United Nations

Environment Programme

Chemicals

South East

South East Asia and

Asia and South P

South Pacific

REGIONAL REPORT

Regionally

acific

Based

RBA PTS REGIONAL REPOR

Assessment

of

Persistent

T

Available from:

UNEP Chemicals

11-13, chemin des Anémones

CH-1219 Châtelaine, GE

Switzerland

Phone : +41 22 917 1234

Fax : +41 22 797 3460

Substances

E-mail: chemicals@unep.ch

December 2002

http://www.chem.unep.ch

UNEP Chemicals is a part of UNEP's Technology, Industry and

Printed at United Nations, Geneva

Economics Division

GE.03-00157January 2003500

UNEP/CHEMICALS/2003/8

G l o b a l E n v i r o n m e n t F a c i l i t y

UNITED NATIONS

ENVIRONMENT

PROGRAMME

CHEMICALS

Regional y Based Assessment

of Persistent Toxic Substances

Australia, Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao People's

Republic, Myanmar, Malaysia, New Zealand, Papua New

Guinea, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam

SOUTH EAST ASIA AND

SOUTH PACIFIC

REGIONAL REPORT

DECEMBER 2002

GLOBAL ENVIRONMENT FACILITY

This report was financed by the Global Environment Facility (GEF) through a global project with co-

financing from the Governments of Australia, France, Sweden, Switzerland and the United States of

America.

This publication is produced within the framework of the Inter-Organization Programme for the Sound

Management of Chemicals (IOMC).

This publication is intended to serve as a guide. While the information provided is believed to be

accurate, UNEP disclaim any responsibility for the possible inaccuracies or omissions and

consequences, which may flow from them. UNEP nor any individual involved in the preparation of

this report shall be liable for any injury, loss, damage or prejudice of any kind that may be caused by

any persons who have acted based on their understanding of the information contained in this

publication.

The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this report do not imply the

expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations of UNEP

concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning

the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.

The Inter-Organization Programme for the Sound Management of Chemicals (IOMC), was

established in 1995 by UNEP, ILO, FAO, WHO, UNIDO and OECD (Participating

Organizations), following recommendations made by the 1992 UN Conference on

Environment and Development to strengthen cooperation and increase coordination in the

field of chemical safety. In January 1998, UNITAR formally joined the IOMC as a Participating

Organization. The purpose of the IOMC is to promote coordination of the policies and

activities pursued by the Participating Organizations, jointly or separately, to achieve the

sound management of chemicals in relation to human health and the environment.

Material in this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted but acknowledgement is requested

together with a reference to the document. A copy of the publication containing the quotation or

reprint should be sent to UNEP Chemicals.

UNEP

CHEMICALS

Available from:

UNEP Chemicals11-13, chemin des Anémones

CH-1219 Châtelaine, GE

Switzerland

Phone: +41 22 917 1234

Fax:

+41 22 797 3460

E-mail: chemicals@unep.ch

http://www.chem.unep.ch

UNEP Chemicals is a part of UNEP's Technology, Industry and Economics Division

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PREFACE............................................................................................... V

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................... VI

1. INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................1

1.2. OTHER PTS ASSESSMENT PROJECTS IN THE REGION .....................................3

1.2.1. Existing Regional Assessments ....................................................................................................... 3

1.2.2. Inter-Regional Links and Collaboration......................................................................................... 3

1.2.3. National Programmes for PTS........................................................................................................ 4

1.3. GENERAL DEFINITIONS OF CHEMICALS..........................................................5

1.3.1. Pesticides ........................................................................................................................................ 5

1.3.2. Industrial Compounds..................................................................................................................... 9

1.3.3. Unintended By-products ................................................................................................................. 9

1.3.4. Regional Specific Chemicals......................................................................................................... 10

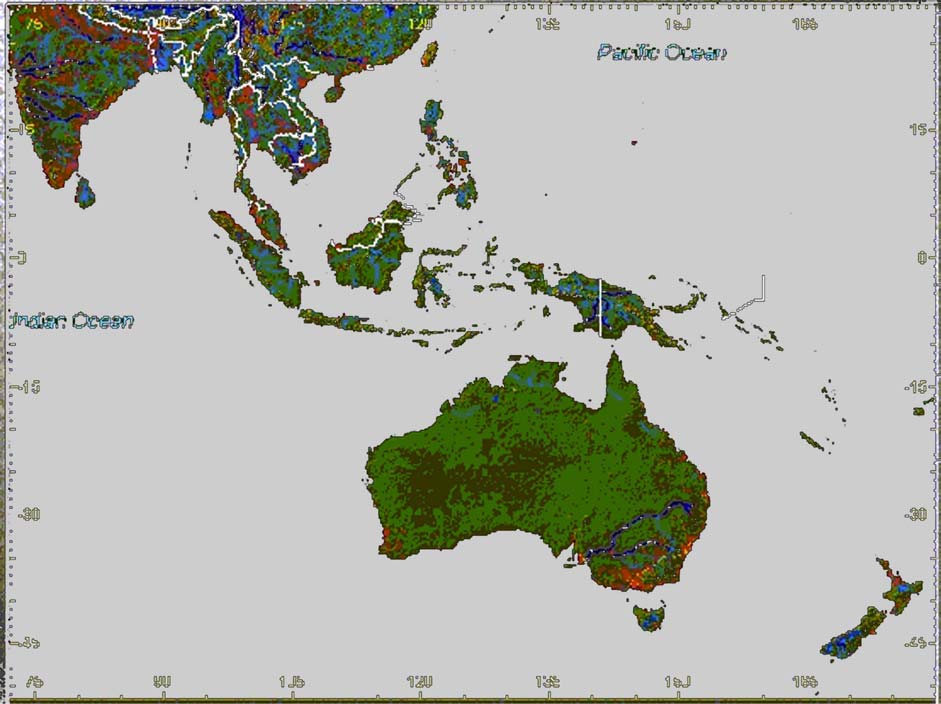

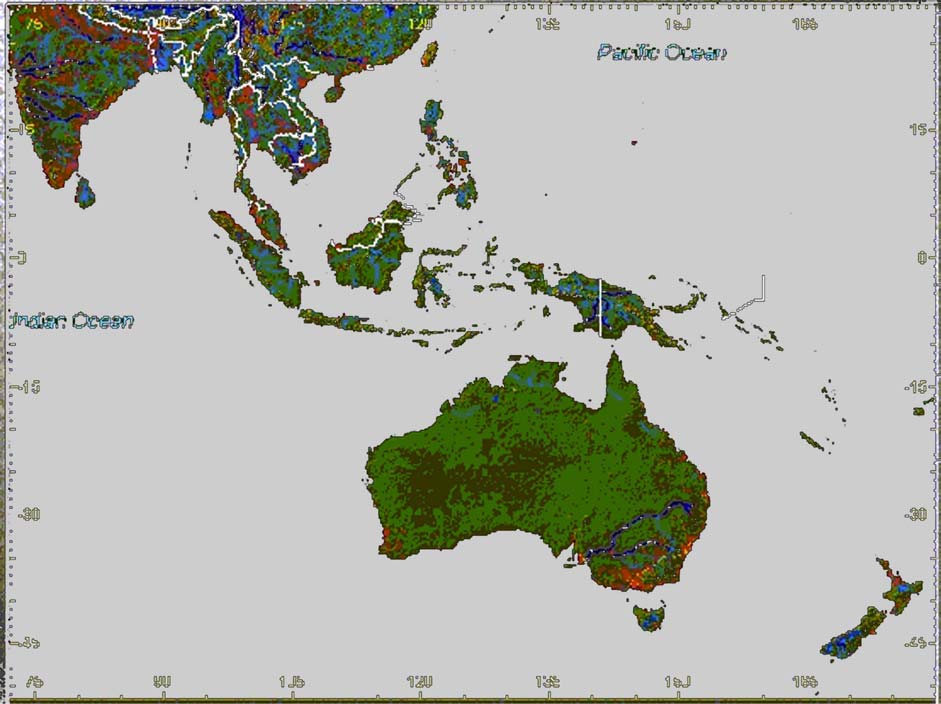

1.4. DEFINITION OF THE SOUTHEAST ASIA AND SOUTH PACIFIC REGIONS ..........16

1.5. PHYSICAL SETTING.......................................................................................17

1.5.1. Physical/Geographical Description.............................................................................................. 17

1.5.2. Climate and Meteorology ............................................................................................................. 18

1.5.3. Region's Freshwater Environments.............................................................................................. 19

1.5.4. Marine Environment..................................................................................................................... 20

1.5.5. Ecological Characteristics of the Region ..................................................................................... 21

1.6. PATTERNS OF DEVELOPMENT/SETTLEMENT .................................................22

1.7. REFERENCES.................................................................................................23

2. SOURCE CHARACTERISATION ...................................................25

2.1. BACKGROUND INFORMATION .......................................................................25

2.2. DATA COLLECTION ......................................................................................29

2.3. PESTICIDES ...................................................................................................29

2.3.1. Aldrin ............................................................................................................................................ 29

2.3.2. Chlordane ..................................................................................................................................... 29

2.3.3. Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT)...................................................................................... 29

2.3.4. Dieldrin......................................................................................................................................... 30

2.3.5. Endrin ........................................................................................................................................... 30

2.3.6. Endosulfan .................................................................................................................................... 31

2.3.7. Heptachlor .................................................................................................................................... 31

2.3.8. Hexachlorobenzene....................................................................................................................... 31

2.3.9. Mirex............................................................................................................................................. 31

i

2.3.10.

Pentachlorophenol (PCP)........................................................................................................ 32

2.3.11.

Toxaphene................................................................................................................................ 32

2.3.12.

