Ballast W

a

ter Risk Assessment

Global Ballast Water

Management Programme

G L O B A L L A S T M O N O G R A P H S E R I E S N O . 8

Port of Khark Island, Islamic Republic of Iran

Ballast Water Risk Assessment

Port of Khark Island

Islamic Republic of Iran

Final Report

AUGUST 2003

Final Report

C. Clarke, T. Hayes, R. Hilliard,

.dwa.uk.com

N. Kayvanrad, A. Parhizi,

H. Taymourtash, V. Yavari,

GLOBALLAST MONOGRAPH SERIES

& S. Raaymakers

More Information?

el (+44) 020 7928 5888 www

Programme Coordination Unit

Global Ballast Water Management Programme

International Maritime Organization

4 Albert Embankment

London SE1 7SR United Kingdom

Tel: +44 (0)20 7587 3247 or 3251

est & Associates, London. T

Fax: +44 (0)20 7587 3261

Web: http://globallast.imo.org

NO.8

A cooperative initiative of the Global Environment Facility,

United Nations Development Programme and International Maritime Organization.

Cover designed by Daniel W

GloBallast Monograph Series No. 8

Ballast Water Risk Assessment

Port of Khark Island

Islamic Republic of Iran

August 2003

Final Report

Chris Clarke*, Terry Hayes*, Rob Hilliard*,

Nasser Kayvanrad+, Hassan Taymourtash+,

Ahmad Parhizi+, Vahid Yavari+ and

Steve Raaymakers#

*Meridian GIS Pty Ltd, Perth, Western Australia

+Ports & Shipping Organisation, Ministry of Road and Transportation, Islamic Republic of Iran

#Programme Coordination Unit, GEF/UNDP/IMO Global Ballast Water Management Programme, International

Maritime Organization

International Maritime Organization

ISSN 1680-3078

Published in September 2003 by the

Programme Coordination Unit

Global Ballast Water Management Programme

International Maritime Organization

4 Albert Embankment, London SE1 7SR, UK

Tel +44 (0)20 7587 3251

Fax +44 (0)20 7587 3261

Email sraaymak@imo.org

Web http://globallast.imo.org

The correct citation of this report is:

Clarke, C., Hayes, T., Hilliard, R., Kayvanrad, N., Taymourtash, H., Parhizi, A., Yavari, V. & Raaymakers, S. 2003. Ballast

Water Risk Assessment, Port of Khark Island, Islamic Republic of Iran, August 2003: Final Report. GloBallast Monograph

Series No. 8. IMO London.

The Global Ballast Water Management Programme (GloBallast) is a cooperative initiative of the Global Environment Facility (GEF),

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and International Maritime Organization (IMO) to assist developing countries to reduce

the transfer of harmful organisms in ships' ballast water.

The GloBallast Monograph Series is published to disseminate information about and results from the programme, as part of the

programme's global information clearing-house functions.

The opinions expressed in this document are not necessarily those of GEF, UNDP or IMO.

Ballast Water Risk Assessment, Port of Khark Island, Islamic Republic of Iran, August 2003: Final Report

Acknowledgements

The Ballast Water Risk Assessment for the Port of Khark Island was undertaken during 2002 and

funded by the GEF/UNDP/IMO Global Ballast Water Management Programme and the Government

of the Islamic Republic of Iran. The study team (Appendix 2) thanks the following for their help and

assistance:

Captain Gholam Abbas Hafezi

National Iranian Oil Exportation Terminal Harbour Master

Captain A. Fallahi

Ports & Shipping Organization, Port of Khark Island

Mr Amir Houshang Ghafourian National Cartographic Centre, Tehran

Ms Faezeh Salami

National Cartographic Centre, Tehran

Ms Atiyeh Mojtahedi

National Cartographic Centre, Tehran

Dr Gustaaf Hallegraeff

University of Tasmania, Hobart

Dr Keith Hayes

CSIRO Centre for Research on Introduced Marine Pests, Hobart

Dr Graeme Hubbert

Global Environmental Modelling Systems (GEMS), Melbourne.

Dr Chad Hewitt

Biosecurity Unit, New Zealand Ministry of Fisheries

Dr Fred Wells

Western Australian Museum, Perth, Western Australia.

The report was formatted and prepared for print by Leonard Webster.

Ballast Water Risk Assessment, Port of Khark Island, Islamic Republic of Iran, August 2003: Final Report

Acronyms

BW

Ballast water

BWM

Ballast water management

BWRA

Ballast Water Risk Assessment

BWRF

Ballast Water Reporting Form (the standard IMO BWRF is shown in Appendix 1)

CFP

Country Focal Point (of the GloBallast Programme in each Pilot Country)

CFP/A

Country Focal Point Assistant

CRIMP Centre

for

Research

on

Introduced

Marine

Pests

(now

part

of

CSIRO

Marine

Research, Hobart, Tasmania)

CSIRO

Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (Australia)

DSS

Decision support system (for BW management)

DWT

Deadweight tonnage (typically reported in metric tonnes)

GCC

Gulf Cooperation Council

GIS

Geographic information system

GISP

Global Invasive Species Programme

GloBallast

GEF/UNDP/IMO Global Ballast Water Management Programme

GT

Gross tonnage (usually recorded in metric tonnes)

GUI

Graphic User Interface

IALA

International Association of Lighthouse Authorities

IHO

International Hydrographic Organization

IMO

International Maritime Organization

I.R.

Islamic Republic of

IUCN

The World Nature Conservation Union

LAT

Lowest Astronomical Tide

MESA

Multivariate environmental similarity analysis

MEPC

Marine Environment Protection Committee (of the IMO)

NCC

National Cartographic Centre (I.R. Iran)

NIMPIS

National Introduced Marine Pests Information System (managed by CSIRO,

Australia)

NIS

Non-indigenous species

OS

Operating System (of any personal or mainframe computer)

PCU

Programme Coordination Unit (of the GloBallast Programme based at IMO London)

PRIMER

Plymouth Routines In Marine Environmental Research

PBBS

Port Biological Baseline Survey

PSO

Ports & Shipping Organisation, Ministry of Roads & Transportation (I.R. Iran)

ROPME

Regional Organization for the Protection of the Marine Environment (the ROPME

Sea Area comprises the coastal and marine waters of Bahrain, Iraq, Islamic Republic

of Iran, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates)

ROR

Relative overall risk

RSA

ROPME Sea Area

SAP

(Regional) Strategic Action Plan

SERC

Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (Washington DC, United States)

VLCC

Very large crude carrier (200,000 300,000 DWT)

ULCC

Ultra large crude carrier (over 300,000 DWT)

ii

Ballast Water Risk Assessment, Port of Khark Island, Islamic Republic of Iran, August 2003: Final Report

Glossary of Terms and Definitions

The following terms and definitions are summarised from various sources including Carlton (1985,

1996, 2002), Cohen & Carlton (1995), Hilliard et al. (1997a), Leppäkoski et al. (2002), Williamson et

al. (2002) and the GloBallast BWRA User Guide. The latter document contains more detailed

definitions with explanatory notes, plus a glossary of maritime terms.

Ballast water

Any water and associated sediment used to manipulate the trim and

stability of a vessel.

Baseline port survey

A biological survey to identify the types of introduced marine species

in a port.

Bioinvasion

A broad based term that refers to both human-assisted introductions

and natural range expansions.

Border

The first entrance point into an economy's jurisdiction.

Cost benefit analysis

Analysis of the cost and benefits of a course of action to determine

whether it should be undertaken.

Cryptogenic

A species that is not demonstrably native or introduced.

Disease

Clinical or non-clinical infection with an aetiological agent.

Domestic

Intra-national coastal voyages (between domestic ports).

routes/shipping

Established

A non-indigenous species that has produced at least one self-sustaining

introduction

population in its introduced range.

Foreign routes/shipping

International voyages (between countries).

Fouling organism

Any plant or animal that attaches to natural and man-made substrates

such as piers, navigation buoys or hull of ship, such as seaweed,

barnacles or mussels.

Harmful marine species

A non-indigenous species that threatens human health, economic or

environmental values.

Hazard

A situation that under certain conditions will cause harm. The

likelihood of these conditions and the magnitude of the subsequent

harm is a measure of the risk.

