Policy and regulatory mechanisms necessary for promoting

nutrient reduction

and

Developing a Code of Good Agricultural Practices -

Harmonization with EU Legislation

by

Henning Lyngsø Foged

Projects Manager, M. Sc. Agricultural Science

International Department

The Danish Agricultural Advisory Centre

E-mail hlf@lr.dk

Web http://www.lr.dk

Abstract

Eutrophication and methemoglobinaemia can be fatal for human and animal and is

caused by especial y nitrate in waters originating from mainly inefficient use of nitrogen

in the agricultural production. Problems are correlated with inefficient use of livestock

manure, increasing herd sizes, increasing animal density and increased use of mineral

fertilisers. Problems in former Soviet Union Countries are furthermore connected with

lack of livestock manure storage facilities and bad manure management practices.

Policies has first been developed and enforced during the last 15 years, but due to a

big inertia in the nutrient turnover it might take decades before this will respond on

water quality indicators. Denmark has been and is a country with a foremost leading

agro-environmental policy, which has served as inspiration for other countries. A

Danish National Nitrogen Management Programme from 1987 has resulted in a 28%

decrease of the nitrogen load from Danish agriculture without harming the agricultural

productivity. The instruments to achieve those goals have been very similar to those

prescribed by EU's Nitrates Directive, here under the need for clear guidelines for

farmers. It is very important to make the elaboration of Code of Good Agricultural

Practices' a process of discussions, where all stakeholders are involved, not at least

farmers' organisations.

Key words: Environment, agriculture, agro-environment, nitrogen, nitrate, policies,

Code of Good Agricultural Practices, nutrient balance, nutrient load, livestock manure,

fertilising

1

Problem complex and definitions

Nutrient reduction deals with reduction of the leaching, surface run-off, sub-surface flow and

soil erosion of plant nutrients - especially N (nitrogen) and to less extent P (phosphorus) to

the environment, especially to water courses.

1

Nutrients cause eutrophication1 of water, which upsets the ecological balance and can result in

undesirable effects, such as fish death and algal blooms. Problems are greatest where farming

is not intensive, and lower in southern Europe.

Nitrates are particularly prone to leaching, and concerns over nitrates in water supplies have

led to legislation in the form of the EU Nitrates Directivei and the setting of limits in drinking

water under the Drinking Water Directive.

Nitrate is soluble and enters water via leaching and run-off while phosphate molecules bind to

eroded soil particles and enters water courses as run-off. Both nutrients can cause severe

eutrophication of water, nitrates affecting mainly coastal waters such as the North Sea and the

Baltic Sea and phosphates affecting rivers and lakes. Eutrophication in both coastal and inland

waters can result, through excessive growth of phytoplankton, in depletion of oxygen from

water bodies, and subsequent death of fish and other aquatic animals. Blue-green algae

associated with eutrophication produce toxins to which fish and terrestrial animals are

susceptible. Changes in the composition of aquatic fauna resulting from eutrophication are to

the detriment of species with high oxygen requirements and the invertebrate community

becomes less diverse. Eutrophication of inland waters, as well as coastal waters, is an

international problem. Symptoms of eutrophication are in Denmark seen mainly in the late

summer, when climatic conditions are optimal for phytoplankton growth.

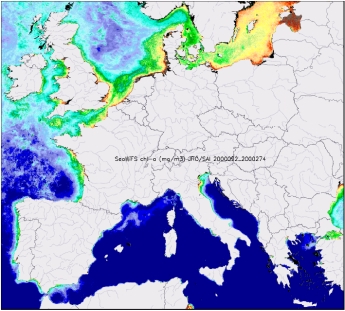

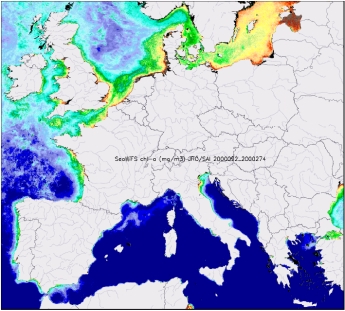

Figure 1

Satellite picture of EU seas chlorophyll-a concentrationsii. Average summer

2000. The red and yellow areas show strong phytoplancton development, one

of the most visible symptoms of eutrophication, with potential adverse effects

(toxic dinoflagellates, oxygen depletion, changes in bottom flora and fauna, etc).