Hexachlorohexanes.................................................................................................................. 32

2.4. INDUSTRIAL CHEMICALS ..............................................................................33

2.4.1. Hexachlorobenzene (HCB) ........................................................................................................... 33

2.4.2. Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs) ............................................................................................... 34

2.5. UNINTENDED BY-PRODUCTS.........................................................................35

2.5.1. Dioxins and Furans (PCDDs/PCDFs) ......................................................................................... 35

2.5.2. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) ................................................................................. 38

2.6. OTHER PTS OF EMERGING CONCERN IN REGION ...........................................38

2.6.1. Organotin Compounds.................................................................................................................. 38

2.6.2. Organomercury Compounds......................................................................................................... 39

2.6.3. Organolead Compounds ............................................................................................................... 39

2.6.4. Chlor. Paraffins, Nonyl/Octyl-Phenols, Phthalates, PBBs and PBDEs ....................................... 40

2.7. HOT SPOTS ...................................................................................................40

2.8. DATA GAPS ..................................................................................................40

2.9. SUMMARY ....................................................................................................41

2.10.REFERENCES ................................................................................................41

3. ENVIRONMENTAL LEVELS, TOXICOLOGICAL AND

ECOTOXICOLOGICAL PATTERNS. ....................................................45

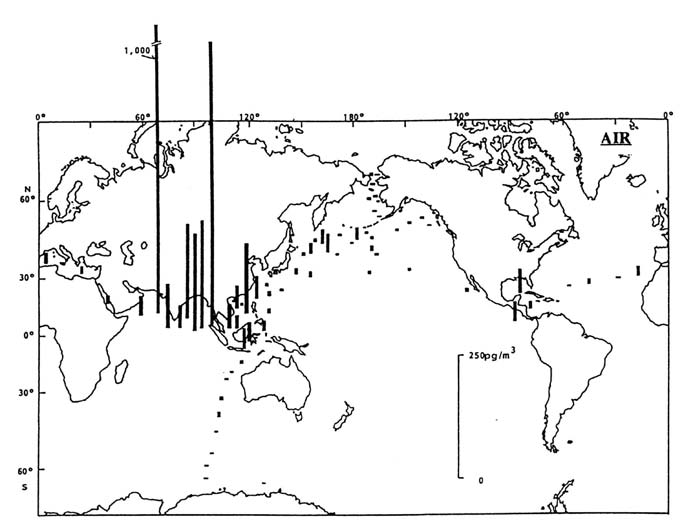

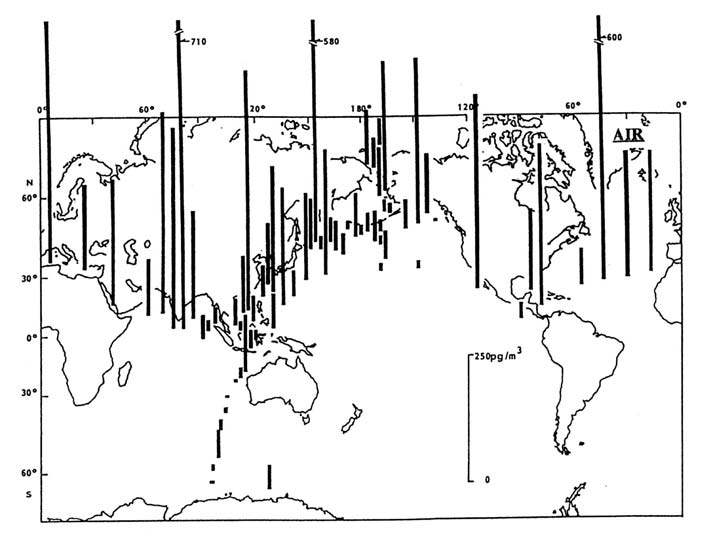

3.1. ENVIRONMENTAL LEVELS ............................................................................45

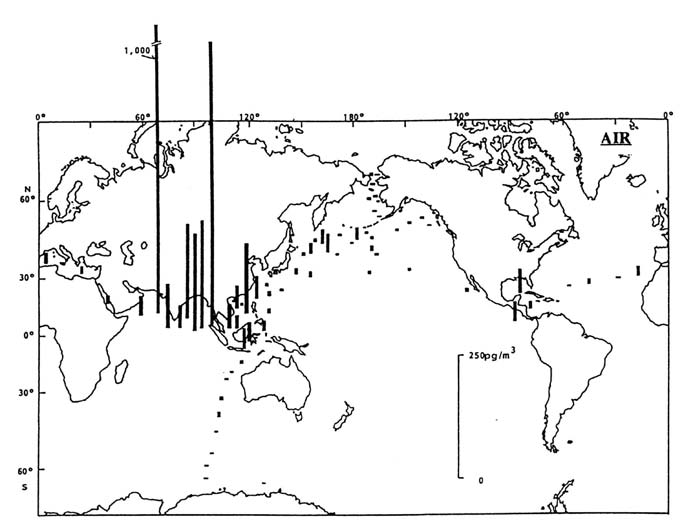

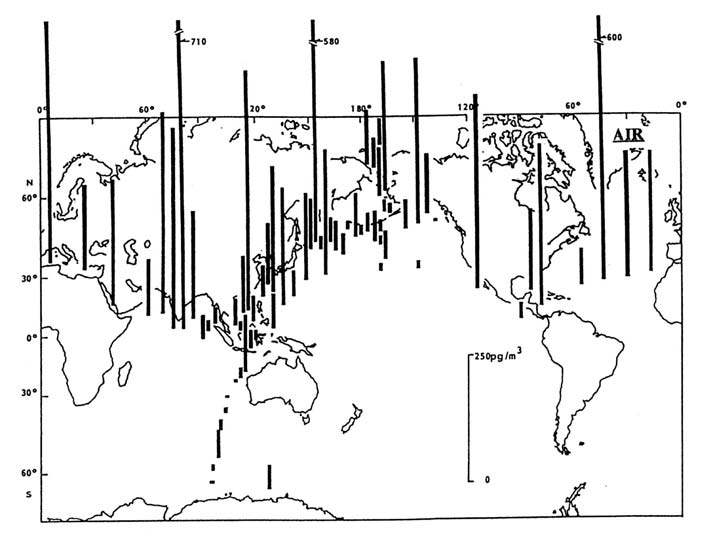

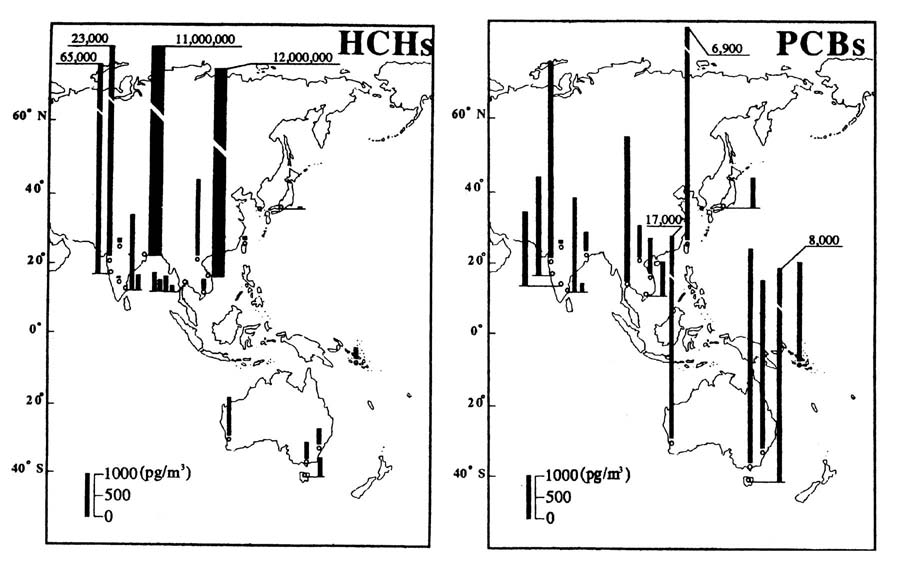

3.1.1. Environmental Media: Air ............................................................................................................ 45

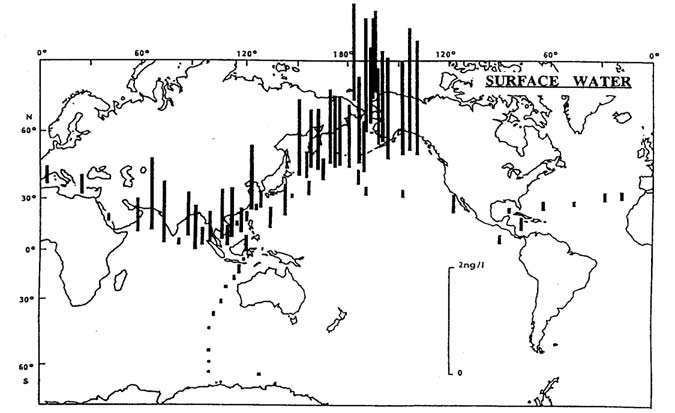

3.1.2. Environmental Media: Water ....................................................................................................... 48

3.1.3. Environmental Media: Sediment................................................................................................... 52

3.1.4. Environmental Media: Soil........................................................................................................... 53

3.1.5. Environmental Media: Animals .................................................................................................... 54

3.1.6. Environmental Media: Humans.................................................................................................... 56

3.1.7. Environmental Media: Vegetation................................................................................................ 59

3.1.8. Data Gaps..................................................................................................................................... 61

3.1.9. Conclusions................................................................................................................................... 61

3.2. SPATIAL AND TEMPORAL TRENDS ...............................................................62

3.3. TOXICOLOGY OF PTS OF REGIONAL CONCERN ...........................................64

3.3.1. Overview of Harmful Effects......................................................................................................... 64

3.3.2. National and Regional Human Health Reports ............................................................................ 65

3.3.3. Health Risk Assessment ................................................................................................................ 69

