Final Report for an Assessment of

the Environment and Health in

the Rwamagasa area, Tanzania.

UNIDO Project EG/GLO/01/G34

Environmental Protection Programme

Commissioned Report CR/04/129

BRITISH

GEOLOGICAL

SURVEY

COMMISSIONED REPORT CR/04/129

Final Report for an Assessment of the

Environment and Health in the

Rwamagasa area, Tanzania. UNIDO

Project EG/GLO/01/G34

J D Appleton, H Taylor, T R Lister & B Smith; British Geological Survey

G Drasch & S Boese-O'Reilly; Institute of Forensic Medicine, Ludwig-

Maximilians-University, Munich

Key words

Mercury, Tanzania, Rwamagasa,

Artisanal, Gold, Mining.

Front cover

Cover picture Covered

amalgamation pond and sluices

at tailings reprocessing site

adjacent to the mbuga of the

River Isingile.

Bibliographical reference

APPLETON, J D, TAYLOR H.,

LISTER T R & SMITH, B.

(BGS); DRASCH, G & BOESE-

O'REILLY, S (Ludwig-

Maximilians-University,

Munich) 2004. Final Report for

an Assessment of the

Environment and Health in the

Rwamagasa area, Tanzania.

UNIDO Project

EG/GLO/01/G34. British

Geological Survey

Commissioned Report,

CR/04/129. 306 pp.

© NERC 2004

Keyworth, Nottingham British Geological Survey 2004

BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY

The full range of Survey publications is available from the BGS

Keyworth, Nottingham NG12 5GG

Sales Desks at Nottingham and Edinburgh; see contact details

0115-936 3241

Fax 0115-936 3488

below or shop online at www.thebgs.co.uk

e-mail: sales@bgs.ac.uk

The London Information Office maintains a reference collection

www.bgs.ac.uk

of BGS publications including maps for consultation.

Shop online at: www.thebgs.co.uk

The Survey publishes an annual catalogue of its maps and other

Murchison House, West Mains Road, Edinburgh EH9 3LA

publications; this catalogue is available from any of the BGS Sales

Desks.

0131-667 1000

Fax 0131-668 2683

e-mail: scotsales@bgs.ac.uk

The British Geological Survey carries out the geological survey of

Great Britain and Northern Ireland (the latter as an agency

London Information Office at the Natural History Museum

service for the government of Northern Ireland), and of the

(Earth Galleries), Exhibition Road, South Kensington, London

surrounding continental shelf, as well as its basic research

SW7 2DE

projects. It also undertakes programmes of British technical aid in

geology in developing countries as arranged by the Department

020-7589 4090

Fax 020-7584 8270

for International Development and other agencies.

020-7942 5344/45

email: bgslondon@bgs.ac.uk

The British Geological Survey is a component body of the Natural

Forde House, Park Five Business Centre, Harrier Way,

Environment Research Council.

Sowton, Exeter, Devon EX2 7HU

01392-445271

Fax 01392-445371

Geological Survey of Northern Ireland, 20 College Gardens,

Belfast BT9 6BS

028-9066 6595

Fax 028-9066 2835

Maclean Building, Crowmarsh Gifford, Wallingford,

Oxfordshire OX10 8BB

01491-838800

Fax 01491-692345

Parent Body

Natural Environment Research Council, Polaris House,

North Star Avenue, Swindon, Wiltshire SN2 1EU

01793-411500

Fax 01793-411501

www.nerc.ac.uk

Foreword

This final report is a published product of a study by the British Geological Survey (BGS) and the

Institute of Forensic Medicine, Ludwig-Maximilians-University, Munich carried out on behalf of UNIDO

as part of Project No. EG/GLO/01/G34 "Removal of Barriers to the Introduction of Cleaner Artisanal

Gold Mining and Extraction Technologies.

The report comprises (1) an Executive Summary jointly compiled by the BGS and the Institute of

Forensic Medicine, Ludwig-Maximilians-University, Munich; (2) an Assessment of the Environment in

the Rwamagasa area (BGS Commissioned Report CR/04/014R); and (3) a Medical Investigation of 250

people living in the Rwamagasa area (compiled by the Institute of Forensic Medicine, Ludwig-

Maximilians-University, Munich)

BGS Report CR/04/129 (Issue 1.0) for UNIDO Contract 03/088

i

BGS Report CR/04/129 (Issue 1.0) for UNIDO Contract 03/088

ii

Contents

Executive Summary

Part 1: Assessment of the Environment in the Rwamagasa area,

Tanzania (British Geological Survey)

Part 2: Assessment of Health in the Rwamagasa area, Tanzania

(Institute of Forensic Medicine, Ludwig-Maximilians-University, Munich)

BGS Report CR/04/129 (Issue 1.0) for UNIDO Contract 03/088

iii

BGS Report CR/04/129 (Issue 1.0) for UNIDO Contract 03/088

iv

Executive Summary

Introduction

Artisanal gold mining is one of the major sources of mercury contamination, especially in developing

countries. Whilst the gold extraction process (known as amalgamation) is a simple technology, it is

potentially very harmful to the environment and can contaminate air, soil, rivers and lakes with mercury.

The health of the miners and other people living within the area affected by mercury contamination may

be negatively affected through inhalation of mercury vapour or contaminated dusts, direct contact with

mercury, through eating fish and other food, and through the ingestion of waters and soils affected by the

mercury contamination.

In response to this problem, the Global Environmental Facility (GEF) of the UN approved funding for the

project Removal of Barriers to the Introduction of Cleaner Artisanal Gold Mining and Extraction

Technologies (also referred to as the Global Mercury Project (GMP)) in March 2002. The Global

Mercury Project was started to help demonstrate ways of overcoming barriers to the adoption of best

practices, waste minimization strategies and pollution prevention measures that limit contamination of

international waters and their associated environments.

In August 2003, the British Geological Survey (BGS), acting under the Natural Environment Research

Council, signed a contract (No. 03/088) with the United Nations Industrial Development Organization

(UNIDO) to carry out limited Environmental and Health surveys and assessments in the Rwamagasa

artisanal gold mining area in the Republic of Tanzania. Rwamagasa was selected by UNIDO as the

demonstration site for Tanzania. The environmental assessment was executed by the BGS whilst the

medical and toxicological investigations were subcontracted to the Institut für Rechtsmedizin der

Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Germany. The regional health authorities in Geita supported

the medical investigations, whilst the environmental assessment was carried out in collaboration with

staff from the Geita Mines Office and from the Kigoma and Mwanza offices of the Tanzania Fisheries

Research Institute (TAFIRI), with the enthusiastic assistance of Mr Aloyce Tesha, Assistant to the

UNIDO Country Focal Point.

Rwamagasa is located in Geita District, which has an area of 7,825 km², 185 villages, and a population

around 712,000 (census of 2002). The number of artisanal miners in the Geita District is unknown by it is

estimated to be as many as 150,000, most of whom are illegal panners. Primary artisanal workings in the

Rwamagasa area are centred on quartz veins in sheared, ferruginous, chlorite mica schists. Grab samples

of vein and wall rock grade 6-62 g/t Au. The only legal mining in the Rwamagasa area is carried out

within the boundaries of the Primary Mining Licence held by Blue Reef Mines where approximately 150

people are involved in mining and mineral processing activities. This is the only site in the Rwamagasa

BGS Report CR/04/129 (Issue 1.0) for UNIDO Contract 03/088

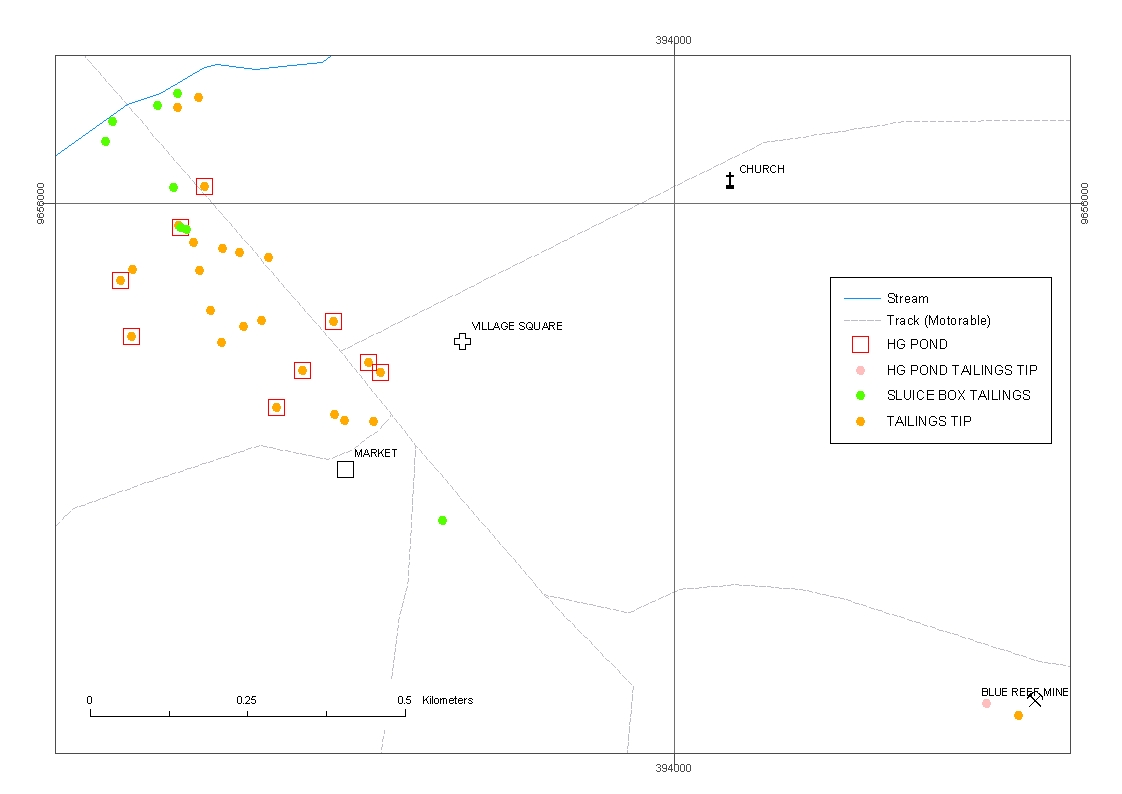

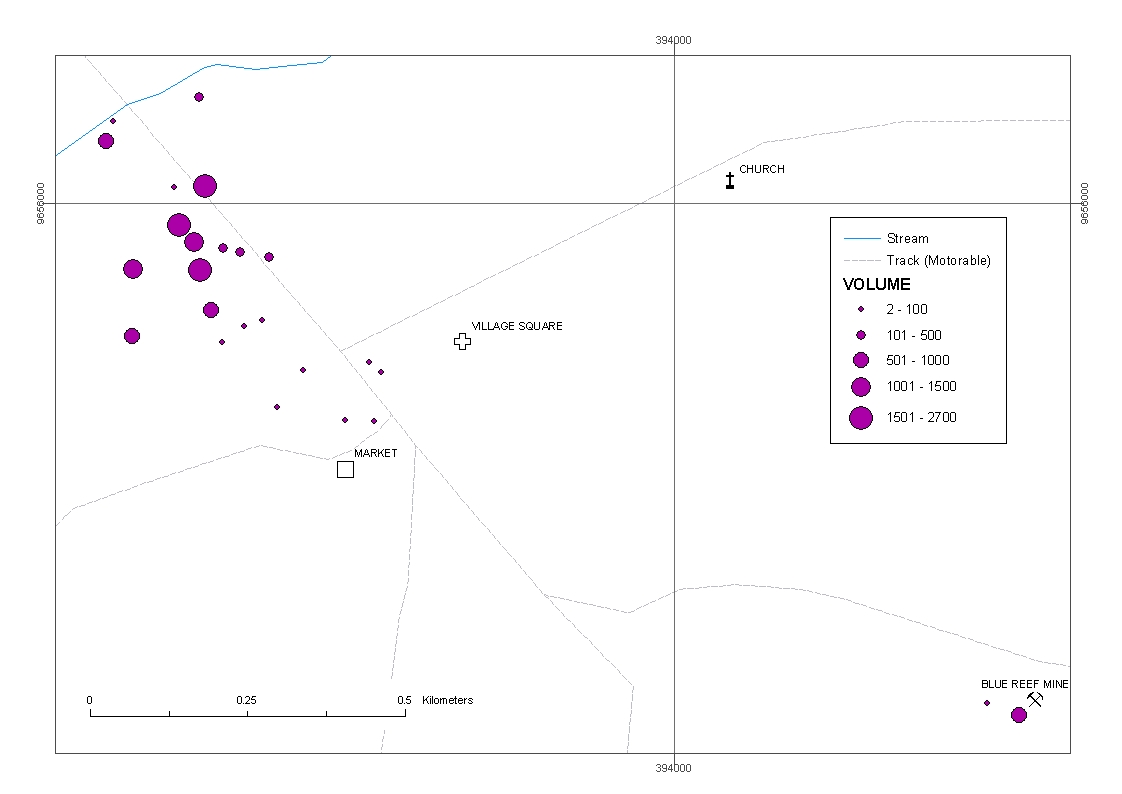

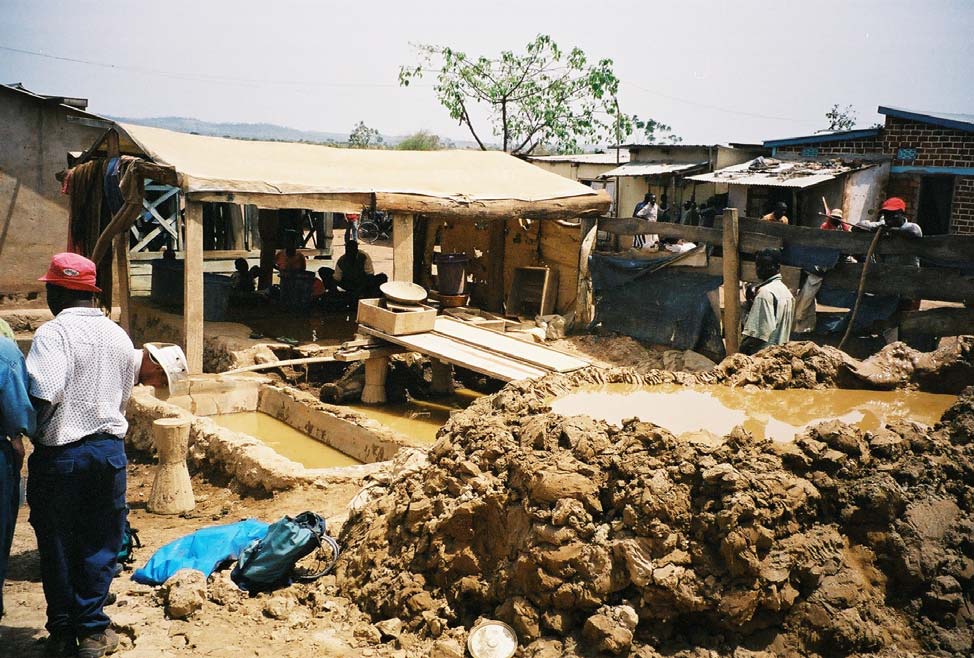

area where primary ore is being mined underground. All other mineral processing activity of any

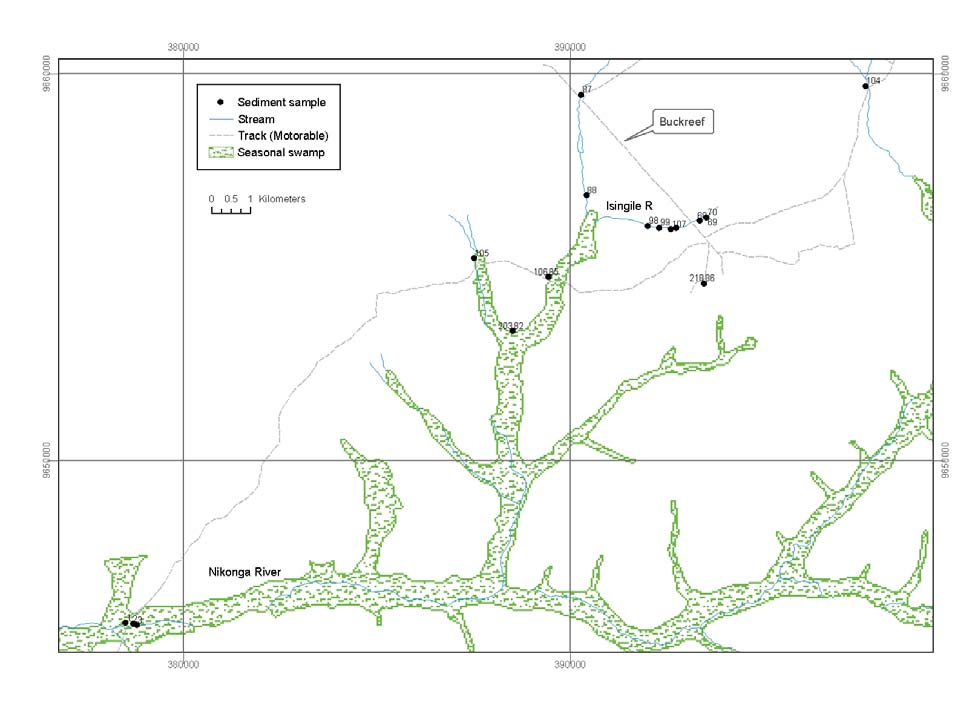

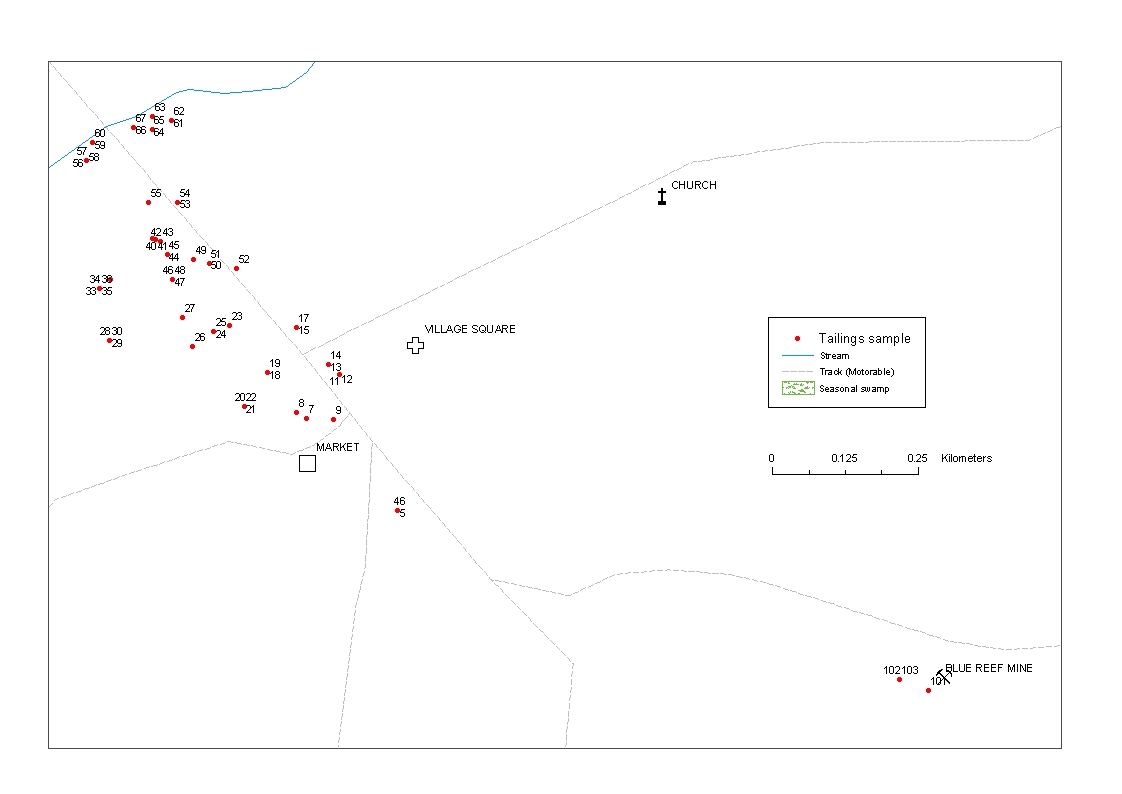

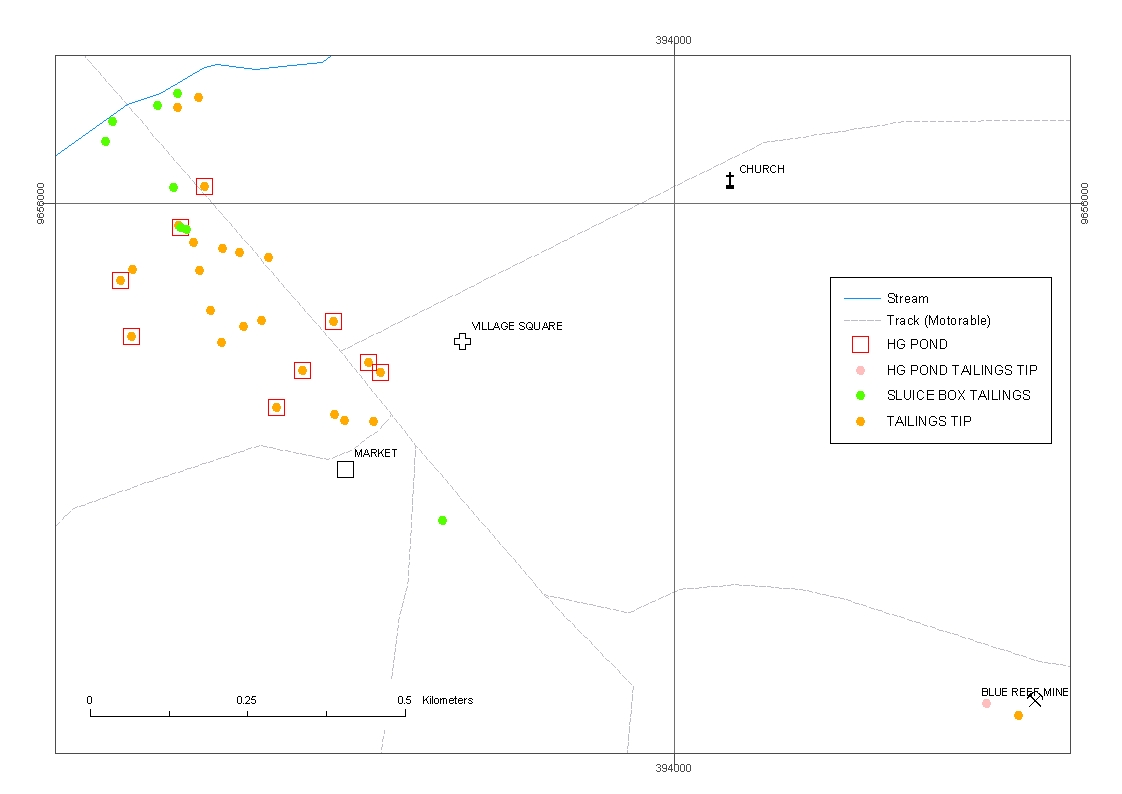

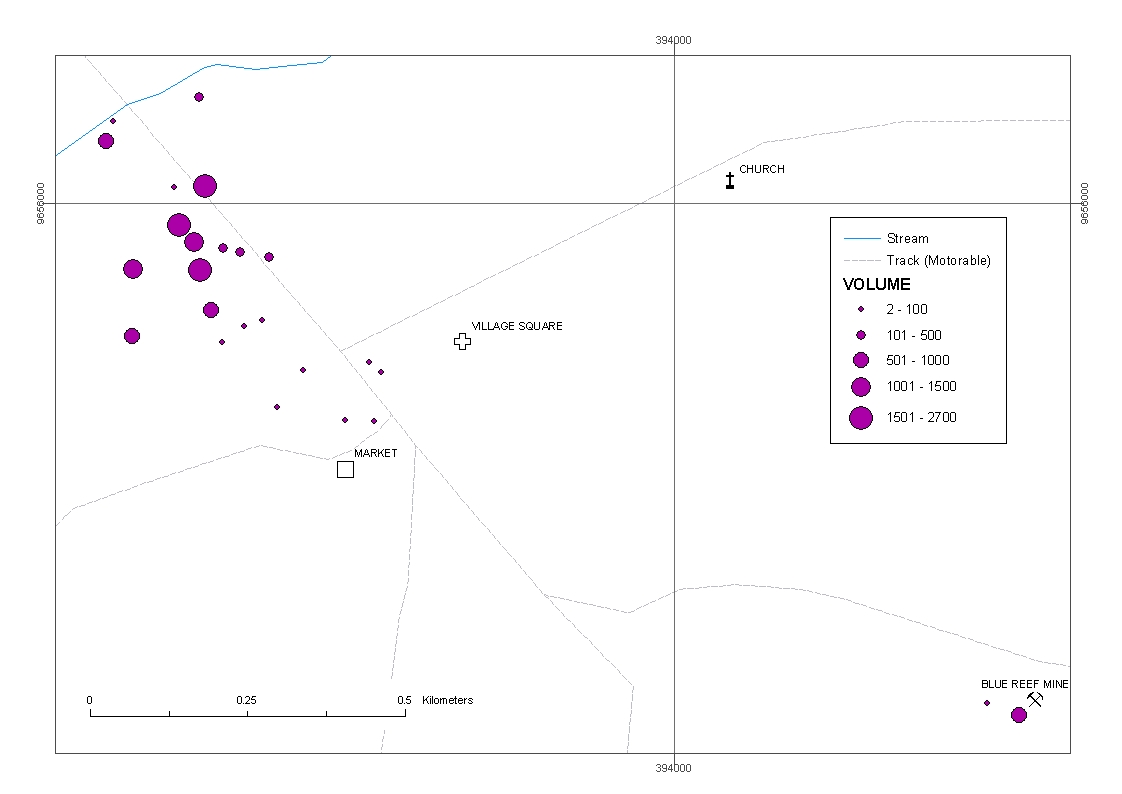

significance is concentrated at the northern margin of Rwamagasa, especially on the land sloping down to

the Isingile River. In this area, there are about 30 groups of historic and active tailings dumps and about

ten localities where small (200 litre) ball mills are operating. The number of people actively involved, at

one particular time, in ball milling, sluicing and amalgamation is probably no more than 300.

