March 6, 2005

Benguela Current Commission (BCC) Economic Study

Prepared by

Ussif Rashid Sumaila, Gordon Munro and Heather Keith

Fisheries Economics Research Unit, Fisheries Centre, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, B.C., V6T 1Z4 Canada

For

The United Nations Office for Projects Services (UNOPS) and Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem (BCLME) Programme

![]()

Table of Contents

Executive Summary 4

1.0. Introduction 12

1.1. Terms of reference 12

1.2. Addressing the terms of reference 13

1.3. The Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem (BCLME) 13

1.4. Shared stocks defined 15

1.5. Are the living marine resources of the BCLME shared? 15

1.6. The legal obligations of coastal states sharing transboundary resources 16

1.7. Economic rationale for joint management of shared stocks 16

2.0. Fisheries resources in Namibia, South Africa and Angola 17

2.1. Namibia 17

2.2. South Africa 17

2.3. Angola 18

3.0. Data and information for economic analysis of the cost of fisheries management 18

3.1. Information for computing benefits of fisheries management 18

3.2. Information for computing costs of fisheries management 33

4.0. Benefit cost analysis of incremental regional cooperation 37

4.1. The status quo (default) scenario 37

4.2. The SAP proposal 38

4.3. The management and task oriented scenario 40

5.0. Addressing specific questions raised by the TOR 41

5.1. Other potential costs and benefits from cooperative management 41

5.2 Justification for an ecosystem based approach to fisheries management 42

5.3. Collaboration with the Institutional Review team 43

6.0. Conclusions and Recommendations 44

ACKNOWLEGDEMENTS

We acknowledge the help and information provided by the following: Johann Augustine, Research Director, MCM, Stephen Cederrand, SADC-MCS, Adriana F. Carlos Costa, Angola, Cormac Cullinan, Chief Executive Officer, En Act International, South Africa, Heidi Currie, Institutional Review Team, Anna Erastus, Director, Economic Planning, MFMR, Hashali Humuakuaya, Director, BCLME Activity Centre, Swakopmund, Mick O’Toole BCLME Technical Director, Gabi Schneider, Director, Geological Survey (Namibia), Andre Share, Director, Resource Management and Allocation (MCM, Marine), Neville Sweijd, BENEFIT Director, Filomina Velho, Angola, all those interviewed by the Institutional Review Team, and many others during the course of this work. The financial support of the BCLME programme is gratefully acknowledged. Sumaila and Munro acknowledge the support of the Sea Around Us project of the Fisheries Centre.

Executive Summary

The Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem (BCLME) programme is a multi-sectoral initiative undertaken by Angola, Namibia and South Africa to facilitate integrated management, sustainable development and protection of the ecosystem and environment as a whole. The key transboundary issues that are being addressed include the migration or straddling of valuable fish stocks across national boundaries, the introduction of invasive alien species via the ballast water of ships moving through the region, and pollutants or harmful algal blooms that can be advected by winds and currents from the waters of one country into another.

The three countries have agreed to a Strategic Action Programme, which includes the establishment of an Interim Benguela Current Commission (IBCC) initially, which is to be developed later into a fully-fledged regional cooperative management body for the Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem.

The main purpose of this study is to analyze the economics of fishery management and other marine industries in the Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem (BCLME), reviewing the case for and against regional co-operation in managing the BCLME. The analysis is undertaken for the major transboundary commercial fisheries of the region using hake as the core species underlying the study.

Economic analysis of the status quo management of the BCLME

We analyze the current domestic costs and benefits of fishery management in Angola, Namibia and South Africa, providing a default scenario for further analysis. The analysis utilizes appropriate and comparable economic yardsticks that provide estimates of costs and benefits of current management systems in the three countries of the BCLME.

Economic analysis of the incremental costs and benefits of regional cooperative management of the BCLME

We identify the incremental costs and benefits attached to and derived from regional co-operation on fisheries management and environmental protection to the three countries individually and to the region as a whole.

We assess the costs and risks associated with non-co-operation in fishery management, environmental monitoring and resource protection regionally.

We also provide a general assessment of the net benefits of joint ecosystem management in the region, and discuss its contribution to broader national and regional development objectives such as food security, poverty alleviation and job creation.

Provide economic case for taking an ecosystem approach to LME management

With input and guidance from other team members, we review and present the economic case for taking an ecosystem approach to LME management relative to traditional fisheries management models in relation to fisheries, and as far as possible non-fisheries benefits (e.g. recreational fishing, coastal tourism).

Is regional cooperative management justifiable economically and socially?

Current knowledge of the BCLME fish stocks indicate that (i) the deep water hake stock is shared by South Africa and Namibia, and the Cape hake stock is also shared if only indirectly through cannibalism, (ii) the pilchard and horse mackerel stocks are shared between Angola and Namibia, (iii) red crabs and bronze whaler sharks are shared between Angola and Namibia, and (iv) bigeye, yellowfin and albacore tunas are also shared by the countries of the BCLME both within their EEZs and on the high seas. Based on this and the key results from the economic theory of shared stocks management, the answer to the question posed is YES, cooperative management of the BCLME is indeed justifiable.

We focus on the commercial values from the fisheries of the Benguela in our analysis. This is not to say that non-commercial values are unimportant, but rather, our point of departure is that if it can be shown that the increase in commercial values from joint management of the resources of the BCLME exceed the cost, then the extra benefits from non-market values will be a bonus. We do not include the initial cost of providing physical structures. That is, we provide an analysis of only the cost of running the new management Commission. A key reason for taking this approach is that the new Commission can use the existing physical structures used by the BENEFIT and BCLME programmes.

To investigate the net commercial benefits from current and future management of the fisheries resources of the Benguela, we analyze, as far as data availability will allow, data on the following key economic indicators: (i) landings, (ii) landed values, (iii) economic rent, (iv) exports, (v) contribution to GDP, and (v) employment/food security, for each of the three countries. Each of these variables will capture an important aspect of the benefits from the fisheries of the Benguela. For instance, the contribution to GDP provides a measure of the importance of fisheries at the macroeconomic level, while economic rent and employment generated provide indications of the contribution of fisheries to the livelihood of people and the profitability of businesses at the micro level. Also, by providing numbers on exports, we provide indications of how the post-harvest sector is impacted, as well as the sector’s contribution to the region’s foreign exchange earnings.

Cost and benefits from the status quo (current) fisheries management

The estimated benefits from the status quo management scenario are given in the table below. We see from the table that significant benefits accrue to the countries in terms of economic rent, export values, jobs, etc.

Table 1ES: Annual landings (000 t.); landed values, economic rent, export value (million N$/rand for Namibia and South Africa; billion Kwanza for Angola); Contribution to GDP (%), and jobs (person years).

|

|

Namibia |

South Africa |

Angola |

|

Landings |

572 |

450 |

220 |

|

Landed values |

1 177 |

1 291 |

11.9 |

|

Economic rent |

602 |

462 |

3.2 |

|

Export values |

1 590 |

711 |

2 676 |

|

Contribution to GDP |

8.5 |

0.45 |

4 |

|

Jobs |

7 200 |

26 000 |

30 000 |

The table below summarizes the estimated cost of current fisheries management by Namibia, South Africa, BCLME

Table 2ES: Annual cost of current fisheries management. Total cost in million N$/rand for Namibia, South Africa, BCLME, BENEFIT and SADC Programme; million Kwanza for Angola.

|

|

Total cost |

|

Namibia |

66 |

|

South Africa |

306 |

|

Angola |

357 |

|

BCLME |

45.6 |

|

BENEFIT |

12.5 |

|

SADC |

6.8 |

From the table above, we see that the total annual cost of management to the countries and the regional programmes, taken together, are well below the economic rent derived from the fisheries.

The estimated potential net benefits

The key economic indicator of the performance of fisheries management is economic rent. Converting the economic rent from the three countries into N$/R, gives a total annual economic rent of R 1289 million. The N$/R equivalent total cost of fisheries management is R 462 million. This indicates a significant net benefit from current fisheries management in the three countries.

The Strategic Action Plan (SAP) contains a proposal for the establishment of an Interim Benguela Current Commission (IBCC). The SAP envisages that the IBCC will be a transitional management entity, which will function as the precursor to the Benguela Current Commission.