3.3.4. Risk Characterisation ................................................................................................................... 72

3.3.5. Data Gaps..................................................................................................................................... 72

3.3.6. Conclusions................................................................................................................................... 73

ii

3.4. ECOTOXICOLOGY OF PTS OF REGIONAL CONCERN.....................................74

3.4.1. Overview of Harmful Effects......................................................................................................... 74

3.4.2. Ecological Databases and Laboratory and Field Studies ............................................................ 74

3.4.3. Observed lethal effects in the environment ................................................................................... 79

3.4.4. Field Studies on Ecosystems ......................................................................................................... 81

3.4.5. Ecological Risk Assessment Studies.............................................................................................. 82

3.4.6. Data Gaps..................................................................................................................................... 84

3.4.7. Conclusions................................................................................................................................... 85

3.5. SUMMARY ....................................................................................................85

3.6. REFERENCES.................................................................................................87

4. ASSESSMENT OF MAJOR PATHWAYS OF CONTAMINANT

TRANSPORT.........................................................................................93

4.1. INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................93

4.2. REGIONALLY SPECIFIC FEATURES .................................................................93

4.2.1. Observations on the Properties of the PTS................................................................................... 93

4.2.2. Interhemispheric Mixing of PTS ................................................................................................... 94

4.3. OVERVIEW OF EXISTING MODELLING PROGRAMS AND PROJECTS ..................95

4.4. TRANSPORT PATTERNS OF PTS IN THE REGION............................................96

4.5. MODELLING THE TRANSPORT OF PTS IN THE REGION..................................97

4.5.1. The Study Area.............................................................................................................................. 97

4.5.2. Fugacity Modelling....................................................................................................................... 98

4.5.3. Application of the Modelling Outcomes to Evaluation of Transport .......................................... 101

4.5.4. Interpretation of the Modelling Outcomes.................................................................................. 103

4.6. DATA GAPS ................................................................................................105

4.7. SUMMARY ..................................................................................................105

4.8. REFERENCES...............................................................................................106

5. PRELIMINARY ASSESSMENT OF THE REGIONAL CAPACITY

AND NEEDS ........................................................................................108

5.1. INTRODUCTION...........................................................................................108

5.2. MONITORING CAPACITY.............................................................................108

5.2.1. PTS.............................................................................................................................................. 108

5.2.2. Organometals ............................................................................................................................. 108

5.2.3. Dioxin Analysis........................................................................................................................... 108

5.2.4. Human Health............................................................................................................................. 109

5.3. EXISTING REGULATION AND MANAGEMENT STRUCTURES.........................109

5.3.1. National ...................................................................................................................................... 109

5.3.2. Regional Initiatives..................................................................................................................... 109

iii

5.3.3. International ............................................................................................................................... 110

5.4. STATUS OF ENFORCEMENT .........................................................................113

5.5. ALTERNATIVES OR MEASURES FOR REDUCTION.........................................115

5.5.1. ASEAN ........................................................................................................................................ 115

5.5.2. Australia ..................................................................................................................................... 116

5.5.3. New Zealand ............................................................................................................................... 116

5.6. TECHNOLOGY TRANSFER ...........................................................................117

5.6.1. Integrated Pest Management ...................................................................................................... 117

5.6.2. Cleaner Production..................................................................................................................... 117

5.7. SUMMARY ..................................................................................................117

5.8. REFERENCES...............................................................................................118

6. FINAL RESULTS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ...........................119

6.1. MAIN RESULTS...........................................................................................119

6.1.1. Sources........................................................................................................................................ 119

6.1.2. Levels/Effects .............................................................................................................................. 120

6.1.3. Pathways and Transport............................................................................................................. 122

6.1.4. Regional Capacity ...................................................................................................................... 122

6.1.5. Regional Prioritisation of Chemicals ......................................................................................... 123

6.2. RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FUTURE ACTIVITIES...........................................124

6.2.1. Capacity Building and Assessment ............................................................................................. 125

6.2.2. Information Management ........................................................................................................... 125

6.2.3. Capacity Building, Implementation and Monitoring .................................................................. 125

iv

PREFACE

In 2000, The United Nations Environmental Program asked The Marine Environment and Resources

Foundation Inc. (MERF) to participate in a global assessment of PTS, and in particular, to produce a

report on PTS for the Southeast Asia and South Pacific Region. This document is intended to meet

that request. This report is one of twelve, which make up the global assessment.

The members of the Regional Team approved by UNEP and subsequently commissioned by MERF to

produce the report were chosen on the basis of the following criteria:

Each member should have extensive technical and scientific experience on PTS related subjects;

Each member should be recognized and respected in their country and in the sub-region as

competent in the PTS field;

The members should come from differing countries to represent a cross-section of the region;

Members should be selected to ensure that competence resides to undertake the writing of the

various chapters of the regional report;

Each member should be accessible by email and have internet access;

Each member should have administrative and technical support of a recognizerecognised

institution; and,

Each member should be fluent in English.

The Team Members thus chosen, were as follows:

Regional Coordinator

Dr. Gil S. Jacinto, Director, Marine Science Institute, University of the Philippines, Diliman, Quezon

City, Philippines

Team Members

Dr. Des W. Connell, Professor, School of Public Health, Griffith University, Nathan, Queensland,

Australia;

Dr. Md. Sani Ibrahim, Associate Professor, School of Chemical Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia,

Pulau Pinang, Malaysia; and,

Mr. Lim Kew Leong, Chief Engineer/Inspectorate, Pollution Control Department, Ministry of the

Environment, Singapore.

Acknowledgements

As in many complex writing endeavours, this report is the product of many persons whose names do

not appear in the cover. Also, this work would not have been possible without the assistance and

support of the institutions where the team members are affiliated, and the help from members of the

Regional Network who provided information on PTS chemicals within the region. The invaluable

contributions from the participants at the two Regional Technical Workshops and the Regional

Priority Setting Meeting are also gratefully acknowledged. Dr. Pythias Espino of the Institute of

Chemistry, University of the Philippines Diliman, provided valuable support in uploading and

validating PTS data into the project's web site.

The Global Environment Facility through UNEP Chemicals provided funds for the project.

v

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Following the recommendations of the Intergovernmental Forum on Chemical Safety, the UNEP

Governing Council decided in February 1997 (Decision 19/13 C) that immediate international action

should be initiated to protect human health and the environment through measures which will reduce

and/or eliminate the emissions and discharges of an initial set of twelve persistent organic pollutants

(POPs). However, in addition to the twelve substances identified and adopted under the Stockholm

Convention of 2001, there are many other persistent toxic substances (PTS) that are of concern and

satisfy the criteria for POPs. The sources, environmental concentrations and effects of these POPs are

to be assessed.

The objective of this project was to deliver a measure of the nature and degree of damage or threat

posed by PTS at national, regional and ultimately, global levels. Findings of the project will provide

the Global Environment Facility (GEF) with a science-based rationale for assigning priorities for

action among and between chemical related environmental issues. It will also determine the extent to

which differences in priority exist among regions. The outcome of this project will be a scientific

assessment of the threats posed by PTS to the environment and human health.

To achieve these results, the globe was divided into 12 regions namely: Arctic, North America,

Europe, Mediterranean, Sub-Saharan Africa, Indian Ocean, Central and North East Asia (Western

North Pacific), Southeast Asia and South Pacific, Pacific Islands, Central America and the Caribbean,

Eastern and Western South America, Antarctica. The twelve regions were selected based on obtaining

geographical consistency while trying to take into account the financial constraints of the project.

Region 8 (Southeast Asia and South Pacific) includes: Australia, Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia,

Indonesia, Lao Peoples' Democratic Republic, Malaysia, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea,

Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Viet Nam.

This report describes the assessment of PTS in Region 8. It focuses on the sources of PTS in the

environment, their concentration levels and impact on biota, their transboundary transport, and

examines the root causes of the problems. As an outcome, the capacity of the region to manage these

problems has been evaluated.

The project has relied upon the collection and interpretation of existing data and information as the

basis for the assessment. No research was undertaken to generate primary data, but projections were

made to fill data/information gaps, and to predict threats to the environment.

Sources of PTS

Information on the importation, use and emissions of PTS is limited in the region. Much of the

attention has been on regulatory measures to phase out or to ban the use of PTS pesticides. Except for

DDT, endosulfan, mirex and lindane, many of the pesticides have been banned or have not been used

for the last 10 years.

Emissions of PCDD/PCDFs and PAHs are widespread but have largely not been quantified. Major

sources include forest and vegetation fires, open burning of wastes, releases from landfills and

industrial processes. PCDD/PCDFs emissions from industrial sources are very much dependent on the

technology in use while landfills, fires and open burning of domestic wastes are uncontrolled sources

in some countries in the region. Regular and widespread occurrences of forest and bush fires are also

major sources of PAHs and PCDD/PCDFs.

While the importation of PCBs has been banned in the region, many countries do not have or maintain

national inventories of PCB-contaminated equipment (e.g. transformers).

Knowledge on the sources of other PTS (e.g. chlorinated phenols and PBDEs) is generally lacking in

the region. This also includes organometallic compounds. Currently, leaded petrol and TBT in

antifouling paints are being phased out.

vi

Levels of PTS

The concentrations of most PTS in various environmental compartments (air, water, soil, sediments,

and biota) were obtained from various sources, mainly published literature reports, project

questionnaires and personal communications.

