GB Monograph Series 9 v2 25/9/03 9:46 am Page 1

1st Inter

national W

Global Ballast Water

Management Programme

orkshop

G L O B A L L A S T M O N O G R A P H S E R I E S N O . 9

on Guidelines and Standards for Ballast W

1st International Workshop

on Guidelines and Standards for

Ballast Water Sampling

ater Sampling

W

orkshop Report

RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL,

7-11 APR 2003

.dwa.uk.com

Workshop Report

Steve Raaymakers

GLOBALLAST MONOGRAPH SERIES

More Information?

el (+44) 020 7928 5888 www

Programme Coordination Unit

Global Ballast Water Management Programme

International Maritime Organization

4 Albert Embankment

London SE1 7SR United Kingdom

Tel: +44 (0)20 7587 3247 or 3251

est & Associates, London. T

Fax: +44 (0)20 7587 3261

Web: http://globallast.imo.org

NO.9

A cooperative initiative of the Global Environment Facility,

United Nations Development Programme and International Maritime Organization.

Cover designed by Daniel W

GloBallast Monograph Series No. 9

1st International Workshop on

Guidelines and Standards for

Ballast Water Sampling

Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: 7-11 April 2003

Workshop Report

Raaymakers, S.

International Maritime Organization

ISSN 1680-3078

Published in October 2003 by the

Programme Coordination Unit

Global Ballast Water Management Programme

International Maritime Organization

4 Albert Embankment, London SE1 7SR, UK

Tel +44 (0)20 7587 3251

Fax +44 (0)20 7587 3261

Email sraaymak@imo.org

Web http://globallast.imo.org

The correct citation of this report is:

Raaymakers S. 2003. 1st International Workshop on Guidelines and Standards for Ballast Water Sampling, Rio de Janeiro,

Brazil, 7-11 April 2003: Workshop Report. GloBallast Monograph Series No. 9. IMO London.

The Global Ballast Water Management Programme (GloBallast) is a cooperative initiative of the Global Environment Facility (GEF),

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and International Maritime Organization (IMO) to assist developing countries to reduce

the transfer of harmful organisms in ships' ballast water.

The GloBallast Monograph Series is published to disseminate information about and results from the programme, as part of the

programme's global information clearing-house functions.

The opinions expressed in this document are not necessarily those of GEF, UNDP or IMO.

1st International Workshop on Guidelines and Standards for Ballast Water Sampling, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 7-11 April 2003

Acknowledgements

The 1st International Workshop on Guidelines & Standards for Ballast Water Sampling was funded

by the Global Environment Facility (GEF), as an activity of the GEF/UNDP/IMO Global Ballast

Water Management Programme (GloBallast). The workshop was hosted and partly sponsored by the

Government of Brazil, through the Federal Department of Environment, with additional sponsorship

and/or support from the following organizations:

· Aliança Navegaçăo e Logística Ltda - Brazilian shipping company of Hamburg Sud.

· International - marine paint company from the group Akzo Nobel.

· Sindicato Nacional das Empresas de Navegaçăo Marítime (Syndarma) Brazilian National

union of shipping companies.

· Petrobrás Transpetro S.A branch of Petrobras responsible for oil transport.

· Marinha do Brasil Brazilian Navy.

· Companhia Docas do Rio de Janeiro - Rio de Janeiro Port Authority.

· Escola Nacional de Botânica Tropical - National School of Tropical Botany.

The efforts of following individuals deserve special thanks for their personal contributions to making

the symposium a success:

· Mr Leonard Webster, Mr Alex Leal C. Neto, Dr Flavio de Costa Fernandes, Ms Karen Larsen

and Ms Julieta da Silva for their sterling efforts in providing organizational support.

· Dr Flavio de Costa Fernandes, Dr Stephan Gollasch, Mr Tim Dodgshun, Mr Matej David, Dr

Chad Hewitt and Mr John Hamer for their role as technical advisers, instructors and/or

facilitators.

· All persons who presented papers, providing the very substance of the workshop.

· All other participants, without who the symposium would not be an event.

Layout and formatting of this report was undertaken by Leonard Webster of the GloBallast PCU.

Delegates photograph

i

1st International Workshop on Guidelines and Standards for Ballast Water Sampling, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 7-11 April 2003

Contents

Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................. i

Delegates Photograph ......................................................................................................... i

1

Introduction & Background..................................................................................... 1

2

Workshop Objectives .............................................................................................. 2

3

Workshop Outputs .................................................................................................. 2

4

Workshop Structure & Programme......................................................................... 3

5

Workshop Participants............................................................................................ 4

6

Workshop Results and Recommendations ............................................................ 4

7

Further Action & Overall Conclusion.................................................................... 19

References ........................................................................................................................ 19

Appendix 1: Workshop Programme

Appendix 2: Workshop Participants

Appendix 3: Selected Papers

Appendix 4: Thursday Working Group Instructions

Appendix 5: Draft Structure for International BW Sampling Guidelines

ii

1st International Workshop on Guidelines and Standards for Ballast Water Sampling, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 7-11 April 2003

1

Introduction & Background

The introduction of harmful aquatic organisms and pathogens to new environments via ships' ballast

water and other vectors, has been identified as one of the four greatest threats to the world's oceans.

The International Maritime Organization (IMO) is working to address the ballast water vector through

a number of initiatives, including:

· adoption of the IMO Guidelines for the control and management of ships' ballast water to

minimize the transfer of harmful aquatic organisms and pathogens (A.868(20)),

· developing a new international legal instrument on ballast water management (Draft

International Convention for the Control and Management of Ships' Ballast Water &

Sediments) currently scheduled to be considered by an IMO Diplomatic Conference in 2004,

and

· providing technical assistance to developing countries through the GEF/UNDP/IMO Global

Ballast Water Management Programme (GloBallast).

The GloBallast Programme is working through six Demonstration Sites/Pilot Countries. These are

Dalian (China), Khark Is (Iran), Mumbai (India), Odessa (Ukraine), Saldanha (South Africa) and

Sepetiba (Brazil). The Programme is managed by a Programme Coordination Unit (PCU) based at

IMO in London, and activities carried out at the Demonstration Sites are being replicated at additional

sites in each region as the programme progresses (further information http://globallast.imo.org).

In developing the draft International Convention, IMO's Marine Environment Protection Committee

(MEPC), through its Ballast Water Working Group (BWWG), has identified ballast water sampling as

an important technical issue that needs to be addressed in the Convention. MEPC has instructed the

BWWG to develop the necessary technical guidelines, in support of the Convention, on ballast water

sampling. Such sampling may be carried out for a number of useful purposes, including:

· To better understand the physics, chemistry and biology of ballast water (scientific research).

· To identify potentially harmful species carried in ballast water (hazard identification /risk

assessment).

· To assess compliance with open-ocean ballast water exchange requirements (compliance

monitoring and enforcement).

· To assess the effectiveness of alternative ballast water treatment methods (ballast water

treatment R&D).

Ballast water sampling equipment and methods have been in a phase of development in recent years,

with different countries and parties around the world trialing different approaches, and a number of

useful documents are now available. These include:

· An outline manual of sampling procedures and protocols prepared for the US Coast Guard

(Carlton et al 1997).

· A practical manual on ballast water sampling published by the Cawthron Institute in New

Zealand (Dodgshun & Handley 1997).

· A review of ballast water sampling methods published by the Centre for Research on

Introduced Marine Pests (CRIMP) in Australia (Sutton et al 1998).

· An international calibration exercise for ballast water sampling conducted under the EU

Concerted Action Programme in 1999 (Rosenthal et al 1999).

· A report from the ballast water sampling Correspondence Group established by the IMO

MEPC Ballast Water Working Group in 2000 (MEPC Paper 45/2/7)

1

1st International Workshop on Guidelines and Standards for Ballast Water Sampling, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 7-11 April 2003

· Sampling methods used by various scientific institutions and regulatory agencies around the

world for ballast exchange compliance testing (e.g. USCG rapid salinity method

http://www.uscg.mil/hq/g-m/mso/mso4/bwgal.html and Port Vancouver zooplankton method.

In order to develop the international technical guidelines for ballast water sampling required by IMO-

MEPC, it is necessary to review these various approaches and other relevant activities.

One of the many areas in which GloBallast is providing technical assistance to the Pilot Countries, is

the sampling of ships' ballast water. In 2002, one of the Pilot Countries, Brazil, initiated an

experimental ballast water sampling programme at nine ports in the country, through its National

Health Surveillance Authority (ANVISA) and with support from the Admiral Paulo Moreira Marine

Research Institute (IEAPM), aimed at assessing the presence of pathogens in ballast water. As a

result, Brazil has developed significant expertise in ballast water sampling and provided an ideal

demonstration site on this issue for the other GloBallast Pilot Countries and other interested parties.