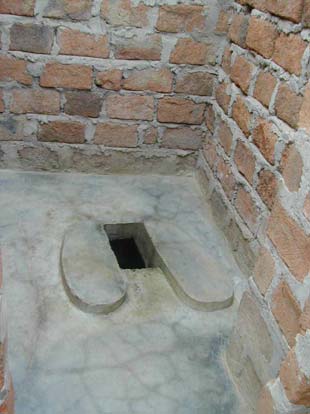

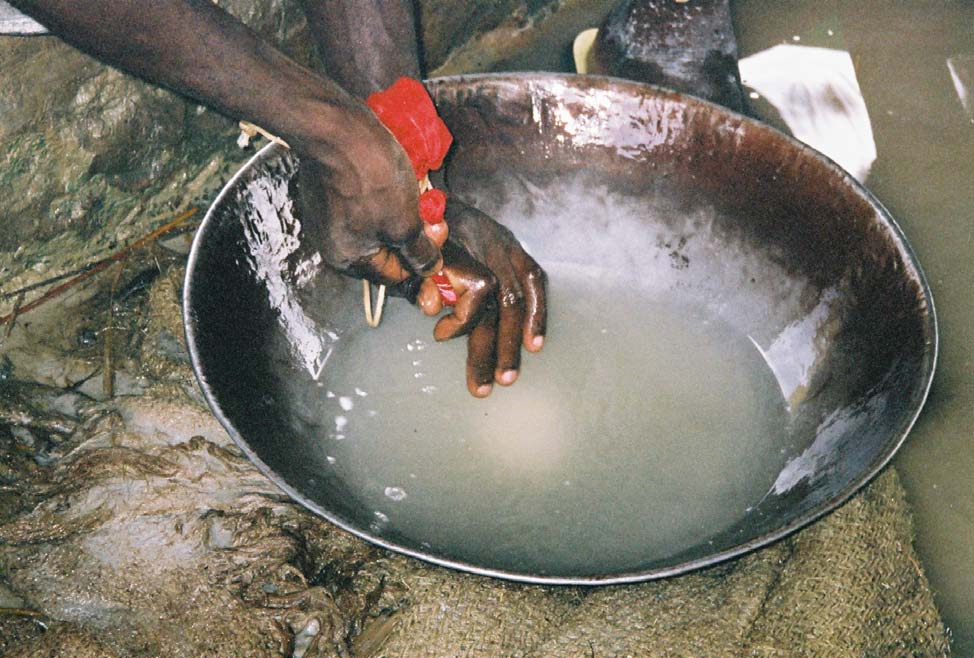

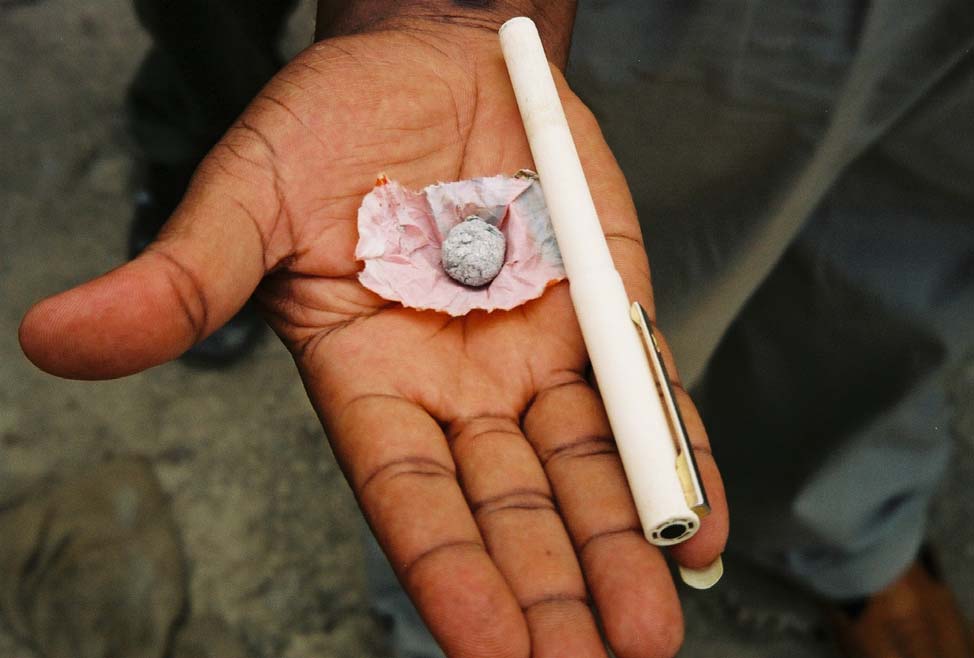

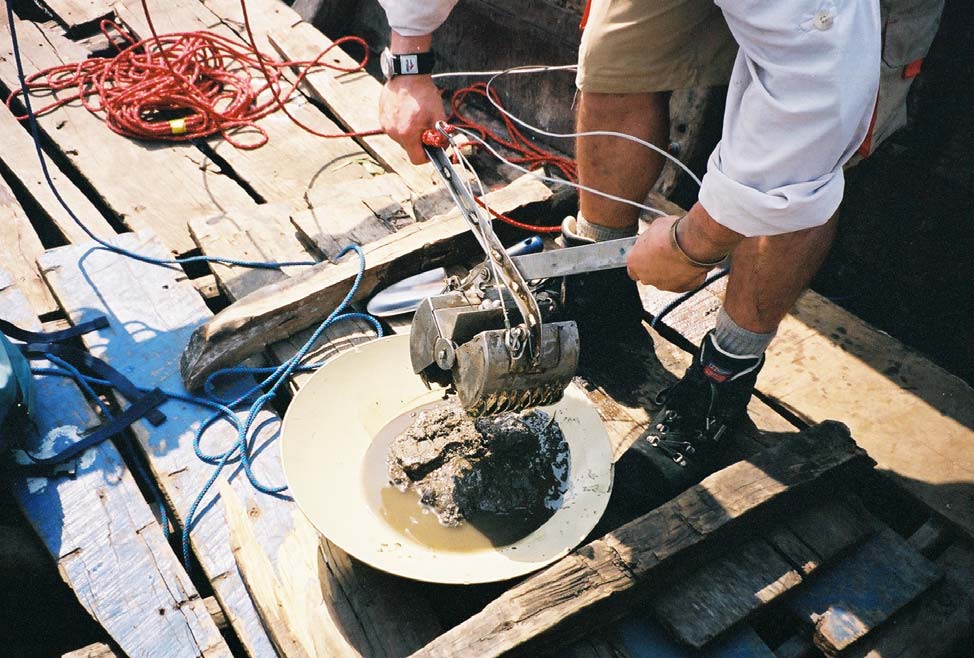

Amalgam is burned in a small charcoal fire, which releases Hg to the atmosphere. Retorts are not used.

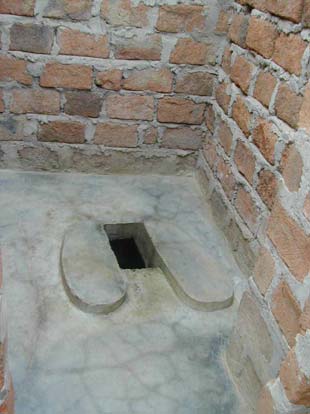

Amalgamation mainly takes place adjacent to amalgamation ponds, which are usually formed of concrete,

but sometimes have only wood walls even though environmental legislation dictates that the Hg

contaminated mineral concentrates and tailings should be stored in concrete lined structures.

The Blue Reef Mine is reported to produce about 1 kg Au per month whereas artisanal miners re-working

tailings produce about 0.5 kg per month. On this basis, approximately 27 kg of Hg will be released to the

environment from the Rwamagasa area each year. Of this, atmospheric emissions from amalgam burning

will be about 14 kg from the Blue Reef mine site and 7 kg from the other amalgamation sites. About 2 to

3 kg Hg will remain in heavy mineral tailings in the amalgamation ponds, which are frequently

reprocessed. It is reported that the number of miners working in the Rwamagasa area was much larger in

the past, so the historical release of mercury would probably have been higher than at present.

The young and strong men, so called healthy workers, are mainly found in the bigger and more

technically equipped properties. Older people, women of all ages and children mainly work in the smaller

artisanal mining properties. Retorts are not used, neither is there any other protection, such as ventilation,

against any kind of mercury contamination. Housing areas, food stalls and the schools are located close to

the sites where amalgamation and burning of the amalgam is carried out. Mineral processing tailings

containing mercury are found within the village adjacent to cultivated land or near local water wells.

Mercury is usually stored in the miner's houses in small soft-drink bottles, near to where they and their

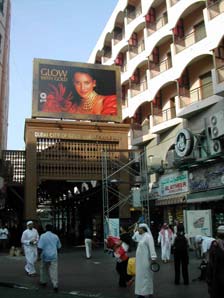

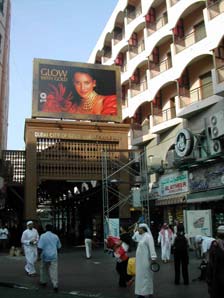

families sleep. The mercury is mainly obtained from Nairobi in Kenya and the gold is either used for

jewellery in Tanzania or sold to Dubai.

Hygiene standards are extremely low and are a reason for many infectious diseases such as diarrhoea,

typhoid and parasitism. There is no effective waste disposal system for either mercury, sanitary or other

domestic waste.

Road accidents, accidents in insecure tunnels and amalgamation plants, malaria, tuberculosis, and

sexually transmitted diseases including AIDS are the dominant causes of morbidity and mortality. No

special health service exists for the mining community the nearest dispensary is about 10 km away. A

local dispensary is under construction, but the construction has been stopped due to lack of money. The

village lacks social welfare services and a police post for security. The nearest district hospital is in Geita.

All non-minor illnesses have to be transferred to Geita hospital, which is adequately equipped for a

district hospital.

BGS Report CR/04/129 (Issue 1.0) for UNIDO Contract 03/088

Environmental assessment field programme

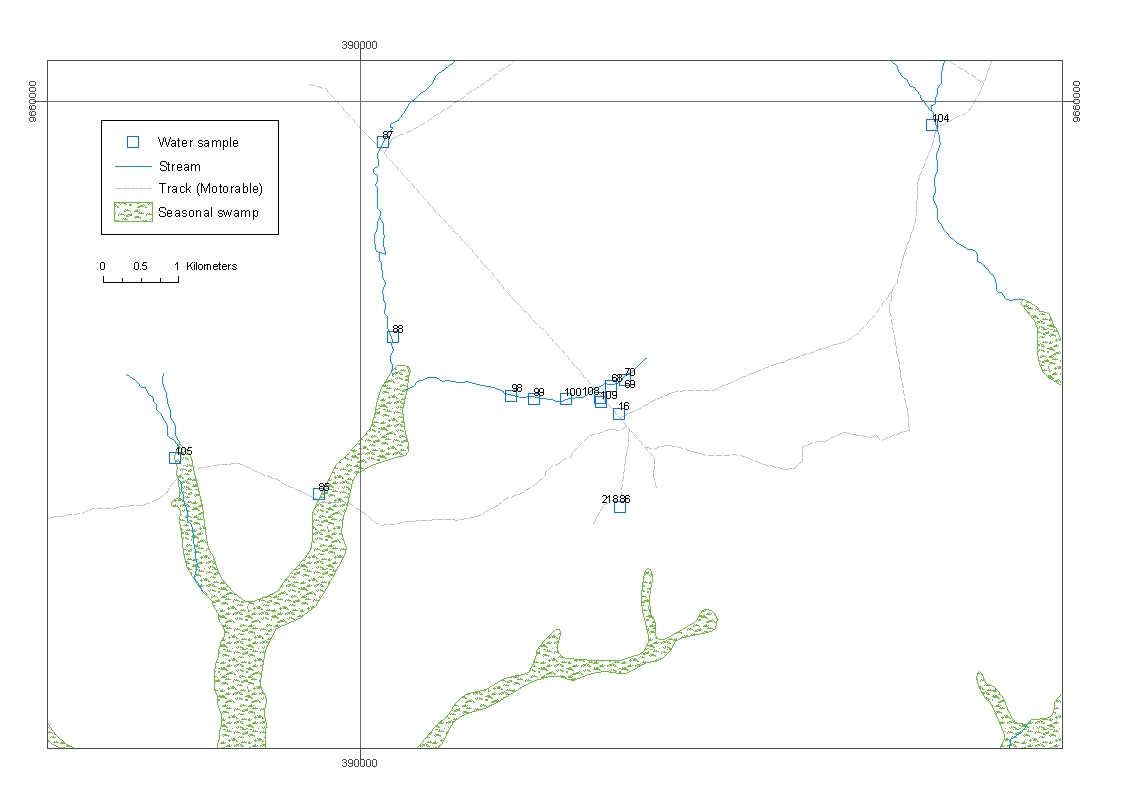

The objective of the environmental assessment was to (i) identify hotspots in the project demonstration

sites, (ii) conduct specified geochemical and toxicological studies and other field investigations in order

to assess the extent of environmental pollution in surrounding water bodies and (iii) devise intervention

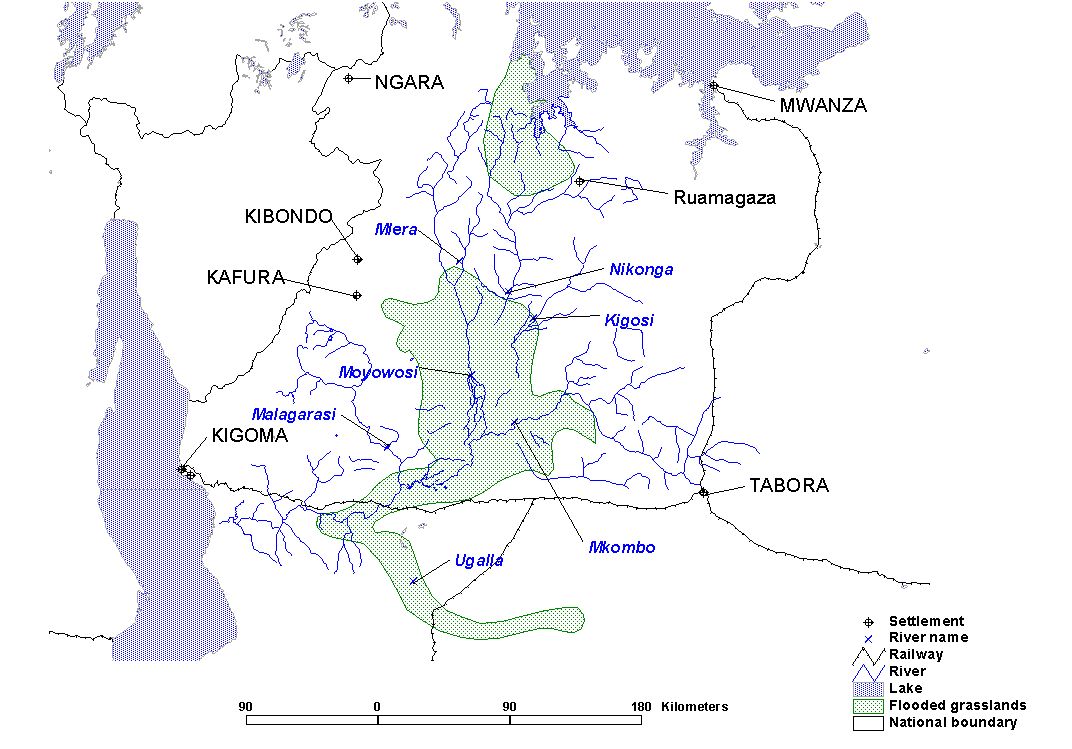

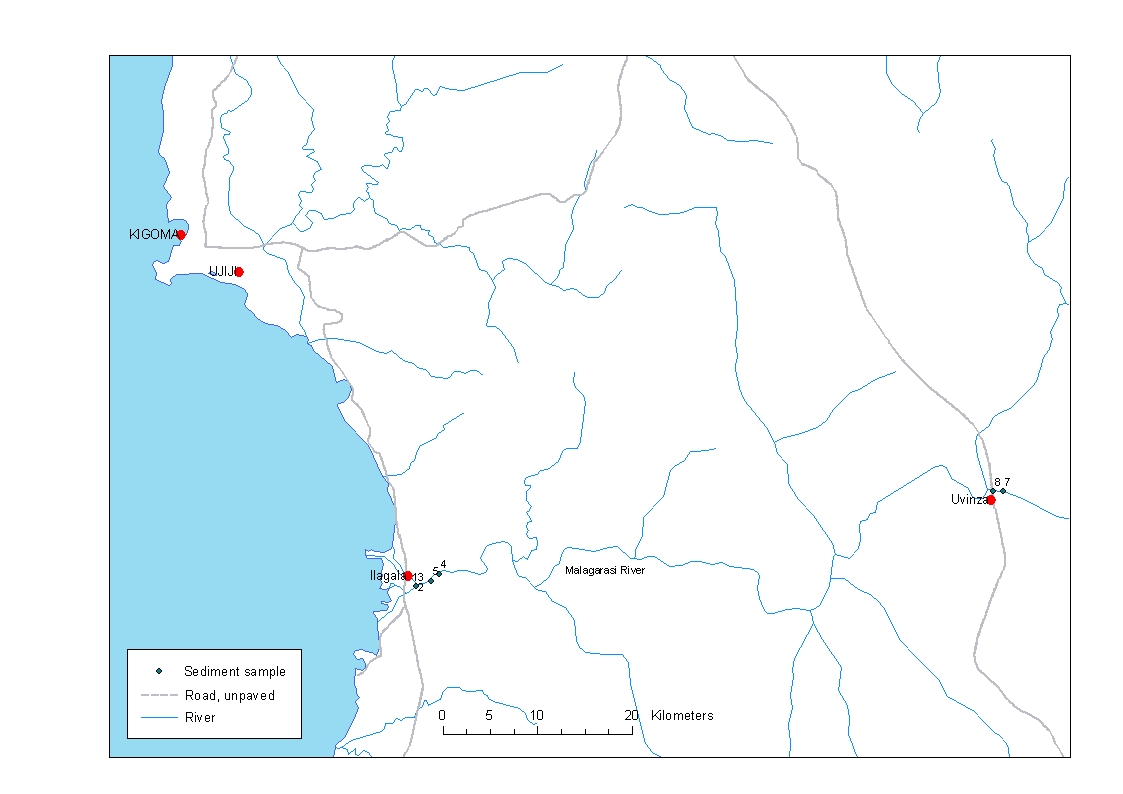

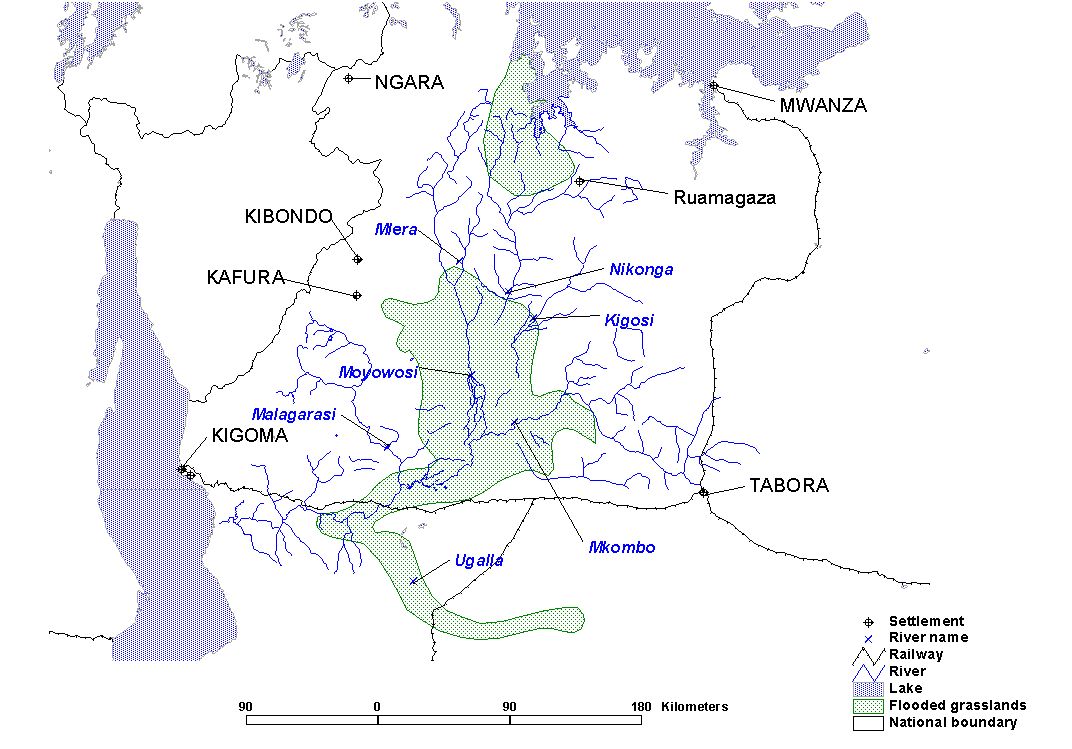

measures. Although Rwamagasa is located only 37 km to the south of Lake Victoria, streams draining the

Rwamagasa `mining hotspot' actually drain SW into the Nikonga River, and then for a further 430 km via

the Moyowosi swamps and the River Malagarasi before reaching Lake Tanganyika near Ilagala, about 50

km to the SSE of Kigoma. One of the major objectives of the project is to assess the impact of mercury

contamination on international waters as well as in the vicinity of the `mining hotspot', so the field

programme was carried out in two areas: (a) the Rwamagasa `mining hotspot' sub-area and (b) the Lake

Tanganyika River Malagarasi sub-area (see Figure ES-1). Dispersion of Hg from Rwamagasa to Lake

Tanganyika is probably relatively unlikely because contaminant Hg will be adsorbed by organic material

in the extensive Moyowozi and Njingwe Swamps and flooded grassland area, located from 120 km to 350

km downstream of Rwamagasa. Whereas the swamps will act as a potential biomethylation zone, they

will also act as an environmental sink for Hg contamination, which is likely to inhibit migration of Hg

into the lower reaches of the Malagarasi River and Lake Tanganyika. The swamp area was inaccessible

within the logistical and budgetary constraints of the current project.

