March 2007

Field and Policy Action for Integrated Land

Use in the Danube River Basin Methodology

and Pilot Site Testing with Special Reference

to Wetland and Floodplain Management

phase 2 of project output 1.4:

Integrated Land Use Assessment and Inventory

of Protected AREAS

AUTHORS

PREPARED BY:

WWF Danube-Carpathian-Programme Office

AUTHORS:

Michael Baltzer,

Christine Bratrich,

Darko Grlica,

Orieta Hulea,

Andreia Petcu,

Gyongyi Ruzsa,

Jan Seffer,

Susanna Wiener,

WWF International

Danube-Carpathian-Programme Office

Mariahilfer Str. 88a/3/9

A-1070 Vienna

PREFACE

This report has been produced to conclude the activities undertaken as part of the project

output 1.4: Integrated Land Use Assessment and Inventory of Protected Areas of the UNDP/GEF

Danube Regional Project Strengthening the Implementation Capacities for Nutrient Reduction

and Transboundary Cooperation in the Danube River Basin.

The report is aimed to provide a summary of the activities and recommendations resulting from

an analysis of both Phase I and Phase II of the project focused on Field and Policy Action for

Integrated Land Use in the Danube River Basin Methodology and Pilot Site testing with special

reference to wetland and floodplain management. The report has been written to provide a

technical record for those considering wetland restoration activities related to changing of land

use.

Integrated Land Use Assessment and Inventory of Protected Areas

page 5

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1.

Introduction .......................................................................................................15

1.1. Aims & Objectives ............................................................................................17

1.1.1.

overall aims ..............................................................................................17

1.1.2.

Specific purpose and objectives of project phase 2..........................................17

1.2. Structure of this report .....................................................................................17

2.

Project Site Descriptions ......................................................................................18

2.1. The Olsavica valley, Tisza sub-basin, Slovakia ......................................................18

2.2. Lower Elan valley, Prut sub-basin, Romania .........................................................20

2.3. The Zupanijski canal, near Budakovac village, Drava sub-basin Croatia....................22

3.

Implementation of Activities in Phase 2 ..................................................................24

3.1. Summary of Activities.......................................................................................24

3.2. Activities related to the application of the methodology for assessing land use ..........26

3.2.1.

Applying the methodology in the selected three pilot sites................................26

3.2.2.

Lessons learned from applying the methodology at the three different pilot

sites 27

3.2.3.

Assessment of applicability, usefulness, and assignability of the methodology .....34

3.3.3

Implementation of action plans in each site ..................................................39

3.3. Activities related to the implementation of proposed restoration measures,

communication, and policy action at the three selected pilot sites:....................................41

3.3.1.

Activities implemented in Slovakia (Olsavica Valley):.......................................41

3.3.2.

Lessons learned from the Slovakian pilot site .................................................44

3.3.3.

Activities implemented in Romania (Lower Elan Valley): ..................................45

3.3.4.

Lessons learned from the Romanian pilot site.................................................49

3.3.5.

Activities implemented in Croatia (Zupanijski canal):.......................................50

3.3.6.

Lessons learned from the Croatian pilot site ...................................................52

3.3.7.

Lessons learned on how to use the methodology to influence policy decision

makers in the three pilot sites (synthesis) ..................................................................53

4.

Conclusions and recommendations ........................................................................57

4.1. General lessons learned ....................................................................................57

4.1.1.

Setting goals and objectives ........................................................................57

4.1.2.

Applying the methodology ...........................................................................58

4.1.3.

Implementing restoration measures on the ground .........................................59

4.1.4.

Using pilot sites for influencing policy decision makers.....................................60

UNDP/GEF DANUBE REGIONAL PROJECT

page 6

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1:

Assessment of the applicability, usefulness and assignability of the

methodology. Data collected at three different pilot sites in the Slovak Republic

(upper Tisza basin), Romania (Elan river), and Croatia (Drava river). .................... 36

LIST OF PICTURES AND GRAPHS

Figure 1: The Danube River Basin and locations of the selected three pilot sites in the

Slovak Republic (Olsavica); Romania (Elan Valley), and Croatia (Virovitica). ........... 18

Figure 2: Olsavica river basin is located in Levocske vrchy Mts. (Hornad Tisza Basin)

with total area 13 km2. ................................................................................... 19

Figure 3: Location of the pilot project site in Romania (3300 ha total, 382 hectares

represent wetlands) in the Elan River Basin, with a total area of 601 km2............... 21

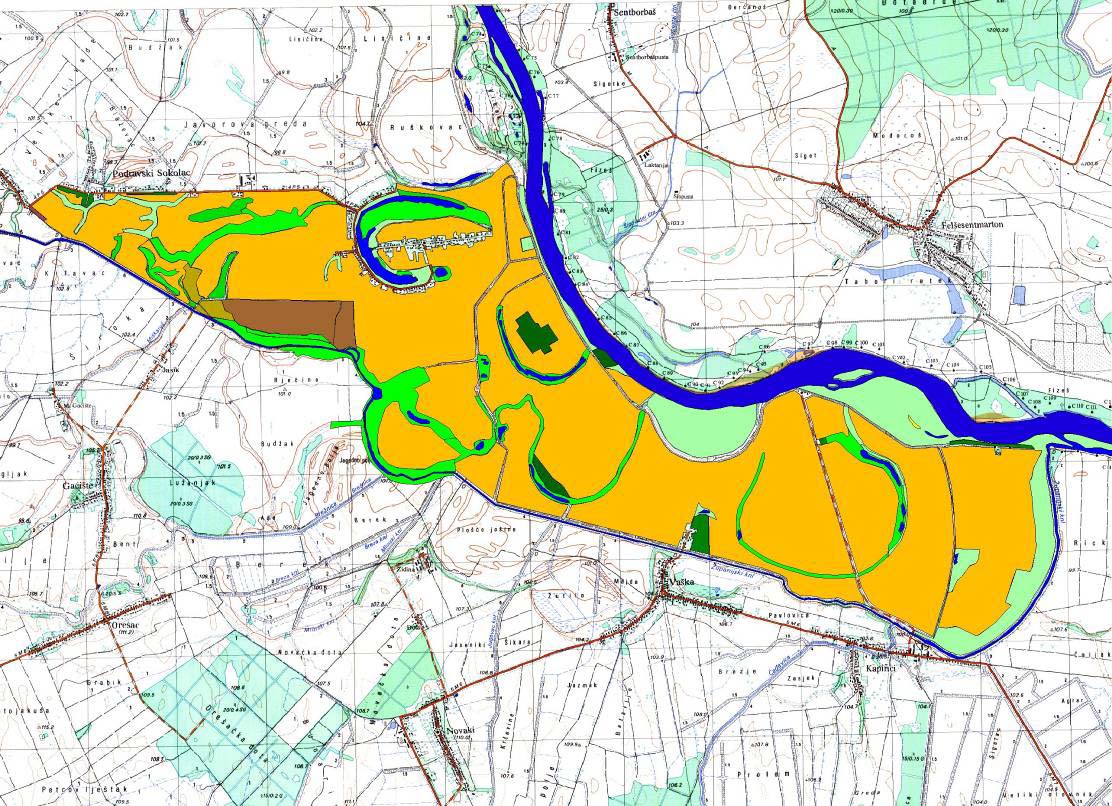

Figure 4: Location of the pilot study site in the Drava river basin southeast of the city of

Virovitica with total area of 2350 ha................................................................. 23

Figure 5: Romania example for GIS mapping: (top left) project location in Romania,

(bottom left) current land-use; (right) proposed alternative landuse to halt

ongoing soil erosion along the hills. .................................................................. 28

Figure 6: Principle overview on how to find / define the optimal status of wetlands

(example from the Slovakian pilot case). ........................................................... 31

