Document of

The World Bank

FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY

Report No: 32367-EAP

PROJECT APPRAISAL DOCUMENT

ON A

PROPOSED GRANT FROM THE

GLOBAL ENVIRONMENT FACILITY TRUST FUND

IN THE AMOUNT OF us$7 MILLION

TO

the kINGDOM

OF Thailand, the PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF China, the SOCIALIST REPUBLIC

OF Vietnam, and the FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED

NATIONS

FOR A

Livestock Waste Management in East Asia Project

February 10, 2006

|

This

document has a restricted distribution and may be used by

recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its

contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank

authorization.

|

CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS

(Exchange Rate Effective January 20,

2006)

|

Currency

Unit

|

=

|

Local Currencies

|

|

US$1

|

=

|

Yuan8.07

|

|

US$1

|

=

|

Baht39.48

|

|

US$1

|

=

|

VND15,902.50

|

FISCAL YEAR

|

January

1

|

–

|

December 31 for

China, Vietnam, FAO

|

|

October

1

|

–

|

September 30 for

Thailand

|

ABBREVIATIONS

AND ACRONYMS

|

|

Area

Wide Integration

|

MOAC

|

Ministry of Agriculture and

Cooperatives (Thailand)

|

|

BOD

|

Biological

Oxygen Demand

|

MOF

|

Ministry of Finance (China,

Thailand, Vietnam)

|

|

CAS

|

Country

Assistance Strategy

|

MOI

|

Ministry

of the Interior

|

|

COD

|

Chemical

Oxygen Demand

|

MOIC

|

Ministry

of Information and Culture

|

|

COP

|

Code

of Practice

|

MONRE

|

Ministry

of Natural Resources and the Environment (Thailand, Vietnam)

|

|

CQS

|

Selection

based on Consultant Qualifications

|

N

|

Nitrate

or Nitrogen

|

|

DARD

|

Department

of Agriculture and Rural Development (Vietnam)

|

NCB

|

National

Competitive Bidding

|

|

DLD

|

Department of Livestock

Development (Thailand)

|

NEG

|

National

Expert Group (China)

|

|

DOF

|

Department

of Finance (Vietnam)

|

NGO

|

Non-Governmental

Organization

|

|

DONRE

|

Department

of Natural Resources and the Environment (Vietnam)

|

NSC

|

National

Steering Committee

|

|

EA

|

Environmental

Assessment

|

OP

|

Operational

Program

|

|

ECNEQA

|

Enhancement

and Conservation of National Environmental Quality Act

|

P

|

Phosphate

or Phosphorus

|

|

EMP

|

Environmental

Management Plan

|

PCD

|

Pollution

Control Department (Thailand)

|

|

EPA

|

|

PIA

|

Project

Implementation Agency

|

|

EPB

|

Environmental

Protection Bureau (China)

|

PIP

|

Project

Implementation Plan

|

|

FAO

|

Food

and Agriculture Organization

|

PIU

|

Project

Implementation Unit (Vietnam)

|

|

GEF

|

Global

Environment Facility

|

PLG

|

Project

Leading Group (Guangdong)

|

|

FM

|

Financial

Management

|

PLO

|

Provincial

Livestock Office (Thailand)

|

|

FMR

|

Financial

Monitoring Report

|

PMO

|

Project

Management Office

|

|

GIS

|

Geographic

Information System

|

RCG

|

Regional

Coordination Group

|

|

IBRD

|

International

Bank for Reconstruction and Development

|

RFO

|

Regional

Facilitation Office

|

|

ICB

|

International

Competitive Bidding

|

RPF

|

Resettlement

Policy Framework

|

|

IDA

|

International

Development Association

|

QCBS

|

Quality

and Cost Based Selection

|

|

IFC

|

International

Finance Corporation

|

SA

|

Social

Assessment

|

|

IMO

|

International

Maritime Organization

|

|

Strategy for Ethnic Minority

Development

|

|

LEAD

|

Livestock,

Environment and Development Initiative of FAO

|

SEPA

|

State

Environmental Protection Agency

|

|

LEP

|

Law

of Environmental Protection

|

SOE

|

Statement

of Expenditures

|

|

LWM

|

Livestock

Waste Management

|

SPP

|

Standing

Pig Population

|

|

M&E

|

Monitoring

and Evaluation

|

TAO

|

|

|

MARD

|

Ministry

of Agriculture and Rural Development (Vietnam)

|

TOR

|

|

|

MM

|

Manure

Management

|

UNDP

|

|

|

MOA

|

Ministry

of Agriculture (China)

|

UNEP

|

|

|

Vice

President:

|

|

Jeffrey

Gutman, Acting EAPVP

|

|

Country

Manager/Director:

|

|

David R. Dollar,

EACCF

Ian C. Porter,

EACTF

Klaus Rohland,

EACVF

|

|

Sector

Director:

|

|

Mark D. Wilson,

EASRD

|

|

Task

Team Leader:

|

|

Weiguo

Zhou, EASRD

|

East Asia And Pacific

Livestock Waste Management in East Asia Project

Contents

Page

A.STRATEGIC

CONTEXT AND RATIONALE 3

1.Country and sector issues 3

2.Rationale for Bank involvement 4

3.Higher level objectives to which the project contributes 5

B.PROJECT

DESCRIPTION 5

1.Lending instrument 5

2.[If Applicable] Program objective and phases 6

3.Project development objective and key indicators 6

4.Project components (see Annex 4 for a detailed description and

Annex 5 for a detailed cost breakdown) 6

5.Lessons learned and reflected in the project design 9

6.Alternatives considered and reasons for rejection 9

C.IMPLEMENTATION 10

1.Partnership arrangements (if applicable) 10

2.Institutional and implementation arrangements 10

3.Monitoring and evaluation of outcomes/results 11

4.Sustainability and replicability 12

5.Critical risks and possible controversial aspects 13

6.Loan/credit conditions and covenants 14

D.APPRAISAL

SUMMARY 14

1.Economic and financial analyses 14

2.Technical 14

3.Fiduciary 15

4.Social 16

5.Environment 16

6.Safeguard policies 16

7.Policy exceptions and readiness 17

Annex

1: Country and Sector or Program Background 18

Annex

2: Major Related Projects Financed by the Bank and/or other

Agencies 28

Annex

3: Results Framework and Monitoring 30

Annex

4: Detailed Project Description 34

1. Livestock Waste Management Technology Demonstration Component

(US$14.2 million) 34

2. Policy and Replication Strategy Development Component (US$4.4

million) 38

3. Project Management and Monitoring Component (US$3.9 million) 43

4. Regional Support Services Component (US$1.5 million) 45

Annex

5: Project Costs 50

Annex

6: Implementation Arrangements 52

Annex

7: Financial Management and Disbursement Arrangements 57

Disbursement Arrangement 62

Funds Flow and Special Account 64

Project

Financing Plan 65

Annex

8: Procurement Arrangements 67

Annex

9: Economic and Financial Analysis 71

Annex

10: Safeguard Policy Issues 80

Annex

11: Project Preparation and Supervision 88

Annex

12: Documents in the Project File 90

Annex

13: Statement of Loans and Credits 91

Annex

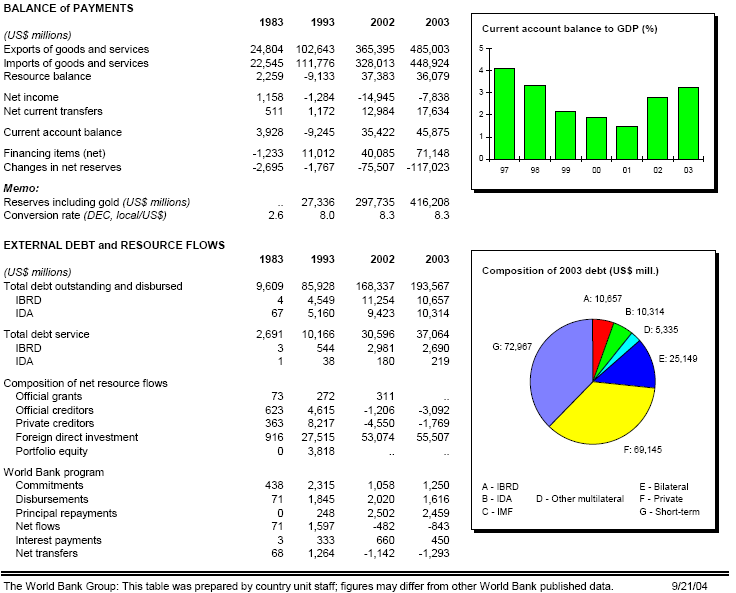

14: Country at a Glance 98

Annex

15: Incremental Cost Analysis 102

Annex

16: STAP Roster Review 112

Map GEF 34271

(Project Area)

