United Nations

Environment Programme

Chemicals

Sub-Sahar

Sub-Saharan Africa

REGIONAL REPORT

an Africa

Regionally

RBA PTS REGIONAL REPOR

Based

Assessment

T

of

Persistent

Available from:

UNEP Chemicals

11-13, chemin des Anémones

CH-1219 Châtelaine, GE

Switzerland

Phone : +41 22 917 1234

Fax : +41 22 797 3460

Substances

E-mail: chemicals@unep.ch

December 2002

http://www.chem.unep.ch

UNEP Chemicals is a part of UNEP's Technology, Industry and

Printed at United Nations, Geneva

Economics Division

GE.03-00151January 2003500

UNEP/CHEMICALS/2003/5

G l o b a l E n v i r o n m e n t F a c i l i t y

UNITED NATIONS

ENVIRONMENT

PROGRAMME

CHEMICALS

Regional y Based Assessment

of Persistent Toxic Substances

Angola, Benin, Botswana, Brunei Darussalam, Burkina Faso, Burundi,

Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Congo (Brazzaville), Cote

d'Ivoire, Democratic Republic of Congo, Djibouti, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea,

Ethiopia, Gabon, Ghana, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia,

Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia,

Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Sao Tome and Principe, Senegal, Seychelles, Sierra

Leone, Somalia, South Africa, Sudan, Swaziland, Tanzania, Togo, Uganda,

Zambia, Zimbabwe

SUB-SAHARAN

REGIONAL REPORT

DECEMBER 2002

GLOBAL ENVIRONMENT FACILITY

i

This report was financed by the Global Environment Facility (GEF) through a global project with co-

financing from the Governments of Australia, France, Sweden, Switzerland and the United States

of America.

This publication is produced within the framework of the Inter-Organization Programme for the

Sound Management of Chemicals (IOMC).

This publication is intended to serve as a guide. While the information provided is believed to be

accurate, UNEP disclaim any responsibility for the possible inaccuracies or omissions and

consequences, which may flow from them. UNEP nor any individual involved in the preparation of

this report shall be liable for any injury, loss, damage or prejudice of any kind that may be caused

by any persons who have acted based on their understanding of the information contained in this

publication.

The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this report do not imply the

expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations of UNEP

concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning

the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.

The Inter-Organization Programme for the Sound Management of Chemicals (IOMC), was

established in 1995 by UNEP, ILO, FAO, WHO, UNIDO and OECD (Participating

Organizations), following recommendations made by the 1992 UN Conference on

Environment and Development to strengthen cooperation and increase coordination in the

field of chemical safety. In January 1998, UNITAR formally joined the IOMC as a

Participating Organization. The purpose of the IOMC is to promote coordination of the

policies and activities pursued by the Participating Organizations, jointly or separately, to

achieve the sound management of chemicals in relation to human health and the

environment.

Material in this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted but acknowledgement is requested

together with a reference to the document. A copy of the publication containing the quotation or

reprint should be sent to UNEP Chemicals.

UNEP

CHEMICALS

Available from:

UNEP Chemicals11-13, chemin des Anémones

CH-1219 Châtelaine, GE

Switzerland

Phone: +41 22 917 1234

Fax:

+41 22 797 3460

E-mail: chemicals@unep.ch

http://www.chem.unep.ch

UNEP Chemicals is a part of UNEP's Technology, Industry and Economics Division

ii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PREFACE ........................................................................................................................................................V

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..........................................................................................................................VII

1

INTRODUCTION...............................................................................................................................1

1.1

OVERVIEW OF THE RBA PTS PROJECT...........................................................................................1

1.1.1 Objectives ...............................................................................................................................................1

1.1.2 Results.....................................................................................................................................................1

1.1.3 Methodology ...........................................................................................................................................2

1.1.4 Management Structure ............................................................................................................................2

1.1.5 Data Processing.......................................................................................................................................2

1.1.6 Project Funding.......................................................................................................................................2

1.2

SCOPE OF SUB- SAHARA AFRICA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT.....................................................3

1.2.1 Existing Assessments..............................................................................................................................3

1.2.2 Methodology ...........................................................................................................................................3

1.3

PTS DEFINITIONS AND PROPERTIES...............................................................................................4

1.3.2 Industrial Compounds .............................................................................................................................7

1.3.3 Regional Specific ....................................................................................................................................8

