Global Mercury Project

Project EG/GLO/01/G34:

Removal of Barriers to Introduction of Cleaner Artisanal Gold Mining and Extraction Technologies

Technical Report

Delineation of the Permanent Preservation Areas

in the Tapajós River Basin:

Toward Environmental Compliance

on Artisanal Gold Mining Areas

by

Carlos Antonio Alvares Soares RIBEIRO

Terrain Analysis Expert

Chief Technical Advisor: Marcello Mariz da VEIGA

Project Manager: Pablo HUIDOBRO

- August 2006 -

2 / 39

Acronynms

CONAMA

Conselho Nacional de Meio Ambiente

(National Council for the Environment)

DEM

Digital Elevation Model

GMP

The Global Mercury Project

HC-DEM

Hydrographically Correct Digital Elevation Model

IBAMA

Instituto Brasileiro do Meio Ambiente e dos Recursos Naturais Renováveis

(Brazilian Institute for the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources)

IBGE

Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística

(Brazilian Institute for Geography and Statistics)

Landsat-TM Land Remote Sensing Satellite Thematic Mapper

NASA

National Aeronautics and Space Administration

PPA

Permanent

Preservation

Area

SNUC

Sistema Nacional de Unidades de Conservaçăo

(National Protected Areas System)

SRTM

Shuttle Radar Topography Mission

TDR

Tradable Development Rights

UTM

Universal Transverse Mercator

WGS84

World Geodetic System 1984

3 / 39

Table of contents

INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................................................................6

I.A.

BRIEF DESCRIPTION OF THE BRAZILIAN FOREST CODE ................................................................................................7

I.B.

OBJECTIVE OF THE STUDY..........................................................................................................................................10

II.

METHODOLOGY..........................................................................................................................................................10

II.A.

STUDY AREA ..............................................................................................................................................................10

II.B.

DATA .........................................................................................................................................................................11

II.C.

DEVELOPMENT OF A HC-DEM - HYDROGRAPHICALLY CORRECT DIGITAL ELEVATION MODEL...............................12

II.D.

FLOODPLAIN DELINEATION ........................................................................................................................................14

II.E.

MAPPING THE PERMANENT PRESERVATION AREAS ....................................................................................................14

II.E.1.

On hill tops ......................................................................................................................................................14

II.E.2.

Along divides...................................................................................................................................................15

II.E.3.

On upland catchments .....................................................................................................................................16

II.E.4.

On riparian zones.............................................................................................................................................16

II.E.5.

On steep slopes ................................................................................................................................................17

III. RESULTS.........................................................................................................................................................................17

IV. SUMMARY OF FINDINGS...........................................................................................................................................19

RECOMMENDATIONS...........................................................................................................................................................20

REFERENCES...........................................................................................................................................................................21

List of tables

Table 1. Riparian zones' width according to the extent of the floodplain. ......................................................16

Table 2. Permanent preservation areas for the Crepori River basin .................................................................18

Table 3. Permanent preservation areas for the Tapajós River basin.................................................................18

List of figures

Figure 1. Location of the Crepori watershed, Brazilian Amazon. ...................................................................10

Figure 2. Location of the Tapajós watershed. ..................................................................................................11

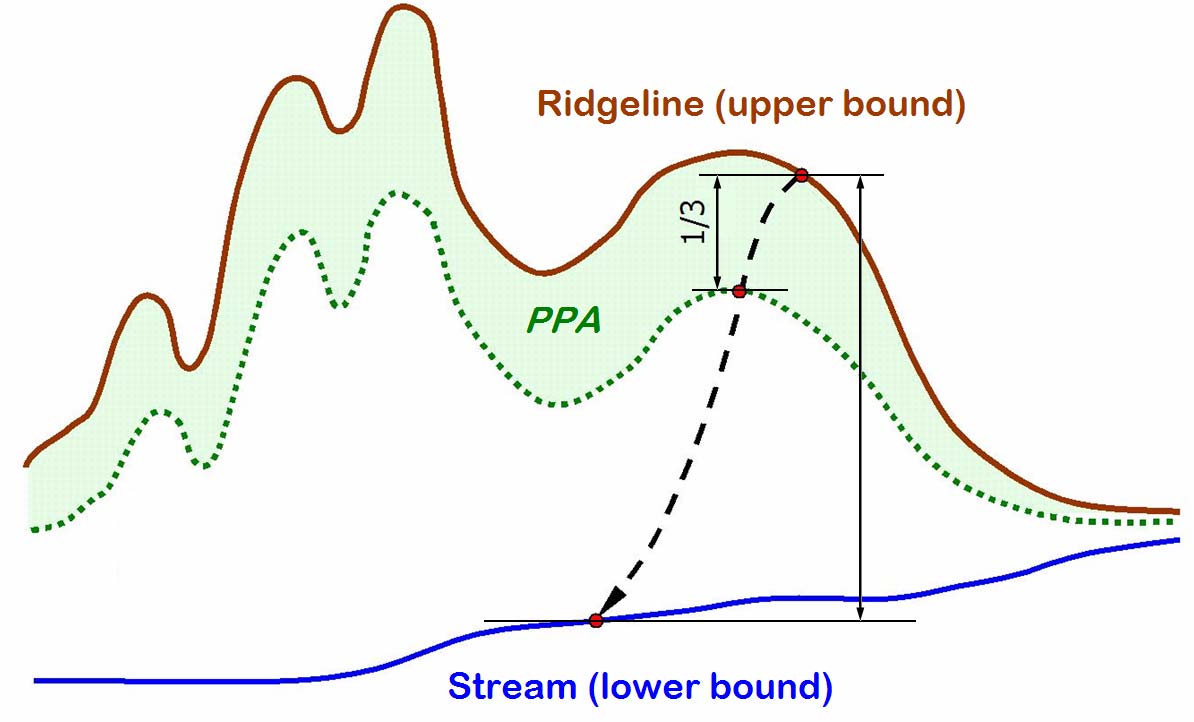

Figure 3. Delineation of permanent preservation areas on hilltops..................................................................15

Figure 4. The upper third portion of a hillside. ................................................................................................15

Figure 5. A 50m-buffer (dark gray) around a spring, overlaid on its drainage area (gray), compose the area

to be protected..................................................................................................................................16

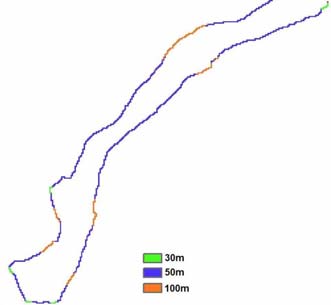

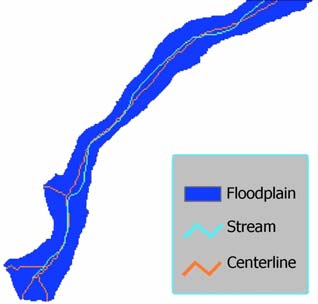

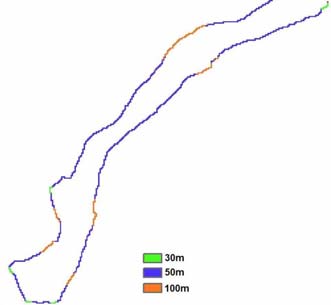

Figure 6. (a) Comparison between the original stream location and the centerline derived for its floodplain,

(b) buffer's width as a function of the floodplain's width,

(c) outline of the riparian zones to be protected bordering the floodplains......................................17

4 / 39

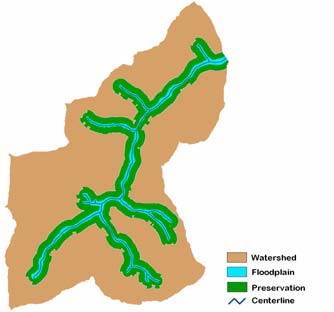

Figure 7. Spatial distribution of the permanent preservation areas..................................................................19

Figure 8. Hydrography of the Crepori watershed ............................................................................................32

Figure 9. Crepori's DEM .................................................................................................................................33

Figure 10. Perspective view of the Crepori basin topography (vertical exaggeration factor: 7x) ...................34

Figure 11. Crepori's permanent preservation areas. ........................................................................................35

Figure 12. Tapajós stream network colour-coded using the Otto Pfafstetter Numbering Scheme..................36

