Perspectives on water and climate change adaptation

W o r l d W a t e r F o r u m

Adapting to climate change

in water resources and water services

in Caribbean and Pacific small

island countries

This Perspective Document is part of a series of 16 papers on «Water and Climate Change

Adaptation»

`Climate change and adaptation' is a central topic on the 5th World Water Forum. It is the lead theme for

the political and thematic processes, the topic of a High Level Panel session, and a focus in several docu-

ments and sessions of the regional processes.

To provide background and depth to the political process, thematic sessions and the regions, and to

ensure that viewpoints of a variety of stakeholders are shared, dozens of experts were invited on a volun-

tary basis to provide their perspective on critical issues relating to climate change and water in the form of

a Perspective Document.

Led by a consortium comprising the Co-operative Programme on Water and Climate (CPWC), the Inter-

national Water Association (IWA), IUCN and the World Water Council, the initiative resulted in this

series comprising 16 perspectives on water, climate change and adaptation.

Participants were invited to contribute perspectives from three categories:

1 Hot spots These papers are mainly concerned with specific locations where climate change effects

are felt or will be felt within the next years and where urgent action is needed within the water sector.

The hotspots selected are: Mountains (number 1), Small islands (3), Arid regions (9) and `Deltas and

coastal cities' (13).

2 Sub-sectoral perspectives Specific papers were prepared from a water-user perspective taking into

account the impacts on the sub-sector and describing how the sub-sector can deal with the issues.

The sectors selected are: Environment (2), Food (5), `Water supply and sanitation: the urban poor' (7),

Business (8), Water industry (10), Energy (12) and `Water supply and sanitation' (14).

3 Enabling mechanisms These documents provide an overview of enabling mechanisms that make

adaptation possible. The mechanisms selected are: Planning (4), Governance (6), Finance (11), Engi-

neering (15) and `Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM) and Strategic Environmental

Assessment (SEA)' (16).

The consortium has performed an interim analysis of all Perspective Documents and has synthesized the

initial results in a working paper presenting an introduction to and summaries of the Perspective

Documents and key messages resembling each of the 16 perspectives which will be presented and

discussed during the 5th World Water Forum in Istanbul. The discussions in Istanbul are expected to

provide feedback and come up with sug· gestions for further development of the working paper as well as

the Perspective Documents. It is expected that after the Forum all docu· ments will be revised and peer-

reviewed before being published.

3

Adapting to climate change in water resources

and water services in Caribbean and

Pacific small island countries

This document serves as a contribution to the 5th World Water Forum (Istanbul, 2009) from a

small island countries' perspective on Topic 1.1 of the Forum: "Adapting to climate change in

water resources and water services: understanding the impact of climate change, vulnerability

assessment and adaptation measures".

Lead author: Marc Overmars, Water Adviser; SOPAC, Pacific Islands Applied Geoscience

Commission, Private Mail Bag, GPO, Suva, Fiji Islands, Tel: 679 338 1377, Fax: 679 337 0040,

marc@sopac.org, www.pacificwater.org.

Co-author: Sasha Beth Gottlieb, Technical Coordinator; GEF-IWCAM Project Coordination Unit,

c/o Caribbean Environmental Health Institute, The Morne, P.O. Box 1111, Castries, St. Lucia, Tel:

758 452-2501, 452-1412, Fax: 758 453-2721, sgottlieb@cehi.org.lc, www.iwcam.org.

Adapting to climate change in water resources

and water services in Caribbean and

Pacific small island countries

Since the 3rd World Water Forum (Kyoto, 2003) the Caribbean and Pacific region have been

collaborating as part of the global Dialogue on Water and Climate (DWC) initiative, which works

»to improve the capacity in water resources management to cope with the impacts of increasing

variability of the world's climate, by establishing a platform through which policymakers and

water resources managers have better access to, and make better use of, information generated

by climatologists and meteorologists« (www.waterandclimate.org).

Respective dialogues held in each region in prepa-

solid background for this perspective document for

ration for the 3rd World Water Forum resulted in a

the 5th World Water Forum.

Joint Programme for Action on Water and Climate

SOPAC2 and CEHI3 as lead coordinating agencies

(JPfA) which guided the implementation of various

for water and sanitation in respectively the Pacific

coping and adaptation strategies over the past years

and Caribbean region have formalized their

in Small Island Developing States (SIDS) of the

collaboration through a MOU between both organi-

Caribbean and the Pacific (Annex 1).

zations signed at Kyoto and have since been working

At the review of the United Nations Barbados

together on a variety of issues related to integrated

Programme of Action for the Sustainable Develop-

water resource management and related adaptation

ment of Small Island Developing States (Mauritius,

to climate change.

2005) the Caribbean and Pacific nations reiterated

Since Kyoto, SOPAC and CEHI have mobilized

their commitment to SIDS SIDS cooperation with

funding for the implementation of the 3rd World

the Joint Programme for Action for Water and Cli-

Water Forum's SIDS portfolio of water actions

mate and the international community was invited to including: Integrated Water Resources Management;

support the implementation of the JPfA and broaden

Hydrological Cycle Observing System; water demand

it to all Small Island Developing States regions

management; water quality capacity-building; water

including the Atlantic and Indian Ocean (Annex 2).

governance; regional water partnerships; and inter-

The Mauritius strategy highlighted the impor-

SIDS water partnerships.

tance of both water resources and climate change

As coordinator for the Pacific & Oceania sub-

and requested the international community to pro-

region under the Asia Pacific Water Forum, SOPAC

vide assistance to Small Island Developing States for

facilitated a review of the Pacific Partnership Initia-

the implementation of priority actions as submitted

tive on Sustainable Water Management4 under which

to the 3rd World Water Forum Portfolio of Water

the above priority actions were financed in the Pacific

Actions for small island countries through, amongst

and the 3rd progress report of the partnership is

others, the Global Environment Facility (GEF), the

guiding the region's contribution to the 5th World

World Water Assessment Programme (WWAP), the

Water Forum.

Global Programme of Action (GPA) and the EU

`Water for Life Initiative'.

The results from the Caribbean and Pacific dia-

logues on water and climate have been documented

in the respective synthesis reports.1 They closely

2

examine the issues to better understand and plan for

Pacific Islands Applied Geoscience Commission,

the impacts of climate change and climate vulner-

www.pacificwater.org.

3

ability on water resources in SIDS, thus providing a

Caribbean Environmental Health Institute,

www.cehi.org.lc.

4 The

3rd Partnership Steering Committee Meeting,

1

Springer (2002) and Scott et al (2002).

September 2008, Apia, Samoa.

1

In general the perspective document aims to provide

further guidance to the efforts in SIDS regions in

coping and adaptation related to water resources

management and provision of water services.