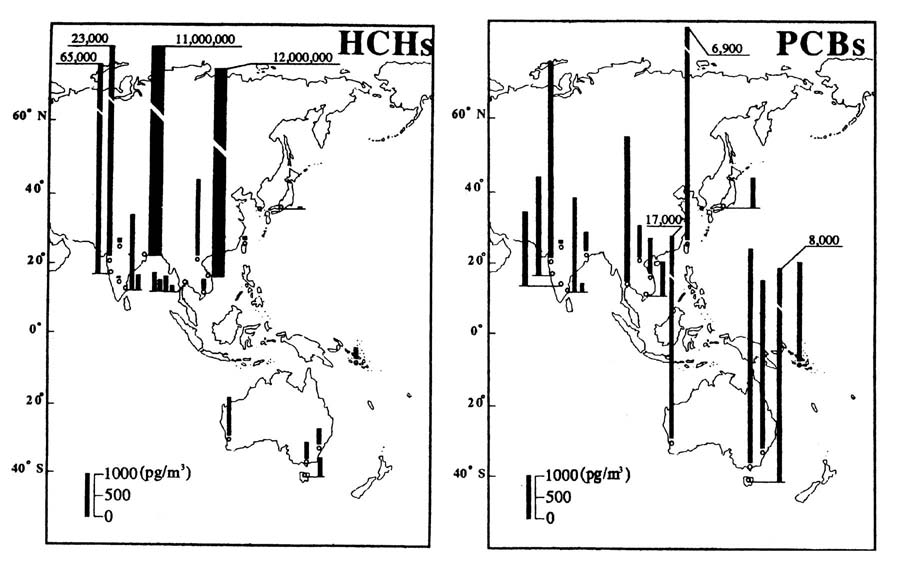

The levels of several PTS in air have been reported to be high in the Southeast Asian countries. In

particular, DDTs, chlordanes, HCHs, and PCBs were found to be relatively high in air above coastal

areas. High levels of DDTs and PCBs were found in soils throughout the region but some sites in

Australia and Viet Nam were reported to be the most contaminated. However, studies of temporal

trends revealed that the DDTs and several other chlorohydrocarbon pesticides are decreasing

exponentially. Endosulfan was found in most sediment in the region, particularly in Malaysia,

suggesting the recent use of this chemical because of its shorter persistence in the environment.

HCHs, particularly lindane, were found at high concentration levels in river waters in the region

particularly Malaysia and Thailand. Other OCPs were also found in relatively high levels but showed

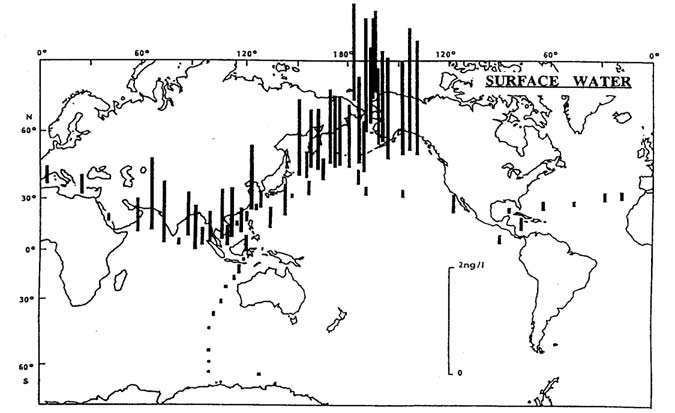

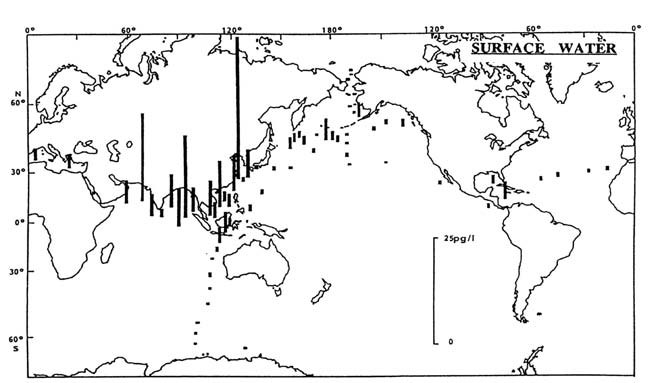

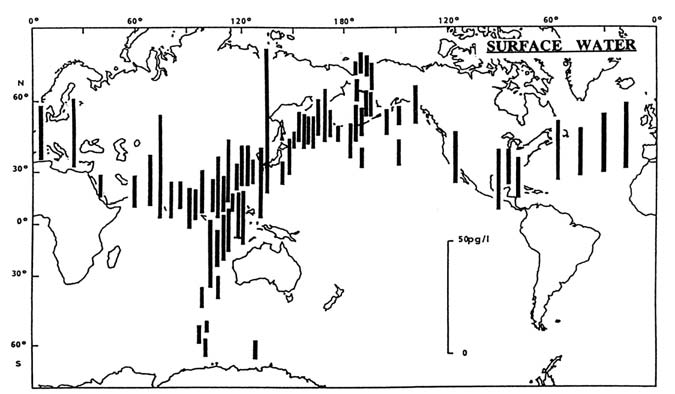

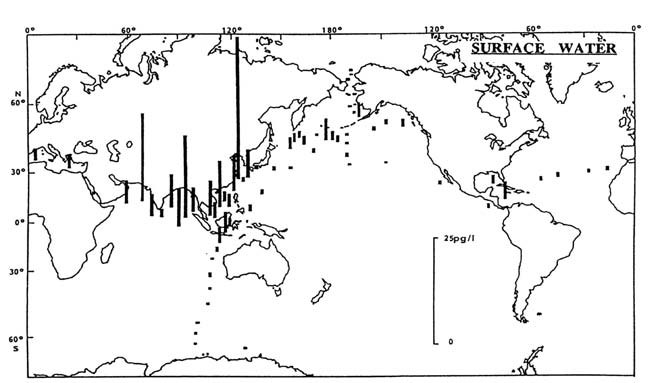

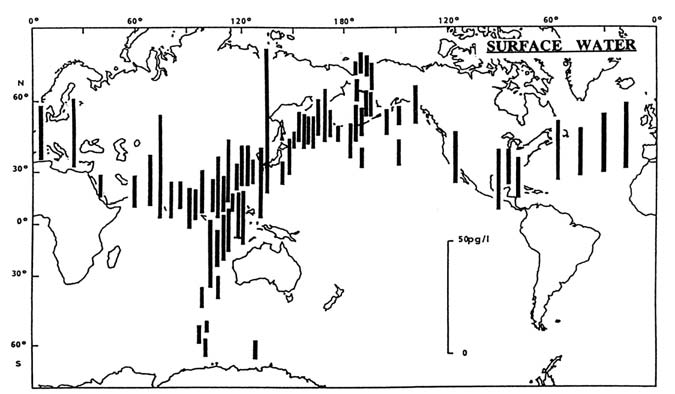

a decreasing trend with time. Surface seawater was also found to contain high levels of HCHs

particularly in seas around Southeast Asia.

The concentration levels of PTS in marine organisms, such as fishes and mussels, have been

extensively studied. The Mussel Watch program reported the widespread presence of a whole

spectrum of PTS in mussels collected from this region, although there were indications that the levels

of PTS such as DDTs, HCHs and PCBs were declining.

PTS levels in humans have not been widely determined although Australia, New Zealand, and

Singapore have undertaken population monitoring studies. New Zealanders have been found to have

very low levels of PTS in blood and breast milk and could provide baseline values to compare with

the region's human population. There is a definite lack of data on the human toxicological effects of

PTS, which are of considerable importance for countries in this region. Data on levels of PTS in food

and vegetables are available but not comprehensive. Most reports on PTS levels in food products

reveal the presence of significant numbers of PTS in most samples and varied concentration levels.

Ecotoxicology and Toxicology

PCDDs/PCDFs were regarded to be of major concern in terms of their potential threat to human

health and the ecosystem in general. Even though data on levels are scarce, estimates on release to the

environment due to industrial and non-industrial activities indicated a significant input to the system.

In view of widespread sources of unintentional releases coupled with high toxicity and accumulative

properties, PCDD/PCDFs are possibly the most important PTS to be evaluated in the future. A greater

effort should be focused on the reduction of unintentional releases of PCDD/PCDFs as well as

monitoring of concentration levels.

The available evidence indicates that DDT concentration levels are falling in the region. However,

DDT and related organochlorine pesticides may occur in significant concentrations and be implicated

in such adverse human health effects as breast cancer and reduced bone density in women. There is

also evidence that endosulfan has been widely used as a substitute for the banned pesticides. This

substance has been shown to have significant effects on human health and the natural environment in

this region.

A number of organochlorine compounds (DDTs, HCHs, chlordane and PCBs) occur in water and

sediments throughout the region in concentrations that exceed guideline values for natural

ecosystems. This would be expected to cause a reduction in the species diversity of natural aquatic

systems in the region and other adverse effects.

The region has urban sources as well as natural sources, such as forest fires, which produce PAHs and

particulates that will have adverse effects on human health.

Most countries in the region have phased out or are regulating the use of organochlorine pesticides,

PCBs and organometals or organometallic compounds. As a result, the concentrations of some PTS

are falling. However, a major regional health issue is concerned with the human health and adverse

ecotoxicological effects resulting from the ongoing presence of PCDD/PCDFs in the environment of

Viet Nam. This has resulted from the extensive use of 2,4,5-T herbicide, contaminated with

PCDD/PCDFs during the Viet Nam war, mainly during the period from 1965-1970.

vii

The analysis of major pathways and PTS transport into and out of the region suggests that the

Southeast Asian sub-region of the Southeast Asia South Pacific region can be considered as a separate

area in relation to transport of PTS due to the presence of ocean currents and atmospheric

convergence zones around the equator. There is no evidence to suggest that Australia and New

Zealand are sources of PTS that could be transported to other areas. On the other hand these countries

do not seem to receive PTS in significant amounts from elsewhere.

Fugacity modelling indicates that the relatively high concentrations of HCHs in air and water in parts

of the Southeast Asia region provide a reservoir for transport to other areas and that water movements

are more important than atmospheric movement for PTS transport. The results suggest that transport

out of the region would be to the north-east through the Kuroshio Current. The transport of PTS from

Southeast Asia towards the south is inhibited by the equatorial ocean and atmospheric convergence

located approximately on the equator.