N.B.: Interferences of humid and suspended matters near estuaries have to be

taken into account.

1

Excessive growth of algae and plants, with potential adverse effects on biodiversity or human uses of water. The precise

definition in the Directive (art. 2.i ) is "Enrichment of water by nitrogen compounds, causing an accelerated growth of

algae and higher forms of plant life to produce an undesirable disturbance to the balance of organisms present in the

water and to the quality of the water concerned".

2

Many believe that ecologic/organic farming (governed by the EU Organic Farming Directive

2092/91iii) without use of mineral fertiliser is a production method, which leads to reduced

leaching of plant nutrients. Investigations carried out by DAACiv have not been able to confirm

this. Organic farming incur use of different practices, whereof some

contribute to reduce nutrient leaching for instance a larger area with

grasslands, while other practices contribute to increase leaching of

nutrients for instance higher use of organic fertilisers and a higher

degree of nitrogen fixating crops in the crop rotation.

Nitrates in potable water are limited by the EU Drinking Water Directivev

to 50 mg/l because of risks to human health such as

methaemoglobinaemia (blue baby syndrome). The period between

leaching and appearance in the saturated zone of the aquifer depends

on geology and can exceed 40 years on sandstone and chalk but is

considerably less than this on more pervious rocks such as limestone.

2

Materials and methods

The present paper is based on own experiences from being project manager and having

provided technical expertise for around 25 projects to assist East European countries with

various aspects of agro-environmental issues in the period from 1994 till now, most of them

having the objectives to harmonize with or implement EU regulations or other international

conventions, here under the provisions of EU's Nitrate Directive. Examples of those projects

can be seen on the homepage for 6 of the projects, which in the period 1997 to 2001

developed improved/new manure standards and fertiliser norms for Baltic countries- the

homepage is seen on http://www.lr.dk/fertilising-baltic. This homepage does also include

presentation of the results of other projects, namely the Codes of Good Agricultural practices

for Baltic countries, Denmark and Poland.

Figure 2

Logo of the fertiliser normative projects.

3 Justification

Nitrates in waters can, as mentioned above be fatal for as well human and animal, here under

fish, and Figure 1 gives are rather good impression of how worried we should be for the quality

of the waters. EU water surveys reveal, that 20% of the monitoring stations in member states

shows values above 50 mg NO3/l. The reason for the high values is a result of several factors,

here under increased number of livestock (livestock density), increased use of mineral fertiliser

and larger herds.

3

Effect of animal density on N-balance

200

e

r

ha

y = 93,609x

150

p

g

R2 = 0,3052

,

K 100

N

of

lus

50

r

p

u

S

0

0

0,2

0,4

0,6

0,8

1

AU per ha

Figure 1

Calculated nitrogen balances at 17 Estonian farms for 2000 and 2001. Although

without statistical significance there is a clear tendency for correlation between

animal density and nitrogen balance.

Holland has according to Andrews (2001)vi a special big problem with the nitrogen balance

(Table 1), which is not surprising, considering the livestock density there. Livestock keeping

combined with bad manure management practices are the main reason for a high nitrogen

balance because the efficient uptake of nitrogen from manure in the crops varies from 0 to

around 75%.

Table 1

Average nitrogen balance in EU member states (Andrews, 2001).

The efficiency of the nitrogen in mineral fertiliser is higher and more stable, i.e. relatively

independent of management practices, namely around 80%. However, the bare rise in use of

mineral fertiliser through the last 50 years gives of course reason for a big increase in the

outlets to the nature, because 20% of nitrogen in mineral fertilisers used today is much more

than it was some years ago.

