UNITED NATIONS ENVIRONMENT PROGRAMME

EAST ASIAN REGIONAL COORDINATING UNIT

NATIONAL REPORT OF MALAYSIA

On the

Formulation of a Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis

And

Preliminary Framework of a Strategic

Action Programme for the Bay of Bengal

C O N T E N T S

Page

Chapter 1 :

NATIONAL REPORT OF MALAYSIA ON THE BAY OF

1

BENGAL LARGE MARINE ECOSYSTEM PROGRAMME

1.

INTRODUCTION

1

1.1 AIM OF REPOR T

1

1.2 MAJOR WATER-RELATED ENVIRONMENTAL

1

PROBLEMS

1.2.1 Air-Related Environmental Problems

2

1.3 COUNTRY BACKGROUND

4

Chapter 2

:

DETAILED ANALYSIS OF MAJOR WATER-RELATED

15

CONCERNS AND PRINCIPAL ISSUES

2.1 POLLUTION

15

2.1.1 Rivers

15

2.1.2 Sedimentation

17

2.1.3 Industrial Waste

17

2.1.4 Domestic Waste

18

2.1.5 Agricultural and Livestock Waste

19

2.1.6 Heavy Metals

20

2.2 MARINE POLLUTION

20

2.2.1 Ports, Harbours and Marine Transport

20

2.2.2 Small Vessel Operation and Discharge

22

2.2.3 Aquaculture Effluents

23

2.2.4 Domestic Discharge from Coastal Population

23

2.2.5 Land Reclamation

25

2.3 FRESHWATER SHORTAGE AND DEGRADATION OF

26

QUALITY

2.3.1 Surface Water

26

2.3.2 Surface Water Demand and Supply

26

2.3.3 Groundwater

28

2.3.4 Water Related Issues and Problems

29

2.3.5 Sensitive and High Risk Areas

31

2.4 EXPLOITATION OF LIVING AQUATIC RESOURCES

32

2.4.1 Living Freshwater Resources

35

2.4.2 Living Marine Resources

38

2.4.2.1 Marine Capture Fisheries

38

2.4.3 Impact of Man-based Activities on Freshwater and

49

Marine Ecosystems

Chapter 3

: ANALYSIS OF SOCIO AND ECONOMIC COSTS OF

51

IDENTIFIED WATER-RELATED PRINCIPAL

ENVIROMENTAL ISSUES

Chapter 4

: ANALYSIS OF THE ROOT CAUSE OF IDENTIFIED

55

WATER-RELATED ISSUES

i

C O N T E N T

Page

Chapter 5

: CONSTRAINTS TO ACTION

58

5.1 INSTITUTIONAL PROBLEMS

58

5.2 LACK OF CAPACITY TO IMPLEMENT POLICIES AND

59

ENFORCE REGULATIONS

5.3 INADEQUATE CENTRAL SEWAGE SYSTEM AND

60

TREATMENT FACILITIES

5.4 INTEGRATED RIVER BASIN MANAGEMENT (IRBM)

61

APPROACH

5.5 PUBLIC AWARENESS ON WATER CONSERVATION

62

5.6 COASTAL POLLUTION

63

5.7 INTEGRATED COASTAL ZONE MANAGEMENT (ICZM)

64

Chapter 6

: ONGOING AND PLANNED ACTIVITIES RELEVANT TO

65

IDENTIFIED ISSUES

6.1 INSTITUTIONAL

65

6.2 LACK OF CAPACITY TO IMPLEMENT POLICIES AND

66

ENFORCE REGULATIONS

6.3 INADEQUATE CENTRAL SEWAGE SYSTEM AND

66

TREATMENT FACILITIES

6.4 LACK OF PUBLIC AWARENESS

68

Chapter 7

: TRANSBOUNDARY ISSUES, KNOWLEDGE GAPS, AND

69

RECENT DEVELOPMENTS

7.1 POLLUTION

69

7.2 EXPLOITATION OF MARINE RESOURCES

73

7.3 COASTAL LAND RECLAMATION

74

7.4 HIGH DEMAND FOR MARINE PRODUCTS

75

7.5 KNOWLEDGE GAPS

76

7.6 RECENT DEVELOPMENTS

77

References

ii

L I S T O F T A B L E S

Page

1.1

: General Economic Data, Malaysia (2002)

6

1.2

: Major Export Items, Malaysia (2002)

8

1.3

: Major Export Markets by Country (2002)

8

1.4

: Major Import Items, Malaysia (2002)

9

1.5

: Major Import Sources by Country, 2002

9

2.1

: Status and Trend of River Water Quality, Malaysia, (1988-1994)

16

2.2

: Distribution of Major Industrial

18

Sources of Water Pollution, West Coast States (1993)

2.3

: Malaysia: Organic Pollution Load Discharged According to Sector

19

(1989 1993)

2.4

: Number of Vessel by Major Ports in the Straits of Malacca (2001-2002)

21

2.5

: Oil Spill Incidents in Malaysia Water Year 1975-1997

22

2.6

: Population by State, West Coast Malaysia (2000)

24

2.7

: Domestic and Industrial Water Demand, West Coast (1980-2000)

27

2.8

: Inshore Vs Offshore landing (tonnes), West Coast Malaysia (1990 2000)

34

2.9

: Freshwater Culture Systems by Species

36

2.10 : Fish Species Landings by Location, Malaysia (2000)

38

2.11 : Number of Licensed Fishing Vessels by Tonnage Class,

43

West Coast Malaysia (1980 2000)

2.12 : Aquaculture Resource Potential in Malaysia

45

2.13 : Aquaculture Production from Brackish/Marine Aquaculture Systems,

45

West Coast Peninsular Malaysia (2000)

2.14 : Mangrove Reserves and State Land Mangroves in Peninsular Malaysia

47

2.15 : Summary of Adverse Impacts of Man-based Activities On the Marine and

50

Freshwater Ecosystems

3.1

: Endangered Marine Resources and Mortality Sources

54

4.1

: Analysis of Root Causes and Socio-Economic Impacts of Water-Related

56

Issues - (a and b)

iii

L I S T O F F I G U R E S

Page

1.1 : Map of Study Area

8

1.2 : Temporal Monsoons Affecting Peninsular Malaysia

12

2.1 : Number of Fisherman Working in Licensed Vessels

33

West Coast Peninsular Malaysia, 2000

2.2 : Composition of Marine Fish Species Group Landings, West Coast

41

Peninsular Malaysia (2000, 1980, 1990)

2.3 : Contribution by Gear Group to Total Landing, West Coast Peninsular

43

Malaysia (2000)

3.1 : The Socio-Economic Costs of Water Resource Degradation

52

iv

NATIONAL STUDY TEAM

PRINCIPAL AUTHOR

Prof. Ishak bin Haji Omar (PhD)

Professor, Faculty of Economics and Management

University Putra Malaysia

43400 Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia

Email: ishak@econ.upm.edu.my

Tel: +6012 3793 047

TECHNICAL ADVISOR

Fauzy Abdullah

Capital Risk Management Sdn Bhd

E703, Phileo Damansara

46350 Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia

Email: fauzy@seacomm.net

Tel: +603 7660 7272

RESEARCH ASSISTANT

Soffie, W.M.

Capital Risk Management Sdn Bhd

E703, Phileo Damansara 1

46350 Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia

Email: soffie@asia.com

Tel: +603 7660 7272

v

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The author wishes to express his sincere gratitude to the following individuals for

providing valuable literature and spending time for an interview;

1. Y.B. Dato' Dr. Hashim Hassan

Secretary-General II

Ministry of Science, Technology and

Environment, Putrajaya, Malaysia.

2. Dr. Mohd Zahit b. Ali

Director

Conservation and Environment Division,

Ministry of Science, Technology and

Environment, Putrajaya, Malaysia

3. Mr. Lee Choong Min

Director

River Division

Department of Environment

Ministry of Science, Technology and

Environment, Putrajaya, Malaysia

4. Dr. K. Kuperan Viswanathan

ICLARM

The World Fish Centre

Penang, Malaysia

5. Prof. Dr. Mohd Ibrahim Hj.

Professor

Mohamed

Faculty Science and Environmental

Studies

UPM, Serdang, Malaysia

vi

UNEP/SCS National Report Malaysia

NATIONAL REPORT OF MALAYSIA ON THE

BAY OF BENGAL LARGE MARINE

ECOSYSTEM PROGRAMME

By

Ishak Haji Omar*

1.

INTRODUCTION

1.1

AIM OF REPORT

The aim of the national report is to review existing information on the use of, and

threats to, the Malaysian coastal and marine resources off the Straits of Malacca and the

adjacent waters of the Andaman Sea and the Indian Ocean. In the process, an attempt is made

to identify, examine, and rank those threats that have transboundary effects on man and the

environment and to determine information gaps that need to be addressed for integrated

management of coastal and marine resources in the region.

