Removal of barriers to the introduction

of cleaner artisanal gold mining

and extraction technologie

in Kadoma, Zimbabwe

Part B: Health Assessment

Final Report

Removal of barriers to the introduction

of cleaner artisanal gold mining

and extraction technologie

in Kadoma, Zimbabwe

Part B: Health Assessment

Final Report

Stephan Boese-O´Reilly, Felicitas Dahlmann, Beate Lettmeier, Gustav Drasch

Institute of Forensic Medicine, Ludwig-Maximilians University,

Munich, November 11th, 2004

UNIDO Project EG/GLO/01/G34 No.03/089

BRGM Project Nr 822657-3

Keywords : Mercury, Amalgamation, Gold, Environmental Assessment, Health Assessment,

Artisanal mining, Cleaner Technology, Fish, Muscle, Chakari, Kadoma, Zimbabwe.

In bibliography, this report should be cited as follows :

Boese-O'Reilly S., Dahlmann F., Lettmeier B., Drasch G. (2004) Removal of barriers to the

introduction of cleaner artisanal gold mining and extraction technologie in Kadoma, Zimbabwe.

Final report, 130 p., 28 Figures, 25 Pictures, 22 Tables, 3 Appendix.

© BRGM, 2005. No part of this document may be reproduced without the prior permission of BRGM.

Health Assessment Kadoma, Zimbabwe

Contents

1. Executive summary..............................................................................................9

2. Study setting and clinical examinations (Stephan Boese-O´Reilly, Beate

Lettmeier, Felicitas Dahlmann) ..................................................................................13

2.1. INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................13

2.2. MERCURY.........................................................................................................14

2.3. ZIMBABWE - KADOMA SMALL SCALE MINING AREA...................................14

2.4. PROJECT DESIGN ...........................................................................................22

2.4.1.Questionnaire.........................................................................................25

2.4.2.Neurological examination.......................................................................25

2.4.3.Neuro-psychological testing ...................................................................27

2.4.4.Tremor-meter .........................................................................................28

2.4.5.Laboratory field project...........................................................................29

2.4.6.Test for protein in urine ..........................................................................31

2.5. GENERAL HEALTH PROBLEMS IN KADOMA DISTRICT...............................31

2.5.1.Health care system in Kadoma district ...................................................31

2.5.2.General health data................................................................................32

2.6. GENERAL HEALTH PROBLEMS IN KADOMA DISTRICT...............................36

2.6.1.Children's health in Kadoma district.......................................................37

2.7. PRELIMINARY CLINICAL RESULTS OF THE HEALTH ASSESSMENT.........38

2.7.1.Clinical and neurological examination ....................................................38

2.7.2.Children's health in Kadoma mining area...............................................40

2.7.3.Hygienic problems..................................................................................41

2.7.4.Social problems......................................................................................41

2.7.5.General problems during the field project ..............................................42

2.7.6.Participation ...........................................................................................42

Final Report

3

Health Assessment Kadoma, Zimbabwe

3. Specimen analysis and statistical results

(Gustav Drasch, Beate Lettmeier) ...................................................................... 43

3.1. LABORATORY METHODS............................................................................... 43

3.1.1.Material and sample storage ................................................................. 43

3.1.2.Sample preparation ............................................................................... 43

3.1.3.Mercury determination and quality control............................................. 43

3.2. STATISTICAL ANALYSIS ................................................................................. 44

3.2.1.Statistical methods................................................................................. 44

3.2.2.Description of mercury levels in urine, blood and hair ........................... 44

3.2.3.Exclusion of data ................................................................................... 46

3.2.4.Forming subgroups due to residence and occupation........................... 46

3.2.5.Mercury Levels compared to Toxicological Threshold Limits ................ 51

3.2.6.Reducing of redundant data for statistical analysis ............................... 53

3.2.7.Scoring of medical results...................................................................... 56

3.2.8.Statistical analysis of mercury levels versus clinical data...................... 59

3.3. DISCUSSION OF THE STATISTICAL ANALYSIS............................................ 61

3.4. DECISION FOR THE DIAGNOSIS OF A CHRONIC MERCURY

INTOXICATION................................................................................................. 61

3.5. PREVALENCE OF THE DIAGNOSIS "MERCURY INTOXICATION" ............... 62

3.6. COMPARISON OF VOLUNTEERS FROM DIFFERENT MINES ..................... 64

3.7. INFLUENCE ON NURSED BABIES ................................................................. 69

3.8. SCREENING OF MERCURY URINE CONCENTRATION IN FIELD................ 71

4. Summary and Recommendations (Gustav Drasch, Stephan Boese-O´Reilly) . 73

4.1. SUMMARY ........................................................................................................ 73

4.2. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................. 75

4.2.1.How to improve "general health"?.......................................................... 75

4

Final Report

Health Assessment Kadoma, Zimbabwe

4.2.2.How to reduce "mercury as a health hazard"? .......................................75

4.2.3.How to improve the "knowledge on mercury as a health hazard" ..........76

4.2.4.How to reduce the "release of mercury into the environment" ...............76

4.3. LITERATURE.....................................................................................................77

5. Acknowledgement..........................................................................................................81

List of figures

Figure 1 - UNIDO project countries............................................................................................13

Figure 2 - Map of Zimbabwe Victoria Falls .............................................................................14

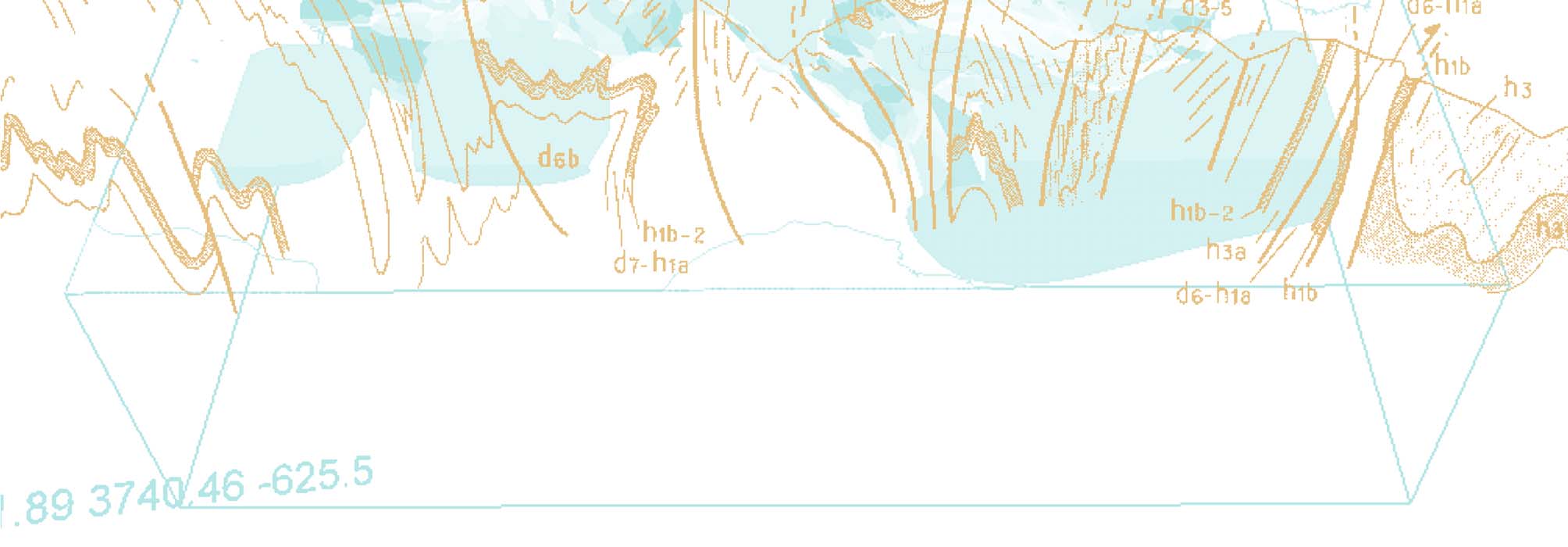

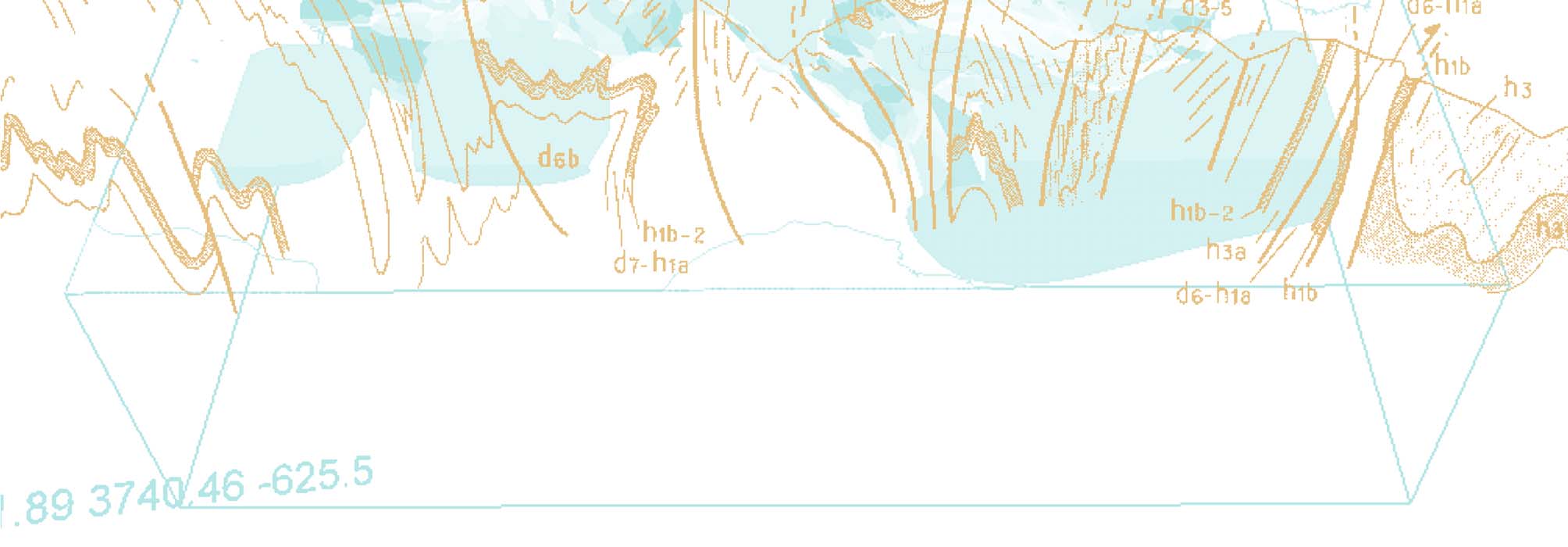

Figure 3 - Local map of Kadoma area (provided by BRGM) .....................................................15

Figure 4 - Age distribution of all volunteers, selected for the statistical evaluation ...................47

Figure 5 - Total mercury concentration in blood samples..........................................................48

Figure 6 - Total mercury concentration in urine samples...........................................................48

Figure 7 - Total mercury concentration in hair samples.............................................................49

Figure 8 - Percentage of inorganic mercury in hair samples. ....................................................50

Figure 9 - Percentage of organic bound mercury in hair samples.............................................50

Figure 10 - Frequency of the anamnestic parameter "metallic taste" ..........................................54

Figure 11 - Children; frequency of the anamnestic parameter "excessive salivation" .................54

Figure 12 - Adults; frequency of the anamnestic parameter "bluish coloration of

gingiva". .....................................................................................................................55

Figure 13 - Adults; frequency of the anamnestic parameter "ataxia of gait"................................55

Figure 14 - Frequency of the anamnestic parameter "dysdiadochokinesia"................................56

Figure 15 - Hg-concentration in blood; comparison of the heavy drinkers with the non

heavy drinkers among the group of amalgam-burners..............................................57

Figure 16 - Hg-concentration in urine; comparison of the heavy drinkers with the non

heavy drinkers among the group of amalgam-burners..............................................58

Figure 17 - Medical score sum of the different subgroups...........................................................59

Figure 18 - Frequency of the diagnosis "mercury intoxication"....................................................63

Figure 19 - Distribution of age versus different mining areas; amalgam-burners only. ...............65

Figure 20 - Distribution of gender versus different mining areas; amalgam-burners only...........65

Figure 21 - Medical score sum versus different mining areas; amalgam-burners only. ..............66

Figure 22 - Hg-concentration in urine versus different mining areas; amalgam-burners

only. ...........................................................................................................................66

Figure 23 - Concentration of total Hg in hair versus different mining areas; amalgam-

burner only.................................................................................................................67

Final Report

5

Health Assessment Kadoma, Zimbabwe

Figure 24 - Hg-concentration in blood versus different mining areas; amalgam-burner

only............................................................................................................................ 67

Figure 25 - Frequency of the clinical parameter "ataxia of gait"; amalgam-burner only.............. 68

Figure 26 - Frequency of the clinical parameter "dysdiadochokinesia"; amalgam-burner

only............................................................................................................................ 68

Figure 27 - Frequency of the diagnosis of a mercury intoxication; amalgam-burner only. ......... 69

Figure 28 - Comparison of the concentration of inorganic Hg-U, as determined in field

and the total Hg-U concentration, as determined in the lab (Linear

regression line and 90% confidence intervals). ........................................................ 71

List of pictures

Picture 1-

Liquid mercury used in Tix mine ............................................................................. 14

Picture 2 - Kadoma village and nearby area. ........................................................................... 16

Picture 3 - Tix mine copper plate and stamp mill. .................................................................... 16

Picture 4 - Tix mine - scratching of amalgam; squeezing amalgam through a cloth;

piece of amalgam; burning amalgam...................................................................... 17

Picture 5 - Small artisanal open pit........................................................................................... 18

Picture 6 - Muzvezve river ........................................................................................................ 18

Picture 7 - Amber Rose mill: stamp mill; cyclotron ................................................................... 19

Picture 8 - Amber Rose mill - tailings; cyanidation tank; pregnant solution; filling the

tanks with tailings .................................................................................................... 20

Picture 9 - Primitive sluice box and James table at Etna village .............................................. 21

Picture 10 - Panning at Etna, piece of amalgam; one sack of stones collected

by a miner in a day.................................................................................................. 21

Picture 11 - Amber Rose village ................................................................................................. 22

Picture 12 - Mayflower school .................................................................................................... 23

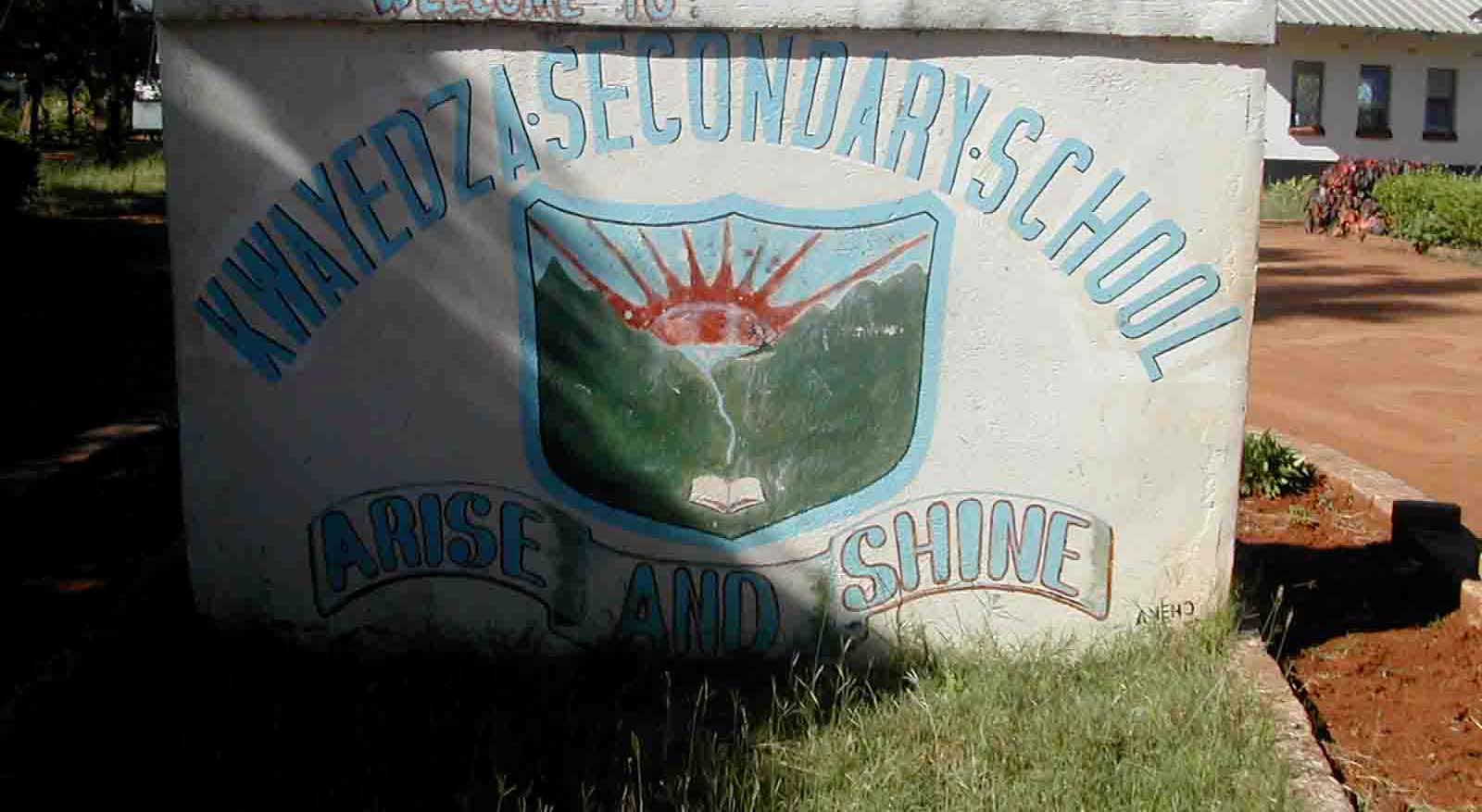

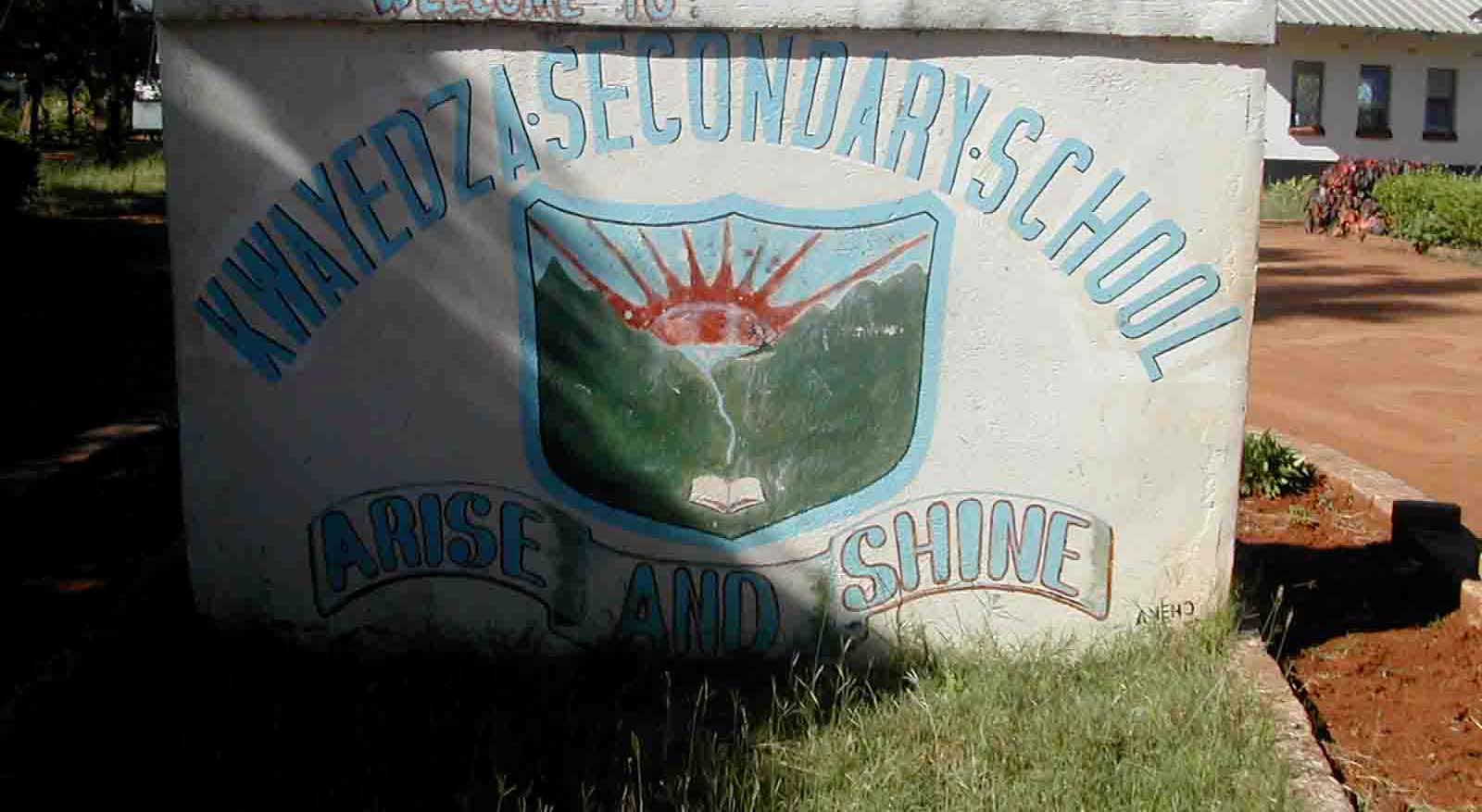

Picture 13 - Kwayedza school .................................................................................................... 23

Picture 14 - Mobile field clinic at Amber Rose mill neuro-psychological testing;

history; laboratory; blood sampling ......................................................................... 24

Picture 15 - Nurses taking the history......................................................................................... 25