The first chapter deals with general water and climate

issues in small island countries. Chapter Two exam-

ines the coping and adaptation strategies adopted by

SIDS and the advances made in implementation and

the need to mainstream climate adaptation into water

resources management and disaster risk reduction.

The final chapter deals with the political will and

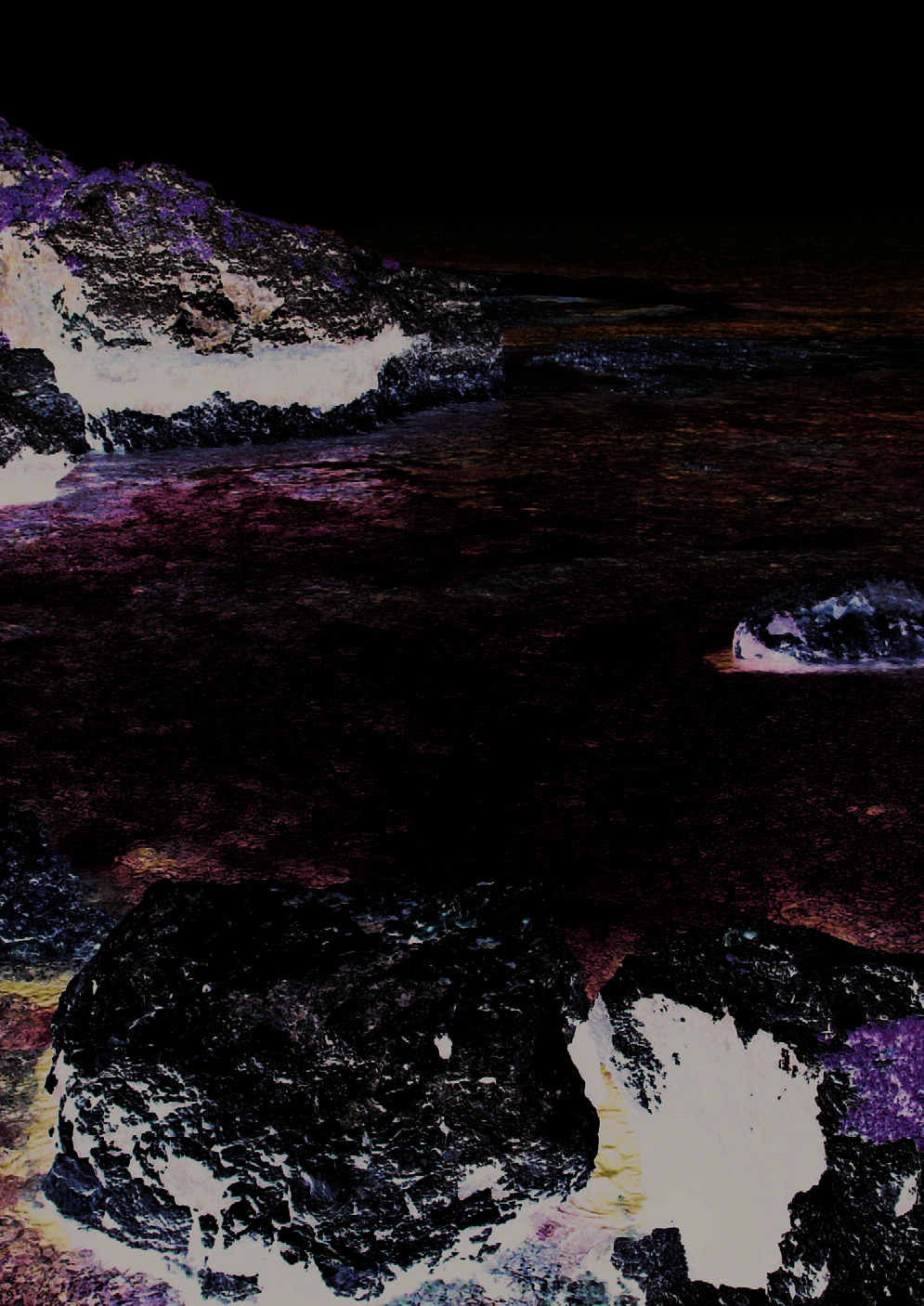

View from Pigeon Island in Saint Lucia (Donna Spencer).

need for additional financing to the water and sani-

tation sector.

CEHI in turn is coordinating the Caribbean's

position at the 5th World Water Forum through the

Americas Regional Process leading to the 5th World

1

Water and climate in small island coun-

Water Forum, with the formulation of a position

tries

paper prepared with support from the Inter-Ameri-

can Development Bank (IADB) and the World Bank.

Small island countries are no different from other

Additionally, CEHI continues to strengthen its man-

countries in that freshwater is essential to human

date of integrating watershed and coastal areas man-

existence and a major requirement in agricultural

agement (IWCAM) in the Caribbean region under its

and other commercial production systems. However,

programme portfolio and, as such, has undertaken

the ability of the island countries to effectively man-

many related activities.

age the water sector differs in Small Island Devel-

This perspective document will:

oping States (SIDS), as they are constrained by their

1 provide examples of `no regrets' approaches,

small size, isolation, fragility, natural vulnerability,

applied in small island countries to cope with

and a limited human, financial and natural resource

current climate variability and adapt to future

base.

climate change, at different levels ranging from

Increasingly variable rainfall, cyclones / hurri-

communities, local administrations and national

canes, accelerating storm water runoff, floods,

governments.

droughts, decreasing water quality and increasing

2 demonstrate the need for a sound knowledge

demand for water are so significant in many small

base and information system, as well as a better

island countries that they threaten the economic

understanding of the relation between water

development and the health of their peoples.

resources, water and health, and climatic

extremes.

3 discuss the need for integrated approaches such

as offered by integrated water resources manage-

ment and drinking water safety planning, and

how these concepts can mainstream climate

adaptation and should be linked to disaster risk

reduction and disaster management.

4 influence policy and decision-makers of small

island countries, and mobilize increased efforts

to take funding for adaptation in the water sector

up in the broader development finance discus-

sions.