1.4

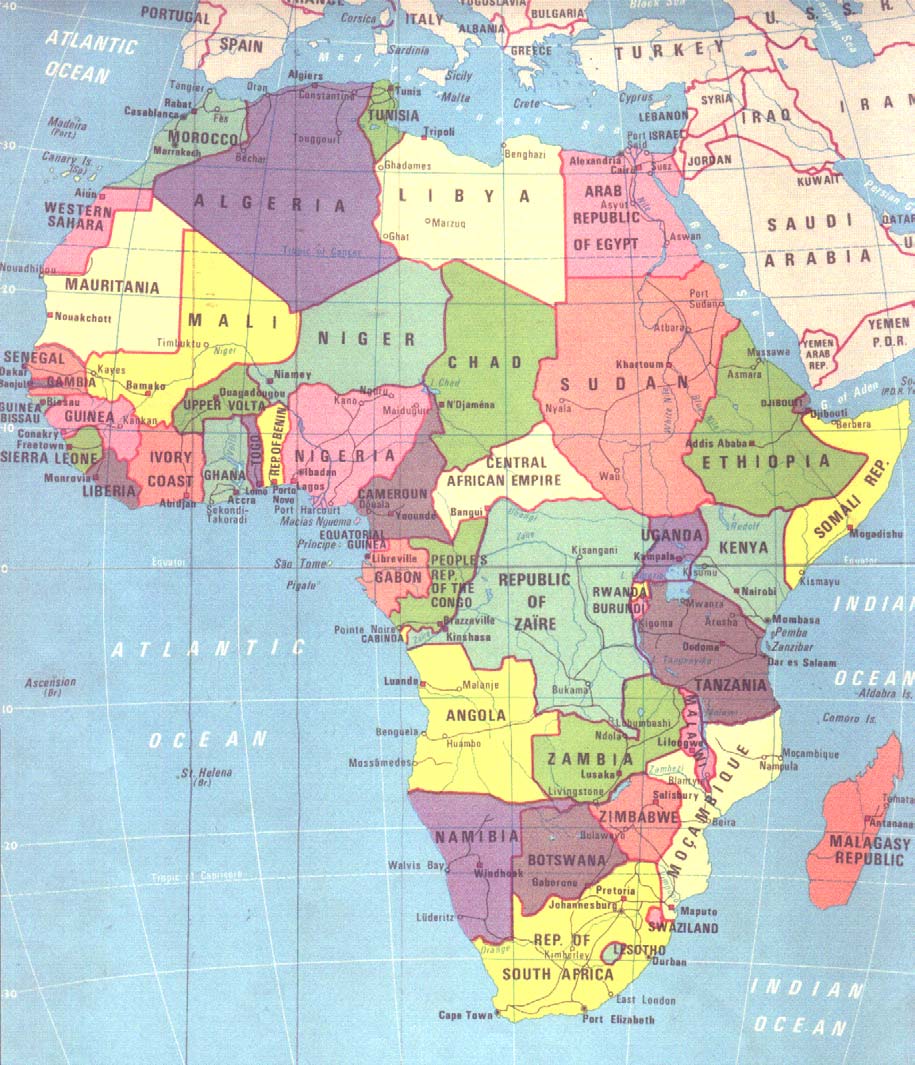

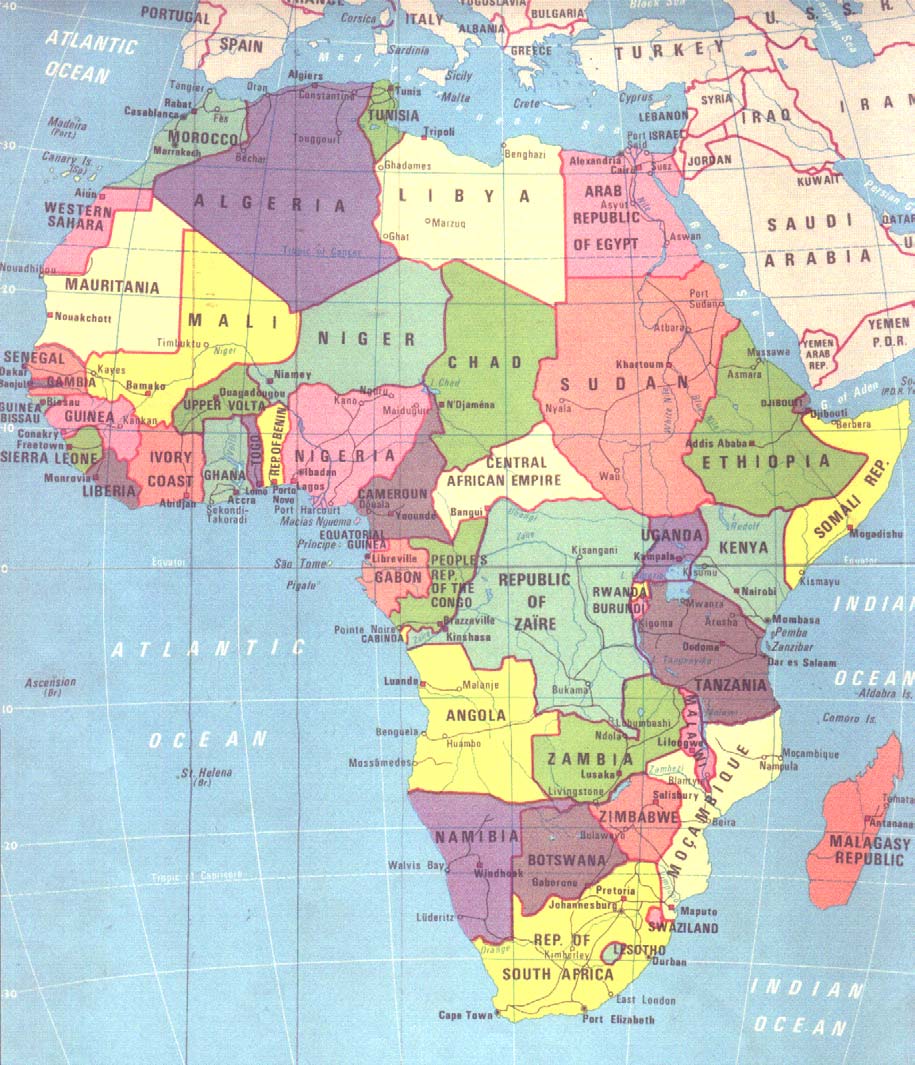

DEFINITION OF THE SUB-SAHARA AFRICA REGION ................................................................13

1.5

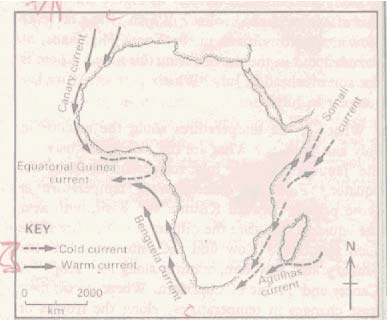

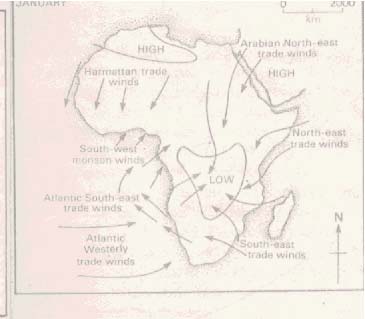

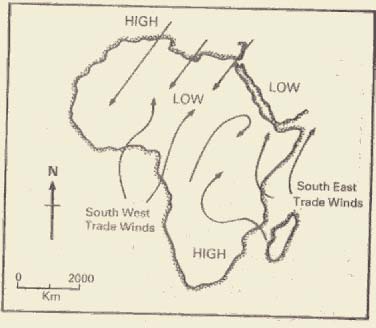

PHYSICAL SETTING ..........................................................................................................................15

1.5.1 Physical/Geographical Description of the Region ................................................................................15

1.5.2 Water Resources ...................................................................................................................................17

1.5.3 Vegetation .............................................................................................................................................19

1.5.4 Wildlife .................................................................................................................................................19

1.5.5 Demography..........................................................................................................................................20

1.6

PATTERNS OF ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT ................................................................................20

1.6.1 Agriculture ............................................................................................................................................21

1.6.2 Forestry and Fishing..............................................................................................................................21

1.6.3 Industry .................................................................................................................................................21

1.6.4 Energy ...................................................................................................................................................21

1.7

SOCIAL ASPECTS...............................................................................................................................22

1.8

SUMMARY ..........................................................................................................................................22

1.9

REFERENCES......................................................................................................................................23

2

SOURCE CHARACTERISATION.................................................................................................24

2.1

INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................................24

2.2

PRODUCTION OF PTS PESTICIDES.................................................................................................24

2.3

THE IMPORT OF PTS PESTICIDES...................................................................................................25

2.4

THE USE OF PESTICIDES AND MAJOR AGRICULTURAL AREAS ............................................30

2.5

IDENTIFICATION OF STOCKS AND RESERVOIRS OF PTS PESTICIDES..................................34

2.5.1 Country Ranking According To Agricultural PTS ...............................................................................37

2.6

SOURCES OF INDUSTRIAL ..............................................................................................................38

2.6.1 Country Ranking According to Industrial PTS Production ..................................................................43

2.7

OTHER SOURCES OF PTS .................................................................................................................45

2.8

IMPORT AND EXPORT STATISTICS OF PTS CONTAINING WASTES.......................................49

2.9

COUNTRY RANKING ACCORDING TO PTS SCORES ..................................................................49

2.10 RANKING OF PTS CHEMICALS FROM SOURCES BY COUNTRIES...........................................51

2.11 SUMMARY: SOURCE CHARACTERISATION................................................................................53

2.11.1 Production And Imports........................................................................................................................53

2.11.2 Use Of PTS Pesticides ..........................................................................................................................53

2.11.3 Stocks Of Obsolete Pesticides...............................................................................................................54

2.11.4 Industrial Chemicals, Including PCBS .................................................................................................54

2.11.5 PTS Production From Open Burning....................................................................................................54

iii

2.11.6 REFERENCES..................................................................................................................................... 54

3

ENVIRONMENTAL LEVELS, TOXICOLOGICAL AND ECOTOXICOLOGICAL

CHARACTERISATION.................................................................................................................. 55

3.1

INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................... 55

3.2

CONCENTRATIONS OF PTS IN ABIOTIC COMPARTMENTS.................................................................... 58

3.2.1 Environmental Media: AIR .................................................................................................................. 61

3.2.2 Environmental Media: Water ............................................................................................................... 61

3.2.3 Environmental Media: Marine Water................................................................................................... 62

3.2.4 Environmental Media: River And Lake Sediments.............................................................................. 62

3.2.5 Environmental Media: Marine Sediments............................................................................................ 65

3.2.6 Environmental Media: Soil .................................................................................................................. 65

3.3

CONCENTRATIONS OF PTS IN BIOTIC MEDIA ........................................................................... 67

3.3.1 PTS in Vegetation ................................................................................................................................ 67

3.3.2 PTS in Animals .................................................................................................................................... 70

3.3.3 PTS in Aquatic Animals....................................................................................................................... 70

3.3.4 PTS in Terrestrial Animals................................................................................................................... 73

3.3.5 PTS in Humans..................................................................................................................................... 73

3.4

EVIDENCE OF HARMFUL EFFECTS............................................................................................... 76

3.4.1 Comparison Of Measured Data With Health And Environmental Quality Criteria............................. 76

3.5

ECOTOXICOLOGICAL DATA AND APPROPRIATE TEST SPECIES .......................................... 78

3.6

RANKING OF PTS CHEMICALS ...................................................................................................... 78

3.7

DATA GAPS ........................................................................................................................................ 87

3.8

SUMMARY.......................................................................................................................................... 87

3.9

REFERENCES ......................................................................................................................................... 88

4

ASSESSMENT OF MAJOR PATHWAYS OF CONTAMINANTS TRANSPORT ................. 91

4.1

INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................ 91

4.2

OVERVIEW OF EXISTING MODELLING PROGRAMMES........................................................... 91

4.3

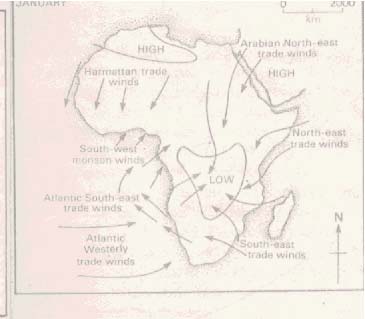

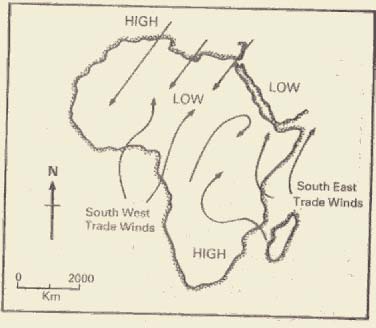

ATMOSPHERIC TRANSPORT .......................................................................................................... 92

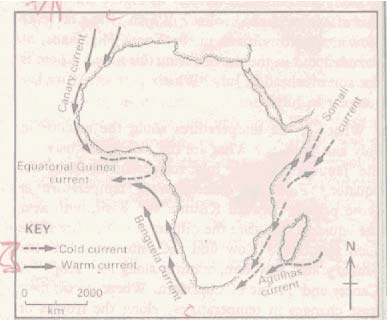

4.4

COASTAL AND MARINE ENVIRONMENT.................................................................................... 92

4.5

TERRESTRIAL ASPECTS.................................................................................................................. 93

4.6

DATA GAPS ........................................................................................................................................ 95

4.7

SUMMARY.......................................................................................................................................... 95

4.8

REFERENCES ..................................................................................................................................... 95