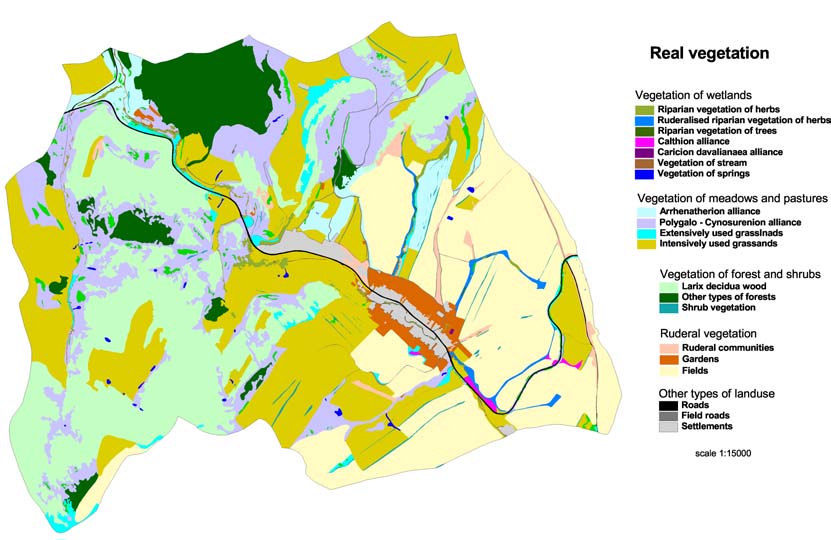

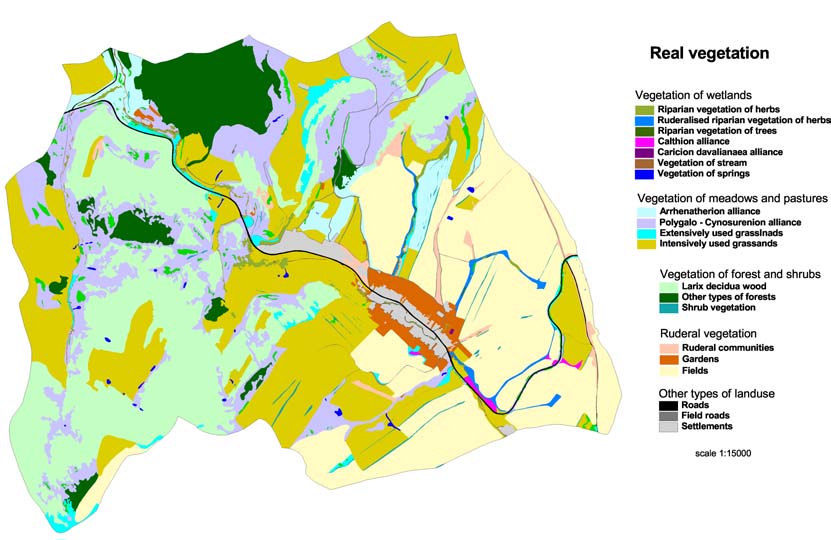

Figure 7: Real (top) and optimal (bottom) status for of wetlands in Olsavica Village

(Slovakia). The image illustrates a possible optimal and realistic occurrence of

wetlands in the Olsavica basin. The maps are based on four sources of

information: (1) a geo-botanical map incl. predicted potential vegetation, (2)

an aerial photo from 1949 showing detail land-use situation and delineated

wetlands, (3) the comparison of wetland types in well preserved down stream

parts, and (4) a 3D model of the terrain used for defining erosive sections of

the channels. ................................................................................................ 32

Figure 8: Technical implementaion of measures to improve the situation of wetlands in

the Slovakian pilot site building small dams to control channel erosion (a,b)

and re-opening of small meanders to improve ecological integrity of the

canalized river and to lower discharge velocity (c,d)............................................ 42

Figure 9: Technical implementation of measures to improve the situation of wetlands in

the Slovakian pilot site mulching of wet grasslands. ......................................... 43

Figure 10: Technical implementation of measures to improve the situation of wetlands in

the Slovakian pilot site planting of native species on stream banks to control

soil erosion organized in close cooperation with local NGOs and authorities. ........... 43

Figure 11: Lower Elan situation under normal flow conditions (a) and during increasing

flood in spring 2006 (b, c, d). The floods reconnected some of the old

meanders and destroyed dikes on the left site of the river course. However,

the originally planed restoration work had to be postponed. ................................. 46

WWF DANUBE-CARPATHIAN-PROGRAMME / BALTZER ET AL.

Integrated Land Use Assessment and Inventory of Protected Areas

page 7

Figure 12: Original plans to re-connect the old meander system along the Lower Elan with

the main river course. Parts of the meanders were naturally reconnected

through the breach of the left bank dike of the Elan River. Current negotiations

with local land-owners aim to maintain the improved situation that has been

caused by the floods....................................................................................... 47

Figure 13: Typical situation of traditional land use on the slopes along the Elan river. 85%

of the total area is split into excessively small plots. Each site is smaller than 1

ha and arraigned in uphill- downhill directions causing massive problems with

soil erosion. .................................................................................................. 48

Figure 14: Technical implementaion of measures to improve the situation of wetlands in

the Romanian pilot site mechanical gully filling by bulldozers along the river

slopes. ......................................................................................................... 48

Figure 15: Proposed Natura 2000 site along the floodplains of the Elan River (Mata-

Radeanu). The site has already been validated at national level. ........................... 49

Figure 16: Map to illustrate technical measures to improve the situation of wetlands at the

Croatian pilot site reconnecting old oxbow system with the main river

channel. Original plans (top) and reviewed situation after finalisation of the

topographic survey (bottom). .......................................................................... 52

UNDP/GEF DANUBE REGIONAL PROJECT

page 8

ABBREVIATIONS

CAP

Common Agricultural Policy

CIS

Common Implementation Strategy of the EU Water Framework Directive

DRB

Danube River Basin

DRP

Danube Regional Project

EC European

Commission

ECO EG

Ecological Expert Group of ICPDR

EU European

Union

GEF

Global Environment Facility

GIS Geographical

Information

System

ICPDR

International Commission for the Protection of the Danube River

IRBM

Integrated River Basin Management

ISPA

EU pre-accession instrument for structural measures

LIFE

The EC financial instrument for the environment

UNDP

United Nations Development Programme

RBM EG

River Basin Management Expert Group of ICPDR

SAPARD

EU pre-accession instrument for agriculture and rural development

measures

WFD

Water Framework Directive (2000/60/EC)

WWF

World Wide Fund For Nature

WWF DANUBE-CARPATHIAN-PROGRAMME / BALTZER ET AL.

Integrated Land Use Assessment and Inventory of Protected Areas

page 9

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Objective 1 of the UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project offers support to policy development

favouring the creation of sustainable ecological conditions for land use and water management.

Within Objective 1, Integrated Land Use Assessment and Inventory of Protected Areas (Output 1.4)

was one of eight project outputs. The project was implemented in two phases: Phase 1 was

conducted between December 2001 and November 2003. Phase 2 started in June 2005 and ended

in December 2006. This report covers only the Integrated Land-use Assessment element of Output

1.4 (the Inventory of Protected Areas is the subject of a separate report).

Overall aim and specific project objectives of Output 1.4:

The overall aim of Output 1.4 was to assist Danube River Basin countries to prepare new land-use

and wetland rehabilitation/protection policies and legislation in line with existing and emerging

legislation, particularly the EU Water Framework Directive.

The specific objectives of this component of Phase 1 of Output 1.4 were to:

(a) develop a straightforward, yet rigorous, land-use assessment methodology that could be

tested and adapted if necessary for use across the region;

(b) select three pilot sites on which the methodology could be tested by implementation of

specific site-based activities including the holding of a workshop at each location to ensure

stakeholder involvement and wider public participation in the identification and assessment

of various future land-use alternatives;

(c) according to the results of the test phase, develop specific proposals for final land-use

concepts at each pilot site, including recommendations for the actions and measures

required to implement the concepts in practice; and

(d) develop a communications strategy to ensure the dissemination of conclusions and

recommendations, including the final land-use assessment methodology, throughout the

Danube River Basin.

The specific objectives of this element of Phase 2 of Output 1.4 were to:

(a) implement technical mitigation measures and alternative concepts that have been

developed in the first phase to achieve integrated land use management at each pilot site

(practical restoration work, regulatory issues, economic fines and incentives, compensation

payments etc.);

(b) mainstream wetland conservation and restoration activities into rural development plans

and policy on local, regional and national levels and securing governmental commitments

to implement the newly proposed concept for integrated land use in the selected case

studies;

(c) demonstrate mechanisms for sustainable wetland use and disseminating project results in

the Danube basin.

UNDP/GEF DANUBE REGIONAL PROJECT

Executive Summary

page 10

Activities completed successfully by the project Output 1.4 include:

(a) Activities related to the application of the methodology for assessing land use:

1. The methodology was applied in the selected three pilot sites Olsavica valley, Tisza sub-

basin, Slovakia; Lower Elan valley, Prut sub-basin, Romania; and Slovakia Zupanisjski

canal, near Budakovac village, Drava sub-basin Croatia;

2. An assessment was completed of the applicability of developing sustainable land-use

concepts at each pilot site that aim at reducing nutrient inputs into water bodies,

particularly through wetland and floodplain rehabilitation and/or restoration;

3. An assessment was completed of the applicability to find practical and policy measures

required to move towards more sustainable land use patterns at each pilot site.

