|

PROJECT CONCEPT

REQUEST FOR PIPELINE ENTRY |

|

Agency’s Project ID: PIMS No. 3246

GEFSEC Project ID:

Country: Belarus, Russian Federation, and Ukraine

Project Title Implementation of Priority Interventions of the Dnipro Basin Strategic Action Programme: Chemical Industrial Pollution Reduction and The Development of Joint Institutional Arrangements.

GEF Agency: UNDP

Other Executing Agency(ies): UNOPS, UNIDO

Duration: 60 Months

GEF Focal Area: International Waters

GEF Operational Program: OP 8

GEF Strategic Priority: IW 1

Estimated Starting Date: July 2007

Estimated WP Entry Date: Nov 2006

Pipeline Entry Date: June 2004 |

|

Financing Plan (US$) |

|

GEF Project/Component |

|

Project (estimated) |

$7,000,000

|

PDF A*

|

|

PDF B**

|

|

PDF C

|

|

Sub-Total GEF |

$7,000,000

|

Project Co-financing (estimated) |

GEF Agency

|

TBD

|

Government

|

$7,300,000

|

Bilateral

|

TBD

|

NGOs

|

$700,000

|

Others

|

TBD

|

|

Sub-Total Co-financing: |

$8,000,000

|

|

Total Project Financing: |

$15,000,000

|

|

PDF Co-financing (details provided in Part II, Section E – Budget |

GEF Agency

|

TBD

|

|

National Contribution |

|

Others

|

|

|

Sub-Total Co-financing: |

|

|

Total Project Financing: |

|

|

* Indicate approval date of PDFA

** If supplemental, indicate amount and date of originally approved PDF |

|

Record of endorsement on behalf of the Governments:

|

(Enter Name, Position, Ministry) | |

Date: (Month, day, year) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This proposal has been prepared in accordance with GEF policies and procedures and meets the standards of the GEF Project Review Criteria for Project Concept approval.

|

|

Frank Pinto

Executive Coordinator |

Nick Remple GEF Regional Coordinator for Biodiversity and International Waters

Project Contact Person |

|

Date: 8 July 2004 |

Tel. and email:, +421-2-59337458, nick.remple@undp.org |

PART I - Project Concept

A - Summary

This Project Concept builds on the previous GEF investment in the Dnipro Basin, the development and country adoption of the Dnipro Basin Strategic Action Programme. As a priority, GEF support will focus on a Full-Sized Project Proposal to directly address the International Waters issue of industrial chemical pollution.

The development of the Dnipro Basin Strategic Action Programme (SAP) followed on from concerns expressed in the 1990s about the progressive degradation of the Dnipro River ecosystem, particularly in the middle and lower reaches. These concerns tied in closely with those raised over the degradation of the Black Sea environment, which led to the GEF support of the Black Sea Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis (TDA) and the Black Sea SAP. This in turn linked with the Danube SAP, now institutionally connected to the Black Sea programme through the “Strategic Partnership addressing Transboundary Priorities in the Danube/Black Sea Basin”.

The GEF project supporting the development of the Dnipro Basin SAP (Annex 4) was approved in December 1999 by the GEF Council, and became effective with inception workshop in 2001.

The development of the Dnipro TDA and SAP was the result of the joint effort of the three riparian countries (Republic of Belarus, Russian Federation, and Ukraine), assisted by international executing agencies. These included UNIDO (United Nations Industrial Development Organisation), IDRC (International Development Research Centre, Canada), IAEA (International Atomic Energy Agency), and UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme).

The SAP is a policy document, negotiated and endorsed by three riparian countries, to be implemented at the highest level of executive power. The SAP focuses on six transboundary priority areas for action to resolve the most urgent issues identified in the TDA: chemical pollution, modification of ecosystems, modification of the hydrological regime, eutrophication, flooding and high ground water levels, and radionuclide pollution.

Of these, the first priority is industrial chemical pollution. This can be categorised as coming from two main industrial sub-sectors, the major industrial complexes, generally with their own treatment facilities, and the groups of smaller urban based industries that discharge effluents through the municipal facilities, the Vodokanals.

Following a review of current donor activities and trends, it appears that major industries may be able to attract investment through other funding agencies. This leaves the more complex tasks of dealing with the large numbers of small industries that cumulatively pose major pollution threats, with the parallel concerns of financing mechanisms and regulation in a sector which is rapidly becoming more privatised.

The GEF Full-Sized Project will therefore address the priority issue of industrial chemical pollution emanating from the smaller urban industries discharging waste through the Vodokanals.

The overall objective of the FPP is to reduce transboundary industrial chemical pollution from small industries currently discharging through municipal waste systems.

This will be addressed through four specific objectives and components:

Objective 1: To introduce cleaner production methods to small industries – including sustainable financing mechanisms and local regulation and monitoring procedures;

Component 1: Pilot Projects to introduce cleaner production methods to small industries discharging through Vodokanals, including sustainable financing mechanisms and local regulation and monitoring procedures

Objective 2: To provide information on the status and progress of the SAP implementation programme to the Dnipro Basin management bodies, and to allow prompt decisions and responses to emergency situations;

Component 2: Transboundary Monitoring and Indicators Programme for SAP implementation;

Objective 3: To introduce harmonised environmental legislation to the three countries, in line with those prevailing in the EU;

Component 3: Harmonization of environmental legislation,

Objective 4: To establish key institutional and management structures within the wider SAP management bodies.

Component 4: Sustainable Institutional and Management Structures for SAP implementation.

B - Country ownership

- Country Eligibility

The proposal is eligible under the GEF OP-8 International Waters, Waterbody-based Operational Programme and falls under International Waters Strategic Priority IW-1, Catalyze financial resource mobilization for implementation of reforms and stress reduction measures agreed through TDA-SAP or equivalent processes. The three countries are eligible for country assistance from the World Bank and from UNDP Technical Assistance Grants.

- Country Drivenness

The three countries have jointly developed a Strategic Action Programme for the Dnipro River Basin, as well as National Action Programmes to carry out interventions to manage pollution and other national and transboundary issues. This project proposal is consistent with the National environmental strategies adopted by the three countries.

In Belarus the key principles in their environmental policies, are set out in the “National Sustainable Development Strategy of Belarus (1997)”, which includes the rational use and protection of water resources.

The “Russian Federation Environmental Doctrine (2002)” emphasises the need for the sustainable use of natural resources, and specifically introduces the “user/polluter pays” principle into environmental management.

In 1991, Ukraine adopted the law “On the Protection of the Natural Environment”, which in turn guided their policy - “Main Directions of the National Policy of Ukraine in the Field of Environment Protection, Nature Resource Use and Environmental Safety”. This policy document recognises the need to work at the basin level, both on environmental rehabilitation and water quality improvements.

While at present there is no single legal framework for environmental cooperation between the three countries, there are existing bilateral agreements between all three countries on the joint use and protection of transboundary waters.

However, in order to provide a stronger joint commitment to action, the countries have drawn up an “Agreement on Cooperation in the Field of Management and Protection of the Dnipro Basin” (The Agreement – Annex 1). This document forms the first part of the SAP and will be endorsed at the highest levels of Government in the three countries; this will then become the main instrument for national and regional actions to implement the SAP.

In the meantime, Ukraine has already made significant commitments to implementing some of the proposed actions in the SAP and the Ukraine NAP. These include the removal of minor sluices and cleaning of tributaries, both of which have led to improvements in water quality, with positive responses from local NGOs.

C – Program and Policy Conformity

- Program Designation and Conformity

The project falls under Operational Programme Number 8, Waterbody-based Programmes and IW SP-1, Implementation of Strategic Action Programmes.

