UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

Policies for the Control of Agricultural Point

and Non-point Sources of Pollution

&

Pilot Projects on Agricultural Pollution Reduction

(Project Outputs 1.2 and 1.3)

Inventory of Agricultural Pesticide Use

in the

Danube River Basin Countries

February 2004

Final Report

GFA Terra Systems

in co-operation with Avalon

Your contact person

with GFA Terra Systems is

Dr. Heinz-Wilhelm Strubenhoff

Danube Regional Project - Project RER/01/G32

"Policies for the control of agricultural point and non-point sources of pollution"

and "Pilot project on agricultural pollution reduction"

(Project Outputs 1.2 and 1.3)

Inventory of Agricultural Pesticide Use in the Danube River Basin Countries

Address

GFA Terra Systems GmbH

Eulenkrugstraße 82

22359 Hamburg

Germany

Telephone: 00-49-40-60306-170

Telefax: 00-49-40-60306-179

E-mail: hwstrubenhoff@gfa-terra.de

Inventory of Agricultural Pesticide Use in the Danube River Basin Countries

1

2

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

Preface

The UNDP-GEF Danube Regional Project supports through this Project Component the development of

policies for the control of agricultural point and non-point sources of pollution and the conceptualization

and implementation of pilot projects on agricultural pollution reduction in line with the requirements of

the EU Water Framework Directive.

The Overall Objective of the Danube Regional Project is to complement the activities of the ICPDR

required to strengthen a regional approach for solving transboundary problems in water management and

pollution reduction. This includes the development of policies and legal and institutional instruments for

the agricultural sector to assure reduction of nutrients and harmful substances with particular attention to

the use of fertilizers and pesticides.

Following the mandate of the Project Document,

Objective 1 stipulates the "Creation of Sustainable Ecological Conditions for Land Use and

Water Management" and under

Output 1.2, "Reduction of nutrients and other harmful substances from agricultural point and

non-point sources of pollution through agricultural policy changes",

Activity: 1.2-3 requires to "Review inventory on important agrochemicals (nutrients, etc) in

terms of quantities of utilization, their misuse in application, their environmental impacts and

potential for reduction"

The present document "Inventory of Agricultural Pesticide Use in the DRB" responds to this mandate in

providing an analysis on the present use of pesticides, the existing mechanisms of regulation and control

and proposed measures for policy reforms and their practical application in line with the requirements of

the EU Directives and regulations.

The result of this study on the use of pesticides constitutes an essential contribution for the Summary

Report on "Policies for the Control of Water Pollution by Agriculture in the Central and Lower Danube

River Basin Countries" containing also the findings on the use of fertilizers as well as on the

introduction of Best Agricultural Practices in the Danube River Basin countries

The findings and analysis in the present report have been prepared by the principal authors Lars

Neumeister and Dr Mark Redman, supported by contributions from the following national experts:

Bosnia & Herzegovina

Prof. Dr Hamid Custovic

(including Republica Srpska)

Dr. Mihajlo Markovic

Bulgaria

Association for Integrated Rural Development

Croatia

Dr Milan Mesic with Prof. Dr. Jasminka Igrc-Barci

Czech Republic

Milena Forejtnikova

Hungary

György Mészáros

Moldova

Alexandru Prisacari

Romania

Dr. Cristian Kleps

Serbia and Montenegro

Prof. Dr. Zorica Vasiljevic

Dr. Vlade Zaric

Slovakia

Dr. Radoslav Bujnovsky

Slovenia

Marina Pintar

Ukraine

Natalia Pogozheva

Inventory of Agricultural Pesticide Use in the Danube River Basin Countries

3

Table of Contents

List of tables

List of figures

Acronyms and abbreviations

Country codes used

Executive

Summary

8

1 Introduction

18

2 Methodology

23

3

Availability Of Data on Pesticide Usage

24

3.1

Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO)

24

3.2 European

Union

24

3.3

Selected DRB countries

25

4

Pesticide usage in the 11 Danube countries

27

5

Problems associated with pesticide use in the drb

31

5.1

Bad Practice by Farmers

31

5.2

Environmental Impact of Pesticide Use

31

6

Potential Policy Reform for Pesticide Pollution Control

37

6.1

Potential for Policy Reform in EU Context

39

6.2

Potential Policy Reform in Wider DRB Context

45

7

Potential Practical Action for Pesticide Pollution Control

48

8

Recommendations for Further Action

54

4

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

Annexes

Annex 1

Chemical Fact Sheets

Annex 2

Pesticide Usage in Bosnia and Herzegovina

Annex 3

Pesticide Usage in Bulgaria

Annex 4

Pesticide Usage in Croatia

Annex 5

Pesticide Usage in the Czech Republic

Annex 6

Pesticide Usage in Hungary

Annex 7

Pesticide Usage in Moldova

Annex 8

Pesticide Usage in Romania

Annex 9

Pesticide Usage in Serbia & Montenegro

Annex 10 Pesticide Usage in Slovakia

Annex 11 Pesticide Usage in Slovenia

Annex 12 Pesticide Usage in the Ukraine

Annex 13 Example of Good Plant Protection Practice for Wheat

Inventory of Agricultural Pesticide Use in the Danube River Basin Countries

5

List of Tables

Table 1:

List of National Experts

2

Table 2

Priority Pesticides in the Danube Region

20

Table 3

Authorisation Status of Danube Priority Pesticides in the 11 Danube

Countries 22

Table 4

Overview of Agricultural Pesticide Use Tracking Systems in the 15 EU

Member States

25

Table 5

Areas of National Territories in the Danube Basin

27

Table 6

Overall Pesticide Consumption in Danube Countries (tonnes)

28

Table 7

Usage of Priority Pesticides in 8 Danube Countries 2001-2002 (tonnes

active ingredients, except Slovenia tonnes formulated product)

29

Table 8

Environmental and Human Toxicty of Selected Priority Pesticides

36

Table 9

Instruments Aiming at the Control of Pollution by Pesticides

38

Table 10

Legislation addressing pesticides in the European Union (without

legislation regarding food safety)