(b) Activities related to the implementation of proposed restoration measures, communication, and

policy action at the three selected pilot sites:

The following activities have been completed during the second project phase.

In Slovakia (Olsavica Valley):

1. Construction of small dams on selected streams to control channel erosion;

2. Reopening of small meanders on a canalised stream;

3. Restoration of wet grasslands to act as a buffer zone between agricultural land

and the stream;

4. Blockage of an underground drainage system to restore water tables;

5. Planting of trees on steep stream banks to control soil erosion;

6. Springs were fenced off to prevent damage from grazing; and

7. Restoration promoted more widely through public awareness information.

In Romania (Lower Elan Valley):

1. A feasibility study and rehabilitation measures of the lower Elan floodplain downstream of

the confluence with Sarat Creek through meander restoration were conducted. (Activities

were only partly completed because of two major flood events in the region that hindered

the full implementation of activities. The activities will be completed immediately after the

project termination. See also below: `constraints and unexpected events');

2. Parts of the Elan river channel were partly reprofiled (activities have been partly completed

because of two major flood events in the region, they will be continued after project

termination, see also below: `constraints and unexpected events');

3. Control of soil erosion on hill slopes through changed land-use, implementation of better

agricultural practices, land reclamation and afforestation;

4. Declaration of the Lower Elan floodplain as a protected area; and

5. Improvement of public awareness and the training of civil society organisations especially

those in local communities and schools.

WWF DANUBE-CARPATHIAN-PROGRAMME / BALTZER ET AL.

Integrated Land Use Assessment and Inventory of Protected Areas

page 11

In Croatia (Zupanisjski canal):

1. Geographical survey of the area to investigate most suitable measures to reconnect the

Drava river to adjacent Podravski Sokolac wetland and Budakovac oxbow and consequently

raise local water tables;

2. Feasibility study to implement the most suitable measure to reconnect water from the

Drava river to adjacent Podravski Sokolac wetland and Budakovac oxbow and consequently

raise local water tables;

3. Dissemination of the findings, conclusions and recommendations from these activities.

Conclusions, lessons learned and implementation constraints

General conclusions

·

The methodology for assessing land use was successfully applied in all three pilot sites.

Other potential users including national and local authorities in the Danube River Basin,

NGOs and international organisations such as the Ramsar Secretariat are encouraged to

make use of this methodology.

·

The technical work and stakeholder involvement during the first phase and at each site was

successful in producing outline action plans for the second project period.

·

The project supplied evidence that by carefully planned landuse changes, it is possible to

provide a significant contribution to wetland restoration and wise management of wetland

resources and services.

·

It also provided evidence that building the capacity of local people on EU policy and the

opportunities that EU policy offer can provide a signification platform for success even for

far-off rural areas in new member states and even in proposed new accession states such

as Croatia.

·

Many of the actions recommended at each pilot site are in line with, and could be more

widely encouraged by, existing policy drivers. Four policy measures and socio-economic

trends in particular were found to support sustainable land-use and wetland restoration

measures:

·

Wetlands are an integral part of the EU Water Framework Directive (WFD);

·

Agriculture is changing across Europe:

·

Wetlands can help to safeguard against floods; and

·

Public participation is now a legal necessity

UNDP/GEF DANUBE REGIONAL PROJECT

Executive Summary

page 12

Lessons learned

The lessons learned from the project indicate clearly that it is important that the key policy drivers

and opportunities described above are promoted at all levels, especially by the European

Commission, the ICPDR, national governments and statutory authorities within the Danube River

Basin and regional authorities. The project supplied evidence that:

·

landuse changes are able to provide a significant contribution to wetland restoration and

wise management;

·

capacity building with local people on EU policy can trigger major success even at far-

off rural areas in the new EU member states;

·

capacity building on the ground will be key for sustainable management solutions in

these areas;

On the other hand, the lessons learned from the project also illustrate the constraints of the

selected policy goals:

·

Policy goals on national or international scale might have been too ambitious. The

project received very good feedback on local scales by demonstrating successful impacts

on local landuse planning and local landuse techniques. It also received positive feedback

on regional scales provided that activities were imbedded in existing structures or concepts

(e.g. the Lower Danube Green Corridor initiative). However, the input on national or even

international level was only weak or impossible. This would require a longer and more

intensive project design.

·

The principle of using "bottom up models" to influence top down decision-making is

important but not entirely sufficient. A pure focus on "bottom up" activities will not show

significant large-scale impact unless activities are not coordinated with ongoing "top down

elements" (e.g. river districts that are preparing WFD implementation processes,

authorities that are working on agri-environmental measures or N2000 designation etc.).

·

With regard to this, the selection of the case study locations was perhaps not

completely appropriate. While the sites provided very adequate opportunities to test and

demonstrate restoration activities related to land-use change, all of the selected regions

were far-off from central decision makers and only the Slovakian and Romanian pilot case

managed to demonstrate a significant footprint on the regional and small footprint on the

national level.

·

The aim "to assist `Danube River Basin countries' to prepare new land-use and wetland

policies and legislation in line with existing and emerging legislation" was also too

ambitious. To aim to assist "Danube River Basin Districts" would have been the more

realistic objective with hindsight.

·

Due to administrative delays at UNDP/GEF concerning the set up of the second tender

process the policy work during the second project phase was facing major temporal

constraints and original goals had to be implemented in too tight a timeframe (see

below).

WWF DANUBE-CARPATHIAN-PROGRAMME / BALTZER ET AL.

Integrated Land Use Assessment and Inventory of Protected Areas

page 13

One overarching policy finding of Output 1.4 is that information on the policy drivers (i.e.

wetlands as integral part of the EU WFD, EU CAP reform, EU Flood Directive, Natura 2000

Directive) is still lacking locally. At local site levels there is still a chronic shortage of information

and knowledge about recent, new and emerging policies and the opportunities associated with

them, including financial instruments, for promoting sustainable land use. To work with local

communities to overcome such serious shortcomings represented the most promising part of

Output 1.4.

·

In terms of "hard" policy findings, many European or Danube-wide policies already

support the actions suggested for each pilot site. For instance, the WFD and other EU and

international instruments such as the Natura 2000 directives and Bern Convention clearly

support wetland restoration as a contribution to Integrated River Basin Management

initiatives. However, implementation is still lacking. Similarly, the ongoing reform of the

Common Agricultural Policy, SAPARD and Rural Development Directive will offer a range of

supportive instruments, although knowledge and uptake of these remains low. The

Horizontal Guidance on Wetlands in principle offers guidance on how wetland restoration,

protection and sustainable management can actively contribute to achieving the WFD

objectives. However, implementation of measures is also quite often lacking.

·

Analysis of "soft" policy aspects from Output 1.4 showed that there are often different

realities in rural areas and at national level possibly as a result of a bottleneck in

administrative capacity at local or regional levels. Access to information on many policy

instruments should also be improved and there is an urgent need to improve the active

involvement of the public, in line with Article 14 of the WFD. The three pilot sites all

highlighted the need for immediate capacity building of governmental institutions and

administrations at regional and local levels for WFD and other types of policy and

programmatic information provision, public awareness and implementation. Such capacity

building actions should also be extended to include NGOs and other stakeholders who can

play a constructive role in implementation of the WFD and other policy instruments.

Implementation constraints

The implementation of proposed practical rehabilitation work at each pilot site, however, faced

several constraints and unexpected events during the second project phase that led to delays in

the implementation and highlight a number of the constraints that restoration projects may face:

a. Adverse weather conditions. The project region was affected by very hard weather

conditions during the second project period between 2005 and 2006: The winter 2005/2006

brought a lot of snow and very low temperatures (down to minus 20 degree) and both years

were hit by major flood events (with a flood probability of more than 100 years). Some of the

planned restoration measures in Croatia and Romania were influenced or delayed due to these

unexpected events.

b. Loss of local project leader. Furthermore, project work in Croatia was affected by the

dramatic fatality of our local project manager David Reeder, who died completely

unexpectedly in September 2006.This caused major delay in the implementation of the work

programme in Croatia since the project management was not able to find an adequate

substitute for David Reeder within the remaining project period. With support of the DRP

headquarters in Vienna, but already with a significant delay, the management team of Output

1.4 succeeded to establish a new coordination team for implementing the remaining measures

UNDP/GEF DANUBE REGIONAL PROJECT

Executive Summary

page 14

at Zupanijski canal in Croatia. This team will be managed directly by Mr. Danko Biondic of

Croatian Waters representing a successful integration of the project in national administrative

structures.

c. Administrative delays under the project management: the start of the second project

phase was delayed due to administrative problems at the coordinating office of the Danube

Regional Project (UNDP/GEF office in Vienna) to set up the tender process. In consequence the

project faced a significant loss of continuity creating partly losses of credibility at the local

scale and lack of institutional memory at all levels of project management (caused by staff

changes). To reactivate former contacts more time was required than expected. This also

triggered some project delays, particularly in Romania. Nevertheless, delayed implementation

of individual measures is still ensured due to existing contracting agreements with local

consultants.