1.2

MAJOR WATER-RELATED ENVIRONMENTAL PROBLEMS

The sources of water-related environmental problems in Malaysia are both land and

sea-based pollution. The fouling of the water ecosystem, natural or man induced, cause

delirious effects such as harm to living resources, hazards to human health, and a hindrance to

economic processes.

Land-based Sources of Pollution

One of the main causes of water/river pollution is the rapid urbanisation on the West

Coast, arising from the development of residential, commercial, and industrial sites,

infrastructural facilities (ports and roads) as well as land reclamation in coastal waters. The

* Professor, Faculty of Economics and Management, University Putra Malaysia, 43400 Serdang, Selangor,

Malaysia. The author takes responsibility for the views expressed in the paper.

1

UNEP/SCS National Report Malaysia

destruction of rainforests and water catchments, and the subsequent erosion of soils together

with the heavily silted run-offs, pollutes the rivers. These and other sources of land-based

pollution are as follows:

· Sediment run-off

· Industrial waste

· Domestic waste

· Agricultural and animal waste

· Heavy metals

Sea-based Sources of Marine Pollution

Next to the Dover Straits in U.K., the Straits of Malacca is the world's second busiest

international shipping lane. Over 15,000 vessels, large and small, utilize the straits waters

daily. Shipping activities, discharges, and accidents are all threats to the marine environment.

In general, the sea-based sources of marine pollution in the coastal waters off the West Coast

of Peninsular Malaysia are:

· Shipping activities (operational discharge, deballasting, tank cleaning,

bilge water and sludge)

· Small vessel discharge (barges and fishing vessels)

· Aquaculture development (prawn and fish culture)

· Domestic discharge from coastal population

· Land reclamation (for commercial/industrial centres)

1.2.1 Air-Related Environmental Problems

Though not directly a water related environmental problem, the haze in 1997 caused

by Indonesia's shifting agriculture and slash-and-burn technique of jungle clearing was one

of Asia's worst man-made catastrophe. The emission of smoke, soot, organic particles and

2

UNEP/SCS National Report Malaysia

noxious gases such as nitrous oxides, sulphur oxides, dioxins, and other volatile compounds

sent the air pollution index in neighbouring Southeast Asian countries beyond the very

unhealthy (201-300) and, for some areas, above the hazardous (>500) level.

Haze is a phenomenon characterised by visibility impairment due to the scattering and

absorption of light by particles and gases in the atmosphere. Its effect to the water

environment is through:

· Emissions of sulphur dioxide (SO2) and oxides of nitrogen (N0x) and related

particulate matter (sulphates and nitrates) that contribute to poor visibility and

impact public health that in form is associated with breathing difficulties,

damage to lung tissue, cancer and premature death.

· Acid rain, as emissions of SO2 and N0x in the atmosphere react with water,

oxygen and oxidants to form acidic compounds. The acid rain raises the acid

levels of lakes and streams making the water unsafe for some fish and other

wildlife.

Indonesian haze has hit the region on a number of occasions in the 1980's and 1990's.

The one in 1977 was the worst incurring an economic loss of US1.3 billion, from close-down

of factories, curtailing of regional flights, drop in tour packages, to vessel accidents in the

Straits of Malacca (www.icsea.org/sea-span).

With Malaysian companies investing in a big way in palm plantations in Kalimantan

and Sumatra and with palm oil prices expected to be bullish, the torching of forest lands in

Indonesia could be on an industrial scale in the future. The monitoring, control, and

management of Indonesian haze has to be on a regional basis among ASEAN members.

Being hit by the ASEAN financial crisis, Indonesia is not in a position to adopt the polluter-

pays principle.

3

UNEP/SCS National Report Malaysia

1.3

COUNTRY BACKGROUND

General Geography

Malaysia is situated in the central part of South-East Asia and occupies a total land

area of 330,434 square kilometres. The land mass comprises three main components:

Peninsular Malaysia and the two states of Sabah and Sarawak, which occupy the coastal strip

of northwest Borneo (Figure 1.1). Peninsular Malaysia is the largest of the three areas,

covering 131,387 square kilometres.

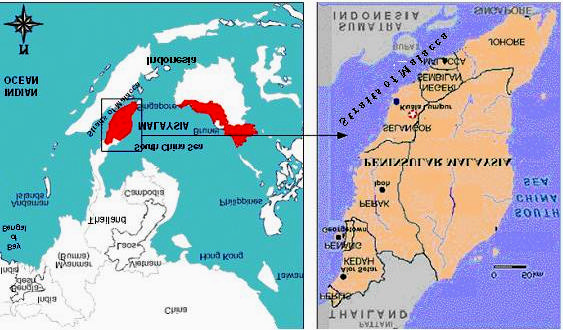

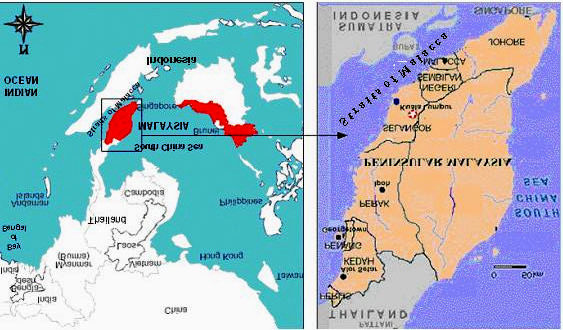

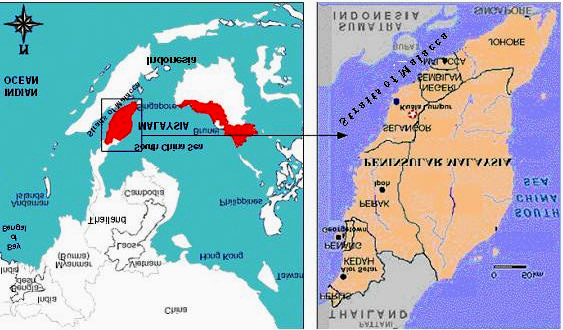

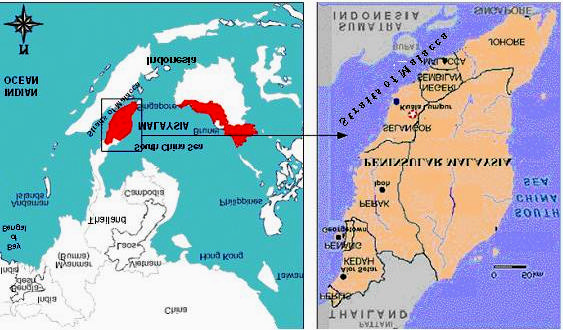

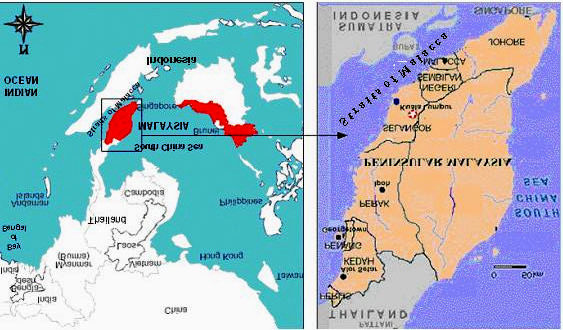

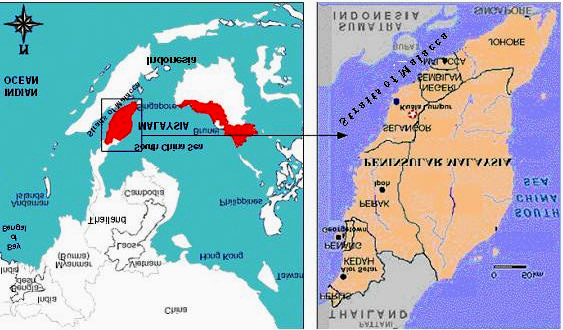

Figure 1.1: Map of Study Area

Malaysia has a long coastline of 4,810 km. Her marine waters consist of a continental

shelf of 148,307 km2 and an Exclusive Economic Zone of 450,000 km2.

Economic Setting

Malaysia consists of a federation of 11 states in Peninsular Malaysia and the states of

Sabah and Sarawak in the north of Kalimantan. Kuala Lumpur, the national capital, Labuan

4

UNEP/SCS National Report Malaysia

and Putra Jaya form the Federal territories. The multiracial population of Malaysia is

composed of 58 percent bumiputra (Malays and indigenous people), 24 percent Chinese, and

the remainder Indians and other minor groups (18 per cent). The population was about 22

million in 2002, with the majority (over 80 per cent) living in Peninsular Malaysia.

Under the Federal Constitution, both land and water are state matters, while public

health and sanitation are concurrent matters on which both can legislate. To some extent, the

federal and state jurisdiction overlaps in environmental management, whereby broad policies

are formulated at the national level for implementation by the respective federal and state

agencies at the ground level. This overlapping of roles and responsibilities at the

implementing level can lead to unnecessary bureaucracy, agency rivalry and slow action.