East Asia and Pacific

Livestock Waste Management In East Asia

Project Appraisal Document

East Asia and Pacific

EASRD

|

Date: February 10, 2006

Country Director: David R. Dollar, Ian C. Porter, Klaus

Rohland

Sector Manger/Director: Mark D. Wilson

Project ID: P079610

Focal Area: International Waters

Lending

Instrument: GEF Grant

|

Team Leader: Weiguo Zhou

Sectors: Animal production (90%); Sewerage (10%)

Themes: Pollution management and environmental health (P);

Rural policies and institutions (P)

|

|

Project Financing Data

|

|

[ ] Loan [ ] Credit [X] Grant [ ] Guarantee

|

[ ] Other:

|

|

|

|

For

Loans/Credits/Others (US$m.): 7.0

|

|

Total Bank

financing (US$m.):

|

|

Proposed terms:

|

|

Financing Plan (US$m)

|

|

Source

|

Local

|

Foreign

|

Total

|

|

BORROWERS

|

16.51

|

0.00

|

16.51

|

|

GLOBAL ENVIRONMENT

FACILITY

|

2.29

|

4.71

|

7.00

|

|

FAO

|

0.00

|

0.50

|

0.50

|

|

Total:

|

18.80

|

5.21

|

24.01

|

|

|

|

Borrower/Recipient:

|

|

People's Republic

of China (China)

Kingdom of

Thailand (Thailand)

Socialist

Republic of Vietnam (Vietnam)

Food and

Agriculture Organization, United Nations (FAO)

|

|

|

|

Responsible Agency:

|

|

Ministry of

Finance, China

Address: Sanlihe

Road, Beijing, China, 100820

Contact Person:

Mr. Wu Jinkang

Tel:

86-10-6855-3102; Fax: 86-10-6855-1125; Email: jk.wu@mof.gov.cn

Guangdong

Provincial Department of Finance, China

Address: 11th

Floor, 26 Cangbian Rd., Guangzhou, China, 510030

Contact Person:

Ms. He Huan

Tel:

86-20-8333-6407; Fax: 86-20-8333-0007; Email:

hehuanzp@gdwbo.gov.cn

|

|

Ministry of

Agriculture and Cooperatives, Thailand

Address: Phayathai

Road, Bangkok, Thailand, 10400

Contact Person:

Mr. Arux Chaiyaku

Tel:

66-2-653-4486; Fax: 66-2-653-4486; Email: aruxc@dld.go.th

Ministry of

Natural Resource and Environment, Vietnam

Address: 83 Nguyen

Chi Thanh Street, Hanoi, Vietnam

Contact Person:

Mr. Nguyen Van Tai

Tel:

84-4-773-4244; Fax: 84-4-773-4245; Email: nvtai@yahoo.com

Food and

Agriculture Organization, United Nations

Address:

C-542, Viale delle Terme di Caracalla –

00100 Rome, Italy

Contact Person:

Mr. Henning Steinfeld

Tel:

39-06-570-54-751; Fax: 39-06-570-55-749;

Email: Henning.Steinfeld@fao.org

|

|

|

|

Estimated

disbursements (Bank FY/US$m)

|

|

FY

|

2006

|

2007

|

2008

|

2009

|

2010

|

2011

|

|

|

|

|

Annual

|

0.35

|

1.75

|

1.75

|

1.40

|

1.05

|

0.70

|

|

|

|

|

Cumulative

|

0.35

|

2.10

|

3.85

|

5.25

|

6.30

|

7.00

|

|

|

|

|

Project implementation period: 5 years

Expected effectiveness date: 7/21/2006

Expected closing date: 12/31/2010

|

STRATEGIC CONTEXT AND RATIONALE

Country

and sector issues

The proposed project addresses one of the most significant and

rapidly growing sources of land-based pollution of the South China

Sea – environmentally unsustainable intensive and

geographically-concentrated livestock

production in China, Thailand and Vietnam.

The South China Sea

is a locally, regionally and globally significant body of water

bordered by countries that are experiencing rapid population and

economic growth and facing similar major environmental challenges.

This bio-geographic region is one of the world’s most

biologically diverse shallow-water marine areas. However, this

biological richness is seriously threatened by two major

environmental problems - over-fishing and land-based anthropogenic

pollution. Without wide-scale preventive action, livestock production

would become the single most important source of organic and chemical

pollution of the main catchments draining into this international

water.

A recent Bank report

reveals that land-based run-off and other inland discharges are

currently estimated to contribute 44 percent of pollution to the

South China Sea. The chemical oxygen demand

(COD) from untreated piggery waste alone in the coastal regions of

Central-south, South-west and East China accounted for 28 percent of

current urban-plus-industrial COD loads in 1996, and this is

projected to rise to as much as 90 percent by 2010.

The East Asia region is the world’s biggest pig and poultry

production area with China, Thailand and Vietnam accounting for over

53 percent of all pigs and 28

percent of all chickens in the world in 2004. The shares of

East Asia and the three participating counties in world livestock

production is expected to continue to grow rapidly over the next

decades fuelled by a growing population, rising incomes and

urbanization. This, coupled with economic and technological

evolution, is causing significant change in the scope and the

structure of the livestock industry. In particular, very intensive

forms of livestock production are appearing rapidly and driving much

of the sector’s development. Large-scale industrial production

accounts for about 80 percent of the total production increase in

livestock products in Asia since 1990. In the future, most livestock

production especially of pigs and poultry is projected to come from

large-scale industrial production, and the majority of these

intensive production farms will be located around major urban centers

that lie in or close to the coastal regions of the South China Sea.

Concentrated livestock production is a major threat to human health,

as evidenced by the recent Severe Acute

Respiratory Syndrome and Avian Influenza outbreaks. It also

causes significant local, regional and global environmental damage,

particularly to freshwater and marine aquatic systems. Current waste

management practices in these participating countries lead to the

predominately direct or indirect discharge through streams and rivers

into the South China Sea. The main sector issues are:

(a) The lack of technical solutions to address and deal with

the problem of nutrient imbalance. In all three participating

countries, there is limited government support for basic livestock

waste management investments. Moreover, these investments address

only the immediate impacts or symptoms of the problem as perceived at

the local level and do not even begin to address the problem of

nutrient imbalance. About 26 percent of the

total area in East Asia suffers from significant nutrient surpluses

which emanate mainly from agricultural sources. Without new

initiatives and technical solutions, countervailing tendencies to

concentrated livestock production would be too weak to overcome the

incentives driving it. Consequently, the imbalance between the level

of nutrient inputs and the absorptive capacity of the land would

worsen progressively with rapidly growing industrial livestock

production.

(b) The lack of policy instruments and replication strategy for

livestock waste management. In all

three participating countries there are national-level general

environmental policies with supporting standards but no replication

strategy for livestock waste management exists. In such policies, the

components dealing with industrial livestock production and waste

management are either missing or very recent and general with little

effective enforcement. The agencies charged with enforcement

generally lack coordination and resources committed to monitor and

enforce the regulations.

Rationale for Bank involvement

The project is fully consistent with the Global Environment Facility

(GEF) International Waters Focal Area Strategic Priorities, in

particular with: (a) IW-1 catalyzing financial resource mobilization

for implementation of reforms and stressing reduction measures

through agreed Trans-boundary Diagnostic

Analysis and Strategic Action Plans; and (b) IW-3 innovative

demonstration of removing the barriers to sustainable industrial

livestock management.

