1

Managing Lake Basins

2

Practical Approaches for Sustainable Use

3

4

(Final Report for GEF-Medium Sized Project: Towards a Lake Basin Management

5

Initiative)

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

Front and back covers to be a single, continuous stylized map of the world with lakes

54

indicated in their native languages. Logos on bottom.

55

1

Additional Front Matter will include:

2

3

Publication Data

4

List of Tables

5

List of Figures

6

List of Boxes

7

List of Acronyms and Abbreviations

8

Dedication?

9

10

Executive Summary (also to be published separately)

11

12

Back Matter will include several Appendices, a Glossary and a CD-ROM of Volume 2

13

(Experience and Lessons Learned Briefs) and Volume 3 (Thematic Papers). An electronic

14

copy of Volume 1 (this main report) will also be included on the CD. The CD will have a

15

search mechanism.

16

17

Draft Final Report: Not for Quotation or Citation

ii

1

Table of Contents

2

3

Table of Contents ........................................................................................... iii

4

Foreword ...................................................................................................... vii

5

Acknowledgements ........................................................................................ ix

6

Structure of the Report ................................................................................... xi

7

Section I. Understanding the Resource ............................................................1

8

Chapter 1: Biophysical Characteristics of Lakes ................................................3

9

Extent and Global Distribution of Lakes ............................................................... 3

10

Lakes and Their Basins ..................................................................................... 3

11

Characteristics of Lakes .................................................................................... 5

12

Long Retention Time ................................................................................... 5

13

Complex Dynamics ..................................................................................... 6

14

Transmissivity............................................................................................ 7

15

Chapter 2. Human Use of Lakes .......................................................................9

16

A Lake; its Development and Management ........................................................... 9

17

The Story of a Lake..................................................................................... 9

18

Commentary ........................................................................................... 10

19

Resource Value of Lakes and Lake Basins........................................................... 13

20

Typical Problems Facing the World's Lakes.......................................................... 15

21

Response to the Problems: Management Interventions......................................... 18

22

The Components of Lake Basin Management ...................................................... 19

23

Section II. Meeting the Governance Challenge................................................ 23

24

Chapter 3. Effective Institutions: Responding to Change ................................. 25

25

Institutions: Society's Response to Scarcity........................................................ 25

26

What are effective institutions? ................................................................... 25

27

A Typology of Institutional Forms for Lake Basin Management ............................... 26

28

Customary and self-regulated management .................................................. 26

29

Coordinating committee............................................................................. 27

30

Coordinating agency ................................................................................. 27

31

Executive (regulatory) agency .................................................................... 28

32

The Role of Local governments ................................................................... 28

33

Evolution of integrated lake basin management .................................................. 29

34

The governance framework for lake basin management ....................................... 30

35

The enabling environment .......................................................................... 30

36

Transparency and accountability.................................................................. 31

37

Customary rights...................................................................................... 31

38

The necessity of harmonization ................................................................... 31

39

Towards effective institutions........................................................................... 32

40

Chapter 4: Identifying Effective Policies: Incentives and Regulations .............. 33

41

A Not-so-simple Example ................................................................................ 34

42

Identifying Potential Policy Responses ............................................................... 35

43

Rules and Regulations--Command and Control Policies.................................... 35

44

Policies that Use Existing Markets................................................................ 37

45

Policies that Create Markets ....................................................................... 38

46

The Policy Matrix ........................................................................................... 39

47

Lessons of Past Experience: Increasing the chances for successful policy

48

implementation ............................................................................................. 43

Draft Final Report: Not for Quotation or Citation

iii

1

Policies, Policy Tools and Governance ................................................................ 45

2

Chapter 5: Involving People: Values, Education and Participation ................... 47

3

Who are the "People"? .................................................................................... 48

4

Farmers and Agriculturalists ....................................................................... 48

5

Business and Industry ............................................................................... 48

6

Youth ..................................................................................................... 48

7

Indigenous People .................................................................................... 49

8

Women ................................................................................................... 49

9

Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) ..................................................... 49

10

Local Governments ................................................................................... 49

11

Public Participation and Empowerment .............................................................. 50

12

Community-level Participation..................................................................... 51

13

Lessons Learned Regarding Public Participation ................................................... 51

14

Chapter 6. Technological Responses: Possibilities and Limitations .................. 55

15

Watershed-based Measures ............................................................................. 58

16

Wastewater Diversion................................................................................ 58

17

Conventional Wastewater Treatment (Primary and Secondary Treatment)........... 58

18

Advanced Wastewater Treatment (Tertiary Treatment) .................................... 59

19

Industrial Wastewater Treatment ................................................................. 60

20

Constructed Wetlands................................................................................ 61

21

Reforestation ........................................................................................... 62

22

In-Lake Measures .......................................................................................... 63

23

Predators ................................................................................................ 63

24

Biomanipulation ....................................................................................... 63

25

Biocides .................................................................................................. 64

26

Aeration.................................................................................................. 64

27

Freshwater Diversion into a Basin ................................................................ 64

28

Dredging................................................................................................. 65

29

Harvesting .............................................................................................. 66

30

Chapter 7. Informing the Process: The Role of Science and Monitoring............ 67

31

Information Needs for Lake Basin Management................................................... 67

32

Use of Scientific Information............................................................................ 67

33

Showing limits to a resource....................................................................... 68

34

Enlightening hard to see connections ........................................................... 68

35

Providing Innovative/Novel Approaches (to solve conflicts) .............................. 70

36

A Note on Modeling................................................................................... 70

37

"Non-use" of Science...................................................................................... 71

38

Value of Monitoring........................................................................................ 72

39

To assess baseline conditions...................................................................... 72

40

To assess effects of a policy........................................................................ 73

41

What to monitor....................................................................................... 73

42

A Note on Serendipity ............................................................................... 74

43

Sharing Information ....................................................................................... 74

44

Use of Indicators ...................................................................................... 74

45

Museums and Information Centers .............................................................. 75

46

Involving People ....................................................................................... 75

47

Organizing/Carrying out Science and Monitoring ................................................. 76

48

Resident Institutes.................................................................................... 76

49

Internationally funded programs ................................................................. 76

50

Fragmentation ......................................................................................... 76

51

How much information is enough? .................................................................... 77

52

Chapter 8. Mobilizing Sustainable Funding ..................................................... 79

53

The Decision Maker's Complaint ....................................................................... 79

54

Locally Generated Funds ................................................................................. 80

Draft Final Report: Not for Quotation or Citation

iv

1

User Fees................................................................................................ 81

2

Pollution Charges...................................................................................... 82

3

An independent source of funding? .............................................................. 83

4

The Principle of Cross-subsidization ............................................................. 84

