CERMES Technical Report No 5

Reforming Governance: Coastal Resources

Co-management in Central America and the Caribbean

Final Report of the Coastal Resources

Co-management Project (CORECOMP)

A project funded by the Oak Foundation

PATRICK McCONNEY and ROBERT POMEROY

EDITORS

Centre for Resource Management and Environmental Studies (CERMES)

University of the West Indies, Faculty of Pure and Applied Sciences,

Cave Hill Campus, Barbados

2006

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We wish to thank the Oak Foundation for generous support and patience, with special mention to

their very capable project officers, Leslie Harroun (USA office) and Imani Morrison (Belize

office), who were a pleasure to work with and truly understand participatory research. Our hard

working partners, most of whom are the authors of essays in this volume, made invaluable

contributions throughout the project. There are a great many other people including government

officials, fisherfolk, MPA stakeholders, students, NGO and CBO staff, too numerous to mention

individually, who assisted us along the way. Final thanks go to our university colleagues for their

support and inputs, with special mention to Maria Pena, CERMES Project Officer, who helped to

compile this report and its associated documents, including the preparation of the project CDs.

Disclaimer

This project report and its associated documents were prepared by the Centre for Resource

Management and Environmental Studies (CERMES) supported by Oak Foundation Grant

Number OCay-02-072. The statements, findings, conclusions and recommendations are the

responsibility of the editors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Oak Foundation or its

officers.

Citation

McConney, P. and R. Pomeroy (editors). 2006. Reforming governance: Coastal resources co-

management in Central America and the Caribbean. Final Report of the Coastal Resources Co-

management Project (CORECOMP). CERMES Technical Report No.5. 63pp.

CERMES Contact

Dr. Patrick McConney

Tel: 246-417-4725

Senior Lecturer, CERMES

Fax: 246-424-4204

UWI Cave Hill Campus

Email: pmcconney@caribsurf.com

St. Michael, Barbados

Web site: www.cavehill.uwi.edu/cermes

i

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .........................................................................................................................................i

1.

THE PROJECT ..................................................................................................................................................1

1.1

BACKGROUND...............................................................................................................................................1

1.2

GOAL AND OBJECTIVES .................................................................................................................................1

1.3

FUNDING.......................................................................................................................................................2

1.4

IMPLEMENTATION.........................................................................................................................................2

1.5

PARTNERSHIPS ..............................................................................................................................................3

1.6

ORGANISATION OF REPORT ...........................................................................................................................4

2.

PERSPECTIVES OF PARTICIPANTS...........................................................................................................5

2.1

BARBADOS....................................................................................................................................................5

2.1.1 BARNUFO and co-management..............................................................................................................5

2.1.2 Some personal perspectives on co-management of the Barbados sea egg fishery...................................7

2.1.3 Holetown Community Beach Park Project ..............................................................................................9

2.2

BELIZE ........................................................................................................................................................11

2.2.1 Facing the challenges: the Friends of Nature experience .....................................................................11

2.2.2 CORECOMP and TASTE: Beneficial capacitation for the co-management process of the Sapodilla

Cayes Marine Reserve (SCMR), Belize...............................................................................................................14

2.2.3 Human resource management concepts for NGOs................................................................................17

2.3

NICARAGUA................................................................................................................................................22

2.3.1 Fisheries Co-management in the Caribbean Coast of Nicaragua.........................................................22

2.3.2 Natural resource co-management in Pearl Lagoon, Nicaragua............................................................24

3.

LEARNING AND ADAPTING .......................................................................................................................28

3.1

STRATEGIC PLANNING.................................................................................................................................28

3.2

CAPACITY BUILDING ...................................................................................................................................30

3.3

STAKEHOLDERS AND POWER.......................................................................................................................31

3.4

ORGANISING AND LEADERSHIP ...................................................................................................................34

3.5

ROLE OF GOVERNMENT...............................................................................................................................36

4.

CONCLUSIONS ...............................................................................................................................................39

4.1

KEY LESSONS LEARNED ..............................................................................................................................39

4.2

DIRECTIONS FOR NEW RESEARCH................................................................................................................39

5.

REFERENCES..................................................................................................................................................41

5.1

OUTPUTS BY COUNTRY ...............................................................................................................................41

5.1.1 Barbados................................................................................................................................................41

5.1.2 Belize .....................................................................................................................................................41

5.1.3 Nicaragua ..............................................................................................................................................43

5.2

POLICY PERSPECTIVES ................................................................................................................................44

5.3

OTHER LITERATURE ....................................................................................................................................44

6.

APPENDICES...................................................................................................................................................47

APPENDIX 1. PROJECT PROPOSAL.............................................................................................................................47

APPENDIX 2. PROJECT PARTNERSHIPS AND ACTIVITIES ............................................................................................57

ii

1. THE PROJECT

1.1 Background

This project arose from the observation, supported by previous studies, that the need to reform

coastal resource governance in the countries of Central America and the Caribbean (CAC) is

urgent. This applies particularly to small-scale fisheries (SSF) and marine protected areas (MPA)

with their associated natural habitats and human socio-economic processes that comprise social-

ecological systems. The fisheries of the CAC region are heterogeneous, including a wide variety

of types, ranges, vessels, gears, problems and approaches to management and development.

Many of the fisheries are fully exploited or overexploited. In particular, nearshore demersal and

coral reef fishes, conch and lobster, and coastal pelagics on which many of the fishers in the

region depend for their livelihoods. Their livelihoods are threatened by resource overexploitation

and environmental and habitat degradation. In addition, tourism and coastal development have

increased conflict among various coastal and marine resource users. The result of these conflicts

is that the biological sustainability of fishery and other marine resources are being systematically

undermined, the norms of equity are being violated, and economic efficiency reduced.

Coastal resource policies in the CAC region have primarily emphasized development without

concomitant conservation and management measures. Only a few countries in the region have

active integrated coastal management programmes. Most countries have weak legislation and no

active fisheries management plans. Regulatory monitoring and surveillance systems have been

inadequately instituted and have not been effective in managing resources. Typically, resource

users have not been much involved in planning and implementing such systems, and insufficient

management capacity has been allocated or built for implementation.

Centralized, top-down management has been widely criticized as a primary reason for the

overexploitation of fisheries and other coastal resources globally and in the region, although

resource users have contributed by doing little to monitor and police themselves. Bureaucrats and

professionals are the main resource managers as resource users are marginalised by technical and

scientific approaches to management. A centralized management approach involves little

effective consultation with resource users and is often not suited to the conditions of small

developing countries in the region. Many of the countries have limited financial means or

technical capacities to manage coastal resources using conventional approaches. Command-and-

control approaches (relying on various technical, input and output control regulations), which

have conventionally been used to manage fisheries, are being seen by an increasing number of

stakeholders to be outdated and inadequate for resolving the increasingly people-centred

problems in fisheries.

