FAO Training Manual for

International Watercourses/River Basins including

Law, Negotiation, Conflict Resolution and

Simulation Training Exercises

Prepared for FAO by Richard Kyle Paisley

University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada V6T 1Z2

rpaisley@interchange.ubc.ca

Preface

Introduction and Objectives of the Training Manual

The project which led to the development of this training manual grew out of discussions with

Stefano Burchi, Director of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO)

Legal Development Division at FAO in Rome, and his colleague Kerstin Mechlem at an FAO Nile

Basin Initiative training session in Bujumbura, Burundi in the Spring of 2006.

Those discussions centered around two observations. The first observation was regarding the

paucity of accessible international training materials succinctly integrating negotiation skills with

international water law training. The second observation was that there appeared to be a niche for

a more "learner centered" training approach to international waters focusing on analysis of experience

and encouraging attendees to become increasingly self directed and more responsible for their

own learning. Under such an approach, first hand and vicarious experiences, dialogue among

learners as well as between instructors and learners, and analysis and interpretation become the

focus of instruction.

This training manual responds to those observations and aims to provide the reader with practical

and "learner-centered" training materials on international water law issues. The materials focus on

international water law and policy education as well as on negotiation training. It is intended to

train both experienced negotiators on the intricacies of negotiating international watercourses as

well as inexperienced negotiators on developing effective negotiation skills and techniques. Further,

this manual is aimed at informing both professionals and interested parties to aid in international

negotiation and conflict resolution concerning international watercourses.

The manual begins with an introductory chapter entitled "Setting the Scene". The subsequent chapter

includes materials on the hydrological cycle and international watercourses. Chapter 3 focuses on the

legal aspects surrounding international watercourses. It is followed by a chapter entitled "Negotiation

and Conflict Resolution". Finally, Chapter 5 provides a series of custom designed simulation training

exercises. These exercises are based on simulation training exercises that the authors have had the

privilege of testing in a number of international drainage basins throughout the world including the

Nile River Basin, the Mekong River Basin, the Syr Darya and Amu Darya River Basins, the Columbia

River Basin and international drainage basins in South America, Mexico/US and Nepal. The sixth and

final chapter concludes with some parting remarks on being part of international negotiations and

hopes for negotiating practice. Appendices contain copies of the key international documents referred

to in the text.

This training manual is written in such a way that these materials can be sent to participants before

the course as preparatory reading. There is also a Teaching Package for the use of instructors which

accompanies this training manual.

i

Disclaimer

DIsclaIMer

The materials in this training manual, including all of the simulation exercises, are entirely made

up for teaching purposes only. Any resemblance between these simulation exercises and any real

situations or real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

This training manual does not necessarily represent the views of FAO or any other international

entity or organization with which the authors are or may previously have been associated including

without limiting the generality of the foregoing the World Bank, the United Nations Development

Programme, the Global Environment Facility, the Mekong River Commission, the Canadian

International Development Agency and/or the Canadian Department of Foreign Affairs.

After initial publication by FAO this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system

or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or

otherwise without the permission in writing of the copyright holder provided acknowledgement

is made.

This draft training manual is a "work in progress". Comments, criticisms and experiences using this

manual are strongly encouraged by emailing Richard Kyle Paisley, University of British Columbia,

Vancouver, Canada at: rpaisley@interchange.ubc.ca

ii

FAO Training Manual for International Watercourses and River Basins

acknowledgements

acknOwleDgeMenTs

The materials in this draft training manual were drawn from a variety of sources, such as the UN,

UNTS, UNFAO, UNILC, World Bank, textbooks and journals, libraries of law schools, and the internet.

The initiative which led to the development of these training materials grew out of discussions with

Stefano Burchi and Kerstin Mechlem, legal officers of the Development Law Service, Legal Office,

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) on the occasion of the Program for

the Regional Workshop on International Water Law and Negotiation Skills for Sharing Transboundary

Resources in Bujumbura, Burundi in the Spring of 2006. Thank you Stefano and Kerstin for your

support and encouragement.

Special thanks also to Bart Hilhorst and Jake Burke of FAO and the SVP Coordination Project and

Information Products for Nile Basin Water Resources Management GCP/INT/945/ITA who also

tremendously supported and encouraged the production of these training materials.

Gratefully acknowledged is the advice and assistance received from Jacob Burke (FAO Rome).

Also gratefully acknowledged is the advice and assistance received from Bo Bricklemyer (The Institute

for Asian Research and The Dr. Andrew R. Thompson Program in Natural Resources Law and Policy,

Faculty of Law, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada); Steve McCaffrey (University of the

Pacific, California, USA); Linda Nowlan (The Institute for Resources, Environment and Sustainability,

University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada); Kyle Robertson and Aaron Wolf (University of

Oregon, Oregon, USA); Jia Cheng, Heather Davidson, Holger Feser, Alex Grzybowski, Glen Hearns,

and Leah Jones.

Also gratefully acknowledged is the advice and assistance received from Gabriel Eckstein, George

Radosevich, and John Scanlon who peer reviewed these materials.

All errors and omissions remain the sole responsibility of the author.

iii

iv

FAO Training Manual for International Watercourses and River Basins

Table of contents

Table Of cOnTenTs

Preface - Introduction and Objectives of the Training Manual ......................................................... i

Disclaimer ............................................................................................................................................. ii

Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................. iii

Table of Contents .................................................................................................................................. v

1 setting the scene

1.1

Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1

2 watercourses and river basins

2.1

Hydrology and the Hydrological Cycle ............................................................................. 3

2.1.1

Explanation of the Processes .............................................................................................. 4

2.1.2

Relative Importance of the Water Exchange Processes .................................................... 6

2.1.3

The Relationship between Surface and Ground Water Resources .................................. 7

2.1.4

The Components of a Watercourse .................................................................................... 8

2.2

International Watercourses and River Basins .................................................................... 9

2.2.1

Background to International Watercourses ....................................................................... 9

2.2.1.1

Traditional Chronology ..................................................................................................... 10

2.2.1.2

Preventive Diplomacy ....................................................................................................... 11

2.2.1.3

Bi/multilateral Entities for Managing, Allocating,

Protecting, and Developing Transboundary Waters ...................................................... 12

2.2.2

Further Reading ................................................................................................................ 12

3 International law in context

3.1

International Law .............................................................................................................. 15

3.2

Hard Law and Soft Law .................................................................................................... 16

3.3

What is a treaty? ................................................................................................................ 17

3.4

Who can Agree to be Legally Bound by a Treaty ............................................................ 18

3.4.1

Bilateral or Multilateral ..................................................................................................... 18

3.4.2

Framework and Self-contained Treaties .......................................................................... 18

3.4.3

Protocols ............................................................................................................................ 18

3.4.4

How Does a State Agree to a Treaty? .............................................................................. 19

3.4.4.1

Signature ............................................................................................................................ 19

3.4.4.2

Exchange of Instruments .................................................................................................. 19

v

Table of contents

3.4.4.3

Ratification ......................................................................................................................... 19

3.4.4.4

Acceptance or Approval .................................................................................................... 19

3.4.4.5

Accession ........................................................................................................................... 19

3.4.4.6

Party to a Treaty ................................................................................................................. 19

3.4.4.7

Depositary .......................................................................................................................... 20

3.4.5

Reservations ....................................................................................................................... 20

3.4.6

Entry into Force ................................................................................................................. 20

3.4.7

Amendments of Treaties ................................................................................................... 21

3.4.8

Which Treaty Takes Precedence in the Event of a Conflict?........................................... 21

3.4.9

Registration and Publication ............................................................................................ 22

3.4.10

Interpreting Treaties .......................................................................................................... 22

3.4.11

Stages of Treaty-Making ................................................................................................... 22

3.4.12

At a Treaty Negotiation ..................................................................................................... 23

3.4.13

Key Features of (Environmental) Treaties........................................................................ 24

3.4.14

Financing MEAs ................................................................................................................ 25