4

Figure 2

Use of mineral fertiliser in EU 15 member states.

Farm size effect on the N-balance

200

a

/

h 150

kg

ce, 100

a

l

a

n

-

b

50

y = 0,0254x

N

R2 = 0,3862

0

0

1000

2000

3000

4000

5000

6000

7000

Farm size, ha

Figure 3

Calculated nitrogen balances at 17 Estonian farms 2000 and 2001. Although

without statistical significance there is a clear tendency of highest balance at the

biggest farms.

5

Figure 4

Average nitrogen turnover on European farms (Andrews, 2001).

Countries in the former Soviet Union has a special problem with the nutrient balances on farms

although a) they have a very low livestock density for instance in Latvia around 0.1 AU per

ha, b) they have in general small herd sizes for instance in Lithuania 2 cows per cattle herd

in average, and c) they have a very small use of mineral fertiliser. The reason is that by the

livestock upon the collapse of the Soviet Union was spread on private farms without manure

stores and without any understanding of manure management practices.

Picture 1

Most of private farms emerged in the FSU has none or insufficient storage

capacity of livestock manure. Photo from Latvia.

Manure management practises were influenced by changed price relations in the FSU on big

farms where the livestock production was continued. On the pig production complex near

6

Pskov city in Russia the farm stopped to mix the slurry with peat for composting/storage and

they had problems to cover the price for spreading of the water diluted slurry on the fields and

started in stead to dump it in a nearby forest, creating a big slurry lake.

Picture 2

Part of slurry lake near Pskjovskij farm.

Picture 3

Surry lake near Pskjovskij farm.

Sileika (2002)vii has made the following figure, which document the special FSU problem

described above for Lithuania. Although the levels of NO3-N are low as compared to the EU

countries it is clearly demonstrated in Figure 5, that a substantial change happened when the

Soviet Union collapsed.

7

3,50

Agricultural rivers

3,00

Natural rivers

l 2,50

mg/

2,00

a

t

i

on,

tr 1,50

e

n

onc 1,00

C

0,50

0,00

1981 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001

Figure 5

Nitrate nitrogen (NO3-N) concentration in the rivers flowing through agricultural

and natural lands in Lithuania.

It should be noted, that there is an enormous inertia in the system of nutrient turnover in the

nature. Grimvall et al. (1997viii) has made a study that reveals, that the inertia of the system of

nutrient loss from land to sea is underestimated; the relatively rapid water quality response to

increased point source emissions and intensified agriculture does not imply that the reaction to

decreased emissions will be equally rapid; long-term experiments with fertilisation have shown,

that important processes in the large scale turnover of nitrogen operate on a timescale of

decades up to at least a century. In line with this the EU Commission writes in a status report

for implementation of the Nitrate Directive, that "it is emphasized, that there is a considerable

time lag between improvements at farm level and soil level and a response in waterbody

quality". The effects of the last 15 years agro-environmental policies and measures in EU will

therefore probably first give full response after several decades.

Picture 4

Simple lagoons like this provides a cheap way of storing livestock manure.

8

4

Brief history of agro-environmental policies

4.1

International agro-environmental policies

EU is the most interesting institution when it comes to agro-environmental policies. In the

following are mentioned some major milestones in the development of the present agro-

environmental policy:

· EU was established in 1957, based on the Rome Treaty. EU's environmental awareness

started in beginning of the 70'es with the elaboration of the 1st environment action program.

· A chapter on environment was included in the EU Treaty in 1986, which gave basis for

issuing of regulations in so far unanimously agreement in the European Council was

reached. Regulations that could be introduced would set a minimum standard for the

member countries that could have stronger rules themselves.

