Centro de Tecnologia Mineral

Ministério da Ciência e Tecnologia

Coordenação de Desenvolvimento Sustentável

ENVIRONMENTAL AND HEALTH ASSESSMENT IN TWO

SMALL-SCALE GOLD MINING AREAS INDONESIA

FINAL REPORT

SULAWESI AND KALIMANTAN

Saulo Rodrigues Pereira Filho

Project Leader

Ronaldo Luiz Correa dos Santos

Roberto C. Villas Bôas

Zuleica Carmen Castilhos

Allegra Viviane Yallouz

Bernhard Peregovich

Débora Maia Pereira

Flavia M.F. Nascimento

Luiz Roberto M. Pedroso

CETEM

Stephan Boese-O'Reilly

Gustav Drasch

Alexandra Dittmann

Sven Illig

Stefan Maydl

Beate Lettmeier

University of Munich

RT2004-016-00 Technical Final Report to UNIDO - RESERVED

July/2004

Brazilian Ministry of Science and Technology

Centre For Mineral Technology CETEM

Institute of Forensic Medicine, Ludwig-

Maximilians University, Munich, Germany

ENVIRONMENTAL AND HEALTH ASSESSMENT IN TWO SMALL-

SCALE GOLD MINING AREAS INDONESIA

TECHNICAL FINAL REPORT

SULAWESI AND KALIMANTAN

Center for Mineral Technology

Ref.: Report Requested by UNIDO, United Nations Industrial

Development Organization, No. P. 2003/007

EG/GLO/01/G34 Removal of Barriers to the Introduction

of Cleaner Artisanal Gold Mining and Extraction

Technologies

July / 2004

Project Staff

CETEM Centro de Tecnologia Mineral

Saulo Rodrigues Pereira Filho

Project Leader

Ronaldo Luiz Correa dos Santos

Roberto Cerrini Villas Bôas

Zuleica Carmen Castilhos

Allegra Viviane Yallouz

Bernhard Peregovich

Débora Maia Pereira

Flavia Maria de Fátima Nascimento

Luiz Roberto Martins Pedroso

University of Munich

Stephan Boese-O'Reilly

Gustav Drasch

Alexandra Dittmann

Sven Illig

Stefan Maydl

Beate Lettmeier

Photos: Dr. Bernhard Peregovich

Acknowledgements

Dr. Gildo de A. Sá Cavalcanti de Albuquerque (in memorian)

CETEM's Director

Dr. Christian Beinhoff

Chief Technical Advisor

Global Mercury Project

UNIDO United Nations Industrial Development Development Organization

Dr. Marcello M. Veiga

Small Scale Mining Expert

Global Mercury Project

UNIDO United Nations Industrial Development Development Organization

Dr. Fernando A. Freitas Lins

Focal Point Brazil - Global Mercury Project

Prof. Dr. Roberto C. Villas Bôas

Assistant Focal Point Brazil - Global Mercury Project

Dr. Arnaldo Alcover Neto

Head of Mineral Analysis Coordination

Luiz Roberto Martins Pedroso

Chemist

Flavia Maria de Fátima Nascimento

Hydrogeologist

Sandra Helena Ribeiro, Gaspar Barbosa Alexandre, Jorge Anronio Pinto de

Moura, Luiz Fernando M. Bandeira, Jorge Luiz Florindo da Cruz

Analytical Technicians

José Augusto Ferreira Junior

Mineral Technician

CETEM's Administration, specially, Mr. Aloisio Moura da Silva

Ms. Fátima Engel

Editing and Coordination of Report Edition

Summary

Executive Summary .........................................................................3

1. Introduction .............................................................................. 15

1.1. Location of the Study Areas in Indonesia ................................... 17

1.1.1. North Sulawesi Talawaan ............................................ 17

1.1.2. Central Kalimantan Galangan....................................... 20

2. Materials and Methods............................................................... 22

2.1. Environmental Assessment .................................................... 22

2.1.1. Sampling strategy....................................................... 22

2.1.2. Sample Preparation and Analyses.................................. 23

2.1.3. Statistical Analyses ..................................................... 24

2.2. Health Assessment ................................................................ 24

2.2.1. Material and sample storage......................................... 24

2.2.2. Study Setting and Clinical Examinations ......................... 24

2.2.3. Health Project in the Field ............................................ 23

2.2.4. Questionnaire............................................................. 26

3. Results and Discussion .............................................................. 30

3.1. Environmental Assessment ...................................................... 31

3.1.1. Geology and Mineral Processing in North Sulawesi

(Talawaan)................................................................. 31

3.2 Geology and Mineral Processing in Central Kalimantan

(Galangan) ........................................................................... 35

3.3. Biogeochemistry of Mercury in North Sulawesi (Talawaan

Watershed)........................................................................... 38

3.4. Biogeochemistry of Mercury in Central Kalimantan (Galangan

Mining Site) .......................................................................... 47

3.5. Mercury in Fish ...................................................................... 54

3.5.1. Human exposure to mercury due to fish consumption .......... 64

3.6. Mercury semiquantitative determination in fish samples in

Manado, Indonesia Training of local users ................................. 66

3.7. Health Assessment ................................................................. 69

3.7.1. General health situation ................................................. 69

3.7.2. Health Assessment Clinical Impression........................... 74

3.7.3. Description of mercury levels in urine, blood and hair .......... 77

3.7.4. Statistical analysis of mercury levels in urine, blood and

hair............................................................................. 82

3.7.5. Control Groups.............................................................. 89

3.7.6. Burdened Groups ........................................................... 91

3.7.7. Mercury Levels compared to Toxicological Threshold

Limits.......................................................................... 91

3.7.8. Scoring of medical results............................................... 98

3.7.9. Statistical analysis of mercury levels versus clinical

data .......................................................................... 100

3.7.10. Discussion of the Statistical Analysis............................. 105

3.7.11. Decision for the Diagnosis of a Chronic Mercury

Intoxication................................................................ 106

3.7.12. Influence on Nursed Babies .......................................... 109

3.7.13. Screening of Mercury Urine Concentration in Field .......... 112

4. Conclusions and Recommendations ......................................... 114

5. References .............................................................................. 123

Acknowledgement ....................................................................... 129

Appendix 1 Tables

Appendix 2 - Health assessment questionnaire

Appendix 3 - Pictures

Appendix 4 - Hg concentrations in sediments, tailings and soils -

Kalimantan and Sulawesi

RT2004-016-00 CETEM/MCT

Executive Summary

The present report describes the results achieved in two small scale gold

mining areas in Indonesia, North Sulawesi (Talawaan) and Central Kalimantan

(Galangan) - as part of the environmental and health assessment (E&HA)

conducted by the Brazilian Centre for Mineral Technology (CETEM) and the

German Institute of Forensic Medicine (IFM) of the University of Munich,

under the general coordination of the United Nations Industrial Development

Organization (UNIDO). The E&HA is a part of the GEF/UNIDP/UNIDO

Global Mercury Project - Removal of Barriers to the Introduction of Cleaner

Artisanal Gold Mining and Extraction Technologies.

The aim of the subcontract was to undertake two environmental and

medical investigations in the Galangan area (Central Kalimantan), and in the

Talawaan area (North Sulawesi), both in Indonesia. The ultimate aim of the

whole UNIDO project is to reduce mercury losses in the project demonstration

sites by means of introducing new technologies, while improving the income of

the miners through more efficient recovery, increasing knowledge and

awareness, and providing policy advice on the regulation of artisanal gold

mining with due consideration for gender issues.

In order to identify sites with high concentration of mercury (hotspots) a

sampling campaign of soils, sediments and biota was conducted, consisting of

768 samples. The present report describes results of mercury analyses in

sediments, soils, tailings, water and biological indicators, as well as clinical

examinations and mercury levels in 500 people living in the Indonesian gold

mining areas. An integrated approach has been applied to describe the

distribution and behavior of mercury in the environment and its health effects,

in order to provide a better understanding of the whole impact caused by

mercury emissions and exposure.

A research team comprising 11 research scientists from CETEM (7

members) and IFM (4 members) commenced with the work in Indonesia in

August 2003 and accomplished the sampling campaign within 30 days.

Environmental Assessment

North Sulawesi - Talawaan

North Sulawesi is a region of the Sulawesi Island in the Celebes Sea.

Manado is the capital of North Sulawesi, and has approx. 600.000 inhabitants.

Manado Bay is surrounded by some famous islands, for example

Bunaken Island. Bunaken National Marine park is well known for its beautiful

coral reefs, which are a tourist attraction. Three small rivers drain into this bay.

They origin from the Talawaan watershed, approx. 20 to 30 km away from

Manado.

3

RT2004-016-00 CETEM/MCT

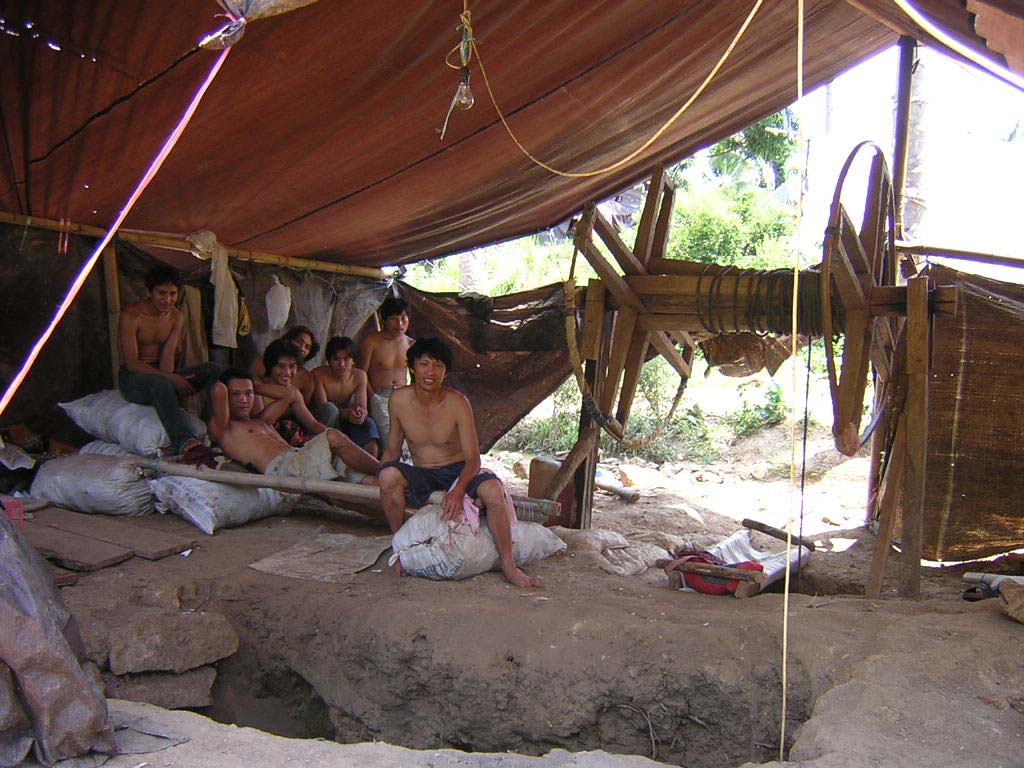

Tatelu is a small village in the Talawaan watershed with approximately

2.000 inhabitants. Next to the village is the mineral processing area. The ore is

excavated in the mountains. A group of 15-20 miners live in very basic camps

beside their tunnel.

The study area includes the drainage basins of the Talawaan and Tatelu

River. The drainages flow through the main gold processing units where

mercury is widely used and released. About one third of the coastline of the

area is within the boundary of the Bunaken National Marine Park. The coastal

environment includes mangrove areas and coral reefs.

According to Turner (2002), the North Arm of Sulawesi is a classic

oceanic island arc that includes porphyry Cu and volcanic-hosted epithermal

Au-Ag deposits. The Ratatotok Au district, located 100 km to the Southwest of

Manado, is hosted in Miocene carbonate rocks deposited in a Northeastern-

trending graben, and covered by andesitic volcanic and volcaniclastic rocks.