Quantifying potential benefits

There are two potential benefits of regional cooperative management. First, it will help minimize the risk of wasteful use of shared stocks. That is, it will mitigate the economic risk of non-cooperative management. Second, it can help increase the cake by arranging harvesting by all countries involved in such a way that shared stocks are allowed to grow to their fullest economic potential.

It appears that the SAP proposal will, at least, minimize the economic risk of non-cooperation by providing scientific information on shared stocks, and a framework within which the countries can manage these resources to mitigate this risk. The maximum value of this risk is the current economic rent derived by all the countries from shared stocks. This is estimated to be equal to N$ 502 million, R 213 million and Kwanza 330 million, in Namibia, South Africa and Angola, respectively. This gives a total economic rent from shared stocks of R 738 million. This amount is actually the maximum potential economic risk of non-cooperation. Without regional cooperative management, there is the risk that all the economic rent from the shared stocks of the BCLME would end up being dissipated. In addition, the lack of joint management will reduce the landed values, jobs, and export revenues derived from shared stocks. At the extreme, most of these values can disappear if overfishing leads to the depletion of the shared fish stocks.

The SAP proposal is not far reaching enough in terms of actual cooperative management of the shared resources. We therefore assume that this scenario is not likely to lead to the second benefit expected from cooperation.

Quantifying potential costs

We assume that the countries will continue their current management functions at the current levels of cost. In addition, each country will incur additional cost to help coordinate the activities of the IBCC with national fisheries management activities. We take as our point of departure, the current cost of running the BCLME, BENEFIT and SADC-MCS programmes, and then adjustment this to incorporate the additional coordination costs alluded to earlier. Due to the lack of data, we assume that each country will incur an additional coordination cost of 5% of current management costs. This assumption implies additional coordination cost of R 3.3, 15.3 and 1.26 (17.85 Kwanza) million for Namibia, South Africa and Angola, respectively.

Table 24: Estimated cost of current fisheries management (R million)

|

Cost elements |

Amount (R million) |

|

Current cost of the BCLME Programme |

45.6 |

|

Current cost of the BENEFIT Programme |

12.5 |

|

Additional coordination costs |

|

|

Namibia |

3.3 |

|

South Africa |

15.3 |

|

Angola |

1.26 |

|

Total |

77.96 |

The estimated potential net benefits

For a total cost of R 77.96 million, this management scenario has the potential to protect and provide insurance against the risk of non-cooperation, at a maximum amount of R 738 million annually. Even if only 15% of this amount is lost due to non-cooperation, our analysis indicates that there will still be a net gain from establishing the IBCC.

This scenario is based on the assumption that each country would designate a lead ministry with primary responsibility for coordinating the participation of all relevant ministries and stakeholders from those countries in BCLME activities. Each lead ministry would also be responsible for driving the implementation of BCLME activities in that country and in reporting back to BCC structures.

Quantifying potential benefits

Similar to the case of the SAP proposal, this cooperative management scenario will remove the economic risk of non-cooperation. The maximum value of this insurance against the risk of non-cooperation is the estimated total economic rent from shared stocks of R 738 million. This management scenario is also far reaching enough in terms of actual cooperative management of the shared resources that, if properly implemented, will potentially lead to the second benefit expected from cooperation, namely, increase size of the cake by arranging harvesting by all countries involved in such a way that shared stocks are allowed to grow to their fullest economic potential. It has recently been estimated that the potential increase in economic rent from Benguela hakes due to the introduction of cooperative management is about 40%. A survey of the literature shows that this is actually a conservative estimate. Much higher gains have been estimated for shared stocks in other parts of the world. Based on this estimate, the total potential benefit of implementing this management scenario in terms of economic rent is R 1033 million.

Quantifying potential costs

We assume that the countries will continue their current management functions at the current levels of cost. We therefore focus on the cost of regional management. We take as our point of departure, the current cost of running the BCLME and BENEFIT programmes, and then make adjustments to this to incorporate the cost of new elements in the management scenario. An annual amount of R 7.5 million is budgeted to cover the cost of convening meetings of the BCC, R 26.8 million per annum to run the Activity Centres/Advisory Groups, R 5 million per annum to cover the cost of operating Permanent and Ad hoc Working Groups, and R10 million to cover the cost of ‘other institutional arrangements’.

Table 4ES: Estimated cost of current fisheries management (R million)

|

Cost elements |

Amount (R million) |

|

Current cost of the BCLME Programme |

45.6 |

|

Current cost of the BENEFIT Programme |

12.5 |

|

Additional costs |

|

|

Ministerial Commission |

7.5 |

|

Permanent and Ad Hoc Working Groups |

5.0 |

|

Advisory Groups |

26.8 |

|

Other institutional arrangements |

10 |

|

Total |

107.4 |

The estimated potential net benefits

The total potential gain from this cooperative management scenario is estimated to be the sum of the insurance against the risk of non-cooperation, and the potential for an increase in the economic rent that can be derived from the shared resources of the BCLME. This is calculated to be R 1 033 million annually. The annual cost of implementing this scenario is estimated at R 107.7 million. Therefore, the potential for achieving significant net benefits from this scenario is high. In fact, only about 10% of the estimated benefits are needed to cover the estimated cost.

Since environmental pollutants do not respect national borders, significant benefits may also be derived from cooperation in this area. Close collaboration with the ministries managing the exploitation of non-living marine resources will be crucial in dealing with environmental problems. Work by the BCLME programme in this respect will form a good basis for the future task of the IBCC in this regard.

Benefits may also be obtained due to the economies of scale with respect to training of regional expertise. Joint management of the Benguela could also result in the cultivation of political goodwill, which may produce a positive effect on conflict resolution between the three countries; and thereby help in the resolution of border problems, for example. The BENEFIT and BCLME programmes have already made significant contributions in this regard.

Ecosystem based management is crucial if regional cooperative management is to succeed. In order words, an essential requirement for the attainment of the net benefits presented above is ecosystem based management. This management approach is beneficial in evaluating management policies that take into consideration the dynamics of the entire area including all components. There are many factors contributing to the productivity of one species, fishing pressure is an important factor but not necessarily the only influence. Ecosystem-based management recognizes that certain non-fishery activities have an impact on the marine ecosystem and have consequences for management. These include predator-prey interactions and land-based and sea-based activities, which affect habitat, water quality, fisheries productivity, and food quality and safety.

In recognition of the importance of ecosystem based management, the three BCLME countries have already indicated their intention to adopt this approach, as it is apparent from their Strategic Action programme. In fact, the BCLME Programme in collaboration with the FAO has already commissioned a project to address the question “Is it possible to introduce a more holistic system of fisheries management in the Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem?” The result of this study will provide the basis needed for the management of the BCLME as a whole, and therefore help Angola, Namibia and South Africa to reap the economic benefits of such management.

It is worth noting that there already exist structures, which would facilitate the formalization of the IBCC. For example, members of the current BENEFIT programme management committee are also members of the BCLME Programme Steering Committee (PSC). There is also a BCLME/BENEFIT liaison committee which regularly meets for consultations. Therefore, there are institutional structures and working relationships between the two programmes that will serve the IBCC very well.

We recommend that the IBCC should commerce at a modest level, using the experience gathered over the years from the BCLME and BENEFIT programmes. This approach will allow for learning and the building of confidence and mutual trusts between the parties, which are all crucial for the success of the Commission. An additional beauty of this approach is that it will initially not need a huge infusion of new resources.

A fundamental issue that must be agreed upon is how to fund the IBCC sustainably. Ultimately the resources for running the IBCC will have to come from the region if the Commission is to be sustainable over the long run. Various funding sources should be explored and analyzed to help determine the combinations of funding opportunities that will work best. One can foresee a funding structure that consists of both internal and external sources, especially in the beginning of the IBCC. The good news is that even if a fraction of the predicted increase in economic rent that would result from joint management is realized, a move to such joint management will more than pay for itself.

Experience from around the world demonstrates that strong political commitments, at the highest level of government, are required to make joint management work. Therefore, if the region decides to establish the IBCC, it would have to fully back it up politically.

To help the new IBCC get on its feet, we recommend that current funding levels by international donors be continued until a selected date sometime in the future, when the national governments of Angola, Namibia and South Africa will take over the full funding of the Commission.

