This report was compiled by:

Susan Taljaard (CSIR, Stellenbosch)

This report was reviewed by:

Dr Pedro M S Monteiro (CSIR, Stellenbosch)

Dr Des Lord (D. A. Lord & Associates Pty Ltd, Perth, Australia)

This report also includes feedback that was received from key stakeholders attending the

Work sessions that were held in each of the three countries:

Namibia: 25 and 26 January 2005

Angola: 7 and 8 February 2005

South Africa: 10 and 11 February 2005

CSIR Report No CSIR/NRE/ECO/ER/2006/0011/C

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

(RECOMMENDED WATER AND SEDIMENT QUALITY GUIDELINES

FOR THE BCLME REGION IN A NUTSHELL)

The United Nations Office for Project Services ("UNOPS") commissioned the CSIR (South

Africa) to conduct this project, of which the main purpose was to obtain:

· A set of recommended water and sediment quality guidelines for a range of

biogeochemical and microbiological quality variables, in order to sustain natural

ecosystem functioning, as well as to support designated beneficial uses, in coastal areas

of the BCLME region

· Best Practice Protocols for the implementation (or application) of these quality guidelines

in the management of the coastal areas in the BCLME region.

An important secondary objective was to get acceptance from key stakeholders in the three

countries on the proposed guidelines and protocols. This was achieved through work

sessions and training workshops held in each of the three countries to which key

stakeholders were invited. The outputs from this project were also incorporated into an

updatable web-based information system (temporary web address:

www.wamsys.co.za/bclme).

The ultimate goal in marine water quality management is to keep the marine environment

suitable (or fit) for all designated uses. To achieve this goal, the quality objectives set for a

particular marine environment should be aimed at protecting the biodiversity and functioning

of marine aquatic ecosystems, as well as designated uses of the marine environment (also

referred to as beneficial uses). It is proposed that three designated uses of marine waters

be recognised for the BCLME region, namely:

· Marine aquaculture (including collection of seafood for human consumption)

· Recreational use

· Industrial uses.

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/04

Page i

Final

January 2006

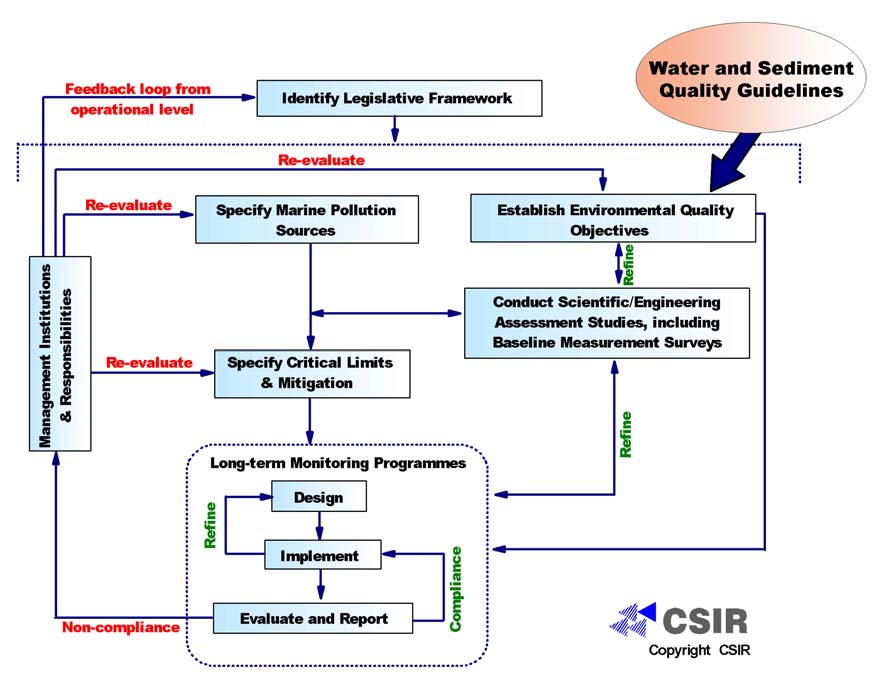

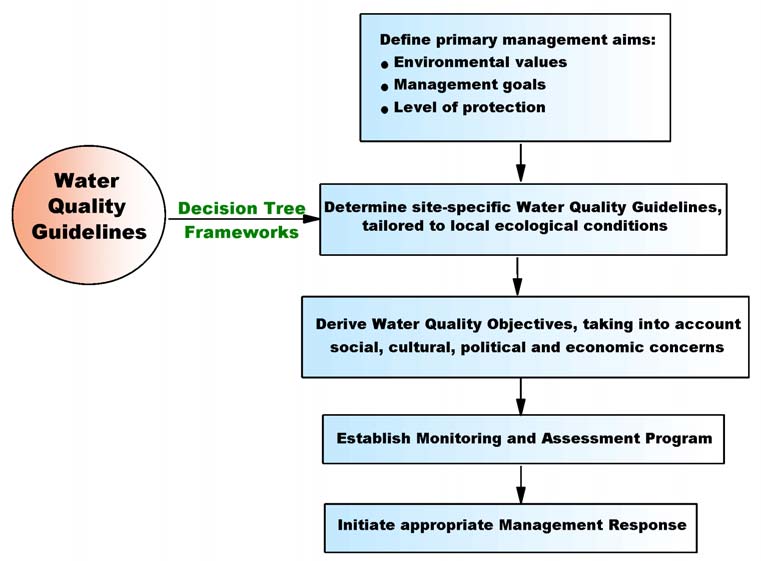

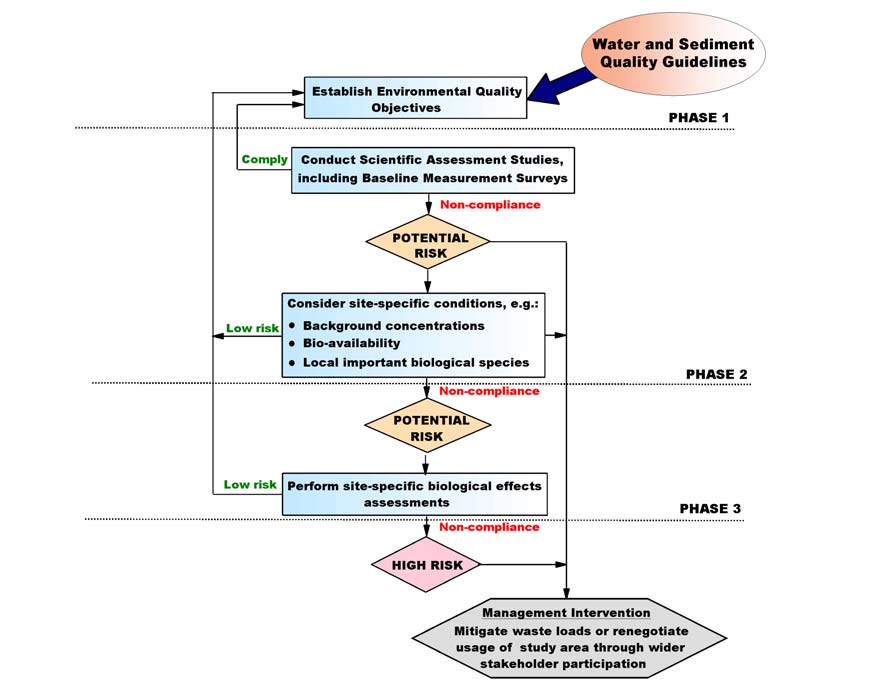

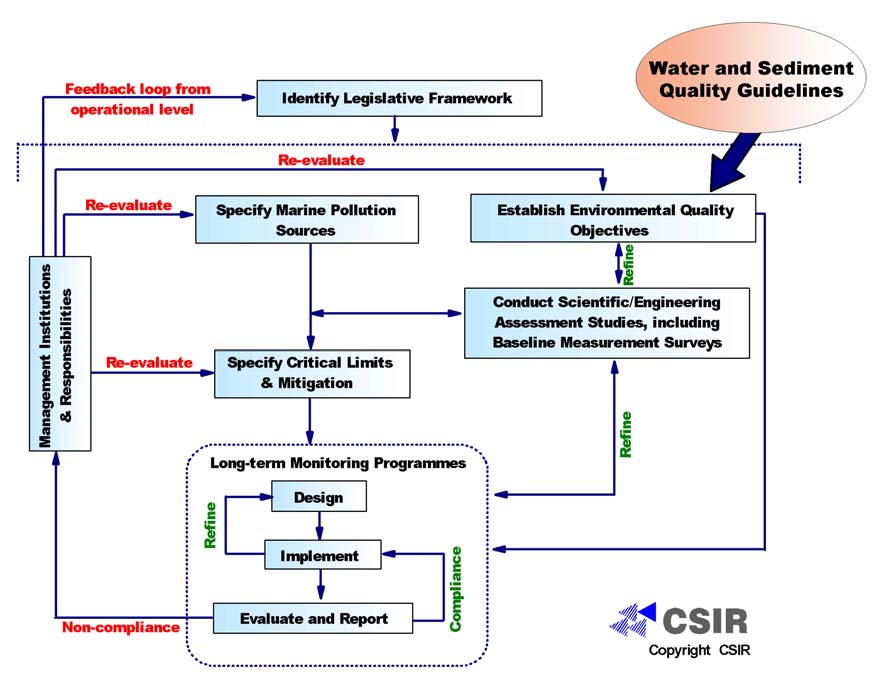

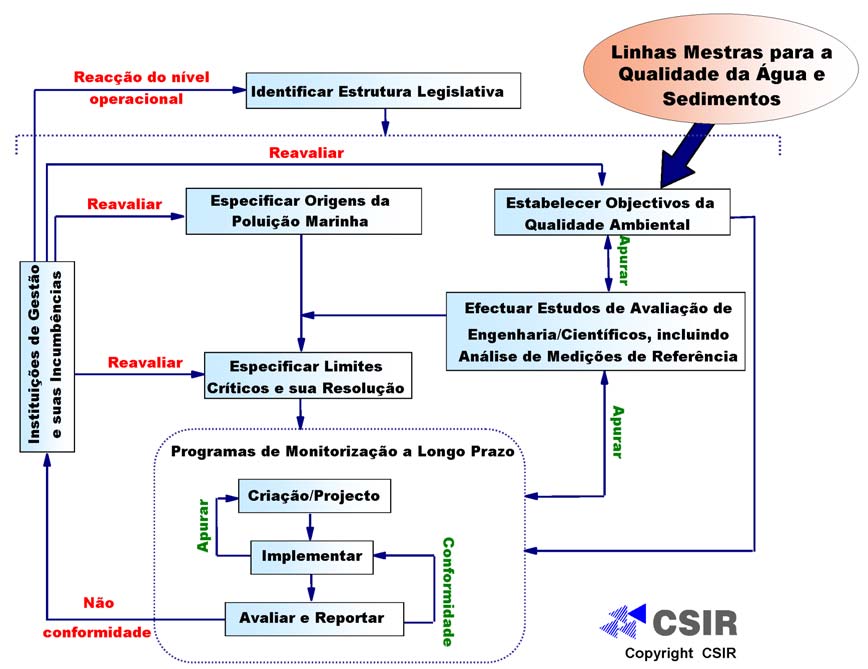

The recommended water and sediment quality guidelines, as part of this section, provide

guidance to managers, local governing authorities and scientists to set site-specific

environmental quality objectives within a study area for the protection of marine aquatic

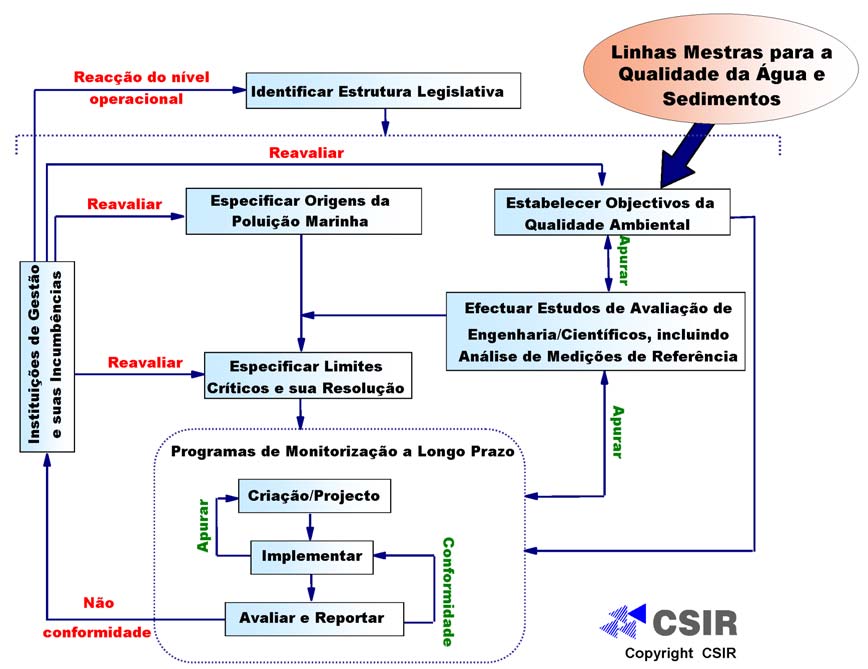

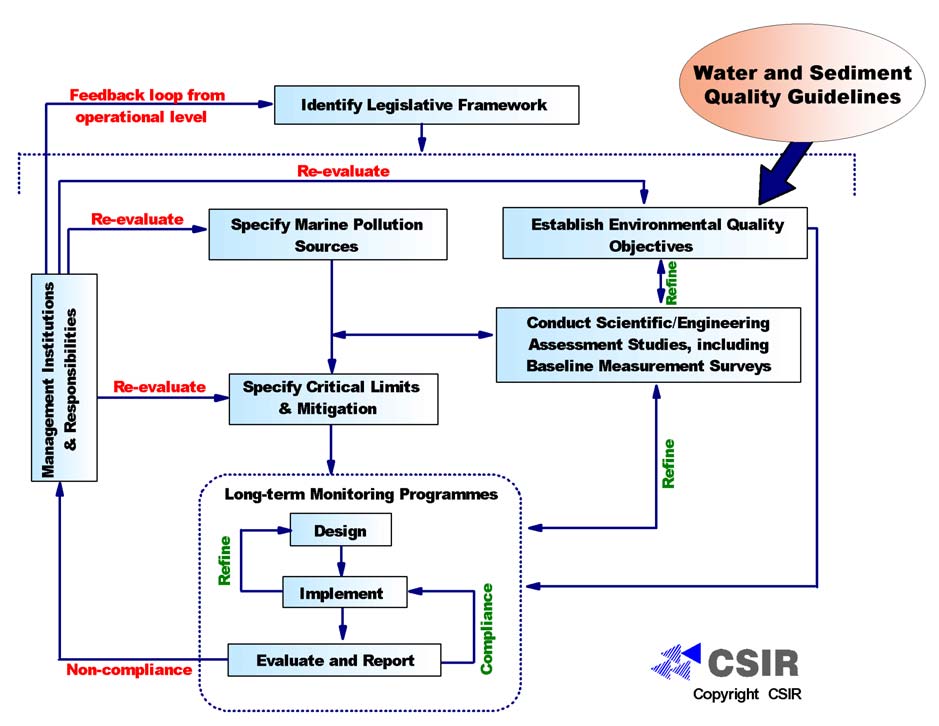

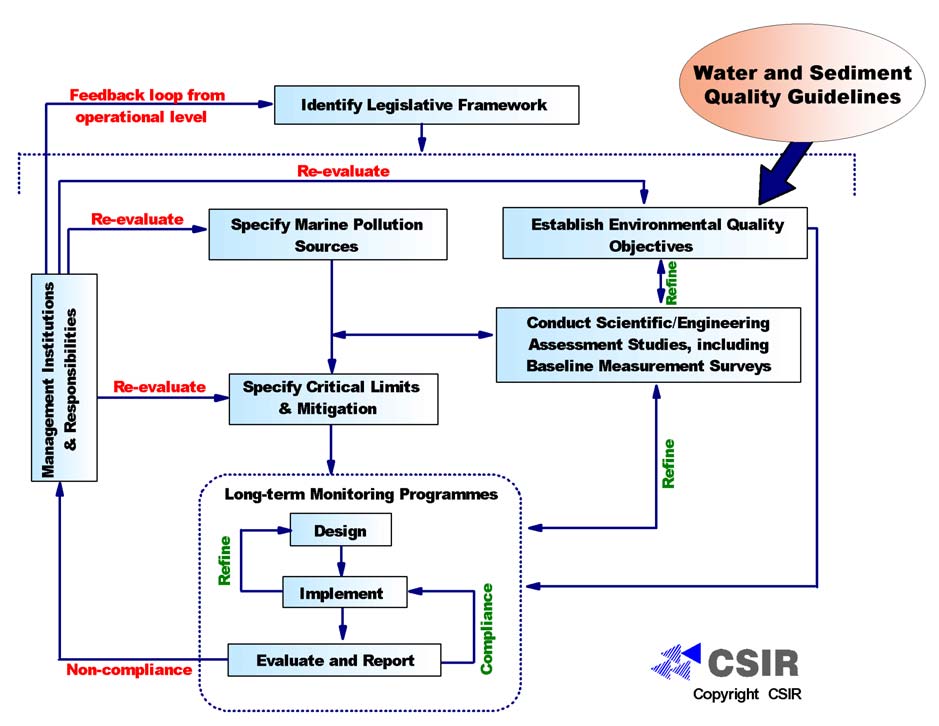

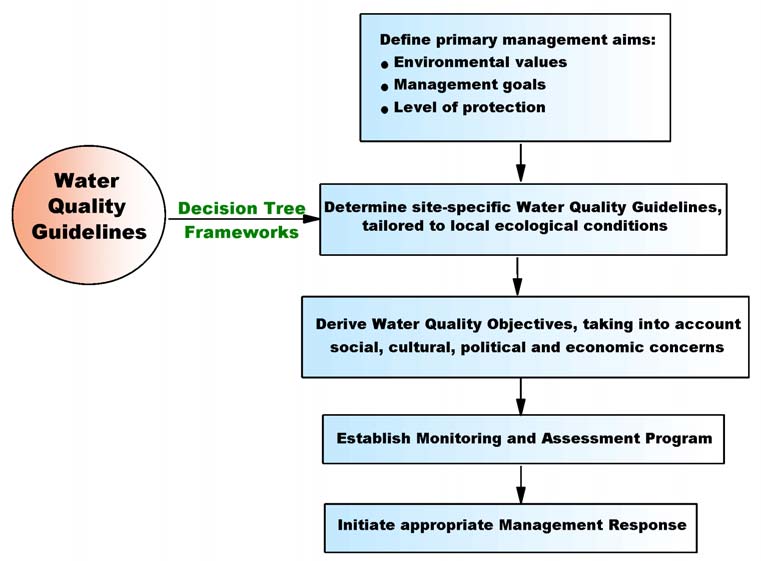

ecosystems and other designated uses. Therefore, in the larger integrated and ecosystem-

based framework, within which marine water quality is managed, water and sediment quality

