Seamounts are hotspots of pelagic biodiversity in the

open ocean

Telmo Moratoa,b,1, Simon D. Hoylea, Valerie Allaina, and Simon J. Nicola

aOceanic Fisheries Program, Secretariat of the Pacific Community, BPD5 98848 Noumea, New Caledonia; and bDepartamento de Oceanografia e Pescas,

Universidade dos Açores, 9901-862 Horta, Portugal

Edited by David Karl, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI, and approved April 13, 2010 (received for review October 6, 2009)

The identification of biodiversity hotspots and their management

to seamounts to identify those pelagic species that are signifi-

for conservation have been hypothesized as effective ways to

cantly associated with seamounts. The dataset comprised a time

protect many species. There has been a significant effort to

series from 1980 to 2007 of species catch data collected on tuna

identify and map these areas at a global scale, but the coarse

longline vessels by independent observers over large areas of the

resolution of most datasets masks the small-scale patterns asso-

western and central Pacific Ocean, coupled with comprehensive

ciated with coastal habitats or seamounts. Here we used tuna

data on the location of seamounts (24).

longline observer data to investigate the role of seamounts in

aggregating large pelagic biodiversity and to identify which

Results

pelagic species are associated with seamounts. Our analysis

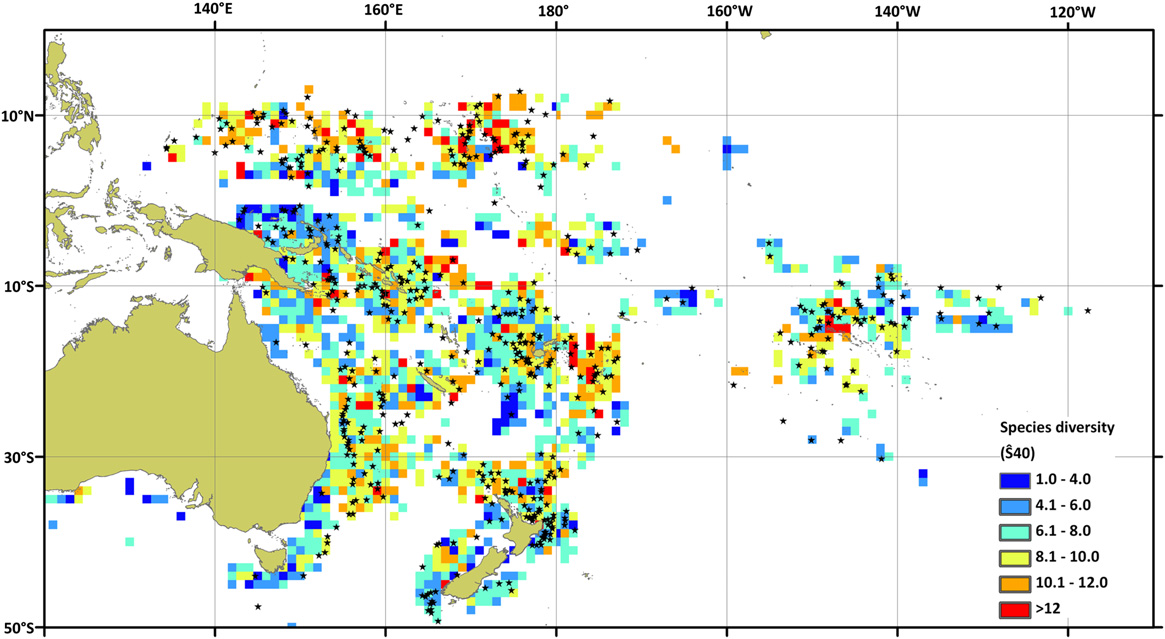

Seamounts as Hotspots of Biodiversity? Rarefied pelagic diversity

indicates that seamounts are hotspots of pelagic biodiversity.