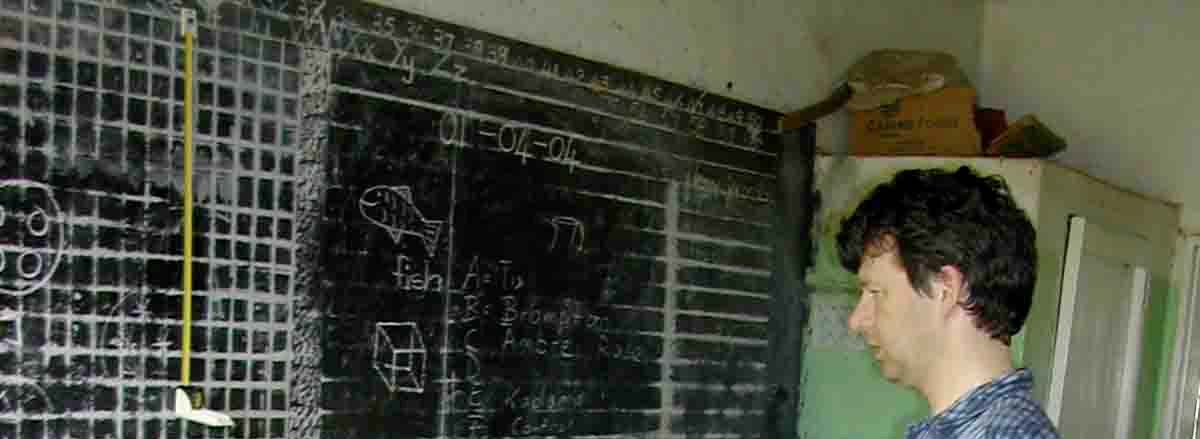

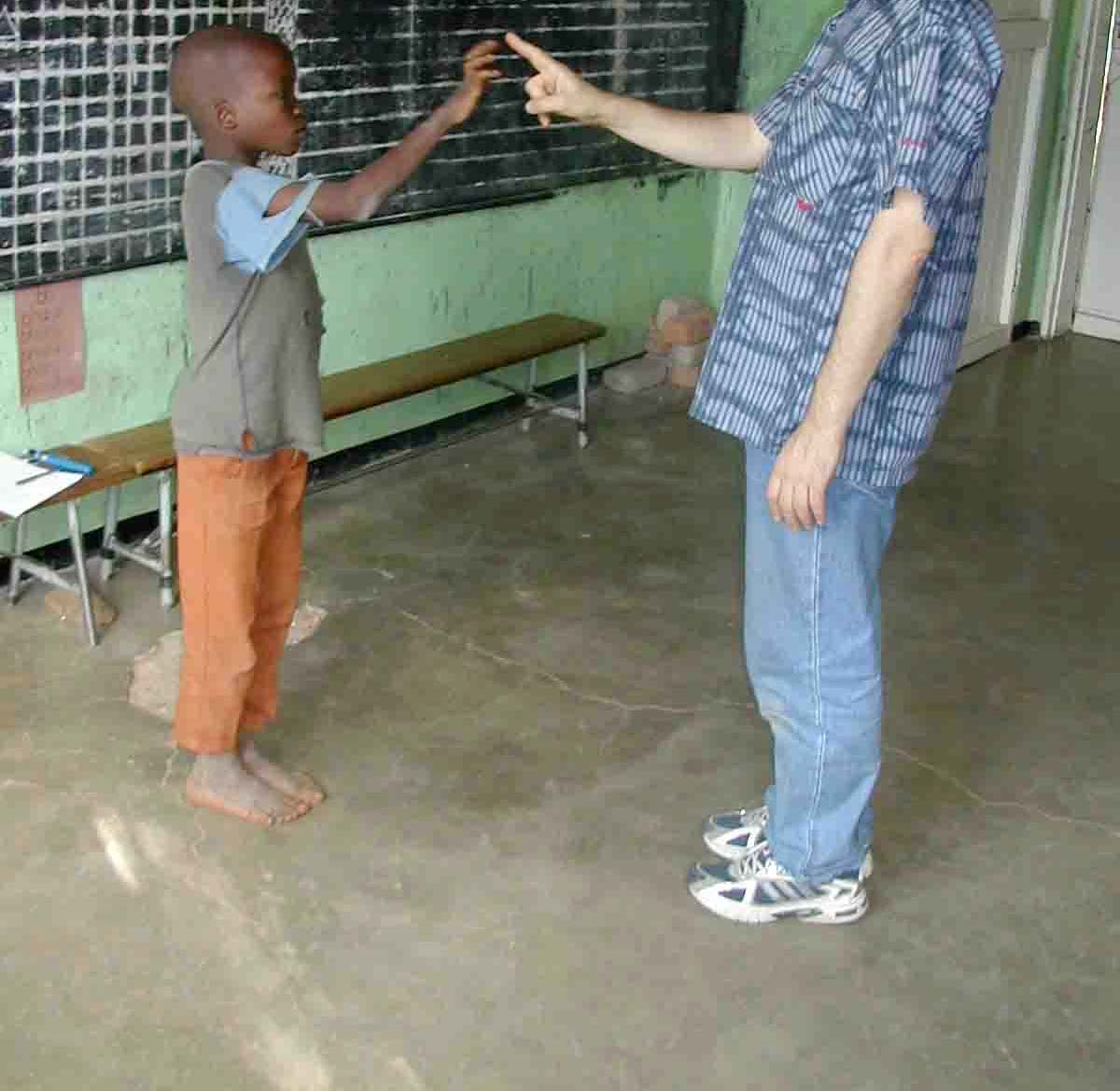

Picture 16 - Neurological examination (PSR reflex; finger-finger-nose test).............................. 26

Picture 17 - Visual field test ........................................................................................................ 27

Picture 18 - Match box text, memory test, pencil tapping test, Frostig test................................ 28

Picture 19 - Tremor-meter .......................................................................................................... 29

Picture 20 - Hair and urine sampling .......................................................................................... 30

Picture 21 - Mobile Hg analyser for urine (Lumex)..................................................................... 30

Picture 22 - Children from Kadoma, all working as miners. ....................................................... 38

6

Final Report

Health Assessment Kadoma, Zimbabwe

Picture 23 - Participants with hypertrophic skin, scars due to mining accident, scar due

to a knife injury ........................................................................................................39

Picture 24 - Dental malformation ................................................................................................40

Picture 25 - Control area Chikwaka ............................................................................................40

List of tables

Table 1 -

Kadoma district demographic data (by Mr. Gift from Kadoma District

Hospital).....................................................................................................................32

Table 2 -

Main causes of out-patient morbidity (under 5 years) (data from Mr. Gift

from Kadoma District Hospital)..................................................................................33

Table 3 -

Main causes of out-patient morbidity (all ages) (date from Mr. Gift from

Kadoma District Hospital. ..........................................................................................33

Table 4 -

Main causes of in-patient morbidity (under 1 year of age) (data from Mr. Gift

from Kadoma District Hospital)..................................................................................34

Table 5 -

Main causes of in-patient morbidity (5 years and over) (data from Mr. Gift

from Kadoma District Hospital)..................................................................................34

Table 6 -

Top five causes of mortality (under 1 year) (data from Mr. Gift from Kadoma

District Hospital).........................................................................................................35

Table 7 -

Top five causes of mortality (5 years and over) (data from Mr. Gift from

Kadoma District Hospital) ..........................................................................................35

Table 8 -

HIV/ AIDS (data from Mr. Gift from Kadoma District Hospital. ..................................35

Table 9 -

Concentration of total mercury in blood, urine and hair.............................................45

Table 10 - Concentration of organic mercury in hair ..................................................................46

Table 11 - Toxicologically established threshold limits for mercury in blood, urine and

hair (HBM = Human Bio-Monitoring; BAT = "Biologischer Arbeitsstoff-

Toleranzwert" (biological work-exposure tolerance limit); BEI = Biological

Exposure Indices)......................................................................................................52

Table 12 - Anamnestic, clinical, neurological and neuro-psychological scoring scale. ..............58

Table 13 - ignificant correlations between anamnestic data and mercury concentration

in bio-monitors (group of amalgam-burners only, n = 116).+ = p < 0.05...................59

Table 14 - Significant correlations between anamnestic data and mercury

concentration in bio-monitors (group of amalgam-burners only, n = 116).+ =

p < 0.05......................................................................................................................60

Table 15 - Significant correlations between clinical data and mercury concentration in

bio-monitors (group of amalgam-burners only, n = 116) .+ = p < 0.05......................60

Table 16 - Significant correlations between neuro-psychological test classes and

mercury concentration in bio-monitors (group of amalgam-burners only, n =

116). + = p < 0.05. .....................................................................................................61

Table 17 - Significant correlations between medical scores and mercury concentration

in bio-monitors (group of amalgam-burners only, n = 116). + = p < 0.05..................61

Table 18 - Decision for the diagnosis "chronic mercury intoxication". ........................................62

Final Report

7

Health Assessment Kadoma, Zimbabwe

Table 19 - Frequency of mercury intoxication. ........................................................................... 62

Table 20 - Distribution of the formed subgroups in the different mining areas. ......................... 64

Table 21 - (Total) mercury concentration in breast-milk samples compared to other

data from the mothers. .............................................................................................. 70

Table 22 - Comparison of the preliminary classified "mercury intoxicated" in field and

by all lab results. ....................................................................................................... 72

List of appendix

Appendix 1 Tables................................................................................................................... 83

Appendix 2 Health assessment questionnaire........................................................................ 99

Appendix 3 Zimbabwe clinical main data.............................................................................. 119

8

Final Report

Health Assessment Kadoma, Zimbabwe

1. Executive summary

Kadoma is a typical small-scale mining area with approximately 235,000 inhabitants in

the Midlands in Zimbabwe. Artisanal small-scale miners use mercury to extract gold

from the ore. It is estimated that approximately a few hundred thousand people work

and live in similar small scale mining communities all over Zimbabwe.

In the selected area there is no clean and safe drinking water, no waste disposal for the

toxic mercury or any other waste or human discharge. Hygienic standards are

extremely low and are a reason for many infectious diseases such as diarrhoea,

malaria and parasitism.

Accidents in insecure tunnels and amalgamation plants, acute respiratory tract

infections, malaria, tuberculosis, and sexually transmitted diseases including AIDS are

the dominant causes of morbidity and mortality. No proper health service exists in the

mining communities. The District Hospital in Kadoma has very limited means.

The extraction of gold with liquid mercury releases serious amounts of mercury,

especially high toxic mercury fumes into the local environment. The health status of

218 volunteers in Kadoma and 55 from a control area in Chikwaka was assessed with

a standardised health assessment protocol from UNIDO (Veiga 2003) by an expert

team from the University of Munich/Germany in April 2004.

The mercury levels in the human bio-monitors were much higher in the exposed

population in Kadoma than in the control group. The exposed population was divided

into sub-groups to compare the levels of exposure. As to be expected the control group

was within a normal range and the amalgam-burners had the highest exposure levels

in all human bio-monitors, while the less exposed population in the mining areas

ranged in between. Child mercury exposure due to living in the mining areas and

working with mercury show similar levels in the bio-monitors as adult amalgam-

burners, children not working but living in the area also have increased levels, mainly

compared to children from the control area. The results of the human bio-monitoring

show clearly the severe exposure of the total population in the mining areas with

mercury; the extreme exposure mainly of amalgam-burners and the especially severe

exposure of children working with mercury. The mercury exposure in the mining areas

is mainly due to exposure with elemental mercury and not due to exposure with methyl-

mercury. The relation of inorganic versus organic mercury in the control population

shows the usual exposure of any population, where most of the mercury exposure

comes from the consumption of methyl-mercury contaminated fish. Whereas in the

mining areas the high amounts of inorganic mercury in hair indicate that the main

exposure in the mining areas more then likely comes from elemental mercury, than

from methyl-mercury exposure through contaminated food. Exposure with elemental

mercury could come from handling mercury with bare hands, but the immanent

exposure with mercury vapour might be the more important pathway, since amalgam-

burners show the highest human bio-monitor levels.

Final Report

9

Health Assessment Kadoma, Zimbabwe

Typical symptoms of mercury intoxication were prevalent in the exposed group. The

medical score sum plus the bio-monitoring results made it possible to diagnose in 70%

of the amalgam-burners, 63% of otherwise occupational burdened population and 23%

of former occupational burdened population a chronic mercury intoxication. 5% of the

not occupationally burdened population showed chronic mercury intoxication and

nobody in the control area was intoxicated. These results confirm severe exposure due

to working with mercury, either by panning with mercury or smelting amalgam.

Child labour in the mining sites is very common from the age of 10 on, the children

work and play with their bare hands with toxic mercury. Of special notice is, that 0% of

the children from the control area, 33% of children living in the area, but not working

with mercury and 69% of the children working with mercury have a chronic intoxication

with mercury.

Mercury can cause severe damage to the developing brain. From 9 breast milk

samples taken, 4 showed increased levels of mercury. The different mining areas in

Kadoma district use slightly different extraction technologies. A comparison of the

various mining areas is difficult due to the relatively small number of participants in

each area, and non-comparable subgroups (number of men, amalgam burners etc).

But it seems that in the Glasgow mill the exposure to mercury may be even bigger than

in the Amber Rose mill, and possibly bigger than in the Tix mill.

Poverty is the main reason for the disastrous health status in the small-scale mining

communities. Struggling for pure survival makes mining for gold a necessity to find any

financial resource. The daily fight for survival requires the miners to put their own

health and the health of their children at risk.

A reduction of the release of mercury vapours from small-scale gold mining into the

atmosphere will not only reduce the number of mercury intoxicated people in the and

milling areas proper, it will reduce the global pollution of the atmosphere with mercury.

Most of the mercury vapours formed by open burning of gold amalgam deposits not

locally but is transported by air on long-range distances all over the globe (Lamborg,

2002). The total release of mercury vapour from gold mining is estimated today up to

1,000 metric tons per year (MMSD 2002), while from all other anthropogenic sources

approximately 1.900 tons were released into the atmosphere (Pirrone, 2001).

These results correspond to former examinations in Zimbabwe, for example the study

from Matchaba-Hove et al. (2001). They found, that "mercury poisoning among gold

panners in Chiweshe and Tafuna communal lands is of public health importance.

Panners should be educated on the possibilities of mercury being a poison. A low cost

and safe technology to separate mercury from the amalgam should be introduced to

the panners".

The result is that mercury is a serious health hazard in the small-scale gold mining area

of Kadoma. The exposure of the whole community to mercury is reflected in raised

mercury levels in the urine, blood and hair. Symptoms of severe damage of the brain

(cerebellum) such as ataxia, tremor and movement disorders were found in the mining

communities. In 70% of the amalgam-burners in Kadoma mercury intoxication was

10

Final Report

Health Assessment Kadoma, Zimbabwe

diagnosed. The background burden in the control group is in the same order of

magnitude as in western industrial countries.

Poverty is the main reason for all health and environmental problems:

- At the moment it does not seem to be acceptable that children live in Kadoma small

scale mining and milling areas. Child labour with hazardous chemicals needs to be

especially addressed. Missing sanitary standards and high exposure to mercury are

the main problems. Sanitary standards need urgent improvement.

- The

occupational related health risk of mining should be assessed in more detail

(accidents, drinking water quality, HIV / AIDS, other sexually transmitted diseases,

malaria, tuberculosis). One first step to reduce the health hazards in Kadoma district

might be a proper zoning into industrial areas, commercial areas and housing areas.

Mainly the smelting of amalgam needs to be performed outside the housing areas,

and "away from the nose" people in charge of amalgam roasting. Imposing basic

hygienic standards, such as proper drinking water and reduction of Anopheles

mosquitoes is essential.

- To reduce the obvious risk of accidents in mining sites, raising awareness is

necessary. Introducing proper mining techniques is necessary (e.g. tunnel safety).

- The risk of sexually transmitted diseases could be reduced, if campaigns for safer

sex were more effective.

- To improve the health status of the communities a better financed health service is

urgently required.

Referring to the clinical testing and laboratory results, mercury is a major health hazard

in the area. Some first suggestions are:

- Child labour with highly toxic substances must be stopped immediately. Legal

restrictions on child labour need to be immediately implemented.

- Women in childbearing age need special information campaigns on this risk of

mercury to the foetus and the nursed baby.

- The participants with intoxication need medical treatment. It is necessary to build up

a system to diagnose and treat mercury related health problems in the area.

Capacity building including establishing laboratory facilities in the Kadoma district is

required to analyse mercury in human specimens. The financial aspect of treatment

and the legal problem of importing drugs (chelating agents like DMPS or DMSA, to

sweep mercury out of the body) need to be solved. Funding of preventive

campaigns and for treatment facilities is needed now.

- Training programs for the health care providers in the Kadoma district and other

health centres in mining areas to raise awareness of mercury as a health hazard.

- Continuous clinical training of local health workers, including a standardised

questionnaire and examination flow scheme (MES = mercury examination score).

- Mercury ambulance: A mobile ,,mercury ambulance" might easier reach small-scale

miners, than any local health office. A bus could be used as a mobile mercury

ambulance. Equipped with the necessary medical and laboratory utensils, the bus

Final Report

11

Health Assessment Kadoma, Zimbabwe

could be driven into the mining areas. Two or three specially trained doctors or

nurses could perform the examinations, and begin to carry out treatment. The bus

could also be used for health awareness programs (e.g. video equipment). Miners in

remote areas might welcome any evening entertainment. Soccer videos might

attract more miners to the bus, than much other information material. Why not ask

e.g. sponsors for such a bus (or truck).

The knowledge on mercury as a health hazard needs to be improved:

- Assessing in a different study design the possibility of mercury related birth and

growth defects, increased abortion/miscarriage rates, infertility problems, learning

difficulties in childhood or other neuro-psychological problems related to mercury

exposure.

- Assessing in a more detailed study the possible transfer of mercury from mother to

child via breast-milk and the related possible adverse health effects. Females at

childbearing age and before urgently need more awareness to refrain from amalgam

burning, at least during pregnancy and nursing.

The release of mercury into the environment needs to be reduced:

- The exposure to mercury for the miners and the community has to be drastically

decreased. Proper mining techniques to reduce the burden of accidents and

mercury exposure are essentially needed. Small-scale miners need all possible

support to introduce cleaner and safer gold mining and extraction technologies.

- The exposure with mercury is avoidable with such simple technology as retorts.

Technical solutions need to go hand in hand with awareness raising campaigns.

- To improve the social, health and environmental situation of artisanal small-scale

gold miners an alliance of local, regional, governmental and intergovernmental

bodies is needed. Cooperation between health, mining and environmental sectors is

needed on local, regional, national and intergovernmental level. E.g. UNIDO and

WHO in Harare could form a nucleus of a national mercury task force.

12

Final Report

Health Assessment Kadoma, Zimbabwe

2. Study setting and clinical examinations

(Stephan Boese-O´Reilly, Beate Lettmeier, Felicitas Dahlmann)

2.1. INTRODUCTION

The Health Assessment project is part of a major UNIDO project to remove "Barriers to

the Introduction of Cleaner Artisanal Gold Mining and Extraction Technologies", which

is performed in six countries. The main funding comes from GEF (Global Environment

Program) through UNDP (United Nations Development Program) to UNIDO (United

Nations Industrial Development Organization). The University of Munich is

subcontractor to BRGM for the health assessment in Zimbabwe.

Figure 1 - UNIDO project countries.

The aim of the subcontract was to undertake a medical investigation of approximately

250 people living in the Kadoma area, in the Midlands of Zimbabwe. The ultimate aim

of the whole UNIDO project is to replace mercury amalgamation in the project

demonstration sites with new technology, while improving the income of the miners

through more efficient recovery, increasing knowledge and awareness, and providing

policy advice on the regulation of artisanal gold mining with due consideration for

gender issues.

Final Report

13

Health Assessment Kadoma, Zimbabwe

2.2. MERCURY

Mercury is a silvery-white shiny heavy metal, liquid at room temperature. Mercury

exists in different forms:

- Metallic (elemental) mercury (Hg0)

Liquid in room temperature (non toxic), as mercury vapor highly toxic.

- Inorganic mercury (salt of Hg2+), Soluble compounds are toxic

- Organic mercury compounds, especially methyl mercury in fish, highly toxic

Picture 1 - Liquid mercury used in Tix mine.

The lungs absorb 80% of mercury vapor. Target organs are the brain (cerebellum) and

the kidney. Mercury is a neurotoxin, nephrotoxin and teratogen. Mercury can cause

acute and chronic intoxication.

2.3. ZIMBABWE - KADOMA SMALL SCALE MINING AREA

Figure 2 - Map of Zimbabwe Victoria Falls.

14

Final Report

Health Assessment Kadoma, Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe is in South-East Africa. The Kadoma district is situated in the Midlands.

Farming is the main activity of the rural population.

1829B2

Chakari

Coetzee

North zone

Glasgow

Summit

1829B4

Kadoma

To Harare

Even Milling center

River/Lake

South Zone

Road, Wide tarred

Road, Narrow tarred

Tix

Alexander

Claw Dam

Milling center

Panners

Amber Rose

City

Figure 3 - Local map of Kadoma area (provided by BRGM).

Kadoma is approx. 150 km east from Harare on a good road. The area is slightly hilly,

and covered by grassland and woodland. The Kadoma mining area spreads on both

sides of the town. The surface is open at many spots, either for tunnels or for

amalgamation areas. Mining operations have been carried out in this area since the

1940`s. After 1980 small-scale mining activities began. Since around the year 2000 the

activities have increased. The infrastructure in Kadoma is good, in the surrounding

mining villages poor. Roads are in an acceptable condition.

Final Report

15

Health Assessment Kadoma, Zimbabwe

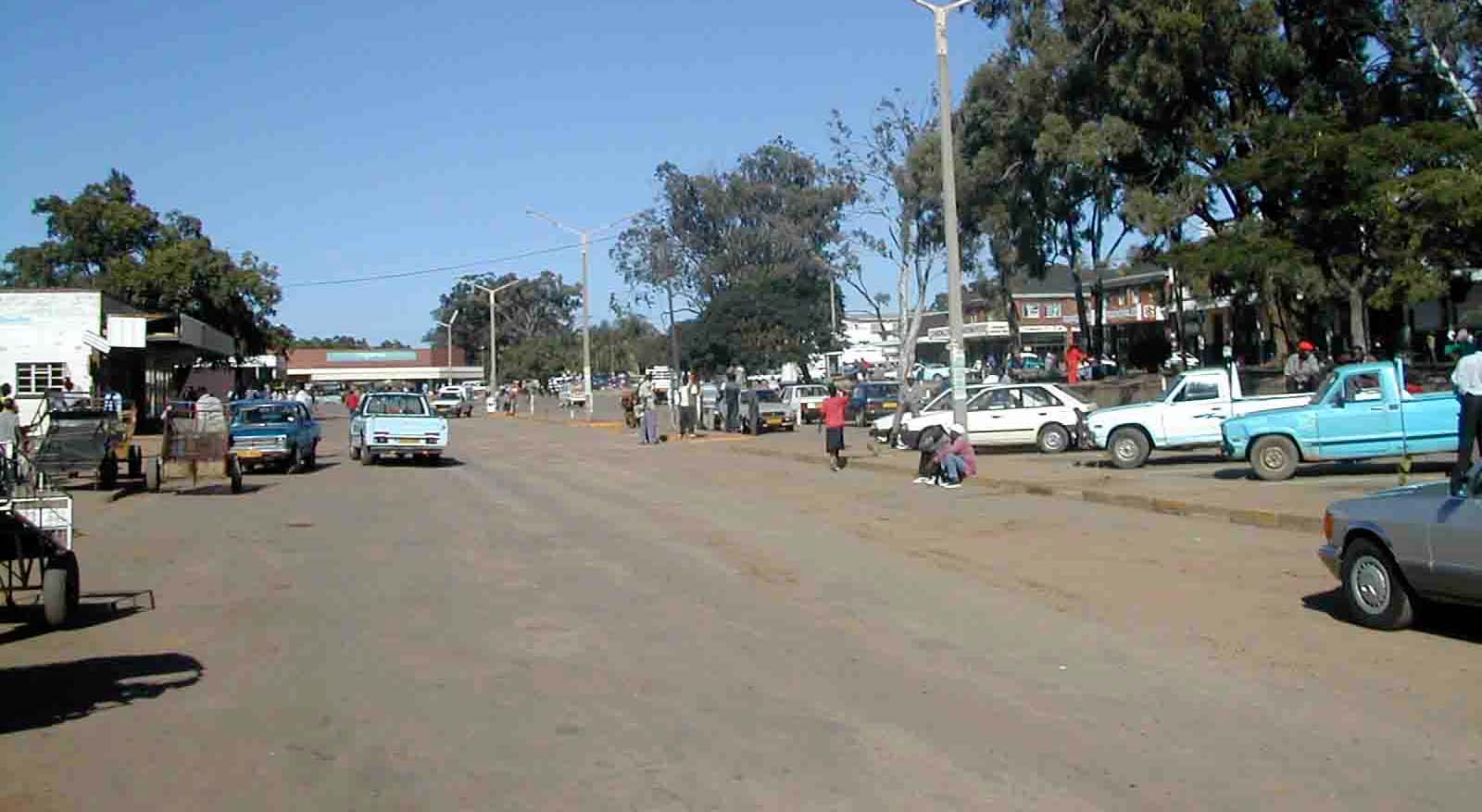

Picture 2 - Kadoma village and nearby area.