The project is fully consistent with GEF OP10 Contaminant-based

Operational Program. Specifically, the project would: (a) demonstrate

how to address land-based pollution (paragraph 10.2); (b) position

the GEF to play a catalytic role in demonstrating ways to overcome

barriers to best practice in limiting contamination of international

waters (paragraph 10.5); (c) address a threat that is imminent, of

high priority, and on which neighboring countries want to take

collaborative action (paragraph 10.5); (d) stress pollution

prevention over remediation (paragraph 10.7); (e) leverage private

investment (paragraph 10.9); (f) involve close cooperation with other

GEF agencies (paragraph 10.9); and (g) be replicated regionally and

globally (paragraph 10.11). The project would contribute to the

objective of the GEF Focal Areas of climate change, OP2 Costal,

Marine, and Freshwater Ecosystems.

The project is also consistent with the objective and potential

eligibility criteria of the proposed GEF/World Bank Strategic

Partnership Investment Fund for Land-based Pollution Reduction in the

Large Marine Ecosystems of East Asia that is under development. The

objective of this Partnership Investment Fund would be to reduce

pollution discharges that have an impact on the seas of East Asia by

leveraging investments in pollution reduction through removal of

technical, institutional and financial barriers. The Partnership

Investment Fund is expected to focus on both urban waste-water

treatment and agricultural pollution reduction.

Higher

level objectives to which the project contributes

The project is consistent with the goal of the Bank’s Country

Assistance Strategies (CASs) in China, Thailand and Vietnam

reflecting the need for rapid economic growth that is environmentally

sustainable.

In China, the CAS (25141-CN, December 19, 2002) aims at assisting the

government in poverty reduction and supporting investments in

environmentally sustainable agricultural and livestock development.

As reflected in the CAS, protecting the environment is an overarching

objective for support by the Bank to sustain rural income growth

while maintaining the natural resource base. This proposed project

would contribute towards these specific CAS goals by promoting

investment on selected livestock farms in an environmentally

sustainable manner to protect the environment around the farms and

towards the South China Sea.

In Thailand, the CAS (25077-TH, January 22, 2003) aims at supporting

the government by complementing its development partnership at the

country level with work on regional and global public goods. The Bank

is already actively involved in a number of regional initiatives and

would strengthen its support for these programs in the coming years.

The Bank would also help share Thailand's development experience

through cooperation with other countries in the region. This proposed

project would contribute towards these CAS goals by promoting an

integrated regional approach in project preparation, implementation

and sharing of experience.

In Vietnam, the CAS (27659-VN, February 19, 2004) sets out three

broad objectives: (a) high growth through a transition to a market

economy; (b) an equitable, socially inclusive and sustainable pattern

of growth; and (c) adoption of a modern public administration, legal

and governance system. The proposed project is in line with these

broad objectives by introducing a replication strategy into the

livestock production sector to promote environmentally sustainable

growth.

The project’s regional approach will maximize its contribution

to the two regional GEF Action Programs by ensuring that: (a) the

region’s three most important countries, in terms of livestock

production and waste pollution, are all involved; (b) their common

interest in protecting ecosystems of the South China Sea is

emphasized; (c) important cross-country synergies are promoted; and

(d) experience from the project demonstration could be replicated

throughout the region.

The proposed project would demonstrate technically, agronomically,

geographically, economically and institutionally workable solutions

to protect the environment under widely different political

structures and social conditions. All three

participating countries have recognized the negative effects of

industrial livestock production on the environment and have endorsed

the proposed project as a means to tackle these issues and as a

national priority for GEF support.

PROJECT DESCRIPTION

Lending

instrument

The proposed project would be financed by a full size, stand-alone

GEF Grant.

[If Applicable] Program objective and phases

Not applicable.

Project

development objective and key indicators

Project

Development Objective

The project’s development objective is to reduce the major

negative environmental and health impacts of rapidly increasing

concentrated livestock production on water bodies and thus on the

people of East Asia. Its global environment objective is to reduce

livestock-induced, land-based pollution and environmental degradation

of the South China Sea.

Key

Indicators of Project Performance

Achievement of the project’s development objective would be

monitored by the following key performance indicators (see also Annex

3, Results Framework and Monitoring):

Demonstrated Livestock waste management practices in the

participating farms/villages within the project area;

Reduced livestock production related surface water pollution in the

project area, including nitrates, phosphates, biological oxygen

demand (BOD), COD and E. coli bacteria;

Development of a Replication Strategy and other policy measures for

addressing livestock waste management, and their local and national

adoption and enforcement;

Development of plans, programs and capacities to achieve a spatial

distribution of livestock production better aligned with

environmental and health objectives;

Reduced human health risk as a result of improved risk management of

pathogens, antibiotics and virus transmission from livestock to

humans; and

Increased public awareness and regional exchange of information on

pollution threats and health problems from livestock waste.

Project components (see Annex 4

for a detailed description and Annex 5 for a detailed cost

breakdown)

On-the-ground demonstrations of innovative, cost-effective livestock

waste management technologies by private livestock producers and

development of a replication strategy will be the project’s

principal outputs. Reflecting this emphasis, nearly 60 percent of

total project cost is budgeted for livestock waste management

technology demonstration activities.

The project design is tailored to fit the specific livestock-rearing

conditions in the three participating countries, particularly the

different average size of pig farms. In Thailand and China, large

industrial pig farms are dominant, while in Vietnam pig farms are

typically small, involving confined household-based production that

is concentrated in particular villages. This structure of Vietnamese

rural society requires that the project’s demonstration

activities be conducted on a communal (village) rather than

individual farm basis. The demonstration farms would all be located

within the concentrated livestock production jurisdictions bordering

the South China Sea.

The proposed project takes a comprehensive approach to integrate

technological solutions, policy development and enforcement, capacity

building and regional synergy to achieve the development objective.

The project would be integrated into the governments’

mainstream programs and based on existing institutional mechanisms.

The project will support activities under four components to be

implemented over a period of five years.

Component 1: Livestock Waste Management

Technology Demonstration (US$14.2 million)

This component, comprising two sub-components: (a) Technology

Demonstration; and (b) Training and Extension, would finance

consultant services and training, and finance goods and civil works

(through sub-grants) related to the development and construction of

cost-effective and replicable livestock waste management systems and

facilities and the implementation of effective waste management

approaches in areas with a high concentration of intensive pig farms.

Its goal is to demonstrate technically, geographically, economically

and institutionally workable solutions to reduce regionally-critical

livestock waste pollution caused by industrial or concentrated

livestock production. The livestock waste management strategies will

focus on reducing excess nutrients (nitrates and phosphates in

particular) and human health risks.

The methods to be used would include: (a) reducing through better

feeding practices the volume of nutrient emission; (b) returning

nutrients to the crop cycle locally or in other areas once processed

and packaged; (c) converting the nutrients to plant-available forms;

(d) destroying the nutrients; and (e) taking measures to minimize

potential human health risks associated with livestock waste

management practices. The actual physical demonstration of improved

livestock waste management would be carried out on farms or in

villages (in Vietnam) proposed on a yearly basis by each

participating country according to agreed selection criteria.

The demonstration activities would be supported by training and

extension to provide (a) farmers with the essential skills and

technical support needed to improve their on-farm manure management

practices and (b) training for capacity building. Activities would

include training of livestock extension agents, farmer associations

and planning officers, study tours for participating farmers on

demonstration farms, preparation of training manuals, collaboration

with livestock extension projects, etc. Details are specified in the

master capacity building development plan prepared by each

participating country.

Component 2: Policy and Replication Strategy Development (US$4.4

million)

This component, comprising two sub-components: (a) Policy Development

and Testing; and (b) Awareness Raising, would finance consultant

services, training and workshops to support the establishment of a

policy and regulatory framework for environmentally sustainable

development of livestock production in each country that will induce

further policy reforms and encourage farmers to adopt improved manure

management practices. This will be achieved through the development

and testing of a Replication Strategy and other policy measures in

each country. Replication potential of alternative livestock waste

management technologies as related to farm scale, affordability,

operational capacity, material availability, reduction of public

health risks and compatibility with the waste-handling methods of the

local farm communities would be assessed to achieve widespread

replication of the tested manure management practices. Specific

activities may vary among participating countries, but the focus

would remain on addressing waste management through: (a) development

and introduction of codes of practice (COP); and (b) development and

implementation of policy measures to direct the geographic focus of

future intensive livestock production. Both would be coordinated with

respective national legislation/programs and tested in synergy with

the Livestock Waste Management Technology Demonstration and Project

Management and Monitoring components. Other activities would include:

(a) the review and revision of existing regulations; and (b) the

development and introduction of livestock waste recycling and

discharge standards. Specific policy packages would be tested in

sub-national jurisdictions and testing experience would be

incorporated in the finalized respective Replication Strategy.

