N e w s l e t t e r

T h e M o n i t o r i n g N e w s l e t t e r

for the Tuna Fisheries of the Western and Central Pacific Ocean -- Issue #7 -- November 2007

Editor: Deirdre Brogan, Fisheries Monitoring Supervisor; Production: Oceanic Fisheries Programme, Secretariat of the Pacific Community,

BP D5, 98848 Noumea Cedex, New Caledonia. Tel: +687 262000, Fax: +687 263818, Email: observer@spc.int or portsampler@spc.int

(This edition is also available on the Oceanic Fisheries Programme website at: http://www.spc.int/OceanFish/Docs/Statistics/index.asp).

Printed with financial assistance from the Global Environment Facility and the European Union.

Welcome to another edition of Fork Length.We have broad-

ened Fork Length's focus to include the many different

aspects of the work that contributes to the proper scien-

tific monitoring of oceanic species in the western and cen-

Contents

tral Pacific Ocean. The newsletter will no longer be confined

to the work of shipboard observers and port samplers, but

DATA COLLECTION

will now include articles on all aspects of the oceanic fish-

eries data system, including collecting and managing infor-

· Unloadings data

p. 2

mation as well as reporting.

· Observer stomach

Infuture editions we'll review the different data types that

sampling identifies new

squid species

p. 4

make up a comprehensive tuna data system. To get things

started, this edition includes an article on unloadings data,

· Species identification

which are recorded by industry and help to verify catch and

manual published p. 5

effort information (i.e. logsheets). Unfortunately, the col-

lection of unloadings data needs to be improved, especially

· Photo competition p. 7

for some of the domestic longline fleets. In an effort to

bring attention to the problem, we look at some of the uses

DATA MANAGEMENT

of these data and discuss how they can be collected.

· Marshall Islands Oceanic

Monitoring Programme

The article on page 10 describes how the national monitoring

p. 10

programme in the Marshall Islands have tackled the responsi-

bilities of meeting both their national and regional data oblig-

· Tuna Data Workshop p. 13

ations. They have addressed earlier problems and are now pro-

ducing great results. If you've ever wondered how other pro-

DATA DISSEMINATION

grammes in the region go about their work, take some time out

· Stock assessment results

to read about how things are done in Micronesia.

p. 14

We've tried to provide something for everyone -- whether

· Data summaries p. 16

you're sampling, collecting information from industry or other

sources, or have been tasked with

TRAINING

either managing or reporting on

· Random sampling of

the data that your national fishery

purse-seine catches p. 18

offices collects. Don't miss our

first-ever photography competi-

· New recruits

p. 19

tion for observers and port sam-

plers. The prize is a generous one,

· Assistance from the

and details of the competition can

Hawaiian Observer

I

S

be found on page 7.

Programme

p. 22

S

· Wallis and Futuna has

N

1

Enjoy Fork Length!

two new observers p. 23

6

0

7

-

0

2

2

4

Fork length -- Issue #7 -- November 2007

2

DATA COLLECTION

Industry data

UNLOADINGS DATA: WHAT IS IT?

How is it collected?

Some data provide information about individual fish.

Other data are collected to provide information Unloadings data should be collected for all gear

about what is happening on a larger scale. One impor- types (i.e. longline, purse seine and pole-and-line),

tant data type -- unloadings data -- shows the total but the approach to recording and collecting the

weight of each fish species taken off the vessel fol- data may be dif erent. For longliners the fishing

lowing each fishing trip. Longline unloadings data also company generally records the actual measured

show the total numberof fish that were unloaded. weight of each individual tuna during the packing

process. This information -- the individual weights

There are other terms for unloadings data; the of exported fish -- is also known as "Packing List

most common is transshipment data. The defini- Data". The fishing company collects this informa-

tions given by the Merriam-Webster online dictio- tion for their own purposes so it should be readily

nary offer some insight into how these terms dif- available. The main challenge with longline unload-

fer. Unload"...to take off: deliver (2): to take the ings data is ensuring that every fish that was

cargo from ...". Transship "...to transfer for fur- unloaded is accounted for. This is especially true

ther transportation from one ship to another..."It for fish that are not immediately exported after

may be helpful to see transshipment (vessel to unloading, but may be marketed differently (i.e.

vessel whether at sea or in port) as a subset of sent to a cannery, the local fish market, or taken

unloadings. The Western and Central Pacific home by the crew). There are two regional stan-

Fisheries Commission (WCPFC) considers the dard unloadings forms for recording unloadings

unloading process to be something that takes information: the standard longline unloadings

place between a fishing vessel and either one or form and the longline unloadings destination form.

several carrier vessels, fishing vessels or unload- The longline unloadings destination allows coastal

ing facilities, which will process or further dis- states to collect economic statistics, which is

patch the catch. These terms are likely to evolve, often a national data reporting requirement.

especially as WCPFC focuses its attention on

improving transshipment procedures.

The transient and sporadic nature of purse-seine

vessel unloadings can test the data collection pro-

Why is it collected?

cedures in port state fisheries divisions; data col-

lectors must be organised and ready to go as soon

Unloadings data are required for each fishing trip as the first vessels arrive in port. Generally, purse-

operating in the region (that is, 100% coverage is seine unloadings data are supplied to fisheries

required). The true value of unloadings data is that departments by the carrier vessel (through its

it can be used to validate other data types, espe- agent), or during the final clearance before exiting.

cially logsheet information. It also has the potential A standard regional purse-seine unloadings form

to be more accurate than logsheet data. At least

two parties have an interest in ensuring that unload-

ings data are accurate -- the fisher or vessel oper-

ator who doesn't want to be paid too little, and the

buyer or fish processor who doesn't want to pay too

much. The needs of both parties help ensure that

accurate data are recorded. Furthermore, the

regionally agreed ban on high-seas transshipment

gives better access to unloading vessels, allowing

national fisheries staff access to cross-check and

verify the unloading information in a way that isn't

possible for catch and effort data. Collecting

unloadings data can also help to highlight vessels

that are not currently providing logsheets, which in

turn has the potential to shed light on any illegal,

unreported and unregulated (IUU) vessels.

Unloading purse-seine catch

Fork length -- Issue #7 -- November 2007

3

formatted by the data collection committee (DCC)

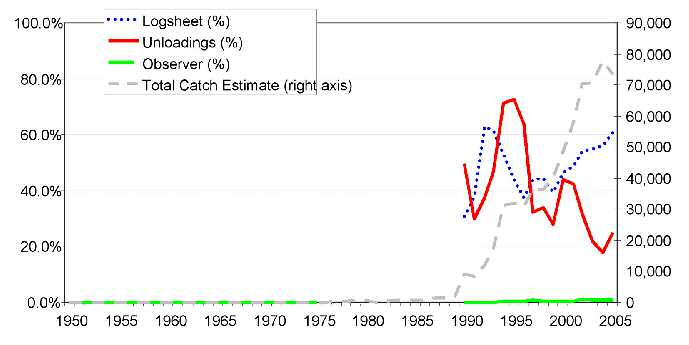

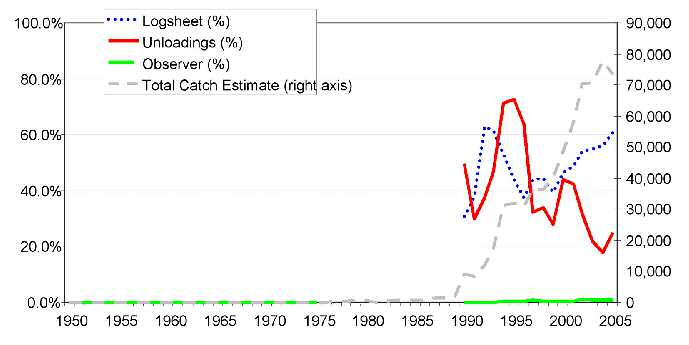

is available online, along with other regional forms: How well are we doing?

