Centro de Tecnologia Mineral

Ministério da Ciência e Tecnologia

Coordenação de Desenvolvimento Sustentável

ENVIRONMENTAL AND HEALTH ASSESSMENT IN TWO

SMALL-SCALE GOLD MINING AREAS BRAZIL

SÃO CHICO AND CREPORIZINHO

FINAL REPORT

Saulo Rodrigues Pereira Filho

Project Leader

Zuleica Carmen Castilhos

Ronaldo Luiz Correa dos Santos

Allegra Viviane Yallouz

Flavia M. F. Nascimento

Silvia Gonçalves Egler

Bernhard Peregovich

Roosevelt Almeida Ribeiro

Débora Maia Pereira

Luiz Roberto Pedroso

CETEM

Luiz César Pereira da Silva

UFF

Elizabeth C. O. Santos

Edílson Brabo

Marcelo O. Lima

Kleber F. Faial

IEC

Prof. German Müller

University of Heidelberg, Germany

RT2004-004-02 Final Technical Report to UNIDO - RESERVED

April 2004

BRAZILIAN MINISTRY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY

CENTRE FOR MINERAL TECHNOLOGY CETEM

ENVIRONMENTAL AND HEALTH ASSESSMENT IN TWO

SMALL-SCALE GOLD MINING AREAS BRAZIL

FINAL REPORT

SÃO CHICO AND CREPORIZINHO

Hg

Center for Mineral Technology

Ref.: Report Requested by UNIDO, United Nations Industrial Development Organization,

No. P. 2003/007 EG/GLO/01/G34 Removal of Barriers to the Introduction of Cleaner

Artisanal Gold Mining and Extraction Technologies

April 2004

Project Staff

CETEM Centro de Tecnologia Mineral

Saulo Rodrigues Pereira Filho

Project Leader

Zuleica Carmen Castilhos

Ronaldo Luiz Correa dos Santos

Allegra Viviane Yallouz

Silvia Gonçalves Egler

Bernhar Peregovich

Roosevelt Almeida Ribeiro

Flavia Maria Nascimento

Débora Maia Pereira

Luiz Roberto Pedroso

UFF Universidade Federal Fluminense

Luiz César Pereira da Silva

IEC Instituto Evandro Chagas

Elizabeth C. O. Santos

Edílson Brabo

Marcelo O. Lima

Kleber F. Faial

Iracina Maura De Jesus

Airton Teixeira

Antônio Carlos Nascimento

Dolores Dias Santos

Edna Cabral

Francisco Monteiro

Gregório Sá Filho

José Góis Dos Santos

Luciano Oliveira

Marcos Miranda

Raimundo Paixão

Raimundo Pio Martins

University of Heidelberg, Germany

Institute of Environmental Geochemintry

Prof. German Müller

Acknowledgements

Dr. Gildo de A. Sá Cavalcanti de Albuquerque (in memorian)

CETEM's Director

Dr. Christian Beinhoff

Chief Technical Advisor

Global Mercury Project

UNIDO United Nations Industrial Development Development Organization

Dr. Marcello M. Veiga

Small Scale Mining Expert

Global Mercury Project

UNIDO United Nations Industrial Development Development Organization

Dr. Fernando A. Freitas Lins

Focal Point Brazil - Global Mercury Project

Prof. Dr. Roberto C. Villas Bôas

Assistant Focal Point Brazil - Global Mercury Project

Dr. Alberto Rogério Benedito da Silva

Small Scale Mining Expert Brazil

Dr. Arnaldo Alcover Neto

Head of Mineral Analysis Coordination

Elizabeth Costa Paiva , Sandra Helena Ribeiro, Jorge Luiz Florindo da Cruz

Analytical Technicians

José Augusto Ferreira Junior

Mineral Processing Technician

CETEM's Administration, specially, Mr. Aloisio Moura da Silva

Ms. Fátima Engel

Editing and Coordination of Report Edition

Mr. Ivo Lubrina

AMOT-MT

Ms. Luciana Boff Turchiello

SEMMA-MT

Summary

Executive Summary ............................................................................................... 3

1. Introduction .................................................................................................... 15

2. Study Areas in Brazil ....................................................................................... 18

3. Materials and Methods..................................................................................... 23

4. Results and Discussion .................................................................................... 27

4.1 São Chico................................................................................................. 28

4.1.1 São Chico reservoir and creek (sampling site A2)............................ 29

4.1.2. Mining area (tailings pile and open pit site A2)............................ 34

4.1.3. Surrounding area and Conrado River (sampling site A3) ................ 36

4.1.4. São Chico Village............................................................................ 37

4.1.5. Remote drainages (site A4)............................................................ 37

4.2. Creporizinho ........................................................................................... 40

4.2.1. Papagaio and Areal (site A5).......................................................... 41

4.2.2. Tabocal (A6) and Bofe (A7)............................................................ 42

4.2.3. Tolentino (A8) and remote areas (A9 to A11)................................. 43

4.3. Mercury in Fish ....................................................................................... 48

4.3.1. Human exposure to mercury due to fish consumption .................... 67

4.3.2. Preliminary assessment of physiological effects in fish

caused by Hg exposure .................................................................. 69

4.3.3. Bioindicators other than fish .......................................................... 73

4.4. Mining Technology and Hg Use Issues..................................................... 78

4.4.1. Alternative Processes..................................................................... 79

5. Alternative low cost method for mercury semiquantitative determination

in fish: training of local users ......................................................................... 81

5.1. Colorimetric Method for Hg Semiquantitive Analysis of Fish .................... 81

5.2. Adapting the minilab for mercury analysis in fish samples ...................... 81

5.3. Developed activities................................................................................ 82

5.3.1. Background.................................................................................... 82

5.3.2. Training new users........................................................................ 82

5.4. Application study .................................................................................... 86

5.5. Further applications................................................................................ 88

6. Health Assessment .......................................................................................... 88

6.1. Introduction ............................................................................................ 88

6.2. Area Of Study And Population .................................................................. 89

6.2.1. "São Chico" Gold Mining Area ........................................................ 89

6.2.2. Laboratory Analysis for Mercury in Urine ....................................... 90

6.2.3. Analysis of Some Variables Contained in the Index Cards

(Preliminary Results). São Chico, Itaituba, Pará-Brazil. 2003 ....... 94

6.2.4. Mercury Burden............................................................................. 98

6.3. "Creporizinho" Gold Mining.................................................................... 103

6.3.1 Laboratory Analysis for Mercury in Urine ..................................... 103

6.3.2 Analysis of Some Variables contained in Cards (preliminary

results) Creporizinho ................................................................. 105

6.3.3. Mercury Burden ........................................................................... 109

7. Conclusions ................................................................................................... 114

REFERENCES...................................................................................................... 116

Appendix 1 - Hg concentrations in sediments, tailings and soils

Appendix 2 Tables and figures of fish data

Appendix 3 - Photos of fish sampling sites and fish collected

Appendix 4 - Hg concentrations in bioindicators other than fish

Appendix 5 Semiquantitative mercury determination in fish

RT2004-004-01 CETEM/MCT

3

Executive Summary

The present report describes the results achieved in two small scale gold mining areas in

the Brazilian Amazon - São Chico and Creporizinho - as part of the environmental and health

assessment (E&HA) conducted by the Centre for Mineral Technology (CETEM) with the

colaboration of the Evandro Chagas Institute (IEC), under the general coordination of the United

Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO). The E&HA is a part of the

GEF/UNIDP/UNIDO Global Mercury Project - Removal of Barriers to the Introduction of

Cleaner Artisanal Gold Mining and Extraction Technologies.

In order to identify sites with high concentration of mercury (hotspots) a sampling

campaign of soils, sediments and biota was conducted, consisting of 647 samples. The present

report describes characteristics of environmental samples and results of mercury analyses in

sediments, soils, tailings and dust from the Brazilian gold mining areas Creporizinho and São

Chico. An attempt to describe the distribution of mercury and to achieve an environmental

assessment of mercury pollution is presented, in order to provide a better understanding of the

impacted environment.

A research team comprizing 23 research scientists from CETEM (8 members) and IEC (15

members) proceeded to Itaituba, State of Para, Brazil, on 3rd of August 2003 and has

accomplished the sampling campaign within 20 days.

Two two artisanal gold mining areas, São Chico and Creporizinho, have been selected for

undertaking the Environmental and Health Assessment in the Artisanal Gold Mining Reserve of

the State of Para, in accordance with the Project´s Coordination Unit, after considering different

criteria, as follows:

- Commitment of the miners with the project´s objectives;

- Their association with local artisanal miners leaderships;

- Production potential and economic stability of the mining activity;

- Representativeness relative to regional standards of technologies and practices;

- Accessibility;

- Spreading potential relative to the project´s achievements.

São Chico General Description

The São Chico mining site (06º 25'31"S and 56º 02'99"W) is just 2 km distant from a

landing strip and in 5 km distance from the Transgarimpeira road, which during the dry season

(June-September) can be used for transportation of equipments and supply from Itaituba, the

main town in this region with 150,000 inhabitants. Due to the bad conditions of this road, it

should be used just for transportation of goods, since the 350 km distance from Itaituba needs

some 20 hours to be overcome. The São Chico village consists only of 63 houses and 134

individuals, being 41% of garimpeiros, 6% of machinery owners, 30% of dealers, 9% of cookers,

among others. The only public service in the village is a health post for malaria diagnosis from

the National Foundation of Health (1 health assistant).

RT2004-004-01 CETEM/MCT

4

Sao Chico Creek was dammed up forming a reservoir behind the village from which

water is used for mining activities that generate mining tailings to waterways. Few families have

backyards in the village, where herbs, fruits, roots, medicinal teas and creeping plants are

cultivated. Primary forest was replaced by pasture in hillsides. Grassland species and some

small trees occur at reservoir's banks.

From the beginning of the very first gold mining activity in 1963, the São Chico village

has shown two main periods os prosperity, one in the end of the 80´s after the opening of the

Transgarimpeira road, and other in the end of the 90´s, when gold rich primary deposits were

discovered. According to cross-checked estimations, about three tons of gold were produced

from the beginning of the gold rush, corresponding to an estimated mercury emission of 7.5

tonnes to the environment. Since the primary gold ore has been crushed in hammer mills and

directly amalgamated in copper plates, and no retorts have been used, the estimated Hg:Au

(lost:produced) emission ratio is about 2.5 for this type of operation.

Nowadays, exploitation of primary gold ore is over, being gold production in São Chico

almost restricted to the reprocessing of tailings produced during the 80´s, when alluvial and

laterite deposits (baixões) were worked using just sluice box for gravity concentration, without

crushing. Tailings are now being concentrated through sluice boxes while the concentrate

follows the same processing circuit as for the former primary ore, while mercury is widely used

in both mineral processing steps, gravity concentration and amalgamation.

Creporizinho General Description

Creporizinho (S 06° 50` 14,1" W 56° 35` 00,0") is a typical gold mining village with 238

wooden residences for an estimated population of 1000 inhabitants. There are grocery shops,

pharmacies and a hotel. Two hundred children go to a primary school, where 5 teachers are

working. Few families have backyards in the village, where herbs, fruits, roots, medicinal teas

and creeping plants are cultivated.

In Creporizinho, located at km 145 on the Transgarimpeira, the Tolentino mining area is

located 10 km NNW from the village and represents 3 different types of small scale gold mining

activities: inactive alluvial deposits (including rework of former tailings and residues)

explored by hydraulic monitor (garimpo de baixão), lateritic deposits explored through open

pit and primary deposits explored through open pit or shaft (garimpo de filão). Samples were

taken in and around this area, in the village, as well as in the drainage basins nearby and

remote, including samples from Crepori River, Creporizinho River and waterbodies in

abandoned open pits.

The study sites in Creporizinho are ca. of 10 to 15 km far from the village. Creporizinho

stream flows nearby the village and is used for water supply water to mining activities.

Overbank deposits are common along its banks. There are many flooded open pits, drains of

mining tailings forming small streams along mining sites. Also herbs sprout up over mining

tailings and wastes, and pastures also replace primary forest, but forest fragments still remain in

some places. Old flooded open pits have macrophytes growing in water.

At Crepori River mining activities have been performed with dredges and hidraulic jets

at riversides. The low-water season exposes alluvial pits originated from dredge activities

during high-water season.

RT2004-004-01 CETEM/MCT

5

Since 1999 novel operations have been introduced in the Tolentino area (S 06° 47` 46,9"

W 56° 36` 27,0"), considering they have reached a sub-surface level (about 10 meters depth) with

gold veins, being 2001 identified as the higher production (said to reach 6,000 kg/year). The

owner of the Tolentino area established a partnership with a group of entrepreneurs who

assembled a plant using mainly hammer/crusher mill, hydraulic jet pumps and centrifuge

concentrators.

Environmental assessment of the mining sites ("mining hotspots")

In order to address the identification and location of mercury hotspots a sampling

campaign of soils and sediments was performed. Amalgamation tailings dumped into drainage

systems originate hotspots of metallic mercury (mining hotspot), where abnormally high

concentrations are to be found in the heavy fraction of sediments. Due to its typical

heterogeneous distribution, one may face enormous difficulties in locating mining hotspost of

mercury in a given mining site, as conventional geochemical exploration techniques have been

used unsuccessfully.

Simple sampling methods, consisting of pan concentrates for mercury analysis were also

used for locating mining hotsposts. Another estrategy, consisting of a sociological approach,

enables the reconstruction of the local mining history and the identification of amalgamation

tailings, through establishing a relationship of confidence among miners and researchers.

The "Geoaccumulation Index" (Igeo) of mercury in bottom sediments has been selected

for quantitative evaluation of contamination levels in aquatic systems (Müller, 1979). Since the

enrichment process of metals in sediments, caused by a given emission, generally follows an

exponential accumulation in fine fractions, the "Igeo" uses a log function for classifying distinct

order of magnitude of contamination, as follows:

Igeo = log2 Cn / 1.5 . Bn where,

Cn is the measured Hg concentration in the fraction -200 # and Bn is the background Hg

concentration. Moreover, the Igeo is divided into 7 classes, from 0 to 6, being class 0 indicative of

null contamination while class 6 represents an extreme contamination.