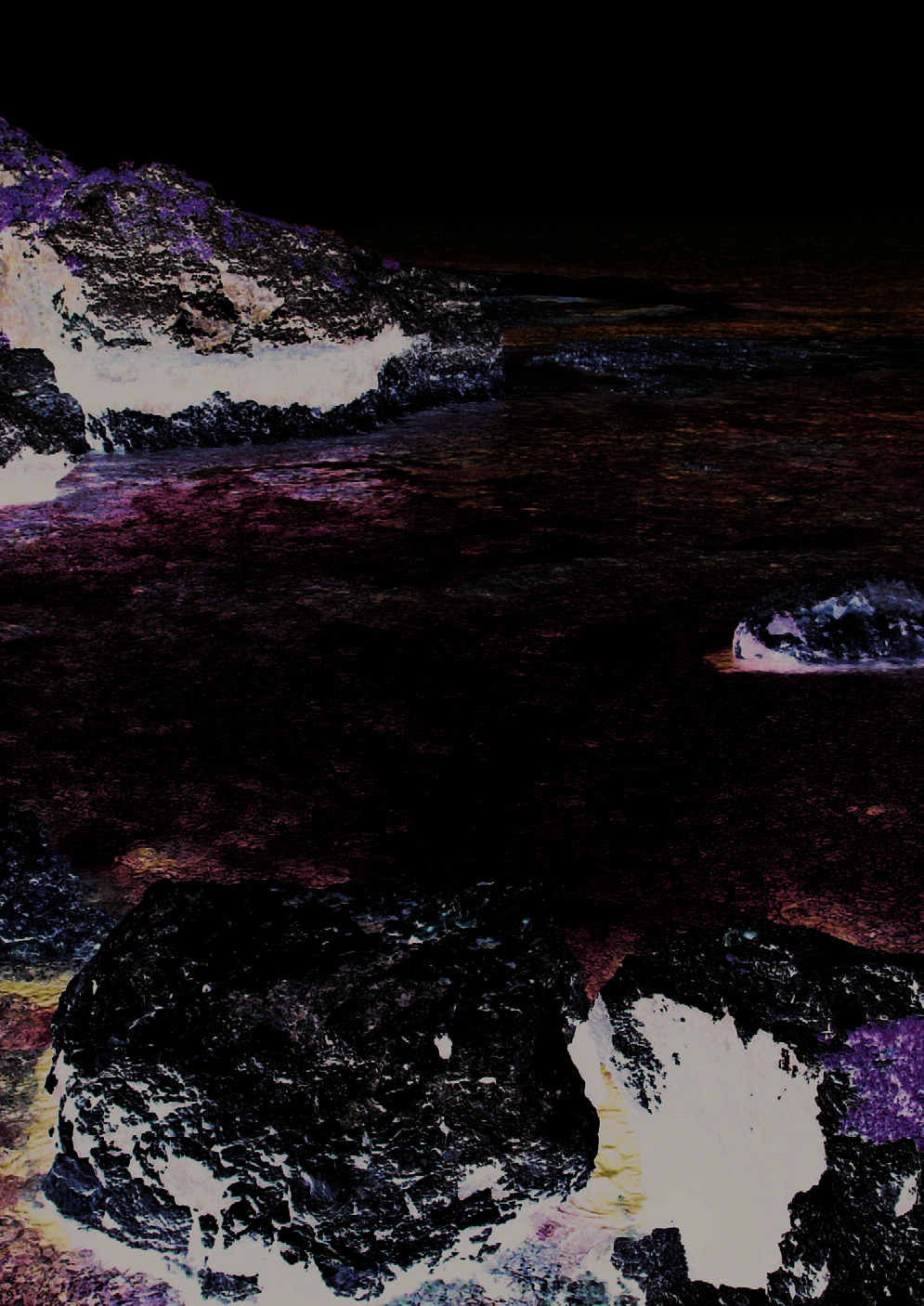

Flooding in Fiji's Rewa Delta (Photo by Marc Overmars).

2

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

Glacial melt, water and SIDS

(IPCC) continues to report that expected climatic

changes will stimulate an increase in extreme

The impacts of glacial melt on SIDS are predicted to

weather events that include higher maximum tem-

be especially destructive, both in the short and long-

peratures, increased number of hot days, more

term, including changes in water temperature, salin-

intense rainfall over some areas, increased droughts

ity, and sea level rise. The GEF-Funded Mainstream-

in others, and an increased frequency and severity of

ing Adaptation to Climate Change (MACC) project

tropical cyclones / hurricanes. Although global cli-

highlighted some of these impacts as:

mate predictions are being made through advanced

· Beach erosion: As the sea level rises, more of the

models the uncertainty over the expected climate

Caribbean SIDS beaches will be reclaimed by the

changes for small island countries is hampering an

Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea.

adequate response. Low skill levels of climate fore-

· Salinisation of soil, aquifers, and estuaries: Sea

casts are preventing reliable predictions exceeding a

level rise will bring salt and brackish waters into

period of 3 months. However, the expected increase

the soil, aquifers and estuaries, thus threatening

in climatic extremes should provide sufficient incen-

drinking water supplies, agriculture, and impor-

tives to `no regrets' approaches dealing with both

tant coastal ecosystems.

floods and droughts.

· Degradation of mangroves, seagrass beds and

Although the contribution of small island coun-

coral reefs: The degradation would be caused by

tries to greenhouse gas emissions is globally insig-

the salinisation and beach erosion, as mentioned

nificant and rank amongst the lowest in the world,

above. Additionally, the sea level rise will trans-

the islands face arguably the heaviest and most

late into a diminished amount of light reaching

immediate burden of climate change such as sea

coral reefs and sea grass beds. The consequence

storm surges and sea level rise affecting the low lying

of their destruction is far reaching, including

atoll islands in the Pacific and in the Caribbean as

decreased fish stocks that live and feed in and

well.

around the reefs; elimination of natural protec-

Unless something is done soon, the severe water

tion from storm surges; decreased tourism activi-

problems across both the Pacific and Caribbean

ties on the reefs, such as snorkeling, scuba div-

regions will considerably worsen under the influence

ing, and fishing; and a decrease in valuable bio-

of climate change. This message was conveyed by

logical diversity.

several Pacific leaders attending the 1st Asia Pacific

· Enhanced storm surges: To further complicate

the matter of diminished protection from storm

surges, as mentioned above, the higher sea level,

combined with other climatic changes, will bring

about enhanced storm surges, wrecking more

havoc on coastal ecosystems and communities

than before.

· Coastal inundation: With over 90% of popula-

tions and economic activities located in the

coastal zones of Caribbean SIDS, flooding will

have a negative impact on economic livelihoods

and human life.

Water Summit5 hosted by Japan in December 2007,

and shared by high-level delegates at the October

2007 launch of the initiative for the development of a

Accessible technology solutions, such as this wetlands filtration

system, are being constructed in Saint Lucia as part of an overall

5

approach to managing wastewater in a changing climate. (Photo

Message from Beppu, 1st Asia Pacific Water Summit,

by Donna Spencer).

December 2007, Beppu.

3

Caribbean Regional Climate Change Strategy at the

CARICOM Secretariat in Guyana.