While there are relatively large potential sources of DDT and PCBs in the region, fugacity modelling

suggests that transport out of the region is not occurring on a significant scale. This analysis is based

on results obtained in the period 1989 to 1991. The situation may have changed during the period up

to the present time.

Capacity, Priorities and Needs

The assessments made in this report have been characterised by the limited amount of information

available or accessible regarding sources, inventories, ecotoxicology, toxicology, and transport of

PTS. Many developing countries in the region lack regulatory infrastructure (including national PTS

registration and control schemes), appropriate legislation and regulations, enforcement mechanisms,

and laboratory infrastructure for quality control and analysis of residual PTS. In addition, financial

constraints make it difficult for countries to implement regulations and mechanisms that may already

be in place. In contrast, Australia, New Zealand, and Singapore do not appear to be faced with such

issues. Australia and New Zealand lead the countries in the region in monitoring, and minimising the

use of or replacing the use of PTS. This includes the National Dioxins Program (Australia) and the

Organochlorines Program in New Zealand. There is scope to transfer technology and experiences

from these countries to the rest of the region.

A major output of the two regional workshops conducted in the course of this study was the

prioritisation of a list of 25 persistent toxic substances for sources, environmental levels,

ecotoxicological effects, human health effects, and data gaps. DDT and PCDD/PCDFs were

considered to be of regional concern with respect to environmental levels, sources, ecotoxicological

and health effects. Endosulfan is also of regional concern because of its continued use in many

countries to replace organochlorine pesticides, and because of its known ecotoxicological effects. In

many parts of the region, forest and vegetation fires are major sources of PAHs. While the short-term

health risks from PAH exposure appear to be low, long-term exposure to PAHs may increase these

risks especially if combined with urban emissions.

Based on the information gathered by the regional team, and the consultations made with various

institutions and participants at the two regional workshops and the priority setting meeting under this

project, a number of needs for the region have been identified and recommendations made. These fall

under two main categories capacity building and information management.

Under capacity building, a major need is to improve analytical facilities and methods for the

determination of PTS, giving emphasis to compounds that are of the greatest cause of concern in the

region. Associated with this, there is a need to develop a set of regional environmental quality

guidelines to evaluate the significance of PTS levels in air, soil, waste, sediment, food and drinking

water. These should relate environmental levels to the occurrence of significant adverse effects on

human health and the natural environment. This could be part of an expanded set of environmental

guidelines already initiated by ASEAN for the region.

Efforts should also be made by countries in the region to develop the software and hardware required

for proper waste management, treatment, minimisation, and disposal facilities for PTS. It would be

advantageous to use the tried and tested multilateral arrangement mechanisms in the region (e.g.

ASEAN-Australia) to bring about projects/activities to support these needs.

viii

The effort of UNEP to use the "toolkit" for PCDD/PCDFs could be expanded to include other

countries in the region in addition to those where the method has been piloted (e.g. Brunei

Darussalam, the Philippines, and Thailand). The procedure could also be developed further to take

into account other priority PTS in the region.

Information management needs to include public information programs, improved handling and

exchange of data, and also information on PTS. Policy makers in governments and developing

countries need accessible information on strategies for improving capacity to regulate and implement

best practices regarding PTS. If continued, the current effort to have a worldwide database on PTS

sources, environmental levels, and national capacity, will benefit from the development of compatible

national databases on PTS.

ix

1. INTRODUCTION

Most chemicals find their way into the environment via various products and processes. Once in the

environment, they can persist for long periods of time or break down into other chemicals with their

own risk (EEA, 1998). They may also produce health or environmental effects when they act together

with other natural or manufactured chemicals that are already in the environment.

Effective risk management for chemicals depends on tracking the pathways, fate and exposure

implications of chemicals. Yet, data identifying the pathways, emissions, environmental fate and

exposure as a base for risk assessment are available for very few chemicals.

Special attention has been given to the persistent toxic organic substances, which are widely found in

the environment. These substances can travel through air, water and living organisms, be released into

the environment in one part of the world, and, through a repeated process of release and deposit, be

transported to regions far away from their original source (UNEP, 2000; EEA, 1998; UN ECE, 1998).

They can become increasingly concentrated in the tissues of animals at higher levels of the food

chain, such as predatory birds and mammals, including humans.

The result is that humans and wildlife are exposed in some cases to very complex mixtures of

chemicals and, in many cases, we have only limited information concerning the harmful effects of

these mixtures at environmental levels of exposure.

1.1. Overview of the RBA PTS Project

Following the recommendations of the Intergovernmental Forum on Chemical Safety, the UNEP

Governing Council decided in February 1997 (Decision 19/13 C) that immediate international action

should be initiated to protect human health and the environment through measures which will reduce

and/or eliminate the emissions and discharges of an initial set of twelve persistent organic pollutants

(POPs). Accordingly, an Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC) was established with a

mandate to prepare an international legally binding instrument for implementing international action

on certain persistent organic pollutants.

These series of negotiations have resulted in the adoption of the Stockholm Convention in 2001. The

initial 12 substances fitting these categories that have been selected under the Stockholm Convention

include: aldrin, endrin, dieldrin, chlordane, DDT, toxaphene, mirex, heptachlor, hexachlorobenzene,

PCBs, PCDD and PCDFs. Besides these 12, there are many other substances that satisfy the criteria

listed above for which their sources, environmental concentrations and effects are to be assessed.

Persistent toxic substances can be manufactured substances for use in various sectors of industry,

pesticides, or by-products of industrial processes and combustion. To date, their scientific assessment

has largely concentrated on specific local and/or regional environmental and health effects, in

particular "hot spots" such as the Great Lakes region of North America or the Baltic Sea.

There is a need for a scientifically-based assessment of the nature and scale of the threats to the

environment and its resources posed by persistent toxic substances that will provide guidance to the

international community concerning the priorities for future remedial and preventive action. The

assessment will lead to the identification of priorities for intervention, and through application of a

root cause analysis will attempt to identify appropriate measures to control, reduce or eliminate

releases of PTS, at national, regional or global levels.

The objective of the project is to deliver a measure of the nature and comparative severity of damage

and threats posed at national, regional and ultimately at global levels by PTS. This will provide the

GEF with a science-based rationale for assigning priorities for action among and between chemical

related environmental issues, and to determine the extent to which differences in priority exist among

regions.

1.1.1.1. Project Activities and Expected Results

The project relies upon the collection and interpretation of existing data and information as the basis

for the assessment. No research will be undertaken to generate primary data, but projections will be

1

made to fill data/information gaps, and to predict threats to the environment. The proposed activities

are designed to obtain the following expected results:

1. Identification of major sources of PTS at the regional level;

2. Impact of PTS on the environment and human health;

3. Assessment of transboundary transport of PTS;

4. Assessment of the root causes of PTS related problems, and regional capacity to manage these

problems;

5. Identification of regional priority PTS related environmental issues; and,

6. Identification of PTS related priority environmental issues at the global level.

The outcome of this project will be a scientific assessment of the threats posed by persistent toxic

substances to the environment and human health. The activities to be undertaken in this project

comprise an evaluation of the sources of persistent toxic substances, their levels in the environment

and consequent impact on biota and humans, their modes of transport over a range of distances, the

existing alternatives to their use and remediation options, as well as the barriers that prevent their

good management.

1.1.1.2. Regional Divisions

To achieve these results, the globe is divided into 12 regions namely: Arctic, North America, Europe,

Mediterranean, Sub-Saharan Africa, Indian Ocean, Central and North East Asia (Western North

Pacific), Southeast Asia and South Pacific, Pacific Islands, Central America and the Caribbean,

Eastern and Western South America, and Antarctica. The twelve regions were selected based on

obtaining geographical consistency while trying to reside within financial constraints.

Region 8 (Southeast Asia and South Pacific) includes: Australia, Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia,

Indonesia, Lao Peoples' Democratic Republic, Malaysia, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea,

Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Viet Nam.

1.1.1.3. Management Structure

The project manager who is based at UNEP Chemicals in Geneva, Switzerland directs the project. A

Steering Group comprising representatives of other relevant intergovernmental organisations along

with participation from industry and the non-governmental community is established to monitor the

progress of the project and provide direction for the project manager. A regional co-ordinator, assisted

by a team of approximately 4 persons, heads each region. The co-ordinator and the regional team are

responsible for promoting the project, the collection of data at the national level and carrying out a

series of technical and priority setting workshops for analysing the data on PTS on a regional basis.

Besides the 12 POPs from the Stockholm Convention, the regional team selects the chemicals to be

assessed for its region with selection open for review during the various workshops undertaken

throughout the assessment process. Each team writes the regional report for the respective region.

1.1.1.4. Data Processing

Data is collected on sources, environmental concentrations, human and ecological effects through

questionnaires that are filled in at the national level. The results from this data collection, along with

presentations from regional experts at the technical workshops, are used to develop regional reports

on the PTS selected for analysis. A priority setting workshop with participation from representatives

from each country results in priorities being established regarding the threats and damages of these

substances to each region. The information and conclusions derived from the 12 regional reports will

be used to develop a global report on the state of these PTS in the environment.

The project is not intended to generate new information but to rely on existing data and their

assessment to arrive at priorities for these substances. The establishment of a broad and wide-ranging

network of participants involving all sectors of society was used for data collection and subsequent

evaluation. Close co-operation with other intergovernmental organisations such as UNECE, WHO,

FAO, UNPD, World Bank and others was obtained. Most have representatives on the Steering Group

Committee who monitor the progress of the project and critically review its implementation.

2

Contributions were garnered from UNEP focal points, national focal points selected by the regional

teams, industry, government agencies, research scientists and NGOs.