5

ASSESSEMENT OF THE REGIONAL CAPACITY AND NEEDS TO MANAGE PTS ........ 97

5.1

INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................ 97

5.2

MONITORING CAPACITY................................................................................................................ 99

5.3

EXISTING POLICIES, REGULATIONS AND MANAGEMENT OF PTS ....................................... 99

5.4

ALTERNATIVES AND/OR MEASURES FOR REDUCTION OF PTS .......................................... 101

5.5

SOCIO-ECONOMIC INTERVENTIONS ......................................................................................... 102

5.6

THE REGIONAL NEEDS.................................................................................................................. 102

5.7

SUMMARY........................................................................................................................................ 104

5.8

REFERENCES ....................................................................................................................................... 104

6

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ....................................................................... 105

6.1

KEY FINDINGS................................................................................................................................. 105

6.2

SETTING OF PRIORITIES ............................................................................................................... 106

6.3

PRIORITIES AS AGREED UPON BY THE PRIORITY SETTING MEETING.............................. 106

6.3.1 Short Term Priorities (1-2 years)........................................................................................................ 107

6.3.2 Medium Term Priorities (2-5 years)................................................................................................... 112

6.3.3 Long Term Priorities (5 to 10 years) .................................................................................................. 114

6.4

AREAS OF PRIORITY FOCUS ........................................................................................................ 115

6.5

FINAL WORD ................................................................................................................................... 115

ANNEX: ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ................................................................................... 116

iv

PREFACE

This report is the product of the collective efforts of the Regional Team Members of the UNEP/GEF

Regionally Based Assessment of Persistent Toxic Substances (RBA PTS) Project for Region V, Sub-Sahara

Africa. It forms part of a global assessment of Persistent Toxic Substances (PTS) as sub-Sahara Africa is one

of the twelve regions designated by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) for this purpose.

Composition of the Regional Team

The Regional Team established within the framework of the project with the following as members prepared

the report:

Regional Coordinator

Prof. Oladele Osibanjo, Director, Federal Ministry Of Environment-University of Ibadan Linkage Centre on

Cleaner Production Technology and Hazardous Waste Management, Department of Chemistry, University of

Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria. osibanjo@infoweb.abs.net or oosibanjo@yahoo.com

Team Members

Prof. Henk Bouwman, Professor, University of Potchefstroom, PU for CHE, P. Bag X6001, Potchefstroom

2520, South Africa. drkhb@puknet.puk.ac.za

Prof. Nabil H. H. Bashir. University of Gezira, Prof. of Pesticides and Toxicology, Faculty of Agricultural

Sciences, P O Box 20 Wad Medani, Sudan. bashirnabil@hotmail.com or bashirnabil@yahoo.com

Prof. Jose Okond'Ahoka, Director, Ministere de la Sante / Expert, Ministere de L'environment, B.P.16789

Kinshasa 1, Democratic Republic Of Congo (DRC). okondahuka_fr@yahoo.fr or agcdongd@yahoo.fr

Dr. Robert Choong Kwet Yive, Lecturer, Department of Chemistry Faculty of Science, University of

Mauritius. Robert@uom.ac.mu

Engr. Hosseah A. Onyoyo, Seven-Engine Techse Ltd, P.O. Box 53832, 0020 City Square, Nairobi, Kenya.

haonyoyo@yahoo.com or stephanoson@yahoo.com

Data Collection and Report Preparation

African experts in academia, research institutes government and non-governmental organizations (NGOs)

provided data existing in the region mainly through the completion of dedicated questionnaires designed by

GEF/UNEP for the study. The data collected was supplemented with data from published literature, research

reports, technical reports as well as personal communication from experts in the region.

The draft report prepared by the Regional Team Members was presented and reviewed at the Technical

Workshops on Sources Characterisation, Impact and Transport of PTS, held in Mombasa, Kenya 29 July - 2

August 2002 and attended by the network of regional experts. The revised draft report was presented to the

Regional Priority Setting Meeting held in Nairobi, UNEP, Kenya, during 30 October to 02 November 2002.

The inputs from the workshops and the meeting are reflected in this report.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Several people and organisations contributed immensely towards the preparation of this report. The

invaluable assistance from members of the Regional Network of Experts who provided information on PTS

chemicals within the region is gratefully acknowledged. The invaluable contributions from the participants at

the Regional Technical Workshops and the Regional Priority Setting Meeting are also profoundly

appreciated. Funds for the project were provided by the GEF through UNEP Chemicals without which the

implementation of this important regional study would have been impossible. The provision of enabling

environment and logistic support for the successful completion of the latter stages of the project, including

the finalisation of this regional report, by Mr. Ahmed Djoghlaf, Director Division of GEF Co-ordination,

UNEP, Nairobi; Dr. Walter Jarman, Programme Officer, GEF Coordinating Office, UNEP, Nairobi, Kenya

and his able assistants, Miss Jackline Oduor and Ms. Theresa Lowe are gratefully acknowledged.

The contributions of Mr. Raphael Dakouri Zadi, Coordinateur du Project POPs & PCB, Ministere de

L'environement et du Cadre De Vie, Service Autonome Des Affaires Internationales, (20bp 650 Abidjan 20,

Cote d'Ivoire; zadid@aviso.ci) in coordinating data collection from some countries including assistance

v

during the Technical Workshops, Regional Priority Setting Meeting and finalisation of the report are

acknowledged.

The special contribution of Mr. Paul Whylie, the PTS Project Manager at UNEP, Geneva for rendering total

support towards the success of the project in spite of daunting difficulties is profoundly appreciated.

vi

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

INTRODUCTION

Forty Seven sub-Saharan African countries including Madagascar and six small island states constitute

Region V, the largest of the twelve regions, for the Regionally Based Assessment (RBA) of Persistent Toxic

Substances (PTS) in a global project funded by GEF/UNEP. This assessment of PTS is a major milestone as

no comprehensive database on hazardous chemicals exists in the region.

PTS SOURCES

The identifiable main sources of PTS in the region are agricultural use of pesticides, production and imports,

vector control, stocks of obsolete and expired pesticides, industrial sources (manufacture, mining and

electricity) and not the least as by-products of combustion including open burning of waste.

Pesticides

Pesticides constitute one of the major sources of PTS in Region V. Except for atrazine produced in South

Africa, PTS pesticides are generally imported and not produced in Region V but pesticide formulation plants

exist in many countries of the region. Sub-Sahara Africa imports less than 5% in terms of value of total

pesticides import of the world. Twenty-two RBA Region V countries each import more than $5 million

worth of pesticides annually.

During the technical workshops, the regional experts identified the most widely used PTS pesticides for

Region V as mainly organochlorine pesticides namely: DDT, Endosulfan, Chlordane, Lindane (HCH),

Heptachlor, Toxaphene, HCB and Aldrin; as well as Atrazine. The workshops also noted the possibility and

likelihood of illegal trade and use of PTS pesticides (including DDT) in the region. Based on pesticide

import data (FAO), South Africa, Nigeria, Cote D'Ivoire, Kenya, Ethiopia, Ghana, Sudan, Tanzania,

Mozambique and Mali are the highest users of pesticides in the region.

A serious problem facing the region now is the issue of stocks and reservoirs of obsolete discarded and

banned PTS pesticides. The FAO estimates that there might be more than 40 000 tons, perhaps even much

more, of these chemicals stocked or discarded over many parts of Africa. Some of these chemicals were

donations from developed countries.

Industrial PTS Chemicals

The major industrial PTS chemicals of concern in the region are adjudged to be the following: PCBs (mainly

from electricity generating industry), HCB (also a PTS pesticide), pentachlorophenol (PCP) and phthalates.

Data is lacking on the use and import of PTS industrial chemicals in the region. This data gap will be

addressed perhaps when most of the countries have carried out "National Chemical Profile" study being

driven by the Intergovernmental Forum on Chemical Safety (IFCS).

Industrial output and electricity generation have been used as criteria to rank countries on the production of

PTS especially PCBs and Dioxins from industrial sources. Accordingly the countries releasing the largest

PTS emissions are South Africa, Nigeria, Zimbabwe, Ghana, Kenya, Democratic Republic of Congo,

Zambia, Cote D'Ivoire, Sudan and Cameroon in that order.

Other Sources Of PTS

The PTS of concern in this category are polyaromatic hydrocarbons and dioxins/furans.

Although not quantified, the main source categories are:

PAHs exhaust emission from combustion of fossil fuels in vehicles and electrical generating sets.

Dioxins and furans Waste (domestic, hospital, industrial) burning is possibly the least known factor in the

production of PCDD/Fs in Africa. A large amount of accidental and deliberate combustion is taking place,

including the burning of rubber tyres as well as stripping insulation of copper wires and cables. Waste

combustion could potentially be the largest source of dioxins and furans in Africa. Moreover, burning of

sugar cane fields, a common practice in sugar producing countries, could also contribute to the formation of

dioxins.