Considering the above, and in order to assist both the GloBallast Pilot Countries and the MEPC-

BWWG with the issue of ballast water sampling, the PCU with support from the Government of

Brazil, convened the 1st International Workshop on Guidelines & Standards for Ballast Water

Sampling in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil from 7 to 11 April 2003.

2 Workshop Objectives

The objectives of this workshop were:

1. To review ballast water sampling activities undertaken by various entities around the world to

date, and to allow discussion and debate comparing methods and results.

2. To initiate greater global coordination and cooperation on this issue, including sharing of

expertise, experiences and data.

3. To review the various ballast water sampling guidelines and standards that are currently

available and adapt them into draft international guidelines, for use by the GloBallast Pilot

Countries and consideration by IMO's Marine Environment Protection Committee (MEPC),

in the context of the new Convention.

4. To provide practical training to the delegates from the GloBallast Pilot Countries in

standardised ballast water sampling methods, to allow them to purchase the necessary

equipment and develop and implement ballast water sampling programmes on return to their

home countries.

3 Workshop Outputs

The workshop was designed to generate the following outputs:

· A Workshop Report (this document) containing papers presented and outlining workshop

results and recommendations for further action, in relation to the above objectives. This will

be submitted to IMO member States (through MEPC) and other relevant bodies.

· Draft International Guidelines and Standards for Ballast Water Sampling for finalisation and

publication by the GloBallast PCU, for consideration by MEPC in the context of the new

Convention, and by other interested bodies.

2

1st International Workshop on Guidelines and Standards for Ballast Water Sampling, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 7-11 April 2003

· Trained personnel from each of the GloBallast Pilot Countries who can plan and commence

ballast water sampling programmes on return to their countries, according to international

standards.

4

Workshop Structure & Programme

Prior to the workshop, the PCU contracted a consultant, Dr Stephan Gollasch (Germany) to:

· Undertake a global review of ballast water sampling programmes to date.

· Plan, prepare and coordinate the pratical equipment and ship-board demonstration activities

for the workshop.

The workshop was convened by the PCU Technical Adviser, with specialist sampling advice from the

consultant and additional expert advice and support from Dr Flavio de Costa Fernandes of IEAPM

(Brazil), Mr Matej David of Lubljulana University (Slovenia), Mr Tim Dodgshun of Cawthron

Institute (NZ), Dr Chad Hewitt of the Ministry of Fisheries (NZ) and Mr John Hamer of the

Coutryside Commission of Wales marine team (UK). Support provided by several of these experts

was funded by their respective institutions and represented significant support for the workshop from

their countries.

The workshop proceeded according to a five-day programme (Appendix 1). The first two days

involved presentation of background papers by international experts, outlining ballast water sampling

activities undertaken by various entities around the world, and allowing discussion and debate

comparing methods and results. Time was also dedicated to classroom demonstrations and hands-on

familiarisation of different types of ballast water sampling equipment.

On the 3rd day a practical demonstration of the various types of sampling methods and equipment was

undertaken aboard the Brazilian Navy tanker `Marajo', at the Nitiroi Naval Base, Rio de Janeiro.

Types of sampling equipment demonstrated included various plankton nets, water samplers and

pumps. The shipboard sampling was followed by the demonstration of techniques for the analysis of

samples and identification of biota in the laboratory.

The remaining days of the workshop were spent in four working groups, `brain-storming' a set of

prescribed questions and tasks, in order to develop the structure and key components for the draft

international guidelines. Each working group contained around 10 people selected to provide a mix of

expertise and broad geographical representation in each group, with a nominated facilitator. The

working group sessions were programmed over the Thursday and Friday (10 and 11 April 2003).

On the Thursday, the groups were tasked with a set of questions designed to establish first principles

and basic concepts, define strategic objectives and identify main subject areas requiring detailed

technical development. Working group questions included:

· the need for guidelines and standards and their objectives,

· the importance of defining the purpose of ballast water sampling,

· the issue of representativeness, efficiency and effectiveness of sampling,

· ship design modifications and improvements to facilitate sampling,

· the concept of standard ballast water sampling kits on-board ships, and

· how to address these issues in guidelines and standards.

The full working group instructions for the Thursday are contained in Appendix 4.

3

1st International Workshop on Guidelines and Standards for Ballast Water Sampling, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 7-11 April 2003

On the Friday, the working groups were provided with a suggested structure for the draft international

guidelines, which had been developed overnight by the PCU and technical advisers, based on the

Thursday working group recommendations, the background papers and the pre-workshop reviews

undertaken by the consultant.

The suggested structure (Appendix 5) divides the draft guidelines in two main parts; main document

and technical annexes. Working groups 1 and 2 were asked to identify the main issues requiring

detailed development in each section of the main body of the suggested structure, while groups 3 and

4 were asked to undertake a similar analysis of the proposed technical annexes.

5

Workshop Participants

The workshop was attended by three `trainees' from each GloBallast Pilot Country, a number of

additional delegates from the host-country Brazil, including ballast water sampling experts, and both

trainees and experts from a large number of other countries. In total, there were 42 participants from

20 countries.

The range of expertise assembled to act as presenters, instructors and facilitators was comprehensive

and included many internationally recognised experts in the field of ballast water sampling, including

Dr Stephan Gollasch (Germany), Dr Flavio de Costa Fernandes (Brazil), Dr Maria Célia Villac

(Brazil), Mr Matej David (Slovenia), Dr Muzaffer Feyzioglu (Turkey), Mr Tim Dodgshun (NZ), Dr

Chad Hewitt (NZ), Mr John Hamer (UK), Ms Silvia Rondon (Columbia), Ms Nicole Mays (USA) and

Mr Don Reid (Canada). Attendance by many of these experts was funded by their respective

institutions and represented significant support for the workshop from their countries.

By design, the workshop participants comprised an extremely diverse group of people, including

individuals with no previous experience what-so-ever with ballast water sampling to world authorities

on the issue, people from the shipping, port, scientific and governmental sectors and people from

countries of differing environmental, economic and socio-political conditions.

A full participants list is contained in Appendix 2.

6

Workshop Results and Recommendations

Background papers

The papers presented are listed in the workshop programme (Appendix 1) and those that focus on

ballast water sampling methods are included in full in Appendix 3. The background papers were

considered most useful in `setting the scene' and providing basic background information, as many of

the `trainees' had very limited previous experience with the issue. Together, the collection of papers

provide an extremely useful information resource, presenting an overview of many of the major

ballast water sampling programmes undertaken globally to date. Topics covered include:

· International reviews and inter-calibrations of ballast water sampling methods.

· Examples of national approaches to the issue, including Australia, Brazil, Columbia,

Germany, New Zealand, Slovenia, Turkey and USA.

· Special considerations such as sampling for pathogens, sampling for ballast tank sediments,

sampling as part of ballast water treatment effectiveness testing and genetic probes / rapid

diagnostic techniques.

· Post-sampling issues such as sample handling, preservation, treatment and analysis.

4

1st International Workshop on Guidelines and Standards for Ballast Water Sampling, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 7-11 April 2003

The main points that were drawn from the papers and the resulting question and discussion sessions

are given below.

General points

· Ballast water sampling programmes are carried out for various purposes by a number of

research groups across many countries using a wide variety of methods and equipment.

· There already exists a wealth of detailed technical information on this issue, including the

outline manual prepared for the US Coast Guard (Carlton et al 1997), the EU inter-calibration

study (Rosenthal et al 1999), the CRIMP review (Sutton et al 1998), the Cawthron Manual

(Dodgshun & Handley 1997) plus the German sampling method and practical experiences

from sampling programmes in countries such as Brazil, Columbia , Slovenia, Turkey and the

UK, as described in the papers in Appendix 3.

· It is important to clearly define the objectives and purpose before proceeding with any

sampling programme. Different objectives and purposes may require very different

approaches, and sampling methods and equipment should be selected to meet the defined

objectives and purpose, e.g:

- a sampling programme carried out by scientists to provide a general understanding of the

physics, chemistry and biology of ballast water may adopt a range of methods applied in a

variety of shipboard situations to measure a range of parameters; whereas

- a sampling programme carried out by Port State Control inspectors to assess compliance

by arriving ships with ballast water exchange at sea, needs to adopt methods that are

simple, portable, rapid and applicable at the port of ballast discharge, and which measure

limited, simple parameters that are indicators of ballast exchange, such as salinity and

presence/absence of oceanic vs coastal species; whereas

- a sampling programme carried out to assess the effectiveness of a new ballast water

treatment technology, needs to sample at least before and after, and possibly during, the

treatment process, ideally using an `in-line ` approach, and which measures parameters

that are indicators of treatment effectiveness, including the achieved

reduction/neutralisation in organisms.