The project addresses significant transboundary environmental concerns in the Dnipro Basin, a water-body shared by the three countries, the Republic of Belarus, the Russian Federation and Ukraine. The importance of these transboundary issues has been demonstrated in the Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis and the Strategic Action Programme, prepared under the current GEF/UNDP project RER/99/G31/A/1G/31.

The SAP development project demonstrated national commitments to joint environmental management, incorporating priority investments into national plans and supporting and establishing an institutional infrastructure necessary to ensure the long-term success of these interventions. These have included the development of the Agreement, the creation of national and regional stakeholder institutions with responsibility for, initially supervising and advising the project, and subsequently functioning as the main SAP advisory and executive bodies

The FPP project will build on previous regional experience of the joint management of shared water bodies, including the on-going GEF programmes supporting the improved management of the Black Sea, the Danube and the Caspian Sea. In doing so, the project will also provides lessons for joint management of other water bodies in the Europe and Central Asia countries (ECA), and deal with issues relating to EU Accession countries and harmonisation with EU Legislation.

2. Project Design

The starting point of the design of the full sized project is the major transboundary issues of the basin, prioritised in the TDA and SAP, developed under the previous GEF project.

The prioritisation criteria included: the transboundary nature of an issue; the scale of impacts on the Dnipro Basin and Black Sea ecosystems; the scale of impacts of an issue on economic activities, the environment and human health; linkages with other environmental issues and economic sectors; and expected multiple benefits.

On the basis of the above criteria, the TDA and the SAP identified six priority regional environmental issues.

Table 1 Priority Environmental Issues identified in the TDA and the SAP

|

Regional Priority of

Major Environmental Issues |

Priority Sectors |

|

Industry |

Agriculture

|

Fisheries

|

Municipal services |

Transport

|

Energy

|

Chornobyl

|

|

1 Chemical pollution |

1 |

2 |

6 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

- |

|

2 Loss of biodiversity/ecosystems |

5 |

1

|

3

|

4

|

6

|

2

|

-

|

|

3 Changed river flow |

5 |

2

|

6

|

4

|

3

|

1

|

-

|

|

4 Eutrophication |

3 |

1

|

4

|

2

|

6

|

5

|

-

|

|

5 Radionuclide Pollution |

2 |

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

3

|

1

|

|

6 Flooding and high groundwater |

2 |

1

|

-

|

3

|

4

|

-

|

-

|

The major environmental issue throughout the region is chemical pollution, stemming directly from Industrial Production[1].

The Water Pollution Index, adopted by all three countries as a tool to assess surface water quality, generally shows increasing water pollution as the river flows downstream, to levels described as “moderately polluted”. Concentrations of metal contaminants are relatively high in transboundary sections of the river, with fishery Maximum Acceptable Concentrations (MAC) exceeded in all water samples. MAC limits were exceeded for zinc, copper, lead and arsenic in fish samples.

The general pattern of industrial and urban development in the Dnipro Basin has been along the main Dnipro River and major tributaries, with heavy chemical, metallurgical and agro-industries dominating the major industrial complexes.

With deteriorating economic conditions within the region in the 1980s and 1990s, industrial production declined. As a result there has not been a major change in industrial pollution load. However, many of the remaining industries are using outdated processes, these discharge significant levels of pollutants.

It is only recently that there has been a reversal of this economic decline, with an expansion of industrial production. In addition there has been a major trend towards privatisation in all three countries, particularly of the smaller industries.

The key document prepared as an input to the SAP and TDA dealing with pollution, is the “Identification and Analysis of Pollution Sources (Hot Spots) – Priority Investment Portfolio”[2].

This report divides priority pollution hot spots into waste discharged from “Vodokanals” (municipal water and sanitation agencies) and other site specific pollution sources. The Vodokanals process wastewater from residential areas as well industrial effluents.

Table 2 Priority Pollution Hotspots

|

Vodokanals

|

Other Priority Pollution Sources |

|

Belarus |

4

|

1 x Refinery Treatment Facility |

|

Russia |

4

|

Intensive Livestock Production Units |

|

Ukraine |

7

|

3 x Metallurgical Combined Works |

While the volume of industrial waste treated by the Vodokanals is generally much less than the volume of domestic waste, the constituents of industrial waste are often the major concern in the treatment processes[3]. The priority concern in the SAP is the combined impact of waste discharged by small industries to the Vodokanals. In many cases these enterprises are either in the private sector or in the process of being transferred to the private sector.

Map 1 Dnipro Basin Priority Pollution Hotspots[4]

In addition, while some donors have been approached to resolve industrial pollution and production constraints for some of the major industries[5], at present no donors have shown their willingness to support the introduction of cleaner production technologies into the smaller industries. This is a clear “gap” that should be addressed by the GEF within the framework of the SAP.

2.1 The Full Sized Project: Implementation of Priority Interventions of the Dnipro Basin Strategic Action Programme: Chemical Industrial Pollution Reduction and the Development of Joint Institutional Arrangements.

The long-term objective of the full sized project focuses on the key issues identified in the TDA and SAP.

The overall objective of the project is to reduce transboundary industrial chemical pollution from small industries currently discharging through municipal waste systems.

This is effectively a refinement of the key objective of the previous GEF supported SAP development project, which was “…to remedy the serious environmental effects of transboundary pollution and habitat degradation in the Dnipro Basin…”.

Component 1: Pilot Projects to introduce cleaner production methods to small industries including sustainable financing mechanisms and local regulation and monitoring procedures

This objective will be achieved through three project outputs, the introduction of appropriate technologies, supported by a sustainable financing system, regulated and monitored by local institutions.

Output 1.1: Cleaner production processes installed in one or more small industries in one or more priority Vodokanals in each country

The project will direct a number of pilot investments to existing small industries, currently discharging through the Vodokanals, to implement a range of cleaner production technologies, including retrofitting cleaner production systems and pre-treatment of effluents. This would assist companies in rationalising their production processes and save money on raw materials, energy, water and water treatment.

The objective is to achieve a win-win situation: enhanced profits through more efficient environmentally sound production; and environmental gains through minimised pollution.

The project will draw on the lessons learned from the Danube TEST Project – Transfer of Environmentally Sound Technology. This approach adopts a critical path analysis, starting with the financial viability of the enterprise, following by a cleaner production assessment, which identifies pollutant reduction measures that an enterprise could undertake using available financial resources. This is followed by an industrial management assessment is undertaken. At the end of these two assessments (cleaner production and industrial management), the enterprise would have sufficient information about its production processes and problems to undertake an environmentally sound technology assessment. The EST assessment would identify the combination of best available techniques (combination of process change, pre-treatment and final treatment) and best available practice (sectoral environmental control strategies and measures) that would bring the enterprise into compliance with environmental norms.

An additional investment under consideration is the establishment of a regional Cleaner Production Centre. This would be based on the experience of establishing the Czech Cleaner Production Centre, which has operated since 1994 under a very similar industrial, institutional and economic development background[6].

