GEF PROJECT BRIEF

1. Identifiers

Project Number

Implementing Agency Project Number not yet assigned

Combating living resource depletion and coastal area degradation

Project Title

in the Guinea Current LME through ecosystem-based regional

actions

Duration

Five years, beginning June 2004

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) /

Implementing Agencies

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP)

Executing Agency

United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO)

Regional: Angola, Benin, Cameroon, Congo, Democratic

Republic of the Congo, Côte d'Ivoire, Gabon, Ghana, Equatorial

Requesting Countries

Guinea, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Nigeria, Sao Tome and

Principe, Sierra Leone and Togo

The countries are eligible under paragraph 9(b) of the GEF

Instrument. The Strategic Action Programme is consistent with

Eligibility

the relevant provisions of regional and global Conventions

relating to International Waters to which the countries are

signatories and/or contracting parties.

GEF Focal Areas

International Waters with relevance to Biological Diversity

GEF Programming Framework OP #9: Integrated Land and Water Component

2. Summary:

This project proposal "Combating Living Resources Depletion and Coastal Area Degradation in the

Guinea Current LME through Ecosystem-based Regional Actions" has a primary focus on the priority

problems and issues identified by the 16 GCLME countries that have led to unsustainable fisheries

and use of other marine resources, as well as the degradation of marine and coastal ecosystems by

human activities. The long-term development goals of the project are: 1) recover and sustain depleted

fisheries; 2) restore degraded habitats; and 3) reduce land and ship-based pollution by establishing a

regional management framework for sustainable use of living and non-living resources in the

GCLME. Priority action areas include reversing coastal area degradation and living resources

depletion, relying heavily on regional capacity building. The project focuses on nine demonstration

projects, designed to be replicable and intended to demonstrate how concrete actions can lead to

dramatic improvements. Sustainability will derive from this improved capacity, strengthening of

national and regional institutions, improvements in policy/legislative frameworks, and the

demonstration of technologies and approaches that will lead to improved ecosystem status. The

priority problems of resource depletion, loss of biodiversity (including habitat loss and coastal

erosion), and land- and sea-based pollution are all addressed through the interventions proposed here.

The project has five main components with associated objectives identified by the root cause analysis

carried out during the project preparation process: i) Finalize SAP and develop sustainable financing

mechanism for its implementation; ii) Recovery and sustainability of depleted fisheries and living

marine resources including mariculture; iii) Planning for biodiversity conservation, restoration of

degraded habitats and developing strategies for reducing coastal erosion; iv) Reduce land and sea-

based pollution and improve water quality; and v) Regional coordination and institutional

sustainability. The activities to be undertaken will complement other projects in the region to provide

a strong foundation for the long-term sustainable environmental management of the GCLME. A

Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis (TDA) and preliminary Strategic Action Programme (SAP) have

been prepared, serving as the basis for preparation of this project proposal. The full Global

Environment Facility (GEF) project will update the TDA as part of a continuing process, and will

endorse a regionally agreed SAP, following clarification of some aspects of the environmental status

of the region, and initiate SAP implementation.

3. Costs and Financing (Million US $)

US$

GEF:

Project:

:

$20.812

PDF B

:

$ 0.637

Subtotal GEF

:

$21.449

Co-Financing:

Governments (cash and in-kind)

$30.356

US

NOAA

:

$0.6

UNDP (in cash and kind)

:

$0.1

UNEP (in cash and kind)

:

$0.13

Norway

:

$2.085

*Private

Sector :

$0.6

Subtotal Co-financing

$33.871

:

Total Project Cost

$55.321

4. Associated Financing (Million US $):

Government

baseline

:

$799.986

TOTAL : $855.307

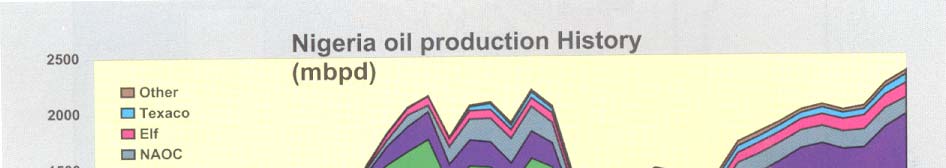

* Discussions still ongoing with Oil Companies in Nigeria and other Private Sector Organizations for co-funding

of the Nigeria and Ghana demonstration projects. UNIDO-ICS will inform of its financial contributions.

5. Operational Focal Point Endorsement(s):

Angola: Mrs. Armindo M. Gomes da Silva

29 September 2003

GEF Focal Point, Ministry of Energy and Water, Luanda

Benin: Mr. Pascal ZOUNVEOU YAHA, GEF OFP

12 August 2003

Ministere de l'Environnement, de l'Habitat et de l'Urbanisme,

Cotonou

Cameroon : Ms. Justin NANTCHOU NGOKO

12 September 2003

Ministry of Environment and Forestry, Yaounde

Congo: Mr. Joachim OKOURANGOULOU, Directeur Général de

4 August 2003

l'Environnement, Ministère de l'Economie Forestière et de

l'Environnement, Brazzaville

Congo Dem. Rep.: Mr. Vincent KASULU SEYA MAKONGA

15 August 2003

Directeur de Developpement Durable, Ministère des Affaires

Foncières, Environnement et Tourisme, Kinshasa/Gombe

Cote d'Ivoire: Mrs. Alimata KONE, Directress Adjoint

10 September 2003

Caisse Autonome d'Amortissement, Abidjan

Gabon: Mr. Chris MOMBO NZATSI, Directeur Général de

8 August 2003

l'Environnement, Ministère de l'Economie forestière, des

eaux, de la pêche, chargé de l'environnement et de la

protection de la nature, Libreville

Ghana: Mr. Edward OSEI NSEKYIRE, Chief Director

31 July 2003

Ministry of Environment, Science and Technology, Accra

Guinea Bissau: Mme. Matilde da Conceicao Gomes Lopes

11 September 2003

Directrice Général de l'Environnement, Ministère des

Resources Naturelles et de l'Environnement

ii

Guinea: Mme. Kadiatou N'DIAYE, GEF Focal Point

6 August 2003

Manager, National Environment Directorate, Conakry

Guinea Equatorial: HE Don Fortunato OFA MBA

09 April 2003

Ministro, Ministro de Pesca y Medio Ambiente, Malabo

Liberia: Mr. Fodee KROMAH, Executive Director

30 July 2003

GEF Focal Point, National Environmental Commission of

Liberia, Monrovia

Nigeria: Mr. Ayodele Adekunle OLOJEDE, GEF Focal Point

8 August 2003

Federal Ministry of Environment, Abuja

Sao Tome & Principe: Mr. Lourenco MONTEIRO DE JESUS

13 August 2003

GEF Focal Point, INDES, Sao Tome

Sierra Leone: Mr. Stephen Syril James JUSU, Director

12 August 2003

GEF Focal Point, Environment Protection Department

Ministry of Lands, Country Planning and the Environment,

Freetown

Togo: Mr. Yao Djiwomu FOLLY, Ing. Des Travaux des Eaux et

7 August 2003

Forets, Directeur de la Protection et du Controle de

l'Exploitation de la Flore, Ministère de l'Environnement et

des Ressources, Lome

6. IA Contact:

(a) Mr. Frank Pinto, Executive Coordinator UNDP/GEF

(b) Mr. Ahmed Djoghlaf, Director & Assistant Executive Director, UNEP/GEF Co-ordination

Office, UNEP, Nairobi, Tel: 254-20-624166; Fax: 254-20-624041; Email:

Ahmed.Djoghlaf@unep.org

iii

ACRONYMS

ACOPS

Advisory Committee for the Protection of the Seas

AfDB

African

Development

Bank

APR

Annual

Programme/Project

Report

BCLME Benguela

Current Large Marine Ecosystem

CBD

Convention

on

Biological

Diversity

CBO

Community

Based

Organization

CCLME

Canary Current Large Marine Ecosystem

CECAF

Fishery

Committee

for the Eastern Central Atlantic

CEDA

Centre for Environment and Development in Africa

COMARAF

Training

and

Research

for

the Integrated Development of African

Coastal

Systems

CPUE

Catch

per

Unit

Effort

CTA

Chief

Technical

Advisor

DIM

Data

and

Information

Management

EIA

Environmental

Impact

Assessment

EQO

Environmental

Quality

Objective

ESI

Environmental

Status

Indicator

FAO

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

FEDEN

Foundation for Environmental Development and Education in

Nigeria

GCC

Guinea

Current

Commission

GCLME

Guinea Current Large Marine Ecosystem

GEF

Global

Environment

Facility

GIS

Geographic

Information

System

GIWA

Global

International

Waters

Assessment

GOG-LME

Gulf of Guinea Large Marine Ecosystem

HAB

Harmful

Algal

Bloom

IA

Implementing

Agency

ICAM

Integrated

Coastal

Areas

Management

ICARM Integrated

Coastal

Area and River Basin Management

ICS-UNIDO

International Centre for Science and High Technology - UNIDO

ICZM

Integrated

Coastal

Zone

Management

IGCC

Interim

Guinea

Current

Commission

IMC

Inter-Ministerial

Committee

IMO

International

Maritime

Organization

IOC-UNESCO

Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission of UNESCO

IUCN

The

World

Conservation

Union

IW:LEARN

International Waters (IW) Learning, Exchange and Resource

Network Program

LBA Land-Based

Activities

LME Large

Marine

Ecosystem

LOICZ

Land-Oceans Interactions in the Coastal Zone

M&E Monitoring

and

Evaluation

MOU Memorandum

of

Understanding

MPPI

Major Perceived Problems and Issues

NAP

National

Action

Plan

NEAP

National

Environmental

Action

Plan

NEPAD

The New Partnership for Africa's Development

NFP

National

Focal

Point

NGO

Non-governmental

Organization

NPA/LBA National

Programme

of Action/Land-Based Activities

NOAA

National

Oceanic

and

Atmospheric

Administration

iv

OP

Operational

Program

PCU

Project

Coordination

Unit

PDF

Project

Development

Facility

PI

Process

Indicator

PIR

Project

Implementation

Review

PPER

Project

Performance

and

Evaluation

Review

PSC

Project

Steering

Committee

RCU

Regional

Coordination

Unit

RPA/LBA

Regional Programme of Action/Land-Based Activities

SAP

Strategic

Action

Programme

TDA

Transboundary

Diagnostic

Analysis

UNDESA

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs

TPR

Tri-Partite

Review

UNDP

United Nations Development Programme

UNEP

United Nations Environment Programme

UNESCO

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

UNIDO

United Nations Industrial Development Organization

USAID

United States Agency for International Development

WACAF

West and Central African Action Plan

WHO

World

Health

Organization

WSSD

World

Summit

on

Sustainable

Development

v

TABLE OF CONTENTS

BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT BASELINE COURSE OF ACTION.......................2

INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................2

GEF PROGRAMMING CONTEXT .....................................................................................8

REGIONAL PROGRAMMING CONTEXT ......................................................................12

NATIONAL PROGRAMMING CONTEXT ......................................................................15

SYSTEM BOUNDARIES ...................................................................................................16

MAJOR PERCEIVED PROBLEMS AND ISSUES ...........................................................16

RATIONALE AND OBJECTIVES (ALTERNATIVE COURSE OF ACTION) ...........20

PROJECT OUTCOMES/COMPONENTS ........................................................................23

END OF PROJECT SITUATION (EXPECTED RESULTS) ...........................................30

TARGET BENEFICIARIES ................................................................................................38

RISKS AND SUSTAINABILITY .........................................................................................39

GEF ELIGIBILITY ...............................................................................................................40

STAKEHOLDER PARTICIPATION..................................................................................40

PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION, INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK AND

NATIONAL AND REGIONAL INSTITUTIONS ..............................................................41

INCREMENTAL COSTS AND PROJECT FINANCING................................................43

MONITORING AND EVALUATION.................................................................................44

LESSONS LEARNED AND TECHNICAL REVIEWS.....................................................46

LIST OF ANNEXES ..............................................................................................................48

ANNEX A INCREMENTAL COST ANALYSIS

49

ANNEX B

LOGFRAME MATRIX

83

ANNEX C

STAP ROSTER TECHNICAL REVIEW

104

vi

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1. Location map for the GCLME, indicating major currents .............................................2

Figure 2. Satellite productivity map of GCLME/ Benguela LME region..................................................... 3

Figure 3. Location map for the GCLME....................................................................................................... 3

Figure 4. Map of distribution of mangroves in the Niger Delta.................................................................... 4

Figure 5. MPPI to SAP Linkage ................................................................................................................. 21

Figure 6. SAP to Project Brief Linkage ...................................................................................................... 23

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1: Ongoing or planned GEF regional projects related to the GCLME ............................................ 10

Table 2. MPPIs and Their Impacts in the GCLME.................................................................................... 18

Table 3: Components and Phases of the Project ......................................................................................... 32

Table 4. Workplan and Timetable............................................................................................................... 35

Table 5: Summary of Project Financing (US$ million) ............................................................................. 43

Table 6: Summary of Baseline and Incremental Costs and Domestic Environmental Benefits ................ 43

Table 7. M&E Activities, Timeframes and Responsibilities ...................................................................... 46

1

BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT BASELINE COURSE OF ACTION