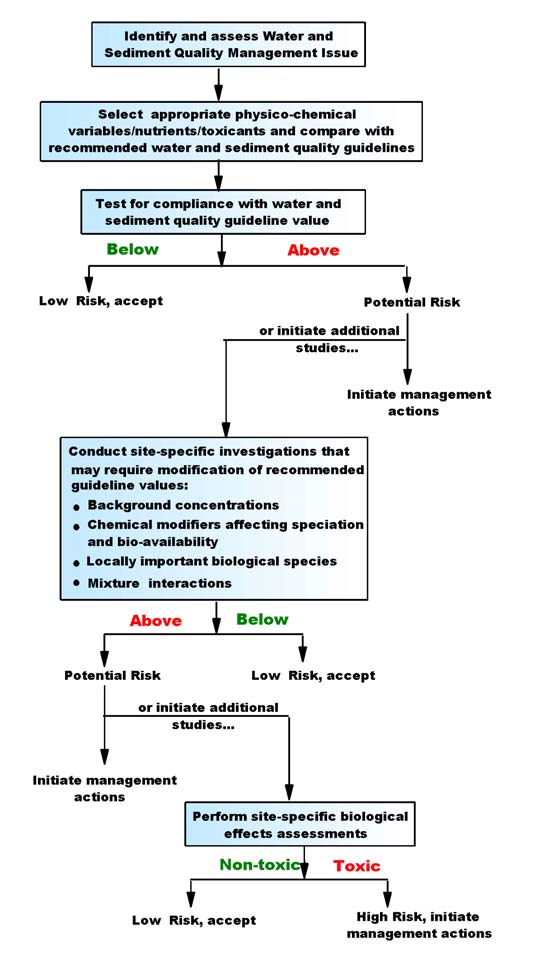

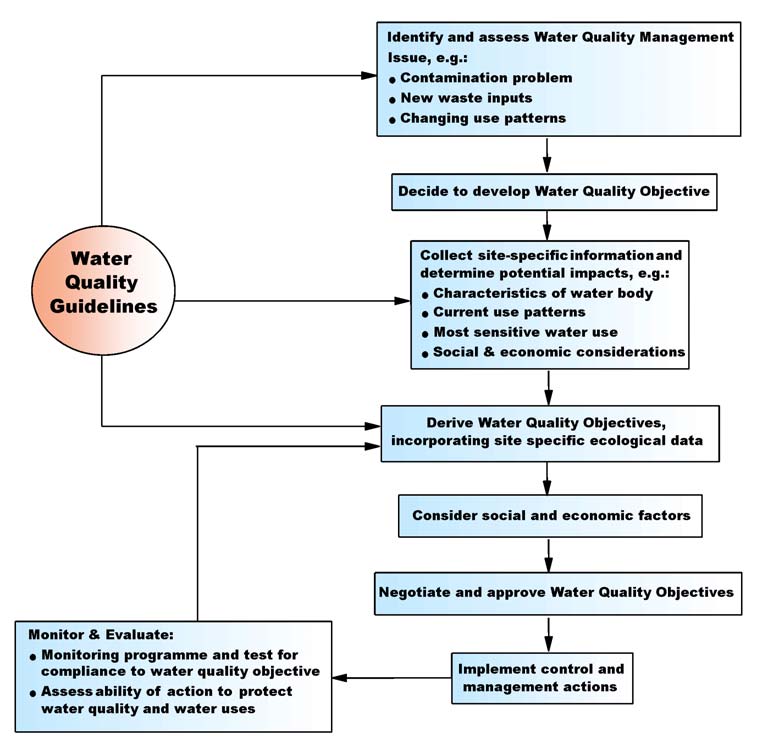

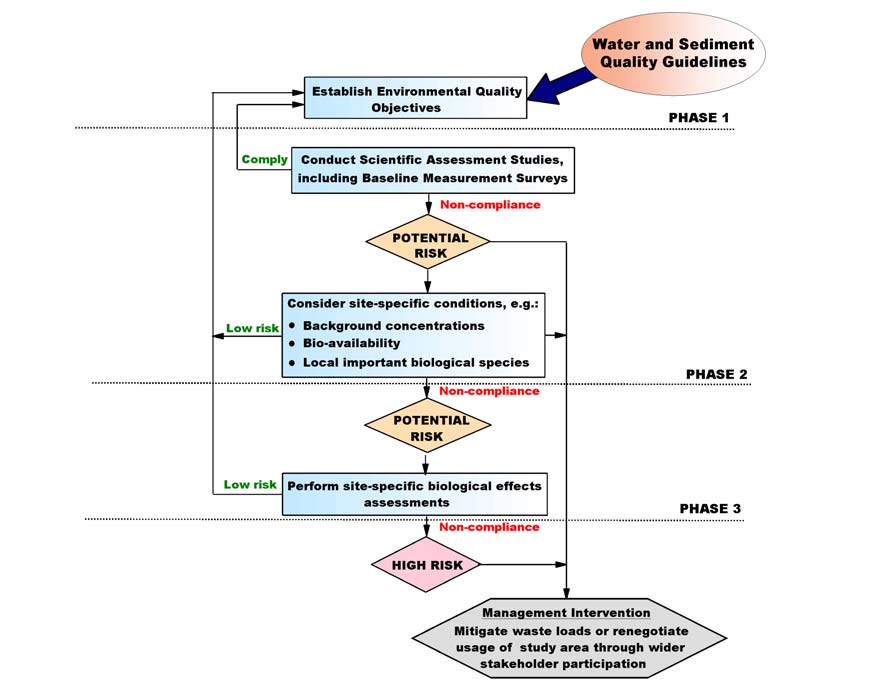

guidelines play a major role in setting environmental quality objectives, as illustrated below:

Below is a summary of the constituent categories for which recommended water and

sediment quality are provided for different designated uses as part of this study:

MARINE

MARINE

INDUSTRIAL

TYPE OF QUALITY GUIDELINE

AQUATIC

RECREATION

AQUACULTURE

USES

ECOSYSTEMS

Objectionable Matter/ Aesthetics

Yes Yes

Physico-chemical variables

Yes

Refer to Marine

Aquatic Ecosystem

Refer to Drinking

Water

Nutrients

Yes

Guidelines

Water Guidelines

Based on site-

Toxic substances

Yes

specific

requirements of

Microbiological indicators

- Yes

Yes

industrial use in

the area

Tainting substances

- Yes -

Refer to Marine

Sediment

Toxic Substances

Yes

Aquatic Ecosystem

-

Guidelines

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/04

Page ii

Final

January 2006

As a rule of thumb, it is recommended that the following simple application rules apply:

1. Compliance with quality guideline values for the Protection of marine aquatic ecosystems

should be aimed at in all coastal waters, except in approved sacrificial zones, e.g. near

wastewater discharges and certain areas within harbours.

2. In addition to (1), the classification system recommended for Marine aquaculture should

be applied in areas where shellfish are collected or cultured for human consumption so

as to manage human health risks. The assumption is that the health of the organisms is

catered for under the Protection of Marine Aquatic Ecosystems (referring to 1).

3. In addition to (1), the aesthetic quality guidelines, as well as the classification system

ranking waters in terms of human health risks for Recreational use, should be applied in

related areas. With reference to toxic substances, it is recommended that suitable

Drinking water quality guidelines be consulted to make preliminary risk assessments,

where these substances are expected to present at levels that could pose a risk to

human health (following the example of the WHO, 2003).

4. In addition to (1), site specific water quality guidelines, based on the requirements of

local Industries, should be applied, where and if applicable.

The recommended quality guidelines and protocols for implementation, as listed below, have

been drawn from a review of international water and sediment quality guidelines. As

information is developed further for specific conditions in the BCLME region, these may be

modified, following the principle of adaptive management.

Recommended Water and Sediment Quality Guidelines: Protection of Marine Aquatic

Ecosystems

Water quality guidelines for the protection of aquatic ecosystems are recommended for the

following constituent categories:

· Objectionable matter

· Physico-chemical

variables

· Nutrients

· Toxic

substances.

Sediment quality guideline values are generally specified only for the protection of aquatic

ecosystems, in particular for toxic substances.

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/04

Page iii

Final

January 2006

Recommended water quality guidelines for objectionable matter (aesthetic):

PROPOSED GUIDELINE

Water should not contain litter, floating particulate matter, debris, oil, grease, wax, scum, foam or any similar

floating materials and residues from land-based sources in concentrations that may cause nuisance.

Water should not contain materials from non-natural land-based sources which will settle to form objectionable

deposits.

Water should not contain submerged objects and other subsurface hazards which arise from non-natural

origins and which would be a danger, cause nuisance or interfere with any designated/recognized use.

Water should not contain substances producing objectionable colour, odour, taste, or turbidity.

Recommended water quality guidelines for physico-chemical variables:

VARIABLE

PROPOSED WATER QUALITY GUIDELINE

Where an appropriate reference system(s) is available, and there are sufficient data for

the reference system, the guideline value should be determined as the range defined by

Temperature

the 20%ile and 80%ile of the seasonal distribution for the reference system. Test

data: Median concentration for the period

Where an appropriate reference system(s) is available, and there are sufficient data for

the reference system, the guideline value should be determined as the 20%ile or 80%ile

Salinity

of the reference system(s) distribution, depending upon whether low salinity or high

salinity effects are being considered. Test data: Median concentration for the period

Where an appropriate reference system(s) is available, and there are sufficient data for

the reference system, the guideline value range should be determined as the range

defined by the 20%ile and 80%ile of the seasonal distribution for the reference system.

pH

pH changes of more than 0.5 pH unit from the seasonal maximum or minimum defined

by the reference systems should be fully investigated.

Test data: Median concentration for the period

Turbidity

Where an appropriate reference system(s) is available and there are sufficient data for

the reference system, the guideline values should be determined as the 80%ile of the

reference system(s) distribution.

Suspended solids

Additionally, the natural euphotic depth (Zeu) should not be permitted to change by more

than 10%.

Test data: Median concentration for period

Where an appropriate reference system(s) is available, and there are sufficient data for

the reference system, the guideline value should be determined as the 20%ile of the

reference system(s) distribution.

Dissolved oxygen

Where possible, the guideline value should be obtained during low flow and high

temperature periods when DO concentrations are likely to be at their lowest.

Test data: Median DO concentration for the period, calculated using the lowest diurnal

DO concentrations.

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/04

Page iv

Final

January 2006

Recommended water quality guidelines for nutrients:

VARIABLE

PROPOSED WATER QUALITY GUIDELINE

Where an appropriate reference system(s) is available and there are sufficient data for

Chlorophyll a

the reference system, the guideline value should be determined as the 80%ile of the

reference system(s) distribution.

Nutrient concentrations in the water column should not result in chlorophyll a, turbidity

and/or dissolved oxygen levels that are outside the recommended water quality

guideline range (see above). This range should be established by using either

suitable statistical or mathematical modelling techniques.

Nutrients

Alternatively, where a modelling approach may be difficult to implement, nutrient

concentrations can be derived using the Reference system data approach: Where an

appropriate reference system(s) is available and there are sufficient data for the

reference system, the guideline value should be determined as the 80%ile of the

reference system(s) distribution.

Recommended water quality guidelines for toxic substances:

TOXIC SUBSTANCES

RECOMMENDED GUIDELINE VALUE in µg/

Total Ammonia-N

910

Total Residual Chlorine-Cl

3

Cyanide (CN-) 4

Fluoride(F-)

5 000

Sulfides (S-)

1

Phenol

400

Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs)

0.03*

Trace metals (as Total metal):

Arsenic

As(III) - 2.3; As(V) - 4.5

Cadmium

5.5

Chromium

Cr (III) - 10; Cr (VI) - 4.4

Cobalt

1

Copper

1.3

Lead

4.4

Mercury

0.4

Nickel

70

Silver

1.4

Sn (as Tributyltin)

0.006

Vanadium 100

Zinc

15

Aromatic Hydrocarbons (C6-C9 simple hydrocarbons - volatile):

Benzene (C6)

500

Toluene (C7)

180

Ethylbenzene (C8)

5

Xylene (C8)

Ortho - 350; Para - 75; Meta - 200

Naphthalene (C9)

70

Poly-Aromatic Hydrocarbons (< C15 - acute toxicity with short half-life in water)

Anthracene (C14)

0.4

Phenanthrene (C14)

4

Poly-Aromatic Hydrocarbons (> C15, chronic toxicity, with longer half-life in water)

Fluoranthene (C15)

1.7

Benzo(a)pyrene (C20)

0.4

Pesticides:

DDT

0.001

Dieldrin

0.002

Endrin

0.002

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/04

Page v

Final

January 2006

Recommended sediment quality guidelines for toxic substances:

RECOMMENDED GUIDELINE

PROBABLE

TOXIC SUBSTANCES

VALUE

EFFECT CONCENTRATION

TRACE METALS (mg/kg dry weight)

Antimony

-

-

Arsenic

7.24

41.6

Cadmium

0.68

4.21

Chromium 52.3

160

Copper

18.7

108

Lead

30.2

112

Mercury

0.13

0.7

Nickel

15.9

42.8

Silver

0.73

1.77

Tin as Tributyltin-Sn

0.005

0.07

Zinc

124

271

TOXIC ORGANIC COMPOUNDS (µg/kg dry weight normalized to 1% organic carbon)