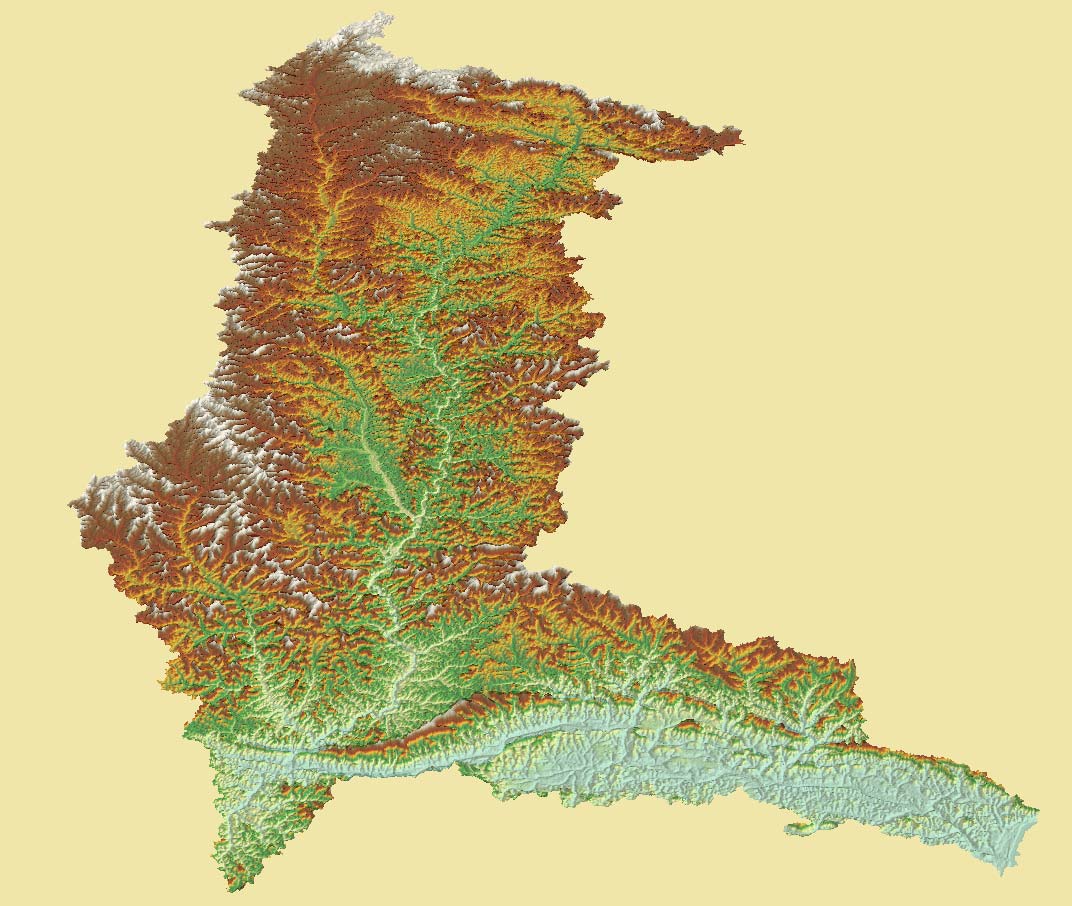

Figure 13. Tapajós DEM..................................................................................................................................37

Figure 14. Perspective view of the Tapajós DEM, showing the limits of the Crepori basin in black (vertical

exaggeration factor: 30x)................................................................................................................38

Figure 15. Tapajós permanent preservation areas............................................................................................39

Appendices

A) CONAMA Resolution no 369 of March 28, 2006

B) Examples of Maps Generated by Hydrographically Correct Digital Elevation Model

5 / 39

Abstract

Project EG/GLO/01/G34: Removal of Barriers to the Introduction of Cleaner Artisanal Gold Mining and

Extraction Technologies

The primary objective of the Global Mercury Project1 is to promote the protection of international waters

from mercury pollution emanating from artisanal gold mining operations. This will be achieved by

minimizing their environmental impacts whilst enhancing the economic development of the mineral sector.

In this sense, one of GMP's goals is to reduce mercury-contaminated sediment mobility into streams

primarily by reestablishing proper native vegetation in the riparian zone. This report supports GMP's

objective by providing 1) a synthesis of existing information relevant to the compliance with permanent

preservation forest areas in Brazil, and 2) GIS-based mapping techniques to assist miners in identifying

conflicts of interest in regard to mining activities and environmental compliance on protected forest areas.

An overview of the process for creating a hydrographically correct digital elevation model, which is the

foundation for automatic delineation of protected areas and tracking the mobility of mercury from mining

sites into the sediments of rivers and streams, is presented. The recent availability of high-resolution

elevation digital datasets, such as those provided by the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission, enabled one to

extend the presented methodology to the whole country.

In order to put in context the conflicts of interest in regard to mining activities and environmental compliance

on protected forest areas, a brief review of Brazilian environmental laws and policies of protected areas is

herein conducted. The latest amendment to the Forest Code has opened for the first time the opportunity to

solve an old, chronic, social and political problem: bringing artisanal gold mining into legality.

The importance of riparian zones in preventing water contamination from surface runoff naturally emerges

from a visual inspection of the results of this study. It is shown that, much more than protecting ecosystems,

the Brazilian environmental legislation will surely lead to healthier and safer watersheds, protecting their

soils from erosion and improving overall water quality, critical for a sustainable good quality of life for

current and future generations of miners and their families.

The maps produced using the proposed methodology will enable both artisanal gold miners and regulators to

develop the confidence to improve current legislations and adopt suitable practices towards environmental

compliance in mining sites.

1 http://www.globalmercury.org

6 / 39

INTRODUCTION

Mining inevitably disturbs land (PETERSON and HEEMSKERK, 2001), promotes wide-ranging disruption

of critical habitats (MOL and OUBOTER, 2004) and leaves profound social impacts on neighboring

communities (BRIDGE, 2004; GRAULAU, 2001; VEIGA et al., 2001). Contamination of surface water and

groundwater supplies is one the most persistent mining effects (BRIDGE, 2004). These processes are well

documented throughout the world and have resulted in numerous environmental laws in many countries,

fostering the development of effective land conservation and reclamation strategies (MOL and OUBOTER,

2004; WORLD BANK, 1998; BILLER, 1994).

The Global Mercury Project (GMP) is orchestrating an innovative worldwide effort to promote better

artisanal gold mining practices. The project's capacity building program aims to reduce mercury-

contaminated sediment mobility into streams primarily by reestablishing proper native vegetation in the

riparian zone. Riparian areas, so defined as zones neighboring surface or subsurface water, constitute

themselves a very unique habitat. Besides providing sustenance for amphibian species, they also connect

aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems. The floodprone area, a gradual transition zone between these two different

worlds, forms an ecotone, holding a rather richer biodiversity (ANDELMAN and FAGAN, 2000). Riparian

habitats extend well beyond the floodplains, being strongly dependent on rainfall and hydrological regimes,

which in turn dictate the associated water levels (VERRY et al., 2004). The resilience of these special

ecosystems is strongly influenced by upstream land use, as water resources and land maintain a very close

relationship. The riparian vegetation is one of the last and yet effective natural barriers to waterways

contamination from surface runoff. Protecting and reclaiming riparian vegetation promotes one of the

primary GMP's goals: to reduce sediment and chemical mobility of mercury into streams from adjacent

artisanal gold mining areas, therefore improving food security and health. In such a scenario, the watershed

emerges as a natural unit for analysis.

Spatial analysis based on hydrographically correct digital elevation models (HC-DEM) would play a major

role in the design of sounder surface-mine reclamation strategies as well as in complying with ongoing

environmental regulations. Accurately modeling surface water runoff, along with strategic stream water

sampling for mercury concentration determination, are critical to 1) identify potential hotspots upstream

sample points, 2) estimate downstream water and riparian zones contamination levels from known mercury

hot spots.

In the present study it was developed an integrative approach using Shuttle Radar Topography Mission

(SRTM) data from National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), and digital hydrography

Brazilian datasets, from Brazilian Institute for Geography and Statistics (IBGE), to produce a

hydrographically correct digital elevation model, the foundation for automating the process of delineating

protected areas, for the Tapajós river, which is located in the Amazon basin. This river was chosen because

of the long-standing history and extent of artisanal gold mining activities in the largest gold province of

Brazil and their impact on international waters.

7 / 39

Enacted four decades ago, the Brazilian Forest Code was conceived to protect the ecosystems of Brazil by

regulating human impacts on environmentally sensitive areas such as riparian zones, along ridgelines and

upland catchments. Permanent preservation areas, the cornerstone of the Forest Code, were meant to create a

vast network of ecological corridors, connecting all biomes and effectively shielding their biodiversity. Any

and all direct economic activity on such areas was defined as crime against the environment subjecting the

offender be it an individual or a legal person, including corporate management to both imprisonment and

fine, even when covered by a valid permit (BENJAMIN, 1998).

The enactment of this law created a delicate situation. Artisanal gold mining activities in Brazil occur mostly

on riparian zones (DALL'AGNOL, 1995; BILLER, 1994), which violates the Brazilian Forest Code. Hence,

artisanal gold miners could never be granted the necessary environmental license, forcing them to operate

outside of the legal framework and to prematurely abandon the ore deposits. This, in turn, increased

environmental damage (MOL and OUBOTER, 2004). Nevertheless, during the Amazon gold rush of 1980s,

in order to solve increasing conflicts between artisanal gold miners, whose presence in the Tapajós River

basin goes back to 1958 MOURA, 2003), and mining companies, the legal owners of mining claims granted

by government, on July 28, 1983 the Ministry of Mines and Energy of Brazil enacted Ministerial Order no

882 defining precisely the limits of an area encompassing 28,745km2 located in the municipality of Itaituba,

in the southwest of the state of Pará, and designated as the Artisanal Gold Mining Reserve of Tapajós, In this

reserve, the exploration of any mineral could only be carried out via artisanal, small-scale mining methods.

Recently the Brazilian National Council for the Environment (CONAMA) enacted regulatory exceptions

(Resolution no 369 of March 26, 2006) to the Forest Code authorizing the intervention or even vegetation

removal on permanent preservation areas, definitely opening a door of opportunity for legalizing artisanal

gold mining in Brazil.

I.A. BRIEF DESCRIPTION OF THE BRAZILIAN FOREST CODE

Being internationally recognized as a country having one of the most advanced environmental legislations,

Brazil still has a long way ahead to fully enforce it (DRUMMOND & BARROS-PLATIAU, 2006). The

country has a wide-ranging system of protected areas, which form part of the National Protected Areas

System (SNUC). The 1965 Brazilian Forest Code, law no 4771, defined two categories of protected forests:

1) Legal Reserves, which require that every property keeps at least 20% of the land to be covered with the

natural vegetation (being it 35% for the savannas of the Legal Amazon, and 80% everywhere else in the

Legal Amazon region), and 2) Permanent Preservation Areas, whose definitions are based on key

geographic watershed features such as divides, riparian areas, hilltops and steep hillsides. While the forests

that make up a legal reserve may be managed but never clear-cut for timber production, on permanent

preservation areas one precludes all direct economic uses of the forested area. Violations to this law are

defined as crimes against the environment subject to both imprisonment and fine.

Low levels of environmental compliance often result from inadequate law enforcement by governmental

agencies (HIRAKURI, 2003). This means nothing less than illegal appropriation of public goods for the sole

8 / 39

benefit of individuals or corporations (BENJAMIN, 1998). Seen as a cornerstone, the Brazilian law no

6938/1981, known as the National Environmental Protection Act, did much more than establish a

contemporary environmental policy framework: it provided the regime of a strict liability standard for

environmental damages. This law defines as crime, subject to imprisonment, all conducts that pose serious

risk to human life or health or to the environment, even when covered by a valid permit (BENJAMIN, 1998).