Co-management, as a process of participation, empowerment, power sharing, dialogue, conflict

management and knowledge generation, holds potential for the region as an alternative coastal

resource management strategy and as a solution to these problems. Co-management will,

however, involve the establishment of new organisations, institutional arrangements, laws and

policies to support decentralization of governance, partnerships for management and stakeholder

participation in management.

1.2 Goal and objectives

The goal of this project was to promote sustainable development of fisheries and other coastal

1

resources, and to enhance food security and livelihoods of those who depend upon these

resources, in the Central American and Caribbean region, through improved governance. The

intermediate objective of the project was to develop information, strategies and policies for

coastal resources governance reform in the Central American and Caribbean region through co-

management. See Appendix 1 for the full proposal. Specific-objectives included:

1) The implementation of co-management pilot projects at selected sites;

2) Capacity building and institutional strengthening of the major partners in co-management,

including government, fishers and non-governmental organisations; and

3) The development of strategies, processes and policies for implementation of co-management

in the region.

The project aimed to demonstrate co-management as a viable alternative management strategy

under varying conditions in the CAC region using a "learning portfolio" approach. General

principles and conditions that facilitate successful fisheries co-management were identified and

documented at both national government and community levels through evaluation and learning

across pilot sites within the portfolio. While co-management may not be a viable alternative

management strategy for all countries and communities, the project sought to establish under

which conditions it can be a sustainable, equitable and efficient management strategy, and to

recommend how it can be successfully implemented. Policy-level frameworks, strategies and

processes for implementing co-management from national to community levels were developed

for consideration in the region. Stakeholders in several countries have taken action at both the

national and community levels to implement co-management strategies.

1.3 Funding

Funds (US$200,000) were provided by the Oak Foundation to the Centre for Resource

Management and Environmental Studies (CERMES) at the University of the West Indies Cave

Hill Campus to implement the project. The initial duration was from 2002 to 2004, but two no-

cost extensions were granted, extending it to mid-2006. The two principal co-investigators were

Dr. Patrick McConney of CERMES and Dr. Robert Pomeroy from the University of

Connecticut-Avery Point in the USA. The former also served as project manager for CERMES.

Adding value to the core funds from the Oak Foundation, were counterpart funds obtained from

a number of sources as a condition of the grant. Among them was complementary funding from

the Lighthouse Foundation in Germany; US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

(NOAA); and UK Department for International Development (DFID). Through these funds more

activities and locations were added to the project which later broadened to include Jamaica and

the Grenadines Islands.

1.4 Implementation

There can be no single (one-size-fits-all) model of co-management for the region. Each situation

is unique and requires the development of plans, institutions and organisational arrangements

that meet the conditions of that site and that country. Within Central America and the Caribbean,

focus countries for project fieldwork were Belize, Barbados and Nicaragua. This selection helped

to determine if co-management can be a viable management strategy under varying conditions

(e.g. political, social, economic, cultural, biophysical and technological). Implementation of co-

management has four main integrated components: 1) resource management, 2) community and

2

economic development, 3) capacity building, and 4) institutional support. It emphasises giving

people the skills and power to solve their own problems and meet their own needs from both

individual and collective perspectives. The amount of responsibility and authority that the state-

level and various local levels have in a co-management arrangement will differ, depending upon

country and site-specific conditions.

The modes of implementation differed by location and were tailored to meet the needs of project

partners (see next section). In summary, workshops were held to plan the country activities and

to implement various aspects of capacity building and institutional strengthening. They included

strategic planning, a variety of technical topics and reviews of situations for institutional

learning. The pilot projects included fieldwork such as surveys and the establishment of groups.

Studies were undertaken and participants attended regional conferences, particularly the annual

meetings of the Gulf and Caribbean Fisheries Institute (GCFI). The latter provided regular

forums for information exchange among participants and with the rest of the region. Project

communications also included a new series of policy briefs, CERMES Policy Perspectives,

which conveyed findings and recommendations on policy, strategies and processes.

1.5 Partnerships

The project was conducted in partnership with non-governmental organisations (NGOs),

research institutions, government agencies, resource user groups and individuals in each country.

Partnership was a key implementation strategy of this project. The principal investigators

provided leadership, coordination and technical assistance in the project, but national-level and

community-level activities were conducted by and with the partners. The partnership

3

arrangement ensured that the capacity of the partners was increased; that local conditions were

recognized and included in all aspects of the project's activities; that project results were owned

from the start of the project by the national partners; and that policy recommendations were

developed with input from local organisations. In Appendix 2 is a list of our major partners and

the activities or events in which they were involved.

1.6 Organisation of report

Chapter 2 contains articles submitted by the major project partners and participants describing

their co-management experiences within and beyond CORECOMP, and their outlook on the

future of coastal resource co-management in the Caribbean. The next chapter sets out the views

of the principal researchers on the lessons from the project on learning and adapting within the

wider context of reforming governance. The final chapter contains conclusions drawn from all

aspects of the project and directions for new research, followed by references consisting mainly

of project outputs. The project proposal is an appendix to this report, but there is also a separate

appendix document with a compilation of small project outputs and reports. The larger reports

and other products are maintained as stand-alone associated documents. All documents are

available on the project CD.

4

2. PERSPECTIVES OF PARTICIPANTS

One of the key principles of co-management is that all stakeholders should have a voice. In

keeping with this we invited our project partners to share their perspectives on the project and on

co-management in general in brief articles. They share their views in this chapter.

2.1 Barbados

2.1.1 BARNUFO and co-management

Submitted by Angela Watson

BARNUFO is the acronym of the Barbados National Union of Fisherfolk Organisations. We are

an umbrella fishery organization with members in both the harvest and postharvest sector. We

are housed within the Fisheries Division of the Ministry of Agriculture in Barbados, and our

stated ambition is to improve the socio-economic conditions of our member fisherfolk

organizations.

We are just seven years old, having been formed on 10 March 1999 with a general membership

at the time of twelve primary organizations. During the past seven years we have been able to

become involved in many activities which sometimes fisherfolk could not link directly to fishing.

We have realized that there is more to fishing than catching a fish and later offering it for sale.

Preservation of the marine environment is of utmost importance, and as a group we realize that

we must become involved because ultimately it is from the marine environment that our

membership would benefit from increased fish catches. It is with this in mind that we first

became involved with CORECOMP as a project through Dr Patrick McConney, we were first

involved with the Barbados sea-egg1 project to try co-management with the Fisheries Division.

The Sea-egg Fishery Co-management project saw fishers being trained by the Fisheries

Biologist, Mr Christopher Parker, in doing actual stock assessment of the fishery after the fishery

had been closed for three years because it was believed there was a collapse of the fishery due to

over-fishing. Fishers were trained in measuring sea-egg size as well as quantity. These fishers

recorded this information on underwater writing tablets and were then encouraged to come into

the Fisheries Division to enter this information into a computerised fisheries database. It was

explained to them how the data gathered could be used to produce the information that would be

needed to inform the open or extended closure of the sea-egg season.