39

Table 11

Mandatory requirements relating to pesticides in the EUREP-GAP Fresh

Produce Protocol

44

List of Figures

Summary Figure 1 Pesticide Consumption in CEE countries and the EU15

8

Figure 1

Pesticide Consumption in CEE countries and the EU15

19

Figure 2

Environmental Fate of Pesticides

32

Figure 3

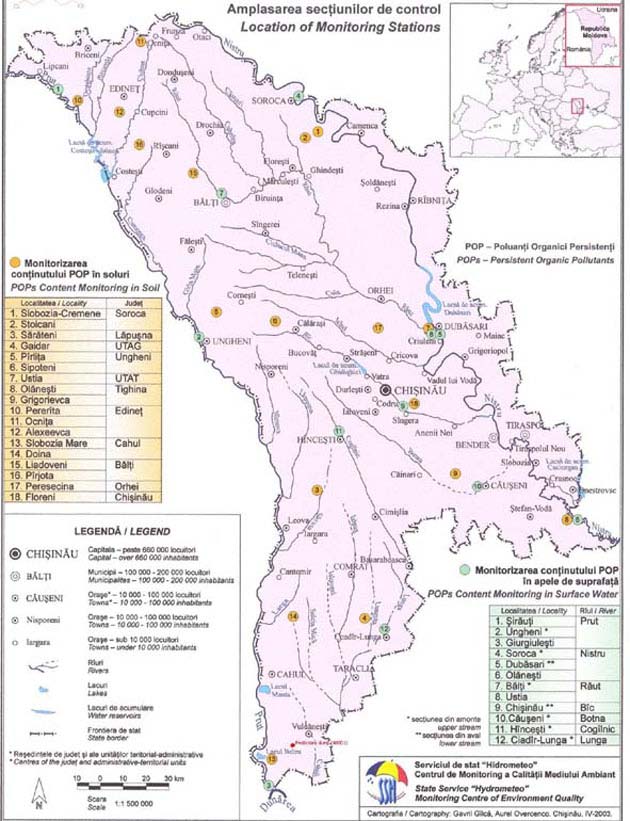

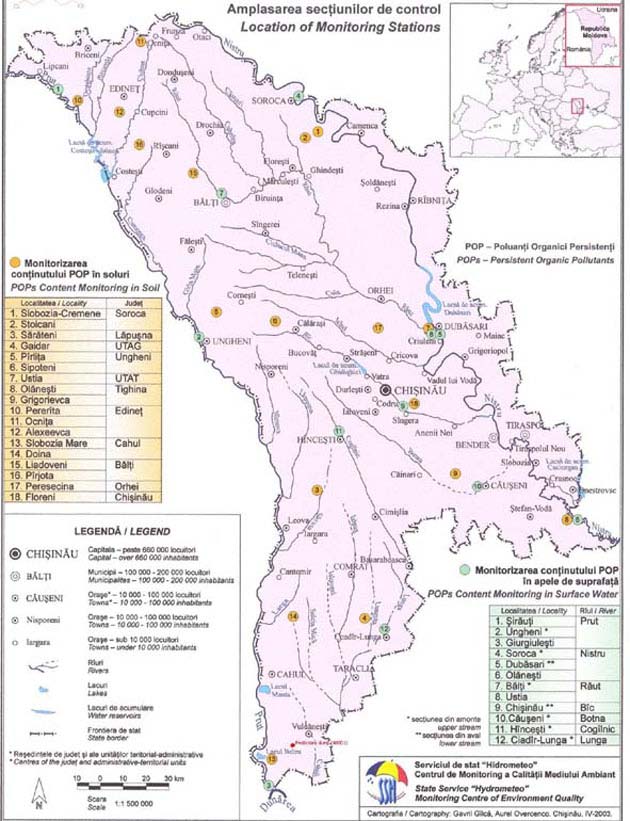

Moldova: Map of Soils Contaminated with POPs Pesticides (Provided by:

Andrei Isac, Ministry of Ecology Construction and Technical

Development) 34

Figure 4

General Exposure Assessment Model based Upon Pesticide Usage Data

35

6

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

Acronyms & Abbreviations

ai

active ingredient

BAP

Best Agricultural Practise

BPP

Best Plant Protection Practice

CAP

Common Agricultural Policy

DRB

Danube River Basin

DRP

Danube Regional Project

EAP

Environmental Action Programme

EC

European Commission

ECPA

European Crop Protection Association

EPPO

European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organisation

EU

European Union

FAO

Food and Agriculture Organisation

GPPP

Good Plant Protection Practice

ICM

Integrated Crop Management

IPM

Integrated Pest Management

PAN

Pesticide Action Network

PIC

Prior Informed Consent

POP

Persistent Organic Pollutant

PUR

Pesticide Use Reporting

WB

World Bank

WFD

Water Framework Directive

Country Codes Used

BG Bulgaria

BH

Bosnia and Herzegovina consisting of 2 entities:

FedBH Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina

RS Republic of Srpska

CZ Czech

Republic

HR Croatia

HU Hungary

MD Moldova

RO Romania

SK Slovakia

SL Slovenia

UA Ukraine

YU

Serbia and Montenegro

(previously the Former Republic of Yugoslavia)

Inventory of Agricultural Pesticide Use in the Danube River Basin Countries

7

8

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

E x e c u t i v e S u m m a r y

1. Overview

The use of pesticides has declined significantly in the countries of Central and Eastern Europe (CEE)

since the political changes and sector reforms of the early 1990s disrupted the process of

modernisation, specialisation and intensification of agricultural production that was characteristic of

the centrally-planned economies in the region.

Reliable data on pesticide use in the CEE region are not available for the decades leading up to 1990.

However, data from the FAOSTAT database show a strong decline in pesticide use in the CEE

countries to about 40% of 1989 levels compared to a relatively small decrease in EU Member States

during the same period (Figure 1).

There are indications, however, that the use of pesticides in the CEE region is increasing again with

concerns especially that enlargement of the EU will further a trend towards the renewed intensification

of crop production, particularly in the more productive regions of central Europe.

At the same time, there are many factors including the risk of water pollution and the impact upon

aquatic ecosystems that are forcing much of European agriculture to rethink the use of pesticides, as

well as many opportunities to promote new management approaches to pesticide use by farmers and

policy-makers.

Summary Figure 1: Pesticide Consumption in CEE countries and the EU151

3 .0

2 .5

2 .0

1 .5

kg/ha

1 .0

0 .5

0 .0

1 9 8 9

1 9 9 0

1 9 9 1

1 9 9 2

1 9 9 3

1 9 9 4

1 9 9 5

1 9 9 6

1 9 9 7

E U 1 5

A C 1 0

Source: Data from the FAOSTAT database of the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation

2. Analysis of Priority Pesticides used in 11 DRB countries

The approach taken has been to focus upon so-called priority pesticides for the DRB. Studies of the

water quality of the Danube River have found a number of polluting substances that regularly occur in

the aquatic environment of the river. Some of these substances are of special concern for

environmental and/or human health reasons and a list of "priority chemicals for the Danube River" has

been prepared. According to Article 7 of the Danube River Protection Convention, which regulates

1 The graph expresses mean consumption of pesticides (active ingredients classed as insecticides, herbicides,

fungicides and others) per unit area of agricultural land.

Inventory of Agricultural Pesticide Use in the Danube River Basin Countries

9

emission limitations and water quality objectives and criteria, the discharge of hazardous substances

from point and non-point sources shall be prevented or considerably reduced.

Annex II defines such hazardous substances and lists under Part 2 A (d) plant protection agents,

pesticides and chemicals used for the preservation of wood, cellulose, paper, hides and textiles etc.

Part 2 B of Annex II lists 40 single hazardous substances. In 2001, substances listed in Annex X of

the European Water Framework Directive 2000/60/EEC were taken into account in revising the

ICPDR list of priority substances. Altogether, the new list contains 41 single substances, thereof 25

chemicals which are used as pesticide active ingredients, and 5 chemicals which are used as inert

ingredients.2

In the Danube River Basin 29 priority chemicals used in pesticide products and their regulatory status

globally and in the European Union have been analyzed. Most substances, except for the inorganic

compounds, are already regulated by international conventions or the European Union including:

· POPs Convention - aims at the elimination or restriction of persistent organic pollutants (POPs),

· EU Water Framework Directive No. 2000/60 - requires that measurements of dangerous priority

substances aim at the phasing-out of these substances within 20 years after the adoption of

measurements,

· EU Authorisation under Directives No. 91/414 and 79/117- only 2 of the Danube priority

pesticides are fully registered in the European Union and listed in Annex I of Council Directive

91/414/EC. For three of the priority pesticides, registration will expire or has already expired and

seven are still in the re-authorisation process. According to Directive 79/117, use of two of the

priority pesticides is banned in the EU.

3. Regulation of Priority Pesticides

The analysis has shown that out of 25 pesticides only three priority pesticides are authorised for use in

all of the DRB countries under study, while seven priority pesticides are not authorised in any of the

countries. There are evidently also differences between the countries.

The Republic of Srpska authorised 15, Romania, Serbia & Montenegro and Slovakia 14 priority

pesticides, while Bulgaria and Moldova authorised eight priority pesticides and the Ukraine only six.

In some countries, there are certain restrictions on specific pesticide products. For example, in

Croatia, it is not allowed to apply Alachlor with a knapsack sprayer or a hand sprayer. It is also not

allowed to use Alachlor on light soils after the maize has emerged. Use of Atrazine is limited to

1.5 kg ai/ha in humid and 1 kg ai/ha in arid areas. Endosulfan cannot be used in oil-seed rape and

forestry. Use of Simazine is permitted only in maize monoculture. TrifIuralin use is not permitted in

post-harvest sown soya bean and sunflower.

4. Use of Priority Pesticides

It has to be stated that there is little information available about the details of the distribution and use

patterns of Priority Pesticides in the DRB countries. From the 11 countries under study, only three

countries maintain pesticide use/sales tracking systems based upon retail sales:

· Hungary - collects sales data from wholesalers and local distributors twice a year. They have to

submit data on the sales in kg as well as on the monetary amounts of individual formulated

pesticide products. Sales data are publicly available in an aggregated format.