Delayed activities to be completed under the Output 1.4 by spring 2007:

In Croatia:

·

Installing a second hydraulic structure or providing an equivalent solution to raise surface

water levels in the channel and adjacent Marcina jama reed beds; if possible realise a

solution to reconnect the system with a semi-natural channel and without hydraulic

structures.

·

Constructing a 150m channel to rehabilitate reed beds around Zanos or providing an

equivalent solution.

·

A workshop for local stakeholders to review the technical steps described above was

postponed until the implementation of the measures by Croatian Waters.

In Romania

·

The work on re-profiling the Elan river channel was partly conducted by the natural flood

events. In summer 2006, part of the dikes was broken and the old meander system was

flooded and re-connected with the Elan river system. Further negotiation is needed to

maintain this situation.

·

The work to improve hydrological conditions at Mata Radeanu fish farm (at confluence of

Elan and Prut rivers) was delayed as the fishpond was completely flooded in summer 2006.

·

The planting of native Salix and Populus saplings along the Elan river had to be postponed

due to very high water levels.

WWF DANUBE-CARPATHIAN-PROGRAMME / BALTZER ET AL.

Integrated Land Use Assessment and Inventory of Protected Areas

page 15

1. INTRODUCTION

This report covers activities within the framework of the UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project (DRP),

the long-term development objective of which is "to contribute to sustainable human development

in the Danube River Basin through reinforcing the capacities of participating countries to develop

effective mechanisms for regional cooperation in order to ensure protection of international waters,

sustainable management of natural resources and protection of biodiversity".1

The DRP was designed in two independent phases. The goal of the first phase was to prepare and

initiate basin-wide capacity-building activities. These initiatives then should be implemented and

tested during second phase of the project (December 2001 to November 2003), for further

consolidation during DRP Phase 2 (June 2005 to December 2006). The DRP comprises 20 Project

Outputs, together covering more than 80 separate activities, which are grouped into four

immediate objectives:

Objective 1: Support for policy development favouring creation of sustainable ecological

conditions for land use and water management;

Objective 2: Capacity building and reinforcement of transboundary cooperation for the

improvement of water quality and environmental standards in the Danube River Basin;

Objective 3: Strengthening of public involvement in environmental decision-making and

reinforcement of community actions for pollution reduction and protection of

ecosystems;

Objective 4: Reinforcement of monitoring, evaluation and information systems to control

transboundary pollution, and to reduce nutrients and harmful substances.

The present study covers Phase 2 activities within Project Output 1.4 Integrated Land Use

Assessment and Inventory of Protected Areas, one of eight Project Outputs under the overall

umbrella of Objective 1. In particular, this report provides findings and recommendations designed

to support sustainable, integrated land-use patterns. These land-use patterns were planned to be

capable of delivering multiple socio-economic and ecological benefits, including nutrient reduction

in streams and rivers.

The report also introduces an overview of the implementation of floodplain and wetland restoration

and management measures, including rehabilitation and/or restoration where appropriate. This

report deals only with implementation measures related with the Integrated Land Use element of

Project Output 1.4. In this respect, it is important to underline that certain activities and outputs

under other Project Outputs are of particular relevance to the issues dealt with in this report.

1 Source: DRP Project Implementation Plan, available at http://www.icpdr.org/undp-drp/

UNDP/GEF DANUBE REGIONAL PROJECT

1. INTRODUCTION

page 16

These include the following:

·

Policy development river basin and water resource management, and agriculture

Project Output 1.1

Development and implementation of policy guidelines for river

basin and water resources management (Activities within this

Output have been developed to mirror the development of

guidelines in the framework of the Common Implementation

Strategy (CIS) of the EU Water Framework Directive (WFD). Of

particular note is Activity 1.1-11 which has been instrumental in

producing a Draft Public Participation Strategy for the DRB,

reflecting the emphasis of the WFD on public participation as a key

cross-cutting issue. The results of this Output should be seen in

the light of the CIS Horizontal Guidance on Wetlands and the

WFD, published in November 2003);

Project Output 1.2

Reduction of nutrients and other harmful substances from

agricultural point and non-point sources through agricultural policy

changes;

Project Output 1.3

Development of pilot projects on reduction of nutrients and other

harmful substances from agricultural point and non-point sources

through agricultural policy changes.

·

Public participation

Project Output 3.1

Support for institutional development of NGOs and community

involvement (notably through establishment of the Danube

Environment Forum);

Project Output 3.3

Organization of public awareness-raising campaigns on nutrient

reduction and control of toxic substances.

These two Outputs have also contributed to preparation of the

Public Participation Strategy for the Danube River Basin, (see

Output 1.1).

·

Monitoring and assessment

Project Output 4.3

Monitoring and assessment of nutrient removal capacities of

riverine wetlands. (Activities under this Project Output have also

been implemented in both phases by WWF, involving the

development of a draft assessment methodology for testing at

pilot sites and monitoring the effect of wetland restoration of Lake

Katlabuh in the Ukrainian part of the Danube Delta).

The outputs of all of the above Project Outputs will need to be taken into consideration to support

to sustainable development in the Danube Basin. Effective mechanisms for regional cooperation to

ensure the protection of international waters should reflect the lessons learned from all different

project components.

WWF DANUBE-CARPATHIAN-PROGRAMME / BALTZER ET AL.

Integrated Land Use Assessment and Inventory of Protected Areas

page 17

1.1. Aims & Objectives

1.1.1. overall

aims

The DRP Project Implementation Plan and the Terms of Reference for Project Output 1.4 identify

the following overall aims:

·

The primary focus is to assist DRB countries to prepare new land use and wetland

rehabilitation/protection policies and legislation in line with existing and emerging

environmental legislation.

·

The Project Output shall address common inappropriate land uses and subsequent impacts

on ecologically sensitive areas and wetlands including the effects of transboundary pollution

with particular attention to nutrients and toxic substances.

·

While targeting action at a high policy level, the Output is also directed towards

demonstrating pragmatic implementation of appropriate land use management on the

ground in pilot activities.

1.1.2. Specific purpose and objectives of project phase 2

Based on the results of project phase 1, the purpose of phase 2 (July 2005 December 2006) was

the implementation of identified approaches for integrated land use assessment, policy concepts,

and mitigation measures. Phase 2 aimed to test the outputs of phase 1 in the context of the three

selected pilot sites and tried to demonstrate its feasibility. It also aimed to magnify the pilot study

results to support Danube River Basin countries in implementing the WFD on a broader scale.

This comprises the following objectives:

·

Implementing of proposed technical mitigation measures and alternative concepts for

achieving integrated land use management at each pilot site (including practical restoration

work, regulatory issues, economic fines and incentives, compensation payments etc.);

·

Mainstreaming of wetland conservation and restoration activities into rural development

plans and policy on local, regional and national levels and securing governmental

commitments to implement the newly proposed concept for integrated land use in the

selected case studies, and

·

Demonstrating mechanisms for sustainable wetland use and disseminating project

results in the Danube Basin.

1.2. Structure of this report

The structure of the report has been designed to present the project results and analysis according

to the structure of the projects objectives and their relation to the separate phases of the project.

Section 2 sets out the aims and objectives of activities under the integrated land-use part of

Project Output 1.4, with reference to the Terms of Reference established by UNDP/GEF. This is

followed by a section providing a description of the project sites and activities undertaken, in three

different DRP Pilot Sites in Croatia, Romania and the Slovak Republic, respectively. The final

chapter sets out the findings and lessons learned which are relevant at a range of different levels

(e.g. field and policy; local, national and international) and for a range of different actors (e.g. Pilot

Site stakeholders, national authorities, ICPDR, EC etc).