This component would also support activities to raise awareness on

development, testing and implementation of the Replication Strategy

focusing on policy measures, environment and public health issues

associated with inadequate manure management.

Component 3: Project Management and Monitoring (US$3.9 million)

This component, comprising two sub-components: (a) Project

Management; and (b) Monitoring and Evaluation, would finance

consultant services, training, office equipment and incremental

operating costs to support efficient project management. The project

would support the establishment and operations of a national

(provincial in China) Project Management Office (PMO) in each

participating country as the secretariat of, and reporting directly

to, the respective National Steering Committee. The PMO, comprising a

project director supported by competent staff and based on existing

administrative structure and physically located within the main

implementing agency of each participating country, would be

responsible for day-to-day project administration. Institutional

capacity, monitoring and evaluation skills of the implementing

agencies at local levels would also be strengthened.

The component would also support effective project monitoring and

evaluation of the social, economic, environmental, human health risks

and other changes brought about by the project, and the dissemination

of project outcomes within the respective participating country.

Monitoring on human health risks associated with the project would

focus on measures taken to minimize potential transmission of

pathogens, antibiotics and their resistant strains from livestock to

humans. Specific activities would be detailed in project monitoring

and evaluation plans developed by each participating country.

Component 4: Regional Support Services (US$1.5 million)

This component, comprising two sub-components: (a) Capacity Building

Support; and (b) Coordination and Facilitation Support, would finance

consultant services, training, workshop, office equipment and

incremental operating costs to provide: (a) capacity-building support

to strengthen the participating countries’ institutional

capacity in project implementation; and (b) regional coordination and

facilitation support to ensure regional coordination and achieve

cross-country synergies and regional replication.

This component would respond to the participating countries’

need for an easily accessible source of support for capacity

building, including support for: (a) decision tools development; (b)

evaluation of project activities and outcomes; and (c) development of

training modules and packages. This component would focus on regional

coordination, facilitation amongst the three participating countries

and the dissemination of project outcomes, decision support tools,

technical guidelines and standards within the three participating

countries and to other countries bordering the South China Sea.

Lessons

learned and reflected in the project design

Key lessons learned from the World Bank’s rural environmental

and livestock operations, the Livestock, Environment and Development

Initiative (LEAD)

earlier Area-Wide Integration (AWI) pilot projects in China, Thailand

and Vietnam, and the government programs are reflected in the

proposed project design and include the following:

The lack of industrial livestock production and waste management

policy instruments and replication strategy, weak policy enforcement

and poor coordination among concerned government agencies are the

key weaknesses in policy frameworks.

The lack of effective analytical tools, appropriate technical

solutions and coordinated inter-agency approaches are the major

lessons in addressing the worsening livestock waste management

issue.

Strong government commitment in compliance, enforcement, and

provision of incentives, and the full involvement of key

stakeholders in project preparation and implementation are critical

to ensure ownership, sustainability and success of the project.

Mitigation measures to reduce nutrient load must yield tangible

benefits for key stakeholders, specifically farmers and local

communities, to ensure adoption and replicability.

The effective implementation of well-developed monitoring and

evaluation plans are the major instrument for assessing project

impact.

The capacity building of project implementing agencies and

regulatory institutions through training, technical assistance and

specialized support is the key to ensure efficient and effective

project implementation.

Alternatives considered and reasons for rejection

In designing the project, the following alternatives were considered

as possible approaches to reduce and prevent pollution from livestock

production but rejected as unfeasible.

(a) Approach to use exclusively regulatory forces.

Regulatory measures could include: (i) capping or reducing the number

of farm animal; and (ii) forced relocation or closing down of

existing farms. These measures may potentially run into major

economic, social and political problems in all participating

countries. Widespread capping or reducing the number of farm animal

is likely to hit the pig production industry hard as well as to

reduce the attraction for investment in livestock farming. Forced

relocation or closing down of existing farms are rarely successful

and acceptable options despite a few cases of large modern farms

established in Thailand where redirection to more suitable areas was

achieved. Such control measures should be reserved only for the most

serious problem cases and used only as a last resort.

(b) Approach to involve all littoral countries bordering South

China Sea. This approach was rejected based mainly on the

limited GEF Grant available for the project. Involving all countries

bordering on the South China Sea (i.e. extending it to include

Cambodia, Malaysia and The Philippines) in the project would probably

result in: (i) the increased complexity of regional coordination; and

(ii) the diminished interest of countries due to much smaller average

GEF Grant allocation to each participating country.

IMPLEMENTATION

Partnership

arrangements (if applicable)

Not applicable.

Institutional and implementation arrangements

2.1 Regional Coordination Group (RCG). Project implementation

would be coordinated and facilitated by a RCG which would consist of

representatives of each participating country and FAO. The RCG’s

principal role would be: (a) to review project progress and make

recommendations to the steering committees in the three participating

countries and to the regional facilitation office for a coordinated

project implementation; (b) to review the regional facilitation

office’s annual work plan; (c) to ensure the inclusion of the

issue of manure management on the political and budgetary agenda of

each country; (d) to facilitate the gradual adoption of common

policies and practices among participating countries; and (e) to

disseminate and publicize the project achievements in countries and

regional organizations connected to the South China Sea. The RCG

would normally meet twice a year during the first year of project

implementation and once a year thereafter.

2.2 National Steering Committee (NSC). A NSC has been

formed by each participating country at the national level with

overall responsibility for project preparation and implementation.

Its members are from key government ministries (e.g. agriculture,

environment and public health) within each country involved in

livestock waste management. The principal functions of each NSC would

be: (a) to review and approve project annual work plans and budgets

in their respective countries; (b) to provide guidance on national

policies and priorities related to livestock waste management and to

help resolve related issues; and (c) to integrate the activities of

various agencies involved in the project and ensure an inter-agency

coordinated approach to project implementation. To provide immediate

guidance to Guangdong PMO, a Project Leading Group (PLG) has been

established at Guangdong provincial level.

2.3 National Project Management Office. A national (provincial

in China) PMO has been established in each country as the secretariat

of, and reporting directly to, the respective NSC. The PMO would be

responsible for day-to-day project administration. Its staff

composition, specific responsibilities, financial budgets and

physical location were decided by the respective NSCs and are

acceptable to the Bank.

2.4 Local Institutional Arrangement. The project management

structure below the national level would vary from one country to

another and is described in detail in Annex 6. Local governments

would make practical institutional arrangements involving various

government agencies for preparation and implementation of respective

project activities. With guidance and support from national PMOs (and

the provincial PMO in Guangdong) and training, local level agencies

would take the primary responsibility for project implementation

within their jurisdictions.

2.5 Stakeholder Involvement. All key stakeholders have been

involved in project preparation and will be continuously involved in

implementation. Stakeholder participation plans have been prepared by

the participating countries which: (a) identified main stakeholders;

(b) specified their major roles; and (c) established the

participation and consultation mechanisms tailored to facilitate the

participation of all stakeholders especially the private sector and

industrial pig producers. The private sector will be responsible for

implementation of the demonstration farms and in villages.

2.6 Implementation Arrangements for the Regional Support Services

Component. FAO would be responsible for implementation of the

Regional Support Services component. A Regional Facilitation Office

(RFO), located in FAO’s Regional Office in Bangkok, would be

set up prior to the effectiveness date of the Grant. RFO would

consist of FAO’s regular program staff serving as Regional

Project Coordinator and the Operations Coordinator, supported by

short-term consultants as needed. Its main functions would be: (a) to

prepare an annual work program to be reviewed by the RCG; (b) to

manage the project activities as agreed with the Bank; and (c) to

serve as the secretariat of the RCG.