Total PAHs

1684

16770

Low Molecular PAHs

312

1442

Acenaphthene

6.71

88.9

Acenaphthalene

44

640

Anthracene

46.9

245

Fluorene

21.2

144

2-methyl naphthalene

-

-

Naphthalene

34.6

391

Phenanthrene

86.7

544

High Molecular Weight PAHs

655

6676

Benzo(a)anthracene

74.8

693

Benzo(a) pyrene

88.8

763

Dibenzo(a,h)anthracene

6.22

135

Chrysene

108

846

Fluoranthene

113

1494

Pyrene

153

1398

Toxaphene

-

-

Total DDT

3.89

51.7

p p DDE

2.2

27

Chlordane 2.26

4.79

Dieldrin 0.72

4.3

Total PCBs

21.6

189

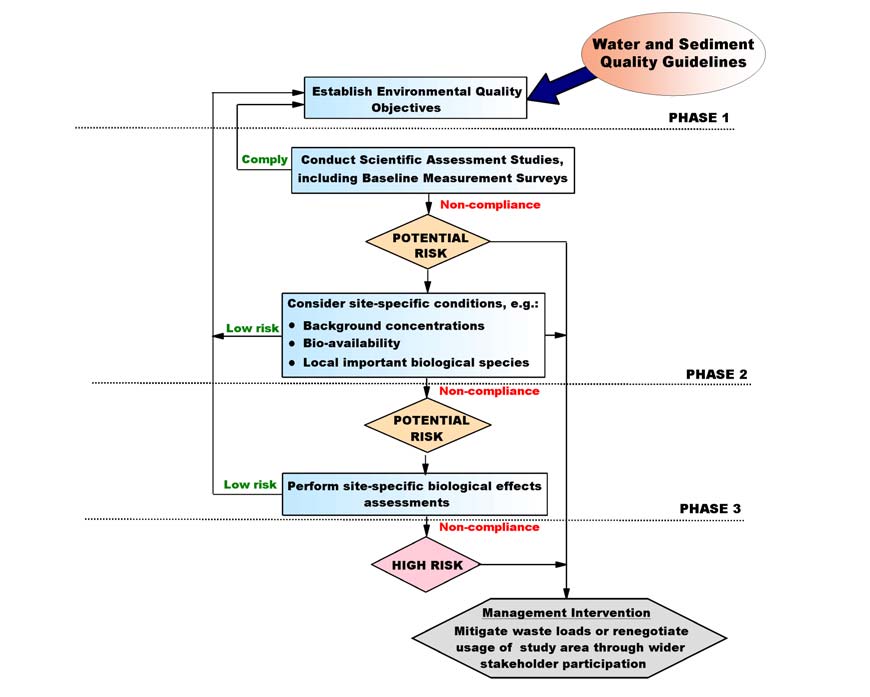

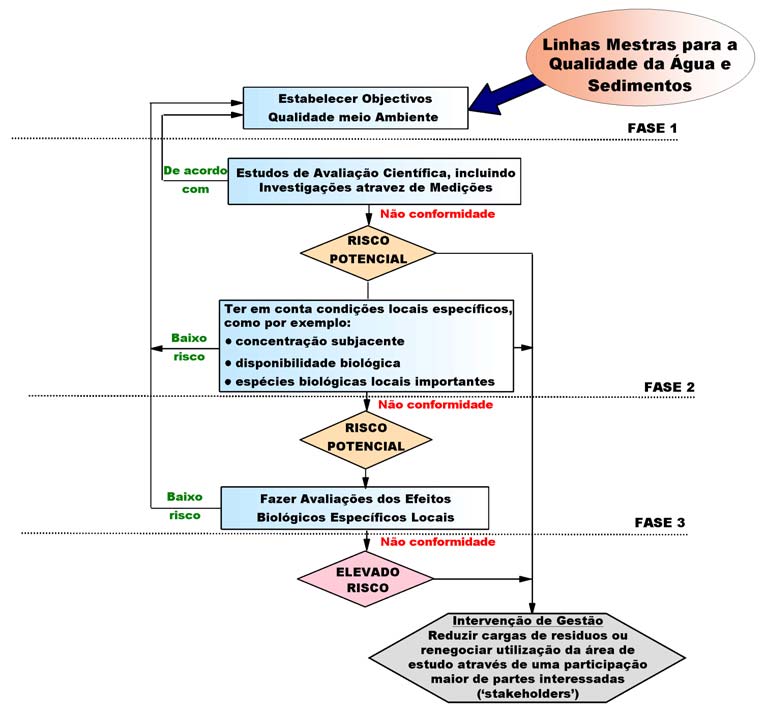

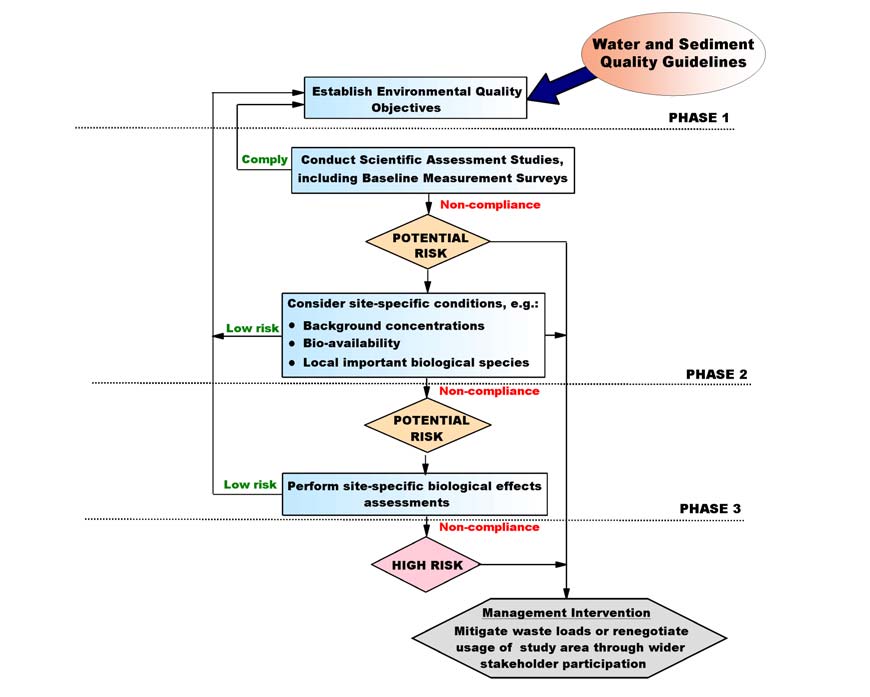

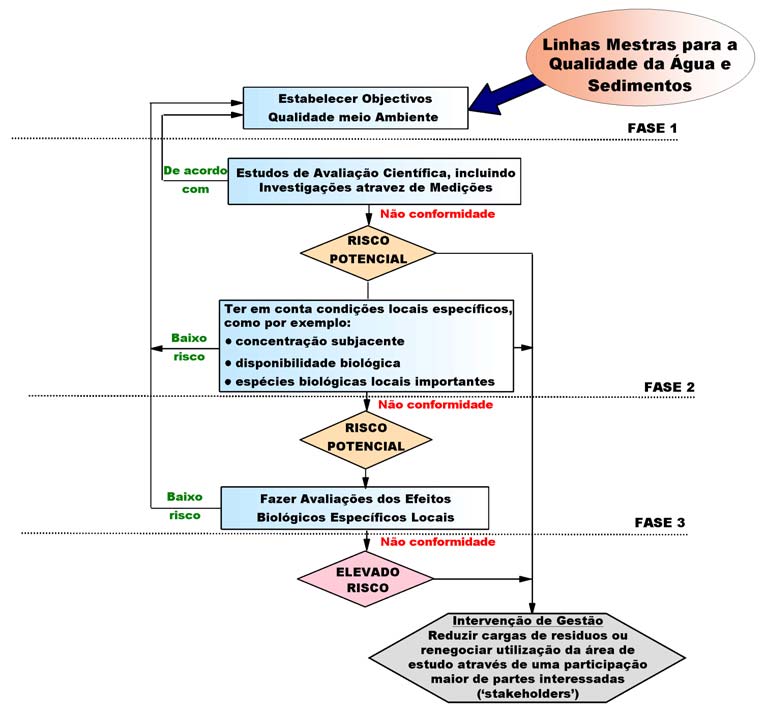

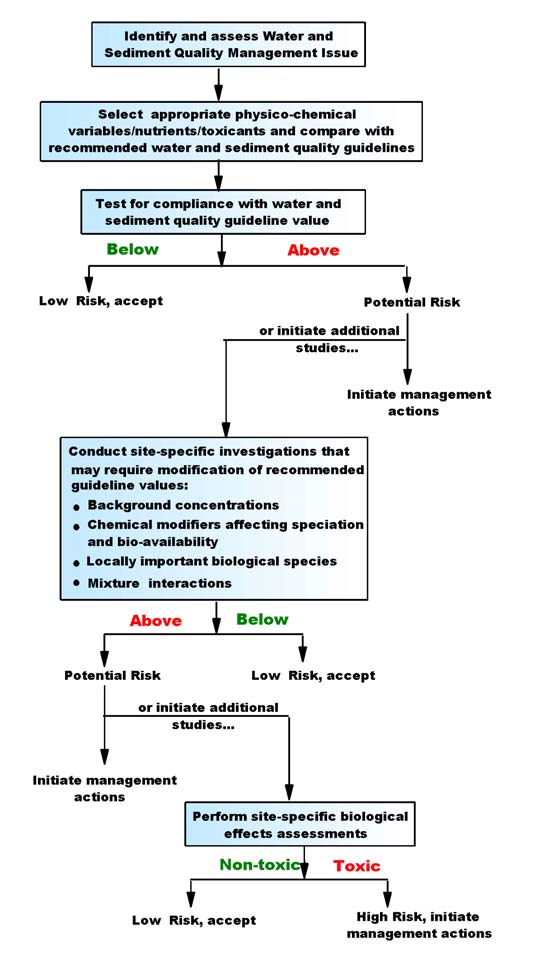

Recommended water and sediment quality guidelines for the protection of marine aquatic

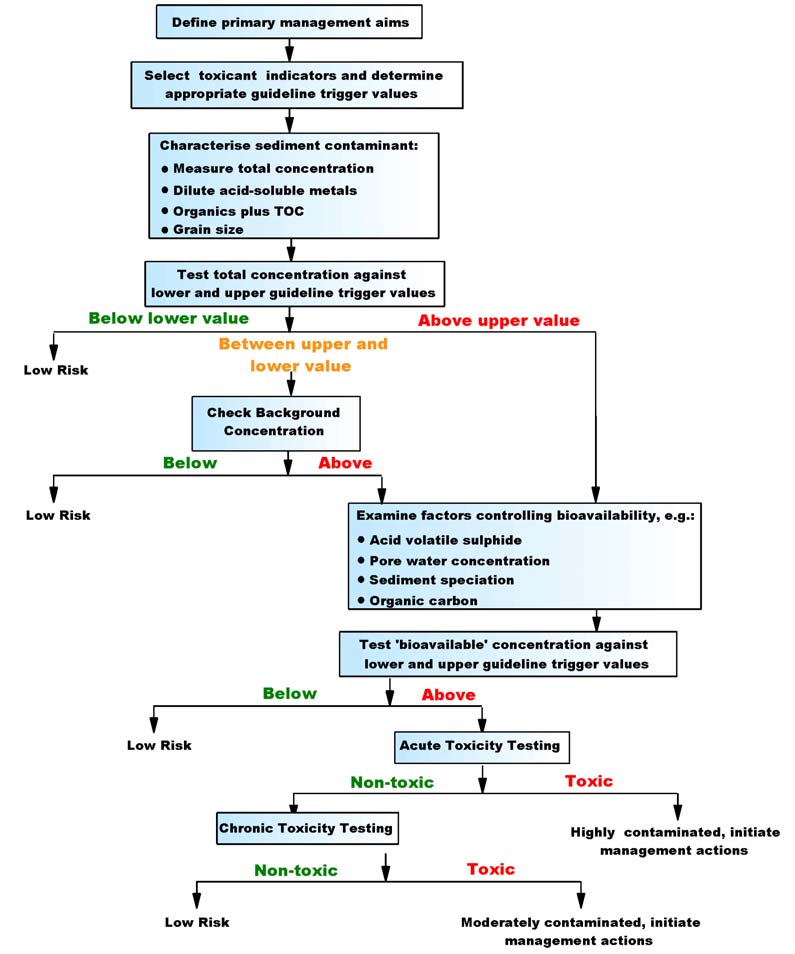

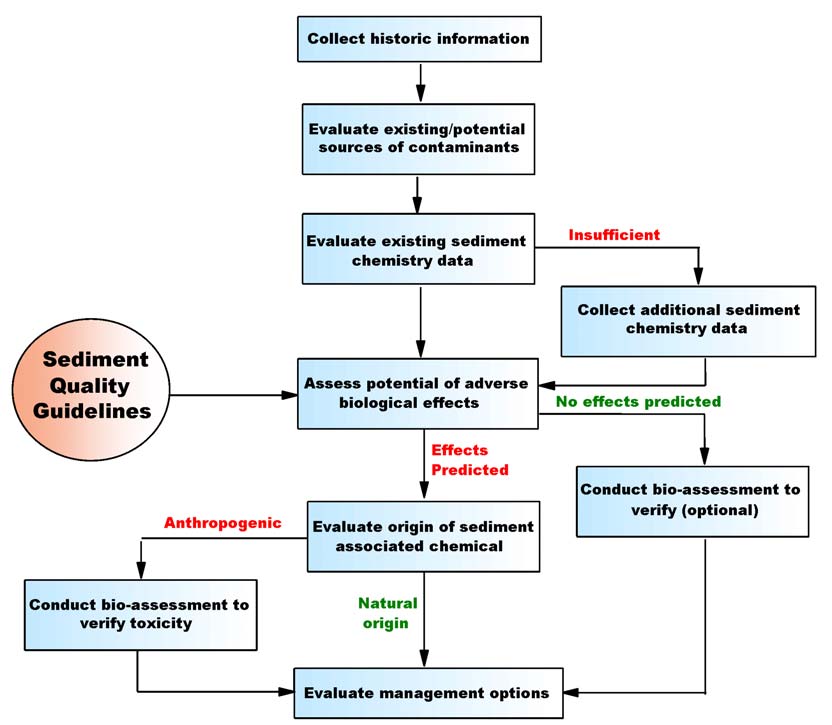

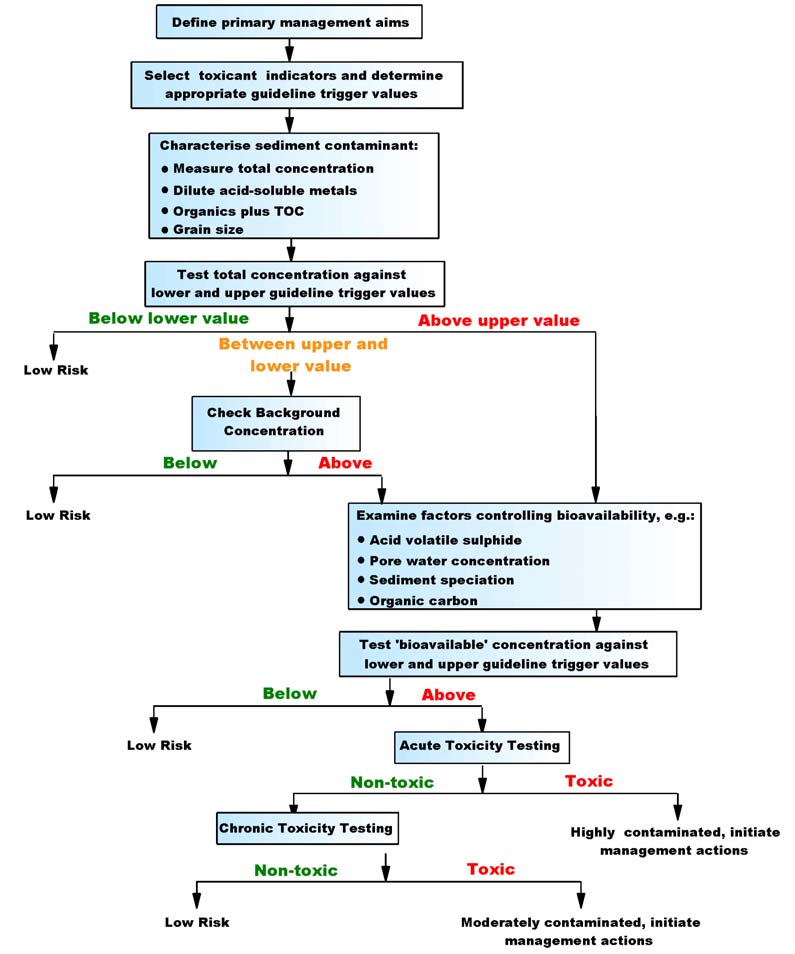

ecosystems should be applied as benchmarks, following a risk assessment or phased

approach as illustrated below:

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/04

Page vi

Final

January 2006

Where scientific assessment studies or monitoring results reveal that recommended quality

guideline values are exceeded, this should trigger the incorporation of additional information

or further investigation to determine whether or not a real risk to the ecosystem exists, and,

where necessary, to adjust the guideline values for site-specific conditions.

Quality guideline values should be compared with the median of the measured or simulated

data set. Where a guideline value was based on professional judgement, the rationale for

the selection of such a value should be provided and a process should be put in place

whereby the adopted value is reviewed and supported or modified in light of emerging

information, following the principle of adaptive management.

Recommended Water and Sediment Quality Guidelines: Marine Aquaculture

In terms of water quality guidelines for marine aquaculture (including the collection and

harvesting of living stock for human consumption), the following are important

considerations:

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/04

Page vii

Final

January 2006

· Protection of the health of the aquatic ecosystem so as to ensure sustainable production

and quality of products

· Protection of the health of human consumers

· Tainting of seafood products.

With reference to the protection of aquatic organisms used in the culture and harvesting of

seafood, it is recommended that the water quality guidelines proposed for the Protection of

aquatic ecosystems be applied, rather than developing a separate series of quality

guidelines.

With reference to the protection of human consumers, it is proposed that the allowable limits

of toxic substances and human pathogens in food products be controlled through legislation.

In terms of shellfish growing areas, microbiological recommended water quality guidelines

aimed at mitigating human health risks are as follows:

INDICATOR

PROPOSED WATER QUALITY GUIDELINE

Median concentrations should not exceed 14 Most Probable Number (MPN) per 100 ml

Faecal coliform

with not more than 10% of the samples exceeding 43 MPN per 100 ml for a 5-tube, 3-

dilution method.

Estimated threshold concentrations for tainting substances are listed below:

THRESHOLD CONCENTRATIONS ABOVE WHICH

TAINTING SUBSTANCE

TAINTING IS LIKELY TO OCCUR (mg/)

Acenaphthene

0.02

Acetophenone

0.5

Acrylonitrile

18

Copper

1

m-cresol

0.2

o-cresol

0.4

p-cresol

0.12

Cresylic acids (meta, para)

0.2

Chlorobenzene

-

n-butylmercaptan

0.06

o-sec. butylphenol

0.3

p-tert. butylphenol

0.03

2-chlorophenol 0.001

3-chlorophenol 0.001

3-chlorophenol 0.001

o-chlorophenol

0.001

p-chlorophenol

0.01

2,3-dinitrophenol

0.08

2,4,6-trinitrophenol

0.002

2,3 dichlorophenol

0.00004

2,4-dichlorophenol

0.001

2,5-dichlorophenol

0.023

2,6-dichlorophenol

0.035

3,4-dichlorophenol

0.0003

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/04

Page viii

Final

January 2006

THRESHOLD CONCENTRATIONS ABOVE WHICH

TAINTING SUBSTANCE

TAINTING IS LIKELY TO OCCUR (mg/)

2-methyl-4-chlorophenol

0.75

2-methyl-6-cholorophenol

0.003

3-methyl-4-chlorophenol

0.02 3

o-phenylphenol

1

Pentachlorophenol

0.03

Phenol

1

2,3,4,6-tetrachlorophenol

0.001

2,4,5-trichlorophenol 0.001

2,3,5-trichlorophenol

0.001

2,4,6-trichlorophenol

0.003

2,4-dimethylphenol

0.4

Dimethylamine

7

Diphenyloxide

0.05

B,B-dichlorodiethyl ether

0.09

o-dichlorobenzene

< 0.25

p-dichlorobenzene 0.25

Ethylbenzene

0.25

Momochlorobenzene 0.02

Ethanethiol

0.24

Ethylacrylate

0.6

Formaldehyde

95

Gasoline/Petrol

0.005

Guaicol

0.082

Kerosene

0.1

Kerosene plus kaolin

1

Hexachlorocyclopentadiene

0.001

Isopropylbenzene

0.25

Naphtha

0.1

Naphthalene

1

Naphthol

0.5

2-Naphthol

0.3

Nitrobenzene

0.03

a-methylstyrene

0.25

Oil, emulsifiable

15

Pyridine

5

Pyrocatechol

0.8

Pyrogallol

0.5

Quinoline

0.5

p-quinone

0.5

Styrene

0.25

Toluene

0.25

Outboard motor fuel as exhaust

0.5

Zinc

5

It is recommended that a classification system for shellfish growing areas be adopted for the

BCLME region and that a dedicated task team be convened to decide on the final approach

for the classification system. In the interim, it is recommended that the classification be

based on the results for Sanitary Surveys that consist of:

· Identification and evaluation of all potential and actual pollution sources (Shoreline

Survey)

· Monitoring of growing waters and shellfish to determine the most suitable classification

for the shellfish harvesting area (Bacteriological Survey).