Based on population figures (2001 estimates), waste production (tons/day), air releases (mg TEQ), and

burned residue (mg TEQ) respectively; the largest potential emitters of dioxins into the environment from

vii

waste burning, a common practice in the region, are: Nigeria, Ethiopia, Democratic Republic of Congo

(DRC), South Africa, Tanzania, Sudan, Kenya, Uganda, Ghana, and Mozambique respectively. A daily TEQ

production of around 60g (21360 g TEQ/year) for dioxins and furans for Region V has been estimated. This

would equate to 0.0003 g TEQ/year per capita, but only for uncontrolled domestic waste combustion, not

including industrial or any other anthropogenic or natural sources, which were not taken into consideration.

This lack of information therefore constitutes a major data gap.

Ranking Of PTS Sources By Countries

At the technical workshops, the experts from the countries present were asked to score the PTS as released

from sources according to levels of concern for that specific country. The experts were asked to rank from 0

for no concern, to 3 for major concern. Some country experts did indicate however, that their scoring was

indicative only, but the combined scores from the countries gave a good indication of the overall level of

relative concern. The country experts rated the unintentional production of dioxins/furans as well as the

problem of PCBs, as the highest concern for most countries. DDT, Atrazine, Endosulfan and Lindane were

ranked as the most important PTS pesticides. Organic lead was the organometallic compound that caused the

most concern. For almost all of these compounds, significant data gaps were also indicated.

ENVIRONMENTAL LEVELS, TOXICOLOGICAL AND ECOTOXICOLOGICAL

CHARACTERISATION

Experts from only 16 countries out of 47 of the region provided data concerning PTS (about 3000 filled

questionnaires) in the environment. These data are relative to the levels and trends of PTS in environmental

media and clinical samples. Toxicological data are generally lacking for the region. Moreover, air, as an

environmental compartment was not given the required attention by most of the countries of the region in

general.

Concentrations Of PTS In Abiotic Compartments Of The Environment (Highlight Of Hotspots: Trend

Analysis)

Sub-Sahara is mainly an agricultural continent and it has been using pesticides for pest and disease control

for more than 50 years. Except for South Africa and Zimbabwe, no systematic pesticide monitoring/analysis

exists in all the countries of the region. These two countries account for more than two thirds of the filled

questionnaires gathered for the region. A big data gap therefore exists in the region as far as levels of PTS in

the environment are concerned.

The data gathered have been grouped according to the period of analysis: 1970 - 1979, 1980 - 1989 and 1990

- 2002 respectively for the purpose of trend analysis. During the 1970 - 1979 period, only seven PTS were

reported (DDT, dieldrin, endosulfan, Lindane, toxaphene, PCBs and HCB) whereas in the second period

(1980 - 1989), the period of awareness, banning and/or restriction, this number increased to nine (DDT,

dieldrin, endosulfan, Lindane, toxaphene, PCBs, HCB, heptachlor and atrazine). DDT, Lindane, endosulfan,

dieldrin, PCBs and HCB were common to both periods. During the third period (1990 - 2002) new chemicals

of agricultural, construction and industrial use, viz. endrin, chlordane, PAHs (pyrene), and nonylphenols

were detected in the region. PCBs and HCB were detected since the 1970's in South Africa and Zimbabwe in

water, vegetation and animals at relatively high levels.

Concentrations Of PTS In Biotic Media

From the data gathered through filled questionnaires, the trend of concentration observed in Sub-Sahara

Africa for PTS is DDT> PCBs> toxaphene. These same data apparently indicate that humans were less

directly exposed than animals and vegetation to PTS during the period 1970 - 2002. However the main risk

remains the food-web contamination. The occurrence of relatively high levels of DDT, PCBs and

dioxins/furans in adipose tissues and blood of occupationally exposed persons is of immense concern.

Equally disturbing is the high levels of HCB, Lindane and endosulfan in human breast milk in the region, in

view of WHO's vigorous campaign that mothers breast milk is best for children. It has been established by

studies in South Africa that Organochlorine Pesticides (OCPs) can be transferred to infants via breast milk.

Thus infants are being exposed to these xenobiotics while the toxicological hazards and risks have not been

studied in many sub-Sahara African countries.

viii

Evidence Of Harmful Effects

Many cases of accidental or intentional release of large amounts of PTS (for fishing or hunting) causing

severe stress to the environment and humans have been reported in the region. For example, the accidental

release of organochlorine pesticides (OCPs) in large quantities had caused massive fish kills in many

countries, such as Senegal, Nigeria and Kenya. Cases of people suffering from diseases as a result of

exposure to organochlorine insecticides while selling, mixing or spraying these were reported in Wad

Medani, Sudan. However there is data gap on PTS contaminated sites and hotspots.

RANKING OF PTS CHEMICALS ON ENVIRONMENTAL LEVELS, TOXICOLOGICAL AND

ECOTOXICOLOGICAL CHARACTERISATION BY COUNTRIES

At the technical workshops, the country experts rated dioxins and PCBs of highest concern in regard to their

levels in the environment. Among the PTS pesticides, it was DDT that was of highest concern followed by

endosulfan, atrazine, Lindane, aldrin, dieldrin, chlordane and heptachlor respectively. A similar pattern of

response was obtained for data gaps, that is, dioxins; PCBs and DDT were the chemicals that the experts

considered of highest priority.

DATA GAPS

At the technical workshops, the experts considered the following list as the major data gaps/issues that need

to be addressed:

PTS atmospheric concentrations in the countries of the region

PTS levels in sediments of the major lakes, e.g. Tana, Victoria, Chad, etc. and the marine

environment

Dioxins and furans in environmental compartments and humans (analytical data exist only in

South Africa),

Systematic studies of the food-web contamination and biomagnifications

The effect of burning crop residues, e.g. cotton, sugarcane, etc.

Effect of improper burning of wastes

The long-term effect of the accumulated stocks of obsolete PTS on the environment and health of

the human and animal populations near them

The effect of the emissions from the chimneys of the sugar and cement factories on the human

and animal populations in their areas and the vicinity, at least within 50 km from the sites, where

some eventually deposit

Concentrations of PAHs and organometallics (mercury and tin) in environmental media and biota.

ASSESSMENT OF MAJOR PATHWAYS OF CONTAMINANTS TRANSPORT

Atmospheric Transport

The uniqueness of the African continent in terms of secondary drift and temperature inversions is significant

in determining the environmental fate of PTS. These conditions can influence the behaviour of PTS. For

example air monitoring data in Zimbabwe and Malawi showed that hot temperatures volatilise sprayed DDT

into pockets of hot air and could drift down stream. DDT can condense on the ground when the temperatures

are low. The distillation and condensation of PTS on top of cold mountains, like the Kilimanjaro, could also

take place, although no data from Africa exists to confirm this.

It is not known whether Africa is a source or sink of global PTS. Current thinking is that the presence of the

Inter-Tropical Convergence Zone will prevent atmospheric transport of PTS to the north and vice versa.

However, whether Africa acts as a source of PTS to the Antarctic is not known.

In this context, the Island states are particularly vulnerable to this atmospheric mode of contamination by

PTS. For the region there is big data gap concerning atmospheric transport of PTS and therefore underscores

the importance of modelling here.

ix

Food Web

Monitoring data from Chapter 3 of the report indicate that DDT and PCBs in fish were two of the PTS most

often encountered since 1970s in the region including the marine environment. The data also indicate

widespread PTS contamination of fruits, vegetables, major cereals, foodstuffs of animal origin, as well as

fish and fish products, breast milk and dairy products. Fish that constitutes the major source of animal

protein for coastal, lacustrine and riparian populations of Region V is thus an indirect source of exposure to

PTS for these populations.

Coastal And Marine Environment

Since most of the socio-economic activities of Region V are associated with rivers and other water bodies

apart from land, it is expected that significant amounts of PTS are transported across boundaries and released

into lakes, seas and oceans. The magnitude of this input is unknown for the region, but it is likely to be

significant and therefore constitutes another major data gap.

Terrestrial Aspects

The aspect of the behaviour of PTS in Region V soil types again constitutes a major data gap. Results

obtained from other parts of the world may not be valid for Region V as the soil type and climatic conditions

are very different.

PRELIMINARY ASSESSMENT OF THE REGIONAL CAPACITY AND NEEDS

In Region V, it is regrettable that whereas most of the national legislations are either general or fragmentary

in nature and non-specific to PTS, some countries do not have any laws regarding hazardous chemicals. It

will be important that national legislations are enacted and/or harmonised to deal with hazardous chemicals

in general and PTS in particular.

A major constraint towards the sustainable management of these hazardous chemicals is the lack of and/or

weak enforcement of regulations. For the region to contribute effectively in the global effort to reduce PTS,

there is need to establish and/or strengthen existing institutions and legal framework through capacity

building and putting in place necessary mechanisms for compliance monitoring and enforcement.

