WORLD

Global Coral Reef Targeted Research and Capacity Building Project

GEF Project Brief

Other

ENV

Date: October 6, 2003

Team Leader: Marea Eleni Hatziolos

Sector Manager/Director: Kristalina Georgieva

Sector(s): General agriculture, fishing and forestry sector

Country Manager/Director: Ian Johnson

(100%)

Project ID: P078034

Theme(s): Other environment and natural resources

Focal Area: I - International waters

management (P)

Project Financing Data

[ ] Loan [ ] Credit [X] Grant [ ] Guarantee [ ] Other:

For Loans/Credits/Others:

Amount (US$m): 0

Financing Plan (US$m): Source

Local

Foreign

Total

BORROWER/RECIPIENT

0.00

0.00

0.00

GLOBAL ENVIRONMENT FACILITY

0.00

11.00

11.00

FOREIGN UNIVERSITIES

0.00

17.09

17.09

Total:

0.00

28.09

28.09

Borrower/Recipient: MEXICO, TANZANIA, PHILIPPINES

Responsible agency: UNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLAND, BRISBANE, AUSTRALIA

University of Queensland

Address: Office of the Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Research)

Brisbane, QLD 4072,

AUSTRALIA

Contact Person: Prof. David Siddle

Tel: 61-7-3365-9044 Fax: 61-7-3365-9040 Email: w.freeman@research.uq.edu.au

Estimated Disbursements ( Bank FY/US$m):

FY

Annual

Cumulative

Project implementation period: May 2004 - March 2009

Expected effectiveness date: Expected closing date:

OPCS PAD Form: Rev. March, 2000

GEF Project Brief (PAD)

A. Project Development Objective

1. Project development objective: (see Annex 1)

The Global Environment Objective is to align, for the first time, the expertise and resources of the coral

reef community around key research questions related to the resilience and vulnerability of coral reef

ecosystems, to integrate the results, and to disseminate them in formats readily accessible to managers and

decision-makers. A related objective is to build much-needed capacity for science-based management of

coral reefs in developing countries, where the majority of reefs are found. The Project Development

Objective is to fill critical gaps in our global understanding of what determines coral reef ecosystem

vulnerability and resilience to a range of key stressors--from localized human stress to climate change--to

inform policies and management interventions on behalf of coral reefs and the communities that depend on

them. These objectives will be achieved through targeted investigations involving networks of scientists, in

consultation with managers, and the dissemination of knowledge within and across regions.

2. Key performance indicators: (see Annex 1)

Because the Project will support targeted research, which is necessarily a long-term process, project

impacts cannot be fully measured within a five year time frame. Expected outcomes focus on process,

knowledge products and capacity, as benchmarks for improved management and stress reduction policies

leading to the sustainability of coral reef ecosystems, the long-term goals of the Project. In this light, key

indicators of project success are described as follows:

1. Formerly fragmented research efforts are coordinated and targeted for the first time around key

sustainability themes. A coalition of scientists and research institutions from developed and developing

countries is built to support this effort.

2. Major partners from different sectors are aligned with this initiative, building momentum toward a

critical mass of resources and a sustained effort.

3. Research results are peer reviewed, synthesized and broadly disseminated to a wide array of

stakeholders.

4. Coral reef managers are empowered with knowledge and tools to make better decisions.

5. Institutional and human capacity for science-based management of coral reef ecosystems is built in

countries where coral reefs are found

6. Policies in these countries to protect coral reefs or mitigate impacts from key stressors are strengthened

as a result of new information

7. Research findings are mainstreamed into World Bank country dialogue and assistance strategies for

countries with coral reefs.

8. Coral reef management projects under early implementation or in preparation--many with GEF

support--incorporate findings into project design.

9. The GEF uses results to guide future resource allocations to address cross cutting issues in Climate

Change, International Waters and Biodiversity and to guide clients in the design of large-scale targeted

research.

B. Strategic Context

1. Sector-related Country Assistance Strategy (CAS) goal supported by the project: (see Annex 1)

Document number: n/a Date of latest CAS discussion: n/a

The global nature of this Project directly supports the Bank's corporate goals for environmental

sustainability outlined in the Environment Strategy (2001). The Strategy's goals of (i) improving quality

of life, (ii) improving quality of the environment and (iii) protecting the global commons are all enshrined in

- 2 -

the Targeted Research Project's global objective of enhancing the sustainability of coral reef ecosystems

through science-based management, for the benefit of the world's coral reefs and the communities that

depend on them. 80% of coral reefs occur in developing countries, with Small Island Developing States

(SIDS) almost completely dependent on their coral reefs for security and livelihoods. Tourism is the largest

earner of foreign exchange for most SIDs, and for tropical countries with extensive coastal zones (e.g.,

Mexico, Belize, Honduras, Tanzania, Indonesia, Philippines), marine tourism is the fastest growing sector

of the tourism market. In addition to supporting a growing international and local tourism market, coral

reefs provide nutrition and livelihoods for millions of people through fishing and tourism related services.

They are essential to environmental security for coastal communities, where one half to two thirds of

populations are concentrated, providing shoreline protection against erosion and the damaging effects of

storms and sea-level rise associated with climate change. Although they occupy only 0.1% of the ocean's

surface, coral reefs are the world's richest repositories of marine biodiversity, and are the largest living

structures on earth. Like their terrestrial counterparts, the rainforests, coral reefs support an array of

environmental goods and services, whose ecological, cultural and economic value exceed our current

capacity to quantify.

Yet, despite their global significance, coral reefs are in decline worldwide. Science magazine devotes an

entire issue (August 15, 2003) to the spectre of coral reef decline. In a lead review article, entitled Climate

Change, Human Impacts and the Resilience of Coral Reefs, the authors identify a range of human

stressors on reefs whose intensity and frequency have resulted in a global threat to coral reefs. The

cumulative impact of this threat is exacerbated by historically high rates of climate change and climate

variability, which together place enormous stress on the ability of reefs to adapt. The Global Status of

Coral Reefs 2002 Report, lists two thirds of the world's reefs as under severe threat from the cumulative

impacts of economic development and associated impacts of climate change. Calls for protection and more

sustainable use of coral reef ecosystems have been a familiar theme in global fora, from the International

Coral Reef Initiative (launched in 1995, in which the Bank played a key role), to the Convention on

Biological Diversity (1995), the International Tropical Marine Ecosystems Management Symposia

(ITMEMS I and II, 1998 and 2003, respectively), and most recently, the World Summit on Sustainable

Development (2002). The WSSD Plan of Implementation identifies coral reefs as unique and vulnerable

ecosystems that play a crucial role in the economies of SIDs and other developing states, and urged

partners to: (i) implement the Framework for Action of the International Coral Reef Initiative (ICRI); (ii)

implement the Jakarta Mandate on Marine Biodiversity of the Convention on Biological Diversity; and (iii)

strengthen capacity globally to manage these ecosystems through science-based management and

information sharing.

While many conservation and management initiatives have been launched in response to these calls (the

Bank, in partnership with the GEF and others currently has over $270 Million in active or pipeline

projects), the effectiveness of these interventions is undermined by a paucity of information about what

determines ecosystem sustainability and resilience to major disturbance events in an environment of

increasing and variable stress. This information can only come from robust empirical observation and

research on stress/response interactions, analysis of ecosystem drivers and threshold points and the tools to

mitigate these effectively. Such systematic research must be targeted to management needs and of sufficient

temporal and geographic scale to discriminate long-term trends from background noise and local ecosystem

response from larger scale, potentially global effects.

The 1997/98 massive coral bleaching episode tied to an El Niño event, in which an estimated 30% of the

world's coral reefs were affected, was a wake-up call to coral reef scientists and managers alike. Managers

of reefs in the Western Indian Ocean, off Central America and in parts of the Pacific were faced with

unprecedented bleaching and mortality as a result of sustained increases in sea surface temperatures (SST)

- 3 -

only one-two degrees centigrade above the mean. While bleaching events due to stress from elevated SST,

sedimentation and changes in salinity (e.g., from storm runoff) were recorded in the literature, long-term

time series data on how individual reefs responded over time to these events, differential mortality and

difference in rates of recovery within and between reef systems were lacking in all but a few cases, making

it difficult to discern patterns of vulnerability from past events or to predict the breadth and pace of

recovery. Understanding the relevance of variations in time and space is an important factor affecting coral

reefs for which little is currently known. The increasing frequency of El Niño and other disturbance events

makes answers to such questions imperative:

l

whether early warning systems are feasible (e.g., through direct measurement of stress in coral

communities, or models of elevated SST and coral bleaching),

l

whether bleaching and associated mortality can be mitigated and how, and

l

whether natural recovery of damaged reefs may be enhanced through restoration at cost-effective

scales.