INTRODUCTION

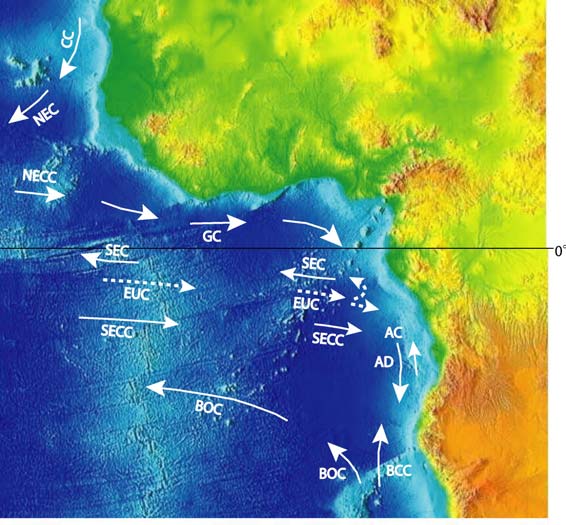

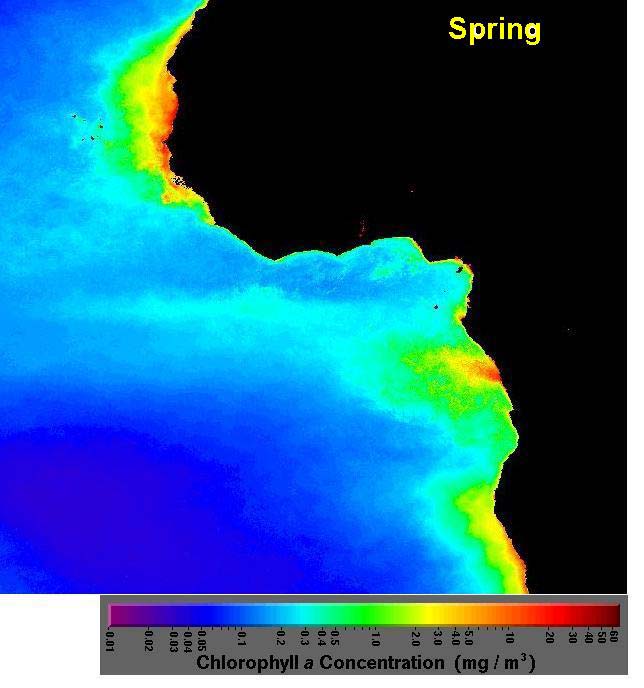

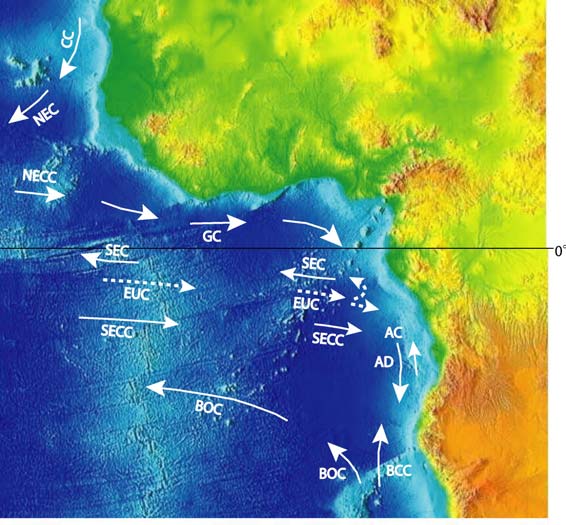

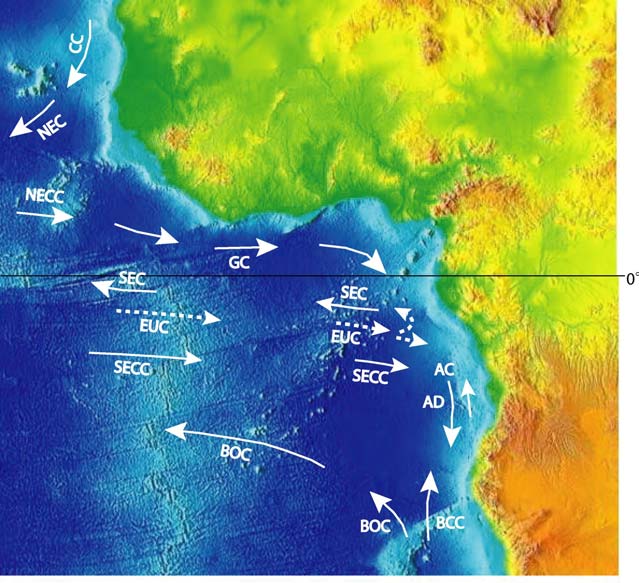

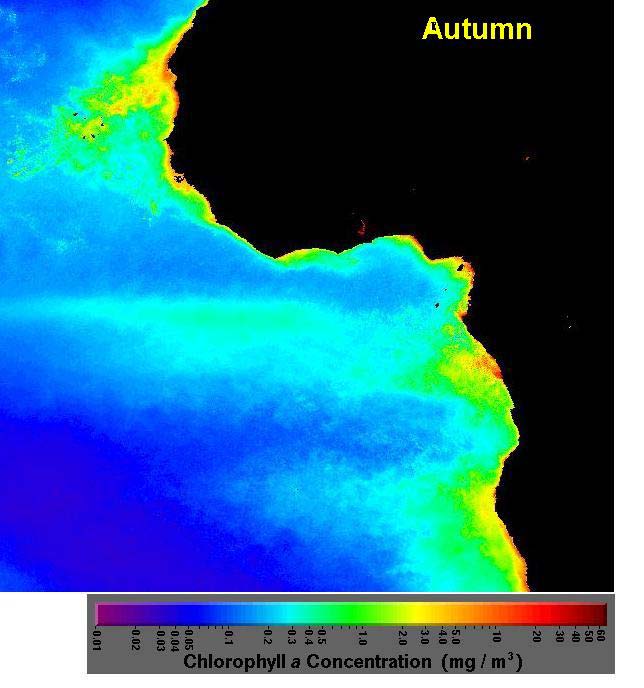

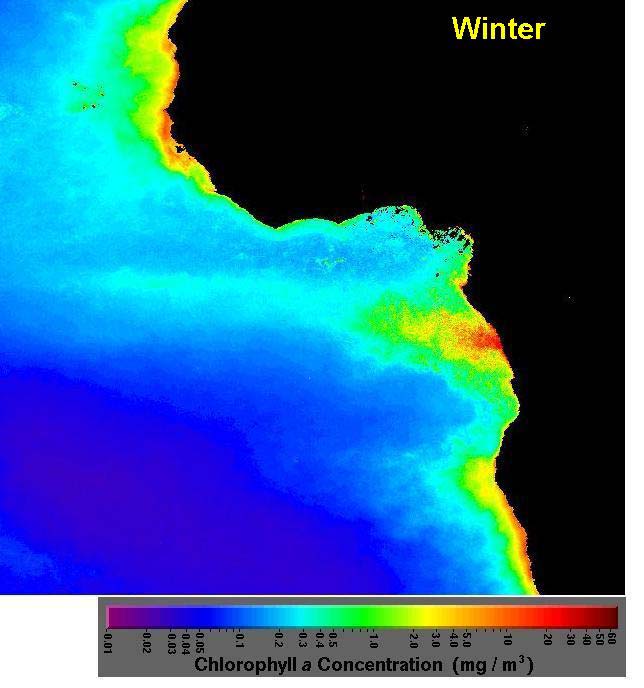

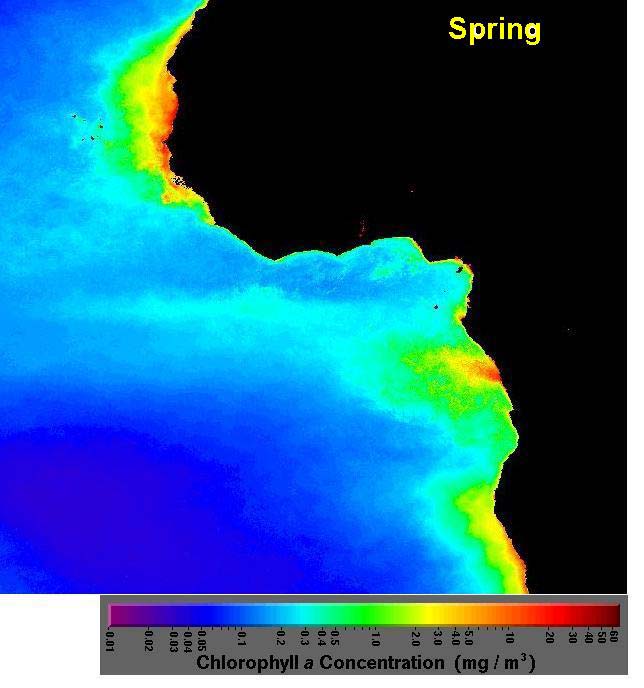

1.

The shared transboundary waters off the coast of western Africa are defined by the Guinea

Current Large Marine Ecosystem (GCLME) that extends from Bissagos Island (Guinea Bissau) in the

north to Cape Lopez (Gabon) in the south. The oceanography of the waters of the Democratic Republic of

Congo, Republic of Congo and Angola is influenced to a considerable extent by the Guinea Current thus

giving ample justification for including the three countries in the Guinea Current Large Marine

Ecosystem (GCLME). Figure 1 shows the area of the Project, along with the major oceanographic

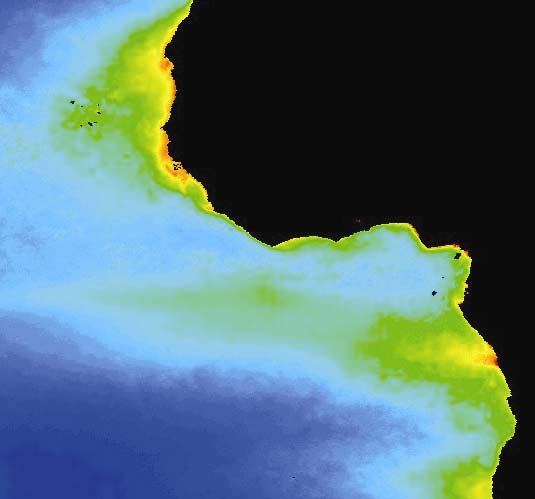

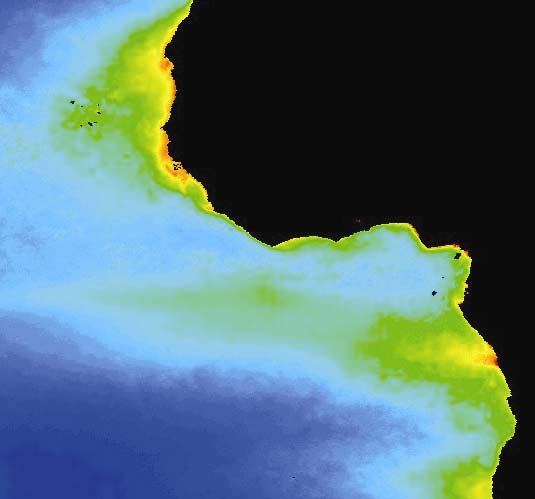

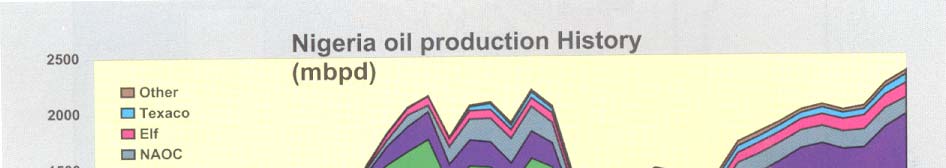

features. The south equatorial current (SEC) forms a logical boundary between the Benguela Current

LME to the South and the GCLME to the north. A similar diagram based on averaged satellite-derived

ocean productivity estimates similarly demonstrates the SEC as the logical boundary between the two

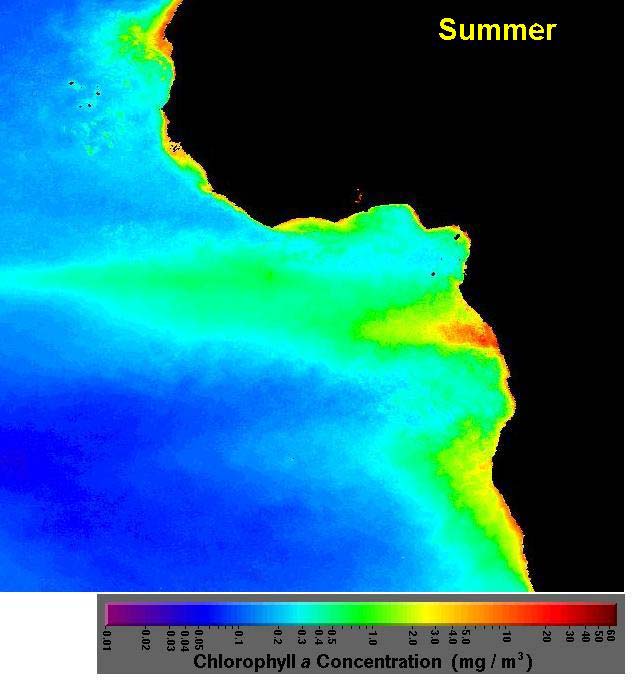

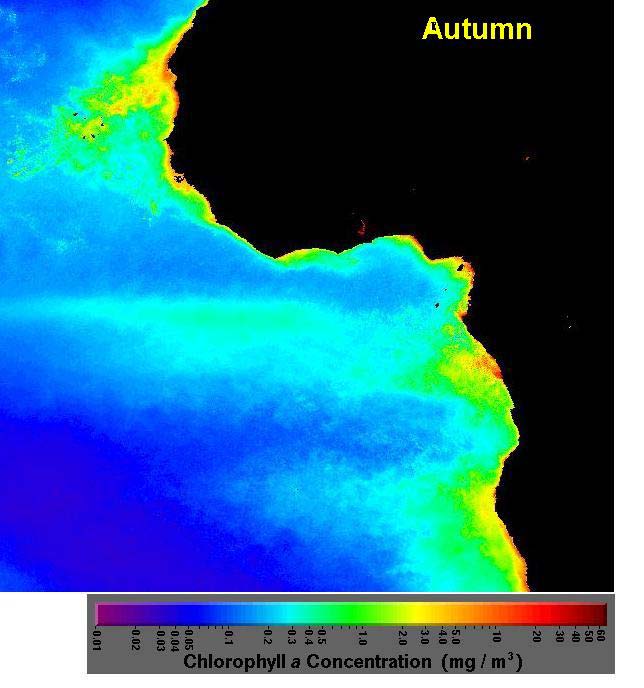

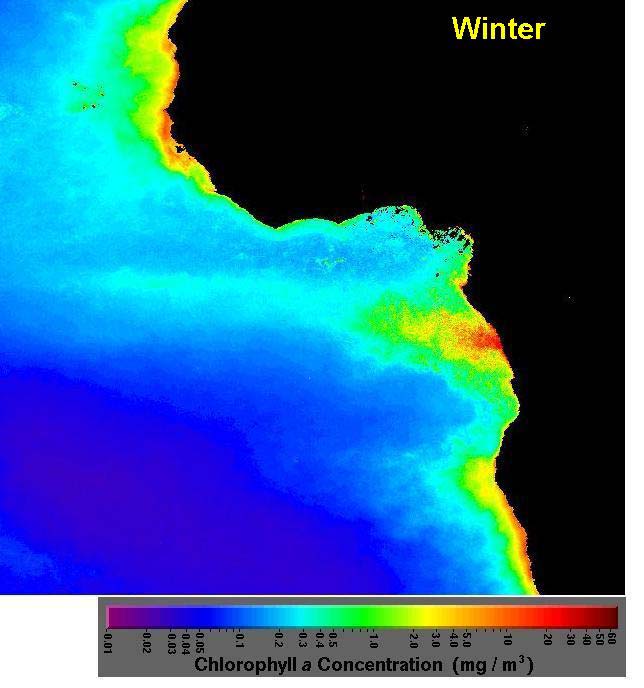

LMEs.

Figure 1 : Location map for the GCLME, indicating major currents

2.