Subsequently the Brazilian Congress passed the law no 7347/1985, extending to non-governmental

organizations standing to sue in environmental affairs. Later, the Constitution of 1988 clearly denoted the

Brazilian society's concerns on environmental protection:

Article 255: All persons are entitled to an ecologically balanced environment, which is an asset for

the people's common use and is essential to healthy life, it being the duty of the Government and of

the community to defend and preserve it for present and future generations.

...

- § 2: Those who explore mineral resources shall restore the degraded environment according to the

technical solution required by the proper government agency, according to the law.

Recognizing the increasing effectiveness and power of criminal law for the protection of human health and

ecosystems, in February 12, 1998 Brazil enacted law no 9605, introducing remarkable innovations in crimes

against the environment, such as the provision for corporate criminal liability, "punishing with one to four

years in jail and a fine anyone who causes pollution of any nature at levels that result or may result in injury

to human health or that cause animal death or significant destruction of flora". The article 66 of this law

instituted the punishment one to three years of incarceration plus fine of any environmental official who

makes false or misleading statements, omits the truth, or does not disclose technical and scientific

information or data in applications for environmental permits or licensing (BENJAMIN, 1998). Among other

legal penalties, the offender is permanently precluded from signing contracts with the government, receiving

tax incentives or any kind of benefit and taking part in any public bids. Furthermore, its activities can be

partially or even totally suspended.

The technical challenges posed to the fulfillment of its constitutional duty to effectively enforce

environmental compliance on permanent preservation areas along with the increasing international pressure

for stopping deforestation in the Amazon rainforest led the Brazilian government to create the National

Protected Areas System in 2000, which was affiliated to the Ministry of Environment and coordinated by the

Brazilian Institute for the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA). The law no 9.985 of

July 18, 2000, has defined two categories: 1) strictly protected areas, which include national parks and

biological reserves, and 2) protected areas of sustainable use, e.g. national forests and extractive reserves.

Paripassu with global environmental awareness, the Brazilian National Council for the Environment enacts

resolution no 303/2002, which has instituted the following types of permanent preservation areas:

1. on hilltops, comprising the upper-third of hills and mountains;

2. along divides, encompassing the upper-third of the hillsides;

3. on upland catchments, so defined by the contributing area of any given spring;

9 / 39

4. on the margins of natural lakes and lagoons;

5. on riparian zones, whose widths depend on the extent of their floodplains;

6. on areas with slopes equal to or greater than 100%; and

7. on any area situated above 1.800m.

The broad category of permanent preservation areas still included provisions for protecting environmentally

sensitive sites such as those used for nesting or refuge by migratory birds, beaches, mangroves, salt marshes

(restingas), permanent swamp areas dominated by palm trees (veredas), habitats of endangered species, and

dunes. Conversely, the mapping of such protected areas cannot be automated.

The historic lack of appropriate maps depicting the limits of permanent preservation areas (RIBEIRO, 2004)

along with the shortage of infrastructure and personnel of governmental institutions to perform inspections

on remote regions (HIRAKURI, 2003; LELE et al., 2000) made it virtually impossible to fully enforce this

law over the Brazilian Amazon. In contrast to the permanent preservation areas, the boundaries of protected

areas, as stated in the law no 9.985, are subjectively defined, being much easier to be mapped and thus

enforced. The study of RYLANDS and BRANDON (2005) indicates the existence of 478 strictly protected

areas spanning over 370,197 km2, and 436 sustainable-use ones covering 745,927 km2, created and enforced

at both federal and state levels. These values comprise, respectively, 4.3% and 8.8% of Brazil's territory

(8,511,965 km2).

An endless polemic on the legality of interfering on permanent preservation areas was recently settled by the

Ministry of Environment of Brazil. In response to the insidious threat posed by invading exotic species to

biodiversity and to ecosystem services provided by riparian vegetation, and in order to legalize the necessary

actions aimed to eradicating, containing the spread and controlling the numbers of invasive species,

CONAMA has enacted resolution no 369 which introduced regulatory exceptions into the Brazilian Forest

Code. This act came into effect on March 29, 2006, instituting a wide range of situations in which the

intervention or even the removal of vegetation on permanent preservation areas is imperative and strictly in

the interest or for the benefit of the general public.

Along with other innovations, this act regulates issues of paramount importance to the mining sector. Among

others activities, the prospecting and the exploration of mineral resources located on those areas and granted

by the proper authority were legally recognized by the Brazilian government as of public utility (art. 2, 1st

part, provision c). Concerning environmental compliance, this represents the first tangible, unparalleled

opportunity over the past 40 years to insert artisanal gold mining into the formal economy and to have it

properly included in local and regional development plans.

Yet, there is a long way ahead before the permit for mining on protected areas is issued. Article 3 of this

resolution states the general conditions:

- nonexistence of technological and locational alternatives for the proposed facilities, activities or

projects;

- compliance with the conditions and standards applicable to water bodies;

10 / 39

- notarized registration of the "legal reserve area";

- absence of risking aggravation of natural processes such as floods, soil erosion or rock sliding.

A map depicting the limits of the permanent preservation areas will dictate if the applicant must or not

request the specific environmental license to operate. The present study represents a first step in addressing

this problem through the development of a method by which these areas can be accurately mapped from

existing geospatial data sources for use in the fulfillment of existing Brazilian legislation.

I.B. OBJECTIVE OF THE STUDY

This study aims to map permanent preservation areas for the Tapajós basin, according to the Brazilian Forest

Code, in order to enable both artisanal gold miners and regulators in improving current legislations and

adopting suitable practices towards environmental compliance in mining sites.

