REPORT No. 4

ECOSYSTEM APPROACHES FOR UNTS/RAF/011/GEF

Cape Town, South Africa

REPORT No. 4

ECOSYSTEM APPROACHES FOR UNTS/RAF/011/GEF

Cape Town, South Africa

FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS

Rome, 2007

Page

1. Introduction 1

2. Progress Reports on benefit-cost analyses 1

a) Angola 1

b) Namibia 3

c) South Africa 5

d) General discussion 9

3. EwE Forecasts of management actions 10

a) South Africa 10

b) Angola 10

c) Namibia 11

d) General discussion 11

4. Ecosystem states, changes and functioning 12

General discussion 13

5. Indicators for EAF 13

General discussion 14

6. Overview of the Benguela Current Commission Interim Agreement 16

7. Regional Shared Stocks EAF issues 17

8. Options for improved approaches to decision-making 19

a) Multicriteria support for decision-making in the Ecosystem approach to

fisheries management 19

b) An application of fuzzy logic to facilitate decision-making 20

c) General discussion 21

9. Institutional needs for EAF 22

a) Angola 22

b) Namibia 22

c) South Africa 23

d) General discussion 23

10. Potential incentives for facilitating EAF 24

11. Research needs for EAF 25

a) Angola 25

b) Namibia 25

c) South Africa 26

d) General discussion 27

12. Proposal for 2nd phase of EAF project for possible submission to BCLME II 28

APPENDIXES

Page

1. Programme 29

2. List of participants 31

3a Progress Report: Angola 35

3b Progress Report: Namibia 49

4a Exploratory EAF management simulations: two South African examples

(BCLME/EAF Workshop, Cape Town, 4–8 September 2006) 55

4b Progress Report in EwE forecast of management actions: Angola 67

4c Simulations of Cape hake recruitment variability and implications for EAF

management in Namibia 73

5. Ecosystem states, ecosystem changes and changes in ecosystem functioning of

the southern and northern Benguela ecosystems 83

6a EAF indicators for the BCLME 99

6b Principles and guidelines for the use of indicators in contributing to the formulation

of management recommendations for commercial fisheries subject to quantitative

assessment or OMP-based regulation 139

7 Regional EAF issues to be considered for the attention of the Benguela

Current Commission 143

8a Multicriteria support for decision-making in the ecosystems approach to fisheries

management 145

8b Using a fuzzy-logic approach to multicriteria decision-making for an ecosystem

approach to fisheries management 178

9a Institutional requirements for EAF: Angola 185

9b Institutional requirements for EAF: Namibia 189

9c institutional requirements for EAF: South Africa 191

10. Creating incentives for EAF management: a portfolio of approaches for consideration

in the Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem 195

11a. EAF research needs identified for Angola 213

11b Research needs identified for implementation of EAF in Namibia 215

11c EAF research needs identified for South Africa 219

12. Draft proposal for the 2nd phase of “EAF Management in the BCLME” for possible

submission to BCLME 2nd phase 227

The 3rd Regional Workshop of the project “Ecosystem Approaches for Fisheries (EAF) Management in the BCLME” (Project LMR/EAF/03/01) was held at the Fountains Hotel, Cape Town from 30 October to 3rd November 2006. The agenda for the workshop is attached to this report as Appendix 1 and the list of participants is attached as Appendix 2.

Kevern Cochrane, the International Project Coordinator opened the workshop. He outlined the current status of the project and the activities and events which had taken place to date. The objectives for the workshop were to: review the results of the benefit cost analyses (BCA) undertaken by each country; consider the key conclusions and recommendations that should be brought to the attention of BCLME and the Benguela Current Commission (BCC); consider future research needs including a possible Phase 2 to this project and to review the structure of the final report. The terms of reference for the project required that recommendations should be provided on a number of key issues related to the implementation of EAF including: indicators for EAF; knowledge and implications of ecosystem states and functioning; EAF issues of regional importance and requiring regional action; improved methods for decision-making; institutional changes and improvements; incentives for implementation of EAF; and research needs at national and regional levels.

The rationale and methods for the benefit cost analyses had been presented and discussed at the 2nd Regional Workshop held in Luanda in March 2006. Subsequently workshops were held in all three countries to undertake BCAs for the fisheries being considered. The results of the workshops were central to the project conclusions and recommendations and should provide the best available information on the options for implementation of EAF and the feasibility and implications of those options. However, it was recognised that the time and scientific requirements for full BCAs were substantial and it had not been possible with the time and resources available in the countries to undertake full and rigorous analyses. The results obtained at the workshops should therefore be viewed as being preliminary1 and the process would need to be repeated in all cases with greater participation from the range of stakeholders in each case and with greater scientific input. In most cases, improved scientific output would require new analyses and results to provide reliable information and in some cases would benefit from collection of new data. However, in cases where urgent decisions might be required, the best available information should be used to inform those decisions.

Angola

Filomena vaz Velho reported on the progress made by Angola in the benefit-cost analyses (see Appendix 3a). Analyses were undertaken for the following fisheries: small pelagic fish; the artisanal fishery; bottom trawl finfish fishery and the bottom trawl deep-sea crustacean fishery. The overall objectives for Angola’s fisheries are common to all fisheries and concentrated on biological and social aspects. The overall biological objectives include to:

• restore biomass of commercially important species to optimal levels of productivity;

• maintain community structure in terms of size structure and species composition;

• minimize impacts of fisheries on threatened, protected or vulnerable species (sea turtles, sharks, marine mammals, other); and

• minimize impacts of fishery on ecosystem;

The overall social objectives include to:

• contribute to poverty alleviation;

• increase opportunities for employment in the fisheries extractive sector and in the fish processing industry in the coastal provinces;

• promote the development of a productive fisheries sector;

• promote reliable supply of fish products to the population, at accessible prices; and

• promote equity in the distribution of employment and income among the regions of the country and in the coastal provinces.

The overall economic objective is to maximize long-term economic benefits from the fishery.

Filomena vaz Velho summarised the results of the RASF workshops which had identified issues within five groupings: research; responsible fishing practices; capacity building; shared stocks and ecosystem damage. In relation to the research, a number of issues related to lack of knowledge were identified that could be addressed through increased research activity in the fields of biology/ecology; technical and fishing gear; socio-economics; and statistics. Responsible fishing issues fell mainly into the categories of inadequate/non-selective gear; by-catch, discards and wastage and conflicts between different sectors of the industry, while capacity-building was required in relation to rehabilitation of support infrastructure; organization of the industry; training of researchers and managers; and professional and managerial training for the industry. Concerns about damage to the ecosystem through pollution, coastal encroachment and urbanization, and litter were also identified. Finally, Angola shares several stocks with neighbouring states which requires cooperation among the countries sharing the stocks, in research; stock assessment and management. The risk levels estimated across all these issues are shown in Appendix 3a) and included a considerable number of issues estimated to be of high or extreme risk.

A range of potential management measures had been identified for each of the five groups and a benefit-cost analysis undertaken for each of the measures. Within the group ‘research’, the highest benefit-cost ratios were estimated for surveys and research into the selectivity and efficiency of fishing gear. The development and implementation of management plans had the highest ratio within the group ‘responsible fishing’ while training of industry workers, researchers and managers was estimated to have the highest ratio in the group ‘capacity-building’. The development of joint management plans and the establishment of joint stock assessment working groups were considered to have the highest benefit to cost ratios for the group ‘shared stocks’ and monitoring of pollution in the group ‘ecosystem damage’.