Alternatives And/Or Measures For Reduction Of PTS

Due to lack of adequate knowledge about the newly developed alternatives, some farmers undercover are

still using PTS pesticides in the region. This calls for aggressive awareness raising amongst these small-

scale farmers of the innovations and the effects of the PTS in order to convince them of the need to turn to

the alternatives. The development of alternative chemicals to replace PTS has however started, though still

on a small scale in the region. In some East African countries for example, most of the banned PTS

pesticides (organochlorines) have been replaced by pyrethrums; some of which are locally manufactured and

formulated. Some international research institutions in Africa are implementing alternatives to PTS

pesticides in agriculture and vector control. For example, Integrated Pest Management (IPM) and Integrated

Vector Management (IVM) have been developed and are currently being implemented in some parts of

Region V along with the rest of the world. Another example is the potential use of the extract of the Neem

tree to control agricultural pests and some fungal diseases instead of the conventional pesticides.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Existing environmental data gaps should be filled as a matter of priority as meaningful policy interventions

to protect humans and the environment from risk of exposure to PTS cannot be achieved in a data vacuum.

Environmental monitoring of PTS levels at the national level in soils, water, sediments, biota, air, livestock

and human blood/breast milk is essential for identifying all the hot spots for remedial action to reduce health

risks to humans.

The pathways and fate of PTS in the region should be studied, so that the critical pathways can be identified,

followed by the evaluation of the relative impact of processes, estimation of transport fluxes, and assessment

of remedial measures. Information is lacking in this critical area.

Capacity building needs in the region deserve priority action to ensure global success of the recent

Stockholm Convention on POPs and other international regulations for the environmentally sound

management of PTS and other hazardous chemicals. Regionally based research including development of an

ecotoxicological database on the African environment is important. Training African experts in the use of

x

models for sound chemicals management and environmental protection is also advantageous to the region

and the international community.

xi

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 OVERVIEW OF THE RBA PTS PROJECT

Following the recommendations of the Intergovernmental Forum on Chemical Safety, the UNEP Governing

Council decided in February 1997 (Decision 19/13 C) that immediate international action should be initiated

to protect human health and the environment through measures which will reduce and/or eliminate the

emissions and discharges of an initial set of twelve persistent organic pollutants (POPs). Accordingly an

Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC) was established with a mandate to prepare an international

legally binding instrument for implementing international action on certain persistent organic pollutants.

These series of negotiations have resulted in the adoption of the Stockholm Convention in 2001. The initial 12

substances fitting these categories that have been selected under the Stockholm Convention are: Aldrin,

Endrin, Dieldrin, Chlordane, DDT, Toxaphene, Mirex, Heptachlor, Hexachlorobenzene, PCBs, Dioxins and

Furans. Beside these 12, there are many other substances that satisfy the criteria listed above for which their

sources, environmental concentrations and effects are to be assessed.

Persistent toxic substances can be manufactured substances for use in various sectors of industry, pesticides,

or by-products of industrial processes and combustion. To date, their scientific assessment has largely

concentrated on specific local and/or regional environmental and health effects, in particular "hot spots" such

as the Great Lakes region of North America or the Baltic Sea.

1.1.1 Objectives

There is a need for the scientifically-based assessment of the nature and scale of the threats to the environment

and its resources posed by persistent toxic substances that will provide guidance to the international

community concerning the priorities for future remedial and preventive action. The assessment will lead to the

identification of priorities for intervention, and through application of a root cause analysis will attempt to

identify appropriate measures to control, reduce or eliminate releases of PTS, at national, regional or global

levels.

The objective of the project is to deliver a measure of the nature and comparative severity of damage and

threats posed at national, regional and ultimately at global levels by PTS. This will provide the GEF with a

science-based rationale for assigning priorities for action among and between chemical related environmental

issues, and to determine the extent to which differences in priority exist among regions.

1.1.2 Results

The project relies upon the collection and interpretation of existing data and information as the basis for the

assessment. No research will be undertaken to generate primary data, but projections will be made to fill

data/information gaps, and to predict threats to the environment. The proposed activities are designed to

obtain the following expected results:

Identification of major sources of PTS at the regional level;

Impact of PTS on the environment and human health;

Assessment of transboundary transport of PTS;

Assessment of the root causes of PTS related problems, and regional capacity to manage these

problems;

Identification of regional priority PTS related environmental issues; and

Identification of PTS related priority environmental issues at the global level.

The outcome of this project will be a scientific assessment of the threats posed by persistent toxic substances

to the environment and human health. The activities to be undertaken in this project comprise an evaluation of

the sources of persistent toxic substances, their levels in the environment and consequent impact on biota and

1

humans, their modes of transport over a range of distances, the existing alternatives to their use and

remediation options, as well as the barriers that prevent their good management.

1.1.3 Methodology

To achieve these results, the globe is divided into 12 regions namely: Arctic, North America, Europe,

Mediterranean, Sub-Saharan Africa, Indian Ocean, Central and North East Asia (Western North Pacific),

South East Asia and South Pacific, Pacific Islands, Central America and the Caribbean, Eastern and Western

south America, Antarctica. The twelve regions were selected based on obtaining geographical consistency

while trying to reside within financial constraints.

1.1.4 Management Structure

The Project Manager who is situated at UNEP Chemicals in Geneva, Switzerland directs the project. A

Steering Group comprising of representatives of other relevant intergovernmental organisations along with

participation from industry and the non-governmental community is established to monitor the progress of the

project and provide direction for the project manager. A Regional Coordinator (RC) assisted by a team of

approximately 4 persons controls each region. The Regional Coordinator and the Regional Team (RT) are

responsible for promoting the project, the collection of data at the national level and to carry out a series of

technical and priority setting workshops for analysing the data on PTS on a regional basis. Besides the 12

POPs from the Stockholm Convention, the regional team selects the chemicals to be assessed for its region

with selection open for review during the various workshops undertaken throughout the assessment process.

Each team writes the regional report for the respective region.

1.1.5 Data Processing

Data is collected on sources, environmental concentrations, human and ecological effects through

questionnaires that are filled at the national level. The results from this data collection along with

presentations from regional experts at the technical workshops are used to develop regional reports on the PTS

selected for analysis. A priority setting workshop with participation from representatives from each country

results in priorities being established regarding the threats and damages of these substances to each region.

The information and conclusions derived from the 12 regional reports will be used to develop a global report

on the state of these PTS in the environment.

The project is not intended to generate new information but to rely on existing data and its assessment to

arrive at priorities for these substances. The establishment of a broad and wide- ranging network of

participants involving all sectors of society was used for data collection and subsequent evaluation. Close

cooperation with other intergovernmental organizations such as UNECE, WHO, FAO, UNPD, World Bank

and others was obtained. Most have representatives on the Steering Group Committee that monitors the

progress of the project and critically reviews its implementation. Contributions were garnered from UNEP

focal points, UNEP POPs focal points, national focal points selected by the regional teams, industry,

government agencies, research scientists and NGOs.

1.1.6 Project Funding

The project costs approximately US$4.2 million funded mainly by the Global Environment Facility (GEF)

with sponsorship from countries including Australia, France, Germany, Sweden, Switzerland and the USA.

The project runs between September 2000 to April 2003 with the intention that the reports be presented to the

first meeting of the Conference of the Parties of the Stockholm Convention projected for 2003/4.

This report provides a regional review of the production, use, environmental impacts and environmental

transport of the group of chemicals known as Persistent Toxic Substances (PTS). The report is based on

existing information only, and did not involve any additional research. The information for the report was

assembled by the Regional Team Members on the basis of information supplied from a wide range of people

throughout the region (the Regional Network) and beyond. The recommendations given in the report on

regional priorities and future needs were developed during the Regional Technical Workshops and the

Regional Priority Setting Meeting.

2

1.2 SCOPE OF SUB- SAHARA AFRICA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT

The chemicals included in this review were the 12 chemicals covered under the Stockholm Convention on

Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs), plus several other PTS chemicals. The 12 POPs are aldrin, chlordane,

DDT, dieldrin, dioxins, endrin, furans, hexachlorobenzene (HCB), heptachlor, toxaphene, mirex and

polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs). Information was also obtained on other PTS chemicals: endosulfan,

hexachlorocyclohexane (HCH), phthalate esters, polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), pentachlorophenol,

organic lead, organic tin and organic mercury. Other chemicals considered for inclusion in the survey were,

atrazine, chlordecone, hexabromobiphenyl, polybrominated biphenyl ethers, chlorinated paraffins,

octylphenols, and nonylphenols.

1.2.1 Existing Assessments

Up to now, there has been no comprehensive regional assessment of organic pollutants in sub-Sahara Africa.

This UNEP/GEF assessment is therefore both a landmark and an important source of regional database on

persistent toxic substances (PTS). A previous sub-regional assessment of POPs (a subset of PTS), excluding

dioxins and furans, in West and Central Africa (WACAF) and East Africa (EAF), had been undertaken in the

past, especially in the early 1980s to the early 1990s. This was done under the aegis of the UNEP Regional

Seas Programme. The assessments, which were limited to selected countries in WACAF and EAF, began with

equipping selected laboratories and training national experts in the countries selected in the analysis of

chlorinated hydrocarbons and heavy metals. The landlocked countries were excluded.

The FAO attempted for the first time in the early 1990s, under the aegis of the Committee of Inland Fisheries

of Africa (CIFA), to collate the levels of chlorinated hydrocarbons (CHCs), specially organochlorine

pesticides (OCPs) and PCBs in water, sediments and biota in Africa, and which was published as a chapter in

the publication " Review of pollution in the African aquatic environment '' (Osibanjo et. al. 1994). This

remains the only existing Regional Assessment of CHCs in the region before this report.