It is crucial for the success of the IBCC that all stakeholders in the fishing sectors of the three countries (or at least a significant majority) strongly support the concept of joint management. Efforts should be put into making this happen.

To help deal with the occasional disputes that are bound to occur from time to time, the parties need to put in place a binding dispute resolution mechanism.

The following points should be given special attention when designing the nature and structure of the IBCC. First, care should be taken to make sure that the sovereignty issue does not become a significant problem. Second, the fact that there is no assurance that the member states will have identical resource management goals is important, and needs to be taken into account. Third, there will be the need for high quality research, the results of which are seen as being credible by all parties. Fourth, secured sustainable funding and strong political commitment by the countries should be at the center of the development of the IBCC.

Finally, the new Commission should put in place structures for collaborating with international organizations such as ICCAT, SADC and SEAFO.

1. 0. Introduction

1.1. Terms of reference

Objectives

The objective of the proposed study is to analyze the economics of fishery management and other marine industries in the Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem (BCLME), reviewing the case for and against regional co-operation in managing the LME.

The analysis is undertaken for the major transboundary commercial fisheries of the region using hake as the core species underlying the study. Insights from the hake analysis are then extended to make inferences about the transboundary management of the other major commercial species, in particular, the pilchard and horse mackerel fisheries. As a further extension, brief descriptions of the potential for managing other natural resources in the Benguela LME, namely, marine mining, offshore oil and gas, maritime transport and tourism sectors, are made as far as it is possible.

Economic analysis of the status quo management of the BCLME

We analyze the current domestic costs and benefits of fishery management in Angola, Namibia and South Africa, providing a default scenario for further analysis. The analysis utilizes appropriate and comparable economic yardsticks that provide estimates of costs and benefits of current management systems in the three countries of the BCLME.

Economic analysis of the incremental costs and benefits of regional cooperative management of the BCLME

We identify the incremental costs and benefits attached to and derived from regional co-operation on fisheries management and environmental protection to the three countries individually and to the region as a whole.

We assess the costs and risks associated with non-co-operation in fishery management, environmental monitoring and resource protection regionally.

We also provide a general assessment of the net benefits of joint ecosystem management in the region, and discuss its contribution to broader national and regional development objectives such as food security, poverty alleviation and job creation.

Provide economic case for taking an ecosystem approach to LME management

With input and guidance from other team members, we review and present the economic case for taking an ecosystem approach to LME management relative to traditional fisheries management models in relation to fisheries, and as far as possible non-fisheries benefits (e.g. recreational fishing, coastal tourism).

Outputs from analyses above

Based on the analysis above, we provide recommendations on the scope and scale of regional co-operation i.e. joint enforcement, scientific investigation, joint stock assessment and monitoring, for different fisheries needed to optimize domestic and regional benefits.

We provided inputs as far as it was feasible to the Institutional Review team in their compilation of the Institutional Review report.

An executive summary, documenting the key findings of the study is included as part of this report. The summary paper will be presented in a format that is presentable to decision makers in the Planning and Finance Ministries of the three countries.

1.2. Addressing terms of reference

To address the questions raised by the TOR, the following will have to be answered:

Are the resources, mainly the living but also the non-living, shared by the countries of the Benguela?

Is there transboundary sharing of the environmental pollutants?

Is joint management of the BCLME necessary?

Can joint managed be justified economically: What does theory and practice have to say about this?

Is joint management politically feasible?

The next sections of the paper will address each of the above and more.

1.3. The Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem (BCLME)

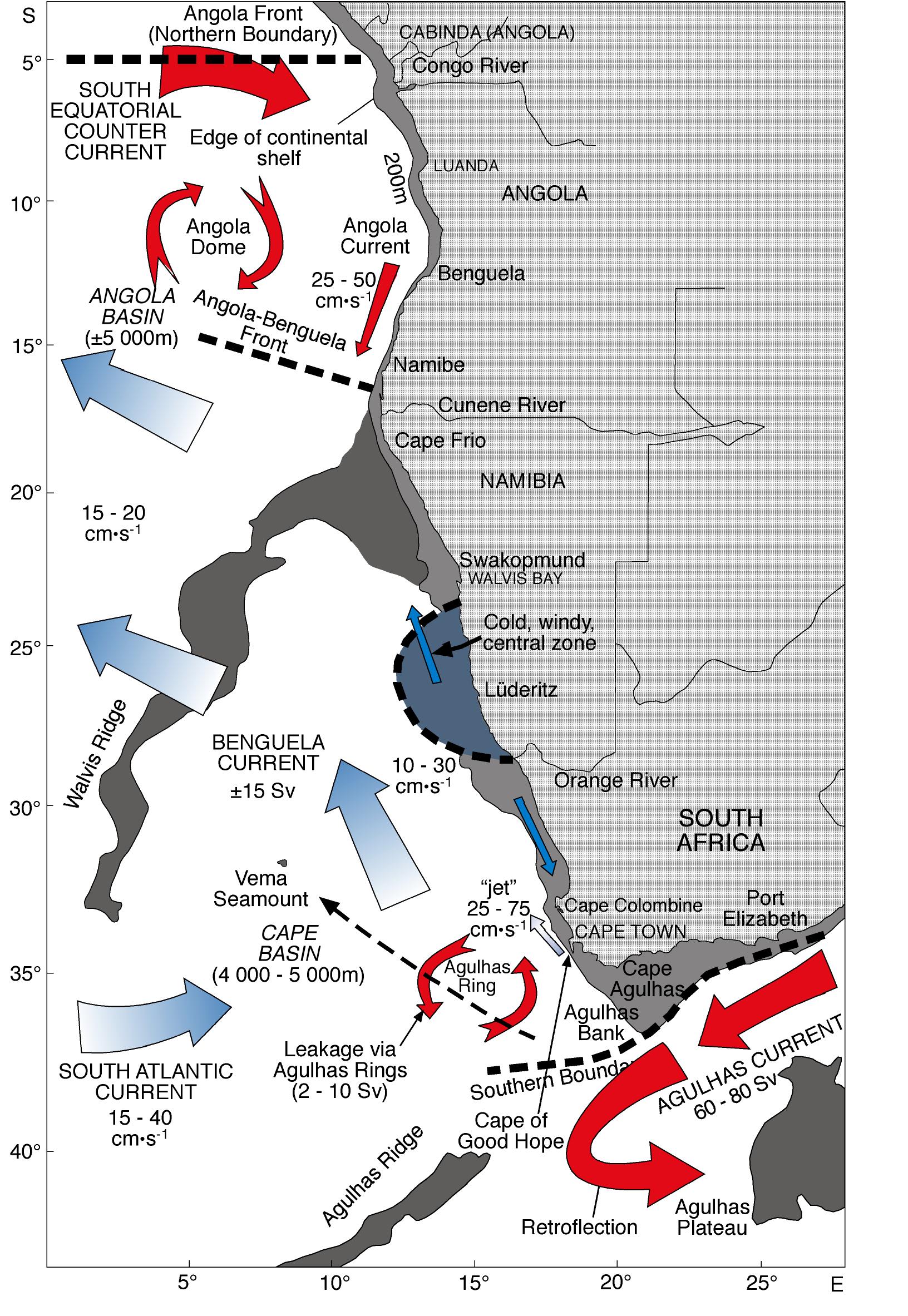

The BCLME can be seen as covering the continental shelf between the Angola-Benguela frontal zone in Northern/Southern Angola and the Agulhas retoflection area, typically between 36 and 37 degrees South (Shannon and O’Toole, 1998). It therefore covers the west coast of South Africa, the entire Namibian coast, and Southern Angola depending on the position of the Angola-Benguela front, which moves seasonally between 14 and 17 degrees South (see Fig. 1). The BCLME is one of the world’s major, productive eastern-boundary currents. It is rich in both pelagic and demersal fish populations, supported by plankton production driven by intense coastal upwelling (see Boyer and Hampton, 2001; Sumaila and Vasconcellos, 2000).