· UN organised the elaboration of the Brudtland Report in 1987:

Brundtland Report

In 1987 the Brundtland Report, also known as Our Common Future, alerted the world to the urgency of

making progress toward economic development that could be sustained without depleting natural

resources or harming the environment. Published by an international group of politicians, civil servants

and experts on the environment and development, the report provided a key statement on sustainable

development, defining it as:

· Development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future

generations to meet their own needs.

The Brundtland Report was primarily concerned with securing a global equity, redistributing resources

towards poorer nations whilst encouraging their economic growth. The report also suggested that

equity, growth and environmental maintenance are simultaneously possible and that each country is

capable of achieving its full economic potential whilst at the same time enhancing its resource base.

The report also recognised that achieving this equity and sustainable growth would require

technological and social change.

The report highlighted three fundamental components to sustainable development: environmental

protection, economic growth and social equity. The environment should be conserved and our resource

base enhanced, by gradually changing the ways in which we develop and use technologies.

Developing nations must be allowed to meet their basic needs of employment, food, energy, water and

sanitation. If this is to be done in a sustainable manner, then there is a definite need for a sustainable

level of population. Economic growth should be revived and developing nations should be allowed a

growth of equal quality to the developed nations

The term "Sustainable development" which we use so often today, comes from the

Brundtland Report, which is only 15 years old. Today "Sustainable development" is a

central issue in EU's development objectives.

Article 2 (ex Article B) of the Treaty of the European Unionix

The Union shall set itself the following objectives:

· To promote economic and social progress and a high level of employment and to achieve balanced

and sustainable development, in particular through the creation of an area without internal

frontiers, through the strengthening of economic and social cohesion and through the

establishment of economic and monetary union, ultimately including a single currency in

accordance with the provisions of this Treaty;

9

· To assert its identity on the international scene, in particular through the implementation of a

common foreign and security policy including the progressive framing of a common defence policy,

which might lead to a common defence, in accordance with the provisions of Article 17;

· To strengthen the protection of the rights and interests of the nationals of its Member States

through the introduction of a citizenship of the Union;

· To maintain and develop the Union as an area of freedom, security and justice, in which the free

movement of persons is assured in conjunction with appropriate measures with respect to external

border controls, asylum, immigration and the prevention and combating of crime;

· To maintain in full the acquis communautaire and build on it with a view to considering to what

extent the policies and forms of cooperation introduced by this Treaty may need to be revised with

the aim of ensuring the effectiveness of the mechanisms and the institutions of the Community.

The objectives of the Union shall be achieved as provided in this Treaty and in accordance with the

conditions and the timetable set out therein while respecting the principle of subsidiarity as defined in

Article 5 of the Treaty establishing the European Community.

· EU's Nitrates Directive was issued in 1991

· EU's CAP reform came in 1992, introducing cross compliance (subsidies for production

conditioned agro-environmental measures taken). When the CAP was reformed in 1992 it

was decided that the intensive production had some unwanted effect on the environment.

Therefore the so-called accompanying measures were introduced. It consisted of an

environmental scheme, a forestall scheme and an early retirement scheme for farmers.

According to the environmental scheme (Directive 2078/92) aid can be given to farmer who

for a period of at least 5 years reduce the use of pesticides and fertilisers, convert

agricultural land into grass-land or introduce organic farming or in other ways extensify the

production. The member states decided which of the measures they would introduce.

· The EU Maastricht Treaty, which came into force in 1993, made it possible to introduce

environmental regulations on basis of qualified majority (62 of 87 members) in the

European Parliament. The treaty introduces integration of environmental considerations in

all sectors.

· The Amsterdam Treaty of 1999 gives further the environmental issues a further focus,

without substantial changes in the principles for implementation of the policies.

· Agenda 2000 CAP reform: Greater consideration of environmental concerns and the

enhancement of an integrated rural development. The generalisation of the remuneration of well-

specified and monitored ecological services is considered as a more efficient instrument for the

protection of the environment than the mere application of cross-compliance conditions.