After the presentation, the International Project Coordinator pointed out that a number of the issues had been grouped into categories that were too broad and that they needed to be broken down further to arrive at issues which could be directly measured and addressed by the fisheries manager. For example, issues related to by-catch, discards and wastage would differ substantially according to the fishery and gear in each case. Similarly, impacts of pollution and coastal encroachment would differ in extent and nature of the impact according to the distribution and life histories of the fished species. It was agreed that the BCA analyses would be revisited and modified, where necessary, to reflect issues and objectives at the operational scale.

In response to a question about which group of issues included the effect of the bottom trawls on the substrate, Filomena Vaz-Velho clarified that these effects were include in the responsible fishing category, since they could be addressed by gear regulations including, for example, the use of lighter or no-contact gear, and area closures such as closing the more sensitive areas to trawling. It was pointed out that the estimated benefit: cost ratios presented were almost always higher in the long-term than in the short-term and clarification was asked on whether this was due to lower costs or higher benefits. In response, Filomena Vaz-Velho answered that both effects were true and that for the management actions proposed, in general, costs tended to be lower in the long-term, while benefits tended to be higher. This was also a consequence of the choices of management actions, since one of the criteria used to select the management actions was precisely that the benefit-cost ratio (bcr) should be high in the long-term. In fact, she suggested, actions whose utility (measured by the bcr) decreased with time would be useful, at most, as transitory measures, and not as long-term measures.

It was pointed out that the management measures presented and examined were general approaches, rather than specific and precise measures that corresponded to actual management of specific fisheries. This approach had been followed by all countries and, in order to move forward into operational, specific actions that could be implemented in the fisheries, these general approaches would need to be converted into specific management regulations. The presenter replied that the Angolan group was aware of this necessity, but that is was necessary to make a trade-off between covering the whole spectrum of Angolan fisheries with general measures, that could later be made operational for different fisheries, and covering only a small section of the fisheries with more detailed measures. At this stage, the Angolan group had decided to follow the first choice, also because all fisheries had been addressed at the first workshops. However, the group is aware that a focusing and operationalization of the measures would be required before this process could be used for actual management.

Another issue relevant to all countries was that of defining the broad objectives for the fisheries, against which the costs and benefits were measured. The countries had defined similar broad objectives for all fisheries. While this was probably correct and appropriate it was understood that the actual weighting to be given to each of the objectives in decision-making would necessarily be different for each fishery. As an example, the economic objectives would probably be given a higher weight by decision-makers for a predominantly industrial fishery like the bottom trawl deep-sea crustacean fishery, while social objectives would probably have the highest weight for the artisanal fishery. It was agreed that decisions on actual weighting would have to be done by top management and decision-makers and were political decisions not scientific ones.

Namibia

The report on the BCAs undertaken by Namibia was presented by Johannes Iitembu. The full presentation is included as Appendix 3b. He explained that a number of issues that had been identified during the RASF workshops were logically grouped.

i) Hake fisheries

Group A: Consisted of issues related to substrate and ecological effects. Among the issues under this group only one issue was considered to be of extreme or high risk, while five were considered to be of medium or low risk. The following potential management responses were proposed to address these issues under this group:

assess the hake species separately;

initiate research and introduce management measures on the effect of trawling and other gear types on substrate , habitat and benthic community;

initiate trophic and diet related studies and introduce an associated management action.

Group B consisted of issues related to retained by-catches. There were four issues under this group of which two were estimated to be of extreme or high risk ranked, while the remaining two were medium or low risk. The following management responses were proposed to address the issues under this group:

introduce appropriate levies and penalties for demersal species;

establish closed areas;

research on by-catches in the hake fishery;

research on impact of hake by-catches in the horse mackerel fishery.

Group C consisted of issues related to incidental by-catches. There were fifteen issues under this group of which two were considered to be extreme or high risk and thirteen of medium or low risk. The following management responses were proposed to address the issues under this group:

assess the extent of mortality of chondrichthyians caused by hake trawling and longlining;

assess and mitigate the impacts on seabirds;

assess the extent of seal shooting and introduce appropriate management measures to reduce this;

enforce the existing pollution laws;

prohibit dumping of fish offal.

Group D consisted of issues related to management and MCS. There were seven issues under this group of which two were considered to be of extreme or high risk while five were of medium or low risk. The following management responses were proposed to address the issues under this group:

establish a task force to investigate alternative capacity building and incentives (including increasing the research budget);

review the existing regulations and revise the penalty structures;

improve communication between stakeholders and liaison in the working group;

optimise observer coverage and the data quality from the observer programme.

The analyses of the benefits and costs of each management response for all the groups were done against the broad hake fishery objectives which were:

ensure sustainable exploitation of the hake stocks (rebuilding, optimize yield, maintain size structure etc.)

minimizes by-catches (incidental mortality of non-commercial species)

maintain biodiversity and ecosystem functioning

mitigate habitats and substrate damage

ensure optimum economic return to industry/country processing value added etc…

optimize social returns, employment, food security, empowerment, social upliftment

maintain adequate research & management capacity

Namibianization.

ii) Small pelagics fishery

In the case of the purse seine fishery the following groupings were used.

Group A: Research. Most of these eleven issues were ranked as having a high or even extreme risk in the RASF workshop. The following management responses were proposed to address these issues:

intensify/expand research on consumption rates of all predators on small pelagic species and determine population trends of the predators (birds, mammals and fish);

increase research on early life stages of all small pelagics, identify relationship between fish (including recruitment) and its environment;

initiate directed research to estimate abundance, spatial and temporal distribution and impacts on pelagic resources (e.g. trophic effects) of jellyfish, gobies and other mesopelagics;

initiate research on trophic structure of the ecosystem (all levels: abundance and consumption);

collate historical data (especially regarding information on the trophic structure of the ecosystem);

research on other small pelagics.

Group B: Management. Under this group only three issues were regarded as EAF issues (as opposed to target resource oriented or TROM issues). They rated in the medium to high-risk categories. Management responses suggested were the following:

rebuild stock by closing the fishery (until a reference point is reached);

reduce predation on pilchard;

constant minimum catch (pilchard TAC);

minimum horse mackerel TAC for purse seiners;

closed season and areas.

Group C: Socio-economics. The four issues addressed under this point were not strictly EAF issues, but always also related to single species management. Their risks rated medium to extreme. The proposed management actions were:

minimum TAC (pilchard), right consolidation/effort reduction;

alternative resource options and value addition;

minimum horse mackerel TAC.

Group D: Communication. The issues grouped under this category mainly addressed miscommunication or a complete lack of communication between relevant stakeholders. Four issues from the RASF workshop were addressed, ranking from medium to extreme risk. The proposed management actions discussed in the BCA workshop were:

more consultative working groups (ministry directorates and industry) with delegation of authority;

create greater public awareness of fisheries;

advisory council members to have a wider representation (different stakeholders);

transparency in decision making (including TAC) at management level.

Benefit-cost analyses of proposed management actions were done for each group against some perceived pilchard fishery objectives.

iii) Midwater trawl fishery

For the Namibian midwater trawl fishery, the RASF workshop in 2005 had identified a total of 54 issues, grouped into 3 categories comprising 8 components. Of the eight components the ‘Governance’ component accounted for the highest proportion of risks followed by ‘External Impacts’, ‘Retained Species’, ’General Ecosystem’ and ‘Non-retained Species’. The lowest proportion of risks was those related to ‘Human Wellbeing’.