Figure 1: The Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem (BCLME)

1.4. Shared stocks defined

The FAO defines shared fish stocks as any fish stock, which is exploited by, more than one state/entity (Munro et al., 2004). The FAO sets forth four non-mutually exclusive categories of such stocks:

fish resources crossing the EEZ boundary of one coastal state into the EEZ(s) of one or more other coastal states – transboundary stocks;

highly migratory species, as set forth in Annex 1 of the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UN, 1982) consisting primarily, of the major tuna species. Being highly migratory in nature, the resources are found, both within the coastal state EEZ, and the adjacent high seas;

all other fish stocks (with the exception of anadromous/catadromous stocks) that are found, both within the coastal state EEZ and the adjacent high seas – known as straddling stocks;

fish stocks found exclusively in the high seas – denoted discrete high seas fish

stocks (Munro, et al., 2004).

Most BCLME fish stocks, in particular hake, are found mainly within the EEZ boundaries of the neighbouring states of Angola, Namibia and South Africa, and not in the high seas (Sumaila et al., 2003). Hence, they fall almost entirely into category (a), transboundary stocks. This is fortunate, since the management of categories (b), (c), and (d) stocks prove to be much more demanding and complex than the management of transboundary stocks (Munro, et al., 2004).

1.5. Are the living marine resources of the BCLME shared?

To address this question, we reviewed the literature and interviewed a number of experts and fisheries managers in the region. In general, almost all the people interviewed believe that a number of commercially important species in the Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem (BCLME) (e.g., hake, horse mackerel, deep sea crab, bronze whaler sharks, tuna, and to a lesser extent, pilchard and anchovy) are widely distributed and move seasonally across national borders, and can therefore be classified as shared stocks. The hake stocks of the Benguela have been classified by a recent review (RFIS, 2002) as a prime candidate for cooperative management in the South African Development Cooperation (SADC) region because of their shared nature and the fact that hake is the most valuable commercial species exploited in the large marine ecosystem. The general understanding is that the deep-water hake (paradoxus) is shared mainly between Namibia and South Africa. Most believe that the shallow water hake (capensis) is not shared directly. But there is evidence to show that there is a predator-prey interaction between the two species, in which case the capensis hake can be considered shared, albeit indirectly. In the case of pilchard and horse mackerel, the general understanding is that the stocks are shared primarily between Angola and Namibia.

1.6. The legal obligations of coastal states sharing transboundary resources

The legal obligations of coastal states such as Angola, South Africa and Namibia, sharing transboundary fish stocks are set forth in the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UN, 1982). The Convention has only one provision pertaining directly to the management of such stocks, namely, Article 63(1), which reads as follows:

Where the same stock or stocks of associated species occur within the exclusive economic zones of two or more coastal States, these States shall seek, either directly or through appropriate sub regional or regional organizations, to agree upon the measures necessary to coordinate and ensure the conservation and development of such stocks without prejudice to the other provisions of this Part [V] (UN, 1982, Article 63(1)).

The Convention imposes a duty upon the relevant coastal states to negotiate over arrangements for the management of transboundary stocks. Importantly, however, the Convention does not impose a duty upon the states to reach an agreement. If the states are unable to reach an agreement, then each state shall manage that segment of the transboundary stock occurring within its EEZ. It shall do so in accordance with the rights and duties relating to fisheries management and conservation by a coastal state within its EEZ, as set forth by the Convention (Munro et al., 2004).

In entering into negotiations with respect to the management of such resources, the coastal states, of course, do so in good faith. To quote the International Court of Justice, the states “----are under the obligation so to conduct themselves that the negotiations are meaningful, which will not be the case when either of them insists upon its own position without contemplating any modification of it” (cited in Munro et al., 2004). Nonetheless, the point remains. If such coastal states enter into meaningful negotiations and find that there is no reasonable basis of cooperation, they have the legal right to decline to enter into a cooperative agreement. Each state would then proceed to manage its share of the resource to the best of its ability. This outcome could arise, for example, if the states came honestly to the conclusion that the costs of establishing a cooperative resource management agreement would exceed the anticipated benefits.

1.7. Economic rationale for shared management

From the discussion in section 2, it can be seen that the fisheries sector ranks high in national importance in Namibia. For instance, fish products accounted for 23% of all exports in 1996 (second only to diamonds), and up to 10% of GDP (Tapscott, 2001). Even though the same cannot be said in the case of South Africa (only about 0.5% of GDP is contributed by the fisheries sector), exports are about the same size as those of Namibia. The industry is also an important source of revenue and food in coastal areas, especially in the Western Cape Province, where about 90% of all South African hake are landed. The sector is an influential source of employment in Namibia, although, in this regard, the fishing sector makes a much smaller contribution to South Africa nationally. Fishing in Angola is less important in terms of formal economic activity but is essential to the social fabric of the country in terms of employment and food security. All in all, the fishing sectors in Namibia, South Africa and Angola are economically and socially important. Even in South Africa, where the economy is much more diverse, the socio-economic incentives of optimising resource rent from the hake fishery are significant.

Many economic studies have demonstrated that non-cooperative management of shared fish stocks has undesirable consequences. Even when a given fish remains within the national borders of a country, there are gains to be made from cooperative agreement if different groups of fishers operate in the fishery. For instance, Sumaila (1997) showed that when two different types of vessel gears with different selectivity patterns are employed to exploit the same stock of fish, cooperative management yields some significant gains. With respect to the shared hake stocks of the BCLME, preliminary work by Armstrong and Sumaila indicate that the potential cost of non-cooperative management of the hake stocks of the BCMLE is significant. Probably amounting to over 40% of the discounted rent that is currently being obtained by Namibia and South Africa (Armstrong and Sumaila, 2004).

2.0 Background to fisheries in Namibia, South Africa and Angola

2.1 Namibia

The fisheries sector is the third-largest of the Namibian economy, behind agriculture and mining. The industrial fishery has generated up to 10% of the country’s GDP in recent years. In 2003, the country’s 335 vessels of which 80% were Namibian flagged, landed over 600 000 tonnes of fish (Iyambo, 2004). Landed value of N$ 1 558 million was realised in 1998 from the country’s fisheries. Exports were valued at N$ 2 147 million in that year, making the sector the second-largest export earner behind mining. It is the second-fastest growing industry in the Namibian economy (behind tourism) with the value of production and exports now being six times greater than at Independence.

The fisheries sector is extremely important in the social economy of Namibia, particularly in Walvis Bay, which is the major fishing port and where most of the processing plants are situated. Local employment in the sector grew rapidly after Independence, with an estimated 6 000 jobs having been created between 1991 and 1994. The number of people directly employed in the fisheries sector in 1996 was about 15 000, of which some 7 500 were fishermen. Of these 43% were foreigners, mainly in the horse mackerel and tuna fisheries, a proportion that has decreased from around 66% in 1993. The demersal fishery is the most valuable fishery in Namibia, with hake the dominant commercial species. Almost the entire demersal catch is exported.

2.2. South Africa

South Africa’s living marine resources of the Benguela Current form the basis of a fishing industry which supports some 26 000 people (mostly in the Western Cape), and supplies food for the whole Southern African subregion. In 1997, the South African fishing industry caught a total of 445 000 tonnes of fish, shellfish and seaweed nationwide, of which more than 90% was taken from the Benguela. The wholesale value of the total processed output in this year was estimated at R 1 953 million, with an export value of R 873 million. Fishing is particularly important in the social economy of the Western Cape, where some entire coastal communities depend directly or indirectly on fishing for their livelihood. However, the fishing industry yields less than 1% of South Africa’s GDP.

Economically, the trawl fishery is the most important sector of the South African fishing industry. Catches of hake, which amounted to 147 000 tonnes in 1997, usually contribute about 70% of the trawl catch and about 80% of its value. In 1997 the landed value of processed products from a total demersal trawl catch of 200 000 tonnes was R 428 million. The value of hake exports in 1997 exceeded R 300 million; about a third of the total revenue from all South African fish and shellfish exports.

2.3. Angola

The fisheries sector is very important in Angola, being the third-most important industry after oil and diamond mining. It provides nearly half of the animal protein of the country, and it is an important source of employment and food to populations of the coastal regions, where it is often the only source of livelihood for the poorer population groups. Domestic consumption of fish, which was estimated at about 11 kg per person per annum in 1994, is the highest in the region.