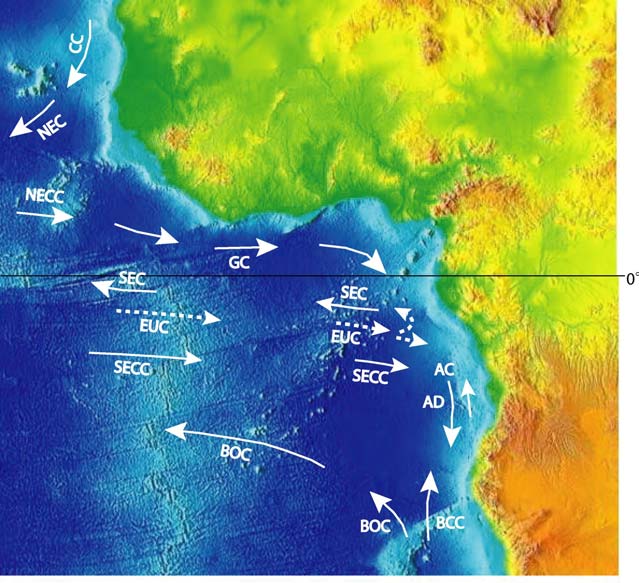

Therefore, the GCLME stretches from the coast of Guinea Bissau to Angola, covering sixteen

countries (Angola, Benin, Cameroon, Congo, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Côte d'Ivoire, Gabon,

Ghana, Equatorial Guinea, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Nigeria, Sao Tome and Principe, Sierra

Leone and Togo: see Figure 3). It embodies some of the major coastal upwelling sub-ecosystems of the

world and is an important center of marine biodiversity and marine food production. Characterized by

distinctive bathymetry, hydrography, chemistry, and trophodynamics, the Guinea Current System

represents a Large Marine Ecosystem (LME) ranked among the most productive coastal and offshore

waters in the world with rich fishery resources, oil and gas reserves, precious minerals, a high potential

for tourism and serves as an important reservoir of marine biological diversity of global significance. The

Guinea Current therefore represents a distinct economic and food fish security source with the continuum

of coastal and offshore waters together with the associated near shore watersheds. Over-exploitation of

fisheries, pollution from domestic and industry sources, and poorly planned and managed coastal

developments and near-shore activities are, however, resulting in a rapid degradation of vulnerable

2

coastal and offshore habitats and shared living marine resources of the GCLME putting the economies

and health of the populace at risk (see Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis, Annex E).

Figure 2 : Satellite productivity map of GCLME/ Benguela LME region

Figure 3 : Location map for the GCLME

3

3.

The GCLME is rich in biodiversity. The fisheries resources of the ecosystem includes a diverse

assemblage of fishes including small pelagics, (sardinellas shad), large pelagics (tuna and billfish),

crustaceans and molluscs (shrimp, lobster, cuttlefish, and demersal species (sparids and croakers). The

presence of invertebrates such as intertidal molluscs (Anadara sp. Crassostrea g.,etc.), reptiles (turtles,

crocodiles), marine mammals such as the West African manatee (Trichechus senegalensis), and some

shark species demonstrate the variety of the species in the GCLME (World Bank Report, 1994). The

remarkable collection of migratory birds, millions of which seasonally visit the West African coast and

mainland regions, illustrates the importance of preserving and maintaining the existing wetlands in this

part of Africa (UNEP Regional Seas Reports and Studies No. 171). Large concentrations of seabirds are

found seasonally in and around Guinea Bissau: these include Larus genei, Geochelidon nilotica, Sterna

maxima lbididorsalis, etc. The Gulf of Guinea islands, near Principe and Sao Tome also have sizeable

sites with colonies of terns, noddies and boobies. It is because of this species diversity and fauna richness

that conservation and preservation policy has been or is being undertaken by some GCLME countries

through the creation and implementation of marine and coastal protected areas

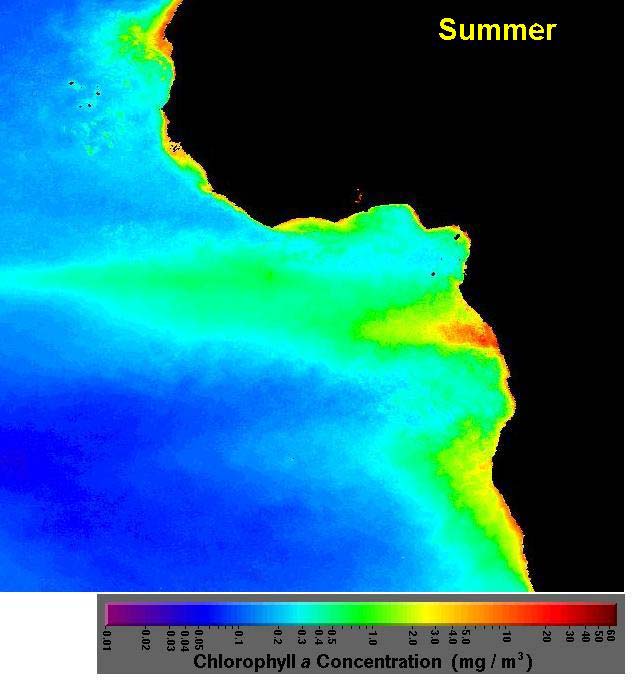

4.

The coastal area also includes important terrestrial flora. Mangroves, typically Rhizophora sp,

Conocarpus sp, Avicennia sp, Mitragyna inermis, Laguncularia sp, occur almost everywhere along the

coasts in the GCLME and are dominant in certain places, such as the Niger Delta of Nigeria which has

Africa's largest and the world's third largest mangrove forests (Figure 4). Mangrove forests provide the

nutritional inputs to adjacent shallow channel and bay systems that constitute the primary habitat of a

large number of aquatic species of commercial importance. The importance of mangrove areas as

spawning and breeding grounds for many transboundary fish species and shrimps is well known.

Presently the mangrove forests are under pressure from over-cutting (for fuel wood and construction

timber) and from other anthropogenic impacts (e.g. pollution), thereby jeopardising their roles in the

regeneration of living resources and as reservoirs of biological diversity (see TDA).

Figure 4: Map of distribution of mangroves in the Niger Delta

5.

The densely populated coastal region is heavily dependent upon the biological resources of the

GCLME. Approximately 40% of the region's 300 million people (more than 1/2 of the population of the

African continent) live in the coastal areas of the GCLME, many of whom are dependent on the lagoons,

4

estuaries, creeks and inshore waters surrounding them for their food security and well being. Rivers,

lagoons, and inshore and offshore waters of the GCLME serve as important sources of animal protein in

the form of fish and shellfish, as well as provide significant income through the coastal fisheries. The

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) estimates the total potential fisheries

yield of the entire region to be in the neighborhood of 7.8 million tons per year. The rich fishery

resources are of both local and transboundary importance with stocks supporting artisanal fisheries and

offshore industrial fisheries from many nations. Most of these straddling and migratory stocks have

attracted large commercial fishing fleets from around the world, especially from the former Soviet Union,

European Union, Eastern Europe, Republic of Korea, and Japan. This wealth of estuaries, deltas, coastal

lagoons and the nutrient-rich upwelling cold waters make a major contribution to the diversity of fish life

in the GCLME region with an estimated 239 fish species, including Sardinella aurita and maderensis,

Thunnus albacares, etc. as pelagic species; Arius sp., Pseudotolothus typus and senegalensis, Dentex sp.,

Octopus vulgaris, Cynoglossus sp., and others as demersal species. Pelagic tuna fishing also constitutes

an important industry in the GCLME region.

6.

These marine and coastal areas, including their upstream freshwater regions, are at present

affected by a number of anthropogenic activities: over-exploitation of fishery resources, impacts from the

land-based settlements and activities from industrial, agricultural, urban and domestic sewage run-off and

other mining activities such as oil and gas (in particular, off the coasts of Angola, Cameroon, Gabon and

Nigeria). The depletion of living resources, uncertainty in ecosystem status (including climate change

effects), deterioration of water quality, and loss of habitats (including coastal erosion) have been

identified as significant transboundary environmental problems in the GCLME region (see section on

major perceived problems and issues).

7.

The region's fish stocks are under threat from overfishing. Since the 1960s, the offshore

commercial fishing efforts have exerted extreme pressures on the resources, placing the fisheries at risk of

collapse. This is exacerbated by the presence of local industrial fleets, predominantly nationally-owned or

part of joint ventures operating in each other's waters under bilateral agreements, as well as the existence

of a large artisanal sector with strong traditional roots and powerful social and political impacts. Pelagic

and demersal fisheries within the region are fully exploited with evidence showing that the landings of

many species are currently declining. The decline in fish availability in the subsistence sector has led to

the adoption of destructive fishing practices such as use of undersize meshes and blast fishing. Based on

present consumption patterns and population growth rates, most of the countries, especially the large

coastal cities of Lagos, Abidjan, Accra and Douala, will need significantly more fish by 2010 just to meet

domestic demand. Despite nutritional requirements and current population growth rates, the industrial

(commercial) fisheries sector in the countries surrounding the GCLME generally exports the trawl

fisheries products to generate foreign exchange, exacerbating the food security situation in the region.

Pressure on the coastal resources is therefore likely to increase significantly in the immediate future, but

Catch per Unit Effort (CPUE) is already exceeding sustainable yields in some countries (Ajayi, 1994, The

Status of Marine Fishery Resources of the Gulf of Guinea: In : Proc. 10th Session FAO, CECAF, Accra,

Ghana, 10-13 October 1994) while species diversity and average body total lengths of the most important

fish assemblages have declined. The GCLME project support from the GEF and other partners will assist

the region to meet the WSSD target for maintaining and restoring fish stocks to levels that can "on an

urgent basis and, where possible, no later than 2015" produce maximum sustained yields.

8.

Uncertainty in ecosystem status makes it impossible to manage the natural resources effectively.

Lack of national budget, inadequate regional capacity, and the general low socio-economic conditions in

much of the region are responsible for this uncertainty in ecosystem status. Ecosystem knowledge is not a

high priority in many of these countries; even if it were, capacity and institutions are lacking. The

possible effects of climate change are also unknown; lacking knowledge of climate change impacts,

effective management and establishment of sustainable development goals are clearly impossible.

5

9

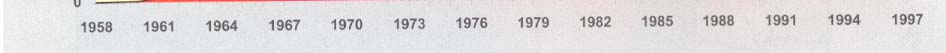

Oil and other industrial activities have been identified as threats to the sensitive GCLME

environment. Some of the countries in the region are oil producers and a few (e.g., Angola, Cameroon,

Gabon and Nigeria) are net exporters. The increasing number of offshore platforms, pipelines, and

various export/import oil terminals means an inevitable exposure to oil pollution. According to the World

Bank (1995), oil producing companies in Nigeria Leone discharge an estimated 710 tons of oil yearly into

the coastal and marine environment. An additional 2100 tons originate annually from oil spills, on

average. The patterns of onshore-offshore winds and ocean currents mean that oil introduced from any of

the offshore or shore-based petroleum activities translates easily into a regional problem. Most of the

countries also have important refineries on the coast, only a few of which have proper effluent treatment

plants, thereby adding to the threat of pollution from oil. Pipelines are at risk, given the unsettled coastal

populations in some of the countries, where frequent pipeline breaches have occurred.