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/04

Page ix

Final

January 2006

The recommended classification system for the BCLME region that is provided is as follows:

CLASS

DESCRIPTION

Approved areas need to be free from pollution and shellfish from such areas are suitable

Approved

for direct human consumption of raw shellfish.

Where areas are subjected to limited, intermittent pollution caused by discharges from

wastewater treatment facilities, seasonal populations, non-point source pollution, or

boating activity, they can be classified as conditionally approved or conditional ly

restricted.

However, it must be shown that the shellfish harvesting area will be open for the

purposes of harvesting shel fish for a reasonable period of time and the factors

Conditionally

determining this period are known, predictable and are not so complex as to preclude a

approved/restricted

reasonable management approach.

When `open' for shellfish harvesting for direct human consumption, the water quality in

the area must comply with the limits as specified for `Approved' area. When `closed' for

direct consumption but `open' to harvesting for relaying or depuration, the requirements

of `Restricted' area must be met. At times when the area is `closed' for all harvesting,

then the requirements of `Prohibited Areas' apply.

Restricted areas are subject to a limited degree of pollution. However, the level of faecal

Restricted

pollution, human pathogens and toxic or deleterious substances are at such a level) that

shellfish can be made fit for human consumption by either relaying or depuration.

An area is classified as `Prohibited' for shellfish harvesting if no comprehensive survey

has been conducted or where a survey finds that the area is:

· adjacent to a sewage treatment plant outfall or other point source outfall with public

health significance

· contaminated by (an) unpredictable pollution source(s)

· contaminated

with

faecal

waste so that the shellfish may be vectors for disease

micro-organisms

Prohibited

· affected by algae which contain biotoxin(s) sufficient to cause a public health risk

· contaminated with poisonous or deleterious substances whereby the quality of

shellfish may be affected.

NOTE: Where an event such as a flood, storm or marine biotoxin outbreak occurs in

either `Approved' or `Restricted' areas, these can also be classified as temporarily

`Prohibited' area.

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/04

Page x

Final

January 2006

Requirements associated with each class in the recommended (interim) classification system

are:

CLASS

REQUIREMENTS

A sanitation survey must be completed according to specification and be reviewed

annually. The area shall not be contaminated with faecal coliform (as listed) and shall

not contain pathogens or hazardous concentrations of toxic substances or marine

biotoxins (an approved shellfish growing area may be temporarily made a prohibited

area, e.g. when a flood, storm or marine biotoxin event occurs). Evidence of potential

pollution sources such as sewage lift station overflows, direct sewage discharges,

septic tank seepage, etc., is sufficient to exclude the growing waters from the approved

category.

Approved

Faecal coliform median/geometric mean of water sample results must not exceed

14/100 ml and the estimated 90th percentile must not exceed 21/100 ml (using

Membrane Filtration) or 14/100 ml and the estimated 90th percentile must not exceed

43/100 ml for a 5-tube decimal dilution test, or 49/100 ml for a 3-tube decimal dilution

test (using Most Probable Number [MPN]).

Total coliform median/geometric mean of water sample results must not exceed 70/100

ml and the estimated 90th percentile must not exceed 230/100 ml for a 5-tube decimal

dilution test, or 330/100 ml for a 3-tube decimal dilution test (using MPN).

Factors determining this period are known, predictable and are not so complex as to

preclude a reasonable management approach. A management plan must be

developed for every conditionally approved/restricted area.

Conditionally

When `open' for shellfish harvesting for direct human consumption, the water quality in

approved/restricted

the area must comply with the limits as specified for `Approved' area. When `closed' for

direct consumption but `open' to harvesting for relaying or depuration, the requirements

of `Restricted' area must be met. At times when the area is `closed' for all harvesting,

then the requirements of `Prohibited Areas' apply.

Faecal coliform median/geometric mean of water sample results must not exceed

70/100 ml and the estimated 90th percentile must not exceed 85/100 ml (using

Membrane Filtration) or 88/100 ml and the estimated 90th percentile must not exceed

260/100 ml for a 5-tube decimal dilution test, or 300/100 ml for a 3-tube decimal dilution

Restricted

test (using MPN).

Total coliform median/geometric mean of water sample results must not exceed

700/100 ml and the estimated 90th percentile must not exceed 2300/100 ml for a 5-tube

decimal dilution test, or 3300/100 ml for a 3-tube decimal dilution test (using MPN).

Prohibited area

No requirements specified.

It is, however, recommended that a dedicated task team, consisting of marine aquaculture

specialists and responsible authorities from the different countries in the BCLME region, be

convened to decide on the final approach to the classification of shellfish growing areas in

the region. This process has already been initiated as part of another project in the BCLME

Programme (Project EV/HAB/04/Shellsan Development of a shellfish sanitation

programme model for application in consort with the microalgal toxins component).

Recommended Water and Sediment Quality Guidelines: Recreation

In terms of water quality, the following key aspects are important in relation to recreational

use of coastal waters:

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/04

Page xi

Final

January 2006

· Aesthetics

· Protection of human health relating to toxic substances

· Protection of human health relating to microbiological contaminants.

For recreational areas, the water quality guidelines related to aesthetics are similar to those

listed under objectionable matter in the Protection of Marine Aquatic Ecosystems (see

above).

With reference to toxic substances, it is recommended that suitable Drinking water quality

guidelines be consulted to make preliminary risk assessments in areas where these

substances are expected to be present at levels that pose a risk to human health.

As for microbiological indicators, it is recommended that both E. coli and Enterococci (faecal

streptococci) be used as indicator organisms. It is also recommended that instead of using

`single' target values that classify a beach as either `safe' or `unsafe', a range of target

values be derived corresponding to different levels of risk:

CATEGORY

95th PERCENTILE OF

ENTEROCOCCI per 100 ml*

ESTIMATED RISK PER EXPOSURE

A <40

<1% gastrointestinal (GI)illness risk

<0.3% acute febrile respiratory (AFRI) risk

B

40 200

15% GI illness risk

0.31.9% AFRI risk

C

201 500

510% GI illness risk

1.93.9% AFRI risk

D >

500

>10% GI illness risk

>3.9% AFRI risk

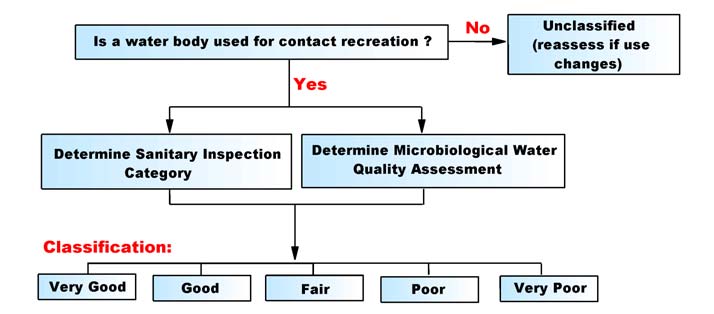

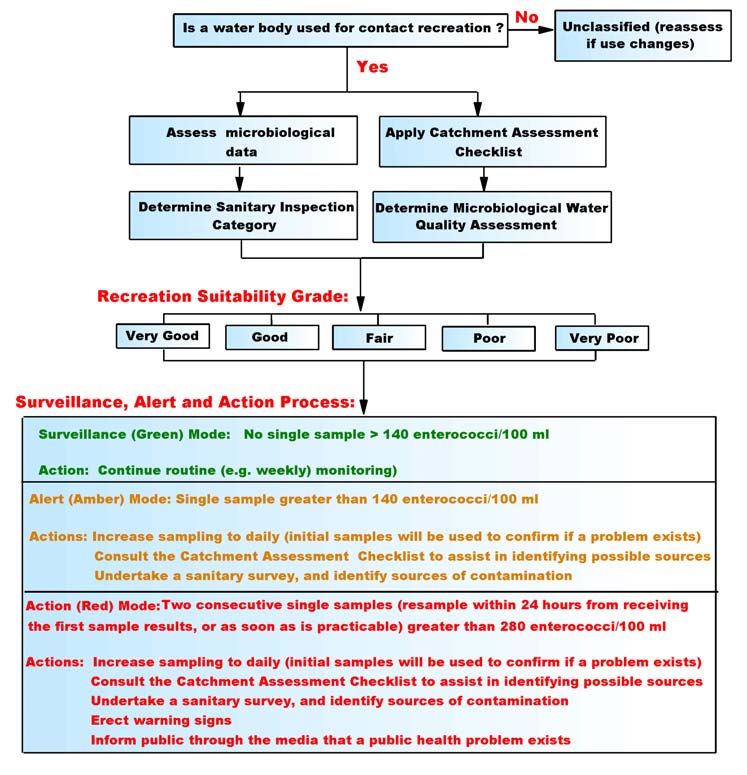

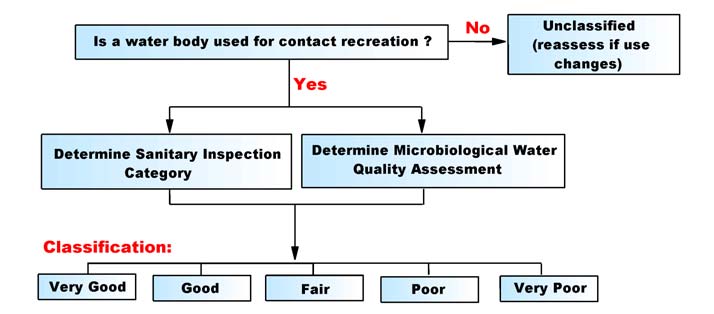

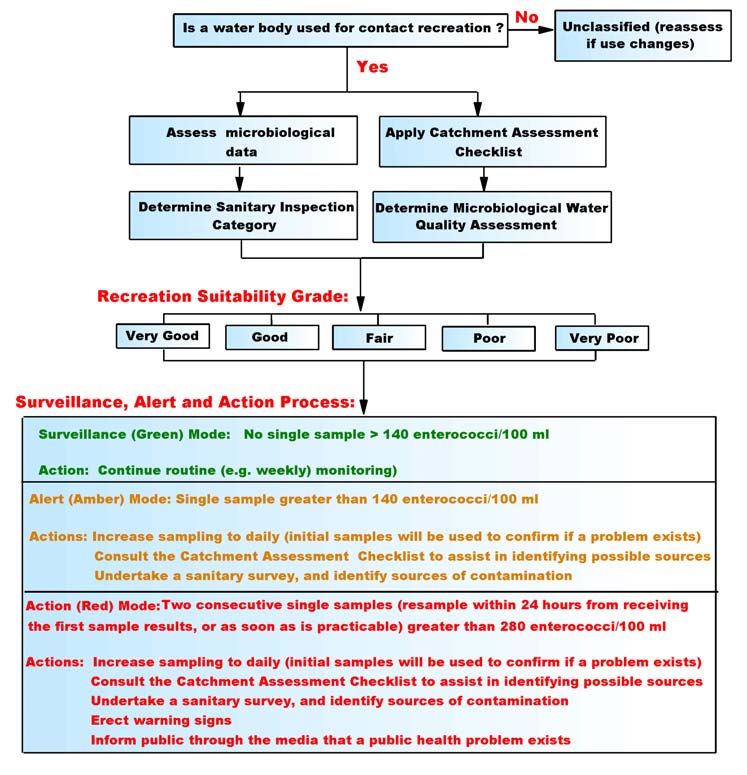

It is recommended that the BCLME region adopt a beach classification system, rather than

the traditional approach of classifying recreational waters as either safe or unsafe. With

reference to water quality, the classification should be based on both a sanitary survey as

well as routine microbiological surveys. The classification rating should be re-evaluated on

an annual basis.

Recommended classification system for recreational areas:

Microbiological Quality Assessment Category

(95th percentile enterococci/100 ml see Table above)

A

B

C

D

Exceptional

(<40)

(41-200)

(201-500)

(>500)