Indigenous/native

A species with a long natural presence that extends into the pre-historic

species

record.

Inoculation

Any partial or complete discharge of ballast tank water that contains

organisms which are not native to the bioregion of the receiving waters

(analogous to the potentially harmful introduction of disease causing

agents into a body as the outcome depends on inoculum strength and

exposure incidence).

Intentional introduction

The purposeful transfer or deliberate release of a non-indigenous

species into a natural or semi-natural habitat located beyond its natural

range.

Introduced species

A species that has been intentionally or unintentionally transferred by

human activity into a region beyond its natural range.

Invasive species

An established introduced species that spreads rapidly through a range

of natural or semi-natural habitats and ecosystems, mostly by its own

means.

iii

Ballast Water Risk Assessment, Port of Khark Island, Islamic Republic of Iran, August 2003: Final Report

Marine pest

A harmful introduced species (i.e. an introduced species that threatens

human health, economic or environmental values).

Non-invasive

An established introduced species that remains localised within its new

environment and shows minimal ability to spread despite several

decades of opportunity.

Pathogen

A virus, bacteria or other agent that causes disease or illness.

Pathway (Route)

The geographic route or corridor from point A to point B (see Vector).

Risk

The likelihood and magnitude of a harmful event.

Risk assessment

Undertaking the tasks required to determine the level of risk.

Risk analysis

Evaluating a risk to determine if, and what type of, actions are worth

taking to reduce the risk.

Risk management

The organisational framework and activities that are directed towards

identifying and reducing risks.

Risk species

A species deemed likely to become a harmful species if it is introduced

to a region beyond its natural range, as based on inductive evaluation

of available evidence.

Translocation

The transfer of an organism or its propagules into a location outside its

natural range by a human activity.

Unintentional

An unwitting (and typically unknowing) introduction resulting from a

introduction

human activity unrelated to the introduced species involved (e.g. via

water used for ballasting a ship or for transferring an aquaculture

species).

Vector

The physical means or agent by which a species is transferred from one

place to another (e.g. BW, a ship's hull, or inside a shipment of

commercial oysters)

iv

Ballast Water Risk Assessment, Port of Khark Island, Islamic Republic of Iran, August 2003: Final Report

Lead agencies

Lead Agency for BW Issues in the Islamic Republic of Iran:

Contact person:

Mr Hassan Taymourtash

Position:

Director General of Safety and Maritime Protection Department and

GloBallast Country Focal Point

Organization:

Ports and Shipping Organization, Ministry of Road and Transportation

Address:

No 751 Enghelab Avenue

Tehran 1599661464

ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF IRAN

Tel:

+98 21 8809555

Fax:

+98 21 8809367

Email: taymourtash@ir-pso.com

Web:

www.ir-pso.com

v

Ballast Water Risk Assessment, Port of Khark Island, Islamic Republic of Iran, August 2003: Final Report

Executive Summary

The introduction of harmful aquatic organisms and pathogens to new environments via ships' ballast

water (BW) and other vectors has been identified as one of the four greatest threats to the world's

oceans. The International Maritime Organization (IMO) is working to address the BW vector through

various initiatives. One initiative has been the provision of technical assistance to developing

countries through the GEF/UNDP/IMO Global Ballast Water Management Programme (GloBallast).

Core activities of the GloBallast Programme are being undertaken at Demonstration Sites in six Pilot

Countries. These sites are the ports at Khark Island (I.R. Iran), Dalian (China), Mumbai (India),

Odessa (Ukraine), Saldanha (South Africa) and Sepetiba (Brazil). One of these activities (Activity

3.1) has been to trial a standardised method of BW risk assessment (BWRA) at each of the six

Demonstration Sites. Risk assessment is a fundamental starting point for any country contemplating

implementing a formal system to manage the transfer and introduction of harmful aquatic organisms

and pathogens in ships' BW, whether under existing IMO Ballast Water Guidelines (A.868(20)) or a

new international Convention.

To maximise certainty while seeking cost-effectiveness and a relatively simple, widely applicable

system, a semi-quantitative approach was followed, using widely-supported computer software. The

semi-quantitative method aims to minimise subjectivity by using as much quantitative data as possible

to identify the riskiest ballast tank discharges with respect to a Demonstration Site's current pattern of

trade. Unlike a fully quantitative approach, it does not attempt to predict the specific risk posed by

each intended tank discharge of individual vessels, nor the level of certainty attached to such

predictions. However, by helping a Demonstration Site to determine its riskiest trading routes,

exploring the semi-quantitative BWRA provides a coherent method for identifying which BW sources

deserve more vessel monitoring and management efforts than others.

This report describes the BWRA activity undertaken for the Port of Khark Island, which is the

Demonstration Site managed by the Ports & Shipping Organisation (PSO) of the Islamic Republic of

Iran. This capacity-building activity commenced in January 2002, with Meridian GIS Pty Ltd

(Meridian) contracted to the GloBallast Programme Coordination Unit (PCU) to provide BWRA

training and software. Under the terms of reference, the consultants worked closely with their in-

country counterparts in a project team co-managed by Meridian and PSO for completing all required

tasks. These tasks required two in-country visits by the consultants (in May and December 2002) to

install the BWRA software and provide `hands-on' instruction and guidance. Most of the data

collation tasks were undertaken before, between and during these visits, with gap-filling work

undertaken by the consultants prior to a short `project wrap-up' visit in February 2003.

The first step was to collate data from IMO Ballast Water Reporting Forms (BWRFs) submitted by

arriving ships to identify the source ports from which BW is imported to the Demonstration Site.. For

periods or vessel arrivals where BWRFs were not collected or were incomplete, gap-filling data were

extracted from the port shipping records held at Khark Island by PSO. These records also help

establish which next ports of call may have been a destination port for any BW taken up at Khark

Island.

A multivariate procedure was then used to identify the environmental similarity between the

Demonstration Site and each of its BW source and destination ports. Comparing port-to-port

environmental similarities provides a relative measure of the risk of organism survival, establishment

and potential spread. This is the basis of the `environmental matching' method, and it facilitates

estimating the risk of BW introductions when the range and types of potentially harmful species that

could be introduced from a particular source port are poorly known.

Another objective of the BWRA Activity was to identify `high-risk' species that may be transferred to

and/or from the Demonstration Site. The customised Access database therefore contained tables and

interfaces for storing and managing the names, distribution and other information on risk species.

vi

Ballast Water Risk Assessment, Port of Khark Island, Islamic Republic of Iran, August 2003: Final Report

Thus the taxonomic details, bioregional distribution, native/introduced status and level of threat

assigned to a species were stored in the database for display, review and update as well as for the

BWRA analysis. For the purposes of the BWRA and its `first-pass' risk assessment, a risk species was

considered to be any introduced, cryptogenic or native species that might pose a threat to marine

ecological, social and/or commercial resources and values if successfully transferred to or from a

Demonstration Site.

During each visit the consultants worked alongside their Pilot Country counterparts to provide skills-

transfer as part of the capacity building objectives of the programme, with the project team divided

into three groups. Group A mapped the port and its resources using ArcView GIS. This group

included counterparts from I.R. Iran's National Cartographic Centre (Tehran) who provided much of

the required GIS data in digital format. Group B was responsible for managing the customised Access

database supplied by the consultants, and for entering, checking and managing the BW discharge data,

as recorded on the BWRFs voluntarily submitted by arriving ships and/or derived from the port's

shipping records. Group B used the database to identify BW source and destination ports, and it is

designed for ongoing input and management of BWRFs. Group C undertook the environmental

matching and risk species components of the Activity, using the PRIMER package to perform the

multivariate analyses for determining the environmental distances between Khark Island and its

source and destination ports.

The various BW discharge, environmental matching and risk species data described above were then

processed by the database with other risk factors, including voyage duration and tank size, to provide

preliminary indication of:

(a) the relative overall risk posed by each BW source port, and

(b) which destination ports appeared most at risk from any BW uplifted at the Demonstration

Site.

