UNDP-GEF Danube Regional Project

Final Report

for

"Development of Indicators for Project Monitoring

and Impact Evaluation"

April 16, 2004

Dr. J. Dogterom

Drs. J.P.E. van Leeuwen

N. Koopmans

G. Robijn

Oudebildtdijk

1058

Leeuwarden

University

for

9075

NK

Westhoek

Professional

Education

The

Netherlands Tesselschadestraat

12

Tel.:

+31-518-491838

8913

HB

Leeuwarden

Fax:

+31-518-491944

The

Netherlands

Email: j.dogterom@tech.nhl.nl

Tel:

+31-58-2961164

Fax:

+31-58-

2961188

Email: j.p.e.van.leeuwen@ecma.nhl.nl

PREFACE

The long term goal of the DRP is to strengthen capacities of key Danube stakeholders and

institutions to effectively and sustainably manage the Danube River Basin's water resources and

ecosystems for citizens of Danube countries.

River basin managers need to be able to monitor changes, hopefully improvements, but also

deterioration in the river basin ecosystem. Moreover, there is the need to be able understand the

effects of measures (policies, investments etc.) in order to make more informed decisions in the

future. It is clear that the development and use of indicators should be an iterative process. The

more indicators are used, the more precisely they can be developed and utilized.

The objective of this assignment was to develop a system of indicators for two purposes:

i.

to monitor the impact of activities carried out by the UNDP/GEF DRP and

ii.

to establish a system to be able to assess and monitor the changes in the DRB system

due to various interventions. I.e. to establish a system of indicators that will function

long after the end of the DRP as a management tool to both understand the effects of

specific interventions, as well as to provide a basis upon which to decide upon new

interventions.

The assignment was intended to propose a system of indicators that is functionable, multi-purpose

and practical. This is a challenging task as it needs to be relevant for the EU WFD, the GEF

guidelines for monitoring and impact evaluation as well as reliable for monitoring the

implementation of the DRPC.

The efforts in this Phase 1 assignment resulted in a clear strategy for introducing a system of

indicators for the DRB. Nevertheless it is a challenging task to develop a system of indicators that

should meet the relatively short-term needs of demonstrating the results of the DRP, while also (and

perhaps more importantly) showing the conditions of the DRB over a longer (perhaps more relevant)

time period. As the old proverb goes, "a journey of a thousand miles, begins with a single step."

Thus, this assignment and the system it proposes should be seen as the starting point.

The results of this component are intended to be a basis for the ICPDR, with the continued

assistance of the DRP, to implement the proposed system of indicators during Phase 2 of the DRP

from 2004-2007.

The report was prepared under the guidance of Jan Dogterom and associated experts. and reflects

the views of this expert team. The report and its contents remain the property of the UNDP/GEF

DRP and should not be used without providing full credit to the DRP.

For further information about the DRP, objectives, activities, results etc. please visit the DRP

webpage at www.undp-drp.org .

Indicators for Project Monitoiring and Impact Evaluation

page 5

CONTENTS

Contents ............................................................................................................................ 3

List of abbreviations............................................................................................................. 7

Executive summary ............................................................................................................. 9

1.

Introduction and Background Information .................................................................. 11

2.

Objective of this activity .......................................................................................... 12

3.

Problem definition................................................................................................... 12

3.1.

Why a system of indicators................................................................................. 12

4.

Concepts ............................................................................................................... 13

4.1.

General ........................................................................................................... 13

4.2.

Indicators for GEF M & E reporting requirements.................................................... 14

4.3.

Indicators for WFD and EEA reporting requirements ............................................... 15

4.4.

GEF and WFD compared..................................................................................... 15

4.5.

Indicator selection criteria and data and information requirements ........................... 16

4.6.

The problem of the baseline................................................................................ 17

5.

Results ................................................................................................................. 18

5.1.

System of indicators for GEF M & E ...................................................................... 18

5.1.1.

Introduction................................................................................................ 18

5.1.2.

Categories of indicators ................................................................................ 18

5.1.3.

Individual indicators..................................................................................... 19

5.1.4.

Recommendation for the selection of a core list of indicators for GEF M&E............ 21

5.2.

System of indicators for WFD/ EEA ...................................................................... 22

5.2.1.

Introduction................................................................................................ 22

5.2.2.

Categories of indicators ................................................................................ 22

5.2.3.

Individual indicators..................................................................................... 24

5.2.4.

Recommendation for the selection of a core list of indicators for the ICPDR .......... 24

6.

Presentation of indicators ....................................................................................... 26

6.1.

Introduction ..................................................................................................... 26

6.2.

6.2 Examples of individual indicators ................................................................... 26

6.2.1.

6.2.1 Driving force indicators ........................................................................ 26

6.2.2.

Pressure indicators ...................................................................................... 27

6.2.3.

State indicators ........................................................................................... 28

6.2.4.

Impact indicators......................................................................................... 28

6.2.5.

Stress reduction/response indicators .............................................................. 29

6.2.6.

Aggregated indicators: the kite diagram.......................................................... 29

6.3.

Clustering and aggregation of indicators .............................................................. 30

6.3.1.

Introduction................................................................................................ 30

page 6

6.3.2.

Consistent aggregation and filtered consistency ............................................... 30

6.3.3.

An example of clustering and aggregation ....................................................... 31

6.3.4.

The technique of clustering ........................................................................... 33

6.3.5.

Aggregating process indicators ...................................................................... 34

6.4.

Detailed presentation of selected indicators........................................................... 35

6.4.1.

Process indicator: assessment of involvement.................................................. 35

6.4.2.

Stress reduction/response indicator: introduction of BAP and implementation of

Nitrate Directive........................................................................................................ 35

6.4.3.

State indicators: trend analysis of concentrations for 1996-2000 for ammonium and

nitrate at 5 stations in the Danube basin...................................................................... 35

6.4.4.

An Indicator for Legal Reform Processes ......................................................... 38

6.5.

Web site format report....................................................................................... 39

7.

Discussion ............................................................................................................. 40

8.

Literature and websites ........................................................................................... 41

Annexes

ANNEX I: Process indicators ..................................................................................... 43

ANNEX II: Stress reduction and response indicators .................................................... 47

Indicators in bold are proposed for the core set .......................................................... 47

17. Reduction of accidental spills .............................................................................. 47

ANNEX III: State indicators...................................................................................... 49

Indicators in bold are proposed for the core set .......................................................... 49

ANNEX IV: Driving Force indicators ........................................................................... 51

Indicators in bold are proposed for the core set .......................................................... 51

ANNEX V: Pressure indicators................................................................................... 53

ANNEX VI: Impact indicators.................................................................................... 55

Indicators in bold are proposed for the core set .......................................................... 55

Annex VII: Methodology for the assessment of stakeholder involvement......................... 56

Annex VIII: Methodology for the assessment of policy implementation ........................... 63

Annex IX: Descriptive sheet of EEA Indicator: implementation of the EU Nitrate Directive

(AGRI17) .............................................................................................................. 69