Carbonates are silicified, decalcified, dolomitized, and have anomalous

concentrations of Hg, As, Sb, Tl and low base-metals, as Zn, Cu and Pb (all <

100 ppm). Therefore, one may realize that a naturally anomalous Hg

background is to be found in North Sulawesi.

It is estimated that 130 milling operations are working in the Talawaan

watershed (Tatelu region). They purchase 10 to 15 kg of

mercury/month/milling unit. A unit with 12 mills recovers 4 to 6 g of gold per

cycle. Generally there are two cycles per day. The mills operate 8 hours/day, 6

days/week.

Most miners are currently storing amalgamation tailings in plastic sacks

to be sold to cyanidation plants. Since a certain portion of the gold is not

recovered from the gold ore by the amalgamation process, the wastes of the

processing sites are collected in sacks and transported by cars to nearby located

cyanidation plants, where the material is chemically processed to extract the

gold left in the amalgamation wastes.

According to a mass balance based on both analytical determinations in

amalgamation wastes and interviews with the miners, the estimated ratio Hglost

: Auproduced in Talawaan falls into the extremely high range of 40 to 60, which is

30 to 40 times higher than average ratios found in SSM worldwide (Veiga and

Baker, 2003; Rodrigues-Filho et al, 2004).

Assuming that 9.6 to 14.4 kg of Hg are lost per unit/month, not less than

15 to 22 tonnes of mercury are being released annually in the entire area of

Tatelu. This characterizes an alarming mercury burden to the environment in

North Sulawesi.

4

RT2004-016-00 CETEM/MCT

North Sulawesi

Nearly no suspended matter can be found in drainages of the Talawaan

watershed due to the ,,young" nature of the rivers, except in the most

dowstream region where a plain supplies the rivers with some silt/clay

material. Moreover this scarcity of clay minerals might reflect the young age of

volcanic activities, since the volcanic rocks have been exposed to weathering for

a relatively short geological time.

Also the extraction process used does contribute to the low contents of

suspended sediments found in the region, since most of the tailings are

recovered to be reprocessed in the cyanidation plants.

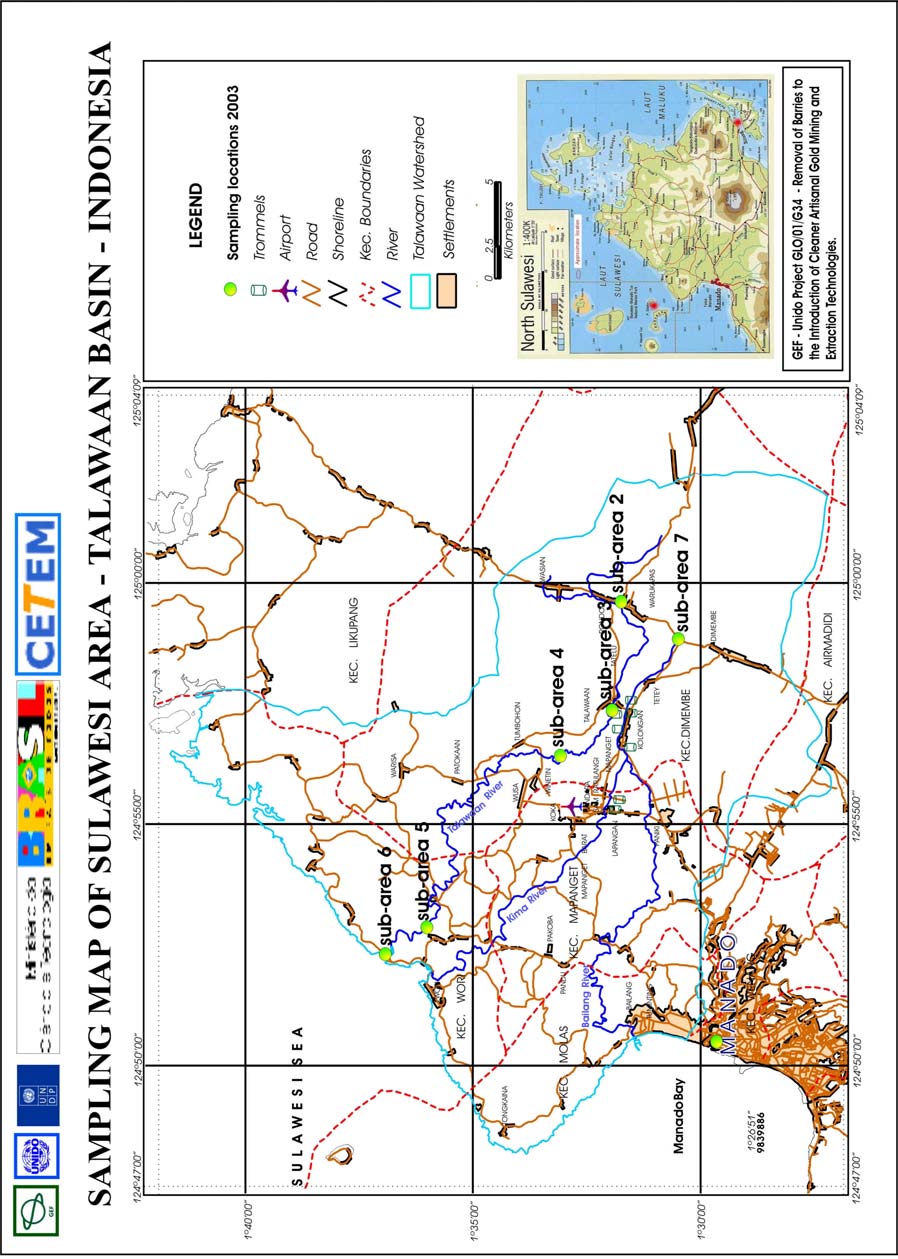

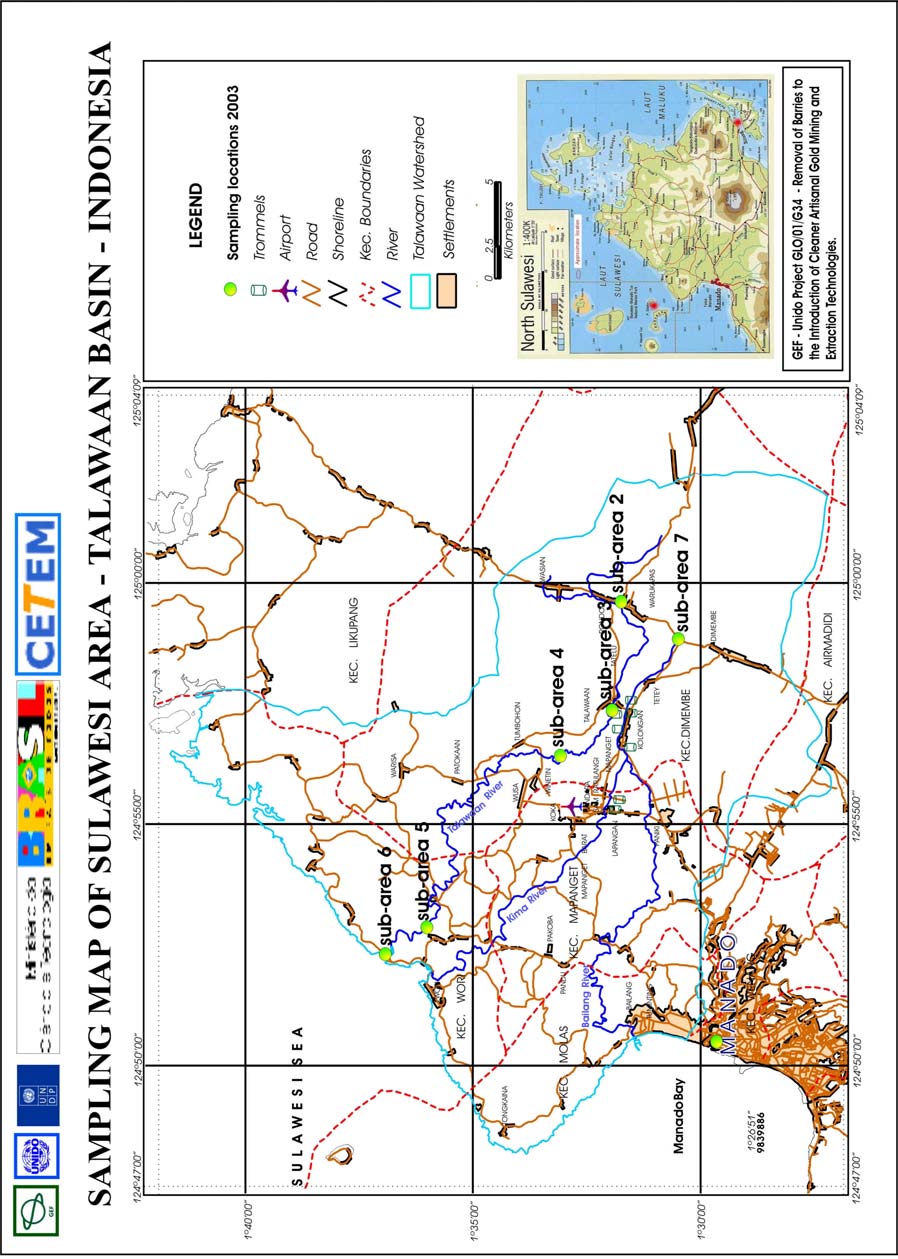

A sampling campaign of soils, sediments, water and biota was conducted

in the Talawaan watershed, consisting of 298 samples split into 156 fish

samples, and 142 samples of sediments, soils, water, plants and other aquatic

organisms, covering the whole study area. The study area was divided into 7

sub-areas from the most upstream are down to the estuary.