During the BCA workshop for the midwater trawl fishery, the issues were grouped as ‘Research’, ‘Management’, Socio-economic’ and 'Compliance’ issues before they were then split into either EAF or ‘Single Species Issues’ (SSA). Costs and benefits were then analysed for those issues, which were deemed ecosystem or EAF issues only. The highest benefit-cost ratios were found to be achievable in the Research group, followed by the Management group. All issues in the Socio-economic group were deemed single species issues and therefore their costs and benefits were not analysed.

The complete reports of the Benefit-Cost Analyses for all three fisheries were submitted to the meeting. Further work and publications will stem from these reports but they are considered the full and final product for the purposes of the EAF Feasibility Project. The South African BCA Report is being prepared for publication as a separate document and, for this reason, is not included as an Appendix to this report.

South Africa

A report of the benefit-cost analysis workshops conducted for three South African fisheries, Demersal Hake, Small Pelagics and West Coast Rock Lobster was presented by Tracey Fairweather. The report was tabled as a document. It was noted that the intention of the report document is to present the conclusions of the Benefit-Cost Analysis Workshops and not to provide a definitive economic study of the three resources. The workshops were intended as a first attempt to “Conduct cost benefit analyses of implementing EAF management for each country” as required by the project. The benefit:cost ratios, summaries and recommendations are considered starting points for the further evaluation of EAF implementation. For several of the issues and management actions presented, further detailed study will be required but issues have now been prioritised and grouped into feasible management actions.

The full report is 100 pages long and as such only the Summary and Recommendations for each fishery were presented along with a few examples of how the Risk Assessment issues had been grouped into management actions. The report of the Benefit-Cost Analyses for all three fisheries are considered the full and final product for the purposes of the EAF Feasibility Project and will be published as a separate project report.

i) South African hake:

This fishery had the most RASF issues raised with most of the high and moderate issues relating to governance and retained species. This trend is echoed in the number of Management Actions and their wording. Issue Groups A, B and C reflect the biological concerns of the fishery and for several management actions the short-term cost is anticipated to be high while the long-term benefits are enormous. In general the most debilitating feature was the lack of experienced and qualified capacity to manage the fishery and research the species affected. Management actions with the highest long-term benefits were manage fishing effort (13), time-area closures & MPAs to protect specific size classes (18), develop joint research program to investigate distribution and stock-structure of both hake species across both coasts and borders (27) and to assess need for joint management if stocks are shared (28 - which is covered by current BENEFIT project).

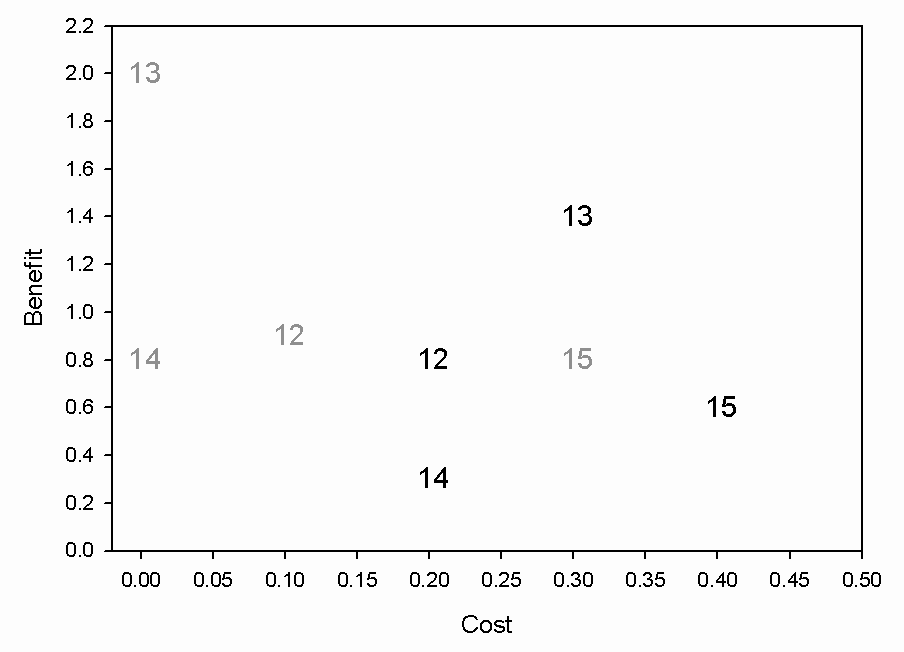

Scatter plots for each management action grouping were given showing the short-term (black) and long-term (grey) average benefit and cost values for each management action. This was intended to show the relative scoring of the management action in the short- and long-term. Below is the plot for issue grouping C (actions 12-15) for the hake fishery. This was done for all three fisheries but only one example is given here.

ii) South African small pelagics:

.2RASF Issues Identified |

50 |

|

EAF Issues Identified |

35 |

|

Consolidated Groupings of Issues |

4 |

|

Number of Management Actions Proposed |

16 |

The small pelagic fishery had almost half the RASF issues raised in the hake fishery. Once again retained species and governance were dominant but none of these issues were extreme. External impacts had several extreme issues which reflect stakeholder awareness of the impact of the environment on the fishery. Thus the management action to develop a framework for holistic research (4) has the highest long-term benefit in the Issue Group Research. Nevertheless the management actions with the highest long-term benefits were dominant in the Resource Management Issue Group. An immediate and large short-term benefit could be achieved if an effective RMWG with broader stakeholder participation (improve commun.) with a view to making it a statutory body (11) could be established. The other two actions are to implement appropriate formal co-management structures (12) and improve access to information for greater public - disseminate & open dialogue (all resources, eg website & roadshows) (13).

iii) South African west coast rock lobster:

.3RASF Issues Identified |

51 |

|

EAF Issues Identified |

32 |

|

Consolidated Groupings of Issues |

4 |

|

Number of Management Actions Proposed |

11 |

The west coast rock lobster fishery had an equivalent number of issues as the small pelagic fishery. Once again, as with the other two fisheries, governance and external impacts were dominant. The external impact which had the highest long-term benefit was to conduct integrated studies to assess magnitude of conflicts with mining industry (7). Management action 9 to urgently develop co-management via WCRL Resource Management Working Group echoes the sentiments of the other two fisheries. Management action 8 to monitor WCRL distribution, abundance & population structure and manage accordingly should provide high long-term benefits.

General Discussion

In discussions on progress in the project as a whole, it was noted that a large number of medium and high priority issues had been identified in all of the countries and that it would not be possible to address all of those in the short-term. It will therefore be necessary to screen them and to select those of highest priority for immediate progress towards implementation. It was also emphasised that the results of the benefit cost analyses are preliminary and that they would need to be reviewed with wider consultation and provision of available, supportive scientific information. It was pointed out that the proposal for a Phase 2 of the project, to be discussed later in the workshop, was intended to support this process in a limited number of fisheries (tentatively one per country).

Members of the fishing industry participating in the workshop expressed appreciation for the project and the consultative process that had been followed. They referred to the need for regional cooperation and consultation which could lead to greater efficiency and cutting of costs in some cases. Supporting the view that the list of issues was probably too extensive to address immediately, they pointed out that it needed to be prioritised, starting with a scientific process followed by consultations. It would be essential in the consultations to ensure that all the right people were around the table. A participant from the Namibian fishing industry suggested that it was important for the fishing industry in the SADC region to strive for common objectives or, at least, to ensure that their objectives were compatible.