The longline unloadings coverage remains low,

http://www.spc.int/oceanfish/Html/Statistics/Forms/index.htm especially for the domestic longline fleet (see

But, it remains common for carrier vessels to submit graph below). Much work still needs to be done in

a "mate's receipt" when asked for unloadings infor- Pacific Island countries to improve the coverage

mation. While it is always better to work towards col- of unloadings data. WCPFC, through its Scientific

lecting the data using the standard form -- this and Technical and Compliance committees, is cur-

ensures all necessary information, as revised and rently reviewing the use, purpose and need for

reviewed by the DCC, is collected -- the mate's unloadings and transshipment data, and it is

receipt does provide much of the required unloadings expected that unloadings data will become a

information. Finally, pole-and-line regional unloadings WCPFC data obligation in the near future.

forms are also available and are used mostly by the

domestic pole-and-line fleet in the Solomon Islands.

Data coverage for domestic longline fleets

Sampling data

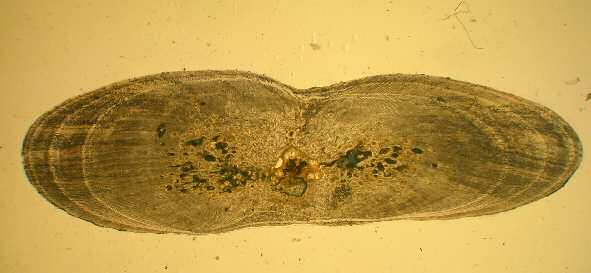

· BIOLOGY OF STRIPED MARLIN

by R. Keller Kopf*

Samples from New Caledonia and Fiji have been

particularly important because they include

Since 2006, observers throughout the southwest rarely seen juvenile striped marlin and also

Pacific have collected samples -- from 268 spawning females. A big thank you goes to the

striped marlin -- for age, growth, and reproduc- Fijian observer programme (which have been vital

tive studies. The project is aimed at determining to the project's success) for its focused efforts

the location and timing of spawning, age-at-matu- on collecting young striped marlin.

rity, size-at-age, and annual growth rates of

striped marlin in the southwest Pacific. Sample Preliminary data suggest that striped marlin

collections were initiated in New Zealand and spawn near 25°S from September through

Australia but have expanded into the tropical January, and the species may live beyond 12

Pacific with the assistance of SPC and longline years of age. Project sampling will continue

observers in New Caledonia and Fiji.

through 2008, so please contact Keller Kopf or

observer@spc.int if you are interested in help-

ing. T-shirts and other awards are available.

* R. Keller Kopf, Charles Sturt University, School of Agriculture and Veterinary Sciences, Wagga Wagga NSW 2670, Australia.

Email: rkopf@csu.edu.au

Fork length -- Issue #7 -- November 2007

4

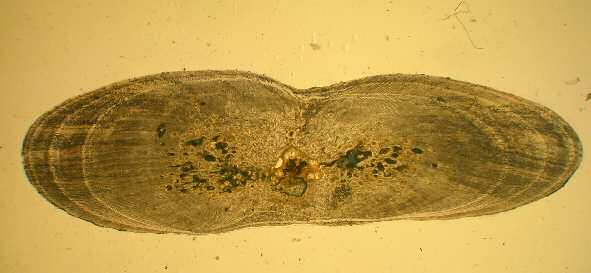

Cross-section of dorsal fin, spine number 5 from a 106 kg female striped

marlin. Note the three clearly visible bands on the outer edge of the spine.

Observer stomach sampling identifies new squid species

Observers from around the region have been asked

to help with sampling stomachs from mainly tuna, fish. In this indirect manner, lancetfish are helping

but also other fish. Stomach samples help scien- to improve our knowledge of the diet of tuna and

tists understand more about what fish eat, how other commercial pelagic species.

they behave and the oceanographic environments

they prefer. By collecting stomach samples from Lancetfish stomach contents have also helped to

mainly tuna, but also other pelagic species, shed light on some of the remote and more inac-

observers can help scientists explore what types cessible areas of the ocean. The lancetfish's abil-

of things tuna eat, how much they eat and how they

and other pelagic species interact. In this article

we look at one pelagic species that lives in the same

environment as tuna and often interacts with it.

While the stomach samples from this fish are

revealing interesting results, observers are

reminded that scientists require samples from all

species, especially tuna, so that they can gain a

better knowledge of how species that inhabit the

same pelagic ecosystem as tuna interact.

It may not be the prettiest species you'll ever

encounter on a longline vessel, but the lancetfish

(Alepisaurussp.) may turn out to be the most inter-

esting. Examination of the stomach contents of a

number of lancetfish has brought important infor-

mation to light. Surprisingly, the prey ingested dur-

ing feeding can be found whole and intact inside

these stomachs, having suffered no significant dam-

age from the digestion process, which takes place

mostly in the intestines. These lightly digested prey

are easier for scientists to identify, especially when

compared with the more heavily digested stomach

contents seen in other pelagic species such as tuna.

The stomach samples taken from lancetfish are now

being used as "reference prey", meaning they can

Top: Lancet fish stomach contents showing

help scientists to identify similar but more exten-

juvenile reef fish

sively damaged prey found in the stomachs of other Bottom: A new squid species. Family Sepiolidae

Photo: R. Young

Fork length -- Issue #7 -- November 2007

5

ity to consume and retain prey from these out-of-

the-way areas has recently led to the discovery sample received. More information is available

of new species. The stomach of a lancetfish col- from your observer coordinator. Perhaps your

lected by Charles Cuewapuru when fishing in New stomach sample will be the next one to reveal a

Caledonian waters contained three whole, well- new species to the world!

preserved squids that lab assistants could not

identify. After consultation with a squid expert in

Hawaii, it was found that these are new species

previously unknown to science. Countless more

unknown marine species are present in the ocean,

and stomach sampling is proving to be one way of

collecting these species. Just as importantly,

lancetfish stomachs also capture the fragile and

soft juvenile stages of many of the common

marine species, including pelagic and reef fishes.

This is crucial information that will help improve

our knowledge of commercial species.

The last lancetfish secret to be revealed is the

pleasure they seem to get from eating their mates!

It's not uncommon for lab technicians at SPC's

stomach sampling laboratory to find lancetfish

inside lancetfish inside other lancet fish.

Please continue to collect and ship more stomach

samples. Stomach sampling kits are available

from SPC and a financial reward is given for each

A selection of stomach contents

taken from a lancetfish

Summary of stomach sampling to date

Observer Programme

Number sampled and at SPC

Number examined, entered

Number that need to be

Number sampled and not yet

in the database

examined

received at SPC

Cook Islands

34

34

French Polynesia

105

67

38

FSM

51

81

30*

New Caledonia

60

60

SPC1

2275

307

1968

Samoa

13

13

Fiji

100

100*

Total

2538

374

2294

130

1PNG tagging trip

*Rec'd Oct' 07

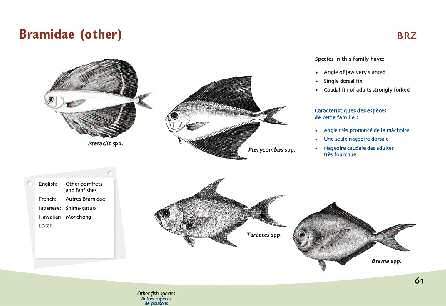

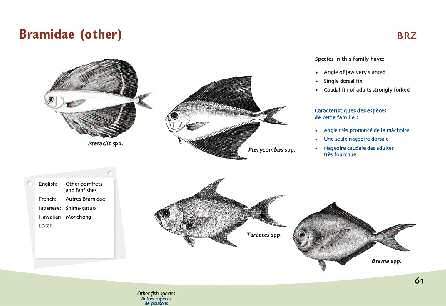

Species Identification manual published

The introduction of the "Marine Species Identification

Manual for Horizontal Longline Fishermen" was a great name in four different languages. The manual has

step forward for tuna data collection. It is a high qual- been distributed to both observers and domestic

ity document with professionally painted fish pictures longline vessels in the Pacific, and has helped to

(the majority done by Hawaiian artist Les Hata, see improve the collection of information recorded on

photo).

both logsheets and observer forms.