1.1.1.5. Project Funding

The project costs approximately US$4.2 million funded mainly by the Global Environment Facility

(GEF) with sponsorship from countries including Australia, France, Germany, Sweden, Switzerland

and the USA. The project runs from September 2000 to April 2003 with the intention that the reports

are presented to the first meeting of the Conference of the Parties of the Stockholm Convention

projected for 2003/4.

1.2. Other PTS Assessment Projects In The Region

Assessment projects/initiatives related to PTS have been going on in the region and some of these are

described below:

1.2.1. Existing Regional Assessments

1.2.1.1. Development of Environment Statistics in ESCAP Region

The broad aim of the project is to improve national capabilities of developing countries in the region

for identifying, collecting, processing, analysing and utilising the data needed for formulating policies

and programs for environment and sustainable development, as well as for monitoring and evaluating

the progress made. The basic objectives of the project are to adopt a set of training materials on

environment statistics and to provide the concerned officials with the available basic standard

international methodological issues of environmental statistics through sub-regional training

workshops (environmental statistics, and environmental and resource accounting) for East and

Southeast Asia, South Asia, the Pacific islands and Central Asia during the years 2000-2001.

1.2.1.2. Global Environment Monitoring System (GEMS) Freshwater Quality Program

The GEMS/Water program is a multi-faceted water science program oriented towards understanding

freshwater quality issues throughout the world. Major activities include monitoring, assessment, and

capacity building. The implementation of the GEMS/Water program involves several United Nations

agencies active in the water sector as well as a number of organisations around the world. Participants

from Region 8 include: Cambodia (in progress), Indonesia, Laos (in progress), Thailand, Viet Nam (in

progress) Australia, Malaysia, New Zealand, Philippines, and Papua New Guinea. Organic chemicals

and contaminants being monitored include: p,p-DDT, o,p-DDT, p,p-DDD, o,p-DDD, p,p-DDE, o,p-

DDE, lindane, alpha-BHC, mirex, aldrin, endrin, dieldrin, PCBs, atrazine, methiocarb, aldicarb, 2,4-

D, and BHC.

1.2.2. Inter-Regional Links and Collaboration

1.2.2.1. ASEAN - Transboundary Haze

Transboundary haze pollution arising from land and forest fires continues to be the most prominent

and pressing environmental problem facing ASEAN today. The HPA addresses the transboundary

haze issue through the following objectives, namely (i) to fully implement the ASEAN Co-operation

Plan on Transboundary Pollution with particular emphasis on the Regional Haze Action Plan (RHAP)

by year 2001; (ii) to strengthen the ASEAN Specialised Meteorological Centre with emphasis on the

ability to monitor forest and land fires and provide early warning on transboundary haze by year

2001; and (iii) to establish the ASEAN Regional Research and Training Centre for Land and Forest

Fire Management by the year 2004. ASEAN Secretariat's RHAP-Co-ordination and Support Unit

continuously monitors the haze situation on a day-to-day and region-wide basis and shares its findings

through its website: the ASEAN Haze Action Online (www.haze-online.or.id).

1.2.2.2. ASEAN - Working Group on Multilateral Environmental Agreements

The purpose of the Working Group is to enhance co-operation between ASEAN member countries

with regards to Multilateral Agreements on the Environment with a view to reaching a common

3

ASEAN approach, where appropriate, in the negotiation and implementation of multilateral

environmental agreements. ASEAN member countries will also have the opportunity to:

(a)

Strengthen the co-operation among each other in the implementation of existing

international instruments or agreements in the field of the environment, taking into

account in particular the needs of ASEAN. ASEAN countries need also to be provided

with technical assistance in their attempts to enhance their national legislative capabilities

in the field of environmental agreements,

(b)

Identify and address issues and problems that prevent the ASEAN countries from

participating in or duly implementing international environmental agreements or

instruments and, where appropriate, to review or revise them with the purpose of further

integrating environmental concerns into the development process;

(c)

Promote and support the effective participation of ASEAN countries in the

negotiation, implementation, review and governance of international environmental

agreements or instruments, including appropriate provision of technical and financial

assistance and other available mechanisms for this purpose;

(d)

Exchange views and information on new or revised Multilateral Environmental

Agreements; and,

(e)

Upgrade ASEAN capacity for negotiations in Multilateral Environmental

Agreements (MEAs).

1.2.2.3. Asia Toolkit Project on Inventories of PCDD/PCDFs Releases

This project is a key element of UNEP's capacity building program assisting countries in identifying

their PCDD/PCDFs sources and releases. It supports the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic

Pollutants where in Article 5 Parties to the Convention are requested to identify and quantify the

release of by-products. The project, which is supported by the US Government, is piloting the Toolkit

in five countries. Participants in this project in Region 8 are: Viet Nam, the Philippines and Brunei

Darussalam.

1.2.3. National Programmes for PTS

1.2.3.1. Assessing National Management Needs forof PTS Pilot Country Study

The Global Environment Facility (GEF) has approved a project preparation and development grant

(PDF-B) for UNEP to prepare a project entitled "Assessing National Management Needs of Persistent

Toxic Substances (PTS)." This project is wholly complimentary to the large-scale initiative of the

PTS project, focussing on national level assessment of issues and problems, costs and alternatives for

action.

At the national level, the objective for the participating countries is the development (or

strengthening) of a Strategic Action Plan for the management of chemicals, particularly PTS

(including POPs). At the global level, the objectives are two-fold: a) to produce widely applicable

guidelines for assessing national level problems related to PTS and the needs of countries in terms of

managing them (these guidelines will be produced on the basis of conducting eight or more country

studies to address, and identify solutions to problems associated with persistent toxic chemicals in a

few representative developing countries and countries in economic transition); and b) to produce a set

of cost-norms for the set of enabling type activities that countries may have to execute in order to

meet their obligations under a POPs Convention.

1.2.3.2. National Dioxins Program

In the 2001-02 Federal Budget, the Australian Government announced funding of $5 million over four

years (2001-2005) for the National Dioxins Program to reduce dioxins and dioxin-like substances in

the environment.

The key actions of the NDP will be implemented over three phases: Phase One gather as much data

as possible about levels of PCDD/PCDFs in Australia; Phase Two assess the impact of

4

PCDD/PCDFs on human health and the environment; and Phase Three in light of these assessed

impacts, reduce and where feasible, eliminate releases of PCDD/PCDFs in Australia.

1.2.3.3. National Pollutant Inventory Australia

The National Pollutant Inventory (NPI), first publicly available on the internet in early 2000, is an

internet database designed to provide the community, industry and government with information on

the types and amounts of certain substances being emitted to the environment. Australian industrial

facilities, using more than a threshold amount for the substances listed on the NPI reporting list, are

required to estimate and report emissions of these substances annually. PTS are included in the list.

Environment Australia also estimates emissions from non-industry sources and facilities that are using

less than the threshold amount for substances listed on the NPI.

1.2.3.4. The Organochlorines Program New Zealand

The Ministry for the Environment's Organochlorines Program began in 1995 with the aim to: research

levels of organochlorines in humans, food and in the environment; reduce industrial emissions of

PCDD/PCDFs to air, land and water; clean up land contaminated with organochlorine residues; and

manage the safe disposal of waste stocks of organochlorine chemicals. The Ministry has completed a

series of investigations into levels of organochlorines in New Zealand. Detailed information is

available in a series of research reports on organochlorines

(e.g., http://www.mfe.govt.nz/issues/waste/ocreports.htm).

1.3. General Definitions Of Chemicals

Substances that are persistent, bioaccumulative and possess toxic characteristics likely to cause

adverse human health or environmental effects are called PTS (persistent and toxic substances). In

this context, "substance" means a single chemical species, or a number of chemical species that form

a specific group by virtue of (a) having similar properties and being emitted together into the

environment; or (b) forming a mixture normally marketed as a single product. Depending on their

mobility in the environment, PTS could be of local, regional or global concern (Wallack et al., 1998).

A subclass of PTS, so called POPs (persistent organic pollutants), is a group of twelve compounds

that have been selected, under the Stockholm Convention and which are prone to long-range

atmospheric transport and deposition (Wallack et al., 1998; UN ECE, 1996). These include aldrin,

endrin, dieldrin, chlordane, DDT, heptachlor, mirex, toxaphene, hexachlorobenzene, PCBs, dioxins

and furans. These will be considered in this regional assessment along with regional specific

chemicals including HCH, PAHs, endosulphan, pentachlorophenol, organic mercury compounds,

organic tin compounds, organic lead compounds, phthalates. PBDEs, HxBBs, chlordecone,

octylphenols, nonylphenols and short chained chlorinated paraffins. The global extent of POPs

became apparent with their detection in areas such as the Arctic, where they have never been used or

produced, at levels posing risks to both wildlife (Barrie et al., 1992) and humans (Mulvad et al.,

1996).

Persistent toxic substances include two main groups of pollutants, persistent organic pollutants (POPs)

and organometallics. POPs are separated into three subgroups, pesticides, industrial compounds and

unintended by-products. One compound, hexachlorobenzene, belongs to all three groups, pesticides

(fungicide), industrial compounds (by-product) and unintended by-products.

The definitions presented here were agreed upon following consultations among the regional co-

ordinators, their team members, and the program manager.

1.3.1. Pesticides

1.3.1.1. Aldrin

Chemical Name: 1,2,3,4,10,10-hexachloro-1,4,4a,5,8,8a-hexahydro-1,4-endo,exo-5,8-

dimethanonaphthalene (C12H8Cl6).

CAS Number: 309-00-2

5

Properties: Solubility in water: 27 µg/L at 25°C; vapour pressure: 2.3 x 10-5 mm Hg at 20°C; log

KOW: 5.17-7.4.