3.4.15

Civil Society Involvement in MEAs ................................................................................. 26

3.5

Principles of International Environmental Law .............................................................. 26

3.5.1

Sovereignty Over Natural Resources ............................................................................... 27

3.5.2

Duty to Prevent Transboundary Pollution and Environmental Harm ........................... 27

3.5.3

Sustainable Use of Natural Resources ............................................................................. 27

3.5.4

Sustainable Development ................................................................................................ 28

3.5.5

Right to a Healthy Environment ...................................................................................... 28

3.5.6

Precautionary Approach ................................................................................................... 29

3.5.7

Common Heritage of Mankind/Common Concern of Humankind ............................ 29

3.5.8

Common but Differentiated Responsibility .................................................................... 29

3.5.9

Intergenerational Equity ................................................................................................... 30

3.5.10

Public Participation ........................................................................................................... 30

3.5.11

Polluter Pays ....................................................................................................................... 30

3.5.12

Liability and Compensation for Environmental Damage .............................................. 30

3.5.13

Duty to Conduct Environmental Impact Assessments .................................................. 31

3.5.14

Duty of Non-discrimination/Environmental Justice ...................................................... 31

3.5.15

Right to Development ...................................................................................................... 31

vi

FAO Training Manual for International Watercourses and River Basins

Table of contents

3.5.16

Other Principles ................................................................................................................ 31

3.6

International Water Law ................................................................................................... 32

3.6.1

General Rules of Law Concerning the Use of International Watercourses .................. 33

3.6.2

Equitable Utilization ......................................................................................................... 34

3.6.3

Equitable Participation: ..................................................................................................... 34

3.6.4

Prevention of Significant Harm ....................................................................................... 35

3.6.5

Rules concerning New Uses ............................................................................................. 35

3.6.6

Rules concerning Pollution ............................................................................................... 36

3.6.7

The Special Case of Shared Groundwater ...................................................................... 36

3.6.8

Links with World Bank Procedures.................................................................................. 36

3.6.9

Bibliography ....................................................................................................................... 37

4 negotiations and conflict resolution

4.1

Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 39

4.2

Conditions for Negotiation .............................................................................................. 40

4.3

Types of Negotiation ......................................................................................................... 43

4.3.1

Horizontal or In-Team Negotiations ............................................................................... 43

4.3.2

Vertical Negotiations ......................................................................................................... 44

4.3.3

Vested Interest Negotiations ............................................................................................ 45

4.3.4

Conciliatory Negotiations ................................................................................................. 46

4.3.5

Spokesperson Negotiations ............................................................................................. 47

4.3.6

Subcommittee Negotiations............................................................................................. 48

4.3.7

Bilateral or Multilateral Negotiations .............................................................................. 49

4.3.8

External Negotiations ....................................................................................................... 50

4.4

Positional Bargaining ........................................................................................................ 51

4.4.1

What is Positional Bargaining? ........................................................................................ 51

4.4.2

When is Positional Bargaining Often Used? ................................................................... 51

4.4.3

Attitudes of Positional Bargainers .................................................................................... 51

4.4.4

How to do Positional Bargaining ..................................................................................... 51

4.4.5

Costs and Benefits of Positional Bargaining.................................................................... 54

4.5

Interest-based Bargaining ................................................................................................ 54

4.5.1

What is Interest-based Bargaining.? ............................................................................... 54

4.5.2

When is Interest-based Bargaining Used? ...................................................................... 54

vii

Table of contents

4.5.3

Attitudes of Interest-based Bargainers ............................................................................ 54

4.5.4

How to do Interest-based Bargaining ............................................................................. 55

4.5.5

Costs and Benefits of Interest-based Bargaining ............................................................ 57

4.6

Making the Transition from Positional to Interest-based Bargaining ........................... 57

4.7

Stages of Negotiation ....................................................................................................... 58

4.8

Preparing to Negotiate ..................................................................................................... 60

4.9

Opening Statements for Negotiators .............................................................................. 65

4.10

Procedural Openings and Issues in Negotiation ............................................................ 66

4.10.1

Negotiator Power and Influence ...................................................................................... 66

4.11

Structured Decision Making for Negotiations ................................................................ 69

4.11.1

Background Materials ....................................................................................................... 72

5 simulation exercises

5.1

Purpose, Value and Scope ................................................................................................. 73

5.2

Simulation Exercise # 1 The Vancouver River Part One .............................................. 73

5.2.1

Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 73

5.2.2

The Simulation .................................................................................................................. 74

5.2.3

Background Materials ........................................................................................................76

5.2.3.1

Theory ................................................................................................................................ 76

5.2.3.2

Supporting Documentation ............................................................................................. 80

5.2.4

Discussion Questions ....................................................................................................... 80

5.3

Simulation Exercise # 2 The "Tree" ................................................................................ 83

5.3.1

Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 83

5.4

Simulation Exercise # 3 Positions vs Interests .............................................................. 84

5.4.1

Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 84

5.5

Simulation Exercise # 4 The "Prisoner's Dilemma" ...................................................... 85

5.5.1

Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 85

5.5.2

Prisoner's Dilemma Exercise ............................................................................................ 86

5.6

Simulation Exercise # 5 The Vancouver River Part Two ................................................ 88

5.6.1

Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 88

5.6.2

The Simulation .................................................................................................................. 90

5.6.3

Background Materials ....................................................................................................... 93

5.7

Simulation Exercise # 6 The Elinehtton River Basin .................................................... 94

viii

FAO Training Manual for International Watercourses and River Basins

Table of contents

5.7.1

Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 94

5.7.2

The Simulation .................................................................................................................. 95

5.8

Simulation Exercise # 7 An International

Groundwater Negotiation Simulation ........................................................................... 99

5.8.1

Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 99

6 conclusion

Conclusion ........................................................................................................................................ 103

glossary

Glossary .......................................................................................................................................... 105

appendices

Appendix A

United Nations Convention on the Law of the Non-navigational Uses of

International Watercourses ............................................................................................. 111

Appendix B

World Bank Operational Manual ................................................................................... 133

Appendix C

Helsinki Rules (Campione Consolidation) ................................................................... 137

Appendix D

Abstract from Commentary to the Helsinki Rules

on the Uses of the Waters of International Rivers ........................................................ 157

Appendix E

Convention on the Protection and Use of

Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes ................................................ 163

Appendix F

Adversaries into Partners: International Water Law and

the Equitable Sharing of Downstream Benefits ........................................................... 185

Appendix G

The Role of Customary International Water Law ......................................................... 207

Appendix H

Beyond the River: The Benefits of Cooperation

on International Rivers ................................................................................................... 209

Appendix I

Current Development: The 1997 United Nations

Convention on International Water Courses ................................................................ 225

ix

x

FAO Training Manual for International Watercourses and River Basins

setting the scene

1

InTrODucTIOn

Fresh water is vitally important to human life. Due to this truth, there is a global water crisis which

requires worldwide attention. Nearly half of the world's population is located within one or more

of over 260 international drainage basins shared by two or more states, and at least 145 nations

have territory within international basins. In response to the emerging global crisis in water

scarcity, there has been a global water agenda in the international forum since 1972. Governments,

experts, and non-governmental organizations have been collaborating in response to this crisis,

with transboundary water agreements being especially important in providing resolutions to this

global water crisis. However, there has yet to be a focus on transboundary water issues and this

manual, in part, has been created in response to that. Transboundary river agreements have played

an increasingly critical role in building confidence in pursuit of peace and security on a regional and

global scale. International agreements governing the utilization of transboundary water resources

have the tendency to stabilize and enhance security on a regional level. Disagreements over water can

heighten international tension and lead to conflict, but the very process of reaching an understanding

for cooperation in a transboundary water context has a stabilizing effect and creates an increasingly

transparent atmosphere. The mere task of negotiation usually widens political participation, builds

political stability and spreads confidence between the basins states. Agreements have the ability

to ameliorate tension and reduce the likelihood of war, but even where the riparians fail to reach

an agreement and merely agree to share information and exchange data, increased confidence

often emerges. Joint cooperation around transboundary watercourses paves the way for regional

cooperation in other domains of politics, economics, environment, and culture.

