GB Monograph Series 14b.qxd 5/25/04 9:46 AM Page 1

Ballast W

ater Risk Assessment

Global Ballast Water

Management Programme

G L O B A L L A S T M O N O G R A P H S E R I E S N O . 1 4

Port of Sepetiba, Federal Republic of Brazil

Ballast Water Risk Assessment

Port of Sepetiba

Federal Republic of Brazil

Final Report

DECEMBER 2003

Final Report

Chris Clarke, Rob Hilliard,

.dwa.uk.com

Andrea de O. R. Junqueira,

Alexandre de C. Leal Neto, John Polglaze

GLOBALLAST MONOGRAPH SERIES

& Steve Raaymakers

More Information?

el (+44) 020 7928 5888 www

Programme Coordination Unit

Global Ballast Water Management Programme

International Maritime Organization

4 Albert Embankment

London SE1 7SR United Kingdom

Tel: +44 (0)20 7587 3247 or 3251

est & Associates, London. T

Fax: +44 (0)20 7587 3261

Web: http://globallast.imo.org

NO.14

A cooperative initiative of the Global Environment Facility,

United Nations Development Programme and International Maritime Organization.

Cover designed by Daniel W

GloBallast Monograph Series No. 14

Ballast Water Risk Assessment

Port of Sepetiba

Federal Republic of Brazil

December 2003

Final Report

Chris Clarke1, Rob Hilliard1,

Andrea de O. R. Junqueira3, Alexandre de C. Leal Neto2,

John Polglaze1 & Steve Raaymakers4

1 URS Australia Pty Ltd, Perth, Western Australia

2 GloBallast Brazil, Rio de Janeiro

3 Departamento de Biologia Marinha, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro

4 Programme Coordination Unit, GEF/UNDP/IMO Global Ballast Water Management Programme, International

Maritime Organization

! International Maritime Organization

ISSN 1680-3078

Published in April 2004 by the

Programme Coordination Unit

Global Ballast Water Management Programme

International Maritime Organization

4 Albert Embankment, London SE1 7SR, UK

Tel +44 (0)20 7587 3251

Fax +44 (0)20 7587 3261

Email sraaymak@imo.org

Web http://globallast.imo.org

The correct citation of this report is:

Clarke, C., Hilliard, R., Junqueira, A. de O. R., Neto, A. de C. L., Polglaze J. & Raaymakers, S. 2004. Ballast Water Risk

Assessment, Port of Sepetiba, Federal Republic of Brazil, December 2003: Final Report. GloBallast Monograph Series No.

14. IMO London.

The Global Ballast Water Management Programme (GloBallast) is a cooperative initiative of the Global Environment Facility (GEF),

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and International Maritime Organization (IMO) to assist developing countries to reduce

the transfer of harmful organisms in ships' ballast water.

The GloBallast Monograph Series is published to disseminate information about and results from the programme, as part of the

programme's global information clearing-house functions.

The opinions expressed in this document are not necessarily those of GEF, UNDP or IMO.

Ballast Water Risk Assessment, Port of Sepetiba, Federal Republic of Brazil, December 2003: Final Report

Acknowledgements

The Ballast Water Risk Assessment for the Port of Sepetiba was undertaken during 2002 and funded

by the GEF/UNDP/IMO Global Ballast Water Management Programme and the Government of

Brazil. The study team (Appendix 2) wishes to thank the following agencies and people for the

assistance:

Companhia Docas do Rio de Janeiro (CDRJ)

Rio de Janeiro

Fundação Estadual de Engenharia do Meio Ambiente (FEEMA)

Rio de Janeiro

Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (ANVISA)

Brasilia

Instituto de Estudos do Mar Almirante Paulo Moreira (IEAPM)

Arraial do Cabo

Ministério do Meio Ambiente (MMA)

Brasilia

Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ)

Rio de Janeiro

Universidade Federal do Paraná (UFPR)

Paraná

Dr Luis Antonio O. Proença

Universidade do Vale do Itajaí, Santa Catarina, Brazil

Dr Chad Hewitt

Biosecurity Unit, New Zealand Ministry of Fisheries, Auckland

Dr Fred Wells

Western Australian Museum, Perth, Western Australia

Dr Gustaaf Hallegraeff

University of Tasmania, Hobart, Tasmania

Dr Keith Hayes

CSIRO Marine Research, Hobart, Tasmania

The report was formatted and prepared for print by Leonard Webster.

i

Ballast Water Risk Assessment, Port of Sepetiba, Federal Republic of Brazil, December 2003: Final Report

Acronyms

ANVISA

Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (National Agency for Health Surveillance)

BW

Ballast water

BWM

Ballast water management

BWRA

Ballast Water Risk Assessment

BWRF

Ballast Water Reporting Form (the standard IMO BWRF is shown in Appendix 1)

CDRJ

Companhia Docas do Rio de Janeiro (Rio de Janeiro Port Company)

CFP

Country Focal Point (of the GloBallast Programme in each Pilot Country)

CFP/A

Country Focal Point Assistant

CRIMP

Centre for Research on Introduced Marine Pests (now part of CSIRO Marine

Research, Hobart, Tasmania)

CSIRO

Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (Australia)

DSS

Decision support system (for BW management)

DWT

Deadweight tonnage (typically reported in metric tonnes)

FEEMA

Fundação Estadual de Engenharia do Meio Ambiente (Foundation for the Study of

Environmental Engineering)

GIS

Geographic information system

GISP

Global Invasive Species Programme

GloBallast

GEF/UNDP/IMO Global Ballast Water Management Programme

GT

Gross tonnage (usually recorded in metric tonnes)

GUI

Graphic User Interface

IALA

International Association of Lighthouse Authorities

IBSS

Institute of Biology of the Southern Seas (Odessa Branch) of the Ukraine National

Academy of Science

IEAPM

Instituto de Estudos do Mar Almirante Paulo Moreira (Admiral Paulo Moreira

Institute of Marine Studies)

IHO

International Hydrographic Organization

IMO

International Maritime Organization

IUCN

The World Conservation Union

LAT

Lowest Astronomical Tide

MESA

Multivariate environmental similarity analysis

MEPC

Marine Environment Protection Committee (of the IMO)

NEMISIS

National Estuarine & Marine Invasive Species Information System (managed by

SERC)

NIMPIS

National Introduced Marine Pests Information System (managed by CSIRO,

Australia)

NIS

Non-indigenous species

OBO

Ore/bulk oil tankers (an rather unsuccessful vessel class now used for oil transport

only)

OS

Operating System (of any personal or mainframe computer)

PCU

Programme Coordination Unit (of the GloBallast Programme based at IMO London)

PRIMER

Plymouth Routines In Marine Environmental Research

PBBS

Port Biological Baseline Survey

ROR

Relative overall risk

SAP

(Regional) Strategic Action Plan

SERC

Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (United States)

VLCC

Very large crude carrier (200,000 300,000 DWT)

UFRJ

Universidade Federal Rio de Janeiro (Federal University of Rio de Janeiro)

ULCC

Ultra large crude carrier (over 300,000 DWT)

ii

Ballast Water Risk Assessment, Port of Sepetiba, Federal Republic of Brazil, December 2003: Final Report

Glossary of Terms and Definitions

The following terms and definitions are summarised from various sources including Carlton (1985,

1996, 2002), Cohen & Carlton (1995), Hilliard et al. (1997a), Leppäkoski et al. (2002), Williamson et

al. (2002) and the GloBallast BWRA User Guide. The latter document contains more detailed

definitions with explanatory notes, plus a glossary of maritime terms.

Ballast water

Any water and associated sediment used to manipulate the trim and

stability of a vessel.

Bioinvasion

A broad based term that refers to both human-assisted introductions

and natural range expansions.

Border

The first entrance point into an economy's jurisdiction.

Cost benefit analysis

Analysis of the cost and benefits of a course of action to determine

whether it should be undertaken.

Cryptogenic

A species that is not demonstrably native or introduced.

Disease

Clinical or non-clinical infection with an aetiological agent.

Domestic

Intra-national coastal voyages (between domestic ports).

routes/shipping

Established

A non-indigenous species that has produced at least one self-sustaining

introduction

population in its introduced range.

Foreign routes/shipping

International voyages (between countries).

Fouling organism

Any plant or animal that attaches to natural and man-made substrates

such as piers, navigation buoys or hull of ship, such as seaweed,

barnacles or mussels.

Harmful marine species

A non-indigenous species that threatens human health, economic or

environmental values.

Hazard

A situation that under certain conditions will cause harm. The

likelihood of these conditions and the magnitude of the subsequent

harm is a measure of the risk.

Indigenous/native

A species with a long natural presence that extends into the pre-historic

species

record.

Inoculation

Any partial or complete discharge of ballast tank water that contains

organisms which are not native to the bioregion of the receiving waters

(analogous to the potentially harmful introduction of disease causing

agents into a body as the outcome depends on inoculum strength and

exposure incidence).

Intentional introduction

The purposeful transfer or deliberate release of a non-indigenous

species into a natural or semi-natural habitat located beyond its natural

range.

iii

Ballast Water Risk Assessment, Port of Sepetiba, Federal Republic of Brazil, December 2003: Final Report

Introduced species

A species that has been intentionally or unintentionally transferred by

human activity into a region beyond its natural range.

Invasive species

An established introduced species that spreads rapidly through a range

of natural or semi-natural habitats and ecosystems, mostly by its own

means.

Marine pest

A harmful introduced species (i.e. an introduced species that threatens

human health, economic or environmental values).

Non-invasive

An established introduced species that remains localised within its new

environment and shows minimal ability to spread despite several

decades of opportunity.

Pathogen

A virus, bacteria or other agent that causes disease or illness.

Pathway (Route)

The geographic route or corridor from point A to point B (see Vector).

Port Biological Baseline

A biological survey to identify the types of introduced marine species

Survey (PBBS)

in a port.

Risk

The likelihood and magnitude of a harmful event.

Risk assessment

Undertaking the tasks required to determine the level of risk.

Risk analysis

Evaluating a risk to determine if, and what type of, actions are worth

taking to reduce the risk.

Risk management

The organisational framework and activities that are directed towards

identifying and reducing risks.

Risk species

A species deemed likely to become a harmful species if it is introduced

to a region beyond its natural range, as based on inductive evaluation

of available evidence.

Translocation

The transfer of an organism or its propagules into a location outside its

natural range by a human activity.

Unintentional

An unwitting (and typically unknowing) introduction resulting from a

introduction

human activity unrelated to the introduced species involved (e.g. via

water used for ballasting a ship or for transferring an aquaculture

species).

Vector

The physical means or agent by which a species is transferred from one

place to another (e.g. BW, a ship's hull, or inside a shipment of

commercial oysters)

iv

Ballast Water Risk Assessment, Port of Sepetiba, Federal Republic of Brazil, December 2003: Final Report

Lead Agencies

Lead Agency for General BW Issues in Brazil:

Contact person:

Mr Robson José Calixto

Position:

Acting Deputy Country Focal Point

Organization:

Ministério do Meio Ambiente (Ministry of Environment)

Address:

Esplanada dos Ministério Bloco B, Sala 831, Brasília - DF

Brazil. 70.068-900

Tel:

+55 61 317 11 56

Fax:

+55 61 224 24 66

Email: robson-jose.calixto@mma.gov.br

Web:

www.mma.gov.br/aguadelastro

Primary contact for BW Risk Assessments in Brazil:

Contact person:

Mr Alexandre de C. Leal Neto

Position:

Country Focal Point Assistant

Organization:

GloBallast - Brazil

Address:

Rua Teófilo Otoni 4, Rio de Janeiro-RJ, Brazil. 20.090-070.

Tel:

+55 21 3870 5674

Fax:

+55 21 3870 5674

Email:

aneto@dpc.mar.mil.br

v

Ballast Water Risk Assessment, Port of Sepetiba, Federal Republic of Brazil, December 2003: Final Report

Executive Summary

The introduction of harmful aquatic organisms and pathogens to new environments via ships' ballast

water (BW) and other vectors has been identified as one of the four greatest threats to the world's

oceans. The International Maritime Organization (IMO) is working to address the BW vector through

various initiatives. One initiative has been the provision of technical assistance to developing

countries through the GEF/UNDP/IMO Global Ballast Water Management Programme (GloBallast).

Core activities of the GloBallast Programme are being undertaken at Demonstration Sites in six Pilot

Countries. These sites are the ports at Sepetiba (Brazil), Dalian (China), Mumbai (India), Khark

Island (Iran), Odessa (Ukraine) and Saldanha Bay (South Africa). One of these activities (Activity

3.1) has been to trial a standardised method of BW risk assessment (BWRA) at each of the six

Demonstration Sites. Risk assessment is a fundamental starting point for any country contemplating

implementing a formal system to manage the transfer and introduction of harmful aquatic organisms

and pathogens in ships' BW, whether under existing IMO Ballast Water Guidelines (A.868(20)) or

the new international Convention.