Indicators for Project Monitoiring and Impact Evaluation

page 7

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

BAP

Best

Agricultural

Practice

BAT

Best Available Technology

BSC

Black

Sea

Commission

BSERP

Black Sea Ecosystem Recovery Project

DABLAS

Danube-Black Sea Task Force

DPSIR

Driving

Force-Pressure-State-Impact-Response

DRP

Danube

Regional

Project

EEA

European

Environmental

Agency

EU

European

Union

GEF

Global Environment Facility

ICPDR

International Commission for the Protection of the Danube River

IWTF

International Waters Task Force

JAP

Joint

Action

Plan

LFM

Logical

Framework

Matrix

M & E

Monitoring and Evaluation

MoU

Memorandum

of

Understanding

OECD

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development

PCU

Programme

Coordination

Unit

PSR

Pressure-State-Response

RBM

Result

Based

Management

RIVM

Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieubeheer (National Institute of

Public Health and Environmental Protection)

SAP

Strategic

Action

Plan

SOP

Standard

Operational

Procedure

UNDP

United Nations Development Programme

UNEP

Untied Nations Environment Programme

WFD

Water

Framework

Directive

WB

World

Bank

Indicators for Project Monitoiring and Impact Evaluation

page 9

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The United Nations Development Programme/Global Environment Facility (UNDP/GEF) is the main

international donor to support implementation of the Convention for the Protection and Sustainable

Use of the Danube River Basin. Support is provided in the frame of the regional Danube Project

(DRP). The Council of the GEF wants to be informed on an annual basis by all projects, financed by

GEF, on the performance of the projects. The Council considers Monitoring and Evaluation (M & E) of

project outputs and outcomes an indispensable tool for project management. It should serve both as

a corrective function during project implementation and as a guide to structure future projects more

effectively. Actually, all GEF projects must include M & E provisions. In this context, the GEF-DRP

has developed a system of indicators as the basis for reporting to the GEF Council. This indicator

system allows to monitor and evaluate project performance and complies with the reporting

requirements of the GEF Council. The GEF M & E unit has defined the types of indicators to be

applied: process indicators, stress response indicators and state indicators. The GEF reporting

requirements and these definitions were used for the development of the indicator system.

At the same time an indicator system is under development now within DG-Environment (DG-ENV)

and the European Environmental Agency (EEA) of the European Commission to comply with the

reporting requirements of the new EU Water Framework Directive (WFD). According the latest

information, DG-ENV will use the Driving Force-Pressure-Status-Impact-Response cycle as the

concept for indicator development.

This report describes the concept of 2 indicator system for GEF and DG-ENV/WFD and presents a

number of examples of individual indicators and methodologies for quantification and assessments,

including aggregation techniques for clusters of indicators.

For the GEF M & E, 3 categories process indicators were defined on basis of the 4 Objectives, as

described in the Logical Framework Matrix in the project document of the DRP. Individual process

indicators proposed, are directly related to the outputs and outcomes of the DRP also formulated in

the Logical Framework Matrix. Methodologies for quantification and aggregation are recommended.

There are 4 categories of stress reduction indicators proposed and 22 individual indicators. Similarly

there are 4 categories of state indicators proposed and 18 individual indicators. These are

considered long lists. Selection of a core list of individual indicators was done on basis of 3 selection

criteria which resulted in a core list of 20 individual stress reduction and state indicators. A number

of examples are presented together with quantification and presentation techniques.

In the DPSIR concept of DG-ENV/EEA, the state and response indicators are identical to the state

and stress reduction indicators in the GEF methodology. There are 6 categories of driving force

indicators proposed and 19 individual indicators of which 11 at the core list. These indicators are

based on information which is collected by national governments and /or Eurostat and should not

require any activities with regard to raw data collection by the ICPDR. There are 4 categories of

pressure indicators proposed and 12 individual indicators of which 10 at the core list. There are 4

categories of impact indicators proposed and 7 individual indicators of which 4 at the core list.

These indicators are based on information which is collected by the ICPDR through the TNMN and

EMIS.

For both systems, 1996 is recommended to be used as the baseline, since the database of the

ICPDR is considered reliable and complete since that year.

Indicators for Project Monitoiring and Impact Evaluation

page 11

1. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND INFORMATION

The Convention for the Protection and Sustainable Use of the Danube River Basin came into force in

October 1998 and has been signed and ratified now by 12 of the 13 eligible countries and the

European Commission. The Convention is the institutional frame for pollution control and the

protection of water bodies and it sets a platform for sustainable use of ecological resources and

coherent and integrated river basin management. The Danube countries have established the

International Commission for the Protection of the Danube River Basin (ICPDR) to support

implementation of the Danube River Protection Convention. International support is provided by a

number of donors to facilitate the implementation of the Convention. At present, the United Nations

Development Programme/Global Environment Facility (UNDP/GEF) is the major contributor providing

support in the frame of the Danube Regional Project (DRP). Institutional arrangements have been

set up and joint measures for pollution reduction and river basin management have been designed

and are in the process of being implemented in order to achieve the objectives of the Convention.

The process of transboundary cooperation has been further stimulated by the requirements of the

new Water Framework Directive (WFD) of the European Union (EU), which came into force on 22

December 2000.

The Parties to the Convention are EU member, Candidate-Member, or have adopted the EU water

policy into their national water policy. The WFD formulates reporting requirements of Member States

to the EU to facilitate the evaluation by the Commission of the progress towards the achievement of

the WFD objectives. At present methodologies for reporting are being designed and tested. New

analytical frameworks are discussed (see ref. 1, 2 and 3). Also the Danubian countries have to adopt

a streamlined reporting system to monitor and evaluate the efficiency of their policies, institutional

settings, investment decisions etc. In this context, a system of indicators to monitor and evaluate

policy efficiency is needed. The system should comply with the WFD reporting requirements.

The GEF is the main international donor to support implementation of the Convention. The Council of

the GEF wants to be informed on an annual basis by all projects, financed by GEF, on the

performance of the projects. The Council considers Monitoring and Evaluation (M & E) of project

results an indispensable tool for project management. It should serve both as a corrective function

during project implementation and as a guide to structure future projects more effectively. Actually,

all GEF projects must include M & E provisions. In this context, the GEF/UNDP-DRP has to develop a

system of indicators, as the basis for reporting to the GEF Council. This indicator system should

allow to monitor and evaluate project performance, and has to comply with the reporting

requirements of the GEF Council.

The GEF/UNDP-DRP has commissioned a consultant to develop proposals for indicator systems for M

& E of the DRP and to assess policy efficiency by the parties to the Danube Convention. This report

presents the results of this activity.

page 12

2. OBJECTIVE OF THIS ACTIVITY

The objective of this activity is:

"Establishing a system for M&E in using specific indicators for process (legal and institutional frame),

stress reduction (emissions, removal of hot spots) and environmental status (water quality, recovery

of ecosystems) to demonstrate results of program and project implementation and to evaluate

environmental effects of implementation of policies and regulations (nutrient reduction)."

This activity addresses the establishment of two types of indicator systems, which have two different

purposes:

> Indicators to monitor and evaluate Project results

> Indicators to evaluate effects of specific policies and regulations

3. PROBLEM DEFINITION

3.1. Why a system of indicators

The improvement of environmental quality in general, incl. in river basins, requires many measures,

ranging from the establishment of institutional structures to increasing public awareness, or to

investments. The process consists of very many, usually small, steps over a considerable period of

time. Information collection on the process itself and its results, and proper interpretation and use of

this information is crucial for efficient use of scarce resources. A transparent system of information

collection and interpretation is therefore a major activity in river basin management.