1.1 Challenges and constraints

The challenges and constraints of sustainable water

resources management in Pacific and Caribbean

island countries and territories were categorized into

three broad thematic areas at the regional consulta-

tion on Water in Small Island Countries held in

preparation for the 3rd World Water Forum in Kyoto

Water Utilities in SIDS, such as these technicians from St. Kitts,

2003 . These are:

are working to address increasing demand and the challenges of

1 Pacific and Caribbean island countries and terri-

climate change. (Photo by Halla Sahley)

tories have uniquely fragile water resources due

to their small size, lack of natural storage. Com-

peting land use and vulnerability to natural and

1.2 Joint programme for action on water & cli-

anthropogenic hazards, including drought,

mate

cyclones and urban pollution. This requires

detailed water resources monitoring and manage- In March 2003, ADB and SOPAC facilitated the Water in

ment and improving collaboration with meteoro-

Small Island Countries sessions at the 3rd World Water

logical forecasting services;

Forum. The global SIDS position that resulted from these

2 Water service providers face challenging con-

sessions was mainly the result of the Dialogue on Water &

straints to sustaining water and wastewater provi- Climate (DWC) session which linked the Pacific and

sion due to the lack of both human and financial

Caribbean regions together on water and climate issues.

resource bases, which restrict the availability of

The close collaboration between the Caribbean

experienced staff and investment, and effective-

and Pacific regions during preparatory work for the

ness of cost recovery. Future action is required in

3rd World Water Forum resulted in the formation of

human resources development, water demand

the Joint Caribbean-Pacific Programme for Action on

management and improving cost recovery;

Water & Climate (JPfA).

3 Water governance is highly complex due to the

The JPfA comprises 22 action elements, common

specific socio-political and cultural structures

to both the Pacific and Caribbean regional consulta-

relating to traditional community, tribal and

tion outcomes, covering four collaborative areas:

inter-island practices, rights and interests. These

research, advocacy and awareness, capacity-building

are all interwoven with past colonial and

and governance. From this immediate priority,

'modern' practices and instruments. These

actions were identified in six areas. The JPfA takes an

require programmes to develop awareness, advo-

Integrated Water Resources Management approach

cacy, and political will at all levels to create a

to addressing water and climate issues in SIDS, as

framework for integrated water resources mana-

demonstrated by the Integrating Watershed and

gement.

Coastal Area Management (IWCAM) in the Carib-

bean, under CEHI and now accompanied by the

Pacific Sustainable Integrated Water Resources and

Wastewater Management Programme (Pacific

IWRM) under SOPAC. The JPfA promotes the trans-

fer of knowledge, expertise, positional statements

and personnel between the two regions to the benefit

of the 34 countries involved.

4

· develop a national implementation strategy for

mitigating and adapting to climate change in the

long term.

In a synthesis of Pacific preliminary national vulner-

ability assessments, Hay and Sem (2000) note the

following adaptations with relevance to water

resources, which are also applicable to Caribbean

SIDS:

· Improved management and maintenance of exist-

ing water supply systems has been identified as a

Raised limestone island of Nauru which is depending on rain-

high priority response, due to the relatively low

water harvesting and desalination. (Photo by Marc Overmars)

costs associated with reducing system losses and

improving water quality;

At the 3rd World Water Forum global SIDS agreed · Centralized water treatment to improve water

to six priority actions, referred to as the Small Island

quality is considered viable for most urban cen-

Countries Portfolio of Water Actions namely:

tres, but at the village level it is argued that more

· Water resources management through the Hydro-

cost-effective measures need to be developed;

logical Cycle Observing System (HYCOS);

· User-pay systems may have to be more wide-

· Water demand management programme;

spread;

· Drinking water quality monitoring;

· Catchment protection and conservation are also

· Improving water governance;

considered to be relatively low cost measures that

· Regional Type II Water Partnership support;

would help ensure that supplies are maintained

· Interregional SIDS water partnership support

during adverse conditions. Such measures would

through the JPfA.

have wider environmental benefits, such as

reduced erosion and soil loss and maintenance of

2

Vulnerability and adaptation assess-

biodiversity and land productivity.

ments

· Drought and flood preparedness strategies

should be developed, as appropriate, including

As reported in the Pacific Synthesis Report on Water

identification of responsibilities for pre-defined

and Climate (Scott et al, 2002) vulnerability and

actions;

adaptation assessments in relation to climate change · While increasing water storage capacity through

are required of signatory countries to the United

the increased use of water tanks and/or the con-

struction of small-scale dams is acknowledged to

Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

be expensive, the added security in the supply of

(UNFCCC). The Pacific Islands Climate Change

water may well justify such expenditure;

Assistance Programme (PICCAP) was developed to

assist with the reporting, training and capacity-

building required under the Convention. Climate

Change Country Teams established under PICCAP

undertook to:

· prepare inventories of greenhouse gas sources

and sinks;

· identify and evaluate emission reduction strate-

gies;

· assess vulnerability to climate change;

· develop adaptation options;

Jamaicans crossing the Hope River following flooding from Hur-

ricane Gustav. (Photo by Franklin McDonald)

5

hence their ability to accommodate the added

stresses arising from changes in climate and sea

level;

· given the limited area and low elevation of the

inhabitable lands, the most direct and severe

effects of climate and sea level changes will be

increasing risks of coastal erosion, flooding and

inundation; these effects are exacerbated by the

combination of seasonal storms, high tides and

storm surges;

· other direct consequences of anticipated climate

and sea level changes will likely include: reduc-

Poor, unregulated settlements on the river's edge in Haiti are

tion in subsistence and commercial agricultural

highly prone to flooding. (Photo by Vincent Sweeney)

production of such crops as taro, bananas and

· Development of runways and other impermeable

coconut; decreased security of potable and other

surfaces such as water catchments is seen as pos-

water supplies; increased risk of dengue fever,

sible, but an extreme measure in most instances.

malaria, cholera and diarrhoeal diseases; and

Priority should be given to collecting water from

decreased human comfort, especially in houses

the roofs of buildings;

constructed in western style and materials (espe-

· Measures to protect groundwater resources need

cially in the Pacific);

to be evaluated and adopted, including those that

· groundwater

resources

of the lowlands of high

limit pollution and the potential for saltwater

islands and atolls may be affected by flooding and

intrusion;

inundation from sea level rise; water catchments

· The limited groundwater resources that are as yet

of smaller, low-lying islands will be at risk from

unutilized in the outer islands of many countries

any changes in frequency of extreme events;

could be investigated and, where appropriate,

· the overall impact of changes in climate and sea

measures implemented for their protection,

level will likely be cumulative and determined by

enhancement and sustainable use;

the interactions and synergies between the

· The development of desalination facilities is con-

stresses and their effects; and

sidered to be an option for supplementing water

· the current lack of detailed regional and national

supplies during times of drought, but in most

information on climate and sea level changes,

instances the high costs are seen as preventing

including changes in variability and extremes

this being considered as a widespread adaptation

have resulted in most assessments being limited

option.