· In recognition of these differences, it is important that any international guidelines and

standards for ballast water sampling are clearly organized so as to facilitate selection of

sampling designs, methods and equipment that meet the defined objectives and purpose.

· There is a clear need for inter-calibration and standardisation of sampling equipment and

methods, although even after international inter-calibration exercises (e.g. Rosenthal et al

1999), individual research groups often revert to `old familiar' methods rather than adapt to

inter-calibrated, standardised approaches.

· The issue of sample representativeness and sampling efficiency is a major limiting factor for

ballast water sampling, in relation to all sampling objectives and purposes.

· There is a lack of technical guidance for sampling of micro-organisms (including pathogens)

in ballast water.

· There is a global need for ongoing, regular review of developments with ballast water

sampling, including cost-benefit analysis and comparison of different sampling techniques.

Such ongoing review could be achieved through biennial convening of international ballast

water sampling workshops by IMO, as follow-ons from this workshop.

Ballast water sampling for general scientific research

· Ballast water sampling methods for the purposes of general scientific research are well

developed and there is a wealth of data available in the literature on the physics, chemistry

and biology of ballast water.

5

1st International Workshop on Guidelines and Standards for Ballast Water Sampling, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 7-11 April 2003

· Sampling ballast water for scientific research, whether for purely academic reasons or to

support management decision making, is perhaps the most flexible and variable form of

ballast water sampling. A number of options from the full range of sampling approaches,

methods and equipment may be suitable, depending on the precise objectives of the scientific

research.

· Given the wide range of potential research objectives, the variety of sampling methods and

equipment available and the existence of an extremely large pool of scientific expertise

around the world, any international guidelines should not be prescriptive or restrictive in

relation to this sampling purpose. Scientists should select the optimum sampling methods and

equipment to suit their specific research objectives, considering the advantages and

disadvantages of each method.

· Perhaps the most significant issue in relation to ballast water sampling for scientific research

purposes, is to ensure some sort of inter-calibration and standardisation of methods and

equipment between groups that are conducting similar research, so as to allow cross-

comparison of results.

Ballast water sampling for hazard analysis/risk assessment

· Ballast water sampling methods for the purposes of hazard analysis/risk assessment (e.g. to

identify potentially harmful species carried in ballast water) are well developed and there is a

wealth of data available in the literature on the biology of ballast water.

· It may be argued that sampling for risk assessment / hazard analysis, primarily to identify

potentially harmful species carried in ballast water, is a form of scientific research. However,

it is a more narrowly defined purpose with clear links to management, and should therefore be

treated as a specific sampling purpose in any international sampling guidelines.

· Sampling to identify potentially harmful species in ballast water may also be connected with

sampling for compliance monitoring and enforcement purposes, especially if the latter is

based on indicator species (see below).

· If the investigator is only interested in certain target species, then the development of genetic

probes as outlined in the paper by Patil (Appendix 3) may be relevant.

· Perhaps the most significant issue in relation to ballast water sampling for risk assessment /

hazard analysis purposes, is sample representative-ness. Sampling via sounding pipes may not

be ideal for this purpose, as it suffers from low representative-ness. If the sampling party is

most concerned about the actual input of introduced species into a receiving port, rather than

what is inside the ballast tanks, then sampling at the point of discharge may be the best

option.

Ballast water sampling for compliance monitoring and enforcement

· Ballast water sampling methods for the purposes of compliance monitoring and enforcement,

are in an early stage of development, and are in particular need of validation, inter-calibration

and standardisation.

· Currently, the only operational procedure available to ships to minimize the transfer of

aquatic organisms is ballast water exchange at sea, as recommended in the IMO ballast water

Guidelines (A.868(20)) and provided for in the draft IMO ballast water Convention. Sampling

to monitor and enforce compliance with ballast water management measures is therefore

currently limited to assessing compliance with ballast exchange.

· Eventually, as alternative ballast water management measures and treatment systems are

approved and accepted by IMO and national jurisdictions, it will be necessary to develop

procedures to assess compliance of these systems with the agreed standards. However, as

alternative ballast water treatment systems are still in the development phase, any

6

1st International Workshop on Guidelines and Standards for Ballast Water Sampling, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 7-11 April 2003

international sampling guidelines would not cover compliance sampling for such systems at

this stage (although many of the sampling methods might be relevant).

· A sampling programme carried out by Port State Control inspectors to assess compliance by

arriving ships with ballast exchange, needs to adopt methods that are simple, portable, rapid

and applicable at the port of ballast discharge, and which measure limited, simple parameters

that are indicators of ballast exchange.

· Sampling the ballast water on arriving ships for physical/chemical parameters is part of the

compliance monitoring `tool box.' The physical and chemical parameters of ballast water

(e.g. pH, salinity, turbidity, organic content etc) may show whether it is open ocean water,

indicating exchange has occurred, or port or coastal water, indicating exchange has not

occurred. The US Coast Guard has developed a very simple, rapid sampling method that

allows boarding officers to measure the salinity of ballast water and assess if exchange was

conducted (refer http://www.uscg.mil/hq/g-m/mso/mso4/bwgal.html).

· The presence/absence of coastal and oceanic species in the ballast water may also be taken as

an indicator of whether the ballast is of coastal or oceanic origin, and therefore, whether or

not exchange has been conducted. The Vancouver Port Corporation has developed a sampling

method based on this approach, and this is being developed further by the State of

Washington (USA).

· Both of these approaches suffer many limitations and qualifications, including the major

constraint of sampling efficiency / representative-ness, and the assumptions that certain

salinity levels and indicator species are indeed coastal and oceanic. Compliance sampling

based on indictor species is also limited by the time frames and taxonomic expertise required

for sample analysis.

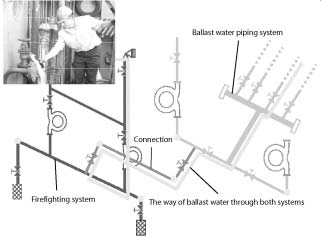

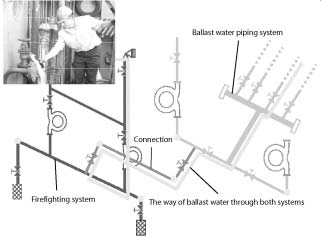

· More effective methods of assessing compliance with ballast exchange requirements would

involve in-line samplers and electronic monitoring systems being fitted to vessels. Such a

system would take data on ballast water parameters such as water levels, temperature, salinity

and pressure, plus operational data such as starting/stopping of pumps, ships' positions (GPS)

and dates and times, from automatic sensors located throughout the ships' ballast and other

operational systems. The data would be recorded in a central processor (including potentially

the ship's voyage data recorder), and transmitted to shore-based offices. This would eliminate

the need for paper-based ballast water reporting forms and the scope for recording and

reporting errors and irregularities. Such systems are under development by the US Coast

Guard and GloBallast Ukraine.

· If the port State enforcement agency is only interested in certain target species, then the

development of genetic probes as outlined in the paper by Patil (Appendix 3, page 75) and the

development of other rapid diagnostic tecniques such as portable flow-cytometry devices may

be relevant.

· It should be noted that if sampling indicates non-compliance with ballast exchange

requirements, there must be a contingency plan (e.g. reception facilities, chemical treatment

as emergency measure, discharge in certain port/near-shore contingency areas).

Ballast water sampling for assessing alternative ballast water treatment methods

· Ballast water sampling methods for the purposes of assessing the effectiveness of alternative

ballast water treatment technologies are in an early stage of development, and are in particular

need of validation, inter-calibration and standardisation. The papers by Cangellosi et al

(Appendix 3) provide some relevant information.

· As alternative ballast water management measures and treatment systems are approved and

accepted by IMO and national jurisdictions, it will be necessary to develop procedures to

assess compliance of these systems with the agreed standards.

7

1st International Workshop on Guidelines and Standards for Ballast Water Sampling, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 7-11 April 2003

· In the meantime, there are over 50 research groups world-wide undertaking R&D of

alternative ballast water treatment systems, and all are using various, often different sampling

methods to assess the effectiveness of their systems.

· A sampling programme carried out to assess the effectiveness of a new ballast water

treatment technology, needs to sample at least before and after, and possibly during, the

treatment process, ideally using an `in-line ` approach. It should measure parameters that are

indicators of treatment effectiveness, including the achieved reduction/neutralisation of

organisms.