The new EU-WFD stipulates this again by putting new and high requirements on the EU Member

States with regard to reporting (art. 15 of WFD). The ICPDR has agreed on a procedure for joint

reporting to the EU, based on national reports of the Parties to the Convention. Issue specific

Working Groups are working on reporting. The products of these working groups have been taken

into account for the development of the proposals for indicators. The proposed system needs also to

support reporting on the efficiency of the Joint Action Programme (JAP) and reporting to the

national governments and the public at large in the Danube Basin.

The efforts of the Danubian countries to protect the Danube river are supported by a series donors

of which GEF/UNDP is the most important one at the moment. In March 2001, Phase 1 of the GEF-

Danube Regional Project started. It is expected, that the Project will continue with Phase 2 per 1

November 2003. According to Objective 4, the Project will support the development of indicators for

project monitoring and evaluation. The development and application of such a system is required by

the donors to the GEF, represented by the GEF Council. The GEF follows its own methodology with

regard to the selection of an indicator system, and the proposed system in this activity should

comply with the requirements of the GEF International Waters Task Force (IWTF, see ref. 4).

In addition, the ICPDR has to report on the implementation of the MoU between the ICPDR and

Black Sea Commission (BSC) on nutrient reduction, which is being supported by the Danube-Black

Sea Joint Technical Working Group.

Indicators for Project Monitoiring and Impact Evaluation

page 13

4. CONCEPTS

4.1. General

Application of environmental indicators became a serious reporting tool in the early nineties with the

Organization for Economic Cooperation and development (OECD) started applying indicators in the

national environmental performance reviews (see ref. 5) and with the United Nations Environment

Programme (UNEP) developing global environmental outlooks (see ref. 6). The concept of indicators

initially included the cycle: pressure- state-response with OECD distinguishing pressure as indirect

pressures (economic activities, demographic developments) and direct pressures (emissions etc).

Indicators according this cycle were proposed for environmental issues like climate change, ozone

depletion, eutrofication, water resources, biological diversity etc. The cycle was extended in 1994

with impact indicators, proposed by RIVM (see ref. 7). The European Environment Agency (EEA)

replaced the OECD definition for pressures in 1999 by 2 distinct indicator types: driving forces and

pressures (see ref. 8). Since then the concept of the cycle: driving force-pressure-state-impact-

response (DPSIR) is widely accepted, eg also by the United Nations Economic Commission for

Europe (UNECE, see ref. 9) and is now being made operational by EEA (see ref. 10).

The EEA is applying this set of indicators for assessment of water resources on the basis of issues:

ecological quality, eutrofication, pollution with hazardous substances and water quantity (see ref. 2).

The use of the DPSIR cycle however shows that the same individual indicator can be relevant in

each issue. This is shown by the latest report of EEA on water (see ref. 2). It is thus questionable

whether the issue approach is the most efficient in terms of transparency. In this report an other

choice has been made: the DPSIR cycle has been applied in an integrated way, not separating the

individual indicators on basis of issues. This approach is considered more appropriate to support

decision making in integrated water resources management. Neither of the concepts mentioned so

far addresses the issue of the baseline. The concept of using a baseline is proposed by the GEF

Waters Program Indicators Steering Group (see ref. 11) and further stressed by the WB GEF

Secretariat (see ref. 4). This concept has been included in the proposals for indicators in this report.

The GEF M & E indicator concept is different from the ones developed by OECD, UNEP and EEA, since

it serves a different purpose. In the following paragraphs a more detailed description of each

concept is presented.

In March 2004, internal reports of EEA showed major potential developments at EEA with regard to

indicator selection and application. An initial list of over 400 indicators may be reduced to a core list

of only 37 indicators of which 3 for biodiversity, 5 for fresh water, 4 for coastal and marine waters, 2

for agriculture and 3 for fisheries. In these internal documents no reference is made to the DPSIR

cycle, not even to the WFD. Since it is not clear how this is coordinated with EU DG-ENV at the

moment and no final decisions are available at this moment, this report will still use the DPSIR cycle

as the main concept.

page 14

4.2. Indicators for GEF M & E reporting requirements

The development of an indicator framework for M & E of GEF International Waters Projects started in

1996 by the former GEF-IWTF. In the 1996 Guidelines for WB-GEF International Water Projects the

distinction was made between performance and process indicators. Performance indicators relate to

the environmental and socio-economic impact of a project. Environmental performance indicators

measure the project's specific contribution to the solution of specific environmental problems. These

indicators use the PSR-framework: for each of the components pressure, state and responses

indicators should be formulated. Socio-economic impact assessments require another set of

indicators, socio-economic indicators.

According to the 1996 Guidelines, in addition to monitoring performance vis-a-vis project objectives,

M&E procedures should also monitor progress in project activities designed to accomplish the stated

project objectives. This is measured by process indicators. Traditionally process indicators relate to

project inputs and project outputs, like procurement and delivery of goods and services. The 1996

Guidelines recognized the increasing importance of capacity-building, human resource development,

and stakeholder involvement for sustainable project outcomes, and recommended that process

indicators for these activities should be developed

The importance of process indicators is stressed even more in the 2002 GEF M&E Indicators (see ref.

12), and in the description of the implementation of the general policy for the International Waters

Projects (see ref. 4). It is recognized that the reversal of environmental degradation in complex

transboundary waters may take decades. Even meaningful commitments to joint management

improvements may take 15-20 years. This means that process indicators are needed to monitor the

actual step-by-step progress toward the adoption of the joint management regimes, country-based

reforms, and priority investments. In addition to these process indicators two other types of

indicators are recommended, i.e. Stress reduction indicators, and Environmental status indicators.

Therefore for M & E of the DRP these 3 indicators are recommended using the following definitions:

Process indicator: process indicators are indicators, that characterize progress in political,

institutional and legal changes (improvements) at regional or national level as the result of a GEF

project intervention. A typical example is the establishment of an interministerial committee to

reduce sectoral stress/pressures on a defined water body by developing sectoral legislation or

regulation or the completion of a Strategic Action Plan (SAP) for a defined water body.

Stress reduction indicator: stress reduction indicators are indicators, that characterize progress in

the implementation of specific measures to reduce stress/pressures on a defined water body as the

result of GEF project intervention. A typical example is a completed investment programme to

reduce pollution loads from point sources in a defined water body or the implementation of a

management plan to protect or restore ecological functions of flood plains, wetlands or fishing zones

in a defined water body.

State indicator: state indicators are indicators, that characterize (quantitatively) the ecological

quality of a defined water body at a specific moment. A typical example is the concentration of

pollutants or the biological characteristics of a specific ecosystem. A state indicator can be related to

a "target value": good ecological status or a water classification system.

