15

Integrated Management of the

Benguela Current Region

A Framework for Future Development

M.J. O'TOOLE,1 L.V. SHANNON,2 V. DE BARROS NETO,3

and D.E. MALAN4

1 Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources, Private Bag X13355, Windhoek, Namibia

2 Oceanography Dept., University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa

3 Instituto de Investigacao Pesqueira, Ministerio das Pescas, Luanda, Angola

4 Chief Directorate: Marine and Coastal Management, Dept. of Environmental

Affairs and Tourism, Cape Town, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Recent initiatives have been developed jointly by Angola, Namibia, and South Africa, three countries

bordering on the Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem (BCLME), to address the legacy of

fragmented management -- a consequence of the colonial and political past -- and to ensure the

integrated sustainable management of the marine and coastal regions in the Southeast Atlantic.

Examples of some of these activities and the processes followed are provided. Science and technology

are recognized as fundamental building blocks underpinning the management process and, at all levels,

the development of capacity -- both human and material -- is an overarching objective. Some recent

successes of a regional fisheries-environment science and technology program BENEFIT are

highlighted and serve to demonstrate the commitment of the three governments to collaboration in this

area. At a country level, brief details are provided about coastal policy development by way of showing

how South Africa proposes to correct some of the wrongs of the past and sustainably utilize one of its

most valuable resources, i.e., the coast itself. At the regional ecosystem management level, information

is given about an embryonic initiative, the BCLME Programme, which will provide a sound basis for

the integration of science, technology, socioeconomics, and management to ensure a sustainable future

for the Benguela Current as an ecosystem and the utilization of its coastal and marine resources.

Transboundary issues feature high on the agenda.

Science and Integrated Coastal Management

Edited by B. von Bodungen and R.K. Turner Ó 2001 Dahlem University Press

230

M.J. O'Toole et al.

It is the view of the authors that the actions taken jointly by Angola, Namibia, and South Africa can

serve not only as a blueprint for the application of science and technology in the southern African

context, but also for the integrated sustainable management of marine and coastal systems which are

shared by two or more countries elsewhere in the developing world.

BACKGROUND AND INTRODUCTION

The Benguela: A Unique Environment

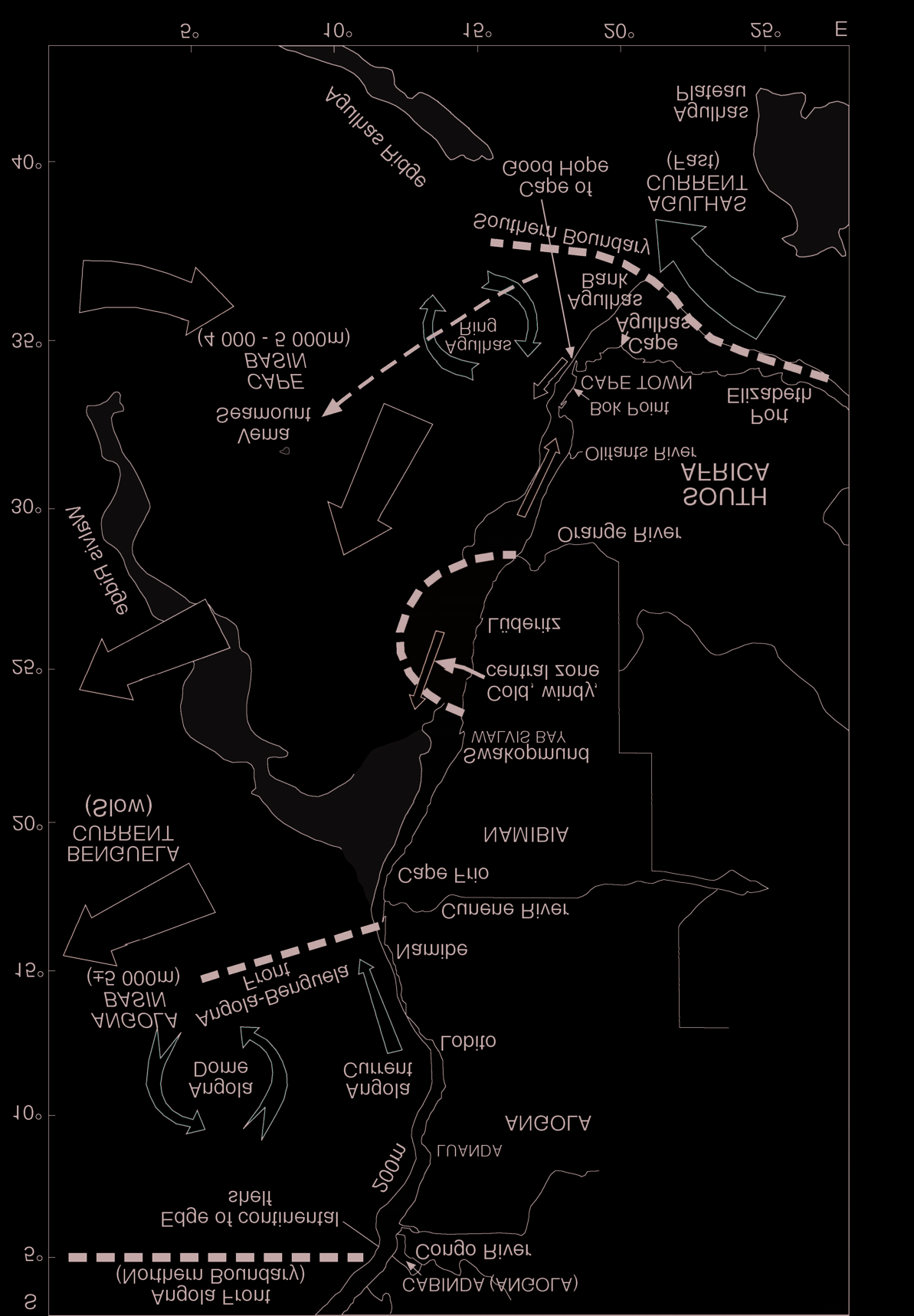

The Benguela Current region is situated along the coast of southwestern Africa, stretching

from east of the Cape of Good Hope in the south northwards to Cabinda in Angola and en-

compassing the full extent of Namibia's marine environment (see Figure 15.1). It is one of the

four major coastal upwelling ecosystems of the world which lie at the eastern boundaries of

the oceans. Its distinctive bathymetry, hydrography, chemistry, and trophodynamics com-

bine to make it one of the most productive ocean areas in the world, with a mean annual pri-

mary productivity of 1.256 g C m2 y1 (Brown et al.1991) -- about six times higher than the

North Sea ecosystem. This high level of primary productivity of the Benguela supports an im-

portant global reservoir of biodiversity and biomass of zooplankton, fish, seabirds, and ma-

rine mammals, while near-shore and off-shore sediments hold rich deposits of precious

minerals (particularly diamonds), as well as oil and gas reserves. The natural beauty of the

coastal regions, many of which are still pristine by global standards, have also enabled the de-

velopment of significant local tourism initiatives. Pollution from industries, poorly planned

and managed coastal developments as well as near-shore activities are, however, causing a

rapid degradation of vulnerable coastal habitats in some areas.