To maximise certainty while seeking cost-effectiveness and a relatively simple, widely applicable

system, a semi-quantitative approach was followed, using widely-supported computer software. The

semi-quantitative method aims to minimise subjectivity by using as much quantitative data as

possible, to identify the riskiest ballast tank discharges with respect to a Demonstration Site's current

pattern of trade. Unlike a fully quantitative approach, it does not attempt to predict the specific risk

posed by each intended tank discharge of individual vessels, nor the level of certainty attached to such

predictions. However, by helping a Demonstration Site to determine its riskiest trading routes,

exploring the semi-quantitative BWRA provides a coherent method for identifying which BW sources

deserve more vessel monitoring and management efforts than others.

This report describes the BWRA activity undertaken for the Port of Sepetiba, which is the

Demonstration Site for the Federal Republic of Brazil, managed by Companhia Docas do Rio de

Janeiro (CDRJ). This capacity-building activity commenced in January 2002, with URS Australia Pty

Ltd (URS) contracted to the Programme Coordination Unit (PCU) to provide BWRA training and

software. Under the terms of reference, the consultants worked closely with their counterparts in a

project team co-managed by URS and the Country Focal Point Assistant (CFPA) for completing all

required tasks. These tasks required two in-country visits by the consultants (in April and August-

September 2002) to install the BWRA software and provide `hands-on' instruction and guidance.

Most of the data collation tasks were undertaken before, between and during these visits, with gap-

filling work undertaken by the consultants prior to a short `project wrap-up' visit in March 2003.

The first step was to collate and computerise data from IMO Ballast Water Reporting Forms

(BWRFs) to identify the source ports from which BW is imported to the Demonstration Site. For

periods or vessel arrivals where BWRFs were not collected or were incomplete, gap-filling data were

extracted from the port shipping records held at the Sepetiba port offices. These records also helped

identify which next ports of call may have been a destination port for any BW taken up at Sepetiba.

A multivariate procedure was then used to determine the relative environmental similarity between

the Demonstration Site and each of its BW source and destination ports. Comparing port-to-port

environmental similarities provides a relative measure of the risk of organism survival, establishment

and potential spread. This is the basis of the `environmental matching' method adopted by the project,

which facilitates estimating the risk of BW introductions when the range and types of potentially

harmful species that could be introduced from a particular source port are poorly known.

Another objective of the BWRA Activity was to identify `high-risk' species that may be transferred to

and/or from the Demonstration Site. The customised BWRA database provided by URS therefore

contained tables and interfaces for storing and managing the names, distribution and other information

on risk species. The taxonomic details, bioregional distribution, native/introduced status and level of

vi

Ballast Water Risk Assessment, Port of Sepetiba, Federal Republic of Brazil, December 2003: Final Report

threat assigned to a species were stored in the database for display, review and update as well as for

the BWRA analysis. For the purposes of the BWRA and its `first-pass' risk assessment, a risk species

was considered to be any introduced, cryptogenic or native species that might pose a threat to marine

ecological, social and/or commercial resources and values if successfully transferred to or from a

Demonstration Site.

During each visit the consultants worked alongside their Pilot Country counterparts to provide skills-

transfer as part of the capacity building objectives of the programme, with the project team divided

into three groups. Group A mapped the port and its resources using ArcView GIS. This group

included counterparts from Rio de Janeiro's State Foundation of Environmental Engineering

(Fundação Estadual de Engenharia do Meio Ambiente - FEEMA) who helped collate and compile

much of the required GIS data. Group B was responsible for managing the customised Access

database supplied by the consultants, and for entering, checking and managing the BW discharge data,

as recorded on the BWRF submitted by arriving ships and/or derived from the port's shipping records.

Group B used the database to identify BW source and destination ports, which was designed by the

consultants for ongoing input and management of BWRFs. Group C undertook the environmental

matching and risk species components of the Activity, using the PRIMER package to perform the

multivariate analyses for determining the environmental distances between Sepetiba and its source

and destination ports.

The various BW discharge, environmental matching and risk species data described above were then

processed by the database with other risk factors, including voyage duration and tank size, to provide

preliminary indication of:

(a) the relative overall risk posed by each BW source port; and

(b) which destination ports appeared most at risk from any BW uplifted at the Demonstration

Site.

This was achieved using a project standard approach, although the database also facilitates instant

modifications of the calculations for exploratory and demonstration purposes. The GloBallast BWRA

also adopted a `whole-of-port' approach to compare the subject port (Demonstration Site) with all of

its BW source and destination ports. The project has therefore established in Rio de Janeiro an

integrated database and geographic information system (GIS) that manages and displays:

· ballast water data obtained from arriving ship BWRFs and port shipping records;

· information on the Demonstration Site's navigational, physical and environmental conditions

and aquatic resources,

· port-to-port environmental matching data,

· risk species data, and

· risk coefficients and graphical categories of risk for ballast discharges.

The results, which were graphically displayed on user-friendly GIS port and world maps as well as in

ranked output tables, help determine the types of management responses.

