Integrated Ecosystem Management in the Prespa Lakes Basin of Albania, FYR of Macedonia and Greece

TECHNICAL ASSESSMENT REPORT

PRESPA PARK COORDINATION COMMITTEE

IN TRANSBOUNDARY ECOSYSTEM MANAGEMENT

[Consultant Report]

Dr. Slavko Bogdanovic

Novi Sad

12 December 2008

The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the

United Nations Development Programme.

A transfrontier region is a potential region, inherent in geography, history, ecology, ethnic

groups, economic possibilities and so on, but disrupted by the sovereignty of governments

ruling on side of the frontier.

DENIS DE ROUGEMONT

L'Avenir est Notre Affaire, Seuil publishers, Paris

1978

The basic principle of transfrontier is to create links and contractual relations in frontier areas so

that joint solutions may be found to similar problems [...]

Regional identities must be sustained and the construction of Europe enriched by the dynamism

and special qualities of local and regional communities situated on each side of a frontier, as

they jointly try to develop a living partnership, true synergy and full solidarity reflecting what a

Europe united in diversity should be.

HANDBOOK OF TRANSFRONTIER FOR LOCAL AND REGIONAL AUTHORITIES IN EUROPE

Council of Europe,

2000

Transboundary watershed problems are best resolved by those who live and work in the

watershed. Further, success in resolving local problems will increase as certain conditions

evolve: local participants gain experience in working together on problems and opportunities; a

systemic, ecosystem framework is used in learning about problems and solutions; and trust

among local participants is nurtured through shared work and discussions of

shared values.

THE INTERNATIONAL WATERSHED INITIATIVE

Second Report to the Governments of Canada and the United States;

IJC--International Joint Commission Canada and United States,

2005

2

CONTENTS

ACRONYMS

6

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

8

I.

INTRODUCTION

11

1.

Brief on Nature of the Prespa Lakes Basin

11

2.

History of Management Efforts

11

3.

Terms of Reference

13

4.

Methodology

13

II.

MISSION SCOPE, CONTENTS AND FINDINGS

15

III.

PRESPA LAKES BASIN IN INTERNATIONAL AND NATIONAL

20

POLICY AND LAW CONTEXT

1.

Introductory Notes

20

2.

Global and European Instruments

20

3.

Community Acquis

22

4.

Mediterranean Wetland Initiative (MedWet)

25

5.

Other Relevant International Initiatives

27

IV.

TRILATERAL CONTEXT

28

1.

Prespa Park Declaration

28

1.1

Event

28

1.2

Content

28

1.3

Notes on Legal Nature

30

2.

Local Level Co-operation

32

2.1

Co-operation between Local Municipalities

32

2.2

Other Examples of Trilateral Co-operation

32

3.

Concluding Notes

33

V.

PRESPA PARK COORDINATION COMMITTEE

35

1.

Description/History

35

2.

Composition

35

3.

Responsibilities

36

4.

Operational Aspects Rules

37

5.

Secretariat

38

6.

Work and Most Remarkable Results

40

7.

Legal Profile

42

8.

Specific Features of Stakeholders

43

9.

Financial Issues

44

10.

Assessment of the PPCC Operations and Evaluation of its

Capacity

46

11.

Assessment of the PPCC Secretariat

47

12.

Some Conclusions

48

3

VI.

SOME SUCCESSFUL CASES

52

1.

Danube River Protection Convention (DRPC)

52

1.1

Territorial Scope

52

1.2

Subject Matter

53

1.3

Forms of Co-operation

54

1.4

Institutional Setting

54

1.4.1

Conference of the Contracting Parties

54

1.4.2

International Commission for the Protection

of the Danube River (ICPDR)

55

1.5

Expenditures

57

1.6

Other Instruments of the ICPDR Legal Regime

58

2.

The Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement (GLWQA)

58

2.1

Brief Introduction

58

2.2

Institutional Setting

59

2.2.1 International Joint Commission (IJC)

59

2.2.2 Great Lakes Water Quality Board

61

2.2.3 Great Lakes Science Advisory Board

61

2.2.4 Great Lakes Regional Office of IJC

62

2.3

Funding

62

3.

The Lake Constance

63

3.1

Introductory Notes

63

3.2

International Conference of Deputies for Fishery

63

in the Lake Constance--IBKF

3.3

International Fishermen's Association of the Lake

64

Constance--IFB

3.4

International Commission for the Protection

64

of the Lake ConstanceIGKB

3.5

International Bodensee ConferenceIBK

65

3.6

International Commission for Boating on the Lake

66

Bodensee--ISKB

4.

Framework Agreement on the Sava River Basin

66

4.1

General Notes

66

4.2

Scope of Cooperation

67

4.3

Mechanisms of Co-operation

69

4.4

Meeting of the Parties

69

4.5

International Sava River Basin Commission (ISRBC) 69

VII.

DRAFT TRILATERAL AGREEMENT

72

1.

Notes on Legal Status of Draft

72

2.

Contents of Draft

72

3.

Instead of Conclusion

73

VIII.

RECOMMENDED ACTIVITIES, ORDER OF STEPS

74

AND TIME FRAME

1.

Introductory Notes

74

2.

Some Explanatory Notes

74

3.

Commitment of the States

75

4.

Recommendations

76

Trilateral Consultative Process (TCP)

76

4

Rapid Comparative Legal Assessment of

77

Cross-Cutting Issues

Performing Pilot SEA in the Prespa Lake Basin

77

Involvement of International Organizations

78

International Prespa Conference

78

5.

Order of Steps & Contents of Activities

79

6.

Time Frame

84

7.

