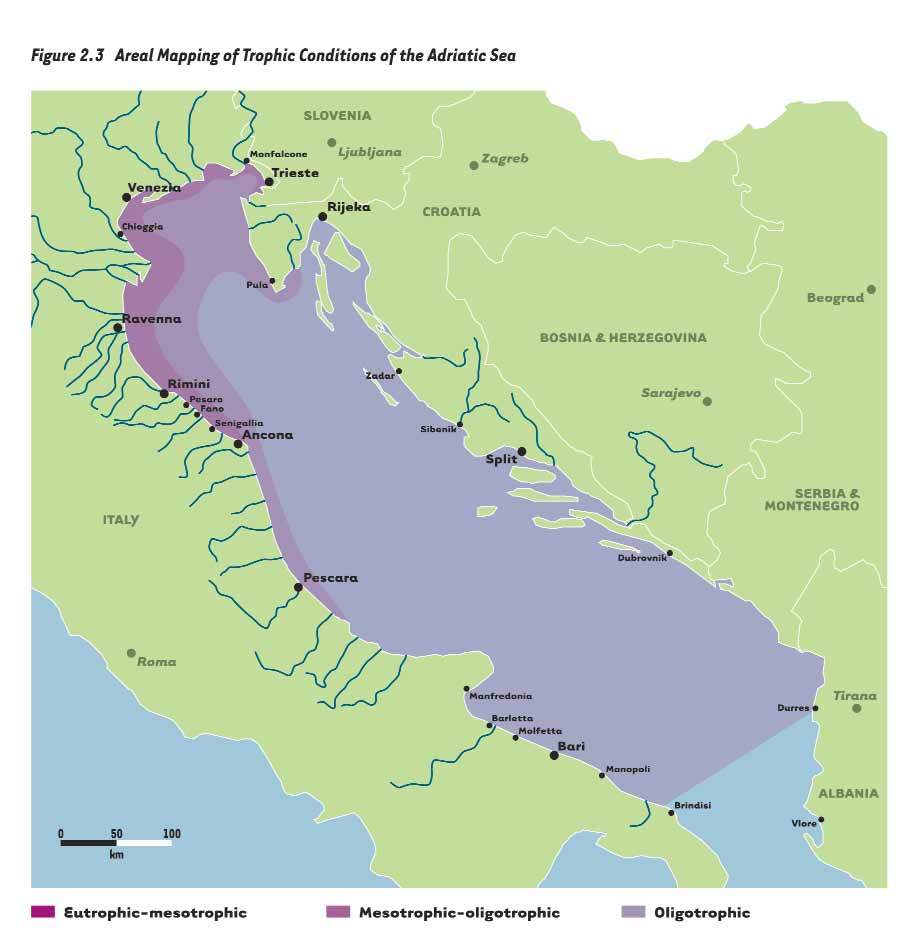

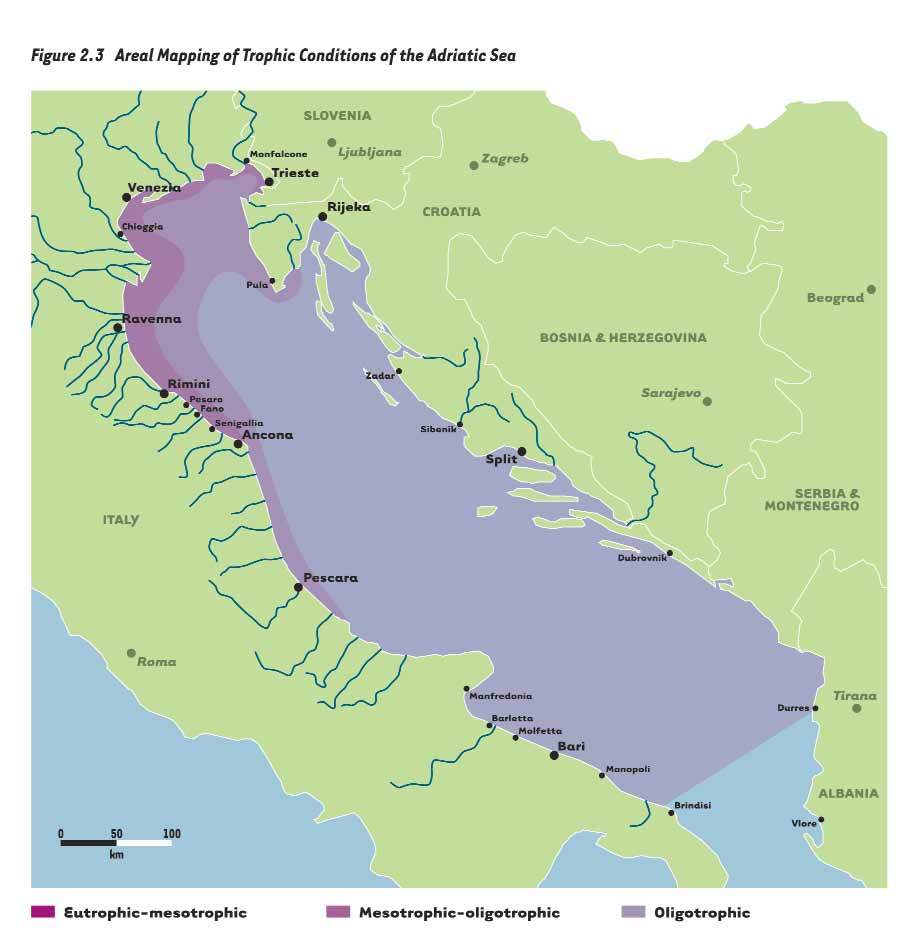

Figure 2.3

Areal mapping of trophic conditions of the Adriatic Sea

27

Figure 2.4

Logarithmic values of total mercury mass fraction in Mullus barbatus

by year at station GOKSU in Turkish coastal waters

30

Figure 2.5

Logarithmic values total mercury mass fraction in Mullus barbatus respectively

by year at stations ISRTMH2 and HMF2 in Israeli coastal waters

30

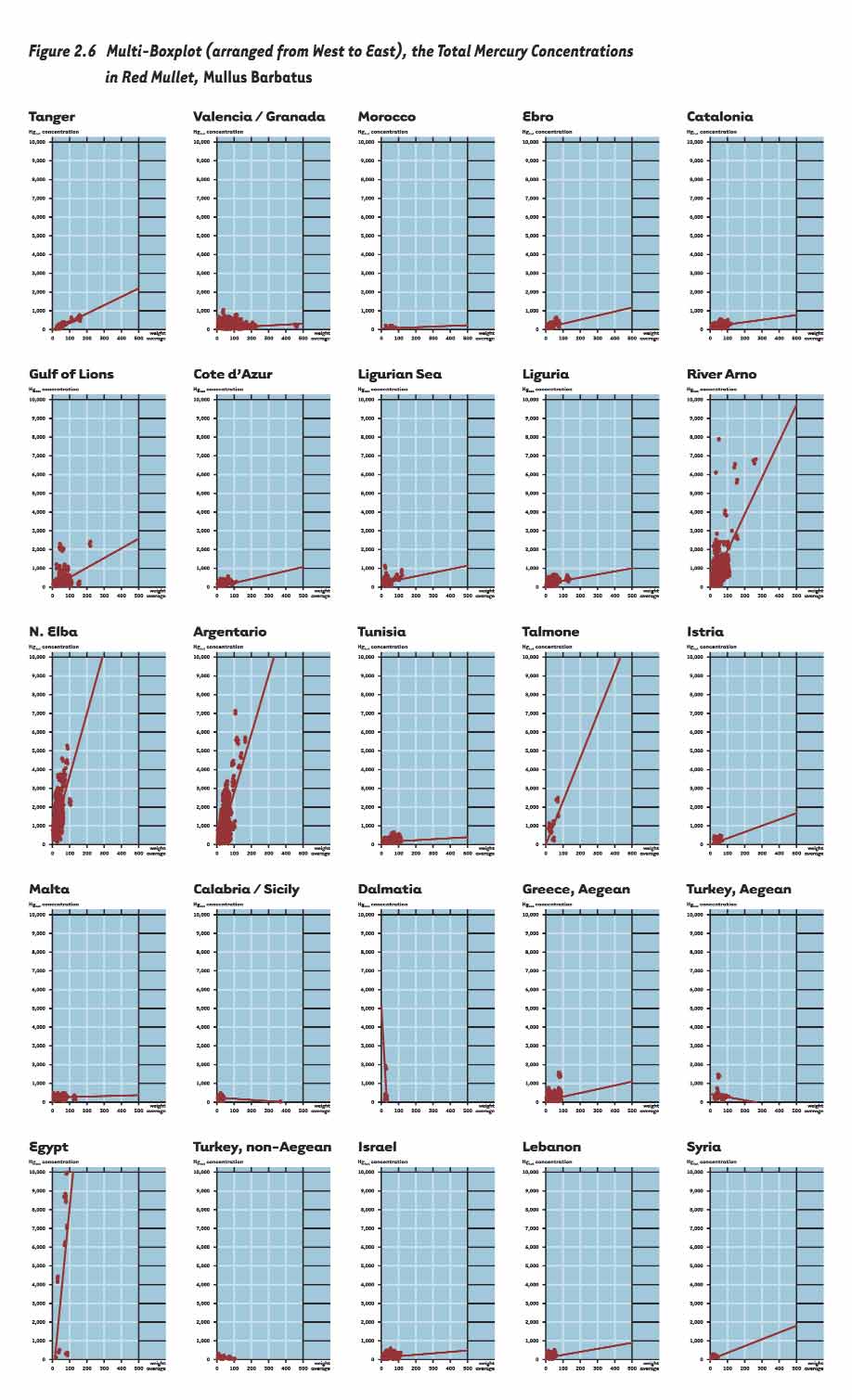

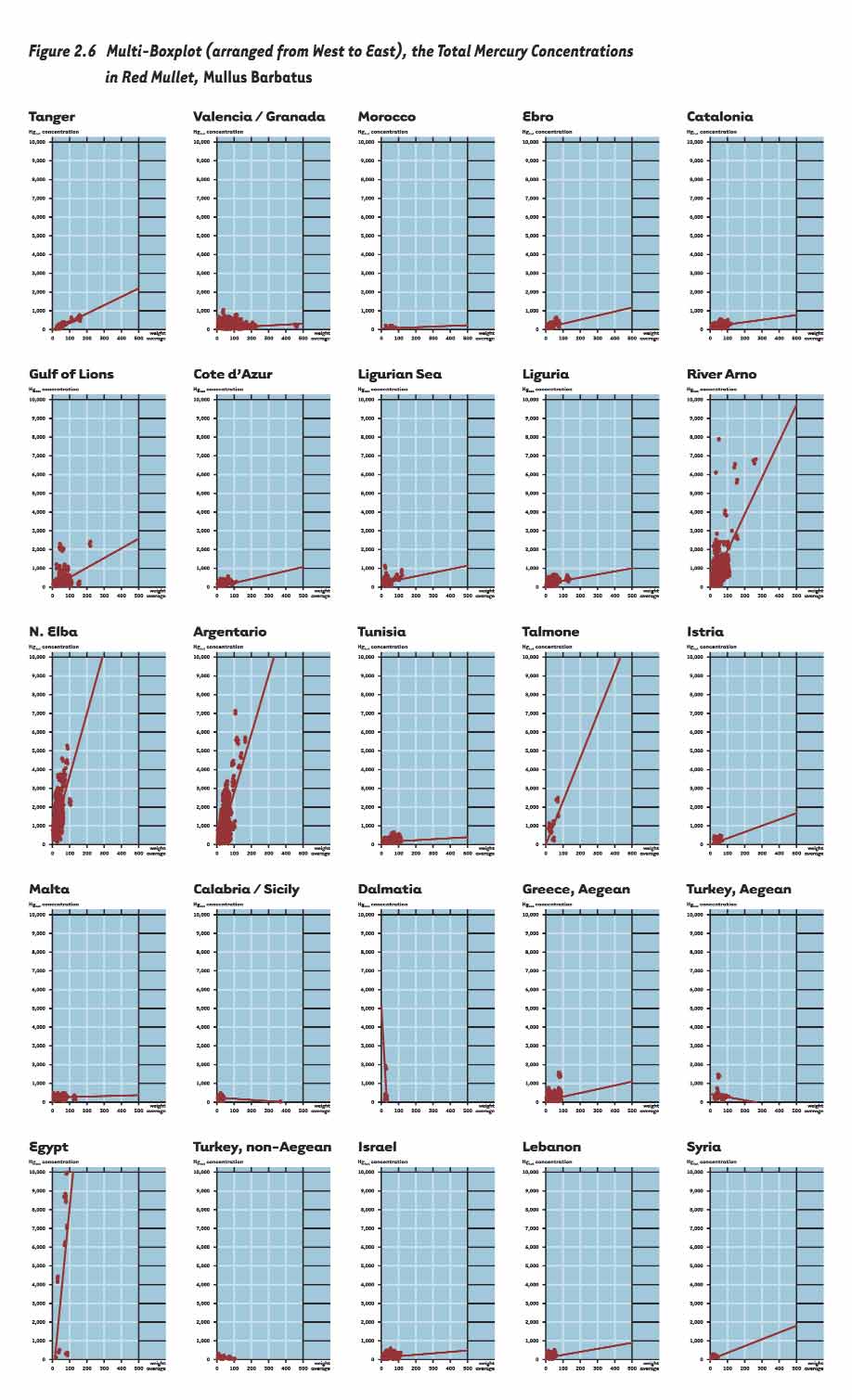

Figure 2.6

Multi-boxplot (arranged from west to east), the HgT concentrations

in red mullet, Mullus barbatus

31

Figure 2.7

PCBs in Audouin's gull eggs

32

Figure 2.8

PCBs in Audouin's gull eggs in the Mediterranean

32

Figure 2.9

DDTs in Audouin's gull eggs

32

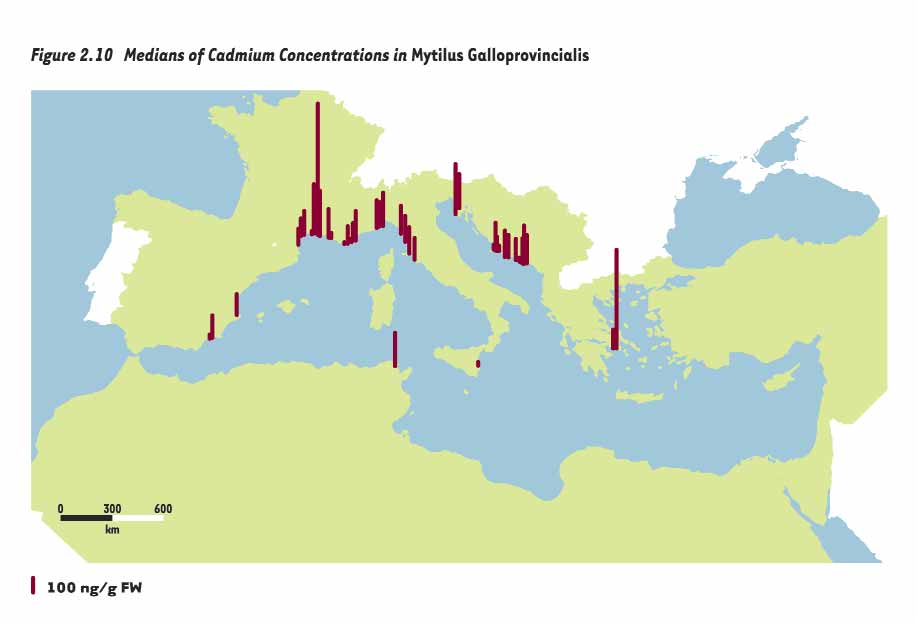

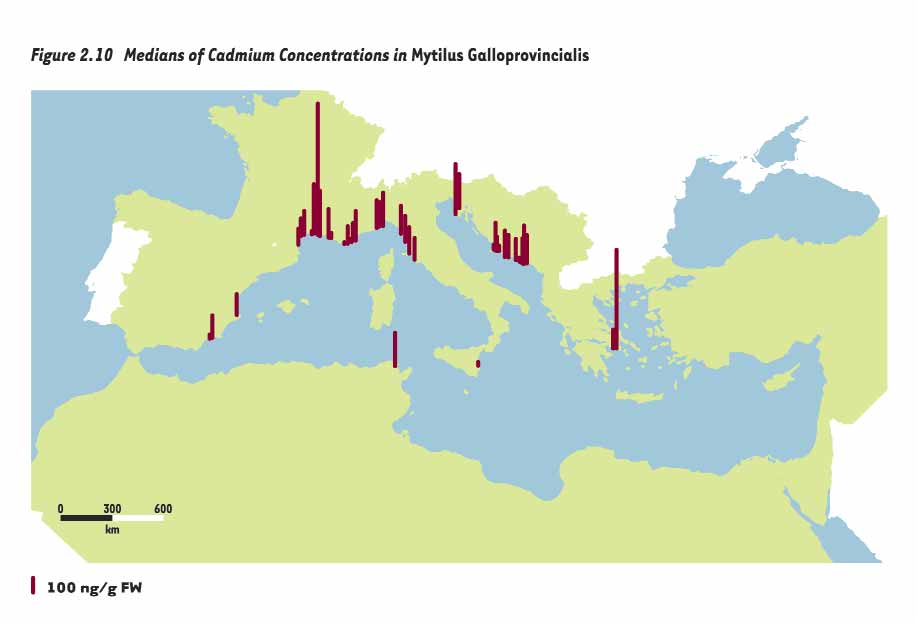

Figure 2.10

Medians of Cd concentrations in Mytilus galloprovincialis

34

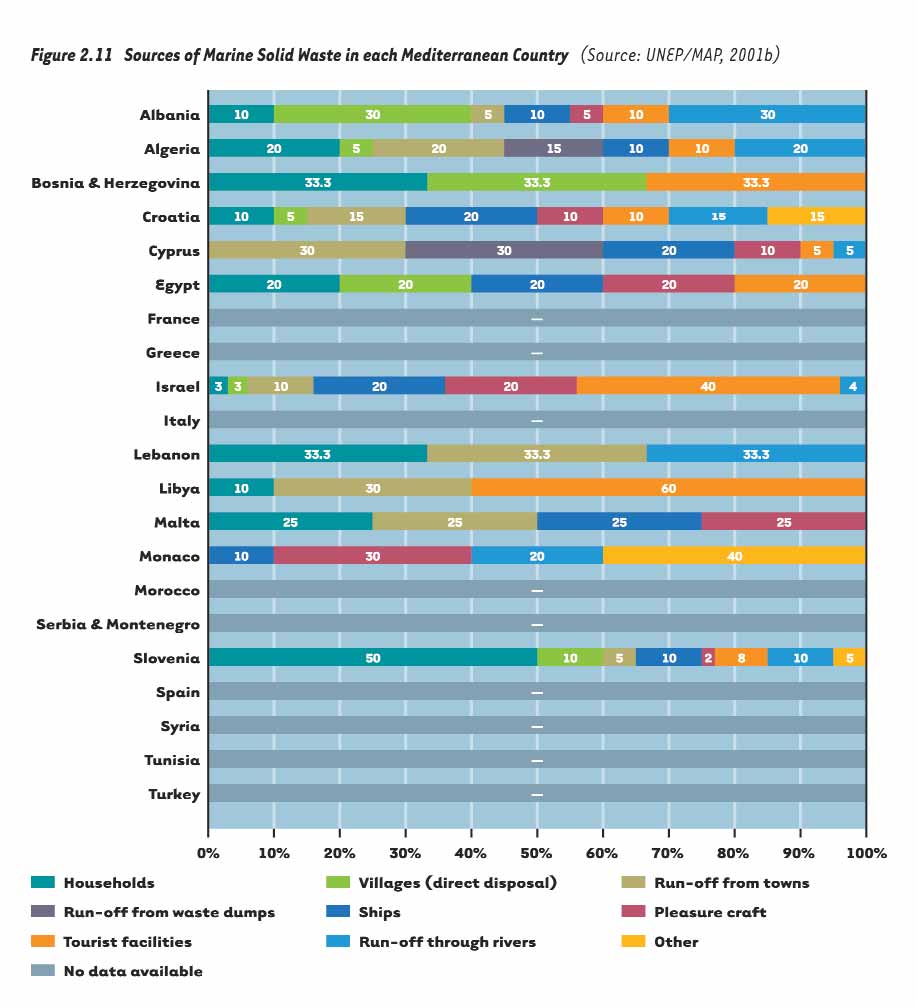

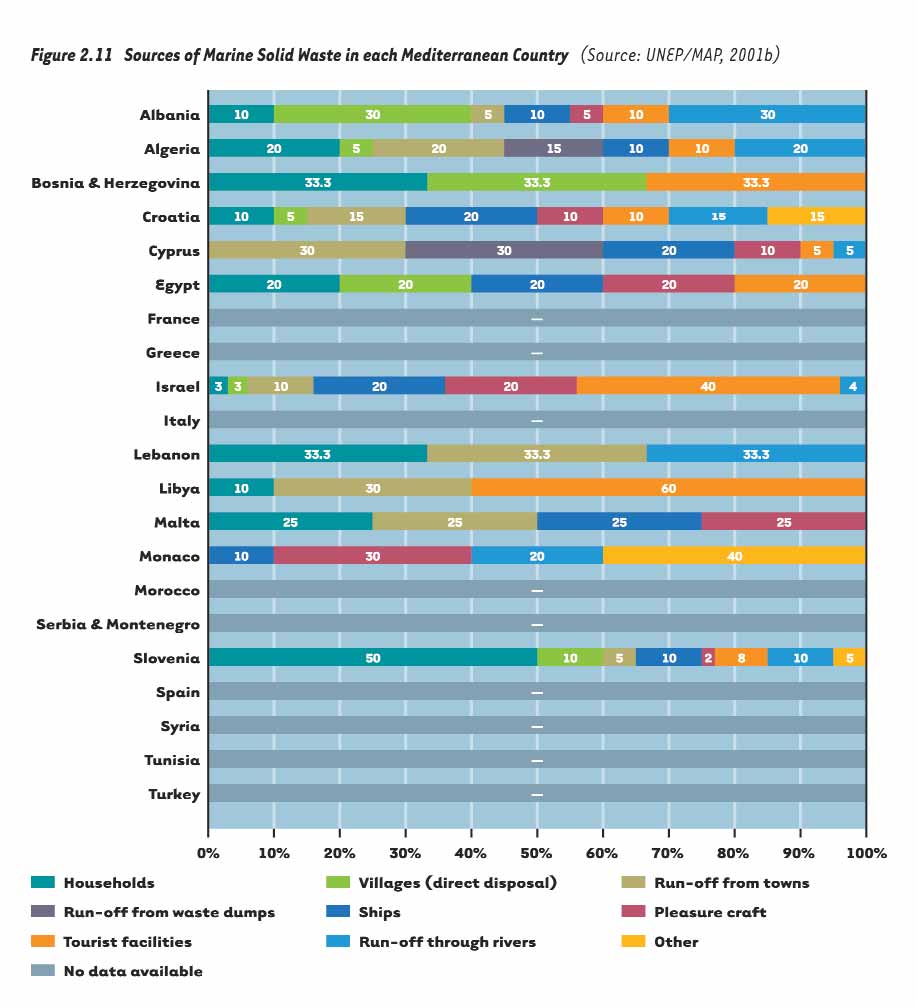

Figure 2.11

Sources of marine solid waste in each Mediterranean country

38

Figure 2.12

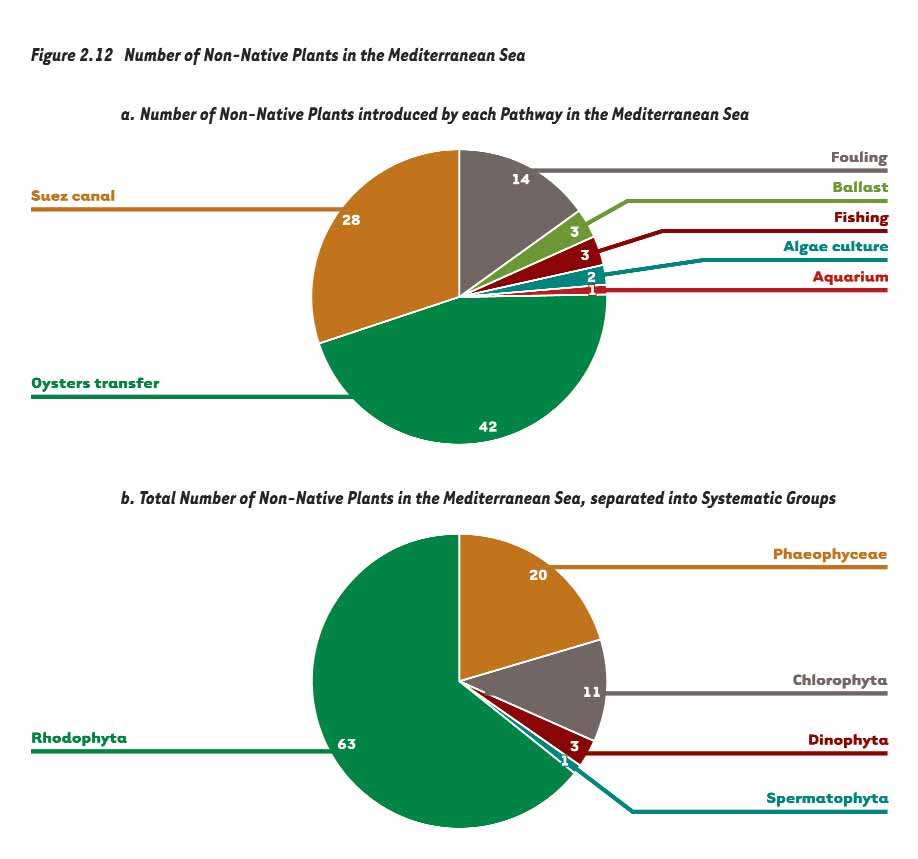

Number of non-native plants in the Mediterranean Sea

40

Figure 2.13

Total marine catches in MT in the Mediterranean