II. METHODOLOGY

II.A. STUDY AREA

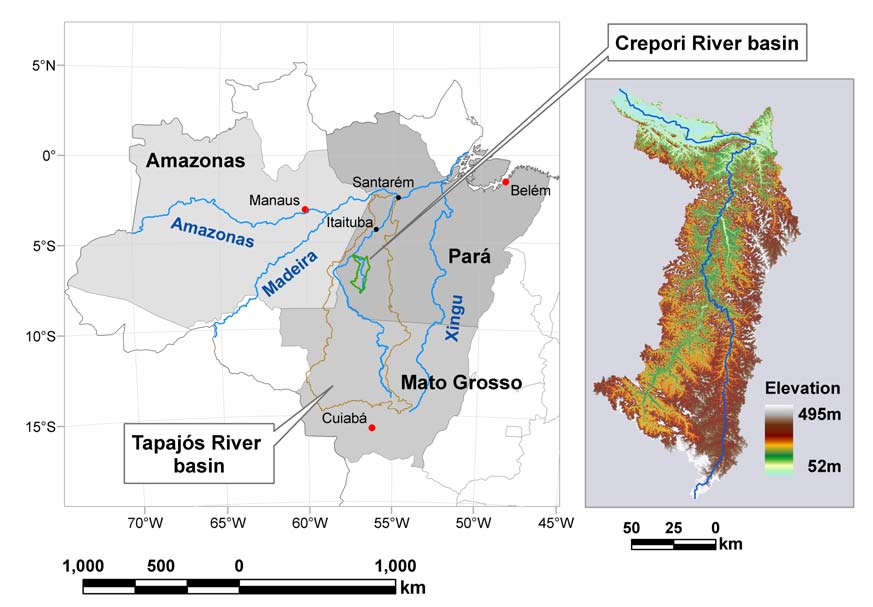

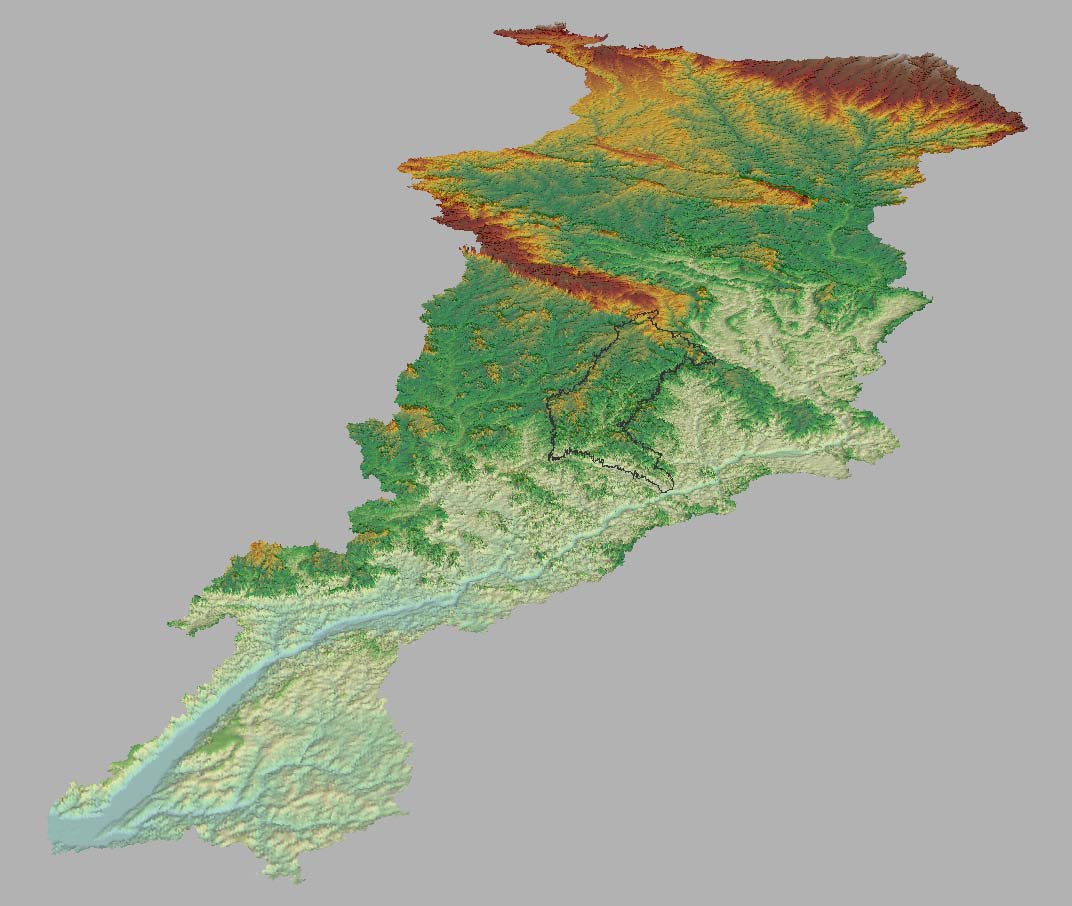

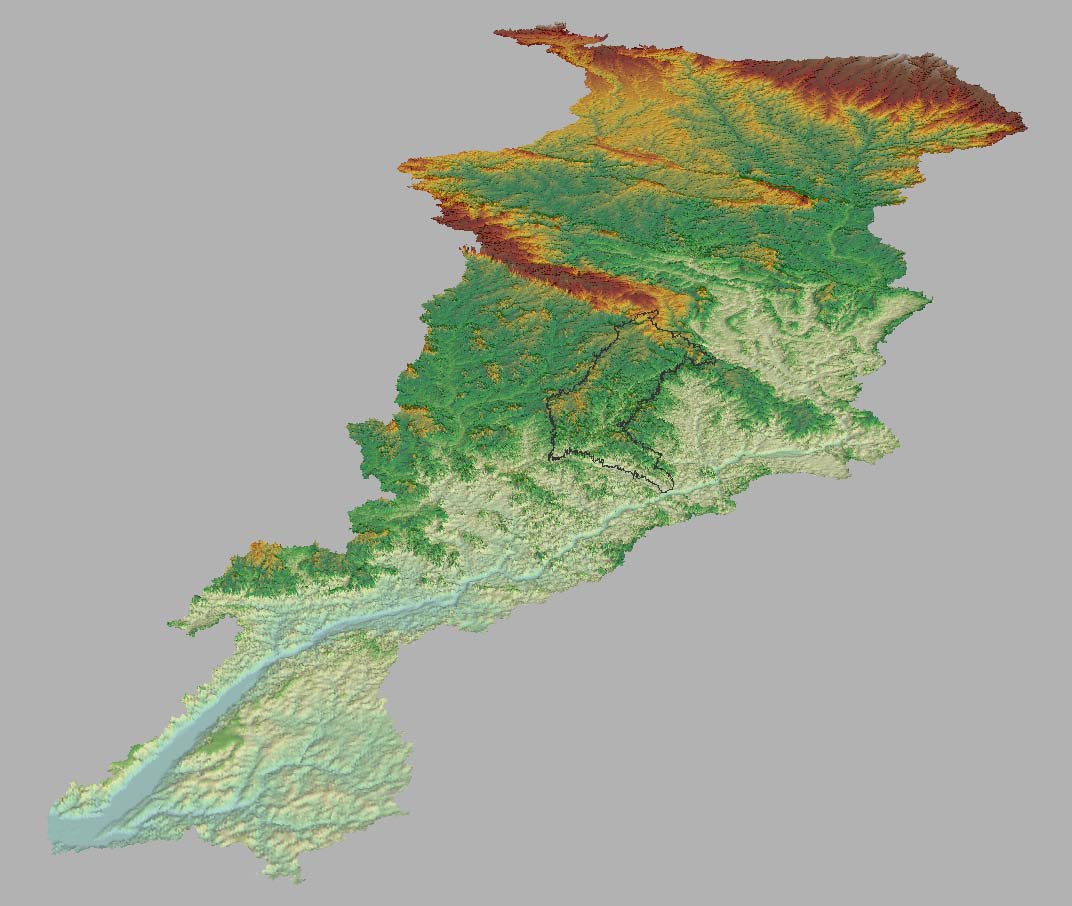

The watershed of the Crepori river, a major tributary of the Tapajós river, was initially selected in order to

ease the tests and the necessary refinements of the proposed methodology. This watershed, located in the

southwest region of the State of Pará, Brazil, drains an area of 13,578 km2 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Location of the Crepori watershed, Brazilian Amazon.

11 / 39

Elevations range from 52m on its confluence with the Tapajós river to 495m above sea level in the uplands to

the south, having an average elevation of 250m (±68m). Its terrain consists of a highly complex network of

numerous small rivers that cut through ground with slopes ranging from 0% to 250%, with an average value

of 13% (±9%). Annual rainfall in this area is just over 2,000 mm and the average temperature is 28oC.

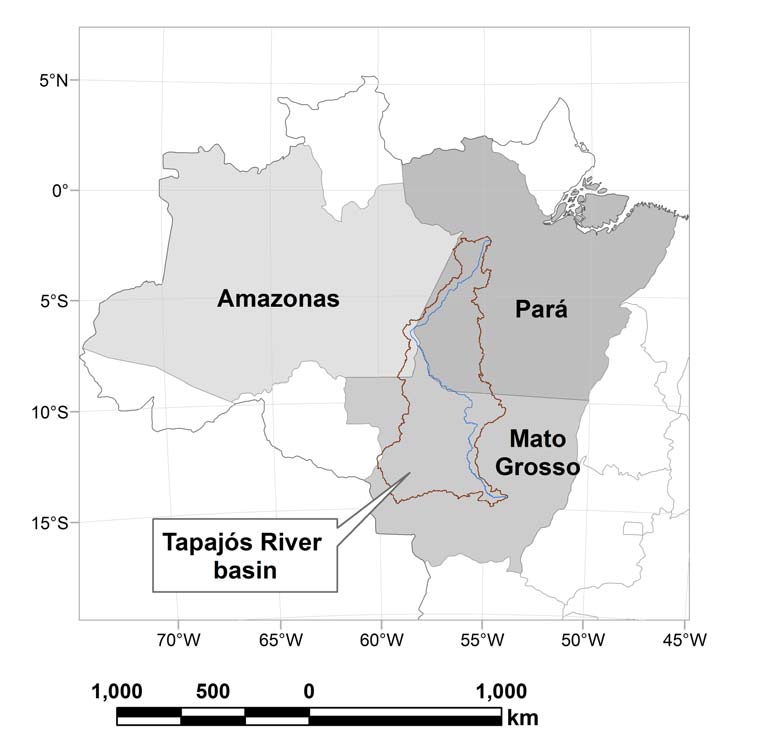

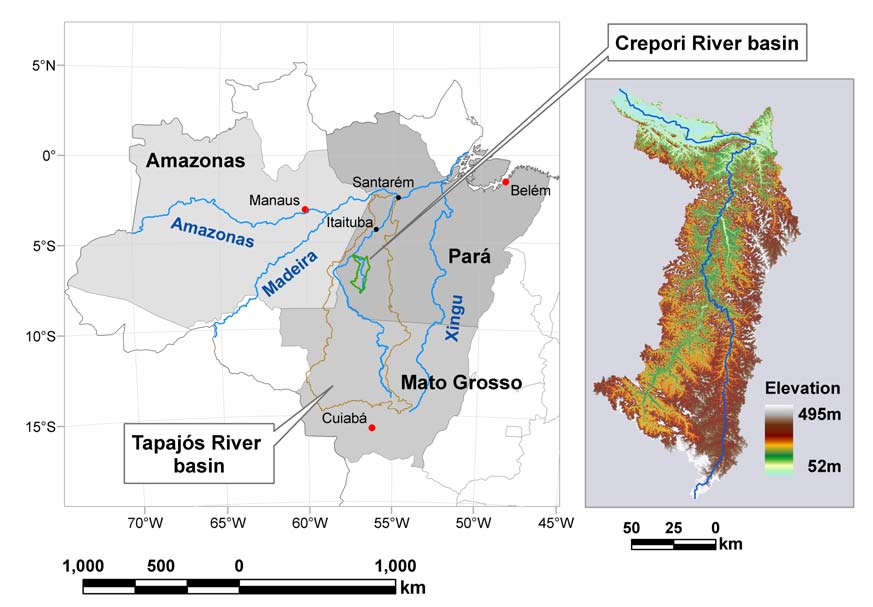

The Tapajós river, one of the most important tributaries of the Amazon river, is formed by the confluence of

the Juruena and Teles Pires rivers. It drains an area of 493,000 km2, spanning over three states of the Legal

