Danube River Basin

Updated Transboundary Diagnostic

Analysis (2006)

Based on EU Water Framework Directive

Analysis Report

Danube Transboundary Analysis

page 1

CONTENTS

1. Summary ...................................................................................................................... 7

2. Introduction ................................................................................................................. 10

2.1. Background to Danube Basin interventions ................................................................. 10

2.2. The need for this updated TDA.................................................................................. 11

2.3. UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project........................................................................... 12

2.4. GEF Danube Black Sea Strategic Partnership............................................................ 13

2.5. Structure of the updated Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis Report. ............................. 14

3. Methodology ................................................................................................................. 15

3.1. Introduction............................................................................................................ 15

3.2. Guidance on TDA..................................................................................................... 15

3.3. Preparation of the EU WFD Danube Basin Analysis....................................................... 16

3.3.1. Background to IRBM in the Danube Basin........................................................ 16

3.3.2. The EU Water Framework Directive ................................................................ 16

3.3.3. Activities undertaken .................................................................................... 17

3.4. Identification of priority transboundary concerns ......................................................... 18

3.4.1. Water-related Environmental Monitoring ......................................................... 18

3.4.2. `Risk of failure' to meet good status................................................................ 18

3.4.3. Priority Transboundary Concerns.................................................................... 18

3.5. Pressure and Impact Assessment / Causal chain analysis ............................................. 19

3.6. Governance analysis ................................................................................................ 20

4. Description of Danube River Basin................................................................................ 21

4.1. Introduction............................................................................................................ 21

4.2. Physical and geographic characterisation.................................................................... 21

4.2.1. Climate and hydrology .................................................................................. 21

4.2.2. The Danube River and its main tributaries ....................................................... 24

4.2.3. Important lakes in the Danube River Basin ...................................................... 25

4.2.4. Major wetlands and other Protected Areas in the Danube River Basin District....... 25

4.2.5. Groundwater in the Danube River Basin District ............................................... 27

4.3. Ecological status ..................................................................................................... 27

4.4. Socio-economic situation.......................................................................................... 28

4.4.1. Social Economic Indicators ............................................................................ 28

4.5. Climate Change....................................................................................................... 28

4.6. Institutional setting ................................................................................................. 29

5. Priority Transboundary Concerns.................................................................................. 31

5.1. Introduction............................................................................................................ 31

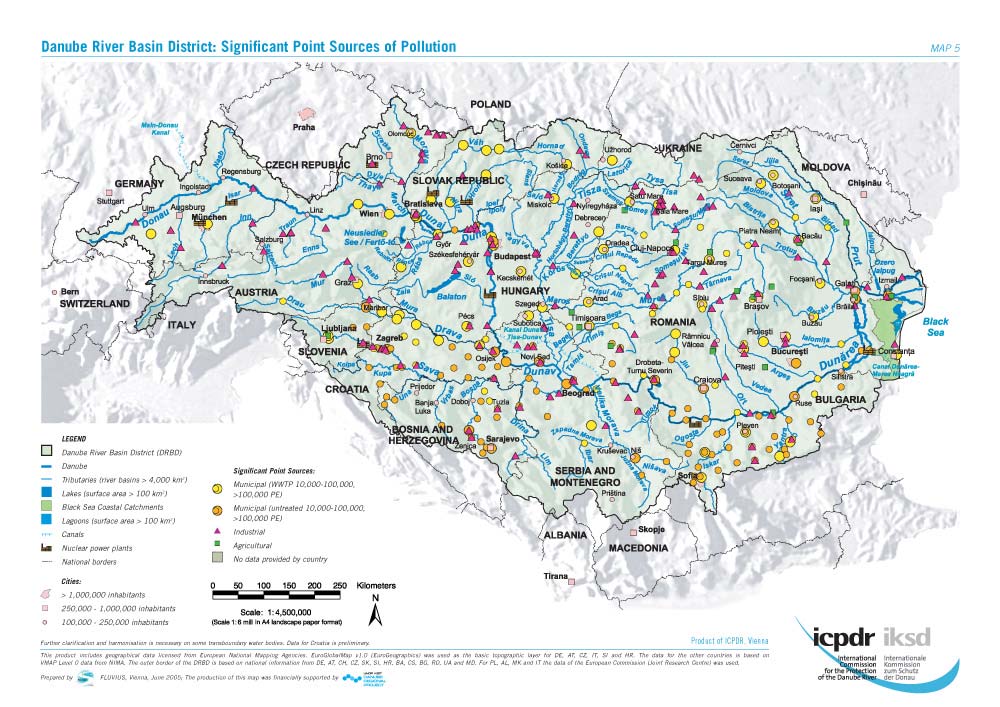

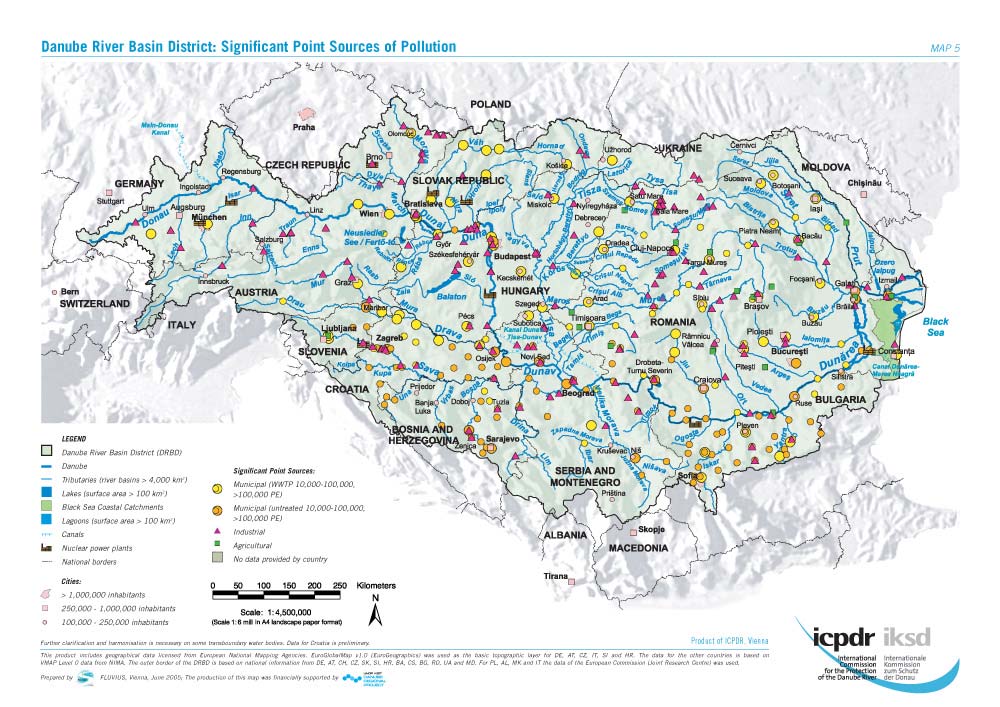

5.2. Significant Point Sources of Pollution ......................................................................... 36

5.3. Contribution of sub-basins to the total point source pollution of the Danube ................... 39

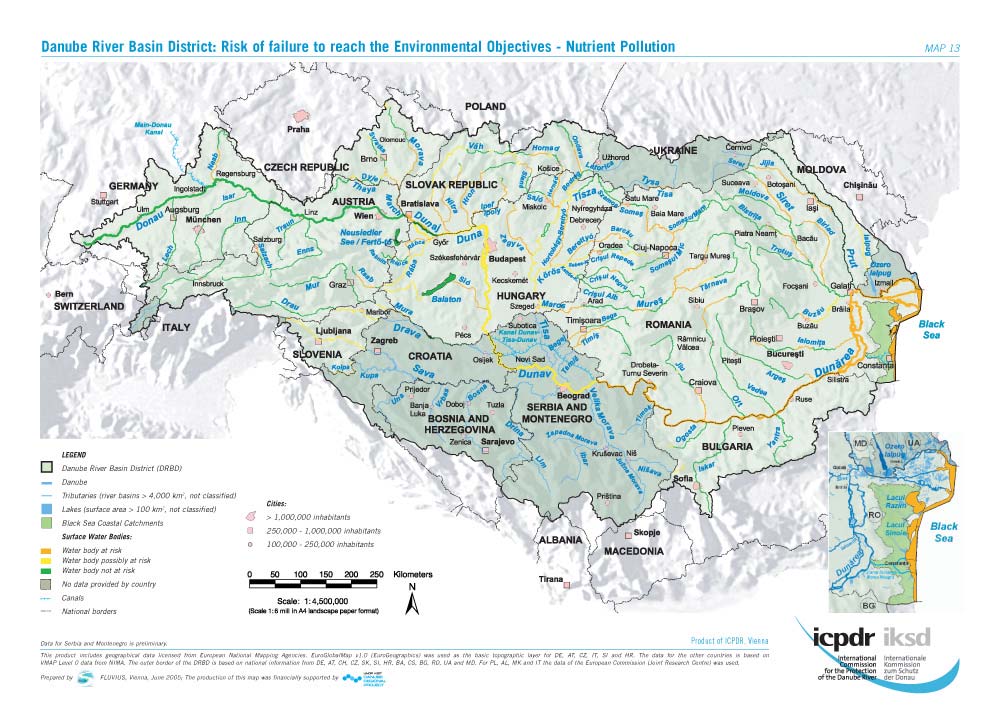

5.4. Nutrient Pollution .................................................................................................... 40

5.4.1. Introduction ................................................................................................ 40

5.4.2. Transboundary importance of nutrients in the Danube River Basin ..................... 41

5.4.3. Drivers and Pressures for Nutrient Pollution.................................................... 42

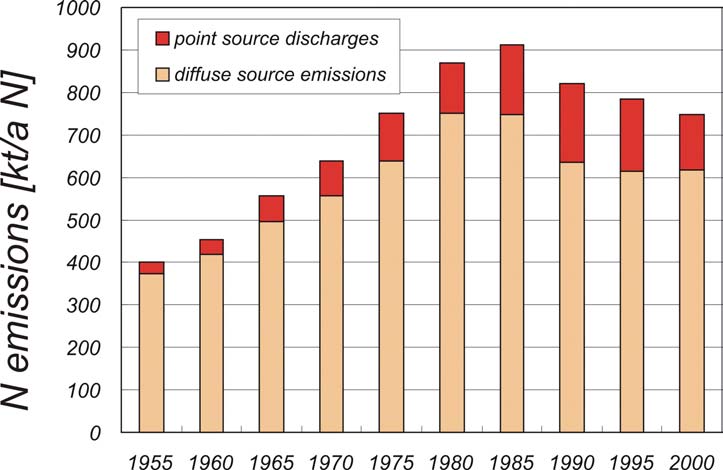

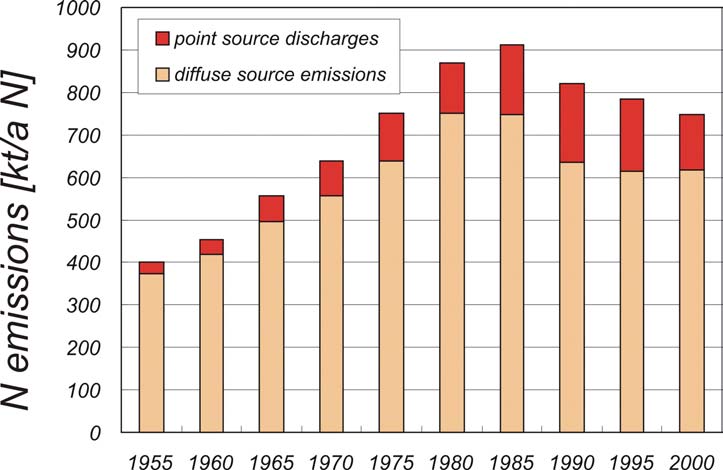

5.4.3.1. Historical development of the diffuse source nutrient pollution into the

Danube River system.................................................................................... 42

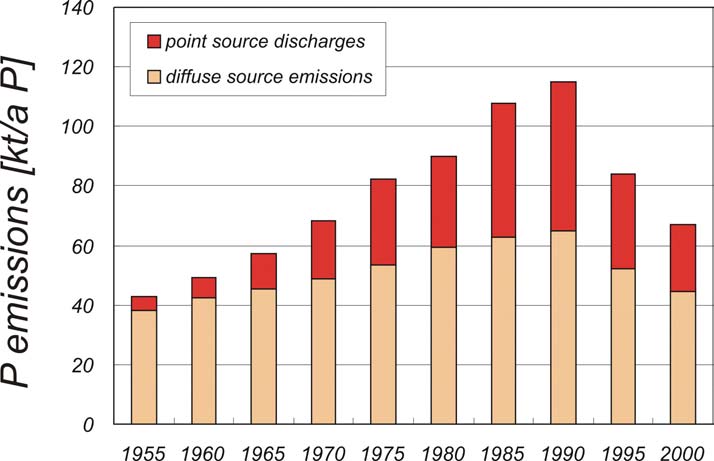

5.4.3.2. Point Source Pressures ................................................................... 45

5.4.3.3. Diffuse source pressures ................................................................. 46

5.4.4. Environmental Impacts of Nutrient Pollution in the Danube River Basin............... 49

page 2

5.4.5. Knowledge gaps........................................................................................... 51

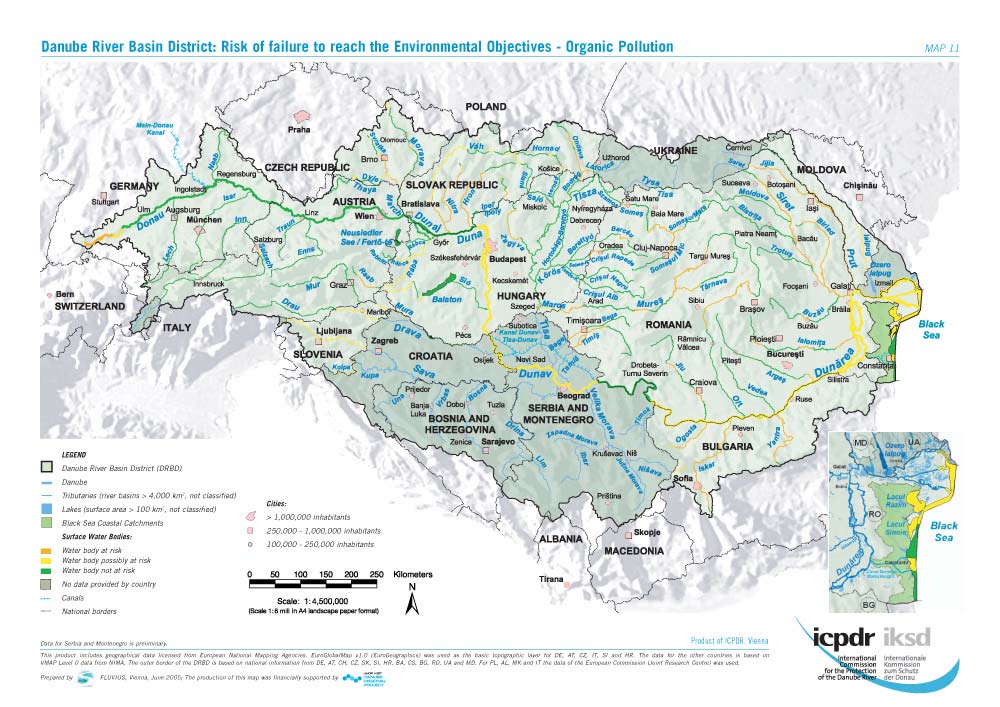

5.5. Organic Pollution ..................................................................................................... 51