Members of the fishing industry drew attention to the need to publicise the concept and importance of EAF within the fishery sector to ensure that all were kept fully informed. This was essential to obtain the buy-in of stakeholders. It was suggested that, once consensus had been reached at the scientific level on the priorities and possible ways forward, a road-show could be held to inform and consult with stakeholders.

One participant (Ben Van Zyl) referred to three pillars of EAF, as agreed at the Bergen Conference: the impact of fisheries on the ecosystem; the impact of the ecosystem on fisheries; and the socio-economic aspects of EAF. He suggested that insufficient attention had been given to the second of these, the impact of the ecosystem of fisheries.

South Africa

Lynne Shannon provided an overview of the EwE simulations undertaken, the details of which are included in Appendix 4a. A model of the southern Benguela for 2000-2004 (unpublished) was used for simulation purposes reported herein, biomasses were fixed at these values so that any changes in model results could be attributed to the altered fishing strategies being explored and not to biomass adjustments being made for groups for which biomass was not a model input. EwE default setup parameter settings were accepted and a 20-year period was examined. Altered fishing strategies were modelled for year 2 and carried through the full simulation period. A simple form of wasp-waist flow control was adopted for the anchovy, sardine, round herring and other small pelagic fish model groups for interactions involving anchovy, sardine, round herrring and other small pelagics. For all other groups, mixed control was assumed. Two issues identified during the risk assessments of the pelagic and hake fisheries were selected as examples for development of Ecopath with Ecosim (EwE) simulations to explore possible ecosystem effects. There were: the by-catch issue in the South African demersal fishery; and the effect of slippage (dumping) of anchovy and sardine.

In relation to the simulations on the by-catch issue, Lynne Shannon noted that, even though the simulations had been unable to capture the interactions and complexities of the demersal fish assemblage in sufficient detail, they had nevertheless highlighted the benefits of reducing fishing mortality on by-catch species, in particular kingklip and monkfish. The simulations had demonstrated that reduced by-catch led to the biomass and overall catches of the fished benthic-feeding demersal fish increasing substantially, with an even larger increase in the catch value, given the high value of the two species compared to others such as hake. She recommended that a detailed demersal fish EwE model should be developed to model the trophic interactions of the demersal fish assemblage (which was not the aim of the existing model adapted here), to facilitate more detailed and robust simulations regarding by-catch issues in the demersal trawl fishery.

In concluding the investigations into discarding of pelagic fish, she noted that the available EwE model was not set up to simulate intra-annual changes or spatial issues and therefore that some important EAF issues could not addressed in this particular exercise but could in principle be done using the EwE software. An EwE model in which zooplankton is further disaggregated was recommended to account for the new dietary studies being undertaken on small pelagic fish and their probable resource partitioning. Modelled discarding was estimated to impact sardine more strongly than anchovy, as was to be expected from the higher fishing mortality of sardine compared to anchovy (0.07 vs. 0.06 yr-1), and also reflecting the differences in prey niche overlaps between anchovy and sardine, which can cause cascading trophic effects. EwE simulations had been found to be sensitive to settings of flow control, and the model exercise conducted here was no exception to the rule. A revised model was in the process of being fitted to new and updated time series data (Shannon et al. in prep.) and should provide an improved basis for testing management strategies such as those described here. The model results showed stronger impacts of slippage in situations with reduced biomass and higher fishing mortality, both with respect to the target species and to the ecosystem as a whole.

Angola

Filomena Vaz Velho made a presentation on the progress that had been made in developing and testing an EwE model of the north-central area of Angola. The PowerP oint presentation providing the details of the model is attached as Appendix 4b.

Development of the model had started in 2005 and further progress had been made at a project workshop in Cape Town in August/September 2006, with additional work done on the model subsequently. The model represented an area of 50 000 km2. It included 28 functional groups of which five were top predators, 9 were finfish species or species groups and the remainder were crustaceans, cephalopods, benthos (micro and meio), zooplankton (large and small), phytoplankton and detritus. Three fisheries had been included in the model, representing the industrial, semi-industrial and artisanal fisheries. It was reported that the model developers had struggled to achieve the necessary mass balance but had finally succeeded for all but two groups, shrimps and phytoplankton. Possible problems with the shrimp group was that biomass and production may have been under-estimated or catch over-estimated. The input parameters for shrimps and phytoplankton needed to be re-checked.

Filomena Vaz Velho also reported that the model would continue to be improved and tested within a new project funded by BENEFIT.

Namibia

Jean-Paul Roux presented preliminary results of a simple model of Cape hake (Merluccius capensis) recruitment taking into account inter-cohort predation (cannibalism) within the first two juvenile cohorts (full report is provided in Appendix 4c). Simulation results showed that this very simplistic model can reproduce the complex apparent dynamics of the interactions between juvenile Cape hake cohorts in Namibia observed in the last 13 years and that cannibalism on the 0+-group by the 1+-group could be the dominant driving factor of Cape hake recruitment dynamics in the Northern Benguela at present. Diet information comparisons between the northern and southern Benguela for these young hakes suggested that the low level of biomass of small pelagic fish and environmental anomalies (e.g. Benguela Niño events) in the northern Benguela at present could be the main causes for the high variability in Cape hake recruitment. A recovery of the small pelagic stocks (sardine and anchovy) could result in higher and more stable recruitment levels. This demonstrated a possible strong interaction between the management of small pelagic fish and the dynamics of an important demersal species through alteration of the trophic pathways.

General Discussion

In the discussions, it was pointed out that the models presented are being developed to potentially assist in providing scientific advice for management actions. One participant suggested that, in relation to ecosystem models, the primary limitations did not lie in the models themselves but in our underlying knowledge of the ecosystem and the processes taking place. Ecosystem models attempt to integrate in a structured way what we do and do not know and so to contribute to our understanding of the interactions in the food web and with humans, to complement the more focused approach provided in most stock assessment models of the interaction between humans (e.g. a fishery) and one or two species. Models can be confusing for many people and the more complex the model, the more difficult it is for non-modellers to understand. People are frequently reluctant to believe results from a model that they perceive to be a ‘ black box’ and it is important to ensure that any model used is well-understood by all and is as transparent as possible. An essential step for dealing with uncertainties in any model is to test the sensitivity of the model, and robustness of results, to plausible ranges of possible values or states. There would be benefit, as with any model, in comparing results from different models as a means of validating their outputs.

It was noted that the latest version of EwE can take cannibalism into account because it allows for detailed age structure within species groups. It was also pointed out that, by changing the vulnerability parameters, it is possible to simulate the range of standard feeding responses (Holling types I to IV) but that this also implicitly determines the nature of the stock recruit relationship. It is therefore important to ensure that the implications of the set of vulnerability settings in an EwE model are well understood.

In response to a question, it was pointed out that EwE is considered to be a useful tool for the project and for providing strategic advice on ecosystem responses to human intervention but is not considered to be the only such tool and that different models have different strengths and weaknesses.

The project had drawn on ongoing work with EwE to provide useful input to some scientific questions. The benefits of using ecosystem models, including EwE, include identification of data gaps, facilitating comparisons and synthesising available information on ecosystems. Within the BCLME activities, progress is being made towards putting together time series of data, fitting the models to observed time series and using them for forward projections. South Africa has been successful in this regard with biological data. However, a problem throughout the region was the poor availability of economic and social data.