to using current knowledge to answer `what if'

questions regarding environmental and human

Amongst the many assessment findings summarized

responses to possible stresses.

by Hay (2000) the following are most relevant to

The first of these findings is particularly significant

water and climate:

since it implies that, in most parts of the Pacific and

· climate variability, development, social change

Caribbean regions, present problems resulting from

and the rapid population growth being experien-

increasing demand for water and increasing pollu-

ced by most small island countries are already

tion of water may be much more significant that the

placing pressure on sensitive environmental and

anticipated affects of climate change.

human systems, and these impacts would be

The final finding is also significant in that it

exacerbated if the anticipated changes in climate

refers to climate variability. In reporting obligations,

and sea level (including extreme events) did mate- The UNFCCC referred specifically to climate change

rialize;

(rather than to climate variability and change), possi-

· land use changes, including settlement and use of bly reflecting the perspective of climate change

marginal lands for agriculture, are decreasing the science existing at the time the Convention was

natural resilience of environmental systems and

drafted. A greater appreciation of the role of variabil-

ity has developed and it is now generally recognized

6

that the impacts of climate change are likely to be

intense hurricanes resulting in billions of dollars in

experienced through changes in variability. These

damage and thousands of deaths caused mainly by

considerations suggest that managing water

flooding. Of the Caribbean countries, Haiti has suf-

resources for variability and extremes is fundamental fered the extreme consequences on account of the

to the issue of adapting to climate change in the

severe degradation of its forests with great loss to life

longer term.

and property.

That conclusion is also supported by the vulner-

ability and adaptation assessments completed for Fiji Some key recommendations derived from these con-

and Kiribati (World Bank, 2000) which provide

clusions include:

examples of climate change impacts on water

· the adoption of a `no regrets' adaptation policy;

resources in high and low islands and reach the con-

· development of a broad consultative process for

clusions that:

implementing adaptation;

· Pacific Island countries are already experiencing

· require adaptation screening for major develop-

severe impacts from climate events;

ment projects;

· island vulnerability to climate events is growing

· strengthen socio-economic analysis of adaptation

independently of climate change;

options.

· climate change is likely to impose major incre-

These recommendations reflect the need for the

mental social and economic costs on Pacific

mainstreaming of climate change adaptation policies

Island countries; and

into water resources management.

· acting now to reduce present day vulnerability

The guidebook on `Surviving Climate Change in

could go a long way toward diminishing the

Small Islands' provides an overview for the assess-

effects of future climate change.

ment of vulnerability of water resources to climate

In the Caribbean region the impacts of rising tem-

changes (Emma L. Tompkins et al, 2005).

peratures are being linked to the recent and very

active hurricane seasons which have spawned several

Table1: Assessment of vulnerability.

Climate change

Exposure

Who or what affected

Sea level rise and saltwater intrusion

Salinisation of water lenses

Human consumption and health

Less fresh water available

Water suppliers

Plant nurseries and parks

Biodiversity, protected areas

Reduced average rainfall

Less fresh water available

Aquifer recharge rates

Droughts

Cisterns and reservoirs

Biodiversity

Increased evaporation rates

Soil erosion

Farming community; crop yields

Biodiversity

Increased rainfall intensity

Runoff and soil erosion

Reduction in crop production

Sedimentation of water bodies

Blocked storm water wells

Adapted from: Hurlston (2004).

The table above shows that climate change is likely to on cisterns may have to consider other means of

increase the exposure of small islands to water short-

accessing water.

ages for various reasons. Specific groups are likely to

be sensitive, for example, those who rely on subsis-

tence agricultural production and families who rely

7

3 Coping

and

adaptation

The Global Water Partnership states in their latest

policy brief that the best approach to manage the

impact of climate change on water is that guided by

the philosophy and methodology of Integrated Water

Resources Management (GWP, 2007). It also states

that the best way for countries to build the capacity to

adapt to climate change will be to improve their abil-

ity to cope with today's climate variability.

For small islands, climate change is just one of

many serious challenges with which they are con-

Many islanders rely on coastal resources. (Photo by Marc

fronted. Adaptation to climate change impacts cer-

Overmars)

tainly requires integration of appropriate risk reduc-

· Key Message 1: Strengthen the capacity of small

tion strategies within other sectoral policy initiatives

island countries to conduct water resources

such as in water resources management (Emma L.

assessment and monitoring as a key component

Tompkins et al, 2005).

of sustainable water resources management.

In the Pacific region, concentration on the poten-

· Key Message 2: There is a need for capacity

tial impacts of climate change on small island com-

development to enhance the application of cli-

munities has even deflected attention and resources

mate information to cope with climate variability

away from the immediate and serious day-to-day

and change.

problems faced by small island nations, particularly

· Key Message 3: Change the paradigm for dealing

in water resources (White I. et al, 2007). The above

with Island Vulnerability from disaster response

obviously does not preclude the application of coping

to hazard assessment and risk management, par-

strategies and adaptation measures to climate varia-

ticularly in Integrated Water Resource Manage-

bility and change, which, on the contrary, is essential

ment (IWRM).

for the sustainable management of water resources

in small island countries and territories.

Actions have been undertaken to address each of the

Regarding the vulnerability of small island coun-

key messages not only in the Pacific but also in other

tries and territories to climate variability and change

SIDS regions.

as well as anthropogenic influences, the required

coping and adaptation strategies have been articu-

lated under a specific theme of `Island Vulnerability'

3.1 Water resources monitoring and

in the Pacific Regional Action Plan on Sustainable

assessment

Water Management (SOPAC, 2002) as follows:

There is a need to invest in adequate water resources

monitoring and assessments in order to cope with

climatic extremes, both droughts (often related to

ENSO events) and flooding (often linked to the

occurrence of cyclones/hurricanes).

Insufficient understanding and knowledge on

how rivers respond to extreme rainfall or how resil-

ient aquifers are in prolonged periods of drought will

compromise the provision of freshwater supplies.

This requires the increased capacity of National

Hydrological Services in flood and drought forecast-

ing as well as a stronger collaboration between them,

water resources managers and water utilities.

Raised limestone island of Niue also known as the `Rock of

Polynesia'. (Photo by Marc Overmars)

8

Awareness of the effects of floods and droughts

on drinking water quality needs to be increased

through closer engagement between water users and

water suppliers. Increased health surveillance and

water quality monitoring should be encouraged espe-

cially in times of disasters.

As examples, the Pacific and Caribbean Hydrological

Cycle Observing Systems are now being established

through support from the European Union Water

Facility and the French Government respectively.