Negotiation and implementation of transboundary water agreements contribute to peace and security.

Collective action and greater cooperation on a global level are necessary for the achievement of goals

in relation to the eminent global water crisis. Transboundary river agreements act as capacity building

measures to enhance peace and security regionally and globally. The perception by countries of the

water problem as a zero-sum game leads these countries to seek to increase control over water, even

to the detriment of others, and tensions over water have contributed to an uneasy political climate

in places such as Central Asia. The presence of a functional treaty can decrease the severity and

frequency of water disputes. Lessons regarding negotiation and implementation of transboundary

water agreements, by facilitating cooperation and learning, give countries the opportunity to exchange

lessons and experiences with each other in a supportive environment.

1

2

FAO Training Manual for International Watercourses and River Basins

2

watercourses and river basins

waTercOurses anD rIver basIns

Water plays a vital role in our society. It is important for nourishment, irrigation and agriculture,

fishing and fish farming, conservation and the environment, flood control, and hydropower

generation. It is also important in terms of navigation, effecting commerce, transportation,

recreation and travel. This chapter explains the hydrological cycle and introduces the reader into the

particularities of international watercourses and river basins.

2.1

Hydrology and the Hydrological cycle

The presence of large quantities of water in each of its three phases (ice, liquid water and vapour) is a

distinguishing feature of the Earth.

Water plays a particularly essential role in the climate system:

· Latent heat processes are a major component of the energy balance.1

· Water vapour and clouds play a major part in determining the radiative balance of the Earth.

· Without water there would be no ecological system for life to exist, there would be

no biosphere.

Most of the Earth's water is in the oceans and only a tiny amount is in the atmosphere. Nevertheless,

atmospheric water vapour and clouds are of major importance in the climate system. The simple fact

that water can exist in each its three phases under the temperature and pressure conditions of the

Earth is also an important factor in determining the Earth's climate:

· In its solid phase, water in glaciers is important for storage of water and because it increases

the Earth's albedo.2

· Water is readily transported as vapour.

· Water formation in the form of cloud droplets: clouds are efficient cleansers of atmospheric

pollution and clouds contribute to an increased global albedo.

Table 1: THe waTer DIsTrIbuTIOn:

Water source:

Percentage of total Water:

Oceans, Seas, & Bays

96.5

Ice caps, Glaciers, & Permanent Snow

1.74

Groundwater

1.7

Soil Moisture

0.001

Ground Ice & Permafrost

0.022

Lakes

0.013

Atmosphere

0.001

Swamp Water

0.0008

Rivers

0.0002

Biological Water

0.0001

Total

100

source: gleick, P. H., 1996: Water resources. In encyclopedia of climate and Weather, ed. by s. H. schneider, oxford university Press,

new York, vol. 2, pp.817-823.

3

1 Latent heat describes the amount of heat which is absorbed or evolved in changing the state of a substance without changing its

temperature, e.g., in freezing or vaporizing water.

2 Earth's albedo is the reflectivity of the Earth's atmosphere and surface combined.

watercourses and river basins

The following diagram shows the principal components of the transformations which water

undergoes. This is known as the Hydrological Cycle.

fIgure 1: PrIncIPal cOMPOnenTs Of THe "HyDrOlOgIcal cycle"

source: school of earth and environment, university of leeds.

2.1.1

explanation of the Processes:

· Evaporation: Takes place from the surface of the oceans, from land and from wet vegetation.

It is strongly temperature-dependent and requires latent heat to be supplied.

· Transpiration: This is the loss of water vapour from the leaf cells of plants. Soil water is taken

up by plant roots and lost to the atmosphere through the leaves, mainly during the day.

· Atmospheric Water Vapour Transport: This is the transport of water in its vapour phase by

the circulation of the atmosphere.

· Cloud Formation: Clouds form when water vapour condenses to form water droplets. This

happens when air cools to a temperature equal to its dew point. The amount of water vapour

in the air can be measured by its vapour pressure. There is a limit to the amount of water

vapour which air can hold at a given temperature. This limit is called the saturation vapour

pressure. The saturation vapour pressure increases rapidly with temperature.

4

FAO Training Manual for International Watercourses and River Basins

2

watercourses and river basins

fIgure 2: saTuraTIOn vaPOur Pressure Of aIr (I.e. THe Pressure aT wHIcH THe aIr

becOMes saTuraTeD) as a funcTIOn Of TeMPeraTure.

Note the very rapid increase with temperature.

source: school of earth and environment, university of leeds.

5

watercourses and river basins

· If air containing a fixed amount of water vapour is cooled (for example because it rises which

causes it to expand), the saturation vapour pressure will decrease. Eventually a temperature

will be reached where the saturation vapour pressure is equal to the actual vapour pressure of

the air. This temperature is the dew point. Any further decrease in temperature would mean

that the vapour pressure would be greater than the saturation vapour pressure, which does

occur to any significant extent. Hence some of the water vapour must condense as liquid

water droplets. This process also involves the release of latent heat. Another way of measuring

the water vapour content is using the relative humidity.

vapour pressure

Relative humidity =

x 100 %

saturation vapour pressure

· As air cools, its relative humidity increases until it reaches 100%. Then condensation must

occur if there is any further cooling.

· In reality, however, condensation cannot occur quite as easily as the above suggests.

Condensation usually only takes place on the surface of small particles called aerosols.

· If the temperature is below 0oC then ice crystals form rather than liquid water droplets.

· Precipitation: water droplets coalesce and eventually become large enough to settle

significantly under gravity. As they fall, they sweep up more droplets and rain droplets

are formed.

2.1.2

relative Importance of the water exchange Processes:

Figure 3 shows the amount of water involved in exchanges between the reservoirs explained above.

The exchanges are measured relative to a total annual global precipitation of 100 units.

The most important point to note is that approximately two-thirds of the precipitation over land is

accounted for by evapotranspiration over land. The other third is due to horizontal transport of water

vapour which was evaporated from the oceans. Now evapotranspiration is strongly affected by land-

use and vegetation. Thus there is the potential for a strong feedback between changes in land-use

and local precipitation. For example, deforestation can mean smaller evapotranspiration which leads

to reduced rainfall.

6

FAO Training Manual for International Watercourses and River Basins

2

watercourses and river basins

fIgure 3: PrIncIPal excHanges anD reservOIrs In THe HyDrOlOgIcal cycle.

2.1.3 The relationship between surface and ground water resources

The hydrologic cycle teaches that, more often than not, surface and ground water resources are

interlinked and highly interdependent. In other words, most of the world's rivers, streams and lakes

are fed by or contribute to one or more aquifers. As a result of these relationships, interlinked surface

and ground waters form a system whereby activities in (or changes to) one part of the system can

result in consequences to other parts of the system.

7

watercourses and river basins

fIgure 4: grOunD waTer-surface waTer InTeracTIOn

The diagram illustrates the

typical relationship between

ground water and surface

water. The surficial aquifer is

recharged through rainfall on

and infiltration into the upland

areas between drainages.

Discharges from the surficial

aquifer occur into local

streams and rivers.

2.1.4

The components of a watercourse:

· Surface Waters

»

Drainage Basin land area drained by an interrelated system of stream, river, lake and/

or other surface waters.

»

Watershed or catchment area drainage area for subsets or sub-basin units of the

drainage basin (i.e., tributaries, streams, etc.).

»

Divide high point on land, which separates two drainage basins or watersheds.

»

Tributary a lesser river/stream that feeds into the main river/stream.

»

Mouth of a river endpoint of a river where it flows into another river or into the sea.

»

Source or headwaters of a river origin of a river/stream.