Picture 3 - Tix mine copper plate and stamp mill.

Some miners work in small-scale mining companies, which are licensed. Equipped with

generators and other technical equipment miners work in tunnels to extract the ore.

The tunnels have a small diameter. The miners try to follow veins, so tunnels are

curved, and tend to be very steep. Miners work in shifts.

Tix mine is close to the big Muzvezve River and approx. 6 km southeast of Kadoma

town. Tix mine was first opened in 1974. When the ore is removed from the tunnels it is

crushed by workers with hammers, and powdered in stamp mills. The ore is then

16

Final Report

Health Assessment Kadoma, Zimbabwe

dispersed with water. Using copper plates, the miners try to concentrate the gold

containing materials. These copper plates are "loaded" with mercury, then the

dispersed fine ore is washed out over the copper plates, during which the gold binds to

the mercury.

Picture 4 - Tix mine - scratching of amalgam; squeezing amalgam through a cloth; piece of

amalgam; burning amalgam.

After some time the millers stop the process and scratch the amalgam from the copper

plates. A cyanide solution is used on the copper plates to enrich the process. This

liquorish mercury compound is squeezed through a cloth and a hard piece of amalgam

is the result. Sometimes the miners use their mouth to hold the cloth whilst squeezing

stronger. The proper amalgam is formed now. The amalgam is smelted on open

wooden fire either beside the stamp mill or in the village.

The ore is gained nearby. The artisanal miners work in smaller units. Their equipment

and tools are very limited.

Final Report

17

Health Assessment Kadoma, Zimbabwe

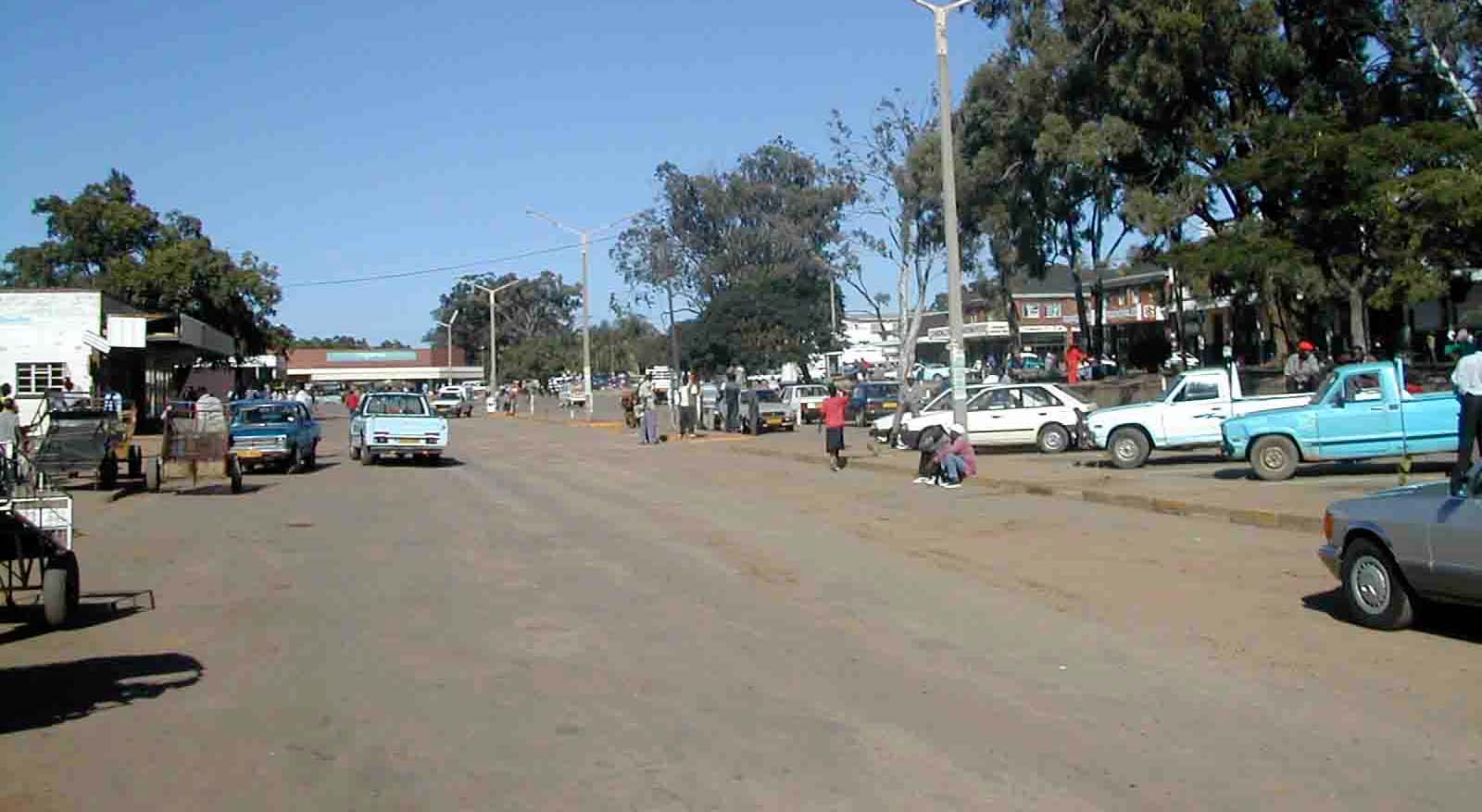

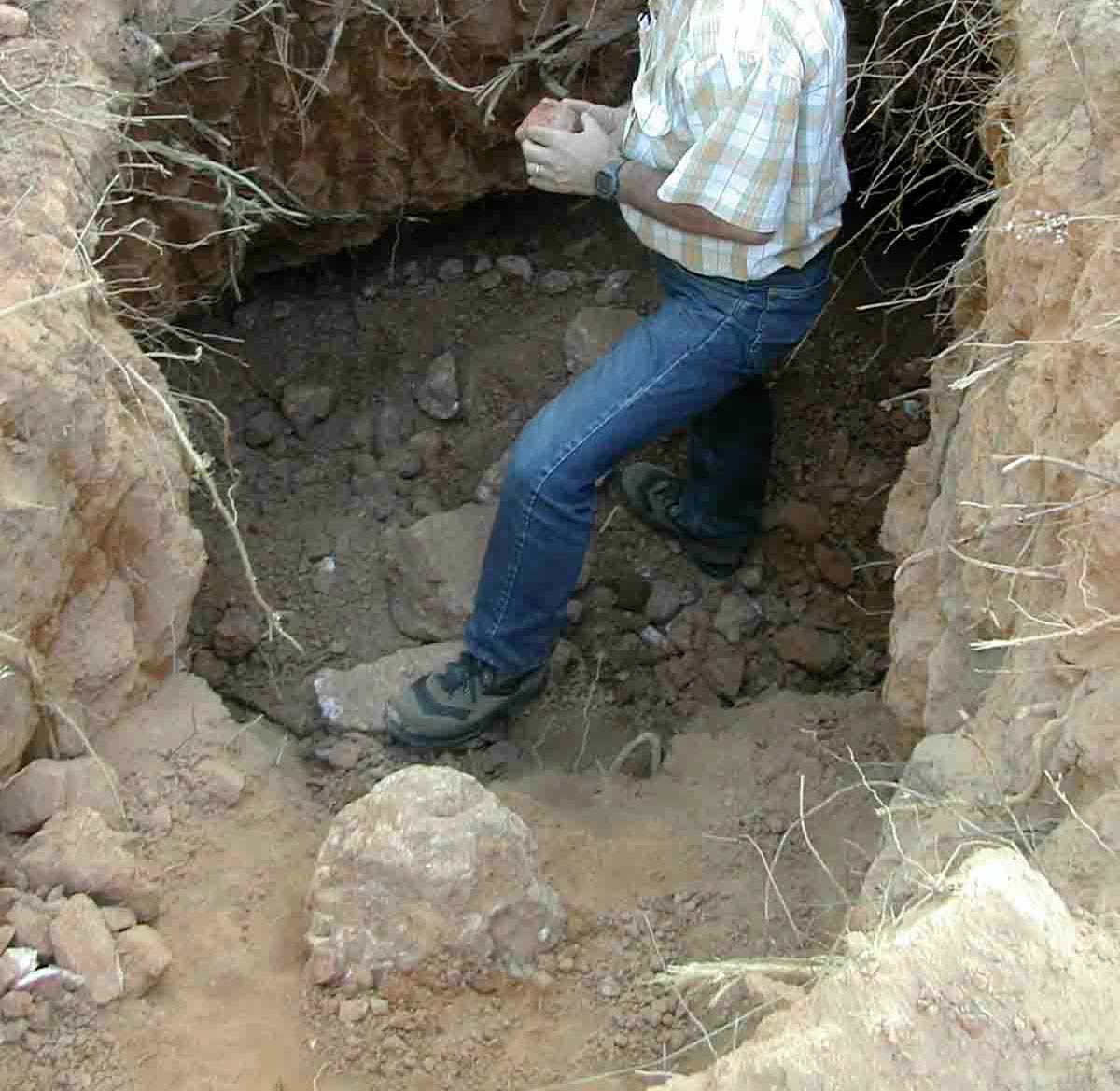

Picture 5 - Small artisanal open pit.

Picture 6 - Muzvezve river.

More than 250 miner families live within 400 meters to the Tix mine. Families consist in

average of-5-6 members (Mtetwa 2004). Within the village further amalgamation

processes take place, including panning and smelting.

Miners use the bush as toilet, since no other facilities exist. The villagers drink the

unsafe water from the river, contaminated with mercury and human excrements. The

local fish, eaten by the miners is high in mercury (see environmental report).

Amber Rose mine is close to the big Muzvezve River and approx. 7 km southwest of

Kadoma town. In this mining area the ore is also crushed by workers with hammers,

and then powdered in stamp mills. The mercury is added at the outlet of the stamp mill

18

Final Report

Health Assessment Kadoma, Zimbabwe

Picture 7 - Amber Rose mill: stamp mill; cyclotron.

into a cyclotron, where the gold binds to the mercury in a combination of a gravity

method and a chemical reaction.

The amalgam is collected by the ore owner. The amalgam is smelted by the owner

either on the spot with a wooden fire or a blow torch, or in his village. The tailings are

further processed by the mill owner. After drying the tailings there are reprocessed in

big cyanidation tanks. In the "pregnant" solution the gold is recovered and filtered out

by carbon. The carbon containing gold is further processed by the stamp mill owner

outside the premises.

Picture 8 Amber Rose mill: tailings and cyanidation tank.

Final Report

19

Health Assessment Kadoma, Zimbabwe

Picture 8 - Amber Rose mill - tailings; cyanidation tank; pregnant solution; filling the tanks with

tailings (end).

The ore is gained nearby. The artisanal miners work in smaller units. The artisanal

miners have very limited equipment and tools. Some just dig small pits in the area.

Other miners dig bigger open pits or even small tunnels.

Approx. 50 miners with their families live on the mining compound, on average with 5

members per family (Mtetwa, 2004).

Blair toilets are used. Drinking water is obtained from boreholes.

Etna mining area

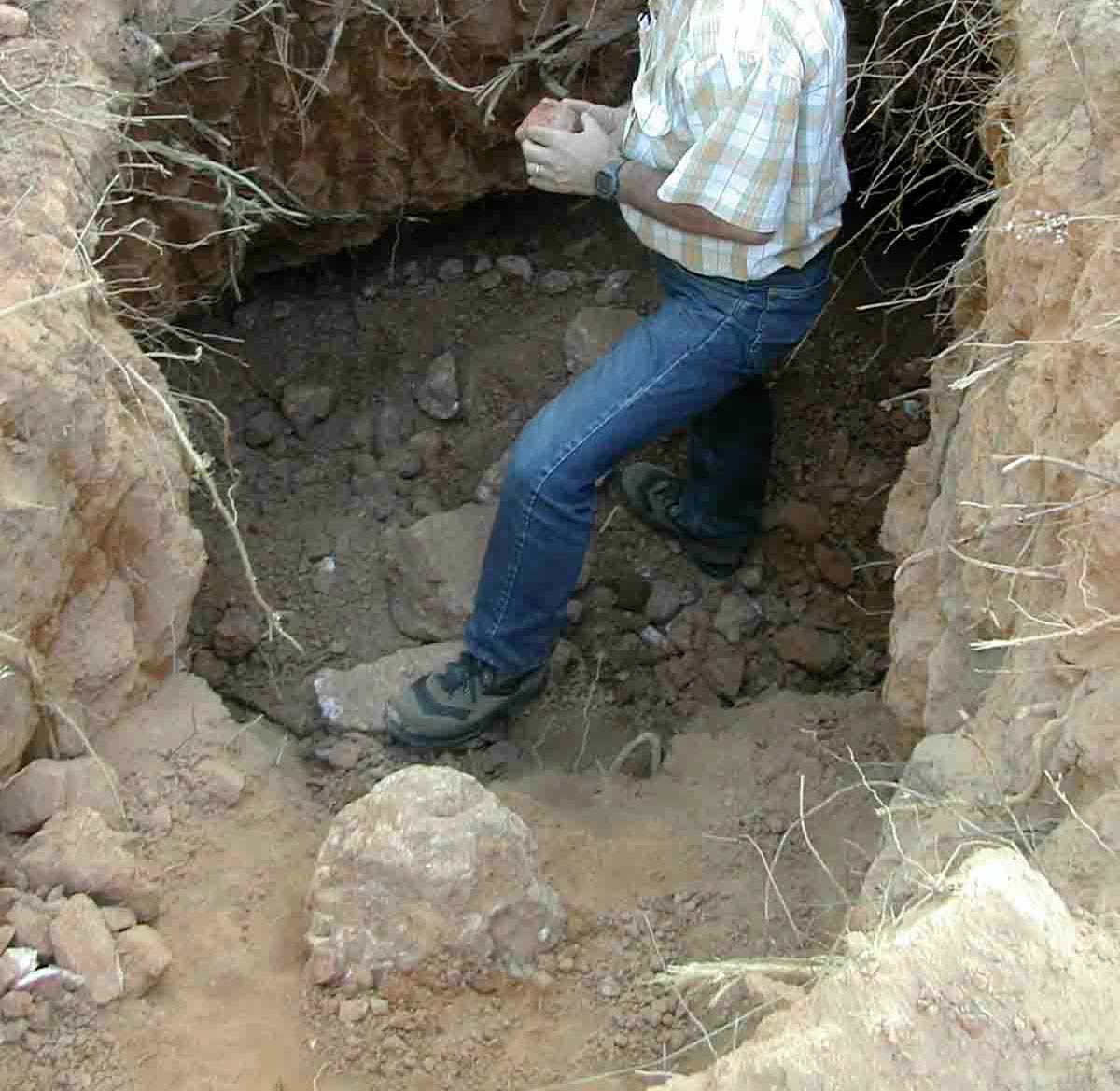

Etna is a large farm approx 30 km south-east outside of Kadoma on off roads. An old

abandoned mine was squatted by artisanal miners a few years ago. Outbreaks of

violence are reported especially in this area. The old mine is underground, miners

nowadays reuse the tunnels, without any safety precautions, and e.g. they take out the

pillars. High rate of lethal accidents are a result of this improper mining technology.

One stamp mill is operating to crush the ore. A copper plate loaded with mercury plus a

ball concentrator with mercury is used to bind the gold to the mercury.

20

Final Report

Health Assessment Kadoma, Zimbabwe

Picture 9 - Primitive sluice box and James table at Etna village.

Many miners crush their ore with pestle and mortar. The powdered ore is panned with

mercury. The amalgam is smelted beside the houses. There is no infrastructure at all,

poverty is very obvious. Children work in all processes.

Picture 10 - Panning at Etna, piece of amalgam;

one sack of stones collected by a miner in a day.

Final Report

21

Health Assessment Kadoma, Zimbabwe

Picture 11 - Amber Rose village.

All areas

The young and strong men, so called healthy workers, are mainly found in the bigger

and technically higher equipped properties. Older people, women of all ages and

children mainly work in the smaller artisanal mining properties. Retorts are not used,

nor any other protection against any kind of mercury contamination. There is no proper

ventilation for the mercury fumes. Housing areas, food stalls and the schools are

nearby to the amalgamation and smelting places. Tailings containing mercury are

everywhere within the village, beside the farming land or beside the local water wells.

The mercury is usually stored in the miner's houses, near to where they and their

families sleep. The mercury is available in Kadoma. The gold is sold to governmental

dealers, or smuggled to South Africa or Botswana by gold buyers.

2.4. PROJECT DESIGN

The "Protocols for Environmental and Health Assessment of Mercury Released by

Artisanal and Small-Scale Gold Miners" were developed by UNIDO in collaboration

with the "Institute of Forensic Medicine" and other international experts (Veiga, 2003).

The "Health Assessment Questionnaire" was partly translated in Shona and was used

(Appendix 2) to examine the general health condition of members of the mining

community and to indicate symptoms of mercury poisoning. History / clinical /

neurological / toxicological tests were used according to the state of the art.

Participants were examined to identify neurological disturbances, behavioral disorders,

motor neurological functions, cognitive capabilities, balance, gait, reflexes etc.. The

data was compiled for statistical purposes and maintained confidentiality regarding all

health related issues.

Team members for the field project were Dr. med. Stephan Boese-O´Reilly

(pediatrician, master of public health, environmental medicine), Dr. med. Felicitas

Dahlmann (physician) and Ms. Beate Lettmeier (pharmacist). Dr. Dennis Shoko was

the National Expert for the Global Mercury Project (UNIDO) with a backup from the

University of Zimbabwe. Mr. Pierre Billaud from BRGM is in charge of the

22

Final Report

Health Assessment Kadoma, Zimbabwe

environmental and health assessment in behalf of BRGM. He accompanied us during

the field project to help organize our project and to complete his environmental

assessment. Assigned to the project were nurses to assist the medical examinations,

Ms. Tapuwa Mwanjira, Ms. Vigilance Parirenyatwa, and Ms. Joan Marembo and Dr.

Edwin Muguti as local medical expert.

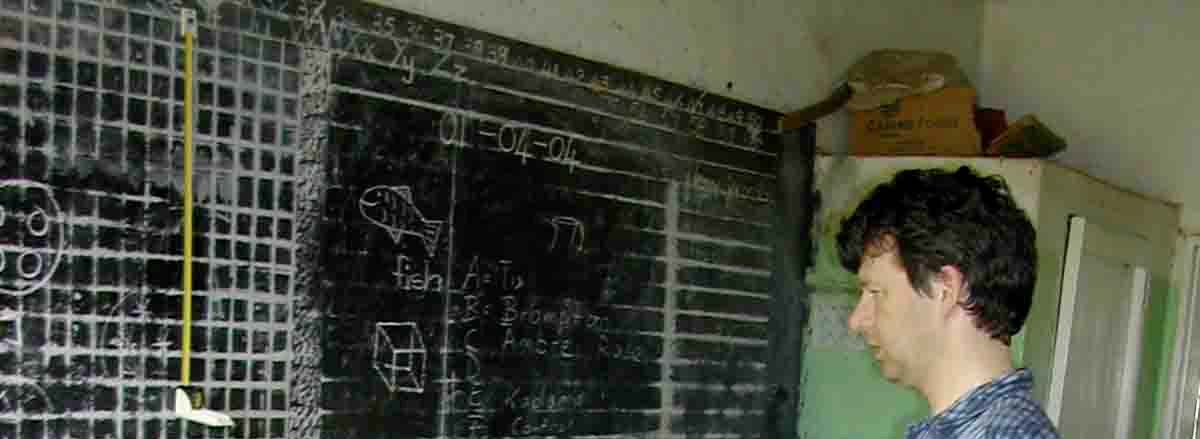

The field project took place from the 4th of April 2004 until the 21st of April 2004. The

equipment was first set up in the school building near Tix mine (Mayflower Primary

School). The school offered its facilities to perform the examination, which was much

appreciated by the health assessment team. The facilities were sufficient to perform the

examinations (four rooms for the team, electricity, toilet, water), including a mobile

analyzer of Hg in urine. In Mayflower school participants from Tix mill, Brompton mine

and Amber Rose mill were examined.

Picture 12 - Mayflower school.

The second place for examinations was in Kwayedza secondary school. The facilities

were very similar. Participants from Glasgow mill, Summit mill, Lilly, Jani and King Chin

were examined there.

Picture 13 - Kwayedza school.

Final Report

23

Health Assessment Kadoma, Zimbabwe

One day the examinations took place in the open. On the mining compound of Amber

Rose mill the equipment was set up onto the two pick-ups, local electricity was used. It

was possible to work there, but the conditions were not as appropriate as in the

schools. Mainly the laboratory equipment was sensitive to the high concentration of

mercury within the area. On the other hand it was much easier for the participants from

the village to see what a health assessment means, and not to be transported

somewhere.

Picture 14 - Mobile field clinic at Amber Rose mill neuro-psychological testing;

history; laboratory; blood sampling.

24

Final Report

Health Assessment Kadoma, Zimbabwe

The control group was examined in Chikwaka. The same method was used, but the

nurses were new. The local health unit supported us. Chikwaka is more than 100 km

away from the mining area, and mercury is not used there.

Blood, urine and hair will be analyzed for mercury at the University of Munich,

Germany.