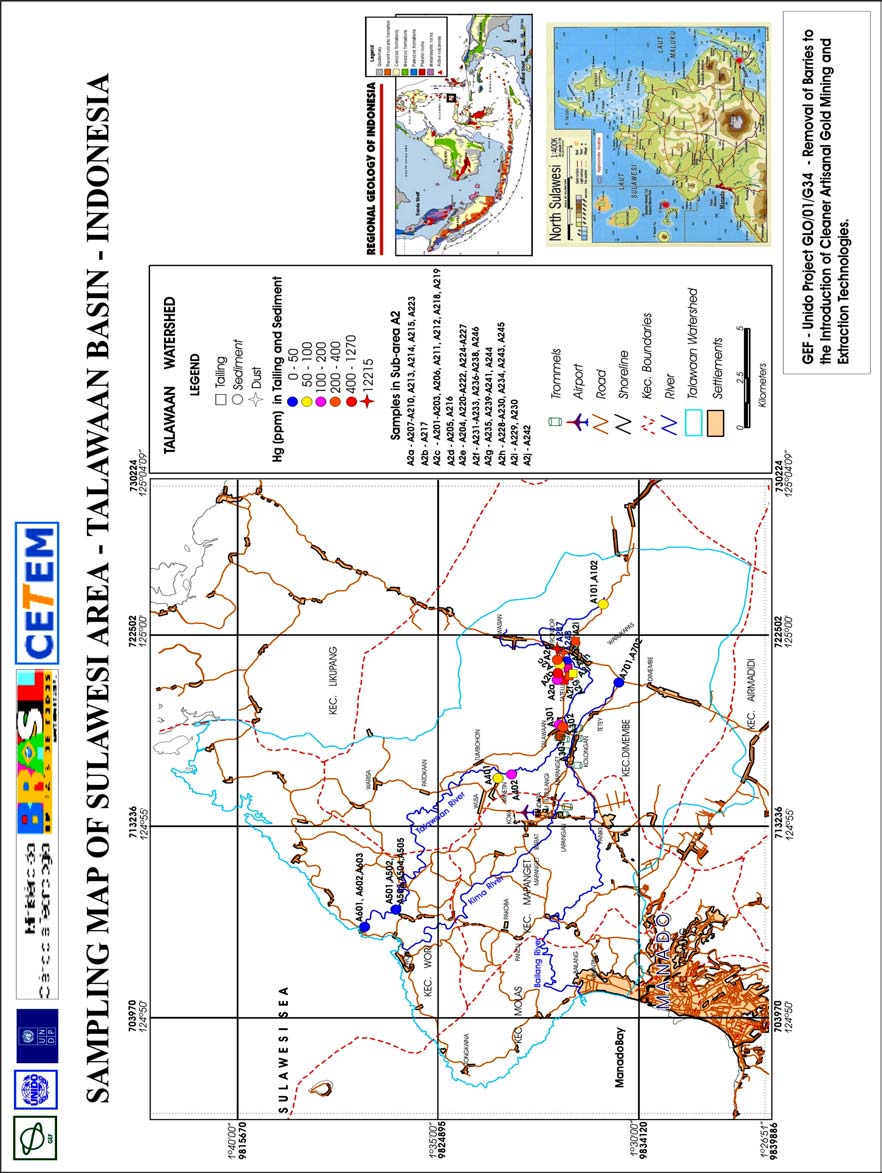

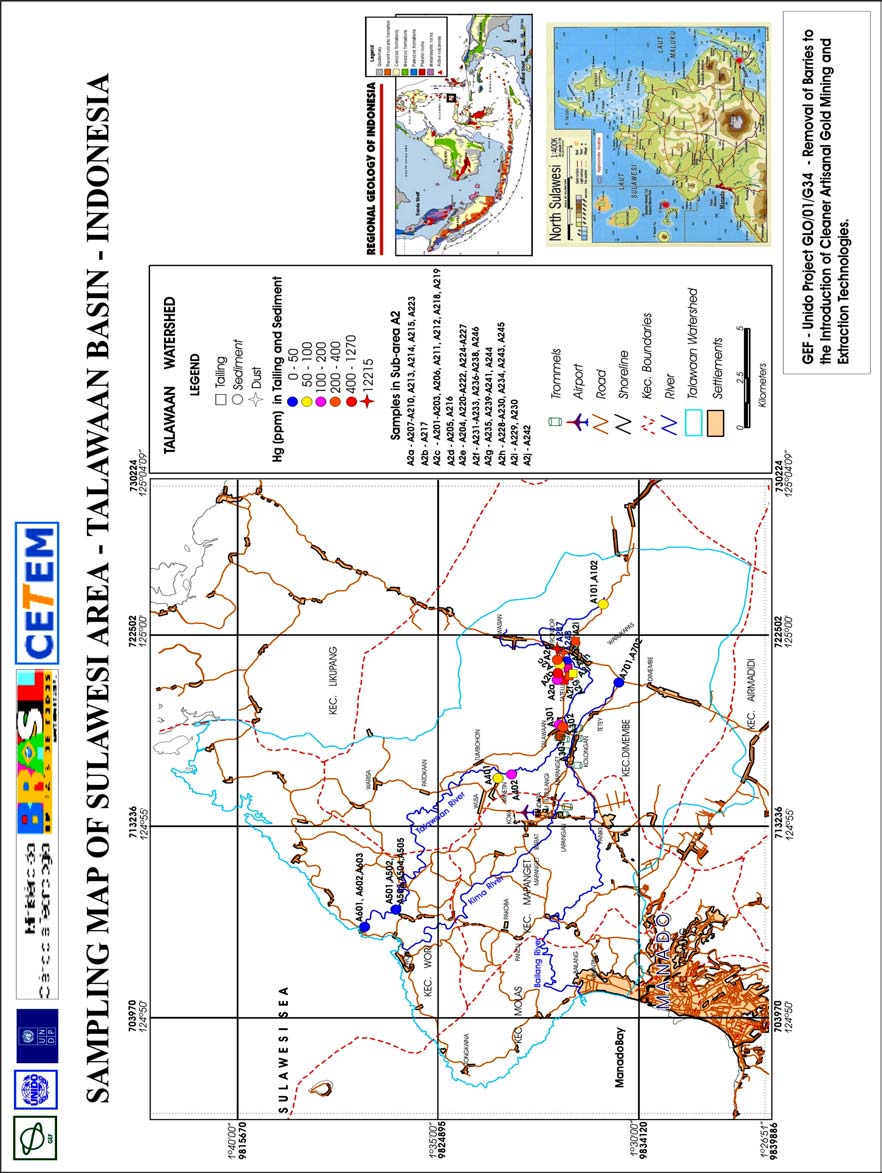

The most upstream sampling site is located close to the spring of

Talawaan river where no mining activity was reported. Unexpectedly, Hg

levels in those samples were 600 times higher than Hg background levels

usually found in sediments in tropical regions (Rodrigues-Filho et al., 2004).

Mercury levels at the spring of the Talawaan River average 60 µg/g in the

sediment fraction < 74 µm (see Figure 16).

A likely explanation for this anomalous Hg level in unaffected sediments

is related to the proximity of the inactive volcano of Mount Kablat, whose

former activity might have generated the conditions for the formation of gold

deposits in the Tatelu region, as well as their associated Hg enrichment. This

Au-Hg association has been observed in other similar gold deposits in North

Sulawesi (Turner, 2002). Another study on mercury contamination of the

Talawaan Watershed also indicates abnormal Hg levels, up to 2.0 µg/g, in

sediments close to its spring (Martens, 2000), whereas no information on the

target grain size fraction has been indicated. However, further investigations on

the mineralogy of these sediments are required to confirm this hypothesis.

The main mining sites are located approximately 5 km downstream close

to the confluence of the Tatelu River and the Talawaan River, where a dam

reservoir has been built for water supply of rice plantations. At this place an

increase of Hg levels in sediments has been observed as a consequence of Hg

releases from amalgamation wastes to the rivers. Mercury concentrations reach

up to 480 µg/g and average 154 µg/g in the sediment fraction < 74 µm (see

Figures 16 and 21).

Mining tailings consisting of amalgamation wastes containing up to

1250 µg/g and an average of Hg concentration of 317 µg/g (see Figures 17 and

21), must be regarded as mining hotspots. Obviously, not all of amalgamation

tailings are transported to the cyanidation plants, since plenty of them were

5

RT2004-016-00 CETEM/MCT

found all over the river banks. Mercury levels found in tailings of this area are

in the same order of magnitude of the values encountered in mining hotspots of

gold mining sites in Brazil (Rodrigues-Filho et al., 2004).

Further downstream and close to the estuary Hg levels in sediments

drop to a mean concentration of 6.7 µg/g, which is even lower than those

encountered in the most upstream part of the river, indicating a dilution effect

caused by runoff of catchment soils (see Figure 16).

As for the assessment of Hg bioavailability by using bioindicators other

than fish, like aquatic plants and mollusks, there is indication that Hg is being

taken up by living organisms in the Talawaan River, as shown by the

distribution of Hg in aquatic plants and mollusks (see Figures 19 and 20).

Mercury uptake by aquatic plants is particularly evident in cyanidation

tailings, where Hg concentrations reach up to 370 µg/g (see Figure 19). This is

likely a consequence of increasing Hg mobility and biovailability through the

formation of mercury-cyanide complexes after cyanidation of highly

contaminated amalgamation wastes.

The mean Hg level in aquatic plants of the Talawaan River, 32.3 µg/g, is

13 times higher than the one observed in the most contaminated SSM site in

Brazil, according to a previous study (Rodrigues-Filho et al., 2004).

Mollusks also indicate an abnormally high Hg bioavailability in the

Talawaan River, with a mean Hg concentration of 2.6 µg/g (see Figure 20). This

mean value is three times higher than the highest Hg concentration found in a

previous study on contaminated coastal sites of the USA (O´Connor, 1993).

Therefore, it is assumed that both factors are contributing to the

indicated high Hg bioavailability, namely an anomalous Hg background in the

area and the cyanidation of amalgamation wastes forming soluble mercury

complexes.

A reduced number of water samples were checked for assessing their

quality in relation to guidelines for drinking water. At the main mining sites,

Hg level in water reachs 1.8 µg/L, while down to the estuarine region Hg levels

drop to a mean value of 0.1 µg/L, which falls below the maximum limit of Hg

for drinking water established by the World Health Organization (WHO, 1980).

This is in accordance with the above mentioned hypothesis, since close to the

cyanidation plant Hg is clearly forming soluble complexes, becoming therefore

susceptible to methylation.

Central Kalimantan (Galangan)

Due to the topographic flat character of the sedimentary basin in the

study area of Central Kalimantan (former Borneo Island), its main rivers,

Katingan and Kahayan, exhibit a strong meandering stream, while the local

6

RT2004-016-00 CETEM/MCT

wetland in Galangan flows gently to two different river basins, to the Katingan

River to Southeast and to the Cempaga River to Southwest.

A 1 km wide forest separates the mining sites from the Katingan River.

The mining area consists of a flat plain seasonally flooded, covered by alluvial,

Quaternary-Tertiary sediments mostly sand and gravel with a thicknesss

ranging from 2 to 10 m above peaty layers. The occurrence of peaty layers is an

indication for a former wetland forest, which now lies some meters above the

groundwater table. Therefore, it seems to be very plausible, that the main part

of the waters from the mining site soaks into its sediments, before it is drained

by means of groundwater run off into the adjacent rivers.

The landscape in Galangan resembles a desert, with some isolated trunks

and stumps of giant trees after deforestation of the rain forest. No significant

vegetation remained and the soil is reduced to a white, fine sand. The alluvial

gold ore deposit consists of a Quaternary-Tertiary (Pleistocene) sedimentary

sequence.

Gold mining is carried out following traditional methods also used in the

Brazilian gold mining areas (secondary deposits) in the Amazon region. In open

pits the gold bearing layers are excavate by a jet of water. The diluted pulp is

then pumped to a carpeted sluices box with an inclination of some 15°, in which

gold particles are supposed to settle down in the carpet due to their high

density. Due to the high turbulence of the pulp flow a considerable part of the

gold is lost to the tailings.

Manual amalgamation of the concentrate is done in ponds consisting of

flooded open pits excavated beside miners' residences. This practice leads to Hg

pollution of the habitat. Amalgam is panned following traditional practice in

wooden pans, whereas excess mercury is squeezed through a piece of cloth

regaining it for further reuse. All families use water from the open pits for

taking bath and washing clothes.

According to a mass balance based on both analysis of amalgamation

wastes and interviews with the miners, the ratio Hglost : Auproduced in Galangan

is estimated of being in the range of 1.5 to 2, which is an average ratio found in

SSM worldwide (Veiga and Baker, 2003; Rodrigues-Filho et al, 2004). Assuming

that 150 to 300 g of mercury are lost per unit/month, 1 to 2 tonnes of mercury

are being released annually to the entire area.

Amalgam is burned in gold shops, commercial stores in a chimney-like

construction, which leads the mercury vapor just outside the house by an outlet

pipe. The gold shops are located in the middle of the village. There is no proper

ventilation for the mercury fumes, where in the rainy season 15 kg of gold is

sold to 20 gold shops and melted in the village, releasing at least 200 kg/annum

of mercury in the village. Housing areas, food stalls and a school are just

nearby.

According to local authorities about 500 processing units exist in the

entire mining area, each one with 4 to 6 miners, who work 10 hours a day,

during 6 days a week. Some 3 to 8 g of gold are recovered per unit/day.