5.5.1. Introduction ................................................................................................ 51

5.5.2. Drivers and Pressures of Organic Pollution....................................................... 52

5.5.3. Environmental impact ................................................................................... 52

5.5.3.1. Dissolved Oxygen........................................................................... 53

5.5.3.2. Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD5)................................................ 53

5.5.3.3. Impact assessment (Saprobic index) ................................................ 53

5.5.4. Knowledge gaps........................................................................................... 54

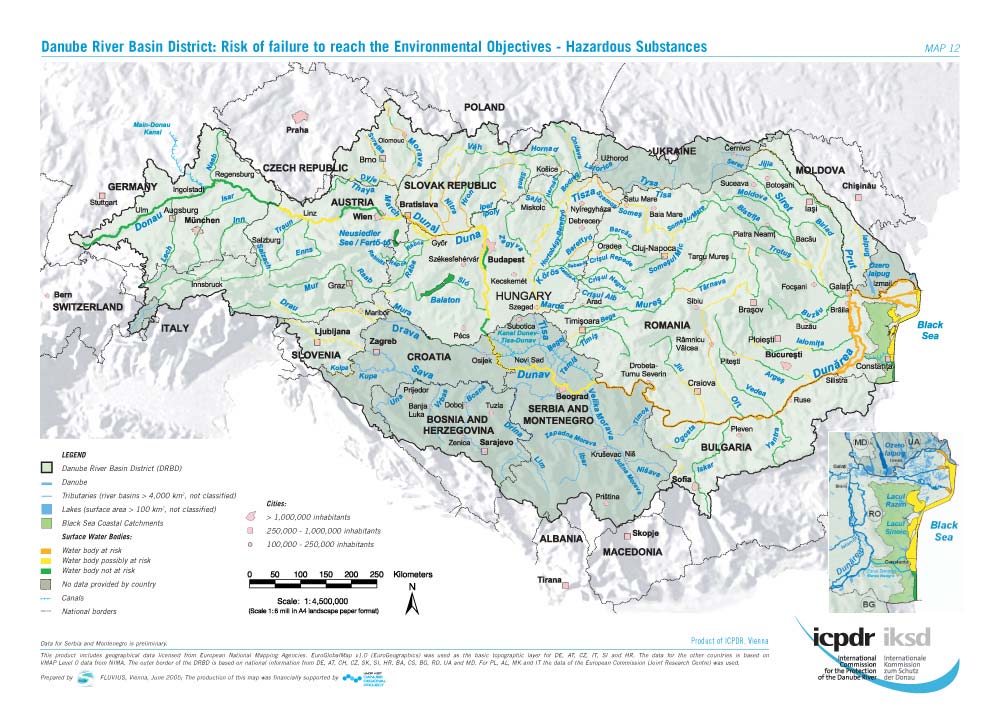

5.6. Contamination with hazardous substances.................................................................. 54

5.6.1. Introduction ................................................................................................ 54

5.6.2. Drivers and Pressures of Hazardous Substance pollution ................................... 55

5.6.3. Environmental impacts of hazardous substances .............................................. 56

5.6.3.1. Heavy metals................................................................................. 56

5.6.3.2. Organic micro-pollutants ................................................................. 60

5.6.4. Knowledge gaps........................................................................................... 61

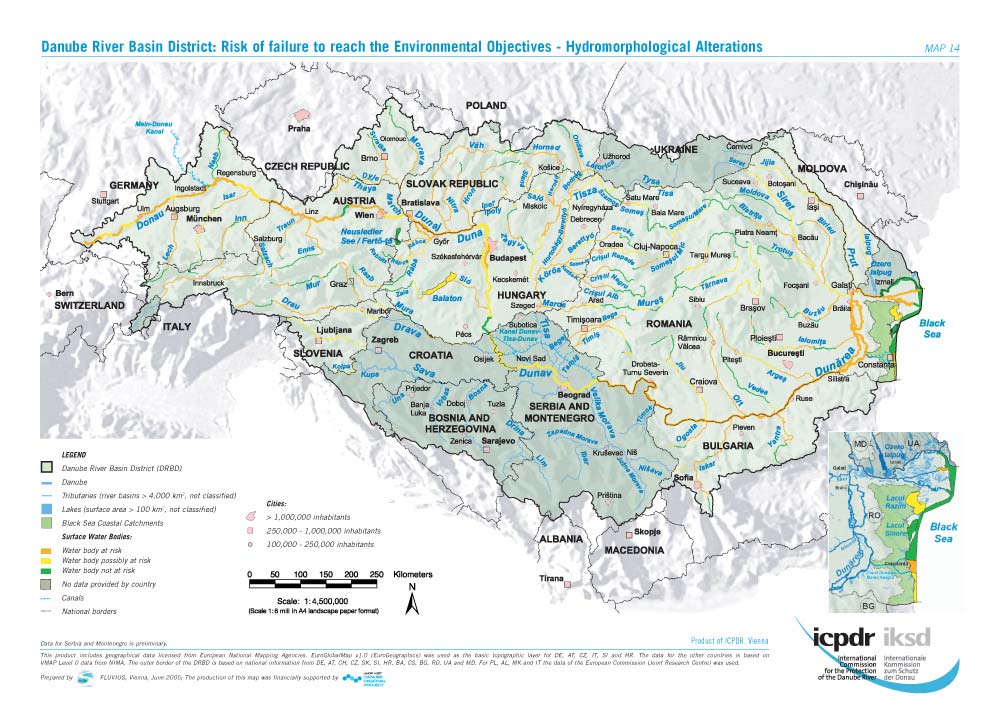

5.7. Hydromorphological alterations ................................................................................. 61

5.7.1. Introduction ................................................................................................ 61

5.7.2. Drivers and Pressures of Hydromorphological Alterations .................................. 62

5.7.3. Environmental impacts (stresses) from hydromorphological alterations............... 62

5.7.4. Knowledge gaps........................................................................................... 66

5.8. Transboundary impacts on the Black Sea ................................................................... 66

5.8.1. Introduction ................................................................................................ 66

6. Stakeholder Involvement in the Danube River Basin .................................................... 71

7. Analysis of Institutions, Legislation and investment needs within the Danube

River Basin ................................................................................................................... 72

7.1. Analysis of Institutions and Legislation....................................................................... 72

7.2. Summary of investments identified............................................................................ 78

List of Figures

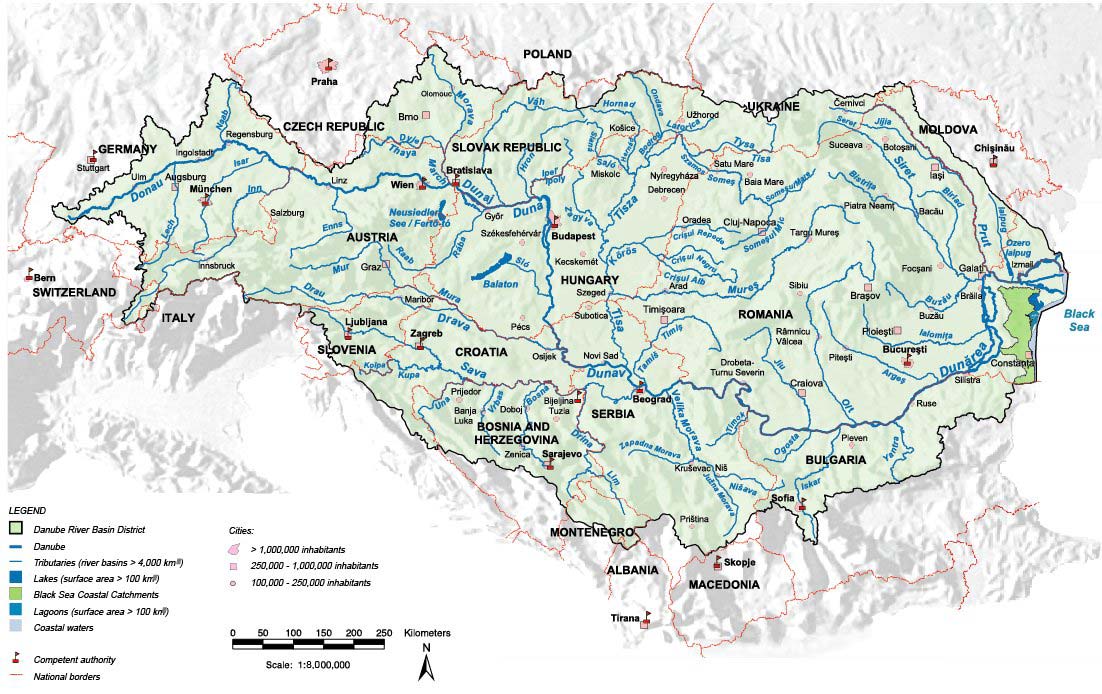

Figure 1:

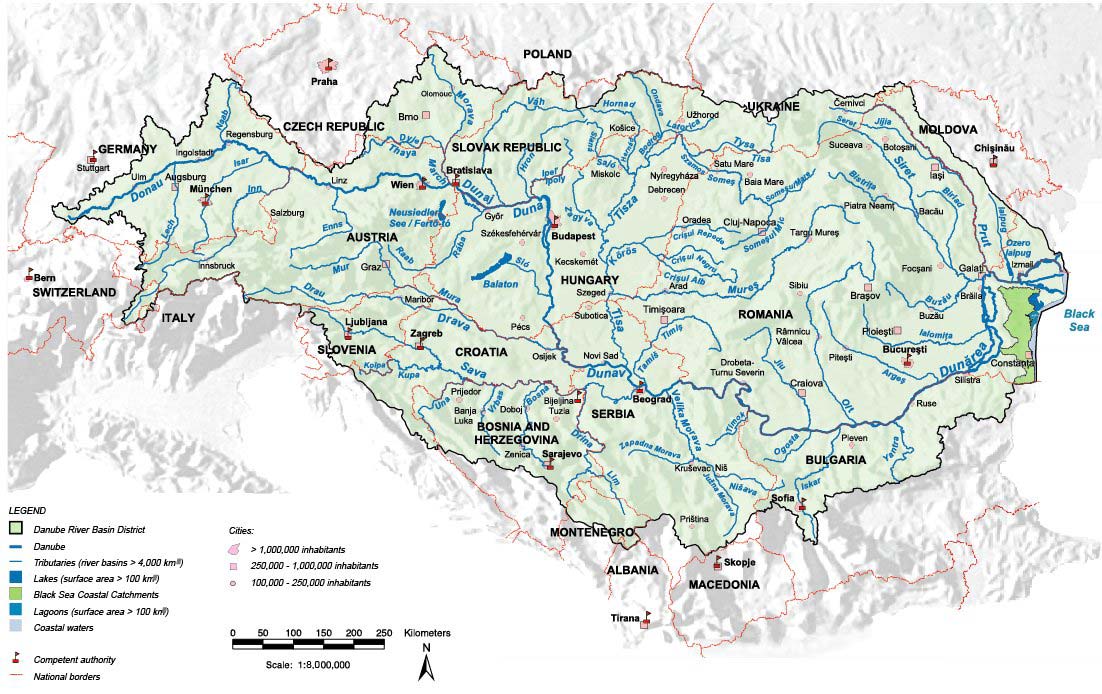

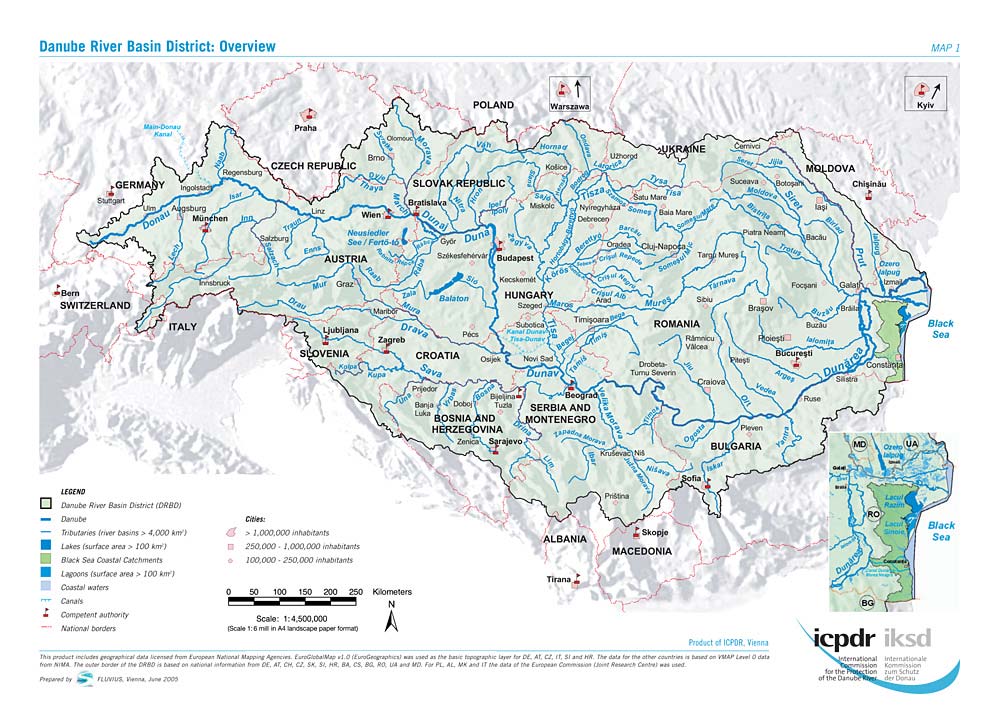

Location of the Danube River Basin ........................................................................ 22

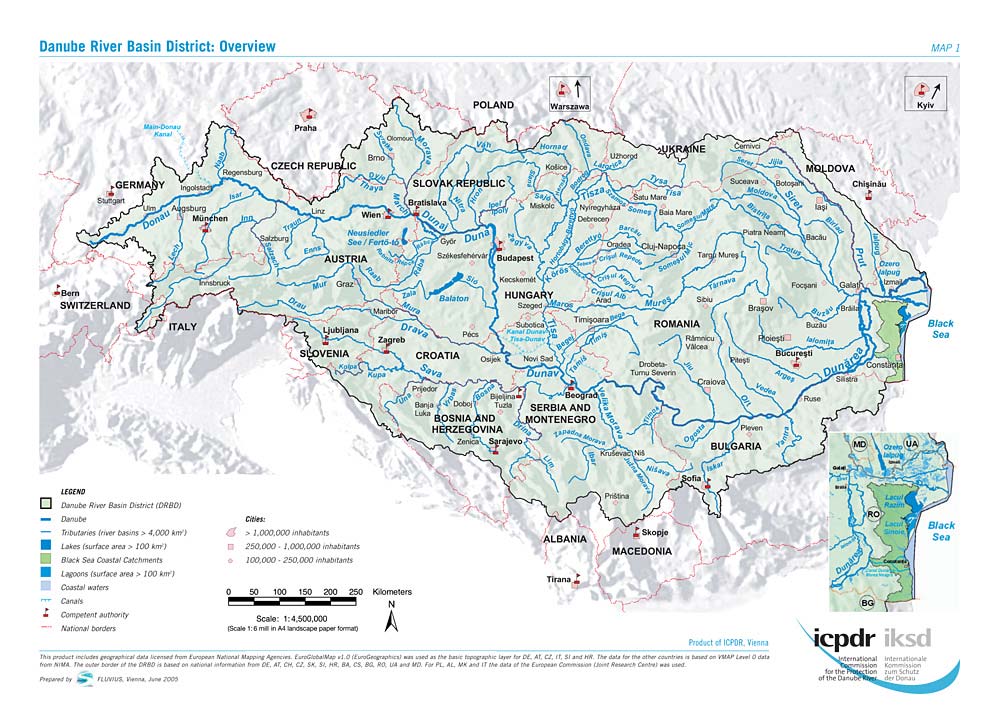

Figure 2:

The Danube River Basin........................................................................................ 23

Figure 3:

Longitudinal profile of the Danube River and contribution of water from each

country (in %) to the cumulative discharge of the Danube (in millions

m3/year), based on data for 1994-1997 using the Danube Water Quality Model .......... 24

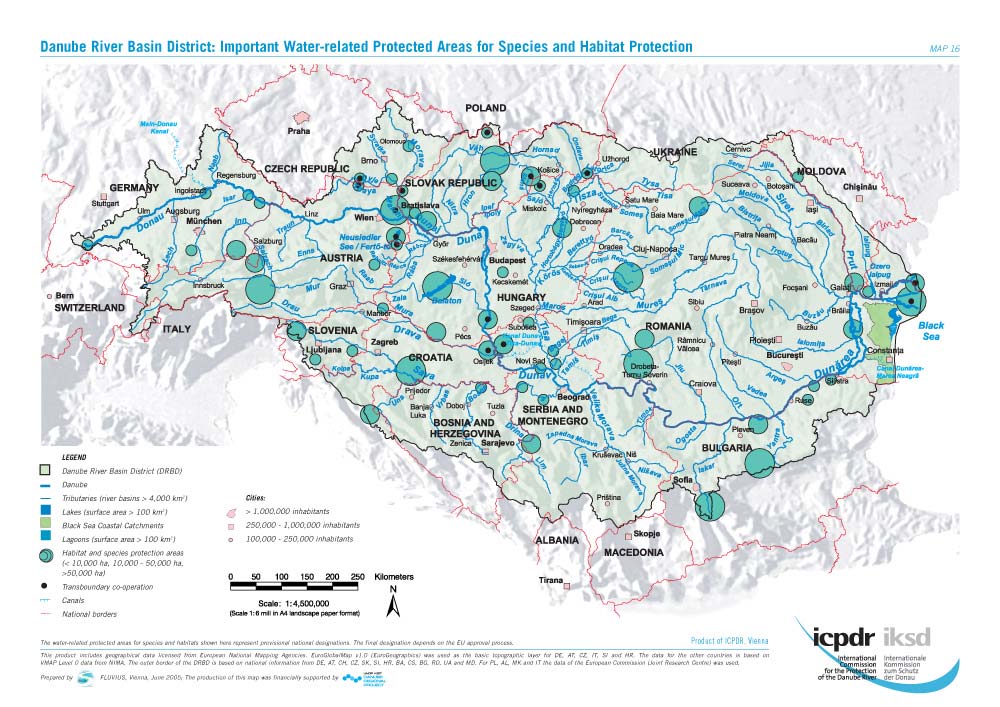

Figure 4:

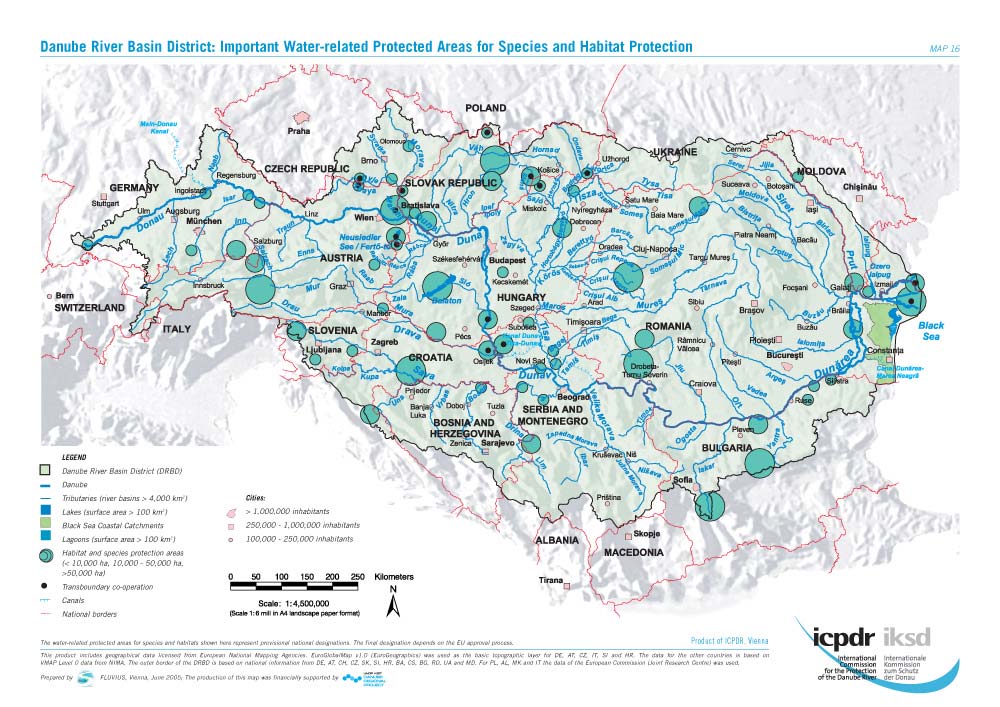

Major Protected Areas within the Danube River Basin ............................................... 26

Figure 5:

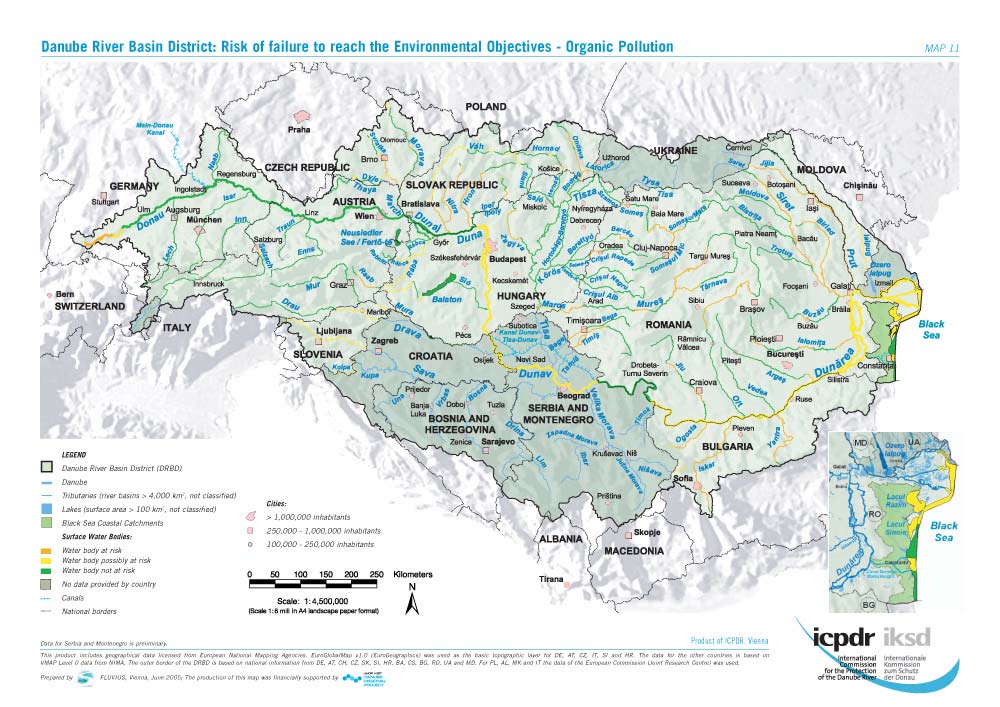

Risk of Failure to Reach Environment Objectives Organic Pollution .......................... 32

Figure 6:

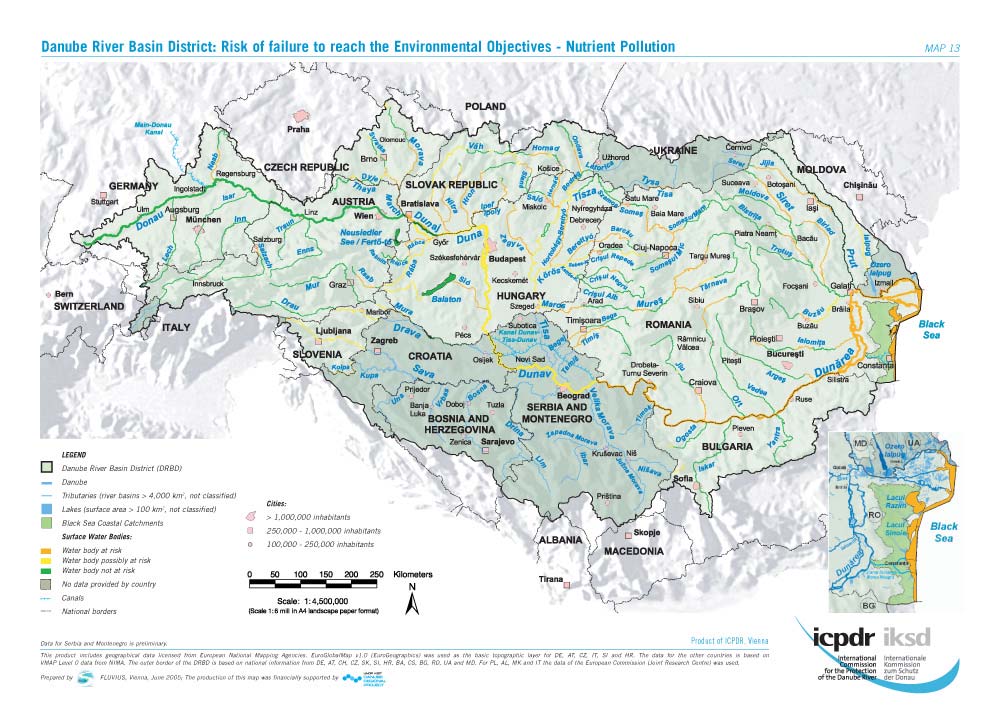

Risk of Failure to reach Environmental Objectives Nutrient Pollution ........................ 33

Figure 7:

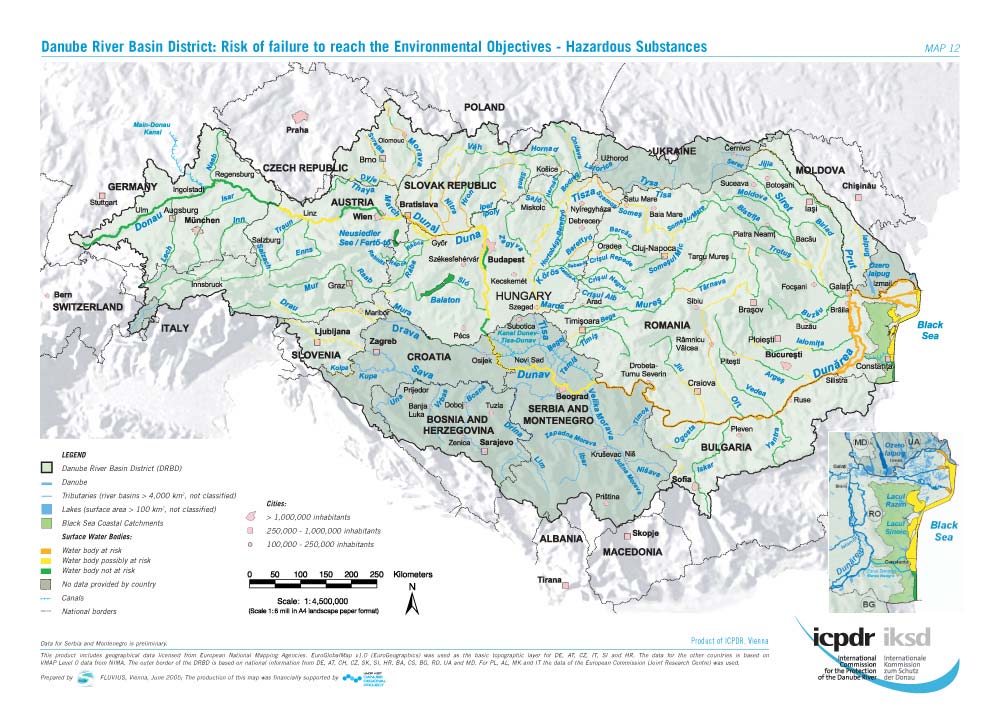

Risk of failure to reach Environmental Objectives Hazardous Substances .................. 34

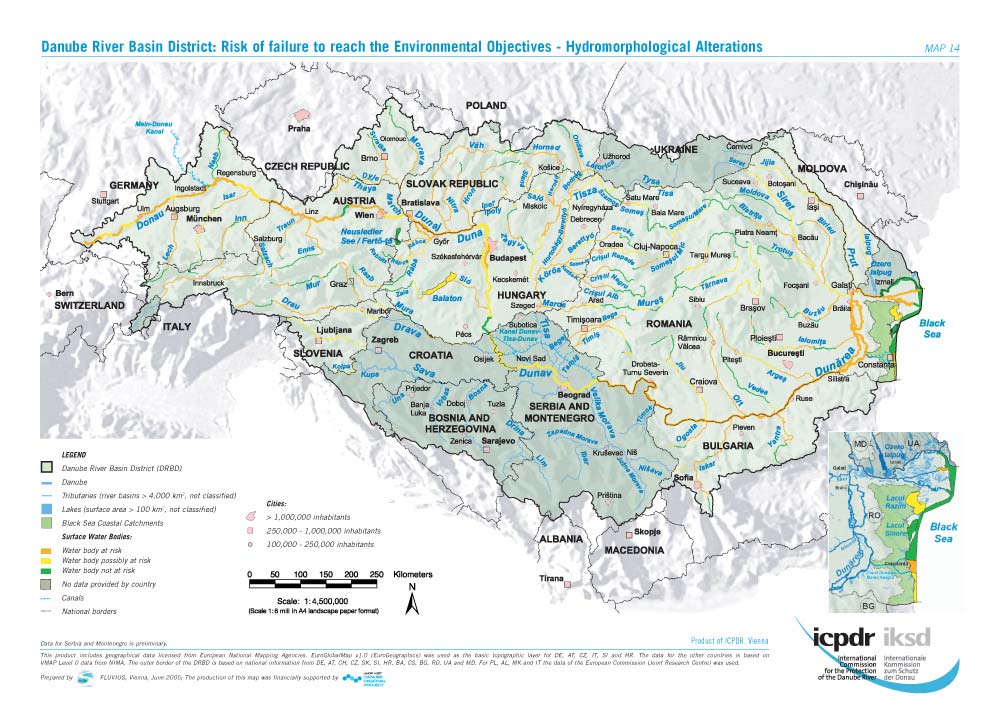

Figure 8:

Risk of failure to reach Environmental Objectives Hydromorphological

Alterations .......................................................................................................... 35

Figure 9:

Risk classification of the Danube, disaggregated into risk categories. Each full

band represents the assessment for one risk category (hydromorphological

alterations, hazardous substances, nutrient pollution, organic pollution).