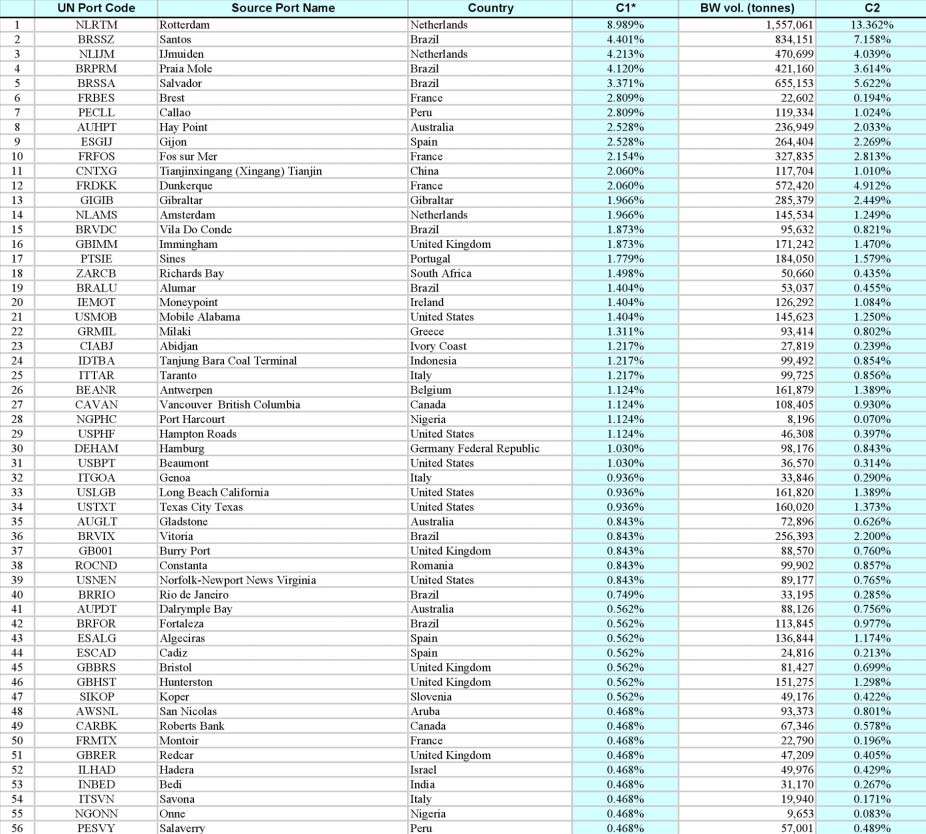

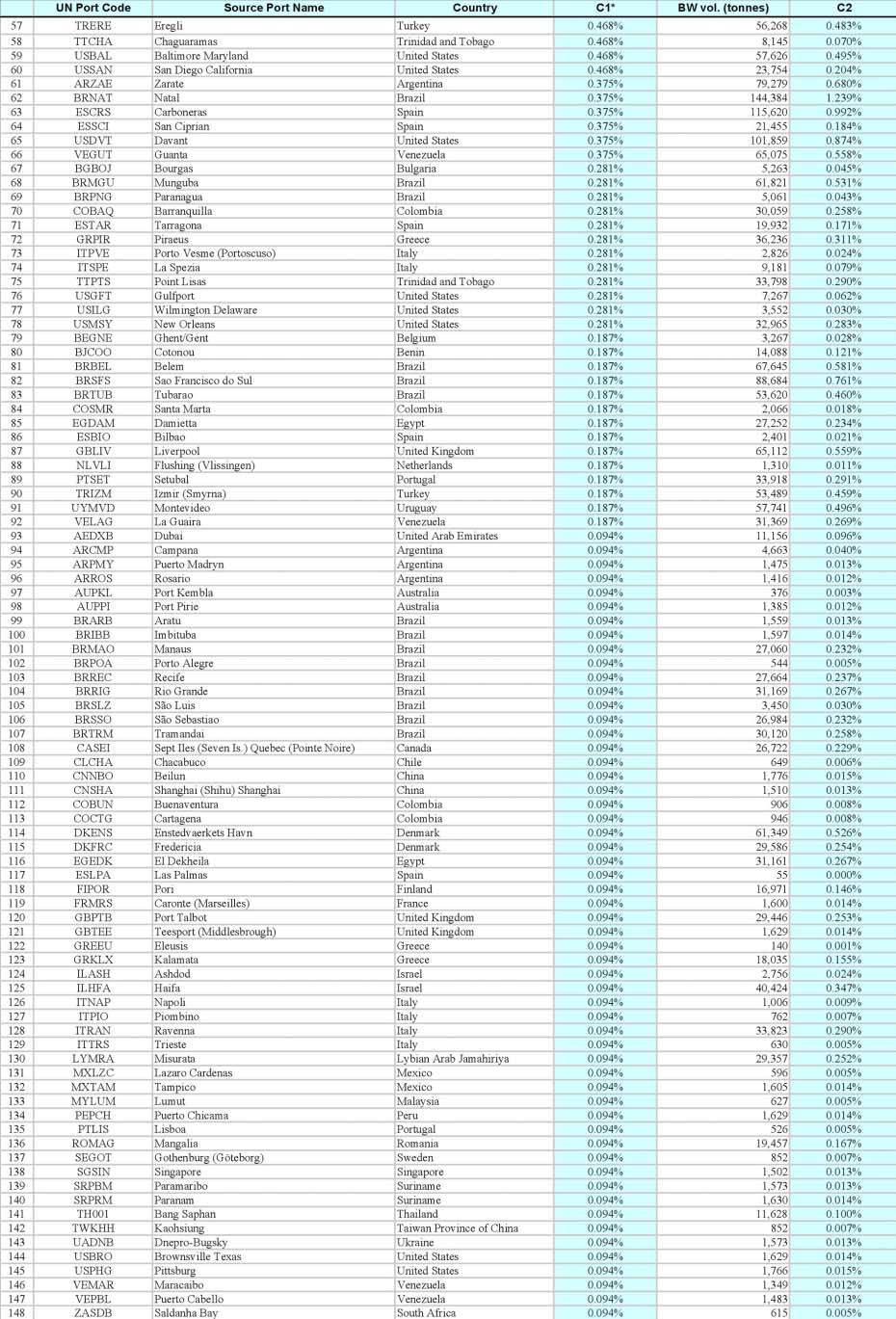

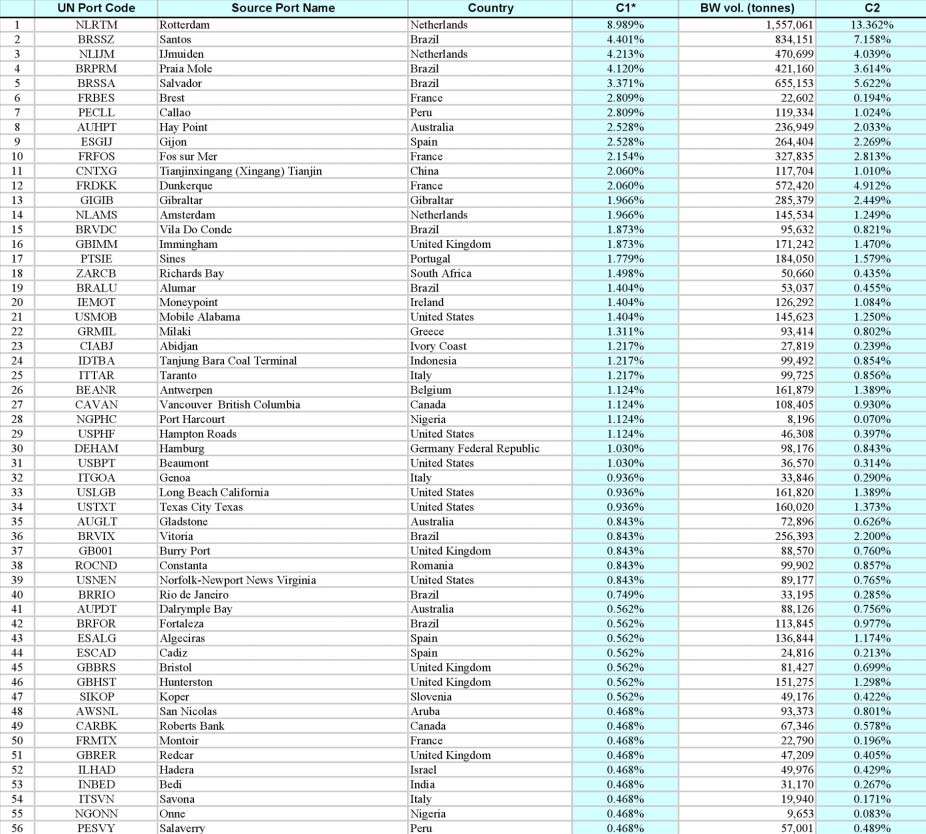

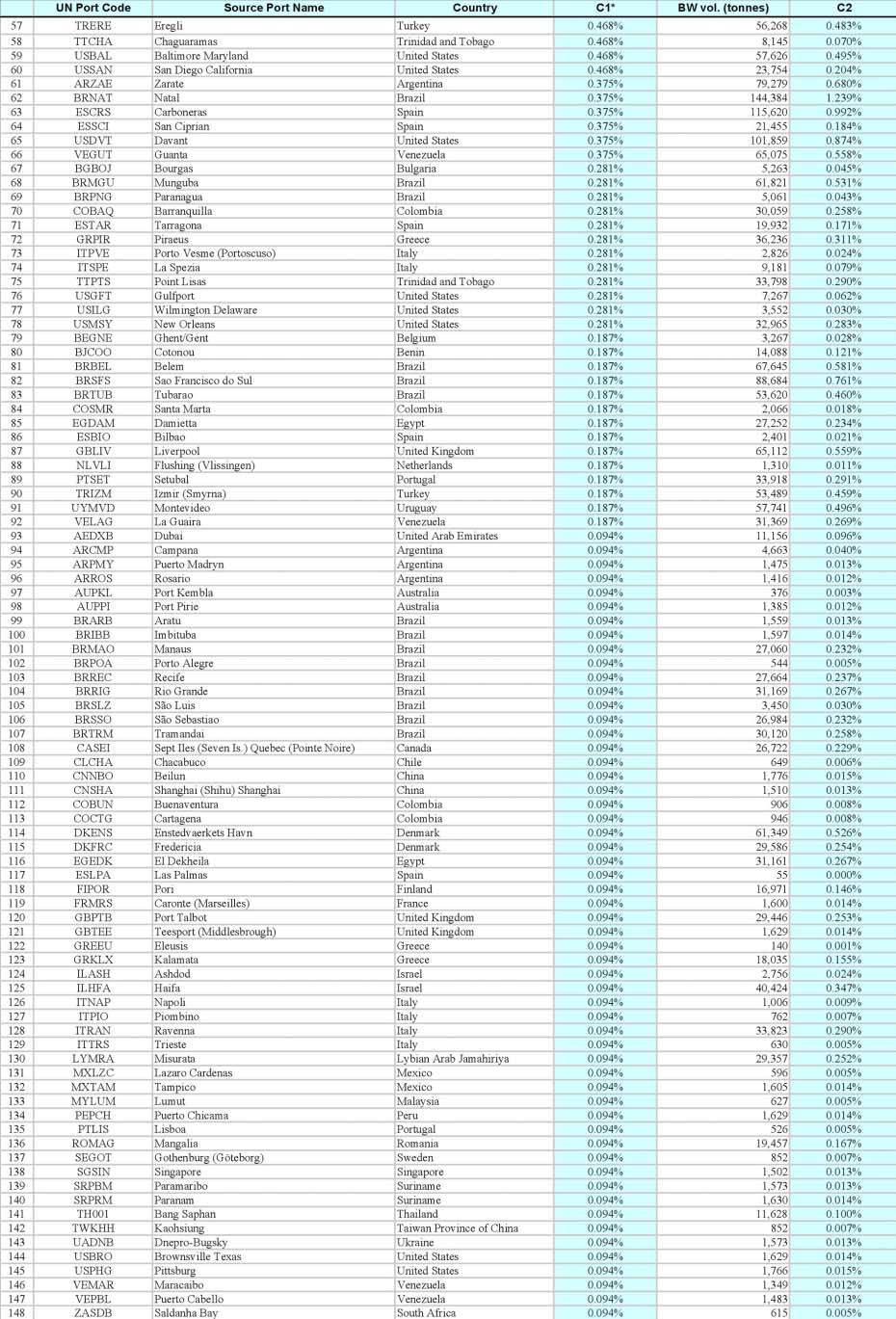

Of the 919 vessel visits and 1540 associated ballast tank discharges added to the database by the end

of the second consultants visit, half originated from BWRFs submitted between January 2001 and

June 2002, the rest being expanded from spreadsheet data provided by the CFP-A from 1998-2000

port shipping records. The total number of BW source ports identified from the tank discharge records

was 148. The source port `supplying' the highest frequency of BW discharges at Sepetiba was

Rotterdam (9%), followed by Santos (Brazil; 4.4%), Ijmuiden (Netherlands; 4.2%) and Praia Mole

(Brazil; 4.1%). The top 16 source ports provided 50% of all source-identified discharges, while only

38 of all source ports (26%) accounted for 75% of the total number of source-identified discharges at

Sepetiba.

vii

Ballast Water Risk Assessment, Port of Sepetiba, Federal Republic of Brazil, December 2003: Final Report

The total volume of BW discharged at Sepetiba from the identified source ports was 11,652,829

tonnes. The source port rankings for discharged volume were similar to those for discharge frequency.

Source ports providing the largest volume of discharged BW were Rotterdam (13.4%), Santos (Brazil;

7.2%) and Salvador (Brazil; 5.6%). The top 11 of identified source ports provided 50% of the total

discharged volume, while only 33 (22%) of all identified source ports accounted for 75% of the source-

identified volume discharged at Sepetiba. Of the top 20 ports, five were in Brazil, three in both the

Netherlands and United States, two in both France and United Kingdom, and one each in Australia,

Belgium, Gibraltar, Portugal and Spain.

Of the 104 potential BW destination ports (i.e. reported Next Ports of Call where BW uplifted at

Sepetiba could be discharged), only 44 of them accounted for >80% of reported Next Ports of Call.

The nearby port of Santos was by far the most frequently reported destination port (over 10%, and

which serves Brazil's largest industrial city of Sao Paulo). Of the 17 ports accounting for the

destinations of >50% of vessel departures from Sepetiba, five were in Brazil, four in Argentina, two

each in France and China, and one each in Bulgaria, Colombia, Mexico and Taiwan Province.

Of the various BW source and potential destination ports, sufficient environmental data were obtained

to include 58% of the former and 56% of the latter in the multivariate similarity analysis by PRIMER.

These ports accounted for 80% of all tank discharges and 67% of all vessel departures respectively.

To allow all identified BW source ports and next ports of call to be part of the `first-pass' risk

assessment, ports not included in the multivariate analysis were provided with environment matching

coefficient estimates. The most environmentally similar port to Sepetiba was Rio de Janeiro (0.86

matching coefficient), while 22 other Brazilian ports had either calculated or estimated coefficients in

the 0.7 - 0.8 range. The nearest similar ports beyond Brazil were the west African port of Abidjan

(0.70), Singapore (0.63) and several Mediterranean ports (>0.6). The most environmentally dissimilar

ports trading with Sepetiba in 1998-2002 were riverine, highly brackish and/or cool water ports in

North America, southern Argentina and north-west Europe (matching coefficients in the 0.2 -0.3

range).

The relative overall risk (ROR) posed by each of Sepetiba's identified BW source ports was

calculated as proportions of the total threat due its contemporary (1998-2002) trading pattern. The

project standard ROR calculations identified 20 of Septiba's148 identified source ports as

representing the highest risk group, in terms of their BW discharge frequency, volume, environmental

similarity and assigned risk species threat. However it was noted that the risk species threat

component calculated for each source port (which varied according to the number of introduced and

native species in its bioregion, and their categorization as either unlikely, suspected or known harmful

species) did not provide a globally reliable list owing to regional biases in aquatic sampling effort and

taxonomic knowledge.

From the 919 visit records, the project standard calculation indicated that Brazilian ports provided the

top 20% of the total ROR (values in the 0.20-0.29). The highest risk ports were led by Santos (ROR

0.290) and Rio de Janeiro (0.285), closely followed by Rio Grande and Praia Mole (0.248). The first

non-Brazilian ports were Montevideo (Uruguay) and Rotterdam (Netherlands), which were grouped

as `High Risk' ports and ranked 22nd and 23rd overall (RORs close to 0.20). The highest risk ports

beyond the Atlantic were the Mediterranean ports of Taranto, Italy (0.201) and the Adiratic port of

Koper, Slovenia (0.199). The highest risk port beyond the Atlanto-Mediterranean area was the Pacific

coast Mexican port of Lazaro Cardenas (ranked 42nd with a ROR value of 0.183). Seventy five of

Sepetibas's BW source ports were ranked in the low (31) and lowest (44) risk categories. These had a

wide distibution and were warm or cool water ports plus riverine/brackish ports. The source port with

the lowest ROR (0.05) was the cool temperate port of Puerto Madryn in southern Argentina.

Based on Sepetiba's pattern of shipping trade in 1998-2002, the ROR results indicated that BW from

vessels arriving from ports in temperate to cool temperate pose far less of threat than those from

Brazil's coast and southern Europe, with the exception of Rotterdam and Lazaro Cardenas in Mexico.

In the case of the Brazilian ports, their relatively close environmental similarities and regular BW

viii

Ballast Water Risk Assessment, Port of Sepetiba, Federal Republic of Brazil, December 2003: Final Report

sources made them dominate the highest risk group. The project standard results therefore indicated a

much higher threat of BW-mediated introductions is posed by vessels arriving in ballast from

Brazilian and southern European ports, and this was logical given Sepetiba's biogeographic location

and trading pattern. The project standard results also indicated that the `first-pass' treatment of the

risk coefficients provides a reasonable benchmark for any investigative manipulations of the risk

formula or database management.

While the tropical and subtropical coastline of Brazil does not appear to be experiencing the level of

harmful invasive species recently reported for the cooler Uruguayan and Argentinean waters, it was

clear that Sepetiba Bay is not immune to the spread of harmful marine species such as

introduced/cryptogenic toxic dinoflagellates that can increase the severity and impacts of red tides.

For a largely tropical country with a high number of brackish and estuarine ports, the issue of water-

borne tropical pathogens such as cholera, typhus and yellow fever and parasites was also recognized.

The BWRA results confirmed that Sepetiba `exports' considerable volumes of BW, much of which

appeared to be destined for other Brazilian ports (especially via bulk carriers departing the coal and

alumina berths and some of the ships leaving the Tecon wharf). However, reliable identification of the

BW destination ports was confounded by the lack specific questions on the IMO-standard BWRFs,

and the uncertainty of knowing if a recorded `Next of Port Call' is where BW is actually discharged.

The most important BW destination port appeared to be Santos, and this port also had one of the

closest environmental matching values to Sepetiba. The results therefore indicated that any unwanted

species which establishes in Sepetiba Bay has a more than reasonable chance of `port-hopping' to

both Santos or Rio de Janeiro via BW-mediated transfers. In the case of more distant ports, the French

Atlantic port of Quimper was a relatively frequent next port of call with a moderate environmental

similarity (0.5). In the case of the risk species currently assigned to Sepetiba's bioregion, noxious

phytoplanktonic species that can make cysts, survive ballast tank conditions and produce suffocating

or toxic red tides in eutrophic inshore waters, represented species deemed likely to cause the highest

potential impacts if introduced to new areas.

The top 20 ports identified in the highest risk category by the project-standard method were all

Brazilian ports. This outcome was to a large part determined by the size of their environmental

matching coefficients, together with the relatively short voyage durations. An investigation of the

project standard's default weightings confirmed that the environmental coefficient was powerful, and

that altering these can lead to unexpected outcomes and create the potential trap of merely playing

`numbers games', particularly if the objective and rationale for altering the project standard

calculation and default input factors are not clearly established. It was recognized there is a good

argument for allowing environmental matching to remain the most influential component of a BWRA

formula when there is any doubt as to the completeness or reliability about the particular risk species

threat. It was therefore concluded that, when evaluating any BWRA results, each risk component of

the calculation should be examined to understand its contribution to the overall outcome, whichever

method is used.