Discovery/Uses: It has been manufactured commercially since 1950, and used throughout the world

up to the early 1970s to control soil pests such as corn rootworm, wireworms, rice water weevil, and

grasshoppers. It has also been used to protect wooden structures from termites.

Persistence/Fate: Readily metabolised to dieldrin by both plants and animals. Biodegradation is

expected to be slow and it binds strongly to soil particles, and is resistant to leaching into

groundwater. Aldrin was classified as moderately persistent with a half-life in soil and surface waters

ranging from 20 days to 1.6 years.

Toxicity: Aldrin is toxic to humans; the lethal dose for an adult has been estimated to be about

80 mg/kg body weight. The acute oral LD50 in laboratory animals is in the range of 33 mg/kg body

weight for guinea pigs to 320 mg/kg body weight for hamsters. The toxicity of aldrin to aquatic

organisms is quite variable, with aquatic insects being the most sensitive group of invertebrates. The

96-h LC50 values range from 1-200 µg/L for insects, and from 2.2-53 µg/L for fish. The maximum

residue limits in food recommended by FAO/WHO vary from 0.006 mg/kg milk fat to 0.2 mg/kg

meat fat. Water quality criteria between 0.1 to 180 µg/L have been published.

1.3.1.2. Dieldrin

Chemical Name: 1,2,3,4,10,10-hexachloro-6,7-epoxy-1,4,4a,5,6,7,8,8a-octahydroexo-1,4-endo-5,8-

dimethanonaphthalene (C12H8Cl6O).

CAS Number: 60-57-1

Properties: Solubility in water: 140 µg/L at 20°C; vapour pressure: 1.78 x 10-7 mm Hg at 20°C; log

KOW: 3.69-6.2. Discovery/Uses: It appeared in 1948 after World War II and was used mainly for the

control of soil insects such as corn rootworms, wireworms and catworms.

Persistence/Fate: It is highly persistent in soils, with a half-life of 3-4 years in temperate climates,

and bioconcentrates in organisms. The persistence in air has been estimated as 4-40 hrs.

Toxicity: The acute toxicity for fish is high (LC50 between 1.1 and 41 mg/L) and moderate for

mammals (LD50 in mouse and rat ranging from 40 to 70 mg/kg body weight). However, a daily

administration of 0.6 mg/kg to rabbits adversely affected the survival rate. Aldrin and dieldrin mainly

affect the central nervous system but there is no direct evidence that they cause cancer in humans. The

maximum residue limits in food recommended by FAO/WHO vary from 0.006 mg/kg milk fat and 0.2

mg/kg poultry fat. Water quality criteria between 0.1 to 18 µg/L have been published.

1.3.1.3. Endrin

Chemical Name: 3,4,5,6,9,9-hexachloro-1a,2,2a,3,6,6a,7,7a-octahydro-2,7:3,6-dimethanonaphth[2,3-

b]oxirene (C12H8Cl6O).

CAS Number: 72-20-8

Properties: Solubility in water: 220-260 µg/L at 25 °; vapour pressure: 2.7 x 10-7 mm Hg at 25°C;

log KOW: 3.21-5.34

Discovery/Uses: It has been used since the 1950s against a wide range of agricultural pests, mostly on

cotton but also on rice, sugar cane, maize and other crops. It has also been used as a rodenticide.

Persistence/Fate: Is highly persistent in soils (half-lives of up to 12 years have been reported in some

cases). Bioconcentration factors of 14 to 18,000 have been recorded in fish, after continuous

exposure.

Toxicity: Endrin is very toxic to fish, aquatic invertebrates and phytoplankton; the LC50 values are

mostly less than 1 µg/L. The acute toxicity is high in laboratory animals, with LD50 values of 3-43

mg/kg, and a dermal LD50 of 5-20 mg/kg in rats. Long-term toxicity in the rat has been studied over

two years and a NOEL of 0.05 mg/kg bw/day was found.

6

1.3.1.4. Chlordane

Chemical Name: 1,2,4,5,6,7,8,8-octachloro-2,3,3a,4,7,7a-hexahydro-4,7-methanoindene (C10H6Cl8).

CAS Number: 57-74-9

Properties: Solubility in water: 56 µg/L at 25°C; vapour pressure: 0.98 x 10-5 mm Hg at 25 °C; log

KOW: 4.58-5.57.

Discovery/Uses: Chlordane appeared in 1945 and was used primarily as an insecticide for control of

cockroaches, ants, termites, and other household pests. Technical chlordane is a mixture of at least

120 compounds. Of these, 60-75% are chlordane isomers, the remainder being related to endo-

compounds including heptachlor, nonachlor, diels-alder adduct of cyclopentadiene and

penta/hexa/octachlorocyclopentadienes.

Persistence/Fate: Chlordane is highly persistent in soils with a half-life of about 4 years. Its

persistence and high partition coefficient promote binding to aquatic sediments and bioconcentration

in organisms.

Toxicity: LC50 values from 0.4 mg/L (pink shrimp) to 90 mg/L (rainbow trout) have been reported for

aquatic organisms. The acute toxicity for mammals is moderate with an LD50 in rats of 200-590

mg/kg body weight (19.1 mg/kg body weight for oxychlordane). The maximum residue limits for

chlordane in food are, according to FAO/WHO between 0.002 mg/kg milk fat and 0.5 mg/kg poultry

fat. Water quality criteria of 1.5 to 6 µg/L have been published. Chlordane has been classified as a

substance for which there is evidence of endocrine disruption in an intact organism and possible

carcinogenicity to humans.

1.3.1.5. Heptachlor

Chemical Name: 1,4,5,6,7,8,8-heptachloro-3a,4,7,7a-tetrahydro-4,7-methanoindene (C10H5Cl7).

CAS Number: 76-44-8

Properties: Solubility in water: 180 µg/L at 25°C; vapour pressure: 0.3 x 10-5 mm Hg at 20°C; log

KOW: 4.4-5.5.

Production/Uses: Heptachlor is used primarily against soil insects and termites, but also against

cotton insects, grasshoppers, and malaria mosquitoes. Heptachlor epoxide is a more stable breakdown

product of heptachlor.

Persistence/Fate: Heptachlor is metabolised in soils, plants and animals to heptachlor epoxide, which

is more stable in biological systems and is carcinogenic. The half-life of heptachlor in soil in

temperate regions is 0.75 2 years. Its high partition coefficient provides the necessary conditions for

bioconcentration in organisms.

Toxicity: The acute toxicity of heptachlor to mammals is moderate (LD50 values between 40 and 119

mg/kg have been published). The toxicity to aquatic organisms is higher and LC50 values down to 0.11

µg/L have been found for pink shrimp. Limited information is available on the effects in humans and

studies are inconclusive regarding heptachlor and cancer. The maximum residue levels recommended

by FAO/WHO are between 0.006 mg/kg milk fat and 0.2 mg/kg meat or poultry fat.

1.3.1.6. Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT)

Chemical Name: 1,1,1-trichloro-2,2-bis-(4-chlorophenyl)-ethane (C14H9Cl5).

CAS Number: 50-29-3.

Properties: Solubility in water: 1.2-5.5 µg/L at 25°C; vapour pressure: 0.2 x 10-6 mm Hg at 20°C; log

KOW: 6.19 for pp'-DDT, 5.5 for pp'-DDD and 5.7 for pp'-DDE.

Discovery/Use: DDT appeared for use during World War II to control insects that spread diseases

like malaria, dengue fever and typhus. Following this, it was widely used on a variety of agricultural

crops. The technical product is a mixture of about 85% pp'-DDT and 15% op'-DDT isomers.

7

Persistence/Fate: DDT is highly persistent in soils with a half-life of up to 15 years and of 7 days in

air. It also exhibits high bioconcentration factors (in the order of 50,000 for fish and 500,000 for

bivalves). In the environment, the product is metabolised mainly to DDD and DDE.

Toxicity: The lowest dietary concentration of DDT reported to cause eggshell thinning was 0.6 mg/kg

for the black duck. LC50 values of 1.5 mg/L for largemouth bass and 56 mg/L for guppy have been

reported. The acute toxicity of DDT for mammals is moderate with an LD50 in rat of 113-118 mg/kg

body weight. DDT has been shown to have an oestrogen-like activity, and possible carcinogenic

activity in humans. The maximum residue level in food recommended by WHO/FAO range from 0.02

mg/kg milk fat to 5 mg/kg meat fat. Maximum permissible DDT residue level in drinking water

(WHO) is 1.0 µg/L.

1.3.1.7. Toxaphene

Chemical Name: Polychlorinated bornanes and camphenes (C10H10Cl8).

CAS Number: 8001-35-2

Properties: Solubility in water: 550 µg/L at 20°C; vapour pressure: 3.3 x 10-5 mm Hg at 25°C; log

KOW : 3.23-5.50.

Discovery/Uses: Toxaphene has been in use since 1949 as a non-systemic insecticide with some

acaricidal activity, primarily on cotton, cereal grains, fruits, nuts and vegetables. It was also used to

control livestock ectoparasites such as lice, flies, ticks, mange, and scab mites. The technical product

is a complex mixture of over 300 congeners, containing 67-69% chlorine by weight.

Persistence/Fate: Toxaphene has a half-life in soil from 100 days up to 12 years. It has been shown

to bioconcentrate in aquatic organisms (BCF of 4247 in mosquito fish and 76,000 in brook trout).

Toxicity: Toxaphene is highly toxic in fish, with 96-hour LC50 values in the range of 1.8 µg/L in

rainbow trout to 22 µg/L in bluegill. Long-term exposure to 0.5 µg/L reduced egg viability to zero.

The acute oral toxicity is in the range of 49 mg/kg body weight in dogs to 365 mg/kg in guinea pigs.

In long-term studies NOEL in rats was 0.35 mg/kg bw/day, LD50 ranging from 60 to 293 mg/kg bw.

