S E C T I O N T I T L E

1

Flowing Freely

How to Improve Access to Environmental Information

and Enhance Public Participation in Water Management

Partners

THE DANUBE REGIONAL PROJECT

The DRP was launched in 2001 as a part of a larger GEF Strategic Partnership

for Nutrient Reduction in the Danube and Black Sea. 13 Danube countries,

NGOs, the EU and the ICPDR are cooperating to improve the environment of

the Danube River Basin, protect its waters and sustainably manage its natural

resources. The DRP's main goal is to strengthen the capacity of the ICPDR and Danube countries to

cooperate in implementing the Danube River Protection Convention and EU Water Framework Directive.

The key project activities focused on: i) Danube River Basin management; ii) agriculture pollution control

through the application of best agricultural practices; iii) industrial and municipal activities, in particular

advising on reduction of phosphates use in laundry detergents and assistance to water and wastewater

utility managers with decision-making tools for pricing and investments; iv) enhancing public participation

through supporting the Danube NGO network - DEF, awareness raising campaigns, a small grants

program, capacity building for officials to implement the requirements of the EU WFD and supporting the

ICPDR communication activities; v) wetlands restoration and management for nutrient reduction.

THE REGIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL CENTER FOR CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE

The REC was established in 1990 to assist in solving environmental problems

in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) by promoting cooperation among non-

governmental organisations, governments, businesses, and by supporting free

exchange of information and public participation in environmental decision

making. The REC has been involved in Danube-related projects since its inception, and has taken an

active role in cooperating with key players to enable NGO and public participation in international

initiatives related to the entire basin. The REC, as observer, closely cooperates with the International

Commission for the Protection of the Danube River (ICPDR) and the relevant stakeholders, ministries

of environment and water management, the Danube Environmental Forum and other key NGOs. It also

actively contributes to different ICPDR expert groups. The REC participated in developing the Danube

River Basin Strategy for Public Participation in River Basin Management Planning 2003-2009,

adopted by the ICPDR in June, 2003. In addition to initiating and implementing the Danube Regional

Project's component 3.4, "Enhancing access to Information and public participation in environmental

decision-making" in five Danube countries and a similar pilot project in Hungary and Slovenia in

partnership with RFF and NYU, the REC has managed projects to support the implementation of the

Aarhus Convention, related EU directives and best practices in public participation in CEE.

NYU SCHOOL OF LAW

NYU School of Law (NYU), a nonprofit academic institution located in New York

City, is one of the preeminent law schools in the United States. The first

"Global Law School," NYU attracts top faculty and students from around the

world to study and contribute to the development of law that meets the needs

of a rapidly globalizing world. The NYU Center on Environmental and Land Use Law enlists NYU

faculty and students, as well as outside experts, to provide developing countries and countries in

transition to market economies with practical assistance in strengthening and enforcing their

environmental and land use laws and policies. In addition to co-developing and co-managing

Component 3.4 of the Danube Regional Program, other representative legal assistance projects

conducted by the Center have included a five-year program to train and assist Chinese law drafters in

their efforts to reform and revise a number of China's key environmental laws, a multi-year research

project for the Rockefeller Foundation to assess the impacts of global trade conflicts over genetically

modified crops on policymaking in developing countries, as well as numerous, targeted legal

assistance projects for environmental NGOs around the world.

RESOURCES FOR THE FUTURE

RFF is a nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization on environmental, energy, and

natural resource issues. Although headquartered in Washington, D.C., RFF works in

nations around the world. RFF was founded in 1952 at the recommendation of William

Paley, then head of the Columbia Broadcasting System, who had chaired a presidential

commission that examined whether the United States was becoming overly dependent

on foreign sources of important natural resources and commodities. RFF is operated as a tax-exempt

organization under U.S. law, with the financial support of individuals and organizations that see the role

research plays in formulating sound public policies. IIDEA (International Institutional Development and

Environmental Assistance), the RFF Program that co-developed and managed this program to enhance

environmental public participation in five Danube-basin countries, helps countries build more effective

systems of environmental protection. Other representative IIDEA efforts have brought together

advocates from throughout Asia to share their varied experiences in shaping a public voice on

environmental issues and produced a ground-breaking study examining and critiquing the policy process

and changes that led to improvements in air quality in Delhi, the most important being the switch of all

commercial vehicles from petrol and diesel to CNG.

Flowing

Freely

How to Improve Access

to Environmental

Information

and Enhance

Public Participation

in Water Management

Magda Toth Nagy,

Jane Bloom Stewart,

and Ruth Greenspan Bell

Edited by Sally Atwater

Designed by Greg Spencer

This publication was prepared within

component 3.4 of the

Danube Regional Project

and was funded by UNDP-GEF.

F L O W I N G F R E E L Y

4

Contents

5

Introduction

6

Background

7

National-level project and its results

8

Local-level demonstration projects

9

Bosnia and Herzegovina

12 Bulgaria

13 Croatia

14 Romania

15 Serbia

16 Recommendations

16 Learn from others' experience

17 Build bridges between information

seekers and information providers

18 Prepare manuals for government officials

20 Explain the procedures to the public

21 Centralize information storage

22 Develop clear procedures for

protecting confidential information

23 Use and maintain electronic tools where appropriate

24 Involve the broader public at all stages

26 Make the most of opportunities to participate

28 Safeguard public participation

rights to prevent their erosion

30 Conclusion

31 Resources and contacts

F L O W I N G F R E E L Y

5

More than half the Danube River basin is

at risk from nutrient pollution, with

Introduction

agriculture the biggest culprit.

Thisbookletdistillsthechallengesidentifiedand

the national-level work of the Project and the demon-

the approaches developed to address them during

stration projects undertaken at the local level. Descrip-

a 28-month effort to increase public access to envi-

tions of those demonstration projects can be found in

ronmental information and promote the participation

boxed text throughout the booklet.

of citizens and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs)

The heart of the booklet is the ten recommendations to

in protecting the Danube River and its tributaries. The

improve access to information on water quality and man-

work was part of a larger effort to reduce pollution from

agement and enhance public participation in environ-

nutrients and toxic substances in five Danube River

mental and water-related decision making. This section

basin countries: Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croa-

describes the challenges to public involvement and the

tia, Romania, and Serbia (at the start of the project, Ser-

effective solutions that participants developed and put

bia and Montenegro). The Project focussed particularly

into action. We believe that these ten recommendations

on supporting public involvement in river basin man-

can help government officials and NGOs at all levels

agement planning, as required by the European Union's

work together with industry and citizens to improve

Water Framework Directive and the Aarhus Convention.

water quality in the Danube River basin and elsewhere.

The booklet begins with some background on the Water

Discussion of the recommendations with specific ideas

Framework Directive and the International Commission

for their implementation begins on page 16. Contact in-

for the Protection of the Danube River (ICPDR) as well

formation and links to details regarding the Project are

as the Aarhus Convention. The next sections summarize

on the last page.