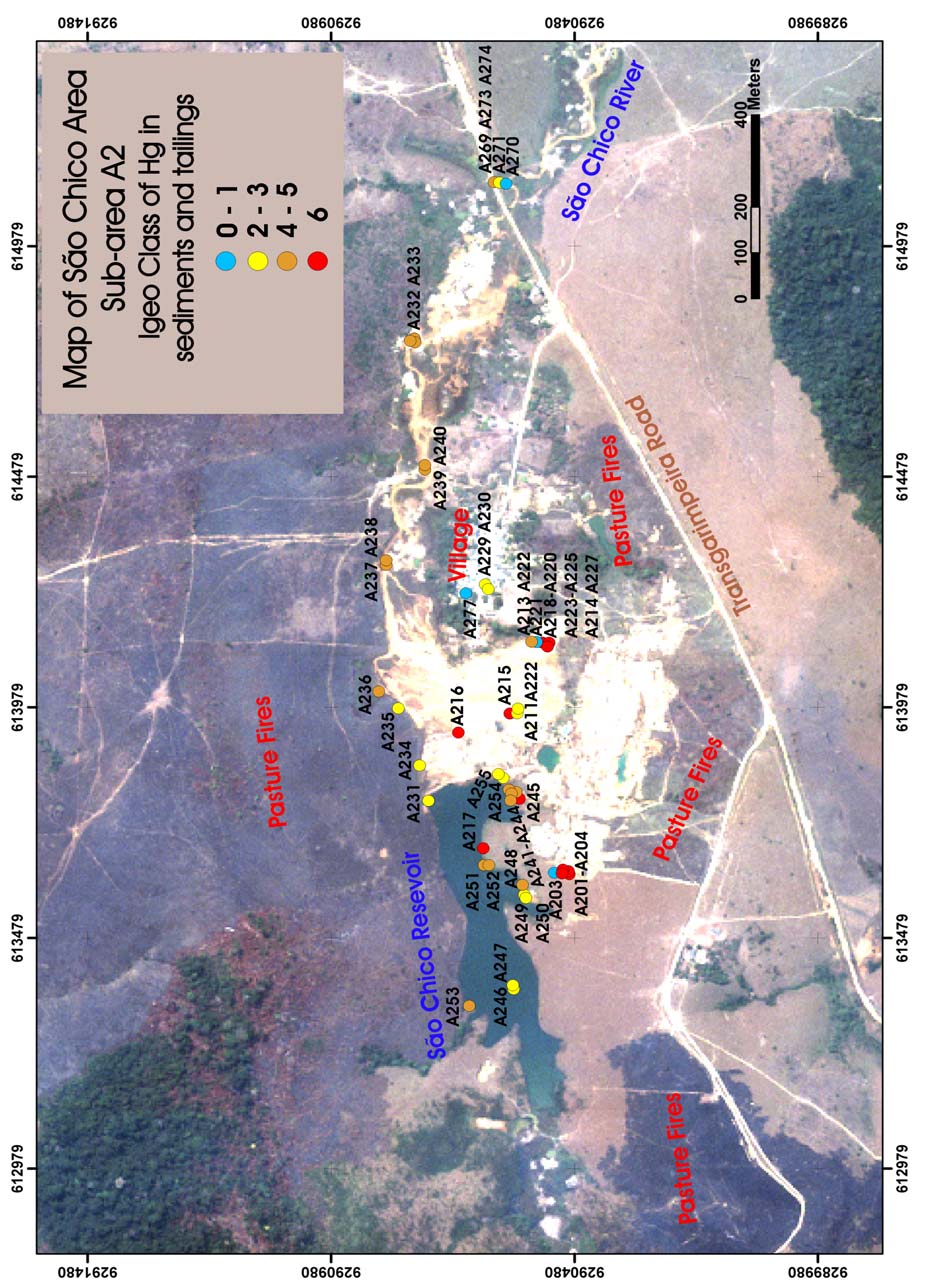

São Chico

An open pit, comprising an area of about 60.000 m2, located at the northern slope of the

valley in São Chico, represents a typical primary gold-ore deposit, as it is recently observed in

the Tapajós Gold Mining Reserve. Superficial lateritic soils got removed in the range of 2 to 10

meters in order to provide access to gold-bearing quartz-veins. Hammer mills and Hg coated

copper plates were placed and constructed in situ. At the eastern margin a very crude

cyanidation plant was constructed, operating from 1999 to 2001. Amalgamation tailings and

other wastes were poured into São Chico reservoir during this period of time. In general,

material comprise silt and sand, as a result of mineral processing of lateritic soils and weathered

rock, mainly of red and yellow colour, originated from Fe-, Mn-, and Al-oxides and

hydroxides.

In the immediate vicinity of São Chico village, 2 km downstream, some "virgin" areas

without any recent and past mining activities were encountered well suitable for

determination of natural background of mercury in sediments and soil. A sediment core,

RT2004-004-01 CETEM/MCT

6

divided into 6 sections, was taken in the bed of the small clear water bearing brook in the forest

area, where no former mining activity have been taken place.

The sediment core was 30 cm deep and revealed that Hg levels decreases with depth.

The lowest background values of the 200# fraction (< 74 µm) was around 0.15 µg/g in the

lowest 15 cm, corresponding to an Igeo class 0, and up to 0.84 µg/g at the surface, or Igeo class

2. This is probably a result of the contribution from atmospheric Hg released from

anthropogenic sources. It has been assumed that the lowest section of the core represents the Hg

background level of this region (around 0.15 µg/g), since this procedure has been successfully

adopted elsewhere (Rodrigues-Filho et al, 2002; Rodrigues-Filho and Maddock, 1997).

Mineralogy of fine sediment fractions in tropical waterways, draining lateritic terrains,

present a general composition of secondary minerals like kaolinite, gibbsite and Fe hydroxides,

and quartz. Significant variations on mineralogy are to be found in the heavy fraction of

sediments rather than in the more mobile, fine fractions.

Between reservoir and village, the valley floor is covered by mining tailings, extending

through an area of approximately 50.000 m2 with an average thickness of 5 meters, originated

from prior alluvial processing and former mining activities in primary ore veins from magmatic,

partially weathered rocks. This tailings pile has been deposited during a period of some 40

years.

A total of 38 composite samples of tailings from this part of the mining area were taken.

Following a typical heterogeneous distribution in tailings, Hg levels in this site confirm the

occurrence of a mining hotspot, reaching concentrations of up to 300 µg/g, whereas 34% of the

samples present an Igeo class 6, corresponding to Hg concentrations higher than 7.5 µg/g in the

200# fraction, and averaging an Igeo class 4.

São Chico Creek flows into Conrado River, 2 km downstream from the village, where its

water gets mixed with drainages from other mining sites, showing high turbidity. The entire

region is drained by the Conrado River, Novo River (15 km from the village) and Jamanxin

River (20 km from the village).

São Chico Creek was dammed up in 1989 at the end of a narrow valley, located around

São Chico village forming a reservoir for supplying the mining site with water to carry out

mining activities. Water covers an area of approximately 50 to 150 m width to 700 m length

(85,000 m2 surface) with an overall depth of less than 5 meters only. Outflow from this reservoir

(during dry season) amounts to less then 5 liters/second.

Since 1989, tailings from both amalgamation and cyanidation activities have been poured

into the reservoir. Due to lack of stream and turbulence nearly all of this material, in particular

suspended load, entering the reservoir could settle down and accumulate. A very small outflow

with nearly clear water feeds the São Chico creek, which drains the entire mining site and flows

through Conrado River, Novo River and Jamanxim into the Tapajós River.

A total of 17 composite samples composed of tailings mixed with sediments - including

settled suspended solids - were taken from reservoir bottom and margins. In general, sediments

comprise sand and silt, covered with a thin layer (< 5 mm) of clay or suspended load and

abundant organic matter. Close to amalgamation wastes and to a former cyanidation plant Hg

levels in sediments reach Igeo classes 5 and 6 (47% of the samples), corresponding to Hg

concentrations higher than 7.5 µg/g in the 200# fraction, while for samples collected in other

parts of the reservoir concentrations decrease to Igeo classes from 3 to 4 (53% of the samples).

RT2004-004-01 CETEM/MCT

7

Considering that these samples were composed of organic-rich clayey sediments, not directly

originated from amalgamation wastes, these values indicate that São Chico reservoir represents

both a mining hotspot, due to its proximity to amalgamation wastes, and an environmental hotspot,

as the distribution of Hg throughout the reservoir´s bottom is relatively homogeneous.

Although a less intense activity of amalgam roasting could be observed in the São Chico

village during the sampling campaign - presently just one gold shop is in operation - dust and

soil are sought to be efficient indicators of atmospheric Hg contamination. The maximum Hg

concentration (1,280 µg/g) was observed in a sample of spider web collected inside the gold

shop of the village, where no exhausting system exists. The others samples, composed of dust,

have been collected inside houses of its immediate neighborhood. Since all of then present

extremely high Hg levels, being the lowest one 20 µg/g, this suggests the need of urgent

measures towards the protection of the population living in this village.

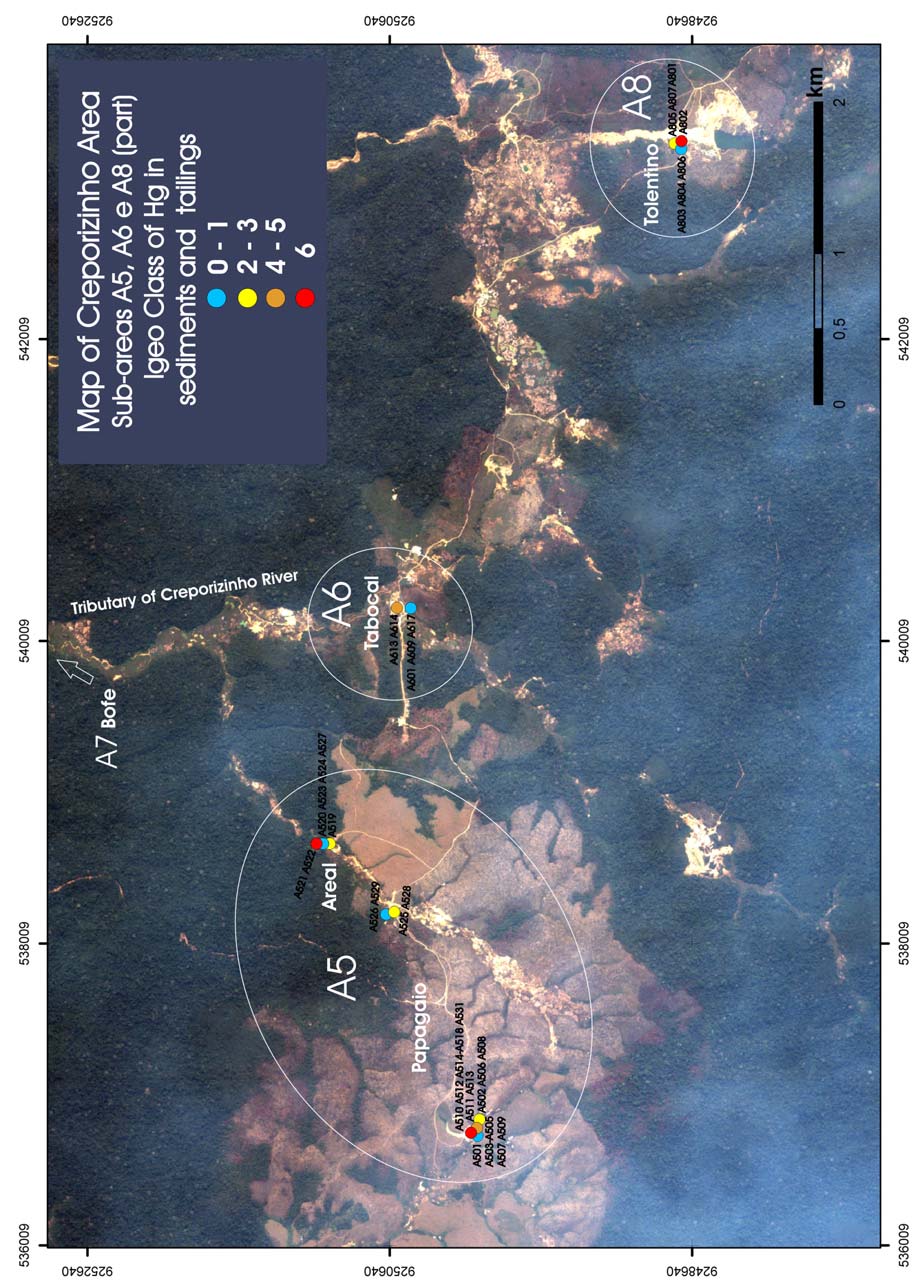

Creporizinho

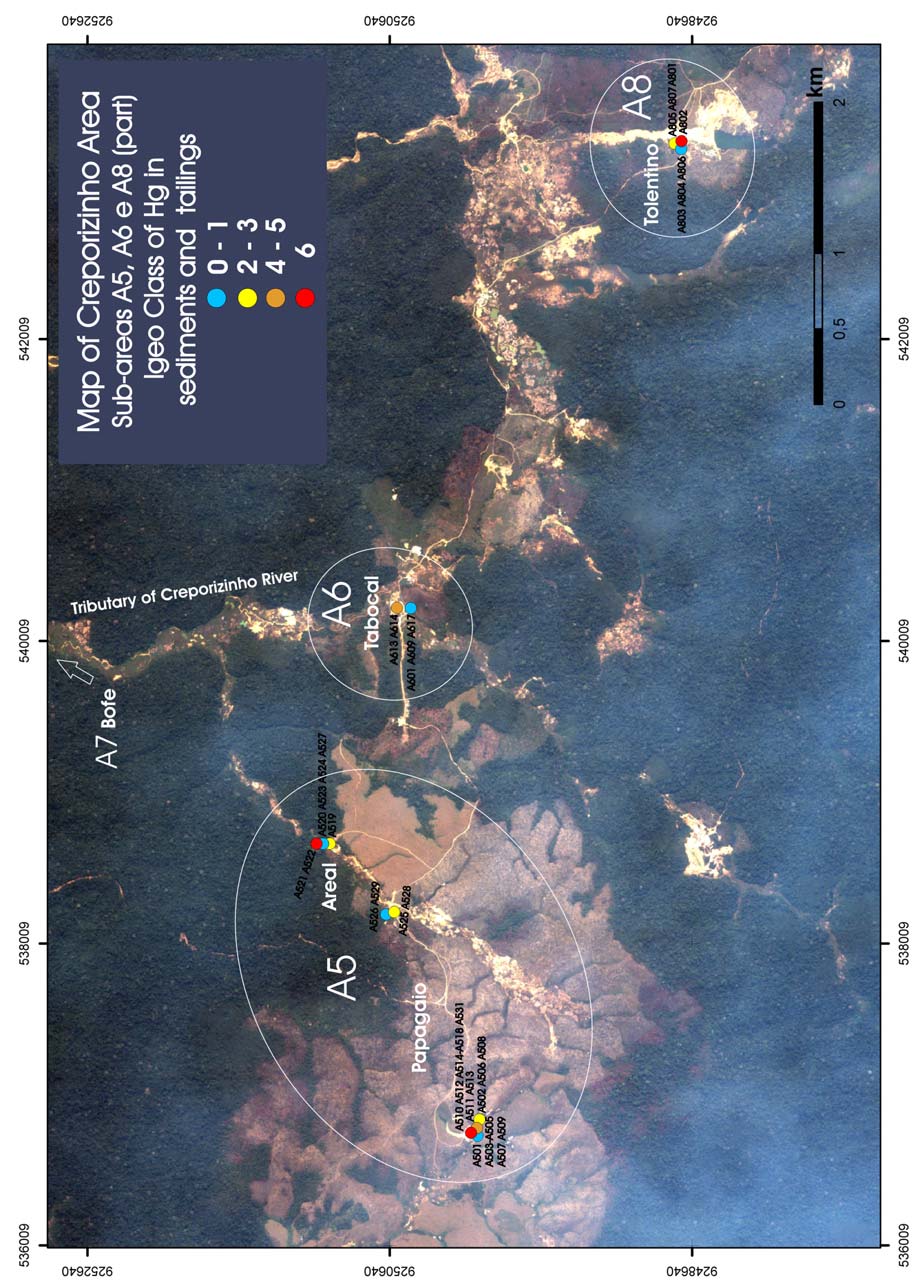

The mining sites of Papagaio and Areal are located circa of 15 kilometres in southeastern

direction from Creporizinho village, where alluvial gold has been explored, and from the

middle of the 90´s exploration of primary started. Nowadays, alluvial mining is very rare, being

mining of lateritic soil, primary ore and reworking of tailings common all over the area.