2.4.1. Questionnaire

The participants filled in a questionnaire with assistance from the nurses. Questions

included:

Working with mercury or with mercury polluted tailings?

Burning amalgam in the open?

Picture 15 - Nurses taking the history.

- Melting gold in the open or with inadequate fume hoods?

- Drinking

alcohol?

- Having a kind of a metallic taste?

- Suffering from excessive salivation?

- Problems with tremor / shaking at work?

- Sleeping

problems?

2.4.2. Neurological examination

All participants were clinically, mainly neurologically examined. Results were mainly

primarily scored according to ,,Skalen und Scores in der Neurologie" (Masur, 2000):

Final Report

25

Health Assessment Kadoma, Zimbabwe

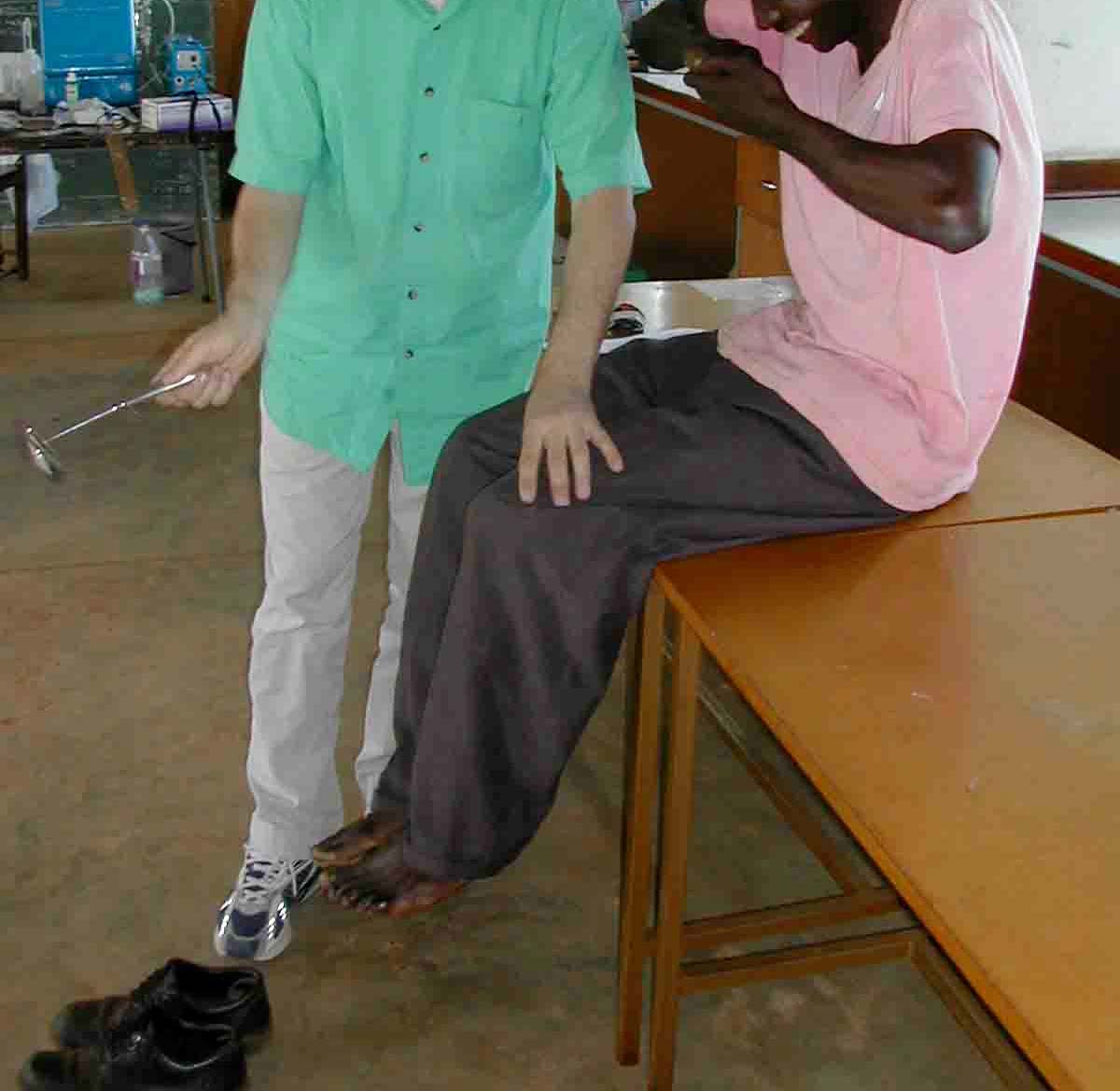

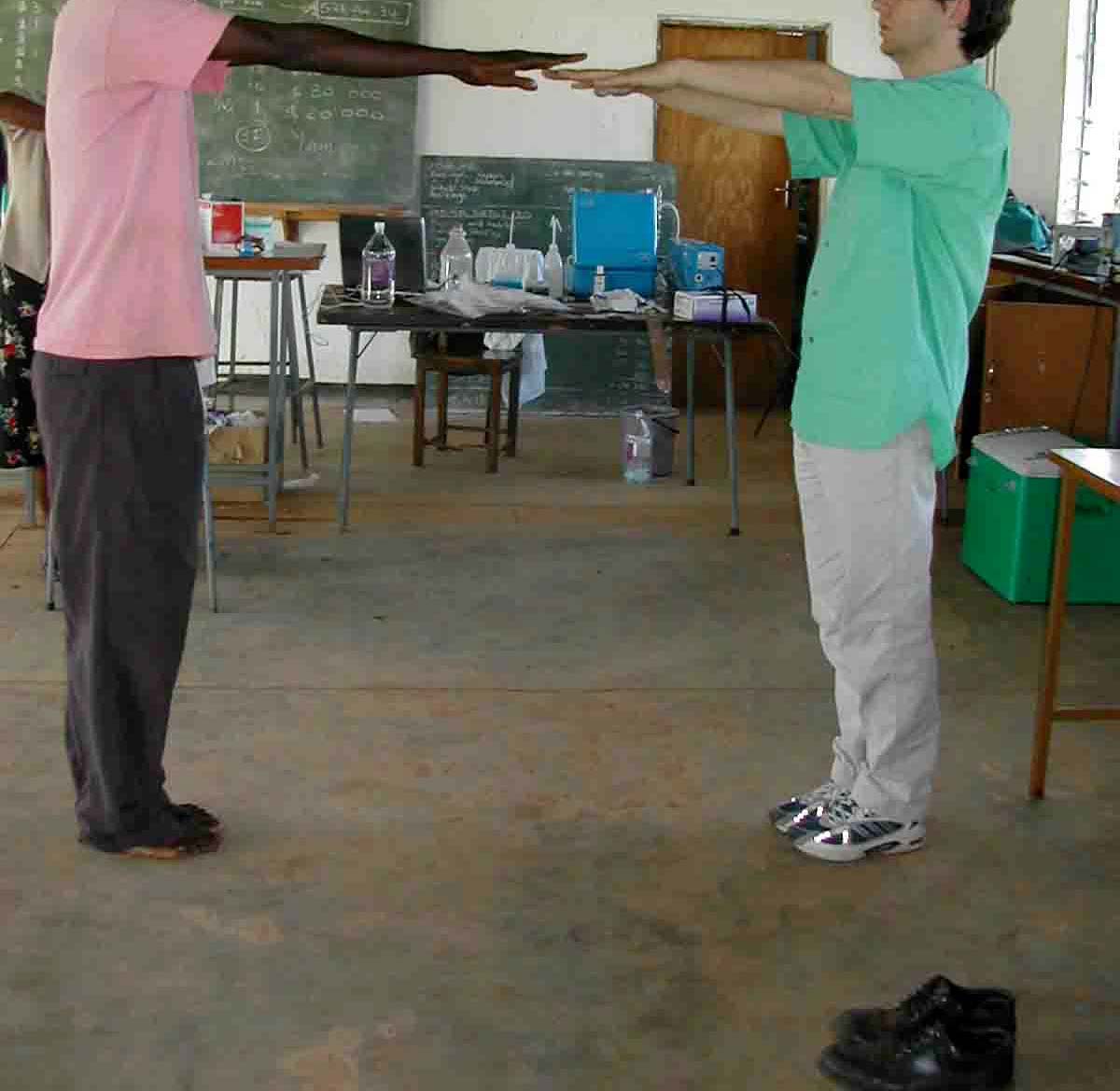

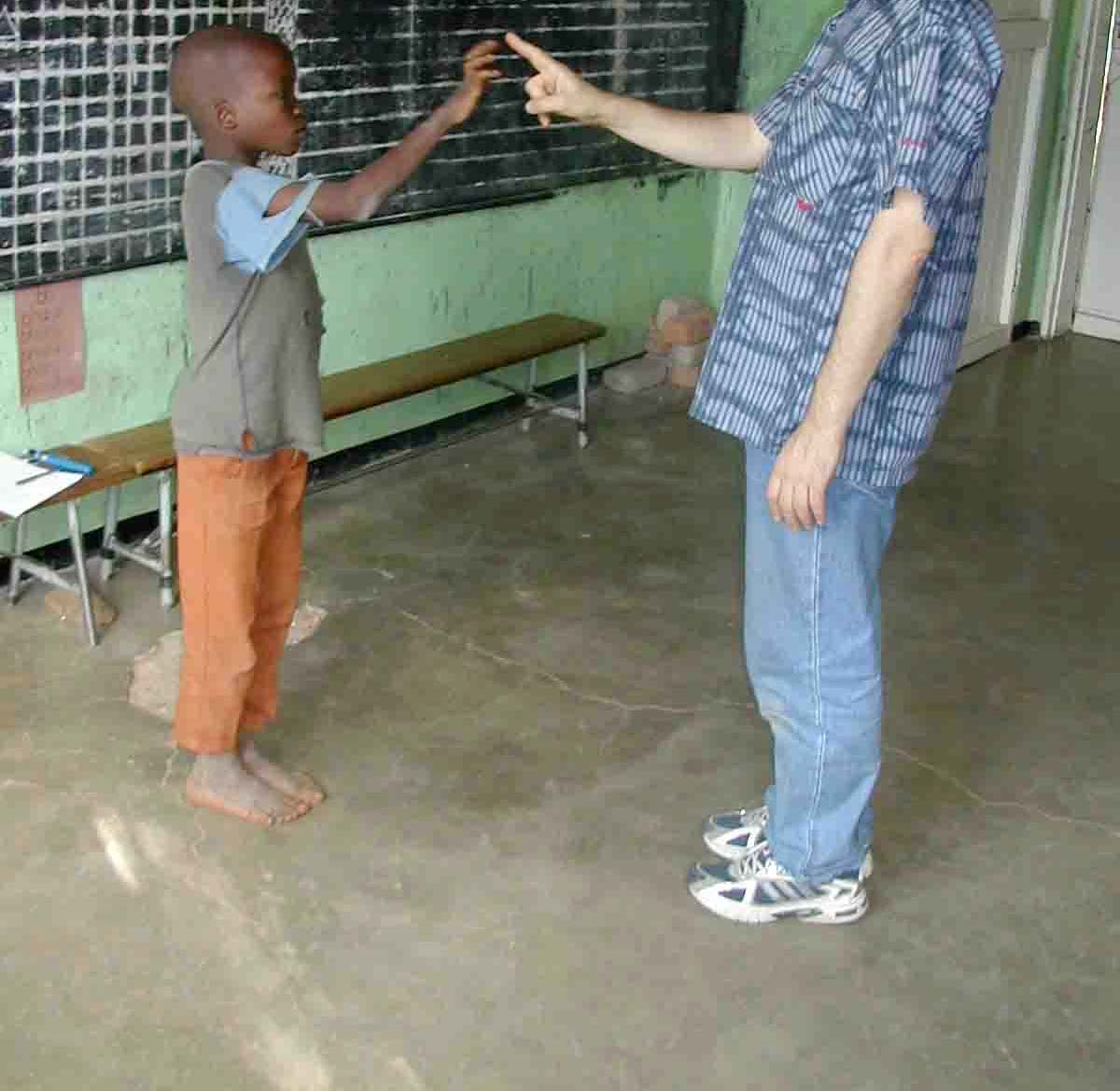

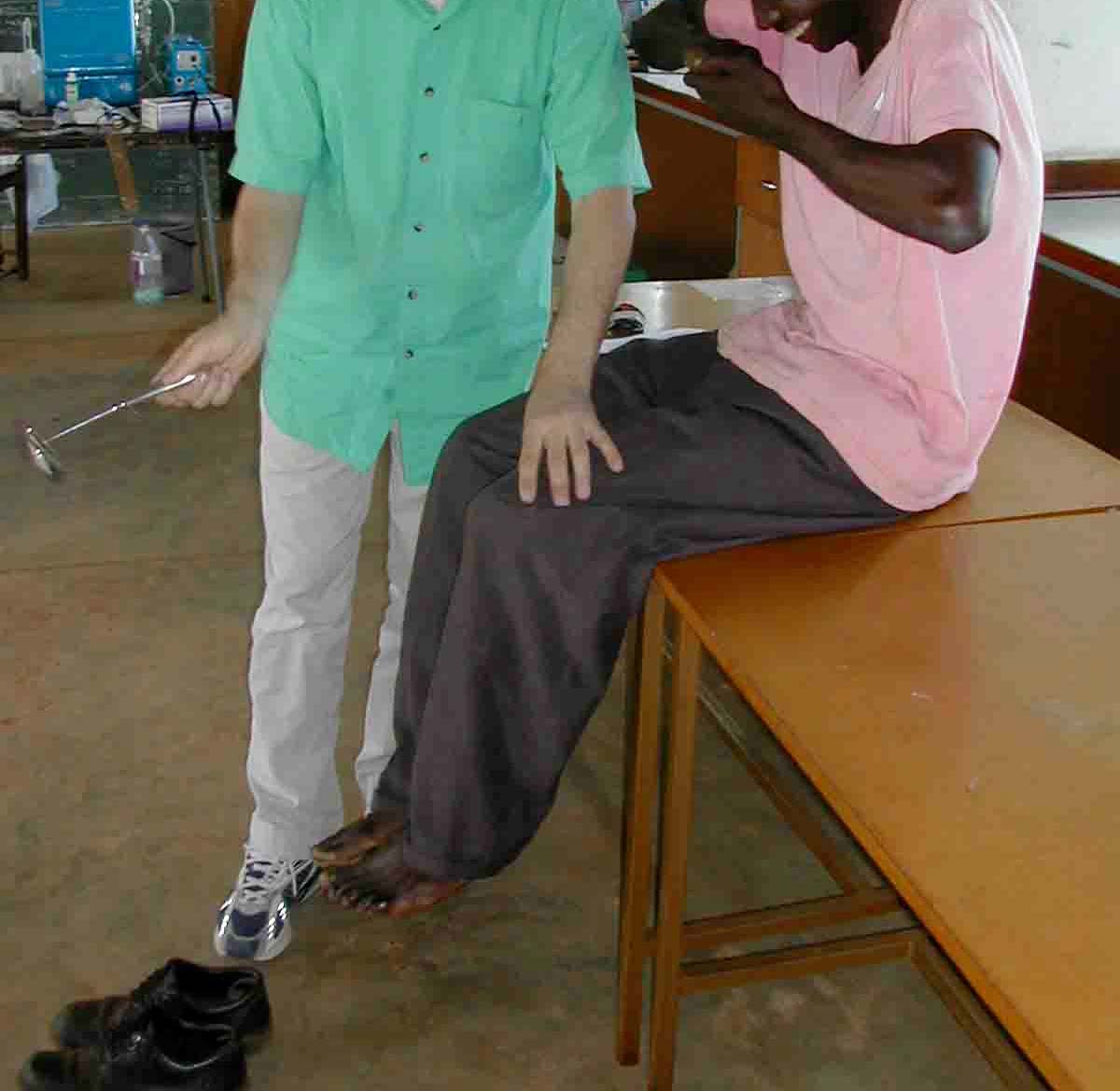

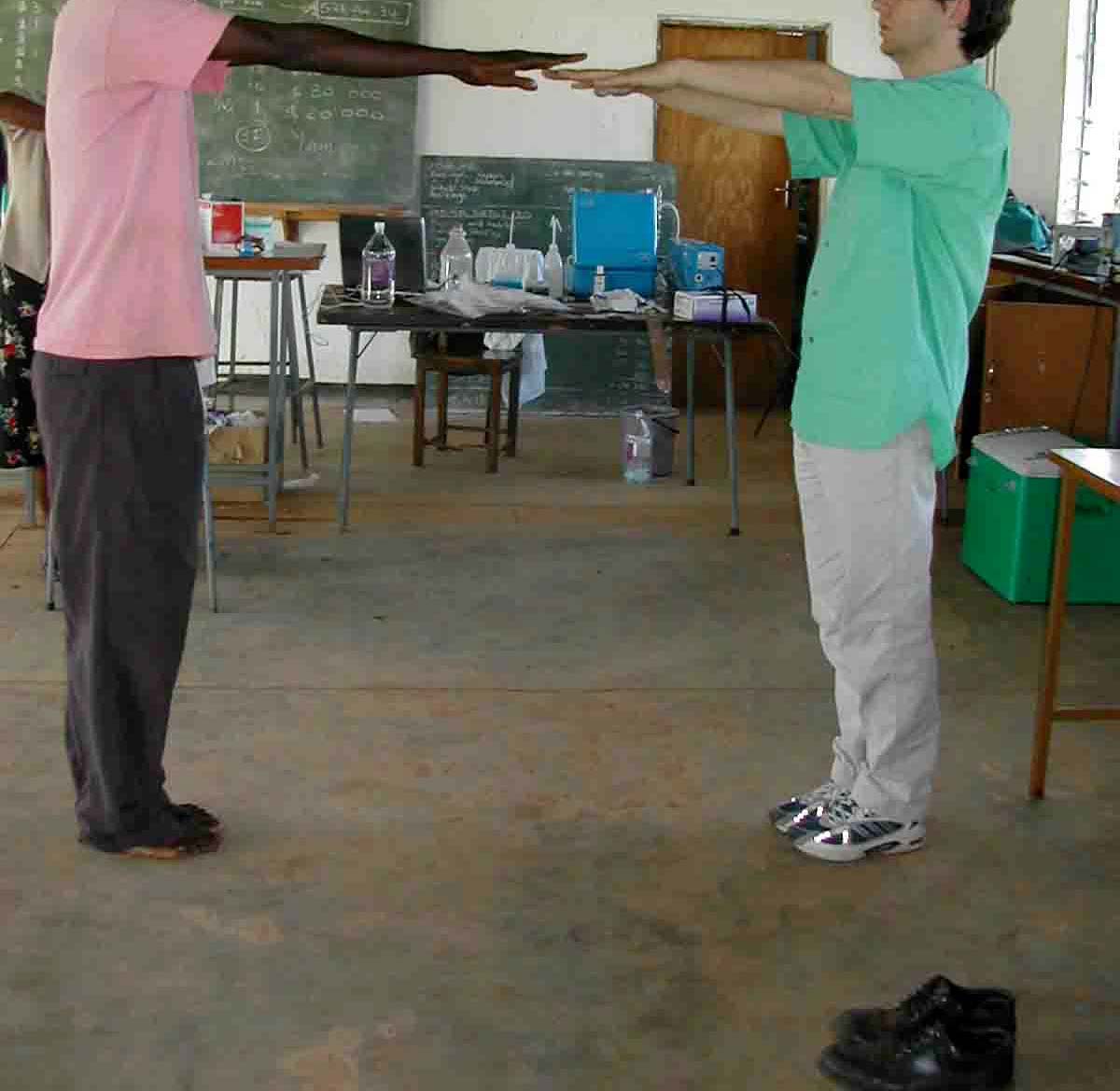

Picture 16 - Neurological examination (PSR reflex; finger-finger-nose test).

26

Final Report

Health Assessment Kadoma, Zimbabwe

- Signs of bluish discoloration of gums,

- Rigidity, ataxia and tremor,

- Test of alternating movements or test for dysdiadochokinesia,

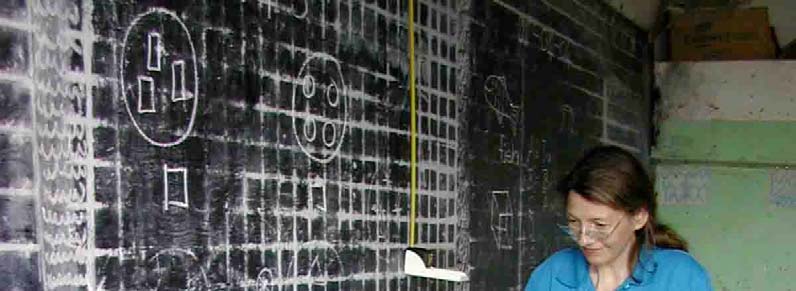

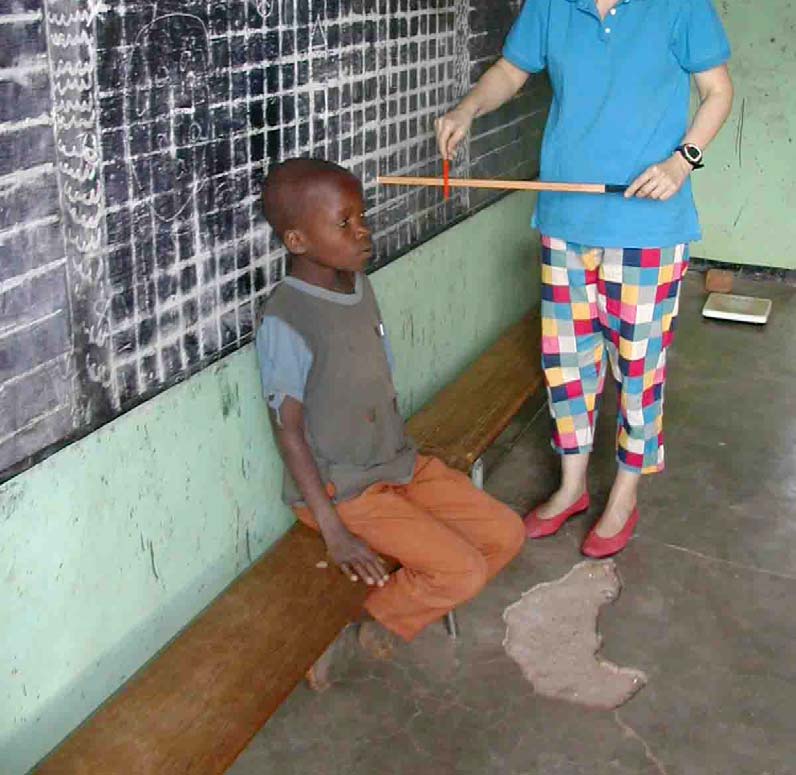

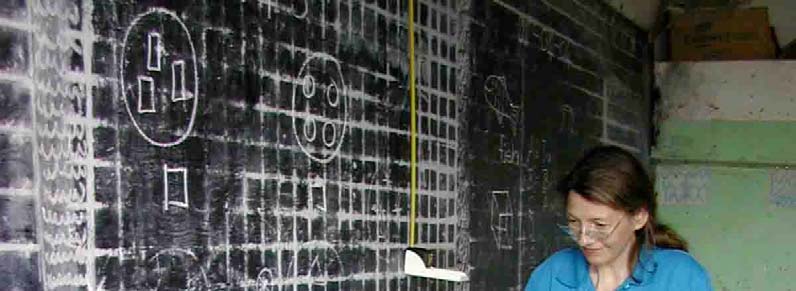

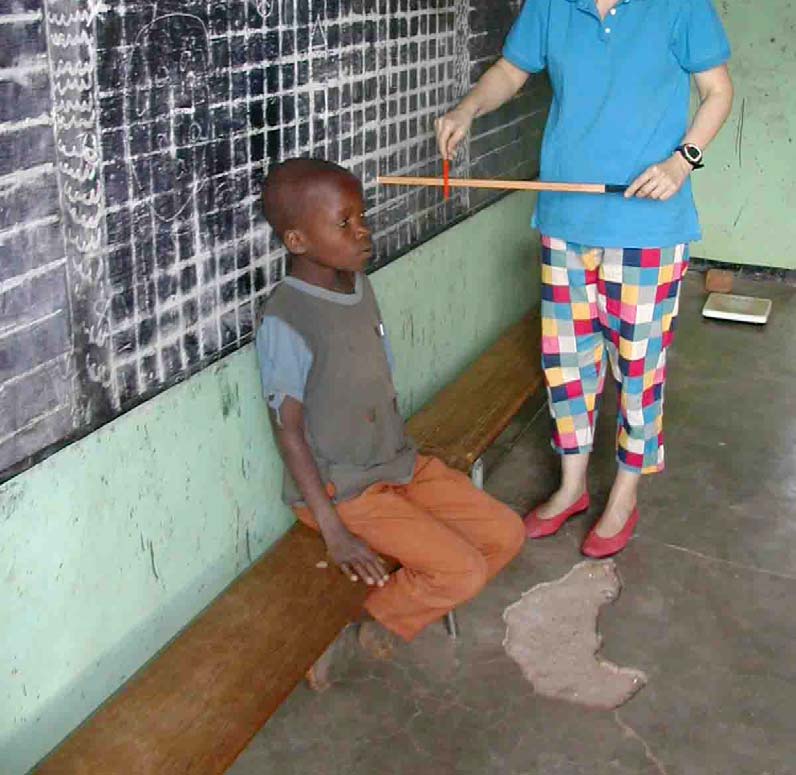

Picture 17 - Visual field test

- Reflexes: knee jerk reflex and biceps reflex.