The Namib Desert, which forms the landward boundary of the greater part of the Benguela

Current system, is one of the oldest deserts in the world, predating the commencement of per-

sistent upwelling in the Benguela (12 million years before present) by at least 40 million

years. The upwelling system in the form in which we know it today is about 2 million years

old. The principal upwelling center in the Benguela, which is situated near Lüderitz in south-

ern Namibia, is the most concentrated and intense found in any upwelling regime. What also

makes the Benguela upwelling and adjacent coast system so unique in the global context is

that it is bounded at both northern and southern ends by warm-water systems, i.e., the tropi-

cal/equatorial Western Atlantic and the Indian Ocean's Agulhas Current, respectively (Shan-

non and Nelson 1996). Sharp horizontal gradients (fronts) exist at these boundaries of the

upwelling system, but these display substantial variability in time and in space -- at times

pulsating in phase and at others not. Interaction with the adjacent ocean systems occurs over

thousands of kilometers. For example, much of the Benguela marine environment, in particu-

lar off Namibia and Angola, is naturally hypoxic -- even anoxic -- at depth as a consequence

of subsurface flow southwards from the tropical Atlantic (cf. Bubnov 1972: Chapman and

Shannon 1985; Hamukuaya et al. 1998). This is compounded by depletion of oxygen from

more localized biological decay processes. There are also teleconnections between the

Benguela and processes in the North Atlantic and Indo-Pacific Oceans (e.g., El Niño). More-

over, the southern Benguela lies at a major choke point in the "Global Climate Conveyor

Belt," whereby on longer time scales, warm surface waters move from the Pacific via the

Integrated Management of the Benguela Current Region

231

Figure 15.1 External and internal boundaries of the Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem,

bathymetric features, and surface (upper layer) currents.

Indian Ocean through into the North Atlantic. (The South Atlantic is the only ocean in which

there is a net transport of heat towards the equator!).

As a result, not only is the Benguela at a critical location in terms of the global climate sys-

tem, but its marine and coastal environments are also potentially extremely vulnerable to any

future climate change or increasing variability in climate -- with obvious consequences for

long-term sustainable management of the coast and marine resources.

232

M.J. O'Toole et al.

Fragmented Coastal and Marine Resource Management: A Legacy of the

Colonial and Political Past

Following the establishment of European settlements at strategic coastal locations where

victuals and water could be procured to supply fleets trading with the East Indies, the poten-

tial wealth of the African continent became apparent. This subsequently resulted in the great

rush for territories and the colonization of the continent -- mostly during the nineteenth cen-

tury. Boundaries between colonies were hastily established, often arbitrary and generally

with little regard for indigenous inhabitants and natural habitats. Colonial land boundaries in

the Benguela region were established at rivers (e.g., Cunene, Orange). The languages and

cultures of the foreign occupiers were different (Portuguese, German, English, Dutch) and so

were the management systems and laws which evolved in the three now independent and

democratic countries of the region -- Angola, Namibia, and South Africa. Moreover, not

only were the governance frameworks very different, but a further consequence of European

influence was the relative absence of interagency (or interministerial) frameworks for man-

agement of the marine environment and its resources and scant regard for sustainability. To

this day, mining concessions, oil/gas exploration, fishing rights, and coastal development

have taken place with little or no proper integration or regard for other users. For example, ex-

ploratory wells have been sunk in established fishing grounds and the wellheads (which stand

proud of the sea bed) subsequently abandoned. Likewise, the impact of habitat alterations due

to mining activities and ecosystem alteration (including biodiversity impacts) due to fishing

have not been properly assessed.

Prior to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea in 1982 (United Nations

1983) and declaration and respecting of sovereign rights within individual countries'exclu-

sive economic (or fishing) zones (EEZs), there was an explosion of foreign fleets fishing off

Angola, Namibia, and South Africa during the 1960s and 1970s -- an effective imperialism

and colonization by mainly First World countries of the Benguela Current Large Marine Eco-

system (BCLME) and the rape of its resources. This period also coincided with liberation

struggles in all three countries and associated civil wars. In the case of Namibia, over whom

the mandate by South Africa was not internationally recognized, there was an added problem

in that prior to independence in 1990, an EEZ could not be proclaimed. In an attempt to con-

trol the foreign exploitation of Namibia's fish resources, the International Commission for

the South-east Atlantic Fisheries (ICSEAF) was established, but this proved to be relatively

ineffectual at husbanding the fish stocks. In South Africa prior to 1994, there was generally a

scant regard for environmental issues or sustainable environmental management. Moreover,

colonialism, civil wars, and the apartheid legacy have resulted in a marked gradient in capac-

ity from south to north in the region. Another consequence of the civil wars has been the pop-

ulation migration to the coast and localized pressure on marine and coastal resources (e.g.,

destruction of coastal forests and mangroves), severe pollution of some embayments, and de

facto impossibility of any form of integrated coastal zone management along large stretches

of the Benguela coast.

While mineral exploration and extraction and developments in the coastal zones obvi-

ously occur within the geographic boundaries of the three countries, i.e., within the EEZs, and

can to a large degree be independently managed by each of the countries, mobile living ma-

rine resources do not respect the arbitrary geographic borders. This has obvious implications

Integrated Management of the Benguela Current Region

233

for the sustainable use of these resources, particularly so in the case of straddling and shared

fish stocks.

Thus the legacy of the colonial and political past is that the management of resources in the

greater Benguela area has not been integrated within countries or within the region. The real

challenge will be to develop a viable joint and integrative mechanism for the sustainable man-

agement of the coast and marine resources of the Benguela as a whole.

Regional Self-help: Joint Action by Three Developing Countries for a

Sustainable Future

This historical scenario poses almost insurmountable problems for the countries bordering on

the Benguela. Notwithstanding this, Angola, Namibia, and South Africa have, over the past

three years, made substantial progress to address the science and management issues in a

pragmatic, cost-effective manner. In this chapter we provide details about some of the joint

(regional) and individual country actions which have been taken to overcome the difficulties,

highlight some recent successes, and outline plans which the three countries collectively have

to ensure that the greater Benguela Current region is sustainably used and managed through

the proper application of science and technology. This approach could well serve as a blue-

print in other parts of the world for the integrated management of marine and coastal systems

which are shared between two or more developing countries.

At the regionallevel the approach has been somewhat different, however, from that which

would normally be taken in developed countries and coastal areas with "concave coastlines"

for the following reasons: First, much of the coast in the Benguela region is relatively pristine

and/or inaccessible -- except for small pockets of urban development. Second, many of the

"coastal" issues concern the marine rather than the terrestrial system. Third, the

transboundary problems which are amenable to management action are those relating to ma-

rine systems, e.g., shared fish resources. (It is just not feasible to attempt to address

transboundary issues associated with, for example, the Congo River and its drainage basin).

Fourth, (natural) environmental variability and change are major factors influencing natural

resources and the way in which these are managed in an open "convex" system, such as the

Benguela. While this cannot be controlled, cost-effective environmental monitoring and ap-

propriate science for better predictability can improve marine and coastal resource utilization

and management. Finally, but perhaps most important, is the need throughout the region to

develop human and infrastructure capacity and to share available knowledge and skills. What

better way to proceed than through the application of the appropriate science and technology!

This is in keeping with the philosophy so well articulated by Sherman (1994).

A REGIONAL MARINE SCIENCE SUCCESS STORY -- "BENEFIT"

In April, 1997, a major regional cooperative initiative was launched jointly by Angola,

Namibia, and South Africa together with foreign partners "to develop the enhanced science

capacity required for the optimal and sustainable utilization of living resources of the

Benguela ecosystem by (a) improving knowledge and understanding of the dynamics of im-

portant commercial stocks, their environment and linkages between the environmental

234

M.J. O'Toole et al.

processes and the stock dynamics, and (b) building appropriate human and material capacity

for marine science and technology in the countries bordering the Benguela ecosystem"

(BENEFIT 1997). The BenguelaEnvironmentFisheriesInteractionTraining Programme

(BENEFIT) evolved out of a workshop/seminar on "Fisheries Resource Dynamics in the

Benguela Current Ecosystem" held in Swakopmund in mid-1995 and hosted by the

Namibian Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources in partnership with the Norwegian

Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD), the German Organization for Technical

Cooperation (GTZ), and the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC) of

UNESCO. BENEFIT has attracted substantial incremental support from overseas countries

and international donor agencies. It remains, however, essentially a regional "self-help" ini-

tiative and has been endorsed by the Southern African Development Community (SADC)

and accepted as a SADC program. It is providing a unique opportunity for development of

partnerships within and beyond the southern African region in science and technology to pro-

mote optimum utilization of natural resources and thereby greater food security in the region.