5

Should people pay for "gifts of nature/basic human rights"? ............................. 84

6

The special case of the "poorest of the poor" ................................................. 85

7

National Funding ........................................................................................... 85

8

External Funding ........................................................................................... 86

9

The Special Case of the Global Environmental Facility (GEF) ............................. 86

10

External funding--necessary? sufficient?....................................................... 87

11

The Sustainability of External Funding, or, is there life after external funding?? ... 87

12

Practical Steps towards Securing Additional Funding ............................................ 88

13

Section III. Synthesis .................................................................................... 91

14

Chapter 9. Plans to Action: Integration of Planning Dimensions ...................... 93

15

Lake Basin Planning ....................................................................................... 93

16

A Framework for Analyzing Lake Basin Planning .................................................. 96

17

Integration of Management Interventions over Time and Space............................100

18

Integration by Encompassing.....................................................................100

19

Integration by Unification..........................................................................101

20

Integration by Broadening.........................................................................101

21

Integration Lessons ......................................................................................102

22

Integration should first take place where the pressures are greatest.................102

23

Integration should be phased over time .......................................................103

24

Integration should be pursued by necessity rather than integration by design ....103

25

Adaptive Management Planning.......................................................................103

26

Planning for Sustainable Lake Basin Management Institutions ..............................104

27

Planning for Lake Basin Governance.................................................................105

28

Chapter 10: Towards the Future ................................................................... 109

29

Reassessing Existing Lake Basin Management Programs ......................................109

30

Dealing With Roadblocks ................................................................................110

31

From Lake Basin Management Initiative to Global Lake Basin Governance ..............112

32

Toward Global Stakeholder Participation and Partnerships ...............................112

33

Toward Enhancement of the Global Lake Basin Management Knowledge Base ....112

34

Appendix A: Economics, Total Value, and Total Economic Value (TEV) ........... 113

35

The concept of Total Value and Total Economic Value (TEV) ..................................113

36

A With-project and Without-project Framework is Applied ...............................114

37

A Note of Caution ....................................................................................115

38

Summary: The Goal of an Economic Analysis ....................................................116

39

Appendix B: Project Details ......................................................................... 121

40

Key Organizations Involved in this Project.........................................................121

41

Objectives and Outcomes...............................................................................121

42

Lake Selection and Characteristics...................................................................122

43

Lake Briefs, Thematic Papers and Regional Workshops ........................................123

44

Website Clearinghouse and e-Forum ................................................................123

45

Steering Committee ......................................................................................123

46

Working Group Meetings ................................................................................123

47

Appendix C: List of Experience and Lessons Learned Brief and Thematic Paper

48

Authors ....................................................................................................... 124

49

Appendix D: Workshop Agendas and Participant Lists................................... 125

50

Appendix E: Summaries of 28 Project Lakes ................................................. 126

Draft Final Report: Not for Quotation or Citation

v

1

References.................................................................................................. 127

2

Glossary ..................................................................................................... 129

3

4

Draft Final Report: Not for Quotation or Citation

vi

1

Foreword

2

3

Lakes and reservoirs are vital to the economic development process. They contain about

4

90 percent of the earth's surface storage of liquid freshwater; are critical elements of the

5

earth's hydrological system; form vital ecosystems for aquatic biodiversity; and provide

6

livelihood and social, economic and aesthetic benefits that are essential for improving the

7

quality of life of the basin communities. Yet they have not received sufficient attention in

8

the global water policy discourse. Increasingly, human activities are profoundly impacting

9

their ecological integrity. Lakes are closed systems with relatively long retention times,

10

which can trap pollutants for extended periods. They have complex dynamics and

11

characteristics, and are particularly vulnerable to a range of anthropogenic stresses. The

12

science of limnology has improved considerably in the past few decades, but our

13

knowledge of how to effectively use science to inform public policy and the management

14

of lakes remains limited. To address the knowledge gap, the World Bank partnered with

15

the GEF, UNDP, UNEP, Ramsar Bureau, USAID, BNWPP, Shiga Prefecture, ILEC, LakeNet,

16

and lake stakeholders to implement a cooperative project to review lessons from the

17

experience of lake basin management at 28 lake basins around the world. Appendix B

18

summarizes the project's objectives, methodology, and implementation arrangements.

19

This report is a key output of the project.

20

21

This report builds on the World Lake Vision presented at the Third World Water Forum,

22

which highlighted key principles of lake basin management, and the recommendation of

23

the World Bank to develop a Lake Basin Management Initiative (see Ayres et al 1996). It

24

also supports the implementation of the World Bank's Environment Strategy and Water

25

Resources Sector Strategy. It is also an important contribution to practical approaches to

26

sustainable lake basin management, supporting the Millennium Development Goals

27

(MDG) on sustainable water resources management.

28

29

The project has produced four major benefits. First, it has focused on practical

30

lessons learned from lake basin management efforts around the world. Although much

31

work has been done to share scientific and technical experiences on lakes--as evidenced

32

by the number of international, government, and academic conferences and

33

publications--less attention has been devoted to analyzing the effectiveness of

34

alternative management approaches, including the policy, institutional, economic, and

35

social dimensions of lake management. A strong scientific knowledge base is critical to

36

sustainable management, but little has been done to draw practical lessons from the

37

implementation of water and environmental policies and institutional reforms, or from

38

involving people in lake basin management programs around the world. This report

39

directly addresses this gap and should help strengthen the human capacity for improved

40

lake and reservoir basin management at the local, basin, national, and global levels.

41

42

Second, the project has created new knowledge. It supported the preparation of lake

43

briefs focusing on experiences and lessons learned for 28 lakes from East, Central, and

44

South Asia; Eastern and Western Europe; Eastern, Central, and Southern Africa; and

45

North, Central, and South America. In addition, the project produced 17 thematic papers

46

on specific lake management issues. Additionally, knowledge was generated and shared

47

by more than 200 lake stakeholders and participants at the three regional workshops

48

held in Burlington, Vermont, USA in June 2003; in Manila, Philippines in September 2003;

49

and in Nairobi, Kenya in Novemb er 2003. Knowledge creation and sharing was also

50

supported by a project-implemented electronic forum that linked global stakeholders in

51

the review of the lake briefs, thematic papers, and this final report.

52

53

Third, the project fills an important gap in lake management experiences on tropical

54

lakes, saline lakes, and lakes in developing countries. A temperate zone bias was

55

avoided by the inclusion of many lakes from tropical, arid, and semi-arid regions. Further,

56

the project included a particular focus on lakes from developing countries where lessons

Draft Final Report: Not for Quotation or Citation

vii

1

have not yet been adequately synthesized or disseminated. Saline lakes are also included

2

in the project.