10.

In addition to oil pollution, water quality in the coastal and marine areas is being degraded,

largely as a result of land-based activities such as agriculture. Agriculture is an important activity in all

the countries of the region. The use of chemical fertilisers and pesticides has markedly increased with the

development of commercial agriculture and the advent of large plantations and the need to improve food

production and protect human health against insect-borne diseases. Although organochlorine-based

pesticides are still used, awareness of their danger has spread so the majority of pesticides are now

organo-phosphorous and carbamate based. Run-off of these chemicals may reach surface or groundwater,

where they may persist for long periods. Inorganic, especially nitrate and phosphate-based, fertilisers are

being used on an increasing scale. Substantial quantities of nutrients originating from domestic and

agricultural effluents, which are used in primary production, are carried to the sea through river outflows.

It has been estimated that approximately 30% of fertilizers applied are actually utilised by the plants while

the remainder finds its way into the atmosphere or into surface waters. These nutrients, when coupled

with sewage pollution, are a serious threat increasing levels of eutrophication in near coastal waters and

especially to lagoons and causing harmful algal blooms. The lagoons, as sensitive and significant habitats

supporting biodiversity and inshore fisheries, are therefore being threatened by agricultural pollution.

These excess nutrients, other pollution and sediments are transported to the GCLME via the rivers in the

region, including the ten major rivers: Congo (Congo), Niger (Nigeria), Volta (Ghana), Wouri

(Cameroon), Comoe, and Bandama (Côte d'Ivoire).

11.

The physical destruction of coastal habitats, including critical wetlands, causes the loss of

spawning and breeding grounds for most living resources in coastal waters and the loss of the rich and

varied fauna and flora of the region including some rare and endangered species. Much of the destruction

is related to often-haphazard physical development, which exerts phenomenal pollution pressures on this

international body of water (WACAF Intersecretariat Co-ordination Meeting, Rome, 1993). Nearly all

major cities, agricultural plantations, harbours, airports, industries as well as other aspects of the socio-

economic infrastructure in the region are located at or near the coast. Results obtained during the Pilot

Phase GOG-LME Project showed that in Ghana, 55 percent of the mangroves and significant wetlands

around the greater Accra area have been decimated through pollution and overcutting. In Benin, the

figure is 45 percent in the Lake Nokoué area, in Nigeria, 33 percent in the Niger Delta, in Cameroon, 28

percent in the Wouri Estuary, and in Côte d'Ivoire, about 60 percent in the Bay of Cocody. Urbanization

and industrialization place increasing pressure on coastal habitats, both through direct physical pressure,

and indirectly through pollution and declining water quality.

12.

Alterations to river flow regimes from dam construction (for irrigation and power generation)

together with high wave action have led to severe coastal erosion problems, issues of which are expected

to be addressed in part in parallel GEF projects in the Volta and Niger River basins. These factors are

combining to cause displacements of structures, people and economies of coastal communities and urban

centres. Harbour construction activities have altered longshore current transport of sediments and in

6

many cases have led to major erosion and siltation problems. Erosion rates caused by port structures in

Liberia, Togo, Benin and Nigeria sometimes reach a staggering 15-25 m per year and threaten

infrastructure and services (Ibe and Quelennec, 1989). Actions to control erosion around these ports are

critically important to maintaining their vitality as sites for growing tourist, recreational, commercial, and

defence needs.

13.

Many of the water-related environmental threats identified in the region are transboundary in

nature. The GCLME Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis (Annex E), formulated by the countries, fully

lists the various transboundary environmental issues/problems, major root causes, transboundary impacts

and consequences and possible measures to contain the threats. Some of these threats are already cause

for concern. A few are already being addressed jointly between nations. Others are likely to grow in

importance with human population growth and increased urbanisation and industrialisation in the

stakeholder countries. These transboundary threats to ecosystem health are caused by human activities

and natural variations which are part of the ecosystems, and some threats could be mitigated through

efficient early warning systems.

14.

Many transboundary threats (e.g., untreated waste) are also of local (national) importance.

Actions in response to local pressures to reduce local impact will often serve also to reduce transboundary

impact. Other actions at national levels, if not integrated with actions of neighboring countries, may

merely displace the problem and even increase the overall transboundary impact. Other transboundary

threats are more widely distributed and may be of a cumulative nature.

15.

The sustainable use and management of the commonly shared resources of the GCLME poses a

great challenge to the bordering countries. Concerted actions by the sixteen participating nations are

absolutely essential to change present unsustainable use of these resources by introducing an ecosystem-

based assessment and management system for sustainable use and management of resources at risk. One

source of stress on the marine environment which is of growing international concern is the impact from

capture fisheries, hence the need to develop, promote, and implement ecologically sound assessment and

management practices in the marine fisheries sector so as to prevent loss of biodiversity and reduce

habitat degradation. Available data suggest that, in addition to the obvious catches of fish for human

needs, by catches have a significant ecological impact and cause mortality amongst fin-fish (particularly

the juveniles of commercial fish species), as well as amongst benthic invertebrates, marine mammals,

turtles and birds. These by-catches need to be controlled. Mariculture offers the possibility of providing

a food source that releases fishing pressure in the capture fisheries and provides livelihoods for rural

coastal areas when fishing effort is reduced. However ecologically unsound mariculture practices can

negatively impact wild resources. Development must proceed in a sound ecological manner to have

fishery and food security benefits.

16.

Recognizing the continuous negative changes in the health and productivity of the GCLME

shared waterbody resulting from human impact and appreciating that living marine resources and

pollutants in coastal and marine environments respect no political boundaries and few geographical ones,

the countries resolved to work together to address their common concerns through suitable management

options. Through various assessments carried out, the countries realized that the traditional sectoral

approach to management had failed in bringing about the needed changes in environmental and living

resource uses and resolved to adopt a holistic and multisectoral approach embodied in the large marine

ecosystem concept. In so doing, the countries, through the Committee of Ministers of the six-country

pilot phase Gulf of Guinea LME project with subsequent endorsement by the 10 new project countries,

sought the assistance of UNIDO, UNDP, UNEP and GEF in implementing an LME project to cover the

natural limits of the Guinea Current. The GEF made available two project preparation and development

facility grants (PDF-B) to enable countries to prepare the necessary analyses and reviews. In accordance

with the GEF Operational Strategy a Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis (TDA) and preliminary

7

Strategic Action Programme (SAP) were prepared through national and regional stakeholder

consultations.

17.

More specifically, the PDF project was responsible for:

· identifying overexploited fish stocks, biodiversity issues, degraded and threatened habitats, and

point and non-point pollution sources;

· undertaking a comprehensive review, synthesis, and analysis of existing data and information

concerning the sources and fate of transboundary pollution as a building block on which to design

appropriate actions;

· reviewing existing national and regional fisheries and environmental legislation relating to the

GCLME and its surrounding environment; and

· providing a framework to support an ecosystem-based approach for the assessment and

management of the GCLME fisheries and coastal zone based on scientific, institutional, legal, and

regulatory structure needed to achieve and sustain the marine resources of the GCLME.

GEF PROGRAMMING CONTEXT

18.

The programming context of this project is the GEF Operational Programme No. 9 "Integrated

Land and Water Multiple Focal Area". This OP lists as an expected outcome "the reduction of stress to

the international waters environment in selected parts of all five development regions across the globe

through participating countries making changes in their sectoral policies, making critical investments,

developing necessary programs and collaborating jointly in implementing ... water resources protection

measures (para 9.10)." The OP also states that "the goal is to help groups of countries utilise the full

range of technical, economic, financial, regulatory, and institutional measures needed to operationalize

the sustainable development strategies for international waters (para 9.2)."

19.

This project is thus in conformity with the GEF Operational Strategy and Operational

Programmes, in particular with the above-mentioned OP #9 - International Waters: Integrated Land and

Water Multiple Focal Area, where there is a focus on an integrated management approach to the

sustainable use of [land and] water resources on an area-wide basis. It will also have relevance to OP #2 -

Biodiversity in coastal and marine ecosystems, and specifically to aspects of eco-system management

including elements of: targeted research, information-sharing, training, institutional-strengthening,

demonstrations, and outreach (or `extension').

20.

The GEF International Waters Operational Programme referred to above emphasizes the need to

introduce and practice ecosystem-based assessment and management action while supporting

"institutional building ... and specific capacity-strengthening measures so that policy, legal and

institutional changes can be enacted in sectors contributing to transboundary environmental degradation."

This project supports institutional capacity building for long-term regional cooperation as well as helping

to strengthen regional capacities in environmental management, monitoring of priority pollutants, public

awareness, and preservation of transboundary living resources.

21.

Under OP 9 several outputs from IW projects are envisaged. These include:

a.

a comprehensive transboundary environmental analysis identifying top priority multi-

country ecosystem-based resource and environmental concerns (already in hand);

b.

a strategic action programme consisting of expected baseline and additional actions

needed to implement an integrated approach to land and water resources assessment and

management (a draft is available; the SAP will be updated during the full project);

c.

documentation of stakeholder participation to determine expected baseline and additional

actions to be implemented as well as community involvement in the project; and

8

d.

implementation of measures related to integrated management of land and water

resources that have incremental costs and that can generate global environmental benefits

in several focal areas.

22

The project preparation process has addressed several of these issues (as indicated above). The

proposed project will satisfy all of the above points. Ministries of environment, ministries with control of

land and water resources, as well as new institutions created by the project will play a key role in the

implementation of project activities, thus enhancing capacity within the institutions as well as

complementing and strengthening existing national efforts to address environmental issues.

Implementation of the final SAP will assist in the systematic assessment and conservation of natural

resources and assist the countries in complying with their national and regional obligations under various

international conventions. At a global level, the project and its SAP will have molded disparate regional

and national activities into a coherent ecosystem-based assessment and management program for the

globally important resources of the GCLME.

23.