· Most importantly, the sampling approach will be determined by the ballast water treatment

standard that the system is being assessed against.

· Other extremely important issues in relation to this type of sampling are experimental design,

including control experiments and adequate replication to achieve acceptable levels of

statistical confidence, and adopting internationally standardised test protocols, so as to allow

direct and meaningful cross-comparisons of tests of different systems.

· This issue is somewhat outside of the scope of this workshop, and international ballast water

treatment standards and test protocols should be set under the draft Convention.

Shipboard sampling practical demonstration

The shipboard sampling practical demonstration took place on-board the Brazilian Navy tanker

`Marajo'on Wednesday 9 April 2003, and was followed by a demonstration of sample analysis

techniques in the laboratory.

It should be noted that the shipboard exercise was not designed as a scientific study in its own right,

but was undertaken simply to demonstrate various types of ballast water sampling equipment and

methods to the workshop participants, provide them with hand-on experience and familiarise them

with the issues that need to be considered and proceures that need to be followed when planning and

undertaking a shipboard sampling programme.

Based on the highly positive feedback from the participants, the shipboard exercise proved highly

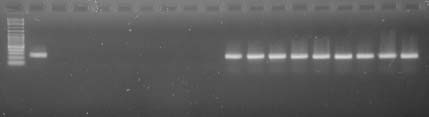

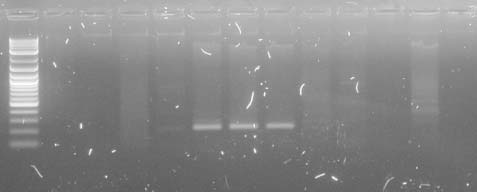

effective in achieving these objectives. The images on the following pages (not exhaustive) represent

some of the activities covered during the practical demonstrations.

The programme was intentionally kept flexible to allow timing of the practical days to suit shipping

availability, and to maintain the programme to achieve the objectives and outputs. In addition to

providing use of the Navy tanker, the GloBallast Country Focal Point - Assistant in Brazil also

organized, through the Rio de Janeiro Port Authority and shipping agents, full access for 50 people to

undertake sampling on a large bulk carrier. Securing sampling access to a large vessel on a short turn-

around time in a major commercial port at such short notice, was a significant achievement by Brazil

and provided excellent experience and demonstration of the organizational procedures and

communication protocols required.

However, through discussions resulting in consensus, the workshop participants decided that given

the strategic nature of the objectives of the workshop, the number of days available and the excellent

and comprehensive practical demonstration gained from the Navy tanker sampling, the second ship-

board exercise was not necessary. The time was used instead for the priority working group sessions.

8

1st International Workshop on Guidelines and Standards for Ballast Water Sampling, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 7-11 April 2003

The tanker `Marajo' kindly made available by the Brazilain Navy for the GloBallast workshop in Rio de Janeiro

Two points of access for ballast water samplng: Left ballast tank sounding pipe (photo: D Oemcke); right ballast tank

manhole. Access via the sounding pipe is quicker, but is more restricted and less representative than via the manhole.

Example of internal ballast tank structure (large bulk carrier), presenting sampling obstacles (photo: D Oemcke)

9

1st International Workshop on Guidelines and Standards for Ballast Water Sampling, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 7-11 April 2003

Example of sediment accuumlation in a ballast tank, requiring special sampling techniques (photo: D Oemcke)

A selection of plankton nets demonstrated at the workshop (photo: M David)

German ballast water expert Dr Stephan Gollasch (right both pictures), demonstratng use of plankton nets lowered into the

ballast tank via a manhole, aboard the Brazilain Navy tanker `Marajo' (photos: A L Neto)

10

1st International Workshop on Guidelines and Standards for Ballast Water Sampling, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 7-11 April 2003

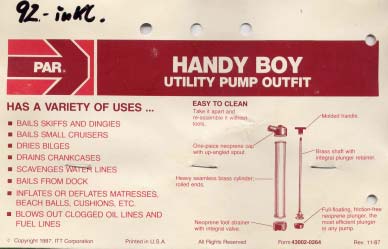

Three types of pumps demonstrated at the workshop (photos: A L Neto)

Brazilian ballast water expert Dr Flavio de Costa Fernandez (right) demonstrating use of pumps to sample ballast water

A Van Doorn water sampler capable of collecting several litres of ballast water via the ballast tank manhole

(photo: M David)

11

1st International Workshop on Guidelines and Standards for Ballast Water Sampling, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 7-11 April 2003

New Zealand ballast water expert Tim Dodgshun (centre-right) demonstrating use of the Van Doorn sampler to GloBallast

Pilot Country representatives aboard the `Marajo'

The Slovenian `Water-Column Sampler' (left) and `Bottom and Sediment Sampler' (right) suitable for deployment via the

ballast tank sounding pipe (photo: M David)

Slovenian ballast water expert Matej David (left) demonstrating deployment of the botton & sediment sampler via a

sounding pipe aboard the `Marajo' (photos: A L Neto)

12

1st International Workshop on Guidelines and Standards for Ballast Water Sampling, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 7-11 April 2003

Cawthron (NZ) ballast tank sediment collector demonstrated at the workshop (photo: T Dodgshun)

Various accessories needed for shipboard ballast water sampling including various sized sieves (right), sample bottles,

plastic buckets etc (photo: A L Neto)

Demonstrating techniques for the laboratory analysis of ballast water samples at the Rio workshop

13

1st International Workshop on Guidelines and Standards for Ballast Water Sampling, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 7-11 April 2003

Working groups

The working groups proved effective at yielding a wealth of information in response to the questions

asked and tasks set, although all groups stated that the workload was ambitious and expressed

frustration at not having more time to address all issues more comprehensively. This was taken as a

positive result, indicating the seriousness of purpose and intensity of engagement of the workshop

participants. Working group results and recommendations are divided according to the Thursday and

Friday sessions.

Thursday working groups

On Thursday 10 April 2003 all four working groups were provided with the same set of

instructions/questions (Appendix 4). Table 1 presents the full responses of all four groups to each

question. An analysis of Table 1 clearly shows that there was a high degree of agreement between the

four working groups in their responses to the six questions. All groups unanimously agreed that:

· There is as definiate need for international guidelines and standards for ballast water

sampling.

· It is essential to define the purpose of any ballasst water sampling programme, as this will

significantly affect the sampling approach, methods and equipment adopted.

· The main purposes for ballast water sampling are:

- Scientific research

- Hazard analysis/risk assessment

- Compliance monitoring

- Testing of BW treatment.

- Raising awareness.

· Any international guidelines should be structured according to the purpose of the sampling.

· The issue of sample representative-ness is of key importance, and must be addressed in any

international guidelines and standards.

· There are a number of ship design improvements that are necessary to facilitate ballast water

sampling, including provision of easier access to ballast tanks and most importanty, provision

for in-line sampling all all satges of the ballast system, and other design changes to improve

representativeness and efficiency of sampling. Refer also Taylor and Rigby (2001).

Three of the four groups agrered that ships should carry a standard ballast water sampling kit,

specifically for the purpose of compliance monitoring.

The Thursday working group responses provide sound guidence on the issues that need to be

addressed in any international guidelines and standards for ballast water sampling. Using the

Thursday working group recommendations, the background papers and the pre-workshop reviews

undertaken by the consultant, the PCU and technical advisers developed a suggested structure for the

draft International Guidelines and Standards for Ballast Water Sampling (Appendix 5), for

consideration by the working groups the following day.

14

1st International Workshop on Guidelines and Standards for Ballast Water Sampling, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 7-11 April 2003

Table 1. Working Group Outcomes (Thursday 10 April 2003)

Working Group Working Group Answers

Questions

WG 1

WG 2

WG 3

WG 4

1. Is there a need

Yes.

Yes.

Yes.

Yes.

for international

Standarisation needed to Objectives of sampling:

Standarisation needed to For scientific research

guidelines and

allow inter-comparison

· Scientific research

allow inter-comparison

(biology of ballast water

standards / what

of results.

· Risk Assessment

of results.

communities) should be

should be

· Compliance

recommended

objectives and

Guidelines need two

monitoring

guidelines, not

Guidelines should be

main subject

main sections:

· Testing of BW

standards.

areas included in

a) sampling for

treatment.

recommended minimum

the guidelines.

scientific purposes

· Raising awareness.

procedures.

Objectives of sampling:

and

For the provisions of the

· Scientific research

b) for compliance

IMO Convention, focus

Objectives of sampling:

· Risk Assessment

testing.

on:

· Scientific research

· Compliance

· Compliance

· Risk Assessment

monitoring.