was significantly higher in seamount habitats than in coastal or

Higher species richness was detected in association with sea-

oceanic waters (Fig. 1A) and was found to be nonlinearly related

mounts than with coastal or oceanic areas. Seamounts were found

to the distance to seamount, with diversity higher close to the

to have higher species diversity within 3040 km of the summit,

summits (Fig. 1B). Rarefied diversity was higher at intermediate

whereas for sets close to coastal habitat the diversity was lower

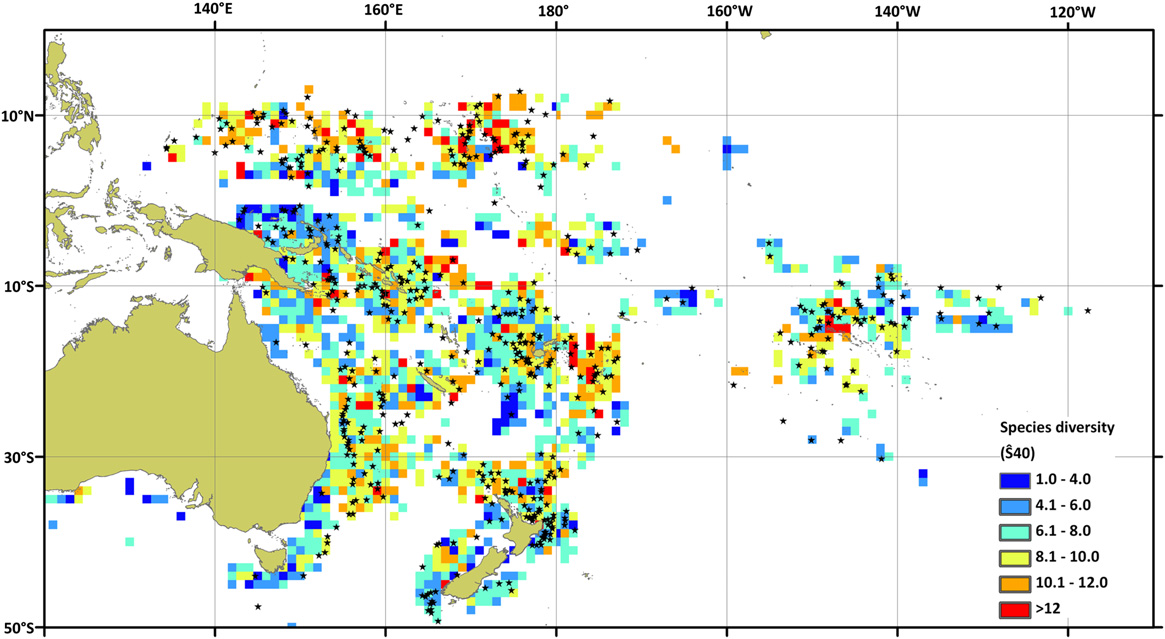

latitudes (1035 °S and 1015 °N; Fig. 1C). Regions with higher

ENTAL

and fairly constant with distance. Higher probability of capture

pelagic diversity included Indonesia, Palau, Federated States of

and higher number of fish caught were detected for some shark,

Micronesia, and Marshall Islands in the Northern Hemisphere

SCIENCES

billfish, tuna, and other by-catch species. The study supports hy-

and Tonga, New Caledonia, and Norfolk Island in the Southern

ENVIRONM

potheses that seamounts may be areas of special interest for man-

Hemisphere (Fig. 2). The relationship for describing species di-

agement for marine pelagic predators.

versity was complex with distance to features, number of hooks,

and latitude the strongest predictors of species diversity (Table

by-catch | fisheries | longline | pelagic predators | seamount conservation

1). When all variables except distance to feature were kept

constant, seamounts were found to have higher rarefied diversity

For the last decade there has been considerable debate about within 3040 km of the summit (Fig. 3). For coastal and oceanic

the status and sustainability of pelagic fisheries around the

habitats the rarefied diversity was lower and not affected by

world (16) and their effects on the ecosystems that support

distance to the feature (Fig. 3). A statistically significant effect of

them (710). Many species may be protected by identifying

moon was not detected for rarefied diversity. The detailed GLM

biodiversity hotspots and managing them for conservation (11).

results are presented in Table S1.