7

RT2004-016-00 CETEM/MCT

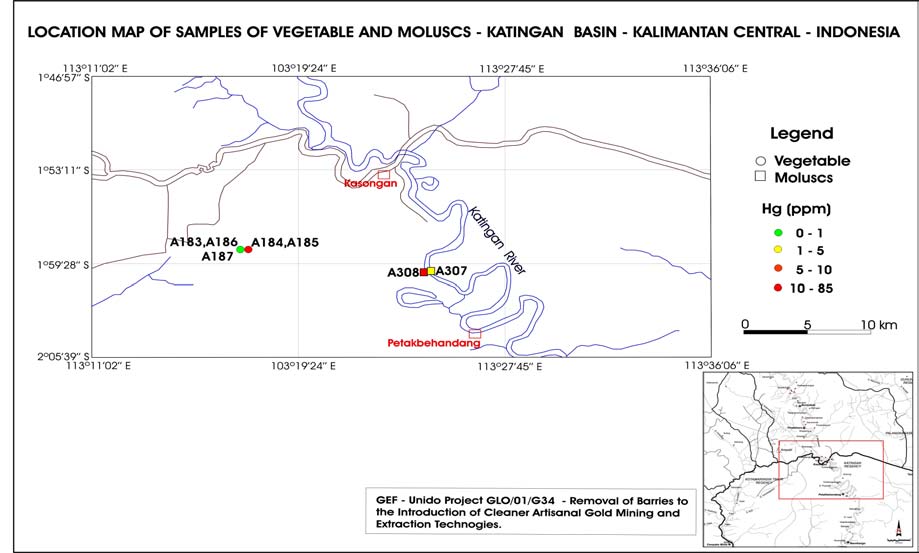

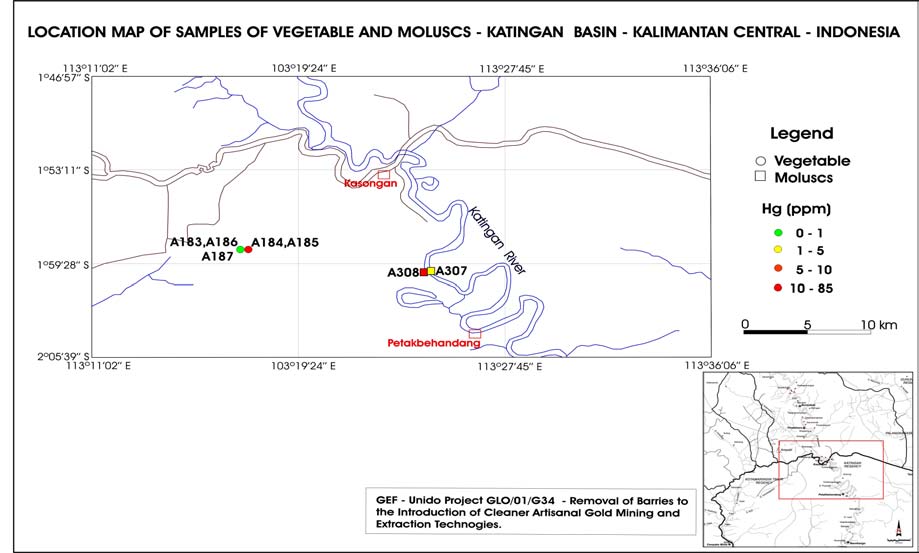

A sampling campaign of soils, sediments, water and biota was conducted

in the Galangan mining site, Katingan Watershed, consisting of 470 samples

split into 264 fish samples, and 206 samples of sediments, soils, water, plants

and other aquatic organisms, covering the whole study area, in order to address

the identification and location of mercury hotspots.

Mercury concentrations in sediments of the Katingan River are in general

significantly lower than in the Talawaan River in North Sulawesi. This is likely

related to both a less polluting mineral processing technique used in Galangan

and an existing lower Hg background in the Katingan Basin. This is indicated

by relatively low Hg levels present in sediments that have been deposited many

years before starting SSM activities in the region. Lower sections of sediment

cores taken in riversides and floodplains of the Katingan River are assumed to

mirror the existing sedimentological conditions prior to the start of the gold

rush (see Figure 23).

Distribution of mercury concentrations in a sediment core from the

Katingan River, upstream of mining sites, shows significantly lower levels,

averaging 0.38 µg/g, than in the cores taken downstream of the mining areas,

averaging 2.87 µg/g, 2.19 µg/g and 2.33 µg/g, respectively in sediment cores

A301, A501 and A601. Therefore, the Hg range found in core 201 indicates an

existing increased Hg background for this study area (see Figures 23 to 26).

Moreover, the sediment cores taken downstream have a similar varying

distribution of Hg levels with depth, showing a common peak of Hg

concentration between depths from 6 to 12 cm, ranging from 8 µg/g in core

A301 to 21 µg/g in core A501, and to 4 µg/g in core 601 (see Figures 24 to 26).

This Hg peak is likely related to a major Hg release from the mining sites some

years ago that probably mirrors a more intense Hg use at the beginning of the

gold rush in 1998.

The distribution of mercury concentrations in individual sediment

samples from the Galangan mining site resembles the levels found along the

downstream section of the Katingan River, as presented in Figure 27. This a

clear indication that sediments from both the mining site and the lower

Katingan River are closely related to each other as a consequence of mercury

discharges from SSM operations.

Nevertheless, those Hg concentrations in the Galangan region are at least

one order of magnitude lower than in the Talawaan region.

The prevailing sandy composition of the mining tailings that is driven by

the type of alluvial deposit with almost no silt-clay fraction is a likely

explanation for the relatively low levels, since Hg released during

amalgamation finds no particulate surface to be adsorbed on, leading to Hg

concentrations even lower than in river sediments (see Figure 28).

On the other hand, although a relatively moderate Hg contamination

degree in amalgamation tailings is to be reported for Galangan, there are strong

indications that mercury finds a favorable condition for becoming highly

8

RT2004-016-00 CETEM/MCT

mobile as indicated by the abnormally high levels found in the organic fine

cover of the tailings, composed basically of algae. This is an indication that

mercury is being dissolved by the organic dark waters of Galangan, which is a

potentially favorable condition for increasing mercury bioavailability through

methylation (see Figure 28).

Mercury in Fish North Sulawesi and Central Kalimantan

The occurrence of fish was investigated in 7 sub-areas, in the Talawaan

mining area, North Sulawesi. Along the Talawaan River, 156 fish specimens of

11 species were collected (gabus, gete-gete, gold fish, guruo, kesa, lalimata,

mujair, nilem, payanka, sepot, supit), one specimen (gold fish) from fish-

farming, while 26 specimens of 5 marine species were bought at the fish market

in Manado (cakalang, deho, tudê, bobara and malalugis).

In Central Kalimantan, 264 fish specimens of 25 species (banta, baung,

bawal, darap, gabus, gold fish, gurame, juah, kalatau, kalui, kapar, karandang,

kelabau, lais, lais lintang, lawang, nilem, papayu, patin, putin, saluang, sapat,

tahuman, tekung, tongkol) were collected. Five specimens of five species were

bought at the fish market in Palangkaraya. It is important to realize that some

specimens came from fish farming inside the Katingan river, such as patin and

tahuman species.

The present results show that total mercury concentrations in fish from

North Sulawesi are higher than in fish from Central Kalimantan area and the

Table 6 shows the minimum and maximum values for Hg in fish in both areas.

The resulted mean of Hg from Central Kalimantan is 0.21±0.36 µg/g (N=264)

and its maximum value is 1.83 µg/g, while in North Sulawesi mean Hg level is

0.58±0.45 µg/g (N=130) and its maximum value reaches 2.60 µg/g.

It is well known that freshwater biota is able to accumulate Hg from

natural and anthropogenic sources. Maximum background levels for Hg in

uncontaminated freshwater fish are in the range of 0.1 to 0.3 µg/g, although

considerably higher levels can be found in large predators.

The mean concentration of Hg (0.36 µg/g) in fish species from this work

was within that range and lower than 0.5 µg/g, the Hg concentration in fish

recommended by WHO (1990) as limit for human protection by Hg exposure by

fish consumption. However, we have to take into account that these species are

smaller and lighter than fish from other aquatic systems influenced by gold

mining, such as Amazon region (CETEM/IEC, 2004). In addition, among the

analyzed fish, 81 specimens, 21% of total fish sampled (389 fish) presented Hg

concentrations above 0.5 µg/g. Whereas in Central Kalimantan less than 10% of

fish samples showed Hg levels above that limit, in North Sulawesi this

percentage amounted to more than 45%. It should be considered that fish from

North Sulawesi are smaller and lighter than fish from Central Kalimantan,

9

RT2004-016-00 CETEM/MCT

suggesting that Hg bioavaliability in Manado can be higher than in Central

Kalimantan.

In North Sulawesi, Hg levels in fish from Toldano river (reference area-

T6) showed the lowest mercury levels, averaging 0.02 µg/g, while T2, a dam

reservoir close to the mining sites, showed the highest mercury levels in fish,

0.85 µg/g being considered as the most contaminated site in the area. The Hg

levels in the reference site are quite low, although they are from the

hydroelectric power plant lake, mentioned, sometimes, as an environment that

may show high mercury methylation rate.

In Central Kalimantan area, fish from flooded open pits in mining site

areas showed the highest Hg levels. These open pits are used for gold

processing and, also, for fishing, bathing and domestic wastes collected. While

the average of Hg in fish from the whole study area are quite low, the Hg levels

in fish from the flooded open pits in the small-scale mining area are considered

as the most contaminated sites. As miners and their families are living close to

those open pits and might often consume those fish, this characterizes a

potential pathway for methylmercury exposure to the local population.

By employing a risk assessment to human health, toxicological, rather

than simply statistical, significance of the contamination can be ascertained. At

a screening level, a Hazard Quotient (HQ) approach (USEPA, 1989), assumes

that there is a level of exposure (i.e., RfD = Reference of Dose) for non-

carcinogenic substances below which it is unlikely for even sensitive

populations to experience adverse health effects. The MeHg RfD value is 1E-04

mg.Kg-1.d-1 (IRIS 1995) and its uncertainty factor is 10 and its confidence level

is medium. Uncertainties of the RfD statistics have been reported, suggesting an

under-estimation of RfD for Hg presented in IRIS, 1995 (Smith and Farris 1996).

However, other authors suggest that there is no safe human exposure to MeHg

and that of all living species, human appear to have weakest defenses against

MeHg (Clarkson 1996). Considerable gaps in our knowledge about this remain.

Our approach, therefore, is to use the human risk assessment proposed

by USEPA, at a screening level. HQ is defined as the ratio of a single substance

exposure level (E) to a reference of dose (E/RfD). When HQ exceeds unity,

there may be concern for potential health effects. The estimated exposure level

was obtained by multiplication of 95th percentil upperbound estimate of mean

Hg concentration considering all fish as suggested by USEPA (1989), by the

adult human ingestion rate for local populations. Most of the works about

riverside population assume consumption rate close to 0.2 Kg.d-1.

As a matter of fact most people in North Sulawesi consume fish from the

market, mainly marine fish or freshwater from fish farming, rather than those

small fish from the study sites.

In Central Kalimantan, it should be taken into account that miners living

close to the P4 study site may consume fish caught in flooded open pits. As they

are not a riverside population, but considering the poverty, one could assume

that the fish consumption rate close to 0.05 Kg.d-1. Finally, the intake dose is

10

RT2004-016-00 CETEM/MCT

estimated by dividing that product by 70 kg, considering an average weight of a

human adult. Although total mercury was quantified in fish, it has been

demonstrated that about 75-95% of total mercury is methylmercury in fish

muscles. Thus, in a conservative approach, it has been assumed that total

mercury in fish represents methylmercury. The resultant HQs for MeHg fall

above the unit for North Sulawesi considering the fish market consumption. For

Central Kalimantan, both total and P4 sampling site, HQ resulted above the

unity, 2.4 and 9.9, respectively, which means that the population is subject to

potential health hazards due to fish consumption. This conclusion is fully in

agreement with indications of mercury exposure achieved by the health

assessment.

Health Assessment North Sulawesi and Central Kalimantan

There is no clean and safe drinking water, no waste disposal for the toxic

mercury or any other waste or human discharge in both study areas. Hygienic

standards are extremely low and are a reason for many infectious diseases such

as diarrhoea, typhoid and parasitism.

Road accidents, accidents in insecure tunnels and amalgamation plants,

malaria, tuberculosis, and sexually transmitted diseases are the dominant

causes of morbidity and mortality. HIV seems to increase within the mobile

men with money ("MMM") subgroup, esp. single male miners. But no accurate

data on the incidence of AIDS exists. Smoking is a very common, unhealthy

habit of the men.

The health centre in Kereng Pangi and Tatelu are able to offer some basic,

but adequate health services in the area. But they are not equipped for the

occupational health hazards in gold mining areas (accidents, mercury).

The extraction of the gold with liquid mercury releases serious amounts

of mercury, especially high toxic mercury fumes into the local environment.

The health status of 492 volunteers in Sulawesi and Kalimantan was assessed

with a standardised health assessment protocol from UNIDO (Veiga 2003) by

an expert team from the University of Munich/Germany in August/September

2003. 23 people had to be excluded from the further statistical evaluation due to

neurological diseases or their age. 222 people come from Sulawesi, and 247

from Kalimantan (see as also Table 5).