All sea-egg fishers were invited to the Fisheries Division for meetings where they were asked

how the industry might be protected. Fishers have shared their ideas openly, even if in some

cases their recommendations were not all legal. Suffice it to say that, most importantly, members

have agreed that village councils of fishers in the known harvesting areas should be responsible

for monitoring in their area with help from and direct contact with the enforcement agencies in

the island.

Our next involvement came with the work for the revision of the Fisheries Management Plan

(FMP). Our FMP is drawn up and revised every three years, and our most recent work, with

external assistance, has been only the second time that we were really involved in such an effort.

We again worked with the Fisheries Division. Meetings were held with the harvest and

postharvest sectors where ideas were sought for the improvement of the fishing industry. Fishers

1 Sea egg is the local name for the white-spined sea urchin Tripneustes ventricosus

5

expressed concerns about the fish trap and seine net fisheries as they contended that some fishers

were actually using illegal size mesh and nets. From this we were able to put some things in

motion. The Fisheries Division has now started a programme to work with the makers of fish

pots to ensure that the correct size mesh is used, but also to introduce to them the bio-degradable

escape panels. Identification marks for fish pots were also looked at, so from this exercise some

transfer of information from authority to industry will take place.

BARNUFO has also, on its own, designed a questionnaire for the seine net fishery. We want to

be able to accurately ascertain the amount of people still involved in the fishery, the net sizes and

discuss what needs to be done to take them from the undersize mesh to the correct one. Site

measurements have not as yet taken place but hopefully this season, with some assistance from

the Fisheries Division, we would be able to complete that project. We would then be looking at a

project to fund replacing undersize mesh with the correct mesh size both for pots, as they are

taken up from the sea, and seine nets.

Co-management continues to be a lofty term. We have been striving with the concept for a few

years and are not quite satisfied that some of the scientists and managers are quite ready to

relinquish some of their responsibilities. We have been saying for years a fisher is a fisher and

although different things will capture their imaginations it most certainly will only be a passing

thing; they will never give up fishing for a desk in an office, it is not in their thinking.

Co-management as a working arrangement could benefit the local fishing industry immensely;

things noticed by fishermen on the water can only enhance what is known by the scientists in

theory. More communication is needed, local knowledge can relieve some burdens on the

scientists but it can also let fishers know that what they know is valuable, and when anything

strange is noticed out there and communicated some larger problems can be avoided.

We in Barbados have worked with quite a few agencies that collect information on things in the

sea, fishers are contracted, scientists are taken to the fishing grounds they need for their research.

But when everything is completed, and research papers are written, they then reside in a library

at a university or some other place of great learning and very seldom is the research ever shared

with the fishers so they can ask questions and maybe understand what they need to do keep the

marine environment pure to ensure sustainable livelihoods for years to come.

Co-management to my mind can be simply explained as people having ultimate respect for each

other. That way we would naturally want to share what we each have. In the fishing industry we

are usually happy when people ask a question about our profession; we are only too happy to

talk. This must run both ways, we cannot continue to pass information and get no feedback. If it

continues much longer you might find yourself being ignored when the information required

could be of utmost importance. Co-management will become a way of life, the fishing industry is

but a small part, people working together for mutual benefit could make the world a better place

to live and we must all play our part.

6

2.1.2 Some personal perspectives on co-management of the Barbados sea egg fishery

Submitted by Christopher Parker

My involvement in CORECOMP arose directly through my job as fisheries biologist with the

Fisheries Division of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, the government

agency responsible for managing fisheries in Barbados. Multi-tasking is a necessity for personnel

in an agency as small as the Barbados Fisheries Division. As such, the fisheries biologist is

responsible for both gathering the scientific information needed for managing fisheries and

implementing the prescribed management measures.

The implementation part of the management process is of course focused on managing people to

promote sustainable utilization of the resource. Having studied the ecology of sea eggs at the

postgraduate level, I considered that I could advise the management process with respect to the

biological aspects of the animals. However, I had no training or indeed natural acumen in the

sociological skills that are needed to effectively organize and manage people. Such sociological

skills are even more important in formulating and implementing co-management arrangements

where the decision-making process is ultimately based on integrating the opinions and even

convictions of people with oftentimes very different perspectives on the same issues. Therefore,

during the course of this project I considered myself a novice in the process of bringing people

together to effect co-management for the sea egg fishery. It is from these perspectives that I offer

the following account of my experiences and opinions.

I first focused on collaborating with fishers to gather scientific information on the status of the

stock. To this end the fishers themselves needed to be trained in underwater survey techniques to

collect the necessary information. To achieve this I formulated a simple sampling programme to

collect information on the abundances and size distributions of sea eggs at a number of index

sites that could be resurveyed in subsequent years to allow inter-annual comparisons of the status

of the stock. With the assistance of some officers of the Fisheries Division, fishers were trained

in the sampling techniques and how the information collected was used for stock assessment

explained to them. The training went very smoothly, the fishers quickly mastered the techniques,

and I think understood the underlying rationales for collecting the data and its application in the

decision-making process. The first island-wide survey was successfully conducted between July

and August 2001, prior to the opening of the harvest season and provided baseline abundance

indices for the sites. Although the numbers of sites and some of the fishers involved have

changed over the subsequent years, an annual survey of these sites using the same sampling

techniques have been conducted every year since 2001 and the information used to determine the

length of the annual harvest seasons. The survival of this collaborative process over time must be

viewed as a major successful outcome of this component of the project.

The main component of CORECOMP was the development of an arrangement to implement

sustainable co-management of the fishery. To this end it has been agreed to form a management

council comprised of representatives of government agencies and fishers that directly advise the

Chief Fisheries Officer on issues pertaining to the fishery including research, regulation and

enforcement. The proposed council must be considered the lynchpin for a successful and

sustainable co-management arrangement and must be put into place as soon as possible. As

presently organized the fisher representatives nominated to serve on the proposed council include

a number of fishers who have continued to show an interest in the decision-making process

7

through participation in the annual surveys or the stakeholder meetings that were held during the

course of the project, mainly to decide on the duration of the annual fishing season. The

establishment of this core group of concerned and involved fishers is probably the single most

important outcome of the project.

Based on my personal experience with working with the persons nominated to serve on the

council, I believe the council will be well equipped in terms of human resources to fulfill its

mandate. However, the survival of the arrangement in the long run depends on how seriously

government treats the council's recommendations. The council is unlikely to survive if its

decisions are overturned by governmental bureaucratic or political interference. This is a real

danger under the present structure whereby the council's recommendations must be passed

through the Chief Fisheries Officer and then the Minister responsible for fisheries. It would seem

that co-management only at the lower end of an essentially top-down management structure can

easily be quashed.