In Peninsular Malaysia, the 11 states can be divided into two economic regions. The

majority of the manufacturing industries, plantations, tin reserves, ports and populations are

concentrated in the west coast states, while the east coast states are sparsely populated and

relatively undeveloped.

The general data on the Malaysian economy are shown in Table 1.1. With a gross

National Product (GNP) of RM310.8 billion and a GNP per capita of RM13,361 (US$3,516),

Malaysia enjoys a reasonable standard of living with low poverty (9.6 per cent of households)

and unemployment rates (3 per cent).

Since independence in 1957, the structure of the Malaysian economy progressed from

a simple agriculture economy to one that is industrial and export-oriented economy.

Subsequently, the share of agriculture dropped from 29 per cent in 1970 to 14 per cent in

2000, while the share of manufacturing jumped from 14 per cent in 1970 to27.8 per cent for

the same period (Dept. of Statistics, 2002).

5

UNEP/SCS National Report Malaysia

Table 1.1: General Economic Data, Malaysia (2000)

329.758 sq km

Area

(incl. inland water) 330,417 sq km

(Peninsular) 131,598 sq km

(Sabah) 73,711 sq km

(Sarawak) 124,449 sq km

Poverty rate

9.6% of households

GDP

RM339.4 billion

GNP

RM310.8 billion

GNP per capita

RM13,361

Current Account Balance

+RM31.2 billion

Exports / imports

RM373.3 bn / RM312.4 billion

CPI change

+1.5% (Q1 2001)

9.64 million

Employment

Agriculture = 14.0%

Mining = 00.5%

Manufacturing = 27.8%

Construction = 08.8%

Services = 48.3%

Unemployment

3.0%

Water coverage

91% of population

Sources: Department of Statistics, Malaysia.

6

UNEP/SCS National Report Malaysia

Table 1.2 shows the major export items of Malaysia in 2002, both in terms of value

and share. Electrical and electronic, palm oil, petroleum, and wood-based industries

contributed over 75 per cent to total export value.

In terms of export markets, Singapore, USA, and Japan were the main trading partners

(Table 1.3). Together, these countries imported merchandise worth about RM27 billion and

accounted almost 50 per cent of Malaysian exports.

Malaysian imports consist mainly of intermediate raw materials and equipment for her

value-added manufacturing activities (Table 1.4). These include mainly electrical and

electronic materials, machinery appliance and parts, metals and iron and steel products.

Similar to export markets, her major import sources were from Japan, USA and Singapore

(Table 1.5).

Study Area

Peninsular Malaysia comprises mainly of highlands, floodplains, and coastal zones.

The mountain range, Banjaran Titiwangsa, which runs from north to south divides the west

coast and east coast states of the Peninsular. Starting from the north, the west coast states that

fringe the Straits of Malacca are Perlis, Kedah, Penang, Perak, Selangor, Negeri Sembilan,

Malacca, and West Johore (Figure 1).

Most rivers on the west coast of Peninsular Malaysia such as Sg. Muda, Sg. Pinang,

Sg. Perak, and Sg. Klang are short and steep. Open water bodies, natural wetlands, and man-

made lakes such as dams, and ex-mining pools are mostly found in the Klang and Kinta

Basins. These water bodies are used for power generation, flood control, national water

supply, recreation, aquaculture and tourism.

7

UNEP/SCS National Report Malaysia

Figure 1.1: Map of Study Area

Table 1.2: Major Export Items, Malaysia (2002)

Value

Share

(RM Million)

(%)

Electrical and electronic

197,986.6

55.9

Palm oil

17,193.2

4.9

Chemical

16,731.9

4.7

Crude petroleum

11,831.8

3.3

Machinery appliances & parts

11,150.5

3.1

LNG

10,451.4

2.9

Wood products

10,451.4

2.9

Textiles and clothing

8,408.3

2.4

Optical and scientific

8,157.3

2.3

Refined petroleum

6,790.1

1.9

Source: Department of Statistics, Malaysia.

Table 1.3: Major Export Markets by Country (2002)

Value (RM Million

Share

(%)

USA

71,501.9

20.2

Singapore

60,663.5

17.1

Japan

39,776.3

11.2

Hong Kong

20,169.3

5.7

China

19,965.8

5.6

Thailand

15,096.0

4.3

Taiwan

13,223.9

3.7

Netherlands

13,146.9

3.7

Korea Republic of

11,823.7

3.3

United Kingdom

8,353.1

2.4

Source: Department of Statistics, Malaysia.

8

UNEP/SCS National Report Malaysia

Table 1.4: Major Import Items, Malaysia (2002)

Value

Share

(RM Million)

(%)

Electrical & electronic

149,469.8

49.2

Machinery appliance & parts

26,659.2

8.8

Chemical

21,525.0

7.1

Manufactures of metal

11,004.7

3.6

Transport equipment

11,540.1

3.8

Iron and steel products

9,746.9

3.2

Optical and scientific

9,139.2

3.0

Refined petroleum

7,496.3

2.5

Crude petroleum

4,780.1

1.6

Textiles and clothing

4,319.9

1.4

Source: Department of Statistics, Malaysia.

Table 1.5:

Major Import Sources by Country, 2002

Value

Share

(RM Million)

(%)

Japan

53,909.6

17.8

USA

49,699.8

16.4

Singapore

36,316.1

12.0

China

23,474.4

7.7

Taiwan

16,803.5

5.6

Korea Republic of

16,079.4

5.3

Thailand

12,017.0

4.0

Germany

11,163.4

3.7

Philippines

9,862.8

3.2

Indonesia

9,688.0

3.2

Source: Department of Statistics, Malaysia.

9

UNEP/SCS National Report Malaysia

Marine Environment

Covering both the continental shelf and exclusive economic zone, Malaysian maritime

waters off the West Coast of Peninsular Malaysia is approximately 600 nautical miles long,

semi-conical in shape, with widths of 220 nautical miles in the northwest and 8 nautical miles

at the Riau Archipelago. A major portion of the waters lies within the continental shelf areas

of 10 to 60m in depth. The deepest area (70m) is in the Andaman Sea at the northern tip of

the Straits, while the shallowest is at the One Fathom Bank in the south.

The current predominantly flows in a northwest direction with rates of 1 to 1.25 knots,

although in some areas it may increase to 5 knots. The tidal range varies from 1.6 to 3.7

meters, with a much higher range inshore. For instance, Port Klang has experienced tides of

up to 5 meters and with a tidal stream of over 4 knots.

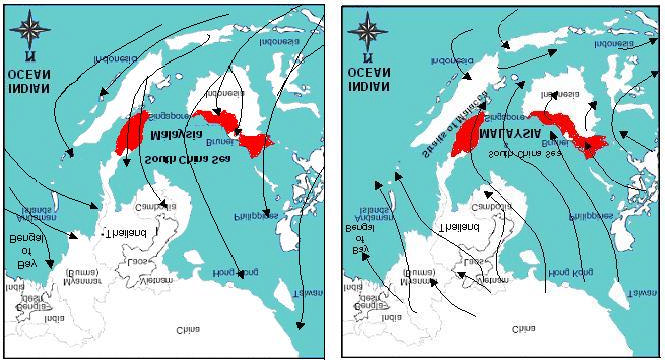

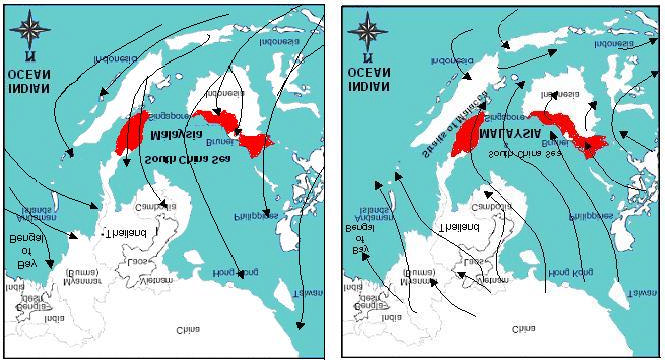

The West Coast of Peninsular Malaysia has an equatorial climate, with an average

annual rainfall of more than 2500mm and a daily temperature that ranges from a minimum of

25°C to a high of 33°C. The area is subjected to two rainy spells, the Southwest monsoon

from June to September and the Northeast monsoon from November to March (Figure 1.2).

During these periods, the marine waters may be rough enough to curtail fishing operations in

the Straits.

The coastal zone along the Straits of Malacca is rich in mangroves, estuaries, coral

reefs, sea-grass meadows and algae beds, mudflats, beaches and small island ecosystems.

Each of these marine-based resources, with its unique habitat, supports a wealth of marine

life, some not well explored nor documented.