F L O W I N G F R E E L Y

6

Background

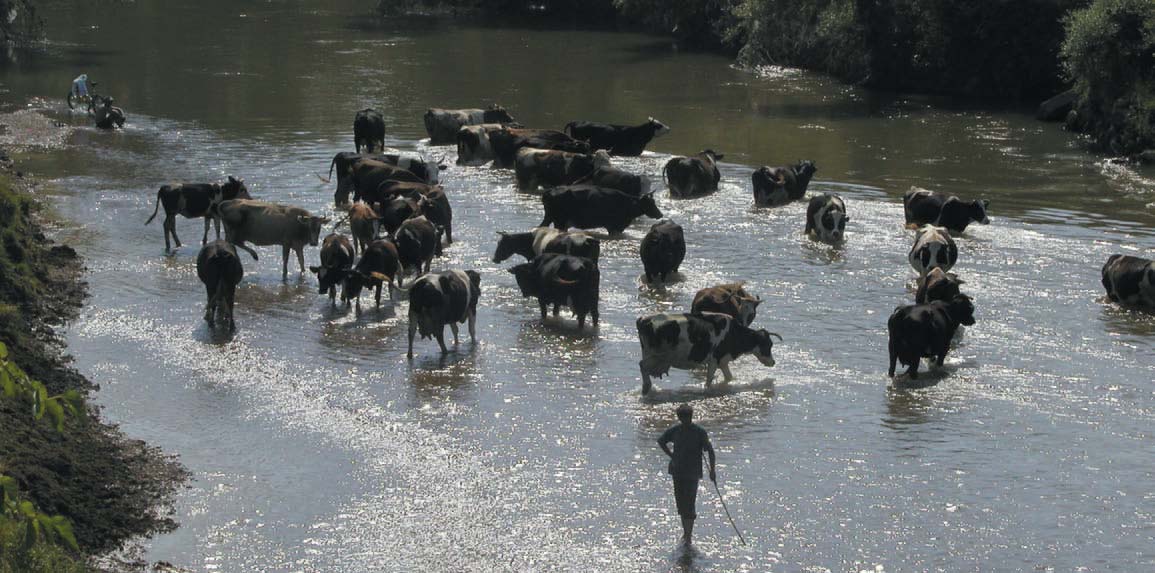

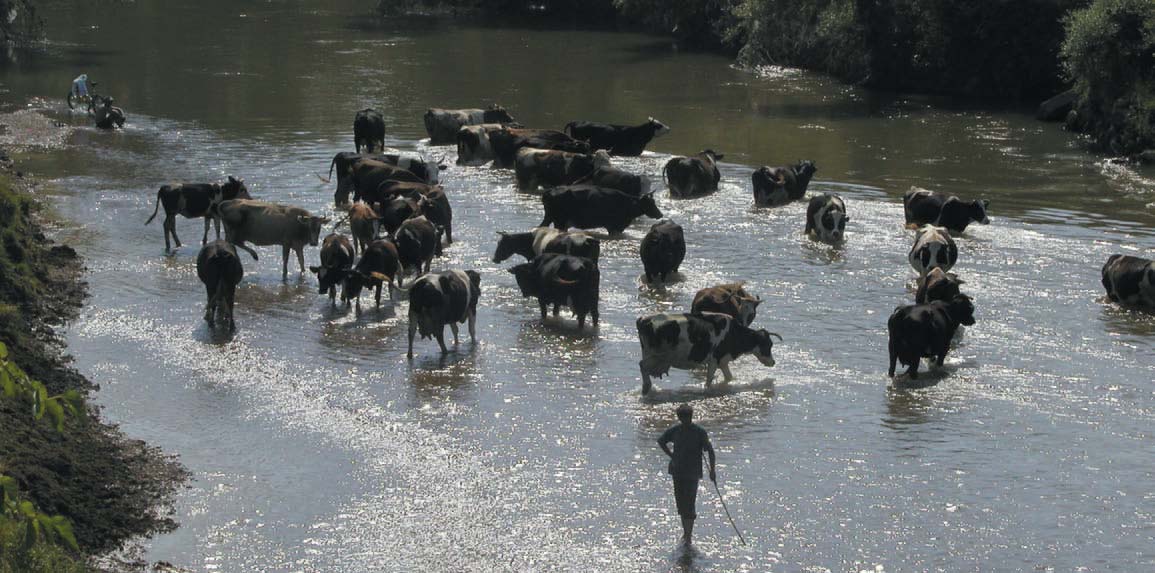

Better basin management means protecting riparian

flora that serves as a natural filter of water pollution.

will be most effective if the interests of different stake-

holders are balanced. Second, public participation pro-

motes enforceability. The more transparent the

objectives, measures, and data for environmental quality,

the greater the care that countries will take to implement

the legislation and the greater the power of their citizens

to influence the direction of environmental protection.

Also calling for public access to information and partici-

pation in environmental decision making is the Aarhus

Convention, which was adopted in 1998 and took effect

in 2001. This convention, which has been ratified by the

European Union and 39 countries, including most

Danube nations, focuses on the relationship between citi-

zens and public authorities as they deal with environ-

TheDanubelinksmorethanadozencountriesand mentalprotectioninademocracy.Theconventiongrants

is the most international river in the world. Most

rights to citizens and imposes obligations on govern-

of these countries and the European Union are co-

ments regarding access to environmental information. It

operating under the Danube River Protection Conven-

takes a rights-based approach, makes a presumption in

tion, via the ICPDR, to ensure the sustainable and

favor of disclosure of information, and encourages the

equitable use of the waters and freshwater resources of

active release of information by governments as well as

the Danube and its tributaries.

responsiveness to citizens' requests. It also sets out mini-

mum requirements for public involvement in various

ICPDR's goals are to safeguard the Danube's water re-

kinds of environmental decision making.

sources for future generations, to promote healthy and

sustainable river systems, and to achieve water flows that

Government agencies in some Danube River basin coun-

are free from excess nutrients, toxic chemicals, and flood

tries, however, do not regularly disseminate the informa-

damage. Governments, technical experts, scientists,

tion that citizens may need to know, and they lack clear

NGOs, and members of civil society cooperate in

rules or procedures for receiving, processing, and respond-

ICPDR on achieving the goals.

ing to information requests. And although citizens and

NGOs express interest in exercising their rights to see

Communicating with stakeholders is important for the

water-related environmental information, they often don't

success of integrated river basin management. ICPDR

know how to submit their requests appropriately, where

therefore encourages all stakeholder groups with a basin-

to direct their requests, what information they are entitled

wide interest to become engaged in its work, including

to, or what to do if their requests are ignored or denied.

participating as observers at high-level meetings, expert

NGOs also face a learning curve in communicating effec-

group meetings, or other stakeholder activities. Active co-

tively with the broader public. For instance, NGOs that

operation has proven successful in ensuring that different

are "expert" groups may be unable to present technical

aspects and approaches can shape water management.

issues in lay language and thereby engage fellow citizens.

Involving the public in decision making on water man-

Integrated river basin management presents an opportu-

agement plans, in fact, is a requirement of the European

nity for NGOs to broaden their public outreach, im-

Union's Water Framework Directive (Article 14). Two

prove their relationships with government agencies, make

reasons for an extension of public participation lie be-

more productive efforts to get involved in the decision-

hind this requirement. First, EU countries share the be-

making process, and make suggestions for the drafting or

lief that measures to achieve environmental objectives

implementation of legislation.

F L O W I N G F R E E L Y

7

There are significant barriers to improving

public access to environmental information

National-level

in many Danube River Basin countries.

project and

its results

In2004,theRegionalEnvironmentalCenterforCentral ∑ Procedurestoinvolvestakeholdersinriverbasin

and Eastern Europe, Resources for the Future (a Wash-

management planning and consult with the public

ington, D.C., think tank), and New York University

were inadequate.

School of Law began a project called "Enhancing Access

to Information and Public Participation in Environmental

To overcome those barriers, project participants studied

Decision-making." The Project was supported by the

"good practices"--techniques that have been effective

Global Environment Facility and the United Nations De-

elsewhere--and used them to develop tools and strategies

velopment Programme as part of the Danube Regional

adapted to their own needs and circumstances. Most

Project, a 13-country initiative to clean up and protect the

chose to develop very practical written aids and tools.

Danube River. The partnership worked with public offi-

For government officials, these included manuals and

cials and NGOs at the national, regional, and local levels

guidelines for ensuring access to information and carry-

in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Romania,

ing out public involvement responsibilities: how to pro-

and Serbia. At the national level, it identified the main

vide better access to environmental information, what to

barriers to public access to information and involvement

do when confidential information is involved, and how

in environmental decision making, and it helped govern-

to promote the broader involvement of the public. For

ment officials and NGOs develop tools and strategies for

NGOs and the public, these included brochures and

overcoming them.

other written guides on how and where to obtain envi-

ronmental information, how to become engaged in

Major barriers were found:

water-related environmental decision making, and what to

∑ Officials had little guidance on how to carry out

do when access to information or participation is denied.

their responsibilities to provide water-related environ-

Also at the national level, the Project inspired recom-

mental information or consult with the public on

mendations (including draft language) for changes in

water management issues.

legislation, guidelines for handling confidential informa-

∑ The lack of centralized databases made it difficult to

tion, recommendations on stakeholder representation

know where environmental information was located

and consultation in river basin committees (the national,

within the government.

regional, or local entities that conduct management

planning in some Danube countries), meta-information

∑ NGOs and citizens did not know their rights to ob-

systems that help environmental officials and the public

tain environmental information and participate in

know which authority holds what information and how

water-related decision making, or they did not under-

to obtain it, and improved websites for better communi-

stand how to exercise these rights.

cation with the public. Many of these activities were ac-

∑ Officials were uncertain about what information

companied by training for officials and NGOs to

should be regarded as "confidential" and withheld

advance their knowledge and ensure that the written aids

from disclosure.

would be understood and used.

F L O W I N G F R E E L Y

8

Local-level

demonstration

projects

Fivedemonstrationprojects,eachlasting10to12

New ideas and ways of approaching problems some-

months, were conducted at Danube River "hot

times seem abstract and hard to pin down. The demon-

spots"--areas identified by ICPDR as having excep-

stration projects tested and refined some new ideas in

tionally high levels of pollution. Supported with very

practice, and also tested reform measures to determine

modest funding, these projects proved to be significant

whether they might be useful at the national level. Be-

learning tools for transferring information and testing

cause these local-level projects were closely tied to coun-

ideas, and they yielded substantial results in a short time.

try-level priority issues and took an iterative approach,

Each was developed and conducted by a local NGO, in

each activity reinforced the others.

most cases in partnership with local or regional environ-

mental government offices. Each tested new approaches

Often, stakeholders lacked experience in working to-

for access to information or citizen involvement to sup-

gether and were unsure how to proceed constructively,

port the cleanup of the hot spot, on the premise that in-

or they had tried and failed to communicate in the past.

dividuals will become more engaged in problem solving

The process of collaborating during the demonstration

if they have greater awareness about local conditions and

projects--combined with technical assistance and tar-

possible solutions. The projects were also intended to

geted, capacity-building local workshops or trainings--

provide models for other Danube hot-spot communities

helped them learn how to build bridges and jointly

and to inform parallel initiatives at the national level.

develop effective strategies.