Reminder Notes on Possible Contents of the

85

Prespa Lakes Basin Agreement

7.1

Some Features of the Agreement

85

7.2

Some Features of the Prespa Management

85

Committee

7.3

Some Notes on the Role and Scope of

Competence of the Prespa Management Committee 85

7.4

Note on Working Guidance

86

BIBLIOGRAPHY

87

ANNEXES

90

Annex I

91

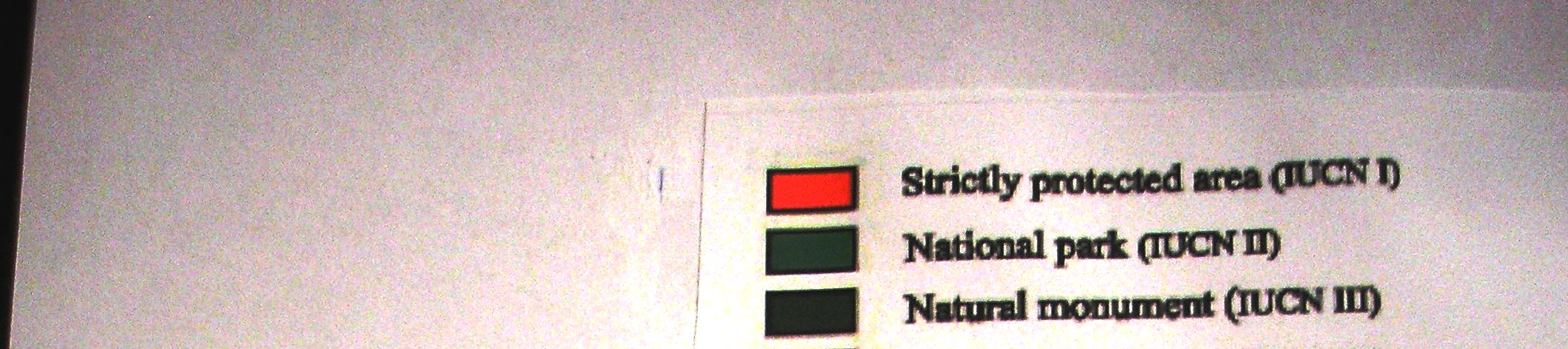

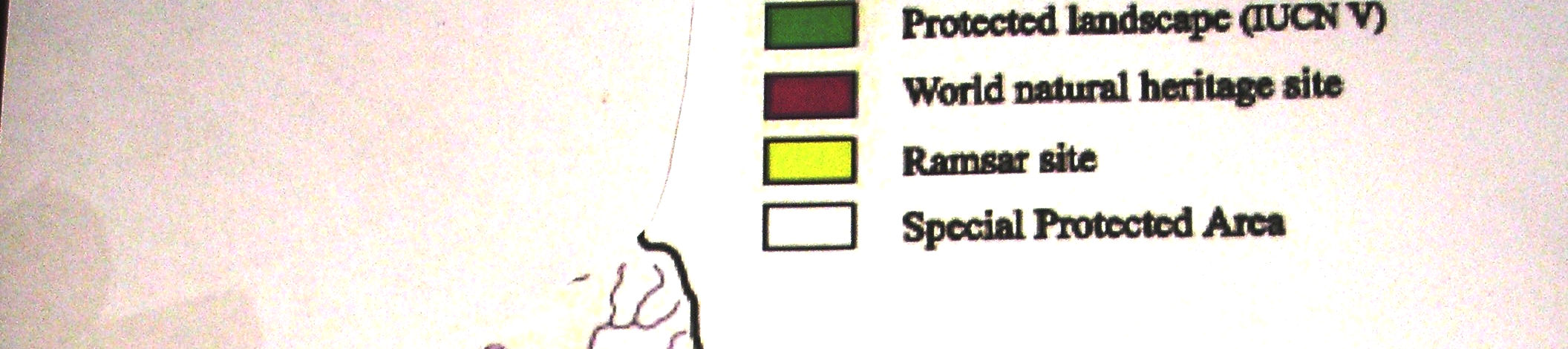

IUCN Guidelines Protected Area Categories Management

ANNEX II

96

Terms of Reference

ANNEX III

99

Assessment Methodology

ANNEX IV

101

Debriefing Note

GRAPHIC CHARTS AND TABLES

The Prespa Lakes Basin

14

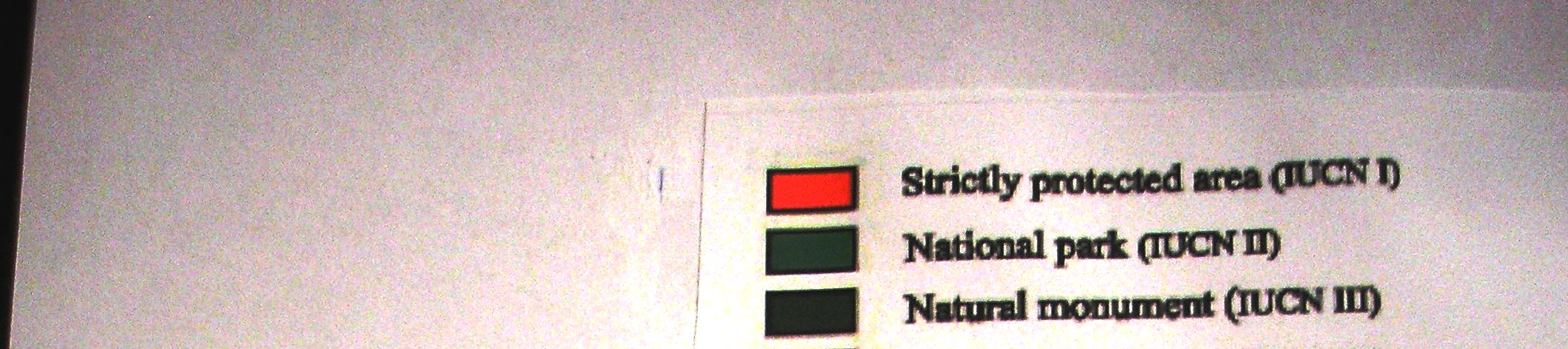

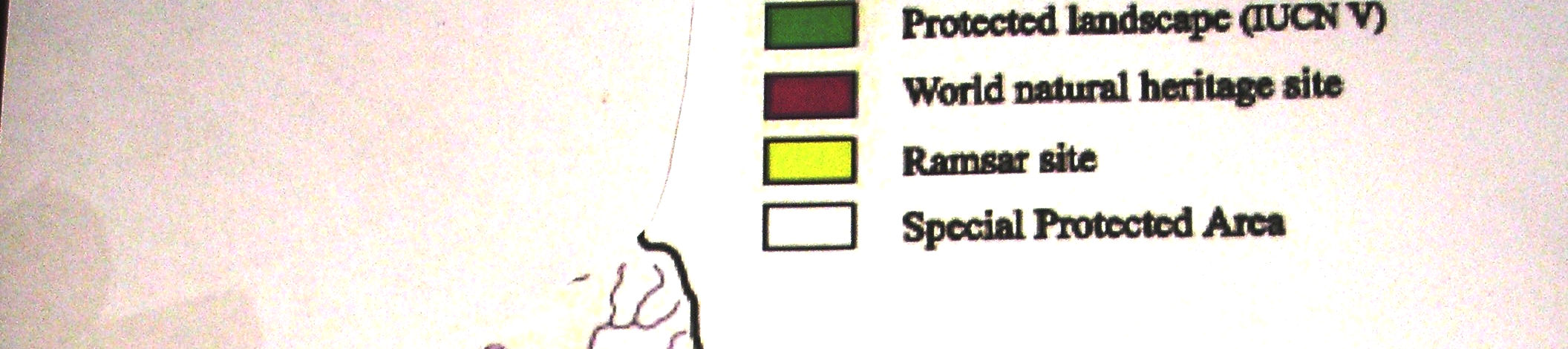

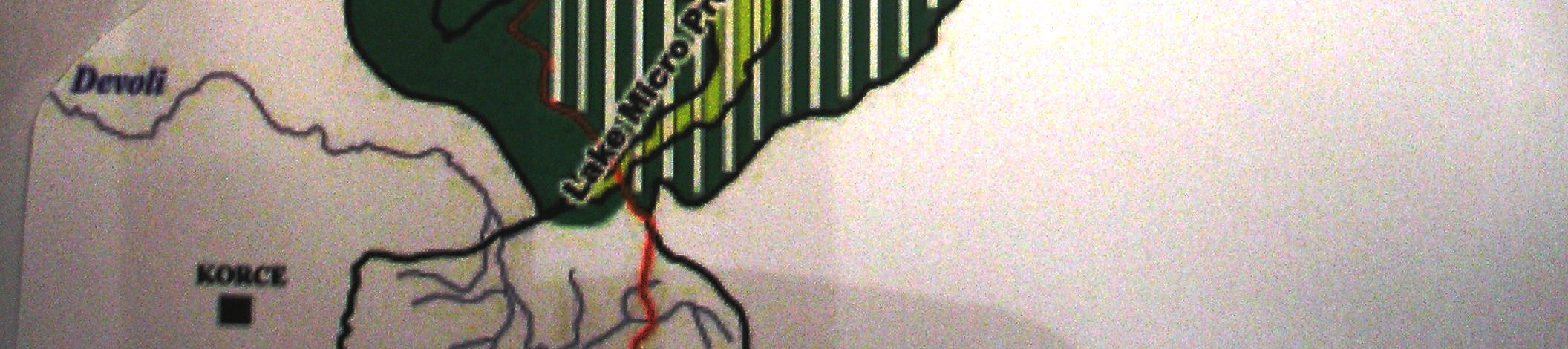

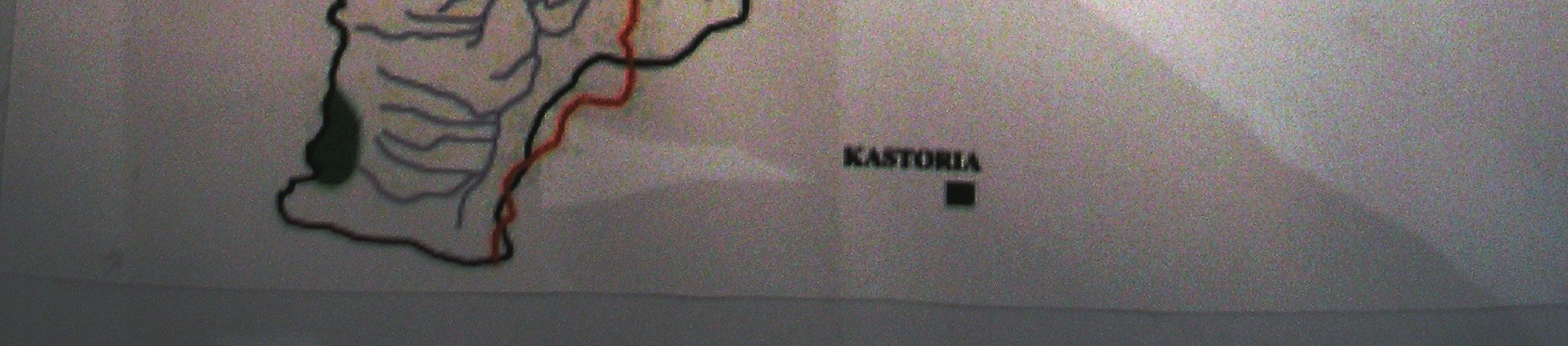

The Prespa Lakes basin Protected Areas

19

List of International Law Agreements Relevant for the Prespa

21

Lakes Basin--Status of signatories and ratifications

Relevant Community Acquis Instruments

25

List of PPCC Meetings

41

Matrix of Management Objectives and IUCN Protected

91

Area Management Categories

5

ACRONYMS

The acronyms used in this Report have the meanings as indicated bellow.

BWT

Boundary Waters Treaty

DRPC

Danube River Protection Convention

EIA

Environmental Impact Assessment

EU

European Union

FASRB

Framework Agreement on the Sava River Basin

GEF

Global Environmental Facility

GEF PD

Global Environmental Facility Project Document

GLWQA

The Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement

IBF

Internationaler Bodenseefischereiverband [International

Fishermen's Association of the Lake Constance]

IBK

International Bodensee Conference

IBKF

Internationale Bevollmächtigtenkonferenz für die

Bodenseefischerei [International Conference of

Deputies for Fishery in the Lake Constance]

ICPBS

International Commission for the Protection of the Black Sea

ICPDR

International Commission for the Protection of the

Danube River

ICSRB

International Commission for the Sava River Basin

IGKB

International Commission for the Protection of the

Lake Constance

IJC

Great Lakes International Joint Commission

IPPC

Integrated Pollution Prevention and Control

ITA

International Transboundary Advisor

KfW

Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau

MAP

Macedonian Alliance for Prespa

MedWet

Ramsar Convention Mediterranean Wetland Initiative

MFA

Ministry of Foreign Affairs

MoU

Memorandum of Understanding

NATO

North Atlantic Treaty Organization

PPCCOA

PPCC Operative Arrangements

OSCE

Organization on Security and Cooperation in Europe

PD

Project Document

PDF B

UNDP Project Document File B

PM(s)

Prime Minister(s)

PPCC

Prespa Protection Coordination Committee

PPNEA

Protection and Preservation of the Natural

Environment in Albania

PTC

Process of Trilateral Consultation

RCLACCI

Rapid Comparative Legal Assessment of Cross-Cutting Issues

REC

Regional Environmental Centre for South Eastern

Europe

ROP

Revised Rules of Procedure [ICPDR context]

SAA(s)

Stabilisation and Association Agreement(s)

6

SAP

Strategic Action Plan for the Sustainable

Development of the Prespa Park

SEA

Strategic Environmental Assessment

SPP

Greek Society for the Protection of Prespa

TAR

Technical Assessment Report

ToR

Terms of Reference

PPCCToR&OA

Terms of Reference and Operational Arrangements

of the PPCC

UNDP

United Nations Development Program

UNDP

United Nations Development Program Project Document

UN ECE

United Nations Economic Commission for Europe

WWF

World Wild Fund

7

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Implementation of the UNDP-GEF Project "Integrated Ecosystem Management

in the Prespa Lakes Basin of Albania, FYR of Macedonia and Greece" has

began in 2007, after several years of preparation, in a regional environment

described as differences in capacity, commitment and national policy across

borders, which are strong constraints, in addition to questions of national

sovereignty and policies, barriers to free trade, unsustainable productive

activities, political instability etc. However, the entire region hosts unique

habitats and species, important from both a European and global conservation

perspective, which make the ecosystem of Prespa Lakes being considered as

one of the Europe's major transboundary "ecological bricks".