The next important step in the co-management process will be expansion of the fisher

representative base. Some of the management decisions that were taken following consultation

with the fishers engaged during the course of this project were not well accepted by many fishers

outside of the "core" group. Of course, there will always be persons who prefer to stay outside of

any consultative decision-making process and decry any decisions taken rather than participate in

the process. However, the fisher representatives on the council must effectively liaise with the

members of the community that they serve so that the interests of the community are really

brought to the table. This is in keeping with the underlying principles of co-management. In

addition, without a truly representative modus operandi, there is a real danger that the fisher

representatives will be viewed merely as auxiliaries of government in a government-driven

arrangement. Developing workable interrelationships between communities and representatives

is likely to be one of the most challenging steps along the co-management path. It is at this point

that the services of experts in this sociological area are desperately needed to facilitate this

process.

The problem of poor enforcement of management regulations has plagued the sea egg fishery for

many years. Lack of effective enforcement obviously makes a mockery of any management

initiative and if unchecked will frustrate and likely eventually destroy any co-management

arrangement. Illegal harvesting of sea eggs during the close season was understandably a major

topic of concern for stakeholders throughout this project. Unfortunately no concrete solutions to

this problem were formulated during the course of the project although there was some positive

thrust in increased public education. Although a continuation and indeed further increase in

efforts to educate the public is important in curbing the incidence of poaching, I believe that the

public is already fairly well sensitized to the dangers of poaching for the sustainability of the

fishery. However, it is really an affluent group of greedy individuals in the society who

ultimately support poaching by paying fishers to harvest sea eggs for them. The only real

deterrent to this activity is therefore to dissuade the financial support for the activity by these

unscrupulous people probably through identifying and publicly embarrassing them. Although

both harvesting and possession of sea eggs during the close season are illegal acts and carry the

same potential punishment, it has so far only been some of the fishers that have been punished.

As such only the "little man" pays. Of course it is always a daunting task to challenge the

affluent and powerful but the reality is that poaching, or at least the temptation to poach, will

continue as long as funding is available. Therefore enforcement will be a major challenge for

8

successful management of this fishery.

Based on the many formal and informal interactions that I had with fishers and the Barbados

National Union of Fisherfolk Organizations (BARNUFO), the umbrella fisherfolk organization,

during this project I believe that there is generally good consensus on the critical management

issues in the sea egg fishery. During the project everyone has learned from each other and mutual

respect has developed among the participants. There is thus a good basis for developing co-

management among those with whom these relationships have been developed. However, the

test of the sustainability of co-management of this fishery will be if this positive working

relationship can be extended to the wider community of stakeholders that, as already mentioned,

must be undertaken for true and undeniable co-management.

2.1.3 Holetown Community Beach Park Project

Submitted by Robin Mahon and Maria Pena

Dr. Mahon's research activities are in coastal and marine resource management, with emphasis

on assessment and management of transboundary resources. Dr. Mahon is Regional Project

Coordinator for the IOCARIBE Large Marine Ecosystem initiative, and is also leader of the

project "Sustainable integrated development and biodiversity conservation in the Grenadine

Islands" being implemented by CERMES, Caribbean Conservation Association, Projects

Promotion Ltd., and the Carriacou Environmental Committee and funded by the Lighthouse

Foundation, Germany. That project focuses on the role of civil society in sustainable

development in the Grenadines and the modalities of effecting change in complex systems. His

previous professional experience includes working for the Department of Fisheries and Oceans,

Canada; FAO; the CARICOM Fisheries Programme and numerous consultancy projects.

Dr. Mahon's interest in CORECOMP was in the use of participatory approaches to develop the

Holetown Community Beach Park. As this area has a number of user conflicts and residential

issues, a participatory approach was seen as essential in obtaining an approach that would be

acceptable to all parties. Dr. Mahon is affiliated with the Holetown Watersheds Group, the civil

society body that undertook the co-management project.

Ms. Maria Pena's interests are also in coastal and marine resource management. Her background

is in fisheries biology and management and presently assists Dr. Patrick McConney and Dr.

Robin Mahon in the coordination of externally funded projects in the Wider Caribbean, outreach

coordination, project research, presentation and report preparation, and BSc and MSc level

teaching. Recent and current activities include involvement in socioeconomic monitoring for

Caribbean coastal management (SocMon Caribbean) and MPA management effectiveness

evaluation in the Tobago Cays, Grenadines and the Negril Marine Park, Jamaica.

9

Ms. Pena has been involved in CORECOMP for the past three years, particularly in monitoring

the sea egg seasons in Barbados of 2003 and 2004 where she compiled an inventory of sea egg

events (print and audio visual media) for the seasons and assisted in report outputs. She has also

been involved in the site development planning phase of the Holetown Beach Park Community

project in Barbados where she informed and surveyed stakeholders in the area about the project,

coordinated meetings with stakeholders and potential funders and assisted with project report

writing. Working on these projects, her interest in sustainable development of marine and coastal

resources has been peeked and she has enjoyed interacting with the resource users whom are

vital to the sustainability of the projects as well as the resources on which they depend.

The following is an overview of our co-management experiences with the Holetown Community

Beach Park project. Generally, the response to the project was encouraging with many

businesses, in the area being interested in the development of the project. Many stakeholders in

the immediate vicinity of the area, particularly household residents and restaurateurs, were

willing to form a committee that would guide the site development phase of the project.

Although stakeholders were engaged at the beginning of the project (see dissemination flyer; and

Pena and Mahon 2005) and they were keen to monitor its progress and development and provide

their inputs, we had difficulty keeping them engaged due to long time delays with inputs, such as

survey maps and coastal engineering plans for the area.

These delays were, and still are, due to our dependency on the professional services of a

surveyor, coastal engineer and landscape planner whose services are being rendered at

significantly reduced rates and as such is the main reason for slow progress of this project since

low priority has been given to these works by the respective contractors. As such we have

continued to experience difficulty in obtaining these inputs.

Supplementary funds towards drafting the development plan for the area were forthcoming from

a number of sources (see Pena and Mahon 2005) but surprisingly, the stakeholders who stood to

benefit most, i.e. those in avenues 1 and 2 were least forthcoming with funds. The impression

gathered was that these stakeholders would willingly make donations only when physical

development project works commenced in the latter stages of the project rather than upfront.

There seemed to be an underlying reluctance of business stakeholders in the Holetown area to

donate funds to this project since it was taking place on Government land, and there was the

view that it should be paid for by government. There was also skepticism regarding the

likelihood that the Government would follow-through with development once the plan was

submitted.

The initial focus of the project was largely establishment of an amenity area that would restore

ecological function, particularly services that protected the marine environment. Stakeholders

however were primarily interested in recurrent flooding and its associated problems within the

area, an issue which could not be comprehensively addressed within the scope of the project

(Pena and Mahon 2005). Another priority for stakeholders in the area was that of security

enhancement. Restaurateurs were particularly interested in this issue and had questioned whether

it was feasible for the project to provide and improve lighting in the area since some of their

customers had been the victims of crime there, with these incidents having negative impacts on

their businesses.