Similar questions have been raised in the context of disease in corals and other reef species, which have

been recorded with alarming frequency in the Caribbean and now threaten parts of the Pacific, including

the Great Barrier Reef. Preliminary studies suggest a correlation between the plethora of new diseases

discovered and their rate and mode of transmission (epizootiology) and climate change. Some hypotheses

even suggest a relationship between coral bleaching and disease, with the former precipitating the latter.

Without understanding of ecosystem processes and how they interact with the range of stressors facing

coral reefs today, management interventions, short of complete removal of the sources of stress, will

continue to be largely guesswork. The precautionary principle is currently our best tool to counteract

threats from economic development and climate change whose impacts we do not fully understand. This is,

however, a blunt instrument which is both economically and socially costly, and hence rarely applied.

An alternative approach is to support management with targeted research. This involves asking the right

questions, e. g., to identify major bottlenecks or drivers to sustain coral reef ecosystem goods and services,

or to improve the cost-effectiveness of applications of existing tools, like Marine Protected Areas and

coastal and ocean zoning, remote sensing and modeling. Targeted research may also lead to development

and application of new tools, such as biotechnology, in the design of bio-indicators of reef stress or

resistance to bleaching, and in the identification of pathogens and their pathways of transmission. At the

macro scale, this might involve the development of new tools like genetic markers to reveal connectivity

between reef systems or techniques to enhance natural recovery and restore reefs damaged from blast

fishing or cyanide. This new knowledge, disseminated and linked to decision-making, has the capacity to

dramatically increase the effectiveness of current and future management interventions. It also lends

credibility and accountability to decision-making and has the potential to generate the political will needed

to make tough trade-offs between conservation and intensive use.

The Coral Reef Targeted Research Project is being designed as part of a long term program that will be

implemented in phases. The first five-year phase will initiate research in areas with significant coral reefs

and Bank/GEF investments. These include sites in Mesoamerica, East Africa, Southeast Asia, and the

Southwestern Pacific. Research nodes will be established at institutions that have the capacity to develop

into Centers of Excellence in the region, and that may serve as resources and information clearing houses to

satellite sites (involved in collaborative research or management), within and between regions. (see section

C.2.)

The Regional Environment Strategies for LAC, AFR and EAP mirror the Corporate Strategy's

- 4 -

commitment to protect the global commons and the integrity of the environment as a basis for sustainable

economic growth. Yet despite the reliance on coral reefs of all the countries in which the targeted research

will be carried out initially (e.g., in Mexico, Belize, Tanzania, Philippines, and PNG), for such things as

tourism, livelihoods, nutrition and security, only one of the CASes refers specifically to reefs as strategic

development resources. This points to the continued emphasis on terrestrial resources and the need for

better valuation of reef ecosystem goods and services. This project will indirectly help to make the links

between coral reef sustainability and more secure livelihoods for coastal communities. It will directly

contribute to safeguarding global commons of outstanding ecological, cultural, and biodiversity value. At

the same time, it will build capacity within reef countries to frame and investigate key questions related to

the sustainability of resources on which they depend. And finally, the Project will disseminate this

knowledge globally and promote its uptake by key decision-makers influencing policies that affect coral

reefs.

1a. Global Operational strategy/Program objective addressed by the project:

Coral reef ecosystems are open and trans-boundary in nature by virtue of the of flow of nutrients,

pollutants, larvae, and adults of migratory species across ecosystem boundaries, and often national

frontiers. Pollutants entering the system are primarily land based, emphasizing connections between

drainage basins and shallow, coastal receiving waters, where most coral reefs are found. Coral reefs are a

major feature of Large tropical Marine Ecosystems. They are extraordinarily diverse and generate an array

of environmental goods and services which are dependent on reef integrity and the maintenance of

ecosystem processes. Effective governance of transboundary aquatic resources is a hallmark of the IW

Focal Area. The Targeted Research Project responds to the strategic priority for the International Waters

Focal Area identified in the GEF FY03-FY06 Business Plan to: "Expand global coverage to other water

bodies of cross-cutting foundational capacity building and innovative demonstration projects."

Through a series of highly integrated investigations in four coral reef regions of the world, the TR Project

will target research to answer key questions related to coral reef vulnerability. It will explore the role of

ecosystem processes as the basis for resilience and sustainability in response to major forms of stress. By

bridging knowledge gaps related to impacts of climate change and localized human stress on the

sustainability of trans-boundary aquatic ecosystems, the project fits within the Integrated Land and Water

Operational Program, OP 9. However, by virtue of its cross-cutting investigations, which will shed light on

the relationship between the effects of climate change on coral reef ecosystem integrity, including

biodiversity and connectivity between reefs, as well as between watersheds and aquatic ecosystems, the

project will have benefits in several different focal areas and operational programs, e.g., f GEF OPs 2, 8,10

and 12. It may also form the basis for a future joint program of work envisioned between Climate

Change, IW and Biodiversity within the Bank.

As noted above, the Project will support capacity building across GEF Focal Areas, by creating a robust

scientific framework within developing countries to investigate the basis for ecosystem vulnerability and

resilience to climate change and localized human pressures. Impacts on ecosystem structure and

Biodiversity will also be examined as part of these investigations. The model for establishing global

networks of researchers to jointly investigate topics of high priority for coral reef ecosystem management,

and to link the results to policy and decision-making, is eminently transferable to other focal areas and

themes. This cross-cutting outcome for capacity building is also identified in the GEF FY03-06 Business

Plan as a priority for the third replenishment phase:

..."Cross-cutting capacity building projects will support capacity building activities outside the scope of

any one focal area but common to achieving the goals of all focal areas. Such activities, particularly

- 5 -

focusing on LDCs and SIDS, will include: (i) foundational capacity building, to establish the basic capacity

of a country to meet its global environmental and sustainable development goals."

The joint investigations and targeted learning that result from collaborative, applied research, involving

networks of developed and developing country scientists, will build the foundation for knowledge-based

management and policies. The research findings and cutting edge tools developed will be disseminated

periodically through a series of management and policy briefs aimed to improve our global capacity to

manage coral reef ecosystems.

2. Main sector issues and Government strategy:

The main threats to coral ecosystem sustainability stem from localized impacts of human pressure and

accelerated climate change. These threats are aggravated by governance issues related to inadequate

information on the cumulative and interactive nature of these impacts on reefs and reef-dependent human

communities, the short-term planning horizons of decision-makers, and the political tradeoffs associated

with economic gains from intensive use (leading to irreversible change in some cases) vs. longer-term

conservation benefits. Human impacts include (i) over-fishing and destructive fishing techniques, which

alter trophic levels and destroy the ecological integrity of reef communities; (ii) land-based sources of

pollution (e.g., sedimentation from deforestation and other poor land-use practices, eutrophication and

Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs); (iii) habitat loss from land reclamation and construction. Impacts

associated with climate change include (i) increased sea surface temperature, sea-level rise and storm

frequency and severity, and (ii) changes in ocean chemistry, all of which undermine reef growth and the

physical integrity of coral reef ecosystems. Together, these impacts have resulted in the direct physical

destruction of reefs and their decline through a variety of mechanisms, including coral bleaching, diseases,

overgrowth of corals by seaweeds and outbreaks of predators. While public sector policies have tended to

be shortsighted, often accelerating reef degradation and loss, management interventions have relied on

surprisingly little empirical information, have been largely reactive to disturbance events, and fragmented.

Up until now, research concerning coral reefs has been dominated by independent, and often opportunistic,

lines of investigation. This has led to a fragmentation of research efforts and a difficulty in distilling

information that can be compiled globally and directly applied to conservation and management.

Furthermore, the process-response models historically used to address environmental degradation have been

primarily reactionary in their approach and scope rather than pro-active. What is lacking are strategic

research frameworks that establish critical baselines in representative locations, determine root causes and

forcing functions under different stress regimes, and yield results, through scenario building and other

decision support tools, that help managers anticipate problems as part of a risk management approach.

Ideally, such research should also provide managers with a suite of cost-effective preventative measures,

as well as an analysis of feasible restoration options. Such results would have tremendous application in

helping guide current conservation and management activities now under implementation with support from

the GEF and its partners, as well as helping to direct future management efforts.