Of the various BWRA objectives and tasks that were undertaken during the activity, reliable

identification of destination ports that may receive BW from the Demonstration Site was confounded

by the lack of specific questions on the IMO-standard BWRFs, and the uncertainty of knowing if the

`Next Port of Call' recorded on a BWRF is where ballast water is actually discharged. Thus presently

there is no mechanism enabling a `reverse BWRA' to be undertaken reliably. In the case of Sepetiba,

several visiting vessels types do not uniformly discharge or uptake their full capacity of BW, with

many of their previous and next ports of call involving part cargo discharge and loading. If more

reliable and `forward-looking' BWRAs are to be undertaken to identify destination ports in the future,

supplementary questions will need to be added to the present IMO-standard BWRF, including the

names of the three last ports of call as well as the port where discharges from each partially or

completely ballasted tank are predicted.

ix

Ballast Water Risk Assessment, Port of Sepetiba, Federal Republic of Brazil, December 2003: Final Report

The main objectives of the BWRA Activity were successfully completed during the 15 month course

of this project, with the various tasks and exploratory/demonstration software providing a foundation

enabling the regional promulgation of further BW management activities by Brazil. Project outputs

included a trained in-country risk assessment team, and an operational BWRA system and User Guide

for use as a demonstration tool in the region. This places Brazil in a good position to provide

assistance, technical advice, guidance and encouragement to other port States in South America.

x

Ballast Water Risk Assessment, Port of Sepetiba, Federal Republic of Brazil, December 2003: Final Report

Table of Contents

Acknowledgements......................................................................................................................................i

Acronyms......................................................................................................................................................ii

Glossary of Terms and Definitions ..........................................................................................................iii

Lead Agencies..............................................................................................................................................v

Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................vi

1

Introduction and Background .........................................................................................................1

2

Aims and Objectives .........................................................................................................................5

3

Methods ..............................................................................................................................................6

3.1

Overview and work schedule...................................................................................................................6

3.2

Resource mapping of the demonstration port.........................................................................................8

3.3

De-ballasting/ballasting patterns ...........................................................................................................10

3.4 Identification

of source ports..................................................................................................................11

3.5 Identification

of destination ports ...........................................................................................................12

3.6 BWRF

database.....................................................................................................................................13

3.7

Environmental parameters.....................................................................................................................15

3.8 Environmental

similarity analysis...........................................................................................................16

3.9

Risk species ...........................................................................................................................................17

3.10 Risk assessment ....................................................................................................................................22

3.11 Training and capacity building ...............................................................................................................27

3.12 Identification

of information gaps...........................................................................................................29

4

Results ............................................................................................................................................. 30

4.1 Description

of port ..................................................................................................................................30

4.2 Resource mapping .................................................................................................................................33

4.3 De-ballasting/ballasting pattern .............................................................................................................35

4.4 Identification

of source ports..................................................................................................................38

4.5 Identification

of destination ports ...........................................................................................................41

4.6

Environmental similarity analysis ..........................................................................................................42

4.7

Risk species ...........................................................................................................................................47

4.8

Risk assessment results ........................................................................................................................52

4.9

Training and capacity building ...............................................................................................................57

4.10 Identification

of information gaps...........................................................................................................58

5

Conclusions and Recommendations .......................................................................................... 60

5.1

Recommendations .................................................................................................................................60

5.2

BWRA recommendations and plans by Pilot Country ..........................................................................61

6

Location and maintenance of the BWRA System...................................................................... 62

References................................................................................................................................................. 63

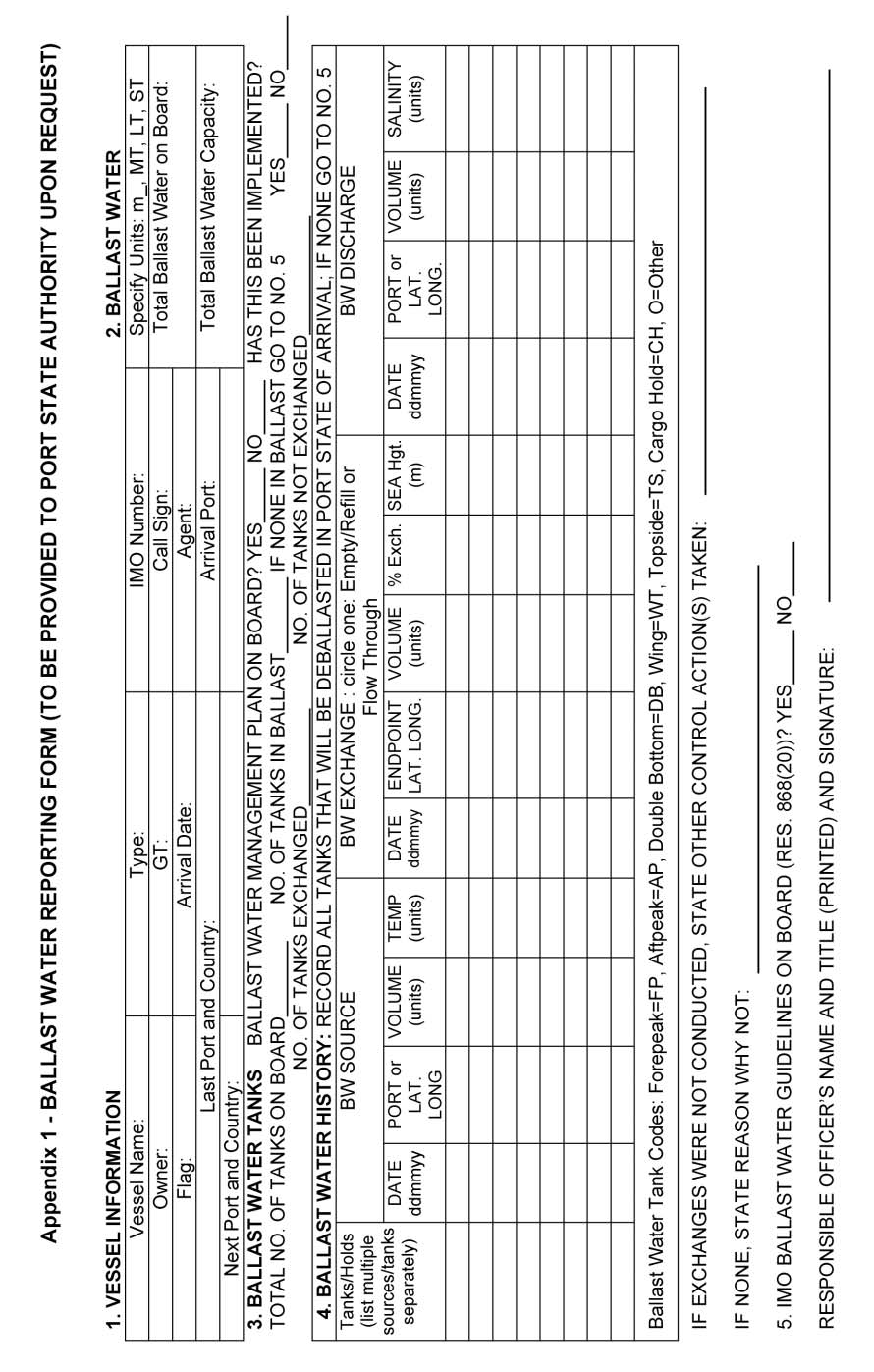

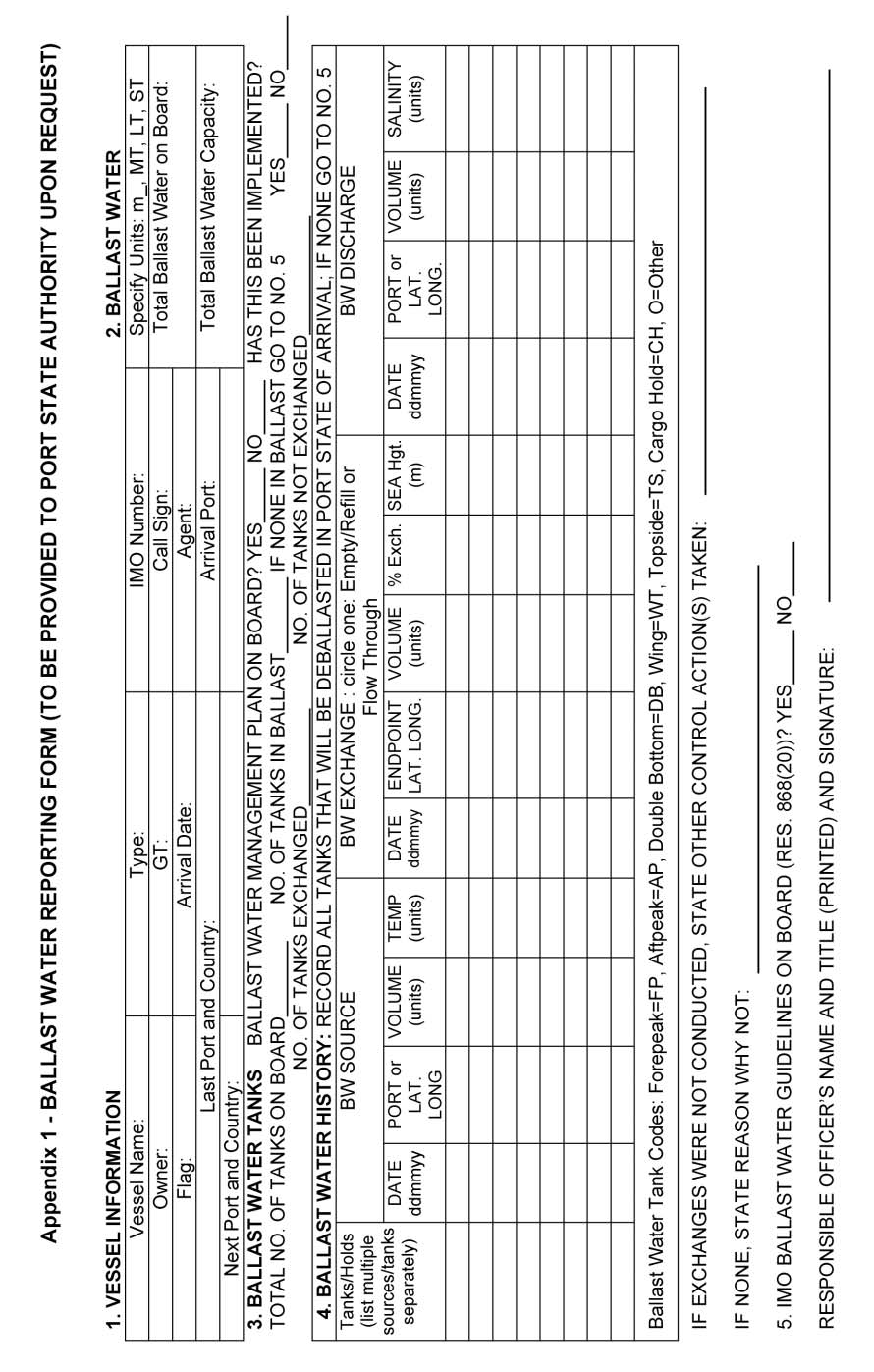

APPENDIX 1: Copy of IMO Ballast Water Reporting Form

APPENDIX 2: Risk Assessment Team for the Port of Sepetiba

APPENDIX 3: Check-list of project requirements

APPENDIX 4: Information sources used for collating Port Environmental Data

APPENDIX 5: Sources and references of Risk Species information

APPENDIX 6: Name, UN code, coordinates and environmental parameters of the 357 ports

used for the multivariate similarity analyses for all Demonstration Sites

APPENDIX 7: Consultants' Terms of Reference

xi

Ballast Water Risk Assessment, Port of Sepetiba, Federal Republic of Brazil, December 2003: Final Report

Figure 1.

Locations of the six GloBallast Demonstration Sites and their various ballast water source

and destination ports. .............................................................................................................................. 3

Figure 2.

Location of Sepetiba and other ports of Brazil........................................................................................ 4

Figure 3.

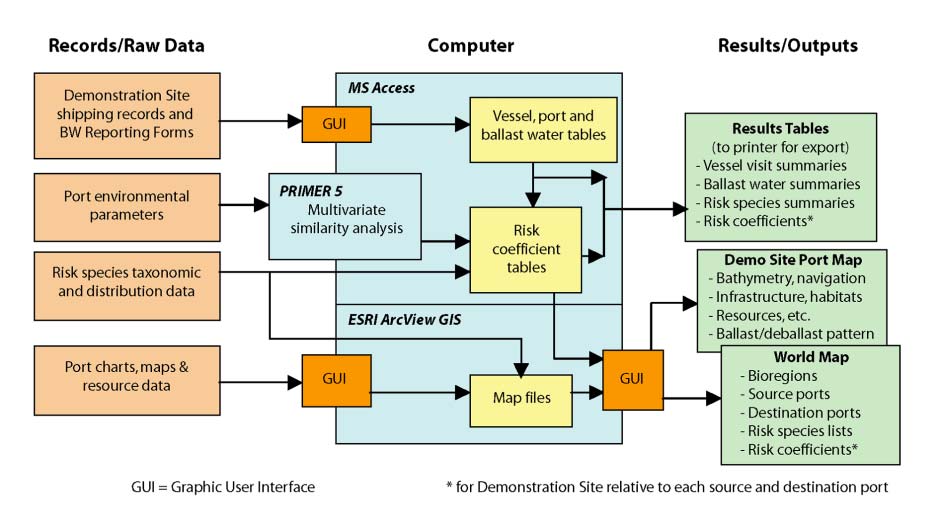

Schematic of the GloBallast BWRA system ........................................................................................... 6

Figure 4.