One major outcome of the delays was that the context for the project changed due to Government

plans and initiatives in adjacent areas, as well as private development, such as Lime Grove. One

10

of the activities that was successful was a project by two visiting students to develop a plan for

the restoration of the ecological area (the pond and adjacent wetland). They acquired a great deal

of useful information from residents, particularly regarding how the area used to be in the past.

Several residents provided historical perspectives on the various flora and fauna that used to be

in the area and the way that they would fish or play in the area as children. This has been

documented for use as the project moves into implementation (see Pena and Mahon 2005).

Challenges of co-management:

· Reliance on supplementary funds and the good will of persons providing technical input

to projects at reduced costs.

· Difference in initial environmental focus of the project and that of stakeholders.

· Change in context for the project owing to adjacent development.

Unless funds are sourced to completely cover the costs of such co-management projects as the

Holetown Community Beach Park project, delays will be inevitable resulting in slow progress of

the project. Despite the delays and other challenges described above, there appears to be a

continuing interest in stakeholders in seeing the area improved. At times when they were

engaged, there was genuine interest and enthusiasm for the project. Clearly, the need still exists

for the development of this area as it is central in Holetown.

N

PARKING

S

AREA

DRAI

S

A

GR

RUBBISH

HEAP

Litter raked

here and

burned

POLICE

Residents

Proposed

throw garbage

COMPOUND

pond

on this heap

Present

pond

UNDERCUT WALL

Protect the wall with

OPEN AREA WITH SHADE

boulders under the

TREES

sand

Leave open recreational

POND

Plant sea grapes in

use

Enlarge pond to the

front

Clean up area

BE

north and east

Provide garbage

ACH Raise inland

SURF-

containers

perimeter with

POSSIBLE BEACH

SIDE

Arrange regular col ection

gabions or boulders

ACCESS

to reduce flooding

May be suitable for

Interpretation sign

enhancement as a small

Remove north wall

could be placed

park with benches, picnic

of drain

here

tables, etc.

Plant mangroves

Leave adequate area for

and other

watersports operators

vegetation along

edge to stabilise

Pond already

JUNK -- Batteries, brake drums,

supports tilapia and

furniture, tyres, boat parts,

SEAVIEW GULLY DRAIN OUTFALL

other fishes that

broken glass, etc.

control mosquitoes

PROJECT AREA

TREE

KEY

HOLETOWN WATERSHEDS GROUP

2.2 Belize

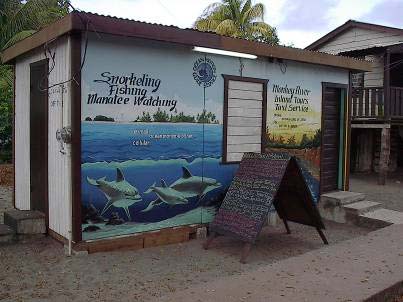

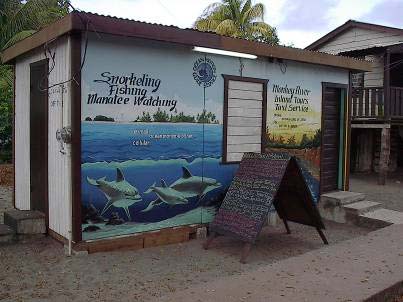

2.2.1 Facing the challenges: the Friends of Nature experience

Submitted by Lindsay Garbutt

Friends of Nature (FoN) is a non-governmental organization (NGO) working in southern central

Belize. Just over five years old, FoN works with five coastal communities, two of them

indigenous communities. On behalf of these communities FoN manages the Gladden Spit and

Silk Cayes Marine Reserve, recognized by the World Wildlife Fund as a "priority site" and is a

key "platform site" for The Nature Conservancy's Mesoamerican Barrier Reef Program. This

reserve is one of the major and most studied sites for spawning aggregation, with more than

twenty-six different species of fishes known to spawn there. In addition it has gained a lot of

attention as one of the very few sites where one can see the whale shark. The interest in viewing

whale sharks has made Gladden a prime tourist site and a major income earner for local tourism

stakeholders. FoN also manages the Laughing Bird Caye National Park, a World Heritage Site

and the second most visited protected area in Belize.

Friends of Nature is led by a team of individuals that almost all come from the local communities

it serves. The strength of the organization is based on the great support that it has received from

11

its local communities. Its Board of Directors is the most representative of any in the region,

involving all thee local stakeholder groups. The partnership with CORECOMP has been a very

positive one for the organization, allowing it to undertake a few small but very essential projects.

Lindsay Garbutt, the Executive Director of FoN, has worked with the organization from its

inception. Born in the coastal village of Monkey River, he has worked as a fisherman, assisted in

the formation and management of fishing cooperatives and has served many years as the

representative of southern Belize to the Fisheries Advisory Board, and the Belize Tourism

Board. At the moment, in addition to being the executive director of FoN, he is also the Focal

Point for TRIGOH, the Tri-National Alliance for the Conservation of the Gulf of Honduras, a

group of NGOs from Belize, Guatemala and Honduras involved in protected areas management

in the Gulf of Honduras.

From its inception FoN has had co-management responsibilities for its two protected areas. The

experience has been mostly positive. The positive relationship is to a great extent based on the

fact that these are two of the very few reserves that were declared as a result of strong

community lobby. It was the stakeholders themselves, essentially fishing and tourism

stakeholders that pushed hard for the declaration of these reserves as protected areas. This has

given FoN a strong sense of ownership and excellent community support. Recognizing this

support FoN has sought to develop programs that have direct impact on the communities

particularly in areas of alternative livelihood and community exchange. Through these two

activities FoN has developed several at-risk youths into professional PADI certified Dive

Masters, providing an essential service that was vitally needed for the further development and

increased local participation and ownership of the tourism industry while at the same time

creating an opportunity for more than twenty young males and females, most of whom had no

secondary education. The community exchanges, primarily with Cuba and Mexico, have

resulted in a major shift in the way fishermen fish. It has allowed fishermen to continue fishing

with the same intensity but using methods that are more sustainable.

CORECOMP funding helped FoN realize two essential projects. The first was a Board of

Directors Orientation Workshop. FoN's Board is made up of representatives of all major

stakeholder groups in the region that the organization works. It includes the Village Council

Chairperson from all five communities. One of the major challenges of NGOs regionally is that

of governance. Through this workshop FoN board members were given an opportunity to

understand the essential of serving on a board of an NGO, their responsibilities. This was vital as

while being successful in their chosen field, few of the members have served on a Board of

Directors previously.