The present project also is consistent with the recent Draft GEF International Waters Focal Area-

Strategic Priorities in Support of WSSD Outcomes for FY 2003-2006. The document lists various

priorities, including:

Priority A. Catalyze financial resource mobilization for implementation of reforms and stress reduction

measures agreed through TDA-SAP or equivalent processes for particular transboundary systems

Priority B. Expand global coverage of foundational capacity building addressing the two key program

gaps and support for targeted learning.

Priority C. Undertake innovative demonstrations for reducing contaminants and addressing water

scarcity issues.

24.

The present project contributes significantly to the WSSD targets for 1) introducing ecosystem-

based assessment and management practices by 2010, and 2) recovering depleted fish stocks to maximum

sustainable yield levels by 2015. It will directly assist in addressing key International Waters gaps, with a

focus on ecosystem-based approaches to management of Large Marine Ecosystems (LMEs) that include

fisheries resources and habitat. The project will also assist in achieving the targets for these priorities for

addressing African Transboundary waters.

25.

This project also is consistent with the "Action plan to respond to the recommendations of the

Second GEF Assembly, the policy recommendations of the Third Replenishment, the Second Overall

Performance Study of the GEF and the World Summit on Sustainable Development" as discussed and

agreed at the May 2003 GEF Council Meeting. It is also consistent with the document "Strategic

Business Planning: Direction and Targets," also discussed and agreed at the May 2003 GEF Council

Meeting. The following internal specific targets are consistent with the GCLME project:

Under Strategic Priority IW-1:

(b) By 2006, GEF will have catalyzed a Strategic Partnership among African coastal nations,

implementing agencies, and global development partners aimed at reversing the depletion of fisheries

resources in the Large Marine Ecosystems (LMEs) of Sub-Saharan Africa as a contribution to WSSD POI

sustainable fisheries target.

Under Strategic Priority IW-2:

9

(a) By 2006, GEF will have increased by at least one-third the global coverage of representative

water bodies (an additional 9-10) with country-driven, science based joint management programs with

GEF assistance.

(c) By 2006, almost one-half of the 27 Large Marine Ecosystems (LMEs) located near developing

countries will have country-driven, ecosystem-based management programs developed with GEF

assistance that contribute to the WSSD POI "sustainable fisheries" target with a view to those programs

being under implementation by 2010.

26.

The GCLME project will both benefit and benefit from other GEF projects being undertaken in

the region and on the global level. Table 1 shows the ongoing GEF regional activities related in some

manner to the GCLME LME. Efforts will be made to ensure synergies among the projects and minimize

duplication of work, by setting aside funds in this project to achieve project integration for these GEF

activities. Examples of these projects include: A global GEF project on "reduction of environmental

impact from tropical shrimp trawling through the introduction of by-catch reduction technologies and

change of management" executed by FAO and implemented by UNEP is already assisting two countries

(Cameroon and Nigeria) in the GCLME region in minimizing the impacts on fisheries of use of wrong

mesh-sizes. The GCLME project would establish linkages with this GEF project in order that some of the

best practices and innovative techniques learned could be replicated in the other GCLME countries. For

coastal erosion, living resource management, conservation of biodiversity in coastal ecosystems and

community management close linkages and coordination with the Volta River GEF project as well as the

World Bank/GEF Coastal Biodiversity Management programme in Guinea Bissau and the World

Bank/GEF Coastal Zone Integrated Management Programme in Benin Republic will help assure

consistency in approaches, cohesiveness of GEF support and optimal use of GEF resources and avoid

duplication efforts in these countries. Strong linkages and coordination will also be achieved with other

upcoming GEF projects, through constant dialogue and communication, notably the World Bank/GEF

Strategic Partnership to promote the sustainable governance of fisheries in African countries and the

World Bank Guinea Coastal Zone Management programme. Under the World Bank "Strategic

Partnership" regional project, country-level investments in sustainable fisheries will be implemented in

concert with the GEF LME projects in Sub-Saharan countries. The initiative will work with the LME

projects (the GCLME for part of the West and Central Africa region) to support the coastal countries in

meeting the targets for sustainable fisheries set by the WSSD, including country-level monitoring,

surveillance and enforcement of national laws and regulations with regard to fisheries and other marine

and coastal resources. In essence, the "Strategic Partnership" would coordinate with and build upon the

GCLME project to facilitate collaboration between national players for country-level fisheries

investments and existing/planned sub-regional fisheries management bodies supported by GCLME

project.

Table 1: Ongoing or planned GEF IW, BD, POPs & MFA projects related to the GCLME

Project GEF

GEF

Countries Est'd. Est'd.

Total

Status

Focal

IA(s)

GEF

Co-

Financing

Area

Financing financing

Addressing

IW UNEP

Benin, $5.7 m.

$10.4 m.

$16.1 m.

Approved

Transboundary

Burkina Faso,

Concerns in the Volta

Côte d'Ivoire,

River Basin and its

Ghana, Mali

Downstream Coastal

and Togo

Area

Reduction of

IW UNEP

Cameroon, $4.8 m.

$4.4 m.

$9.2 m.

Approved

Environmental Impact

NIgeria (part

from Tropical Shrimp

of global)

10

Trawling through

Introduction of By-

catch Technologies and

Change of

Management

Reducing Reliance on

IW UNEP

Benin,

$3.4 m.

$4 m.

$7.4 m.

Pdf-b

Agricultural Pesticide

Guinea et al.

Use and Establishing a

Community Based

Pollution Prevention

System in the Senegal

and Niger River Basins

Development and

IW UNEP

Cote

d'Ivoire,

$0.75 m.

$0.97 m.

$1.72 m.

Approved

Protection of the

Ghana,

Coastal and Marine

Nigeria et al.

Environment in Sub-

Saharan Africa

Reversing Land and

IW UNDP/

Benin,

$13 m.

$16.7 m.

$29.7 m.

Approved

Water Degradation

WB

Cameroon,

Trends in the Niger

Cote d'Ivoire,

River Basin

Guinea,

Nigeria et al.

Reduction of

IW UNEP

Cote

d'Ivoire,

$6 m.

$7.5 m.

$13.5 m.

Pipeline

Environmental Impact

Ghana,

from Coastal Tourism

Nigeria

through Introduction of

Policy changes and

strengthening public-

private partnerships

Review of the Existing

IW UNEP

Guinea, TBD TBD TBD Pdf-a

Agreements on River

Nigeria,

Basins in West Africa

Benin,

and development of a

Cameroon,

regional water protocol

Cote d'Ivoire

Benin ICARM Coastal

BD

WB

Benin

$5 m.

$25 m

$30 m.

Pdf-b

Area Management

Control of Exotic

BD

UNDP

Cote d'Ivoire

$3 m.

$1.9 m.

$4.9 m.

Approved

Aquatic Weeds in

Rivers and Coastal

Lagoons to Enhance

and Restore

Biodiversity

Coastal Wetlands

BD

WB

Ghana

$7.2 m.

$1.1 m.

$8.3 m.

Approved

Management

Guinean Coastal Zone

BD

WB

Guinea

$5 m.

$25 m.

$30 m.

Pdf-b

Integrated Management

and Preservation of

Biodiversity

Coastal and

BD WB

Guinea-

$5.1 m.

$4.4 m.

$9.5 m.

Pdf-b

Biodiversity

Bissau

Management Program

Conservation of

BD UNEP

GCLME $0.75 m.

$0.75 m.

$1.5 m.

Pipeline

Marine Turtles and

countries

their Habitat in the

11

Atlantic Coast of

Africa

POPs Enabling

POPs UNEP

Benin,

$2 m.

----

$2 m.

Approved

Activity Preparation

Cameroon,

of National

Cote d'Ivoire,

Implementation Plan

Guinea

POPs Enabling

POPs UNIDO

Gabon,

$3.5 m.

----

$3.5 m.

Approved

Activity Preparation

Ghana,

of National

Guinea-

Implementation Plan

Bissau,

Liberia,

Nigeria,

Togo, Sao

Tome &

Principe

Enhancement and

MFA UNEP

Cameroon, TBD TBD TBD Pdf-a

Conservation of

Benin, Ghana

Ecosystem Functions

for River Basins and

Associated Coastal

Areas in Central Africa

Strategic Partnership IW WB

Countries

of

TBD TBD TBD PDF-b

for Sustainable

Sub-Saharan

Fisheries Management

Africa

in the LMEs of SSA

GRAND TOTALS

---- ----

----

$57.2 m.

$94.1 m.

$151.3 m. ----

REGIONAL PROGRAMMING CONTEXT

27.

The outstanding accomplishments of the Pilot-Phase GEF Gulf of Guinea Large Marine

Ecosystem (GOG LME) Project (1995 - 1999), as verified in Tri-Partite Review Reports and the Final In-

Depth Evaluation, are ample proof of the catalytic and defining roles that GEF incremental funding can

play. Some of the results achieved are included here. Annex K provides a more in-depth review of the

pilot phase.