- 6 -

3. Sector issues to be addressed by the project and strategic choices:

Addressing these challenges will require a new research paradigm. Based on agreed priorities identified in

extensive consultations with coral reef scientists and managers during the Block A phase, this project seeks

to coordinate and target research for the first time in this community's history. It will establish a global

network of eminent coral reef scientists working together across disciplines and regions so that (i) key

knowledge gaps can be systematically addressed to reduce uncertainty in the context of management , (ii)

targeted research is multidisciplinary, drawing on a blend of biophysical and social sciences, (iii) the

research is integrated across space and time to allow for a synoptic view of coral reef ecosystem dynamics

in response to stress at local, regional and global scales and (iv) research findings are effectively

communicated to decision-makers. (vi) These findings will be followed up at the policy level, by the Bank

in country dialogue with clients with coral reefs, as to appropriate policy actions and investments.

Strategic choices involve the design of a global project for targeted research vs. a series of regional or

national-level projects to support science based management of reefs. Other strategic choices involve the

institutional arrangements and flow of funds for a global project which will be implemented across four

sub-regions. Another key strategic choice has been to focus capacity building on creating the investigative

framework and robust methodology to prioritize and test hypotheses in the field that will inform

management, rather than to focus on management per se. Other initiatives, like the International Coral

Reef Action Network (ICRAN) and NGO supported community-based management efforts are designed to

focus on the latter. This strategic choice has clear implications for the fundamental nature and design of the

Targeted Research Project.

C. Project Description Summary

1. Project components (see Annex 2 for a detailed description and Annex 3 for a detailed cost breakdown):

Below are summarized the overall components of the TR project, the structure of the participating

elements, the key reforms to be sought, the benefits and target population, and the institutional and

implementation arrangements.

Project compnents are organized around the following three needs:

a. Addressing Knowledge and Technology Gaps

Over the past ten years, an increasing awareness of the importance of coral reefs has been evident,

especially in light of their rapid decline in many regions, and their significance to developing countries.

However, what remains fundamentally unknown about these ecosystems is alarming, especially when

management interventions are becoming increasingly important. Significant gaps in understanding some of

the basic forcing functions affecting coral reefs remain. This targeted research framework will

systematically define those information gaps, and prioritize them in an order of strategic importance to

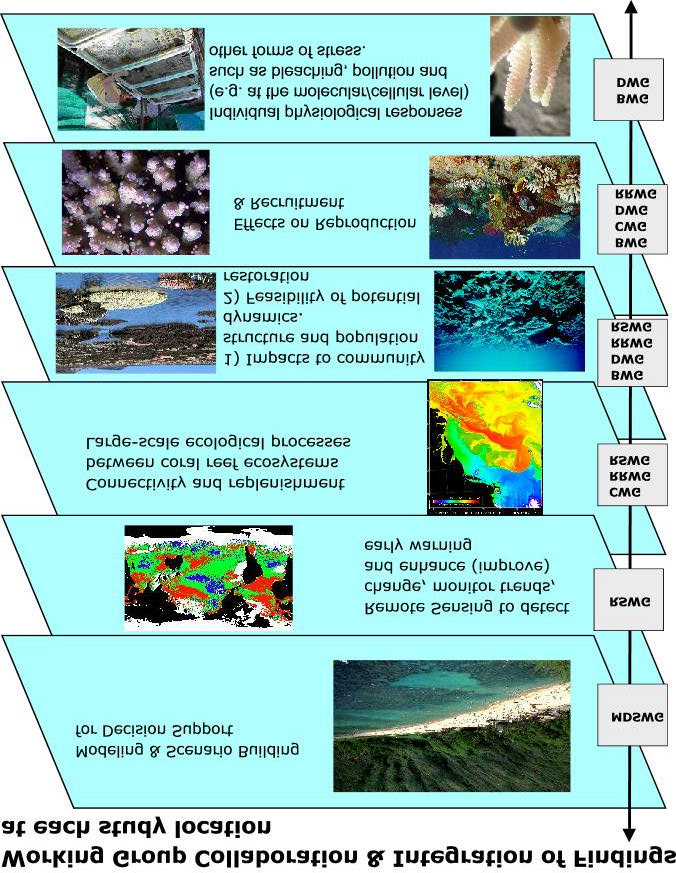

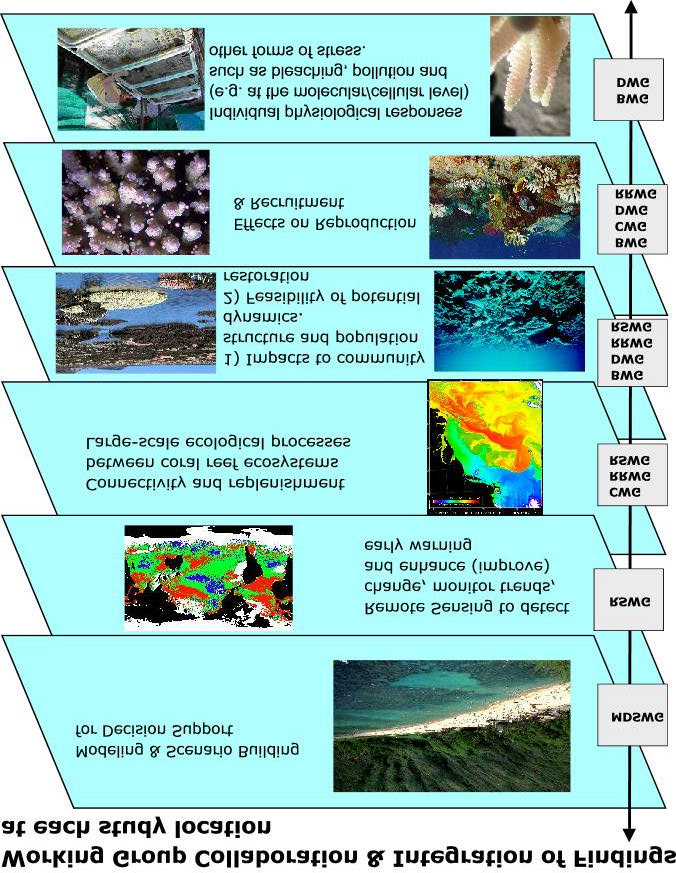

management, so that the resulting information and tools developed can lead to credible outcomes. Figure 1

shows the intent of a thematic integration coordination between the working groups at a given site. Based

upon fiscal limitation, not all working groups can begin targeted investigations in all 4 regions initially.

However, the intent is to have all working groups engaged in all locations within the project's first phase.