The second project funded by CORECOMP was the provision of funds for the initial meeting of

the proposed Southern Fishermen Association. As tourism in the area has grown the fishermen,

many of whom have diverted into tourism, have felt themselves slowly becoming more

marginalized. Given that those who work in the tourism industry, the countries foremost foreign

exchange earner and industry, are generally more educated and have more access to the political

decision makers, the feeling is that more and more they are the ones that have representation on

all the major boards and are invited to all the major forums. The fact that tourism is essentially

owned by foreigners, who have far superior experience in lobbying, and certainly a much greater

access to the powers that be, has contributed even more to this feeling. Too the tourism

stakeholders are more organized and better funded.

12

To combat this widening gap FoN has with the assistance of CORECOMP worked towards

developing a strong fishermen association. This will allow for a greater level of unity among the

fishermen as they come together on a regular basis to discuss their concern and will create a

body that is large enough and with enough political strength to assure their representation on all

bodies that affects or can enhance or impact their activities.

As a boy I remember a speech given to a group of fishermen by an old community leader.

During this speech in which he was soliciting the support of the local fishermen for the formation

of a fishing cooperative he said, "as fishermen what we need is individual cooperation".

Essentially little has changed in the thirty two years since I first heard the need expressed in this

manner. Co-management is essentially getting a group of independent, very strong minded

individuals to cooperate for their personal benefit while respecting their essential individuality.

Most of these individuals, particularly those in the fishing industry, have never had a boss and

rarely have the personality or desire to want one. Co-management therefore almost always

involves tip-toeing around these several egos and understanding the values of these individuals.

It also often means gaining their confidence; very hard to earn but certainly more than worth the

price. It is a difficult, sometimes torturous, and always tricky, process. It is dealing with a group

of individuals that are often short of book learning but extremely intelligent with a clear

knowledge of what they want and an even clearer idea of what they do not want. In particular for

Friends of Nature, it has been even more challenging trying to deal with a variety of stakeholders

whose interests often are diametrically opposed. The tourism stakeholders want more protected

areas for their rising client base and the fishermen who feel that their fishing ground is constantly

diminishing.

Some of the major challenges for FoN have been:

1.

Managing whale shark tourism: The predictable presence of whale shark in the reserve

from March to June of each year has brought unprecedented growth to the tourism

industry of this area. Unregulated, with everyone trying to get their piece of the pie, this

activity was slowly getting out of control and was headed towards the reality of killing

the goose and losing the golden egg. Through the efforts of FoN a Whale Shark

Committee was formed to provide advice to the Fisheries Department for the regulation

of this activity. This group worked hard and in less than three seasons this activity is the

most regulated and best managed tourism activity in the country. Carrying capacity is set

and respected, a slot system has been put in place and today whale shark tourism at the

Gladden Spit and Silk Caye Marine Reserve is an example of good management in the

region.

2.

Southern Fishermen Association: In March of this year FoN brought together a group of

fishermen from throughout the southern half of Belize for a fishermen forum. This

meeting was the first of its kind and the first time that fishermen had ever met in this

manner. The meeting was very positive if at times loud. The decisions coming out of the

meeting were clear and definitive and there is a clear belief on the part of the fishermen

that they must unite, that protected areas has largely benefited them and they are

recognizing that if they become partners with the managers of these reserves that it will

impact greatly on the long term protection of the resource that ensure their livelihood.

3.

Community relations: For quite a while FoN has been trying to find better ways to

interact with the communities. In spite of regular consultation we consistently receive

reports, particularly from consultants, that the community is saying that they don't know

13

who or what FoN is. Over the past year FoN has began to change the way we do

consultation. As opposed to holding meetings in community centers and waiting for the

community members to come out FoN now goes to them. We take a team comprising the

different units of our organization from rangers to biologist to outreach personnel and the

management team and do a house to house visit usually accompanied by the board

member that represents that community. The Board of Directors has also taken a decision

to hold each board meeting in a different community followed by a community meeting

in which the community members get an opportunity to interact directly with the board.

This is a work in progress but initial review suggests that there is much more awareness

about the organization on an individual community basis.

Protected areas management is more about people and less about resources. Left to its own, a

natural resource has a way of replenishing itself. Recognizing that it's about people, FoN's motto

is: "Protecting our natural resource by developing our human resources". It has worked for us.

While we place great emphasis on the sustainable use of our resources we are very cognizant of

the fact that human beings must survive. These resources are more the property of these

communities than anyone else. Our major effort, therefore, is on building a lasting relationship

with the local resource users. While our co-management agreement is signed with the

Government of Belize and the Fisheries Department, it is our stakeholders that are the real

partners, our real co-management partners. Working with CORECOMP has gone a long way

towards creating a better co-management relationship with our stakeholders because we share the

same value. Too, CORECOMP does not only provide financing but provides good sound support

at all levels.

While there are many challenges that we have overcome there are still many even greater

challenges to overcome. The communities are not as interested in what you did for me yesterday

as much as what will you do for me today. It's a constant challenge. But where the challenges are

great the successes are even more rewarding. Friends of Nature has determined from its

inception that co-management is the way it chooses to manage the resources with which it has

been entrusted. Co-management is the way we choose to do it. For those of us who have grown

up in these communities we do not see co-management as a complicated scientific process. We

see it as the only RIGHT way to do it. We see it as a way of life.

2.2.2 CORECOMP and TASTE: Beneficial capacitation for the co-management process of the

Sapodilla Cayes Marine Reserve (SCMR), Belize

Submitted by Jack Nightingale

My name is Jack Nightingale and I function as the acting Executive Director (ED) for the

community co-management NGO, TASTE (Toledo Association for Sustainable Tourism and

14

Empowerment). TASTE along with myself has been engaged in the co-management of the

Sapodilla Cayes Marine Reserve (SCMR) for five and one half years. We are a small group of

three full time employees and a large program.

I bring a varied skill base to the NGO. I have been an aircraft electrical technician; a modern

dancer, choreographer and professor; a marketing and sales officer in high technology business;

a carpenter and builder; tour guide, tourism NGO worker, board member and now an

environmental NGO, ED (acting). A chequered career that has provided me with an enormous

skill based background. I am profoundly concerned with human development both in the

worldly and spiritual contexts. I (and we in TASTE) have had a wonderful time in this co-

management project.

We have worked with CORECOMP in the following areas:

· Co-management process workshop

· Participation in 3 Gulf and Caribbean Fisheries Institute (GCFI) conferences

· TASTE board effectiveness workshop

· Proposal writing workshop

· Socio-economic monitoring workshop

· Management retreat

Building capacity in all these areas has been essential to our growth.

In Belize, the most regular of co-management conditions is delegated responsibility to the NGO

partner. In the case of TASTE and the Department of Fisheries (Government of Belize), it has

been an evolving co-management relationship from a co-operative condition moving towards a

delegated position. It was at the very first workshop with CORECOMP, "the co-management

process", that we were clearly able to identify the process we all were in. A crude plan of this

process was one of the outputs. We, the co management partners, have both witnessed growth of

the SCMR and in its co-management, as measured against this original plan.