This was achieved using a project standard approach, although the database also facilitates instant

modifications of the calculations for exploratory and demonstration purposes. The GloBallast BWRA

also adopted a `whole-of-port' approach to compare the subject port (Demonstration Site) with all of

its BW source and destination ports. The project therefore established in Tehran an integrated

database and geographic information system (GIS) that manages and displays:

· ballast water data obtained from arriving ship BWRFs and port shipping records;

· information on the Demonstration Site's navigational, physical and environmental conditions

and aquatic resources,

· port-to-port environmental matching data,

· risk species data, and

· risk coefficients and graphical categories of risk for ballast discharges.

The results, which were graphically displayed on user-friendly GIS port and world maps as well as in

ranked output tables, help determine the types of management responses. Seventeen source ports

provided the top 20% of the total cumulative threat for the Port of Khark Island (in terms of their BW

source frequency, volume, environmental similarity and assigned risk species). They were led by

Kaohsiung in Taiwan Province (ROR = 0.229; S-ROR = 1.0), followed by five Middle East ports

(Jebel Ali, Doha, Umm Said, Fujairah, and the Red Sea oil reception terminal at Ain Sukhana).

Highest risk ports beyond the Middle East were Okinawa and Chiba (Japan) and Ulsan (Korea). The

majority of ports in the next group were located in South and East Asia, including ports in India (2),

Sri Lanka (1), Japan (7), China (1), Taiwan Province (1), Korea (2) and Philippines (1). Only one

European port attained a `high risk' category (Eleusis in Greece).

Low risk source ports were in north Europe, North America and South Africa, plus some in South and

East Asia. The lowest risk port was the Port of Come by Chance, located in Newfoundland (Canada).

The generally much higher threat of introductions posed by BW sources in the Middle East and Asia

vii

Ballast Water Risk Assessment, Port of Khark Island, Islamic Republic of Iran, August 2003: Final Report

than in north America and Europe (an order of magnitude difference) is logical with respect to Khark

Island's geographic location and current pattern of trade. The results also implied that any introduced

species which establishes in a port in the ROPME Sea Area, or nearby Red Sea and west Arabian Sea,

could be readily spread by local ship movements involving shuttle services, bunkering and/or part-

loading of cargo.

Of the various BWRA objectives and tasks, reliable identification of destination ports that may

receive BW from the Demonstration Site was confounded by the lack of specific questions on the

IMO-standard BWRFs, and the uncertainty of knowing if the Next of Port Call recorded on a BWRF

is where Ballast Water is actually discharged. Thus presently there is no mechanism enabling a

`reverse BWRA' to be undertaken reliably. In the case of the RSA, Next and Last Port of Call

involving bunkering, crew-change or cargo top-up visits added to the problem. In the case of the Port

of Khark Island, this was not a issue since almost all visiting ships arrive to collect liquid or dry bulk

cargo. However, if more reliable, forward-looking BWRAs are to be undertaken to identify

destination ports in the future, supplementary questions will need to be added to the present BWRF,

including the names of the three last ports of call as well as the port where discharges from each

partially or completely ballasted tank are predicted.

The main objectives of the BWRA Activity were successfully completed during the 13 month course

of this project, with the various tasks and exploratory/demonstration software providing a foundation

enabling the regional promulgation of further BW management activities by I.R. Iran. Project outputs

included a trained in-country risk assessment team, and an operational BWRA system and User Guide

for use as a demonstration tool in the region of the Port of Khark Island. This places the Islamic

Republic of Iran in a strong position to provide assistance, technical advice, guidance and

encouragement to other port States of the ROPME Sea Area.

viii

Ballast Water Risk Assessment, Port of Khark Island, Islamic Republic of Iran, August 2003: Final Report

Table of Contents

Acknowledgements......................................................................................................................................i

Acronyms......................................................................................................................................................ii

Glossary of Terms and Definitions ..........................................................................................................iii

Lead agencies ..............................................................................................................................................v

Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................vi

1

Introduction and Background .........................................................................................................1

2

Aims & Objectives.............................................................................................................................5

3

Methods ..............................................................................................................................................6

3.1

Overview and work schedule...................................................................................................................6

3.2

Resource mapping of the demonstration port.........................................................................................8

3.3

De-ballasting/ballasting patterns ...........................................................................................................10

3.4

Identification of source ports..................................................................................................................10

3.5

Identification of destination ports...........................................................................................................12

3.6

BWRF database.....................................................................................................................................13

3.7

Environmental parameters....................................................................................................................15

3.8

Environmental similarity analysis ..........................................................................................................16

3.9

Risk species ...........................................................................................................................................17

3.10

Risk assessment ....................................................................................................................................21

3.11

Training and capacity building ...............................................................................................................26

4

Results ............................................................................................................................................. 29

4.1 Description

of port ..................................................................................................................................29

4.2 Resource mapping .................................................................................................................................33

4.3 De-ballasting/ballasting pattern .............................................................................................................34

4.4 Identification

of source ports..................................................................................................................36

4.5 Identification

of destination ports ...........................................................................................................40

4.6

Environmental similarity analysis ..........................................................................................................41

4.7

Risk species ...........................................................................................................................................46

4.8

Risk assessment results ........................................................................................................................49

4.9

Training and capacity building ...............................................................................................................53

4.10

Identification of information gaps...........................................................................................................54

5

Conclusions and Recommendations .......................................................................................... 57

Recommendations.............................................................................................................................................57

BWRA recommendations and plans by Pilot Country (IR Iran).......................................................................57

6

Location and Maintenance of the BWRA System...................................................................... 59

Port resource mapping and GIS display requirements: ...................................................................................59

Ballast water reporting form database:.............................................................................................................59

Port environmental and risk species data: .......................................................................................................59

References................................................................................................................................................. 60

APPENDIX 1:

Copy of IMO Ballast Water Reporting Form

APPENDIX 2:

Risk Assessment Team for the Port of Khark Island

APPENDIX 3:

Check-list of project requirements

APPENDIX 4:

Information sources used for collating Port Environmental Data

APPENDIX 5:

Sources and references of Risk Species information

APPENDIX 6:

Name, UN code, coordinates and environmental parameters of the 357 ports

used for the multivariate similarity analyses for all Demonstration Sites

ix

Ballast Water Risk Assessment, Port of Khark Island, Islamic Republic of Iran, August 2003: Final Report

Figure 1.

Locations of the six GloBallast Demonstration Sites and their various ballast water source

and destination ports. .............................................................................................................................. 3

Figure 2.

Location of Khark Island and other ports in the ROPME Sea Area....................................................... 4

Figure 3.

Schematic of the GloBallast BWRA system ........................................................................................... 6

Figure 4.

Thematic layers used for the Port Map GIS............................................................................................ 9

Figure 5.

Working page of the Excel spreadsheet used to estimate BW discharges ......................................... 11

Figure 6.

The three tabs of the GUI used for entering the BWRF data............................................................... 14

Figure 7.

Part of the GIS world map of marine bioregions, showing the code names of the regions in

and near the ROPME Sea Area............................................................................................................ 18

Figure 8.

Complete GIS world map showing the marine bioregions [to improve clarity, not all bioregion

codes are shown in this example] ......................................................................................................... 19

Figure 9.

Database GUI used for manipulating the BWRA calculation and weightings ..................................... 23

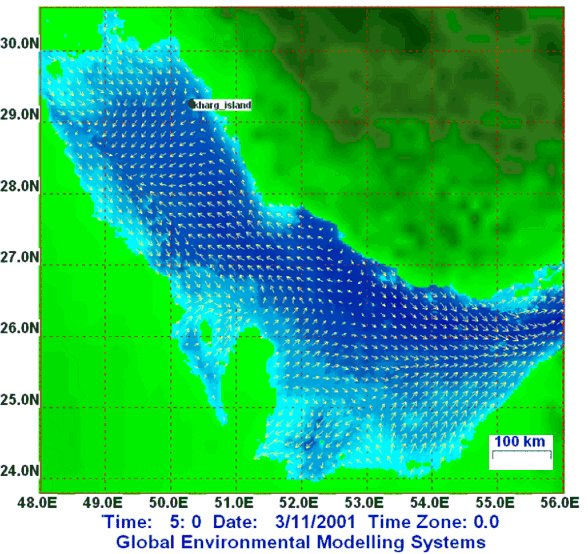

Figure 10.

Annual wind rose typical of the RSA region (supplied by GEMS) ...................................................... 29

Figure 11.