Table 3 Vodokanals from which Pilot Projects will be identified for Cleaner Production Methods and Pre-treatment of Effluents from Small Industries

|

Country/Vodokanal |

Industries/ some pretreatment |

Comments

ND – No Data |

|

Belarus |

|

|

|

Retchitsa Vodokanal |

ND / 0

|

Industrial effluent forms 1/3 of treated waste |

|

Minsk Vodokanal |

ND

|

|

|

Mogilev Gorvodokanal |

ND

|

Man-made fibres, heavy metals and other waste |

Gomelvodokanal

|

ND

|

|

|

Russia |

|

|

|

Smolensk Vodokanal |

50 / 20

|

Mainly Food and Electronics |

|

Briansk Vodokanal |

ND

|

States industries have “pre-treatment if required” |

|

Novozybkov Vodokanal |

ND

|

|

|

Kursk Vodokanal |

ND

|

Industrial effluents exceed MAC |

|

Ukraine |

|

|

Kyiv Vodokanal

|

300 / 65

|

Heavy metal contamination of sludge |

|

Dnipropetrovsk Vodokanal |

130 / 30

|

Mainly Food, Electronics and Engineering |

|

Zaporizhya Vodokanal[7] |

90 / 15

|

Metallurgical, Food, Electronics and Engineering |

|

Chernihiv Vodokanal |

40 / 10

|

Heavy metal contamination of sludge |

|

Zhytomyr Vodokanal |

40 / 9

|

Mainly Food, Electronics and Engineering |

|

Loutsk Vodokanal |

30 / 4

|

Food, Engineering and Processing |

|

Kherson Vodokanal |

45 / 10

|

Mainly Food, Electronics and Engineering |

Many of these small industries are now in the private sector, or in the process of being privatised, as a result there are a whole new set of accompanying issues that require attention, including financing mechanisms, and regulatory and legislative control mechanisms.

Output 1.2: Sustainable Financing Mechanisms introduced to support the implementation of Cleaner Production Methods in Small Industries

The focus of this component will be on the private sector, and there is already considerable experience to draw on from within the region.

These could include soft loans, tax incentives, licensing and tariffs, an approach adopted in the EBRD/GEF project proposal “Danube Pollution Reduction Programme – Financing of Pollution Reduction Projects by Local Financial Intermediaries”.

The initial investment costs could be met through loans, either at “soft” rates, or with the incremental cost component of cleaner production provided as a grant, or with the loans discountable against future taxes[8]. The tax options could include incentives for future maintenance of facilities and reduced effluent challenge – taxes on effluent load and discharge, or tax reductions on reduced effluent load and discharge[9].

However, both existing and proposed financial mechanisms need to be supported by legislation and regulating institutions.

Output 1.3: Appropriate Regulation and Monitoring Procedures introduced for Small Industries discharging into Vodokanals

Clearly this component links closely with the previous output, sustainable financing mechanisms, as these mechanisms would become a component of regulatory procedures.

There are three elements to this intervention, defining acceptable discharge patterns, introducing legal and institutional regulatory mechanisms, and establishing appropriate monitoring procedures..

As a starting point, the impacts of different pollutants need to be considered, and different approaches reviewed to setting standards. With some pollutants the water quality objectives may be set by the total annual load of a particular pollutant or group of pollutants, or by the maximum acceptable concentration of that pollutant in the effluent.

There are then effectively two approaches to regulation, end of pipe control and process based control. The objective of the two approaches is the same – to limit the discharge of pollutants at the point of discharge to “acceptable” levels. While traditionally the end of pipe approach has been most commonly adopted, the “process-based control” approach is now strongly promoted by the EU through the 1996 “Integrated Pollution Prevention and Control Directive". This authorises a specific industrial process (cleaner production technology or pre-treatment facility), occasionally in conjunction with limited, or site specific, effluent quality specification.

The present institutional arrangements for regulation are constrained by lack of resources, and in many cases historical conflicts between the need to encourage industrial production and the need to protect the environment. Regulations tend to be set at national levels, with little room for local flexibility. The GEF pilot projects will to explore the possibility of establishing local government bylaws to allow municipal authorities to set their own criteria according to local conditions – including Best Available Technology (or best available technology not entailing excessive costs BATNEEC).

The final component is monitoring compliance and effectiveness of operation. Whether regulation is through process control or emission levels and patterns, the objective is to reduce emissions. The key will be to monitor at the point of discharge to indicate either compliance or the effectiveness of the allowed process. Secondly monitoring will be carried out at the point of discharge of the Vodokanal – or of the quality of processed sludge.

Outcomes:

· Reduced pollution loads to the Dnipro from small industries/vodokanals

· Improved profitability of selected small enterprises

· Reduced use of local and imported raw materials

· Improved local legal and regulatory frameworks for small industries

Component 2: Transboundary Monitoring and Indicators Programme for SAP implementation;

One of the principles incorporated into all SAPs is the free exchange of information. This is specifically written into the Dnipro River Basin “Agreement”, the formal starting point for the three countries to implement the SAP. Article 9 deals with the establishment of a Transboundary Monitoring Programme and the collection and analysis of information, including transboundary pollution loads and sources of contamination. Article 10 deals with the establishment of an “Interstate Environmental Data Base”, an on-line resource for the distribution and free exchange of environmental information.

An outline transboundary monitoring programme has been developed by the Intergovernmental Monitoring Group established during the development of the SAP. The programme takes into account recommendations of the UN ECE Working Group on environmental monitoring and assessment established within the framework of the Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes (Helsinki, 1992).

As it stands, the Transboundary Monitoring Programme is focused on specific quantifiable river water parameters. To establish the success of the SAP, a wider framework is required, including the use of Process Indicators, Stress Reduction Indicators and Environmental Status Indicators. The project will broaden the remit of the TMP and include parameters based on the framework drawn up by the International Waters Task Force (IWTF) and presented in a GEF report in 2002[10]. The programme will also draw on the proposals for Transboundary Monitoring prepared by the TACIS Transboundary Water Quality Monitoring Project, which had a particular focus on the major Dnipro tributary, the Pripyat River[11].

The project will support the establishment of the regional targeted transboundary monitoring programme with information needs and end-users clearly identified. This will run in conjunction with national monitoring programmes and is therefore clearly an incremental cost associated with the international management of a shared river basin.

The programme is expected to be implemented over fifteen years, in three stages. By the end of Stage 1, the first five years, the monitoring component will have produced the following Outputs:

· Output 2.1: Laboratories and hydrological stations re-equipped to minimum agreed regional standards;

· Output 2.2: Measurement quality control system established, including inter-laboratory comparative analysis;

· Output 2.3: Completed inventory of transboundary water pollution sources, including diffuse sources;

· Output 2.4: Coordinated classification of water quality and mass transfer assessment methods developed;

· Output 2.5: Comprehensive expeditionary inspections of Dnipro basin transboundary locations completed

· Output 2.5: System of process, stress reduction and environmental status indicators adopted and reporting mechanisms agreed

Outcomes: Effective and sustainable mechanisms in place for monitoring long-term SAP implementation.

Component 3: Harmonization of environmental legislation

One of the actions proposed in the SAP is the “harmonisation of legislation relating to the prevention of chemical, nutrient and radionuclide pollution in line with EU approaches”

Considerable work has already been undertaken during the development of the TDA and the SAP, and the conclusions presented in two reports. These were the “Harmonisation of Environmental Legislation of The Dnipro River Countries with the Legislation of EU Member States”, prepared by the National Working Groups of Belarus, Russia and Ukraine; and “Environmental Legislation of Russia, Ukraine and Byelorussia Compared with the Principles of EU Environmental Law”, prepared by UNIDO[12]..

The three countries have ratified the ECE (UN) Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Water Bodies and International Lakes”. While originally focused on the member countries of the Economic Commission for Europe, this convention has been extended to include other shared water bodies.

This is a specific issue for Ukraine, where both the government and the main opposition advocate joining the EU and strengthening ties with Europe. In addition, while the Republic of Belarus and the Russian Federation are unlikely to be accepted into the EU in the immediate future, they are also interested in bringing national legislation in line with the EU, where it might be useful in advancing the process of reformation.

It is clear that the harmonisation of legislation is often a long-term process, and the SAP envisages this is as taking up to fifteen years to complete. However, it is likely that changes will be introduced gradually, and the project will advise on implementing appropriate legislative changes as they are developed, and will monitor compliance with this legislation as it is implemented.