The manual includes all of the major pelagic species

that interact with longline vessels in the Pacific

area. Each page of the manual shows a painting, the

3-letter FAO species code, a line diagram with the

main identification features, as well as the common

Fork length -- Issue #7 -- November 2007

6

The publication was a collaborative effort by

many people, with the outstanding contribution

being made by the hard working at-sea

Useful Group Codes

observers. The information collected by a multi-

tude of observers over a number of years was

BIL

Billfish

used to define the list of species included in the

MAR

Marlin

manual. If you're an at-sea observer and have

MAM

Marine Mammals

recorded information or taken photographs on

DLP

Dolphins

the type of species that interact with longline

ODN

Toothed whales

vessels, your work is included in this publication.

MYS

Baleen whales

WLE

Whales

TTX

Turtles

Your contribution is both acknowledged and

RMV

Manta and Devil Rays

appreciated -- thank you!

BIZ

Birds

U

SKH

Sharks

SING THE MANUAL

SPN

Hammerhead sharks

THR

Some species in the manual are only described to

Thresher sharks

the group code level (that is a collection of similar

ALI

Lancetfish

fish, or fish from the same scientific family).

MOP

Sunfish

Group codes are helpful when the full species code

TRP

Dealfish

is not known or cannot be established. It is

not always possible to fully identify a species.

This may happen if there has not been enough

time to see the species, if it was struck off

before it was landed or had some identifica-

tion features removed (i.e. cut or bitten off).

Group codes are also effective if an observer

does not have enough experience to fully

recognise the species.

If it's not possible to record a full species code

then try to record a group code. Whenever

possible, avoid recording only the very basic

species code UNS -- (unspecified species), as

this gives very little information. However,

there will be times when the UNS species code

will be the only one that is appropriate to use.

If you do record UNS or group species codes, The group code BRZ (for pomfrets and other fan fishes)

try to provide a further description of the

is described in the longline species manual.

species by doing one of the following:

1) Taking some photographs of the specimen.

2) Bringing the specimen or parts of the speci-

men back to shore for further identification.

3) Drawing the species and writing a full descrip-

tion in the written report. Don't shy away from

this you may be surprised how revealing your

drawing can be even if you have no faith in your-

self as an artist. With this information your

debriefer and/or national coordinator may be

able to help you establish the full species name.

Some of the "rarer" species that will be encoun-

tered periodically on longline vessels may not be

pelagic (open ocean) species but rather deepwater

Flying gurnard

Fork length -- Issue #7 -- November 2007

7

or bottom dwelling (benthic) species that have Observers in some national programmes may

gone astray. These non-pelagic species are not encounter more deepwater species than others,

available in the longline species manual, but many especially if their vessels regularly fish close to

will be described in the soon-to-be-published SPC seamounts. Try to identify all rare species. Each

deepwater species guides. An example of a benth- national observer programme should aim to build up

ic species that recently interacted with a longline a reference folder showing the rarer species that

vessel is this flying gurnard (Dactyloptena orien- have been encountered. This will help when it

talis), which was observed by Steve Beverly.

comes to training both the active observers and

any new observers to join the team in later years.

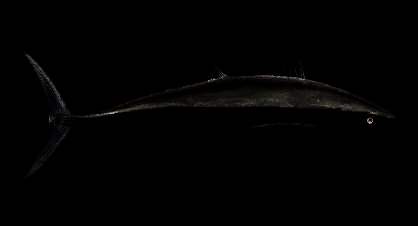

Photography competition

Photographs taken by observers were found to be useful when compiling the identification manual. It is

also helpful to have good photographs for training purposes, and for enhancing publications and reports

on observer work. To encourage observers to take more photographs SPC & FFA are running a photo

competition for field staff (observers and port samplers), with three digital cameras offered as the

main prizes. There will be more than one chance to win, as the competition will be repeated in the future,

but the subject topic will be different. You can see the full details of the first competition on page 8.

Some tips for taking photos at sea

· Keep the sun behind you;

· Avoid taking photos in the mid-day sun;

· Watch out for shadows (especially your own) covering the fish. Bright cloudy days are best for photog-

raphy. Otherwise, it is best to take the photo in full shade with a flash or in full sun without a flash. Avoid

taking pictures in half sun, half shade;

· Use a contrasting background. Blue and green tarpaulins are recommended and a pile of netting is great

if it is not the same colour as the fish;

· Allow for some space around the fish if using a disposable camera (the viewer is somewhat misleading).

Whenever possible, focus in as close to the object as possible, so that there are no other distracting

objects in the frame;

· Try to take as many photos as you can. Take them from different angles as well as close-ups so that later

on you will have a choice of photos to pick from. You may only end up with one or two good photographs

even though you take 10 or more. Even professional photographers throw away more than 90% of their

photos;

· Ideally, a ruler should be placed in the photo so the size of the fish can be gauged. If you have no ruler

then place a well-known object such as a cigarette pack or pencil so that the fish size can easily be com-

pared;

· If possible, place a label with information about date, time position, etc., near enough to the pho-

tographed object for it to appear in the photo. But not somewhere that gets in the way or distracts from

the main subject of the photo;

· The international convention is that fish are placed with their head to the left of the photograph.

Fork length -- Issue #7 -- November 2007

8

RULES AND REGULATIONS

coordinators and are always available by

1. Photographs of the following three subjects request from observer@spc.int);

can be submitted:

· Tuna -- A single photo or a series of 10.In the unlikely event that none of the submit-

photos (three maximum)

ted photographs are thought to merit the

· Billfish -- A single photo or a series of

prize it will be held over and added to the

photos (three maximum)

next photographic competition;

· Purse-seine brailing--A single picture or

a series of pictures (five maximum);

11.Only photographs taken during 2007 and up

until 31 March 2008 should be submitted;

2. A single photograph or a sequence of pictures of

the same subject will make up one competition 12.Photographs that have been previously sub-

entry. A maximum of three pictures for each mitted to SPC/FFA will not be considered;

entry can be submitted for tuna and billfish, and

amaximum of five for purse-seine brailing;

13.Ashortlist of the top 20 entries for each sub-

ject will be selected by the Statistics Section

3. The participant (the photographer) must have of SPC and the Observer Programme of FFA.

completed an FFA/SPC basic observer training The winning photographs will be selected from

course or be a recognised SPC port sampler;

the shortlist by an invited judge;

4. Entries will be judged for both clarity and 14.One digital camera will be offered for what is

artistic value. The intention of the competi- judged to be the best photograph or series of

tion is to generate good photographs for photographs in each subject area;

training purposes and possibly fishery

reports. Participants should keep this in mind 15.The judgement of SPC and FFA will be final;

when taking their photographs;

16.Winners will be announced in the next (8th)

5. A participant can submit up to three entries edition of the Fork Length newsletter and/or

per competition. Any person found to be sub- by email to national observer coordinators on

mitting more than three entries will be dis- 1 June 2008;

qualified from the current and future compe-

titions;

17.All submitted photographs remain the proper-

ty of SPC and FFA and will not be returned at

6. The photograph can be either a digital or a the end of the competition. Should the photo-

hardcopy photograph. Digital photos must be graph be used in future SPC/FFA publications,

at least 300 dpi;

acknowledgement to the photographer will be

given;

7. All photographs must be submitted to SPC by

1 April 2008 (date of the email for electronic 18.The digital camera prize will have a maximum

submissions and the date of postmark for value of USD 200. The make and model of the

standard photographs sent in the mail). camera will be chosen by SPC and announced

Observer coordinators are asked to assist with the result of the competition. SPC will

competitors in sending email entries to not replace the digital camera prize with an

obsphotocomp@webmail.spc.int;

equivalent monetary amount. T-shirts and

caps may also be given as runner-up prizes.