F L O W I N G F R E E L Y

9

Citizen involvement is the key to reducing pollution

problems.

Eko-Zeleni Lukavac, an NGO, sought to ensure that

local residents could get the information to which

they are entitled under Bosnian law. First came a sur-

vey of residents and interviews with government au-

thorities. Citizens said they wanted to receive regular

reports and be able to request information, but infor-

mation storage was not centralized, and the layers of

authority in Bosnia and Herzegovina created uncer-

tainty about where to find it. Information that was re-

leased was often in technical language or

difficult-to-use formats.

The survey and interviews were followed by roundtable

discussions and capacity-building meetings to examine

the problems and possible solutions. The latter in-

cluded training authorities on how to deal with citi-

zens' requests and how to keep them informed

regularly.

Project participants created a "plain-language" leaflet to

raise general awareness about local water pollution and

indicate where citizens could find information and how

to ask for it. The leaflet included contact information

for authorities at the local, cantonal, and ministry levels,

as well as for industrial firms. A sample letter of request

was included.

BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA

Eko-Zeleni Lukavac then held a workshop to improve

Location: Lukavac City

authorities' and firms' capacity to organize and deliver

Goal: Include citizens, NGOs, industry, and

information. Participants discussed concerns and pro-

government authorities in decision process

posed solutions. Examples of good practice were cited,

with emphasis on improving the process of handling in-

NGO: Ecological Association of Citizens

formation requests and exchanging information among

"Eko-Zeleni" Lukavac

local authorities.

Project leader: Husejin Keran

A result of the demonstration project--in a community

whose residents had great difficulty sharing information

and evaluating options--was to bring in fresh points of

InBosniaandHerzegovina'sTuzlaCanton,heavyin- viewonconstructivesolutions.Thishelpedpreparethe

dustry has significant impacts on air and water qual-

way for a more open management planning process.

ity and the health of Tuzla residents. The

One measure of success was that the local cement indus-

municipalities and other authorities do not have ade-

try offered to host the workshop and, with the munici-

quate information about the pollutants or know what

pality, cosponsor future leaflets to keep the community

additional data are needed.

informed.

F L O W I N G F R E E L Y

10 LOCAL-LEVEL DEMONSTRATION PROJECTS

3

Local-level demonstration projects

F L O W I N G F R E E L Y

L O C A L - L E V E L D E M O N S T R A T I O N P R O J E C T S

11

4

5

1

2

F L O W I N G F R E E L Y

12 LOCAL-LEVEL DEMONSTRATION PROJECTS

The Osam River may be the

most polluted in Bulgaria.

BULGARIA

The NGO then held a workshop with the major stake-

Location: Lovech and Troyan counties

holders to discuss proposals for better information ac-

Goal: Test information access, help improve it

cess and participation. More information requests were

made to test whether government authorities, whose rep-

NGO: Ecomission 21st Century

resentatives had been invited to participate in the proj-

Project leader: Nelly Miteva

ect, had voluntarily changed their practices. In a second

workshop, participants refined proposals for making in-

TheOsamRiverissaidtobethemostpollutedin formationmoreaccessibleandencouragingothercoun-

Bulgaria. Nevertheless, the people of Lovech and

ties in Bulgaria to adopt similar best practices.

Troyan counties know little about how the water-

The activities were accompanied by a public outreach

shed is managed. Although industry is not the only

campaign to get media coverage on water quality and

cause of pollution, one plant that may be a major con-

human health issues and the difficulties of accessing in-

tributor has operated with an outdated pollution control

formation. The outreach was supported with municipal

permit, and the details of a permit for another impor-

websites, Internet networks, and a brochure for NGOs

tant plant were not publicly available.

and citizens that explains how to obtain information

Ecomission 21st Century, an NGO, addressed the prob-

(http://www.rec.org/REC/Programs/PublicParticipation/

lem by testing information access and building aware-

DanubeRiverBasin/project_products/bulg). The pro-

ness to mobilize the local community. Questionnaires

posed changes and best practices for public access to in-

and information requests were sent to regional and local

formation procedures were sent on CDs to local

institutions in Lovech and Troyan counties. Requests

authorities and other municipalities.

were made for data on water quality and human health,

pollution sources, and risks; a copy of an industrial per-

One unexpected result of the project was an order by

mit of the major polluter; and information on the moni-

the Lovech regional governor requiring mayors to define

toring and enforcement of the permit requirements. The

and mark zones where bathing would be allowed, fol-

responses were analyzed, and barriers to accessing water-

lowing a request for information about safe

related information were identified.

swimming.

F L O W I N G F R E E L Y

L O C A L - L E V E L D E M O N S T R A T I O N P R O J E C T S

13

CROATIA

Location: Osijek

Goal: Enhance public involvement

in wastewater management

NGO: Green Osijek Ecological Association

Project leader: Jasmin Sadikovic

InOsijek,Croatia,500,000litersofuntreatedwastewater

are pumped into the River Drava every day. In nearby

Cepin, the Cepin Oil Factory pumped its wastewater

into drainage canals, affecting residents' agricultural pro-

duction and drinking water, until the NGO Green Osijek

alerted the local and national media and the practice

stopped. But current information regarding these issues is

locked behind plant doors. Indeed, the region lacks waste-

water management, civic transparency, and public partici-

pation in environmental decision making.

In its demonstration project, Green Osijek undertook

several activities to combat the inaccessibility of environ-

mental information. Stakeholders in Osijek (including

institutions, NGOs, factories, and government agencies)

were identified and invited to join a "water forum" for

the online and in-person exchange of environmental in-

formation. Participants wanted an open, informal ap-

proach, so the NGO set up Osijek Water Forum as a

communication platform to coordinate the flow of in-

formation, encourage participatory processes, and sup-

port activities that address priority problems. Through

the Forum, participants identified priorities: wastewater

A water forum

management, improvement of laws and their implemen-

encourages different

tation, and better internal and external communication

stakeholders to hear

on water-related issues. Workshops were then held to

each other's points of

view and collaborate on

help stakeholders learn how to communicate on water

solutions to water

issues, organize a public participation process, and be-

pollution problems.

come involved in planning Osijek's new wastewater treat-

ment plant.

A public outreach campaign has raised awareness about

pollution problems and possible solutions. A poster, to

be developed in cooperation with the town and local

water authorities, will be distributed to public institu-

help of a Green Osijek member who is also a journalist.

tions, schools, and NGOs. The forum will take advan-

Many stakeholders support continuation of the Water

tage of International Water Day to introduce materials

Forum for discussing and developing solutions to local

on how to conserve water and access water-related infor-

water management issues. Green Osijek has volunteered

mation. The news media covered the activities, with the

to continue the coordination of the Forum.