· Ground Waters:

»

Ground Water water occupying voids, cracks or other spaces between particles of clay,

silt, sand, gravel or rock within a geologic formation.

»

Aquifer a permeable geologic formation (such as sand or gravel) that has sufficient

water storage and transmitting capacity to provide a useful water supply via wells and

springs.

»

Water Table the level in the geologic formation below which all voids or cracks are

saturated; the top of the saturated zone.

»

Recharging Aquifer an aquifer that is connected to the hydrologic cycle and has a

continuous and significant source of recharge.

»

Non-Recharging Aquifer an aquifer that is completely detached from the hydrologic

cycle and obtains insignificant or no recharge.

8

FAO Training Manual for International Watercourses and River Basins

2

watercourses and river basins

»

Ground Water Mining pumping an aquifer at a rate exceeding recharge.

»

Aquifer-Stream relationship:

Effluent (Gaining) Stream a relationship whereby the water table is at higher

elevation than an intersected stream channel and slopes downward toward the

stream. In such relationships, the aquifer recharges the stream.

Influent (Losing) Stream a relationship whereby the water table slopes downward

from the stream to the aquifer. In such relationships, stream water percolates into

the underlying aquifer recharging the aquifer.

Ultimately, the hydrologic cycle exhibits that surface and ground water resources are interlinked and

highly interdependent. Most of the world's rivers, streams and lakes are fed by or contribute to one or

more aquifers. As a result of these relationships, interlinked surface and ground waters form a system

whereby activities in, or changes to, one part of the system can result in consequences to other parts

of the system. While this understanding has been recognized among scientists for decades, until

recently it received little attention in the political or legal arenas. More troubling, this understanding is

still sorely neglected in the vast majority of international agreements.

The value of water is also an important aspect of international watercourses. How states value water

is especially relevant for resolving conflicts in a multitude of ways. For some, water is a property

right and a commodity that is subject to the free market; others value it in relation to its significance

for human survival; others, still, assess water as an integral component of the natural environment;

and some appreciate water in relation to its cultural, religious, and societal significance. The idea of

valuation often is at the core of disputes over fresh water resources. On the international front, fresh

water disputes often involve issues of human rights, health, the right to develop and environmental

and pollution issues, all of which relate to how States and their citizens value water.

The implications of issues regarding both the hydrological cycle and the importance of water

valuation are extremely relevant to the principle of equitable and reasonable use of water which lies at

the core international law.

2.2

International watercourses and river basins3

River basins and groundwater aquifers which cross international boundaries present increased

challenges to effective water management where hydrologic needs are often overwhelmed by political

considerations. While the potential for paralyzing disputes are especially high in these basins, the

record of violence is actually greater within the boundaries of a nation. Moreover, history is rich with

examples of water acting as a catalyst to dialogue and cooperation, even among contentious riparians.

2.2.1

background to International watercourses

There are over 260 watersheds and countless aquifers which cross the political boundaries of two or

more countries. International basins cover 45.3% of the land surface of the earth, affect about 40% of

the world's population, and account for approximately 80% of global river flow (Wolf et al. 1999).

These basins have certain characteristics that make their management especially difficult, the most

notable of which is the tendency for regional politics to regularly exacerbate the already difficult task

of understanding and managing complex natural systems.

9

1 The material in this section relies on material originally developed by Professor Aaron Wolf including Beach, L., J. Hamner, J.

Hewitt, E. Kaufman, A. Kurki, J. Oppenheimer, and A. Wolf. Transboundary Freshwater Dispute Resolution: Theory, Practice and

Annotated References. Tokyo and New York: United Nations University Press, 2000.