The main areas of concern fall under the six EU directives.

|

Document |

Priority |

|

Framework Directive 2000/60/ЕС, which establishes the guidelines for the activity in the sphere of water policy. |

I |

|

Directive 96/61/ЕС on integrated prevention of pollution and control [6] |

II |

|

Directive 91/271/ЕЕС on municipal sanitary water treatment [7] |

II |

|

Directive 80/788/ЕЕС on drinking water quality |

III |

|

Directive 76/160/ЕЕС on water quality in recreational bathing areas |

III |

|

Directive 91/676/ЕЕС on the protection of water from nitrates arriving to natural environment with agricultural waste |

III |

Outputs:

· Output 3.1: Framework Directive 2000/60/ЕС Water Policy – additional policy issues included as addenda to the Agreement and incorporated into the revised SAP;

· Output 3.2: Directive 96/61/ЕС Integrated Pollution Control –.action programmes developed to eliminate of the discharge of contaminants included in List 1 and the reduction of the discharge of contaminants included in List 2 of the Directive. A comparison of each article of the Directive with national legislation in the format of concordance tables, and a a timetable for introduction of changes and amendments to national legislation.

· Output 3.3: Directive 91/271/ЕЕС Municipal Sanitary Water Treatment – legislation modified to set timetable for provision of systems for inhabited centres of over 15,000 people and subsequently 2,000 to 15,000. Environmentally sensitive areas classified and specific guidelines developed. Adoption of EU monitoring practices.

· Output 3.4: Directive 80/788/ЕЕС Drinking Water Quality – adoption of EU drinking water quality standards (or maintain higher standards if local legislation already requires it), develop a timetable for introduction of changes and amendments to national legislation.

· Output 3.5: Directive 76/160/ЕЕС Water Quality in Recreational Bathing Areas – adoption of EU drinking recreational bathing water quality standards, develop a timetable for introduction of changes and amendments to national legislation.

· Output 3.6: Directive 91/676/ЕЕС – Protection of Water from Nitrates from Agricultural Waste – a comparison of each article of the Directive with national legislation in the format of concordance tables.

Outcome: Improved national and regional legislative frameworks for transboundary pollution reduction in the Dnipro River basin.

Component 4: Sustainable Institutional and Management Structures for SAP implementation

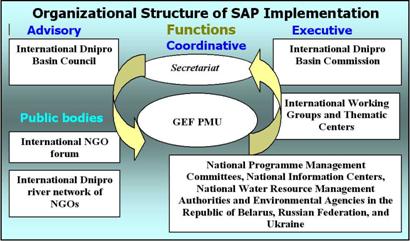

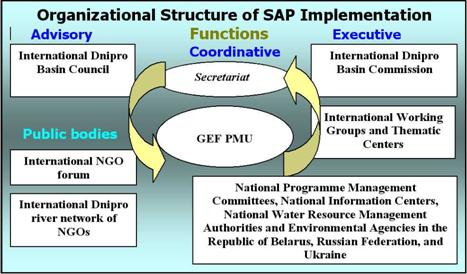

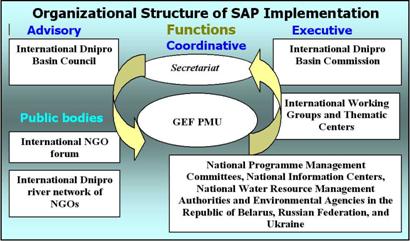

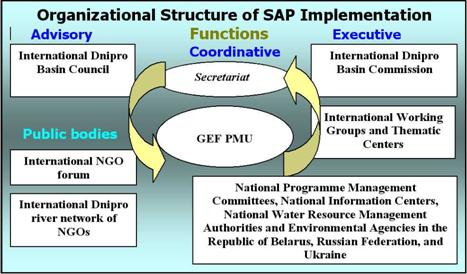

The Agreement proposes an outline institutional framework to supervise the functioning of the SAP. Article 4 states that the countries will establish the Dnipro Basin Commission, to be assisted by a permanent secretariat, responsible for providing organisational and technical support. This in turn is advised by the Dnipro Basin Council, a permanent body including government bodies, scientific research organisations; major water users (industries and institutions) and non-governmental environmental organisations and other community groups.

One of the key tasks of the management body will be to monitor and report on the progress of implementing the SAP and to revise the TDA and SAP in response to changes in environmental challenges.

Figure 1 Proposed Institutional Structure to Implement the SAP[13]

Most of the proposed institutional bodies are already functioning – even if only in a fledgling role – under the GEF SAP development project.

One of the major tasks of the management body will be to attract and coordinate bi-lateral and multi-lateral co-financing for projects. By the time the full project is initiated there will have been two Donor Conferences, the first held in 2004 and the second proposed for 2006. The objective of these conferences is to confirm co-financing for SAP activities, both those included in the proposed full project, and other parallel activities that are considered as priorities in the SAP. This approach to Donor coordination will be included as a regular procedure within the SAP management activities and may be supported by the full sized project.

Clearly there are major costs associated with establishing and running this institutional framework. The overall costs will vary according to the size of the institutions, the frequency of meetings, attendance at meetings and required outputs[14]. The three countries will cover the principal costs of setting up and starting to run the Commission and Secretariat; the full sized project will provide technical assistance and some preliminary support to the processes of establishing and running these bodies.

Outputs:

· Output 4.1: Agreed timetable and regular meetings of management bodies and records of meetings publicly available;

· Output 4.2: Confirmed and sustainable budgetary provisions for supporting the SAP management bodies;

· Output 4.3: Regular reporting procedures in place, including the interpretation of monitoring data to guide decision making and policy modification;

· Output 4.4: Stakeholder involvement expanded to include private sectors, specifically private industries and CBOs and other local organisations in areas affected by SAP interventions;

· Output 4.5: 5 Year revised and updated SAP and TDA, in response to impacts of SAP implementation projects, new challenges and modified environmental quality objectives, annual amendments as required.

Outcomes: Permanent and sustainable multi-country institutional (policy and executive) and participatory mechanisms established and operational for long-term integrated management of the Dnipro River basin.

2.2 Project Alternatives

2.2.1 No Further GEF Investment

The GEF has already made a considerable investment in supporting the regional development of the SAP and in defining preliminary interventions to counteract major environmental issues, especially those of a transboundary nature.

This involvement goes back to 1995, when the three countries agreed upon a memorandum requesting UNDP assistance in the development of a GEF Environmental Management Plan for the Dnipro Basin. In 1996, a preliminary grant was made available (RER/95/G42/A/1G/31) for the compilation of data for the preparation of a TDA. In parallel with this the International Development Research Centre (IDRC Canada) had been developing a series of independent initiatives focused on the rehabilitation of the Dnipro River Basin.

In 1999, the GEF agreed to fund the full development of the SAP and TDA, with UNDP as the Implementing Agency. This programme was managed by UNOPS as the Executing Agency, and continued to involve IDRC as well as bringing in UNIDO and the IAEA for specialist support to specific studies.

Meanwhile, the initial focus of the GEF and Implementing Agencies in developing the Black Sea SAP, has expanded into the GEF Strategic Partnership addressing Transboundary Priorities in the Danube/Black Sea Basin. By definition this includes the Dnipro Basin, and indeed Belarus, the Russian Federation and Ukraine are specifically included in recent projects.

Given the previous and ongoing, it would be inconsistent for the GEF not to fund a full project proposal on the management of transboundary industrial chemical pollution, addressing this regional priority for the Dnipro Basin and the Black Sea.

2.2.2 Developing a Multi-sectoral Project Proposal

One option for GEF involvement would be to support the SAP across a wide range of multi-sectoral interventions, establishing a more holistic programme of management.