- Pathological reflexes: Babinski reflex and mento-labial reflex.

- Sensory

examination.

- Test of the field of vision 1.

2.4.3. Neuro-psychological testing

The following tests were carried out (Zimmer, 1984 ; Lockowandt, 1995 ; Masur, 2000):

- Memory disturbances: Digit span test (Part of Wechsler Memory Scale) to test the

short term memory.

1 The visual field was measured in a very simple way without the need of any electricity: The test person

was sitting in front of a blackboard, when the examination took place in a school building, or in front of a

wall at the examination site out in the field. The person was asked to keep her head leaned on the

blackboard/ wall, where a line of 50 cm had been drawn to the right and to the left from a point in the

middle of the back of her head. Also the distance between the blackboard/ wall and the outer corner of the

person's eye had been measured (cal ed "base line" in the test). Then an inch rule was hold onto the 50

cm point at the right in a 90 degree angle to the blackboard/ wall on level with the person's right eye and a

red ballpoint pen was moved along this ruler until the test person said: "stop!" to show, that the pen

entered her visual field. The inches, in our case "centimetres", the ballpoint pen had been stopped, were

recorded. The same procedure had been performed at the left side of the person: The inch rule on the 50

cm point at the left in a 90 degree angle to the blackboard/ wall on level with the person's left eye, the red

ballpoint pen moved along the ruler until the test person said "stop!". With these parameters the visual field

afterwards can be calculated with mathematical methods.

Final Report

27

Health Assessment Kadoma, Zimbabwe

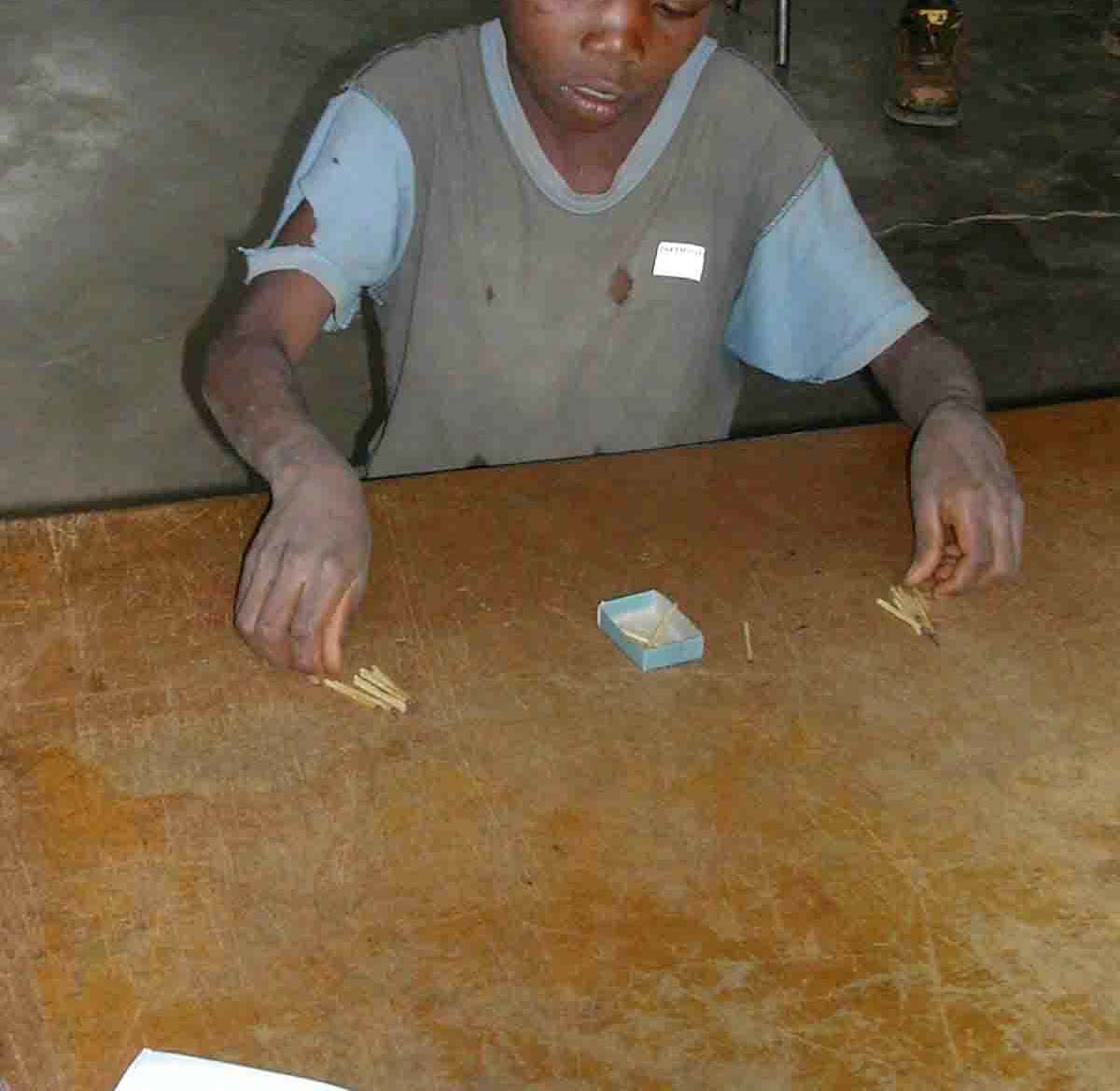

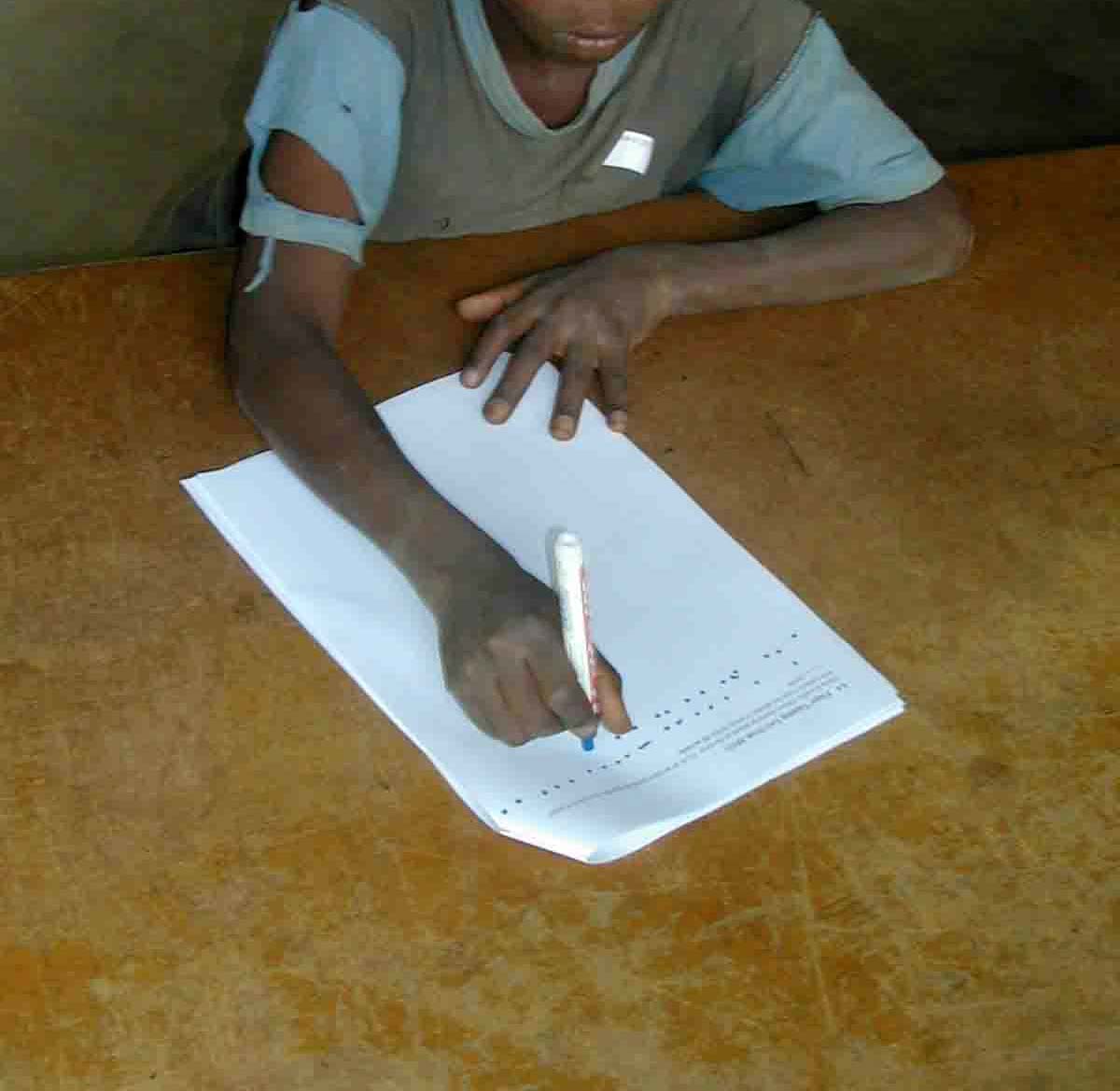

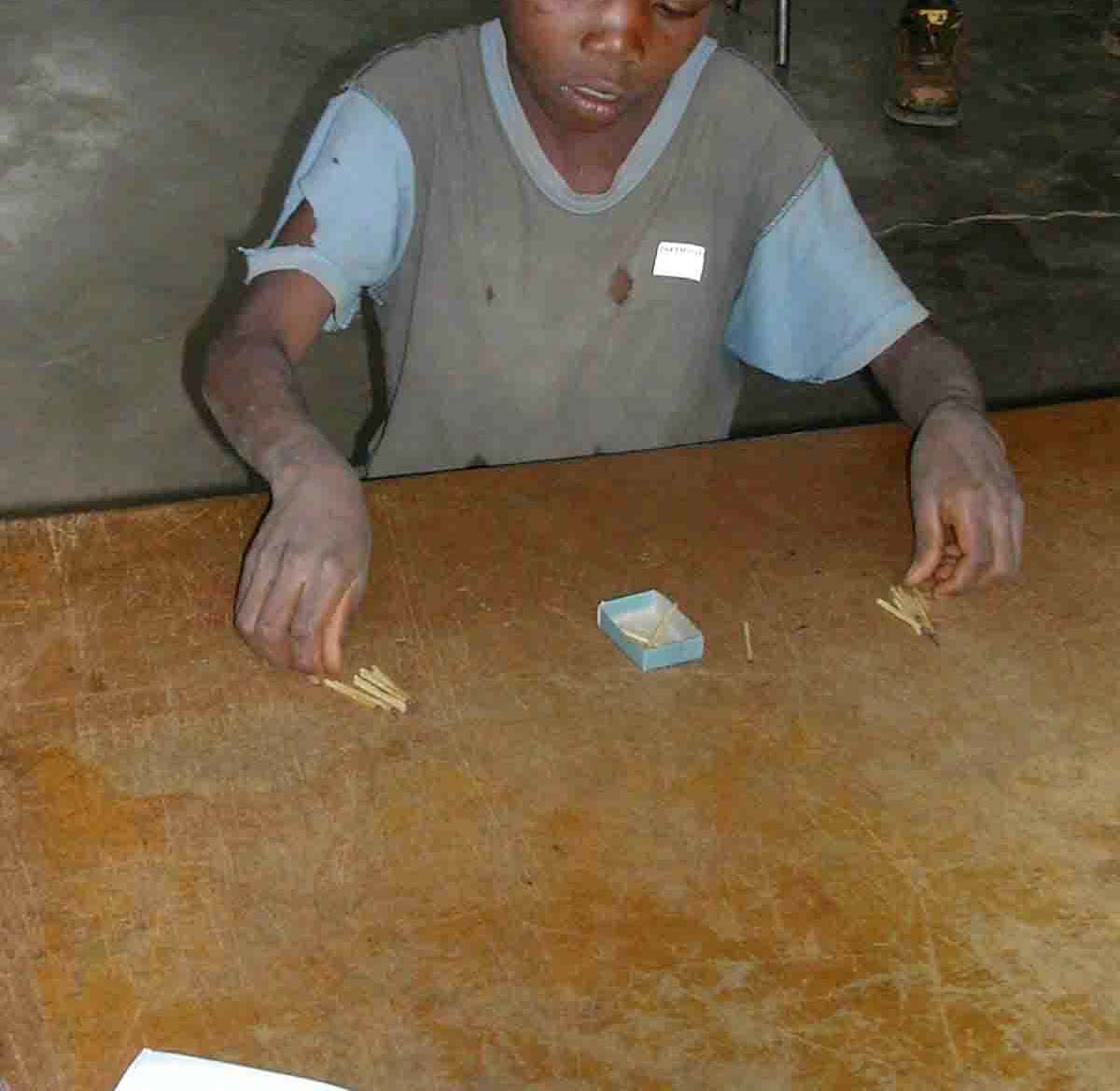

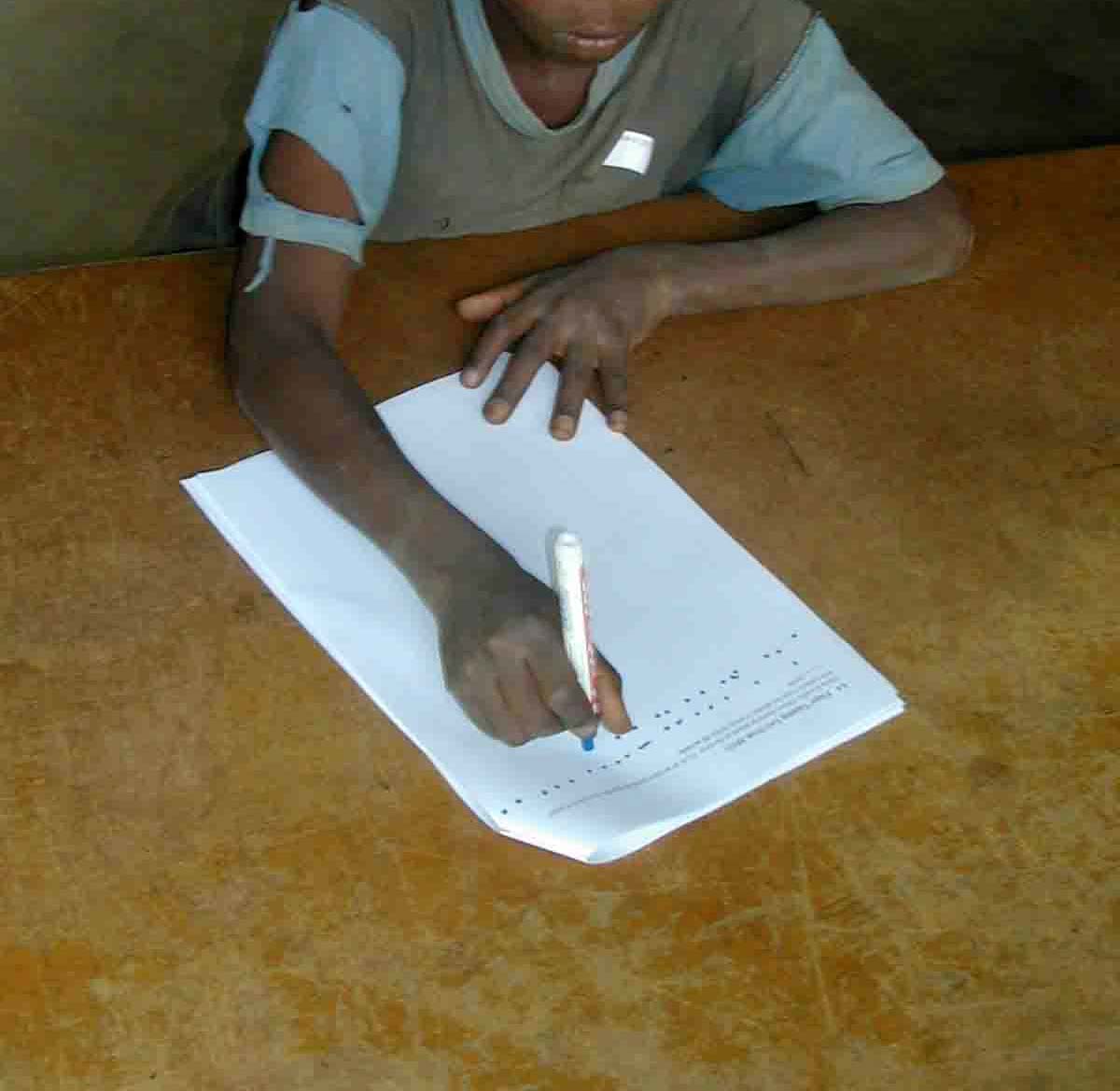

- Match Box Test (from MOT) to test co-ordination, intentional tremor and

concentration.

- Frostig Score (subtest Ia 1-9) to test tremor and visual-motoric capacities.

- Pencil Tapping Test (from MOT) to test intentional tremor and co-ordination.

Picture 18 - Match box text, memory test, pencil tapping test, Frostig test.