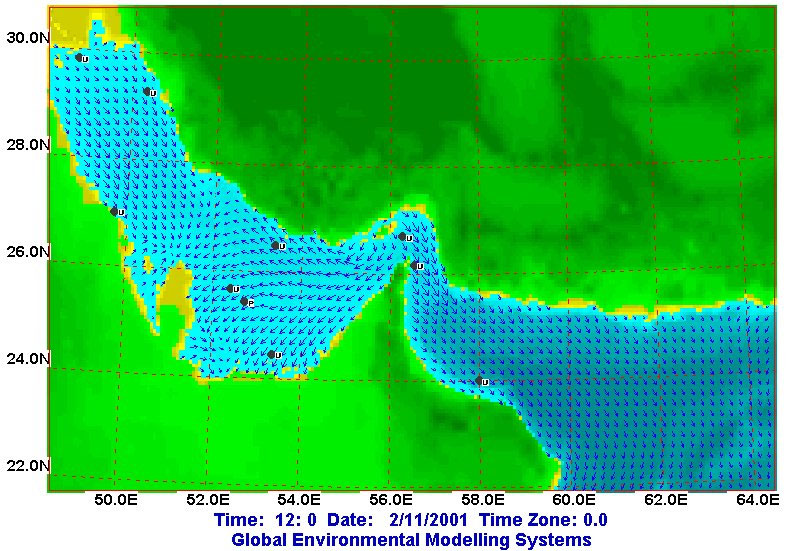

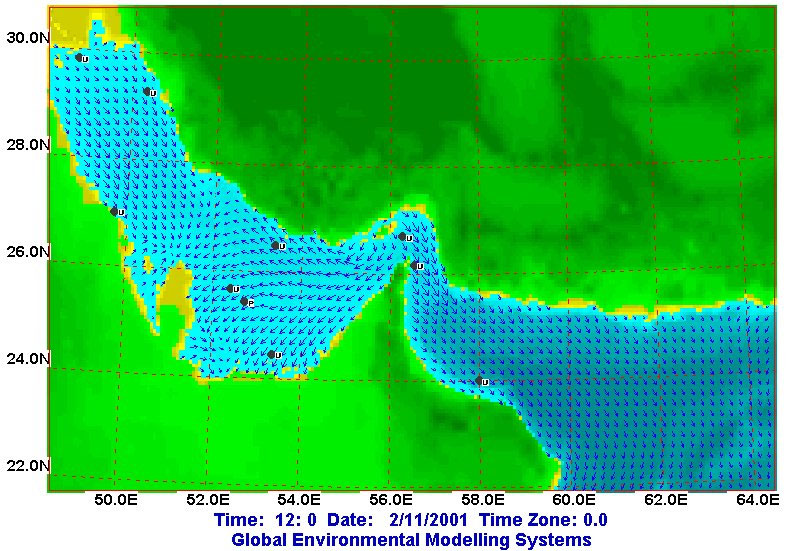

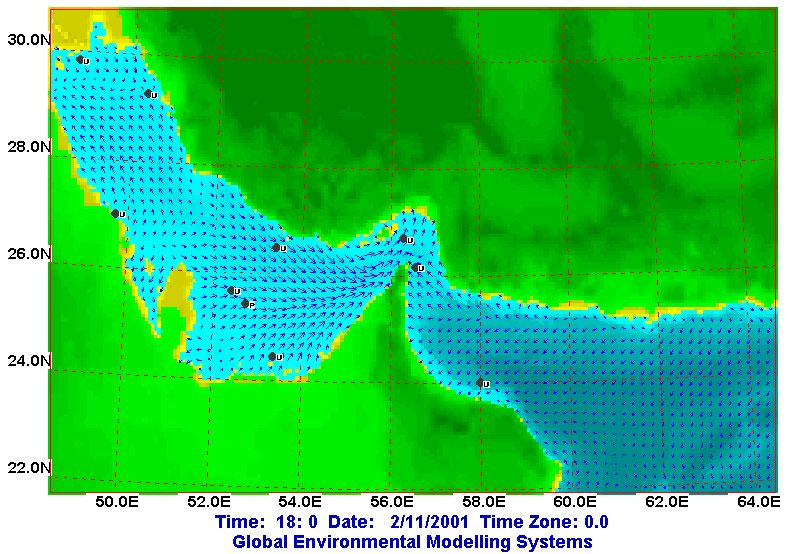

GCOM3D predictions of wind- and tidal-driven surface currents during strong northerly winds and

spring tides, showing the complex circulation pattern and model verification locations in the RSA.

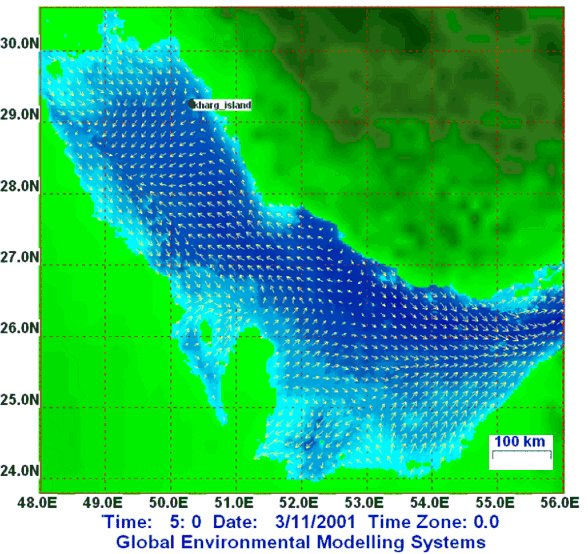

Bottom plot shows the opposing tidal phase (supplied by GEMS, Melbourne)................................... 30

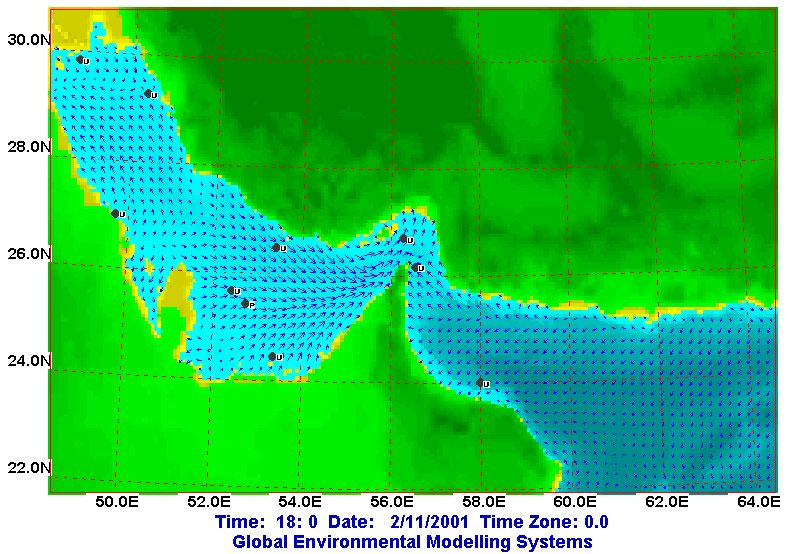

Figure 12.