However, this is contrary to the fundamental concept of the SAP, which accepts that there will always be resource constraints, and therefore sets priorities for interventions. The regional priority identified in the TDA and the SAP is industrial chemical pollution. If resources are adequate to significantly address this issue, then this would, by definition become the focus of the next phase of GEF activities.

In addition, other projects and other agencies have already committed themselves to actions in other sectors, both at the national and regional levels. Indeed the World Bank-GEF Investment Fund, under the Strategic Partnership addressing Transboundary Priorities in the Danube/Black Sea Basin, will finance a range of initiatives to reduce nutrient load into the Black Sea, and while mentioning only the Danube, specifically includes Russia, Belarus and Ukraine[15].

The GEF has also been approached to fund biodiversity projects both specifically linked to the Dnipro[16] and more generally in the basin, dealing with forestry, grasslands and agriculture. The EBRD is also financing investments in agribusiness and industry to improve performance and reduce pollution, although so far these are largely limited to Ukraine.

While the SAP is in itself a mechanism to supervise and report on the management of multi-sectoral and regionally prioritised interventions, it is also a mechanism for setting priorities. Given resource constraints the GEF should focus on the development of institutional implementing mechanisms for the SAP and direct interventions in industrial chemical pollution, the regional priority identified in the SAP and TDA.

3. Sustainability

The preliminary investments in developing the SAP and TDA, and in the preparation of a FPP, are not designed as sustainable planning processes, however the subsequent management of the SAP and the interventions implemented under the SAP must be institutionally and financially sustainable.

The project will focus on smaller industries discharging untreated or partially treated waste into municipal systems. In many cases it is these industries that are now being privatised. However, these interventions must be technically and financially sustainable, and supported by appropriate legislative and regulatory mechanisms. The design of the project specifically draws on the Danube “TEST” approach which takes technical and financial viability as a starting point for evaluating further investment in cleaner production technology.

At the SAP management level, the project will look at the proposed management structures and recommend low cost management systems, including a limited secretariat and targeted meetings. The “Agreement” commits the participating countries to “Convene”, “Establish”, and to “Provide the legal support to and ensure the sustainable operation” of the Commission, the Council, the Secretariat and the International NGO Forum.

The agreement specifies a time-frame for reviewing and if necessary revising the TDA and the SAP – every five years.

However, the main indication of real commitment to implementing the SAP is when the countries themselves undertake the financing of the SAP management bodies, and of the activities indicated in the SAP and NAPs. To some extent, this has already occurred in Ukraine, where certain activities listed in the NAP have been carried out in advance of formal approval of the Agreement or the SAP.

- Replicability

The lessons from the project are particularly relevant to the other CIS and NIS countries, many of which have the same heritage of water management and environmental legislation, and are undergoing similar problems of environmental degradation and industrial and economic transformation.

The previous GEF project, developing the Dnipro Basin SAP, had the benefit of two closely related programmes, the Black Sea and the Danube SAPs which have developed into the GEF Strategic Partnership Addressing Transboundary Priorities in the Danube/Black Sea Basin. In addition, the project was able to access information from other SAP planning exercises held throughout the world, including the Tumen River, Lake Tanganyika and the Caspian Sea[17].

The co-operation required by the three countries to jointly develop an agreed TDA and SAP, was greatly enhanced by their common heritage in terms of scientific background, environmental legislation and economic development.

The move to ever-closer ties with the EU, largely supported through TACIS, has introduced other common elements. The revised TACIS council regulation, running from 2000 to 2006, focuses on six aspects, including institutional and legal reform, environmental protection and private sector and economic development.

The project has developed a web site, specifically to publicise project activities[18], the site has a dual English and Russian interface. Copies of project reports and other relevant materials can be downloaded from the site. Many of the reports are in both languages. The site also includes a discussion forum, in Russian.

As a component of the SAP, this site will be further developed and expanded, and a full web based environmental database will also be established (http://www.dnipro-ecobase.org.ua). The results of future SAP interventions will be published and available in English and Russian on the project web site, along with evaluations of the processes used to develop these interventions. SAP management reports will also be made publicly available.

Within the GEF structure, the lessons from the preparation of the Dnipro SAP will feed into IW LEARN and the training programme currently under development, “The TDA/SAP approach in the GEF International Waters Programme”. Following on from this, the implementation of priority institutional and technical interventions to reduce chemical pollution will all provide replicable lessons for other programmes throughout the region.

Of immediate relevance to other donor agencies is the continued river basin management planning process underway on the Pripyat River[19], a major tributary of the Dnipro, as part of the EU/TACIS funded Transboundary Water Quality Project. This project deals with three other shared river bodies, where, at present only water quality monitoring is taking place. However, in the future this is hoped to extend to management planning, at which point the experiences of preparing a TDA and SAP and subsequently implementing the SAP, become immediately relevant.

The focus of the GEF FPP on waste treatment and cleaner production processes in smaller and often privatised industries, reflects an economic and industrial development situation that is similar throughout much of the CIS. The pilot projects initiated by the GEF under the full project, will therefore provide models that could be replicated in many of the CIS countries. This information will be available in English and Russian on the project web site, and will be made available at regional and international conferences.

As part of the FPP, the project will participate in regional meetings of the GEF Black Sea and Danube River programmes, and through UNIDO in regional meetings on Cleaner Production Technologies.

5. Stakeholder Involvement

During the preparation of the TDA and the SAP, considerable attention was paid to involving a broad range of stakeholders in the determination of environmental and social priorities and in identifying appropriate interventions.

While planning systems differ in each of the participating countries, formal government planning mechanisms involving ministries, research institutions and parastatals, were supplemented through the creation of an International NGO Forum, supported by the International Dnipro River NGO Network.

In order to ensure the continuation of this broad stakeholder involvement in the implementation of the SAP, the project established the International Dnipro Basin Council. The first council meetings were held in 2003. This structure will continue as an advisory body to the SAP management organisation, including the proposed International Dnipro Basin Commission supported by the secretariat.

According to the Council by-law, each riparian country is represented by 23 members drawn from Natural Resources and Environmental Ministries, leading scientific and research institutions and organisations, other government bodies, local self-government bodies of the riparian regions (oblasts), environmental non-governmental organisations and other non-governmental bodies.

The Council may invite observers and experts from other interested ministries and other central government bodies, local executive bodies, local self-government bodies, manufacturing enterprises, scientific institutions and civic organisations of the riparian countries as well as representatives from international organisations.

In addition, during the previous project phase, the preparation of the TDA and SAP, the project provided support to the International Dnipro River NGO Network. Under the framework of implementing the SAP, public and non-governmental organisations will continue to play an important role in the rehabilitation of the Dnipro Basin at all levels.

The SAP includes the following actions to enhance public participation and ownership.

· The enhancement of national legal systems to support public initiatives and ensure the active and effective participation of non-governmental organisations in the implementation of the Dnipro Basin Rehabilitation Programme;

· The acknowledgement and consideration of the interests of the public, as a matter of priority, in the process of formulation and implementation of local environmental action plans;

· The monitoring of SAP implementation by the public;

· Dissemination of information on the state of the Dnipro Basin and participation of the NGOs in this process;

· The integration of environmental considerations into educational programmes adopted in the riparian countries, and active involvement of the NGOs in the promotion of the integrated basin management approach.

This same process of public participation and formal stakeholder involvement through the NGO Forum and the Council, will be active during the implementation of the full sized project. It will also become a permanent component of the SAP management body, providing links with broader funding mechanisms, and reviewing the preliminary implementation of the SAP.

The FPP will include some initial financing to the International Dnipro River Network / International Dnipro Forum of Environmental NGOs, however long term financing will be negotiated as part of the overall costs of SAP management and with support from other NGO sources and from the private sector.

