United Nations

Environment Programme

Chemicals

Centr

Central and North

al and Nor

East Asia

REGIONAL REPORT

th East

Regionally

Asia

RBA PTS REGIONAL REPOR

Based

Assessment

of

T

Persistent

Available from:

UNEP Chemicals

11-13, chemin des Anémones

CH-1219 Châtelaine, GE

Switzerland

Phone : +41 22 917 1234

Fax : +41 22 797 3460

Substances

E-mail: chemicals@unep.ch

December 2002

http://www.chem.unep.ch

UNEP Chemicals is a part of UNEP's Technology, Industry and

Printed at United Nations, Geneva

Economics Division

GE.03-00155January 2003500

UNEP/CHEMICALS/2003/7

G l o b a l E n v i r o n m e n t F a c i l i t y

UNITED NATIONS

ENVIRONMENT

PROGRAMME

CHEMICALS

Regional y Based Assessment

of Persistent Toxic Substances

Afghanistan, China, Democratic People's

Republic of Korea, South Korea, Japan,

Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia, Russian

Federation, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan

CENTRAL AND NORTH EAST

ASIA

REGIONAL REPORT

DECEMBER 2002

GLOBAL ENVIRONMENT FACILITY

This report was financed by the Global Environment Facility (GEF) through a global project with co-

financing from the Governments of Australia, France, Sweden, Switzerland and the United States of

America

This publication is produced within the framework of the Inter-Organization Programme for the Sound

Management of Chemicals (IOMC)

This publication is intended to serve as a guide. While the information provided is believed to be

accurate, UNEP disclaim any responsibility for the possible inaccuracies or omissions and

consequences, which may flow from them. UNEP nor any individual involved in the preparation of

this report shall be liable for any injury, loss, damage or prejudice of any kind that may be caused by

any persons who have acted based on their understanding of the information contained in this

publication.

The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this report do not imply the

expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations of UNEP

concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning

the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.

The Inter-Organization Programme for the Sound Management of Chemicals (IOMC), was

established in 1995 by UNEP, ILO, FAO, WHO, UNIDO and OECD (Participating Organizations),

following recommendations made by the 1992 UN Conference on Environment and Development

to strengthen cooperation and increase coordination in the field of chemical safety. In January

1998, UNITAR formally joined the IOMC as a Participating Organization. The purpose of the

IOMC is to promote coordination of the policies and activities pursued by the Participating

Organizations, jointly or separately, to achieve the sound management of chemicals in relation to

human health and the environment.

Material in this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted but acknowledgement is requested

together with a reference to the document. A copy of the publication containing the quotation or

reprint should be sent to UNEP Chemicals.

UNEP

CHEMICALS

Available from:

UNEP Chemicals11-13, chemin des Anémones

CH-1219 Châtelaine, GE

Switzerland

Phone: +41 22 917 1234

Fax:

+41 22 797 3460

E-mail: chemicals@unep.ch

http://www.chem.unep.ch

UNEP Chemicals is a part of UNEP's Technology, Industry and Economics Division

ii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PREFACE.........................................................................................VI

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................VII

1

INTRODUCTION ....................................................................... 1

1.1

OVERVIEW OF THE RBA PTS PROJECT .............................................................................1

1.1.1 Objectives ...............................................................................................................................1

1.1.2 Results.....................................................................................................................................1

1.2 METHODOLOGY .....................................................................................................................2

1.2.1 Regional

Divisions..................................................................................................................2

1.2.2 Management

Structure............................................................................................................2

1.2.3 Data

Processing.......................................................................................................................2

1.2.4 Project

Funding.......................................................................................................................2

1.3

SCOPE OF THE CENTRAL AND NORTH EAST ASIA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT ........3

1.3.1 Existing

Assessments..............................................................................................................5

1.3.2

Intra-Regional Links and Collaboration .................................................................................5

1.3.3 Omissions

and

Weaknesses ....................................................................................................5

1.4 METHODOLOGY .....................................................................................................................5

1.5

GENERAL DEFINITIONS OF CHEMICALS..........................................................................6

1.5.1

Persistent Toxic Substances - Pesticides ................................................................................6

1.5.2

Persistent Toxic Substances Industrial Compounds ............................................................9

1.5.3

Persistent Toxic Substances Unintentional By-Products...................................................10

1.5.4

Regional Specific Chemicals ................................................................................................10

1.6

DEFINITION OF THE CENTRAL AND NORTH EAST ASIA REGION............................13

1.7 PHYSICAL

SETTING .............................................................................................................15

1.8

PATTERNS OF DEVELOPMENT/SETTLEMENT...............................................................17

2

SOURCE CHARACTERISATION ........................................... 19

2.1 BACKGROUND

INFORMATION TO PTS SOURCES ........................................................19

2.1.1

Scoring of PTS......................................................................................................................19

2.2

PRODUCTION, USE AND EMISSION..................................................................................21

2.2.1

Persistent Toxic Substances - Pesticides ..............................................................................21

2.2.2

Persistent Toxic Substances Industrial Compounds ..........................................................27

2.2.3

Persistent Toxic Substances Unintentional by-Products ...................................................31

2.2.4 Organic

Metals......................................................................................................................41

2.3 DATA

GAPS ............................................................................................................................43

2.4

SUMMARY OF HOT SPOTS AND MOST SIGNIFICANT REGIONAL SOURCES .........43

2.5 CONCLUSIONS ......................................................................................................................44

3

ENVIRONMENTAL LEVELS, TOXICOLOGICAL AND

ECOTOXICOLOGICAL PATTERNS....................................... 45

3.1 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................45

3.1.1

Scoring of PTS......................................................................................................................45

iii

3.2 LEVELS

AND

TRENDS .........................................................................................................46

3.2.1 Air/Deposition ......................................................................................................................46

3.2.2

Surface Waters (Water and Sediment)..................................................................................48

3.2.3 Groundwater .........................................................................................................................51

3.2.4 Soils ......................................................................................................................................51

3.2.5 Aquatic

Biota ........................................................................................................................53

3.2.6 Terrestrial

Biota ....................................................................................................................57

3.2.7

Time Trends of PTS in the Region .......................................................................................58

3.3

TOXICOLOGICAL AND ECOTOXICOLOGICAL EFFECTS OF PTS...............................60

3.3.1 Introduction...........................................................................................................................60

3.3.2

Toxicology of PTS of Regional Concern..............................................................................61

3.3.3

Ecotoxicology of PTS of Regional Concern.........................................................................63

3.4 HOT

SPOTS .............................................................................................................................64

3.5 DATA

GAPS ............................................................................................................................64

3.6 CONCLUSION.........................................................................................................................64

4

MAJOR PATHWAYS OF CONTAMINANT TRANSPORT ..... 65

4.1 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................65

4.1.1 General..................................................................................................................................65

4.1.2 Regionally

Specific

Features ................................................................................................65

4.2 MEASUREMENTS/MODELLING

APPROACH

FOR TRANSPORT ASSESSMENT.......65

4.3

OVERVIEW OF EXISTING MODELLING PROGRAMS AND PROJECTS ......................66

4.3.1 Japan .....................................................................................................................................66

4.3.2

Republic of Korea.................................................................................................................66

4.3.3 Russian

Federation................................................................................................................67

4.3.4

Other Modelling Programs ...................................................................................................67

4.4 EXISTING

MONITORING

PROGRAMMES CONCERNING PTS TRANSPORT.............67

4.5

TRANSBOUNDARY MOVEMENT OF PTS.........................................................................68

4.5.1 Atmospheric

Transport .........................................................................................................68

4.5.2 Terrestrial

Hydrology

Related to PTS Transport..................................................................74

4.5.3

Oceans as Pathway................................................................................................................76

4.6 DATA

GAPS ............................................................................................................................77

4.6.1

What Information Needs To Be Collected?..........................................................................77

4.6.2

How Should It Be Collected? ...............................................................................................77

4.7 CONCLUSIONS ......................................................................................................................78

5

PRELIMINARY ASSESSMENT OF THE REGIONAL

CAPACITY AND NEED TO MANAGE PTS............................ 79

5.1 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................79

5.2 MONITORING

CAPACITY....................................................................................................79

5.2.1 Environmental

Monitoring ...................................................................................................79