8. All entries must be marked with the "name of

the subject/name of the participant" (e.g.

Tuna/Dike Poznanski). That is the file name

for electronic entries, or should be marked on

the back of the photograph for hard copy

entries);

9. All entries must come with a completed com-

petition entry form, signed by the national or

sub-regional observer coordinator. (Competi-

tion entry forms will be available from observer

Fork length -- Issue #7 -- November 2007

9

Time Out: Questions and answers with Fijian port samplers

· How many trained port samplers are there in

Fiji?

· How many days a week is port sampling done?

There is a team of 10 trained port samplers. three to four days.

The samplers also work as at-sea observers

and take up the port sampling work when not · How many vessels are sampled during a day?

observing.

Usually between one and three.

· How many unloading ports are there in Fiji? · Do you use callipers or measuring tapes to

There are four: Main port, Muaiwalu Jetty, measure fish?

Fiji Fish Jetty (all in Suva) and Levuka on Aluminium callipers.

Ovalau Island.

· Where are the callipers stored?

· How do you get to the port of unloading?

At the unloading port.

Transport is provided from the port samplers'

homes to the unloading port by the Ministry · Is the vessel's hold checked?

of Fisheries.

Yes, always.

· What type of vessels do you sample?

· Do you have anything to share with other port

Offshore longline vessels, distant-water long- samplers in the region?

line vessels and some purse-seine vessels that Always be at the port before the vessel

call into Levuka.

starts to unload. Be careful with the length

measurement and species code, and bring your

· What is the target coverage level?

species identification manual with you every

20%.

time.

Fijian port samplers Eroni Bautani and Sailosi Naiteqe take time out.

Fork length -- Issue #7 -- November 2007

10

DATA MANAGEMENT

The Marshall Islands Oceanic Monitoring Programme

with Manasseh Avicks, Dike Poznanski and Berry Muller

Afull-time team of eight staff

and 20 contract samplers are involved. From their office in Majuro, the staff

employed in the oceanic divi- monitors a national fleet of five Marshallese

sion of the Marshall Islands purse-seine vessels (that landed 41,000 metric

Marine Resources Authority tonnes of tuna in 2006)1and 223 foreign-licensed

(MIMRA). The team work to vessels (that caught 12,919 metric tonnes of tuna

ensure that the Republic of in the Marshall Islands' exclusive economic zone

the Marshall Islands (RMI) fulfils its flag, -- EEZ -- during 2006). They also oversaw

coastal and port state data provision responsibil- approximately 750 longline unloadings and 100

ities to the Western and Central Pacific purse-seine unloadings in 2006 as part of their

Fisheries Commission (WCPFC), while keeping in port state responsibilities.

mind their own national data needs as established

by the RMI's 1997 Marine Resources Act. This A first-time visitor to MIMRA is struck by how

work is achieved alongside their reporting and close their offices are to the action. Situated on

compliance roles. Sam Bati (Deputy Director), an islet within the atoll, their workplace is only

Xavier Myazoe (Deputy Chief Licensing Officer), steps away from the unloading port, with locally

Berry Muller (Chief Oceanic Officer), Slam Kalen based foreign longliner vessels unloading their

(Assistant Licensing Officer), Manasseh Avicks fish almost on MIMRA's doorstep. These longlin-

(Observer Coordinator) and Dike Poznanski ers have links to China and the Federated States

(Assistant Observer Coordinator) are all of Micronesia (FSM), and appear at the local

"fish base" approximately every 10 days, eager to

MIMRA staff, from left to right and top to bottom: Xavier,

Berry, Eminra, Slam, Motelang, James and Manasseh.

(Dike is on the back page)

1. Data from Annual Report Part I Information on Fisheries, Research, and Statistics -- Republic of the Marshall Islands

presented to WCPFC SC3.

Fork length -- Issue #7 -- November 2007

11

unload their catch of large bigeye and yellowfin

tunas, which will be air-freighted to Japan for The collection of logsheet and port sampling data

the sashimi market. Despite the proximity of the is complemented by the collection of unloadings

main office to the longline unloading port, data. While the regional standard longline unload-

MIMRA made the decision to appoint and perma- ings form is in use, the collection method is some-

nently locate a new Port Sampler Supervisor what unique. The data are recorded electronical-

(James Elio) at the base. His presence has ly by the local fishing agent, and the MS Excel

already had a noticeable effect on the collection file is then forwarded by the agent to MIMRA via

of data from this locally based fleet. James has email. Finally, with the help of SPC the informa-

built a relationship with the fishing agents and tion is imported directly into the tuna fisheries

his presence is a daily reminder to them of their database (TUFMAN). Even though the data are

reporting requirements. This Marshallese initia- recorded electronically, the benefit of having an

tive is one that other countries in the region on-site staff member to remind fleet managers

could consider. James, in cooperation with the to send their Excel files in a timely manner can't

Port Sampling Assistant (Lomodro Jobas), col- be underestimated. James is also responsible for

lects the longline logsheets from either the fish- completing the Fishing Trip and Port Visit Log for

ing captain or the fleet manager before the ves- the locally based fleet. These data are used as

sel unloads its catch.

baseline information and help ensure that RMI

achieves full coverage for coverage for logsheet,

This team, supported by the port samplers, then unloadings and port sampling data.

proceeds to sample 100% of the vessels that

unload, and 100% of the fish that are unloaded. In The Marshall Islands strongly enforces the

fact, while the regional target for port sampling regional ban on transshipment at sea, while

coverage is 20%, MIMRA has shown their initiative actively encouraging the transient purse-seine

and set a national target of 100% coverage. Their fleet to unload in Majuro to allow some of the

motives are to improve data collection, to better positive economic benefits to flow to the local

capture data discrepancies, and to highlight any community. The re-opening of the local loining

illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing (IUU) plant in October 2007 will also ensure that purse-

vessels. Unloading is synchronised with the com- seine unloading will continue in the future. It's

mercial airline schedule, so the aluminium callipers easy for locals to follow the movements of the

are put to work on most Mondays, Wednesdays and purse seiners as they make their way in and out of

Fridays. It's a full day's commitment from the team the main lagoon to unload. At night their presence

(08:00 h to 17:00 h) and may extend to a 12-hour is even more obvious, as the bright deck and cabin

day if the fish are really biting.

lights light up the lagoon. While local residents

may be generally aware of the vessels' move-

ments, MIMRA staff carefully monitor all

Longline boats line up at the "fishbase" in Marshall Islands

Fork length -- Issue #7 -- November 2007

12

licensed vessels from the moment

they move into the EEZ. Following

mandatory reporting by telex, a ves-

sel's arrival into the port of Majuro

is clearly marked on the large office

whiteboard that dominates the

oceanic division office. Despite a

strong computing environment, the

office whiteboard remains the

method of choice to ensure the

whole team is aware of which vessels

are in port, and which tasks need to

be completed. Vessels full with fish

and eager to unload are first met by

port inspection officers, who carry

out national boarding procedures

using the locally created boarding

checklist form. This work is carried

out by the licensing team with sup-

port from experienced observers.