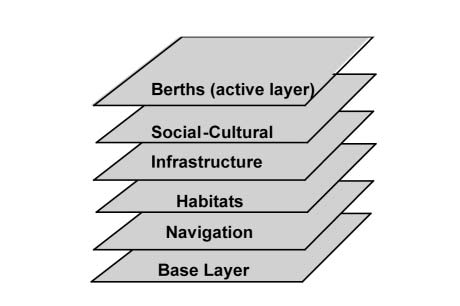

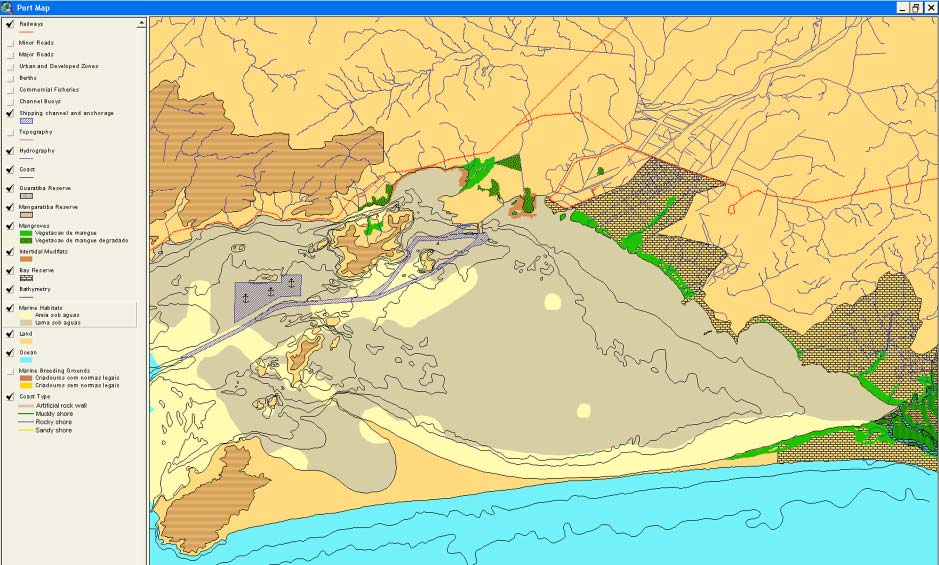

Thematic layers used for the Port Map GIS............................................................................................ 9

Figure 5.

Working page of the Excel spreadsheet used to estimate BW discharges ......................................... 12

Figure 6.

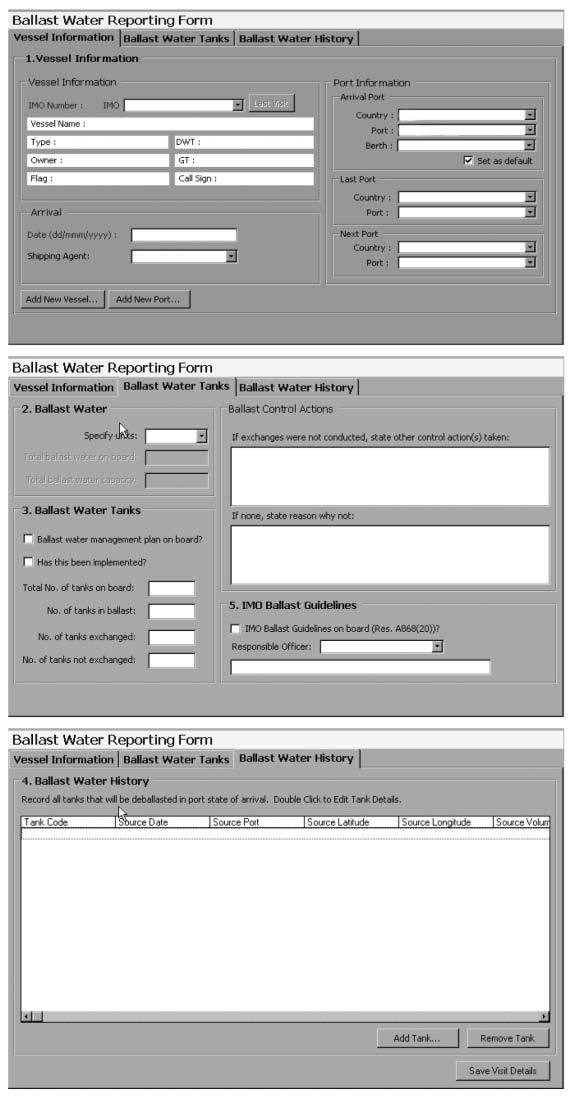

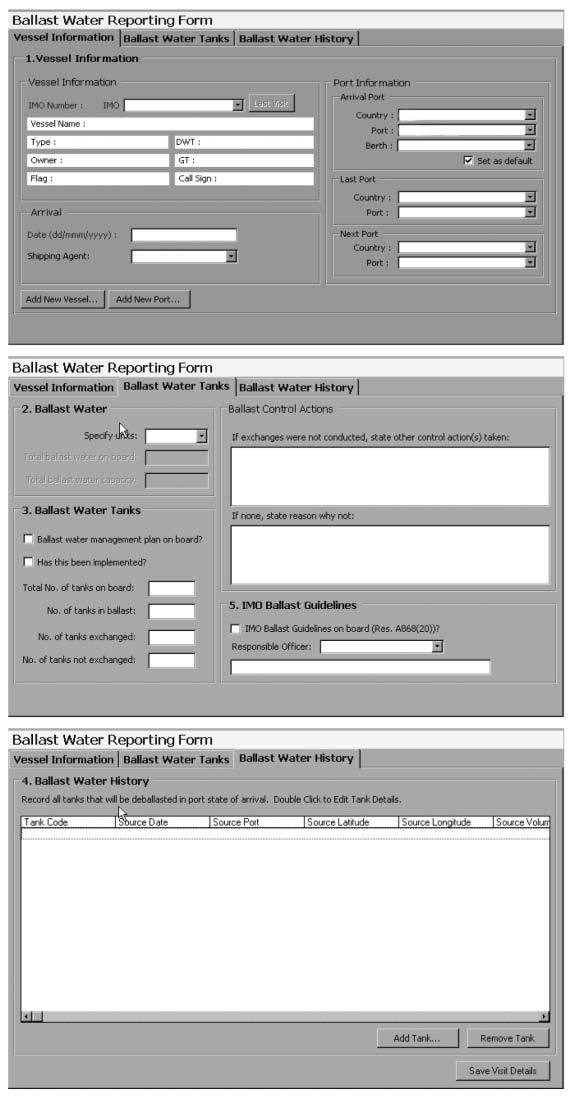

The three tabs of the GUI used for entering the BWRF data............................................................... 14

Figure 7.

Part of the GIS world map of marine bioregions, showing the code names of those in the

South American region .......................................................................................................................... 19

Figure 8.

Complete GIS world map showing the marine bioregions

[to improve clarity, not all bioregion codes are shown in this example]............................................... 20

Figure 9.

Database GUI used for manipulating the BWRA calculation and weightings ..................................... 23

Figure 10.

Annual wind rose typical of Sepetiba Bay region

(Angra dos Reis; 23o 0.5' S 44o 19.0' W; for 30 years)..................................................................... 30

Figure 11.

GIF frame of modelled ballast water plume dispersing from Sepetiba,

at the 40 hour mark for tide and SW winds (a) and tide plus calm conditions (b) ............................... 31

Figure 12.

GIF frame of modelled ballast water plume dispersing from Sepetiba by the

action of tide and NE winds at the 40 hour (a) and 80 hour (b) marks ................................................ 32

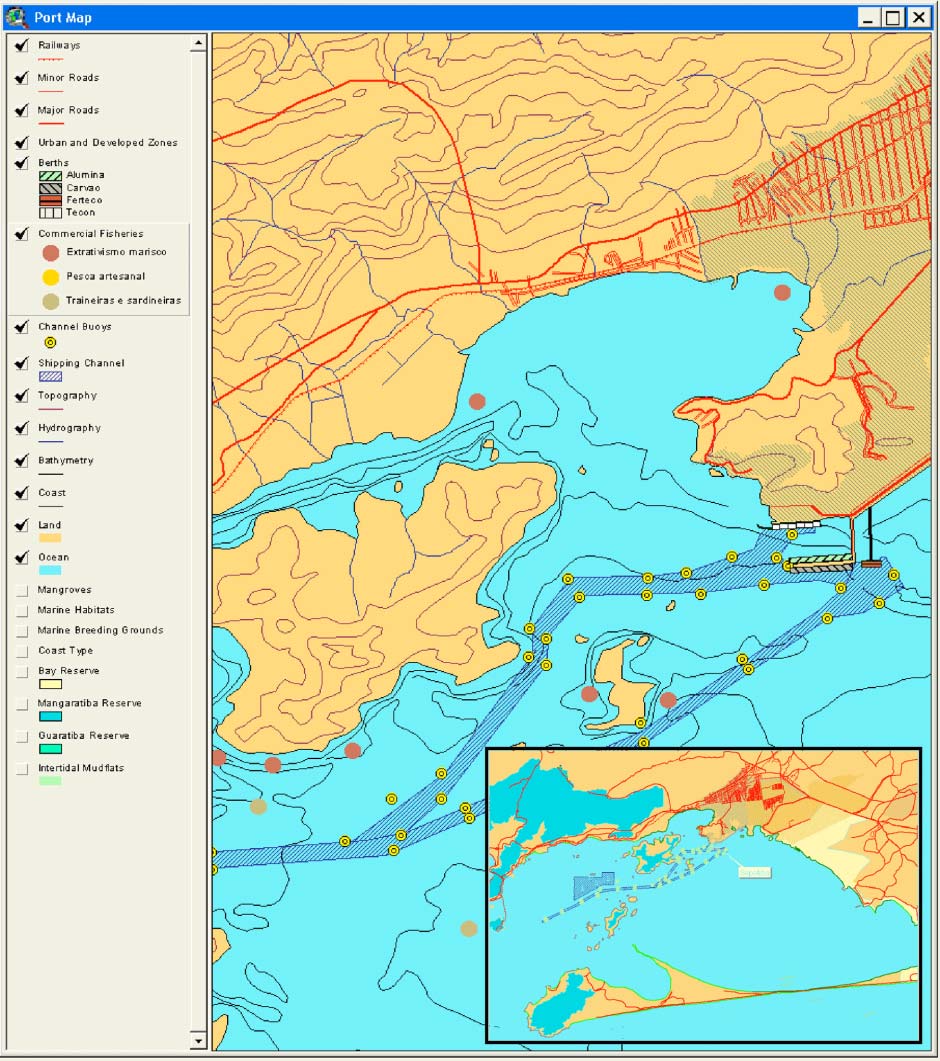

Figure 13.