3

4

Finally, the report derives lake management lessons from internationally funded

5

projects, principally Global Environment Facility (GEF)-financed lake basin projects, as

6

well as lake projects financed by the World Bank and other agencies and governments.

7

Over the last decade, the GEF has provided the most significant financial support for lake

8

basin management projects through its three implementing agencies (World Bank, UNDP,

9

UNEP). The experience gained from the national and international lake projects reviewed

10

in this report has provided a wealth of new information from lake environments that have

11

not been studied well. The GEF has recognized that analysis and dissemination of past

12

lake basin management experiences will guide ongoing and future programs on these

13

lakes, as well as in other lakes and reservoirs.

14

15

At the broadest level, the report's intended audience includes communities, technical

16

staff and policymakers working on lake basin management, particularly the staff from

17

government and nongovernmental agencies, research and policy institutions, and funding

18

agencies. The report will be most useful to decision makers. This report also provides

19

guidance for the GEF, the World Bank, and other GEF implementing agencies such as

20

UNDP and UNEP for current and future lake basin management programs.

21

22

Draft Final Report: Not for Quotation or Citation

viii

1

Acknowledgements

2

3

This Main Report is a key output of the GEF Medium Size Project--Towards a Lake Basin

4

Management Initiative: Sharing Experiences and Lessons from GEF and Non GEF Lake

5

Basin Management Projects. The project was implemented by the World Bank and

6

executed by the International Lake Environment Committee (ILEC), with support from

7

LakeNet, between March 2003 and December 2004. The project was implemented as a

8

cooperative program supported by a partnership of multilateral and bilateral agencies,

9

local governments, non-governmental organizations, academic and research institutions,

10

individuals, and # resource persons and # stakeholders from 28 lake basins from Africa,

11

Asia, Europe, and Americas. Project implementation was supported by funds from the

12

GEF, USAID, and the government of Shiga Prefecture in Japan, the Bank Netherlands

13

Water Partnership Program, ILEC and the World Bank.

14

15

Project Implementation was led by Rafik Hirji of the World Bank and managed by

16

Masahisa Nakamura of ILEC. An international project Steering Committee consisting of

17

representatives from various organizations including Stephen Lintner, Chair (The World

18

Bank), Barbara Best (USAID), Peter Bridgewater (Ramsar Convention), Alfred Duda

19

(GEF), Sean Khan (UNEP) and Dann Sklarew (UNDP) provided overall guidance to project

20

implementation, and the preparation of the main report.

21

22

The ILEC and Lakenet Project Management Team and Secretariat also included Hiroya

23

Kotani, Genjiro Furukawa, Thomas Ballatore, Victor Muhandiki, Chiharu Uyama, and TBD

24

from ILEC, and David Barker, Lisa Borre and TBD from LakeNet. Richard Davis, Kisa

25

Mfalila, Sharon Esumei, Diane Flex, Robin Broadfield, Siree Malaise and Samson Kaber

26

from the World Bank supported data collection and project administration.

27

28

The 28 lake basin management briefs and 17 thematic papers on specialized topics

29

related to lake basin management formed other substantive outputs of the project. The

30

papers and the authors are listed in Appendix C and provided on the attached CD-ROM.

31

Additionally, Appendix D lists over 200 key stakeholders who reviewed the draft lake

32

briefs and thematic papers at three regional workshops for 12 lakes from Americas,

33

Europe and Central Asia held in Vermont, USA (June 2003), 8 lakes from East and South

34

Asia held in Manila, Philippines (September 2003) and 8 lakes from Eastern, Southern

35

and Central Africa held in Nairobi, Kenya (November 2003). These workshops were

36

organized with support from St. Michaels College in Burlington, Vermont, Laguna de Bay

37

Lake Development Authority in Manila, Philippines, and Pan-African START Secretariat in

38

Nairobi, Kenya. Regional co-ordination of the Lake Briefs was provided by Thomas

39

Ballatore of ILEC (Asian Lake Briefs), David Barker of LakeNet (North American, South

40

American and European Lake Briefs) and Victor Muhandiki of ILEC (African Lake Briefs).

41

Draft and final lake briefs and thematic papers and the main report were posted on the

42

project supported electronic forum for public comment. The final draft briefs for the 14

43

GEF supported lake basin management programs were also reviewed by the respective

44

implementing agency task managers.

45

46

The Main Report was prepared by a team, led by Masahisa Nakamura who served as

47

Senior Editor/Report Editor, and was composed of Thomas Ballatore, David Barker, Lisa

48

Borre, John Dixon, Walter Garvey, Victor Muhandiki, Masahisa Nakamura, James Nickum,

49

and Walter Rast. While working together as a team, each chapter had one or more lead

50

authors as follows: Chapter 1 (Biophysical Characteristics) Ballatore and Muhandiki;

51

Chapter 2 (Human Use of Lakes) Nakamura and Davis; Chapter 3 (Institutions) Nickum

52

and Nakamura; Chapter 4 (Policy) Dixon; Chapter 5 (People) LakeNet; Chapter 6

53

(Infrastructure) Ballatore, Chapter 7 (Role of Information) Rast and Ballatore; Chapter 8

54

(Financing) Dixon; Chapter 9 (Planning) Nakamura, Davis and Garvey; and Chapter 10

55

(Towards the Future) Garvey and Nakamura. Appendix A on Economics was prepared by

56

Dixon. Walter Rast and Richard Davis were the technical co-editors of the Report.

57

Draft Final Report: Not for Quotation or Citation

ix

1

Many others also contributed: TBD for preparation of maps; TBD for editing of the Lake

2

Briefs; TBD for Desk Top Publishing; TBD for production of the CD containing the Lake

3

Briefs and Thematic Papers. Add other acknowledgments as appropriate.

4

5

Preparation of the Main Report was supported by a series of Working Group Meetings of

6

the core team members and other lake basin stakeholders including Oyugi Aseto, Adelina

7

Santos-Borja, Eric Odada, Sonia Davila-Poblete and Sven Erik Jorgensen.

8

9

Michael Glantz from the National Center for Atmospheric Research and Nick Davidson

10

from the Ramsar Bureau peer reviewed the final report.

11

12

The Project Managers are very grateful to the funding agencies, steering committee

13

members, and all contributors including consultants, authors, reviewers, workshop

14

organizers and participants, and other supporters of the project and its outputs.