BENEFIT has been planned in two five-year phases (19972002, 20022007). The sci-

ence and technology component of BENEFIThas three foci: resource dynamics, the environ-

ment (of the resources), and linkages between resources and the environment. These foci are

increasing knowledge of resource dynamics through improved research on the resources and

their variable environment. The capacity development component of the program is being ad-

dressed through a suite of task-oriented framework activities to (a) build human capacity, par-

ticularly in areas of greatest need and greatest historical disadvantage, (b) develop, enhance,

and maintain regional infrastructure and cooperation, and (c) to make the countries in the re-

gion and the region as a whole more self-sufficient in science and technology. The linkages

between the three science foci and the suite of framework activities are illustrated schemati-

cally in Figure 15.2. BENEFIT has a Secretariat based in Namibia, while management meet-

ings are held on a rotating basis in Angola, Namibia, and South Africa.

The launch of BENEFIT in April 1997 coincided with two major research cruises/surveys

of the AngolaBenguela Front focusing on fisheries and environmental issues. (This front is

situated west of Angola and is thought to play an important role as a permeable "boundary"

between the tropical Atlantic and the upwelling region of the Benguela). During the past two

years, BENEFIThas increasingly gathered momentum: funding for priority projects has been

allocated and real progress in human capacity development has been made. Some recent

achievements are briefly:

· Several reports and scientific/technical papers have been published on the results of the

1997 AngolaBenguela Front surveys, and several regional scientists and technicians

received hands-on training at sea, in the laboratory, and in data analysis.

· A German-sponsored BENEFIT training course was conducted in Namibia in 1997,

and a number of regional scientists received further training subsequently in Germany

and in Norway.

· Fifteen fisheries and fisheries-environment projects were approved for funding in

1999.

· Two training workshops have taken place (1998 and 1999) and a BENEFIT Training

Plan to complement the Science Plan is under development.

Integrated Management of the Benguela Current Region

235

SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY FOCI

FOCUS 1

FOCUS 2

FOCUS 3

Fish Resource

FishEnvironment

Environment

Dynamics

Interactions

Capacity Development

B E N E F I T

and Training

Networking

Science and

and

Data and

Modeling

Technology

Communications

Information

and

Transfer

Systems

Analysis

FRAMEWORK ACTIVITIES

Figure 15.2 Schematic of the BENEFIT structure showing the interlinking science and technology

foci and framework activities.

· In the first half of 1999, over 50 persons from the broad SADC region (i.e., including

East African nations) have been trained during three BENEFIT cruises, including a

40-day survey of resources and the environment which extended between Cape Town

and Luanda, primarily funded by the African Development Bank and the World Bank.

BENEFITand related activities provide clear evidence of the desire and capability of Angola,

Namibia, and South Africa to work together to solve common marine/fisheries science prob-

lems in the Benguela region in partnership with the international community.

A COUNTRY-BASED APPROACH TO ICM: SOUTH AFRICA

AS AN EXAMPLE

The Need

In comparison with many other countries, South Africa's coastal areas have a low overall

population density and large areas that are relatively underdeveloped, particularly in terms of

opportunities for the poorer sections of the community. This is a result of a number of factors,

including migrant labor, apartheid planning policies, and historical population movements.

The coastal population is now growing as a result of recent political and economic changes in

South Africa. These changes include the removal of barriers to movement, a decline in inland

236

M.J. O'Toole et al.

extractive industries, and increasing opportunities associated with coastal resources, such as

tourism and port development. Future economic growth in South Africa is likely to concen-

trate along the coast and the pace of development in coastal areas is already accelerating. For

example, five out of the eight Spatial Development Initiatives are linked to the coast and the

direct contribution of coastal areas and resources to the gross domestic product of South Af-

rica is estimated as 37%. This presents a unique management challenge for government, in-

dustry, and civil society.

Coastal Management Policy Programme in South Africa

The Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism initiated the Coastal Management

Policy Programme (CMPP) to promote integrated management of the coast as a system, in or-

der to harness its resources for sustainable coastal development. An extensive process of pub-

lic participation, supported by specialist studies, began in May, 1997, guided by a policy

committee representing the interests of national and provincial government, business, and

civil society. ACoastal Policy Green Paper was published in September, 1998, followed by a

Draft White Paper for Sustainable Coastal Development in March, 1999 (Draft White Paper

1999).

The Draft White Paper advocates the following shifts in emphasis:

· In the past, the value of coastal ecosystems as a cornerstone for development was not

sufficiently acknowledged in decision making in South Africa. The policy outlines the

importance of recognizing the value of the coast.

· In the past, coastal management was resource-centered rather than people-centered and

attempted to control the use of coastal resources. The policy stresses the powerful

contribution that can be made to reconstruction and development in South Africa

through facilitating sustainable coastal development. Maintaining diverse, healthy,

and productive coastal ecosystems will be central to achieving this ideal.

· In the past, South African coastal management efforts were fragmented and

uncoordinated, and were undertaken largely on a sectoral basis. The policy supports a

holistic approach by promoting coordinated and integrated coastal management,

which understands the coast as a system.

· In the past, a "top-down" control and regulation approach was imposed on coastal

management efforts. The policy proposes introducing a new facilitatory style of

management, which involves cooperation and shared responsibility with a range of

stakeholders.

However, the institutional capacity to support the integrated approach required to manage

coastal development is currently weak, and there is little awareness of the issues among key

stakeholders. This both limits the opportunities associated with the coast and threatens the

sustainability of development. An action plan to address these issues is presented in the Draft

White Paper and centers on four key themes:

1. Developing and supporting an appropriate (integrated) institutional and legal frame-

work across government.

2. Awareness, education, and training programs for government, the private sector, and

civil society.

Integrated Management of the Benguela Current Region

237

CEC

CEC Sub-Committee Coastal Management

(Chaired by DEAT)

KZN

EC

WC

NC

Provincial Working Groups

For each province:

Lead Provinical Government Department

Other Departments

Provincial Coordinator

Local Demonstration

Provinical Projects

Projects Coordinators

Local Demo Projects

Figure 15.3 Proposed institutional structure for implementation of the Draft White Paper (1999) for

sustainable coastal development in South Africa. CEC: Committee for Environmental Coordination

(national body); DEAT: Dept. of Environmental Affairs and Tourism; KZN: Kwa-Zulu Natal; EC: East-

ern Cape; WC: Western Cape; and NC: Northern Cape.

3. Information provision in the form of decision support for provincial and local govern-

ment, monitoring programs, and applied research.

4. Local projects to demonstrate the benefits of effective coastal management and to ad-

dress national and provincial priority issues.

Acyclical process of review and revision underpins the coastal policy. This allows successive

implementation generations to reflect evolving priorities, visions, and institutional capacity.

Figure 15.3 represents the institutional structures through which the coastal policy will be

implemented.

Context of the Coastal Policy Within the Benguela Current Region of South Africa

The Draft White Paper provides a brief overview of South Africa's coast to sketch the context

of the policy in relation to the thirteen coastal regions defined for the purposes of the policy

formulation process. The two sections applicable to the Benguela Current region study are

the Namaqualand and West Coast coastal divisions. These are bounded by the Orange and

Olifants Rivers, and the Olifants River and Bok Point, respectively. The following extracts

are lifted from the Draft White Paper.

Namaqualand

The Northern Cape province is comprised of only a single coastal region, the Namaqualand

coastal region. Some 390 km long, the Namaqualand region is a sparsely inhabited area,

238

M.J. O'Toole et al.

much of which is semi-desert and is largely undeveloped. Alack of physical access to coastal

resources and isolation from the center of provincial administration contribute to high pov-

erty levels in the coastal communities.

Although dominated by large mining and fishing companies, the Namaqualand region has

the second lowest economic growth rate in South Africa and unemployment has more than

doubled since 1980. Challenges include declining fish stocks, poor road infrastructure, lack

of sheltered bays for ports, and limited agricultural potential. The closure of many land-based

diamond mining operations provides an opportunity for extensive rehabilitation programs to

be carried out -- to rehabilitate the natural environment and to create alternative livelihoods

for people.