Indicators for Project Monitoiring and Impact Evaluation

page 15

4.3. Indicators for WFD and EEA reporting requirements

The reporting requirements for the WFD are described in art. 15. This article refers to articles 5, 8

and 13, incl. annex VII. In these articles, the principles of information and data collection and

assessment (art. 5 and 8) and for the content of the River Basin Management Plan (art. 13 and

annex VII) are laid down. These principles are further elaborated in the Guidance Documents, which

have been produced by the EU to support harmonized implementation of the WFD. These can be

found on the EU website. The purpose of the system of reporting is to evaluate policy performance

of the EU Member States. At present there is general consensus among international organizations

to apply the DPSIR cycle for the assessment of success of environmental policy. The EU-WFD has

accepted this approach as the basis for reporting (see ref. 1). The following definitions apply to

these indicators:

Driving Force indicator: driving force indicators are indicators, that characterize (quantitatively)

the development of anthropogenic activities with an impact on a defined water body. A typical

example is economic growth (eventually per sector: agriculture, transport, etc) or demographic

development.

Pressure indicator: pressure indicators are indicators, that characterize (quantitatively) the

pressure on a defined water body. Pressures are the direct effect of driving forces: the results of

human activities with adverse effects on the environmental quality of a defined water body. A typical

example is the load of toxic pollutants from point or non-point sources or fish catch.

State indicator: state indicators are indicators, that describe the ecological quality of a defined

water body at a specific moment. A typical example is the concentration of pollutants or the

biological characteristics of a specific ecosystem. A state indicator can be related to a "target value":

good ecological status or a water classification system.

Impact indicator: impact indicators are indicators, that characterize (quantitatively) the

environmental consequences of driving forces/pressures. These consequences are the change (loss)

of desired functions of a defined water body. A typical example is the deterioration of an ecosystem

by reducing biodiversity or the loss of water resources for drinking water production.

Response indicator: response indicators are indicators, that characterize the outcome of political,

managerial or economic human interventions to address the impact of pressures or to

improve/restore the environmental status of a defined water body: "the human feed back system".

A typical example is the implementation of an investment programme in waste water treatment

plants or the legal enforcement of best agricultural practices (BAP).

4.4. GEF and WFD compared

Although serving different purposes, there is a relationship between process indicators, stress

reduction indicators and environmental status indicators on the one hand, and the components D, P,

S, I, R in the WFD framework on the other hand.

Process indicators, relating to legislation, institution building etc., are in the present situation in the

Danube basin not real response indicators, in the sense of the DPSIR-cycle. Rather they are

indicators of progress in the pre-response phase. Building up institutions, inter-governmental

cooperation, legislation etc. are necessary pre-conditions for responding. In this sense the GEF-

page 16

project should help the Danube countries to use the WFD-system in the future, by assisting in the

development of different components.

Stress reduction, on the other hand, can be seen as a response in the meaning of the WFD cycle.

For environmental status indicators according to the GEF it seems, that there is no difference with

the status indicators according to the WFD.

In conclusion, there are possibilities for using indicators developed in the GEF-project also for WFD

reporting requirements. Therefore It is important to keep in mind that GEF related indicators should

be compatible with WFD indicators.

4.5. Indicator selection criteria and data and information

requirements

Selection criteria

The OECD (see ref. 5 and 13), UNEP (see ref. 6) and very recently EEA (see ref. 10) have published

criteria for selection of environmental indicators. The lists of these 3 international organizations

show more or less overlap. For the selection of indicators for M & E of the DRP and for reporting by

the ICPDR according WFD-EEA requirements, criteria have been derived from these lists by

combining different criteria from the lists and simplify them for the specific purposes of reporting on

the Danube basin.

For the selection of indicators, the following criteria have been applied:

1. Policy

relevant

Indicators must support policy development and decision making; there should be a relation

with policy priorities and policy objectives and targets as described in policy documents,

conventions, legislation and regulations.

2. Analytically sound and robust

Indicators must be scientifically and technically well founded and robust. They must be

representative, readily available and routinely collected. They must be consistent in space and

time: it must be possible to define a baseline. Data must be collected in Standard Operational

Procedures (SOP) within fixed reporting periods.

3. Communicative

powerful.

Indicators should be communicative powerful. Results have to be communicated in Annual

Reports, websites, press communications and during stakeholder consultations.

4. For process indicators: structural

In the GEF M & E indicator system, process indicators should be connectable to each other, for

instance in an input-output-outcome scheme.

Data and information requirements

Although the indicator systems to be developed will serve the GEF and WFD reporting purposes, it

would be highly preferable if selected indicators use the same data sets or other sources of

Indicators for Project Monitoiring and Impact Evaluation

page 17

information The indicators to be selected will need raw data sets and information, which has been or

will be collected by GEF-DRP and/or the ICDRP Secretariat. The ICPDR has set up, with help of

UNDP/GEF and other donors, an extensive system of data and information collection. Data is

collected in existing reporting procedures. Collecting data is costly, and the collection of new types

of data or information should be avoided, unless it appears, that data or information, critical for

monitoring and evaluating project results and/ or policy compliance by ICDRP members, is missing.

The ICPDR data base has 2 main sub databases: the TNMN database and the EMIS database. These

lists of variables are considered a long lists of variables, which are the basis for the selection of a

core list.

4.6. The problem of the baseline

The indicator system(s) will assess different types of changes: environmental quality, capacity for

waste water treatment, institutional settings, public awareness, biodiversity etc. These changes

need to be assessed in relation to the process of river basin management over time. Therefore, the

situation at the start of the process has to be defined: the baseline. According the GEF International

Waters Program (GEF-IWP) Indicators Steering Group, the definition of the baseline is the following:

"The situation that existed at the beginning of a Project, defined in terms of intergovernmental

institutional arrangements, human activities, which degrade the environment or environment

status."

This definition is related to the specific use of an indicator system for the assessment of the process.

It concerns indicators of the (change of the) institutional arrangements and human activities, which

degrade the environment. It does not include indicators on the (change of the) environment itself. A

number of questions has been considered:

1. Using this definition, is the baseline the situation in the basin at the start of the 1st GEF

Environmental Program for the Danube River Basin (EPDRB) in 1992 or at the beginning of

the present GEF-DRP? This limited interpretation would probably be enough for the GEF

Council.

2. Is it necessary to use a broader definition for the baseline, and to include the environmental

status of the basin at the beginning of the EPDRB or at the moment of signing the Danube

Protection Convention, or the establishment of the ICPRD Secretariat?

In the GEF reporting requirements, the establishment of the baseline is a clear issue. In the WFD

and the recent EEA report (see ref.2), there is no reference to any baseline.

Since the ICPDR has a reliable database on pressures, status and investments (responses) in the

Danube basin since 1996, 1996 is proposed as the baseline for both sets of GEF and EEA-WFD

indicators.

page 18

5. RESULTS

5.1. System of indicators for GEF M & E

5.1.1. Introduction

The proposed selection of categories of indicators and individual indicators for GEF M & E is

presented in this paragraph. The process indicators should have a direct relationship with the

objectives, outputs and outcomes, as presented in the Project Document of the DRP, in particular

with the Logical Framework Matrix (LFM). The stress reduction indicators consist of indicators

related to implementation of policies; this implies development, implementation and enforcement of

policy measures, such as new legislation and regulations, but also investments as a result of policy

implementation. According the GEF M & E definition, loads of pollutants are an environmental stress.

In the DPSIR cycle, loads of pollutants are pressures and policy enforcement and investments are

responses. In the GEF M & E system this distinction cannot be made. Therefore, loads are presented

here under stress reduction indicators. State indicators are clearly defined. The categories proposed

are based on the present structure of the TNMN database.