GCOM3 output for neap tide currents and weak northerly winds, plus red arrows depicting

start of anti-clockwise gyre (supplied by GEMS, Melbourne). ............................................................. 31

Figure 13. Part of the GIS Port Map showing navigation, infrastructure and the active berth layer for

Khark Island. .......................................................................................................................................... 32

Figure 14. Part of the GIS Port Map showing the marine habitat layer................................................................. 33

Figure 15. BW discharge statistics displayed by the GIS Port Map for the T-Jetty .............................................. 35

Figure 16. BW discharge statistics displayed by the GIS Port Map for the Sea Island Terminal at

Khark Island. .......................................................................................................................................... 35

Figure 17. BW discharge statistics displayed by the GIS Port Map for the Chemical Jetty at Khark Island........ 36

Figure 18. GIS output showing the location and relative importance of BW source ports with respect to

frequency of tank discharges (C1) at Port of Khark Island................................................................... 36

Figure 19. GIS output showing the location and relative importance of the source ports with respect to the

volume of tank discharges (C2) at Port of Khark Island....................................................................... 39

Figure 20. GIS output showing the location and frequency of destination ports, recorded as the Next

Port of Call in the Port of Khark Island BWRFs and shipping records................................................. 40

Figure 21. GIS output showing the location and environmental matching coefficients (C3) of BW source

ports identified for the Port of Khark Island........................................................................................... 42

Figure 22. GIS output showing the location and environmental matching coefficients (C3) of the destination

ports identified for the Port of Khark Island........................................................................................... 46

Figure 23. GIS output showing the location and risk species threat coefficients (C4) of the BW source

ports identified for the Port of Khark Island........................................................................................... 46

Figure 24. GIS output showing the location and categories of relative overall risk (ROR-cat) of source

ports identified for the Port of Khark Island........................................................................................... 50

Figure 25. Frequency distribution of the standardised ROR values...................................................................... 53

x

1

Introduction and Background

The introduction of harmful aquatic organisms and pathogens to new environments via ships' ballast

water (BW) and other vectors, has been identified as one of the four greatest threats to the world's

oceans. The International Maritime Organization (IMO) is working to address the BW vector through

a number of initiatives, including:

· adoption of the IMO Guidelines for the control and management of ships' ballast water to

minimize the transfer of harmful aquatic organisms and pathogens (A.868(20));

· developing a new international legal instrument (Draft International Convention for the

Control and Management of Ships' Ballast Water and Sediment),, as currently scheduled to

be considered for adoption by an IMO Diplomatic Conference in February 2004; and

· providing technical assistance to developing countries through the GEF/UNDP/IMO Global

Ballast Water Management Programme (GloBallast).

Core activities of the GloBallast Programme are being undertaken at Demonstration Sites in six Pilot

Countries. These sites are the ports at Khark Island (I.R. Iran), Dalian (China), Mumbai (India),

Odessa (Ukraine), Saldanha (South Africa) and Sepetiba (Brazil). Activities carried out at the

Demonstration Sites will be replicated at additional sites in each region as the programme progresses

(further information http://globallast.imo.org).

One of GloBallast's core activities (Activity 3.1) has been to trial a standardised method of BW risk

assessment (BWRA) at each of the six Demonstration Sites. Risk assessment is a fundamental starting

point for any country contemplating implementing a formal system to manage the transfer and

introduction of harmful aquatic organisms and pathogens in ships' BW, whether under the existing

IMO Ballast Water Guidelines (A.868(20)) or the forthcoming Convention.

A port State may wish to apply its BW management regime uniformly to all vessels that call at its

ports, or it may wish to assess the relative risk of vessels to its coastal marine resources and apply its

regime selectively. Uniform application or the `blanket' approach offers the advantages of simplified

administration and no requirement for `judgement calls' to be made. This approach also requires

substantially less information management effort. If applied strictly, the uniform approach offers

greater protection from unanticipated bio-invaders, as it does not depend on the reliability of a

decision support system that may not be complete. However, the key disadvantage of the strict blanket

approach are the BW management costs imposed on vessels which otherwise might not be forced to

take action. It also requires a substantial vessel monitoring and crew education effort to ensure all

foreign and domestic flagged ships are properly complying with the required BW management

actions.

A few nations have started to develop and test systems that allow more selective application of BW

management requirements, based on voyage-specific risk assessments. This `selective' approach

offers to reduce the numbers of vessels subject to BW controls and monitoring, and is amenable to

nations that wish to reduce the introduction, and/or domestic spread, of `targeted' marine species only.

More rigorous measures can be justified on ships deemed to be of high risk if fewer restrictions are

placed on low risk vessels.

For countries/ports that choose the selective approach, it is essential to establish an organized means

of evaluating the potential risk posed by each arriving vessel, through a `Decision Support System'

(DSS). However, this approach places commensurate information technology and management

burdens on the port State, and its effectiveness depends on the quality of the information and database

systems that support it. A selective approach that is based on a group of targeted species may also

leave the country/port vulnerable to unknown risks from non-targeted species.

1

Ballast Water Risk Assessment, Port of Khark Island, Islamic Republic of Iran, August 2003: Final Report

Before a port State decides on whether to adopt the blanket or the selective approach, it needs to carry

out some form of risk assessment for each port under consideration. Ballast water risk assessments

(BWRAs) can be grouped into three categories1:

· Qualitative Risk Identification: this is the simplest approach, and is based on subjective

parameters drawn from previous experience, established principals and relationships and

expert opinion, resulting in simple allocations of `low', `medium' and `high' risk. However it

is often the case that subjective assessments tend to overestimate low probability/high

consequence events and underestimate higher probability/lower consequence events (e.g.

Haugom et al, in Leppäkoski et al 2002).

· Semi-Quantitative Ranking of Risk: this `middle' approach seeks to increase objectivity and

minimise the need for subjective opinions by using quantitative data and ranking of

proportional results wherever possible. The aim is to improve clarity of process and results,

thereby avoiding the subjective risk-perception issues that can arise in qualitative approaches.

· Quantitative Risk Assessment: this is the most comprehensive approach which aims to

achieve a full probablistic analysis of the risk of BW introductions, including measures of

confidence. It requires significant collation and analysis of physico-chemical, biological and

voyage-specific data, including key lifecycle and tolerance data for every pre-designated

species of risk (`target species'), port environmental conditions, ship/voyage characteristics,

the BW management measures applied, and input and evaluation of all uncertainties. The

approach requires a high level of resourcing, computer networking and sophisticated

techniques that are still being developed1.

The purpose of GloBallast Activity 3.1 has been to conduct initial, first-pass BWRAs for each

Demonstration Site. To maximise certainty while seeking cost-effectiveness and a relatively simple,

widely applicable system, the middle (semi-quantitative) approach was selected.

The first step of the GloBallast method is to collate data from IMO Ballast Water Reporting Forms

(BWRFs) (as contained in Resolution A.868(20); see Appendix 1) to identify the source ports from

which BW is imported to the demonstration port. For periods or vessel arrivals where BWRFs were

not collected or are incomplete, gap-filling data can be extracted from port shipping records.

Source port/discharge port environmental comparisons are then carried out and combined with other

risk factors, including voyage duration and risk species profiles, to give a preliminary indication of

overall risk posed by each source port. The results help determine the types of management responses

required, while the BWRA process provides a foundation block enabling application of more

sophisticated BW management DSSs by Pilot Countries.

The GloBallast approach is not the only one available but is considered to combine the best elements

of the semi-quantitative method to provide useful results within the available budget (US$250,000

spread across the six pilot countries). It has also taken a `whole-of-port' approach which compares the

subject port (Demonstration Site) with all of its BW source and destination ports. The outputs include

published reports, trained in-country risk assessment teams and an operational BWRA system for use

as demonstration tools in each of the six main developing regions of the world, plus a platform and

database to facilitate further DSS development. The GloBallast BWRA activity has therefore

established an integrated database and information system to manage and display:

· ballast water data from arriving ship BWRFs and port shipping records;

· data on the demonstration port's physical and environmental conditions and aquatic

resources,

· port-to-port environmental matching data,

· risk species data, and

· ballast water discharge risk coefficients.

1 for further details see the GloBallast BWRA User Guide.

2

1 Introduction and Background

The results provide a knowledge base that will help the Pilot Countries and other port States to

evaluate the risks currently posed by BW introductions, identify high priority areas for action, and

decide whether to apply a blanket or selective BW management regime. If a selective regime is

adopted, vessel and voyage-specific risk assessments can then be applied using systems such as those

being developed and trialled by the Australian Quarantine & Inspection Service (AQIS Decision

Support System), Det Norsk Veritas in Norway (EMBLA system) and the Cawthron Institute in New

Zealand (SHIPEXPLORER system), and/or by further development of the GloBallast system. If a

uniform approach is adopted, the results help identify which routes and vessel types warrant the most

vigilance in terms of BW management compliance checking and verification monitoring, including

ship inspections and ballast tank sampling.

The geographical spread and broad representativeness of the six Demonstration Sites also mean that

the results help plug a very large gap in the existing global knowledge base. Figure 1 indicates the

broad global spread of the GloBallast risk assessment activity. As a result of this activity,

comprehensive data are now available on source port and destination port linkages, environmental

parameters, environmental matching coefficients, risk species and relative overall risk of BW

transfers for the six GloBallast Demonstration Sites and a total of 723 ports around the world. Project

outcomes will therefore place governments, scientists, the shipping industry and the general public in

a stronger, more enlightened position to deal with the BW problem.