42

Figure 2.14

Fish and fisheries exports in mil US$ from the Mediterranean

43

Figure 2.15

Fish and Fisheries imports in mil US$ to the Mediterranean

43

Figure 2.2.1

Causal Chain Analysis

45

Figure 2.16

Total landings in MT of marine catches by Mediterranean and Black Sea countries

46

-6

»

»

Figure 2.17

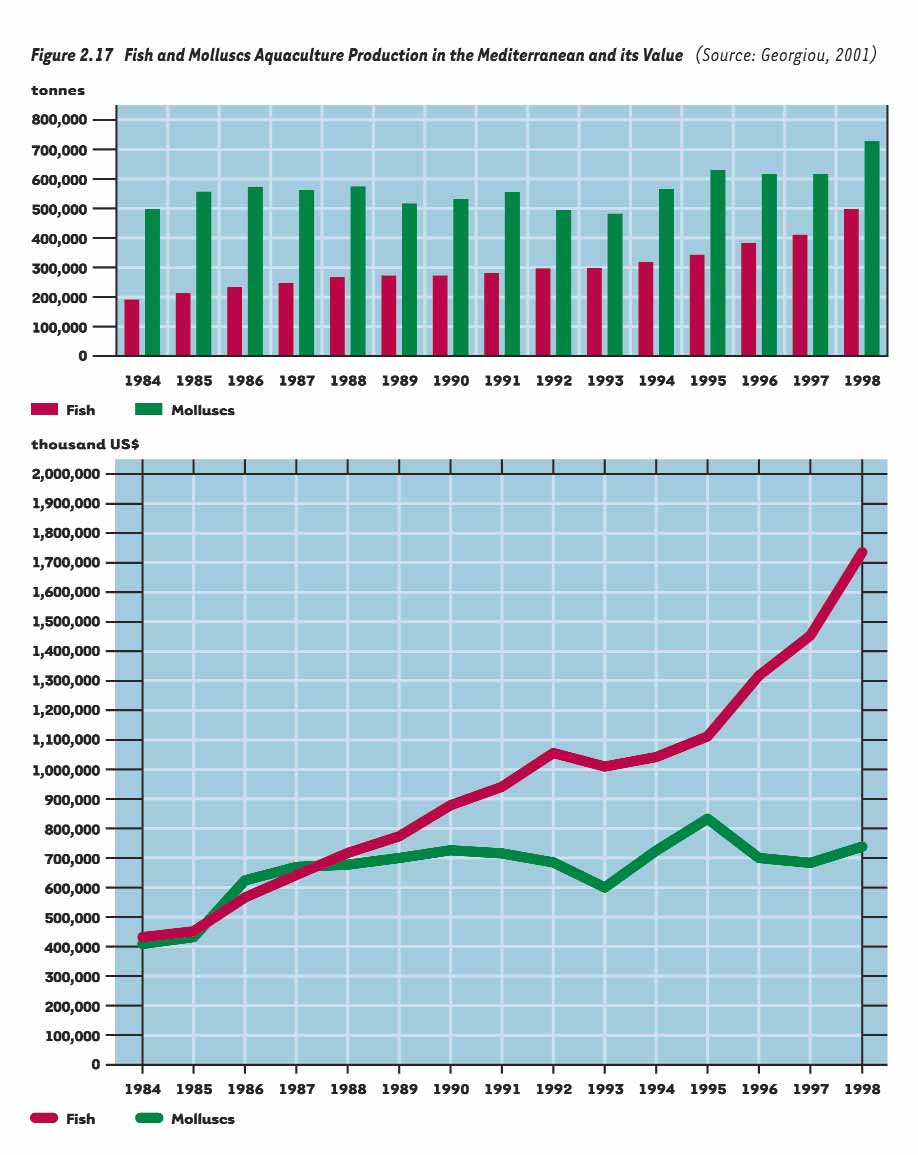

Fish and molluscs aquaculture production and value

of the Mediterranean countries for the years 1984 to 1998

48

Figure 2.18

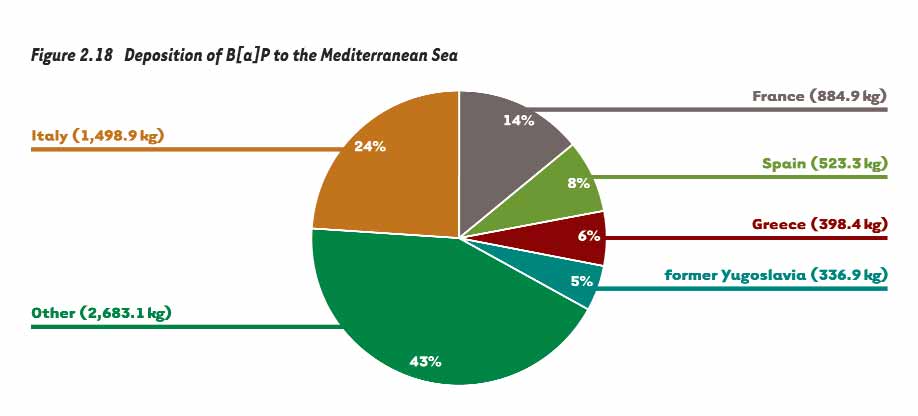

Deposition of B[a]P to the Mediterranean Sea

53

Figure 2.3.1

Causal Chain Analysis

55

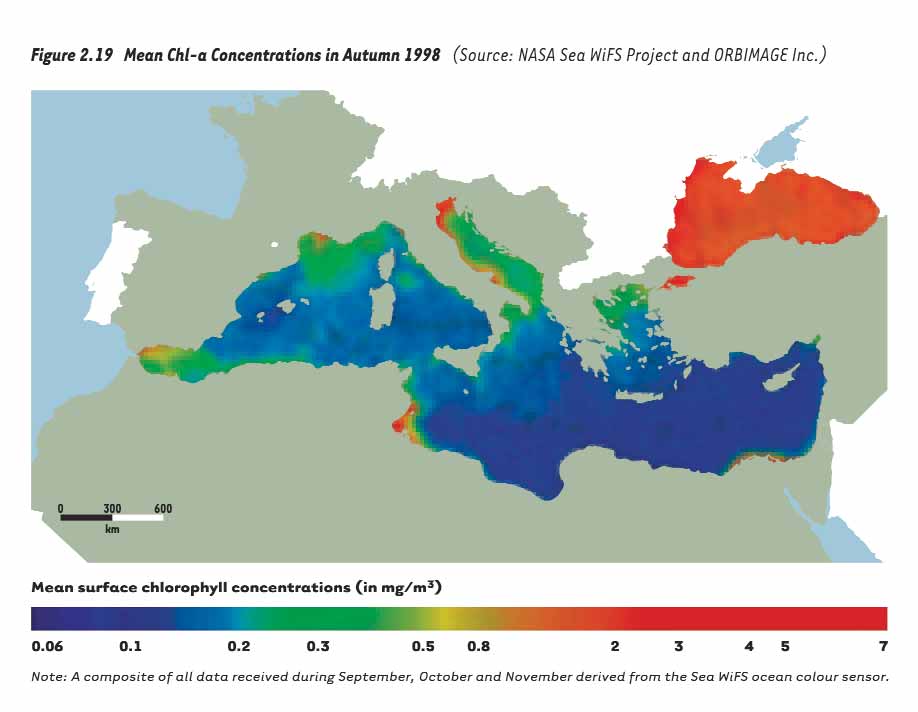

Figure 2.19

Satellite image illustrating average chlorophyll variations

in surface water of the Mediterranean Sea, winter 197985

56

Figure 2.20

Phosphorus load into the Mediterranean Sea from agriculture,

domestic / industrial activities and aquaculture

57

Figure 2.21

Nitrogen load into the Mediterranean Sea from agriculture,

domestic / industrial activities and aquaculture

57

Figure 2.22

Consumption of fertilizers in Mediterranean countries 19701990 in 10,000 t

58

Figure 2.23

Average of Mediterranean regional shares in emissions of lead (Pb),

Cadmium (Cd), Zinc (Zn) and Copper (Cu)