10

UNEP/SCS National Report Malaysia

Figure 1.2

Temporal Monsoons Affecting Peninsular Malaysia

I) South West Monsoon

II) North East Monsoon

Pollution Control and Management

The main legislation protecting the environment in Malaysia is the Environmental

Quality Act (EQA), 1974. The legislation sets limits to allowable pollutant levels for both

land and sea-based sources as well as for prescribed development activities as specified under

the Environmental Impact Assessment Regulations (1987). There are other regulations to

complement the Environment Quality Act, 1974, such as laws governing resource use

(National Forestry Act, 1984, Fisheries Act, 1985, and Exclusive Economic Zone Act, 1984),

vessel operation and conduct (The Merchant Shipping Ordinance, 1952), land use pattern

(National Land Code, 1965, and Land Conservation Act, 1960), and other local government

by-laws on earthworks, earth removal, mining, sanitation and solid waste disposal.

Thus, with respect to water resources, the most important legislation in Malaysia

governing water quality management is the Environmental Quality Act (EQA), 1974. The

objective of the EQA is basically twofold: pollution prevention, abatement and control as

11

UNEP/SCS National Report Malaysia

well as environment enhancement. There are at least six sets of regulations under EQA, 1974,

for control of water pollution and the environment, and these are:

· Environmental Quality (Prescribed Premises)(Crude Palm Oil Regulation,

1974)

· Environmental Quality (Prescribed Premises)(Law Natural Rubber)

Regulation, 1979.

· Environmental Quality (Sewage and Industrial Effluents) Regulations, 1979.

· Environmental Quality (Prescribed Premises)(Schedules Waste Treatment and

Disposal Facilities), Regulations, 1989.

· Environmental Quality (Scheduled Wastes) Regulations, 1989.

· Environmental Quality (Prescribed Activities Environmental Impact

Assessment) Order, 1987.

The above regulations stipulate the standards and procedures for handling the various

types of domestic and industrial wastes.

Stakeholders and Water Resource Management

The conservation, use, and management of water resources, freshwater or marine, is

everyone's concern. The general public, private sector, national and local governments, non-

governmental organizations, and international agencies have a role and responsibility to

ensure proper and sustainable use of water resources.

In Malaysia, the administration and management of water resources is carried out by

Federal and various state government agencies. The Federal Government sets the policies and

undertakes studies at the national level for overall planning and development purposes.

Recently, the Federal Government initiated the National Water Resource Studies (till year

2050) and established the National Water Resource Council (1998) with the responsibility of

streamlining water resource development and management activities of all states.

12

UNEP/SCS National Report Malaysia

As mentioned earlier, the relationship between the states and Federal Government in

terms of legislative and executive powers is governed by the Federal Constitution. Under the

Constitution, land is a state matter and, hence, state governments have legislative powers over

rivers, lakes, streams, aquifers, including turtles and riverine fishing. The key agencies that

deal with the implementation, management and monitoring of water resources include the

following: -

· Department of Irrigation and Drainage (under the Ministry of

Agriculture)

Involves in development works, operations, and maintenance of water

supply and infrastructures. Also, provides other technical services such

as flood control, coastal pollution information, hydrological data

collections, irrigation and river conservancy.

· Department of Environment (DOE) (under Ministry of Science,

Technology and Environment)

Mission is to promote, ensure and sustain sound environmental

management in the process of nation building. Has responsibility to

ensure the water in rivers is clean by controlling and monitoring

pollution. Also undertakes mitigated measures through implementation

of the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) for projects.

· State Water Departments

State agencies are responsible for water abstraction, treatment, and

distribution to consumers and industrial users.

· Local Authority

The local authorities indirectly influence the state of rivers and water

resources through their overall development plans and land use

decisions.

· Department of Town and Country Planning (Ministry of Local

Government)

Controls land use patterns and pace of development as the Department

gives the final approval to developers. Land-use zoning directly affects

river and water resources.

· Forestry Department

Responsibility to manage state gazetted forests, peat wetlands and

mangrove forests as well as catchment areas and rivers within forests. It

also controls logging activities through the selective management system

(SMS).

13

UNEP/SCS National Report Malaysia

Besides the state and federal agencies, some of the local community groups and

NGOs that are active on environmental issues include: Friends of the Earth (Sahabat Alam

Malaysia), World Wildlife Fund for Nature (Malaysia), Malaysian Institute of Marine Affairs

(MIMA), Malaysian Nature Society, Malaysian Fisheries Society, Environmental Protection

Society of Malaysia, Public Media Club, and various charity organizations.

Malaysia participates actively in the regional and international fora on environment

and has good working relationships with a number of international organizations. Some of

these linkages include United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP), United Nations

Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), Food and Agriculture Organization

(FAO), Coordinating Body on the Seas of Asia (COBSEA), UNESCO, GEF/UNDP/IMO,

and PEMSEA.

14

UNEP/SCS National Report Malaysia

2.

DETAILED ANALYSIS OF MAJOR WATER-RELATED

CONCERNS AND PRINCIPAL ISSUES

2.1

POLLUTION

Often associated with the flow of residuals, pollution can be defined as the presence

of matter or energy that has undesired effects on the environment. Pollutants pose a risk to

life support ecosystems and can be difficult to control. Water pollutants are many, if not

more than their polluting sources.

2.1.1 Rivers

Rivers with their loads of municipal, industrial and agricultural wastes eventually end

up discharging these at the estuaries and polluting the coastal marine waters. Under the

previous Malaysian Water Quality Programme, a total of 116 rivers encompassing 892

sampling stations were monitored by the Dept. of Environment throughout the country.

Assessment of water quality in these stations were measured in terms of biological and

chemical characteristics and compared against the national water quality standards.

Table 2.1 shows the status and trend of river quality for the period 1988-1994. It can

be seen from the water quality measured in terms of Biological Oxygen Demand (BOD)

caused by organic decomposition, ammoniacal nitrogen (NH3-N) emitted from sewage and

animal waste, and suspended solids from soil erosion and sedimentation all registered

negative overall trend (deteriorated) for the period 1988-1994. The overall water quality

index, measured for its physical, chemical and biological characteristics in form of turbidity,

salinity, temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen and electrical conductivity, also worsened for all

116 rivers over the same period.

15

UNEP/SCS National Report Malaysia

Table 2.1: Status and Trend of River Water Quality, Malaysia, (1988-1994)*

Status in 1994

Overall Rate of Change

Pollutants

Polluted

Slightly

Clean

(1988-1994)

Biological Oxy.

13

18

83

-0.88

Deteriorated

Demand (BOD)

(13%)

(15%)

(72%)

Suspended Solids

66

16

34

-0.91

Deteriorated

(SS)

(57%)

(14%)

(29%)

Ammonia cal

36

35

45

-1.72

Deteriorated

Nitrogen (NH3-N)

(31%)

(30%)

(39%)

Overall Water

14

64

38

-0.92

Deteriorated

Quality Index

(12%)

(55%)

(33%)

(WQI)

* A total of 116 rivers were evaluated.

Source: Dept. of Environment Malaysia (1994).

From the table, suspended solids and ammoniacal nitrogen were the main pollutants

accounting for 57 per cent and 36 per cent of the total polluted rivers respectively.

Since 1995, there were no documented statistics on river water assessment that was

published by the DOE, as the Natural Water Quality Programme was contracted to a private

company, Alam Sekitar Malaysia Sdn Bhd (ASMA). However, in 2000 the DOE resumed the

data collection but the format was changed from river to basin-based reporting, depriving

inter-period comparisons. This time around, the DOE covered 931 water-monitoring stations

which were located within 120 river basins (DOE, 2001). Of these 931 monitoring stations,

489 (53%) were found to be clean, 303 (33%) slightly polluted, and 135 (15%) polluted.

Even though the outcomes are not exactly comparable to those of 1994, because of sample

size and location of stations, nonetheless the broad picture indicates a general improvement

in water quality of the Malaysian rivers. This improvement could be due to several factors

that include a slowdown of economic activities and property development due to the Asean

16

UNEP/SCS National Report Malaysia

financial crisis, relocation of swine farms away from rivers, and the improved awareness of

the general public on environmental pollution due to intensive public and NGO campaigns.

2.1.2 Sedimentation

The rapid pace of urbanization, indiscriminate destruction of rainforests and

catchments for the establishment of new townships and industrial sites have resulted in the

high sedimentation of rivers in the littoral states of the Straits of Malacca. Prior to

urbanisation, rainwater gets absorbed by the vegetation, infiltrates the ground and takes time

to get to the rivers. Without vegetation, the run offs are excessive, rapidly eroding both

land surfaces and river banks. The heavy loads of sedimentation that empties into the rivers

are a hazard to both human and aquatic life.

2.1.3 Industrial Waste

The common forms of industrial pollution are suspended particulate emissions that

cause air pollution, BOD discharges that cause water pollution, and toxic waste discharges

that affect all elements. Over 80 per cent of the total volume of industrial water discharge in

Malaysia originate from four categories of manufacturing activities (1) food and beverage

processing, (2) industrial chemicals and chemical products, (3) rubber products

manufacturing and (4) textile and leather products (Table 2.2).

Rivers in the highly industrialized states of Penang, Perak, Selangor, Malacca and

Johore were most affected by industrial waste.