This approach is well established for terrestrial systems and

marine tropical reefs (12, 13), but less so for the pelagic eco-

Highly Migratory Pelagic Species Aggregating Around Seamounts. To

identify which species aggregate around seamounts, the re-

systems of the open ocean (11). Simulation modeling has in-

lationship between CPUE and distance to seamounts was ex-

dicated that management techniques such as area closure are

amined for individual species. There were sufficient data to

likely to help conserve many pelagic species (11). Accordingly,

analyze 37 taxa. Of these, seamount aggregation effects were

there has been a significant effort to identify and map pelagic

detected for 41% of the taxa (15 taxa of shark, billfish, and pe-

biodiversity hotspots at a global scale, but progress has been

lagic teleost fish), although the opposite effects were detected for

limited. The coarse resolution of most datasets masks the small-

only 3 taxa (Table 2). For the shark taxa the probability of

scale patterns associated with coastal habitats or seamounts (14).

catching the species increased closer to seamounts for porbeagle

Hotspots that have been identified in open ocean areas have

shark (Lamna nasus), short-finned mako shark (Isurus oxy-

been typically associated with particular environmental factors

rinchus), and silky shark (Carcharhinus falciformis) and de-

and mesoscale oceanographic features such as latitude, fronts, or

creased for pelagic stingray (Pteroplatytrygon violacea). The

eddies (14, 15). The dynamism of pelagic environments can

average number caught per set was also higher closer to sea-

significantly reduce the efficacy of conservation measures (16).

mounts for silky sharks. We did not detect an effect of seamount

To address this issue, dynamic marine reserves that move with

on the probability of being caught for blue shark (Prionace

the wildlife have been suggested (17), but such approaches may

glauca), but observed that in sets that caught the taxa the average

not be workable (18).

number caught was higher closer to seamounts. For the billfishes

Many seamounts are important aggregating locations for

and tunas the probability of catching the species increased closer

highly migratory pelagic species (1923), but their role in ag-

to seamounts for yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares), blue marlin

gregating pelagic biodiversity is largely unknown. If seamounts

are hotspots for pelagic biodiversity then they may prove to be

suitable areas for conservation measures in open ocean envi-

Author contributions: T.M., V.A., and S.J.N. designed research; T.M., V.A., and S.J.N. per-

ronments. Morato et al. (23) demonstrated that seamounts ag-

formed research; S.D.H. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; T.M. and S.D.H. analyzed

gregate some visitor species but did not demonstrate that this

data; and T.M., S.D.H., V.A., and S.J.N. wrote the paper.

behavior can be generalized. Building upon this previous work,

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

we examine the role of seamounts in aggregating pelagic bio-

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

diversity by applying ocean basin scale generalized linear models

1To whom correspondence should be addressed. E-mail: t.morato@gmail.com.

(GLMs) to location-specific fisheries catch data. In addition, we

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.

analyzed catch per unit of effort (CPUE) in relation to distance

1073/pnas.0910290107/-/DCSupplemental.

www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.0910290107

PNAS Early Edition | 1 of 5

A

B

C

7.0

8.0

8.5

6.9

7.8

8.0

7.6

6.8

40)

(

7.4

7.5

6.7

sity 6 6

7.2

7.0

6.6

7.0

6.5

6.5

Diversity

6.8

6.0

6.4

6.6

6.3

5.5

Species

6.4

6.2

5.0

6.2

R²

R² = 0.81

6.1

6.0

4.5

SM

Shore

Oceanic

0

20

40

60

80

100

-55 -45 -35 -25 -15 -5

5 15

Habitat

Distance to seamount summit (km)

La tude

Fig. 1.

Mean expected species diversity (±95% confidence limits) rarefied from 40 individuals (^

S40) as a function of (A) the main habitat [seamount (SM),

shore and oceanic] where all means are significantly different at = 0.01 (ANOVA and Tukey's honestly significant difference test), (B) distance to seamount

summit where the fitted logarithmic regression is also shown (shaded line), and (C) 5 ° latitude.

(Makaira nigricans), and swordfish (Xiphias gladius) and de-

gregation effects on both probability of capture and number

creased for albacore (Thunnus alalunga) and shortbill spearfish

caught were also observed for the unidentified species category.