UNDP/GEF DANUBE REGIONAL PROJECT

2. PROJECT SITE DESCRIPTIONS

page 18

2. PROJECT

SITE

DESCRIPTIONS

Olsavi

Olsav ca pilot site

Elan Valley p

y ilot

Vir

Vi o

r vi

v tica

ti pilot site

ca

Figure 1:

The Danube River Basin and locations of the selected three pilot sites in

the Slovak Republic (Olsavica); Romania (Elan Valley), and Croatia (Virovitica).

2.1. The Olsavica valley, Tisza sub-basin, Slovakia

Activities in Slovakia were focused on the Olsavica valley which is located in Levoca district of

Presov county and lies within the Hornad Basin (Tisza sub-basin, Figure 2). The whole district is

on the border between Central and Eastern Slovakia, and located in the eastern part of the

Levocske vrchy hills, which are part of the Carpathian Mountain range (720920 m above sea

level).

·

Project area

The total area of the pilot site is 1367 ha. The border was defined on the catchment area of

Olsavica stream, which is a tributary and one of the spring systems of the Torysa River.

According to the regional geomorphological division (Mazur, Luknis 1980) Levocske vrchy

belongs to the Western Carpathians. Levocske vrchy (Levoca Hills) is a mountainous area of

north-eastern Slovakia built of flysch rocks with a central ridge. The central part of the area is

the Levocska vysocina. The central ridge is huge with forks separated by deep valleys. The

highest hill is Cierna hora at 1,289 m above sea level. The Levocska vysocina borders the

Levocska vrchovina in the west and the Levocske planiny in the south. The relief has an upland

character, but also has plateau characteristics.

WWF DANUBE-CARPATHIAN-PROGRAMME / BALTZER ET AL.

Integrated Land Use Assessment and Inventory of Protected Areas

page 19

·

Land-cover

The most dominant land-cover types are spruce forests, grasslands, extensive pastures with

European larch (Larix decidua) and arable land. The regional geological structures mean that

the area has an abundant groundwater supply, with the sandstone yielding a number of fissure

springs. Wetlands are represented by fragments of submontane and montane floodplain forests,

fens, tall sedges and wet grasslands, though these are much reduced due to human impacts

(see below).

Figure 2:

Olsavica river basin is located in Levocske vrchy Mts. (Hornad Tisza

Basin) with total area 13 km2.

·

Major threats

The village Olsavica has been subjected to significant flooding with consequent property and

personal damage, since the mid-1980s. The flooding is thought to be largely the result of

agricultural intensification, during the late 1970s and early 1980s. Intensification measures

included installation of a dense network of subsurface and surface drainage canals, and removal

of the historical terraces and grassland buffers. Springs and wetlands in upper part of Olsavica

valley have been drained and subjected to intensive agriculture, fertilizer and manure use.

In addition to local flooding, the area suffers from massive soil erosion, which, together with

excessive runoff, contributes to sediment and nutrient loading of watercourses. These factors

together are likely to have a negative impact on downstream water quality and to increase the

risk of flooding elsewhere in the basin. Soil erosion has led to a decrease in the area of land

available for arable cultivation.

·

Conservation values

The area has high nature conservation value, but Olsavica valley is not included within any

formally recognised protected area, although a significant part of it is designated as a water

supply protection area. Zone A, established in 1983 should positively influence some 1,062 ha

of agricultural land, while Zone B, established in 1993 by a decision of the District Environment

Department in Presov, should apply to a further 562 ha of farmland. In practice, the farming

UNDP/GEF DANUBE REGIONAL PROJECT

2. PROJECT SITE DESCRIPTIONS

page 20

cooperative does not strictly respect the water supply protection areas, because there is no

compensation/incentive for doing so.

·

Socio-economical situation

Olsavica depends on farming and has suffered from rural depopulation in recent years. The

principal economic stakeholder is the agricultural enterprise `OlsavicaBrutovce' which farms

some 2,290 ha, of which approximately 1,936 ha is grassland. The remaining c.350 ha are

located mainly in the upper part of the valley and subject to intensive arable production. The

process of land (re-)privatization in Olsavica Valley was initiated several years ago but is still

incomplete. Most private landowners rent their land to the agricultural cooperative.

2.2. Lower Elan valley, Prut sub-basin, Romania

Activities in Romania were concentrated on the Elan River, a tributary of the Prut River, in

Vaslui and Galati Counties (Figure 3). The Elan basin lies within the Moldavian Plateau of

eastern Romania. The total surface of the basin is of 601 km2. The local topography shows

typical features of a range of "rolling hills".

·

Project area

The `Lower Elan' Basin pilot site comprises an area of almost 3,300 hectares being situated

immediately upstream of the confluence between the Prut and Elan Rivers. The main village of

Murgeni within the Lower Elan basin lies 35 km east of the city of Barlad (Vaslui County) and 90

km north of the city of Galati (Galati County) as measured by road distance. Within the pilot

project site, about 620 hectares represent the floodplain, out of which permanent wetlands

cover 382 hectares (divided into 364 hectares of reed swamp and 18 hectares of water bodies).

·

Major threats

The natural Elan ecosystem has been disrupted in several ways. Upstream, the Posta Elan

Reservoir was intended to fulfill combined flood protection and water supply functions. However,

due to construction of the reservoir, dike-building along the right bank of the Elan River, and

canalisation of the main channel, this side of the floodplain is no longer flooded and large areas

were developed for agricultural use during the Ceaucescu period. The land was leveled and

extensive drainage systems were installed. After the political changes of the 1990s the collective

farms were broken up and ownership was reclaimed by local inhabitants. The former floodplain

drainage system collapsed and the land is now cultivated by the landowners. The left-bank

floodplain has effectively acted as a sedimentation basin, with a rapid build-up of sediment.

Excessive hillside erosion is recognized as a major environmental threat throughout the

Moldavian Plateau of eastern Romania. In 1950, the traditional hillside agricultural system of

cultivation up and down slopes (i.e. across, not with, the contours) prevailed. Most of the land

was split into excessively small plots, each of less than one hectare in size. Except in a few

localised areas, there were no concerns about the threat from soil erosion and a minimum

awareness of conservation practices. After 1950, theses areas were incorporated into collective

farms. Many innovative research studies on soil erosion control were initiated and conservation

practices were considered a national priority. By the end of 1989, up to 30 percent of the

agricultural land with erosion potential had been ameliorated. To make things worse, during the

last decade, the state has ceased funding for soil erosion control and such investment does not

represent a priority for landowners.

WWF DANUBE-CARPATHIAN-PROGRAMME / BALTZER ET AL.

Integrated Land Use Assessment and Inventory of Protected Areas

page 21

Figure 3:

Location of the pilot project site in Romania (3300 ha total, 382

hectares represent wetlands) in the Elan River Basin, with a total area of 601 km2.

·

Conservation values

The Lower Elan wetlands are extremely important, for both people and biodiversity because of

their functions for flood peak mitigation, agriculture, water supply, fisheries, and habitats for

flora and fauna: The Lower Elan wetlands also help to reduce flood peak mitigation, provide

agriculture support, water supply, fisheries support and habitat provision for flora and fauna.

Although damaging floods are far less prevalent than formerly (due to dam construction

upstream) the Lower Elan Floodplains may still have a vital role to play during exceptional

rainfall events.

·

Socio-economical situation

The local commune, Murgeni, has around 8,660 inhabitants and an area of 13,240 hectares.

Because there is very little industry in the area the inhabitants use their land for livestock

rearing (sheep and cattle) and extensive cultivation of crops (especially maize and sunflower

but also some vineyards) without any assistance from irrigation. Cattle are allowed to graze in

certain areas throughout the year, and, after the hay crop is cut, graze the whole floodplain. In

case of severe drought (as in 2003) the reed beds are used as food for cattle. There is a

fishpond complex close to the confluence of the Elan and Prut, but collapse of the retaining dike

means that there is insufficient water for fish production and biodiversity values have also

decreased.

The resource functions of the floodplain are also significant. Drinking water for people and

livestock, small-scale irrigation and groundwater replenishment is desperately needed in the

area given that the average water deficit is about 200 mm/year. Provision of potable water is a

UNDP/GEF DANUBE REGIONAL PROJECT

2. PROJECT SITE DESCRIPTIONS

page 22

major challenge given that the water from the three groundwater boreholes in the area cannot

be used for drinking purposes without treatment.