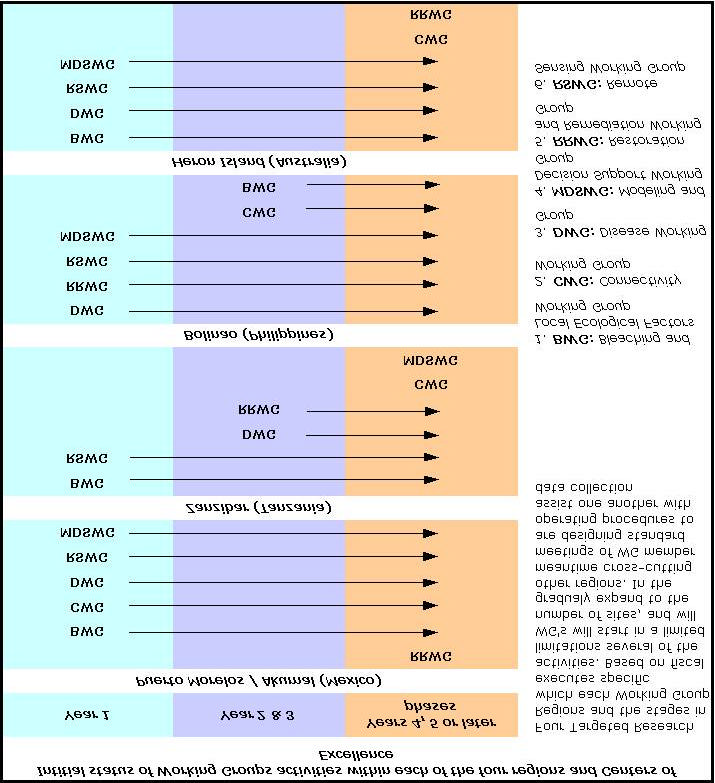

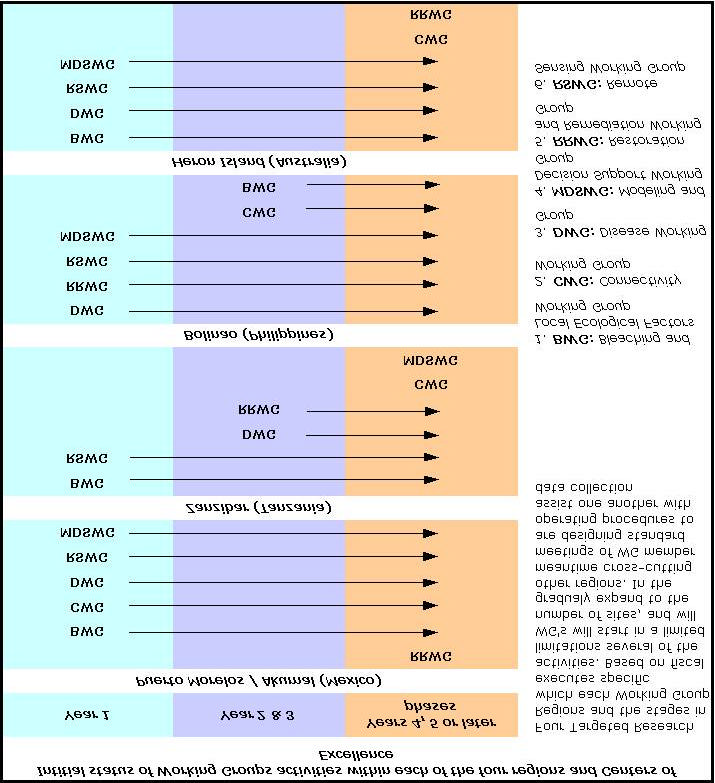

Figure 2 shows the locations and stages in the project at which the working groups will engage within each

region. Standard operating procedures are being developed to ensure that working groups assist one another

by conducting sampling and experimentation, where relevant, on each other's behalf. Furthermore, policies

developed at regional and national levels can also be strengthened to help bring about better legislation to

sustain the products and services provided to SIDS and coastal communities by coral reefs.

- 7 -

Figure1 - Major coral reef research themes and the integration of research across

working groups. By employing this layering approach, there is greater leverage in

relating information across themes and within the initially limited numberof studysites.

Sites may increase in replication as this model evolves over the course of the Targeted

Research program.

The project is organized around six key themes and research questions, which will be investigated by

interdisciplinary teams of developing and developed country scientists. These themes were identified

through extensive consultation over the course of project preparation to encompass the kinds of knowledge

- 8 -

and management tools that underpin sustainability science for coral reefs. They include:

i. The physiological mechanisms and ecological consequences of large area (or massive) coral reef

bleaching, particularly in response to sea surface temperature anomalies, like the El Niño/Southern

Oscillation episodes, and the potential consequences of their changes in frequency;

ii. The nature, severity and spread of coral reef diseases, some of which may be responsible for major

shifts in the structure, function, health and sustainability of coral reefs;

iii. The importance of physical and biological connections (or "connectivity") between coral reefs, whether

within or between different regions of International Waters. This also has direct bearing on the

environmental conditions and key design factors needed to establish and sustain effective Marine

Protected Areas (MPAs);

iv. The tools, technologies and efficacy of restoring coral reefs that have been severely degraded or

destroyed, and the key organisms and environmental conditions to consider when rehabilitating a given

coral reef environment;

v. The application of advanced technology, particularly remote sensing, to refine information and

enhance the rate and scale at which knowledge can be generated and applied. This includes the need to

modify technology so that it can be practically deployed and sustained within developing countries;

vi. The need to develop decision support tools and scenario building which integrate economic

development with bio-physical and other forcing functions to determine coral reef ecosystem response

to (different kind and rates of) change or stress. Included in this type of analysis may be the impact of

human stress on altering trophic relationships on coral reefs, particularly the relationship between

nutrients, overfishing, and the overgrowth of corals by seaweeds and the reversibility of transistions

between coral dominated and algal-dominated states. Such models will incorporate the economic value

of coral reefs, the socio-economic factors that affect the sustainable use of coral reefs, and the factors

that inhibit translation of science into management.

- 9 -

Figure 2 - Study Site locations and the stages at which working groups will engage.

b. Promoting Scientific Learning and Capacity Building

Currently, most coral reef research is based in universities and research institutes in the developed world,

while most coral reefs are located in developing countries. Rectifying this global discrepancy is a key

- 10 -

mission of this project. To accomplish this, the research themes outlined above will be explored in different

regions. This will serve both to ensure that the information ultimately used by managers is regionally

appropriate, and to allow the training of local scientists so that they can respond to future developments.

The Targeted Research investigations will focus around four "Centers of Excellence" (COE) in four major

coral reef regions (Western Caribbean (Universidad Autónoma Nacional de México), Eastern Africa

(Marine Science Institute, Zanzibar, Tanzania), Southeast Asia (Marine Science Institute, University of the

Philippines), and the central south Pacific (University of Queensland, Australia). These COEs will serve

as nodes for targeted learning and capacity building between developed and developing country scientists.

Specific learning exchanges are already underway in which interdisciplinary teams of researchers have the

opportunity to formally exchange ideas, and jointly implement research techniques and methods.

Large-scale experimental designs also offer the opportunity to engage both researchers and managers in the

design, testing and implementation of the priority, targeted experiments. Through twinning arrangements

between various universities and research institutions, coral reef scientists from developing countries will

exchange with partner institutions to learn cutting edge techniques in e.g., the identification of coral

pathogens, measurements of metabolic stress linked to specific environmental stressors, the use of genetic

markers to track larval dispersal and connectivity, and application of agent-based modeling techniques to

simulate coral reef ecosystem response to various forms of stress.

The Targeted Research Project will support a series of workshops each year which will bring researchers in

the various working groups together to orient field research, brief each other on findings and based on these

results, modify and design the next phase of investigation.

c. Linking Scientific Knowledge to Management and Policy

A key outcome of this work will be to improve our predictive capability in assessing impacts to coral reef

ecosystems, in the face of cumulative stress from increasing coastal populations, changes in climate and

other uncertainty. These targeted investigations are being designed to feed into decision support systems for

managers, policy makers, and other stakeholders.

The results generated from the targeted investigations will be formulated for various users. Over the course

of project implementation, the information and tools produced will be disseminated as knowledge products

to enhance the management of coral reefs. These products may range from in-situ diagnostics (for example,

disease assessment and bio-indicators of specific forms of stress and metabolic response in coral reef

organisms, to markers for larval recruitment indicating source and sink reefs) to remote sensing products

and applications to assess the state of coral reef health. In addition to these tools, a series of management

and policy briefs will be developed periodically by the Steering Committee and released to targeted

audiences. These audiences include Bank Country Directors and Country Assistance Strategy (CAS) and

Poverty Reduction Strategy (PRS) teams, GEF project teams, policy-makers, and member of regional and

global fora (e.g, the IPCC, CSD, ICRI, SBSTTA, Regional Seas Conventions).

Links will be made between research results and management efforts in the four nodal regions. Each

Center of Excellence will serve as the conduit of information to satellite sites and various user/stakeholder

groups (including NGOs and others involved in MPA management, coastal zone management and marine

regulation, national and community-based coral reef management activities, ecosystem monitoring efforts,

etc. see Figure below.) NGOs active in the region, represent a particularly cost-effective means to

communicate findings to managers and help convert them into low-tech solutions for direct

- 11 -

application to developing country management needs. These include tool kits for managers, such

as the one TNC has prepared for building resilience into MPA design, as well as those involving

bio-indicators to assess stress in key reef species. At the other end of the spectrum, high level

audiences will be kept abreast of research findings through publications of each of the working groups (a

list of those already out or in press since project preparation is available on request); through Steering

Committee briefings, and in the form of periodic management and policy briefs (précis). The Project will

also make use of the IW:Learn Project (a GEF/UNDP/UNEP/WB Knowledge Management Project for

International Waters) to help disseminate research findings. Electronic fora and roundtable discussions

focusing on key themes emerging from the targeted investigations may be supported through the IW:Learn

Project and open to the relevant community of practice.

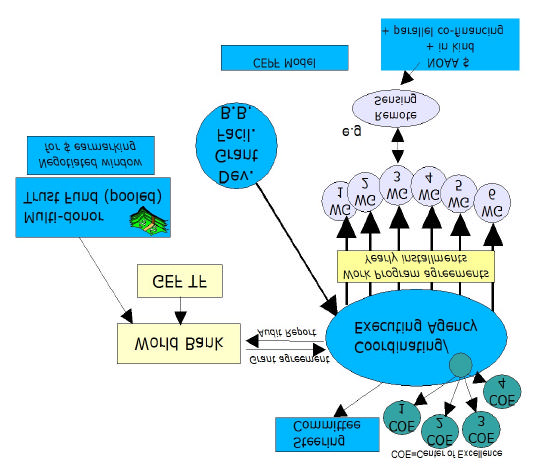

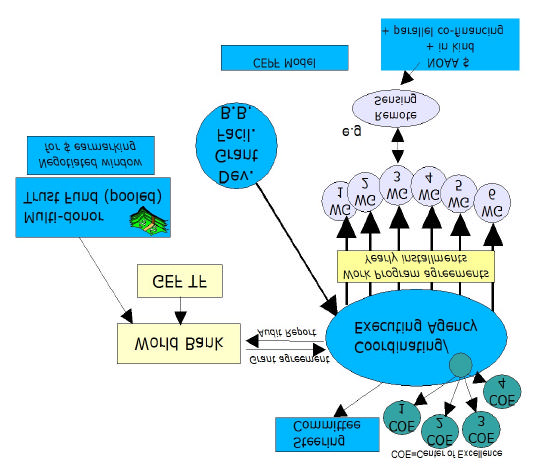

Figure 3 - Illustration of the institutional linkages involved in designing, implementing and disseminating the results of the targeted investigations.