In presenting the paper (attached to this report as Appendix 5), Lynne Shannon explained that, despite their possibly expected similarities, the northern and southern Benguela have shown very different ecosystem dynamics in recent decades. Differences between the two parts of the Benguela may be related to the fact that the southern Benguela upwelling region is bounded by the shallow Agulhas Bank, with an associated diverse demersal fish assemblage. Both systems are affected by dramatically different environmental perturbations. For example, the northern Benguela is regularly affected by low oxygen events, and by large-scale warm water events such as Benguela Niños.

The ecosystem structure and trophic functioning of the northern Benguela in recent years seems to have differed from the way in which the system functioned in the 1970s. Between the late 1960s and the late 1970s, anchovy and sardine stocks were replaced by a suite of zooplanktivorous fish including horse mackerel, mesopelagic fish and pelagic goby. Most fish stocks in the northern Benguela underwent large declines towards the end of the 1990s at the time of major environmental anomalies while jellyfish Chrysaora hysoscella and Aequorea aequorea have attained large abundances during the same period, possibly changing the energy flow through the northern Benguela food web. Overall, the northern Benguela appears to have undergone a regime shift since the 1980s with the effects of an unfavourable environment having been exacerbated by heavy exploitation. This has resulted in extreme modifications to the pelagic ecosystem there (Cury and Shannon, 2004)2.

Resources in the southern Benguela also varied substantially between 1980 and 2004, but seemingly without a shift to a completely new ecosystem state. Despite the differences in fish stock sizes and catches (particularly of small pelagics) between 1980 and the mid 1990s, the trophic models used by Shannon et al. (2003)3 did not reveal a change in the overall trophic functioning of the southern Benguela between 1980 and 1997. It has been argued that the southern Benguela experienced a pelagic species replacement rather than a clear regime shift to a different ecosystem state because ecosystem functioning remained relatively constant over that period.

Lynne Shannon outlined the trophic models of the southern Benguela that are available for the periods 1980-1989 and 1990-1997, as well as a comparable model of the period 2000-2004. In the case of the northern Benguela, several models have been constructed (see Appendix 5 for details). In order to facilitate meaningful comparisons between systems, models of both systems have been standardized according to established methods (Moloney et al. 20054). In the same way, standardized, updated models were constructed for the northern Benguela for the 1960s, 1980s and 1995-1999 and used to illustrate the main ecosystem changes that have occurred off Namibia. Details of those changes were presented to the workshop. In addition, models of the southern Benguela have been fitted to time series data and used to quantify ecosystem changes (Shannon et al. 2004a5). These studies supported earlier findings which indicated that environmental factors have been more important drivers of South African ecosystem dynamics than fishing over the latter part of the 20th century (Shannon et al. 2004b6).

General Discussion

There was considerable discussion on the significance of ecosystem states for fisheries management. There were differences of opinion on what constituted a change in state and the definition of an ecosystem state and reference was made to published work on this issue (e.g. Bakun 2004, Cury and Shannon 2004, de Young et al. 2004, Jarre et al. 2006, Mantua 20047). Nevertheless, it was recognised by all participants that the state of the northern Benguela ecosystem had changed within the last decade or so and that this needed to be recognised in the assessment and management of the affected resources. It was also pointed out that had it been recognised earlier that the ecosystem was in a changed, less productive phase, it would have been possible for management to respond to this sooner with likely beneficial consequences for the stock.

In other cases, there were three possibilities: i) ecosystems did not change significantly and important rates and parameters could be considered to be constant; ii) there are discrete and distinct states in ecosystems and that management regimes need to be established for each state; or iii) ecosystems are substantially dynamic and parameter values can change significantly, requiring constant review and, where appropriate, changes in assessment assumptions (e.g. changes in the value of M and recruitment variability) and management regimes. There was no consensus on which of the three was more likely but the majority viewed that option i) was unlikely.

It was noted that results from the EwE simulations of the southern Benguela indicated that the predation rate on sardine (total amount of sardine consumed/ sardine biomass) was estimated to have increased by about 25% since 1990. Since predation mortality comprises most of M, this likely indicates a similar rise in M, a possibility which should be investigated further.

An overview of criteria for selection of indicators for EAF was presented by Gabriella Bianchi which was followed by an overview of indicators for each priority issue/management objective for South Africa main fisheries, by Lynne Shannon. Both presentations were based on the background paper included as Appendix 6a.

Principles and guidelines for the use of indicators to complement single stock assessments, based on the document provided in Appendix 6b, were presented by Doug Butterworth.

Based on the overview above, Bianchi presented six principles to be considered when selecting indicators for fisheries management under an EAF. One principle relates to the need for a strict relationship of the selected indicator to specific management objectives. It was noted, however, that consideration should be given to developing a set of indicators to monitor the marine environment independently of specific fisheries management objectives, to allow for environmental reporting. Such a scheme should also result in consistent time series and these, in turn, could form the basis for developing various new indicators as needed, but also for exploratory data analyses.

A good correlation with the property for which management objectives have been set (e.g. biological, ecological, social and economic) and a consistent response to changing levels of fishing are also necessary features of the selected indicators. If these relationships are not clearly demonstrated, the indicators will be less useful and in some cases could be misleading. In particular, for indicators used to determine fisheries management measures it is important to show that the selected indicators respond primarily to changes in the management measure and, conversely, have low responsiveness to other causes of change.

Indicators should be observable, both in technical and economic terms, within the economic and human resources available, and should be relevant to the social and institutional context.

Different indicators may be appropriate to specific time and space scales and these were therefore considered as two very important criteria.

Stakeholder participation in all steps of the decision making process is one of the pillars of EAF. This requires that indicators are acceptable, and therefore understood, by all stakeholders, both within the fishery system and by the public.

It was noted that once the indicators have been filtered through the above criteria, there is still the important challenge of setting meaningful reference points. These could be chosen through modelling and, in the case of poor data/models, reference points could also be set empirically or even heuristically. Where it is not possible to set reference points, reference directions may be useful. An additional difficulty is related to integrating a wide variety of indicators to facilitate management action. The need for developing meta decision rules that summarise the direction of action for the various issues and indicators was stressed, as well as the lack, so far, of well established procedures for this.

General Discussion

As regards indicators for ecosystem effects of fishing, the workshop agreed that indicators could be split into four categories:

i) target species affected by the fishery

ii) non-target & dependent species affected by the fishery (e.g. vulnerable species)

iii) effects on ecosystem as a whole (diversity, trophic levels)

iv) environment effects on fisheries.

Specific comments that emerged from the discussion were as follows:

Assumptions for indicators must be clearly defined in relation to the biology of the species in question, community, property or the ecosystem as a whole;

It is preferable to use a suite of indicators to guide management action. These indicators must not present duplicate information or data which is already contained within existing stock assessment models or there is a risk of using the same data twice and interpreting it differently to the way in which it is incorporated in the model. It is preferable to use indicators which can be assessed rigorously for categories i) and ii). Indicators for categories iii) & iv), for which sufficiently rigorous assessment will frequently be impractical or impossible, will need to be evaluated by more general understanding, for example by considering trends and combinations of trends;

Indicators in categories iii and iv can be used to inform management on possible trends that could be relevant to management of the fishery (including wider implications within the context of EAF) and, where considered necessary, will be placed in a ‘red-light’, warning box. They could be used for strategic decision-making or as considered relevant (see Figure);

Developing indicators which are understandable to all stakeholders will increase their usefulness as a management tool. Basic ecosystem state and environmental indicators should be incorporated into the background provided for management recommendations and documents;

Consideration should also be given to distributing information on the state of indicators to the public on a regular basis to keep them informed on the status and trends of fisheries and the ecosystem;

Society sets objectives but experts are needed to design the systems for fulfilling those objectives. An important component of designing such systems is, where possible, to hold workshops or other consultative processes with relevant stakeholders to define the decision rules to be used in the management actions.