5.1.2. Categories of indicators

5.1.2.1. Process indicators

The basis for selection of process indicators is found in the DRP Project Document, in particular the

LFM. Ideally the system of process indicators should be part of the LFM of a project. For each

objective outputs, outcomes and the related quantifiable indicators should be formulated and

methods to measure progress and quality should be defined in advance.

In the LFM of the DRP, this is only partly done. In order to be able to apply a consistent set of

indicators, the structure of the project document and the LFM have to be consistent as a start. The

grouping of objectives and the formulation of outputs and outcomes in the Phase I and Phase II

documents and LFMs is not considered consistent. For example: the output 4.4 of Objective 4 would

logically fit better under Objective 2: capacity building etc. and output 2.2 has a strong relationship

with all outputs in Objective 4. Therefore the following rearrangement of outputs under 3 main

Objectives are proposed: see annex I.

1. Consolidation and operation of institutional mechanisms for cooperation under the ICPDR

2. Development of policy guidelines and legal and institutional instruments

3. Strengthening of public participation

5.1.2.2. Stress reduction indicators:

These indicators should measure the result of interventions by the Danube countries, that result in

improvement of the environmental conditions. These interventions are formulated in policy and legal

documents as the Danube River Protection Convention, the JAP, the Danube-Black Sea Task Force

(DABLAS) work programmes and other international and national legal documents and regulations.

Indicators for Project Monitoiring and Impact Evaluation

page 19

Such interventions should be followed by investments, which result in a reduction of pollutant loads

and/or recovery of the ecosystem. Any policy cannot succeed without stakeholder involvement and

sufficient public support. Therefore implementation of programmes for stakeholder involvement and

public awareness raising are considered to contribute to stress reduction. The following categories

are proposed:

1. Implementation and enforcement of regional and national legislation and regulations

2. Investments

3. Reduction of pollutant loads

4. Implementation of stakeholder involvement and public awareness raising programmes

5.1.2.3. State indicators:

The stress reduction interventions should result in improvement of the environmental conditions in

the Danube basin. The state indicators should reflect these conditions. The ICPDR is collecting a

vast amount of data on the Danube status. The categories proposed should be based on the

information collected at one hand; on the other hand the quality of the ecosystem has to be covered

as well. The following categories are therefore proposed:

1. Hydrology

2. Water quality

3. Ecological quality

4. Suspended solids/sediment quality

5.1.3. Individual indicators

5.1.3.1. Process indicators

The GEF has accepted a Result Based Management approach (RBM). This means that the emphasis

should lie on output and outcome indicators, as the overall performance of the process is measured

in these terms. Economy and efficiency are of course necessary, but are in RBM considered mainly

as an internal responsibility of the management of the process, with only limited reporting

requirements. The delivery of outputs as planned (timeliness, quantity etc.) is also the responsibility

of the management of the process, and it should explicitly be held accountable for this. Whether the

outputs will have the desired outcomes, is the joint responsibility of the management and the other

stakeholders. They should assess if the outputs in principle have the desired quality. Even when the

quality is high, the desired outcome can be absent, due to other factors as the political situation,

absence of funding etc.

Framework

The framework used for identification of output and outcome indicators is derived from the Value for

Money Analysis (VMA). One starts a production process with a budget. With the budget inputs are

bought, usually manpower and materials. With the inputs certain outputs are produced: products

and services or activities. The outputs lead to outcomes. In general that is a satisfied customer. In

page 20

this case the customer (the GEF Council) is satisfied when there are observable changes in

development conditions.

Process indicators are indicators, which measure the budget, inputs, outputs and outcomes, or the

relationships between them. The most important relationships are:

(a)

inputs/budget an indicator for the economy of the process;

(b)

outputs/inputs an indicator for the efficiency;

(c)

outcome/outputs an indicator for the effectiveness, or quality;

(d)

outcome/budget an indicator for the value for money; it is the product of the

aforementioned three indicators. Economy * efficiency * effectiveness = Value for

Money.

The framework is presented in box 5.1.

The Value for Money Framework

The Value for Money framework is often used as a help to analyze how a production process is going.

Take the example of the baking of bread. The baker starts with a Budget; next he buys flour, hire people

to work for him etc. - he buys Inputs. Activities undertaken with help of these inputs lead to Outputs:

bread, cake, cookies etc. Once sold this will lead to Value for Money for the customer, or customer

satisfaction, and to an income for the baker.

Suppose the baker isn't doing as well as he wants to do; then the question arises where he should focus

his attention to improve the situation. Is he, compared to the competition, lacking in Economy, Efficiency

or Effectiveness?

Outputs

Effectiveness

Efficiency

Quality

Outcomes

Inputs

Value for money

Economy

Budget

In the Result Based Management philosophy, the donor acts like a customer. The focus is on the

Outcomes of projects, and the donor compares the Value for Money he gets from different competing

projects. The idea is also that this will force the project management to watch carefully the three E's,

without direct overview in these respects by the donor.

Indicators for Project Monitoiring and Impact Evaluation

page 21

The tables in Annex I present the activities, the related outputs and outcomes and the individual

indicators proposed to measure progress and quality.

In Chapter 6 some examples of individual process indicators will be presented in detail with

proposals for measuring progress and quality.

In the 1st column of the tables in annex I, it can be indicated whether or not a specific activity has

been completed in Phase I. It is possible in principle to do the evaluation of these activities by using

the proposed indicators. For those activities that continue in Phase II, it is recommended to apply

the process indicators for both Phase I and II at the same time, considering Phase I and II as one

project.

5.1.3.2. Stress reduction indicators:

The individual stress reduction indicators, grouped according the 4 defined categories, can be found

in Annex II. This list is considered a long list from which a core list can be selected (see par 5.1.4).

5.1.3.3. State indicators:

The individual state indicators, grouped according the 4 defined categories, can be found in Annex

III. This list is considered a long list from which a core list can be selected (see par 5.1.4).

5.1.4. Recommendation for the selection of a core list of indicators for GEF M&E

Process indicators

Annex I presents the long lists for process indicators. In par 6.3 a methodology is presented for the

aggregation of individual indicators into one aggregated indicator. In principle, an aggregated

indicator for each of the 3 categories, presented in par. 5.1.2.1, which are directly related to the

objectives, outputs and outcomes of the DRP, as presented in the LFM, can be produced. Process

indicators serve the purpose of M & E for the GEF Council and are part of an internal reporting

process. For this purpose, the whole set is necessary and cannot be reduced to a core list. For the

purpose of external reporting, it is questionable, whether the results of process indicators should be

reported. Certainly aggregated indicators will not have strong external communicative power. The

results of a number of activities should be reported externally however. These could include for

instance the revision of protocols, the implementation of a small grants programme, the

development of the DANUBIS, the implementation of EU Directives and maybe others, to be decided

by the GEF team in consultation with the ICPDR Secretariat. This type of external reporting can be

done by a narrative in an annual report.

Recommendation 1: it is advised to distinguish internal and external reporting for process

indicators. For internal reporting 3 aggregated indicators are recommended; for external reporting

narrative reporting is advised for activities to be selected by the GEF Team/ICPDR Secretariat.