A total of 30 composite samples composed of tailings mixed with sediments and soils

from this part of the mining area were collected. Except 12 samples of amalgamation wastes

(A510 to A518 in Papagaio and A521, A522 and A531 in Areal), which fall in the Hg Igeo class 6,

the general distribution of Hg throughout both Creporizinho mining sites indicates an

expressive lower level of Hg contamination, comparing with the ones from São Chico.

The mining sites Tabocal and Bofe present a similar picture in terms of mineral

processing techniques and waste disposal as in Papagaio. A total of 16 samples of tailings and

sediments were collected. Nevertheless, Hg levels in sediments and tailings are significantly

lower than in Papagaio, indicating either less intense Hg losses or a lower mobility of Hg from a

given mining hotspot, resulting in Igeo classes close to the background, except for 3 samples

reaching the Igeo class 4, revealing a low degree of Hg contamination in inorganic samples.

Tolentino mining site is located circa 5 km in southeastern direction from Creporizinho

village, on the way to Papagaio. This is the only garimpo visited in Creporizinho area that works

with "modern" equipment, like ball mills and centrifuges. The majority of processed material

comes from primary ore deposits, extracted from gold-bearing quartz veins in magmatic rocks

in the nearby surroundings and transported by trucks to the processing unit, while

amalgamation is applied to gravity concentrates. Only a smaller part of the gold production

comes from secondary material, both, lateritic soils and tailings, resulting from former mining

activities in the entire area.

A total of 12 composite samples of sediments mixed with tailings from this site were

collected. Although one single sample reaches Igeo class 6, the whole data set, averaging an Igeo

class 2, indicates that Hg contamination is less significant than in other areas considered in this

study.

RT2004-004-01 CETEM/MCT

8

Evaluate the nature and extent of the mercury pollution in agricultural produce, especially in

those being part of the main diet

At São Chico mining sites 27 samples of herbs and vegetable foodstuffs were collected

close to mining tailings and backyards of the village. No aquatic plants could be found in

flooded open pits, neither in the lake at São Chico mining site. At Creporizinho mining sites 29

samples of herbs, macrophytes and vegetable foodstuffs were collected in the village and close

to the mining sites.

Total mercury values for soil samples at São Chico study area are significantly higher

than background value - 0.15 µg/g - for this area. Although mean values in soils samples from

São Chico (1.7 µg/g) are higher than soils samples from Creporizinho (0.99 µg/g), no significant

differences between them at < 0.05 were obtained.

Data on produces and wild plants were combined with aboveground and root plant

parts for both study areas to compare mean total mercury concentrations. Only aboveground of

produces samples from the São Chico mining site presents significantly higher values for

mercury levels than samples from Creporizinho area (mean of 2.55 µg/g vs. 0.12 µg/g). Since

Hg concentrations are much higher in aboveground parts of vegetable produces at São Chico

study area than in Creporizinho, the uptake in produce plants is likely to occur through

atmospheric deposition, as a result of amalgam burning. This makes the vegetables produced in

backyards of the village, particularly leaves, a further potential pathway of Hg exposure to the

population, besides fish consumption and inhalation of Hg vapour.

The present results also indicate that mercury concentrations in wild plants parts from

Creporizinho study area increased with mercury concentrations in soil. Apparently, they

function as a excluder, restricting transport of metal upwards to aerial parts. Since Hg

concentrations are much higher in aboveground of produces at São Chico study area than in

Creporizinho, the uptake in produce plants is likely to occur through atmospheric deposition,

but further studies with a larger sample set are necessary to confirm this hypothesis.

In foodstuffs other than fish mercury exists mainly in inorganic form, while the

gastrointestinal absorption is close to 7%. The average total contents of mercury in edible parts

(leaves and stems of cabbage and chive, pulp of cassava and "cara" roots, and pulp of cashew

fruit) were 0.21 ± 0.26 µg/g w wt (n = 13) for São Chico, and 0.01 ± 0.01 µg/g w wt (n = 7) for

Creporizinho. We estimate the average dietary daily intake of vegetables and roots close to 100

g, for an adult with 70 kg. Considering 0.3mg the provisional tolerable mercury intake per

person weekly (PTWI), the ingestion of total mercury from those foodstuffs falls close to the

PTWI in São Chico area, whereas in Creporizinho area the estimated Hg ingestion falls in a

range much lower than the PTWI. However, it should be taken into account the small

gastrointestinal absorption of inorganic mercury, which results in 0.017 mg/week for São Chico

and 0.0007 mg/week for Creporizinho.

The translocation of mercury from soil through roots to aboveground in produce plants

was not significant in both studies areas.

Nature and extent of mercury pollution in the river system adjacent to the hot spot area

Sampling and analysis of total suspended solids (TSS) and bioindicators in aquatic

systems play a pivotal role in assessing mercury mobility and the nature of pollution. Mercury

transported onto suspended particles may be deposited in riverside deposits forming mercury

RT2004-004-01 CETEM/MCT

9

sinks, which are potential sources for mercury remobilization, since mercury is adsorbed onto

fine particles and prone to form soluble complexes, mainly in the presence of humic substances.

Since metallic mercury can be transported downstream onto particulate matter, it is

assumed that mercury can be oxidized and promptly form soluble complexes in the presence of

organic substances. Therefore, the accumulation of these organic-rich sediments receiving loads

of soluble-mercury complexes may account for an environmental hotspot, since mercury

biovailability increases. High contents of organic matter in sediments have been sought during

sampling.

Since sampling of TSS by filtering through 0.45 µm membranes has been reported as

controvertial, due to its unefficiency of recovering enough material for analysis, it was sought

naturally settled TSS samples where favorable hydrodynamic conditions were to be found.

São Chico

According to the present results, the estimate of 7.5 tonnes of mercury released into the

environment in São Chico is consistent. High mercury levels were found not only near

amalgamation tailings, which are mining hotspots with up to 300 µg/g of Hg, but also

associated with suspended solids inside the reservoir and up to at least 20 km downstream, as

indicated by the high Hg levels averaging an Igeo class 4 along the São Chico Creek, and further

up to the mouth of the Novo River into the Jamanxin River, where Hg levels reach Igeo classes

from 4 to 6. This is an indication that the mercury load released in São Chico is becoming mobile

and prone for transportation onto suspended particles downstream.

A likely explanation for this particular mercury behaviour in São Chico, associated with

suspended particles, is due to the introduction in 2001 of cyanidation by heap leaching from

amalgamation tailings, which was undertaken at the margin of the dam reservoir situated

upstream of the main mining site in São Chico, the so-called Montanha. Therefore, the formation

of cyanide-mercury complexes into the reservoir is likely to be responsible for increasing

mercury mobility downstream. This type of chemical treatment is being prepared to be

undertaken once more through the storage of amalgamation tailings.

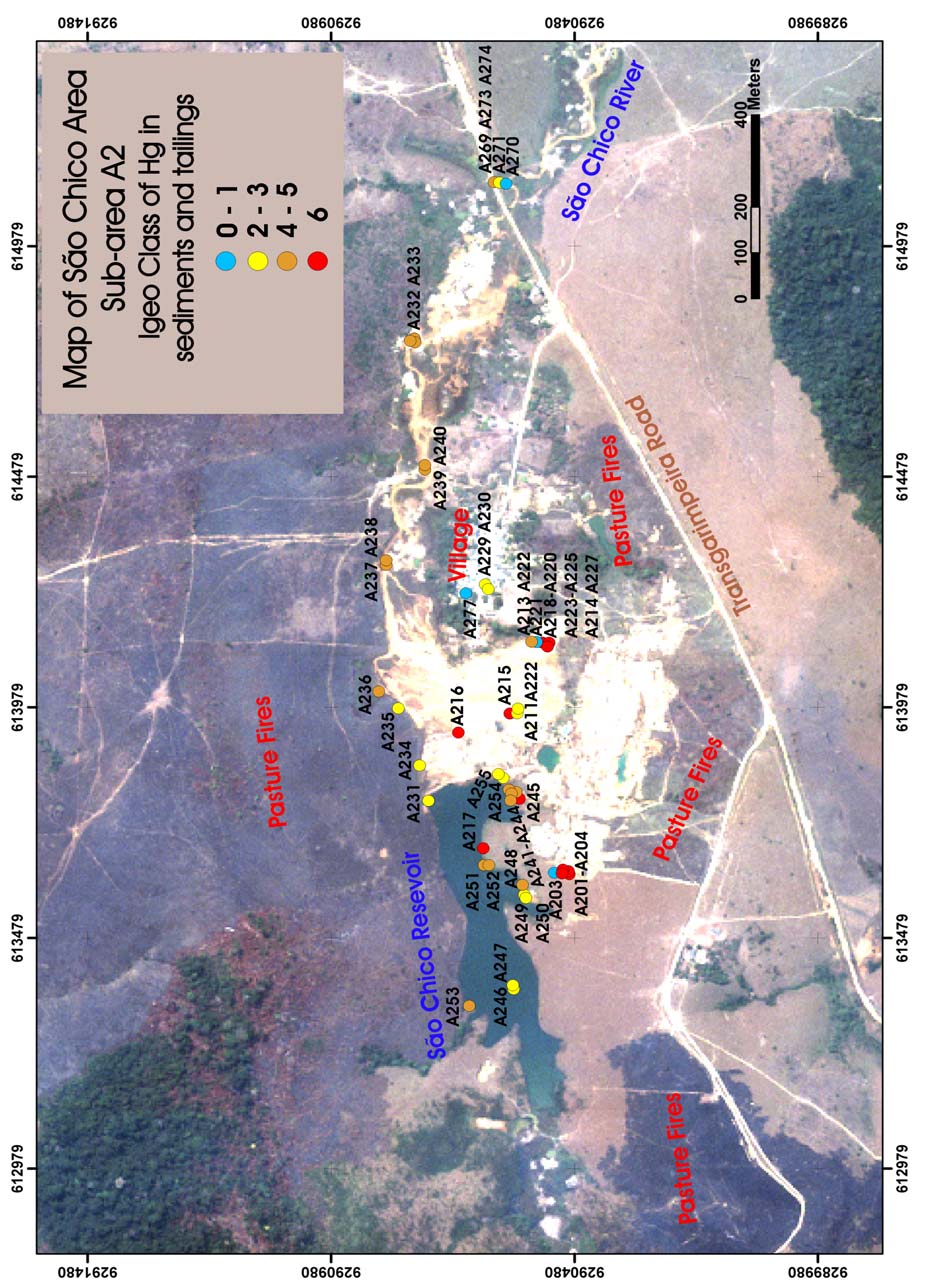

Similarly, another important factor contributing to Hg mobilization in São Chico is likely

to be related to fires yearly practiced for cleaning up pasture throughout the study area, as it

could be observed during the sampling campaign, when the surrounding pasture, very close to

the reservoir and tailings, has been burned three days long. The sudden elevation of the soil

temperature is likely to be very effective in releasing Hg from mining hotspots in soils to the

atmosphere, thus enhancing its mobility. The extension of the area impacted by pasture fires is

also visible from the satellite image in detailed scale of São Chico mining site.

The cyanidation attempt of amalgamation tailings together with the physical and

chemical features of the dam reservoir, a semi-closed aquatic system with high organic contents

in sediments and anoxic conditions in the botton, make this environment a promising field

opportunity for a better understanding of the behavior of mercury in aquatic systems in the

presence of cyanide, and surrounded by pasture fires. Therefore, a more detailed investigation

in the São Chico reservoir is enthusiastically recommended.

The physiochemical parameters in the water column of the São Chico reservoir are

consistent with usual water parameters of Amazonian rivers, and fall in the range of near-

neutral pH and low electrical conductivity (low salinity). Lower values of dissolved oxygen are

due to anoxic conditions in the botton of the reservoir. Those physiochemical conditions are

RT2004-004-01 CETEM/MCT 10

favourable to the stability of elemental mercury. Thus, one may realize that further factors are

likely being responsible for Hg mobility in this aquatic system, such as biochemical processes

through microbiological activity and/or anthropogenic ones, among which the cyanidation

attempt and pasture fires are to be highlighted.

Veiga et al. (1994) indicated the significant role that deforestation plays among the most

important emission sources of Hg in tropical countries, where forest fires are contributing to

increase Hg emissions worldwide through the release of Hg baselevels present in biomass.

Futher downstream, a total of 15 composite sediment samples were collected from the

Conrado River, Novo River and Jamanxin River, in order to evaluate to which extension the Hg

load released from São Chico is influencing the sediment chemical composition. In general,

sediments comprise a thin layer of settled suspended load and organic matter covering riverine

deposits in overbanks and riversides.