There are (in Belize) inherent weaknesses in the government as managers of protected areas.

These weaknesses are evident and are very critical to success creation. Principally they are (a)

FUNDING and (b) BUREAUCRACY.

The constant lack of funds weakens any programs that the government (or NGO) wishes to

employ. Bureaucracy does not empower the human resources with "ownership", "sharing power

with" relationships or "good governance" practices. These features are self evident and do not

need further expression. NGOs in Belize tend to follow government modelling for management

processes, which makes them weak also. NGOs with fully delegated responsibilities look like

`mini-governments' to the community stakeholders in protected areas. TASTE found itself, and

still finds itself, attempting an impossible creation: "To be the model community co-manager".

We are not failing but neither are we creating the success that we envision.

There are many features, which interfere:

1. The communities have been given promises by other NGOs, which can never be

complied with.

2. We never give promises but we fall into the NGO `form' and therefore are seen as giving

promises.

3. Governments practice "patronage", so do NGOs; we do not, and are blamed for not doing

so. YET "good governance" says no to patronage.

15

We walk a line that is narrow and full of treacherous reefs. However, we have succeeded in

environmental education, outreach programming, co-operation, collaboration and partnering in

biophysical monitoring of the SCMR, alternate economic opportunities and youth empowerment.

We have been able to build a highly useful infrastructure as part of a public use programme,

which works strongly for sustainability. We have not yet attracted philanthropy or donations to

the SCMR that will give us a breathing space and allow the Department of Fisheries to go all the

way with delegated responsibility. The position of delegated responsibility is a goal.

From a personal point of view, the single most important lesson is to not take on the challenges

of Executive Directorship without a fully active Board of Directors.

It is essential that the Board members are willing to seek funding and donations and that they are

willing to take on tasks of representation. It is so very easy to take on all the roles if you are keen

to get a job done. When looking at the idealized version of a Board of Directors as described in

the trainings, I would have had 50% more time for other tasks that were taken up by carrying out

Board member duties.

We have had good luck with grant writing and seem to be able to hold our own. Learning such

things as log frame, management by results has helped our skill sets enormously. Even more

significantly they help in how to think about the issues.

It is precisely in this mode, clear thinking process, that presents without doubt the four major

gaps of all MPA management:

1. Lack of enforcement.

2. Lack of lobbying and advocacy.

3. Lack of public education programs (not environmental education, although that is weak

in most places also).

4. Lack of alternate economic opportunities.

We are full of good science and scientific understanding. Common sense tells us clearly that the

world's biodiversity is diminishing. We are full of plans, politics, hierarchies, management

schemes and trainings. Common sense tells us that greed still is in the driver's seat and "power

over" wins from "power with" sharing.

Common sense clearly lets us know that we have not yet fixed that which needs fixing.

I have no doubt that one of the main thrusts of conservation activity is the desire to fix that which

needs fixing. Without a focus to the four gaps mentioned, and real time desire to meet these

challenges head on, will we have any MPAs to co-manage?

We are not always the darlings of the community (this is an understatement anywhere). We have

had stakeholder issues that have required conflict resolution, but not too many. As ever,

participation is hard to create but we find that new stakeholders (youth) offer stronger

participation and more goodwill. Everywhere on earth greed and power are in the driver's seat.

This is as true for stakeholders as NGOs. Treading the middle way is not easy.

With the growth of anything there are needs which must be met. Our co-management has been

groomed with professional help along the way. CORECOMP and CERMES have done a great

job for TASTE-SCMR. Every workshop and the GCFI events have been instructive and helpful

to the process. We in TASTE are looking forward to the next 5 years of positive growth but,

even more importantly, we wish to be able to measure the positive impact we are having in the

SCMR.

16

Looking to the future for TASTE we see the possible full funding we need for obtaining the

delegated co-management in one or other forms. First, the most useful from our point of view

would be to be completely independent from other organizations and be able to present our style

and perspective without too much compromise. However, the second choice will be in the

merging of TASTE with another NGO to create a larger organization with a broader range of

responsibility. This second choice is on the burner and being looked into by board members and

stakeholders. A funder has particular interest in that option, seeing a more economic use of

resources. With a backer behind this choice it becomes more interesting.

Allow me to note here that this is close to the greatest difficulty to confront all NGOs. That

difficulty is the need to keep the organization alive and kicking, taking more energy and

resources than can be put into the activities for which the organization was created. Self-service

becomes more of the goal than serving the need. Finding that balance, to my mind is the main

question.

I conceive of an SCMR that is 50% sustainable in the next 3-5 years. This will require that the

management plan become operational so that we may utilize and place the zonation in the

reserve. It will require full cooperation from the private sector to keep tourism according to a

plan of carrying capacity; it will require far more ownership from workers and stakeholders; and

will require regional participation.

The threats that most affect the reserve are from sources of contamination. These must be

identified and met head on with regional programs of advocacy and lobbying. No easy task, and

by far the most significant. If we cannot keep the corals and biodiversity in the reserve then 50%

sustainability is ridiculous.

2.2.3 Human resource management concepts for NGOs

Submitted by Jack Nightingale

How broad are the issues that govern the life of the people who work for and around your NGO?

What are the primary goals, based on your mission and vision that create the working

environment? Do they reflect the essence of that vision, that mission? Are the human interactions

you generate from your NGO or organization generating "power with" sharing or are they

dominating "power over" hierarchical dictates? If you have studied governance and understand

the basis for good governance, are you practicing it?

Human resources can be considered as everything from throwaway slave labour to the finest

mutually beneficial relationships you could possibly create.

It is typical in this day and age to avoid thinking about these questions and to accept the status

quo of the work place. The speed with which we are to achieve or meet goals precludes time

17

spent thinking about humans, relationships and service. This status quo condition does little but

provide a job for someone, thus giving him, or her, an income. (Let us note here immediately

that this single fact of a job might create more for the individual than ever before and allow for

children to eat regularly). This is positive. However, it might do very little for the overall

improvement of man or his condition, especially in relation to the workplace.

NGO's are created around specific social and environmental conditions. Very high-sounding

language is used in their mission statements and in the expression of their vision. Whenever

presentations are given to donors, funders, boards of directors, stakeholders and community

members, it always seems as if the NGO is beneficial and godlike in its munificence. If however,

you study its day-to-day human interactions you are likely to find top down decision-making,

power over management conditions and poor relationships between all the people. Typically

high staff turnover reflects these poor governance conditions. Does this mean that the high

sounding words of the vision and mission are a fake?

Of course if you look everywhere in life you will find the same conditions in operation. The

private sector is rampant with poor governance. Governments are ridiculous in their bureaucratic

behaviours and their sense of service to the people is a joke.