Stress reduction indicators

Annex II presents the long lists for stress reduction indicators. There are 22 stress reduction

indicators proposed. It is difficult to see how this number can be reduced for internal reporting. Each

of the indicators proposed has a direct relation with the assessment of compliance with the Danube

River Protection Convention and the JAP and DABLAS. For external use, a core list of indicators with

strong communicative power can be proposed.

page 22

Recommendation 2: the matrix in annex II presents the recommendation for a core list based on

the score for each of the criteria presented in par. 4.5

State indicators

Annex III presents the long lists for state indicators. In this Annex, the full list of the 52 TNMN

determinands for water and 22 for sediment should be presented. For reasons of convenience, the

TNMN determinands have been grouped in such a way that 18 state indicators are proposed. It is

difficult to see how this number can be reduced for internal reporting. Each of the indicators

proposed is agreed within the TNMN. For external use, a core list of indicators with strong

communicative power can be proposed.

Recommendation 3: the matrix in annex III presents the recommendation for a core list based on

the score for each of the criteria presented in par. 4.5.

5.2. System of indicators for WFD/ EEA

5.2.1. Introduction

The proposed selection of categories of indicators and individual indicators for WFD/EEA is presented

in this paragraph. The categories of indicators are presented on basis of the DPSIR cycle. The

driving force indicators consist of categories of indicators, that present the development in sectors of

the economy with pressure on the environment as a result. The pressure indicators present the

consequences of economic activities and human interventions on the river and its ecosystem. State

indicators are clearly defined. The categories proposed are based on the present structure of the

TNMN database. The impact indicators describe the change or loss of functions of the river and its

ecosystem. The response indicators are related to implementation of policies; this implies

development, implementation and enforcement of policy measures, such as new legislation and

regulations, but also investments as a result of policy implementation.

5.2.2. Categories of indicators

5.2.2.1. Driving Force indicators

These categories of indicators should reflect the development in activities in economical sectors,

which potentially result in pressures on the environment. OECD used to call driving forces: indirect

pressures. EEA did not report on driving force indicators in its latest indicator based assessment of

European waters (see ref. 2). Driving forces relate to production and consumption. Traditionally a lot

of statistical information is collected on these subjects, including indicators and indexes. There seem

to be enough possibilities for the DRP to use the existing information. The following categories have

been selected on basis of their direct effects on the environment:

1. Demographic developments

2. Industrial production

3. Agricultural production

4. Transport

Indicators for Project Monitoiring and Impact Evaluation

page 23

5. Energy production

6. Tourism

5.2.2.2. Pressure indicators

These indicators should reflect the environmental consequences for the Danube basin as the result

of economic activities and human interventions in the hydrology of the river. They result from the

use of the river for discharges, water abstraction, shipping, tourism, electricity production etc. The

following categories are proposed:

1. Physical interventions

2. Hazardous pollutant loads

3. Nutrient loads

4. Accidental spills

5. Use of natural resources

5.2.2.3. State indicators

The state indicators should reflect the environmental conditions in the Danube basin. The ICPDR is

collecting a vast amount of data on the Danube status. The categories proposed should be based on

the information collected at one hand; on the other hand the quality of the ecosystem has to be

covered as well. The following categories are the same as proposed for the GEF M & E indicators:

1. Hydrology

2. Water quality

3. Ecological quality

4. Suspended solids/sediment quality

5.2.2.4. Impact indicators

Impact indicators reflect the loss of functions and other damages to the river system. They usually

are the result of synergistic effects from different pressures. Impact indicators provide the real

signals on deterioration of the system, while state indicators should be regarded "intermediate"

indicators. A change of state does not necessarily mean that the ecosystem suffers an impact.

Impact indicators should also have a relation with the desired functions of the river system. The

following categories are proposed:

1. Loss of habitats

2. Loss of biodiversity

3. Loss of fisheries resources

4. Economical damages

5.2.2.5. Response indicators

These indicators should measure the result of interventions by the Danube countries, that result in

reversal of impacts and improvement of the environmental conditions. These interventions are

formulated in policy and legal documents as the Danube River Protection Convention, the JAP,

page 24

DABLAS and other international and national legal documents and regulations. Such interventions

should be followed by investments, which result in a reduction of pollutant loads and/or recovery of

the ecosystem. Any policy cannot succeed without stakeholder involvement and sufficient public

support. Therefore implementation of programmes for stakeholder involvement and public

awareness raising are considered to be responses.

The following categories are proposed:

1. Implementation and enforcement of regional and national legislation and regulations

2. Investments

3. Implementation of stakeholder involvement and public awareness raising programmes

5.2.3. Individual indicators

5.2.3.1. Driving Force indicators

The individual driving force indicators, grouped according the 6 defined categories, can be found in

Annex IV. This list is considered a long list from which a core list can be selected (see par 5.2.4).

5.2.3.2. Pressure indicators

The individual pressure indicators, grouped according the 5 defined categories, can be found in

Annex V. This list is considered a long list from which a core list can be selected (see par 5.2.4).

5.2.3.3. State indicators

The individual state indica tors, grouped according the 4 defined categories, can be found in Annex

III and are the same as for the GEF M & E.

5.2.3.4. Impact indicators

The individual impact indicators, grouped according the 4 defined categories, can be found in Annex

VI. This list is considered a long list from which a core list can be selected (see par 5.2.4).

5.2.3.5. Response indicators

The individual response reduction indicators, grouped according the 3 defined categories, can be

found in Annex II. The list for WFD/EEA is the same as for GEF M & E with the exception of loads,

which are defined as pressures under the DPSIR cycle (see annex V). This list is considered a long

list from which a core list can be selected (see par 5.2.4).

5.2.4. Recommendation for the selection of a core list of indicators for the ICPDR

Driving force indicators

Annex IV presents the long list of 19 driving force indicators. Such indicators relate to general

demographic and economic developments and are usually collected and reported by the

governments in the basin and the EU through Eurostat. There seems no need for the ICPDR to

Indicators for Project Monitoiring and Impact Evaluation

page 25

collect additional information. The long list can be used for internal purposes. For external reporting

a core list is recommended.

Recommendation 4: the matrix in annex IV presents the recommendation for a core list based on

the score for each of the criteria presented in par. 4.5

Pressure indicators

Annex V presents the long lists for pressure indicators. There are 12 pressure indicators proposed. It

is difficult to see how this number can be reduced for internal reporting. Each of the indicators

proposed has a direct relation with the assessment of compliance with the Danube River Protection

Convention and the JAP and DABLAS. For external use, a core list of indicators with strong

communicative power can be proposed.

Recommendation 5: the matrix in annex V presents the recommendation for a core list based on

the score for each of the criteria presented in par. 4.5

State indicators

For the recommendation for a core list of state indicators, see annex III and par. 5.1.4. under state

reduction indicators.

Impact indicators

Annex VI presents the long lists for impact indicators. There are 7 impact indicators proposed. It is

difficult to see how this number can be reduced for internal reporting. Each of the indicators

proposed has a direct relation with the assessment of compliance with the Danube River Protection

Convention and the JAP and DABLAS. For external use, a core list of indicators with strong

communicative power can be proposed.