Colours indicate the risk classes. * SK territory. ...................................................... 36

Figure 10:

Significant Point Source of Pollution ....................................................................... 38

Danube Transboundary Analysis

page 3

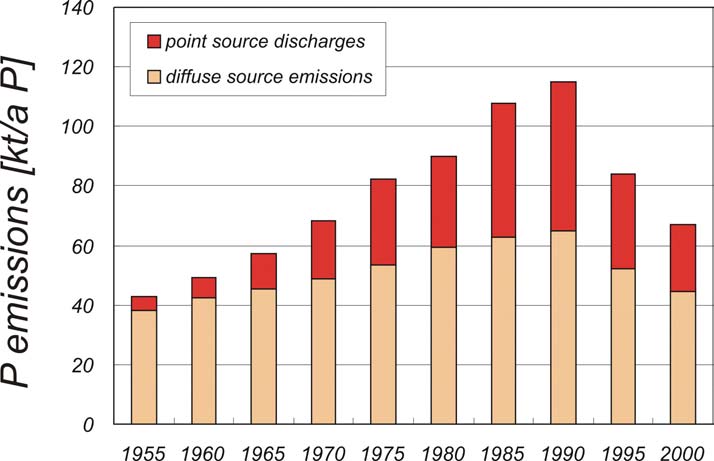

Figure 11:

Temporal changes of the nitrogen emissions into the total Danube river system

for the years 1955 to 2000 (MONERIS) .................................................................. 44

Figure 12:

Temporal changes of the phosphorus emissions into the total Danube river

system for the years 1955 to 2000 (MONERIS) ....................................................... 45

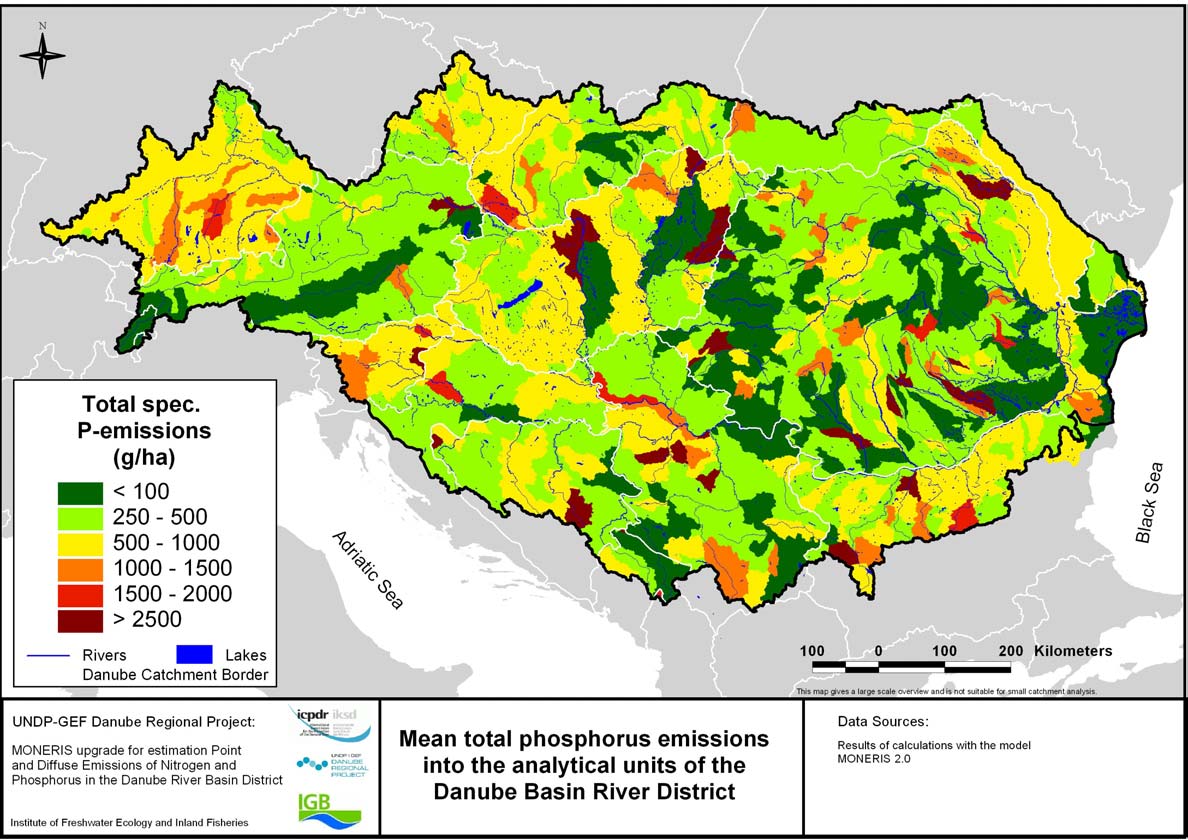

Figure 13:

Total estimated nutrient emissions for the Danube river basin in the period

1998-2000; result of the MONERIS application for the WFD Danube River Basin

Analysis Report ................................................................................................... 45

Figure 14:

Estimated diffuse nutrient pollution by pathways for the total Danube river

systems for the period 1998 to 2000 from the MONERIS model for the WFD

Danube River Basin Analysis Report ....................................................................... 46

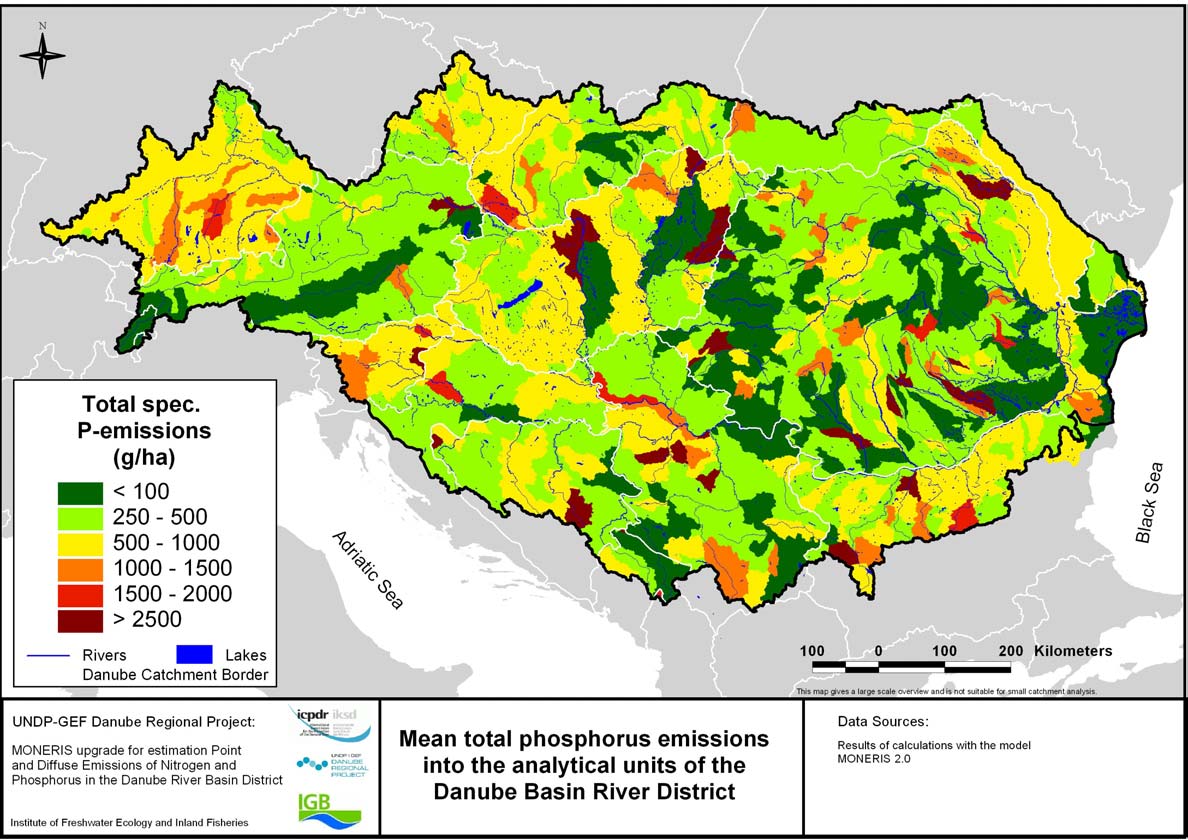

Figure 15:

Mean total Phosphorus emissions into the analytical units of the Danube Basin

River District ....................................................................................................... 47

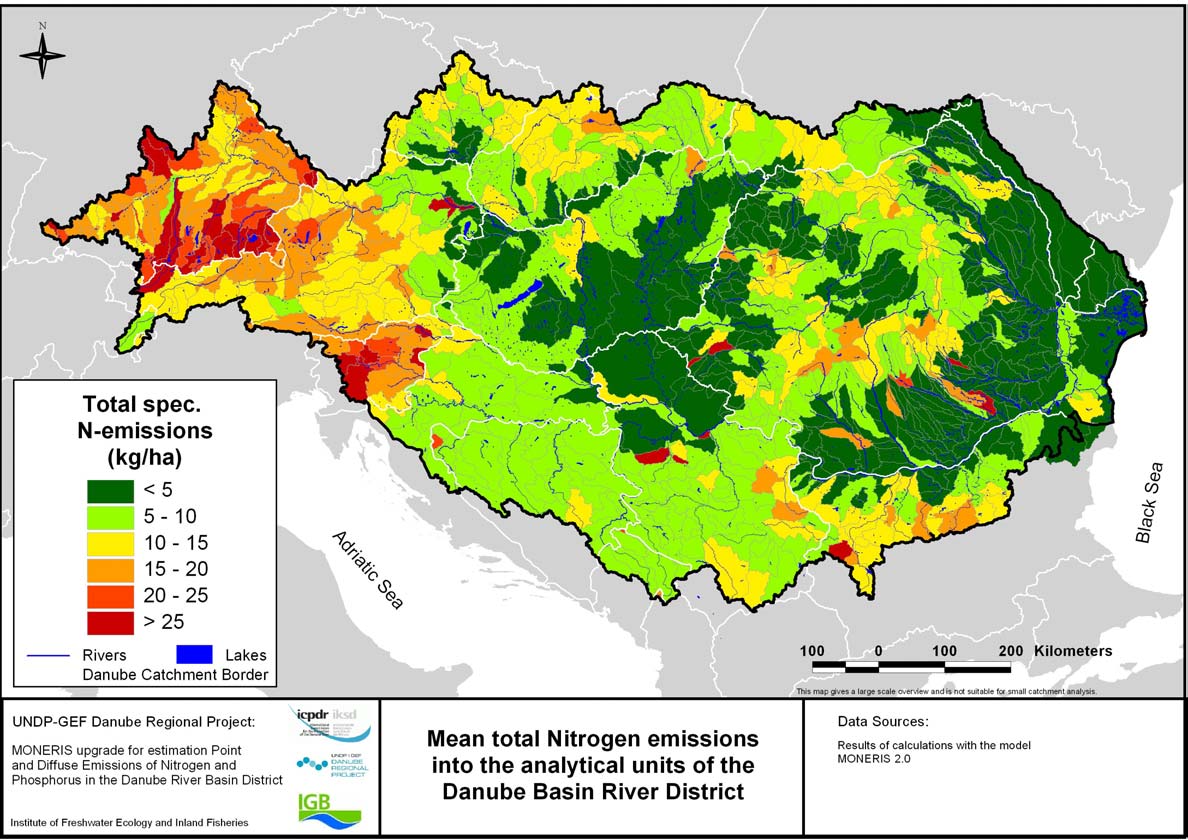

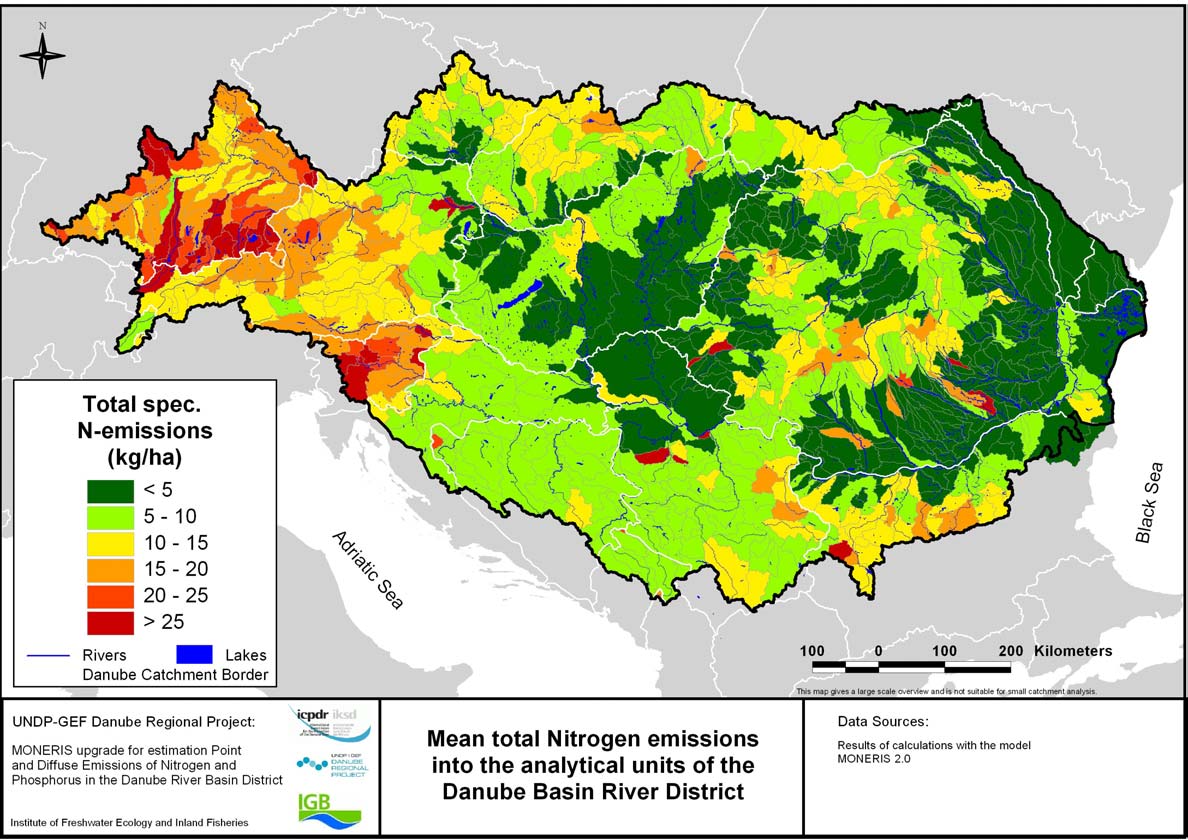

Figure 16:

Mean total Nitrogen emissions into the analytical units of the Danube Basin

River District ....................................................................................................... 48

Figure 17:

River load profiles of nitrogen (a) and phosphorus (b), subdivided over

countries of origin derived from simulations with the Danube Water Quality

Model (DWQM) during the GEF-UNDP Danube Pollution Reduction Programme,

1999 UNDP/GEF (1999a) ...................................................................................... 50

Figure 18:

Information related to the concentrations of chlorophyll- in the Danube and its

large tributaries, on the basis of TNMN field data from 2003 ..................................... 50