2 `Inert' ingredient: These are substances which can enhance the efficiency of the active substance, make a

product more degradable or easier to use.

10

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

· Czech Republic - all professional pesticide users have to keep spray records for 3 years. Farms

larger than 10 ha are required to submit summaries to the Department of Information. Farmers

report on amounts applied by formulated product, crop and geographical region. Usage data are

publicly available by crop and amount of active ingredient. Data on pest and disease infestations

are also published. Pesticide sales data are also collected by the Czech Crop Protection

Association.

· Slovakia - started a pesticide sales reporting system in 1999. All traders are required to report

sales data annually: manufacturer, importer, distributors and retailers. They are required to report

the name and amount of formulated products for agricultural and non-agricultural pesticides. Sales

data are publicly available by amounts of active ingredient, chemical class, use type and by postal

code3. All farmers have to keep detailed records of their pesticide use and are required to submit

summaries to the Central Control and Testing Institute of Agriculture.

National data was analyzed for 8 countries showing that the reported total use of priority pesticides is

highest in Hungary and the Czech Republic - which is probably due to the fact that these two countries

have comprehensive pesticide use tracking systems. In Hungary, the reported use is 10 times higher

than in the Czech Republic, with copper as the most widely used pesticide. This is probably due to the

fact that Hungary cultivates approximately 99,000 hectares of vineyards plus a large area with fruits

and vegetables, while the Czech Republic cultivates only approximately 11,000 ha of grapes. Copper

is globally used in large amounts in vineyards and orchards to control fungus and is approved as a

pesticide in organic agriculture according to EU regulations.

As part of the inventory, data was also collected on the main crops that pesticides are applied to. As

might be expected, it is clear from this data that a high percentage of crops in the DRB countries do

not receive any pesticide applications at all. The findings can be summarized as following:

a) The priority pesticides are high-use pesticides, accounting for over 20% of total pesticide use in

some countries;

b) The use of priority pesticides is associated with specific crops:

· Atrazine is mostly used in maize;

· Alachor is used in maize, rape seed and sunflower;

· copper compounds in vineyards, orchards and in vegetables, including potatoes;

· 2,4-D is mostly used in cereals;

· the insecticides Chlorpyrifos, Malathion and Endosulfan are used in orchards, vineyards, rape

seed, alfalfa and vegetables.

c) The intensity of use in treated areas can be higher than the one commonly found in western

European countries.

Since many soils in the Danube catchment area, particular those closer to the river, are very good for

intensified crop production, it seems likely that these observations at a national level are all directly

relevant to the DRB catchment and that pesticide use on cultivated soils in the catchment will most

likely be higher than national averages reported.

5. Problems Associated with Pesticide Use

Although pesticide use is currently relatively low in the DRB countries (compared, for example, to the

EU Member States), it is important not to be complacent about the risks of pesticide pollution since:

1. Priority pesticides, as well as other pesticides, are frequently detected in surface and ground water

in the DRB catchment area and pose a serious hazard to the environment and human health.

3 Communication with Martin Hajas (Central Control and Testing Institute of Agriculture) and Jozef Kotleba

(Ministry of Agriculture).

Inventory of Agricultural Pesticide Use in the Danube River Basin Countries

11

2. Seven priority pesticides are not authorised in the Danube countries, some of them continue to be

hazardous due to old stockpiles and residues in soils and sediments.

3. The uncontrolled and illegal trade of pesticide products leading to the use of banned pesticides

(e.g. DDT) by farmers is reported as a problem in many countries although this is a sensitive

issue that is difficult to verify. There is particular concern that certain countries lacking an

effective pesticide control system (e.g. Ukraine) are gaining a reputation as a "dumping market"

for obsolete and illegal products.

4. There are reports of high pesticide use in certain areas and on certain high value crops - this

includes priority pesticides that pose a serious hazard to the environment and human health. In

particular, the priority pesticides 2,4-D, Alachlor, Trifluralin, Atrazine and copper compounds are

high use pesticides in most of the DRB countries. They are mostly used on cereals, rapeseed,

sunflower and maize, and in orchards and vineyards.

5. Poor storage of pesticides, including old pesticide stores, continues to be a problem in many

countries. In the Ukraine, there are some 20,000 tons of obsolete pesticides still in storage often

under bad conditions and posing a serious threat to human health and the environment (e.g.

infiltration into groundwater). In Bulgaria, 35% of the pesticide storehouses are reported to be in

bad condition. In Moldova, some 6,000 tonnes of obsolete pesticides are reported to be in storage

on former State and Collective farms, including single stores containing up to 4 tonnes. Several

countries maintain databases containing the location, amounts and storage conditions of the

pesticides, including the use of GIS-based maps in Moldova and the Ukraine.

6. Whenever farmers apply pesticides, there are many examples of "bad practice" that contribute to

the risk of pesticide pollution. Those most commonly reported by the national experts were:

· Use of pesticides in excess of recommended rates in particular, the over-application of

maize with the herbicide Atrazine (up to 2-3 times the recommended rate) is consistently

reported as a serious problem in the DRB countries. In many cases, over-application is due to

lack of knowledge/training and the tendency to apply larger amounts in the belief that this will

increase the effectiveness of the pesticide products a tendency that is made worse now by the

increasing occurrence of weed resistance to Atrazine. The overuse of Atrazine is arguably one

of the most significant pesticide problems in the DRB and accentuated in countries where

large areas of maize are grown and/or most of the maize is routinely treated with Atrazine

for example, in Croatia it is estimated that 87-100% of the 324,000 ha of maize grown is

treated with Atrazine.

· The unauthorised use of pesticides on crops they are not registered for (e.g. use of

Lindane on vegetables) is reported to be a common problem in most countries.

· The cleaning of spraying equipment and disposal of unused pesticide, pesticide

containers and "spray tank washings" nearby to (or even in!) water courses such as rivers

and ponds.

· The drift of pesticide spray to adjacent areas due to the old spraying equipment used (most

spraying equipment used in the DRB region is now more than 15 years old), plus poor

knowledge and lack of operator training (e.g. spraying in windy conditions).

· Lack of knowledge of and/or compliance with obligatory "buffer zones" for surface

waters and other protected areas.

· The poor timing of pesticide application due to poor knowledge and lack of operator

training leads to inefficient application and increased risk of pollution.

12

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

6. Potential for Pollution Control

The current low use of agricultural pesticides in the countries of the DRB presents a unique

opportunity to develop and promote more sustainable agricultural systems before farmers become

dependent again upon the use of agro-chemical inputs.

However, pesticide use is always related to agricultural policy. Farmers grow those crops which are

economically most viable - if agricultural policy, for example, supports subsidy schemes and market

policies for a small number of crops, the range of crops grown by farmers will be limited, crop

rotations be simple or non-existent and, consequently, pesticide use will increase.

There is, for example, concern that with EU enlargement and the expansion of the Common

Agricultural Policy (CAP) into the DRB countries joining the EU there is a risk of increasing pesticide

use due to:

· increasing areas cultivated with cereals and oilseeds due to the availability of EU direct

payments for farmers growing these crops in the new Member States;

· increased intensification of crop production, including the greater use of mineral fertilisers and

pesticides, particularly in the more favourable areas with better growing conditions;

· a reduction in mixed cropping and an increase in large-scale cereal monocultures in some

areas which are dependent upon agro-chemicals for crop protection.

There are numerous policy instruments that can be used to control pesticide pollution such as:

· Use reduction (ICM and IMP standards),

· Advice and compulsory training,

· Performance standards (cut-off criteria, eco-audit),

· Design standards,

· Permits (also transferable permits),

· Taxes and subsidies,

· Crop insurance

These control instruments provide a framework that can be elaborated and filled with more detailed

measures. However, the selection of the most appropriate policy instruments for the DRB countries

will depend upon the establishment of a clear policy strategy for controlling pesticide pollution,

together with clear policy objectives.

According to the aims of the Danube Protection Convention, the risk of pollution should be stopped at

its source with regard to pesticide use this is generally assumed to mean4:

a) withdrawing

approval

for the use of those pesticides that pose the greatest threats to public

health and the environment;

a) reducing the use of those pesticides that remained approved for use;

b) improving the management by farmers of those pesticides that remain approved for use.