Since the main contribution in terms of Hg emissions to the Novo River comes from the

São Chico region, showing its high turbidity, one may realize that due to its indicated

association onto suspended particles, Hg released from São Chico is prone to be transported

downstream up to a distance at least as long as 20 km. However, a further in-depth study is

required to verify this indication.

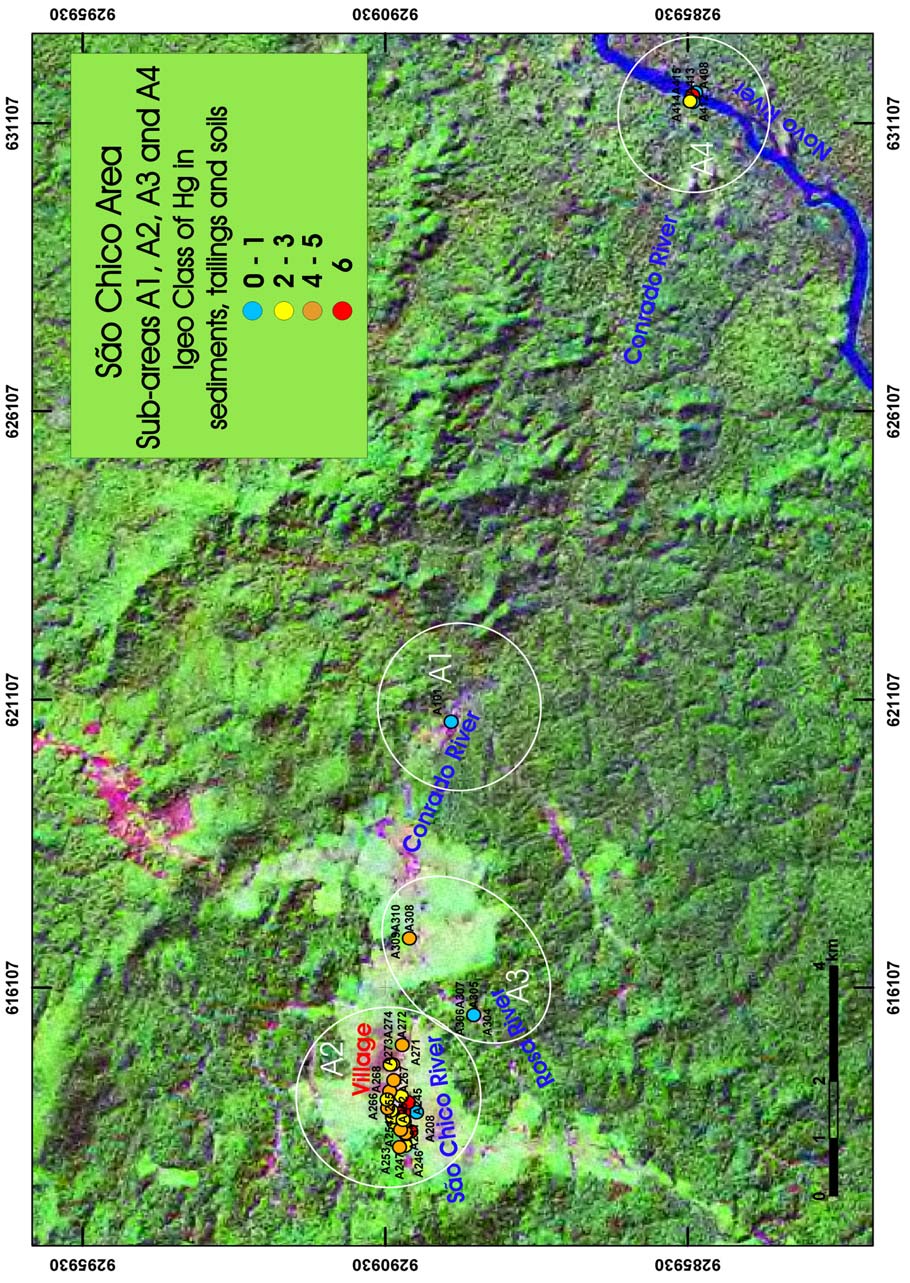

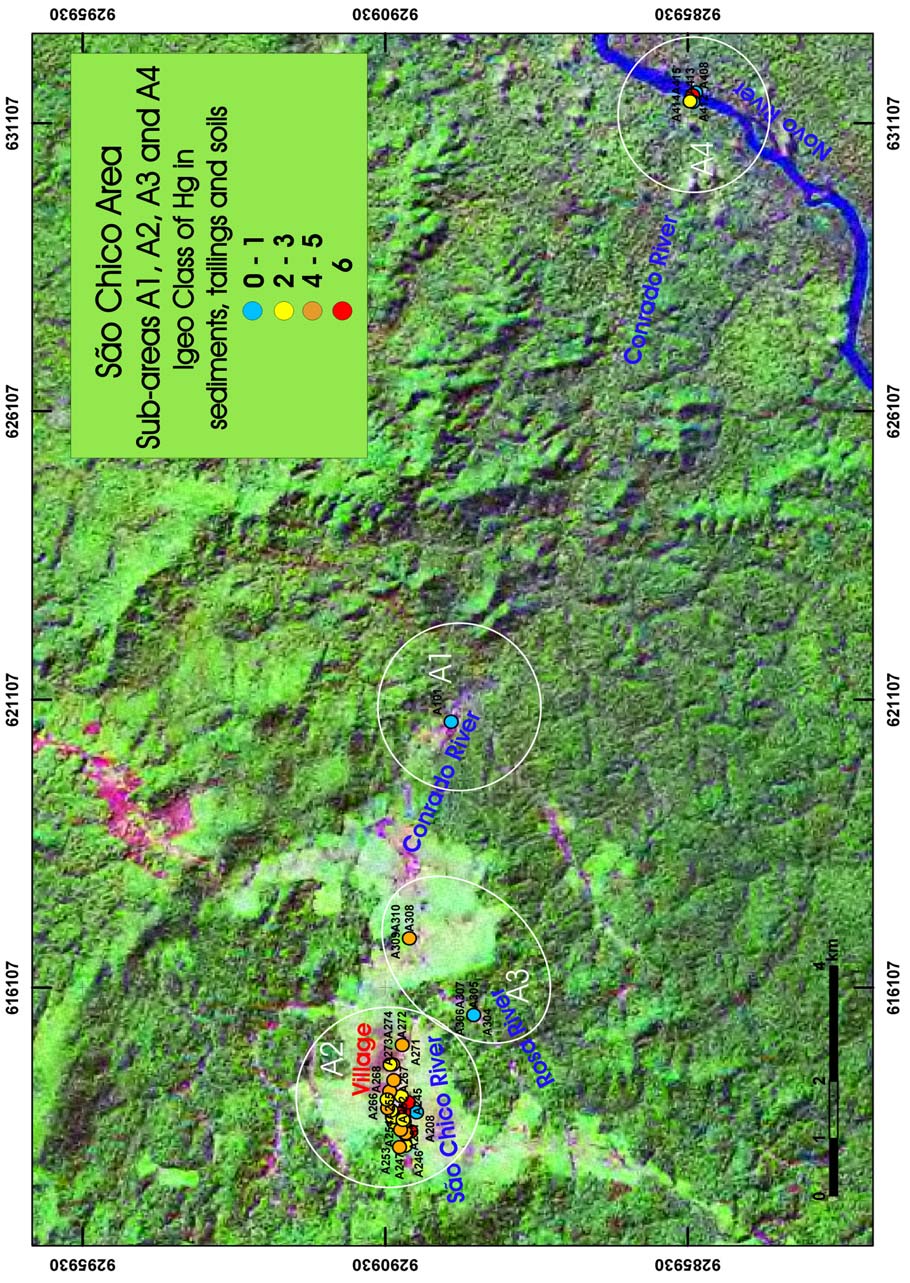

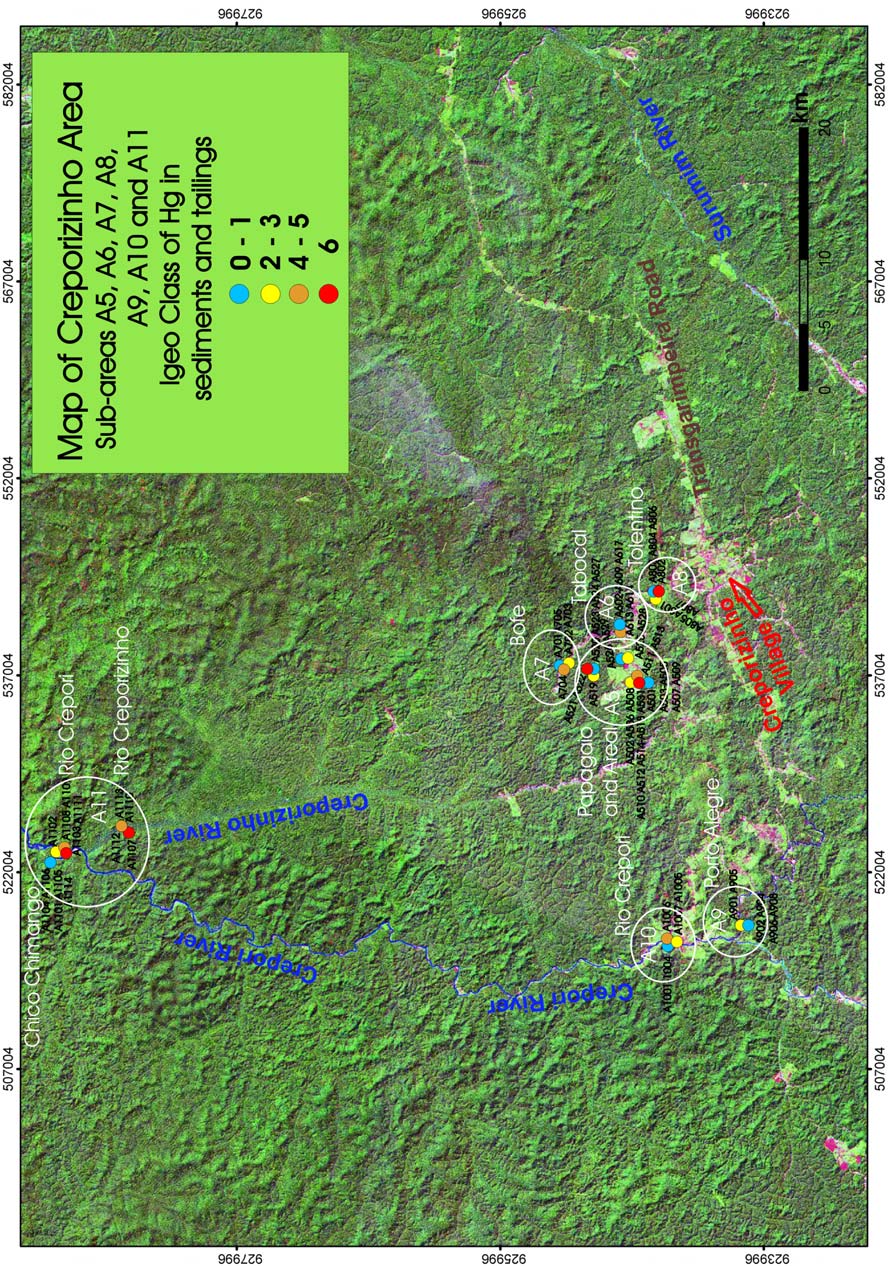

A general distribution of Igeo classes of Hg in sediments, tailings and soils throughout

the whole São Chico area is presented in a satellite image of the study area. It is to be

highlighted the occurrence of significantly high Hg levels associated with fine sediments (< 200#

fraction) up to 20 km downstream from the São Chico mining area, where 5 of 15 samples fall in

the range of Igeo classes 3 to 6.

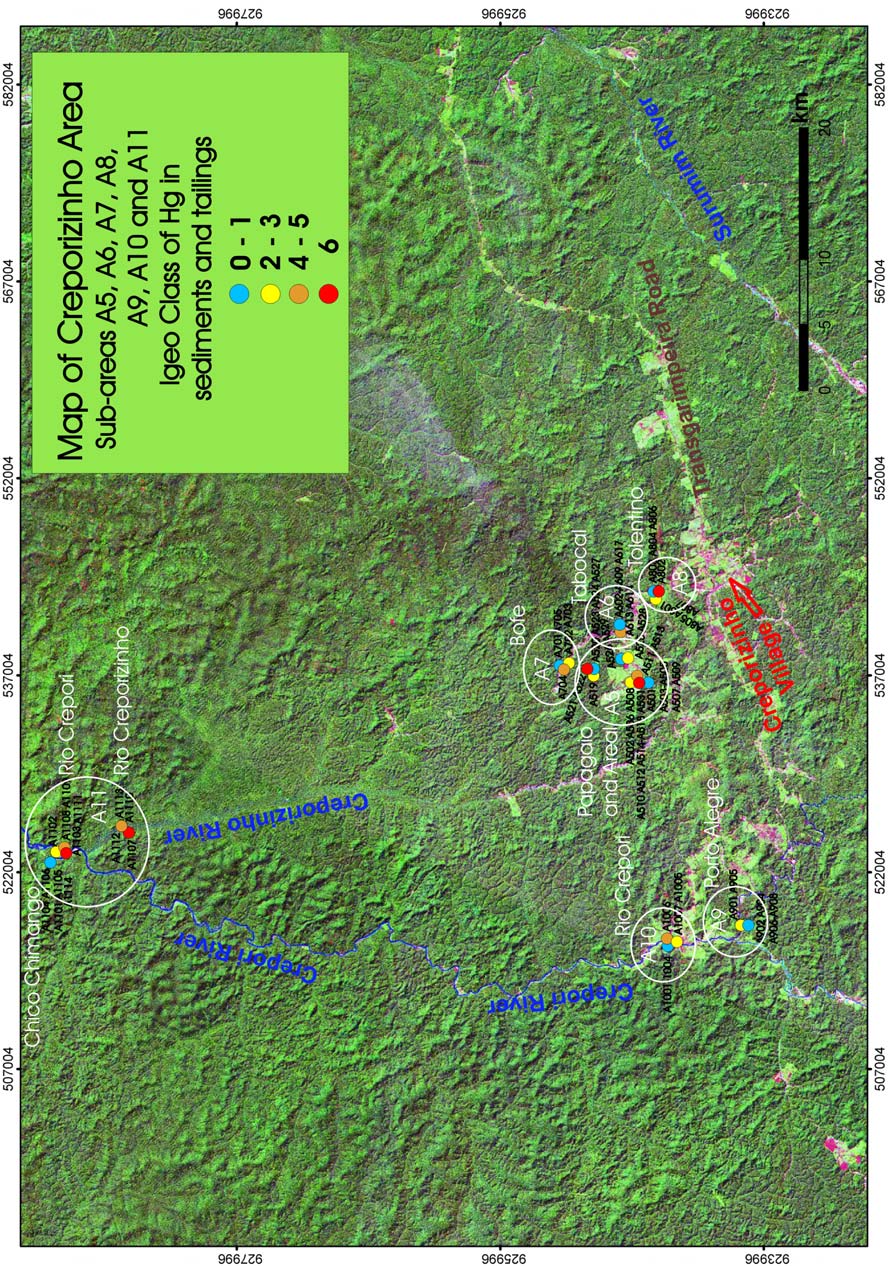

Creporizinho

The most downstream area along the Crepori River, close to the mouth of the

Creporizinho River, which drains the mining sites considered in this study lies circa of 40 km

from the mining sites. Although among 11 samples there are significant indications of Hg

contamination in fine sediments, pointing that Hg is being transported onto suspended particles

downstream, one may face in this case severe difficulty in tracing the source of Hg. This

difficulty is due to the existence of several mining operations throughout the Crepori river basin.