Figure 1. Locations of the six GloBallast Demonstration Sites and their various ballast water source and

destination ports.

This report describes and presents the results of the first Ballast Water Risk Assessment (BWRA)

carried out for the Port of Khark Island, Islamic Republic of Iran, during 2002. This GloBallast

Demonstrate Site is a major oil export terminal which is located in the north-west part of the ROPME

Sea Area (Figure 2).

3

Ballast Water Risk Assessment, Port of Khark Island, Islamic Republic of Iran, August 2003: Final Report

Figure 2. Location of Khark Island and other ports in the ROPME Sea Area

4

2 Aims & Objectives

The aims of the GloBallast BWRA for the Port of Khark Island were to:

1. Assess and describe as far as possible from available data, the risk profile of invasive aquatic

species being both introduced to and exported from Khark Island in ships' BW, and to identify the

source ports and destination ports posing the highest risk for such introductions.

2. Help determine the types of management responses that are required, and provide the foundation

blocks for implementing a more sophisticated BW management system for the Port of Khark

Island.

3. Provide training and capacity building to in-country personnel, resulting in a fully trained risk

assessment team and operational risk assessment system, for ongoing use by the Pilot Country,

replication at additional ports and use as a demonstration tool in the region.

The specific objectives of the BWRA for the Port of Khark Island were to:

1. Identify, describe and map on a Geographic Information System (GIS) all coastal and marine

resources (biological, social/cultural and commercial) in and around the port that might be

impacted by introduced marine species.

2. Characterise, describe and map (on GIS) de-ballasting and ballasting patterns in and around the

port including locations, times, frequencies and volumes of BW discharges and uptakes.

3. Identify all ports/locations from which BW is imported (source ports).

4. Identify all ports/locations to which BW is exported (destination ports).

5. Establish a database at the nominated in-country agency for the efficient ongoing collection,

management and analysis of the data collected at the Port of Khark Island via standard IMO

BWRFs.

6. Characterise as far as possible from existing data, the physical, chemical and biological

environments for both Khark Island and each of its source and destination ports.

7. Develop environmental similarity matrices and indices to compare the Port of Khark Island with

each of its source ports and destination ports, as a key basis of the risk assessment.

8. Identify as far as possible from existing data, any high-risk species present at the source ports that

might pose a threat of introduction to the Port of Khark Island, and any high-risk species present

at this port that might be exported to a destination port.

9. Identify any information gaps that limit the ability to undertake the aims and objectives and

recommend management actions to address these gaps.

5

3

Methods

3.1

Overview and work schedule

The BWRA Activity for the Port of Khark Island was conducted by Meridian GIS Pty Ltd (Meridian),

under contract to the GloBallast Programme Coordination Unit (PCU). The consultants worked

alongside their Pilot Country counterparts during the country visits to provide training and skills-

transfer as part of the capacity building objectives of the programme. Structure and membership of the

joint project team is shown in Appendix 2.

The consultants adopted an innovative, modular approach that integrated three widely used computer

software packages to provide a user-friendly tool for conducting, exploring and demonstrating semi-

quantitative BWRAs. As shown in Figure 3, the key software comprised:

· Microsoft Access - for the main database;

· PRIMER 5 [Plymouth Routines In Marine Environmental Research] - a versatile multivariate

analysis package from the United Kingdom enabling convenient multivariate analysis of the

port environmental data; and

· ESRI ArcView 3.2 Geographic Information System (GIS) - to graphically display the results

in a convenient, readily interpretable format using port and world maps.

The work schedule commenced with project briefing meetings with personnel from all six

Demonstration Sites to arrange logistics and resource needs, during the third meeting of the

GloBallast Programme's Global Task Force, held in Goa, India on 16-18 January 2002. The majority

of tasks subsequently undertaken for the Port Khark Island were completed during two in-country

visits by the consultants (2-9 May and 7-23 December 2002), with information searches and data

collation undertaken by both consultant and pilot country team members between and after these

visits. A two-day `project wrap-up' visit was subsequently made by one of the consultants in February

2003.

Figure 3. Schematic of the GloBallast BWRA system

6

3 Methods

The specific tasks of the week-long first visit were to:

· Install and test the Access, ArcView and PRIMER software and the functionality of the

computer system at the Ports & Shipping Organisation (PSO) head offices in Tehran.

· Familiarise the project team with the GloBallast BWRA method by seminar and work-

shopping.

· Commence GIS training and developing the port map for the Demonstration Site.

· Commence training on the use of the various Graphic User Interfaces (GUI) of the Access

Database for inputting and editing BW discharge data.

· Visit Khark Island to obtain port shipping records, tour the port facilities and obtain habitat

and coastal resource information.

· Review the port shipping records and available BWRFs to identify trading patterns, vessel

types, key BW source ports and likely destination ports.

· Check available port environmental data and identify potential in-country and regional

sources of same.

· Commence listing risk species and identifying potential in-country or regional sources of

same.

· Identify critical information gaps and the data assembly work required before the second visit.

During the longer second visit by the consultants, the environmental and risk species data were added

to the database, more vessel arrival, BW and voyage data were entered and checked, the first BWRA

was undertaken, and a workshop was held to review the initial results and identify future actions.

During the third visit on 16-17 February 2003, the consultants supplied PSO with updated versions of

the database and BWRA User Guide on CD-ROM, which included additional source port environment

and risk species data (as obtained from the BWRA Activities conducted at the other five

Demonstration Sites). The results of the February 2003 version are reported here.

Throughout the schedule, the joint project team was divided into three groups to facilitate training and

progress (Appendix 2). Group A was responsible for developing the port map and graphically

displaying results via the GIS. All coastal and marine resources (biological, social/cultural and

commercial) in and around the port that might be impacted by aquatic bio-invasions were mapped

using the ArcView GIS, using specific layers to show the bathymetry, navigation aids, port

infrastructure and tables of the port's de-ballasting/ballasting patterns (including frequencies and

volumes of discharges and uptakes for the berth locations).

Group B was responsible for managing the customised Access database supplied by the consultants,

and for entering, checking and managing the BW data, as collated from the BWRFs submitted by

arriving ships (and/or derived from shipping records for periods or arrivals when BWRFs were not

obtained or incomplete). This database was used to identify source and destination ports, and was

designed for ongoing input and management of future BWRFs.

NB. The requirement for arriving ships to submit IMO-style BWRFs (Appendix 1 and down-

loadable from http://globallast.imo.org/guidelines) to the relevant port State authorities is a

fundamental and essential first basic step for any port State wishing to commence a ballast

water management programme2.

Group C was responsible for collating the port environmental and risk species data, undertaking port-

to-port environmental similarity analyses and performing the BWRA. Thirty four environmental

2 Several port States (e.g. Australia) and Demonstration Sites (e.g. Dalian, Odessa) have produced their own

BWRFs, the latter using a translated format to permit improved BWRF understanding and completion by

local shipping. Such BWRFs need to include all questions of the IMO standard form. Problems arising from

voluntary submission of BWRFs are described in Section 4.12.

7

Ballast Water Risk Assessment, Port of Khark Island, Islamic Republic of Iran, August 2003: Final Report

variables were collated for the Demonstration Site and the majority of its source and destination

ports3, including sea water and air temperatures, salinities, seasonal rainfall, tidal regimes and

proximity to a standardised set of intertidal and subtidal habitats. Where water temperature data or

salinity data could not be found for a source or destination port, values were derived for the riverine,

estuarine or coastal location of the port with respect to the temperature and salinity data ranges of its

IUCN marine bioregion, plus ocean maps depicting sea surface temperature/salinity contours at

quarter degree and degree scales (as obtained from CRIMP [now CSIRO Marine Research], URS

Australia Pty Ltd and other sources; Appendix 3).