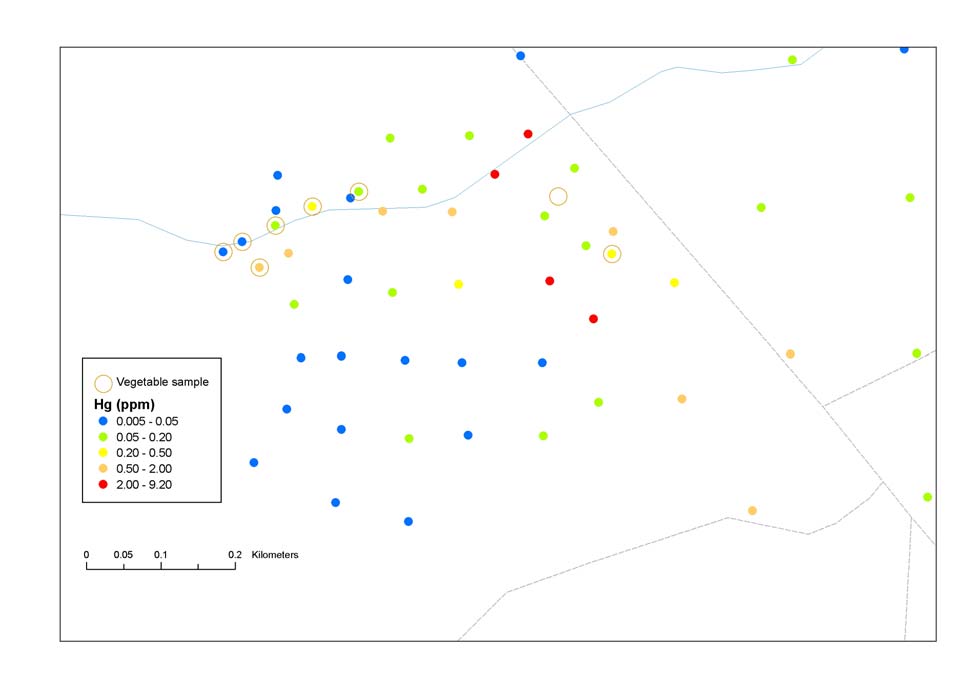

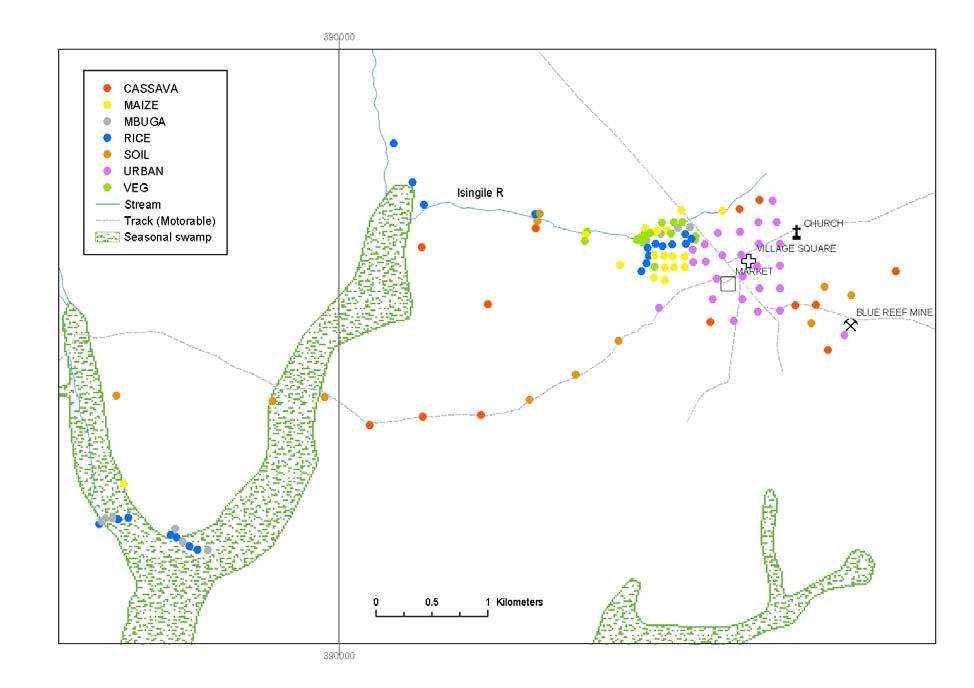

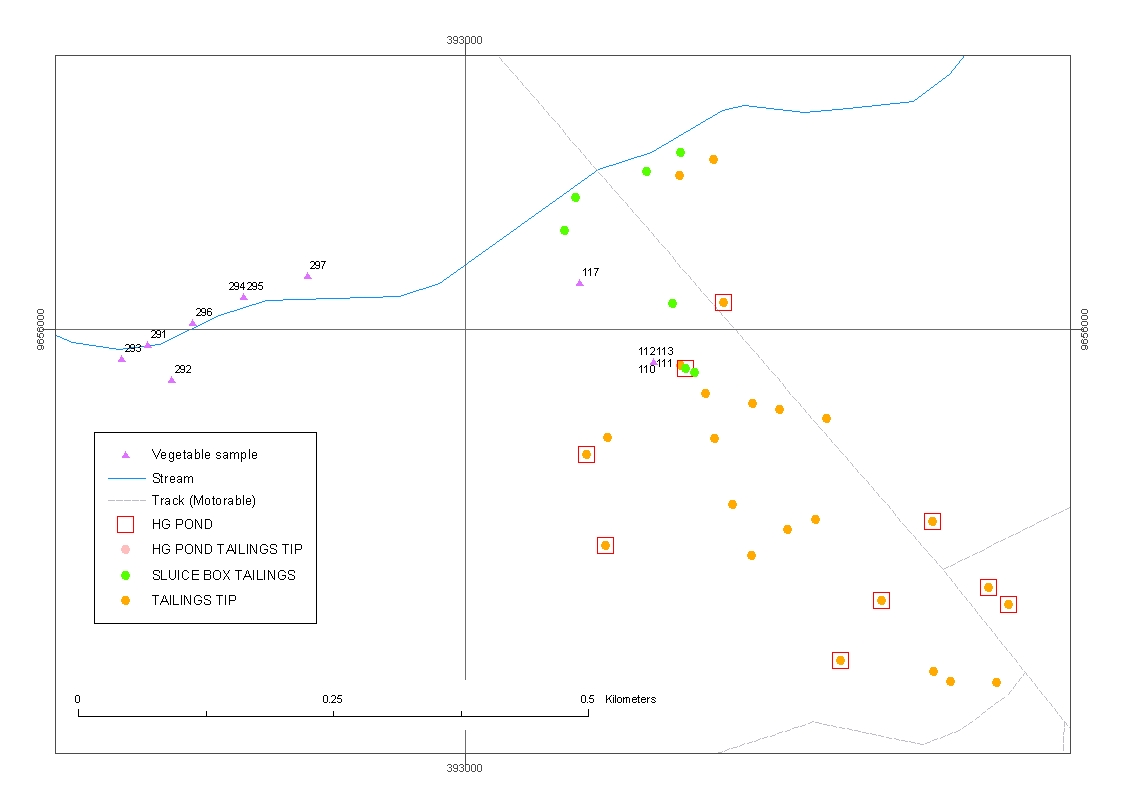

The environmental field programme was carried out during the dry season at which time there was little

evidence that large quantities of contaminated tailings were being washed into the Isingile River.

However, waste water and tailings from amalgamation `ponds' were observed at one site to be

overflowing onto an area where vegetables were being grown. If large quantities of Hg contaminated

tailings are dispersed onto the seasonal swamp (mbuga) area adjacent to the Isingile River during the wet

season, then this may lead to the significant dispersion of Hg both into the aquatic system and onto

agricultural sites being used for rice, maize, and vegetable cultivation.

Previous studies in the Lake Victoria Goldfields area indicate that dispersion of Hg from tailings is

relatively restricted, not least because Fe-rich laterites and seasonal swamps (mbugas) act as natural

barriers or sinks attenuating the widespread dispersion of Hg in sediments and soils.

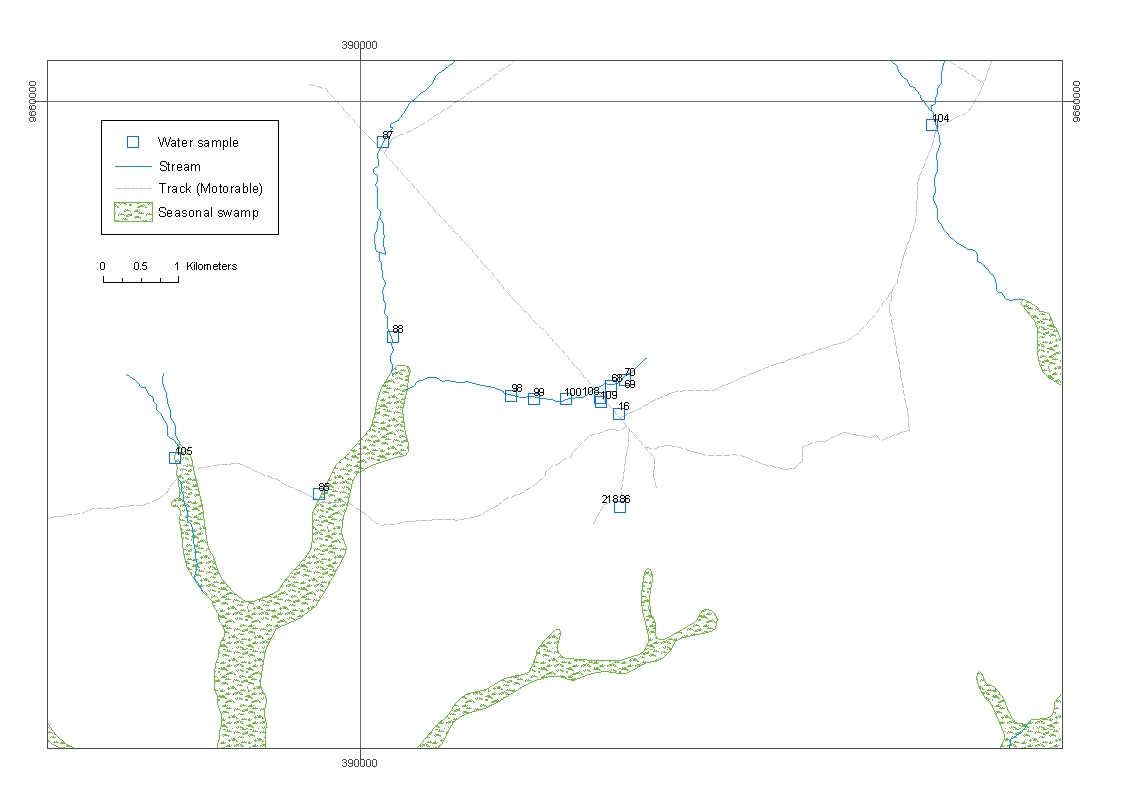

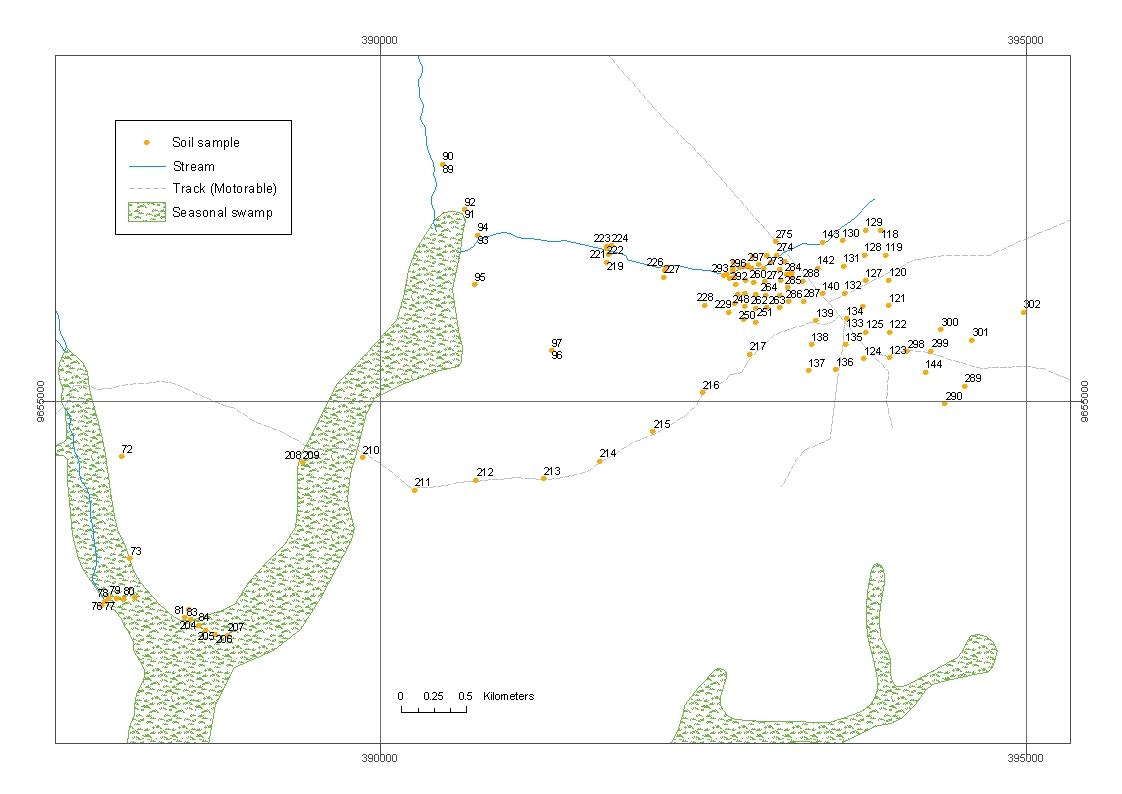

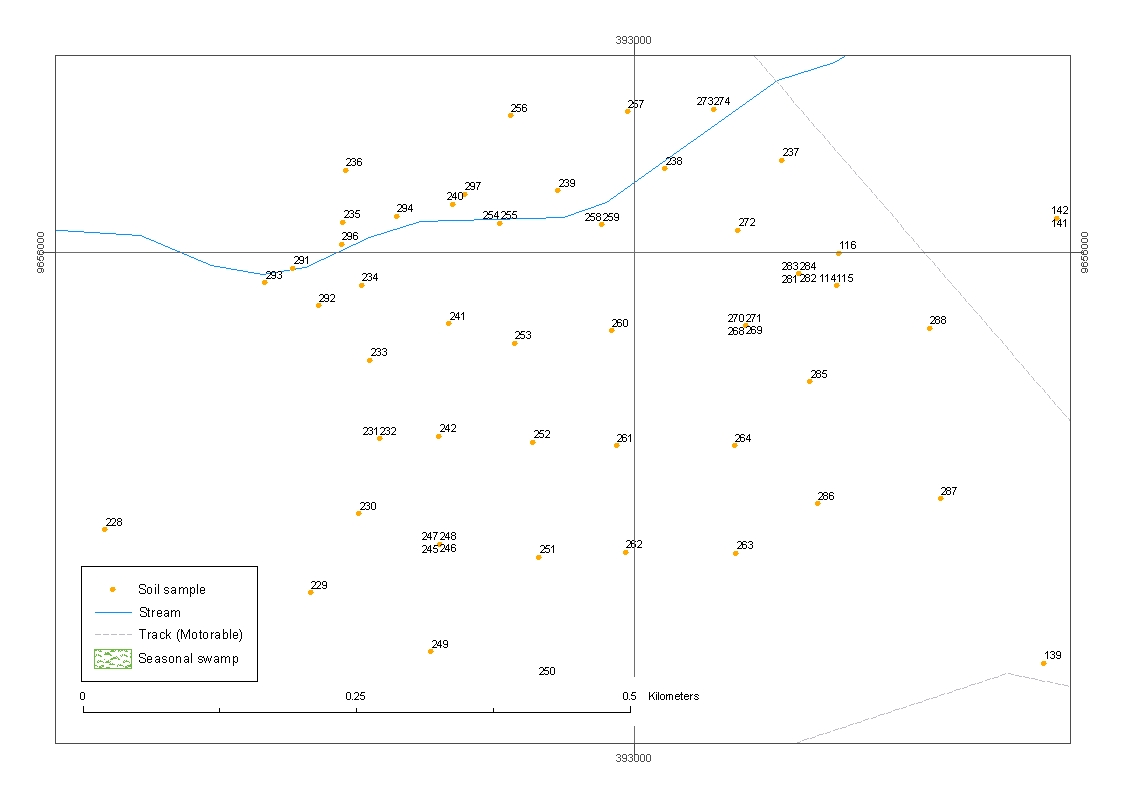

A field programme was carried out in SeptemberOctober 2003 leading to the collection of a total of 38

water, 26 drainage sediment, 151 soil, 66 tailings, 21 vegetable and 285 fish samples. Preparation and

analysis of the samples was carried out in the UK and Canada. Analytical data for duplicate field samples,

replicate analyses and recovery data for Certified Reference Materials indicate a level of analytical

precision and accuracy that is appropriate for this type of environmental survey. Cd, Cu, Pb and Zn were

determined in drainage sediment, tailings and soil samples, in addition to Hg and As (which were

specified in the ToR and BGS's proposal) on the basis that these could be useful indicators of

mineralization and/or anthropogenic contamination. The range of chemical substances determined in the

samples collected, and the range of media sampled should not be considered to represent a comprehensive

environmental survey. In addition, the results reported here refer only to the sites sampled at the time of

BGS Report CR/04/129 (Issue 1.0) for UNIDO Contract 03/088

the survey and should not be extrapolated to infer that elevated levels of contamination are not present at

other sites or elsewhere in the district or region. The results presented reflect the level of resources

available for the environmental assessment.

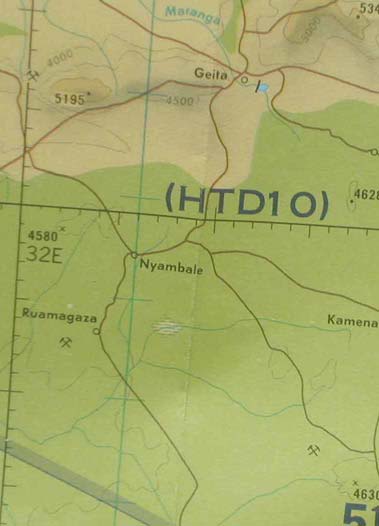

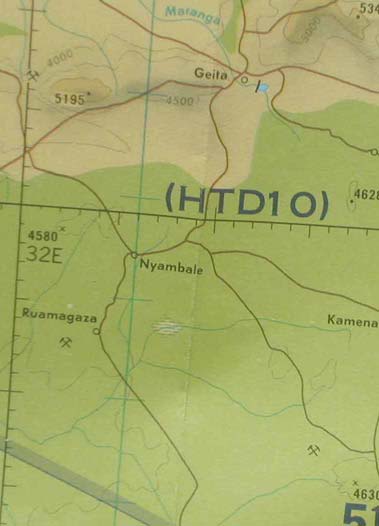

Figure ES-1. Location of the River Malagarasi and Rwamagasa sub-areas in northwest Tanzania.

Nature and extent of the mercury pollution in the river system adjacent to the hot spot area

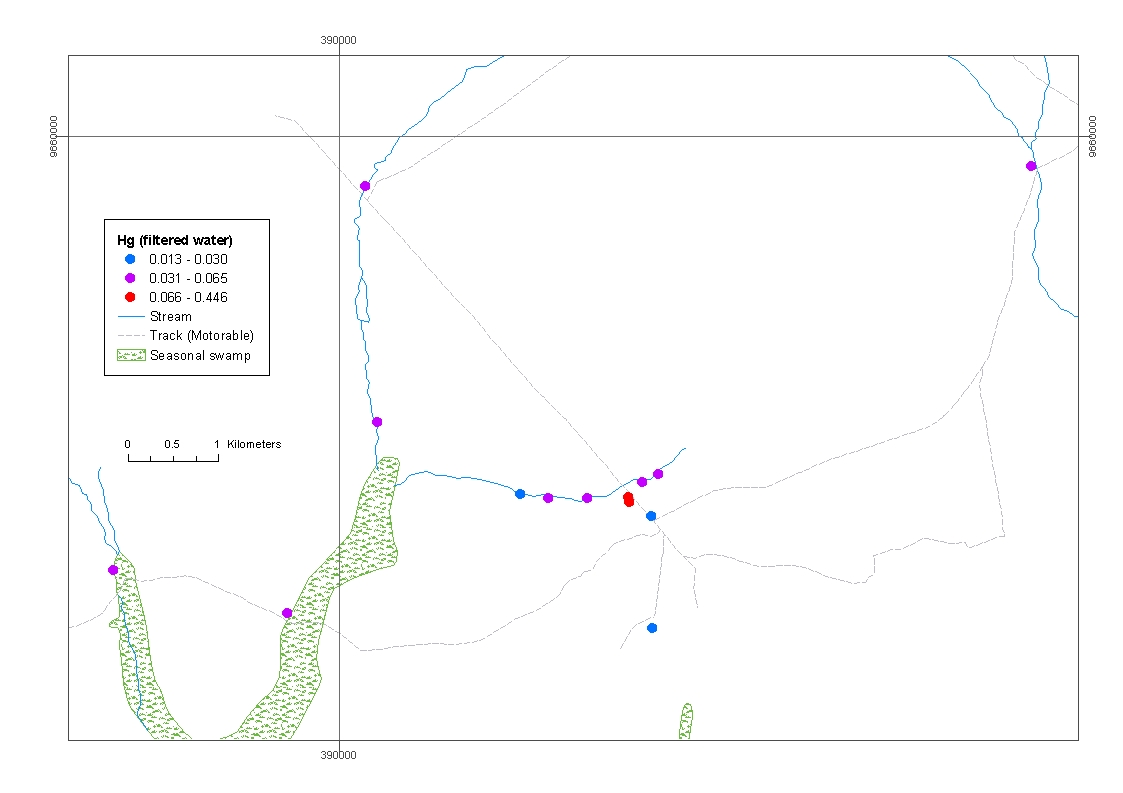

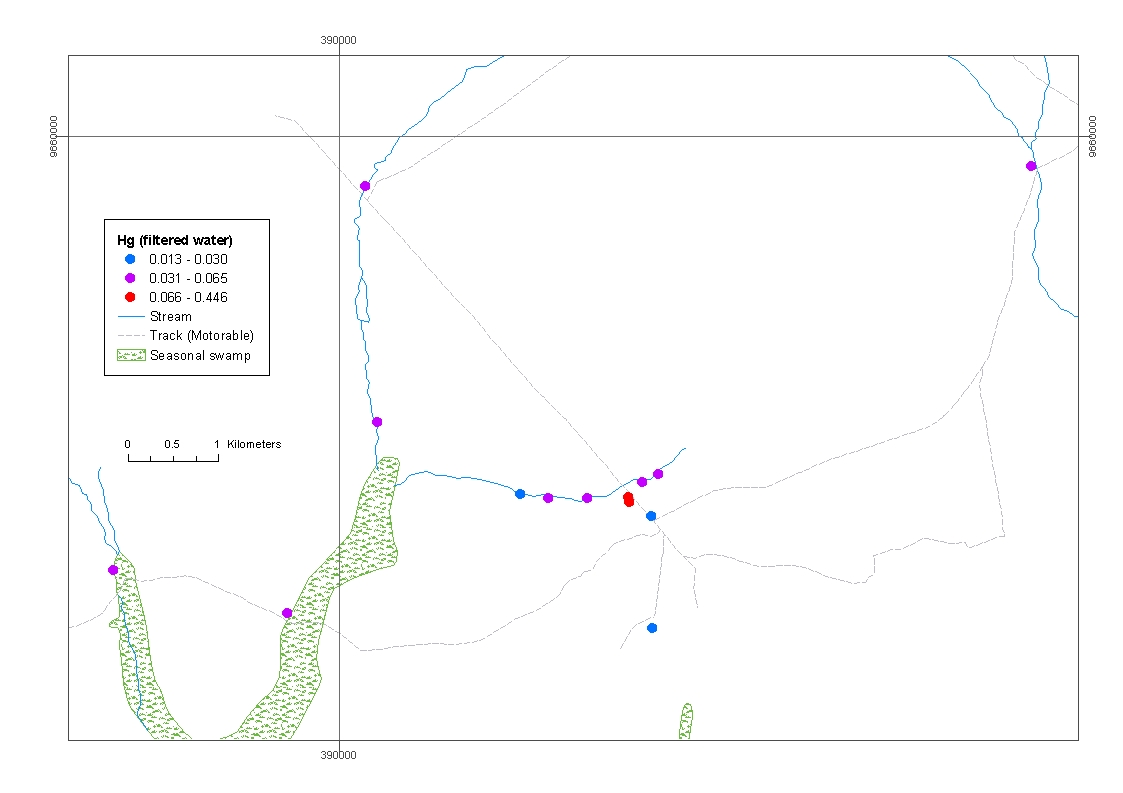

At the time of sampling, mercury in filtered drainage water samples ranged from 0.01 to 0.03 µg/L in the

R. Malagarasi and from 0.01 to 0.07 µg/L in the Rwamagasa area. None of the filtered water samples

exceeded any of the Tanzanian Water Quality Standards or other national and international water quality

standards, or criteria, for drinking water, protection of aquatic biota or the protection of human health.