15

Draft Final Report: Not for Quotation or Citation

x

1

Structure of the Report

2

3

The report is organized in ten chapters under three sections. Section I includes two

4

chapters that provide the background for understanding the challenges facing lakes, and

5

their potential values and uses as a key resource for sustainable livelihoods and

6

development around the world, as well as for maintaining important life-supporting

7

ecosystems . Section II, with six chapters, forms the core of the report. It presents the

8

key lessons learned on the main themes of lake management from the 28 case studies

9

and 17 thematic papers: institutions, incentives and regulations, involving people,

10

technology, information, and financing. Section III, with the final two chapters, is a

11

synthesis of the report. The chapter on planning brings all the themes of Section II

12

together and discusses how lake basin management is carried out in practice. The final

13

chapter presents guidelines for taking action to improve the conditions of a lake and the

14

people and nature that both depend on it.

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

Chapter 1:

Chapter 2:

22

Section I:

Biophysical Characteristics

Human Use

Understanding the Resource

23

of Lakes

of Lakes

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

Chapter 3:

31

Institutions

32

33

34

Section II:

Chapter 4:

Chapter 5:

Chapter 6:

35

Meeting the

Incentives and

Involving People:

Technological

Governance Challenge

Regulations

Values and

36

Response

Participation

37

38

39

Chapter 7:

Chapter 8:

40

Information

Finance

41

42

43

44

45

46

Chapter 9:

47

Plans to Action

48

Section III:

49

Synthesis

50

Chapter 10:

51

Towards the

52

Future

53

54

55

56

57

Draft Final Report: Not for Quotation or Citation

xi

1

Draft Final Report: Not for Quotation or Citation

xii

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

Section I. Understanding the Resource

24

25

This section is comprised of two parallel chapters: the former (Chapter 1) discusses

26

biophysical aspects of lakes and the latter (Chapter 2) looks at how lakes are used and

27

how those uses have typically been developed and governed. Both chapters are written

28

with a prototypical lake in mind and we hope that the story told will resonate with people

29

everywhere. Taken together, these two chapters provide the background necessary to

30

understand the challenges facing lakes, and their potential values and uses, as a key

31

resource for promoting sustainable human livelihoods and development around the world,

32

as well as for maintaining important life-supporting ecosystems .

33

Draft Final Report: Not for Quotation or Citation

1

1

Chapter 1: Biophysical Characteristics of Lakes

2

3

Extent and Global Distribution of Lakes

4

5

Lakes are widespread and plentiful: considered collectively they contain more than 90%

6

of the available liquid freshwater on the earth's surface (Shiklomanov 1993). Although

7

there is no definitive count, there are at least several million lakes on the planet. Most

8

are small and often located in remote areas. Several hundred lakes are over 500 km3 in

9

surface area, however, making them major features of the global landscape.

10

11

Lakes are found on all continents of the world, even on Antarctica, which is home to

12

many saline surface lakes, and even some lakes buried under kilometers of ice (e.g.,

13

Lake Vostok). The distribution of lakes is governed primarily by variations in geology and

14

climate: geology in the sense that the land surface must contain a depression capable of

15

storing water; climate in the sense that there must be a balance between the amount of

16

inputs (precipitation) and outputs (evaporation, leakage to groundwater, outflowing

17

rivers) for the water to accumulate to large volumes. Where these two factor come

18

together most clearly, such as in the glacial deposit areas of North America and Europe,

19

lakes are hyper-abundant. Humans also construct artificial lakes by damming flowing

20

rivers. These reservoirs and impoundments are most often built in regions of the world

21

that lack substantial numbers of natural lakes, and are used primarily to address

22

recurring problems of water shortages (drought) or excesses (floods).

23

24

Lakes and Their Basins

25

26

Because of their unique properties, lakes occupy a significant niche in the global

27

hydrologic cycle, the means by which nature supplies water throughout our planet. A lake

28

is first and foremost a natural ecosystem, containing a large volume of water, and a

29

mixture of interacting living and non-living components. In fact, there is no way to

30

separate the influences of either component on the other.

31

32

A complete lake system, however, consists both of the depression in the land surface that

33

contains the water (the lake itself), as well as the land surface (drainage basin; see Box

34

1.1 on terminology) which surrounds the lake. Although water can also enter a lake from

35

underground sources (groundwater flow), the major water inputs are usually from

36

surface inflows (i.e. rivers, streams) and direct precipitation. The water entering a lake

37

from its drainage basin picks up and carries materials from the land to the lake, making

38

lakes good reflections of land-use and other human activities in their catchments.

39

40

The concept of the linkage between a lake and its surrounding drainage basin is of

41

fundamental importance in lake management. Problems with lakes can originate within

42

the lake itself (such as over-fishing), be transmitted to the lake from its upstream

43

drainage basin (such as agri-chemicals from irrigation areas), or in a few cases come

44

from outside the drainage basin (such as acid rain). Use of the lake's resources can also

45

impact on downstream communities. Thus, recognition of this fundamental interrelation

46

between the lake and its upstream and downstream drainage basin is an essential part of

47

effective lake management efforts. In this document, we will discuss the management of

48

the lake and its resources and so will focus on the lake and its upstream drainage basin,

49

as articulated in Principle 2 of the World Lake Vision (World Lake Vision Committee,

50

2003):

51

52

"A lake drainage basin is the logical starting point for planning and

53

management actions for sustainable lake use."

54

55

A further discussion on drainage basins, as well as an illustration of common types, is

56

illustrated in Boxes 1.1 and 1.2.

57

Draft Final Report: Not for Quotation or Citation

3

Box 1.1. Watershed, Catchment, or Basin?

Water somehow gets into a lake. In some cases, like Lake Victoria--a large, relatively shallow great lake--most

of the water enters as direct precipitation. For most lakes, however, the large majority of water enters as

precipitation runoff from surrounding land. For decision makers, what is happening on that surrounding land is

tremendously important because it has profound effects on the lake itself. Therefore, it is widely recognized

today that lake management cannot stop at the lakeshore but must extend to the surrounding land, and even

beyond in cases where atmospheric transport is important.

The problem is finding a common term for that surrounding land. Nowadays, several terms are used almost

interchangeably. The first is "catchment". The meaning is intuitive--the catchment is the area around a lake

that "catches" precipitation, which then drains to the lake (noting of course evaporation, evapotranspiration,

seepage to groundwater, etc. that occur along the way). A similar term is "drainage basin", which maintains the

intuitive flavor of "catchment"--namely, it is the area from which water "drains" to the lake. "Watershed" used

to mean the boundary between two catchments (or drainage basins!) but has become synonymous with the

catchment itself, not just the infinitely thin dividing line around the edge of the catchment. "Basin" literally is

like a wash basin--the area covered only by water--in this case, the lake itself. However, this use of the term is

not common among policy makers and "basin" too has come to be simple shorthand for "drainage basin".

Finally, "lake basin" is a drainage basin with a lake in it. Naturally there are catchments, drainage basins and

watershed without lakes in them; lake basins must have a lake to live up to their name!