This can be achieved through a combination of necessary policy reforms and the promotion of

appropriate practical action by farmers. However, the potential to achieve these outcomes varies

greatly between countries in the DRB and is above all related to the fact whether a country is currently

preparing for EU accession or not.

This review of pesticide use is undertaken during a period of great change in the Danube River Basin

(DRB) with Hungary, Czech Republic, Slovakia and Slovenia being in the final stages of preparation

for accession to the EU in 2004, followed by Bulgaria and Romania preparing for EU accession in

2007 or later.

4 OECD (1995). Sustainable Agriculture: Concepts, Issues and Policies in OECD Countries. Organisation for

Economic Co-operation and Development, Paris.

Inventory of Agricultural Pesticide Use in the Danube River Basin Countries

13

The policy-making context for agricultural pollution control in the DRB is therefore undergoing

significant change and preparation for joining the EU is currently a major driving force for the reform

of agricultural pollution control policies in the six mentioned countries.

In the European Union, there are several Directives addressing the regulation of pesticides, including:

· Directive 79/117EC on the prohibition of pesticides;

· Directive 80/68/EEC on the protection of groundwater against pollution caused by certain

dangerous substances (the Groundwater Directive);

· Directive 80/778/EEC on the quality of water intended for human consumption (the Drinking

Water Directive) to be replaced by Directive 98/83/EC from 2003;

· Directive 91/414/EEC concerning the placing of plant protection products on the market;

· Directive 2000/60/EC establishing a framework for Community action in the field of water

policy (the Water Framework Directive).

The Directive with the highest potential for the control of water pollution by pesticides is the Water

Framework Directive 2000/60/EC (WFD). Similar to the previous Dangerous Substances Directive

(76/464EC), which was repealed by the WFD, pollution control is based upon chemical lists. The list

of main pollutants consists of chemical classes and use types, therefore it includes priority substances

and priority hazardous substances per se.

The EU Rural Development Regulation 1257/1999 (the "second pillar" of the CAP) makes provision

for Member States to encourage more environmentally-friendly farming methods, including practices

and actions that reduce the risk of agricultural pollution.

This offers an opportunity for supporting the control of pesticide reduction in those DRB countries

preparing to join the EU, by allowing them to develop EU co-financed schemes that:

a) offer grant-aided investment (up to 50%) in agricultural holdings;

b) provide training in organic farming or integrated crop management practices as well as training for

farming management practices with a specific environmental protection objective;

c) introduce agri-environment schemes that offer area payments to support the adoption of organic

farming and ICM in orchard, vine and vegetable production, the creation of uncultivated buffer

strips, conversion of arable to pasture land and the introduction of more diverse crop rotations.

Another useful tool will be the "verifiable standards of Good Farming Practice (GFP)" that all farmers

receiving payments from agri-environment and less-favoured area schemes funded by the Rural

Development Regulation - the so-called CAP `Second Pillar' - must comply with across the whole of

their farm5.

Good Farming Practice (GFP) is a relatively new concept to emerge within the EU and its practical

implementation is still being tested in many Member States. Obviously, the interpretation of what

constitutes a "reasonable" standard of farming will vary from country to country; however, it is

generally assumed that it will consistently involve farmers following relevant existing environmental

legislation, and not deliberately damaging or destroying environmental assets, including the pollution

of watercourses.

GFP is likely to become an even more important element of agricultural policy in future and is very

relevant to promoting the better use of pesticide use by farmers, especially on those areas of the farm

that are not suitable for agri-environment payments and continue to be farmed relatively intensively.

5 Section 9 of EC Regulation No. 1750/1999, which sets out the rules for several measures including agri-

environment, states that: "Usual good farming practice is the standard of farming which a reasonable

farmer would follow in the region concerned.....Member states shall set out verifiable standards in their rural

development plans. In any case, these standards shall entail compliance with general mandatory

environmental requirements."

14

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

While the four DRB countries (Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary and Slovenia) joining the EU in

2004 will shortly have the possibility to utilize the opportunities outlined above, the two remaining

DRB countries of Romanian and Bulgaria are unlikely to join the EU before 2007. However, financial

assistance is also available for these countries for developing and implementing similar measures with

SAPARD co-funding - the special Pre-accession Programme for agricultural and rural development.

Similarly, Croatia, Bosnia & Herzegovina and Serbia & Montenegro may use funding from the EU

CARDS programme that supports implementation of measures in line with the requirements of the EU

WFD.

Inventory of Agricultural Pesticide Use in the Danube River Basin Countries

15

7. Recommendations for Policy Reform

The national governments of all DRB countries should aim to effectively control pesticide pollution in

order to minimise the risks presented to human health, the quality of environmental resources, and the

integrity of natural ecosystems in the region.

The following objectives are recommended for all national strategies aiming to control pesticide

pollution from agriculture, together with comments on policy instruments that should be adopted

where appropriate to the national context (not all policy instruments are appropriate to all

countries).

OBJECTIVE 1: Reduce the levels of harmful active substances used for crop protection by

prohibiting and/or substituting the most dangerous priority pesticides with safer (including non-

chemical) alternatives

1.1 Pesticide Ban - the use of Atrazine, Lindane, Diuron and Endosulfan needs to be banned

immediately. Atrazine is the pesticide most often detected in the Danube basin, Lindane, Diuron

and Endosulfan are toxic and persistent pesticides.

1.2 Pesticide Phase-out - the use of all other priority pesticides which are authorised should be

reduced to a minimum, and the use should be phased out if possible, and substituted by less-

dangerous pesticides, including non-chemical alternatives. Considering the current low levels of

pesticide use and a lower dependency of farmers upon these chemicals in the DRB regions, the

targets for further pesticide reduction can be ambitious.

1.3 Cut-off Criteria - in order to prevent the replacement of the priority pesticides which are going to

be banned or phased out with other hazardous pesticides, cut-off criteria for the approval of other

pesticides need to be defined. Pesticides with distribution coefficients (Koc ) below 300g/l (low

absorption to soil, prone to leaching and run-off) and a half life greater than 20 days need to be

regulated (prohibition, taxes and transferable permits are possible policy tools). Persistent

pesticides should not receive authorisation.

OBJECTIVE 2: Improve controls on the use and distribution of pesticides

2.1 Monitor Trade - retailers, importers and distributors should be required to supply information on

the amounts of all pesticide sold. Retail sellers need to keep records of their sales of pesticide

products and to submit annual reports to national authorities.

2.2 Control Trade - all DRB countries must work towards stopping the uncontrolled and illegal trade

of pesticides. The authorities at the borders should receive training on the issue of illegal pesticide

trade. National legislation should enable authorities to effectively prosecute those selling illegal

pesticides and to penalise them with high fines.

2.3 Raise Awareness agricultural extension services and farmers should get access to information

about the dangers of illegal and often unlabelled pesticides.

2.4 Monitor Pesticide Use effective monitoring of pesticide use at the farm level is an essential tool

for improving the control of pesticide use and distribution, as well as assessing environmental

risks, developing non-chemical alternatives etc. Uniform record keeping by farming is essential

for a functioning pesticide monitoring system. National regulation must require that pesticide use

records are kept by all pesticide applicators (as in the Czech Republic and Slovakia) according to

certain minimum standards and are reported to the relevant authorities.

2.5 Elimination of Obsolete Pesticides all efforts must be made to immediately secure and remove

stockpiles of obsolete pesticides.

16

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

OBJECTIVE 3: Encourage the proper use of pesticides by farmers and other operators

3.1 Raise Farmers' Awareness - simple and easy to understand information materials, combined

with well-targeted publicity campaigns, can be very effective in raising farmers' awareness of the

dangers of improper pesticide use and the importance of key issues such as the safe storage,

handling, and disposal of pesticide products. Retail stores, extension services and other

organisations working with farmers can serve as effective distributors of information material.