circumstances

Very Low

Very good

Very good

Fair

Follow-up

Low

Very good

Good

Fair

Follow-up

Sanitary

Moderate

Good Good Fair Poor Action

Inspection

High

Good Fair Poor

Very

poor

Category

Very high

Follow-up Fair Poor Very

poor

Exceptional

circumstances

Action

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/04

Page xii

Final

January 2006

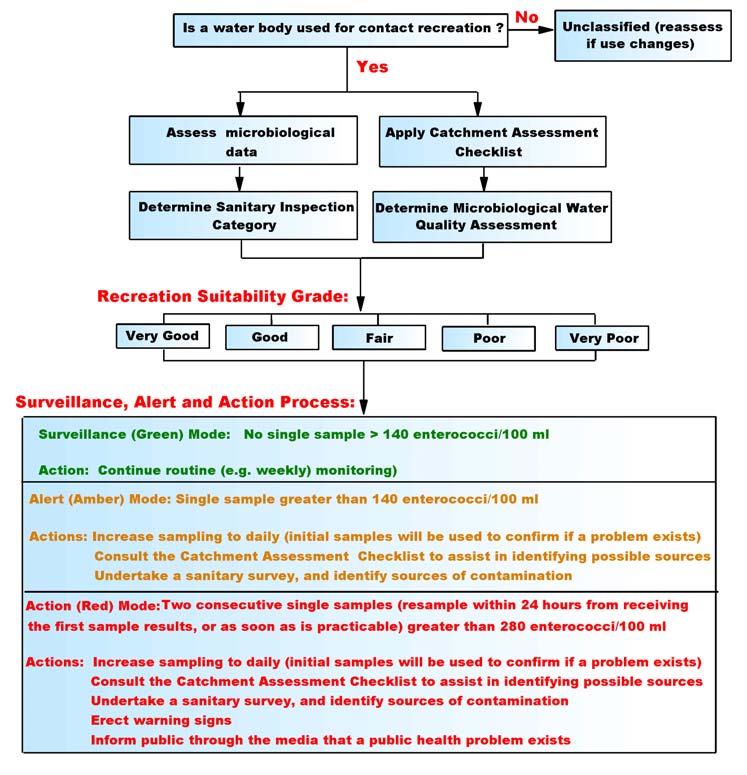

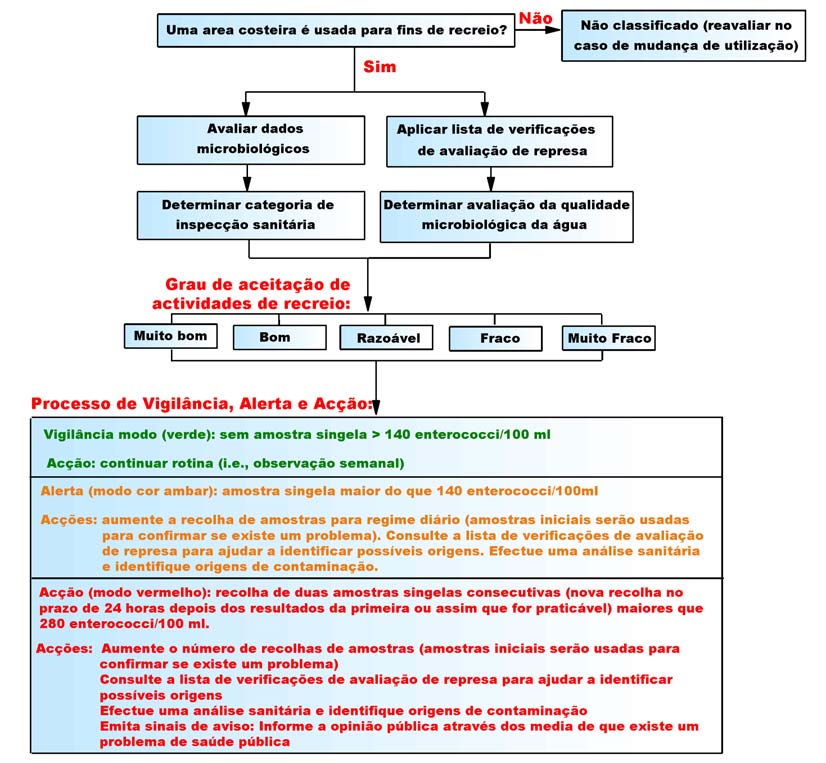

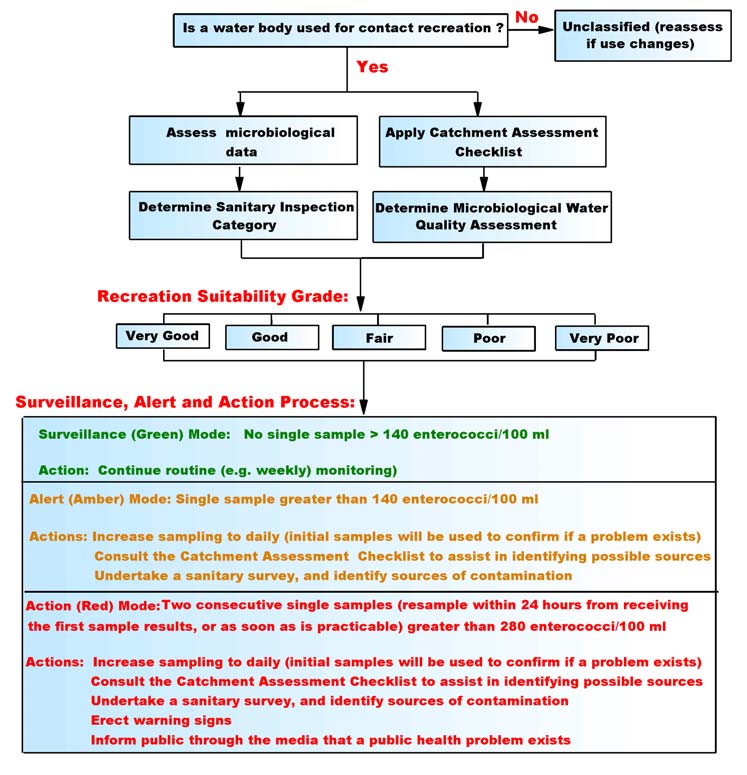

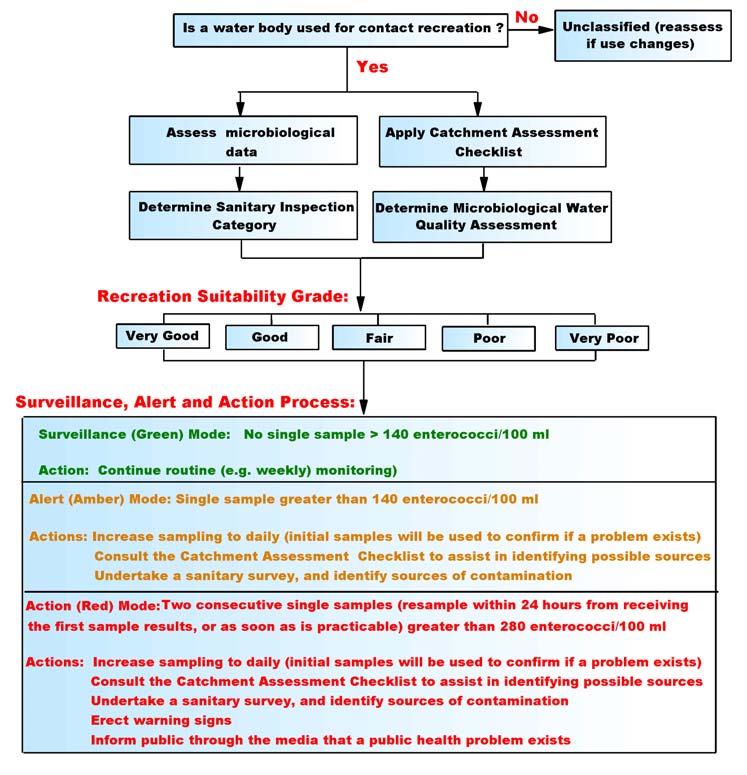

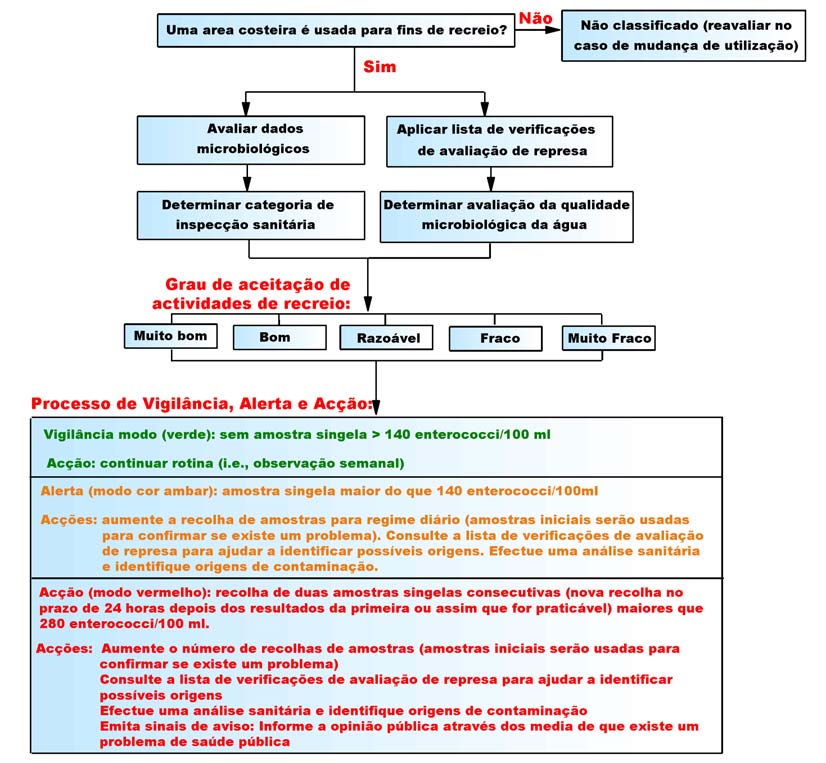

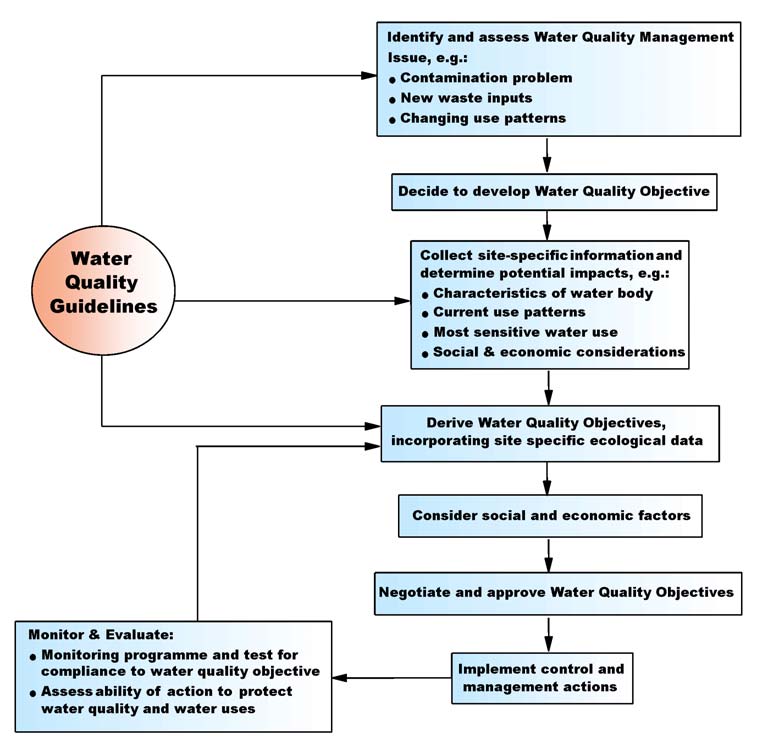

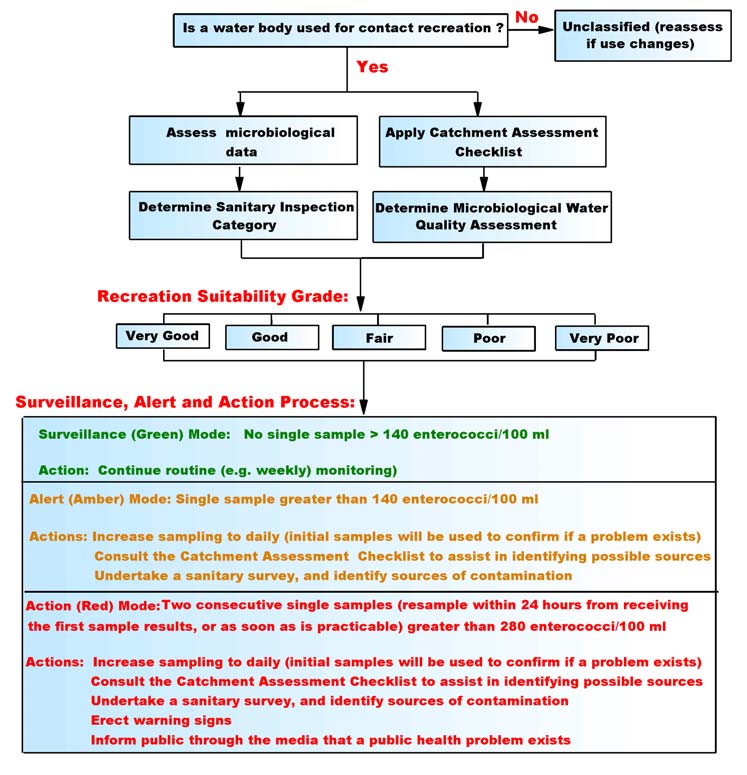

The implementation of the classification system, as well as the proposed day-to-day

management system, is schematically illustrated below:

The Way Forward

· The recommended guidelines still need to be officially approved and adopted by

responsible authorities in each of the three countries. It is recommended that the output

of this project be used as a starting point for such initiatives.

· The quality guidelines and protocols developed as part of this project form an integral

part of the management framework for land-based marine pollution sources

(developed as part of another BCLME project BEHP/LBMP/03/01).

In the interim, until such time as a management framework and quality guidelines have

been incorporated in official government policy, it is proposed that the quality guidelines

developed as part of this project, together with the proposed management framework,

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/04

Page xiii

Final

January 2006

be applied as preliminary tools towards improving the management of the water quality

in coastal areas of the BCLME region.

· As part of the official water and sediment quality guidelines to be adopted in each of the

three countries, it is recommended that the preferred analytical methods for the

different chemical and microbiological variables also be included.

· The updatable web-based information system (temporary web address

www.wamsys.co.za/bclme) that was developed as part of this project can be a very

useful decision-support and educational tool provided that it is maintained and updated

regularly. In the short to medium term, it is recommended that one or more of the

BCLME offices within the three countries takes on this responsibility.

· To facilitate wider capacity building in the BCLME region of the management of marine

pollution in coastal areas, it is strongly recommended that the output of this project be

included in a training course. In this regard, the Train-Sea-Coast/Benguela Course

Development Unit is considered the ideal platform from which to develop and present

such training (www.ioisa.org.za/tsc/index.htm).

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/04

Page xiv

Final

January 2006

RESUMO EXECUTIVO

(LINHAS MESTRAS RECOMENDADAS PARA A QUALIDADE DA ÁGUA E

SEDIMENTOS PARA DA REGIÃO DO BCLME EM SUMÁRIO)

o Gabinete das Nações Unidas Para Prestação de Serviços "UNOPS") contratou o CSIR

(África do Sul) para executar este projecto, cujo objectivo principal era o de obter:

· Um conjunto de linhas mestras sobre qualidade da água e sedimentos para uma gama

de variáveis de qualidade biogeoquímicas e microbiológicas, de modo a sustentar o

funcionamento de um ecossistema natural, assim como apoiar os usuários nas áreas

costeiras da região do BCLME.

· Protocolos de Boa Prática para a implementação (ou aplicação) destas linhas mestras

no que se refere à gestão das áreas costeiras na região do BCLME.

O objectivo secundario de relevo foi a aceitação pelos "stakeholders" dos três paises das

linhas mestras propostas e dos protocolos. Isto foi levado a efeito atravéz das sessões de

trabalhos e "workshops"de treino nos tres paises aos quais os mesmos "stakeholders"

foram convidados. Os productos deste projecto foram integrados num sistema informatico

da "web" que poderá ser actualizado (endereço web temporário:

www.wamsys.co.za/bclme).

O objectivo primario na gestão da qualidade da água marinha é o de manter o ambiente

marinho adequado (ou saudável) para todos os usos apontados. Para atingir este fim, os

objectivos estabelecidos para um ambiente marinho em particular devem apontar para a

protecção à biodiversidade e funcionamento dos ecosistemas aquático-marinhos, bem

como para os usos designados do ambiente marinho (também referidos como usos de

benefício). É proposto que três usuários para a região do BCLME sejam reconhecidos a

saber:

· Aquacultura marinha (incluindo recolha de marisco para consumo humano)

· Uso recreativo

· Usos industriais

As linhas mestras sobre qualidade de água e sedimentos recomendadas, como parte desta

secção, fornecem orientações aos gestores, autoridades de governo locais e cientistas de

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/04

Page xv

Final

January 2006

modo a definirem objectivos de qualidade ambiental específicos numa área de estudo para

a protecção dos ecossistemas aquático- marinhos e outros usos designados.

Consequentemente, nos grandes sistemas integrados e ecossistemas onde a qualidade da

água do mar é gerida, as linhas mestras da qualidade da água e sedimentos

desempenham um papel importante na implementação dos objectivos da qualidade

ambiental como ilustrado abaixo:

Indica-se abaixo um resumo das categorias constituintes para as quais a qualidade da água

e sedimentos recomendadas, são fornecidos para diferentes usuários como parte do

presente estudo:

TIPO DE LINHAS MESTRAS PARA A

ECOSISTEMAS

AQUACULTURA

FINS

AQUÁTICO

RECRIAÇÃO

QUALIDADE DE ÁGUA

MARINHA

INDUSTRIAIS

MARINHOS

Matéria objectável /Estética

Sim

Sim

Refere-se a

Variáveis físico-químicas

Sim

orientações do

Refere-se a

Água

Nutrientes Sim

ecosistema aquático-

orientações para

marinho

água potável

Baseado em

Substâncias tóxicas

Sim

requisitos

Indicações microbiológicas

-

Sim

Sim

específicos de

fins industriais

Substâncias contaminantes

-

Sim

-

na zona

Refere-se a

Sedimentos

orientações do

Substâncias tóxicas

Sim

-

ecosistema aquático-

marinho

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/04

Page xvi

Final

January 2006

Como regras básicas, recomenda-se que sejam aplicadas as seguintes regras simples:

1. A conformidade com os valores orientativos de qualidade para Protecção dos

ecosistemas aquático-marinhos deve ser um dos objectivos em todas as águas

costeiras, excepto em certas zonas já aprovadas, ou seja, junto a áreas de descarga de

águas residuais e certas áreas junto aos portos.

2. Adicionalmente ao ponto (1), a classificação do sistema recomendado para aquacultura

marinha deve ser aplicada em áreas onde existe recolha de marisco ou em cultivo para

consumo humano, de modo a gerir os riscos de saúde para o ser humano. Assume-se

que a condição sanitária dos organismos é devidamente tida em conta, ao abrigo da

Protecção dos Ecosistemas Aquático-marinhos (referindo ponto 1).

3. Adicionalmente ao ponto (1), as linhas mestras de qualidade estética, bem como o

sistema de classificação que categorizam as águas para uso de recriação

relativamente aos riscos de saúde para o ser humano devem ser aplicadas nas

respectivas áreas. Quanto a substâncias tóxicas, recomenda-se a consulta das Linhas

mestras para qualidade de água potável, a fim de ser efectuada uma análise de risco

preliminar, onde se espera que tais substâncias apresentem níveis que possam colocar

a saúde pública em risco (seguindo o exemplo da OMS [WHO, 2003]).

4. Em adição ao ponto (1), as orientações da qualidade específica da água, baseada nos

requisitos das indústrias locais, devem ser usadas sempre que aplicáveis.

As orientações e protocolos de qualidade recomendados para implementação, como se

indica abaixo, foram criadas a partir de uma revisão de orientações para a qualidade da

água e sedimentos a nível internacional. Uma vez que a informação se desenvolve a partir

de condições específicas na região do BCLME, podem as mesmas ser alteradas, seguindo

o princípio de gestão adaptável.

Linhas Mestras Recomendadas para a Qualidade da Água e Sedimentos: Protecção

dos Ecosistemas Aquático-Marinhos

São recomendadas as seguintes orientações de qualidade para a água dos ecosistemas,

dentro das várias áreas:

· Matéria objectável

· Variáveis físico-químicas

· Nutrientes

· Substâncias

tóxicas.

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/04

Page xvii

Final

January 2006

Os valores da qualidade de sedimentos são normalmente especificados apenas para a

protecção de ecosistemas aquáticos, em particular para substâncias tóxicas.

Linhas mestras recomendadas para a qualidade da água no que respeita a matéria

objectável (estética):

DIRECTRIZ PROPOSTA

A água não deve conter lixos, partículas de matérias flutuantes, detritos, óleo, gordura, cera, escuma, espuma

ou materiais e resíduos flutuantes similares provenientes de fontes terrestres em concentrações que poderão

causar incómodos.

A água não deverá conter materiais provenientes de fontes terrestres não naturais os quais assentarão para

formar depósitos objectáveis.

A água não deverá conter objectos submersos e outros riscos na subsuperfície que sejam de origem não

natural e os quais podem constituir perigo, causar riscos ou interferir com qualquer uso

designado/reconhecido.

A água não deverá conter substâncias produtoras de cor, odor, sabor ou turvação objectáveis.

Linhas mestras recomendadas para a qualidade da água no que respeita a variáveis físico-

químicas:

VARIÁVEL

DIRECTRIZ PROPOSTA PARA A QUALIDADE DE ÁGUA

Quando um sistema ou sistemas de referência apropriados estão disponíveis, e

existem dados suficientes para o sistema de referência, o valor directriz da distribuição

Temperatura

sazonal deverá ser definido pelo valor de 20% e 80% da distribuição sazonal para o

sistema de referência. Teste de dados: Concentração mediana (ou média) para o

período.