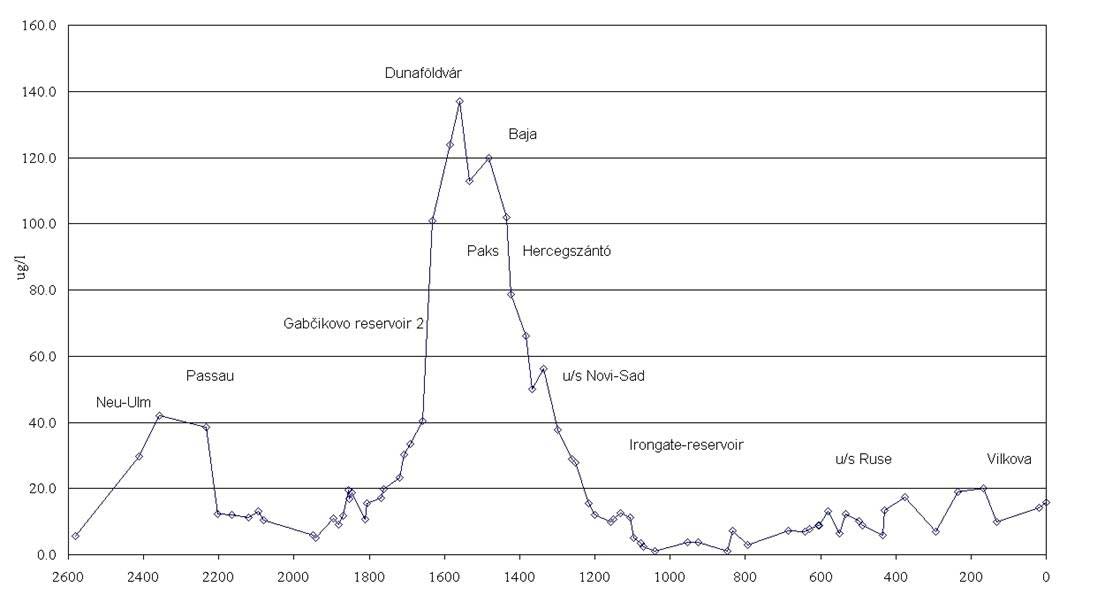

Figure 19:

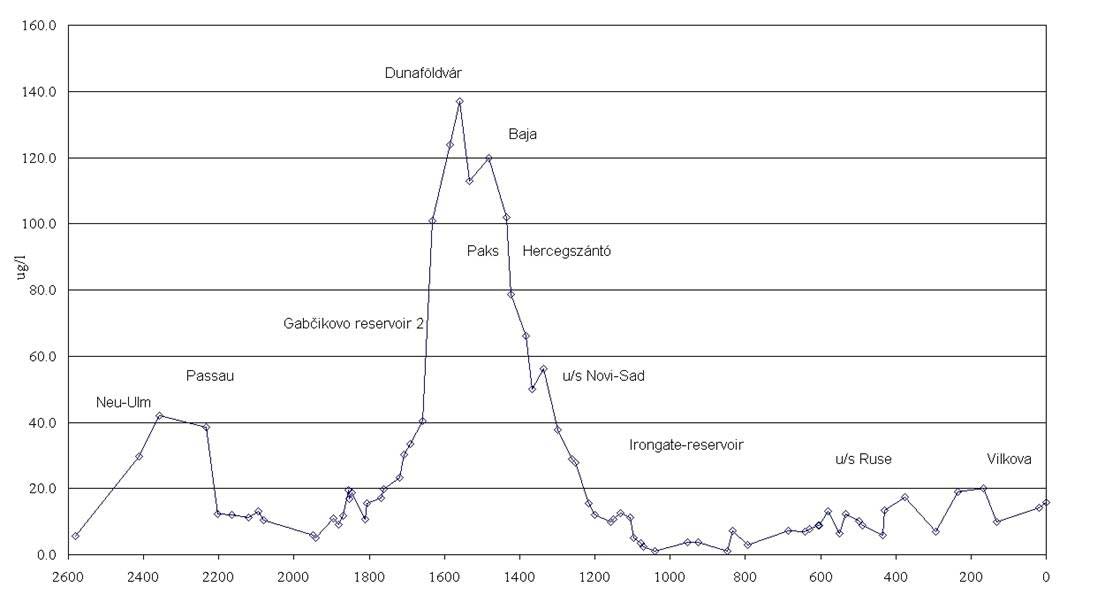

Concentrations of chlorophyll- [µg/l] in the Danube River on the basis of field

data collected during the JDS ................................................................................ 51

Figure 20:

TNMN Water quality classes for cadmium and for mercury in 2001............................. 57

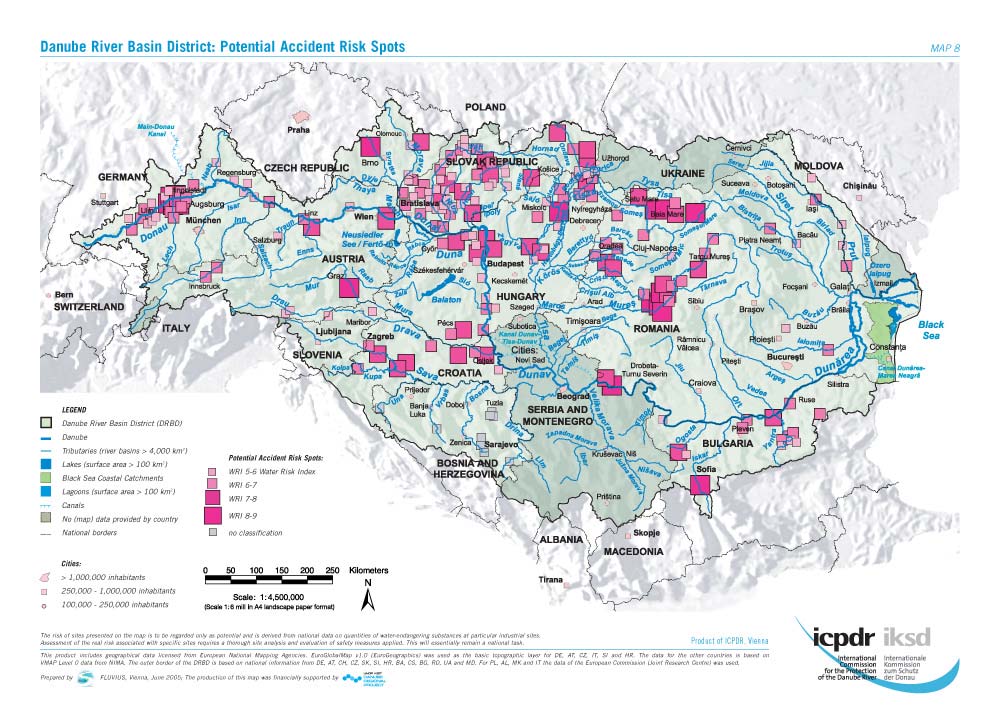

Figure 21:

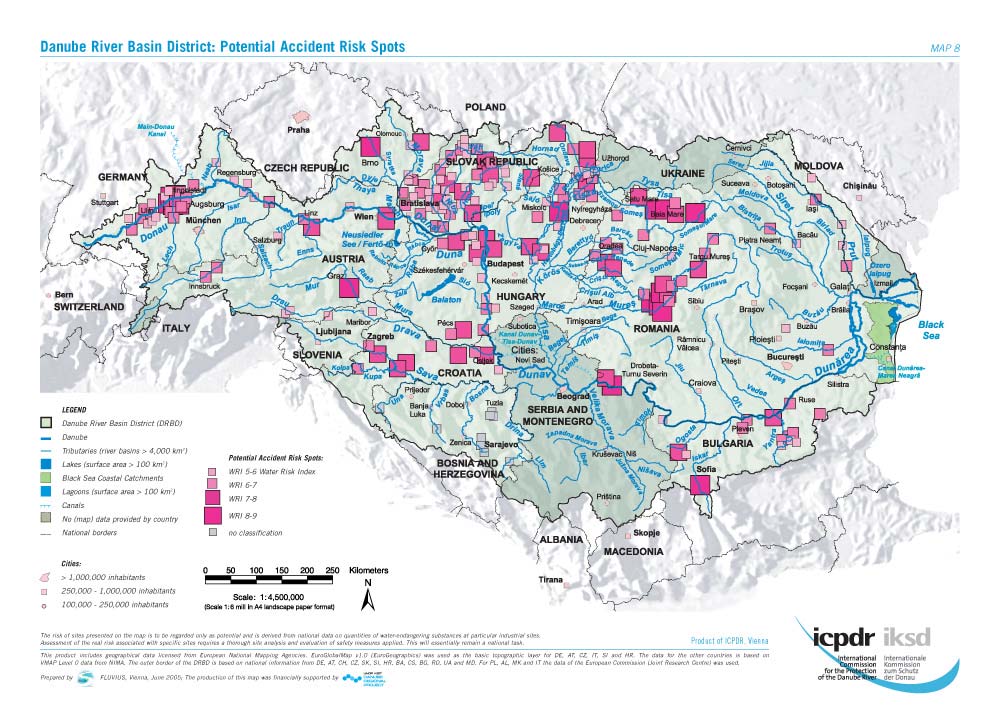

Potential Accident Risk Spots................................................................................. 58

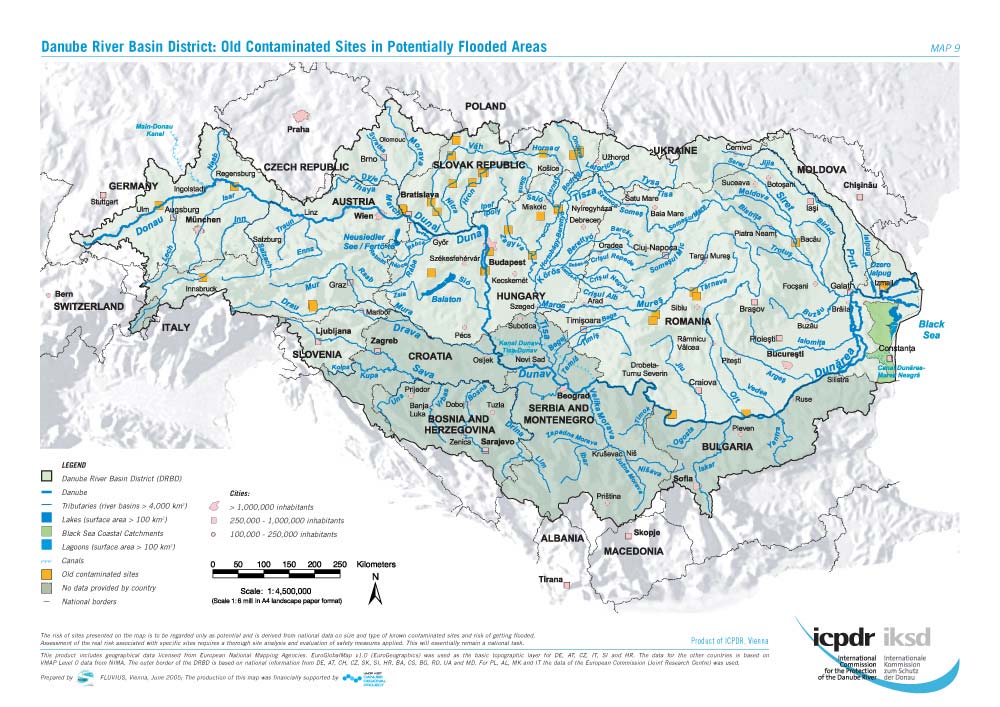

Figure 22:

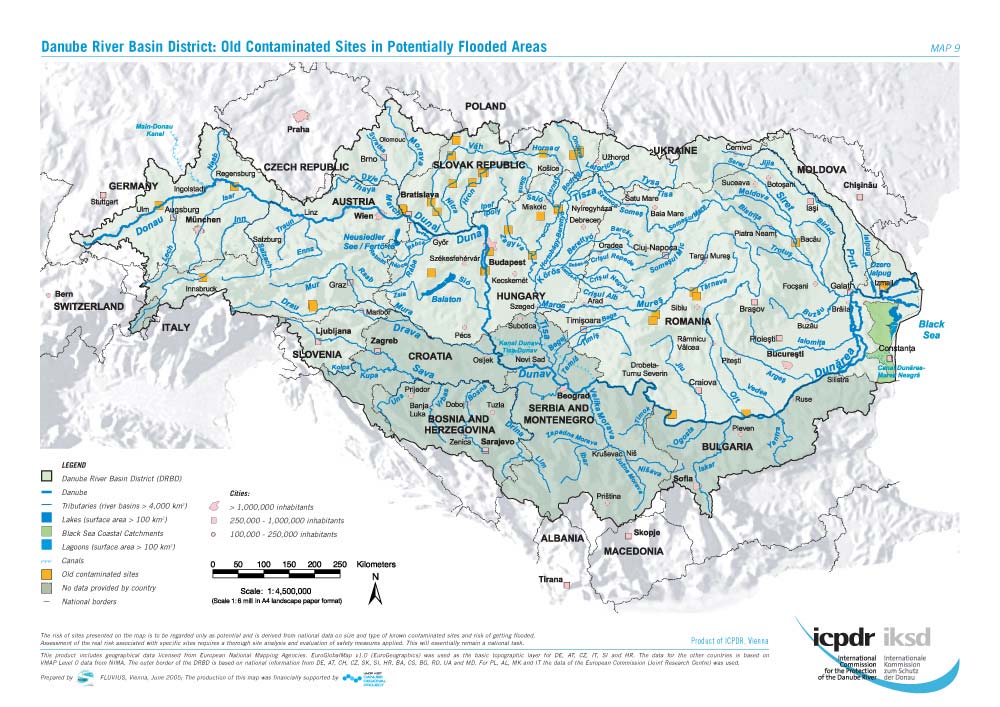

Old Contaminated Sites in Potentially Flooded Areas ................................................ 59

Figure 23:

TNMN Water quality classes for Atrazine in 2001 ..................................................... 60

Figure 24:

Danube River annual nutrient loads and flows to the Black Sea (1988-2005)............... 68

Figure 25:

Number of macrozoobenthos species near Constanta, Romania (1960s-2003)............. 69

Figure 26:

Long-term dynamic of phytoplankton abundance and biomass in the western

Black Sea coastal area (Galata transect): A) Average phytoplankton abundance

[cells/l] and biomass [mg/m3] by periods (1961-2005); B) Average biomass

[mg/m3] in September [1999-2005]...................................................................... 69

Figure 27:

Long-term dynamics of Copepoda and Cladocera abundance (log transformed)

at 3 miles station off cape Galata (Western Black Sea) during summer of the

period 1967-2005 (the data 1967-2003 by Kamburska et al. 2006). .......................... 70

Figure 28:

Organisation Structure under the Danube River Protection Convention ....................... 72

page 4

List of Tables

Table 1:

General socio-economic indicators ......................................................................... 28

Table 2:

Definition of significant point source pollution on the basin-wide level ........................ 37

Table 3:

Significant point sources of pollution in the Danube River Basin District

according to the criteria defined in Table 2.............................................................. 37

Table 4:

Municipal, industrial and agricultural point source discharges of COD, BOD,

total nitrogen and phosphorus from significant sources according the criteria of

Table 2 (based on ICPDR Emission Inventory data of 2002) ...................................... 39

Table 5:

Consumption of pesticides (in t/a) in some Danube countries and specific

pesticide consumption (kg per ha agric. area and year) in 2001 according to

the FAO database on agriculture ............................................................................ 56

Table 6:

Status of water-related policy, programmes and National Environmental Action

Plans in the DRB countries .................................................................................... 77

Table 7:

Summary of investments and project nutrient reductions. ........................................ 78

Table 8:

Overview of implementation of EU Directives .......................................................... 79

Danube Transboundary Analysis

page 5

GLOSSARY

AQC

Analytical Quality Control

AT Austria

BAP Best

Agricultural

Practice

BAT

Best Available Technique

BEP

Best Environmental Practice

BG Bulgaria

BH

Bosnia and Herzegovina

BOD Biological

Oxygen

Demand

BSERP

(UNDP/GEF) Black Sea Ecosystem Recovery Project

CAP

EU Common Agricultural Policy

CARDS

European Commission assistance for former Yugoslavia

CCA

Causal Chain Analysis

COD Chemical

Oxygen

Demand

CS

Serbia and Montenegro (now two countries)