According to the results of a survey conducted in 1992, there were at that time around 30 000 workers directly involved in activities of the fisheries sector, of which some 18 000 were involved in artisanal fisheries. The remainder were involved in industrial fisheries and public administration. In addition, it was estimated that some 5 000 persons (mainly women) were involved in informal fish trade activities. A more recent report (Delgado and Kingombo, 1998) puts the number of artisanal fishermen a few years later at over 23 000, and the number of people involved in informal fish trading at between 20 000 and 30 000. Current numbers directly involved in fishing (not including subsistence fishers) are estimated at 25 000 (Duarte, 2002 pers. comm.). Many artisanal fishers are not able to make a living solely from fishing, and supplement their incomes by, for example, agricultural and commercial activities.

At present, roughly half of the revenue from fish and fish products in Angola comes from exports, which varied in value between US$ 27 million in 1993 and US$ 46 million in 1995. Prawns are the most important product, making up 48% of the total revenue from the fishery sector in 1995, for example. The main export markets are Europe for prawns and demersal fish, African countries for small pelagic fish including horse mackerel, and Japan for tuna and crab.

3.0. Data and information for economic analysis of the cost of fisheries management

3.1. Information for computing benefits of fisheries management

The benefits of fisheries management can be assessed by asking the question, to what extent are the fisheries management objectives for a given management jurisdiction being met. In general, one can summarize the fisheries management objectives of Namibia, Angola and South Africa, and indeed most fishing nations in the world, into three interconnected objectives, namely, (i) an ecological objective, that is, ensuring the long term sustainability of the resource base, (ii) an economic objective, that is, fishing in an economically efficient manner, and (iii) a social objective, that is, ensuring that fishing takes place in an equitable manner with respect to all stakeholders. We will emphasize in this discussion the economic and social benefits. All we will say with respect to the performance of the ecological objectives is that, relative to many fisheries in the world, the resources of the Benguela are considered to be reasonably well managed to ensure their long term sustainability (Shannon et al., 2004; Sumaila et al., 2004).

We focus on the commercial values from the fisheries of the Benguela in what follows. This is not to say that non-commercial values are unimportant, but rather, our point of departure is that if it can be shown that the increase in commercial values from joint management of the resources of the BCLME exceed the cost, then the extra benefits from non-market values will be a bonus. To investigate the net commercial benefits from current and future management of the fisheries resources of the Benguela, we analyze, as far as data availability will allow, data on the following key economic indicators: (i) landings, (ii) landed values, (iii) economic rent, (iv) exports (v) contribution to GDP and (v) employment/food security, for each of the three countries.

We do not include the initial cost of providing physical structures. That is, we provide an analysis of only the cost of running the new management Commission. A key reason for taking this approach is that the new Commission can use the existing physical structures used by the BENEFIT and BCLME programmes.

Each of these variables will capture an important aspect of the benefits from the fisheries of the Benguela. For instance, the contribution to GDP provides a measure of the importance of fisheries at the macroeconomic level, while economic rent and employment generated provides indications of the contribution of fisheries to the livelihood of people and the profitability of businesses at the micro level. Also, by providing numbers on exports, we provide indications of how the post-harvest sector is impacted, as well as the sector’s contribution to the region’s foreign exchange earnings.

As would be expected, there are data limitations. Namibian fisheries data on the variables to be analyzed were more readily available. Data on South African fisheries were patchier. In the case of Angola, we could hardly find any data. This means that we had to make a number of assumptions in analyzing the data available to us. Most of the data we report below are from the mid and late 1990s. Sometimes we have data for a number of years, sometimes we have data for only one year. For our analysis, we employ annual data, depending on data availability, we use average annual values, or just the data for one year. This approach will not give us perfect estimates of costs and benefits but will provide us with estimates of these that would be good enough for our purpose. That is, to provide reasonable estimates of the costs and benefits of incremental regional cooperative management of the resources of the Benguela.

Namibian data and information

Landings

The table below reports total official Namibian fish landings for the period 1994 to 1998, for the major commercial species of Namibia. We see from the table that even though landings from pilchard have been very volatile, the total landings have remained within the 500-650 000 t. range, with an average landings of about 571 500 t. over the years.

Table 1: Landings of fish, 1994-1998 (1000 tonnes). Source: MFMR, Namibia

|

|

1994 |

1995 |

1996 |

1997 |

1998 |

|

Pilchard |

116 |

43 |

1 |

28 |

69 |

|

Anchovy |

25 |

48 |

1 |

2 |

5 |

|

Hake |

112 |

130 |

136 |

118 |

151 |

|

Horse Mackerel |

365 |

311 |

321 |

302 |

312 |

|

Monk |

12 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

16 |

|

Kingclip |

2 |

4 |

4 |

2 |

2 |

|

Tuna |

4 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

|

Rock lobster |

0.1 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

0.2 |

0.4 |

|

Crab |

4 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

|

Orange roughy |

0.03 |

6 |

13 |

19 |

11 |

|

Alfonsino |

0 |

1 |

2 |

0.4 |

0.2 |

|

Other |

8 |

11 |

32 |

27 |

35 |

|

Total |

648 |

568 |

524 |

511 |

606 |

Of the average landings of 571 500 t. between 1994 and 1998 reported in table 1, about 507 400 t. or 89% is landings of hake, horse mackerel, pilchard, tuna and crab, that is, the species that are known to be shared.

Landed values

Landed values from Namibia’s fisheries are reported in the table below. The average total landed values from all commercial fisheries for the period 1994 to 1998 is calculated from the table as N$ 1 177 million in current value.

Table 2: Landed value of Namibian fish, by fishing method (current $ millions)

|

|

1994 |

1995 |

1996 |

1997 |

1998 |

|

Pelagic |

106 |

96 |

29 |

74 |

103 |

|

Demersal |

404 |

494 |

597 |

595 |

802 |

|

Midwater |

267 |

243 |

449 |

386 |

462 |

|

Deepwater |

0.2 |

48 |

109 |

137 |

106 |

|

Tuna |

39 |

22 |

13 |

10 |

8 |

|

Linefish |

4 |

5 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

|

Crab |

32 |

18 |

20 |

17 |

27 |

|

Rock Lobster |

6 |

10 |

18 |

14 |

28 |

|

Other |

23 |

9 |

11 |

12 |

14 |

|

Total landed value |

881 |

945 |

1251 |

1252 |

1669 |

Using data reported in Stuttaford (1999), we calculated the proportion of the total landings reported in table 1 above that can be assigned to species that are known to be shared. The results from our calculations are reported in table 3. Using this as a basis, we compute and report in table 2 the landed values from the various groups reported in table 1.

Table 3: Proportion of shared stocks in landings of pelagic, demersal trawl and longline, midwater trawl, tuna and crab groups. Source: Stuttaford (1999).

|

|

1994 |

1995 |

1996 |

1997 |

1998 |

Average |

|

Pilchard (pelagic) |

0.66 |

0.29 |

0.01 |

0.21 |

0.54 |

0.34 |

|

Hake (demersal) |

0.87 |

0.85 |

0.82 |

0.75 |

0.82 |

0.82 |

|

Horse mackerel (Pelagic) |

0.19 |

0.35 |

0.78 |

0.66 |

0.20 |

0.43 |

|

Horse mackerel (midwater) |

0.99 |

0.99 |

0.98 |

0.98 |

0.99 |

0.99 |

|

Tuna |

1.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

|

Horse mackerel (demersal) |

0.01 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

0.00 |

0.01 |

|

Crab |

1.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

As can be seen from the table, hake and horse mackerel dominate the landed values from the demersal and midwater trawl groups. Taken together, we also see that horse mackerel and pilchard dominant the landed values from the pelagic group.

Table 4: Landed values (N$ millions) from shared stocks.

|

|

1994 |

1995 |

1996 |

1997 |

1998 |

Average |

|

Pilchard |

70 |

28 |

0.30 |

15 |

55 |

34 |

|

Hake |

350 |

421 |

489 |

444 |

661 |

473 |

|

Horse mackerel (Pelagic) |

20 |

34 |

23 |

48 |

20 |

29 |

|

Horse mackerel (midwater) |

265 |

240 |

441 |

379 |

457 |

356 |

|

Tuna |

39 |

22 |

13 |

10 |

8 |

18 |

|

Horse mackerel (demersal) |

3 |

3 |

5 |

5 |

4 |

4 |

|

Crab |

32 |

18 |

20 |

17 |

27 |

23 |

|

Total landed value |

778 |

767 |

991 |

918 |

1233 |

937 |

|

Total for Hake, Horse mackerel, Pilchard |

707 |

727 |

958 |

891 |

1198 |

896 |

From the table, we calculate that shared stocks contributed on average about 80% (N$937 million) of the landed values from Namibia’s fisheries. It is also worth noting that 76% of the total landed values come from what we describe as the ‘big three’, namely, hake, pilchard and horse mackerel. These three species provide 96% (N$ 896 million) of the landed values from shared stocks.