Figure. Indicator flow chart

The need for objective and transparent decision-making was stressed as important. This should apply not only when rigorous assessments are available, but also when only more general information is available but is still considered to be sufficiently important to require consideration. Furthermore, in those cases where rigorous assessments are not available but negative trends have been shown and accepted as being meaningful, reasons for not taking any management action should be justified, i.e. it should be demonstrated that the risk of not taking any corrective action to avoid negative outcomes can be considered to be low.

Frikkie Botes presented an overview of the Benguela Current Interim Agreement. He explained that, now in its fifth year, the BCLME Programme had already allocated more than US$10 million in support of 75 scientific and economic research projects in the region. The purpose of the BCLME Programme is for participating countries and their institutions sharing the Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem to have the understanding and capacity to utilise a more comprehensive ecosystem approach and to implement sustainable measures to address transboundary ecosystem related environmental concerns collaboratively.

He provided background to the project and reported that, at the onset of the BCLME, the littoral countries had agreed on a program of actions (the Strategic Action Programme - SAP) aimed at achieving the integrated management of the ecosystem, including the creation of the Benguela Current Commission, and a vast array of local, national and regional actions. At that time it was planned that the proposed project would support the countries in this effort through the establishment of the Interim Benguela Current Commission (IBCC), the development of a series of assessments, surveys and plans, training and capacity building (the latter defined by the signatories of the SAP as of the "highest priority"), and the securing of additional financing.

With the support of the Global Environment Facility (GEF), which finances environmentally sustainable projects and its implementing agency, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), this collaborative effort has now resulted in the Benguela Current Commission, the first of its kind in the world. The Commission was formally established when the Governments of South Africa and Namibia signed the interim agreement on 29 August 2006 in Cape Town and the government of Angola signed on 31 January, allowing for their joint management of the Benguela Current's marine resources. The Benguela current extends from east of Port Elizabeth and north to Angola's Cabinda province and the BCC is an institutional structure that will link the three countries in the management of the BCLME, one of richest and most productive marine ecosystems on earth. The three countries will collectively manage trans-boundary environmental issues such as shared fish stocks and will work together to mitigate the impacts of marine mining and oil and gas production on the marine environment.

A study conducted by fisheries economists from the University of British Columbia in 2004 concluded that the net benefits of regional co-operative management are huge as against the risk of non-cooperation. Some of the conclusions of that study included that the establishment of the BCC would:

reduce wasteful use of shared stocks and increase catch potential of fisheries throughout the BCLME

allow stocks to grow to their fullest economic potential

incur modest costs (sustainable funding is available)

require strong political commitment which is already present in the region

This Interim Agreement of the BCC applies to the area of the Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem to the extent that it falls within the internal waters, territorial seas or exclusive economic zones of the Contracting Parties, as well as to all human activities, aircraft and vessels under the jurisdiction or control of the Contracting Party to the extent that these activities, or the operation of such aircraft or vessels result, or are likely to result, in adverse impacts. The BCC will have links to SADC, SEAFO and ICCAT.

Some important features of the interim agreement include the following.

The Contracting States shall use their best endeavours to bring into force by no later than 31st December 2012, a binding legal instrument that will establish a comprehensive framework to implement an ecosystem approach to conservation and development of the Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem.

The BCC shall be funded from funds provided by the Contracting Parties and donors. Unless otherwise agreed, the Contracting Parties shall contribute in equal proportions to the budget of the Commission.

In the event of a dispute between Contracting Parties concerning the interpretation or implementation of this Interim Agreement, the Contracting Parties concerned shall seek a solution through negotiation. If the Contracting Parties concerned cannot settle the dispute through negotiation they shall agree in good faith on a dispute resolution procedure which may include jointly seeking mediation by a third party (which may be a Contracting Party that is not involved in the dispute).

The Contracting Parties have entered into this Interim Agreement without prejudice to any claims that they may have in relation to the delimitation of their maritime boundaries and nothing in this Interim Agreement or done pursuant to it, shall be construed or interpreted as conduct on the part of a Contracting Party signifying that it either consents to, or disputes, a particular maritime boundary.

The full text of the Interim Agreement between the three BCLME countries, Angola, Namibia and South Africa on the establishment of the Benguela Current Commission is available from the BCLME Programme Coordinating Unit (PCU) in Windhoek, Namibia.

Kevern Cochrane introduced the topic. He started by drawing attention to some of the functions of the Ecosystem Advisory Committee of the BCC (Full presentation included as Appendix 7). These included:

(a) to support decision-making by the Management Board, the Ministerial Conference and the Contracting Parties by providing them with the best available … information, and expert advice concerning the conservation and ecologically sustainable use and development of the BCLME; and

(b) to build capacity … to generate and provide the information and expert advice referred to in (a) on a sustainable basis.

It will be essential for the Advisory Committee to be aware of the high priority regional issues and to advise the appropriate BCC institutions on how to address those issues. He went on to highlight some of the major regional issues that had come out of the RASF and BCA workshops.

In the case of deepwater hake M. paradoxus, the workshops in both Namibia and South Africa had emphasised the need to cooperate bilaterally in research and management. There had been consensus that such cooperation should proceed in a stepwise manner. The first step could be based on informal agreements and cooperation that included: a joint research strategy and sharing of data for stock assessment; an attempt to control and balance effort across the sectors and countries; coordination in by-catch policies for by-catch species that were also shared, research into and protection of benthic substrate and habitat which otherwise could compromise recruitment and sustainable use of stock; and research into and appropriate action on external influences on the species including pollution on eggs and larvae. The second step would involve formal, binding agreements that addressed: a joint management strategy and administrative cycles (recognising that allocations within each country would remain a national issue); effort control and by-catch policies and practices; data collection and an observer programme; compliance; and possibly efforts to co-ordinate marketing to maximise profit.

The RASF and BCA workshops in Angola and Namibia had also arrived at similar conclusions on the need for cooperation in management of the sardine S. sagax stock shared between those countries. The objective of joint management would be to coordinate and harmonize management of the stock in order to rebuild it and ensure optimal benefits were obtained from it. This would best be served through a bilateral agreement that included bilaterally agreed TACs; joint surveys using standardized methodology; sharing fishery statistics and other relevant information; and bilateral working groups involving the range of stakeholders.

Based on these examples and other outcomes from the project, the following important questions needed to be considered:

what are the priority species and ecological issues for regional consideration;

where is the action required e.g.

consultative structures (between or within countries);

management measures (TAC, effort control, etc);

enforcement and surveillance;

monitoring;

management of or responses to ecosystem impacts (by-catch, habitat damage, environmental variability..);

impacts of other human activities;

research.