Even with a), scientists

monitoring

· Compliance

· Testing of BW

are likely to continue

· Testing of BW

monitoring.

treatment.

using

treatment.

· Testing of BW

equipment/methods they

treatment.

are used to.

Main subject areas:

· Support developing

· Standardisation

IMO convention.

The guidelines under b)

· Practicability

should include

· Representativeness

Main subject areas:

recommendations from

· Comparativeness

· Procedural approach

the ship perspective,

· Quantitativeness

(protocol) to sampling,

including not causing

(relate to the standard

accessing & boarding

undue delay.

of the Convention)

vessels (as annex or

· Quality control

separate document).

Objectives of sampling:

· International

· `Hello' to `Goodbye'

· Risk assessment,

acceptance

coverage.

hazard analysis

· Operable by all

· Technical aspects.

(statistic).

countries

· Sampling point access.

· Awareness, capacity

· Equipment

building, training

standardisation

purposes.

(explicite)

· Verification of BW

· Volumes to be

management/treatment

sampled (minimums)

systems (efficiency,

· Sample handling

effectiveness).

· Collection,

preservation, labelling.

What if sampling proves

· Parameters to be

non-compliance? Need

specified.

contingency plan

(reception facilities,

chemical treatment as

emergency measure,

discharge in certain port

areas)

2. Importance of

Essential.

Essential.

Very important.

Imperative.

defining the

Implies certain sampling

Guidelines for sampling

Intrinsic to specifying

purpose of BWS.

approach, methods and

for scientific and

methodology.

equipment.

regulatory purposes

should be mandatory,

while sampling for

awareness raising

purposes should not be

tied to strict guidelines.

15

1st International Workshop on Guidelines and Standards for Ballast Water Sampling, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 7-11 April 2003

Working Group Working Group Answers

Questions

WG 1

WG 2

WG 3

WG 4

3. Sample

Of key importance.

Important

Obviously important.

Depends on definition of

representative-

Representativeness is

Represenativeness

First level should be the

`representativeness'.

ness.

important for science

affected by whether

represent-ativeness of

Affected by the

and crucial for

sampling done in-tank,

the ship. Tanks may

objectives of the

compliance testing.

in-line or at point of

contain water from

sampling, parameters of

Compliance testing has

discharge.

different origins.

evaluation and

to be representative for

Guidelines should aid in

management standards

legal reasons. The

selection of tank(s) to be selected.

consequence matters.

sampled. Sampler have

freedom to select the

Management primarily

It is scientifically proven

tank

interested in

that BW sampling

representing risk

studies are an

Second level is

(realised or potential)

underestimate - far from

representativeness of the rather than ecological

being representative.

tank (two types.) Access representation of the

determines one type.

ballast community.

No way to sample the

Where samples are taken

whole ship so

determines the other.

selection of ballast

tank(s) for sampling is

Third level is

critical (sample all

representativeness of the

types?).

actual sample.

· Select tanks based on

Replications of samples

risk assessment (e.g.

(implications for

origin of BW, target

statistical analysis).

species).

Volume to be sampled.

· Identify critical areas

that are likely to

Fourth level is

contain species of

representativeness of the

concern within a ship

analysis. Has to be

or tank.

practical with respect to

· Modelling could be

time and cost

used to identify the

(management

most representative

constraints)

tanks for sampling.

Identify most

representative methods

(by the knowledge today

this may be access via

manhole and sampling

using nets).

Sampling personnel

need to be independent

from the ship.

16

1st International Workshop on Guidelines and Standards for Ballast Water Sampling, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 7-11 April 2003

Working Group Working Group Answers

Questions

WG 1

WG 2

WG 3

WG 4

4. Ship design

Yes.

Yes.

Yes.

Resounding Yes.

improvements to

(especially new ships)

· In-line samples or

Would also make life

· Issues of access

facilitate BWS.

· Ease/enable sampling

integrator.

easier for the captain

· Issues of effiency

access.

· In-tank collection

and crew.

(time)

· Provide power supply.

system (top, middle

· Problem of existing

· Issues of accuracy

· Enable representative

and bottom).

ships.

(representativeness)

sampling at the

· Net access not

· Need for close

For new ships:

discharge point.

required.

consultation with

· In-line ports (ballast

Plus retrofit exisiting

working mariners.

pump)

ships.

· Improvements begin

· Sample points

with awareness of

plumbed in tanks with

ongoing need for

pumps

sampling access.

· Recommend

· In-line taps with de-

numerical simulation

ballasting pipe.

models to identify

· Reduction in

appropriate locations

obstructions below

for in-tank plumbed

access hatches.

sample ports.

For existing ships:

· Easier access

· More comprehensive

access

5. Standard

Yes.

Yes.

No response recorded

Yes.

shipboard ballast

· Use to be restricted to · For compliance

· For compliance

water sampling

sampling for

monitoring.

monitoring.

kit.

compliance

· A standard ballast

· To increase

monitoring purposes.

water sampling kit

transparency and

· Guidelines are needed

would facilitate crews

consistency of

on how to use the

compliance

sampling and time

sampling equipment.

monitoring and

efficiency.

· May be legal

overcome problems

· Stanadrd comtents

implications if no

with compliance of the

depend on the

proper maintenance of

same ship in different

sampling methods

onboard sampling kit.

ports.

which depend on

· All ships (no matter

standards.

what type and age)

· It should provide a

need to have an

suite of tools to enable

identical/most

accurate, efficient and

appropriate sampling

timely sampling

kit (for sampling at

discharge point, a tap

is required and a tool

to concentrate the

water).

· Scientific sampling kit

should not be required

onboard as objectives

and methods of

scientific studies vary

to a large extent.

6. Other major

Any international BW

Port baseline and

There are some existing

The following should be

issues.

sampling guidelines and

information exchange is

protocols for sample

considered further:

standards should be

required to support

volumes and replicates.

· The utility of ballast

revewed and updated

internationally

water sampling to

regularly (e.g. to account standardised BW

support or validate

for developing

samping efforts.

risk assessment.

technology)

· Comparison of

different methods for

biases.

· Comparison of source,

in-tank and discharge

waters

17

1st International Workshop on Guidelines and Standards for Ballast Water Sampling, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 7-11 April 2003

Friday working groups

On Friday 11th April each group was provided with the `skeleton' of draft international sampling

guidelines as contained in Appendix 5 (without the inserted text). Groups 1 and 2 were asked to insert

the man issues that need to be addressed under each main section of the guidelines, while groups 3

and 4 were asked to do the same for the proposed technical annexes to the guidelines.

The summarized responses of the groups are inserted in each section of the proposed structure for the

draft guidelines in Appendix 5, which:

· establishes an overall framework and structure for international guidelines and standards for

ballast water sampling,

· outlines the main sections that such guidellines should be divided into,

· lists the main issues that need to be addressed in each section, and

· identifies the main exisiting sources of detailed technical information that can be used to

`flesh-out' each section of the guidleines.

The outputs of this exercise therefore provide a comprehensive foundation upon which the full text of

international ballast water sampling guidelines can be rapidly developed.

Working groups discussing the development of international ballast water sampling guidelines at the Rio workshop

18

1st International Workshop on Guidelines and Standards for Ballast Water Sampling, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 7-11 April 2003

7 Further Action & Overall Conclusion

The GloBallast PCU, with assistance from the sampling consultant (S Gollasch) and several experts

who attended the workhop, are building on the framework developed at the workshop as contained in

Appendix 5, to produce draft international guidelines for ballast water sampling. It is intended that

the guidelines will comprise a comprehensive and detaled technical manual that will provide practical

guidance to any group wishing to undertake ballast water sampling programmes anywhere in the

world.

It is planned that these will be released for stakeholder comment in late 2003, and made available to

IMO MEPC and other interested parties for consideration, and published as part of the GloBallast

Monograph Series.

In additon, the representatives from the GloBallast Pilot Countries who attended the workshop, are

using the information and experience acquired to consider the development of ballast water sampling

activities at the GloBallast Demonstration sites.

Overall, the 1st International Workshop on Guidelines and Standrads for Ballast Water Sampling was

considered a success in achieving its stated objectives.

References

Dodgshun, T. & Handley, S. 1997. Sampling Ships' Ballast Water: A Practical Manual. Cawthron

Report No. 418.

Carlton J.T., Smith, D.L., Reid, D., Wonham, M., McCann, L., Ruiz, G & Hines, A. 1997. Ballast

Sampling Methodology. An outline manual of sampling procedures and protocols for fresh, brackish,

and salt water ballast. Report prepared for U.S. Department of Transportation, United States Coast

guard, Marine Safety and Environmental Protection, (GM) Washington, D.C. 20593-0001 and U.S

Coast Guard Research and Development Center, 1082 Shennecossett Road, Groton, Connecticut,

06340-6096.