Purse seiners moor a short distance

away from the "fish base". Transport

to the vessels is provided by vessel

skiffs during unloading hours (07:00

hrs 22.00 hrs). Port samplers (who

are locally known and legally referred

to in RMI as observers) are assigned

to every unloading purse-seine vessel,

unless the vessel has been sampled

by an at-sea observer. Lengthfre-

quency sampling is in keeping with the

regional norm of 20% coverage, and

regional standard purse-seine port

sampling forms are used. A national

monitoring form (the Purse Seine to

Carrier Report Form) tallies the net

movements and highlights any dis-

crepancies between the vessel unload-

Majuro's busy lagoon (top)

ing tonnages and those of the MIMRA

MIMRA's Director Glen Joseph on board

observer. The vessel unloading ton-

the F/V Zhong Yuan Yu 944 (bottom)

nages are recorded by the vessel on their mate's

receipt, and these are collected by the sampling

observer or the port inspection officer.

Although established in 1995, the national observer

programme became effective following the recruit-

More detailed fishery information is collected by ment of an overseas Observer Coordinator to inject

the observer programme. The Marshall Islands experience and onsite advice to the programme.

has a strong and growing national observer pro- Manasseh Avicks (a Solomon Islander) was chosen

gramme, and it may be the only place in the and recruited in late 2003 in a joint initiative

Pacific where the current Director of Fisheries between MIMRA and SPC. The appointment of

has actually carried out an observer trip. This Manasseh has had a positive impact on the Marshall

insight and MIMRA's acceptance of the benefits Islands observer programme, with consistent

of a national observer programme along with improvements in the number of trips and the sam-

their adherence to the regional observer policy pling coverage. In addition to the valuable experi-

has helped them develop a strong observer pro- ence Manasseh brought from outside RMI, the local

gramme that meets national needs and fulfils knowledge of Dike Poznanski, the Assistant

regional obligations.

Observer Coordinator, has also helped in developing

and shaping the local observer programme.

Fork length -- Issue #7 -- November 2007

13

Trained RMI observers typically board two dif-

ferent types of vessels. Most new observers help people out, but observers will be politely

start their careers with a trip on locally based directed back to their fishing agent or their own

foreign longliners. These vessels generally stay national observer coordinator if they abuse their

at sea for around 10 days; while the trips aren't welcome". The follies of a few can affect the rep-

long, conditions are far from luxurious. There are utation of all observers; hopefully in the future,

cockroaches, and the day's menu can be as much all transient observers will behave in a manner

of a personal challenge as the language barrier. that respects both their host's welcome and their

However, they also get a chance to board purse- colleagues' professional reputations.

seine vessels with far superior living conditions.

As Majuro is a busy purse-seine unloading port, The Marshall Islands observer programme is per-

and RMI is a signatory to the sub-regional observ- forming well. They have benefited from a high

er programmes (the United States Multilateral number of basic observer trainings, and past

Treaty and the FSM Arrangement), purse-seine problems relating to keeping trained observers

trips make up a large proportion of any local on the team are slowly being resolved. With

observer's trips.

debriefing in place and a clear intention to meet

regionally recommended coverage levels, and

Marshallese observers don't just encounter fish. excellent ongoing support from their Director,

Being stationed at a major transshipment port, RMI's national observer programme is currently

they may well meet some of their regional peers one of the most dynamic in the region. The

who end their observer trips in the port of broader oceanic fisheries team has also worked

Majuro. The Flame Tree Hotel is a recognised consistently over the last few years to improve

haunt for transient observers seeking to share the collection and management of information

experiences, and a warm Pacific welcome is required to monitor migratory oceanic species,

extended to all visiting observers. Unfortunately, and have made impressive improvements:

this welcome has been abused on occasion, and it logsheet and unloadings data coverage has

is not MIMRA's responsibility to help out irre- increased exponentially and is now close to 100%.

sponsible observers. As Manasseh puts it When asked what their secret was they replied

"Everybody gets one chance. We are happy to "It has to come from the heart".

Tuna Data Workshop

The inaugural Tuna Data Workshop (TDW-1) took

tuna statistics staff away from their desks for The full report of the workshop is available from

one week, brought people together, and allowed the Global Environment Fund's Pacific Islands

them the time and space to reflect on tuna data Oceanic Fisheries Management project website

systems while enjoying the congenial settings of http://www.ffa.int/gef/node/31. The Global

SPC's conference centre. Presentations from SPC Environment Fund was the main sponsor of the

and FFA staff provided background material and workshop.

up-to-date information to generate discussion and

to stimulate problem-solving in small working A second Tuna Data Workshop (TDW-2) is

groups. The workshop concentrated on data col- scheduled for the first quarter of 2008. The

lection; topics included the reasons for collecting

data, national and regional data obligations, types

of data to collect, "best practices" for tuna data

systems, and tuna fishery data collection system

problems and solutions.

The workshop produced a checklist (see page 14)

for establishing or reviewing tuna fishery data

collection systems.

Participants of the first Tuna Data Workshop

Fork length -- Issue #7 -- November 2007

14

second workshop will build on the experiences of

the first workshop, with data dissemination or system. Much like TDW-1, the workshop will use a

data reporting, becoming the main focus. The combination of presentations, group discussions

workshop's main objective will be for participants and exercises to help participants acquire the

to acquire the understanding and skills necessary skills needed to produce National Fishery Reports

to produce annual catch estimates for their for the WCPFC Scientific Committee meetings. It

national fleets, which is their main data-report- is also expected that time spent at the workshop

ing obligation to the WCPFC. TDW-2 wil help will give participants a better understanding of

participants explore the data methodologies that the best practises for scientific monitoring of

are best suited to their own national tuna data their oceanic fish stocks at the national level.

TUNA DATA SYSTEM CHECKLIST

1. Obligations for collecting data*

2. Functions of data to be collected are described

3. Protocols/methods for collection/submission*

4. Reference to data collection forms to be used*

5. Required "coverage" of data*

6. Resources and training required are available (e.g. where does funding come from)

7. Schedule for the provision of data*

8. Consequences for non-compliance in collection and provision of data*

9. Contact points for data*

· Who records the data

· Who provides the data (e.g. Fishing Company representative)

· Who receives the data (Fisheries Division staff member)

· The respective liaison points in regards to problems with data

· Procedures for liaising with respect to problems with data*

10. Quality control procedures (in the data collection system; e.g. audit/reviews)

11. Feedback mechanisms from data management (mechanisms/procedures for data management staff

to liaise with data collection staff, e.g. on data quality issues)

12. Data security issues in data collection (addressing both Fisheries Division and Fishing Companies

concerns)

13. Mechanism for integrating/sharing data collection systems with other countries

* indicates items suggested for inclusion in conditions for fishing access

DATA DISSEMINATION

Current stock assessment results delivered

at the Third WCPFC Scientific Committee Meeting

WHAT TUNA WERE CAUGHT IN 2006?

less than the record in 2005 (2,204,335 mt).