HELCOM and AGENDA 21 are to my mind not interesting when it comes to environmental

policies as their policies are based on especially EU policies. Sanctions and instruments to

implement decisions are rather limited, which also shows in the performance figures: There are

per 6. Marts 2002 134 valid HELCOM recommendations (the first being from 5 May 1980), and

only 23 of them are implemented (10 of the HELCOM recommendations deals with agriculture

but non of them are implemented!!).

4.2

Danish agro-environmental policies

The Danish Government issued already in 1987 the "National Nitrogen Management

Programme2", which in EU Nitrate Directives terminology an Action Programme stipulating

2

In Danish: "Vandmiljøplanen"

10

mandatory measures for the whole Danish territory. The goal was to reduce the outlet of

nitrogen from agriculture with 100,000 tonnes. The instruments were e.g.

· building of storage capacity for manure;

· fertiliser planning;

· green cover;

· requirements to nutrient efficiency;

· requirements to animal density;

· rules on spreading time for manure; etc.

All in all it seems as though EU's Nitrates Directive, which came 4 years after, was heavily

influenced by the Danish National Nitrogen Management Programme.

A National Nitrogen Management Programme II was launched in December 1998, sharpening

the requirements, for instance by introducing a 10% reduction of fertiliser norms from the

agronomy based recommendations, increasing the requirements to storage capacity for

manure, animal density on farms, utilisation of nutrients in the manure, etc.

5 Policy

instruments

Policies without instruments to carry them out are worthless. Basically there are two major sets

of instruments, which in popular terms can be characterised as "whips" or "carrots":

· The "whips" means measures, which have the goal to force decisions to be implemented,

i.e. regulations and standards, enforced by control units. One (principal) example is the

Nitrate Directive including its requirements for Code of Good Agricultural Practices,

vulnerable zones, mandatory measures, etc.

· "Carrots" means generally financial incentives, for instance subsidies. One

example is EU's LIFE program which supports the sustainable

development objectives of the EU with 640 million in the period 2000-

2004.

The effect of advice, training and information should, however, not be underestimated as

efficient instruments to carry through decided agro-environmental policies. An environmental

and economic interest goes hand in hand a long part of the way: Fertiliser planning, nutrient

balance calculations and soil sampling are examples of measures which are directly profitable,

while agro-environmental investments in storage capacity or improved spreading technology

require 50% subsidisation to be profitable for the farmers. It should also be noted that farmers

are much more happy to achieve environmental goals by own voluntary initiative than by

enforcement or financial support, the latter being affiliated with much administration and

creating envy in the society.

The basis for use of instruments have since the 70'ties been the EU environment action

programs. The present 6th environment action program sets the frames for the European

environment policies until 2010: Increasing awareness for the need to integrate environmental

policies in other sector policies: Agriculture, Transport, Business and Energy.

Examples of financial incentives to Danish farmers:

· 45%-50% support was given to establish storage capacity for manure

· The Danish Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Fisheries gives a financial support to farmers

who elaborate "green accounts" for their farms; the support is 805 per year if the farmer

makes the green accounts for at lest 5 years.

· Subsidies are given on basis of Directive 2078/92 see Table 2.

11

Table 2

Subsidies in connection with the Danish environment protection program.

Subsidies, DKK3/ha

Yield in spring barley, hkg/ha

< 45

45-60 60-70

> 70

60% N-fertilisation

500 625 850 950

Non-use of pesticides

600 650 700 700

Non-use of pesticides in zones

1,65 kr./m

Catch-crops in cereals etc.