Rosenthal, H., Gollasch, S. & Voigt, M. (eds.) 1999. Final Report of the European Union Concerted

Action "Testing Monitoring Systems for Risk Assessment of Harmful Introductions by Ships to

European Waters" Contract No. MAS3-CT97-0111, 72 pp. (plus various appendices).

Sutton, C.A., Murphy, K., Martin, R. B. & Hewitt, C. L. 1998. A review and evaluation of ballast

water sampling protocols. CRIMP Technical Report, 18

Taylor, A. H. & Rigby, G. 2001. Suggested Designs to Facilitate Improved Management and

Treatment of Ballast Water on New and Existing Ships. Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry

Australia. Ballast Water Research Series Report No. 12. AGPS Canberra. Esp section 2.2

19

Appendix 1:

Workshop Programme

Appendix 1: Workshop Programme

Monday 7 April - Day One:

Opening & Background Papers

08:00

Bus departs Hotel Atlantico Copacabana for venue

Venue: Solar da Imperatriz

Rua Pacheco Leăo No. 2040

Jardim Botânico, Rio de Janeiro

08:30

Registration

Opening (Conveners/facilitators: Dandu Pughiuc and Steve Raaymakers, IMO/GloBallast PCU)

09:00

Opening Statement: .......................................................................................................................................... Host Country

09:15

Opening Statement: ............................................................................... Mr Mike Hunter, Chairman IMO/MEPC BWWG

09:30

Introduction, Aims & Objectives: ..................................................................... Steve Raaymakers, IMO/GloBallast PCU

10:00

Group photograph and Morning Tea.

Session One: Ballast Water Sampling - General Background Papers

10:30

Inter-calibration Results from the EU Concerted Action Programme: .......................... Dr Stephan Gollasch, Consultant

11:15

The NZ Practical Manual on Ballast Water Sampling:......................................... Tim Dodgshun, Cawthron Institute NZ

11:45

The CRIMP Review and Evaluation of BWS Protocols: .............................. Dr Chad Hewitt, NZ Fisheries (ex CRIMP)

12.00

The Brazilian National BWS Programme: .............................................................Dr Flavio de Costa Fernandes, IEAPM

13.00

Lunch

Session Two: Ballast Water Sampling Selected Examples

14:00

Ballast Water Sampling in the Republic of Slovenia:................................................ Mr Matej David, Univ. of Ljubljana

14:30

Ballast Water Sampling in Turkish Ports: .................................................... Dr. A. Muzaffer Feyzioglu, Karadeniz Univ.

15.00

The Ponta Ubu Terminal Ballast Water Sampling Program......................................... Mr Douglas Siqueira de Medeiros

15:30

Afternoon Tea.

16:00

The German Ballast Water Sampling Manual: ............................................................... Dr Stephan Gollasch, Consultant

16:30

The Ballast Water Issue in Mexico:.......................................................... Dr Yuri Okolodkov, Metro Autonomous Univ.

17:00

Panel/group discussion for Sessions One & Two

17:30

Close Day One. Bus returns to hotel.

19:00

Reception (hosted by Brazil)

Tues 8 April - Day Two:

Background Papers & Classroom Demonstrations

08:30

Bus departs Hotel Atlantico Copacabana for workshop venue

Announcements & Housekeeping

Session Three: Ballast Water Sampling Special Considerations

09:00

Sampling Ballast Water for Pathogens - the Columbian Approach ......................... Ms Silvia Rondon, Colombian Navy

09:30

Sampling Ballast Sediments and other Challenges....................................................................Dr John Hamer, CCW UK

10.00

Sampling to Test Effectiveness of BW Exchange on `MT Lavras' ................................................. Dr Maria Celia Villac

10:30

Morning Tea

1

1st International Workshop on Guidelines and Standards for Ballast Water Sampling, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 7-11 April 2003

11.00

Sampling Approaches and Recommendations by the Great Lakes Project .....................Mr Donald M. Reid, Consultant

11.30

Results of the NEMW Ballast Discharge Monitoring Device Workshop.................................................Ms Nicole Mays

12.00

Genetic Probes and Rapid Diagnostic Techniques ..............................................................Dr Chad Hewitt, NZ Fisheries

12:15

Panel/Group Discussion for Session Three

12:30 Lunch

Session Four: Post-Sampling Considerations

13:30

Sample Handling, Preservation, Treatment & Analysis .......................... T Dodgshun/S Gollasch/F Fernandes /J Hamer

14:00

Group discussion

14:30 Afternoon Tea

Session Five: Sampling Equipment Classroom Demonstrations & Hands-on Familiarisation

15:00

Classroom demonstration of various types of equipment (groups)........T Dodgshun/S Gollasch/F Fernandes / M David

16:30

Group discussion & briefing for days three & four

17:00 Close Day Two.

Weds 9 April - Day Three:

Shipboard Practical Exercises

08:00

Bus departs hotel for port.

08:30

Shipboard sampling.

12:30 Lunch.

13:30

Shipboard sampling continues.

15:00

Return Workshop venue. Sample processing in lab.

17:00 Close Day Three.

Thurs 10 April - Day Four:

Shipboard Practical Exercises

08:00

Bus departs hotel for port.

08:30

Shipboard sampling.

12:30 Lunch.

13:30

Shipboard sampling continues.

15:00

Return Workshop venue. Sample processing in lab.

17:00 Close Day Four.

19:00

Social Function (Hosted by IMO/GloBallast)

2

Appendix 1: Workshop Programme

Fri 11 April - Day Five:

International Guidelines & Standards

08:30

Bus departs Hotel Atlantico Copacabana for workshop venue

09:00

Briefing/Working Group Instructions: ...........................................................................................................S Raaymakers

09:15

Presentation of initial draft International Guidelines and Standards for Ballast Water Sampling.....................S Gollasch

10:00

Break into Working Groups. Identify the main items that need to be addressed in finalising

the guidelines and standards.

(Some issues to consider are listed below).

10:30

Morning Tea.

11:00

Working Groups continue.

12:30

Lunch

13:30

Working Groups report/general discussion/conclusions & recommendations.

15:00

Close Workshop

Some issues to be considered by Working Groups in finalising the Draft

International Guidelines and Standards for BWS

(not exhaustive)

1. The initial draft Guidelines and Standards.

2. The information presented in the background papers on days one and two.

3. Lessons learnt during shipboard exercises on days three and four.

4. Existing BWS manuals and other relevant guidelines.

5. The purpose of the sampling (e.g. scientific research, hazard identification/risk assessment,

compliance monitoring & enforcement, assessment of BW treatment effectiveness).

6. Pre-planning and organizing.

7. Communications / relations with the ship.

8. Health and safety.

9. Sampling from ballast tanks versus sampling at point of discharge.

10. Sampling for physical and chemical parameters versus sampling for organisms.

11. Methods for sampling ballast tank sediments.

12. Different equipment types for different organism types.

13. Sample handling, preservation and storage.

14. Sample analysis.

15. Data recording and reporting requirements.

3

Appendix 2:

Workshop Participants

Appendix 2: Workshop Participants List

GloBallast Pilot Countries

Brazil

Mr Gabriel Dreyfus Weibert Cattan

Directorate of Ports and Coasts

Tel: +55 21 38 70 52 22

BRAZIL

Fax: +55 21 38 70 56 74

Email: gcattan@alternex.com.br

Dr Flavio da Costa Fernandes

Head of Biology Division

Tel: +55 22 2622 9013

Instituto de Estudos do Mar Alm. Paulo Moreira (IEAPM)

Fax: +55 22 2622 9093

Rua Kioto, 253 Arraial do Cabo

Email: flaviocofe@yahoo.com

Rio de Janeiro - RJ, CEP: 28930-000

BRAZIL

Mr Alexandre de C. Leal Neto

Country Focal Point Assistant, GloBallast

Tel: +55 21 3870 5674

Diretoria de Portos e Costas (DPC-09)

Fax: +55 21 3870 5674

Rua Teófilo Otoni, 4

Email: aneto@dpc.mar.mil.br or

Rio de Janeiro - RJ, CEP: 20.090-070

alexcln@ppe.ufrj.br

BRAZIL

Mrs Fátima de Freitas Lopes Soares

Rio de Janeiro State Environmental Agency (FEEMA)

Dr Luciano Felício Fernandes

Taxonomy & Ecology of Phytoplankton

Tel: +55 41 266 2046

Federal University of Paraná (UFPR)