Institutional Nodes, or Centers of Excellence, will provide the quality control and research rigor required to carry out the experimental design

formulated by the working groups and endorsed by the Steering Committee. Capacity building is the result of collaboration between a COE and other

research facilities in selected locations with coral reef ecosystems, through formal exchanges, targeted learning and collaborative research. Research

results are channeled to management projects and activities to inform decision making, and to policymakers to introduce needed reforms. Similar

clusters of node and satellite institutions are envisioned in each region and some of the working groups may overlap in their use of field sites and

clusters to carry out investigations.

- 12 -

Project Cost Table

Indicative

Bank and

% of

GEF

% of

Component

Costs

% of

other co-

Bank

financing

GEF

(US$M)

Total

financing

financing

(US$M)

financing

(US$M)

1. Knowledge & Technology Gaps

14.00

50.7

8.50

51.2

5.50

50.0

2. Promoting Learning and Capacity Building

6.00

21.7

3.00

18.1

3.00

27.3

3. Linking Scientific Knowledge to Management

4.10

14.9

2.10

12.7

2.00

18.2

4. Project Administration

3.50

12.7

3.00

18.1

0.50

4.5

Total Project Costs

27.60

100.0

16.60

100.0

11.00

100.0

Total Financing Required

27.60

100.0

16.60

100.0

11.00

100.0

Structural Elements

The primary structural elements are 1) six working groups organized around the research themes

summarized above, 2) four regional nodes chosen to reflect the biological and cultural diversity of the

world's reefs and to take advantage of existing local strengths, and 3) a Steering Committee, composed of

the chairs of the six working groups plus additional outside experts, representatives of the four regional

nodes, the "CEO" of the project responsible for implementing the Project (representing the executing

agency), and a representative of the World Bank .

Working Groups

Working groups are arranged around the six research themes outlined above and composed of developed

and developing country scientists from around the world. Each working group has developed a detailed

work program (see Annex 2 for a detailed description of key hypotheses to be tested and criteria for priority

setting) which has been reviewed by the Steering Committee. This work program defines the investigations

to be carried out under Component 1. Research plans, standard methods and inter-institutional

collaboration, including twinning arrangements for graduate students and post-docs between developed and

developing country institutions, are being coordinated to maximize knowledge sharing and capacity

building (see section 3 below). The working groups have prioritized questions to be addressed within each

theme, through field-based hypothesis testing. The research questions and field locations have been

organized so as to maximize synergies between groups and to produce a robust framework for the ongoing

creation of knowledge and new tools essential for adaptive management of coral reefs. Knowledge will be

disseminated widely and in a format useable by decision-makers.

Regional Nodes

Following extensive discussion by the Steering Committee, four regional nodes have been selected to reflect

the biological and cultural diversity of coral reefs throughout the world, and centers of coral reef research

which have (or may have) the capacity to serve as Centers of Excellence. Each of the working groups will

conduct core elements of their investigations at at least two of the four regional nodes during the first five

years of the Program. The nodes represent the three major coral reef regions of the world the western

Pacific (which is the center of coral reef biodiversity), the Indian Ocean (which has suffered extensively

from recent episodes of coral bleaching associated with climate change), and the western Atlantic (whose

reefs are substantially different from Pacific and Indian Ocean reefs).

In each of the four areas, a regional activity and training center or COE has been identified:

- 13 -

l

Western Caribbean: Universidad Autónoma Nacional de México

l

Eastern Africa: Marine Science Institute, Zanzibar, Tanzania

l

Southeast Asia: Marine Science Institute, University of the Philippines

l

Central south Pacific: University of Queensland, Australia

These sites were selected on the basis of significant ongoing GEF and other donor investments in coral reef

management, and where considerable baseline data already exist, along with a critical mass of coral reef

scientists and infrastructure--essential to carrying out the research. It is the intent of the Project to build

the capacity of the three developing country sites to help transform them into real Centers of Excellence for

coral reef research.

The COEs will interact with other research institutions and NGO's in the area.

Current study site locations within each region include (i) the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef System (Puerto

Morelos/Akumal, Mexico and Glover's Reef Marine Station, Belize), (ii) Bolinao (and the Hundred

Islands), northwest Philippines, (iii) Zanzibar, Tanzania (iv) Papua New Guinea, (v) Heron Island, (vi) and

Palau. Other potential locations, including sites in Indonesia, are also under consideration.

Steering Committee (a.k.a Synthesis Panel)

A guiding Steering Committee helps gives direction to the targeted research program (see Component 1)

and ensures that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. This Committee also serves as a formal

interlocutor with other disciplines, such as development economics and law, to enhance the relevance and

uptake of results by policymakers. It synthesizes and interprets results and modifies the focus of

investigations as needed to benefit management and policy Examples include the development and

dissemination of a series of management and policy briefs in a form easily internalized by several audiences

(see Component 2.)

The Steering Committee consists of the heads of each of the six thematic working groups, representatives

from each of the four regional nodes, the person from the implementing agency responsible for the

day-to-day operation of the program, several outside experts representing coral reef scientists, economists,

and managers, and a representative of the World Bank Group. One of the outside experts chairs the

Steering Committee. Procedural details for the functioning of the Steering Committee will be developed

prior to Project implementation.

2. Key policy and institutional reforms supported by the project:

Key Policy and Institutional Reforms

The key policy reforms to be sought will be (i) better information and knowledge transfer of those practices

that can most effectively alleviate localized human stress that may contribute to increased vulnerability of

coral reefs to the effects of climate change; (ii) development of institutional and human resource capacity to

support coordinated, long-term investigations into the nature of stress/response interactions determining

coral reef sustainability in the face of cumulative stress from natural and human-induced causes; (iii)

facilitating the linkages between science and management to visualize future scenarios (e.g., of resource

state and provision of goods and services ) based on current patterns and trends, identify appropriate

regulatory and incentive-based interventions, and build support for sustained conservation of coral reefs.

Although this framework is designed to address targeted research globally, the Project aims to shape policy

- 14 -

decisions affecting the sustainability of coral reef ecosystems at national and local levels. It aims to do this

by developing accurate stress/response and ecosystem dynamic models and decision support that will

significantly improve our understanding of coral reef ecosystem resilience, vulnerability to difference

forms of stress (from local, human-induced stress, to climate change impact), and the steps that can be

taken to reduce uncertainty in designing management interventions. Scenario building, which will allow the

forecasting of reef ecosystem response to stress under different management/use options (including

upstream or offsite development), will provide decision-makers with the basis for significantly improved

management interventions and the design or strengthening of relevant policies that contribute to the

sustainability of coral reef ecosystems for generations to come.

What is needed is a change in the way coral reef science is pursued in support of management and in the

way development decisions which may affect coral reefs are made. This involves a commitment by the

public sector to sustained, targeted and high quality empirical work directed at resolving key unknowns as a

fundamental priority. Once these key, targeted gaps in knowledge are filled, the dissemination of this

information to policymakers, the scientific community, industry, coastal managers and the general public

will have positive impacts on management interventions and policy. Ultimately, the Targeted Research will

support policies related to mitigating the causes and effects of climate change, improve those practices and

technology that most effectively reduce land bases sources of pollution to reefs, over-fishing, and the

application of tools to enhance natural resilience and recovery of reefs to stress. (This includes better

zoning of coastal landscapes and seascapes, and terrestrial corridors contiguous with reefs, adoption of

improved field techniques to assess reef health or factors such as disease, light, heat and other stressors

which may elicit coral bleaching; or may facilitate artificial restoration.)