On the other hand, the highest values of Igeo classes averaging class 5 - are represented

by samples collected in the Creporizinho River that drains the mining sites considered in this

study. This is an indication of Hg contamination whose source is related to mining activities

located 40 km upstream, but further studies are required to confirm this hypothesis.

Additionally, the so-called Porto Alegre site and the mouth of a clear stream to the

Crepori River are located upstream of the investigated mining areas, but downstream of other

existing mining sites along the Crepori River. There, a less intense Hg contamination in

inorganic samples is to be reported for the Crepori River, where Igeo classes of Hg range from 0

to 4, being predominant values close to the background, with Igeo classes from 0 to 1.

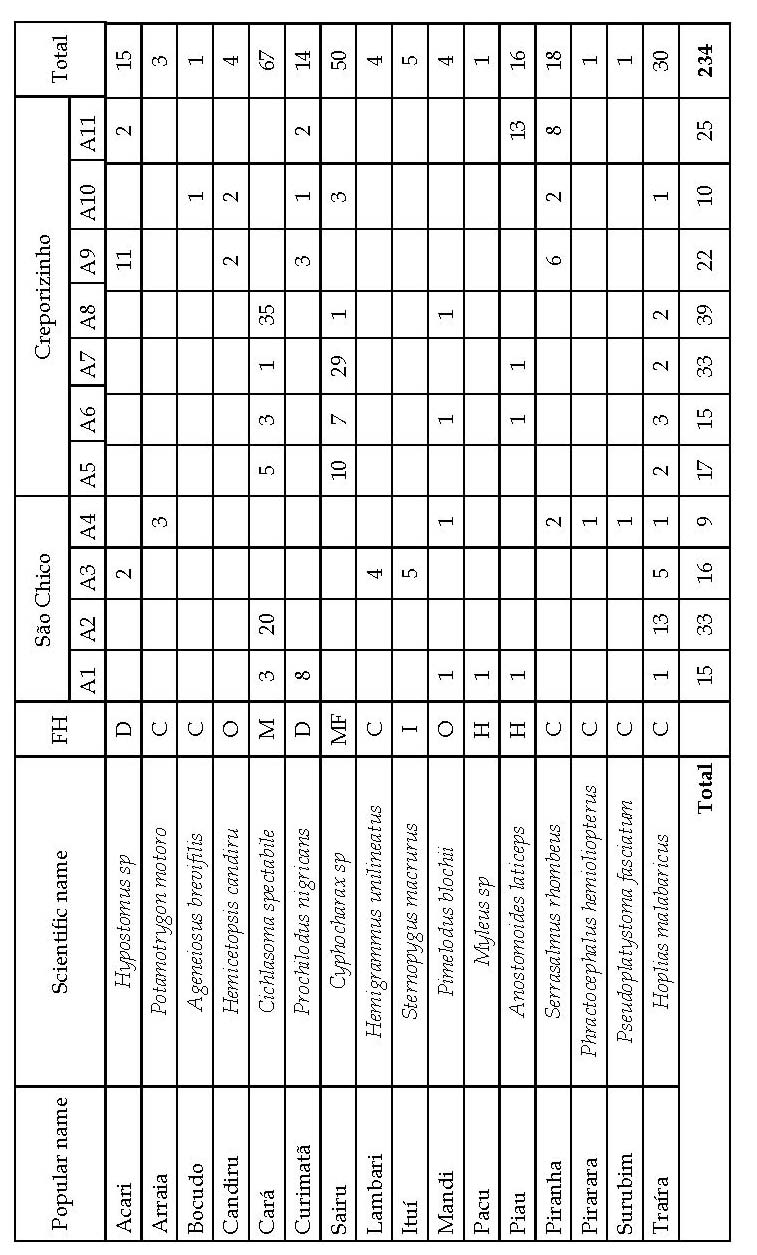

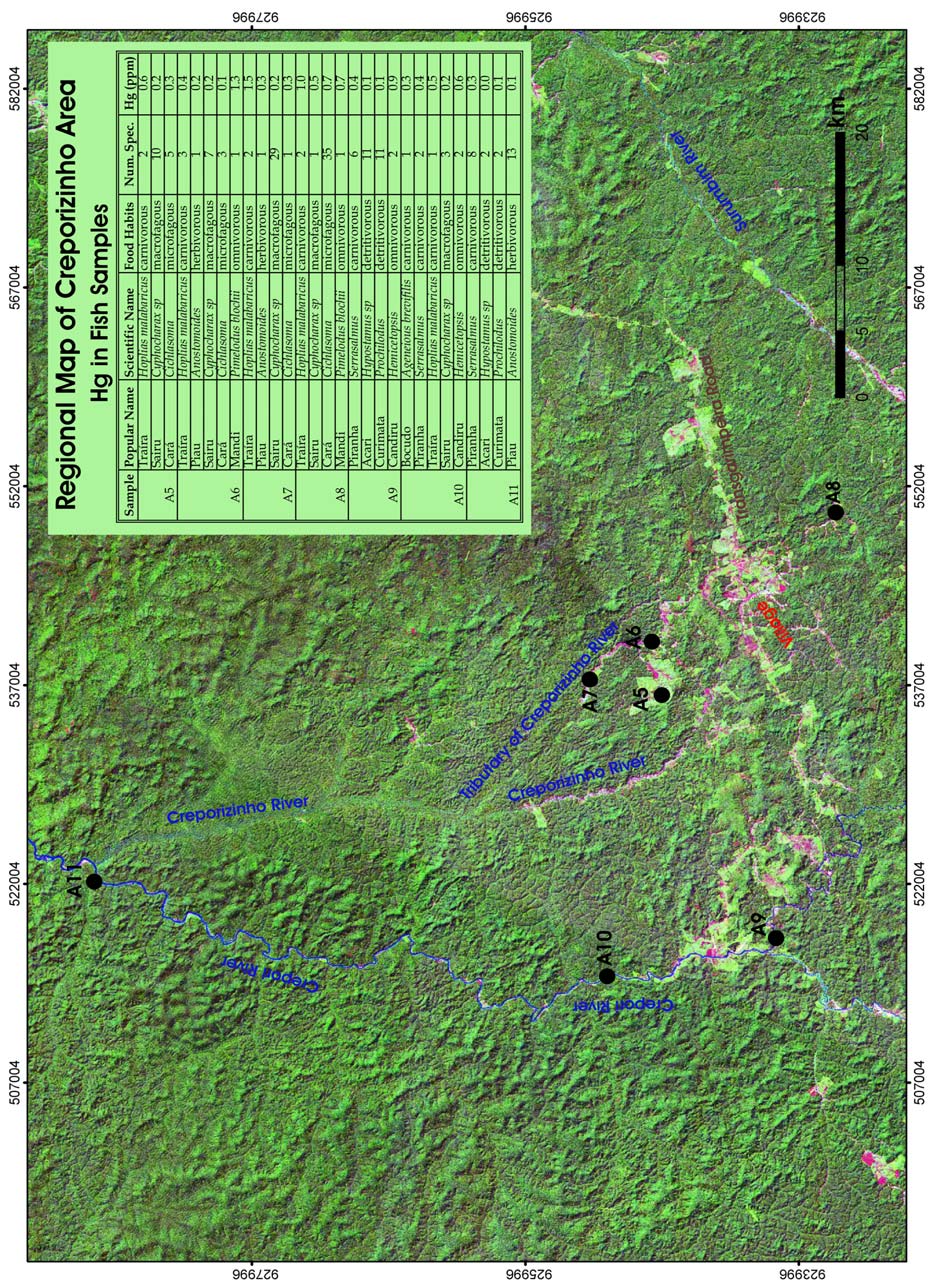

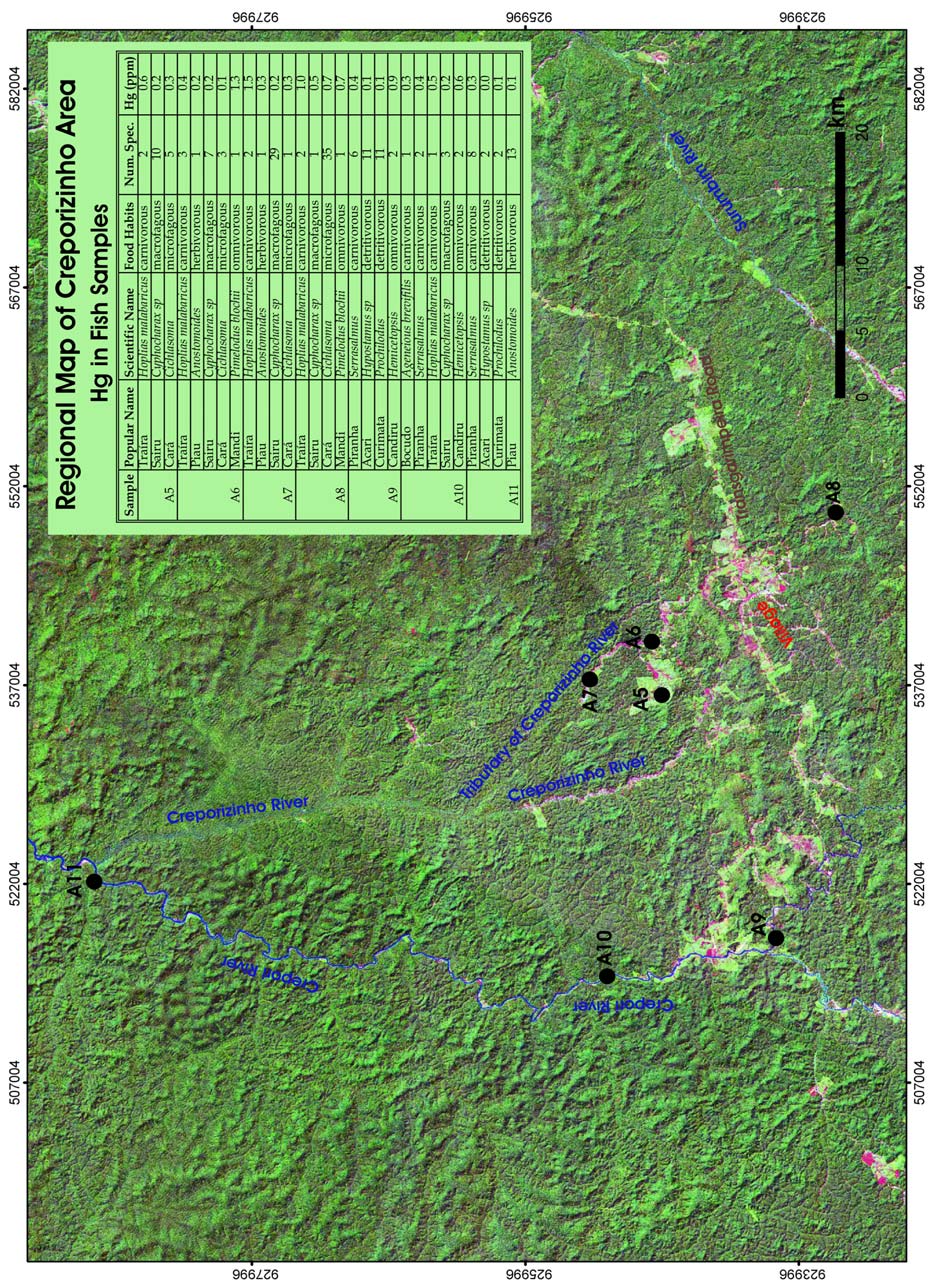

Mercury in Fish

Fish sampling was conducted in August 2003, at São Chico and Creporizinho mining

sites, where the mining activities are distributed along the tributaries of the Tapajós River. These

RT2004-004-01 CETEM/MCT 11

two areas belong to two distinct hydrographic basins: Jamanxin river basin and Crepori river

basin, respectively.