The Project aims to mainstream ecosystem management objectives and

priorities into productive sector practices and policies. It is designed to

strengthen capacity for restoring ecosystem health and conserving biodiversity

first at national level in Albania and FYR of Macedonian Prespa by piloting

ecosystem-oriented approaches to spatial planning, water use management,

agriculture, forest and fishery management, and conservation and protected

areas management. The third littoral State, Greece, which is the member of EU

Community, is not a direct beneficiary of the GEF funding but actively

participates through parallel financing.

The Project also aims to strengthen on-going transboundary co-operation in the

resource managements and conservation, by empowering the existing

transboundary institution Prespa Park Co-ordination Committee, which was

formed pursuant to the Declaration on Protection and Sustainable Development

of the Prespa Lakes and their Surroundings signed by the prime Ministers of the

three littoral States, 2 February 2000.

"Assessment of the Role of the Prespa Park Co-ordination Committee" is a

project task the purpose of which is to provide the review of existing practices

and challenges in trans-boundary ecosystem management and water

governance in the Prespa Lakes Basin. The emphases was expected to be

placed on an assessment of the mostly informal operations of the Prespa Park

Co-ordination Committee over the past six years and the recommendation of

options for the appropriate legal and institutional arrangements for formal and

effective transboundary ecosystem management, water governance and

sustainable development in the Prespa Lakes Basin. Based on the findings of

the assessment, the task comprises formulation of concrete recommendations

and a detailed plan outlining next steps for the institutional maturation of the

PPCC and its future role. The ToR consists of a number of more detailed

requirements, which finally include presentation of the findings of the

assessment at an identified stakeholder workshop for comments and feedback.

Following the accepted Assessment Methodology, a research into the all

relevant issues was undertaken, including a 12-day mission in the three Prespa

Lakes Basin States, with the aim of meeting representatives of various involved

8

authorities and bodies, as well as NGOs interested in the Prespa Lakes co-

operative process, and a short travel to Vienna aimed at participation on the

meeting in the ICPDR, organized for the representatives of the three States,

PPCC Members and Members of the PPCC Secretariat.

As the result, the Technical Assessment Report (TAR) was prepared, consisting

of eight Chapters and 4 Annexes (containing explanatory material relevant to

management of protected area in the Prespa region and this assessment),

Bibliography and List of Acronyms are added.

An Introduction is contained in the Chapter I, with a brief description of Nature

of the Prespa Lakes Basin and history of management efforts, as well as the

ToR and Assessment Methodology. The Chapter II contains a short review of

the mission scope, contents the concise listing of findings--the results of talks.

The Chapter III consists of a review of international and national policy and law

aspects, relevant for the Prespa Lakes Basin. The review is aimed at

highlighting the broader global and UN ECE framework requirements, and

requirements of the Community acquis, and interdependence of national policy

and law systems on those developments.

The Chapter IV contains a legal analysis of trilateral context of the Prespa

Lakes Basin co-operation. The legal nature of the Prespa Park Declaration was

examined, and notes on local level trilateral co-operation were given. The

conclusions based on those findings indicate the policy character of

Declaration, and lack of stronger commitment that would lead to acceptance of

binding regular duties (firstly of the financial character) of the three States. In

the same time, indication was made on significant positive consequences in

trilateral co-operation based on the Declaration, in spite of lack of a firm legal

ground.

The Chapter V deals with description and history of the Prespa Park

Committee, its composition, responsibilities, operational aspects, and

Secretariat, its work and most remarkable results, its legal nature (profile),

relevant financial issues and finally arrives at several conclusions. It points out

the legal character of Tirana International Working Meeting itself and

conclusions adopted there, the legal effects of those conclusions (which

basically are only authoritative recommendations) on the Prespa Lakes littoral

States, and, in that context, the legal and real effects of the PPCC conclusions.

The Chapter VI contains brief reviews of the four successful cases of

international legal regimes established in regards of shared water resources.

Those are Danube River Protection Convention, the Great Lakes Water Quality

Agreement, The Lake Constance treaties, and the Framework Agreement on

the River Sava Basin. The criteria for choosing these four international cases

were their functionality (including financial sustainability) and time duration. All

of them have elements that could be elaborated and examined (in parallel with

other relevant material) for the needs of the future tripartite Prespa Lakes Basin

agreement.

9

The Chapter VII contains some considerations on the Draft Trilateral Agreement

i.e. notes on its legal status, a brief review of its contents and several notes

instead of conclusions. Detailed examination of the text was not done due to its

complexity. The text should be used during official trilateral consultations,

together with other relevant materials.

The Chapter VIII contains recommended activities, order of steps and time

frame. Instead of recommending a ready made solution that would bring

institutional and financial sustainability, the TAR suggests a process of official

consultation (expert level work) of the three Prespa Lakes Basin States to be

established that would lead to development of a text of trilateral agreement in

regards of the Prespa Lakes Basin, and all legal and financial documents

necessary for establishment and beginning of work of a Prespa Management

Committee, agreed on in such an agreement. Additionally, several research and

administrative activities are proposed to be undertaken with aim of providing

various details in regards of national legal systems of the three States, expected

to be needed for the consultation work, and supporting the Prespa process itself

at the international stage. A graphic chart with detailed time frame, spanning a

period of 36 months was attached.

10

I.

INTRODUCTION

1.

Brief on Nature of the Prespa Lakes Basin

The Prespa region, situated in the Balkan Peninsula and encompassing parts of

Albania, FYR of Macedonia and Greece, is a high altitude basin that includes the

interlinked Macro Prespa and Micro Prespa Lakes and their surrounding

mountains. It is considered to be an ecosystem of global significance and has been

identified as one of Europe's 24 major trans-boundary "ecological bricks". The

entire Prespa region hosts unique biotopes that are important from both a

European and global conservation perspective. The lakes and wetlands are

important over wintering, breeding and feeding sites for numerous species of birds.

The flora is composed of over 1,500 species, of which 19 are endemic. The aquatic

ecosystems are also rich in endemic species and the avifauna is highly diverse,

and includes the world's largest breeding colony of the globally vulnerable

Dalmatian pelican and the endangered Pygmy cormorant. The lake area also hosts

mammals, such as bear, wolf and lynx that are endangered in Europe. In addition,

the lake region is considered to be of great cultural and historical importance.1

The unique values of this ecosystem, however, are being progressively eroded

because of either changes in or intensification of specific human activities including

unsustainable patterns of exploitation of natural resources, and inappropriate land-

use practices that result in progressive soil and water contamination, loss of forest

cover, erosion and wildlife loss. Prolonged drought and tectonic activity over the

past two decades have also contributed to a several meter decrease in the water

level in the lakes. Since the Prespa Lakes region extends across national

boundaries, it is also subject to different, uncoordinated and even conflicting

management regimes and policies, which further exacerbate the threats to the

ecosystem as a whole, and make unilateral and piecemeal response measures

ineffective.2

2.

History of Management Efforts

Thus, the development and implementation of a regional, integrated approach to

the region's conservation and management is of paramount importance. The

Governments of the three Prespa Lakes littoral States have recognized the

importance of conserving the region's biodiversity through setting up a number of

legal regimes establishing of the five protected areas3, i.e.:

· In Albania, the Prespa National Park4 was established in 1999, for rehabilitation

and sustainable protection of critical terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems of

Macro and Micro Prespa Lakes area;

1 Taken over from: Terms of Reference Prespa Park Co-ordination Committee, REPORT OF

THE SECOND EXTRAORDINARY MEETING OF THE PRESPA PARK CO-ORDINATION

COMMITTEE, Annex II. Web site: http://www.medwet.org/prespa/park/PPCCextraordinary2.pdf.

Last visited 28.10.2007.

2 Ibid.

3 The data taken over from: REPORT OF THE SECOND EXTRAORDINARY MEETING OF

THE PRESPA PARK CO-ORDINATION COMMITTEE, Annex I. Also can be found on the web

site http://www.medwet.org/prespa/basin/areas.html.

4 National Park is the IUCN Category II protected area, managed mainly for ecosystem

protection and recreation. It is a natural area of land and/or sea designated to:

a) Protect the ecological integrity of one or more ecosystems for present and future generations;

11

· In Greece, the Prespa National Forest (in accordance with national forestry

legislation) was designated in1974 for protection of Micro and Macro Prespa

lakes and their catchment area. In 1975, the same area was declared a

"landscape of exceptional beauty"5. Micro Prespa was declared a Ramsar Site6

in 1974 and, recently, Greece applied for the recognition of the Macro Prespa

as a designated Ramsar site.

The Greek side of the Prespa wetland system is a special Protection Area

(SPA), under the EEC Birds Directive7. The entire Prespa Lakes and their

catchment area have been included in the Greek National List of the NATURA

2000 protected sites network, in accordance with EEC Directive on protection

of fauna, flora and their habitats8 and the EEC Birds Directive.

· In FYR of Macedonia, the Pelister National Park was established in 1948, and

Galicica National Park in 1958. Bird Sanctuary Ezerani9 was declared Ramsar

Site in 1996, and Strict Nature Reserve10 and Macro Prespa was declared, in

accordance with national legislation, a Natural Monument11 in 1977.

More on the nature of the proclaimed regimes in the context of IUCN concept of

Protected Area Management Categories, i.e. on the concept origin, on the

management objectives, relevant issues, and description of the IUCN Categories

relevant at the moment for the Prespa Lakes Basin, can be found in the ANNEX I to

this Report. Those data are presented in this Report because of their significance

for determination of scope of competence and tasks of national and international

authorities and bodies responsible for compliance with accepted/adopted

b) Exclude exploitation or occupation inimical to the purposes of designation of the area; and

c) Provide a foundation for spiritual, scientific, educational, recreational and visitor opportunities,

all of whom must be environmentally and culturally compatible. See at web site:

http://www2.wcmc.org.uk/protected_areas/data/sample/iucn_cat.htm. Last visited 28.10.2007.