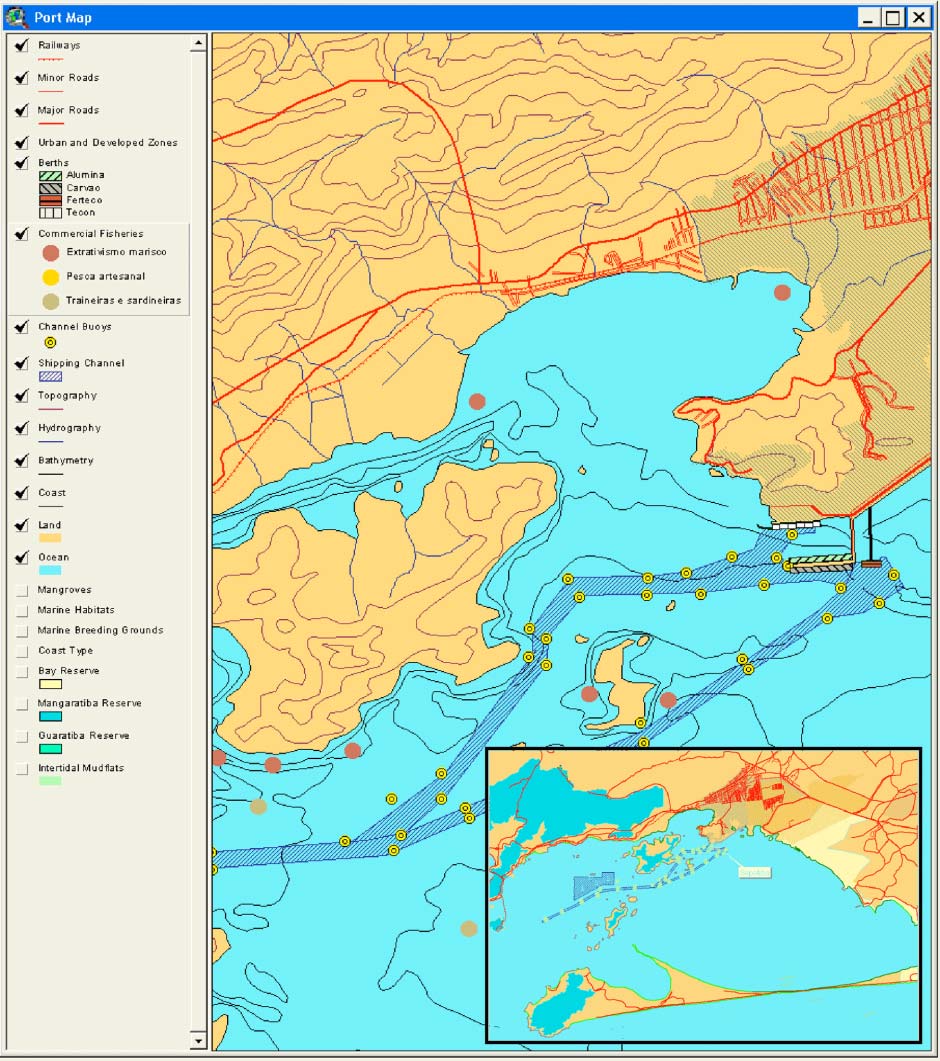

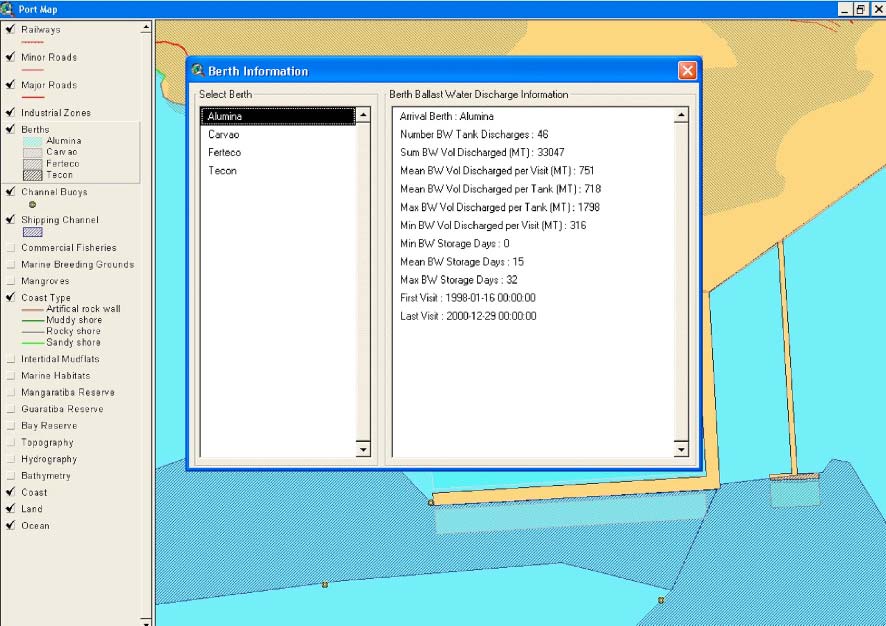

Part of the GIS Port Map showing the navigation, infrastructure and active berth layers

for Sepetiba (inset shows approach channels and anchorage) ........................................................... 33

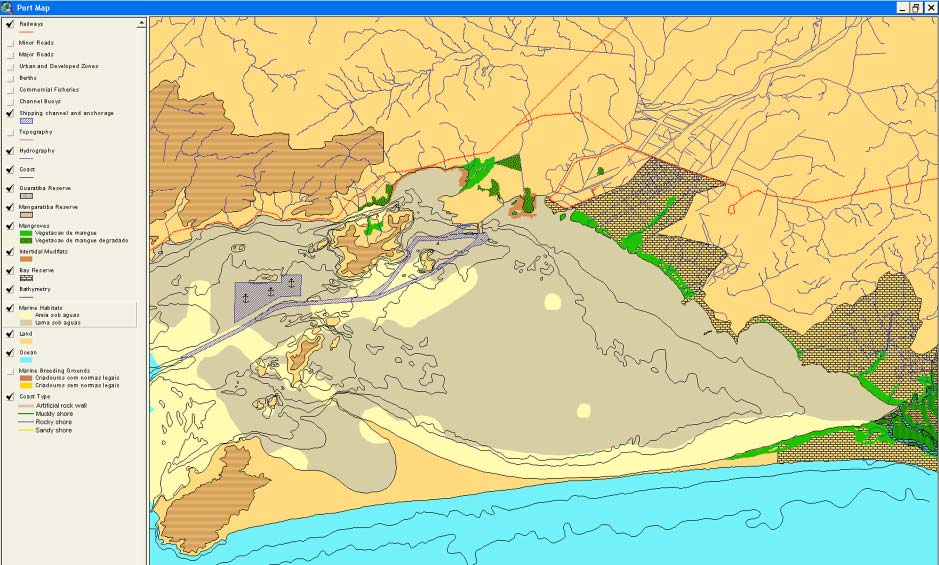

Figure 14.

Part of the GIS Port Map showing the marine habitats and reserve layers......................................... 34

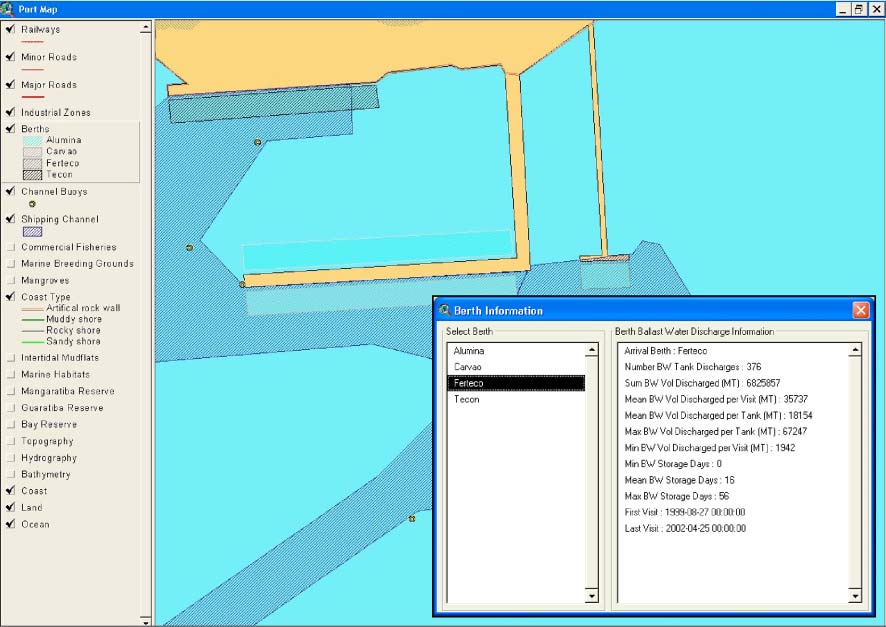

Figure 15.

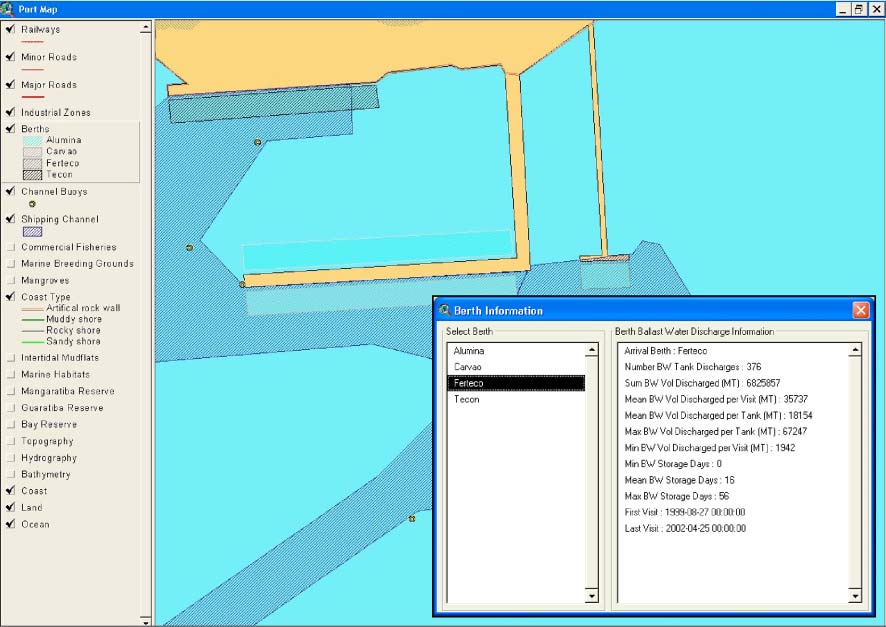

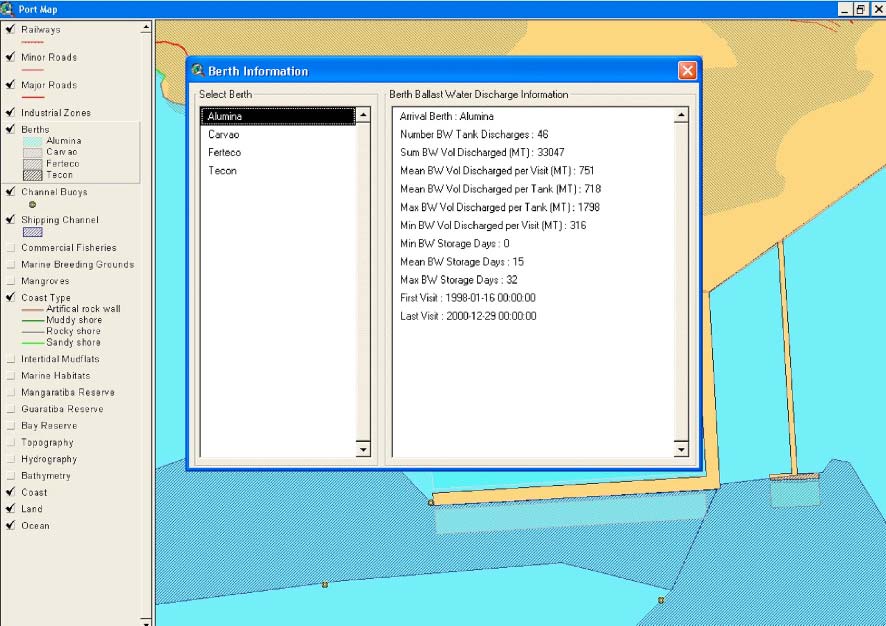

BW discharge statistics displayed by GIS Port Map for the Ferteco (iron ore) export terminal.......... 36

Figure 16.

BW discharge statistics displayed by GIS Port Map for the multi-use Tecon terminal ....................... 37

Figure 17.

BW discharge statistics displayed by GIS Port Map for the Alumina dry and liquid bulk terminal...... 37

Figure 18.

GIS output showing the location and relative importance of BW source ports with respect to

frequency of tank discharges (C1) at Port of Sepetiba......................................................................... 38

Figure 19.

GIS output showing location and relative importance of the source ports with respect to

the volume of tank discharges (C2) at Port of Sepetiba....................................................................... 39

Figure 20.

GIS output showing the location and frequency of destination ports, recorded as the

Next Port of Call in the Port of Sepetiba BWRFs and shipping records .............................................. 41

Figure 21.

GIS output showing the location and environmental matching coefficients (C3) of

BW source ports identified for the Port of Sepetiba ............................................................................. 43

Figure 22.

GIS output showing the location and environmental matching coefficients (C3) of

the destination ports identified for the Port of Sepetiba........................................................................ 43

Figure 23.

GIS output showing the location and risk species threat coefficients (C4) of

the BW source ports identified for the Port of Sepetiba ....................................................................... 48

Figure 24.

GIS output showing the location and categories of relative overall risk (ROR)

of source ports identified for the Port of Sepetiba ................................................................................ 53

Figure 25.

Frequency distribution of the standardised ROR values...................................................................... 53

xii

1

Introduction and Background

The introduction of harmful aquatic organisms and pathogens to new environments via ships' ballast

water (BW) and other vectors, has been identified as one of the four greatest threats to the world's

oceans. The International Maritime Organization (IMO) is working to address the BW vector through

a number of initiatives, including:

· adoption of the IMO Guidelines for the control and management of ships' ballast water to

minimize the transfer of harmful aquatic organisms and pathogens (A.868(20));

· developing a new international legal instrument (International Convention for the Control

and Management of Ships' Ballast Water and Sediments, as adopted by an IMO Diplomatic

Conference in February 2004); and

· providing technical assistance to developing countries through the GEF/UNDP/IMO Global

Ballast Water Management Programme (GloBallast).

Core activities of the GloBallast Programme are being undertaken at Demonstration Sites in six Pilot

Countries. These sites are the ports at Sepetiba (Brazil), Dalian (China), Mumbai (India), Khark

Island (Iran), Odessa (Ukraine) and Saldanha Bay (South Africa). Activities carried out at the

Demonstration Sites will be replicated at additional sites in each region as the programme progresses

(further information at http://globallast.imo.org).

One of GloBallast's core activities (Activity 3.1) has been to trial a standardised method of BW risk

assessment (BWRA) at each of the six Demonstration Sites. Risk assessment is a fundamental starting

point for any country contemplating implementing a formal system to manage the transfer and

introduction of harmful aquatic organisms and pathogens in ships' BW, whether under the existing

IMO Ballast Water Guidelines (A.868(20)) or the new Convention.