The Lower Elan wetlands also support the deposition of nutrient-rich sediments carried by the

river. This brings important benefits further downstream to the Prut and Danube Rivers, through

the reduction of nutrient loads, mainly nitrogen and phosphorous from agricultural sources, but

also from human wastes and industrial discharges. Some of these nutrients are taken up by

wetland/floodplain vegetation and reed harvesting in winter effectively removes them from the

system, as well as providing important raw materials for local villagers.

2.3. The Zupanijski canal, near Budakovac village, Drava sub-

basin Croatia

Activities in Croatia were focused on the Budakovac wetlands. They lie on the old floodplain of

the River Drava in Croatia, southeast of the city of Virovitica (Figure 4). Before river regulation,

drainage and land reclamation works were carried out, from the late Eighteenth Century

onwards. This was a flood-prone region where the river meandered extremely, creating an

extensive pattern of oxbow lakes, river branches and islands on both sides of the river.

·

Project area

The entire study-area, extending laterally towards the river, covers some 18 km2 and contains

four villages. The pilot site is 2350 ha in extent in a section of the River Drava, which forms the

basis of the border between Hungary and Croatia. Some oxbows remain, although atrophied,

but the meander scars are clearly evident on modern maps through land-use variation and

particularly on multi-band satellite images. Many of these oxbows, both in Hungary and Croatia,

are suitable for rehabilitation. This section is a classic expression of European lowland, lower-

course rivers.

·

Major threats

River regulation and drainage works since the Nineteenth Century have lowered the river-level

and the water-table, such that the wetlands are now much reduced. This has been exacerbated

in 2002 by the deepening of the Zupanijski canal, a canalized river, which runs alongside the

wetlands, in such way that the level of the Budakovac oxbow lake has fallen by one meter, as

has the groundwater, and many old oxbows and branches have almost dried out.

Where the treated mix of municipal and industrial wastewater enters the Zupanijski canal, the

presence of nitrates and phosphates remains so high that the water is Category V in quality.

Further downstream the canal passes several villages and the quality drops, presumably

indicating that untreated wastewater from these settlements reaches the canal. None of the

villages benefits from a piped water supply or from any form of wastewater treatment. The

result is that by the time the canal reaches the Drava River, the water is Category II in terms of

nitrate and phosphate content. Under certain circumstances, water quality entering the Drava

is thought to be significantly lower. For example, during annual maintenance at the Viro facility,

municipal wastewater is fed directly into the Zupanijski canal without treatment. Furthermore,

though nutrient concentrations are theoretically diluted in wet periods, the fact that storm water

and sewage are not separated in the municipality of Virovitica makes treatment difficult due to

the excessive volumes involved.

WWF DANUBE-CARPATHIAN-PROGRAMME / BALTZER ET AL.

Integrated Land Use Assessment and Inventory of Protected Areas

page 23

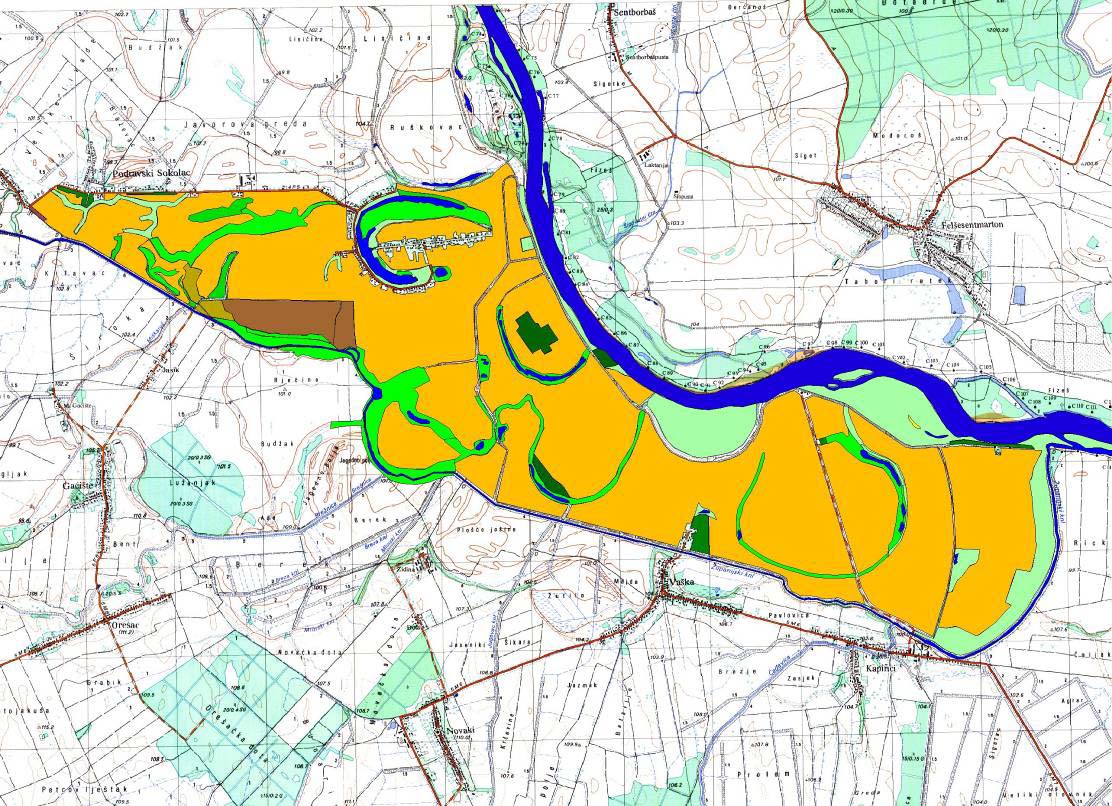

Figure 4:

Location of the pilot study site in the Drava river basin southeast of the

city of Virovitica with total area of 2350 ha.

·

Conservation values

The Zupanijski Canal and the former floodplain wetlands show a high potential for bio-

remediation and therefore also a high potential for raising the average quality of water reaching

the Drava-Danube system. This triggers additional conservation benefits, including improved

fishery production and a general improvement in wetland habitat extent and quality. The most

effective bio-remediation is on a stretch where the canal could not be straightened because of

inaccessibility to machinery, so it follows the curve of the old natural oxbow for a few hundred

metres. Here, water quality reaches Category I.

·

Socio-economical situation

Most people living in the villages within the pilot site make their livings from agriculture and

some from forestry. Rural development is urgently needed so that people in the region can

share the same opportunities as those elsewhere in Europe, with provision of piped drinking

water and adequate sanitation being a basic step. The area is environmentally rich and a path of

sustainable development has great potential; the development of long-term environmental

management schemes and peaceful transboundary co-operation are fundamental. Following the

fall of the former Socialist Federative Republic of Yugoslavia and the establishment of the

Croatian Republic in 1990, land (re-)privatization began in 1995. As elsewhere in Central and

Eastern Europe, this process has been very complex; many owners failed to claim back their

land or could not substantiate their claims. As a result, some land is now owned privately, some

by the state; some is owned privately but used by the state, and vice-versa. In addition,

Hrvatske vode (Croatian Waters) owns all waterways and some six metres of bank on either

side.

UNDP/GEF DANUBE REGIONAL PROJECT

3. IMPLEMENTATION OF ACTIVITIES IN PHASE 2

page 24

3. IMPLEMENTATION OF ACTIVITIES IN PHASE 2

3.1. Summary of Activities

In line with the aims and objectives described in Section 2, the activities set out in the Terms of

Reference were planned to be implemented primarily between September 2005 and June 2006. A

project team was formed by WWF International's Danube-Carpathian Programme to coordinate this

work at international level and to ensure field-level implementation at the selected Pilot Sites. The

methodology for assessing land use was successfully applied at all three pilot sites and other

potential users including national and local authorities in the Danube River Basin, NGOs and

international organisations such as the Ramsar Secretariat are encouraged to make use of this

methodology.

In summary the following activities have been completed successfully by the project Output 1.4:

(a) Activities related with the application of the methodology for assessing land

use:

1. Application of the methodology at the selected three pilot sites Olsavica valley, Tisza sub-

basin; Lower Elan valley, Prut sub-basin, Romania; and Slovakia Zupanijski canal, near

Budakovac village, Drava sub-basin Croatia;

2. Assessment of the applicability of the methodology to develop sustainable land-use

concepts at each pilot site and to find practical and policy measures required to move

towards more sustainable land use patterns at each pilot site.