5.2.2

Methods of Monitoring.........................................................................................................80

5.2.3

Items Actually Monitored.....................................................................................................85

5.3

EXISTING REGULATIONS AND MANAGEMENT STRUCTURES .................................86

5.3.1

Laws and Regulations...........................................................................................................86

5.3.2 Administrative

Institutions ...................................................................................................92

iv

5.4

STATUS OF ENFORCEMENT...............................................................................................94

5.5

ALTERNATIVES/MEASURES FOR REDUCTION .............................................................96

5.5.1

Intentionally Produced PTS ..................................................................................................96

5.5.2

Unintentionally Produced PTS .............................................................................................97

5.6 TECHNOLOGY

TRANSFER..................................................................................................97

5.7 IDENTIFICATION

OF

NEEDS ..............................................................................................98

5.7.1

Overview of Status................................................................................................................98

5.7.2 Existing

Difficulties..............................................................................................................98

5.7.3 Capacity

Building .................................................................................................................99

5.7.4 Follow-up

Activities ...........................................................................................................100

6

CONCLUSIONS .................................................................... 101

6.1 IDENTIFICATION

OF

BARRIERS......................................................................................101

6.2 IDENTIFICATION

OF

PRIORITIES....................................................................................101

6.2.1 Sources................................................................................................................................101

6.2.2 Pathways .............................................................................................................................101

6.2.3

Environmental Levels, Toxicological and Ecotoxicological Effects..................................102

6.3

RECOMMENDATION FOR FUTURE ACTIVITIES..........................................................102

REFERENCES .............................................................................. 103

ANNEX 1 ....................................................................................... 113

v

PREFACE

STRUCTURE OF THE REGIONAL TEAM

The following members comprise the Central and North East Asia Regional team:

Regional Co-ordinator

Prof Ming H WONG

Institute for Natural Resources and

Environmental Management

Hong Kong Baptist University

Kowloon Tong, Hong Kong SAR

Regional Team Members

Dr Yasuyuki SHIBATA

Dr Kyunghee CHOI

Environmental Chemodynamics Section

Environmental Risk Assessment Division

Environmental Chemistry Division

National Institute of Environmental Research

National Institute for Environmental Studies

(NIER)

(NIES)

Ministry of Environment

Tsukuba, Japan

Inchon, Republic of Korea

Dr Noriyuki SUZUKI

Dr Elena GROSHEVA

Endocrine Disruptors & Dioxin Research Project

Russian Federation Ministry of Natural Resources

National Institute for Environmental Studies

Albert Beim Institute of Ecological Toxicology

(NIES)

Irkutsk Region, Russian Federation

Tsukuba, Japan

Dr Shin-ichi SAKAI

Ms WANG Ji

Research Center for Material Cycles and Waste

Areal & Ecological Inspection Division

Management

Department of Environment Protection Inspection

National Institute for Environmental Studies

State Environmental Protection Administration

(NIES)

(SEPA)

Tsukuba, Japan

Beijing, PR China

Assistants

Ms ZHOU Hong - Assistant to Ms WANG Ji

Technical Supporting Division

Chemical Registration Center of SEPA

Beijing, PR China

Ms Anna LEUNG Assistant to Prof Ming H WONG

Institute for Natural Resources and

Environmental Management

Hong Kong Baptist University

Kowloon Tong, Hong Kong SAR

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This report is very much a joint effort. In addition to the Regional team members, we would like to thank all the

experts and representatives from different countries who contributed significantly in data collection and/or

taking part in technical workshops. Special thanks are due to Dr Diana Graham who served as a resource person

in the Regional Priority Setting Meeting. Last, but not least, we would like to thank Mr Paul Whylie, the

Project Manager at UNEP Chemicals, for his continual support and patience.

vi

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

1. As part of the global project supported by UNEP/GEF, this report presents findings of an assessment of

sources, fates and effects related to the 12 Stockholm Convention chemicals which include pesticides

(aldrin, endrin, dieldrin, chlordane, DDT, toxapnene, mirex, heptacholor, hexachlorobenzene), industrial

chemicals (PCBs and also hexachlorobenzene) and unintentional by-products (PCDD/PCDF), as well as six

additional chemicals (PAHs, organic mercury compounds, organic tin compounds, HCH, brominated flame

retardant [PBDE]), and pentachlorophenol (PCP) at the Central and North-East Asia (Region VII) which

includes 11 countries: China, Japan, Republic of Korea, Democratic People's Republic of Korea, Russian

Federation, Mongolia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan.

2. This report is based on data gathering and interpretation of existing information, and through questionnaires

related to information on sources, environmental concentrations and impacts of PTS, and also by

participating in two technical workshops, using a Regional expert network comprising scientists,

researchers, and representatives from government, industry and NGOs in different countries within this

Region.

3. There is wide variation between the 11 countries of this Region in terms of geography, industrialization,

economic development and environmental monitoring and remediation. These variations are reflected in

the amount of information available on PTS and their management. In general, data on PTS within the

Region is still rather sparse especially in countries with their economies in transition.

4. The results of the scoring exercise derived from the 1st Technical Workshop indicated that PCDD/PCDF,

PCBs, PAHs, DDT and HCH are chemicals of Regional concern meaning that there is either a) a major

production of the chemical for local and export use, b) evidence of the chemical as a contaminant in large

scale production of other chemicals, c) known emissions of the chemical from large scale incinerators or

chlorine bleaching of pulp or other related combustion facilities, d) evidence of leakage from major

stockpiles of the chemical, e) large-scale use of the chemical throughout the Region, and/or f) spatial and/or

temporal trends increasing Regionally from levels above threshold. With regard to data gaps, there is

insufficient and/or unreliable data on 8 of the 18 chemicals. These are mainly industrial chemicals (PCBs,

PBDE, HCB) and unintentional by-products (PCDD/PCDF, PAHs). There is also insufficient information

available for PCP and organic mercury compounds.

5. The environmental levels, toxicological and ecotoxicological effects of PTS within the Region have been

assessed by means of data collection and literature review. The results of the scoring exercise derived from

the 2nd Technical Workshop revealed that PCDD/PCDF, PCBs, DDT and PAHs are chemicals of Regional

concern in terms of environmental levels and ecotoxicological effects, and these five plus HCH are

Regional concern for human health. With regards to data gaps, there are insufficient reliable data on 7 of

the 18 chemicals. These chemicals are mainly industrial chemicals (PCBs, HCH, and PBDE) and

unintentional by-products (PCDD/PCDF, PAHs). There is also insufficient data related to DDT and

toxaphene. More information is needed concerning the temporal and spatial distributions of PTS in

different ecological compartments, especially in developing countries and countries with their economies in

transition. It is difficult to compare data generated by different countries using different sampling, sample

preparation and analytical methods.

6. Due to the wide range of meteorological and geographical parameters of Region VI, there is insufficient

information on the pathways of contaminant transport. Some countries have experience of transport

assessment by modelling: such as hemispheric MSCE-POP by EMEP, multimedia modelling by Korea

(POPsME and EDCSeoul) and Grid-Catchments integrated MMM by Japan. In general, the transboundary

transport of PTS within the Region is not yet well described neither by modelling or monitoring

approaches. Source inventory data, monitoring data, modelling data, and source pattern/fingerprints are

urgently needed for the assessment of PTS in the Region.

7. The Regional capacity and need to manage PTS of the 11 countries within the Region were assessed

through collection of information by country representatives. Japan and Republic of Korea, especially the

former, have comparatively well-established PTS management systems within the Region. China has

monitored the import and export of toxic chemicals since 1994, and is in the process of establishing an

inventory of POPs, pesticides and PDF-B with a national implementation plan (NIP) as required by the

Sockholm Convention. The Russian Federation started an environmental administration of chemicals and

relevant research some time ago whilst the management of PTS in other countries was initiated more

vii

recently. The difficulties involved in the management of PTS for most countries within the Region include

a) lack of funds, b) lack of information, c) lack of advanced or best available technology, d) insufficient

knowledge and training of special personnel, e) low public awareness, and f) lack of coordination of

government departments dealing with PTS.