63

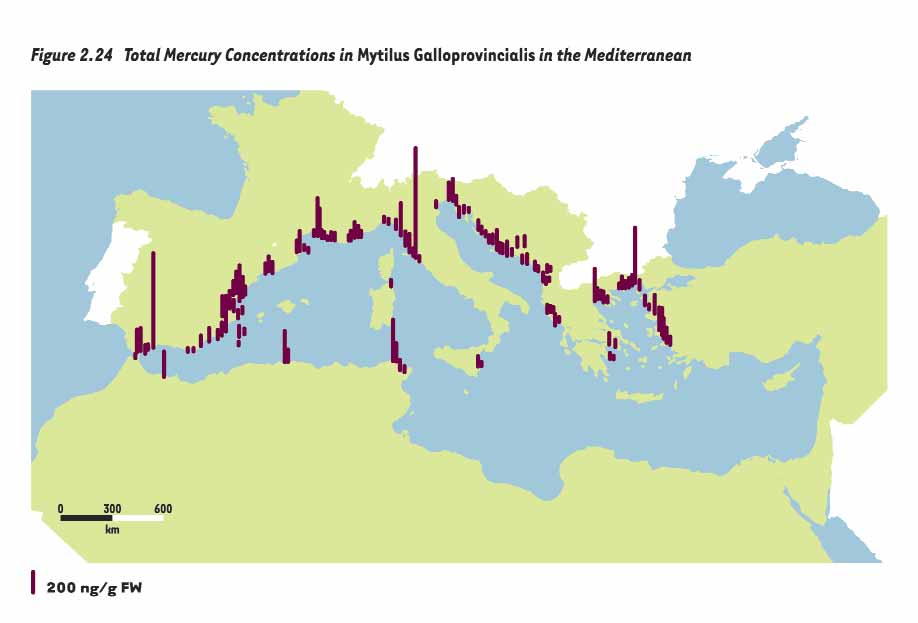

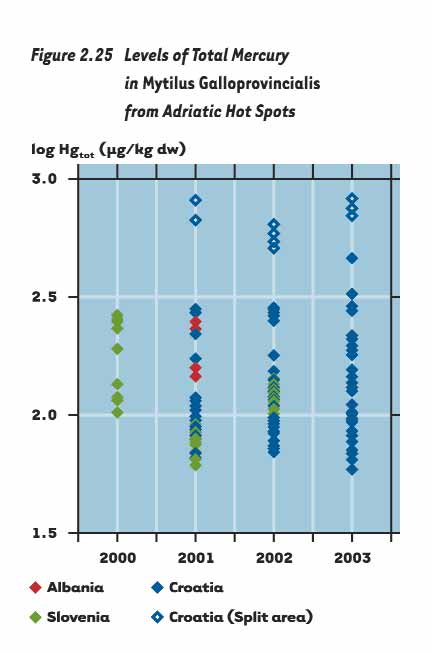

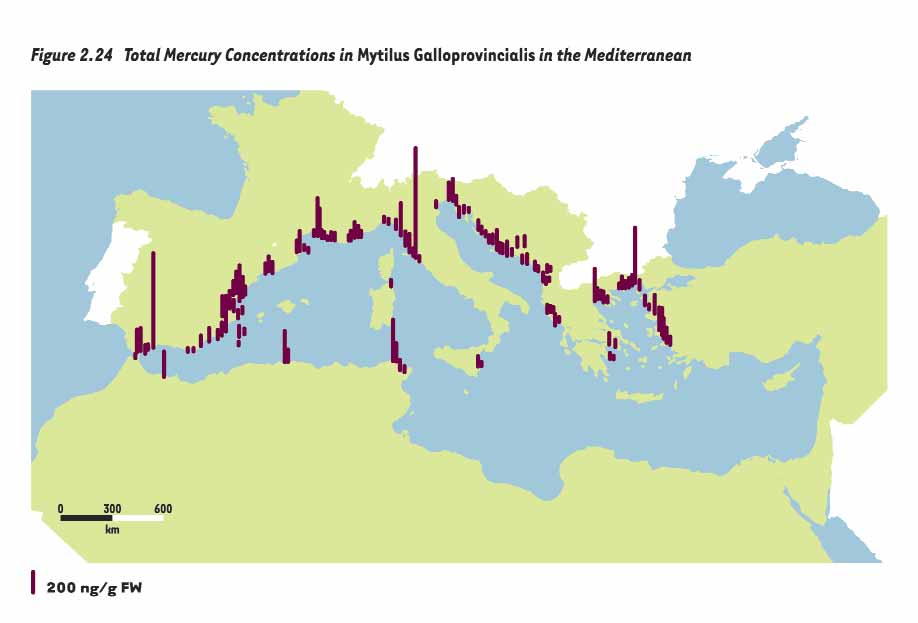

Figure 2.24

HgT concentrations in Mytilus galloprovincialis in the Mediterranean

64

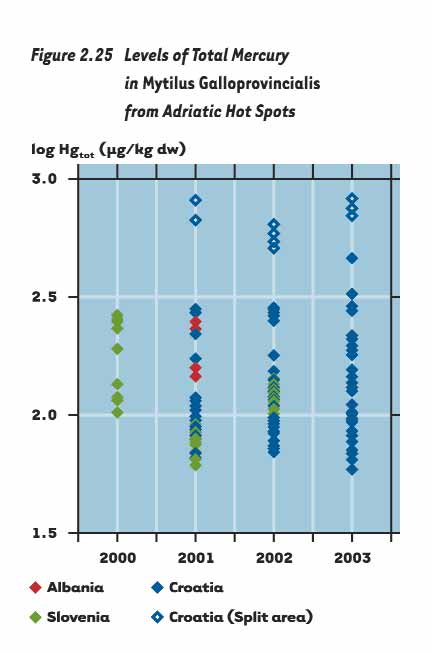

Figure 2.25

Levels of total mercury in Mytilus galloprovincialis from Hot Spots

64

Figure 2.26

Cd in Mullus barbatus sorted by zones and arranged from west to east

65

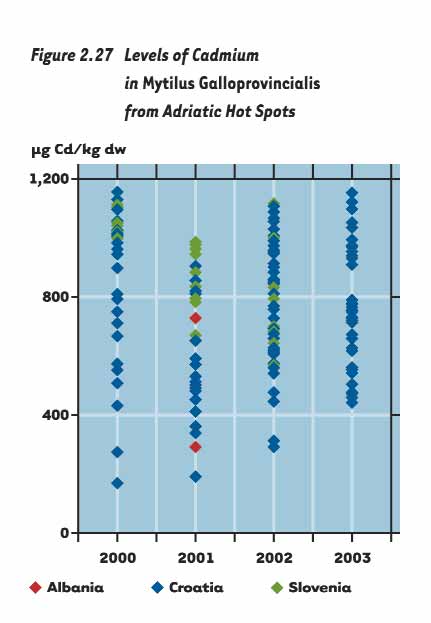

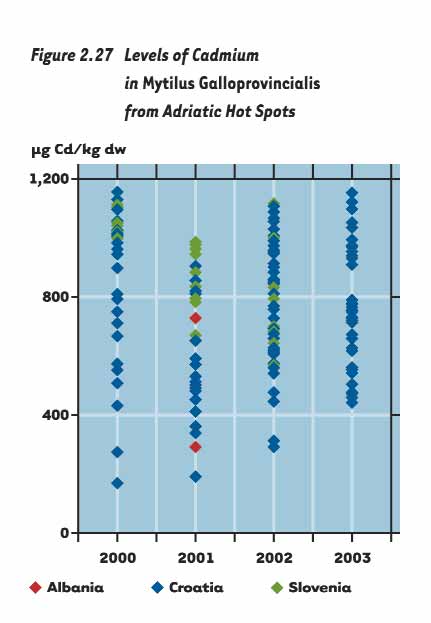

Figure 2.27

Levels of Cadmium in Mytilus galloprovincialis from Hot Spots

66

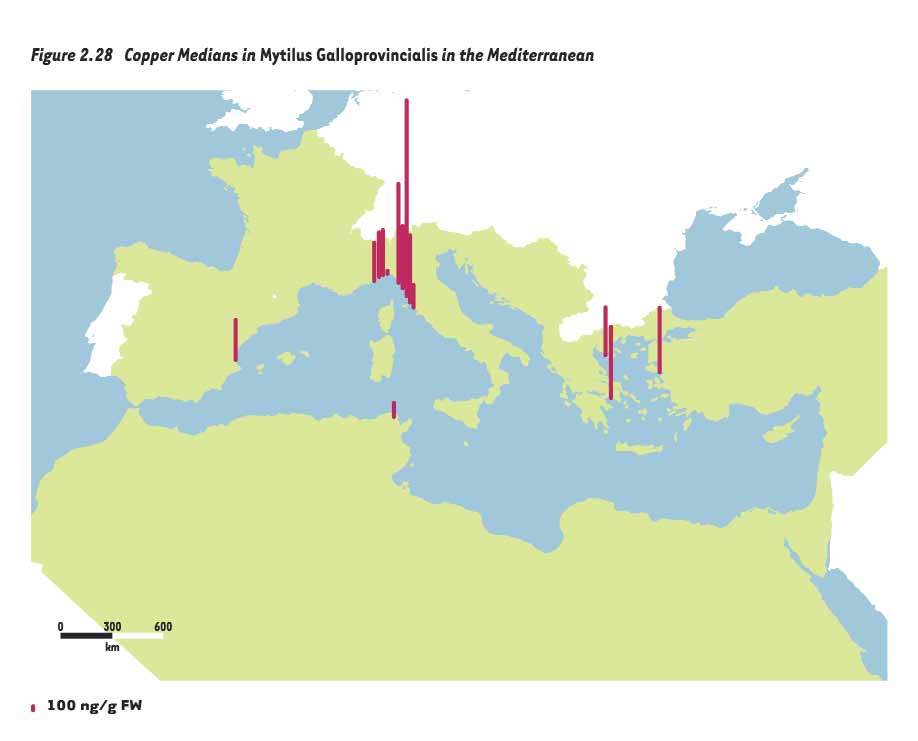

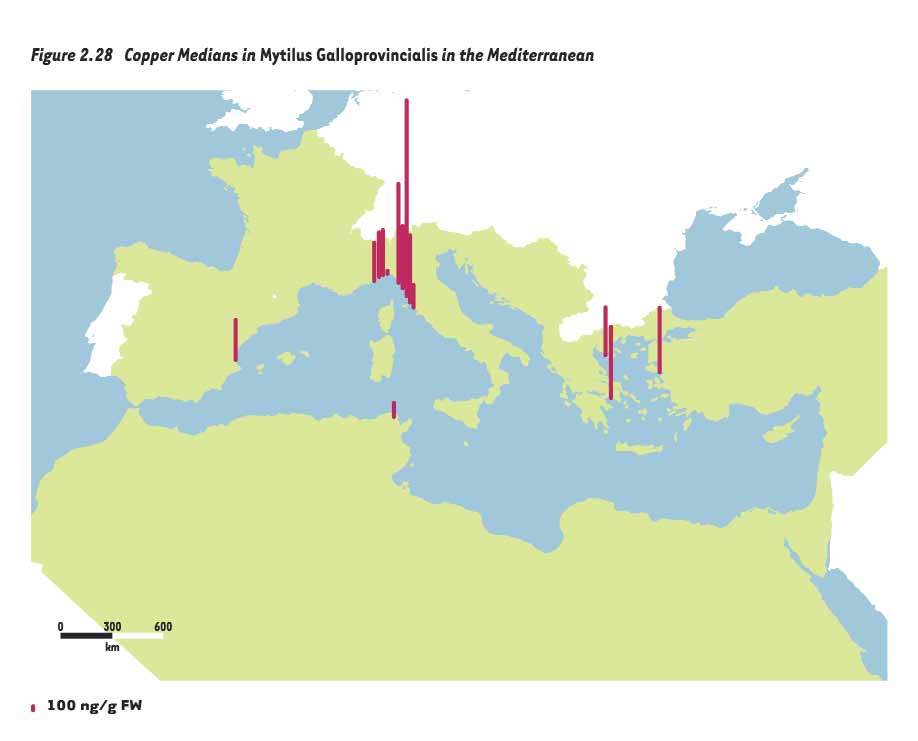

Figure 2.28

Cu medians in Mytilus galloprovincialis

67

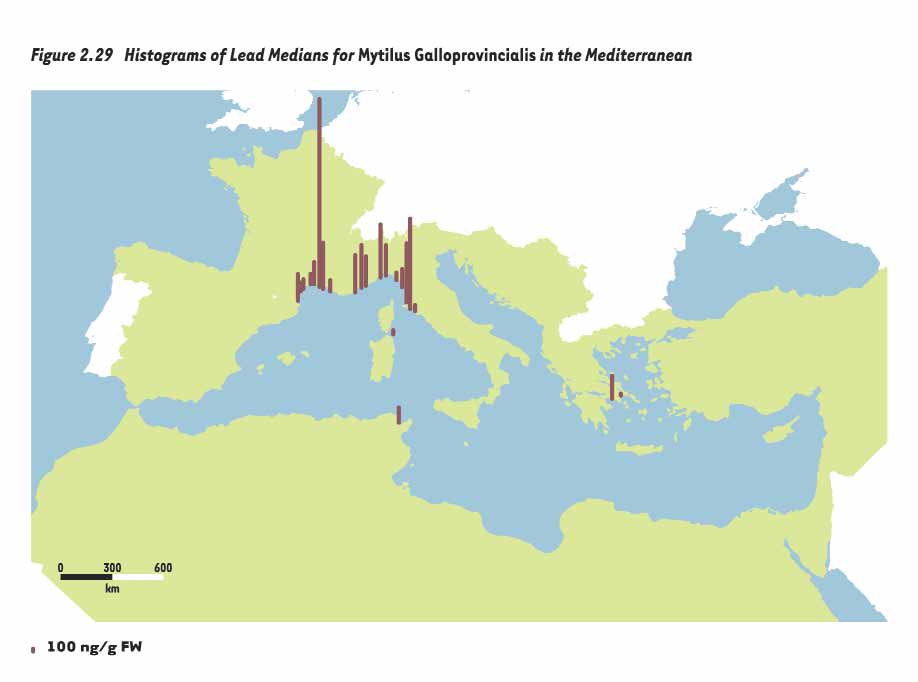

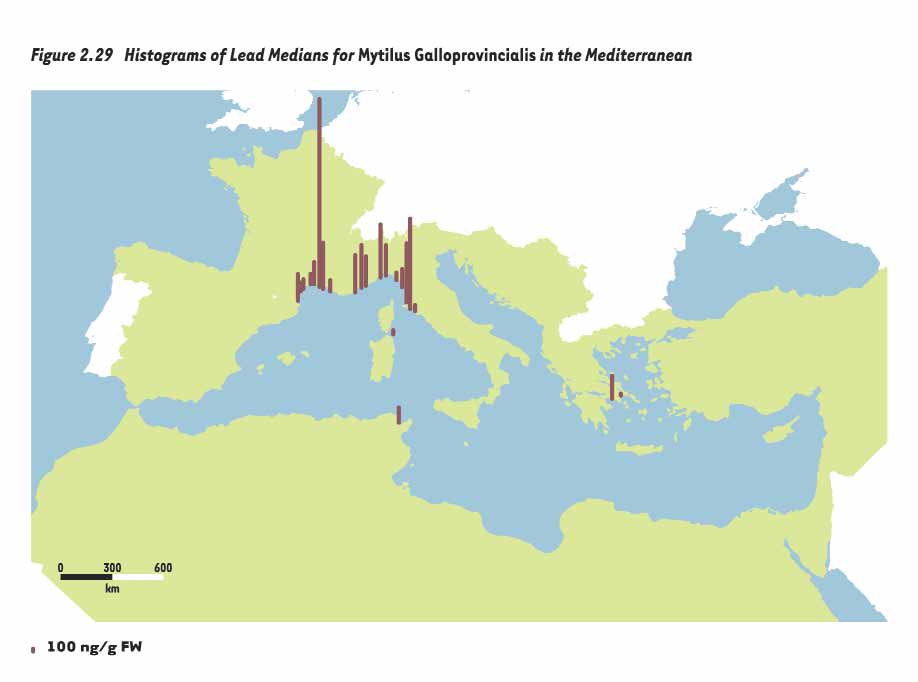

Figure 2.29

Histograms of Pb medians for Mytilus galloprovincialis

68

Figure 2.30

PCBs and DDTs in sediment (ng/g d.w.)