A detailed description of the project’s institutional and

implementation arrangements is presented in Annex 6 and included in

the Project Implementation Plans (PIPs).

Monitoring and evaluation of outcomes/results

A Monitoring and Evaluation (M&E) Plan has been prepared by each

participating country and included in the country-specific PIPs.

These M&E Plans have been reviewed by the Bank. Process

indicators, stress reduction indicators and environmental status

indicators relevant to International Waters projects are included in

the M&E Plans. The M&E Plans specify the details of the scope

of and activities for monitoring and evaluation. The scope would

include: (a) nitrate, phosphate, BOD, COD and E. coli bacteria

discharge at the end-of-pipe of the individual farms or community and

at critical downstream locations; (b) the number of standing pig

population (SPP) covered by farms adopting sound livestock waste

management systems; and (c) the extent of awareness and regional

exchange of information on pollution threats and health problems from

livestock waste.

The activities would include: (a) progress monitoring, including the

monitoring of the status of project implementation progress

indicators; (b) livestock waste management system monitoring which

would include, at farm and community level, the monitoring of system

efficiency and the effect of the project manure management

interventions on public and animal health; (c) environmental

monitoring, which would include monitoring of the major physical,

chemical and biological characteristics of unit processes, or

surface- and ground-water measurement, where applicable, within

project areas (micro-watersheds) and at the end-of-pipe on

demonstration farms; and (d) project impact monitoring, which would

include monitoring of the implementation of stakeholder participation

plans, annual social impact review and public consultation, impact on

human health, and long-term project impact. Annex 3 provides a

detailed description of the monitoring framework. Specific plans for

monitoring the long-term project impact would be developed during

project implementation and finalized at project completion.

Sustainability

and replicability

4.1 Sustainability

The project is designed to be sustainable in several respects. To the

extent possible, it would be based on technologies that are

cost-effective, replicable and environmentally sustainable. For

technologies such as improved feed efficiency or fertilization

techniques that lower production cost, sustainability would be

inherent. The project would ensure that manure treatment systems

promoted would have sufficiently low operation and maintenance costs

to be financially sustainable by livestock producers as estimated for

the demonstration farms under the first year’s implementation.

Financial analysis concluded fair financial returns for medium and

large-sized industrial pig farms which are the targeted farms under

this project with a higher standard of systems in manure management.

To a large extent, the project’s long-term sustainability would

be ensured through the strengthening of policy frameworks for the

livestock sector. While there are risks of insufficient enforcement,

the project would attempt to mitigate such risks in several ways: (a)

sufficient incentives to ensure the private sector’s

willingness to invest in livestock waste management technologies

would be sought through increased stakeholder participation in the

decision-making process, including favorable pricing policies for

livestock waste management systems’ outputs such as ,

electricity and organic fertilizer, local public health risk

reduction programs, and introduction of carbon fund; (b) raising of

public awareness would encourage local communities to seek more

consistent enforcement of environmentally-friendly solutions; and (c)

the strengthening of public institutions and systematic monitoring of

livestock development policies, including their environmental impact,

would lead to improvements in each country’s capacity for

sustainable livestock development as well as benefits for the global

environment. The project’s M&E plans would ensure that its

environmental and social benefits are adequately measured, valued and

disseminated which would further promote its sustainability. The

governments of the participating countries have provided assurances

about the priority nature of this project and their commitment to

ensure adequate government support, including financial resources for

sustainability beyond the completion of this project.

4.2 Replicability

The project is expected to yield only limited direct impact on water

quality of the South China Sea because the selected demonstration

areas represent negligible fractions of the total pollution load.

Consequently, it has been designed to maximize replicability beyond

its immediate impact areas. A noticeable pollution reduction in the

South China Sea catchment areas, therefore, can be achieved through

the replication of the demonstrated livestock waste management

practices throughout the participating countries and in other

countries bordering the South China Sea. Specific project activities

for replication of improved livestock waste management approaches

would include: (a) the development and implementation of a

replication strategy; (b) specialized training, cross-visits and

study tours for interested farmers, local officials, decision makers,

etc.; (c) engaging farmers groups, local communities, NGOs,

government agencies and other stakeholders; (d) support for local

pressure through public-awareness building; and (e) the dissemination

of demonstration results through training, targeted workshops and the

development of an internet portal for in-country and regional

replication.

The aim of the project’s replication strategy is the eventual

integration of the project’s successful demonstrations into

each country’s overall livestock waste management strategy and

their scaling up. During this process, opportunities for integrating

livestock waste management activities in future Bank and other

donor-supported investments would be sought. Through the regional

dissemination activities, which would target primarily the three

participating countries but eventually also other countries draining

into the South China Sea, other countries in the region could benefit

from the knowledge and experience gained under the project. The

project would also provide valuable experiences beyond the East Asia

region. Close cooperation with other international livestock

management projects and assistance agencies would ensure that a

successful project approach can be replicated in other regions that

face similar environmental problems from industrial livestock

production. The project would ensure that all aspects of its design

and implementation are well documented and easily publicly available

to support dissemination and replication efforts.

Critical risks and possible controversial aspects

The proposed project would address challenging environmental issues

in the countries of the East Asia region. No controversy is

envisaged. Potential risks may include:

Inadequate collaboration among key

agencies. agricultural, environmental and public health ministries

in the countries involved have sometimes non-compatible interests

and priorities and are not accustomed to working together;

A lack of participation by and weak support from local populations

and civil society, as well as a weak partnership with the private

sector;

Failure in coordination among participating

countries due to ineffective regional coordination arrangement, lack

of country ownership, failure to observe commitments, etc.;

Operational failure resulting from: (i) inadequate financial

incentives provided for the private sector to invest in waste

management systems; (ii) inadequate political will and human

resources to enforce nutrient management regulations; (iii) a lack

of local community and farmers support for maintaining communal

systems; (iv) operational and management support by PMOs not

available or inadequately accessible, (v) government co-financing

contributions not available in sufficient amount or in a timely

manner;

Technical failure occurring as a result of: (i) inappropriate choice

of technology and system; (ii) design, equipment or material

failure; or (iii) farm expansion; and

The potential transmission of pathogens, antibiotics and their

resistant strains from livestock to humans under the project.

Loan/credit conditions and covenants

The RCG and RFO would be established before Grant effectiveness.

Project management organizations, including the RCG, the RFO, the

NSCs, the National (Provincial in China) PMOs and Guangdong PLG

would be maintained throughout the project implementation period

with composition, staffing and terms of reference acceptable to the

Bank.

APPRAISAL SUMMARY

Economic

and financial analyses

1.1 Range of analysis. Although nearly 60 percent of the

project’s total cost represents on-farm investments for

demonstration of improved livestock waste management technologies,

the main benefits would be environmental, health and institutional.

Consequently, the appropriate economic analysis is a

cost-effectiveness analysis to determine whether the project could

achieve its development objective at the least economic cost. A

second important aspect relates to the financial attractiveness to

project participants of technologies and approaches to be promoted.

1.2 Economic analysis. The cost-effectiveness analysis

examines potential alternative technical solutions for reducing

fluxes of selected critical nutrients (N and P) and BOD and COD of

livestock waste into the target environment and estimates the unit

cost of their removal from the chain. The analysis confirms that, in

terms of reducing the flow of critical pollutants to the South China

Sea, the range of technical solutions to be promoted under the

project is cost-effective.

1.3 Financial analysis. The financial analyses for all

participating countries find that Level 1 (meeting minimal domestic

requirements) types of manure management are affordable or profitable

for all livestock production farms. However, the higher standard type

of systems in manure management as proposed under the project are

affordable for medium and large-scale industrial pig farms which are

the targeted farms under this project. Smaller farms in villages can

also afford the technologies provided that they are successful in

defraying part of the costs through manure sales, fish production or

similar means under the support of the project. In the short term,

sufficient financial incentives would be needed to help early

adopters of such technologies. In the long run, production costs

would be reduced through productivity improvements and by shifting

farms away from towns to areas where land for recycling and other

factors of production, such as labor, energy and clean water, are

likely less costly.