Quando um sistema ou sistemas de referência apropriados estão disponíveis, e

existem dados suficientes para o sistema de referência, o valor directriz da distribuição

Salinidade

sazonal deverá ser definido pelo valor de 20% e 80% da distribuição do(s) sistema(s)

de referência, dependendo se os efeitos de baixa ou alta salinidade estão a ser

considerados. Teste de dados: Concentração mediana (ou média) para o período.

Quando um sistema ou sistemas de referência apropriados estão disponíveis, e

existem dados suficientes para o sistema de referência, o valor directriz da distribuição

sazonal deverá ser definido pelo valor de 20% e 80% da distribuição do(s) sistema(s)

de referência

pH

Mudanças de pH superiores a 0.5 unidades de pH do máximo ou mínimo sazonal

definidos pelos sistemas de referência deverão ser investigados por inteiro.

Teste de dados: Concentração mediana (ou média) para o período

Turvação

Quando um sistema ou sistemas de referência apropriados estão disponíveis, e

existem dados suficientes para o sistema de referência, o valor directriz da distribuição

sazonal deverá ser definido pelo valor de 20% e 80% da distribuição do(s) sistema(s)

de referência

Sólidos suspensos

Adicionalmente, não deve ser permitido mudar a profundidade natural (Zeu) em mais de

10%.

Teste de dados: Concentração mediana (ou média) para o período

Quando um sistema ou sistemas de referência apropriados estão disponíveis, e

existem dados suficientes para o sistema de referência, o valor directriz da distribuição

sazonal deverá ser definido pelo valor de 20% e 80% da distribuição do(s) sistema(s)

Oxigénio dissolvido

de referência.

Quando possível o valor directriz deverá ser obtido durante períodos de baixa corrente

e alta temperatura quando as concentrações de OD têm maior probabilidade de

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/04

Page xviii

Final

January 2006

VARIÁVEL

DIRECTRIZ PROPOSTA PARA A QUALIDADE DE ÁGUA

apresentar os seus valores mais baixos.

Teste de dados: Concentração mediana de OD para o período, calculada, usando as

concentrações diurnas mais baixas de OD

Linhas mestras recomendadas para a qualidade da água no que respeita a nutrientes:

VARIÁVEL

DIRECTRIZ PROPOSTA PARA A QUALIDADE DE ÁGUA

Quando um sistema ou sistemas de referência apropriados estão disponíveis, e

existem dados suficientes para o sistema de referência, o valor directriz da

Clorofila a

distribuição sazonal deverá ser definido pelo valor de 20% e 80% da distribuição

do(s) sistema(s) de referência.

Concentrações de nutrientes na coluna de água não devem resultar em clorofila a,

turvidade e/ou níveis de oxigénio dissolvido fora do intervalo recomendado na

directriz de qualidade de água (ver acima). Tal deverá ser estabelecido utilizando

técnicas de modelagem estatísticas ou matemáticas apropriadas.

Nutrientes

Em alternativa, onde uma abordagem de modelação pode ser difícil de implementar,

a concentração de nutrientes pode ser derivada utilizando uma abordagem de

sistema de dados Referenciais: Quando um sistema ou sistemas de referência

apropriados estão disponíveis, e existem dados suficientes para o sistema de

referência, o valor directriz da distribuição sazonal deverá ser definido pelo valor de

20% e 80% da distribuição do(s) sistema(s) de referência.

Linhas mestras recomendadas para a qualidade da água no que respeita a susbtâncias

tóxicas:

SUBSTÂNCIAS

VALOR DIRECTRIZ RECOMENDADO em µg/

Total Amoníaco-N

910

Total Residual Cloro-Cl

3

Cianeto (CN-) 4

Fluoreto(F-)

5 000

Sulfuro (S-)

1

Fenol

400

Poli Cloretos Biphenyls (PCBs)

0.03

Vestígios metálicos (em metal Total):

Arsénico

As(III) - 2.3; As(V) - 4.5

Cádmio 5.5

Crómio

Cr (III) - 10; Cr (VI) - 4.4

Cobalto

1

Cobre

1.3

Chumbo 4.4

Mercúrio

0.4

Níquel

70

Prata

1.4

Sn (tal como Tributyltin) 0.006

Vanádio 100

Zínco

15

Hidrocarbonetos Aromáticos (C6-C9 hidrocarbonetos simples - volátil):

Benzeno (C6)

500

Toluene (C7)

180

Etilbenzeno (C8)

5

Xylene (C8)

Ortho - 350; Para - 75; Meta - 200

Naftaleno (C9)

70

Hidrocarbonetos Poli-Aromáticos (< C15 toxicidade elevada com baixa duração de vida em água)

Antraceno (C14)

0.4

Fenantreno (C14)

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/04

Page xix

Final

January 2006

SUBSTÂNCIAS

VALOR DIRECTRIZ RECOMENDADO em µg/

Hidrocarbonetos Poli-Aromáticos (> C15, toxicidade crónica, com maior duração de vida na água)

Fluoranteno (C15)

1.7

Benzo(a) pireno (C20)

0.4

Pesticidas:

DDT

0.001

Dieldrina

0.002

Endrina

0.002

Linhas mestras recomendadas para a qualidade dos sedimentos no que respeita a

substâncias tóxicas:

VALOR DE DIRECTRIZ

EFEITO DE CONCENTRAÇÃO

SUBSTÂNCIAS TÓXICAS

RECOMENDADO

PROVÁVEL

VESTÍGIOS METÁLICOS (mg/kg peso em seco)

Antimónio -

-

Arsénico 7.24

41.6

Cádmio 0.68

4.21

Crómio 52.3

160

Cobre 18.7

108

Chumbo 30.2

112

Mercúrio 0.13

0.7

Níquel 15.9

42.8

Prata 0.73

1.77

Estanho tal como Tributyltin-Sn 0.005

0.07

Zínco 124

271

COMPOSTOS ORGÂNICOS TÓXICOS (µg/kg peso seco normalizado para 1% carvão orgânico)

Total PAHs

1684

16770

Baixo Valor Molecular PAHs

312

1442

Acenafteno

6.71

88.9

Acenaftaleno

44

640

Antraceno

46.9

245

Fluoreto

21.2

144

2-metilo naftaleno

-

-

Naftaleno

34.6

391

Fenantreno

86.7

544

Alto Peso Molecular PAHs

655

6676

Benzo(a) antraceno

74.8

693

Benzo(a) pireno

88.8

763

Dibenzo(a,h)antraceno

6.22

135

Criseno

108

846

Fluoranteno

113

1494

Pireno

153

1398

Toxofilo

-

-

Total DDT

3.89

51.7

p p DDE

2.2

27

Cloreto 2.26

4.79

Dieldrina 0.72

4.3

Total PCBs

21.6

189

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/04

Page xx

Final

January 2006

As linhas mestras recomendadas para a qualidade da água e sedimentos para protecção

dos ecossistemas aquático - marinhos devem ser aplicados como referências, no

seguimento de uma avaliação de risco ou aproximação por fases, como ilustrado abaixo:

Sempre que os estudos de avaliação científica ou os resultados da verificação revelem que

os valores de qualidade recomendados são excedidos, dever-se á produzir informação

suplementar ou efectuar-se mais investigação, a fim de determinar se existe ou não um

factor de risco real para o ecossistema e, sempre que necessário, ajustar esses valores

para condições locais específicas.

Os valores de qualidade orientativos devem ser comparados com os dados medidos ou

simulados. Se um valor orientativo tiver tido por base um julgamento profissional, a

fundamentação lógica para a selecção desse valor deve ser fornecida e deve ser

implementado um processo, onde o valor adoptado seja revisto e apoiado ou modificado, à

luz da informação ora emergente, seguindo o princípio de gestão adaptável.

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/04

Page xxi

Final

January 2006

Linhas mestras recomendadas para a qualidade da água e sedimentos: aquacultura

marinha

No que diz respeito às orientações da qualidade da água para aquacultura marinha

(incluindo a recolha de seres vivos para consumo humano), estas são considerações

importantes:

· Protecção do estado de saúde do ecosistema aquático, de modo a assegurar uma

produção sustentável e produtos de qualidade

· Protecção do estado de saúde dos consumidores humanos

· Contaminação de marisco.

Fazendo referência à protecção de organismos aquáticos utilizados na cultura e recolha de

pescado, recomenda-se que as orientações da qualidade da água propostas para a

Protecção dos ecosistemas aquáticos sejam aplicadas, em vez de recorrer a uma série de

orientações separadas.

Quanto à protecção dos consumidores humanos, propõe-se que os limites admitidos de

substâncias tóxicas e micróbios patogénicos em produtos alimentares sejam controlados

através de legislação.

No que concerne as áreas de crescimento de marisco, as orientações microbiológicas

recomendadas procuram reduzir os riscos de saúde humano como se indica:

INDICADOR

DIRECTRIZ PROPOSTA PARA A QUALIDADE DE ÁGUA

Concentrações medianas não deverão exceder 14 Número Mais Provável

Coliforme fecal

(NMP) por 100 ml com não mais de 10% das amostras a exceder 43 NMP por

100 ml por um tubo de 5, método de diluição 3.

Concentrações limite estimadas para substâncias contaminadoras são dadas abaixo:

LIMIARES DE CONCENTRAÇÕES ACIMA DOS

SUBSTÂNCIA CONTAMINADORA

QUAIS A CONTAMINAÇÃO É PROVÁVEL

ACONTECER (mg/)

Acenafeteno 0.02

Acetofenona

0.5

Acrilonitrilo 18

Cobre

1

m-cresol

0.2

o-cresol

0.4

p-cresol

0.12

Ácidos cresílicos (meta, para)

0.2

Clorobenzina

-

n-butilmercaptano

0.06

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/04

Page xxii

Final

January 2006

LIMIARES DE CONCENTRAÇÕES ACIMA DOS

SUBSTÂNCIA CONTAMINADORA

QUAIS A CONTAMINAÇÃO É PROVÁVEL

ACONTECER (mg/)

o-sec. butilfenol

0.3

p-tert. butilfenol

0.03

2-clorofenol 0.001

3- clorofenol

0.001

3- clorofenol

0.001

o- clorofenol

0.001

p- clorofenol

0.01

2,3-dinitrofenol

0.08

2,4,6-trinitrofenol

0.002

2,3 diclorofenol

0.00004

2,4-diclorofenol

0.001

2,5- diclorofenol

0.023

2,6- diclorofenol

0.035

3,4- diclorofenol

0.0003

2-metil-4-clorofenol

0.75

2-metil-6-clorofenol

0.003

3-metil-4-clorofenol

0.02 3

o-fenifenol

1

Pentaclorofenol

0.03

Fenol

1

2,3,4,6-tetraclorofenol

0.001

2,4,5-triclorofenol 0.001

2,3,5-triclorofenol

0.001

2,4,6-tricorofenol

0.003

2,4-dimetilfenol

0.4

Dimetilamina

7

Difenilóxido

0.05

B,B-diclorodietil éter

0.09

o-diclorobenzeno

< 0.25

p-diclorobenzeno 0.25

Etilbenzeno

0.25

Momoclorobenzeno 0.02

Etanatiol

0.24

Etilacrilato

0.6

Formaldeide

95

Gasolina 0.005

Guaicol

0.082

Querosene

0.1

Querosene plus caolín

1

Hexaclorociclopentadieno

0.001

Isopropilbenzeno

0.25

Nafta 0.1

Naftaleno

1

Naftol

0.5

2-Naftol

0.3

Nitrobenzeno

0.03

a-metilestireno

0.25

Óleo, emulsificável

15

Piridino

5

Pirocatecol

0.8

Pirogalol

0.5

Quinolino

0.5

p-quinona

0.5

Estireno

0.25

Tolueno

0.25

Combustão de fuel em motores fora de bordo

0.5

Zinco

5

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/04

Page xxiii

Final

January 2006

Recomenda-se que seja adoptado pela região do BCLME um sistema de classificação para

as áreas de crescimento de marisco e que um grupo de trabalho dedicado seja nomeado, a

fim de tomar decisões quanto à abordagem final a ter no que respeita ao sistema de

classificação. Neste entretanto, recomenda-se que essa classificação assente nos

resultados das Análises Sanitárias, que consistem em:

· Identificação e avaliação de todas as origens potenciais e reais de poluição

(investigação costeira)

· Avaliação de águas em crescimento e marisco para determinar a classificação mais

adequada para as áreas de recolha de marisco (Análise bacteriológica).

O sistema de classificação recomendado para a região do BCLME é a seguinte:

CLASSE

DESCRIÇÃO

As áreas aprovadas devem estar isentas de poluição e o marisco daí oriundo é próprio

Aprovado

para consumo humano directo de marisco em cru.

Nas áreas sujeitas ou limitadas a poluição intermitente causada por descargas de

tratamentos de águas residuais, populações sazonais, poluição não identificada, ou

actividades náuticas, podem ser classificadas como "aprovadas condicionalmente" e/ou

restringidas.

No entanto, deve ser elucidado que a área de recolha e apanha do marisco estará

Aprovado

aberta para a apanha de marisco durante um período de tempo razoável e que os

condicionalmente

factores que determinam este período são conhecidos, previsíveis e não são

/restringido

complexos ao ponto de ir contra uma gestão razoável.

Quando "abertas" para a apanha de marisco para consume humano directo, a

qualidade da água na área deve estar de acordo com os limites tal como especificados

para "Áreas aprovadas". Quando "fechadas" para consumo directo, mas "abertas" para

a apanha devido a reposição ou depuração, devem ser cumpridos os requisitos de

"Área restringida". Alturas há em que a área está "fechada" para qualquer tipo de

recolha e nesse caso aplicar-se-ão os requisitos de "Áreas proibidas".

As áreas restringidas estão sujeitas a um grau de poluição limitado. No entanto, o nível

de poluição fecal, micróbios patogénicos humanos e substâncias tóxicas ou perniciosas

Restringido

atingem um tal nível que o marisco pode estar bom para consumo humano, ou por

recolocação ou por depuração.

Uma área é classificada como "Proibida" se não tiver sido efectuada uma análise

profunda ou sempre que uma análise verifique a existência de:

· Unidade adjacente de tratamentos de águas residuais ou outra origem semelhante

com repercussões significativas na saúde pública

· Contaminação devido a causas de poluição imprevisíveis

· Contaminação por restos fecais, fazendo com que o marisco seja vector de

doenças micro-orgânicas

Proibido

· Algas que contenham biotoxinas suficientes para causar risco de saúde pública

· Contaminação com substâncias venenosas ou nocivas que possam afectar o

marisco.

NOTA: Quando ocorrer uma cheia, tempestade ou contaminação marítima por

biotoxinas em áreas "Aprovadas" ou "Restringidas", estas podem ser também

classificas temporariamente como áreas "Proibidas".

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/04

Page xxiv

Final

January 2006

Os requisitos associados a cada classe nos sistemas de classificação recomendados (no

entretanto) são:

CLASSE

REQUISITOS

Deve ser feita um levantamento sanitário de fundo, segundo as especificações, a

qual deve ser revista anualmente. A área não deve estar contaminada com resíduos

fecais coliformes (como listados) e não deve ter micróbios patogénicos ou

concentrações perigosas de substâncias tóxicas ou biotoxinas marinhas (uma área

de marisco aprovada pode ser temporariamente declarada "área proibida" quando,

por ex., houver cheias, tempestades ou contaminação por biotoxinas). A evidência de

causas de poluição potencial, tais como provenientes de estações de tratamentos de

esgotos, descargas de esgotos directas, de tanques sépticos, etc, é mais do que

Aprovado

razão para excluir qualquer área da categoria de "aprovado".

Os resultados das amostras de coliformes fecais medianas/geométricas não devem

exceder os 14/100 ml e o percentil 90 estimado não deve ser superior a 21/100 ml

(usando Membrana de Filtragem) ou 14/100 ml e o percentil 90 estimado não deve

ser superior a 43/100ml para um ensaio de diluição decimal a-5-tubos, ou 49/100 ml

para um ensaio de diluição decimal a-3-tubos (usando Número Mais Provável

(MPN)).

Os factores que determinam este período são conhecidos e não são tão complexos

ao ponto de impossibilitar uma abordagem de gestão razoável. Deve ser

desenvolvido um plano de gestão para cada área condicionalmente

aprovada/restringida.

Aprovado

condicionalmente

Quando "abertas" para a apanha de marisco para consume humano directo, a

/restringido

qualidade da água na área deve estar de acordo com os limites tal como

especificados para "Áreas aprovadas". Quando "fechadas" para consumo directo,

mas "abertas" para a apanha devido a reposição ou depuração, devem ser cumpridos

os requisitos de "Área restringida". Alturas há em que a área está "fechada" para

qualquer tipo de recolha e nesse caso aplicar-se-ão os requisitos de "Áreas

proibidas".

Os resultados das amostras de coliformes fecais medianos/geométricos não devem

exceder 70/100 ml e o percentil 90 estimado não deve ser superior a 85/100 ml

(usando Membrana de Filtragem) ou 881/00 ml e o percentil 90 estimado não deve

ser superior a 260/100 ml para um ensaio de diluição decimal a-5-tubos, ou 300/100

ml para um ensaio de diluição decimal a-3-tubos (usando Número Mais Provável

Restringido

(MPN)).

Os resultados das amostras de coliformes fecais medianos/geométricos não devem

exceder 700/100 ml e o percentil 90 estimado não deve ser superior s 2300/100 ml

para um ensaio de deluição decimal a-5-tubos, ou 3300/100 para um ensaio de

diluição decimal a-3-tubos (usando Número Mais Provável (MPN)).