3. Benefits and target population:

Benefits and Target Population

The benefits of this project are primarily global, however, there will also be regional and local benefits as a

result of many of the findings. The targeted research is directed at filling critical gaps in our understanding

of how coral reef ecosystems around the world respond to different types of threats, how to mitigate these

threats, and how best to enhance natural resilience to and recovery from major disturbances. Only with

systematic investigations designed to identify the nature of ecosystem response to such threats and to

discriminate significant trends in coral reef ecosystem response from natural variability (background noise),

can science provide the guidance needed to managers and stakeholders who rely on coral reef ecosystem

goods and services for livelihoods, or value their biological, cultural and intrinsic worth.

The major benefits of the TR will be:

l

networks of developed and developing country scientists collaborating on the testing of strategic,

priority hypotheses related to determinants of coral reef vulnerability and resilience under various

forms of stress;

l

capacity and long-term commitments for targeted learning within and across regions strengthened

l

a rigorous framework in place for science based management of coral reef ecosystems in four key

regions of the world;

l

informed decision making backed by solid science that reduces uncertainty, and guidance to GEF

and other partners on the range of options and most cost-effective investments to improve the

condition of coral reefs globally.

Development benefits include a globally coordinated scientific community skilled in developing

- 15 -

investigative frameworks designed to reduce uncertainty regarding key issues related to ecosystem

sustainability within and between regions, and to develop cost-effective tools and knowledge that will

significantly improve coral reef management at the local level. Beneficiaries, therefore, include (i) the

community of established coral reef scientists, who will have the opportunity to collaborate on a global

scale on agreed priorities essential to effective, long-term management, (ii) the emerging generation of new

coral reef researchers who will be trained in cutting edge investigative techniques by the best scientists in

the field, to answer these and other questions, as they emerge, related to the survival of coral reef

ecosystems, as we know them, around the world.

Managers (including public sector, NGOs, CBDOs and policy-makers will also benefit from this Targeted

Research as the recipients of knowledge and key information that will help them make the case for better

practices and policies aligned with conservation and sustainable use of coral reef ecosystems. The Targeted

Research preparation has consulted extensively with on-going scientific and management efforts related to

coral reefs. Current coral reefs management initiatives, such as ICRAN, which is now an operational

network of ICRI, will benefit by strengthening management recommendation and options as a result of this

project. NGO program, such as the Nature Conservancy's "Transforming Coral Reef Conservation for the

21st Century" will also use results, and is collaborating with this project to further conservation objectives.

Important indirect beneficiaries are the hundreds of millions of people who either rely on coral reefs for

environmental security and economic livelihoods; enjoy reefs for their recreational, cultural and spiritual

value; or stand to gain from biodiversity and ecological services that have yet to be assessed.

The GEF and its implementing agencies, including the World Bank, will also benefit significantly from the

guidance emerging over the course of this targeted research program, to assess the cost-effectiveness and

long-term impact of current interventions and improve upon them; the need to re-orient strategic assistance,

and how to achieve synergy across related focal areas (e.g., international waters, biodiversity and climate

change).

4. Institutional and implementation arrangements:

A major study to identify the most appropriate institutional arrangements and flow of funds for the

implementation of the project was commpleted as part of project preparation. The results of the study have

recommended the establishment of a global implementing agency (the Project Executing Agency or PEA)

with overall responsibility for project execution and administrative accountability to the Bank. The PEA

must be established by a host organization that has global reach, is a leader in the field of coral reef

research and management, and will be able to provide continuing management support. The host

organization must have high standards of corporate governance and international recognition to ensure

compliance with Bank and GEF fiduciary policies and be able attract other donor support. The

management arrangements will facilitate rapid disbursement at the field level with several technical

working groups working at a number of global locations.

A Steering Committee consisting of Technical Working Group Chairs and independent members will

provide technical guidance to the PEA (see also section E.4). The themes to be addressed by the Technical

Working Groups are selected by the Steering Committee, and the composition of Technical Working

Groups is under the purview of each Working Group Chair. The targeted research will be implemented by

scientists within these Technical Working Groups and will involve, whenever possible, the regional Centers

of Excellence located the beneficiary countries.

The PEA will operate independently, but will receive guidance from the Steering Committee which will be

responsible for reviewing the overall management of the project and performance of key project staff,

- 16 -

evaluating the existing funding situation and future prospects, and reviewing progress made towards both

targeted research and capacity building in all Working Groups and Centers of Excellence.

The PEA will have a fully dedicated staff to oversee project implementation, outreach and communication

activities, and future planning (including development activities to identify future co-financing and new

partnerships). Such a staff will include, at a minimum, a senior level Executive Director, a Project

Coordinator, an Outreach and Communications Specialist, and a Financial Manager. These will be full

time positions, preferably working out of the same centralized project office. In addition, the PEA will hire,

as necessary, short term consultants to 1) design workshops to integrate the research efforts of the

Technical Working Groups, 2) oversee capacity-building efforts within the regions, and 3) disseminate

synthesized results of targeted research to recipients involved in coral reef management, such as

decision-makers, non-governmental organizations, and donor organizations.

In addition to the core management group that works together out of a centralized location, one or more

data managers or data repository system, such as ReefBase, will be necessary. This person or persons will

not only manage databases for the TR, but also develop and implement mechanisms for accessing such data

-- for the scientists involved in the project (possibly through some sort of secure Intranet) and for the public

at large. The need for such a position will of course increase through the life of the project. Staffing for this

activity need not be housed in the PEA office, but rather could be at the site of the data repository.

The Technical Working Groups will be responsible for planning detailed research activities in each

specialty, including choices regarding individual projects and institutions, as well as budgetary decisions

involving resource allocations and procurements. Chairs of the Technical Working Groups will develop

and submit annual work plans to the PEA, to be reviewed and approved by the Steering Committee. Each

chair will also be responsible for evaluating progress made towards the stated goals of the Technical

Working Group which he/she heads.

The PEA will receive scientific advice from the Steering Committee (and its sub-committees), which will

convene (physically and/or electronically) regularly to review annual work plans, provide specific input to

the PEA on integrative activities, and assess progress made towards the stated goals of the project. This

Steering Committee will develop the big picture view of what is being learned through the targeted

research, and will work to actively integrate the findings of the technically disparate working groups. The

Steering Committee will also be responsible for identifying gaps in research that should be filled through

adjustments of the plans of the Technical Working Groups, or by the addition of new working groups. As

such, the Steering Committee will have responsibility for developing research plans for the second and third

phases of the project, beyond the first tranche of funding. The Steering Committee will be served by the

Project Executing Agency staff, including its Executive Director, Project Coordinator, and Outreach and

Communications Specialist. More detail on institutional arrangements and flow of funds will be provided

in a separate annex to the PAD.

D. Project Rationale

1. Project alternatives considered and reasons for rejection:

The global knowledge creation and capacity building that is part of this program is consistent with the

GEF's new strategic emphasis on targeted learning to build indigenous capacity within its clients for

strategic and effective environmental decision-making. The Targeted Research is the first full size project

for Targeted Research in the IW Focal Area to be presented to the GEF. It is innovative in its approach to

build this capacity by creating networks of the best scientists in the developing and developed world to

- 17 -

collaborate on key questions of global concern, include young professionals in the fieldwork and formal

degree level training associated with the research and, through such north-south/south-south partnerships,

establish centers of excellence for coral reef research and management in strategic locations coinciding with

the distribution of major coral reef ecosystems. The nature of this cross regional/global approach

necessarily involves incremental costs which must be borne by facilities such as the GEF and other

stakeholders in the marine conservation community.

Previous studies of large-scale environmental impacts have already shown that organizing response,

damage assessment and restoration programs in a reaction-based model results in significant financial and

societal costs to both the affected and responsible parties. Alternatively, this approach suggests a proactive

model to prioritize and target specific investigations that can plan for and hopefully intervene with

management alternatives in anticipation of future environmental impacts and stresses. This approach can

have valuable implication for both governments and industry, so that future actions can focus on

preventative interventions, rather than curative ones.

An alternative to this approach is the no-project alternative, which would perpetuate the problems of

uninformed/reactive management rather than science based/pro-active management, and isolated, country-

specific research. The latter which, while valuable, would not have the spin-off and global learning impact

of the networked research and integrated problem solving that is the hallmark of this Targeted Research

and Capacity Building Program.

2. Major related projects financed by the Bank and/or other development agencies (completed,

ongoing and planned).Please refer to the Map annex to see where many of these Projects are located in

relation to the Centers of Excellence.

Latest Supervision

Sector Issue

Project

(PSR) Ratings

(Bank-financed projects only)

Implementation

Development

Bank-financed

Progress (IP)

Objective (DO)

Improving management of highly

Coral Reef Rehabilitation and

S

S

threatened, economically important

Management Project

environmental goods and services in the (COREMAP): Phases I-II

epicenter of marine biodiversity.