Potential exists for the harvesting of underutilized coastal resources, such as mussels and

limpets, for small-scale industries that add value to fishing and agriculture, and for

small-scale mining. Other natural assets, such as the annual wildflower display, a high diver-

sity of succulent plant species, and the stark beauty of the area offer potential for nature-based

tourism with community participation. More equitable distribution of mining and fishing

concessions and the development of value-added activities could contribute to retaining reve-

nue in local communities.

West Coast

The West Coast region has displayed significant growth and a relatively strong economy, al-

though rural areas remain poor. Impetus for growth has come from the deep-water port of

Saldanha and the proximity of the region to the Cape Metropolitan area. Despite the limited

supply of freshwater, substantial investment has been attracted to the region for mariculture,

shipping, industrial, manufacturing, tourism, and recreational activities. Much of the area is

arid, which limits agricultural potential. The region is, however, well known for its strandveld

and fynbos vegetation, which attracts many visitors to the region each spring. The region is at

the center of South Africa's fishing industry, with rich fishing grounds supporting capi-

tal-intensive industries.

Economic development through industrialization, property development, and tourism has

brought challenges for the management of the coast, including air and water pollution,

salination of the coastal aquifer, restricted access to coastal resources, ribbon development,

and inappropriate land use. Economic development is also attracting many job seekers to the

region, increasing the need for infrastructure and government services. Potential exists in the

region for the development of small-scale industries that add value to fishing, floriculture,

and mariculture, and for tourism promotion initiatives, including the development of rail and

air links.

Implementing the Coastal Policy in South Africa

Concurrent with the process of formal ratification of the Draft White Paper, the Department

of Environmental Affairs and Tourism has translated the "Plan of Action" into a preliminary

five-year implementation proposal. This is being used to seek implementation finance to en-

sure a reduced lead-in time between policy adoption and policy implementation. Once pro-

ject funds are secured, detailed design will follow, involving provincial government,

Integrated Management of the Benguela Current Region

239

appropriate stakeholders, and specialist individuals and organizations. This process was

completed in 2000, and it is hoped that the coastal policy will become government policy.

Meanwhile, to maintain momentum of the CMPP, an interim phase program is underway to

bridge the gap between the policy formulation and implementation phases. Activities in-

clude: specialist advice on an appropriate legislative framework, preparing for the appoint-

ment of National and Provincial Coordinators, initiating a needs assessment for public

awareness and education programs, preparing and distributing a newsletter to coastal stake-

holders, and developing a coastal management web site to better disseminate information.

AN INTEGRATED REGIONAL APPROACH TO THE SUSTAINABLE

MANAGEMENT OF THE BENGUELA CURRENT AS A LARGE

MARINE ECOSYSTEM: THE BCLME PROGRAMME

In a large marine ecosystem (LME), such as the Benguela Current System, sustainable man-

agement at the ecosystem level under conditions of environmental variability and uncertainty

is a regional issue. The mobile components of the BCLME do not respect arbitrary

geopolitical (country) boundaries. Several fish stocks straddle or are shared between the

countries or otherwise migrate through the Benguela. Actions by one country, e.g.,

overexploitation or habitat destruction of their part of a migrating or shared resource, could in

effect negatively impact on one or both neighboring countries. Joint management and protec-

tion of shared stocks is one of the few available options to the countries bordering the

Benguela Current. In this manner, a better sense of ownership of the regions'resources can be

attained, as "owners" tend to protect their property more than those enjoying a free service.

There is thus a strong need for harmonizing legal and policy objectives and for developing

common strategies for resource surveys, and investment in sustainable ecosystem manage-

ment for the benefit of all the people in the Benguela region. Only concerted regional action

with the enablement from the international community to develop regional agreements and

legal frameworks and assessment/implementation strategies will in the longer term protect

the living marine resources, biological diversity, and environment of the greater Benguela.

While shared living resources present the most obvious case for comanagement, there are

many examples of nonshared "resources" that can benefit from sharing of expertise and man-

agement structures developed and implemented in individual countries. These include inter

alia mining, declining coastal water quality (pollution abatement and control, oil spill

clean-up technology), oil/gas extraction, coastal zone development, tourism and eco-tourism

development, mitigation of the effects of introduced species (exotics), and harmful algal

blooms, which can also have system-wide impacts.

Whereas the governments of Angola, Namibia, and South Africa have made excellent

progress in partnership with members of the international community in addressing the sci-

ence and technology needs for fisheriesin the region through the BENEFITProgramme, a vi-

able regional framework for management for shared fish resources and the ecosystem as a

whole, including the coastal zone, is lacking. Building on BENEFIT and on the success of

LME initiatives elsewhere in the world (e.g., Black Sea; see Black Sea 1996), whereby incre-

mental funding is made available by the Global Environmental Facility (GEF) of the World

240

M.J. O'Toole et al.

Bank for the development of management structures that address transboundary problems

(and which structures become self-funding after 35 years), Angola, Namibia, and South Af-

rica with GEF assistance are in the process of developing a LME management initiative for

the Benguela Current: the BCLME Programme. This program is a broad-based multisectoral

initiative aimed at sustainable integrated management of the Benguela Current ecosystem as

a whole. It focuses on a number of key sectors, including fisheries, impact of environmental

variability, sea-bed mining, oil and gas exploration and production, coastal zone manage-

ment, ecosystem health, and socioeconomics and governance. Transboundary management

issues, environmental protection, and capacity building will be of primary concern to the pro-

gram. It builds on existing regional capacity and goodwill, and could serve as a blueprint for

the design and implementation of LME initiatives in other upwelling regions and elsewhere

in the developing world. Moreover, the BCLME Programme will address key regional envi-

ronmental variability issues that are expected to make a major contribution towards under-

standing global fluctuations in the marine environment, including climate change.

The BCLME Programme provides an ideal opportunity for the international community

to assist the three countries in the region to develop appropriate mechanisms that will ensure

the long-term sustainability of the ecosystem. In 1998 a small grant was made by the GEF via

the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) to facilitate the development of a

comprehensive proposal. The process involved, which is lengthy and complex, follows pre-

scribed procedures. In essence it is a participatory process involving all key stakeholders in

the private and public sectors of the participating countries. Two regional workshops involv-

ing over 100 regional and international experts were held (Croll 1998; Croll and Njuguna

1999), consensus was built, a set of six comprehensive thematic reports or integrated over-

views were commissioned (fisheries, environment, mining, coast, oil and gas,

socioeconomics), an exhaustive Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis (TDA) was undertaken,

a Strategic Action Programme (SAP) is being developed, and, finally, a Project Brief formu-

lated. At first appearance the process appears overly bureaucratic and unwieldy, but having

gone through the various stages it is clear that the process is rigorous, necessary, and logical.

For example, the integrated overviews provided essential input into the subsequent TDA

whereby the essential elements were formulated and prioritized through (consensus) group

work as per the path issues ® problems ® causes ® impacts ® uncertainties ® socioeco-

nomic consequences ® transboundary consequences ® activities/solutions ® priority ®

outputs ® costs.

Key aspects of the TDAand SAP follow the next section, which considers BCLME exter-

nal boundaries.

Geographic Scope and Ecosystem Boundaries

Conducting a comprehensive TDA is only possible if the entire LME, including all inputs to

the system, is covered in the study. In the case of the Benguela, which is a very open system

where the environmental variability is predominantly remotely forced, this should then in-

clude the tropical Atlantic sensu latu, the Agulhas Current (and its link with the Indo-Pacific),

the Southern Ocean, and the drainage basins of all major rivers which discharge into the

greater Benguela Current region, including the Congo River. Clearly, such an approach is

Integrated Management of the Benguela Current Region

241

impracticable, and more realistic and pragmatic system boundaries must be defined to de-

velop and implement a viable ecosystem management framework. The principal external and

internal system boundaries are shown in Figure 15.1.

