UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

Strengthening the Implementation Capacities for Nutrient

Reduction and Transboundary Cooperation in the Danube

River Basin

Development and maintenance of the

DBAM

Project Component 2.3-4: Final Report

October 15, 2003

Prepared by:

Jos van Gils, WL | Delft Hydraulics

Development and Maintenance of the DBAM

i

Contents

1

Introduction ................................................................................................................ 1

1.1

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project ........................................................... 1

1.2

Development and maintenance of the DBAM ............................................... 2

1.3

The current report............................................................................................ 3

1.4

Acknowledgements......................................................................................... 3

2

Brief description of the model................................................................................... 4

2.1

General ............................................................................................................ 4

2.2

Mathematical description................................................................................ 4

2.3

Implementation ............................................................................................... 6

2.4

The accuracy of the DBAM............................................................................ 7

3

Review of existing information ................................................................................. 9

3.1

The Rhine Alarm Model ................................................................................. 9

3.1.1

The tracer experiments ...................................................................... 9

3.1.2

The model calibration ...................................................................... 12

3.1.3

Further research ............................................................................... 13

3.2

The Danube Basin Alarm Model .................................................................. 14

3.2.1

Set-up and implementation of the AEWS, DBAM pre-study ........ 14

3.2.2

Implementation of the DBAM ........................................................ 14

3.2.3

Methods for calibration experiments ("project AE2") .................... 15

3.2.4

Strengthening the Danube AEWS ................................................... 16

3.3

Experience from the Elbe River ................................................................... 18

3.3.1

The July 1997 tracer experiments in the Elbe River....................... 18

i i

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

3.3.2

The ALAMO model......................................................................... 19

3.4

Advances in transport modelling.................................................................. 20

3.5

Specific conditions in the Danube Basin...................................................... 20

4

Synthesis: Calibration Options ............................................................................... 21

4.1

Integrated "DBAM usability enhancement plan"......................................... 21

4.1.1

Accuracy of the DBAM................................................................... 21

4.1.2

Maintenance of the DBAM ............................................................. 22

4.2

Scope and objectives of the DBAM calibration exercises........................... 22

4.3

Existing data or additional tracer experiments? ........................................... 22

4.4

Set-up of additional tracer experiments........................................................ 24

4.4.1

Selection of tracer substance ........................................................... 24

4.4.2

Sampling and analysis ..................................................................... 24

4.4.3

Selection of stations and observation windows .............................. 25

4.4.4

Collection of hydrology data ........................................................... 26

5

Preparation of the Workshop.................................................................................. 27

6

Recommendations for follow-up (Workshop Report).......................................... 28

6.1

Availability and utilisation of the DBAM .................................................... 28

6.1.1

Current status ................................................................................... 28

6.1.2

Target accuracy of the DBAM ........................................................ 28

6.1.3

Hydrology data ................................................................................ 29

6.1.4

Rating curves and velocity tables.................................................... 30

6.2

Future calibration of the DBAM, supported by tracer experiments ............ 31

6.2.1

Current status ................................................................................... 31

6.2.2

Scope and objectives (including priorities)..................................... 31

6.2.3

Existing data or new experiments?.................................................. 32

6.2.4

Selection of tracers .......................................................................... 32

6.2.5

Sampling and analysis ..................................................................... 32

J. van Gils, WL | Delft Hydraulics

Development and Maintenance of the DBAM

i i i

6.2.6

Density of stations ........................................................................... 32

6.2.7

Frequency of sampling .................................................................... 33

6.2.8

Hydrology data ................................................................................ 33

6.2.9

Organisation and financing.............................................................. 33

7

Epilogue ..................................................................................................................... 34

8

References.................................................................................................................. 35

A

Draft Workshop Agenda....................................................................................... A1

B

Workshop presentations ........................................................................................B1

C

List of attendants to the Workshop ..................................................................... C1

D

Inventory "availability and utilisation of the DBAM" (G. Pinter) .................. D1

E

Draft ToR for maintenance of the DBAM ...........................................................E1

F

Suggested extension of functionality ....................................................................F1

G

Existing data inventory......................................................................................... G1

H

Relevant legislation for tracer experiments ....................................................... H1

I

Guidelines for tracer mass calculation and exceedance of MAC ......................I1

I.1

Estimation of the required mass of tracer.................................................... I1

I.2

Estimation of the distance where concentrations exceed the MAC ........... I2

I.3

General considerations................................................................................. I2

J

Guideline for frequency of sampling.................................................................... J1

K

Outline of Calibration Manual ............................................................................ K1

K.1

Description of available data ..................................................................... K1

K.2

Calibration methodology ........................................................................... K1

K.3

Processing of available data....................................................................... K2

K.4

Calibration process..................................................................................... K2

K.5

Reporting.................................................................................................... K2

K.6

Upgrading the DBAM................................................................................ K2

K.7

References .................................................................................................. K3

i v

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

J. van Gils, WL | Delft Hydraulics

Development and Maintenance of the DBAM

1

1

Introduction

1.1

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

The UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project started in 2001 with the long-term development objective

to contribute to sustainable human development in the Danube River Basin through reinforcing the

capacities of the participating countries in developing effective mechanisms for regional co-operation

and co-ordination in order to ensure protection of international waters, sustainable management of

natural resources and biodiversity. In this context, the Project supports the ICPDR, its structures and

the participating countries in order to ensure an integrated and coherent implementation of the

Strategic Action Plan 1994 (SAP 1994), the Common Platform and the forthcoming Joint Action Plan

and the related investment programmes in line with the objectives of the Danube River Protection

Convention (DRPC).

The overall objective of the Danube Regional Project is to complement the activities of the

International Commission for the Protection of the Danube River basin (ICPDR) required to provide a

regional approach and global significance to the development of national policies and legislation and

the definition of priority actions for nutrient reduction and pollution control with particular attention to

achieving sustainable trans-boundary ecological effects within the Danube river basin and the Black

Sea area.

One of the immediate objectives is Capacity building and reinforcement of trans-boundary co-

operation for the improvement of water quality and environmental standards in the Danube river basin.

In view of this objective, Phase 1 of the Project comprises a component directed towards the

Improvement of procedures and tools for accidental emergency response with particular attention to

trans-boundary emergency situations (Project Output 2.3).

In the remainder of this document the UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project will be referred to as "the

Project".

2

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

1.2

Development and maintenance of the DBAM

The Danube Basin Alarm Model (DBAM) is an operational model for the simulation of the transport

and decay of substances that have been released during accidental spills. The model forms an integral

part of the Danube Accident Emergency Warning System (AEWS) in operation in the Danube River

Basin, and supports the assessment of the consequences of accidental spills for the river water users.

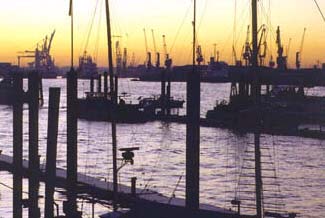

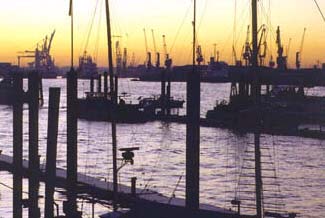

See Figure 1-1.

Figure 1-1: Application of the Danube Basin Alarm Model to the cyanide incident in the Tisa river (January 2000).

The DBAM model-system is used by the Principal International Alert Centres (PIACs) of the Danube

AEWS as a tool to evaluate the possible impacts of a trans-boundary water pollution incident. First of

all the DBAM is aimed to assess the expected concentration of a pollution plume and its time of

arrival at a particular river section downstream.