(Tetrapturus angustirostris). For the other pelagic teleost fish the

Discussion

probability of catching the species increased closer to seamounts

for ribbon fish (Trachipterus trachypterus), butterfly kingfish

Our analyses suggest that seamounts are hotspots of pelagic

(Gasterochisma melampus), big-scaled pomfret (Taractichthys

biodiversity, because they show consistently higher species rich-

ness than do shore or oceanic areas. Moreover, our study indi-

longipinnis), Atlantic pomfret (Brama brama), and long-snouted

cates that higher species diversity is likely to occur within 3040

lancetfish (Alepisaurus ferox). The average number caught per

km of seamount summits. This study also demonstrates that

successful set was also higher closer to seamounts for butterfly

many marine predators and other visitors are associated with

kingfish but lower for ribbon fish and big-scaled pomfret. We did

seamounts. The GLM model did not take into account the

not detect an effect of seamount on the probability of being

species being targeted or the depth and time of sets as in-

caught for short-snouted lancetfish (Alepisaurus brevirostris) and

formation on these variables was not contained within the da-

moonfish (Lampris guttatus), but observed that the average

tabase. These factors may influence the results but are unlikely to

numbers caught per successful set were higher closer to sea-

affect the overall patterns, which are robust.

mounts for both species. For the other 19 species, statistically

Associations with seamounts have been previously described

significant trends were not detected (Table S2). Seamount ag-

for a few species of tuna (20, 23, 25, 26), sharks (22, 27), billfishes

Fig. 2.

Expected species diversity rarefied from 40 (^

S40) individuals as a function of 1 × 1 degree cells. Stars denote locations of seamounts with longline sets

close to their summits.

2 of 5 | www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.0910290107

Morato et al.

Table 1.

Summary statistics for the GLM single-variable

survey, and enforce. The establishment of a network of marine

elimination analyses relating species diversity with habitat and

reserves on seamounts may help to conserve pelagic biodiversity

other variables

and achieve sustainability of marine predator species, such as

porbeagle shark, short-finned mako shark, silky shark, blue

df

Deviance

AIC

P

shark, yellowfin tuna, blue marlin, swordfish, ribbon fish, but-

49,748

54,383

terfly kingfish, big-scaled pomfret, Atlantic pomfret, long-

Year

22

50,977

54,654

<0.001

snouted lancetfish, short-snouted lancetfish, and moonfish.

Moon

7

49,792

54,380

0.133

Month

11

49,939

54,410

<0.001

Materials and Methods

Lat5

12

52,747

55,115

<0.001

Fisheries and Seamount Data. The Western and Central Pacific Ocean (WCPO)

Long5

26

50,793

54,599

<0.001

is by far the most important tuna fishing ground in the world, contributing

Flag_Fleet

29

51,295

54,720

<0.001

50% (2.4 million tons in 2007) of the global tuna catches (38) at an eco-

nomic value of US$3.8 billion. The longline fishery in the WCPO has a smaller

EEZ

21

50,848

54,623

<0.001

catch (10% of the total), but its value is relatively high (30% of the total

Hooks (ns, df = 10)

10

56,736

56,061

<0.001

value). It targets adult bigeye (Thunnus obesus), yellowfin (T. albacares), and

log(dist.) × feature

2

49,807

54,394

<0.001

albacore tuna (T. alalunga), and in some cases sharks or swordfish (X. gla-

dius), and operates with fairly standard gear con

AIC, Akaike

figurations that comprise

's information criterion; df, degrees of freedom; EEZ, Exclusive

a main line, branch lines between

Economic Zone; ns, natural cubic splines.

floats, and float lines. The Secretariat of

the Pacific Community (SPC) maintains the regional database for fisheries

observer programs in the WCPO, which commenced in 1980. The study area

(28, 29), some seabirds (23, 30), and some marine mammals (23,

extends from 35 °N to 50 °S in latitude and from 130 °E to 120 °W in lon-

gitude (Fig. S1). All longline sets from the period 19802007 were extracted

31), mostly at an individual seamount scale. Our study suggests,

from the SPC's observer dataset, which include trips conducted onboard

however, that seamount associations are probably more common

industrial and semi-industrial vessels from the Pacific Island Countries and

and widespread than previously anticipated. The resolution of

Territories and from distance-water fishing nations. Depth of fishing was not

the data collected does not provide any opportunity to identify

recorded but is known to vary according to setting strategies. The database

the mechanistic explanations for why seamounts aggregate bio-

contains 23,546 longline sets with the number of hooks per set ranging from

ENTAL

diversity. However, seamounts generate conditions such as in-

a few hundred to several thousand, averaging 2,000 hooks per set. Ob-

creased vertical nutrient fluxes and material retention that

server quality was assumed to be consistent across all sets. The dataset

SCIENCES

promote productivity and fuel higher trophic levels (3234).