For statistical purposes a control group was selected in Air Mandidi

(Sulawesi), the adults and children there showed low levels of mercury in all

bio-monitors and a low medical score, indicating that they were not exposed to

mercury (see Figure 3, 5, 7). In Kalimantan a control group, mainly women

were selected approx. 35 km away in Tangkiling, a village situated at a different

river system. The urine levels of this group were low during the analysis,

performed during the field project. The urine levels were confirmed in the later

re-analysis in the University laboratory (see Figure 4). But unexpectedly the

blood and hair analysis showed increased levels of mercury in these

11

RT2004-016-00 CETEM/MCT

participants (see Figure B6 and 8). Nevertheless, this is in accordance with the

indications from the environmental assessment, namely a elevated Hg

background in sediments, a reatively high Hg mobility and a high Hg

biovailability, which is likely related to existing dark water rivers in the area.

The medical score sum between the control group in Sulawesi, and the

group in Tangkiling also differs (see Figure 18 and 19). Fish eating habits

contribute to the internal exposure leading to the hypothesis that the population

in Tangkiling is exposed through fish from the local river (see Figure 9, 10. 11).

For the statistical analysis Tangkiling was considered to be another exposed

area, and only the control group from Air Mandidi (Sulawesi) was used for all

statistical comparisons.

The mercury levels in the bio-monitors urine, blood and hair were

significantly higher in all exposed populations than in the control group (see

Figure B3 to B10). Mainly amalgam-smelters showed mercury levels above the

toxicological threshold limit HBM II in urine, blood and hair. Mainly inorganic

mercury contributes to the high body burden of the workers.

Some few cases, all from Galangan in Kalimantan, showed extreme high

mercury concentrations in blood and extreme high concentrations of organic

bound mercury in hair. This may be explained by fishing in heavily mercury

contaminated pit holes in this mining area, as observed from the results of Hg

in fish from the flooded open pits.

Typical symptoms of mercury intoxication were prevalent in the exposed

groups. The medical score sum plus the bio-monitoring results made it possible

to stablish in Tatelu (Sulawesi) in 33 out of 61 amalgam-smelters the diagnosis

of a chronic mercury intoxication, and in 4 out of 17 mineral processors. Within

the other population in Tatelu 2 out of 18 people showed a mercury

intoxication. In the control group there was no case of a mercury intoxication.

In Kereng Pangi (Kalimantan) in 41 out of 69 amalgam-smelters the

diagnosis of a chronic mercury intoxication was made, and in 13 out of 30

mineral processors. Within the other population in Kereng Pangi 23 out of 67

people showed a mercury intoxication. In the Tangkiling group 8 out of 36

people were found to be intoxicated, and 4 out of 10 former miners.

Children working with mercury were found as intoxicated in 9 out of 51

children in Tatelu, and 2 out of 8 children in Kereng Pangi. Children not

working, but living in the exposed areas were intoxicated in 5 out of 27 cases in

Kereng Pangi and in no case in Tatelu. None of the children from the control

area are intoxicated.

The percentage of intoxications among amalgam-smelters is similar in

Tatelu (54,1%) and Kereng Pangi (59,4%). In Rwamagasa / Tanzania 25,3% of

amalgam smelters were found to be intoxicated, and in the gold mining area of

Mt. Diwata in the Philippines, 85.4 % of the amalgam-smelters were intoxicated

(Drasch 2004b, Drasch 2001). The difference cannot be explained by a different,

i.e. a safer burning technique in Rwamagasa. Moreover, it must kept in mind,

that the maximal burden (as expressed in the top mercury concentrations found

12

RT2004-016-00 CETEM/MCT

in the bio-monitors) was even higher than in Mt. Diwata. In the less exposed

population and the children, the rates of intoxication are much higher in Kereng

Pangi.

An explanation for these differences cannot be found only in the

amalgam smelting techniques. The main difference between Tatelu and Kereng

Pangi is, that in Tatelu the general population does not live within the mining

area itself, so they are less exposed. And the difference to Mt. Diwata is that the

Galangan area around Kereng Pangi is flat compared the mountainous area of

Mt. Diwata. The difference to Tanzania might be explained by the much lower

exposure to liquid mercury in Rwamagasa, due to a lower output of gold from

the ore.

Child labour in the mining sites is very common from the age of 10 years

of age and upwards, the children work and play with their bare hands with

toxic mercury. Mercury can cause severe damage to the developing brain. It is a

dramatic outcome, that already 17,6% of the children working with mercury in

Tatelu and 25% of the children working in Kereng Pangi with mercury,

respectively 18,5% of the children living in Kereng Pangi, had a mercury

intoxication. E.g. in Kereng Pangi some gold-smelting shops (Toko Mas) are

situated opposite the mosque and one school.

Nursed babies of mothers living in Kereng Pangi are at special risk. In 10

out of 15 breast-milk samples of nursing mothers, mercury levels were above

comparison levels of 2 µg/l. In two cases the levels were extremely high, well

above reference dose levels of US-EPA.. In addition to a placental transfer of

mercury during pregnancy from the mother to the foetus (as has been proved in

other studies) this high mercury burden of nursed babies is a new, up to now

unknown health hazard in mining communities.

Poverty is a main reason for the bad health status of the small-scale

mining communities. Struggling for pure survival makes mining for gold a

necessity to find any financial resource. The daily fight of survival forces the

miners put their own health and the health of their children at risk.

A reduction of the release of mercury vapours from small-scale gold

mining as in Indonesia into the atmosphere will not only reduce the number of

mercury intoxicated people in the mining area proper. It will reduce the global

pollution of the atmosphere with mercury, because most of the mercury vapour

formed by the open burning of gold amalgam is not deposited locally, but is

transported by air over long-range distances all over the globe (Lamborg 2002).

The total release of mercury vapour from gold mining is estimated today up to

1,000 metric tons per year (MMSD 2002), while from all other anthropogenic

sources approximately 1.900 tons were released into the atmosphere (Pirrone

2001).

The primary result is, that mercury is a serious health hazard in the

small-scale gold mining areas of Tatelu (Sulawesi) and Kereng Pangi

(Kalimantan). Working for many years in the amalgamation or burning process,

especially amalgam-burning resulted in severe symptoms of mercury

13

RT2004-016-00 CETEM/MCT

intoxication. The exposure of the whole community to mercury is reflected in

raised mercury levels in the urine, and symptoms of brain damage like ataxia,

tremor and movement disorders. In over 50% of the amalgam-smelters from

both areas a mercury intoxication (according to the definition of UNIDO (Veiga

2003)) was diagnosed. Former miners, mineral processors and the general

population in the mining areas were also intoxicated. Especially frightening are

high levels of mercury in breast milk samples in Kereng Pangi (Kalimantan),

and the high incidence of child labour. This high incidence of child labour

ensues in the very early child mercury intoxication in both areas.

The background burden in the control group in Air Mandidi (Sulawesi)

is in the same order of magnitude as in western industrial countries.

Although mercury is heavily burdening the environment in North

Sulawesi, health hazards due to methylmercury exposure, as indicated by

results in fish, hair, blood and breast milk, are more likely occurring in Central

Kalimantan. This may be explained by a combination of factors, namely the

adverse living conditions in Galangan that make the population dependent on

fishing in flooded open pits; a high mercury bioavailability in dark water

systems, and an increased mercury background in the local environment, as

indicated by the environmental assessment. In contrast, there is a lack of

pathways between methylmercury present in the environment and the local

population in North Sulawesi, since the availability of fish in the Talawaan

River is very limited, resulting in consumption from marine fish. On the other

hand, it is predictable that the huge mercury burden found in both biological

and inorganic samples from the Talawaan River is also, to a certain extent,

taken up by the marine biota occuring in the Manado Bay.

14

RT2004-016-00 CETEM/MCT

1. Introduction

The present report describes the results achieved in two small scale gold

mining areas in Indonesia in North Sulawesi and Central Kalimantan - as

target areas of the environmental and health assessment (E&HA) conducted by

the Centre for Mineral Technology (CETEM) and the Institute of Forensic

Medicine (IFM-University of Munich) under the general coordination of the

United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO). The E&HA is a

part of the GEF/UNIDP/UNIDO Global Mercury Project - Removal of Barriers

to the Introduction of Cleaner Artisanal Gold Mining and Extraction

Technologies.

In order to identify sites with high concentration of mercury (hotspots) a

sampling campaign of soils, sediments and biota was conducted, consisting of

768 samples split into 420 biological indicators as fish, plants and shells, and 348

inorganic indicators as sediments, soils and water. The present report describes

characteristics of environmental samples and results of mercury analyses in

samples from Indonesian gold mining areas in Talawaan (North Sulawesi) and

Galangan (Central Kalimantan). An attempt to describe the distribution of

mercury and to achieve an environmental assessment of mercury pollution is

presented. A research team comprizing 11 scientists from CETEM (7 members)

and IFM (4 members) proceeded to Indonesia in September 2003 and has

accomplished the sampling campaign within 35 days.

The Health Assessment project is part of a major UNIDO project to

remove "Barriers to the Introduction of Cleaner Artisanal Gold Mining and

Extraction Technologies", which is performed in six countries. The main

funding comes from GEF through UNDP to UNIDO. The University of Munich

is subcontractor to CETEM for the health assessment in Indonesia.

The aim of the subcontract was to undertake two medical investigations

of approximately 250 people living in the Karang Pangi area (Kalimantan), and

of approximately 250 people living in the Tatelu area (Sulawesi), both in

Indonesia. The ultimate aim of the whole UNIDO project is to reduce mercury

losses in the project demonstration sites by means of introducing new

technologies, while improving the income of the miners through more efficient

recovery, increasing knowledge and awareness, and providing policy advice on

the regulation of artisanal gold mining with due consideration for gender

issues.

Over 100 years ago, the Dutch complained of artisanal gold mining in the

nearby Ratatotok region in the North Sulawesi, and illegal miners still operate

in that region. In 1997, the awarding of a gold mine concession to the Aurora

Mining Co. of Australia in the Dimembe Sub-district in the North Sulawesi

Province, northeast of Manado City, gave rise to a gold rush of artisanal miners

to the area and this rush has expanded to include thousands of miners

(Limbong et al., 2003). According to this author, fluctuation of Hg levels in

water and sediment in relation to the sampling sites and gold processing plant

15

RT2004-016-00 CETEM/MCT

locations within the Talawaan Watershed provide insight into the pathway of

Hg dispersion from gold processing plants throughout the river system.

Increasing Hg levels in fish samples provided strong indication of a high

bioaccumulation within this contaminated area.

Mercury

Mercury is a silvery-white shiny heavy metal, liquid at room

temperature. Mercury exists in different forms:

- Metallic (elemental) mercury (Hg0)

- Liquid in room temperature (less toxic), as mercury vapor highly toxic

- Inorganic mercury (salt of Hg2+)

The lungs absorb 80% of mercury vapour. Target organs are the brain

(cerebellum) and the kidney. Mercury is a neurotoxin, nephrotoxin and

teratogen. Mercury can cause acute and chronic intoxication.

Chronology of the Field Work in Indonesia

August 2nd 2003 (Munich Jacarta) IFM´s staff proceeded to Jacarta;

August 4th 2003 (Jacarta Palankaraya/Kalimantan) IFM´s staff proceeded to

Palenkaraya, and on the next day to the Central Kalimantan mining area;

August 15th 2003 (Palenkaraya Manado) IFM´s staff transfer to Manado;

August 17th 2003 (Manado Talawaan) IFM´s staff proceeded to the Talawaan

area;

August 29th 2003 (Talawaan Manado) IFM´s staff transfer to Manado;

August 30th 2003 (Rio de Janeiro Jacarta) CETEM´s staff proceeded to

Jacarta, and one day later to Manado;

September 1st 2003 IFM´s and CETEM´s staff meeting with Indonesian

Projects´s counterparts in Manado for Field Work Briefing;

September 2nd 2003 (Manado Talawaan) CETEM´s staff proceeded to the

Talawaan area; IFM´s staff proceeded back to the office;

September 12th 2003 (Talawaan Manado) CETEM´s staff transfer to Manado;

September 13th 2003 (Manado Palenkaraya) CETEM´s staff transfer to

Palankaraya, and one day later to the Central Kalimantan mining area;

September 25th 2003 (Palenkaraya Jacarta Rio de Janeiro) CETEM´s staff

proceeded to Jacarta, and one day later back to the office for laboratory work

and Field Work Report.