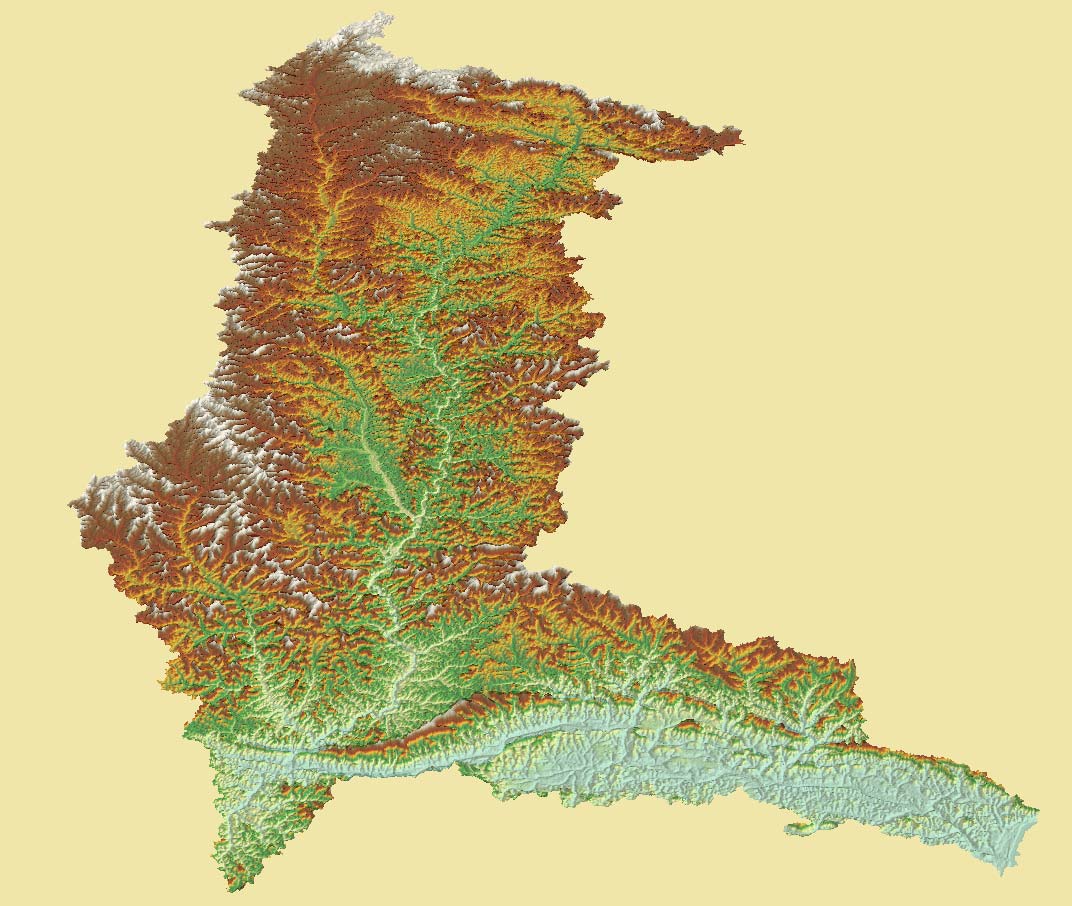

Amazon: Mato Grosso, Pará and a small part on the Amazonas state (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Location of the Tapajós watershed.

The elevation within this watershed varies from 0m to 896m, presenting an average of 304±136m. The

maximum slope is 222% and the average value is 6.7±6.6%.

II.B. DATA

The most recent version of SRTM data, version 2, also known as the finished version, was released by

NASA for South America in October 2005. Although available at 30m (1 arc-second) in resolution for the

United States, data for areas outside were degraded to 90m (3 arc-seconds). The corresponding datasets are

12 / 39

sometimes referred to as SRTM1 and SRTM3 respectively. These data can be freely downloaded from the

Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Center's ftp site (ftp://e0srp01u.ecs.nasa.gov), being organized

into 1ş x 1ş tiles of geographic coordinates (latitude, longitude).

The digital stream network dataset, provided by the Brazilian Institute for Geography and Statistics (IBGE),

was created by scanning and vectorizing its 1:250,000-scale maps.

II.C. DEVELOPMENT OF A HC-DEM - HYDROGRAPHICALLY CORRECT

DIGITAL ELEVATION MODEL

In order to ensure that the divides of the selected target watershed would be accurately depicted in the final

digital elevation model (DEM), a 20km buffer was defined around its stream network, therefore requiring a

total of 85 SRTM3 tiles to cover the entire area. An error in the routine2 used to convert SRTM elevation

data files into ESRI grid format caused a ˝ pixel shift of each tile toward South and West. The error was

fixed and all the 85 tiles were then mosaicked into one seamless DEM. To preserve map accuracy during

subsequent spatial analyses, this DEM was projected to UTM coordinates, zone 21S, keeping the same

datum (WGS84) of the original SRTM data. The next step was to convert its cells to a point dataset, each

point lying in the center and carrying on the elevation value of the respective cell.

Although explicitly stated in both ArcGIS and ArcInfo manuals that "there is no software limit on the size of

the output grid", the truth is that there is, in fact, a 1024 Mb internal, non-documented limit on the size of the

resulting DEM. This limitation is even stronger (only 512Mb) if one decides to use the new Topo_To_Raster

routine instead of Topogrid. This software restriction imposed the analysis area to be subdivided into 33 sub-

basins. The solution adopted for splitting the area prioritized the accuracy of divides and riverbeds

delineations over geometric tiling simplicity, i.e., avoiding the traditional rectangular scheme.

The digital stream network dataset, representing the centerlines of the hydrography, was checked for

connectiveness and downstream orientation of all its arcs, a key condition for creating a HC-DEM

(HUTCHINSON, 1996). Polygons buffering each one of the 33 sub-basins were created in such a way that

any sub-basin would overlap the adjacent ones along the respective divide. Then the original stream network

vector dataset was clipped using those polygons.

The software used for generating the DEMs was the ArcGIS version 9.1 running on Windows Server 2003.

A significant amount of pre-processing was required to prepare the vector data for input to TOPOGRID, the

interpolation routine used by ArcGIS. This routine allows for drainage enforcement, a technique that

produces more accurate terrain surface representations and better placement of streams. TOPOGRID requires

each stream segment to be oriented downstream, and that there should be no polygons (lakes) or braided

streams in the network. The cell size of the output DEM was set to 30m, within the accuracy of the digital

hydrography dataset (25m) and matching the resolution of Landsat-TM imagery.

2 SRTMGRID.AML, available in the Notes_for_ARCInfo_users.pdf file

13 / 39

The removal of spurious sinks was performed on the DEM generated by TOPOGRID using the FILL

command, available in ArcToolbox, to eliminate any eventual depression that would otherwise block

downstream flow. Even using TOPOGRID with drainage enforcement, the digital hydrography does not

always coincide with the bottom of the DEM valley, creating peaks and sinks on the vertical profile of the

stream network. Drastic changes in elevation values may occur as a result of applying the traditional stream

burning techniques to correct the vertical profile of the rasterized stream network (SAUNDERS, 1999). In

order to minimize the changes in the original DEM surface values along hydrography cells, we modified the

method proposed by HELLWEGER (1997). Initially, the vector hydrography was rasterized and the resulting

grid was thinned to 1-cell wide by using the shortest path algorithm to connect the cells associated to the

springs to the cell of the basin's outlet. Next, the vertical profile of this raster hydrography was extracted

from the depressionless DEM and then inverted. The cells associated with the springs were assigned

NODATA and a 1-cell buffer along all the hydrography received zero as elevation value. This raster was

then filled to remove any spurious sinks which, in fact, promoted the removal of eventual spurious peaks

along the stream network because of its inversion. The resulting hydrography profile was inverted again,

bringing it back to the correct vertical position. The spring cells received their original elevation values and a

large value (5,000m) was subtracted from all stream cells. The FILL command was executed once more, this

time getting rid of the spurious sinks. The maximum difference between these results and the previous stream

profile, minus 0.5m, was calculated and added to all stream cells, assuring that none of them would be higher

than the bordering ones.

The DEM surface within a 5-cell buffer along each side of the hydrography was then replaced by ramps

mathematically created between the borders of the buffer and the stream network's cells. The overlapping of

some buffers occurred whenever the distance between any two streams was less then 10 cells. Such

situations, not contemplated in the Hellwerger's method, are usually found in meandering rivers, leading to

miscalculation of the elevation values for the associated ramps. To avoid this problem, it was necessary to

identify the centerlines of the areas of superimposition, keeping their original elevation values.

Flow direction is vital for deriving subsequent hydrographic information about a surface and therefore, this

dataset should be as accurate as possible given the input data (SAUNDERS, 1999). The derivation of the

flow direction grid for the reconditioned DEM required three steps, each one for a different region: (1) for

cells lying outside the buffer, the flow direction was derived using the depressionless DEM values converted

to millimeters and then to integer, (2) for cells inside the buffer but not belonging to the hydrography, their

flow directions were imposed towards the closest river cell using the COSTBACKLINK command, and (3)

for cells belonging to the stream network, their directions were forced to follow the shortest path to the

basin's mouth, also using the COSTBACKLINK command. This strategy was conceived to guarantee that

the surface runoff within the buffer would converge to the stream cells and, once there, it would flow

towards the outlet.

14 / 39

II.D. FLOODPLAIN DELINEATION

The first step in determining the extent of the protected riparian zone is to define the limits of its floodplain.

The traditional approaches for mapping floodplain boundaries primarily consist on the establishment of a set

of straight-line cross-sections along the stream network and then determining the water surface elevations for

each cross-section (AKERMAN et al., 2000). Depending on the terrain topography and the flood extension,

this may lead to wrong results since the downslope path that flood water would follow may not be

necessarily perpendicular to a given stream point for a large extent (BRIVIO et al., 2002; TATE et al., 2002).

This is usually the case for many rivers of the Amazon basin, such as the Tapajós. Furthermore, if any cross-

section intercepts more than once the floodplain, only the portion closer to the stream is reliable, the other

ones being disregarded.

To circumvent these limitations, a grid-based method was developed to provide flood elevations for any grid

cell, taking into account the path followed by the surface runoff during the flooding event and thus

generating a more accurate representation. The flood heights along the stream cells are calculated using

observed water levels at gauges. These values are then converted to millimeters, in order to retain the

precision of the original data, and finally to integer, to satisfy the requirements of the WATERSHED

command which dictates that the ID of the source cell must be an integer value. This command will delineate

the contributing area that drains to a given source cell, assigning its ID to all cells that make up the respective

catchment. The WATERSHED command also requires as input a grid depicting the direction of the flow out

of each DEM cell. So, using the flood heights as IDs of the stream cells, the output grid will describe the

zone of influence of every stream cell, in accordance with the runoff flow path. The original DEM is

subtracted from resulting surface. The flood extent is obtained by selecting all cells with positive values, i.e.,

areas with a depth greater than zero.

II.E. MAPPING THE PERMANENT PRESERVATION AREAS

Specific routines for automatically mapping the following categories of protected areas were developed:

II.E.1. On hill tops

The hills were isolated by inverting the reconditioned DEM. The cell associated with the peak of each hill

was a sink, and the basis of its hill was defined by the boundary of respective watershed. The minimum and

the maximum elevation values of each hill were calculated and the cells corresponding to its upper third were

flagged as protected areas (Figure 3).

15 / 39

Figure 3. Delineation of permanent preservation areas on hilltops.