3.2 Develop National Codes of Good Practice national authorities should agree upon clear and

simple codes of good crop protection practice when using pesticides. There are numerous

frameworks for such codes, but as a minimum they should provide guidance to farmers on:

· basic elements of crop protection;

· choice of chemicals available for crop protection, including obsolete/illegal pesticides;

· integrated crop management and non-chemical alternatives for weed, pest and disease

control;

· quantity and types of pesticide product to use;

· pesticide storage;

· use of spray equipment, including cleaning equipment;

· disposal of surplus pesticides and spray mixture (diluted pesticide);

· disposal of empty pesticide containers;

· records of application;

· protective clothing and emergency procedures.

3.3 Mandatory Farming Training - comprehensive training is the most important instrument to

prevent pesticide pollution at the farm level. All farmers and other operators (e.g. contract

workers) who wish to purchase and apply pesticides should be required to have a licence

confirming that they have participated in an approved training programme. As a minimum,

training should highlight the possible adverse effects of pesticides and promote the National Code

of Good Practice for the storage of pesticides, safe handling and application of pesticides, correct

use of spraying equipment, disposal of unused pesticide and containers, and record keeping (see

above).

3.4 Develop Appropriate Extension Capacity agricultural extension services play a key role in

raising awareness and improving the technical skills of farmers with respect to good crop

protection practice, however they often require support in developing the necessary capacity to do

this. National funding should be provided for the training of advisers in good practice and modern

extension techniques, as well as the development of appropriate institutional frameworks for

extension services (including the link to progressive and well-funded research programmes).

3.5 Use Economic Instruments to Promote Good Practice where government schemes provide

support to farmers, the principle of "cross-compliance" can be applied. This involves the

establishment of certain conditions (e.g. compliance with verifiable standards of good agricultural

practice) that farmers have to meet in order to be eligible for government support.

OBJECTIVE 4: Promote certified organic farming, together with integrated crop management

(ICM) systems, as viable alternatives to conventional pesticide use

4.1 Raise Farmers' Awareness viable alternatives to conventional pesticide use, such as organic

farming and ICM, should be actively promoted to farmers through the preparation of simple and

easy-to-understand information materials, combined with well-targeted publicity campaigns.

Organic farming is the most developed of all alternative farming systems and has the highest

potential for a reduction of the use of toxic pesticides (especially since the former intense use of

copper compounds in organic vegetables and fruit has been controlled), plus there are a number of

market opportunities available to organic farmers in the DRB countries.

Inventory of Agricultural Pesticide Use in the Danube River Basin Countries

17

4.2 Develop Relevant Legislation the national legislation for the definition of organic farming

systems in compliance with internationally recognised standards should be developed and

implemented as a high priority (particularly those in accordance with EC legislation) in order to

promote the development of domestic markets and international trade.

4.3 Develop Appropriate Extension Capacity agricultural extension services and farm advisers

play a fundamental role in the re-orientation of farmers towards new production systems,

particularly systems such as organic farming and ICM, which require higher levels of technical

knowledge and management. National funding should be provided for the development of

appropriate extension capacity as 3.4 above.

4.4 Develop On-farm "Quality Assurance Schemes" - in addition to their growing interest in

organic food and farming, the food processing and retail sectors of many European countries are

developing additional "on-farm quality assurance schemes" that promote integrated crop

management and the sale of food products that have been grown with reduced or minimal

pesticide inputs. National authorities in the DRB should support the development of such

"market-led" initiatives since they offer a potential market opportunity for DRB farmers and will

contribute to reducing the risk pesticide pollution now and in the future.

4.5 Use Economic Instruments to Promote Organic Farming and ICM farmers converting to

organic farming and ICM techniques can incur certain additional costs associated with reductions

in input, the establishment of new crop rotations, the adoption of new technologies etc. These

costs can be a significant obstacle to farmers who decide to make the transition from a

conventional farming system. Where national funds and/or other forms of co-financing are

available, national authorities should encourage farmers to convert to organic farming and ICM by

offering appropriate levels of compensatory payment.

18

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

1 I n t r o d u c t i o n

Overview

Pesticides are used to control a wide range of agricultural pests, diseases and weeds. They have

become an integral part of modern European agriculture and their use is one of the most significant

factors contributing to the high levels of agricultural productivity observed in many western European

countries where most cultivated crops receive at least one, and usually many more, pesticide

applications per year.

The development and widespread use of pesticides has largely taken place over the last 50 years with a

succession of more sophisticated and effective pesticide products being introduced. Each of these

pesticide products contains a number of constituents including the active ingredient (ai) (or mixture

of active ingredients) which is specifically intended to kill those pests, diseases or weeds that are

considered noxious or unwanted in modern agricultural production.

Pesticides contribute to higher yields, improved crop quality and higher economic returns for farmers.

Data on their use by farmers is, however, far from comprehensive and accurate data on their

consumption is frequently missing from many European countries. This makes the assessment of

trends in their use rather difficult, especially since the products used by farmers vary enormously

between countries/regions according to seasonal, climatic, agronomic and geomorphological factors.

In spite of this, it is very clear that the use of pesticides has declined significantly in the countries of

Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) since the political changes and sector reforms of the early 1990s

disrupted the process of modernisation, specialisation and intensification of agricultural production

that was characteristic of the centrally-planned economies in the region.

Reliable data on pesticide use in the CEE region are not available for the decades leading up to 1990.

However, data from the FAOSTAT database show a strong decline in pesticide use in the CEE

countries to about 40% of 1989 levels compared to a relatively small decrease in EU Member States

during the same period (Figure 1).

There are indications, however, that the use of pesticides in the CEE region is again increasing, with

concerns especially that enlargement of the EU will sustain a trend towards the renewed intensification

of crop production, particularly in the more productive regions of central Europe.

At the same time it must be said that there are various factors forcing much of European agriculture to

rethink pesticide use and many opportunities to promote new management approaches to pesticide use

by farmers and policy-makers.

Inventory of Agricultural Pesticide Use in the Danube River Basin Countries

19

Figure 1

Pesticide Consumption in CEE countries and the EU156

3 .0

2 .5

2 .0

1 .5

kg/ha

1 .0

0 .5

0 .0

1 9 8 9

1 9 9 0

1 9 9 1

1 9 9 2

1 9 9 3

1 9 9 4

1 9 9 5

1 9 9 6

1 9 9 7

E U 1 5

A C 1 0

Source: Data from the FAOSTAT database of the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation

Aim of this Report

The aim of this report is to present an inventory of major pesticide use the Danube River Basin (DRB)

countries, together with descriptions of observed misuse, potential impact upon the environment and

potential for reduction.

The approach chosen has been to focus upon so-called priority pesticides for the DRB. Studies of the

water quality of the Danube River have found a number of polluting substances that regularly occur in

the aquatic environment of the river. Some of these substances are of special concern for

environmental and/or human health reasons and a list of "priority chemicals for the Danube River" has

been prepared.

According to Article 7 of the Danube River Protection Convention, which regulates emission

limitations and water quality objectives and criteria, the discharge of hazardous substances from point

and non-point sources is to be prevented or considerably reduced. Annex II defines such hazardous

substances and lists under Part 2 A (d) plant protection agents, pesticides and chemicals used for the

preservation of wood, cellulose, paper, hides and textiles etc. Under Part 2 B of Annex II, a number

40 single hazardous substances is listed. In 2001, substances listed in Annex X of the European Water

Framework Directive 2000/60/EEC were taken into account in revising the ICPDR list of priority

substances. Altogether, the new list contains 41 single substances of which 25 are chemicals which

are used as pesticide active ingredients and 5 are chemicals which are used as inert ingredients.7

6 The graph expresses mean consumption of pesticides (active ingredients classed as insecticides, herbicides,

fungicides and others) per unit area agricultural land.

7 `Inert' ingredient: These are substances which can enhance the efficiency of the active substance, make a

product more degradable or easier to use. `Inerts' are mostly handled as trade secrets of the manufacturer,

which means they are not labelled on the product.