5 Under the IUCN Category V protected landscape/seascape is protected area managed mainly

for landscape/seascape conservation or recreation. It is area of land with coast or sea as

appropriate, where the interaction of people and nature over time has produced an area of

distinct character with significant aesthetic, ecological and/or cultural value, and often with high

biological diversity. Safeguarding the integrity of this traditional interaction is vital to the

protection, maintenance and evolution of such an area. Id.

6 According to Article 2, Paragraph 1 of the Ramsar Convention, each Contracting party has

right to designate suitable wetlands within its territory for inclusion in a List of Wetlands of

International Importance, maintained by the Ramsar Bureau. According to Paragraph 2,

wetlands shall be selected for the List on account of their international significance in terms of

ecology, botany, zoology, limnology or hydrology. In the first instance wetlands of international

importance to waterfowl at any season should be included.

7 Directive 79/409/EEC of 2 April 1979 on the conservation of wild birds.

8 Directive 92/43/EEC of 21 May 1992 on the conservation of natural Habitats and wild Fauna

and Flora.

9 Bordering northern section of the Macro Prespa Lake, and aimed at protection of migratory

waterfowl and other water bird species.

10 Strict nature reserve/wilderness protection area under the IUCN Category Ia, managed

mainly for science or wilderness protection, is an area of land and/or sea possessing some

outstanding or representative ecosystems, geological or physiological features and/or species,

available primary for scientific research and/or environmental monitoring.

11 Natural monument under the IUCN Category III is a protected area managed mainly for

conservation of special natural features. It is area containing specific natural or natural/cultural

feature(s) of outstanding or unique value because of their inherent rarity, representativness or

aesthetic qualities or cultural significance.

12

international and national legislation in conformity which the protected areas are

declared with.

Commitment to development of a tripartite co-operative approach to the

management of the Prespa Lakes Basin the Prespa Lakes littoral States expressed

through the Prime Ministers' Declaration on the Creation of the Trans-boundary

Prespa Park and the Environmental Protection and Sustainable Development of the

Prespa Lakes and their Surroundings, signed at Aghios Germanos on 2 February

2000. Pursuing such commitment, on the invitation of the Secretary General of the

Ramsar Convention12 delegations from the three Prespa Lakes Basin States,

composed of representatives of environmental authorities and other public

services, as well as NGOs and several international organizations, met at the

International Working Meeting in Tirana on 16--17 October 2000 concluded the

Prespa Coordination Committee for the Prespa Park (PPCC) to be established.13

The PPCC was created as a "provisional" body composed of members

representing national environmental authorities, local communities and NGOs from

the three countries with the voting right and one "ex officio" observer,

representative of the MedWet, without voting right (10 members in total). According

to the position taken by the participants of the Tirana meeting, this "provisional"

body was designed to operate for the period 2000--2002. Its official establishment

was seen to be carried out through a joint document (formal agreement) signed at

the ministerial level, after evaluation of the work of the PPCC at the end of 2002.14

UNDP-GEF Project "Integrated Ecosystem Management in the Prespa Lakes Basin

of Albania, FYR of Macedonia and Greece" was developed with intention to

catalyze the adoption and implementation of ecosystem management interventions

in the Prespa Lakes Basin shared between the three States, that would integrate

ecological, economic and social goals with the aim of conserving globally significant

biodiversity and conserving and reducing pollution of the transboundary lakes and

their contributing waters.15 The Assessment of the PPCC in Transboundary

Ecosystem Management, which this report is dealing with, is a Project task the

realization of which falls at the beginning of the Project implementation.

3.

Terms of Reference

This Report is the expected output based on the findings of research activities

carried out in accordance with the ToR, attached in the ANNEX II to the Report.

4.

Methodology

The methodology applied for fulfilling the tasks designed in the ToR, comprised:

· Detailed planning of all expected activities, including making of an analytical

review of the project task and expected results;

12 UN Convention on Wetlands of International Importance Especially as Waterfowl Habitat,

signed at Ramsar, 2 February 1971.

13 See Conclusions 1-5.

14 Appendix I to the Conclusions of the International Working Meeting. For more details on

further developments in trilateral co-operation in regards of Prespa Lakes Basin and various

aspects of the PPCC and its operations see infra Chapter V.

15 UNDP Full Size Project Document, Brief Description.

13

· Collection of relevant national documentation;

· Identification of applicable international policy and legal regimes;

· Analysis and systematization of collected material;

· A field mission in all three Prespa Lakes littoral States in order to meet

representatives, members, staff and experts of authorities, bodies and

organizations involved/interested in the Prespa process;

· A one-day travel to Vienna with the aim of participation in visit and talks with

representatives of the ICPDR, together with the PPCC Members, Members

of the PPCC Secretariat and representatives of environmental authorities of

the three Prespa Lakes littoral States;

· Preparing plan (contents) of Technical Assessment Report (TAR);

· Preparing Draft of (this) TAR;

· Presentation of TAR at a workshop open to the widest circle of stakeholders;

· Preparing and delivery the Final TAR on the basis of Draft TAR and

feedback of involved organizations and experts.

Detailed Assessment Methodology has been given in the ANNEX III to this

Report.

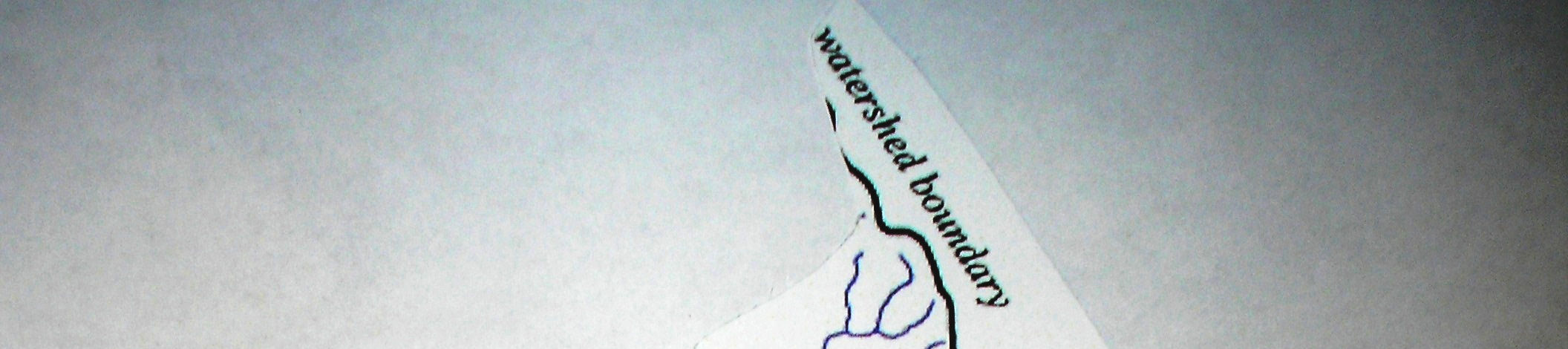

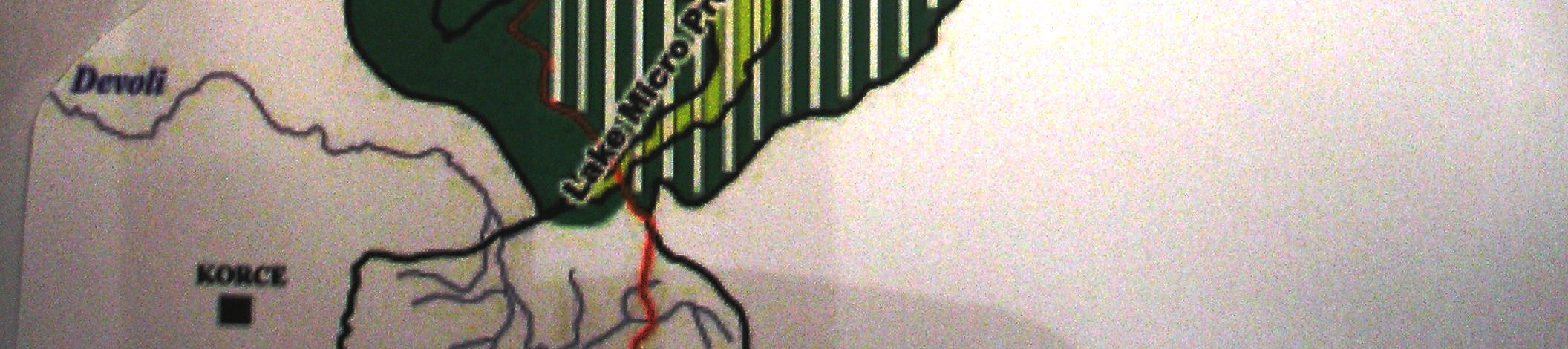

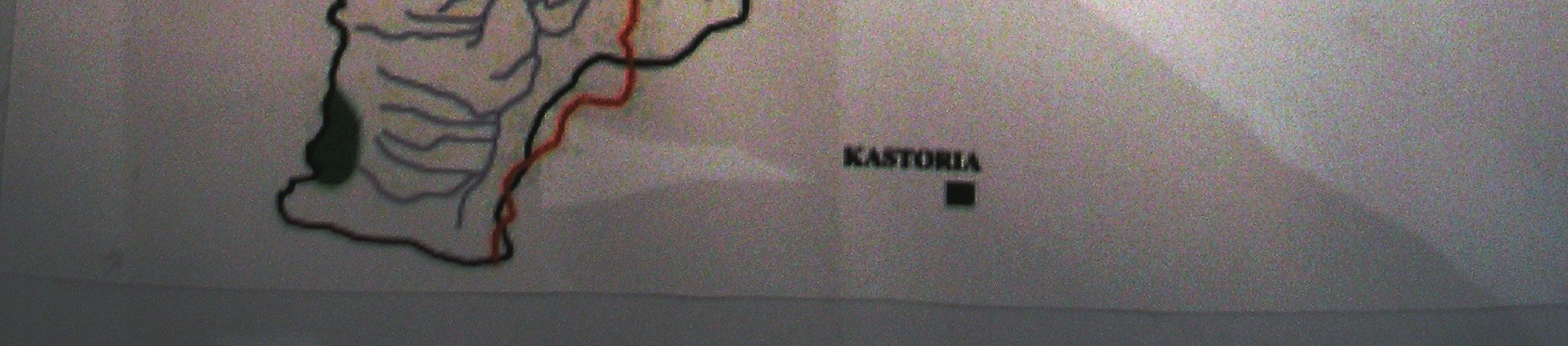

The Prespa Lakes Basin*

* Source: O. Avramoski: ANALYSIS OF PUBLIC PARTICIPATION PRACTICES IN

ECOSYSTEM APPROACHES TO ENVIRONMENTAL MANAHEMNT IN THE REGION OF

OHRID AND PRESPA LAKES, p. 72.