A port State may wish to apply its BW management regime uniformly to all vessels that call at its

ports, or it may wish to assess the relative risk of these vessels to its coastal marine resources and

apply its regime selectively. Uniform application or the `blanket' approach offers the advantages of

simplified administration and no requirement for `judgement calls' to be made. This approach also

requires substantially less information management effort. If applied strictly, the uniform approach

offers greater protection from unanticipated bio-invaders, as it does not depend on the reliability of a

decision support system that may not be complete. However, the key disadvantage of the strict blanket

approach are the BW management costs imposed on vessels which otherwise might not be forced to

take action. It also requires a substantial vessel monitoring and crew education effort to ensure all

foreign and domestic flagged ships are properly complying with the required BW management

actions.

A few nations have started to develop and test systems that allow more selective application of BW

management requirements, based on voyage-specific risk assessments. This `selective' approach

offers to reduce the numbers of vessels subject to BW controls and monitoring, and is amenable to

nations that wish to reduce the introduction, and/or domestic spread, of `targeted' marine species only.

More rigorous measures can be justified on ships deemed to be of high risk if fewer restrictions are

placed on low risk vessels.

For countries/ports that choose the selective approach, it is essential to establish an organized means

of evaluating the potential risk posed by each arriving vessel, through a `Decision Support System'

(DSS). However, this approach places commensurate information technology and management

burdens on the port State, and its effectiveness depends on the quality of the information and database

systems that support it. A selective approach that is based on a group of targeted species may also

leave the country/port vulnerable to unknown risks from non-targeted species.

1

Ballast Water Risk Assessment, Port of Sepetiba, Federal Republic of Brazil, December 2003: Final Report

Before a port State decides on whether to adopt the blanket or the selective approach, it needs to carry

out some form of risk assessment for each port under consideration. Ballast water risk assessments

(BWRAs) can be grouped into three categories1:

· Qualitative Risk Identification: this is the simplest approach, and is based on subjective

parameters drawn from previous experience, established principals and relationships and

expert opinion, resulting in simple allocations of `low', `medium' and `high' risk. However it

is often the case that subjective assessments tend to overestimate low probability/high

consequence events and underestimate higher probability/lower consequence events (e.g.

Haugom et al, in Leppäkoski et al. 2002).

· Semi-Quantitative Ranking of Risk: this `middle' approach seeks to increase objectivity and

minimise the need for subjective opinions by using quantitative data and ranking of

proportional results wherever possible. The aim is to improve clarity of process and results,

thereby avoiding the subjective risk-perception issues that can arise in qualitative approaches.

· Quantitative Risk Assessment: this is the most comprehensive approach which aims to

achieve a full probablistic analysis of the risk of BW introductions, including measures of

confidence. It requires significant collation and analysis of physico-chemical, biological and

voyage-specific data, including key lifecycle and tolerance data for every pre-designated

species of risk (`target species'), port environmental conditions, ship/voyage characteristics,

the BW management measures applied, and input and evaluation of all uncertainties. The

approach requires a high level of resourcing, computer networking and sophisticated

techniques that are still being developed1.

The purpose of GloBallast Activity 3.1 has been to conduct initial, first-pass BWRAs for each

Demonstration Site. To maximise certainty while seeking cost-effectiveness and a relatively simple,

widely applicable system, the middle (semi-quantitative) approach was selected.

The first step of the GloBallast method is to collate data from IMO Ballast Water Reporting Forms

(BWRFs) (as contained in Resolution A.868(20); see Appendix 1) to identify the source ports from

which BW is imported to the demonstration port. For periods or vessel arrivals where BWRFs were

not collected or are incomplete, gap-filling data can be extracted from port shipping records.

Source port/discharge port environmental comparisons are then carried out and combined with other

risk factors, including voyage duration and risk species profiles, to give a preliminary indication of

overall risk posed by each source port. The results help determine the types of management responses

required, while the BWRA process provides a foundation block enabling application of more

sophisticated BW management DSSs by Pilot Countries.

The GloBallast approach is not the only one available but is considered to combine the best elements

of the semi-quantitative method to provide useful results within the available budget (US$250,000

spread across the six pilot countries). It has also taken a `whole-of-port' approach which compares the

subject port (Demonstration Site) with all of its BW source and destination ports. The outputs include

published reports, trained in-country risk assessment teams and an operational BWRA system for use

as demonstration tools in each of the six main developing regions of the world, plus a platform and

database to facilitate further DSS development. The GloBallast BWRA activity has therefore

established an integrated database and information system to manage and display:

· ballast water data from arriving ship BWRFs and port shipping records;

· data on the demonstration port's physical and environmental conditions and aquatic

resources,

· port-to-port environmental matching data,

1 for further details see the GloBallast BWRA User Guide.

2

1 Introduction and Background

· risk species data, and

· ballast water discharge risk coefficients.

The results provide a knowledge base that will help the Pilot Countries and other port States to

evaluate the risks currently posed by BW introductions, identify high priority areas for action, and

decide whether to apply a blanket or selective BW management regime. If a selective regime is

adopted, vessel and voyage-specific risk assessments can then be applied using systems such as those

being developed and trialled by the Australian Quarantine & Inspection Service (AQIS Decision

Support System), Det Norsk Veritas in Norway (EMBLA system) and the Cawthron Institute in New

Zealand (SHIPPING EXPLORER), and/or by further development of the GloBallast system. If a

uniform approach is adopted, the results help identify which routes and vessel types warrant the most

vigilance in terms of BW management compliance checking and verification monitoring, including

ship inspections and ballast tank sampling.

The geographical spread and broad representativeness of the six Demonstration Sites also means that

the results help plug a very large gap in the existing global knowledge base. Figure 1 indicates the

broad global spread of the GloBallast risk assessment activity. As a result of this activity,

comprehensive data are now available on source port and destination port linkages, environmental

parameters, environmental matching coefficients, risk species and relative overall risk of BW

transfers for the six GloBallast Demonstration Sites and a total of 723 ports around the world. Project

outcomes will therefore place governments, scientists, the shipping industry and the general public in

a stronger, more enlightened position to deal with the BW problem.

Figure 1. Locations of the six GloBallast Demonstration Sites and their various ballast water source and

destination ports.

This report describes and presents the results of the first Ballast Water Risk Assessment (BWRA)

carried out for the Port of Sepetiba (Brazil) during 2002. This GloBallast Demonstration Site is a

relatively modern bulk commodity and general cargo handling port which was expanded during the

late 1990s to relieve pressure on the crowded facilities inside Rio de Janeiro harbour, which lies some

60 km to the east (Figure 2).

3

Ballast Water Risk Assessment, Port of Sepetiba, Federal Republic of Brazil, December 2003: Final Report

Figure 2. Location of Sepetiba and other ports of Brazil

4

2

Aims and Objectives

The aims of the GloBallast BWRA for the Port of Sepetiba were set by the GloBallast Programme

Coordination Unit (PCU), in accordance with Terms of Reference developed by the PCU Technical

Adviser (Appendix 7) and were to:

1. Assess and describe as far as possible from available data, the risk profile of invasive aquatic

species being both introduced to and exported from Sepetiba in ships' BW, and to identify the

source ports and destination ports posing the highest risk for such introductions.

2. Help determine the types of management responses that are required, and provide the

foundation blocks for implementing a more sophisticated BW management system for the

Port of Sepetiba.

3. Provide training and capacity building to in-country personnel, resulting in a fully trained risk

assessment team and operational risk assessment system, for ongoing use by the Pilot

Country, replication at additional ports and use as a demonstration tool in the region.

The specific objectives of the BWRA for the Port of Sepetiba were to:

1. Identify, describe and map on a Geographic Information System (GIS) all coastal and marine

resources (biological, social/cultural and commercial) in and around the port that might be

impacted by introduced marine species.

2. Characterise, describe and map (on GIS) de-ballasting and ballasting patterns in and around

the port including locations, times, frequencies and volumes of BW discharges and uptakes.

3. Identify all ports/locations from which BW is imported (source ports).

4. Identify all ports/locations to which BW is exported (destination ports).

5. Establish a database at the nominated in-country agency for the efficient ongoing collection,

management and analysis of the data collected at the Port of Sepetiba via standard IMO

BWRFs.

6. Characterise as far as possible from existing data, the physical, chemical and biological

environments for both Sepetiba and each of its source and destination ports.

7. Develop environmental similarity matrices and indices to compare the Port of Sepetiba with

each of its source ports and destination ports, as a key basis of the risk assessment.

8. Identify as far as possible from existing data, any high-risk species present at the source ports

that might pose a threat of introduction to the Port of Sepetiba, and any high-risk species

present at this port that might be exported to a destination port.

9. Identify any information gaps that limit the ability to undertake the aims and objectives and

recommend management actions to address these gaps.

5

Ballast Water Risk Assessment, Port of Sepetiba, Federal Republic of Brazil, December 2003: Final Report

3

Methods

3.1

Overview and work schedule

The BWRA Activity for the Port Sepetiba was conducted by URS Australia Pty Ltd (URS) under

contract to the GloBallast PCU, in accordance with the Terms of Reference (Appendix 7). The

consultants worked alongside their Pilot Country counterparts during the country visits to provide

training and skills-transfer as part of the capacity building objectives of the programme. Structure and

membership of the joint project team is shown in Appendix 2.

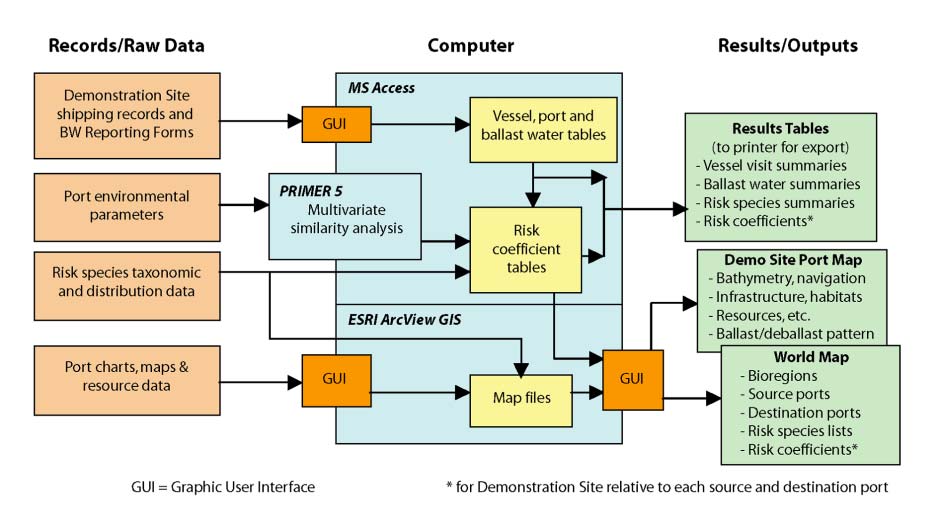

The consultants adopted an innovative, modular approach that integrated three widely used computer

software packages to provide a user-friendly tool for conducting, exploring and demonstrating semi-

quantitative BWRAs. As shown in Figure 3, the key software comprised:

· Microsoft Access - for the main database;

· PRIMER 5 [Plymouth Routines In Marine Environmental Research] - a versatile multivariate

analysis package from the United Kingdom enabling convenient multivariate analysis of the

port environmental data; and

· ESRI ArcView 3.2 Geographic Information System (GIS) - to graphically display the results

in a convenient, readily interpretable format using port and world maps.

Figure 3. Schematic of the GloBallast BWRA system

The work schedule commenced with project briefing meetings with personnel from all six

Demonstration Sites to arrange logistics and resource needs, during the third meeting of the

GloBallast Programme's Global Task Force, held in Goa, India on 16-18 January 2002 (Appendix 3).

The majority of tasks subsequently undertaken for the Port of Sepetiba were completed during two in-

country visits by the consultants (14-19 April and 22 August-06 September 2002), with information

searches and data collation undertaken by both consultant and pilot country team members between

and after these visits. A `project wrap-up' visit was subsequently made by one of the consultants on

12-14 March 2003.

6

3 Methods

The specific tasks of the week-long first visit were to:

· Install and test the Access, ArcView and PRIMER software and the functionality of the

computer system that was located in office space provided in the FEEMA building at Rio de

Janeiro.

· Familiarise the project team with the GloBallast BWRA method by seminar and work-

shopping.

· Commence GIS guidance and developing the port map for the Demonstration Site.

· Commence training on the use of the various Graphic User Interfaces (GUI) of the Access

Database for inputting and editing BW discharge data.

· Visit Sepetiba to tour the port facilities, obtain information on the ballasting practises of

visiting ships and gain an understanding of the coastal habitats and local marine resources.

· Review available BWRFs and port shipping records to identify trading patterns, vessel types,

key BW source ports and likely destination ports.

· Check available port environmental data and identify potential in-country and regional

sources of same.

· Commence listing risk species and identifying potential in-country or regional sources of

same.

· Identify critical information gaps and the data assembly work required before the second visit.

During the longer second visit by the consultants, the environmental and risk species data were added

to the database, more vessel arrival, BW and voyage data were entered and checked, the first BWRA

was undertaken, and a workshop was held to review the initial results and identify future actions.