20

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

Priority Pesticides in the Danube Region

International

Status EU Water

Status EU

Conventions

Frame Work

Directive

Directive 2000/60

91/414 and

79/117

No. Ingredient

CAS Number Use type PIC

POP

Priority

Priority

Dangerous

Active Ingredients

1 2.4-D

94-75-7 Herbicide

Annex

I

2 Alachlor

15972-60-8

Herbicide

Yes

pending

3 Aldrin

309-00-2 Insecticide Yes Yes

banned

4 Atrazine

1912-24-9 Herbicide

Yes* pending

Copper compounds

7440-50-8 Fungicide

5

Copper carbonate, basic

1184-64-1

Fungicide

Notified

6 Copper

hydroxide

20427-59-2

Fungicide

Notified

7 Copper

oxychloride 1332-40-7

Fungicide

Notified

8 Copper

sulfate

(basic) 1344-73-6

Fungicide, not

listed

Algaecide

9 Malachite

(copper

1319-53-5 Fungicide

not

listed

equivalent 57%)

10 Chlorfenvinphos

470-90-6 Insecticide

Yes

out

7/03

11 Chlorpyrifos

2921-88-2 Insecticide

Yes*

pending

12 DDT

50-29-3

Insecticide

Yes Yes

banned

13 Diuron

330-54-1 Herbicide

Yes*

Dossier

14 Endosulfan

115-29-7 Insecticide

Yes*

pending

15 Endosulfan - alpha

959-98-8

Insecticide

Yes

not listed

16 Ethylene

dichloride

107-06-2 Fumigant,

Yes Yes not

listed

Insecticide

Hexachlorocyclohexanes

17

Lindane (gamma-HCH)

58-89-9

Insecticide

Yes

Yes

out 6/02

18 delta-HCH

608-73-1 Insecticide Yes

Yes* not

listed

19 Isoproturon

34123-59-6 Herbicide

Yes

Annex

I

20 Malathion

121-75-5 Insecticide

Dossier

21 Pentachlorphenol

(PCP)

87-86-5

Wood

Yes Yes* out

7/03

Preservative,

Microbiocide,

22 Simazine

122-34-9 Herbicide

Yes*

pending

23 Trifluralin

1582-09-8 Herbicide

Yes*

Zinc and its Compounds

24

Zinc sulphide

7440-66-6

Herbicide

not listed

25 Zinc

phosphide

1314-84-7 Rodenticide

not

listed

Inert Ingredients

1 1,1,1-trichloroethane

71-55-6 Solvent

not

listed

2

Chloroform,

67-66-3 Solvent,

Yes not

listed

Trichloromethane

Fumigant

3 Lead

7439-92-1 Inert

Yes not

listed

4

Methylene chloride

75-09-2

Solvent

Yes

not listed

5

Trichloro ethylene

79-01-6

Inert

not listed

* candidate priority dangerous substance

Sources: European Union (1991): Council Directive 91/414/EEC of 15 July 1991 concerning the placing of plant protection products on the

market, Official Journal 230, Brussels, Belgium

United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) POPs website: www.chem.unep.ch/pops or Stockholm Convention (POPs Convention)

website: www.pops.int/United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP), website of Interim Secretariat for the Rotterdam Convention

(PIC convention): www.pic.int

European Community, Official Journal L331/1, Entscheidung Nr. 2455/2001/EG Des Europäischen Parlaments und des Rates vom 20.

November 2001 zur Festlegung der Liste prioritärer Stoffe im Bereich der Wasserpolitik und zur Anderung der Richtlinie 2000/60/EG, Brussels

European Council (1978): Council Directive of 21 December 1978 prohibiting the placing on the market and use of plant protection products

containing certain active substances plus its amendments, Official Journals: L 33, 8.2.1979; L 296, 27. 10. 1990; L 159, 10. 6. 1989; L 212, 2. 8.

1986; L 71, 14. 3. 1987; L 212, 2. 8. 1986; L 152, 26. 5. 1986; L 91, 9. 4. 1983

U.S.Environmental Protection Agency, Inert Ingredients of Pesticide Products: http://www.epa.gov/opprd001/inerts/fr54.htm

Inventory of Agricultural Pesticide Use in the Danube River Basin Countries

21

Table 1 lists the 29 priority chemicals used in pesticide products and their regulatory status globally

and in the European Union. The table shows that most substances, except for the inorganic

compounds, are already regulated by international conventions or the European Union including:

POPs Convention

The POPs convention aims at the elimination or restriction of persistent organic pollutant (POPs),

while the PIC (prior informed consent) convention ensures that countries importing certain chemicals

are informed prior to the import, and that information about the hazards of the particular chemicals is

disseminated.

Water Framework Directive

The European Water Framework Directive 2000/60EC requires that measurements regarding

dangerous priority substances aim at the phase-out of these substances within 20 years after the

adoption of measurements. Regarding priority substances, a stepwise discontinuation of the pollution

is required in the same timeframe.

EU Authorisation

Only two of the Danube priority pesticides are fully registered in the European Union and listed in

Annex I of Council Directive 91/414/EC. For three of the priority pesticides, registration will expire

or has already expired and seven are still in the re-authorisation process. According to Directive

79/117, the use of two of the priority pesticides is banned in the EU.

Table 2 shows that only three priority pesticides are authorised for use in all of the DRB countries

under study, while seven priority pesticides are not authorised in any of the countries. There are also

differences between the countries. The Republic of Srpska authorised 15, Romania, Serbia &

Montenegro and Slovakia 14 priority pesticides, while Bulgaria and Moldova authorised eight priority

pesticides and the Ukraine only six.

In some countries, there are certain restrictions upon specific pesticide products. For example, in

Croatia it is not allowed to apply Alachlor with a knapsack sprayer or a hand sprayer. It is also not

allowed to use Alachlor on light soils after the maize has emerged. Use of Atrazine is limited to

1.5 kg ai/ha in humid and 1 kg ai/ha in arid areas. Endosulfan cannot be used in oil-seed rape and

forestry. Use of Simazine is permitted only in maize monoculture. TrifIuralin use is not permitted in

post-harvest sown soya bean and sunflower.

22

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

Authorisation Status of Danube Priority Pesticides in the 11 Danube Countries

BH

Active Ingredients

FedBH RS BG HR CZ HU MD RO YU SK SL UA No

2,4-D

Y

Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y 12

Copper sulphate (basic)

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y Y

12

Trifluralin

Y

Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y 12

Alachlor

Y

Y Y Y Y Y N Y Y Y Y Y 11

Copper hydroxide

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y N

11

Copper oxychloride

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y N

11

Chlorpyrifos

Y

Y N Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y 11

Atrazine

N

Y Y R Y Y Y Y Y Y B N 9

Malathion

N

Y N Y N Y Y Y Y Y Y Y 9

Isoproturon

N

Y Y Y Y Y N Y Y Y Y N 9

Endosulfan Y

Y

N

R

Y8 Y N Y Y Y Y N 9

Simazine N

Y

N

R

Y9 N N Y Y Y Y N 6

Zinc

phosphide

N

Y N N Y Y N N Y Y Y N 6

Diuron

Y

N N N N Y N Y N N N N 3

Lindane

(gamma-HCH)

N

Y N N N N N Y N N B N 2

Chlorfenvinphos

Y

Y N N N N N N N N N N 2

Malachite (copper equivalent N

N N N N N N N N Y N N 1

57%)

Copper carbonate, basic

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

Y

N

N N

1

Aldrin

B

B B B B B B B B B B B 0

DDT

B

B B B B B B B B B B B 0

alpha-endosulfan

N

N N N N N N N N N N N 0

Ethylene

dichloride

N

N N N N N N N N N N N 0

delta-HCH

N

N N N N N N N N N B N 0

PCP

(pentachlorophenol) N

N N N N N N N N N N N 0

Zinc

sulphide

N

N N N N N N N N N N N 0

Number

authorised

10

15 8 12 12 13 8 14 14 14 12 6

Y= Authorised; N= Not authorised; B= Banned; R= Restricted

8 Endosulfan is authorised, but there is no registered product containing Endosulfan.

9 Simazine is authorised, but there is no registered product containing Simazine.

Inventory of Agricultural Pesticide Use in the Danube River Basin Countries

23

2 M e t h o d o l o g y

In line with the process developed in the Inception report, the international expert team hasd

developed templates and guidelines for the collection and analysis of data and information related to

the use of pesticides in 11 DRB countries. Also, information from existing data sources on pesticide

use available at global and EU level have been collected to compare with the situation in the DRB.