The provisional catch of tuna in the Convention About 70% of the catch (1,537,524 mt) was skip-

Area (the Convention for the Conservation and jack tuna, which

Management of Highly Migratory Fish Stocks in was the highest

the Western and Central Pacific Ocean) for ever, continuing the

2006 was estimated at 2,189,985 mt, the second trend of consecu-

highest annual catch recorded, and only slightly tive record catches

since 2002. The

Fork length -- Issue #7 -- November 2007

15

yellowfin catch (426,726 mt 19%) was about 5%

lower than in 2005, but still around the average The 2006 South Pacific albacore catch was esti-

catch level for the period since 2000. The mated to be about 68,000 mt. Most of the catch

Convention Area bigeye catch for 2006 (125,874 is taken by longline, and albacore represents a

mt 6%) was also lower than in 2005, but slight- significant component of the catch by domestic

ly higher than the average catch level for the longline fisheries. The latest stock assessment

period since 2000.

for albacore indicates that the current catch

levels are sustainable and the stock could sup-

W

port higher yields. However, increased catches

HAT IS THE CURRENT STATUS OF TUNA STOCKS

may reduce the abundance of species and, conse-

IN THE CONVENTION AREA?

quently, catch rates for the longline fishery may

The results of a recent stock assessment indi- fall below economically viable levels.

cated that the "bigeye stock is not currently in

an overfished state; however, exploitation rates MEETING OUTPUTS

are high and current levels of catch are not sus-

tainable in the medium term". In response to Six specialist working groups make up the WCPFC

these results, the WCPFC Scientific Committee Scientific Committee. These are the Biology,

recommended a 25% reduction in fishing mortal- Ecosystem and Bycatch, Fish Technology, Methods,

ity (fishing effort) to prevent the stock from Stock Assessment and the Statistics Specialist

being overfished. In simple terms, this means Working Group. While outputs from all these work-

that while there are still enough bigeye in the ing groups do have relevance for scientific monitor-

western and central Pacific Ocean (WCPO) to ing staff the most relevant group is the Statistics

maintain their total numbers by reproduction, Specialist Working Group (ST-SWG). We have

there are only barely enough, and there are high reported on some of the meeting outputs here.

risks that by continuing to catch the same num-

ber of bigeye the overall total number of bigeye Overviews of Gaps / Issues with Data

might be reduced in the coming years, especially

if changes in some environmental factors (such The list of outstanding data that was recently

as water temperature) were to cause more nat- submitted to the WCPFC was presented. It was

ural deaths or reduce reproduction.

noted that important data gaps still exist and

include data from the Indonesian and Philippines

The stock assessment results maintain that "the domestic fisheries as well as the distand-water

yellowfin stock in the WCPO is not in an over- longline fishery. The impact of data gaps (includ-

fished state although there is a considerable ing late and/or absent data) on the stock assess-

probability that overfishing is occurring. Any ments result and, thus, the ability of the WCPFC

future increase in fishing mortality would not to provide the best available advice was dis-

result in any long-term increase in yield and may cussed. Access to a database that will highlight

move the yellowfin stock to an overfished state". important data gaps should be available from the

This means that current yellowfin catches are at WCPFC website in the coming year.

the maximum level that can be supported by the

stock over the long term. Any further increase in

fishing effort is likely to reduce the stock's abil-

ity to sustain the current catch level.

The total skipjack catch in 2006 was estimated

to be 1,537,000 mt -- the highest on record.

While no formal stock assessment was conducted

this year, all indicators suggest that "the skip-

jack tuna stock of the WCPO is not overfished

owing to recent high levels of recruitment and a

modest level of exploitation relative to the

stock's biological potential". This means that the

skipjack stock is still in a healthy state. The

recent high levels of catch have been attained by

an increase in recruitment and higher levels of

fishing effort by the purse-seine fleet.

Fork length -- Issue #7 -- November 2007

16

Regional Observer Programme

4. Sample other biological parameters, such as

The scientific objectives and priorities for the gender, stomach contents, hard parts (e.g.

proposed Regional Observer Programme (ROP), otoliths, first dorsal bone), tissue samples,

as well as data standards, were discussed and and collect data to determine relationships

accepted by the ST-SWG (see below). At the between length and weight, and processed

end of the discussion, over 100 data standards or weight and whole weight;

data fields were accepted as the starting point

by the group. However, a large number of data 5. Record information on mitigation measures

standards still require discussion and this will be utilised and their effectiveness; and

done through the Intercessional Working Group,

or the WCPFC. We hope to report on this in the 6. Record information on the catch and fishing

next edition of Fork Length.

effort during baitfishing, when baitfishing is

undertaken by the tuna fishing vessel.

For now the accepted scientific objectives and

priorities for the ROP are to:

Procedures for the provision of annual catch

estimates and effort and size data

1. Record the species, fate (retained or discard-

ed) and condition at capture and release (e.g. These procedures were fine-tuned and updated

alive, barely alive, dead etc) or the catch of by the ST-SWG. The latest edition of these

target and non-target species; depredation important data procedures is available as

effects; and interactions with other non-tar- Appendix IV of the Third Regular Session of the

get species, including species of special inter- Scientific Committee (SC3) report.

est (i.e. sharks, marine reptiles, marine mam-

mals and sea birds);

Data confidentiality, security,

and dissemination

2. Collect data to allow the standardization of

fishing effort, such as gear and vessel attrib- It is likely that the WCPFC will put into place the

utes, and fishing strategies. etc;

new information security policy that was presented

and discussed at SC3. New revisions to the rules

3. Sample the length and other relevant mea- and procedures for access to and the dissemination

surements of target and non-target species; of data were accepted by the ST-SWG.

