IMPROVING THE UNDERSTANDING OF THE

DANUBE RIVER IMPACT ON THE STATUS OF

THE BLACK SEA

W Parr*, Y Volovik*, S Nixon# and I Lipan*

*UNDP-GEF Black Sea Ecosystem Recovery Project

#WRc plc

Draft report to the Black

Sea Danube Technical

Working Group

November

2005

1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1.

SUMMARY....................................................................................................................1

2.

INTRODUCTION ..........................................................................................................3

2.1

Background ............................................................................................................ 3

2.2

Aims ........................................................................................................................ 3

3.

INITIAL ASSESSMENT OF THE DANUBE RIVER ON THE CHEMICAL

AND BIOLOGICAL STATUS OF THE BLACK SEA...............................................5

3.1

Danube loads into the Black Sea ....................................................................... 5

3.2

Status of the Black Sea........................................................................................ 6

3.2.1

Nutrient concentrations in the water column................................................... 6

3.2.2

Secchi depth .................................................................................................... 7

3.2.3

Turbidity ......................................................................................................... 7

3.2.4

Chlorophyll-a................................................................................................... 7

3.2.5

Aquatic vegetation........................................................................................... 8

3.2.6

Dissolved oxygen content................................................................................ 8

3.2.7

Phytoplankton ................................................................................................. 9

3.2.8

Zooplankton ................................................................................................. 10

3.2.9

Macrozoobenthos (biomass, percentage of key groups)................................. 10

3.2.10 Pollutants ...................................................................................................... 10

4.

THE BLACK SEA REGIONAL INTEGRATED MONITORING AND

ASSESSMENT PROGRAMME (BSIMAP) ............................................................. 13

4.1

Background .......................................................................................................... 13

4.2

BSIMAP aims and purposes ............................................................................. 13

4.3

Reference/baseline conditions.......................................................................... 14

4.4

BSIMAP proposed spatial coverage ................................................................ 14

4.5

BSIMAP parameters........................................................................................... 15

4.6

BSIMAP proposed monitoring frequencies..................................................... 17

4.7

Recent years BSIMAP reporting....................................................................... 17

5.

CONSIDERATIONS FOR IMPROVING THE COLLECTION AND

INTERPRETATION OF BLACK SEA MONITORING DATA................................ 19

5.1

Funding and equipment ..................................................................................... 19

5.2

Relevant and proposed legislation ................................................................... 19

5.2.1

Strategic Action Plan for the rehabilitation and protection of the Black

Sea................................................................................................................. 19

5.2.2

Existing European Union directives .............................................................. 19

5.2.3

Proposed Marine Framework Directive......................................................... 20

5.3

Spatial and depth coverage of monitoring stations ....................................... 21

5.4

Reference site selection..................................................................................... 22

5.5

River inflows......................................................................................................... 23

5.6

Seasonality and sampling frequency ............................................................... 23

5.7

Historical data availability for trend analysis................................................... 24

5.8

Sources and types of current and historic pollutants .................................... 24

5.9

Pollution impacts ................................................................................................. 25

5.10

Data analysis and interpretation ....................................................................... 25

6.

INDICATORS OF STATUS OF THE BLACK SEA.................................................27

6.1

River inputs (loads)............................................................................................. 27

2

6.2

Nutrient concentrations in the water column .................................................. 27

6.3

Secchi depth and turbidity ................................................................................. 28

6.4

Chlorophyll ........................................................................................................... 28

6.5

Aquatic vegetation .............................................................................................. 28

6.6

Dissolved oxygen content.................................................................................. 29

6.7

Phytoplankton ...................................................................................................... 29

6.8

Zooplankton ......................................................................................................... 29

6.9

Zoobenthos .......................................................................................................... 30

6.10

Pollutants.............................................................................................................. 30

APPENDIX A DANUBE RIVER LOADS INTO THE BLACK SEA ...................................33

A.1

Overview of data used the Trans-National Monitoring Network............... 33

A.2

Load assessment ................................................................................................ 34

A.3

Reporting of loads to DBS JTWG..................................................................... 35

APPENDIX B - STATUS AND TRENDS IN QUALITY OF THE NORTH-WESTERN

SHELF OF THE BLACK SEA..................................................................................37

B.1

Overview of data used ...................................................................................... 37

B.2

Nutrient and oxygen concentrations in the water column............................ 38

B.2.1

Data used ...................................................................................................... 38

B.2.2

Representativeness and outliers ..................................................................... 38

B.2.3

Monitoring sites/areas................................................................................... 38

B.2.4

Descriptive statistics of data analysed ............................................................ 39

B.2.5

Number of samples collected in different months and seasons...................... 43

B.2.6

Seasonality..................................................................................................... 44

B.2.7

Linear trend analysis ...................................................................................... 45

B.3

Chlorophyll .......................................................................................................... 49

B.3.1

Meteorological and oceanographic factors affecting seasonal and annual

chlorophyll dynamics..................................................................................... 49

B.3.2

Remote data used and approach .................................................................... 50

B.3.3

Chlorophyll concentrations in the Black Sea (SeaWiFS satellite data)............. 50

B.3.4

Overview of chlorophyll dynamics (1998-2004)............................................. 54

B.4

Aquatic vegetation .............................................................................................. 56

B.5

Phytoplankton ...................................................................................................... 57

B.6

Zoobenthos ......................................................................................................... 57

B.6.1

Assessment of macrozoobenthic community status in the North-Western

Shelf of the Black Sea (Oct 2003) .................................................................. 57

B.6.2

Evidence for recovery of mussel beds on the North-Western Shelf of the

Black Sea (Mee 2005)..................................................................................... 63

B.7

Pollutants in sediments ..................................................................................... 64

B.7.1

Overview of data used................................................................................... 64

B.7.2

Chlorinated pesticides.................................................................................... 65

B.7.3

PCBs ............................................................................................................. 70

B.7.4

Heavy metals ................................................................................................. 73

APPENDIX C -

DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS FOR NUTRIENT AND

DISSOLVED OXYGEN CONCENTRATIONS IN NORTH-WESTERN

SHELF WATERS, 1990-2003 ..................................................................................75

APPENDIX D - RESULTS OF ROSNER'S TEST FOR OUTLIERS ....................................77

3

APPENDIX E - RESULTS OF TESTS FOR SEASONALITY OF NUTRIENTS AND

DISSOLVED OXYGEN .............................................................................................79

APPENDIX F PROPOSED BSIMAP MONITORING SITES, 2005...................................83

APPENDIX G DRAFT QUALITY ASSURANCE MISSION REPORT AND

RECOMMENDATIONS.............................................................................................87

G.1

Introduction .......................................................................................................... 88

G.2

Turkey ................................................................................................................... 89

G.2.1

Institute of Marine Sciences and Management, University of Istanbul,

Istanbul ......................................................................................................... 89

G.2.2

Recommendations......................................................................................... 89

G.3

Romania ............................................................................................................... 90

G.3.1

National Institute for Marine Research and Development "Grigore

Antipa", Constanta ........................................................................................ 90

G.3.2

Recommendations......................................................................................... 90

G.4

Bulgaria................................................................................................................. 91

G.4.1

Regional Environmental Inspectorate of Varna, Varna.................................. 91

G.4.2

Institute of Oceanology, Varna...................................................................... 91

G.4.3

Recommendations......................................................................................... 92

G.5

Ukraine.................................................................................................................. 93

G.5.1

Ukrainian Scientific Centre of the Ecology of Sea (Ukr/SCES), Odessa ........ 93

G.5.2

State Inspection for Protection of the Black Sea, Odessa............................... 93

G.5.3

Hydrometeorological Bureau Laboratory, Port of Illichivsk........................... 94

G.5.4

Ukrainian Land and Resource Management Center, Kiev .............................. 94

G.5.5

Recommendations......................................................................................... 94

G.6

Russian Federation............................................................................................. 96

G.6.1

Environmental Protection Inspectorate Laboratory, Sochi ............................ 96

G.6.2

Hydrometeorological Laboratory, Sochi ........................................................ 96

G.6.3

Environmental Protection Inspectorate Laboratory, Tuapse.......................... 96

G.6.4

Environmental Protection Inspectorate Central Laboratory, Krasnodar ........ 97

G.6.5

Recommendations......................................................................................... 97