watercourses and river basins

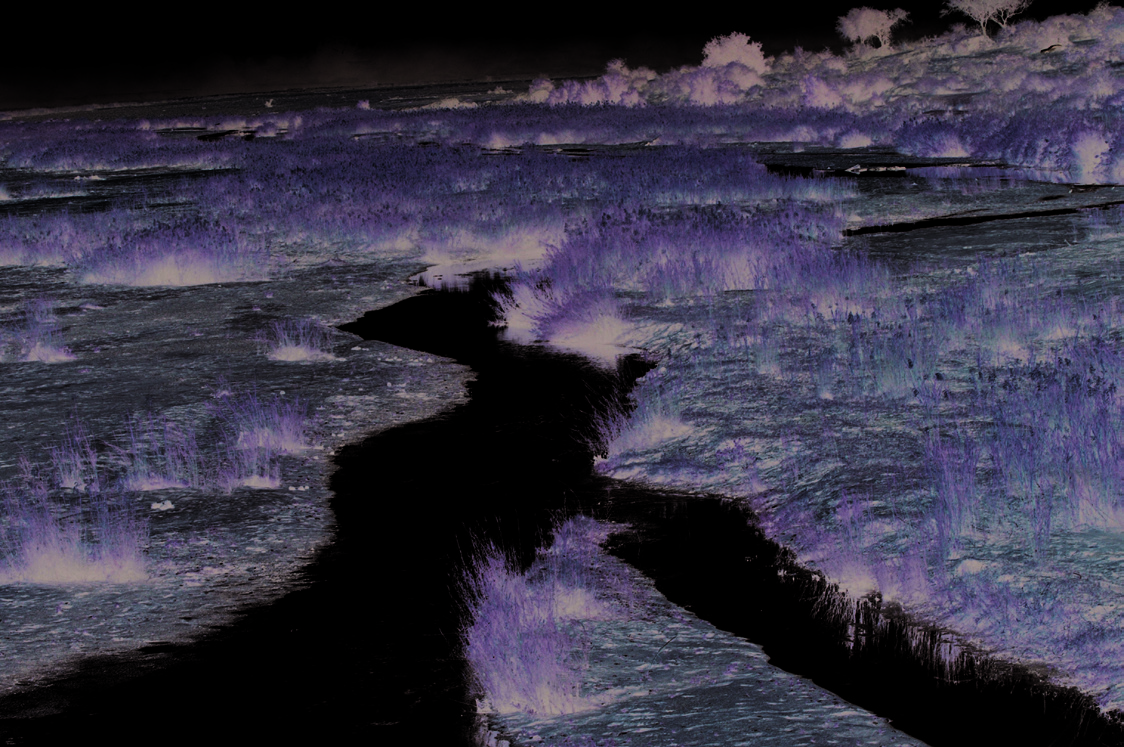

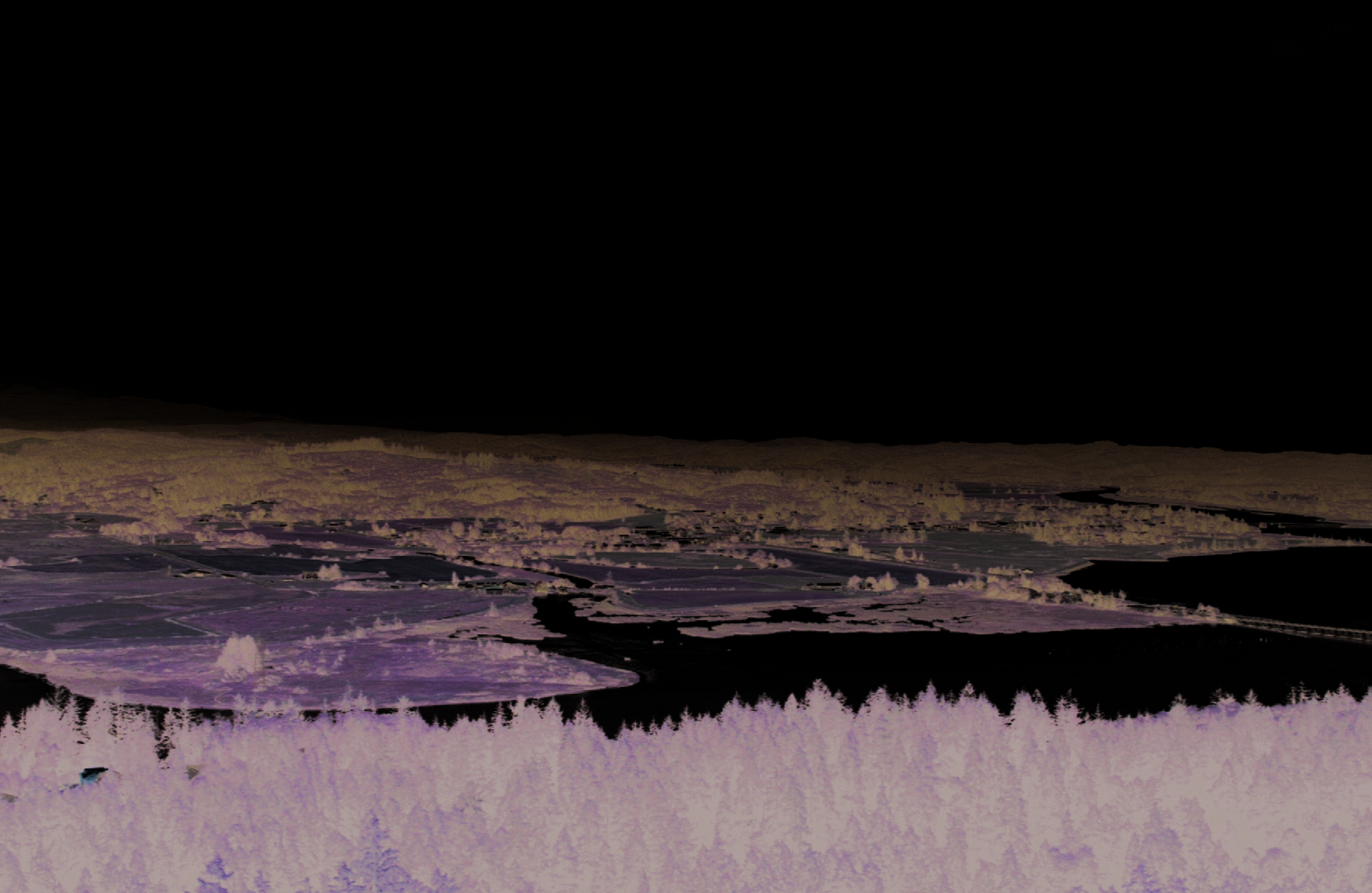

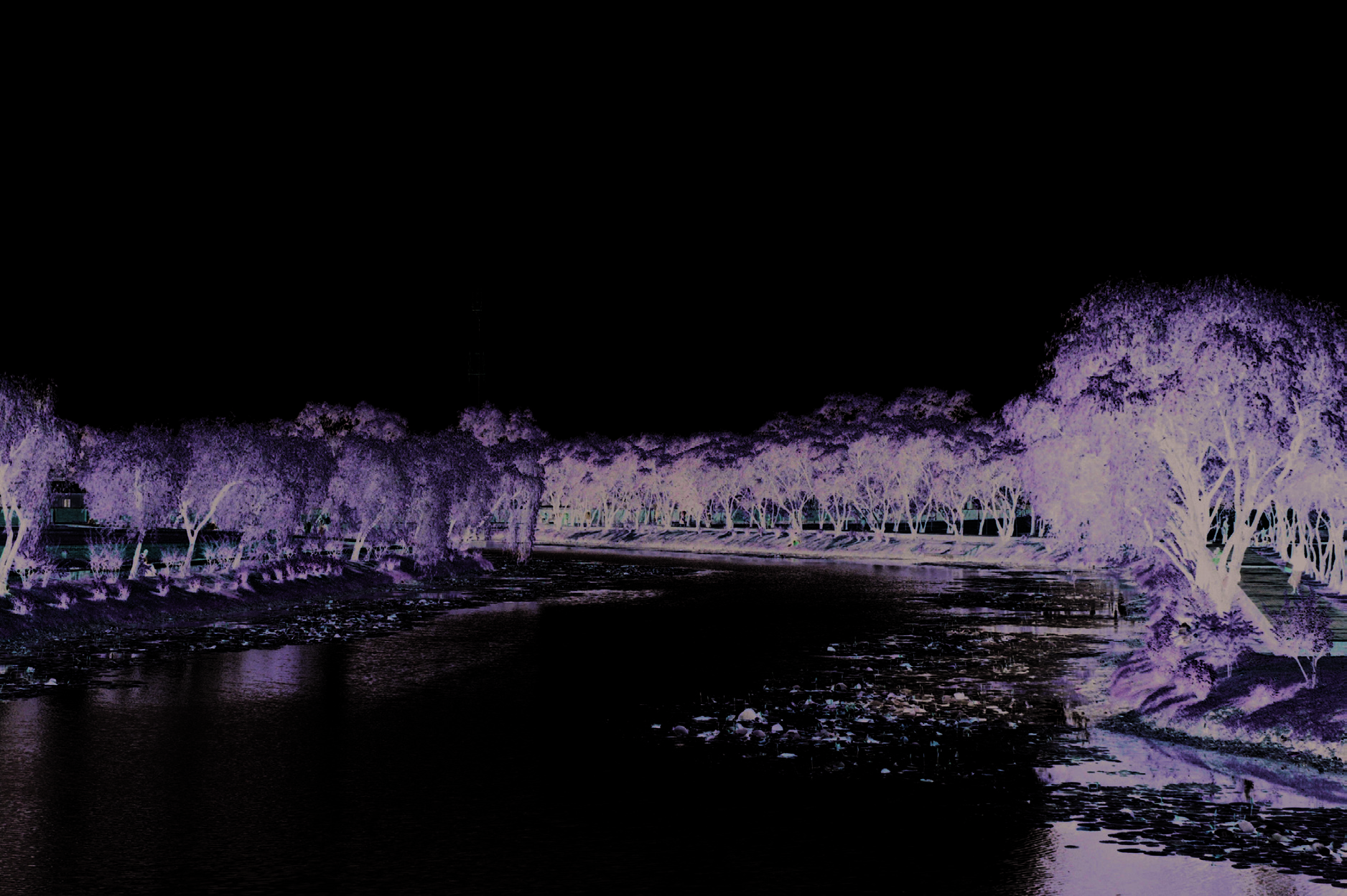

fIgure 5: InTernaTIOnal basIns Of THe wOrlD

2.2.1.1. Traditional chronology

According to Wolf, a general pattern has emerged for international basins over time. Generally

riparians of an international basin implement water development projects unilaterally, first on water

within their territory, in attempts to avoid the political intricacies of the shared resource. At some

point, one of the riparians, usually the regional power, will implement a project which impacts at least

one of its neighbours. This might be to continue to meet existing uses in the face of decreasing relative

water availability, as for example Egypt's plans for a high dam on the Nile or Indian diversions of the

Ganges to protect the port of Calcutta. It might also be to meet new needs reflecting new agricultural

policy, such as Turkey's GAP project on the Euphrates. This project which impacts one's neighbours

can, in the absence of relations or institutions be conducive to conflict resolution, or become a flash

point for heightened tensions and regional instability requiring years or, more commonly, decades to

resolve.

10

FAO Training Manual for International Watercourses and River Basins

2

watercourses and river basins

2.2.1.2. Preventive Diplomacy

Wolf notes:

[T]he record of acute conflict over international water resources is overwhelmed by

the record of cooperation. The last 50 years has seen only 37 acute disputes (those

involving violence) and, during the same period, 157 treaties negotiated and signed.

In fact, the last (and only) war fought specifically over water took place 4,500 years

ago, between the city-states of Lagash and Umma along the Tigris River. Total

numbers of events in the last 50 years are equally weighted towards cooperation:

507 conflict-related events, and 1,228 cooperative. The most vehement enemies

around the world either have negotiated water sharing agreements, or are in the

process of doing so as of this writing. Violence over water seems neither strategically

rational, hydrographically effective, nor economically viable. Shared interests along a

waterway seem to consistently outweigh water's conflict-inducing characteristics.