CZ Czech

Republic

DE Germany

DEF Danube

Environmental

Forum

DPRP

UNDP/GEF Danube Pollution Reduction Programme

DPSIR Drivers-Pressures-State-Impact-Response

DRB

Danube River Basin

DRP

(UNDP/GEF) Danube River Project

DRPC

Danube River Protection Convention

EBRD

European Bank for Reconstruction and Development

EC European

Commission

EEA

European Environment Agency

EG

ICPDR Expert Group

EIB European

Investment Bank

EU European

Union

FAO

Food and Agricultural Organisation

GDP

Gross Domestic Product

GEF

Global Environment Facility

GIS Geographical

Information

System

HMWB

Heavily Modified Water Bodies

HR Croatia

HU Hungry

ICPDR

International Commission for the Protection of the Danube River

page 6

IRBM

Integrated River Basin Management

JAP

ICPDR Joint Action Plan

JDS

Joint Danube Survey

MD Moldova

MONERIS

Modelling Nutrient Emissions in River Systems

MS

Member State of the EU

N Nitrogen

NGO Non-Governmental

Organisation

NW Northwest

P

Phosphorus

Phare European

Commission

assistance programme for Eastern Europe

RBM River

Basin

Management

RBM

River Basin Management

RBMP

River Basin Management Plan

rkm

River kilometre (for the Danube 0 rkm is the mouth of the river)

RO Romania

RR

Roof Report Danube Basin Analysis Report completed for EU WFD

RS

Serbia (previously Serbia and Montenegro)

SAP

Strategic Action Plan

SAP Strategic

Action

Plan

SI Slovenia

SIP SAP

Implementation

Plan

SK Slovakia

t/a Tonnes

per

year

TDA

Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis

TNMN Trans-National

Monitoring

Network (water quality programme of ICPDR)

UA Ukraine

UNDP

United Nations Development Program

UNECE

United Nations Economic Commission for Europe

UNEP

United Nations Environment Program

WB World

Bank

WFD

EU Water Framework Directive

WWTW Wastewater

Treatment

Work

Danube Transboundary Analysis

page 7

1. SUMMARY

As the `most international river basin in the world', the Danube River Basin has been subjected to

considerable environmental pollution over many years. Whilst the main problems associated with this

pollution were observed in the Black Sea northwest shelf, seen through the frequent anoxic events as

resulting from nutrient and organic pollution, the majority of the Danube Basin has also been

impacted, by nutrients, organic pollution, hazardous substance pollution and hydromorphological

alterations (resulting in the loss of wetlands/floodplains and interrupting fish migration).

The Danube River Basin has also been the subject of many investigations and studies funded by a wide

range of organisations, with the GEF and the European Commission providing the most sustained

inputs. In addition the countries of the Danube River Basin have actively supported and contributed to

these investigations. These previous studies have resulted in a number of key assessments and

recommendations, in particular a Strategic Action Plan (1994), Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis

(1999), a Joint Action Plan (2000) and most recently in compliance with the EU Water Framework

Directive, a Danube River Basin Analysis (2005). This updated Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis

(2006) is based on the results of the UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project and these previous

assessments, most significantly, the 2005 Danube Basin Analysis/

The collapse of the former Eastern economies had a beneficial impact on the environment of the

Danube and the Black Sea as industry and agriculture declined. However the region was left with a

legacy of poor infrastructure (for example municipal wastewater treatment works and low connectivity

of the population in some areas to sewer networks) and out-dated environmentally unfriendly

agricultural practices. Efforts to improve the situation have been underway for a number of years.

Wastewater treatment plants are under construction and the upper Danube (the new EU Member

States) improvements in nutrient concentrations and loads are starting to be observed. The situation in

the lower Danube is still to show signs of improvements in the nutrient loads, but the processes are

being introduced for investments, changes in legislation and EU accession that can be expected to

show benefits in a number of years.

Improvements in the environment of the Northwest Black Sea have been observed in recent years

showing positive signs of recovery from the historical pollution. Dissolved oxygen has improved and

the diversity and number of benthic organisms have increased.

The Danube Basin still has many environmental problems, but a mechanism exists through the

International Commission for the Protection of the Danube River (ICPDR) to discuss these issues and

to collectively define the priorities. The EU and the accession process have undoubtedly assisted the

implementation of IRBM throughout the Danube Basin in the form of the EU Water Framework

Directive (WFD). But the contribution of UNDP/GEF and other donors should not be underestimated in

assisting with the accession process.

The implementation of the EU WFD and the strict time-line required by this legislation to achieve `good

status' should be seen as a catalyst to the future improvement of the Danube River and the reduction

of impacts on the Black Sea. In 2009 a River Basin Management Plan will be submitted by the ICPDR

covering transboundary issues and by each country addressing national issues. These plans will contain

concrete specifications to reduce the pollution and the European Commission will be monitor the

implementation of the plan. Failure to follow the agreed plans will result in EC legal actions against the

Member State.

Not all countries of the Danube Basin are EU Member States. The non-EU countries still have many

challenges. Importantly, all the countries have agreed to adopt and implement the WFD, but it would

page 8

be unrealistic to assume that this implementation will be to the same level in the non-EU countries due

to obvious financial limitations.

This updated Transboundary Analysis (based largely on the findings of the 2005 Danube River

Analysis) identified four key concerns that are a priority for the Danube River Basin and the impact of

the Danube River on the Black Sea.

·

Nutrient Pollution potentially leading to over enrichment by nutrients and eutrophic

conditions. The main sources were identified as point emissions (both municipal wastewater

and industrial discharges) and diffuse sources, predominately from agriculture.

·

Organic Pollution potentially leading to low dissolved oxygen levels in the receiving water.

The main sources were identified as inadequate wastewater treatment from municipalities and

from diffuse sources.

·

Hazardous substances potentially leading to environmentally toxic conditions. The main

sources were identified as industrial (both active and from previous industrial sites) and

accidental pollution from shipping or mining activities.

·

Hydromorphological Alterations that have led to a loss of wetlands, impact on natural

aquatic conditions and present migration barriers for fish. Hydromorphological alterations are

the result of engineering works in rivers and lakes for navigation, hydropower generation, flood

prevention, etc.

The main focus of the GEF interventions in the Danube River Basin have been directed towards

nutrient pollution and its reduction. This is reflected in the level of information on this specific topic in

this updated Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis.

The future priorities to be addressed in the Danube River Basin with respect to nutrient pollution can

be summarised as:

The decrease of the Danube River nutrient loads in the last decade is partly a positive side

effect of the economic crisis in the middle and lower Danube Basin. The ongoing economic

recovery will potentially result in increasing nutrient loads to the Black Sea. However, the

economic development in these countries is a social necessity, even if an increase in the level

of production probably will lead to an increase of nutrient emissions to the environment in the

future. Therefore, the challenge is to compensate these possible increases by a decrease of

emissions from point and diffuse sources and to level the increase of emissions.

From the present state of knowledge we can derive that future emission control efforts can

best be concentrated on phosphorus (being the limiting nutrient). Furthermore, measures

directed at dissolved P-compounds, which are easily available for algae growth, are most

effective.

The introduction of P-free detergents, P-removal at municipal and industrial wastewater

treatment plants and the avoidance of agricultural point sources are such measures. In the

same time, nitrogen removal from point sources (treatment plants) will play an important role

in nitrogen management, as diffuse sources from agriculture in the Eastern Danubian countries

are bound to increase as a result of the expected economic growth.

The ICPDR and the UNDP/GEF have been actively supporting actions to address diffuse nutrient

sources through a range of interventions including the introduction and piloting of Best

Agricultural Practice in the lower Danube Basin and the promotion of wetlands for nutrient

retention (together with the other benefits of flood mitigation, groundwater recharge and

biodiversity). In addition the DRP has also been supporting activities addressing reduction of P

in washing detergents. This has recently led to a recommendation by the ICPDR for the

Danube Transboundary Analysis

page 9

introduction of P-free detergents across the Danube River Basin and that this will be initiated in

Romania.

Under the EC DABLAS programme a priority list of projects has been identified that would lead

to nutrient reduction from municipal, industrial and land-use sources. The implementation of

these projects seeking investments would have a positive impact on the nutrient pollution.

An agreement has been reached between the International Commissions of the Danube and

the Black Sea for the reversal of nutrient loads to those in 1996 as a long-term objective and

to achieve the mid-1990s levels in the short term. Based on recent work by the MONERIS

model it is expected that full implementation of the EU UWWT Directive (including nutrient

removal in all WWTW larger than 10,000 pe) will result in acceptable loads of phosphorus

being discharged to the Black Se. However this estimate does not take account of any

increases from agricultural sources that can be expected as economic conditions improve. The

model also indicated that additional measures (above those required by the EU directives) may

be needed to ensure that nitrogen loads return to the 1996s levels.

page 10

2. INTRODUCTION

The Danube River Basin is the second largest basin in Europe and the most international in the world

with 181,2 countries within the basin. The last fifteen to twenty years have seen significant changes in

the regions, with the collapse of the former eastern economies and the accession of some of these of

these countries to the European Union. GEF assistance has been provided to the region since 1991 and

together with the EU accession process has significantly assisted with the implementation of Integrated

River Basin Management. An important additional driver for the considerable interest in the Danube

Basin has been the concern on the impact of the Danube River on the northwest Black Sea shelf in the

last decades.

The Danube Countries have had a long history of collaboration and co-operation on the Danube River.

From the Danube Navigation Convention signed in Belgrade in 1948 (which had its roots in the Paris

conferences in 1856 and 1921), the recognition of the importance of water management with the

signing of the Bucharest Declaration (1984), the UNECE Transboundary Water Convention (Helsinki

Convention), the establishment of the Danube River Protection Convention (DRPC) to the latest

European Union water directive the Water Framework Directive (WFD). The principles enshrined in

the UNECE Convention and the DRPC clearly established the importance of Integrated River Basin

Management (IRBM) within the Danube basin.

The Danube Basin has been a story of unique co-operation between UNDP/GEF IRBM support and the

EU accession process. The EU accession (and in particular the EU WFD) has greatly assisted in

accelerating the implementation of IRBM within the basin supported by all the Danube countries. The

support provided by UNDP/GEF has complemented the overall accession process by providing

strengthening of institutions and experts involved in IRBM necessary for EU membership.

This document provides a current assessment of the main issues that are considered to be a threat to

the Danube Basin environment based on extensive work undertaken by the countries in meeting the

EU WFD with support from the UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project.

2.1.

Background to Danube Basin interventions

The Danube River Basin has been the subject of extensive investments, research and capacity building

initiatives from a wide range of international donors (and basin national governments) over the last 15

years, and is now at a stage of comparative maturity with respect to understanding the issues

affecting the basin. Complementing this international assistance there has been the development and

implementation of a clear legal basis for co-operation in the region (the DRPC) and the establishment

of a strong, mature and sustainable International Commission (the ICPDR).

GEF through UNDP has been heavily involved in the Danube Basin since 1991. Together with the

European Commissions PHARE programme (and other donors) they created the Danube Programme

Co-ordination Unit that focussed on the implementation of the Environmental Programme for the

Protection of the Danube Basin (EPDRB). These interventions led to the preparation in 1994 of the

Strategic Action Plan (SAP) for the Danube River that was then transformed into an operational

implementation plan. The understanding of the key pollution issues within the basin was further

1 Austria, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Czech Republic, Slovenia, Slovakia, Serbia and Montenegro, Germany,

Hungary, Romania, Moldova, Ukraine, Bulgaria, Albania, Italy, Macedonia, Poland, Switzerland

2 Recently Serbia & Montenegro have elected to split into two countries. The total number of the countries in the

Danube Basin is now 19.

Danube Transboundary Analysis

page 11

refined under the UNDP/GEF Danube Pollution Reduction Programme that identified the significant

`hotspots' in the basin and prepared a detailed Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis in 1999. The

findings of the TDA were instrumental in developing the objectives of the current UNDP/GEF Danube

Regional Project. Linked to these activities, the newly (1998) ratified Danube Convention, through the

ICPDR, prepared an update of the 1994 SAP in the form of the Joint Action Plan (2000) which

contained the findings of the TDA and pollution `hot-spots' within the basin and provided

recommendations for their mitigation. These outputs were transformed into a prioritised list of

pollution reduction investment opportunities, aimed at a range of funding institutions, covering

municipal, industrial, land use and wetland restorations focused on nutrient and organic pollution

reduction. With the implementation of the EU WFD in 2000 the ICPDR, with significant support from

the UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project, prepared an Analysis Report (or characterisation assessment)

for the whole basin. This Analysis Report is an important precursor to the development of a legally

binding river basin management plan for the Danube Basin.

In summary the key successes within the Danube River Basin include:

> The support of the EPDRB jointly by GEF and EC PHARE;

> The development of the Strategic Action Plan and it implementation;

> The preparation and signing of the Danube River Protection Convention;

> The establishment of a strong and sustainable Commission for the Danube Basin;

> The preparation of a TDA;

> The preparation of the Joint Action Plan;

> The prioritisation of investments needed to reduce pollution in the basin (DABLAS);

> Support of the Countries and the ICPDR by UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project in a wide

range of pollution reduction activities;

> Preparation and submission of the EU WFD Danube Basin Analysis report.

These (and other) successes have contributed to the current situation of a well-understood and

characterised river basin within an International Convention agreement and supported by a well

developed and mature Commission. The ICPDR's Joint Action Plan, with support from the EC DABLAS

initiative, has prepared a prioritised list of investments that, when implemented, would address many

of the pollution issues within the basin, including those that are transboundary in nature. The

estimated total costs of these projects are in excess of 4,000 M USD which is expected to result in a

reduction of nitrogen emissions > 50 kt/a and of phosphorus emissions of 9 kt/a. To date (end of

2005) estimates for projects completed or underway are expected to result in a nutrient reduction of

25 kt/a of nitrogen and 4 kt/a of phosphorus. (To put these figures in context: the total emissions to

the Danube Basin are estimated as 758 kt/a for nitrogen and 70 kt/a for phosphorus, with the

measured loads to the Black Sea estimated as 400 kt/a for nitrogen and 12 kt/a for phosphorus.

Within the EU WFD there is a clear timescale where these remaining pollution issues have to be

addressed. The detail of the investments and the actions needed to achieve the `good status' required

by the WFD will be developed over the next two years as a `Programme of Measures' to be included in

the River Basin Management Plan to be submitted to the European Commission as a binding intention

of action in 2009.

2.2.

The need for this updated TDA

The Danube River Basin and the activities that have been undertaken are of interest to a broader

audience particularly outside the region. Whilst the Danube is the `most international basin in the

page 12

world' it has benefited in recent years from the cohesive influence, and financing not only from GEF but

also from the European Union. A key environmental driver in Europe has been the introduction of the

Water Framework Directive that imposes legal requirements on the EU Member States to achieve `good

ecological status' in its water bodies by 2015.

The WFD Analysis Report has many similarities to the GEF Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis as a

stepping-stone to the development of an agreed Strategic Action Plan (or its EU WFD equivalent - the

River Basin Management Plan). This similarity includes the objectives, methodology and outputs of the

assessment. In addition, the objectives of the WFD are analogous to the more widely adopted concepts

of IRBM, and the tools used to implement the WFD (e.g. the Danube Basin Analysis and River Basin

Management Plan) are comparable with those used by GEF International Waters (TDA and SAP). The

common ground between these two policy approaches also includes the requirement for a continuous

process of adaptive management to review and refine the management plans on a five or six year

cycle.

Although these conditions (EU accession) in the Danube make the region unique, there are many

lessons that can be learnt for International Waters programmes elsewhere and this document aims at

portraying the Danube Analysis report in the more familiar global TDA format as the `Danube River

Basin updated TDA (2006).