contains catch data for 352 taxa, but only 50 taxa were recorded in >500

ENVIRONM

longline sets (Table S3). The number of recorded species as a function of

Seamounts also have unique "magnetic signatures" that may

fishing effort reached an asymptote (at 1020 million hooks), indicating

contribute to their use as rest stops or feeding grounds for many

that the sample size obtained from the observer programs was sufficient to

pelagic species such as sharks, whales, and other migrants (35,

perform the biodiversity analyses (Fig. S2).

36). It is likely that the mechanistic explanation is a combination

Catch by species was returned as number, size, and weight. Date and

of factors that make seamounts suitable mating, feeding, and

geographic location of the set, number of hooks, and flag and fleet of the

nursery grounds for highly migratory pelagic species as well as

fishing boat were also extracted. The distance of each longline set to the

benthic organisms (37).

closest seamount was estimated using the simple spherical law of cosines and

Higher pelagic biodiversity has previously been noted in in-

a Pacific seamount dataset containing 7,741 features (24, 39). Additionally,

distances of longline sets to the closest shore were estimated using a land

termediate latitudes (11) and our analyses support this hypoth-

shapefile (including atolls). Longline sets were then categorized by habitat

esis. However, we also noted high diversity in some tropical

as seamount sets (distance to seamount < distance to shore and < 100 km),

latitudes. In previous studies, data have been scarce for the

coastal sets (distance to shore < distance to seamount and < 100 km), or

tropical latitudes between 10 °N and 10 °S, whereas the observer

oceanic sets (distance to shore and distance to seamount >100 km). The

data used in this study provided more comprehensive coverage.

longline dataset contained 10,602 seamount sets, 5,164 coastal sets, and

Further development of observer programs to ensure compre-

7,780 oceanic sets.

hensive spatial and temporal coverage is encouraged.

Conserving biodiversity hotspots has been demonstrated to

Biodiversity Analyses. Species richness is known to increase with sample size,

and differences in richness may be caused by differences in sample size. To

yield significant conservation benefits (11). Therefore, our

solve this problem, we used rarefaction techniques to account for differences

analyses support the utility of seamounts as potential locations

in fishing effort (number of hooks) among longline sets (40, 41). The

for offshore marine reserves. Seamount habitats are easier to

expected number of species (^

S40), standardized to 1,000 hooks per longline

conserve than ephemeral areas because they are easier to map,

set, was rarefied for subsamples of 40 individuals from the total number of

Fig. 3.

The effect of the variables distance × feature on species diversity rarefied from 40 individuals (^

S40). One variable was predicted at a time from the

results of the GLM by fixing the other variables.

Morato et al.

PNAS Early Edition | 3 of 5

Table 2.

Statistics for all by-catch species that were observed in >500 of 10,602 sets (n > 500),