The multivariate analysis of the port environmental data was undertaken using PRIMER 5, with the

similarity values between the Port of Khark Island and its source and destination ports converted into

environmental matching coefficients then added to the database. Species in or near source ports that

were deemed to pose a threat if introduced to the Demonstration Site, together with species at the

Demonstration Site that might be exported to a destination port, were identified from all available

sources found by the project team. These sources included preliminary results from the Port

Biological Baseline Surveys (PBBS); as recently completed at each Demonstration Site by another

GloBallast Activity, plus searches of `on-line' databases such as those under ongoing development by

the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC), the Australian Centre for Research on

Introduced Marine Pests (CRIMP), the Baltic Regional Marine Invasions Database and the Global

Invasive Species Programme (GISP). The species taxonomic information and bioregional

distributions were also added to the Access database. The combined BW discharge, environmental

matching and risk species coefficients provided the basis of the semi-quantitative risk assessment.

Graphic User Interfaces (GUIs) customised by the consultants for the Access database and ArcView

GIS were used to generate results tables and graphical outputs that were displayed on interactive maps

of the Demonstration Site and World bioregions. The various BWRA outputs can be printed, exported

to other software, or viewed interactively to enhance the user-friendliness and management utility of

the system.

The methods used to attain each objective of the BWRA Activity are summarised in the following

sections, with technical details of the risk assessment procedures provided in the GloBallast BWRA

User Guide. This manual was developed by the consultants to facilitate BWRA training and

demonstrations for all six GloBallast Pilot Countries. The BWRA User Guide comprises a separate

document that accompanies this report, and is available from the GloBallast PCU

(http://globallast.imo.org).

3.2

Resource mapping of the demonstration port

The port resources were mapped using ArcView GIS to display the bathymetric, navigational and

infrastructure features, including habitats and social-cultural features.

The National Cartographic Centre (NCC) in Tehran did not have an electronic chart covering Khark

Island in digital format at the time of the first visit, but indicated a detailed hydrographic survey had

recently been completed and that electronic bathymetric data would be available before December

2002. Thus the bathymetry and some navigational data were acquired digitally from a CARIS

electronic chart provided by the NCC during the consultant's second visit.

3 The complete set of source and destination ports identified for the six Demonstration Sites (723) remained

unknown until the end of the BWRF/port record data collation, database entry and checking phases (i.e. end of

the second round of in-country visits; 22 December 2002). A gap-filling effort was made by the consultants to

obtain the environmental parameters during January 2003, but this had to focus on the most frequently

recorded of these ports, since there was insufficient time or resources to order charts and search for the

environmental data for all of them (the majority of which were associated with few or only single vessel

arrivals). For these ports, their environmental matching values were provided by a comparison method

described in Section 4.6.

8

3 Methods

NCC also supplied two 1:25,000 topographic sheets (6048 II NW and 6048 I SW) covering Khark

Island, and these were acquired from a Microstation DGN format file, together with two 1:25,000

nautical charts of the neighbouring coast (Bandar Rig and Bandar Genaveh) in the same format. A

small scale chart of the northern ROPME Sea Area (RSA) was also acquired. The topographic sheets

were imported into ArcView and combined, and relevant data for the port map was also extracted

from the other files. Features taken included the major roads, large buildings, tanks and cultural sites.

The Iranian nautical chart showing the port and its approaches (I.R. Iran Series No. 11; Jazireh-Ye

Khark to Ganaveh) was also scanned for digital capture at 300 dpi. This chart also shows the nearby

mainland coast and has small-scale insets showing the export terminals and small boat harbours at

Khark Island. The images were registered in ArcView enabling extraction of relevant data including

annotated habitat details collected during the team's port visit in May 2002. The latter comprised the

boundaries of certain intertidal, subtidal and artificial marine habitats that were annotated to this chart

during the port visit.

The scope of the port map therefore includes the rocky Khark Island and its nearby sand cay, the

port's approaches and anchorage areas, and part of the adjacent mainland coastline. Symbols based on

the international IHO/IALA system were used to depict navigational features. For clarity and

convenience of data management and display, each `theme' of information was added as a separate

layer that were standardised as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Thematic layers used for the Port Map GIS

The protocol for each layer is described in the GloBallast BWRA User Guide and summarised below:

Base Layer: The base layer includes important planimetric features such as depth contours, jetties,

important channels and other permanent or at least semi-permanent `reference' features that are

unlikely to change or move. The key features of the base layer for the Port of Khark Island comprised:

· The island and mainland coastlines (as depicted by the high tide mark on the nautical charts).

· The low tide mark (i.e. the 0 metre bathymetric contour of hydrographic charts).

· 5 metre isobath (often the first continuous contour below the low tide mark).

· 10 metre, 20 metre and 30 metre isobaths.

· Edges of the main shipping channels (often blue or purple lines showing the boundary of

depths maintained by port dredging programs).

Some key land features, including main roads, hill tops, towers and other prominent structures, were

also added to the base layer. The colour scheme of this layer closely followed that of standard nautical

charts to maintain the familiar depth effect.

Navigational Layer: The standard navigational symbols of the IHO/IALA system were followed as

closely as possible. ArcView's symbol libraries do not contain these international navigation symbols,

9

Ballast Water Risk Assessment, Port of Khark Island, Islamic Republic of Iran, August 2003: Final Report

and convenient third-party symbology could not be found despite extensive searches of public domain

web resources. Closest-match symbols were therefore developed for this purpose, using the UK

Hydrographic Office Chart No. 5011 (= IHO INT 1) as the main source for all point and pattern

symbols.

Habitat Layer: This layer used a standardised, logical colour scheme to facilitate recognition of the

main intertidal and subtidal habitat types in and near the port. It contains all habitat information

obtained from the field observations and benthic sampling data from the PBBS, together with the

annotations made by the BWRA team during the port tour. The latter was undertaken by launch, on

foot and snorkelling during 6-7 May 2002, with the boat inspection including a full circumnavigation

of the island. Colour 35 mm photographs and a 45 minute VHS video were obtained to record

significant features. Delineation of some boundaries for the habitat layer was supplemented from

features displayed by the nautical charts. These included the upper and lower boundaries of sand

beaches, rocky shores, cliff lines, high tidal lagoons and marsh areas, and fringing coral reef. Symbols

on the same charts that denoted the presence of sand, mud or rocky seafloor also helped fill in gaps.

Infrastructure Layer: This shows the key components of the port and its surrounding accommodation

and petroleum processing and export facilities, including the main tank farms, small boat harbour,

large buildings and other visually dominant structures on Khark Island.

Social-Cultural Layer: Features added to this layer included the urban and accommodation area used

by the port and oil terminal workers, mosques and significant shipwrecks that have been essentially

left undisturbed and respected as war grave sites. There is no dedicated fishing port on Khark Island,

nor any recreational, commercial or mariculture fishery areas, so these type of social resources were

not present for adding to this layer.

Berth Layer: An `active' berth layer was added to show the principal berthing and anchoring areas at

the Port of Khark Island. Their names and numbering system were supplied by PSO island staff. The

same nomenclature was also used for the berthing area information stored in the Access database, to

allow display of statistical summaries of the BW source and discharge data on the correct locations of

the GIS port map (the GloBallast BWRA User Guide shows how the database-GIS link is established).

3.3

De-ballasting/ballasting patterns

The deballasting/ballasting patterns at Khark Island were ascertained during the port visit (6-7 May

2002) where a meeting was held with the PSO Harbour Master to confirm the range of overseas and

domestic trade, pilotage and draft requirements, anchorage areas and deballasting/ballasting practises

and locations. Port shipping records were also inspected during this visit, and batches of these were

identified for photocopying to enable data verification and extraction at the PSO offices in Tehran.

Further information was obtained from the BWRFs that PSO had introduced to the Port of Khark

Island in April 2000, plus analysis of the port shipping records for periods/visits where BWRFs were

unavailable or incomplete4. It was relatively simple to determine where and which vessels probably

discharged BW by identifying their type and berthing location, because the port has dedicated liquid

and dry bulk export terminals plus a small vessel harbour where the various supplies and construction

materials for operating the terminals and onshore facilities are imported. Most of the latter cargo

arrives in coastal craft which have no ballasting requirement when unloading.

3.4

Identification of source ports

To provide confidence as to which ports are the predominant sources of BW discharged at Khark

Island, a sample of approximately 1500 vessel visits was generated by collating information on as

many ship visits as possible over the previous three years (March 1999 - November 2002) and adding

4 These records listed the vessel name, arrival and departure dates, berth, last and next ports of call, and cargo details.

10

3 Methods

the details to the Access database. Source ports were therefore identified from the BWRFs, and from

batches of photocopied shipping record sheets obtained from PSO's Khark Island office for March

1999 and subsequent months.