16

RT2004-016-00 CETEM/MCT

1.1. Location of the Study Areas in Indonesia

A large number of artisanal gold mining workers in Indonesia indicates

that this activity has great importance as an informal employment opportunity

in rural areas. However all related processes of separating gold ores using

mercury are undertaken with a low level of technical knowledge and skills, no

regulation, and with disregard for the safety of human health and environment.

The situation is generating serious potential health and environmental risks.

According to official estimates of Department of Energy and Mineral Resources,

there were more than 500 locations where some 100,000 illegal small-scale gold

miners were active in 2000, whereas more than 500,000 people depend on this

activity for their livelihood (Aspinall, 2001). Artisanal and small scale gold

mining covers West and Central Java, Sumatra, Central and East Kalimantan,

North Sulawesi and others, while nearly 180 tonnes of mercury are released to

the environment annually (UNIDO, 2002).

1.1.1. North Sulawesi - Talawaan

North Sulawesi is a region in the Celebes Sea. Manado is the capital of

North Sulawesi, and has approx. 600.000 inhabitants.

Manado is beautifully situated directly at the sea, and Manado Bay is

surrounded by some famous islands, for example Bunaken island. Bunaken

National Marine park is well known for its beautiful coral reefs, which are a

tourist attraction. Three small rivers drain into this bay. They origin from the

Talawaan watershed, approx. 20 to 30 km away from Manado. These rivers

come from the Klabat mountain in the mining area of Tatelu. The countryside is

very hilly, and dominated by palm trees, and intensive farming. Gold fish is

cultivated in fish ponds in the Talawaan area.

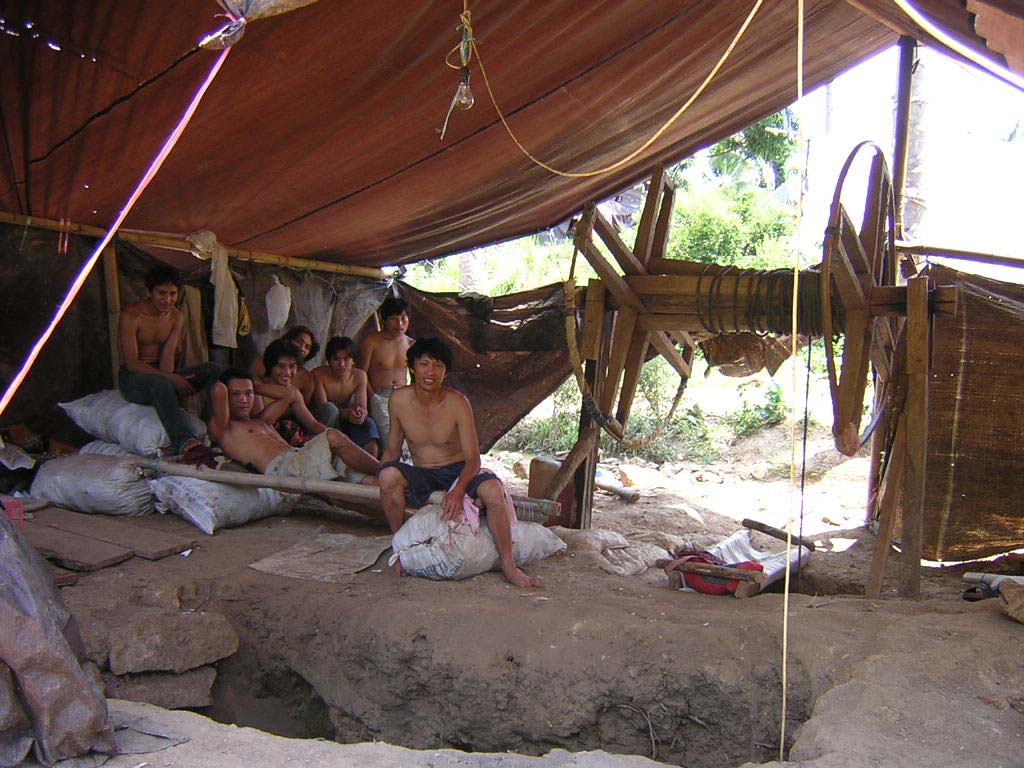

Tatelu is a small village with approx. 2.000 inhabitants. Next to the

village is the mining area. The ore is mined up in the mountains. A group of 15-

20 miners live in very basic camps beside their tunnel.

The tunnels have a small diameter, just enough that one person can fit in,

and are dug by hand. Tunnels are not very deep, approx. 20-35 meters. The

miners try to follow veins, so tunnels are curved, and tend to be very steep.

Miners work in shifts.

Although mainly young men work and live here, some women and a

few children also live near the tunnels. The ore is carried out in sacks, and the

sacks are brought downhill (approx. 30 minutes away) with the support of

buffalo carts.

The processing area is still dominated by men, but many women and

quite a few children live here too. Numbers of active miners in the mountain

and in the valley seem to vary, most estimations were close to 2.000 active

miners.

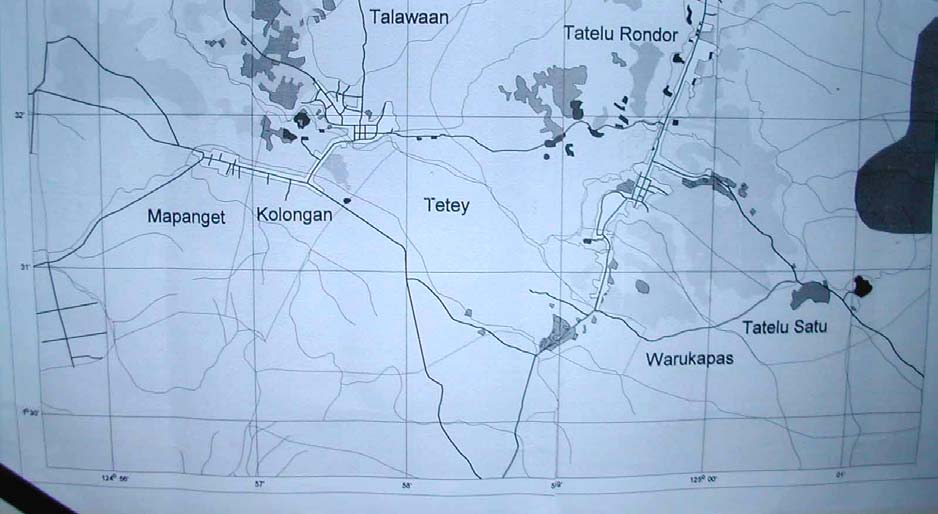

In the Talawaan region, located at the Northern part of Sulawesi Island,

the main mining area (N 001° 31` 51,2" E 124° 58` 53,2") lies in the Dimembe

17

RT2004-016-00 CETEM/MCT

sub-district, between the villages of Talawaan and Tatelu besides a small creek,

draining into Talawaan River and supplying water for small scale gold mining

(SSM) activities.

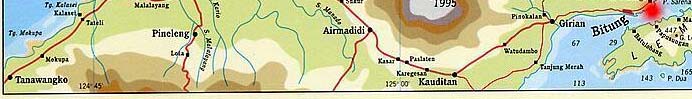

The Talawaan watershed drains from the peak of Mount Klabat (the

highest point with 1.995 m), into the western coast of Kabupaten Minahasa and

Kota Manado. Mining activity is extended throughout an area of 34.400 ha.

The study area includes the drainage basins of the Talawaan and Tatelu

River. The drainages flow through the main gold processing units where

mercury is widely used and released. About one third of the coastline of the

area is within the boundary of the Bunaken National Marine Park. The coastal

environment includes mangrove areas and coral reefs.

Over 100 years ago, there were artisanal gold mining activities in the

nearby Ratatotok region in North Sulawesi, whereas illegal miners still operate

in that region. In 1997, the awarding of a gold mine concession to the Aurora

Mining Co. of Australia in the Dimembe Sub-district in the North Sulawesi

Province, northeast of Manado City, gave rise to a gold rush of artisanal miners

to the area and this rush has expanded to encompass thousands of miners

(Limbong et al., 2003).

The distance from the peak of Mount Klabat to the sea is approximately

20 km. Talawaan and Bailang Rivers flow through the main center of the

mining area (Figure 1). Land use in the Talawaan Watershed is primarily

agricultural and is dominated by plantations of coconut, clove, and nutmeg.

There are also associated areas of irrigated rice cultivation and fishponds.

Cattle, pigs, goats, chickens and ducks are reared in the region.

There is no important industry located along the banks of the main rivers

(Martens, 2000). Fishing is carried out in the coastal areas, and crabs and

molluscs are also collected in the area for human consumption. There are also

small aquaculture activities around brackish water in the area.

The population of the area is estimated to reach approximately 150,000

inhabitants (Martens, 2000). The majority of households in the area are

dependent upon agriculture as their main source of income and sustenance, but

the number of individuals involved in gold mining has increased rapidly since

1998.

The mining areas are located in the villages of Tatelu, Warukapas,

Rondor, and Talawaan of the Dimembe sub-district. By June 2001, there were

approximately 400 gold processing plants in the entire area, while nowadays it

is estimated a number of 130 units in the Tatelu area alone. The processing

plants are mostly built close to river margins. Processing plants are primarily

located in the upper part of the watershed. This mining area is more accessible

than other mining areas in the North Sulawesi Province, since it is located in an

agricultural area near the villages, and is also close to Manado, the capital of the

province.

18

RT2004-016-00 CETEM/MCT

According to results obtained by Limbong et al. (2003) the fluctuation of

Hg levels in water and sediments in relation to the sampling sites and gold

processing plant locations within the Talawaan Watershed provide insight into

the pathway of Hg dispersion from gold processing plants throughout the river

system. Increasing Hg levels in fish samples provided strong indication of a

high bioaccumulation within the area. According to the authors, environmental

contamination due to Hg from artisanal gold mining activities is elevated.

Therefore, reduction of Hg emission from the processing plants should be of

immediate concern. A regular monitoring program would be necessary in order

to better elucidate the rate of bioaccumulation and biomagnification. Such a

program would also facilitate a more detailed risk assessment regarding human

health issues.

TALAWAAN

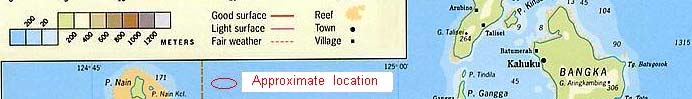

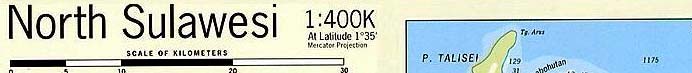

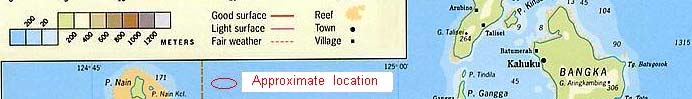

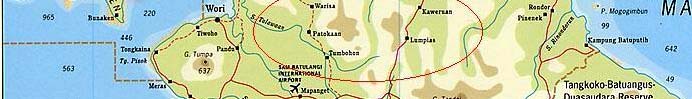

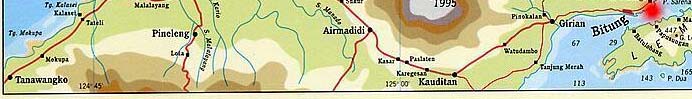

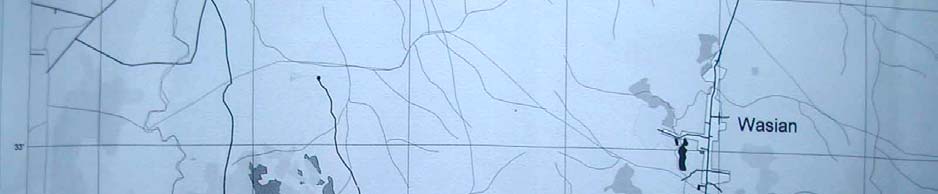

Figure 1 - Approximate location of the Talawaan Watershed. Source:

perso.wanadoo.fr/pnoel/ map_sula.htm

19

RT2004-016-00 CETEM/MCT

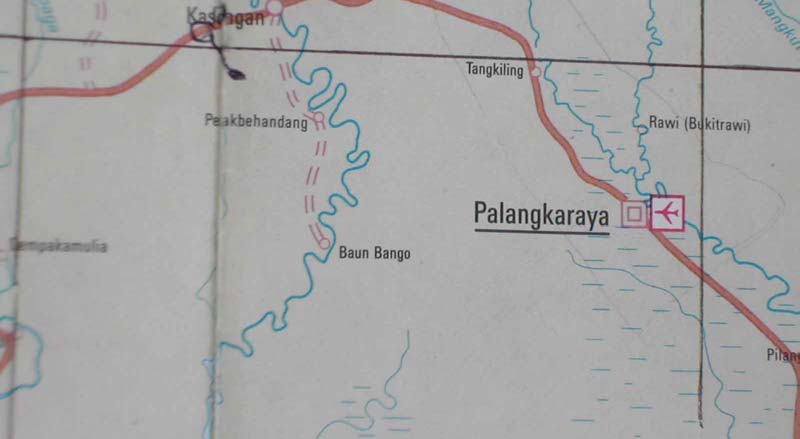

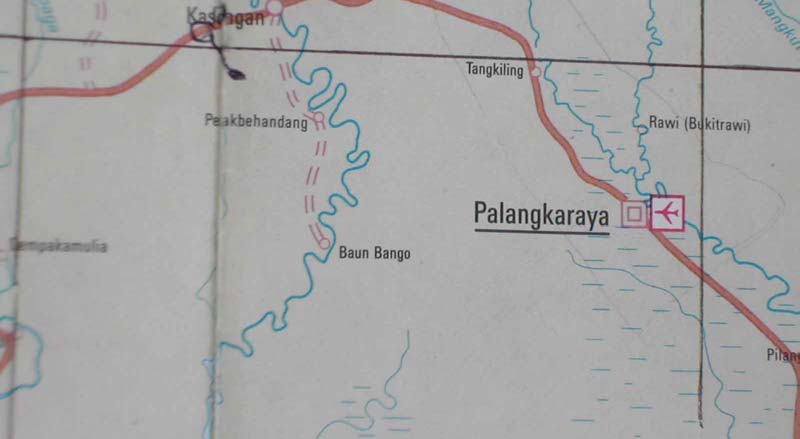

1.1.2. Central Kalimantan - Galangan

Katingan District, located in the southern-central part of the Island of

Kalimantan, also known as Borneo Island, the main mining site is Galangan

(001° 59' 16,4" S 113° 17' 09,1" E), also known as Ampalit, lying on the right

margin of the Katingan river which drains into the Java Sea about 200 km to the

South (Figure 2).

Galangan mining site is located just 7 km away from Kereng Pangi

village, district of Katingan, which provides infrastructure for miners in

Galangan.. This region can be reached by automobile, taking 90 minutes from

Palangkaraya (the capital city of Central Kalimantan Province). The geographic

coordinates of this region are from 01°56,563' S to 02°00,349' S and 113°16,565' E

to 113°17,182' E.

In Central Kalimantan from Palangkaraya airport it takes approximately

40 minutes by car to Tangkiling (control area), and another 30 minutes to

Kasongan (District capital). Another 20 minutes further to the west is located

the village of Kereng Pangi (mining town).

The climate is wet tropical with mean daily temperatur of 32 °C and two

main seasons, a dry season helding from May to September and a rainy season

from October to April. The approximate precipitation in the rainy season reachs

271-418 mm, whereas in the dry season these values decrease to 33-179 mm.

The earliest incidence of small scale mining activity in Central

Kalimantan has begun at Tewah-north of Palangkaraya, upstream of Kahayan

River, in 1987. Illegal miners worked at several places in the area belonging to

the mining company PT. Tambang Tewah Perkasa. The places known as

Gudang Setengah, Sumurmas, and Batu api were target, whereas the

Sumurmas village formed due to the mining activity. The Indonesian

Government has undertaken various programs and implemented law

enforcement to regulate their activity. Nevertheless, from these locations illegal

mining spread all over Central Kalimantan, one of them known as Galangan (J.

Dwipriambodo Report, 2003).

Galangan is on the eastside of the Contract Work Area of PT. Ampalit

Mas Perdana (Gold Mining Company) that recently stopped its activities in the

area.

The small scale gold mining activity has begun in this area in 1998, while

at the end of 1999 there were at least 437 processing units. In the middle of year

2000 more miners came and so this number increased to more than 500 units

(according to the monitoring data of August 2000, Mines and Energy Office of

Central Kalimantan). Since each unit is operated by 4-6 worker, so there are at

least 2,500 workers directly involved in the mining activity in this area.

Most miners came to Galangan from outside this island, most of them

from Java, South Kalimantan and Madura, before ethnical conflict of 2001,

when hundreds of miners were killed, being the remaining miners from

20

RT2004-016-00 CETEM/MCT

Madura expeled. The causes of this gold rush in Galangan can be described as a

combination of the following factors:

- impact of the Indonesian economic crisis in the middle of 1997 that

caused significant unemployment;

- Easy

accessibility;

- Relatively simple technology and low capital cost.

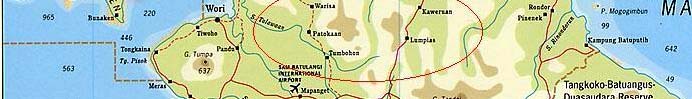

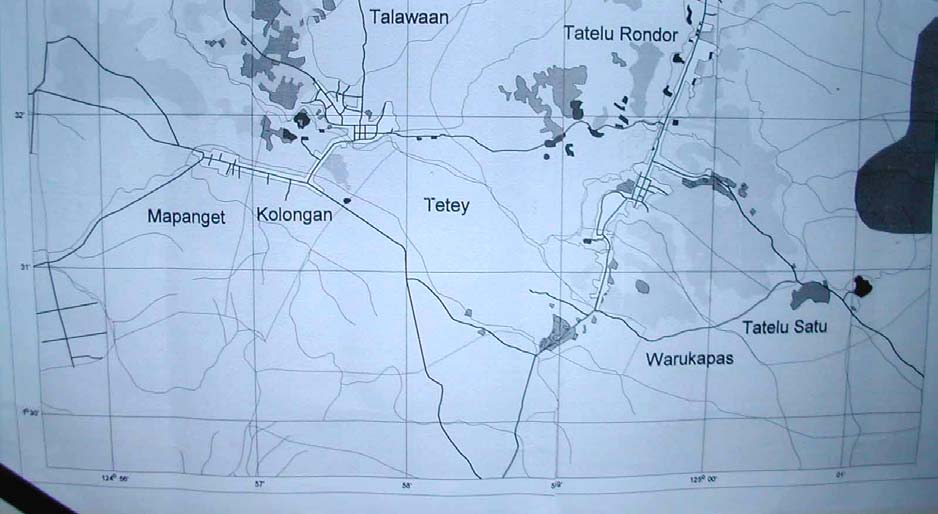

Figure 2 - Map of study areas in the Galangan Mining site (Central

Kalimantan)

21

RT2004-016-00 CETEM/MCT

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Environmental Assessment

2.1.1. Sampling estrategy

A sampling campaign of soils, sediments and biota was conducted,

consisting of 768 samples split into 420 biological indicators as fish, plants and

shells, and 348 inorganic indicators, as sediments, soils and water in order to

address both the identification and evaluation of mercury hotspots.

Amalgamation tailings dumped into drainage systems originate hotspots of

metallic mercury (mining hotspot), where abnormally high concentrations are to

be found in the heavy fraction of sediments.

Due to its typical heterogeneous distribution, one may face enormous

difficulties in locating a mining hotspot of mercury and its dispersion patterns

downstream in a given mining area, as conventional geochemical exploration

techniques have been used unsuccessfully in previous studies. Therefore, the

introduction of novel sampling and analytical methods has been required,

including in situ mercury analyses by either a semi-quantitative colorimetric

method or a quantitative field analyser.

Individual and composite substrate (soil and sediment) samples were

collected with an plastic shovel, labeled, and stored in plastic bags. Composite

samples were obtained mixing sub-samples in the plastic bags.

Sampling and analysis of total suspended solids (TSS) and water in

aquatic systems play a pivotal role in assessing mercury mobility and the

nature of pollution. Mercury transported either in solution or onto suspended

particles may be deposited in riverside deposits forming mercury sinks, which

are potential sources for mercury remobilization, since mercury is adsorbed

onto fine particles and prone to form soluble complexes, mainly in the presence

of humic substances. Therefore, high contents of organic matter in sediments

have been sought during sampling.

Simple sampling methods, consisting of pan concentrates for mercury

analysis were also used for locating mercury hotspots. Another approach

enables the reconstruction of the local mining history and the identification of

amalgamation tailings, through establishing confidence among miners and

researchers, so that they agree to indicate places where former activities have

been conducted.

Some physiochemical parameters are considered important for assessing

the mobility of mercury in the environment, and its eventual bioaccumulation

and/or biomagnification in fish, mainly as methilmercury. Therefore,

physiochemical parameters of water, such as temperature, electrical

conductivity, pH and dissolved oxygen were determined in the drainage waters

by multi-electrodes.

22

RT2004-016-00 CETEM/MCT

Since sampling of TSS by filtering through 0.45 µm membranes has been

reported in some cases as controvertial, due to its unefficiency of recovering

enough solid material for analysis, it was sought naturally settled TSS samples

where favorable hydrodynamic conditions were to be found.

Fish samples were collected by gill-netting and fishing line with a fish-

hook. Each specimen was weighed (Wt), and its length (Lt) was measured at the

time of collection.

Plant samples were collected manually or using a shovel to dig out the

roots, washed several times, labeled, stored in plastic bags and frozen.

Approximately three replicates of each specimen were collected. In laboratory,

plants samples were washed with tap water and cleaned with a small brush to

remove potential aerial superficial mercury contamination. Roots, stems and

leaves were analyzed separately. Wet materials were used to obtain total

mercury concentrations in plant parts. Water contents in plant samples were

utilized to transform wet weight concentration to dry weight concentration.

2.1.2. Sample Preparation and Analyses

Preparation of sediment, soil and tailing samples consisted of

homogenization followed by wet sieving for separating grain size fractions

above and below 200 # (74 µm). After that, each fraction has been dried at 40 °C

for analysis.

After removing the individual axial muscle (fillet) of fish, each sample

was placed in polyethylene bags and in ice boxes, and frozen after reaching

hotel facilities.

The method used in the laboratory for the determination of total mercury

in environmental samples (soils, sediments, fish) follows the methodology

developed by Akagi and Nishimura (1991). It involves acid digestion followed

by reduction to elemental mercury, aeration and measurement of mercury

absorption with cold vapor atomic absorption spectrometry.

The sample digestion procedure insures complete digestion of organic

materials and at the same time avoiding mercury loss by using a combination of

acids and oxidizing agents. This combination involves a mixture of nitric,

perchloric and sulfuric acids. Additionally, water is added to protein-rich

samples, to avoid frothing upon heating. The sample is then heated at 250oC for

20 minutes. The sample solution is reduced by staneous chloride, generating

elemental mercury vapor, which is then circulated in a closed system.

Absorbance is measured when equilibrium of mercury vapor between gas and

liquid phases is reached. The use of a syringe with needle when adding the

reducing agent avoids loss of mercury by vaporization. The detection limit of

the method is 0.5 ng Hg.

Hg was analyzed in the fish muscle through Atomic Absorption

Spectrophotometer (KK.Sanso SS) using a Vapor Generation Accessory-VGA

(CVAAS). For the analysis of Hg-total, approximately 0.5 g of tissue was

23

RT2004-016-00 CETEM/MCT

weighed in 50-ml-vol flasks, to which was added 2 ml of HNO3-HClO4 (1:1), 5

ml of H2SO4, and 1 ml of H2O (Hg free), and heated on a hot plate to 230-250°C

for 20 minutes. After cooling, the digested sample solution was made up to 50

ml with water. An aliquot (5 ml) of digested sample solution was introduced in

the Automatic Mercury Analyzer Hg 3500. The difference in duplicate sample

analyses was less than 10% (precision of measurements was 90%). The accuracy

of analyses was estimated with analyses of biological tissue standard reference

materials from International Atomic Energy Agency. The results indicated that

sample preparation and analytical procedures consistently produced accurate

measures of Hg concentrations.