The experience from the last accidental pollution events indicates that the AEWS and in particular

DBAM needs substantial improvement to become a satisfactory tool for adequate management of

trans-boundary contamination from catastrophic events.

In this context, part of the Project Output 2.3: "Improvement of procedures and tools for accident and

emergency response with particular attention to trans-boundary emergency solutions", is focused on

the maintenance and calibration of the Danube Basin Alarm Model (Activity 2.3-4).

J. van Gils, WL | Delft Hydraulics

Development and Maintenance of the DBAM

3

1.3

The current report

A specific Inception Report describes the activities of the International Consultant in relation to the

planned outputs under Activity 2.3-4 of the Project (WL | Delft Hydraulics, 2002). The general

objective for the work done by the International Consultant is:

To provide a technically sound basis for the DBAM calibration (during Phase 2 of the Project)

and for the future use of the model.

The present document constitutes the Final Report of these activities. It starts with a brief description

of the Danube Basin Alarm Model (Chapter 2). Next, a review of existing information is presented

(Chapter 3). Chapter 4 presents a short study, which analyses the different options for the calibration

of the model. This study results in alternative approaches towards the calibration, which are clearly

laid out for discussion with the ICPDR (APC/EG) and the Project staff in a dedicated Work Shop (held

in Ljubljana on 8-9 September 2003). Implications for the use and maintenance of the model are taken

into consideration.

Chapter 5 continues with some information regarding the preparation of the Workshop mentioned

above, while Chapter 6 discusses the results from the Workshop.

Chapter 6 in particular together with the annexes to this report constitute a specification for and

boundary conditions to the activities to be carried out during Phase 2 of the Danube Regional Project.

1.4

Acknowledgements

The Consultant acknowledges the co-operation of the DRP project staff, the ICPDR Secretariat staff as

well as the APC/EG members. Furthermore, we express our appreciation for the contribution of Dipl.-

Ing. Werner Blohm (Institut für Hygiene und Umwelt, Hamburg) to the Workshop, in relation to the

Elbe alarm model ALAMO.

4

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

2

Brief description of the model

2.1

General

The Danube Basin Alarm Model aims at predicting the travel time of and the concentration in a cloud

of pollutants released in the river system as the result of an accidental spill. The focus is on large scale

events of a trans-boundary nature. The model is intended to be used for a first and rapid assessment

under operational conditions: the run-time should be short and the necessary input data should be

limited.

In view of the requirements above, a 1-dimensional approach has been selected: the variation of the

concentration along the Danube and its main tributaries is calculated. The cloud of pollutants is

supposed to be well mixed over the conveying part of the river cross-section.

Following the example of other large European rivers, the so-called "dead zone model" was adopted.

This model includes two major physical phenomena: (1) the transport of the cloud of pollutants as a

whole in a downstream direction by the river flow, and (2) the mixing and dilution of the cloud. An

important aspect of the latter phenomenon is the mixing of water between the main stream of the river

and (semi-)stagnant parts of the river cross-section or "dead zones".

2.2

Mathematical description

The governing mathematical equations of the dead zone model are:

2

C

C

C

+U

- D

= -e C - C

2

(

s )

t

x

x

Cs = e(C -Cs)

t

(1)

Where:

C

concentration in the main stream (g/m3)

Cs

concentration in the dead zone (g/m3)

U

mean flow velocity (over the main stream) (m/s)

D

longitudinal dispersion coefficient in the main stream (m2/s)

e

mass transfer coefficient between the dead zones and the main

stream (/s)

ratio between the cross section of the dead zone and the cross

section of the main stream (-)

J. van Gils, WL | Delft Hydraulics

Development and Maintenance of the DBAM

5

For reasons of efficiency and accuracy, an analytical solution technique is used. This provides a

solution in a closed mathematical formula for a given location x at a given time t, as a result of a spill

of a mass M (g) at location x = 0 at time t = 0:

2

M / Q

( t - x/

u

)

G

t - x/ u

c(x,t)=

× exp

xc

t

xc

[ -

] 1

+

H (

)

3

2

2

2

4 D t/

4 D t/

u

u

6

xc

2 D t/

xc

u xc

(2)

Where:

U

u =

xc

1+

2

2

U W

D = h u*

(Semi-empiric after Fisher)

Q

river discharge (m3/s)

H3(z)

3rd Hermite polynomial (= z3 - 3z)

Gt

skewness coefficient (-)

W

river width (m)

h

river depth (m)

u*

shear stress velocity (m/s)

constant of proportionality (-)

The parameters (longitudinal dispersion) and (dead zones) are the main calibration parameters.

The solution mentioned above is extended with a factor accounting for the decay of the spilt pollutant:

c(x,t)= c

(x,t) × exp -kt

without decay

( )

(3)

Where:

k

decay rate (1/s)

6

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

The "dead zone model" is commonly accepted as a basis for spill models in river systems: the same

mathematical model is used in the Rhine basin, the Elbe basin and for several rivers in France. It

should be noted however, that there are other ways to solve the mathematical equations. The Elbe

model for example uses a numerical approach, whereas in France the so called "mixing cell" method

is used. The different solution techniques do not have significant implications with respect to the

potential model accuracy and the calibration method (supposing that the implementation is done

properly).

2.3

Implementation

The equations (1) and (2) mentioned above are valid for a uniform river stretch with constant flow

characteristics. For the practical application to the Danube river and its main tributaries (see Figure

1-1), the solution has been expanded for confluences and bifurcations, taking into account the spatial

variability of the hydraulic characteristics of the river system.

The actual calculation procedure consists of two steps:

1. The calculation of the hydraulic coefficients (discharge Q(x) and velocity U(x)).

2. The calculation of the concentration C(x,t).

The hydraulic coefficients Q and U are calculated on the basis of actual hydrological input data:

observed values of either the water level or the discharge at selected hydrological stations at the time

of the accident. The DBAM uses tabulated relations between the water level and the discharge ("rating

curves") to calculate the actual discharge. In a similar way, tabulated relations between the

discharge/water level and the velocity are used to calculate the actual velocity.

Strictly speaking, the hydraulic coefficients Q and U are a function of space only. By evaluating them

at the time of the passage of the cloud for every individual river stretch, they are effectively made time

dependent.

The concentrations are computed on the basis of actual spill input data: the location of the spill and

the amount of material spilled.

The output of the DBAM is presented by animations, tables and graphs, showing the temporal and

spatial variation of the pollutant concentration and the variation along the river of the travel time of the

cloud and the peak concentration in the cloud.

The input of data as well as the presentation of the results is supported by a modern Windows-based

Graphical User Interface. (GUI).

J. van Gils, WL | Delft Hydraulics

Development and Maintenance of the DBAM

7

2.4

The accuracy of the DBAM

References: H. Hartong ea. (2000).

In order to explain the notion "accuracy" for the case of the Danube Basin Alarm Model, it is

necessary to explain some backgrounds. We will describe below which are the essential steps in the

calculation method of the DBAM, and which are the potential inaccuracies arising from each step.

Table 2-1 summarises this description .