Economic rent

Only the estimated economic rent from the big three species are reported in the table below due to the lack of data on other species. Economic rent is the surplus after all costs related to fishing have been deducted. Given the dominance of these species, it should not be a problem to extrapolate these numbers to cover all commercial species using landed values information provided in the proceeding section of this report.

Table 5. Resource rent for pilchard, hake, and horse mackerel

(N$ million). Source: Lange (2004).

|

|

Pilchard |

Hake |

Horse Mackerel |

Total Rent |

|

1994 |

229 |

159 |

40 |

429 |

|

1995 |

201 |

209 |

39 |

449 |

|

1996 |

* |

192 |

51 |

243 |

|

1997 |

95 |

261 |

49 |

406 |

|

1998 |

150 |

640 |

91 |

881 |

* less than 1.0

Apart from a dip in economic rent in 1996 due to a dramatic drop in rent from pilchard, the reported rent has been steady at around N$ 400 million, with a huge increase in 1998, mainly due to a trebling of economic rent from hake. For the period under consideration, an average economic rent of N$ 482 million was made from the three species. Given that the ‘big three’ contribute about 80% of the landed values in this period, we estimate a total annual average economic rent of N$ 602 million for all of Namibia’s commercial species.

The big three commercial species (hake, pilchard and horse mackerel) are shared stocks, and they contributed an average economic rent of N$ 482 million. Given that the ‘big three’ contribute about 96% of the landed values from shared stocks in this period, we estimate an average economic rent from shared stocks of N$ 502 million.

Export values

A great majority of Namibian fish products are sold in foreign markets. The table below shows the export earnings that accrued to Namibia from exporting fish products.

Table 6: Export value of Namibian fish, by fishing method (current $ millions)

|

|

1994 |

1995 |

1996 |

1997 |

1998 |

|

Pelagic |

458 |

395 |

44 |

233 |

374 |

|

Demersal |

484 |

600 |

715 |

712 |

1077 |

|

Midwater |

261 |

237 |

432 |

373 |

453 |

|

Deepwater |

0.3 |

71 |

156 |

196 |

156 |

|

Tuna |

66 |

51 |

47 |

46 |

8 |

|

Linefish |

4 |

5 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

|

Crab |

32 |

18 |

20 |

17 |

27 |

|

Rock lobster |

9 |

16 |

22 |

17 |

29 |

|

Other |

23 |

9 |

11 |

12 |

14 |

|

Total export value |

1338 |

1401 |

1451 |

1612 |

2147 |

We see that over the years under consideration, there has been an increase in the value of Namibian fish exports, with a lot of the heavy lifting coming from the demersal group (read ‘hake’). The average export value for the period from 1994 to 1998 is N$ 1 590 million.

Using the data on the proportion of total landings of Namibian fish that are shared as a basis (table 3); we compute and report in table 7 the export values that can be assigned to shared stocks.

Table 7: Export values from shared stocks.

|

|

1994 |

1995 |

1996 |

1997 |

1998 |

Average |

|

Pilchard |

301 |

115 |

0.45 |

48 |

201 |

133 |

|

Hake |

419 |

512 |

585 |

531 |

888 |

587 |

|

Horse mackerel (Pelagics) |

87 |

138 |

34 |

153 |

74 |

97 |

|

Horse mackerel (midwater) |

259 |

234 |

425 |

365 |

448 |

346 |

|

Tuna |

66 |

51 |

47 |

46 |

8 |

44 |

|

Horse mackerel (demersal) |

4 |

4 |

6 |

6 |

5 |

5 |

|

Crab |

32 |

18 |

20 |

17 |

27 |

23 |

|

Total landed value |

1168 |

1073 |

1117 |

1167 |

1650 |

1235 |

|

Total for Hake, Horse mackerel, Pilchard |

1070 |

1003 |

1051 |

1104 |

1615 |

1169 |

Of the total average export value of N$ 1 590 million, 78% (N$ 1 235 million) is derived from species that are known to be shared. The big three commercial species contribute 74% of the total export value, and 95% of the export value derived from shared stocks.

Contribution to GDP

Table 8: Contribution of the fishing industry to GDP (current $ millions). Source: www.mfmr.gov.na

|

|

1994 |

1995 |

1996 |

1997 |

1998 |

|

Fishing |

349 |

376 |

477 |

491 |

616 |

|

Fish processing |

494 |

550 |

354 |

525 |

861 |

|

Total contribution |

843 |

927 |

831 |

1,017 |

1,477 |

|

Percentage of GDP |

8.6% |

9.0% |

7.0% |

7.8% |

10.1% |

The contribution to GDP ranged between 7.8 and 10% in the five years from 1994 to 1998, with an average of 8.5% over the years. Given that the estimated landed value derived from shared stocks is 80% of the total for all species, we can attribute the portion of the contribution to GDP to these stocks. That is, shared stocks contribute about 6.8% to Namibia’s GDP.

Employment/food security.

The fisheries sector is important as a source of employment in Namibia, particularly, in Walvis Bay, which is the major fishing port and where most of the processing plants are situated. We report in the table below, the number of jobs in the fishing sector from 1994 to 1998.

Table 9: Employment in Namibian fisheries by fishing method (person years). Source: MFMR, Namibia.

|

|

1994 |

1995 |

1996 |

1997 |

1998 |

Average |

|

Pelagic |

493 |

445 |

476 |

562 |

374 |

470 |

|

Demersal |

1967 |

2427 |

3016 |

2649 |

2212 |

2454 |

|

Midwater |

2664 |

2409 |

2141 |

2100 |

1606 |

2184 |

|

Deepwater |

|

|

|

261 |

139 |

71 |

|

Tuna |

1112 |

1356 |

940 |

957 |

1205 |

1114 |

|

Linefish |

268 |

342 |

294 |

277 |

316 |

1497 |

|

Crab |

190 |

147 |

118 |

73 |

101 |

126 |

|

Rock lobster |

550 |

674 |

541 |

525 |

429 |

544 |

|

Total employment |

7244 |

7800 |

7526 |

7404 |

6382 |

7271 |

From the table we see that the total number of jobs in the fishing industry has remained between 6 300 and 7 800 during the five years under study, with an average of about 7 200 per year. More interestingly, as a result of the Namibianisation policy of the MFMR, the percentage participation of Namibians in the labour force has increased significantly from 89%, 65%, 1%, 57%, 31% to 97%, 79%, 9%, 71% and 65%, respectively, in the pelagic, demersal, midwater, crab and tuna fisheries (Armstrong et al., 2004). Hence, most of these positions were filled by Namibians, thereby providing them with the income they need to buy food for their families, and thus improve their food security.

Table 10: Employment from shared stocks (person years).

|

|

1994 |

1995 |

1996 |

1997 |

1998 |

Average |

|

Pilchard |

325 |

130 |

5 |

117 |

201 |

155 |

|

Hake |

1704 |

2071 |

2470 |

1975 |

1824 |

2009 |

|

Horse mackerel (Pelagics) |

93 |

156 |

371 |

370 |

74 |

213 |

|

Horse mackerel (midwater) |

2644 |

2390 |

2105 |

2057 |

1588 |

2155 |

|

Tuna |

1112 |

1356 |

940 |

957 |

1205 |

1114 |

|

Horse mackerel (demersal) |

15 |

15 |

25 |

23 |

10 |

17 |

|

Crab |

190 |

147 |

118 |

73 |

101 |

125 |

|

Total employment |

6082 |

6255 |

6033 |

5570 |

5004 |

5789 |

|

Total for Hake, Horse mackerel, Pilchard |

4780 |

4752 |

4975 |

4540 |

3698 |

4549 |

Once again the data reported in the table above demonstrates that shared stocks provide the bulk of the reported jobs, providing about 80% (5 789 jobs) of the total. The central role of hake, horse mackerel and pilchard in Namibia’s fisheries is highlighted here too.