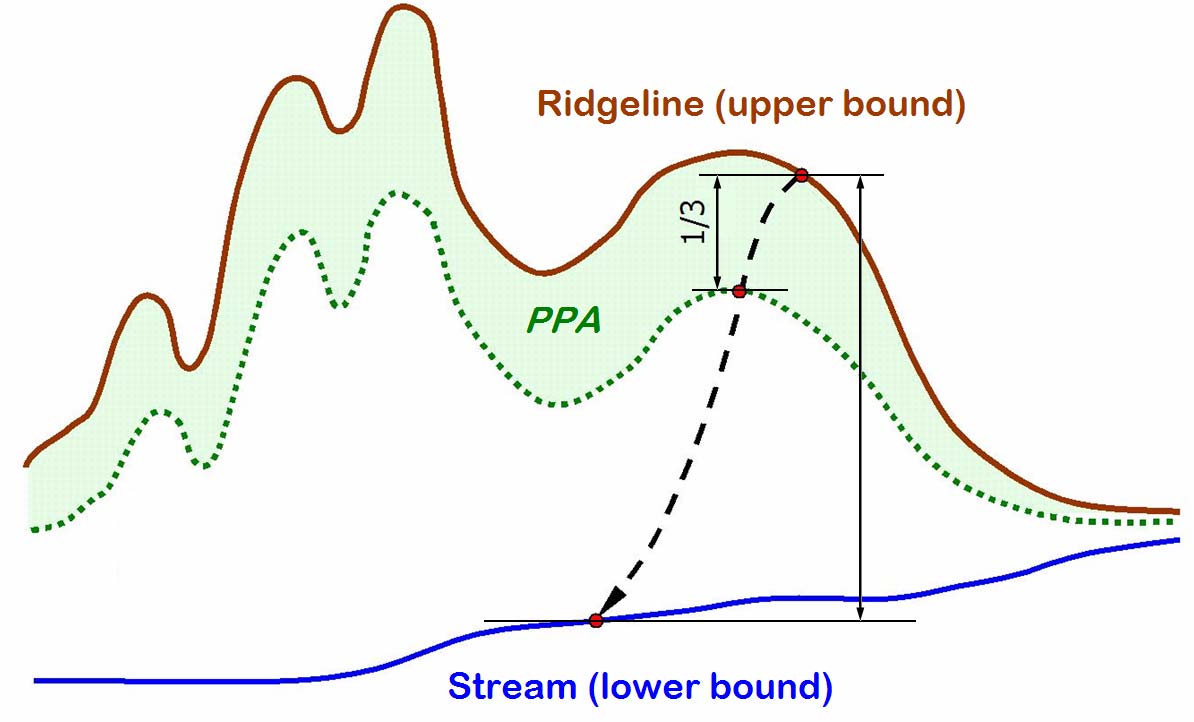

II.E.2. Along divides

The areas to be protected along the ridgelines comprise the upper third of the hillsides. In order to map them,

for every cell in the landscape one needs to know what is the elevation of its closest cell to the divide (upper

bound) and also what is the elevation of its closest cell to the hydrography (lower bound). These three cells

must lie along the same flow path in order to find the relative vertical position of a given cell in respect to its

base. Only after that it is possible to select the cells belonging to the hillside's upper third (Figure 4).

Figure 4. The upper third portion of a hillside.

16 / 39

II.E.3. On upland catchments

This category of permanent preservation areas combines the area within a 50m radius around each spring

with the respective catchment (Figure 5). A grid containing only the cells associated to the springs was used

as input to the WATERSHED command in order to derive the contributing area, as well as to define a 50m-

radius buffer around them.

Figure 5. A 50m-buffer (dark gray) around a spring, overlaid on its drainage area (gray), compose the area to

be protected.

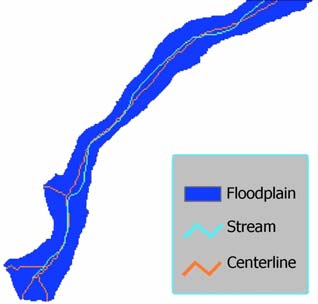

II.E.4. On riparian zones

The delineation of protected areas along watercourses relies on determining the width of the floodplains

associated to their highest water levels reached at the peak of the raining season.

Table 1. Riparian zones' width according to the extent of the floodplain.

Floodplain's width

Riparian zone's width

[meters]

[meters]

< 10

30

10..50

50

50..200 100

200..600 200

> 600

500

It is worth to mention that the protected areas' widths must be added to the respective floodplain's width.

The challenge of finding the floodplain's width dwells in delineating the centerline of the inundated area.

Our approach can be summarize in the following steps: (1) identify the floodplain's extent for the stream

network under analysis and vectorized the resulting grid, (2) identify the cells lying on the borders of the

floodplain and convert them to a point dataset, (3) create a Thiessen polygon dataset for those points, (4) clip

the Thiessen lines with the polygon portraying the floodplain extent, (5) remove the Thiessen lines touching

the border of the floodplain polygon, to further reduce the amount of lines to work with, (6) manually select

17 / 39

the centerlines and save them into a separate dataset (we suggest to use the shortest path algorithm to connect

the initial segment to the final one of each major centerline to speed up this process, which tends to be very

tedious and labor intensive), (7) rasterize the centerline dataset and generate an Euclidean-distance surface

from these cells, (8) extract the distance of each borders' cell to the closest cell of the centerline and multiply

the results by two, (9) reclassify the resulting grid using the ranges shown inTable 1, (10) convert those cells

to a point dataset and create buffers for them according to the respective riparian width values, (11) rasterize

the buffer polygon dataset and finally merge the resulting grid with the floodplain one in order to produce the

map of the permanent preservation areas. The main steps of this process are depicted on Figure 6.

(a)

(b)

(c)

Figure 6. (a) Comparison between the original stream location and the centerline derived for its floodplain,

(b) buffer's width as a function of the floodplain's width, (c) outline of the riparian zones to be

protected bordering the floodplains.

II.E.5. On steep slopes

Any portion of the terrain whose slope is greater than 100%, which is equivalent to an angle of 45o, is

protected under the Brazilian Forest Code. One must ensure that the Z units match the dataset planar

coordinates in order to generate the correct results when applying the SLOPE command; if not, a proper Z

factor must be calculated and then applied.

Once being delimited, the grids of all categories of protected areas were then mosaicked to produce the final

map of the permanent preservation areas for the Tapajós River basin.

III. RESULTS

The Crepori stream network used in the interpolation of the SRTM data is presented in Figure 8, while

Figure 9 portrays the resulting digital elevation model, after the necessary refinements along the

hydrography. A perspective view of its relief is shown in Figure 10.

18 / 39

Using a cell size of 30m, the rasterization of the Crepori stream network resulted in 2,911 stream links. The

extent of the longest river was equal to 438km. The results of the delineation of the protected areas,

performed for each one of the 2,911 corresponding catchments, are shown in Error! Reference source not

found..

Table 2. Permanent preservation areas for the Crepori River basin

Category Area

[km2]

Percentage of basin's area

Upland catchments

289

2%

Along ridgelines

2,273

17%

Riparian zones

3,060

23%

Hilltops 4

---

Steep slopes

1

---

Overall protection

5,383

40%

The Figure 11 depicts the environmental protection provided by the permanent preservation areas delineated

for the Crepori River basin.

In order to ease the management of the Tapajós hydrography digital dataset, its segments were coded based

on the Otto Pfafstetter Numbering Scheme (Figure 12), a self replicating topological system for assigning

IDs to watersheds (VERDIN and VERDIN, 1999). The original method was modified to work with stream

lengths instead of watershed areas. The Tapajós HC-DEM is presented in Figure 13 and its perspective view,

in Figure 14. Using the same cell size, the rasterization of the Tapajós stream network resulted in 77,892

stream links. Its longest watercourse spanned over 2,612 km. The results of the delineation of the protected

areas, performed for each one of the 77,892 corresponding catchments, are shown in Table 3 and the

respective map, in Figure 15.

Table 3. Permanent preservation areas for the Tapajós River basin

Category Area

[km2]

Percentage of basin's area

Upland catchments

17,300

3%

Along ridgelines

50,326

10%

Riparian zones

104,344

21%

Hilltops 27

---

Steep slopes

5

---

Overall protection

164,518

33%

The overall protection values presented on Table 2 and Table 3, being lower than the total sum of all

individual categories contributions, indicate the occurrence of some overlapping between two or more

categories of permanent preservation areas, e.g., on upland catchments and along ridgelines.

19 / 39

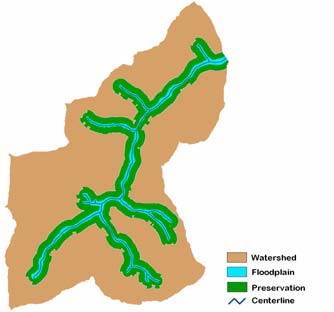

A map showing the extent of the overall protection provided by the Brazilian Forest Code for a small portion

of the Tapajós basin is presented in Figure 7. Two categories of natural corridors emerge from the visual

inspection of this illustration: one formed along the catchments' divides, and another bordering the

floodplains.

Figure 7. Spatial distribution of the permanent preservation areas

IV. SUMMARY OF FINDINGS

· Recent technological advances in Geographic Information Systems and high-resolution topographic

satellite imagery, such as those provided by the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission, along with the

methodology presented in here, created the necessary conditions for automatically delineating permanent

preservation areas and thus enabling environmental compliance. This represents a solid step toward

expanding the use of this methodology to a global scale.

· Even for plain topography the permanent preservation areas would account for approximately 1/3 of the

Tapajós watershed's total area.

20 / 39

· The higher percentage of Crepori's permanent preservation areas shows that this basin has proportionally

higher hills than the Tapajós basin. This is also confirmed by comparing their average slope values.

· The permanent preservation areas associated to riparian zones are preferred sites for artisanal gold

mining due to easy access and water availability.