Phase 1 of the calculation procedure is the collection of the necessary hydrology input data (water

levels and/or river discharges). In order to achieve optimal accuracy it is necessary to have accurate

hydrology and meteorology forecasts for the full duration of the pollution event. For reference, this

period lasted about 4 weeks in case of the Baia Mare spill. It is clear that it is not realistic to assume

accurate hydrology and meteorology forecasts over such a long period. The inaccuracy arising from

this step affects only the operational use of the DBAM, when it is used in a "forecasting mode". In an

analysis in "hind casting mode" with historical hydrology data, there is no inaccuracy as a result of

phase 1. This fact offers a possibility to isolate this source of inaccuracies from the remaining sources.

Phase 2 of the calculation procedure is the computation of discharges from water levels, or vice versa,

by using the built-in rating curves of DBAM. It is well-known that the concept of rating curves has its

limitations and that rating curves are not constant over time. Therefore, the use of rating curves always

adds a certain degree of inaccuracy to the result. The latest version of the DBAM allows the user to

avoid this inaccuracy by supplying both the water level and the discharge (if these data are available).

Again, this fact offers a possibility to isolate this source of inaccuracies from the remaining sources.

Phase 3 of the calculation concerns the computation of the stream flow velocity from the built-in

tables. This step presents an additional source of inaccuracy.

Finally, phase 4 of the calculation concerns the actual computation of the propagation of the cloud of

pollutants (travel time and concentrations). The fact that the DBAM has not yet been calibrated is a

possible source of inaccuracies during this last phase of the computation. It is not immediately

possible to isolate this inaccuracy from the part introduced in phase 3.

A final word needs to be said about the inaccuracy stemming from the assumptions underlying the

concepts of the DBAM. First, there is the fact that the DBAM uses a constant hydrology per river

segment ("quasi-steady"). This aspect is more relevant in hind casting mode, with full hydrology

records available, than it is in forecasting mode, when the hydrology forecasts are absent or inaccurate

anyway. Nevertheless, the current version of the DBAM allows for the input of a fully time dependent

set of hydrology data, so that the inaccuracy on this point can be minimised. A second conceptual

problem may be the assumption of 1-dimensionality, which means that no variations in the river

velocity or the pollutant concentration over the cross-section are taken into account. This problem is

always present, and should be expected to influence the results close to the spill position or close to

confluence points.

8

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

Table 2-1: An overview of the sources of inaccuracy for the operational use of the DBAM.

Phase in the calculation procedure

Potential inaccuracies

1) Collection of hydrology input data during the event

Inaccuracy or even unavailability of long term

meteorological forecasts and hydrology forecasts

2) Computation of discharges from water levels, or vice

Inaccuracy of the rating curves in DBAM

versa, by using rating curves

3) Computation of river stream flow velocity, by using

Inaccuracy of the velocity tables in DBAM

built-in tables and the actual water level or river

discharge

4) Computation of the propagation of the cloud of

Inaccuracy of the calibrated model coefficients

pollutants (travel time, concentration level)

(affecting travel time and concentration) and

(affecting only concentrations)

Overall concept of DBAM

Inaccuracy

of

the

underlying

assumptions,

in

particular:

· 1-dimensional modelling approach (no variations

over the cross-section);

· quasi steady hydrology

J. van Gils, WL | Delft Hydraulics

Development and Maintenance of the DBAM

9

3

Review of existing information

3.1

The Rhine Alarm Model

References: IKSR/KHR Expertengruppe (1993).

3.1.1

The tracer experiments

The Rhine Alarm Model (RAM) performs a similar role as the DBAM in the Rhine Alarm System.

Furthermore, the RAM has the same mathematical foundation as the DBAM. Therefore, the

information with respect to the calibration of the RAM is directly relevant for the calibration of the

DBAM.

The calibration of the RAM was based on 8 large scale tracer experiments with fluorescent tracers

between 1988 and 1991. The organisers claim that tracer experiments on a similar scale had thus far

not been reported. Figure 3-1 provides an overview.

1 0

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

Figure 3-1: Overview of tracer experiments carried out in the Rhine Basin.

The tracer experiments were as much as possible planned to cover a range of discharge conditions.

High flow conditions were to be avoided: they occur infrequently, which makes them less relevant,

while the river transport characteristics may deviate strongly from those under regular conditions.

J. van Gils, WL | Delft Hydraulics

Development and Maintenance of the DBAM

1 1

The tracer experiments focused on dissolved substances, since these were considered to present the

largest threat to the riverine ecosystem. They also focused on the longitudinal transport and spreading

of the tracer. Incomplete vertical and lateral mixing over the conveying part of the cross section was

not a subject of study.

Three different tracer types were considered: salt, radio nuclides and fluorescent tracers. Salt was

rejected because the background levels and the analysis sensitivity would require unrealistically high

amounts inputs. Radio nuclides were rejected because of the legal restrictions for their use.

Consequently fluorescent tracers were chosen.

Fluorescent tracers are suitable because they can be detected in very small concentrations. Three

different substances with different stability were used: Uranine (half-life time 11 h), Acid Red or

Rhodamine WT (half-life time 1300 h = 54.2 d) and Rhodamine B (half-life time 780 h = 32.5 d). For

the large-scale experiments only the latter two were used.

The tracer releases were intended to be momentaneous releases. The real duration of the discharge was

2 to 6 minutes, except for one release of Rhodamine WT where the duration was 70 minutes due to the

formation of a deposit in one of the barrels.

The amounts of tracer released, and the local discharge at the point of release are summarised below.

Experiment

Tracer used

Discharge (m3/s)

Tracer mass (kg)

MV 09/88

Uranine

712 (Rheinfelden)

235

MV 07/89

Uranine

490 (Rheinau)

200

MV 04/89

Rhodamine WT

1170 (Rheinfelden)

100

MV 09/90

Rhodamine WT

663 (Rheinfelden)

100

MV 06/91

Rhodamine WT

1820 (Rheinfelden)

100

MV 11/88

Rhodamine WT

550 (Rheinfelden)

74.5

MV 05/90

Rhodamine B

1008 (Rheinfelden)

80

MV 07/91

Rhodamine B

1722 (Rheinfelden)

80

Most of the concentration measurements were done with automatic samplers. The samples were stored

in brown coloured bottles (to avoid photolysis). Analyses took place in the laboratory, usually with

spectral fluorimeters (UV-spectrometry) following the "Synchronscan" method. This is a cheap

method. The detection limits of this method are 2 ng/l for Uranine and 6 ng/l for Rhodamine WT.

Occasional checks were done with the more accurate but also more time-consuming and expensive

HPLC method. The results of these checks matched well.

Simultaneously, in-situ measurements were carried out from ships in some cases. These did not

provide information to directly support the model calibration, but they did provide useful background

information for data interpretation. Such exercises are particularly useful to get a quick impression of

vertical and lateral concentration gradients.

The selection of the (lateral position of the) sampling sites proved critical. Based on the assumption

that the tracer mixes rapidly in the vertical and lateral direction, one would expect that this is not a

critical factor. Confluences of (large) tributaries without tracers however, may cause substantial lateral

concentration differences. Except for such occasions, the sampling was preferably done in the middle

of the river, for example using bridges or power stations.

1 2

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

The experiments were organised jointly by the different institutes and agencies involved. Each

delivered manpower, sampling and analysis at its own expenses. The results were gathered and

reported in close co-operation.

The report concludes:

·

the data from the tracer experiments were very fit for purpose;

·

it is recommended to simultaneously measure the flow discharge, and especially the variation

of it during the passage of the cloud;

·

the precise determination of the local flows is even more important for river stretches affected

by dams;

·

it is recommended to follow-up the large scale tracer experiments, aimed at catching the

longitudinal dispersion, with smaller scale experiments to study lateral dispersion phenomena,

in the vicinity of the discharge and near confluences;

·

Rhodamine B should not be used anymore, due to the associated environmental risks;

·

It is recommended to carry out all analyses in one laboratory.