F L O W I N G F R E E L Y

14 LOCAL-LEVEL DEMONSTRATION PROJECTS

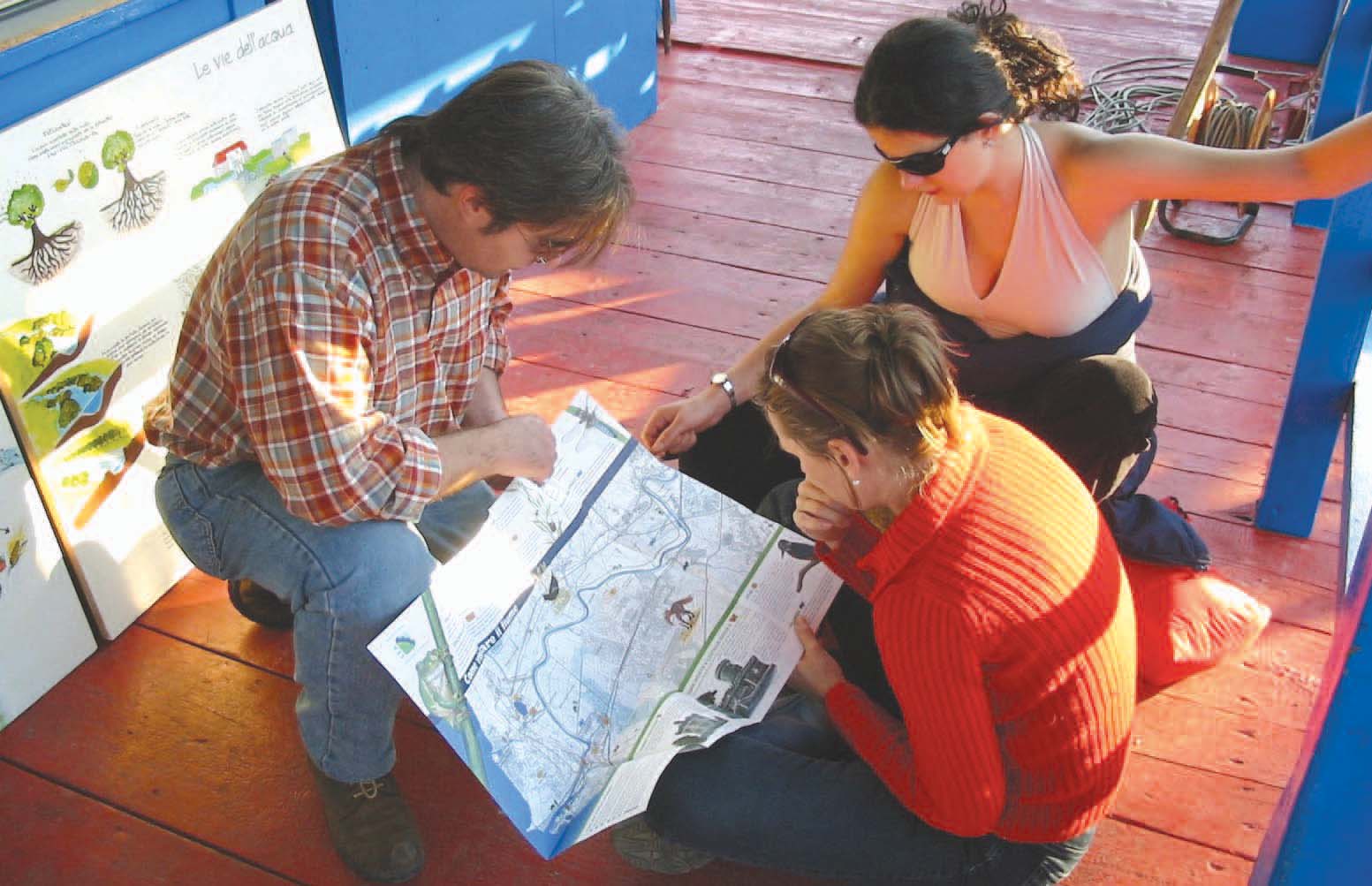

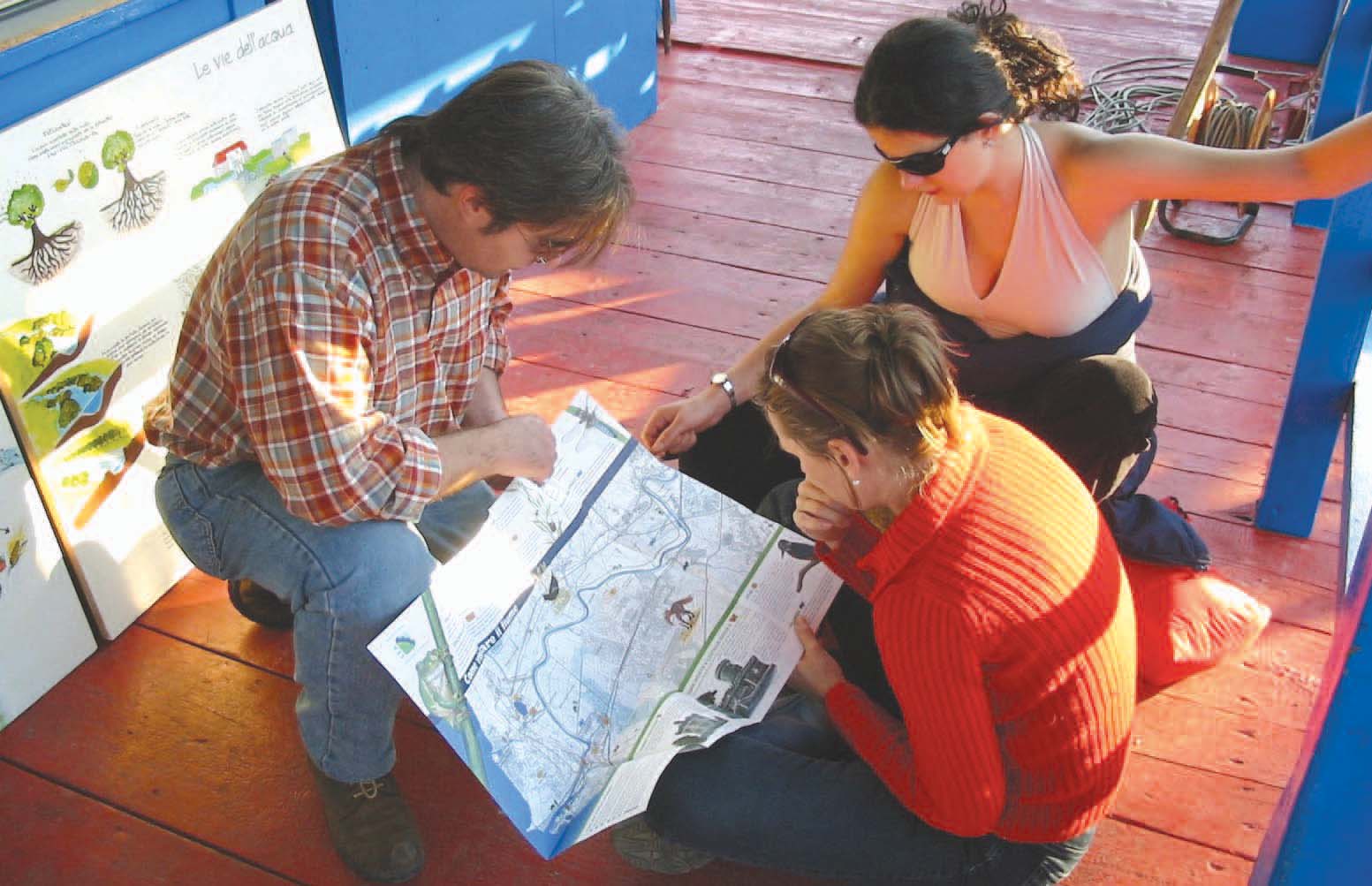

Project work

w

in

i Romania involved educational

field trips for river

r

stakeholders.

ROMANIA

concern is the lack of communication and interaction

Location: Mures River basin

between the river basin committees and local communi-

ties. The demonstration project considered how to im-

Goal: Improve the process for NGO involve-

prove public involvement in the water management

ment in water management planning

planning process of the Mures River Basin Committee

NGO: Focus Eco Center

and worked with local authorities, NGOs, and the pub-

lic on the challenges of complying with the directive.

Project leader: Zoltan Hajdu

Focus Eco Center headed an effort to promote access to

T

information and public participation by building a net-

he Mures River basin, specifically around the city

work of local stakeholders, particularly from the NGO

of Tirgu Mures, is severely polluted from local

sector, with an interest in water basin management. It

wastewater, upstream wastewater, hog farms, indus-

developed a list of interested parties and encouraged

trial plants, and agricultural and urban runoff. Because

them to participate in the decision-making processes of

of the pollution, the cost of drinking water in Tirgu

the committee.

Mures, Iernut, and surrounding rural areas is the highest

in the country.

Recommendations for improvements in the representa-

tion of NGOs and citizens on the Mures committee, in-

Planning at the river basin level is central to Romanian

cluding a new approach for selecting NGO delegates

efforts to implement water management planning, in ac-

and examples of good practices used elsewhere, were

cordance with the EU Water Framework Directive. How-

shared with Romania's ten other river basin committees.

ever, national-level NGOs believe that the process by

The now-published "Guide on Good Practices for Im-

which representatives of civil society are elected to river

plementing the EU Water Framework Directive" could

basin committees (which play an advisory role in water

provide useful information for similar stakeholder

management planning) needs improvement. Another

groups involved in water management planning.

F L O W I N G F R E E L Y

L O C A L - L E V E L D E M O N S T R A T I O N P R O J E C T S

15

SERBIA

Aarhus Convention, and national environmental legis-

Location: Bor, Serbia

lation, along with mailing lists and discussion forums

to increase the f low of water-related information be-

Goal: Create a useful and accessible

tween interested parties.

database for information managers

The NGO also created collection points for gathering,

and the public

processing, and distributing information (tasks that

NGO: Association of Young Researchers Bor

will be taken over by municipal authorities); con-

ducted a public outreach campaign on water-related is-

Project leader: Toplica Marjanovic

sues; and developed an information resource

network.

BorisaminingandindustrialcenterinEastern

Serbia. Industrial discharges and domestic

sewage pollute the water and banks of the Bor

and Krivelj rivers. The pollution endangers Bor

County as well as other river-based communities in

Serbia and neighboring Bulgaria, significantly affecting

the quality of water in the West Balkans and the

Danube basin.

Local stakeholders have shown interest in environmen-

tal issues--a local environmental action plan and a dis-

trict environmental action plan were adopted in recent

years--but authorities in Bor lack money, equipment,

and data.

The demonstration project in Bor tackled the prob-

lems related to the management of environmental and

water-related data. Information was stored in different

institutions and not shared among them, for example,

and there was no standardized system for its storage

and management. Officials had insufficient knowledge

of the legal procedures to follow when responding to

public information requests and were unfamiliar with

information technologies.