Landward Boundary

With the exception of the Congo River, the main impact of discharges from rivers flowing

into the South East Atlantic tends to be episodic in nature, i.e., in terms of significant

transboundary concerns, these are limited to extreme flood events. (Their drainage basins

nevertheless do include a major part of the southern African hinterland.) The Congo River,

however, exerts an influence that can be detected over thousands of kilometers of the South

Atlantic and drains much of Central Africa. From a practical point of view, it is quite beyond

the scope of the BCLME to attempt to include the development of any management structures

for a river such as the Congo. With respect to land sources of pollution in the BCLME (ex-

cluding the Congo River area), these are only really significant in the proximity of the princi-

pal port cities (e.g., Cape Town, Luanda, Walvis Bay), and the effects are generally very

localized. Nevertheless, some of the problems experienced in these areas are common in na-

ture and could be addressed through similar remedial actions. Like coastal development, their

impacts generally do not have a transboundary character. (By contrast, pollution from ships,

major oil spills, introduction of exotic species, and associated harmful algal blooms, for ex-

ample, are transboundary concerns). From a BCLME perspective, the landward boundary

can thus, for all practical purposes, be taken as the coast. Specific allowances can be made in

some areas on a case-by-case basis (e.g., during episodic flooding from the Orange and

Cunene Rivers, which are situated at the country boundaries of South AfricaNamibia and

NamibiaAngola, respectively).

Western Boundary

The Benguela Current is generally defined as the integrated equatorward flow in the upper

layers of the ocean in the South East Atlantic between the coast and the 0° meridian. The

BCLME Programme will accordingly use 0° as the western boundary. For practical manage-

ment purposes, however, the focus will be on the areas over which the three countries have

some jurisdiction, i.e., their EEZs which extend 200 nautical miles seawards from the land.

Southern/Eastern Boundary

The upwelling area of the BCLME extends around the Cape of Good Hope, seasonally as far

east as Port Elizabeth. This extreme southern part of the ecosystem is substantially influenced

by the Agulhas Current, its Retroflection (turning back) and leakage of Indian Ocean water

into the Atlantic south of the continent. As the variability of the BCLME is very much a func-

tion of the complex ocean processes occurring in the Agulhas CurrentRetroflection area,

this will be taken as the southern boundary with 27°E longitude (near Port Elizabeth), being at

the extreme eastern end.

242

M.J. O'Toole et al.

Northern Boundary

While the AngolaBenguela Front (Shannon et al. 1987) comprises the northern extent of the

main coastal upwelling zone, upwelling can occur seasonally along the entire coast of An-

gola. There are, in any event, strong linkages between the behavior of the AngolaBenguela

Front (and the oceanography of the area to the south of it) and processes occurring off Angola,

especially the Angola Dome and the Angola Current. Unless these are considered as an inte-

gral part of the BCLME, it will not be feasible to evolve a sustainable integrated management

approach for the Benguela. Moreover, there is a well-defined front at about 5°S, viz. the An-

gola Front (Yamagata and Iizuka 1995), which is apparent at subsurface depths. This front is

the true boundary between the Benguela part of the South Atlantic and the tropical/equatorial

Gulf of Guinea system. Anorthern boundary at 5°S would thus encompass the Angola Dome,

the seasonal coastal Angola Current, and the area in which the main oxygen minimum forms,

and the full extent of the upwelling system in the South East Atlantic. A pragmatic northern

boundary is thus at 5°S latitude, which is close to the northern geopolitical boundary of An-

gola (Cabinda).

Issues and Perceived Main Transboundary Problems, Root Causes, and Areas

Where Action Is Proposed: The TDA

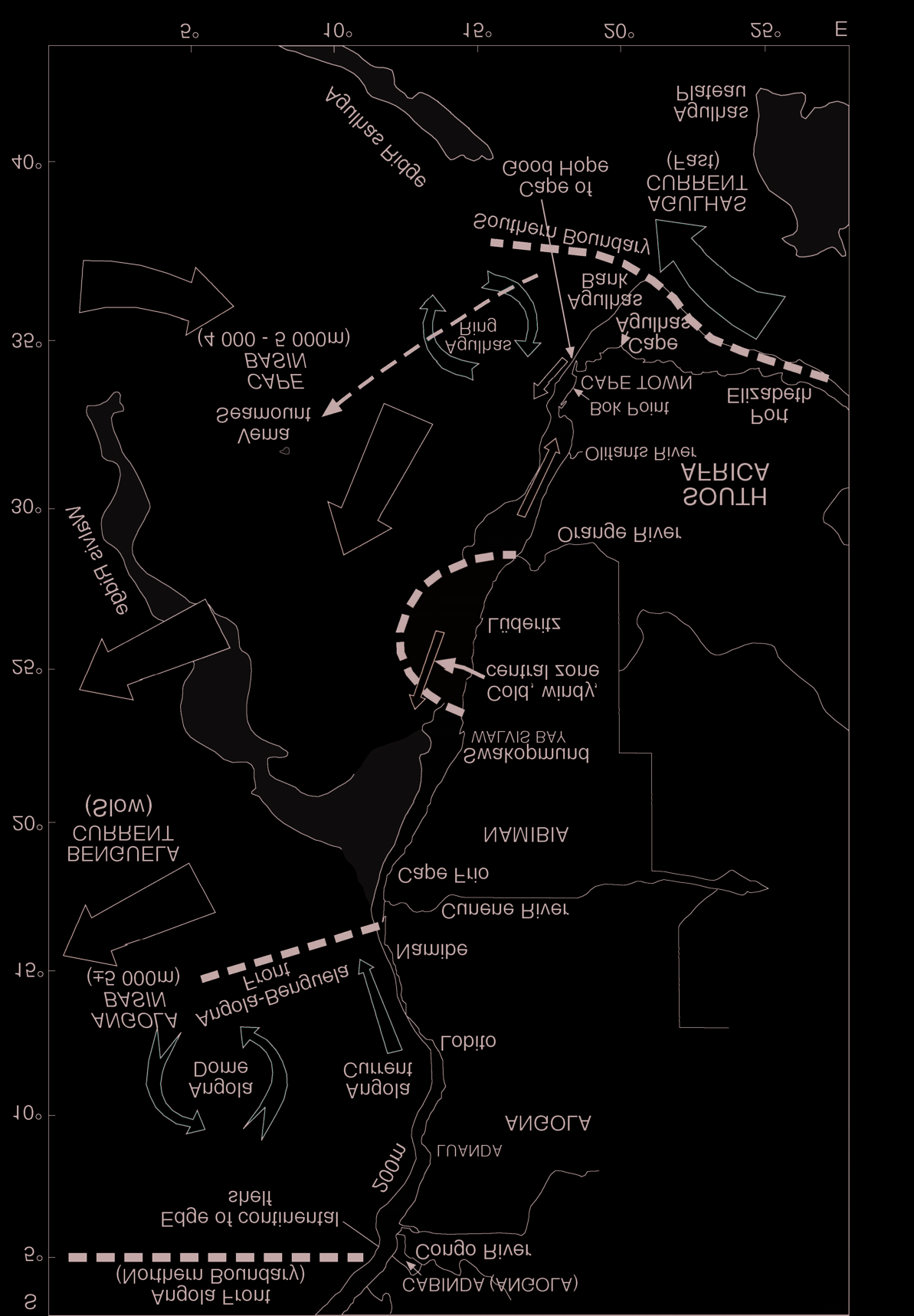

Through the participatory TDA process involving regional stakeholders and international

LME experts, seven major transboundary problems were identified, their root causes estab-

lished, and suites of action formulated (BCLME TDA1999). These are summarized concep-

tually in Figure 15.4 and expanded in the accompanying synthesis matrix (see Table 15.1).

The latter is a "logistical map" which encapsulates the essence of the TDA.