for both the binary and the lognormal components of the GLM

Binary

Lognormal

Species

N

AIC

LogdistSM

SM effect

AIC

LogdistSM

SM effect

Sharks and Rays

Blue shark

7,115

1.84

0.0153

-4.34

-0.0431

Higher

Porbeagle shark

1,572

-5.40

-0.1976

Higher

1.28

0.0262

Silky shark

1,890

-1.20

-0.0954

Higher

-1.92

-0.0591

Higher

Pelagic stingray

2,116

-5.18

0.1149

Lower

0.82

0.0241

Short-finned mako shark

2,207

-4.62

-0.1111

Higher

0.69

0.0199

Billfishes and similar

Swordfish

3,973

-1.21

-0.0668

Higher

0.76

-0.0178

Blue marlin

1,977

-2.36

-0.0936

Higher

0.63

0.0214

Shortbill Spearfish

1,451

-4.75

0.1405

Lower

2.00

-0.0013

Tuna, bonito and mackerel

Albacore

6,898

-2.64

0.1164

Lower

-12.50

0.0662

Lower

Yellowfin

6,420

-3.12

-0.1095

Higher

1.88

0.0068

Pelagic fish and others

Longsnouted lancetfish

3,268

-2.46

-0.0859

Higher

1.53

0.0143

Atlantic pomfret

2,365

-2.22

-0.1077

Higher

0.95

-0.0322

Moonfish

3,065

0.49

-0.0465

-0.24

-0.0258

Higher

Big-scaled pomfret

892

-5.62

-0.1694

Higher

-2.46

0.0678

Lower

Butterfly kingfish

1,013

-5.46

-0.1848

Higher

-8.94

-0.0980

Higher

Ribbon fish

577

-5.85

-0.3128

Higher

-0.94

0.0956

Lower

Short-snouted lancetfish

741

1.34

-0.0511

-0.37

-0.0575

Higher

Unidentified taxa

1,603

-0.77

-0.0810

Higher

-0.53

-0.0504

Higher

For each component we present the effect of including the term for distance to seamount on the AIC (AIC),

the parameter estimate for the relationship with log(distance to seamount), and whether the effect represents

a significantly higher or lower catch rate close to seamounts (SM). Only those taxa with statistically significant

trends are shown here. The complete table is shown in Table S2.

individuals in the sample. This methodology has been extensively used to

and was within 100 km (Fig. S3). We modeled the data in two parts using a -

compare the species richness obtained from longline fishing fleets (11, 14,

lognormal GLM (44). In the first (binomial) part we modeled the probability

42). The effects of habitat type and distance to habitat feature were ana-

of catching any of the species in a set. In the second (lognormal) part we

lyzed for the estimated rarefied richness.

modeled the number caught in sets where at least one animal was caught.

GLM techniques were used to standardize rarefied richness and to eval-

We used AIC to test for effects of distance to seamount by modeling the

uate whether the presence of habitat features and the distance to the feature

data with and without a seamount term. The explanatory variables included

were significant explanatory variables. The explanatory variables included in

in the models were the same as in the biodiversity analyses. The models

the model were year as a proxy for temporal variability, moon phase as the

adopted to standardize data were

relationship between lunar periodicity and catch rates as has been demon-

strated for a wide variety of commercially exploited species (e.g., ref. 43),

Logit½pðspecies 0Þ year þ moon phase þ month þ lat5 þ long5

geographical area, fleet type, distance to the closest feature, and fishing

n

effort. Akaike's information criterion (AIC) was used to compare the model

þ flagfleet þ hooks þ LogðdistSMÞ;

fits using different relationships with distance to feature, with log-trans-

formed having the better fit. The model used was

where speciesn 0, and

^S40 ~ Year þ moon phase þ month þ lat5 þ long5

þ

flagfleet þ Logðdistance to featureÞ· feature

speciesn year þ moon phase þ month þ lat5 þ long5 þ flagfleet

þ

þ

nsðhooks; df ¼ 10Þ:

hooks þ LogðdistSMÞ:

Years included in the standardization were 1982 and 19872007 because ^

S40

estimates were not available for other years. Moon phase was divided into

We examined the residuals to check that the assumptions were not vi-

eight categories from new to full. The geographical areas used in the

olated for each model. By-catch species were considered to be associated

standardization were squares of 5 ° latitude and longitude because they

with seamounts if the seamount distance effect was statistically sig-

originate better fit than many other approaches. Vessels were categorized

nificant and negative (i.e., higher catch rate when closer to sea-

on the basis of a combination of their flag and fleet type. Effort was mea-

mount summits).

sured as the natural cubic splines (ns) of the number of hooks in each

longline set. The species being targeted and the depth and time of a set can

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS. We thank Nick Davies and Michael Manning for help

influence the nontarget species caught. Information on these variables was

with the modeling and Emmanuel Schneiter, Colin Millar, and Peter Williams

not contained within the database and fleet type and number of hooks

for help with the Observer database. We thank the two anonymous

were used as a proxy measures for these variables.

reviewers for their comments, which greatly improved the manuscript. We

acknowledge the Secretariat of the Pacific Community member countries for

the collection and provision of observer data. We particularly acknowledge

Analyses of the GLMs for Each Highly Migratory Pelagic Species. We used GLM

the important work done by the national observer programs throughout the

techniques to standardize catch data for each by-catch species caught in at

region. This research is part of the Pacific Islands Oceanic Fisheries

least 500 sets of the 10,602 sets for which a seamount was the closest feature

Management Project supported by Global Environment Facility.