1.2.2 Methodology

Information on the PTS chemicals was obtained through various means. Data on current production and use

was solicited from the relevant government agencies within the region. Heavy reliance was placed on CIA

Fact book, Internet, and where this failed, all other data were obtained from published papers and reports.

Additional information was obtained through searches of the published literature and through direct contacts

with researchers, government agencies and the regional network of experts. All of the information collected

from the above sources were entered into a series of standard questionnaires, which were provided by UNEP

Chemicals for this purpose. The data was also entered into the UNEP PTS database in Geneva (which is

accessible online www.unep.org; password required) to facilitate processing and analysis, and also to allow

for future updating and review.

The regional team members were responsible for promoting the project, collection of data at the national level

and, analysing the data on PTS on a regional basis. Data and information were collected on sources,

environmental concentrations, human and ecological effects through questionnaires that were filled at the

national level in the 47 countries of the region. Each regional team member was responsible for data

collection in at least 6 countries. The regional team held organizational meetings and were responsible for

filling the data from about 3000 questionnaires returned on to the UNEP PTS database.

The data gathering was aimed at obtaining information on all the chemicals mentioned in 1.1above. However,

as can be seen later in Chapter 3, data was not available on some of the chemicals, already indicating a

significant data gap, although this does not preclude their existence within the region. The potential for this

and the need for appropriate regional investigations, are discussed later in this report.

All the collected data, reviewed in the regional report, were analysed for technical accuracy and completeness

during the Regional Technical Workshops and the Regional Priority Setting Meeting. This report incorporates

the inputs from the participants during the Regional Technical Workshops and the Regional Priority Setting

Meeting. The recommendations given in Chapter 6 were based on the earlier comments made during the

3

Regional Technical Workshops, which were further enriched and endorsed by the Regional Priority Setting

Meeting.

1.3 PTS DEFINITIONS AND PROPERTIES

The substances assessed in this report are as follows: aldrin, chlordane, DDT, dieldrin, endrin, heptachlor,

hexachlorobenzene, mirex, toxaphene, PCBs, dioxins, furans, chlordecone, hexabromobiphenyl, HCH (lindane),

PAHs, PBDE, chlorinated paraffins, endosulfan, atrazine, pentachlorophenol, organic mercury compounds,

organic tin compounds, organic lead compounds, phthalates, octylphenols and nonylphenols. All the substances

in the PTS list under study were adopted for the region with the assumption that some or all of the chemicals must

have been used at one time or the other for specific purposes. The regional survey data is meant to be used as

benchmark for identifying PTS existing in the region. The non-identification of a PTS is however considered as a

data gap, rather than non-existence of the chemical in the region as searches were conducted for all the chemicals.

Summary of physico-chemical properties, including eco-toxicological and safety data, on each of the PTS

chemicals is given below.

1.3.1.1 Aldrin

Chemical Name: 1,2,3,4,10,10-Hexachloro-1,4,4a,5,8,8a-hexahydro-1,4-endo,exo-5,8-dimethanonaphthalene

(C12H8Cl6). CAS Number: 309-00-2

Properties: Solubility in water: 27 µg/L at 25°C; vapour pressure: 2.3 x 10-5 mm Hg at 20°C; log KOW: 5.17-

7.4.

Discovery/Uses: It has been manufactured commercially since 1950, and used throughout the world up to the

early 1970s to control soil pests such as corn rootworm, wireworms, rice water weevil, and grasshoppers. It

has also been used to protect wooden structures from termites.

Persistence/Fate: Readily metabolized to dieldrin by both plants and animals. Biodegradation is expected to

be slow and it binds strongly to soil particles, and is resistant to leaching into groundwater. Aldrin was

classified as moderately persistent with half-life in soil and surface waters ranging from 20 days to 1.6 years.

Toxicity: Aldrin is toxic to humans; the lethal dose for an adult has been estimated to be about 80 mg/kg

body weight. The acute oral LD50 in laboratory animals is in the range of 33 mg/kg body weight for guinea

pigs to 320 mg/kg body weight for hamsters. The toxicity of aldrin to aquatic organisms is quite variable, with

aquatic insects being the most sensitive group of invertebrates. The 96-h LC50 values range from 1-200 µg/L

for insects, and from 2.2-53 µg/L for fish. The maximum residue limits in food recommended by FAO/WHO

varies from 0.006 mg/kg milk fat to 0.2 mg/kg meat fat. Water quality criteria between 0.1 to 180 µg/L have

been published.

1.3.1.2 Dieldrin

Chemical Name: 1,2,3,4,10,10-Hexachloro-6,7-epoxy-1,4,4a,5,6,7,8,8a-octahydroexo-1,4-endo-5,8-

dimethanonaphthalene (C12H8Cl6O). CAS Number: 60-57-1

Properties: Solubility in water: 140 µg/L at 20°C; vapour pressure: 1.78 x 10-7 mm Hg at 20°C; log KOW:

3.69-6.2.

Discovery/Uses: It appeared in 1948 after World War II and used mainly for the control of soil insects such as

corn rootworms, wireworms and cat worms.

Persistence/Fate: It is highly persistent in soils, with a half-life of 3-4 years in temperate climates, and

bioconcentrates in organisms. The persistence in air has been estimated in 4-40 hrs.

Toxicity: The acute toxicity for fish is high (LC50 between 1.1 and 41 mg/L) and moderate for mammals

(LD50 in mouse and rat ranging from 40 to 70 mg/kg body weight). However, a daily administration of 0.6

mg/kg to rabbits adversely affected the survival rate. Aldrin and dieldrin mainly affect the central nervous

system but there is no direct evidence that they cause cancer in humans. The maximum residue limits in food

recommended by FAO/WHO varies from 0.006 mg/kg milk fat and 0.2 mg/kg poultry fat. Water quality

criteria between 0.1 to 18 µg/L have been published.

4

1.3.1.3 Endrin

Chemical Name: 3,4,5,6,9,9-Hexachloro-1a,2,2a,3,6,6a,7,7a-octahydro-2,7:3,6-dimethanonaphth[2,3-

b]oxirene (C12H8Cl6O). CAS Number: 72-20-8

Properties: Solubility in water: 220-260 µg/L at 25 °C; vapour pressure: 2.7 x 10-7 mm Hg at 25°C; log KOW:

3.21-5.34

Discovery/Uses: It has been used since the 50s against a wide range of agricultural pests, mostly on cotton

but also on rice, sugar cane, maize and other crops. It has also been used as a rodenticide.

Persistence/Fate: Is highly persistent in soils (half-lives of up to 12 years have been reported in some cases).

Bioconcentration factors of 14 to 18,000 have been recorded in fish, after continuous exposure.

Toxicity: Endrin is very toxic to fish, aquatic invertebrates and phytoplankton; the LC50 values are mostly less

than 1 µg/L. The acute toxicity is high in laboratory animals, with LD50 values of 3-43 mg/kg, and a dermal

LD50 of 5-20 mg/kg in rats. Long-term toxicity in the rat has been studied over two years and a NOEL of 0.05

mg/kg bw/day was found.

1.3.1.4 Chlordane

Chemical Name: 1,2,4,5,6,7,8,8-Octachloro-2,3,3a,4,7,7a-hexahydro-4,7-methanoindene (C10H6Cl8).

CAS Number: 57-74-9

Properties: Solubility in water: 56 µg/L at 25°C; vapour pressure: 0.98 x 10-5 mm Hg at 25 °C; log KOW:

6.00.

Discovery/Uses: Chlordane appeared in 1945 and was used primarily as an insecticide for control of

cockroaches, ants, termites, and other household pests. Technical chlordane is a mixture of at least 120

compounds. Of these, 60-75% are chlordane isomers, the remainder being related to endo-compounds

including heptachlor, nonachlor, diels-alder adduct of cyclopentadiene and

penta/hexa/octachlorocyclopentadienes.

Persistence/Fate: Chlordane is highly persistent in soils with a half-life of about 4 years. Its persistence and

high partition coefficient promotes binding to aquatic sediments and bioconcentration in organisms.

Toxicity: LC50 from 0.4 mg/L (pink shrimp) to 90 mg/L (rainbow trout) have been reported for aquatic

organisms. The acute toxicity for mammals is moderate with an LD50 in rat of 200-590 mg/kg body weight

(19.1 mg/kg body weight for oxychlordane). The maximum residue limits for chlordane in food are, according

to FAO/WHO between 0.002 mg/kg milk fat and 0.5 mg/kg poultry fat. Water quality criteria of 1.5 to 6 µg/L

have been published. Chlordane has been classified as a substance for which there is evidence of endocrine

disruption in an intact organism and possible carcinogenicity to humans.

1.3.1.5 Heptachlor

Chemical Name: 1,4,5,6,7,8,8-Heptachloro-3a,4,7,7a-tetrahydro-4,7-methanoindene (C10H5Cl7).