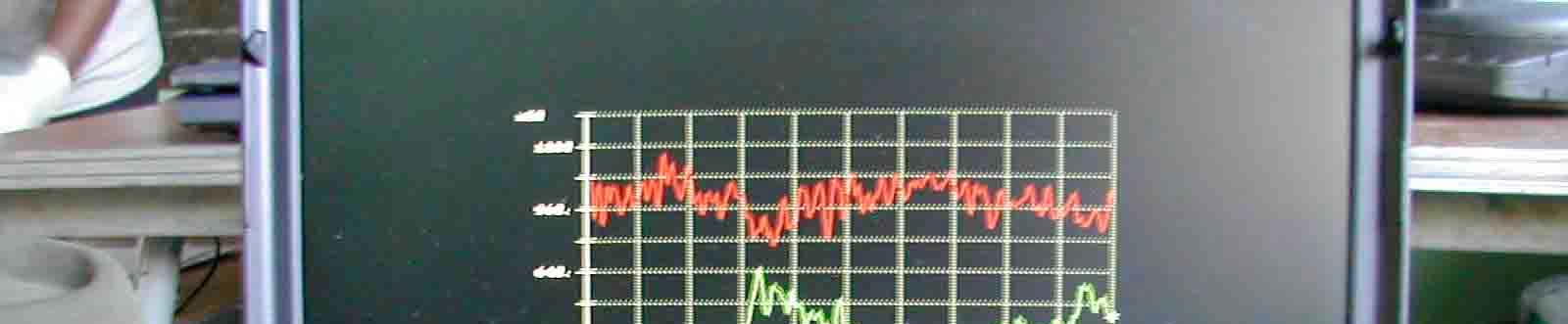

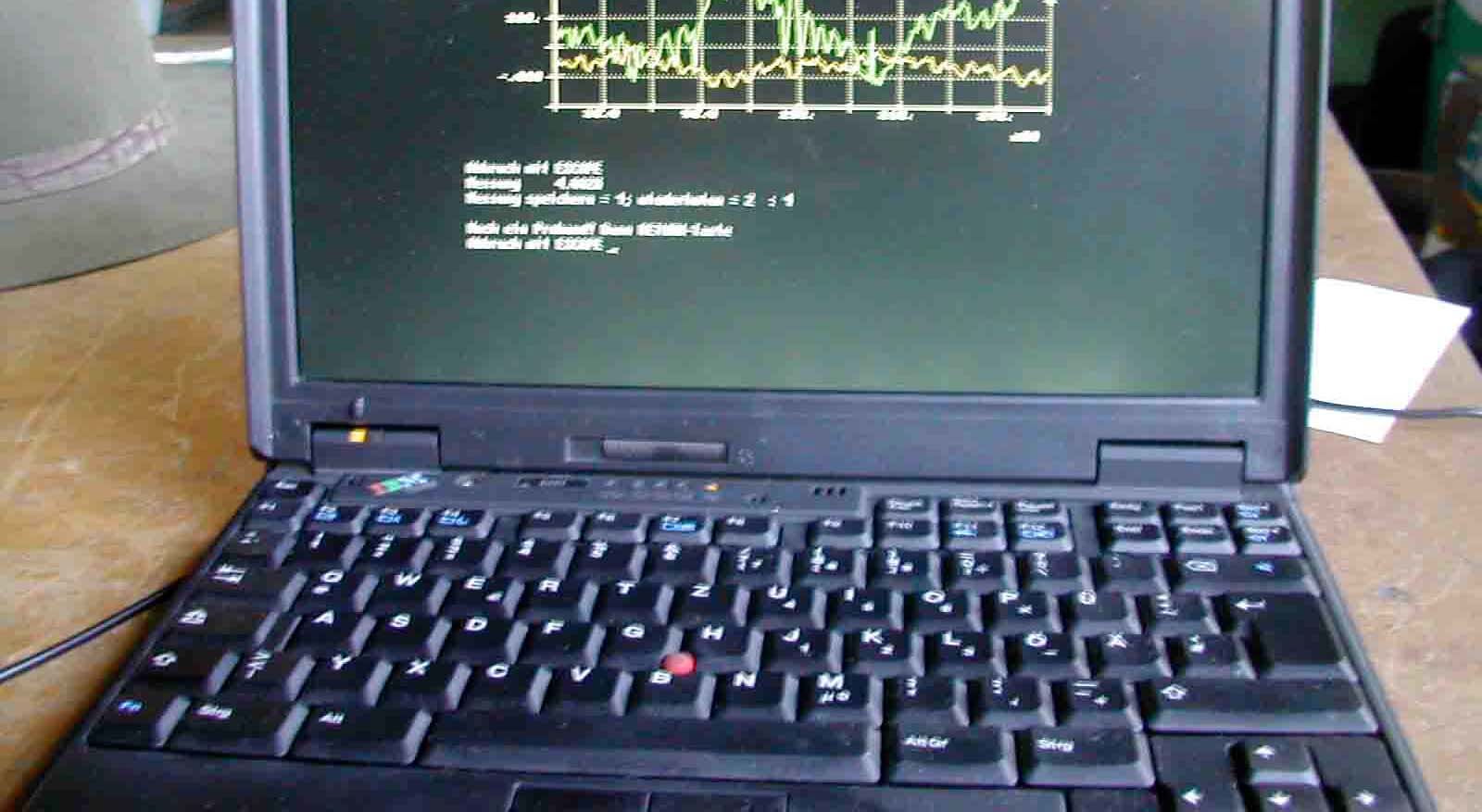

2.4.4. Tremor-meter

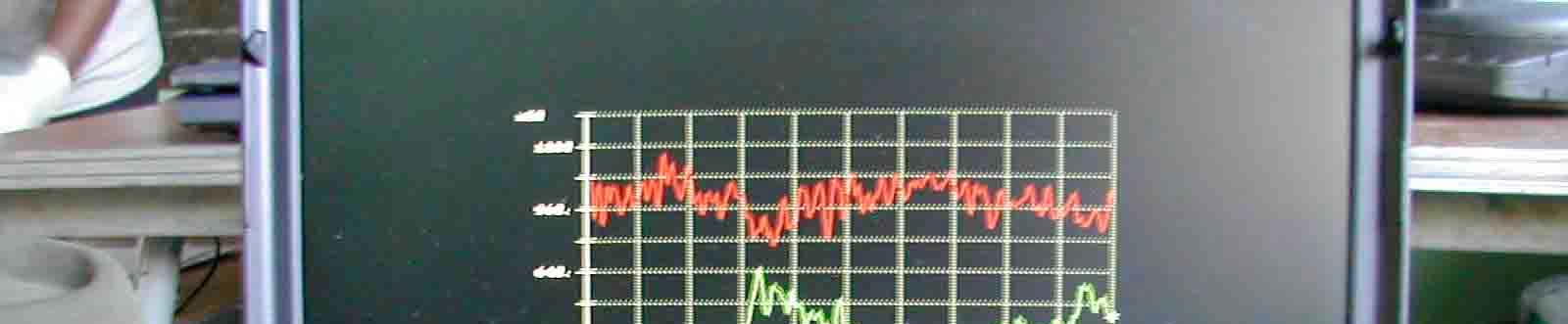

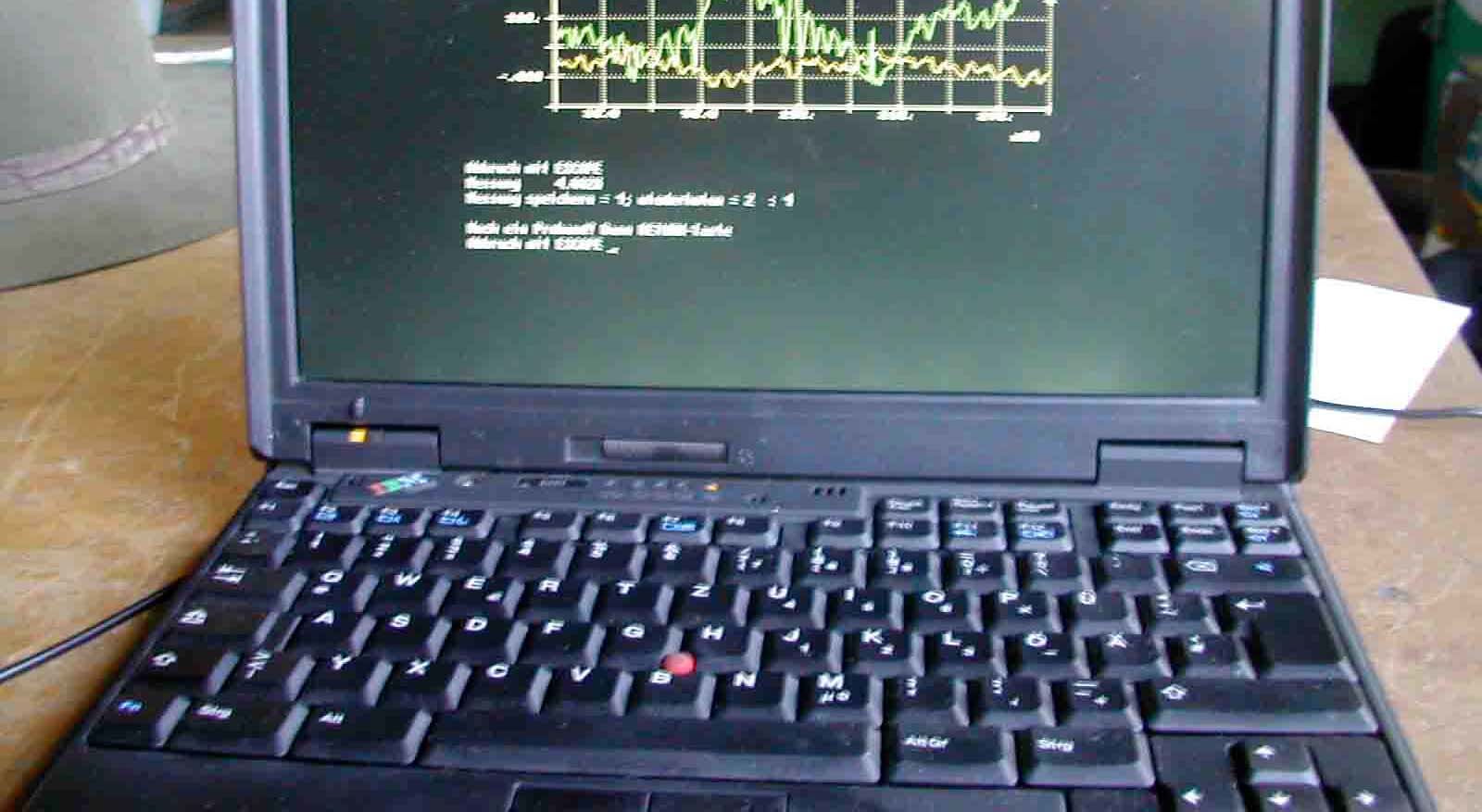

A new approach to measure tremor in a more objective way was performed. PD Dr.

Boetzel from the Neurological Clinic, University Hospital in Munich supplied the team

with an instrument to measure tremor. This instrument is still at a developmental stage.

A small sensor was placed on the fingertip (right and then left side) of each participant.

A special electronic unit, developed by the University, measured the signal and the

digital signals were recorded onto a laptop.

28

Final Report

Health Assessment Kadoma, Zimbabwe

Picture 19 - Tremor-meter.

Three different measurements were performed:

- Arms outstretched for intentional tremor.

- Arms bend with the finger tip pointing to the nose for intentional tremor.

- Arms outstretched - moving fast for 30 cm from left to right and back for movement

analysis.

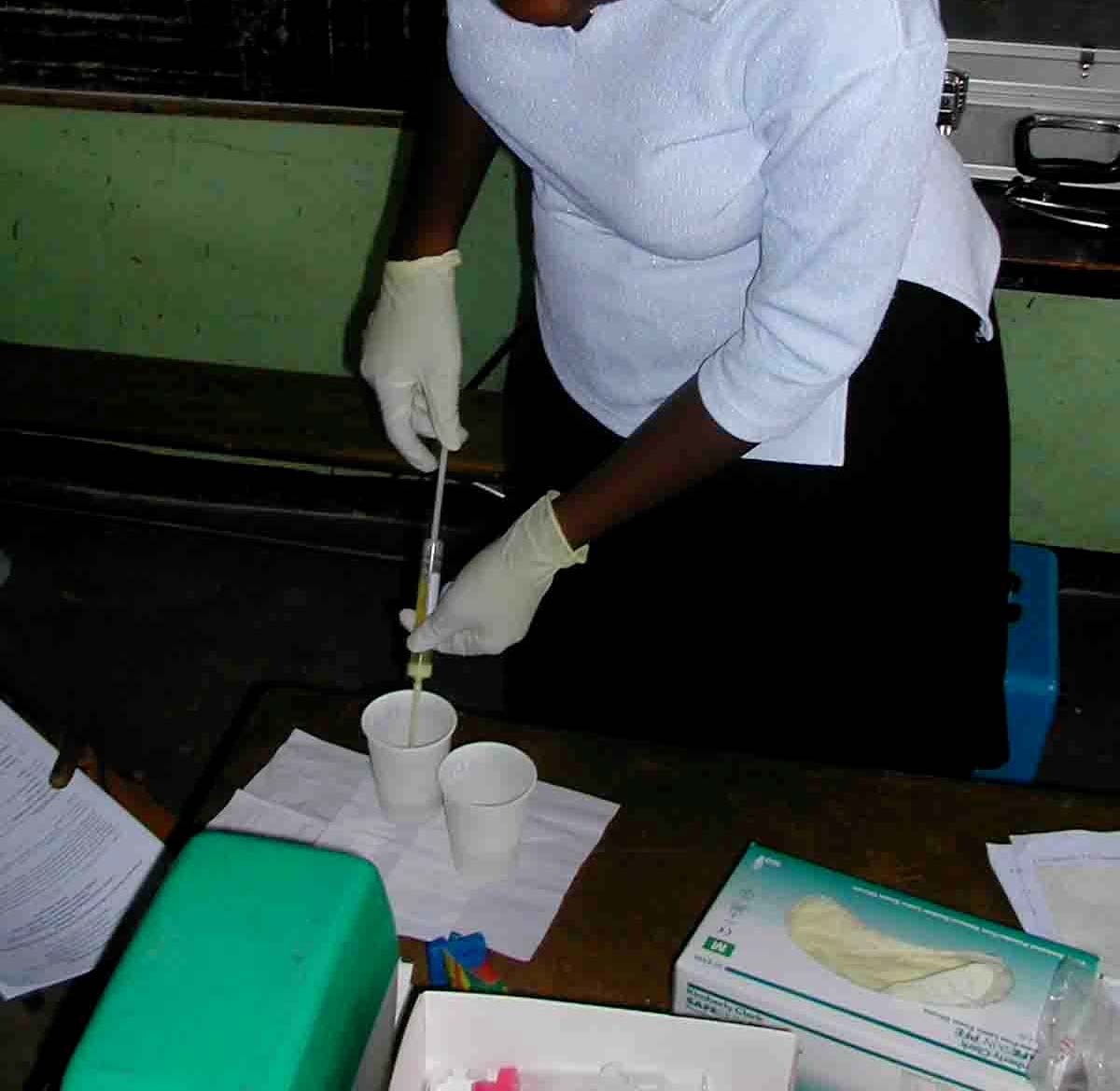

2.4.5. Laboratory field project

a) Specimens

The following specimens were taken, and two tests (Hg in urine and proteinuria) were

performed immediately:

- Blood (EDTA-blood 10 ml)

- Urine (spontaneous urine sample 10 ml)

Urine protein test

inorganic Hg in urine

- Hair.

The specimen urine and blood were cooled after collection until arrival in the laboratory

in Munich, Germany. Video and photo documentation of the examinations was carried

out.

Final Report

29

Health Assessment Kadoma, Zimbabwe

Picture 20 - Hair and urine sampling.

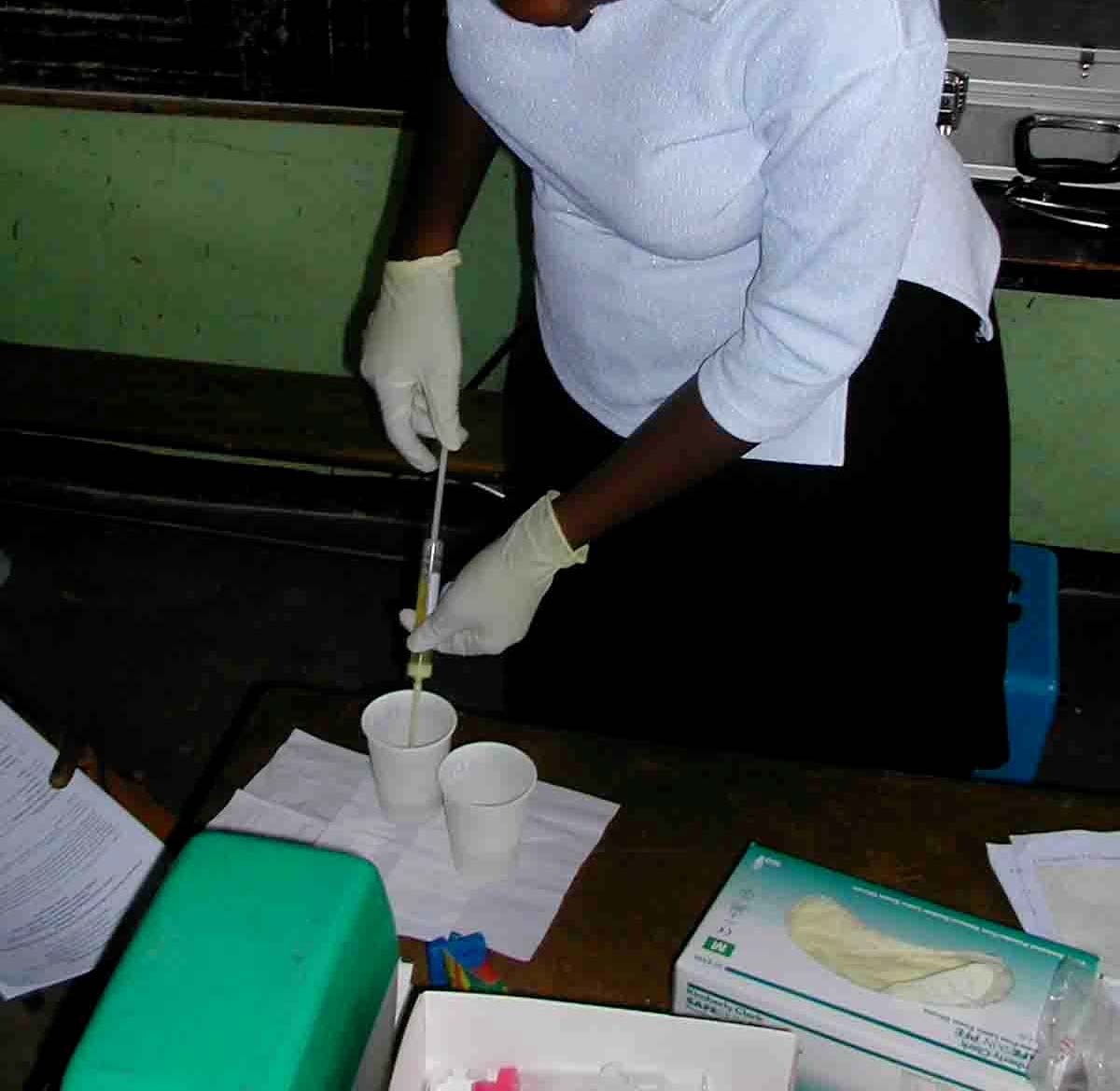

b) Lumex

A mobile Hg analyzer (Lumex RA-915+ with liquid attachment RP-91; Maassen GmbH,

Germany) was used to quantify inorganic mercury in urine with atomic absorption

spectrometry. For this 1 ml or less of the urine was filled with a pipette into the reaction

vessel filled with 10 ml of a tin(II)chloride-solution (5% in a 3% hydrochloric-acid). A

mercuric nitrate solution (100 ng/ml) was used as standard for calibration and control.

All the solutions were prepared with bottled drinking water due to the lack of distilled water.

The urine samples will be re-analyzed in the "Institute of Forensic Medicine", Munich,

Germany, to verify the results.

Picture 21 - Mobile Hg analyser for urine (Lumex).

30

Final Report

Health Assessment Kadoma, Zimbabwe

2.4.6. Test for protein in urine

Proteinuria was tested with a commercial kit (Bayer). The test is based on the error-of-

indicator principle.

Test reagents are 0.3% w/w tetrabromophenol blue; 99.7% w/w buffer and non-reactive

ingredients. At a constant pH, the development of any green color is due to the

presence of protein. Colors range from yellow for "negative" reaction to yellow-green

and blue-green for a "positive" reaction. The test area is more sensitive to albumin than

to globulin, hemoglobin, Bence-Jones proteins and muco-proteine. The test area is

sensitive to 15 mg/dl albumin. The test strip was dipped into the native urine and the

result was taken after 1 minute.

The test is semi-quantitative. Possible results are 0, 10, 20, 30, 100 and 300 mg

Protein/dl urine.

2.5. GENERAL HEALTH PROBLEMS IN KADOMA DISTRICT

Doctors, nurses, engineers, teachers and participants were interviewed on possible health

effects in relation to the mining and milling activities. The data from the two sociological

studies were very useful sources of information (Mtetwa, 2003 and Mtetwa, 2004).

2.5.1. Health care system in Kadoma district

The population is estimated to be 238,122 for the year 2003 (< 1 year of age are 7,620,

< 5 years 35,004, 5-14 years 66,912, > 15 136,206). 56,911 women are in the age

group 15-49, 10,573 women were pregnant.

The health service for the wide spread mining communities is situated in Kadoma town.

Village health workers can be found in the villages. They can treat minor illnesses as

well as primary malaria treatment. They support family planning, including distribution

of condoms. This service is provided free of charge.

The next district hospital is in Kadoma town. General surgery is performed in Kadoma, and

most of the infectious diseases can be treated in Kadoma, otherwise patients have to be

referred to Harare. The medical services in the hospital are charged to the patients. Some

patients cannot afford the charges in the hospital, but even more problematic are the high

medication costs. Kadoma district hospital is soundly built but there is a great lack of

financial resources to maintain the hospital and the equipment. Most of the more

technically advanced laboratory equipment does not function anymore. The pharmacy in

the hospital lacks many essential medication. The pediatric ward, for example cannot

obtain the necessary medication to treat asthma or some kinds of pneumonia. Children die

due to these lack of resources. Also there is no ambulance available to transport injured

miners, the miners cannot afford private transport expenses if they are injured. The staff

fluctuation is also a problem as experienced staff leaves the hospital to work in the private

sector or to work abroad. Our team was urgently asked to provide essential technical and

medical equipment to the hospital.

Final Report

31

Health Assessment Kadoma, Zimbabwe

The public health service is based at the district hospital. Mother and child care, family

planning, follow-up of the chronically ill, providing health information, and

environmental health are the duties of the public health service, all of which are free of

charge.

Several private medical practitioners treat patients in Kadoma. Traditional healers

(herbalists), so-called "machiremba", are part of the health care system.

All health care services have been steadily declining since a few years due to a

drainage of experienced and well trained health care providers to other developed

countries, caused by a lack of financial resources and unfavorable working conditions.

2.5.2. General health data

Health indicators can be used to compare health situations in this case between

countries. Life expectancy at birth is one commonly used health indicator. Life

expectancy for females in 2002 in Zimbabwe was 38.0 years, and for males 37.7 years

(WHO 2004).This is an extremely low life expectancy, even compared to other

countries in the area like Tanzania (47.5 years for females and 45.5 years for males) or

Ghana (58.8 for females, 56.3 for males) and Indonesia (67.9 for females, 64.9 for

males) (WHO 2004).

In 2003, 235,531 people were registered in the Kadoma district . A high percentage of

young people, 14.7 % under 5 years, and 28.1 % between 5 and 14 years were noted

(see table 1).

Number

In %

Total population as of 2003

235531

100

Population under 1 year

7537

3.2

Population under 5 years

34623

14.7

Population 5-14 years

66184

28.1

Population 15+ years

134724

57.2

Women 15 - 49 years

56292

23.9

Pregnant women

10458

4.44

Expected deliveries 4.32

10191

4.32

Table 1 - Kadoma district demographic data (by Mr. Gift from Kadoma District Hospital).

32

Final Report

Health Assessment Kadoma, Zimbabwe

Absolute No % of Total New Cases

1.Acute Respiratory Infections

15385

35.0

2.Malaria

5369

12.2

3.Diarrhoea

4804

10.9

4.Skin Diseases

3785

8.6

5.Diseases of the eye

1840

4.2

6.Symptoms & ill Defined Conditions

1660

3.8

7.Injuries

1638

3,7

8.Nutritional Deficiency

740

1.7

9.Dysentery

226

0.5

10.STD

112

0.3

Remaining Diseases

8340

19.0

Total New Cases

43899

100.0

Table 2 - Main causes of out-patient morbidity (under 5 years) (data from Mr. Gift from Kadoma

District Hospital).

Absolute No

% of Total New Cases

1

Acute Respiratory Infections

44339

21.9

2

Malaria

31887

15.8

3

Skin Diseases

12955

6.4

4

Diarrhoea

12831

6.3

5

Symptoms & ill Defined Conditions

12734

6.3

6

STD

12340

6.1

7

Injuries

11818

5.8

8

Diseases of the Eye

5606

2.8

9

Dental Conditions

2692

1.3

10 Dysentery

1298

0.6

Remaining Diseases

53593

26.5

Total New Cases

202093

100.0

Table 3 - Main causes of out-patient morbidity (all ages) (date from Mr. Gift from Kadoma

District Hospital).