Conservation and Sustainable

S

S

Use of the Mesoamerican

Barrier Reef System

Gulf of Aqaba Environmental

S

S

Action Plan

Red Sea Strategic Action Plan

S

S

Implementation (Bank, UNEP

and UNDP)

Coral Reef Monitoring Network

S

HS

in Member States of the Indian

Ocean Commission (COI),

within the Global Reef

Monitoring Network (GCRMN)

Coastal and Marine

S

U

Biodiversity Management

- 18 -

Project, Mozambique

Coastal and Marine

U

S

Biodiversity Conservation in

Mindanao, Philippines

Marine Biodiversity Protection

S

S

and Management (MSP),

Samoa

Hon Mun MPA Pilot Project

HS

S

(MSP), Vietnam

CORALINA Project, San

HS

HS

Andres, Colombia

Coastal Zone Integrated

Management Program, Benin

(Pipeline)

Guinean Coastal Zone

Integrated Management and

Preservation of Biodiversity

(Pipeline)

Coastal and Biodiversity

Management Program, Guinea

Bissau (Pipeline)

Marine and Coastal

Biodiversity Conservation,

Senegal (Pipeline)

Sustainable Coastal

Livelihoods, Tanzania

(Pipeline)

Mainstreaming Adaptation to

Climate Change in Caribbean

(Pipeline)

Other development agencies

Selected UNDP Activities

Tanzania: Development of

Mnazi Bay Marine Park

Comoros: Conservation of

Biodiversity and Sustainable

Development in the Federal

Islamic Republic of the

Comoros

Mauritius: The Management

and Protection of the

Endangered Marine

Environment of the Republic of

Mauritius

India: Management of Coral

Reef Ecosystem of Andaman

and Nicobar Islands

Maldives: Conservation and

Sustainable Use of Biodiversity

- 19 -

Associated with Coral Reefs in

the Maldives

Vietnam: Coastal and Marine

Biodiversity Conservation and

Sustainable Use in the Con Dao

Islands

Philippines: Conservation of

the Tubbataha Reef National

Park

Philippines: Biodiversity

Conservation and Management

of the Bohol Islands

Papua New Guinea: Milne-Bay

Province Marine Integrated

Conservation

Belize: Conservation and

Sustainable use of the Barrier

Reef Complex

Cuba: Priority Actions to

Consolidate Biodiversity

Protection in the

Sabana-Camaguey Ecosystem

UNEP Activities

Reversing Degradation Trends

in the South China Sea and

Gulf of Thailand

Integrating Watershed and

Coastal Area Management in

Small Island Developing States

of the Caribbean

Development and Protection of

the Coastal and Marine

Environment in Sub-Saharan

Africa

Reduction of Environmental

Impact from Tropical Shrimp

Trawling through Introduction

of By-catch Technologies and

Change of Management

Other Donors

International Coral Reef

Initiative (ICRI)

International Coral Reef Action

Network (ICRAN)

IP/DO Ratings: HS (Highly Satisfactory), S (Satisfactory), U (Unsatisfactory), HU (Highly Unsatisfactory)

- 20 -

3. Lessons learned and reflected in the project design:

Historically, research components of GEF projects dealing with coastal and marine ecosystems have

focused on assessing and monitoring baseline conditions. Several have documented declines in the resource

base, but few, if any, have supported experimental research that would improve our understanding of

ecosystem function or factors that regulate ecosystem response to various kinds of threats. A recent

Consultative Group meeting of the WB/GEF MesoAmerican Barrier Reef System Project held in Belize

(October 03), flagged the Targeted Reseach Project as a much needed complement to the work the MBRS

Project is undertaking in sustainable fisheries, monitoring of ecosystem health and policy harmonization in

coral reef related sectors in the four participatin countires. This includes: (i) managing spawning

aggregations of commercially valuable reef fish (and links to the TR Connectivity Working Group), (ii)

implementing the first regional Synoptic Monitoring Program of Reef Health for the MBRS (with links to

the TR Remote Sensing Working Group and to the the Disease and Bleaching Working Groups); and (iii)

technical input to the MBRS Policy Woking Groups on harmonizing policies and good practice related to

shared resources of the MBRS (with links to the TR Modeling and Decision Support Working Groups).

Similarly, the COREMAP II Project Team and NGOs (TNC) working alongside, have indicated very

strong interest in collaboration with the TR Working Group on Reef Restoration and Rehabilitation, to test

new tools for restoring dynamited and cyanide damaged reefs in the region. Given the emphasis on

ecosystem-based management endorsed by the GEF, the WSSD and others for favoring a holistic approach

to natural resources management, there is a need to understand the nature and pathways of ecosystem

drivers to identify bottlenecks in ecosystem function and how best to address these.

Lessons learned from past experience with public sector financed-research have been incorporated into the

design of the Targeted Research, as follows: (i) target research on strategic priorities which will

significantly enhance knowledge required for effective management, (ii) identify near-to-medium term

products and tools that can be applied in the interim to demonstrate the benefits of a committed, targeted

research program; (iii) ensure transparency and full-fledged participation in partnerships between

developed and developing countries, and (iv) disseminate knowledge as widely as possible, taking care to

tailor messages to different target audiences.

Historically, the coral reef scientific community has been fragmented in its approach to conducting

investigations in a coordinated manner, and over both space and time. The TR framework presents the first

opportunity for the coral reef scientific community to pool its intellectual resources and energies--in a

collaborative mode with developed and developing country scientists--to design targeted investigations that

will address key unknowns and ultimately contribute to improving human welfare. The research framework

has emphasized the need to prioritize gaps in knowledge, sequence investigations to build on knowledge

obtained by one or more working groups, analyze and synthesize results (with the help of the Steering

Committee), and disseminate these as discrete knowledge products and innovative tools to stakeholder

groups. As the results from these investigations come on line, the Steering Committee will be in a position

to collectively address how the information may best be used to affect management options, influence

policy, contribute to the accuracy of economic models involving coral reefs and dependent communities,

and improve the quality of life through enhancing the sustainability of strategic resources.

- 21 -

4. Indications of borrower and recipient commitment and ownership:

This project is global in scope, and will involve more than 70 international scientists and a host of scientific

institutions from around the world. The proposal has the strong support of the nodal agencies in the four

countries involved (Mexico, Tanzania, the Philippines and Australia), as evidenced by the letters of

endorsement from these institutions. The coral reef community in these and other countries in the regions

who will benefit from direct involvement in the research or from the management information that will be

generated by it are also enthusiastic about this global effort. A strong role for the COEs is envisioned in

terms of engaging other institutions in the region in the research, building capacity among the next

generation of coral reef scientists and serving as an information clearing house to a range of stakeholders

(from local communities to national and regional level policy-makers). These activities are consistent with

the missions of the COEs, and their roles in providing technical advice for the formulation of national and

regional policies. To create local buy-in, each Center of Excellence will serve as the conduit of information

to satellite sites and various user/stakeholder groups and projects within each region. NGOs active in the

region will help to communicate findings to managers and help convert them into low-tech solutions for

direct application to developing country management needs. These include tool kits for managers, such as

the one The Nature Conservancy has prepared for building resilience into MPA design, as well as those

involving bio-indicators to assess stress in key reef species.

5. Value added of Bank and Global support in this project:

Of the 184 member countries of the World Bank, more than 90 countries rely on coral reefs as natural

economic assets. However, most of these reefs and associated resources are components of larger

transboundary marine ecosystems, which require multi-country approaches to manage and conserve. The

Bank has considerable experience in transboundary water resources management through a growing

portfolio of Regional Seas and International Waters programs. More recently, experience in promoting

regional cooperation in the conservation and sustainable use of the world's second longest barrier reef

system--the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef System--has provided a model for regional coordination,

involving multinational technical and policy working groups, on which the TR Project can build.

The Bank is in a unique position to provide global leadership on needed policy reforms that may be

implicated by the TR findings. World Bank Country and Sector Directors will be apprised periodically of

the research results and their implications for the Bank's clients, by an internal Project working group of

Bank Task Team Leaders of coastal and marine resource management projects. Result can form the basis

for ESW, flagging the value of goods and services provided by coral reefs and what is at stake, or feed

directly into the Country Dialogue with clients with coral reefs, and the Country Assistance Strategy and

the PRSP process. Where appropriate, new investment projects may be identified to reduce stress on coral

reefs and the threat to reef-dependent communities, as in Tanzania, where a Sustainable Coastal

Livelihoods Projects is being designed as a follow up to the PRSP.