Under the guidance of the international expert team,, national experts in each of the DRB countries

under study have been asked to undertake a survey and to collect:

1. data available on the amount of pesticides applied in DRB countries and how they are used (e.g.

what crops are they applied to, number of applications etc.);

2. information available on bad practice by farmers and others regarding the use of these pesticides;

3. information on legal and control mechanisms and measures for compliance.

The experts mainly submitted data based upon sales data and on recommendations included in the

pesticide product registration. Actual use data by location, crop and active ingredient were generally

not available and could not be submitted. Therefore the figures presented in this report relate to

general estimations of national usage of the priority pesticides, except for the Czech Republic where

some sub-national data has been prepared.

The results obtained are summarised by country. Detailed information on registered products and their

usage by country is presented in Annexes 2 - 11.

The section on environmental impact assessment includes chemical fact sheets for selected priority

pesticides. Each fact sheet comprises physical and chemical properties related to environmental

behaviour, environmental fate, environmental risk associated with them and human and environmental

toxicity.

Based on the analysis of data and information received in the national survey, a first set of policy

recommendations for reducing pesticide usage have been outlined.

These policy recommendations shall be further developed in Phase 2 of the Project to be introduced in

national legislation, assuring a harmonized approach in the use and application of pesticides in the

DRB, responding to the requirements of the EU WFD and to the objectives of the Danube River

Protection Convention

24

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

3 A v a i l a b i l i t y o f D a t a o n P e s t i c i d e U s a g e

Information on the amount and identity of pesticides applied, at a particular location, on a certain date

can be extremely useful in the protection of human and environmental health and in pest management.

Accurate information on pesticide use can help provide better risk assessments and illuminate pest

management practices that are particularly problematic so that they may be targeted for the

development of alternatives.

In spite of the fact that pesticides are among the most toxic substances released into the environment,

little information is available about the details of their distribution and use patterns.

The following section briefly outlines available data collected:

· by the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO);

· in the European Union; and

· in three DRB countries Hungary, Czech Republic and Slovakia, operating pesticide use/sales

tracking systems.

3 . 1 F o o d a n d A g r i c u l t u r e O r g a n i s a t i o n ( F A O )

The FAO has collected data on pesticide usage and consumption for more than three decades. Data

are collected for major groups (insecticides, herbicides, fungicides etc.) and chemical classes such as

urea herbicides, organophosphate insecticides etc. Data usually refer to quantities of active

ingredients sold or used in the agricultural sector. For some countries, data about uses/ sales to the

non-agricultural sector are included. Some countries provide data by formulated products. The data

collected are publicly available and present the most comprehensive globally database on pesticide

use.

3 . 2 E u r o p e a n U n i o n

The common way to track data on pesticide use in the EU is the collection of sales data. The most

recent data published by EUROSTAT are from 1999. For some Member States, these data include

non-agricultural pesticide sales. Some Member States also include sales data of sulphur, sulphuric

acid and mineral oil or gases which are used as pesticides in large quantities. Table 3 presents an

overview of pesticide tracking systems in EU Member States.

In 2003, Eurostat published more detailed pesticide use data. For this data collection, Eurostat

contracted the pesticide industry through the European Crop Protection Association (ECPA). The

members of ECPA submitted data from their annual surveys and other market research panels. The

publication covers the period 1992 - 1999 and includes pesticide sales data by chemical class for a

number of crops. Even sales data for some active ingredients were made available. For each Member

State, a list of the five top active ingredients per crop group was presented.

Inventory of Agricultural Pesticide Use in the Danube River Basin Countries

25

Overview of Agricultural Pesticide Use Tracking Systems in the 15 EU Member States

Member State Collection of Sales Data

Pesticide

Mandatory

Pesticide

Surveys

Record

Use

Keeping

Reporting

Austria

Volume active ingredients

not regular

no

no

Belgium

Volume formulated products

3-4 crops

for apples,

no

per year

pears and glass

house crops

Denmark

Monetary value and volume of

no yes no

formulated products and active

ingredients

Finland

Monetary value and volume of

no no no

formulated products and active

ingredients (obligatory reporting)

France Yes

no no

no

Germany

Volume active ingredients

no

no

no

Greece

Volume formulated products

no

no

no

Ireland

Volume active ingredients

no

no

no

Italy Yes

no no no

Luxembourg Yes

no

no

no

Portugal

Monetary value and volume of

no no no

active ingredients

Spain Yes

no no no

Sweden

Monetary value and volume of

no yes no

formulated products

The

Volume of formulated products

monthly 1

yes no

Netherlands

and active ingredients

crop

United

Monetary value

yes

yes

for aerial

Kingdom

applications

Source: PAN Germany 200210, OECD 200011

3 . 3 S e l e c t e d D R B C o u n t r i e s

From the 11 DRB countries under study, only three countries maintain pesticide use/sales tracking

systems based upon retail sales - Hungary, the Czech Republic and Slovakia.

Hungary

Hungary collects sales data from wholesalers and local distributors twice a year. They have to submit

data on the sales in kg as well as on the monetary amount on the basis of individual formulated

pesticide products. Sales data are publicly available in an aggregated format.

10 L. Neumeister (2002): Pesticide Use Reporting; Legal Framework, Data Processing and Utilisation, Full

Reporting Systems in California and Oregon, Pestizid Aktions-Netzwerk e.V. (PAN Germany), Hamburg,

Germany.

11 OECD Series on Pesticides, Number 7 (1999): OECD Survey on the Collection and Use of Agricultural

Pesticide Sales Data: Survey Results, Paris, France.

26

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

Czech Republic

In the Czech Republic, all professional pesticide users have to keep spray records for 3 years. Farms

larger than 10 ha are required to submit summaries to the Department of Information. Farmers report

on amounts applied by formulated product, crop and geographical region. Usage data are publicly

available by crop and amount of active ingredient. Data on pest and disease infestations are also

published.

Sales data are collected by the Czech Crop Protection Association, which is an associate member of

the ECPA.

Slovakia

Slovakia started a pesticide sales reporting system in 1999. All traders are required to report sales data

annually: manufacturer, importer, distributors and retailers. They are required to report the name and

amount of formulated product for agricultural and non-agricultural pesticides. Sales data are publicly

available by amounts of active ingredient, chemical class, use type and by postal code12.

All farmers have to keep detailed records of their pesticide use and are required to submit summaries

to the Central Control and Testing Institute of Agriculture.

12 Communication with Martin Hajas (Central Control and Testing Institute of Agriculture) and Jozef Kotleba

(Ministry of Agriculture).

Inventory of Agricultural Pesticide Use in the Danube River Basin Countries

27

4

P e s t i c i d e U s a g e i n t h e 1 1 D a n u b e

C o u n t r i e s

Due to the fact that pesticide use reporting systems only exist in a few Danube countries (Hungary,

the Czech Republic and Slovakia), the GFA national experts were asked to provide (where available)

national usage data for the priority pesticides.

Table 4 shows the total area of the Danube countries and their share of the territory of the Danube

River basin. It shows that Romania, with 28% of its territory, has the largest share of the Danube

Basin, and that 97% of the country belongs to the basin. National pesticide usage/sales data are equal

to usage in the Danube basin for countries which belong almost entirely (Hungary, Romania, Slovak

Republic) to the basin.

Notwithstanding this, the intensity of pesticide usage varies regionally. Agricultural conditions

prevailing along the Danube river are particular suitable for crop growing, and pesticide use is most

likely much higher than in less suitable areas.

0 gives an overview of pesticide use in Danube countries taken from the FAO database. Data for

Bosnia & Herzegovina, Bulgaria and the Ukraine are not available from this source. In some cases,

the latest data are from 1993, but even the most recent data are already 5 years old.