Water resources on atoll islands like South Tarawa in Kiribati are

Water quality monitoring is being supported through being affected by climate variability and change. (Photo by Marc

NZAID in the Pacific, and the Institut de recherche

Overmars)

pour le développement (France), the Caribbean

resources agencies and their response capability to

Environmental Health Institute and the Caribbean

extreme phenomena; (c) integration of these agen-

Institute for Meteorology and Hydrology in the

cies into the region's development decision-making;

Caribbean region.

and (d) improved cooperation among the region's

The Pacific HYCOS programme is providing sup-

national water agencies, including the real-time cir-

port to National Hydrological Services in the region

culation of water and environment data.

and is building their capacity in flood and drought

forecasting as well as in basic monitoring of water

resources. This information is essential for any cli-

mate adaptation initiative whether they focus on

domestic (water supply), agricultural (irrigation) or

industrial (hydropower) use of water. The need for

thorough analysis of hydro(geo)logical information

and water quality, as well as water quantity data, is

frequently overlooked by adaptation programmes

which sometimes make assumptions on the impacts

of climate on water resources without adequate

research. If we do not know how aquifers respond to

droughts or how rivers respond to floods it will be

impossible to make sensible decisions on adaptation

measures which are aiming to deal with the increase

of climatic extremes.

The Carib-HYCOS project seeks to enhance natu-

ral disaster mitigation capabilities by the use of

modern flood forecasting and warning systems;

strengthen water management capabilities by

improving the knowledge base of water resources

concerning quantity, quality and use; increase

exchange of information and experience, particularly

during natural disasters; and develop technological

capabilities (including training and technology

transfer) appropriate to the circumstances and reali-

ties of each country. It is expected that the project

implementation will result in: (a) better understand-

ing of the regional hydrological phenomena and

trends in order to rationalize the use of water

Water Quality Monitoring in Dominica. (Photo by Sasha Beth

resources; (b) modernization of the region's water

Gottlieb)

9

adopted by both the utility and the general public,

will enhance the ability of Pacific and Caribbean

island countries and territories to overcome droughts

and maintain sufficient standards of drinking water

quality.

The Pacific Island Climate Update (ICU) sup-

ported by NZAID provides such information to end-

users in the Pacific in a regional overview, whereas

the strengthening of NMSs is being undertaken

under an AusAID-funded climate prediction pro-

gramme. Both are linked to climate centres in the

Pacific islands, the United States, France, Australia

and New Zealand.

In the Caribbean, a joint collaboration between

the Caribbean Community Climate Change Centre

(CCCCC), the Caribbean Institute for Meteorology

and Hydrology (CIMH) and the Brace Center for

Water Resources Management of McGill University

will see the development of a Caribbean Drought and

Precipitation Monitoring Network for the region that

will be hosted at the CIMH.

Through the analyses of rainfall data and use of

GIS in Tuvalu, under the Pacific HYCOS programme,

support is provided to an AusAID and EU-funded

Hydrological monitoring, such as on the island of Espirito Santo,

initiative, Vulnerability and Adaptation, to provide all

Vanuatu, is essential for water resources management in small

households on the main atoll of Funafuti with a

island countries. (Photo by Marc Overmars)

rainwater harvesting tank in order to provide a stra-

tegic water storage to overcome extended periods of

droughts which are often linked to ENSO episodes.

3.2 Using climate information

The UNEP, through CEHI, is supporting similar

efforts in Caribbean SIDS by using GIS-assisted

There is a need to make use of climate forecasts to

mapping methods of rainfall capture potential and

support decision-makers in the water sector.

water availability to promote the practice of rainwater

Research into the interaction of the ocean and

harvesting in water stressed parts of the region.

atmosphere over the last two decades has resulted in

an impressive ability to observe and account for many

of the factors governing climatic variability at the

seasonal and inter-annual time scale.

National Meteorological Services are being

strengthened in their capacity to develop techniques

that are able to produce climate forecasts of modest

skill, but this information is not easily accessible and

available for interpretation by water resources and

water supply managers. Particularly for the rainfall

dependent low lying atoll islands, strategies to cope

with extended periods of drought will largely depend

on their ability to make interpretations of three-

monthly rainfall forecasts.

Strategic storage of rainwater and the introduc-

Outer islands in the Pacific are depending on increasingly vari-

tion of water saving or water conservation measures

able rainfall (Photo by Marc Overmars)

10

reserves, low lying atolls or raised limestone islands.

Improved hygiene behaviour and awareness of the

linkages between drinking water and health are

essential, and participatory approaches and commu-

nity-based monitoring are needed for urban as well

as rural communities.

The introduction of DWSP is promoted in the

Rainwater harvesting such as on Banaba, Kiribati (l) and

Pacific through an AusAID-funded programme by

Mabouya Valley, Saint Lucia (r) has been under utilised in many

SOPAC in collaboration with WHO, whereas the U.S.

small island countries. (Photos by Marc Overmars and Donna

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is

Spencer)

promoting this new concept together with CEHI in

the Caribbean.

3.3 Mainstreaming risk management

There is a need to mainstream risk management into

water supply and water resources management,

building on the integrated approaches adopted by

Pacific and Caribbean island countries and territories

such as Drinking Water Safety Planning (DWSP) and

Integrated Water Resources Management.

Drinking Water Safety Planning is defined as "a

comprehensive risk assessment and risk manage-

ment approach that encompasses all steps in the

water supply from 'catchment to consumer' to con-

Children are particularly vulnerable to the adverse impacts of

sistently ensure the safety of water supplies" (WHO,

climate change, felt in the lower reaches of watersheds, such as

2004). It addresses all aspects of drinking water sup-

the Haina Watershed in the Dominican Republic. (Photo by

ply through an integrated approach focusing on the

Donna Spencer)

control of abstraction, treatment and delivery of

drinking water in combination with attention for

An example of an appropriate adaptation strategy for

awareness and behaviour change.

water is provided by Tonga where the nationally-

This requires close collaboration between the

developed Drinking Water Safety Plan by the Tonga

water supplier, the water quality and health regulator Water Board and the Ministry of Health guided the

and the water resources managers in conjunction

scoping of an EU-funded drought resilience building

with a strong participation of communities living in

project valued at 1.1 million euros focused on risk

catchments of high volcanic islands, on top of water

prevention instead of response. In the Caribbean, the

Spanish Town water supply system in Jamaica was

the first pilot of a DWSP approach through the joint

collaboration between the local National Water

Commission and the CDC. The approach is presently

being replicated in Guyana (part of the Caribbean yet

on the South American mainland), again in partner-

ship with the CDC and CEHI. The collective experi-

ences of both countries will be applied when intro-

ducing the process to the other Caribbean SIDS.