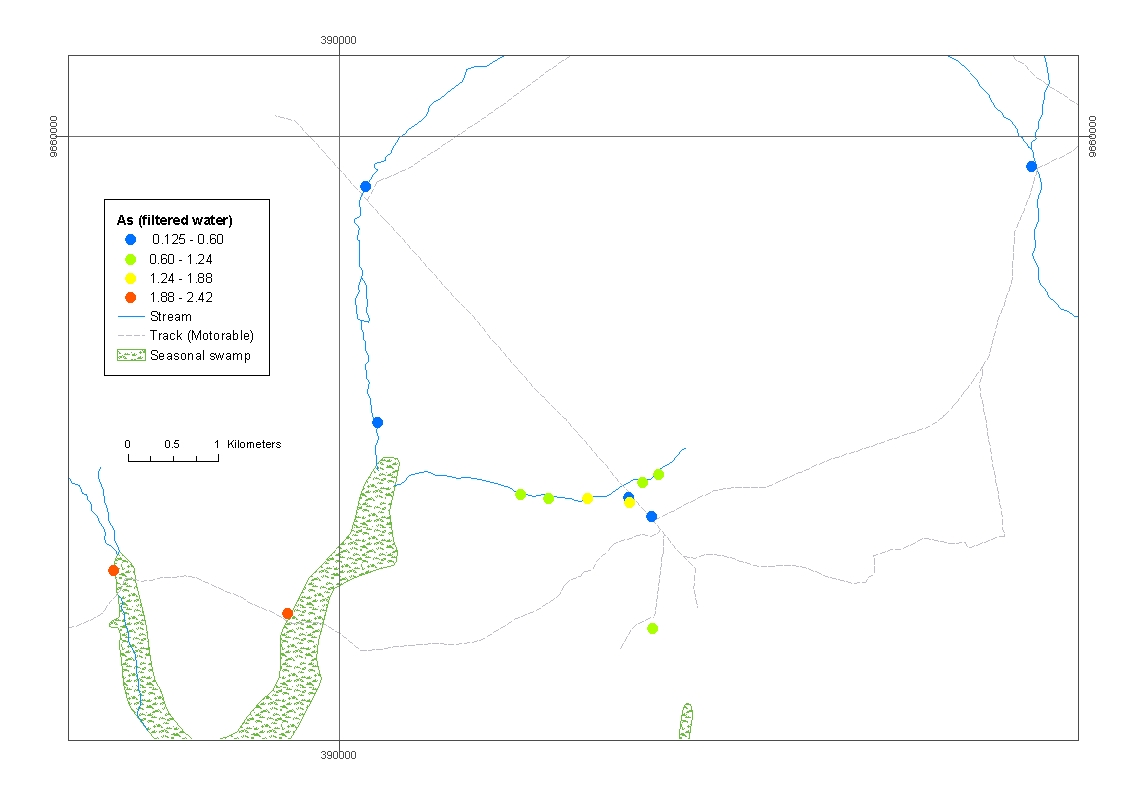

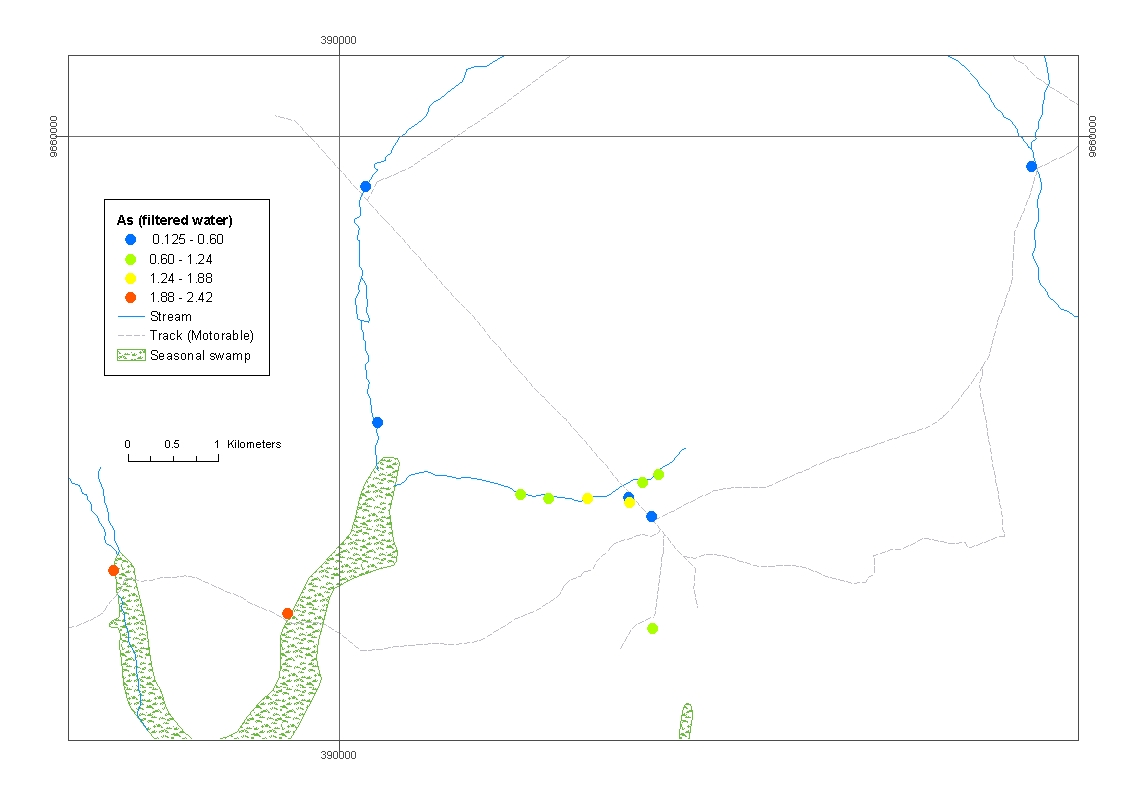

Arsenic in filtered water ranged from 0.1 to 2.4 µg/L and none of the samples collected exceeded any

water quality standards or criteria.

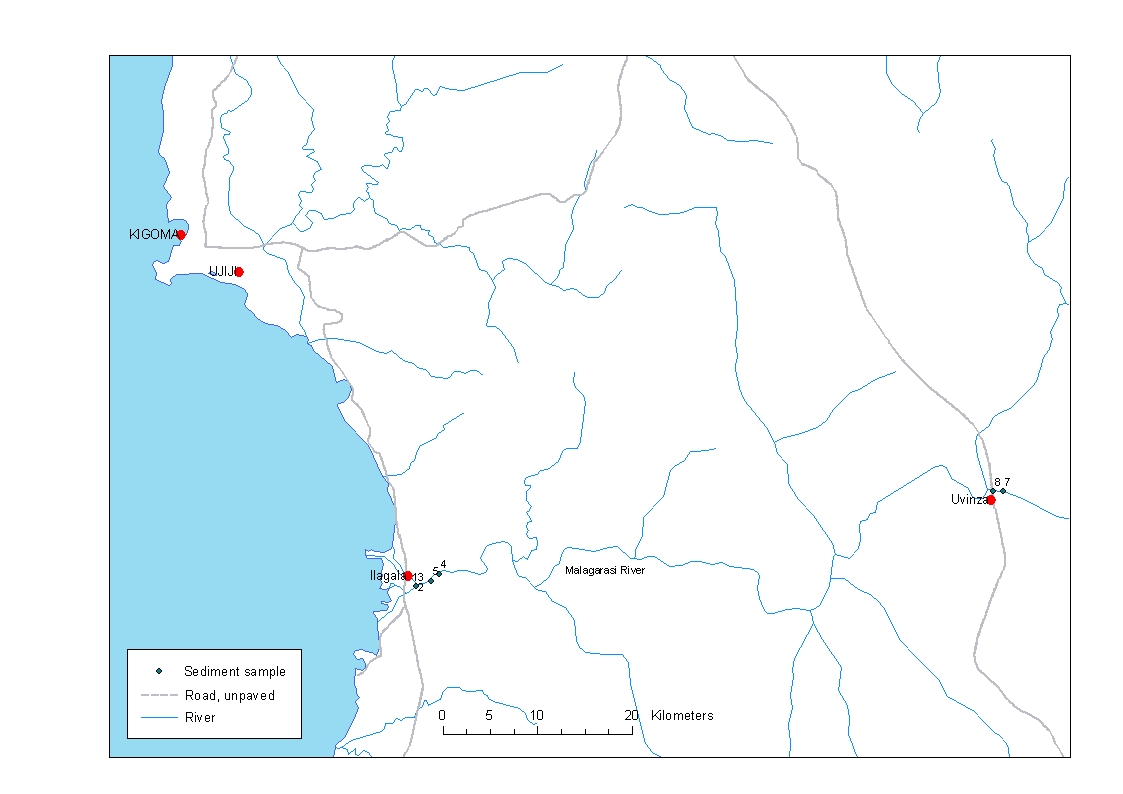

Hg concentrations in the fine fraction of streams sediments from the River Malagarasi at Ilagala range up

to 0.65 mg/kg, which is rather high for an area that does not appear to be unduly affected by

anthropogenic contamination. Concentration of Hg in the fine fraction, together with adsorption of Hg

onto Fe and organic material, may in part explain these relatively enhanced Hg concentrations, but these

hypotheses need to be verified by further studies. Other possible sources include the geothermal springs at

Uvinza or contamination of sediment by mercuric soap, which may be used by some people for skin

lightening.

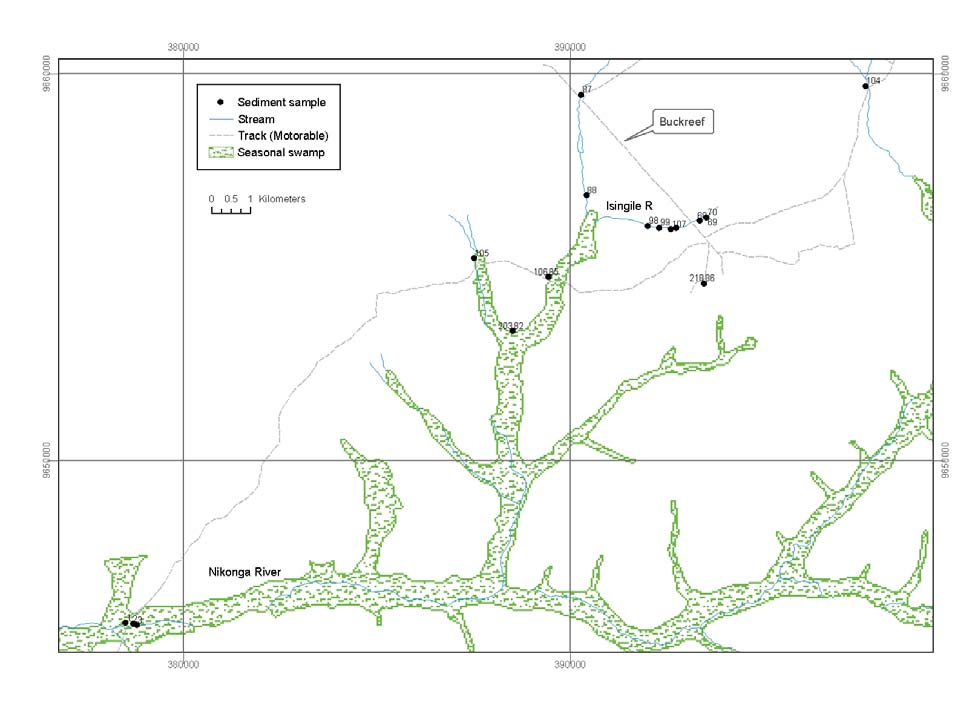

In the Rwamagasa area, Hg in the fine fraction of drainage sediments ranges from 0.08 to 2.84 mg/kg,

although Hg does not exceed the Toxic Effects Threshold (1 mg Hg/kg) of the Canadian Sediment

Quality Criteria for the Protection of Aquatic Life for more than 2 km downstream from the major

BGS Report CR/04/129 (Issue 1.0) for UNIDO Contract 03/088

mineral processing centre located to the south of the Isingile River. Toxic Effects Thresholds for As, Cd,

Cu, Pb and Zn are not exceeded in drainage sediments from the Rwamagasa area.

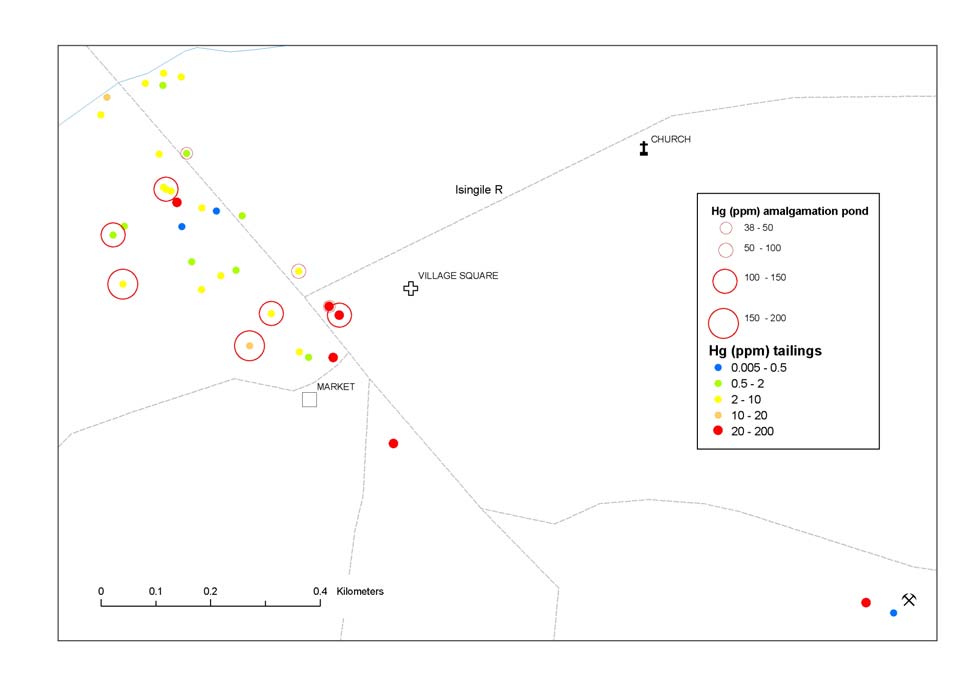

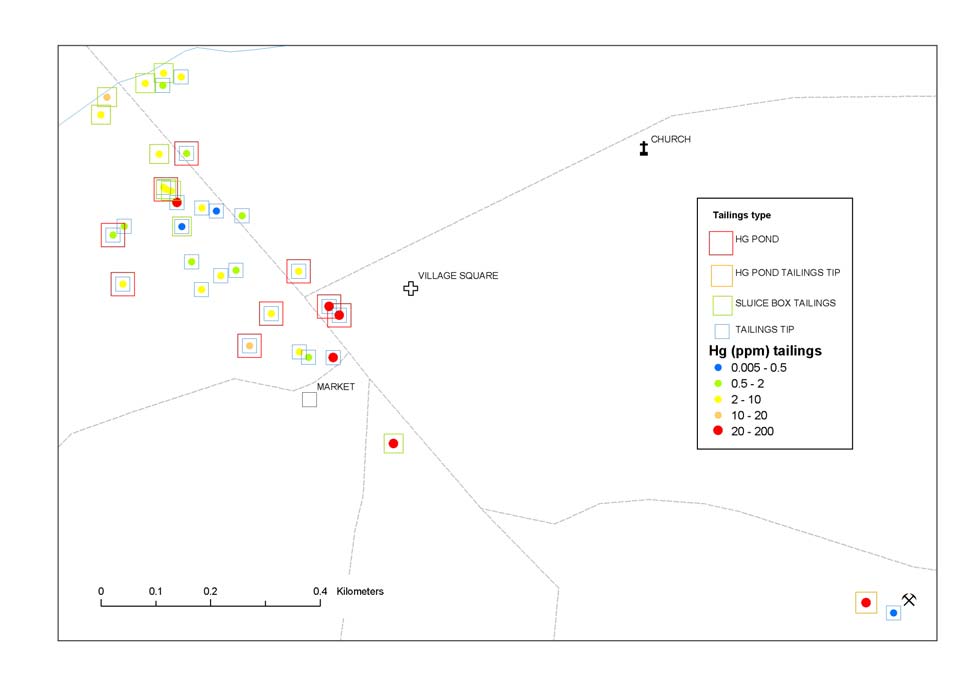

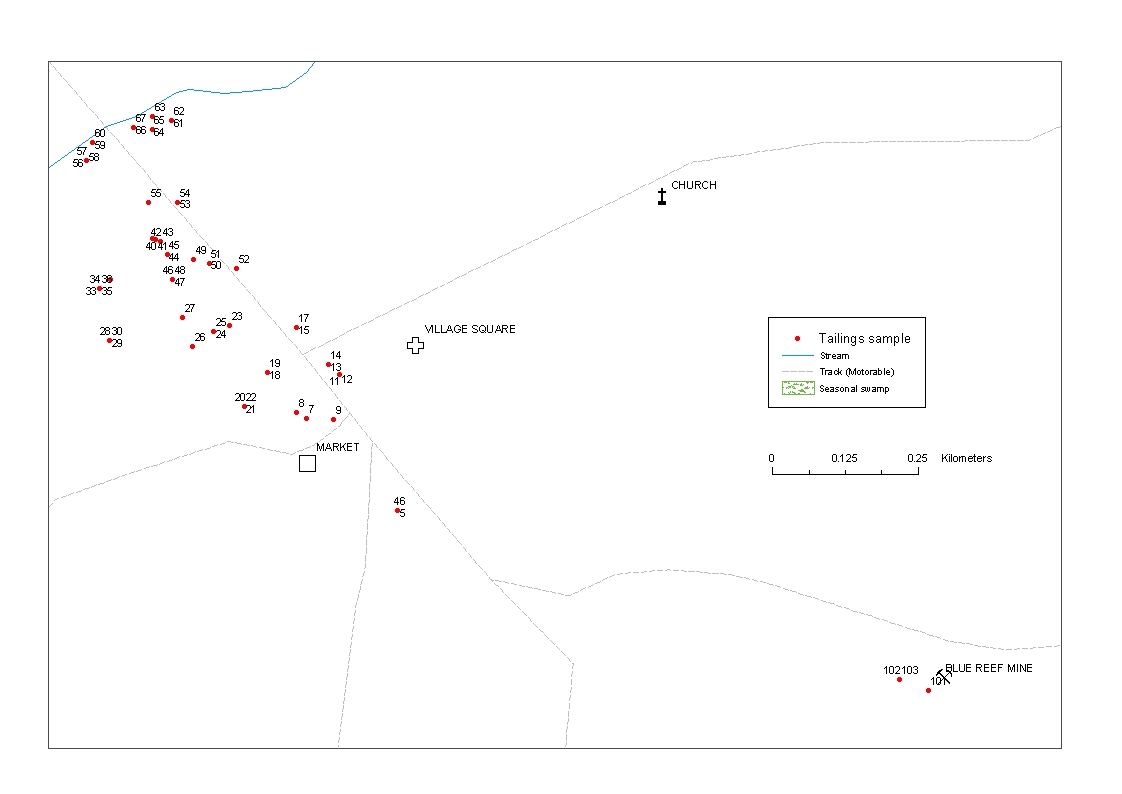

Environmental assessment of the "hot spot" area based on sampling of mineral processing wastes

and soils

There is little difference between mercury concentrations in samples taken from historic (dry) primary

tailings piles (mean 5 mg/kg) and samples taken from recent sluice box tailings (mean 3 mg/kg). Hg in

tailings samples from the amalgamation ponds and amalgamation pond tailings (mean 86 mg/kg) are on

average about 20 times higher. The high level of Hg in the primary and sluice box tailings is the result of

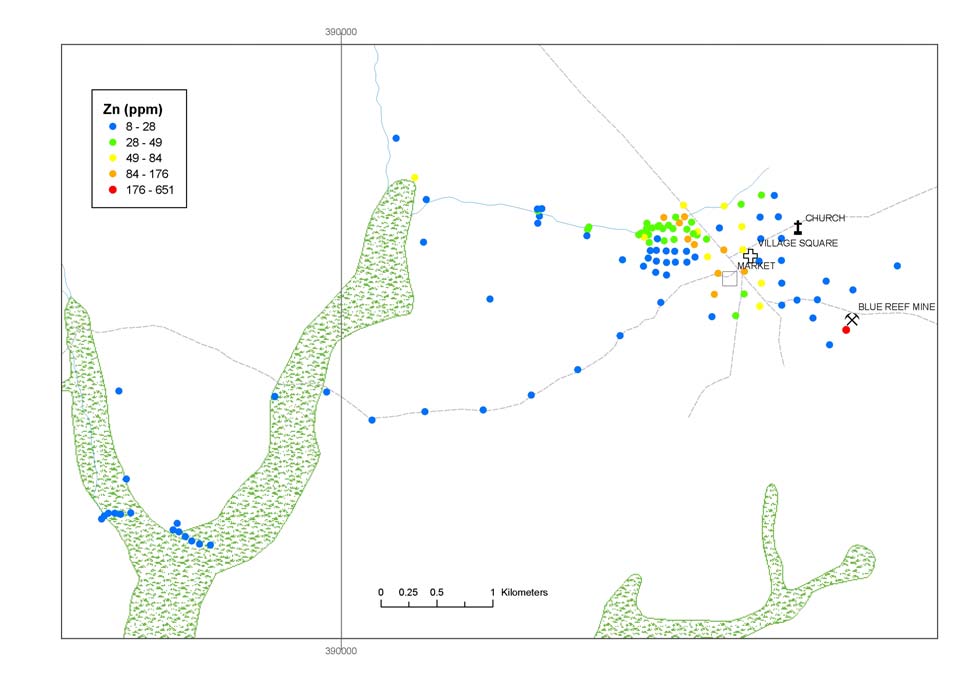

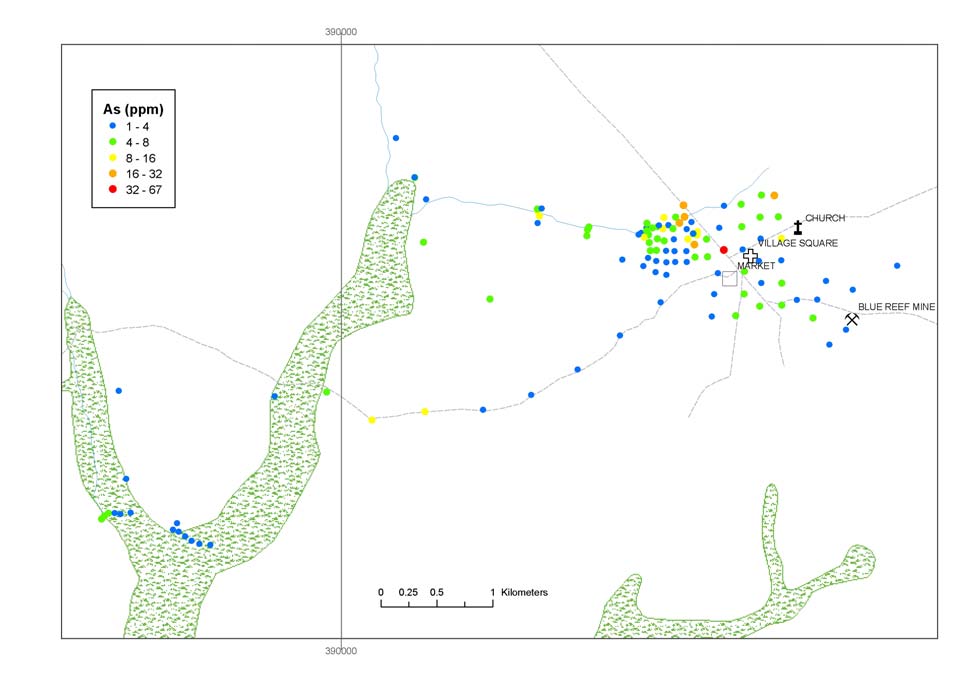

recycling/reprocessing of amalgamation pond tailings. An association between Cd-Cu-Hg-Zn probably

reflects contamination from mercury used in amalgamation combined with metals that are possibly

derived from the ball mills and galvanised roof sheets. Correlations between arsenic and iron probably

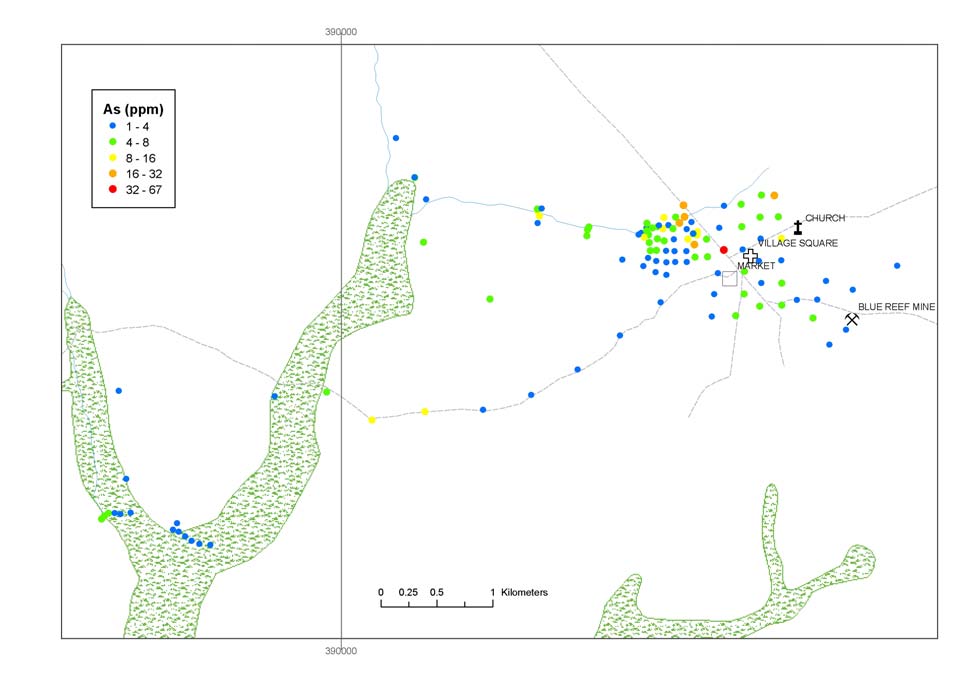

reflect the influence of trace quantities of arsenopyrite and pyrite in the gold ore. Both these hypotheses

need to be verified.