APPENDIX H - PROPOSED MANDATORY PARAMETERS AND ANNUAL

MONITORING FREQUENCIES - BSIMAP.............................................................99

APPENDIX I REPORTED BSIMAP MONITORING FREQUENCIES, 2001 and

2003 .......................................................................................................................... 103

APPENDIX J - REFERENCES .............................................................................................. 107

4

List of Abbreviations

UNDP

The United Nations Development Programme

GEF

The Global Environmental Facility

BSERP

The Black Sea Ecosystems Recovery Project

PIU

The Project Implementation Unit

JTWG

Joint Technical Working Group

BSC

Black Sea Commission

PDF-B

GEF Project Development Fund, Phase B

ICPDR

International Commission for the Protection of the Danube River

BSIMAP

Black Sea Integrated Monitoring and Assessment Programme

DIN

Dissolved Inorganic Nitrogen

N Nitrogen

AQC Analytical

Quality

Control

ISO

International Standard Organisation

NATO

North Atlantic Treaty Organisation

JRC

Joint Research Centre of the European Commission

SD Secchi

depth

DOW

Dissolved Oxygen (as determined by the Winkler titration method)

NH4 Ammonium

NO2 Nitrite

NO3 Nitrate

PO4 Ortho-phosphate

SiO4 Silicate

BOD, BOD5

Biological Oxygen Demand (5 days)

COD

Chemical Oxygen Demand

ANOVA

Analysis of variance

HRPT

High Resolution Picture Transmission

GSFC DAAC Goddard Space Flight Centre Distributed Active Archive Centre

SeaDAS

SeaWiFS Data Analysis System

PCB Polychlorinated

biphenyl

PNG

Portable Network Graphics format

SeaWiFS Sea-viewing

Wide Field-of-view Sensor

BSMS

Black Sea Main Stream

TSS

Total suspended solids

NW North-Western

PMA

Pollution Monitoring and Assessment

QA Quality

Assurance

POC

Particulate Organic Carbon,

PN

Particulate Nitrogen

DON

Dissolved Organic Nitrogen

SRP

Soluble Reactive Phosphorus = PO4-P

DSi

Dissolved Silicate

1

1. SUMMARY

For the first time, this report makes use of available data to assess the impact of the Danube River on the

North Western Shelf of the Black Sea and examines the pragmatism of a series of environmental

indicators, originally agreed by the Black Sea-Danube Joint Technical Working Group (JTWG) for

doing this. The inability to establish baseline (reference) conditions meant that rather than a true impact

assessment, a spatial `state of the environment' comparative approach had to be adopted.

A large body of evidence is available to suggest that nutrient loads to the Black Sea via the Danube

River have fallen substantially over the last 10-15 years. However, the Danube Trans-National

Monitoring Network has not been in operation for such a long period of time and the adoption of good

quality assurance procedures has meant that only three years worth of nutrient loading data are currently

available (a fourth year, 2003, is due to be published soon). This is too short a period to undertake a

trend analysis of river loads. However, a number of statistically significant trends (improvements in

water quality) have been detected in the Danube River (notably nutrients) over the last 10-15 years, with

up to 30% annual reductions (1996-1998) in some (ammonium) concentrations.

Unfortunately, recent improvements in Black Sea water nutrient concentrations have been much less

dramatic when average results are considered. Indeed, in direct contrast to the Danube, some Black Sea

trends are positive, showing up to 3-5% increases in nutrient concentrations. It is likely that a longer lag

period is required before the benefits of reduced riverine nutrient loads to the North Western Shelf will

be reflected within the Sea itself, a conclusion which is supported by the recent publication of a nutrient

budget for the North Western Shelf (Fig. 3.1). Regardless of these recent results, data presented for one

Romanian site (Constanta) show dramatic improvements in orthophosphate concentrations since the

mid-1980s (Fig. B.6). This figure shows an overall decrease in nitrate concentrations since the mid-

1970s, albeit with an increase in more recent years.

The Danube clearly has had a major historical impact on the North-Western Shelf, but the Sea appears

to be recovering as a functional ecosystem, with dissolved oxygen and macrozoobenthos data appearing

to be the best indicators of this. However, the Danube appears still to be a significant source of other

contaminants both organic (some PCBs and chlorinated pesticides) and inorganic (heavy metals).

Huge capital investment in sewage treatment within the Danube River Basin has improved the situation

with regard to nutrients and major organic pollution of the river, but any improvements in heavy metals

loads and diffuse sources of pollution are much more difficult to assess, particularly as the current

assessment does not involve source apportionment modeling. For this, inputs from other rivers, (local)

direct discharges to the marine environment, atmospheric deposition and the historical contribution to

surface sediment contamination need to be fully evaluated. However, statements about the impact of the

Danube have be taken in context: even for increased levels of those pollutants which are associated with

the Danube inflow, sediment concentrations are not massively elevated offshore of where the River

enters the Sea; and comparable concentrations of many of these parameters have been recorded at sites

that are much less heavily influenced by the Danube. The implication of this is that pollutant export

from coastal regions (much smaller areas than that of the Danube Basin) is proportionally greater (on an

areal basis) than from the land drained by the Danube.

The use of chlorophyll-a (chl-a) concentrations as an environmental status concentration is critically

reviewed. While it is still regarded as a useful indicator, a wide range of factors need to be considered in

data interpretation. As an indicator, chl-a concentration requires extensive interpretation and

explanation. The use of remote sensing data for estimating chlorophyll results has been a worthwhile

exercise, but uncertainty over the temporal and spatial variability of these results when compared with

laboratory-measured chl-a introduces a further question mark over their utility.

1

Macroalgal morpho-functional parameters indicate that the major impact of the Danube is restricted to a

relatively small part of the North Western Shelf. This is unlikely to be the case, bearing in mind results

from zoobenthos monitoring studies, and is more likely to be a reflection of the very small number of

monitoring locations. The macroalgal results should also be treated with caution because they are prone

to bias from localized sources of nutrients (e.g. costal sewage treatment works outfalls). Morpho-

functional parameter information was the only data available for use in this report, but the Black Sea

Commission's Pollution Monitoring and Assessment Advisory Group recently proposed the use of

vegetation indicator species (Zostera marina and Cystoseira barbata) as indicators of trophic status

within BSIMAP

Monitoring of phytoplankton and zooplankton populations has not yet produced comparable data from

the six Black Sea riparian countries, although it is expected that this situation will improve in the near

future. Although there are clear advantages to the identification of phytoplankton taxa, biomass

monitoring appears to be considerably more expensive is perhaps a weaker indicator than chlorophyll-a

determination. However, if the ratio of diatoms:dinoflagellates is to be used as an indicator of trophic

status, with results expressed on a biomass, rather than a cell number, basis, the biomass of individual

taxa and taxonomic groups must continue to be measured. The benefits of zooplankton monitoring as an

environmental status indicator are unclear at this stage, although such results should help explain

variability in phytoplankton/chl-a monitoring results. However, the number, size and biomass of

Noctiluca spp. (a genus of non-photosynthetic dinoflagelates) are considered important indicators of

environmental status. Although in taxonomic terms Noctiluca spp are classed as phytoplankters, the

large size (300-600 µm) of these organisms means that they are monitored during zooplankton

monitoring exercises.

Gross organic loads to (BOD5) and organic concentrations within (total organic carbon) the Black Sea

are necessary indicators of trophic status and of the impact of the Danube River (and other pollutant

sources). Monitoring of BOD5 loads to the sea will continue to be undertaken, but a recent proposal of

the PMA Advisory Group to change BOD5 from a mandatory to an optional parameter (with good

reasons), and to maintain total organic carbon as an optional parameter, means that there is a risk of

organic status within the Black Sea being ineffectively monitored in future years.

No turbidity or Secchi depth data were available for analysis within this report

The existing Black Sea Integrated Monitoring and Assessment Programme (BSIMAP) is described and

factors for consideration in updating this are discussed Proposals to increase the number of biological

monitoring metrics for the 2006-2011 BSIMAP are considered. There is a need for some countries to

identify appropriate reference sites within the BSIMAP, and a need for more detail regarding what

parameters are to be measured and what indicators should be used. Important decisions will need to be

made in the near future over updating the Black Sea Information System in terms of whether raw or

processed biological data should be reported to the Black Sea Commission.

.