BWRFs were first collected from arriving ships by PSO staff at Khark Island in April 2000, and the

number of ships voluntarily submitting these forms was close to 40 per month in the first year (i.e.

approximately 60% of total arrivals). The forms were initially sorted by source port and country then

entered into the database. Before a new port was added to the database, the port and country name

spelling, its location coordinates, bioregion and unique UN Port Code number were checked using the

Lloyds Fairplay World Ports Guide and world bioregion list in the database (port data input is

detailed in the GloBallast BWRA User Guide).

Completed BWRFs for April and May 2000 (85) were cross-referenced with the port shipping records

for the same period (140 visits). Of the 55 visits where ships had not (or incorrectly) completed a

BWRF, 25 were mostly product and gas tankers shuttling between the Bandar Abbas refinery in

southern I.R. Iran and Khark Island. The remaining 30 were crude oil tankers and two bulk carriers

loading sulphur (Section 4.3).

For vessels arriving before BWRFs were requested by PSO, or which submitted incomplete or did not

submit forms, details were obtained from the PSO port shipping records. However these records show

only the Last Port of Call, which may not be the BW source. To confirm which last ports of call were

probable BW sources (and avoid allocating a bunkering, crew-change or maintenance port as such),

cross-checks were made of the source ports and last ports of call reported in other BWRFs. The

Lloyds Fairplay Port Guide and Lloyds Ship Register5 were also used to confirm source port trade

and the vessel's IMO identification number, vessel type and DWT of arriving ships respectively.

Many gaps in the port shipping records or BWRFs could therefore be filled by checking, for any

arrival, the vessel name, type and DWT, its previous visit history, last port/s of call and apparent

charter/liner trade, and by using a customised Excel spreadsheet supplied by the consultants to

estimate the amount BW discharged or taken up6 (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Working page of the Excel spreadsheet used to estimate BW discharges

The BWRFs were also analysed for completeness and accuracy. In the case of unusual (or missing)

BW values, these were checked using the same Excel spreadsheet to determine likely volumes based

on vessel type, DWT, last port/source port and loading record. This BWRF checking and gap-filling

5 A CD-ROM version of the 2001 Lloyds Ship Register was supplied to each Demonstration Site by PCU. These are much

faster to use than the large `directory style' hard-copy volumes.

6 The BW spreadsheet contains coefficients of ballast water taken up or discharged when loading or discharging

cargo (as percentages of DWT for each vessel type), based on ballast water capacity and discharge data from

other studies, BWRFs and Lloyds Ship Register.

11

Ballast Water Risk Assessment, Port of Khark Island, Islamic Republic of Iran, August 2003: Final Report

exercise was undertaken by Group B team members working in Tehran and Khark Island before and

during the second in-country visit, with the database of almost 1500 vessel visits constructed by:

· entering visit details from the port shipping records for the pre-BWRF period (March 1999-

April 2000) on the Excel spreadsheet, and using the Fairplay Port Guide and Lloyds Ship

Register to add or correct port details, vessel names, IMO ship numbers, types and DWTs;

and

· cross-checking incomplete, unusual or missing BWRFs with port shipping records, using the

Lloyds Ship Register, Fairplay Port Guide and the Excel spreadsheet to correct errors or add

missing data4,5.

3.5

Identification of destination ports

Since `prevention is better than cure', it is usually most effective to address environmental problems

as close to their source as possible. In the case of ballast-mediated aquatic bio-invasions, actions to

help ships prevent the uptake of organisms from ballasting areas may be more effective than trying to

treat the organisms once they are inside the tanks, or trying to manage the problem at the discharge

port. To date, however, the majority of actions addressing ballast-mediated introductions have been

driven and undertaken by ports and port States that receive BW, with little activity occurring at the

locations of BW uptake. The GloBallast programme has therefore been attempting to shift some of

the focus from shipboard/point-of-discharge measures towards reducing the uptake of organisms in

the first place.

Knowing the destinations where departing vessels will discharge their BW is an important step in

helping port States to reduce the spread of unwanted and potentially harmful species (either

introduced or native to their own ports) to their trading partners. It is also critical for preventing

unwanted species translocations between a State's domestic ports and/or its neighbouring foreign

ports. Determining the destinations of BW exported from the Demonstration Site was therefore an

objective of the GloBallast BWRA (Section 2).

Both the BWRFs and port shipping records for Khark Island list the Next Port of Call of all departing

vessels, and these were added to the database for analysis. However the next port of call may not be

where BW carried by a departing ship is discharged, either fully or partly. For example, the next port

may be a bunkering, crew-change or maintenance port, a port where a `top-up' or other minor cargo is

loaded, or a convenient regional `hub' port where ships anchor and wait for new sailing instructions.

To overcome this problem, a supplementary question needs to be added to the present IMO BWRF,

i.e. requesting the name of the port where discharge from each ballast tank is predicted. These ports

can be predicted by ships engaged on a regular liner service (e.g. most container ships, vehicle

carriers, Ro-Ro ships, LNG carriers and some bulk carriers). However for other ship types (and

occasionally the former) ship officers cannot reliably anticipate where BW discharges will be

necessary. For example, for bulk carriers, general cargo ships and tankers engaged in spot charter

work (or when completing a charter period), these vessels may often depart in ballast having received

a general sailing order to proceed towards a strategic location until further instructions.

In the case of the Port of Khark Island, there is little import of bulk cargo except for some fuel

products brought by a shuttle tanker from the Bandar Abbas refinery. Although the vast majority of

ships departing Khark Island have no or very little BW on board, the next ports of call were added to

the vessel visit data and examined, so that the Pilot Country team could gain experience for BWRAs

undertaken for a more cargo import/BW export-oriented port.

Adding the next port of call also improves the trading history for each vessel, and these can be useful

when trouble-shooting missing or incorrect BWRF data. As with the source ports, any new next port

of call added to the database was provided with its country name, UN Port Code, world bioregion and

location coordinates to enable its frequency of use by departing vessels to be displayed on the GIS

world map (port input details are in the GloBallast BWRA User Guide).

12

3 Methods

3.6

BWRF database

The Access database developed by the consultants manages all items on the IMO standard BWRF.

Entry, editing and management of the BWRF records are undertaken using a series of GUIs, as

described in Section 2 of the BWRA User Guide. The three `tab' pages of the GUI used for general

BWRF data and the individual ballast tank inputs are shown in Figure 6.

Items not listed on the BWRF but required by the database to run the risk analysis and display the

results on the GIS include the geographic coordinates, bioregion and UN code (a unique five letter

identifier) of every source and destination port, plus the DWT and berthing location of every arrival at

the Demonstration Site.

Many berthing locations had to be identified from the port's shipping records because the BWRA

objectives include identifying the locations within a Demonstration Site where deballasting/ballasting

occurs (Section 2). After the consultants first in-country visit (May 2002), PSO officers at Khark

Island began annotating the berthing location to submitted BWRFs to help reduce the data-entry

workload. Another item requiring frequent look-up was the vessel's deadweight tonnage (DWT)since

the BWRF requests only the gross tonnage (GT). As noted in Section 3.4, adding the DWT (present in

the Lloyds Ship Register) enables convenient checks of reported volumes and gap-filling of missing

values (see below).

Not all of the BWRF question fields need to be completed by a ship's officer to provide a visit record

that can be saved to the database and later included in the risk analysis. A basic visit record can be

established if three key items are entered. These are outlined in red on the input GUIs (Figure 6) and

are:

· Vessel identification - a unique 7 digit IMO number that remains the same for the life of the

ship, irrespective of any name changes;.

· Arrival date.

· A ballast tank code (which appears on the `Add Tank' sheet and provides an `All Tanks'

option for BWRFs that were submitted without individual tank details).

Without these items the database cannot save a visit / tank record or any other associated information.

Whether or not a saved record is included by the database for the risk analysis depends on which other

BWRF fields were completed or gap-filled. Key items are the source port and volume for each (or all)

ballast tanks discharged, and the berthing location. As described in Sections 3.4 and 3.5, important

BWRF information that is missing or incorrect can usually be substituted or corrected by cross-

checking with port shipping records, the Lloyds Ship Register and a comprehensive port directory