This may seem quite confusing, but is actually simple--all the terms really mean the same thing--the land

surrounding a lake. In this report, we try to use "drainage basin" but all the terms are inevitably used at

different places in this report and in the lake briefs and thematic papers.

1

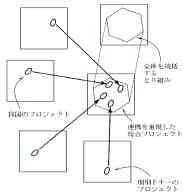

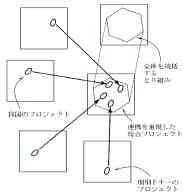

Box 1.2. Common Types of Drainage Basins

There are a wide variety of drainage basins types--each with profound effects for lake management and use.

Some of the more common types are illustrated below.

Closed Drainage Basin (endorheic basin)--A closed

basin with no water outlet (river, stream). Water

leaves the lake only through evaporation or seepage

to groundwater. This high rate of evaporation

generally leads to higher salinity (total ionic

concentration) in a lake. Thus, most lakes in closed

basins are either saline (total ionic concentration >3

g/L) or are becoming so. Examples of closed basin

lakes include the Aral Sea, and Lakes Chad and Issyk-

Kul.

Open Drainage Basin (exorheic basin)--An open

basin with a water outlet(s). Water leaves the lake by

one or more rivers, allowing ions (components of

salinity) to be flushed. Thus, the water remains

"fresh" (i.e., low salinity--drinkable). Most lakes in this

report are in open drainage basins. Examples are

Lakes Champlain, Constance and Dianchi.

Coastal Drainage Basin--A drainage basin with

flows to and from the ocean. Fresh water typically

enters the lake through rivers draining to it. The lake

Ocean

sometimes drains (via a river) to the ocean;

sometimes the ocean drains to the lake. This can lead

to complex salinity relationships. Examples include

Lake Chilika and, to a lesser extent, Laguna de Bay.

Draft Final Report: Not for Quotation or Citation

4

Mixed Flow Drainage Basin--A drainage basin with

flows that reverses depending on the season. In

contrast to a coastal lake, the flows typically come

from a freshwater river. This reversal of flow leads to

large fluctuations in lake water level and area. Tonle

Sap is an example of this type of lake. In this case,

the size of the lake's drainage basin is seasonal, since

the connecting river inflow is seasonal.

1

2

Characteristics of Lakes

3

4

The fact that the word "lake" is applied to such diverse waterbodies as Lake Baikal (1,637

5

m deep, 31,500 km2 of surface area, and 25 million years old) and Lake Baringo (2.5 m,

6

108 km2 of surface area, and a few thousand years old) indicates that, in spite of the

7

tremendous diversity of lakes around the world, they share some common characteristics.

8

These characteristics are examined below with the implications for management noted.

9

10

Long Retention Time

11

12

Rivers flow--lakes don't. Specifically stated, rivers are lotic (flowing water) whereas lakes

13

are lentic (standing water). Of course, that is an over-simplification--lakes have outlets

14

and their water is flushed, but the period of flushing is quite long, reaching over

15

hundreds of years for some lakes. This flushing period is called the retention time (or

16

hydraulic residence time) and is equal to the volume divided by the outflow. For most

17

lakes, the volume is so massive it dwarfs the flow, leading to long residence times. For

18

example, Lake Malawi contains around 18,400 cubic kilometers (km3) of water, but the

19

flow out of the lake (through rivers and evaporation) is just 66 km3 per year. With that

20

much water, Lake Malawi, like most other lakes, is a permanent feature of the landscape

21

on the human-time scale.

22

23

Long retention time has several important implications. One is that lakes are relatively

24

stable. Even in severe droughts, lakes still have some water in them: their large volumes

25

mask short-term variations. There are exceptions of course, usually of lakes in closed

26

basins like the Aral Sea, which is known to have dried up 3 times in the last 2 millennia.

27

Nevertheless, most lakes hold and can absorb large amounts of water, buffering both

28

floods and droughts. Acting as a "pool" of water, they present a flat surface allowing for

29

easy navigation. Additionally, long-retention time implies a slow rate of flow which allows

30

for more time (than in a river for example) for suspended materials to settle to the

31

bottom--this means that lakes act as sinks for many materials. Also, by simply being

32

around for a long time, they foster civilizations and can become symbols of a culture (like

33

rivers, of course).

34

35

Another implication is that long-term stability coupled with relative "isolation" provides

36

sufficient conditions for complex ecosystems to evolve in lakes. Just as islands can be

37

viewed as "islands of land in an ocean of water," lakes can be characterized as "islands of

38

water in an ocean of land." Both situations represent isolated ecosystems within which

39

area-unique biological communities can develop and evolve. Lake Malawi provides an

40

example of what millions of years of relative isolation, coupled with natural selection, can

41

accomplish--over 500 endemic (native) fish species exist in this lake. However, this

42

biodiversity can be rapidly destroyed, as demonstrated by the major loss of fish

43

community structure in Lake Victoria. This illustrates the important point that lake

44

ecosystems are very resilient when faced with stresses that have existed over

45

evolutionary-time scales but they are ext remely vulnerable to "new" stresses (usually

46

anthropogenic) that the ecosystem has never faced before.

47

Draft Final Report: Not for Quotation or Citation

5

1

Finally, and most importantly for management, once a lake is degraded, it takes a very

2

long time--if ever--to put things right. The implication is that before a decision is taken

3

that adversely affects a lake, one must be really sure that is a wise course to take

4

because turning back the clock is very hard, very costly, and often, just plain impossible.

5

The loss of fish species in Lake Victoria is a clear example; the long-term release of toxic

6

chemicals from sediment is another. Thus, the long retention time of lakes leads to lags

7

in response that makes them poorly matched to the human management timescale.

8

9

Complex Dynamics

10

11

In addition to long retention time, lakes are complex systems: what you put into a lake is

12

not necessarily what you get out. And what you get out depends on how much was put

13

in, when, and in what order. This complex response is termed "hysteresis" and is

14

illustrated in Figure 1.1.

15

16

D

C

*

*

Time

Plankton

Concentration

Time

*

B

A *

Nutrient Concentration

17

Figure 1.1. An example of complex dynamics of a lake.

18

19

Imagine a relatively pristine (oligotrophic) shallow lake lying at point A in Figure 1.1.

20

Nutrient concentration is quite low, so the concentration of plankton living in the lake (an

21

indicator of trophic state) is also low--there is not enough food to go around. As human

22

population around the lake grows and as incomes increase, nutrient loading to the lake

23

(and therefore concentration in the lake) inevitably increases, but the plankton

24

concentration increases only slightly (to point B), reflecting the ecosystem's natural

25

capacity to absorb external influences and neutralize them. Then, with only a slight

26

additional increase in loading, the lake ecosystem changes dramatically, with a sudden

27

increase in plankton density--often exhibited as an algal bloom (point C). The algal

28

bloom is an easy-to-see sign that something is going wrong in the lake and that uses are

29

being impaired; consequently, local people call on politicians to implement policies to

30

decrease nutrient loading.