2

2. INTRODUCTION

2.1 Background

Work conducted in the previous GEF PDF-B and Phase I BSERP programmes, and discussion between

the ICPDR and the Black Sea Commission via their Joint Technical Working Group has led to the

selection of a number of environmental status indicators for the Black Sea. These are considered to be

key elements underlying the work of the BSC and its Permanent Secretariat, and thus should play a

crucial role in the design of the Black Sea Integrated Monitoring and Assessment Programme

(BSIMAP). These indicators are:

1. Nutrient concentrations in the water column DIN/total N, phosphate/total phosphorus and

silicate.

2. Secchi depth

3. Turbidity

4. Chlorophyll-a concentrations

5. Macroalgae (indicative species) presence/absence

6. Dissolved oxygen content

7. Phytoplankton (key taxa, biomass and average volume of cells)

8. Zooplankton (biomass and percentage of key groups, number of Noctiluca)

9. Macrozoobenthos (biomass, percentage of key groups)

10. Pollutants (toxicants) organic and inorganic.

Despite the large capital investments made in the 17 countries represented by the BSC and the ICPDR,

no assessment has yet been made of the impact of the Danube River on the Black Sea. Water quality in

the Danube River has certainly improved in recent years, with riverine nutrient loads to the Black Sea

having fallen substantially during this period (see also Table B.8). A number of studies have greatly

helped to quantify and assess the impacts of such reductions on the status of the Black Sea itself, as well

as contributing to the selection of indicators (e.g. SCRFEP, 1998; Anon, 1999; Kroiss et al, 2005), but

individually these studies have either not considered all indicators or have been limited in terms of the

area of their assessment.

This document is extremely important from both political and scientific perspectives. It is not

anticipated that definitive answers will be produced as a result of the analysis, but an initial investigation

of what information the available data are able to provide should be of great interest to both

Commissions.

2.2 Aims

This document aims to provide the first holistic use of available data in assessing the impact of the

Danube on the Black Sea, focusing on the environmental status (chemical and biological) of the North

Western Shelf. In order to do this, the assessment is divided into two parts:

· Danube River inputs (loads) to the Black Sea

· The Environmental status of the North Western Shelf

Data and the conclusions drawn from them are presented, and the current Black Sea Integrated

Monitoring and Assessment Programme (BSIMAP) is explained. Finally, a discussion is presented on

factors that should be considered in the further development of the BSIMAP.

3

It is emphasized that not all data sources have been used in this report; only those that were immediately

available to the authors.

4

3.

INITIAL ASSESSMENT OF THE DANUBE RIVER ON THE

CHEMICAL AND BIOLOGICAL STATUS OF THE BLACK

SEA

The conclusions shown in this section of the report are drawn from an assessment of available data

undertaken by members of the BSERP, Phase 2 Project Implementation Unit., with further details

presented in Appendix B. Where possible, an analysis of historical data is provided in an attempt to look

for trends exhibited by each of the indicators. In addition, supporting data has been added from

alternative sources to those outlined below.

Unfortunately, due to the paucity of baseline/reference data (see Section 4.3), it has not been possible to

provide a true `impact' assessment of the Danube River on the Black Sea. Instead, results for the

majority of indicators are presented as spatial patterns

The following four major sources of data (collated during BSERP, Phase 1) have been used in the

current assessment:

· NATO funded Black Sea cruises

· UNDP-GEF funded International Study Group research cruises

· UNDP-GEF funded pilot monitoring exercises

· Recent data gathered as part of the BSERP (Phase 1)

3.1

Danube loads into the Black Sea

Annual pollutant loads from the Danube River to the Black Sea are discussed in detail in Appendix A,

with results summarised in Table 3.1, below. The 3-year period for which loads are available is too short

a timescale over which to undertake a trend analysis, so no such analysis ha been presented. Thus, even

though there appears to have been an increase in ammonium, nitrate and inorganic nitrogen, and a

decrease in ortho-phosphate over this period, there is little basis for assuming that these changes

represent trends.

Table 3.1

Annual loads of pollutants/contaminants from the Danube River into the Black Sea

(2000-2002)

Parameter

2000

2001

2002

Mean (2001-2003)

Suspended solids

5,100,000

3,700,000 5,100,000

4,633,333

NH4-N 62,100

67,592

71,584

67,092

NO3-N 252,540

355,852

413,980

340,791

NO2-N 9,315

8,350

11,212

9,626

Inorganic N1 299,000

437,000

493,000 409,667

PO4-P 6,100

5,200

5,000

5,433

Total P

10,900

13,100

12,000

BOD5 395,000

303,000

343,000

347,000

1 Inorganic loads presented in this table differ from the sum of ammonium, nitrate and nitrite loads because of the different

calculation methodologies described in Appendix A.

5

3.2

Status of the Black Sea

3.2.1

Nutrient concentrations in the water column

No data on total nutrient concentrations were available for analysis. Nitrogen-nutrient data were

provided as separate nitrate, nitrite and ammonium data, and analysed as individual parameters, not as

dissolved inorganic nitrogen.

Overall, nutrient concentrations in waters of the North-Western Shelf show relatively small differences,

perhaps with slightly higher concentrations in the waters off the Bulgarian coast.

While there is evidence of some nutrient concentrations in the Danube River undergoing a major

decrease during the 1990s, (Appendix B, Section B.2.7), these decreases are most apparent for

ammonium, with a much smaller (but still statistically significant) improvement for nitrate

concentrations at one site over the same period (1996-200). Ammonium typically constitutes only a

minor fraction of DIN (comprised predominantly of nitrate), and is an even smaller constituent of total

nitrogen. Thus, reductions in ammonium concentrations are probably a better indicator of improved

sewage treatment processes and the dissolved oxygen status in the river (i.e. improving substantially)

than they are of improving nitrogen contamination. No phosphorus data were available for the Danube

River from the data sources used for this analysis.

Nevertheless, it is clear that the reduction in inorganic nitrogen concentrations in the Danube is not

reflected in waters of the Black Sea North-Western Shelf. In fact, between 1990 and 2003 the overall

picture that emerges is of increasing nitrate concentrations in North Western Shelf waters of Bulgaria,

Romania and Ukraine (Table B.7).

Not surprisingly, seasonality occurs in nutrient concentrations, most noticeably for ammonium and

nitrate. However, the available Black Sea data did not provide adequate coverage of the colder months

of the year (Table B.4), whereas the data available for the Danube River represented all seasons evenly

(Table B.5).

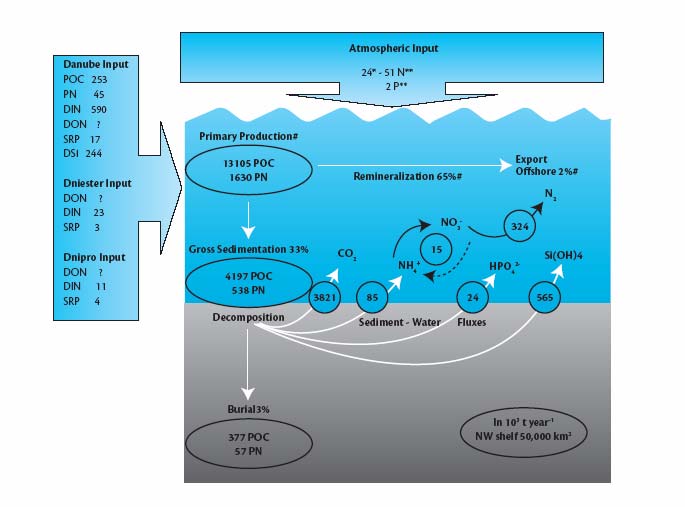

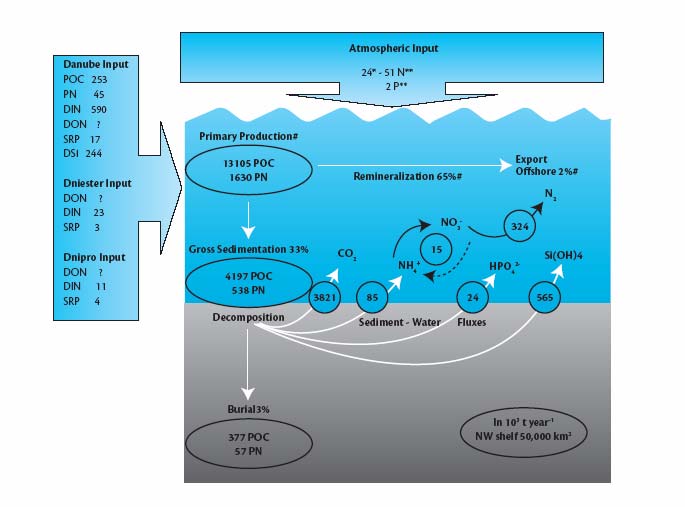

A preliminary nutrient balance for the mid-1990s has been prepared for the 50,000 km2 area of the

North-Western Shelf, focusing on inputs from the Danube, Dniester and Dnipro rivers, together with

estimates of atmospheric inputs and nutrient recycling within the system itself (Fig. 3.1). Benthic

nutrient recycling is a significant internal nutrient source for the pelagic system, sustaining high

productivity by the release of phosphorus and nitrogen from the sediment (in the same range as river

inputs). The shelf sediments release about twice as much silicon as the load discharged by the Danube.