CAS Number: 76-44-8

Properties: Sol. in water: 180 µg/L at 25°C; vapour pressure: 0.3 x 10-5 mm Hg at 20°C; log KOW: 4.4-5.5.

Production/Uses: Heptachlor is used primarily against soil insects and termites, but also against cotton

insects, grasshoppers, and malaria mosquitoes. Heptachlor epoxide is a more stable breakdown product of

heptachlor.

Persistence/Fate: Heptachlor is metabolised in soils, plants and animals to heptachlor epoxide, which is more

stable in biological systems and is carcinogenic. The half-life of heptachlor in soil is in temperate regions 0.75

2 years. Its high partition coefficient provides the necessary conditions for bioconcentrating in organisms.

Toxicity: The acute toxicity of heptachlor to mammals is moderate (LD50 values between 40 and 119 mg/kg

have been published). The toxicity to aquatic organisms is higher and LC50 values down to 0.11 µg/L have

been found for pink shrimp. Limited information is available on the effects in humans and studies are

inconclusive regarding heptachlor and cancer. The maximum residue levels recommended by FAO/WHO are

between 0.006 mg/kg milk fat and 0.2 mg/kg meat or poultry fat.

1.3.1.6 Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT)

Chemical Name: 1,1,1-Trichloro-2,2-bis-(4-chlorophenyl)-ethane (C14H9Cl5). CAS Number: 50-29-3.

Properties: Solubility in water: 1.2-5.5 µg/L at 25°C; vapour pressure: 0.2 x 10-6 mm Hg at 20°C; log KOW:

6.19 for p,p'-DDT, 5.5 for p,p'-DDD and 5.7 for p,p'-DDE.

5

Discovery/Use: DDT appeared for use during World War II to control insects that spread diseases like

malaria, dengue fever and typhus. Following this, it was widely used on a variety of agricultural crops. The

technical product is a mixture of about 85% p,p'-DDT and 15% o,p'-DDT isomers.

Persistence/Fate: DDT is highly persistent in soils with a half-life of up to 15 years and of 7 days in air. It

also exhibits high bioconcentration factors (in the order of 50000 for fish and 500000 for bivalves). In the

environment, the product is metabolized mainly to DDD and DDE.

Toxicity: The lowest dietary concentration of DDT reported to cause egg shell thinning was 0.6 mg/kg for the

black duck. LC50 of 1.5 mg/L for largemouth bass and 56 mg/L for guppy have been reported. The acute

toxicity of DDT for mammals is moderate with an LD50 in rat of 113-118 mg/kg body weight. DDT has been

shown to have an estrogen-like activity, and possible carcinogenic activity in humans. The maximum residue

level in food recommended by WHO/FAO range from 0.02 mg/kg milk fat to 5 mg/kg meat fat. Maximum

permissible DDT residue levels in drinking water (WHO) is 1.0 µg/L.

1.3.1.7 Toxaphene

Chemical Name: Polychlorinated bornanes and camphenes (C10H10Cl8). CAS Number: 8001-35-2

Properties: Sol. in water: 550 µg/L at 20°C; vapour pressure: 3.3 x 10-5 mm Hg at 25°C; log KOW : 3.23-5.50.

Discovery/Uses: Toxaphene has been in use since 1949 as a nonsystemic insecticide with some acaricidal

activity, primarily on cotton, cereal grains fruits, nuts and vegetables. It was also used to control livestock

ectoparasites such as lice, flies, ticks, mange, and scab mites. The technical product is a complex mixture of

over 300 congeners, containing 67-69% chlorine by weight.

Persistence/Fate: Toxaphene has a half-life in soil from 100 days up to 12 years. It has been shown to

bioconcentrate in aquatic organisms (BCF of 4247 in mosquito fish and 76000 in brook trout).

Toxicity: Toxaphene is highly toxic in fish, with 96-hour LC50 values in the range of 1.8 µg/L in rainbow

trout to 22 µg/L in bluegill. Long term exposure to 0.5 µg/L reduced egg viability to zero. The acute oral

toxicity is in the range of 49 mg/kg body weight in dogs to 365 mg/kg in guinea pigs. In long term studies

NOEL in rats was 0.35 mg/kg bw/day, LD50 ranging from 60 to 293 mg/kg bw. For toxaphene exists a strong

evidence of the potential for endocrine disruption. Toxaphene is carcinogenic in mice and rats and is of

carcinogenic risk to humans, with a cancer potency factor of 1.1 mg/kg/day for oral exposure.

1.3.1.8 Mirex

Chemical Name: 1,1a,2,2,3,3a,4,5,5a,5b,6-Dodecachloroacta-hydro-1,3,4-metheno-1H-

cyclobuta[cd]pentalene (C10Cl12). CAS Number: 2385-85-5

Properties: Solubility in water: 0.07 µg/L at 25°C; vapour pressure: 3 x 10-7 mm Hg at 25°C; log KOW: 5.28.

Discovery/Uses: The use in pesticide formulations started in the mid 1950s largely focused on the control of

ants. It is also a fire retardant for plastics, rubber, paint, paper and electrical goods. Technical grade

preparations of mirex contain 95.19% mirex and 2.58% chlordecone, the rest being unspecified. Mirex is also

used to refer to bait comprising corncob grits, soya bean oil, and mirex.

Persistence/Fate: Mirex is considered to be one of the most stable and persistent pesticides, with a half-life is

soils of up to 10 years. Bioconcentration factors of 2600 and 51400 have been observed in pink shrimp and

fathead minnows, respectively. It is capable of undergoing long-range transport due to its relative volatility

(VPL = 4.76 Pa; H = 52 Pa m 3 /mol).

Toxicity: The acute toxicity of Mirex for mammals is moderate with an LD50 in rat of 235 mg/kg and dermal

toxicity in rabbits of 80 mg/kg. Mirex is also toxic to fish and can affect their behaviour (LC50 (96 hr) from 0.2

to 30 mg/L for rainbow trout and bluegill, respectively). Delayed mortality of crustaceans occurred at 1 µg/L

exposure levels. There is evidence of its potential for endocrine disruption and possibly carcinogenic risk to

humans.

1.3.1.9 Hexachlorobenzene (HCB)

Chemical Name: Hexachlorobenzene (C6H6). CAS Number: 118-74-1

Properties: Sol. in water: 50 µg/L at 20°C; vapour pressure: 1.09 x 10-5 mm Hg at 20°C; log KOW: 3.93-6.42.

Discovery/Uses: It was first introduced in 1945 as fungicide for seed treatments of grain crops, and used to

make fireworks, ammunition, and synthetic rubber. Today it is mainly a by-product in the production of a

large number of chlorinated compounds, particularly lower chlorinated benzenes, solvents and several

6

pesticides. HCB is emitted to the atmosphere in flue gases generated by waste incineration facilities and

metallurgical industries.

Persistence/Fate: HCB has an estimated half-life in soils of 2.7-5.7 years and of 0.5-4.2 years in air. HCB has

a relatively high bioaccumulation potential and long half-life in biota.

Toxicity: LC50 for fish varies between 50 and 200 µg/L. The acute toxicity of HCB is low with LD50 values of

3.5 mg/g for rats. Mild effects of the [rat] liver have been observed at a daily dose of 0.25 mg HCB/kg bw.

HCB is known to cause liver disease in humans (porphyria cutanea tarda) and has been classified as a possible

carcinogen to humans by IARC.

1.3.2 Industrial Compounds

1.3.2.1 Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs)

Chemical Name: Polychlorinated biphenyls (C12H(10-n)Cln, where n is within the range of 1-10). CAS

Number: Various (e.g. for Aroclor 1242, CAS No.: 53469-21-9; for Aroclor 1254, CAS No.: 11097-69-1);

Properties: Water solubility decreases with increasing chlorination: 0.01 to 0.0001 µg/L at 25°C; vapour

pressure: 1.6-0.003 x 10-6 mm Hg at 20°C; log KOW: 4.3-8.26.

Discovery/Uses: PCBs were introduced in 1929 and were manufactured in different countries under various

trade names (e.g., Aroclor, Clophen, Phenoclor). They are chemically stable and heat resistant, and were used

worldwide as transformer and capacitor oils, hydraulic and heat exchange fluids, and lubricating and cutting

oils. Theoretically, a total of 209 possible chlorinated biphenyl congeners exist, but only about 130 of these

are likely to occur in commercial products.

Persistence/Fate: Most PCB congeners, particularly those lacking adjacent unsubstituted positions on the

biphenyl rings (e.g., 2,4,5-, 2,3,5- or 2,3,6-substituted on both rings) are extremely persistent in the

environment. They are estimated to have half-lives ranging from three weeks to two years in air and, with the

exception of mono- and di-chlorobiphenyls, more than six years in aerobic soils and sediments. PCBs also

have extremely long half-lives in adult fish, for example, an eight-year study of eels found that the half-life of

CB153 was more than ten years.

Toxicity: LC50 for the larval stages of rainbow trout is 0.32 µg/L with a NOEL of 0.01 µg/L. The acute

toxicity of PCB in mammals is generally low and LD50 values in rat of 1 g/kg bw. IARC has concluded that

PCB are carcinogenic to laboratory animals and probably also for humans. They have also been classified as

substances for which there is evidence of endocrine disruption in an intact organism.