In the discussion that followed, the workshop developed the table below identifying the species and species groups that were recommended to BCC for consideration for regional cooperation. In addition, it was agreed that BCC should also give consideration to addressing regional environmental issues and providing a regional service in this regard. Environmental matters that are relevant to two or more countries include, for example, monitoring and mitigating the impacts of red tides, low oxygen events and other large scale environmental events and anomalies. BCC could also encourage and perhaps facilitate monitoring for agreed ecosystem and environmental indicators and providing regular information on the state (or health) of the ecosystem and advising on its implications for fisheries and related activities. It may also be able to play a similar role in the monitoring of pollution from e.g. land-based activities, oil and gas exploration and extraction and offshore mining, considering and advising on their implications for fisheries (including health related aspects) as well as ensuring that the interests of the fisheries sector are taken into account in the development and management of the coastal zone and the EEZ as a whole.

Species and species groups to be recommended to the BCC for regional consideration. Entries marked with two asterisks (**) are considered top priority and those with one asterisk (*) of middle priority.

|

Species |

Technical matters |

Assessments |

Comments

|

|

Seabirds |

** - Gear trials for exclusion gear. - Protection status for breeding sites. - Consideration of protection status for spp. (ACAP) |

Endemic species status |

There is a multi-national MoU on monitoring endangered spp. In addition, BCC should consider coordination of NPOAs on seabirds. |

|

Tunas |

*There may be a need for effort control within the context of ICCAT framework. |

|

|

|

Turtles |

These are a global conservation concern. BCC should give attention to any international commitments by BCLME states. There is a need to collect data on fisheries related mortality, including through the use of observers |

|

Leatherback turtles are critically endangered. BCC needs to give attention to any international obligations and commitments of its members e.g. COFI. 2005. There are directed fisheries in all three BCLME states. |

|

Pelagic sharks |

There is a need for effort control within the context of ICCAT |

|

|

|

Hake

|

|

**Note was taken of the Benefit Workshop on shared stocks in May 2006, and the intentions for on-going attention to regional cooperation on these species were supported. |

|

|

i) impact of hake fishery on seabirds |

**South Africa already has regulations covering gear exclusion and mitigation devices for seabirds in both the long-lining and trawl fisheries. Namibia should give attention to implementing similar measures. |

|

|

|

ii) by catch of commercially important species in hake fishery |

Snoek, kingklip and monk in South Africa and Namibia |

|

These stocks may be shared between South Africa and Namibia, which would require a cooperative and coordinated approach to their management, including by-catches |

|

Crab |

|

**A joint Angola-Namibia working group has been established |

Shared between Angola and Namibia. BCC should ensure that the cooperative approach is maintained and strengthened where necessary. |

|

Cunene and Cape horse mackerel |

|

**A bilateral agreement is in place but, while Angola has a minimum size limit, Namibia does not, which is cause of concern |

Shared between Angola and Namibia. BCC should ensure that the cooperative approach is maintained and strengthened where necessary. |

|

Sardine |

|

**A joint Angola-Namibia working group has been established and transboundary surveys have been undertaken. |

Shared between Angola and Namibia. BCC should ensure that the cooperative approach is strengthened and extended to management. |

|

Demersal sharks |

|

Current knowledge of the status of the stocks is not adequate. |

These species are impacted by many fisheries. BCC should help to coordinate the implementation of NPOAs for the conservation and management of sharks. |

|

Seals |

|

*Joint assessment across the three countries is justified |

|

|

Dentex |

**The species is taken as by-catch in the horse mackerel and hake fisheries. |

|

It is a targeted fish in Angola and a retained by-catch species in Namibia. BCC should give attention to optimising its use between the two countries. |

Multicriteria Support for Decision-Making in the Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries Management

Theo Stewart and Alison Joubert introduced their paper on “Multicriteria Support for Decision-Making in the Ecosystems Approach to Fisheries Management” (Appendix 8a).

They explained that a core feature of adopting a broad ecosystem approach to fisheries management is that decision making needs to give consideration to widely divergent effects

on different sectors of the ecosystem, and to potentially conflicting values and goals of

different stakeholders. The search for solutions satisfying all those perspectives,

values and goals to the greatest extent creates the need for effective decision support to those involved in fisheries management. The principles underlying multiple criteria decision making (MCDM) have been developed over the past 30 years within the broad arena of operational research and management science. This has led to the existence of a number of different, sometimes divergent, schools of thought which are still not fully integrated. The paper and presentation provided a broad overview of the different schools and approaches as they could each be of value for certain aspects of decision making in fisheries management.

The authors pointed out that the fundamental paradigm of MCDA is that, in order

to ensure that all stakeholder interests and concerns are fully taken into account in planning and decision making, the process must include:

explicit identification of the relevant criteria according to established principles;

evaluation of alternative courses of action or policies in terms of each criterion individually; and

synthesis of the individual preference orderings by an aggregation across criteria which recognizes both the importance of each criterion relative to the others, and the extent to which improved performance on one criterion may or may not compensate for losses on others.

They went on to discuss the process and provide examples of criteria and value tree structuring and to provide an overview of MCDA approaches. The objective of MCDA is to aggregate the preferences in terms of each criterion into an overall preference order or, alternatively, to classify the preferences into classes such as “excellent”, “very good”, etc. Several different approaches have been developed for this and were described by the authors. These included: value measurement or scoring; outranking methods in which, for each pair of alternatives, an assessment is made of the strength of evidence for and against the assertion that “a is at least as good as b”; goal programming and reference point approaches in which alternatives are assessed according to how well they satisfy identified goals or aspiration levels of achievement; and rule-based methods which can be considered to be a generalization of the other three, in which decision rules are constructed in order to classify alternatives into

reference classes on the basis of the attribute values. Direct (constructive) and inverse (holistic) methods for constructing preference models were described followed by some general comments on subjective assessments of quantitative parameters by groups. Finally the topics of uncertainty and risk, and time value and discounting were introduced.

An application of fuzzy logic to facilitate decision-making

Barbara Patterson introduced the paper “Using a fuzzy-logic approach to multi-criteria decision-making for an ecosystem approach to fisheries management” (Appendix 8b). She explained that a transparent decision-support system (DSS) prototype was developed to assist in balancing the many conflicting goals and objectives that need to be weighed in order to implement EAF. The system was developed using commercially-available NetWeaver and Geo-NetWeaver software. The DSS tracks the fulfilment of EAF goals based on information collated in the risk assessment for sustainable fisheries (RASF) workshop report for the South African small pelagics fishery. The system is designed as a tool for monitoring and evaluating the success of EAF implementation. The South African small pelagics fishery targeting sardine was chosen as the first test case because there is good knowledge of this (recovering) fishery. Sardines are favoured by predators and are utilised for both canning and fishmeal, thus providing a good example case for EAF.

The structure of the prototype follows the hierarchical tree approach recommended in the FAO guidelines for responsible fisheries (FAO 2003). After eliminating any areas of overlap, the final list of issues contained 12 from RASF category Ecological Wellbeing, five from category Human Wellbeing and eight from category Ability to Achieve. This prototype was enhanced during a consultative process with key experts. Input parameters are based both on quantitative and data expert opinion. An 11 point scale was chosen by which experts were asked to rate the trueness of a given proposition, e.g. “No unaccounted dumping of small sardine is taking place in the sardine directed fishery”.

Sensitivity tests were being undertaken to evaluate the system in terms of robustness to input changes, the impacts of individual parameters, the influence of system structure and the appropriateness of the input scales for parameters based on expert opinion. Preliminary results suggested that the system is robust towards input changes. A negative truth value impacts stronger than a positive truth value and sensitivity is lower when the truth values of remaining parameters are low. Sensitivity is highest when truth values of remaining parameters are high and the value of the parameter under investigation is low. In other words the system is conservative.