750 900 1,100

1,300

Extensive management of permanent grassland, < 80 kg N/ha

815 1,115 1,415 1,500

Do, 0 kg N/ha

1,300 1,600 1,950 2,150

Set-aside

2.600

Set-aside in drinking water areas

2,780 3,500 4,500 5,000

Preservation of grassland and nature areas

200 - 2.300

Yield in spring barley, hkg/ha

u. 30

30 45

o. 45

Restoration of wetlands

1,500

3,175 / 3,275

3,275

6

Developing a Code of Good Agricultural Practices -

Harmonization with EU Legislation

The Danish Agricultural Advisory Centre was in 1997 contacted by Dr Torben Bonde, who was

then an employee of The Danish Environmental Protection Agency, the official Danish

representative of EU's Nitrate Commission as well as of a formal work group established by

HELCOM, the HELCOM PITF/Project Team on Agriculture. Dr Torben Bonde requested on

behalf of the HELCOM4 work group The Danish Agricultural Advisory Centre to assist Baltic

countries and Poland in their preparation of Codes of Good Agricultural Practices. The Danish

Agricultural Advisory Centre had already prepared projects within the agro-environmental

sector in those countries since 1994, and had therefore a good insight into the present

3

DKK 1.00 = 0.134

4

HELCOM: The Helsinki Commission - http://www.helcom.fi

12

legislation, institutional set-up etc. and soon project documents for Latvia, Lithuania and

Poland were produced and approved for funding from DANCEE5.

Denmark had with the launch of the National Nitrogen Management Programme in 1987

already decided to designate the whole territory as vulnerable zone (like later on Germany,

Austria, Luxemburg, Netherlands and Finland did), and has therefore with reference to article

3.5 of the Nitrate Directive no obligation to elaborate an official Code of Good Agricultural

Practices as the Action Programme covers the whole territory. Actually due to the National

Nitrogen Management Programme we did hardly feel in Denmark that EU's Nitrate Directive

was issued in 1991.

Anyway it was decided by Danish farmers' organisations, under which The Danish Agricultural

Advisory Centre belongs, to elaborate an unofficial Code of Good Agricultural Practices to

encourage farmers to raise standards even more; Danish agriculture exports 2/3 of the

production, and have always been dependent on a good product quality image, which today is

much associated with ethics standards of the production methods. The Danish Agricultural

Advisory Centre coordinated the elaboration of this voluntary Code of Good Agricultural

Practices, and of its up-date 2 years ago.

6.1 Methodology for elaboration of Codes of Good Agricultural

Practices

Handbooks and manuals are available on the Internet concerning elaboration of Code of Good

Agricultural Practices for instance Handbook for Implementation of EU Environmental

Legislationx. We did, however not find those guidelines useful. The main pre-conditions for a

successful CGAP development are the following:

· It shall be understood by the actors, that the elaboration of CGAP's require the

undertaking of a process of discussions, which can increase the perception of the subject

and try the arguments of own and opposite views.

· It is important to involve all stakeholders in a balanced discussion where both agricultural

and environmental interests are heard and considered.

· It is important to understand the code as an instrument, a political manifesto based on

agro-environmental facts, and that codes are a mix of recommendations and already

existing rules, here under also the importance of the designation of vulnerable zones.

CGAP's were elaborated in Poland, Latvia and Lithuania on basis of discussions in work

groups, where experts from authorities (ministries, etc.), education, science, advisory services,

and not at least farmers' organisations took part. The number of work group experts was 35-

60. The broad composition of the work groups ensured a very high degree of ownership to the

CGAP's among all stakeholders afterwards, and comforted both the dissemination of the

booklets with the CGAP's but especially of the messages contained in it. It is possible to

elaborate a CGAP as a work of a few scientists or ministry employees, but in that case the

CGAP will never be accepted by stakeholders, and difficult to disseminate.

6.2 Major difficulties for elaboration of Codes of Good Agricultural

Practices

The elaboration of Codes of Good Agricultural Practices is a very interesting work, but it will

only be successful if there are taken hand of the major difficulties:

· It shall be ensured any qualified discussion takes place on basis of (an understanding for

what is) a manure standard, and secondly on information on agricultural and environmental

5

DANCEE: Danish Cooperation for Environment in Eastern Europe see under

http://www.mst.dk

13

statistics. Most experts we have worked with did not know what a manure standard is, and

this is hampering the work, as the Nitrate Directive in its essence deals with livestock

manure. It also took many efforts to explain that manure standards must be expressed as

ex. storage values as the Nitrate Directive is concerned about the amounts of manure

coming to the fields.