8. It can be concluded that the major barriers of PTS management of developing countries and countries with

economies in transition in the Region is the lack of fund for technology transfer. Safe disposal of obsolete

pesticides such as DDT and their substitutes should receive high priority. Capacity building for technical

and management personnel to deal with PTS, and raising the awareness of the general public are urgently

need in these countries. A Regional organization is recommended to be established for setting up a

monitoring network using standardized methodologies. The more reliable data generated could be used to

more accurately assess the fates and effects, including the transboudnary movement of PTS in the Region.

viii

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 OVERVIEW OF THE RBA PTS PROJECT

Following the recommendations of the Intergovernmental Forum on Chemical Safety, the UNEP Governing

Council decided in February 1997 (Decision 19/13 C) that immediate international action should be initiated to

protect human health and the environment through measures which will reduce and/or eliminate the emissions

and discharges of an initial set of twelve persistent organic pollutants (POPs). Accordingly an

Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC) was established with a mandate to prepare an international

legally binding instrument for implementing international action on certain persistent organic pollutants. These

series of negotiations have resulted in the adoption of the Stockholm Convention in 2001. The initial 12

substances fitting these categories that have been selected under the Stockholm Convention include: aldrin,

endrin, dieldrin, chlordane, DDT, toxaphene, mirex, heptachlor, hexachlorobenzene, PCBs, dioxins and furans.

Beside these 12, there are many other substances that satisfy the criteria listed above for which their sources,

environmental concentrations and effects are to be assessed.

Persistent toxic substances can be manufactured substances for use in various sectors of industry, pesticides, or

by-products of industrial processes and combustion. To date, their scientific assessment has largely

concentrated on specific local and/or Regional environmental and health effects, in particular "hot spots" such

as the Great Lakes Region of North America or the Baltic Sea.

The substances of greatest concern are anthropogenic organic compounds with certain distinctive

characteristics:

· PERSISTENCE IN THE ENVIRONMENT

· RESISTANCE TO DEGRADATION

· ACUTE AND CHRONIC TOXICITY

· BIO-ACCUMULATION

· LONG RANGE TRANSPORT BY AIR, WATER OR MIGRATORY SPECIES ACROSS STATE

BOUNDARIES

1.1.1 Objectives

There is a need for a scientifically-based assessment of the nature and scale of the threats to the environment

and its resources posed by persistent toxic substances that will provide guidance to the international community

concerning the priorities for future remedial and preventive action. The assessment will lead to the

identification of priorities for intervention, and through application of a root cause analysis will attempt to

identify appropriate measures to control, reduce or eliminate releases of PTS, at national, Regional or global

levels.

The objective of the project is to deliver a measure of the nature and comparative severity of damage and

threats posed at national, Regional and ultimately at global levels by PTS. This will provide the GEF with a

science-based rationale for assigning priorities for action among and between chemical related environmental

issues, and to determine the extent to which differences in priority exist among Regions.

1.1.2 Results

The project relies upon the collection and interpretation of existing data and information as the basis for the

assessment. No research will be undertaken to generate primary data, but projections will be made to fill

data/information gaps, and to predict threats to the environment. The proposed activities are designed to obtain

the following expected results:

· Identification of major sources of PTS at the Regional level;

· Impact of PTS on the environment and human health;

· Assessment of transboundary transport of PTS;

· Assessment of the root causes of PTS related problems, and Regional capacity to manage these

1

problems;

· Identification of Regional priority PTS related environmental issues; and

· Identification of PTS related priority environmental issues at the global level.

The outcome of this project will be a scientific assessment of the threats posed by persistent toxic substances to

the environment and human health. The activities to be undertaken in this project comprise an evaluation of the

sources of persistent toxic substances, their levels in the environment and consequent impact on biota and

humans, their modes of transport over a range of distances, the existing alternatives to their use and remediation

options, as well as the barriers that prevent their good management.

1.2 METHODOLOGY

1.2.1 Regional

Divisions

To achieve these results, the globe is divided into 12 Regions namely: Arctic, North America, Europe,

Mediterranean, Sub-Saharan Africa, Indian Ocean, Central and North East Asia (Western North Pacific), South

East Asia and South Pacific, Pacific Islands, Central America and the Caribbean, Eastern and Western South

America, Antarctica. The twelve Regions were selected based on obtaining geographical consistency while

trying to reside within financial constraints.

1.2.2 Management

Structure

The project is directed by the project manager who is located at UNEP Chemicals in Geneva, Switzerland. A

Steering Group comprising of representatives of other relevant intergovernmental organisations along with

participation from industry and the non-governmental community is established to monitor the progress of the

project and provide direction for the project manager. Each Region is controlled by a Regional coordinator

assisted by a team of approximately 4 persons. The co-ordinator and the Regional team are responsible for

promoting the project, the collection of data at the national level and to carry out a series of technical and

priority setting workshops for analysing the data on PTS on a Regional basis. Besides the 12 POPs from the

Stockholm Convention, the Regional team selects the chemicals to be assessed for its Region with selection

open for review during the various workshops undertaken throughout the assessment process. Each team writes

the Regional report for the respective Region.

1.2.3 Data

Processing

Data is collected on sources, environmental concentrations, human and ecological effects through

questionnaires that are filled in at the national level. The results from this data collection along with

presentations from Regional experts at the technical workshops, are used to develop Regional reports on the

PTS selected for analysis. A priority setting workshop with participation of representatives from each country

results in priorities being established regarding the threats and damages of these substances to each Region.

The information and conclusions derived from the 12 Regional reports will be used to develop a global report

on the state of these PTS in the environment.

The project is not intended to generate new information but to rely on existing data and its assessment to arrive

at priorities for these substances. The establishment of a broad and wide- ranging network of participants

involving all sectors of society was used for data collection and subsequent evaluation. Close cooperation with

other intergovernmental organizations such as UNECE, WHO, FAO, UNPD, World Bank and others was

obtained. Most have representatives on the Steering Group Committee that monitors the progress of the

project and critically reviews its implementation. Contributions were garnered from UNEP focal points, UNEP

POPs focal points, national focal points selected by the Regional teams, industry, government agencies,

research scientists and NGOs.

1.2.4 Project Funding

The project costs approximately US$4.2 million funded mainly by the Global Environment Facility (GEF) with

sponsorship from countries including Australia, France, Germany, Sweden, Switzerland and the USA. The

project runs between September, 2000 to April, 2003 with the intention that the reports be presented to the first

meeting of the Conference of the Parties of the Stockholm Convention projected for 2003/4.

2

1.3 SCOPE OF THE CENTRAL AND NORTH EAST ASIA REGIONAL ASSESSMENT

As defined in the UNEP/GEF's Guidance Document for the Collection, Assembly and Evaluation of Data on

Sources, Environmental Levels and Impacts of Persistent Toxic Substances, persistent toxic substances share

the following characteristics (UNEP, 2000):

· organic (including organometallic) substances;

· slowly degraded in the environment;

· accumulating in biota and;

· toxic

Many PTS have the ability to be transported over long distances across international boundaries through

atmospheric, aquatic or biological media. They are detectable even in areas where the chemicals have never

been used. Due to their affinity to lipids, PTS are absorbed by the fatty tissue of people and animals. They are

bioaccumulated and biomagnified through the food chain. PTS pose adverse health effects, such as

reproductive disorders, developmental deformities and cancer in both humans and wildlife. As a consequence

to their significant threat to both our environment and to our health, PTS are a major concern at the local,

national, Regional and global level. A subset of the PTS are Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) which are

organochlorine compounds that persist in the environment, resist degradation, and produce acute and chronic

toxicity.

The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) has identified twelve POPs to be the initial chemicals

targeted for global elimination or restriction of production and use. Under the Stockholm Convention, an

international legally binding treaty formally adopted on 22 May 2001, global awareness on the adverse effects

of POPs has been heightened. The treaty requires governments from over 122 countries to take action on the

POPs through minimizing and eliminating the production, import, export, disposal, and use. The twelve POPs,

also known as the dirty dozen, consists of the pesticides aldrin, chlordane, DDT, dieldrin, endrin,

hexachlorobenzene, heptachlor, mirex, and toxaphene; the industrial chemicals polychlorinated biphenyls

(PCBs) and hexachlorobenzene (which is also a pesticide mentioned above); and the unintentional by-

products polychlorinated dibenzoparadioxins (PCDD) and polychlorinated dibenzofurans (PCDF). The

treaty comes into force when it has been ratified by 50 countries. It is a sound and effective treaty that can be

updated and expanded over the decades to proactively manage POPs. The Stockholm Convention has

provisions for adding a chemical to the list of POPs if the chemical meets the criteria for persistence in the

environment, bioaccumulation, and transportability. This provision helps to ensure that the treaty remains

dynamic and responsive.