The concept and the approaches which IWRM

embodies - namely, the need to take a holistic

approach to ensure the socio-cultural, technical,

Pollution of vulnerable groundwater lenses are a major concern

economic and environmental factors are taken into

for many small island countries. (Photo by Marc Overmars)

11

account in the development and management of

including climate variability before they can adapt to

water resources - has been practiced at a traditional

future climate changes.

level for centuries in some islands.

A recent WHO/SOPAC report revealed that the

For small island countries and territories these

annual incidence of diarrhoeal diseases in the Pacific

IWRM plans would need to include drought and dis-

still nearly matches the numbers of its inhabitants

aster preparedness plans. Pollution on land from

with 6.7 million cases of acute diarrhoea each year,

inadequate wastewater disposal, increased sediment

responsible for the annual death of 2,800 people,

erosion and industrial discharges are impacting

most of them children less than 5 years old. Country

upon coastal water quality and fisheries stock which

statistics on access to improved sanitation and

sustain entire island populations. This requires small improved drinking water indicate that on average

island countries and territories to look at managing

approximately only half of the total population of the

water resources not only within the watershed but

Pacific island countries are served with any form of

also the receiving coastal waters.

improved sanitation or drinking water

The introduction of IWRM in SIDS is being pro-

(WHO/SOPAC, 2008).

moted through the GEF-IWCAM Programme by

CEHI and the Pacific IWRM Programme by SOPAC

under the Global Environment Facility and EU Water

Facility.

Through close alignment of climate adaptation

programmes also funded through the GEF in the

Caribbean (CPACC, MACC, and SPACC) and the

Pacific (PACC) the opportunity arises to ensure that

flood and drought management is being addressed

in the countries concerned within an IWRM frame-

work. Use can be made of the established APEX

bodies that can function as National Water and Cli-

mate Committees and steering committees for both

Providing safe drinking water to communities is posing increas-

adaptation and integration of water resources man-

ing challenges to small island countries. (Photo by Marc

agement.

Overmars)

At present there is still a disconnect between risk

management, climate adaptation and water

In the Caribbean, flood events associated with

resources management with receiving small island

successive tropical storms and hurricanes in recent

countries, donors and supporting agencies working

years have prompted stepped-up surveillance and

in different silos foregoing the principles of main-

monitoring by national public health agencies in

streaming in ongoing natural resources management terms of control of outbreaks of dengue fever and

processes.

diarrhoeal diseases. Although in most countries of

This needs to be changed through interventions

the Caribbean access to potable drinking water is

at the highest levels such as through the Prime

upwards of 80% (with the exception of Haiti), inter-

Minister's Office, Ministries of Planning or Finance

ruptions to water supply following storms is a sig-

and guided by a sound information base on water

nificant risk factor in terms of maintaining health

and climate.

and sanitation.

The 1st Asia-Pacific Water Summit held in

December 2007 in Beppu, Japan, was attended by six

4

Political will and financing

Pacific Island Leaders from the Federated States of

Micronesia, Palau, Tuvalu, Nauru, Niue and Kiribati,

It is generally recognized that improving the way we

as well as Ministers from Fiji, the Cook Islands and

use and manage our water today will make it easier to Papua New Guinea. SOPAC, as focal point for the

address the challenges of tomorrow. With respect to

Oceania component of the Asia-Pacific Water Forum,

climate change it is evident that SIDS will have to

provided support to countries participating in the

deal with the current challenges and constraints

12

Summit and facilitated a special session on water and

climate in small island countries.

The large participation by Pacific Heads of State

at this Summit was a testament of their strong politi-

cal commitment to meeting future water challenges

and their efforts to cope with an increasingly variable

climate, and adapt to the future effects of global cli-

mate change.

The Pacific leaders attending the summit in

Beppu reaffirmed their commitment to give the

highest priority to water and sanitation in economic

and development plans; improve governance, effi-

Improving access to water and sanitation requires political will

ciency, transparency and equity in all aspects related

(Photo by Marc Overmars)

to the management of water, particularly as it

impacts on poor communities; take urgent and

Heads of Government meeting (July 2008), a

effective action to prevent and reduce the risks of

Regional Task Force on Climate Change was estab-

flood, drought and other water-related disasters; and lished to provide technical advice to participants,

support the region's vulnerable small island states in specifically focusing on COPS negotiations.

their efforts to protect lives and livelihoods from the

Combined with adequate priority given to water

impacts of climate change (APWF, 2007).

and sanitation in national development plans and

The Summit specifically raised attention to the

strategies, these actions will provide the best

opportunity that presents itself at this moment: to

approaches to achieve the MDG target of halving the

mainstream Climate Adaptation, Disaster Risk

proportion of people without access to safe drinking

Reduction and Water Safety Planning into Integrated

water and basic sanitation by 2015 and to be prepared

Water Resources Management.

for the future. Harmonization of donor agency pro-

The commitment shown at Beppu still needs to

grammes are in this respect key to maximizing the

be converted into action but signs of countries link-

impact of actions, and this would need to be sup-

ing national priorities such as improving access to

ported by a regional framework for monitoring

safe drinking water and sanitation to climate adapta-

investments and results.

tion efforts and risk reduction are promising, such as

in Tuvalu, Kiribati, Tonga, the Marshall Islands and

Nauru.

Acknowledgements

Commitments from donors to increase funding

for both climate adaptation and water and sanitation

We would like to acknowledge the valuable contri-

are promising as demonstrated by AusAID, EU, GEF, bution of the following persons who made the com-

World Bank and other donor agencies. Rather than

pletion of this article possible: Dr Christopher Cox,

implementing `quick fixes' focused on infrastruc-

Programme Director, and Mrs Patricia Aquing,

tural improvements, adequate attention should be

Executive Director of the Caribbean Environmental

paid to the building of local capacity to improve the

Health Institute; Mr Vincent Sweeney, Regional Pro-

management of water services and resources in order ject Coordinator of the GEF-IWCAM Project; and the

to achieve a degree of sustainability of interventions.

Water Sector of SOPAC.

Climate change issues are addressed at the

regional level by the Council for Trade and Economic

(COTED) of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM).

References

Additionally, Caribbean Heads of Government have

included climate change as a specific item on the

Asia Pacific Water Forum (2007). Message from

agenda of their meetings. Currently, the Prime

Beppu 1st Asia Pacific Water Summit, Decem-

Minister of Saint Lucia has the responsibility within

ber 2007, Beppu, Japan.

the CARICOM Cabinet for climate change and sus-

GWP (2005). Policy Brief 4: Catalyzing Change: A

tainable development issues. At the last Caribbean

Handbook for Developing Integrated Water

13

Resources Management (IWRM) and Water Effi-

White, I. et al (2007). Society-Water Cycle Interac-

ciency Strategies. GWP. Stockholm, Sweden.

tions in the Central Pacific: Impediments to

Hay, J. E. (2000). Climate change and small island

Meeting the UN Millennium Goals for Freshwater

states: A popular summary of science-based

and Sanitation. In: Proceedings 1st International

findings and perspectives, and their links with

Symposium Water and Better Human Life in the

policy. Presentation to 2nd Alliance of Small

Future. RIHN, Kyoto, Japan.