Fax: +55 41 361 1759

Setor de Cięncas Biológicas - Botânica - CP 19031

Email: lucfel@bio.ufpr.br

Jardim das Américas

Curitiba - Parana, CEP 81531-990

BRAZIL

Mr Cláudio Gonçalves Land

Naval Architect & Marine Engineer

Tel: +55 21 2534 9411 or +55 21

Supply Dept/Logistic & Planning

2534 6454

Petróleo Brasileiro SA (PETROBRAS)

Fax: +55 21 2534 6454 or +55 21

Operation & Control of Shipping Management Division

2534 6455

Av. República do Chile 65, Room 1901

Email: cgland@petrobras.com.br

Rio de Janeiro - RJ, CEP 20035-900

BRAZIL

Mr Celso Mauro

Environmental Assessment & Monitoring (AMA)

Tel: +55 21 3865 6659 or +55 21

Research & Development Centre (CENPES)

3865 7117

Petróleo Brasileiro SA (PETROBRAS)

Fax: +55 21 3865 6973

Cid. Universitária, Ilha do Fundăo, Av. 1-Quadra 7

Email:

Rio de Janeiro - RJ, CEP: 21949 - 900

celso@cenpes.petrobras.com.br

BRAZIL

1

1st International Workshop on Guidelines and Standards for Ballast Water Sampling, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 7-11 April 2003

Mrs Karen Tereza Sampaio Larsen

Instituto de Estudos do Mar Alm. Paulo Moreira (IEAPM)

Tel: +55 22 2622 9017

Rua Kioto 253 - Arraial do Cabo

Fax: +55 22 2622 9093

Rio de Janeiro - RJ, CEP: 28930-000

Email: karen.larsen@mail.com

BRAZIL

Mrs Marestela H. Schneider

Ag. Nac. Vigilância Sanitária - ANVISA

Tel: +61 448 1094

W3 Norte - Quadra 515

Fax: +61 448 1223

3 Andar, Brasilia DF

Email:

BRAZIL

marestela.schneider@anvisa.gov.br

or mhuppes@yahoo.com.br

Mr Douglas Siqueira de Medeiros

Port of Ubu (SAMARCO)

Tel: +55 27 3361 3806 or +55 27

Oceânica, 1803/202-Praia do Morro

9949 0133

Guarapari CEP29.200-000- ES

Fax: +55 27 3361 9747

BRAZIL

Email: siqueira@samarco.com.br

or cdtv@escelsa.com.br

Dr Maria Célia Villac

Marine Phytoplankton Ecologist

Tel: +55 12 232 4022

Rua Domingues Ribas, 81

Fax: +55 12 3635 1237

Taubaté, SP

Email: mcvillac@biologia.ufrj.br

12060-000

BRAZIL

China

Mr Ji Shan

Senior Engineer

Tel: +86 411 262 5031

Liaoning Maritime Safety Administration

Fax: +86 411 262 2282

1 Gang Wan Jie, Zhong Shan Qu

Email: naming@fm365.com

Dalian

PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF CHINA

116001

Mr Jiang Yuewen

Team Manager

Tel: +86 411 467 1429 Ext 210

National Marine Environmental Monitoring Centre

Fax: +86 411 467 2396

42 Ling He Jie, Sha He Kou Qu

Email: ywjiang@nmemc.gov.cn

Dalian

PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF CHINA

116023

Mr Wang Lijun

Biologist

Tel: +86 411 467 1429 Ext 202

National Marine Environmental Monitoring Centre

Fax: +86 411 467 2396

42 Ling He Jie, Sha He Kou Qu

Email: ljwang@nmemc.gov.cn

Dalian

PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF CHINA

116023

2

Appendix 2: Workshop Participants List

India

Dr A C Anil

Scientist

Tel: +91 832 245 6700

National Institute of Oceanography (NIO)

Fax: +91 832 245 6701

Dona Paula

Email: acanil@darya.nio.org

Goa - 403 004

INDIA

Dr Sanjay Vasant Deshmukh

Director (Research)

Tel: +91 22 2845 0101 or +91 22

Rambhau Mhalgi Prabodhini

2845 0102/3

Keshav Srushti, Uttan Village

Fax: +91 22 2845 0106

Bhayander (W), Thane 401 106

Email: docsvd@yahoo.com or

INDIA

drsanjaydeshmukh@vsnl.com

Dr. (Mrs) Geeta Joshi

Country Focal Point (A), India

Tel: +91 22 2261 3651-54 Extn

c/o Directorate General of Shipping

303

Jahaz Bhavan, W.H Marg

Fax: +91 22 2261 3655

Mumbai 400 038

Email: geeta@dgshipping.com

INDIA

Dr S S Sawant

Scientist

Tel: +91 832 245 6700 extn 4367

Marine Corrosion and Materials Research

or +91 832 228 5288 (Home)

National Institute of Oceanography (NIO)

Fax: +91 832 245 6701

Dona Paula

Email: sawant@darya.nio.org

Goa - 403 004

INDIA

I. R. Iran

Mr Jamal Pakravan

Head of Marine Environment Protection in Port Aut.

Tel: +98 761 564015/17 or +98

Ports & Shipping Organization

761 564025/27

Bandar Abbas Port Aut.

Fax: +98 761 564056

Shahid Rajaee Port Maritime Safety Office

ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF IRAN

Eng Ahmad Parhizi

Head of Search & Rescue & Marine Protection Dept.

Tel: +98 21 880 9326

Ports and Shipping Organization

Fax: +98 21 880 9555

Ministry of Road and Transportation

Email: parhizi@ir-pso.com

No 751 Enghelab Avenue, PO Box 15994

Tehran 1599661 1464

ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF IRAN

3

1st International Workshop on Guidelines and Standards for Ballast Water Sampling, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 7-11 April 2003

South Africa

Mr Adnan Awad

GloBallast, Int'l Maritime Organization

Tel: +27 21 402 3365

c/o Dept of Environmental Affairs & Tourism (DEAT)

Fax: +27 21 402 3340

Marine and Aquatic Pollution Control

Email:

Private Bag X2, Roggebaai 8012

adawad@mcm.wcape.gov.za

Cape Town

SOUTH AFRICA

Ms Letitia Greyling

Manager, Environmental Research & Best Practices

Tel: +27 11 242 4144

National Ports Authority

Fax: +27 11 242 4260

P O Box 32696

Email: letitiag@npa.co.za

Braamfontein

Johannesburg 2017

SOUTH AFRICA

Mr Jimmy Norman

Pollution Officer - Saldanha Bay

Tel: +27 83 290 6984

National Ports Authority

Fax: +27 22 703 4116

Private Bag X1

Saldanha 7395

SOUTH AFRICA

Ukraine

Dr Borys Aleksandrov

Director (Researcher in Marine Biology)

Tel: +380 482 250 918

Odessa Branch

Fax: +380 482 250 918

Institute of Biology of Southern Seas

Email: alexandrov@paco.net

National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine

37, Pushkinska Str.

65011 Odessa

UKRAINE

Mr Yevgen Patlatyuk

Head of Division

Tel: +38 0482 25 14 47 or +38

State Inspection for Protection of the Black Sea

0482 711 75 35

Ministry of Ecology & Natural Resources

Fax: +38 0482 35 51 88

30 Bunina str.

Email: steibs@te.net.ua

65026 Odessa

UKRAINE

Mr Vladimir Rabotnyov

Head of Information & Analytical Centre for Shipping Safety

Tel: +380 482 219 483 or +380

State Dept. of Maritime & Inland Water Transport

482 219 488

Ministry of Transport

Fax: +380 482 219 483

1, Lanzheronovskaya str.