· adoption of Ministerial level ACCRA DECLARATION(1998) aimed at institutionalising a new

ecosystem-wide paradigm consistent with GEF operational guidelines for joint actions in

environmental and living resources assessment and management in the Gulf of Guinea and

beyond;

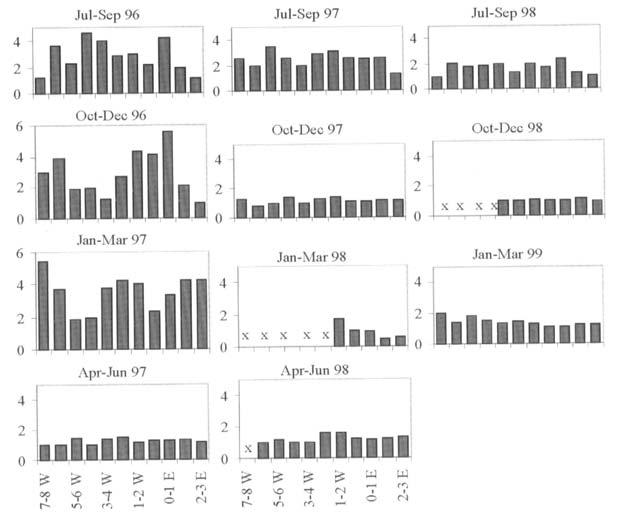

· substantial progress in building regional and national water quality, productivity and fisheries

assessment and management capabilities based on standardised methodologies;

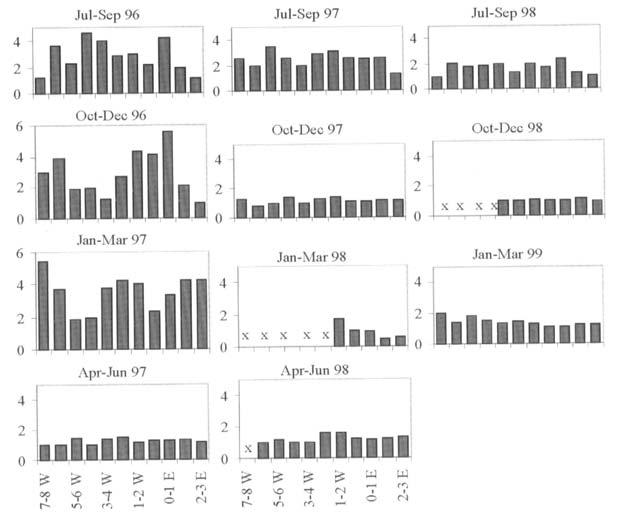

· planning and implementation of two co-operative surveys( first in the western gulf in July/

August, 1996 and second in the entire Gulf, in Feb/March, 1999) of demersal fish populations

conducted by the six countries . The data, albeit limited, have served already as the basis for

certain common national regulatory actions for the co-ordinated management of the fish stocks

of the Gulf;

· definition of regional effluent standards based on a detailed survey of industries and

recommendations made for the control and significant reduction of industrial pollution;

· deriving from the detailed industrial survey, a successful campaign for reduction, recovery,

recycling and re-use of industrial wastes based on the concept of the <<waste stock exchange

management system >> was launched in Ghana as a cost-effective waste management tool and

will be extended to other project countries;

12

· initiation of co-operative monitoring of the productivity of the LME using ships of opportunity.

The results give indications of the carrying capacity of the ecosystem which enables projections

on food security and by extension, social stability in the sub- region;

· preparation of coastal profiles for the six project countries, followed by the development of

national Guidelines for Integrated Coastal Areas Management (ICAM) and the preparation of

draft national ICAM plans which were in different stages of adoption by the end of the Pilot

Phase Project;

· establishment of cross-sectoral LME committees in the participating countries consistent with the

cross sectoral approach implied in integrated management;

· accelerating the creation of national and regional data-bases, using harmonised architecture, as

decision making support tools;

· facilitating the establishment of a functional non-governmental organisation (NGO) regional

network;

· promoting active grassroots and gender participation in discussion, decision-making and

interventions in environmental and resources management;

· active collaboration arrangements with other projects and organisations in the region;

· initiation of community-based mangrove restoration activities in all six project countries;

· successful completion of 41 training workshops with 842 participants ,416 in regional workshops

and 426 in National ICAM workshops resulting in the setting up of a regional network of over

500 contactable specialists linked by electronic mail; and

· development of a preliminary Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis (TDA) for the Gulf of Guinea.

28.

The Pilot Phase project, although limited to six countries, initiated the work of mitigating

pollution pressures on International Waters of the Gulf of Guinea and stemming the loss of biological

diversity and fisheries overexploitation by fostering regional co-operation predicated policies and

strategies as well as joint institutional mechanisms. An Executive Summary of the Final In-Depth

Evaluation is attached as Annex K.

29

Eager to preserve the gains of the pilot phase, the Ministers adopted "The Accra Declaration" (see

Annex L) which aimed at institutionalising a new ecosystem-wide paradigm consistent with the GEF

Operational Guideline for joint actions in the environmental and natural resources assessment and

management in the Gulf of Guinea. The Ministers called for initiation of a second phase of an expanded

project to include 10 additional countries to coincide with the natural limits of the Guinea Current Large

Marine Ecosystem. The Ministers also addressed a letter to the UNDP Administrator requesting him to

intervene with the GEF Secretariat for a substantial grant of US$ 20 million for an expanded Second

Phase Project (Annex M).

30.

The environmental goals of the project are consistent with of the Abidjan Convention for Co-

operation in the Protection, Management and Development of the Marine and Coastal Environment of the

West and Central African Region adopted in March 1981. The Abidjan Convention and its Protocol on

Cooperation in Combating Pollution in Cases of Emergency constitute the legal components of the West

and Central African (WACAF) Action Plan. The Convention expresses the decision of the WACAF

Region (from Mauritania to Angola at the time of adoption) to deal individually and jointly with common

marine and coastal environmental problems. The Convention also provides an important framework

through which national policy makers and resource managers can implement national control measures in

the protection and development of the marine and coastal environment of the WACAF Region. The

Emergency Protocol was designed with an orientation towards combating and operationally responding to

massive pollution in case of marine accidental oil and chemical spills.

31.

At its first meeting (Abidjan, 20-22 July, 1981), the newly constituted Steering Committee of the

Convention defined the following priorities:

13

· Development of oil spill contingency plans

· Combating coastal erosion

· Prevention, monitoring and control of marine pollution

· Rational development of coastal zones

· Capacity building particularly in the areas of documentation and legislation on coastal and

marine management.

32.

Since its entry into force in August 1984, Parties to the Abidjan Convention have, with UNEP's

assistance, undertaken a number of activities including:

· development of programmes for marine pollution prevention, monitoring and control in

cooperation with IMO, FAO, UNIDO, IOC-UNESCO, WHO, IAEA, etc.

· development of programmes for monitoring, controlling and combating coastal erosion

dominantly with UNESCO and UNDESA.

· development of national environmental impact assessment programmes for particular coastal

sites

· development of national environmental legislation in cooperation with FAO and IMO.

33.

As originally envisaged in the provisions of the Convention, the WACAF Regional Coordination

Unit, was to co-ordinate the implementation of the West and Central African Action Plan and was to

ensure the most efficient use of the regional sea through concerted actions by Member States and the

optimal utilisation of their shared living resources. It was to co-ordinate regional (as opposed to national)

development of the coastal and marine environment and to assist in the prevention and resolution of

disputes that might arise between and among the Parties to the Convention. However, lack of resources

for the Regional Coordination Unit (RCU) has adversely affected the implementation of the above-

mentioned projects.

34.

These weaknesses in the Abidjan Convention and its RCU are being addressed in a companion

project, "Implementation of the NEPAD Partnership Programme as it relates to land-based pollution in

the West and Central African -Regions as a contribution to the Abidjan Convention." This project,

submitted for funding to the Government of Norway by the Coordination Office of the Global Program of

Action for the Protection of the Marine Environment from Land-based Activities, will go hand-in-hand

with the present project to develop increased capacity in the region. This project has five major

components:

· COMPONENT 1: STRENGTHENED WEST & CENTRAL AFRICAN REGIONS (WACAF/RCU)

· COMPONENT 2: NATIONAL PROGRAMMES OF ACTION FOR THE PROTECTION OF THE MARINE

ENVIRONMENT FROM LAND-BASED ACTIVITIES (NPA)

· COMPONENT 3: INTEGRATED COASTAL AREA &-RIVER BASIN MANAGEMENT (ICARM)

· COMPONENT 4: PHYSICAL ALTERATIONS AND DESTRUCTION OF HABITATS (PADH)

· COMPONENT 5: COORDINATION AND SUPPORT

With a total budget of U.S. $2.075 million, this project complements the proposed GEF project by

addressing specific areas of the GEF project (IIg, IIIC, IVb, IVc, and Va).

35.

There is an encouraging history of co-operation between the countries bordering the GCLME

even if the results, outputs and impacts have been variable. Examples of collaborative activities under the

Abidjan Convention include "Control of Coastal Erosion in West and Central Africa (WACAF/3)",

"Manual on Methodologies for Monitoring Coastal Erosion in West and Central Africa (WACAF/6)",

"Assessment and Control of Pollution in the Coastal and Marine Environment of West and Central Africa

(WACAF/2 phases I and II)", and WACAF/11 on " Integrated Watersheds and Coastal Area Management

14

Planning and Development in West and Central African Region". The countries in the GCLME sub-

region also participated in the continent wide UNDP/UNESCO Regional Project (RAF/87/038) on

Training and Research for the Integrated Development of African Coastal Systems (COMARAF) and

have experience of joint programming in the context of the Fishery Committee for the Eastern Central

Atlantic (CECAF) under the aegis of FAO which has been trying to promote joint actions on living

resource evaluation and fishery statistics.

36.

Such activities have created a new awareness of mostly domestic issues and engendered a certain

sense of urgency on environmental matters. However, their overall impact has been impaired by a lack of

success in focusing on transboundary ecosystem-wide International Waters problems and the need to

strengthen environmental and resource stewardship at both national and regional levels. This lack of

focus has been exacerbated by the absence of a mechanism for funding incremental costs in the existing

Regional Seas Programmes, and a lack of resources for an effective co-ordination Secretariat. A

proposed strategy for revitalising both the Abidjan and Nairobi Conventions exists and was embodied in

the GEF funded Medium Sized Project implemented by Advisory Committee for the Protection of the

Seas (ACOPS) and which ended with a "Partnership Conference" in September 2002 on the sidelines of

the World Summit on Sustainable Development (Rio + 10 Conference) in South Africa. There is little

direct evidence that the strategy was successful.

37.

Most of the new projects in the region under GEF funding including those of its co-operating

Agencies (UNDP, World Bank and UNEP), such as the Canary and Benguela Currents LME Projects, the

Niger, Senegal and Volta River Basins Projects, the Congo Basin Data and Information Management

Project, the Control of Aquatic Weeds Project in Cote d'Ivoire, etc., have sought to draw attention to

current inadequacies of national and regional institutions and programmes to address the large scale and

complex transboundary problems that characterise International Waters. These institutions are

consequently helping, through Incremental funding, the countries involved in these projects to resolve

such problems by augmenting their capabilities and promoting collaboration to achieve regional

institutionalisation of joint mechanisms for comprehensive and durable ecosystem wide management.

NATIONAL PROGRAMMING CONTEXT

38.