72

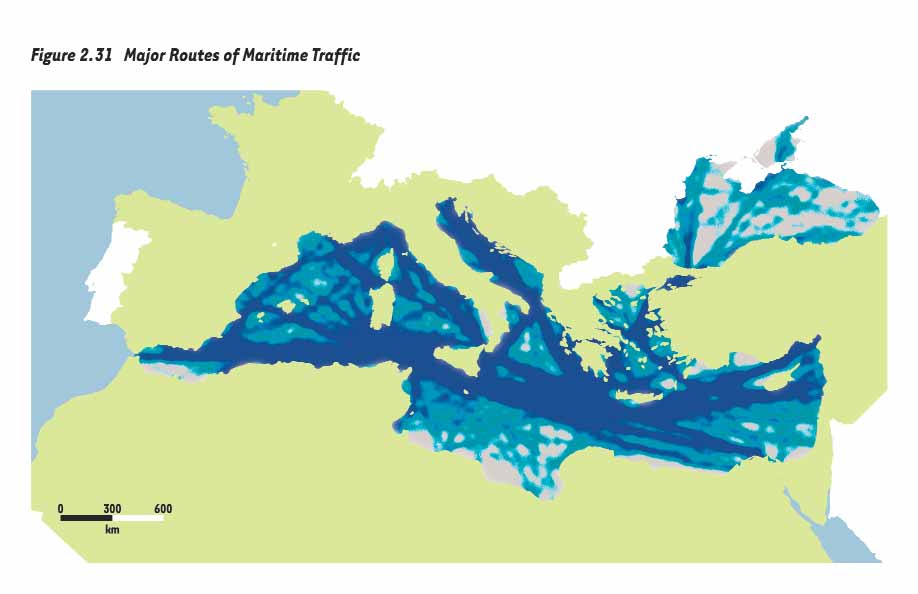

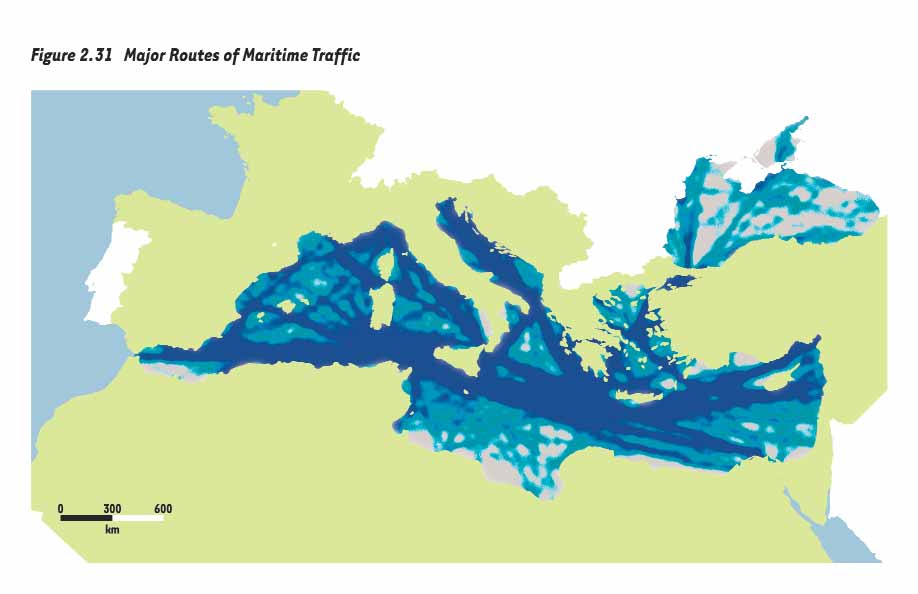

Figure 2.31

Major routes of maritime traffic

78

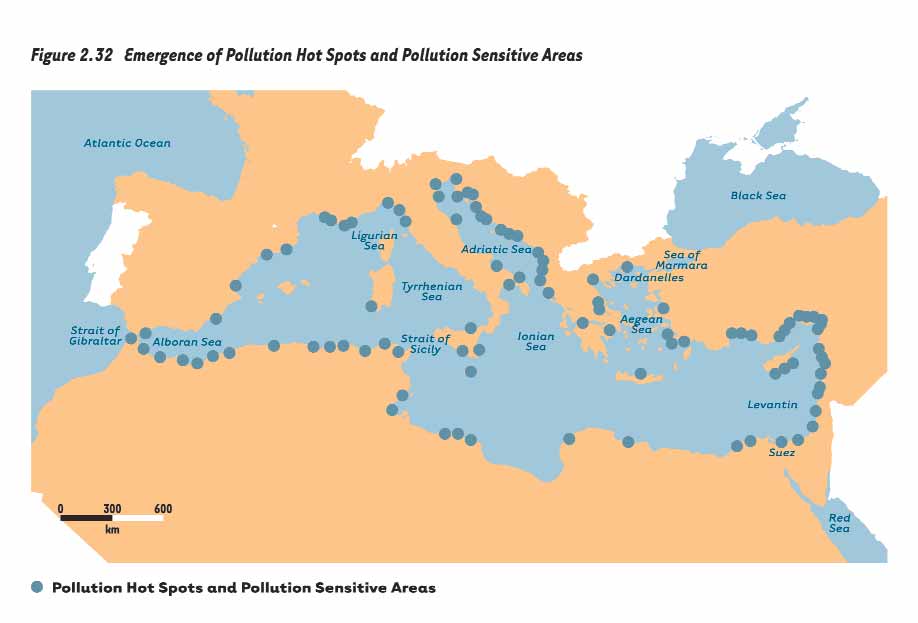

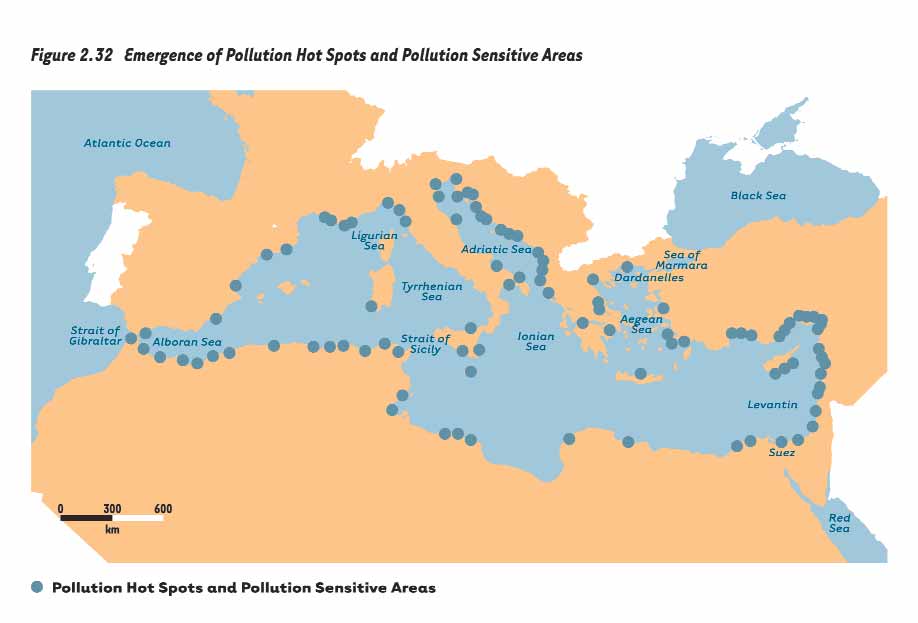

Figure 2.32

Emergence of Pollution Hot Spots and Pollution Sensitive Areas

81

Figure 2.4.1

Causal Chain Analysis

84

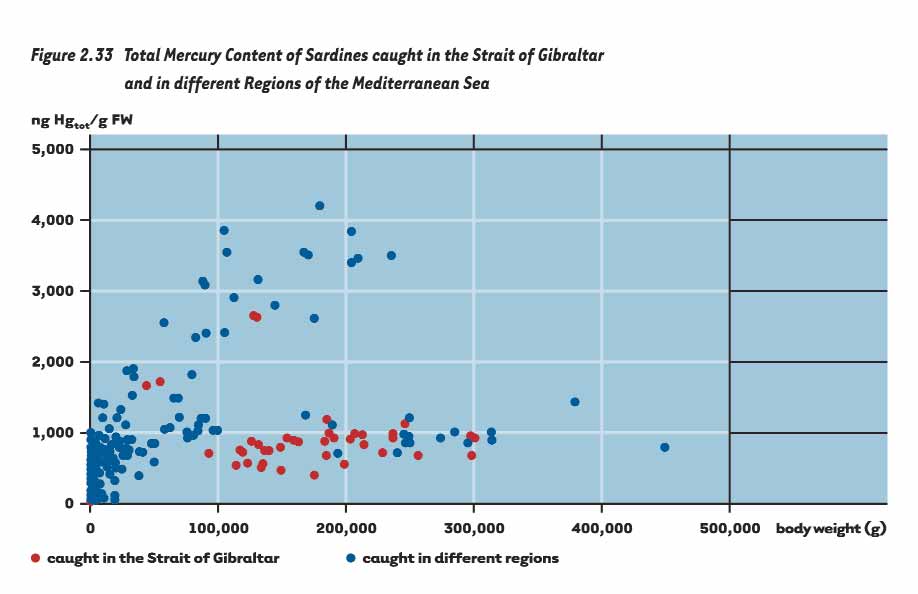

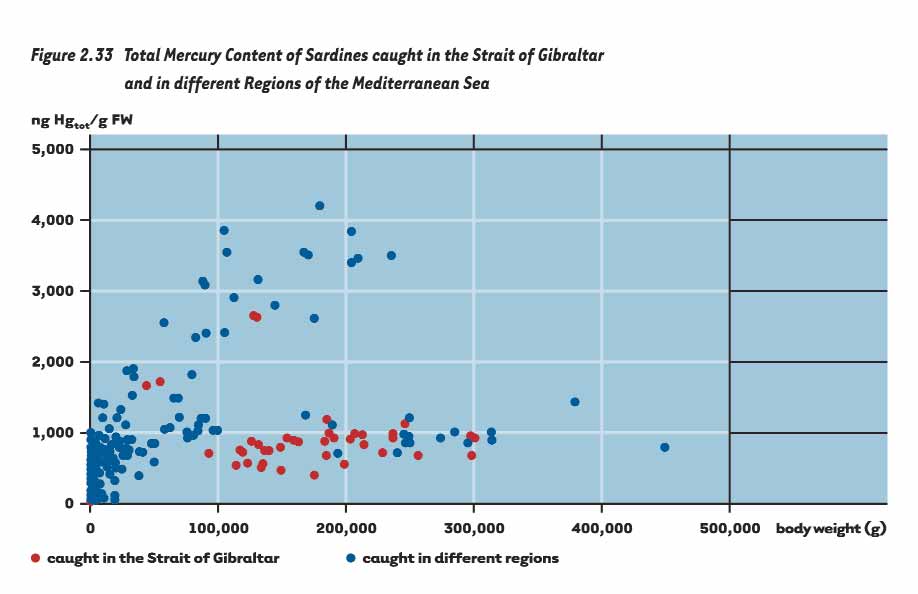

Figure 2.33

Total mercury content of sardines caught in the Strait of Gibraltar

and in different regions of the Mediterranean Sea

86

List of Figures

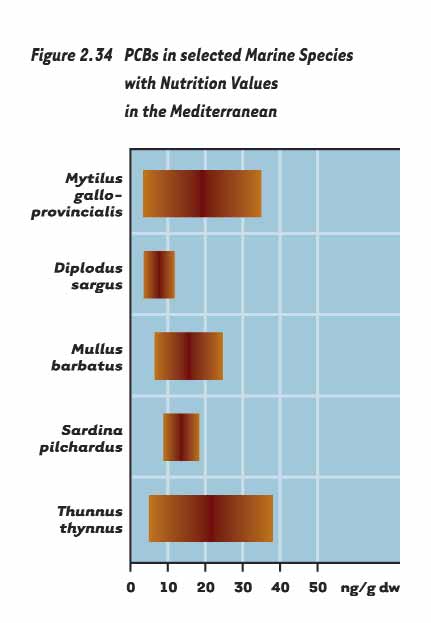

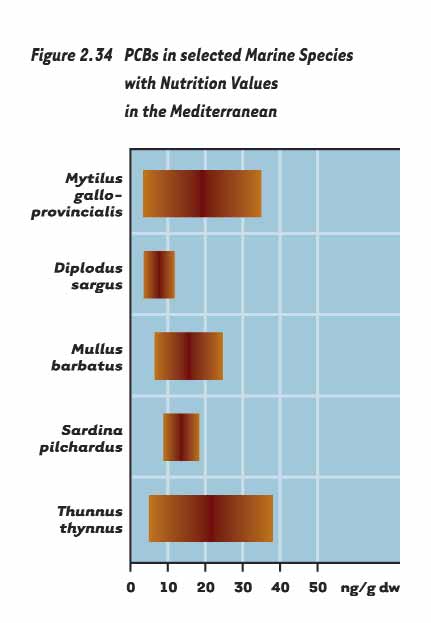

Figure 2.34

PCBs in selected marine species with nutrition values in the Mediterranean

86

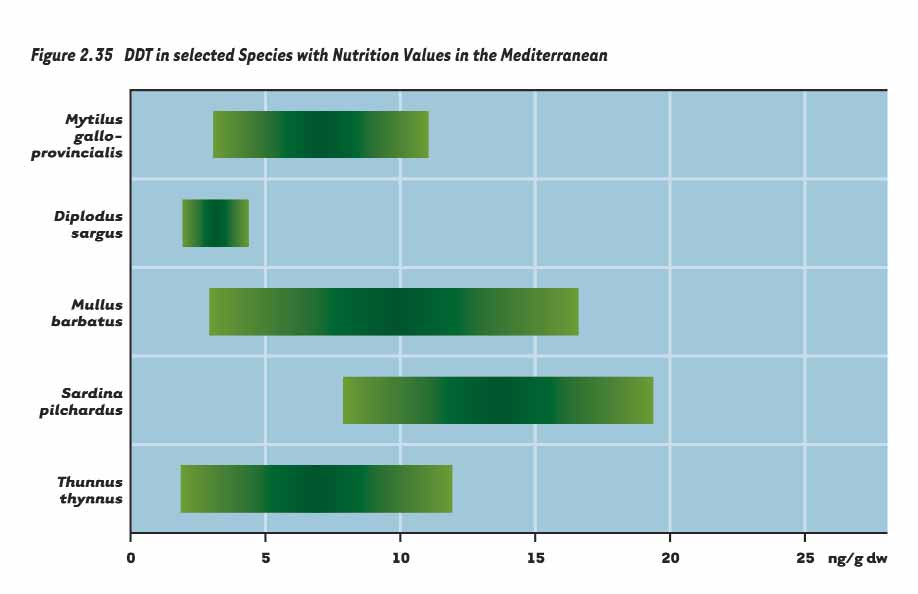

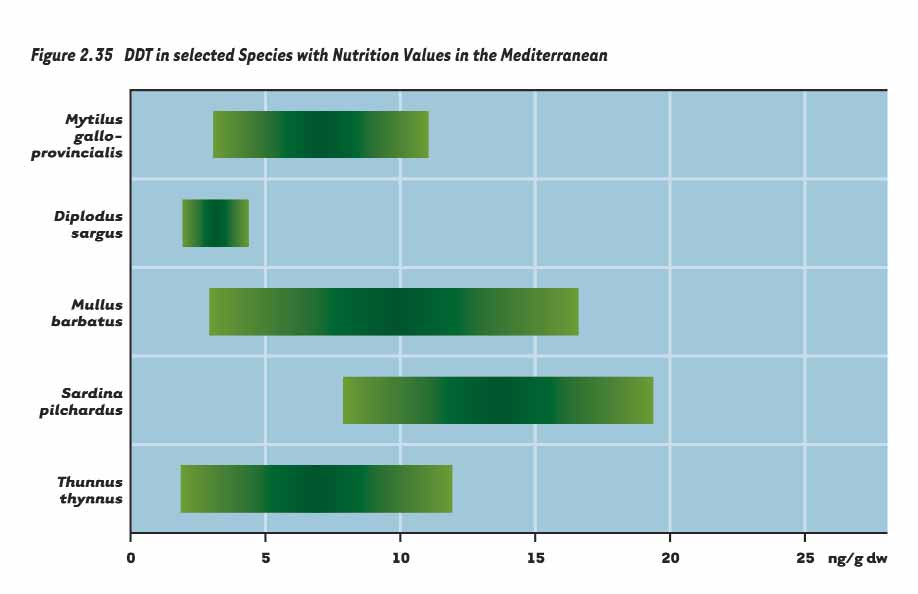

Figure 2.35

DDT in selected species with nutrition values in the Mediterranean

90

Figure 2.36

Percentage of foodborne disease outbreaks caused by fish and shellfish

in Italy, Spain and France 199398

93

Figure 2.37

Notified cases of food borne disease outbreaks in Spain, Italy, Greece and France 199398