· Most experts want to write lyrics, but this cannot be used in a Code of Good Agricultural

Practices. It is necessary to be precise and concrete if the codes shall give any meaning,

and if it shall be possible to implement (and control) in practice.

· Some experts want to neglect the existence of the EU Nitrates Directive and instead

discuss phosphorus.

· It is necessary to specify codes, that are voluntary, that are compulsory (based on existing

legislation) and that are not relating to the EU Nitrates Directive (if all types shall be

included in the Code of Good Agricultural Practices).

· It is necessary to write in a pedagogic language and with an appealing layout.

· It is necessary to exclude all non-relevant text.

· Balancing agricultural and environmental interests require a highly respected, unbiased

local project manager. The foreign project manager shall not be part of the negotiations.

Some main goals for any CGAP should be the following:

· It will be possible to elevate the CGAP or part hereof to national law without further elaboration.

· The provisions should therefore in general be presented in a pedagogic and transparent way -

calculation examples are good for understanding, and it must be ensured all relevant help tables

are present.

· There should be added practical guidelines for the farmers, such as reference to handbooks and

institutions that can provide information, training and advise on the touched subjects.

· A farmer should for his own farm and with help of the CGAP booklet be able to calculate 1) animal

units on his farm, 2) a fertiliser plan for each of his fields, and 3) the necessary storage capacity for

manure, here under for silage effluents and other liquid and solid substances that are stored

together with the manure.

The codes should be as short and precise as possible. They should also have the following

characteristics:

1. They

should

be

possible to implement in practise.

2. They

should

be

possible to control for implementation on the individual farm.

3. They

should

be

formulated in a way so it is easily understood whether they are

compulsory (based on legislation) or voluntary (recommendations).

4. They should be expected to have an environmental effect if they are implemented, and the

environmental effect should be possible to measure by environmental indicators.

5. They should be explained in plain language, without specific academic and technical

terms.

6. They should describe what the farmer should do or have to do, and not contain explanations,

guidelines and alike.

7. They

should

not contain adjectives like good, soon, shortly after and alike.

14

6.3 Examples of difficulties with formulation of codes

In the following are some examples from Lithuania, which shows how difficult it can be to

formulate codes. 2.12 is not a code but an explanation:

2.12

Perennial meadows and pastures protect the environment from pollution (especially those that

are located close to water bodies, in flooded places, in soils with high water level, and on very

steep slopes) and on the same time they are cheap and valuable fodder for animals.

3.12 is not concrete (it must be explained what soon is), and it is not based on present

legislation, but a HELCOM recommendation, that shall be transposed to Lithuanian law - in

stead of "have to" it should say "should":

3.12

Slurry and urine spread on bare soils have to be incorporated by effective measures such as

trailing hoses (trailing hoses does not incorporate slurry and urine into the soil!) or harrowing as soon

as possible after application. In crop fields urine has to be incorporated by special sprinklers

and if crop cover is thick then by drag hoses or other effective measures.6

Code 3.14 is not concrete - "most suitable technology" must be replaced with concrete

explanation of which technology there "should be" used (not has to as it is based on a

HELCOM recommendation), and the phrase "shall ensure higher fertiliser effectiveness

causing lowest negative effect on crops and environment" should be replaced with a "should

be" phrase and a precise statement about the fertiliser efficiency (for instance 50% utilisation

of N):

3.14

Farm has to choose the most suitable (available) fertiliser application technology that shall

ensure higher fertiliser effectiveness causing lowest negative effect on crops and environment.7

Code 4.10 includes a very specific academic and technical term "entomophylic" which should

be replaced by other words that explains the same, or followed by a list of these plants under

the code:

4.10

Plants that necessarily require pesticides should not be sown close to entomophylic plants that

have plenty of beneficial insects, pollinators, and close to territories of vulnerable environment,

i.e. water bodies, karstic pits, preserves, etc.