· Accurately mapping and quantifying current and potential gold mining sites on permanent preservation

areas on a regional basis would enable the proposition of tradable development rights (TDR) programs

for fulfilling the requirement of rehabilitating degraded permanent preservation areas, on alternative

locations within the same watershed. This is the next step of this work.

· The mapping of permanent preservation areas will allow for identifying areas where land use change is

legally allowed.

· The Brazilian Forest Code provides a robust and intelligent framework to establish natural preserves

countrywide based on solid ecological grounds. Riparian vegetation is one of the last and yet effective

natural barriers to waterways contamination from surface runoff. Protecting and reclaiming riparian

vegetation would promote one of the primary GMP's goals: to reduce sediment and chemical mobility of

mercury into streams from adjacent artisanal gold mining areas, therefore improving food security and

health in mining communities.

· Much more than just protecting ecosystems, the compliance with these environmental regulations will

surely lead to healthier watersheds, protecting their soils from erosion and improving water quality and

quantity, that are critical for the livelihood of the artisanal gold miners' families.

· The results from our study offer ample information to stakeholders, illuminating the reality of political

willingness to enforce land use designations and to improve the current legislation.

RECOMMENDATIONS

· GMP should develop a comprehensive and seamless Web-based GIS library of geodatasets depicting

updated land use/land cover, the extent of floodplains during the rainy season, the limits of permanent

preservation areas as stated in the law, and the location of artisanal gold mining sites, at the level of

catchments, for the watersheds associated to the GMP sites.

· This information can then be proactively used by GMP team to analyze, propose and manage an

international fund for promoting tradable development rights programs towards environmental land

reclamation of abandoned artisanal gold mining sites.

21 / 39

· Considering that artisanal gold mining activities in Brazil occur mostly on riparian zones, and given the

new provisions of the Brazilian Forest Code, artisanal miners should be persuaded not to mine river

banks nor close to watercourses, reducing environmental impacts related to mercury use, land

degradation, and river siltation. GMP shall carry out a series of workshops to present these maps to the

mining communities, get the opinion of miners about their potential impact and use, and assist them in

complying with complicated legalities in order to best attain the GMP goals.

· GMP should foster the development of mining cooperatives to enable artisanal gold miners to benefit

from the opportunities recently provided by resolution no 369 of CONAMA.

These actions will strengthen the trustworthiness of GMP among stakeholders as a key instrument of changes

towards safer and better artisanal gold mining worldwide.

REFERENCES

ACKERMAN, C.T.; EVANS, T.A.; BRUNNER, G.W. Paper 8 HEC-GeoRAS: linking GIS to hydraulic

analysis using Arc/INFO and HEC-RAS. p.155-176 in: MAIDMENT, D.; DJOKIC, D. (eds.).

Hydrologic and hydraulic modeling support with geographic information systems.. Environmental

Systems Research Institute, Redlands, CA. 2000. 216p.

ANDELMAN, S.J.; FAGAN, W.F. Umbrellas and flagships: Efficient conservation surrogates or expensive

mistakes? Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000. Vol.

97, No. 11. pp.5954-5959.

BENJAMIN, A.H.V. Criminal law and the protection of the environment in Brazil. Proceedings of the Fifth

International Conference on Environmental Compliance and Enforcement. Monterey, CA. 1998. Vol. 1.

pp.227-234.

BILLER, D. Informal gold mining and mercury pollution in Brazil. Policy Research Working Paper 1304.

World Bank. Washington, D.C. 1994. 28p.

BRIDGE, G. Contested terrain: mining and the environment. Annual Review of Environment and Resources.

2004. Vol. 29. pp.205-259.

BRIVIO, P.A.; COLOMBO, R.; MAGGI, M.; TOMASONI, R. Integration of remote sensing data and GIS

for accurate mapping of flooded areas. International Journal of Remote Sensing. 2002. Vol. 23, No. 3.

pp.429-441.

DALL'AGNOL, R. Mining without destruction? Problems and prospects for the garimpos and major mining

projects. p.205-233 in: CLÜSENER-GODT, M.; SACHS, I. (eds.). Brazilian perspectives on sustainable

development of the Amazon region. UNESCO, Paris. 1995. 330p.

22 / 39

DRUMMOND, J.; BARROS-PLATIAU, A.F. Brazilian environmental laws and policies, 1934-2002: a

critical overview. Law & Policy. 2006. Vol. 28, No. 1. pp.83-108.

GRAULAU, J. Peasant mining production as a development strategy: the case of women in gold mining in

the Brazilian Amazon. European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies. 2001. pp.71-104.

HIRAKURI, S. R. Can law save the forest? Lessons from Finland and Brazil. CIFOR, Bogor Barat,

Indonesia. 2003. 120p.

HUTCHINSON, M.F. A locally adaptive approach to the interpolation of digital elevation models. In: Third

International Conference/workshop on Integrating GIS and Environmental Modeling. Proceedings: CD-

ROM. National Center for Geographic Information and Analysis. University of California, Santa

Barbara, 1996.

LELE, U.; VIANA, V.; VERISSIMO, A.; VOSTI, S.; PERKINS, K.; HUSAIN, S.A. Brazil - Forests in the

Balance: Challenges of Conservation with Development. Evaluation Country Case Study Series. World

Bank Operations Evaluation Department. The World Bank. Washington, D.C. 2000. 195p.

MOL, J.H.; OUBOTER, P.E. Downstream effects of erosion from small-scale gold mining on the instream

habitat and fish community of a small neotropical rainforest stream. Conservation Biology. 2004. Vol.

18, No. 1. pp.201-214.

MOURA, D.O. O debate público sobre o valor da Floresta Amazônica e a imprensa. in: XXVI Congresso

Brasileiro de Cięncias da Comunicaçăo. Proceedings. Sociedade Brasileira de Estudos Interdisciplinares

da Comunicaçăo, Belo Horizonte, MG. 2003.

PETERSON, G.D.; HEEMSKERK, M. Deforestation and forest regeneration following small-scale gold

mining in the Amazon: the case of Suriname. Environmental Conservation. 2001. Vol. 28, No. 2. pp.117-

126.

RIBEIRO, C.A.A.S; SOARES, V.P. GIS for a greener Brazil: automated delineation of natural preserves. in:

2004 ESRI User Conference. CD-ROM, Environmental Systems Research Institute Inc., Redlands, CA,

2004.

RYLANDS, A.B.; BRANDON, K. Brazilian Protected Areas. Conservation Biology. 2005. Vol. 10, No. 3.

pp.612-618.

TATE, E.; MAIDMENT, D.; OLIVERA, F.; ANDERSON, D. Creating a terrain model for floodplain

mapping. Journal of Hydrologic Engineering. 2002. Vol. 7, No. 2. pp.100-108.

VEIGA, M.M.; SCOBLE, M.; McALLISTER, L. Mining with communities. Natural Resources Forum.

2001. Vol. 25. pp.191-202.

23 / 39

VERDIN, K.L.; VERDIN, J.P. A topological system for delineation and codification of the Earth's river

basins. Journal of Hydrology, 1999. Vol. 218, nos. 1-2. pp.1-12.

VERRY, E.S.; DOLLOFF, C.A.; MANNING, M.E. Riparian ecotone: a functional definition and delineation

for resource assessment. Water, Air, and Soil Pollution: Focus. 2004, Vol. 4. pp.6794.

WORLD BANK. Environmental Assessment of Mining Projects. pp.179-194 in: Environmental Assessment

Sourcebook. Washington, D.C. 1998.

24 / 39

Appendix A

CONAMA Resolution no 369 of March 28, 2006

1st Session

General dispositions

Article 1. This Resolution defines the regulatory exceptions for which the proper environmental agency

might authorize intervention or vegetation removal on permanent preservation areas regarding the

implementation of facilities, plans, activities or projects of public utility or social interest or for carrying out

sporadic, low environmental impact tasks.

§ 1: It is prohibited the intervention or vegetation removal on permanent preservation areas associated

to springs, to swamp areas dominated by palm trees (veredas), to mangroves and to dunes originally

covered by vegetation, according to the provisions II, IV, X, and XI of art. 3 of the CONAMA

Resolution no. 303 of March 20, 2002, except in cases of public utility as set forth in provision I of

art. 2 of this Resolution, and for ensuring access to water to people and animals in the terms of the § 7

of art. 4 of the Law no. 4771 of September 15, 1965.

§ 2: The statement aforementioned in art. 2.I.c of this Resolution does not apply to the intervention or

vegetation removal on permanent preservation areas associated to swamp areas dominated by palm

trees (veredas), to salt marshes (restingas), to mangroves, and to dunes, as stated on provisions IV, X,

and XI of art. 3 of the CONAMA Resolution no. 303 of March 20, 2002.

§ 3: The authorization for intervention or vegetation removal on permanent preservation areas

associated to springs, as stated in provision II of art. 3 of the CONAMA Resolution no. 303/2002, is

bound to the issuance of the water right certificate for the respective water body, as stated in art. 12 of

the Law no. 9433 of January 8, 1997.

§ 4: The authorization for intervention or vegetation removal on permanent preservation areas might

only be granted after the entrepreneur providing conclusive evidence of full compliance with all legal

obligations applicable to these areas.

25 / 39

Article 2. The proper environmental agency might only authorize intervention or vegetation removal on

permanent preservation areas, when such a request is appropriately characterized and motivated by means of

a previous, autonomous administrative process, specifically started for that purpose, and upon the full

compliance with the requirements set forth in this Resolution and in all applicable Federal, State, and

Municipal normative requirements, as well as with the existing legal provisions in the Regional Action Plan,

Ecological-Economic Zoning, and Conservation Unit Management Plan, that may exist for the area, and only

for the following situations:

I. regarding public utility:

a. the activities related to national security and sanitary protection;

b. the necessary infrastructure construction concerned to the public services of transportation,

sanitation, and energy;

c. the prospecting and the exploration of mineral resources granted by the proper authority, excluded

sand, clay, clay-shale, and gravel;

d. the establishment of public urban green areas;

e. archeological research;

f. the public utilities for implementing the necessary infrastructure for acquiring and transporting

water supply and treated effluents;

g. the implementation of the utilities necessary for acquiring and transporting water supply and

treated effluents for aquiculture private projects, dependent upon the full compliance with the

criteria and requirements set forth in paragraphs 1 and 2 to art. 11 of this Resolution.