Final Report

33

Health Assessment Kadoma, Zimbabwe

The main causes of out-patient morbidity for children in the Kadoma district are mainly

acute respiratory tract infection, and malaria or diarrhoea (see table 2). The main

causes of disease to be admitted to hospital for children are acute respiratory tract

infection, diarrhoea, problems around birth (perinatal pathology) and malaria (see

table 4). The main causes of death for children are the same as for hospital admission

(see table 6).

The estimated infant mortality rate in Kadoma district with 38.8 deaths per year / 1000

live births is compared to the country wide rate of 70.7 relatively low; to compare

Tanzania 109.2, Ghana 61.6, and Indonesia 39.3 (WHO 2004). Kadoma district seems

to be in the upper region of health indicators within Zimbabwe.

For adults acute respiratory tract infections, malaria and skin diseases are the main

causes of out-patient morbidity (see table 3). Apart from birth deliveries the main

causes to be admitted to hospital for adults are acute respiratory tract infections,

injuries and malaria (see table 5). The main causes of death for adults are AIDS related

diseases, acute respiratory tract infections, diarrhoea, tuberculosis and malaria (see

table 7).

Absolute No

% of Total New Cases

1

Acute Respiratory Infections

741

50.1

2

Diarrhoea

206

13.9

3

Perinatal Pathology

101

6.8

4

Malaria

85

5.8

5

Symptoms & ill Defined Diseases

75

5.1

Total New Cases

1478

100.0

Table 4 - Main causes of in-patient morbidity (under 1 year of age)

(data from Mr. Gift from Kadoma District Hospital).

Absolute No

% of Total New Cases

1

Normal Deliveries

3634

25.5

2

Acute Respiratory Infections

1178

8.3

3

Injuries and Poisonings

1112

7.8

4

Malaria

1041

7.3

5

Aids Related Diseases

809

5.7

Total New Cases

14247

100.0

Table 5 - Main causes of in-patient morbidity (5 years and over) (data from Mr. Gift from

Kadoma District Hospital).

34

Final Report

Health Assessment Kadoma, Zimbabwe

Infant mortality rate

No. of Deaths

/ 1000 live births

1

Acute Respiratory Infections

106

2

Diarrhoea

31

3

Perinatal Pathology

25

4

Malaria

11

5

Symptoms & ill Defined Disease

11

Total Under 1 Deaths

215

Total Live Births

5547

38.8

Table 6 - Top five causes of mortality (under 1 year) (data from Mr. Gift from Kadoma District

Hospital).

No. of Cases

No. of Deaths

Case Fatality Rate (%)

1

Aids Related Diseases

809

208

25.7

2

Acute Respiratory Diseases

1178

159

13.5

3

Diarrhoea

686

123

17.9

4

Tuberculosis

780

123

15.8

5

Malaria

1041

105

10.1

Table 7 - Top five causes of mortality (5 years and over) (data from Mr. Gift from Kadoma

District Hospital).

AGE GROUP IN

YEARS

FEMALE

MALE

HIV Tests No. +ve

% +ve

HIV Tests No. +ve

% +ve

0 - 4

38

22

57.9

44

26

59.1

5 14

45

28

62.2

16

9

56.3

15 -19

25

17

68.0

6

1

16.7

20 - 29

138

101

73.2

126

106

84.1

30 - 39

203

167

82.3

256

194

75.8

40 -49

75

49

65.3

110

62

56.4

50 - 59

28

19

67.9

56

23

41.1

60+

8

5

62.5

23

10

43.5

AGE UNKNOWN

4

0

0.0

36

19

52.8

TOTAL

564

408

72.3

673

450

66.9

Table 8 - HIV/AIDS (data from Mr. Gift from Kadoma District Hospital).

Final Report

35

Health Assessment Kadoma, Zimbabwe

The HIV/AIDS data from Kadoma district is very frightening (see table 8). Most applied

tests were positive (66% in males, 72% in females). The main age group of positive

tests is in the 20-29 and 30-39 year old population-group. These age groups are the

most sexual active age groups. At the same time these younger people are the main

work force at the moment and for the near future. The very high percentage of positive

tested people gives very serious concern to the public health sector, and might explain

the very low life expectancy in Zimbabwe.

2.6. GENERAL HEALTH PROBLEMS IN KADOMA DISTRICT

The main health problems in the mining area seem to be:

Dangerous tunnels, many lethal accidents occur each year in the Kadoma district.

Exact figures seem not to exist. Best estimations are in the range of 50 lethal accidents

per year in the mining areas. Miners reported of collapsing tunnels, due to improper

mining technologies (missing tunnel safety precautions). Medical treatment is not

available in the informal mining area proper, only in the nearby town of Kadoma.

Infectious diseases are widespread. A very high percentage of the surveyed population

had malaria, many of them within the last year. Malaria is diagnosed clinically and

treated orally mainly with Chloroquine and SP (Fansidar). Tuberculosis is endemic, but

not epidemic. Tuberculosis is treated under a governmental program. According to the

WHO scheme daily-observed treatment (DOT) with quadruple treatment for 2 months

(Isoniazid, Rifampicin, Pirazinamid, Etambutol) and follow-up double treatment for 4

months (Isoniazid, Rifampicin) is performed. Bilharzia occurs occasionally, no

screening program is performed at the moment, and treatment with Prazaquantile is

available in the hospital.

Sexually transmitted diseases (STD) are common. Promiscuity and prostitution are

common in the mining areas. Gonorrhea and cancroids are common. No screening is

performed, in the hospital gonorrhea is treated syndromatically with Benzadine-

penicillin, Doxycyclin, Metronidazole and Kanamycin.

HIV/Aids data was not available for the surveyed population. Cases of Aids are known

and treatment of the symptoms is available in the hospital. Antiviral treatment is not

available in the hospital, except for the mother child program. Prescriptions of antiviral

medication are available from the private medical practitioners, but the medication is

too expensive for most patients. Testing for HIV/Aids is voluntary.

Malnutrition in Zimbabwe has increased within the past two years due to drought over a

period the last years. The first food supply donations began last year (2003)

Malnutrition together with the HIV increases the susceptibility for other lethal infections

such as TB and malaria.

The dental status of people differs. Some people have many stumps but many people

have fairly good teeth. Most children have quite good teeth. The dental service in

Kadoma district hospital is closed due to the lack of a dentist.

36

Final Report

Health Assessment Kadoma, Zimbabwe

Insufficient sanitary conditions cause diarrhea. It is a major cause of infant mortality in

the mining areas in Kadoma district.

Pneumonia, upper respiratory infections, skin diseases, eye diseases (cataracts,

conjunctivitis) are other important causes of diseases in the mining areas in Kadoma

district.

The volunteers, we examined, presented diseases such as asthma, skin infections,

scars, hematuria etc.. These conditions should have been diagnosed and treated much

earlier.

Smoking is more common among men than among women. Alcohol consumption

seems to be higher in the informal small-scale mining areas. Drinking is very common

in the villages, mainly for men, since there are no other activities in the small-scale

mining areas for example no TV. The illegal use of smoking "dagga" seems to be done

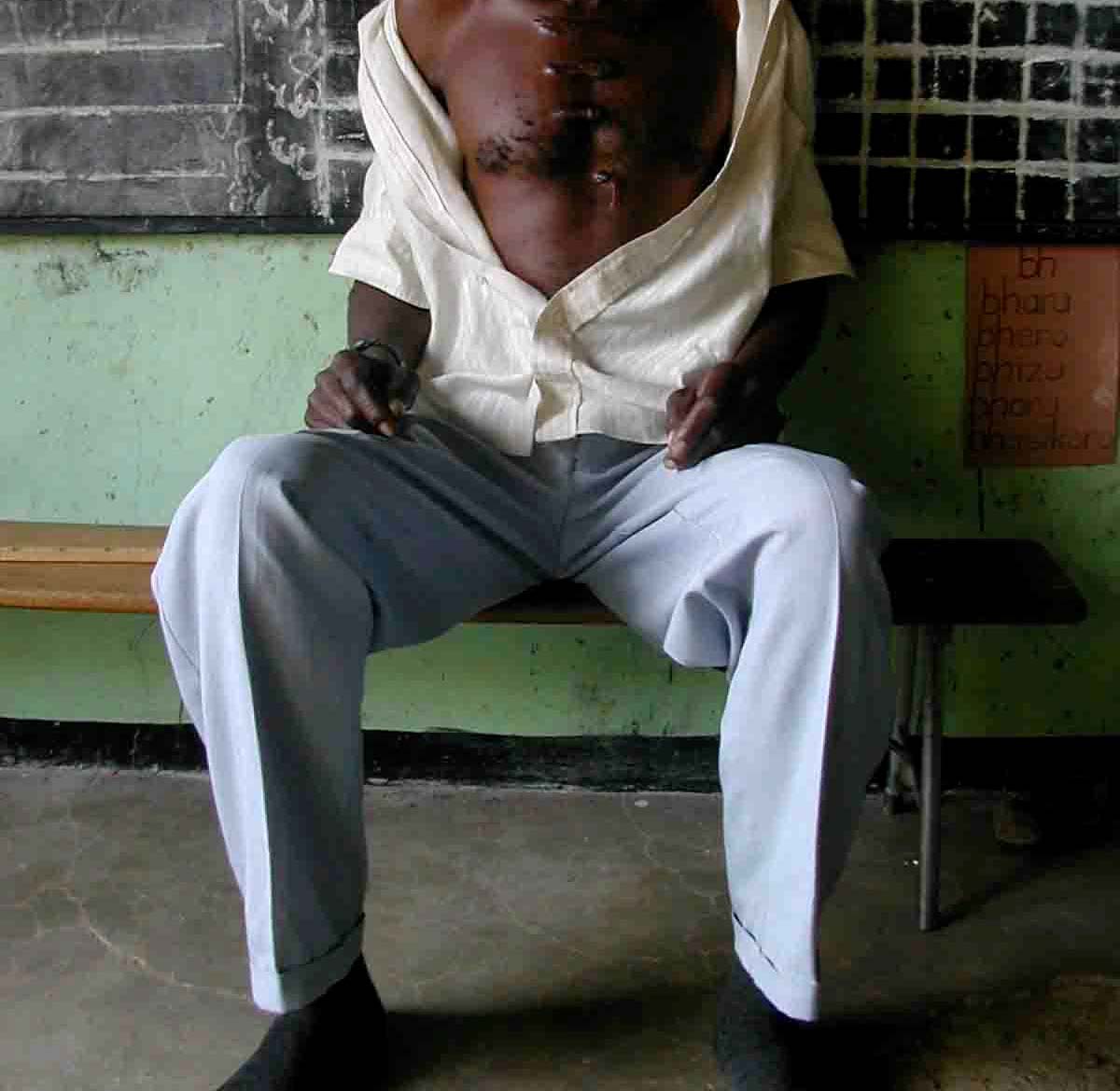

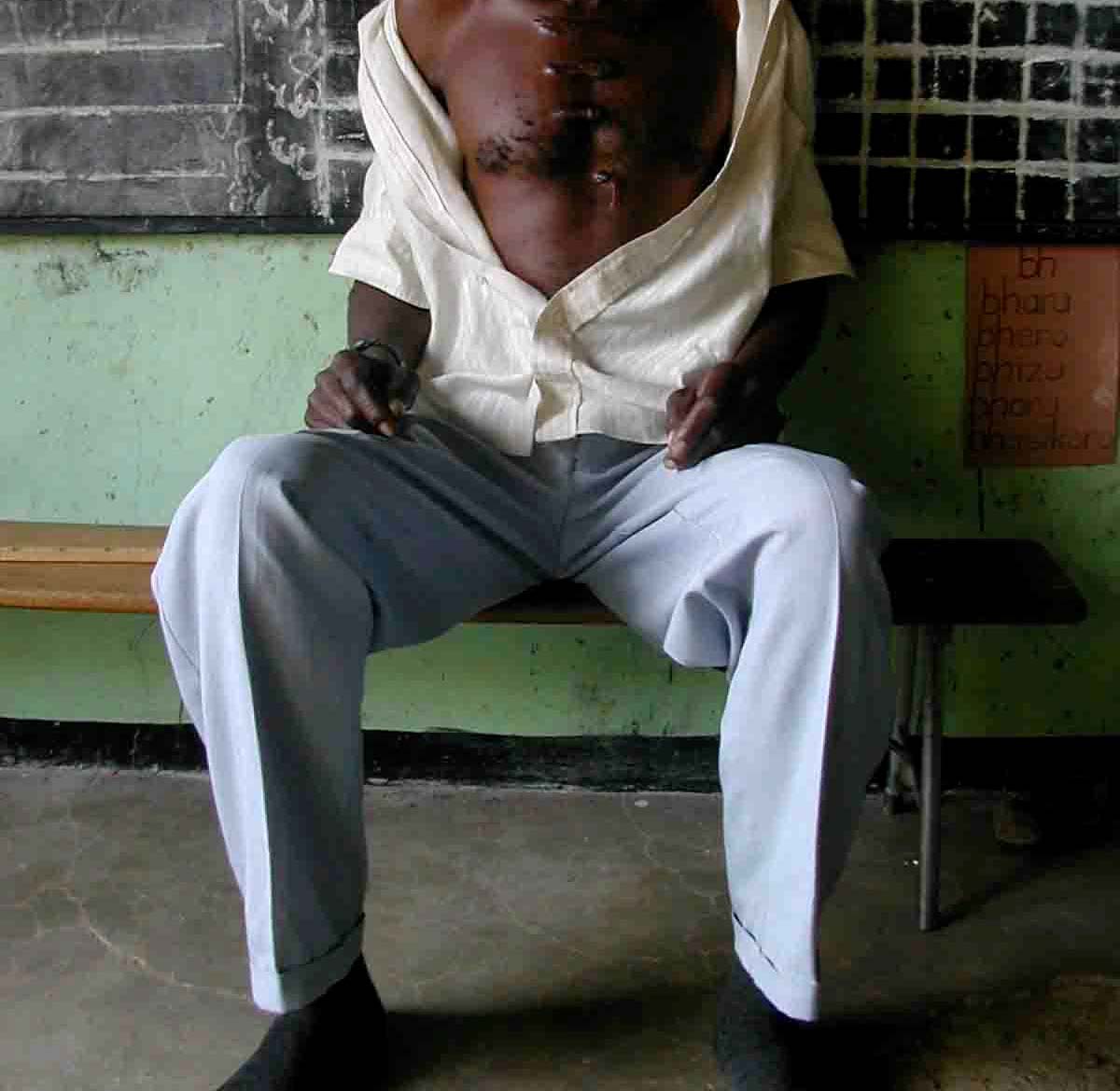

amongst younger male miners.

2.6.1. Children's health in Kadoma district

A high proportion of the population in the area is children under the age of 12. The

main health problems of children in the Kadoma informal mining areas seem to be

malnutrition and malaria: Due to poor sanitary conditions infectious diseases like

gastro-intestinal infections and malaria are very common and are a risk for children's

health.

Children experience high exposure to mercury in the area. They have access to fluid

mercury and play with this mercury with their hands. They live within the huts where

amalgamation and smelting is carried out and are therefore also exposed to mercury

fumes.

Some children do not attend school. Many children and teenagers work after school or

at weekends. Children begin to work in this area as young as 10 years of age. They

work in the amalgamation and smelting process with direct contact to mercury.

This is child labor at its worst limits, partially physically very hard, partially related to a

high exposure of mercury. Accidents related to work are a health hazard for these

children.

Not only mercury is a health hazard for children working in the mines. Some of the

children also work with cyanide, or with nitric acid. They inhale the toxic gases and are

in danger of damaging their respiratory system. The team examined three 8-12 year

old boys who had been coughing heavily in a dry manner. These children were not only

using cyanide but also nitric acid for cleaning the copper plates. Two of them might

have been mentally retarded, their look was almost dull, e.g. the orders for carrying out

the neuro-psychological tests had to be repeated several times until they reacted. The

children would prefer to go to school instead of working as a "panner" or miner, as one

10 year old boy expressed, but they have no choice due to the poverty of their family.

Final Report

37

Health Assessment Kadoma, Zimbabwe

Picture 22 - Children from Kadoma, all working as miners.

2.7. PRELIMINARY CLINICAL RESULTS OF THE HEALTH ASSESSMENT

The health assessment was performed according to the UNIDO health assessment

protocol (Veiga, 2003). The declaration to volunteer was translated in Shona (see

appendix 2). The 3 nurses interviewed all 217 participants. These participants were

physically examined including neurological testing. Specimens (blood, urine, hair) of

nearly all participants were taken at that time. A mobile Hg analyser was used to

determine total mercury in urine. Video and photo documentation was carried out.

2.7.1. Clinical and neurological examination

The clinical impression was, that some workers from Kadoma showed severe

symptoms, related to the classical picture of a mercury intoxication. They reported

sleep disturbances, excessive salivation, tremor, and metallic taste. Intentional tremor,

mainly fine tremor of eye lids, lips and fingers, ataxia, dysdiadochokinesia and altered

tendon reflexes were observed.

One woman, who had been working since 14 years with mercury showed severe

symptoms of a clinical mercury intoxication with ataxia, strong hypomimia, altered

reflexes and primitive reflexes. A seventeen year old young man, working since the age

of 10, had a very strong tremor of the eyelids, and could not even close the eyes

completely anymore.

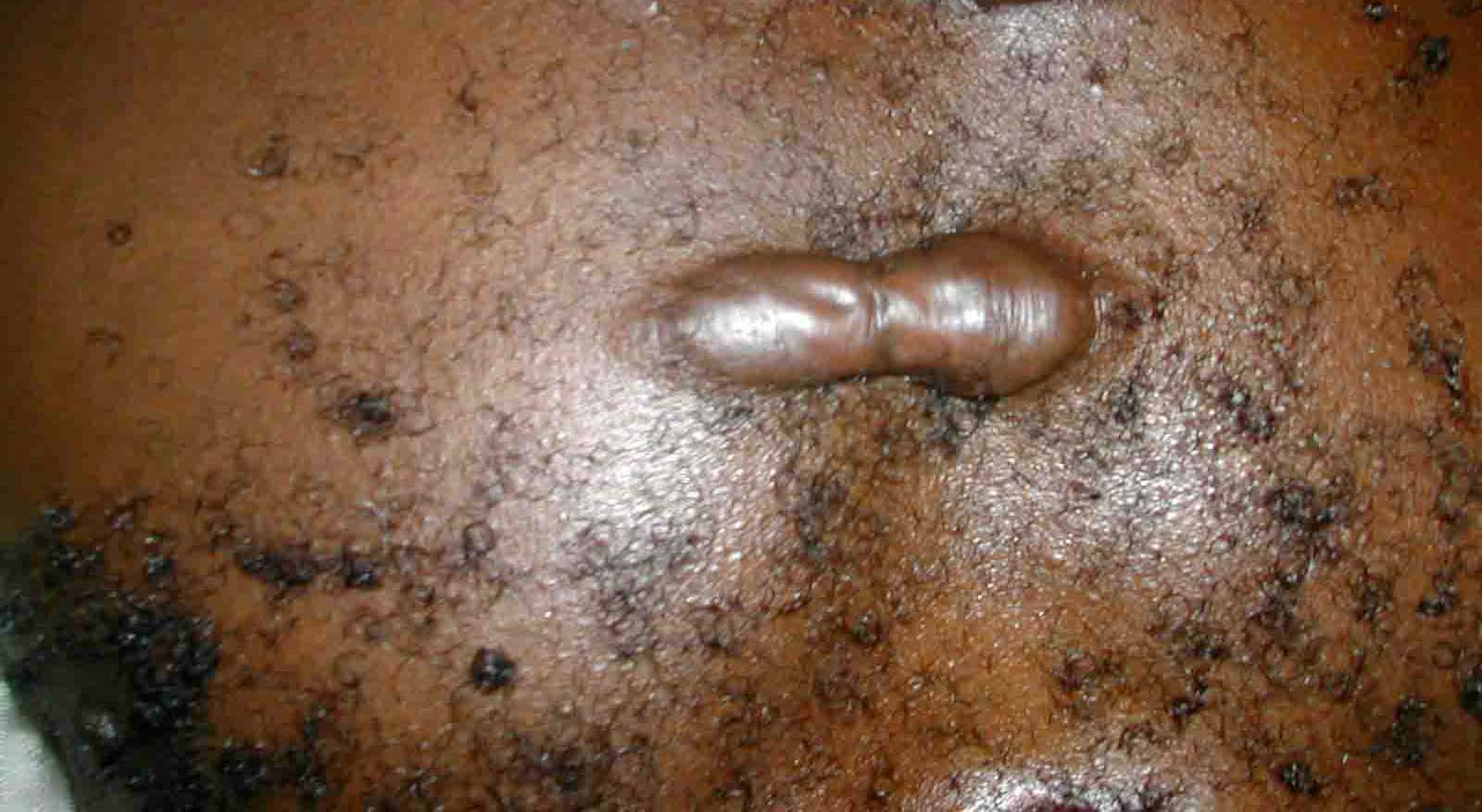

Other health problems observed were keloid formation due to hypertrophic scars. This

is not related to mercury, but shows the lacking capacities of the health care system.

One participant showed a severe scar on his foot due to a mining accident (collapsing

unprotected tunnel). Another participant had a scar at his neck due to a fight in the

mining area.

38

Final Report

Health Assessment Kadoma, Zimbabwe

Picture 23 - Participants with hypertrophic skin, scars due to mining accident,

scar due to a knife injury

It should be noted that many workers from Kadoma were primarily very healthy and

strong young men (healthy worker effect).

Participants who worked for more than 5 to 10 years in the area seemed to have more

severe clinical symptoms. But most miners did not work for that long in this area. It is

possible that we missed the most severe cases. Due to the lack of a highly developed

social system in Zimbabwe, some very sick workers might also have moved back to

their original homes and families elsewhere in Zimbabwe.

Final Report

39

Health Assessment Kadoma, Zimbabwe

2.7.2. Children's health in Kadoma mining area

The health status of the children in the area is poor. Malnourished and undernourished

small children are not uncommon (Kwashiorkor). Many children suffer from skin

problems, diarrhea and upper respiratory tract infections. Malaria is by far the most

serious health hazard for children in this area. Most children were physically fairly fit,

and well socialized.