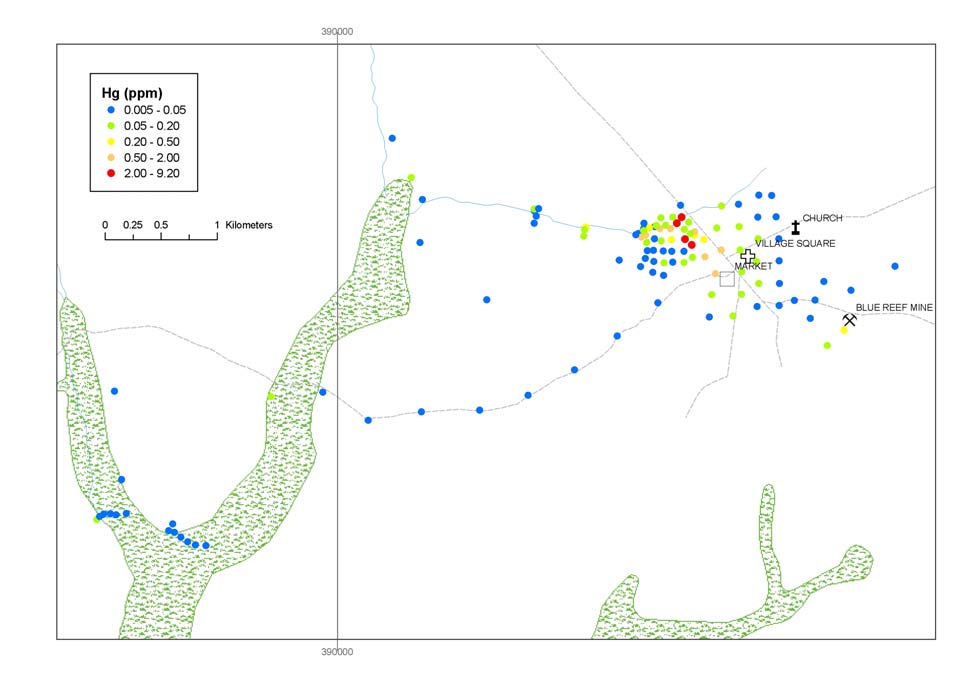

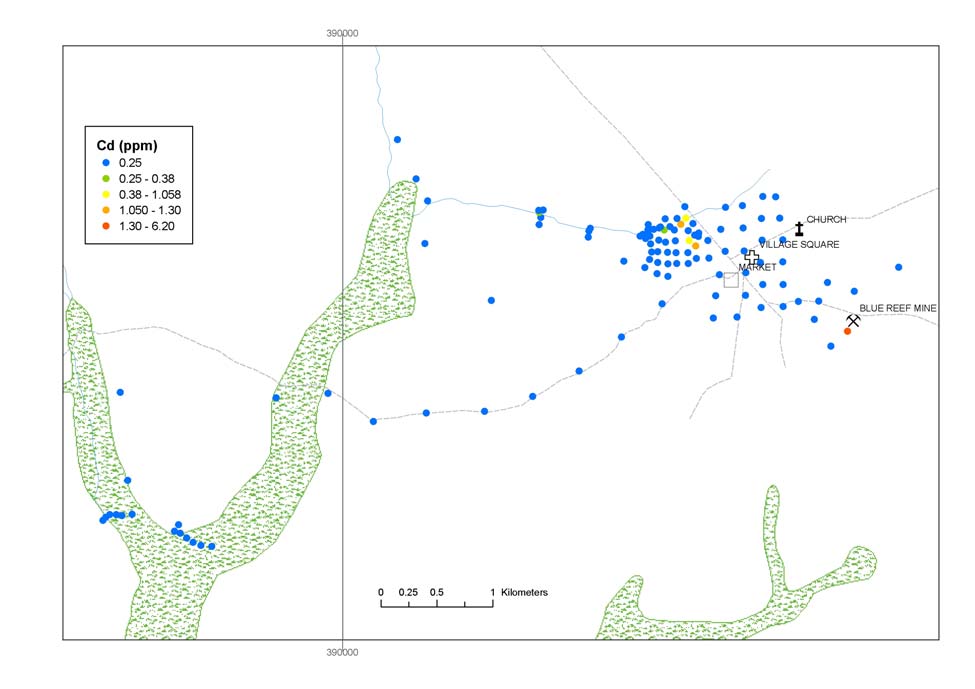

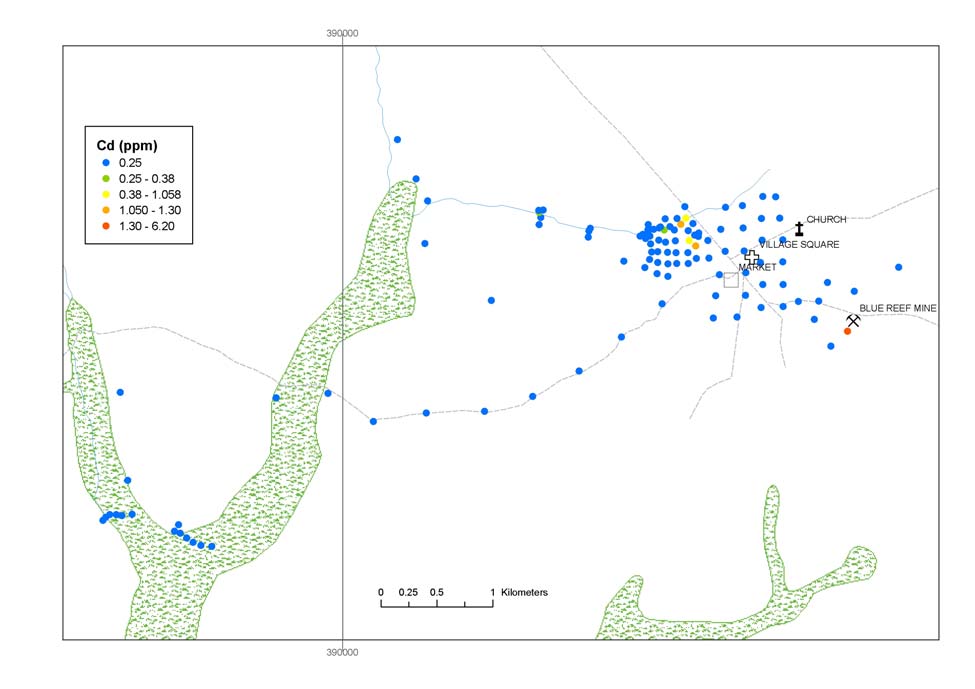

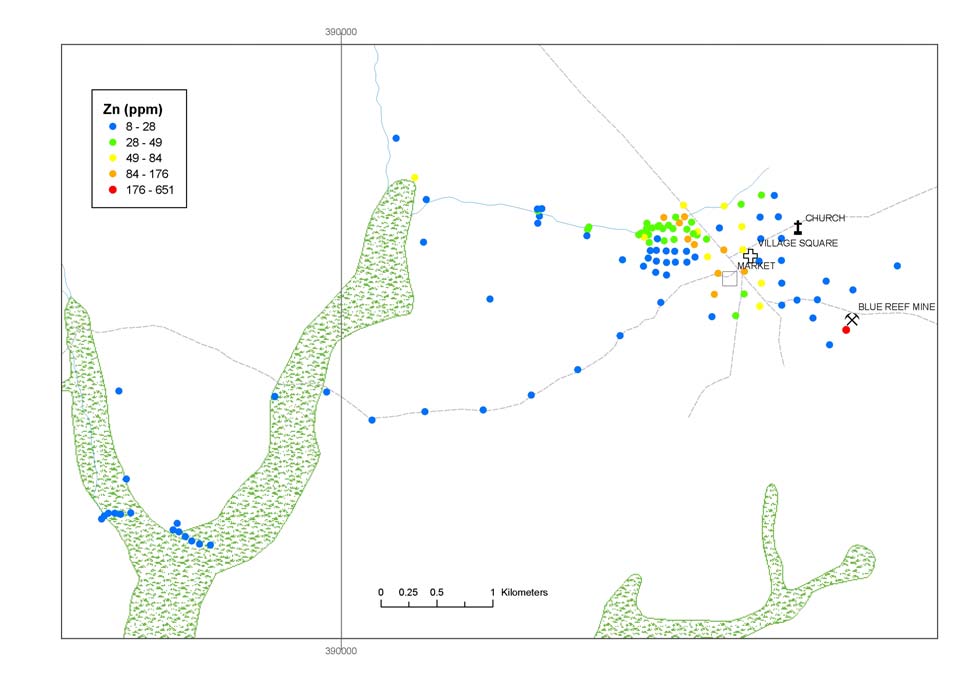

At the time of the survey, generally low concentrations of Hg occurred in most of the analyzed soils used

for cassava, maize, and rice cultivation, as well as mbuga and unclassified soils located away from the

urban centre of Rwamagasa and associated mineral processing areas. Higher concentrations are found in

urban soils and also in mbuga and vegetable plot soils adjacent to the Isingile River, close to the mineral

processing areas. Hg in the urban soils is probably mainly derived from air borne transport and deposition

of Hg released during the burning of amalgam, although this has not been verified. High Hg appears to

occur in the mbuga and vegetable plot soils where these are impacted by Hg-contaminated water and

sediment derived from mineral processing activities located on the southern side of the Isingile River. In

these soils there is a clear association between Cd-Cu-Zn, which reflects contamination from metals that

are possibly derived from the ball mills and/or galvanized roof sheets. An association between As, Cu and

Fe probably reflects the influence of the weathering products of arsenopyrite and pyrite found in the gold

ore, although this needs to be verified.

Mercury exceeds (1) the maximum permissible concentration of Hg in agricultural soil in the UK (1

mg/kg) in 12 soil samples; (2) the Canadian Soil Quality Guideline for agricultural soils (6.6 mg/kg) in

three samples; and (3) the UK soil guideline value for inorganic Hg for allotments (8 mg/kg) in two

samples.

Cadmium and zinc exceed the maximum permissible concentrations for agricultural soil in the UK (3 mg

Cd/kg and 200 mg Zn/kg) in only a few soil samples. Arsenic exceeds the Canadian Soil Quality

Guideline for agricultural soils (12 mg/kg) in nine agricultural and urban soils.

Soil profile data demonstrate that surface contamination by mineral processing waste in some agricultural

soils affects the root zone. Hoeing of the soils is likely to result in mixing of surface Hg contamination

throughout the root zone, although this has not been verified.

BGS Report CR/04/129 (Issue 1.0) for UNIDO Contract 03/088

Nature and extent of the mercury pollution in agricultural produce, especially in those being part of

the main diet

Hg in vegetable and grains samples collected from the agricultural areas potentially impacted by mercury

contamination are mainly below the detection limit of 0.004 mg/kg Hg with concentrations of 0.007 and

0.092 mg/kg Hg recorded in two yam samples and 0.035 mg/kg Hg in one rice sample. A positive

correlation between Hg in agricultural crops and soil was not detected during the present survey. Hg in

beans, onions and maize samples purchased at Rwamagasa market are below the detection limit (<0.004

mg Hg/kg) whilst two dehusked rice samples contain 0.011 and 0.131 mg/kg Hg. The concentrations of

Hg in rice are similar to those recorded in rice grown on the highly contaminated soils of the Naboc

irrigation system on the island of Mindanao in the Philippines.

Mercury in fish: biomarkers for mercury methylation and potential food sources

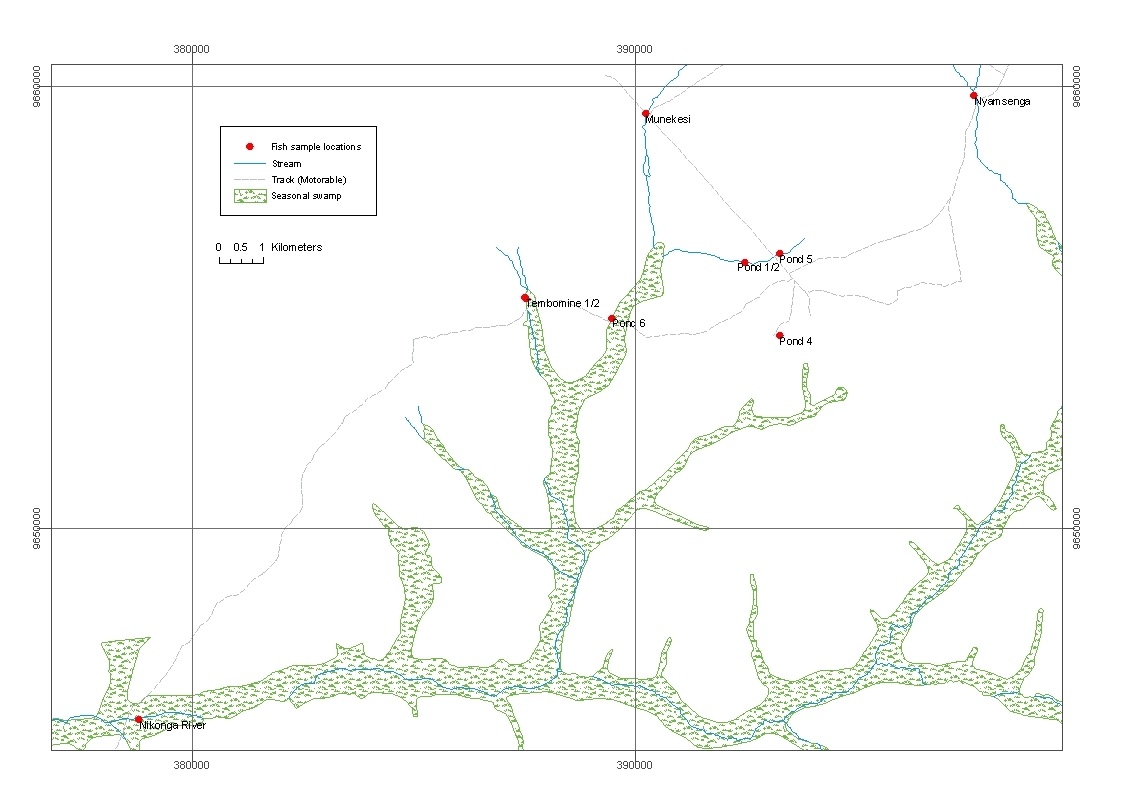

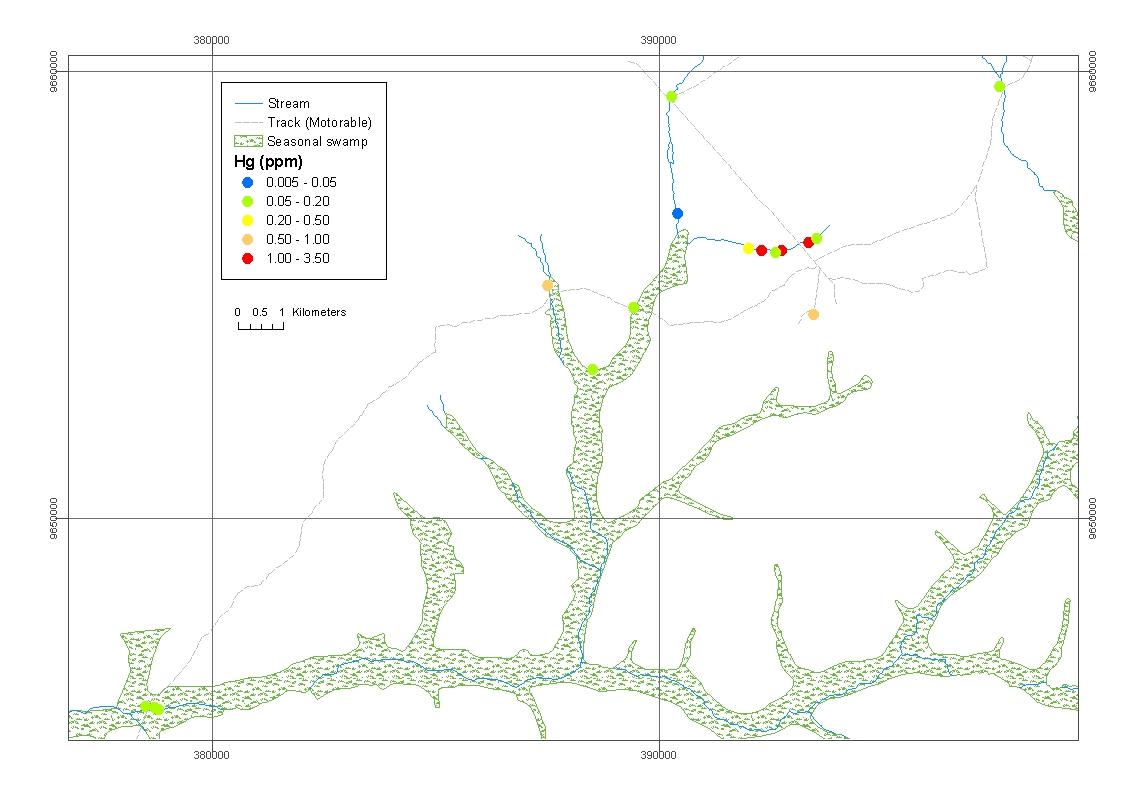

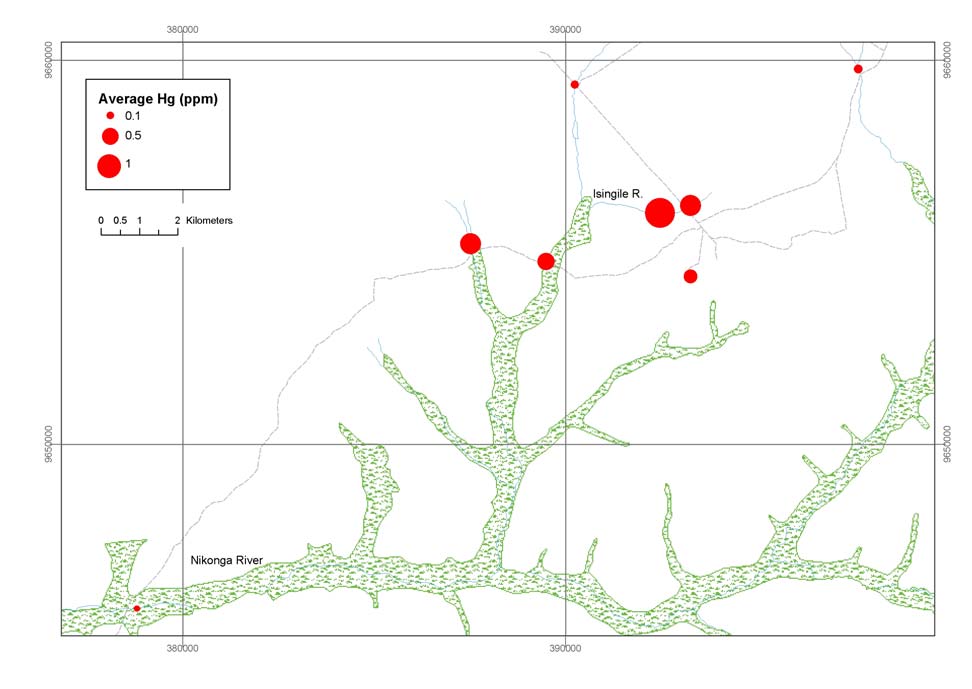

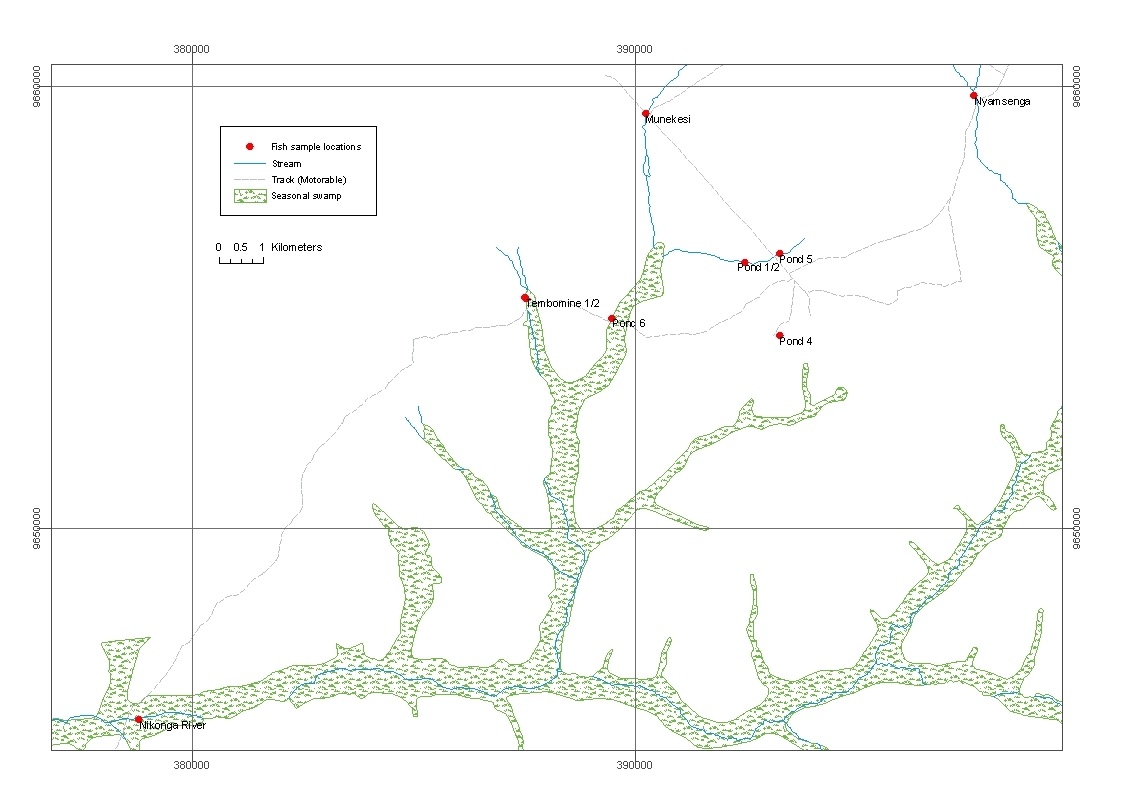

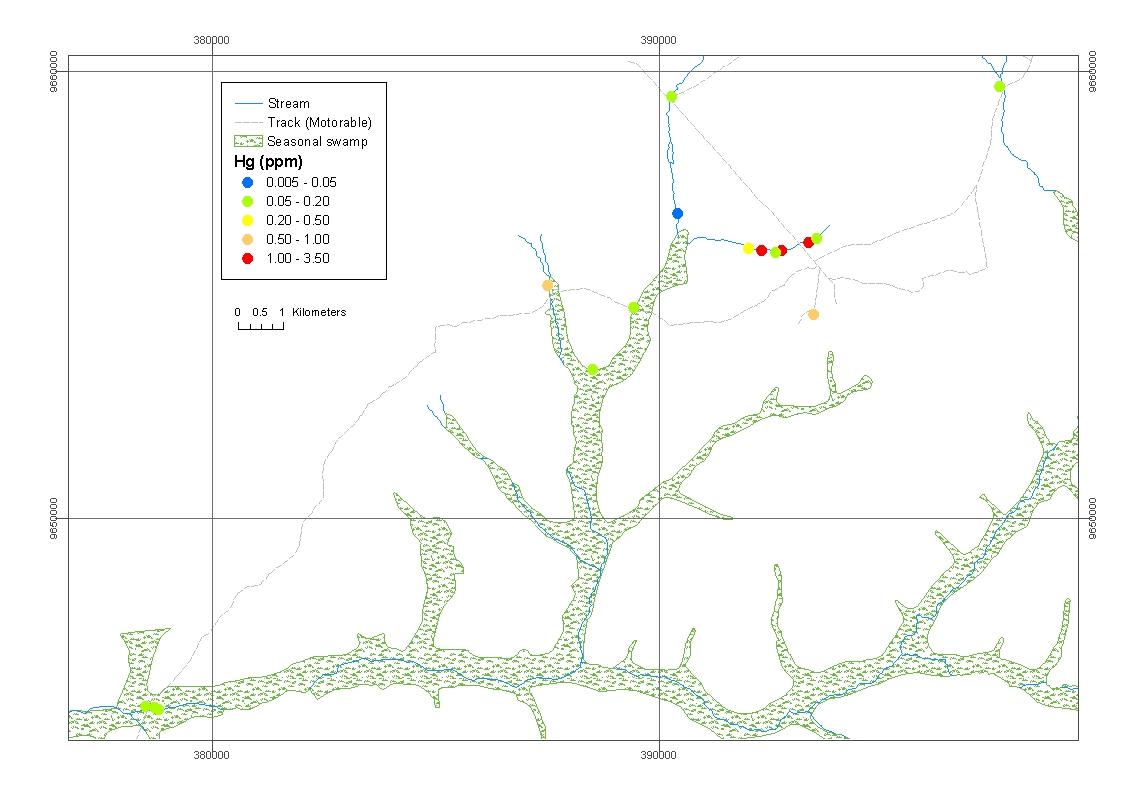

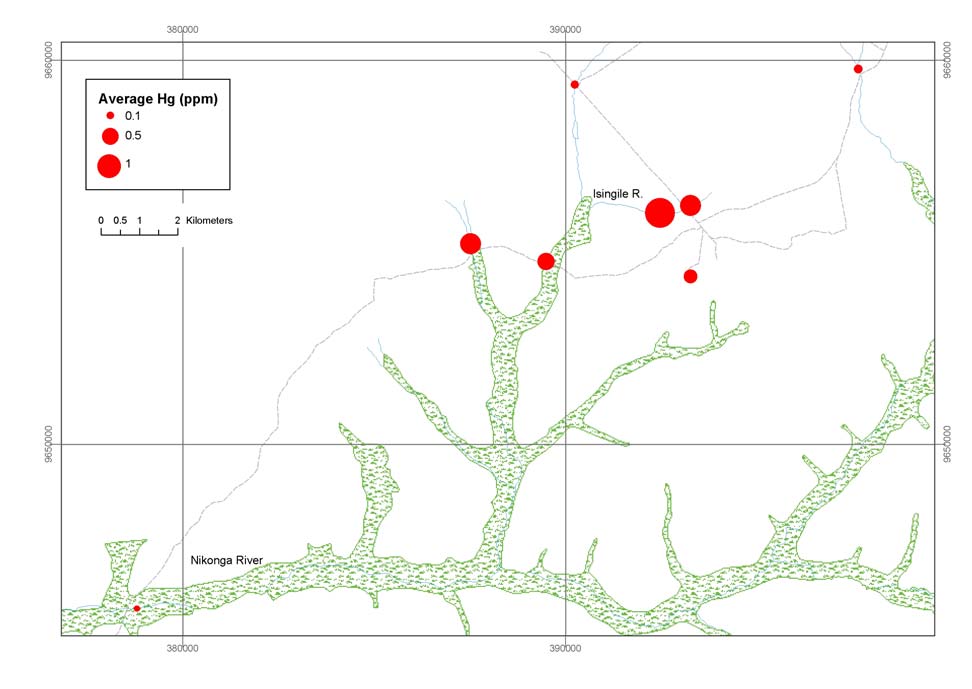

The main fish species used as bioindicators of mercury contamination included perch (Lates spp),

tigerfish (Brycinus spp), tilapia (Oreochromis spp), catfish (Clarias spp). Fish tissue THg data indicates

that the sites sampled in the immediate area of mining activities at Rwamagasa, are the worst affected

(Figure ES-2) and should be considered environmental `hotspots' and sites of biomethylation. Many fish

tissue samples from these sites fail export market standards (0.5 mg/kg) and also exceed the WHO

recommended standard for the protection of health of vulnerable groups (0.2 mg/kg). Mercury in fish

collected from the Nikonga River, approximately 25 km downstream from Rwamagasa, have low Hg

concentrations. This suggests that the impact of mercury contamination on aquatic biota is relatively

restricted, which is confirmed by the generally low mercury concentrations in drainage sediment and

mbuga soils at distances more than about 6 km downstream of the main mineral processing area (or

`hotspot'). However, this observation will need to be verified by more detailed studies. Fish length vs.

mercury concentration plots for fish from the River Malagarasi and Malagarasi delta area of Lake

Tanganyika (collected from Uvinza and Ilagala) confirm generally low mercury concentrations that are

similar to levels found in similar species in Lake Victoria (Figure ES-3). All fish samples collected from

the Malagarasi River area are below the WHO threshold for vulnerable groups (0.2 mg/kg). This suggests

that mercury contamination from the Rwamagasa artisanal gold mining centre does not have a significant

impact on fish stocks in either the lower reaches of the River Malagarasi or the International Waters of

Lake Tanzania.