During the third visit in March 2003, the consultants supplied the CFP-A with updated versions of the

database and BWRA User Guide on CD-ROM, which included additional source port environment

and risk species data (as obtained from the BWRA Activities conducted at the other five

Demonstration Sites). The results of the March 2003 version, plus subsequent corrections to some of

the vessel visit records and environmental matching assignments (made by the CFP-A in consultation

with URS), are reported here.

Throughout the schedule, the joint project team was divided into three groups to facilitate training and

progress (Appendix 2). Group A was responsible for developing the port map and graphically

displaying results via the GIS. All coastal and marine resources (biological, social/cultural and

commercial) in and around the port that might be impacted by aquatic bio-invasions were mapped

using the ArcView GIS, using specific layers to show the bathymetry, navigation aids, port

infrastructure and tables of the port's de-ballasting/ballasting patterns (including frequencies and

volumes of discharges and uptakes for the berth locations).

Group B was responsible for managing the customised Access database supplied by the consultants,

and for entering, checking and managing the BW data, as collated from the BWRFs submitted by

arriving ships (and/or derived from shipping records for periods or arrivals when BWRFs were not

obtained or incomplete). This database was used to identify source and destination ports, and was

designed for ongoing input and management of future BWRFs.

The requirement for arriving ships to submit to the relevant port State authority a completed

form that complies with the IMO BWRF (Appendix 1) is a fundamental and essential first basic

step for any port State wishing to commence a BW management programme2.

2 Several port States (e.g. Australia) and Demonstration Sites (e.g. Dalian, Odessa) have produced their own

BWRFs, using translated formats to permit improved BWRF understanding and completion by local shipping.

Such BWRFs need to include all questions of the IMO standard form. Problems arising from voluntary

submission of BWRFs are described in Section 4.10.

7

Ballast Water Risk Assessment, Port of Sepetiba, Federal Republic of Brazil, December 2003: Final Report

Group C was responsible for collating the port environmental and risk species data, undertaking port-

to-port environmental similarity analyses and performing the BWRA. Thirty four environmental

variables were collated for the Demonstration Site and the majority of its source and destination

ports3, including sea water and air temperatures, salinities, seasonal rainfall, tidal regimes and

proximity to a standardised set of intertidal and subtidal habitats. Where water temperature data or

salinity data could not be found for a source or destination port, values were derived for the riverine,

estuarine or coastal location of the port with respect to the temperature and salinity data ranges of its

IUCN marine bioregion, plus ocean maps depicting sea surface temperature/salinity contours at

quarter degree and degree scales (as obtained from CRIMP [now CSIRO Marine Research], URS and

other sources; Appendix 4).

The multivariate analysis of the port environmental data was undertaken using the PRIMER package,

with the similarity values between the Port of Sepetiba and its source and destination ports converted

into environmental matching coefficients then added to the database. Species in or near source ports

that were deemed to pose a threat if introduced to the Demonstration Site, together with species at the

Demonstration Site that might be exported to a destination port, were identified from all available

sources found by the project team. These sources included preliminary results from the Port

Biological Baseline Surveys (PBBS; as recently completed at each Demonstration Site by another

GloBallast Activity), plus searches of `on-line' databases such as those under ongoing development

by the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC), the Australian Centre for Research on

Introduced Marine Pests (CRIMP; now CSIRO Marine Research), the Baltic Regional Marine

Invasions Database and the Global Invasive Species Programme (GISP) (Appendix 5). The species

taxonomic information and bioregional distributions were also added to the Access database. The

combined BW discharge, environmental matching and risk species coefficients provided the basis of

the semi-quantitative risk assessment.

Graphic User Interfaces (GUIs) customised by the consultants for the Access database and ArcView

GIS were used to generate results tables and graphical outputs that were displayed on interactive maps

of the Demonstration Site and World bioregions. The various BWRA outputs can be printed, exported

to other software, or viewed interactively to enhance the user-friendliness and management utility of

the system.

The methods used to attain each objective of the BWRA Activity are summarised in the following

sections, with technical details of the risk assessment procedures provided in the GloBallast BWRA

User Guide. This manual was developed by the consultants to facilitate BWRA training and

demonstrations for all six GloBallast Pilot Countries. The BWRA User Guide comprises a separate

document that accompanies this report, and is available from the GloBallast PCU

(http://globallast.imo.org).

3.2

Resource mapping of the demonstration port

The port resources were mapped using ArcView GIS to display the bathymetric, navigational and

infrastructure features, including habitats and social-cultural features. The scope of the Sepetiba port

map extends from the open seaway at the mouth of Sepetiba Bay, and along the port's approaches

past the anchorages to its terminals and berths located at Madeira Island. The map also extends further

3 The complete set of source and destination ports identified for the six Demonstration Sites (723) remained

unknown until the end of the BWRF/port record data collation, database entry and checking phases (i.e. end of

the second round of in-country visits; 22 December 2002). A gap-filling effort was made by the consultants to

obtain the environmental parameters during January 2003, but this had to focus on the most frequently

recorded of these ports since there was insufficient time or resources to order charts and search for the

environmental data for all of them (the majority of which were associated with few or only single vessel

arrivals). For these ports, their environmental matching values were provided by a comparison method

described in Section 4.6.

8

3 Methods

eastward to encompass the edges of the bay and landward to show the port hinterland and watershed

drainages.

Approximately 305 km2 of Sepetiba bay and its hinterland were already in a ArchInfo digital map

format owing to a detailed watershed study undertaken for the Rio de Janeiro's Secretary of State of

Environment in 1997. However there was no subtidal or navigational information, and vector-based

electronic nautical charts were not available for the Sepetiba region. Counterparts from the Fundação

Estadual de Engenharia do Meio Ambiente (Foundation for the Study of Environmental Engineering)

(FEEMA) generated the bathymetry and navigation layers using their digitising table to capture

salient details of port infrastructure, shipping channels and anchorages from the 1:20,000 Baia de

Sepetiba Brazilian nautical chart. Point and pattern symbols were based on the international

IHO/IALA system for nautical charts.

Infrastructure and social cultural information was captured by importing and re-registering FEEMA

ArchInfo files showing transportation lines and land uses, plus digital data extracted from other files

showing local drainage and river systems, terrestrial contours, habitats and reserves. Some intertidal

habitat were also available in digital format from the 1997 study, and these were supplemented by

subtidal habitat information provided by Group C.

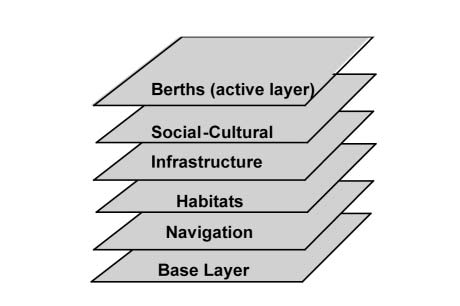

For clarity and convenience of data management and display, each `theme' of information was added

as a separate layer that followed the scheme shown in Figure 4. Additional layers were provided to

incorporate various FEEMA coastal zone data, including a colour Landsat image of Sepetiba bay.

Two GIF files showing projected movements of discharged BW from tide-only and by two tide/wind

regimes were provided by the CFP-A and these were linked to the port map.

Figure 4. Thematic layers used for the Port Map GIS

The protocol for the five main layers are described in the BWRA User Guide and summarised below:

Base Layer: The base layer includes important planimetric features such as depth contours, jetties,

important channels and other permanent or at least semi-permanent `reference' features that are

unlikely to change or move. The key features of the base layer for the Port of Sepetiba comprised:

· Coastlines of the mainland and various islands within Sepetiba Bay (as depicted by the high

tide mark on the nautical charts).

· The low tide mark (i.e. the 0 metre bathymetric contour of hydrographic charts).

· 5 metre isobath (often the first continuous contour below the low tide mark).

· 10 metre, 20 metre and 30 metre isobaths.

· Edges of the main shipping channels (often blue or purple lines showing the boundary of

depths maintained by port dredging).

9

Ballast Water Risk Assessment, Port of Sepetiba, Federal Republic of Brazil, December 2003: Final Report

The colour scheme of the base layer follows that of standard nautical charts to maintain the familiar

land/sea depth effect.

Navigational Layer: The standard navigational symbols of the IHO/IALA system were followed as

closely as possible. ArcView's symbol libraries do not contain these international navigation symbols,

and convenient third-party symbology could not be found despite extensive searches of public domain

web resources. Closest-match point and pattern symbols were therefore developed for this purpose,

using the UK Hydrographic Office Chart No. 5011 (= IHO INT 1) as the source.

Habitat Layer: This layer used a standardised, logical colour scheme to facilitate recognition of the

main intertidal and subtidal habitat types in and near the port. It contains coastal habitat information

provided by FEEMA, with some of the natural and artificial habitat boundaries based on notes and

map annotations made by BWRA team members during the port tour, and sediment information

provided by the CFP-A from the Sepetiba PBBS. The port tour was undertaken by vehicle and foot on

15 April 2002. Delineation of some intertidal and subtidal habitat boundaries was supplemented from

seafloor and coastal features displayed on the Baia de Sepetiba nautical chart. These included the

intertidal mud flats, sand beaches and rocky shorelines, plus symbols denoting the presence of sand,

mud or rocky substrate.

Infrastructure Layer: This layer shows the urban and developed land surrounding the port, including

roads and railway lines.

Social-Cultural Layer: Social-cultural features include the three different coastal reserves near the

port and two wildlife breeding grounds, plus the locations of mariculture sites and recognised

recreational fishing areas and sardine grounds in Sepetiba Bay. There is no dedicated fishing port in

Sepetiba Bay, with the nearest ramps and a small jetty used by recreational and artesanal fishing boats

located at the head of a shallow embayment 4 km north of the port.

Berth Layer: An `active' berth layer was added to show the principal berthing and anchoring areas at

the Port of Sepetiba. Their names and numbering system were supplied by the Port of Sepetiba

engineer. The same nomenclature was also used for the berthing area information stored in the Access

database, to allow display of statistical summaries of the BW source and discharge data on the correct

locations of the GIS port map (the GloBallast BWRA User Guide shows how the database-GIS link is

established).

3.3

De-ballasting/ballasting patterns

The deballasting/ballasting patterns at Sepetiba were discussed during the port visit (15 April 2002)

where a meeting was held at the port manager's office to confirm the types of port trade, pilotage

rules and draft requirements, current anchorage areas and deballasting/ballasting practises and

locations. Copies of port shipping records covering 1998-2001 had been previously supplied to the

CFP-A for a previous project.

Further information was obtained from the shipping records of Sepetiba's port authority (Companhia

Docas do Rio Janeiro - CDRJ) for periods where BWRFs were unavailable or incomplete4. It was

relatively simple to determine where and which arriving ships discharged or uplifted BW by

identifying their berthing location and vessel type, because the port has dedicated bulk import and

export terminals plus a new multipurpose terminal capable of handling vehicles, containers, break-

bulk and general cargo. However many ships arriving at the latter only part discharged and/or part

loaded cargo and it was often unclear if and how much ballast water was being discharged or taken

up, particularly by ro-ro vessels and container ships.

4 These records listed the vessel name, arrival and departure dates, berth, last port of call, and cargo details.

10

3 Methods

3.4 Identification of source ports

To provide confidence as to which ports were the predominant sources of BW discharged at Sepetiba,

visit records from a spreadsheet containing information extracted from Sepetiba's port shipping

records for the 1998-2000 were added to the Access database. Source ports were therefore identified

from BWRFs (January 2001 - June 2002) and from shipping record information previously obtained

from the Sepetiba port office.

BWRFs had been collected from arriving ships by the Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária,

(National Agency for Health Surveillance) (ANVISA); Brazil's federal agency for border health and

quarantine control), at Sepetiba since June 2000 on a voluntarily basis. Completion and submission of

this form became mandatory after January 2001 due to Resolution 17, a national regulation

established by ANVISA to all vessels that claim Free Pratique (as reviewed in November 2001 as

Resolution 217). BWRFs collected from 1 January 2001 were entered into the database. Before a new

port was added to the database, the port and country name spelling, its location coordinates, bioregion

and unique UN Port Code number were checked using the Lloyds Fairplay World Ports Guide and

world bioregion list in the database (port data input is detailed in the GloBallast BWRA User Guide).

Whenever possible, BWRFs were cross-referenced with port shipping records since many of the

former were partly or incorrectly completed. For vessels arriving before BWRFs were collected, or

which submitted incomplete or no forms, gap-filling details were obtained from the port's shipping

records. However these records show only the Last Port of Call, which may not be the BW source. To

identify which last ports of call were probable BW sources, cross-checks were made of source ports

and last ports of call reported in other BWRFs by the same or similar types of vessel. The Lloyds

Fairplay Port Guide and Lloyds Ship Register5 were also used to confirm source port trade and the

vessel's IMO identification number, vessel type and DWT of arriving ships respectively.

Many gaps in the BWRFs and port shipping records could therefore be filled by checking, for any

arrival, the vessel name, type and DWT, its previous visit history, last port/s of call and apparent

charter/liner trade, and by using a customised Excel spreadsheet supplied by the consultants to

estimate the amount BW discharged or taken up6 (Figure 5). This was less easy for the vessels