Most of the 12 POPs are subject to an immediate ban, however, DDT has been granted a health-related

exemption because it is needed in many countries to control malarial mosquitoes. These countries are permitted

to use DDT until a suitable alternative is found.

The objectives of the Regionally Based Assessment of Persistent Toxic Substances project are complementary

to the Stockholm Convention. The project a) identifies sources of PTS; b) assesses the impact of PTS on human

health and the environment; c) assesses transboundary pathways of PTS, d) assesses root causes of PTS

problems and capacity to manage Regionally; and e) identifies Regional and global priority PTS environmental

issues.

For this project, the globe has been divided into 12 Regions -Arctic, North America, Europe, Mediterranean,

Sub-Saharan Africa, Indian Ocean, Central and North East Asia, South East Asia and South Pacific, Pacific

islands, Central America and the Caribbean, Eastern and Western South America, and Antarctica. In each

Region, the collection of PTS data is to be managed by a Regional Co-ordinator who is assisted by a team of

approximately 4 persons. Each Region is to collect information on the twelve Stockholm POPs in addition to

other PTS which are of potential concern for the Region. The following is a list of chemicals provided by

UNEP Chemicals for possible consideration by each Region.

3

Table 1.1: List of PTS for Regional Consideration

Stockholm Convention POPs

Other PTS

Aldrin

Chlordecone

Chlordane

Hexabromobiphenyl

DDT

HCH

Dieldrin

PAHs

Endrin

Polybrominated Diphenyl Ether (PBDE)

Heptachlor

Chlorinated Paraffins

Hexachlorobenzene (HCB)

Endosulphan

Mirex

Atrazine

Toxaphene

Pentachlorophenol (PCP)

PCBs

Organic Mercury Compounds

Dioxins

Organic Tin Compounds

Furans

Organic Lead Compounds

Phthalates

Octylphenols

Nonylphenols

Upon consultations with experts within the Region, the Regional team of the Central and North East Asia

selected the following PTS in addition to the 12 POPs to be considered of potential concern for the Region:

· HCH

· Pentachlorophenol (PCP)

· PAHs

· Organic Mercury Compounds

· PBDE

· Organic Tin Compounds

The Stockholm Convention allows participating parties to register specific exemptions for the 12 POPs. The

following is a list, received as of 22 May 2001, for specific exemptions for the countries of Region VII (UNEP,

2001a) (Table 1.2). It should be noted that the list is not a preliminary draft of the register of specific

exemptions to be established under article 4 of the Convention.

Table 1.2 Extract from Revised List of Requests for Specific Exemptions in Annex A and Annex B and acceptable

purposes in Annex B to the Stockholm Convention (UNEP, 2001a)

Country

Specific exemption or acceptable purpose

China

Production and use of chlordane as a termiticide in buildings and dams

Production and use of hexachlorobenzene as an intermediate

Production and use of mirex as a termiticide

Production and use of DDT as an intermediate

Production and use of DDT for disease vector use in accordance with Part II of Annex

B of the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants

Japan

Wooden articles in use treated with chlordane as a termiticide in the structures of

houses

Wooden articles in use treated with heptachlor as a termiticide in the structures of

houses

Republic of Korea

Use of chlordane as an additive in plywood adhesives

Use of heptachlor in articles in use in general

Use of PCBs in articles in use in accordance with Part II of Annex A of the Stockholm

Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants

Russian Federation

Use of PCBs in dielectric solvents for industrial electric equipment

Production and use of hexachlorobenzene as an intermediate Production and use of

DDT for disease vector use in accordance with Part II of Annex B of the Stockholm

Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants

4

1.3.1 Existing

Assessments

Assessment of PTS in some of the countries of the Region, especially in the more developed countries, has

been conducted. The Ministry of the Environment of Japan has been systematically conducting surveys for

nearly three decades to monitor environmental levels of some of the POPs, such as DDT and HCB (Japan

started monitoring in 1974). In 2002, the Ministry of the Environment reorganised the environmental

monitoring and started POPs monitoring. In the Republic of Korea, research projects on POPs/PTS include the

10-year National Research Plan (1999-2008) and projects to investigate endocrine disrupting chemicals.

Chemical information exchange systems such as Chem-Net Korea and ESCAP Clearinghouse system have

been implemented for public dissemination of PTS information. In China, preliminary surveys on PCBs were

carried out in the middle of the 1990's. A two-year project to provide an inventory of POP pesticides has

recently began. Furthermore, laboratories for the monitoring of PCDD/PCDF are also being established in

China. In Hong Kong SAR, a 3-year project "A Study of Toxic Substances Pollution in Hong Kong",

commissioned by the Environmental Protection Department, is currently being finalised. Its primary focus is on

identifying and quantifying pollutants, including PTS, released into local waters to establish a Priority Toxic

Substances List. The Russian Federation has concentrated on assessment of the PCB inventory and sources and

environmental levels of PCDD/PCDF. In some of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) countries,

compilation of inventories of sources has only recently began. For example, Tajikistan started an inventory of

PTS sources in 1998. In Mongolia, source inventory of PTS has not started yet due to lack of professional

capacity.

1.3.2 Intra-Regional Links and Collaboration

Within Region VII, only Japan and Republic of Korea have collaboration projects on PTS. The Ministry of

Environment, National Institute of Environmental Research (NIER), of the Republic of Korea has been

working closely with the Ministry of the Environment, National Institute for Environmental Studies (NIES) of

Japan on a project to investigate endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDC), such as PCDD/PCDF and PCBs.

1.3.3 Omissions and Weaknesses

Information for this report is based mainly on literature review and information submitted by country experts

and relevant government departments. Information collected via questionnaires prepared by UNEP-Chemicals

on sources, concentrations, and impacts has not been comprehensive due to lack of human resources and lack

of available data from some of the countries. Of the completed questionnaires received, the majority of the

information has been on environmental concentrations with little information provided in relation to sources of

PTS. In addition to poor documentation of source inventories of pesticides, information with regards to the fate

of the pesticides has not been well documented (i.e. whether the pesticides have been exported, stockpiled,

etc.). Previously, there have not been any formal established communication channels on PTS between the

countries of the Region (perhaps except Japan and Republic of Korea), therefore dialogue concerning PTS

issues has been weak and should be developed.

1.4 METHODOLOGY

The development of this report was carried out through the gathering and interpretation of existing information,

including literature review (journals, reports, databases), and through the contribution of a Regional expert

network. Prior to this project, there had been no Regionally-coordinated network on PTS, aside from a

collaborative project between two countries (Japan and Republic of Korea). To establish the Regional expert

network, country experts on PTS, scientists, researchers, government, industry and NGOs were informed of the

UNEP/GEF project and invited to participate. The expert network contributed to the project by filling

questionnaires relating to information on sources, environmental concentrations and impacts of PTS, and by

participating in two technical workshops. The questionnaires, thirteen in total, were developed by UNEP-

Chemicals specifically for this project and can be found in the project website: www.chem.unep.ch/pts. All

completed questionnaires were stored in the project website database. During the two technical workshops- 1st

Technical Workshop (Sources and Concentration of PTS in the Environment, 18-20 March 2002, Tokyo,

Japan) and the 2nd Technical Workshop ((Eco)toxicological Impact and Transboundary Transport of Persistent

Toxic Substances, 14-16 May 2002, Hong Kong, PR China), background discussion papers were presented by

the Regional team, and invited participants presented technical papers on the situation of PTS in their countries.