BGS Report CR/04/129 (Issue 1.0) for UNIDO Contract 03/088

Figure ES-2. Average mercury concentration (mg/kg) in catfish (Clarias spp.), Rwamagasa area.

4.0

3.5

3.0

500 µg/kg

2.5

200 µg/kg

g/kg 2.0

µ

1.5

Log THg

Barbus and Haplochromis Pond 1 and 2

Barbus, Brycinus and Haplochromis Pond 4 and 6

1.0

Brycinus and Hydrocynus Ilagala

Lates malagarasi Ilagala

Barbus Uvinza

0.5

Lates nitolicus LVEMP

Linear (Barbus, Brycinus and Haplochromis Pond 4 and 6)

Linear (Lates nitolicus LVEMP)

0.0

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

1.2

1.4

1.6

1.8

-0.5

Log L cm

Figure ES-3 Hg (µg/kg) related to length (cm) in piscivorous, insectivorous and planktivorous fish from (a) the

Rwamagasa area, (b) River Malagarasi Lake Tanganyika (Ilagala, Uvinza) and (c) Lake Victoria (Lake Victoria

Environmental Management Project, Machiwa et al. 2003).

BGS Report CR/04/129 (Issue 1.0) for UNIDO Contract 03/088

Exposure to environmental mercury

None of the water samples collected from the river network, or associated drainage ponds exceeded the

WHO or local Tanzanian guideline values of 1 µg Hg/l for drinking water. Whilst this suggests that

mineral processing operations have not contaminated local surface waters and shallow groundwaters it

does not indicate whether drinking water used by the local people has been contaminated with Hg or other

non-related substances. More extensive monitoring of drinking water sources (which was not the focus of

the current investigations) should be considered as a component of any subsequent follow up work.

The only samples of filtered water collected during the survey that contained relatively high Hg

concentrations (max. 0.45 µg Hg/l) were from amalgamation ponds. This highlights the need for careful

management of waste-waters from these ponds and monitoring of any nearby drinking water supplies.

The average mercury concentration recorded for samples of rice grain grown on soils potentially

impacted by mercury contamination was 0.026 µg/g (dry wt.). Consequently, the amount of mercury

entering the body, assuming an average consumption of 300g rice/day is 0.055 mg THg/week (equivalent

to 0.46 µg MeHg/kg bw/week), which is much lower than the Provisional Tolerable Weekly Intake

(PTWI) of 0.3 mg for total mercury and 1.6 µg/kg bw/week for methyl mercury in the diet set by the

WHO and the FAO. These are likely to maximum inputs because most people in the Rwamagasa area

will consume less than 300 g rice/day because they will also consume cassava and maize, which are

generally grown on soils with low Hg. This observation needs to be verified by more detailed studies.

The vast majority of people in the Rwamagasa area principally eat Tilapia (Oreochromis spp.), Perch

(Lates spp.) and dagaa (dagan; Rastrineobola spp. and equivalents) from Lake Victoria. Catfish (Clarias

spp; kamare, mumi) is eaten by less than 10% of those people. Consumption of 250g perch, 500g tilapia

and 250g of catfish each week would result in an intake of 27 µg THg/week (equivalent to 0.35 µg

MeHg/kg bw/week) for residents of Ilagala-Uvinza area, 44 µg THg/week (equivalent to 0.58 µg

MeHg/kg bw/week) for Rwamagasa residents consuming only fish from Lake Victoria, 56 µg THg/week

(equivalent to 0.75 µg MeHg/kg bw/week) for people in the Rwamagasa background area consuming

tilapia and perch from Lake Victoria and catfish from the local streams, and 259 µg THg/week

(equivalent to 3.45 µg MeHg/kg bw/week) for people in the Rwamagasa area consuming tilapia and perch

from Lake Victoria and catfish from mining impacted streams. Apart from the latter group, these inputs

related to fish consumption are well below the WHO/FAO Provisional Tolerable Weekly Intake (PTWI)

of 300 µg for total mercury and 1.6 µg MeHg/kg bw/week in the diet. It appears that only those people

consuming catfish from the Isingile River, and other mining contaminated locations such as Tembomine,

are likely to be at risk of exceeding the PTWI for mercury.

People consuming 300g/day of rice grown on the mercury contaminated Isingile mbuga soils and 1kg of

fish from Lake Victoria would have a combined estimated MeHg input of 1.04 µg MeHg kg bw/week,

which is two thirds of the methyl mercury PTWI.

BGS Report CR/04/129 (Issue 1.0) for UNIDO Contract 03/088

Whereas it is not known whether individuals practice geophagia in the Rwamagasa area, elevated

exposures to Hg could result from the occasional deliberate and habitual consumption of contaminated

soils and dusts. For example, the Provisional Tolerable Weekly Intake (PTWI) of 0.3 mg for total

mercury in the diet set by the WHO and the FAO, which is equivalent to 26 µg THg/day for a 30kg child

would be exceeded by an individual practising geophagia (central estimate and worst-case) or on a case

by case basis by an individual occasionally consuming soil/dust (worst-case). The practice of geophagy

by pregnant females would be of particular concern in this regard given the sensitivity of the foetus to

mercury.

The inadvertent ingestion of dusts and soils even those having Hg concentrations significantly above the

regional background, and hence considered to be moderately contaminated, does not appear to lead to a

significant excess exposure to mercury. For example comparison of exposures due to inadvertent

ingestion of soils and/or dusts (0.72 to 1.8 µg THg/day or 5 to 13 µg THg/week) is typically less than

individual exposure via other dietary sources water, rice and fish.

However, given the uncertainties involved in estimating inadvertent dust and soil intake in the rural

Rwamagasa environment, exposure via this route, in addition to more classical geophagic behaviour,

should be considered when planning remedial/intervention measures. Such measures could include the

marking and fencing off of waste tips and areas of enhanced contamination and improvements in hygiene

(washing of hands and food preparation such as the drying of cassava and other crops directly on the

ground and the use of soil as a desiccant to aid the storage of groundnuts and beans). Whilst geophagy

does have an important cultural and possibly nutritional benefit, the resulting levels of potential exposure

to young adults and pregnant woman are high enough to suggest that this practice should be positively

discouraged within the mining districts. If it was demonstrated that geophagy is practiced in the

Rwamagasa area, the importation of geophagic materials into local markets from outside the

contaminated region should be encouraged and the negative effects of using local soils conveyed though

local woman's groups and childhood development officers.

Medical investigation methodology

The extraction of the gold with liquid mercury releases serious amounts of mercury, especially high toxic

mercury fumes into the local environment. The health status of 211 volunteers in Rwamagasa artisanal

gold mining area and 41 non-exposed people from a nearby control area in Katoro, located 30 km distant

from Rwamagasa was assessed with a standardised health assessment protocol from UNIDO (UNIDO

2003) by an expert team from the University of Munich, Germany in October/November 2003. The health

assessment protocol was developed by UNIDO in collaboration with the Institut für Rechtsmedizin der

Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Germany and other international experts. The "Health

Assessment Questionnaire" was partly translated in Swahili to be used to examine the general health

condition of members of the mining community and to indicate symptoms of mercury poisoning. State of

BGS Report CR/04/129 (Issue 1.0) for UNIDO Contract 03/088

the art anamnestic, clinical, neurological, neuro-psychological and toxicological tests were used. All

participants were examined to identify neurological disturbances, like ataxia, tremor and coordination

problems. The data was compiled for statistical purposes and confidentiality regarding all health related

issues was maintained.

Results of the medical investigation

Mercury concentrations in the bio-monitors urine, blood and hair were significantly higher statistically in

the exposed population from Rwamagasa compared with the Katoro control group, but only some

amalgam burners showed mercury levels above the toxicological threshold limit HBM II in urine (Figure

ES-4), blood and hair. A speciation of mercury in hair demonstrates that mainly inorganic mercury

(including mercury vapour) contributes to the high body burden of the artisanal miners. Low mercury

concentrations in all bio-monitors (especially: blood) of volunteers not occupationally exposed to

mercury in Rwamagasa indicate that there is no relevant secondary exposure of humans to mercury in this

area by air, drinking water or food, especially locally caught fish.

Only a few statistically significant correlations were detected between Hg concentrations in bio-monitors

(urine, blood and hair) and anamnestic/clinical data for the amalgam-burners sub-group. Significant

correlations included those between the anamnestic data (i) "tremor at work" with Hg in urine, blood and

total Hg in hair and (ii) Hg in blood with tiredness, lack of energy, weakness, and problems with

concentration and clear thinking. The only significant correlation between a classical clinical indicator

and Hg in biomonitors was "Heel to knee tremor" with Total Hg in hair whilst significant correlations

with the "Matchbox test" were found with Hg in urine and blood. Whereas on a group basis Hg in the

target tissue (i.e. brain) correlates well with Hg in urine, blood and hair of people with significantly

different levels of occupational or environmental exposure, the poor correlations between classical

clinical indicators of mercury intoxication and Hg in bio-indicators within the group of amalgam-burners

in the present study probably reflects large inter-individual differences (i.e. an individual's biomonitor Hg

level may not directly indicate their target tissue (brain) Hg burden). In an individual who has suffered

from chronic exposure to Hg, damage to the central nervous system may have occurred months or years

before the biomonitor samples were analysed. Biomonitor data indicate an individual's recent body-

burden whereas the clinical indicators probably indicate an individual's past or cumulative Hg burden.

This would explain why the former occupationally exposed group shows a high median medical score

whilst the group's biomonitor Hg levels are only slightly elevated. When the results of individual

anamnestic, clinical and neurological tests are summed together, significant correlations exist (i) between

Hg in urine and blood with the anamnestic score and (ii) between Hg in urine and the sum of all the

anamnestic, clinical and neurological tests. It was shown that for the Rwamagasa amalgam-burner group,

which is predominantly exposed to inorganic Hg (including Hg vapour), the Hg concentration in urine is a

sound predictor for a Hg intoxication.

BGS Report CR/04/129 (Issue 1.0) for UNIDO Contract 03/088

Typical symptoms of mercury intoxication were prevalent in the exposed group. For example, combining

the medical score with the bio-monitoring results made it possible to diagnose chronic mercury

intoxication in 25 out of 99 amalgam burners, and in 3 out of 15 former amalgam burners (Figure ES-5).

Table ES-1 shows the mercury concentrations in biomonitors for the group of intoxicated amalgam

burners.

Hg-blood

Hg-Urine

T-Hg-Hair

MeHg-Hair

(µg/l)

(µg/g crea.)

(µg/g)

(µg/g)

N

25 25 20 18

median

8.6 13.2 4.1 0.77

maximum 33.3 36.8 48.7 5.25

Table ES-1: Mercury concentrations in biomonitors of the 25 intoxicated amalgam burners (in some cases hair

samples were not available)

40

30

HBM II

20

)

g crea.

10

HBM I

Lab (µg/

g

-U

H

0

N =

31

9

23

96

67

12

Katoro control group

Rwama. not occup.

Rwama. other occup.

Katoro former occup.

Rwama. amalg.-burner

Rwama. former occup.

Figure ES-4: Total mercury concentration in urine (µg Hg/g creatinine), determined in laboratory (expanded y-axis;

occup. = occupational)

BGS Report CR/04/129 (Issue 1.0) for UNIDO Contract 03/088

Diagnosis: Mercury Intoxication

30%

25%

20%

15%

10%

5%

0%

Katoro, control

group

Katoro, former

occupational

Rwamagasa, not

burdened

occupational

Rwamagasa,

burdened

amalgam-burner

Rwamagasa,

other

Rwamagasa,

occupational

former

burdened

occupational

burdened

Figure ES-5: Frequency of the diagnosis of mercury intoxication in the different sub-groups.

Within the other population groups in Rwamagasa (i.e. people not occupationally exposed to mercury)

and in the Katoro control group no cases of mercury intoxication were diagnosed. The percentage of cases

diagnosed with mercury intoxication within the amalgam burners was lower in Rwamagasa than in the

comparable small-scale gold mining area of Mt. Diwata in the Philippines, for example, where 85% of the

amalgam burners were intoxicated (Drasch 2001). The difference in the level of intoxication cannot be

explained by a different (i.e. a safer) amalgam burning technique in Rwamagasa. Moreover, it must kept

in mind, that the maximal burden (as expressed in the top mercury concentrations found in the bio-

monitors) was comparable to Mt. Diwata. The impression gained during the field programme was that

this difference might be explained just by a lower amount of mercury used for gold extraction in the

Rwamagasa area, reflecting the lower level of gold production. This results in a lower number people

exhibiting high levels of mercury intoxication.

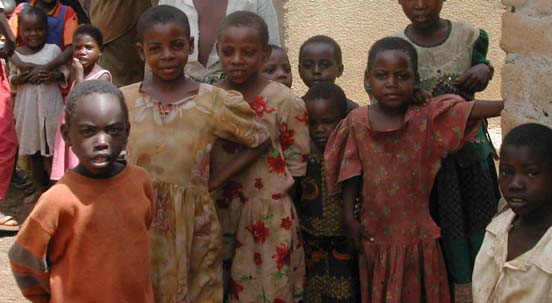

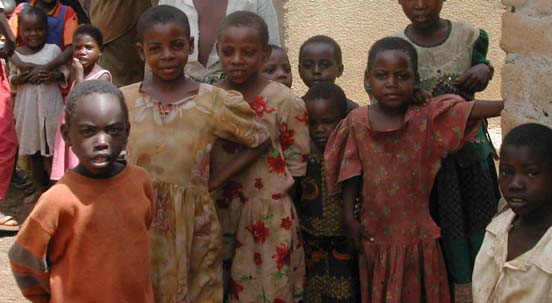

Child labour in the Rwamagasa mining sites is very common from the age of 10. The children work and

play with their bare hands with toxic mercury. This is very important because mercury can cause severe

damage to the developing brain.

Nursed babies of amalgam burning mothers are at special risk. Extremely high mercury concentrations

were detected in two out of five breast-milk samples from nursing mothers who worked as amalgam

burners. In addition to a placental transfer of mercury during pregnancy from the mother to the foetus (as

has been proved in other studies) this high mercury burden of nursed babies should be a cause of great

concern.

BGS Report CR/04/129 (Issue 1.0) for UNIDO Contract 03/088

Poverty is the main reason for the poor health status of the small-scale mining communities. Struggling

for survival frequently makes gold mining a necessity in order to obtain financial resources. The daily

fight for survival makes the miners put their own health and the health of their children at risk.

A reduction of the release of mercury vapours from small-scale gold mining like in Tanzania into the

atmosphere should not only reduce the number of mercury intoxicated people in the mining area but it

will also reduce global atmospheric pollution, because a significant proportion of mercury vapours

formed by burning of amalgam in the open-air may be transported long-range distances (Lamborg, 2002).

The total release of mercury vapour from artisanal gold mining is currently estimated to be up to 1,000

metric tons per year (MMSD, 2002), while approximately 1.900 tons of mercury from all other

anthropogenic sources were released into the atmosphere (Pirrone, 2001).

Mercury is undoubtedly a serious health hazard in the small-scale gold mining area of Rwamagasa.

Working for many years in the amalgamation process, especially amalgam burning has resulted in severe

symptoms of mercury intoxication. The exposure of the whole community to mercury is reflected in

raised mercury levels in the urine, and the detection of the first symptoms of brain damage such as ataxia,

tremor and movement disorders. Mercury intoxication (according to the definition of UNIDO (UNIDO

2003)) was diagnosed in 25% of the amalgam burners from Rwamagasa. In addition, intoxication was

also detected in some people that had formerly worked with mercury and amalgam. People from

Rwamagasa who are not directly involved in amalgam burning, have a higher mercury burden than the

control group, although the majority of these people are not intoxicated. The background mercury burden

in the Katoro control group is the same order of magnitude as in western industrial countries.

Recommendations for monitoring water quality and biota

Monitoring is expensive and costs can be reduced if the main exposure routes are known. Hence there is a

need for a more intensive study to link exposures from various pathways to mercury levels in blood prior

to the development of monitoring or remediation strategies.

Monitoring in the environmental survey followed, as closely as was practicable, the internationally

accepted protocols recommended by UNIDO (2003). It is recommended that water monitoring be carried

out in the Rwamagasa drainage system during the wet season in order to test for mercury dispersion in

solution and in the suspended sediment. The short term and medium term temporal variation in these

pollution indicators should also be investigated.

Continuous monitoring equipment capable of determining Hg at low concentrations in drainage systems

is, as far as the authors of this report are aware, not available commercially. So any monitoring system

would be periodic rather than continuous. Quarterly monitoring will probably be adequate for the Isingile

and Nikonga Rivers for a period of two years. If no significant Hg concentrations are detected during that

period, and there are no significant changes in the amount of mineral processing and associated factors,

then annual monitoring, following the USEPA recommendations, will probably be adequate.

BGS Report CR/04/129 (Issue 1.0) for UNIDO Contract 03/088

The only effective option to prevent continuing Hg pollution of the Isingile River and surrounding

agricultural areas is to require (a) the removal of all the existing mineral processing waste currently

located close to the Isingile River and (b) the termination of all mineral processing activities in the

vicinity.

Monitoring of drinking water from wells in the Rwamagasa area was not carried out during the current

survey, but should be considered when designing any future water quality monitoring systems.

Monitoring of biota (fish and agricultural crops) has been carried out as part of the current study and

could be carried out periodically using the UNIDO sampling protocols (UNIDO, 2003), which document

procedures for the periodic monitoring of aquatic biota. Periodic monitoring of agricultural crops could

also be carried out, although the results of this study indicate that little Hg is present in most of the crops.

Due to time and funding constraints, the current study was able to sample only a relatively limited

number of sites. For this reason it is recommended that a more comprehensive survey should be carried

out, in order to verify the results presented in this study.

Recommendations for the remediation and possible rehabilitation of mercury `hot spots'

The present survey did not detect any concentrations of Hg in solution that would require remediation, as

they did not exceed water quality standards. Should future water quality monitoring detect concentrations

that require remediation, then a number of remediation technologies may be appropriate.

From a practical point of view, there would be little justification in trying to remediate and rehabilitate the

Hg contaminated bottom sediments of the Isingile River until (a) the releases of Hg contaminated mineral

processing tailings from the Rwamagasa area have been terminated, (2) the risk of future contamination

of the drainage system by progressive or catastrophic releases of Hg contaminated processing waste has

been eradicated. It is, however, relatively unlikely that the tailings piles located adjacent and to the south

of the Isingile are a potential source of catastrophic contamination as the waste piles are relatively small

and the slopes are relatively gentle. However, both (i) the highly contaminated amalgamation pond

tailings and (ii) the primary and sluice box tailings that have been contaminated with mercury as a result

of reprocessing the amalgamation pond tailings are probably the main source of potential mercury

contamination in the Rwamagasa area and dispersal of these tailings needs to be avoided. Removal of the

tailings to a safe containment facility, underlain and covered with lateritic material (hydrous ferric oxides)

should be considered. As far as the authors are aware, no clean-up goals for mercury have been set in

Tanzania, although this needs to be verified.

The principal remediation-rehabilitation options for Hg-contaminated soils and sediments in the Isingile

River Rwamagasa area include (i) excavation of Hg-contaminated soil and disposal to an off-site secure

landfill or depository, (ii) electroleaching, comprising wet extraction followed by electrolytic preparation

of the leachate is an emerging and potential alternative cleanup method that is reported to offer a cheaper

BGS Report CR/04/129 (Issue 1.0) for UNIDO Contract 03/088

and more environmentally friendly alternative to thermal treatment or the acid leaching process. The cost

of these potential remediation options has not been estimated.

Specific practical remediation measures cannot be recommended until a much more detailed assessment

has been made of Hg concentrations in the agricultural soils, their uptake by crops and transfer into the

human food chain. On the basis of evidence collected during this survey, it appears that significant

amounts of mercury are not adsorbed into the grain of the agricultural plants. If this can be confirmed by

more detailed site specific studies (involving further collection and analysis of soil and rice grain samples

from exactly the same sites, for example) it may be possible to confirm that there is little or no potential

for a direct negative impact on human health caused by the consumption of rice and other crops grown on

these relatively high Hg soils. Mercury uptake by other crops (such as maize or cassava) grown on soils

that are currently used for rice should also be evaluated in case such a change in agricultural practices

would increase the potential exposure of the local population.

Recommendations for reduction of the release of mercury into the environment

The exposure to mercury for the miners and the community has to be drastically decreased. Proper mining

techniques to reduce the accidents and mercury exposure are essential. Small-scale miners need all

possible support to introduce cleaner and safer gold mining and extraction technologies.

The Local Mines Office in Geita needs to ensure that the small scale miners follow relevant mining and

environmental regulations and approved practices, such as making sure that all amalgamation is carried

out in cemented ponds and that all tailings from these amalgamation ponds are stored in appropriate

cemented storage areas that prevent dispersal of mercury contamination onto adjacent land and into water

courses.

Exposure to mercury vapour is avoidable with the application of simple technological improvements such

as retorts. Technical solutions need to go hand in hand with awareness raising campaigns.

An alliance of local, regional, governmental and intergovernmental bodies is needed to improve the

social, health and environmental situation of artisanal small-scale gold miners. Cooperation between

health and environmental sectors is needed on local, regional, national and intergovernmental level; for

example, UNIDO and WHO in Dar es Salaam could form a nucleus of a national mercury task force.

Recommendations for reduction of mercury as a health hazard

The clinical testing and laboratory results indicate that mercury is a major health hazard in the

Rwamagasa area especially for those artisanal miners who burn amalgam. A lower, but significant, level

of Hg intoxication is observed in those residents of Rwamagasa who have no occupational exposure.

In order to reduce the level of risk from mercury it is suggested that:

BGS Report CR/04/129 (Issue 1.0) for UNIDO Contract 03/088

1. Child labour with highly toxic substances must be stopped immediately. Legal restrictions on

child labour need to be implemented immediately.

2. Women of childbearing age need special information campaigns on the risk of mercury to the

foetus and the nursed baby and advice on how to avoid, or at least reduce, exposure.

3. Participants in the medical assessment diagnosed with mercury intoxication need medical

treatment. A system is required for the diagnosis and treatment of mercury related health-

problems. Capacity building, including establishing laboratory facilities to analyse mercury in

human specimens is required. The financial aspect of treatment and the legal problem of

importing drugs (such as chelating agents like DMPS or DMSA, required to remove mercury

from the body) need to be solved. Funding of preventive campaigns and for treatment facilities is

now needed.

4. Training programs for the health care providers in the district in Geita and other health centres in

mining areas is required to raise awareness of mercury as a health hazard and advise people how

they can reduce their own and their children's environmental and occupational exposure to

mercury.

5. Clinical training of local health workers, including the use of a standardised questionnaire and

examination flow scheme (MES = mercury examination score). Particular attention needs to be

paid to collecting information on individual's environmental and occupational exposure as this

will aid the detailed assessment of exposure routes and the design of strategies that will help to

reduce mercury exposure.