Email: rabotn@te.net.ua

65026 Odessa

UKRAINE

4

Appendix 2: Workshop Participants List

GloBallast PCU

Mr Dandu Pughiuc

Chief Technical Adviser

Tel: +44 (0)20 7587 3247

Programme Coordination Unit

Fax: +44 (0)20 7587 3261

Global Ballast Water Management Programme

Email: dpughiuc@imo.org

International Maritime Organization

http://globallast.imo.org

4 Albert Embankment, London SE1 7SR, United Kingdom

Mr Steve Raaymakers

Technical Adviser

Tel: +44 (0)20 7587 3251

Programme Coordination Unit

Fax: +44 (0)20 7587 3261

Global Ballast Water Management Programme

Email: sraaymakers@imo.org

International Maritime Organization

http://globallast.imo.org

4 Albert Embankment, London SE1 7SR, United Kingdom

Dr Stephan Gollasch

Invasion Biologist

Tel: +49 40 390 54 60

Institut fuer Meereskunde

Fax: +49 40 360 309 47 67

Bahrenfelder Str. 73a

Email: sgollasch@aol.com

22765 Hamburg

GERMANY

General Participants

Dr Abdulaziz M Al-Suwailem

Manager, Marine Studies Section

Tel: +966 (3) 860 1426

Center for Environment & Water

Fax: +966 (3) 860 1205

King Fahd University of Petroleum & Minerals

Email: suwailem@kfupm.edu.sa

P.O. Box 2017

Dhahran 31261

KINGDOM OF SAUDI ARABIA

Mr Matej David

Assistant

Tel: +386 5 6767 222

University of Ljubljana

Fax: +386 5 6767 130

Faculty of Maritime Studies and Transportation

Email: matej.david@fpp.uni-lj.si

Pot Pomorscakov 4

SI-6320, Portoroz

SLOVENIA

Mr Tim Dodgshun

Senior Research Technician

Tel: +64 3 548 2319

Cawthron Institute

Fax: +64 3 546 9464

Private bag 2

Email: timd@cawthron.org.nz

Nelson

NEW ZEALAND

5

1st International Workshop on Guidelines and Standards for Ballast Water Sampling, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 7-11 April 2003

Dr. A. Muzaffer Feyzioglu

Karadeniz Technical University

Tel: +90 462 752 2805

Faculty of Marine Sciences

Fax: +90 462 752 2158

61530 Camburnu

Email: muzaffer@ktu.edu.tr

Trabzon

TURKEY

Dr Bella Galil

Senior Scientist

Tel: +972 4 856 5272

National Institute of Oceanography, ISRAEL

Fax: +972 4 851 1911

IOLR

Email: Bella@ocean.org.il or

POB 8030

galil@post.tau.ac.il

Haifa 31080

ISRAEL

Dr John Hamer

Marine Industries Liaison Officer

Tel: +44 1247 385 735

Countryside Council for Wales

Fax: +44 1248 385 510

Maes Y Ffynnon

Email: j.hamer@ccw.gov.uk

Ffordd Penrhos

Bangor

Gwynedd LL57 2DN

Dr Chad Hewitt

CTO Marine Biosecurity

Tel: +64 4 470 2582

Ministry of Fisheries

Fax: +64 4 470 2686

Te Tautiaki I nga tini a Tangaroa

Email: chad.hewitt@fish.govt.nz

P.O. Box 1020

101-103 The Terrace

Wellington, 6001

NEW ZEALAND

Mr Mike Hunter

Head, Environmental Quality Branch

Tel: +44 2380 329 199

UK Maritime and Coast Guard Agency

Fax: +44 2380 329 204

2/21 Spring Place

Email: mike_hunter@mcga.gov.uk

105 Commercial Road

Southampton SO15 1EG

Ms Nicole Mays

Policy Analyst

Tel: +1 202 464 4010

Northeast-Midwest Institute

Fax: +1 202 544 0043

218 D St, SE

Email: nmays@nemw.org

Washington DC 20003

USA

Prof Yury Okolodkov

Laboratorio de Fitoplancton Marino y Salobre

Tel: +52 55 58 04 64 75 (office) or

Departamento de Hidrobiología

+52 55 56 58 96 31 (home)

Universidad Aut'a Metropol'a, Iztapalapa (UAM-I)

Fax: +52 55 58 04 47 38

Av. San Rafael Atlixco, No.186

Email: yuri@xanum.uam.mx or

Col. Vicentina, A.P. 55-535

yuriokolodkov@yahoo.com

Mexico D.F. 09340, MEXICO

6

Appendix 2: Workshop Participants List

Mr Donald Reid

Consultant, Northeast Midwest Institute, Washington DC

Tel: +1 613 829 3642

200 Grandview Road

Fax: +1 613 829 3642

Nepean, ON

Email:

KS6 8B1

110400.1271@compuserve.com

CANADA

Ms Silvia Rondón

Jefe Division Estudios Ambientales

Tel: +57 669 4104

Centro de Investigacions Oceonagraficas & Hidrograficas

Fax: +57 669 4297

(CIOH)

Email: srondon@cioh.org.co

Direccion General Maritima

Escuela Naval

Almirante Padilla, Isla de Manzanillo

Cartagena

COLOMBIA

Ms Sonja Stiglic

Environmental Engineer

Tel: +385 1 3039 409 or +385 1

Adriatic Pipeline (JANAF)

3039 999

10000 Zagreb

Fax: +385 1 3095 482

Ulica grada Vukovara 14

Email: sonja.stiglic@janaf.hr

CROATIA

7

Appendix 3:

Selected Papers

In order as presented to the Workshop1

1 Only papers that detail ballast water sampling methods are included. Papers are published as

submitted by the authors and neither the GloBallast PCU nor IMO accepts any responsibility for the

content of these papers.

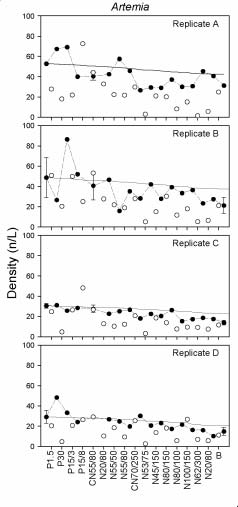

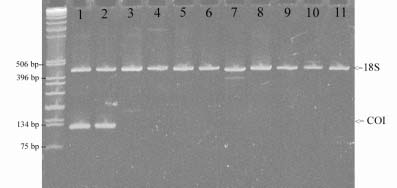

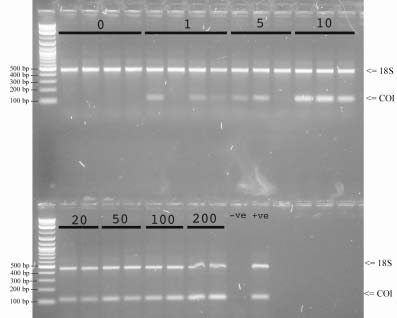

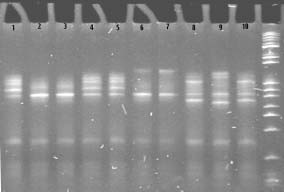

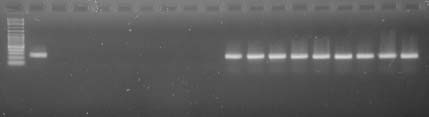

Comparison of ship sampling techniques1

S. Gollasch1, H. Rosenthal1, H. Botnen2, M. Crncevic3, M. Gilbert4, J. Hamer5, N. Hülsmann6,

C. Mauro7, L. McCann8, D. Minchin9, B. Öztürk10, M. Robertson11, C. Sutton12, and

M.C. Villac13

1 GoConsult, Germany

2 Unifob, Norway

3 The Polytechnic of Dubrovnik, Croatia

4 Dep. of Fisheries and Oceans, Canada

5 University of Wales, United Kingdom

6 Institut für Zoologie, Germany

7 Petroleo Brasiliero (PETROBRAS), Brazil

8 Smithsonian Environmental Research

Centre, USA

9 Marine Organism Investigations, Ireland

10 University of Istanbul, Turkey

11 FRS Marine Laboratory, United Kingdom

12 CRIMP, Australia

13 Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro,

Brazil

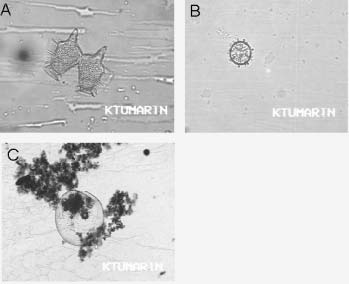

Abstract

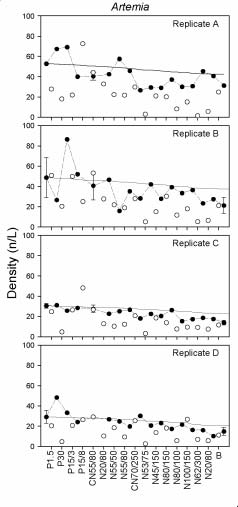

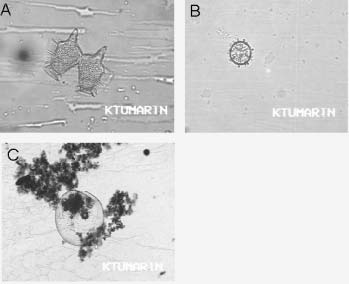

During a European Union Concerted Action study on species introductions with ships, an

intercalibration workshop on ship ballast water sampling techniques considered various

phytoplankton and zooplankton sampling methods. For the first time, all the techniques in use world-

wide prior 1998 were compared using a plankton tower as a model ballast tank spiked with the brine

shrimp while phytoplankton samples were taken simultaneously in the field (Helgoland Harbour,