D - Financing

1) Financing Plan

The full sized project will receive co-financing from a range of sources. As a starting point, this will include national government contributions, as well as contributions from NGOs and the private sector. Parallel financing, dealing with other aspects of transboundary pollution, is already under consideration through alternative GEF financing channels and other international funding agencies.

Following the first Donors Conference, the World Bank have clarified their interests in jointly supporting elements of the SAP. The Pollution Reduction in Industry Loan (under preparation for the Ukraine) is targeting many of the industrial environmental hot spots as identified by the SAP. More generally, the bank supports reforms in the environmental sector under Programmatic Adjustment Loans (PAL II is currently underway) - through indexing environmental fees and fines and through the introduction of Integrated Pollution Permits for Industrial Enterprises. The bank is also proposing to establish a Municipal Development Fund Project (under preparation) which would finance priority investments in water supply/wastewater treatment and municipal solid waste management.

The EBRD is in discussion with the three countries on the provision of loans to small industries, loosely based on their experience of previous investments in the region. In December 2003, the EBRD stated that one of their key objectives for the Ukraine was the support of private sector development through establishing credit lines and equity funding in joint ventures and local private companies. Similar financial commitments are indicated in their “Statement of cumulative net commitments” to Russia and Belarus.

2) Cost Effectiveness

The success of direct investment in the introduction of Clean Production Processes to small industries depends on the cost effectiveness of the enterprises and the proposed production systems.

The objective is for a win-win situation, with enhanced profits through more efficient environmentally sound production; with environmental gains through minimised pollution. The starting point for the TEST approach piloted under the Danube SAP, is that the target enterprise must be initially financially viable over a five year period, to merit investment in improved production technologies. In many cases the need is for retrofitting facilities to keep the industries competitive while reducing emissions and complying with local regulations. A starting point is often the introduction of energy reducing processes, leading to immediate financial returns that can then be reinvested in other aspects of cleaner production.

E - Institutional Coordination and Support

1. Core Commitments and Linkages

The World Bank has endorsed the new 2004 to 2007 Country Assistance Strategy for Ukraine[20]. The World Bank has existing Country Assistance Strategies with the Russian Federation covering the period 2003 to 2005 and with Belarus covering the period 2002 to 2004[21]. The project proposals are coherent with the proposed strategies for development outlined in the three CAS documents.

2. Consultation, Coordination and Collaboration between and Among Implementing Agencies, Executing Agencies and the GEF Secretariat

The preceding GEF project, “The Preparation of a Strategic Action Programme (SAP) for the Dnipro River Basin and Development of SAP Implementation Mechanisms”, directly involved a number of Implementing Agencies and Executing Agencies.

The Implementing Agency was UNDP, and the Executing Agency was UNOPS. Both agencies were able to bring in considerable International Waters expertise, both from projects in the area (the Caspian Sea, the Black Sea, the Danube) as well as projects in other regions.

Much of the evaluation of industrial development and pollution was carried out under the guidance of UNIDO[22], as well as the review on Environmental Legislation. The IAEA had the responsibility for reviewing management of nuclear facilities and disposal sites, and for recommending reforms as inputs for the SAP. UNEP provided limited support recruiting a consultancy group to present the GIWA[23] methodology to a preliminary TDA workshop.

Finally the project participated in the 2nd GEF Biennial International Waters Conference, organised by GIWA (Global Internal Waters Assessment).

The input from these agencies has been incorporated in the SAP and TDA, and has led to the development of the specific proposals incorporated in the full sized project.

The Implementing Agency of the full project is expected to be UNDP and again the executing agency UNOPS. Expertise from UNIDO will be drawn on to further develop the pilot projects to introduce cleaner production methods and effluent pre-treatment to small industries, typically in the private sector.

The FPP is expected to bring in and/or work in parallel with a wider range of agencies, including the World Bank and the EBRD.

PART II - Project Development Preparation

N/A

Part III – Response to Reviews

A - Convention Secretariat

N/A

B - Other IAs and relevant ExAs

N/A

C - STAP

N/A

Draft

ANNEX 1 - AGREEMENT ON COOPERATION IN THE FIELD OF USE AND PROTECTION OF THE DNIPRO BASIN

The Parties to this Agreement – the Council of Ministers of the Republic of Belarus, the Cabinet of Ministers of the Russian Federation, and the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine – hereinafter referred to as the Parties,

Recognising the historic, economic, social, and cultural significance of the Dnipro River in the formation and development of the three nations of the Republic of Belarus, Russian Federation, and Ukraine;

Conscious of the role of the Dnipro Basin in the formation of ecosystem and climatic processes in the whole European region, and its impact on the Black Sea ecosystem;

Concerned about the ecological state of the Dnipro Basin, and problems relating to the provision of good quality drinking water supply and the conservation of biological and landscape diversity;

Recognising that the efforts currently being made at the local, national, and international level are not sufficient to ensure the substantial improvement of the ecological state of water bodies in the Dnipro Basin, and aware of the threat of loss of the Dnipro Basin ecosystem;

Convinced of the need for agreed political decisions in the field of nature use and environment protection in the Dnipro Basin;

Recognising that the rehabilitation of the Dnipro Basin ecosystem can only be ensured through the focused and coordinated action at the international and national level;

Appreciating the role of the public and the need for raising the public awareness on issues relating to the environmental rehabilitation of the Dnipro Basin,

Referring to the provisions of:

· The global and regional UN Conventions, to which the riparian countries of the Dnipro Basin are parties,

· The bilateral and multilateral agreements on cooperation in the field of environment protection and joint use/protection of transboundary water bodies;

· The Directive 2000/60/ЕС of the European Parliament and Council of 23 October 2000, that sets out the guiding principles and approaches pursued by the European Union in the field of water policy.

HAVE AGREED AS FOLLOWS:

Article 1

The Parties shall develop and pursue an agreed policy in the field of environment protection in the Dnipro Basin, based on the Strategic Action Programme for the Dnipro Basin and the Mechanisms for its Implementation (hereafter referred to as ‘the SAP’), which constitutes an integral part of this Agreement (Annex 1).

Article 2

In accordance with the objectives defined in the SAP, the Parties commit themselves to achieving:

· The sustainable nature use and environment conservation in the Dnipro Basin;

· The environment quality that is safe for human health;

· The protection and conservation of biological and landscape diversity.

Article 3

In order to attain the objectives specified in Article 1 of this Agreement, the Parties shall take necessary steps to:

· Provide the improved legislative/regulatory and institutional mechanisms that are adequate and appropriate for ensuring the sustainable use of natural resources and protection of the environment in the Dnipro Basin at the national level;

· Establish the institutional framework for the international management of the Basin, including the adequate legislative framework for multi- and bilateral cooperation; and enhance cooperation with the international donor agencies in the field of environmental rehabilitation of the Dnipro;

· Provide the legal and institutional framework for encouraging and promoting the public participation in the decision-making process at the national and international level;

· Harmonise the environmental legislation of the riparian countries of the Dnipro Basin with that of the EU;

· Ensure safe water consumption and use in the Dnipro Basin;

· Achieve a reduction in anthropogenic load, for a range of priority chemical substances;

· Adjust the level of anthropogenic load, to take account of assimilating capacity of the Basin;

· Minimise the threat of adverse impact of radioactive pollution on the human health and environment;

· Ensure safe living conditions in the areas affected by flooding events and elevated groundwater levels;

· Ensure the stable ecological state of water bodies, river floodplains, and riparian ecosystems;

· Ensure the conservation and restoration of wetlands that constitute an integral part of the European ecological network;

· Achieve and maintain the optimal pattern of nature reserves and agricultural landscapes;

· Achieve and maintain the optimal forest cover that ensures the sustainability of the Dnipro Basin ecosystems and takes account of their specific zonal features;

· Ensure the stable ecological state of meadows and steppes;

· Create and maintain favourable conditions for the reproduction of native, endemic, and migratory fish species;

· Achieve and maintain the optimal network of nature reserves and ecological corridors.