Área proibida

Sem requisitos especificados

Contudo, recomenda-se que uma equipa técnica, formada por especialistas em aquacultura

e autoridades responsáveis dos diferentes países na região do BCLME, seja formada para

decidir no tipo de abordagem final para a classificação das áreas de cultivo de marisco

nesta região. Este processo foi já iniciado, como parte de um outro Programa do BCLME

(Projecto EV/HAB/04/Shellsan - Development of a shellfish sanitation Desenvolvimento de

cuidados sanitários para cultivo de marisco), um modelo de aplicação em conjunto com

componente de toxinas de microalgas.

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/04

Page xxv

Final

January 2006

Linhas mestras recomendadas para a qualidade da água e sedimentos: actividades

de recreio

Em termos de qualidade da água, os pontos chave seguintes são importantes no que se

refere à utilização recreativa das águas costeiras:

· Estética

· Protecção da saúde pública face a substâncias tóxicas

· Protecção da saúde pública face a contaminantes microbiológicos.

Para áreas de recreio, as orientações da qualidade da água que se prendem com o aspecto

estético são semelhantes às apresentadas na lista sob o título matérias objectáveis, em

Protecção dos ecosistemas aquático-marinhos (ver acima).

Quanto a substâncias tóxicas, recomenda-se a consulta das orientações para a qualidade

da água potável, de modo a fazer-se uma avaliação preliminar dos riscos nas áreas onde

tais substâncias podem apresentar-se a níveis que ponham em causa a saúde pública.

Quanto a indicadores microbiológicos, recomenda-se que tanto o E.coli e o Enterococci

(faecal streptococci) sejam usados como organismos indicadores. Recomenda-se, por outro

lado, que em vez de utilizar valores-alvo "singulares" que classifiquem uma praia de

"segura" ou "não segura", seja feita uma derivativa de valores-alvo que correspondam a

níveis de risco diferentes:

95° PERCENTIL DE

CATEGORIA

RISCO ESTIMADO POR EXPOSIÇÃO

ENTEROCOCCI por 100 ml

<1% risco de doença gastrointestinal (GI)

A <40 <0.3% risco de febre respiratória aguda (AFRI)

15% risco de doença GI

B

40 200

0.31.9% risco de AFRI

510% risco de doença GI

C

201 500

1.93.9% risco de AFRI

>10% risco de doença GI

D >

500

>3.9% risco de AFRI

Recomenda-se que a região do BCLME adopte um sistema de classificação de praias em

vez de fazer a abordagem tradicional de classificação de águas para a prática de

actividades de recreio como sendo seguras ou não seguras. Reportando-nos à qualidade da

água, a classificação deve ser baseada tanto na análise sanitária como nas análises

microbiológicas de rotina. O índice de classificação deve ser reavaliado anualmente.

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/04

Page xxvi

Final

January 2006

Sistema de classificação recomendado para áreas de recreio:

Categoria de Avaliação Qualidade Microbiológica

(percentile 95 enterococci/100 ml ver Tabela acima de )

A

B

C

D

Circunstâncias

(<40)

(41-200)

(201-500)

(>500)

excepcionais

Muito baixa

Muito boa

Muito boa

Razoável

A seguir

Baixa

Muito boa

Boa

Razoável

A seguir

Categoria

Moderada

Boa Boa

Razoável

Fraca

Acção

de

Alta

Boa Razoável Fraca Muito

fraca

Inspecção

Muito alta

A seguir

Razoável

Fraca

Muito fraca

sanitária Circunstâncias

excepcionais

Acção

A implementação do sistema de classificação, bem como do sistema de gestão dia-a-dia

proposto, é esquematizado abaixo:

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/04

Page xxvii

Final

January 2006

O caminho a seguir

· As linhas mestras recomendadas necessitam todavia de serem oficialmente

aprovadas e adoptadas pelas autoridades responsáveis em cada um dos três países.

Recomenda-se que o resultado deste projecto seja usado como ponto de partida de tais

iniciativas.

· As linhas mestras de qualidade e protocolos desenvolvidos como fazendo parte deste

projecto formam parte integral da estrutura de gestão das origens da poluição marinha

(concebido como parte de um outro projecto BCLME - o BEHP/LBMP/03/01).

· Neste entretanto, até que a estrutura de gestão e as orientações de qualidade tenham

sido incorporadas na política oficial do governo, propõe-se que essas linhas mestras

concebidas como parte do projecto, em conjunto com a estrutura de gestão proposta,

sejam aplicadas como ferramentas preliminares com vista à melhoria da gestão da

qualidade da água nas áreas costeiras da região do BCLME.

· Como parte das orientações oficiais da qualidade da água e sedimentos a serem

adoptadas em cada um dos três países, recomenda-se que também sejam incluídos os

métodos analíticos de eleição para as diferentes variáveis químicas e microbiológicas.

· O sistema de informação actualizável com suporte na Internet (endereço web

temporário: www.wamsys.co.za/bclme) criado como parte deste projecto pode ser útil

para apoiar a tomada de decisão e como ferramenta educativa, desde que mantido e

actualizado com regularidade. A curto e médio prazo, recomenda-se que um ou mais

escritórios do BCLME no âmbito dos três países seja por esse facto responsável.

· A fim de facilitar uma maior e mais vasta capacidade de construção no seio da região do

BCLME no que respeita à gestão da poluição marinha nas áreas costeiras, é fortemente

recomendado que os resultados deste projecto sejam incluídos num curso de

formação. Assim sendo, a Unidade de Desenvolvimento do Curso (Train-Sea-

Coast/Benguela Course Development Unit) é tido como a plataforma ideal para

desenvolver e a presentar essa formação (www.ioisa.org.za/tsc/index.htm).

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/04

Page xxviii

Final

January 2006

TABLE OF CONTENTS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................................................... i

TABLE OF CONTENTS ......................................................................................................................................xxix

LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................................................... xxxii

LIST OF FIGURES............................................................................................................................................ xxxiii

ACRONYMS, SYMBOLS AND ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................ xxxiv

INTRODUCTION ______________________________________________________________________ 1

1. SCOPE OF WORK ____________________________________________________________________ 2

2. PROJECT APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY _____________________________________________ 3

3. CURRENT STATUS IN BCLME REGION___________________________________________________ 7

SECTION 1. INTERNATIONAL REVIEW - WATER QUALITY GUIDELINES FOR

PROTECTION OF MARINE AQUATIC ECOSYSTEMS ________________________1-1

1.1

INTRODUCTION __________________________________________________________________ 1-2

1.2

INTERNATIONAL APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY ___________________________________ 1-5

1.2.1 Objectionable matter __________________________________________________________ 1-5

1.2.2 Physico-chemical variables _____________________________________________________ 1-6

1.2.3 Nutrients ____________________________________________________________________ 1-9

1.2.4 Toxic Substances ____________________________________________________________ 1-12

1.3

INTERNATIONAL IMPLEMENTATION PRACTICES ____________________________________ 1-23

SECTION 2. INTERNATIONAL REVIEW - SEDIMENT QUALITY GUIDELINES FOR

THE PROTECTION OF MARINE AQUATIC ECOSYSTEMS ____________________2-1

2.1

INTRODUCTION __________________________________________________________________ 2-2

2.2

INTERNATIONAL APPROACH AND METHODOLOGIES _________________________________ 2-3

2.2.1

National Status and Trends Program Approach (effects range approach) _________________ 2-7

2.2.2 Equilibrium Partitioning Approach (US-EPA) _____________________________________ 2-13

2.3

INTERNATIONAL IMPLEMENTATION PRACTICES ____________________________________ 2-14

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/04

Page xxix

Final

January 2006

SECTION 3. INTERNATIONAL REVIEW - WATER QUALITY GUIDELINES FOR

MARINE AQUACULTURE_______________________________________________3-1

3.1

INTRODUCTION __________________________________________________________________ 3-2

3.2

INTERNATIONAL APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY ___________________________________ 3-4

3.2.1 Protection of Aquatic Organism Health____________________________________________ 3-4

3.2.2 Protection of Human Health ____________________________________________________ 3-5

3.2.3 Tainting of Seafood Products ____________________________________________________ 3-9

3.3

INTERNATIONAL IMPLEMENTATION PRACTICES _____________________________________ 3-9

3.3.1 National Shellfish Sanitation Program Approach ___________________________________ 3-10

3.3.2 European Union's Approach ___________________________________________________ 3-14

SECTION 4. INTERNATIONAL REVIEW - WATER QUALITY GUIDELINES FOR

RECREATION ________________________________________________________4-1

4.1

INTRODUCTION __________________________________________________________________ 4-2

4.2

INTERNATIONAL APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY ___________________________________ 4-3

4.2.1 Aesthetics ___________________________________________________________________ 4-4

4.2.2 Toxic Substances _____________________________________________________________ 4-6

4.2.3 Microbiological contaminants ___________________________________________________ 4-6

4.3

INTERNATIONAL IMPLEMENTATION PRACTICES ____________________________________ 4-10

4.3.1

World Health Organisation Approach _____________________________________________ 4-11

4.3.2 European Union Approach_____________________________________________________ 4-14

4.3.3 Blue Flag Campaign _________________________________________________________ 4-16

4.3.4 Canada ____________________________________________________________________ 4-18

SECTION 5. INTERNATIONAL REVIEW - WATER QUALITY GUIDELINES FOR

INDUSTRIAL USE _____________________________________________________5-1

SECTION 6. RECOMMENDED WATER AND SEDIMENT QUALITY GUIDELINES FOR

COASTAL AREAS IN THE BCLME REGION________________________________6-1

6.1

RECOMMENDED BENEFICIAL USES_________________________________________________ 6-2

6.2

RECOMMENDED WATER QUALITY GUIDELINES: PROTECTION OF MARINE AQUATIC

ECOSYSTEMS ___________________________________________________________________ 6-3

6.2.1 Approach and Methodology _____________________________________________________ 6-3

6.2.2 Protocol for Implementation ____________________________________________________ 6-9

6.3

RECOMMENDED SEDIMENT QUALITY GUIDELINES: PROTECTION OF MARINE AQUATIC

ECOSYSTEMS __________________________________________________________________ 6-10

6.3.1 Approach and Methodology ____________________________________________________ 6-10

6.3.2 Protocol for Implementation ___________________________________________________ 6-12

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/04

Page xxx

Final

January 2006

6.4

RECOMMENDED WATER QUALITY GUIDELINES: MARINE AQUACULTURE ______________ 6-13

6.4.1 Approach and Methodology ____________________________________________________ 6-13

6.4.2 Protocol for Implementation ___________________________________________________ 6-16

6.5

RECOMMENDED WATER QUALITY GUIDELINES: RECREATION________________________ 6-19

6.5.1 Approach and Methodology ____________________________________________________ 6-19

6.5.2 Protocol for Implementation ___________________________________________________ 6-20

SECTION 7. THE WAY FORWARD _______________________________________7-1

SECTION 8. REFERENCES _____________________________________________8-1

Appendix A

Summary of International Marine Water Quality Guideline Values for the

Protection of Marine Aquatic Ecosystems·

Appendix B

Summary of International Sediment Quality Guideline Values for the

Protection of Marine Aquatic Ecosystems

Appendix C

Summary of International Marine Water Quality Guideline Values for Marine

Aquaculture.

Appendix D

User Manual for Web-based Information System

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/04

Page xxxi

Final

January 2006

LIST OF TABLES

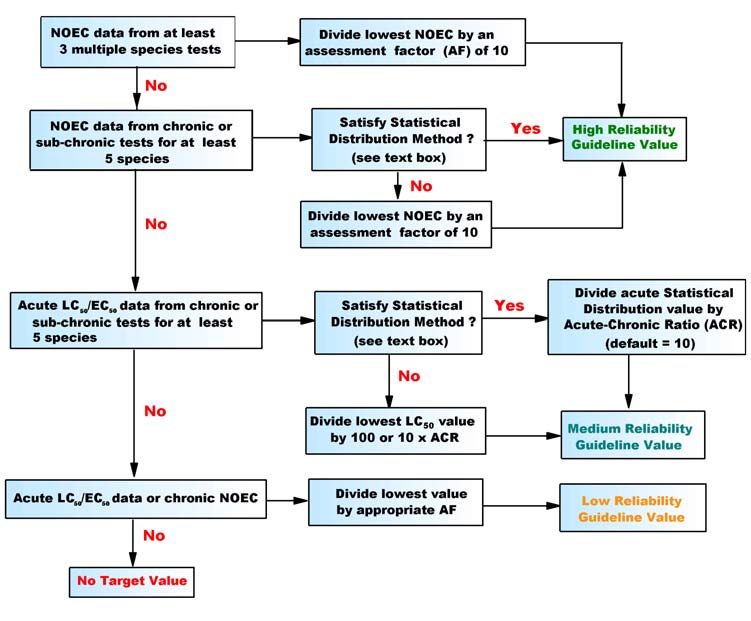

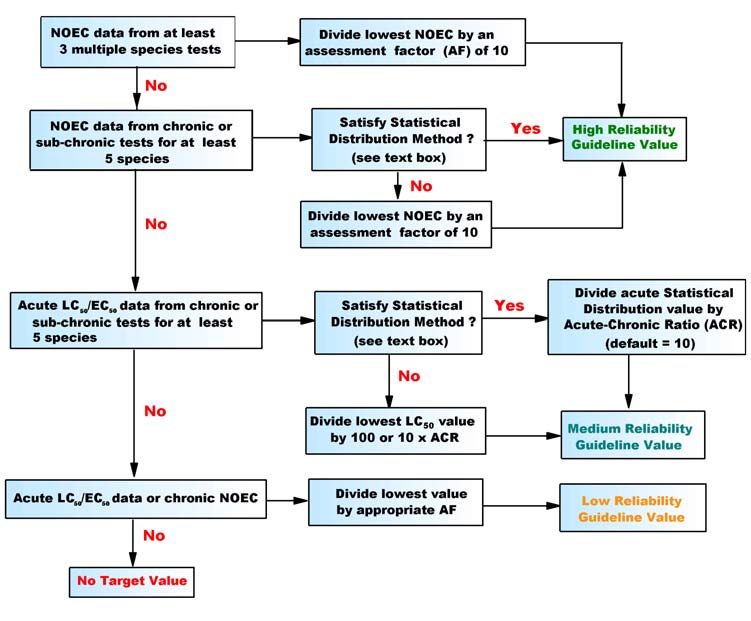

TABLE 1.1: Summary of the minimum toxicological data requirements for the derivation of water quality

guidelines for the protection of marine aquatic ecosystems: Toxic substances.......................1-14

TABLE 3.1: South African legal standards for chemical and microbiological constituents in the flesh of

shellfish and fish used for human consumption ..........................................................................3-5

TABLE 3.3: Summary of National Shellfish Sanitation Program classification approach for shellfish growing

areas ..........................................................................................................................................3-12

TABLE 3.4: EC: Classification of shellfish growing areas ...........................................................................3-14

TABLE 4.1

Summary of available water quality guidelines related to aesthetics ...........................................4-5

TABLE 4.2

Summary of microbiological water quality guidelines recommended for recreational waters

(marine)........................................................................................................................................4-7

TABLE 4.3: The World Health Organisation microbiological target values recommended for recreational

waters (representing different risk levels) (WHO, 2003)...............................................................4-8

TABLE 4.4: The European Union proposed microbiological target values recommended for recreational

waters (representing different risk levels) (CEC, 2002)................................................................4-9

TABLE 4.5: The World Health Organisation Recreational Classification system ..........................................4-12

TABLE 4.6: The European Union Recreational Classification system (CEC, 2002)......................................4-15

TABLE 4.7

Blue Flag Campaign: South African Criteria related to Water Quality .......................................4-17

TABLE 6.1: Summary of constituent categories for the recommended water and sediment quality for different

designated uses ...........................................................................................................................6-2

TABLE 6.2

Recommended water quality guidelines for objectionable matter (aesthetic) for coastal areas in

the BCLME region........................................................................................................................6-4

TABLE 6.3 Recommended water quality guidelines for physico-chemical variables in coastal areas of the

BCLME region..............................................................................................................................6-5

TABLE 6.4 Recommended water quality guidelines for nutrients in coastal areas of the BCLME region .....6-7

TABLE 6.5 Recommended water quality guidelines for toxic substances for coastal areas in the BCLME

region (current South African guideline values listed in brackets where available) .....................6-8

TABLE 6.6

Recommended interim sediment quality guidelines for the Protection of marine aquatic

ecosystems in coastal areas of the BCLME region....................................................................6-11

TABLE 6.7

Recommended microbiological indicator guidelines for areas where shellfish are collected or

cultured for direct human consumption in the BCLME region ....................................................6-14

TABLE 6.8

Recommended guidelines for tainting substances in areas used for marine aquaculture in the

BCLME region............................................................................................................................6-15

TABLE 6.9

Recommended (interim) classification system of shellfish growing areas in the BCLME region 6-17

TABLE 6.10: Summary of requirements associated with each class in the recommended (interim) classification

system of shellfish growing areas in the BCLME region...........................................................6-18

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/04

Page xxxii

Final

January 2006

TABLE 6.11: Recommended water quality guidelines for microbiological indicator organisms versus risk rates

for coastal areas in the BCLME region .....................................................................................6-20

TABLE 6.12: Recommended classification system for recreational areas in coastal areas of the BCLME

region........................................................................................................................................6-21

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1.1:

Schematic illustration of the guideline derivation procedures followed for Australia and New

Zealand (adapted from ANZECC, 2000)...................................................................................1-16