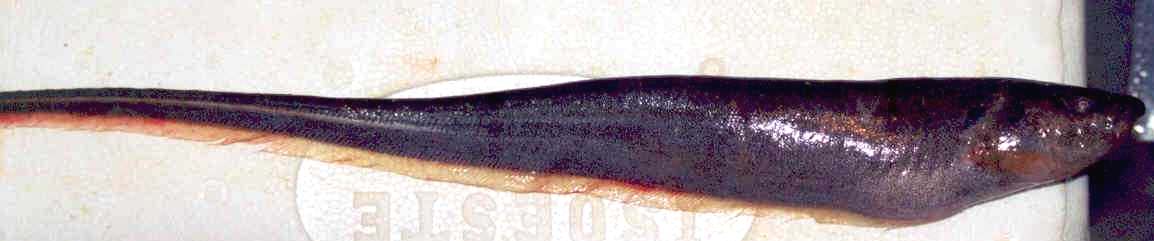

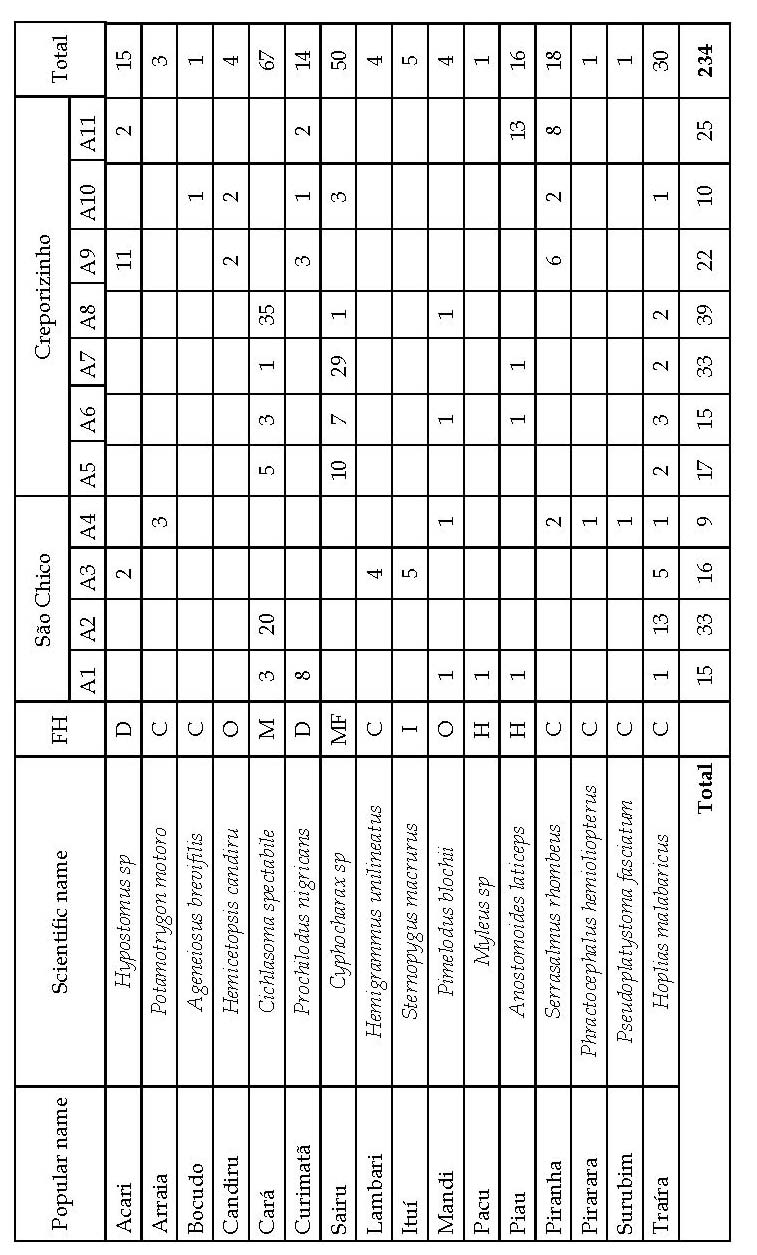

It was investigated the mercury levels in fish from 11 sites: 4 in São Chico and 7 in

Creporizinho. A total of 234 fish specimens of 16 species were collected: 73 specimens belonging

to 13 species in São Chico and 161 specimens of 11 species in Creporizinho. A total of 9 common

species could be collected in both areas (acari, cará, curimatã, lambari, mandi, piau, piranha and

traíra).

It is well known that freshwater biota is able to accumulate Hg from natural and

anthropogenic sources. Maximum background levels for Hg in uncontaminated freshwater fish

are in the range of 0.1 to 0.3 µg/g, although considerably higher levels can be found in large

predators. The mean concentration of Hg (1.04µg/g) in fish species from this work was similar

to those observed in other contaminated Amazonian rivers (Lacerda & Solomons, 1991; Akagi et

al, 1994, Malm et al., 1996; Bidone et al., 1997; Castilhos et al., 1998).

However, São Chico area has shown Hg levels in fish that are considered abnormally

high (2.53µg/g ± 3.91; n=73), compared with results from previous studies. In Creporizinho area

(n=161), mercury levels in fish resulted in 0.36±0.33µg/g. Additionally, the results show that the

minimum values for Hg in fish are similar between areas (0.027µg/g and 0.025µg/g), whereas

the maximum values are one order of magnitude higher in São Chico (21.90µg/g) than in

Creporizinho area (2.10µg/g). Among the analyzed fish in both areas, 82 specimens (35% of the

total) from 6 species (37,5% of the total) presented Hg concentrations above 0.5 µg/g, the Hg

concentration in fish recommended by WHO (1990). Whereas in Creporizinho 22% of fish

samples showed Hg levels above that limit, in São Chico this percentage increases to more than

60%. This is a further indication that mining hotspots in São Chico are becoming environmental

hotspots, strengthening the results and conclusions obtained in the geochemical survey.

Additionally, the results show that the minimum values for Hg in fish are similar

between areas, whereas the maximum values are one order of magnitude higher in São Chico

than in Creporizinho area.

Comparisons with global means of Hg in fish, however, may result in a certain

misinterpretation, since observations on given species of marine and freshwater fish indicate

that Hg concentrations in fish tissue increase with increasing age, as inferred from length

(WHO, 1990); it is also strongly affected by fish species and size (length and weight) and, in

addition, it is generally agreed that Hg concentrations in carnivorous fish are higher than in

non-carnivorous species (e.g., Watras and Huckabee 1994), due to the indirect Hg

bioaccumulation or biomagnification. It was investigated a relationship between fish length and

Hg levels, by correlation analysis with log-transformed and non-transformed data and, also, by

using the mean values of the length intervals. The objective was to assess the Hg contamination

in those sites and to find an indicator of Hg bioavailabiliy by using fish species.

The present results show that fish from São Chico are more contaminated, heavier and

larger than those from Creporizinho area. However, no correlation was found between fish Hg

concentration and weight or length when analyzing all specimens in both areas. Comparing

mercury levels in fish from each site within each study area (São Chico and Creporizinho) the

results showed that fish from the São Chico Reservoir present the highest mercury levels in São

Chico and are smaller than fish from the other sites.

RT2004-004-01 CETEM/MCT 12

In order to assess the Hg biomagnification processes in the ichthyofauna of the study

areas, data were worked out whereby distinct food habits and their correspondent Hg

concentrations were taken into account and analyzed. The fish were classified as carnivorous

(arraia, bocudo, lambari, piranha, pirarara, surubim e traíra) and noncarnivorous. The non-

carnivorous fish species were classified into (i) detritivorous (acari and curimatã); (ii)

herbivorous (pacu and piau), (iii) insectivorous (ituí), (iv) macrophagous (sairu), (v)

microphagous (cará) and omnivorous (candiru and mandi). As expected, carnivorous species

showed higher Hg concentrations than in non-carnivorous species for total data and for both

studied areas.

In São Chico area, the Hg levels in carnivorous species are higher than in detritivorous.

When this analysis is performed considering only noncarnivorous, the microfagous species are

different of the herbivorous, detritivorous and insectivorous species. In Creporizinho, the

species of detritivorous, herbivorous and macrofagous showed different Hg levels of the

carnivorous, microfagous and omnivorous ones, being macrofagous species different of

detritivorous ones. This results is very interesting and one could suggest that mercury transfer

in the trophic chain in those studied areas could be distinct, since in Creporizinho, omnivorous

showed higher Hg levels than carnivorous.

In Creporizinho area, fish from the site A8 showed higher Hg levels than all the other

sites (A5, A6, A7, A9, A10 and A11), and the specimens are also smaller than fish from the most

of the other sites (A6, A9, A10 and A11). However, significant positive correlation between Hg

in muscles and length were found in sites A6, A7 and A9, and a negative correlation in A11,

whereas no significant correlation was found for A2 nor to A8.

Carás and Traíras from São Chico have higher mercury levels than the ones from

Creporizinho, whereas others species (Piranha, Acari, Curimatã, Piau and Mandi) did not show

any difference between areas. The ratio of total mercury levels in Trairas and Carás from several

sites of two study area ranged from about 2 to 4, meaning that the carnivorous specie

accumulates Hg from 2 to 4 times more than noncarnivorous species. In addition, the results

showed that Hg levels only in Traíras from A2 are higher than Traíras from the other sites,

which are similar one each other. Mercury levels in Carás from A1 and A2 are higher than Carás

from A5, A6, and A8. Mercury levels in Carás from A5 and A6 are similar each other and lower

than levels in Carás from A8.

A toxicological approach has been used for the risk assessment to human health. Hazard

Quotient (HQ) results show for all study sites values above one, from 1.5 to 28.5, except for A11,

which is considered a reference area. The São Chico reservoir (A2) showed the higher values of

HQ, followed by A1, A4, and A3. In Creporizinho area, the HQ values are close to 2 for all sites,

except in A8, where the HQ attained 3.3.

It should be stressed that the present modeling is an evaluation tool, and therefore its

uncertainty should be taken into account for interpretation of results and conclusions. From the

present results, however, one could indicate that possibly in all sites, except in A11, and

depending on their dietary habits, populations are subject to potential hazards and health effects

due to fish consumption, being site A2 the most evident case of mercury pollution. Therefore,

further in-depth studies on Hg bioavailability are highly recommended for the overall study

area, while an awareness campaign should address to the local population the risk of consuming

fish from the site A2.

RT2004-004-01 CETEM/MCT 13

According to the correlation analyses, there is correlation between Hg and length and/or

weight, in Creporizinho area, with Curimatã and Piranha' species, and in São Chico area, the

species Curimatã and Ituí showed positive and significant correlation between Hg and length.

The other species, including Traíra species, did not show any correlation in both areas.

Considering specific species collected from different sites, Curimatã from A1 and Acari from A9

showed significant correlation between Hg and length and Piranha from A11 showed significant

correlation between Hg and weight.

Although Traíras and Carás did not show any correlation between mercury levels and

length or weight when total data were analyzed in São Chico and/or Creporizinho and, even,

when data from each site was considered, we decided to investigate the correspondence

between log of length and log of mercury levels in muscles, as advised by the UNIDO Protocol.

We have chosen these species because they are distributed throughout the studied aquatic

systems, have different food habits and the number of specimens collected is large enough. The

data analyzed showed very low correlation between parameters for all Traíras from São Chico

and Creporizinho, as well as for Traíras from different sites. Carás also did not show any

correlation in São Chico and Creporizinho, neither in sites of those areas. Other species, like as

Sairu from Creporizinho, A5, A6, A7; Piau from A11 and Piranha from A11 did not show any

correlation. The results showed strong positive correlation between log length and log mercury

levels only for Curimatã from A1 (São Chico area), Acari and Piranhas from A9 (Creporizinho

area), showing the same tendency found with non-transformed data.

Considering the low correlation coefficient resulting from analysis of log transformed

data for most part of species studied, we decided to investigate the correspondence between

length intervals and the average mercury levels in fish muscles, trying to decrease the high

variability in data, considering, firstly, data not log transformed and, secondly, log transformed

data. The linear equation for Traíras from A2 with log transformed data shows a positive and

significant correlation. It is very interesting result, but it should be considered that changes in

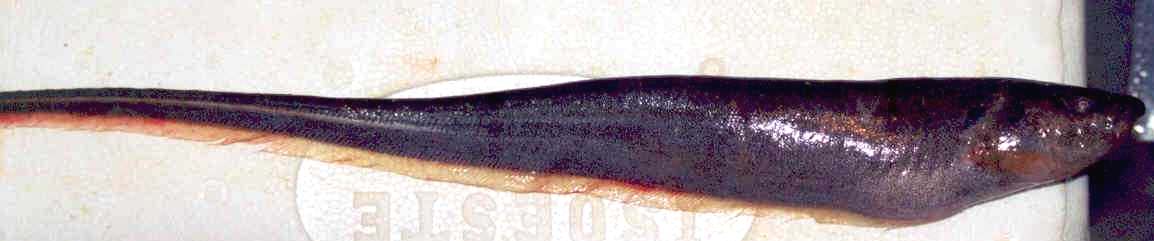

length intervals could change this linear relationship. However, considering the present results,

one could suggest that Traíras can be used as indicator organism for mercury contamination, at

least in Amazonian contaminated sites.

Although Traira does not show good correlation between Hg and length, it should be

used as a Hg bioindicator for the following reasons: It shows the fairly highest Hg levels; it has

the most widespread distribution in tropical drainages; in contrast to other species it is easily

adapted to adverse conditions in impacted areas and, it is appreciated for eating. Although the

indication of absence of correlation shows that this species do not fit well with the modelling

proposed in the Protocol, this has a potential negative effect in the human population (easy to

catch and appreciated as food). In addition, Piranhas, Curimatã and Acari are also good

indicators for specific sites, suggesting that, in order to find an indicator of Hg contamination, a

search for a site-specific fish species, with more than one species for different sites, could bring

better results.

The relationship between Hg levels in fish and Hg in sediments can be used as an

indicative of bioavailability of Hg in aquatic system. In order to investigate this availability, we

performed the ratio between Hg levels in fish and Igeo classes of Hg in sediments. Traíra and

Piranha (carnivorous species) and Cará and Curimatã (non carnivorous species) were chosen

because they were collected in São Chico and Creporizinho areas and represent different food

habits. All sites showed this ratio below 0.5 considering all species, except A2 and A7 for Traíra,

RT2004-004-01 CETEM/MCT 14

which resulted in 1.5 and 1.8, respectively. The results suggest that A2 and A7 showed higher

mercury bioavailability than the other sites.

In order to assess the potential ecological effects in Amazonian fish from aquatic systems

influenced by gold mining, Hg in tissue and its hematological and biochemical responses were

measured in each fish specimen. The results of total Hg in fish muscles and fish blood and

biochemical parameters were used as effects biomarkers in ecological risk assessment. It was

investigated biochemical parameters as enzyme activities, such as amino-alanina transferase-

ALT; amino- spartate transferase-AST; creatina kinase and creatinine, and hematological

parameters, such as hematocrit, hemoglobin, erythrocytes and total leukocyte count;

trombocytes-leukocytes count in blood of fish from São Chico and Creporizinho.

A total of 42 fish specimens of those species (Carás and Traíras) were collected: 27

specimens in São Chico (18 Carás and 9 Traíras) and 15 specimens in Creporizinho (11 Carás

and 4 Traíras).

All biochemical parameters measured in the present work did not show any difference

between both areas, probably as a result of the low number of specimens, which did not permit

performing the correlation analysis. In addition, those biochemical parameters could not be

sensible as mercury biomarkers. However, the data are important because they can be used as

biochemical reference values for Amazonian fish, considered as rare data.

Traíras and Carás from Creporizinho showed higher globular volume and erythrocytes

number and/or mean globular volume than the ones from São Chico. Mercury levels and

globular volume showed significant negative correlation for both species, suggesting that

mercury levels may cause decrease in number of erythrocytes, which are smaller than normal

ones and are characteristic of regenerative anemia.