Why then focus this human resource management concept to NGOs?

It is precisely because NGOs pretend to high social and environmental concerns that they also

could lead the way in human relationship issues, setting a new pace for others to follow. It is not

anywhere near good enough to maintain status quo apathy or mediocrity. Just because you know

that government institutes function with poor governance, and that private sector businesses that

are financially successful and operate under poor governance exist, they should not be the guides

to your choices of management regimes.

It is true to say that history has not produced much in the way of good governance. This is

principally because there is a paucity of good leadership. It is also because no one thinks about

good governance. The ideas of good governance are not discussed openly. How can people be

expected to know about something if the ideas are not shared? Of course one must remember that

there is a natural resistance to this knowledge since it goes against greed and power (over)

experience. Most humans in their poor condition crave power over others and believe that the

world owes them a living, and a darn good one at that. Accumulation and access to resources are

gobbled up by individuals in the knowledge that only they should have it. If this attitude or

worldview persists, we are truly doomed.

In the meantime and before any doom overtakes us, we have opportunity to apply good human

resource management principles in our NGOs.

There are a few main principles in good human resource management:

· Consider the words "human resource"

· Consider the word "good"

· Consider the word "management"

As we started out by saying that human resource could be anything from slavery to the finest

mutually beneficial relationship, we should look at these two ends of the spectrum.

· Slavery is the usage of captive human resources without regard to the humanity, needs,

freedom, development, living conditions, health, welfare, education or ability to survive

of those same resources (the people).

18

· The finest mutually beneficial relationship would be the fullest consideration of a human

resource including full awareness of humanity, needs, freedom, development, living

conditions, health, welfare, education and the ability to survive and share fully.

There are multiple places in between these two ends. The qualities of either end will clearly

appear in the systems chosen. It is not difficult to see where people who provide jobs, choose to

apply these qualities. When a boss shouts at someone that they are lazy, good for nothings, it is

easy to see the dilemma the boss and the human resource experience.

Obviously the worker could care less about the job and so allows those feelings to govern

actions. The boss wants something done but doesn't care about who is doing it or why. This

scenario is common and everyone experiences it, even in school. If you have never thought about

relationships or do not care for the experience of relationships, you are bound to fall into poor

habits either side of the equation. In order to manage human resources you must first of all care

about relationships. If you care about relationships you probably care about humans. If you care,

then the words "human resource" means something you care about. Caring implies that feelings

and thoughts about other humans are co existent. It also stretches to both parties. All feelings and

thoughts of all parties co exist and are responded to. This condition satisfies the word "good".

All parties feeling good about each other qualify this. This is a condition in which

communications are optimized and efficient work is possible. Management is simply the tool by

which you bring about this condition.

It could be crudely stated then that good human resource management is simply the way in

which caring about each other is turned into efficient use of time and other resources to bring

about a mutually defined goal.

Let us look at this from the point of view of governance. Governance is the system by which

things and people are governed (managed). The results of poor governance are clear. People feel

dissatisfied and upset. They might revolt or build strong resistance to this poor governance (think

of slavery). Good governance would bring wonderful qualities of support, strengthening,

efficiency, creativity and good will. Here is a tried but true aphorism that allows choice for

governance. There are only three possible futures from this now:

· Things get worse.

· Things remain the same.

· Things get better.

If anyone in any group perceives that things are not getting better then the chances are that they

are not. This means that the things get better scenario is mutual (a consensus). All are in

agreement. In the case of governance, `good' would have to bring mutual benefits. Obviously

good governance must imply a' things get better' condition from wherever we are. What then

might constitute good governance?

Good governance begins with the self and the self alone. Ask yourself how you govern yourself.

Is it full of indulgence? Do you love your self or hate your self? How do you care for your self?

Do you doubt yourself? There are hosts of questions to ask your self if you really want to know

how you govern your self. It is a lifetime's work to really come to understanding about your self

so it does no good to have too high an expectation of the knowledge of self. Yet, good

governance begins with the self.

If you start by being kind to your self and can find time to really reflect on how it operates in the

19

world, you will quickly make discoveries. If you hate yourself you can only see negative

frameworks for every experience. Your choices on how to govern yourself are going to be hard

and rough. Good governance can contain perceptions of self that allow for growth. They can be

critical but not destructive. Positive perceptions are of course the most useful. If it is difficult to

find positive perceptions about yourself you will need to find some outside assistance. Find

someone who understands what good governance is and ask for help. Do not ask critical people

or people who see only negative things.

Once on the road to good self-governance, you can think about good governance of your own

immediate family. Are you a dictator with them? Do you allow them to talk and interact? Do you

say there is only one-way to do it, my way or the by way? Do you love them? Do you even like

them? This begins another round of analysis of your own behaviours. Good governance of your

own family will allow them to grow and become their own beings. You will make space for them

to be themselves and yet function within mutually defined tolerance of each other's behaviours.

You will like them enough to care that they are making good choices for themselves. You will

take the time to see things the way they do.(living a while in their shoes) You will practice tough

love when negative behaviours erupt. You will especially look to the meaning of "partner for

life".

The third level of good governance is in your local community, your neighbourhood, the school

your kids attend, the sports teams they play in. Now begins a really difficult phase of good

governance since now many strangers will test what you have learned from the first two phases.

Blowing it all away is now the simplest thing to do. Patience is a virtue and this is where this

rubber meets the road. This is where you have to remember that good governance begins with

yourself. The rest is an obvious and clear progression through village, town, region, nation and

world stages. This makes it clear why good governance is so very difficult. How many people

have done this kind of work in preparation for any kind of governance?

Now let's bring this concept down to where we started this essay, an NGO. An NGO (non-

governmental organisation) is usually dedicated to some form of development in communities.

This development could be social, ethnic, infrastructure, legal, advocacy and lobby,

environmental, health, agricultural or a mixture of many aspects of development. Of course it is

interesting to note the designation of non-governmental. It would appear that it is important to

stress the difference. That is a thought full of conflict.

Perhaps the biggest distinction is the `not for profit status' that NGOs legally operate with. It is

this status that creates Civil Society as the third leg of society, the other two legs being the Public

Sector (government) and the Private Sector (business and for-profit status). The not for profit

status implies a standpoint or a worldview. This worldview is moralistic. It is important that

development (see the list above) be implemented without the profit motive since the profit

motive might produce opportunity to be criminal. The simple truth that emerges is that when

people wish to act criminally they will, regardless of position or status. The other fact is that

humans are awfully good at hiding their acts from selves. This is the basis of disillusionment for

many people from the other two sectors of society. The moral standpoint has no basis in reality.

Then of course, those two other sectors are full of criminality.

So what does this chase leave us with? It would seem, that human nature, the lower aspects

govern all. This is a good place to start looking at NGO's and their human resource management.

It states clearly that NGO's are as vulnerable as government and the private sector to base

20