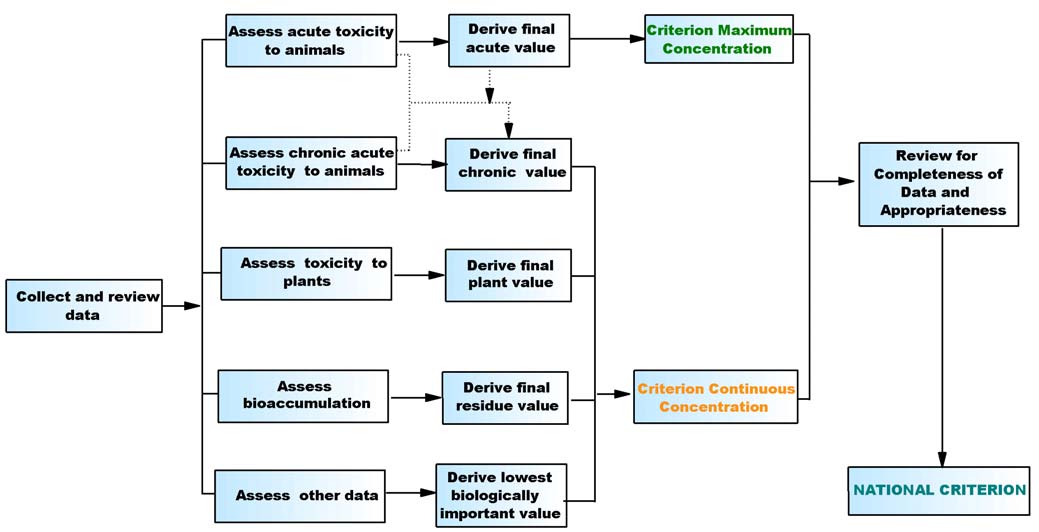

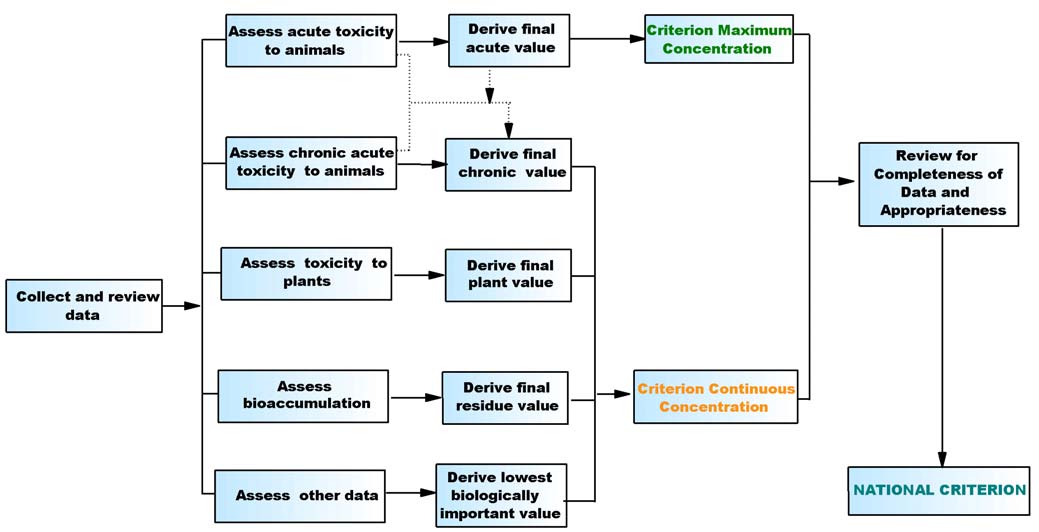

Figure 1.2:

Schematic illustration of the guideline (criterion) derivation procedures followed by the US-EPA

(adapted from Russo, 2002) .....................................................................................................1-17

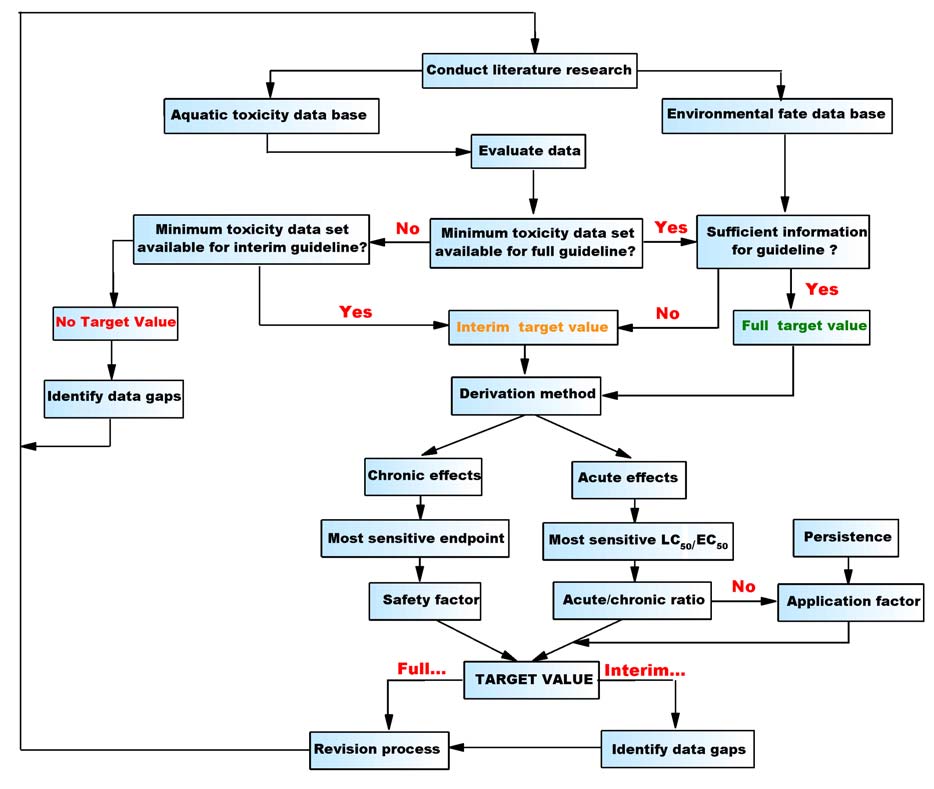

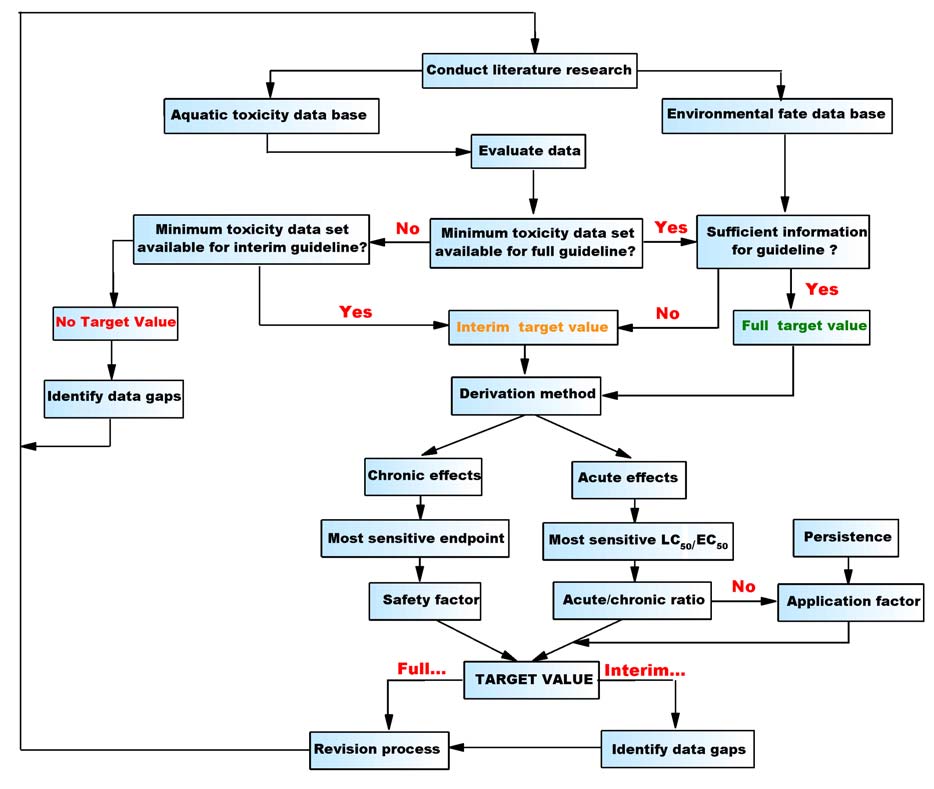

Figure 1.3:

Schematic illustration of the guideline derivation procedures followed for Canada (adapted from

CCME, 1999a)..........................................................................................................................1-19

Figure 1.4:

Implementation of water quality guidelines in the broader water quality management framework

(adapted from ANZECC, 2000) ................................................................................................1-24

Figure 1.5:

Decision tree framework for assessing toxic substances in ambient waters using water quality

guidelines (ANZECC, 2000) .....................................................................................................1-25

Figure 1.6:

Implementation of water quality guidelines in Canada (adapted from CCME, 1999a)..............1-26

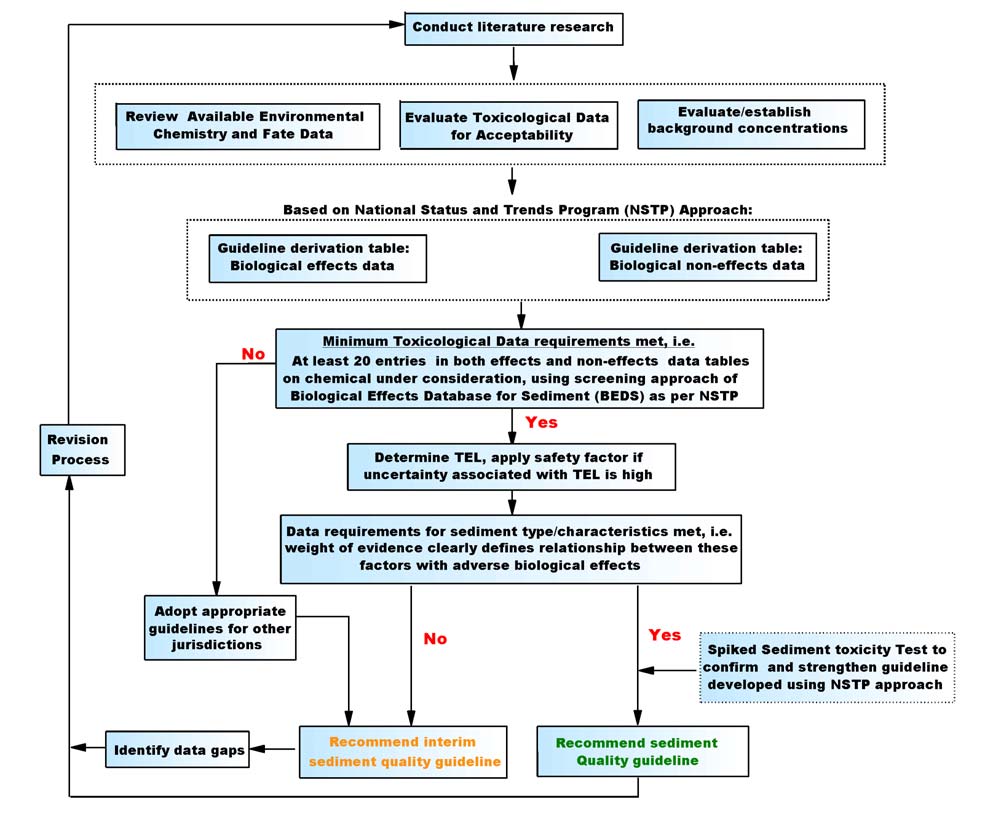

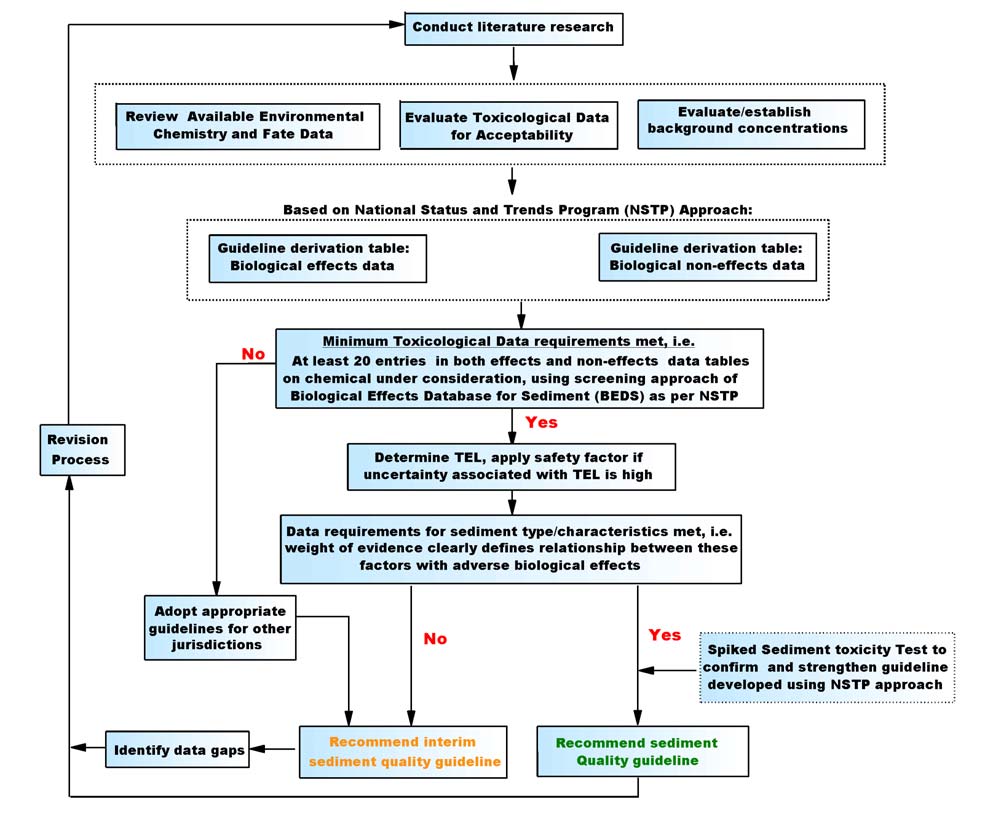

Figure 2.1:

Canadian protocol for the derivation of sediment quality guidelines

(adapted from CCME, 1995).....................................................................................................2-11

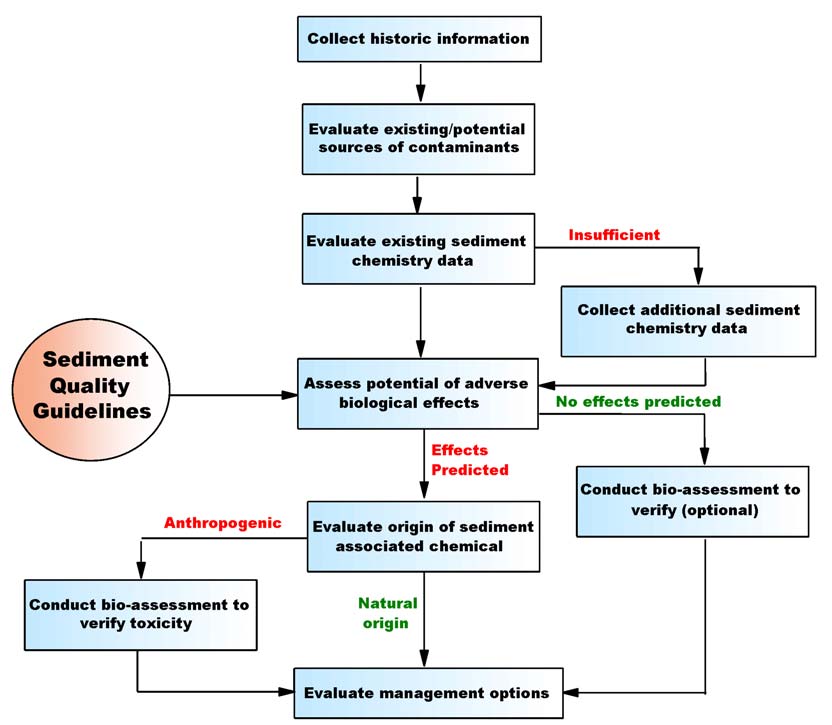

Figure 2.2:

Implementation of sediment quality guidelines in Canada (adapted from CCME, 1995).........2-15

Figure 2.3:

Application of sediment quality guidelines in Australia and New Zealand as part of monitoring

programmes (ANZECC, 2000) .................................................................................................2-16

Figure 4.1:

The recreational beach grading process of the WHO (adapted from WHO, 2003)...................4-12

Figure 4.2:

New Zealand grading and surveillance, alert and action process for the management of

recreational use of marine waters (adapted from New Zealand Land Ministry of Environment,

2003) ........................................................................................................................................4-14

Figure 6.1:

Schematic illustration of the recommended implementation process of recommended water

quality guidelines in the coastal zone of the BCLME region .......................................................6-9

Figure 6.2:

Grading, surveillance, alert and action process for the management of recreational use of marine

waters recommended for the BCLME region............................................................................6-22

BCLME Project BEHP/LBMP/03/04

Page xxxiii

Final

January 2006

ACRONYMS, SYMBOLS AND ABBREVIATIONS

ACR

Acute-Chronic Ratio

ANZECC

Australia and New Zealand Environment and Conservation Council

ANZFA

Australia New Zealand Food Authority

AQUIRE

Aquatic Toxicity Information Retrieval Database

Agriculture and Resource Management Council of Australia and New

ARMCANZ

Zealand

ASSAC

Australian Shellfish Sanitation Advisory Committee

AWRC