Article 4

Within the framework of this Agreement, the Parties shall:

· Convene the Conference of the Parties as a supreme body responsible for managing the Dnipro Basin;

· Establish the International Dnipro Basin Commission, to be assisted by a permanent Secretariat. The Secretariat shall be responsible for the provision of organisational and technical support to the activities of the International Dnipro Basin Commission;

· Provide the legal support to and ensure the sustainable operation of the International Dnipro Basin Council, International Dnipro Basin Thematic Centres, and the International Forum of Non-Governmental Organisations (NGO);

· Coordinate the activities of the International Dnipro Basin Commission and bilateral Governmental Commissions on Use and Protection of Transboundary Water Bodies.

Article 5

The Parties shall identify the list of participants to the Conference of the Parties and grant the powers of a supreme international basin management body to this Conference. The primary function of the Conference of the Parties shall be the review of the implementation of this Agreement upon the report of the Commission. Based on this report, the Conference of the Parties shall make appropriate decisions and recommendations, adopted by consensus. The Conference of the Parties shall be convened upon recommendation of the International Dnipro Basin Commission (hereafter referred to as ‘the Commission’), at least on a three-year basis.

The Conference of the Parties shall be convened within one month at the request of any Contracting Party under extraordinary circumstances.

Article 6

In order to facilitate the implementation of the provisions of this Agreement and coordination of joint activities, the Parties shall assign the appropriate executive and administrative functions to the International Dnipro Basin Commission.

The Statute of the International Dnipro Basin Commission and its Secretariat shall be approved by the Conference of the Parties.

Article 7

The Parties shall delegate to the International Dnipro Basin Commission the responsibility for overall coordination of activities of the International Dnipro Basin Thematic Centres and International Expert Working Groups, the National Programme Management Committees, the International NGO Forum, the International Dnipro River NGO Network, set up within the framework of the UNDP-GEF Dnipro Basin Environment Programme and designed to facilitate the implementation of the SAP.

Article 8

The International Dnipro Basin Council (hereinafter referred to as ‘the Council’) shall act as a permanent advisory and consultation body. The Council shall comprise the representatives of the central and territorial executive authorities and local self-governance bodies from the three countries of the Dnipro Basin; the specialists representing leading scientific research organisations; the representatives of major water users (industries and institutions) in the Dnipro Basin, and/or their groups and associations; and the representatives of the non-governmental environmental organizations and other community groups.

The Leaders of the delegations representing each Contracting Party shall act as the Co-Chairmen of the Council and shall approve the list of representatives from each country of the Dnipro Basin.

In its activities, the Council shall closely interact with the Commission, its permanent and ad hoc bodies, national organizations and institutions from the three riparian countries of the Dnipro Basin.

The Council Statute shall be approved by the Conference of the Parties.

Article 9

The Parties shall facilitate the implementation of the Transboundary Monitoring Programme, which constitutes an integral part of this Agreement (Annex 2), in order to:

· Collect reliable information on the ecological state of the Dnipro Basin and make forecasts on potential changes in this state;

· Control the transboundary pollution loads and sources of contamination;

· Make prompt decisions in emergency situations and provide a solid scientific basis for the settlement of potential conflicts;

· Measure the progress and success of the SAP implementation and adjust the identified environmental rehabilitation strategy for the Dnipro Basin in a timely manner, if and where a need arises.

Article 10

The Parties shall agree the procedure for the processing and exchange of information on the basis of the Interstate Environmental Data Base. As part of this Agreement, the Parties shall approve the Procedure for the Interstate Exchange of Environmental Information (Annex 3).

Article 11

The Parties shall initiate the preparation of the Dnipro Basin State of the Environment Report, to be issued every five years, and the Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis. Based on these documents, the Parties shall review and amend, if and where necessary, the Strategic Action Programme for the Dnipro Basin and the Mechanisms for its Implementation, at the international and national level.

Article 12

Any dispute arising in relation to the interpretation or application of the provisions of this Agreement shall be resolved through consultations and negotiations.

Amendments to this Agreement shall be adopted by consensus of the Parties, and any such amendment shall have the form of a separate protocol, which shall come into force and effect in accordance with this Article of the present Agreement and constitute an integral part of this Agreement.

Article 13

The Parties shall jointly develop the rules and procedures on the liability for a failure in the performance of obligations defined by the provisions of this Agreement.

Article 14

The present Agreement shall not limit, alter or affect the rights and obligations of the Parties ensuing from other existing international agreements, relating to the issues covered in this Agreement, or any future international agreements that may be signed in relation to the subject and objectives of the present Agreement.

Article 15

The present Agreement is open for accession by any other country committed to its objectives and tasks.

The present Agreement can be acceded to by any international organisation, provided that the objectives and principles stated in this Agreement are shared by an acceding party.

Article 16

The present Agreement shall come into force and effect on the date of its signing by the authorised representatives of the Parties.

Article 17

Upon the expiry of fifteen years from the effective date of this Agreement, any Party may withdraw from this Agreement by providing a written notification of renunciation to the other Parties. The renunciation shall take effect on the 31st of December of the year that follows the year of reception of the notification of denunciation by the other Parties.

In witness whereof the Parties hereto executed this Agreement in the city of ____________ on “____” ________________2004 in the Belorussian language, the Russian language, and the Ukrainian language in three copies, each of them being equally valid. The binding and controlling language for all matters relating to the meaning and interpretation of the provisions of this Agreement shall be the Russian language.

The following Annexes constitute an integral part of this Agreement:

Annex 1. Strategic Action Programme for the Dnipro Basin and the Mechanisms for its Implementation

Annex 2. Transboundary Water Monitoring Programme for the Dnipro Basin

Annex 3. Rules and Procedure of the Interstate Dnipro Basin Environmental Data Base

The original copies of this Agreement and Annexes to it shall be stored at the State Archive Offices of the Governments of the riparian countries of the Dnipro Basin.

|

For and on behalf of the Government of the Republic of Belarus |

For and on behalf of the Government of the Russian Federation |

For and on behalf of the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine |

|

_____________________ |

____________________ |

___________________ |

ANNEX 2 – THE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY OF THE TDA

This document is the result of the collaborative effort of the leading specialists of the Republic of Belarus, Russian Federation and Ukraine, assisted by many international experts. It represents the first-ever attempt to produce an in-depth and comprehensive analysis of the environmental situation within the whole Dnipro Basin.

Information gathered by the national experts from the three riparian countries and materials produced by IDRC, UNIDO and IAEA within the framework of the Project are unique, both in terms of their wealth and depth of analysis. This material has covered a broad range of economic, environmental, institutional and other activities, as well as their environmental consequences.

This analysis employed new information gathering mechanisms, the experience of a number of GEF projects to date in the design of the Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis, and tools originally developed for the Global International Waters Assessment (GIWA), to provide a maximum focus on transboundary issues without ignoring national concerns and priorities.

The Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis (TDA) for the Dnipro River Basin was produced using the most reliable scientific information as a basis for examining the state of the environment and the root causes of environmental degradation within the Basin. The TDA identifies the key environmental issues in the Basin and its transboundary sections, and assesses the significance of these issues for the whole Basin and each riparian country. The completed analysis involved justification of the most urgent transboundary issues and examination of the root causes of environmental degradation in the Basin. The need for preventive and corrective actions was also justified.