Information contained within technical papers was incorporated into the background discussion papers for the

development of this draft Regional report. During the technical workshops, the participants were divided into

5

working groups to discuss prioritisation of sources, environmental levels, (eco)toxicological effects,

transboundary transport of chemicals, and data gaps of each of the 18 chemicals with the aid of a scoring

system developed by UNEP-Chemicals. In final plenary sessions, participants from the respective workshops,

upon collective agreement, assigned overall scores to each chemical. The scoring mechanism was a tool used to

prioritise the chemicals. The scoring results were a collective effort of all the participants of the workshops.

The scoring sheet (Annex 1) together with the final scores are listed in Chapter 2 and Chapter 3.

1.5 GENERAL DEFINITIONS OF CHEMICALS

The following are the general definitions of the 18 persistent toxic substances presented as the 12 Stockholm

Convention POPs followed by the 6 Regional specific chemicals:

Stockholm Convention POPs

1.5.1 Persistent Toxic Substances - Pesticides

1.5.1.1 Aldrin

Chemical Name: 1,2,3,4,10,10-Hexachloro-1,4,4a,5,8,8a-hexahydro-1,4-endo,exo-5,8-dimethanonaphthalene

(C12H8Cl6).

CAS Number: 309-00-2

Properties: Solubility in water: 27 µg/L at 25°C; vapour pressure: 2.3 x 10-5 mm Hg at 20°C; log KOW: 5.17-

7.4.

Discovery/Uses: It has been manufactured commercially since 1950, and used throughout the world up to the

early 1970's to control soil pests such as corn rootworm, wireworms, rice water weevil, and grasshoppers. It

has also been used to protect wooden structures from termites.

Persistence/Fate: Readily metabolised to dieldrin by both plants and animals. Biodegradation is expected to be

slow and it binds strongly to soil particles, and is resistant to leaching into groundwater. Aldrin was classified

as moderately persistent with half-life in soil and surface waters ranging from 20 days to 1.6 years.

Toxicity: Aldrin is toxic to humans; the lethal dose for an adult has been estimated to be about 80 mg/kg body

weight. The acute oral LD50 in laboratory animals is in the range of 33 mg/kg body weight for guinea pigs to

320 mg/kg body weight for hamsters. The toxicity of aldrin to aquatic organisms is quite variable, with aquatic

insects being the most sensitive group of invertebrates. The 96-h LC50 values range from 1-200 µg/L for

insects, and from 2.2-53 µg/L for fish. The maximum residue limits in food recommended by FAO/WHO

varies from 0.006 mg/kg milk fat to 0.2 mg/kg meat fat. Water quality criteria between 0.1 to 180 µg/L have

been published.

1.5.1.2 Chlordane

Chemical Name: 1,2,4,5,6,7,8,8-Octachloro-2,3,3a,4,7,7a-hexahydro-4,7-methanoindene (C10H6Cl8).

CAS Number: 57-74-9

Properties: Solubility in water: 56 µg/L at 25°C; vapour pressure: 0.98 x 10-5 mm Hg at 25 °C; log KOW: 4.58-

5.57.

Discovery/Uses: Chlordane appeared in 1945 and was used primarily as an insecticide for control of

cockroaches, ants, termites, and other household pests. Technical chlordane is a mixture of at least 120

compounds. Of these, 60-75% are chlordane isomers, the remainder being related to endo-compounds including

heptachlor, nonachlor, diels-alder adduct of cyclopentadiene and penta/hexa/octachlorocyclopentadienes.

Persistence/Fate: Chlordane is highly persistent in soils with a half-life of about 4 years. Its persistence and

high partition coefficient promotes binding to aquatic sediments and bioconcentration in organisms.

Toxicity: LC50 from 0.4 mg/L (pink shrimp) to 90 mg/L (rainbow trout) have been reported for aquatic

organisms. The acute toxicity for mammals is moderate with an LD50 in rat of 200-590 mg/kg body weight

(19.1 mg/kg body weight for oxychlordane). The maximum residue limits for chlordane in food are, according

to FAO/WHO between 0.002 mg/kg milk fat and 0.5 mg/kg poultry fat. Water quality criteria of 1.5 to 6 µg/L

have been published. Chlordane has been classified as a substance for which there is evidence of endocrine

disruption in an intact organism and possible carcinogenicity to humans.

6

1.5.1.3 Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane

(DDT)

Chemical Name: 1,1,1-Trichloro-2,2-bis-(4-chlorophenyl)-ethane (C14H9Cl5).

CAS Number: 50-29-3.

Properties: Solubility in water: 1.2-5.5 µg/L at 25°C; vapour pressure: 0.2 x 10-6 mm Hg at 20°C; log KOW:

6.19 for pp'-DDT, 5.5 for pp'-DDD and 5.7 for pp'-DDE.

Discovery/Use: DDT appeared for use during World War II to control insects that spread diseases like malaria,

dengue fever and typhus. Following this, it was widely used on a variety of agricultural crops. The technical

product is a mixture of about 85% pp'-DDT and 15% op'-DDT isomers.

Persistence/Fate: DDT is highly persistent in soils with a half-life of up to 15 years and of 7 days in air. It also

exhibits high bioconcentration factors (in the order of 50000 for fish and 500000 for bivalves). In the

environment, the product is metabolised mainly to DDD and DDE.

Toxicity: The lowest dietary concentration of DDT reported to cause egg shell thinning was 0.6 mg/kg for the

black duck. LC50 of 1.5 mg/L for largemouth bass and 56 mg/L for guppy have been reported. The acute

toxicity of DDT for mammals is moderate with an LD50 in rat of 113-118 mg/kg body weight. DDT has been

shown to have an estrogen-like activity, and possible carcinogenic activity in humans. The maximum residue

level in food recommended by WHO/FAO range from 0.02 mg/kg milk fat to 5 mg/kg meat fat. Maximum

permissible DDT residue levels in drinking water (WHO) is 1.0 µg/L.

DDT for control of disease vectors is exempt from ban under Annex B of the Stockholm Convention.

There is no continuous record of world production of DDT, and estimates of its usage vary. UNEP suggested

that annual world consumption from 1971 to 1981 was 68,800 t (UNEP, 1990). Currently, most uses of DDT is

for public health vector control. In 1990, the production of DDT was estimated at 2800 t

(UNEP/FAO/PIC/INC.1/inf.1, 1996).

1.5.1.4 Dieldrin

Chemical Name: 1,2,3,4,10,10-Hexachloro-6,7-epoxy-1,4,4a,5,6,7,8,8a-octahydroexo-1,4-endo-5,8-

dimethanonaphthalene (C12H8Cl6O).

CAS Number: 60-57-1

Properties: Solubility in water: 140 µg/L at 20°C; vapour pressure: 1.78 x 10-7 mm Hg at 20°C; log KOW:

3.69-6.2.Discovery/Uses: It appeared in 1948 after World War II and used mainly for the control of soil insects

such as corn rootworms, wireworms and catworms.

Persistence/Fate: It is highly persistent in soils, with a half-life of 3-4 years in temperate climates, and

bioconcentrates in organisms. The persistence in air has been estimated in 4-40 h.

Toxicity: The acute toxicity for fish is high (LC50 between 1.1 and 41 mg/L) and moderate for mammals (LD50

in mouse and rat ranging from 40 to 70 mg/kg body weight). However, a daily administration of 0.6 mg/kg to

rabbits adversely affected the survival rate. Aldrin and dieldrin mainly affect the central nervous system but

there is no direct evidence that they cause cancer in humans. The maximum residue limits in food

recommended by FAO/WHO varies from 0.006 mg/kg milk fat and 0.2 mg/kg poultry fat. Water quality

criteria between 0.1 to 18 µg/L have been published.

1.5.1.5 Endrin

Chemical Name: 3,4,5,6,9,9-Hexachloro-1a,2,2a,3,6,6a,7,7a-octahydro-2,7:3,6-dimethanonaphth[2,3-

b]oxirene (C12H8Cl6O).

CAS Number: 72-20-8

Properties: Solubility in water: 220-260 µg/L at 25 °C; vapour pressure: 2.7 x 10-7mm Hg at 25°C; log KOW:

3.21-5.34.

Discovery/Uses: It has been used since the 50s against a wide range of agricultural pests, mostly on cotton but

also on rice, sugar cane, maize and other crops. It has also been used as a rodenticide.

Persistence/Fate: Is highly persistent in soils (half-lives of up to 12 years have been reported in some cases).