Technical

Technical design of the project focused on introducing technical

solutions to address the key issue of nutrient imbalance in livestock

waste management. The design, reflected in the Livestock Waste

Management Technology Demonstration component, was based on: (a) the

cost-effectiveness of proposed technologies to the waste handling

methods of pig farms; (b) the expected environmental performance of

the proposed technologies relative to the nutrient management goals

of the project; and (c) the replication potential relative to the

financial, material and labor skill availability in the participating

countries.

The project would introduce a package of technology options for each

selected demonstration farm and village to consider. These manure

management technologies are in wide use, including European and North

American countries, and have been proved to be effective. Locally,

technologies have also been developed but there is a lack of

monitoring data for evaluation of their environmental, agronomic and

economic effectiveness. The actual technologies to be used would be

tailored to fit specific conditions of each selected demonstration

farm and village.

Fiduciary

3.1 Financial management. In each of the three participating

countries and FAO, a financial management assessment was conducted to

determine whether the financial management capacity will be able to

meet the requirements of BP/OP10.02. The assessments concluded that

the proposed implementing agency in each country and for the

project’s Regional Support Services component has the ability

to satisfactorily manage the accounting and disbursement of the Grant

and to meet the minimum financial management requirements of the

Bank. The Financial Management Action Plan (Annex 7) addresses

weaknesses and the actions to be taken to strengthen the financial

management arrangements. After mitigation, the project’s

overall financial management risks are considered moderate. Each

implementing agency will maintain the financial accounts and records

and issue financial management reports for the project activities for

which they are responsible. Semi-annual financial monitoring reports

and annual financial statements will be submitted to the Bank by each

country and by the FAO for the Regional Support Services component of

the project. The annual financial statements will be audited by

auditors acceptable to the Bank and the audit reports will be

submitted to the Bank within six months of the end of the fiscal year

for each country’s project activities. For the project

activities under the Regional Support Services component, audit

reliance will be placed on the assurance on the use of the project

funds through the audited biannual financial statements of the FAO.

However; if the Bank has reason to believe that there is a cause for

a specific audit examination of the Regional Support Services

component, the Bank may request FAO to undertake a project specific

audit.

3.2 Procurement capacity assessment. Separate procurement

capacity assessments were carried out by the Bank's procurement

specialist for each country. These assessments revealed that the

capacity of China is generally adequate since it has both qualified

procurement staff and good experience with Bank procurement while

that of Thailand and Vietnam is relatively weak. Accordingly, the

procurement risk rating for China is moderate and for Thailand and

Vietnam is high. The overall procurement risk of the project is rated

high. Specific recommended actions to build up the procurement

capacity of individual PMOs are summarized in Annex 8.

3.3 Procurement arrangements. Procurement for the proposed

project would be carried out in accordance with the Bank’s

“Guidelines: Procurement Under IBRD Loans and IDA Credits”

dated May 2004 and “Guidelines: Selection and Employment of

Consultants by World Bank Borrowers” dated May 2004, and

the provisions stipulated in the Legal Agreements. General

procurement arrangements for the project are provided in Annex 8.

Separate Procurement Plans covering the first 18 months of project

implementation have been agreed by the Bank with each participating

country which will be updated annually or as required to reflect the

actual project implementation needs and improvements in institutional

capacity. These Procurement Plans for the initial period of the

project are included in respective PIPs.

Social

Field-level surveys were conducted in the selected demonstration

sites during project preparation. The social assessment team

collected data, reviewed reports and provided extensive inputs to the

project preparation and design. Target groups were disaggregated

based on gender, economic class and ethnicity. The nature and quality

of the interactions between various target group constituencies and

local agencies that regulate, support and influence the engagement of

the primary beneficiary groups in livestock production and manure

management were analyzed. The extent to which negative impacts cause

social conflict varies between the countries and different

demonstration sites. Detailed assessment findings are

presented in Annex 10.

Environment

During project preparation, national procedures

and the Bank’s safeguard policies were diligently followed. The

Environmental Assessments (EAs) have been carried out in all three

participating countries. The EA documents and the Environmental

Management Plans (EMPs) have been prepared, incorporating the Bank’s

comments, and found to be satisfactory. The project is

designed to reduce nutrient loading, mainly nitrates and phosphates,

and the BOD and COD that are polluting the international waters and

causing significant environmental and social impact including

increased eutrophication, fish kills, destruction of natural mangrove

and coral reef ecosystems of the coastal zone of the South China Sea.

It would also decrease the incidence of water-borne and zoonotic

diseases, not only within the livestock raising communities but also

for other water users living downstream of the livestock-raising

areas. The overall impacts of the project are expected to be both

significant and positive. The majority of identified negative impacts

are believed to be short-term and reversible.

Safeguard policies

|

Safeguard Policies Triggered by the

Project

|

Yes

|

No

|

|

Environmental Assessment (OP/BP/GP

4.01)

|

[x]

|

[ ]

|

|

Natural Habitats (OP/BP

4.04)

|

[ ]

|

[x]

|

|

Pest Management (OP

4.09)

|

[ ]

|

[x]

|

|

Cultural Property (OPN

11.03, being revised as OP 4.11)

|

[ ]

|

[x]

|

|

Involuntary Resettlement (OP/BP

4.12)

|

[x]

|

[ ]

|

|

Indigenous Peoples (OD

4.20, being revised as OP 4.10)

|

[x]

|

[ ]

|

|

Forests (OP/BP

4.36)

|

[ ]

|

[x]

|

|

Safety of Dams (OP/BP

4.37)

|

[ ]

|

[x]

|

|

Projects in Disputed Areas (OP/BP/GP

7.60)

|

[ ]

|

[x]

|

|

Projects on International Waterways (OP/BP/GP

7.50)

|

[ ]

|

[x]

|

Triggered safeguard policies by the project include: (a)

Environmental Assessment; (b) Involuntary Resettlement; and (c)

Indigenous Peoples. The project was classified as a Category B

project based on the Task Team’s environmental screening and

stakeholders discussions.

6.1 OP4.01 Environmental Assessment. EAs were carried

out for the project in each country. No major critical negative

environmental impacts of the project are foreseen. Since the project

is aiming to reduce nutrient loading and other pollutants present in

livestock manure and to improve the environmental condition of the

livestock-producing communities and downstream water users, it should

not have any significant and/or long-lasting negative environmental

impacts. Potential impacts on human health have been assessed and

specific measures to minimize the potential transmission of

pathogens, antibiotics and their resistant strains will be taken by

all participating farms. The proposed EMPs have fully considered

potential project impacts on the natural and social environments and

have proposed a detailed plan to ensure that positive environmental

impacts are further enhanced and the negative impacts are kept to

minimum.

6.2 OP4.12 Involuntary Resettlement. Respective

Resettlement Policy Frameworks (RPFs) have been developed

and approved by participating countries that comply with the

requirements of the Bank’s OP4.12 Involuntary Resettlement.

Based on the task team’s visits to the selected project sites,

no land acquisition is foreseen at these sites. Thus, the preparation

of a Resettlement Plan is not required for the first year of project

implementation. However, specific Resettlement Plans would be

required from individual countries in subsequent years of project

implementation when additional project sites are selected which

necessitates the process. Respective RPF will apply.

6.3 OD4.20 Indigenous Peoples.

A Strategy for Ethnic Minority Development (SEMD)

plan has been developed and approved by

each participating country that complies with the requirements

of the Bank’s OD4.20 Indigenous Peoples. The social assessment

carried out in three participating countries confirmed that the

selected demonstration sites do not involve any

indigenous peoples. Thus, preparation of an Ethnic Minority

Development Plan is not required for the first

year of project implementation. However, specific Ethnic

Minority Development Plans would be required from individual

countries in subsequent years of project implementation when

additional project sites are selected which necessitates the process.

Respective SEMD will apply.

Policy

exceptions and readiness

This project complies with all applicable Bank policies.

Demonstration farms and villages for the first year’s

implementation have been selected. Engineering design documents for

the first year’s activities are being completed prior to Grant

effectiveness. The project procurement documents for the first year’s

activities are being completed prior to Grant effectiveness. The

draft PIPs have been reviewed by the Bank and found to be realistic

and of satisfactory quality.