As a result of this analysis, key areas for environmental action have been identified as an initial basis for developing detailed strategic environmental programmes at the international and national level that aim to ensure the sustainable use and protection of natural/water resources in the Dnipro Basin.

The TDA identifies information gaps and deficiencies in the national legislative and institutional framework of the riparian countries. The experts examined the role of various economic sectors, the socio-economic situation, and the existing level of public awareness and involvement in decision-making on environmental issues.

The causal chain analysis was completed for each priority transboundary issue using the GIWA methodology modified by the national experts from the three riparian countries.

Detailed characterisation of the Dnipro Basin is presented in the Basin Passport, produced as part of the Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis. The Basin Passport reflects concise information on a broad range of aspects of the existing situation in the Basin, including its physical and geographic characteristics, administrative and territorial setting, resources, socio-economic indicators, anthropogenic pressures and the consequences of the Chernobyl accident. It also contains a list of international environmental agreements signed by the three riparian countries.

Six priority transboundary issues relating to five major areas of concern were identified using the GIWA methodology and prioritised in terms of their significance.

An indicator-based approach was employed in this analysis, using a suite of indicators supported by relevant factual information and reflecting specific features of the Dnipro Basin. These indicators can be used as important monitoring tools in the Strategic Action Programme (SAP) and National Action Plans (NAPs).

Causal chain analysis (using a suite of pressure/status/impact indicators) enabled the identification of the most significant immediate, sectoral and root causes of key environmental issues in the Basin.

The TDA document provides a useful basis for the development of the SAP and NAPs that will embody the priority actions on environmental rehabilitation in the Dnipro Basin.

The full TDA can be downloaded at: http://www.dnipro-gef.net/tda.php

ANNEX 3 Examples of Regional and National Projects Linked to SAP Objectives

|

Regional Priority |

Countries |

Donor |

Comments |

|

Chemical pollution |

|

|

|

|

Small Industries Discharging through Vodokanals |

B, R, U |

GEF FPP |

PDF B Project (Note also deals with SAP Institutional Development and Transboundary Monitoring) |

|

Loans to Industries direct and through banks |

U |

EBRD |

Direct and indirect investment in development of small and medium industries |

|

Loans to Industries direct and through banks |

B |

EBRD |

Limited investment in development of small and medium industries |

|

Loans to Industries direct and through banks |

R |

EBRD |

Investment in small and medium industries - unclear how many in the Dnieper Basin |

|

Large Industries |

U |

World Bank |

Have completed their own Hot Spots study |

|

|

|

|

|

Loss of biodiversity/ecosystems |

|

|

|

|

Protected areas in the Polesie Region |

B |

GEF |

Separate Country Projects Under development |

|

Protected areas in the Polesie Region |

U |

GEF |

Separate Country Projects Under development |

|

|

|

|

|

Changed river flow |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Eutrophication |

|

|

|

|

Nutrient Reduction from Municipalities, Industry and Agriculture |

16, incl. B, R, U |

World Bank / GEF |

Under the Strategic Partnership on the Danube and Black Sea Basins |

|

Zaporizhya Vodokanal Development and Investment Programme |

U |

EBRD |

Loan for the improvement of water treatment, discharging into the Dnieper River. Considering further loans to other Vodokanals |

|

Public-Private Partnership for rehabilitation and operation of wastewater treatment facilities |

U |

DFID, DANIDA, EBRD |

A number of related projects supporting workshops, pre-investment studies and investment |

|

|

|

|

|

Radionuclide Pollution |

|

|

|

|

Related to Chernobyl |

U, B |

IAEA, DFID, UNDP,CIDA, Japan… |

Many projects dealing with decontamination, social and environmental impacts… |

|

|

|

|

|

Flooding and high groundwater |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Transboundary Monitoring |

|

|

|

|

Transboundary Water Quality Monitoring and Assessment |

B, R, U and others |

EU TACIS |

Includes the Pripyat River - a major tributary of the Dnieper and extends to River Basin Planning |

|

|

|

|

|

Capacity Building and Institutional Development |

|

|

|

|

Local Environment Action Plans |

U |

US AID |

|

|

GIS Remote Sensing |

U |

US AID |

|

|

EcoLinks - public partnerships |

U |

US AID |

|

|

Local Environmental Management Training |

U |

US AID |

|

ANNEX 4

DNIPRO RIVER BASIN STRATEGIC ACTION PROGRAMME

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Republic of Belarus |

|

Russian Federation |

|

Ukraine |

|

Dnipro Basin Strategic Action Programme and Implementation Mechanisms |

Kyiv, Ukraine 2004

UNDP-GEF

Acknowledgements

This project is the result of the collaborative efforts of many people – professionals and experts that contributed their new ideas, suggested improvements, both in shape and substance, produced the final draft of the SAP document, including tables and graphics, committed to seek endorsement and approval of the SAP by the respective governments of the three riparian countries and, last but not least, undertook to disseminate this document among wide stakeholder circles within the Dnipro Basin.

The list below identifies many of the people who participated in the SAP preparation process. Much to our regret, this list is far from being exhaustive – a great number of other people have been actively involved in the SAP process, including managers from key ministries and agencies, scientists, mass media, non-governmental organizations, nature users concerned about the state of environment, students and their teachers.

On behalf of the UNDP-GEF Dnipro Basin Environment Programme, we would like to express our thanks and pay honour to all these people for their efforts dedicated to the conservation and rehabilitation of the Dnipro – the great Slavic river.

We extend our special thanks to:

- Prof. Laurence Mee and Dr. Martin Bloxham who provided excellent methodological guidance throughout the TDA/SAP process and helped to deliver the desired outputs in accordance with the requirements of the United Nations Development Programme and Global Environment Facility;

- Nick Hodgson and Andrew Menz, for their valuable comments provided in the course of the TDA/SAP preparation;

- the IDRC team that includes, without limitation, Jean-H. Guilmette, Ken Babcock, Myron Lahola, Olena Dronova, Igor Iskra, Jan Barica, Nick Tywoniuk, Darko Poletto;

- the expert team from the SNC-Lavalin Engineers&Constructors Inc., led by John Payne and Eugeny Dobrovolsky;

- and the international team of experts from the Republic of Belarus, Russian Federation, and Ukraine, who had to bear the burden of the SAP preparation: Yuri Andriychenko, Alexander Anischenko, Alexander Apatsky, Sergei Balashenko, Nikolai Bambalov, Galina Chernogaeva, Eugeny Grigoriev, Anatoliy Hrytsenko, Roman Khimko, Iliya Komarov, Alexey Kovalchuk, Natalia Levina, Nikolai Mikheev, Victor Omelianenko, Eduard Reznik, Victor Romanenko, Alexander Stankevich, Nikolai Tsygankov, Oleksandr Vasenko, Mykola Vedmid, Natalia Zakorchevna.

Contents

1. Introduction............................................................................................. 12

2 Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis........................................................ 12

2.1 Physical and Geographical Characteristics.......................................................................... 12

2.2 Socio-Economic Characteristics........................................................................................ 12

2.3 Priority Transboundary Issues of the Basin......................................................................... 12

2.4 Immediate Causes of Transboundary Issues....................................................................... 12

2.5 Underlying Sectoral Causes of Transboundary Issues......................................................... 12

2.6 Root Causes of Transboundary Environmental Issues......................................................... 12

3 Strategy for Environmental Rehabilitation of the Dnipro Basin............. 12

3.1 Long-Term Objectives...................................................................................................... 12

3.2 Steps to be Taken to Ensure the Environmental Rehabilitation of the Dnipro Basin.............. 12

I Sustainable Nature Use and Environment Protection in the Dnipro Basin............................. 12

II Environment Quality that is Safe for Human Health................................................. 12

III Conservation of Biological and Landscape Diversity............................................... 12