Bioconcentration factors of 14 to 18,000 have been recorded in fish, after continuous exposure.

7

Toxicity: Endrin is very toxic to fish, aquatic invertebrates and phytoplankton; the LC50 values are mostly less

than 1 µg/L. The acute toxicity is high in laboratory animals, with LD50 values of 3-43 mg/kg, and a dermal

LD50 of 5-20 mg/kg in rats. Long term toxicity in the rat has been studied over two years and a NOEL of 0.05

mg/kg bw/day was found.

1.5.1.6 Heptachlor

Chemical Name: 1,4,5,6,7,8,8-Heptachloro-3a,4,7,7a-tetrahydro-4,7-methanoindene (C10H5Cl7).

CAS Number: 76-44-8

Properties: Solubility in water: 180 µg/L at 25°C; vapour pressure: 0.3 x 10-5mm Hg at 20°C; log KOW: 4.4-

5.5.

Production/Uses: Heptachlor is used primarily against soil insects and termites, but also against cotton insects,

grasshoppers, and malaria mosquitoes. Heptachlor epoxide is a more stable breakdown product of heptachlor.

Persistence/Fate: Heptachlor is metabolised in soils, plants and animals to heptachlor epoxide, which is more

stable in biological systems and is carcinogenic. The half-life of heptachlor in soil is in temperate Regions 0.75

2 years. Its high partition coefficient provides the necessary conditions for bioconcentrating in organisms.

Toxicity: The acute toxicity of heptachlor to mammals is moderate (LD50 values between 40 and 119 mg/kg

have been published). The toxicity to aquatic organisms is higher and LC50 values down to 0.11 µg/L have been

found for pink shrimp. Limited information is available on the effects in humans and studies are inconclusive

regarding heptachlor and cancer. The maximum residue levels recommended by FAO/WHO are between 0.006

mg/kg milk fat and 0.2 mg/kg meat or poultry fat.

1.5.1.7 Hexachlorobenzene

(HCB)

Chemical Name: Hexachlorobenzene (C6Cl6)

CAS Number: 118-74-1

Properties: Solubility in water: 50 µg/L at 20°C; vapour pressure: 1.09 x 10-5 mm Hg at 20°C; log KOW: 3.93-

6.42.

Discovery/Uses: It was first introduced in 1945 as fungicide for seed treatments of grain crops, and used to

make fireworks, ammunition, and synthetic rubber. Today it is mainly a by-product in the production of a large

number of chlorinated compounds, particularly lower chlorinated benzenes, solvents and several pesticides.

HCB is emitted to the atmosphere in flue gases generated by waste incineration facilities and metallurgical

industries.

Persistence/Fate: HCB has an estimated half-life in soils of 2.7-5.7 years and of 0.5-4.2 years in air. HCB has

a relatively high bioaccumulation potential and long half-life in biota.

Toxicity: LC50 for fish varies between 50 and 200 µg/L. The acute toxicity of HCB is low with LD50 values of

3.5 mg/g for rats. Mild effects of the [rat] liver have been observed at a daily dose of 0.25 mg HCB/kg bw.

HCB is known to cause liver disease in humans (porphyria cutanea tarda) and has been classified as a possible

carcinogen to humans by IARC.

1.5.1.8 Mirex

Chemical Name: 1,1a,2,2a,3,3a,4,5,5a,5b,6-Dodecachloroacta-hydro-1,3,4-metheno-1H-

cyclobuta[cd]pentalene (C10Cl12).

CAS Number: 2385-85-5

Properties: Solubility in water: 0.07 µg/L at 25°C; vapour pressure: 3 x 10-7 mm Hg at 25°C; log KOW: 5.28.

Discovery/Uses: The use in pesticide formulations started in the mid 1950's largely focused on the control of

ants. It is also a fire retardant for plastics, rubber, paint, paper and electrical goods. Technical grade

preparations of mirex contain 95.19% mirex and 2.58% chlordecone, the rest being unspecified.

Persistence/Fate: Mirex is considered to be one of the most stable and persistent pesticides, with a half-life is

soils of up to 10 years. Bioconcentration factors of 2600 and 51400 have been observed in pink shrimp and

fathead minnows, respectively. It is capable of undergoing long-range transport due to its relative volatility

(VPL = 4.76 Pa; H = 52 Pa m 3 /mol).

8

Toxicity: The acute toxicity of Mirex for mammals is moderate with an LD50 in rat of 235 mg/kg and dermal

toxicity in rabbits of 80 mg/kg. Mirex is also toxic to fish and can affect their behaviour (LC50 (96 h) from 0.2

to 30 mg/L for rainbow trout and bluegill, respectively). Delayed mortality of crustaceans occurred at 1 µg/L

exposure levels. There is evidence of its potential for endocrine disruption and possibly carcinogenic risk to

humans.

1.5.1.9 Toxaphene

Chemical Name: Polychlorinated bornanes and camphenes (C10H10Cl8).

CAS Number: 8001-35-2

Properties: Solubility in water: 550 µg/L at 20°C; vapour pressure: 3.3 x 10-5 mm Hg at 25°C; log KOW : 3.23-

5.50.

Discovery/Uses: Toxaphene has been in use since 1949 as a nonsystemic insecticide with some acaricidal

activity, primarily on cotton, cereal grains fruits, nuts and vegetables. It was also used to control livestock

ectoparasites such as lice, flies, ticks, mange, and scab mites. The technical product is a complex mixture of

over 300 congeners, containing 67-69% chlorine by weight.

Persistence/Fate: Toxaphene has a half life in soil from 100 days up to 12 years. It has been shown to

bioconcentrate in aquatic organisms (BCF of 4247 in mosquito fish and 76000 in brook trout).

Toxicity: Toxaphene is highly toxic in fish, with 96-hour LC50 values in the range of 1.8 µg/L in rainbow trout

to 22 µg/L in bluegill. Long term exposure to 0.5 µg/L reduced egg viability to zero. The acute oral toxicity is

in the range of 49 mg/kg body weight in dogs to 365 mg/kg in guinea pigs. In long term studies NOEL in rats

was 0.35 mg/kg bw/day, LD50 ranging from 60 to 293 mg/kg bw. For toxaphene exists a strong evidence of the

potential for endocrine disruption. Toxaphene is carcinogenic in mice and rats and is of carcinogenic risk to

humans, with a cancer potency factor of 1.1 mg/kg/day for oral exposure.

1.5.2 Persistent Toxic Substances Industrial Compounds

1.5.2.1 Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs)

Chemical Name: Polychlorinated biphenyls (C12H(10-n)Cln, where n is within the range of 1-10).

CAS Number: Various (e.g. for Aroclor 1242, CAS No.: 53469-21-9; for Aroclor 1254, CAS No.: 11097-69-

1);

Properties: Water solubility decreases with increasing chlorination: 0.01 to 0.0001 µg/L at 25°C; vapour

pressure: 1.6-0.003 x 10-6 mm Hg at 20°C; log KOW: 4.3-8.26.

Discovery/Uses: PCBs were introduced in 1929 and were manufactured in different countries under various

trade names (e.g., Aroclor, Clophen, Phenoclor). They are chemically stable and heat resistant, and were used

worldwide as transformer and capacitor oils, hydraulic and heat exchange fluids, and lubricating and cutting

oils. Theoretically, a total of 209 possible chlorinated biphenyl congeners exist, but only about 130 of these are

likely to occur in commercial products.

Persistence/Fate: Most PCB congeners, particularly those lacking adjacent unsubstituted positions on the

biphenyl rings (e.g., 2,4,5-, 2,3,5- or 2,3,6-substituted on both rings) are extremely persistent in the

environment. They are estimated to have half-lives ranging from three weeks to two years in air and, with the

exception of mono- and di-chlorobiphenyls, more than six years in aerobic soils and sediments. PCBs also have

extremely long half-lives in adult fish, for example, an eight-year study of eels found that the half-life of

CB153 was more than ten years.

Toxicity: LC50 for the larval stages of rainbow trout is 0.32 µg/L with a NOEL of 0.01 µg/L. The acute toxicity

of PCB in mammals is generally low and LD50 values in rat of 1 g/kg bw. IARC has concluded that PCB are

carcinogenic to laboratory animals and probably also for humans. They have also been classified as substances

for which there is evidence of endocrine disruption in an intact organism.