Annex 1: Country and Sector or Program Background

East Asia And Pacific:

Livestock Waste Management in East Asia Project

A. REGIONAL BACKGROUND

The South China Sea is a locally, regionally and globally significant

body of water surrounded by countries that are experiencing rapid

population and economic growth and facing major and similar

environmental challenges. This bio-geographic region is one of the

world’s most biologically diverse shallow-water marine areas.

Of the three major near-shore marine habitat types - coral reefs,

mangroves and sea grasses - the South China Sea has 45 mangrove

species out of a global total of 51, almost all 70

currently-recognized coral genera, and 20 of 50 known sea grass

species, as well as several endangered shellfish species. However,

this biological richness is seriously threatened by two major

environmental problems; over-fishing and land-based anthropogenic

pollution. Pollution run-off and inland discharges to the South

China Sea are estimated to contribute 44 percent of marine pollution,

followed by atmospheric depositions (34 percent), marine

transportation (12 percent) and others (10 percent). Land-based

pollution reaches marine ecosystems by three main routes: rivers,

drains and direct discharge. It is severely degrading seawater and

sediment quality (e.g., causing “red tides”) and damaging

marine habitats (including coral reefs, mangroves and sea grasses).

The United Nations Environment Program (UNEP)/GEF Reversing

Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of

Thailand Project estimates that agricultural wastes are the second

largest land-based source of marine pollution (after human sewage).

The GEF/United Nations Development Program (UNDP)/International

Maritime Organization (IMO) Regional Program on Partnerships in

Environmental Management for the Seas of East Asia has also

identified agriculture, and particularly livestock production, as a

major source of land-based pollution of its target ecosystems.

Livestock production is such a major source of land-based pollution

in East and South East Asia because the region is the world’s

most important livestock production area. East Asia is particularly

dominant in the pig and poultry sectors, which are the two biggest

livestock-based sources of water (and other) pollution. Today, East

Asia accounts for considerably more than half of the world’s

stock of pigs and more than one-third of the world’s stock of

poultry.

In 2004, China, Thailand and Vietnam alone accounted for over 53

percent of all pigs and 28 percent

of all chickens in the world.

These shares of East Asia in world livestock production are rising

fast. Fuelled by a growing population, rising incomes and

urbanization, demand for livestock products in the region is growing

at an extremely high rate and will skyrocket over the next decades.

This rise in demand, coupled with economic, technological and

political evolution, is causing significant change in the scope and

the structure of the livestock industry. In particular, very

intensive forms of livestock production are growing rapidly and

driving much of the sector’s development. In fact, large-scale

industrial production accounts for roughly 80 percent of the total

production increase in livestock products in Asia since 1990. In the

future, most livestock production, especially of pigs and poultry, is

expected to come not from traditional production systems that have

characterized the region for centuries but from large-scale

industrial production.

The vast majority of these intensive pig farms are located around the

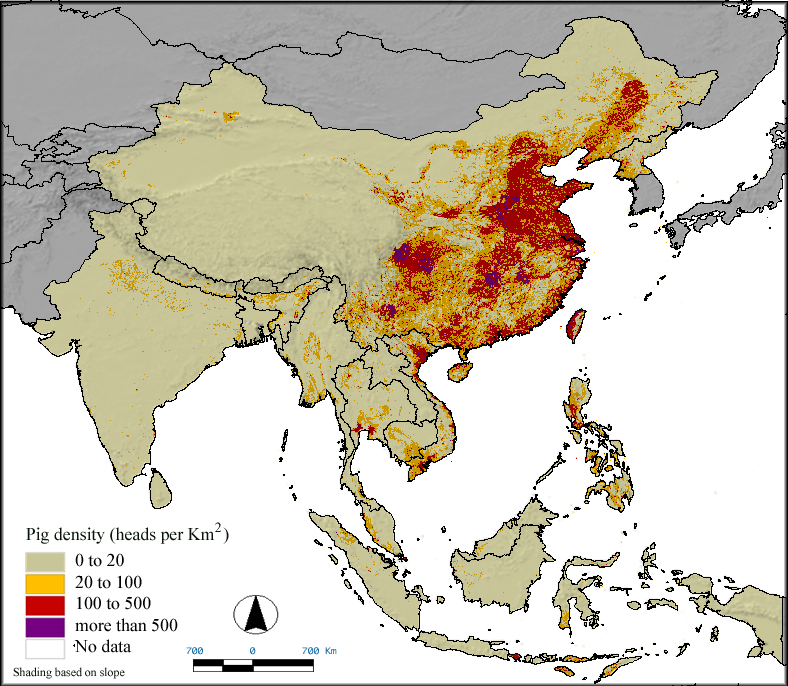

major urban centers that lie in or close to the coastal regions of

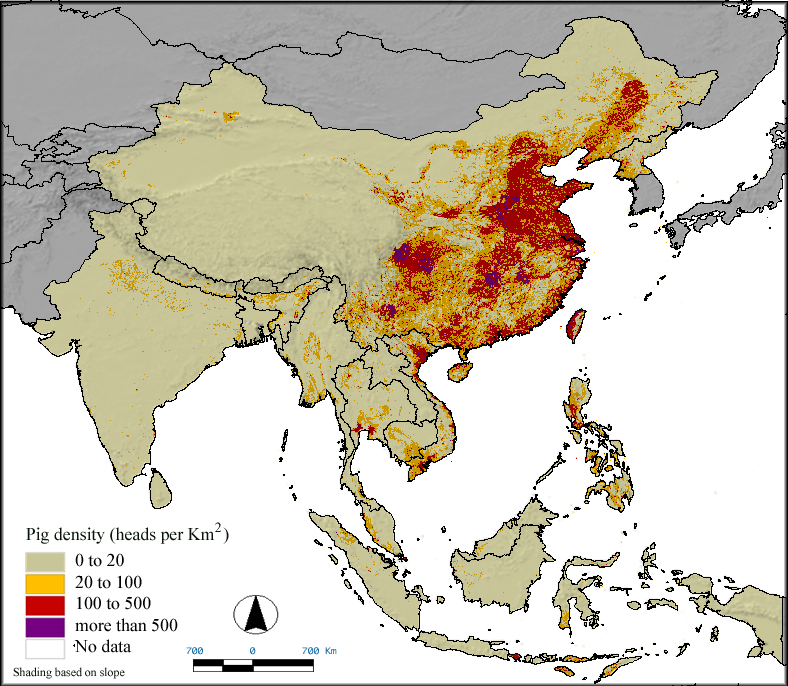

the East and South China Sea (cf. Map 1). The reason for this

geographic concentration of production is that it is advantageous for

the farms to be close to the consumer and feed input market, given

that, in most countries, infrastructure (including roads, cold

chains, marketing and handling facilities) is still under

development.

Map 1:

Estimated pig densities in Asia (1998 to 2000)

D

ue

to the high animal concentration and the insufficient agricultural

land destined to the production of feed within these peri-urban

areas, most feed inputs are brought from elsewhere. Considering that

a large proportion of the nutrients contained in feed are not

retained in the animal’s body but excreted in urine and manure,

the result is an excessive concentration of nitrogen and phosphorus

compounds in the periphery of the urban

areas which results in significant water, land and air pollution. An

initial estimate indicates that 26 percent of the total area in East

Asia suffers from significant nutrient surpluses which emanate mainly

from agricultural sources.