4 of 5 | www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.0910290107

Morato et al.

1. Baum JK, et al. (2003) Collapse and conservation of shark populations in the

25. Klimley AP, Jorgensen SJ, Muhlia-Melo A, Beavers SC (2003) The occurrence of

Northwest Atlantic. Science 299:389392.

yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares) at Espiritu Santo Seamount in the Gulf of

2. Myers RA, Worm B (2003) Rapid worldwide depletion of predatory fish communities.

California. Fish Bull (Wash DC) 101:684692.

Nature 423:280283.

26. Rodríguez-Cabello C, Sánchez F, Ortiz de Zárate V, Barreiro S (2009) Does Le Danois

3. Hampton J, Sibert JR, Kleiber P, Maunder MN, Harley SJ (2005) Fisheries: Decline of

Bank (El Cachucho) influence albacore catches in the Cantabrian Sea? Cont Shelf Res

Pacific tuna populations exaggerated? Nature 434:E1E2.

29:12051212.

4. Hilborn R (2006) Faith-based fisheries. Fisheries 31:554555.

27. Klimley AP, Richard JE, Jorgensen SJ (2005) The home of blue water fish. Am Sci 93:

5. Sibert J, Hampton J, Kleiber P, Maunder M (2006) Biomass, size, and trophic status of

top predators in the Pacific Ocean. Science 314:17731776.

4249.

6. Langley A, et al. (2009) Stock assessment of yellowfin tuna in the western and central

28. Sedberry GR, Loefer JK (2001) Satellite telemetry tracking of swordfish, Xiphias

Pacific Ocean. Western Central Pacific Fisheries Commission, Scientific Committee, 5th

gladius, off the eastern United States. Mar Biol 139:355360.

Regular Session (Western Central Pacific Fisheries Commission, Port Villa, Vanuatu).

29. Poisson F, Fauvel C (2009) Reproductive dynamics of swordfish (Xiphias gladius) in the

Available at: http://www.wcpfc.int/system/files/documents/meetings/scientific-committee/

southwestern Indian Ocean (Reunion Island). Part 2: Fecundity and spawning pattern.

5th-regular-session/stock-assessment-swg/working-papers/SC5-SA-WP-03%20%

Aquat Living Resour 22:5968.

5BYFT%20Assessment%20%28rev.1%29%5D.pdf.

30. Amorim P, et al. (2009) Spatial variability of seabird distribution associated with

7. Pauly D, Christensen V, Dalsgaard J, Froese R, Torres F, Jr (1998) Fishing down marine

environmental factors: A case study of marine Important Bird Areas in the Azores.

food webs. Science 279:860863.

ICES J Mar Sci 66:2940.

8. Jackson JBC, et al. (2001) Historical overfishing and the recent collapse of coastal

31. Parrish FA (2009) Do monk seals exert top-down pressure in subphotic ecosystems?

ecosystems. Science 293:629638.

Mar Mamm Sci 25:91106.

9. Worm B, et al. (2006) Impacts of biodiversity loss on ocean ecosystem services. Science

32. Genin A, Dayton PK, Lonsdale PF, Spiess FN (1986) Corals on seamounts provide

314:787790.

evidence of current acceleration over deep sea topography. Nature 322:5961.

10. Baum JK, Worm B (2009) Cascading top-down effects of changing oceanic predator

33. Lueck RG, Mudge TD (1997) Topographically induced mixing around a shallow

abundances. J Anim Ecol 78:699714.

11. Worm B, Lotze HK, Myers RA (2003) Predator diversity hotspots in the blue ocean.

seamount. Science 276:18311833.