The Danube Basin Analysis has been a significant achievement by the countries of the basin

coordinated by the ICPDR and, technically and financially assisted by the UNDP/GEF Danube Regional

Project. A detailed assessment of the basin has been completed, endorsed at a senior national level

and submitted as a legal requirement to the European Commission, providing the first detailed

overview of issues of transboundary importance. Whilst not all countries within the Danube River Basin

are EU Member States or in the process of acceding to the EU (nine out of the thirteen3,4 countries of

the Danube River Basin will be EU members) all the Contracting Parties to the ICPDR (all thirteen

countries) asserted that the implementation of the WFD would have the highest priority within the

ICPDR. In 2006, all the environment ministers of the Danube River Basin reaffirmed this in writing.

This updated TDA does not offer a comprehensive assessment of the Danube Basin as a stand-alone

document. It builds on the previous many studies and makes reference to them (including TDA, SAP

and more recent action plans by the ICPDR) but utilises the WFD Danube Analysis to express the

analysis in a GEF International Waters context.

2.3.

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

In 2001, GEF launched their final basin-wide intervention to support the activities of the Danube

countries and the ICPDR with a particular focus on IRBM, nutrient reduction and transboundary co-

operation in the basin, consistent with implementing the Danube River Basin SAP. The project was

implemented by UNDP and co-executed by UNOPS and the ICPDR. The UNDP/GEF Danube Regional

Project (DRP) has provided considerable support to the countries and the ICPDR for the preparation of

the Danube Basin Analysis. An overview of the main activities and achievements of the UNDP/GEF

DRP is provided on data DVD, containing all the project activities.

3 Austria, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Czech Republic, Slovenia, Slovakia, Serbia and Montenegro, Germany,

Hungary, Romania, Moldova, Ukraine, Bulgaria.

4 Five of the Danube Basin countries (Poland, Italy, Switzerland Albania and Macedonia) are not Contracting Parties

to the ICPDR as the area of the Danube Basin on their territory is less than 2000 km2

Danube Transboundary Analysis

page 13

2.4.

GEF Danube Black Sea Strategic Partnership

Until the 1960s, the Black Sea was known for its productive fishery, scenic beauty, and as a resort

destination for millions of people. Since that time, as with other water bodies around the world,

massive over fertilisation of the sea by nitrogen and phosphorus from agriculture, municipal, and

industrial sources has seriously degraded the ecosystem, disrupted the fisheries, reduced biodiversity,

posed health threats to humans, and resulted in billions of dollars of economic losses to the economies

of the 6 countries.

The Danube River as one of the main sources of nutrients flowing to the Black Sea is also facing a

problem of pollution by nutrients and toxic substances due to industrial activities, extensive

agriculture, growing municipal communities that have a negative impact on the river including its,

water quality, water uses (e.g. water supplies for inhabitants), aquatic life, etc.

Pollution from the Danube Basin countries has created this transboundary water quality problem. Since

1992, efforts have been underway with European Union and GEF support to gradually reverse the

situation in the Danube and the Black Sea Basin.

Through its Operational Strategy the GEF identified that there is a need to: (a) build the capacity of

countries to work together, (b) jointly understand and set priorities based on the environmental status

of their water body, (c) identify actions and develop the political commitment to address the top

priority transboundary problems, and then (d) to implement the agreed policy, legal, and institutional

reforms and investments needed to address them.

Following the previous GEF assistance and building on the achieved results and efforts of the

participating countries in the Danube Black Sea Region, a Strategic Partnership was developed, with

aim to accelerate implementation of nutrient reduction measures and policy/legal/institutional reforms

in the basin.

GEF and its Implementing Agencies are implementing the Strategic Partnership consisting of capital

investments, economic instruments, development and enforcement of environmental law and policy,

strengthening of public participation, and monitoring of trends and compliance over the period of

2001-2007 for the countries of the Danube/Black Sea basin.

This Partnership is composed of three complementary parts:

1.

The Black Sea Ecosystems Recovery Project - a GEF Black Sea Regional capacity building and

technical assistance element implemented (in cooperation with the Black Sea Commission

under the leadership of UNDP and with the assistance of UNEP for defined components;

2.

The Danube Regional Project - a GEF Danube River basin regional capacity building and

technical assistance element implemented (in cooperation with the ICPDR) under the

leadership of UNDP;

3.

The GEF/World Bank Partnership Investment Fund - a GEF / World Bank supported Investment

Fund for Nutrient Reduction focused on single country nutrient reduction investments.

In addition, activities of the countries, EC, EBRD, EIB, and bilateral support aimed at similar objectives

targeting reduction of nutrients and toxic pollutants, as well as the ongoing Dnipro project, are

considered as contribution to the Strategic Partnership.

Both, the Danube Regional Project and its sister project based in Istanbul - the Black Sea Ecosystems

Recovery Project will strengthen the respective Commissions and will assist countries in their efforts to

adopt necessary policy, legal and institutional reforms and enforcement of environmental regulations

(with particular attention to the reduction of nutrients and toxic substances). The GEF/World Bank

Nutrient Reduction Investment Fund is entailing direct investments aimed at concrete reductions in

page 14

pollution, primarily nutrients, at the national level that can then be replicated throughout the Danube

and Black Sea region.

2.5.

Structure of the updated Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis

Report.

This updated TDA is largely based on the EU Water Framework Directive `Danube River Basin Analysis'

report that was prepared by the countries of the basin and submitted to the European Commission as

a legal obligation in 2005. As there has been an initial TDA (1999, prepared by the UNDP/GEF Danube

Pollution Reduction Programme), this document updates the most critical parts of this initial TDA with

information available from the Danube River Basin Analysis report. In addition the approach adopted

for this update has been to follow as closely as possible the terminology and conclusions accepted by

the Danube countries for the Danube Basin Analysis Report, but attempts to present these conclusions

within the structure of a TDA.

There are a number of `gaps' in this report as compared to a traditional TDA. For example, a full

stakeholder analysis is not presented (although as a requirement for the EU WFD, full stakeholder

engagement and public participation has been an integral part of the Danube Basin Analysis). Limited

socio-economic information has also been collected in the region for the WFD report (this only

addressed socio-economic aspects of water and water use in the basin).

The most important aspect of this report is that it is based on reports that have been prepared and

endorsed by the countries, under the guidance of the ICPDR, and consequently the information it

contains has a high level of national acceptance.

The structure of this report follows that recommended for a TDA as:

> Methodology: This section provides an understanding of the process (political, institutional

and technical) leading to the submission of the EU WFD Danube Basin Analysis to the European

Commission. The considerable support that was provided by the UNDP/GEF DRP is

summarised. The four key transboundary concerns (nutrient pollution, organic pollution,

hazardous substance pollution and hydromorphological alterations) are covered.

> Description of the Danube River Basin: This section provides an introduction to the basin

characteristics including the environmental status and institutional arrangements within the

basin.

> Priority Transboundary Concerns: The section begins with an assessment of the whole

basin in terms of the `risk' of failing to meet the WFD expectations of `good ecological status'

by 2015. Each of the four issues is addressed in detail, based on the information collected for

the Danube Basin Analysis. An important component of the work of the ICPDR and the

UNDP/GEF DRP has been an assessment of the impact of the Danube on the Black Sea. A

recent report, prepared for the GEF Council is used to supplement the information available in

the Danube Basin Analysis report.

> Stakeholder Involvement in the Danube River Basin: As explained above, a full

stakeholder analysis as expected within a TDA is not reported. However the key activities that

have been undertaken in the basin involving a wide range of stakeholders including the

broader public are summarised in this update.

> Analysis of Institutions, Legislation and Investments: This section provides an

introduction to the water and environmental management within the Danube River Basin, both

at a national and at the transboundary levels to identify causes of the transboundary concerns.

Danube Transboundary Analysis

page 15

3. METHODOLOGY

3.1. Introduction

This updated TDA has been developed using material developed in previous and on-going programmes

including:

> SAP (1994) Strategic Action Plan developed under the Environmental Programme for the

Danube River Basin (EPDRB) managed by the Danube Programme Co-ordination Unit (PCU)

and funded by UNDP/GEF and the EC Phare environment programme;

> SIP (1995) - SAP Implementation Plan;

> UNDP/GEF Danube Nutrient Reduction Programme (1997 1999)

> TDA prepared under UNDP/GEF Danube Nutrient Reduction Programme (1999),

> ICPDR Joint Action Plan 2000- 2005,

> EU WFD submissions co-ordinated by the ICPDR and in particular the `Danube Basin Analysis'

approved by the ICPDR in December 2004 and submitted to the EC in March 2005;

> EC supported DABLAS programme (specific reports in 2002 and 2004),

> UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project (2001 2006)

The key source for this TDA has been the EU WFD Danube River Analysis (the full report is available on

the DRP data DVD and is also available to download from www.icpdr.org).

This section of the Transboundary Analysis Report provides a brief description of the process that led

to the submission of the EU WFD Danube River Analysis together with a synthesis of this report with

other sources to provide an understanding of the key transboundary issues.

3.2. Guidance

on

TDA

A Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis (TDA) is an objective, non-negotiated analysis using best

available verified scientific information that identifies key transboundary concerns and their root causes

. It provides the factual basis for the formulation of a Strategic Action Programme (SAP), which will

embody specific actions (policy, legal, institutional reforms or investments) that can be adopted

nationally, usually within a harmonised multinational context, to address the major priority

transboundary concerns identified in the TDA, and over the longer term enable the sustainable

development and environmental protection of the specific transboundary system.

Historically, advice on TDA and SAP approaches given by GEF has been rather limited. However, the

experiences of senior IA portfolio managers, IW Chief Technical Advisors and practitioners from a

number of IW projects, together with GEF IW Focal Area Programme Study, provided an opportunity to

develop more formal guidelines to assist with the preparation of TDAs and to ensure inter-regional

comparability.

Consequently a GEF guidance document was developed to provide a road map for best practice in

formulating a TDA and a SAP as part of a GEF IW project. It was prepared on the basis of discussions

between specialists from UNDP, UNEP and the GEF Secretariat, together with practitioners who had

completed the process in freshwater and marine systems. The final document reflected the experience

obtained in developing TDA/SAPs between 1996 and 2003 but was not intended as a prescriptive

page 16

formula, merely a guide that should be adapted to the cultural socio-economic and political realities of

each region.

The GEF IW TDA/SAP "best practice" approach consists of the following steps:

> Identification and initial prioritisation of transboundary concerns;

> Gathering and interpreting information on environmental and water resources impacts

and socio-economic consequences of each priority concern;

> Causal chain analysis (including root causes)

> Completion of an analysis of institutions, laws, policies and projected investments

It focuses on transboundary concerns without ignoring national ones, sets priorities and identifies

information gaps, policy distortions and institutional deficiencies. The analysis is cross-sectoral and

examines national economic development plans, civil society (including private sector) awareness and

participation, the regulatory and institutional framework and sectoral economic policies.

This TDA update, based on the EU WFD analysis, attempts to follow the overall concept for a TDA but

clearly the source material and the objectives within the ICPDR and the UNDP/GEF DRP have some

differences.

3.3.

Preparation of the EU WFD Danube Basin Analysis

3.3.1. Background to IRBM in the Danube Basin

The Danube River Protection Convention forms the overall legal instrument for cooperation and

transboundary water management in the Danube River Basin. The main objectives of the Convention

are to ensure that surface waters and groundwater are sustainably and equitably used, and that the

basin's riverine ecosystems are conserved and restored. (See sections 4.6 on Institutional setting and

ng and Governance Analysis respectively.)

3.3.2. The EU Water Framework Directive

The EU Water Framework Directive (WFD) is the legislative framework for water management in

Europe (all EU member states are legally bound by this legislation). It sets clear objectives that a good

water quality status must be achieved by 2015 and that sustainable water use is ensured throughout

Europe. Specifically, the WFD

> Sets uniform standards in water policy throughout the European Union and integrates

different policy areas involving water issues,

> Introduces the river basin approach for the development of integrated and coordinated river

basin management for all European river systems,

> Stipulates a defined time-frame for the achievement of the good status of surface water and

groundwater,

> Introduces the economic analysis of water use in order to estimate the most cost-effective

combination of measures in respect to water uses,

> Includes public participation in the development of river basin management plans

encouraging active involvement of interested parties including stakeholders, non-

governmental organisations and citizens.

Danube Transboundary Analysis

page 17

The EU WFD requires Member States to individually comply with the Directive and to actively co-

ordinate their compliance with other countries (both members and non-members) within a river basin.

3.3.3. Activities

undertaken

To prepare the Danube Basin Analysis the ICPDR created a River Basin Management Expert Group

(RBM EG) to lead and co-ordinate the inputs from a number of other ICPDR Expert Groups (see Figure

28). The RBM EG requested technical assistance from a range of national and international experts to

assist with the analysis of basin and to develop new methodologies for assessing the pressures and

their impacts on the aquatic environment.

The preparation and submission of the WFD analysis (in accordance with Article V of this directive) was

divided into two sections.

> Part `A' Issues of basin-wide or transboundary importance co-ordinated by the ICPDR

(referred to as a `Roof Report'); and

> Part `B' National reports prepared and submitted by each country to the EC.

The Danube Basin Analysis (and this TDA update) is associated with Part A, reporting on issues of

transboundary importance.

The UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project provided significant resources to assist with this work,

including the provision of experts, workshops and meetings. The main technical assignments

conducted by the DRP in the preparation of the Danube Basin Analysis includes:

> Identification of heavily modified water bodies (HMWB);

> Hydromorphological pressures, impacts and risk assessment;

> Characterisation of groundwaters;

> Nutrient loads and eutrophication;

> Significant point and diffuse sources of pollution;

> Identification and characterisation of water bodies;

> Preparation of maps;

> Economic analysis on water use;

> Agrochemical inventories.

In addition the DRP supported a wide range of technical meetings and workshops leading to the final

agreement of the Danube Analysis Report.

The WFD and the first main output (Danube Basin Analysis report) provide considerable broadening of

the information traditionally assembled for a TDA. Significantly the WFD is a legal requirement for the

majority of the Danube Basin countries that places clear obligations on the implementation of the

actions identified to reduce pollution. In addition the WFD requires the countries to periodically review

and update their plans in process similar to the `adaptive management' framework recommended by

the GEF.

page 18

3.4. Identification

of

priority transboundary concerns

The key tools used in the identification of the priority transboundary concerns included:

> Results of environmental and water monitoring programmes;

> Risk assessment of meeting the required good status of the WFD

> Expert judgement in the absence of appropriate data.

3.4.1. Water-related Environmental Monitoring

The ICPDR has created a monitoring network that was designed to detect changes of transboundary

significance. The Trans-National Monitoring Network (TNMN) is a monitoring programme for chemical

and biological variables at 79 monitoring sites on the Danube and its major tributaries. The TNMN was

established in 1996 and all countries contribute data to this programme. An analytical quality control

(AQC) system (for chemical determinands) is in place to ensure the comparability of results. In

addition to the in-laboratory routine AQC, a programme of inter-laboratory check-samples is operated

covering all the main determinands

In 2001 the ICPDR initiated an integrated river survey the Joint Danube Survey (JDS). This exercise,

which will be repeated every 5 6 years, has contributed a significant data set that was utilised in the

preparation of the Danube Basin Analysis report. In particular, it provided considerable data on

biological determinands.

3.4.2. `Risk of failure' to meet good status

The WFD requires Member States to carry out an assessment of the likelihood that water bodies will

fail to meet the environmental quality objectives by 2015. The objectives include both the overall

objective to achieve good status by 2015, and additional specific objectives that apply to protected

areas as defined by other legislation. The objectives also depend on the current status of the water

body, since Member States must generally prevent any deterioration in the status.