The DSS synthesizes a large amount of information, which is important for EAF where many different aspects and factors have to be considered. The system aims at improving understanding rather than achieving precision by focusing on the direction of the effect of variables. The strength of the approach lies in the ability to include variables which are difficult to measure. It provides a means of rendering value judgments explicit and transparent. The process of developing the prototype DSS had already been perceived as helpful by the scientists and managers involved. The process of prioritizing and structuring the main factors has helped to bring into focus the gaps in the way the social dimension for the small pelagic fishery are addressed at present. It seems that knowledge on the linkages between the status of the natural resource base, the management of the fishery and the implications for the people whose livelihoods depend on the utilization of the resource are not well represented in the decision-making process. Further efforts are needed and perhaps different approaches have to be found to elicit expertise on socio-economic and institutional issues.

General Discussion

In the general discussion following both presentations, it was suggested by one participant that, while it was desirable for all stakeholders to be involved in the formal process of multi-criteria-decision making, in practice decision-makers were reluctant to use this approach and that the task generally fell on the scientists. This problem was acknowledged but others thought it essential to persevere in trying to get decision-makers to use formal techniques to facilitate improved decisions.

There was considerable discussion about the importance of transparency and the role that formal MCDM techniques can play in facilitating transparency. As an example, a participant from the fishing industry queried the problems that are being faced in the rock lobster industry in South Africa as a result of some quota applications being sub-economic and suggested that this was a result of government having given insufficient attention to economic stability in the criteria it had used in rights allocations. In his view there are four major legs that need to be considered in fisheries, including EAF. Those are: political, social, economic and environmental, and it is essential to maintain the correct balance between those four. Theo Stewart responded that this case provided a good example of the need to ensure that the criteria used in MCDM are the most appropriate ones.

In response to a question, Barbara Patterson pointed out that weightings can be used with fuzzy-logic decision-making methods and that different levels in the hierarchy can be weighted independently. Therefore, for example, it would be possible for scientists to determine the weightings for scientific criteria and decision-makers to determine the weighting for policy criteria in a single tree. In this regard, Theo Stewart informed the group that while the contribution of the weightings to the output was clear in value-based techniques, they were less so when used with fuzzy-logic.

The importance of using sensitivity analyses was stressed. Barbara Patterson drew attention to the bias towards biological and ecological issues in the South African hierarchical tree developed for the small pelagic fishery and the resulting skewness of the system, and its outputs in this direction. This demonstrates the importance of ensuring representative participation in the development of such systems. The importance of the psychological issue of how questions are framed was discussed as the framing can significantly alter the likely response. It is important to be aware of the problems and careful consideration should be given to how to frame questions and the criteria.

Many workshop participants agreed on the importance of using such methods in fisheries management. It was suggested that in the BCLME countries, the process to provide scientific advice was formalised and rigorous but that management decisions were often made in a haphazard and unstructured way. Formal methods also provide an audit trail of the decision-making process. Formal decision-making encourages transparency, fairness and participation and should be put in place and encouraged. Returning to the theme of the need to improve co-management, which cropped up many times during the workshop, the importance of joint responsibility and joint decision-making by stakeholders was emphasised. Some suggested that a top-down, command and control system of management is still widespread globally and is still the predominant style in the BCLME countries and that this needed to be changed.

Angola

Filomena Vaz Velho presented an overview of the institutional requirements for EAF that had been identified in the RASF and BCA workshops (full presentation included as Appendix 9a). Overall, there was a need to establish an effective resource management structure that included improved communication with stakeholders. Within the management structure, a need for an improved procedure for allocation of access rights, especially in the artisanal sector and for operational management plans for all sectors and resources had also been recognized. In relation to research and management there were several areas where improvement was required, including improvements in data quality and information flow, training and career paths for researchers and management and the establishment of an on-board observer programme. Several problems in the existing MCS capacity were also identified while improved support to fisher communities and organizations was also highlighted as an important requirement. It was also reported that multi-sectoral coordination needed to be strengthened, both within the context of EAF and recognising the wider interactions inherent in integrated coastal area management.

Namibia

Ben van Zyl presented the overview of institutional requirements for EAF in Namibia. He briefly explained the fisheries management process in Namibia as background information. The TAC recommendations are presented to the Marine Resources Advisory Council which advises the Minister, who presents the recommendation to Cabinet for approval. Once approved, the TAC is then divided into quotas and allocated to individual companies. The institutional needs presented had been raised by stakeholders during the risk assessment and benefit-cost workshops (hake, pilchard and horse mackerel).

The full list of institutional requirements identified by the stakeholders included a number of different issues related to management, compliance, the existing legal framework and other components of the management process and structure (Appendix 9b). Some of the highest priority requirements included:

the lack of approved management plans including reconciled objectives based on an integrated approach with reference points;

the need to strengthen and complete data recording, capture and storage;

problems with attracting and retaining qualified and experienced staff and a research budget that was considered to be inadequate for the demands placed on it;

the need for regular updating of legislation to keep up with policy decisions (e.g. the NPOA on sharks);

the need to address problems with the current allocation system in order to meet the policy standard of strengthening the Namibianisation of the fishing sector;

the need for wider representative participation in council and working groups to include, for example, public interests and conservation groups;

the need to strengthen local capacity and development in joint venture agreements in order to achieve desired outcomes; and

the need for implementation of transparency in quota transferability.

South Africa

Tracey Fairweather presented the institutional needs that had been identified for successful implementation of an ecosystem approach to fisheries in South Africa (Appendix 9c). These were issues that had been raised by stakeholders during the risk assessment and benefit-cost workshops held as part of the BCLME EAF project. There were three main areas that required urgent attention:

1. capacity, not only in numbers but also in skills, for management, research and compliance;.

2. sufficient finances to achieve research objectives and provide advice to management and monitor catches;

3. data management, noting that the research section is lacking a data manager and that data management is a complex task requiring co-ordination with the monitoring and compliance unit in order to ensure all necessary data are collected and stored usefully.

General Discussion

All BCLME countries indicated that lack of capacity in their institutions was a critical factor affecting service delivery. This related particularly to research and management staffing, but not exclusively. Capacity in other departments, such as policy, economics and social sciences related to marine fisheries was problematic. This was seen as a major inhibitor for future capacity to deal with EAF in these countries. Furthermore, the lack of opportunity for advancement and career paths was a major concern.

In South Africa, and to a lesser extent, Namibia, the process of transformation and poor salaries were also cited as issues that exacerbated the institutional capacity problems.

In plenary, the following issues were identified :

Diminishing capacity in South Africa and Namibia combined with loss of institutional memory and knowledge is resulting in lack of confidence by stakeholders in scientific and management outputs. Further, pressure and/or interference in the process of making scientific recommendations compromises scientific objectivity.

All countries suggested that there was a strong need to develop an effective resource management structure for EAF that included the main stakeholders with particular reference to the fishing industry. This should include co-management in which stakeholders were directly involved in the decision-making process.

In Angola, there is a particular need to improve communication with the oil industry as this had direct ecosystem effects and often oil-related activities were given precedence over fisheries. Similarly, in Namibia, this concern applied to the ongoing development of marine diamond mining.

The need for increased capacity to sustain long-term ecosystem monitoring, the deployment of scientific observers and improved data management was emphasized.

In Angola improvement of surveillance and compliance as well as addressing access rights relating specifically to artisanal fisheries was critical if the implementation of EAF was to be effective.