Regional action is clearly required in three main areas: (a) sustainable management and

utilization of resources, (b) assessment of environmental variability, ecosystem impacts and

improvement of predictability, and (c) maintenance of ecosystem health and management of

pollution. Within each of these areas is a suite of subactions. Each of these is examined more

fully in the next level of the TDAto determine causes (of the relevant subproblem), likely im-

pacts, risks and uncertainties, socioeconomic consequences, transboundary consequences,

proposed activities/solutions, their priority and incremental costing (i.e., cost over and above

costs presently spent by national governments), and anticipated outputs. By way of illustra-

tion we have extracted one of the several subtables from the BCLME TDA document (Table

15.2). This table is in reality only a summary of the comprehensive information and assess-

ment which comprised the TDAprocess. It does, however, illustrate how transboundary con-

cerns can be addressed through the application of a logical analysis framework, i.e., the TDA,

which in turn provides essential input into the compilation of a SAP.

Strategic Action Programme for the BCLME

The Strategic Action Programme being developed (BCLME SAP 1999) is in essence a con-

cise document that outlines regional policy for the integrated sustainable management of the

BCLME as agreed by the governments of Angola, Namibia, and South Africa. The SAP

spells out the challenge (regional problems), establishes principles fundamental to integrated

Integrated Management of the Benguela Current Region

243

GENERIC ROOT CAUSES

Inadequate capacity

Poor legal

Poor legal

Inadequate

Inadequate

Inadequate planning

Inadequate

Insufficient public

Insufficient

development

Inadequate

framework at the

framework at

implementation of

implementation

at all levels

planning at all

involvement

capacity develop-

public

(human and

regional and

available regulatory

the regional

of available

levels

involvement

infrastructure) and

ment (human &

national levels

and national

instruments

regulatory

training

infrastructure)

and training

levels

instruments

Complexity of

Inadequate financial

MAJOR TRANSBOUNDARY PROBLEMS

ecosystem and high

Complexity of

mechanisms and

Inadequate

degree of variability

ecosystem and

support

financial

· Decline in BCLME commercial fish stocks

high degree of

mechanisms

and nonoptimal harvesting of living resources

variability

and support

· Uncertainty regarding ecosystem status and

yields in a highly variable environment

· Deterioration in water quality: chronic and

catastrophic

· Habitat destruction and alteration, including

inter alia modifications of seabed and coastal

zone and degradation of coastscapes

· Loss of biotic integrity and threat to

biodiversity

· Inadequate capacity to assess ecosystem

health

· Harmful algal blooms

Sustainable

Assessment of

Assessment of

Maintenance of

management and

Sustainable

environmental

Maintenance

environmental

ecosystem health

utilization of

management

variability

of ecosystem

variability

,

, eco-

and management of

resources

and utilization

ecosystem impacts

health and

system impacts,

pollution

of resources

and improvement of

management

and improvement

predictability

of pollution

of predictability

AREAS WHERE ACTION IS REQUIRED

Figure 15.4 Results of the Transboundary Diagnostic Analyses (TDA): Overview of major

transboundary problems, generic root causes, and areas requiring action in the BCLME.

management in the region, specifies the nature, scope, and timetable for deliverable manage-

ment policy actions (based on TDAinput), details the institutional arrangements (structures)

necessary to ensure delivery, elaborates on wider cooperation (i.e., cooperation between the

BCLME region and external institutions), specifies how the BCLME Programme will be fi-

nanced during the start-up and implementation phase (five years), and outlines approaches to

ensure the long-term self-funding of the integrated management of the BCLME.

Key details of the BCLME SAP are briefly as follows.

The Challenge

The legacy of fragmented management -- inadequate planning and integration, poor legal

frameworks and inadequate implementation of existing regulatory instruments, insufficient

public involvement, inadequate capacity development, and inadequate financial support

mechanisms -- superimposed on a complex and highly variable environment have mani-

fested themselves, for example, in the decline of fish stocks, nonoptimal utilization of

244

M.J. O'Toole et al.

Table 15.1 Synthesis matrix.

Perceived Major Problems

Transboundary Elements

Major Root

Activity

Causes*

Areas**

Decline in BCLME commercial

Most of region's important harvested

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, A, B, (C)

fish stocks and nonoptimal

resources are shared between countries, or

6, 7

harvesting of living resources

move across national boundaries at times,

requiring joint management effort.

Uncertainty regarding ecosystem

Environmental variability and change

1, 2, 3, 7

A, B, C

status and yields in a highly

impacts on ecosystem as a whole, and poor

variable environment

predictive ability limits effective

management. The BCLME may also be

important to global climate change.

Deterioration in water quality:

While most impacts are localized, the

2, 3, 4, 5, 7

C

chronic and catastrophic

problems are common to all three countries

and require collective action to address.

Habitat destruction and alteration, Uncertainties exist about the regional

2, 3, 5, 6, 7

A, C, (B)

including inter alia modification of cumulative impact from mining on benthos

seabed and coastal zone and

and ecosystem effects of fishing.

degradation of coastscapes

Degradation of coastscapes reduce regional

value of tourism.

Loss of biotic integrity (e.g.,

Fishing has altered the ecosystem, reduced

1, 3, 5, 6

A, C, (B)

changes in community

the gene pool, and caused some species to

composition, species diversity,

become endangered/threatened.

introduction of alien species) and

Introduced alien species are a global

threat to biodiversity, endangered

transboundary problem.

and vulnerable species

Inadequate capacity to monitor/

There is inadequate capacity in the region to 1, 2, 5, 7

A, B, C

assess ecosystem (resources,

monitor the resources and the environmental

environment, and variability

variability, and unequal distribution of the

thereof)

capacity between countries.

Harmful algal blooms (HABs)

HABs are a common problem in all three

1, 2, 3, 6, 7

A, B ,C

countries and require collective action to

address.

*Main Root Causes:

1. Complexity of ecosystem and high degree of variability (resources and environment)

2. Inadequate capacity development (human and infrastructure) and training

3. Poor legal framework at the regional and national levels

4. Inadequate implementation of available regulatory instruments

5. Inadequate planning at all levels

6. Insufficient public involvement

7. Inadequate financial mechanisms and support

**Area Where Action Is Proposed:

A. Sustainable management and utilization of resources

B. Assessment of environmental variability, ecosystem impacts, and improvement of predictability

C. Maintenance of ecosystem health and management of pollution

resources, increasing pollution, habitat destruction, threats to biodiversity, all of which have

transboundary implications. The challenge is to halt the changing state of the BCLME and,

where possible, reverse the process through the development and implementation of sustain-

able integrated management of the ecosystem as a whole. More specifically:

Integrated Management of the Benguela Current Region

245

· Overexploitation of commercial fish stocks and the nonoptimal harvesting of living

resources in the ecosystem are causes of concern, particularly as most of the important

harvested resources are shared between countries and overharvesting in one country

can lead to depletion of that species in another and changes to the ecosystem as a whole.

· Inherent high environmental variability in the marine system and associated

uncertainty and poor predictability limits the capability to manage resources

effectively. The challenge is to improve predictability of "events" and their

consequences.

· Deterioration of water quality in the BCLME and associated problems are common to

all three countries and require collective action to address. Catastrophic events (e.g.,

major oil spills, system-wide anoxia) can impact across geopolitical boundaries

requiring sharing of expertise and technology.

· Habitat destruction, alteration and modification to the seabed and coastal zone, and

degradation of coastal areas is accelerating. The regional cumulative impacts are

unknown and need addressing to ensure sustainable resource utilization and tourism.

· Increased loss of biotic integrity and the introduction of alien species (e.g., ballast

water discharges) threatens vulnerable and endangered species and biodiversity of the

BCLME and impacts at all levels, system wide.

· There is inadequate institutional, infrastructural, and human capacity at all levels to

monitor, assess, and manage the BCLME. Moreover, there is an unequal distribution of

existing capacity.

· Harmful algal blooms occur in coastal waters of all three countries and all face similar

problems in terms of impacts, monitoring, and management. Collective regional action

is necessary.

Principles Fundamental to Cooperative Action

The following principles are being proposed for consideration by the three governments:

· Application of the precautionary principle.

· Promote anticipatory actions (e.g., contingency planning).