3.1.2

The model calibration

The RAM was calibrated on a subset of the available tracer experiments, and verified on the remaining

data.

Target parameters were (effective dead zone parameter) and (longitudinal dispersion parameter).

The parameter affects both the travel speed and the concentration levels, while the parameter only

affects the concentration levels.

The calibration consisted of two stages:

·

estimation of and over reaches between two subsequent observation points by

mathematical formulas from the observed transport time (referring to the passage of the peak

concentration) and the observed overall dispersion;

·

refinement of the estimate by formally minimising the average deviation between the

observed and the computed concentrations (that is: minimising / and /).

The calibration report mentions other sources of inaccuracy than the imperfect calibration of and ,

but no effort is made to quantify them.

The calibration circumvents the estimation of a third parameter , expressing the decay of the tracer by

re-running the model for every river stretch with the locally recovered tracer mass, with the decay of

the tracer set to 0.

J. van Gils, WL | Delft Hydraulics

Development and Maintenance of the DBAM

1 3

At the end the following conclusions are drawn:

·

values of the parameter are in the range of 0 to 0.3;

·

values of the parameter are in the range of 0.002 (for canals), to 0.01 (rivers of moderate

slope) and 0.02 (lowland rivers);

·

incomplete mixing downstream of the release point and of confluences leads to deviations

between the predicted and the observed transport time;

·

except for the first 50 to 100 km, the model reproduces the transport times typically within

5%;

·

due to the fact that the decay of the tracer has not been included in the calibration and

verification process, no estimate could be made as to the accuracy of the predicted

concentrations;

·

the shape of the clouds of pollutants could very well be represented by the model.

3.1.3

Further research

Additional work has been done on the Rhine Alarm Model, based on available records from accidents

and on regular water quality monitoring (Lorenz, 1997 and Vollstedt, 2000).

1 4

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

3.2

The Danube Basin Alarm Model

3.2.1

Set-up and implementation of the AEWS, DBAM pre-study

References: WL | Delft Hydraulics (1994), WL | Delft Hydraulics (1996a), WL | Delft Hydraulics (1996b).

These references present no relevant information in the present context.

3.2.2

Implementation of the DBAM

References: VITUKI Plc, STU, ICIM, NIMH and RIZA (1996).

The first version of the DBAM was completed in 1996. This included the development of the software

and the compilation of the underlying river schematisation as well as the rating curves and the river

velocity tables.

The calibration of the model was not a part of the implementation. The model parameters were given

estimated values, derived from the experience with the RAM. However, a "tracer feasibility study"

was carried out and reported. This study consisted of separate contributions from the different

Consortium members from The Netherlands, Romania, Hungary and Slovakia.

On several occasions the authors mention the possible use of natural tracers. Concentration differences

of certain pollutants between a tributary and the main river can be used to track the lateral dispersion

process. Temporal variations of the concentration of certain parameters can be used to track

longitudinal dispersion. The latter occurs in the Rhine river due to large non-constant brine discharges.

The Hungarian section of the report mentions the possibility to in-situ measure the conductivity of the

water with sounding techniques, which is cheap, fast and reliable.

A distinction is made between large scale experiments to calibrate the longitudinal spreading and small

scale experiments to investigate specific areas (Bös-Gabcikovo, islands near Budapest, Iron Gates,

Delta, etc.) and to investigate lateral mixing. For the former a suggestion is done to cut the Danube in

two: upstream and downstream of the Iron Gates reservoir.

Suggestions are made for the locations for future tracer experiments, but it is not always clear what are

the underlying objectives and conditions.

From the report it shows that substantial experience with small scale tracer experiments exists in

Hungary and, to a lesser extent, in Slovakia. This shows among other things from the detailed

recommendations on the organisational aspects, such as the mobilisation steps listed in the Hungarian

section.

Some creative ideas of the Romanian author are worth mentioning. A suggestion is made to use floats

as an indicator of transport time (like it is routinely done in marine research). Furthermore, the idea is

formulated to use remote sensing images to analyse lateral mixing phenomena downstream of

tributary inflows. It should be investigated if such techniques have been successfully applied

elsewhere.

J. van Gils, WL | Delft Hydraulics

Development and Maintenance of the DBAM

1 5

Other aspects mentioned are:

·

the need for a permit to apply fluorescent tracers;

·

the recommendation to carry out sampling at locations inside the regular water quality

monitoring networks;

·

to treat singularities like locks, dams and barrages with special attention;

·

practical experience with the tracer sodium fluorescine (reported detection limit 0.02 mg/l).

3.2.3

Methods for calibration experiments ("project AE2")

References: Phare Environmental Consortium (1998).

This reference presents an extensive volume of work carried out in preparation to the calibration of the

DBAM. It was mainly based on the sources of information discussed above. Although a lot of valuable

information was presented by the author, this reference does not present a clear and concise synthesis

of the collected information. At present we have used the Executive Summary to identify aspects of

interests and scanned the remaining text for the necessary details.

The report presents the use of Br-82 (radioactive) and Rhodamine WT (fluorescent) tracers as proven

technology. The use of these tracers is supposed to be inhibited or complicated by environmental

legislation (not in a concrete way however, by stating that the use of tracer X violates regulation Y of

country Z). Therefore, alternative techniques are identified based on the injection of "natural tracers"

(suspended matter, biological material), remote sensing images and existing concentration gradients

(WWTP effluents). These techniques are however classified as "experimental", and their application

should be preceded by a pilot project. No clear choice is made.

The report proposes a seven step calibration procedure which is claimed to be realistic and feasible.

This procedure deviates from the one used in the Rhine Basin in the sense that it makes use of

supportive "HD-AD" models. This is motivated by cost considerations (minimizing expensive field

work) and time considerations (implementation time). The use of an alternative procedure is not

supported by an objective comparison in terms of implementation time and implementation costs

between the proven Rhine Basin approach and the suggested alternative approach. In contradiction to

the initial conclusion, the use of the proposed new approach necessitates a pilot project to investigate

the feasibility (!).

Contrary to the Rhine approach, a focus on in-situ measurements is proposed. This is probably based

on costs considerations. Again, no objective comparison is presented.

The role of the proposed supportive "HD-AD" models is twofold: (1) to plan the experiments and (2)

to avoid multiple experiments under different flow conditions.

The cost estimates presented are dominated by investment costs for the tracer experiment equipment,

which is presumably bought for the sole purpose of calibrating the DBAM.

1 6

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

3.2.4

Strengthening the Danube AEWS

References: H. Hartong ea. (2000).

This project did not pay a lot of attention to the calibration aspects of the DBAM. Some preparatory

works were carried out:

·

the verification and (where necessary) correction of the rating curves and the velocity tables of

the DBAM (constituting two sources of model inaccuracy, see par. 2.1);

·

an inventory of existing 1D "HD-AD" models (following the proposed role of such models in

the calibration methodology proposed in the project AE2, Phare Environmental Consortium,

1998).

In the conclusions attention was requested for the maintenance of the rating curves and the velocity

tables of the DBAM as well as the continuous evaluation of the operational availability of the

necessary hydrology input data. Both are intended to minimise the related sources of model

inaccuracy.