9

1.5.3 Persistent Toxic Substances Unintentional By-Products

1.5.3.1 Polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins (PCDD) and Polychlorinated dibenzofurans (PCDF)

Chemical Name: PCDD (C12H(8-n)ClnO2) and PCDF (C12H(8-n)ClnO) may contain between 1 and 8 chlorine

atoms. Dioxins and furans have 75 and 135 possible positional isomers, respectively.

CAS Number: Various (2,3,7,8-TetraCDD: 1746-01-6; 2,3,7,8-TetraCDF: 51207-31-9).

Properties: Solubility in water: in the range 0.43 0.0002 ng/L at 25°C; vapour pressure: 2 0.007 x 10-6 mm

Hg at 20°C; log KOW: in the range 6.60 8.20 for tetra- to octa-substituted congeners.

Discovery/Uses: They are by-products resulting from the production of other chemicals and from the low-

temperature combustion and incineration processes. They have no known use.

Persistence/Fate: PCDD/PCDF are characterised by their lipophilicity, semi-volatility and resistance to

degradation (half life of TCDD in soil of 10-12 years) and to long-range transport. They are also known for

their ability to bio-concentrate and biomagnify under typical environmental conditions.

Toxicity: The toxicological effects reported refers to the 2,3,7,8-substituted compounds (17 congeners) that

are agonist for the AhR. All the 2,3,7,8-substituted PCDDs and PCDFs plus coplanar PCBs (with no chlorine

substitution at the ortho positions) show the same type of biological and toxic response. Possible effects include

dermal toxicity, immunotoxicity, reproductive effects and teratogenicity, endocrine disruption and

carcinogenicity. At the present time, the only persistent effect associated with dioxin exposure in humans is

chloracne. The most sensitive groups are fetus and neonatal infants.

Effects on the immune systems in the mouse have been found at doses of 10 ng/kg bw/day, while reproductive

effects were seen in rhesus monkeys at 1-2 ng/kg bw/day. Biochemical effects have been seen in rats down to

0.1 ng/kg bw/day. In a re-evaluation of the TDI for dioxins, furans (and planar PCB), the WHO decided to

recommend a range of 1-4 TEQ pg/kg bw, although more recently the acceptable intake value has been set

monthly at 1-70 TEQ pg/kg bw.

1.5.4 Regional Specific Chemicals

1.5.4.1 Hexachlorocyclohexanes

(HCH)

Chemical Name: 1,2,3,4,5,6-Hexachlorocyclohexane (mixed isomers) (C6H6Cl6).

CAS Number: 608-73-1 (-HCH, lindane: 58-89-9).

Properties: -HCH: solubility in water: 7 mg/L at 20°C; vapour pressure: 3.3 x 10-5 mm Hg at 20°C; log KOW:

3.8.

Discovery/Uses: There are two principle formulations: "technical HCH", which is a mixture of various

isomers, including -HCH (55-80%), -HCH (5-14%) and -HCH (8-15%), and "lindane", which is essentially

pure -HCH. Historically, lindane was one of the most widely used insecticides in the world. Its insecticidal

properties were discovered in the early 1940s. It controls a wide range of sucking and chewing insects and has

been used for seed treatment and soil application, in household biocidal products, and as textile and wood

preservatives.

Persistence/Fate: Lindane and other HCH isomers are relatively persistent in soils and water, with half lives

generally greater than 1 and 2 years, respectively. HCH are much less bioaccumulative than other

organochlorines because of their relatively low lipophilicity. On the contrary, their relatively high vapour

pressures, particularly of the -HCH isomer, determine their long-range transport in the atmosphere. BCF for

lindane is 1400.

Toxicity: Lindane is moderately toxic for invertebrates and fish, with LC50 values of 20-90 µg/L. The acute

toxicity for mice and rats is moderate with LD50 values in the range of 60-250 mg/kg. Lindane was found to

have no mutagenic potential in a number of studies but endocrine disrupting activity.

1.5.4.2 Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs)

Chemical Name: PAHs are a group of compounds consisting of two or more fused aromatic rings.

CAS Number: Various

Properties: Solubility in water: 0.00014 -2.1 mg/L at 25ºC; vapour pressure: from 0.0015 x 10-9 to 0.0051

10

mmHg at 25°C; log KOW: 4.79-8.20

Discovery/Use: Most of these are formed during incomplete combustion of organic material and the

composition of PAHs mixture vary with the source(s) and also due to selective weathering effects in the

environment.

Persistence/Fate: Persistence of the PAHs varies with their molecular weight. The low molecular weight

PAHs are the most easily degraded. The reported half-lives of naphthalene, anthracene and benzo(e)pyrene in

sediment are 9, 43 and 83 hours, respectively, whereas for higher molecular weight PAHs, their half-lives are

up to several years in soils/sediments. The BCFs in aquatic organisms frequently range between 100-2000 and

it increases with increasing molecular size. Due to their wide distribution, the environmental pollution by PAHs

has aroused global concern.

Toxicity: The acute toxicity of low PAHs is moderate with an LD50 of naphthalene and anthracene in rat of 490

and 18000 mg/kg body weight respectively, whereas the higher PAHs exhibit higher toxicity and LD50 of

benzo(a)anthracene in mice is 10mg/kg body weight. In Daphnia pulex, LC50 for naphthalene is 1.0 mg/L, for

phenanthrene 0.1 mg/L and for benzo(a)pyrene is 0.005 mg/L. The critical effect of many PAHs in mammals is

their carcinogenic potential. The metabolic action of these substances produce intermediates that bind

covalently with cellular DNA. IARC has classified benz[a]anthracene, benzo[a]pyrene, and

dibenzo[a,h]anthracene as probable carcinogenic to humans. Benzo[b]fluoranthene and indeno[1,2,3-c,d]pyrene

were classified as possible carcinogens to humans.

1.5.4.3 Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers (PBDE)

Chemical Name: Polybrominated diphenyl ethers (C12H(10-n)BrnO, where n = 1-10). As in the case of PCBs the

total number of congeners is 209, with a predominance in commercial mixtures of the tetra-, penta- and octa-

substituted isomers.

CAS Number: Various (PeBDE: 32534-81-9; OBDE: 32536-52-0; DeBDE: 1163-19-5)

Properties: Solubility in water: 0.9 ng/L at 25°C (PeBDE); vapour pressure: 3.85 x 10-3 to <10-7 mmHg at 20-

25 °C; log KOW: 4.28 - 9.9.

Discovery/Uses: Since the 1960's, three commercial PBDE formulations have been in production. The

pentabrominated product is used principally to flame retard polyurethane foams in furniture, carpet underlay

and bedding. Commercial octa is a mixture of hexa- (10-12%), hepta- (44-46%), octa- (33-35%) and

nonabromodiphenyl (10-11%) ethers. It is used to treat a wide variety of thermoplastics and is recommended

for injection moulding applications such as high impact polystyrene (HIPS). The deca product (a single

congener) is used predominantly for textiles and denser plastics such as housings for a variety of electrical

products in particular TVs and computers.

Persistence/Fate: Data on environmental fate, although limited, suggest that biodegradation is not an important

degradation pathway, but that photodegradation may play a significant role. They have already been found in

high concentrations in marine birds and mammals from remote areas. The half-lives of PBDE components in rat

adipose tissue varies between 19 and 119 days, the higher values being for the higher brominated congeners.

Toxicity: The available data suggest that the lower (tetra- to hexa-) PBDE congeners are likely to be

carcinogens, endocrine disruptors, and/or neurodevelopmental toxicants. Studies in rats with commercial

PeBDE indicate a low acute toxicity via oral and dermal routes of exposure, with LD50 values > 2000 mg/kg

bw. In a 30-day study with rats, effects on the liver could be seen at a dose of 2 mg/kg bw/day, with a NOEL at

1mg/kg bw/day. The toxicity to Daphnia magna has also been investigated with a reported LC50 of 14 µg/L and

a NOEC of 4.9 µg/L. Although data on toxicology is limited, they have potential endocrine disrupting

properties, and there are concerns over the health effects of exposure.