(b) Activities related with the implementation of proposed restoration

measures, communication, and policy action at the three selected pilot sites:

In Slovakia (Olsavica Valley):

1. Building of small dams on selected streams to control channel erosion;

2. Reopening of small meanders on canalised stream;

3. Restoring wet grasslands to act as a buffer zone between agricultural land and the stream;

4. Blocking of underground drainage system to restore water tables;

5. Planting trees on steep stream banks to control soil erosion;

6. Fencing of springs to prevent damage from grazing; and

7. Promoting restoration more widely through public awareness information.

In Romania (Lower Elan Valley):

1. Conducting a feasibility study and rehabilitation measures of the lower Elan floodplain

downstream of the confluence with Sarat Creek through meander restoration (activities

have been partly completed because of two major flood events in the region, they will

continue after project termination, see also below: `constraints and unexpected events');

2. Re-profiling of parts of the Elan river channel (activities have been partly completed

because of two major flood events in the region, they will continue after project

termination, see also below: `constrains and unexpected events');

3. Control of soil erosion on hill slopes through changed land-use, implementation of better

agricultural practice, land reclamation and afforestation;

WWF DANUBE-CARPATHIAN-PROGRAMME / BALTZER ET AL.

Integrated Land Use Assessment and Inventory of Protected Areas

page 25

4. Declare Lower Elan floodplain a protected area; and

5. Improve public awareness and train civil society organisations especially those in local

communities and schools.

In Croatia (Zupanijski canal):

1. Geographical survey of the area to investigate most suitable measures to reconnect the

Drava river to adjacent Podravski Sokolac wetland and Budakovac oxbow and consequently

raise local water tables;

2. Feasibility study to implement the most suitable measure to reconnect water to reconnect

the Drava river to adjacent Podravski Sokolac wetland and Budakovac oxbow and

consequently raise local water tables;

3. Dissemination of the findings, conclusions and recommendations from these activities.

Some of the activities to implement restoration measures, however, had to be postponed due to

the following unexpected events:

·

In both years 2005 and 2006 the Danube basin was affected by very hard weather

conditions. In summer 2005 and in spring 2006 the lower Danube region was hit by

extreme flood events. More than 80 people were killed and more than 40,000 people had

to be evacuated in the region of the Lower Danube Green Corridor alone. In addition, the

winter 2005/2006 was very hard and brought a lot of snow and very low temperatures.

Some of the planned restoration measures in Croatia and Romania were influenced or

delayed due to these unexpected weather events. It was agreed with the coordinator of the

DRP coordinator to postpone some of the activities to ensure their successful

implementation. The results of the final project output needs to be evaluated in the context

of these adverse weather circumstances.

·

Furthermore, project work in Croatia was affected by the fatality of our local project

manager David Reeder who died in September 2006. This caused a major delay in Croatia

since the project management was not able to find an adequate substitute for David within

the remaining project period. With support of the DRP headquarters in Vienna, the project

team of the Output 1.4 managed to establish a new coordination group for implementing

the remaining measures at Zupanijski canal in Croatia. This team will be managed directly

by Mr. Danko Biondic of Croatian Waters. This represents a successful integration of the

project in national administrative structures. The final implementation of the project

activities is contractually terminated in Spring 2007.

·

Finally, the start of the second project phase was delayed due to administrative problems

at the coordinating office of the Danube Regional Project (UNDP/GEF office in Vienna). In

consequence the project faced a significant loss of continuity creating partly losses of

credibility at the local scale and lack of institutional memory at all levels of project

management (caused by staff changes). To reactivate former contacts more time was

required than expected. This also triggered some project delays, particularly in Romania.

Nevertheless, implementation of individual measures is still ensured due to existing

contracting agreements with local consultants.

UNDP/GEF DANUBE REGIONAL PROJECT

3. IMPLEMENTATION OF ACTIVITIES IN PHASE 2

page 26

(c) The following specific activities of the Output 1.4 are delayed and will be completed

by spring 2007:

In Croatia:

1. Installing a second hydraulic structure or providing an equivalent solution to raise surface

water levels in the channel and adjacent Marcina jama reed beds; if possible realise a

solution to reconnect the system with a semi-natural channel and without hydraulic

structures;

2. Constructing a 150m channel to rehabilitate reed beds around Zanos or providing an

equivalent solution;

3. A workshop at which local stakeholders have to review the technical steps described above

was consequently postponed until Croatian Waters will implement the measures.

In Romania

1. The work on re-profiling the Elan river channel was partly conducted by the natural flood

events. In summer 2006, parts of the dikes were broken and the old meander system was

flooded and re-connected with the Elan river system. Further negation is needed to remain

this situation.

2. The work to improve hydrological conditions at Mata Radeanu fish farm (at confluence of

Elan and Prut rivers) was delayed after the fish pond was permanently flooded in summer

2006;

3. also the planting of native Salix and Populus saplings along the Elan river had to be

postponed due to very high water levels.

In Slovakia:

No significant project delay occurred.

3.2. Activities related to the application of the methodology for

assessing land use

3.2.1. Applying the methodology in the selected three pilot sites

In the first project period (2001-2003) WWF's project coordination team together with its partners

produced a methodology consisting of seven stages:

1. GIS mapping of the pilot site, including key water and wetland features;

2. Identifying

all

strategies, plans and policies that relate to activities undertaken in and

around the pilot site and the threats, impacts and pressures to wetlands and floodplains at

the pilot site;

WWF DANUBE-CARPATHIAN-PROGRAMME / BALTZER ET AL.

Integrated Land Use Assessment and Inventory of Protected Areas

page 27

3. Assessing

the

ecologically optimal conditions for wetland management and nutrient

reduction at the pilot site2.

4. Undertaking

a

gap analysis to assess the difference between current and `ecologically optimal'

land-use for wetlands and nutrient reduction in the area as a step towards generating options

for appropriate land-use;

5. Organising

participatory stakeholder workshops to generate appropriate land-use options

including a vision and objectives for the catchment;

6. Undertaking

a

policy analysis to identify the policy and funding obstacles or opportunities for

each of the management options;

7. Selecting options and developing action plans to take the work forward.

This methodology has been applied in three pilot sites in the Slovak Republic (Olsavica valley, in

the uppermost Tisza basin), in Romania (Lower Elan Basin, Prut River Basin) and in Croatia,

Romania (Drava floodplain, near Virovitica; see Figure 1). It is important to bear in mind that the

application of the methodology was not a strictly chronological sequence and many of the stages

were developed simultaneously. Indeed, the need to treat the methodology as a flexible tool and

not as a prescriptive, step-by-step, strictly controlled `recipe' was a key point that underlined in the

findings of the first project phase.

3.2.2. Lessons learned from applying the methodology at the three different

pilot sites

3.2.2.1. GIS mapping - a crucial starting point

For each pilot site, GIS maps were prepared showing the theoretical `ecological optimum' for land

cover/land use, taking into account the former distribution and extent of wetlands based on field

evidence (e.g. geomorphology/topography, pedology and surviving natural/semi-natural vegetation

and habitats), historical maps/documents, and discussions with local people. The `ecological

optimum' was then used to defining feasible and appropriate alternatives for future land use and

other inputs including the constraints inherent to working in the `real world' (see Romanian

example in Figure 5). At all three pilot sites GIS mapping was considered to be the most successful

tool to support an ecological assessment and to provide potential restoration alternatives. This

approach was appreciated at all three pilot sites. However, it was also emphasised that a

successful use of the mapping tool requires qualified institutions, equipment and experts. This

might create difficulties if the methodology was to be transferred to other distant rural regions.

2 Note that the terminology of "ecological optimum" does not imply that this is necessarily the desired state of

land-use. Rather, it is the land-use that would, if no other factors were operating, provide the best ecological

conditions. Socio-economic factors may mean that, while the ecologically optimal conditions are not

themselves realistically achievable, land-use that incorporates some elements of the ecological optimum might

be appropriate.

UNDP/GEF DANUBE REGIONAL PROJECT

3. IMPLEMENTATION OF ACTIVITIES IN PHASE 2

page 28

Figure 5:

Romania example for GIS mapping: (top left) project location in

Romania, (bottom left) current land-use; (right) proposed alternative landuse to halt

ongoing soil erosion along the hills.