14

II.

MISSIONS SCOPE, CONTENTS AND FINDINGS

According to the ToR, a mission was designed with the aim of collecting

information on sources relevant for this project and on current views on the

Prespa process that would indicate commitment in the three States to further

development of the Prespa process and establishment of a trilateral sustainable

institutional arrangement, based in international law, with a secretariat regularly

funded by the budgets of all three Prespa Lakes littoral States. UNDP Home

based FYR of Macedonia planned the mission, organized meetings and

provided all needed logistic support. The mission was realized smoothly,

without delays and almost fully in accordance with plan, in the period 15--26

October 2007. What only were missing from the list of activities were meetings

with the representatives of MFAs of Greece and FYR of Macedonia. In a tight

time schedule it was not possible to arrange such meetings, despite repeated

attempts of the hosts. Additionally, a three-days mission to Vienna was

organized and undertaken 5--7 November, with aim of participate at the

meeting of the Governmental representatives, PPCC and NGOs with the

ICPDR officials.

The mission in three countries comprised travels, meetings and discussions.

The mission had began from Resen (FYR of Macedonia), continued in Aghios

Germanos, Municipality of Prespa and Athens (Greece), Tirana, Korca and

Municipality of Liqenes (Albania), Resen, Skopje and again Resen (FYR of

Macedonia) where it was finished.

During the mission, numerous meeting were held with:

· UNDP and Project personnel;

· WWF Greece and Ramsar Med/Wet representatives and experts;

· Representatives, members, staff and experts of national environmental and

water authorities;

· Representatives of the IPA Unit of the Ministry for Integration and MFA

Albania;

· Regional authorities, bodies and organizations competent for various

aspects of the Prespa Lakes Basin;

· Mayors of the three Prespa Lakes Municipalities (Liqenes, Prespa and

Resen);

· Representatives of national NGOs involved in the Prespa Process (SPP,

P.P.N.E.A);

· Representatives of local NGOs active in the Prespa area and their coalition

in FYR of Macedonia;

· Representatives of business interests;

· PPCC Members and members of its Secretariat.

More details on the mission and activities that follow are contained in the

Debriefing Note and List of Participants in Talks during the Mission, attached to

this report in ANNEX IV.

Various information and documents collected during the mission were used for

writing of this Report. The facts noted are presented elsewhere in the Report

15

and there is no need for reporting here in detail on each of talks. Yet, a brief list

of specific details from the meetings and talks during the mission, concerning

views on and observations of some aspects of on-going cooperative trilateral

Prespa process and future set-up are worth to be given here. They indicate

differences and similarities in views expressed during the talks. Follows a

condensed and non-exhaustive review of opinions, observations, and

proposals:

· Cooperation between three States in regards of Prespa is possible at the

technical level. There is green light for funding programs by Greek

Government, but there are difficulties with legal technicalities. So such

funding had been provided through the NGOs. That solution is not negative,

but better one should be found.

· In search for such solution, political issues should be isolated from

environmental ones. The opinion was expressed that it is still premature for

legally binding agreement between the three Prespa States, But, it was

noted that there are no criteria of such maturity. In any case, no proposal

should be put without previously provided political support. Possible legal

options/arrangements should be explored;

· It is pointed out that entire trilateral co-operation is going through the

national environmental authorities. But those authorities need a proper legal

basis for work. The work on co-operation should be better organized, and

based on an instrument legally stronger than the PMs Declaration;

· The Prespa process co-operation has by now been driven by NGOs,

because of lack of commitment of the Governments and lack of leadership.

All questions and dilemmas should be put at the table clearly. There is need

for new and strengthened mandate. Now is time to put proposal(s) that could

not be avoided;

· Continuation of the Prespa process should be carried on through renewal of

political support. In case of consultations, the consultation process should be

defined;

· A process of (technical) consultations could be initiated and lobbying in

favour of such process would help;

· The basic problem in the Prespa region is political; social-economic

problems come after that. Solution of political problems will bring economic

and social revival into the region;

· Additionally, it was expressed expectation that political obstacles for full

transboundary cooperation shall be lifted soon, what could provide

spectacular results;

· National Parks have been included into the PPCC activities as observers.

National Parks in FYR of Macedonia and Albania have good cooperation

that is developing in a good direction. Such cooperation between FYR of

Macedonia and Greece is conditioned by opening a cross border point and

ease of visa regime.

· The on-going is preparation of drafting and signing a trilateral Protocol on

Collaboration of the Municipalities from three States, adjacent to Prespa

lakes (i.e. Liqenes, Prespa and Resen). This has been considered as having

a (strong) symbolic political significance;

16

· The transboundary cooperation in the Prespa region is affected by the

existing visa regime;

· There is need for opening a new border cross between Greece and FYR of

Macedonia in Markova Noga;

· The Euro Region comprising Prespa area (inter alia, in FYR of Macedonia

the Prespa area and Municipalities of Bitola, Prilep and Ohrid) has facing

functional difficulties. The cause has been seen as coming from the fact that

the Euro Region does not have its own institutional structure, but has been

run through the national authorities;

· The EU integrations have been seen as very important for the Prespa

region, and ways are looking for joint (transbondary local level) programs

that could be funded by EU;

· A tripartite agreement on Prespa Park area, as the only proper solution, has

been drafted and it should be considered at the informal meeting of three

Ministers competent for environmental protection, which should decide on

action to be taken. It was expressed opinion that Albania could facilitate

such communication;

· There are no legal obstacles for conclusion of a trilateral Prespa Lakes

Basin treaty. The obstacles were supposed to be political only;

· The Draft of Trilateral Prespa Agreement was initiated by the PPCC and

worked out by the MedWet Office;

· A trilateral MoU could be signed between environmental Ministers, which the

three Governments would confirm. Such instrument would be the ground for

requesting international donors support;

· Another idea vas mentioned, i.e. the UNDP to develop a text of draft

trilateral agreement on the Prespa Lakes Basin;

· Further activities (i.e. technical consultations) on drafting the Prespa

agreement and establishment of an international personality for co-

ordination should be financed by the UNDP project;

· Agreement on process of technical consultations should be reached. Such

process should be initiated as soon as possible. It was estimated that the

entire process would last some two and a half years.

*****

· In forthcoming activities regarding conclusion of a (new) Prespa treaty,

facilitating of the process by prominent international organizations (e.g. EC,

CoE, UNECE, OSCE and others) would be acceptable and beneficial;

· Involvement of international organizations into further activities regarding

Prespa process would be welcome;

*****

· The members of the PPCC Secretariat, representing the P.P.N.E.A (AL) and

Coalition of NGOs Resen, have been working without any compensation;

· The problem of PPCC is capacity of personnel. The members of Secretariat

should be paid for their work.

· The Secretariat of the PPCC acting through the NGOs is no more workable

solution. Governments of three States should provide funding regularly;

17

· The Ohrid Lake Secretariat was formed on the request of World Bank, after

finalization of a project funded by World Bank. After completion of the UNDP

project the Prespa Committee should be established with a strong legal

position;

· The PPCC should continue its operations until new institution is set-up;

· For the Prespa Lakes Basin a permanent body should be established. The

case of the Lake Constance should be studied;

*****

· The idea of an international conference having the Prespa process in focus

would be beneficial;

· The possibility for forming an International Prespa Trust Fund should be

investigated;

· Environmental

impact

assessments

and

strategic

environmental

assessments are important for the Prespa Lakes Basin;

· Spatial planning and water management should be incorporated into the

Prespa process;

· The role of Integrated Water Management of the Prespa Lakes Basin should

be recognized and stressed;

*****

· MFA of Albania would be happy to help in developing the treaty on Prespa

Lakes Basin and express wish to be included into the consultation process

on that subject;

· It is pity that Albanian Ministry of Integration was not involved in the Prespa

process. The Ministry would like to be included in further activities, which

shall be supported;

· MFA of the FYR of Macedonia must be included in the forthcoming activities

regarding Prespa Lakes Basin;

*****

· Different stakeholders (NGOs, protected areas, business associations) need

various kind of support in order to be able mutually to connect closer and

participate in the Prespa Lakes management process;

*****

Open talks during the mission on certain legally specific details in regards of

composition of administrative structure of the future trilateral institutional Prespa

Lakes Basin set-up have risen concerns from the NGO sector16 that all the

cooperation process developed by now would collapse if representatives of

NGOs, Municipalities and Protected Areas are not included as members of

future management body (with decision-making power). As a paradigm for

choosing appropriate solution, the Ohrid Lake Agreement was proposed, as

well as current trend of forming stakeholder representative bodies for

management of protected areas in Greece and FYROM.

Detailed discussion on such specific issues at that stage of the assessment was

terminated, with the notes that nobody has ready-available solution for the

16 Namely, concerns were expressed on supposition that a solution is going to be proposed

comprising only States' representatives in the future Prespa coordinative body (with decision-

making power) without having representatives of NGOs and other stakeholders in that decision-

making body, but only as positioned in the decision-making advisory body/bodies,

18

Prespa Lakes Basin management and that nobody can bring solution to any

region from somewhere outside The solution should not be a set-in-advance-

option and must be arrived at through the process which will result in the feeling

of ownership of all participating parties.