6. A mobile "mercury ambulance" might ensure that small-scale miners can be reached more

efficiently than from a permanent local health office. A "mercury ambulance" equipped with the

necessary medical and laboratory utensils bus could be driven into the artisanal mining areas.

Two or three specially trained doctors or nurses could perform the examinations, and begin to

carry out treatment. The ambulance could also be used for health awareness programs (e.g. video

equipment). Miners in remote areas might welcome evening entertainment and soccer videos

might attract more miners to the "mercury ambulance", than much other information material.

Sponsors could be sought for a "mercury ambulance", which could be based on a truck or bus

chassis.

Recommendations to increase awareness of the risks of mercury

(a) Assess in a different study design the possibility of mercury related birth and growth defects,

increased abortion/miscarriage rates, infertility problems, learning difficulties in childhood or other

neuro-psychological problems related to occupational and/or environmental mercury exposure.

BGS Report CR/04/129 (Issue 1.0) for UNIDO Contract 03/088

(b) Assess in a more detailed study the possible transfer of mercury from the environment to, mother to

child via breast-milk and related possible adverse health effects. Females at childbearing age and before

urgently require more awareness to refrain from amalgam burning, at least during pregnancy and nursing.

If this is not possible, a discussion whether to provide them with milk powder and high purity drinking

water together with training them to prepare hygienically appropriate formula food for their babies needs

to be based on a larger data base and a different epidemiological approach.

(c) Assess the relative importance of the main potential sources of exposure for people in Rwamagasa

who are not occupationally exposed to mercury (i.e. airborne Hg-vapour; ingestion of Hg-contaminated

dust through hand-to-mouth contact or on unwashed or inadequately washed food; ingestion of locally

grown Hg-contaminated crops; Hg-contaminated fish from local streams; deliberate occasional or

habitual consumption of soil (geophagia)). This has not been evaluated adequately and requires further

integrated investigation by a team of environmental, public health, medical and toxicological specialists.

Recommendations for improvement of general health.

Poverty is considered to be the main reason for most of the health and environmental problems in the

Rwamagasa area. At the moment it does not seem to be acceptable that children live in Rwamagasa

because of inadequate sanitary standards and high exposure to mercury. The improvement of sanitary

standards is needed urgently.

The relative occupational health risks of mining should be assessed in more detail (accidents, malaria,

drinking water quality, sexually transmitted diseases, tuberculosis, HIV / AIDS). One option to reduce the

health hazards in Rwamagasa might be a proper zoning into industrial areas, commercial areas and

housing areas. The imposition of basic hygienic standards, such as proper drinking water and reduction of

Anopheles mosquitoes would also lead to an improvement in the health of the local people. Raising safety

awareness and the introduction of appropriate mining techniques (such as better tunnel safety) will help to

reduce the risk of accidents at mining sites. The risk of sexually transmitted diseases could be reduced if

campaigns for safer sex were more effective. An appropriate health service is urgently required to

improve the health status of the Rwamagasa community.

References

Drasch G, Boese-O'Reilly S, Beinhoff C, Roider G, Maydl S. 2001. The Mt. Diwata study on the

Philippines 1999 - assessing mercury intoxication of the population by small scale gold mining. Science

of the Total Environment 267, 151-168

BGS Report CR/04/129 (Issue 1.0) for UNIDO Contract 03/088

Lamborg CH, Fitzgerald WF, O'Donnell J, Torgersen T. 2002 A non-steady-state compartment model of

global-scale mercury biogeochemistry with interhemispheric gradients. Geochim Cosmochim Acta

66:1105-1118.

MMSD, 2002. Breaking New Ground: Mining, Minerals, and Sustainable Development. International Institute for

Environment and Development. Earthscan Publications Ltd, London, UK. As available at

http://www.iied.org/mmsd/finalreport/index.html per September 2002.

Pirrone N, Munthe J, Barregård L, Ehrlich HC, Petersen G, Fernandez R, Hansen JC, Grandjean P, Horvat M, Steinnes E,

Ahrens R, Pacyna JM, Borowiak A, Boffetta P, Wichmann-Fiebig M. 2001. Ambient Air Pollution by Mercury (Hg)

Position Paper. Office for Official Publications of the EC. (available on

http://europa.eu.int/comm/environment/air/background.htm#mercury).

UNIDO, 2003. Protocols for Environmental and Health Assessment of Mercury Released by Artisanal and Small-

Scale Gold Miners. UNIDO, Vienna.

BGS Report CR/04/129 (Issue 1.0) for UNIDO Contract 03/088

Part 1

Assessment of the Environment in the Rwamagasa

area, Tanzania

by

British Geological Survey

BGS Report CR/04/129 (Issue 1.0) for UNIDO Contract 03/088

BGS Report CR/04/129 (Issue 1.0) for UNIDO Contract 03/088

Final Report for Assessment of

Environment in the Rwamagasa

area, Tanzania. UNIDO Project

EG/GLO/01/G34.

Environmental Protection Programme

Commissioned Report CR/04/014R

BGS Report CR/04/129 (Issue 1.0) for UNIDO Contract 03/088

BGS Report CR/04/129 (Issue 1.0) for UNIDO Contract 03/088

BRITISH

GEOLOGICAL

SURVEY

COMMISSIONED REPORT CR/04/014R

Final Report for Assessment of

Environment in the Rwamagasa area,

Tanzania. UNIDO Project

EG/GLO/01/G34.

J D Appleton, H Taylor, T R Lister & B Smith

Key words

Mercury, Tanzania, Rwamagasa,

Artisanal, Gold, Mining.

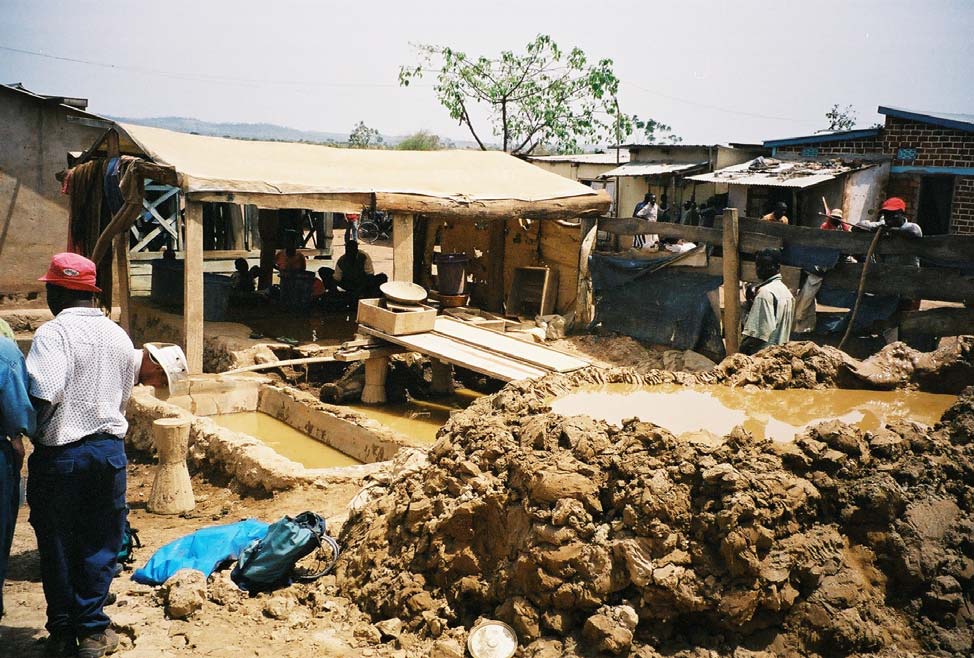

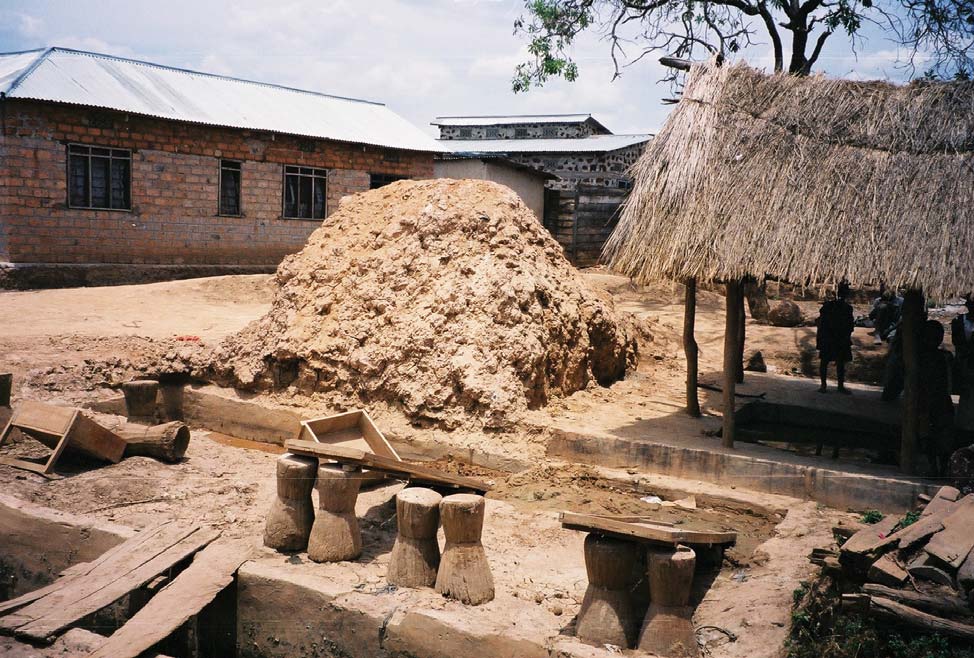

Front cover

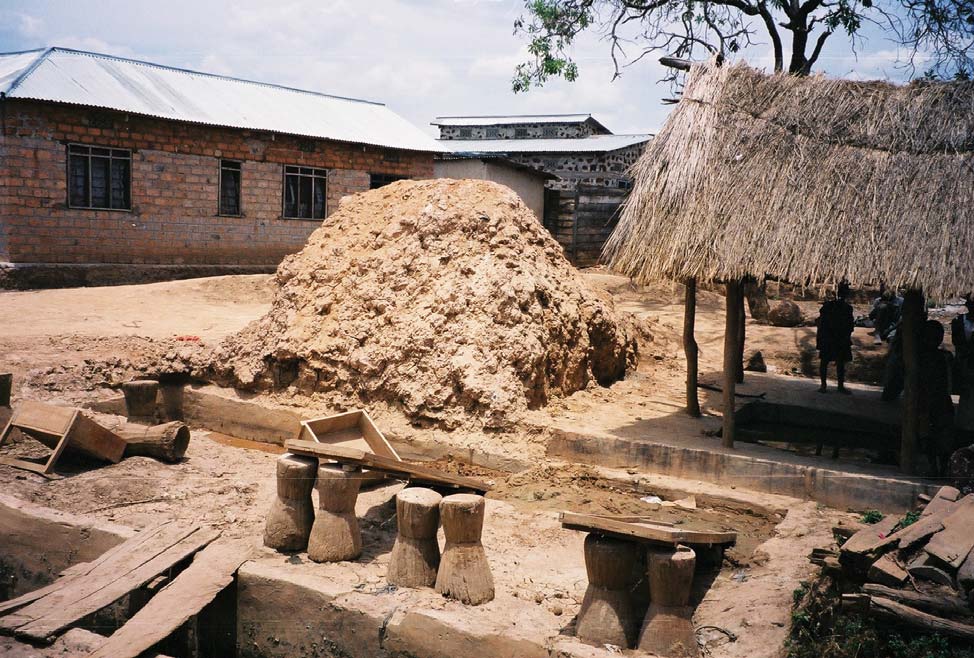

Cover picture Sluicing &

amalgamation site in the centre

of Rwamagasa village.

Bibliographical reference

APPLETON, J D, TAYLOR H.,

LISTER T R & SMITH, B.

2004. Final Report for

Assessment of Environment in

the Rwamagasa area, Tanzania.

UNIDO Project

EG/GLO/01/G34. British

Geological Survey

Commissioned Report,

CR/04/014R. 159 pp.

© NERC 2004

Keyworth, Nottingham British Geological Survey 2004

BGS Report CR/04/129 (Issue 1.0) for UNIDO Contract 03/088

BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY

The full range of Survey publications is available from the BGS

Keyworth, Nottingham NG12 5GG

Sales Desks at Nottingham and Edinburgh; see contact details

0115-936 3241

Fax 0115-936 3488

below or shop online at www.thebgs.co.uk

e-mail: sales@bgs.ac.uk

The London Information Office maintains a reference collection

www.bgs.ac.uk

of BGS publications including maps for consultation.

Shop online at: www.thebgs.co.uk

The Survey publishes an annual catalogue of its maps and other

Murchison House, West Mains Road, Edinburgh EH9 3LA

publications; this catalogue is available from any of the BGS Sales

Desks.

0131-667 1000

Fax 0131-668 2683

e-mail: scotsales@bgs.ac.uk

The British Geological Survey carries out the geological survey of

Great Britain and Northern Ireland (the latter as an agency

London Information Office at the Natural History Museum

service for the government of Northern Ireland), and of the

(Earth Galleries), Exhibition Road, South Kensington, London

surrounding continental shelf, as well as its basic research

SW7 2DE

projects. It also undertakes programmes of British technical aid in

geology in developing countries as arranged by the Department

020-7589 4090

Fax 020-7584 8270

for International Development and other agencies.

020-7942 5344/45

email: bgslondon@bgs.ac.uk

The British Geological Survey is a component body of the Natural

Forde House, Park Five Business Centre, Harrier Way,

Environment Research Council.

Sowton, Exeter, Devon EX2 7HU

01392-445271

Fax 01392-445371

Geological Survey of Northern Ireland, 20 College Gardens,

Belfast BT9 6BS

028-9066 6595

Fax 028-9066 2835

Maclean Building, Crowmarsh Gifford, Wallingford,

Oxfordshire OX10 8BB

01491-838800

Fax 01491-692345

Parent Body

Natural Environment Research Council, Polaris House,

North Star Avenue, Swindon, Wiltshire SN2 1EU

01793-411500

Fax 01793-411501

www.nerc.ac.uk

BGS Report CR/04/129 (Issue 1.0) for UNIDO Contract 03/088

Foreword

This draft final report is an interim published product of a study by the British Geological Survey (BGS)

carried out on behalf of UNIDO as part of Project No. EG/GLO/01/G34 "Removal of Barriers to the

Introduction of Cleaner Artisanal Gold Mining and Extraction Technologies.

Acknowledgements

A large number of individuals contributed to the planning and execution of the field programme. In

addition to the collection of data, many individuals have freely given their advice, and provided the local

knowledge so important to the effective execution of the field programme.

The assistance of the UNIDO (Vienna) Coordinating Unit staff, Dr Christian Beinhoff, Dr Marcello

Veiga, Ludovic Bernaudat, and M. Latrech is gratefully acknowledged. The completion of the field

programme in Tanzania would not have been possible without the assistance of Felix Ugbor (UNIDO

Country Representative), Victor Akim (National Programme Officer), William Smith (UNIDO driver).

Fish sampling in the Kigoma area was greatly assisted by the Tanzania Fisheries Institute (TAFIRI)

Centre Director Mr D Chitamweba and technician Mr Kashushu. Fish sampling in the Rwamagasa area

was carried out with the assistance and advice of Dr Oliva Mkumbo, technician Wabeya and driver Miko.

TAFIRI (Mwanza) loaned the project a Land Rover to assist with the fish-sampling programme. Geita

Mines Officer Mr John Nayopa provided advice and assistance with obtaining an export permit for the

environmental samples whilst technicians Kulwa Kabadi and Joseph Manaku assisted with the field-

sampling programme. Rwamagasa Village Executive Officer, Mr Doto Kaparatus ensured good

collaboration from the miners and farmers.

Advice on mercury contamination and artisanal gold mining was kindly provided by the following

individuals during a series of meetings held in Dar es Salaam and Mwanza: Mr Gray L Mwakalukwa

(Commissioner for Minerals and UNIDO Country Focal Point); Mr M Z Mraba (Zonal Mines Officer,

Mwanza); Professor Yunus D Mgaya and Dr John F Machiwa (Faculty of Aquatic Sciences and

Technology, University of Dar es Salaam); Dr Ben Ngatunga (Deputy Director, Tanzania Fisheries

Research Institute, TAFIRI, Kyela); Dr Diamantino P Azevedo, John Bomani and Manfred Akstinat

(Southern and Eastern Africa Mineral Centre SEAMIC); Samuel Msangi (Principal Environmental

Management Officer) and Mr Mwaipopo (Directorate of Environmental Compliance & Enforcement,

National Environment Management Council, NEMC); Ms Kisanga (Department of the Environment,

Vice Presidents Office) and Emmanuel W Jengo (Executive secretary, Tanzania Chamber of Mines).

Professor Mruma (Head of the Geology Department, University of Dar es Salaam) kindly provided nitric

acid and deionised water as well as advice on past and current research activities carried out by staff in his

BGS Report CR/04/129 (Issue 1.0) for UNIDO Contract 03/088

i

Department. Dr F K Mwanisi, District Medical Officer, Geita kindly agreed to collaborate with the

Medical assessment being carried out by sub-contractors led by Prof Gustav Drasch, University of

Munich, Germany. Mr Korodias Shoo (Environment Officer) and Mr Graeme McIlveen (Manager,

Safety, health & Environment) at Geita Mine are thanked for permitting project staff to store fish, water,

and sediment samples in the Environment Dept. fridge and freezer.

Last, but not least, the BGS would like to acknowledge with gratitude the enthusiastic assistance, advice

and cooperation of Mr Aloyce Tesha, Assistant to the Country Focal Point, before, during and after the

field programme. The project driver, Omar S Makulu, is thanked for his skilful and careful driving.

The advice and assistance of Mark Allen and colleagues, BGS (sediment, soil and tailings sample

preparation), Barbara Vickers, BGS (water analysis), Andrew Scott, Laboratory Manager Environment,

Direct Laboratory Services Ltd., Wolverhampton, UK (fish and vegetable analysis), Rick McCaffrey,

Clarence Leong and Wai Szeto, ACME Analytical Laboratories, Vancouver, Canada (soil, sediment and

tailings analysis) is gratefully acknowledged. The report was edited by Professor Barry Smith (BGS,

Environment Protection Programme Manager) and Dave Holmes (BGS, Head of Environment and

Hazards Directorate).

BGS Report CR/04/129 (Issue 1.0) for UNIDO Contract 03/088

ii

Contents

Foreword .......................................................................................................................................................i

Acknowledgements.......................................................................................................................................i

Contents...................................................................................................................................................... iii

Summary ......................................................................................................................................................1

1

Introduction .........................................................................................................................................1

2

Background ..........................................................................................................................................4

2.1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................4

2.2 River Malagarasi .........................................................................................................................5

2.3 Rwamagasa .................................................................................................................................7

3

Sampling and analytical methods.....................................................................................................10

3.1 Sampling ...................................................................................................................................10

3.1.1

Drainage sediment and water ............................................................................................... 10

3.1.2

Mineral processing waste (Tailings)..................................................................................... 12

3.1.3

Soil........................................................................................................................................ 15

3.1.4

Crops..................................................................................................................................... 17

3.1.5

Fish ....................................................................................................................................... 18

3.2 Sample preparation and analysis ...............................................................................................23

3.2.1

Water .................................................................................................................................... 23

3.2.2

Sediments, tailings and soils................................................................................................. 24

3.2.3

Fish and vegetables............................................................................................................... 27

4

Mercury in water, sediment, tailings, soil, crops and fish..............................................................30

4.1 Water .........................................................................................................................................30

4.2 Drainage sediment.....................................................................................................................33

4.3 Mineral processing waste material (Tailings) ...........................................................................38

4.4 Soil ............................................................................................................................................42

BGS Report CR/04/129 (Issue 1.0) for UNIDO Contract 03/088

iii

4.5 Agricultural crops......................................................................................................................50

4.6 Fish............................................................................................................................................52

4.6.1

Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 52

4.6.2

Results by site and species.................................................................................................... 54

4.6.3

Length mercury relationships ............................................................................................ 59

4.6.4

Summary............................................................................................................................... 62

5

Exposure to Environmental Mercury..............................................................................................63

5.1 Drinking Water..........................................................................................................................63

5.2 Foodstuffs..................................................................................................................................64

5.2.1

Locally produced rice, maize, cassava and vegetables......................................................... 64

5.2.2

Fish ....................................................................................................................................... 65

5.3 Inadvertent and deliberate ingestions of soil and dust ..............................................................67

5.3.1

Inadvertent ingestion of small quantities of soil and dust .................................................... 68

5.3.2

Occasional deliberate consumption of soil and dust (pica) .................................................. 69

5.3.3

Geophagia............................................................................................................................. 69

5.3.4

Predicted Exposures from soil/dust ingestion....................................................................... 70

5.3.5

Discussion and conclusions .................................................................................................. 71

6

Monitoring systems for water quality and biota.............................................................................72

6.1 Water quality.............................................................................................................................72

6.1.1

Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 72

6.1.2

Monitoring of water quality in the Nikonga River system ................................................... 75

6.2 Biota ..........................................................................................................................................78

7

Measures for the remediation and possible rehabilitation of the "hot spot" ...............................79

7.1 River system..............................................................................................................................79

7.1.1

Water .................................................................................................................................... 79

7.1.2

Sediment ............................................................................................................................... 79

7.2 Soil ............................................................................................................................................80

8

Role of government departments, the mining industry and research institutions.......................84

8.1 Ministry of Energy and Minerals ..............................................................................................84

BGS Report CR/04/129 (Issue 1.0) for UNIDO Contract 03/088

iv

8.2 National Environment Management Council............................................................................86

8.3 Department of the Environment................................................................................................86

8.4 United Nations Industrial Development Organisation ..............................................................87

8.5 University of Dar es Salaam......................................................................................................87

8.6 Tanzania Fisheries Research Institute .......................................................................................87

8.7 Southern and Eastern African Mineral Centre ..........................................................................88

8.8 Lake Victoria Environmental Management Project (LVEMP).................................................88

9

Summary and recommendations......................................................................................................89

9.1 Sample preparation and analysis ...............................................................................................89

9.2 Mercury in water sediment, tailings, soil, crops and fish..........................................................90

9.3 Exposure to environmental mercury .........................................................................................91

9.4 Monitoring systems for water quality and biota........................................................................93

9.5 Measures for the remediation and possible rehabilitation of mercury `hot spots' ....................94

10 References...........................................................................................................................................96

Appendix 1 ...............................................................................................................................................102

Terms of Reference ...........................................................................................................................102

Appendix 2 ...............................................................................................................................................107

Table A-2-1 Fish data: species, dimensions, location and sample type.............................................107

Appendix 3 ...............................................................................................................................................113

Table A-3-1 Replicate analyses of sediment, tailings and soil samples ............................................113

Table A-3-1 Replicate analyses of sediment, tailings and soil samples (contd)................................114

Table A-3-2 Analytical and precision (RPD) data for soil and tailings duplicate samples ...............115

Table A-3-3 Analytical data for duplicate sediment samples............................................................117

Table A-3-4 Replicate analytical data for ACME Internal Standard DS51 .......................................117

Table A-3-5 Comparison of Hg determinations by BGS and ACME ...............................................118

Table A-3-6 Hg CV-AAS data for ACME Internal Standard DS5 ...................................................118

Table A-3-7 Hg results for standard reference materials BCR 422 (Cod muscle) and BCR-060

(Lagarosiphon major (Aquatic plant)). .............................................................................................119

Table A-3-8 Analytical precision (%Relative Percent Difference, %RPD) for fish and vegetable

samples ..............................................................................................................................................120

BGS Report CR/04/129 (Issue 1.0) for UNIDO Contract 03/088

v

Table A-3-9 Combined sampling and analytical precision (Relative Percent Difference) for duplicate

fish samples .......................................................................................................................................121

Appendix 4 ...............................................................................................................................................122

Table A-4-1 Rwamagasa, sediment, soil and tailings samples: location and analytical data ............122

Table A-4-2 Ilagala-Uvinsa sediment samples: location and analytical data ....................................127

Table A-4-3 Hg (µg/L) in filtered water samples, Rwamagasa area .................................................127

Table A-4-4 Hg (µg/L) in filtered water samples, Kigoma area .......................................................128

Table A-4-5 As (µg/L) in filtered water samples, Rwamagasa area .................................................128