3.2.2.2. Data availability the essential baseline

At all three pilot sites good maps and data were available. Detailed studies, however, had to be

produced according to the needs of each pilot site. In Slovakia, e.g. the Slovak Technical

University, Department of Water Management carried out four studies for the Grassland Medium

Sized GEF project oriented for flood prevention and soil erosion. In Romania, good maps of the

project site were available both at the local and regional levels. The project team was able to

gather all key socio-economic and biodiversity data required. Local authorities were extremely

cooperative, providing the requested maps at suitable scales and all needed information. The most

useful was the information on the local agriculture conditions and landownership. In Croatia data

access was very good at local scale but rather difficult on regional scales. Support by national

authorities was weak. At all three pilot sites it was stressed that success and failure of applying the

WWF DANUBE-CARPATHIAN-PROGRAMME / BALTZER ET AL.

Integrated Land Use Assessment and Inventory of Protected Areas

page 29

methodology depends on sound data availability and therefore indirectly on the power of existing

personal networks. Future wetland restoration projects should therefore focus on establishing a

well-linked and well-coordinated network of scientists, authorities and project staff, which can

guarantee continuity on the ground. The main gap was identified as the difficulty to receive

detailed information e.g. on precise position, contours and slopes of small streams or on the

hydrological functioning of the site. Since this information is essentially needed to design sound

restoration measures the temporal project frame was sometimes too strict. Further projects in

other regions should therefore include already a "buffer" in the project proposals to ensure that the

compilation of reliable background information will be feasible.

3.2.2.3. Visible information material a key to create convincing arguments

At all three pilot sites the importance of visible and communicative information material was

demonstrated. Translating administrative, cadastral, topographic, soil and vegetation information

into GIS based overview maps to demonstrate the differences between historical and current land

use practices created a lot of stakeholder support. In particular GIS mapping proved to be a very

helpful tool to integrate various information, especially for land use assessment. The maps

produced served as a very good basis to select the necessary measures in order to improve land

and water resources and management techniques at each pilot sites. They also played a key role

during the various stakeholder meetings to educate local participants. Visible information (photos,

maps, animations) have been considered to be key to create convincing arguments on local

stakeholder level. However, it is very important that the information material will be used in a

simple language without including too many scientific data. Therefore, the comparison between

historical maps, images or data with current situation should be applied whenever the methodology

would be used in other regions or river basins.

3.2.2.4. The influence of individuals - "go or no go" for project success

Key for gathering successful baseline data and general project support was the fact that local

consultants are closely connected with the local, regional and if possible national administration

(e.g. as the Romanian project consultant was employed by `Romanian Waters'). Unless, there is no

such direct link to relevant authorities, the impact of individual projects on a larger scale is very

much restricted. Our lessons learned from Croatia clearly indicate that information has been

available at county level. Copies of the maps of the study area and detailed satellite maps were

provided for free. However, within the central government, it was very difficult to gain information

more abstracted from the project site. At the ministerial level, personal contacts were helpful to

receive specific information. Support and follow-up activities were also more difficult to maintain at

the central government level.

Given the fact that this project was implemented under the umbrella of the UNDP/GEF Danube

Regional Project some of the project activities might have been implemented under unusually

advantaged conditions. In contrast, the applicability of the methodology in other regions could be

rather difficult unless prominent donor support was provided. Finding the right contact person on

the ground who will be able to connect authorities, institutions and highly recognised partners (e.g.

donors, VIPs, international organizations) will be key for success or failure of future projects.

UNDP/GEF DANUBE REGIONAL PROJECT

3. IMPLEMENTATION OF ACTIVITIES IN PHASE 2

page 30

3.2.2.5. Identifying strategies, plans & policies necessary but not sufficient

During this project phase one of the biggest challenges was getting in contact with the Croatian

Waters Company (HV), who holds all of the technical data, which were needed for the

implementing the second project phase. The physical planning of this study area was entirely

within the jurisdiction of the county authorities. Lack of access to the right key persons at national

administrative level caused therefore significant project delays. This constraint marks a critical

lesson learned from the project. It is vital to the success of the project to identify individuals within

the local and national government that will remain in their position over a long period of time that

will support the restoration activities and feel responsible for the successful implementation of the

project. A "system-inherent ambassador" has to be found who will ensure that the suggested

alternatives will be also implemented in practice. Sufficient buy-in with key stakeholders is required

to ensure smooth access to resources and decision-makers.

3.2.2.6. Gap analysis to assess the difference: current state & `ecologically

optimal'

The assessment of the ecologically optimal conditions for wetland management and nutrient

reduction was designed to portray the ecological conditions that are best suited to the site.

However, this does not imply that this is necessarily the desired state of land-use and therefore a

blueprint for restoration. This part of methodology was important to identify root causes of

biodiversity loss and the consequences of ignoring those causes.

It was also essential to help plan the future restoration measures. All three case studies found it a

very useful tool and supported discussions with stakeholders. The principle of this part of the

methodology is shown in Figure 6. However, at all three pilot sites it was shown that the `ecological

optimum' concept can be an unwanted distraction, since even with most careful explanation it is

likely to be misinterpreted by some stakeholders as the `target scenario' for environmentally

oriented organizations such as WWF and its partners. It seems to be the use of the word

`optimum' that generates this misunderstanding, so an alternative, such as `former land-cover

situation' may be more appropriate. However, it is also important to carefully stress that `former'

means prior to the most adverse land-use changes, rather than to a theoretical situation before

humans were present at all. A very successful application of this part of the methodology was

provided by the Slovakian pilot site, in Olsavica Village, one of the oldest settlements in the Spis

region. This region is an historical territory of Eastern Slovakia, which was constituted as an

independent territorial and administrative unit at the end of the 12th century. At the beginning of

the 19th Century, the land was owned by two farmers, but in the second half of the century local

farmers bought the land to set up small properties. The main source of livelihood was agriculture

and crafts. A cooperative farm was established in 1959 and the majority of local people are

economically dependent on it. This agricultural enterprise Olsavica-Brutovce is located in the

mountainous region, which is not very favourable for intensive agricultural production. The daily

life of local people is connected with farming. During the recent decades, the village has

experienced a considerable decrease in the number of inhabitants. Due to lack of possibility for

getting jobs, many young people left to find jobs in neighbouring cities.

WWF DANUBE-CARPATHIAN-PROGRAMME / BALTZER ET AL.

Integrated Land Use Assessment and Inventory of Protected Areas

page 31

Pote

Po nc

te ia

nc l

ia

Ve

V ge

e ta

ge t

ta i

t o

i n

o from

r

Cu

C rre

rr n

e t v

n ege

e ta

ge t

ta i

t on

o

3D mo

3D m del of

veget

vege atio

a n

tio

1949

194

terr

r ain

Analys

y is and

syn

sy thes

he i

s s

i

Optima

tim l sta

t tus

t

of

wetl

we a

tl n

a ds

Analys

y is and

n

synt

y hesi

hes s

Re

R st

s oratio

at n plan

Impl

Im ement

em

atiton

i

of restorat

of restora i

t on

o

Figure 6:

Principle overview on how to find / define the optimal status of

wetlands (example from the Slovakian pilot case).

Since erosion is a persistent problem for farming in Olsavica and because the proportion of arable

land has decreased as a consequence, the discussion about implementation of new environmentally

friendly management techniques has been received positively by the staff of the enterprise, in spite

of the fact that this new type of farming is more complicated. The gap analysis and GIS based

demonstration of "optimal state of wetlands" (Figure 6, Figure 7) provided a lot of helpful support

to convince farmers to try to switch to another type to cultivate their lands. In particular the

habitat map was an essential part of the restoration plan. It was used as a baseline information

layer to compare old aerial photos with the potential vegetation of an ecologically optimal status.

UNDP/GEF DANUBE REGIONAL PROJECT

3. IMPLEMENTATION OF ACTIVITIES IN PHASE 2

page 32

Figure 7:

Real (top) and optimal (bottom) status for of wetlands in Olsavica

Village (Slovakia). The image illustrates a possible optimal and realistic occurrence of

wetlands in the Olsavica basin. The maps are based on four sources of information:

(1) a geo-botanical map incl. predicted potential vegetation, (2) an aerial photo from

1949 showing detail land-use situation and delineated wetlands, (3) the comparison

of wetland types in well preserved down stream parts, and (4) a 3D model of the

terrain used for defining erosive sections of the channels.

WWF DANUBE-CARPATHIAN-PROGRAMME / BALTZER ET AL.

Integrated Land Use Assessment and Inventory of Protected Areas

page 33

3.2.2.7. Participatory stakeholder workshops for appropriate land-use options

At all three pilot sites, most of the key stakeholder groups were generally supportive of any efforts

to reduce pollution, flooding or to take efforts to improve groundwater levels and revive fishponds.