31

32

Reducing the nutrient load requires changes in human behavior--that requires political

33

will--and like most things political, it only lasts until the next election. The difficulty for a

34

decision maker is that the lake cannot simply go from C back to B. There are likely to

35

have been irreversible changes to the ecosystem (in this case, phytoplankton have

36

replaced macrophytes as the dominant species), so the path is usually from C to

37

something like D. That means sacrifice over a long period without much to show for it,

38

i.e. plankton concentrations are still high; blooms are still occurring. That is a tough road

39

for a decision-maker to walk. Chapter 7 talks about the role of information and illustrates

40

how science can be used to find where a lake lies on the graph (between A and D).

41

Science can also offer shorter paths from C back to A through things like biomanipulation

42

and in-lake restoration methods.

43

Draft Final Report: Not for Quotation or Citation

6

1

The complex nature of lake ecosystems also gives rise to various indirect effects such as

2

biomagnification. Biomagnification refers to the increase in concentration

3

("magnification") of certain compounds in organisms ("bio") as one goes up the food

4

chain (i.e., as organisms at lower positions in the food chain are eaten by organisms at

5

higher positions in the chain). Compounds such as PCBs and dioxins are extremely

6

soluble in fat (lipophilic) and therefore remain in the bodies of organisms that consume

7

them. Those organisms may get eaten, indirectly transferring the lipophilic compound to

8

the predator. The Laurentian Great Lakes provide a good example of this phenomenon

9

(See Table 1.1). As shown in the table, the concentration of PCBs increases up the food

10

chain. This implies that organisms higher up the food chain (including humans) are

11

exposed to higher concentrations and therefore are at higher risk.

12

13

Table 1.1. Biomagnification of PCBs in the Laurentian Great Lakes

Organism

PCB concentration

(relative to conc. in phytoplankton)

Humans

?

Herring Gull Eggs

4960

Lake Trout (a large fish)

193

Smelt (a small fish)

47

Zooplankton

5

Phytoplankton

1

14

(Adapted from USEPA and Government of Canada, 1995)

15

16

Note that for a decision maker and any one eating Lake Trout (or Herring Gull Eggs!),

17

this is a real problem. It is ironic that while the lake's complex food chain makes

18

existence of valuable fish like the Lake Trout possible, the same complexity leads to

19

indirect effects like biomagnification that may make the fish dangerous to eat.

20

21

Transmissivity

22

23

Lakes integrate; they are the mixing pots of nature. They receive inputs from their

24

catchments (and beyond), mix the inputs together, transform them and spread them out

25

again. Additionally, fish, water and even pollution are able to move around more or less

26

freely in all directions. This property--transmissivity--is the third key characteristic of

27

lakes.

28

29

One important implication of transmissivity is that a problem at a lake is shared by most

30

users. Rivers provide a simple counter-example: pollution at one point in a river

31

immediately flows downstream, often leading to a disconnection between those causing

32

the pollution and those affected by it. This can result in upstream-downstream conflict.

33

The transmissive nature of lakes means that one user's effect on another is spatially

34

spread out and shared, including by the original user. This is very similar to global

35

warming: the effects of one person's emission of greenhouse gases are felt by all,

36

including the emitter.

37

38

Another implication of transmissivity is that most uses of lakes (see Chapter 2 for a full

39

description) are non-excludable; that is, it is costly to exclude users from accessing a

40

given lake resource. As Box 1.3 describes, when access to resources is costly to control,

41

open access is the default regime. This is not desirable because open access, combined

42

with human nature, invariably leads to overuse and destruction of the resource base. It is

43

important to note that this physical property of lakes--transmissivity--profoundly affects

44

a social issue--how the use of lake resources is managed.

45

46

Overall, these three defining characteristics--long retention time, complex dynamics, and

47

transmissivity--when taken together, make lakes what they are: beautiful, valuable,

48

complex, but also vulnerable and difficult to manage. Lessons learned on how societies

49

govern resource use--how they control access to various lake resources--is the

50

remainder of this report.

51

Draft Final Report: Not for Quotation or Citation

7

1

2

Box 1.3. Some "common" terms and their meaning: common-pool resources, common property and

the commons.

Most readers have likely heard of the "tragedy of the commons", an idea made popular by a 1968 article in

Science by Garrett Hardin. This article captured the spirit of the times and has gone on to trigger a massive

research effort on environmental management. The problem is that the term "commons" used by Hardin was

misleading because it is often assumed to refer to common property; however, Hardin's main point was that

open access to resources usually leads to overexploitation, something shown clearly in the lake briefs. To

avoid confusion, we define below some terms used in this report.

Common-pool resources are resources for which one person's use takes away from another's use and for

which it is hard to exclude other users. The table below compares common-pool resources against other types

of resource by examining two characteristics: rivalry and excludability. Rivalry (also sometimes called

subtractability) means that one person's use of a resource subtracts from the amount available to other users

(e.g. someone catching fish reduces the amount someone else can catch--at least over the short-term). For

non-rival goods, one person's use does not affect another's (e.g. everyone can enjoy the climate-moderating or

aesthetic benefits derived from a lake). Excludability refers to the cost of controlling someone's access to a

resource. Non-excludable goods have a positive cost for restricting access.

Excludable

Non-excludable

Rival

Private good Common pool resource

Non-rival Club good

Public good

Many of the resources provided by lakes are common-pool; good examples are fishing, water extraction, and

the use of the lake as a sink for pollutants. Some uses like flood control are public goods. For almost all uses, it

is costly (but socially desirable) to exclude users.

Access to a given resource of a lake can either be open (open access) or closed (private, common, or

government property). Common property is a type of institution that gives the rights of use of a resource to a

defined group. That group usually has rules specifying how the group's members can use the resource. Lake

Naivasha is an excellent case of a riparian group (Lake Naivasha Riparian Association) using the lake as

common property. Private property and government (public) property are also widespread ways that societies

have developed to control access to "open access" resources.

The stand-alone term "commons" is often used as short hand for either common-pool resources or for

common property, often leading to confusion about what is being discussed (i.e. the nature of the resource or

the type of property regime governing its use?). Some may think of the "commons" as a shared, public

resource often with no control over access.

Overall, it is important to clearly distinguish between the characteristics of a resource and the characteristics of

the management regime governing use of the resource. Also, one must note that a lake may provide various

resources, each with different characteristics, but many sharing a common-pool or public good nature.