South African data and information

Landings

The South African fishing industry caught an average 503 000 tonnes of fish, nationwide between 1994 and 1998 (see Table 11 below). It is reported that over 90% of this was taken from the Benguela side of the South African EEZ. Therefore 450 000 tonnes can be said to be taken from the BCLME. Of this, 294 000 tonnes are landings of shared stocks.

Table 11: Landings of fish, 1994-1998 (000 tonnes). Source: Stuttaford (1999)

|

|

1994 |

1995 |

1996 |

1997 |

1998 |

|

Hake |

146 |

139 |

158 |

148 |

149 |

|

Kingclip |

3 |

3 |

3 |

4 |

3 |

|

Monk |

5 |

6 |

6 |

8 |

8 |

|

Panga |

1 |

1 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

|

Sole |

0.9 |

0.8 |

1 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

|

Snoek (demersal) |

6 |

7 |

6 |

5 |

7 |

|

H. mackerel (demersal) |

12 |

9 |

15 |

23 |

19 |

|

Or. roughy |

|

0.005 |

0.003 |

0.001 |

0.001 |

|

Oreo dory |

|

0.02 |

0.4 |

0.6 |

0.2 |

|

Toothfish |

|

|

1 |

1 |

2 |

|

Pilchard |

93 |

115 |

105 |

117 |

128 |

|

Horse mackerel (pelagic) |

8 |

2 |

19 |

13 |

27 |

|

Chub mackerel |

2 |

3 |

1 |

4 |

0.1 |

|

Anchovy |

156 |

170 |

41 |

60 |

108 |

|

Redeye |

54 |

77 |

47 |

92 |

52 |

|

Rock lobster |

3 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

3 |

|

Snoek (line) |

8 |

9 |

7 |

6 |

7 |

|

Tuna |

4 |

4 |

3 |

3 |

9 |

|

Yellowtail |

0.8 |

0.8 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

|

Mullet |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0.9 |

|

Squids |

6 |

7 |

7 |

4 |

6 |

|

Total |

510 |

558 |

425 |

495 |

529 |

Landed values

The landed values from South Africa’s fisheries in 1997 are given in the table below. The sum of landed values for the fisheries of South Africa is estimated at R 1 434 million. Using the fact that over 90% of South African landings are from the BCLME, we estimate that R 1 291 million landed value is derived therefrom.

Table 12: Landed value of South African fish, by fishing method (R millions) for 1997. Source: Stuttaford (1999)

|

|

All South Africa |

Benguela* |

|

Demersal |

474 |

427 |

|

Pelagic |

439 |

395 |

|

Rock Lobster |

167 |

150 |

|

Crustacea |

226 |

203 |

|

Line, small nets |

128 |

115 |

|

Total |

1434 |

1291 |

* 90% of total

Using data from Stuttaford (1999), we determined the proportion of shared stocks in the catch of demersal, pelagic, and line groups, and report it in table 13 below. This was then used to calculate the portion of the total landed values that can be assigned to shared stocks. The results of these calculations are reported in table 14 below.

Table 13: Proportion of shared stocks in catch of demersal, pelagic, and line groups.

|

|

1994 |

1995 |

1996 |

1997 |

1998 |

Average |

|

Hake (demersal) |

0.78 |

0.78 |

0.77 |

0.72 |

0.73 |

0.76 |

|

Horse mackerel (demersal) |

0.06 |

0.05 |

0.07 |

0.11 |

0.09 |

0.08 |

|

Horse mackerel (pelagic) |

0.03 |

0.005 |

0.09 |

0.04 |

0.08 |

0.05 |

|

Pilchard (pelagic) |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.5 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

|

Tuna (line) |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

0.06 |

0.15 |

Table 14: Landed values ($R millions) from shared stocks in 1997.

|

|

All South Africa |

Benguela* |

|

Hake (demersal) |

341 |

307 |

|

Horse mackerel (demersal) |

52 |

47 |

|

Horse mackerel (pelagic) |

5 |

4.5 |

|

Pilchard (pelagic) |

45 |

41 |

|

Tuna (line) |

18 |

16 |

|

Total |

462 |

416 |

*90% of total

Economic rent

Due to the lack of data on the economic rent from South Africa’s fisheries, we estimate average annual economic rent using the ratio of economic rent to total landed values in Namibia as a proxy. This ratio is 0.51. Hence, for landed values of R 1 291 million, the estimated economic rent is R 660 million. Of this amount R 213 million can be assigned to shared stocks. This approach to estimating economic rent for South Africa can be justified because the fishing industry in the two countries is very similar, also, in terms of their cost structure.

Export values

Export values in 1998 are reported in the table below for all fish landed in South Africa (R 790 million), and for fish taken from the BCLME (R 711 million). Using the proportion of landed values derived from shared stocks (R 416 million) to landed values derived from the BCLME as a whole (R 462 million), we calculate the amount of export value that can be assigned to shared stocks to be R 642 million.

Table 15: Export value of South African fish in 1998 (R millions).

|

|

All South Africa |

Benguela* |

|

Hake |

267 |

240 |

|

Kingclip |

0.80 |

0.7 |

|

Horse mackerel |

36 |

32 |

|

Pilchard |

23 |

20 |

|

Snoek |

4 |

3.6 |

|

Anchovy |

0.22 |

0.2 |

|

Tuna |

79 |

71 |

|

Rock lobster |

112 |

101 |

|

Other |

269 |

242 |

|

Total |

790 |

711 |

* 90% of total

Contribution to GDP

The fishing sector as a whole yields about 0.5% of South Africa’s GDP. The contribution to GDP is more related to economic rent than any of the other variables under consideration. Hence, we apply the ratio of economic rents derived from the BCLME part of South Africa to that derived from South African fisheries as a whole to allocation the contribution to GDP to shared stock, and then do the same with respect to shared stocks to determine the contribution by shared stock. This gives contribution to GDP by fish in the BCLME as a whole and shared stock in the BCLME of 0.45% and 0.15%, respectively.

Employment/food security

South Africa’s living marine resources of the Benguela Current form the basis of a fishing industry, which supports some 26 000 people (mostly in the Western Cape), and supplies food for the Southern African sub region. Fishing is particularly important in the social economy of the Western Cape, where some entire coastal communities depend directly or indirectly on fishing for their livelihood. We can assign part of this employment to shared stocks in proportion to the ratio of shared stock landing (294 000 tonnes) to total Benguela landings (450 000 tonnes). This gives an estimate of employment from shared stock of 16 980 jobs.

Angolan data and information

Landings

We relied on landings of Angolan fish reported by the FAO, and made available at www.fishbase.org, and catches of Angolan fish reported at the Sea Around Us project website: www.seaaroundus.org. The numbers obtained from these sources are reported in Table 16. It should be noted, in particular, that there were no landings of pilchard in the years being analyzed.

Table 16: Landings of fish, 1994-1998 (000 tonnes): Sources: www.seaaroundus.org and www.fishbase.org

|

Year |

1994 |

1995 |

1996 |

1997 |

1998 |

|

H. Mackerel |

173 |

117 |

116 |

101 |

76 |

|

Sardinella |

35 |

41 |

18 |

24 |

55 |

|

hakes |

0.57 |

0.25 |

1 |

1 |

0.12 |

|

Chub mackerel |

0.80 |

0.05 |

0.02 |

0.90 |

0.39 |

|

drums or croaker |

15 |

14 |

18 |

19 |

12 |

|

Crevaile jack |

0.04 |

0.04 |

0.04 |

0.02 |

0.09 |

|

Catfishes |

9 |

6 |

12 |

12 |

9 |

|

Seabreams |

3 |

8 |

3 |

2 |

8 |

|

Cutlass fishes |

0.02 |

0 |

0.03 |

0.05 |

0.004 |

|

Butter fishes |

6 |

3 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

|

Croakers |

3 |

1 |

4 |

2 |

7 |

|

Little tunny |

0.12 |

0.12 |

0.24 |

0.08 |

0.40 |

|

Snappers |

4 |

2 |

5 |

5 |

4 |

|

Prawns* |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

|

others |

26 |

18 |

23 |

21 |

34 |

|

Total |

277 |

211 |

207 |

193 |

211 |

* Includes three species: Aristeus varidens, Parapenaeus longirostris, Natantia

The average annual catch is 220 000 tonnes, of which about 117 000 tonnes are from shared stocks.