1.3.2.2 Polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins (PCDDs) and Polychlorinated dibenzofurans (PCDFs)

Chemical Name: PCDDs (C12H(8-n)ClnO2) and PCDFs (C12H(8-n)ClnO) may contain between 1 and 8 chlorine

atoms. Dioxins and furans have 75 and 135 possible positional isomers, respectively. CAS Number: Various

(2,3,7,8-TetraCDD: 1746-01-6; 2,3,7,8-TetraCDF: 51207-31-9).

Properties: Solubility in water: in the range 0.43 0.0002 ng/L at 25°C; vapour pressure: 2 0.007 x 10-6

mm Hg at 20°C; log KOW: in the range 6.60 8.20 for tetra- to octa-substituted congeners.

Discovery/Uses: They are by-products resulting from the production of other chemicals and from the low-

temperature combustion and incineration processes. They have no known use.

Persistence/Fate: PCDD/Fs are characterized by their lipophilicity, semi-volatility and resistance to

degradation (half life of TCDD in soil of 10-12 years) and to long-range transport. They are also known for

their ability to bio-concentrate and biomagnify under typical environmental conditions.

Toxicity: The toxicological effects reported refers to the 2,3,7,8-substituted compounds (17 congeners) that

are agonist for the AhR. All the 2,3,7,8-substituted PCDDs and PCDFs plus coplanar PCBs (with no chlorine

substitution at the ortho positions) show the same type of biological and toxic response. Possible effects

include dermal toxicity, immunotoxicity, reproductive effects and teratogenicity, endocrine disruption and

carcinogenicity. At the present time, the only persistent effect associated with dioxin exposure in humans is

chloracne. The most sensitive groups are fetus and neonatal infants.

Effects on the immune systems in the mouse have been found at doses of 10 ng/kg bw/day, while reproductive

effects were seen in rhesus monkeys at 1-2 ng/kg bw/day. Biochemical effects have been seen in rats down to

7

0.1 ng/kg bw/day. In a re-evaluation of the TDI for dioxins, furans (and planar PCB), the WHO decided to

recommend a range of 1-4 TEQ pg/kg bw, although more recently the acceptable intake value has been set

monthly at 1-70 TEQ pg/kg bw.

1.3.3 Regional Specific

1.3.3.1 Atrazine

Chemical Name: 2-Chloro-4-(ethlamino)-6-(isopropylamino)-s-triazine (C10H6Cl8).

CAS Number: 19-12-24-9

Properties: Solubility in water: 28 mg/L at 20°C; vapour pressure: 3.0 x 10-7 mm Hg at 20°C; log Kow: 2.34.

Discovery/Uses: Atrazine is a selective triazine herbicide used to control broadleaf and grassy weeds in corn,

sorghum, sugarcane, pineapple, christmas trees, and other crops, and in conifer reforestation plantings. It was

discovered and introduced in the late 50's. Atrazine is still widely used today because it is economical and

effectively reduces crop losses due to weed interference.

Persistence/Fate: The chemical does not adsorb strongly to soil particles and has a lengthy half-life (60 to >100

days). Atrazine has a high potential for groundwater contamination despite its moderate solubility in water.

Toxicity: The oral LD50 for atrazine is 3090 mg/kg in rats, 1750 mg/kg in mice, 750 mg/kg in rabbits, and 1000

mg/kg in hamsters. The dermal LD50 in rabbits is 7500 mg/kg and greater than 3000 mg/kg in rats. Atrazine is

practically nontoxic to birds. The LD50 is greater than 2000 mg/kg in mallard ducks. Atrazine is slightly toxic to

fish and other aquatic life. Atrazine has a low level of bioaccumulation in fish. Available data regarding atrazine's

carcinogenic potential are inconclusive.

1.3.3.2 Hexachlorocyclohexanes (HCH)

Chemical Name: 1,2,3,4,5,6-Hexachlorocyclohexane (mixed isomers) (C6H6Cl6). CAS Number: 608-73-1

(-HCH, lindane: 58-89-9).

Properties: -HCH: sol. in water: 7 mg/L at 20°C; vapour pressure: 3.3 x 10-5 mm Hg at 20°C; log KOW: 3.8.

Discovery/Uses: There are two principle formulations: "technical HCH", which is a mixture of various

isomers, including -HCH (55-80%), -HCH (5-14%) and -HCH (8-15%), and "lindane", which is

essentially pure -HCH. Historically, lindane was one of the most widely used insecticides in the world. Its

insecticidal properties were discovered in the early 1940s. It controls a wide range of sucking and chewing

insects and has been used for seed treatment and soil application, in household biocidal products, and as

textile and wood preservatives.

Persistence/Fate: Lindane and other HCH isomers are relatively persistent in soils and water, with half lives

generally greater than 1 and 2 years, respectively. HCH are much less bioaccumulative than other

organochlorines because of their relatively low liphophilicity. On the contrary, their relatively high vapor

pressures, particularly of the -HCH isomer, determine their long-range transport in the atmosphere.

Toxicity: Lindane is moderately toxic for invertebrates and fish, with LC50 values of 20-90 µg/L. The acute

toxicity for mice and rats is moderate with LD50 values in the range of 60-250 mg/kg. Lindane resulted to have

no mutagenic potential in a number of studies but an endocrine disrupting activity.

1.3.3.3 Endosulfan

Chemical Name: 6,7,8,9,10,10-Hexachloro-1,5,5a,6,9,9a-hexahydro-6,9-methano-2,4,3-benzodioxathiepin-3-

oxide (C9H6Cl6O3S). CAS Number: 115-29-7.

Properties: Solubility in water: 320 µg/L at 25°C; vapour pressure: 0.17 x 10-4 mm Hg at 25°C; log KOW:

2.23-3.62.

Discovery/Uses: Endosulfan was first introduced in 1954. It is used as a contact and stomach insecticide and

acaricide in a great number of food and non-food crops (e.g. tea, vegetables, fruits, tobacco, cotton) and it

controls over 100 different insect pests. Endosulfan formulations are used in commercial agriculture and home

gardening and for wood preservation. The technical product contains at least 94% of two pure isomers, - and

-endosulfan.

Persistence/Fate: It is moderately persistent in the soil environment with a reported average field half-life of

50 days. The two isomers have different degradation times in soil (half-lives of 35 and 150 days for - and -

isomers, respectively, in neutral conditions). It has a moderate capacity to adsorb to soils and it is not likely to

8

leach to groundwater. In plants, endosulfan is rapidly broken down to the corresponding sulfate, on most fruits

and vegetables, 50% of the parent residue is lost within 3 to 7 days.

Toxicity: Endosulfan is highly to moderately toxic to bird species (Mallards: oral LD50 31 - 243 mg/kg) and it

is very toxic to aquatic organisms (96-hour LC50 rainbow trout 1.5 µg/L). It has also shown high toxicity in

rats (oral LD50: 18 - 160 mg/kg, and dermal: 78 - 359 mg/kg). Female rats appear to be 45 times more

sensitive to the lethal effects of technical-grade endosulfan than male rats. The -isomer is considered to be

more toxic than the -isomer. There is a strong evidence of its potential for endocrine disruption.

1.3.3.4 Pentachlorophenol (PCP)

Chemical Name: Pentachlorophenol (C6Cl5OH). CAS Number: 87-86-5.

Properties: Solubility in water: 14 mg/L at 20°C; vapour pressure: 16 x 10-5 mm Hg at 20°C; log KOW: 3.32

5.86.

Discovery/Uses: It is used as insecticide (termiticide), fungicide, non-selective contact herbicide (defoliant)

and, particularly as wood preservative. It is also used in anti-fouling paints and other materials (e.g. textiles,

inks, paints, disinfectants and cleaners) as inhibitor of fermentation. Technical PCP contains trace amounts of

PCDDs and PCDFs

Persistence/Fate: The rate of photodecomposition increases with pH (t1/2 100 hr at pH 3.3 and 3.5 hr at pH

7.3). Complete decomposition in soil suspensions takes >72 days, other authors reports half-life in soils of 23-

178 days. Although enriched through the food chain, it is rapidly eliminated after discontinuing the exposure

(t

1/2 = 10-24 h for fish).

Toxicity: It has been proved to be acutely toxic to aquatic organisms and have certain effects on human

health, at the time that exhibits off-flavour effects at very low concentrations. The 24-h LC50 values for trout

were reported as 0.2 mg/L, and chronic toxicity effects were observed at concentrations down to 3.2 µg/L.

Mammalian acute toxicity of PCP is moderate-high. LD50 oral in rat ranging from 50 to 210 mg/kg bw have

been reported. LC50 ranged from 0.093 mg/L in rainbow trout (48 h) to 0.77-0.97 mg/L for guppy (96 h) and

0.47 mg/L for fathead minnow (48 h).

1.3.3.5 Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs)

Chemical Name: PAHs is a group of compounds consisting of two or more fused aromatic rings. CAS

Number:Various