1.5.4.4 Pentachlorophenol

(PCP)

Chemical Name: Pentachlorophenol (C6Cl5OH).

CAS Number: 87-86-5.

Properties: Solubility in water: 14 mg/L at 20°C; vapour pressure: 16 x 10-5 mm Hg at 20°C; log KOW: 3.32

5.86.

Discovery/Uses: It is used as insecticide (termiticide), fungicide, non-selective contact herbicide (defoliant)

and, particularly as wood preservative. It is also used in anti-fouling paints and other materials (e.g. textiles,

11

inks, paints, disinfectants and cleaners) as inhibitor of fermentation. Technical PCP contains trace amounts of

PCDD and PCDF

Persistence/Fate: The rate of photodecomposition increases with pH (t1/2 100 h at pH 3.3 and 3.5 h at pH 7.3).

Complete decomposition in soil suspensions takes >72 days, other authors reports half-life in soils of 23-178

days. Although enriched through the food chain, it is rapidly eliminated after discontinuing the exposure (t

1/2 =

10-24 h for fish). Highest measured BCF was 771.

Toxicity: It has been proven to be acutely toxic to aquatic organisms and have certain effects on human health

at very low concentrations. The 24-h LC50 values for trout were reported as 0.2 mg/L, and chronic toxicity

effects were observed at concentrations down to 3.2 µg/L. Mammalian acute toxicity of PCP is moderate-high.

LD50 oral in rat ranging from 50 to 210 mg/kg bw have been reported. LC50 ranged from 0.093 mg/L in

rainbow trout (48 h) to 0.77-0.97 mg/L for guppy (96 h) and 0.47 mg/L for fathead minnow (48 h).

1.5.4.5 Organic Mercury Compounds

Chemical Name: The main compound of concern is methyl mercury (HgCH3).

CAS Number: 22967-92-6

Properties: Solubility in water: 0.1 g/L at 21°C (HgCH3Cl) and 1.0 g/L at 25ºC (Hg(CH3)2); vapour pressure:

8.5 x 10-3 mm Hg at 25°C (HgCH3Cl); log KOW: 1.6 (HgCH3Cl) and 2.28 (Hg(CH3)2).

Production/Uses: There are many sources of mercury release to the environment, both natural (volcanoes,

mercury deposits, and volatilisation from the ocean) and human-related (coal combustion, chlorine alkali

processing, waste incineration, and metal processing). It is also used in thermometers, batteries, lamps,

industrial processes, refining, lubrication oils, and dental amalgams. Methyl mercury has no industrial uses; it is

formed in the environment by methylation of the inorganic mercurial ion mainly by microorganisms in the

water and soil.

Persistence/Fate: Mercury released into the environment can either stay close to its source for long periods, or

be widely dispersed on a Regional or even world-wide basis. Not only are methylated mercury compounds

toxic, but highly bioaccumulative as well. The increase in concentration of mercury as it transfers through the

aquatic food chain results in relatively high levels of mercury in fish consumed by humans. Ingested elemental

mercury is only 0.01% absorbed, but methyl mercury is nearly 100% absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract.

The biological half-life of mercury is 60 days.

Toxicity: Long-term exposure to organic mercury can permanently damage the brain, kidneys, and developing

fetus. The most sensitive target of low level exposure to metallic and organic mercury following short or long

term exposures appears to be the nervous system.

1.5.4.6 Organic Tin Compounds

Chemical Name: Organotin compounds comprise mono-, di-, tri- and tetrabutyl and triphenyl tin compounds.

They conform to the following general formula (n-C4H9)nSn-X and (C6H5)3Sn-X, where X is an anion or a

group linked covalently through a hetero-atom.

CAS Number: 56-35-9 (TBTO); 76-87-9 (TPTOH)

Properties: Solubility in water: 4 mg/L (TBTO) and 1 mg/L (TPTOH) at 25°C and pH 7; vapour pressure: 7.5

x 10-7 mm Hg at 20°C (TBTO) 3.5 x 10-8 mmHg at 50ºC (TPTOH); log KOW: 3.19 - 3.84. In sea water and

under normal conditions, TBT exists as three species in seawater (hydroxide, chloride, and carbonate).

Discovery/Uses: They are mainly used as antifouling paints (tributyl and triphenyl tin) for underwater

structures and ships. Minor identified applications are as antiseptic or disinfecting agents in textiles and

industrial water systems, such as cooling tower and refrigeration water systems, wood pulp and paper mill

systems, and breweries. They are also used as stabilizers in plastics and as catalytic agents in soft foam

production. It is also used to control the shistosomiasis in various parts of the world.

Persistence/Fate: Under aerobic conditions, TBT takes 1 to 3 months to degrade, but in anaerobic soils may

persist for more than 2 years. Because of the low water solubility it binds strongly to suspended material and

sediments. TBT is lipophilic and tends to accumulate in aquatic organisms. Oysters exposed to very low

concentrations exhibit BCF values from 1000 to 6000.

Toxicity: TBT is moderately toxic and all breakdown products are even less toxic. Its impact on the

environment was discovered in the early 1980's in France with harmful effects in aquatic organisms, such as

12

shell malformations of oysters, imposex in marine snails and reduced resistance to infection (e.g. in flounder).

Molluscs react adversely to very low levels of TBT (0.06-2.3 µg/L). Lobster larvae show a nearly complete

cessation of growth at just 1.0 µg /L TBT. In laboratory tests, reproduction was inhibited when female snails

exposed to 0.05-0.003 µg /L of TBT developed male characteristics. Large doses of TBT have been shown to

damage the reproductive and central nervous systems, bone structure, and the liver bile duct of mammals.

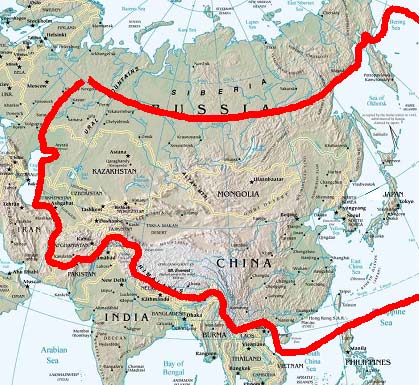

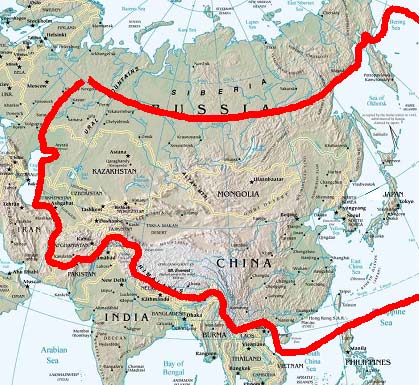

1.6 DEFINITION OF THE CENTRAL AND NORTH EAST ASIA REGION

The Central and North East Asia Region consists of the 11 countries: China, Japan, Republic of Korea,

Democratic People's of Korea, Mongolia, Russian Federation and the five Commonwealth of Independent

States (CIS)- Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. China and the Russian

Federation are two of the world's largest countries. The total population in the Region is estimated to be about

1.6 billion, a quarter of the world population. Agricultural activity is extensive in the Region and is an

important factor which may cause pesticide over usage, water pollution and water management problems.

China China is the third largest country in the world with a land area of 9.6 million km2. The land border is

22800 km long, and the coastline is 18000 km long. It is located approximately between latitudes 4ºN - 53ºN

and longitudes 73ºE 135ºE. It has the largest population in the world estimated to be 1.3 billion in July 2001

(excluding Taiwan province and Jinmen, Mazu Island of Fujian province which has a population of 22.3

million).

Since the start of the policy of economic reform and opening to the outside world in 1978, China's economy

has grown remarkably by positively affecting the agricultural and industrial sectors. Agricultural output

doubled in the 1980's, and industry expanded. The gross domestic product (GDP) was approximately 9600

billion in 2001. The major industries include metallurgy (iron, steel), coal, crude oil, machinery, textiles,

cement, chemicals, and electronics.

Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (SAR) and Macau SAR both have the power of self-governing

directly under the central government of China, according to the policy of "one country, two systems".

Japan Japan is a technologically advanced country consisting of a chain of islands located on the western edge

of the North Pacific Ocean east of the Korean Peninsula. The islands occupy a total area of approximately