However, the shelf acts also as a sink for nutrients. Perhaps surprisingly, modeled atmospheric nitrogen

deposition appears to be of relatively minor importance, amounting to only 4-8% of the river inputs. The

importance of nutrient cycling in deeper waters and the contribution of this to the overall nutrient budget

has still to be determined. It is clear from this budget just how much greater and more important the

Danube is than either the Dneister or the Dnipro as a nutrient source for the North-Western Shelf.

6

Figure 3.1

Nutrient budget for the North-Western Shelf of the Black Sea during the mid-1990s

(Mee, 2005, Mee et al, 2005, based on Friedrich et al, 2002)

i

All fluxes, except for measured river inputs, are calculated for a 50,000 km2 shelf area.

Data marked with # are taken from model calculations in Gregoire & Friedrich (2004) and

Gregoire & Lacroix (2003). Danube input represents the average input of 1991-1995

(Cociasu et al, 1996) except for POC and PN (Reschke et al, 2002). Dniester and Dnipro

inputs were taken from Topping et al (1999). Literature data on atmospheric inputs

reflect high uncertainties; values here are from Sofief et al (1994).

3.2.2 Secchi

depth

No Secchi depth data were available for the current assessment.

3.2.3 Turbidity

In essence, Secchi depth and turbidity are different measuring techniques for monitoring the same

parameter (light penetration through the water column). No turbidity data were available for the current

assessment.

3.2.4 Chlorophyll-a

Chlorophyll-a has long been used as an indicator of trophic status of fresh and marine waters, but

caution needs to be applied in the comparative analysis of results from different waterbodies or different

areas of large waterbodies, such as the Black Sea, since spatial difference may be high. Probably the

best example of this variability is from freshwater lakes, where for any given (limiting) nutrient

concentration, 95% confidence limits for long-term average chlorophyll-a results are an order of

magnitude apart (OECD 1982).

Chlorophyll-a is the only pigment present in all photosynthetic algae and higher plants, and is used as a

surrogate of phytoplankton biomass/standing crop when measured spectrophotometrically. Very few

data were available on chlorophyll-a measurements, and certainly not enough to make an assessment of

7

the trophic status of the North-Western Shelf in comparison to other areas of the Black Sea. However, a

considerable amount of remote sensing chlorophyll data has been collated and processed for the Black

Sea. It is these results which are discussed below.

Satellite data does not only include chlorophyll-a, however, it also records other types of chlorophylls

and chlorophyll-like substances. A major problem with the use of satellite imagery is, therefore ground-

truthing of the satellite data, Remote sensing chlorophyll-a data are usually calibrated/validated against

in-situ chlorophyll-a, but as the ratio of chlorophyll-a to other types of chlorophyll and chlorophyll-like

substances varies from between phytoplankton taxa, at any one time, satellite data provide only an

estimate of chlorophyll-a concentrations. The remote sensing chlorophyll maps of the Black Sea

presented in this report (e.g. Appendix B, Fig. B.12) show higher concentrations in the Sea of Azov, and

along the Bulgarian/Romanian/West Ukrainian coast, where the impact of the Danube would be

greatest. Remote sensing data records chlorophyll levels only in the very surface of waterbodies,

whereas laboratory-analysed chlorophyll-a levels can be measured for any depth from which water is

sampled.

Elevated chlorophyll levels in the Sea of Azov have been explained in terms of the shallow nature of the

water. While the reasons underlying this explanation remain unclear, they could also explain (partly at

least) the elevated levels in transitional waters of the Danube. Possible reasons for these elevated levels

are:

· Carry-over of freshwater phytoplankton into the Black Sea.

· Greater mixing of waters, resulting in increased resuspension of benthic material (including

detrital chlorophyll-like substances).

· Possible increases in phytoplankton growth rates (primary productivity) due to increased nutrient

concentrations. However, phytoplankton growth is not limited at nutrient concentrations greater

than 10 µg/l PO4-P in the presence of 100 µg/l dissolved inorganic nitrogen. It is paradoxical that

above these levels of nutrient concentration, although the rate of growth of phytoplankton does

not increase substantially, the standing crop of phytoplankton (and therefore chlorophyll-a) can

increase dramatically.

· The shallower the water, the more light that is available to drive planktonic photosynthesis.

Thus, the greater the primary productivity in shallow waters and the greater chance of increased

chlorophyll levels occurring.

3.2.5 Aquatic

vegetation

Two indicator species have been selected for use in the Black Sea: Cystoseira barbata (a brown

seaweed) and Zostera marina (a macrophytic sea grass). No data were available on the distribution of

these species within the Black Sea, but their presence/absence will be mandatory BSIMAP mandatory

parameters for monitoring during 2006-2011.

However, a methodology using rocky shore macroalgae morpho-functional indices to monitor trophic

status has been developed and tested at seven transects in the Sea (Appendix B, Section B.4).

The results of this assessment demonstrate a higher trophic status of rocky shores close to the Danube

delta than those further away, but concerns are raised that this methodology is more prone to local

influences (e.g. relatively small local discharges) than offshore biological methodologies (e.g.

zoobenthos assessments) when investigating the impact of the Danube.

3.2.6

Dissolved oxygen content

During the period 1990-1995, there was minor variability in dissolved oxygen levels in Romanian

coastal waters, with annual mean levels of 315-345 µM/l (Appendix B, Table B.3). These data suggest

8

that hypoxia was not a problem during this period, but hypoxia only needs to occur for a very short

period of time for ecological damage to occur.

From the early 1970s through the 1980s, tens of thousands of km2 of the Western Black Sea were under

hypoxic conditions (depleted oxygen). Oxygen levels increased throughout the 1990s, evidence of

which is presented in Section B.6.2 (Fig. B.20) with regard to mussel community age class distributions.

Clearly, the mussel beds have recovered to a large extent, particularly in the North of the North-Western

Shelf.

Further evidence of the onset of the increasing degradation of the North-Western Shelf waters

throughout the 1970s and early 1980s is shown in Fig. 3.2. The dramatic autumnal recovery in oxygen

status during the mid-1990s and early 2000s is illustrated in the lower half of the same figure.

Figure 3.2

Area of oxygen depletion (1974, 1978 and 1983) and percentage oxygen saturation

levels (1996, 1999 and 2003) in the North-Western Shelf of the Black Sea (Kroiss

2004)

2

3

1

200 m

Danube

Danube

Danube

45.0

120

1

90

60

40

100

140

80

50

120

100

44.6

30

100

90

80

80

40

5

0

7 6 0

0

0

100

1

70

0

44 .2

60

120

80

80

50

6

0

60

43.8

September 1996

September 1999

September 2003

29.0

30.0

29.0

30.0

29.0

30.0

3.2.7 Phytoplankton

Because of sampling and analytical methodology differences, data from Bulgaria, Romania and Ukraine

have not been comparable. However, at a recent workshop in Odessa (15-19August 2005) a first Black

Sea Regional phytoplankton intercalibration exercise was undertaken to facilitate comparison of

historical data, and agreement was reached over the use of standardised sampling/processing equipment.

No formalised lists of key taxa or other phytoplankton trophic status metrics have yet been made, but

these are expected as a reported output of the Odessa workshop.

Data are presented in Appendix B (Section B.5) for phytoplankton populations off the coast of Romania,

which show a marked change coinciding with the temporary return of eutrophic conditions in 2001.