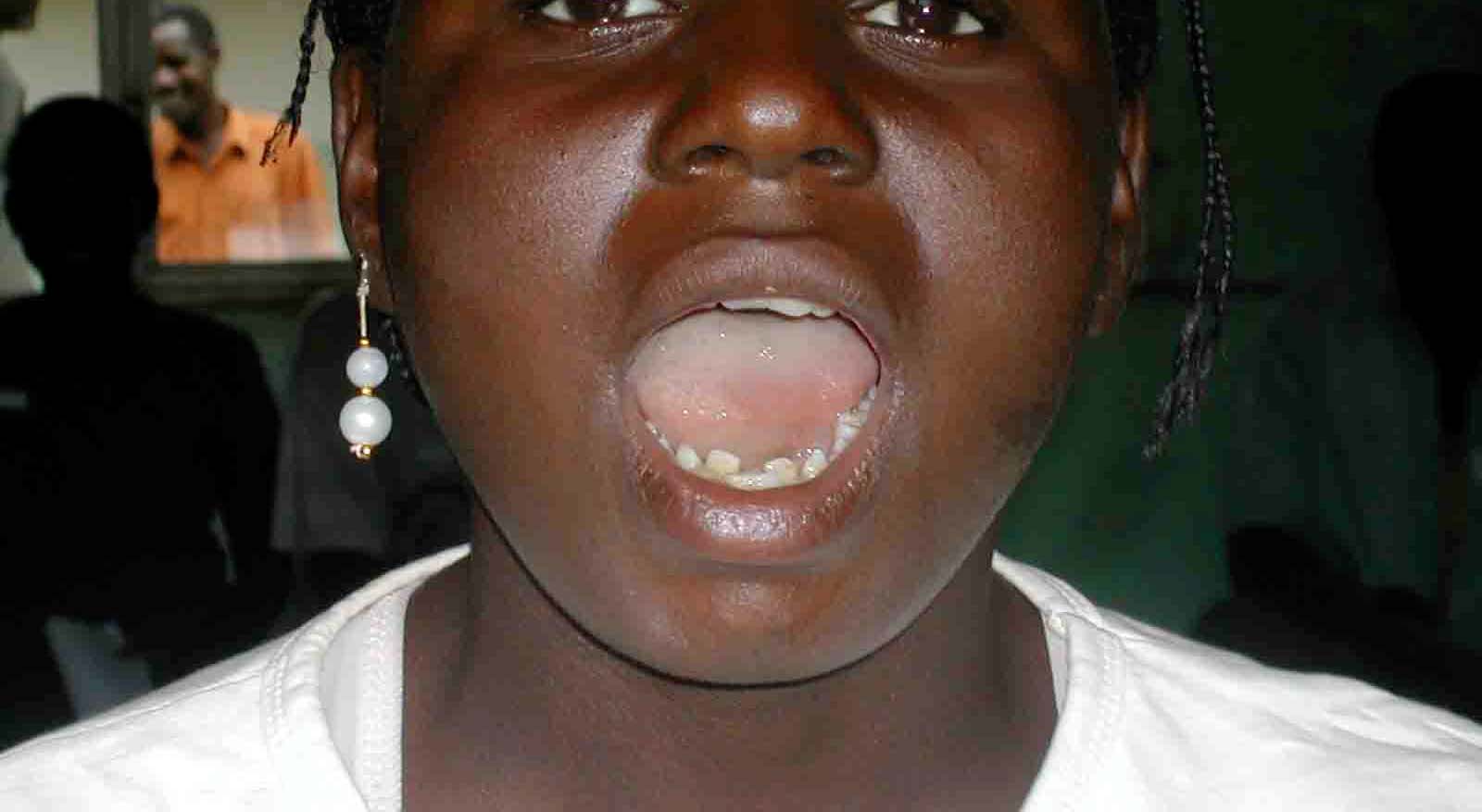

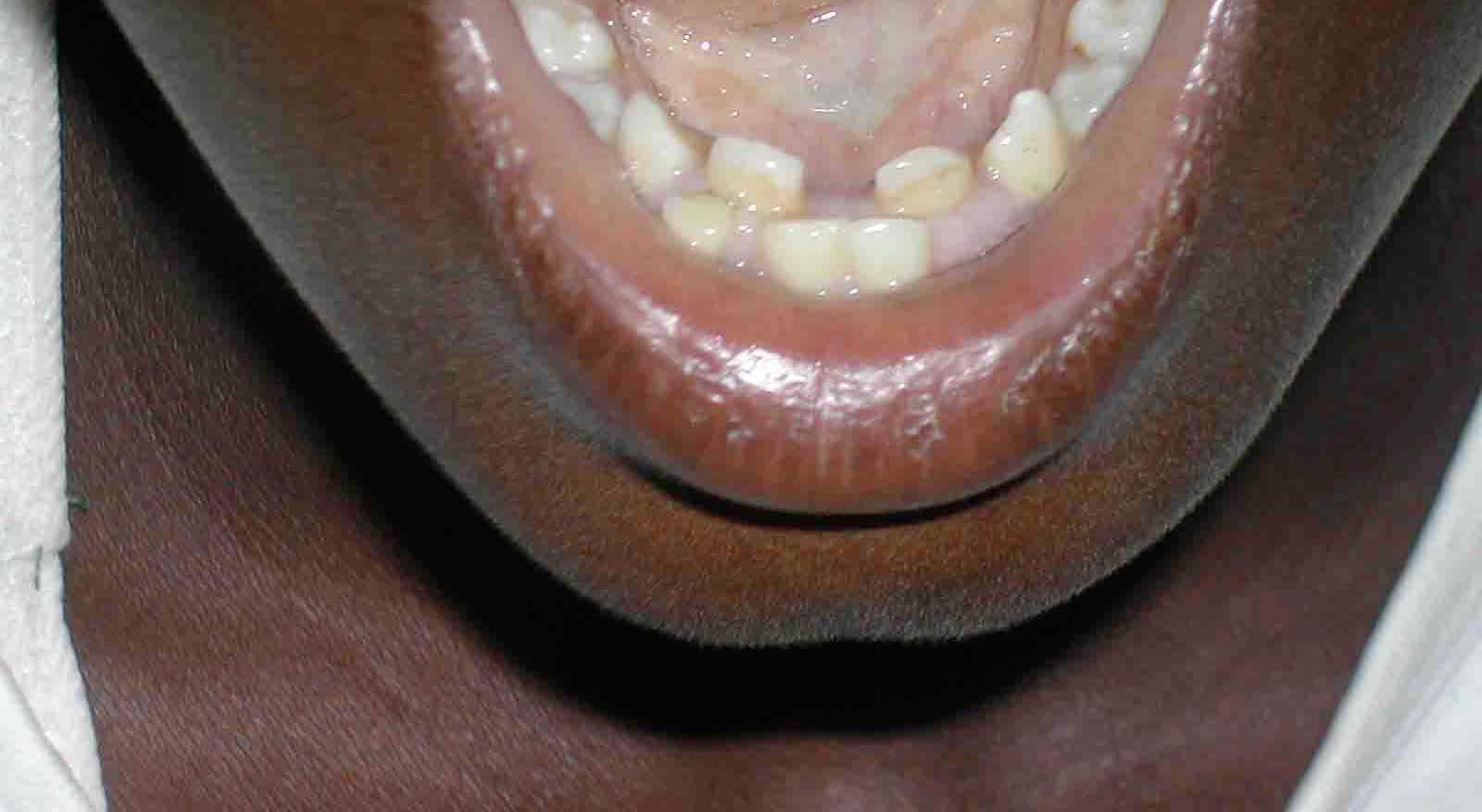

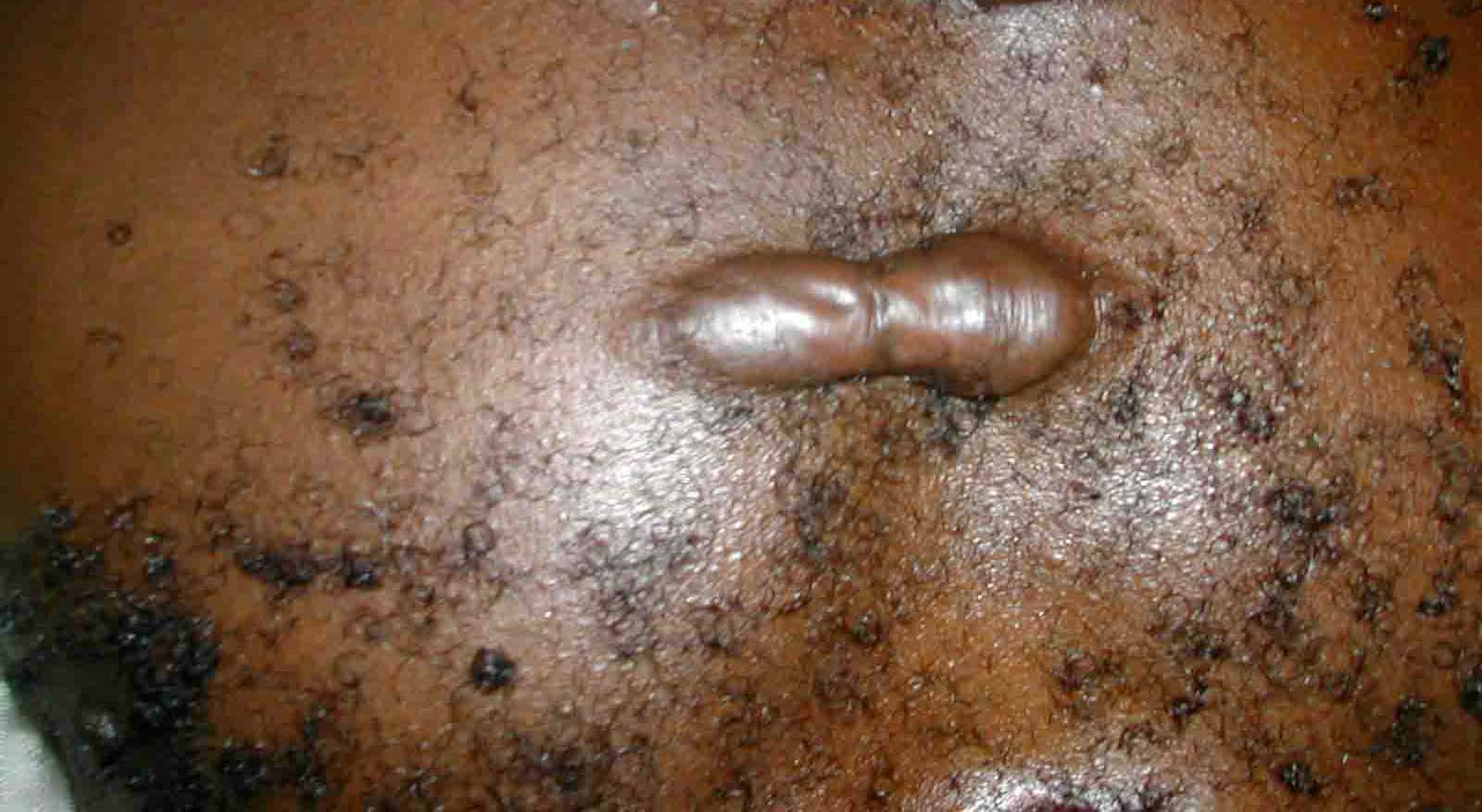

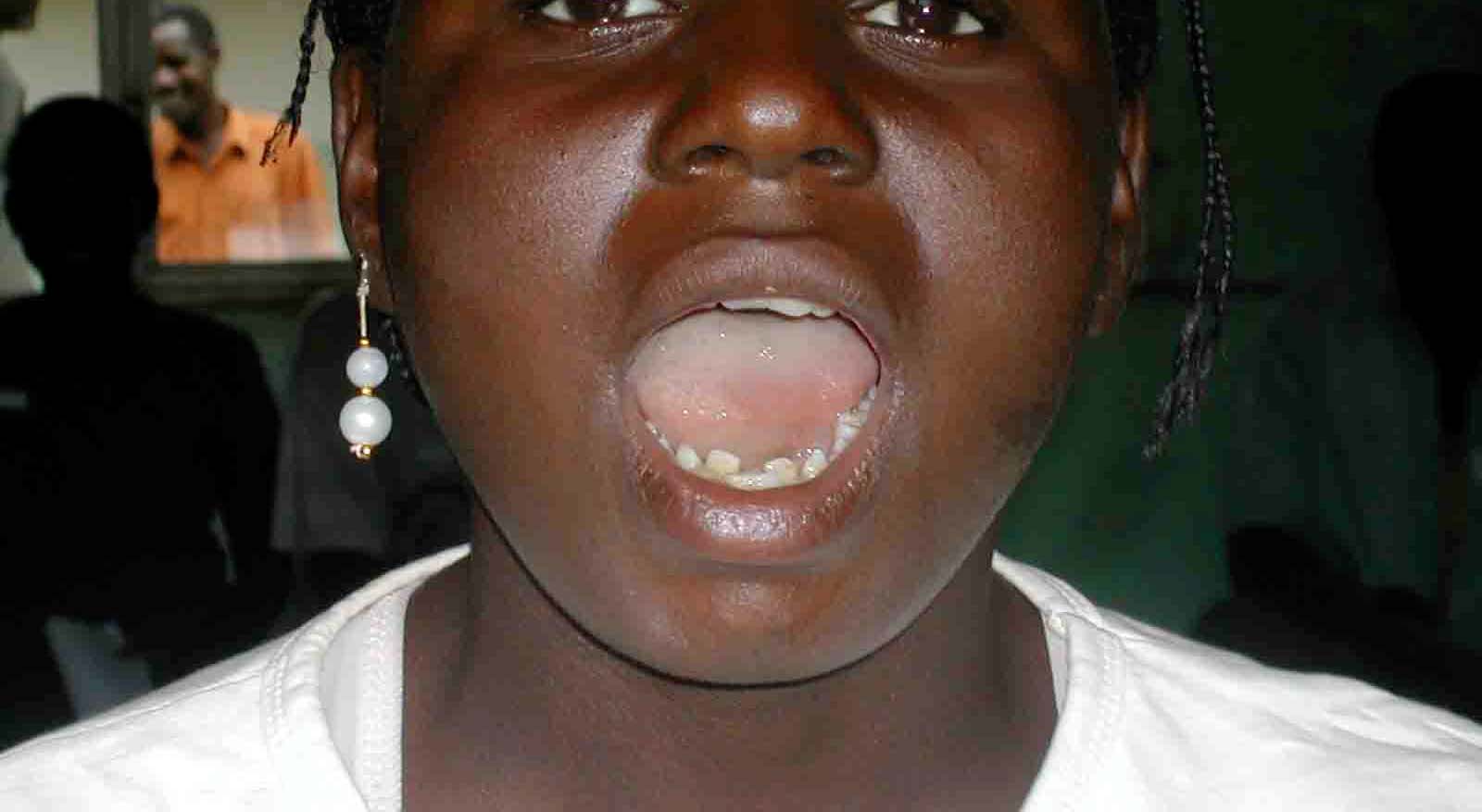

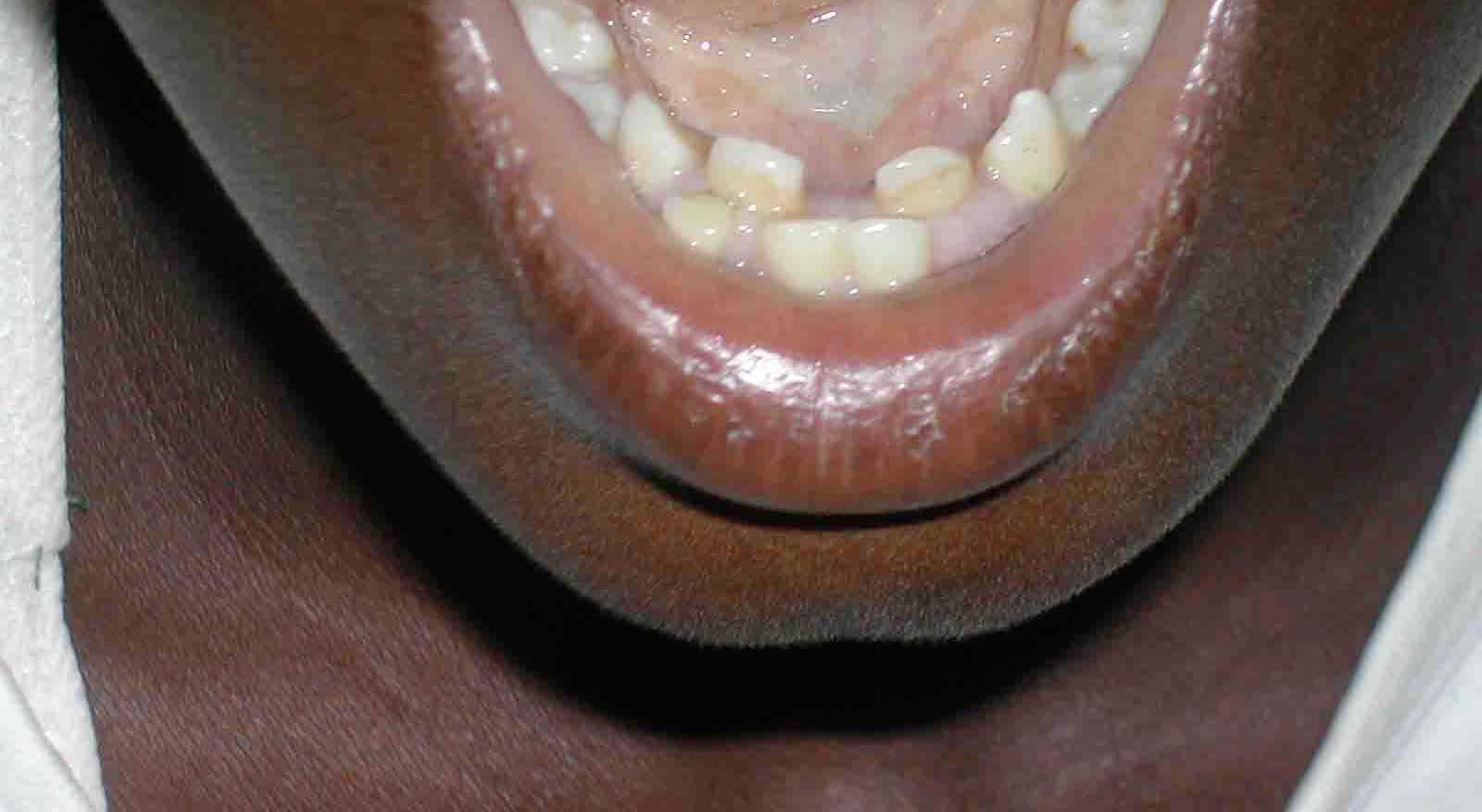

One child showed a dental malformation, a double formation of front teeth. In Minamata

disease skeletal malformations were linked to mercury. A single case cannot be linked

to a special cause, but it would be of great interest to analyze with a different approach

malformations in the area. A first clinical impression was, that some children were

either mentally retarded, or physically retarded.

Picture 24 - Dental malformation.

Picture 25 - Control area Chikwaka.

The control group in Katoro was healthy and did not show any special health problems

(55 people).

40

Final Report

Health Assessment Kadoma, Zimbabwe

2.7.3. Hygienic problems

The interviews highlighted some other problems:

In Kadoma town hygienic standards differ within the different town areas. The town is

overcrowded with migrant workers. Most people in the town have access to safe

drinking water. In town there is a waste water system draining to sewage tanks. Waste

collection functions.

In contrast the hygienic condition is poor in the villages where informal small-scale

mining occurs. Water is gained from the river, boreholes, or wells. Water is not safe

due to inappropriate hygienic conditions, and due to mercury leaking into the

waterways. The drinking water is sometimes turbid, which is a sign of insufficient

hygienic quality. Due to mining activities there are many small pools in the area. These

pools are certainly an excellent habitat for transmitters of vector borne diseases, like

Malaria. Most informal small-scale miners to not have any toilet, they just use the bush.

2.7.4. Social problems

In Kadoma district approximately half of the population is directly involved in the mining

and milling activities in the area. Estimations are in the range of 30,000 miners plus

family members, in total approximately 150,000 people. Some miners live with their

families in the mining areas, others live in Kadoma town, where no mining activities

take place.

Only few of the miners have a licensed small-scale mine, most miner work as artisanal

small scale miners. Many of these miners are work migrants. Lack of other employment

and hope of getting "easy money" (gold-rush) are the main reasons to migrate to the

Kadoma area and to begin to work as a small-scale miner. It is possible to get legal

permits for mining in Kadoma at the office of the department of the ministry of mines by

paying an affordable fee.

Living in remote villages means living outside of the security regulations. Since the gold

rush in the year 2000 and later, miners squatted some areas. Mainly old mines, that

were not in use anymore were penetrated. Miners enter the tunnels without any safety

precautions. Occasionally fights break out between miners to get personal access to

the gold promising ores. Sometimes miners exiting the tunnels with ore containing gold

are attacked from other miners. Gold buyers also run the risk of being attacked. Fights

between miners, often drunken, occur often in the villages. There are just very rough

estimations on the death toll of these conflicts, possibly more than 100 miners die each

year due to criminal activities. Neither the police, nor the mining or health authorities

have any exact figures nor do they have any control over the situation. Investigations

by specialists in forensic medicine do not exist.

Some miners are aware of the possibility of environmental and health hazards due the

use of mercury. But due to the lack of job opportunities elsewhere they continue to use

mercury.

Final Report

41

Health Assessment Kadoma, Zimbabwe

2.7.5. General problems during the field project

The infrastructure in the Kadoma district is poor but sufficient to perform the

examination. It is only due to excellent preparation of the field project by UNIDO

Harare, Dennis Shoko and BRGM, Pierre Billaud, that the project was successful at all.

The regional health authorities accepted the project. But on the national level there was

no support for the project. When asked for support before the start of the project, the

Ministry of Health did not support the health assessment. At the end of the project there

was some support from the Ministry of Health due to the intervention of Dr. Muguti, so

that at least the team could export the human bio-monitoring samples.

A problem was the poverty of the population in the area. Many participants suffered

from severe diseases that had not been adequately diagnosed or treated for months

and years due to a lack of resources. During the field project the medical experts

(pediatrician, general practitioner and a surgeon) and the pharmacist diagnosed,

referred or treated many people in Kadoma. Medication was provided free of charge to

the people. This medication was donated by Allacher Apotheke (Munich).

2.7.6. Participation

After the team had finished the examinations at the end of the project, it visited the

workers of Tix mill in their village. As many of the miners had been previously

examined by our team, the acceptance for our team within the village was greater than

expected. On previous projects our teams had been treated with more suspicion. Many

of the Tix miners spoke with the team about the project, about the results of the

examinations and asked, when they would receive the results of their personal mercury

burden of blood and urine.

When the health assessment team came to Tix mill in the first days, the miners were a

little bit suspicious of its intentions. But then most of the people came to the

examination site as if to a feast - often in their best clothes. For them this also seemed

to be a question of honour and dignity.

The people first had to gain confidence in the team and when the team made it's final

visit to the Tix mine community the team members almost seemed to be "old friends".

42

Final Report

Health Assessment Kadoma, Zimbabwe

3. Specimen analysis and statistical results

(Gustav Drasch, Beate Lettmeier)

3.1. LABORATORY METHODS

3.1.1. Material and sample storage

From 273 participants in Zimbabwe 269 blood samples, 273 urine samples and 233

hair samples were taken. The blood samples were taken in EDTA-coated vials. The

urine samples were acidified with acetic acid. To avoid de-gradation, all blood and

urine samples were stored permanently and transported by flight to Germany in an

electric cooling box. Until analysis these samples were stored continuously at 4 °C.