Appendix 5

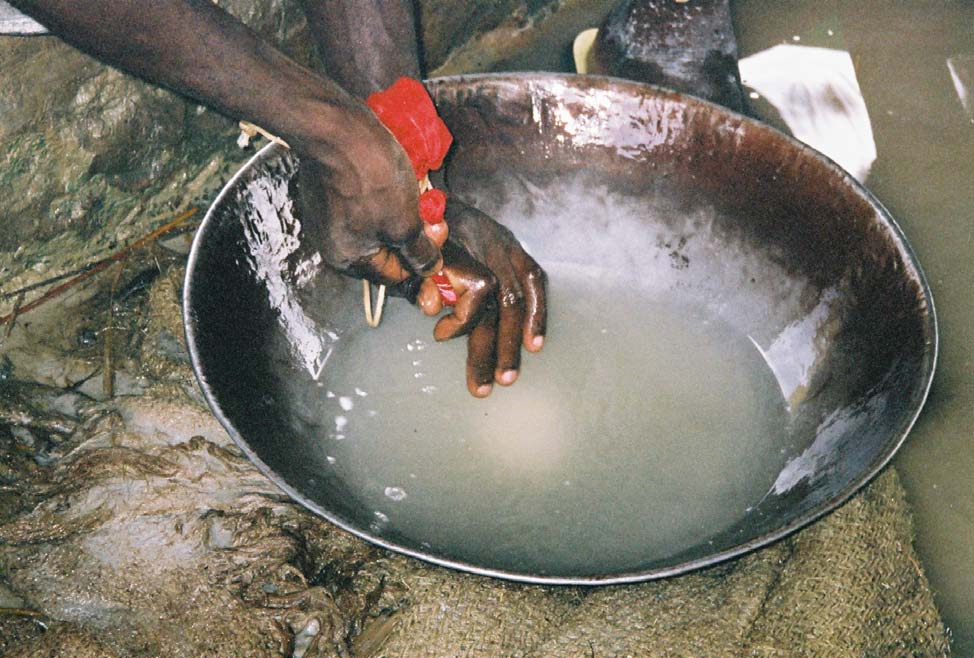

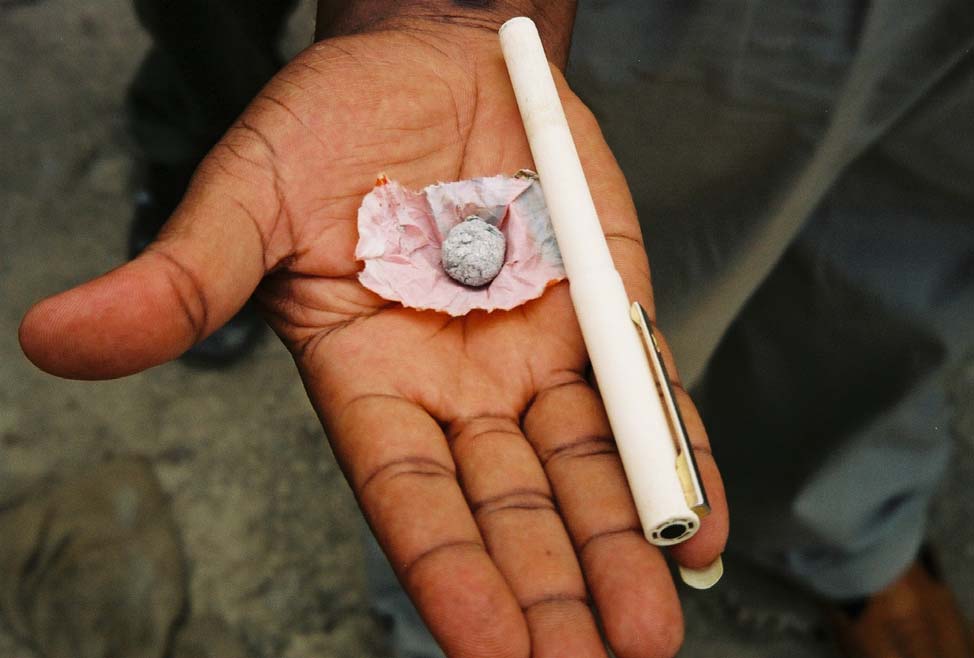

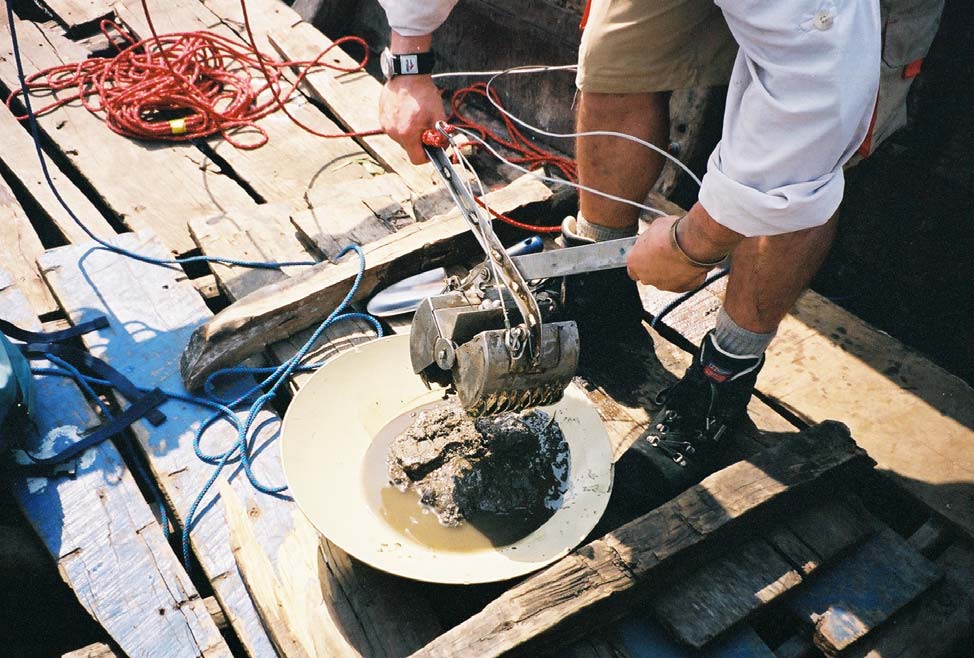

: PLATES........................................................................................................................129

BGS Report CR/04/129 (Issue 1.0) for UNIDO Contract 03/088

vi

Summary

Introduction

Artisanal gold mining is one of the major sources of mercury contamination, especially in developing

countries. Whereas the gold extraction process (known as amalgamation) is a simple technology, it is

potentially very dangerous and contaminates the air, soil, rivers and lakes with mercury. The health of the

miners and other people living within the area affected by mercury contamination may be negatively

affected through inhalation of mercury vapour, direct contact with mercury and through eating fish and

other food affected by the mercury contamination.

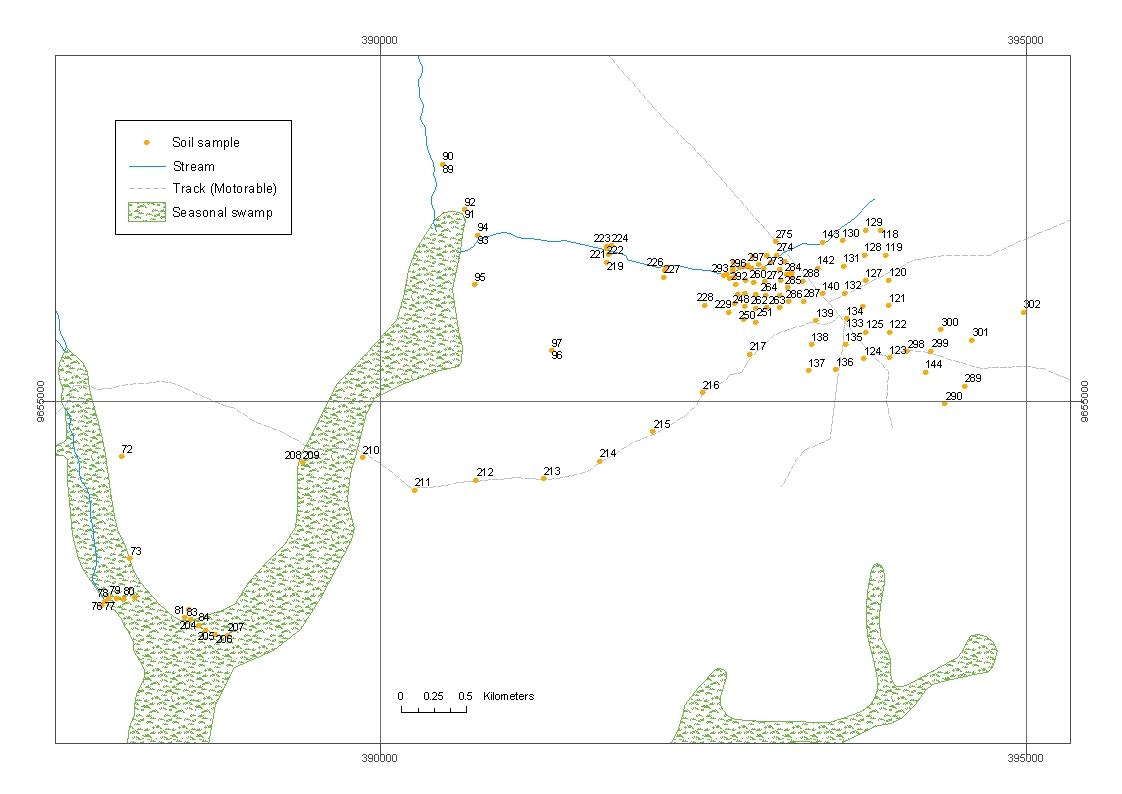

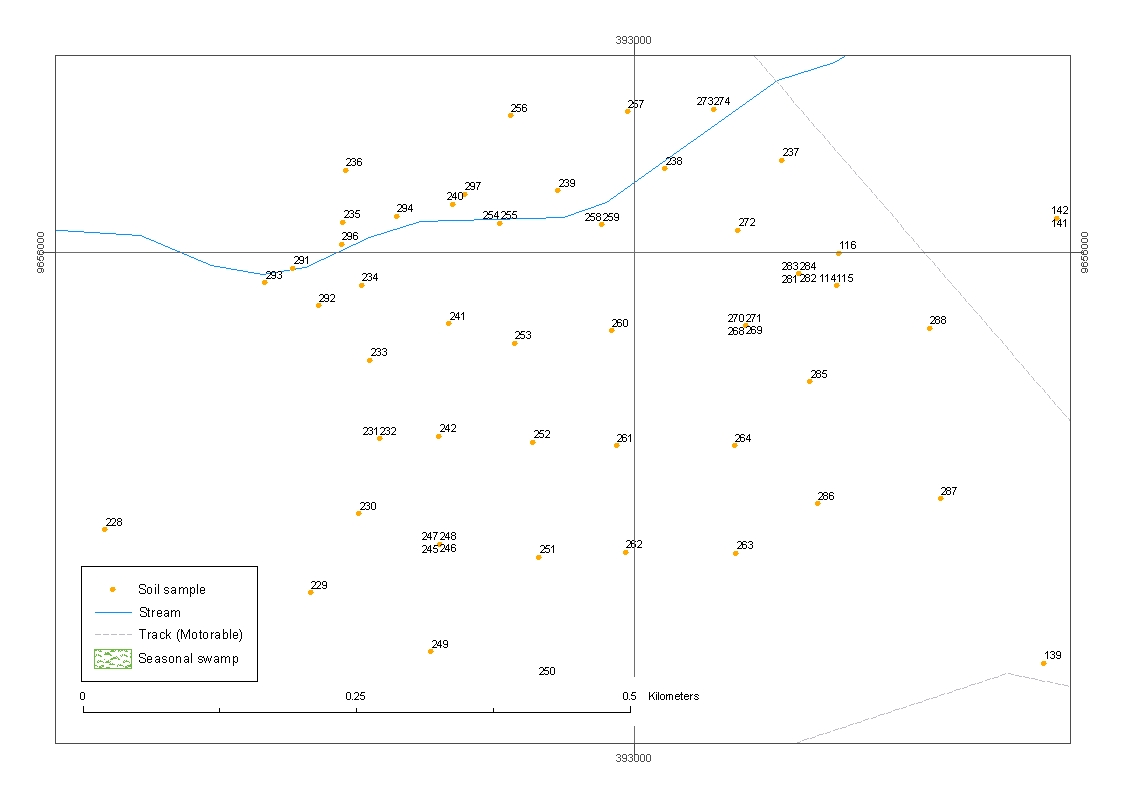

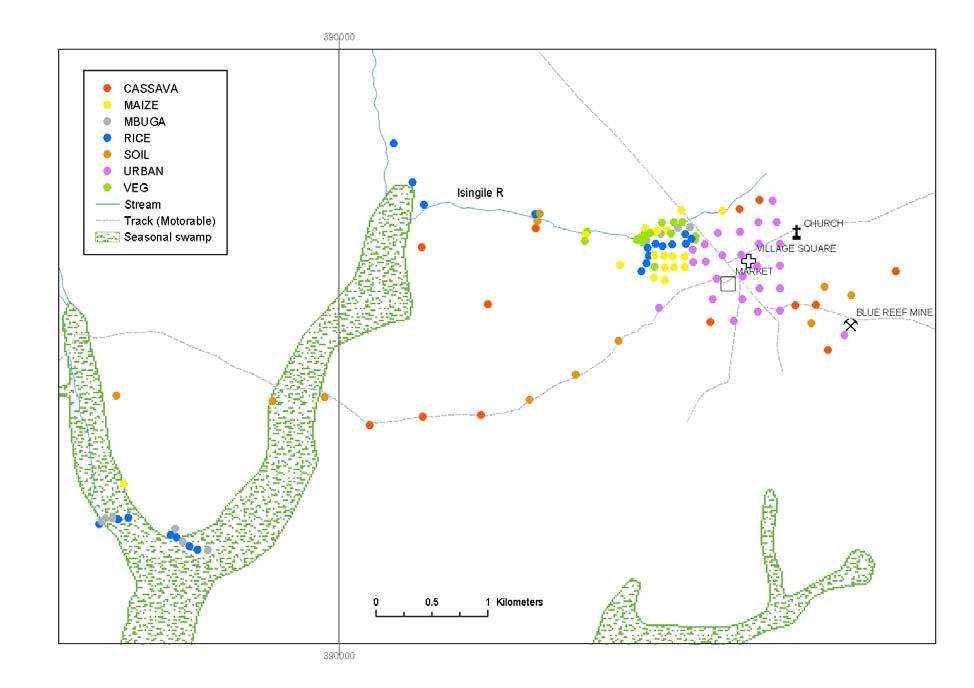

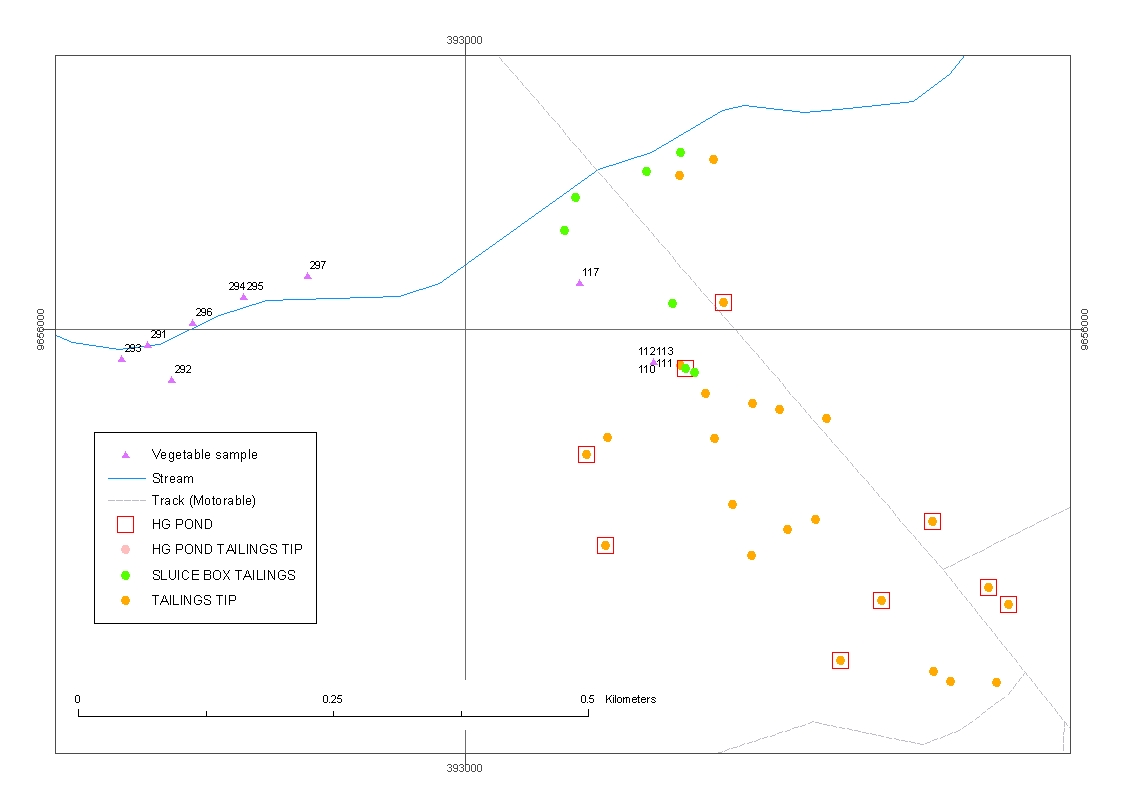

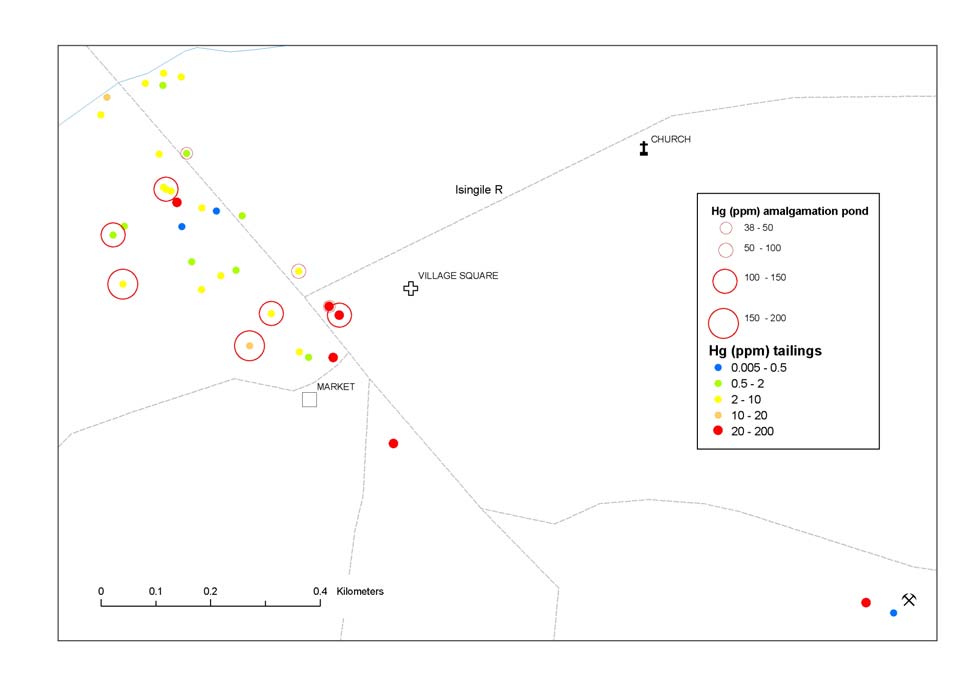

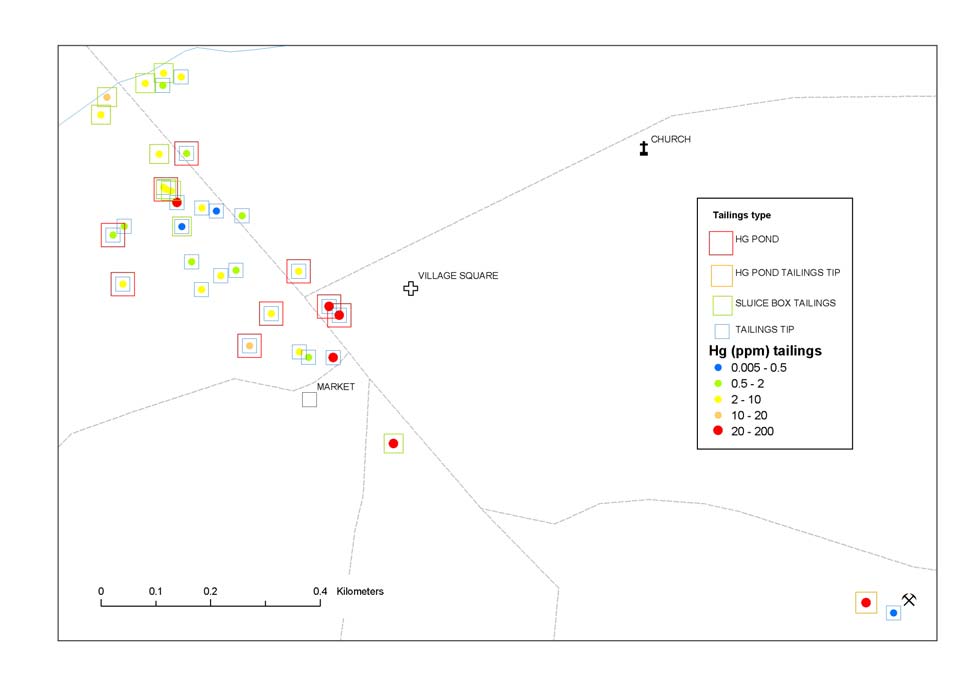

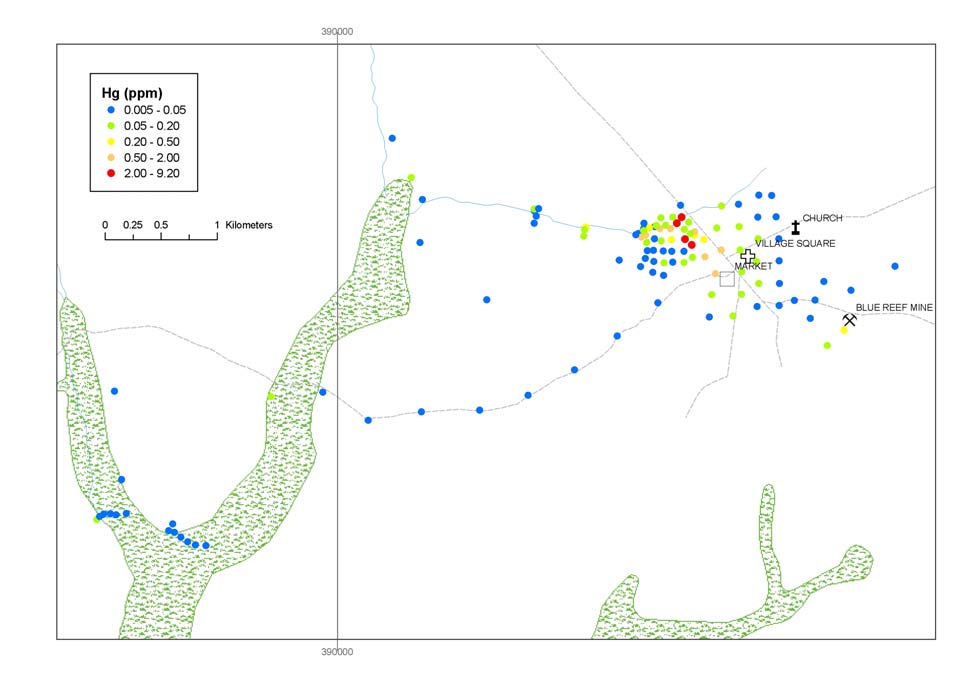

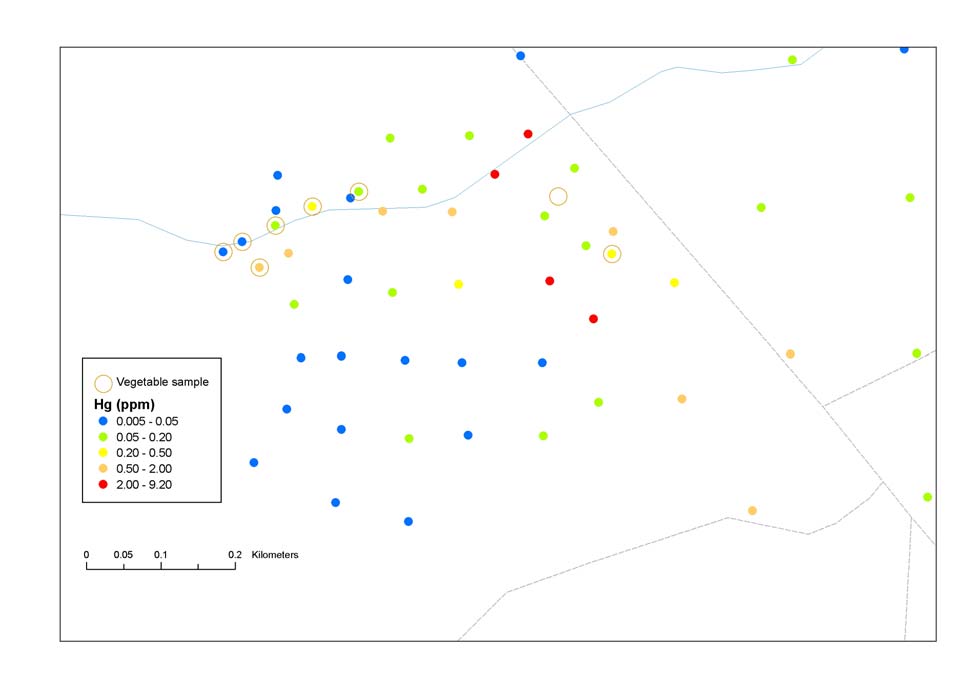

In response to this problem, the Global Environmental Facility (GEF) of the UN approved funding for the