RT2004-004-01 CETEM/MCT 15

1. Introduction

The present report describes the results achieved in two small scale gold mining areas in

the Brazilian Amazon - São Chico and Creporizinho - as part of the environmental and health

assessment (E&HA) conducted by the Centre for Mineral Technology (CETEM) with the

colaboration of the Evandro Chagas Institute (IEC), under the general coordination of the United

Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO).

In order to identify sites with high concentration of mercury (hotspots) a sampling

campaign of water, soils, sediments and biota was conducted, consisting of 658 samples. The

present report describes characteristics of environmental samples and results of mercury

analyses in samples from the Brazilian gold mining areas Creporizinho and São Chico. An

attempt to describe the distribution of mercury and to achieve an environmental assessment of

mercury pollution is presented, in order to provide a better understanding of the impacted

environment.

A research team comprizing 23 research scientists from CETEM (8 members) and IEC (15

members) proceeded to Itaituba, State of Para, Brazil, on 3rd of August 2003. On the same day, a

meeting has been organized by the Local Association of Miners (AMOT) with CETEM´s team,

the Municipal Secretaries of Environment and Health (SEMMA and SEMS), and a representative

of the State Secretary of Science, Technology and Environment (SECTAM), since the local

authorities required a comprehensive explanation about the activities to be performed during

the field work of the Environmental and Health Assessment for the Global Mercury Project

(GMP).

The following benefits should be seen as a voluntary contribution from UNIDO, CETEM

and IEC to the mining community of Itaituba through this E&HA work, in addition to the

project objectives thenselves:

- Gratuitous medical assisstance including diagnosis, treatment recommendation and

medicines for the whole mining communities of São Chico and Creporizinho, encompassing

700 people;

- Restoration of a local laboratory in Itaituba for implementing an innovative semi-

quantitative method for mercury analysis in fish samples, including training of 5

technicians from the local Secretaries (SEMS, SEMMA and SECTAM) during two weeks;

- Improvements on the installations of both schools, in São Chico and Creporizinho, which

served as field laboratories for CETEM´s team.

The Global Mercury Project, funded by GEF and co-funded by UNDP and UNIDO, is

complemented by a suite of ongoing activities that are financed either through the participating

countries' resources and/or bilateral programs. The main goals of the GMP are (Veiga and

Baker, 2003):

o Reduce mercury pollution caused by artisanal miners on international waters;

o Introduce cleaner technologies for gold extraction and train miners;

o Develop capacity and regulatory mechanisms within local governments that will enable the

sector to minimize mercury pollution;

o Introduce environmental and health monitoring programs;

RT2004-004-01 CETEM/MCT 16

o Build capacity in local laboratories to assess the extent and impact of mercury pollution.

The monitoring component of the Global Mercury Project (GMP) has specific goals

described in the Objective 3 of the project proposal: "identify hotspots in project demonstration sites,

conduct geochemical and toxicological studies and other field investigations in order to assess the extent of

environmental (mercury) pollution in surrounding water bodies and devise intervention measures".

Small-scale or artisanal gold mining is an essential activity in many developing countries

as it provides an important source of livelihood, particularly in rural regions where economic

alternatives are critically limited. Artisanal mining encompasses small, medium, informal, legal

and illegal miners who use rudimentary processes to extract more than 30 different mineral

substances worldwide. Artisanal mining activities are not necessarily limited to small-scale

mining activities. When a large number of individuals excavate a single site, the resulting pit

diameter can be as large as 2 km. This is the case of Serra Pelada, an infamous ASM site in the

Brazilian Amazon where, during the 1980's, more than 80,000 miners gathered to manually

extract about 90 tonnes of gold from the same open pit. The International Labour Organization

(ILO, 1999) estimates that the number of artisanal miners is currently around 13 million in 55

countries and rising, which suggests that 80 to 100 million people worldwide depend on this

activity for their livelihood. Gold is easy to transport across borders and easily sold, and is by far

the main metal being extracted. Worldwide it is estimated that more than 2.5 million women

and 250,000 children are directly employed in artisanal mining (Hinton et al, 2003).

Although the use of mercury in mineral processing is illegal in most countries, mercury

amalgamation is the preferred method employed by ASM. When used correctly, mercury is an

effective, simple and very inexpensive reagent to extract gold (e.g., 1kg of Hg costs from 1 to 2g

of Au). A variety of mining and amalgamation methods are used in artisanal mining operations

and they must be primarily surveyed to establish a reliable environmental assessment (Veiga

and Baker, 2003).

The extent of mercury losses from a specific site is defined by Au-Hg separation

procedures; mercury often is discharged with contaminated tailings and/or volatilized into the

atmosphere. Typical amalgamation methods used by ASM are listed below (Veiga and Meech,

1995):

- Whole ore is amalgamated: mercury is mixed with the whole ore in pump boxes or

introduced in sluices during gravity concentration or amalgamated when copper plates are

used.

- Only gravity concentrates are amalgamated: mercury is mixed with concentrates in

blenders or barrels and separation of amalgam from heavy minerals is accomplished by

panning in waterboxes, in pools or at creek margins.

Many miners are nowadays amalgamating only gravity concentrates. This is an

important improvement in artisanal mining methods, resulting in significant decreases in Hg

consumption and emissions. Using this method approximately 14 grams of mercury is required

to amalgamate 1 kg of concentrate (ratio Hg:Concentrate » 1:70). Amalgamation is efficient for

particles coarser than 200 # (0.074 mm) and for liberated or partially liberated gold (Wenqian &

Poling, 1983).

Although artisanal mining has shown some positive contributions worldwide, it has also

suffered negative conceptualization as a misnomer to mineral sector development by host

Governments. Whereas some countries choose to ignore the existence of such activities, others

RT2004-004-01 CETEM/MCT 17

lack adequate legal frameworks to regulate them. As a result, the activities are carried out

illegally thus denying the host Governments the badly needed revenues (Beinhoff, 2002).

The increasing societal demand for actions and strategies towards sustainability of small-

scale gold mining in developing countries has led experts to face the challenge of managing the

hazards associated with mercury contamination from active and abandoned mine sites.

Mercury contamination in drainage systems and its health effects are the most frequent subjects

on environmental researchs dealing with small-scale gold mining worldwide. Also, filling of

river beds with mineral matter originated from runoff of abandoned mining waste piles and

tailings generally causes both silting of waterways and elevation of Hg concentrations in the

environment.

From the end of the 80's onwards the extraction of gold in rain forest areas and wetlands

worldwide, in the form of SSGM operations, are receiving increased attention from scientists

and public planners. Moreover, the formidable impacts caused by mercury usage in industrial

activities, be it in chemical factories or energy production, as it is inherent in coals used in

thermal power plants, and in agriculture as part of herbicides compounds are well documented

in the literature. As well teeth amalgams are an old concern, recently revived in the scientific

literature (Villas-Bôas, 2001).

Inhalation of mercury vapor is the primary exposure pathway to miners, gold shop

workers and people living near areas where mercury is handled. High methylmercury

concentrations in fish in waterways contaminated by mercury released from mining sites is the

main means of exposure to local residents in rural communities. Because fish are plentiful and

inexpensive fish are the main protein source for community residents, but can also result in

consumption of greater amounts of methylmercury than health authorities advise (Veiga and

Baker, 2003).

Biota is the ultimate indicator of bioavailability of any form of Hg. Mercury, particularly

MeHg, is highly biomagnified in the food web and reaches its highest concentrations in fish,

especially fish-eating, carnivorous fish. Mercury concentration in fish is usually expressed on a

wet weight basis as parts per million (ppm) which is equivalent to mg/kg or µg/g. The natural

background in fish has been estimated to be between 0.05 to 0.3 ppm Hg and may be less than

0.01 ppm Hg in small, short-lived herbivorous species (Suckcharoen et al, 1978).

By employing toxicological methods for the risk assessment to human health,

significance of the contamination can be ascertained. At a screening level, a Hazard Quotient

(HQ) approach (USEPA, 1989), assumes that there is a level of exposure (i.e., RfD = Reference of

Dose) for non-carcinogenic substances, like mercury, below which it is unlikely for even

sensitive populations to experience adverse health effects.

There are three physiological responses regarding the translocation of metals to

aboveground plant tissues. The excluder response, where aboveground tissues concentrations

are low until a critical soil concentration is reached, and an unrestricted transport occur with

toxicity results. The indicator response, when tissues and environmental concentrations are

proportional, with a passively regulated transport and uptake. The accumulator response, when

metal is actively accumulated through a highly specialized physiology (e.g. hyperaccumulators

species). Shoot : root ratios could be a measure of the degree of metal transport, a higher amount

of metal in above-ground than in roots could indicate an no restricted metal uptake (Windham

et al., 2003).

RT2004-004-01 CETEM/MCT 18

Assimilation through plants plays a major role in the entry of mercury into terrestrial

food chain (WHO, 1990). The assimilation of mercury by plants does not depend only on its

concentration in soil, but also on the ratio of soil and air mercury contamination, on bio-

chemical conditions of soil and on meteorological conditions. The assimilation from the soil by

roots depends on soil type, content of humic acid, microbiological activity, pH, and redox

potential. The assimilation through leaves depends on type of plant, air contamination and

atmospheric aerosol deposition (Vecera et al., 1999). Bryophites and lichens without any roots,

assimilate mercury only from air and water and can be used as active biomonitors (Fernández et

al., 2002). Further studies show that certain plant species, such as carrots, lettuce and

mushrooms in particular, are likely to assimilate more mercury than other plants growing at the

same place, but on the other hand, they show that mercury levels in plants bear little

relationship to the mercury content of soils (Nichols et al., 1997).

Mercury toxicity and sources of exposure depends on its chemical form. For organic and

inorganic mercury compounds, diet is the most important source for the majority of organisms.

In terrestrial food webs, mercury exists in an inorganic form, and accumulates in plants.

However, it does not biomagnify in the organisms that feed on them (Nichols et al., 1997).

Concentrations of mercury in most foodstuffs are often below the detection limit, usually less

than 20 g.g-1 wet weight, with mercury mainly in the inorganic form (WHO, 1991, as cited by

UNEP, 2002), with gastrointestinal absorption close to 7%. WHO (1990, as cited by UNEP, 2002)

estimates an average daily intake of inorganic mercury of 3.6 µg/day, for populations not

occupationally exposed, whereas its retention in the body averages 0.25 µg/day, as a result of

consumption of foodstuffs other than fish.

A Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (1972, as cited by IPCS, 1976)

established a provisional tolerable weekly intake (PTWI) of 0.3 mg of total mercury/person (of

which 0.2 mg should be in methylmercury form), being these amounts equivalent to 5 µg /kg of

body weight, and 3.3 µg/kg relative to methylmercury.

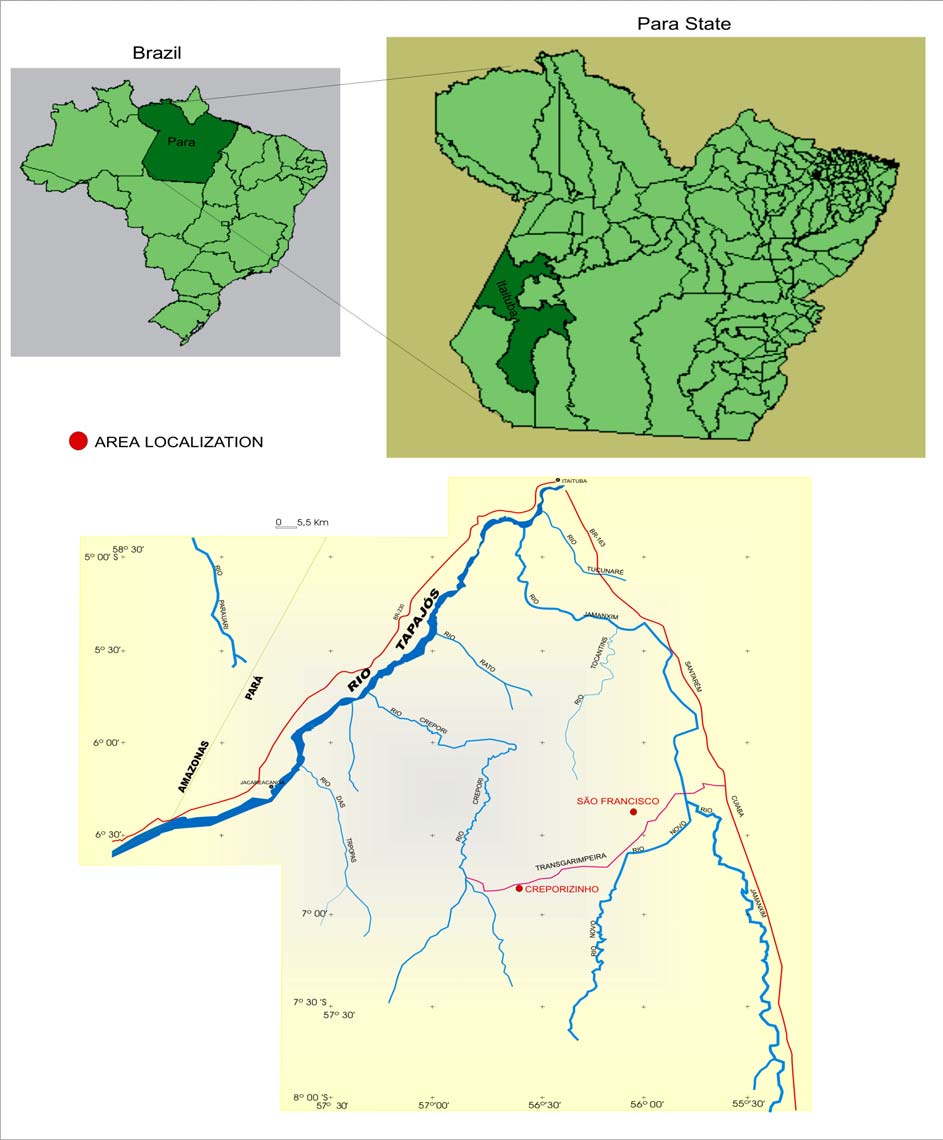

2. Study Areas in Brazil

Two artisanal gold mining areas, São Chico and Creporizinho, have been selected for

undertaking the Environmental and Health Assessment in the Artisanal Gold Mining Reserve of

the State of Para, in accordance with the Project´s Coordination Unit, after considering different

criteria, as follows:

- Commitment of the miners with the project´s objectives;

- Their association with local artisanal miners leaderships;

- Production potential and economic stability of the mining activity;

- Representativeness relative to regional standards of technologies and practices;

- Accessibility;

- Spreading potential relative to the project´s achievements.