93

Figure 2.38

Coastal cities (with over 10,000 inhabitants) with wastewater treatment facilities

in the Mediterranean

96

Figure 2.39

Type of wastewater treatment in Mediterranean coastal cities

96

Figure 2.40

Water discharged by Mediterranean coastal cities

96

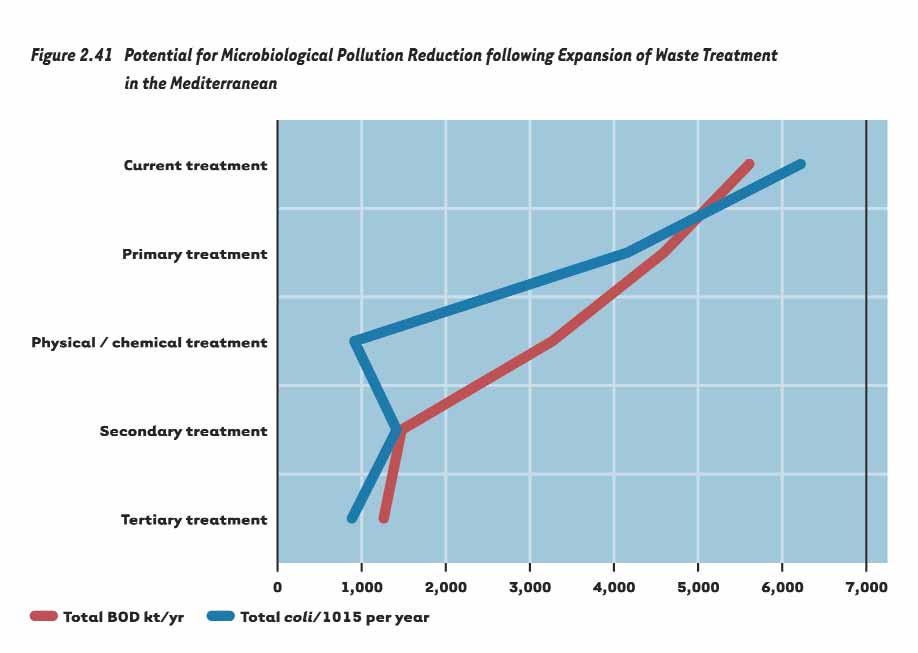

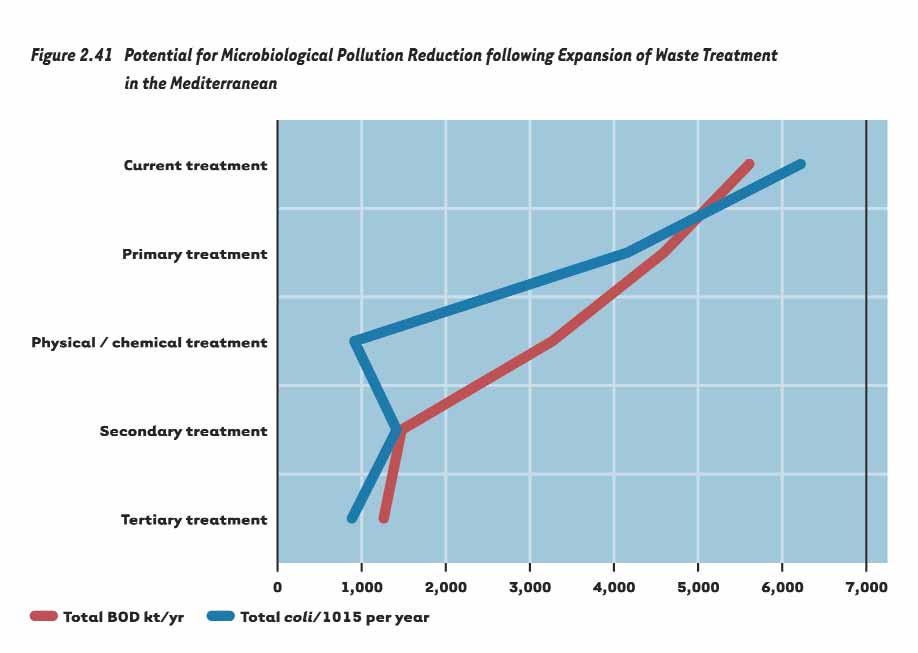

Figure 2.41

Potential for microbiological pollution reduction following expansion

of waste treatment in the Mediterranean

97

Figure 2.42

Changes in the quality of bathing water on the Marseille coast

since the beginning of the 1980s

99

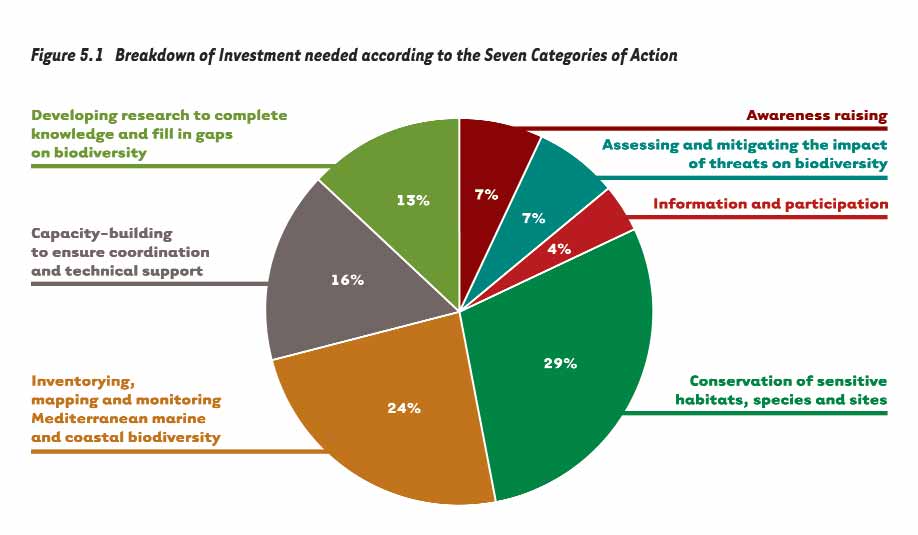

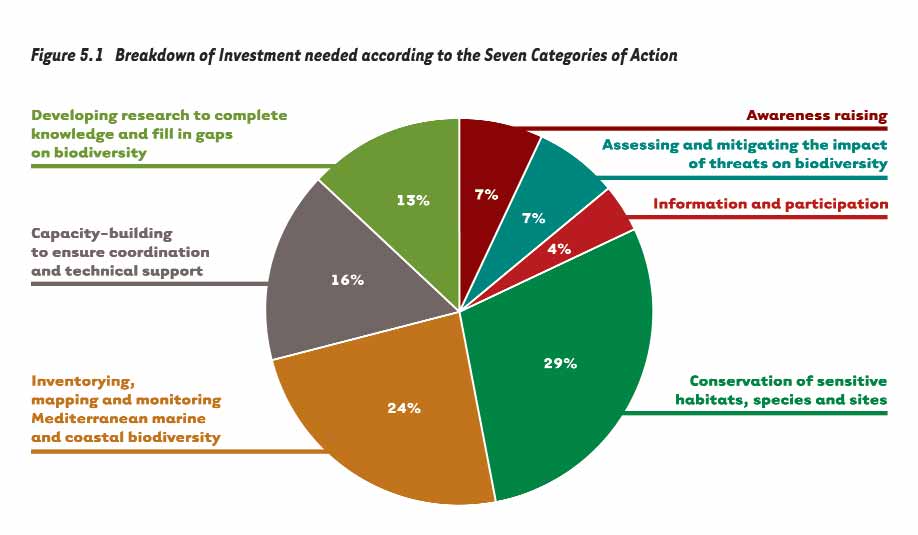

Figure 5.1

Breakdown of investment needed according to the 7 categories of action

153

-5

Acronyms & Abbreviations

AB

Algal Bloom

ACCOBAMS

Agreement for the Conservation of Small Cetaceans of the Black Sea, Mediterranean Sea

and Contiguous Atlantic Area

ADRIAMED

Scientific Cooperation to support Responsible Fisheries in the Adriatic Sea

BAT

Best Available Technology

BEP

Best Environmental Practices

BOD

Biolochemical Oxygen Demand

BSEP

Black Sea Environment Programme

BSP

Baltic Sea Programme

CBD

Convention on Biological Diversity

CD

Compact Disc

CFP

Common Fisheries Policy

CITES

Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora

cm/s

centimeters per second

COD

Chemical Oxygen Demand

COFI

Committee on Fisheries

CPUE

Catch per Unit Effort

CZ

Coastal Zone

Acronyms & Abbreviations

DL

Daily Limit

dw

dry weight

EBRD

European Bank for Reconstruction and Development

EC

European Commission

EEA

European Environment Agency

EIA

Environmental Impact Assessment

EIN

Environmental Information Networking

EQO

Environmental Quality Objective

ER

Emergency Response

EU

European Union

EUCC

European Union for Coastal Conservation

EU SCOOP

European Union Scientific Cooperation

EU WFD

European Union Water Framework Directive

FAO

Food and Agricultural Organization, UN

g

gram

GDP

Gross Domestic Product

GEF

Global Environment Facility

GESAMP

Joint Group of Experts on the Scientific Aspects of Marine Pollution

GFCM

General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean

-4

GIS

Geographical Information System

»

GNP

Gross National Product

HAB

Harmful algal bloom

HDI

Human Development Index

IAEA

International Atomic Energy Agency

IARC

International Agency for Research on Cancer

ICCAT

International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas

ICES

International Council for the Exploration of the Seas, UN

ICZM

Integrated Coastal Zone Management

IMO

International Maritime Organization

IOC

Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission

IPPC

Integrated Pollution Prevention and Control

IRPTC

International Register of Potentially Toxic Chemicals

ITCAMP

Integrated Coastal Area Planning and Management

kg

kilograms

km

kilometer

l

liter

LBS

Land-Based Sources

LRTAP

Long Range Transboundary Air Pollution

LEARN

Learning Exchange and Resource Network

m

meter

MAP

Mediterranean Action Plan

MARPOL

International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships

MEA

Multilateral Environmental Agreement

Acronyms & Abbreviations

MED POL

Mediterranean Pollution Action Program

METAP

Mediterranean Environmental Technical Assistance Program

MG

Mytilus galloprovincialis (mussel)

mm

millimeter

MPPI

Major Perceived Problems and Issues

MT

metric ton

NAP

National Action Plan

NATO

North Atlantic Treaty Organization

NEAP

National Environmental Action Plan

NEC

National Emissions Ceilings

NGO

Non-Governmental Organization

NSA

National Shellfish Association

OECD

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

OSPAR

Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North East Atlantic

PAH

Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons

PCDD

Polychlorinated dioxins

PCDF

Polychlorinated Drans

PCU

Programme Coordination Unit

PDF

Project Development Facility

pg

Picogram

-3

PIC (Convention)

Prior Informed Consent

PIP

Priority Investment Portfolio

»

PPP

Purchasing Power Parity

ppt

parts per thousand

PSSA

Particularly Sensitive Sea Area

PTIW

Pretreatment of Industrial Wastes

PTS

Persistent Toxic Substances

QA

Quality Assurance

QC

Quality Control

RA

Regional Action

REMPEC

Regional Marine Pollution Emergency Response Center for the Mediterranean Sea

RFO

Regional Fisheries Organization

SAC

Scientific Advisory Committee

SAP

Strategic Action Programme

SAP BIO

Strategic Action Programme for Biodiversity in the Mediterranean Region

SAP MED

Strategic Action Programme to Address Pollution from Land-Based Activities

SC

Steering Committee

SEA

Strategic Environmental Assessment

SME

Small and Medium Enterprise

SPA

Specially Protected Areas

SPAMI

Specially Protected Areas of Mediterranean Importance

TDA

Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis

TDI

Total Daily Intake

TEQ

Toxicity Equivalent Quotient

Acronyms & Abbreviations

THC

Total Hydrocarbon Concentration

TOR

Terms of Reference

TPB

Toxic, Persistent, and Bioaccumulative substances

TSS

Total Suspended Solids

UN

United Nations

UNCED

United Nations Conference on Environment and Development

UNECE

United Nations Economic Commission for Europe

UNECE/EMEP

United Nations Economic Commission for Europe / Co-operative programme for monitoring

and evaluation of long range transmission of air pollutants in Europe

UNDP

United Nations Development Programme

UNEP

United Nations Environment Programme

UNESCO

United Nations Education, Science and Culture Organization

UNIDO

United Nations Industrial Development Organization

UNOPS

United Nations Office for Project Services

WB

World Bank

WHO

World Health Organization

WMO

World Meteorological Organization

WSSD

World Summit on Sustainable Development

WTO

World Trade Organization

ww

wet weight

WWTP

Wastewater Treatment Plant

-2

WWW

World Wide Web

SIS (TDA) FOR THE MEDITERRANEAN SEA

Y

TIC ANAL

Y DIAGNOS

TRANSBOUNDAR

-1

FOREWORD

The Mediterranean region has witnessed sub-

lution. In particular, the first Transboundary Diagnostic

stantial progress during the last few years in the fight

Analysis (TDA, 1997) was an innovative and original

against land-based pollution. The Protocol on land-

piece of work for the region that, by coupling pollution

based pollution sources (LBS) to the Barcelona

data with an analysis of root causes and possible pol-

Convention, in force since June 1983, has managed to

lution control measures, indicated for the first time a

promote awareness and shared participation on the

concrete road map for the reduction and elimination of

issue of pollution from land, and the MED POL

pollution. With the support of GEF, the Mediterranean

Programme has supported capacity building pro-

countries worked in a new and more effective direction

grammes and has helped the gathering of large

and, as a result, they are soon to adopt solid and polit-

amounts of information and data on sources, levels

ically supported National Action Plans for the reduc-

and effects of marine pollution. However, it was only at

tion of pollution. Considering the progress made, the

the end of the nineties that the Mediterranean, on the

developments at the regional and international levels

long wave of the Rio Summit and the adoption of the

and the need to update and complete the existing data

UNEP Global Programme of Action (GPA) to address

and information, a second TDA has been prepared to be

FOREWORD

pollution from land-based activities, started moving

used once again as the basis for prioritizing and imple-

towards concrete action for pollution reduction. The

menting action. Furthermore, the present TDA achieved

signature of an amended LBS Protocol (1996) and the

an additional step compared with the 1997 TDA, that is

adoption of a Strategic Action Programme (SAP MED)

the use of the Environmental Quality Objectives adopt-

to address pollution from land-based activities (1997)

ed in the SAP MED, the recently adopted SAP for biodi-

can be considered the turning points since they offered

versity (SAP BIO) and the Code of conduct for fisheries.

to Mediterranean countries effective instruments and a

This has led to the identification of specific targets,

concrete road map to achieve gradual reduction and

deadlines and specific interventions and actions to be

elimination of land-based pollution by the year 2025.

adopted by the countries in the framework of their

The shift from assessment to control of pollution was

National Action Plans (NAPs) and the SAP MED. The

supported by several factors, the most important of

present TDA therefore represents once again a refer-

them being the interest and the concrete backing of the

ence point for all Mediterranean countries and the

Global Environment Facility (GEF). GEF believed in the

basis for action for the years to come.

political and technical potential of the region and has

supported a number of fundamental steps that have

Francesco Saverio Civili

now created a very promising momentum in the fight

MED POL Programme Coordinator

against land-based pollution in the Mediterranean. The

process of preparing and adopting the SAP MED was in

fact substantially supported by GEF by offering the

methodology and the experience gained in other

regions and by transferring them in the Mediterranean.

Through GEF, the Mediterranean countries in fact man-

aged to identify the marine pollution hot spots --the

basis for achieving pollution reduction-- and prepared

0

for the first time an assessment of transboundary pol-

SIS (TDA) FOR THE MEDITERRANEAN SEA

Y

TIC ANAL

Y DIAGNOS

TRANSBOUNDAR

i.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

i.1 TDA Content and Process

of interest to the Global Environment Facility's (GEF)

The purpose of conducting a Transboundary

International Waters (IW) focal area.

Diagnostic Analysis (TDA) is to scale the relative

The Mediterranean Sea environment is affected

importance of sources and causes, both immediate

by activities in heavily industrialized, developed coun-

and root, of transboundary `waters' problems, and to

tries in the northwest sector of the Sea, as well as by less

identify potential preventive and remedial actions.

industrialized activities in the southern and eastern

The TDA provides the technical basis for refinement

parts of the Sea. The GEF-eligible countries in the region

of both the National Action Plans (NAPs) and the

include Albania, Algeria, Bosnia & Herzegovina, Croatia,

Strategic Action Programme (SAP) in the area of

Egypt, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Slovenia, Syria,

international waters of the GEF.