Data summaries

Summary of completed observer trips for all observer programmes*

2005

Observer Programme

Gear

Number of Trips

Fiji

L

39

Federated States of Micronesia

L

8

Kiribati

L

1

Marshall Islands

L

26

New Caledonia

L

4

French Polynesia

L

17

Papua New Guinea

L

20

Palau

L

1

Tonga

L

1

Solomon Islands

P

9

FSM Arrangement

S

51

Federated States of Micronesia

S

11

Kiribati

S

1

Marshall Islands

S

17

Papua New Guinea

S

135

Solomon Islands

S

35

US Treaty

S

15

Fork length -- Issue #7 -- November 2007

17

2006

Observer Programme

Gear

Number of Trips

Fiji

L

27

Federated States of Micronesia

L

11

Kiribati

L

3

Marshall Islands

L

63

New Caledonia

L

7

French Polynesia

L

20

Papua New Guinea

L

14

Tonga

L

19

Western Samoa

L

2

FSM Arrangement

S

56

Federated States of Micronesia

S

7

Kiribati

S

13

Marshall Islands

S

19

Papua New Guinea

S

138

US Treaty

S

14

Summary of port sampling data*

Size Sampling

2005 - Country

Port

Gear

Vessels

SKJ

YFT

BET

ALB

OTH

TOT

American Samoa

Pago Pago

L

104

1,233

2,120

824

17,874

570

22,621

Cook Islands

Avatiu

L

2

0

45

21

13

67

146

Levuka

L

55

134

127

47

25,376

0

25,684

Levuka

S

3

3,988

239

123

0

0

4,350

Fiji

Suva

L

93

1,467

19,212

4,995

46,586

20,310

92,570

Fiji Total

5,589

19,578

5,165

71,962

20,310

122,604

Pohnpei

L

26

0

1,290

905

19

1

2,215

FSM

Pohnpei

S

4

600

0

0

0

0

600

FSM Total

600

1,290

905

19

1

2,815

Majuro

L

40

0

3,489

4,872

8

10

8,379

Marshall Islands

Majuro

S

12

5,993

610

368

0

17

6,988

Marshall Islands Total

5,993

4,099

5,240

8

27

15,367

Koumac

L

9

0

2,445

498

14,399

2,860

20,202

New Caledonia

Noumea

L

8

0

1,621

188

3,490

1,407

6,706

New Caledonia Total

0

4,066

686

17,889

4,267

26,908

Niue

Alofi

L

6

191

163

18

400

93

865

French Polynesia

Papeete

L

59

66

6,056

7,191

21,387

7,922

42,622

Palau

Koror

L

147

0

44,603

24,126

31

1,208

69,968

Tonga

Nuku'alofa

L

15

137

3,176

1,923

6,913

7,861

20,010

Samoa

Apia

L

41

1,330

3,914

1,350

30,369

3,881

40,844

Size Sampling

2006 - Country

Port

Gear

Vessels

SKJ

YFT

BET

ALB

OTH

TOT

American Samoa

Pago Pago

L

99

1,244

1,421

917

21,771

757

26,110

Levuka

L

41

386

11

6

22,339

0

22,742

Fiji

Suva

L

13

220

3,116

707

3,587

5,163

12,793

Fiji Total

606

3,127

713

25,926

5,163

35,535

FSM

Pohnpei

S

34

7,894

21

0

0

0

7,915

Majuro

L

50

0

21,586

22,781

3

1,298

45,668

Marshall Islands

S

30

13,271

977

506

0

0

14,754

Marshall Islands Total

13,271

22,563

23,287

3

1,298

60,422

Koumac

L

13

0

3,969

343

16,484

3,049

23,845

New Caledonia

Noumea

L

2

0

244

29

278

130

681

New Caledonia Total

0

4,213

372

16,762

3,179

24,526

Niue

Alofi

L

1

101

188

112

541

420

1,362

French Polynesia

Papette

L

54

49

2,289

4,526

34,821

8,690

50,375

Koror

L

152

1

39,201

37,812

26

1,712

78,752

Palau

Malakal

L

106

0

9,269

5,717

1

164

15,151

Palau Total

1

48,470

43,529

27

1,876

93,903

Tonga

Nuku'alofa

L

15

1,238

4,566

2,383

12,255

5,152

25,594

Samoa

Apia

L

13

44

756

146

1,907

193

3,046

* All data received and registered at SPC by Sept 2007

Fork length -- Issue #7 -- November 2007

18

TRAINING

Random sampling of purse-seine catches

Large numbers of individual fish are caught and

landed by purse-seine vessels. It is not physical- it was the first fish you sampled that day. It is not

ly possible for samplers to measure every one of feasible to carry out sampling while blindfolded, but

these fish. To get around this problem, purse- this is ideally how sampling should be carried out.

seine fish are generally sampled randomly.

Random sampling is a vital competency for every Never choose a fish because you think it hasn't

purse-seine sampler and every active sampler shown up on your data form recently. If you've

should be able to demonstrate physically and seen some bigeye tuna in the catch, but have not

convey verbally the important aspects of this measured any during your sampling session, that's

technique when required. Are you sure that you okay. Do not worry about the results you get.

are carrying out your random sampling correctly?

Do you think you would pass a competency test? If you have carried out your random sampling

correctly your results will always be right

Please take the time now to review the correct pro-

cedures for random sampling. Talk about random NEVER be tempted to collect a fish because:

sampling with your colleagues and your coordina-

tors. Describe to them exactly how you are carry- · you haven't sampled that species yet;

ing out your random sampling. They can help you

decide if you are doing it correctly. One reason that · you haven't sampled that size of fish yet

random sampling must be carried out correctly is (either very large or very small fish);

because only one fish among thousands in the ocean

is sampled, therefore a small sampling mistake may · it looks good;

be multiplied thousands of times when the informa-

tion is used to calculate the whole tuna population. · it's easier to lift out than other fish.

For random sampling, samplers are normally asked Do not let the crew select the fish for you. They

to take five fish from every brail/net that they have not been trained to carry out random sampling

sample. The key to random sampling is to always col- and are quite likely to make an incorrect selection

lect the first fish that come to hand. The main dif- (i.e. they might choose the largest fish). Try to

ficulty with carrying out this technique is that as come up with your own random sampling technique

random sampling continues, samplers can uncon- and stick to it. Some suggested random sampling

sciously build up a prejudice about which type of methods include: Selecting an area of the net,

fish they think they should choose next. They may preferably an area close to you, and grabbing all the

think, "I haven't recorded any small skipjack yet", fish whose tails point towards you; or selecting a

and then go ahead and unconsciously select that small area of the net and taking all the fish that

fish. Clear your mind and collect the next fish as if land there; or selecting an area of the net and grab-

bing all the fish whose heads point towards you.

One other thing to remember, however, is that

when you select a particular area of the net to

sample from, give some thought as to how or why

the fish got to that area. If they have the same

chance as every other fish in that brail to get to

that area, regardless of their species or size,

then it is a good area to sample from. If, howev-

er, only smaller fish can reach that area -- per-

haps because it is a corner -- then this is not a

good area to sample from.

There may be some physical restrictions to car-

rying out random sampling properly, such as when

Avoid pre-selecting or choosing fish

the brailing is too fast or the fish are too large

when random sampling

to remove. If these physical restrictions exist,

Fork length -- Issue #7 -- November 2007

19

try to reduce the number of species that are

sampled (normally five). If it is still not possible your sampling form and either stop sampling or

to carry out random sampling, explain this on choose a different sampling protocol (i.e. non-

random species sampling).

RANDOM SAMPLING IS IMPORTANT.

TAKE THE TIME TO LEARN THE TECHNIQUE AND TO CARRY IT OUT PROPERLY.

New recruits

by Siosifa Fukofuka

Eighty-eight new observers have joined our ranks since 2004; below is an outline of the training

courses that have been held since then.

Country

Start Date Number of Number of

participants certified

observers

Marshall Islands

Jan-05

14

10

Federated States of Micronesia*

Apr-05

12

9

PNG

Jul-05

20

16

Samoa*

Aug-05

10

9

Marshall Islands

Feb-06

15

7

Palau

Jun-06

12

12

PNG

Jul-06

16

15

Marshall Islands*

Feb-07

9

5

Tonga

Aug-07

8

5

*Sub-regional courses

A look around the wheelhouse during

basic training in the Marshall Islands

Fork length -- Issue #7 -- November 2007

20

· Marshall Islands

25 January11 February 2005

Fourteen trainees attended the training after

passing the selection test. Ten trainees were

certified with SPC/FFA certification.

Back row: Manasseh Avicks (MIMRA

Coordinator), Siosifa Fukofuka (SPC),

Gordon Paul, Leban Jelton,

Lino Thompson, Dickson Betti,

Laan K. Loran, Karl Staisch (FFA)

Front row: Chris Alberttar,

Waisiki Baleikorocau,

Embi Ruben, Franny Zacharaia

· Federated States of Micronesia Course

18 April6 May 2005

Nine new observers received SPC/FFA certifica-

tion. Two participants were from Palau, two from

Nauru and eight from FSM. Staff from the US

National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) in

Hawaii assisted with the course, especially with

the identification of species of special interest

and de-hooking presentations.

Learning to dehook turtles

· Papua New Guinea

421 July 2005

In July 2005, 20 participants, select-

ed from a pool of over 1000 appli-

cants, attended a course conducted

by SPC, FFA and the PNG National

Fisheries College (NFC).