Island States (AOSIS) workshop on climate

WHO/SOPAC (2008). Sanitation, hygiene and

change negotiations, management and strategy,

drinking water in Pacific island countries, Con-

Apia, Samoa.

verting commitment into action. World Health

Hay, J. E. & Sem G. (2000). Vulnerability and adap-

Organization, Manila, Philippines.

tation: evaluation and regional synthesis of

WHO (2004). Guidelines for Drinking Water Quality:

national assessments of vulnerability and adapta-

3rd Edition. World Health Organization. Geneva,

tion to climate change. South Pacific Regional

Switzerland.

Environment Programme, Apia, Samoa.

World Bank (2000). Adapting to Climate Change.

Hurlston, L.-A. (2004) Global Climate Change and

Vol. IV in Cities, Seas and Storms, Managing

The Cayman Islands: Impacts, Vulnerability and

Change in Pacific Island Economies. Papua New

Adaptation. Report prepared during a visiting

Guinea and Pacific Island Country Unit, World

fellowship in the Tyndall Centre for Climate

Bank, Washington, US.

Change Research, University of East Anglia,

Norwich, UK.

Scott, D., Overmars, M., Falkland, A. & Carpenter,

Marc Overmars

C. (2003). Synthesis Report Pacific Dialogue on

SOPAC, Pacific Islands Applied Geoscience

Water and Climate, SOPAC, Suva, Fiji.

Commission, Private Mail Bag, GPO, Suva, Fiji Islands

SOPAC (2002), Pacific Regional Action Plan on Sus-

marc@sopac.org, www.pacificwater.org

tainable Water Management. ADB and SOPAC,

Suva, Fiji.

Sasha Beth Gottlieb

Springer, C. (2002). Water and Climate Change in

GEF-IWCAM Project Coordination Unit, c/o Caribbean

the Caribbean. CEHI, St Lucia.

Environmental Health Institute, The Morne, P.O. Box

Tompkins, E. L. et al (2005). Surviving Climate

1111, Castries, St. Lucia

Change in Small Islands: A Guidebook. Tyndall

sgottlieb@cehi.org.lc, www.iwcam.org

Centre for Climate Change Research, Norwich,

UK.

14

Annex 1

JOINT CARIBBEAN AND PACIFIC PROGRAMME FOR ACTION

ON WATER AND CLIMATE

A. RESEARCH (11 Action Elements)

1) Strengthen the application of climate information and strengthen the links between

meteorological and hydrological services;

2) Strengthen institutional capacity for data generation;

3) Develop rainfall and drought prediction schemes based on existing models;

4) Enable regional support to develop water application of climate information and

prediction;

5) Implement a programme of climate analysis for assessment of extreme weather

events; develop minimum standards for risk assessments;

6) Implement actions to strengthen national capacity (equipment, training, etc.) using the

model outlined in the Pacific Hydrological Cycle Observation System (HYCOS)

proposal and recommendations regarding water quality;

7) Implement a programme of targeted applied research projects to address knowledge

gaps in line with recommendations and priorities presented;

8) Develop and/or implement minimum standards for conducting island water resources

assessment and monitoring;

9) Implement appropriate water quality testing capability and associated training at local,

national and regional levels;

10) Strengthen and enhance communication and information exchange between national

agencies involved with meteorological, hydrological and water quality data collection

programmes (including water supply agencies and health departments);

11) Utilize the research capabilities at regional science institutions;

B. PUBLIC EDUCATION, AWARENESS AND OUTREACH (4 Action Elements)

1) Provide high level briefings on the value of hazard assessment and risk management

tools;

2) Support community participation in appropriate water quality testing programmes

targeted at environmental education and awareness of communities, using existing

and proposed programmes as models;

3) Recognize the value of informal community groups;

4) Include the media as a specific institution.

C. EDUCATION AND TRAINING (2 Action Elements)

1) Enhance education and career development opportunities in the water sector;

2) Implement hydrological training for technicians in line with the recommendations

presented in a proposal to meet training needs;

D. POLICY AND INSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENT (5 Action Elements)

1) Build environment to facilitate the emergence of an IWRM framework;

2) Incorporate the community in policy development at the ground level;

3) Build capacity in the use of a risk management approach to integrated resource

management, in EIAs;

4) Develop appropriate policy/legislative instruments;

5) Harmonize legislation, regulations and policy.

15

Annex 2

Mauritius Strategy for the Further

Implementation of the Programme of Action for the

Sustainable Development of Small Island Developing States

Port Louis, Mauritius, 15 January 2005

V. Freshwater resources

27. Small Island Developing States continue to face water management and water access

challenges, caused in part by deficiencies in water availability, water catchment and storage,

pollution of water resources, saline intrusion (which may be exacerbated, inter alia, by sea-

level rise, unsustainable management of water resources, and climate variability and climate

change) and leakage in the delivery system. Sustained urban water supply and sanitation

systems are constrained by a lack of human, institutional and financial resources. The access to

safe drinking water, the provision of sanitation and the promotion of hygiene are the

foundations of human dignity, public health and economic and social development and are

among the priorities for Small Island Developing States.

28. Small Island Developing States in the Caribbean and the Pacific regions have demonstrated

their commitment to SIDS SIDS cooperation with the Joint Programme for Action for Water

and Climate. The international community is invited to support the implementation of this

programme, and the proposal to broaden it to all Small Island Developing States regions.

29. Further action is required by Small Island Developing States, with the necessary support

from the international community, to meet the Millennium Development Goals and World

Summit on Sustainable Development 2015 targets on sustainable access to safe drinking water

and sanitation, hygiene, and the production of integrated water resources management and

efficiency plans by 2005.

30. The international community is requested to provide assistance to Small Island Developing

States for capacity-building for the development and further implementation of freshwater and

sanitation programmes, and the promotion of integrated water resources

management, including through the Global Environment Facility focal areas, where

appropriate, the World Water Assessment Programme, and through support to the Global

Programme of Action Coordination Office and the EU "Water for Life Initiative".

31. The Fourth World Water Forum, to be held in Mexico City in March 2006, and its

preparatory process will be an opportunity for the Small Island Developing States to continue

to seek international support to build self-reliance and implement their agreed priority actions

as submitted to the Third World Water Forum Portfolio of Water Action, namely: integrated

water resources management (including using the Hydrological Cycle Observing System);

water demand management; water quality capacity-building; water governance; regional water

partnerships; and inter-small island developing State water partnerships.

16