RT2004-004-01 CETEM/MCT 19

São Chico (06º 25'31"S and 56º 02'99"W)

The garimpo São Chico is just 2 km distant from a landing strip and in 5 km distance

from the Transgarimpeira road, which during the dry season (June-September) can be used for

transportation of equipments and supply from Itaituba, the main town in this region with

150,000 inhabitants. Due to the bad conditions of this road, it should be used just for

transportation of goods, since the 350 km distance from Itaituba needs some 20 hours to be

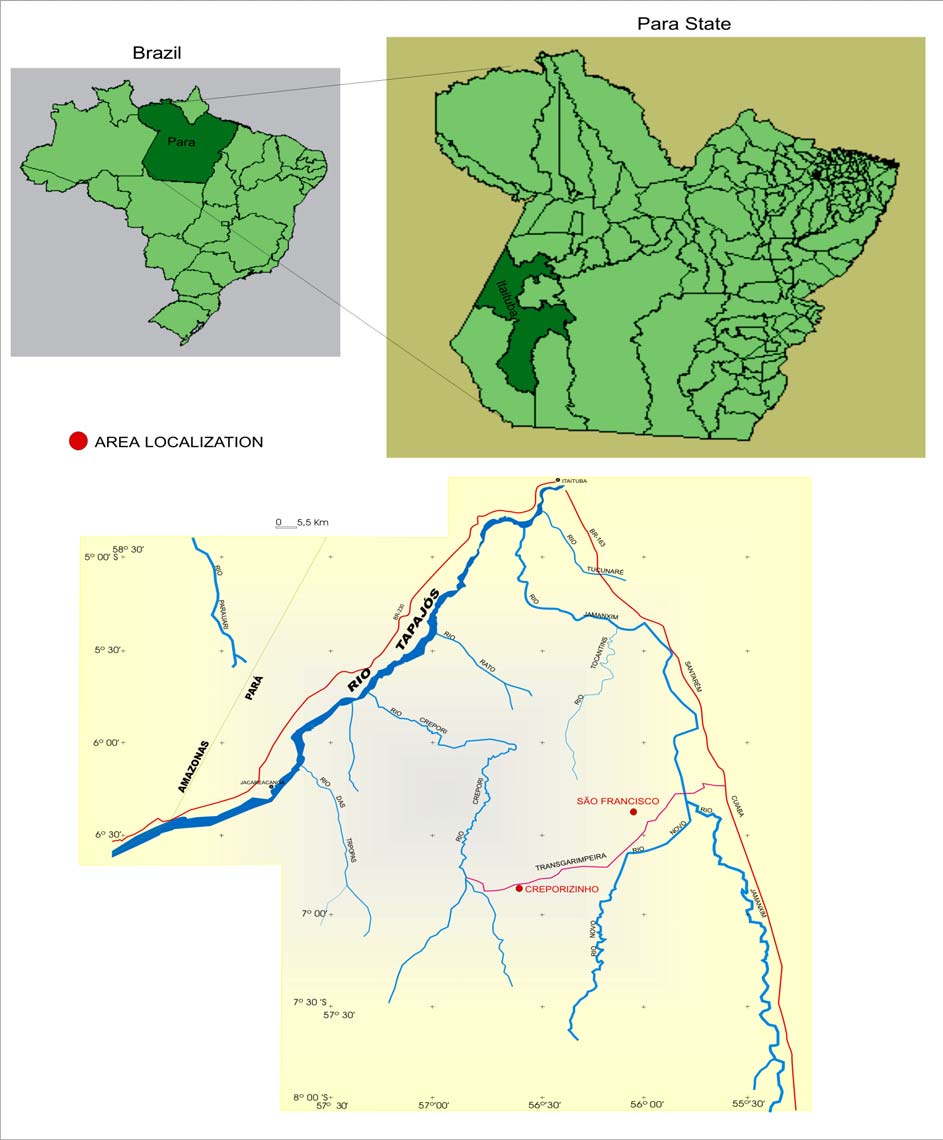

overcome (Figure 1).

The São Chico village consists only of 63 houses and 134 individuals, being 41% of

garimpeiros, 6% of machinery owners, 30% of dealers, 9% of cookers, among others. The only

public service in the village is a health post for malaria diagnosis from the National Foundation

of Health (1 health assistant)(Armin Mathis, Sociological Report, July 2003).

At São Chico mining site a small village has been established on the bottom of a valley.

The topography is undulating with mean altitudinal differences between plateaus and stream

valleys of 10-20 m.

Sao Chico stream was dammed up forming a reservoir behind the village from which

water is used for mining activities that generate mining tailings to waterways (Figure 2). Few

families have backyards in the village, where herbs, fruits, roots, medicinal teas and creeping

plants are cultivated. Primary forest was replaced by pasture in hillsides. Grassland species and

some small trees occur at reservoir's banks.

From the beginning of the very first gold mining activity in 1963, the São Chico village

has shown two main periods os prosperity, one in the end of the 80´s after the opening of the

Transgarimpeira dirt road, and other in the end of the 90´s, when gold rich primary deposits were

discovered. According to revised estimations, about two tons of gold were produced during the

last gold rush, while a total estimated mercury emission to the environment reachs three tons

since 1963.

RT2004-004-01 CETEM/MCT 20

Itaituba

0 '------' 20 km

São Chico

Creporizinho

Figure 1 - Location Map of the Target Areas in the Tapajós Basin, Brazil

RT2004-004-01 CETEM/MCT 21

Figure 2 - Main tailing deposit in São Chico: lies at the slope of a valley, between the village

(to the right) and a dam reservoir (on the left)

Creporizinho (S 06° 50` 14,1" W 56° 35` 00,0")

Creporizinho is a typical gold mining village with 238 wooden residences for an

estimated population of 1000 inhabitants. There are grocery shops, pharmacies and a hotel.

Electricity is based on diesel engines. The 200 children go to a primary school, where 5 teachers

are working. Gold is bought at any corner. Few families have backyards in the village, where

herbs, fruits, roots, medicinal teas and creeping plants are cultivated.

Both study sites, Tolentino and Papagaio, were said to start its prospective/extraction

activities since 1968 (manual extraction). From 1985 on started to work with machinery

consisting basically on processing alluvial colluvial terraces. They have privilegiated the using

of hydraulic jet pumps coupled with riffled or carpeted sluice boxes in order to concentrate gold

prior to amalgamation.

Creporizinho study sites are ca. 10 km far from the village. Creporizinho stream flows

nearby the village and is used for water supply water to mining activities. Overbank deposits

are common along its banks. There are many flooded open pits, drains of mining tailings

forming small streams along mining sites. Also herbs sprout up over mining tailings and wastes,

and pastures also replace primary forest, but forest fragments still remain in some places. Old

flooded open pits have macrophytes growing in water.

From 10 to 15 kilometres in southeastern direction from Creporizinho village lies the

mining area of "Luis Preto", comprising the Garimpos Papagaio (Figure 3), Tapocal an Areal

Alluvial gold has been mined and from the middle of the 90´s exploration of primary ore began,

more or less successfully. Nowadays, alluvial mining is very rare, mining of lateritic soils,

primary ore and reworking of residues and tailings from former mining activities became

common all over the area.

RT2004-004-01 CETEM/MCT 22

Figure 3 Panoramic view of the Papagaio area in Creporizinho

In the Papagaio mining site (S 06° 47` 00,2" W 56° 40` 03,2"), primary ore from open pits

and from shafts is extracted, transported to the processing unit, located on top of a hill, where

material gets ground and undergoes amalgamation through mercury-coated copper plates. In

the neighbouring Tapocal, Bofe and Areal areas, prevailing mining activities concentrate on

reprocessing of tailings and residues mainly located along recent or past courses of creeks or

small rivers. Amalgam is usually roasted locally.

At Crepori River mining activities were performed with dredges and hidraulic jets at

riversides. The low-water season exposes alluvial pits originated from dredge activities during

high-water season.

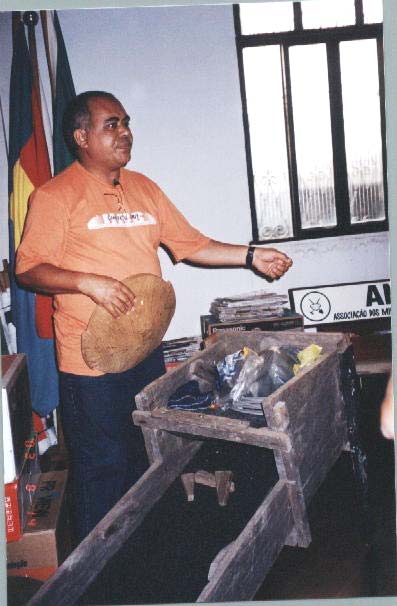

Since 1999 novel operations have been introduced in the Tolentino area (S 06° 47` 46,9"

W 56° 36` 27,0"), considering they have reached a sub-surface level (about 10 meters depth) with

gold veins, being 2001 identified as the higher production (said to reach 6,000 kg/year). The

owner of the Tolentino area established a partnership with a group of entrepreneurs who

assembled a plant using mainly hammer/crusher mill, hydraulic jet pumps and centrifuge

concentrators (Figure 4).

Figure 4 - Processing plant at Tolentino mining site3. Materials and Methods

RT2004-004-01 CETEM/MCT 23

In order to address the identification and location of mercury hotspots a sampling

campaign of soils and sediments was performed. Amalgamation tailings dumped into drainage

systems originate hotspots of metallic mercury (mining hotspot), where abnormally high

concentrations are to be found in the heavy fraction of sediments. Due to its typical

heterogeneous distribution, one may face enormous difficulties in locating mining hotspost of

mercury in a given mining site, as conventional geochemical exploration techniques have been

used unsuccessfully. Therefore, the introduction of novel sampling and analytical methods was

required, including in situ mercury analyses by a semi-quantitative colorimetric method.

Sampling and analysis of total suspended solids (TSS) and water in aquatic systems play

a pivotal role in assessing mercury mobility and the nature of pollution. Mercury transported

either in solution or onto suspended particles may be deposited in riverside deposits forming

mercury sinks, which are potential sources for mercury remobilization, since mercury is

adsorbed onto fine particles and prone to form soluble complexes, mainly in the presence of

humic substances.

Since metallic mercury can be transported downstream onto particulate matter, it is

assumed that mercury can be oxidized and promptly form soluble complexes in the presence of

organic substances. Therefore, the accumulation of these organic-rich sediments receiving loads

of soluble-mercury complexes may account for an ecological hotspot, since mercury

biovailability increases. High contents of organic matter in sediments have been seeked during

sampling.

Simple sampling methods, consisting of pan concentrates for mercury analysis were also

used for locating mercury hotsposts. Another estrategy, consisting of a sociological approach,

enables the reconstruction of the local mining history and the identification of amalgamation

tailings, through establishing a relationship of confidence among miners and researchers.

Some physico-chemical parameters are considered important for assessing the fate of

mercury in the environment, and its eventual bioaccumulation and/or biomagnification in fish,

mainly as methilmercury. Therefore, besides the investigation of natural and/or anthropogenic

mercury concentrations in sediments and water, the physiochemical parameters of water, such

as temperature, electrical conductivity, pH and dissolved oxygen were determined in the

drainage waters by multi-electrodes.

Since sampling of TSS by filtering through 0.45 µm membranes has been reported as

controvertial, due to its unefficiency of recovering enough solid material for analysis, it was

sought naturally settled TSS samples where favorable hydrodynamic conditions were to be

found. An example of settled TSS on the São Chico Creek is ilutrated in Figure 5.

RT2004-004-01 CETEM/MCT 24

Figure 5 Fine layer of settled TSS on São Chico Creek margins

The "Geoaccumulation Index" (Igeo) of mercury in bottom sediments has been selected

for quantitative evaluation of contamination levels in aquatic systems (Müller, 1979). Since the

enrichment process of metals in sediments, caused by a given emission, generally follows an

exponential accumulation in fine fractions, the "Igeo" uses a log function for classifying distinct

order of magnitude of contamination, as follows:

Igeo = log2 Cn / 1.5 . Bn where,

Cn is the measured Hg concentration in the fraction -200 # and Bn is the background Hg

concentration.

Moreover, the Igeo is divided into 7 classes, from 0 to 6, being class 0 indicative of null

contamination while class 6 represents an extreme contamination.

Preparation of sediment, soil and tailing samples consisted of homogenization followed

by wet sieving for separating grain size fractions above and below 200 # (74 µm). After that,

each fraction has been dried at 40 °C for analysis.

The analytical method used in the field was undertaken by a portable atomic absorption

for mercury analysis (LUMEX), which allows simple and direct determinations in different

matrixes without acid digestion.

The method used in the laboratory for the determination of total mercury in

environmental samples (soils, sediments, fish) follows the methodology developed by Akagi

and Nishimura (1991) (Speciation of Mercury in the Environment, in: Advances in Mercury

Toxicology, edited by T.Suzuki et al.). It involves sample digestion with strong acids followed

by reduction to elemental mercury, aeration and measurement of mercury absorption with cold

vapor atomic absorption spectrometry.

The sample digestion procedure insures complete digestion of organic materials and at

the same time avoiding mercury loss by use of a combination of acids and oxidizing agents. This

combination involves a mixture of nitric, perchloric and sulfuric acids. Additionally, water is

RT2004-004-01 CETEM/MCT 25

added to protein-rich samples, to avoid frothing upon heating. The sample is then heated at 250

oC for 20 minutes.

The sample solution is reduced by staneous chloride, generating elemental mercury

vapor, which is then circulated in a closed system. Absorbance is measured when equilibrium of

mercury vapor between gas and liquid phases is reached. The use of a syringe with needle when

adding the reducing agent avoids loss of mercury by vaporization. The detection limit of the

method is 0.5 ng Hg. The flowchart below shows a scheme of the procedure.

Hg was analyzed in the fish muscle through Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer

(KK.Sanso SS) using a Vapor Generation Accessory-VGA (CVAAS). For the analysis of Hg-total,

approximately 0.5 g of tissue was weighed in 50-ml-vol flasks, to which was added 2 ml of

HNO3-HClO4 (1:1), 5 ml of H2SO4, and 1 ml of H2O (Hg free), and heated on a hot plate to 230-

250°C for 20 minutes. After cooling, the digested sample solution was made up to 50 ml with

water. An aliquot (5 ml) of digested sample solution was introduced in the Automatic Mercury

Analyzer Hg 3500. The difference in duplicate sample analyses was less than 10% (precision of

measurements was 90%). The accuracy of analyses was estimated with analyses of biological

tissue standard reference materials from International Atomic Energy Agency. The results