This basic observer course was the

seventh conducted in PNG by SPC/FFA

since 1996. Trainees attended the

course for five weeks with three

weeks for the observer component

carried out by SPC/FFA and two

weeks for sea safety, fire fighting

and first aid carried out by NFC.

Sixteen observers were eventually Back row: Joe Arceneaux (NMFS), Jaremiah Kuau, Lindsay

certified. Three female participants Kovero, Douglas Kenats , Simon Tibli, Michael Chamoko,

Walter Rusiat, Kaluwin Pondros, Groverto Kukuh, Miller

attended the course and two were Loras, Udill Jotham, Karl Staisch (FFA), Siosifa Fukofuka

certified.

(SPC); Front row: Cosmas Hecko, Garry Elias, Ilaitia

Taudarepa, Lyndsay Mundri, Emil Billy, Suluet Elaizah ,

Kerry Ragagalo, Elsie Gemelaia, Keith Agen, Sylvia Lohumbo

Fork length -- Issue #7 -- November 2007

21

· Samoa

29 August16 September 2005

Back row: Michael Forsyth, Matele Ievali,

Kimaere Biteiti (Kiribati), Steven Ve'a Neufeldt,

Mijieli Vakatubou (Fiji),

Kirennang Tokiteba (Fiji)

Front row: Sataraka Solomona,

June Kwanairara (Solomon Islander FFA),

Patrick Itara (Kiribati)

· Marshall Islands

13 February3 March 2006

Front row: Oriana Villar (NMFS),

Lenest Debrum, Leto Toto, Cliff Phillip,

Atran Samuel, Caston Caleb, Johnny Debrum

Back row: Helmer Mote, Alington Abij,

Frank Ward, Fred Mckay, Faliton Aisea,

Paulwin Jennop, Johnny Debrum,

Caston Caleb, Sashimi Debrum,

Paulton Mote, Lawremce Jitiam

· Palau

1230 June 2006

Back row: Johnny Sambal, Moses Nestor,

Kitridge Worstwick (Yap),

Masubed Tkel, Dominic Kyota

Second row: Fred Ramarui, Ricky Narruhn

(Pohnpei), Ian Tervet, Samuel Ldesel,

Jesse Rumong, Allen Maldangesang

Front row: Jim Kloalechad, Erwin Edmond

(Pohnpei), Moses Nestor, Rngei Taima

· Papua New Guinea

1228 July 2006

Sixteen trainees attended the courses. Most

trainees were previously employed as port samplers

based out of the six PNG unloading ports (Madang,

Rabaul, Kavieng, Wewak, Port Moresby and Lae).

Fifteen participants completed the course.

Back Row: Karl Staisch (FFA), Rakum Tumaleng,

Ashley Barol, Lawrence Pero, Elizah Lucas, Towai

Pelly, Ben Oli, Mathew Suarkia, Gauwa Gedo,

Dawn Golden (NMFS), Siosifa Fukofuka (SPC)

Front Row: Joyce Akaru (NFA), Jacinta, Robert

Rarap, George Pomat, Suluet Elaizah, John Igua

Dickson Ronney, Daniel Sau

Absent: Ataban Gibson

Fork length -- Issue #7 -- November 2007

22

· Marshall Islands

28 February20 March 2007

Tuna longliner unloading in Majuro. New

trainees (FSM and Marshalls) watch the

Marshall Islands port sampler Lomodro Jibas

at work measuring tuna.

· Tonga

122 August 2007

The basic observer training course carried out in

Tonga was noteworthy for a number of reasons. Also, PNG had the foresight to send one of their

The main trainer (Siosifa Fukufuka) was Tongan, of own senior observers, Glen English, to the train-

course, but FFA was represented by Ambrose ing to contribute as a trainer as they develop

Orianihaa (and not Karl Staisch) for the first time. their own path towards a national capacity for

observer training.

Standing: Glen English (PNG), Mehesala Tupou,

Sione Manu, Tonga Tuiano, Taani He, Ambrose

Orianihaa (FFA)

Front row: Siosifa Fifita, Mosese Mateaki,

Penisoni Vea, Siosifa `Amanaki

Absent: Sione Mahe

· Assistance from the Hawaiian Observer Programme

(NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service)

Trainers and debriefers from Honolulu provided

assistance for most of the above training courses,

especially in the identification and handling of marine

mammals and sea turtles. Fork Length would like to

acknowledge their contribu-

tion to the SPC/FFA observ-

er courses, keeping both the

trainees and the SPC/FFA

trainers up-to-date on these

important subjects.

Left: Stuart Arceneaux (Joe)

Some debriefers who

going through billfish identifi-

assisted with the training

cations, PNG course 2006

were Adam Baily, Colleen,

Right: Dawn Golden in Class,

Oriana Villa and Tom

FSM course - Pohnpei 2005

Swenarton.

Fork length -- Issue #7 -- November 2007 23

· Wallis and Futuna has two new observers

by Charles Cuewapuru

After passing the pre-selection test conducted

locally by the "Service de l'Économie Rurale et de la

Pêche du Territoire de Wallis et Futuna" two new

observer candidates were flown to New Caledonia to

take part in longline observer training. The course

was held by SPC (with Charles Cuewapuru as the

main trainer) and the local marine school. The train-

ing course was run during November (2006) and con-

sisted of two weeks of class work followed by a 15-

day dishing trip onboard the local longline fleet.

At the end of their training, the observers flew back

to Wallis and Futuna, where it is hoped they will play

an important role in the observation of the new

exploratory fishing campaign that is expected to

start up. This exploratory fishing, by a commercial

company, hopes to gauge the potential for the com-

mercial fishing of pelagic fish (including pomfrets),

deepwater snappers and groupers. Because none of

these stocks have ever legally been fished intensively

for profit, the work of the observers will allow scien-

tists to survey the fishery both before, during and Keller Kopf (Charles Sturt University) explains

after this potential new fishery is developed.

sampling techniques to the new Wallis and

Futuna recruits Salua Wilfrid

and Valetino Polelei

© Copyright Secretariat of the Pacific Community, 2007

All rights for commercial / for profit reproduction or translation, in any form, reserved. SPC authorises the partial reproduction or translation of

this material for scientific, educational or research purposes, provided that SPC and the source document are properly acknowledged. Permission

to reproduce the document and/or translate in whole, in any form, whether for commercial / for profit or non-profit purposes, must be requested

in writing. Original SPC artwork may not be altered or separately published without permission.

Original text: English

Secretariat of the Pacific Community, Marine Resources Division, Oceanic Fisheries Programme, BP D5, 98848 Noumea Cedex, New Caledonia

Telephone: +687 262000; Fax: +687 263818; E-mail: observer@spc.int; http://www.spc.int/OceanFish

Around the region

It looks like tuna are not the only migratory species in the Pacific Islands. Below are staff from the

region who have recently taken up new monitoring-related positions, as well as other travelling staff.

Left: Congratulations and good luck to Karl Staisch on his appointment

as the new WCPFC Observer Programme Coordinator

Middle: Palau's recently promoted Port Sampling Supervisor (Rimirch Katosang, left)

and the new Observer Coordinator (Ian Tervet on the right) busy with port sampling paper work.

Right: The newly appointed Solomon Island Observer Coordinator Derek Suimae

Left: Hudson Wakio who has quickly become comfortable in his new position

as the Solomon Island National Tuna Data Coordinator

Middle: FFA's new Observer Programme Manager, Tim Park.

Welcome back to the region Tim

Right: Alfred Lebehn, FSM (left) and Dike Poznanski, RMI (right) who were on attachment

with the Statistics and Monitoring Section of the Oceanic Fisheries Programme in Sept 2007