E. Summary Project Analysis (Detailed assessments are in the project file, see Annex 8)

1. Economic (see Annex 4):

Cost benefit

NPV=US$ million; ERR = % (see Annex 4)

Cost effectiveness

Incremental Cost

Other (specify)

The activities and costs subsumed under this Project are entirely incremental, as they support global

learning and capacity building for science-based decision-making. Baseline research activities in client

counties consist mostly of coral reef monitoring and localized investigations. Apart from monitoring

- 22 -

activities, these efforts are not systematically networked at the national or regional level, nor are they

designed to shed light on specific stress response relationships, or the variability in response (i.e., in

resilience or vulnerability) that reef ecosystems may display depending on the type, intensity and

cumulative nature of the stress. In contrast, the GEF Targeted Research Project is designed to focus on

strategic questions directly related to the sustainability of coral reef ecosystems at different sites, under

varying stress regimes, and to compare these results across regions. The interdisciplinary nature of the

working groups, the geographic and temporal scale of the research program (across four distinct coral reef

regions, over 15 years), and the networked nature of the research, will require a degree of cooperation and

support that cannot be sustained by any one country. The transboundary nature of coral reef ecosystems,

the threats to their sustainability, and the fundamental gaps in our understanding of system behavior and

recovery potential, require a multinational effort that spans a range of variability within and between

systems. Multinational working groups and cross regional learning and capacity building will ensure that

this is a truly global effort, extending well beyond the boundaries of the research sites and countries

involved.

No other organization is presently undertaking such a coordinated and targeted program of research to

inform managers and policymakers on cost-effective options for coral reef conservation and management.

This program would simply not be possible without GEF funding. The GEF serves as an organizing force

around which a significant proportion of the community of practice for coral reef research is being united

for the first time. The preparation activities have galvanized partner participation, and have resulted in

resources and efforts to be realigned, but the GEF support will be catalytic in launching this Targeted

Research. The GEF will also serve as a powerful catalyst to leverage funds from an array of partners and

collaborators who are committed to supporting one or more aspects of the research. The critical mass of

investigators and supporting institutions who are being brought together as a result of this initiative will

have an unprecedented impact on the way ecosystem research is conducted in the future.

An incremental cost analysis has been prepared and is attached as Annex 4. The total Project Cost is

estimated at US $28.8 million. GEF is asked to contribute $11 million, or approximately half the cost of

implementing this first phase of the overall Targeted Research Program. Over $12 million has been

identified as in-kind co-financing, and at least $5 million in cash co-financing is being sought from a

number of sources to implement the work program presented here. These include: collaborating research

institutions such as the University of Queensland, US NOAA and the University of Exeter, as well as from

Foundations, Bilaterals and Trust Funds. In addition to cash, participating research institutions are

expected to contribute substantial in-kind resources, in terms of access to field laboratory facilities,

services, and staff time. The team is approaching a number of Private Foundations, which have specific

programs for marine conservation, scientific research or climate change, as well as corporations with an

interest in promoting marine tourism and travel. The latter have already pledged significant in-kind

co-financing in the form of reduced hotel and air fares for Project researchers. Preliminary discussions

within the Bank indicate strong interest and the possibility for co-financing from the Development Grant

Facility, which has partnered with the GEF in the past (e.g., through the Critical Ecosystem Partnership

Fund) and from Bilaterals with ongoing coral reef programs (e.g., Australia and Japan). Working Groups

have also been seeking co-financing directly through national research funding agencies and collaborating

institutions (e.g., US NOAA). An additional $10-20 Million in leveraged cash and in-kind resources

(including personnel and equipment), not directly under the Project's control, will be raised from

collaborating institutions. New partnerships are expected to emerge once GEF financing is committed and

the Project gains momentum on the ground. (see section on Finance below).

2. Financial (see Annex 4 and Annex 5):

NPV=US$ million; FRR = % (see Annex 4)

- 23 -

The Project Executing Agency shall be the principal recipient of GEF funds, other donor funds and funds

to be contributed by the participating governments. The PEA shall be fully accountable for all project

funds and shall ensure timely disbursement of funds to participating project implementing institutions. PEA

shall be responsible overall project management and coordination including procurement, financial

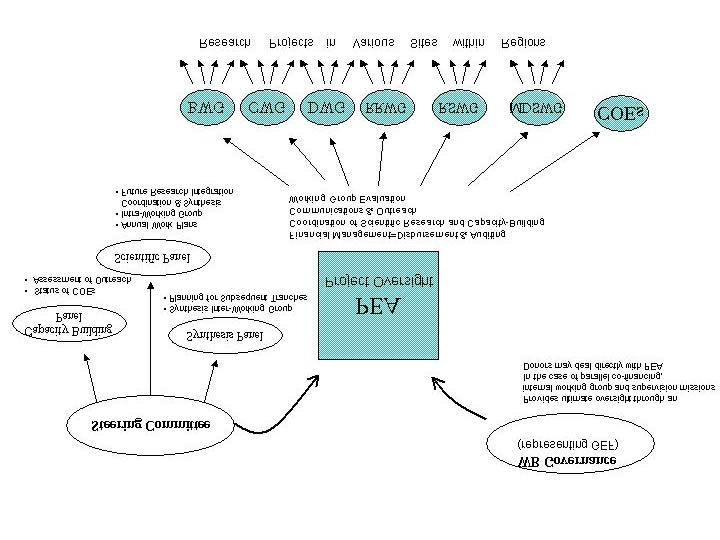

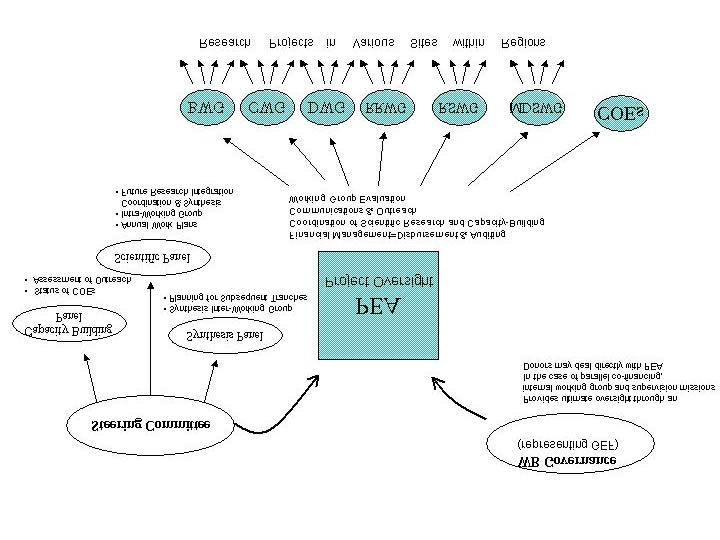

management and project administration. Figure 4, below, illustrates one Flow of Funds Model based on

existing Bank programs, to accommodate the diverse source of funds and the potential for new co-financing

expected to emerge throughout Project implementation. This includes establishment of a multi-donor Trust

Fund, administered by the World Bank, which can receive funds from a variety of donors to support agreed

Project objectives, and may even accommodate earmarking for specific Project components in some cases.

The financial management and reporting aspects of the Project will be described in Annex 6.

Figure 4 - Diagram of Funds Flow Model for the Targeted Research.

Fiscal Impact:

N/A (no loans involved)

3. Technical:

The six targeted research working groups will coordinate investigations and results through use of

complementary study designs and locations, and through targeted learning exchanges. By coordinating the

targeted investigations, the working groups are building an information base that can directly relate

findings across space and time (see Figure 1). Such complementary data collection not only strengthens

- 24 -

findings but also enhances correlations at different spatial scales. Investigations within many of the

Working Groups will also contribute to specific model development to support their respective areas of

inquiry, and to contribute to the decision support. The standard operating procedures developed under the

Project will contribute to more effective technical exchange by ensuring consistent application of methods

and protocols. This has tremendous implications for extending technical capacity and standard approaches

within the client countries. Combined with targeted learning exchanges, this technical approach allows a

broad spectrum of researchers within both developed and developing countries to present and debate

relevant issues about priority hypotheses, the logistics required to implement targeted research, and to share

various experiences. This model is proving to be highly effective in knowledge sharing, and in transcending

previous communication barriers. While certain locations will continue to experience limitations in

infrastructure (i.e. Internet throughput--which is largely based on given Country's telecommunications

infrastructure), these focused exchanges will help to mitigate this constraint within Centers of Excellence

in each region.

In concert with the Synthesis Panel, the working groups members and supporting staff will design, plan and

disseminate policy briefs and guidelines for the application of relevant findings into management and policy

operations. These will be made available directly to clients, Bank country teams and sector units, the GEF,