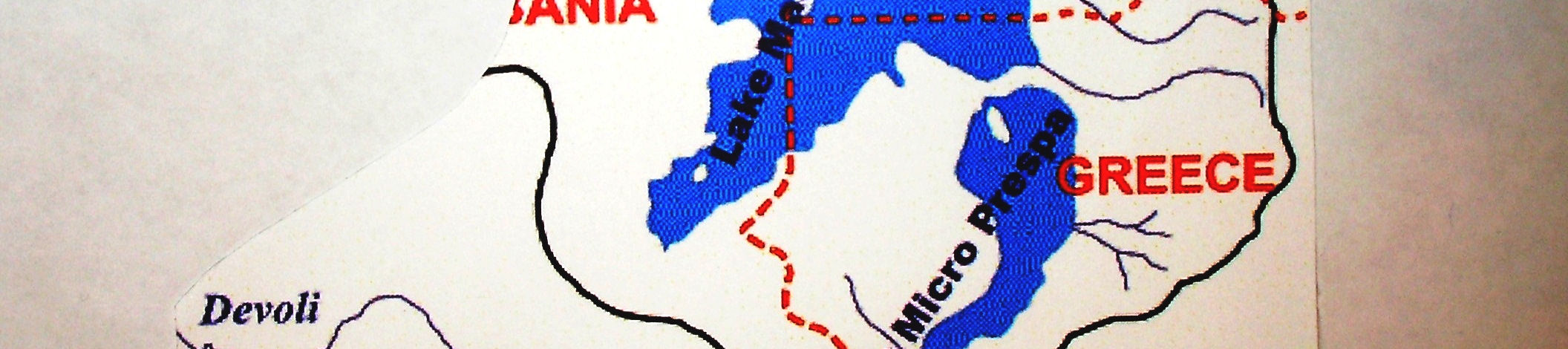

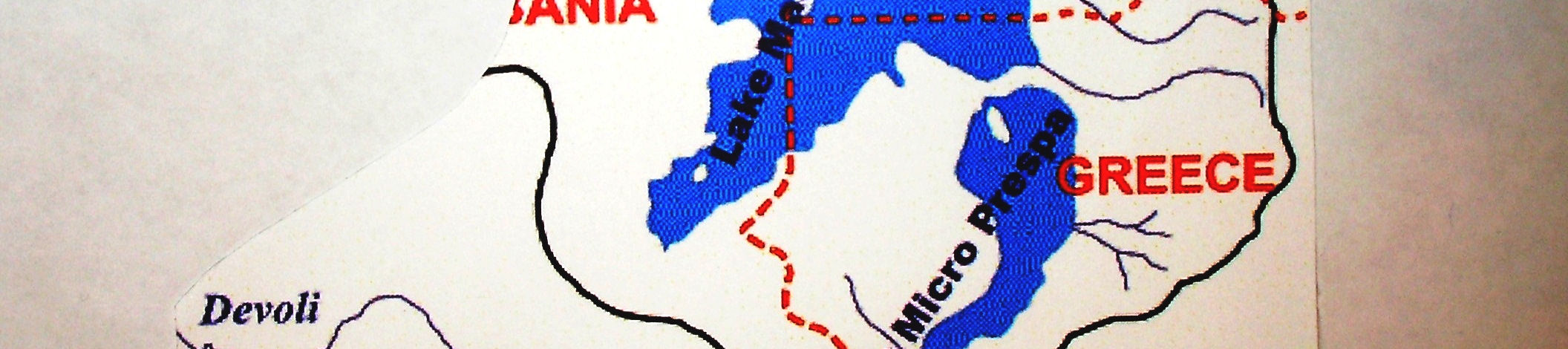

The Prespa Lakes Basin Protected Areas **

** Source: O. Avramoski: ANALYSIS OF PUBLIC PARTICIPATION PRACTICES IN

ECOSYSTEM APPROACHES TO ENVIRONMENTAL MANAHEMNT IN THE REGION OF

OHRID AND PRESPA LAKES, p. 81.

19

III.

THE PRESPA LAKES BASIN IN INTERNATIONAL AND NATIONAL

POLICY AND LAW CONTEXT

1.

Introductory Notes

Instruments of international law and policy relevant to various aspects of water

resources and environment could be classified in different ways. For example,

concerning their territorial scope they could be global and regional, multilateral

and bilateral, as river/lake basin or sub-basin related etc. They could be

classified as legally binding (e.g. international treaties, like conventions,

agreements, protocols etc), "soft-law" (representing non-binding, evolving law,

law in development), or policy instruments (expressing commitments of certain

subjects to adopt certain decisions and measures etc.) There is no need for

further elaboration of this, more or less theoretical issues.

It is important to note that nowadays a huge variety of international law and

policy instruments relates to the same natural phenomenon, focusing often on

one or several of its aspects. Compliance (transposition, implementation,

enforcement) with international duties taken over through signing a binding legal

instruments is as a rule split between different national authorities, being

competent for certain issues only (and often having different and conflicting

views). So, an integrative (ideally it would be a holistic) approach, that would

comprise such management dimensions as preservation, protection and use of

natural resources in an area, as well as economic and social development

(what would be comprised by the concept of sustainable development) is a real

challenge for national authorities competent for a shared natural unit (for

instance river/lake basin). Therefore the issue of good governance is under

rising attention whenever transboundary cooperation is at stake.

2.

Global and European Instruments

The Prespa Lakes Basin is not an exemption in that sense. The table attached

bellow shows a list of binding international instruments applicable at the

moment, inter alia on the Prespa Lakes Basin too, with data indicating the

status of the three Prespa Lakes Basin States. It is possible to note that there

are several global multilateral conventions developed under the aegis of UN or

its agencies and several regional multilateral conventions developed in Europe

by CoE and UNECE. Indication on status of the Prespa Lakes Basin States is in

the same time indication on the commitment of the States to sign and ratify the

listed international treaties. Commitment to implement of those treaties is

another and separate issue. Compliance of the State with those treaties should

be seen today but as much as in future in the context of the EU integration

processes. The reason for this is the fact that European Community is the Party

of a number of them, making them a part of the Community Acquis.

It is evident that the list is not exhaustive. It could be broadened. However, it is

not possible to make an exhaustive and comprehensive review of binding

international instruments in the framework of this Assessment. What is more

important is clear pointing out the problem of transposition of all those

instruments into the national law systems and their enforcement.

Implementation of listed global and regional instruments is of the same legal

20

nature for all three countries of the Prespa Lakes Basin. They are equal Parties

to those conventions, and share responsibility with other contracting parties for

achievement of the goals established by those instruments.

It is should be noted that the three littoral States of the Prespa Lakes are not the

parties to all the listed international treaties. The most interesting thing is the

case of the UN Convention on the Law on Non-Navigational Uses of

International Watercourses (New York, 1997) that was signed by the all three

States and yet not ratified. Further, FYR of Macedonia is not the Party of the

Convention on the protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and

International Lakes (Helsinki, 1992), Albania and FYR of Macedonia still did not

ratify the Protocol on Strategic Environmental Assessment (Kiev, 2003), and

Greece did not ratify PRTR Protocol (Kiev, 2003). Lack of ratification of those

international treaties the EC is the Party of is a signal that there is not yet

political will of the States to be bound by those international treaties. In spite of

that fact, all three littoral States (the Greece being an EU Member State, and

other two being the SEE States participating in the process of stabilisation and

association with the EU) are in position to implement those international treaties

whether through their duties as Parties of them or through duty to transpose,

implement and enforce Community acquies part of which are in compliance with

those international treaties.

List of International Law Agreements Relevant for the Prespa Lakes Basin

Status of Signatories and Ratification17

Albania

Greece

FYR of Macedonia

Title

Signed

Ratified

Signed

Ratified

Signed

Ratified

GLOBAL INSTRUMENTS

UN Convention on Wetlands of

International Importance,

X

X

X

especially as Waterfowl

1994

1975

1991

Habitat (Ramsar, 1971)

UN Convention on

International Trade in

X

X

X

Endangered Species of Wild

2003

1992

1999

Flora and Fauna (CITES)

(Washington, D.C., 1973)

UN Convention on Migratory

Species and Wild Animals

X

X

X

(Bonn, 1979)

2000

1999

UN Convention on Biological

Diversity (Rio de Janeiro,

X

X

X

1992)

1994

1994

1994

Cartagena Protocol on

Biosafety to the Convention on

X

X

X

Biological Diversity (Montreal,

2005

2004

2006

2000)

UN Convention on the Law on

Non-Navigational Uses of

X

X

X

International Watercourses

1997

1997

1997

17 The data shown in this Table were collected from: UNDP, ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY IN

SOUTH-EASTERN EUROPE, and the web sites of listed legal instruments

21

(New York, 1997)

UNESCO Convention

Concerning the Protection of

X

X

X

the World Cultural and Natural

1989

1981

1974

Heritage (Paris, 1972)

COUNCIL OF EUROPE (CoE)

Convention on the

Conservation of European

X

X

X

Wildlife and Natural Habitats

1998

1983

1999

(Bern, 1979)

UNITED NATIONS ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR EUROPE (UNECE)

Convention on Environmental

Impact Assessment in a

X

X

X

Transboundary Context

1991

1998

1999

(Espoo, 1991)

Convention on the Protection

and Use of Transboundary

X

X

Watercourses and

1994

1996

International Lakes (Helsinki,

1992)

Convention on Access to

Information, Public

X

X

X

Participation in Decision-

2001

2006

1999

making Process and Access to

Justice in Environmental

Matters (Aarhus, 1998)

Protocol on Strategic

Environmental Assessment

X

X

X

(Kiev, 2003)

2005

2003

2003

Protocol on Pollutant Release

and Transfer Registers (Kiev,

X

X

2003)

2003

2003

3.

Community Acquis

In regards of Community acquis, the situation is significantly different. Specific

legal instruments (Directives, Regulations and Decisions) adopted in EU are

making the part of the Community acquis. A non-exhaustive list of the most

important EC legal instruments relevant to the subject matter of this Report is

attached bellow.