However, the same data also cast doubt on the use of what has been considered one of the most robust

9

phytoplankton trophic status indicators (the diatoms:dinoflagellates ratio), when used in terms of cell

numbers. No data on phytoplankton biomass were available to compare results.

3.2.8 Zooplankton

No data were available on zooplankton biomass, percentage of key groups or No of Noctiluca. Because

of sampling and analytical methodology differences, historical data from Bulgaria, Romania and

Ukraine have not been comparable. However, at a recent workshop in Odessa (15-19 August 2005) a

first Black Sea Regional zooplankton intercalibration exercise was undertaken to facilitate comparison

of historical data, and agreement was reached over the use of standardised sampling/processing

equipment. No formalised lists of key taxa or other zooplankton trophic status metrics have yet been

made, but these are expected as a reported output of the Odessa workshop.

3.2.9 Macrozoobenthos

(biomass,

percentage of key groups)

Macrozoobenthos populations of the North Western Shelf are discussed in detail in Appendix B, Section

B.6. The Danube Delta region of the Shelf shows clear signs of impact from the Danube itself, although

the zoobenthic population is not as heavily impacted there as it is closer to Odessa, where other sources

of contamination and disturbance are likely to be the predominant causative factors. Other areas of the

North-Western Shelf are less heavily impacted.

While there are still obvious signs of the impact of the Danube, the situation has improved substantially

from that in the mid-late 1990s (Appendix B, Section B.6), but a reversal of the status of the zoobenthos

ecosystem to that observed in the 1980s and early 1990s is still possible. For example, year 2001 was a

dry year, causing reduced mixing of waters and resulting in extensive hypoxia, leading to the death of

benthic organisms. In Fig. B.20, for example, recruitment of young mussels in 2001 (1+ for year 2003)

was very low in marine areas south of the Danube Delta, but much improved in more northerly waters.

3.2.10 Pollutants

Sediment contamination with organic and inorganic contaminants is discussed in detail in Appendix B,

Section B.7. Overall, results indicate an impact of the Danube on coastal sediments of the North

Western Shelf, particularly with regard to heavy metals, albeit that any increases in sediment

contamination levels are relatively small when considering the catchment area of the Danube compared

to the catchment area of coastal land which drains directly into the North Western Shelf.

Levels of contamination at individual sites will reflect land export of contaminants as a result of

contaminant production/use in coastal areas, direct discharges to the marine environment, illegal waste

dumping at sea and atmospheric deposition, as well as river inputs. While surface sediment samples

were used for the vast majority of the analyses presented, there is also the risk of a historical `shadow'

reflecting sediment contamination. This is primarily due to bioturbation mixing of marine sediments

by burrowing animals - so older, deeper and possibly more contaminated sediments (reflecting levels

occurring before the Danube clean-up programme of the 1990s and early 2000s) may become

incorporated into surface sediments.

For a number of chlorinated pesticides (dieldrin, lindane, opp DDD, opp DDT, pp'DDD, pp'DDT,

DDMU, op'DDE, pp'DDE and HCHa) the highest concentrations were found in Ukrainian sediment,

with concentrations diminishing in a southerly direction. For two of these contaminants (dieldrin and

op'DDE), however, increased concentrations were again recorded in Bulgarian sediments. Elevated

levels of HCB, HCH, lindane, heptachlor, aldrin and endosulfan were also detected at Bulgarian sites.

For three pesticides (cis- and trans-chlordane and a-HCH), maximum levels were associated with the

Sulina branch of the Danube, although for a-HCH, comparable levels were detected at a number of other

sites.

10

The massive level of DDT contamination recorded at one Ukrainian site is considered much more likely

to reflect illegal discharges/dumping than land run-off.

PCB concentrations were highest at more northerly sites of the North-Western Shelf. Maximum

concentrations of ten PCBs (aroclor 1260, PCBs 149, 153, 170, 174, 177, 180, 183, 187 and 194) were

associated with Danube River input via the Sulina Channel. For a further twelve PCBs (aroclor 1254,

PCBs 44, 49, 52, 87, 101, 105, 110, 118, 128, 138 and 201) maximum concentrations were recorded in

Ukrainian sediment, levels which could also reflect inputs from the Dneister and Dnipro rivers.

Sediment concentrations of all PCBs except one (PCB 201) were low in north Bulgarian sediment, but

for most PCBs greater contamination was detected in southerly Bulgarian sediments.

For eight metals, highest sediment concentrations are associated with inputs from the Sulina Branch of

the Danube Delta, albeit that elevated levels of contamination of some metals (cobalt, nickel copper and

aluminium) were also noted in samples from off the coast of southern Bulgaria. A sampling site off the

coast of Ukraine also had elevated levels of arsenic. However, as stated for organic contaminants, the

Ukrainian result is also likely to reflect greater influence of inputs from the Dnipro and Dneister rivers.

11

12

4.

THE BLACK SEA REGIONAL INTEGRATED

MONITORING AND ASSESSMENT PROGRAMME

(BSIMAP)

4.1 Background

The underlying principles of the Convention on Protection of the Black Sea against Pollution imply a

holistic approach to monitoring and assessment of the Black Sea ecosystem. These principles have been

considered in the development of the Black Sea Integrated Monitoring and Assessment Programme

(BSIMAP), which seeks to maximize the use of historical data from previously established monitoring

sites for trend analysis, supported by new additional sites to improve the assessment of the current

chemical/ecological status of the Black Sea. The main purpose of the BSIMAP is therefore to provide

data for `state of the environment' reporting, but the sites, parameters and monitoring frequencies also

reflect data requirements for compliance with other national and international legislation and

agreements. The same data should also be suitable for undertaking broad-scale `impact assessment'

investigations of major pollutant and water sources, such as assessing the impact of major rivers (in this

case the Danube, the largest river feeding the Black Sea). However, for impact assessments to be

undertaken, unimpacted baseline conditions need to be established.

4.2

BSIMAP aims and purposes

A consensus was reached by the BSC institutional network (including its Pollution and Monitoring

Advisory Group) that the BSIMAP should:

1. Build on established national monitoring programmes.

2. Be compatible with underlying WFD principles.

3. Utilise standardised, sampling, storage, analytical techniques, assessment methodologies and

reporting formats. [Reporting formats have been specified, but are sometimes not followed.

Standardised manuals for phytoplankton, zooplankton and zoobenthos are currently being

updated and a series of workshops were held during summer/autumn 2005 to promote

harmonization of techniques and train workers from all coastal countries. Standardised

procedures for nutrient analysis and chlorophyll-a have also been produced.]

4. Include agreed quality assurance/quality control procedures. [These have not yet been fully

established. However, a draft mission report from December 2002 (now somewhat out of date),

prepared by Dr Stephen de Mora and Dr Oksana Tarasova is included as Appendix G, describing

the infrastructure, equipment and staff available (primarily for chemical analysis) in those

organisations responsible for Black Sea monitoring in five of the six riparian countries (Georgia

is excluded). Limits of detection and accuracy and precision targets are not specified for any

parameters.]

A first regional quality assurance intercomparison exercise was undertaken in 2004 for metals,

nutrients, chlorinated pesticides and petroleum hydrocarbons. Seven laboratories from five

countries participated (no Turkish laboratories took part in the exercise), albeit with different

laboratories participating for different groups of chemicals The results of this exercise remain

confidential, but as may be expected from the first exercise of this type, the results suggest that

there is a considerable amount of work required by the participating laboratories. During 2005,

the Black Sea Commission provided the funds for all countries to participate in the IAEA-MEL

Quasimeme chemical quality assurance exercise. Additional quality assurance exercises are

13

planned for 2005/2006 on nutrients in seawater, organic contaminants in sediment and heavy

metals in sediment as part of the BSERP.

Preliminary results from plankton intercalibration exercise undertaken during August/September

2005 show a major variability in results obtained by individual laboratories, differences which in

large part are probably due to the alternative methodologies and equipment used by individual

countries. The workshop on macrozoobenthos, included an intercomparison exercise (again with

some important inter-laboratory differences being reported), albeit with full agreement having

been reached on a standardised methodology and equipment for use by all six countries.]