2.1.3. Statistical Analyses

Statistical significance between Hg concentrations and allometric

parameters (weight and length) among fish from different SSM sites were tested

using parametric Student's T-test after Levene's test for equality of variance, or,

if the underlying assumptions for parametric testing are not met, a

nonparametric test of significance, the Mann-Whitney U-test was employed.

The significant level considered was the probability level 0.05. Correlation

analyses were determined with both the Pearson correlation coefficient and/or

the Spearman rank correlation coefficient. Significance of the correlation was

determined with a two-tailed Student's t test. One-way ANOVA followed by

Duncan pos-hoc were performed when appropriate for testing differences

among groups.

Quality assurance/quality control (QA/QC) concerns were addressed

through the use of analytical duplicates. Analytical duplicates were included

with each sample, and duplicate analyses for each sample were checked to

assure that the relative percent difference between duplicates was no greater

than 10%.

2.2. Health Assessment

2.2.1. Material and sample storage

From 492 participants in Indonesia 491 blood samples, 492 urine samples

and 488 hair samples were taken. The blood samples were taken in EDTA-

coated vials. The urine samples were acidified with acetic acid. To avoid de-

gradation, all blood and urine samples were stored permanently and

transported by flight to Germany in an electric cooling box. Until analysis these

samples were stored continuously at 4 °C.

2.2.2. Study Setting and Clinical Examinations

The "Protocols for Environmental and Health Assessment of Mercury

Released by Artisanal and Small-Scale Gold Miners" were developed by

24

RT2004-016-00 CETEM/MCT

UNIDO in collaboration with the Institute of Forensic Medicine, LMU of

Munich, and other international experts (Veiga 2003).

The declaration to volunteer was translated in Bahasa Indonesia as well

as the "Health Assessment Questionnaire" (Appendix 2). The questionnaire

was used to examine the general health condition of members of the mining

communities and to indicate symptoms of mercury poisoning. Anamnestic /

clinical / neurological / toxicological tests were used according to the state of

the art. Participants were examined to identify neurological disturbances,

behavioural disorders, motor neurological functions, cognitive capabilities,

balance, gait, reflexes etc.. The data was compiled for statistical purposes and

maintain confidentiality regarding all health related issues. All participants

were physically examined including neurological testing.

2.2.3. Health Project in the Field

The health project in the field took place from the 2nd of August 2003

until the 8th of September 2003. In Kalimantan the equipment was set up in the

health centre of Kereng Pangi, in Sulawesi in the village hall of Tatelu. Both

facilities were sufficient to perform the examinations, including a mobile

analysis of Hg in urine samples (examination rooms for the team, electricity,

toilet, water).

Team members for the health project in the field were Dr. med. Stephan

Boese-O´Reilly (paediatrician, master of public health, environmental

medicine), Stefan Maydl (physician), Alexandra Dittmann (pharmacist) and

Sven Illig (Physician). Mrs. Selinawati was the Assistant Country Focal Point to

UNIDO and comes from the Indonesian Ministry of Energy and Mineral

Resources. Assigned to the project were nurses to assist the medical

examinations, Asnedi, Muhlis Afatzli, Lesi, Gunarti, Emilia and Susanti in

Kalimantan including Dr. Robertus Pamuryanto; and in Sulawesi J. Palit,

Perumahan Banua Buha Asri and Mrs. Marly Gumalag. These nurses

interviewed all participants.

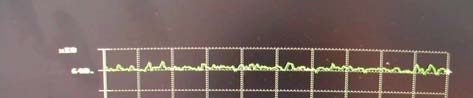

A mobile Hg analyser was used to determine total mercury in urine.

Video and photo documentation was carried out.

The control group for Kereng Pangi / Kalimantan was examined in

Tangkiling. The control group for Tatelu / Sulawesi was examined in Air

Mandidi. The same methods and teams as in the gold-mining areas were used.

The local health unit in Tangkiling supported the examination. Tangkiling is

approx 35 km away from the mining area, and mercury is not used in the

village. In Air Mandidi the local school and drinking water company supported

the examination. Air Mandidi is approx. 30 km away from the mining area, and

mercury is not used in the area.

Blood, urine and hair were analysed for mercury later at the Ludwig-

Maximilians-University of Munich, Germany.

25

RT2004-016-00 CETEM/MCT

2.2.4. Questionnaire

The participants filled in a questionnaire with assistance from the nurses.

Questions included:

Working with mercury or with mercury polluted tailings?

Burning amalgam in the open?

Melting gold in the open or with inadequate fume hoods?

Drinking alcohol?

Having a kind of a metallic taste?

Suffering from excessive salivation?

Problems with tremor / shaking at work?

Sleeping problems?

Neurological examination

All participants were clinically, mainly neurologically examined. Results

were mainly primarily scored according to ,,Skalen und Scores in der

Neurologie" (Masur 1995):

Signs of bluish discoloration of gums

Rigidity, ataxia and tremor

Test of alternating movements or test for dysdiadochokinesia

Test of the field of vision

Reflexes: knee jerk reflex and biceps reflex

Pathological reflexes: Babinski reflex and mento-labial reflex

Sensory examination

Neuro-psychological testing

The following tests were carried out (Zimmer 1984, Lockowandt 1995,

Masur 1996):

Memory disturbances: Digit span test (Part of Wechsler Memory Scale) to test

the short term memory

Match Box Test (from MOT) to test co-ordination, intentional tremor and

concentration

Frostig Score (subtest Ia 1-9) to test tremor and visual-motoric capacities

Pencil Tapping Test (from MOT) to test intentional tremor and co-ordination

26

RT2004-016-00 CETEM/MCT

Visual field test

The visual field was measured in a very simple way without the need of

any electricity. It was added to the health assessment protocol.

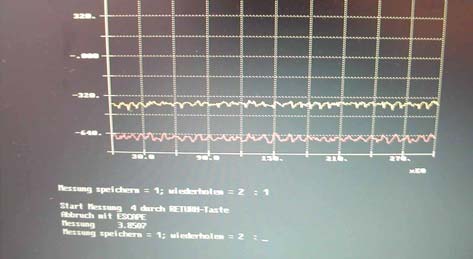

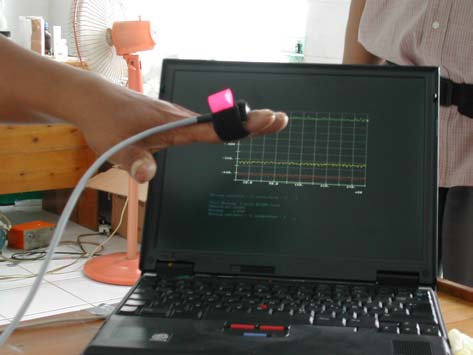

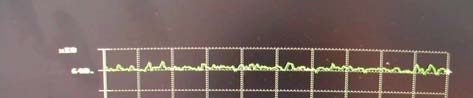

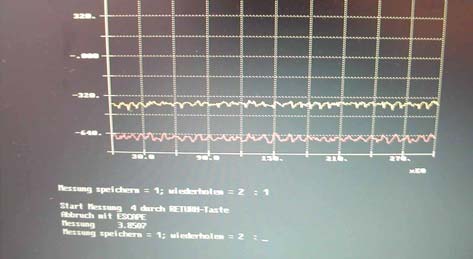

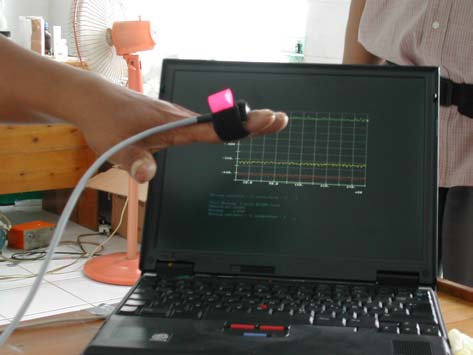

Tremor-meter

A new approach to measure tremor in a more objective way was

performed. PD Dr. Boetzel from the Neurological Clinic, University Hospital in

Munich supplied the team with an instrument to measure tremor. This

instrument is still at a developmental stage. A small sensor was placed on the

fingertip (right and then left side) of each participant. A special electronic unit,

developed by the University, measured the signal and the digital signals were

recorded onto a laptop.

Three different measurements were performed:

Arms outstretched for intentional tremor

Arms bend with the finger tip pointing to the nose for intentional tremor

Arms outstretched - moving fast for 30 cm from left to right and back for

movement analysis.

Due to a few technical problems not all participants could be tested.

There are no results yet available.

The second objective way, the video tapping of finger tremor still needs

to be evaluated, but was good to perform.

Specimens

The following specimens were taken, and two tests (Hg in urine and

proteinuria) were performed immediately:

Blood (EDTA-blood 10 ml)

Urine (spontaneous urine sample 10 ml)

Hair

If a woman was breastfeeding, she was asked for a breast milk sample (to

analyse for mercury).

The specimens urine, blood and breast milk were cooled permanently

after collection until arrival in the laboratory in Munich, Germany.

Laboratory

A mobile Hg analyser was used (Hg-254 NE, Seefelder Messtechnik,

Seefeld, Germany). It is possible to quantify inorganic mercury in urine. 1 ml

urine was diluted with 100 ml water (bottled drinking water). A 2 ml solution

of 10% tin(II)chloride in 6N hydrochloric acid was added to the water-urine

27

RT2004-016-00 CETEM/MCT

solution. The sample was analysed by atomic emission spectrometry. Bottled

drinking water was used as zero standard, and a mercuric nitrate solution as

standard. In most cases it was possible to analyse the sample. One urine sample

can be analysed in approximately 3 minutes. All urine samples were re-

analysed in the "Institute of Forensic Medicine", Munich, Germany.

Test for protein in urine

Protein in urine was tested with a commercial kit (Teco diagnostics

URS10). The test is based on the error-of-indicator principle. Test reagents are

0,3 % w/w tetrabromophenol blue; 99,7 % w/w buffer and non-reactive

ingredients. At a constant pH, the development of any green colour is due to

the presence of protein. Colours range from yellow for "Negative" reaction to

yellow-green and blue-green for a "Positive" reaction. The test area is more

sensitive to albumin than to globulin, haemoglobin, Bence-Jones proteins and

muco-protein. The test area is sensitive to 15 mg/dl albumin. The test strip was

dipped into the native urine and the result was taken after 1-2 minutes. The test

is semi-quantitative. Possible results are 0, trace, 30, 100 and 300 mg Protein / dl

urine.

Sample preparation

Hair: 20 mg 200 mg (if available) hair was cut in small pieces and weight

exactly. All mercury was extracted from the hair samples by shaking with 10 ml

hydrochloric acid 6 N for 15h at room temperature in the dark. Parts of the elute

were analysed by CV-AAS with two different reduction agents (see below).

Intentionally washing steps with water, detergents or organic solvents

like acetone were not performed before the elution. Washing procedures with

different solvents are frequently applied before hair analyses with the aim to

remove air-borne heavy metal pollution from the surface of the hair. But as

shown in literature, a distinct differentiation between air-borne and interior

mercury cannot be achieved which such washing procedures (Kijewski 1993).

Orientating pre-experiments with washing hair samples from burdened groups

supported this assumption. After washing some samples from the same strain,

the results were not reproducible. Therefore the hair samples were eluted

without any further pre-treatment.

Blood, urine: Aliquots of up to 1.0 ml were analysed directly without further

pre-treatment (method see below).

Mercury determination and quality control

The total amount of mercury in the samples (blood, urine, elute from

hair) was determined by means of so-called cold-vapour atomic absorption

spectrometry (CV-AAS), using a Perkin-Elmer 1100 B spectrometer with a MHS

20 and an amalgamation unit, Perkin-Elmer, Germany. Sodium-borohydride

28

RT2004-016-00 CETEM/MCT

(NaBH4) was applied for the reduction of all mercury (inorganic and organic