Based on data collected during the Baia Mare spill event, some test computations have been carried

out with version 2.00 of the Danube Basin Alarm Model. The observed river stretches are the Somes-

Tisa on Hungarian territory and the Danube on its course along the Romanian border. From these

calculations the following conclusions were drawn:

·

The accuracy of the predicted travel times is good over longer distances: the cumulative error

is 6% for the Somes-Tisa stretch (about 600 km) and 5% for the Danube stretch (about 1000

km).

·

Looking at smaller river stretches of about 100 km, larger errors occur in the predicted travel

times: up to 25% in both the Somes-Tisa and the Danube cases. These errors are not

systematic however, over longer distances they tend to compensate.

·

The error of the predicted peak concentrations along the Tisa is between 26% and 57%. For

the Danube this aspect has not been analysed.

Some additional test computations were carried out based on the Somes-Tisa stretch, in order to get an

insight in the potential improvements from the future calibration of the DBAM. From these

calculations the following conclusions were drawn:

·

It will be possible to improve the predicted travel times drastically, by tuning the space

dependent parameter.

·

If certain river stretches turn out to need values of outside of the expected range without any

physical reason for it, it is necessary to check and if necessary improve the rating curves and

velocity tables in the DBAM.

·

It will be possible to improve the predicted peak concentrations to a large extent, by tuning the

space dependent parameter.

·

Nevertheless, one should not expect a perfect fit with respect to the predicted concentrations,

due to the conceptual limitations of the DBAM.

J. van Gils, WL | Delft Hydraulics

Development and Maintenance of the DBAM

1 7

With respect to the calibration the following recommendations were made:

·

to focus on travel times first;

·

to use as much as possible historical data from recorded spills;

·

to try to find data for different spills under different hydrological conditions;

·

not to forget the inaccuracies stemming from the use of rating curves and velocity tables;

·

to use good quality authentic field data from the responsible authorities to correct the rating

curves and velocity tables.

In addition to this, carefully planned tracer experiments can be used to fill in the gaps.

A question mark was placed at the use of 1D HD-AD models, as suggested by the AE2 project (Phare

Environmental Consortium, 1998). Particular concerns are:

·

a HD-AD model does not have any predictive power with regard to the main calibration

parameters of the DBAM ( and );

·

while a numerical HD-AD model is better in representing the full dynamics of the river flow,

it has a major drawback as compared to the analytical DBAM: it suffers from a fundamental

inaccuracy called "numerical dispersion" which is bound to seriously complicate the

calibration of dispersion-like processes;

·

both the DBAM and any hydrodynamic model are only reliable if the data behind them are

reliable: if a hydrodynamic model is available based on much better data than the DBAM,

these data can be used immediately to improve DBAM, without the intermediate step of

setting up and running the hydrodynamic model.

1 8

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

3.3

Experience from the Elbe River

In the Elbe catchment the Internationalen Alarmmodell Elbe (ALAMO) is used to calculate the

transport and dilution of a cloud of pollutants in the river. To support the calibration and validation of

this model, several tracer experiments have been carried out (ao. in July and December 1997). The text

below provides relevant aspects related to the planning and execution of the July 1997 experiment.

Furthermore, some technical details about the model.

3.3.1

The July 1997 tracer experiments in the Elbe River

Reference: H. Hanisch ea. (1997).

The tracer experiment was carried out along the German part of the Elbe, between Schmilka, at the

Czech-German border and Geesthacht, upstream of Hamburg. The distance is 580 km, the overall

travel time 11 days.

The experiment was done with the tracer substance Amidorhodamine G. It was selected for different

reasons: (1) no toxicological effects were found during specific tests by the German Institut für

Wasser-, Boden- und Lufthygiene, (2) it has suitable physical characteristics (good solubility and

stability, not affected by adsorption to particles), and (3) its fluorescence does not depend on the

temperature and the pH. The literature provides a limit concentration of 100 µg/l.

The amount of tracer applied was determined as 10 kg per 100 m3/s of river discharge. The discharge

of the tracer was made from a ship traversing the river, to obtain as much as possible initial transversal

mixing of the tracer substance. Only in the immediate vicinity of the discharge (7 km downstream)

concentrations just above the limit concentration of 100 µg/l were observed. The use of this tracer was

fully satisfactory.

The density of stations was significant: 28 stations over 580 km of river stretch (average distance

between stations about 20 km).

The experiment was based on sampling and subsequent analysis of the samples. In-situ measurements

at distinct locations were used for timing the "sampling time window" at the stations immediately

downstream. The river discharge turned out to be highly variable during the period preceding and

during the tracer experiment. The estimates for the sampling windows made before the experiment

were inaccurate: the in-situ measurements were used to adapt these estimates during the course of the

experiment.

The operation of the samplers proved to be sensitive to failures and servicing. The samplers from the

upstream stations were transported to a downstream station after the passage of the cloud. This is a

way to optimise the necessary amount of equipment.

The samples were analysed by Spectral Fluorometer (Perkin Elmer) in a central laboratory.

Simultaneous measurements of the river discharge were carried out during the experiment at different

stations.

The experiment was organised within a period of 10 weeks, which was in retrospect too short.

J. van Gils, WL | Delft Hydraulics

Development and Maintenance of the DBAM

1 9

3.3.2

The ALAMO model

Reference: Presentation by W. Blohm (Appendix B).

The ALAMO model is in many respects comparable to the DBAM. The underlying mathematical

concepts are identical (paragraph 2.2). Regarding the implementation some differences exist. These

are listed below.

· The ALAMO solves the governing mathematical equations by a numerical method.

· The ALAMO does not accept an observed time series for the concentration C(t) as input (in stead

of a spill location and a spill mass).

· The ALAMO automatically retrieves its hydrology input data.

· The ALAMO includes a list of substances and relevant alarm levels.

· The ALAMO produces a spill report in ASCI format.

· The error in the predicted travel time was 4% before calibration and decreased to 2% after

calibration. This error is much smaller than that in the Rhine Alarm Model, maybe because of the

relative simplicity of the river system (few tributaries, no weirs).

2 0

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

3.4

Advances in transport modelling

Recent publications indicate that the results from tracer experiments can be treated in such a way that

they can separately assess the accuracy of the velocity tables and the values of the model parameters

and (van Mazijk, pers.comm.). In the terminology of paragraph 2.4, this means that the inaccuracy

corresponding to Phase 3 of the calculation can be separated from the inaccuracy stemming from

Phase 4. This will be further elaborated in the project preparatory documents.

3.5

Specific conditions in the Danube Basin

Although the cases of the rivers Rhine and Elbe and several French rivers present successful examples

of the use of tracer experiments to calibrate models like the DBAM, the specific characteristics of the

Danube Basin should be taken into consideration:

·

natural environment: geometry (2800 km length, at least 2 major international tributaries) and

hydrology (an average of 6000 m3/s);

·

social environment: 13 countries, different languages, large differences in GDP;

·

water management infrastructure: inhomogeneous environmental legislation, possibly varying

quality of institutions and staff to organise and support tracer experiments and to analyse

samples.

J. van Gils, WL | Delft Hydraulics

Development and Maintenance of the DBAM

2 1

4

Synthesis: Calibration Options

4.1

Integrated "DBAM usability enhancement plan"

The objectives for the current project demand a solid base for the DBAM calibration and future use.

This requires that sufficient conditions are created to optimise the accuracy of the DBAM.

Furthermore, this requires that the DBAM is properly maintained.

4.1.1

Accuracy of the DBAM

The accuracy of the DBAM depends on more than just an accurate calibration of the model parameters

and . Table 4-1 lists some conditions to ensure optimal model performance (see also paragraph 2.4).