17

UNEP/SCS National Report Malaysia

Table 2.2: Distribution of Major Industrial Sources of Water Pollution,

West Coast States (1993)

Major Pollution Sources/Industries

Raw Natural

Rubber

Food and

Textile &

States

Palm Oil

Rubber

Product

Beverages

Leather

Paper

Chemicals

Total

Selangor

31

8

252

174

92

87

194

838

Johor

67

39

32

199

203

43

76

659

Pulau Pinang

4

8

58

164

76

38

77

425

Perak

48

26

54

102

1

1

28

260

Kedah

4

28

47

55

33

23

18

208

Negeri Sembilan

13

20

43

25

14

11

21

147

Melaka

2

10

28

48

55

22

27

192

Perlis

0

2

8

3

2

0

15

30

169

141

522

770

476

225

456

2759

Total States

Contribution by

6.13%

5.11%

18.92%

27.91%

17.25%

8.16%

16.53%

100.00%

Pollution Source

Total MALAYSIA

287

18

597

1169

545

292

560

3468

Contribution by

Pollution Source (%) 8.28%

0.52%

17.21%

33.71%

15.72%

8.42%

16.15%

100.00%

Overall Contribution

79.56%

to Total Pollution

Source: Dept. of Environment Malaysia (1994).

2.1.4 Domestic Waste

Domestic or human waste affects the environment in at least three ways. When solid

waste is burnt it pollutes the air, when sewage is inadequately treated it contaminates

drinking water; and when sanitation is poor, it results in water and insect-borne diseases.

Lack of proper sewage disposal and treatment systems result in the waste being discharged

directly into the rivers and seas.

Table 2.3 shows the organic pollution load discharge according to sectors. In 1993,

the pollution load measured in BOD from domestic sewage accounted for 67% of total BOD

load, followed by agricultural and animal waste (22%), manufacturing industries (7%), and

agro-based industries (2.7%). One interesting feature that needs investigation is the rapid

increase in BOD loads from the other sectors over the years, resulting in a decline in the

amount of domestic sewage from about 80 per cent in 1989 to 67 per cent in 1993.

18

UNEP/SCS National Report Malaysia

Table 2.3:

Malaysia: Organic Pollution Load Discharged According to Sector

(1989 1993)

Year

1989

1990

1991

1992

1993

1

2

BOD Population BOD Population BOD Population BOD Population BOD Population

Sector

Load Equivalent Load Equivalent Load Equivalent Load Equivalent Load Equivalent

1. Agro-based

Industries

(Palm Oil &

11

0.22

15

0.30

12

0.24

30

0.60

28

0.56

Raw Natural

Rubber)

2. Manufacuturing

21

0.42

25

0.50

25

0.50

27

0.54

77

1.54

Industries

3. Agriculture

(Animal

60

1.20

65

1.30

65

1.30

211

4.20

230

4.60

Husbandry)

4. Population

366

7.32

380

7.60

385

7.70

481

9.63

698

13.96

(Sewage)

Total

458

9.16

485

9.7

487

9.74

749

14.97

1033

20.66

Source: Dept. of Environment Malaysia (1994).

2.1.5 Agricultural and Livestock Waste

As can be seen in Table 2.3, there has been a more than three fold increase in

livestock waste over the years. Agricultural wastes from agro-based industries, such as

wood, palm oil, and rubber processing mills were also on the increase. Johore, Selangor, and

Perak collectively accounted 65.7 per cent of the total number of identified sources of

pollution in the agro-based and manufacturing sector (DOE, 2001).

Livestock waste, pesticides, and fertilizers pollute our rivers and coastal waters. As

coastal aquaculture systems are located mainly in sheltered coastal waters of the Straits of

Malacca, these agricultural wastes, carrying bacteria and heavy metals, can be a health

hazard if transmitted to the fish species cultured. There are very few studies on this causal

link, although food poisoning incidences are often associated with cultured mussels and

cockles.

19

UNEP/SCS National Report Malaysia

2.1.6 Heavy Metals

The Department of Environment reported consistently much higher concentrations of

heavy metals in rivers of the littoral states of the Straits of Malacca than in other parts of the

country. Admittedly, this is due to extensive land use and industrialization, especially in

Penang, Perak, Selangor and Malacca.

Penang has a large electronic industry and producing computer chips and semi-

conductors generates a lot of wastewater, toxic chemicals and hazardous gases. In Malacca,

the river alongside Alor Gajah Industrial Estate is polluted with heavy metals such as

mercury, copper, and zinc that are higher than the permissible limits.

2.2

MARINE POLLUTION

The extent of marine pollution in the Straits of Malacca and adjacent waters depends

mainly on the discharges of land-based activities from rivers, shipping operations,

aquaculture effluents, domestic discharge from coastal population, land reclamation and from

illegal dumping of waste.

2.2.1 Ports, Harbours and Marine Transport

Usually, cargo and oil ports are not major sources of pollution, except when shipping

accidents, oil spills and groundings take place. With the busiest tanker traffic in the world,

vessels that patronize the Straits, docked, berthed, anchored, laid-up, steaming or being

serviced carry inherent risks where an accident can develop into an environmental

catastrophe. Such risks are real but difficult to quantify as shipping statistics are difficult to

compile. Although ships passing through are now required to report under the International

Maritime Organization's Mandatory Ship Reporting System (1998) these, at times, do not

20

UNEP/SCS National Report Malaysia

follow specific routes. Besides this, there are many cross traffic cargo vessels that service

intra regional trade as well as thousands of licensed and unlicensed fishing vessels operating

in the same sea space.

Table 2.4 presents an attempt to collate available statistics on the number of vessels

that call on the major ports along the Straits for the period 2000-2002. Penang and Port

Klang were the busiest ports and, in 2002, accounted over 85 percent of the traffic.

Table 2.4:

Number of Vessel by Major Ports in the Straits of Malacca

(2001-2002)

Port

2000

2001

2002

Penang

7,263

7,460

7,328

Port Klang

12,804

1,303

13,175

Sungai Udang

955

1,066

987

Port Dickson

1,185

1,152

908

Malacca

1,356

1,090

1,137

Tg. Bruas

461

462

423

TOTAL

24,024

24,533

23,958

Source: Compiled from Marine Department, Malaysia.

With thousands of large and small vessels plying the Straits a total of 476 accidents

took place between 1978-1994 (Gunalan, 1999). Also, there were 18 major oil spill incidents

(Table 2.5) due mainly to collision, grounding and human error.

Another source of marine pollution in the Straits is the non-accidental oil discharge as

routine ship maintenance requires pumping out bilge water and, to a lesser extent, ballast

water. Gunalan (1999) reported that vessel maintenance alone is capable of generating

888,000 tonnes of waste per year, consisting of 150,000 tonnes of oily bilge water sludge, 18

tonnes of solid waste and 720,000 tonnes of sewage. While a National Contingency Plan has

been drawn up by the Malaysian government to control and mitigate oil spills in the Straits,

21

UNEP/SCS National Report Malaysia

the threat of non-accidental oil discharge to the coastal marine environment has been

overlooked.

Table 2.5: Oil Spill Incidents in Malaysia Waters Year (1975-1997)

Year

Name of Ship

Location

Cause

Type and Quantity

of Oil Spill

1975

SHOWA MARU

The Straits of Singapore

Grounding

Crude oil 4000 tons

1975

TOLA SEA

The Straits of Singapore

Collision

Fuel oil 60 tons

1976

DIEGO SILANG

The Straits of Malacca

Collision

Crude oil 5500 tons

1976

MYSELLA

The Straits of Singapore

Grounding

Crude oil 2000 tons

1976

CITTA DI SAVONNA

The Straits of Singapore

Collision

Crude oil 1000 tons

1977

ASIAN

The Straits of Malacca

Collision

Fuel oil 60 tons

1978

ESSO MERSIA

The South China Sea

Collision

Fuel oil 505 tons

1979

FORTUNE

The South China Sea

Collision

Crude oil 10000 tons

1980

LIMA

The Straits of Singapore

Collision

Crude oil 700 tons

1981

MT OCEAN TREASURE

The Straits of Malacca

Human Error

Fuel oil 1050 tons

1984

BAYAN PLATFORM

The South China Sea

Human Error

Crude oil 700 tons

1986

BRIGHT DUKE/MV

The Straits of Malacca

Collision

-

PANTAS

1987

MV STOLT ADV

The Straits of Singapore

Grounding

Crude oil 2000 tons

1987

ELHANI PLATFORM

The Straits of Singapore

Grounding

Crude oil 2329 tons

1988

GOLAR LIE

The Straits of Singapore

Grounding

-

1992

NAGASAKI SPIRIT

Near Medan, Indonesia

Collision

Crude oil 13000 tons

1997

EVOIKOS / ORADIN

The Straits of Singapore

Collision

Fuel oil 25000 tons

GLOBAL

1997

AN TAI

The Straits of Malacca

Material

Fuel oil 237 tons

Fatigue

Source: Marine Department, Malaysia.