Tunisia, and Turkey. Serbia & Montenegro was not par-

Y

This TDA, was elaborated on the basis of the

ticipated in the Project. Other countries participating in

previous TDA adopted in 1997, as well as extensive

these GEF activities include the non-eligible countries

information gathered since that time. The 1997 TDA

of Cyprus, France, Greece, Israel, Italy, Malta, Monaco

was based on more than three years of activities.

and Spain. Together, these countries account for much

Numerous meetings and workshops were held to pro-

of the coastline of the Mediterranean Sea. The chal-

i. EXECUTIVE SUMMAR

vide inputs to the TDA, various studies were carried out

lenges to conducting a successful GEF/IW project in a

and reports were commissioned to support the TDA.

region having such disparate mixes of development are

The 1997 TDA also benefited from information made

great. Problems associated with industrial countries

available by the Mediterranean Action Plan (MAP)

(e.g., organochlorines, hydrocarbons, PCBs, etc.) are

Secretariat through its business as usual activities.

mixed with environmental problems associated more

This TDA serves as an update of the 1997 TDA

often with developing countries (agricultural dis-

and was prepared during the implementation of the

charges, solid waste disposal, sewage treatment).

full GEF Project. To complete this update, a set of

Thus, the activities resulting from this GEF intervention

reports were prepared. An "Assessment of the Trans-

will be mixed and varied.

boundary Pollution Issues in the Mediterranean" was

The first step (Figure i.1) in the TDA process is to

drafted and then discussed at the regional experts'

identify the major perceived problems and issues

meeting (a list of participants is provided in Annex I)

(MPPIs). This step was performed through a participato-

where the major perceived issues were identified.

ry process. These MPPIs then were the basis for the

Based on the outcomes of this meeting, an updated

analysis phase, during which time the MPPIs were inves-

draft of the TDA was prepared, circulated for com-

tigated for validity. Do data support the MPPI as a prior-

ments and finalized.

ity concern? What data are necessary to evaluate the

The TDA provides the expert opinion on the

MPPI? What do the Stakeholders think about the impor-

state of the environment and priority problems. It

tance of the MPPI? What are the causes of the MPPI

terminates in a list of actions that are recommended

(causal chain analysis)? What are the environmental

for consideration. This list of recommendations must

impacts of the MPPI? What are the socio-economic

be considered in the context of national priorities

impacts of the MPPI? The analysis phase ends with a de

and regional priorities. In addition, the list of recom-

facto ranking of the relative importance of the various

mendations is not exhaustive. Rather, the list is

MPPIs. This importance is based on the perspective of the

i

designed to address the major transboundary issues

GEF/IW, as the TDA is a product of the GEF/IW process.

SIS (TDA) FOR THE MEDITERRANEAN SEA

Y

These steps lead to investigation of the

have finite and defined duration, and be associated

TIC ANAL

Quantitative Understanding of the Environment, which

with definable and measurable indicators.

is the TDA. This quantitative understanding by nature

What steps are necessary to achieve the EQOs,

Y DIAGNOS

has uncertainties: the data are not perfect, they are too

given the present condition of the environment?

infrequent, they are too sparsely located around the

Some EQOs may need no additional steps, except

region, the analytical methods are imperfect, etc.

perhaps routine implementation. Other EQOs may

However, the TDA is based on expert judgment of the

require vast changes in environmental practices and

TRANSBOUNDAR

best available data. The TDA then is followed by agree-

conditions to achieve them. To move towards the

ment of overarching regional Quality Objectives: if the

EQOs, targets are set: targets are time-constrained

TDA gives the present status of the environment, what is

and quantifiable in their impact. The targets give the

the common vision of the desired status? What environ-

initial movements towards the EQOs, but they are

mental goals are desirable for the Mediterranean Sea?

mainly Status Indicators. The activities or interven-

These are the Environmental Quality Objectives (EQOs).

tions that lead to the achievement of the targets are

After the MPPIs are ranked and the EQOs agreed,

the main output of the TDA: they represent experts'

the root causes are then examined using a causal chain

opinions about how to achieve the EQOs best given

analysis. The causal chain analysis reviews the immedi-

the existing conditions (environmental, institution-

ate causes of the MPPIs, as well as the root causes con-

al, capacity, state of knowledge, etc.). This section,

tributing to creation of those MPPIs. The root causes

therefore, summarizes the results of this process.

normally are the target of interventions; such interven-

The TDA focuses on the major Transboundary

tions at the root cause level generally provide more sus-

issues. Transboundary is the regional context for the

tainable and effective results.

TDA, and separates national issues from issues eligi-

The root causes and the MPPIs generally

ble for incremental assistance from GEF to achieve

"drive" the next step in the process: selection of spe-

global benefits. Transboundary can be defined from

cific targets and actions to move towards achieve-

several perspectives. It can be an environmental

ii

ment of the EQOs. These targets must be realizable,

issue that originates in one country, but affects other

countries (river discharge is an example). It can be

i.2 Mediterranean Sea Environmental Status

an environmental issue that comes from many coun-

and its Major Transboundary Issues

tries (air pollution, Transboundary rivers). In some

The identification of the major perceived

cases, Transboundary has been defined as a problem

issues is the first step in the TDA process and it con-

common to several target countries even though they

stitutes the justification for the subsequent in-depth

may not have common sources; however, this is not a

analyses. The significance of the perceived issues and

general definition.

problems should be substantiated on environmental,

Borrowing from methodology commonly used

economic, social, and cultural grounds. The following

in the European Union and other regions, the TDA

list of major perceived problems and issues was final-

process identified three Environmental Quality

ized to include four existing problems / issues:

Objectives (EQOs), which represent the regional per-

· MPPI 1: Decline of Biodiversity

spective of major goals for the Mediterranean envi-

· MPPI 2: Decline in Fisheries

ronment. The use of EQOs helps to refine the TDA

· MPPI 3: Decline of Seawater Quality

process by achieving consensus on the desired status

· MPPI 4: Human Health Risks

of the Mediterranean Sea. Within each EQO (which is

These perceived1 problems and issues form the

a broad policy-oriented statement), several specific

basis for the subsequent analysis, in which each of

targets were identified. Each target generally had a

these problems and issues is addressed from a status

timeline associated with it, as well as a specific level

perspective: what do we know about each problem /

of improvement / status. Thus, the targets illustrate

issue? What data support the quantification of the

the logic chain for eventual achievement of the EQO.

extent of the problem / issue? Do the data support

Finally, specific interventions or actions were identi-

these as real problems and issues, or just as percep-

fied to permit realization of each of the targets,

tions? This analysis took place on a scientific level,

Y

within the time frame designated. For the purposes of

including biological, oceanographic, physical, social,

this TDA, the time frames were limited to the first five

and other perspectives on the problem. This is in effect

or ten year periods, with some targets achieved prior

the "status" assessment. Next came the Causal Chain

to that time.

Analysis, where the major perceived problems and

In summary, this TDA follows the general GEF

issues were analyzed to determine the primary, sec-

i. EXECUTIVE SUMMAR

TDA Guidelines for International Waters projects.

ondary and root causes for these problems / issues.

However, an additional step was achieved, that is,

Identification of root causes is important, because

use of Environmental Quality Objectives, in order to

these tend to be more systemic and fundamental con-

facilitate consensus on the desired state of the

tributors to environmental degradation. Interventions

Mediterranean Sea after the next pentade or decade.

and actions directed at the root causes tend to be more

The EQOs naturally led to identification of specific

sustainable and effective than interventions directed

targets to be met within the desired time frame, and

at primary or secondary causes. However, because the

from there identification of specific interventions

linkages between root causes and solution of the per-

and actions that can be considered in the framework

ceived problems are often not clear to policymakers,

of the NAPs and SAP.

interventions commonly are directed at primary or sec-

The TDA is comprised of several sections:

ondary causes. This TDA attempts to make the linkages

· The first Section is the Executive Summary.

between root causes and perceived problems more

· Section 1 is the Introduction.

clear, to encourage sustainable interventions at this

· Section 2 is the technical basis of the TDA,

level. Fortunately, root causes are common to a num-

addressing the MPPIs.

ber of different perceived problems and issues, so

· Section 3 is the Legal and Institutional

addressing a few root causes may have positive effects

Framework Analysis.

on several problems and issues.

· Section 4 is the Stakeholder Analysis.

Finally, the analysis recognizes that society

· Section 5 covers the Environmental Quality

commonly acts within a number of nearly independ-

Objectives.

1 "Perceived" is used to include issues which may not

Section 1 summarizes much knowledge of the

have been identified or proved to be major problems as

Mediterranean's natural and socio-economic

yet due to data gaps or lack of analysis or which are

regimes. Environmental characteristics are identi-

expected to lead to major problems in the future under

iii

fied, and socio-economic aspects addressed.

prevailing conditions.

ent sectors (agriculture, industry, transport, etc.),

nearshore fisheries, particularly for arti-

which are poorly coordinated and often have con-

sanal fisheries; loss of tourism and its

flicting interests and associated policies. Within

documented economic benefits; and loss

these sectors, various Stakeholders have interests in

of cultural heritage.

the Mediterranean Environment, both affecting and

b. Analysis: Particularly heavily impacted are

being affected by that environment. Sectors and

seagrass habitats (including Posidonia

their Stakeholders work in an uncoordinated and

meadows and eelgrass meadows, inter

sometimes conflicting fashion, but they typically

alia) that have been affected by eutroph-

affect the Mediterranean environment in similar

ication, bottom trawling, dredging, and

ways. Loss of habitat, for instance, may be caused by

other human activities. These are high

activities of various sectors (transport, farming,

ecological service habitats. Additional

industry), and by various types of Stakeholders (gov-

habitats include biogenic constructions by

ernmental policy-makers, ranchers grazing animals,

both vegetal and animal coral builders,

small farmers). A major concern of this TDA, there-

and comprises also some very sensitive

fore, has been to identify common root causes and

deep-water coralline habitats, though

link them with improvements to perceived problems

these effects are less well known. Coastal

and issues. A Stakeholders analysis has been com-

wetlands, including lagoons and estuaries,

pleted, and is summarized in this TDA.

are adversely affected by pollution, land

The result of the analysis is a prioritization of

reclamation, mismanagement of the

the MPPIs for later regional intervention, supported

phreatic basins (aquifers), and river diver-

by GEF. In order to avoid long lists of unfocused inter-

sion / loss of flow. Invasion by alien

ventions, the TDA should identify concrete priorities

species is an ongoing process, and forms

for action, and justify their status as a transbound-

part of the basis for the Mediterranean's

ary concern.

high biodiversity. Although introduction of

SIS (TDA) FOR THE MEDITERRANEAN SEA

The TDA analysis of the major perceived prob-

alien species by humans is a priority prob-

Y

lems and issues can be summarized as follows:

lem to be addressed, preventing invasion

1. Decline in biodiversity: strongly trans-

by new species by natural means is not.

TIC ANAL

boundary.

Primary causes of decline in biodiversity

a. Brief statement of the problem: Some crit-

include excess supply of nutrients, bottom

Y DIAGNOS

ical habitats are severely threatened by a

fishing, by-catch, degradation and un-

variety of human activities. Major threats

controlled human presence of breeding

to the biodiversity of the area include pol-

and / or nursery areas for marine pul-

lution (sewage, oil, nutrients), invasive

monata and fish, pollution, solid waste

TRANSBOUNDAR

species, introduced species, land recla-

disposal, competing land uses including

mation, river damming and flow modifica-

land reclamation, alteration of river flows

tion, over-fishing, by-catch, and adverse

and constituents, and introduction of

effects of fishing gear and uses on marine

alien species. Root causes for this MPPI

habitats (e.g., bottom trawling), solid

include poor stakeholder awareness and

waste disposal at sea, uncontrolled tourist

participation, inadequate control over

presence in ecologically sensitive areas as

fishing effort and gear employed, insuffi-

well as inadequate public and stakehold-

cient scientific knowledge and monitoring

ers awareness, and inadequate or non-

of the biodiversity in the region and relat-

existent legislation and available enforce-

ed processes, as well as inadequate imple-

ment means. Ecological effects include

mentation of treaties and international

disruption of biocenosis; dramatic change

agreements, lack of investment in waste-

in community structure; disruption of key

water treatment, and poor solid waste dis-

ecotones, some of which are globally valu-

posal practices.

able; and adverse impacts on endangered

c. Priority Areas for GEF Intervention:

species. Socio-economic impacts of

i. One target for reversing decline in biodi-

decline in biodiversity include loss of high

versity is preservation of key Mediterra-

iv

value ecological services; reduction in

nean biotopes such as seagrass and other

marine vegetation beds (Posidonia, eel-

ed in Table i.3. GEF's role could be

grass, and others listed in the Red Book),

directed at reducing nutrient and BOD

coralligenous, sea mounts, wetlands,

discharges, to reduce the eutrophica-

marine caves, etc., and creating condi-

tion of the Sea.

tions for their enhancement. The priority

2. Decline in fisheries: strongly transboundary.

areas for this activity are encountered

a. Brief statement of the problem: Various

throughout the region, and their proper

threats to fisheries include pollution, over-

mapping is a priority still in need of com-

fishing, loss of habitat, excessive bycatch,

pletion.

deleterious fishing gear, lack of enforment

ii. A second target for GEF intervention is

of laws and agreements in the high seas,

addressing other important sites at

and sophisticated methods to find and

risk that are important for marine

catch fish. Concern has arisen that there is

biodiversity. These are elements of

an underlying problem of long-term deple-

biodiversity that, due to their abun-

tion in Mediterranean marine catches. In

dance, special importance, or endan-

fact, most of the Mediterranean fishery

gered status, require special atten-

resources, be they demersal, small pelagic

tion. Figure i.2 shows the locations of

or highly migratory species, have long been

the areas where the resources require

considered overexploited. The issue is

attention, according to the list of

transboundary because many fish are

Table i.1.

either migratory or represent shared

iii. A third target for GEF intervention is

stocks. Overall, the fisheries are overseen

expanding the number of protected

by the General Fisheries Commission for the

Y

areas in the Mediterranean Sea, and to

Mediterranean (GFCM).

facilitate the management and a

b. Analysis: Fish catch information shows

well-established networking for exist-

some remarkable constancy on time peri-

ing ones. Regional mechanisms for

ods of decades, and even more so in years,

Protected Areas exist (e.g., SPAMI).

fluctuating only by a factor of two or less in

i. EXECUTIVE SUMMAR

However, most of these are in the

total catch. However, the number of fishing

northwest Mediterranean Sea. Some

vessels has increased markedly during this

main priority areas of particular inter-

time, increasing in some countries by a

est are listed in Table i.2 and some are

factor or three or four. Composition of the

shown in Figure i.3.

catch has also changed with time, though

iv. A fourth GEF target area is to reduce

not as dramatically as in some areas such

eutrophication of coastal waters. To

as the Yellow Sea. The most targeted

address this, sewerage and wastewater

species already show signs of intensive

treatment plants, a primary source of

exploitation. Catch-per-unit effort (CPUE)

excess nutrients, must be expanded in

and other measurements and biological

coverage. The map of areas where

indicators such as reduction of individual

eutrophication has been reported to

fish sizes led the GFCM to conclude that

exist is shown in Figure i.4. Note, unfor-

most of the commercial fish stocks are

tunately, that the southern and east-

considered fully or over-exploited. Major

ern Mediterranean countries have not

causes of decline in fisheries include pollu-

reported on eutrophication, though

tion (especially eutrophication leading to

satellite images show that if it happens

loss of suitable benthic habitat), loss of

there, it is local. Eutrophication is a

habitat, overfishing, antiquated (not

common problem, but a local problem,

habitat friendly) fishing methods (primari-

though its effects are widespread and

ly in southern countries), overly sophisti-

transboundary. The primary areas

cated and hence efficient fishing methods

where wastewater treatment plants are

(in some countries). Root causes include

required to avoid damage to sensitive

inadequate stakeholder awareness and

v

habitats (see Section 2.3.6.4) are list-

involvement; lack of enforcement and

SIS (TDA) FOR THE MEDITERRANEAN SEA

Y

TIC ANAL

Table i.1 Transboundary Sites at Risk related to Mediterranean Marine Biodiversity

Y DIAGNOS

Species / site of interest

Countries concerned

Seagrasses

All countries (mentioned in NAPs of Tunisia, Libya)

Benthic species including coralligenous communities

All countries

Sea mounts and canyons

All countries

Cetaceans

All countries

TRANSBOUNDAR

Ligurian Sea: France, Italy, Monaco

Alboran Sea: Spain, Morocco

Northern Adriatic: Italy, Slovenia, Croatia

Ionian Sea: Albania, Italy, Greece

Aegean Sea: Greece, Turkey

Mediterranean Monk seal

Western: Morocco, Algeria, Tunis

Ionian: Albania, Greece

Aegean: Greece, Turkey

Eastern: Turkey, Cyprus, Syria, Libya

Mediterranean marine turtles

All countries

Green turtle

Eastern: Greece, Cyprus, Lebanon, Syria, Turkey

Loggerhead

Ionian: Italy, Albania, Greece

Southern: Tunisia, Libya, Egypt

Aegean: Greece, Turkey

Eastern: Cyprus, Lebanon, Syria, Turkey

Alboran: Spain, Morocco

Elasmobranches

Alboran: Spain, Morocco

Southern: Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Malta, Italy

Fish breeding and nursery areas

All countries

Mediterranean shearwater

Spain-Morocco, Algeria

Mixed Atlantic and Mediterranean fauna and flora

Alboran Sea: Morocco, Spain

Representative Mediterranean marine ecosystems

Bonifacio Straight (and western tip of Sicily)

with endangered / endemic species

France, Italy

vi

Table i.2 Marine and Coastal Sites of Particular Interest identified by Country, with Relevant Actions listed

Country

Sites and / or type of action

Albania

· Rehabilitation of the Kune-Vaini lagoon system

· Proclamation of the Marine National Park of Karaburuni Area

Algeria

· Selection of marine sites to be protected: Habibas Islands, Rachgoun island,

PNEK marine area, Taza-Cavallo-Kabyles shoal, Gouraya, Chenoua-Tipaza,

Plain Island, Collo peninsula, Cape Garde, Aguellis Islands, Tigzirt marine area

· Conservation of the Al Kala wetlands

Bosnia & Herzegovina

· Identification of processes in the Neum karst coastal area

· Management of the sensitive area of the Mali-Ston Bay

· Biodiversity protection of the lower Neretva with the Hutovo Blato wetland

and of the delta of the Neretva River as a unique eco-system

Croatia

· Transboundary management plan for the Lower Neretva Valley

including Malostonski Bay

· Management plans for national parks and nature parks (Kornati-Telascica,

Velebit-Paklenica, Biokovo, Krka, Vransko jezero, Brijuni, Mljet)

· Management plan and protection of Cres-Losinj Archipelago with surrounding sea

· Protection and management of rivers: Mirna (including Motovun forest);

Cetina (including Pasko field); Zrmanja

· Protection of sand and muddy shores in NW part of Ravni Kotari

· Protection of Sandy Beaches Saplunara and Blace on the Mljet Island

· Protection of Konavle area

· Fisheries management at Jabuka Pit (Fossa di Pomo)

Cyprus

· Adoption and implementation of the provisions of the EU Habitat and Bird

Directives and completion of the NATURA 2000 network (38 proposed sites)

and incorporation of proposed sites in town and country planning legislation,

local plans and countryside policy

Egypt

· Combating eutrophication in the coastal lakes of the Nile Delta

· Development and management of the Matruh Nature Conservation Sector (MNCZ)

Y

Greece

· 121 sites out of 238, included in the Greek National list of the Natura 2000 net-

work, host marine and coastal habitats and habitats of important species.