II. regarding social interest:

a. the activities that are essential to protecting the integrity of native vegetation such as, prevention,

combat and control of wildfire, soil erosion control, eradication of invading species, and crops'

protection with native species, according to the guidance provided by the proper environmental

agency;

b. the environmentally sustainable agroforest management practices carried out on small properties

or on rural family-owned properties, as long as those management practices do not change the

status of the native vegetation cover, hamper its regeneration, and jeopardize the ecological

functions within the assessment area;

c. legalization of a sustainable land parceling for urban areas;

26 / 39

d. the prospecting and the exploration of sand, clay, clay-shale, and gravel, granted by the proper

authority.

III. the sporadic and low environmental impact intervention or vegetation removal activities, bound to the

parameters stated in this Resolution.

Article 3. The intervention or vegetation removal on permanent preservation areas shall only be authorized

when the applicant, in addition to other requirements, demonstrates the:

I. nonexistence of technological and locational alternatives for the proposed facilities, activities or

projects;

II. compliance with the regulations and standards applicable to water bodies;

III. notarized registration of the "legal reserve area" ;

IV. and absence of risking aggravation of natural processes such as floods, soil erosion or accidental rock

sliding.

Article 4. All facilities, plans, activities or projects of public utility, social interest or low environmental

impact, shall be granted authorization for the intervention or vegetation removal on permanent preservation

areas, issued by the proper environmental agency on an autonomous administrative process, according to the

terms established in this Resolution, within the realm of the licensing or authorization process, technically

motivated, in conformity with the applicable environmental rules.

§ 1: The intervention or vegetation removal on permanent preservation areas aforementioned in the

caput of this article is conditioned to authorization of the proper state environmental agency, only

after having all required permits from the proper federal or municipal environmental agency,

whenever applicable, in view of the terms of the § 2 of this article.

§ 2: The intervention or vegetation removal on permanent preservation areas located on urban areas is

conditioned to the authorization of the proper municipal environmental agency, provided that the

municipality has an Environmental Council with deliberative power, and a Local Action Plan or

Urban Directives Law, in case of municipalities with population less than 20,000, subject to prior

agreement of the proper state environmental agency, founded on technical assessment.

§ 3: The following situations do not require authorization from the proper municipal environmental

agency:

27 / 39

I - public safety and civil defense emergency response;

II - and the activities foreseen in the Complementary Law no. 97 of June 9, 1999, regarding

military preparedness exercises for deployment of army forces in view of their

constitutional role, performed in military areas.

Article 5. Prior to the issuance of authorization for intervention or vegetation removal on permanent

preservation areas, the proper environmental agency will define the mitigation and compensatory ecological

measures that the applicant shall satisfy, as found in paragraph 4 of article 4 of the Law no. 4771/1965.

§ 1: Regarding ventures and activities subject to environmental licensing, the mitigation and

compensatory ecological measures, set forth by this article, will be defined within the realm of the

respective licensing process, not precluding the obligation to satisfy the requirements stated on article

36 of Law no. 9985 of July 18, 2000, if applicable.

§ 2: The mitigation and compensatory ecological measures set forth in this article entail effective

rehabilitation or reestablishment of the permanent preservation areas and shall take place within the

same subbasin, with primary consideration being given to be:

I - within the area of influence of the venture;

II - or on the headwater regions of the streams.

Article 6. The planting of native species for the purposes of rehabilitation of permanent preservation areas

does not require authorization of the proper government agency, as long as this act adheres to any obligations

previously accorded, and to all applicable normative and technical requirements.

2nd Session

Regarding Prospecting and Exploration of Mineral Resources

Article 7. The intervention or vegetation removal on permanent preservation areas for mineral resources

extraction, considering the 1st Session of this Resolution, shall be conditioned upon the presentation of

environmental impact study and its environmental impact report, as part of the environmental licensing

process, in addition to other requirements such as:

I. presentation of proof of mineral rights' ownership granted by the Ministry of Mining and Energy,

by any of the titles foreseen in the current legislation;

28 / 39

II. justification for the need to perform mineral resources exploration on a permanent preservation area

and the nonexistence of technological and locational alternatives for exploring such mineral

deposit;

III. environmental impact assessment related to the mineral exploration activities and their cumulative

effects on permanent preservation areas, together with ongoing and predictable exploration

activities within the watershed where the mineral deposit is located, and for which the

environmental impacts reports are available in the proper agencies;

IV. mineral resources exploration shall be carried out by qualified, legally accredited personnel,

properly trained on mineral resources extraction and on controlling its impact to the environment

and to living organisms, it being required the presentation of the annotation of technical

responsibility ART or equivalent accredited documentation, which shall remain valid after the

mining closure up to the completion of the environmental rehabilitation;

V. compatibility with the water resources plan's guidelines, if one exists for the area;

VI. proof that the mining site is not located on remnant forest areas of primary Atlantic Forest.

§ 1: In case of mineral resources extraction activities not having the potential to pose substantial

environmental impact, the proper environmental authority granting permission for intervention or

vegetation removal on a permanent preservation area may substitute, by means of a motivated

decision, the requirement of environmental impact study/environmental impact report by other kind

of environmental studies set forth in the legislation.

§ 2: In case of mineral resources prospecting activities posing potential substantial environmental

impact, the permission for intervention or vegetation removal on a permanent preservation area,

subject to the regulations found in 1st Session of this Resolution, is conditioned upon the presentation

of the environmental impact study/environmental impact report, in the environmental licensing

process, in addition to satisfying other requirements such as:

I. presentation of proof of mineral rights' ownership granted by the Ministry of Mining and

Energy, any of the titles foreseen in the current legislation being accepted;

II. mineral prospecting shall be carried out by qualified, legally accredited personnel, properly

trained on mineral resources prospecting and on controlling its impact to the environment

and to living organisms, it being required the presentation of the annotation of technical

responsibility ART or equivalent accredited documentation, which shall remain valid

29 / 39

until the end of the mineral resources prospecting activities and up to the completion of the

environmental rehabilitation.

§ 3: The studies set forth in this article shall be demanded at the beginning of the environmental

licensing process, independently of any other technical studies that may be requested by the

environmental agency.

...

§ 6: The mine tailings, stockpiles, mining effluents treatment systems facilities, mineral processing

plants, as well as all mining facilities can only interfere with permanent preservation areas in special

exception cases, explicitly recognized by the proper environmental agency in the environmental

licensing process, along with the proof of the nonexistence of any other technical alternative or place

to explore the ore deposit.

§ 7: In case of activities related to either mineral resources prospecting or exploration, the notarized

registration of the "legal reserve area" found in article 3, shall only be demanded when:

I. the mine entrepreneur is also the proprietor or the landholder,

II. there is an onerous juridical contractual relation between the mine entrepreneur and the

proprietor or the landholder, for the purposes of mining operations.

§ 8: In addition to mitigation and compensatory ecological measures, set forth in art. 5 of this

Resolution, the owners of mineral prospecting and mineral exploration rights on permanent

preservation areas are obligated to rehabilitate the degraded environment, as stated in §2 of art. 225 of

the Brazilian Federal Constitution and in the current legislation; the completion of the Degraded Land

Rehabilitation Plan is considered to be a duty of relevant environmental interest.

...

6th Session

Final dispositions

Article 12. Whenever the licensing process demands environmental impact study and its environmental

impact report, the applicant shall submit, until 31 March of each year, a detailed annual report, containing the

30 / 39

georeferenced delimitation of the permanent preservation areas, signed by the main administrator, along with

proof of having satisfied all obligations set forth in each license or authorization issued.

Article 13. The authorizations for intervention or vegetation removal on permanent preservation areas which

have been granted but not executed yet shall be updated by the proper environmental agency, according to

the terms of this Resolution.

Article 14. Non-compliance with the terms of this Resolution will subject the offender to the penalties

foreseen in the Law no. 9605 of February 12, 1998 and to the sanctions foreseen in the Decree no. 3179 of

September 21, 1999.

Article 15. The licensor agency shall record, in the National System of Information on the Environment

(SINIMA), all information regarding the licenses granted for the implementation of facilities, plans and

activities classified as public utility or social interest.

§ 1: The National Council for the Environment (CONAMA) shall create, during the first year this

Resolution went into force, a Task Force within the realm of the Technical Chamber for Land and

Biomes Management, for monitoring and analyzing the outcomes of this Resolution.

§ 2: The report of the aforementioned Task Force will integrate the Environmental Quality Report, as

referred to on provisions VII, X, and XI of the art. 9 of Law no. 6938/1981.

Article 16. The requirements and duties expressed in this Resolution characterize obligations of relevant

environmental interest.

Article 17. The National Council for the Environment (CONAMA) shall create a Task Force to prepare and

present, within one year, a proposal for standardizing the methodology for rehabilitation of permanent

preservation areas.

Article 18. This Resolution shall come into force on the date of its publication.

31 / 39

Appendix B Examples of Maps Generated by Hydrographically Correct Digital Elevation Model

32 / 39

Figure 8. Hydrography of the Crepori watershed

33 / 39

Figure 9. Crepori's DEM

34 / 39

Figure 10. Perspective view of the Crepori basin topography (vertical exaggeration factor: 7x)

35 / 39

Figure 11. Crepori's permanent preservation areas.

36 / 39

Figure 12. Tapajós stream network colour-coded using the Otto Pfafstetter Numbering Scheme.

37 / 39

Figure 13. Tapajós DEM

38 / 39

Figure 14. Perspective view of the Tapajós DEM, showing the limits of the Crepori basin in black (vertical

exaggeration factor: 30x).

39 / 39

Figure 15. Tapajós permanent preservation areas