To improve access to information, raise awareness of

wastewater problems, and increase public participa-

tion in the resolution of problems, a local NGO, the

Association of Young Researchers Bor, invited stake-

holders to discuss the current situation and potential

solutions at a roundtable meeting, and then pub-

lished the results.

The NGO next developed a database for information

on wastewater and drinking water and provided train-

Information and communications technology

ing in its use. Accessible to all managers of water-re-

can help store, process, and deliver the data

lated information and to the public, this tool includes

that citizens need to make intelligent

information about the Water Framework Directive, the

decisions about water management.

F L O W I N G F R E E L Y

16

A study tour to the United

States highlights good practices

Recommendations

in public participation.

1 Learn from others' experience

Why reinvent the wheel? Adapting other coun-

tries' tools for increasing access to environmental

information and public participation can be a

smart strategy.

Research can uncover good practices employed in other

countries. Even more effective is direct experience with

successful foreign systems. By engaging in study tours,

workshops, and other personal encounters with their

counterparts in other countries, officials and NGOs can

examine the potential applicability of the tools used ef-

fectively elsewhere to circumstances at home.

Exchanges are a valuable way to jump-start improve-

EXAMPLES

ments in access to information and public participation,

Study tours inspire new ideas

particularly in countries that have little history of such

Bulgarian officials and NGO experts traveled to the

programs. All countries benefit from these exchanges,

United States (US tour pictured) and the Netherlands

which can result in increased public involvement and

on study tours to see effective programs in action. Ex-

thus enlarge the constituency for Danube River basin

posure to good practices, procedures, and criteria

protection in the region generally.

for handling confidential information helped them pre-

pare practical guidance and draft recommendations

Be careful, however, not to let outsiders determine solu-

for improving methods of handling confidential infor-

tions for local circumstances with which they may be

mation for the Bulgarian Ministry of Environment and

unfamiliar. Legal, cultural, practical, and institutional

Water.

contexts differ among countries, and foreign good prac-

tices likely need to be adapted for the home country.

Research on good practices

leads to proposed improvements

How to tap the experience

Assisted by knowledge of how public involvement

of other countries

works in water management in the United States

and countries of the European Union, Romanian

∑ Promote and expand direct exchanges of knowledge

NGOs identified and recommended constructive op-

and experience through workshops, study tours to

tions for selecting citizen and NGO representatives

other countries, meetings of stakeholder forums, and

for membership on river basin committees. They

other face-to-face encounters.

also found ideas for increasing public input to the

committees' decision making. A report that helped

∑ Identify countries that have relevant and effective

them do this is available at http://www.rec.org/

public involvement programs and requirements and

REC/Programs/PublicParticipation/DanubeRiver-

a good record of implementing them in practice.

Basin/project_products/rom_selected_prac-

∑ Invite foreign counterparts to participate in training

tices_rbc.pdf.

F L O W I N G F R E E L Y

17

workshops and share experiences in practical meth-

EXAMPLES

ods for increasing public access to information and

Stakeholders set aside differences

public involvement in water-related decision making.

and focus on solutions

These workshops should be conducted in appropri-

ate national languages for officials at national, re-

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, citizens, NGOs, and in-

dustrial firms in Lukavac, Tuzla Canton, met to con-

gional, and local levels.

sider the impacts of pollution on their shared

∑ In some cases, it may be appropriate to seek outside

interests and look for joint solutions. Previous ef-

help and ask foreign colleagues to review and give

forts had been unproductive and confrontational. A

advice on drafts of government manuals and

local NGO, Eko-Zeleni Lukavac, brought together rel-

brochures for citizens and NGOs, in writing by-laws,

evant authorities and stakeholders. Because of the

constructing databases, developing website content,

collaborative approach, a local company decided to

and creating other products

participate and offered its factory as a meeting site,

setting a new, civil tone for discussions.

∑ Study other countries' official guidelines for han-

dling claims of confidential business information.

A "water forum" hosts discussions

∑ Consider the costs of establishing and maintaining a

particular practice, and know what training and human

Local communication about water quality in Osijek,

resources will be needed to implement it successfully.

Croatia, now has an Internet-based platform, the

Water Forum. The forum is a virtual place for gov-

∑ Assess the viability of options used elsewhere. Adapt

ernmental authorities, NGOs, citizens, and other

good practices used in other countries to the particu-

stakeholders to discuss water issues, including the

lar circumstances of the home country.

planned construction of a wastewater treatment

plant. Coordinated by an NGO, Green Osijek, this low-

cost approach hosts information exchanges

2 Build bridges between information

through the Internet; participants may hold actual

seekers and information providers

meetings as appropriate. More information is avail-

able at www.zeleni-osijek.hr.

NGOs, citizens, and government officials may not

always be comfortable working together, but they

are necessary partners in solving water quality

problems.

Building bridges between those who have the informa-

Project work in Croatia involved

tion and those who want it can help increase public

outreach to industrial stakeholders.

involvement in water-related decision making and gen-

erate support for protection of valuable water re-

sources. Both sides need to understand the value of

this collaboration and recognize that it serves their

own interests and goals.

One way to strengthen communication between offi-

cials, NGOs, and the public is to engage all stakehold-

ers in collaborative capacity building. This can include

a broad range of joint activities: workshops, training

sessions, discussion forums, joint efforts to develop

databases, and study tours. NGOs can play a vital and

constructive role here.

Short-term joint activities can build a foundation for

F L O W I N G F R E E L Y

18 RECOMMENDATIONS

future efforts. But to sustain cooperation over the long

3 Prepare manuals for

term, ongoing processes to facilitate communication and

government officials

collaboration among stakeholders and government

officials are essential. Such efforts require steady but

Government officials have many responsibilities and

modest funding, as the results of the demonstration

work under severe time constraints. Provide them

projects show.

with written guides that have the answers they need.

One idea tested by a demonstration project was creating

Whether called manuals, guides, deskbooks, handbooks,

a virtual forum where people could "meet" regularly to

or guidelines, written aids can help relevant government

discuss water management and planning, pollution con-

officials at all levels--national, regional, and local-- pro-

trol, and other common interests. Collaborative efforts

vide public information and engage citizens in water

to develop basic water databases also proved to be unify-

management planning. Such manuals have two func-

ing experiences.

tions: informing officials of their responsibilities and in-

forming officials of citizens' rights.

Both short- and longer-term collaborative activities, in-

cluding forums for dialogue and capacity-building work-

The manual must be designed and written so that it is ac-

shops, are needed to increase public involvement in

tually used, not put on a shelf. A collaborative, open draft-

ing process will let the end users help determine the best,

water-related decision making throughout the Danube

most useful way to present information. It will also engage

River basin and should be implemented at the regional,

the stakeholders and build trust and mutual respect.

national, and local levels.

Simply writing a manual and giving it to government of-

ficials will not be effective if the ministry has not used

How to promote collaboration

such written guides before. It is necessary to first tap the

among stakeholders

expertise, experience, and viewpoints of the end users

and encourage "buy-in" to the concept of a manual. The

∑ Identify what information the public needs.

manual will have to be introduced into daily practice,

∑ Establish partnerships between NGOs and govern-

and that means providing training in its use.

mental authorities to set up effective databases and

One common problem is personnel turnover in govern-

information access systems.

ment offices. An effective manual is one that is well-em-

∑ Test the system by making requests for information

bedded in the practices of the institution even as

and giving feedback to officials about how it is work-

officials come and go. New personnel must therefore be

ing and where improvements need to be made.

trained in its use.

Manuals should be updated based on feedback from

∑ Inform the public about how and where to obtain

users. Feedback can be informal, but actively seeking

environmental information.

feedback from manual users is preferable. For example,

∑ Raise public and youth awareness by disseminating

after the manual has been in use for 6 to 12 months, a

nontechnical information on national and local water

questionnaire can be sent to users, asking them what

pollution problems and their potential solutions.

works and what needs to be improved.

∑ Develop rules and procedures that help water author-

Another challenge is keeping the manual current and ac-

ities consult with the public.

commodating changes in law, policy, and evolving good

practice. Flexible formats (like three-ring binders) make

∑ Hold forums for dialogue between the public, gov-

it simple to substitute or add pages to a manual. Elec-

ernmental authorities, and other stakeholders on

tronic formats, of course, are very easy to update, but

water management issues.

whether a web-based manual is appropriate depends on

∑ Encourage consistent participation over time to pro-

users' actual level of access to the Internet and familiar-

mote continuity and allow trust to develop.

ity with its use.

F L O W I N G F R E E L Y

R E C O M M E N D A T I O N S

19

How to write a manual for government officials

∑ Engage the government officials who will be respon-

∑ Know the target audience: what do the future users

sible for handling information requests and ask them

want and need?

to contribute to and comment on the drafts.