Areas of National Territories in the Danube Basin

Country Total

Area

of

Area of National

% of National

% of DRB

National

Territory in the

Territory in DRB

Occupied by

Territory (km2)

DRB (km2)

National Territory

Romania

238,391

232,200

97

28.4

Hungary

93,030

93,030

100

11.4

Serbia & Montenegro

102,173

88,919

87

10.9

Slovak Republic

49,036

47,064

96

5.8

Bulgaria

110,994

46,896

42

5.7

Bosnia &

51,129 38,719

76

4.7

Herzegovina

Croatia

56,542

34,404

61

4.2

Ukraine

603,700

32,350

5

4.0

Czech Republic

78,866

21,119

27

2.6

Slovenia

20,253

16,842

83

2.1

Moldova

33,700

12,025

36

1.5

TOTAL 1,437,814

663,568

100

28

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

Overall Pesticide Consumption in Danube Countries (tonnes)

Czech

Hungary

Moldov

Croatia Republic

13

a

Romania Slovakia Slovenia FRY

1996 1998 1996 1993 1998 1998 1998 1998

Fungicides &

Bactericides

Benzimidazoles 23

67

226

15

3

Diazines,

Morpholines 2

63

21

14

6

Dithiocarbamates 239 291 329

114

240

Inorganics 1.114

206

1.067

377

Mineral Oils

60

11

135

51

4

Other Fungicides

20

156

1.625

466

106

Total Fungicides &

Bactericides 1458

794

3.403

6.500

741

880

Herbicides

Amides

555 556 1,227

292

487 16

Bipiridils 7

30

202

Carbamates

Herbicides 24

72

557

11

111

3

Dinitroanilines 11

105

1,123

216

88

34

Other Herbicides

212

971

1,567

437

688

116

Phenoxy Hormone

Products

153 545 854

197

621 41

Sulfonyl Ureas

8

26

49

Triazine 483

204

711

19

321

33

Triazoles, Diazoles

14

9

710

88

9

Uracil

11

Urea derivates

75

124

195

6

34

Total Herbicides

1,528

2,642

6,496

1,178

5,400

2,316

277

1,748

Insecticides

Botanical &

Biological Products

2

2

2

Carbamates

Insecticides

24 14 57

8 1

Chlorinated

Hydrocarbons 6

129

62

2

Organo-Phosphates 92 79 1,219

295

85 27

Other Insecticides

17

16

466

27

37

40

Pyrethroids 7

10

208

187

38

1

Total Insecticides

148

119

2,081

571

2,100

170

71

729

Plant Growth

Regulators

35

398

11

Rodenticides

Anti-coagulants

126

Other Rodenticides

1.050

4

2

Total Rodenticides

33

1176

4

152

2

Total Usage

3,123

4,079

13,866

2,450

14,000

3,075

1,091

3,357

Source: FAOSTAT Database

13 Formulated product.

Inventory of Agricultural Pesticide Use in the Danube River Basin Countries

29

0presents a summary of the national pesticide use data that was submitted by the national experts for

eight countries. The table shows that the total use of priority pesticides is the highest in Hungary and

the Czech Republic, which is probably due to the fact that these two countries have comprehensive

pesticide use tracking systems. In Hungary, reported use is 10 times higher than in the Czech

Republic, with copper as the most widely used pesticide. This is most likely due to the fact that

Hungary cultivates approximately 99,000 of vineyards plus a large area with fruits and vegetables,

while the Czech Republic cultivates only about 11,000 ha grapes.

Copper is generally used in large amounts in vineyards and orchards to control fungus and it is

approved as a pesticide in organic agriculture according to EU regulations.

The data show that, in general, copper compounds contribute to the highest use, followed by Atrazine,

2,4-D and Trifluralin.

The pesticide usage data that were submitted are in general rather an estimation. They are based upon

sales data (except for the Czech data) and often neglect trade. Uncontrolled trade into the country was

reported in three countries.

The data collected present a picture of the situation at national level. An estimation of pesticide use in

the Danube catchment is not possible, except for countries of which large parts are located in the

catchment (Hungary, Romania, the Slovak Republic and Slovenia (83%)).

Usage of Priority Pesticides in 8 Danube Countries 2001-2002 (tonnes active ingredients,

except for Slovenia kg formulated product)

BH

Fed BH

RS

HR

CZ

HU

MD

YU

SK

SL*

UA Total**

2002 2001 2001

2002

2001

2002 2002 2002 2001 2001

Copper sulphate

15

4

47

10,093

1,129

7

13

11,295

Atrazine 1

73

406

145

520

115

85

1,344

Copper oxychloride

4

129

451

45

163

19

12

810

2,4-D 24

6

120

83

408

40

0

11

21

27

719

Alachlor

5

37

255

13

80

390

Trifluralin 1

2

100

111

4

96

25

3

339

Chlorpyrifos

13

111

48

8

38

2

218

Copper hydroxide

2

1

37

110

21

10

9

83

189

Malathion

3

9

5

124

0

15

155

Isoproturon

130

3

9

67

141

Endosulfan

82

0

2

82

2,4-D EHE

6

36

42

Diuron

21

0

21

Simazine

10

0

2

10

Zinc phosphide

3

2

2

7

Lindan

1

0

1

Total 56

99

563

1,046

11,869

1,251

524

314

204

42

15,763

* Data for Slovenia is presented as kg of formulated product

The data show that in none of the countries, 100% of the crops are treated with priority pesticides.

However, the priority pesticides are high-use pesticides accounting for over 20% of the total use in

some countries. Treatment data suggest that a high percentage of crops in Danube countries do not

receive pesticide applications at all. However, soils in the Danube catchment and particularly those

close to the river, are very good for intensified crop production. Pesticide usage in these areas is most

likely higher than the national average.

30

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

The use of priority pesticides is associated with specific crops:

· Atrazine is mostly used in maize.

· Alachor is used in maize, rape seed and sunflower;

· copper compounds are used in vineyards, orchards and in vegetable production, including

potatoes.

· 2,4-D is mostly used in cereals.

· The insecticides Chlorpyrifos, Malathion and Endosulfan are used in orchards, vineyards, rape

seed, alfalfa and vegetables.

Inventory of Agricultural Pesticide Use in the Danube River Basin Countries

31

5 P r o b l e m s A s s o c i a t e d w i t h P e s t i c i d e U s e i n

t h e D R B

Although pesticide use is currently relatively low in the DRB countries (compared for example to the

EU Member States) it is important not to be complacent about the risks of pesticide pollution since:

1. Pesticide use is reported to be high in certain areas and for certain high value crops - this includes

priority pesticides that pose a serious hazard to the environment and human health.

2. Where farmers use pesticides, there are many examples of "bad practice" that contribute to the risk

of pesticide pollution.

3. There is concern that with EU enlargement and the expansion of the Common Agricultural Policy

(CAP) into the DRB countries joining the EU, there is a risk of:

· increasing areas cultivated with cereals and oilseeds due to the availability of EU direct

payments for farmers growing these crops in the new Member States;

· increased intensification of crop production, including the greater use of mineral fertilisers and

pesticides, particularly in the more favourable areas with better growing conditions;

· a reduction in mixed cropping and an increase in large-scale cereal monocultures in some

areas.

5 . 1 B a d P r a c t i c e b y F a r m e r s

The national experts reported several significant problems associated with the use of pesticides:

· Wrong time of application due to poor education;

· Poor storage conditions;

· Overuse of Atrazine and Chlorpyrifos;

· Drift of pesticides to adjacent areas due to old spraying equipment and poor knowledge;

· Cleaning of spraying equipment close to surface or even in surface waters;

· Uncontrolled trade.

5 . 2 E n v i r o n m e n t a l I m p a c t o f P e s t i c i d e U s e

Pesticides can be released into the environment in many ways. After application, depending on their

chemical and physical properties, they may run-off from fields and make their way into ditches, rivers,

lakes. Ultimately, they reach the oceans through the water cycle. They may also leach into

groundwater, which is then discharged into streams or is subsequently used for irrigation. Drift,

evaporation and precipitation carry pesticides into both, nearby and far away habitats. Via the food

chain, accumulated in animal tissue, persistent and bioaccumulative pesticides can travel far distances

and arrive at places in which they were never applied. Figure 2 illustrates the behaviour of pesticides

in the environment.

32