2.2.2 Small Vessel Operation and Discharge

Besides the oil and petroleum tankers as well as large container carriers that ply the

Straits of Malacca, another significant cause of marine pollution is from the fishing

operations and, to a lesser extent, the cargo vessels that transport goods between

neighbouring countries. About 13,000 vessels or 37% of Malaysian fishing vessels are

operating from the shores of the littoral states along the Malacca Straits. The waste

discharged from fishing vessels, villages and jetties, and the indiscriminate encroachment of

trawlers into inshore waters pollute as well as destroy the breeding grounds of aquatic

resources.

22

UNEP/SCS National Report Malaysia

2.2.3 Aquaculture Effluents

With the levelling of fish landings, marine aquaculture is seen as an important

alternative for fish production, especially along the sheltered coastal areas of the Straits of

Malacca. Although the aquaculture industry is sensitive to water pollution, it is also a

polluter to the marine environment (Chua, at. el., 1997). Semi and intensive culture of finfish

and prawns has often been associated with eutrophication of coastal waters and the spread of

disease. For example, aquaculture pollution from the intensive culture of groupers, sea-bass

and snappers, is often caused by faeces and uneaten food, as well as nutrient discharges

which reduce dissolved oxygen in the water and cause high BOD. The adverse effects of

aquaculture effluents on water quality are seldom reported. In general, poor management of

aquaculture effluents has resulted in the outbreak of fish diseases that often incur more

financial losses to the farmers than the damage to the marine environment due to

eutrophication..

However, of more pressing concern than aquaculture effluents is the destruction of

the mangrove ecosystem in order to accommodate the rapid expansion in aqua farming.

2.2.4 Domestic Discharge from Coastal Population

The West Coast states are well developed and have the highest concentration of the

Malaysian population. Table 2.6 shows that the West Coast has 58.62% of the national

population despite having only 20.46% of the total land area. Penang, Selangor, Malacca, and

Perlis have population densities that are multiples of the national average.

23

UNEP/SCS National Report Malaysia

Table 2.6:

Population by State - Malaysia (2000)

% of

Negeri

Pulau

Total

MALAYSIA

Total

Johor

Kedah

Melaka

Sembilan

Perak

Perlis

Pinang

Selangor

Malaysia

AREA

Area in square

18,987

9,425

1,652

6,644

21,005

795

1,031

7,960

67,499

329,847

20.46%

kilometres

POPULATION

SIZE AND

COMPOSITION

Total population 2,740,625 1,649,756 635,791

859,924

2,051,236

204,450

1,313,449

4,188,876

13,644,107

23,274,690

58.62%

Population density

(per square

144

175

385

129

98

257

1,274

526

373.5*

71

kilometre)

Urban population

65.2

39.3

67.2

53.4

58.7

34.3

80.1

87.6

486

62

783.55%

(%)

* Average

Source: Department of Statistics, Malaysia, 2002

24

UNEP/SCS National Report Malaysia

With the cities, towns, industrial sites, fishing ports and villages located in close

proximities to river mouths and coastal waters, improper treatment of the sewage discharge

seeps into the drainage system and pollutes the rivers and seas. Poor sanitation is also a

source of water-borne diseases.

Domestic wastewater comprising of used water from toilets, bathrooms, laundry,

kitchen and synthetic cleaning chemicals, if not properly treated, is toxic to humans, plants,

and wildlife. Presently, the wastewater is collected by a system of sanitary sewers and

treated at municipal plants before being discharged to rivers, but these are still inadequate

even in urban centres (Keizrul Abdullah and Azuhan Muhamed, 1998).

2.2.5 Land Reclamation

Land reclamation for housing, infrastructure, and industrial purposes has an adverse

impact on mangroves, cockle mudflats and fish stocks if not properly planned as it affects

both the stability of the coastline and sustainability of capture and culture fisheries. For

instance, land reclamation off Prai in Penang for industrial purposes, and subsequent

discharges from factories, has threatened cockle farming at Kuala Juru because of high

sedimentation and the incidence of heavy metals. It was reported that the heaviest

concentration of mercury was near Nan Sing Textile factory, Kuala Juru, where the water

contained 2.30ppm of mercury, 460 times the permissible level in the US.

(http://www.surforever.com/sam/a 2z/content3.

With 76 coastline reclamation projects covering 97,000 ha in the pipeline,

particularly the large ones in Kedah, Penang, Perak and Selangor, there is an urgent need for

a thorough EIA appraisal on the impact of land reclamation on the marine ecosystem.

25

UNEP/SCS National Report Malaysia

2.3 FRESHWATER SHORTAGE AND DEGRADATION OF QUALITY

2.3.1 Surface Water

In Malaysia, rainfall is the only source of freshwater, especially during the wet

monsoon seasons. The annual downpour amounts to above 900 billion m3, of which 566

billion m3 is in form of surface runoff, 360 billion m3 is lost through evaporation, and 64

billion m3 is trapped in aquifers (Govt. of Malaysia, 1982). The volume of groundwater

resources stored in aquifers is estimated at 5000 billion m3. Even though groundwater

accounts for 90 per cent of total freshwater resources, 97 per cent of the national water

supply for domestic, agricultural, and industrial use originates from surface runoffs.

Surface water resources are trapped mainly in dams or reservoirs at water catchment

areas, chlorinated, and channelled through pipes to the end-users. Some rural folks living in

squatter settlements and villages along riverbanks utilize surface runoffs directly from the

rivers.

2.3.2 Surface Water Demand and Supply

The national demand for water is expected to grow at a rate of about 4 per cent

annually, and projected to be almost 20 billion m3 by 2020. Of this, 5.8 billion m3 is for

annual domestic and industrial water demand and the remainder for irrigation purposes

(Keizrul, 1998). On a per day basis, consumption of water has increased from 7.6mn m3 in

1995 to 10.4mn m3 in 2000 (Mak, 2002).

With the present irrigated rice bowl areas in Kedah and Butterworth not expected to

increase significantly in the future, the share of agricultural relative to domestic and

industrial demand for water is expected to fall. On the , especially in Penang, Selangor and

26

UNEP/SCS National Report Malaysia

Malacca, the domestic and commercial demand for water is expected to increase further

given the current pace of urbanisation and industrial growth.

Table 2.7 illustrates the rapid growth in water demand for the states fringing the

Straits of Malacca. Between 1980-2000, there was more than a three-fold increase in

domestic and industrial water demand. With many catchments areas on the under intense

pressure from land development activities, and the rapid rise in domestic and industrial

demand from urban centres downstream, there have been frequent shortages and disruptions

in water supply to the end users in recent years.

Table 2.7:

Domestic and Industrial Water Demand, (1980-2000)

(million m3)

State

1980

1985

1990

2000

Perlis

7

9

16

37

Kedah

49

82

113

266

Penang

124

169

236

343

Perak

145

216

327

596

Selangor

470

658

787

1201

Negeri Sembilan

62

102

131

197

Malacca

30

43

61

112

Johore*

159

258

338

578

Total

1,046

1,537

2,009

3,324

* For the whole state

Source: Dept. of Irrigation and Drainage

On the supply side, the availability of water has also increased from 9.5mn m3 per

day in 1995 to 12.8mn m3 in 2000. Under the Water Resource Master Plan (till 2050), an

allocation of RM52 billion has been made for 62 water projects, including 47 dams.

Recently, another RM 3.4 billion has been set aside under the 8th Malaysia Plan (2001-2004)

to fund ongoing projects, upgrade the distribution network, and repair existing infrastructure.

27

UNEP/SCS National Report Malaysia

2.3.3 Groundwater

Groundwater resources are replenished by rainfall and through seepage from streams.

Despite the abundance of groundwater, it only accounts for 3 per cent of total water use.

The under utilization of groundwater resources is due to several factors and these include;

the lack of information or maps to indicate their locations, perception that the supply is non-

sustainable and harmful due to effluent seepages, and the lack of local expertise on

groundwater technology. Furthermore, the present disposal of industrial and domestic waste

in landfills in suburban areas poses a threat as the leachates can contaminate the groundwater

with chemicals, heavy metals, and bacteria (E. coli).

Groundwater is extracted mainly through wells, especially in very rural areas for

domestic use and irrigation. With water supply readily available to over 90 percent of the

communities, planners previously gave little thought on groundwater development. Also,

for practical reasons, investments in groundwater systems are expensive for urban dwellers

because of the high capital outlays and operating costs. However, since the recent water

crisis, the DOE has taken preliminary steps to determine the quality and distributions of

groundwater through the national groundwater-monitoring programme in 1997. By 2001, the

DOE had established 79 monitoring wells in Peninsular Malaysia and another 19 in

Sarawak.

Samples taken were analysed for volatile organic components (VOC), pesticides,

heavy metals, anions, bacteria, phenolic compounds, radioactivity, total hardness, total

dissolved solids (TDS), pH, temperature, conductivity and dissolved oxygen. The

groundwater status was determined by comparing against the National Guidelines for Raw

Drinking Water Quality (1990). The results indicate iron, manganese, nitrates, and arsenic

wastes (especially near landfills) contents in groundwater were significant (DOE 2003).