Efforts are being made to set up and manage the Natura 2000 sites,

ensuring the appropriate short, medium and long term funding mechanism

· Seven Ramsar sites on the Montreux list

Lebanon

· National Action Plan for the conservation of the Tyre Coast Nature Reserve

Libya

· Bays and coastal lagoons: Ain El-Gazalah Bay, Bumbah Bay, Ain Ziana lagoon,

i. EXECUTIVE SUMMAR

Farwa lagoon

· Wadis: Wadi Al-Hamsah, Wadi Al-khabtah, Wadi Ka'am, Tawrurgha spring and

salt marshes

Malta

· Xlendi Bay Munxar / SW Gozo

· Dwejra bay and Qawra San Lawrenz / W Gozo; mouth of Wied Ghasri N. Gozo

· Reqqa Point N. Gozo; Xwejni N. Gozo

· Ramla Bay and San Blas Bay NE Gozo

· Mgarr ix-xini SE Gozo

· Cominotto, Ras l-Irqieqa SW Comino

· Ras Il-Qammieh N/NW Malta

· Cirkewwa NW Malta

· Ahrax Point NW Malta

· Sikka l-Bajda NW Malta

· St. Pauls Island and Mistra Bay N Malta

· Qawra Point N Malta

· Merkanti Reef Northern coast of Malta

· Off Lazzarett (Marsamxett Harbour)

· Zonqor Reef (off Zonqor Point) East Malta

· Sikka tal-Munxar (off St. Thomas Bay) E. Malta

· Delimara Peninsula SE Malta

· Wied Iz-zurrieq S Malta

· Ghar Lapsi; Migra Ferha SW Malta

· Ras Il-Wahx SW Malta

· Hamrija Bank S Malta

· Filfla, an islet in SW Malta

Slovenia

· Shared management (with Croatia) of the Dragonja River

· Debeli Rtic natural monument (marine and coastal)

· Sv. Nikolaj salt-marsh (coastal salt-marsh)

· Skocjanski Zatok nature reserve (coastal lagoon)

· Posidonia oceanica meadow (marine)

· Strunjan nature reserve (marine and coastal)

· Stjuza natural monument (coastal lagoon)

· Rt Madona natural monument (marine)

· Secovlje salt-works landscape park (salinas) Ramsar site from 1993

Tunisia

· Remedial measures for the impact of dams on the Ichkeul Ramsar site

vii

SIS (TDA) FOR THE MEDITERRANEAN SEA

Y

TIC ANAL

Y DIAGNOS

TRANSBOUNDAR

viii

Table i.3 Locations where Sensitive Ecosystems are threatened by Eutrophication

Designation / location

Country

Priority

Kuna-Vain lagoons

Albania

High

Gulf of Ghazaouet, Gulf of Arzew-Motaganem, Bay of Algiers,

Algeria

High

Bay of Annaba, Gulf of Skikda, Bay of Bejaia, Bay of Zemmouri

Beirout, Tripoli, Jounieh, Saida, Sour

Lebanon

High

Anchor Bay

Malta

High

Tanger Bay, Smir Bay, Mouloya Estuary, Martil Beach, Sfiha Beach

Morocco

High

Ghar El Melh

Tunisia

High

Adana, Izmir Bay, Icel, Mersin-Kazanli, Hatay-Samandag, Aydin

Turkey

High

monitoring; insufficient alternatives to

Therefore, this MPPI is not as high a priority

fisheries employment; and lack of regula-

for GEF intervention, though institutional

tion in some countries. Environmental

strengthening might improve existing man-

impacts of decline in fisheries include

agement practices. Addressing other MPPIs

imbalance in some ecosystems due to loss

(decline in biodiversity, decline in seawater

of top predators; other environmental

quality) will per force contribute to

impacts are related to fisheries impacts

improvement of fisheries.

such as destruction of bottom habitat

3. Decline of seawater quality: strongly trans-

(seagrass beds) by bottom trawling and

boundary.

Y

excessive bycatch including endangered

a. Brief statement of the problem: Increasing

species (such as turtles, scarce bird and

trends in eutrophication and its related

elasmobranch species, etc.). Socio-eco-

oxygen deficiency and bloom of nuisance

nomic impacts of declining fisheries

species (e.g., jellies such as Noctiluca);

include loss of income and employment;

presence of hot spots of pollution leading

i. EXECUTIVE SUMMAR

loss of cultural practices; possible decline

to decline in biodiversity, fisheries, dis-

in food security.

eases or loss of health in marine organ-

c. Priority areas for GEF interventions: In gen-

isms, and overall water quality; human

eral, the need for GEF interventions in fish-

health problems from consuming fish and

eries is only weakly motivated. A regional

shellfish or contacting polluted waters;

fisheries commission already exists, and

loss of endangered species; and overall

some sub-regional fisheries commissions

imbalance of some ecotones (e.g., sea-

also exist. There is no overarching evidence

grass meadows) all result from decline in

that existing commissions are not func-

seawater and sediment quality. Although

tioning well, but they are not enough by

many of these effects are local in extent,

themselves to cope with the underlying

they have transboundary consequences.

environmental problems affecting the fish-

Important transboundary consequences

eries stocks in the Region. There are no dra-

arise due to ocean currents transporting

matic declines in important commercial

pollutants throughout the Sea; migration

fisheries, although as a multispecific fish-

and transport of various life stages of

eries there is some evidence for decline in

marine organisms (e.g., dinoflagellate

commercial catches during the recent

cysts) to other parts of the Sea from pol-

decades. GFCM indicates that most of the

luted areas; marine transport through

commercial fish stocks are fully-to-over-

shipping; and transport through the

exploited. Big pelagic fisheries also have

atmosphere.

experienced some decline. Twelve national

b. Analysis: Budgets for heavy metals,

action plans listed priority fisheries related

organochlorines, hydrocarbons, nutrients,

actions, most of which were to minimize the

pesticides, and other pollutants entering

ix

effects of overfishing on the environment.

the Mediterranean Sea from land, from

the atmosphere, and from sea (shipping),

c. Possible Interventions by GEF: There are

have been developed during the PDF-

several areas where intervention by GEF

phase of the project. At the same time,

may be able to assist in improving the sea-

limited but available data and observa-

water quality of the Mediterranean Sea.

tions on declining health of marine popu-

i. Reduce nutrient and BOD loading to the

lations (ecotoxicology) linked to various

sea from sewage: this intervention is

pollutants point to ecosystem effects

addressed as part of MPPI 1. In addition,

from declining seawater quality.

those cities identified in Table i.4 above

Increases in frequency, intensity, dura-

could benefit perhaps from both sewer-

tion, and spatial extent of eutrophication

age and treatment, and / or improved

have raised alarms about pollution. This

industrial processes prior to discharge

study has identified a series of land-

of wastewater to sewers and / or the

based pollution hot spots around the

Sea. Similar process improvements

Mediterranean (Figure i.5) (Annex III),

would be required for atmospheric dis-

including 125 for all countries (France was

charge, since atmospheric discharge is a

not included), and 92 for GEF-eligible

major pathway for certain pollutants,

countries. These hot spots were identified

including excess nutrients, to the Sea.

geographically, and classified as to cause

The goal would be to reduce the dis-

of the hot spot (industry, sewage, agricul-

charge of excess BOD and nutrients to

ture, etc.). In addition to these hot spots,

the coastal and offshore waters.

ecosystems have been identified that are

ii. Reduce discharge of toxic materials to

associated with the hot spots with the

the Sea: The point sources of pollution

highest pollutant loads (Figure i.6). Sixty-

identified above bring toxic heavy

two ecosystems associated with the high-

metals, toxic organochlorines, toxic

SIS (TDA) FOR THE MEDITERRANEAN SEA

est pollutant-load hot spots have been

hydrocarbons, and other toxins to the

Y

identified, of which forty-five are in GEF-

Sea either directly through discharge

eligible countries. Table i.4 shows the 20

to the Sea, or indirectly through

TIC ANAL

cities in the Mediterranean with the most

atmospheric transport to the Sea. Of

BOD discharges to the Sea from industrial

concern are toxic, persistent, and

Y DIAGNOS

sources.

bioaccumulative (TPBs) contaminants;

TRANSBOUNDAR

x

Y

i. EXECUTIVE SUMMAR

Table i.4 The 20 Urban Centres discharging the most BOD

Country

Urban centre

BOD5 disch. (kt/yr)

Algeria

Algiers*

58.87

Greece

Athens*

58.00

Italy

Naples

44.4

Egypt

Alexandria

43.6

Spain

Barcelona (+San Adrian del Besos)

41.2

Algeria

Oran*

28.06

Turkey

Izmir

26.3

Algeria

Skikda*

19.94

Israel

Tel-Aviv (Shafdan)*

19.75

Algeria

Bejaia*

19.73

Libya

Tripoli*

16.06

Turkey

Mersin*

14.3

Turkey

Antalya*

13.29

Italy

Palermo

13.0

France

Marseilles

12.0

Spain

Malaga

11.5

Lebanon

Greater Beirut area*

10.18

Tunisia

Tunis Centre

8.3

Italy

Bari-Barletta

7.7

Italy

Piombino

7.5

* Updated information since 2002

xi

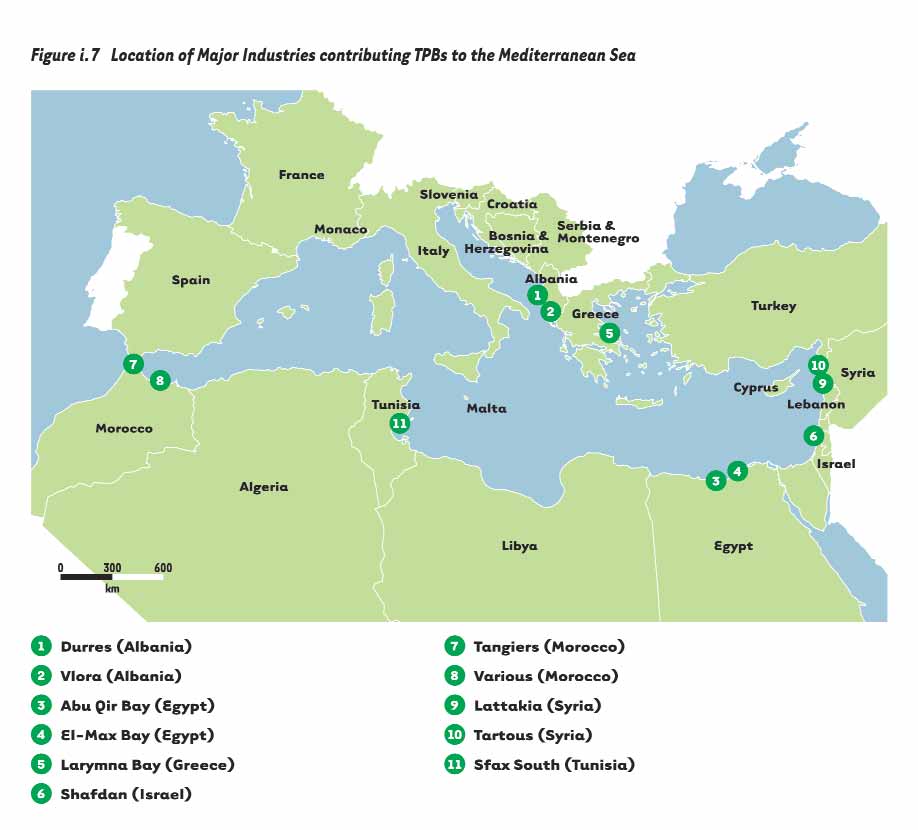

Figure i.7 shows the locations of the

locations, and also in general due to

major industrial sources of TPBs listed

dumping at sea by ships and pleasure

in Table i.5.

craft. Figure i.8 shows the Mediterra-

iii. Urban and other solid waste: urban solid

nean-wide partitioning of sources of

waste is dumped at sea in some coun-

solid wastes that make it to the Sea.

tries, leading directly to deterioration

Figure 2.11 in the main text breaks this

of water quality. Solid waste has been

distribution out, country-by-country.

identified as a major issue at certain

Interestingly, none of the countries

SIS (TDA) FOR THE MEDITERRANEAN SEA

Y

TIC ANAL

Y DIAGNOS

TRANSBOUNDAR

Table i.5 Some of the Main Sources of TPBs to the Mediterranean (Source: UNEP/WHO, 1999)

TPB (kg/yr)

Hg

Cd

Pb

Cr

Cu

Zn

Ni

Others (t/yr)

Abu Qir Bay (Egypt)

31+

193+

362+

2,669+

3,394+

859

1,906 (oil)

Tartous (Syria)*

140

10

50

310

540

200 (oil)

Lattakia (Syria)*

130

20

50

130

640

2.480

91 (oil)

El-Mex Bay (Egypt)

1,278

1,562

530

25,430

46,524

1,319 (oil)

Shafdan (Israel)*

80

270

2,510

8,330

19,610

67,130

3,850

Sfax South (Tunisia)

3,456

17,000

Larymna Bay (Greece)

313,170

Tangiers (Morocco)*

20

490

60

720

440

1,800

270

* Updated information since 2002

xii

Y

identified solid waste as a major priori-

bial and viral pollution. In addition, the

ty in their National Action Plans.

response of the ecosystem to stress may

Plastics are identified as the dominant

induce toxicity that may affect humans,

source of marine litter, making up some

such as toxic dinoflagellates that arise from

i. EXECUTIVE SUMMAR

75% of the litter on the sea surface and

eutrophic conditions in some instances.

seabed. Major areas where industrial

Primary pathways for human health risks

waste has been identified as a problem

include ingestion of water or seafood prod-

are in the attached Table i.6.

ucts, contact with contaminated seawater

4. Human health risks: weakly transboundary.

(or in some cases, beaches), and perhaps

a. Brief statement of the problem: Pollutants

contact with contaminated sea food (for

that degrade the ecosystem also present

marine products workers). Those at risk

risks to human health, including not only

include marine products workers, recre-

heavy metals, organochlorines, pesticides,

ational beach users, swimmers, divers, and

hydrocarbons, and the like, but also micro-

consumers of marine food products.

Table i.6 Selected Locations where Major Industrial Waste Problems exist

Designation / location

Country

Wastes

Durres

Albania

Hexavalent chromium salts

Vlora

Albania

Mercury

Skikda and Annaba in the east, Algiers-Oued Smar

Algeria

Various

and Rouiba-Reghaia in the centre, Oran-Arzew

in the west, and on the other the industrial complexes

of Ghazaouet, Mostaganem, Béjaia and Jijel

Abu Qir Bay

Egypt

Various: industrial discharges

Various

Lebanon

Various

Various

Morocco

Mining wastes

xiii

b. Analysis: Though incomplete data are

these targets. What policies are required? What leg-

available on this topic, there is ample

islative acts? What investments? What capacity

evidence that human health risks are

building? What infrastructure? These specific steps

possible through the pathways described

are identified in this TDA as activities or interven-

above. There are no ecosystem health

tions. The steps form the "workplan" to achieve the

risks arising from the Human health risks

targets within the agreed time frame. The progression

(though the two are related). There are

from EQOs, to targets, to concrete activities is a logic

serious socio-economic impacts, how-

chain that leads to consensus on complex environ-

ever, such as loss of tourist revenue, loss

mental issues.

of sales of marine products (such as

The three EQOs developed for the Mediterra-

when bivalves are contaminated and the

nean Sea are listed below, along with the MPPIs with

industry is shut down), and loss of cul-

which they are associated:

tural use of the marine resources.