5. Be affordable. [The economies of the six countries are all suffering to various extents, with that

of Georgia being most depressed. With environmental matters being low on the political agenda,

funding for environmental monitoring tends to receive scant political support, so while a

comprehensive list of parameters and high monitoring frequencies can be supported technically,

from a pragmatic viewpoint, a smaller list of monitoring sites, less expensive parameters and less

frequent sampling/monitoring is more likely to achieve governmental funding. Clearly, those

countries aiming for EU accession in the near future (Romania and Bulgaria; Turkey at a later

date) will need to comply with the monitoring requirements of EU Directives. In general terms,

organic compounds are more expensive to analyse for than inorganic compounds, and not all

countries have the equipment or technical ability to analyse for them. However, not all countries

have the capacity/ability to analyse for some inorganics, e.g. mercury.]

The Black Sea Commission and its advisory bodies/institutional framework believes that to achieve

further harmonisation, common environmental quality criteria/objectives should be established and the

Black Sea Information System further developed to facilitate regional State of the Environment

reporting.

4.3 Reference/baseline

conditions

The establishment of baseline (reference) conditions is at the heart of the EU Water Framework

Directive (WFD), since all biological monitoring results should be presented in the form of

environmental quality indices (EQIs), i.e.:

Result at monitoring site

EQI = Result at reference site

Reference conditions for impacted sites can be established using three main approaches:

· Status at quasi-pristine (but otherwise comparable) site

· Expert judgment

· Modeling

However, the reality is that the first of these three methods is the most practical and robust, particularly

when considering ecological monitoring. The reasons for choosing some individual monitoring site

locations remain unclear, although as already indicated, there is a historical justification for many of

these sites to enable trend analysis using historical data.

4.4 BSIMAP

proposed

spatial

coverage

Perhaps the most obvious aspect of the BSIMAP is that it is restricted to the Black Sea there are no

monitoring sites in the Sea of Azov. While it is very obviously a transboundary waterbody, both the

Ukrainian and Russian governments consider it to be outside of the scope of BSIMAP, despite its

influence on the Black Sea. However, some protocols of the Black Sea Commission also cover the Sea

of Azov. These include the Black Sea Biodiversity and Landscape Conservation Protocol and the draft

14

revised Protocol for the Protection of the Black Sea against Pollution from Land-Based Sources and

Activities.

Article I of the Convention (on the Protection of the Black Sea against Pollution) defines the area of

application as the Black Sea proper, with the southern limit constituted by the line joining Capes

Kelagra and Dalyan. It also states that the Black Sea shall include the territorial sea and exclusive

economic zone of each Contracting Party in the Black Sea. However, any protocol to the Convention

may include areas outside of the Black Sea `proper' for the purposes of that protocol. The Black Sea

`proper' is thus interpreted as excluding the Sea of Azov.

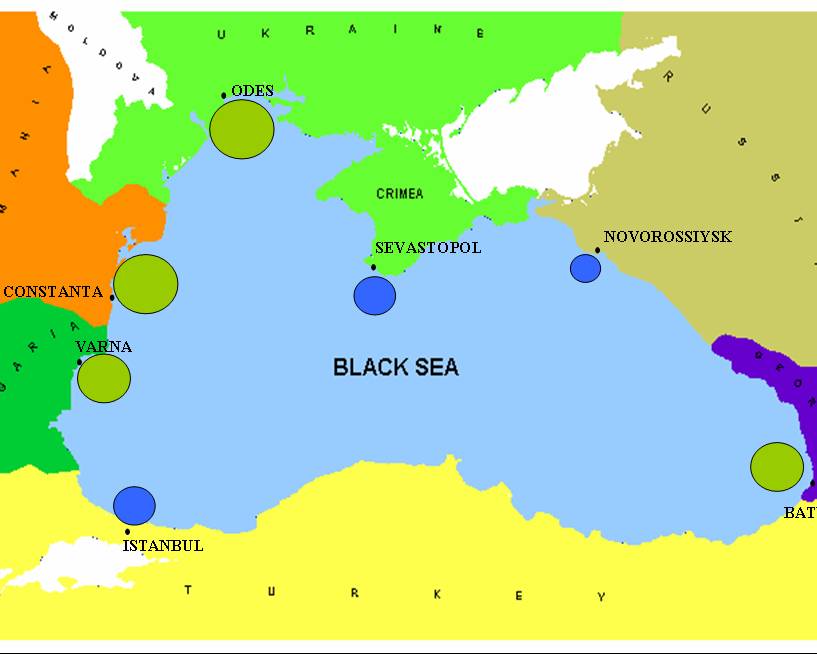

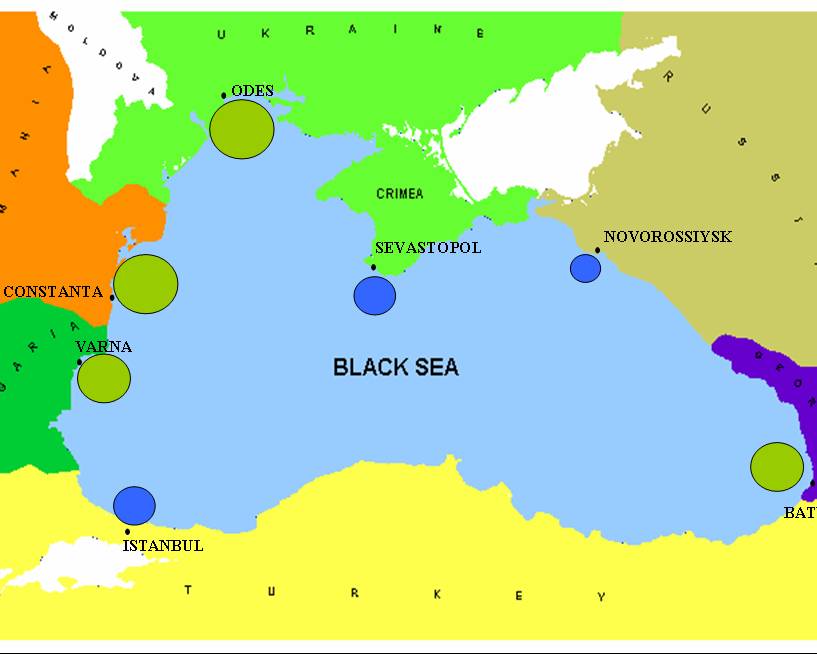

In 2005, the Turkish government funded monitoring at an additional 63 sites (Table 4.1), with many of

these sites being relatively unimpacted. Thus, over half of the current BSIMAP sites are now along the

Turkish coast, greatly improving the spatial coverage of the integrated programme (see Fig. 4.1, with

coordinates shown in Appendix F), albeit with the Ukrainian and Russian coasts still remaining only

sparsely covered. Improved spatial coverage of BSIMAP remains an aim of the Black Sea Commission

Permanent Secretariat. It is hoped to increase the number of Georgian and Russian monitoring sites in

future years.

Table 4.1

Number of national monitoring sites included in the BSIMAP, with an indication of

spatial coverage

Territorial waters

Pollution Sampling sites

Length of coast, Average distance

of

hot spots

km

(km) represented

per sampling site

Bulgaria 9

5

300 60

Georgia 6

5

310 62

Romania 5

21

225

17

Russian Federation 4

5

475

95

Turkey

10

3 (66 from

1400

466 (21 from

2005)

2005)

Ukraine 9

14

1628 116

4.5 BSIMAP

parameters

A list of compulsory and recommended (optional) parameters has been specified by the BSC Permanent

Secretariat. The paucity of national funding for environmental monitoring means that only mandatory

parameters are considered in this report, since optional parameters tend to be monitored by few (if any)

countries. Mandatory parameters are shown in Appendix H.

This list of compulsory parameters does not fully tie-up with the list of indicators agreed by the JTWG,

and detail is sometimes omitted from the recommendations. The recommendations for monitoring in

2005 include phytoplankton as the only mandatory biological parameter.

For nitrogenous nutrients, data are requested for ammonia, nitrite and nitrate, but for reporting purposes

it would preferable to add these parameters together to give dissolved inorganic nitrogen (DIN), an

accepted surrogate of bioavailable nitrogen, albeit composed overwhelmingly of nitrate. Total nitrogen

and total phosphorus are also requested as part of the BSIMAP but, to date, few countries have

monitored theses as standard parameters.