Table 4-1: An overview of the conditions for optimal accuracy of the DBAM.

Phase in the calculation procedure

Conditions for accuracy

1) Collection of hydrology input data during the event

Actual hydrology data for the stations included in the

DBAM can be obtained under conditions of use.

2) Computation of discharges from water levels, or vice

Rating curves in DBAM are accurate.

versa, by using rating curves

3) Computation of river stream flow velocity, by using

Velocity tables in DBAM are accurate.

built-in tables and the actual water level or river

discharge

4) Computation of the propagation of the cloud of

DBAM is properly calibrated.

pollutants (travel time, concentration level)

Overall concept of DBAM

Underlying assumptions affecting the model accuracy

are well understood, in particular:

· 1-dimensional modelling approach (no variations

over the cross-section);

· quasi steady hydrology

As a part of the present project, the Consultant also intends to make recommendations related to

aspects 1), 2) and 3) from Table 4-1. This implies that somehow arrangements must be made to

periodically verify the operational accessibility of the necessary hydrological input data as well as to

periodically check the DBAM rating curves and velocity tables. The Workshop participants are

requested to provide the necessary input to draft these recommendations.

2 2

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

4.1.2

Maintenance of the DBAM

To ensure the sustainable and efficient use of the DBAM, maintenance provisions should be in place,

which could for example consist of:

· Archiving of software, data and documentation;

· Distribution of software, data and documentation;

· Upgrades of software and documentation for new platforms (Windows 2000, Windows XP).

· Functional upgrades of software.

· Regular upgrades of hydrology stations, rating curves and velocity tables (see 4.1.1).

As a part of the present project, the Consultant intends to make recommendations in this respect. The

Workshop participants are requested to provide the necessary input to draft these recommendations.

4.2

Scope and objectives of the DBAM calibration exercises

Since the Rhine Alarm Model (RAM) is based on identical principles as the DBAM, the calibration of

the RAM presents a very relevant example. For the calibration of the RAM, a hierarchic set of

objectives was defined:

· In view of the trans-boundary use of the model, to first focus on the main river and the large

international tributaries, in order to properly evaluate the longitudinal dispersion.

· To follow up with detail studies, directed towards river anomalies (locks, weirs, dams, reservoirs)

and lateral dispersion phenomena (vicinity of the discharge, confluences).

It should be confirmed by the Workshop participants that this approach is also suitable for the Danube.

As a next step, this should be made more concrete: which international tributaries will be part of the

calibration exercises? In view of the possible budget and time restrictions, different classes of priority

could be distinguished.

4.3

Existing data or additional tracer experiments?

Carrying out tracer experiments on the scale of the Danube River is a costly exercise. A very relevant

question is to what extent existing data can be used to evaluate and calibrate the longitudinal

dispersion of pollutants in the Danube and its main tributaries.

Two types of existing data can be used:

· Records from accidental spills.

· Continuous records of the water quality, related to parameters showing distinct temporal gradients

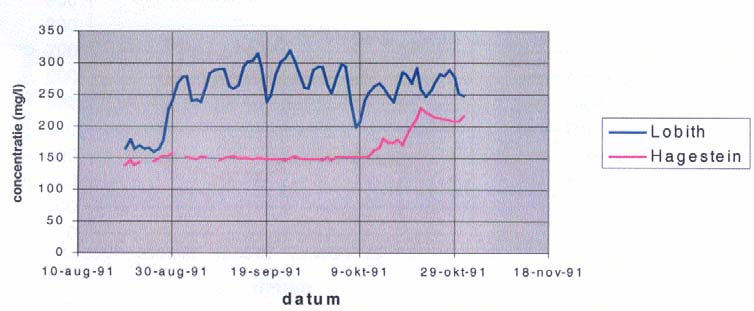

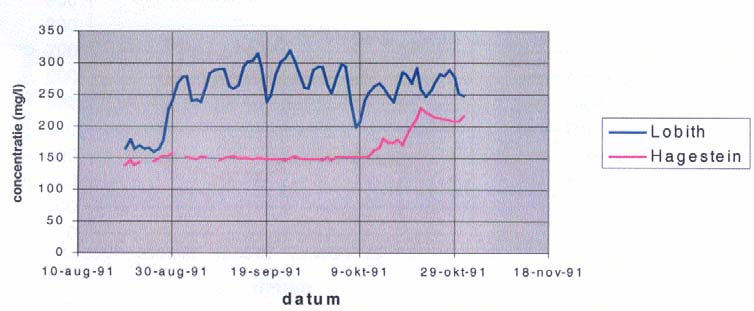

(see for an example Figure 4-1).

J. van Gils, WL | Delft Hydraulics

Development and Maintenance of the DBAM

2 3

Figure 4-1: Example of continuous concentration records showing strong temporal gradients. The chlorides concentration at

Lobith (Rhine river, border Germany-The Netherlands) shows a strong increase near the end of August 1991.

This increase arrives at Hagestein (Lower Rhine river, about 80 km downstream of Lobith with several weirs

in between) around half of October. This information has been used to calibrate and validate the Rhine Alarm

Model on this particular stretch.

The following information should be available (for both types of data):

· The concentration as a function of time at 2 or more locations.

· The necessary hydrology data as a function of time at all DBAM hydrology stations along the river

stretch of interest. The frequency should be daily at least.

The Consultant needs to be able to judge to what extent existing data could be used for calibration

purposes. The Workshop participants are requested to provide the necessary input. They will have to

do so in the period before the actual workshop, or in the period immediately following the workshop.

2 4

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

4.4

Set-up of additional tracer experiments

4.4.1

Selection of tracer substance

Different (types of) tracers can be considered in regard to the set-up of additional experiments.

Table 4-2 provides some options, with their respective advantages and disadvantages.

Table 4-2: Overview of different types of tracer substances.

Type of tracer

Advantage(s)

Disadvantage(s)

Salt

Low ecological impact

Extremely high dosage required to

significantly exceed background

Low price

level (> 10 mg/l).

Radio nuclides

High sensitivity (detection possible

Legal restrictions (?)

at very low concentrations)

Proven technology (?)

Possibility of in-situ analysis (?)

Fluorescent tracers

Proven technology

Possible adverse ecological

impacts.

Relatively high sensitivity

(detection possible at low

Legal restrictions (?)

concentrations)

Possibility of in-situ analysis

Other natural tracers (suspended

Low or no ecological impact

Experimental (feasibility study

matter, biological material)

required)

The Workshop participants are requested to provide the necessary input for selecting the most

appropriate option. Especially relevant are the relevant legal restrictions which apply in the different

Danube countries.

4.4.2

Sampling and analysis

The tracer experiments in the Elbe and the Rhine rely on the collection of samples and a subsequent

analysis in the laboratory. Two contradicting requirements/recommendations exist with respect to the

sampling and analysis:

· it is necessary to analyse the samples rapidly, in view of the ongoing decay of the tracer material;

· It is recommended to carry out all analyses in one laboratory.

J. van Gils, WL | Delft Hydraulics

Development and Maintenance of the DBAM

2 5

Considering the large size of the Danube and its major trans-boundary tributaries, this may lead to two

alternative approaches:

"Central" approach

"Decentral" approach

Collect samples from the whole experiment and

Collect samples from limited river stretches and

transport to one central laboratory for analysis

transport to several laboratories for analysis (e.g. one

per country)

Transport times tend to become higher (crossing

Transport times will be lower

borders critical)

Comparability of results optimal

Comparability sub-optimal, can be mitigated by

analysing "border samples" in two laboratories

The Workshop participants are requested to provide the necessary input for selecting the most

appropriate option.