∑ Use a collaborative, open drafting process to engage

∑ Consult within the agency and among agencies to

stakeholders and build trust and mutual respect.

get official support for the manual. Obtain high-

Start the discussion with an outline. Share first and

level commitment, such as official letters of en-

interim drafts. Call meetings to discuss the manual

dorsement that can be used when the manual is

and include stakeholders in communications be-

completed.

tween meetings. Hire a professional to facilitate the

∑ Ensure that the manual correctly states the rights of

meetings, whenever feasible, to help create a positive

atmosphere and ensure a productive outcome.

citizens to obtain environmental information and

participate in environmental decision making, as well

as the legal responsibilities of government officials;

the manual should provide unbiased guidance on in-

terpreting legal requirements.

∑ Make the manual concise, practical, and easy to fol-

EXAMPLE

low. Use the local language.

Government ministers

endorse manuals

∑ Illustrate the manual with concrete examples of both

In Serbia, the Man-

good practices to follow and bad practices to avoid.

ual for Authorities

Use country experience (where it exists) or create re-

on Access to Infor-

alistic hypothetical examples (where it does not). If

mation on Environ-

the best practices of other countries are cited, convey

mental and Water

the context in which they are used and assess how

Issues was recom-

transferable they are.

mended for use by

the Director of the

∑ Include flowcharts, lists, boxes, schemes, and other

Water Directorate,

graphic design elements if they aid comprehension.

Ministry of Agricul-

ture, Forestry and

∑ Prepare a dissemination plan to ensure distribution

Water Manage-

to all officials who need it.

ment, and was pre-

sented and

∑ Coordinate the issuance of the manual with the

distributed through

timetables and legal requirements of the Water

the directorate's

Framework Directive and other relevant international

website. The man-

agreements and national laws.

ual and the en-

dorsement are available at

∑ Hold workshops to introduce the manual and train

http://www.minpolj.sr.gov.yu/images/materiali/Pri

government personnel in using it.

rucnikzapredstavnikejavnevlasti.pdf.

∑ Make the manual available on the ministry's website

In Romania, the Manual for Authorities on Environ-

so that it is publicly available and the procedures are

mental and Water-related Access to Information

transparent.

and Public Participation in Decision-making with

Focus on EU WFD has been published with the logo

∑ Make sure the manual is transferred to new employ-

of the ministry and disseminated to water and envi-

ees. Provide copies and training as part of new em-

ronmental authorities by the State Secretary of the

ployee orientation.

Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Develop-

ment with a recommendation that it be used.

∑ Reserve copies for the library of the ministry or agency.

F L O W I N G F R E E L Y

20 RECOMMENDATIONS

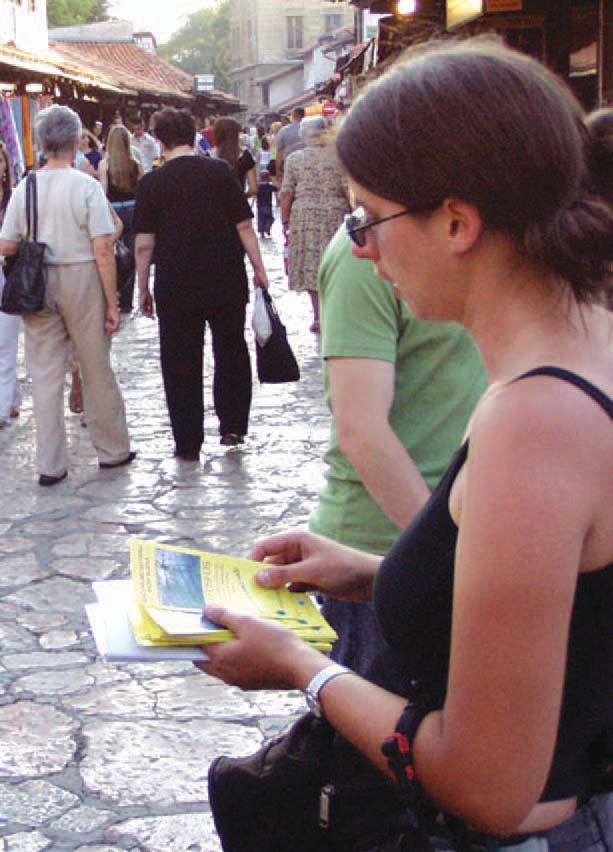

4 Explain the procedures to the public

sider, especially when drafting brochures that encour-

age citizens' requests and participation.

Asking government authorities for environmental

A major challenge in preparing and disseminating

information is not a familiar practice for most

brochures is cost. Even with a generous budget, the

members of the public; they welcome practical

number of brochures printed may be insufficient to

tools that show them how to exercise their rights.

meet the demand, and the inexpensive alternative, a

These aids will be most helpful if they are tailored to the

web-based tool, may not be appropriate if ordinary citi-

targeted users: the general public or NGOs, but some-

zens lack regular or affordable access to the Internet.

times both. NGOs tend to be more organized and edu-

cated on the issues than the general public, so these

different audiences may have different needs.

How to prepare a brochure

Some individuals and NGOs know they have a right to

for citizens or NGOs

obtain information but need more specific assistance.

∑ Test the current system by making specific requests

Whether it is a simple brochure or a more extensive citi-

to governmental authorities, then use the results to

zens' "toolkit" or NGO website, the goal is to provide a

help stakeholders and others identify potential im-

clear, easy-to-follow roadmap to information dispersed

provements.

among various authorities at various levels of govern-

ment. The brochure should tell NGOs and citizens what

∑ Make sure the brochure will be appropriate for the

information can be found at which agency, help them

targeted users. Collaborate with them in a series of

formulate requests for information, provide contact in-

meetings--not just one--and identify barriers to in-

formation, and say what to do if the request is denied or

formation access and public participation and the

ignored. It should also indicate how they can participate

content of the brochure. Use a professional facilita-

in water management planning.

tor to keep meetings positive and productive.

Traditions of informal access to information--for ex-

∑ Between meetings, communicate with future users

ample, asking someone you know who works in the

and ask for feedback in an open process that builds

government--might work for some people but in prac-

trust and mutual respect.

tice undermine official regimes for public access to in-

formation. Brochures, toolkits, and other written

∑ Include all the necessary information in the

information can encourage use of the new, legitimate

brochure: citizens' rights to information, where to

system and help citizens and NGOs become informed

send a request, what language is best to use, how to

consumers and users of information. Two important

appeal denials, when and how to participate in fu-

goals are served: good brochures make it easier for

ture decision making. Provide model requests.

government to serve the needs of the public, and they

∑ Use respectful language and a neutral tone, even

help citizens understand better how they can partici-

when identifying problems in the system. The

pate in future decision making.

brochure should build the public's trust in govern-

Because the tools facilitate use of the information and

ment authorities and the government's comfort in

participation system and test how it is functioning,

working with NGOs and citizens. At the same time,

they pave the way for more and better public access in

whatever problems exist, do not dissuade the public

the future. The tools can also make the authorities'

from seeking information or participating.

jobs easier by helping citizens prepare requests that are

clear, specific, and sent to the appropriate place.

∑ Give drafts to officials and ask them to comment

on content and tone.

NGOs that want to prepare citizen tools should con-

sider what language is most useful for the public and

∑ Don't attempt to make the brochure serve every

most productive in dealing with the government. Tone

need. No brochure can answer every question;

is important. Even when NGOs and governments have

highly specific guidance on appeals procedures, for

good relationships, there are still sensitivities to con-

example, may not be appropriate.

F L O W I N G F R E E L Y

R E C O M M E N D A T I O N S

21

EXAMPLES

Bulgarians test the system

A "green" phone and brochure help Croatians

Efforts by the NGO Ecomission 21st Century to engage Bul-

Association Franjo Kostec, an NGO, prepared a brochure that

garian citizens and NGOs in submitting information re-

tells Croatians how to get water-related information at envi-

quests to local, regional, and national authorities not only

ronmental and water agencies, with addresses and websites.

improved the skills of local communities in seeking and ob-

The brochure offers tips for gaining access to information

taining information, but also tested what kind of water man-

and becoming involved. It also directs citizens to a "green"

agement information was being withheld as confidential.

phone operated by the NGO Green Action. They can call this

The results helped the NGO propose improvements in na-

number if they need assistance in getting information or find-

tional legislation and practice. More information is available

ing ways to participate. The brochure is available at

at http://www.bluelink.net/water/public/.

ww.rec.org/REC/Programs/PublicParticipation/Danube

RiverBasin/project_products/croatia_brochure_for_ngos.pdf.

Romanian NGOs produce a toolkit

Brochure explains citizens' rights

Four practical fact sheets help the public find information

and get involved in decision making. Fact sheet 1, "Access

A brochure for Bosnia and Herzegovina describes the envi-

to environmental and water information," summarizes Ro-

ronmental and health problems associated with polluted

manian legal requirements and lists what information is

water and explains why the public needs to be involved in

available at national, regional, and local institutions. Fact

solving them. It identifies public involvement opportunities

sheet 2, "Public participation issues," describes public hear-

under current national and international legislation, explains

ings and how they work. Fact sheet 3, "Accessing informa-

citizens' rights and procedures for obtaining information

tion using the Public Information Law," details the process

and participating in decision making, and provides examples

of obtaining information and offers a format for information

of good practices for public involvement from other coun-

requests. Fact sheet 4, "Accessing information using the

tries. The brochure is available at ww.rec.org/REC/

Environmental Law," concerns environmental data specifi-

Programs/PublicParticipation/DanubeRiverBasin/pro-

cally and suggests a sample form for information requests.

ject_products/bih_brochure_for_ngos.pdf.