Landed values

We are not aware of any reported landed values from Angolan fisheries. We will therefore make estimates based on some reasonable assumptions. For some of the fish groups, we were able to use South Africa landed prices from Stuttaford (1999) to calculate the equivalent price in Angola currency, the Kwanza (1R=14.2 Kwanza as of January 10, 2005). We were able to calculate landed values for horse mackerel, hake, chub mackerel, drum, snapper, and prawn from South African price data. For the other species, we made estimates from landed prices in other markets (see sources in table 17). The total landed value for Angola as calculated from the table is 119 178 million Kwanza, of which horse mackerel, sardinella, drums and seabreams are key contributors.

Table 17: Landed values of fish, 1997 (million Kwanza)

|

Year |

1997 |

|

H. mackerel |

6291 |

|

Sardinella |

1642 |

|

Hake |

57 |

|

Chub mackerel |

18

|

|

Drums or croaker |

1179 |

|

Crevaile jack |

0.003 a |

|

Catfishes |

840 b |

|

Seabreams |

1234 c |

|

Cutlass fishes |

0.95 |

|

Butter fishes |

419 d |

|

Croakers |

33 a |

|

Little tunny |

1.6 |

|

Snappers |

128 |

|

Prawns |

74 |

|

Total |

11918 |

b Source: Vietnam market price

c Source: www.eurofish.org

d Source: Taiwan market price

Of the total landed value of about 11.9 billion Kwanza, only 640 million is derived from species known to be shared.

Economic rent

Due to the lack of data on the economic rent from Angola’s fisheries, we estimate average annual economic rent in Angola to be 75% of the ratio of economic rent to total landed values in South Africa. By this we are assuming that the South African industry is more efficient that the Angolan. This ratio is 0.26. Hence, for landed values of Kwanza 11.9 billion, the estimated economic rent is Kwanza 3.2 billion. Of this amount, Kwanza 172 million can be assigned to shared stocks.

Contribution to GDP

The sector generates about 4% of the country’s GDP. Applying the proportion of landed values from shared to the total landed value; we estimate the contribution of shared stocks to Angola’s GDP to be 0.22 %.

Exports

At present, roughly half of the revenue from fish and fish products in Angola comes from exports, with an estimated value of Kwanza 2670 million in 1995. The main export markets are Europe for prawns and demersal fish, African countries for small pelagic fish including horse mackerel, and Japan for tuna and crab. Again, using the ratio of landed values from shared stocks to total landed values as a basis, we estimate that Kwanza 14.4 million is derived from shared stocks.

Employment/food security

The fisheries sector provides nearly half of the animal protein of the country, and is an important source of employment and food to populations of the coastal regions, where it is often the only source of livelihood for the poorer population groups. Domestic consumption of fish, which was estimated at about 11 kg per person per annum in 1994, is the highest in the region. According to the results of a survey conducted in 1992, there were at that time around 30 000 workers directly involved in activities of the fisheries sector, of which some 18 000 were involved in artisanal fisheries. The remainder were involved in industrial fisheries and public administration. In addition, it was estimated that some 5 000 persons (mainly women) were involved in informal fish trade activities. The number of artisanal fishermen a few years later has been estimated at over 23 000, and the number of people involved in informal fish trading at between 20 000 and 30 000. Many artisanal fishers are not able to make a living solely from fishing, and supplement their incomes by, for example, agricultural and commercial activities. We estimate that out of the total number of jobs of 30 000, about 1 600 come from shared stocks.

3.2. Information for computing costs of fisheries management

Fisheries management functions are defined variously by different countries but in essence they consist of three main processes, namely, (i) stock assessment, that is, the scientific assessment of the stock size and age distribution of the given fishery; (ii) setting total allowable catches (TACs), preparing rules and regulations related to the TACs, licensing vessels and fishermen, and disseminating the rules and procedures for the coming years fishery; and third, monitoring, control and surveillance (MCS), that is, enforcement and policing functions. Carrying out these functions cost money, which it is hoped will be justified because management is supposed to result in benefits to a given country by making sure that the country’s fisheries management objectives are met.

For the countries of the Benguela region, fisheries management functions are currently carried out either by the countries themselves domestically, or by regional cooperative management organizations. At the moment the active regional organizations in the region are the Benguela Fisheries Environment Interaction & Training Programme (BENEFIT), the Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem (BCLME) Programme and the Southern African Development Cooperation (SADC) Fisheries.

Namibian data and information

Table 18 presents the cost of fisheries management in Namibia for 1997 categorized into three groups, namely, research, MCS and other.

Table 18: Domestic fisheries management costs for Namibia.

|

Section |

Costs ($N millions) |

|

MCS |

34.46 |

|

Research |

22.24 |

|

Other |

9.26 |

|

Total |

65.96 |

$1N=0.1666USD as at Nov. 22, 2004.

Assuming that 1997 is a typical year, Namibia’s total estimated domestic expenditure or cost of fisheries management is about N$ 66 million (US$ 11 million) per year.

We need to isolate the portion of the total amount of N$ 66 million that can be attributed to shared stocks. One could go about apportioning the cost of fisheries management to the various commercial species in a number of ways. Here, we choose to calculate the cost of management per landed value of fish, and then use this to calculate the cost of managing shared stocks by multiplying the per landed value cost with the landed values of the relevant shared stocks.

The average landed value of all fish landed in Namibia between 1994 and 1998 is N$ 1 177 million. Hence, the cost of fisheries management per landed value is N$ 0.06 (that is, 65.96/1 177).

The deep water hake stock is shared by South Africa and Namibia, and the Cape hake stock is also shared if only indirectly through cannibalism. The average landed value of hake for the period under investigation is about N$ 473 million. Hence, the cost of fisheries management that can be assigned to hake is N$ 26.5 million.

The pilchard and horse mackerel stocks are shared between Angola and Namibia. On average, the landed values from pilchard and horse mackerel were N$ 33.79 and N$ 388.99 million, respectively. Therefore the costs of fisheries management that may be assigned to these species are N$ 1.89 and N$ 21.8 million for pilchard and horse mackerel, respectively.

Red-crabs are shared between Angola and Namibia. The landed value from red-crabs, which make up almost all of the crab landings in Namibia, is N$ 22.8 million. Hence, the cost of fisheries management assigned to this species is N$ 1.3 million.

Bigeye, yellowfin and albacore tunas are also shared by the countries of the BCLME both within their EEZs and on the high seas. The average Namibian landed values from tunas in the period under study is N$ 18.30 million, all of which was made up of values from these three shared species of tunas. Therefore the management cost that can be assigned to tuna is N$ 1 million.

Hence, the portion of the total fisheries management cost of N$ 65.96 million that can be assigned to shared stocks is about N$ 52.5 million per year.

South African data and information

The estimated annual domestic cost of fisheries management in South Africa is reported in Table 19.

Table 19: Estimated annual domestic fisheries management costs for South Africa.

|

Section |

Costs (R millions) |

|

Administration |

72 |

|

Resource management |

61 |

|

Research and development |

51 |

|

MCS |

55 |

|

Patrol, research vessels |

101 |

|

Total |

340 |

1R=1N$=$0.1666 USD as at Nov. 22, 2004.

From the table we see that the annual cost of managing South Africa’s fisheries is about R 340 million (US$ 56.6 million). It is estimated that 90% of the total South African landings of 445 000 tonnes is taken from the BCLME. Hence, one can allocate 90% of the total cost of managing South Africa’s fisheries or R 306 million to the management of fisheries operating in the BCLME. Out of this amount, R 200 million can be allocated to shared stocks based on the proportion of shared stock to BCLME landings.

Angolan data and information

We could not find cost data for Angola. From our reading, we found that regulation in Angola is constrained by the lack of operating funds and inadequate equipment and staff. These constraints have limited the amount of management initiatives in the country. To make our analysis complete, we assume conservatively that the cost of fisheries management in Angola per landed value is only half of those of Namibia. From Namibian cost and landed value information, we calculate the ratio of management cost to landed value to be 0.06. We therefore apply half of this number (0.03) to determine the cost of fisheries management in Angola to be Kwanza 357 million, of which Kwanza 19.2 million is apportioned to the management of shared stocks.

Data and information on the BENEFIT Programme