Failure to achieve the objectives on surface waters may be the result from a very wide range of

pressures, including point source discharges, diffuse source discharges, water abstractions, water flow

regulation and morphological alterations. These and other pressures5 that could affect the status of

aquatic ecosystems must be considered in the analysis. The risk assessment is therefore based on

information collected in the pressure and impact analysis.

3.4.3. Priority Transboundary Concerns

On the basis of the data from the TNMN, the risk assessment and expert judgement, the ICPDR's River

Basin Management Expert Group (RBM EG) identified the main pressures (immediate causes) in the

Danube River Basin as:

> Point source pollution (e.g. from urban and industrial wastewater treatment plants or

management sites). Impacts on water bodies can result from the input of nutrients, organic

substances and hazardous substances;

5 The equivalent GEF terminology would be `stresses' rather than `pressures'.

Danube Transboundary Analysis

page 19

> Diffuse source pollution (e.g. from agriculture and urban use activities). Impacts on water

bodies can result from the input of nutrients (e.g. fertilisers), organic substances (e.g. from

manure) and hazardous substances (e.g. pesticides and herbicides).

> Hydrological alterations (e.g. water abstraction, hydro-peaking, flow regulation). Impacts

on water bodies can result from changes to the hydrological conditions and the impact of this

on, for example, biological communities;

> Morphological alterations (e.g. impoundments, weirs, bank reinforcements, channelling).

Impacts on water bodies can result from hydraulic engineering measures altering the

structural characteristics of the water body, for example restricting fish migration due to

dams.

From these main pressures (or stresses) on the Danube River Basin the RMB EG identified the four

priority transboundary concerns as:

> Nutrient pollution from diffuse (e.g. agriculture) and point sources (e.g. municipal

wastewater);

> Organic pollution - from diffuse (e.g. agriculture) and point sources (e.g. municipal

wastewater);

> Hazardous substances from point sources (e.g. industry) or diffuse sources (e.g.

agriculture or contaminated sites); and

> Hydromorphological alterations from flood defences, hydropower, navigation etc.

3.5.

Pressure and Impact Assessment / Causal chain analysis

The approach used in the Danube Analysis followed the `DPSIR' Drivers, Pressures, State, Impact

and Response6 that is used extensively by the EC and EEA to assess the performance of policy

initiatives. This has much similarity to the Causal Chain Analysis (CCA) more usually undertaken in a

TDA. The approach adopted in the Danube (to establish the pressures on the environment and their

impact on the ecology) has been accepted by all the countries and is an important precursor to the

river basin management plan and the `programme of measures', where the issues identified in the

Danube Basin Analysis are mitigated. This mitigation will require significant policy reforms and

investments from the countries endorsing the Danube Basin Analysis report.

The Danube Basin Analysis identified gaps in the existing information in the assessment of pressures

and their impacts. The Danube countries are currently working to address these gaps prior to the

submission of the WFD River Basin Management Plan in 2009. This plan, through the agreed

`Programme of Measures' will detail the activities that will be undertaken by the countries to achieve

the required `good status' for the Danube Basin water bodies.

The pressures and impacts assessment adopted for the preparation of the Danube River Analysis

followed a four-step process:

1.

Describing the driving forces, especially land use, urban development, industry, agriculture

and other activities which lead to pressures, without regard to their actual impacts;

2.

Identifying pressures with possible impacts on the water body and on water uses, by

considering the magnitude of the pressures and the susceptibility of the water body;

3.

Assessing the impacts resulting from the pressures; and

6 In GEF terminology, drivers equate to underlying causes, pressures to immediate causes, status to environmental

impacts and impacts to socio-economic impacts

page 20

4.

Evaluating the likelihood of failing to meet the objective.

While pressures from sources resulting from a large number of human activities (e.g. households,

industrial activity, power generation, agriculture, forestry, fish farming, mining, navigation, dredging,

etc.) have an impact, only those pressures that have significant impacts on the basin-wide level were

addressed in the `Roof Report' of the Danube River Analysis.

3.6. Governance

analysis

The overall management and co-ordination of the Danube River Basin is the responsibility of the

ICPDR. The ICPDR is composed of the countries of the Danube Basin and the structure of this

institution is described later. A number of studies have been conducted over the last 15 years that

describe the progress of the Danube countries in migrating their environment legal and policy

instruments to be compliant with EU and other international obligations.

The UNDP/GEF DRP, within the period 2002-2006, conducted a thorough analysis of institutional and

policy frameworks in all Danube countries, which enabled policy reform recommendations to be

developed addressing overall water governance.

Specific analytical studies on inter-ministerial coordination and government decision-making

mechanisms, on policy, legislation and institutional set-ups have been carried out with focus on

agricultural and industrial pollution and wetland management. The analysis of existing situation,

capacities and structures, and policy reform recommendations for economic analysis of water

resources and further development of public water infrastructure were also developed.

The UNDP/GEF DRP and the ICPDR studies and analysis addressed policy development and

implementation, legislative reforms and environmental laws enforcement as well as mechanisms and

conditions for resource allocation and investment needs for elimination of major transboundary

environmental issues by the main stakeholders.

Danube Transboundary Analysis

page 21

4.

DESCRIPTION OF DANUBE RIVER BASIN

4.1. Introduction

This section provides an overview of the Danube River Basin, covering the physical characteristics of

the basin, a summary of the status of the main water bodies and an introduction to the institutional

arrangements within the basin.

4.2.

Physical and geographic characterisation

The Danube River Basin7 is the second largest river basin in Europe after the Volga covering 801,463

km². It lies to the west of the Black Sea in Central and South-eastern Europe (see Figure 1, Figure 2).

Due to its geologic and geographic conditions the Danube River Basin can be divided into 3 main parts.

> The Upper Danube Basin is from the sources in the Black Forest Mountains to the Gate of

Devín, to the east of Vienna.

> The Middle Danube Basin is from the Gate of Devín to the impressive gorge of the Danube at

the Iron Gate, which divides the Southern Carpathian Mountains in the north and the Balkan

Mountains in the south.

> The Lower Danube Basin covers the Romanian-Bulgarian Danube sub-basins downstream of

Cazane Gorge and extends to the Danube Delta and the Black Sea.

The Danube River Basin shows a tremendous diversity of habitats through which rivers and stream

flow including glaciated high-gradient mountains, forested midland mountains and hills, upland

plateaus and through plains and wet lowlands near sea level.

4.2.1. Climate and hydrology

Due to its large extension from west to east, and diverse relief, the Danube River Basin also shows

great differences in climate. The upper regions in the west show strong influence from the Atlantic

climate with high precipitation, whereas the eastern regions are affected by Continental climate with

lower precipitation and typical cold winters. In the area of the Drava and Sava, influences from the

Mediterranean climate, can also be detected. The precipitation ranges from < 500 mm to > 2000 mm

in the region.

7 The area of the DRB was determined digitally with GIS. If other sources are consulted this value may vary slightly,

because other methods of calculation have been used.

page 22

Figure 1: Location of the Danube River Basin

The hydrologic regime of the Danube River is distinctly influenced by the regional precipitation

patterns. This is well illustrated in Figure 3, which shows the surface water contribution from each

country to the cumulative discharge of the Danube. Austria shows by far the largest contribution (22.1

%) followed by Romania (17.6 %). This reflects the high precipitation in the Alps and in the Carpathian

mountains. In the upper part of the Danube the Inn contributes the main water volume adding more

water to the Danube than it has itself at the point of confluence of the two. In the middle reach it is

the Drava, Tisza and Sava, which together contribute almost half of the total discharge that finally

reaches the Black Sea.

Danube Transboundary Analysis

page 23

Figure 2: The Danube River Basin

page 24

Altitude

Discharge

Discharge

in m a.s.l.

Upper Danube

Middle Danube

Lower Danube

in m3/s

per country:

700

7000

m3/s

%

Ukraine

Moldova

279

4,3

Romania

49

0,7

600

6000

Bulgaria

Bosnia i Herzegovina

1151

17,6

Serbia and Montenegro

Croatia

500

5000

Slovenia

243

3,7

Hungary

Slovak Republic

574

8,8

400

Czech Republic

4000

Austria

741

11,3

Germany

Elevation

421

6,4

202

3,1

300

3000

283

4,3

125

1,9

81

1,2

200

2000

1448

22,1

100

1000

952

14,5

0

0

2800 2600 2400 2200 2000 1800 1600 1400 1200 1000 800

600

400

200

0

6551

100,0

Distance from the

Inn

Drava

Sava

Delta

Black Sea in km

735 m3/s

577 m3/s

1564 m3/s

6550 m3/s

Tisza

Iron Gates

794 m3/s

5520 m3/s

Figure 3: Longitudinal profile of the Danube River and contribution of water from each country (in

%) to the cumulative discharge of the Danube (in millions m3/year), based on data for 1994-1997

using the Danube Water Quality Model8

4.2.2. The Danube River and its main tributaries

The Danube rises in the Black Forest (Schwarzwald) in Germany at an altitude of about 1,000 m. The

Danube river and receives its name at the confluence of Brigach and Breg in Donaueschingen. The

Danube flows predominantly to the south-east and reaches the Black Sea after 2,780 km where it

divides into 3 main branches, the Chilia, the Sulina, and the Sf. Gheorghe Branch. At its mouth the

Danube has an average discharge of about 6,500 m3/s. The Danube Delta lies in Romania and partly in

Ukraine and is a unique "World Nature Heritage". The entire protected area covers 675,000 ha

including floodplains, and more than 600 natural lakes larger than one hectare, and marine areas. The

Danube is the largest tributary into the Black Sea.

The most significant tributaries of the Danube River include:

> The Tysa/Tisza/Tisa River basin is the largest sub-basin in the Danube River Basin

(157,186 km²). It is also the longest tributary (966 km) of the Danube. By flow volume it is

second largest after the Sava River.

> The Sava River is the largest Danube tributary by discharge (average 1,564 m³/s) and the

second largest by catchment area (95,419 km²).

> The Prut River is the second longest (950 km) and the last tributary of the Danube, with its

mouth just upstream of the Danube Delta.

8 Developed during the Danube River Pollution Reduction Programme in 1999, UNDP/GEF (1999b).

Danube Transboundary Analysis

page 25

A list of the main tributaries and their characteristics are presented in the WFD Danube River Basin

Analysis.

4.2.3. Important lakes in the Danube River Basin

In the Danube River Basin there are a multitude of natural lakes. Most of them are small, but some are

also very large, with areas of several square kilometres. The middle Danube region shows some

characteristic steppe lakes, of which the most prominent ones are Neusiedlersee / Fert-tó and Lake

Balaton.

4.2.4. Major wetlands and other Protected Areas in the Danube River Basin

District

Floodplain forests, marshlands, deltas, floodplain corridors, lake shores and other wetlands are

essential components in the Danube River Basin's biodiversity and hydrology. Many of the larger

wetland areas are transboundary in nature. The wetlands in the Alps and Carpathians also represent

valuable drinking water reserves for millions of people.

The current extent of wetlands in the DRB is only a remnant of the former wetland systems and it is

estimated that over 80% of former wetlands and floodplains have been lost. The main wetland and

protected areas of transboundary importance are shown in Figure 4.

page 26

Figure 4: Major Protected Areas within the Danube River Basin

Danube Transboundary Analysis

page 27

4.2.5. Groundwater in the Danube River Basin District

Besides porous aquifers there are many karstic aquifers in the DRB. Due to their high permeability

karstic aquifers are highly vulnerable to contamination. The percolation time for contaminants is very

short and therefore natural purification processes are very limited. For selected countries such as

Bulgaria, Croatia, and Serbia and Montenegro, groundwater resources represent as much as 30 % of

total internal renewable water resources.

A large number of transboundary aquifers exist in the region. Not much is known at present about the

availability of groundwater or potential extraction capacity in many countries, although aquifers are the

main sources for drinking and industrial water.

4.3. Ecological

status

Some sections of the Danube River are still rather untouched ecosystems and, despite possible

pollution problems, constitute a unique heritage to be preserved. In addition, the Danube River Basin

still hosts many species and habitats of outstanding ecological value and unique importance for

biodiversity. In particular the Danube Delta is of global significance. The future management of the

river basin needs to ensure that the focus of measures is not only the restoration of affected water

bodies but equally important is the preservation of those few areas that are still ecologically intact.

The current analysis shows that, in the last two decades, considerable improvements in environmental

conditions in the Danube basin have been made. Where investments, e.g. in wastewater treatment,

have taken place, the improvement of the water quality is visible. However, a major part of pollution

reduction can be attributed to the decline of industries and agricultural activities in the middle and

lower parts of the basin since 1989. In these areas investments for a sustainable reduction of pollution

levels has just started and will have to continue for another 10 to 20 years.

The Danube River Basin contains a large number of wetlands offering unique habitats for a rich and

diverse aquatic community. Many of these areas have high protection status such as the large wetland

complexes protected under international conventions, others still deserve to be designated as

protected areas, but have not been granted such status. 80 % of the historical floodplain on the large

rivers has been lost during the last 150 years mainly from significant hydromorphological alterations,

and many already protected areas deteriorate due to new human interventions. Still today, many

wetlands are under pressure (stress) from navigation, hydropower plants, intensive agriculture and

forestry as well as from new infrastructure projects. Wetland restoration can bring many benefits, in

particular for flood protection. As a first step, an inventory of the most important water-related

protected areas for species and habitat protection has been established for the Danube River Basin.

The Danube Delta has suffered significant impacts from anthropogenic activities in the last 50 years.

These were caused in part by high nutrient loads and heavy metals from the Danube. Nutrient inflow

has led to eutrophication of the delta arms and its lakes; elevated concentrations of heavy metals

occur especially in the delta lakes. In addition, severe hydromorphological alterations and intensive

agriculture and forestry have led to the loss and deterioration of large areas of land formerly unused

and interconnected within the delta. As a consequence species and habitat diversity has declined. The

large number of hydraulic structures on the Danube and its tributaries has also considerably reduced

the sediment transport thereby bringing the growth of the Danube Delta into the Black Sea in parts to

a halt.

page 28

Although considerable restoration measures have been undertaken in the last decade new canalisation

projects are still being planned and implemented. Sound environmental impact assessments need to

be carried out and alternative solutions found in order to protect this unique natural heritage of global

importance.

4.4.

Socio-economic situation

4.4.1. Social

Economic

Indicators

There are significant differences in the GDP between the western Danube Basin (Austria and Germany)

and the eastern region (Moldova and Ukraine). These historic differences have an obvious impact on

the country's ability to address the environmental issues identified in the Danube Basin Analysis

report.

Table 1: General

socio-economic

indicators

GDP

Total

GDP per capita

GDP per capita

population

(in million EUR)

(million )

(in EUR per capita) (in PPP EUR per capita)

Albania 14

<0.01

1,390

na

Austria

198,611

7.7

25,795

25,521

Bosnia i Herzegovina

3,493

2.9

1,204

na

Bulgaria

7,266

3.5

2,076

8,010

Croatia

12,942

3.1

4,175

7,460

Czech Republic

15,247

2.8

5,461

13,226

Germany

285,075

9.4

30,321

29,215

Hungary

50,663

10.1

5,016

11,243

Italy

403

0.02

20,225

22,457

Macedonia 19

<0.01

1,921

6,020

Moldova 394

1.1

358

na

Poland

187

0.04

4,672

9,230

Romania

38,908

21.7

1,795

5,264

Serbia and Montenegro

8,628

9.0

959

na