Furthermore, once cooperative water regimes are established through treaty, they turn out to be

impressively resilient over time, even between otherwise hostile riparians, and even as conflict is

waged over other issues. For example, the Mekong Committee has functioned since 1957, exchanging

data throughout the Vietnam War. Secret `picnic table' talks have been held between Israel and Jordan,

since the unsuccessful Johnston negotiations of 1953-55, even as these riparian nations were in a legal

state of war. Further, the Indus River Commission not only survived through two wars between India

and Pakistan, but treaty-related payments continued unabated throughout the hostilities.

Despite their complexity, the historical record shows that water disputes get resolved, and that

the resulting water institutions can be tremendously resilient. The challenge for the international

community is to get ahead of the "crisis curve", to help develop institutional capacity and a culture

of cooperation in advance of costly, time-consuming crises, which in turn threaten lives, regional

stability, and ecosystem health.

One productive approach to the development of transboundary waters has been to examine the

benefits in a basin from a multi-resource perspective. This has regularly required the riparians to get

past looking at the water as a commodity to be divided, and rather to develop an approach which

equitably allocates not the water, but the benefits derived.

According to Wolf, the most critical lessons learned from the global experience in international water

resource issues are as follows:

1. Water crossing international boundaries can cause tensions between nations which share the

basin. While the tension is not likely to lead to warfare, early coordination between riparian

states can help ameliorate the issue.

2. Once international institutions are in place, they are tremendously resilient over time, even

between otherwise hostile riparian nations, and even as conflicts are waged over other issues.

3. More likely than violent conflict occurring is a gradual decreasing of water quantity or quality,

or both, which over time can affect the internal stability of a nation or region, and act as an

irritant between ethnic groups, water sectors, or states/provinces. The resulting instability may

have effects in the international arena.

4. The greatest threat of the global water crisis to human security comes from the fact that

millions of people lack access to sufficient quantities of clean water for their well being.

11

watercourses and river basins

2.2.1.3. bi/multilateral entities for Managing, allocating, Protecting, and

Developing Transboundary waters

Commissions and other bi/multilateral organizations are especially relevant to the management,

allocation, protection, and development of transboundary waters. Such entities have been employed

on a multitude of transboundary rivers in Europe; in North America, on the Great Lakes, the Rio

Grande and the Colorado River; in Africa on the Okavango and Zambezi Rivers and for Lake Chad;

in Asia on the Mekong River; in Latin America on the frontier waters between Guatemala and

Mexico and on the Uruguay River.

"Meaningful progress in improving water resources management across jurisdictional boundaries requires

effective mechanisms to be developed for an informed and structured dialogue about contentious issues as a

means of resolving disagreements as they arise, and an agreed means for implementing the decisions that are

taken. This requires an open and transparent process to be put into effect, one that facilitates the development

of mutual trust and understanding over time. Creating river basin organizations (RBOs) has been actively

promoted as a way of peacefully managing shared water resources and there are many good examples of RBOs

from across the globe."

It has to be mentioned that often there exists no `perfect' solution in a transboundary water

issues--but only the `best' possible under all of the current political, social, economic and

environmental circumstances.

Negotiations surrounding the role and functions of bi/multilateral entities have revolved around

power; politics; history; culture; the economy and the environment.

2.2.2

further reading

Amery, Hussein and Aaron Wolf, eds., Water in the Middle East: A Geography of Peace

(Austin: University of Texas Press, 2000).

Beach, L., J. Hamner, J. Hewitt, E. Kaufman, A. Kurki, J. Oppenheimer, and A. Wolf,

Transboundary Freshwater Dispute Resolution: Theory, Practice and Annotated References

(Tokyo and New York: United Nations University Press, 2000).

Biswas, Asit ed., International Waters of the Middle East: From Euphrates-Tigris to Nile

(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994).

Blatter, Joachim and Helen Ingram, eds., Reflections on Water: New Approaches to Transboundary

Conflicts and Cooperation (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2001).

Cech V., Thomas, John Wiley and Sons, "Principles of Water Resources: History, Development,

Management and Policy", Inc. 2003

Elhance, Arun Hydropolitics in the Third World: Conflict and Cooperation in International River Basins

(Washington DC: US Institute of Peace Press, 1999).

Kliot, Nurit, Deborah Shmueli, and Uri Shamir (1997), Institutional Frameworks for the Management of

Transboundary Water Resources, Haifa, Israel: Water Research Institute. (Two volumes.)

12

FAO Training Manual for International Watercourses and River Basins

2

watercourses and river basins

Milich, Lenard and Robert G. Varady, "Openness, Sustainability, and Public Participation: New Designs

for Transboundary River Basin Institutions", The Journal of Environment and Development, 8 (3) 258-306

(1999).

Paisley, Richard Kyle, "International Water Law, Transboundary Water Resources and Development Aid

Effectiveness", 1 Indian Jurid. Review 67 (2004).

Paisley, Richard Kyle, Cuauhtémoc León, Boris Graizbord and Eugene Bricklemyer, Jr., "Transboundary

Water Management: An Institutional Comparison among Canada, the United States and Mexico",

Ocean and Coastal Law Journal (University of Maine School of Law), 9 (2), 177 (2004).

Paisley, Richard Kyle, "Adversaries into Partners: International Water Law and Down Stream Benefits",

Melbourne Journal of International Law, 3 (2) 280 (2002).

Paisley, R. K., and McDaniels T., "International Water Law, Pollution Risk and the Tatshenshini River",

35 Nat. Res. J. 111 (1995).

Phillips, David et al., "Trans-Boundary Water Cooperation as a Tool for Conflict Prevention and for

Broader Benefit-sharing". Prepared for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Sweden. Phillips Robinson

and Associates, Windhoek, Namibia (2006).

Sadoff, C.W. and Grey, David , "Beyond the River: the Benefits of Cooperation on International

Rivers", Water Policy, 4, 389-403, (2002).

Wolf, Aaron ed., Conflict Prevention and Resolution in Water Systems (Cheltenham, UK: Edward

Elgar, 2001).

13

14

FAO Training Manual for International Watercourses and River Basins

3

International law in context

InTernaTIOnal law In cOnTexT4

3.1

International law

International law is the set of rules that states use to manage their relations. International law is

different from national law. In a national legal system, a central law-making body or legislature makes

the laws, the executive implements the laws and secures their observance and the judiciary interprets

and applies the law. There are no equivalents to these bodies in the international legal system.

The main concept of international law is sovereignty, defined as "the supreme, absolute and

uncontrollable power by which any state is governed". A state's sovereign power to control activities

inside its boundaries is limited by the international legal rules that the state has agreed to follow.

In the international law field, the tension between sovereignty and protection of the environment

often surfaces.

Sovereign states make the rules that govern their citizens and that apply within the limits of their

territorial jurisdiction, including the land within their borders, internal waters, territorial sea and the

air above these areas extending to the point at which the legal regime of outer space begins. Each of

these territorial areas is defined by legal rules. Areas outside the national jurisdiction of each state

include the high seas, deep sea bed, atmosphere and outer space, and certain limited land areas in

Antarctica. These areas are sometimes called the "global commons" and international rules also govern

these areas.

International legal rules develop by consent among states. Treaties affect only those states that

consent or agree to be legally bound by the written agreement. International laws are formed when

states need to cooperate with other states. This need to cooperate creates an incentive to comply

with international law. However, conditions do change, which can lead to violations of international

law. Law breaking states may attract diplomatic pressures, sanctions, reprisals, and in extreme cases,

military intervention.

International law is derived from express written agreements between states, usually called treaties,

as well as from other sources such as custom, the customary practice of states who believe they are

legally required to conform to certain practices.

International law encompasses global, multilateral or bilateral agreements, as well as customary law,

state practice, institutions that develop and administer the law and the extra-territorial application

of domestic law. Among other things, international law attempts to control, limit and prevent

environmental damage and promote a clean and healthy environment. Environment is a broad topic,

including fresh and salt water, soil, land, atmosphere, all living creatures and all other aspects of the

physical environment.