Therefore, it is misleading to speak of a lake, as a whole, as a common-pool resource: it is clearer to specify

which use of the lake is being referred to.

3

4

Draft Final Report: Not for Quotation or Citation

8

1

Chapter 2. Human Use of Lakes

2

3

A Lake; its Development and Management

4

5

The Story of a Lake

6

7

People settled around the lake shore many millennia ago. While the population was low,

8

the resources that it offered were abundant and there was little conflict between different

9

settlements over use of these resources. The fish caught by one community did not

10

seriously impair the ability of another community to obtain fish; the water drawn for

11

domestic use did not noticeably lower the lake level. But, as the lake's population

12

increased, some of these resources came under pressure. This happened first with the

13

fish. Following some years of low rainfall, fish catches began to decline and those fish

14

that were caught were smaller than before. The more experienced fishermen realized

15

that this was because the wetlands were not being flooded and the fish could not breed

16

successfully. Conflicts started to break out between different communities about access

17

to the best fishing grounds. Fortunately, the rains returned before these conflicts became

18

unmanageable, the breeding grounds became available and the fish populations

19

recovered.

20

21

Nevertheless, the incident caused the leaders of the fishing communities to agree on

22

some rules of access to fishing grounds that would reduce tensions. Each community had

23

the right to send only a specific number of boats to these areas. Also the wetlands were

24

agreed to be off limit during the period when they were flooded and the fish were

25

spawning. Any transgressors would be judged by an assembly of the leaders of the

26

lakeshore communities with those found guilty being banned from fishing and even

27

expelled from their community.

28

29

A more difficult problem arose many years later with the influx of a group of farming

30

families into the catchment feeding into the lake. As they prospered and grew, these

31

families cleared increasing areas of land. The land began to erode during the wet season

32

and the wetlands at the entrance to the lake began to silt up. Again fish breeding was

33

interrupted and fish numbers began to decline. However, the farmers did not accept the

34

claims of the fishing communities that they were causing the siltation of the wetlands.

35

They believed that the rivers were always silty during the wet season and that the

36

decline in fish catch was nothing to do with them. Although this caused bad blood

37

between the farmers and fisherfolk, it did not lead to violence because other fish

38

breeding grounds were still operating and the fisherfolk were able to compensate by

39

moving further offshore, and building fish traps and fish ponds. Nevertheless, a distance

40

developed between the two groups that was never bridged and to a large extent they led

41

separate lives.

42

43

Over time, the lakeshore communities expanded into towns. The town people, while not

44

relying directly on fishing for their incomes, continued to identify with the lake. They

45

were proud of its scenery, enjoyed its waters for recreation and used it for easy transport

46

of their goods to other destinations. They also used it to dispose of their wastes. Rubbish

47

was dumped in creeks to be eventually flushed into the lake. To keep up with the

48

amenity offered by other towns throughout the country, the local council installed

49

sewage removal and primary treatment of the effluent to remove the worst of the

50

organic matter. The resulting effluent was then disposed of in the lake at a convenient

51

distance from the town.

52

53

A major expansion of the region occurred many years later when the national

54

government decided to develop a large irrigated cotton growing area upstream of the

55

lake to take advantage of increasing European demand for cotton. The development was

56

widely welcomed by the region's business interests (they had lobbied strongly for it), and

57

the town councils were briefed on the plan and endorsed it. Of course, the land had to be

Draft Final Report: Not for Quotation or Citation

9

1

expropriated from the farmers who had settled there many generations earlier but, in

2

compliance with national laws, the government intended to provide them with alternative

3

agricultural land some days travel away. Many of the town people and the fisherfolk were

4

uneasy about this development but had no means of finding out much about it, let alone

5

influencing it. They felt little solidarity with the farming communities and actually felt

6

quite relieved when the irrigation area went ahead. New, wealthier farmers appeared and

7

the old groups were moved away.

8

9

At first the new irrigation area appeared to cause no problem. The region prospered with

10

the additional income and the towns grew rapidly to provide necessary services. A

11

government agriculture office was opened in the major town and many new people

12

arrived to take advantage of the employment opportunities in the irrigation area.

13

14

However, after some decades problems started to appear in the lake. Dense mats of

15

weeds began to grow around the mouths of the town creeks and spread into the boat

16

harbours. Waterweeds even began to appear near the fish pens. Since the region had

17

long ceased to be dependent on the fishing industry, this was seen more as a nuisance

18

than a major problem by many people. In fact, some entrepreneurial women harvested

19

the weeds to use for weaving. More alarmingly to most people, the water near the towns

20

quite quickly and unexpectedly turned dirty and had a musty smell. Many of the

21

townspeople, particularly the older residents who remembered the beauty of the lake

22

when they were younger, were seriously upset and complained to the town council. The

23

fishermen were also worried, but for a different reason. They had trouble launching their

24

boats through the weeds and they had trouble selling their fish because of the

25

widespread perception that the fish were dirty and tasted bad.

26

27

There was a strong local opinion that the problem was caused by the upstream irrigators

28

although the government officials in the Agricultural office claimed that it was nothing to

29

do with their industry and that the problem resulted from the expansion of the towns.

30

Under pressure, the government promised to upgrade the sewage treatment plant for the

31

town to remove nutrients from the sewage since this could be completed within three

32

years. They also promised to launch a scientific investigation into the causes of the

33

problem.

34

35

Commentary

36

37

This story, while only a microcosm of all that can occur in lakes, illustrates many

38

important features of lakes and their management. It shows that:

39

·

At the broadest level, lakes provide a variety of uses or values to people and

40

these values change over time, from initial subsistence values through to later

41

aesthetic and cultural values;

42

·

There are potential limitations on the use of these resources as the demand for

43

them increases--this can appear as simple over-exploitation of fish, or as a more

44

subtle overuse of the lake's capacity to absorb wastes;

45

·

Competition for these resources intensifies and authorities--sometimes local

46

leadership groups, sometimes more distant governments--intervene to resolve

47

conflicts;

48

·

Rules of behavior are discussed and agreed, and structures (councils,

49

government departments) are established to administer and apply these rules;

50

·

Uncertainty is central to management; unpredictable natural variations in rainfall

51

can cause problems; some conflicts are not neatly resolved; there are different

52

views about the causes of eutrophication; etc;

53

·

Knowledge, both local experience (e.g. the importance of fish breeding areas)

54

and scientific knowledge can play a central role in making management more

55

effective;

Draft Final Report: Not for Quotation or Citation

10

1

·

Lakes are not worlds unto themselves. The difficulty of managing lakes without

2

involving groups from the upstream catchments, for some problems, is

3

illustrated by the siltation problem;

4

·

Also the importance of influences from outside the region is illustrated by the

5

effect that international markets had on development of the irrigation area;

6

·

The choices that a decision maker faces are heavily constrained by other

7

developments--the town's sewage treatment system was originally introduced

8

for aesthetic and sanitary reasons, and subsequent actions to reduce nutrient

9

loading to the lake had to take account of the existence of this point nutrient

10

source; and,

11

·

Finally, the need for a coordinated, planned approach to take account of these

12

linked influences so that the overall benefits are maximized is hinted at.