28

UNEP/SCS National Report Malaysia

Much has still to be done for groundwater utilization as data on the distribution and relative

abundance of groundwater resources, wells, and users are still scanty for macro planning.

2.3.4 Water Related Issues and Problems

Drought

In recent years, the water situation in the West Coast, especially Penang, Klang

Valley, Negeri Sembilan and Malacca, has worsened. In1998, the prolonged drought caused

by the El-Nino resulted in a water crisis and many parts of the country had to be rationed for

water. Water demand from new growth centres such as the Kuala Lumpur International

Airport and the Multimedia Super Corridor (MSC) further aggravated the drought effect

causing frequent cutbacks in water supplies to neighbouring townships. This crisis has

alerted the government of the need for prudent and integrated approach to water resource

management so as to sustain commercial and industrial activities in order to achieve

economic growth.

Floods

Floods occur due to the inability of streams and rivers to drain excess water from

heavy downpours. About 29,000 km2 or 9 per cent of the country's land area is flood-prone

affecting the livelihood of 2.7 million people, both rural and urban dwellers. Even the

aquaculture farms in coastal waters suffered high mortalities of fish, prawns and cockles

from reduced salinity and heavy sedimentation due to sudden and excessive intrusions of

freshwater from streams and rivers. Due to the freshwater intrusions, mussels culture in

Malacca, cockles at Kuala Juru and prawn farms at Kuala Muda have incurred heavy

financial losses.

29

UNEP/SCS National Report Malaysia

In the urban centres, there has been a steady increase in the incidence of flash floods.

The Klang Valley and Penang are two areas most susceptible to flash floods even after a

short spell of heavy downpour, causing massive traffic jams that may last for hours. Flood

mitigation measures, such as widening and deepening of drainage systems, are expensive but

do not seem to be able to curb with the heavy downpours.

Water pollution

As with most Asean countries, man tend to be the main culprits to water pollution.

Indiscriminate dumping of domestic and industrial wastes and the silting of rivers due to

erosion caused by the destruction of forests and catchment areas pollute as well as reduce the

carrying capacities of rivers. Water pollution reduces availability of good quality water,

increases water treatment costs, and is also an ecological hazard affecting both human and

aquatic life. Water pollution is a concern for all nations.

Management Issues

The management of national water resources, both from supply and demand

perspectives, is not easy with an uneven distribution of residents, catchment areas, and

differing financial capabilities of the states. As land is a state matter under the Malaysian

Constitution, the powers of the federal agencies are limited at the ground level and this

complicates the implementation of projects, particularly those that are of national interest.

Malaysia has an abundance of sector-based regulations but not those that focus on the

polluter-pays principle.

Exploration and Exploitation of Groundwater

With catchment areas gradually reduced for economic development and with an

abundance of groundwater resources, efforts must be made to explore and map out the viable

30

UNEP/SCS National Report Malaysia

locations for the exploitation of groundwater. Human capacity building and collaboration

with countries such as Denmark, Germany and Holland, which have considerable experience

in groundwater supply systems, can assist in our new focus for future water needs.

2.3.5 Sensitive and High Risk Areas

Most of the Straits of Malacca and coastal areas around densely populated urban and

industrial centres can be considered sensitive and high-risk locations. These places pose

direct and indirect threats to public health and aquatic resources as well as the sustainability

of coastal biodiversity.

Starting from the north of the Malacca Straits, the Muda River has deteriorated from

industrial and urban discharge due to rapid development at Sungai Petani, the state's new

growth centre. Presently, the polluted river is threatening fish cage culture systems and the

mangrove ecosystem downstream. Other rivers such as Sg. Pinang and Sg. Juru have also

been degraded due to upstream economic growth, endangering the coastal life support

systems affecting both aquaculture yields and fish landings.

In the central and southern regions, the high risk locations that are prone to flash

floods, water pollution, and ecological damage, are Klang Valley, upper Kinta Valley,

Linggi and Malacca Basins. Many urban rivers, lakes, and ponds that serve these areas are

unfit for use as these are overloaded with non-point source (NPS) pollutants and storm

water-generated waste.

The biggest danger to the marine and coastal resources, including the lives of

fishermen, comes from the perpetual threat of oil spills and vessel accidents from ships that

patronize the international straits. Such accidents are bound to damage marine life as well as

life support systems such as mud flats, mangroves and coral reefs.

31

UNEP/SCS National Report Malaysia

2.4 EXPLOITATION OF LIVING AQUATIC RESOURCES

The fishery sector is an important economic sector to the growing population as it

continues to provide animal protein, employment and foreign exchange earnings.

In 2000, total fish production from marine capture, brackish/marine aquaculture and

freshwater culture systems was 1.43 million tonnes valued over RM5.4 billion or about 1.6%

of the GNP. Employment for the sector amounted to over 106,000 people or about 1.10% of

the national total.

Marine captured fisheries contributed over 88% of the total fish production and

provided 77.3% of employment in the sector. Overall, coastal fisheries is the major

contributor to the sector with a production of 1.115 million tonnes or about 72% of total

value of fish production.

West Coast Marine Fishery

West Coast of Peninsular Malaysia remains the most productive fisheries region in

Malaysia. In year 2000, the West Coast marine waters contributed 535,188 tonnes or 41.61%

of Malaysia's total marine landings. It also dominates other regions in aquaculture

production, contributing over 89% and 54% of the total fish production from brackish/marine

aquaculture and freshwater culture systems respectively.

West Coast marine fishery employs some 31,000 fishermen (Figure 2.1) using around

13,095 vessels of which 98% were those licensed for inshore fishery and operating within 30

nautical miles from land. These vessels contributed 513,508 tonnes or 96% of the aggregate

marine fish landing for the West Coast. Notice that there was a general decline in the number

32

UNEP/SCS National Report Malaysia

of fishermen over time. In part, the gazetting of coastal waters for port activities such as the

Klang and Malacca ports had displaced fishermen from vicinity villages (Ishak, 2000).

Figure 2.1: Number of Fisherman Working in Licensed Vessels

West Coast Peninsular Malaysia, 2000

2000

30,922

1999

30,669

1998

29,765

1997

30,258

1996

30,363

1995

33,433

1994

30,744

1993

32,382

1992

37,403

1991

38,213

1990

39,594

1989

41,782

1988

37,487

1987

38,792

1986

38,815

1985

43,778

1984

47,339

1983

47,028

1982

51,189

1981

56,997

1980

59,729

-

10,000

20,000

30,000

40,000

50,000

60,000

No. of Fishermen

Source Annual Fisheries Statistics

In 2000, there were only 186 offshore fishing vessels operating in the West Coast. In

spite all the government efforts to encourage fishermen to venture into deep-sea fishing,

landings from this sector only contributed about 21,610 tonnes or 4 % of total fish production

(Table 2.8). In 2003, the Fishery Development Authority (LKIM) bought five 80-tonner

fishing vessels from Japan for the exploitation of skipjack tuna in the Indian Ocean . If

successful, the venture may attract others to participate in deep-sea fisheries.

33

UNEP/SCS National Report Malaysia

Table 2.8:

Inshore Vs Offshore landing (tonnes), 1990-2000

West Coast Malaysia, 1990 - 2000

INSHORE (< 30 n.m.)

OFFSHORE ( = > 30 n/m.)

< 70 GRT

Total

% of

= > 70 GRT

Total

% of

Total

No. of

Landing

Total

(No. of Vessels) Landing

Total

Landing

Vessels

(tonnes)

Landing

(tonnes)

Landing

(tonnes

1990

16,801 494,842

96.94%

193

15,629

3.06%

510,471

1991

16,474 365,266

93.86%

185

23,897

6.14%

389,163

1992

15,693 452,604

95.49%

194

21,391

4.51%

473,995

1993

14,116 423,228

94.78%

190

23,287

5.22%

446,515

1994

13,269 439,564

95.49%

168

20,738

4.51%

460,302

1995

16,277 501,214

94.78%

172

27,604

5.22%

528,818

1996

14,509 485,980

94.21%

167

29,848

5.79%

515,828

1997

14,218 483,896

93.88%

154

31,533

6.12%

515,429

1998

14,048 521,334

94.58%

164

29,848

5.42%

551,182

1999

13,463 475,950

95.17%

163

24,131

4.83%

500,081

2000

12,909 513,508

95.96%

186

21,610

4.04%

535,118

1990-

2000

468,853

95.01%

24,501

4.99%

100%

Average

Source Annual Fisheries Statistics

34

UNEP/SCS National Report Malaysia

2.4.1 Living Freshwater Resources

Freshwater Aquaculture

The living freshwater resources cover fishing activities in ponds, cages, lakes, ex-

mining pools, hydroelectricity impoundments, reservoirs and others. Inland fishing is done on

a part-time basis and is supplemented by other agricultural pursuits. The contribution of

inland fisheries is small, about 4.1% of total fish production in the West Coast.