International law is not confined to purely environmental subjects, but is very much intertwined

with other pressing issues facing the world: the North-South divide; excessive and inequitable

consumption patterns; poverty; human health; human rights; international and national trade; and

investment and financial regimes.

15

4 The material in this section relies on materials originally developed by Linda Nowlan including in Nowlan, Linda et. al., "Kyoto,

Pops and Straddling Stocks: Understanding Environmental Treaties", West Coast Environmental Law Association, Vancouver,

Canada. (2003).

International law in context

3.2

Hard law and soft law

The sources of international law are sometimes characterized as "hard law" and "soft law". Treaties are

hard law. States that negotiate and ratify treaties intend to be legally bound and are expected to make

all efforts to comply with these laws. However, soft law is increasingly important in the development

of international law. Soft law has been called more flexible, dynamic, and democratic than hard law.

Its creation does not depend on formal negotiations between authorized diplomats. Soft law can be

initiated or substantially influenced by NGOs, international institutions like UNEP or the World Bank.

Different groupings of states can also significantly affect soft law development as in the case of the

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

Hard law includes conventions, treaties, agreements and protocols, all different names for legally

binding written agreements between states. In the field of international environmental law, treaties

or MEAs contain most international legal obligations. Treaties are created to codify existing and

emerging practices and to create new binding rules. All the international rules concerning treaties

that have developed over years of state practice have been collected and codified in a treaty called the

Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties. The Vienna Convention defines what a treaty is, outlines the

procedures for states to demonstrate their consent to be bound by the treaty, sets the rules for treaty

procedure, and addresses other matters such as determining priority between treaties.

Soft law refers to documents like declarations, guidelines, resolutions and statements of principle

or codes of conduct that are not legally binding. It includes United Nations resolutions, conference

declarations such as the Rio and Stockholm Declarations and statements from major UN bodies such

as the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP). Some observers would also classify statements

from major non-governmental organizations such as the IUCN WWF World Conservation Strategy as

being a form of soft law.

Soft law declarations may also be negotiated by private sector corporations, or by these corporations

in partnership with an international organization. Examples include UNEP's Statement on Financial

Institutions and the Environment and the numerous corporate social responsibility commitments made

by individual corporations or by geographical or industry sectors. Some soft law statements like the

Global Reporting Initiative, an attempt to harmonize corporate social and environmental reporting

procedures, cut across industry sectors.

Soft law is becoming more common internationally. Soft law instruments may lay the foundation for

later legally binding agreements. For example, the 1989 UNEP FAO Prior Informed Consent (PIC)

guidelines for certain toxic chemicals and pesticides led to the 1998 Rotterdam Prior Informed Consent

(PIC) Convention, and the FAO's 1983 International Undertaking on Plant Genetic Resources led to the

adoption of the 2001 International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture.

Though soft law generally creates aspirational goals rather than strict legal duties, this is not always

the case. On occasion a non-binding document is so precise and detailed that it could easily be

mistaken for a treaty. An example is the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, revised in 2000.

As the Foreword from the OECD Secretary General states: the Guidelines are an example of the type

of multilateral instrument that will be used more and more in future to set rules, which, though not

legally binding, are meant to work, be implemented, followed up and monitored.

An important aspect of soft law is decisions of "Conferences of the Parties" (or COPs) to various

treaties. Technically, these decisions are not legally binding unless they are incorporated into the

16

FAO Training Manual for International Watercourses and River Basins

3

International law in context

treaty, but they often flesh out essential details of treaties. For instance, extensive detailed decisions

of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change are essential to the working and effectiveness of

the Kyoto Protocol. Although technically not legally binding, the COP decisions on implementation of

the Kyoto Protocol have a force that is almost equivalent to the Protocol itself, setting out in detail how

compliance will be determined and what states are required to do.

Whether states and others comply with soft law commitments in the same manner as they do binding

treaty law remains a subject of debate. Initial research findings suggest that soft law compliance

is more likely when the soft law instruments are linked to binding international agreements or to

existing regional and national legal arrangements.

3.3

what is a treaty?

A treaty between nations is similar to a legal contract between individuals. It is a written agreement

that all parties involved consented to and intend to guide their actions. In the international arena

treaties are agreements between states to take common action on a problem that transcends

national boundaries. Treaties have a fixed geographic scope. A treaty often, but not always, creates an

international organization to carry out the work defined by the Parties, take new decisions and further

develop the applicable international law.

The Vienna Convention defines a treaty as "an international agreement concluded between states in

written form and governed by international law whether embodied in a single instrument or in two or

more related instruments and whatever its particular designation".

Treaties may be known by other names, such as conventions, protocols, covenants, pacts, charters

or agreements, but the different names have no legal significance. If the agreement is between states,

in written form, and is intended to be legally binding and governed by international law, then it is

a treaty.

To decide whether a particular agreement is a treaty, the intent of negotiating parties must be

examined. If they intended to be bound by international law, there will usually be some evidence of

that intent in the words of the agreement. If the agreement says "The Contracting Parties hereby agree

...", or uses other terms such as "rights" or "obligations", that is evidence of an intention to be bound.

If the agreement says that the states (not Parties) "declare" their intent, as in the Declaration on the

Establishment of the Arctic Council, that is evidence that the states did not intend to create a legally

binding treaty. The Rio Declaration on Environment and Development is another example of a non-

binding statement by states. States intentionally use the title `Declaration' when they do not intend to

create legally binding commitments, and on occasion even more explicitly emphasize that a document

is not a treaty, as in the "Non-Legally Binding" Forest Principles adopted in Rio.

A treaty cannot conflict with a "peremptory norm" of international law (jus cogens norm). These norms

are universal, applicable to all states and cannot be contracted out of through the treaty process.

Further, Article 53 of the Vienna Convention states that a treaty is void if it conflicts with a peremptory

norm of international law. The most widely known examples of these norms are prohibitions against

genocide and slavery.

17

International law in context

3.4

who can agree to be legally bound by a Treaty

Nation states are the primary subjects of the international legal system. The majority of treaties are

between states. Some other entities such as associations of states, like the European Union or the

United Nations also have the "legal personality" which allows them to conclude treaties. A treaty

can be concluded between a state and an international organization, or between two or more

international organizations, but not between a state and a corporation.

3.4.1

bilateral or Multilateral

Treaties may be bilateral--i.e., have two states as Parties--or multilateral--i.e., have more than

two states as Parties. The major environmental treaties, such as the climate change and biodiversity

agreements, are multilateral. Both these treaties have 186 Parties as of 2002. These are very high rates

of membership--there are 191 states that are members of the United Nations.

3.4.2

framework and self-contained Treaties

A "framework treaty" is a type of treaty that contains general obligations, usually with a procedure

for reaching more detailed agreement on specific obligations through protocols or subsequent

legal agreements in the future. This type of multilateral treaty has become common for global

environmental subjects. Examples of framework treaties include the UN Framework Convention on

Climate Change, the Convention on Biological Diversity and the Vienna Convention for the Protection of the

Ozone Layer. All three of these treaties have at least one Protocol: the Kyoto Protocol under the UNFCC;

the Biosafety Protocol under the CBD; and the Montreal Protocol on ozone, the only one of these

Protocols in force as of 2002.

A self-contained treaty works through annexes or appendices which are revised periodically by the

Contracting Parties at Conferences or meetings. Examples of this type of Convention include the

World Heritage Convention, which maintains a World Heritage List of natural and cultural sites whose

outstanding values should be preserved for all humanity, and the Convention on International Trade in

Endangered Species (CITES), which maintains three different Appendices of species at risk. Revising an

Appendix or List is usually easier than negotiating a new Protocol or addition to a treaty, but is only

suitable for subjects that can easily be set out in a list.