For toxaphene, there is strong evidence of the potential for endocrine disruption. Toxaphene is

carcinogenic in mice and rats and is of carcinogenic risk to humans, with a cancer potency factor of

1.1 mg/kg/day for oral exposure.

1.3.1.8. Mirex

Chemical Name: 1,1a,2,2a,3,3a,4,5,5a,5b,6-dodecachloroacta-hydro-1,3,4-metheno-1H-

cyclobuta[cd]pentalene (C10Cl12).

CAS Number: 2385-85-5

Properties: Solubility in water: 0.07 µg/L at 25°C; vapour pressure: 3 x 10-7 mm Hg at 25°C; log

KOW: 5.28.

Discovery/Uses: The use in pesticide formulations started in the mid 1950s, largely focused on the

control of ants. It is also a fire retardant for plastics, rubber, paint, paper and electrical goods.

Technical grade preparations of mirex contain 95.19% mirex and 2.58% chlordecone, the rest being

unspecified. Mirex is also used to refer to baits comprising corncob grits, and soya bean oil.

Persistence/Fate: Mirex is considered to be one of the most stable and persistent pesticides, with a

half-life in soils of up to 10 years. Bioconcentration factors of 2,600 and 51,400 have been observed

in pink shrimp and fathead minnows, respectively. It is capable of undergoing long-range transport

due to its relative volatility (VPL = 4.76 Pa; H = 52 Pa m 3 /mol).

Toxicity: The acute toxicity of mirex for mammals is moderate with an LD50 in rats of 235 mg/kg and

dermal toxicity in rabbits of 80 mg/kg. Mirex is also toxic to fish and can affect their behaviour (LC50

(96 hr) from 0.2 to 30 mg/L for rainbow trout and bluegill, respectively). Delayed mortality of

crustaceans occurred at 1 µg/L exposure levels. There is evidence of its potential for endocrine

disruption and possibly carcinogenic risk to humans.

8

1.3.1.9. Hexachlorobenzene (HCB)

Chemical Name: Hexachlorobenzene (C6Cl6)

CAS Number: 118-74-1

Properties: Solubility in water: 50 µg/L at 20°C; vapour pressure: 1.09 x 10-5 mm Hg at 20°C; log

KOW: 3.93-6.42.

Discovery/Uses: It was first introduced in 1945 as fungicide for seed treatments of grain crops, and

used to make fireworks, ammunition, and synthetic rubber. Today it is mainly a by-product in the

production of a large number of chlorinated compounds, particularly lower chlorinated benzenes,

solvents and several pesticides. HCB is emitted to the atmosphere in flue gases generated by waste

incineration facilities and metallurgical industries.

Persistence/Fate: HCB has an estimated half-life in soils of 2.7-5.7 years and of 0.5-4.2 years in air.

HCB has a relatively high bioaccumulation potential and long half-life in biota.

Toxicity: LC50 for fish varies between 50 and 200 µg/L. The acute toxicity of HCB is low with LD50

values of 3.5 mg/g for rats. Mild effects on the [rat] liver have been observed at a daily dose of

0.25 mg HCB/kg bw. HCB is known to cause liver disease in humans (porphyria cutanea tarda) and

has been classified as a possible carcinogen to humans by IARC.

1.3.2. Industrial Compounds

1.3.2.1. Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs)

Chemical Name: Polychlorinated biphenyls (C12H(10-n)Cln, where n is within the range of 1-10).

CAS Number: Various (e.g. for Aroclor 1242, CAS No.: 53469-21-9; for Aroclor 1254, CAS No.:

11097-69-1)

Properties: Water solubility decreases with increasing chlorination: 0.01 to 0.0001 µg/L at 25°C;

vapour pressure: 1.6-0.003 x 10-6 mm Hg at 20°C; log KOW: 4.3-8.26.

Discovery/Uses: PCBs were introduced in 1929 and were manufactured in different countries under

various trade names (e.g. Aroclor, Clophen, Phenoclor). They are chemically stable and heat resistant,

and were used worldwide as transformer and capacitor oils, hydraulic and heat exchange fluids, and

lubricating and cutting oils. Theoretically, a total of 209 possible chlorinated biphenyl congeners

exist, but only about 130 of these are likely to occur in commercial products.

Persistence/Fate: Most PCB congeners, particularly those lacking adjacent unsubstituted positions on

the biphenyl rings (e.g. 2,4,5-, 2,3,5- or 2,3,6-substituted on both rings) are extremely persistent in the

environment. They are estimated to have half-lives ranging from three weeks to two years in air and,

with the exception of mono- and di-chlorobiphenyls, more than six years in aerobic soils and

sediments. PCBs also have extremely long half-lives in adult fish, for example, an eight-year study of

eels found that the half-life of CB153 was more than ten years.

Toxicity: LC50 for the larval stages of rainbow trout is 0.32 µg/L with a NOEL of 0.01 µg/L. The

acute toxicity of PCB in mammals is generally low and LD50 values in rats of 1 g/kg bw. IARC has

concluded that PCBs are carcinogenic to laboratory animals and probably also for humans. They have

also been classified as substances for which there is evidence of endocrine disruption in an intact

organism.

Unintended By-products

1.3.3.1. Polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins (PCDDs) and Polychlorinated dibenzofurans (PCDFs)

Chemical Name: PCDDs (C12H(8-n)ClnO2) and PCDFs (C12H(8-n)ClnO) may contain between 1 and 8

chlorine atoms. PCDD/PCDFs have 75 and 135 possible positional isomers, respectively.

CAS Number: Various (2,3,7,8-TetraCDD: 1746-01-6; 2,3,7,8-TetraCDF: 51207-31-9).

Properties: Solubility in water: in the range 0.43 0.0002 ng/L at 25°C; vapour pressure: 2 0.007 x

10-6 mm Hg at 20°C; log KOW: in the range 6.60 8.20 for tetra- to octa-substituted congeners.

9

Discovery/Uses: They are by-products resulting from the production of other chemicals and from the

low-temperature combustion and incineration processes. They have no known use.

Persistence/Fate: PCDD/PCDFs are characterised by their lipophilicity, semi-volatility and resistance

to degradation (half-life of TCDD in soil of 10-12 years) and long-range transport. They are also

known for their ability to bio-concentrate and biomagnify under typical environmental conditions.

Toxicity: The toxicological effects reported refer to the 2,3,7,8-substituted compounds (17 congeners)

that are agonist for the AhR. All the 2,3,7,8-substituted PCDDs and PCDFs plus coplanar PCBs (with

no chlorine substitution at the ortho positions) show the same type of biological and toxic response.

Possible effects include dermal toxicity, immunotoxicity, reproductive effects and teratogenicity,

endocrine disruption and carcinogenicity. At the present time, the only persistent effect associated

with PCDD/PCDFs exposure in humans is chloracne. The most sensitive groups are foetuses and

neonatal infants.

Effects on the immune systems in the mouse have been found at doses of 10 ng/kg bw/day, while

reproductive effects were seen in rhesus monkeys at 1-2 ng/kg bw/day. Biochemical effects have been

seen in rats down to 0.1 ng/kg bw/day. In a re-evaluation of the TDI for PCDD/PCDFs (and planar

PCB), the WHO decided to recommend a range of 1-4 TEQ pg/kg bw, although more recently the

acceptable intake value has been set monthly at 1-70 TEQ pg/kg bw.

1.3.4. Regional Specific Chemicals

1.3.4.1. Hexachlorocyclohexanes (HCH)

Chemical Name: 1,2,3,4,5,6-hexachlorocyclohexane (mixed isomers) (C6H6Cl6).

CAS Number: 608-73-1 (-HCH, lindane: 58-89-9).

Properties: -HCH: solubility in water: 7 mg/L at 20°C; vapour pressure: 3.3 x 10-5 mm Hg at 20°C;

log KOW: 3.8.

Discovery/Uses: There are two principal formulations: "technical HCH", which is a mixture of

various isomers, including -HCH (55-80%), -HCH (5-14%) and -HCH (8-15%), and "lindane",

which is essentially pure -HCH. Historically, lindane was one of the most widely used insecticides in

the world. Its insecticidal properties were discovered in the early 1940s. It controls a wide range of

sucking and chewing insects and has been used for seed treatment and soil application, in household

biocidal products, and as textile and wood preservatives.

Persistence/Fate: Lindane and other HCH isomers are relatively persistent in soils and water, with

half-lives generally greater than 1 and 2 years, respectively. HCH are much less bioaccumulative than

other organochlorines because of their relatively low liphophilicity. On the contrary, their relatively

high vapour pressures, particularly of the -HCH isomer, determine their long-range transport in the

atmosphere.

Toxicity: Lindane is moderately toxic for invertebrates and fish, with LC50 values of 20-90 µg/L. The

acute toxicity for mice and rats is moderate with LD50 values in the range of 60-250 mg/kg. Lindane

was found to have no mutagenic potential in a number of studies but possesses an endocrine

disrupting activity.

1.3.4.2. Chlorinated Paraffins (CPs)

Chemical Name: Polychlorinated alkanes (CxH(2x-y+2)Cly). They are manufactured by chlorination of

liquid n-alkanes or paraffin wax and contain from 30 to 70% chlorine. The products are often divided

into three groups depending on chain length: short chain (C10 C13), medium (C14 C17) and long (C18

C30) chain lengths.

CAS Number: 108171-26-2

Properties: They are largely dependent on the chlorine content. Solubility in water: 1.7 to 236 µg/L

at 25°C; vapour pressure: 6.78 x 10-2 to 8.47 x 10-9 mm Hg at 20°C; log KOW: in the range from 5.06

to 8.12.

10

Discovery/Uses: The largest application is as a plasticiser, generally in conjunction with primary

plasticisers such as certain phthalates in flexible PVC. The chlorinated paraffins also impart a number