It is important to note that the Prespa Park Process, that has began in 2000 as

rooted in certain global legal frameworks (Ramsar Convention and MedWet

Initiative) was parallel to the processes of stabilization and association (SAA) in

Albania and FYR of Macedonia. With development of the SAA, the Prespa

Lakes Basin has become subject to the specific legal regimes developed in EU,

much broader and stronger (than policy commitment contained in the Prespa

lakes declaration) and relying on the consent of the States to be bound by them

(largely through adopting SAAs with EC).

Greece as an EU Member Sate participates with other Member States in

development of Community acquis and shares Community acquis as a part of

its national law system (the EU Directives being transposed into the national

legislative instruments) with other EU Member Sates. That means that Greece

22

has duty of enforcement of legislation containing transposed requirements of

EU, and duty of reporting on enforcement to the European Commission.

Naturally, this is not an abstract duty, but obligation comprising all the

instruments listed bellow. As an indication on the level and pace of Greece

compliance (or commitment to comply in accepted time frame) with the

Community acquis can serve the following case. The Commission of the

European Communities, as a powerful watchdog of the constitutive EU treaties,

submitted in 2007 its first report on the first stage in the implementation of the

Water Framework Directive 2000/60/EC. Analysis of transposition of the

Community acquis into the national legal system of Greece (EU 15 country) has

revealed that the transposition had been only partially completed, and a "non-

conformity" case was opened in 2005 and application to the Court has been

submitted.18 Greece adopted a Presidential Decree19 aimed at the fulfilment of

duty of transposition, but the assessment still has to be done.20 Today, in the

time of finalization of this Report there is a competent authority in place in

Greece, the river basin districts are designated and Greek part of the Prespa

Lakes Basin is a part of the Water District Western Macedonia.

In case of Albania and FYR of Macedonia, the situation is different. The both

countries are on their ways of accession to EU. Among other things the

accession process comprises transposition of entire Community acquis into

their national law systems. In this case, all the EU Directives relevant to water

river/lake basin and ecosystem management are expected to be transposed

into national legal systems, the new legislation implemented and enforced.

Therefore the structural changes of their law systems are in place. The old

legislation inherited from former socialist times and adopted during times of

evolving democracy must be harmonized with the EU requirements and new

legislation adopted, in a planned (and time-consuming) process.

Among other things, the both States adopted new laws relating to waters aimed

at transposition of the EU acquis.21 Assessment of the level and quality of

transposition of the EU requirements in these (and other relevant laws) is

subject to a specific activity of the authorities of both States and EC. It is not

possible in this Report to give any such kind of assessment. What can be

pointed out is the duty of the EC periodically to assess progress in association

process of both countries and initiate specific activities aimed at transposition of

the acquis, and its implementation and enforcement in the frameworks of

national legal systems.

18 C-426/06..

19 On 8 March 2007.

20 Commission STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT accompanying document to the

COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND THE

COUNCIL "Towards Sustainable Water management in the European Union", Brussels,

22.03.2007, SEC(2007) 362, p. 10.

21 For example, Albania adopted the LAW No. 9 103, date 10.7.2863 ON THE PROTECTION

OF TWMSBOUNDARY LAKES, and FYR of Macedonia Water Law, ("Official Gazette of the

Republic of Macedonia" No. 4/2008).

23

These integrations processes were addressed by the recent Environmental

Ministerial Conference Environment for Europe"22 Namely, the success of

regional environmental cooperation was seen as based on being deepened and

extended to include inter alia:

· Regional cooperation in the framework of Stabilization and Association

Process;

· Implementation of UN ECE multilateral treaties;

· Biodiversity conservation and ecological network;

· Protection and sustainable development of mountain areas;

· Watershed management such as Sava River Basin Commission;

· Environmental management and investments at the local level;

· Cooperation with other sectors such as agriculture and tourism;

· Stronger and more dynamic coordination of donor assistance;

· Transfer of experiences between the countries in the region and from the

neighbouring EU Member States.23

In such circumstances the new trilateral legal and the Prespa Lakes Basin

institutional set-up for the Prespa Lakes Basin should be developed. All those

details relating to compliance of the three States with their internationally

accepted duties, as well as details (including time-frame) in regards of

transposition of EU requirements and implementation (enforcement) of new

legislation, are important for adequate and proper designation of scope of

competence of future Prespa Lakes Basin institution and as much as possible

exact definition of its role in transboundary cooperation in regards of integrated

ecosystem management of the Prespa Lakes Basin.

Added should be that a detailed review of national authorities competent for

implementation of relevant international treaties and transposition of the

Community acquis, with their specific responsibilities in regards thereof, and

mutual official relations, should be clearly known to official drafters of the text of

trilateral Prespa Management Agreement.24 Representatives of those

authorities should bee invited to participate in development of relevant parts of

the Agreement.

22 Held in Belgrade, September 2007.

23 UNDP, ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY IN SOUTH-EASTERN EUROPE, Podgorica, 2007

24 It is the reason that a Rapid Comparative Legal Assessment of Cross Cutting Issues was

proposed to be undertaken at the very beginning of the process of trilateral consultations. See

infra, p. 77. Such approach was the basis for preparation a UNDP study entitled DESCRIPTION

AND ASSESSMENT OF THE MACEDONIAN LEGAL, REGULATORY, AND INSTITUTIONAL

FRAMEWORK, by Andreja Stojkovski in 2004. The structure of investigation and findings is

exactly to what seems now being necessary at disposal of participants of the tripartite

consultation process, if, of course such idea is accepted. The findings relating to FYR of

Macedonia seam now outdated and the findings should be reviewed and up-dated. Additionally

the similar structure study should be prepared for both Albania and Greece, and a joint

comparative report should be prepared. Such study, covering comparatively legal issues of all

three countries, would fill the existing gap of legal analysis, notable in many instances.

24

17.11.2007

THE LIST OF RELEVANT COMMUNITY ACQUIS INSTRUMENTS

Directive 79/409/EEC of 2 April 1979 on the Conservation of Wild Birds

Council Directive 80/68/EEC of 17 December on the protection of groundwater against

pollution caused by certain dangerous substances

Council Directive 86/278/EEC of 12 June 1986 on the protection of the environment, and in

particular of the soil, when sewage sludge is used in agriculture

Council Directive of 21 May 1991 concerning urban waste water treatment (91/271/EEC)

amended by the Directive 98/15/EC - (UWWT Directive)

Council Directive of 15 July 1991 concerning the placing of plant protection products on the

market (91/414/EEC)

Council Directive 91/676/EEC concerning the protection of waters against pollution caused by

nitrates from agricultural sources (Nitrate Directive)

Directive 92/43/EEC of 21 May 1992 on the Conservation of Natural Habitat and of Wild Fauna

and Flora

Council Directive 96/61/EC of 24 September 1996 Concerning Integrated Pollution Prevention

and Control

Council Directive 96/82/EC of 9 December 1996 on the major-accidents involving dangerous

substances (Seveso Directive)

Council Regulation (EC) 3897 of 9 December 1996 on the Protection of Species of Wild Fauna

and Flora by Regulating Trade Therein

Council Directive 97/11/EC of 3 March 1997 Amending Directive 85/337/EEC on the

Assessment of the Effects of Certain Public and private Projects on the Environment

Directive98/8/Ec of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 February 1998

concerning the placing of biocidal products on the market

Directive 2000/60/EC of the Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2000 establishing a

Framework for the Community Action in the Field of Water Policy

Directive 2001/42/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 June 2001 on the

Assessment of the Effects of certain Plans and Programs on the Environment

Directive 2003/35/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 May 2003 Providing

for Public participation in respect of the Drawing up of certain Plans and Programs and

Amending with regard to Public Participation and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters

Directive 2003/4/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 28 January 2003 on

Public Access to Environmental Information and Repealing Council Directive 90/313/EEC

Commission Decision of 17 August 2005 on the establishment of a register of sites to form the

intercalibration network in accordance with Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament

and of the Council (C(2005) 3140) (2005/646/EC)

Directive 2006/7/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 February 2006

concerning the management of bathing water quality and repealing Directive 76/160/EEC

(Bathing Water Directive)

Directive 2006/11/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 February 2006 on

pollution caused by certain dangerous substances discharged into aquatic environment of the

Community (repeals Directive 76/464/EEC and partially 91/692/EEC i 2000/60/EC)

Directive 2006/44/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 6 September 2006 on

the quality of fresh waters needing protection or improvement in order to support fish life

Directive 2006/118/EC of the European Parliament and the Council of 12 December 2006 on

the protection of groundwater against pollution and deterioration

Directive 2007/2/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 March 2007

establishing an Infrastructure for Spatial Information System in the European Community

(INSPIRE)

4.

Mediterranean Wetland Initiative (MedWet)

Mediterranean Wetland Initiative was founded in 1991 to encourage

international collaboration among Mediterranean countries, specialized centres

and international NGOs in protecting wetlands. It is governed by the Conference

25

of the Contracting Parties of the Ramsar Convention, which meets once a three

years to review the work carried out by and approve a programme of fork and

budget for the next triennium. The MedWet Committee is composed of 25

Mediterranean countries, Palestinian Authority, The European Commission,

intergovernmental organisations and international conventions and non-

governmental organizations and five wetland centres. The Committee meets

once a one and a half year to review progress in the work undertaken and

advise the Ramsar Convention bodies on issues related to the Mediterranean

wetlands and the work of MedWet.

The MedWet is a forum where its members meet as equal to discuss, identify

key issues and take positive action to protect wetlands, for man and

biodiversity. It is a source of information and knowledge. MedWet helps

Mediterranean countries to evaluate economic, social and biodiversity values of

wetlands, provide technical tools and ensure good management of wetlands. In

2002 MedWet became formally recognized initiative under the Ramsar

Convention. On the 8th Meeting of the Conference of the Contracting Parties to

the Ramsar Convention25 the "Guidance to the Development of Regional

Initiatives in the Framework of the Ramsar Convention" was adopted. The

overall aim of the regional initiatives has been defined in this Guidelines as

promotion of the Ramsar Convention in general and implementation of the

Ramsar Strategic Plan in particular, through regional and sub-regional co-

operation on wetland-related issues of common concern.