The participating countries are at various stages of industrialization and various levels of socio-

economic development. The rapid economic development that has occurred in this region over the last

decade has taken place largely at the expense of the living marine resources and the environment. A

significant barrier to planning for more ecosystem-based and-sustainable modes of development has been

the absence of adequate ecological and economic evaluation of habitats and the goods and services they

provide, resulting in development decisions being made on the basis of short-term economic gains.

Numerous actions are taking place at the national and regional levels to address the environmental

problems that have resulted from the rapid pace of development and industrialization, which have

occurred over the last decade. Nigeria, for example, has a national mangrove reforestation programme,

and all countries have activities and programmes related to the conservation of significant biological

diversity including wetlands. Many of the actions at a national level are undertaken outside the

framework of integrated or coordinated joint programmes of action for the GCLME transboundary issues

resulting in either significant duplication and overlap, or no action at all.

39.

The lack of a regionally coordinated approach to preventive and remedial actions significantly

reduces their effectiveness, and recognizing this the countries bordering the GCLME have initiated a

number of joint programmes involving two or more countries within the region in the past including joint

programming in the context of the Fishery Committee for the Eastern Central Atlantic (CECAF) under

the aegis of FAO which has been trying to promote joint actions on living resource evaluation and fishery

15

statistics. The pilot phase Gulf of Guinea LME project further facilitated the strengthening of regional

collaboration among some of the countries. There is an encouraging history of co-operation between the

countries bordering the GCLME even if the results, outputs and impacts have been variable. Examples of

collaborative activities under the Abidjan Convention 1981 include "Control of Coastal Erosion in West

and Central Africa (WACAF/3)", "Manual on Methodologies for Monitoring Coastal Erosion in West and

Central Africa (WACAF/6)", "Assessment and Control of Pollution in the Coastal and Marine

Environment of West and Central Africa (WACAF/2 phases I and II)", and WACAF/11 on " Integrated

Watersheds and Coastal Area Management Planning and Development in West and Central African

Region".

40.

In the absence of a GEF intervention, it is probable that the present types of sectoral-based

interventions which have been demonstrated during the past twenty years as being ineffective in halting

the pace of environmental degradation will continue. Without a concerted ecosystem-based regional

approach to environmental management it is unlikely that the present rates of habitat degradation and

living marine resources depletion will be slowed. The likely consequence of such a scenario is the loss of

globally significant biological diversity during the next century, combined with collapse of fish stocks

and food security in the region.

41.

Unresolved territorial disputes are a source of sensitivity in the region. During the last several

years the countries have demonstrated a willingness to co-operate in matters relating to environmental

management, and there is an increasing recognition that the benefits resulting from co-operative

environmental management actions are not dependent on the resolution of such sensitive issues.

Recognizing the sensitivities of the area, however, it has been agreed that no activities shall be undertaken

under this project in disputed areas of the GCLME, nor shall issues of sovereignty be addressed directly

or indirectly through project activities.

SYSTEM BOUNDARIES

42.

The Guinea Current is the dominant feature of the shallow ocean off the coast of countries in

western Africa stretching from Guinea Bissau in the north to Angola in the south. The distinctive

bathymetry, hydrography, productivity and trophodynamics of this shallow ocean qualify it as a Large

Marine Ecosystem (LME) and is indeed recognised as one of the sixty-four LMEs delineated globally.

43.

The boundaries of the Guinea Current area can be defined geographically and oceanographically.

Geographically, the GCLME extends from approximately 12 degrees N latitude south to about 16 degrees

S latitude, and variously from 20 degrees west to about 12 degrees East longitude. From an

oceanographic sense, the GCLME extends in a north-south direction from the intense upwelling area of

the Guinea Current south to the northern seasonal limit of the Benguela Oceanographic Current (Figure

1). In an east-west sense, the GCLME includes the drainage basins of the major rivers seaward to the GC

front delimiting the GC from open ocean waters (a time- and space-variable boundary).

MAJOR PERCEIVED PROBLEMS AND ISSUES

44.

The process of developing the sixteen-country Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis and

preliminary Strategic Action Programme (TDA/SAP) included the formation of National committees in

each participating country to prepare comprehensive, country-based analyses of water-related

environmental problems and concerns. The assessments conducted included analyses of ecosystem-wide

issues of environmental and resource sustainability from the perspective of system: 1) productivity, 2)

16

fish and fisheries, 3) pollution and ecosystem health, 4) socio-economics, and 5) governance in an effort

to identify the most important transboundary natural resource management problems.

45.

The first drafts of the national reports were submitted and evaluated at the Stocktaking workshop

in May 2001, which prepared a comparative weighting of all identified major issues. On the basis of the

national reports, a Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis (TDA) was prepared, reviewed and updated by

country and regional experts in two subsequent meetings in April and June 2003. The results of the TDA

provide the scientific, technical and socio-economic bases for the choice of priority actions proposed in

this project and which served as the basis for development of a preliminary Strategic Action Programme

(SAP) that would provide greater long-term, system wide, environmental and socio-economic benefits to

the countries. Governments, NGO'S, economic sector operatives, the public and all other affected

stakeholders participated in TDA formulation thus fostering broad based involvement and support for the

project.

46.

The TDA identifies the regional priorities among water-related problems and concerns, their

socio-economic and sectoral root causes, and the extent to which the problems are transboundary in either

origin or effect. The four major transboundary environmental problems/issues (MPPI) identified in the

TDA are:

1.

Decline in GCLME fish stocks and unsustainable harvesting of living resources;

2.

Uncertainty regarding ecosystem status, integrity (changes in community composition,

vulnerable species and biodiversity, introduction of alien species) and yields in a highly

variable environment including effects of global climate change;

3.

Deterioration in water quality (chronic and catastrophic) from land and sea-based activities,

eutrophication and harmful algal blooms;

4.

Habitat destruction and alteration including inter-alia modification of seabed and coastal

zone, degradation of coastscapes, coastline erosion.

47.

Table 2 outlines the major transboundary elements of the four major perceived problems

identified in the GCLME, as well as their environmental and socio-economic impacts.

17

Table 2. MPPIs and Their Impacts in the GCLME

MPPI

Transboundary

Environmental Impacts

Socio-economic Impacts

Elements

I. Decline in GCLME fish · Loss of income from · Loss of biodiversity

· Reduced income

stocks and unsustainable

regional and global · Changes in food web

· Loss of employment

harvesting of living trade of marine products · Changes in community · Population migration

resources

· Region-wide decrease structure due to over- · Conflicts between user

in biodiversity of the

exploitation of one or

groups

marine living resources

more key species

· Loss of recreational

including the

· Increased vulnerability

opportunities

disappearance of high-

of commercially- · Decline in protein

quality critical natural

important species

· Loss of income from

resources

· Long-term changes in

regional and global

· Region-wide destructive

genetic diversity

trade in coastal

fishing techniques

· Stock reduction

products

degrading mangrove

· Loss of predators

habitats

· Habitat degradation

· Increasing catch effort

due to destructive

on pelagic species such

fishing technique

as tuna, sardinella

· Non-compliance with

the FAO Fisheries Code

of Conduct

· Region-wide pollution

II. Uncertainty regarding · The major causes of · Major change in

· Lost earnings

ecosystem status, integrity

climate change are ecosystem production

· Disruption of way of

(changes in community global

· Changed ocean

life

composition, vulnerable · Harvested fish species

currents

· Destruction of property

species and biodiversity,

are shared between · Changed ocean

and lives

introduction of alien countries

temperature structure

· Reduced crop yields

species) and yields in a · Exotic species have · Diminished role of

· Loss of tourism

highly variable

been introduced into the

ocean as co2 sink

environment including the

GCLME from other · Increased natural

effects of climate change

regions

hazards

· Increased droughts

· Changes in upwelling

frequency, location and

intensity

III. Deterioration in water · Many of the rivers · Reduced productivity

· Economic loss

quality (chronic and flowing into the

· Much altered

· Disruption of

catastrophic) from land GCLME are

biodiversity

communities

and sea-based activities,

transboundary

· Red tides and algal

· Increased sickness and

eutrophication and

· Sea-based pollution can

blooms

death

harmful algal blooms

be transported across · Invasion of water

· Aesthetic loss and lower

borders

weeds

quality of life

· Loss of regional tourism · Permanently changed

· Biodiversity loss

revenue

LME

· Reduced fishery yields

· Introduction of exotic · Loss of recreational

species.

value

· Eutrophication

· Population migration

· Bioaccumulation of

toxics

· Increased turbidity

18

IV. Habitat destruction · Marine living resources · Loss of spawning

· Loss of global heritage

and alteration including

are often migratory

breeding grounds

· Decimation of life

inter-alia modification of · Coastal zone habitats · Loss of rich and varied

support systems

seabed and coastal zone,

are the backbone for the

fauna and flora

· Forestry loss

degradation of

productivity of marine

including endangered

· Economic and aesthetic

coastscapes and coastal

and coastal habitats

species

loss

erosion

· The coastal habitats · Loss of CO2

· Increased pollution

provide feeding and

sequestration

· Increased flood and

nursery grounds to · Loss of pollution buffer

erosion risk

migratory species

· Loss of flood and storm · Loss of agricultural

· The coastal habitats are

surge protection

lands

accumulating

· Depletion of

· Loss of cultural heritage

transboundary pollution

mangroves

· Reduction in income

· Degradation of coastal · Loss of natural

from fisheries

habitats contribute to

productivity

· Loss of recreational

the overall decline of

areas

regional and global

biodiversity

· Impact to migratory

species and their

habitats

48.

The identified Root Causes of the four transboundary environmental problems include:

· Complexity of ecosystem and high degree of variability (resources and environment),

· Lack of an ecosystem-wide funded and coordinated assessment and management system

for the productivity of coastal and marine living resources of critical importance to the

nations bordering the GCLME,

· Inadequate capacity development (human and infrastructure) and training,

· Poor or ineffective legal framework at the regional and national levels; inadequate

implementation of national regulatory instruments; lack of regional harmonization of

regulations,

· Inadequate implementation of available regulatory instruments,

· Inadequate planning at all levels,

· Lack of regional agreements;

· Insufficient or inappropriate institutional structures;

· Insufficient public/stakeholder involvement,

· Inadequate financial mechanisms and support,

· Poverty,

· Insufficient financing mechanisms and support,