Recommendation 6: the matrix in annex VI presents the recommendation for a core list based on

the score for each of the criteria presented in par. 4.5

Response indicators

For the recommendation for a core list of response indicators, see annex II and par. 5.1.4. under

stress reduction indicators.

page 26

6. PRESENTATION OF INDICATORS

6.1. Introduction

Selected indicators can be assessed and presented in many ways. In this chapter a number of

examples for assessment and presentation techniques will be presented. In par. 6.4 examples of a

process indicator, a stress reduction/response indicator, pressure indicators and state indicators will

be presented in detail. EEA is working on the application of many indicators which in principle could

be relevant for management in the Danube and the Black Sea. A list has been published of 240 of

such indicators. For many of these indicators "descriptive sheets" have been developed describing

the indicators and the method of assessment and presentation. The indicators have a code, referring

to the issue addressed, and a number. For a number of these EEA indicators, the code and the

number is given in annexes I-VI. The descriptive sheets can be found on the EEA website. However,

EEA is now considering to make a core list of 37 environmental indicators, only some of them for

water (see ref. 10). This list is expected to be published at the end of March 2004. It is not clear

yet, what will happen with the descriptive sheets.

The GEF-DRP and the GEF-BSERP are fully familiar with the well known techniques of assessment

and presentation of many indicators, in particular for pressures, state and impact. They are reported

in the TNMN Yearbooks and in the Black Sea Status and Trend reports. Usually these indicators are

presented by graphs, histograms, pies and maps. There is no need to present these techniques here

again. Other frequently used assessment and presentation techniques are the spider web

presentation, the kite diagram (see ref. 4) and the "mondriaan" (a matrix with colours indicating

scores). It is also possible to present different indicators in one graph, eg loads and concentrations

(see ref. 3).

Many good examples of presentation of indicators can be found in the report: Environmental

indicators in Latvia, 2002 (see ref. 3, and website: www.lva.gov.lv) from which a number of

presentations have been copied.

6.2. 6.2 Examples of individual indicators

6.2.1. 6.2.1 Driving force indicators

Two examples are presented from ref. 3: Water consumption in different sectors, 1991-2000, and

life stock patterns, 1990-2000.

Indicators for Project Monitoiring and Impact Evaluation

page 27

6.2.2.

Pressure indicators

One example is presented from ref. 3: Water abstraction, 1991-2000 and two examples from ref.

15: loads of inorganic nitrogen and phosphorous.

page 28

6.2.3. State indicators

Two examples are presented from ref. 3: Oxygen concentrations in the bottom layer of the Gulf of

Riga, 1973-2000, and mean yearly nitrogen concentration in the Daugava River (at Piedruja, border

with Belarus), 1994-2000

6.2.4. Impact indicators

One example is presented from ref. 3: Saprobiological quality of small rivers, 1998-2000

Indicators for Project Monitoiring and Impact Evaluation

page 29

6.2.5. Stress reduction/response indicators

Two examples are given from ref. 3: Number and area of certified biological farms in Latvia and

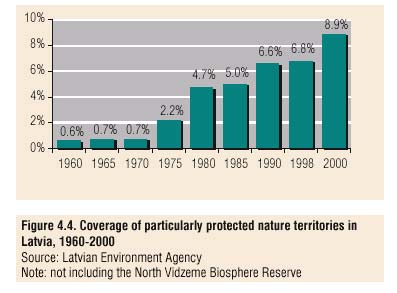

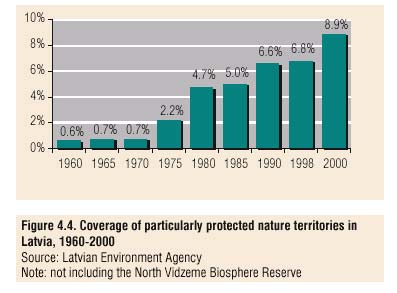

coverage of particularly protected nature territories in Latvia, 1960-2000.

6.2.6. Aggregated indicators: the kite diagram

An example of an aggregated indicator is found in ref. 14. The figure is copied from this article.

Proposals for aggregated indicators can only be developed after a decision on individual indicators

has been made. This example is on fishery, but similar presentations can be made for other sectors

like agriculture and tourism.

page 30

6.3. Clustering and aggregation of indicators

6.3.1. Introduction

Very often in a project there are so many, and so detailed, indicators available that there is the risk

of losing manageability, overview and clarity. In this case there is a need for simplification. This can

be done by selecting indicators, and by aggregating them. Selection is a common procedure; the

process of reducing the number of indicators in which the EEA is presently involved is a clear

example. The selection of a flagship species as a key indicator is also a well known procedure. The

indicators that finally found their place in this report are also the result of a selection process.

Aggregation of indicators seems to be less common. There are some exceptions: an index as the

saprobiotic index is well known; another example is an indicator as the Biological Oxygen Demand

(BOD) which in fact is the aggregate of a large number of (partly unknown) chains of reactions. One

of the reasons for reluctance to aggregate data seems to be the fear to land in a quagmire of

discussions about assigning weights to variables. However, as will be shown, a correct clustering and

aggregation procedure mainly bypasses the whole issue of weights.

In the social sciences, especially in economics, aggregation is a standard procedure (see ref. 18). No

one can handle for example an input-output model of the size 800*800. Aggregation of sectors till a

6*6 model is reached, or even a one-sector model, is the solution. Other examples of aggregated

quantities are index numbers, the representative firm or consumer, market segments etc.

The purpose of this note is to introduce some concepts and to show how aggregation can work. The

focus is on aggregation as a tool for achieving manageability and clarity, by organizing data in a

hierarchy. Its use thus is mainly one of helping to make management and policy decisions, and as a

tool for reporting.

Aggregation in this case is done ex post, after the data are collected. This means that the procedure

is principle harmless: one can always opt for another procedure if the aggregation doesn't meet its

objective.

6.3.2. Consistent aggregation and filtered consistency

In aggregation micro variables are aggregated by an aggregation function into macro variables. This

is usually done by first grouping or clustering micro variables, and next performing some operation

on these clusters (taking the mean for example) to construct one macro variable for the group. The

aggregation is, loosely defined, called totally consistent if all relations that hold for a set of micro

variables also hold for the corresponding set of macro variables (see ref. 19). The behavior of the

micro system can in that case be completely identified with the behavior of the macro system. A

simple example: if the reduction of emission of 2531 chemical substances is exactly the same, say

34,12% for all 2531, then the aggregation of those 2531 data into one indicator ("reduction of

emission is 34.12%") is totally consistent.

If the consistency is not total, aggregation means loss of information. Each aggregation has a loss

function; generally that aggregation scheme that minimizes the loss function is considered the

optimal scheme.

Total consistency is rare. For policy and management purposes it is also not a very useful concept.

The basic question here is if a decision reached on basis of the aggregated macro system is the

same as the decision based on using the micro system. If that is the case, the aggregation is

Indicators for Project Monitoiring and Impact Evaluation

page 31

partially consistent. More precisely, in this case the aggregation fulfills the conditions of filtered

consistency, where the decision acts like a filtering device.