∑ Use the contact lists of NGOs and NGO networks

5 Centralize information storage

as well as other lists of interested persons, and where

feasible and appropriate provide both hard and elec-

Governments benefit from basic inventories of

tronic copies to all relevant government agencies

water-related data in their possession, and the pub-

and public information services to ensure the widest

lic needs to know where this information can be

possible public dissemination. Keep the brochure

found within the agencies.

up-to-date so that it ref lects changes in law, policy,

Environmental information relating to water is generally

good practice, frequently asked questions, and feed-

back from users. A web-based brochure is ideal but

dispersed among many ministries and government of-

only if most citizens have access to the Internet and

fices at the federal, state, entity, regional, and local lev-

are comfortable using online material.

els. As a result, citizens have great difficulty

determining where to direct a request and what infor-

∑ If resources are available, supplement the brochure

mation is available.

with information centers and "green phones" to

help answer citizens' questions and resolve prob-

A critical first step in resolving this problem is to de-

lems. Such centers are in the government's best in-

velop a system that identifies where the information can

terest if they promote clear, specific, well-directed

be found. As important end users of the information,

requests for information and appropriate participa-

NGOs, in collaboration with government authorities,

tion in decision making.

can help develop a system that gathers and organizes the

F L O W I N G F R E E L Y

22 RECOMMENDATIONS

EXAMPLES

∑ To encourage agencies to participate, emphasize the

A meta-system orients citizens

value of sharing data. Even officials who might have

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, a consultant helped gov-

reservations about releasing their data can see that

ernment authorities and NGOs develop a meta-infor-

having access to additional information can enhance

mation system for locating water-related information

the value of their own data and help avoid overlaps.

within the multiple levels of a particularly fragmented

government structure. The system helps citizens find

∑ Bring the different information holders together to

out where the information they need is located. For

discuss how best to share and integrate their data,

each of 324 institutions, it identifies a contact person,

and include future users who can help the officials

gives website address and hyperlink, describes the in-

understand how the data system will be used in prac-

stitution, and indicates what information is held there.

tice by members of the public and NGOs seeking

The system is available at http://www.rec.org/REC/

water-related environmental information.

Programs/PublicParticipation/DanubeRiverBasin/

project_products/default.html.

6 Develop clear procedures for

An NGO and local authorities

protecting confidential information

create a database

Working with local authorities and companies, an

Industry must be confident that governments will

NGO, Association of Young Researchers in Bor, Ser-

not endanger their competitive position by disclos-

bia, established a standardized database for water

resources and made it accessible to government au-

ing legitimate business secrets.

thorities, water users, and the public. The database

Lack of clarity about what information should be re-

will be transferred to the municipality's Environment

garded as confidential is one reason why data are often

Protection Department, and the NGO has trained

withheld from disclosure. Governments should establish

municipal employees in operating and maintaining it.

clear rules on what is confidential--and what is not--so

that officials do not mistakenly deny requests for infor-

mation or provide only partial responses.

Inevitably, some business information will fall in a

information, particularly by identifying what informa-

"gray" area and be neither clearly confidential nor

tion the public needs.

clearly public. It is critical to provide some means to re-

Some countries have legal requirements for the creation

solve such ambiguity. One method is ombudsman of-

of integrated environmental databases. When imple-

fices, which are established by parliaments to represent

mented, these can help ensure that information is shared

the interests of the public by investigating citizens'

among the agencies that hold it--and that if an agency

complaints of improper government actions and clarify-

receives a misdirected request, staff can easily forward it

ing legal ambiguities. Although their decisions are usu-

to the appropriate agency.

ally not legally binding, ombudsmen are respected for

their neutrality, expertise, and reasoned opinions, which

are always made publicly available. Their judgments are

How to develop a centralized

generally accepted, and courts can also review especially

data system

difficult issues.

∑ Identify the key offices and people with water-related

Setting up procedures to review and grant or deny re-

information. This may require considerable effort.

quests for potentially confidential information requires

∑ If possible, construct an electronic system that coor-

thought about both content and process. Depending on

dinates, links, or integrates multiple sources of data

the complexity of the issues, high-level administrators

and information.

may need to become involved.

F L O W I N G F R E E L Y

R E C O M M E N D A T I O N S

23

EXAMPLE

7 Use and maintain electronic tools

Bulgaria considers

where appropriate

a "public interest test" approach

Electronic access can simplify information access

In the Lovech-Troyan area, Ecomission 21st Century,

for the public and make easier the job of govern-

an NGO, built on a previous effort to identify gaps in

legislation and practice and conducted several

ment officials responsible for providing information.

rounds of test requests for information. Analysis of

Some countries have already constructed electronic sys-

the results helped form the basis for recommended

tems that coordinate multiple sources of data and infor-

procedures for handling business confidentiality.

mation; others have not. No electronic approach can be

Recommendations include implementing a public in-

established until the government has identified what in-

terest test and supplementing the current rulebook

formation is available where. But ultimately, it will be

of the Ministry of Environment and Water.

convenient for all stakeholders if information requests

can be submitted and answered online.

Developers of these systems should anticipate and resolve

multiple practical impediments. Websites and computer

databases require constant maintenance and updating,

How to manage confidentiality claims

which in turn require skills and expertise. However, mu-

∑ Consult with both the public and business when set-

nicipal offices are often staffed by people who lack the

ting criteria for confidentiality but be clear that the

necessary skills--or don't even have computers.

government agency holding the information has the

Because resources are limited, in some cases business

authority--and the responsibility--to make the final

may subsidize the cost of establishing and maintaining a

decision (subject, where applicable, to court review).

∑ Use a public interest test to balance the need for

confidentiality against the value of providing public

access. This approach is used successfully in the

United States and within the European Union.

EXAMPLE

∑ Clearly articulate criteria for confidentiality and

make them public.

River basin authorities

coordinate websites

∑ Require authorities to notify business when poten-

tially confidential information is requested.

Authorities in Bulgaria conducted a needs assess-

ment with representatives of the Danube River

∑ Require business to substantiate claims of confiden-

Basin Directorate and other organizations and

tiality for specific documents within a set time.

developed a common approach for their websites.

∑ Require authorities to release requested information if

The goal was to make the sites more functional and

business fails to substantiate claims of confidentiality.

offer comparable information in similar formats.

The revised websites now explain procedures for

∑ Ensure that legal assistance and advice will be avail-

requesting information, provide hyperlinks to other

able when needed to government officials tasked

websites with environmental data, offer environ-

with responding to requests.

mental information, and include a form for request-

∑ Require authorities to provide adequate explanation

ing information plus frequently asked questions

when refusing information requests on the grounds

(FAQs). A manual was prepared for webpage man-

of confidentiality.

agers. See two of these websites at

http://www.dunavbd.org/index.php?x=46

∑ Provide mechanisms for challenging and reviewing

(Danube River Basin Directorate) and http://

decisions.

www.lovech.bg/Read.php?id=537 (Lovech County).

F L O W I N G F R E E L Y

24 RECOMMENDATIONS

website in return for a hyperlink, but government web-

No one sector can solve environmental problems alone.

sites under these arrangements must maintain their inde-

Although it is sometimes difficult to get people with di-

pendence and neutrality.

verse backgrounds and points of view to communicate

and cooperate, working together helps break down the

obstacles to providing access to information and encour-

How to set up electronic systems

aging public participation. More effective approaches

for providing information

can then be devised. Initiating dialogue takes hard work

because of resistance from all sides, including reluctant

∑ Start by identifying the offices and people with infor-

authorities and hesitant stakeholders.

mation.

Authorities do not always take seriously comments com-

∑ Assess the needs of target users and define the con-

ing from stakeholders who lack technical knowledge or

tent of the information system or website with

are not experts. The public has considerable knowledge

their help.

and power, and can be a galvanizing force. Subtle, tact-

∑ Develop an easy-to-navigate design that either pro-

ful, and careful work is necessary to help authorities rec-

vides the information or links to the site where it is

ognize the value of public input and participation to

stored. Hyperlinks to other sites will maximize the

their work, as well as to shape ideas from NGOs and cit-

information flow.

izens into viable contributions.

∑ Offer contact information for the government

staffers who handle specific issues, as well as the web-

How to make public participation

site addresses of their ministries.

efficient and effective

∑ Write text that is brief and easy to use and understand.

∑ Make the additional effort to engage the citizenry be-

cause it will provide long-term benefits.

∑ Promote the website to potential users.

∑ Recognize that citizens may have important local

∑ Ask users for feedback and facilitate comment. Peri-

knowledge to contribute to environmental problem

odic improvements to the website will be necessary.

solving but may need encouragement and advice on

∑ Provide ongoing training to website managers.

how to communicate it so that it is timely and relevant

to the decision-making process.