13

14

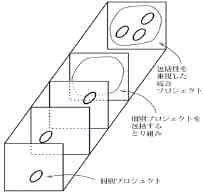

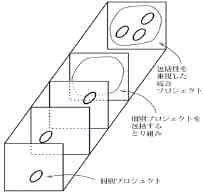

This story is also shown in diagram form in Figure 2.1. The upper part of the figure

15

shows the change in values supplied by the lake and its catchment over time. During the

16

expansion phase there is a steady increase in values as an increasing number of

17

resources are used--fish, water supply, transport, aesthetic enjoyment, recreation, etc.

18

19

Two development interventions, the introduction of improved fishing techniques (D1) and

20

the introduction of irrigated agriculture (D2), lead to significant increases in the values

21

extracted from the lake basin. At the same time (lower part of the figure) there is a

22

gradual deterioration in the state of the lake from the side effects of these and other

23

developments. At some point (V1) this deterioration in the lake's environment--

24

increasing nutrient levels, spread of weeds and algae, unsightly and smelly water--begins

25

to affect the value of the resources that can be extracted from the lake and overall

26

production plateaus and then begins to decline (V2). Remedial actions (C1) such as

27

upgrading of sewage treatment plant and the ban on use of phosphate-based detergents

28

lead to improvements in water quality and the values extracted from the lake increase

29

again. While there are cases in which the degradation of lake environment is small and

30

the response to the restoration efforts is rapid, most often, the degradation may turn out

31

to be more extensive than expected and the restoration efforts may prove to be

32

extremely costly and time-consuming (R1), if not impossible (R2). The management

33

authorities and the communities often do not have the resources to invest in

34

conservation/remediation interventions (either structural or non-structural) to the point

35

where the lake returns to pristine conditions. Nevertheless, at the end of the story, the

36

communities may be better off than they were at the beginning.

37

38

While the above story illustrates many important features of lakes and their management,

39

each lake possesses unique features, as is shown in the 28 lakes briefs. Each lake has its

40

own set of resources values, its own set of problems and its own set of potential

41

management actions. In the above story, the government accepted that the town sewage

42

was the most likely cause of the algae and aquatic weeds and agreed to invest in

43

remedial upgrade works because of the high value the townspeople placed on a clean and

44

enjoyable lake. In other towns, it is possible that the townspeople would not have the

45

same pride in their lake and would rather see the funds spent on further development

46

investments. Such judgments depend on the values that people place on the resources of

47

each lake, the physical characteristics of each lake that lead to biophysical manifestations

48

of problems, and the socio-political characteristics of the decision processes for each lake.

49

50

Draft Final Report: Not for Quotation or Citation

11

1

V1: Gradual

deterioration

D2:

of resource

More

Development

value

intervention 2

V2: Sharp

decline in

resource

D1:

value

Development

intervention 1

Resource

value

C1

D2

D1

C1:

Conservation/

remediation

intervention

Less

Time

Better

E1: Gradual

R2: Full

deterioration of

restoration is

D1

environment

rarely possible

State of

lake

environme

D2

E2: Prolonged

state of

degradation

C

R1: Recovery

1

is slow

Worse

Time

2

Figure 2.1. Changing resource value through development and conservation/remediation

3

interventions.

4

5

Draft Final Report: Not for Quotation or Citation

12

1

Resource Value of Lakes and Lake Basins

2

3

The wide range of uses of lakes and their catchments are amply shown in the 28 lakes

4

briefs. These various uses all contribute to the total value of the lake. Among the uses

5

cited are the following:

6

7

· "...direct use of the lake for fisheries in net present value terms ... is then some

8

PhP30.5 million" (Laguna de Bay).

9

· "...a potential source of water supply for Northeastern Estonia and the Estonian

10

capital Tallinn" (Lake Peipsi).

11

· "...provides water supply for domestic (in the dry years), and industrial and

12

agricultural uses" (Lake Dianchi).

13

· "...biodiversity offers a resource base for tourism attraction" (Lake Baringo).

14

15

Many lakes also provide valuable services to nature, such as serving as habitats for

16

aquatic fauna and flora. These services are also part of the total value of lakes and their

17

basins. One such service is the provision of genetic materials, e.g., for improving fish

18

strains used in aquaculture. Another such service is as regulator of extreme hydrologic

19

events such as floods and droughts.

20

21

The value of lake water and the resources in the lake-basin ecosystem can be divided

22

into "use" and "non-use" values, the terms that are typically used by economists to

23

divide the totality of the goods and services from any resource.

24

25

Use values are divided into direct use and indirect use values. Direct use values are those

26

that come directly from using various parts of the lake ecosystem. These include

27

both "consumptive" uses and "non-consumptive" uses. Consumptive uses are those that

28

occur when the user actually consumes the resource (e.g. catching fish or waterfowl,

29

harvesting of reeds and other plants, diversion of water for human use or irrigation). This

30

categorization of types of values from lakes is shown in Figure 2.2.

31

Total Economic Value

Use Values

Non-use Values

Direct Values

Indirect

Option

Bequest

Consumptive

Values

Values

Values

and non-

Ecosystem

Premium

Benefits for

consumptive

functions and

placed on

future

use of

services

possible future

generations

resources

uses

Existence Values

"Knowing that it is

there..."

32

33

Figure 2.2. Categories of Uses of Lake Resources

34

35

Lake fishermen in the story were engaging in a consumptive, direct-use of the lake's

36

resources. A key point about consumptive uses is that use by one person reduces the

37

amount available for others to use, called `rivalry' by economists (see Box 1.3 for further

Draft Final Report: Not for Quotation or Citation

13

1

discussion). In contrast, non-consumptive direct uses do not reduce the amount of the

2

resource available to others. Non-consumptive uses include certain types of recreation,

3

aesthetic and amenity values, or general ecosystem services. The later residents of the

4

town who enjoyed the aesthetics of the lake were engaged in non-consumptive, direct

5

use of the lake resource. Boating and sailing are also non-consumptive, direct uses. In

6

these cases the "users" does not actually consume the resource, or reduce the

7

availability of the resource for other users.

8

9

Of course, in the extreme, you can have so many people using the lake in a non-

10

consumptive, direct use manner that congestion sets in and crowding can reduce the

11