In fact, taking a decision normally means that the decision maker inevitably will aggregate data,

although most of the time implicitly. The reason is that the decision space normally had far fewer

dimensions than the data space. Take, as an example, the decision whether a new wastewater

treatment plant should be built. On a policy level the decision space has only two dimensions: (1)

Where? and (2) How big? (with a choice for the coordinates {0,0} if the decision is not to build). On

a management level the decision space, about for example the design of the WWTP, will have more

dimensions (Which type?) but it is very unlikely that it will be of the same order as the data space.

For this reason decisions will be very often quite insensitive to the aggregation scheme, or in other

words, robust with respect to it.

6.3.3. An example of clustering and aggregation

To get the flavor of clustering and aggregation, consider the following simple example. Suppose that

in a project loads in a river are reduced. The management of the project wants to inform the

sponsors about the results; there are data about loads of six substances (A-F), during three years,

as summarized in Table 1 and Figure 1.

Table 1: Loads of six substances, in kton/yr

Substance Yr 2000 Yr 2001 Yr 2002

A 100

90

87

B

2000 1760 1700

C

150 138 126

D

50 40 35

E

20 13 19

F

200 156 72

Figure 1: Loads of six substances, in kton/yr

2500

A

2000

B

1500

C

1000

D

E

500

F

0

2000

2001

2002

page 32

The picture that emerges from these data as presented is not very clear; the only conclusion that

can be inferred seems to be "As can be seen in Figure 1, there is in all cases some reduction."

If we normalize the data, by setting the loads in the year 2000 on 100, the picture becomes slightly

more clear (see Figure 2, although we have to look careful.

Figure 2: Loads of six substances, in percentages relative to yr 2000

100

A

80

B

60

C

40

D

E

20

F

0

2001

2002

The conclusion could be: "As can be seen in Figure 2, the loads are reduced till around 80% of the

level of 2000."

However, the moment we express a reduction as an average number we run the risk of getting

swamped in a quagmire of discussions about weights: how should we weight in 2002 a reduction of

1 kton, or 5%, of substance F, to a reduction of 300 kton, or 15% of substance B? Usually there are

as many opinions as participants in the discussion that ends also usually without any clear

conclusion.

Clustering of the data can help us to get around that quagmire.

As a first step, in Table 2 and Figure 3 the data for reduction are presented.

Table 2: Reduction of loads in per units, base year 2000

Substance

Yr 2001

Yr 2002

A 0.10

0.12

B 0.12

0.15

C 0.08

0.18

D 0.20

0.30

E 0.05

0.35

F

0.22

0.28

Indicators for Project Monitoiring and Impact Evaluation

page 33

Figure 3: Relative reduction of loads for six substances, base year 2000

0.4

A

0.3

B

C

0.2

D

0.1

E

F

0

2000

2001

2002

2003

In this case, a simple visual inspection (see Figure 1) leads to the identification of three groups or

clusters: (1) ABC (2) DF and (3) E. The loss of information if we take averages within the clusters

will be small. Note that the question whether we should take some kind of weighted average is not

very relevant, as the differences within the clusters are quite small. Once clustered, we end up with

Figure 4:

Figure 4: Relative reduction of loads for clusters of substances, base year 2000

0.4

G1 (n=3)

0.3

G2 (n=2)

G3 (n=1)

0.2

0.1

0

2000

2001

2002

2003

Now a clear conclusion can be drawn: "As can be seen in Figure 4, the reduction of the loads is in

most cases in the order of 20%, with a rising trend, with the exception of cluster 3, consisting of the

substance E."

Some policy and management questions now can be answered ("Are the results of the project

satisfactory? Should we do more?"), and other questions can be formulated ("Why is substance E

behaving different from the rest? What's the reason of the difference between cluster ABC and

cluster DF? Where should we concentrate efforts?" Questions, which perhaps can be answered by

going back to the basic data.

6.3.4. The technique of clustering

In the example above, we arrived at three clusters by visual inspection of a scatter diagram. The

case is quite simple: six variables, two dates, one dimension (the relative reduction). In practice

cases will be complicated, involving for example several hundred variables, ten years, and several

page 34

dimensions (add for example quantity and harmfulness as dimensions to take into consideration as

clustering criteria). In such cases it is of course necessary to us a computer program.

A clustering computer program is usually based on a hierarchical clustering procedure. Clusters are

formed stepwise, beginning with pairs of cases that are near to each other, using in general a

squared distance criterion. Next other cases are added. As clusters grow, the loss of information will

become bigger. In Figure 5 this procedure is illustrated with a clustering tree for the example

presented above, using the program ClustanGraphics (see ref. 20).

Figure 5: Clustering tree for reduction of loads for six substances (A-F)

On the vertical axis the substances A-F are shown; going to the right the way they are clustered can

be seen. First A/B and D/F are clustered, next C is added to the cluster AB, etc. The criterion for the

ordering of the steps is minimization of loss of information as a consequence of the formation of the

cluster. That loss is based in this case on the sum of the squared distances of the members of a

cluster to the mean of that cluster. The loss of information is shown horizontally. As can be seen

the formation of first the first two clustering steps (AB and DF), and the second clustering, the

addition of C to AB, barely lead to a loss of information. In the next step - the clustering of ABC and

DF to ABCDF -the loss of information would increase hugely, so it seems wise to stop with three

clusters; ABC, DF and E; for this reason they are shaded blue, while the not performed clustering is

shaded yellow.

6.3.5. Aggregating process indicators

In this report three groups of process indicators are distinguished: (1) Institutional (2) Policy and

(3) Public Participation indicators. As there are at present no data available, it is of course

completely unclear if the indicators will show a cluster like behavior that will conform to this

grouping. One should simply try and see. The only precondition is a normalization of the indicators,

for example on a scale of 0-5 (see also Annex VIII).

Indicators for Project Monitoiring and Impact Evaluation

page 35

6.4. Detailed presentation of selected indicators

6.4.1. Process indicator: assessment of involvement

In annex VII a detailed methodology for the assessment of stakeholder involvement is presented. It

is presented here as a process indicator, which is used in the context of project performance

assessment. However, assessment of stakeholder involvement is equally relevant as a stress

reduction/response indicator in the context of policy development and implementation.

6.4.2. Stress reduction/response indicator: introduction of BAP and

implementation of Nitrate Directive

In annex VIII a detailed methodology for the assessment of a stress reduction/response indicator is

presented, using the implementation of the EU Nitrate Directive as an example. EEA has presented a

methodology in a descriptive sheet: AGRI17 (annex XI). The methodology is based on the structure

of the Directive and the descriptive sheet AGRI17 with some adaptations.

6.4.3. State indicators: trend analysis of concentrations for 1996-2000 for

ammonium and nitrate at 5 stations in the Danube basin

Statistical trend analysis for concentrations result in a quantified assessment of the trends in a state

indicator, eg the concentration of a specific pollutant, over a defined period of time at a specific

location. There are several software packages which in principle are suitable to be used. A number

of examples is presented here, calculated with SPSS. In this procedure data are checked for

seasonal patterns and outliers, and linear regression is calculated. The software calculates on basis

of these fits the probability of trends and gives a value for the significance. Results are presented

for ammonium and nitrate.

As can be seen from Table 3 there is a strong decline of measured ammonium

concentrations for all locations, except L0430-L, with reductions up till 78% in five

years.