1. Reduce the impacts of LBS on Mediterranean

c. Possible GEF interventions: Since human

Marine Environment and Human Health:

health is not directly a topic for interven-

addresses MPPIs 3 and 4, and to a lesser

tion by GEF/IW, no areas of interventions

extent MPPIs 1 and 2.

can be proposed here. However, some of

2. Sustainable Productivity from Fisheries:

the interventions arising from other

addresses MPPI 2.

MPPIs may improve the health situation,

3. Conserve the Marine Biodiversity and Eco-

including sewerage and treatment of dis-

system: Addresses MPPI 1.

charges, and reduction of nutrient inputs

Each of these EQOs had targets defined as a

leading to decreased eutrophication.

means of achieving these EQOs. The targets associat-

ed with the EQOs were identified as follows in Table i.7.

i.3 Environmental Quality Objectives

SIS (TDA) FOR THE MEDITERRANEAN SEA

Environmental Quality Objectives (EQOs) are

i.4 Priority Actions and Interventions

Y

a means to develop broad Stakeholder agreement on

for NAPs/SAP

the major environmental objectives of the region.

Following the identification of environmental

TIC ANAL

They are useful for communication of the desired

quality objectives and their associated targets, specif-

state of a particular environment or component of

ic interventions / actions were identified to achieve

Y DIAGNOS

the environment. They represent consensus views of

first the targets, and ultimately, the EQOs. These prior-

environmental priorities, or visions of what the envi-

ity actions and interventions can be categorized within

ronment should look like in the future. Often, EQOs

one or more of the following major groupings:

are simple restatements of existing consensus views.

· Policy actions

TRANSBOUNDAR

EQOs can be regional or national.

· Legislative / regulatory reform

EQOs commonly have specific targets identi-

· Institutional strengthening

fied with them. The targets are quantitative state-

· Capacity building

ments of progress towards achieving a particular EQO,

· Baseline investments

and generally have associated timelines or mile-

· Incremental investments

stones. The targets generally are focused on relatively

· Scientific investigation

short-term goals (for instance, 5 years), which are

· Data management

achievable on time frames that governments can

· Information and awareness actions

understand. If the timelines are too long, governments

The priority areas and actions, listed by EQO,

may tend not to act, but rather leave the solution to

are given in Table i.8. More detailed activities and

the next administration. The targets must also be real-

interventions listed by EQO are found in Section 5.

izable: they must be achievable at a reasonable pace

and cost. If the targets are too ambitious, they may be

ignored. Better to have an achievable, modest target,

than an aggressive, unreachable target.

Once EQOs and targets are identified; it is rel-

atively straightforward to identify specific or con-

xiv

crete steps required in the next few years to achieve

Table i.7 Targets Categorized according to Environmental Quality Objective

Environmental Quality Objectives

Targets

I. Reduce the impacts of LBS

1. By 2005 dispose of sewage from cities of more than 100,000 people

on Mediterranean Marine

in conformity with LBS. By 2025, dispose all sewages in conformity

Environment and Human Health

with LBS.

2. By 2005, create a solid waste management system in all cities of

more than 100,000 people. By 2025, create solid waste management

for all urban agglomerations.

3. By 2005, conform to air quality standards for all cities of more than

100,000 people. By 2025, all cities to conform to air quality standards.

4. By 2005, reduce inputs, collect, and dispose of all PCBs otherwise

entering the marine environment. By 2010, phase out all inputs of POPs.

5. By 2010, achieve 50% reduction in TPB by Industry. By 2025, industrial

point source discharges and emissions conform with LBS and standards.

Other targets for heavy metals, organohalogen compounds,

and radioactive materials:

· By 2005, collect and dispose of all obsolete chemicals

in an environmentally safe manner.

· By 2005, collect and dispose of 50% of lubrication oils

in an environmentally safe manner.

· By 2010, reduce industrial nutrient input by 50%.

· By 2010, 20% reduction of generation of hazardous wastes, of which

half are safely disposed.By 2025, all hazardous wastes disposed in

safe manner.

Y

· By 2010, achieve 20% reduction of generation of batteries, and

dispose of 50% of batteries in an environmentally safe manner.

By 2025, dispose of ALL batteries in an environmentally safe manner.

· By 2025, reduce inputs of agricultural nutrients.

II. Sustainable Productivity

1. Implement the Code of conduct for fishing.

from Fisheries

2. Assessment, control and elaboration of strategies to prevent impact

i. EXECUTIVE SUMMAR

of fisheries on biodiversity.

3. Promote the adequate monitoring and survey of the effectiveness

of marine and coastal protected areas.

4. Assist countries to protect marine and coastal sites of particular

interest.

5. Declare and develop of new Coastal and Marine Protected Areas

including in the high seas.

6. Assist countries in the development of existing marine and coastal

protected areas.

7. Control and mitigate the introduction and spread of alien

and invasive species.

8. Control and regulation of aquaculture practices.

9. Promote public participation, within an integrated management scheme.

10. Preserve traditional knowledge of stakeholders.

11. Coordinate and develop common tools to implement National

Action Plans (NAPs) related to fisheries.

III. Conserve the Marine

1. Improve the management of Marine and Coastal Protected Areas.

Biodiversity and Ecosystem

2. Enhance the protection of endangered species and habitats.

3. Reinforce relevant national legislation.

4. Foster the improvement of knowledge of marine and coastal biodiversity.

xv

Table i.8 Areas and Actions for Priority Intervention

Major Concerns

Priority Actions

Where to intervene

Decline of

Implementation of SAP BIO

All Mediterranean countries

Biodiversity

Rehabilitation of coastal Solid Waste landfills

Eastern, Southern Mediterranean countries

Reduction of 50%of industrial BOD by 2010

All Mediterranean countries

Reduction of riverine inputs of nutrients

Adriatic region

Follow up investment of 12 preinvestment

12 GEF eligible countries:

studies for Hot Spots in GEF eligible countries

Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia, Libya, Egypt,

Syria, Lebanon, Turkey, Albania, Croatia,

Slovenia, Bosnia & Herzegovina

Conservation of habitats

Rehabilitation of wetlands

(refer to countries reports in SAP/BIO)

Implementation of ICZM in locality where

Demonstration projects have been

achieved (amount of localties in brackets):

Turkey (1), Lebanon (1), Syria (1),

Spain (2), Italy (4), Greece (5),

Morocco (1), Algeria (1), Tunisia (1),

Malta (1), Egypt (1), Israel(1)

Control of inputs of alien species

Management of ballast water

in all Mediterranean Countries

Decline in

Implementation of FAO Code of conduct

Eastern Mediterranean, Adriatic

Fisheries

and southern Mediterranean

Control of inputs of alien species

Management of ballast water

in all Mediterranean Countries

Implementation of EC related Directives

EU Mediterranean countries

Implementation of SAP BIO

All Mediterranean countries

SIS (TDA) FOR THE MEDITERRANEAN SEA

Decline of

Reduction of 50% of industrial BOD

All Mediterranean countries

Y

seawater quality

Implementation of SAP/NAP list

All Mediterranean countries

of priority actions for POPs

TIC ANAL

Implementation of SAP/NAP list

All Mediterranean countries

of priority actions for industrial releases

Eastern Mediterranean countries, Syria,

Lebanon, Turkey, Israel, Egypt

Y DIAGNOS

Implementation of regional plan

Obsolete chemicals in Southern, Eastern

for reduction of 20% hazardous waste

and former Yugoslavia Mediterranean

countries

Treatment of urban wastewater

Refer to table on cities without WWTP.

Section 2.4

TRANSBOUNDAR

Follow up investment of 12 preinvestment

12 GEF eligible countries:

studies for Hot Spots in GEF eligible countries

Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia, Libya, Egypt,

Syria, Lebanon, Turkey, Albania, Croatia,

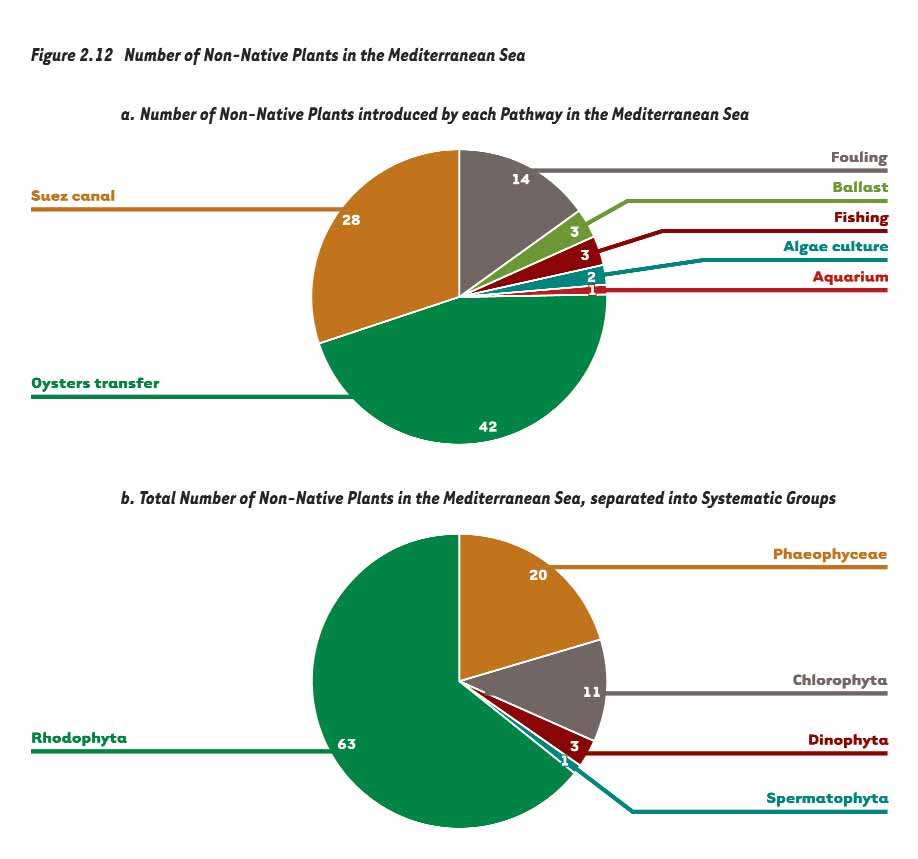

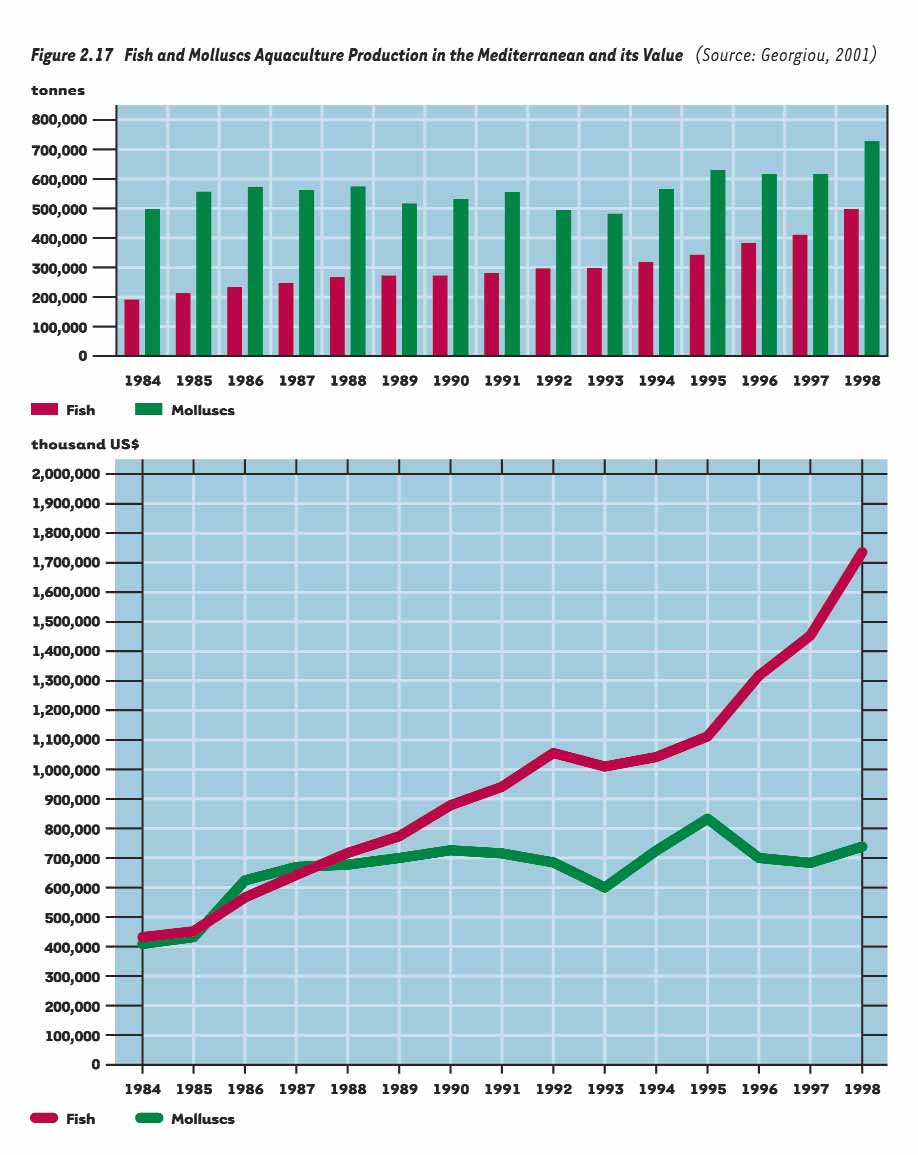

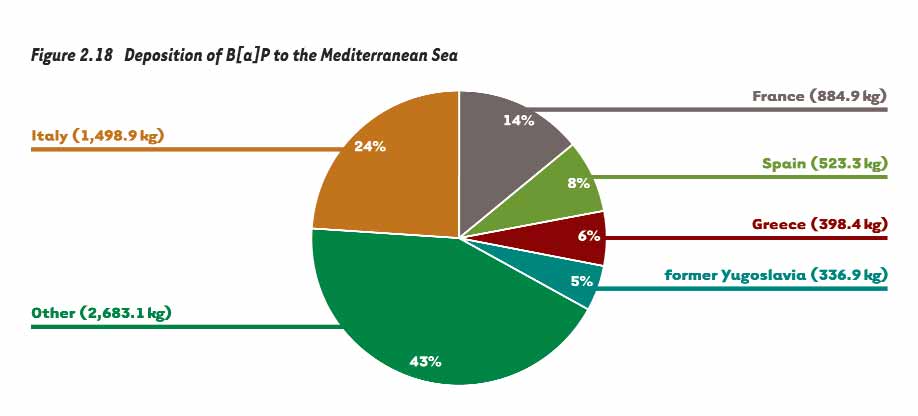

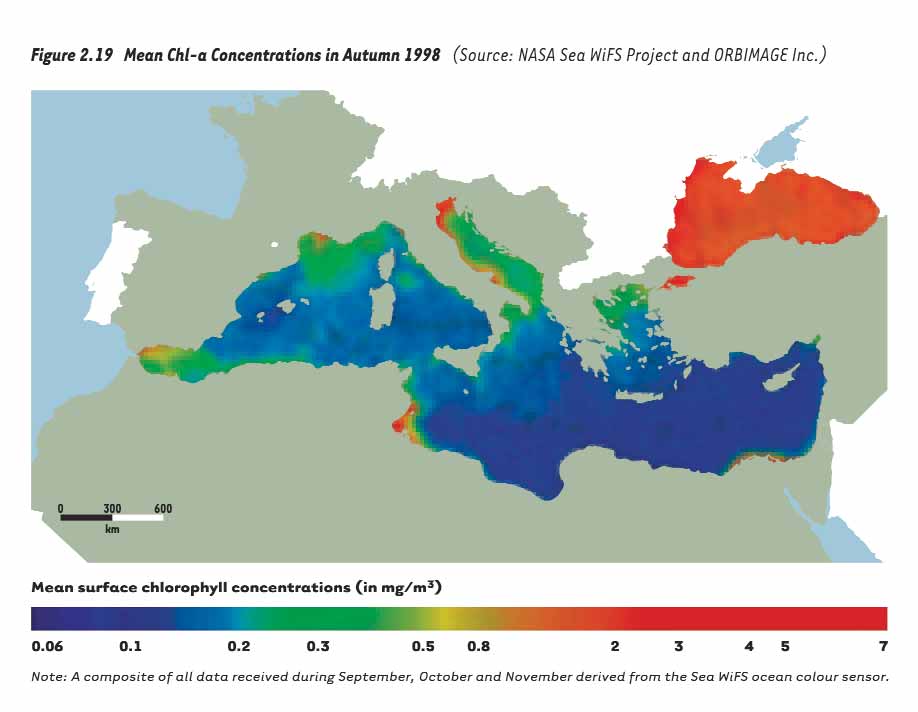

Slovenia, Bosnia & Herzegovina