∑ Be realistic about what can be accomplished and rec-

ognize that some of the information the public

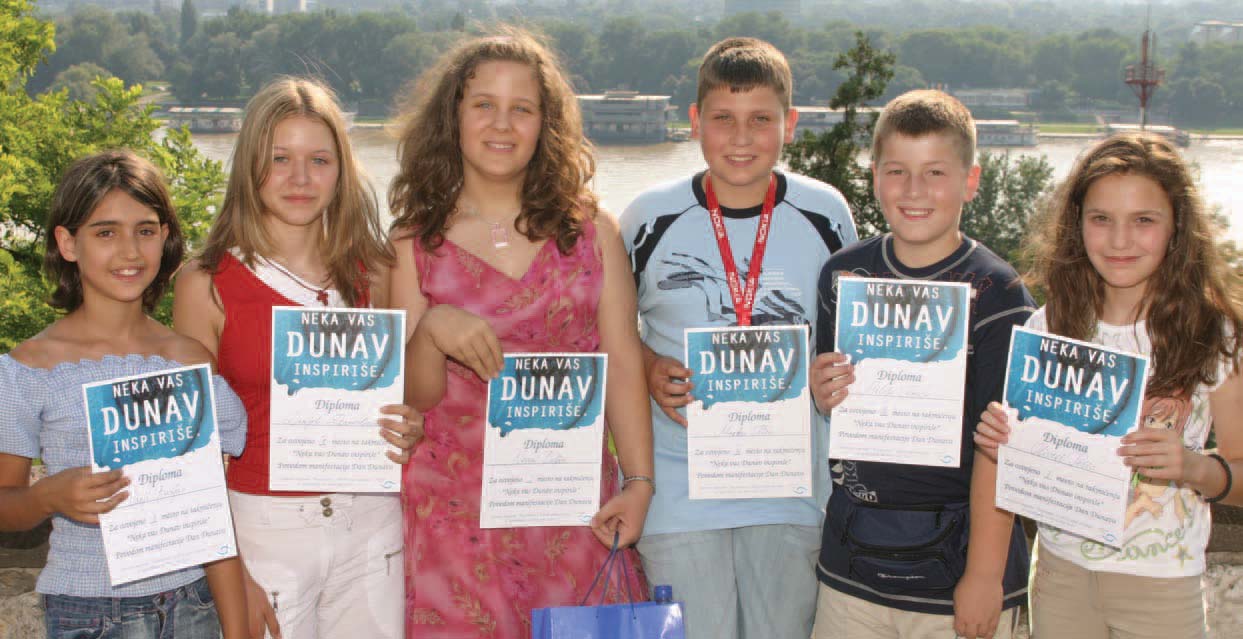

∑ Find ways to communicate with children and youth.

wants might not yet be collected by the government.

Not only will they be the caretakers of the future, they

By the same token, identifying gaps in the system

help extend the reach of current environmental infor-

can be an important first step toward ensuring that

mation by relaying the messages to their families,

they are filled in the future.

schools, and communities. Studies show that high

school students have much higher environmental

awareness if they were involved in environmental edu-

8 Involve the broad public at all stages

cation activities in primary school.

∑ When designing activities for youth and children, in-

Effective public participation involves engaging the

volve them in the planning.

extended public, not just NGOs and groups already

∑ Engage youth in technical activities such as biological

organized around environmental and water issues.

monitoring. Funds for training and supervising them

Participatory processes are essential for carrying out na-

will be necessary.

tional activities and demonstration projects and critical

∑ Take advantage even of unfortunate events: oil spills or

to developing the sense of ownership, accomplishment,

accidental exposures to hazardous materials can be-

and satisfaction necessary to build a foundation for fu-

come opportunities for learning, awareness raising, dia-

ture efforts to clean up and protect water resources.

logue, and problem solving.

F L O W I N G F R E E L Y

R E C O M M E N D A T I O N S

25

Kindling their interest now will help

secure their involvement in the future.

EXAMPLES

Publications spark radio

and TV coverage

Ministry introduces schoolchildren

The Association of Young Researchers, an NGO in Bor, Ser-

to water pollution issues

bia, produced a leaflet and a special edition of its bulletin,

In Romania, the Ministry

Ekobor, that examined the causes of local water pollution,

of Environment and Sus-

described monitoring needs, and explored ways to control

tainable Development de-

the pollution. The publications were distributed to partici-

veloped appealing

pants of the local roundtable, the media, and citizens in

materials on the Danube

hard copies and through the organization's website. In addi-

and water pollution

tion, the NGO produced or participated in local radio and

geared specifically to pri-

television programs about local water pollution problems.

mary school children.

Details are available at www.etos.co.yu.

With lively illustrations

(some by children), they

Radio program emphasizes

introduce the issues in

collaboration

ways that relate to chil-

dren's own experience.

A radio program in Bulgaria about access to environmental

More information is avail-

information demonstrated constructive collaboration by in-

able at

cluding an NGO representative, the head of the Information

http://www.mmediu.ro/

Center of the municipality of Lovech (whose office provides

ape/coltul_copiilor.htm.

environmental and water-related information), and the legal

adviser of the Danube River Basin Directorate. The pro-

[a child's illustration from

gram included a roundtable discussion that highlighted the

the Directi Managementul Resurselor de Apa booklet of

problems and best practices of providing access to infor-

June 2005 entitled "APA: O Poveste Fara Sfarsit."]

mation about water issues.

F L O W I N G F R E E L Y

26 RECOMMENDATIONS

Events like Danube Day can

engage the broader public in

river basin management

∑ To broaden the circle of citizens engaged in environ-

mental protection activities, frame the issues in ways

that are relevant to the community. How does water

quality affect the lives of local residents and their

children? What can they realistically do about it?

∑ Find common ground and common interest and

show the benefits of cooperation.

∑ Establish good relations with the news media and

build partnerships for publicizing the right to infor-

mation and its uses in controlling local water pollu-

tion. Campaigns to raise awareness about local water

pollution, access to environmental information, and

public participation can be conveyed in news articles

and spots in local or national broadcast media.

∑ Stage events to engage the broader public, such as:

- celebration of Danube Day (29 June, www.icpdr.

org/icpdr-pages/danube_day.htm),

- Danube Box (an education toolkit),

- Generation Blue (Austria's youth water program,

www.aqa.at/projekte/generationblue),

- the Austrian water prize "Neptun," a "children's

corner" on websites,

- World Water Monitoring Day (18 October,

www.worldwatermonitoringday.org),

- green schools and workshops,

- national and international school networks, and

- educational materials produced by ministries.

∑ Time local events to coincide with larger-scale efforts

to magnify the audience and impact.

EXAMPLE

9 Make the most of opportunities

NGO finds communication problems

on river basin committees

to participate

In Romania, an NGO's assessment of the legal and

practical barriers to public involvement in the Mures

Cooperation between government and NGOs in

River Basin Committee led to recommendations for

river basin committees requires willing parties and

improvements. In particular, the NGO examined how

some funding; transboundary efforts face special

communication and decision making occurred

challenges.

within the committee and how committee members

River basin committees are one way to increase public

involved their stakeholders. One outcome was a

participation opportunities for the public and NGOs. De-

manual on how to improve public access to informa-

tion and public participation. The recommendations

veloping a successful process in one river basin may have

will assist national authorities in making changes to

spillover benefits if the effort becomes a model for others.

improve the functioning of river basin committees.

F L O W I N G F R E E L Y

R E C O M M E N D A T I O N S

27

Government support can enhance the deliberations and

outcomes of river basin committees. It will be impossi-

ble to involve everybody, but the more inclusive and

representative these groups and the more expertise and

knowledge they acquire, the more influence they can

have on decision making. For maximum impact, NGO

stakeholders should take the initiative, organize them-

selves, delegate representatives to serve on advisory or

consultative committees, and prepare proposals.

Transboundary water management presents special chal-

lenges for public participation. Because many rivers and

river basins are international, productive efforts to solve

environmental problems require careful attention to com-

monalities and differences on both sides of the border.

Cultural differences between countries can affect the

work of committees dealing with transboundary river is-

sues. Parallel public participation processes must be har-

monized and run in several countries simultaneously.

How to take full advantage of

committee efforts

∑ To finance public participation in river basin man-

agement and planning, seek provincial or state fund-

ing (e.g., German Lšnder provide resources from the

state budget) or contributions from local authorities.

∑ Involve people early in the process. The upfront in-

vestment of time and resources will be most efficient

for governmental authorities.

∑ Consider using existing associations of stakeholders,

including NGOs, rather than trying to create a

wholly new public participation process.

∑ Reinforce good decision making and democratic val-

ues with transparent processes.

∑ Ensure broad representation on the committee by

using a fair election or selection process that is trans-

parent and sensitive to stakeholders' interests.

∑ Determine the roles and responsibilities of committees

that serve an advisory function: offering comments,

providing access to information, giving feedback, dis-

seminating links to and from the public, and incorpo-

rating informal input into decision making.

Anglers form an important constituency