4.4.3

Selection of stations and observation windows

From the existing experience it follows that two aspects are very important:

· The stations should not be too close to river anomalies or large tributary inflows.

· For reasons of efficiency the "observation window" should be carefully selected. The DBAM in its

present form could be used for that purpose, allowing for a 10-20% error in the propagation time

of the cloud. In-situ observations could be used to check and possibly correct the observation

windows during the experiments (as in the July 1997 Elbe experiment).

Alternative approaches can be distinguished with respect to the station density:

High density of stations

Low density of stations

Typical distance between subsequent stations << 100

Typical distance between subsequent stations > 100

km

km

Spatial variation of calibration parameters well

Spatial variation of calibration parameters not so well

resolved

resolved

Smaller number of tracer experiments for the same

Higher number of tracer experiments for the same

budget, so less opportunities to check DBAM at

budget, so more opportunities to check DBAM at

different flow regimes

different flow regimes

Smaller number of tracer experiments for the same

Higher number of tracer experiments for the same

budget, so less opportunities to check DBAM along

budget, so more opportunities to check DBAM along

different tributaries

different tributaries

2 6

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

From prior experience we know that the spatial variability of the calibration parameters can well be

derived from general river characteristics. It is probably more effective to check the quality of the

built-in rating curves and velocity tables at different flow regimes or along different tributaries. This is

an argument in favour of the low density of stations approach.

The Workshop participants are requested to provide the necessary additional input for selecting the

most appropriate option.

4.4.4

Collection of hydrology data

A very clear recommendation from earlier exercises is the complete collection of the relevant

hydrology data. The water levels and/or river discharges data should be obtained as a function of time

at all DBAM hydrology stations along the river stretch of interest. The frequency should be daily at

least. It should be emphasised that without this information the execution of tracer experiments is

useless.

The Workshop participants are invited to provide the necessary recommendations to guarantee the

availability of the necessary hydrology data.

J. van Gils, WL | Delft Hydraulics

Development and Maintenance of the DBAM

2 7

5

Preparation of the Workshop

The main questions raised in the Synthesis above have been addressed during a dedicated Workshop.

This workshop has been attended by the APC/EG members, which represent the beneficiaries of

present project: the 13 member countries of the ICPDR (see Appendix C).

The short term objectives of this Workshop were dual: to (1) ensure sufficient understanding of the

DBAM and its calibration procedure with the APC/EG members, and (2) to obtain input from the

participants to complete the preparation of the calibration of the DBAM.

An additional medium term objective is to ascertain the support from the APC/EG members for the

calibration and future use of the DBAM.

The workshop consisted of different parts:

· Explanations: (a) DBAM principles, and (b) factors determining the accuracy of the DBAM;

· Elaborations: (a) DBAM usability enhancement, (b) scope and objectives, (c) existing data vs.

additional experiments, and (d) set-up of additional experiments;

· Evaluations: formulation of conclusions and recommendations of the remainder of the project.

Part 1 was presented by the Consultant, while the parts 2 and 3 have been elaborated by the Workshop

participants, facilitated by the Consultant and the UNDP/GEF project staff.

Appendix A provides the Draft Agenda of the Workshop, which was accepted without modifications

and followed without major changes.

Separately the Consultant has prepared the required Templates for Planning, Organising,

Documentation and Evaluation of Workshops (Nauheimer, 2002).

Appendix B provides the relevant presentations used during the Workshop, prepared by the Consultant

and by Dipl.-Ing. Werner Blohm (Hamburg, Institut für Hygiene und Umwelt), who was invited to

present some aspects of the use of the Elbe alarm model ALAMO.

2 8

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

6

Recommendations for follow-up

(Workshop Report)

The present chapter presents the conclusions and recommendations which were formulated during the

Workshop by the participants. The chapter follows the structure presented in the Calibration Options

Chapter 4. First, the availability and the utilisation of the DBAM will be discussed. This discussion

will provide the necessary conditions (including the necessary maintenance arrangements) for any

calibration exercise to be successful. Next, the specific aspects of a future calibration action will be

outlined.

Since the Workshop followed exactly the same agenda as the lay-out of the present chapter, this

chapter can be read as the Workshop Report.

Although it was not a primary subject of the Workshop, some extensions of the present DBAM

functionality were suggested. For the sake of completeness, they are listed in Appendix F. It should be

noted that these suggestions are not necessary preconditions for the future use of the DBAM.

6.1

Availability and utilisation of the DBAM

6.1.1

Current status

Preceding the workshop, an inventory was made by the APC/EG member György Pinter of the current

status with respect to the availability and utilisation of the DBAM. The inventory is included as

Appendix D to this report.

The inventory reveals that few Principal International Alert Centres (PIACs) are actually using the

DBAM. The reasons for this are:

· Unavailability of the software;

· installation problems;

· running problems.

Both the installation and running problems are caused by the fact that the latest DBAM version

(2.00.02, October 2000) is not suited for use on modern Windows-based platforms like Windows 2000

and Windows XP.

There was agreement between the participants that the first problem should be solved by distribution

of the latest version of the software through Danubis. The latter two problems should be tackled by

making adequate maintenance provisions (Appendix E contains draft ToR for such provisions).

6.1.2

Target accuracy of the DBAM

During the Workshop, the present accuracy of the (uncalibrated) DBAM was discussed, as well as the

factors which determine its accuracy (see paragraph 2.4). A relevant question is how accurate the

DBAM should be, in view of its role in the AEWS.

J. van Gils, WL | Delft Hydraulics

Development and Maintenance of the DBAM

2 9

The Workshop participants agreed that the target accuracy in the prediction of the travel time of a

cloud of pollutants should be a 5% (relative error). This value is equal to the reported accuracy of the

Rhine Alarm Model after calibration. The Elbe model is reported to be more accurate, most probably

due to the fact that the Elbe is a simpler river to model: it is a natural river without bifurcations and

parallel stretches.

No concrete value for the accuracy of the predicted peak concentration was discussed. The Rhine

Alarm Model was not calibrated on this particular aspect. In stead, the calibration targeted at

prediction the right shape of the cloud of pollutants. Of course, this would indirectly guarantee the

correct prediction of the concentrations if the spill mass and the decay rate of the spilt substance are

known. Since it is in practice very hard to obtain reliable estimates of these numbers, it is hard to set

targets for the accuracy of the predicted concentrations. Our expert opinion is that an error by a factor

of 2 is probably the best achievable accuracy under operational conditions.

6.1.3

Hydrology data

The availability of hydrology data under operational conditions is an important factor affecting the

accuracy of the DBAM. During the Workshop different questions were discussed:

· What is current practice in collecting hydrology data?

· Is there any transfer of this information between the countries?

The PIACs mostly use only the hydrology data from their own country. Exchange of data is arranged

on an ad-hoc basis through personal contacts and/or through the AEWS system. The representative of

Slovenia reported this as being unsatisfactory: the travel time of the river demands a faster means of

data exchange.

· Is there an organisation collecting these data on a Danube wide scale?

· To what extent could this information be collected from the Internet?

To the knowledge of the Workshop participants, there is no organisation collecting the data at the

Danube scale. The Internet only provides part of the necessary data.

· Is it possible to use predefined hydrology conditions files for operational use of the DBAM?