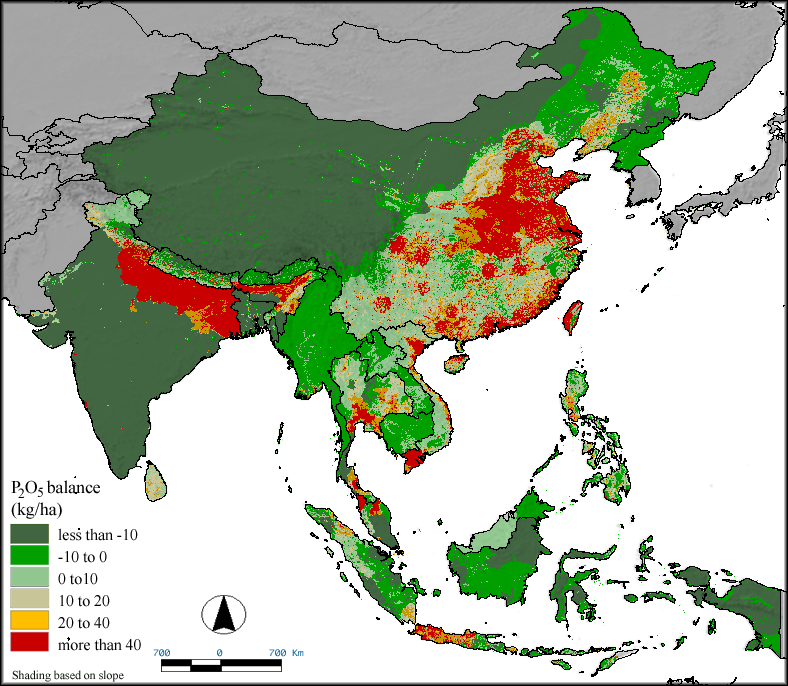

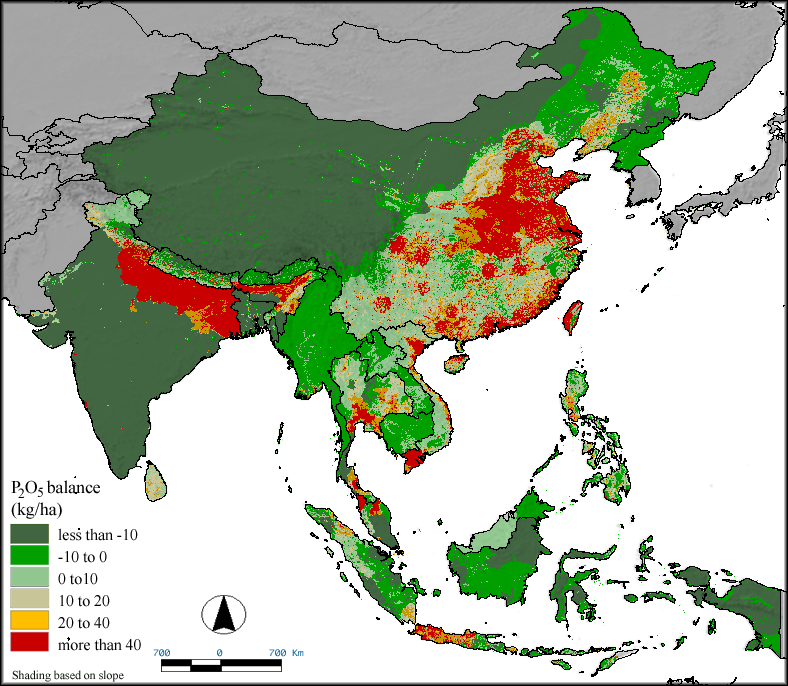

Preliminary estimations of nutrient mass

balances in the region, which include manure and chemical fertilizers

as source of nutrients and crops as the main nutrient sink, have been

made for a coastal band of 50 km from the South China Sea (cf. Map

2). These estimates indicate nitrogen and phosphorus overloads on the

coastal land, with hotspots in the Mekong Delta (7.2 and 3.1 tons per

km2,

respectively), the mouth of the Red River (6.3 and 4.0 tons per km2,

respectively) and the whole Chinese coast of the South China Sea (3.1

and 2.4 tons per km2,

respectively). Currently, animal manure is estimated to account for

47 percent of the phosphorus supply and 16 percent of the

nitrogen supply. With the dramatic expected increase in demand for

meat and milk, this share will continue to grow.

M

ap

2: Estimated P2O5

mass balance for agricultural land in Asia (1998 – 2000)

Source of Maps 1 and 2: Bioresource Technology Volume

96, Issue 2, January 2005 by Pierre Gerber, Pius Chilonda, Gianluca

Franceschini and Harald Menzi.

In greenhouse gas emissions, livestock

contributes about 20 percent of global methane emission and 10

percent of global N2O

(nitrous oxide, a much more aggressive greenhouse gas) emission. The

table below presents a summary of a study conducted in the framework

of project preparation.

Estimated Nitrogen and Phosphorus Fluxes and Their Main Inland

Sources

|

Country

|

Nutrient

|

Potential

Load (ton)

|

Share

of Inland Sources (%)

|

|

Pig

Production

|

Domestic

Waste-water

|

Other

Sources

|

|

Guangdong

|

N

|

530,434

|

72

|

9

|

19

|

|

P

|

219,824

|

94

|

1

|

5

|

|

Thailand

|

N

|

491,262

|

14

|

9

|

77

|

|

P

|

52,795

|

61

|

16

|

23

|

|

Vietnam

|

N

|

442,022

|

38

|

12

|

50

|

|

P

|

212,120

|

92

|

5

|

3

|

The LEAD provided financial and technical assistance to China,

Thailand and Vietnam to help them begin to address this problem by

carrying out AWI pilot projects during 2001 to 2003. The results

clearly indicate the environmental degradation that industrialized

livestock production is causing to freshwater ecosystems and to the

seas of South and East Asia. However, the studies in all three

countries also show that they lack effective tools and institutions

to address this problem. The measures being introduced mainly seek to

mitigate the symptoms (end-of-pipe pollution) but do not address the

underlying cause of excessive concentration of livestock production.

Despite an increasing awareness of the issue in these countries,

technical solutions and policy instruments are still to be developed

and implemented.

B. COUNTRY BACKGROUND

In all three participating countries, national-level environmental

policies with supporting standards are in place. The components

dealing with livestock pollution are recent (within the last 5

years), tend to be rather arbitrary and are not yet effectively

enforced in general. China and Vietnam are in the process of revising

major parts of the national legislation.

The agencies charged with enforcement (Environmental Protection

Bureau - EPB in Guangdong, the Pollution Control Department - PCD in

Thailand and the Environmental Protection Agency - EPA in Vietnam)

lack the resources to monitor and enforce the regulations. Currently,

the PCD in Thailand has 10 staff for some 60,000 farms and the EPA in

Vietnam has 22 stations. Guangdong provincial EPB has equally limited

resources to undertake extensive monitoring. In Thailand, farmers can

refuse access to PCD monitors necessitating a court order to gain

access.

Provincial regulations in China and Vietnam are somewhat stricter

than the national regulations and possibly more realistic in terms of

enforcement. In Thailand, provincial and local authorities are

permitted to develop their own environmental management plans under

the Enhancement and Conservation of National Environmental Quality

Act of 1992 (ECNEQA) but none appears to have yet done so for

livestock operations. In all provincial and sub-provincial

jurisdictions in the region, monitoring and resources designated for

these activities are far from adequate. Local-level enforcement is

compromised by a combination of weak enforcement capacity, overriding

importance assigned to immediate economic and employment issues, and

the influence of entrenched commercial interests that conflict with

good environmental management.

Concern and complaints are mainly focused on odor rather than on

water pollution. There is a common lack of widespread awareness and

comprehension of the scale and consequences of pollution. In all

three participating countries there is a general preference for

targeting enforcement of regulations on medium-sized and large

producers but to exempt small producers. Farmers are generally

focused on commercial and production interests and are less

responsive to environmental concerns. The

countries’ key polices and programs to address environmental

degradation from livestock production on which this project would

build are:

China

The Government of China is in the process of

establishing guidelines for limiting the impact of intensive

livestock production on the environment. The government

intends to use a combination of command and

control regulations and other economic instruments to get producers

to reduce the amount of pollution coming from livestock. In

1996, the Ministry of Agriculture introduced a regulation requiring

that all new large livestock farms establish environmental facilities

and storage facilities for manure. The Ministry has also presented a

draft for national standards (how much) for pollution from livestock

production and drafted a detailed regulation (how to do and size of

fine) to implement the standards. In 1998, the State Environmental

Protection Agency (SEPA) set up a facility to evaluate pollution from

livestock production. In 1999, a rural division of SEPA was

established with the objective to focus on environmental pollution. A

new regulation by SEPA on "Discharge Standard of Pollutants from

Livestock and Poultry Breeding" became effective on January 1,

2003.

The Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference has

appealed to the provincial government to take action against

pollution from agriculture. In May 2001, the