15

Figure 4.1

BSIMAP proposed monitoring sites, 2005

Ukraine

Russian Federation

Romania

Bulgaria

Georgia

Turkey

16

The list of 2005 compulsory parameters does not adequately tie-up with the list of indicators agreed by

the Black Sea-Danube JTWG (Section 2), e.g. phytoplankton as the only mandatory biological

parameter (Appendix H, Table H.1). However, the revised list of compulsory parameters for 2006-2011

Appendix H, Table H.2), proposed at a recent PMA Advisory Group meeting, much more closely

matches the agreed list of indicators, but detail is sometimes missing from both the agreed list of

indicators and the specified reporting parameters of the Black Sea coastal countries. For example, no

decisions appear to have been made on the format for reporting macrozoobenthos data although

biomass and percentage of key groups has been agreed on as the indicator, should these key groups be

taxonomic or functional feeding groups (Appendix B, Section B.6). Alternatively, should a biotic index

be used (Section 6.9)? This also poses very large questions for data collation/storage as part of the Black

Sea Information System (BSIS): should raw data be quested by the Commission or processed data?

Clearly raw data would be of benefit for future development work on indicators. In addition there is still

a need to reach agreement on standard taxonomic lists for use by all countries; at present different

countries are still calling some taxa by different names.

Monitoring for a limited number of toxic heavy metals (cadmium, copper, mercury and lead) is

mandatory within the BSIMAP, which appears appropriate given the limited funding available.

However, the addition of other heavy metals should require only a marginal increase in expenditure and

is likely to be beneficial for future impact assessment studies. No guidance is presented on whether

total or dissolved heavy metals should be monitored this is an important consideration which should

be addressed in terms of loading to the Sea, bioaccumulation and toxicity to marine biota.

4.6

BSIMAP proposed monitoring frequencies

Up until 2005, the BSIMAP specified the same monitoring frequency for all compulsory parameters in

all countries (Appendix H). For most of the compulsory parameters (phytoplankton, nutrients, petroleum

hydrocarbons, salinity, oxygen balance parameters, suspended solids and physico-chemical parameters)

this frequency is set at 4 times per year.

For fish catch statistics annual reporting is required, which again appears pragmatic, given how the data

are reported nationally.

For the four heavy metals, a monitoring frequency of only once per year is specified by the Black Sea

Commission Permanent Secretariat. This appears to be an extremely low monitoring frequency for

analysis of either trends or step changes, and is likely to result in only very large changes being detected

at a statistically significant level. However, at a recent meeting of the PMA Advisory Group, during a

discussion on whether monitoring of heavy metals in the water column should be mandatory (as

opposed to monitoring of sediment contamination), it was stated that the purpose of monitoring the

water column was only to define `background levels' throughout the Sea.

While the Commission specifies a minimum monitoring frequency of 4 times per year for most of the

compulsory parameters, Bulgaria aims to samples seven times a year, and will continue to do so, while

at the 63 new (2005 onwards) Turkish sites, monitoring will only be undertaken twice a year.

4.7

Recent years BSIMAP reporting

Appendix I shows the maximum number of results reported to the Black Sea Commission for samples

collected during the years 2001 (Table I.1) and 2003 (Table I.2) for each of the BSIMAP sites. Sites 51

to 113 (see Appendix F) are excluded from these tables, since formal monitoring only began at those

sites during 2005. For Tables I.1 and I.2 results are grouped into the following categories:

17

· Oxygen balance parameters (including BOD5, dissolved O2 [% saturation] and dissolved O2

[mg/l])

· Nutrients (including ammonia, nitrite, nitrate, silicate and ortho-phosphate neither total P nor

total N are monitored by any laboratory)

· Heavy metals (including cadmium, copper, mercury and lead)

· Organic pollutants (petroleum hydrocarbons)

· Other water column physico-chemical parameters (including temperature, pH, salinity, total

suspended solids and Secchi depth)

· Chlorophyll-a

The information in Appendix I therefore represents a rather optimistic view of historical monitoring. For

example, if BOD5 had only been reported on three occasions during 2001, but dissolved oxygen (%

saturation and mg/l had both been reported on 10 occasions during that year, then the oxygen balance

parameters group would be shown as having been monitored on 10 occasions (250% of the

recommended monitoring frequency). The tables show enormous variability in the number of reported

data for individual sites and in the types of parameters which were monitored, making the BSIMAP

appear rather uncoordinated.

18

5.

CONSIDERATIONS FOR IMPROVING THE COLLECTION

AND INTERPRETATION OF BLACK SEA MONITORING

DATA

5.1 Funding

and

equipment

Perhaps the most obvious statement to make is that there is little use in defining or agreeing to a

monitoring programme if insufficient funds are made available to measure the minimum (mandatory)

monitoring parameters. This funding needs to cover transportation costs (including provision of a

boat/ship), monitoring and analytical equipment costs, including consumables, as well as staff costs.

5.2

Relevant and proposed legislation

The most relevant international policies and agreements in terms of monitoring the Black Sea are

considered to be the Strategic Action Plan for the rehabilitation and protection of the Black Sea, the

Water Framework Directive and the proposed Marine Framework Directive.

5.2.1

Strategic Action Plan for the rehabilitation and protection of the Black Sea

Article 54 of the Black Sea Strategic Action Plan (BSSAP) states that "A Black Sea Monitoring System,

based upon biological effects measurements and measurements of key contaminants will be established

in compliance with the Bucharest Convention. It will consist of the integration of obligatory monitoring

programmes, to be included in the National Strategic Action Plans, and an independent quality

assurance system. It is advised that the Istanbul Commission develop such a quality assurance system

through its advisory group on Pollution monitoring and assessment by 1998." The Black Sea SAP will

shortly be updated for presentation to the Black Sea Commission and the six national governments

5.2.2

Existing European Union directives

Bulgaria and Romania are expected to join the European Union in 2007. Turkey is a candidate country

with whom accession negotiations have not yet started. Once these countries have joined the EU they

will have to implement the EU legislation relating to marine waters.

The most significant EU policy relating to the water environment is the Water Framework Directive.

The Water Framework Directive covers all waters, including inland waters (surface water and

groundwater) and transitional and coastal waters up to one sea mile (in terms of monitoring ecological

status and for the chemical status also territorial waters which may extend up to 12 sea miles) from the

territorial baseline of a Member State, independent of the size and the characteristics.

Member States have to characterise their waters in terms of numbers and types of water bodies, and

identify the pressures upon them. A surface water body is defined as a discrete and significant element

of surface water such as a transitional water or a stretch of coastal water. The main purpose of

identifying "water bodies" is to enable status to be accurately described and compared to environmental

objectives. Physical features (geographical or hydromorphological) should be used to identify discrete

elements of surface water. A water body should not contain significant elements of different status and

must be capable of being assigned to a single ecological status class with sufficient confidence and

precision through the Directive's monitoring programmes.

To that end, Member States have to implement monitoring programmes that enable the classification of

surface water bodies into one of five classes. Monitoring is termed surveillance, operational or

investigative each with defined objectives. Operational monitoring is to be undertaken in water bodies

thought to be at risk of failing environmental quality objectives and will focus monitoring on those

determinands most relevant to the pressures creating the risk. Surveillance monitoring should include

19

sufficient water bodies to provide an assessment of the overall surface water status within each

catchment and sub-catchment of the river basin district: to achieve this water bodies not at risk (i.e. high

and good status) and those at risk will have to be monitored. Member States will also have to determine

how many monitoring stations are required in each water body (or groups of water bodies) to determine

its status.

Bulgaria and Romania have identified and characterised their water bodies as required by Article 5 of

the Water Framework Directive: two coastal water bodies and types were identified along the 300 km of

Bulgaria's, and three water bodies and two types identified along the 225 km and Black Sea coastlines

(Member States are only required to identify water bodies in coastal waters, not territorial waters). For

comparison 556 coastal waterbodies have been identified in the UK along 5167 km of coastline, giving

approximately one waterbody per 9.3 km. In Bulgaria and Romania there is an average of one water

body per 150 km and 75 km of coastline, respectively.

The European Commission is also developing a Daughter Directive to the Water Framework Directive

under Article 16 on environmental quality standards and emission controls for Priority Substances. At

the present time environmental quality standards for the concentration of the substances in water

(including coastal waters) will be established, but not for concentrations in biota or sediment. The

Daughter Directive will re-iterate the need for these substances to be monitored not only in water for

determining chemical status and checking compliance with the EQSs, but also for their presence in

sediment and biota to demonstrate compliance with the "no-deterioration" objective of the Water

Framework Directive (Article 4(1)(i).