(high-low-medium flow situation)

The participants to the Workshop judged that this was definitely a valuable approach. This allows the

PIAC staff to carry out an approximate assessment plus sensitivity analysis without any data at all.

The participants agreed that the ultimate solution will be that all PIACs can access the necessary data

via the internet directly. Where such data are not public, the PIACs should obtain access rights for

AEWS purposes only (all PIACs should be issued passwords to the websites of the

Hydrometeorological Institutes in the basin).

3 0

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

This should be realised in two steps:

· At the technical level it should be formulated exactly what information is needed from what

source. Any technical optimisations should be carried out at this stage.

· At the political level, a request for these data to be made available should be submitted to the

Heads of Delegation.

It should be noted that an effort as specified under (1) has been carried out in 2000 (Hartong, 2000).

6.1.4

Rating curves and velocity tables

The accuracy of the DBAM built-in tables is yet another important factor affecting the accuracy of the

DBAM. Therefore, the maintenance of these tables was jointly recognised as a precondition for the

sustainable use of the DBAM.

The national Hydrometeorological Services in the Danube countries are in most cases the owners of

the data in the DBAM tables. Therefore, these institutions should also maintain them. Table 6-1

provides a brief overview. For details, we refer to (Vituki, 1996).

Table 6-1:

Overview of institutes owning the data supporting the DBAM built-in tables.

Country

Institute

Hungary

Vituki

Croatia

Croatian Waters/ State Hydrometeorological Institute

Serbia and Montenegro

Hydrometeorological Institute

Bulgaria

Institute of Hydrology and Meteorology

Romania

Hydrology and Water Management Institute (Romanian Waters)

Slovakia

Slovak Hydrometeorological Institute

Czech Republic

Czech Hydrometeorological Institute

Slovenia

Environmental Agency of Slovenia

It was agreed that the APC/EG members will have the responsibility to liaise with these services and

obtain updated information on a regular basis. The "central level" (ICPDR/DRP) will be responsible to

archive the data and provide upgrades of the DBAM based on this new data.

The built-in tables from the existing version should be made available on Danubis.

J. van Gils, WL | Delft Hydraulics

Development and Maintenance of the DBAM

3 1

6.2

Future calibration of the DBAM, supported by tracer

experiments

6.2.1

Current status

The pre-calibration accuracy of the DBAM was discussed on the basis of the evaluation of the Baia

Mare incident (Hartong, 2000). The accuracy of the predicted travel time of the cloud over longer

distances is quite satisfactory: a relative error of 5% (500-1000 km). Over shorter distances however,

the errors are significantly larger (up to 25%). This is clearly insufficient.

The participants rightly point at the validity of the underlying model concepts and the reliability of the

data input data as inherent factors limiting the accuracy of the accuracy of the DBAM under

operational conditions. The future calibration efforts will have to be organised in such a way that these

factors are eliminated as much as possible. This will be elaborated below.

6.2.2

Scope and objectives (including priorities)

The Workshop participants discussed the scope and objectives for the future DBAM calibration.

Below, the main conclusions are formulated.

Apparently, the DBAM and therefore also the future calibration focuses on transboundary rivers.

Given the scale of the basin, it is considered infeasible to carry out a basin-wide calibration exercise

initiated from the central level. Such an approach is infeasible both from a technical and from a

political point of view.

In stead, it is advised to carry out the future calibration on the basis of local initiatives by a limited

number of Danube states ("bottom-up" approach).

The prioritisation of the areas for calibration should be based on different considerations. The first

aspect is the presence of hot spots (sites of high potential risk for accidental spills). An inventory of

such sites is already available. A second aspect is the presence of areas with sensitive water uses. An

inventory of such areas is expected to be available at the end of 2004. On the basis of the above

considerations, the Workshop participants agreed on a number of concrete proposals, including a

prioritisation. Table 6-2 gives an overview.

Table 6-2:

Overview of priority areas for model calibration.

Area

Priority

Sava basin (co-operation with Sava initiative)

1

Upper Tisa (Spill in Uh, followed till inflow of Zagyva)

1

Middle Danube (water intake Budapest)

2

Lower Danube (joint Romanian-Bulgarian border stretch)

2

Drava

2

Prut

3

3 2

UNDP/GEF Danube Regional Project

6.2.3

Existing data or new experiments?

The Workshop participants agreed that available existing data should be used in the future calibration

of the DBAM. The following information should be available (for both types of data):

· The concentration as a function of time at 2 or more locations.

· The necessary hydrology data as a function of time at all DBAM hydrology stations along the

river stretch of interest. The frequency should be daily at least.

An inventory of such data based on information provided by the participants is given in Appendix G..

6.2.4

Selection of tracers

Regarding the selection of tracers for possible future experiments in the Danube basin, two guiding

principles were agreed upon during the Workshop:

· Permitting is a major issue. The Phare Environmental Consortium (1998) has made an inventory

of relevant legislation. Appendix H provides an actualised overview.1

· Only proven technology should be used.

The use of salt may be an interesting option for smaller rivers. The Hungarian representative in the

APC/EG indicated that on the Sajo river a planned intermittent large discharge of chlorides can be

used as a tracer experiment.

Appendix I provides guidelines on the tracer mass to be applied for a river with given physical and

hydrological characteristics, in relation to the detection limit of the tracer substance in question and the

maximum allowable concentration (MAC). These guidelines can be used to minimise permitting

problems.

6.2.5

Sampling and analysis

The participants agreed that the selection of a central or decentral sampling and analysis strategy is to

be made separately for every individual experiment. In the case of a decentral approach, a preparatory

intercalibration programme between candidate institutes should be included in the project plan.

The APC/EG experts indicated that the comparability of the results from different laboratories should

not present a major problem in the case of fluorescent tracers, since the analysis is simple.

6.2.6

Density of stations

The participants agreed that the density of stations should be decided separately for every individual

experiment. Small fast flowing rivers need a higher density than larger rivers. Local knowledge should

a decisive factor in this respect.

1 Recently, BASF has conducted tracer experiments in theRhine with Na-24-Acetate, a radio nuclide.

Apparently, there is room for such experiments in the German legislation.

J. van Gils, WL | Delft Hydraulics

Development and Maintenance of the DBAM

3 3

Decisions about the position of sampling in the cross section should be made consciously: either cross

sections where incomplete mixing is expected should be avoided (as during the Rhine experiments), or

samples should be taken at different positions, as in the Transnational Monitoring Network TNMN

(Left-Middle-Right).

It should be noted that during the Elbe tracer experiment, initial lateral mixing was obtained by

releasing the tracer from a ship traversing the river.

6.2.7

Frequency of sampling

The participants agreed that the frequency of sampling should be decided separately for every

individual experiment. Small fast flowing rivers need a higher frequency than larger rivers. Based on

the mathematics of the DBAM a rule of thumb can be established (Appendix J).

6.2.8

Hydrology data

The Workshop participants agreed that the complete collection of the relevant hydrology data is a

necessary condition for every tracer experiment. The water levels and/or river discharges data should

be obtained as a function of time at all DBAM hydrology stations along the river stretch of interest.

The frequency should be daily at least.

6.2.9

Organisation and financing

Regarding the organisation of future tracer experiments, the participants agreed that a decentral

approach is the most appropriate. The necessary activities should as much as possible be carried out

and financed by the participating countries. The central level would have a purely supportive role,

which consists of:

· Initiating activities.

· Organisational support.

· Methodological support.