3.4.3

Protocols

In the environmental field, the term "Protocol" is usually used to describe a legally binding agreement

that elaborates on, or contains detailed substantive commitments to implement the objectives of

a framework treaty. For example, a number of Protocols for specific air pollutants exist under the

UNECE Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution. Protocols must be agreed, signed and

ratified separately from the framework treaty. An Optional Protocol to a treaty establishes additional

rights and obligations, and allows some willing Parties to go farther than the original treaty. An

example from the human rights field is the Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and

Political Rights.

18

FAO Training Manual for International Watercourses and River Basins

3

International law in context

3.4.4

How Does a state agree to a Treaty?

The Vienna Convention provides that states can demonstrate their intent to be legally bound by a treaty

in a variety of ways, including: signature, exchange of instruments constituting a treaty, ratification,

acceptance or approval, accession, or any other agreed means.

3.5.4.1 signature

Most often a state will indicate its intention to become a Party by first signing the treaty. Two different

purposes for signature must be distinguished: a state can sign a treaty to indicate approval of the

final text or to show consent to be bound by the treaty. Signature alone is usually insufficient to show

consent to be legally bound to a multilateral treaty, but shows that the state is willing to proceed

with the international law-making process. Additional steps, such as ratification, are usually required.

Environmental treaties commonly state that they will be "open for signature" until a specified date.

When a state signs a treaty, it agrees to refrain from any acts which would defeat the object and

purpose of the treaty.

3.5.4.2 exchange of Instruments

This procedure allows states to exchange instruments, or written documents, to conclude the treaty.

Usually, an exchange of instruments will be used to formalize a bilateral treaty.

3.5.4.3 ratification

This is the most common way states show consent to be bound by environmental treaties. The Vienna

Convention defines ratification as "the international act so named whereby a state establishes on the

international plane its consent to be bound by a treaty". Ratification occurs when a state completes

the necessary formal procedures for executing an instrument of ratification, and then exchanges this

document with another state for a bilateral treaty or, for a multilateral treaty, sends it to a depository,

the place where all the documents of ratification are collected.

3.5.4.4 acceptance or approval

These are alternatives to ratification which have the same legal effect as ratification. Many

environmental treaties say that they are "subject to ratification, acceptance or approval", leaving it up

to the state to decide which procedure to follow.

3.5.4.5 accession

This procedure allows a state to agree to be bound by a treaty that has already been concluded by

other states. Accession will be used, for example, if the treaty has come into force. Accession has the

same legal effect as ratification.

3.5.4.6 Party to a Treaty

Before a treaty enters into force, a state that has demonstrated its intent to be bound is called a

"contracting state." Only after the treaty has entered into force is a state that has consented to be

19

International law in context

bound called a "Party." Throughout this Guide, when the term "Party" is used, it refers to a state that is

legally bound by a particular treaty.

3.5.4.7 Depositary

To demonstrate that a state has agreed to the treaty, an instrument or document showing ratification

(or its equivalent) is deposited, or placed, in a specified location. A treaty will usually designate a

depositary such as a location in a country or, more often today, an international organization like

the United Nations. The UN Secretary General is the depositary for over 500 multilateral treaties.

Depositaries must accept all ratifications and documents related to the treaty, examine whether all

formal requirements have been met, deposit them, register the treaty and notify Parties of all new

developments regarding the treaty.

3.4.5

reservations

A state does not usually need to agree to every single provision of a treaty in order to become a Party

to that treaty. It can contract out of one or more of the treaty's obligations by entering a reservation to

the treaty. A reservation is defined by the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties as:

"A unilateral statement, however phrased or named, made by a state, when signing,

ratifying, accepting, approving or acceding to a treaty, whereby it purports to exclude

or to modify the legal effect of certain provisions of the treaty in their application to

that state."

For example, Norway is a party to the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling but

has issued a reservation about the catch quotes on whaling imposed by the treaty. The Convention

on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna (CITES) allows Parties to enter

reservations or a unilateral statement that it will not be bound by the provisions of the Convention

relating to trade in a particular species listed in the Appendices as endangered. This procedure has

been used, for example, by some African states for the elephant, and France, Denmark and Finland for

the mountain weasel. The underlying purpose of a more permissive policy regarding reservations is

based on the interest of encouraging as many states as possible to join treaties.

Reservations are allowed unless the treaty specifically states that they are not allowed. For example,

the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea and the Kyoto Protocol do not allow for reservations. A state

must agree to be legally bound by every provision of those treaties or decide not to consent to them

at all.

Reservations are forbidden if they are incompatible with the object and purpose of the treaty.

3.4.6

entry into force

A treaty enters into force and becomes binding law for those states that have consented to be bound

(and those states only) in a manner and on the date provided for in the treaty or as the negotiating

states may agree. The treaty itself will usually specify how it enters into force.

The most common way for a treaty to enter into force is when ratification by a set number of the

negotiating states occurs. For example, Canada signed and ratified the UN Fish Agreement (UNFA), or

the Agreement on Highly Migratory or Straddling Stocks, but it was not legally binding on Canada until it

20

FAO Training Manual for International Watercourses and River Basins

3

International law in context

entered into force. That treaty required thirty states to ratify it before it entered into force. The required

number of ratifications was reached in 2001, and UNFA entered into force on December 11, 2001.

After a state signs a treaty, but before it enters into force and becomes legally binding, a contracting

state is obliged to refrain from acts which would defeat the object and purpose of the treaty. In the

context of environmental treaties, this obligation means that a state would be prohibited from taking

any environmentally damaging action covered by the treaty before it entered into force.

Sometimes, to enter into force, a treaty specifies that additional requirements must be met by the

states that agree to be legally bound. The 1984 Protocol to the Convention on Long-Range Transboundary

Air Pollution required ratification by 19 states within the geographical scope of the protocol, namely

Europe, before it came into force. The Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer came

into force only after ratification by 11 states representing at least two-thirds of the 1986 estimated

global consumption of the controlled ozone depleting substances. The rules for entry into force of

the Kyoto Protocol require two conditions to be met: ratification by 55 Parties to the climate change

convention and ratification by Annex I Parties (developed countries) that accounted for 55% of that

group's carbon dioxide emissions in 1990.

3.4.7

amendments of Treaties

Treaties may be amended by agreement between the Parties, normally by concluding an additional

written agreement. Amendments change the original treaty provisions only for those Parties that

adopt the amendment. A state is not required to adopt any amendments to the original treaty and

is allowed to remain a Party to the treaty, but not to the subsequent amendments. A treaty will often

specify particular amendment procedures. If it does not contain these procedures, any amendments

will require the consent of all Parties.

3.4.8

which Treaty Takes Precedence in the event of a conflict?

If there are two treaties with conflicting provisions, and both treaties have identical Parties, then the

law is clear. The later treaty will take precedence to the extent of the conflict. The earlier treaty will

apply only to the extent that its terms are compatible with those of the later treaty.

Treaties often contain provisions about their relationship to subsequent treaties. "Conflict clauses"

or "savings clauses" can be used to prevent disputes. The clauses are used to record the intention of

negotiators and not leave the dispute to be resolved by the rules of the Vienna Convention. In the

environmental arena, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) contains a unique clause,

Article 104, "Relation to Environmental and Conservation Agreements", which states that the

trade provisions in listed MEAs all "trump" NAFTA in the event of an inconsistency between their

provisions and those in NAFTA:

Nothing in this Agreement shall be construed to affect the existing rights and obligations

of the Parties under other international environmental agreements, including conservation

agreements, to which such Parties are party.

Other trade treaties, such as the WTO Agreements, do not contain similar provisions.

Another example of this type of clause appears in one of the Preamble paragraphs to the Biosafety

Protocol: emphasizing that this Protocol shall not be interpreted as implying a change in the rights and

obligations of a Party under any existing international agreements.

21

International law in context

3.4.9

registration and Publication

The United Nations Charter requires every treaty and every international agreement entered into by