The ornamental fish industry, which requires smaller establishment (tanks) and under

controlled environment, has steadily gained importance. In 2000, the industry produced about

306 million aquarium fishes valued at RM72 million (Lim and Chuah, 2002).

Freshwater aquaculture is probably the most diversified in terms of species and

culture systems. There are almost 20 species that are cultured using at least four different

culture systems. The main culture systems by species are shown in Table 2.9.

Expansion of freshwater aquaculture industry has been slow, despite early optimism

of its potential contribution to national fish production. The discharge of agricultural

chemicals and pesticides to heavily silted rivers has limited the growth in the industry. In

recent years, excavated ponds for recreational fishing is gaining popularity around urban

centres.

35

UNEP/SCS National Report Malaysia

Table 2.9:

Freshwater Culture Systems by Species

Culture System

Intensive Culture

Semi-Intensive

Pond

Poly

Chinese Carps

Carps

Mono

Tilapia, Catfish, Prawns Tilapia, Catfish, Snakehead, Goby, Prawns

Integrated

X

Carps

Cage

Poly

X

Mono

Tilapia, Catfish

Tilapia, Catfish

Tank

Mono

Tilapia, Catfish

X

Pen

Poly

X

Carps

Mono

X

Tilapia, Catfish

Integrated

X

Tilapia, Catfish

Note: X seldom practised

36

UNEP/SCS National Report Malaysia

Swamps and Water Bodies

Swamp forests act as carbon sinks and play an important role in regulating floods, as

well as a source of water during droughts. These are also the home to diverse animals and

plants besides being an important source of timber, fish and medicinal products. Land

development, unabated logging and improved drainage, tend to dry out the top peat layers

making them fire hazards and causing a loss in biodiversity.

Besides the swamps, mining for minerals, especially alluvial tin and sand, caused

widespread degradation of areas with mineral deposits leaving behind sandy, barren and

unfertile land, unattended water bodies, and silted waterways. Landslips, particularly of

open-cast alluvium mines, also pose a hazard to life and property.

Paya Indah, covering 4000 hectares of degraded tin-mining land and bogged peat

swamp forest, including the Kuala Langat Forest Reserve, has been gazetted in 1996 as the

Malaysian Wetland Sanctuary. This is a high-profile environmental project and, with the

Prime Minister as its patron, this initiative reflects Malaysia's continued commitment to

Agenda 21 and Ramsar obligations.

Another government initiative is a RM20 million 5 year-project to promote the

conservation and sustainable use of peat swamp forests in three sites in Pahang, Sabah and

Sarawak (New Straits Time, 10/9/2003). This project funded by the United Nations

Development Programme/Global Environment Facility (UNDP/GEF) in collaboration with

the Danish International Development Agency (Danida) is intended to develop a model to be

used in sustainable management and conservation of Malaysia's 3.3 million hectares of peat

swamp forests.

37

UNEP/SCS National Report Malaysia

However, present legislations governing the use of wetlands and mining are still

inadequate due to the absence of clear guidelines, standards or benchmarks for sustainable

utilization of the resource.

2.4.2 Living Marine Resources

2.4.2.1 Marine Capture Fisheries

The main marine species landed in Malaysia are classified under pelagics, demersal,

crustacean/shellfish, mollusks/cephalopods and trash fish. Table 2.10 shows the amount and

type of marine species caught by region in terms of tonnage. The West Coast region

dominates for most species groups in Malaysia.

Table 2.10:

Fish Species Landings by Location, Malaysia (2000)

Trash

%

Fish &

of

Demersal

Pelagics

Crustacean Mollusks

Others

Total

Total

Region

(tonnes)

(tonnes)

(tonnes)

(tonnes)

(tonnes)

(tonnes)

Malaysia

West Coast

75,680

126,987

67,211

47,635

217,605

535,118

41.62%

East Coast

55,032

196,822

7,797

25,447

113,677

398,775

31.02%

East Malaysia

103,886

105,673

34,710

15,353

92,181

351,803

27.36%

Total Malaysia

234,598

429,482

109,718

88,435

423,463 1,285,696

100%

% by Species

18.25%

33.40%

8.53%

6.88%

32.94%

100%

Group

Source: Annual Fisheries Statistics

38

UNEP/SCS National Report Malaysia

Pelagic species dwell and feed on plankton and zooplankton near the water surface.

Most of the pelagic species are transboundary and migrate along coastal and EEZ waters.

Those of economic importance are the mackerels (Rastrelliger), scads (Decapterus), sardines

(Sardinella), tunas (Thunnaus, Auxis), pomfrets (Parastormateus) and anchovy

(Encrasicholina). These pelagic species are caught mainly by purse-seiners and trawlers.

Pelagic species are difficult to manage as these are mainly shared stocks with neibouring

coastal nations. Any conservation efforts or restrain on catch by one country will result in a

gain for others. The optimal management of shared stocks is an area that requires

collaborative effort among the littoral nations of the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Sea.

Demersal fish resources are bottom-dwelling and often carnivorous. The marine

species require light to hunt for food and are found in shallow waters, usually among

mangroves rocks and reefs. Those of commercial value are threadfin bream (Enmities),

bigeye (Piracanthus), barracuda (Sphyraena), red snapper (Lutjanus), and groupers.

Demersal fishes are mainly caught by trawlers, traditional gear types, and hook and line.

Attempts have been made by the Malaysian government to increase the productivity of

fishery resources through the establishment of artificial reefs with the hope of creating a new

breeding ground for marine fishes. A study by Zainuddin and Razak (2000) and recent

evidence on the increase in marine landings on the West Coast suggest that artificial reefs

can enhance fish productivity. However, a detail study on this is needed, to determine the

extent of productivity increases as well as the fish species that are attracted to the artificial

habitat.

Of concern to Malaysian fisheries, especially the West Coast fisheries, is the large

amount of trash fish landed recently, over 200,000 tonnes or about 40% of total catch. Trash

fish is an assortment of commercial and non-commercial species which are processed into

fishmeal or other foods. The abundance of trash fish landings is an indicator that the West

39

UNEP/SCS National Report Malaysia

Coast fisheries has been over exploited, that is a level of fishing effort which produces a

catch over the maximum sustainable yield (MSY).

The West Coast fisheries is also important for other marine species that are of

commercial value such as prawns and mollusks. These species are both cultured and caught

from the wild. In aggregate, West Coast prawns and mollusks landings contributed about

61% and 54% respectively of the national output. The increase in squid and cuttlefish

landings recently is another phenomenon that can be linked to an over capitalized fishery.

The general pattern in the species mix of landings over time is shown in Figure 2.2

(a to c). The ranking in terms of contribution by species group to total landing has been

consistent over the three decades indicating that the fishery, though over exploited, has been

relatively stable.

40

UNEP/SCS National Report Malaysia

Figure 2.2: Composition of Marine Fish Species Group Landings

West Coast Peninsular Malaysia

a)

Composition of Marine Species Groups Landing

West Coast Peninsular Malaysia (2000)

Demersal

Trash Fish &

14.14%

others

40.67%

Pelagics

23.73%

Mollusks

8.90%

Crustacean

12.56%

b)

c)

Composition of Marine Species Group

Compostion of Marine Species Group

Landing

Landing

West Coast Peninsular Malaysia (1980)

West Coast Peninsular Malaysia (1990)

Demersal

Demersal

Trash Fish &

14.15%

12.07%

others

Trash Fish

37.33%

& others

Pelagics

42.42%

25.81%

Pelagics

27.85%

Mollusks

Mollusks

Crustacean

6.39%

Crustacean

4.87%

14.83%

14.28%

41

UNEP/SCS National Report Malaysia

There has been a decline in the number of licensed fishing vessels over the years from

22,082 in 1980 to 13,095 in 2000 (Table 2.11). Most of the increase in landings in the West

Coast was due to technological development, through the use of better fishing techniques,

synthetic instead of fibre nets, large powered vessels and the rapid adaptation of trawl gear

since the mid-1960's. Figure 2.3 shows the relative share of the gear groups. As expected, the

mobile gear types, trawlers and purse-seiners landed the most, about 79% of the total catch.

One of the main problems in the West Coast fishery is the encroachment of trawlers

into the coastal fishing grounds of traditional fishermen that has resulted in frequent conflicts

between the two. Also, there are inter-country conflicts arising from the encroachment by

Thai and Indonesian fishing boats into Malaysian waters, some have resulted in violence and

even death (Ishak, 1994). The present trend in employing foreign fishermen, especially from

Thailand to man offshore vessels has also created social problems resulting in hostility

between the local and foreign fishermen.

Besides the above, and of international concern, is piracy in the Straits of Malacca

that is prevalent even in present times. For the first half of 2003, one quarter or 64 cases of

piracy incidents worldwide occurred in Indonesian waters. Four ships were reported hijacked

and 43 boarded while attempted attacks were made on 17 vessels (The Sun, 28 July 2003).

Malaysia, with her better naval and marine capabilities to monitor her coastline had only five