34. White M, Bashmachnikov I, Arístegui J, Martins A (2007) Seamounts: Ecology,

Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:98849888.

12. Myers N, Mittermeier RA, Mittermeier CG, da Fonseca GAB, Kent J (2000) Biodiversity

Fisheries and Conservation, eds Pitcher TJ, et al. (Blackwell Science, Oxford, UK), pp

hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 403:853858.

6587.

13. Roberts CM, et al. (2002) Priorities for tropical reefs marine biodiversity hotspots and

35. Pitcher TJ, Bulman C (2007) Seamounts: Ecology, Fisheries and Conservation, eds

conservation. Science 295:12801284.

Pitcher TJ, et al. (Blackwell Science, Oxford, UK), pp 282295.

14. Worm B, Sandow M, Oschlies A, Lotze HK, Myers RA (2005) Global patterns of

36. Morato T, Bulman C, Pitcher TJ (2009) Modelled effects of primary and secondary

predator diversity in the open oceans. Science 309:13651369.

production enhancement by seamounts on local fish stocks. Deep Sea Res II 56:

ENTAL

15. Etnoyer P, Canny D, Mate B, Morgan L (2004) Persistent pelagic habitats in the Baja

27132719.

California to Bering Sea (B2B) ecoregion. Oceanography (Wash DC) 17:90101.

37. Fréon P, Dagorn L (2000) Review of fish associative behaviour: Toward a gen-

16. Martell SJD, et al. (2005) Interactions of productivity, predation risk, and fishing effort

SCIENCES

eralisation of the meeting point hypothesis. Rev Fish Biol Fish 10:183207.

in the efficacy of marine protected areas for the central Pacific. Can J Fish Aquat Sci

38. Lawson TA (2008) Tuna Fishery Yearbook 2007 (Western and Central Pacific Fisheries

ENVIRONM

62:13201336.

Commission, Kolonia, Pohnpei, Federal States of Micronesia).

17. Norse EA (2006) Protecting the least-protected places on earth: The open oceans.

39. Kitchingman A, Lai S (2004) Seamounts: Biodiversity and fisheries. Fisheries Centre

MPA News 7:4.

18. Malakoff D (2004) New tools reveal treasures at ocean hot spots. Science 304:

Research Report 12.5, eds Morato T, Pauly D (Fisheries Centre, Univ of British

11041105.

Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada), pp 712.

19. Tsukamoto K (2006) Oceanic biology: Spawning of eels near a seamount. Nature 439:

40. Hurlbert SH (1971) The nonconcept of species diversity: A critique and alternative

929.

parameters. Ecology 52:577586.

20. Holland K, Grubbs D (2007) Seamounts: Ecology, Fisheries and Conservation, eds

41. Heck KL, van Belle G, Simberloff D (1975) Explicit calculation of the rarefaction

Pitcher TJ, et al. (Blackwell Science, Oxford, UK), pp 189201.

diversity measurement and the determination of sufficient sample size. Ecology 56:

21. Kaschner K (2007) Seamounts: Ecology, Fisheries and Conservation, eds Pitcher TJ,

14591461.

et al. (Blackwell Science, Oxford, UK), pp 230238.

42. Boyce DG, Tittensor DP, Worm B (2008) Effects of temperature on global patterns of

22. Litvinov F (2007) Seamounts: Ecology, Fisheries and Conservation, eds Pitcher TJ, et al.

tuna and billfish richness. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 355:267276.

(Blackwell Science, Oxford, UK), pp 202206.

43. Lowry M, Williams D, Metti Y (2007) Lunar landings--Relationship between lunar

23. Morato T, et al. (2008) Evidence of a seamount effect on aggregating visitors. Mar

phase and catch rates for an Australian gamefish tournament fishery. Fish Res 88:

Ecol Prog Ser 357:2332.

1523.

24. Allain V, et al. (2008) Enhanced seamount location database for the western and

44. Stefansson G (1996) Analysis of groundfish survey abundance data: Combining the

central Pacific Ocean: Screening and crosschecking of 20 existing datasets. Deep Sea

Res I 55:10351047.

GLM and delta approaches. ICES J Mar Sci 53:577588.

Morato et al.

PNAS Early Edition | 5 of 5