Further, regional and sub-regional initiatives were envisaged as be based on a

bottom-up approach, entailing from the beginning not only participation of

administrative authorities, but also other relevant stakeholders. Such initiative

was also seen as basing its operations upon strong scientific and technical

backing and on the network of collaboration established upon clearly defined

terms of reference and seeking collaboration with other intergovernmental or

international partners. In this document, a regional initiative was directed to

require both political and financial support from the Contracting Parties of the

Ramsar Convention, and other partners in the region. Financial support from

the Ramsar Convention's core budget was envisaged to last in principle not

more than three years, and after that period, financial support should be phased

out, with expectation that such regional initiative is able to generate its own

resources and become financially self-sufficient.26

Analyses of legal implications of above concisely cited rules contained in the

Ramsar Guidelines would fall far beyond the scope of this TAR, and moreover

there is no specific need for that. However, noted must be that the legal side of

proposed regional and sub-regional initiatives (i.e. legal and institutional aspects

of such co-operation) remained in the Guidelines completely out of perception.

Between political commitments, which are naturally unavoidable in interstate co-

operation, and sustainable funding of a transboundary institutional

arrangements and activities, without which there would be no co-operation at

25 Held in Valencia, Spain, 18--26 November 2002.

26 Ramsar Contracting Parties 8th Meeting (COP8), Resolution VIII, Annex I, p. 3.

26

all, a reliable legal framework should be adopted, without which the gap

between certain political will and desired sustainable results cannot be bridged

over. The case of Prespa Lakes Initiative clearly proves this.

5.

Other Relevant International Initiatives

Besides the MedWet Initiative, other European initiatives aimed ultimately at

halting biodiversity loss should be mentioned here, as relevant to the Prespa

Lakes Basin. All three Prespa Lakes Basin States have been participating in

those initiatives and on-going activities, expressing their commitment to achieve

goals jointly designated with other participating countries.

The Pan-European Ecological Network (PEEN) is "a non-binding conceptual

framework which aims to enhance ecological connectivity across Europe, by

promoting synergies between nature policies, land-use planning and rural and

urban development at all scales".27 Following was the Resolution on Biodiversity

adopted at Kiev by the environment ministers in 2003, which committed them to

identifying the core areas, corridors and buffer zones of the PEEN, by 2006 and

put such areas and zones under favourable management conditions by 2008.

The core areas have been formally designated as protected areas (e.g. Ramsar

sites, World Heritage sites, Biosphere reserves, Natura 2000 sites, etc). A

Guideline was developed for designation and development of the Pan-

European Network28.29

The Natura 2000 is a network consisting of Special Protection Areas under the

Birds Directive and Special Conservation Areas under the Habitat Directive. An

European Commission Communication calls for Member States of the EU to

"reinforce the coherence and connectivity of the Natura 2000 network. It also

highlights the need to restore biodiversity and ecosystem services in non-stop

protected rural areas of the EU. Compliance with those objectives is the key to

the implementation of the PEEN within the EU".30

The CoE Emerald network initiative (1999) has been seen as a very successful

for the EU-12 countries in preparing their contribution to the Natura 2000

network before accession. The initiative has been developed under the Bern

Convention, aimed to extend a common approach to the designation and

management of protected areas, equivalent to Natura 2000, to non-EU

countries in Europe and countries in Northern Africa.31

27 CoE: 3rd International symposium of the Pan-European Ecological Network Fragmentation

of Habitats and Ecological Corridors Proceedings; Riga, October 2002; Environmental

Encounters No. 54, Council of Europe, Strasbourg, 2000.

28 General Guidelines for the Development of the Pan-European Ecological Network; Nature

and Environment Series, No. 107, Council of Europe, Strasbourg, 2000.

29 EEA: EUROPE'S ENVIRONMENT--THE FOURTH ASSESSMENT, Copenhagen, 2007, pp.

186--187.

30 Op. cit. pp.190--192.

31 Op. cit. pp.190--192.

27

IV.

TRILATERAL CONTEXT

1.

Prespa Park Declaration

1.1

Event

The celebration of the World Wetland Day, 2 February 2000, on the occasion of

29th anniversary of the signing of the Ramsar Convention, was the event when

the Prime Ministers of the three States Contracting Parties to the Convention,

i.e. of Albania, Greece and FYR of Macedonia, had met in Aghios Germanos,

Greece, to sign the Declaration on creation of the Prespa Park32. The Prespa,

an area which was said as being "beyond its pure environmental importance

[...] a meeting point between three countries and a crossroads of cultural

exchanges"33, was for a moment in world focus, the place where indication of

"necessity to create a `planetary patriotism'" was expressed, with full awareness

that survival of natural environment should be a subject of elaboration of the

highest national authorities34.

The event, which was considered a part of "the all-round process of

reconstruction of South-Eastern Europe [...]" offering "the right opportunity to

integrate our environmental concerns in such sectors as economic development

and infrastructure"35, marked the beginning of a trilateral process requiring

"political commitment, significant investment and a lot of work in research,

innovative development projects and training."36 With signing the Declaration,

the PMs committed themselves to "join forces across the borders of their

sovereign nations to establish a protected area that should provide great

benefits for the local people and at the same time should contribute to

conserving biodiversity of the planet".37

1.2

Content

The Declaration consists of six Paragraphs, expressing agreement, recognition,

awareness, decision to declare and commitment for enhancing cooperation, of

the Prime Ministers of the three Prespa Lakes littoral States.

The PMs agreed that the Prespa Lakes and their surrounding catchments have

significant international importance due to uniqueness of their:

· Geomorphology;

· Ecological wealth; and

· Biodiversity.

32 Declaration on the Creation of the Prespa Park and the Environmental Protection and

Sustainable Development of the Prespa Lakes and their Surroundings.

33 Address at World Wetland Day ceremonies by H.E. Mr Costas Simitis, PM of Greece. See

web site: http://www.ramsar.org/wwd/0/wwd2000_rpt_prespa2.htm. Site last visited 04.12.2006.

34 Address at World Wetland Day ceremonies by H.E. Mr Ljupco Georgievski, PM of FYR of

Macedonia. Id.

35 Address at World Wetland Day ceremonies by H.E. Mr Ilir Meta, PM of Albania. Id.

36 Mr Delmar Blasco, Secretary General of the Ramsar Convention.

37 Id.

28

Besides, the Prespa Lakes and their surroundings:

· Provide habitat for various and rare species of flora and fauna;

· Offer refuge for the migratory bird populations;

· Constitute a much needed nesting place for many species of birds

threatened with extinction.38

The Declaration recognized that conservation and protection of the ecosystem

of such importance, not only renders a service to Nature, but also:

· Creates opportunities for the economic development of adjacent areas in

littoral countries;

· Proves compatibility of traditional activities and knowledge with conservation

of nature.39

The Declaration expressed awareness of large dependences of conservation of

Nature and sustainable development on respecting of governments and people

of international legal instruments aimed at protection of natural environment. In

that regard, international collaboration has been seen as complementing

national efforts.40

The Declaration recognized the value and importance of work of NGOs,

apparently pointing out the work of the Greek Society for the Protection of

Prespa as an outstanding example of a pioneer approach to wetland

management, which was honoured in 1999 with the Ramsar Convention Award.

In the same context the benefit of public awareness for achieving the goals of

the nature protection and sustainable development was underlined.41

Having in mind the contents of the first four Paragraphs, PMs decided to

declare, in the context of the WWF Living Planet Campaign, the "Prespa Park"

as the first transboundary area in South-eastern Europe, which shall consist of

respective areas around the Prespa Lakes in the three countries declared a

Ramsar Protected Site.42

In the final part of Declaration, the commitment to enhanced co-operation with

regard to environmental matters between competent authorities of the three

countries was declared. This commitment was expressed with the words "joint

actions would be considered [...]". The content of envisaged considerations has

been designed as to:

38 Prespa Park Declaration, first Paragraph.

39 Op. cit, Second Paragraph.

40 Op. cit, Third Paragraph.

41 Op. cit, Fourth Paragraph.

42 Op. cit, Fifth Paragraph

29

· "Maintain and protect unique ecological values of the "Prespa Park";

· Prevent and/or reverse the causes of its habitat degradation;

· Explore appropriate management methods for the sustainable use of the

Prespa Lakes water; and

· Spare no efforts so that the "Prespa Pak" become and remain a model of its

kind as well as an additional reference to the peaceful collaboration among

our countries".43

1.3

Notes on Legal Nature

From the formal legal standpoint, the Declaration is a trilateral document:

· Signed by the PMs (neither on behalf of the three States nor on behalf of the

Governments of the three States)44;

· Not ratified in any form by respective national authorities;

· Having no legislative status neither in international law nor in the three

States.

In that sense, the Declaration is a (more political than) policy document, agreed

on a very high authoritative level. That fact might explain the remarkable

positive impact on development and results of trilateral co-operation in the

following years.

From the material legal standpoint, several details deserve more analytical

attention here. One such detail is commitment of the PMs that, in the text of

Declaration, comprises only "consideration" of joint actions. No commitment to

take over obligations, or undertaking of certain actions/activities was agreed on.

The same is true for adoption of national legislation45, which would transpose

this political document into the legal obligation of the States, or for regular

funding from the State budgets of enhanced activities of transboundary co-

operation.

The "Prespa Park" is only a symbolic "transboundary park"46. There is no such

legal concept as "Transboundary Park" in international law or in national law

systems of the three littoral States. An attempt to give some legal content to the

notion of "Prespa Park" was made in Declaration through determination that

area would comprise "Ramsar Protected Sites". Connected to this, two further

notes should be made. First, such determination of geographical scope of the

"Prespa Park" seems insufficient to cover all existing protected areas in the

three Prespa littoral States47. Second, such determination is far too narrow in

43 Op. cit, Sixth Paragraph.

44 Cf., for example, the title of the Ohrid Lake treaty, i.e.: AGREEMENT BETWEEN THE

GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF MACEDONIA AND THE COUNCIL OF MINISTERS

OF THE REPUBLIC OF ALBANIA FOR THE PROTECTION AND SUSTAINABLE

DEVELOPMENT OF LAKE OHRID AND ITS WATERSHED (Skopje, 17.06.2004).