Monitoring of surface freshwaters, estuarine, coastal and marine waters is also required for the Nitrates

Directives where marine waters are referred to as those in "exclusive economic zones". The geographic

extent of marine waters included in the requirements of the Urban Waste Water Treatment Directive is

not clear: Annex II, (criteria for the identification of sensitive and less sensitive areas) includes estuaries

and coastal waters in terms of sensitive areas, whereas marine water bodies are included in the criteria

for less sensitive areas. Coastal waters are defined as "waters outside the low-water line or the outer

limit of an estuary". The European Commission has developed informal guidance on monitoring

required for the Nitrate's Directive which includes water quality determinands such as nitrate but also

relevant biological determinands such as phytoplankton, aquatic vegetation, benthic invertebrates and

fish.

The European Commission is also developing guidance on eutrophication for the Water Framework

Directive. It compares how eutrophication is understood, defined and assessed in EC Directives,

policies, guidance and research, and proposes a new conceptual framework for eutrophication

assessment across all water categories and policies. The guidance includes a chapter on monitoring with

the aim of integrating the monitoring requirements stemming from the various obligations dealing with

eutrophication.

5.2.3

Proposed Marine Framework Directive

The proposed Marine Framework Directive (arising from the Commission's Marine Strategy) would be

applicable to all European marine waters under the sovereignty or jurisdiction of the Member States. It

would, therefore, cover marine waters within a country's exclusive economic zone (up to 200 nautical

miles from the baseline from which the breadth of territorial waters are measured). The strategy is also

directed at non-EU countries bordering these areas (presumably including those Black Sea countries that

are not EU candidate countries) and at the relevant international organisations in which countries

cooperate (e.g. the Black Sea Commission). The objective of the Directive would be to protect, conserve

and improve the quality of the marine environment in these marine waters through the achievement of

good environmental status within a defined time period. The directive will define/establish ecosystem-

20

based marine regions as the implementation unit. The latter will be defined on the basis of their

hydrological, oceanographic and bio-geographic features. Monitoring and assessment programmes will

have to be developed for each marine region taking into account existing monitoring and assessment

programmes. Monitoring would also be required offshore of territorial waters within economic zones,

the delineation of which has not yet been completed by all Black Sea countries. It is, therefore, likely

that the geographical extent of monitoring of the Black Sea will have to be increased by at least some of

the Black Sea countries.

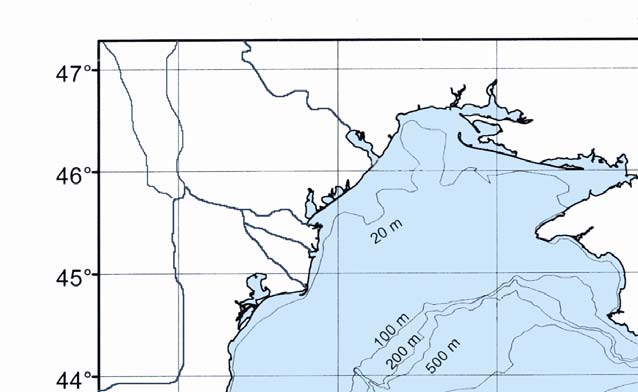

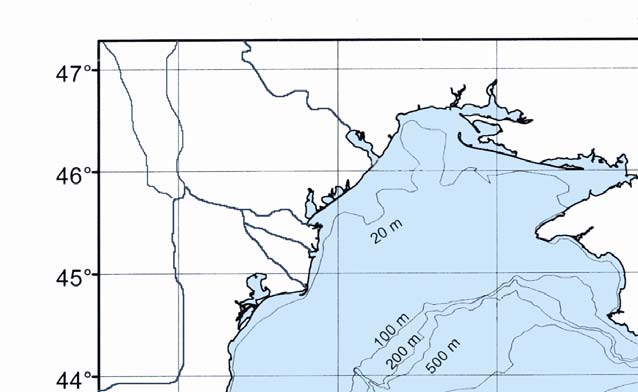

5.3

Spatial and depth coverage of monitoring stations

Table 4.1 and Appendix F summarise the numbers of stations per country and the average distance

represented per sampling site. If the spatial coverage of stations could be increased then new stations

should not only be located to detect potential impacts from identified sources (hot spots) such as point

source discharges or diffuse inputs via rivers, but also at points further away where impacts are expected

to be less. In particular reference sites (see below) should be established against which values of

determinands measured at the impacted sites could be compared. The approach used in Romania seems

an appropriate one if resources are limited, where stations have been established seaward along a line

perpendicular to the coast where the main sources of pollution appear to be. Of course stations further

offshore may also be impacted by pollutants carried by the prevailing currents from other parts of the

Black Sea. Similarly, the zone of influence of river inputs and major discharges should also be covered

by monitoring.

The selection of stations (and determinands to be monitored) would also be facilitated by the approach

adopted for the Water Framework Directive, that is transitional and coastal waters are characterised in

terms of the types and numbers of water bodies and then the pressures potentially impacting them

identified. The identification of pressures includes those arising from point sources along the coast and

offshore, diffuse sources such as pollution from shipping and the flows from the larger rivers. This is the

process that Romania and Bulgaria have started as candidate EU countries and which Turkey will start

at some point in its EU entry negotiations.

The typifying of water bodies helps the comparison of like-with-like when it comes to comparing

monitoring results and assessing state from different parts of the same country and across the Black Sea

as a whole. For example, comparing the biological community attributes and metrics (such as diversity)

from relatively low salinity and shallow parts of the Black Sea with relatively high salinity deep parts of

the Black Sea may not be valid and lead to the wrong conclusions about their relative quality. The

division of coastal waters in terms of types and potential status could help obtain (through surveillance

monitoring) a representative view of quality along the coast rather than just of the worse quality areas.

The physical factors that could be considered in determining whether stations are within water bodies or

areas of similar and comparable types would include depth of water, salinity, degrees of exposure and

sea bed characteristics (i.e. sedimentary or rocky). The Water Framework Directive working group on

intercalibration identified three depths for the identification of comparable types for intercalibration:

shallow with a depth of less than 30 m, of intermediate depth 30 to 50 m and deep greater than 50 m.

For example, in the Black Sea a `natural' decrease in macrozoobenthic community diversity is observed

in the deeper waters of the North-Western Shelf reflecting the greater environmental stress at these

depths. In terms of salinity, the least saline parts of the Black Sea are in the North-Western Shelf in

relation to the main river inputs. Differences in salinity should be taken into account when monitoring

for any biological determinands as aquatic communities will vary in relation to salinity. Nitrate

concentrations will also vary in relation to salinity particularly as the rivers are significant sources of

nutrients to the Black Sea. Allowing or normalising for salinity will improve the robustness of trend

analysis of nitrate concentrations at stations where salinity varies significantly between sampling

occasions.

21

In terms of depth the sampling for some water quality determinands such as nutrients and chlorophyll

should take into account the potential vertical stratification of the water column (e.g. presence of a

pycnocline) and the varying depths of maximum phytoplankton biomass. For example samples for

chlorophyll would ideally be taken throughout the euphotic zone at regular intervals or by taking

continuous measurements with a fluorometer. Once a few seasons/years of data have been obtained the

results could be statistically assessed to see if there was any opportunity to reduce the number of

samples without losing any information (i.e. where maximum chlorophyll concentrations are occurring).

As an example, for the Baltic Sea the standard sampling depths for chlorophyll-a are 1 m, 5 m, 10 m, 15

m and 20 m. Samples integrated over 1 to 10 m are also acceptable.

One of key criteria of the present BSIMAP is the affordability of monitoring in each of the countries. It

is quite clear that the present monitoring in some of the countries is not adequate to obtain an overview

of the state of coastal waters of the Black Sea (and also maybe not for the assessment of all hot spots).

As the largest proportion of the total cost of monitoring probably is generally with undertaking sampling

(ships, personnel etc.) cruises (compared to the cost of sample analysis) then it might be the better

option to undertake sampling at more stations and at an increased number of depths over the water

column for water quality samples, rather than increasing the monitoring frequency. In addition, more

monitoring stations in the open, offshore waters of the Back Sea (particularly in the North-Western

Shelf area and in the deeper central area) would enable a more complete spatial assessment of water

quality/ecological status to be made.

No guidance is currently offered to countries on the depth at which water should be sampled. Nutrient