· Stimulate use of clean technologies.

· Promote use of economic and policy instruments that foster sustainable development

(e.g., polluter-pays-principle).

· Include environmental and health considerations in all relevant policies and sectoral

plans.

· Promote cooperation among states bordering the BCLME.

· Encourage the interests of other states in the southern African region.

· Foster transparency and public participation within the BCLME Programme.

· The three governments will actively pursue a policy of cofinancing with industry and

donor agencies.

Institutional Arrangements (Structures)

It has been suggested that an Interim Benguela Current Commission (IBCC) be established to

strengthen regional cooperation. Its Secretariat and subsidiary bodies could be fully

246

and

capacity

to

disposal

1999).

data

Angola

in

waste

TDA

standards

relationship

mechanism

zones

baseline

period

peace

no

commitment

fect

to

hazardous

or

recovery

BCLME

Few Performance thresholds National building Cause-ef

Recovery Cost Return

Accumulation Illegal

from

Risks/Uncertainties

· ·

·

·

· · ·

· ·

(taken

and

quality

dominance

fauna

impacts equipment

ganisms

or

water

species

coastal

fishing

of

yields

in

degradation of

aesthetic to

health

edible

mortality

Public Reduced Unsafe Changes

Coastline Mortality flora

Faunal Negative Damage

Impact

· · · ·

· ·

· · ·

Improvement

recycling

incentives

pollution:

of

oil settlement

few

and

and vessels

development

waste informal

vessels/equipment

settlements

communities

on

of

from

management

coastal pollution

awareness

pollution

coastal

coastal management

coastal

and

oil

pollution

policy in

conflict

error

of

of

discards

public disposal

fishing

pollution

of

worthiness

waste

health

Unplanned Chronic Industrial Sewage Air Mariculture Lack Growth

Sea Military Sabotage Human

Growth Poor Little Illegal Poverty Ghost Fishing

Causes

· · · · · · · ·

· · · ·

· · · · · · ·

or

vol- the

ecosystem

and

pol- aggra-

and

the

of

water

cities,

it, contami-

major

pollution treatment

through

of fragile

a

serious

unforeseen

substantial

within

of from straddling

is

coastal

coastal

water inadequate

A

risk

to infrastructure.

in developments of was created

and

throughout

and

areas

transported

There

Maintenance

has Aging

spills: is

ge

damage coastal

Coastal

which

problem.

oil

lar

oil region

litter: problem

expansion of

the

of environments

and

of

a

significant

15.2

is

Deterioration quality: rapid much unplanned, "hotspots." infrastrucure icy/monitoring/enforcement vates

Major ume BCLME this nation coastal accidents, stocks

Marine

C1.

C2.

growing BCLME.

T

able

Problems

C3.

247

re-

pack-

on

manage-

available

quality

legislation

agreements

agreements

water

plan

and

and control

and

for

uplift

plans

incentives

policies

Outputs

protocols pollution

contingency

protocols

material/documents

solutions

resources

beaches

Shared ment Regional Improved Socioeconomic

Regional Shared Rehabilitation Regional

Cleaner Education gionally Standardized aging/recycling

Anticipated

·

· · ·

· · · ·

· ·

·

1

1

2

1

1

2

2

3 1

3

3

2 3

1 1 2 2 1

Priority

con-

de-

plan

recovery

notification

environmental

working

pollution

pollution

enforcement

pollution

of

of

packaging

on

of

facilities

policies

marine

regional framework fective

enforcement

standard

regional

ef

control contingency

indicators/criteria

in

education

projects prevention

awareness

recycling

awareness

and surveillance

state

reception

Develop quality Establish groups Training control Plan/adapt monitoring Establish agencies Demo trol Joint

Port Regional velopment Research/modeling periods Public procedures

Litter Harmonization legislation Public Port Regulatory Standardized Seafarer

Activities/Solutions

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

· ·

·

·

· ·

· · · · ·

gan-

(bor-

or

strad-

solu-

contain-

on

for rehabili-

pollutant

pollutant

transport

Consequences

marine

of seals

common

protection

impacts

sharing

site

e.g.,

stocks spots"

surveillance, etc.

wetlands)

T

ransboundary transport Migration isms, Negative dling "Hot tions

Resource ment, tation, Ramsar der Transboundary transport

T

ransboundary

T

ransboundary

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

pro-

quality

life

of

(e.g. salt

quality

costs

income

informal

costs

in

Consequences

impacts

impacts

tourism

quality

health yields resource

employment

fisheries,

yields resource

fishing

costs tourism

continued

of

of

of health

of creation

Loss Higher Altered Reduced Aesthetic Lowered Loss

Opportunity tourism, duction) Altered Reduced Aesthetic

Loss Public Cleanup Loss Job sector

15.2

· · · · · · ·

·

· · ·

· · · · ·

Socioeconomic

T

able

C1

C2

C3

248

M.J. O'Toole et al.

functional by January, 2001. Meanwhile, the three governments have signed the SAPand the

GEF Council recently approved the funds for the BCLME Programme (approximately US$

15 million). As envisaged, the IBCC will be implementing the organization for the BCLME

SAP and will be supported by advisory groups as necessary. The following initial advisory

groups are likely to be:

· Advisory Group on Fisheries and Other Living Resources,

· Advisory Group on Environmental Variability and Ecosystems Health,

· Advisory Group on Marine Pollution,

· Advisory Group on Information and Data Exchange,

· Advisory Group on Legal Affairs and Maritime Law,

· Advisory Group on Industry and the Environment.

It is anticipated that the IBCC would regularly review the status and functions of the above

advisory groups and also establish ad hoc groups to help implement the SAP. Within the

IBCC, a Project Coordination Unit would play a key role in coordination, networking, com-

munication and information exchange for the BCLME Programme. It has been proposed that

three activity centers (one per country) be established to facilitate coordination within the

partner countries and to serve as centers for specialist BCLME actions (e.g., resource assess-

ment, methodology and calibration, regional environmental monitoring and networking, ma-

rine pollution, etc.).

Policy Actions

The policy actions by and large build on and give effect to (with deadlines) the actions speci-

fied in the TDA that are necessary to address the suite of identified priority transboundary

problems and issues. As full coverage of these is beyond the scope of this paper, we present

here a few examples which still need to be agreed and approved by the three governments:

· Joint surveys and assessment of shared stocks of key species will be undertaken

cooperatively between 20012005 to demonstrate benefits of this approach. The three

countries endeavor to harmonize the management of the shared stocks.

· A regional mariculture policy to be developed by December, 2002.

· The three governments commit themselves to compliance with the FAO (Food and

Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations) Code of Conduct for Responsible

Fisheries (FAO 1995).

· A regional framework for consultation to mitigate the negative impacts of mining be

developed by December, 2002, and mining policies relating to shared resources and

cumulative impacts to be harmonized.

· A regional network for reporting harmful algal blooms to be implemented in 2002.

· Wastewater quality criteria for receiving waters to be developed by June, 2002, for

point source pollution.

· Astrategy for the implementation of MARPOL73/78 in the BCLME region be devised

by December, 2000.

· Existing data series and material archives to be used to establish an environmental

baseline for the BCLME.

Integrated Management of the Benguela Current Region

249

· Aregional biodiversity conservation management plan and framework to be developed

by December, 2003.

· A comprehensive regional strategic plan for capacity development and maintenance

for the BCLME to be finalized by June, 2001.