Alternative: There should be established a no-spray boundary zone towards entomophylic plants

that have plenty of beneficial insects and territories of vulnerable environment, i.e. water bodies,

karst pits, preserves, etc.

Code 4.14 is not possible to control in practise; it is not a code but an explanation:

6

4 HELCOM 1992 February 6. Recommendation 13/8. Reduction of ammonia emissions from

manure during field fertilisation

7

HELCOM 1992 February 6. Recommendation 13/9. Reduction of nitrogen, mainly nitrate, leaching

from agricultural land

15

4.14

Quality of spreading (or spraying) of crop fields with plant protection products is one of the main

requirements for good agricultural practice.

To make Code 4.14 correct (if we have understood the meaning of it), it should probably be

formulated as (but is it then overlapping with Code 4.3?):

4.14

Persons who spray field crops should have undergone a practical and theoretical training and

certification.

4.4 is probably not possible to implement on very many farms, as they can't reduce the use of

pesticides if they (as most farms) don't use any pesticides on beforehand:

4.4

In farm of good agricultural practice the amount of pesticides has to be reduced.8

We question the possibility to implement code 3.4. We are in doubt whether farmers will find it

economically justified analysing soil samples on a routine basis for "the amount of humus,

calcium, magnesium, sulphur and micro elements (boron, manganese, zinc, molybdenum,

copper and cobalt)", and to our professional knowledge we also question the relevance for

subsidisation of this:

3.4

It is necessary to analyse agrochemical characteristics of arable layer every five years at least in

order to regulate proper plant nutrition and soil fertility. The following characteristics have to be

investigated: pH, the amount of humus, mobile phosphorus and potassium, calcium,

magnesium, sulphur and microelements (boron, manganese, zinc, molybdenum, copper and

cobalt). (It is for practical farming not necessary to analyse soil samples for these things.)

i

Council Directive 91/676/EEC of 12 December 1991 concerning the protection of waters against

pollution caused by nitrates from agricultural sources

ii

The Implementation of Council Directive 91/676/EEC concerning the Protection of Waters

against Pollution caused by Nitrates from Agricultural Sources. Synthesis from year 2000

member States reports Report COM(2002)407.

iii

Council Regulation (EEC) No 2092/91 of 24 June 1991 on organic production of agricultural

products and indications referring thereto on agricultural products and foodstuffs

iv

Knudsen, Leif, Hans Spel ing Østergaard & Ejnar Schultz. 2000. Kvælstof et næringsstof og et

miljøproblem (In English: Nitrogen a plant nutrient and an environmental problem.)

Landbrugets Rådgivningscenter. Århus. 112 p.p.

v

Council Directive 80/778/EEC of 15 July 1980 relating to the quality of water intended for human

consumption

8 Council Directive 91/414/EEC, Commission Directive 93/71/EEC

16

vi

Andrews, K. 2001. Study on the impact of community environment water policies on

economic and social cohesion.

http://europa.eu.int/comm/regional_policy/sources/docgener/studies/pdf/enviwat.pdf

vii

Personal information from Dr. A. S. Sileika, Lithhuanian Institute of Water Management.

viii

Timescales of nutrient losses from land to sea - a European perspective. Grimvall, A. Stålnacke,

P, and Tonderski, A. Proceedings from "With river to the sea". 7th Stockholm Water Symposium

and 3rd International Conference on the Environmental Management of Enclosed Coastal Seas

(EMES). Stockholm 10 15 August 1997. 12 p.p.

ix

Treaty of the European Union - http://www.europa.eu.int/eur-

lex/en/treaties/dat/eu_cons_treaty_en.pdf

x

Handbook for Implementation of EU Environmental Legislation -

http://europa.eu.int/comm/environment/enlarg/handbook/water.pdf

17