Wider Cooperation

The three countries, individually and jointly, would encourage enhanced cooperation with

other regional bodies such as BENEFIT, SADC (Southern African Development Commu-

nity), the future South East Atlantic Fisheries Organization (SEAFO), NGOs, UN Agencies,

donors, and other states with an interest in the BCLME.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

We have attempted to illustrate the joint approach taken by Angola, Namibia, and South Af-

rica in partnership, where appropriate, with the international community to manage the ma-

rine and coastal resources of the Benguela Current region sustainably through the application

of science and technology. Examples have been provided of a fisheries science initiative,

BENEFIT, country-based ICM, and holistic approach to regional marine and coastal man-

agement using the emerging BCLME Programme as the catalyst. These are some of the build-

ing blocks, but there are others. For example, at the science and technology level, strong links

have been built with a number of parallel, but distinctly different, initiatives. These include

(a) South Africa's established and internationally acclaimed Benguela Ecology Programme

(BEP) (see Siegfried and Field 1982), which has resulted in the publication of thousands of

publications on the Benguela ecosystem since 1982 (see, e.g., Payne et al. 1987, 1992; Pillar

et al. 1998), (b) the ENVIFISH Programme (Environmental Conditions and Fluctuations in

Distribution of Small Pelagic Fish Stocks), which is a three-year European Union funded pro-

ject between seven EU states and Angola, Namibia, and South Africa focusing primarily on

the application of satellite data in environmentfisheries research and management, and

which commenced in October, 1998, and (c) VIBES (Variability of Exploited Pelagic Fish

Resources in the Benguela Ecosystem in Relation to Environmental and Spatial Aspects), a

bilateral FrenchSouth African initiative focusing on the variability of pelagic fish resources

in the Benguela and the environmental and spatial aspects of the system, which also com-

menced in 1998. At the socioeconomic and management levels, bilateral arrangements be-

tween the three Benguela countries and various overseas states have materially assisted the

development and application of sustainable management policies, while enhanced regional

cooperation at all levels across disciplines is actively promoted by SADC. In the fisheries

context, the future SEAFO is likely to play a pivotal role in the sustainable management of

living marine resources.

In Figure 15.5 we have attempted to show how the various science and management initia-

tives fit together, both at the country level and regionally in the Benguela. Clearly, appropri-

ate science and technology are the cornerstones of the integrated sustainable management. At

all levels and in all disciplines and functions, strong emphasis has been placed on capacity

development.

250

M.J. O'Toole et al.

INTEGRATED

SUSTAINABLE MARINE AND

COASTAL MANAGEMENT

IN THE BENGUELA

CURRENT REGION

Management

BCLME

at country level

Programme

Angola

Namibia

Other regional

S. Africa

Socioeconomics

science &

at country

technology (e.g.,

level

ENVIFISH

BENEFIT

VIBES, etc.)

Science &

Science &

technology

technology

& capacity

at country

building

level

Figure 15.5 Schematic showing the interlinking of science, technology, and management in the

BCLME at country and regional levels.

The collaborative approach by Angola, Namibia, and South Africa is highly relevant

within a broader regional context, i.e., within SADC, as it provides an example how member

states with very different resource bases (human, infrastructure, financial) can work together

using science and technology as a unifying factor to underpin responsible management of a

complex system. Taken one step further it can help convert the vision of an African Renais-

sance into reality. More than that, we suggest that the approach and action by the countries

bordering on the Benguela Current could serve as a blueprint in other parts of the developing

world for the integrated sustainable management of marine and coastal systems which are

shared between two or more countries.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

What we have attempted to synthesize in this paper represents the collective wisdom and vision of a

large number of local, regional, and international experts, and an example of the commitment by the

governments of three southern African states to sustainable development and wise management of the

region and its natural resources. In preparing this manuscript, we have drawn on published and

unpublished documents as well as from the BCLME TDAand SAP and an article by L.V. Shannon and

M.J. O'Toole entitled "The Benguela: Ex Africa Semper Aliquid Novi," which has been drafted for a

book on large marine ecosystems edited by G. Hempel. We acknowledge permission given by the

Windhoek Office of the United Nations Development Programme to use information from the TDA

developed for the BCLME Programme and the invaluable input by Mr. C. Davis of the U.K. Department

for International Development into the section dealing with ICM in South Africa.

REFERENCES

BCLME SAP (Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem Strategic Action Plan). 1999. Strategic

Action Plan for the Integrated Management and Sustainable Development and Protection of the

Integrated Management of the Benguela Current Region

251

Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem. Windhoek: UNDP (United Nations Development

Programme).

BCLME TDA. 1999. Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem Programme (BCLME)

Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis (TDA). Windhoek: UNDP.

BENEFIT (Benguela-Environment-Fisheries-Interaction-Training Programme). 1997. BENEFIT

Science Plan. Swakopmund: BENEFIT Secretariat.

Black Sea. 1996. Strategic Action Plan for the Rehabilitation and Protection of the Black Sea. Istanbul:

Global Environmental Facility/UNDP Black Sea Environmental Programme.

Brown, P.C., S.J. Painting, and K.L. Cochrane. 1991. Estimates of phytoplankton and bacterial biomass

and production in the northern and southern Benguela ecosystems. S. Afr. J. Mar. Sci. 11:537564.

Bubnov, V.A. 1972. Structure and characteristics of the oxygen minimum layer in the South-eastern

Atlantic. Oceanology 12:193201.

Chapman, P., and L.V. Shannon. 1985. The Benguela ecosystem. 2. Chemistry and related processes. In:

Oceanography and Marine Biology: An Annual Review, vol. 23, ed. M. Barnes, pp. 183251.

Aberdeen: Aberdeen Univ. Press.

Croll, P. 1998. Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem (BCLME). First Regional Workshop, United

Nations Development Programme, 2224 July 1998, Cape Town, South Africa. Report prepared for

Global Environmental Facility/UNDP Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem Programme.

Windhoek: UNDP.

Croll, P., and J.T. Njuguna. 1999. Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem (BCLME). Second

Regional Workshop, United Nations Development Programme, 1216 April 1999, Okahanja,

Namibia. Report prepared for Global Environmental Facility/UNDP Benguela Current Large

Marine Ecosystem Programme: Windhoek: UNDP.

Draft White Paper. 1999. Draft White Paper for Sustainable Coastal Development in South Africa.

Pretoria: Dept. of Environment Affairs and Tourism.

FAO (Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations). 1995. Code of Conduct for

Responsible Fisheries. Rome: FAO.

Hamukuaya, H., M.J. O'Toole, and P.M.J. Woodhead. 1998. Observations of severe hypoxia and

offshore displacement of Cape hake over the Namibian shelf in 1994. S. Afr. J. Mar. Sci19:5759.

Payne, A.I.L., K.H. Brink, K.H. Mann, and R.H. Hilborn, eds. 1992. Benguela Trophic Functioning. S.

Afr. J. Mar. Sci. 12:11108.

Payne, A.I.L., J.A. Gulland, and K.H. Brink, eds. 1987. The Benguela and Comparable Ecosystems. S.

Afr. J. Mar. Sci. 5:1957.

Pillar, S.C., C.L. Moloney, A.I.L. Payne, and F.A. Shillington, eds. 1998. Benguela Dynamics: Impacts

of Variability on Shelf-sea Environments and Their Living Resources. S. Afr. J. Mar. Sci.19:1512.

Shannon, L.V., J.J. Agenbag, and M.E.L. Buys. 1987. Large- and meso-scale features of the Angolan

Benguela Front. S. Afri. J. Mar. Sci. 5:1134.

Shannon, L.V., and G. Nelson. 1996. The Benguela: Large scale features and processes and system

variability. In: The South Atlantic: Past and Present Circulation, ed. G. Wefer, W.H. Berger, G.

Siedler, and D.J. Webb, pp. 163210. Berlin: Springer.

Shannon, L.V., and M.J. O'Toole. 2000. The Benguela: Ex Africa semper aliquid nov, ed. G. Hempel, in

press.

Sherman, K. 1994. Sustainability, biomass, yields, and health of coastal ecosystems: An ecological

perspective. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 112:277301.

Siegfried, W.R., and J.G. Field, eds. 1982. A Description of the Benguela Ecology Programme

19821986. South African National Scientific Programmes Report No. 54. Pretoria: CSIR (Council

for Scientific and Industrial Research).

United Nations. 1983. United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea 1982. New York: United

Nations.

Yamagata, T., and S. Iizuka. 1995. Simulation of tropical thermal domes in the Atlantic: A seasonal

cycle. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 25:21292140.